Editor-In-Chief

!"#$%&'#($%)

Design Director

*%$+,&-./+0#(1

Associate Editor

2$$3%&'%%4"#5

Marketing Director

*3//&6..7%(

Web Editor

!"#$%&'()*+)',-'".

Advertising Directors

8.1%(9&:.// ;%39"&!/<))

Associate

Photo Editor

=(34#&>4;%%"#$

Assistant Editors

?#<(%$&',(@# ;35&25%+(.

Publisher

!<)#$$#"&!#4"+%A#

Photo Editor

B%9%&?#().$&

Creative Director

2/#$$#&-%.C"%C#$

Managing Editor =55#&D(#$E#(9

Associate Managing Editor F3E/.)&!#/.$9#,

Assistant Design Director

2/%G#$+%(&H%/1#4"

Associate Copy Chief I#)"#&*%11%(

Associate Web Editor 2/%4&'.J#/#+

Contributors

2#+#5&!..(5#K&>#(3%/&I,/%(K&;#9"%(3$%&I,/%(K&2+#5& *#C$%(K&'%9"#$,&6..EK&8#4"%/&F%1.L<EK&2/%G& >%$(3)E,K&8,#$&M.)%7"K&-3$#&;<L53E

Designers

M#4N<%/3$%&6#$9<K!9%7"#$3%&?3$).$K& >#99"%@&*#(%K&M#$%&>394"%//K&M3//3#$&'.+%K& >#(3#$$%&!355.$)K&!#(#"&H#((3)K&;%//,&'#((, >#(3))#&!4"..$.A%(K&>%/3))#&'(%99%//

Photographers

B#9(34E&>46<%K&:#$&;(#<))K&I,/%(&!<9"%(/#$+K& 6.$.(&?#51K&B"3/&*#/9%()K&6"#(/%)&O%)%$4LE3K& 2$+(%@&'<(E/%K&?.(%$&6%//%$9#$3K&;#93%>46<%K& 834E,&8".+%)K&2$+,&:%P%/A3)

Copy Sta

6#(./3$%&?<$#K&-3$#&><))3.K&>%/3))#&*%3/%(K& *%$+,&8#$+N<3)9K&;#9"(,$&B.9(#LK&>#(3#&D#13#$.K& ?#<(%$&6.$.A%(K&I(#A3)&'.)@%// Adviser >#(E&I#9C%

It’s funny—putting this issue together, we had no intention of featuring so many articles that turn the journalistic knife on the student body. But, that’s how it turned out. Fortunately, we’ve warped into a self-loathing society, a generation that seems to get grati cation from mildly criticizing ourselves, so it shouldn’t go over too poorly.

Stories of terrible landlords are more than abundant, lling kids’ heads the moment that lease is signed in the early weeks of fall quarter. But Rachel Nebozuk’s “At Your Service” tells instead of those rare landlords that seem to operate in the tenants’ best interests—something that can’t be easy to do with the way we treat these rentals.

Adam Wagner’s “InActivism” shows the current state of activism as less than impressive, serving more as a way to get together with like-minded people rather than to make actual change.

Perhaps most critical is Annie Beecham’s “Trophy Kids,” which examines the growing sense of entitlement in our generation. Known as Generation Y, we’ve become accustomed to getting everything handed to us, awarded an ‘A’ and a gold star for mediocre work. Some professionals see this as being detrimental to our future, but a few key students are making a case for the opposite.

Still, we nd a few light spots in “Trash Talk,” “First Class Male” and “Patch Work,” all of which highlight some of Athens’ hardest working men, and Backdrop’s take on the infamous Cosmo quiz, “What Brew Are You?”

It’s an exciting time, beginning a new year of Backdrop, and we’ve made a few changes, some less obvious than others. Some might say they’re too ambitious, but we think they’re for the better. And if growing up in this generation has taught us anything, we’re sometimes always right.

Love and happiness, Shane

Barnes

What

Gawking

Professor

Big

BY NIKLOS SOLANTAY

1) It’s your signi cant other’s birthday today. You buy him/her:

A. A birthday card on the way over.

B. A Smith & Wesson J-Frame .38 Special.

C. A hamburger phone.

D. An o -brand robotic vacuum cleaner.

E. A cat (he/she is allergic).

2) It’s the rst warm weekend in spring. Time to:

A. Observe the scantily clad students from your window.

B. Kill something with four legs.

C. Display your acoustic skills in a high tra c area.

D. Celebrate with a fresh-cut pair of jean shorts.

E. Catch a wave (lose your swimsuit).

3) You spot a hottie at the other end of the bar. You:

A. Load the roo e under your sleeve.

B. Show o your tribal tattoo.

C. Prepare a witty observation.

D. Send nachos with all the xings!

E. Compliment his/her costume (It isn’t Halloween).

4) When you get home after a long day of classes, the rst thing you do is:

A. Chase the birds away and remove the tarp.

B. Disarm the traps.

C. Tweet about getting home after a long day of classes. Sigh!

D. Get in that recliner.

E. Remember to call (forget his/her name).

5) Thing most likely to hurt:

A. Everything.

B. Your back.

C. Your heart.

D. Your class.

E. Your groin (You pulled it while watching TV).

6) If you get lost driving through the Appalachian hills, it’s most likely:

A. Because you couldn’t see past the engine smoke.

B. A false alarm — there’s no way you’d ever get lost in the Appalachian hills.

C. e beginning of a horror lm.

D. Time for a barbecue break!

E. After you asked for directions (asked for directions).

7) If you could be any animal you’d be:

A. A bottom feeder.

B. A bald eagle.

C. Something beautiful and eccentric.

D. One of them talking sh.

E.A baby seal (got clubbed).

8) If you don’t agree with the results of this quiz, you intend to:

A. row an unnecessary, partycrippling t.

B. Load that extra bullet into the chamber.

C. Write a song about your frustration.

D. Use this magazine to light the grill.

E. Forward an o -color e-mail (to the entire company).

Mostly As You’re Natty. People avoid you whenever possible. You’re a last resort and if someone calls on you, it’s only to ll space and pawn you o to strangers. You’re the last one to leave the party, and by the time people are getting acquainted with you, the party is basically over.

Mostly Bs You’re Busch. You think camou age is both useful and acceptable for everyday use. You’ve decided to present yourself to the world as someone who nds hunting, shing and racing as the greatest sports of which man is capable. is comes naturally because you’re blander than your peers. You understand that not every ght requires a cause, and you are more likely to kill that kid by accident.

Mostly Cs You’re Pabst Blue Ribbon. You’re the original batch, man. Your image is in constant struggle. You want more than anything for your peers to see you as an authentic classic by which others should follow. Unfortunately, you know the only way to stay popular in the niche you’ve found is to feign enthusiasm for indie rock bands and follow in the shadow of more capable hipsters.

Mostly Ds You’re living the High Life! You pack more class into your Dockers shorts than anyone else on the block. Sure, it’s not the nicest block — occasionally there are shots red at night — but where else could you get land this cheap? You live for those simple moments when it all seems to come together: Good friends, lawn sports and birthday cards that make an animal noise when you open them.

Mostly Es You’re Keystone. ere always is something a little bit o about you. Whether it’s yelling your best friend’s name in the heat of the moment or building your entire brand image around moments of incredible failure, everyone can always count on you to bring the party (to an end).

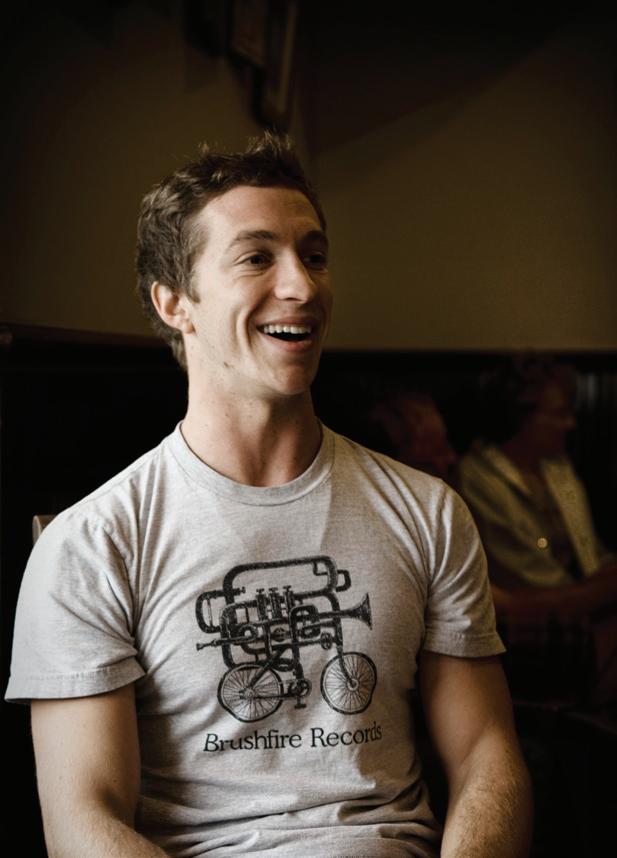

We’ve looked at some of the nest professors at OU, but now we’re checking out the hottest crop of grad students

BY ELIZABETH SHEFFIELD

Dave Gilli, 25, a former Californian, can cook, surf and wow you with his physiological vocabulary. Oh yeah, and he’s in really great shape.

