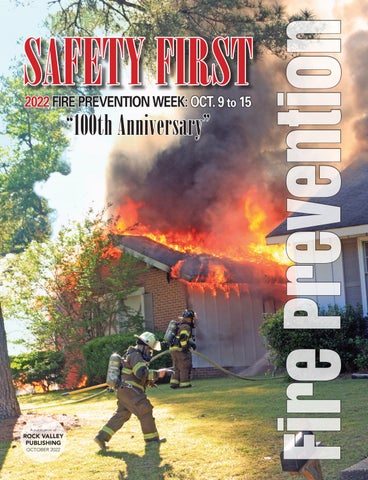

Fire Prevention Week began after the Great Chicago Fire

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago during Oct. 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly 3.3 square miles (9 km2) of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left more than 100,000 residents homeless.

The fire began in a neighborhood southwest of the city center. A long period of hot, dry, windy conditions, and the wooden construction prevalent in the city, led to the conflagration. The fire leapt the south branch of the Chicago River and destroyed much of central Chicago and then leapt the main branch of the river, consuming the Near North Side.

Help flowed to the city from near and far after the fire. The city government improved building codes to stop the rapid spread of future fires and rebuilt rapidly to those higher standards. A donation from the United Kingdom spurred the establishment of the Chicago Public Library.

ORIGIN

The fire is claimed to have started at about 8:30 p.m. on Oct. 8, in or around a small barn belonging to the O’Leary family that bordered the alley behind 137 DeKoven Street. The shed next to the barn was the first building to be consumed by the fire.

City officials never determined the cause of the blaze but the rapid spread of the fire due to a long drought in that year’s summer, strong winds from the southwest, and the rapid destruction of the water pumping system, explain the extensive damage of the mainly wooden city structures.

There has been much speculation over the years on a single start to the fire. The most popular tale blames Mrs. O’Leary’s cow, who allegedly knocked over a lantern; others state that a group of men were gambling inside the barn and knocked over a lantern. Still other speculation suggests that the blaze was related to other fires in the Midwest that day.

The fire’s spread was aided by the city’s use of wood as the predominant building material in a style called balloon frame. More than two-thirds of the structures in Chicago at the time of the fire were made entirely of wood, with most of the houses and buildings being topped with highly flammable tar or shingle roofs.

All of the city’s sidewalks and many roads were also made of wood.[6] Compounding this problem, Chicago received only 1 inch (25 mm) of rain from July 4 to Oct. 9, causing severe drought conditions before the fire, while strong southwest winds helped to carry flying embers toward the heart of the city.

In 1871, the Chicago Fire Department had 185 firefighters with just 17 horsedrawn steam pumpers to protect the entire city. The initial response by the fire department was timely, but due to an error by the watchman, Matthias Schaffer, the firefighters were initially sent to the wrong place, allowing the fire to grow unchecked. An alarm sent from the area near the fire also failed to register at the courthouse where the fire watchmen were, while the firefighters were tired from having fought numerous small fires and one large fire in the week before. These factors combined to turn a small barn fire into a conflagration.

SPREAD

When firefighters finally arrived at DeKoven Street, the fire had grown and spread to neighboring buildings and was progressing toward the central business district. Firefighters had hoped that the South Branch of the Chicago River and an area that had previously thoroughly burned would act as a natural firebreak.

All along the river, however, were lumber yards, warehouses, and coal yards, and barges and numerous bridges across the river. As the fire grew, the southwest wind intensified and became superheated, causing structures to catch fire from the heat and from burning debris blown by the wind.

Around midnight, flaming debris blew across the river and landed on roofs and the South Side Gas Works.

With the fire across the river and moving rapidly toward the heart of the city, panic set in. About this time, Mayor Roswell B. Mason sent messages to nearby towns asking for help. When the courthouse caught fire, he ordered the building to be evacuated and the prisoners jailed in the basement to be released.

At 2:30 a.m. on the 9th, the cupola of the courthouse collapsed, sending the great bell crashing down. Some witnesses reported hearing the sound from a mile (1.6 km) away.

As more buildings succumbed to the flames, a major contributing factor to the fire’s spread was a meteorological phenomenon known as a fire whirl. As overheated air rises, it comes into contact with cooler air and begins to spin, creating a tornado-like effect. These fire whirls are likely what drove flaming debris so high and so far. Such debris was blown across the main branch of the Chicago River to a railroad car carrying kerosene.The fire had jumped the river a second time and was now raging across the city’s north side.

