Alexandra Greenberg Editor-in-Chief backdropmag@gmail.com

Alexandra Greenberg Editor-in-Chief backdropmag@gmail.com

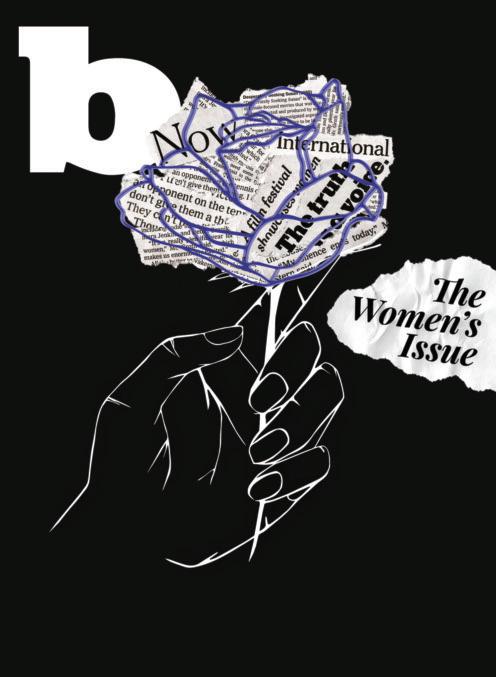

By the end of 2017, three things dominated my thoughts. First: good, honest journalism is more important now than ever. Second: the world and the people who inhabit it are f awed, but I hope everyone is capable of realizing their wrongdoings, making amends and choosing better decisions in the future. T ird: women are powerful, amazing human beings. Yes, we feature women and their accomplishments in all issues of Backdrop magazine, but starting 2018 of with an in-depth look at their achievements and barriers seems imperative. An unprecedented number of sexual assault allegations appeared in our country’s headlines in the past year, and although some may view the new year as a blank slate, that’s not what we need.

We need to build upon progress made by generations of strong individuals who stood up to injustice and discrimination. We need people such as Beverly Jones, who was a key part of Ohio University’s equal opportunity developments in the ’60s and ’70s (pg. 28). We need Ti f any Anderson, a trans woman who works to dispel traditional ideas of gender and the roles that come with it (pg. 20). We need Kristyn Brandenburg and Shrouq Aleithan, graduate students who fearlessly pursue careers in male-dominated STEM felds (pg. 8). We need Leigh Ferrero and Ky Cobb, mentors in the Young Women Leaders Program who help adolescent girls develop con fdence through supportive and empowering relationships (pg. 14).

I’m thrilled to present the Women’s Issue, our tribute to those who dreamed of a better future for women and those who make it happen. I hope you enjoy it, and Happy New Year.

All the best,

Like new! 3 bedroom, 2 1/2 bath townhouses featuring spacious open & bright floor plan, onsite parking with garage, deck and much more. Close to everything… bike path, OU, O’Bleness Hospital, easy access to all major highways.

Like new! 2 bedroom, 2 1/2 bath townhouses featuring spacious open & bright floor plan, onsite parking with garage, deck and much more. Close to everything… bike path, OU, O’Bleness Hospital, easy access to all major highways.

1 1/2

at the end of a quiet southside street, central air, washer/dryer, plenty of offstreet parking.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF ALEXANDRA GREENBERG

MANAGING EDITOR ADAM MCCONVILLE

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR ABBEY KNUPP

ASSOCIATE EDITORS ALEXIS MCCURDY & LILLI SHER

COPY CHIEF ELIZABETH HARPER

COPY EDITORS DARYL DAVIDSON, ANNELIE GOINS, AVERY KREEMER, MORGAN MEYER, CORINNE RIVERS

WRITERS RACHAEL BEARDSLEY, JESSICA DEYO, KATE KINGERY, CLAIRE KLODELL, ALLY LANASA, HALEY RISCHAR

WEB EDITORS JULIE CIOTOLA & MICHAELA FATH

DIRECTOR OF RECRUITMENT DARIAN RANDOLPH

VIDEO EDITOR CHRISTIAN GOODE

Send an email to backdropadvertising@gmail.com to get started.

PUBLISHER IGGY COSSMAN

CREATIVE DIRECTOR EMILY CARUSO

ART DIRECTORS TAYLOR DIPLACIDO & JESSICA KOYNOCK

DESIGNERS HALEIGH CONTINO, KAITLIN HENEGHAN, JYLIAN HERRING, KATE KINGERY, MADDIE KNOTSMAN, ASHLEY LAFLIN, SAMANTHA MUSLOVSKI, MORGAN MEYER, MAGGIE WATROS

DIRECTOR OF MEMBER RELATIONS MARIE CHAILOSKY

MARKETING DIRECTOR SARAH NEWGARDE

PHOTO EDITOR SARAH WILLIAMS

ONLINE PHOTO EDITOR MADDIE SCHROEDER

ASSISTANT PHOTO EDITOR MAX CATALANO

PHOTOGRAPHERS AUTUMN CROUSE, CELIA SNYDER, LANDER ZOOK

Stop by one of our weekly meetings at 8 p.m. Tuesdays in Scripps 116.

Follow us on Twitter @BackdropMag

Q&A

IN THEIR OWN SKIN

One trans student challenges traditional ideas of gender to find their identity and their voice ............................................... 20

STAY IN THE GAME

Despite gender inequality in sports, OU's female athletes have found ways to keep playing.

AN AGENT OF CHANGE

24

Alumna Beverly Jones helped create progressive university policies and laid the foundation for Title IX implementation at OU 28

EMPOWERMENT THROUGH COURSEWORK

Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies faculty share their thoughts on feminism, history and how to promote equality through education. 6

CALCULATED STEPS TO SUCCESS

Female OU graduate students who study science discuss their experiences in predominantly male fields ................................... 8

A UNIVERSAL PROBLEM

International students discuss how cultures of sexual assault vary worldwide.............. 10

REDRESSING STANDARDS

Limited clothing sizes in uptown boutiques exclude some shoppers 12

LEAD BY EXAMPLE

By pairing OU students and Athens Middle School girls, the Young Women Leaders Program addresses challenges young women face ... 14

HARVESTING CHANGE

From raising cattle to brewing kombucha, female business owners and farmers defy gender stereotypes in Southeast Ohio ............. 16

GIVE ME SAMOA THAT

Scouting for a new dessert? Check out Backdrop’s recipe for Samoa ice cream cake. .......... 18

ON THE BRICKS

The best events featuring women in Athens this spring 32

PHOTO STORY THE ROOT OF THE PROBLEM

The lack of specialized hair salons in Athens forces black women to find other solutions 34

SEXY BACK (SAFELY)

SPEAKING UP ABOUT “DOWN THERE” Students share personal experiences in The Vagina Monologues performances 42

VOICES STAND UP, FIGHT BACK

After learning to defend against sexual assault, a Backdrop writer reflects on her experiences. 44

An OU gallery director and artist portrays motherhood in her art .................... 46

PHOTO HUNT

Spot the five differences between these photos taken at the Women's March 47

instructors demonstrate why the subject benefits everyone.

WBY JESSICA DEYO | PHOTOS BY AUTUMN CROUSE

hen teaching courses in Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies (WGSS), faculty attempt to engage students in their coursework by providing context to real-world events. Loran Marsan, an assistant lecturer in WGSS, and Nicole Reynolds, an associate professor of English and WGSS, share their personal outlooks on the value

of their courses and the importance of feminism in society. Both women have completed women's studies coursework at a graduate level. A wide variety of classes, ranging from WGSS 1000: Intro to Women’s Gender and Sexuality Studies, to WGSS 4500: Advanced Feminist Teory, ofer additional information on the subject. b

We cover intersectional analysis, history and theory related to gender, as well as sexuality and the history of the feminist and queer movements. And we pay special attention to intersectional issues of diferences between races, classes, ages and ability levels. So, we never just talk about women [and how] all women are the same because they aren’t. We pay a lot of attention to that in all of our classes.

We are still in a space where those things like women studies, African-American studies, even flm studies and media studies [are misunderstood]. People generally have a hard time comprehending what we do because we do so many things. We have to start out from day one, convincing students that we deserve to be here and are qualifed to teach them.