What is attractive about the subject you teach? e best part about exercise physiology is that it all involves the human body. As weird as it sounds, the human body is a form of art.

What makes you feel the most sexy?

I don’t wanna sound completely shallow. Part of the reason I’m in ex-phys is because I can learn how to take care of my own body, and I would say that when I am fully engaged in physical exercise is when I reach a level of true—a “positive body image,” if you will.

What are your hobbies?

I love to cook. Meals, for me, bring people together. I think that’s the reason I exercise so much. e more I work out, the more I can eat.

Have you ever been hit on by a student?

No, but I’m the most naïve person. If a girl came up to me and hit me in the face and asked me for my number, I wouldn’t know it.

Favorite beauty regiment?

I used to have hair down to my shoulders and drive a Volkswagen bus. Girls would come up to me and ask me what kind of conditioner I used. I told them salt water. I would say the ocean is the most healing. What did you want to be when you were a kid? An astronaut. I still kind of want to be an astronaut, actually. I still kind of want to go to the moon. Planet earth is kind of capped out.

Are you Single? No. She’s in school in Marietta. But my younger brother is single.

Walker, 28, was born, raised and educated in Athens. This well-read, outdoorsy babe has the world at her feet.

What is attractive about the subject you teach?

English attracts the really eccentric, eclectic characters out of the university. It’s the people who think outside the box. I’m attracted to the oddities of people.

What makes you feel sexy?

I love heels. You’ll probably never see me without heels on, but I’m only 5’1.’’

What are your hobbies?

Hanging out with friends, keeping up with reading.

Have you ever been hit on by a student? No, actually I haven’t. My students are really polite. I’d probably just laugh.

Do you have a favorite beauty regiment?

I do my hair a lot. I do my hair in every di erent style.

What did you want to be when you were a kid?

I wanted to be a doctor. But I was really no good at chemistry. I quit pre-med when I was a junior here. I didn’t want to be the doctor who got Cs.

Where have you traveled?

I’ve been to Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Italy, France, Germany, Spain and Canada. I love traveling. I’ve been fortunate that I’ve gotten to do that.

Where would you like to travel next?

I haven’t been to Amsterdam. I heard it’s one of the best cities in the world.

Are you single?

Kind of. Yes. No. I guess I’m seeing someone, who, actually, doesn’t live in Athens. I think that’s why it’s working. My younger sister Whitney is [single] though.

The good, the bad and the ugly –professors tell how to stay classy in class

BY AADAM SOORMA

The scenario plays out on a daily basis: That all too familiar buzz begins burning a hole in your pocket. Your gaze shifts downward, xated. Your ngers begin dancing across keypad. You keep low and out of sight, so as to not get called out. On day one, the syllabus clearly read: “Turn cell phones o during class time.” But that doesn’t matter right now. Suddenly, an eerie feeling sets in; everyone around you falls silent and the professor has stopped lecturing. An embarrassing moment ensues.

Professor of Journalism Bill Reader explains,“I expect students to do more than just listen to me talk and do the work.” He adds, “It’s hard to come up with an example of good behavior though, because good behavior is the norm.”

Good students show up to class on time, participate, study for the exams and generally fare well. But being attentive

“Sometimes grades don’t even matter when the time comes for recommendations,” Ridpath adds.

“Some things just stand out so much, they’re hard to ignore.” For Dr. Jeremy Webster, dean of the Honors Tutorial College, in-class feasts are those things.

“I don’t mind when students eat a little something,” Webster says. “But when it’s like…spaghetti? Or something very

Ridpath has one instance of ugly behavior seared into his memory.

“I was teaching a graduate course and there was a day when we were hosting an esteemed guest speaker,” Ridpath explains. “As he gave his speech I noticed some of the students were on their laptops and actually laughing at their screens. Turns out, they were all IMing each other about the guest speaker –

and engaging in the class, however, will only get you so far.

“I think it all comes down to common sense,” B. David Ridpath, professor of Recreation and Sport Sciences says. “If you were on a date with a signi cant other, you wouldn’t be sitting there texting or picking up your phone or reading e Post. Why would you do that in class?”

aromatic and smelly; where everyone sits in a roundtable format and has to watch you eat. at’s when it becomes a distraction.”

“Something small is all right. I understand you’re busy and this is your only chance in a hectic schedule. But that kid’s spaghetti incident was really over the top.”

right in front of him.”

Ridpath bit his tongue for the next few moments, before unleashing on the unsuspecting students.

“I allowed the gentleman to nish and pulled him in the hall to o er my sincerest apology. en I marched back into the classroom and you could have heard a pin drop when I was through with them.”

When you think of Ohio University what do you think of? Court Street? Parties? Baseball is probably one of the last things that crosses your mind, wedged right between sobriety and at land. Marc Krauss and his extended, polished piece of lumber (referred to by insiders as a “baseball bat”), is about to change that. After posting a batting average of .402, hitting 27 home runs, knocking in 70 runs and becoming the rst player in OU baseball history to win MAC Player of the Year, Krauss was drafted in the Second Round of the Amateur Baseball Draft by the Arizona Diamondbacks. We decided to catch up with the now former Bobcat on his transition to the Major Leagues, his di cult decision to leave Athens behind and the economic crisis—just kidding: the dude is stinking rich now.

BY ALEC BOJALAD

! How did it feel to be drafted?

Coming in, I had some expectations to go pretty high, based on what I had heard from di erent people, and I had a pretty good season. It was de nitely a relief to hear my name. ere had been so much hype and build-up at that point that I just kind of wanted to get it over with.

! How early into your college career did you realize that you had a chance to be drafted?

It was always a dream. I didn’t realize it was a good possibility until I was done with my rst full year at Ohio. I was a Freshman of the Year and also a Freshman All-American. I knew I had talent and the ability to play with the best of the best and that I had a chance professionally as well.

! Was it di cult to balance academics and athletics?

It was, it was tough. You need to spend a lot of time on both. You’ve got to nd that equilibrium and gure out

what works best for you. It was tough, but everybody helps each other out on the team and the coaches were good at working things out. It wasn’t too tough, but it de nitely wasn’t easy.

! Have you met any of the current Diamondbacks?

I got a chance to meet most of the guys a er I signed my contract. I got to take batting practice with the team before a game out here in Phoenix. It was a pretty surreal experience: being in a Major League clubhouse and being with all these guys that I had been watching on ESPN. ey’re all pretty regular guys. ey just told me to keep working hard so that I can get to that level.

! How have you been adjusting to life on the road as a Minor Leaguer? It’s di erent. You can’t really settle in too much. I was in South Bend, Indiana, and we’d play at home for a week then head out on the road for another week. So you’re pretty much

just living out of a suitcase, which can get tough at times. It’s something you have to deal with. It’s de nitely a di erent daily grind from when I was at Ohio though.

! Are you satis ed with your performance so far?

I adjusted pretty well. Everything from starting my professional career to changing from metal bats to wooden bats and jumping on a team midseason. Obviously the knee injury hit. It’s part of the game. It could’ve been worse. I’m focused on getting ready and getting healthy for 2010. But for my rst season, I thought I did pretty well.

! What will you miss most about Athens? I love Athens just like everyone else. I’m gonna miss everything. Luckily, I still have the chance to get back. I can go back for one more year sometime. I’ll be around in the o -season, visiting. I had a great three years there. ey treated me well. And it was a lot of fun.

His wavy white hair is pulled back casually into a ponytail. His eyes kindly twinkle behind his glasses which are perched atop his nose. He has a warm, rosy-cheeked smile and a merry laugh. He works diligently behind an enormous screen- visuals of sound waves dance across the display as he perfects the track. First he isolates the vocals, then the full orchestration, then the percussion, then replays the whole recording. He does not overlook any detail. He says he wants his work to be “undeniable.” Described by his clients as positive and mellow, Bernie Nau works hard to produce music and share it with the world. He owns Peachfork Studios in Pomeroy, Ohio, which hosts artists like e Royales, Wheels on Fire, Majesty and Blitzkreig.

Address:37076PeachforkRoad

Pomeroy,OH45769

Telephone:(740)992-3724

Websites:www.peachforkstudios.com myspace.com/peachforkstudios info@peachforkstudios.com

a weekend. A combination of good equipment, a comfortable atmosphere and Nau’s musicality ultimately distinguish Peachfork’s outstanding recordings.

a musician. You really understand the form. It makes [them] more comfortable. You’re not always talking with them from a technical point of view.”

Nau moved to Athens because of its thriving music scene and opened a studio on Richland Avenue in 1995. However,

Nau sees a wide variety of genres at the studio. Styles range from Celtic to punk rock to bluegrass. “It’s fun to work with people and see what their personalities are and try to get the best recording we can,” he says. With clients recording music for HBO or hosting the International Bluegrass Awards, Peachfork undoubtedly produces great work. “It’s the cream of the crop” says recording artist and OU student Mike Saig. His band, Majesty, recorded an EP at Peachfork over the course of

“The other night we were doing a recording and for the rst time in, I don’t know how long, I actually saw the stars. You know, all the star.”

