BREAKS FAST ON THE THIRD SEX

TEXAS TWO-TONE YONI KROLL VS. LOS KURADOS

ANNE ISHII IN COSMIC UNION WITH HYUNJIN CHA

Plus sonorous notations on the subject of AMBARCHI, BERTHLING & WERLIIN / 10cc / XIU XIU

JACK NITZSCHE / HARVEY MILK / THE FALL

LINDSEY BUCKINGHAM / TIERRA WHACK / NICO

JON SAVAGE / ISAIAH OWENS / DEPECHE MODE

ERANG / SISTERS WITH TRANSISTORS / CATE LE BON

TOSHIMARU NAKAMURA / THE LADIES / ALEX SILVA

HIS NAME IS ALIVE / RON JOHNSON RECORDS

HELADO NEGRO / THE GO-BETWEENS &

“There is no time that I don’t want to disappear into sound.”

—Kristin Hersh,

In high school, my car was a snapshot of my musical identity, proudly displaying two bumper stickers: on the left a Throwing Muses decal, & on the right a Melvins sticker styled like the KISS logo. These seemingly different yet psychically connected bands were the never-ending soundtrack of my waking & dreaming life. Between these aural bookends was an ongoing cacophony of punk, jazz, noise, math rock, folk, indie, pop & more.

from Seeing Sideways: A Memoir of Music and Motherhood (University of Texas Press, 2021)

If you’re reading this issue, you too dwell in a world where all sounds coexist & collaborate in unimaginable ways.

Sound Collector Audio Review reminds you to be curious. May the reviews in this issue expand your musical horizons & bring new excitement to the spaces where you escape & explore.

Be seeing you, —Laris

Kreslins,Publisher/Listener

Hope Gangloff is an American painter based in New York City who is known for her vividly colored portraiture. @hopeloff

Eileen Wolf Echikson has completed work for the Philadelphia Museum of Art, World Cafe Live, Vans Shoes, & Philadelphia-based musician Sad13. Peep their latest pages on Instagram, @soupywoman

Paul Rodriguez is a painter who lives in Philadelphia, PA.

Ian Holman is an illustrator & cartoonist living in Brooklyn. He self-publishes a comic-book series titled Minotaur’s Daughter

Chicago-native Steve Krakow is known as a “psychedelic guru” of sorts, & is the creator of the Galactic Zoo Dossier a hand-drawn magazine published by Drag City since 2001.

PUBLISHER

Laris Kreslins

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

W. T. Nelson

EDITOR

Ilyn Welch

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Jason Laan

Mike Rich

OPERATIONS CONSULTANT

Brian Adoff

BUSINESS OPERATIONS

Justin Geller

ADS & DISTRIBUTION

Laris Kreslins

UNDER ASSISTANT

WEST COAST PROMO MAN

Ed Tettemer

BACK OFFICE SUPPORTERS

Anonymous Anonymity, LLC

Billy Silverman

OUTER GROOVE SUPPORTERS

Chris McKenna

Chris Ronis & Sage Lehman

Ari Sass

Kate Sawall Sils

Mike Treff

Matty Wishnow

Derek Stukuls works as an illustrator in the town of Krumville nestled deep within the Catskill Mountains. When not drawing, Derek wrestles bears & helps turtles cross the road

Hanna Lee is a Korean American artist, art therapist & art educator who resides in Philadelphia, PA.

Karli Bresler is an illustrator based in New Jersey whose work mainly focuses on odd, colorful characters usually drawn with marker & color pencil. Her influences are artists such as Daniel Clowes, Joe Murray, Paolo Puck, with a hint of Junji Ito. You can view her work on Instagram @karli.bresler.

Diane Barcelowsky is an artist, art educator & advocate for the arts in our public schools.

Meghan Turbitt is a cartoonist whose comics have been published in The New Yorker The Philadelphia Inquirer & The Nib, & is a grant recipient of Koyoma Provides.

With humble tools like a sketchbook & fountain pen, Anna Rodriguez blends traditional & digital mediums to craft imagery that reflects her inner world, offering viewers a glimpse into her creative thought process. Instagram: @tumbleweedgrows

Eric Schack is a lapsed creative & active adult educator, living his life in the Chihuahuan Desert of southern New Mexico. He’s a Pisces & likes Chinese food.

Lomaho Kretzmann lives in Los Angeles. He works at a pizza shop.

