EVENING AUCTION NEW YORK | 20 NOVEMBER 2025 | 6 PM AND

MODERN DAY AUCTION NEW YORK | 21 NOVEMBER 2025 | 10:30 AM & 2 PM

ALL EXHIBITIONS FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC

SATURDAY 8 NOVEMBER

12 PM–5 PM

SUNDAY 9 NOVEMBER

1 PM–5 PM

MONDAY 10 NOVEMBER

10 AM–5 PM

TUESDAY 11 NOVEMBER 10 AM–5 PM

WEDNESDAY 12 NOVEMBER 10 AM–5 PM

THURSDAY 13 NOVEMBER 10 AM–5 PM

FRIDAY 14 NOVEMBER 10 AM–5 PM

SATURDAY 15 NOVEMBER 10 AM–5 PM

SUNDAY 16 NOVEMBER 1 PM–5 PM

MONDAY 17 NOVEMBER 10 AM–5 PM

TUESDAY 18 NOVEMBER 10 AM–1 PM

WEDNESDAY 19 NOVEMBER 10 AM–5 PM

945 MADISON AVENUE NEW YORK, NY 10021 +1 212 606 7000

SOTHEBYS.COM

FOLLOW US @SOTHEBYS #SOTHEBYS

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THE PROPERTY IN THIS SALE, PLEASE VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/PRITZKER

CHAIRMEN

LISA DENNISON

Chairman, Americas Lisa.Dennison@Sothebys.com

HELENA NEWMAN

Chairman, Europe

Chairman, Impressionist & Modern Art Worldwide Helena.Newman@Sothebys.com

OLIVER BARKER

Chairman, Europe Oliver.Barker@Sothebys.com

BENJAMIN DOLLER

Chairman, Americas Benjamin.Doller@Sothebys.com

AMERICAN ART

STEFANY MORRIS

Head of American Art Stefany.Morris@Sothebys.com

CAROLINE SEABOLT

Head of Modern Day Auction Caroline.Seabolt@Sothebys.com

KATIE MAHER

Associate Specialist Katie.Maher@Sothebys.com

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART

JULIAN DAWES

Vice Chairman

Head of Impressionist & Modern Art, Americas Julian.Dawes@Sothebys.com

SCOTT NIICHEL

Vice Chairman

Head of Middle Market for Modern & Contemporary Art Scott.Niichel@Sothebys.com

SIMON SHAW

Senior Advisor Simon.Shaw@Sothebys.com

EDITH EUSTIS

Global Head of Research, Impressionist & Modern Art Edith.Eustis@Sothebys.com

ALLEGRA BETTINI

Head of Modern Evening Auction Allegra.Bettini@Sothebys.com

SARA LAND

Specialist, Modern Evening Auction Sara.Land@Sothebys.com

GENEVIEVE RICHARDSON Cataloguer, Modern Evening Auction Genevieve.Richardson@Sothebys.com

SALE NUMBER

N12130 “PRITZKER”

BIDS DEPARTMENT

+1 212 606 7414 bids.newyork@sothebys.com

Telephone bid requests should be received 24 hours prior to the sale. This service is offered for lots with a low estimate of $5,000 and above.

PRE-SALE COORDINATOR

Bridget Quinn Impressionist & Modern Art Bridget.Quinn@Sothebys.com

POST SALE SERVICES

Samit Sinha

Client Accounts Receivable Manager Impressionist & Modern Art uspostsaleservices@sothebys.com +1 212-606-7444

COLLECTION SALE MANAGEMENT

Melissa Cooper Head of Collection Sale Management Melissa.Cooper@Sothebys.com

AUCTION & EXHIBITION INFORMATION 5

SPECIALISTS AND ENQUIRIES

44

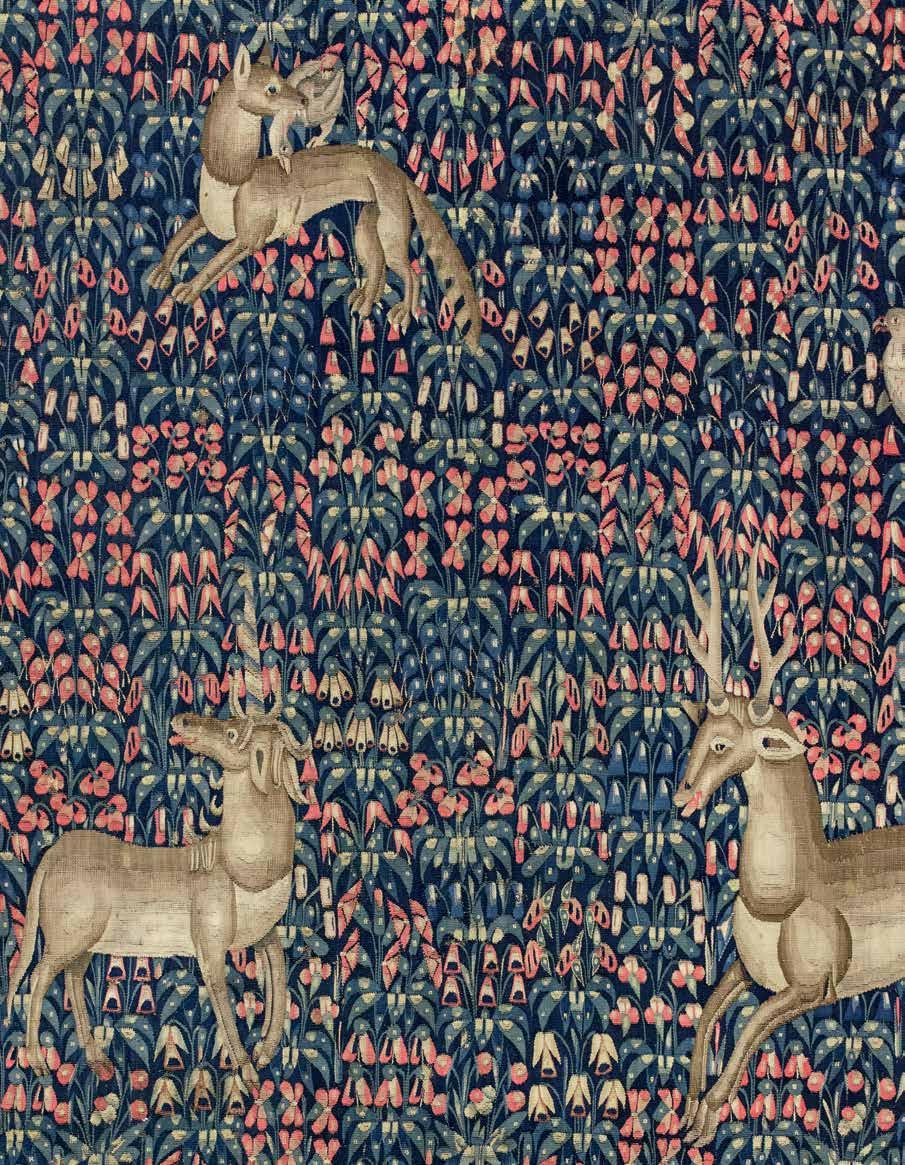

THE CINDY AND JAY PRITZKER COLLECTION

EVENING AUCTION 20 NOVEMBER 2025

LOTS 1–13

DAY AUCTION 21 NOVEMBER 2025

WESTERN ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS AUCTION

SOTHEBY’S LONDON, DECEMBER 2025

IMPORTANT AMERICANA AUCTION

SOTHEBY’S NEW YORK, JANUARY 2026

MASTER SCULPTURE AND WORKS OF ART AUCTION

SOTHEBY’S NEW YORK, FEBRUARY 2026

CHINESE WORKS OF ART AUCTION

SOTHEBY’S NEW YORK, MARCH 2026

INDIAN AND HIMALAYAN ART AUCTION

SOTHEBY’S NEW YORK, MARCH 2026

CLASSIC DESIGN AUCTION

SOTHEBY’S NEW YORK, APRIL 2026

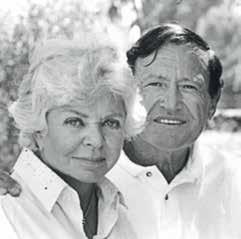

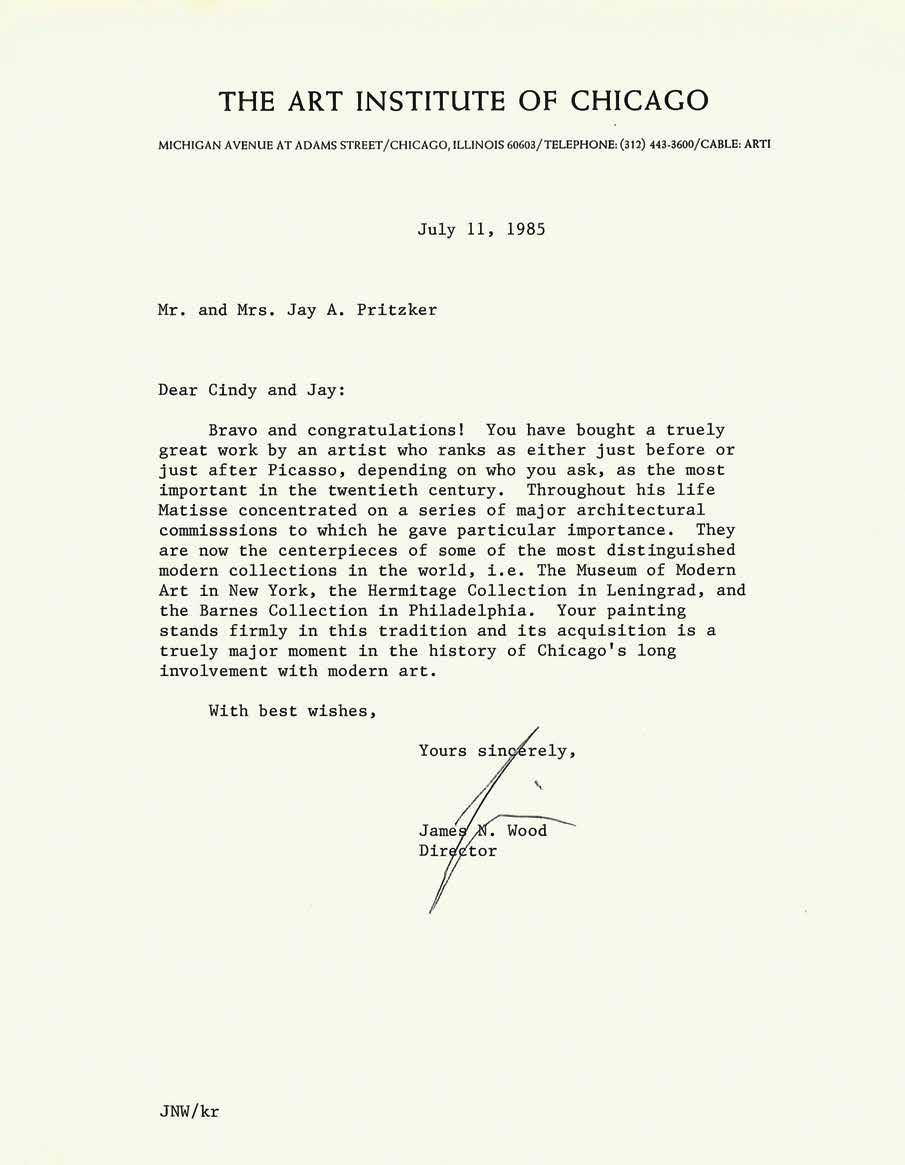

The Cindy and Jay Pritzker Collection represents a lifetime of passion for collecting and a love of art. Known for their quiet generosity and a belief in the power of civic commitment to uplift communities, they championed art and culture in all its forms – not least through the founding of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, recognized globally as the field’s highest honor.

For nearly five decades works from their collection including masterpieces by Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Henri Matisse, have remained within the private home of a couple whose lives were devoted to Chicago, the city they loved. Cindy and Jay Pritzker were instrumental in transforming the city’s cultural and civic heartbeat, breathing life into its institutions, organizations, and communities.

Nowhere is this devotion more evident than in Cindy’s leadership in bringing Chicago’s Harold Washington Library Center into being. As President of the Chicago Public Library Board and founding chair of the Library Foundation, she mobilized the civic will and philanthropic support that made the nation’s largest public library a reality. Cindy was also a driving force behind Chicago’s Millenium Park and the Jay Pritzker Pavilion designed by Frank Gehry.