Nau has been accumulating stateof-the-art equipment since 1975 and says it’s become his “obsession”; highquality microphones and instruments are abundant in the studio. Peachfork’s absorbent foam walls eliminate unwanted sound and ultimately contribute to highquality recordings. e studio uses both digital and analog recording, and sessions cost about $50 per hour. However, Nau always tries to work with an artist’s budget. For instance, a bluegrass group managed to record an album in a day with a $320 budget.

Bernie Nau Owner of Peachfork Studio

While other studio owners have studied audio production, the Canton native began his career during the 1970s as a musician and learned through pure observation. After recording sessions with his band Brimstone, Nau would stay and ask the audio engineers questions about the recording process. His experience from being a musician helps him relate to his clients and provide reliable advice for arranging and editing tracks. “It’s really helpful to be

obnoxious trucks and screeching tires frequently interrupted the recording process, so he chose to relocate to Peachfork Road (hence the studio’s name) in the remote hills of Pomeroy about ve years ago. Situated on top of a steep hill and in a completely isolated eld, the location is extremely suitable for recording. “We don’t have ambient noise [here],” Nau says. Mike praises Peachfork’s solitary location. “ e other night we were doing a recording and for the rst time in, I don’t know how long, I actually saw the stars. You know, all the stars. Just being out there helps when you’re stressed.”

“As soon as the musician can stop worrying . . . you can get a good performance because they’re not preoccupied or second guessing what they’re doing.” Nau

In addition to its tranquil outdoor landscape, Peachfork’s internal atmosphere also calms the musicians. e kitchen is available for any food or beverage needs, and the place has

a co eehouse feel to it: it’s warm, comfortable and cozy. Colorful Afghan rugs adorn the oors, and soft lights make for a relaxed setting. Nau tries to tend to his clients’ needs and does not want them to feel intimidated at all. “Other studios look a bit sleeker but [musicians] say it feels like home,” he says. Nau says his biggest challenge is getting his clients to relax. e calmer an artist is, the better the nished product. One of his techniques to ful ll this mission is to tell an artist to practice a song immediately before recording. e oblivious artist is,

in fact, being recorded the entire time. Some may consider this technique a manipulative trick, but the sound is much more genuine and comfortable as opposed to staged.

Artists who record at Peachfork laud

Nau’s fantastic musical ear. He hears subtle aws in music and can easily tell if something is out of tune, leaving the musicians worry and hassle-free. “As soon as the musician can stop worrying, you can get a good performance because they’re not preoccupied or second guessing what they’re doing,” Nau says. When asked about publicity, Nau says that most people hear about Peachfork via word of mouth. “Someone hears the results and that’s all they need,” he says. Lately, he is trying to get more people out to the studio by o ering some demo sessions and other promotional things. Peachfork is a mere 20 miles from Athens, yet it feels a world away from the chaos of Court Street. In Mike’s words, the privileged musician steps out into “a eld of complete beauty” at Peachfork.

The Rarely Herd hosted the International Bluegrass Awards in Nashville

Hilarie Burhans recorded a track for the HBO series “Deadwood”, Ohio banjo champion

Wheels on Fire recently toured in Europe

Blitzkrieg local metal legends

The Royales local dance/blues band

Majesty local indie/ambient rock band

Jane Roth eld one of the top ddle players in the nation

Charlie the mailman is a notorious gure on OU’s campus, but few of his customers know the story behind the man — until now.

BY SUSANNAH SACHDEVA

Asnaking line of customers lls the o ce. It evokes Grand Central Station: everyone has places to go and people to see, things to do and packages to send. Echoes of tapping feet and ngers make the rush apparent, and the man behind the counter is silencing them one by one. It’s a busy if not stressful situation, but he’s in good spirits and has a grin on his face.

“Hey! What can I do for you today?” he asks with his reliably cheery tone of voice.

is is Charlie olin, the Santa Claus of postal workers. Charlie is the clerk in charge at the Baker University Center post o ce at Ohio University. And while he may not have Santa’s belly or full, white beard, he has all of Santa’s joyfulness and then some, including a great sense of humor.

“ ey changed my prescription,” he said of his constant happiness. “I have better drugs now.”

Charlie’s fabulous funny bone and infectious charm is not taken for granted, nor is it new. He has been a proud and friendly employee of the United States Postal Service for 23 years now— with 13 logged at the Baker post o ce where he always has been, as he likes to put it, “the boss and the entire crew.” at job description includes public relations, as Charlie’s made almost as many friends as letters he’s mailed.

“I go as fast as I can. People know I’m not standing here talking to somebody or sitting in the back drinking co ee.”

“I was out for two and a half years, and then I got hired here,” Charlie said. “When you apply to the post o ce, you pick three or four di erent o ces to apply to. I got hired in Athens.” at was back in 1986. Now, Charlie is an old pro at this postman game. He’s faster than any post o ce clerk out there, as many of his customers can attest.

“I go as fast as I can,” Charlie said. “People know I’m not standing here talking to somebody or sitting in the back drinking co ee.”

Charlie Tholin

“I like to keep a little running banter going. I know just about everybody who comes in here by name. A lot of these people aren’t customers,” Charlie said. “ ey’re friends.”

Charlie recalls an OU student who visited him years after graduating. He remembered her face instantly, though he couldn’t immediately recollect her name. After chatting for a few minutes, he recalled her name— rst and last— as well as the fact that she spent time in Samoa with the Peace Corps. at encounter occurred 10 years ago, yet he still remembers the conversation in its entirety.

Charlie is a postman with the memory of an elephant and the gratefulness of the Dalai Lama. He’s had ups and downs in his career, and ultimately those brought him to Athens. But it was luck that brought him to the postal service.

In 1975 Charlie was working construction in New York, where he grew up. Once that fell through, he moved south to work at the oil re neries outside of Galveston, Texas. at, too, fell through, and upon being given only $60 a week to live o of from unemployment, he made yet another change. He followed a friend of his who had come up to Parkersburg, W.Va., to help build a powerhouse in Willow Island. A few years later he was laid o again and began sending applications to any place that would take them.

Although Charlie used to stress about the constant out-the-door line, it doesn’t bother him anymore. He knows people are on a schedule, and he tries hard to serve everyone quickly—but even Santa can get weary after a long day of work.

“You guys overwhelm me sometimes. Mondays and days after holidays, it’s just a line out the door,” he said. “It’s exhausting sometimes. But, by the same token, somebody will always come in and ask me something that just makes me laugh.”

Other times, people will come in and make him cringe.

Some students don’t know how to label a letter. Others don’t take Charlie’s advice on packaging, even after speci cally asking him for it. One student came in to ask Charlie if he had any extra stamps.

“Indeed I do,” Charlie replied, surprisingly devoid of sarcasm. e student paid and went over to the table to put together the contents of his envelope. After watching the student struggle for three minutes, Charlie did it for him. e student thanked the helpful postman and left. “Stu like this just boggles my mind,” Charlie said.

Any person employed at a university is bound to face some semi-dumb questions and exasperating occurrences, but the way Charlie sees it, at least he gets to hear some interesting stories along the way.

“I get to meet people from all over the world,” Charlie said. “I actually get to talk to some of them on o times, and it’s really interesting to get a personal glimpse of Palestine, or Ghana or China.”

Since OU has a signi cant international community, Charlie has sent mail just about everywhere: Mongolia, Siberia, Kenya, Ghana, the U.K. and many more. He’s even sent mail to Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso.

Charlie has conversations with everyone and anyone, discussing anything and everything. One of the few things he rarely exposes, however, is the phoenix tattoo on his arm.

“It just struck me. I had wanted a tattoo for a long time, and I looked and I looked,” he said. “ ere was just something when I saw that one and I said, ‘I really like that.’ I had it done a couple years after I had heart surgery.” Another thing most people don’t know: Charlie had an aortic aneurism in 2000.

With endless relocations and layo s earlier in life and a heart surgery to boot, Charlie has been through a lot. But, as his customers are able to tell, he doesn’t let it get to him.

“You make your job,” Charlie said. “I don’t think anyone really enjoys working for a living. ere’s no sense in being miserable, though. You don’t want me to be miserable. I don’t want you to be miserable. It just makes your day go a lot easier if you’re more positive.”

BY ELIZABETH SHEFFIELD

“Always makes me think of fall when you smell that decaying, pumpkin smell,” he says, separating the wires of the deactivated, electric fence. He gestures toward a lame pumpkin, lopsided with rot. “ ey do not like to grow where the grass grows. ey always go bad.”

Gypsy examines Schoss and the pumpkin patch with an air of duty, then returns her nose to the ground in the pursuit of groundhogs — her favorite. Tyler Schoss is a White’s Mill employee of 11 years and is often referred to as “Gypsy’s owner.” Beginning mid-June, the two of them work side-by-side on the bank of the hocking —

Schoss tending to the pumpkin patch and Gypsy tending to, well, inspections of sorts.

For many, October in Athens connotes Halloween and all-around drunkenness. For Schoss, along with the rest of the White’s Mill sta , this is just the onset of another season. Luckily, this is a change for the better.