I do think it should be. I think the root of a liberal arts education has historically been to create well-rounded and invested citizens. If we are going to do that, then yes. Just as much as everyone needs to take a science class, everyone should have to take some sort of class that focuses on us as people, how we function within the world and how that afects other people and other places.

I think it can be empowering to everyone, and I have had male students come tell me how much my class has changed their [lives]. We are educating on issues that are important to women, as well as sexual minorities, and also men.

IN A WORLD THAT SOMETIMES SHAMES FEMINISM, HOW DO YOU RESPOND THROUGH WGSS?

An education campaign, I guess. You hear this all the time, ‘I’m not a feminist, but,’ and then whatever follows the ‘but’ is ‘Well, I believe in equal pay, I believe in, [etc.]’ Right? So, people sort of reject the word but embrace the principles. Tat can be frustrating. We need to hang on to the word feminism; there has been so much profound accomplishments and success around it.

IS THERE ANY WAY THROUGH CLASS THAT YOU CAN REACH UNINTERESTED STUDENTS?

It seems that every day, really, I just come in and say, ‘Here’s the front page of Te New York Times today. Let’s talk about how this is relevant in terms of race, culture, class, gender,’ all of the issues I am tuned into as a decent human being these days. I try to make things topical and try to point out the relevance of what we are talking about to the issues that unfold around us.

WOULD YOU SAY THERE IS A GROWTH IN INTEREST AMONG STUDENTS ENROLLED?

I think so. I think there is always something they can take away from it. … I think the work is really about trying to demonstrate that the questions that we focus on in class are deeply relevant to issues that are happening in our community, as well as in the U.S. I’d like to think that in the course of … the semester, the saying that comes out is the 1970s feminist activism that ‘personal is political,’ that a lot of the decisions that you make in your own personal life on a day-to-day level have larger relevance and consequence.

Grads through the WGSS program go on and continue to do amazing things through their jobs, [such as] working in survivor advocacy programs, and

a lot of our certifcate students go on to do legal work where they are helping to advocate [for] the poor or the homeless. Tere [are] a lot of ways that the training our students get is translated into positive social change, and then faculty are often sort of tapped on by diferent types of community programs. b

BY CLAIRE KLODELL | PHOTOS BY MADELINE HORDINSKI | ILLUSTRATION BY MORGAN MEYER

Women in the U.S. made up nearly 47 percent of the workforce in 2016, according to the U.S. Department of Labor statistics. Representation of women in STEM felds, however, is another story.

Only 24 percent of STEM jobs in 2015 were held by women, according to a report “Women in STEM: 2017 Update” from the Department of Commerce. Female scientists at Ohio University are aware of the discrepancy, but most refuse to acknowledge that as an obstacle.

“It’s just something that exists, and until I started paying attention, I never realized there were any issues,” says Kristyn Brandenburg, a graduate student studying physics and astronomy.

Brandenburg works in the Edwards Accelerator Lab, which is located at the bottom of University Terrace and resembles the Hawkins National Laboratory in the Netfix series Stranger Tings Te entrance across from the Clippinger Laboratory leads to an underground tunnel.

Brandenburg is simulating her own data in hopes of building a particle detector for the laboratory. Te detector she is creating, called the “long counter,” will count the neutrons released when alpha beams hit a piece of material. She works alongside Andrea Richard, another graduate student, who is analyzing data from an experiment conducted at Michigan State University.

“During the frst year of graduate school, it’s just classes all the time, so it’s really intense. You just work with your classmates, and you don’t even realize the ratio,” Richard says.

Shrouq Aleithan’s experience is more difcult than most female students in STEM careers. Te graduate student moved to Athens from Saudi Arabia six years ago to obtain an education, and she now works in the Clippinger Laboratories and uses lasers to test nanomaterials.

Aleithan lived in a town very similar to Athens, so OU holds a certain familiarity for her. Despite the absence of a college campus in the center of her town, the size of Athens resembles that of the place she calls home. When Aleithan was a child, she was encouraged by her parents to read books and write, in

Brandenburg and Richard work by the 4.5-MV tandem accelerator vault.

hopes of becoming a poet. However, she dreamed of pursuing another lifestyle.

“I was curious about nature, and I like to ask questions and fnd out the answer,” she says.

She aspires to become a teacher so she can introduce science as more than a vocabulary word to the girls who grow up without it.

“I think there should be more of an equal ratio between men and women, because everyone has a diferent perspective to

ofer,” she says. “Women and men see things diferently. We can use this to make the world better.”

Richard believes it’s important to include researchers with multiple perspectives in order to see a full picture in research.

“If the ultimate goal of science is to progress our understanding of the universe, we can’t do that if we are only sampling the ideas from one part of the population,” she says. “It’s not a good idea.”

Aleithan believes the U.S. public education system can be extremely hypocritical when it attempts to make STEM felds more appealing to female students. Most schools claim to aspire to attain a higher level of representation, yet Aleithan has noticed the opposite occur with her niece.

“She just tells me all the time, ‘I’m really bad at math, I don’t like math, the teachers tell me that I’m not very good at math.’ ” Aleithan says. “When they’re young, girls get told how they’re not very good at math and maybe they should do something else. I think that anyone can do anything.”

Aleithan believes science should be a mandatory course for schools worldwide. She questions how students will know if they are interested in science if they are never introduced to it.

“Science improves girls’ ways of thinking and looking at life,” Aleithan says. “I think it’s their right to study science and be involved in activities. After that, they can determine their goal, and what they’d like to do in life. If they want to be involved and study science in a way that they’d like, and be happy, they might not know they’d be good scientists later.”

Richard says if children are not introduced to someone who has accomplished something they have never heard of, the possibility of such a thing will remain ambiguous.

“When I was in high school, and middle school especially, I didn’t know anyone who went to college. I was the frst person

in my family to attend university,” Brandenburg says. “People that are in these positions should come back to high schools and just talk to the students, and that’s one of things that I do when I’m on break.”

Science shows about stars inspired Brandenburg to study them, starting her on the track toward science as early as middle school. Richard, however, was unsure whether or not she could be a full-time scientist.

“I’m pretty sure that when I was in school, I didn’t know if science was a real job or not,” she says. “Ten, I went to undergrad and I was like, ‘Oh, these people exist!’ ” b

International women offer a new perspective on campus sexual violence in the U.S.

BY RACHAEL BEARDSLEY PHOTOS PROVIDED BY ASHLEY CHONG & FATIMAH HANI HASSAN

Students across the U.S. face the grim reality of frequent sexual violence on campus. Twenty percent of undergraduate and 10 percent of graduate or professional female students experience rape or sexual assault through physical force, violence or incapacitation in college, according to the 2015 Association of American Universities Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct. International students make up about 4 percent of Ohio University’s student population, and those international women can ofer a new perspective on sexual violence in America.

Sexual harassment has been an acknowledged problem on American college campuses since the '50s, with sociologist Eugene Kanin publishing “Male Sex Aggression on a University Campus” in 1957. Still, some international women say sexual violence was not a factor in deciding whether or not to study abroad in the U.S. Instead, other benefts convinced them to choose an American university.

“I have a background in French, so my frst instinct was to go to a French university,” says Rosa Armstrong, a French and international studies graduate student from Ghana. “One thing that made the diference for me was the graduate assistantship that would allow me to work, gain experience and get an education at the same time.”

Ashley Chong, a junior from Malaysia studying forensic chemistry, says the decision was spontaneous.

“I wanted more opportunities,” Chong says. “I just went to one of the colleges back in my country, and I thought, ‘OK, I’m just gonna go abroad.’ I’m an adventurous person.”

All international students, regardless of gender, may

face some of the same frustrations when transitioning to life abroad. Chong says she’s encountered Americans who assume international students have limited English skills, while English is actually her frst language. Internships and jobs also pose challenges, Chong says, because study visas can restrict international students to on-campus positions.

But, as women living in America, there are added challenges. An NBC and Wall Street Journal poll from October 2017 found almost half of American working women have been harassed at their jobs. With the recent sexual assault allegations in the media, more women are getting the courage to speak out about their own experiences. But America has only just begun to address its sexual assault problem.

Fatimah Hani Hassan, a doctoral candidate studying speech-language pathology, compared the culture of sexual violence in America and Malaysia. Hassan, who studied abroad at OU for her master’s degree before returning for her Ph.D., says women’s issues in Malaysia have also improved in past years.

