The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago during Oct. 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly 3.3 square miles (9 km2) of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left more than 100,000 residents homeless.

The fire began in a neighborhood southwest of the city center. A long period of hot, dry, windy conditions, and the wooden construction prevalent in the city, led to the conflagration. The fire leapt the south branch of the Chicago River and destroyed much of central Chicago and then leapt the main branch of the river, consuming the Near North Side.

Help flowed to the city from near and far after the fire. The city government improved building codes to stop the rapid spread of future fires and rebuilt rapidly to those higher standards. A donation from the United Kingdom spurred the establishment of the Chicago Public Library.

The fire is claimed to have started at about 8:30 p.m. on Oct. 8, in or around a small barn belonging to the O’Leary family that bordered the alley behind 137 DeKoven Street. The shed next to the barn was the first building to be consumed by the fire. City officials never determined the cause of the blaze but the rapid spread of the fire due to a long drought in that year’s summer, strong winds from the southwest, and the rapid destruction of the water pumping system, explain the extensive damage of the mainly wooden city structures.

There has been much speculation over the years on a single start to the fire. The most popular tale blames Mrs. O’Leary’s cow, who allegedly knocked over a lantern; others state that a group of men were gambling inside the barn and knocked over a lantern. Still other speculation suggests that the blaze was related to other fires in the Midwest that day.

The fire’s spread was aided by the city’s use of wood as the predominant building material in a style called balloon frame. More than two-thirds of the structures in Chicago at the time of the fire were made entirely of wood, with most of the houses and buildings being topped with highly flammable tar or shingle roofs.

All of the city’s sidewalks and many roads were also made of wood.[6] Compounding this problem, Chicago received only 1 inch (25 mm) of rain from July 4 to Oct. 9, causing severe drought conditions before the fire, while strong southwest winds helped to carry flying embers toward the heart of the city.

In 1871, the Chicago Fire Department had 185 firefighters with just 17 horse-drawn steam pumpers to protect the entire city. The initial response by the fire department was timely, but due to an error by the watchman, Matthias Schaffer, the firefighters were initially sent to the wrong place, allowing the fire to grow unchecked. An alarm sent from the area near the fire also failed to register at the courthouse where the fire watchmen were, while the firefighters were tired from having fought numerous small fires and one large fire in the week before. These factors combined to turn a small barn fire into a conflagration.

When firefighters finally arrived at DeKoven Street, the fire had grown and spread to neighboring buildings and was progressing toward the central business district. Firefighters had hoped that the South Branch of the Chicago River and an area that had previously thoroughly burned would act as a natural firebreak.

All along the river, however, were lumber yards, warehouses, and coal yards, and barges and numerous bridges across the river. As the fire grew, the southwest wind intensified and became superheated, causing structures to catch fire from the heat and from burning debris blown by the wind. Around midnight, flaming debris blew across the river and landed on roofs and the South Side Gas Works.

With the fire across the river and moving rapidly toward the heart of the city, panic set in. About this time, Mayor Roswell B. Mason sent messages to nearby towns asking for help. When the courthouse caught fire, he ordered the building to be evacuated and the prisoners jailed in the basement to be released.

At 2:30 a.m. on the 9th, the cupola of the courthouse collapsed, sending the great bell crashing down. Some witnesses reported hearing the sound from a mile (1.6 km) away.

As more buildings succumbed to the flames, a major contributing factor to the fire’s spread was a meteorological phenomenon known as a fire whirl. As overheated air rises, it comes into contact with cooler air and begins to spin, creating a tornado-like effect. These fire whirls are likely what drove flaming debris so high and so far. Such debris was blown across the main branch of the Chicago River to a railroad car carrying kerosene.The fire had jumped the river a second time and was now raging across the city’s north side. Despite the fire spreading and growing rapidly, the city’s firefighters continued to battle the blaze. A short time after the fire jumped the river, a burning piece of timber lodged on the roof of the city’s waterworks. Within minutes, the interior of the building was engulfed in flames and the building was destroyed. With it, the city’s water mains went dry and the city was helpless. The fire burned unchecked from building to building, block to block.[citation needed]

Finally, late into the evening of Oct. 9, it started to rain, but the fire had already started to burn itself out. The fire had spread to the sparsely populated areas of the north side, having consumed the densely populated areas thoroughly.

