- A n Island Sanctuary like no o th er

- A n Island Sanctuary like no o th er

News

Must-see exhibitions opening in December and January.

COLLECTED WISDOM

The world’s largest private collector of Rembrandts, philanthropist and metals investor Tom Kaplan reflects on the artist’s radicalism and the creativity of the Dutch Golden Age.

By James Haldane

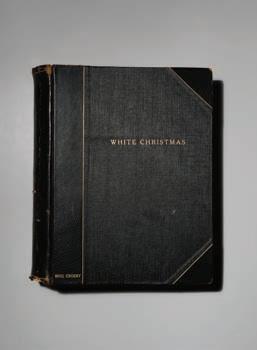

“Swinging on a Star: The Collection of Bing & Kathryn Crosby” captures a lifetime of passion, taste and festive charm. Their son Harry Crosby reflects on some of their cherished treasures before the lots go under the hammer. As told to James Haldane

For wine and spirits enthusiasts, bidding and bacchanalia go handin-hand at charity auctions that raise millions for philanthropic causes. By Jay

Cheshes

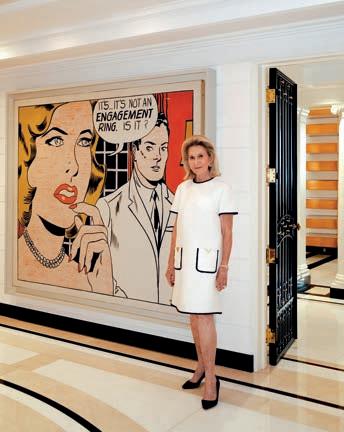

How a breakthrough Roy Lichtenstein painting ended up in the home of a woman who admired it in her youth.

By Lucas Oliver Mill

From top: A pair of JAR sapphire and diamond pendant earrings from “A Legacy of Elegance: Jewels from an Exceptional Collection,” at Sotheby’s New York on December 8; a book of musical arrangements from “White Christmas,” inscribed to Bing Crosby by composer Joseph J. Lilley; Serge Poliakoff’s “Composition abstraite,” 1959, from “Modern and Contemporary Art” at Sotheby’s Paris on December 3; Anne-Floor Wetemans wears a Brunello Cucinelli coat and Soeur gloves.

A century after its founding, the Bauhaus Dessau in Germany provides the backdrop for a story in classic tailoring—where timeless forms echo the school’s principles of function and beauty.

Photography by Jeremy Everett Styling by Virginie Benarroch

For Laurie Simmons and Carroll Dunham, work-life balance begins at home, which happens to be a country estate in Connecticut. By Sarah Medford

Photography by Stephen Kent Johnson

Investment-grade timepieces built for daily life: refined, resilient and collectible.

Photography by François Coquerel Styling by Chloe Grace Press

Set Design by Nara Lee

In an excerpt from his new book, Andrew Graham-Dixon brings fresh archival detective work to the Dutch master and rediscovers the exact doorway captured in a beloved masterpiece. By Andrew Graham-Dixon

A new wave of artists is reviving Japan’s age-old tradition, inventing fresh techniques and sophisticated forms. By Akari Endo-Gaut

Photography by Takashi Homma

Partner

The sale of the Orient

By James Haldane

Photography by Stephen Kent Johnson

From Old Masters to Hollywood heroes—and inside the home of an artist couple still reshaping the contemporary canon—we are seeing the classics anew.

This issue explores The concept of “the classic” from every angle. Art history is full of enduring motifs, and today’s collectors often prize archetypal works in the highest regard, but what does it truly mean to achieve this status? It’s certainly not about standing still— classics have to remain relevant.

On December 12, “Sotheby’s Icons: Back to Madison” will open. This exhibition at our new New York home, the Breuer—an architectural classic in its own right—will present more than 25 legendary artworks and objects that have passed through our salerooms, borrowed back from collections around the world. In one of our Specialist columns, Courtney Kremers, Head of Private Sales in the Americas and one of the forces behind the show, tells the remarkable story of one of its highlight pieces: a Warhol silkscreen of Marilyn Monroe whose mystique was enriched when, sitting in the artist’s famous Factory, it was unexpectedly pierced by a bullet.

Our cover story visits the home studios of artist couple Laurie Simmons and Carroll Dunham, two figures who’ve been on the New York scene since the 1970s, when it was redefining what art could look like. Both now in the fifth decade of their careers, they show no signs of slowing down, revealing the power of relocating their practices to a different context: their country home in Connecticut. Checking in with another New York art-scene transplant, this time in Florida, we visit the Palm Beach home of Ronnie Heyman, president emerita of MoMA’s board of trustees, and hear the story of her remarkable Lichtenstein for Collector Walls.

Moving to other art forms, we unpack the collection of true Hollywood legends

Bing and Kathryn Crosby, which will be offered at auction on December 18. Featuring memorabilia from their performing careers in film and music and works from their personal art collection, and narrated by the recollections of their son, Harry Crosby, it certainly carries the charge of nostalgia.

Sentiment for the past can, of course, inspire new creation. Our back-page story revisits the auction staged by Sotheby’s in 1977 of carriages from the decommissioned Orient Express, which sparked the service’s modern incarnation and the luxury travel company Belmond. It just so happened to be attended by another vintage movie star, Grace Kelly, who stepped aboard the Express for the journey to the Monaco train station, where the glamorous sale was staged.

Old Masters are perhaps the ultimate classics, especially for this time of year, as typified by this heart-warming work by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, part of a dynasty of five generations of painters celebrated for often revisiting the same scenes. Its rich colors inform our three editorial acts. Meanwhile, philanthropist and Old Master devotee Tom Kaplan answers our Collected Wisdom Q&A, reminding us that artists are the true engines of classic

creation, saying: “It doesn’t take a genius to buy Rembrandt, it takes a genius to be Rembrandt.” And we excerpt Andrew Graham-Dixon’s new book “Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found,” which draws on fresh archival research to offer a striking new interpretation of the Dutch Golden Age master.

On the theme of design, this issue’s Artist Portfolio was shot in Germany by photographer Jeremy Everett at the Bauhaus Dessau, a UNESCO World Heritage site, where he sets fashion’s latest looks against Walter Gropius’s rectilinear designs. And we travel to Japan with photographer Takashi Homma for a tour of four workshops where a new guard of lacquer artisans is reinterpreting an ancient technique with fresh thinking and form.

Classics, it seems, have no expiration date—they simply wait for the next generation to fall in love with them all over again.