“[It’s] one of the reasons I really like it here,” Schoss says. “ ere’s always something di erent that changes with the seasons. It’s like having four seasonal jobs.”

White’s Mill — located on the junction of routes 56 and 682 — was, until the 1970s, a working mill, originally constructed in Meigs County, then later rebuilt in Athens in 1913. As we

approach the attic, Schoss mentions the hearsay resident ghosts, but dismisses them quickly, redirecting his story to the postcard view from the riverside window.

Today, part of the mill is used as a store — selling bulbs, seeds, decorative owerpots and even Native American jewelry. All the pre-picked pumpkins from the adjacent patch rest on plywood bleachers. However, this year White’s Mill experienced a harvest of what Schoss estimates to be barely half of 2008’s harvest of 900 orange, carve-ready gourds.

Many of the blossoms fell o early, Schoss explains as he examines the remaining orange owers on the stalky vines. ose that survived were faced with the adversities of powdery mildew: a fungus that stunts, distorts and sometimes kills plant matter.

“Next year is probably a year to take o , let [the land] kind of recuperate — plant something in there, like a cover crop,” Tyler suggests.

Of course, Schoss will weather this change, as he does with every turn of the season. As he says, “It would take wild horses to pull him away from [this job].” No doubt his with furry, black and white companion Gypsy by his side.

We’ve heard enough about the bad guys. Backdrop’s favorite landlords work 24-7 to keep your place in one piece.

BY RACHEL NEBOZUK

It’s the day after Christmas. While children everywhere are admiring their heaping piles of presents, Michael Kleinman is receiving news of a considerably less exciting holiday surprise. The local mailman has discovered water gushing from one of Kleinman’s properties on Congress Street. Kleinman hops on Route 33 toward Athens, where the house’s seven female tenants — all Ohio University students — are missing, home for break. And this leak isn’t exactly a trickle; more a waterfall, crashing down the yard and into the one-way street.

As a veteran college town landlord, Kleinman isn’t surprised at the news of the thriving Congress Street river. He begins moving furniture out of the house, using a system of post-itnotes to document where each piece belongs. This is a day in the life of an Athens landlord, one who owns 72 properties — 72 chances for something to go awry.

Because there are so many houses and apartments to keep !"#$%&'(#)#*)+#)&#,-.%/".//+#0./&)-1#%1#2--.*#$%&'#&3%"1#)34!/*# town to deal with the dramas of student leasers. Included in the daily escapades are problems like uprooted bushes, busted *3+$)--(#54431#6)33.*#7346#1&%-.&&4#'..-1#)/*#"%".1#8-499.*# with tampons. It’s safe to say that Kleinman has seen it all, and so have the 120 other brave landlords in Athens.

Mark and Marcia Shubert, of Amesville, Ohio, bought their 231&#"34".3&+#%/#&'.#:;1<#='.+#8!33./&-+#-.)1.#&'3..#'4!1.1# and one apartment near OU’s campus. Marcia, the brains of the operation, and Mark, the brawn, run the whole shebang themselves. While many of the large student rental agencies in Athens have full crews of cleaners, landscapers, electricians and plumbers, Mark does all of the above himself. “Our good &./)/&1#*.2/%&.-+#4!&/!6>.3#&'.#/4&?14?944*#4/.1(@#A)38%)# says, “But I would have to say that we got a bit hardened >.8)!1.#.B./#&'.#>.1/#&./)/&1#8)/#>.#B.3+#')3*#4/#'4!1.1<@ Landlords are the metaphorical moms and dads for students -%B%/9#4/#&'.%3#4$/#743#&'.#231&#&%6.<#C&D1#)#-)/*-43*D1#E4>#&4#&)F.# care of students’ mess-ups. Of course, it’s a landlord’s number one priority to watch over properties and make sure precious %/B.1&6./&1#)3./D^%/9#!"#%/#5)6.1#G,-.%/6)/#')1#4/-+#')*#

&$4#23.1#1%/8.#'.#1&)3&.*#3./&%/9#%/#HI:I<J#K!&#>.-%.B.#%+#/4&(# it’s also a priority of most landlords to make sure tenants are safe, comfortable and happy. For example, Marcia recalled one instance when a girl called in the middle of the night to ask if Mark would come over and kill a hairy spider that she had spotted in her bedroom. The couple also got a phone call during the wee hours from tenants who reported a heavily intoxicated stranger had wandered into their house and was sleeping in their living room. Like mothers and fathers, these college town landlords are there to scare away the monsters from under the bed — and chase the drunk people off the couch.

While it may seem like a right of passage to trash college homes, it doesn’t usually occur to students that they may feel a little embarrassed about it after graduation. Zack Jones, a L;;:#MN#)-!6/!1#$%&'#)#/.$#O934$/?!"@#E4>(#$'4#)*6%&1#&4# trashing his former apartment at Riverpark Towers, says he has one or two regrets of his own. “I do regret putting holes in the $)--#>+#*3%B%/9#94-7#>)--1#7346#&'.#./*#47#&'.#')--$)+(@#P4/.1# 1)+1(#OC&#$)1#*!6>(#>!&#C#4/-+#3.93.&#&')&#>.8)!1.#C#94/.*# 743#&'.#*)6)9.<@

Jones says that all the other damage he caused to the apartment with his two rommates was all in good fun. The roommates threw spaghetti on their white walls, spilled an entire bottle of hot sauce on the carpet, regularly threw patio furniture off their balcony and shattered their sliding glass door. Surprisingly, Jones said he even received some of his security deposit back at the end of the year. Still, looking back as an alumnus, he’s not embarrassed of his destructive behavior.

In a profession that seems so stressful, it’s a wonder that people in the rental business like Kleinman and the Shuberts don’t have any regrets themselves. On the stresses of his E4>(#,-.%/6)/#1)+1#&')&#&'.3.#%1#)993)B)&%4/#%/#)/+#>!1%/.11# where money is involved. To stay level-headed, he takes every individual renovation, repair and dispute and learns something from it with the goal of bettering his business. “I used to own )#"%QQ)#1'4"(@#'.#1)+1#$%&'#)#-)!9'(#O)/*#>.%/9#)#-)/*-43*# %1#.)1%.3<@

BY ALEX MENRISKY

ILLUSTRATIONS BY MATTHEW WARE

In an environment where creative writing classes are based on e ort instead of skill—and the grade is the most important letter on the page—one edgling group of writers is banding together in search of the perfect piece.

Before anyone speaks, a young man stands at the head of the table, eyebrows raised quizzically behind his bookish glasses. His surprise at the large number of people ling into the room, however, does not betray him as he starts his spiel with enthusiasm and candor. Even as he nds himself interrupted again and again by the opening and closing of the door, the smile that covers his bearded face continues to grow wider and wider. Seth Lopez is more than happy to see the eager new members pour into the rst meeting of e Group, his literary brainchild. e Group, a campus organization that explores all sides of writing creatively, spends its Tuesday and ursday nights around conference tables in Ellis Hall room 113 and Baker University Center room 239, respectively, reading and critiquing the literary pursuits of its members.

“I’d like to say that we’re a workshop outside of a workshop. A workshop without a grade,” Seth, the club’s president and founder, says. “[It’s] a workshop where you can kind of loosen up a little more, and it’s not about getting

an A or a B or a C.” After realizing early last school year that no creative writing club existed on campus, he worked hard to bring appreciation and practice to the art. e junior communications major is pleased with the way his pet project took o , even if

"It's not about getting an A or a B or a C."

few members

regularly attend meetings.

But fewer members make for a better workshop. Meetings start o with a nice appetizer of socialization, followed by a course of readings by the brave, and they nish o the meal with polite criticism (both positive and negative) by other members.

At the rst meeting of the year, however, the introductory appetizer was meatier

than usual—the new members practically spilled into the room, introduced themselves, gave quick quips about why they were there and overviews of their writing histories. As the names ew, Seth was quick to joke and laugh with his new acquaintances, welcoming them into the fold with the other execs, demonstrating just how open and informal e Group really is.

In this case, too many cooks don’t spoil the gravy at all. Writers of all disciplines meet to discuss their pieces—anyone from poets to novelists to short story a cionados. ere’s room for all shapes and sizes here. And e Group caters to this diversity, equally dividing its attention among poetry, short stories and chapters.

“It’s really relaxed, and everybody can feel really comfortable reading their work,” Shelby Campbell, the de facto vice president of e Group, says. “And nobody’s going to say anything dream-crushing to each other about their work, so it’s really nice.” Shelby, one of the rst to ock to Seth’s vision, was placed in a position of leadership

this year as numbers continued to grow and opportunities for activities began to present themselves.

Not only do these budding literary artists critique one another’s work, they also o er a strong network of writing resources. When a piece reaches the point of stunning quality, Group members encourage one another to publish with campus literary journals and even legitimate national outlets, such as online literary magazines.

“I think everyone in e Group is really pushing towards not even just campus publications,” Seth says, “but publication online, [in] literary magazines, stu like that. I think everyone really tries, and a few members have actually been successful.”

up time slots for open mic nights at the Front Room Co ee House.