Once the fire had ended, the smoldering remains were still too hot for a survey of the damage to be completed for many days. Eventually, the city determined that the fire destroyed an area about 4 miles (6 km) long and averaging 3⁄4 mile (1 km) wide, encompassing an area of more than 2,000 acres (809 ha).

Destroyed were more than 73 miles (117 km) of roads, 120 miles (190 km) of sidewalk, 2,000 lampposts, 17,500 buildings, and $222 million in property, which was about a third of the city’s valuation in 1871.

On Oct. 11, 1871, General Philip H. Sheridan came quickly to the aid of the city and was placed in charge by a proclamation, given by mayor Roswell B. Mason:

“The Preservation of the Good Order and Peace of the city is hereby intrusted to Lieut. General P.H. Sheridan, U.S. Army.”

To protect the city from looting and violence, the city was put under martial law for two weeks under Gen. Sheridan’s command structure with a mix of regular troops, militia units, police, and a specially organized civilian group “First Regiment of Chicago Volunteers.” Former LieutenantGovernor William Bross, and part owner of the Tribune, later recollected his response to the arrival of Gen. Sheridan and his soldiers:

“Never did deeper emotions of joy overcome me. Thank God, those most dear to me and the city as well are safe.”

General Philip H. Sheridan, who saved Chicago three times: the Great Fire in October 1871, when he used explosives to stop the spread; again after the Great Fire, protecting the city; and lastly in 1877 during the “communist riots,”riding in from 1,000 miles away to restore order.

For two weeks Sheridan’s men patrolled the streets, guarded the relief warehouses, and enforced other regulations. On October 24 the troops were relieved of their duties and the volunteers were mustered out of service.

Of the approximately 324,000 inhabitants of Chicago in 1871, 90,000 Chicago residents (1 in 3 residents) were left homeless. 120 bodies were recovered, but the death toll may have been as high as 300. The county coroner speculated that an accurate count was impossible, as some victims may have drowned or had been incinerated, leaving no remains.

In the days and weeks following the fire, monetary donations flowed into Chicago from around the country and abroad, along with donations of food, clothing, and other goods. These donations came from individuals, corporations, and cities. New York City gave $450,000 along with clothing and provisions, St. Louis gave $300,000, and the Common Council of London gave 1,000 guineas, as well as £7,000 from private donations. In Greenock, Scotland (pop. 40,000) a town meeting raised £518 on the spot.[16] Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Buffalo, all commercial rivals, donated hundreds and thousands of dollars. Milwaukee, along with other nearby cities, helped by sending fire-fighting equipment. Food, clothing and books were brought by train from all over the continent. Mayor Mason placed the Chicago Relief and Aid Society in charge of the city’s relief efforts.

Operating from the First Congregational Church, city officials and aldermen began taking steps to preserve order in Chicago. Price gouging was a key concern, and in one ordinance, the city set the price of bread at 8¢ for a 12-ounce (340 g) loaf.

Public buildings were opened as places of refuge, and saloons closed at 9 in the evening for the week following the fire. Many people who were left homeless after the incident were never able to get their normal lives back since all their personal papers and belongings burned in the conflagration.