“We used to have very strong paternalistic views,” Hassan says. “But I think that for quite some time, that thinking has changed. All women have freedom in terms of trying to achieve higher educational status kind of similar to what I see here in the States.”

She says she hears about more sexual assault allegations on American campuses than on their Malaysian counterparts. For Hassan, the threat of violence seems stronger here.

“You never really hear much about female students being harassed by male students in Malaysia, especially when the college surrounding is very Islamicoriented,” Hassan says. “Some people say that it is a

bit extreme, but it provides this protective mechanism for the female student to feel secure and safe, and sometimes helps them thrive.”

However, lack of reports or conversations does not always mean lack of occurrence. A 2011 survey of 369 undergraduates at the Universiti Sains Malaysia found 75.1 percent have experienced sexual harassment in the form of unwanted sexual conduct. More than half of those students were female. Sexual harassment is a “silent issue” in Malaysian education, according to Ashgar Ali Ali Mohamed, a professor at International Islamic University Malaysia and an author on the subject.

Although campus sexual violence is a problem in both countries, OU students report a higher rate of occurrence. Out of 1,350 OU students who responded to a survey, 82 percent said they have experienced sexual misconduct on campus, ranging from unwanted sexual comments to rape, according to OU’s Presidential Advisory Committee on Sexual Misconduct report sent to students in spring 2016.

Armstrong was upfront about the culture of sexual harassment at OU.

“I think OU is a very sheltered community,” Armstrong says. “Athens is like a whole world on its own; OU has its own subculture. Tat whole conversation and narrative about how [victims of assault] dress or how they look or how they invite whatever they get, I don’t believe in all that.”

In Ghana, Armstrong says, women face many of the same problems American women see on a daily basis. She says feminists in both countries have long been trying to fght back.

“It’s not that easy to be that free as a woman because

we’re still under the scrutiny of society, and society is, of course, the patriarchy,” she says. “In Ghana, there’s feminist conversation; women are free to do what they want, but we have limitations still.”

But, Armstrong says, she can’t make generalizations about all Ghanaian women.

“My reality as a black, educated Ghanaian woman is diferent from a black, uneducated Ghanaian woman,” she says. “… I can defend myself if something happens to me. I know where to go to [bring] the man to justice. I can travel, I can move around, I can go online and engage. I’m not the right person to say that it’s easy or it’s difcult for women in Ghana.”

Some women, such as Chong, choose to focus on their work, rather than letting those obstacles distract them.

“I’m not big into feminist activities,” she says. “I kind of let my achievements, how I present myself, speak on behalf of that.”

As an international student, she is hesitant to put herself into any sort of confict. Going to a protest could result in an arrest, and that could mean expulsion and deportation under the guidelines of a study visa. Te fear of violence and confrontation, however, sometimes goes beyond sexual assault. Although Armstrong expresses concern about assault on campus, she says general violence worries her the most.

“College campuses are some of the most dangerous places you can be living now in the U.S.,” she says. “It’s not even about avoiding places now, it could happen anywhere. I just don’t feel safe in the U.S.” b

Women address the lack of plus-sized clothing in Athens boutiques.

BY ALLY LANASA | PHOTO BY AUTUMN CROUSE

Standing in front of a Court Street boutique’s front window, a student may feel a combination of a few things: admiration, anxiety, envy, insecurity or frustration. Behind the glass sits a display of three mannequins, all tall with trim waistlines. Tey wear a size small, but the average woman doesn’t. Te student may see herself refected in the glass and imagine she’s wearing the same outft as the mannequin, but she knows even if the store carries her size it will not accommodate her curves and will only draw attention to what she considers to be her "problem area." In a matter of seconds, she decides not to try the outft on to spare herself from disappointment and continues on her way.

Retail has become a fast-fashion industry, yet it is slow to include all body types, especially in small towns such as Athens.

Tere are many contributing factors to limited sizing in stores. Financial concerns are one of those constraints, says Ann Paulins, senior associate dean for Research & Graduate Studies and professor of retail merchandising and fashion product development at Ohio University. She says it is more expensive for a store to have a wider range of sizes, so unless it would be proftable to expand its inventory, the company wouldn’t make more sizes available. Manufacturers may not ofer the sizes, and marginalization often plays a role, Paulins says.

“It’s not very diferent than the fact that African-American women and men have a hard time fnding hair products in a place like Athens,” Paulins says. “Te universal design in accommodating people is not frst and foremost if people are looking to make a proft and do it in a way that is efcient.”

Some students who wear above a size large have found it difcult to shop in uptown boutiques. Bluetique and Figleaf typically ofer only sizes small,

medium and large in tops and up to a size 13 in bottoms. Te Other Place ofers sizes small to 3X, but has limited styles.

“It has been a difcult struggle to bring larger sizes to Athens,” says April Knox, store manager of and buyer for Te Other Place. “A lot of people are still unaware that we have plus-size clothing, and those that may be aware are often embarrassed.”

Helen Horton, a sophomore studying journalism, frequently feels excluded when shopping in such stores.

“Honestly, I am always afraid that there’s not going to be anything to ft me because most of the sizes that I have seen are usually extra small to large, and I usually do not ft into a large. It’s usually an extra-large,” she says. “So, all my friends always get these cute clothes and really cute things from the stores Uptown, and I really don’t have that opportunity because a lot of stores don’t cater to my size.”

Horton is disappointed by the fashion industry’s lack of inclusivity. From her experiences in Athens boutiques and other more mainstream retail stores, she has developed low expectations, often assuming stores will not carry her size and resorting to online shopping instead.

Senior Elizabeth Potter, who is studying arts management through the Bachelor of Specialized Studies program, has similar experiences to Horton. She is frustrated at the lack of options, especially in Athens. Potter says the few retail stores in the area do not have a wide range of sizing or are rarely afordable.

“It always makes me feel like I don’t ft in … and I need to do more to ft somebody’s standard, even though that’s not necessarily true,” she says. “I just don’t ft into the clothes that they have available here; it defnitely has an efect on my self-esteem.”

Potter has struggled to fnd fattering clothing for her body type. She says options for her size tend to “fall into that baggy, tube-like structure.” Tat is a result of the designer’s failure to account for the various measurements that proportion ft, Paulins says.

“You have to consider the 3-D form, and every form is not directly proportionately bigger or larger in every measurement area,” Paulins says.

According to a PBS NewsHour video starring Tim Gunn from October 2016, designers do not want to dress larger women because they are “complicated, diferent and difcult.” Te average American woman wears between a size 16 and 18, which is considered plus size in the fashion industry. Gunn questions why retailers have not demanded more from designers when they have the power to refuse or limit the space designers have in stores if they do not provide options for larger women. He says about 80 million women are marginalized and invisible due to unattainable standards of thinness equating to beauty.

“We’re pretty well entrenched with the ideal, and so particularly for women, but also for men, it becomes very difcult to feel good about yourselves,” Paulins says. “Social comparison is real, and it’s detrimental to self-esteem in many cases.”

Horton’s and Potter’s self-esteem and body image have declined as a result of social comparison and fashion standards. However, Horton strives to remain positive despite her struggles with shopping Uptown.

“Of course, it kind of makes me feel a little bad only because it’s like societal pressure to ft in and wear what everyone else is wearing, but I mean I can just roll with the punches because worse come to worst, I can order online,” she says.

Potter prefers not to shop online because it is harder to know

how the style will ft and how the fabric will feel on her body.

“When you shop online, you have to pay really specifc attention to the detail in the description like the inches and actually like measure yourself before you buy stuf because online shopping can be even more difcult,” she says.

Potter started an online boutique, Lizzie & Bleu, as a direct result of her uptown shopping struggles. She strives to ofer a wide range of styles and sizes to accommodate all women. She hopes to open a store in Athens because she cares about giving her customers the opportunity to feel the fabric to ensure that they will be comfortable in what they wear.

“Overall, I try to keep anywhere from an extra small to 6X, which is what I have in stock right now,” she says. “Te sizes vary based on what I can get right now.”

Like Potter, Te Other Place is interested in expanding its style choices for all body types. Te store is working on its market strategy for larger sized clothing.

“We try to include posts on our social media about looking great in our larger sized clothing, but there’s a fne line on suggesting these to customers in person,” Knox says. “We don’t want to ofend anyone. We honestly are still struggling a little with the best way to present these sizes.”