Despite the fire spreading and growing rapidly, the city’s firefighters continued to battle the blaze. A short time after the fire

jumped the river, a burning piece of timber lodged on the roof of the city’s waterworks. Within minutes, the interior of the building was engulfed in flames and the building was destroyed. With it, the city’s water mains went dry and the city was helpless. The fire burned unchecked from building to building, block to block.[citation needed]

Finally, late into the evening of Oct. 9, it started to rain, but the fire had already started to burn itself out. The fire had spread to the sparsely populated areas of the north side, having consumed the densely populated areas thoroughly.

AFTERMATH

Once the fire had ended, the smoldering remains were still too hot for a survey of the damage to be completed for many days. Eventually, the city determined that the fire destroyed an area about 4 miles (6 km) long and averaging 3⁄4 mile (1 km) wide, encompassing an area of more than 2,000 acres (809 ha).

Destroyed were more than 73 miles (117 km) of roads, 120 miles (190 km) of sidewalk, 2,000 lampposts, 17,500 buildings, and $222 million in property, which was about a third of the city’s valuation in 1871.

On Oct. 11, 1871, General Philip H. Sheridan came quickly to the aid of the city and was placed in charge by a proclamation, given by mayor Roswell B. Mason:

“The Preservation of the Good Order and Peace of the city is hereby intrusted to Lieut. General P.H. Sheridan, U.S. Army.”

To protect the city from looting and violence, the city was put under martial law for two weeks under Gen. Sheridan’s command structure with a mix of regular troops, militia units, police, and a specially organized civilian group “First Regiment of Chicago Volunteers.” Former LieutenantGovernor William Bross, and part owner of the Tribune, later recollected his response to the arrival of Gen. Sheridan and his soldiers:

“Never did deeper emotions of joy overcome me. Thank God, those most dear to me and the city as well are safe.”

General Philip H. Sheridan, who saved Chicago three times: the Great Fire in October 1871, when he used explosives to stop the spread; again after the Great Fire, protecting the city; and lastly in 1877 during the “communist riots,”riding in from 1,000 miles away to restore order.

For two weeks Sheridan’s men patrolled the streets, guarded the relief warehouses, and enforced other regulations. On October 24 the troops were relieved of their duties and the volunteers were mustered out of service.[10]

Of the approximately 324,000 inhabitants of Chicago in 1871, 90,000 Chicago residents (1 in 3 residents) were left homeless. 120 bodies were recovered, but the death toll may have been as high as 300. The county coroner speculated that an accurate count was impossible, as some victims may have drowned or had been incinerated, leaving no remains.

In the days and weeks following the fire, monetary donations flowed into Chicago from around the country and abroad, along with donations of food, clothing, and other goods. These donations came from individuals, corporations, and cities. New York City gave $450,000 along with clothing and provisions, St. Louis gave $300,000, and the Common Council of London gave 1,000 guineas, as well as £7,000 from private donations. In Greenock, Scotland (pop. 40,000) a town meeting raised £518 on the spot.[16] Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Buffalo, all commercial rivals, donated hundreds and thousands of dollars. Milwaukee, along with other nearby cities, helped by sending

fire-fighting equipment. Food, clothing and books were brought by train from all over the continent. Mayor Mason placed the Chicago Relief and Aid Society in charge of the city’s relief efforts.

Operating from the First Congregational Church, city officials and aldermen began taking steps to preserve order in Chicago.

Price gouging was a key concern, and in one ordinance, the city set the price of bread at 8¢ for a 12-ounce (340 g) loaf.

Public buildings were opened as places of refuge, and saloons closed at 9 in the evening for the week following the fire. Many people who were left homeless after the incident were never able to get their normal lives back since all their personal papers and belongings burned in the conflagration.

After the fire, A. H. Burgess of London proposed an “English Book Donation”, to spur a free library in Chicago, in their sympathy with Chicago over the damages suffered.Libraries in Chicago had been private with membership fees. In April 1872, the City Council passed the ordinance to establish the free Chicago Public Library, starting with the donation from the United Kingdom of more than 8,000 volumes.