“I feel like the more people we get involved, maybe we’ll get something where we have a tangible thing we can put our names on,” speculates group member Kevin Tasker, a junior majoring in creative writing. “Some kind of zine or a book or an anthology or something like that. I don’t know what exactly Seth had in mind. He’s always scheming, so I don’t know what the deal is for sure.”

"Everybody can feel really comfortable reading their work."

But Seth and Shelby have been cooking up a lot more than stories recently. Seth’s newest quest is to spread word of his organization to all corners of the university. His target: the new crop of freshmen. Schemes of recruitment aside, Seth is con dent he’s starting to get the publicity he’s searched for—the large turnout this fall as evidence.

“I do believe it is becoming fairly wellknown,” Seth remarks con dently. “In the English department, especially. But I would like to expand a lot more, so the campus knows more about it.”

“We’re trying for more social activities,” Seth says, his voice quickening with excitement at the prospect of ne-tuning his organization’s community outreach.

“I had a plan for an outdoor literary magazine, where I would print out people’s work … and I would post them all over the place.”

e Group has brainstormed plenty of other ideas as well, and already has set

With all the incoming members e Group has been receiving, especially freshmen, things are looking up. One of the most anticipated byproducts of this in ux is the added publicity, fueling a machine that will bring in even more new material.

But for now, the members of e Group are content to give one another advice and praise in regards to their work. e absence of any other creative writing group on campus makes this organization a rare jewel.

“It’s great to see such enthusiasm for literary conversation,” faculty adviser Mark Halliday says. “ is kind of informal shared focus on creative work is one of the best ways to get the most out of college.”

But for the students, it’s all about sharing their work and exploring the writing they love. “It gives everybody that is interested in writing a place to come together and meet and talk about writing and their own work,” Shelby says. “For me, it gives a really nice environment to get together with other people with a similar interest. [You] get to be inspired by everyone else in e Group.”

BY KIM AMEDRO

You’ve settled into your new digs at OU and decide it’s time to throw a party. With alcohol involved, there’s a ne line between having fun and getting busted. So what do you do?

Eh, it’s the weekend before Halloween. You decide to take it easy. Only your usual group is fortunate enough to get your invite to drink last weekend’s leftovers. You underestimated your supply. Beer run! You also underestimated the amount of liquor your friend could tolerate. She stumbles ahead of you and is screaming at passing groups. She’s under 21. Why did you bring her? It’s not like she can buy the beer or even help carry it back in this state.

First, line your yard in caution tape. Next, pin up the “No One Under 21 Allowed” sign. Now, call a few friends and tell them to invite as many people as they want.

Eh, you worry about everything. Why would they pick your house anyway? You go to smoke with your buddies…

You know about two-thirds of the faces at the party and everyone seems to be staying in the boundaries and keeping trash o the sidewalks. You overhear some odd questions and notice a stranger. Your gut feeling says…

Everyone is outside on your lawn, with nowhere to “go.” Literally. A golden stream catches your eye and you follow it back to its origin.

Kick it o Animal House style: pen kegger! Toga, toga!

Your neighbor wanted to get his band in on the gig. He walks in around 8 to set up the amps and the speakers. Unfortunately, the crowd ramps up around midnight and the band goes wild, destroying your eardrums, but feeding the party.

Noise Violation (Friday and Saturday after 12 a.m.)

An Athens o cer locks eyes on your adorably inebriated friend. He charges straight for her as she starts to lose her balance. When asked to identify herself she…

Busted for possession. You shouldn’t have blown o that odd situation. Now you might lose your right to federal nancial aid and, despite living o campus, you may also face judiciaries.

Undercover. So you approach the conversation and try to feel the situation out with your own Q and A. However, so long as it isn’t entrapment, the o cer can lie his/her way out of identi cation, just like any other underage partier.

Public Urination. For 100 buckaroos you could’ve gotten public toilets and saved yourself the legal trouble.

Whips out her fake ID that couldn’t even get her into The Junction. But, she is only a day away from turning 21. That’s another o ense. She’ll have to appear in court and will automatically face two to ve days in jail.

This is aside from the court fee costs, nes, jail time and driver’s license suspension. Plus, with all the reinstatement fees and increased insurance costs…

You get slammed for furnishing alcohol. Wave goodbye to next quarter’s books. Mandatory $500 ne on top of the court fees.

Gives only her name and address and shows only her student ID. Even though she’s under arrest, the o cer can’t convict her as long as she doesn’t admit to being underage.

Luckily it’s her rst o ense, and she goes through the diversion program. Unfortunately it costs her close to $250 and twelve hours of community service.

If you rack up more than four of the listed o enses below, your party can be shut down as a “Nuisance Party.” beer or intoxicating liquor to an underage person. by an underage person the property owner of tra c on the public streets and sidewalks or that impedes the ability to render emergency servicesvenience or damage to property which is hereby declared to be an unlawful public nuisance.

BY RYAN JOSEPH PHOTOGRAPHS BY CHARLES YESENCZKI

Tvhe back end of the garbage truck devours the old, brown couch like a ve-year-old massacres a celery stick. e sofa—a nostalgic, ’70s blast-from-the-past, cracked, splintered and exceptionally withered— disappears as the garbage truck uses its awesome power and rear-end loader to shove it into its mouth.

From a safe vantage point inside a 1998 Oldsmobile Intrigue, watching this dismantling is cathartic.

e Waste Management employees—driver Rick Beasley with assistance from Route Manager Ted Hollingshed—

“It’s funny what kind of misconceptions you’ll hear about Waste Management drivers and garbage men, in general.”

diligently whipped the edi ce’s waste into the butt of the monstrous green vehicle. Hollingshed—a former Waste Management driver—didn’t miss a beat in helping Beasley, even though he now works in Waste Management Corporate.

drive our company trucks.”

From watching and talking to Beasley and Hollingshed, any misconceptions about sanitation engineering seem moot.

“When people see garbage men they think it’s much dirtier of a job,” Beasley says.

Beth Schmucker, Waste Management Community Relations Manager

“It’s funny what kind of misconceptions you’ll hear about Waste Management drivers and garbage men, in general,” Beth Schmucker, Waste Management Community Relations Manager, says from the back seat.

“ ey’re capable men who have been rigorously interviewed and trained to

Beasley mentions this before I follow him on his Athens route. He had been picking up trash since 4 a.m. His uniform is barely scu ed from the ve-and-a-half hours of work he had already put in that day.

“People think it would smell bad—I was one of those people—but it’s not near as bad you think,” he says.

Beasley is a well-kept man in his early 40s. He’s donning a neon-yellow vest and brown boots. His sunglasses re ect my image as he a ably explains the areas where he picks up trash.

“On Mondays I serve Green eld, Tuesdays I serve Athens, Wednesday I go into Nelsonville, ursday I go into Albany and Friday I serve e Plains.”

While serving each community, Beasley says there are di erences between collecting trash in rural settings as compared to urban areas.

“Really when it comes to picking up trash, there isn’t a whole lot of di erence,” he says. “It’s just when you’re in the city, it’s just so much more quicker. In the country, it’s more driving and you’re trying to t on these narrow, country roads. In the city it’s all about trying not to hit anything, so safety is the most important aspect about collecting trash in the city.”

In the matter of an hour-and-a-half I know more about sanitation engineering than any journalist should.

“People think it would smell bad—I was one of those people—but it’s not near as bad you think.”

Beth Schmucker, Waste Management Community Relations Manager

Waste Management, based in Houston, Texas, is the largest waste management company in North America. Its signature green “W” and golden “M” can be found roaming the streets from Los Angeles to Toronto to San Juan (although, ironically, they do not service the Ohio University campus).

Waste Management is leading the way in transforming waste usage in the industry. e company is starting to employ methods to not just store our waste, but also put it to use.

“Waste Management is very involved in waste energy,” Hollingshed says. “We’re one of the leaders in waste energy. We use the waste that we pick up to power homes and to power electricity. ” Schmucker adds, “Four of our land lls here in Ohio have gas-to-energy plants where the methane gas is converted into usable energy. at’s really the future of renewable energy.”

Along with being the largest processor of waste in North America, Waste Management is also the largest recycler. Coupling with the company’s sustainability goals, Waste Management hopes

to double its processing of recycled goods from seven million tons to 14 million tons by 2020.

Re-using land ll sites are also a top priority of the company. “We are also involved with the Wildlife Habitat Council,” Schmucker says. “We’ve got 49 of our sites that are certi ed by the council, so we’re providing habitats for local, native wildlife and we’re reusing our land for uses other than what people conventionally think land lls are used for.”

Before following Beasley on his route, Hollingshed and Beasley recount tales of routes that have garnered odd discarded items. Although Waste Management collects and processes a myriad of objects, some things Waste Management cannot handle.

“ e oddest thing I saw in the trash was a college student,” Hollingshed mentions. “Lucky for him, it was a rear-load dumpster, so we saw him. If it were a front-load dumpster there’s a good chance he would’ve ended up in the truck.”

Fine Leather Goods

Jewelry, Clothing & Accessories

Specialty Foods

Soaps & Lotions ! Complimentary

Wrapping

BY ADAM WAGNER

Sometimes inspiration to stand up for a social cause comes in the wake of watching a large, passionate rally—other times it’s the nudging persuasion of a friend, or a moving documentary. For Ohio University graduate student Erin Dame, the decision to become an active participant in reforming marijuana laws came during an event at Purdue University called Cannabash—a music festival calling for drug reform hosted by the Purdue University chapter of Students for Sensible Drug Policy.