However, small businesses are restricted by the fashion industry’s unwillingness to cooperate and the stigma present with plus-size clothing. Paulins’ advice for them is to develop a department approach while being careful not to marginalize groups of women.

“It’s not just a problem Uptown; it’s a problem way, way higher than that,” Potter says. b

Undergraduates and middle schoolers build confidence and independence by working together in the Young Women Leaders Program.

BY JULIE CIOTOLA | ILLUSTRATIONS BY TAYLOR DIPLACIDO

Instilling confdence in young adults presents diferent challenges based on individual identities. Societal pressures and stereotypes can create a burden that discourages originality. Te Young Women Leaders Program (YWLP) at Ohio University seeks to overcome such challenges by pairing college students with young girls in hopes of building supportive and empowering relationships that foster leadership.

“We want the women who come into our program to leave [with more confdence] than they had coming in and to think about how they can make their group and culture healthier,” Geneva Murray, director of OU's Women’s Center, says. “It’s all about being healthy with each other.”

Te YWLP began in 1997 at the University of Virginia with the goal of teaching young girls how to have confdence, open communication and healthy relationships. Since its establishment, several institutions have formed sister sites, including Auburn University. In 2009, the program went global when chapters were established in Cameroon and Nicaragua. OU established a sister site in spring 2014. Te program requires

mentors to enroll in a class, taught by Murray, that focuses on issues facing young girls and how to combat those problems.

Mentors are paired with a seventh- or eighth-grade girl from Athens Middle School, and the duo meets once a week for group activities. Mentors are also expected to meet with their mentees outside of the scheduled time in hopes of forming a personal connection, Murray says. Te program size varies each semester, and for the 2018 spring semester, eight mentors are enrolled.

Tough OU’s YWLP was inspired by the University of Virginia’s program, it has been restructured since its establishment.

“Over the last summer we completely revamped the program,” Murray says. “We still use parts from the [University of Virginia], but we also have really pushed ourselves to think more in terms of a hands-on, arts-based practice for some of the programs because we know that is really efective for kids this age.”

During the weekly meetings, mentors and mentees engage in meaningful discussion and activities. Te activities challenge the mentees to critically think about media messages and refect

The biggest problem is learning to trust their own voice, that what they have to say is important.”

OLIVIA COBB, YWLP LEADER

on their personal relationships, Murray says.

Currently, the YWLP is partnering with the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine to work on a project called “Photo Voice.” Te goal of the project is to understand how gender is perceived by young girls and what factors infuence this notion.

“We give the kids disposable cameras and we tell them a question that we want them to take pictures of to answer for us,” Murray says. “Te question we are looking at for this semester was ‘What does it mean to be a girl?’ Tey were asked to take pictures of objects or lighting or rooms or whatever they could come up with. Tey are going to write captions to help us understand what it means to be a girl.”

Other activities include “Find the Photoshop,” where mentees look at images of popular media and pinpoint where they have been edited. Mentees and mentors also selected songs with negative messages about women and worked together to rewrite lyrics with an empowering meaning.

Olivia Cobb, a senior studying English, participated in the YWLP as a mentor last spring and now works alongside Murray as a leader of the program. Olivia says the purpose of the weekly activities is to create an environment conducive to self-refection and candid communication.

Tough each mentee faces diferent challenges, Olivia says fnding confdence is universally difcult.

“I think the biggest problem is learning to trust their own voice, that what they have to say is important and that they can say it loudly,” Olivia says.

Leigh Ferrero, a YWLP mentor and senior studying psychology, says another problem young girls face is practicing healthy communication strategies.

“Te program is great for dealing with confict,” Ferrero says. “We did one specifc thing dealing with mindfulness. We talked about a time when you acted out without thinking about what you were doing, and what would have happened if you would have just stopped and chilled for a minute.”

Tough mentors are expected to act as role models toward mentees, the program is a mutually benefcial experience, Olivia says. Working with young girls who are learning about their identity and how to express themselves often provokes personal contemplation.

“Tere’s a lot of self-refection built into the course,” Olivia says. “You’re working with these fantastic humans who are going through it, and having that back and forth and being open to someone else’s experience is a really strong empathy builder. It really challenged me to be respectful instead of knowing.”

Ky Cobb, a junior studying journalism, is currently a mentor in the program and says the YWLP provides a diferent perspective about popular culture and the issues young girls face.

Ky and Ferrero reject the idea that gender is binary, and both identify as nonbinary. Despite the program being focused toward

young women, both mentors say they do not feel excluded.

“Tere hasn’t been anything in particular that makes me feel like anything diferent than any other mentor,” Ferrero says.

Ky, who uses they/them pronouns, says encouraging mentees to challenge gender norms is an important part of the program.

“We try to just use gender inclusive language and introduce them to the idea that you don’t have to ft into a certain gendered box,” Ky says.

Seeing the mentees openly discuss personal topics gives them a renewed sense of hope in the future.

“We have a lot of minds that are coming up and it almost seems like all of these problems we have might not seem too terrible if our generation can work with the next generation,” Ky says.

Ky also believes that the program would have been benefcial for them as a middle schooler.

“It would have been so nice to learn about the pressures society puts on young women and how to counteract those and how to not let them afect you into high school as you’re growing,” Ky says. b

“FIND THE PHOTOSHOP” “PHOTO VOICE” HANDS-ON, ARTS-BASED ACTIVITIES REWRITING LYRICS

Women in Southeast Ohio forge their paths in the local food scene.

BY LILLI SHER | PHOTOS PROVIDED BY BECKY CLARK, JUNITA

From making pickles to raising cattle, female farmers and producers across Southeast Ohio are defying gender stereotypes in the feld and contributing to the local food scene in a variety of ways.

Junita Lapp, the owner of Lapp It Up Kombucha, grew up living on a farm in a Mennonite home.

“We grew up milking cows, gathering eggs, raising gardens, but I never really personally enjoyed the actual growing

part,” she says. “I’ve always been more of a cook, processing food.”

Lapp became interested in kombucha, a type of fermented tea, when she frst tried it while working at a health foods store about four and a half years ago. After making a batch with her friend’s mom, she thought more seriously about doing it as a business.

Lapp It Up Kombucha is produced in a commercial kitchen in Zanesville and sold at the Athens and Zanesville farmers markets and various restaurants and locations throughout Ohio.

Lapp says the main barrier to starting her business was not that she was a woman, but that she grew up in a strict Mennonite community. If her family had not left the community when she was 14, she says she would not be a female business owner due to the rigid gender roles present in the community.

“Even though I knew how to produce food, I had literally no connections with the professional realm of food industry,” she says. “I kind of went out a limb when I did this, looking back. None of my friends own their own businesses … so I had a lot of people supporting me, but no one really knew how to help me.”

Lapp says she has also dealt with sexism and unwanted male attention. She bought a fake wedding ring to wear to avoid harassment while working.

“I actually heard from other vendors that they’d had problems, and they recommended [buying a ring],” she says.

“Tat’s one of the most difcult things for me. It is tough being a woman in business, and especially for me being the sole owner. I don’t have a partner, so it’s a ton of work, a lot of stress, but the rewards are worth it for me.”

Lapp says she has been able to strengthen her business and make valuable connections through networking, selling products at local farmers markets and working with Food Works Alliance, a business incubator in Zanesville.

“I’m a frm believer [that] if you just do what you’re passionate about, take the risk and put your whole heart into it, people are going to notice that,” she says. “And they’re going to come to you.”

Becky Clark, the owner of Pork and Pickles, a local butchery and pickle product line, has been “into food her whole life.”

She was homeschooled on a 500acre farm in West Virginia where her family would curate its own food. After moving to Athens as teenager with her family, Clark eventually graduated from Ohio University.

Despite her strong background in farming and food production, Clark only realized she wanted to work in the professional food industry after college when she was living in Portland, Oregon. Attending culinary school in Portland and working in

kitchens in Pittsburgh inspired Clark to move back to Athens and start Pork and Pickles.

“Tere’s a lot of diferent sectors of Pork and Pickles, which I think is kind of derived from all of my past experiences and things that I fnd interesting, and what I want to be doing with my life,” Clark says.

Pork and Pickles currently has fve components: cooking classes, pork products, the pickle product line, catering and pop-ups, which involves opening a makeshift kitchen and serving its menu in diferent places around Athens. A permanent Pork and Pickles restaurant will open in Devil’s Kettle in April.