The fire also led to questions about development in the United States. Due to Chicago’s rapid expansion at that time, the fire led to Americans reflecting on industrialization. Based on a religious point of view, some said that Americans should return to a more old-fashioned way of life, and that the fire was caused by people ignoring traditional morality. On the other hand, others believed that a lesson to be learned from the fire was that cities needed to improve their building techniques.

Frederick Law Olmsted observed that poor building practices in Chicago were a problem:

Chicago had a weakness for “big things,” and liked to think that it was outbuilding New York. It did a great deal of commercial advertising in its house-tops.

The faults of construction as well as of art in its great showy buildings must have been numerous. Their walls were thin, and were overweighted with gross and coarse misornamentation.

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

EDITORIAL

Olmsted also believed that with brick walls, and disciplined firemen and police, the deaths and damage caused would have been much less.

Almost immediately, the city began to rewrite its fire standards, spurred by the efforts of leading insurance executives, and fire-prevention reformers such as Arthur C. Ducat. Chicago soon developed one of the country’s leading fire-fighting forces

More than 20 years after the Great Fire, ‘The World Columbian Exposition of 1893’, known as the ‘White City’, for being lit up with newly invented light bulbs and electric power.

Business owners, and land speculators such as Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard,

quickly set about rebuilding the city.

The first load of lumber for rebuilding was delivered the day the last burning building was extinguished. By the World’s Columbian Exposition 22 years later, Chicago hosted more than 21 million visitors.

The Palmer House hotel burned to the ground in the fire 13 days after its grand opening. Its developer, Potter Palmer, secured a loan and rebuilt the hotel to higher standards, across the street from the original, proclaiming it to be “The World’s First Fireproof Building.”

In 1956, the remaining structures on the original O’Leary property at 558 W. DeKoven Street were torn down for construction of the Chicago Fire Academy, a training facility for Chicago firefighters, known as the Quinn Fire Academy or Chicago Fire Department Training Facility.

A bronze sculpture of stylized flames, entitled Pillar of Fire by sculptor Egon Weiner, was erected on the point of origin in 1961.

A publication of Rock Valley Publishing LLC

1102 Ann St., Delavan, WI 53115 • (262) 728-3411

EDITOR: Melanie Bradley

CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Heather Ruenz

PAGE DESIGNER: Jen DeGroot

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR:

Vicki Vanderwerff

FOR ADVERTISING OPPORTUNITIES: Call (262) 725-7701 EXT. 125

On the evening of Oct. 8, 1871, more than 300,000 weary residents of the great city of Chicago went to bed expecting nothing more than a quiet night’s sleep followed by an ordinary Monday of going to work or tending family. Instead, these unprepared citizens found themselves pursued by an inferno, driven into the waters of Lake Michigan or running far onto the open prairie north and west of the city. SUBMITTED PHOTO Fire Prevention WeekDRYER FIRE

Washer, dryer fires typically are caused by failure to clean out lint, mechanical failures

The estimated annual number of washer and dryer fires fell during the early 1980s before leveling off through the early 1990s, when they began a slight upward trend. Since 2001, the year to year fluctuation has been more volatile, though the annual number of fires in recent years is consistently lower than those recorded before the 2000s, with the exception of an estimated 19,400 fires in 2007. An estimated 14,000 fires involving washers and dryers in 2009 represents the low point, with an estimated 15,050 fires in 2014.

The leading factor contributing to the ignition of home fires involving clothes dryers was failure to clean, accounting for one-third (33 percent) of dryer fires.

These fires were associated with half of the clothes dryer fire deaths, as well as 34 percent of civilian injuries and 26 percent of direct property damage. Other leading factors contributing to ignition of dryer fires were mechanical failure or malfunction (28 percent), electrical failure or malfunction (17 percent), and heat source too close to combustibles (5 percent). Equipment not being operated properly was a factor in just 2 percent of fires, but 49 percent of dryer deaths, although caution is called for in interpreting this finding due to the small numbers.

A mechanical or electrical failure or malfunction was involved in the vast majority of home fires involving washing machines. Mechanical failures or malfunctions were involved in 44 percent of home washing machine fires and electrical failure or malfunction in 42 percent of the fires.

Grill fires reported to local fire departments

US fire departments responded to an estimated average of 10,600 home structure and outdoor fires involving grills per year during 2014–2018. These fires caused an average of 10 civilian deaths, 160 civilian injuries, and $149 million in direct property damage annually. The term grill in this report includes all grills, hibachis, and barbecues.