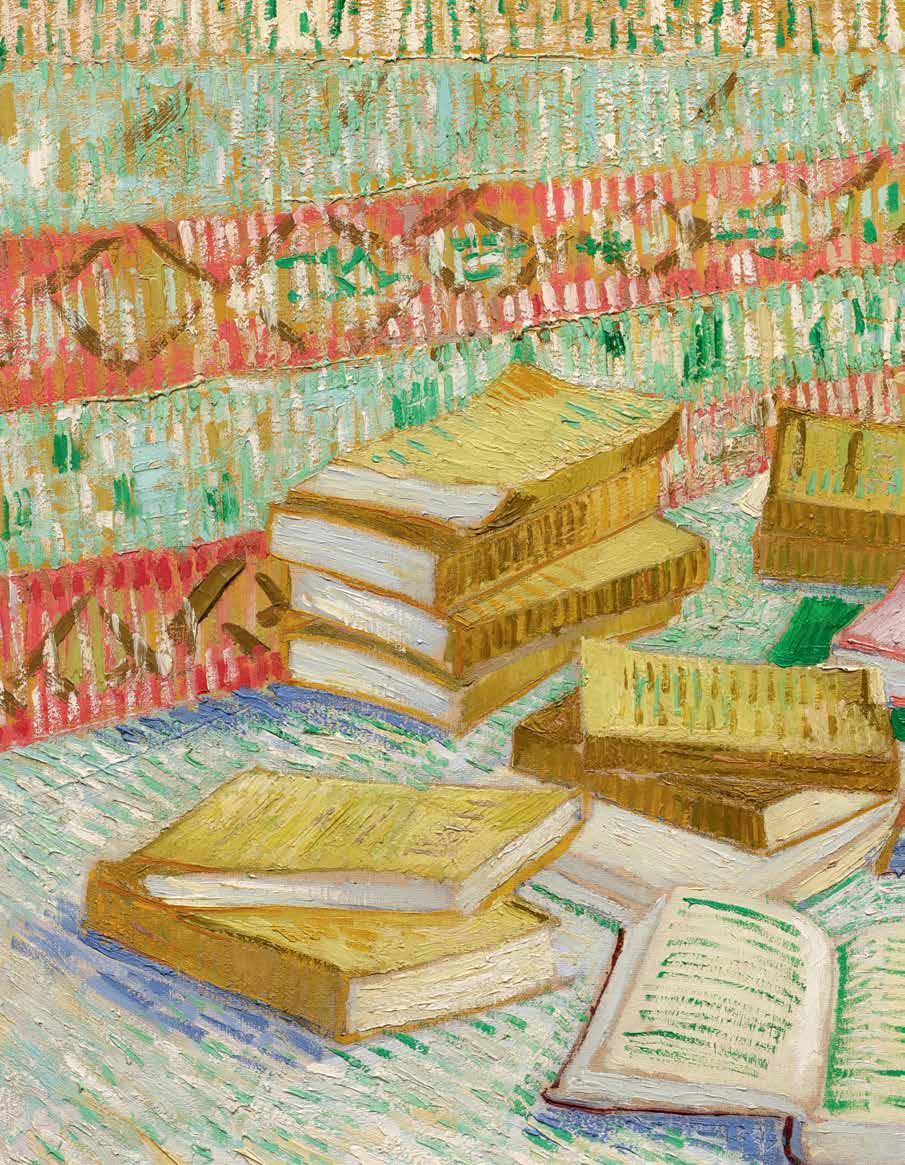

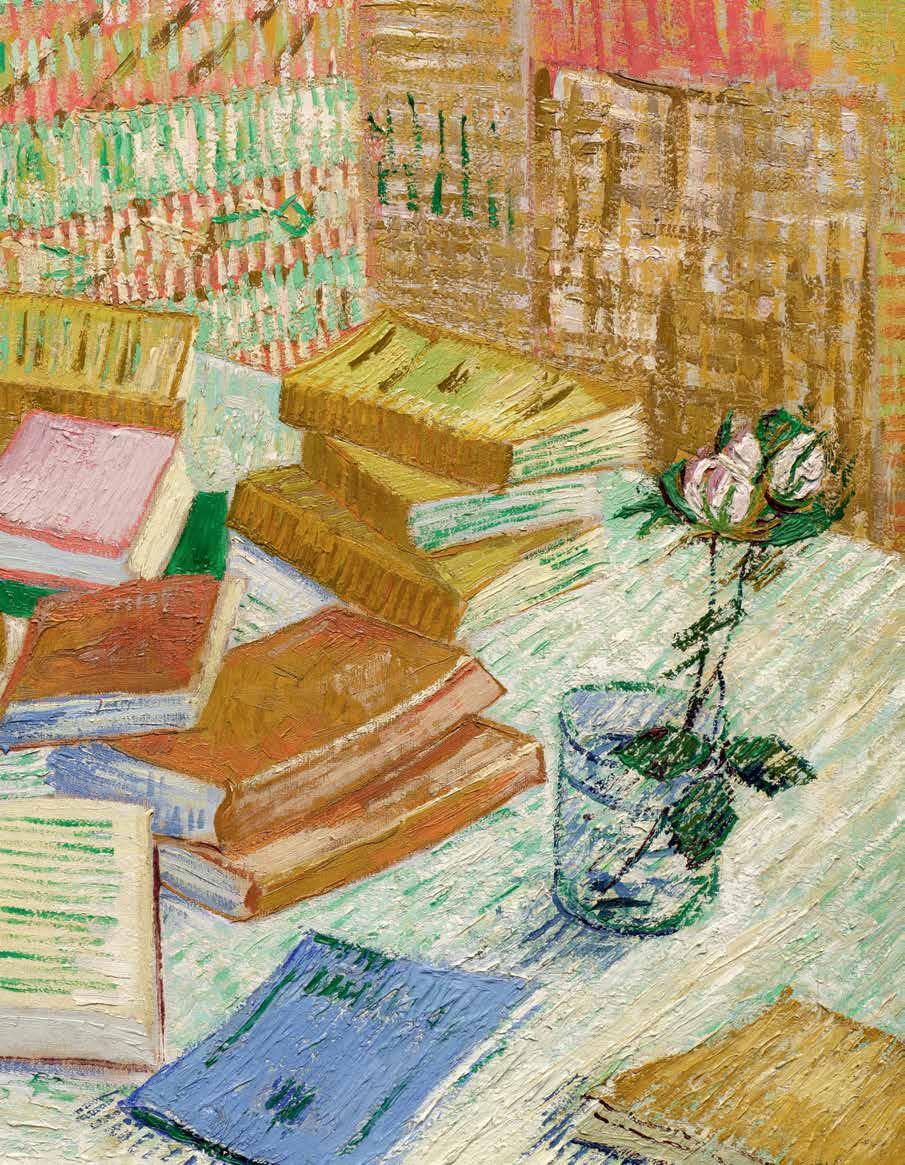

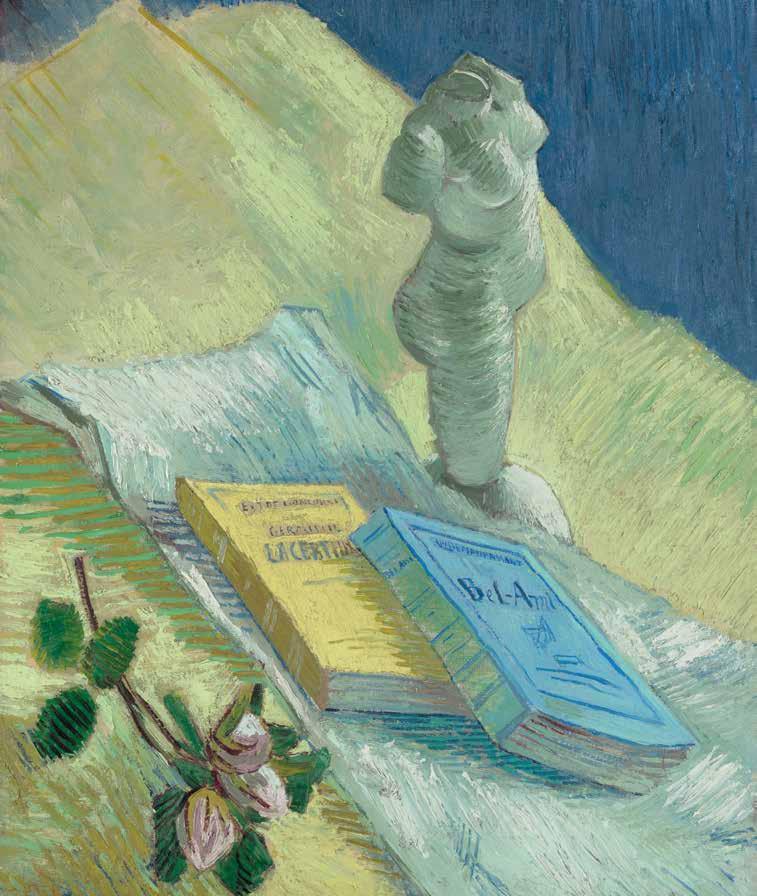

It is fitting, then, that the collection is led by van Gogh’s masterpiece Piles de romans parisiens et roses dans une verre (Romans parisiens) (1887) – a still life of books by an artist who read voraciously – echoing Cindy’s own lifelong passion for literature and her conviction that education, like art, is essential to the enrichment of public life.

Cindy possessed a remarkable instinct and impeccable taste. Like the van Gogh, each work in the Pritzker Collection was carefully chosen by Cindy and Jay and is of exceptional quality.

“I could have gone to graduate school for years and never learned as much as he (Jay) taught me that day.”

— WARREN BUFFETT

Jay Pritzker was viewed as one of the great entrepreneurs of his generation. One of his most renowned investments occurred in 1957 at the Los Angeles International Airport, where he saw an opportunity: with the acceleration of air travel for business, there was a demand for a new kind of accommodation catering to the needs of an emerging generation of business travelers. He purchased the nearby Hyatt House motel, laying the foundation for what would become the global Hyatt Hotels empire. Further, his acquisitions included firms such as Trans Union, McCall’s Magazine, and Ticketmaster. He soon established his reputation as a visionary businessman, known for his personal integrity and for identifying opportunities with remarkable speed. As Warren Buffett said, recounting a 1954 chance meeting: “I could have gone to graduate school for years and never learned as much as he (Jay) taught me that day.”

Over time, the Pritzker family became synonymous with civic engagement, as is reflected in the numerous Chicago institutions that now bear their name: from the Pritzker School of Medicine at the University of Chicago to the Pritzker Garden at the Art Institute of Chicago to the Jay Pritzker Pavillion in Millennium Park and the Pritzker Family Children’s Zoo at the Lincoln Park Zoo.

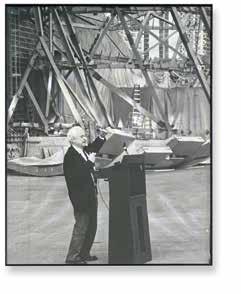

The creation of the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1979 was a joint venture between this remarkable couple. It was a natural extension of Cindy and Jay’s deep admiration for design and its role in the built environment. The positive public response to the newly built Hyatt Regency in Atlanta was an inspiration; helping them understand the profound impact of architecture on daily life. The purpose of the Pritzker Prize is to honor a living architect or architects whose built work demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision, and commitment, which has produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture. This statement reflects the elegance with which they approached every task from collecting to civic engagement. The Pritzker Architecture Prize is now the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in the world of architecture. Over its 47 years the Prize has presented the talents of Frank Gehry, I.M. Pei, Zaha Hadid, Jean Nouvel, Richard Rogers, Sir Norman Foster, Rem Koolhaas, Renzo Piano, Hans Hollein, Diébédo Francis Kéré, Tadao Ando and Shigeru Ban – figures whose designs represent some of the most important architectural achievements of recent times, shaping communities around the world.

“Cindy Pritzker’s legacy lives in every branch, every program, and every reader who finds inspiration within our libraries. She built more than a library system: she built a Chicago where knowledge, culture, and opportunity belong to us all.”

Cindy Pritzker, also a Chicago native, emerged as a cultural visionary whose leadership transformed Chicago’s civic identity. One of her most celebrated achievements was overseeing the development of the Harold Washington Library Center, Chicago Public Library, which opened in 1991 as one of the largest libraries in the United States. With ten floors of resources and a distinctive Winter Garden enclosed in glass, the library became both an important and functional resource as well as an architectural landmark. Cindy chaired the library board for nearly a decade, during which time she championed the construction or renovation of dozens of neighborhood branches, crucially expanding access

to education and information for communities across the city. Cindy’s influence extended further into Chicago’s civic life, not least playing a decisive role in the creation of Millennium Park. She secured Frank Gehry, a Pritzker laureate, to design the sweeping stainless steel bandshell that now stands as the Jay Pritzker Pavilion. This structure, with its flowing ribbons of steel, has become one of the city’s most iconic landmarks, hosting concerts and cultural gatherings that bring residents and visitors together. Her leadership ensured that the park would serve not only as a space of recreation but also as a cultural epicenter.

Through her decades of work, Cindy redefined what it meant to be a civic leader. She combined vision with practicality, ensuring that projects not only reflected ambition but also delivered real benefits to the public. For many, she became the city’s “philanthropic first lady,” remembered for her ability to turn bold ideas into enduring institutions.

Cindy and Jay Pritzker are remembered as figures who fused vision, philanthropy, and leadership. Jay’s entrepreneurial brilliance and integrity, combined with Cindy’s passion for civic life and the arts, left an indelible mark on the city of Chicago and beyond. Their joint legacy is a testament to the transformative power of giving, serving as a model for how individuals can enrich communities and inspire lasting change across generations.

BY JOACHIM PISSARRO

Freud’s term unheimlich, (often translated as “the uncanny”) designates something that unsettles us. It feels both familiar and unfamiliar. When applied to art, the unheimlich, “uncanny”, evokes those works that surprise us, that take us out of our realm of known quantities. We are suddenly confronted with the unexpected, something new, yet not totally unknown. It is in this fascinating context that the Cindy and Jay Pritzker Collection yields something unique to itself.