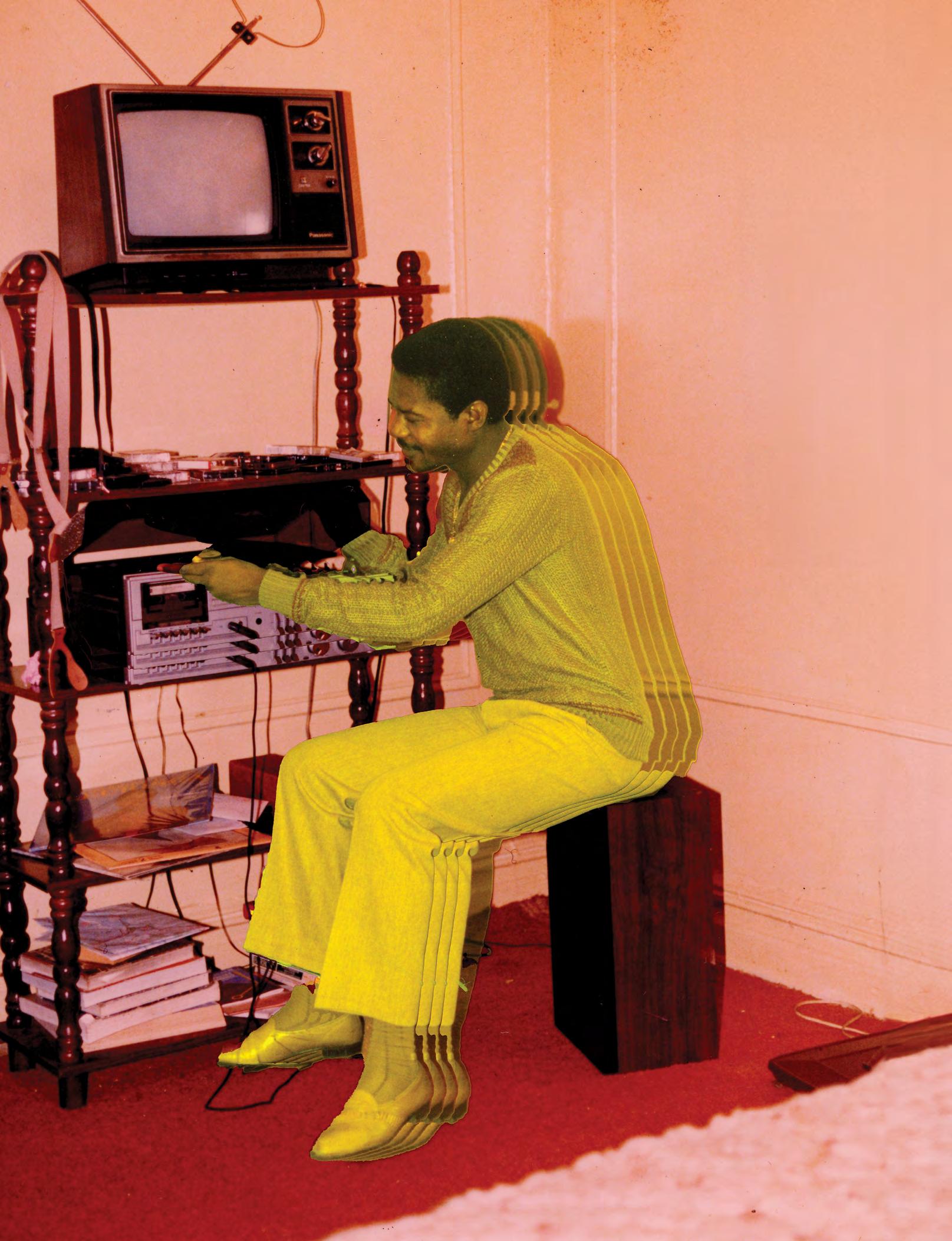

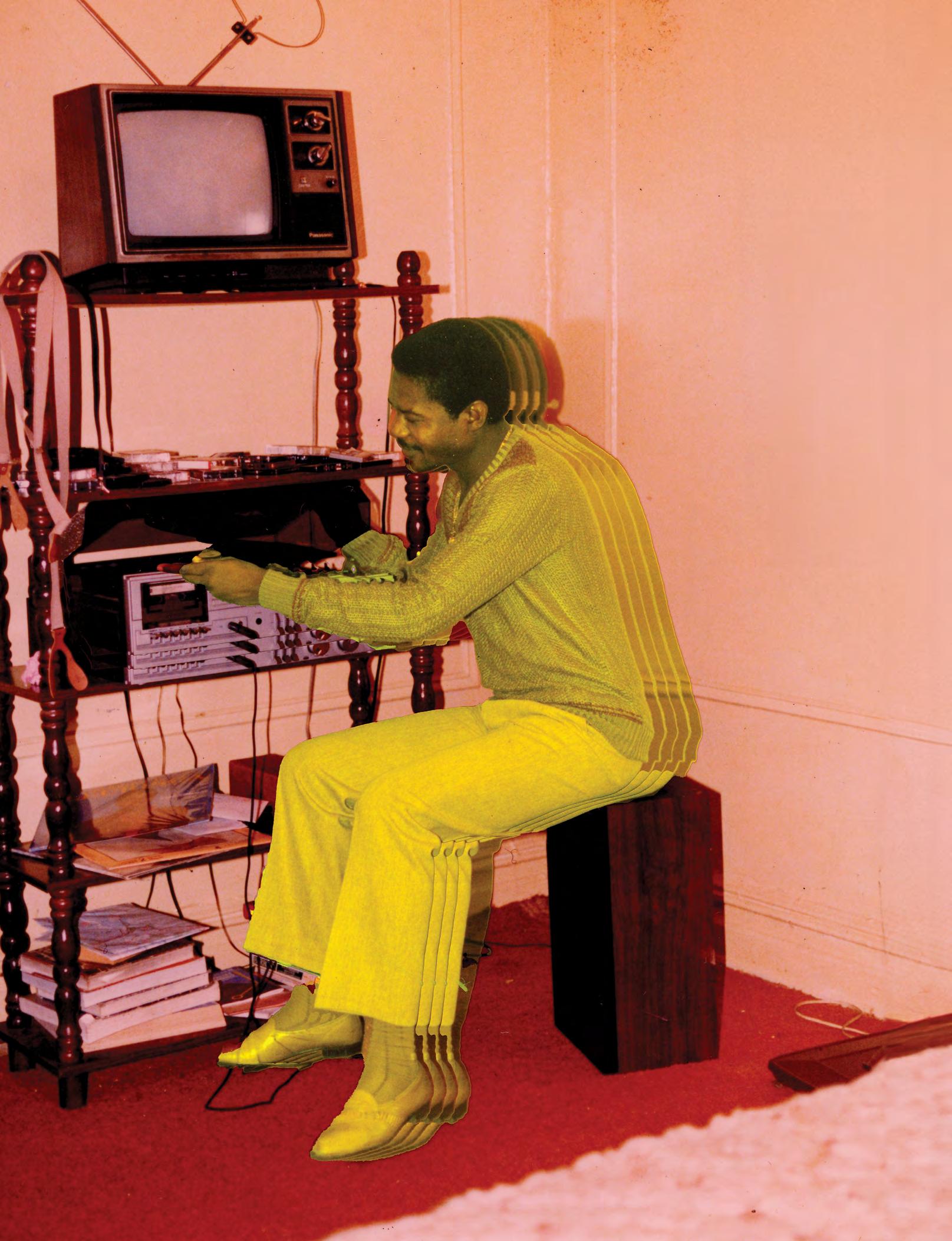

Hisham Akira Bharoocha is a multimedia artist based in Brooklyn, New York, who makes large-scale murals, paintings, drawings, collages, audio/visual installations & performances & was a founding member of Black Dice.

Joe W. Sams is the founder of Uncle Dad Productions & creator of The Guy Who Waves at Things

Noelle Egan is a printmaker, librarian, bookseller & union organizer based in Philadelphia. She is co-owner of Brickbat Books, a funny little used bookstore in the Queen Village neighborhood of Philly.

Dale Flattum (TOOTH) is the bass player, vocalist & tape wrangler in the band Steel Pole Bath Tub. When not making noise, he makes artwork & takes photographs

Jodie Vicenta Jacobsen Melrose is a visual artist,designer & professor living in Brooklyn, New York, with her talented husband, two kids, two dogs & a whole lotta love.

Jess Rotter is an illustrator & artist based in LA.

David Edelsztein is a passionate music collector & enthusiast. He has worked as an animator, illustrator & designer for diverse companies such as Cartoon Network, Nickelodeon, BBC, etc.

Benjy Ferree is a singer-songwriter & visual artist. He lives 7.5 blocks from Fats Domino’s house in Arabi, Louisiana.

Tia Roxae is inspired by body horror, dark manga & ero guro nansensu. A fan of ’60s-’70s surreal/psychedelic cinema & deli cate, ethereal visuals, Tia’s work welds the abstract & bizarre with everyday reality.

Branko Jakominich is an artist & musician living in South Philadelphia. He is 6' 3".

Melinda R. Smith is an artist & writer. Her work can be found at melindarsmith.com or on Instagram @ melindarsmith

Naomieh Jovin blends original photography with images from family collections. Honors include an award from the Magnum Foundation Fund, a Mural Arts Philadelphia Fellowship for Black Artists, & a residency at the TILT Institute for the Contemporary Image.

DAY SAVERS

Anonymous, Mike Eidle, Andrew Fearon, Frank Ferraro, Kendra Gaeta, Linda Gheen, Jacobus Holt, Marko Jarymovych, Maria T. Sciarrino & Dora Shoturma

PRINTED BY

Evergreen Printing in the USA

THANKS TO

Iryna Halaway & the Kreslins Family

SOUND COLLECTOR MAGAZINE founded in 1997 by Laris Kreslins & Mark Halaway in Philadelphia, PA

SOUND COLLECTOR AUDIO REVIEW is published triannually by Box Theory, LLC. © 2024. All contents in Sound Collector Audio Review are copyrighted & are protected by all applicable laws. Nothing contained herein may be reprinted, copied or redistributed in any form without the written consent of the publisher. All views within are held by the writers in question. Sound Collector Audio Review does not subscribe to a collective ideology & disputed works may be taken up directly with the writers or be battled within our Letters-to-the-Editor section (which does not exist because we have yet to receive one). All letters, submissions, gifts, donations, etc. are property of Sound Collector Audio Review unless specifically requested to be returned.

Forward all subscription requests, submissions & advertising inquiries to:

SOUND COLLECTOR P.O. BOX 139

HUNTINGDON VALLEY, PA 19006

SOUNDCOLLECTOR.COM

Instagram: @soundcollectormagazine Facebook: /soundcollectormag

EDITORIAL info@soundcollector.com

ADVERTISING ads@soundcollector.com

SUBSCRIBE

Sound Collector Audio Review delivered to your door soundcollector.com/subscribe

Download the following albums featured in this issue of Sound Collector in The Qobuz Download Store

When I was in my late 20s & early 30s, I went on a lot of very bad & very mediocre dates. So many bad dates that I started thinking of dating as a sociological experiment aimed at uncovering the deepest, weirdest corners of Brooklyn & the outer boroughs—including, unfortunately, Staten Island. It was, embarrassingly, almost pathological. I took so many first dates to Lodge, the restaurant around the corner from my apartment, that the Lodge host eventually called me out on it. I ended up going on a date with him too.

These dates. What can I say?

At one point a year or so before I met my now-husband, I ended up matching with a book publisher who lived in Prospect Heights on OkCupid. We met up at a restaurant in his neighborhood for a casual midafternoon drink, picking a couple of seats at the bar. Sadly, the date was over before it really began because a lanky redhead wearing a holey, faded Pastels tee walked into the bar a few minutes after us & took the stool next to me.

Truckload of Trouble

PAPERHOUSE 1993

Suck on The Pastels

CREATION RECORDS 1988

Sittin’ Pretty CHAPTER 22 1989

Up for a Bit with The Pastels

GLASS RECORDS 1987

were the likes of Primal Scream & the Shop Assistants. They were pretty far removed from what we were doing, so I’m not sure how relevant that tag ever was, really. I feel a kinship with those bands, for sure, but past that, it’s hard to see the similarities.”

I did not want to fuck the book publisher. The drunk indie rocker in the Pastels tee on the other hand…

What is it about The Pastels that makes them so laconically cool?

The original Pastel, Brian Taylor, was a friend of Alan Horne, the founder of Glaswegian indie label Postcard Records, which released bands like Orange Juice & Josef K. Taylor recruited Stephen McRobbie (who later adopted the moniker Stephen Pastel) to start his new band. Taylor taught McRobbie how to play rudimentary guitar & added drummer Chris Gordon to the lineup.

Gordon didn’t last long, & his short stint marked the beginning of a revolving door of players. The list of former members & collaborators fills a CVS receipt. All told, nearly a

dozen musicians have been members of The Pastels at some point during the band’s 40-year tenure, & another two dozen have contributed to Pastels projects in some way, including Teenage Fanclub’s Norman Blake, Dean Wareham, & The Vaselines’ Eugene Kelly. This fluctuation may be owing to McRobbie’s rooting The Pastels in socialist collectivism, or it could be that people are just kind of flaky.

Early on, McRobbie & Taylor honed the sound, a shambolic guitar pop heavily influenced by the Velvet Underground & the Modern Lovers, but also edged up by coming of age during the Thatcherite era. The band’s “anyone can do this” mentality led to a pleasantly primitive sound.

They released their first single, “Songs For Children,” in 1982, fol-

lowing it up with a slew of singles on Creation, Glass, & Rough Trade. Some of those early songs were compiled onto 1987’s Up for a Bit with The Pastels, the band’s first full-length release, most notably “Crawl Babies,” a languorous track that would make its way to a million mixtapes.

They got their big break—or a break anyway—when they were chosen to appear on the NME’s C86 comp alongside other indie groups of the time, like Shop Assistants, The Mighty Lemon Drops, & The Wedding Present. The release became a defining moment in indie Brit pop mythos. But to McRobbie it didn’t make sense.

“I think that C86 tag is something I always felt weighed down by,” he told The Line of Best Fit blog in 2013. “I mean, we were on that tape, & so

The C86 association would, for better or worse, follow them around forever. The band became lumped in with the “twee” indie pop of the era, a categorization that irked McRobbie.

“Being subversive is not a natural state for me. But I always feel horrified at certain things,” he told Pitchfork in 2013. “For instance, we’re all in our 30s & 40s, so we’re all connected to each other’s families. We have that strong sense of community, & I like the idea of people doing well in a kind of equal society. As a socialist, I’m always into that. So I feel angry at people calling a lot of these ideas we have twee because I can’t think of anything less twee.”

I’m not really sure when I first encountered The Pastels, but it was likely in the early ’90s, when fanzines, mail-order catalogs & mixtapes were the way you found out about music. I had a pen pal— of course he was named Simon— from Glasgow who included them on a mixtape for me. The song was “Speedway Star,” one of their more discordant & rambling tracks.