The estimated 10,600 home grill fires reported annually included around 4,900 fires per year in or on structures (46 percent). All the grill fire deaths, 100 of the associated fire injuries (64 percent) and $135 million in direct property damage per year (91 percent) resulted from fires involving structures.

On average, 5,700 outside and unclassified grill fires were reported annually during this period (54 percent). These fires caused an average of 60 civilian injuries and $14 million in direct property damage.

While grill fires are more common in the warmer months, people grill all year. According to the Hearth, Patio & Barbecue Association (HPBA), two-thirds of grill owners grill on the Fourth of July, and more than half grill on Memorial Day and Labor Day. They also found that some households have more than one type of grill or smoker.

The leading area of origin for structure fires involving grills was an exterior balcony or open porch, and 44 percent of the property damage from grill structure fires resulted from fires that started there.

A grill fire that starts on a balcony can easily spread to an exterior wall and, from there, into concealed structural spaces. Courtyards, terraces, and patios were the most common areas for outside or unclassified grill fires. While most grills are intended for outdoor use, some are intended for the kitchen. Only grills intended for indoor use should be used inside.

Overall, grill fires were most likely to start when either cooking materials (including food) or flammable or combustible liquids or gas ignited. The latter were more commonly seen in gas grill fires. The 10 percent of grill structure fires that began with the ignition of exterior wall coverings or finishings caused 45 percent of the grill structure fire property loss.

Five of every six (8,900, or 84 percent) grills involved in home fires during 2014–2018 were fueled by gas, while 1.300, or 12 percent, used charcoal or another solid fuel. The leading causes of grill fires varied by power and fuel source and by whether the fire involved a structure.

The leading factors contributing to grill fires overall were failure to clean, leaks or breaks, leaving the grill unattended, and having the grill too close to something that could catch fire. Failure to clean and leaks or breaks were more commonly seen in gas grill fires than in fires involving solid-fueled grills.

While changes to the data collection rules may have impacted these trends, it is clear that gas grill fires have become much more common. In the 1980s and 1990s, the number of gas grill fire climbed while solid-fueled grill fires declined. In 1980, gas grill fires were roughly 1.3 times as common as solid-fueled grill fires. In 2018, gas grill fires were six times as common. For more information about trends, see the companion

THERMAL BURNS ASSOCIATED WITH GRILLS

An estimated average of 19,700 people per year went to hospital emergency departments because of injuries associated with grills or barbecues in 2014–2018. Roughly half of these injuries (9,500) were thermal burns. More than half of the thermal burns were non-fire burns typically caused by contact with a grill or its contents. Children under five years of age accounted for two-fifths of the grill contact burns.

One out of every 10 total grill injuries was a contact burn incurred by a young child. There were numerous cases of young children with burned hands after touching a hot grill or grill part. The following examples, taken from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database, show how grills can cause thermal burns.

THERMAL BURN EXAMPLES

A 24-year-old man was burned when he tried to relight a grill with lighter fluid, and it exploded in his face.

A 46-year-old man suffered burns over 10–19 percent of his body after using gasoline to light a grill. The canister ignited and ignited his shirt.

A 48-year-old woman was lighting a grill when the gas line disconnected, shooting flames into her face and hair.

A 32-year-old man suffered burns to his face and arm when, at first, a gas grill would not ignite, but then burst into flames.

A 47-year-old man suffered facial burns when lighting a gas grill while wearing a nasal cannula for medical oxygen. A father had his 7-month-old daughter in a chest carrier when he got too close to a grill. The girl was burned on her foot and knee.

A 4-year-old girl ran over a hot coal that had just been poured out of a grill and burned her foot.

A 7-year-old boy was playing football at home and ran into a hot grill.

A 2-year-old boy fell into a grill that was turned off but still hot. He suffered first-degree burns to his cheek, chest, and forearm.

An 18-month-old girl fell and hit her face on a grill.

Escape planning for older adults

PLAN FOR YOUR ABILITIES:

Making a home fire escape plan for yourself and/or the older adults in your household means making plans for your abilities and home environment:

* Reduce the risk of trips/falls during an escape by removing clutter in the hallways, stairways, and near exits/windows for a clear, safe path out of your home. Make sure all windows and doors are able to open in an emergency.

* If you use a walker or wheelchair, check all exits to be sure you can fit through the doorways.