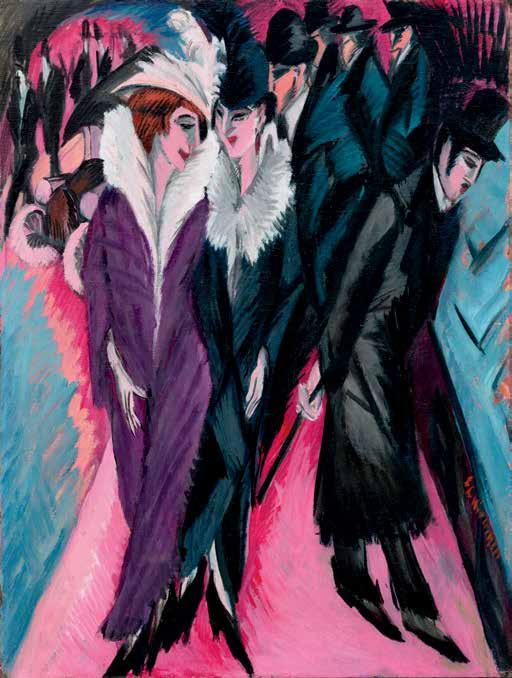

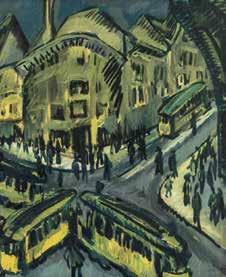

Art history intersects with the commercial art world in that both entities recognize certain universally acclaimed standards and values. While this canon is in many ways necessary, it can reduce our understanding of artists and art history to recognizable themes: Vincent van Gogh as a painter of sunflowers, Henri Matisse the painter of odalisques or as the master of cut-outs, Paul Gauguin as the chronicler of Tahiti. The genius of the Pritzker Collection lies in its resistance to such clichés: it reveals works by those universally acclaimed artists in an unexpected and daring light.

The Pritzkers’ unique curatorial sense was nurtured by a deep instinctual sensibility. The Pritzkers, whose name is eponymous with the most famous architectural prize, brought to art collecting the same attentiveness to volume, space, form and objectality. They were drawn to works that embody purity of shape, solidity of mass and the tensions of solid juxtapositions. Seen together, the collection has the clarity and coherence of an architectural masterplan: every work contributes to a vision of art that is spacious, structural, and resonant.

The result is a collection that feels both daring and refined, a group of works that do not repeat what is already known but expand the canon in surprising and meaningful ways. Each of these exceptional works allows us to encounter each artist anew, reminding us that true connoisseurship lies in the courage to choose beyond the predictable.

Among the most striking examples is van Gogh’s Piles de romans parisiens et roses dans une verre (Romans parisiens) of 1887, a still life that departs radically from van Gogh’s fields and flower-compositions for which he is best known. Here, instead of nature in bloom, we find the intimate presence of books: a subject that reveals a lesser-known but essential dimension of the artist’s creative world.

The subject itself is rare within van Gogh’s oeuvre. Of nearly nine hundred canvases, fewer than ten focus on books, and Romans parisiens is the largest and most ambitious of them. Here van Gogh identifies not with flowers or fields, the images that came to define his posthumous reputation, but with novels, the “livres jaunes,” yellow-backed paperbacks by Zola and the Goncourt brothers that he read voraciously. The painting is, in effect, an oblique self-portrait: van Gogh as a reader and an intellectual, immersed in the world of literature as deeply as he was in the field of paint—the two fields (painting and literature) being inherently bound together and nurturing each other in van Gogh’s creative psyche.

This counters one of the most enduring myths about the artist. Too often, van Gogh has been portrayed as a creature of instinct, a man driven by frenzy and madness, devouring paint like an animal, as he is portrayed in films such as Lust for Life (1956) or The Life and Death of Vincent van Gogh (1987). The reality, illuminated by van Gogh’s letters and his “poetry albums,” is far richer. Van Gogh spoke, read, and wrote in four languages; he copied hundreds of poems into albums he created for himself and his friends; he read incessantly, drawing inspiration from literature, poetry, philosophy, and the scriptures. His art was not the product of blind instinct but of a cultivated, literary, deeply thoughtful and sophisticated mind.

As van Gogh himself wrote to Theo, he admired writers like Zola and the Goncourts because they told “life as we feel it ourselves,” truth unvarnished, raw yet meaningful. The painting embodies this very ethos: a still life that is also a meditation on truth, reading, and the intellectual passion of an artist far more sophisticated than the stereotype suggests. Instead of the familiar myth of the tormented genius, we encounter a cultivated, literate, modern man: a painter who, despite the complexities of his psyche, read, wrote, and reflected to unparalleled levels. Rare, complex, and revealing, Romans parisiens exemplifies the collection’s daring ability to expand the canon, to show us the richness of an artist beyond cliché. This fascinating example epitomizes the Pritzkers’ own creative imagination as they assembled this edifying collection together.

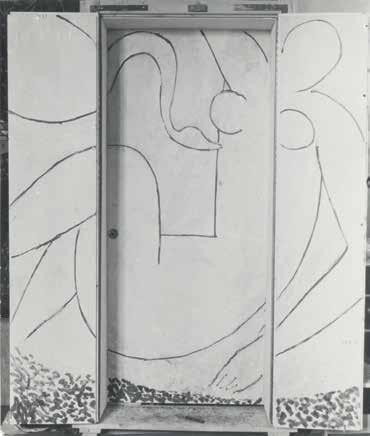

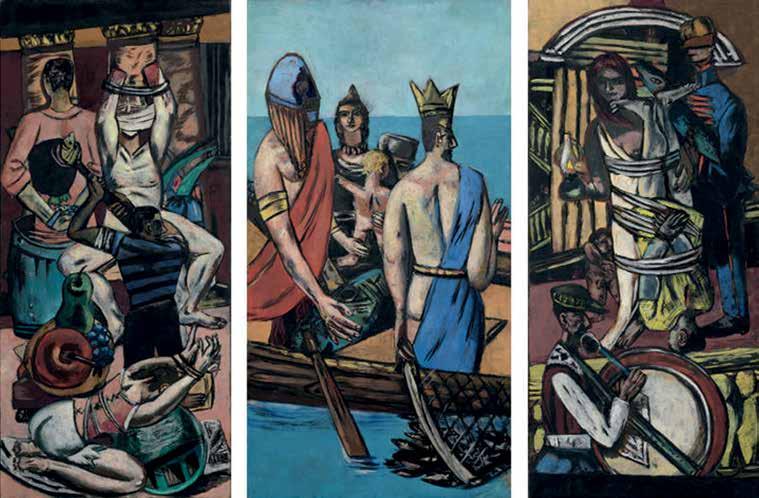

Equally enlightening is Léda et le cygne. There Matisse turns not to canvas but to painting directly on a door and a set of shutters which he had joined together. This rare convergence led the artist to a new dimension where art, sculpture and architecture are all intertwined.

Commissioned for a private Parisian home, the triptych transforms these found architectural elements into a mythological tableau. Across three panels, fields of vermillion paint frame the encounter of Leda and her courtier/seducer, Zeus having metamorphosed into a swan.

On the interior of the flanking panels the scene is enlivened by Matisse’s finely incised foliage motifs, while on the exterior he finely applied luxurious gold leaf. Light, form, and functionality all brought together to give this work its maximum impact, an object transformed.

This duality makes it unique. Unlike his canvases or cut-outs, Léda et le cygne is a total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk): decorative and architectural, intimate and monumental. It is sculptural in its volume, painterly in its surface, and mythological in its subject. The myth itself, simultaneously erotic and violent, adds a charge of vitality and tension uncommon in Matisse’s late work, where serenity usually prevails.

In the canon, Matisse is most often remembered for color as pure shape. Yet this rare commission shows him engaging with art as an environment, exploring how painting could inhabit and transform space. Within the Pritzker Collection, Léda et le cygne stands as a singular work that embodies both the architectural sensibility of the collectors and the daringness of an artist rethinking the very dimensions of painting.

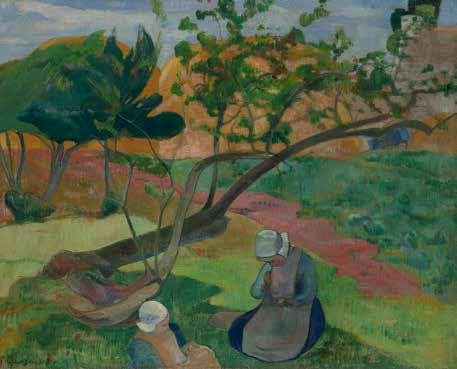

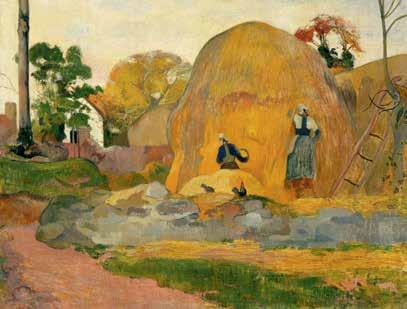

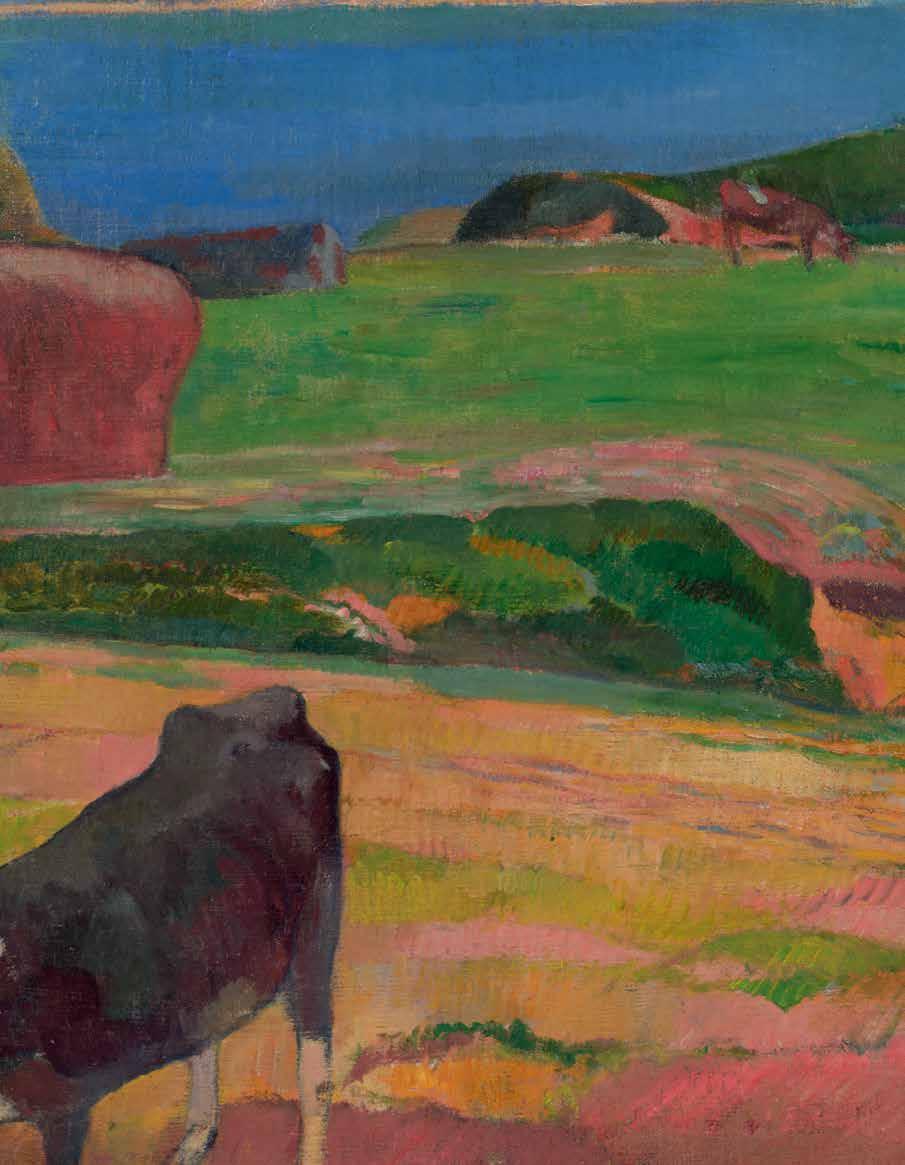

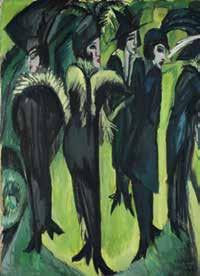

Paul Gauguin’s La Maison du Pen du, gardeuse de vache is not the kind of luminous, tropical painting typically associated with the artist’s name. Far from his most recognizable Tahitian scenes, this work presents instead a Breton landscape: a solitary cowherd beside a stark farmhouse perched on windswept cliffs in remote Le Pouldu. In its day, such a modest rural motif would have definitely struck a chord as an anti-monumental statement. It is precisely in such works that Gauguin forged the vocabulary that would become the corner stone for modern painting.

The painting exemplifies Gauguin’s pivotal Breton period, where, disillusioned with Impressionism and urban Paris, he turned to Brittany, the furthest most and wildest province of France, in search for raw authenticity, and a total break from what he called “civilization”. Here, he experimented with compressed space, a high horizon, decorative flat color, and bold contours, drawing influence upon Japanese prints and folk art, with which he was intimately acquainted. The palette, while brightened by his trip to Martinique, remains more restrained compared to his later work, but the vision is already abstracted and stylized, departing from Impressionism and laying the foundation for Synthetism and his later, much-celebrated Tahitian paintings

What makes La Maison du Pen du so important, despite its unassuming and relatively quiet subject, is that it marks Gauguin’s first true artistic breakthrough: his turn from observation to invention, from naturalism to symbolic, memory-driven abstraction. In Pritzker’s collection, the painting is significant because it reminds us that artistic revolutions begin in quiet places, with works that might appear atypical but reveal their audacity, and their future promise.