But Erin, now 24, wasn’t always opposed to harsh drug policies. In fact, she wasn’t completely aware of the policies in existence. Herself a marijuana user since her freshman year at Purdue, she found herself at Cannabash on April 20, 2004, listening to a lawyer orate facts during a break between bands: 825,000 yearly marijuana arrests, 85 percent of which are solely for possession. e numbers “literally shook”

Erin to her core. After the lawyer’s speech, she promptly became involved in the quest for drug reform, temporarily dropping out of school to work for the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws.

of which decry the downfall of Western civilization that will be brought on by Communist-leaning, agburning college students. It may seem like a quaint generalization, but the fact that the most recent of these books was published in 1975 indicates that America’s way of thinking about activism is outdated.

e sit-ins and ery confrontations between police and citizens are no longer the norm. Instead, activists are likely to work with the establishment to enact some form of change.

The more involved I got, the more I loved it. Honestly, I get a high from doing it because I’m not only helping other people, but I’m helping myself.

Erin Dame Graduate Student

Erin dedicated the next year of her life to ghting for drug reform, traveling from campus to campus around the nation, debating Drug Enforcement Administration agents about the merits of reform and helping people set up local chapters of the organization. Erin’s is an example of a new kind of activism, one predicated on discussion and patience as opposed to anger and action. e common perception of activism, however, has not yet caught up to its realities.

Type “activism” into the subject eld on any one of Alden Library’s computers, for instance. e search doesn’t return any speci c results, instead directing you to “student movements” and a subset of 27 books, many

at does not mean that the goals of activism have changed, as many modern activists have the same ideals as their angrier predecessors— only their methods have changed, moving toward negotiation instead of hostility, and receiving more than a touch of modernization. “I think at the core they’re the same priorities,” senior Molly Shea, an active member of Students for a Democratic Society, said. “[We still want] a just, equal society where people are treated with respect and have equal opportunities. But as far as speci c issues, I think it’s totally di erent.”

e way activists communicate has not totally changed, as they still rely on word-of-mouth or yer campaigns to spread the “good word.” E-mail, however, has become the preferred intra-group mode of communication. Molly believes that this has had mixed results. “ e advantage is de nitely that you can reach more people quickly,” she said. “But at the same time that message becomes impersonalized.…It’s way less e ective.”

Erin agreed, but also said that the best way to convince people to become involved is to make them

“understand [that] the activism that they do, whether it’s them passing out yers or whatever small things, contributes to the movement.”

“It’s less angry. I hate to generalize that, but in a university setting, especially here at [Ohio University], it’s less angry,” Erin said. “We nd that sit-ins may not be as appropriate as going at it from an inside view and trying to change things by working with the administration, instead of alienating them or working against them.”

is placid face of activism may be a ecting the number of people who join the movement. Instead of disrupting newscasts with violent protests demanding change, today’s activists work on taking baby steps forward, accepting that they nally may reach their end goal one day. Although, for many amateur activists, these gradual changes rarely make them feel like they are actually making an impact, leading to a general feeling of helplessness. “People don’t think their voices count, so they go to clubs and they make these connections, and then the clubs might try their hand at activism and things might not work out,” Erin said. “People get discouraged.”

e way to convince new activists to stick with their causes of choice seems to be to tie them into the community—an idea that is fundamental to most activists’ goals. It is by interacting with communities, both locally and nationally, that activists develop a sense of how to convey their messages and, more importantly, just what those messages should be.

“If you don’t feel connected with the people around you, you have no reason to act in solidarity with someone who lives in West Virginia and literally has black water that they’re supposed to be drinking,” Molly said. “You have no reason to care that a generation from now people won’t have woods to hike around in. You don’t have a reason to care unless you have a sense of community and a

sense of connectedness to di erent people.”

Erin emphasized the necessity of a community in terms of making a point, citing the idea that a single person marching to Washington, D.C., would have little e ect, but that a million undoubtedly would cause an uproar. A sense of community amongst people in general, let alone in the realm of activism, is proving more di cult today. is apathy has proven to be even more of a plague to activism than it is to politics. “It seems like back in the ’60s or ’70s, the general youth culture was activist, and now it seems to be more a select few that are activists,” Molly said.

Erin, who helped register voters last fall with the Power Vote campaign, reiterated that point saying, “People didn’t know how to register to vote, and a lot of people didn’t care to know. People don’t think these issues concern them when they really do.”

Ending apathy and jumpstarting activism can come from the most unexpected place, though— like Erin’s revelation at Cannabash. Erin found that beginning her career as an activist provided her with a sense of pride that nothing else could give her. “ e more involved I got, the more I loved it. Honestly, I get a high from doing it because I’m not only helping other people, but I’m helping myself,” Erin said. “I’m making these connections and I’m seeing how this kind of activism helps other people…It’s taken over my whole life. I’m kind of addicted to activism. It really is what I do almost all day, every day, and the people I work with are my family and all of my friends.”

Molly said she sees a positive future for activism, as the state of the environment, in particular, is leading to “more of youth culture…getting back into activism and organizing, building communities, because things have gotten to a place where people realize that it’s important again.”

BY BETHANY COOK

PHOTOGRAPHS BY ERICA MCKEEHAN

While some Ohio University students would sacrifice a right hand to be able to call a Palmer Street estate “home,” this isn’t the case for all. Senior Dani Fulmer chose her abode atop the hill of Mound Street for its serenity. Dani and her roommates, seniors Brooke Shanesy and Brandy Hayes, used their creative abilities to turn a typical college rental house into a home.

To save money, the girls went the DIY-route with many aspects of the room. Psychedelic tie-dyed sheets hanging on the wall and ceiling are products of the girls’ handiwork, as are the curtains. Dani, using a special paint from e Home Depot, painted a chalkboard along one of the walls for visitors to draw on at their leisure.

Dani’s favorite room is the “pillow room.” True to its name, the room’s only pieces of lounge furniture are pillows, with the exception of a small futon. “We didn’t have any furniture, so we used a bunch of pillows,” Dani said. e unique space provides an escape where the girls watch movies and hang out.

BY SHANE BARNES

Decked out in whites, creams and grays, junior Kait Orr’s West State Street apartment is a sort of serene refuge on campus. With homemade decorations, secondhand furnishings and splashes of color in unexpected places, this is one of the most livable student houses we’ve ever seen.