Clark says she commits to working with local farmers and businesses. Dexter Run Farms raises the pigs for Pork and Pickles. Tey are bought as piglets, and both the farmers and Clark are attentive to how they’re raised.

“As pig farmers, they’re getting direct feedback from a butcher that they might not get otherwise,” she says. “For me, I’m getting my direct hand in how these pigs are being raised.”

Pork and Pickles also partners with OU’s student gardens by purchasing produce to fund internships for students in the local food scene.

“Tey’re planting directly for us, so it’s like they know they have a customer,” she says. “Te students will come out and help

us with a processing day and really get to see their product from seed to fnal plate.”

Clark says she faces age discrimination, as well as sexism, in her feld. She and other young food producers in Athens are trying new methods of marketing the agricultural hub of Southeast Ohio on social media. Others question their approach.

“I feel like people still question what I’m doing, or kind of talk down to me or patronize me sometimes,” she says. “A lot of it is this mentality of ‘I’ve been doing this for 30 years, this local food movement, so what’s this new idea coming in?’

”

She says the deep-rooted sexism she faces manifests in subtle ways, such as men not shaking her hand in a business setting. A former employee interested in butchering once started to work for her, but he quickly began to act as though he knew more than her.

“I felt like every directive that I would give him would be turned into a conversation, or that my authority or my knowledge was constantly being questioned,” she says. “It’s kind of that mentality, like, ‘Oh, little girl, what do you know about butchery?’ ”

on their farm for nearly 40 years. Teir products are sold or used at the Athens Farmers Market, Casa Nueva and various other places throughout Southeast Ohio.

However, Shew says she did not anticipate becoming a farmer. She studied biochemistry at Goucher College and was a social worker for a few years after graduation.

She lived on a commune that did a bit of farming, which eventually led her and her husband to purchase a homestead in West Virginia. She says living on their own farm without prior farming knowledge presented a challenge.

“We had to learn everything, [which] kind of threw us into the muddy mix,” Shew says. “We learned from our neighbors; we learned from reading a lot, anything we could get a hold of. Our friends had more experience than we did, so they would help dispel myths and help us learn how to do things.”

Shew and her husband are full-time farmers, which she says is a rarity today. She says most of the other farmers in Morgan County have at least one partner work of the farm to get health insurance and maintain a steady income.

Although Shew and her husband divide the work evenly on their farm, sometimes she still feels less involved in the operation.

“Sometimes, I feel like the lesser partner, and he says, ‘No, you’re not,’ because he says half of farming is marketing and I was the main marketer the entire time we had fruit because we had a store at our house as well as the farmer’s market,” she says. “… In the orchard, I worked right along beside him. I was pruning and planting. … We just worked together on that.”

Shew says she often did “traditional woman things” on the farm, such as preparing dinner and doing laundry. She says she doesn’t see that as inherently wrong but rather as the “most efcient way” for her and her husband to use their labor.

“I never felt horribly prejudiced against because I was a woman,” she says. “I think there was a certain amount of prejudice because we were hippies, we were from the city, we hadn’t had any farming experience, but that went for both of us. I would encourage any woman that wanted to get into farming to go for it.” b

Try this delicious dessert worthy of a badge of honor.

BY ADAM MCCONVILLE | PHOTO BY SARAH WILLIAMS | ILLUSTRATIONS BY JYLIAN HERRING

The Girl Scouts have been selling cookies as a fundraiser for more than 100 years, helping young girls develop both business skills and confdence. Feb. 17 marked the start of Girl Scout Cookie deliveries for 2018, and soon the well-known desserts will be everywhere. Although no one can argue with eating the cookies straight out of the box, Backdrop has a fresh take on an old favorite: the caramel and coconut Samoas. Te crunchy cookie pairs perfectly with softened ice cream in a Samoas ice cream cake. Add a mug of hot cocoa, and you’re good to go! b

2 boxes (28 individual) Samoas Girl Scout Cookies, crushed (substitute with Oreos if desired)

6 tablespoons butter

½ gallon of vanilla ice cream, slightly softened

½ cup shredded coconut

2 tablespoons caramel sauce

2 tablespoons chocolate sauce

1. Crush amount aside

2. Melt butter

3. Line a

4. Spread of the pan,

Allow ice cream to thaw to a soft-serve consistency, then fold in caramel, chocolate and coconut until marbled.

1. Spread the mixture on top of the crushed cookies.

2. Smooth the ice cream so it is flat, then sprinkle with setaside crushed cookies and some coconut.

3. Cover with a second sheet of plastic wrap, then freeze for at least two hours.

4. When serving, drizzle slices with additional caramel and chocolate.

Tiffany Anderson, a trans woman, creates their own version of femininity.

BY ALEXIS MCCURDY | PHOTOS BY MADDIE SCHROEDER

Beyond the realm of TV, where shows such as Te Big Bang Teory and Two and a Half Men perpetuate idyllic standards of femininity and masculinity, lies another demographic. Tere are those who fall somewhere in between, navigating their way through the extremes.

Ohio University junior Tifany Anderson, a trans woman who uses they/them and she/her pronouns, fnds themselves in that pool. Life for Anderson has been a continuous journey mentally, emotionally and physically.

“A lot of the people that you see on TV aren’t always representative of the whole community,” Anderson says. “Laverne Cox is a good person to look at because of how she carries herself and her accomplishments, but we have to keep in mind that we’re not all one monolith. Tere are those of us who are trans but don’t seek to transition, and that’s perfectly OK. Tat doesn’t invalidate our trans-ness in any way.”

With only the awareness of the words “gay” and “lesbian” in the formative years of their childhood, Anderson knew the label “male” didn’t quite ft them but lacked the knowledge of the word “transgender” to comfortably identify themselves.

“For the most part, I really kind of kept that under wraps,” Anderson said. “I originally came out as gay in high school, because I didn’t know that the term ‘trans’ was a thing or I didn’t really know much about it. It wasn’t until 11th grade that I came out as trans to some friends. For the early years of my life, I didn’t really make that known to anybody.”

TV played a role in Anderson’s ability to fnd their identity. While watching TV as a preteen, Anderson learned about the term “transgender” but did not understand the full extent of the word at the time. After much refection, Anderson ofcially came out as trans during their senior year of high school.

Because Anderson didn’t make their gender identity known throughout the majority of their school years, they didn’t run into trouble. Both their community and household were unwelcoming to the idea of trans identities. Anderson stayed silent for as long as possible, which left them without a support system.

Anderson found it hard to confront problematic statements made by friends after coming out.

“I never talked to them about it or questioned them about it because I was still fguring out myself,” Anderson says. “When I frst came out, there wasn’t a whole lot of trans characters on TV. Te ones you did see and hear adhered to the gender binary. So they identifed as a trans woman and were really feminine, and the trans men were really masculine.”

Anderson says their gender expression, the way in which they express their gender identity through

appearance, dress and behavior, is more gender neutral. Anderson uses two names interchangeably: Tifany, the name they chose, and Alex, their birth name.

Anderson’s venture to OU presented a chance to evolve.

Tey initially hesitated to let people know they were trans until their peer mentor through the LINKS program explained that college ofered a newfound freedom of self-expression. Te peer mentor encouraged Anderson to lose their fear of rejection. Te idea of open-minded students comforted Anderson and gave them courage to begin to embrace their true self.

delphin bautista, director of the LGBT Center, received a concerned call after Anderson arrived at OU. “Tis is about Tifany, a trans person coming to OU. Are they going to be supported?” the caller asked.

Te call was from one of Anderson’s family members, but it is unclear which. Nevertheless, bautista, who uses they/them pronouns and uses the lowercase spelling of their name, responded with an enthusiastic “Yes!” From then, bautista coordinated with the Ofce for Multicultural Student Access and Retention to assist Anderson in personal growth and to serve as a supportive resource.

“[Anderson] would come into the center and kind of quietly sit in a corner,” bautista says. “You could tell they were observing and listening. Tey were just very quiet and then, little by little, they kind of broke out of their shell and just started to engage and participate in diferent conversations.”

From participating in the LGBT Center’s drag shows to performing in Te Vagina Monologues, Anderson rapidly became a dynamic member of the LGBT community at OU.