Max Beckmann’s Der Wels, while representing a recurring subject in his later work, stands out as a pivotal example that reveals a decisive transformation in the artist’s career, precisely the kind of moment that defines the Pritzker Collection. Painted in Paris in 1929, it captures Beckmann at the threshold of his mature style, where allegory, monumentality, and psychological tension converge with bold new force. The thick, assertive brushwork and heavy black outlines signal this shift unmistakably: form becomes dense and sculptural, color carries weight, and every contour feels charged with symbolic intent. Within its compressed, stage-like space, four figures: a fisherman, two women, and a monumental catfish, enact a scene that is at once ordinary and metaphysical. The strength of the image lies precisely in this duality: the seemingly banal motif of fishing conceals a powerful religious allegory. The catfish, recurring throughout Beckmann’s late work, takes on an almost devotional role, a modern emblem of transcendence rising from the everyday. Through this convergence of myth, faith, and human presence, Der Wels reveals a Beckmann who no longer observes but declares—a painter entering his full maturity, fusing the sacred and the profane into a single vision.

Tracing back to Freud’s notion of the unheimlich, the uncanny, the Pritzker Collection distinguishes itself with works that surprise rather than confirm our expectations. These selections show artists in moments that feel both familiar and unfamiliar: works that expand their language, unsettle their stereotypes, and reveal the breadth of their vision, and the manifold complexities of their creative imaginary processes of great artists.

Van Gogh appears not as a tormented painter of fields, ceaselessly on edge, but as a cultivated and sophisticated reader and thinker; Matisse not only as a master of color, but as an artist who could transform found objects into a dazzling triptych; Gauguin not yet in Tahiti, but on the threshold of a revolution whose first step unfolded in the Breton countryside.

The Pritzkers’ choices show artists thinking differently, testing boundaries, and creating with unexpected delicacy or force. Many other works in the collection share this quality, but even the few highlighted here demonstrate a clear vision: to collect with a total independence from trends and market forces, to value the particular, and to see beyond the predictable. In this way, the collection does more than assemble exceptional works of art. It exemplifies connoisseurship as a renewed act of courage: the willingness to trust one’s eye, to embrace the unanticipated, and to understand that the canon itself is not fixed but open, expansive, and alive.

1886 - 1966

Torse enjoué

stamped with artist’s monogram and numbered V/V (on the interior)

bronze height: 43 ¼ in. 110 cm.

Conceived in 1965 and cast in a posthumous edition of 5; this example cast by Rudier on 7 February 1973.

$ 800,000-1,200,000

PROVENANCE

Galerie Artcurial, Paris

Edouard Loeb, Paris

Feingarten Galleries, Los Angeles

Acquired from the above on 21 April 1978 by the present owner

EXHIBITED

Musée des Beaux-Arts du Havre, Jean Arp, 1973 (not in catalogue)

LITERATURE

Eduard Trier, Marguerite Arp-Hagenbach and François Arp, Jean Arp: Sculpture, His Last Ten Years, New York, 1968, no. 355, p. 128, illustration of another cast; p. 129

Exh. Cat., Madrid, Museo Español de arte contemporáneo, Jean Arp, [1886-1966]: Esculturas/ Relieves/ Obra Sobre Papel/ Tapices, 1985, no. 59, p. 134, illustration of another cast

Claude Weil-Seigeot and Renaud Ego, Atelier Jean Arp et Sophie Taeuber, Paris, 2012, pp. 18 and 24, illustration in color of another cast (in photographs of Fondation Arp’s sculpture garden); p. 198, illustration in color of another cast

Arie Hartog and Kai Fischer, Hans Arp: Sculptures–A Critical Survey, Ostfildern, 2012, no. 355, pp. 194 and 215, illustration of another cast

Atotem to the evolution of sculpture and the enduring inspiration of the human figure, Torse enjoué stands among the most dynamic works of Jean Arp’s late oeuvre.

In 1954, Arp received the Grand Prix for Sculpture at the Venice Biennale. This crowning achievement of his career was shortly followed by a retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. This newfound fame and financial stability at last afforded Arp the opportunity to see many of his earlier plaster forms cast in bronze and carved in marble. In this process, Arp would look back to his earlier sculptures for inspiration, including many of his Torse forms. Such renown and retrospective reflection did not stifle the artist’s creative ambition. As Serge Fauchereau writes, “Arp was not the kind of man who would feel as if he had ‘made it.’ He was to take his study of form even further to develop those forms he had discovered” (Serge Fauchereau, Arp, Barcelona, 1988, p. 26). The decade that followed—the last of his life—would reveal an artist continually striving for innovation and one working with undiminished vitality in the pursuit of new formal solutions.

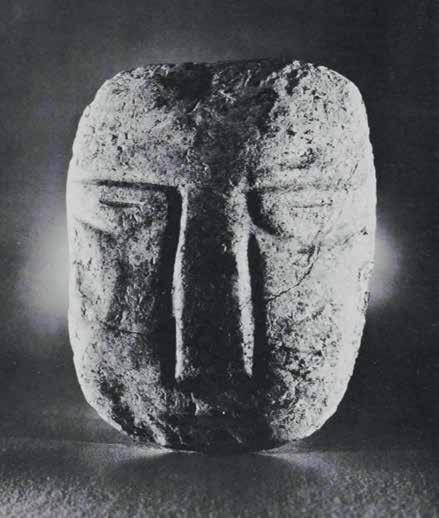

Arp’s travels in the late 1950s and early 1960s— to North America, Mexico, Egypt, the Middle East and Germany—provided the artist with an ever-expanding visual vocabulary. Exposure to Pre-Columbian sculpture, monumental statues of Egypt and Assyria, Renaissance limewood carvings, Cycladic and classical Greek forms deeply enriched his formal repertoire (see fig. 1). Steeped in these historical precedents, Arp incorporated the essence

and fragmentation of such forms, integrating them into his unique sculptural language. In Torse enjoué, the human torso is abstracted and transformed, simultaneously evoking nature while defying literal representation.

This dialogue with ancient simplicity also finds kinship in the work of Constantin Brancusi, whose pursuit of the “essence of things” profoundly influenced twentieth-century sculpture. Arp’s smooth, organic surfaces echo Brancusi’s polished marble and bronze forms, yet diverge in temperament—where Brancusi seeks the sublime and eternal, Arp embraces a sense of playful metamorphosis, aligned with the Surrealist spirit of chance and transformation. His “joyful torso” does not merely symbolize the body; it becomes a poetic game between abstraction and figuration, between conscious form and the spontaneous emergence of shape.

Well known and lauded for his lyrical, biomorphic forms, Arp in the 1960s endowed many of his favored motifs with increased angularity and juxtapositions of shape. Within this context, Torse enjoué emerged. Whereas Arp’s first Torse from 1930 was clearly extrapolated from the bodily form, conveying the undulations of shoulders, back and buttocks, the artist’s mature variations on the theme witness a greater liberation of form. Though still rooted in the human figure, the swelling curves of Arp’s Torse enjoué are at turns punctuated by rectilinear planes, conjuring forms that transcend mere corporeality. Through this contrast of carefully composed angles and arcs, Arp compels the viewer to move around the sculpture in order to fully engage with its dimensionality and behold its spatial presence.

Torse enjoué presents a culmination of Arp’s remarkable oeuvre, bridging the playful experimentation of his Dada reliefs and the geometry of his early collage with the formal sophistication of his late work to create a dynamic synthesis of figure and abstraction. “The starting-point for my work is from the inexplicable, from the divine, from the fact that I can wake up, that I move, act, am suspended and live, that I can give birth to poetry, drawing, sculpture, handwriting, lines, planes, choice of colors and forms;

that I am conscious of flowers, stones, an odd fragment of marble, of a look, a step, a silhouette, a human figure, of the shape of a cloud. The inexplicable that binds me to a twig, a particle of earth, spots, or flashes of lightthat is what decides the expressive content of my work. My tasks are tied to day-dreams, with no scorn at all for the matter from which they are fashioned”(quoted in Exh. Cat., New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Jean Arp, 1972, p. 30).

In Torse enjoué, Arp achieves a harmonious convergence of the figurative and the organic, seamlessly integrating the human torso with biomorphic forms. The sculpture transforms the body into a site of metamorphosis, where natural and anthropocentric elements coexist in dynamic interplay. Held in The Cindy and Jay Pritzker Collection for nearly fifty years, this work represents the sole example of Torse enjoué to appear at auction in nearly as long. Another cast of this form belongs to the collection of the Fondation Arp in Clamart, France.

1866 - 1944 Ins violett (Into Violet)

signed with artist’s monogram and dated 25 (lower left); dedicated Der verehrten Frau E. Reichelt herzlichst

Kandinsky (on the artist’s mount); titled Violett, dated 1925 (on the reverse of the artist’s mount)

watercolor and pen and ink on paper on the artist’s mount image: 13 ¾ by 8 ¾ in. 35 by 22.2 cm.

mount: 19 ⅜ by 13 ⅝ in. 49.3 by 34.5 cm.

Executed in January 1925.

$ 700,000-1,000,000

PROVENANCE

Elfriede Reichelt, Breslau (acquired directly from the artist in exchange for photographs in April 1926)

Galerie Jacques Benador, Geneva (acquired by 1956)

Heinz Berggruen, Paris (acquired by 1956)

Hanover Gallery, London (acquired in 1956 and until 1958)

Heinz Berggruen, Paris (acquired by 1958)

Mr. and Mrs. Peter Bensinger, Chicago (acquired by 1959)

Linda Olin, Chicago (until 1982)

Richard Gray Gallery, Chicago

Acquired from the above on 10 November 1982 by the present owner

EXHIBITED

Dresden, Graphisches Kabinett Hugo Erfurth and Erfurt, Angermuseum, Kunstverein, Sieben Bauhausmeister, 1925

Paris, Berggruen & Cie., Klee et Kandinsky: une confrontation, 1959, n.p., illustrated (titled Violett)

New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture Collected by Yale Alumni, 1960, no. 199, p. 192, illustrated (titled Violet)

LITERATURE

The artist’s handlist, I, no. 188

John Prossor, “An Introduction to Abstract Painting,” Apollo, vol. LXVI, no. 392, October 1957, fig. II, p. 76, illustrated (titled Violett)

Vivian Endicott Barnett, Kandinsky Watercolours, Catalogue Raisonné, vol. II, Ithaca, 1994, no. 750, p. 145, illustrated

“In any case of translation into the abstract or the employment of non-objective forms, the artist’s sole judge, guide, and principal consideration should be his feeling. …Since art affects feeling, it can only be effective through feeling.”

— WASSILY KANDINSKY

Dedication to Elfriede Reichelt on the mount of the present work

Opposite left: Fig. 1

Elfriede Reichelt, Portrait of Wassily Kandinsky, Breslau, 1926

Opposite right: Fig. 2

Elfriede Reichelt, Portrait of Wassily Kandinsky,

, 1926

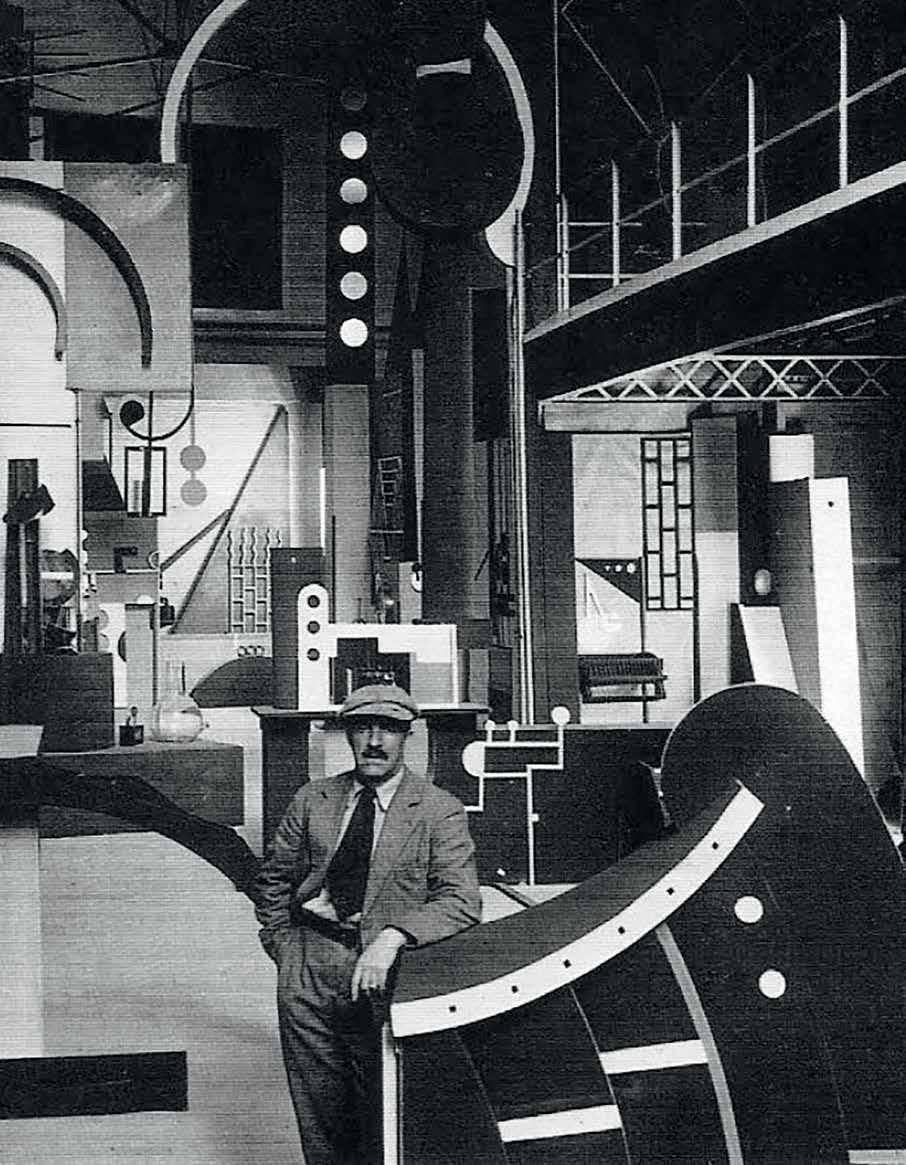

1925 marked a creative apogee in Wassily Kandinsky’s involvement at the Bauhaus. In June of the same year, mounting political pressures forced the school to relocate from its original location in Weimar to Dessau. Kandinsky quickly found inspiration in the industrial city and the functionalist aesthetic of the school’s new building which its founder Walter Gropius designed. In July of the same year, Kandinsky began work on his second seminal text Punkt und Linie zu Flache (Point and Line to Plane), begun in July and completed in November of the same year.