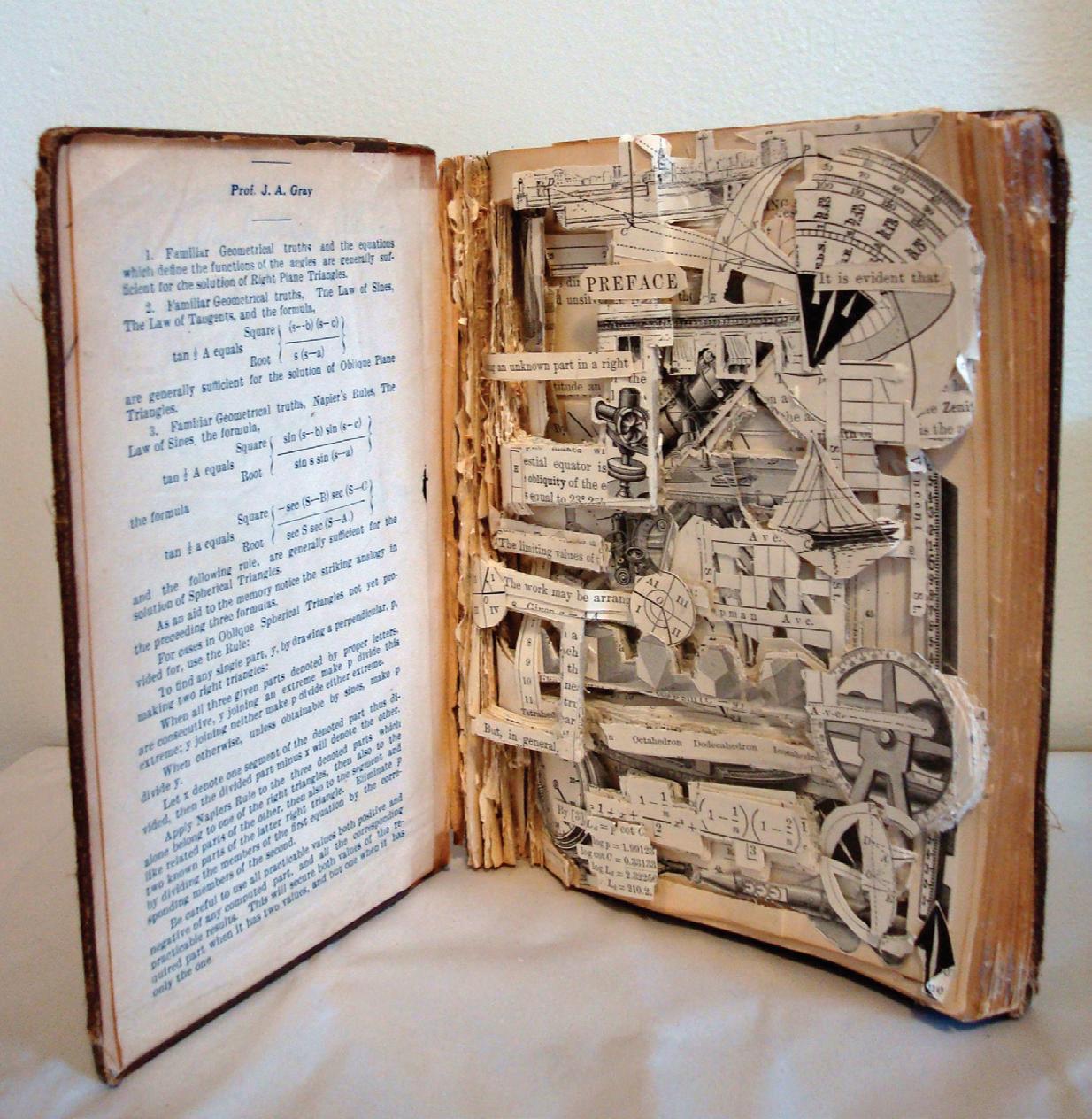

Being an art major, it’s not a surprise that most of what makes Kait’s apartment stand out is homemade. “I bought 11 books at a garage sale for $1. I didn’t really think about how to do it, I just did it. I wanted them to hang from the ceiling, but here they are,” Kait said. “I’m going to burn them one day.”

Kait’s chairs hearken back to an almost Kubrick aesthetic, back when ergonomics were big and burnt oranges and olive greens were chic. Along with the futon in her living room, there’s plenty of seating for painting parties, or whatever it is that artsy people do.

Kait’s apartment is lined in what is perhaps the most ingenious standby solution for shelving: cinderblocks and particleboard. “My parents gave me $60 and told me to gure out shelving. So I went to Lowe’s. e wood was only $1.16 per slat.” It’s a good thing it was so cheap; she used it as a small table in her living room, as well as a nightstand in her bedroom.

WRITTEN AND PHOTOGRAPHED BY MARIEL & KATHERINE TYLER

Our road to vegetarianism was a mildly smooth one. Aside from our love of Hebrew National hot dogs, our dad’s barbeque and a sandwich or burger here and there, our diets were never heavily meat-based, and withdrawal has been almost nonexistent. But being an almost vegetarian is nothing like being a vegetarian, and we’re learning that meal-by-meal. Living o -campus has actually helped this new lifestyle stay a oat. Having to rely on our cooking skills has made us quite savvy in the kitchen, and experimenting with new vegetarian dishes has become a hobby. Here are a few of our favorites, inspired by The Chubby Vegetarian blog. Try them out on some of your friends—vegetarian or not—these dishes can be enjoyed by all.

2 medium sized potatoes

2 cups of grated potatoes or frozen hash browns

2 large eggs

1 medium onion

½ teaspoon white pepper

½ teaspoon salt

3 tablespoons

¼ cup of vegetable oil

Makes 10 latkas

Set the oven to 350 degrees. Poke holes in peeled potatoes with a fork, wrap in foil and bake until soft. While potatoes are baking, lightly beat three eggs with salt and white pepper, and set aside. Once potatoes are done, mash and thoroughly combine them with the hash browns. Chop the onion and add to the potatoes until well mixed. Add the eggs and the our, and mix until well combined. In a pan, heat oil to 250-320 degrees (about medium heat). Form the

mixture into palm sized patties. e patties need to cook for about ve minutes on the rst side and two on the other. If they brown too quickly, the oil is too hot, but if the latkes don’t sizzle when you put them in the pan, the oil isn’t hot enough. Once dark and golden, place the latkas on a plate with a paper towel to absorb the excess grease. ese are best directly after frying. Serve with sour cream and applesauce.

12 cherry tomatoes

1 can of Cannellini beans

2 cups of frozen spinach

1 cup of polenta

¼ cup of milk

3 cups of vegetable stock

8 cloves of garlic

Olive oil

Italian seasoning

Salt and pepper to taste

Serving Size: 4-6

Preheat the oven to 415 degrees. Cut tomatoes in half, and place in an oven safe dish. Drizzle in olive oil, salt and pepper. Peel the garlic, drizzle with olive oil and wrap in foil. Put tomatoes and garlic in the oven for 40 minutes, or until the skin of tomatoes begin to darken. Melt butter in a pot with a palm full of Italian seasoning. Add polenta to the pot and mix. Warm the vegetable stock and add to the polenta mixture in three parts, mixing to ensure no clumps form. Once all stock is added, cook on stove for 30 minutes. Mix eggs and milk in a separate bowl. Stir the

egg and milk mixture into the heated polenta for two to three minutes or until well mixed. Put polenta in an oiled dish and place in oven for 15 minutes or until rm.

Once tomatoes and garlic are done, remove tomatoes and set aside. Sautee garlic in olive oil, and add the beans to the saucepan. Add salt and pepper to taste and set aside. Sautee spinach. Remove polenta from oven and let cool. Melt butter in a pan, and pan fry the polenta. Cover in mozzarella or provolone cheese. Plate the polenta, and top with sautéed spinach, beans and tomatoes.

For the members of a generation devoid of hard knocks, the only thing certain about their future is that they’re not ready for it.

BY ANNIE BEECHAM

PHOTOGRAPHS BY RICKY RHODES

Erica Cohen will graduate early, after fall quarter 2009. at’s two quarters premature of the traditional four-year plan. She’ll have an online journalism degree from the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism, with dueling minors in business and political science. She has a job and apartment already secured in Manhattan, and she will move there in December. She will spend this winter applying for law schools and working full time.

And one year from now, if things go as planned, she’ll be enrolled in law school. ough she hasn’t yet taken the LSAT, not a doubt exists in her mind that she will be admitted to one of the schools on her short list. She knows this because she doesn’t fail. “I don’t lose. I refuse to lose,” she says. If Erica wants something, she does everything in her power to get it. If Erica’s name sounds familiar, it’s

because last spring she organized a bone marrow drive at Ohio University that attracted the largest number of people of any bone marrow drive ever in the U.S. Because of the drive’s success, Erica Cohen is in the Guinness Book of World Records. So, until law school begins next fall, and while the rest of her senior class is still in Athens scrambling to nish on time, she’ll be working as a donor recruitment coordinator, organizing college bone marrow drives nationally in New York City for the same nonpro t agency that sponsored the drive at OU.

Erica Cohen is the prototype of Generation Y—those born between 1980 and 2001—and while her foresight and early success are impressive, she’s typical of this developing demographic. Generation Y, Generation Next, the NetGeneration, the iGeneration, the millennials—they’re all names for the largest generation of

Americans ever—92 million. eir parents, the baby boomers, often referred to as omnipresent “helicopter parents,” are a strong 78.3 million.

Millennials are classi ed as technologically savvy perfectionists, multitaskers and driven individuals who work well in teams. It’s clear that a segment of the generation possesses Erica Cohen-like drive toward school and their edgling careers, but these occasional overachievers are the recipients of both lavish praise and harsh criticism—increasingly the latter— from older generations. And as the eldest batch of the millennials makes its debut into the workforce, those critics are forced to deal with them mano a mano — that is, if the young college grads actually get jobs.

A meager 19.7 percent of 2009 college grads reported jobs upon graduation, down from 26 percent in 2008 and 51 percent in 2007, according to a survey by the National Association of Colleges and Employers. at the job market is poor is not news to anyone, but for a generation that hates to lose, it’s frustrating on a deeper, more personal level, but who’s to blame for this generation’s stunted ability to accept loss?

It’s easy to blame helicopter parents. ey coddled and cared for their children, and worried about something called “selfesteem,” a quality that became as fragile as glass—it would surely shatter with the impact of the tiniest of criticisms. e millennials grew up familiar only with success, and failure became a dirty, impossible outcome.

Pampered childhoods colliding with a poor economy can lead to bad things for the millennials heading out into the world. “I think parental pressure from my generation is intense for some, but I also think that anyone who’s at all aware of what’s happening in the world knows it’s the most di cult economy in a generation since the ’30s probably,” omas Korvas, Director of Career Services at OU, says. If less than 20 percent of 2009 college grads left school without a job, then senior accounting and business pre-law major Je rey Peterka is bucking the trend for the 2010 graduating class. e

Minnesota native had signed — before his senior year—with Deloitte accounting rm in Minneapolis to begin full time in fall 2010. Like Erica, he represents the ner traits of a millennial, and likely won’t feel the e ects of a poor job market in the foreseeable future. He spent last summer as an account executive for Hays Companies in Minneapolis. On campus, he’s the President of the business fraternity Delta Sigma Pi, and he’s involved with the Student Leadership Development Program. His studying habits are nely tuned, with about three hours a day devoted to out-of-class work. His dream job, to own a company in the medical industry, does not seem far out of reach. Je rey is the type of student that Korvas usually encounters in OU’s Career Services Department. Discussing the issue of students acting entitled to the perfect job out of school Korvas says, “I’ve seen those statements and read the literature. With the students I’ve counseled, advised and so on, I have not seen that. I think they’ve been very hard workers, and I really haven’t felt the entitlement issue.” he adds, “I think students have to break away and learn to think for themselves, speak for themselves and make decisions for themselves—which might be a little harder for students in that generation,”

Trophy Kids, too, is another term for the millennials. It’s a reference to the fact that millennials grew up playing games of soccer and basketball, at dance class and other sessions, that were rewarded with trophies for both the winning and losing teams (“I have a big collection of trophies, all on my mantle,” Je rey says). It also refers to the idea that members of this generation are the metaphorical “trophies” of their parents, who’ve spent countless time and money to pave an easy, e ortless path to success for their precocious children.