Anderson says they’ve become more vocal about being trans since coming to college.

“Emotionally, I would say that in terms of me as a person, I’m less apologetic about it,” Anderson says. “I have gotten to the point that when I’m here, I don’t have to be as silent about who I am, especially since I’ve started transitioning.”

bautista says seeing Anderson’s evolution has been a reminder that experiencing gender is a journey.

“It’s been exciting to see [Anderson] go from being very quiet — and still being quiet because they are a soft-spoken person — but being very loud in doing so,” bautista says. “Tey are very ferce in terms of being on panels, and every so often they’ll look at me when asked a question and are like, ‘How honest can I be?’ and my answer is always go for it. Tere’s this willingness to shake it up.”

bautista has come to be a mentor to Anderson. Te two connected because they are both trans individuals

of color whose gender expressions are relatively neutral.

“It’s a mutual learning in that, yes, I’m the director and everything that comes with that, but I learn just as much from [Anderson] and their experiences, questions and struggles and celebrations,” bautista says. “It helps me sort of better understand my own self, as well as be able to create a safer space for other students.”

Anderson says they are thankful that since bautista has been in charge of the LGBT Center, there is an open acceptance of their intersectional identities of being black and queer. Anderson has often felt frustrated with the lack of discussion surrounding trans individuals at that crossroad.

Being at that intersection causes Anderson to have heightened fear of their surroundings, considering the political climate, which causes them to fear physical violence.

“Being trans for me would be diferent from somebody who is white and who is trans. For the most part, I still have to be very careful,” Anderson says. “… Te issue is that trans women of color are killed, and it’s not often talked about. But there’s a serious problem with that happening. Tat’s something I have to be careful of pretty much anywhere I go. Unfortunately, there’s this stigma that trans women are, especially when it comes to men, that we’re trying to trick them or something like that.”

Being strategic in what part of themselves they show, and to whom, is something Anderson must attempt to balance for their own safety.

According to news organization Mic, the murder rate for black trans women between the ages 15 and 34 is about one in 2,600. Te National Center for Health Statistics reports the murder rate for all Americans in the same age range as one in 12,000.

But Anderson fnds courage by actively talking with students and faculty members about what it means to be trans, listening to others’ experiences, and responding to questions.

“Tere are people who are always going to fnd something to say about me, whether I’m trans, queer or black; it’s not going to matter,” Anderson says. “So, I might as well just be who I am. When people do say those things, I just have to deal with it as it comes.”

Te beginning process of transitioning is also vexing, Anderson says. Before Anderson could be given hormones, they had to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria. Anderson says the requisite is problematic because being trans is not an illness.

Once Anderson was cleared to start hormones, they met with a doctor at OU. Te doctor explained to them both risk factors and benefts and started them on a low-dosage of testosterone blockers and estrogen. Gradually, the dosage increased, and Anderson underwent several blood tests for the frst six months to ensure that everything was going well.

“Medically, transitioning, I would say, has been a roller coaster,” Anderson says. “It’s been nice to see my body’s changing, but at the same time I have to re-familiarize myself with it. Tere are certain things that still kind of make me uncomfortable about my body, but even so, I still try to adapt to the changes and make sure everything’s going OK as it should.”

Anderson now thinks about their place in society as their entry into the workforce approaches. Although Anderson is studying

both engineering and Women’s Gender and Sexuality Studies (WGSS), they plan to pursue WGSS as a major.

Tey aim to work at a nonproft organization. However, Anderson says they have to research companies that are accepting of trans individuals and are in LGBT-friendly areas.

A 2015 survey from the National Center for Transgender Equality found trans individuals in the U.S. experience unemployment at three times the rate of the general population and the rate increases to four times for trans people of color. Tirty percent of trans respondents reported being mistreated, fred or denied a promotion due to their gender identity in the 12 months before the survey was taken.

Te trans community has experienced some ups and downs in recent years. Under former President Obama’s administration in 2016, Title IX was expanded to protect and provide trans individuals with resources. Students were able to self-identify as trans in residence halls, athletics centers and on ofcial documents. Some of that expansion has since been revoked by President Trump.

When I'm here, I don’t have to be as silent about who I am."

Nevertheless, bautista is choosing to focus on more positive triumphs, such as the proliferation of trans characters on TV, which jump-starts conversation about gender, as well as the increased engagement of trans individuals in religious circles.

Te next step in society, Anderson says, is lessening the emphasis placed on people’s gender and sexuality. Anderson says they would enjoy more fuidity in that discussion.

“I would also like to see a society that doesn’t place so much on gender binaries and have these essentialist roles where if you are perceived as male, you’re expected to do these things. If female, you’re expected to do these things.” Anderson says.

Te media aids in heightening the emphasis, bautista says. Tey believe trans women are held to a higher standard of femininity than cisgender women, women whose gender identity corresponds with their birth sex. Tey acknowledge cisgender women are pressured as well by beauty standards in the media. However, bautista thinks trans women are pressured to prove their womanhood.

“You [prove womanhood] by embodying extreme notions of femininity,” bautista says. “Your womanhood, in a way, is an object or product, rather than just who you are.”

Anderson says people can help strengthen the trans community by educating themselves about diferent identities and engaging in discussion. For now, they’ll just keep fghting.

“What I’ve learned from studies is that progress is never linear,” Anderson says. “You’re going to have periods where we have great progress, and there will be periods where we have a lot of pushback. I think in order for that change to come, we have to keep that in mind. And also if pushback happens, we have to be willing to push through that. We have to be willing to share our stories and educate people the best we can. Tat’s the only way we’re going to get to that point.” b

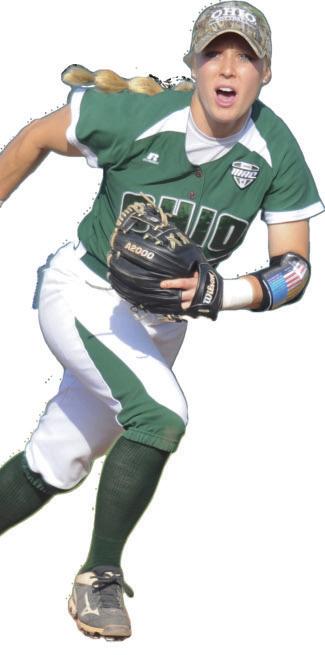

Female student athletes with a passion for playing sports defy the odds.

BY ELIZABETH HARPER | PHOTOS PROVIDED BY OHIO ATHLETICS

By the time adolescent girls turn 14 years old, they stop playing organized sports at two times the rate boys do, according to a Women’s Sports Foundation report from 2016.

Playing sports gives people of all ages the chance to exercise, become mentally and physically stronger and learn about what it takes to be on a team. Girls who quit playing sports lose those opportunities, but those who push forward and continue to play experience opportunities that afect who they are and how they will live the rest of their lives.

Taylor Saxton, a redshirt senior and second baseman on Ohio University’s softball team, started playing softball when she was in fourth grade, and it has taught her a lot over the years.

“I’ve learned the valuableness of mental toughness, of being able to deal with failure,” Saxton says. “You can’t let it take you out of your game. You have to learn something from it.”

Other female OU athletes echo similar sentiments. Teir passion for sports drives them to work hard to excel, and without that, they would be totally diferent people.

Some women fnd a lifelong passion in playing sports, but the challenges they face in high school and college can afect their ability to be taken seriously as athletes, as well as their chances to hone their skills.

One reason for the high rate of girls dropping out of sports is a lack of access to quality athletic opportunities. Te Women’s Sports Foundation reported in 2016 that high school girls have 1.3 million fewer opportunities to play high school sports than boys have.

Additional issues such as high costs, a lack of transportation, the quality of athletic facilities, social stigmas and a lack of positive role models can all infuence a girl’s desire and ability to play sports

through her teens. But for those who have the opportunity, the benefts for girls and women who can and do continue to play sports are signifcant.

Sophia Boothby, a sophomore studying environmental biology and a feld hockey goalie, has been playing feld hockey since she was in second grade. But in high school, she had several experiences that made it difcult to feel as though she was being taken seriously as an athlete.

“My junior year physics teacher tried to tell me that I wasn’t a real athlete because I was a girl, and I proved him wrong,” Boothby says, grinning. “I made him play feld hockey against me, and I won.”