Executed in January, Ins violett (Into Violet) at once offers a beautifully articulated compendium of the theories between color and form, point and line, and Kandinsky’s overarching ideation on the notion of correspondence, which he continued to expand on in his teachings at the Bauhaus. It anticipates the profoundly generative impulse which would come to characterize his artistic output of the period.

Throughout his eleven year tenure as a teacher at the Bauhaus, Wassily Kandinsky’s watercolors were a formative means of theoretical and methodological experimentation. His work within the medium was prolific; according to his personal handlists, Kandinsky executed 183 watercolors between 1922 and 1926 alone. It was not until 1924, however, that each entry was recorded with its own unique title, rather than one that positioned it as a preparatory work for a culminating oil painting. This indication that Kandinsky had begun to understand his watercolors as independent to his larger format works, and equal in importance, is deeply felt in the luminous Ins Violett

Within the elegantly balanced composition, Kandinsky creates a world contained unto itself— one whose component parts are familiar, and exist within our lived reality, but which are relieved of the representational meaning that we ascribe to them. At first glance, there is a distinctly hieratic arrangement to these elements: the totemic form floating at right, the ascending stack of blocks at left, and the stepped diagonal between them, all of which impart a sense of architectural rigidity to the whole. At the same time, the structural integrity of that arrangement is immediately destabilized by the magnetic pull of the various diagonals. The title, Ins violett, serves as yet another instruction to the eye, a directive which draws the viewer’s gaze to the wash of violet in the upper register, conferring on the whole the suggestion of a vertical ascent. Without the aid of contextual or spatial moorings, each of these elements becomes untethered from its physical placement within the composition and is released into a rhythmic oscillation, alternately receding away from and projecting out of the surface. The transparency of their coloration calls into flux the geometry of their outline, particularly in the areas where intermingling forms give way to new shapes in their point of contact. To the uninitiated viewer, the behavior of these forms and colors offers perhaps the most explicit articulation of Kandinsky’s theories in practice.

A defining feature of his Dessau period was precisely this overlapping of shapes and colors, which reintroduced a sense of spatial depth that had been missing from his earlier Bauhaus works. One cannot help but ascribe physical properties to these

elements, which makes comparison to his earlier figurative compositions a particularly apt point of reference for the innovations that Ins Violett reveals. In his 1909 landscape, for example, the beginnings of Kandinsky’s theorization on the psychological quality of color is present, which he so brilliantly translates in the present work (see fig. 4). Though not yet entirely liberated from its figurative subject, and still conceived within a representational framework, the Fauvist brushstrokes simultaneously evoke their real-world counterpart through the simplest of formal means and begin to behave independently of the objects they describe. Yet, just more than fifteen years later in 1925, any semblance of narrative is removed from the elements within the composition. Whereas in Häuser in Murnau (Houses in Murnau), Kandinsky elicits an emotional response through means of expression and the frenetic energy of its articulation, within Ins violett, he removes any qualifier from his brushstrokes. Color is relieved of its descriptive

obligation and form of its representational obligation. If one imagines the row of houses lining the hillside as equivalent to the two scalloped diagonal lines, or even further to the curlicue, the transformation which Kandinsky’s work underwent within the intervening period becomes aboundingly clear. Whereas the color yellow as used to describe the sunlit facades of the structures is inextricably linked to the sentimentality of the time of day which Kandinsky depicts in the landscape, we are here left to consider the behavior of color itself as a subject.

The aesthetic theories governing many of Kandinsky’s compositions throughout his career derived from his 1911 treatise, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, in which he praised the power of color and its influence on the viewer. Like many of his contemporaries working in Russia at the time, Kandinsky was deeply influenced by the principles of Suprematism. Founded by Kazimir Malevich, and based on the notion of the supremacy of pure feeling

in the pictorial arts, Suprematism rejected nature in favor of a geometric abstraction reduced to its most fundamental form (see fig. 5). Kandinsky’s own theories on art were based on his tangential notion of an “innermost necessity,” communicated between artist and viewer through the perceptual effects engendered by different pairings of shape and color. Kandinsky contended that colors carry inherent psychological effects which can be heightened or diminished when articulated within certain shapes, which also bear innate perceptual qualities. The objective of his idea of non-objectivity—a reduction of shape to its most essential form—was to remove from representation any obligation to an object beyond itself, so that those pairings can be read without the emotional meaning we attach to figurative painting. The art object and the arrangement of its formal elements thus become a means for universal, subliminal communication.

Two months after completing the present work, Kandinsky began on a major oil painting, Gel-RotBlau (Yellow-Red-Blue), now housed in the Centre Georges Pompidou (see fig. 3). As testament to the strength of the composition he achieved within Ins violett, the arrangement of forms is translated almost exactly onto the left-hand side of the canvas, poised in conversation with an explosion of overlapping organic shapes on the right. The rhythmic, synesthetic quality he is able to achieve through the juxtaposition and counterbalance of these opposing formal languages offers among the most visceral articulations of Kandinsky’s ability to engage each of the senses through the arrangement of elements within a work.

In April 1926, shortly after the oil painting was completed, Kandinsky gifted the watercolor to the German photographer Elfriede Reichelt in exchange for portraits she had taken of the artist and his wife, Nina. The inscription on the artist’s mount, Der verehrten Frau E. Reichelt herzlichst Kandinsky (To the esteemed Mrs. E. Reichelt, Kandinsky) serves as a poignant foreshadow of the acclaim with which Reichelt’s photography would soon come to be met. Her portraits of Kandinsky from the mid-1920s in particular stand among the most recognizable of the period (see figs. 1 and 2). Ins violett offers a portrait of Kandinsky in another form—capturing within its painted surface a record of the artist at a moment of profound creative invention.

“As the number of colors or forms is endless, the combinations and effects are, also, infinite. This material is inexhaustible.”

— WASSILY KANDINSKY

1853 - 1890

Jardin public avec bancs à la Place Lamartine

reed pen and ink and pencil on paper 10 ⅛ by 13 ¾ in. 25.8 by 34.8 cm.

Executed in late April 1888.

$ 2,000,000-3,000,000

The authenticity of this work has been confirmed by the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

PROVENANCE

Theo van Gogh, Paris (acquired by descent from the artist)

Johanna van Gogh-Bonger and Vincent Willem van Gogh, Amsterdam and Laren (acquired by descent from the above)

J.H. de Bois, Haarlem (acquired from the above in 1912)

Dr. Heinrich Stinnes, Cologne-Lindenthal (acquired from the above on 7 April 1928)

Stuttgarter Kunstkabinett, 26 April 1951, lot 1345 Auctiones AG., Basel, 24 January 1970, lot 81

Heinz Berggruen Galerie, Paris (acquired by 1970)

Kornfeld und Klipstein, Bern, 20-22 June 1979, lot 461

Alice Adam, Chicago (acquired at the above sale)

Acquired from the above on 3 July 1979 by the present owner

Opposite: Fig. 1 Vincent van Gogh, Entrée du parc public à Arles, AugustOctober 1888, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

EXHIBITED

Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum, Tentoonstelling van schilderijen en teekeningen door Vincent van Gogh, 1905, no. 471 (titled In een park)

Cologne, Kunstverein and Frankfurt, Moderne Kunsthandlung Marie Held, 1910, no. 34 (titled Tuin met bank, huis op de achtergrond )

Frankfurter Kunstverein, Vincent van Gogh. Zeichnungen und Aquarelle, 1970, no. 59, p. 92; pl. 59, illustrated (titled Vue de Jardin and dated September 1888)

LITERATURE

Jacob-Baart de la Faille, L’Oeuvre de Vincent van Gogh, catalogue raisonné, Paris, 1928, no. 1487, vol. III, p. 147; vol. IV, pl. CLXV, illustrated (titled Vue de Jardin)

Jacob-Baart de la Faille, The Works of Vincent van Gogh, His Paintings and Drawings, Amsterdam and London, 1970, no. 1487, p. 519, illustrated (titled The Park and dated September 1888)

Charles W. Millard, “A Chronology for Van Gogh’s Drawings of 1888,” Master Drawings, vol. XII, no. 2, 1974, pp. 161 and 165 note 64

Jan Hulsker, “The Intriguing Drawings of Arles,” Vincent, Bulletin of the Rijksmuseum Vincent van Gogh, vol. 3, no. 4, 1974, no. F 1487, pp. 28 and 30 (titled The Park)

Jan Hulsker, The Complete van Gogh, Paintings, Drawings, Sketches, New York, 1980, no. 1410, p. 320, illustrated (dated April-May 1888)

Walter Feilchenfeldt, Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cassirer, Berlin, The Reception of van Gogh in Germany from 19021913, Amsterdam, 1988, no. F 1487, p. 135 (titled The Park)

J.F. Heijbroek and E.L. Wouthuysen, Kunst, kennis en commercie. De kunsthandelaar J.H. de Bois (1878-1946), Amsterdam and Antwerp, 1993, p. 205

Liesbeth Heenk, Vincent van Gogh’s Drawings,. An Analysis of their Production and Uses, Dissertation, University of London, 1996, p. 178

Jan Hulsker, The New Complete Van Gogh, Paintings, Drawings, Sketches, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 1996, no. 1410, p. 320, illustrated

Exh. Cat., Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum and New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Vincent van Gogh: The Drawings, 2005, p. 149

Marije Velekoop and Roelie Zwikker, Vincent van Gogh Drawings, Volume 4, Arles, Saint-Rémy & Auvers-sur-Oise, 1888-1890, London, 2007, fig. 331C, p. 90, illustrated

Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten and Nienke Bakker, ed., Vincent van Gogh, The Letters, The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition, vol. 4, London, 2009, letter no. 602, p. 73, illustrated

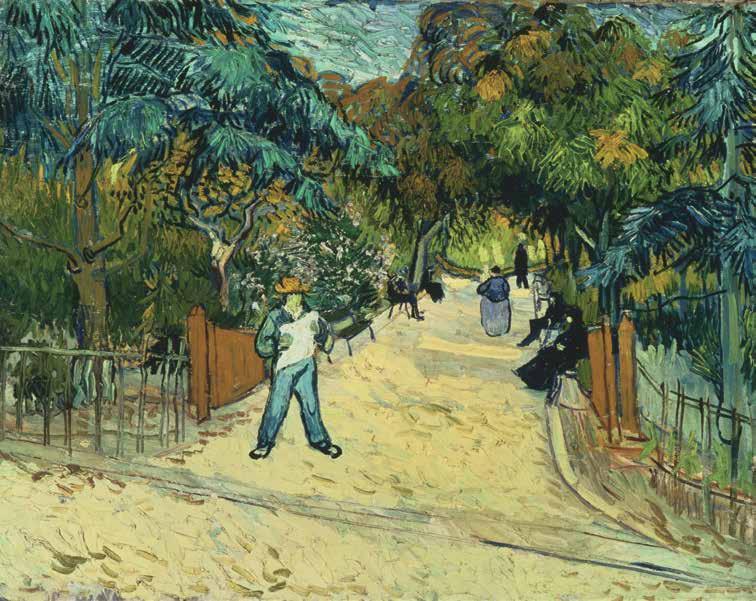

Dating to late April 1888, Jardin public avec bancs à la Place Lamartine is one of the first drawings depicting the public gardens near Place Lamartine in Arles which van Gogh executed following his move to the luminous Provençal city two months prior.

Moving to Arles from Paris in February 1888 in search of color—which was quickly becoming the main instrument of creative expression for the artist—van Gogh would spend approximately fifteen months there. This period in his oeuvre is universally recognized, as Roland Pickvance aptly notes, as “the zenith, the climax, the greatest flowering of van Gogh’s decade of artistic activity” (Exh. Cat., New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Van Gogh in Arles, 1984, p. 11).

It was also a place where van Gogh envisioned the creation of what he called “The Studio of the South,” an artistic commune where he and fellow

artists—among them, his kindred spirit Paul Gauguin—could live and work together. The famous Yellow House, where van Gogh would rent four rooms in from May 1888, and which for the artist acted as a personification of that dream, was located in Place Lamartine and adjacent to the public gardens that the present work depicts. Jardin public avec bancs à la Place Lamartine is as such directly linked to the location which held incredible significance for the artist during this period.

It was in Arles that drawing once again—since van Gogh’s early career as an artist in the native Netherlands—became an important part of his creative practice and routine. In part, this was due to the new, inspiring surroundings—whether Arles itself, the surrounding Montmajour Abbey, the La Crau plain, or the nearby Mediterranean seaside—which encouraged the artist to capture his impressions

Opposite:

with amplified immediacy. In one of the letters to his brother Theo from May 1888, he exclaimed:

“I have to draw a lot… things here have so much style. And I want to arrive at a more deliberate and exaggerated way of drawing” (Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, 29 or 30 May 1888, letter no. 617)

Van Gogh’s turn to drawing was likewise driven by his fascination with Japanese prints, an interest he had an opportunity to fully engross himself in during his recent sojourn in Paris. In another letter to his brother dated 9 April—closely preceding the creation of the present work—the artist remarked that he “… must do a tremendous lot of drawing, because I want to make some drawings in the manner of Japanese prints” (quoted in Exh. Cat., New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Van Gogh in Arles, 1984,

p. 54). Yet, the same letter contains a more practical reason for van Gogh taking up drawing that year. His brother Theo, who supported the artist financially, was experiencing commercial difficulties; focusing on drawing, due to its less costly nature, would allow van Gogh to alleviate his brother’s expenses.