Kristina O’Neill, Editor in Chief @kristina_oneill

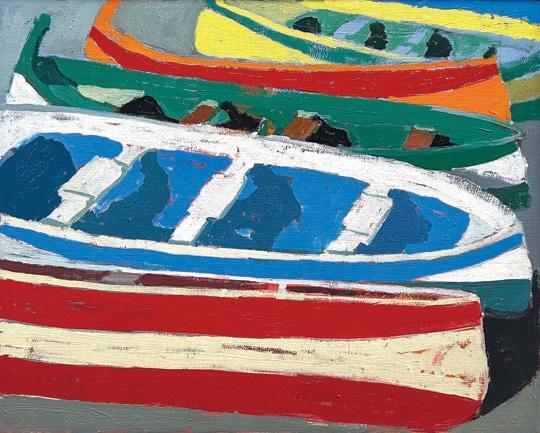

Paintings from North America, South America, Europe, Asia & Morocco

Mitchell Johnson is one of the most well-known artists working in California, in large part due to the regular appearance of his paintings in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, and The Wall Street Journal over the past fourteen years. His work has been the subject of two museum retrospectives and numerous solo exhibitions, and his paintings are included in the permanent collections of more than 35 museums.

In a 2025 WhiteHot Magazine article, the legendary art critic Donald Kuspit declared that Johnson’s paintings “are astonishing masterpieces of phenomenological perception, fraught with what the philosopher George Santayana calls ‘hushed reverberations.’”

Johnson’s paintings will be on exhibit at Galerie Mercier in Paris in March 2026.

Takashi Homma is a photographer from Tokyo. His recent books include “Tokyo Olympia” (Nieves) and “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji” (Mack). This year he presented “SONGS—The Most Important Things of Refugees,” a collaborative project with the UNHCR, at Japan’s Setouchi Triennale. The Lure of Lacquer, p88.

Editor in Chief – Kristina O’Neill

Creative Director – Magnus Berger

Editorial Director – Julie Coe

Director of Editorial Operations –Rachel Bres Mahar

Executive Editor – James Haldane

Visuals Directors – Dana Kien, Jennifer Pastore

Design Director – Henrik Zachrisson

Entertainment Director –Andrea Oliveri for Special Projects

Editorial Assistant – Max Saada

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Akari Endo-Gaut, Frank Everett, Cary Leitzes, Sarah Medford, Lucas Oliver Mill

CULTURESHOCK

Chief Executive Officer – Phil Allison

Chief Operating Officer – Patrick Kelly

Head of Creative – Tess Savina

Production Editors – Rachel Potts, Antonia Wilson, Emma Nicklin

Picture Editor – Catharine Page

Art Editor – Gabriela Matuszyk

Designers – Ieva Misiukonytė, Michael Kelly

Chief Subeditor – Mark Grassick

Subeditors – Hannah Jones, Bobby McGee, Victoria Stapley-Brown

PARTNERSHIPS

Head of Global Partnerships –Eleonore Dethier

Virginie Benarroch is a Parisbased fashion stylist and creative consultant. A former fashion editor-at-large for Vogue Paris, she contributes to magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, i-D, Vogue France and The Gentlewoman. Her commercial clients include Chanel, Gucci, Hermès, Toteme and Ralph Lauren. The Artist Portfolio, p50.

Stephen Kent Johnson is a photographer based in New York City. An editorial art director by training, he started photographing professionally 12 years ago. He shoots for designers, architects and publications including Architectural Digest, WSJ. Magazine, The World of Interiors and Wallpaper*. Breathing Space, p68.

Andrew Graham-Dixon is an art historian, biographer and broadcaster who has made numerous landmark series for the BBC. He previously served as the main art critic for The Independent and The Sunday Telegraph, and is author of “Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel” and “Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane.”

Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found, p84.

PUBLISHING

US (New York and Northeast) Fashion – Judi Sanders LGR Media Plus judi@lgrplus.com

US (New York and Northeast) Jewelry & Watches – Lisa Fields lisa.fields.consultant@sothebys.com

US (New York and Northeast) Design – Angela Okenica aokenica@gmail.com

US (Southeast and West Coast) Mark Cooper TL Cooper Media markcooper@tlcoopermedia.com

US Galleries and Museums – Ian Scott TL Cooper Media ian.scott.consultant@sothebys.com

UK and France

Charlotte Regan Cultureshock charlotte@cultureshockmedia.co.uk

Italy

Bernard Kedzierski and Paolo Cassano K. Media bernard.kedzierski@kmedianet.com paolo.cassano@kmedianet.com

Switzerland

Neil Sartori Media Interlink neil.sartori@mediainterlink.com

France

Guglielmo Bava

Kapture Media gpb@kapture-media.com

India and GCC Region Marzban Patel Mediascope marzban.patel@mediascope.co.in

SOTHEBY’S

Chief Executive Officer – Charles F. Stewart

Chief Marketing Officer – Gareth Jones

General Inquiries

sothebysmagazine@sothebys.com

Please note that all lots are being offered for sale subject to Sotheby’s Conditions of Business for Buyers (which include our Authenticity Guarantee), which can be found on the relevant sale page on www.sothebys.com. Sotheby’s, Inc. License No. 1216058. © Sotheby’s, Inc. 2025. Information here within is correct at the time of printing. All content in this magazine is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced, published or redistributed without the permission of the relevant copyright owner. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and obtain permission to reproduce the material. Please get in touch relating to any omission or inquiry.

Chief Public Relations Officer – Karina Sokolovsky

Global Head of Brand – Jacqueline King

Global Head of Content and Campaigns – Nick Marino

Global Head of Growth – Tracy Heller

Global Head of Social Media and Editorial – Anne Johnson

Global Head of Video Production – Rachel Roderman

Head of Events and Preferred, Americas – Richard Drake

Head of Events, UK – Lydia Soundy

Head of Procurement – Eduardo Guerra

Production Manager – Stephen J. Stanger

Mitchell Johnson is one of the most well-known artists working in California, in large part due to the regular appearance of his paintings in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, and The Wall Street Journal over the past fourteen years. His work has been the subject of two museum retrospectives and numerous solo exhibitions, and his paintings are included in the permanent collections of more than 35 museums.

In a 2025 WhiteHot Magazine article, the legendary art critic Donald Kuspit declared that Johnson’s paintings “are astonishing masterpieces of phenomenological perception, fraught with what the philosopher George Santayana calls ‘hushed reverberations.’”

Johnson’s paintings will be on exhibit at Galerie Mercier in Paris in March 2026.

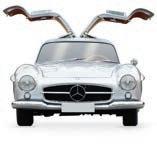

PARIS JANUARY 28

Held at the Salles du Carrousel of the Louvre Palace and offering superior supercars, past and present.

1954 Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Gullwing. €1,250,000-€1,750,000, “RM Sotheby’s Paris.”

NEW YORK DECEMBER 17

Marquee global offerings and the first-ever auction of real estate at the iconic Breuer building.