After the fire, A. H. Burgess of London proposed an “English Book Donation”, to spur a free library in Chicago, in their sympathy with Chicago over the damages suffered.Libraries in Chicago had been private with membership fees. In April 1872, the City Council passed the ordinance to establish the free Chicago Public Library,

starting with the donation from the United Kingdom of more than 8,000 volumes. The fire also led to questions about development in the United States. Due to Chicago’s rapid expansion at that time, the fire led to Americans reflecting on industrialization. Based on a religious point of view, some said that Americans should return to a more old-fashioned way of life, and that the fire was caused by people ignoring traditional morality. On the other hand, others believed that a lesson to be learned from the fire was that cities needed to improve their building techniques. Frederick Law Olmsted observed that poor building practices in Chicago were a problem: Chicago had a weakness for “big things,” and liked to think that it was outbuilding New York. It did a great deal of commercial advertising in its house-tops. The faults of construction as well as of art in its great showy buildings must have been numerous. Their walls were thin, and were overweighted with gross and coarse misornamentation.

Olmsted also believed that with brick walls, and disciplined firemen and police, the deaths and damage caused would have been much less.

Almost immediately, the city began to rewrite its fire standards, spurred by the efforts of leading insurance executives, and fire-prevention reformers such as Arthur C. Ducat. Chicago soon developed one of the country’s leading fire-fighting forces

More than 20 years after the Great Fire, ‘The World Columbian Exposition of 1893’, known as the ‘White City’, for being lit up with newly invented light bulbs and electric power.

Business owners, and land speculators such as Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard, quickly set about rebuilding the city. The first load of lumber for rebuilding was delivered the day the last burning building was extinguished. By the World’s Columbian Exposition 22 years later, Chicago hosted more than 21 million visitors.

The Palmer House hotel burned to the ground in the fire 13 days after its grand opening. Its developer, Potter Palmer, secured a loan and rebuilt the hotel to higher standards, across the street from the original, proclaiming it to be “The World’s First Fireproof Building.”

In 1956, the remaining structures on the original O’Leary property at 558 W. DeKoven Street were torn down for construction of the Chicago Fire Academy, a training facility for Chicago firefighters, known as the Quinn Fire Academy or Chicago Fire Department Training Facility. A bronze sculpture of stylized flames, entitled Pillar of Fire by sculptor Egon Weiner, was erected on the point of origin in 1961.

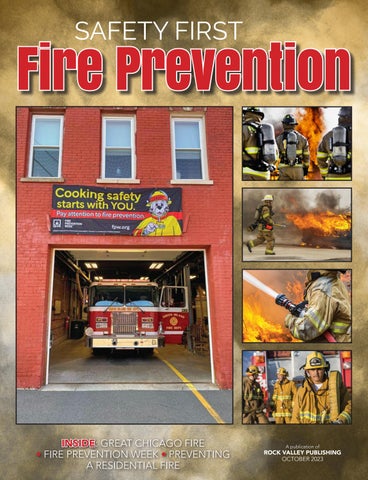

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) – the official sponsor of Fire Prevention Week for more than 100 years –has announced “Cooking safety starts with YOU! Pay attention to fire prevention” as the theme for Fire Prevention Week, Oct. 8-14.

This year’s focus on cooking safety works to educate the public about simple but important steps they can take to help reduce the risk of fire when cooking at home, keeping themselves and those around them safe.

According to NFPA, cooking is the leading cause of home fires, with nearly half (49 percent) of all home fires involving cooking equipment; cooking is also the leading cause of home fire injuries.

Unattended cooking is the leading cause of home cooking fires and related deaths. In addition, NFPA data shows that cooking is the only major cause of fire that resulted in more fires and fire deaths in 2014-2018 than in 1980-1984.

“These numbers tell us that more public awareness is needed around when and where cooking hazards exist, along with

Founded in 1896, NFPA is a global self-funded nonprofit organization devoted to eliminating death, injury, property, and economic loss due to fire, electrical and related hazards. The association delivers information and knowledge through more than 300 consensus codes and standards, research, training, education, outreach and advocacy; and by partnering with others who share an interest in furthering the NFPA mission. For more information, visit www.nfpa.org. All NFPA codes and standards can be viewed online for free at www.nfpa. org/freeaccess.