* Keep your walker, scooter, cane, or wheelchair by your bed/ where you sleep to make sure you can reach it quickly.

* Keep your eyeglasses, mobile phone, and a flashlight by your bed/where you sleep to be able to reach them quickly in an emergency.

* Consider sleeping in a room on the ground floor to make emergency escape easier.

* If you cannot escape safely, keep your door shut, place a towel or blanket at the bottom of the door and stand near the window for fire service to reach you. You can use a flashlight to shine out the window to alert emergency personnel. Call 911 to let the fire department know you are inside the home.

* If you are deaf, hearing impaired, or have trouble hearing, install a bedside alert such as a bed shaker alarm that works with your smoke alarm to alert you of a fire. Strobe light alarms can be added to your smoke alarms for a visual alert. These can be found on line or in most retail and hardware stores.

* For people who are visually impaired or blind, the sound of the smoke alarm can become disorienting in an emergency. Practice the escape plan with the sound of the alarm to become familiar with, and practice with the extra noise.

* If you have a service animal, agree on a plan to keep the animal with you during an emergency.

* When looking for an apartment or high-rise home, look for one with an automatic sprinkler system

* For people with cognitive disabilities, work with their healthcare providers and local fire department to make a plan that works for their needs.

GET OTHERS INVOLVED IN YOUR PLAN

Make your fire escape plan together with your caregiver and other family members who live/spend time in your home.

Many Fire Departments keep a directory of people who need extra help. Call your fire department to let them know who in your home may need extra help/may not be able to escape safely.

* Get more information on older adult fire and fall safety.

* Get more information on evacuation and emergency planning for people with disabilities

Harlem-Roscoe Firefighters responded to a propane fired grill on fire) on Harrison Street in Roscoe. Damage was contained to the grill and outside wall of the garage. No one was injured. HARLEM-ROSCOE FD PHOTO Fire Prevention Week Keep your walker, scooter, cane, or wheelchair by your bed/where you sleep to make sure you can reach it quickly.HOME FIRE ESCAPE planning and practicing

It is important for everyone to plan and practice a home fire escape. Everyone needs to be prepared in advance, so that they know what to do when the smoke alarm sounds. Given that every home is different, every home fire escape plan will also be different.

Have a plan for everyone in the home. Children, older adults, and people with disabilities may need assistance to wake up and get out. Make sure that someone will help them!

SMOKE ALARMS

Smoke alarms sense smoke well before you can, alerting you to danger. Smoke alarms need to be in every bedroom, outside of the sleeping areas (like a hallway), and on each level (including the basement) of your home. Do not put smoke alarms in your kitchen or bathrooms.

Choose an alarm that is listed with a testing laboratory, meaning it has met

certain standards for protection.

For the best protection, use combination smoke and carbon monoxide alarms that are interconnected throughout the home. These can be installed by a qualified electrician, so that when one sounds, they all sound. This ensures you can hear the alarm no matter where in your home the alarm originates.

IMPORTANCE OF FIRE PREVENTION

In a fire, mere seconds can mean the difference between a safe escape and a tragedy. Fire safety education isn’t just for school children. Teenagers, adults, and the elderly are also at risk in fires,

making it important for every member of the community to take some time every October during Fire Prevention Week to make sure they understand how to stay safe in case of a fire.

On this site, you’ll find loads of educational resources to make sure that every person knows what to do in case of a fire. We have everything from apps to videos to printables and much more, to

Family’s home safety action plan

Develop a home fire escape plan and practice it at least twice a year.

Having a home fire escape plan will make sure everyone knows what to do when the smoke alarm sounds so they can get out safely.

• Draw a map of your home, marking two ways out of each room, including windows and doors.

• Children, older adults, and people with disabilities may need assistance to wake up and get out. Make sure they are part of the plan.

• Make sure all escape routes are clear and that doors and windows open easily.

• Pick an outside meeting place (something permanent like a neighbor’s house, a light post, mailbox, or stop sign) that is a safe distance in front of your home where everyone can meet.

• Everyone in the home should know

the fire department’s emergency number and how to call once they are safely outside.

• Practice! Practice! Practice! Practice day and nighttime home fire drills. Share your home escape plans with overnight guests.

When You Hear a Beep, Get On Your Feet! Get out and stay out. Call 9-1-1 from your outside meeting place.