Van Gogh’s drawings executed in Arles are widely considered among the artist’s true masterpieces, marked by brilliant spontaneity, freshness and confidence of execution. In no small part, this is due to the fact that during this period van Gogh once again turned to drawing with reed pen, a method he had briefly attempted while working in the Netherlands in the early 1870s. While the Dutch reed quickly proved unsuitable for drawing purposes, the Midigrown reed was superlative in quality, and van Gogh

began experimenting with it with great vigor and determination soon after his arrival.

With its brilliant variety of size, shape and intensity of strokes on display, the present work highlights how the use of reed pen—here combined with subtle pencil lines which the artist employed in the first instance to delineate some of the compositional elements— allowed van Gogh to achieve a new level of expressivity in his draftsmanship. As Colta Ives notes on this:

“Only after switching from quill pen to reed in Provence did he successfully inject into his designs the purposely rough, unstudied quality that became the primary source of their power, transforming otherwise static scenes into charged fields. Respecting the quirkiness of each mark and giving it room to be recognized, he came to appreciate and finally achieve that balance between blank paper and black lines that characterizes the superlative reed-pen drawings of his

fellow countryman Rembrandt” (Exh. Cat., Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum and New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Vincent van Gogh: The Drawings, 2005, p. 11).

In its subject matter, Jardin public avec bancs à la Place Lamartine is closely related to several important oils executed during the same period and held in major museum collections: L’Entrée des jardins publics à Arles (The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.), Soleil du midi (The Poet’s Garden) (The Art Institute of Chicago) and Voie du jardin public d’Arles (Kröller-Muller Museum, Otterlo) (see figs. 1, 4 and 5).

Writing about the public gardens near the Place Lamartine and the interest they held for van Gogh, Judy Sund remarks that “Unlike many of his artist contemporaries—Claude Monet being the most notable example—van Gogh was never able to paint in a garden of his own making. But over the course of several

Above: Fig. 4 Vincent van Gogh, Allée dans un jardin public à Arles, September 1888, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Opposite: Fig. 5 Vincent van Gogh, Le Jardin du Poète, 1888, The Art Institute of Chicago

“I have to draw a lot […] things here have so much style. And I want to arrive at a more deliberate and exaggerated way of drawing.”

—

LETTER FROM VINCENT VAN GOGH TO THEO VAN GOGH, 30 MAY 1888 (LETTER NO. 617)

months in Arles, he took vicarious possession of the gardens across the street, imbuing each section with personal associations and enthusiasms that, in turn, infused the images he made there” (Exh. Cat., London, National Gallery, Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, 2024, p. 46).

Beyond the idea of “The Studio of the South,” which van Gogh hoped Arles and the Yellow House would come to embody, the concept of “a poet’s garden”, that is, garden as a space of poetic imagination, preoccupied van Gogh deeply during this period. It was inspired in part by his reading of Francis Petrarch and Giovanni Boccaccio, two Italian Renaissance poets who made gardens a central theme of their creative vision.

At the same time, van Gogh had in mind his close friend Gauguin, whom he was expecting to receive in Arles shortly and whom he considered a poet, a master of imagination-driven painting (see fig. 3).

Most of the oils depicting the public gardens were intended for the room in the Yellow House which hoped Gauguin would occupy upon his arrival in Provence (see fig. 2). The importance of Jardin public avec bancs à la Place Lamartine—a superbly executed drawing that has formed part of Cindy and Jay Pritzker’s distinguished collection for forty-six years— is as such further amplified by it being one of the first works depicting a space that proved crucial for ’s imagination during a critical stage in his career.

Above left

LE PARC ET L’ÉTANG

DEVANT LA MAISON JAUNE

pencil, pen and reed pen and ink on paper

12 ¾ by 20 in.

32 by 50.1 cm.

1888 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Above right

PARC À ARLES AVEC UN COIN

DE LA MAISON JAUNE

reed pen and ink and pencil on paper

13 ¾ by 10 ¼ in.

35 by 25.9 cm.

1888 Private Collection

Right

PARC AVEC ARBUSTE

pencil, reed pen and pen and ink on paper

10.0 by 13 ⅝ in.

25.8 by 34.6 cm.

1888 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

The present work was part of a group of drawings sent by Vincent van Gogh to his brother Theo on the first day of May in 1888. The Van Gogh Museum has identified this work, alongside three others (F1476, F1513 and F1421) as all likely accompanying this letter and illustrating Vincent’s new home.

reed pen and ink and pencil on paper

10 ⅛ by 13 ¾ in.

25.8 by 34.8 cm.

“I’ve just sent you a roll of small pen drawings... among them you’ll find a hasty croquis on yellow paper, a lawn in the public garden at the entrance to the town. And in the background a house more or less like this one. A, well—today I rented the right hand wing of this building.... It’s painted yellow outside, whitewashed inside—in the full sunshine.... I hope I’ve been lucky this time—you understand, yellow outside, white inside, right out in the sun, at last I’ll see my canvases in a really bright interior. The floor’s made of red bricks. And outside, the public garden, of which you’ll find two more drawings.”

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, 1 May 1888, letter no. 602

1865 - 1925

Femme couchée dormant (Le Sommeil)

signed F. Vallotton and dated 99 (lower left) peinture à la colle on paper laid down on board mounted on cradled panel

22 by 30 ⅛ in. 55.8 by 76.5 cm. Executed in 1899.

$ 1,800,000-2,500,000

PROVENANCE

Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris

Paul Rosenberg, Paris (acquired from the above in 1900)

Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 21 May 1909, lot 43 (consigned by the above)

Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris (acquired at the above sale)

Pierre Goujon, Paris (acquired by 1914)

Lily Goujon-Reinach, Paris (acquired by descent from the above)

Private Collection, Paris (acquired by descent from the above) Wildenstein & Co. Inc., New York (acquired from the above in 1985)

Acquired from the above on 3 April 1986 by the present owner

EXHIBITED

Paris, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Oeuvres de Bonnard, Maurice Denis, Ibels, Aristide Maillol, Hermann Paul, Ranson, Roussel, Sérusier, Vallotton, Vuillard, 1900, no. 7 (titled Sommeil )

New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery; Houston, Museum of Fine Arts; Indianapolis Museum of Art; Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum and Lausanne, Musée cantonal des BeauxArts, Félix Vallotton: A Retrospective, 1991-93, no. 19, p. 24, illustrated in color; pp. 113 and 297 (catalogued as oil on board) (New Haven); no. 19, p. 24, illustrated in color; pp. 113 and 313 (Lausanne)

LITERATURE

Livre de Raison, no. 411

Thadée Natanson, “Félix Vallotton, peintre,” L’Art décoratif. Revue internationale d’art industriel et de décoration, vol. II, issue 19, October 1899-March 1900, p. 5, illustrated (titled Dormant)

André Fontainas, “Art moderne,” Mercure de France, vol. 34, May 1900, p. 544

Julius Meier-Graefe, “Félix Vallotton,” Dekorative Kunst. Illustrierte Zeitschrift für angewandte Kunst, vol. VI, issue 7, 1900, p. 293, illustrated (titled Im Schlaf )

Mir Iskousstva, Le Monde artiste, Saint Petersburg, nos. 2-3, 1901, p. 64, illustrated

Hedy Hahnloser-Bühler, Félix Vallotton et ses amis, Paris, 1936, no. 411, p. 284

Exh. Cat., Kunsthaus Zürich, Félix Vallotton, Werkverzeichnis 1865-1925, 1938, no. 411, p. 49

Günter Busch, Bernard Dorival, Patrick Grainville and Doris Jakubec, Vallotton, Lausanne, 1985, pl. 97, p. 101, illustrated; p. 234 (as oil on canvas)

Marina Ducrey, Félix Vallotton, His Life, His Technique, His Paintings, Lausanne, 1989, p. 82; p. 83, illustrated in color

Exh. Cat., Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts and Marseille, Musée Cantini, Le très singulier Vallotton, 2001, p. 58 (note 29)

Marina Ducrey and Katia Poletti, Félix Vallotton, 18651925, L’Oeuvre peint, Lausanne, 2005, no. 283, vol. I, p. 252, illustrated in color; pp. 251 and 273; vol. II, p. 173, illustrated in color

On flap: Félix and Gabrielle Vallotton in Lausanne, May 1899

Félix Vallotton’s tightly composed painting of a slumbering woman is among his most vivid and accomplished interior scenes. Choosing to show only the model’s vulnerable face emerging from the swathe of patterns that envelop her, he creates an image that is at once serene and suffocating—the textiles becoming a dominating force that verges on the overwhelming, while the dark, weighty furniture reinforces both the heaviness of sleep and a sense of domestic confinement. Painted in 1899, Femme couchée dormant (Le Sommeil) is almost certainly a portrait of Vallotton’s new bride Gabrielle RodriguesHenriques (née Bernheim). The couple married in May of that year, triggering a complete change in the artist’s way of life and a significant shift in his practice. Gabrielle was a wealthy widow and the daughter of the successful art dealer Alexandre Bernheim—one of the most important promoters of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art in Paris. “I have known her for four years,” Vallotton wrote to his brother, “she is surely a good woman with whom I will get along easily. She has three children, the oldest is fifteen, the youngest seven, thus they are grown, they like me and I will love them. We expect to live together without changing our habits or almost,

me at my work, she in her interior, it will be very reasonable” (quoted in Exh. Cat., New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Vallotton, 1991, p. 271). Marriage brought Vallotton a combination of personal stability and companionship, along with a marked elevation in social status and valuable professional connections. In many respects, it was a happy and strategic union, though not without its underlying strains. In this bourgeois alliance—where wealth and standing seemed as significant as love and affection (see figs. 1 and 3)—Vallotton embraced the very elements he had previously critiqued: women, marriage, society and money, all subjects he had satirized in his celebrated print series Intimités, published just a year before his wedding. The union ended his long friendship with the anarchist artist Charles Maurin, who felt Vallotton had conformed to bourgeois norms, while his fellow Nabis painter Édouard Vuillard remarked on the change with the comment, “There seems to have been a revolution” (quoted in ibid., p. 34). By joining his life with Gabrielle’s, Vallotton surrendered the fiercely guarded independence he had long valued, and in doing so, left behind Hélène Chatenay, the working-class seamstress who had been his mistress since 1892.

Vallotton was born in 1865 to a Protestant family in the Swiss city of Lausanne. He left for Paris aged sixteen, where he enrolled at the Académie Julian and showed a remarkable facility for portraiture. In 1885 his work was exhibited publicly for the first time, when two of his paintings were accepted into the Salon. Yet such progress wasn’t enough to ease the financial strains that he faced, and he turned to illustration, writing and art restoration to make ends meet. By the late 1890s, Vallotton was renowned as the principal illustrator for Le revue blanche, the leading cultural journal in Paris, known for his sharply observant woodcuts that were praised for their bold black-andwhite contrasts, flattened silhouettes, and biting social commentary. After marrying, Vallotton could afford to all but give up his print work. He was now able to devote himself to his first love, painting, and his new

lifestyle opened up a rich vein of subject matter in the subtle intimacies of domestic life, with Gabrielle serving as his favorite model.

Not least among the changes in Vallotton’s life was his departure from the bohemian Latin Quarter, where he had lived since arriving in Paris. In June 1899, he secured an apartment at 6 rue de Milan, in the heart of the 9th arrondissement—a fashionable new district close to the Saint-Lazare train station filled with middle-class households and new apartments. Here, Vallotton inhabited the very world he so often critiqued in his art, where outward respectability and so often masked private chaos (see fig. 2). It was the same world that playwright Georges Feydeau skewered in his 1886 farce Tailleur pour dames (Ladies’ Dressmaker), where the 9th-district setting served as shorthand for the bourgeois society

he lampooned. Yet amid the ironies that defined Vallotton’s life, his paintings of Gabrielle and their home from this period convey a subdued sense of warmth, domestic ease, and personal contentment. Even Gertrude Stein noted that he was “very happy with his wife and she was a very charming woman” (Gertrude Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, New York, 1933, p. 61).

The family lodgings, on the fifth floor of the Rue de Milan building, included a studio under the roof for Vallotton to work. Yet Femme couchée dormant is not set in Gabrielle’s spacious bedroom, familiar from paintings such as Femme se coiffant, 1900 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris), nor in his studio. Vallotton’s biographer, Marina Ducrey, has suggested that the somewhat masculine furnishings indicate the scene may be set in the artist’s own bedroom. The same wallpaper and wooden bed with its red-andgold cover reappear in Nu de dos dans un interieur of 1902 (Kunsthalle Bremen), where the figure of a half-dressed woman seen from behind anticipates Vallotton’s later preoccupation with sculptural nudes in interior settings. These subjects, however, ran in parallel to his treatment of Gabrielle, whose modesty he always preserved. She was frequently portrayed against the backdrop of their home, whether playing the piano, at her toilette, arranging the linen cupboard, or interacting with her children—she is the guardian of the hearth, central to the home they dwell in. However, in such works, Vallotton did not attempt literal portraits: her stylized features and silhouette evoke less a likeness than an atmosphere, a distilled sense of the feminine woven into the rhythms of everyday life.