NEW YORK FEBRUARY 4-6

Paintings, drawings, sculpture and 19th-century and European art.

Jan Jansz. den Uyl the Elder, “Still Life with a Pewter Jug, a Silver Tazza, Glassware and Other Objects on a Tabletop,” circa 1633. $2,000,000$3,000,000, “Light and Life: The Lester L. Weindling Collection.”

NEW YORK DECEMBER 8-17

High jewelry, watches, handbags, fashion, sneakers, books, real estate, wine and spirits.

PARIS DECEMBER 3

Works by celebrated artists of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Fernand Léger, “L’étoile de Mer,” 1936. €260,000€450,000, “Modern & Contemporary Art.”

NEW YORK DECEMBER 10-11

Presenting creations by the 20th century’s greatest designers.

11200 E Canyon Cross Way, Scottsdale, Arizona. Listed for $24,000,000. Starting bids expected between $7,000,000-$14,000,000, “Exceptional Global Properties.”

JAR, rock crystal and sapphire ‘Papillon’ clip-brooch, Paris. $300,000-$500,000, “A Legacy of Elegance: Jewels from an Exceptional Collection.”

François-Xavier Lalanne, “Hippopotame Bar,” pièce unique, 1976. $7,000,000-$10,000,000, “Important Design: Featuring the Schlumberger Collection.”

visit sothebys.com/calendar

NEW YORK DECEMBER 18

Offering an intimate glimpse into the lives, loves and legacies of two Hollywood legends.

An exceptionally rare and impressive Fabergé jeweled aventurine quartz model of a lion, St Petersburg, circa 1900. Estimate upon request, “Swinging on a Star: The Private Collection of Kathryn & Bing Crosby.”

RIYADH JANUARY 31

Featuring an exceptional array of artworks by Saudi and international artists.

Anish Kapoor, “Untitled,” 2015. $600,000-$800,000, “Origins.”

PARIS DECEMBER 11

Presenting rare works of utmost quality, prestigious provenances and illustrious histories.

An early Louis XV gilt-bronze and engraved brass mounted brown tortoiseshell and mottle ebony première-partie marquetry bureau plat ‘à têtes de femme,’ circa 1735-40, by Boulle Fils. €400,000-€600,000, “Treasures.”

LONDON DECEMBER 3-5

Old Master and 19th-century works of art and antique sculpture.

Hans Eworth, “Portrait of Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk,” 1563. £2,000,000£3,000,000, “Old Master & 19th Century Paintings Evening Auction.”

PARIS DECEMBER 10

Masterfully illustrating the diversity of creations from these continents.

Nsapo-Nsapo, “Maternity,” Democratic Republic of Congo. €40,000-€60,000, “Art of Africa, Oceania and the Americas.”

PARIS DECEMBER 16

Built over 40 years and showcasing legendary Bordeaux vintages and iconic Burgundies.

1983 Romanée Conti Magnum. €20,000-€30,000, “The Monumental Cellar of Willy Michiels.”

A 15th-century Jewish prayer book glimmers with gold and fantastical illumination— a radiant testament to a story of devotion and survival.

RaRely does one encounteR a manuscript that embodies so many worlds—faith and art, persecution and survival—yet the splendid Rothschild Vienna Mahzor is such a treasure. Completed in 1415 by the hand of a Jewish scribe, Moses, son of Menachem, this monumental High Holiday prayer book reveals both the refinement of

medieval book arts and the fragility of Jewish life in Central Europe.

We can almost imagine Moses at his desk, meticulously copying the liturgy of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur for a wealthy patron who desired a volume both functional and luxurious. Its size, opulence and artistry indicate that the Mahzor was intended for communal rather than private use. The decorations astonish—folios brimming with animals and fantastical creatures set in Gothic archways, curling scrollwork and burnished gold initial-word panels. The parchment was carefully prepared to receive vivid mineral and organic pigments—deep lapis blues, verdant copper

BY SHARON LIBERMAN MINTZ International Senior Specialist, Judaica

greens, and cinnabar reds—whose brilliance is undimmed after six centuries.

The decoration reveals the influence of the Lake Constance school of illumination, a vibrant artistic tradition that flourished along the borders of southern Germany, Switzerland and Austria in the 14th century, distinguished by its architectonic panels, elaborate foliate scrolls and a lively cast of hybrids rendered in a distinctive palette.

The Mahzor was created nearly a century later, yet its decoration clearly draws upon the tradition. One theory suggests that Jewish refugees from the Lake Constance area brought their illuminated manuscripts to Vienna after the destruction of local Jewish communities in the Black Death persecutions of 1348-49. Thus, the Rothschild Vienna Mahzor stands as an artistic descendant.

Yet history weighed heavily on this masterpiece. Within a decade of its completion, persecution engulfed Vienna’s Jewish community in 1420-21, decimating Jewish life in the city. The Mahzor traveled on, its margins soon inscribed with notes adapting the prayers to the Polish as well as the Western Ashkenazi liturgical rites—evidence of new readers in new lands. By the 19th century, it surfaced in Nuremberg, where Salomon Mayer Rothschild (1744-1855) purchased it for his son Anselm Salomon (1803-1874) for 151 gold coins. A dedicatory leaf embellished with the family’s coat of arms was added, attesting to their pride of ownership.

The Mahzor’s journey did not end there. Confiscated during the Nazi era, it was placed in the Austrian National Library where it remained for decades until its recent restitution to the Rothschilds. Today, this magnificent codex testifies not only to the endurance of Jewish devotion and artistry but also to survival against the odds.

The Rothschild Vienna Mahzor, Vienna, 1415. $5,000,000-$7,000,000, February 5, Sotheby’s New York.

“Sotheby’s Icons: Back to Madison” unites works from auction history, celebrating the moments that shaped art, collecting and culture

Icons lIve where hIstory and culture meet. Last month, when we opened the doors of the Breuer, our new New York headquarters, an architectural landmark by a Bauhaus titan—meticulously restored by Herzog & de Meuron—it felt both new and familiar. Returning to Madison Avenue, where Sotheby’s first established its U.S. presence in 1964, feels like coming full circle.

To mark the occasion, we’re presenting “Sotheby’s Icons: Back to Madison,” a loan exhibition of more than two dozen exceptional artworks and objects borrowed from around the world, spanning centuries, media and some of the most defining moments in art history. Each embodies

a milestone in our history—having sparked bidding battles or, in some cases, anchored landmark collections as it passed through our salerooms—and holds an enduring place in the broader cultural imagination. Few works embody that duality better than Andy Warhol’s “Shot Orange Marilyn.” Its story is legendary. One afternoon at the Factory in 1964, Warhol’s friend Ray Johnson arrived with a woman named Dorothy Podber, who asked if she might “shoot” a stack of freshly completed Marilyn canvases. Warhol agreed, assuming she meant to photograph them. Instead, Podber pulled a revolver from her purse and fired a single bullet through the stack. Half provocation, half vandalism, that moment became part of the work’s DNA.