OU’s feld hockey team is Division I, the highest level of collegiate athletics sanctioned by the NCAA. Boothby says she received an ofer to play for OU’s feld hockey team, an impressive feat, but her commitment day lacked the fanfare that often accompanies other collegiate Division I sports.

“When I signed to go to college, my athletic director didn’t show up,” she says. “None of the people higher up in my high school showed up, but if a football player was even going [to play] Division III, everybody was there. So, it was just kind of frustrating showing personal achievement that kind of goes unnoticed sometimes.”

Despite disappointments similar to those Boothby experienced, there are many personal benefts of playing sports in high school.

According to a 2016 report from the Women’s Sports Foundation, high school girls who play sports are more likely to get better grades and to graduate than those who don’t. Tey also tend to have a more positive body image and have better psychological health, in addition to being in good physical health. Girls and women who play sports have higher levels of confdence and lower levels of depression than those who don’t.

Taylor Saxton

Tere are also benefts that extend into the professional sphere. Dominique Doseck, a junior and guard on the women’s basketball team, says many skills learned on the court are equally useful of the court.

“You have to work well with others. Tat defnitely helps in real life, especially work force [and] sports management related type stuf,” she says. “Communication is another thing. Basketball takes you a lot of places, especially [at] young ages, and you meet a lot of new people.”

As girls get older, the challenges only increase for female athletes. Legislation such as Title IX, which exists to work against gender inequality in federally funded education and activities, has changed the scene of collegiate sports since it was passed in 1972.

Because most colleges receive some amount of federal funding, women argued they should have the same athletic opportunities as men.

Both Doseck and Saxton say they have noticed disparities between men’s and women’s sports, although they haven’t experienced them personally.

“Te good thing about OU, we do have good resources here and the same type of access to the resources as the men’s teams,” Saxton says. “I think [the diference] comes with revenue generation, who brings the most recognition to the school, and it’s not the softball team.”

OU sponsors more NCAA sanctioned teams for women than men, with nine women’s teams and six men’s teams.

Tough in many schools Title IX has lead to more opportunities for female athletes, a 2014 report from the NCAA indicated that female students receive 43 percent of participation opportunities at NCAA schools, despite making up 57 percent of college student populations. Te same report showed that men receive 55 percent of NCAA college scholarship money at Division I and II schools.

“Since we’re not the moneymaking sport of the school, you get less benefts from the NCAA,” Boothby says. “Tat’s just how it works, and it makes sense, but it’s still kind of frustrating sometimes when you have to sit and watch the other sports get a lot, to be honest.”

Female athletes see teams that make more revenue receive more apparel, go on more trips and have more money set aside by the NCAA for their scholarships.

“Te only thing that’s frustrating about it is, we all put

in the same amount of work,” Boothby says. “It’s not that women work harder [or] guys work harder; it’s just that at the end of the day, the guys make more money, and so they get more benefts from it.”

Te dedication and passion athletes have for their sport is evident in the time and energy they invest in improving their performances. Over the years, sports become so integral to athletes’ lives that it can be difcult to leave them behind after high school or college.

Tat leads some athletes to look for ways to stay involved in athletics even after they graduate, whether as a career or a volunteer position. Few athletes go on to play their sport professionally, but fortunately, there are other options. Doseck chose to study sports management as part of her plan for life after college.

“[I want] to coach, actually, coach college basketball. And then my fallback type of thing would be an athletic director, possibly,” Doseck says. “Tat’s where sports management really came in, but I just really can’t see my life not being involved with sports somehow, some way.”

Saxton is also pursuing a degree in sports management, which led to her securing a job as an account executive with Legends Hospitality and its Dallas Cowboys account following graduation in the spring.

“After college I’ll leave softball behind and move on to the next thing,” Saxon says. “If I was ever ofered something [to play professionally] I’d have to consider it, but my heart says I should move on.”

Tough Doseck would consider playing basketball professionally, whether in the U.S. or overseas, she’s long been aware that many college athletes don’t go on to play professionally.

“I think at a younger age it was more of a dream then what it is now,” Doseck says. “… Te practicality of it, you know, is what brought me to the realization that the odds of it happening [aren’t great]. … A lot of college players don’t.”

Still, female athletes can make a diference by pursuing sports, not just for themselves, but also for those watching them. Saxton says seeing positive role models in sports can encourage young women to continue to play.

“If you have strong athletes who are women who are standing up for what they believe in, then the younger eyes looking at you think they can make a diference too, and maybe you can make change,” Saxton says. b

Dominique Doseck

BY HALEY RISCHAR

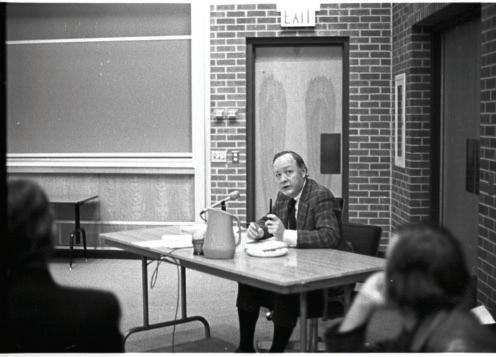

PHOTOS PROVIDED BY OHIO UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ARCHIVES & SPECIAL

“We had to wear skirts to dinner. We couldn’t have dinner Sunday nights in the dorm unless you had high heels. As a freshman, you had to be in your room by 10 p.m., but it was like that just about everywhere,” says Beverly Jones, an Ohio University alumna, women's activist, attorney and consultant.

Jones, a freshman at OU in 1964, found those rules to be a nuisance. With an already present interest in women’s issues, she sought to write her honors thesis for a senior English class on the self-actualization of women. Te English department at the time encouraged Jones to change her topic due to the belief that women, by defnition, could not be self-actualized.

“I wouldn’t change [the topic], and the English department said I would have an incomplete and couldn’t graduate,” she says. “... So, I didn’t graduate. I wouldn’t graduate from a school that said I couldn’t be a full human being.”

Jones stayed in Athens for what would have been her senior year, eventually getting a secretarial job in Cutler Hall, a position usually held by recent graduates.

“I don’t think anybody realized I hadn’t actually graduated,” Jones says. “... I just kept doing the same thing. I kept giving speeches. I got a radio program with WOUB. I spoke all over the place — on the proposition that society would be a better place if women were given equal rights.”

Jones was a key part of OU’s equal opportunity developments, helping to shape more progressive policies leading up to the introduction of Title IX.

Te dean of the business school took notice of Jones’ eforts and ofered her a place

Beverly Jones shares her story of helping OU address women’s inequality in the 1960s and 1970s.

in the Master of Business Administration program, making her the frst woman admitted in the program. Once accepted, Jones’ undergraduate diploma mysteriously appeared in the mail.

“It was not fun to be the only woman there; it was a very conservative group at the time, and really, most students didn’t want women in these programs,” Jones says. “Nobody would be my partner. Faculty members sometimes made it clear that they didn’t want women there, but I knew that it would be like that.”

Jones’ life wasn’t limited to the MBA program. She created a group comprised of women interested in equal education opportunities and spoke about women’s issues around campus.

“My commitment to myself was to do one thing a day,” she says. “So, sometimes that might just be speaking in class, or, when I was working at Cutler, making a point, but I just did it constantly day after day.”

Because of Jones’ dedication to furthering opportunities for women, the president of OU at the time, Claude Sowle, requested Jones to work for him part-time and to write a report on the status of women at the university.

At a general faculty meeting on June 10, 1971, Sowle listed upgrading the role and treatment of women as things to be accomplished, saying that the university was not doing all it

should to remove discriminatory practices.

During the meeting, Sowle announced the appointment of Jones, going by Price at the time, for the position of special assistant to the president, charged with the responsibility of conducting a review on the treatment of women at OU.

“Tis is an important assignment,” Sowle said. “Mrs. Price will fnd it possible to complete this special assignment no later than March 31, 1972.”

In 1972, Te Post endorsed Jones and her women’s liberation eforts, saying there was no doubt she would fnd inequalities in hiring practices, wages and other areas.

“By looking at the University's hierarchy, such as its senior administrators and even its Board of Trustees, it is evident that social and racial institutional discrimination exists,” said the 1972 Post article.