Hear a Chirp, Make a Change!

A chirping alarm needs attention. Replace the batteries or the entire alarm if it is older than 10 years old. If you don’t remember how old it is, replace it.

Make the first Saturday of each month “Smoke Alarm Saturday”!

A working smoke alarm will clue you in that there is a fire and you need to escape. Fire moves fast. You and your family could have only minutes to get

out safely once the smoke alarm sounds.

• Smoke alarms should be installed in every sleeping room, outside each sleeping area, and on every level of the home, including the basement.

• Test all of your smoke alarms by pushing the test button. If it makes a loud beep, beep, beep sound, you know it’s working. If there is no sound or the sound is low, it’s time to replace the battery.

If the smoke alarm is older than 10 years old, you need to replace the whole unit.

• If your smoke alarm makes a “chirp,” that means it needs a new battery. Change the battery right away.

• Make sure everyone in the home knows the sound of the alarm and what to do when it sounds.

Things to know when in a high-rise fire

People living in a high-rise apartment or condominium building need to think ahead and be prepared in the event of a fire.

It is important to know the fire safety features in your building and work together with neighbors to help keep the building as fire-safe as possible.

BE PREPARED

• For the best protection, select a fullysprinklered building. If your building is not sprinklered, ask the landlord or management to consider installing a sprinkler system.

• Meet with your landlord or building manager to learn about the fire safety features in your building (fire alarms, sprinklers, voice communication procedures, evacuation plans and how to respond to an alarm).

• Know the locations of all available exit stairs from your floor in case the nearest one is blocked by fire or smoke.

• Make sure all exit and stairwell doors are clearly marked, not locked or blocked by security bars and clear of clutter.

• If there is a fire, pull the fire alarm on your way out to notify the fire department and your neighbors.

• If the fire alarm sounds, feel the door before opening and close all doors behind you as you leave. If it is hot, use another way out. If it is cool, leave by the nearest way out.

• If an announcement is made throughout the building, listen carefully and follow directions.

• Use the stairs to get out. Typically you should not use the elevator unless directed by the fire department. Some buildings are being equipped with elevators intended for use during an emergency situation. These types of elevators will clearly be marked that they are safe to use in the event of an emergency.

ESCAPE 101

Go to your outside meeting place and stay there. Call the fire department. If someone is trapped in the building, notify the fire department.

If you can’t get out of your apartment because of fire, smoke or a disability, STUFF wet towels or sheets around the door and vents to keep smoke out.

Call the fire department and tell them where you are.

Open a window slightly and wave a bright cloth to signal your location. Be prepared to close the window if it makes the smoke condition worse.

Fire department evacuation of a high-rise building can take a long time. Communicate with the fire department to monitor evacuation status.

progressive leader

open die forging

The true story of Smokey Bear

One spring day in 1950, in the Capitan Mountains of New Mexico, an operator in one of the fire towers spotted smoke and called the location in to the nearest ranger station. The first crew discovered a major wildfire sweeping along the ground between the trees, driven by a strong wind. Word spread rapidly, and more crews reported to help. Forest rangers, local crews from New Mexico and Texas, and the New Mexico State Game Department set out to gain control of the raging wildfire.

As the crew battled to contain the blaze, they received a report of a lone bear cub seen wandering near the fire line. They hoped that the mother bear would return for him. Soon, about 30 of the firefighters were caught directly in the path of the fire storm. They survived by lying face down on a rockslide for over an hour as the fire burned past them.

Nearby, the little cub had not fared as well. He took refuge in a tree that became completely charred, escaping with his life but also badly burned paws and hind legs. The crew removed the cub from the tree, and a rancher among the crew agreed to take him home. A New Mexico Department of Game and Fish ranger heard about the cub when he returned to the fire camp. He drove to the rancher’s home to help get the cub on a plane to Santa Fe, where his burns were treated and

bandaged.

Rescued!

News about the little bear spread swiftly throughout New Mexico. Soon, the United Press and Associated Press broadcast his story nationwide, and many people wrote and called, asking about the cub’s recovery. The state game

warden wrote to the chief of the Forest Service, offering to present the cub to the agency as long as the cub would be dedicated to a conservation and wildfire prevention publicity program. The cub was soon on his way to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., becoming the living symbol of Smokey Bear.