In the years that followed, “Shot Orange Marilyn” gathered new layers of meaning. It was sold by visionary early pop art collectors Leon Kraushar and Karl Ströher, whose holdings helped introduce the movement to Europe. When it appeared at auction at Sotheby’s New York in 1998, it

BY COURTNEY KREMERS Vice Chairman, Head of Private Sales, Americas

carried not only Warhol’s legacy but also the momentum of the contemporary market. The result—$17.3 million—was more than four times the artist’s previous record and the second-highest price ever achieved for a contemporary painting at auction at the time. That evening marked a turning point: the moment when contemporary art entered the realm of blue-chip history.

Warhol’s vibrant orange background heightens the intensity of Marilyn’s face. Her features are familiar yet curiously remote, as though she exists somewhere between film still and apparition. That tension between reality and reproduction, glamour and decay, is what makes this work feel timeless. When I look at it, I see New York itself: brilliant, endlessly reproduced and impossible to contain.

It will appear alongside other defining objects from our past, from Willem de Kooning’s “Interchange” to Banksy’s “Girl with Balloon,” which was famously shredded mid-auction in London and became “Girl Without Balloon.” Together, they form a retrospective not of artists alone but of a fabled auction house, a story also captured in the new book “Icons: 100 Extraordinary Objects from Sotheby’s History,” which recounts further pivotal works, moments and the people who shaped them.

For a 281-year-old company, this marks the beginning of a new chapter, continuing our enduring commitment to celebrating art, history and culture for all. I hope visitors to New York for the holidays will come to the Breuer and discover that the best show this season is right here on Madison Avenue. “Icons” is meant for everyone curious to experience the truly extraordinary.—As told to James Haldane

Andy Warhol, “Shot Orange Marilyn,” 1964. Made possible by Kenneth C. Griffin. On view in “Sotheby’s Icons: Back to Madison” at Sotheby’s New York, December 12–21.

RM 63-02

In-house skeletonised automatic winding calibre

50-hour power reserve (± 10%)

Baseplate and bridges in grade 5 titanium

Universal 24-hour time display

Oversize date

Function selector

Case in 5N red gold and grade 5 titanium

Limited edition of 100 pieces

Act One

The Opening Bid, in which we present news from the worlds of art, books, culture, design, fashion, food, philanthropy and travel—alongside the Global Agenda, which highlights not-tobe-missed exhibitions opening in December and January.

Edited by Julie Coe

the elegant world of late style legend Doris Brynner arrives in Paris this January as Sotheby’s presents her collection of art, fine jewelry and fashion archives. Born in the former Yugoslavia, raised in Chile and settled in France, Doris absorbed international influences before marrying movie star Yul Brynner in 1960. A friend of designers from Pierre Cardin to Karl Lagerfeld, she was hired by Dior in the late 1990s to overhaul the brand’s home department— on Peter Marino’s recommendation, no less. Doris’s daughter, Victoria Brynner, recalls two phases of her mother’s style: “The ’50s to ’60s were very much straight lines, lots of black and white, with luxurious accessories.” That elegance is captured in a Balenciaga dress Doris wore to the 1963 London premiere of “Cleopatra” (estimate €3,000-€5,000). While reviewing her mother’s wider wardrobe, Victoria says, “we discovered that one of the Balenciaga dresses was shorter than the dress Cristóbal [Balenciaga] had originally designed, and he was not a man easily convinced of changing his designs.”

“As years went by,” Victoria continues, “life became more colorful.” A diamond brooch gifted by family friend Elizabeth Taylor (estimate €20,000-€40,000) holds further memories: “I have photographs of her in her 80s—she often wore it at the neck on a pink silk shirt with a Mao collar. She was dedicated to everything being impeccable.”—James Haldane

Eva Jospin, Grottesco and Claire Tabouret, D’un Seul Souffle open at the Grand Palais in Paris.

From top left: ANL/Shutterstock; BORNXDS. Opposite, from left: Mr. Tripper; photography by Alec Guerrini, Printemps New York. Below, from left: Kitazawa Jun, “Fragile Gift: The Kite of Hayabusa,” 2024, at ARTJOG2024. Photo by Aditya Putra Nurfaizi; Helene Schjerfbeck, “Self-Portrait,” 1912. Photo by Finnish National Gallery / Yehia Eweis; Eva Jospin, “Diorama,” 2025 © Benoît Fougeirol, courtesy of Galleria Continua; Helmut Lang, “New York City Taxi Top,” 2002. © MAK / Christian Mendez; Zao Wou-Ki, “Untitled,” 1995. Zao Wou-Ki © ProLitteris, Zurich, 2025, courtesy of M+, Hong Kong; Samuel Fosso, “Untitled from the series African Spirits,” 2008. © 2025 Samuel Fosso; Sonia Delaunay, “Les Montres Zénith,” 1914. Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Jacques Faujour, courtesy of GrandPalaisRmn.

Architect henry JAcques Le MêMe, known as the inventor of the ski chalet, spent two years working in the Parisian workshop of art deco master Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann before setting off in 1925 for the mountains of Megève. There, he was commissioned by Baroness Noémie de Rothschild— who was developing a ski resort in the area—to create her own home in the style of a Savoyard farmhouse. The villa, with its generously proportioned spaces and updated folkloric touches, was a hit, and brought Le Même many more clients. He ended up designing around 250 chalets in the region, including Le Sarto, a 1941 property now owned and operated by the French hospitality brand Iconic House. A seven-bedroom refuge, it was given a careful renovation by design studio Claves, which added an indoor pool, sauna and gym. As with each Iconic House property, the stay comes with a private chef who creates custom dishes rooted in the local cuisine.

Below: Le Sarto, a chalet in the French Alps, is part of the Iconic House portfolio. Right: A ceramic mural by artist Héloïse Rival, installed in one of the main bathrooms.

At Printemps’ New York store, buyers can experience the thrill of Parisian second-hand shopping without getting on a plane. Marie Blanchet, founder of Mon Vintage, handpicks the best fashions of yesteryear, such as a 1980s Yves Saint Laurent “Le Smoking” or a 1998 Christian Dior by John Galliano gown, with new drops arriving each month.

Paco Rabanne Rhodoïd knit dress with gold-rhodoid discs, sold with its original mini case and sewing pattern, $3,850; us.printemps.com

Helmut Lang: Séance de Travail 1986-2005 opens at the MAK Museum in Vienna.

Leather goods brand Savette and interior designer Alyssa Kapito recently debuted a series of calfskin-clad boxes, dishes and trays, informed by art deco furnishings and accessories.