I had been big on Sarah Records bands, which I’d discovered via Prodigy message boards & ordered from record distro catalogs like Vinyl Japan & Parasol. In pre-internet times, it was so much harder to learn the lineages of your favorite bands, & it was only later that I came to realize that it was The Pastels that had influenced bands like Boyracer & BMX Bandits, & not the other way around.

If you ask a Pastels fan—or at least

me—what song epitomizes the band, it’s “Nothing to Be Done,” appearing on their 1989 release Sittin’ Pretty, which I just learned is also a repeated phrase in Waiting for Godot

The band’s best songs are those where McRobbie lets his voice fall heavily & loosely on the melody, where his vocals flirt on the edge of going off tune, & it lends songs

sound, but we’re always trying to expand the parameters of that sound.”

The band waited 16 years to release their next record, Slow Summits, which padded out their spare sound with horn & string sections. In the intervening years, they scored a film & a stage play. Early member Annabel “Aggi” Wright (the subject of the wry 1992 Black Tambourine

It’s a voice that evokes a slackery, petulant vibe. You can practically see the anorak falling off his shoulders.

like “Speedway Star,” “Baby Honey” & “Nothing to Be Done” extra charm. It’s a voice that evokes a slackery, petulant vibe. You can practically see the anorak falling off his shoulders (a look that was, btw, captured in the 2013 photo book A Scene in Between).

During The Pastels’ most fertile period in the ’80s, the band was releasing up to three singles a year, most notably “Comin’ Through,” a seriously catchy song about an ambiguous relationship. In 1989, they released Sittin’ Pretty, a grungy, riffy, dirtier take on their pop songs. A contemporaneous New York Times review offered a backhanded compliment for the record: “Their brute-force passion is a slap in the face of acknowledged limitations.”

The Pastels followed up Sittin’ Pretty with the 1993 album Mobile Safari & 1997’s Illumination, neither of which achieved the same carefree fuck-off tone of the band’s earlier work—though maybe that was by design. McRobbie told Pitchfork in 2013 that he wasn’t interested in rehashing the past.

“We always feel new when we do something, & it always seems to connect in some way with what we’ve done before. But there’s always a freshness for us when we play together. It never feels like we’re trying to play a new version of ‘Nothing to Be Done’ or ‘Crawl Babies.’ We have a certain group

track “Throw Aggi Off the Bridge”) left the band. McRobbie & drummer/ singer Katrina Mitchell worked on projects with Tenniscoats, Jarvis Cocker, & Jad Fair. McRobbie went in on a record store, Monorail Music, in Glasgow, & he & Mitchell started their own label, Geographic, an imprint of Domino. The band’s Instagram was somewhat recently updated, though it’s unclear if they plan to release more music.

It’s rare nowadays that anything is inaccessible or off-limits. Anyone with a few minutes & a Spotify account can peruse “related artists” to learn about their favorite band’s favorite bands. Even still, The Pastels feel hidden away, a band that’s never quite gotten the audience or appreciation they deserve. That may be why seeing a guy in a wornout Pastels T-shirt had such a strong effect. Because finding out about bands like The Pastels felt more effortful than listening to whatever rotated on the radio or played on 120 Minutes

I never saw the Pastels T-shirt guy again, though it turned out he was in a band I knew—a band that had, in a classic 2010s way, placed a song in a Starbucks commercial, which was probably what was funding his Saturday afternoon bar escapades.

But the try-less energy of The Pastels remains something to aspire to & something to love.

One of the greatest psych-folk albums of all time was first birthed in the unlikely environs of a Beverly Hills dental office, spawned from a friendly dialogue between patient & practitioner— amid the heady rush of nitrous-oxide fumes & the murmuring drone of the dental drill. The patient was Leonard Rosenman, a classical conductor & composer who had become singled out for film scores after meeting & befriending James Dean & composing music for both East of Eden & Rebel Without a Cause. Rosenman would later work on soundtracks for the original Planet of the Apes & Star Trek franchises, & would win Academy Awards for Music—in 1976 for his score for Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon & in 1977 for Hal Ashby’s Bound for Glory

But even that day in the dental chair in 1969, Rosenman was a powerful Hollywood figure, already well on his way to becoming one of the most influential film composers of his era, with a private home studio outfitted with cutting-age recording equipment & access to some of the most talented session players in the industry. Rosenman would eventually utilize all of the latter in what would become perhaps his most remarkable collaboration—a multilayered, ambient, experimental psychedelic concept album, written by the young woman who, that day in the dentist’s office, just happened to be cleaning his teeth. Nearly 50 years later, in an LA Weekly interview, that very same dental assistant would clearly recall the moment. “One day Leonard looked up at me while I was working on him & said, ‘I can’t believe this is all you do.’” Rosenman’s instincts were in fact correct. Cleaning teeth most certainly was not the then26-year-old Linda Perhacs’ only skill. She had in fact been conceiving & writing music—dreamlike, meditative tracks which she had been recording, using a 12-string guitar in her sunny Topanga Canyon kitchen. “I gave him a cassette of all the little songs I had been making,” Perhacs remembers. “He

Eileen Wolf Echikson

called the very next day—woke me up on a Saturday morning—& said, ‘How soon can you get here?’”

Perhacs arrived at Rosenman’s home studio the following morning & was immediately immersed in a luxuriant deep dive into musical history. “Leonard told me, ‘We’re going to fill your whole being with music, from every century & only the best music. All to help speed your growth pattern.’” The two spent the day listening to Rosenman’s favorites: baroque, classical & jazz masterworks, as well as contemporary film scores & orchestral compositions. Until then, Perhacs had been self-taught, drawing much of her inspiration not from other musicians or the pop & folk music of the era, but from spiritual & fine art, as well as from her passion for theosophy, the 19th century philosophy that embraces a mix of

ancient Eastern, esoteric, & mystical traditions. Perhacs also drew upon her own dreams & meditative visions. She had been affected since childhood by the sensate condition known as synesthesia, where one confuses the senses, sometimes mistaking sight for sound & vice versa. For Perhacs, the musical creative process did not mean writing scales or classic notations. Instead, she had been creating her o wn visual-musical language for decades, writing her songs as illustrated “scrolls.” These were essentially visual compositions, music as image & art as a mirror for sound. After her initial, daylong immersion at Rosenman’s, Linda headed back to her Topanga cabin. It was then, while driving Ventura Freeway at night, that she had one of her most cathartic synesthesia visions. “I looked up in the sky,” she recalled

later, “there were lights—not stars but lights, very bright & vividly colored, & I realized, ‘You are seeing music.’ So, I pulled over & started writing & drawing as quickly as I could.” The following day she shared her song scroll (as well as the others she had created over the years) with Rosenman. After seeing these, the composer decided to go ahead & immediately start recording sessions with her, working both at his home & sneaking Perhacs into the massive state-of-the-art soundstage at Universal Studios during off hours. Together, Rosenman & Perhacs would translate her prolific archive of illustrated compositions into an album that remains singularly unique, a wildly heady mix of groovy folk jams, sensual ballads, & truly cosmic experiments. There is the funky, folksy strut of “Paper Mountain Man,” the misty morning meditation of “Chimacum Rain,” the under-the-sea fantasy of “Dolphin,” the nonchalant ennui of “Hey, Who Really Cares?” (which would serve as theme song for the brief run of a 1970 ABC drama called Matt Lincoln). The entire record resonates with experimentation, underscored by Perhacs’ distinct warmth, openness & idealism, the album a remarkable reflection of both her innate, intuitive talent & Rosenman’s prodigious production skills.

All this magic ultimately culminates in the title track, “Parallelograms,” an epic, complexly layered space-age adventure—Eno-esque long before Eno would explore similar ambient territories. The piece is the intricately eloquent sonic translation of Perhacs’ Ventura Freeway starry sky scroll. In the end, “Parallelograms” is more an experience than a song. Running nearly five minutes long, the track is a jaw-dropping example of Perhacs’ weirdly spiritualist approach to composing—a kind of psychic psychedelia. She would later describe her most well-known song as “a sound sculpture, an air-painting in motion, a series of three-dimensional shapes in color & sound, moving from speaker to speaker—all musical notes forming color & shape

Jessica Hundley is an author, filmmaker & journalist. She has written for the likes of Vogue Rolling Stone & The New York Times & has authored books on artists such as Dennis Hopper, David Lynch & Gram Parsons.

to reflect their unique frequencies.”

The drawings she had created that first evening—after her & Rosenman’s inspo/history download session, after seeing colored lights blinking in the dark & pulling over wide eyed onto warm SoCal pavement—were not scribbles of common musical notes, but bright watercolor splotches of colors, bold, unexpected shapes & vaguely mathematical equations. For Perhacs, the scroll was a definitive guide to her musical vision for the track. Yellows translated to “high flutes,” blues to “a splash of table” the geometric shapes represented, “the wavelength of that particular sound.” The song would take over

Perhacs would languish in relative obscurity for decades. She would dutifully drive to her job at the dental office in Beverly Hills each day, cleaning teeth & doling out wisdom. Parallelograms’ small initial pressing ran out quickly, but against all odds it did not disappear. For over 30 years it was passed around, bootlegged, & obsessed over. With the re-release of this lost classic in 2008, Perhacs was suddenly thrust into the limelight, the album earning her the admiration of a new generation of fans who connected to her futuristic masterpiece. Since then, Perhacs’ sound has been embraced by the likes of Daft Punk & Devendra Banhart &

She had been creating her own visual-musical language for decades, writing her songs as illustrated “scrolls.”

three weeks to record, with Rosenman at the boards, Perhacs’ scroll as key inspiration. The looping, dronelike chorus of “Parallelograms” features 24 interwoven tracks of Perhacs’ voice echoing through ring modulators. The result is a hypnotic science-fiction symphony, that has yet to be replicated. Parallelograms the album, is 11 tracks of some of the greatest in pioneering psych-folk songwriting. But the song “Parallelograms” is something else entirely—a visit to another planet, a message from a future we’ve yet to arrive at, an aspirational utopian soundtrack, a vision that just might correlate with, say, the paintings of Hilma af Klint. Perhacs would recall Rosenman saying of the track: “This piece will carry the album. Even if the executives don’t understand it right now—this track will keep this album alive for years to come.” Rosenman was right on both counts. The executives didn’t understand. The album, released in 1970 with little fanfare, was not a success. Although Parallelograms would be dubbed by the LA Weekly in 2010 as “one of the most mystifying & beautiful moments of the psychedelic era, on par with any outré work of the time,” the album was a resounding commercial flop.

sampled by acts as diverse as The Notorious B.I.G., Lowkey, & Prefuse 73. Perhacs would go on, at age 70 & onwards, to perform, collaborate & experiment with a slew of contemporary artists, among them the aforementioned Daft Punk & Banhart, as well as Sufjan Stevens, Four Tet, & Mikael Akerfeldt of the Swedish death metal band Opeth.