Smokey received numerous gifts of honey and so many letters he had to have his own zip code. He remained at the zoo until his death in 1976, when he was returned to his home to be buried at the Smokey Bear Historical Park in Capitan, New Mexico, where he continues to be a

Smokey cub sitting on a Piper PA-12 Super Cruiser

In 1952, Steve Nelson and Jack Rollins wrote the popular anthem that would launch a continuous debate about Smokey’s name. To maintain the rhythm of the song, they added “the” between “Smokey” and “Bear.” Due to the song’s popularity, Smokey Bear has been called “Smokey the Bear” by many adoring fans, but, in actuality, his name never changed. He’s still Smokey Bear.

Sparky the fire dog teaches kids about fire safety

Every firefighter has been asked two questions: 1) Do you slide down a pole? and 2) Do you have a fire dog in your station? While it is uncommon to find them in the stations any longer, the history of the Dalmatian as a member of the firefighting force goes back over a century. When fire units were deployed using horse-drawn carriages, the Dalmatians would run ahead barking and warning people that the fire wagon would soon be rushing by.

Others would settle in and run beside the wagon, helping to keep the horses calm as they got closer to the blaze. They would also protect the horses from attacks by other dogs and would then stand guard over the equipment while the firefighters did their job. They were brave, loyal, and dedicated to serve. They are a perfect mascot, and provide a fitting tribute for the fire service today.

Sparky was created by the National Fire Protection Association in 1951 and has become the Fire Safety mascot of the Fire Service. Sparky is a Dalmatian who provides child friendly lessons on fire safety and, in so doing, honors the legacy of these loyal dogs as members of the fire service team.

DRYER FIRES

Fires involving electrical failure or malfunction accounted for a much higher share of direct property damage (60 percent) than those involving mechanical failure or malfunction (23 percent). Other factors contributing to fires involving washing machines included equipment overloaded (3 percent), failure to clean (3 percent), unclassified misuse of material or product (2 percent), heat source too close to combustibles (2 percent), equipment unattended (2 percent), installation deficiency (2 percent), and unclassified factor (2 percent).

Fires involving clothes dryers usually started with the ignition of something that was being dried or was a byproduct (such as lint) of drying, while washing machine fires usually involved the ignition of some part of the appliance.

The leading items first ignited clothes

dryer fires were dust, fiber, or lint (27 percent) and clothing (26 percent) and included unclassified soft goods or wearing apparel (10 percent), linen (5 percent), and mattress or bedding (3 percent). In washing machine fires, by contrast, the leading items first ignited were electrical wire or cable insulation (26 percent), appliance housing or casing (24 percent), conveyor belt, and drive belt, or v-belt (11 percent). Clothing was the item first ignited in 8 percent of washing machine fires, with another 3 percent of fires ignited by dust, fiber, or lint.

Similar to fires involving clothes dryers, the leading items first ignited in combination washer/dryers were dust, fiber, or lint (23 percent), clothing (20 percent), and appliance housing or casing (17 percent), with electrical wire or cable insulation a factor in another 8 percent of fires.

Do you remember the lessons of “Stop-Drop-And Roll!”? A common tradition in the fire service is that the rookie gets chosen to put on the costume, but when the Chief is willing to take on the role of Sparky, they set the tone for their firefighters that fire safety and prevention education is everyone’s business. This is the legacy of Chief Clover and many more like him who have dedicated their lives to making their communities safer places to live.

ESCAPE PLAN

make sure you have the resources you need to keep your family, your community, and your city safe.

PLANNING

• A closed door may slow the spread of smoke, heat, and fire. Install smoke alarms inside every sleeping room and outside each separate sleeping area. Install alarms on every level of the home. Smoke alarms should be interconnected. When one smoke alarm sounds, they all sound.

According to an NFPA survey, only one of every three American households have actually developed and practiced a home fire escape plan. While 71% of Americans have an escape plan in case of a fire, only47% of those have practiced it. •Onethird of American households who made an estimate thought they would have at least 6 minutes before a fire in their home would become life-threatening. The time available is often less. And only 8% said their first thought on hearing a smoke alarm would be to get out!

Judy Bell helped her mother take care of Smokey. Orphaned black bear cub “Smokey II” was the second live representation of Smokey Bear from 1975 to his death in 1990. SUBMITTED PHOTOS Fire Prevention Week Smokey cub sitting on a Piper PA-12 Super Cruiser. wildfire prevention legend.