From $400; savette.com

American artist Sterling Ruby’s salvaged-wood wall reliefs inspired his collaboration with Parisian jeweler Repossi: an 18-karat champagne-gold sculptural brooch topped with a diamond.

$58,000; repossi.com

on the western shore of Lake Como, just across the water from the picturesque peninsula town of Bellagio, Edition has opened its latest hotel in a 19th-century palazzo. Inside, white-oak flooring and creamy plaster walls mix with walnut paneling and marble trim to create an

atmosphere of quiet confidence. The 148 rooms are outfitted with furniture by Neri&Hu, and some feature French balconies commanding panoramic lake views. Argentine chef Mauro Colagreco, who heads the three-Michelin-star Mirazur, in Menton, France, is overseeing the gourmet offerings, which include a convivial Italian restaurant and a poolside Mediterranean lounge.

In Dallas, Texas, this winter, a new cohort of horologists will receive their diplomas as the first graduating class from the city’s Rolex Watchmaking Training Center. The students, who started the 18-month tuition-free course in 2024, will finish having learned the technical and theoretical aspects of the trade, with a focus on Rolex timepieces in particular. The final exam is taken at Geneva headquarters. The Swiss brand sees the Texas program as an investment in its future.

sTarTeD In 2020, the vintage furniture dealer and rental service Somerset House has expanded rapidly in its first five years—so much so that co-founders Alan Eckstein and Haley Lowenthal recently opened a 10,000-square-foot gallery in the Long Island City neighborhood of Queens. The light-filled showroom, with views of the area’s fast-rising skyline, has ample room for arranging and displaying the robust inventory of 20th-century hits: Pierre Paulin sofas, Paolo Buffa case goods, Poul Henningsen lighting, Pierre Jeanneret tables, Lina Bo Bardi chairs and much more. The space also hosts an on-site restoration workshop, where important pieces are carefully refurbished, and a design studio.

A new gold cuff from New York jeweler Seaman Schepps features a fascinating range of vintage intaglios—stones with recessed carvings— in vibrant array.

the institute of contemporary art, Miami regularly times its winter show openings to the return of Art Basel, and this year the exhibitions on view as of December 2 are a thought-provoking mix of genres and styles. “Richard Hunt: Pressure” gathers the sculptor’s abstract metal pieces for the first survey of his work since his 2023 death, while “Joyce Pensato” brings together the late painter’s riffs on cartoon characters. And with “Andreas Schulze: Special,” the German artist marks his first solo U.S. museum show. The surrealism-meets-pop nature of Schulze’s paintings, especially the over-the-top colors and out-there proportions, sends up consumer culture and art-world pretensions of the kind familiar to many fairgoers.

Headstrong –Basquiat on Paper opens at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebæk, Denmark.

The forthcoming book “Icons: 100 Extraordinary Objects from Sotheby’s History” recounts the house’s remarkable record through the treasures it’s sold, such as the infamous Banksy (right) that started shredding itself the moment the gavel came down.

$90; phaidon.com

For the seventh series of Louis Vuitton’s artist-designed Artycapucines bags, Takashi Murakami has dreamed up 11 fantastical creations, including the Capucines EW Dragon model, which draws on his mural-size work “Dragon in Clouds—Indigo Blue.”

Price on request; louisvuitton.com

Martin Parr: Global Warning opens at the Jeu de Paume in Paris. Come Together: 3,000 Years of Stories and Storytelling opens at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City.

Divine Color: Hindu Prints from Modern Bengal opens at the MFA Boston.

Carroll Dunham: Drawings, 19742024 opens at the Art Institute of Chicago.

With a team built to match your every ambition, we can help transform your world. From renowned art services to sophisticated wealth and business strategies and powerful philanthropic solutions, we’re here to help pave the way for what’s next. Whatever your passion, unlock more powerful possibilities with Bank of America Private Bank.

What would you like the power to do?

OBSESSIONS

In the basement of the Breuer, Sotheby’s new Manhattan HQ, the design studio Roman and Williams is preparing to open Marcel, a restaurant debuting this spring. A sneak peek is available now, though, with Brutal Beauty, a series of new tabletop offerings, sold by the firm’s retail arm, RW Guild. Co-founders Robin Standefer and Stephen Alesch commissioned Japanese and Korean artisans to produce ceramics and glassware expressly for Marcel’s tables. And together they’ve created the Hyssop collection, featuring whitebronze candleholders and bud vases with ribbed fluting details. “Marcel Breuer was a compulsive maker and creator,” says Standefer. “Stephen and I feel a huge kinship to him in that way.”

From $425; rwguild.com

For over 160 years, Printemps has embodied the chic spirit of Paris.

Now in New York, the French maison presents a luminous pied-à-terre where fashion, beauty, design, and hospitality converge. Thoughtfully curated at every turn and exquisitely realized by multi-award-winning architect and designer Laura Gonzalez, the space invites you to wander, linger, and indulge in a truly one-of-a-kind experience.

PRINTEMPS NEW YORK

1 Wall Street, New York, New York 10005

us.printemps.com| @printempsnewyork

Airshare has immediate access to the Challenger 3500 and Phenom 300.

Other fractional programs require deposits on aircraft deliveries that never arrive as promised. We believe your expectations should be much higher.

With Airshare, you can be flying private today. Fractional shares and jet cards are available now in the Challenger 3500 and Phenom 300—so you can travel on your terms, not theirs.

Let’s get you in the air.

Visit FlyAIRSHARE.com or call (800)225-2862.

Act Two

In which we delve into creating and collecting, tracking the place art has on our walls, discussing the long-sought works that got away, learning from artists’ well-loved tools of the trade and exploring the world of wine and spirits connoisseurship.

The world’s largest private collector of Rembrandts, philanthropist and metals investor Tom Kaplan, reflects on the artist’s radicalism and the creativity of the Dutch Golden Age.

BY JAMES HALDANE

How did you begin collecting? In 2003, I was introduced to Sir Norman Rosenthal from the Royal Academy in London. When I explained that my wife, Daphne, was then the collector—she focused on 20th-century design—Norman asked, “If you did collect, what would it be?” Since encountering a Rembrandt at age six, I’d sought them out in galleries, so I said, “I’d like a painting by Gerrit Dou, Rembrandt’s first pupil, but they’re probably all in museums.” Norman explained, “They don’t come up every day, but one can acquire them.” Months later, he told me about a dealer with an intriguing work. Despite being signed, it wasn’t firmly attributed to Dou because it’s painted on silvered copper, rather than wood panel. I viewed it and immediately recognized it as a Dou. That was my first painting.

How has your career influenced your collecting and vice versa? I’m a firm believer in coincidence and made my fortune in silver with a discovery in Bolivia. Within months, another Dou came to me and I met the dealer Otto Naumann, and my wife and I started buying, on average, a painting a week for the next five years.