In 2014, she released her first album in 44 years, the acclaimed The Soul of All Natural Things, followed by I’m a Harmony in 2017. She toured Europe & the United States, all while retaining her job as a dental hygienist before finally retiring in 2019. Her legacy as one of the most unprecedented & pioneering voices in psychedelic, ambient & new-age genres still endures, crystallized in her groundbreaking debut.

Parallelograms is an album that feels miraculously fresh & continually nuanced upon each listen, a multifaceted gem of a record that reflects the contemplative folk of the era, alongside acid-tinged grooves, technological experimentation, exploratory symphonic compositions, the first stirrings of revolutionary feminist angst, & the unbridled, unapologetic visionary journeying of a modern creative mystic.

Robert Forster is talking on my deck in The Gap, Brisbane. Cicadas hum, the sun beats down. Swimming pools are hidden by the barrage of green. “Those cicadas are so loud,” he says. “My wife can hear them down the phone from Germany.”

A few years ago, Forster wrote an article for Australian magazine The Monthly—“The 10 Rules of Rock and Roll.” The rule I most agree with is his final one: “The three-piece band is the purest form of rock & roll expression.” It’s a theory I propagated in my 1991 review of Nirvana’s career-destroying Nevermind: “Trios are perfect. Live, & on record. When they get the balance right, there’s no stopping them. Think of The Jam, Young Marble Giants, Dinosaur Jr., Hüsker Dü, Cream, The Slits…”

I was being sarcastic about Cream, but to that list, I should have added The Go-Betweens. Typical though: their windswept, insular beauty hidden by the glare of the spotlight on others (most obviously, The Smiths in the decade when the Australian group could have easily broken big). A major influence on my London gig-going days in the early ’80s, The Go-Betweens’ laconic, jarring yet romantically inclined songs soundtracked the aftermath of many a useless, confused tryst. The band confused me too: so weirdly normal, so normally weird on stage & in the flesh. I listen to their 1983 album Before Hollywood now & am torn between two vistas—the rainy backstreets of an oddly gentrified Willesden Green in London, & the open spaces & cruel spring rain of my former adopted hometown of Brisbane. At that stage of their “career,” there were three of them: the trio of Forster, the sadly missed Grant McLennan, & much underrated drummer Lindy Morrison.

Appropriate then, that a good deal of Before Hollywood was recorded among the decaying former glo-

ries of Kevin Coyne’s beloved Eastbourne on England’s faded south coast. The album resonates with an awkward English gait & yearningfor-Queensland roaming that feels both timeless & rooted in one specific era.

“The past is a foreign country,” L.P. Hartley remarked in his book of useless, confused trysts, The Go-Between. “They do things differently there.”

And always the rain. There are a lot of mentions of rain

in Go-Betweens songs. They sing of it on their third album, 1984’s sumptuous Spring Hill Fair: “The rain surrenders to the town” in “Bachelor Kisses.” In “Spring Rain,” on 1986’s Liberty Belle and the Black Diamond Express, we hear: “When will change come/just like spring rain.” Living in The Gap, surrounded by green & infuriating birdsong—our home was a few streets down from Robert’s, who we’d bump into in the local Woolworths—you could understand

why. During the spring, water teems down the streets, creating rivulets & flurries. Sometimes it threatens further. The humidity becomes overwhelming, & there’s no escape.

The Go-Betweens had an attention to nature & surroundings that belied their youth, & a love for the girl-group-influenced pop of the Velvet Underground & Jonathan Richman, & strange rhythmical noises of Talking Heads.

The songwriting team of Forster (tall, eyeliner, iconoclastic) & McLennan (smaller, frank, romantic) understood that, as one music critic put it, while poetry doesn’t always fit into pop music, “pop music can fit into poetry if you hold it at just the right angle.” The Go-Betweens had a lack of self-consciousness that was intoxicating. On Before Hollywood, listen to the haunting future nostalgia of “Dusty in Here.” Or McLennan’s gorgeous, autobiographical “Cattle and Cane.”

I recall a boy in bigger pants like everyone just waiting for a chance

“Cattle and Cane” is rightly listed among the greatest Australian songs ever recorded. As fellow Aussie musician Paul Kelly recalls, hearing it for the first time while driving in Melbourne, “My skin started tingling, & I had to pull over...[it] had an odd, jerky time signature which acted as a little trip switch into another world—weird & heavenly & deeply familiar all at once…I could smell that song…What planet was this from?”

I loved The Go-Betweens because their songs felt so vulnerable, without apologies. Their tunes & image ran contrary to so much of what macho swaggering rock music was about. A bridge between adolescence & adulthood. Melody offset by darkness. A strange, strange beauty.

Everett True is an English music journalist & musician also known as The Legend, a moniker that served as title for a zine he produced early in his career. His written work has appeared in New Musical Express Melody Maker The Stranger, & The Age

In May of 1986 the NME released a snapshot of the contemporary UK indie scene in the form of a cassette called C86. While the term C86 is now synonymous with the kind of shambling indie pop associated with The Pastels, Shop Assistants, & early Primal Scream, there was a more abrasive, discordant, & altogether more challenging side to the original compilation. This aspect of C86 was largely represented by five tracks—those by The Shrubs, A Witness, Stump, MacKenzies, & Big Flame—all contributed by the Long Eaton-based label Ron Johnson (this isn’t to ignore the brilliant Bogshed, who were on their own Shelfish label).

There was nobody named Ron Johnson. Instead the label was started by a man named Dave Parsons. Parsons was swept up into the nascent punk scene as a teenager in the late ’70s, traveling to Nottingham to see bands such as The Damned, Buzzcocks, Joy Division, The Jam, Scritti Politti, Cabaret Voltaire & more. He collected records from independent labels such as Rough Trade, Fast Product, & Small Wonder.

Parsons had this to say about his younger self: “I collected monomaniacally & gained a pretty encyclopedic knowledge of punk/new wave around the time. I also lived the punk dream out in a determined, tunnel-visioned fashion.” Parsons’ early experiences in punk motivated him to start the band that would become Splat!, who were active in the Nottingham/Derby area. Influenced by contemporary (and confrontational) bands like The Fall & The Birthday Party, Splat! members Mark Grebby & Paul Walker also took inspiration from such disparate genres as jazz & prog.

Splat! recorded their first self-titled EP in 1983 & managed to convince a distributor—Red Rhino (later called Nine Mile)—to sell their records. The EP drew the attention of John Peel, & brought about an

interview in Sounds magazine. The band called their brand-new label

Ron Johnson, after the fake name drummer Paul Walker would give to policemen. At this time, Parsons famously worked the night shift at a biscuit warehouse (cookies, for our American readers), which later led the NME to title their Ron Johnson piece “Biscuit Maker’s Break Out,” a cheeky reference to The Fall’s second single.

Apart from Splat!, the first band signed to Ron Johnson was Big Flame (stylized as bIG fLAME), a fervently left-wing act (named af-

ter the British socialist & feminist organization) who made blistering avant-punk played at breakneck speed—a sort of Minutemen on amphetamines, or simply “Manchester’s premier jazz fuck trio.” Parsons had heard Big Flame on John Peel’s program & sent them a letter asking if they’d like to be on his label. This resulted in 1985’s Rigour, catalog number ZRON3, which made its way into the UK independent charts. Big Flame would continue their relationship with Ron Johnson until they broke up in 1986, with the “Why Popstars Can’t

Dance” single being released that same year.

In September 1987, over a year after C86, Ron Johnson released its own compilation, The First After Epiphany, catalog number ZRON21. It was intended to be a sampler, an attempt at generating interest in the label. It was only the second full-length album (after A Witness’ I Am John’s Pancreas) over the course of 21 releases (Ron Johnson dealt in 7-inch & 12-inch singles almost exclusively). Each of the bands on the label were asked to record a unique song, which were then organized in chronological order according to when the bands were first signed. The product was an aural history of the label & an introduction to the distinctive Ron Johnson sound.

The First After Epiphany began with Parsons’ own Splat!—“Mistook” is a nauseating dirge with shades of early Public Image Limited. The aforementioned Big Flame provided the obscurely titled “XPQWRTZ,” a blast of fierce, jagged noise emblematic of the group. XPQWRTZ was later the name of an aughts music blog (run by Simon Williams of the band Sarandon) that would introduce the author of this article to a staggering number of obscure UK indie bands—more than any teenager from New Jersey should rightfully know.

Hailing from Stockport, Greater Manchester, A Witness were the only band to have a measure of financial success on Ron Johnson, with their full-length album I Am John’s Pancreas drawing a modest profit. A Witness were in possession of a drum machine instead of a human drummer, which added an aura of menace to their songs. “Dipping Bird” was indeed menacing, purposefully slowed down, with distorted vocals & mechanical percussion. Tragically, A Witness’ guitarist Rick Aitken passed away in a climbing accident in 1989.