Erica and Je rey both attribute their collegiate success to personal drive rather than parent-induced pressure. “My parents were very supportive and pushed me to do my best,” Erica says, “but they’ve always been more likely to say, ‘Look, Erica, slow down.’”

Professor of English Mark Rollins is a rm believer in positive reinforcement, but he sees how too much can be destructive. “On the one hand, our societies and our families have tried to reinforce students with positive reinforcement with a trophy or reward: everybody who goes home from the birthday party gets something,” Rollins says, “but maybe that’s counterproductive because sometimes you just have to say, ‘you know, you didn’t move fast enough at musical chairs.’”

Even Erica recognizes this phenomenon: “ ere’s a level of competition in our generation that I’m not sure exists in other generations. ere’s almost this cutthroat mentality that it’s either you or me because one person has to be on top. It’s just this general idea now that people can’t stand to lose.”

And when it comes to grades, millennials like their As. “People will go nuts if they don’t get an A. A is for excellence—above and beyond. I think B is honorable, that’s great,” Rollins, who has a 2.3 out of 5 for average easiness on ratemyprofessors. com, says. “Believe me, when you read evaluations, ‘he grades too hard, he expects too much’—I just live with it.”

Older generations are grappling to understand the nuances of millennials, as the generation enters the working world. Author Ron Alsop’s advice book, e Trophy

institutional environment, if you sit at a meeting, and somebody asks you what you think, ‘What are your thoughts on this?’ and you sit there, ‘Gee I don’t know,’ they don’t give you an F—they say ‘Goodbye, you’re out.’”

Rollins has observed an inability to communicate and express ideas, but doesn’t nd it to be exclusive to this generation. Rather, the expression of ideas is a skill to be learned during the college years, which is why he operates his class in a Socratic, discussion oriented manner.

I think students have to break away and learn to think for themselves, speak for themselves and make decision for themselves.”

Thomas Korvas Director of Career Services, OU

Kids Grow Up, o ers tips for those managing millennials in the workforce, such as: “Millennials require careful handling when their performance isn’t up to par. Harsh criticism can provoke tears— or even resignation,” and the one that might make this generation the most uncomfortable, “Managers need to provide millennials with an unusual amount of hand-holding, reminding them of project deadlines and telling them such elementary things as the importance of turning o cell phones during client meetings.” Obviously, Alsop paints a portrait of a severely ill-prepared young adult.

Rollins, too, sees certain characteristics that may hamper the millennials in the workforce. “When you go into a corporate environment, or an

Korvas, one of the illustrious baby boomers, nds that students may lack certain communication skills—thanks to the pervasiveness of technology like the Internet that millennials have never lived without. “One concern we’ve had, even as a university, is students being too involved with their games and technology, and not really getting out and developing those communication skills. ey aren’t as engaging as some generations— they tend to rely more on technology as entertainment, as opposed to people. I think that’s something to at least be aware of and think through,” though he says, “it’s certainly not a label on every individual.”

Alsop notes in his book that millennials possess a special mix of endearing and not-so-endearing qualities that result in an “intriguing and potentially explosive brew.”

While some are critical of the generation, many others view them as a viable population of eager employees with new perspectives. When the economy rebounds and hiring picks up, several classes of unemployed, fresh college graduates will be ghting for the same job positions—several million young adults, known for their competitive streaks, on a simultaneous job hunt makes for an interesting frenzy. Korvas, however, is optimistic that millennials will ourish outside of their protective environments but warns, “ ere’s always a pebble in the road, and that’s something you’re going to have to deal with and become comfortable with yourself and your skills.”

With the popularity of bikes on the rise, high-end cycles are becoming a commodity. The Athens Bike Co-Op keeps things grounded, though, and provides real-world knowledge to those bike enthusiasts willing to learn.

BY SHANE BARNES

IPHOTOGRAPHS BY TYLER SUTHERLAND

n a garage under a house and down perpendicular alleyways, there’s music, but the old rabbit-ear radio is breaking in and out so often that the instruments begin to stutter. With ve people, the Athens Bike Co-Op is packed. Bike parts clutter the oor space: frames, chains, handlebars, derailers, stripped naked and ready for reassembly. Sixtyseven wheels, some bent like Dali clocks, hang from the ceiling. “Low ying cyclecraft,” a nearby sign reads. en, another, hand-painted: “Be Patient, We’re Busy Trying To Save e World”—a lofty statement that captures the Co-Op’s mission perfectly.

e thing about the Co-Op is that all of the bikes, all of the dozens of rusted chains, broken pedals and crimped derailers, are donated or rescued. Operating under a basic, “build two, keep one” rule, the Co-Op encourages experimentation as a way of learning how to upkeep bikes, and every time someone learns to make a bike for themselves, the Co-Op gains the other working one, which it later sells or keeps as a spare to loan to anyone who needs a way to get around. And, for getting around, there’s no doubt that bikes have become more popular in Athens: recent numbers indicate that 46 percent of residents travel to work by some form other than automobile. But for a place that wants to change the world, 46 percent isn’t enough.

e Co-Op’s ultimate goal is to promote a sort of sustainability, holding up an ethos along the lines of the “teach a man to sh” proverb, and these teachers are all volunteers.

ere’s a de nite intimidation factor in the world of bikes, but the Co-Op’s three regulars—Jon, Eric and Cusi (Ku-zay— it’s Incan)—are more than happy to extend a grease-stained hand and the knowledge of almost 20 collective years to even the most uninitiated, wannabe cyclists. ese are the guys that make the Co-Op work.

“We don’t x peoples’ bikes for them,” Cusi says. “We show

them what to do, but they have to x it themselves. en they can come back and use the space and tools whenever they want.”

A Cincinnati native, Cusi Ballew has been back and forth between Athens and Anywhere Else for the past 10 years—and he’s been at the Co-Op for nearly six, since way back when it was a facet of the now-defunct community center, e Wire. He’s a world-wary traveler, having learned most of what he knows about bikes in a co-op in Madison, Wisconsin. Since then, he’s made Athens his base, initially coming here to join his brother, who was a student at Ohio University. While Cusi has recently noticed that the CoOp is concentrating more on selling bikes (both in-house for $30-50 and also in designated bike sales, often held on College Green, for roughly $30-100) than teaching bike skills to newcomers, he still sees knowledge as the Co-Op’s main product. “Speaking strictly numbers, there are more people. But there’s a big di erence in the use of the space,” Cusi says. More and more people are coming to buy bikes rather than learn.

The Co-Op’s ultimate goal is to promote a sort of sustainability, holding up an ethos along the lines of the “teach a man to fish” proverb, and these teachers are all volunteers.

Eric Cornwell, Athens native and longtime Co-Op volunteer, is the perfect example of a successful bike convert. When he rst came to the Co-Op he was barely able to change a tire, and now he’s improvising a grip-removal tool from a spare pipe. He measures the angle roughly, then saws at the pipe, showering the oor with sparks. He checks his work, measures again and then cuts some more. Rinse and repeat, until the small space smells like the Fourth of July and the stubborn yellow handlebar grips have been removed. en Jon, who had been waiting in the wings, straddles the bicycle’s frame and shimmies the brake controls onto what is soon to be a BMX-ready bike. is teamwork, this cooperation, is what the Co-Op hopes to encourage others to do.

“We don’t just want to get people on bikes—we want to get them involved,” Eric says.

“ e best thing about bikes is that generally everyone can at least maintain a bike pretty well,” Cusi says. “With modern cars you can’t even change the oil unless you’re a mechanic.”

Top Left: Kent Weber, a senior audio production major at OU, repairs the chain on his bike at the Co-Op on September 24, 2009. The bike was given to him by a roommate and needed a few repairs. Top Right: Jack Martin and Ryan Ford bike around Athens as part of Critical Mass on September 26, 2009. Critical Mass is a monthly bike ride held on the last Friday of the month. Bottom Left: Trevor Raymond Davis waits for Critical Mass to start on September 26, 2009. Bottom Right: All the participants of the Critical Mass ride on September 26, 2009, before the ride.

BY NIKLOS SALONTAY

PHOTOS DAN KRAUSS

Leave Athens, the only blue fortress in a sea of conservative mores, and it’s clear that after all these years there are still strongholds of the old Appalachia. Knowing this, it’s still hard to believe that there are men living in these forgotten hills. They’re fairly common though—just another facet of rural poverty in this old and impoverished land. Today, a photographer, writer and editor trudge through woods of Athens to nd one.

The map is beginning to show wear