What was your very first collection, maybe as a child or a teenager? When I was about 10, I bought my first coin— a sestertius of the Emperor Hadrian. The dealer gave me a book called “Roman Coins and Their Values.” It triggered a love of history that changed my life.

How do you live with your collection? From 2003 to 2017, we created the only lending library of Old Masters—anony-

mously. We called it The Leiden Collection in homage to Rembrandt’s birthplace, though it spans the Dutch Golden Age. We revealed ourselves in 2017 with an exhibition at the Louvre encouraged by Arthur Wheelock of the National Gallery in Washington. He’d said, “It’s wonderful that you lend, but you have a unique study collection—you need a catalog.” At the opening I was asked, “How can you not live with even one of your Rembrandts?” Our attitude is, how can we?

What piece did you get for an especially good deal? In the early days, I was buying Rembrandts for the price of a Warhol. It’s nothing against Warhol, but there are only 40 Rembrandt paintings in private hands versus thousands of Warhols.

Why is philanthropy important? I lead a purpose-driven life. It’s how I approach business—I’ve been known as “gold’s evangelist” for 20 years—and my nonprofit passions: wildlife conservation, promoting universal values through art, and saving cultural heritage in war zones. My wife comes from a family renowned for its philanthropy, so it’s second nature to her. The concept of biodiversity conservation was once viewed as niche. You had to lead by example, so that’s what we were known for first.

What tools of the trade do you use to build your collection? I prefer going through dealers and private transactions with auction houses. Around half of our 220 paintings were bought privately

versus at auction. When you have passion, decisiveness and can pay quickly, it’s a lethal combination.

Favorite city for art and why? Going to Amsterdam, to the Rijksmuseum, is like a pilgrimage for me.

Most important art historical figure?

The Louvre exhibition pushed me to share a narrative I’d been privately harboring— the case for Rembrandt as the universal artist. The iconoclasm of his late period, in paint application, color and impressionism, reflected a novel ability to convey beauty and created a style that became such an influence, from Goya to Delacroix to Picasso to today. Van Gogh famously said that he could sit in front of “The Jewish Bride” for two weeks, just with water and bread. You see a genetic transmission from Rembrandt’s brush through to nearly all contemporary art, including artists from China to the UAE. He was the liberator.

What’s the best compliment someone has paid to your collection? When I first met Emmanuel Macron, he said, “I saw what happened with your exhibition. If you’d been French, you might have beaten me for the presidency.” What I say is this: it doesn’t take a genius to buy Rembrandt, it takes a genius to be Rembrandt.

Best impulse buy? During the financial crisis, I approached Steve Wynn to buy

a Rembrandt self-portrait. Otto Naumann negotiated the deal, and Steve made it a condition that I also buy his Vermeer. I told Otto instantly, “Done.” And hence “Young Woman Seated at a Virginal” became part of The Leiden Collection.

Which collectors do you admire? It’s always thrilled me that even after Steve Wynn’s eyesight deteriorated, he stayed a collector. After selling me his two most important Old Masters, he bought another Rembrandt.

What’s the piece that got away? What was my holy grail is now in the collection: “Bust of a Bearded Old Man,” Rembrandt’s smallest painting. It’s spectacular. If it were a more typical size, it would be a billion-dollar painting. I’d coveted it for 15 years and, finally, the owner said, “Here’s the price”—apparently the highest price per square inch of any painting ever paid. I’ve never looked back.

What tips do you have for collectors just starting out? Buy what you love and find people you trust. Get to know the auction houses and the dealers. I was lucky in my relationships, with George Wachter at Sotheby’s, Ben Hall at Christie’s, and my triumvirate of dealers—Otto, Johnny Van Haeften and Salomon Lilian. Our collection could not have been built without their enthusiasm and commitment to my sense of mission.

Which piece doesn’t ‘fit’ in your collection but still works? It’s a magnificent work that I’ve chosen to sell to benefit Panthera, the only global organization solely focused on the preservation of wild cats. Perhaps 20 years ago, before we had a Rembrandt painting, Otto called me up about a Rembrandt drawing of a lion— knowing that we don’t collect works on paper. There’s been nothing like it in the decades since. When I saw those eyes, I marveled at how Rembrandt could give more interior life to a cat than almost any artist can give to a human. I hope people will bid high, because every single dollar is going to conservation.

What exhibition are you looking forward to visiting? The Leiden Collection is staging what is apparently the largest exhibition of privately held Dutch 17th-century paintings ever organized in the U.S., at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach through March. It’s the counterpart to a show at the H’ART Museum in Amsterdam earlier this year—featuring 17 Rembrandt paintings alone, it nearly doubled that city’s population of works by the artist. We’ve brought our Vermeer and Carel Fabritius too, and 60 more paintings. For me, it’s a pleasure because I almost never see them, and I hope that visitors come away with a greater understanding of how everyday life was celebrated during the Dutch Golden Age. •

From Hollywood glamour to exquisite Fabergé, “Swinging on a Star: The Collection of Bing & Kathryn Crosby” captures a lifetime of passion, taste and festive charm. Their son, Harry Crosby, reflects on some of its most cherished treasures before they go under the hammer at Sotheby’s New York on December 18.

BY

Opposite page: Gold records presented by Decca, inscribed “To Bing on his birthday and in commemoration of 19 ‘Over a Million’ record sellers— May 2, 1957,” including “White Christmas” (over 9 million sold in 1957), “Silent Night” (over 6 million) and “Jingle Bells” (over 5 million).

This page: Custom 1960s coat-dress with matching capelet, likely created for Kathryn to wear on one of Bing’s Christmas television specials, in which the family often appeared.

My father didn’t coMe from a fancy background, and neither did my mother. But he had already built a career in music and film by the time they met in 1953. He had the trappings of a home and the experience of raising four boys after being widowed from his first wife, Dixie Lee. My mother was raised in West Columbia, Texas, and from a young age loved acting. She got into the University of Texas at 17, and after a year in the drama department moved to California to become a contract player.

The studios worked like a trade school—you were paid a few dollars a week while learning every aspect of filmmaking: screen tests, choreography, assisting directors, watching producers at work. That’s where they met, but it wasn’t automatic. He was 30 years older, she was 20, and it took four years to court, building a deep, trusting partnership.

It wasn’t until I got older and began understanding the business side that I really appreciated what Dad achieved. Music and film technology were shifting in the 1920s as his career took off: radio was emerging, films were moving from silent pictures to talkies and the record business was evolving. In the ’30s, he worked closely with Jack Kapp at Decca Records, and together they had a long and successful run. Dad developed a new way of singing into the microphone—intimate, unlike standing before a full orchestra and belting. That’s why they called him The Crooner.