Stump, best known for the Beef-

Dana Katharine lives in Philadelphia & hosts Don’t Back the Front on WPRB 103.3 FM. She graduated with a master’s in human rights from the University of Glasgow, but currently makes a living working at a record store.

heartian lurch of “Buffalo” (how much is the fish?), contributed “Big End” to The First After Epiphany Stump had signed to Ron Johnson to record their first EP, the charmingly titled Mud on a Colon, which received a positive reception from the music press & attention from major labels. Stump’s relationship with Ron Johnson turned out to be brief & they left before the recording of their album A Fierce Pancake, which was released on Ensign Records. Stump had difficulty finding the crossover appeal they were looking for when

ny they provided “Knock,” a propulsive track with prominent cowbell. The Ex also released the 1936, A Spanish Revolution double 7-inch on Ron Johnson, which came with a 144-page book consisting of short essays & previously unpublished photos of the Spanish Revolution. Artistically this was a triumph for Ron Johnson, but financially it was a failure despite selling 15,000 copies. Ron Johnson’s distributor, Nine Mile, had set the price before the records were manufactured in Europe, resulting in the label losing

The band called their brand-new label Ron Johnson, after the fake name drummer Paul Walker would give to policemen.

they signed to a major label, & the band broke up in 1988.

Scotland was represented by Glasgow’s MacKenzies & the disjointed funk of “Man with no Reason,” which came complete with a wailing saxophone. MacKenzies released only a small handful of 12& 7-inch singles during their brief existence, all on Ron Johnson.

The Shrubs sounded like no band before or since, manic & swirling, with vocalist Nick Hobbs’ howl at the forefront. Hobbs (who had been kicked out of Stump for being “too serious”) claimed Captain Beefheart, Frank Zappa, Pere Ubu, Henry Cow, & The Fall as influences. For The First After Epiphany they offered up “Blackmailer,” which found Hobbs hollering surrealist lyrics over a snaking bassline & skronky guitar.

Dutch band The Ex, with their revolutionary leftist politics & metallic clangor, were the only band on Ron Johnson that came from outside the UK, & they remain the only band still active to this day, having released an LP as recently as 2018. For The First After Epipha-

Johnson acts, but it predicted the direction the group would soon go in. By the time they had recorded the “Who Works The Weather?” single, the very last record on Ron Johnson, they had added a glossier sheen to their sound.

Bringing up the rear was the very last band signed to Ron Johnson, Leamington Spa’s enigmatic Jackdaw With Crowbar (this is ignoring the Sewer Zombies, a hardcore band along the lines of Napalm Death or Extreme Noise Terror, who didn’t fit in with the label’s established sound). “Crow” consisted of deranged clucking & hollering over a dark-&-dirty blues riff. It was enough to garner the attention of John Peel, who played it on his program & had Jackdaw With Crowbar on for a handful of sessions.

Parsons admits that The First After Epiphany perhaps had a greater influence at the time than he realized, having now encountered people who were introduced to the label through the compilation. Besides being a history of Ron Johnson, The First After Epiphany provided a look into just one aspect of a DIY music scene united by a commit-

site in 2011, Parsons stated that “without [Peel’s] support, those six or so years of indie industriousness would never have been the same, or, possibly/probably, even possible.”

By 1988 Ron Johnson had folded, due to the simple fact they didn’t sell enough records to cover costs— 7-inch & 12-inch singles, the label’s release format of choice, weren’t purchased as much as LPs. (Recall that A Witness’ full length was one of the few releases to draw in a profit.) Parsons admitted that if they had been more business minded, perhaps the label would have lasted longer. But he also conceded that “if things had been different, it wouldn’t have been Ron Johnson.”

Quoted in John Robb’s book Death to Trad Rock, A Witness’ bassist Vince Hunt recalled that “Ron Johnson had five bands on C86, all hugely different & inventive, but a cult about that label never developed around C86 like it did about the jangly bands.” It makes a certain amount of sense that the pop side of C86 would be the one most widely remembered & celebrated (not to mention mimicked). However, it seems unfair that the music released by Ron Johnson remains comparatively forgotten, particularly in the

money on every copy sold.

Like Big Flame & A Witness before them, Twang were also from Manchester. Their contribution to The First After Epiphany, “Here’s Lukewarm,” is bass heavy, with spurts of spastic guitar & shouted lyrics. Following Twang was Birmingham’s The Noseflutes, who had existed since 1980 under various names, all uniformly bizarre (The Blaggards, The Cream Dervishes, Extroverts in a Vacuum, & The Viable Sloths being just a few).

“Bodyhair Up in the Air” is as weird as the title suggests, featuring a wiggly jaw harp & bizarre lyrics about body hair.

The Great Leap Forward were founded by former Big Flame member Alan Brown. They had stronger pop inclinations than Big Flame, but were no less strident in their politics (as evidenced by their name, an overt reference to Communist China). “Drowning Speechless,” with its horn section & sampled vocals, still maintained the scratchy, roughshod approach typical of Big Flame & other Ron

It seems unfair that the music released by Ron Johnson remains comparatively forgotten, particularly in the United States.

ment to making radical & uncompromising music, with Thatcher’s Britain serving as a backdrop. Like thousands of other independent bands & labels, Ron Johnson had a champion in John Peel. Peel recorded sessions with ten out of the 12 bands on the label, with A Witness & Big Flame racking up four sessions each. John Peel’s year-end Festive Fifty included Ron Johnson bands in 1986, 1987 & 1988. In a celebration of Peel featured on the Louder Than War web-

United States where our own ’80s noise-rock bands are allowed a certain measure of posthumous renown. Despite the label’s relatively short existence, the unapologetically confrontational & innovative bands on Ron Johnson make for thrilling listening to this day. Dave Parsons likened the label’s brief run to “a bright, shortlived incandescence—much like Big Flame at their best—& the second half was more of a falling spent firework.”

It’s been a thrill watching 10cc finally get their due as true sonic geniuses, rather than a lightweight ’70s AOR nostalgia act. From vids of audio nerds picking apart the insanely beautiful layers of “I’m Not in Love,” to kids hearing the same song on some Marvel movie’s soundtrack, I’ll support their rediscovery in any way. The beyond-quirky band has even reformed this year for an American tour, so the time is ripe for their criminally cheap oeuvre to be reassessed. Their catalog & list of credits/side projects are fairly deep & intimidating, so here’s a primer that also acts as a loose timeline of the band’s unique tale.

Strawberry Bubblegum:

A Collection of Pre-10cc Strawberry Studios Recordings 1969–1972 Castle Music compilation 2003

Every member of 10cc started off as a cream-of-the-crop industry player or songwriter, with Graham Gouldman being the most famed for writing “For Your Love” for the Yardbirds & “Bus Stop” for the Hollies. Gouldman also wrote for bubblegum labels like Buddah, as did Kevin Godley, Lol Creme, & Eric Stewart. Stewart played guitar for the Mindbenders of “A Groovy Kind of Love” fame & invested in his own Strawberry Studios. All four could experiment in this bunker, recording catchy but sophisticated 45s under monikers like Festival, Frabjoy and Runcible Spoon, Hotlegs, & Grumble. Some of the best are included here, including the first sessions where they all played together, like the mind-melting-but-melancholic “Umbopo” by Doctor Father.

Space Hymns Vertigo 1971

At Strawberry, the fellows recorded all genres, from the very nor-

mal Neil Sedaka to the unearthly Ramases & Selket. Ramases, a.k.a. heating repairman Barrington Frost, served in the army before he received divine word he was the reincarnation of the Pharaoh Rameses—so he shaved his head & began wearing flowing robes. His gentle, space-glam voice graced some of the most transcendent singles of the era, & one more album before he sadly committed suicide. All of 10cc dish out their cosmic chops on this LP, with Creme/Stewart’s modulated guitars/synths & Gouldman’s tasty bass featured on the spacious “Life Child.” The ethereal “Molecular Delusion” has deep coatings of voice & sitar, & “Earth People” utilizes fried backward effects nicely. “Jesus Come Back” anticipates the ultramelodic 10cc ballad sound,

complete with acoustic guitar, bubbly bass, & perfect harmonies.

10 cc 10cc

UK RECORDS 1972

It’s a mystery to me why the lesser UK Records put out 10cc’s incredible debut after Apple Records balked. The Dadaistic Bonzos territory of ’50s pastiches “Donna” & “Johnny, Don’t Do It” seem way up the Fab Four’s alley—but my fave is the bizarro pre-post punk “Sand in My Face,” which takes its subject matter from a Charles Atlas comic ad. Side two is where things get really brilliant, with the progressive groove pop of “Speed Kills” with its mad pitch shifting, freaked solos,

Steve Krakow a.k.a. Plastic Crimewave is an artist, musician & writer based in Chicago.

& tight throb. The massively intricate hits “Rubber Bullets” & “The Dean & I” have that “Brian Wilson produced by Todd Rundgren” vibe, where everything but the kitchen sink is thrown into a bed of dense sound. There’s the catchy but dirty “The Hospital Song” with its chorus about getting off, as yes, the 10cc name refers to the average amount of semen in, er, a release.