Contact: Lorraine Carli, Public Affairs Office: (617) 984-7275

ways to prevent them,” said Lorraine Carli, vice president of the Outreach and Advocacy at NFPA.

“This year’s Fire Prevention Week campaign will work to promote tips, guidelines, and recommendations that can help significantly reduce the risk of having a cooking fire.”

Following are cooking safety messages that support this year’s theme, “Cooking safety starts with YOU! Pay attention to fire prevention”:

* Always keep a close eye on what you’re cooking. For foods with longer cook times, such as those that are simmering or baking, set a timer to help monitor them carefully.

* Clear the cooking area of combustible items and keep anything that can burn, such

as dish towels, oven mitts, food packaging, and paper towels.

* Turn pot handles toward the back of the stove. Keep a lid nearby when cooking. If a small grease fire starts, slide the lid over the pan and turn off the burner.

* Create a “kid and pet free zone” of at least three feet (one meter) around the cooking area and anywhere else hot food or drink is prepared or carried.

“Staying in the kitchen, using a timer, and avoiding distractions that remove your focus from what’s on the stove are among the key messages for this year’s Fire Prevention Week campaign,” said Carli.

Fire Prevention Week is celebrated throughout North American every October, and is the oldest public health observance

on record in the U.S. Entering it’s 101st year, Fire Prevention Week works to educate people about the leading risks to home fires and ways they can better protect themselves and their loved ones. Local fire departments, schools, and community organizations play a key role in bringing Fire Prevention Week to life in their communities each year and spreading basic but critical fire safety messages.

To learn more about Fire Prevention Week and this year’s theme, “Cooking safety starts with YOU! Pay attention to fire prevention,” visit www.fpw.org. Additional Fire Prevention Week resources for children, caregivers, and educators can be found at www.sparky.org and www. sparkyschoolhouse.org.

House fires are preventable. Every homeowner and family member should take the time to do the following to ensure fire safety.

The first step is to install enough smoke detectors throughout your home. Aim for one on every floor, in each sleeping area, and outside of each sleeping area. Most home security systems automatically include smoke detectors. Test detectors once every month to ensure they work and that the batteries are still good. Replace batteries once a year, and completely replace detectors every 10 years.

Do not disable any smoke detectors while cooking, as this can potentially result in tragedy. Fortunately, detector technology has improved, and “false” alarms due to cooking have decreased.

Once you’ve got the smoke detectors installed, it’s time to make sure that you have fire extinguishers readily available throughout your residence. These come in handy should you experience a small fire.

Using a fire extinguisher prevents you and your family from having to battle a bigger fire. Keep them in the kitchen, garage, and any workshop areas of your home. Similar to smoke detectors, fire extinguishers should be checked regularly to ensure they work properly.

If you are not sure how to use a fire extinguisher, contact your local fire department for training information to get you started. You’ll be able to learn how to properly use and maintain an extinguisher.

Let’s face it, kids are curious. This is a good and bad thing, but when it comes to something life-threatening like fire, curiosity can quickly turn into danger. Children under age six account for about 43 percent of home fires started by play, according to the National Fire Protection Association. These fires cause deaths, injuries, and property damage, just like other types of fire. It’s essential to educate children about the potentially deadly consequences of playing with fire. Keep matches and lighters away from children, and inform them to stop, drop, and roll if their clothes catch on fire. Also, teach them about what firefighters do and not hide from them when they are in sight.

Many people panic in emergencies, so an escape plan can mean the difference between life and death. The goal should be for everyone to get out of the house in three minutes or less.

Discuss the plan in detail with your family members so everyone is on the same page. The plan should include at least two escape routes from every bedroom. Everyone should be familiar with basic fire safety procedures, including these:

* Checking doors for heat before opening them

* Staying low on the ground to avoid smoke

* Knowing the closest way out

These little things go a long way to save lives during a fire. Make physical or digital copies of valuable documents such as health records so they’re quickly

retrievable if a fire takes place. Practice your fire escape plan. Fire drills are critical for people of all ages and let you test your plan for weaknesses. Ensure that everything at home is in working order. For example, windows should not be stuck, and if you have any window screens, they should be easily removable. If you use security bars, make sure they are quick release.