One equality issue Jones was particularly enraged about was the removal of women from the Ohio University Marching Band. In 1967, marching band director Gene Trailkill made the decision that the band would become an all-male unit for the following school year, making OU the frst Mid-American Conference to do so.

He defended his decision, saying he could work men harder,

according to a 1967 Post article. When questioned about his choices in a follow-up 2002 Post article, Trailkill had no regrets.

“In the mid to late ’60s, women were diferent than they are now,” Trailkill said in a quote in the 2002 article. “In the ’60s, if I said, ‘Go and do something,’ they just did it. Nowadays, you say do something they say, ‘Why? Give me 10 good reasons.’ ”

Tat decision infuriated Jones and inspired her to request the inclusion of women in the marching band within her report.

“It was a wonderful symbolic battle to take up, … because the whole idea of women not being capable to be in the band was ridiculous,” Jones says. “... [Te band] got male students to write letters; the letters were so absurd. Te one I remember most vividly said something about women not being able to play cymbals because of their breasts. I mean, it was just ridiculous.”

In a 1967 interview with Te Post, Mike McCormack, a drummer for the Marching Men of Ohio, said “there was a lot of bitter feeling the women felt slighted. But the band was nothing until it went all-male. We felt we could do a better job that something new, and exciting, was going to come out of it. I guess we can all agree that it did.”

Jones went on to submit a report of 21 recommendations for Sowle, focusing on modifying women’s salaries and the athletic

budget. Her fndings included that the more than $1 million Intercollegiate Athletics budget — including about $288,000 in grants-in-aid to male athletes, plus other scholarships -— represented a large portion of university funds while providing few benefts to female students.

According to the OU “Schedule of Income and Expenditures – Intercollegiate Athletics,” in 1970, OU’s women’s athletic expenditures were $913, compared to the basketball budget of $44,440 and the football budget of $124,249.

With those fndings, Jones recommended the university commit itself to drastically reduce aid to male athletes within the MAC and for the Women’s Intercollegiate Athletics program to be granted a signifcantly higher share of the total Intercollegiate Athletics budget.

On June 20, 1974, the Ofce of Civil Rights of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare published its proposed regulations covering Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. Tose regulations prohibited sex discrimination in education programs or activities in institutions receiving federal funds.

Sowle was fully aware of the implications Title IX would have on intercollegiate athletic programs and the problems the incoming interim president, Harry Crewson, would have with

those new regulations. Sowle briefed Jones on how she should proceed with Title IX compliance after his resignation.

Jones sent President-elect Crewson a memo announcing that she was arranging a series of meetings in early October 1974 for discussion of Title IX implications. She also recommended that Crewson request a plan written by her on areas that are still not under compliance with the new regulations.

According to Te Interim Presidency of Harry B. Crewson, a comprehensive history of the president written by his assistant Robert Mahn, Crewson requested that Jones meet with deans and department heads in each major administrative area to discuss the proposed Title IX regulations and answer questions about their implications for the university.

In letters between band director Ronald Socciarelli and Crewson, the two decided to withdraw academic credit for participation in the marching band for the 1974-75 academic year. Tat decision was made to avoid legal issues regarding sex discrimination under Title IX.

Socciarelli and Crewson believed a transition year was necessary before the band would become co-ed again. Tey worked closely with Jones to prepare a plan outlining recruitment and selection procedures that allowed both men

I spoke all over the place — on the proposition that society would be a better place if women were given equal rights.”

and women to compete for positions in the 110-member band. Academic credit was reinstated for the 1975-76 academic year along with the admission of women.

On July 18, 1975, Jones submitted her resignation due to her acceptance to law school, stating, “My current position as Assistant to the President for Equal Opportunity Programs has been exciting, and quite an education in itself, and I am grateful for the experience.”

A press bulletin was released on Sept. 13, 1975, stating that the 1974-75 academic year would be “one of transition” for the OU marching band as preparations were made to allow the admittance of women in the fall of 1975.

Te release said actions were being taken to ensure that the university would be in full compliance with Title IX of the Higher Education Act and its implementation guidelines.

Jones believes OU, especially Sowle, was ahead of the curve when it came to tackling civil rights and other important issues.

“Ohio University has a lot to be proud of, not only for women, but grappling with civil rights and other issues early and talking about things that needed to be discussed,” Jones says. b

Check out the best events featuring women this spring.

by Mary Shelley

FEBRUARY 5 - MAY 31

The exhibit will showcase varied editions and formats of Frankenstein, as well as some of the texts that inspired the story, on the fourth floor of Alden Library.

FEBRUARY 17 AT 1 P.M.

During halftime of the Bobcat women’s basketball game, nominated women leaders will be invited to the court to be recognized by the Celebrating Women Committee for their outstanding leadership at OU.

FEBRUARY 27 AT 7 P.M.

As part of the Women Pioneers Series, the Athena Cinema will be showing a documentary about Jane Goodall, a scientist whose work with chimpanzees was revolutionary. Never-before-seen footage from the National Geographic archive will hit the screen in this free showing.

BY ABBEY KNUPP

FEBRUARY 28 AT 5:45 P.M.

Although combat roles in all branches of the military finally opened to women in December 2015, many women were serving in Iraq and Afghanistan as early as 2003. Come to Baker Theater to learn more about the history of women’s involvement in combat.

Women’s History Month Keynote: Sara Safari

MARCH 1 AT 6:30 P.M.

In Nelson Commons, author and speaker Sara Safari will share her experience of climbing Mount Everest to raise awareness for victims of human trafficking and young girls who are forced into an early marriage. During her climb, she survived earthquakes and avalanches to return to the ground and help the thousands of people impacted.

MARCH 8 AT 7:30 P.M.

The lives of Frida Kahlo, Rufina Amaya and Alfonsina Storni will be explored in the Glidden Recital Hall through a combination of chamber music and theatrical performance.

APRIL 4 AT 4 P.M. - APRIL 5 AT 7 P.M.

Take Back the Night empowers survivors of sexual assault to take back spaces that are common sites of violence. The event will feature conference-style workshops about rape culture as well as a keynote speaker and a march.

UNIVERSITY ALUMNI ASSOCIATION

students make the most of their college experience connected with OHIO after they graduate.

B B O T

BobcaThon is a dance marathon on campus to raise awareness and funds for seriously ill children and their families staying at the Ronald McDonald House Charities of Central Ohio. BobcaThon culminates in a 12 hour Dance Marathon in February. You can sign up to be a dancer or volunteer today! www.bobcathon.com

SAB is a professional organization that strives to connect students to the University and Bobcat alumni through exciting programs and initiatives. SAB has passionate, creative, and hardworking undergraduates who make a difference on campus. Look out for Homecoming Events including the Yell Like Hell Pep Rally. More information can be found at www.ohiosab.com

QUESTIONS? Contact Katrina Heilmeier at heilmeik@ohio.edu or 740.597.1216

Lack of hair care products poses a challenge for black women.

BY SARAH WILLIAMS

Numerous hair salons populate the city of Athens, but many black women are unable to beneft from the services ofered at those salons. Black hair requires practices and products that aren’t often readily available in areas with predominantly white populations, such as Southeast Ohio. Tat leaves black women in Athens with two choices: travel long distances for salons and stylists who ofer a wide variety of professional services or seek out friends and

acquaintances who can help with protective styles. Nikiiyah Gest, a junior studying education, braided Bratz Dolls’ hair when she was younger. Eventually, she started practicing on herself and watching YouTube videos to perfect her technique. When she could no longer fnd an inexpensive salon that ofered natural hair care, she began doing her own hair as a junior in high school. Last year, she began helping other Ohio University students who had the same struggles. b

“My vision board inspires me to keep pushing and know my worth,” Gest

says. “It’s

embracing my culture and everything I stand for.”

“I have also noticed that cultural appropriation regarding hair is very prevalent in Athens,” Gest says. “… Sometimes, I see other people getting recognition for hairstyles that their culture was not responsible for creating while cultures such as my own get backlash for being ourselves.”

BY MARIE CHAILOSKY

INFOGRAPHIC BY EMILY CARUSO

Te Pink Tax is a term that refers to the higher price tag afxed to products “for” women, such as razors, soap and dry cleaners, which are often colored pink to indicate they were for women.

Te New York City Department of Afairs conducted a study and found that women pay $1,351 more than men a year for the same services. Collectively, Ohio women spend $4 million a year on the Pink Tax.