Outside the studio, his passions took a different form. He loved horses, from thoroughbreds to hunters, and the culture surrounding them, including English sporting art. He befriended Charles

Howard, owner of Seabiscuit, and owned a horse called Meadow Court, who won the Irish Derby in 1965. He moved easily between racetracks and galleries, surrounded by people, horses and paintings, from Herring to Munnings.

Dad wanted his talent to thread through all parts of society, regardless of background or creed, so he was careful about politics, preferring to entertain without dictating opinions. That neutrality and his unassuming nature once made his Palm Springs home a haven for John F. Kennedy, who needed a place to escape in 1962. Frank Sinatra had thought Kennedy would use his house, but I think the appeal was Dad’s relaxed attitude: “The keys are under the plant. Just have fun, and turn the lights out when you leave.”

My mother, though younger, was a quick study. Early in their marriage, she told my father, “I’m not that interested in jewelry, but I like this thing called Fabergé.” She discovered A La Vieille Russie, a Russian imperial art and antique gallery founded in Kiev that later relocated to New York, and studied under its matriarch, Ray Schaffer. She absorbed every detail and became fiercely discerning, especially about the animals—from the big lion to the little mouse. She learned as much as any dealer and spent hours on the phone negotiating trades. She wasn’t buying just to deal though—she wanted to acquire and keep things.

That was my parents’ way. They didn’t just collect—they lived with what they loved: always curious, always careful, always enjoying the process. •

page, from left:

of

“Dad wanted his talent to thread through all parts of society, regardless of background or creed.”

—Harry Crosby

This page, from top: Fabergé gold-mounted nephrite pipe holder, made in Saint Petersburg circa 1900 and purchased from A La Vieille Russie; Tiffany & Co. cigarette box gifted to the Crosbys by President John F. Kennedy, engraved with a personal message in his handwriting.

Opposite page, clockwise from top left: A selection of Bing’s signature hats, by makers including Cavanagh and Dobbs & Co., adopted after early hair loss and later integral to his personal style; portrait of Kathryn Crosby in her late 20s, painted by Sam Manning, which hung in the couple’s bedroom; group of ornate walking sticks and an umbrella owned by Bing; portrait of Bing by Sam Manning, featuring his signature hat and pipe—accessories central to his persona both on and off screen.

For wine and spirits enthusiasts, bidding and bacchanalia go hand-in-hand at annual blowouts that raise millions for philanthropic causes.

BY JAY CHESHES

The hospices de Beaune charity wine auction kicks off every year on the third weekend in November, as it has since 1859, with a public sale of wines en primeur, the latest vintages sold by the barrel just weeks after harvest. The bidding is furious in the packed Halle de Beaune, with nearly 600 guests filling the main market hall in the heart of Burgundy wine country, their winning bids raising millions, locally, for public health. For almost two centuries this annual wine sale has kept the region’s healthcare system going, buyers betting early on the fruits of the hospital’s own vineyards—150 acres bequeathed over the years to the Hôtel-Dieu, which was founded in 1443.

Following the auction, there are three days of festivities, with the Hospices sale kicking off the annual bacchanal known as Les Trois Glorieuses, as wine-soaked banquets run through to the Paulée de Meursault, a long Monday lunch.

As the cult of Burgundy wine has grown internationally, what was once a local celebration has become a global attraction, drawing wine pilgrims from around the world.

“All of Beaune is bubbling,” says Ludivine Griveau, régisseur (director) and winemaker at the Hospices de Beaune since 2015. “The population triples or quadruples that weekend. It’s also a party for the people, around this sale of wine.”

Griveau, who shifted her entire production to organic last year, is in a unique position in the wine world, with her focus on charity over profits. Proceeds from her wines have helped fund a new hospital in Beaune that’s nearing completion. “We never forget that we are working for a hospital, for charity, for health,” she says. “We are driven by this sentiment that we really have a special mission.”

For the past five years, Sotheby’s has partnered with the Hospices de Beaune, supplying world-class auctioneers and enabling online bidding through its digital platforms. Since 1978, it has included a special offering of one exceptional

barrel: the Pièce des Présidents, carefully chosen by the winemaker and sold by candlelight at a banquet with celebrity hosts such as Eva Longoria and Dominic West. In 2022 a barrel of Corton Grand Cru broke auction records there, selling for 810,000 euros ($939,000). “It’s really my coup de cœur,” says Griveau, of her selection for the event.

Over the years, the Hospices de Beaune’s winning mix of wine, food and philanthropy has become a benchmark for the world of wine and spirits, fueling a global circuit of other charity auctions. The first truly successful homage debuted in 1981. After being inspired by the Burgundy auction, Robert Mondavi returned home and convinced his fellow winemakers in the Napa Valley Vintners association to organize the first edition of what would become known as Auction Napa Valley.

“He saw how they were taking the wines of Beaune and making a difference in their community,” says Stacey Dolan Capitani, a marketing executive with Napa Valley Vintners, who has been involved with the auction since 1997. “And he wanted to instill that same spirit in the Napa Valley, leveraging the reputation and the quality of our wines to make a significant impact on the community.”

The first Napa auction, benefiting the local hospital, was held in the summer of 1981 at Mondavi’s resort hotel, Meadowood. Temperatures were scorching that day. “The auctioneer had an ice bucket under the table to put his feet in because he was sweating so much,” says Capitani. “But it was successful. They raised a couple hundred thousand dollars, and it was the start of something beautiful.”

In 1989 the Napa Valley Vintners added a separate barrel auction to the weekend-long program, offering wines donated by member wineries, sold by the case direct from the barrel. Hosted by a different winery every year, it’s held on the Friday night before the big Saturday auction.

Over the years Auction Napa Valley has taken the basic tenets of the Hospices de Beaune and run wild with them, adding auxiliary dinners—intimate affairs held at wineries across Napa—and adding increasingly dramatic and experiential auction lots, all donated by members of Napa Valley Vintners. At the auction last summer these once-in-a-lifetime experiences included an Antinori and Stag’s Leap package, comprising six nights at the Tuscany winery and a trove of large-format wines from the Napa vintner, that sold for $550,000.

For most of its 44-year history, Auction Napa Valley was headquartered at Meadowood, even after Mondavi sold the property to winemaker Bill Harlan. But the Glass Fire that ravaged the region and engulfed the resort in 2020 left the main auction homeless. The organizers have had to downsize since then.

This past summer the live Saturday auction was held at nearby Chandon and attended by 300 guests (down from nearly 1,000 at Meadowood). The entire weekend’s auctions raised $6.5 million for local charities (versus the $12 million raised in 2019). But with the rebuilding at Meadowood nearing completion, Auction Napa Valley may soon return in full force to the place where it began. “We’ll get back to the days of glory,” says Capitani. “Meadowood is always going to be our home, and we can’t wait to return.”