Ready.gov has a blueprint for developing a family/household communications plan for emergencies. The site also provides emergency plans for parents, kids, and pet

owners.

* Collect data on potential meeting places in your neighborhood, relatives’ contact information, any medical issues responders need to know about, and places your family could stay for a while. The meeting place could be a neighbor’s house, a landmark, or even the end of your driveway if it’s far enough from the house. Think about accessibility needs. For instance, older family members may benefit from a medical alert system that enables easier contact with relatives and emergency responders.

* Share information such as meeting places and contact numbers with everyone in the household. Input contact numbers in all residents’ phones and devices. Include

terms such as “911” or “Emergency” in the entry so all these numbers come up when you search the designated term. Create group lists to reach multiple people at once, and make sure everyone knows how to text, call, or otherwise reach out to their emergency contacts. Let your emergency contacts know about medical issues they should share with responders.

* Practice the plan. Each resident should get in touch with at least one emergency contact and send a group text. Verify that everyone in the household, children included, knows how to call 911. Look over the plan at least once a year, and update it as needed. Remind others in the household about it, too.

Cooking is such a routine activity that it is easy to forget that the high temperatures used can easily start a fire. During 2014–2018, cooking was the leading cause of reported home fires and home fire injuries and the second leading cause of home fire deaths.

Cooking caused an average of 172,900 reported home structure fires per year (49 percent of all reported home fires in the US). These fires resulted in an average of 550 civilian deaths (21 percent of all home fire deaths) and 4,820 civilian injuries (44 percent of all reported home fire injuries) annually.

The vast majority of reported cooking fires were small. The percentage of apartment fires started by cooking was nearly twice that of cooking fires in one- or two-family homes. But apartments are also more likely to have monitored smoke detection systems than are one- and

two-family homes.

Such systems could result in fire department responses to incidents that might have been handled by the occupants if the fire department had not been alerted.

Ranges or cooktops were involved in 61 percent of reported home cooking fires, 87 percent of cooking fire deaths, and 78 percent of cooking fire injuries. Households that used electric ranges showed a higher risk of cooking fires and associated losses than those using gas ranges.

The term home encompasses one- or two-family homes, including manufactured homes and apartments or other multifamily housing.

Death and injury estimates exclude firefighter casualties.

Unattended cooking was the leading cause of cooking fires and casualties. Clothing was the item first ignited in less than one percent of these fires, but

clothing ignition led to 8 percent of the home cooking fire deaths.

Cooking oil and grease fires are a major part of the cooking fire problem. More than one-quarter of the people killed by cooking fires were asleep when they were fatally injured. More than half of the non-fatal injuries occurred when people tried to control the fire themselves.

The report also shows that:

• Cooking caused more home fire deaths in 2014–2018 than in 1980–1984.

• An average of 470 home cooking fires were reported per day in 2018.

• The peak days for home cooking fires were Thanksgiving and Christmas. Unless otherwise specified, the statistics presented in this report are estimates derived from the United States Fire Administration’s National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS) and NFPA’s annual

Candles are not in short supply come the holiday season. During Chanukah, candles are an integral component of celebrating the miracle of oil that burned in the Temple for eight days.

Celebrants of Kwanzaa utilize candles to represent the seven principles of the holiday. Christians light candles during Christmas services and in their homes to represent the light Jesus brought to the world.

There is no denying the warmth and beauty candles can bring to a home when they are flickering delicately. But candles have open flames, so caution must reign supreme when they are in use.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission says 85 percent of candle fires can be prevented by following some key safety precautions. The National Fire Protection Association says Christmas is the most dangerous day for candle fires. Here is how to burn candles safely.

• Always trim wicks to 1⁄4-inch before burning candles. Long or crooked wicks can cause uneven burning, dripping or flaring.