10 cc

Sheet Music

UK RECORDS 1974

Their second album is my top pick for consistent 10cc greatness, & it slaps right out of the gates with the bonkers “The Wall Street Shuffle,” before launching into the genius cut-up pop of “The Worst Band in the World.” “Hotel” epitomizes their brainy, studio whiz aesthetic, with passages of pure sonics, a jam-packed vintage Caribbean art-pop groove, sizzly guitars, polyrhythms, & canned vocals. The quartet worked in all combinations for this LP, & Godley declared: “We’d really started to explode creatively and didn’t recognize any boundaries. We were buzzing on each other and exploring our joint and individual capabilities. Lots of excitement and energy at those sessions and, more importantly, an innocence that was open to anything.” Those sentiments are displayed on the sublime & ethereal “Old Wild Men” & the skittery, complex “Clockwork Creep,” which describes the final minute before the detonation of a bomb on a plane. The propulsive “Silly Love” is full of bizarro changes galore, while pure ambient sounds à la Cluster start off the cynical, lovely, talk-boxed “Somewhere in Hollywood.” The sophisticated “Baron Samedi” has all sorts of rhythmic innovation & vocals that spiral into oblivion, whereas “The Sacro-Iliac” is a misleadingly gentle tune about new dance crazes & getting trashed (“I’ve never been freaky or funky or laid back” seems to sum up the 10cc aesthetic).

10 cc

The Original Soundtrack

MERCURY 1975

10cc finally hit the big time with their third LP & signed to Mercury, mostly due to the strength of “I’m Not in Love” (which the label got a preview of). This maudlin but groundbreaking anthem is still a breathtaking mix of meticulous voice choir perfection & downer melody (and you need the full sixplus-minute LP version!). It was also 10cc’s first major US chart action, & the rest of the album is also brilliant. Godley & Creme’s over-the-top “Une Nuit a Paris” is a nine-minute, multipart “mini-operetta” that tells the tale of a tourist in Paris who sleeps with a prostitute & is conned in the red-light district, then is shot dead by a cop. “Blackmail” is a strange dancegroover not far off from the Stories; “Flying Junk” is pure Beatley psych pop turned inside out; & the infectiously goofy minor hit “Life Is a Minestrone” harkens back to the ’50s-meets-’70s sound of their first few albums. The album closer, “The Film of My Love,” has an early drum-machine stammer, & a similarly silly, retro-gazing croon. While I do love the band Yes, I have to agree with Rolling Stone’s Ken Barnes, who wrote, “Musically there’s more going on than in ten Yes albums, yet it’s generally as accessible as a straight pop band.”

10 cc How Dare You!

MERCURY 1976

Their fourth platter was sadly the last with the full original genius lineup, as Godley & Creme would soon depart to form their own duo. This LP went to number one in New Zealand (so you know it’s gotta be good!) but only a few singles barely made the charts stateside, like “I’m Mandy Fly Me” & “Art for Arts Sake.” Both represent 10cc’s brand of progressive pop well with compositional anarchy, brainy lyrics, hooks, dissonance, insane playing, & studio manipulation— what more could you want? “Lazy Ways” & “Don’t Hang Up” are gorgeous baroque-psych tunes on par with prime-era the Left Banke, whereas “I Wanna Rule the World” & the title track are forward-think-

ing, bizarre art rock (with their trademark speed/pitch adjusting of instruments). In an interview at the time of its release, Gouldman told Melody Maker: “I think there’s been a progression on every album, & I think we’ve done it again. It’s a strange mixture of songs. There’s one about divorce, a song about schizophrenia, a song about wanting to rule the world, the inevitable money song, & an instrumental.”

Losing Godley & Creme made for an intentionally streamlined LP effort. Stewart’s production & tunes still glimmer, along with Gouldman’s expert songwriting & new live drummer Paul Burgess. Despite the press snarkily calling them “5cc,” “Good Morning Judge” was written by the full quartet previously, & still has that odd swagger of past 10cc. Smooth smash “The Things We Do for Love” conjures a Carl Wilson/Emitt Rhodes collaboration. “Marriage Bureau Rendezvous” recalls Parachute-era Pretty Things with its elongated harmonies, & “People in Love” is a nice weeper with mellotron textures, though both were the most softly straightforward 10cc tunes yet. The sleazy blooz-groove of “Modern Man Blues” counters this, with schizo changes & guitar wank, & “Honeymoon with B Troop” is similarly weird, almost resembling the art-glam of Cockney Rebel.

“You’ve Got a Cold” has a funky & stoned Wings vibe, while the still forward-thinking “Feel the Benefit” starts as a lovely string-soaked ditty à la ELO, before it morphs into a few different movements from dancey to prog rock. Sporting a great Hipgnosis cover, the title was taken from a sign on the road to their studio. Gouldman said, “Every day I used to travel down from London & see the sign DECEPTIVE BENDS. It struck me to be quite a subtle word the Department of Transport was using, & Eric agreed it was a nice title.”

10 cc

Bloody Tourists

MERCURY 1977

Gouldman & Stewart were augmented by a live band for the Bends

LP tour, & for this album they utilized most of that crew, including ace keyboardist Tony O’Malley. The dubbed-out & infectiously weird “Dreadlock Holiday” was 10cc’s last major commercial success—but the spaced-out moog ballad “For You and I” also graces the LP, along with the sophisticated power-riffer “Take These Chains.” “Shock on the Tube (Don’t Want Love)” has a mutant hard-rockin’ disco vibe, & the slow blues cabaret of “The Anonymous Alcoholic” morphs nicely into a psychedelic soul/dance floor thumper, proving 10cc could still get freaky (even with the serious subject matter of addiction at its core). “Life Line” is a lovely & heady tune (with more reggae touches) & “Tokyo” nearly resembles Eno or Mark Hollis’s ambient-pop moves. “From Rochdale to Ocho Rios” finds the band dabbling in Caribbean rhythms & steel drums, & maybe it’s not terribly well advised. “Everything You Wanted to Know About!!! (Exclamation Marks)” wins some kind of best title award for sure, & it’s a pretty odd slice of dynamic guitar shredding. It should be noted the Hipgnosis cover was rejected by Genesis previously & this was also the first album to feature the distinctive 10cc logo.

Godley & Creme

L MERCURY 1978

I’d be remiss to not mention the brilliant works by 10cc’s Godley & Creme. Their second duo album pits Todd R’s Wizard production overload against Queen’s bombastic suites, adding something uniquely their own. As with Queen, there’s goooooooey harmonies on “This Sporting Life,” a song about jumping off a ledge. Truly bizarre dub/post-punk elements are sprinkled into the madly sliced-up tunes “Punchbag” & “Sandwiches of You,” the latter being a single! There’s an element of wacky Zappa too, who is name-dropped on the plaintive but satirical “Art School Canteen.” Andy MacKay from Roxy Music plays sax on the demented “Foreign Accents,” & there’s elements of Roxy’s postmodern glam through the LP too, especially on the oddly groovin’ “Group Life.” The intense proto-new-wave “Hit Factory” (which almost sounds like Cabaret Voltaire meets The Normal) transforms into the dark “Business Is

Business,” which comes closest to old-school 10cc territory, or maybe Nilsson on a bad trip? The cover depicts an “L-plate,” used in some countries to designate vehicles with novice drivers. Who knew?

Godley & Creme

Consequences

MERCURY 1977

Though slightly out of sequence, I had to end on the most excessive, extravagant, & confounding 10cc-related project. I’m not even sure where to start with this triple LP, which was conceived as an excuse to show off their guitar manipulation device, the Gizmotron (which vibrated strings to get a symphonic sound like an EBow). The concept of the album is “the story of man’s last defense against an irate nature” & took 18 months to record. The first platter veers from hallucinatory soundscapes to musique concrete, & dips into tripped-out dub & old-timey opera. It’s an ambitious trek into production possibilities, with a track mimicking a burial from the inside of a coffin! The other two discs feature sublime tunes like “Five O’clock in the Morning” & “Lost Weekend,” which features Sarah Vaughan. The last album side has some 17 movements, so the perhaps overreaching album became a bit of an albatross for the group when punk hit. Godley stated, “There was a seismic, paradigm shift. I knew we were doomed. We emerged blinking into the light, and everyone was wearing safety pins and bondage trousers. We’d been working on a semi-avant-garde orchestral triple album with a very drunk Peter Cook, while outside it was like a nuclear bomb had dropped.” The album was savaged by critics, & Godley was devastated, but Creme got it. “I could see why it was laughed at, it does look like a pretentious pile of old stuff. We were self-indulgent pop stars, there’s no question about it.” The album was also released in two abridged versions that focused on the tunes, like the doo-wopi nfused “Cool, Cool, Cool” (with King Crimson’s Mel Collins on sax), & the blissed-out “Sailor.” This opus demands repeat listens to fully absorb, which is surely the hallmark of a great work.

All of 10cc’s various sonic endeavors reveal new details with age, so time to dig back in.

Afew nights ago I started rereading the article Lester Bangs wrote about The Marble Index, Nico & John Cale’s acclaimed 1968 collaboration.* It’s an extraordinary piece of writing, full of memorable phrases & images:

Warholvian deathly otherness… The only trouble is that there is so much beauty mixed in with the ugliness… A jewel with facets of disease running all through it… “He built a cathedral for a woman in hell, didn’t he?”… a soft look would kill her… a junkie for the glimpses of the pit… There’s a ghost born every second... The only sin is denial… groanings of bowed basses like famished carnivores in some deep bog… when I first set out to write this article I got very high—I was so stupid I thought I’d just let the drugs ease my way into Nico’s domain of ghosts, then trot back & write down what I’d found there…

Bangs’ review is in two parts. The second, shorter section consists of an impressionistic analysis of two songs, “Frozen Warnings” & “Evening of Light.” At the start, Lester announces that he will “quote from the lyrics with a minimum of interpretation, & then tell what Cale’s music sounds like.” He sticks to this quote-andtell formula for “Frozen Warnings,” but when he gets to “Evening of Light,” so powerful is the spell cast upon the young rock scribe by Nico’s words that Lester the Interpreter can’t hold back—& indeed,

Meredith

The Marble Index ELEKTRA 1968

why should he?