The poetics of domestic space and the sphere of women were a common theme within the Nabis artistic circle, where familiar interiors became stages for both symbolic meaning and aesthetic experimentation. However, unlike Pierre Bonnard or Édouard Vuillard, who reveled in patterned surfaces and chromatic harmonies, Vallotton tended to keep

his forms pared back, his palettes restricted, and his compositions taut (see figs. 4 and 5). This austerity has often been interpreted as a moral stance, or a reflection of Vallotton’s detached, outsider persona: his images were not ornamental frills but sober statements, their impact heightened by an economy of means. In this regard, the deliberate clash of patterns of Femme couchée dormant may be seen as more than a record of bourgeois taste. It draws Vallotton into the current of late nineteenth-century anxieties about decoration itself. At the fin de siècle, ornament was charged with meanings that went far beyond style. In Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s novel

The Yellow Wallpaper (1892), tangled motifs became both prison and torment, their proliferating forms a metaphor for female entrapment within the bourgeois home. By the early 1900s, Adolf Loos would condemn such embellishment as a sign of cultural decline, insisting that true progress lay in the elimination of ornament altogether. Between these poles, artists found in decoration a language for the unseen.

Gauguin’s arabesques and color harmonies became emblems of the spiritual; Vuillard dissolved figures into wallpaper and fabric to evoke the psychic pressure of domestic life; while the florid curlicues of the Art Nouveau movement sought a return to nature during an era of rapid industrialization and political unrest. Vallotton’s interiors, by contrast, thrum with a quieter but no less unsettling tension: the designs he painted so meticulously in this work seem at once to stabilize and to smother.

The charged interplay between exuberant patterning and methodical execution in Femme couchée dormant may also be due to Vallotton’s use of peinture à la colle (distemper), a medium favored by the Nabis for its saturated, matte tones. Applied quickly while heated, it can yield either a fresco-like crusted surface or, when used thinly as here, an open, swiftly brushed effect. Forms, textures and light effects have all been deliberately simplified, echoing the strong graphic sensibility of Vallotton’s woodcuts and the Japanese prints that influenced them. However,

“I love her very much, which is the main reason for this marriage, and she loves me back; we know each other thoroughly, and each have full confidence in the other.”

— FÉLIX VALLOTTON WRITING ABOUT GABRIELLE VALLOTTON, SPRING 1899

we also see a reintroduction of spatial perspective and a heightened realism compared to the paintings executed before his marriage, suggesting Vallotton was forging a new direction that harmonized his academic grounding with the innovative approaches of his contemporaries. Vallotton himself did not see originality—so often ascribed to his woodcuts by his peers—as an essential part of the artistic process. As he wrote in 1905, in a contribution to the Mercure de France on recent artistic trends: “I don’t believe that art ever takes new directions, its goals are perpetual, immutable, and have been so forever” (quoted in

Exh. Cat., New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Vallotton, 1991, p. 33). Always determined to follow his path, Vallotton moved through the volatile cultural, social and political landscape of fin-de-siècle France with singular independence (see figs. 6 and 7). He inhabited many worlds, yet his art pursued its own steadfast, uncompromising course, indifferent to the currents swirling around him.

Acquired from Wildenstein & Co. in 1986, Femme couchée dormant has remained in The Cindy and Jay Pritzker Collection for nearly forty years and comes to auction for the first time since 1909.

BY EVGENIA KUZMINA

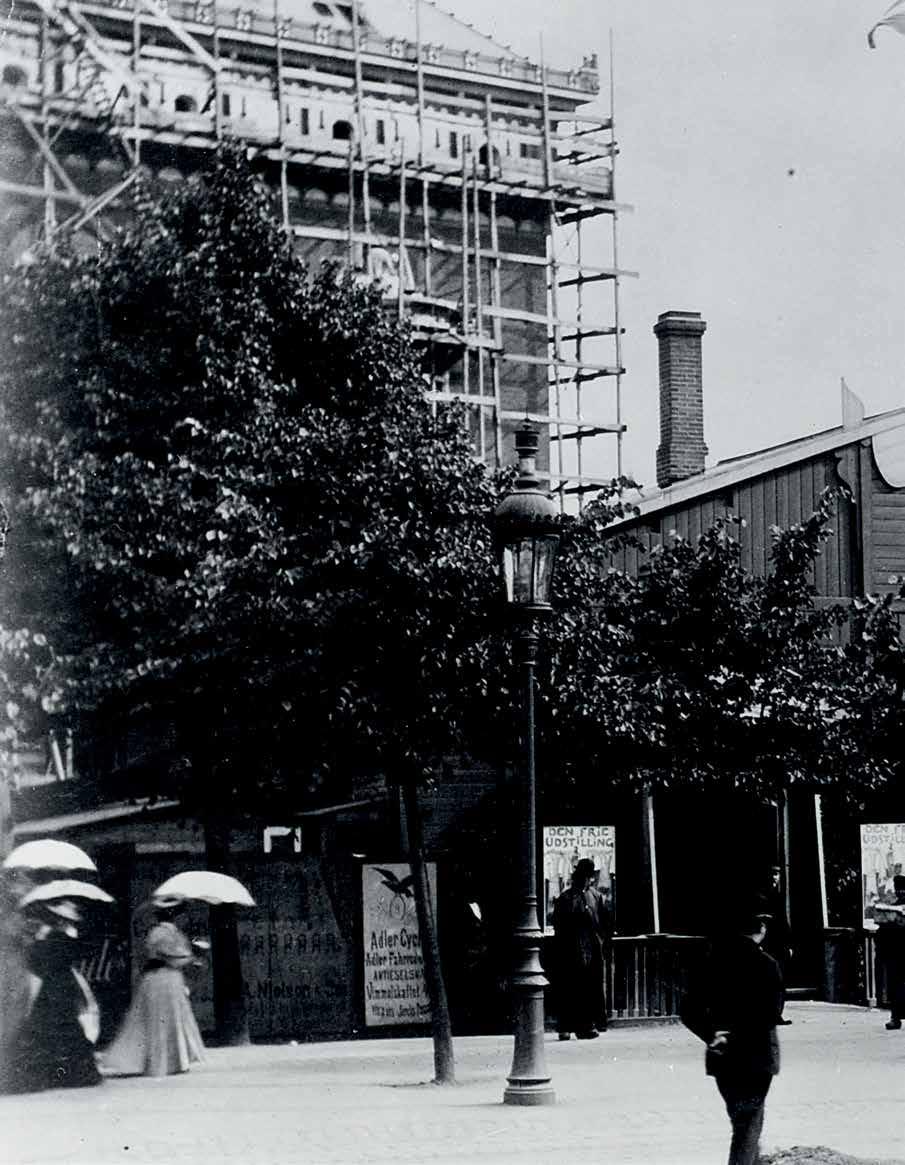

Shown for the first time at Gauguin’s major retrospective in Copenhagen in 1893, La Maison du Pen du, gardeuse de vache from 1889, depicting the isolated house known as Pen-Du (or “black slope” in Breton), failed to find a buyer. Theodor Thorup described it as follows in his review of the exhibition: “What a marvelous atmosphere reigns in this Breton coastal landscape, with its white-painted house on its green lawn. And such a painting sells for 300 Danish kroner! One does not notice that there is great artistic sense in Copenhagen until this painting is sold.”1 The painting subsequently came into the possession of Heinrich Thannhauser’s gallery in Munich, who sold it in 1916 to Otto Nyquist, a Danish soldier and writer, editor-in-chief of the magazine Norsk militært tidsskrift. Exported to the United States in 1930, it found its way into several American private collections, including that of Charlse J. and Aline Liebman, before entering the collection of the German-born composer Werner Josten and his wife Margaret in 1955, who loaned it for the last time to the Gauguin retrospective exhibition at the Cincinnati Museum in 1971. Since then, this work has never been shown to the public.

¹ Cf. Th. Th. [Theodor Thorup], “Den frie Udstilling: Paul Gauguin,” Aarhus Amtstidende 27, no. 100 (May 1, 1893), p. 1.

The use of a vibrant palette bathes the canvas in a warm light. Harmony is achieved through the juxtaposition of primary colors that express a strong emotional and decorative surge. Far from conventional laws of perspective, the composition is constructed from the juxtapositions of geometric planes which create an offset perspective. Thus, we can see that there is no center to the composition and that the vanishing line seems to shift to the right. In the foreground the peasant woman, whose face dissolves into abstraction, as well as the orange haystack form a vertical axis that is paralleled by the silhouette of the cow on the left. A diagonal line can be traced between the cow and the house, creating a complex interplay between different geometric planes.

Gauguin had previously incorporated the cow motif with angled foreshortening in several of his other works, reminiscent of Japanese prints (see fig. 2). In La Maison du Pen du, one is particularly reminded of the drawing Bretonnes et vaches, held in the collection of the Albertina Museum (see fig. 1). The cow’s protruding bone structure, seen from the side, is recognizable in other works by Gauguin, such as Bord de l’eau, veau et vache (DW 2092), Gardeuse de vaches sur la plage de Bellangenet from 1886 (DW 234), Cours d’eau sous les arbres, Martinique from 1887 (DW246), or La Vache rouge from 1889 (PG588L3).

La Maison du Pen du is a pivotal work in Gauguin’s Breton period. The simplification of forms, disjointed perspectives, and fragmentation of faces are strikingly modern and herald the avant-garde artistic movements that would dominate the art world in the twentieth century. It is no coincidence that artists such as Pablo Picasso and Wassily Kandinsky gave Paul Gauguin a prominent place as a precursor in their manifestos.

La Maison du Pen Du is one of the first depictions of this modest building, which many painters from the Pont-Aven school helped to make famous4. In his letter to Vincent van Gogh on October 20, 1889, the artist wrote: “[...] What I have done most of this

year, are simple peasant children, walking indifferently along the seashore with their cows. But since I do not like the trompe l’oeil of the open air or of anything else, I try to put into these desolate figures the savagery that I see in them and that is also in me. [...]”5

Paul Sérusier painted this building twice: once from a spot slightly closer to the edge of the cliff than Gauguin’s6; Charles Filiger depicted it many times in his compositions from 1890.7 Gauguin returned to this motif, using it in the background of La Petite Gardeuse de vaches (PGJ0NB) and painting it from a different angle in 1890, in another Maison du Pen-Du (PG80SZ; see fig 3). The rocks to the left of the house form the motif of La Moisson au bord de la mer (PG9MHR) from 1890 and are also repeated in the background of La Perte du pucerage (PGZ6NC).

² DW refers to n. of cat. Gauguin: premier itinéraire d’un sauvage : catalogue de l’oeuvre peint, 1873-1888, Milano : Skira ; Paris : Wildenstein Institute, 2001

³ No. PG fait refers to the numbering in Gauguin: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings, 1889–1903. Edited and compiled by the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, Inc.

4 It should be noted that these artists, who were later grouped together under the label of Pont-Aven, were captivated by the rural and maritime landscapes of this region, often using the local people going about their daily business as models. Cf. Wladyslawa Jaworska, Paul Gauguin et l’école de Pont-Aven (Neuchâtel: Éditions Ides et Calendes, 1971)

5 Douglas Cooper, ed., Paul Gauguin: 45 Lettres à Vincent, Théo et Jo van Gogh; Collection Rijksmuseum Vincent van Gogh, Amsterdam (The Hague: Staatsuitgeverij; Lausanne: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 1983), pp. 273, 275

6 Marcel Guicheteau, Paule-Henriette Boutaric, and Georgette Guicheteau, Paul Sérusier (Paris: Éditions Side; Cergy-Pontoise: Graphédis éditeur, 1976); no. 21, p. 200.

7 Filiger: dessins, gouaches, aquarelles, exh. cat. (Saint-Germain-en-Laye: Musée départemental du Prieuré, 1971), p. 45.

1848 - 1903

La Maison du Pen du, gardeuse de vache

signed P. Gauguin and dated 89 (lower right) oil on canvas

24 by 29 ¼ in. 61.1 by 74.2 cm.

Executed in summer 1889.