• Keep candles at least 12 inches away from anything that can burn.

• Use candle holders that are sturdy and will not tip over easily.

• Use a long match or long lighter to light candles to prevent fingers and hands from getting too close to the flames.

• Run used matches under water to cool them down and prevent fires from

occurring after matches are disposed in the trash.

• Never leave a candle unattended. It should be in sight at all times.

• Place and store candles beyond the reach of children and pets where they will be less likely to get knocked over.

• Never touch or move a candle while it is burning or while the wax is liquefied.

• Place candles on stable, heatresistant surfaces.

• Keep candles away from drafts, vents and air currents.

• Follow candle manufacturers’ recommendations on burn time and proper use.

• When utilizing multiple candles, place them at least three inches apart from one another. This reduces the chances for the candles to melt one another, or create their own drafts that will cause the candles to burn improperly.

• Extinguish a candle if the flame becomes too high or flickers repeatedly.

• Refrain from burning a candle longer than three hours at a time, and never burn a candle when there is less than one centimeter of wax at the base.

• Use a candle snuffer to safely extinguish a candle, and make sure the candle is completely out (wick ember is no longer glowing) before leaving the room.

Candles can be awe-inspiring components of holiday decor. But caution must always be the top priority when lighting candles inside a home.

One spring day in 1950, in the Capitan Mountains of New Mexico, an operator in one of the fire towers spotted smoke and called the location in to the nearest ranger station. The first crew discovered a major wildfire sweeping along the ground between the trees, driven by a strong wind. Word spread rapidly, and more crews reported to help. Forest rangers, local crews from New Mexico and Texas, and the New Mexico State Game Department set out to gain control of the raging wildfire.

As the crew battled to contain the blaze, they received a report of a lone bear cub seen wandering near the fire line. They hoped that the mother bear would return for him. Soon, about 30 of the firefighters were caught directly in the path of the fire storm. They survived by lying face down on a rockslide for over an hour as the fire burned past them.

Nearby, the little cub had not fared as well. He took refuge in a tree that became completely charred, escaping with his life but also badly burned paws and hind legs. The crew removed the cub from the tree, and a rancher among the crew agreed to take him home. A New Mexico Department of Game and Fish ranger heard about the cub when he returned to the fire camp. He drove to the rancher’s home to help get the cub on a plane to Santa Fe, where his burns were treated and bandaged.

News about the little bear spread swiftly throughout New Mexico. Soon, the United Press and Associated Press broadcast his story nationwide, and many people wrote and called, asking about the cub’s recovery. The state game warden wrote to the chief of the Forest Service, offering to present the cub to

the agency as long as the cub would be dedicated to a conservation and wildfire prevention publicity program. The cub was soon on his way to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., becoming the living symbol of Smokey Bear.

Smokey received numerous gifts of honey and so many letters he had to have his own zip code. He remained at the zoo until his death in 1976, when he was returned to his home to be buried at the Smokey Bear Historical Park in Capitan, New Mexico, where he continues to be a wildfire prevention legend.

In 1952, Steve Nelson and Jack Rollins wrote the popular anthem that

would launch a continuous debate about Smokey’s name. To maintain the rhythm of the song, they added “the” between “Smokey” and “Bear.” Due to the song’s

popularity, Smokey Bear has been called “Smokey the Bear” by many adoring fans, but, in actuality, his name never changed. He’s still Smokey Bear.

Pets can be excitable. Though dogs anxious to get outdoors and play with their owners may be the first image of excited pets to come to mind, cats also can be compelled to move quickly when they hear sudden, loud noises or if they’re startled by visitors.

Excited pets can pose a safety hazard in homes where open flames are commonplace. In fact, the National Fire Protection Association estimates that around 1,000 home fires each year are started by pets. Pet owners can implement strategies recommended by the American Kennel Club and ADT Security Services to reduce the risk of fire in their homes.