The lines that set him off are these:

In the morning of my winter

When my eyes are still asleep

A dragonfly lay in the cold dark snows

I’d sent to kiss your heart for me

In response to which, Lester writes:

(Nico’s concept of love: While she lies interred in the endless wastes of the arctic night, she has sent an insect to the object of her affections, to kiss his

heart yet. But even the insect must die before it can reach him, the soft rustling of its gentle wings stilled under drifts that eventually preserve its frozen corpse for eternity under a snowbank that becomes an ice mountain, the insect & Nico having become one in endless sleep, for they were the real lovers in the first place after all.)

Gentle wings yet.

The original aim of this note—modest enough—was to point out that Bangs’ remarkable parenthetical reverie might be based on a misunderstanding of Nico’s lyrics. After reading the above lines as Lester transcribed them, it occurred to me that maybe he got it wrong; maybe it wasn’t a dragonfly Nico sent to kiss her lover’s heart; no, by another reading, she “went big” & sent the cold dark snows

As it turns out, we were both wrong.

In 2007—25 years after Bangs’ death from an accidental drug overdose at the age of 33—Rhino Entertainment put out The Frozen Borderline 1968-1970, a two-CD compilation comprising The Marble Index & Desertshore (the other much-lauded Nico/ Cale collaboration, from 1970). The Frozen Borderline offers remastered versions of all the tracks on the two albums, alternative versions of many songs, demos & outtakes. On the alternate version of “Evening of Light,” Cale’s instrumental accompaniment is lower in the mix, so it’s easier to hear what Nico is singing:

In the morning of my winter

When my eyes are still asleep

was born in Dublin, Ireland. He lived in New York City for many years, where some of his plays were produced by the Tribeca Lab theatre group. He published a novel in 2004 & relocated to Northern California in 2021.

A dragonfly lady in a coat of snow

I’d send to kiss your heart for me

A dragonfly lady in a coat of snow

I’d send to kiss your heart for me

So, Nico’s emissary is the dragonfly—I was wrong. The dragonfly doesn’t expire in the cold dark

Meanwhile, John Cale is busy weaving a sound apocalypse—cruel, distressing, bass heavy, exploding worlds of pain— around Nico’s fairy-tale imagery; worlds that Bangs will describe with great imaginative verve...

snows—Lester was wrong.†

Here’s the thing: Does it matter if the dragonfly is alive or dead?

A meaningless question, you may say—the dragonfly lady exists only in Nico’s mind; she’s the object of a wish, an intention (“I’d send…”). Here, Nico’s imagery is in good compliance with folk Ro-

mantic poetic conventions. Meanwhile, John Cale is busy weaving a sound apocalypse—cruel, distressing, bass heavy, exploding worlds of pain—around Nico’s fairy-tale imagery; worlds that Bangs will describe with great imaginative verve in the final paragraph of his review.

But wait a minute. What exactly is a “dragonfly lady”? A female dragonfly? Or a human being whose appearance or demeanor somehow evokes that beautiful creature? We’d give anything now to ask the songwriter what she had in mind, but no one is there. (For J.H.)

*Lester Bangs, Your Shadow Is Scared of You: An Attempt Not to Be Frightened by Nico,” New Wave Rock magazine, 1983 (submitted 1978). It can be found in Mainlines, Blood Feasts & Bad Taste: A Lester Bangs Reader, edited by John Morthland, 2003.

†Lester Bangs was, no question, a very gifted writer & critic but there’s no ducking the fact that he was also, at times, a willfully sloppy researcher. A couple of examples come to mind: in one of the several articles he wrote scolding Miles Davis for failing (in Lester’s opinion) to live up to his genius, he refers to the soundtrack album Davis recorded for Louis Malle’s film Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Elevator to the Gallows). According to Bangs, this was a recording that “Miles laid down with some European nobodies way back in 1958.” Quite apart from the chauvinism evinced by labeling French jazz luminaries Barney Wilen, René Urtreger & Pierre Michelot “nobodies,” if you, Lester, had just taken the time to dig out your copy & check the personnel info, you’d have seen that the drummer on the session was the great Kenny Clarke a.k.a. Liaqat Ali Salaam. Another time—an even more egregious example of Bangs stomping on the facts— he accused Miriam Linna (of The A-Bones & Norton Records fame) of being a white supremacist!

It would be inaccurate to say that there is a surge of new music from the Asian continent surfacing in American scenes. But that is how the moment presents itself when one attends a concert showcasing the music I am describing: traditional instrumental music originating from Korea, played or created by Koreans in America, often in ensemble with others in the Asian diaspora. Today I will just talk about three out of many astonishing performers in this cadre. So back to the idea of this being a surge. One reason we might describe this moment as a “surge” or even a resurgence, is because for the most part, the music is presented in arts settings where all work needs to feel superlatively novel. This may be a defect of the improv scene, but I do not mean to disparage scenes just to make fun of my friends. I am mocking, instead, the museum-led high-to-low cascade of pretension that imbues so much promotion of “different” musical performances. Performances that should be deemed extraordinary for having done its one & only job—to excite sensation in listeners. But no two shows may be alike in a museum unless it’s a pithy community program washed & repeated in some performative demonstration to their funding overlords that the establishment has not forsaken the literal neighborhood it oppresses. I’m sorry if I sound like I have a chip on my shoulder. It’s because I do. The kind of music I am trying to describe is not given a lot of commercial access, but its practices are not promoted with the purpose of recruitment. That is not just because it avoids Western acceptance, or necessarily because it is denied Western privileges. It is not due to the esotericism of style or

Doyeun

Leo Chang Transference

GLACIAL ERRATIC 2018

Hyunjin Cha

[Live Performance]

the mental/geographic distance listeners have to traverse just to understand cultural context & specificity. It may be that the music gets to exist without opportunity, as long as it can be occasionally used as an appendage. This, to me, still

feels suspiciously like colonialism, & is why I insist on spelling it out. Everybody knows where Korea is now thanks to the internet, & most of us can even identify the major cultural touchpoints, thanks to the Asian internet. The geography mat-

ters less when I speak of artists like Leo Chang, whose blended cultural extractions & various childhood homes—in China, Korea & the Pacific Rim—give him many ideas of literal folk. He plays traditional Asian musical instruments that complement raw voice & noise, like the piri, a flute-like wind instrument, excited gongs, & acousmatic digital inventions (the VOCALNORI most notably). With operatic agendas carried out by itinerant ensemble groupings, his craftwork is both a diorama & an oracle of Asian identity & epigenetic memory.

One of his latest ensemble formats is Nakji, or octopus in Korean. I watched their Philadelphia outing in the fall, shortly before Chang released his album Transference with the Mung Music label out of Seoul, Korea. The album is ethereal & atmospheric in equal & opposite ways that the live show was kinetic & punctuated. The Mung label, run by musician & recording engineer Sunjae Lee, is also worth following. Lee records everything on an old TASCAM recorder in what looks like a very intimate studio. In the Philadelphia iteration of Nakji, Leo was accompanied by another Korean traditional musician, Doyeun Kim. She plays the gayageum, a Korean lap-string instrument. Most notably, Kim is also a vocalist, & in both instruments, she wields the bravery of experimentalism & improvisation, while exposing the potential for the traditional mouthfeel sound touch of Korean sonics. That is to say, it feels uncannily old & new at once. For example, Kim says that her vocal practice is not itself derived from pansōri, a traditional shamanistic singing style requiring an absurd level of chord train-

Anne Ishii is a writer & musician based in Philadelphia. She is Executive Director of Asian Arts Initiative & has published over 20 translations & writes a lot about Asian idendity & gender.

ing, but the comparison is begged at least viscerally when one hears the outlines of jagged noise enveloping her pneumatic voice. These vocals are not present in her albums available for purchase, but even the simple pairing of a gayageum with guest acoustic guitarists proves profound in her lovely album Macrocosm

Readers may allow me the hackneyed metaphor: in the record-

traditional Korean percussion, she was first taught ho-heu, or breathing-based movement. She learned how to move her body, & control her energy, before making any sounds. This mind-body connection, the channeling of energy, & correlating breathe to voice to stick to drum, is the embodied practice we think of when listening to jazz drummers like Milford Graves & Susie Ibarra, but I am here

For the many Asians in the world with the kind of energy exhibited by Cha, Kim & Chang, I feel more cosmic continuity within the body than ever.

ings of Chang & the performances with Kim, I picture a ripe persimmon falling in slow motion to the ground, as we listeners witness its nectar reveal itself in a perfect semblance of liquid wholes, while the shredded flesh breaks up the plane of air like a wooden stake.

The musician who provokes me most in this appreciation of current Korean instrumentalists, is one who doesn’t have an album to be cited here. One who requires a live audience. Hyunjin Cha is a Korean percussion, string & voice performer. I had the opportunity to interview her years ago, after being floored by her drum ensemble Uriol. I failed to get the original recording published in a timely manner, which I still hope to get broadcast if I ever find the time to get my dream radio show off the ground. I digress. I’m taking this opportunity to share a gem from that conversation, for her words have permanently imprinted in my thoughts as I process what it means to broker Asian American sound, & be an Asian drummer.

“When I first struck the big drum, I thought to myself, Oh my god, I am FIGHTING THIS DRUM. It is my entire body playing the drum. And though people may find it ridiculous—that movement & energy & vibes are what control all sound—I can prove it in my performance & in my classes. It is! It is!” Cha talks about how in learning

to say no one is doing it like Hyunjin Cha. I’d describe her style as athletic, powerful but also empowering. If Kim & Chang’s persimmon falls to the ground & bursts with passion fruit, it is because of the gravity of this drummer.