$ 6,000,000-8,000,000

PROVENANCE

Mette Gauguin, Copenhagen (on consignment from the artist circa 1893)

Moderne Galerie Heinrich Thannhauser, Munich (acquired by 1916)

Otto Nyquist, Oslo (acquired from above through A.S. Mohr & Sønner, Bergen, Norway on 29 July 1916)

Charles J. and Aline Liebman, New York (acquired by 1930)

Parke-Bernet Galleries, Inc., New York, 7 December 1955, lot 63 (consigned by the above)

Werner and Margaret Josten, New York (acquired at the above sale and until at least 1971)

Peter W. Josten, New York (acquired by descent from the above and until at least 1984)

Richard L. Feigen & Co., New York

Acquired from the above on 22 October 1997 by the present owner

EXHIBITED

Copenhagen, Vesterbors Passage, Den Frie Udstilling, 1893, no. 149 (titled Kystlandskab. Bretagne)

New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Summer Exhibition: Painting and Sculpture: Retrospective, 1930, no. 37, p. 5 (titled Breton Landscape)

New York, Wildenstein, Paul Gauguin, 1946, no. 5, p. 19, illustrated; p. 63 (titled Landscape, Brittany and dated 1889)

New York, Wildenstein, Gauguin, 1956, no. 16, p. 16; p. 36, illustrated (titled Landscape, Brittany)

Paris, Galerie Charpentier, Cent oeuvres de Gauguin, 1960, no. 52, n.p., illustrated (titled Paysage du Pouldu) Munich, Haus der Kunst, Paul Gauguin, 1960, no. 40, p. 9; p. 25, illustrated (titled Landschaft bei Le Pouldu) Vienna, Österreichische Galerie im Oberen Belvedere, Paul Gauguin, 1848-1903, 1960, no. 19, p. 37; pl. 5, illustrated (titled Landschaft bei le Pouldu)

New York, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Gauguin and the Decorative Style, 1966 (titled Landscape, Brittany: The Lone House)

Cincinnati Art Museum, The Early Work of Paul Gauguin: Genesis of An Artist, 1971, no. 22, p. 12; p. 27, illustrated (titled The Lone House (La Maison Isolée))

LITERATURE

Theodor Thorup, “Den frie Udstilling: Paul Gauguin,” Aarhus Amtstidende, vol. 27, no. 100, 1 May 1893, p. 1

Katalog der Modernen Galerie Heinrich Thannhauser, München, Munich, 1916, pp. XXIX and XXVIII, pl. 33, illustrated (titled Bretonische Landschaft)

Pola Gauguin, My Father Paul Gauguin, 1937, New York, p. 129, illustrated (titled Landscape)

The Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Summer 1951, p. 32

René Huyghe, Le Carnet de Paul Gauguin, vol. II, Paris, 1952, pp. 168-69

John Rewald, Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin, New York, 1956, p. 285, illustrated (titled Landscape at Le Pouldu)

Raymond Nacenta, Gauguin, Paris, 1960, n.p., illustrated (titled Paysage du Pouldu)

Claude Roger-Marx, “Des chefs-d’oeuvre de Gauguin sortent des collections particulières,” Le Figaro littéraire, 23 January 1960, p. 14, illustrated (titled Paysage)

Georges Boudaille, Gauguin, Paris, 1964, p. 113, illustrated in color (titled The Lonely House)

Georges Wildenstein, Gauguin, Paris, 1964, no. 364, p. 139, illustrated (titled La Maison isolée)

Gérard Legrand, Gauguin, Paris, 1966, p. 16; p. 19, illustrated in color (titled La Maison isolée)

Wayne Andersen, “Gauguin’s Motifs from Le Pouldu: Preliminary Report,” Burlington Magazine, vol. 112, no. 810, September 1970, fig. 65, p. 616, illustrated (titled La Maison isolée)

Wladyslawa Jaworska, Paul Gauguin et l’école de PontAven, Neuchâtel, 1971, p. 235, illustrated in color (titled Paysage breton, la maison isolée)

G. M. Sugana, L’Opera completa di Gauguin, Milan, 1972, no. 179, p. 98; p. 97, illustrated (titled Pastora e mucca in riva al mare (La casa isolata))

Lee van Dowski, Die Wahrheit über Gauguin, Darmstadt, 1973, no. 170c, p. 263 (titled La Maison isolée)

Vojtěch Jirat-Wasiutyński, Gauguin in the Context of Symbolism, Dissertation, Princeton University, 1975, vol. 1, p. 185 (titled La Maison Isolée)

Pierre Leprohon, Paul Gauguin, Paris, 1975, pp. 168 and 381 (titled La Maison isolée and dated summer 1890)

Ziva Amishai-Maisels, “A Gauguin Sketchbook: Arles and Brittany,” Israel Museum News, no. 10, April 1975, pp. 71 and 75 (note 18; titled Isolated House)

Elda Fezzi, Gauguin: The Complete Paintings, vol. I, London, 1979, no. 350, p. 88, illustrated (titled Shepherdess and Cow by the Sea)

Douglas Cooper, ed., Paul Gauguin: 45 Lettres à Vincent, Théo et Jo van Gogh, Amsterdam, 1983, pp. 273 and 275 (note 5)

Exh. Cat., Charlottenlund, Ordrupgaard, Gauguin og Van Gogh i København i 1893, 1984, no. 37, p. 84, illustrated (titled Kystlandskab. Le Pouldu. Landscape at Le Pouldu)

La Route des Peintres en Cornouaille: 1850–1950, Quimper, 1990, p. 98 (titled Maison du Pan du)

Belinda Thomson, ed., Gauguin by Himself, Boston, 1993, pl. 122, p. 158, illustrated in color (titled Landscape at Le Pouldu / Isolated House)

Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent van Gogh: The Letters, vol. V, London, 2009, no. 828, p. 163

Stefan Koldehoff and Chris Stolwijk, eds., The Thannhauser Gallery: Marketing Van Gogh, Brussels, 2017, pp. 46 and 124 (titled Landschaft mit Kühen)

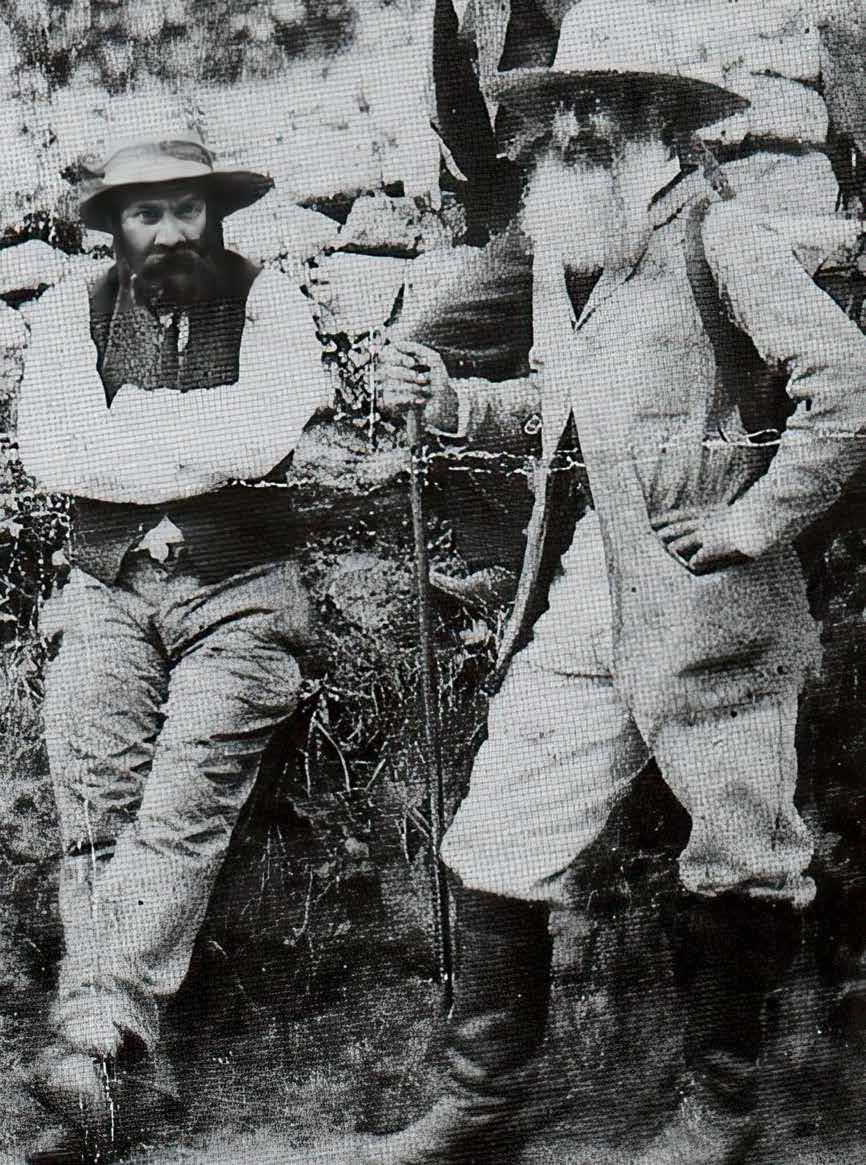

La Maison de Pen du, gardeuse de vache, painted in summer of 1889, is an evocative example of Paul Gauguin’s Pont-Aven style. Painted in Le Pouldu, a village situated several miles east of the busier town of Pont-Aven, the present work captures the bucolic landscape and seascape of this remote part of Brittany. The late 1880s and early 1890s were the most crucial and fruitful of Gauguin’s career. Through several stays in Brittany, time in Paris, a trip to Martinique and his famed collaboration with Vincent van Gogh in Arles, Gauguin’s artistic practice and signature style and imagery developed into one of the most recognizable in modern art. It is from this period that La Maison de Pen du, gardeuse de vache springs, a canvas which synthesizes the impact of the tropical colors of Martinique, van Gogh’s florid brushwork and the impact of Japanese prints (see figs. 1 and 2).

As early as the 1860s, Brittany had served as an inspiration for many artists who were drawn to the verdant landscape and traditional customs. In apposition to the Impressionists, who sought to depict the encroaching change of the industrial revolution on the cities, suburbs and countryside of France, the artists who flocked to Brittany were in search of a more traditional agrarian society, undisturbed by the rapid acceleration of modern life. Gauguin’s aims were similar in his first trip to the region. Writing to his friend Emile Schuffenecker he stated “I love Brittany which I find savage and primitive. When my clogs ring on the granite ground I hear the dull and powerful sound that I am looking for in painting” (quoted in Victor Merles, ed., Correspondence de Paul Gauguin, Paris, 1984, letter 141, p. 172).

The present work takes as its subject an anonymous cowherd, set against the rolling countryside towards the sea. A boat scuds across the water at far right and an abandoned house, which featured in a number of other works by Gauguin and other artists at this time, sits atop the rocky promontory. This picture combines the striking palette that typified Gauguin’s work in Martinique and a modern compositional structure that owes much to Japanese printmaking, particularly Hiroshige. This appropriation of Japanese style would prove significant in the Nabis movement to

which Gauguin’s work in Brittany gave rise. The decorative treatment of the landscape and the flattening of perspectival space illustrate Gauguin’s bold artistic vision. As Judy Le Paul explains: “Aware of the way Japanese artists constructed certain of their landscapes, Gauguin began to turn away from Western influences. The general rule of a centrally placed horizon… gave way to a horizon near the top of the canvas or even raised beyond its boundaries. Using a steep perspective, Gauguin narrowed the field of vision, consciously cutting up the landscape to concentrate on one detail or fragment at the

“The eight paintings by Gauguin stretch with still more emphatic variations from two Breton landscapes, fresh and moving in color, to Adolph Lewisohn’s “Ia Orana-Maria,” in which one may find for the looking something of the nature of his “escape” from civilization, an escape made with all the essentials of sophistication packed in with the rest of his spiritual and intellectual luggage. Artistically if not esthetically he makes here an impressive figure, his color is sumptuous on the walls of this most initiated of museums, his design is arresting without introducing the element of deformation. His “Ia Orana-Maria” is our Ave Maria….” — ELIZABETH LUTHER CARY, REVIEWING SUMMER EXHIBITION: PAINTING AND SCULPTURE: RETROSPECTIVE AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART , NEW YORK IN THE NEW YORK TIMES , 29 JUNE 1930, P. 107

expense of another” (Judy Le Paul, Gauguin and the Impressionists at Pont-Aven, New York, 1987, p. 80). In the present work Gauguin employs this technique to masterful effect building a dynamic landscape that is full of local incident and detail.

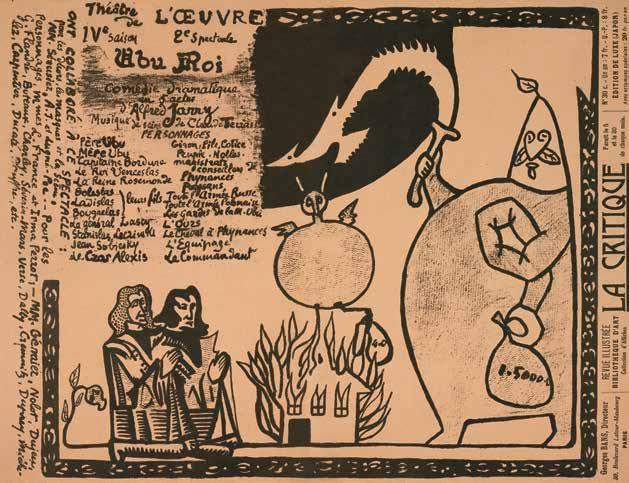

La Maison de Pen du, gardeuse de vache has a distinguished early exhibition history. It was included in the famed 1893 Den Frie Udstilling (The Free Exhibition), where Vincent van Gogh’s work was also exhibited. This Danish artist’s association was founded just two years prior and was created in the manner of the Salon des Refusés in Paris. “What a simply wonderful atmosphere,” wrote Theodor Thorup, “there is in the coastal landscape from Brittany with the white-painted house on the green point. And a picture like this is being sold for 300 Kr.! One cannot feel that there is any great sensitivity to art in Copenhagen, seeing that it is not sold yet” (Theodor Thorup, “Den frie Udstilling: Paul Gauguin,” Aarhus Amtstidende, vol. 27, no. 100, 1 May 1893, p. 1). Nearly forty years later, the present work was one of eight Gauguin’s included in the 1930 Summer Retrospective at the new Museum of Modern Art in New York. In their review, The New York Times stated: “The eight paintings by Gauguin stretch with still more emphatic variations from two Breton landscapes, fresh and moving in color, to Adolph Lewisohn’s “Ia Orana-Maria,” in which one may find for the looking something of the nature of his “escape” from civilization, an escape made with all the essentials of sophistication packed in with the rest of his spiritual and intellectual luggage. Artistically if not esthetically he makes here an impressive figure, his color is sumptuous on the walls of this most initiated of museums, his design is arresting without introducing the element of deformation. His “Ia Orana-Maria” is our Ave Maria….” (Elizabeth Luther Cary, “What Has Been Chosen,” The New York Times, 29 June 1930, p. 107). This exhibition, held just a year after the museum opened, firmly demonstrated Gauguin’s place as one of the great doyens of modern art.