Be especially careful around and mindful of open flames

Pets can easily tip over candles and gain access to fireplaces when open flames are burning. Extinguish such flames whenever leaving a room, or ask someone to come in and look after pets so they are not left unattended around flames. Even candles on fireplace mantels pose a hazard as curious cats can leap onto mantelpieces and tip over the candles.

Purchase flameless candles

Flameless candles are a great option for pet owners whose pets are energetic or especially curious. Flameless candles are battery-powered and provide ambient light without an open flame.

Consider crating pets or limiting access to certain areas if animals are not yet house-trained Puppies and kittens are especially curious and eager

to explore their new surroundings. That makes it easy for them to find trouble even in areas where pet owners think there isn’t any. Confine pets to crates during times of day when you plan to light candles or the fireplace or install gates to keep them out of rooms where they can access open flames.

Stove knobs are another potential fire hazard in homes with curious pets. Knob covers prevent pets from accidentally turning on burners when no one is looking. Pet owners who let their pets roam free around the house while they’re at work or out running errands should cover stove knobs before leaving their homes.

Charcoal grills and firepits are not indoors, but they can still pose a fire hazard outside. If necessary, keep pets indoors when grilling or sitting around the firepit. If you want them to be outdoors at these times, prevent them from accessing areas where the grill and firepit are located.

Pets tend to be curious, and that curiosity can be dangerous around open flames. Some simple tips can reduce the risk of home fires caused by pets.

Over a five-year period beginning in 2015 and 2019, fire departments across the United States responded to roughly 347,000 home structure fires per year. That data, courtesy of the National Fire Protection Association, underscores the significance of home fire protection measures.

Smoke detectors are a key component of fire protection, but there’s much more homeowners can do to protect themselves, their families, their belongings, and their homes from structure fires.

• Routinely inspect smoke detectors. Smoke detectors can only alert residents to a fire if they’re working properly. Battery-powered smoke detectors won’t work if the batteries die.

Routine smoke detector check-ups can ensure the batteries still have juice and that devices themselves are still functioning properly. Test alarms to make sure the devices are functioning and audible in nearby rooms. Install additional detectors as necessary so alarms and warnings can be heard in every room of the house.

• Hire an electrician to audit your home. Electricians can inspect a home and identify any issues that could make the home more vulnerable to fires. Ask electricians to look over every part of the house, including attics and crawl spaces.

Oft-overlooked areas like attics and crawl spaces pose a potentially significant fire safety threat, as data from the Federal Emergency Management Association (FEMA) indicates that 13 percent of electrical fires begin in such spaces.

• Audit the laundry room. The laundry room is another potential source of home structure fires. NFPA data indicates around 3 percent of home structure fires begin in laundry rooms each year. Strategies to reduce the risk of laundry room fires include leaving room for laundry to tumble in washers and dryers; routinely cleaning lint screens to avoid the buildup of dust, fiber and lint, which the NFPA notes are often the first items to ignite in fires linked to dryers; and ensuring the outlets washing machines and dryers are plugged into can handle the voltage such appliances require. It’s also a good idea to clean dryer exhaust vents and ducts every year.

• Look outward as well. Though the majority of home fires begin inside, the NFPA reports that 4 percent of such fires begin outside the home. Homeowners can reduce the risk of such fires by ensuring all items that utilize fire, including grills and firepits, are always used at least 10 feet away from the home.

Never operate a grill beneath eaves, and do not use grills on decks. Never leave children unattended around firepits, as all it takes is a single mistake and a moment for a fire to become unwieldy.

• Sweat the small stuff. Hair dryers, hair straighteners, scented candles, clothes irons, and holiday decorations are some additional home fire safety hazards. Never leave candles burning in empty rooms and make sure beauty and grooming items like dryers, straighteners and irons are unplugged and placed in a safe place to cool down when not in use.

Fire departments respond to hundreds of thousands of home fires each year. Some simple strategies and preventive measures can greatly reduce the risk that a fire will overtake your home.