There is a unique opportunity for an artist who thrives in the spontaneity of a time-based practice, in the unique “retro-acculturation” that the generationally moreAmerican-than-Asians of us are obligated to perform. In our lives, cultural labor is freedom. For the many Asians in the world with the kind of energy exhibited by Cha, Kim & Chang, I feel more cosmic continuity within the body than ever. A purposeful revelation between what is moved & what is moving. These bodies are making some really big sounds. And now to return to my incredibly solipsistic preamble. I issue a warning meant as much for myself as it is for you: If you want to consume music informed by the mythologies & history of the Korean peninsula, or to see Koreans in the diaspora perform the music of psychic energies of this magnitude of spiritual purity, you, dear reader, must be willing to become consumed with no imperial clothing. Surrender the chips of distinction, historiography, politics. You, my dear listener, must be ready to afford this music a belief system, & to believe it when you hear it

The term Deep Listening was coined by the late American contemporary composer Pauline Oliveros. The concept is hers too. It’s a practice of focused yet open listening, both for musicians in performance & for humans existing. Oliveros said that Deep Listening means “expanding the attention.” As a philosophy, it’s a call to open the mind & the heart to others & the world around us via the ears. Oliveros gets a shout-out on Helado Negro’s latest album Phasor. The lead single & first track, “LFO (Lupe Finds Oliveros),” links the composer to Lupe Lopez, a Fender employee in the 1950s who wired amplifiers, now a legend among guitar gearheads for the quality of sound her amps produce. What’s the connection between a patron saint of tuning in & an alchemist of electrical amplification? There are many, & this is just one hypertextual rabbit hole on an album with plenty of them.

Incidentally or no, Phasor itself rewards close listening. Roberto Carlos Lange, the artist who makes music under the trippy, slightly confounding name Helado Negro, has released his most precise & restrained collection of songs, & one of the quieter in a discography full of quiet gems. The careful dialing back allows the songs more room to breathe, or maybe it gives the listener more room to listen.

This is also his most artfully elusive album. Many of the songs on Phasor have no center. Lange layers bright synth lines, guitar riffs & upbeat rhythms weightlessly & sets them in motion. They interlock & slide past each other, sometimes creating the transitory illusion of a pop song. Lean in closer & you’ll hear intricate patterns, elements of free jazz, South American folk, sounds collected & synthesized, but few simple melodies, & yet the album is always delightful listening. Some of Phasor’s sounds were gathered from the output of the SalMar Construction, a one-of-a-kind generative synthesizer, which uses a supercomputer to control analog oscillators. It was built in 1969

by American composer Salvatore Martirano with musicians & engineers at the University of Illinois. It still resides at the university. Lange had the opportunity to visit & interact with the Sal-Mar in 2019 & recorded the five-hour session.

Speaking over Zoom from his home studio in Asheville, North Carolina, Lange recalls his encounter with the instrument as bewildering & exciting. “It’s just a really strange machine and, in regard to how it operates, not very intuitive,” he explains. When working on this project, he pulled out the hard drive with the recording of his time with the Sal-Mar. Some of those sounds are now woven into the album’s many layers. They’re present on

“LFO,” for one, though chopped up & almost impossible to identify. Lange says working with the sounds of the Sal-Mar inspired him, in particular, “to always be open & curious & make sure I’m not restricting myself to being dogmatic about anything, to make sure I’m not thinking, ‘The song must have a chorus,’ or ‘The song must have a hook.’” Indeed, many songs on the album don’t, though they still come off breezy & sweetly tuneful. Lange’s excellent pop instincts obscure his experimental interests. This is far from the only apparent contradiction inherent to Phasor For example, aesthetically, it’s both lush & meticulous, an English garden in a biodome. The album might

be easy to listen to from start to finish, a mix of down-tempo funk & warm acoustic psych, but it’s tougher to approach analytically, constructed as it is from all these moving parts & slippery paradoxes.

One of the most interesting of these tensions is that it’s driven by a fascination with sound in the abstract, but also full of human stories about love & pain. The abstract & the conceptual are foregrounded, but there is still a lot of content that is emotional, even directly autobiographical. One of the album’s catchiest & most fully realized songs is “Best for You and Me,” a musical vignette that sketches, in writerly detail, a night from Lange’s Floridian youth during his parents’ divorce. Here sound serves storytelling, & Lange is a terrific storyteller. Everything is wrapped in a gauzy quality, like the gentle, humid breezes of a South Florida evening.

This is one of Phasor’s paradoxes that resolves easily: Lange’s search for the right sound is often in service of the emotional tale he is spinning. Lange offers a moment on the final track “Es Una Fantasia” as an example.

“After I come out of the verse, when I’m like, ‘Dime otra vez,’ you hear this voice that’s reverbed out. It speaks to the concept of the song, of this fantasy that’s in your head, & these voices in your head that are kind of bouncing around. I know reverb is a really simple, overused thing, but I think it’s such an effective tool. It takes you somewhere immediately. I love using it in those ways where you can be effective in driving home where you are in a place in a song,” he shares. Critical listening is possibly antithetical to deep listening, at least in the way Pauline Oliveros meant it. Listening critically is a process of filtering, separating & naming, even if it’s with the benign goal of identifying different elements in music to discern their meaning. There’s nothing wrong with that kind of listening, but the most rewarding way to approach Phasor, or anything in Helado Negro’s discography, might be to simply listen deeply.

Beverly Bryan writes about music & lives in Queens. There’s a chance she made that playlist you like.

Created in Barcelona, Spain, by Jaume Sisa of the band Musica Dispersa, Orgia is an absolutely brilliant album from start to finish! Produced in 1970 (though originally released in 1971 by Concentric), the solo record is more song-oriented than his group’s i mprovisational Musica Dispersa from that same year. The work is a bizarre mixture evoking both Bob Dylan & Os Mutantes.

The first song “Carrer” starts with stoned laughter & kicks with thick, super-compressed bass, layered percussion, harmonica, Jaume’s totally original singing supported by swirling, wild backing vocals. On the next song, “Joc De Boles (Simfonia Atomica),” Jaume’s voice ventures into crazy territory à la Robert Wyatt, winding in & out of a slippery acid-bent guitar line. A layered kazoo section with lots of little percussions ends the track. The short “Comiendo pollo” follows with floating organ, clicking typewriters providing the rhythmic accompaniment. “En El castell” is a typical Spanish acoustic piece with more harmonica, reverbed-out whipcrack percussion, & lovely female vocals.

arrangement. “Cap A La Roda” is one of the strangest of the lot: an acoustic song with stereo hand drums, a dimension-opening break with crowd noise, & weird spoken bits popping out on top of the mix.

The moving “Els Reis De Pais Deshabitat” is a haunting number with ghostly female backups. The song builds gradually with an accordion/piano section eventually joined by chord organs & group vocals.

“El Casament” is another psychedelic masterpiece. Its Morricone–esque slide guitar transports me to a black-&-white spaghetti-western desert, where I hallucinate vividly from peyote & heat. From there, I stumble towards the visage of a crystal palace during the instrumental “L’Amor

A Les Rodes De La Presó” before being greeted warmly by brass cascades on the epic “La Presó De Les Rodes De L’Amor.” The last track, “Pasqua Florida a L’Illa d’Enlloc,” provides closure with an angelic choir of friends & bandmates.

“Relliscant,” a 30-second Dada snippet, precedes “Paisatge,” a Beatle-esque piano-based tune with a beautiful string-&-horn

Orgia’s cover art is surreal & the reissue comes in a nice digipack. The lyrics are in Catalan, which was at one time banned in Spain in an effort to suppress the identity of a population whose roots stretch back to the Middle Ages. There are unfortunately no translations provided, but this is still one of my favorite recent reissues.

John Kiran Fernandes of The Olivia Tremor Control is owner of the Cloud Recordings record label.

It’s Friday night & Los Kurados—“Austin’s Premiere Ska Party Band (that also has a shit ton to say)” according to their official description—are about to take the stage for the first of three gigs scheduled for the pre-South by Southwest weekend. The seven-piece band has been around for more than a decade, playing countless shows & putting out a number of albums. Their music is dynamic, exceptionally catchy & incredibly fun.

Made up of four musicians born in Mexico & three from the States & with songs mostly in Spanish, Los Kurados considers what they’re doing as being heavily influenced by the Mexican ska—or MexSka genre. Their name stems from the popular Mexican beverage curado, a mix of pulque & fruit with a history traced to the Aztec period. The band was actually conceived in Mexico after guitarist Poncho went back home to visit around 2012 & decided it was finally time to follow his dreams of playing music. He grew up in Mexico City, home to a vibrant ska scene stretching back decades.

“I called a meeting with some friends & explained that I always wanted to have a ska band [and asked] everyone to pick an instrument,” he told Sound Collector “The next day only one person showed up.” That was Juan, the band’s first drummer. Well, potential drummer, Poncho noted with a laugh, as Juan didn’t own any drums at the time.

The two decided to come back to Austin to try & put together the rest of the band. Vocalists Angel Ortiz & the luchador-mask-wearing Chester Chetos—who doubles as hype man—were the next recruits. Although the lineup fluctuated a bunch in those early years—as the group figured out not just what they were doing but also how to pull it off—it’s been pretty steady since around 2015. Members are the dual singers, guitarist Poncho,

Eric Brown on drums, bassist Bruce Alvarez, saxophone player Rosey Armstrong & her husband Kurt Armstrong on the trombone. Backgrounds of the band members are Mexican, white European, indigenous, & African American, a union Ortiz refers to as quintessentially “Texican” in nature. Multicultural is the name of their 2017 album

The first Los Kurados show was, as depicted by Poncho, a bit of a disaster: “The crowd only let us play two & a half songs ’cause we sounded so terrible. We were so drunk! The only person with musical experience was Bruce. He was okay. Everyone else was a mess.” The fact that they went on at three a.m. probably didn’t help. Not a very

auspicious start but in many ways a proper one.