In the decades since Auction Napa Valley first brought the ethos of the Hospices de Beaune to the U.S., many other wine auctions have sprung up to raise funds for philanthropic causes. Most are modest in scale but a few, such as Naples Winter Wine Festival, are more ambitious. The charity auction model has caught on in the spirits world, too. Scotch whisky producers set the standard for the industry four years ago, with the launch of the Distillers One of One. The first big high-profile public-facing sale of Scotch whisky for charity, the biennial event features only unique bottlings—all one of one—and was first presented over a languid lunch in a stately home outside Edinburgh in fall 2021.

Held every two years at Hopetoun House and bringing together the biggest players in the world of Scotch whisky, the Distillers One of One is the brainchild of the Worshipful Company of Distillers. This London livery company has a 400-plus-year history of working with Scotch whisky producers and a long, but discreet, tradition of charitable giving. It had organized small, internal charity auctions over the years, with liverymen selling precious bottles from their own cellars to their colleagues, but it had never held a public event. In 2018, one attendee at a small auction brought a custom bottle—a one-off—created just for the evening, and bidding went through the stratosphere. The first kernel of the One of One started there.

“We thought if this one lot could fetch a significant amount, what would happen if every single lot were a one-off, if every single lot were created for the auction?” says Beanie GeraedtsEspey, Managing Director of the Distillers One of One. The company reached out to distilleries across Scotland about donating unique bottlings for a public auction that would raise funds to help create opportunities for disadvantaged Scottish youth battling unemployment and homelessness. All the biggest corporate players signed on, offering some of their most precious liquid in lavish decanters that double as works of fine art. The inaugural event raised $2.7 million, and this year’s brought in $3.9 million total against a $1.1 million low estimate.

“The idea was to get everybody to give for charity their rarest whisky, a unique bottle of it, and try to make that whisky, and the bottle, stand out from anything else they do,” says Jonny Fowle, Global Head of Whisky at Sotheby’s, who has been involved in the auction since its inception. “It requires every brand in the industry to work together. So, you put aside competition, and you embrace community, which is quite an unusual thing to do.”•

How a breakthrough Roy Lichtenstein painting ended up in the home of a woman who admired it in her youth.

BY LUCAS OLIVER MILL

One autumn afternOOn in 1961, Ivan Karp, a director at New York’s Leo Castelli Gallery, met with Roy Lichtenstein to see four new works the artist had created. These canvases, known as the “comic book paintings,” featured scenes and images that Lichtenstein pulled from comic strips and advertisements and blew up on a grand scale. The largest of the four shown to Karp was “The Engagement Ring.”

In the context of abstract expressionism’s dominance, these paintings must have seemed shockingly new when Karp first laid eyes on them. The encounter left a lasting impression: Soon after, Lichtenstein began exhibiting with Castelli, which set him on the path to becoming one of the greatest American artists of the 20th century.

The following year, in 1962, Lichtenstein had his first solo exhibition with Castelli. The entire show sold out before it had even opened to the public, with all the paintings placed with Castelli’s top collectors. The buyer of “The Engagement Ring” was Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo from Milan. In fact, Panza had bought a total of seven Lichtensteins from Castelli, each for just $600. They were swiftly shipped over to Italy. However, problems arose when Giuseppe Panza’s wife caught sight of them. “My wife does not like Lichtenstein,” he would confess in a 1985 interview. Panza traded “The Engagement Ring,” along with two other Lichtensteins, with an Italian art dealer, getting three paintings by James Rosenquist in return. “Every time I think back to this mistake, I feel bad,” Panza recalled.

The painting headed back to the United States and came under the ownership of another of Castelli’s top clients, the real estate developer Robert Rowan. Again, this was fleeting, and by 1971, the painting had oscillated back to Italy, now purchased by Ernst Wilhelm Sachs, brother to Gunter Sachs, both heirs to a German industrial fortune.

Ernst lived in the Palazzo Chigi-Odescachi in Rome, a grand Baroque palace that was transformed in the late 1960s by Giorgio Pes and Roberto Federici. Spurred by Gunter’s enthusiasm for art, Ernst began building his own collection.

He hung “The Engagement Ring” in his grand living room, above the fireplace and a plush sunken seating area. The room was an ode to American pop art: major works by Andy Warhol and Tom Wesselmann—an “Orange Car Crash” painting and a “Great American Nude”—hung on the adjacent walls. Soon after the apartment was completed, Warhol visited Sachs for dinner. Clearly smitten by the placement of his painting, he snapped a few Polaroids of Ernst’s then-girlfriend, Marie Laure Zoppas Gardoni, in front of it.

Unfortunately, Ernst’s striking bachelor pad was short lived. In 1977, Ernst was tragically caught in a heli-skiing avalanche accident and died at the age of 47. His apartment in Rome was cleared and the art collection dispersed.

Years earlier in New York, another admirer had fallen under the painting’s spell. A young woman by the name of Ronnie Feuerstein arrived in 1969 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see curator Henry Geldzahler’s latest show—a major retrospective on the New York School. There, she encountered “The Engagement Ring.” Transfixed by its beauty, she rushed to buy the paperback catalog, which featured the work inside. (She still owns the catalog to this day.)

Two decades later, Ronnie and her husband, Samuel Heyman, had a remarkable opportunity to buy the work, in a sale brokered by Gagosian. Not long after, Castelli organized for the Heymans to dine with Roy and Dorothy Lichtenstein at Chanterelle in New York. At the dinner, Roy told the Heymans the story behind the painting. “The woman is a nurse, and he is a doctor. She’s in love with him, but he has a girlfriend, and he just told her on the page before that he bought his girlfriend a gift,” recalled Ronnie, who is president emerita of MoMA’s board of trustees. “All she wanted to know was that it wasn’t an engagement ring, because then her hopes would be dashed.”

What struck me most in that very moment, talking to Ronnie as she stood next to the painting in the foyer of her Palm Beach, Florida, residence, was her own resemblance to the woman in it. “I love her lips, her pearls,” she said softly, “and the little tear in her eye.” •

Clockwise from left: Roy Lichtenstein’s “The Engagement Ring,” 1961, and Andy Warhol’s “Orange Car Crash,” 1963, in the Rome apartment of Ernst Sachs, photographed by Carla de Benedetti in the early ’70s; Ronnie Heyman at home in Florida with “The Engagement Ring” and Donald Judd’s “Untitled,” 1985, photographed by Lucas Oliver Mill in 2025; Lichtenstein at Leo Castelli Gallery, photographed by Bill Ray in 1962.

Act Three

In which we go back to school at the Bauhaus Dessau, visit Laurie Simmons and Carroll Dunham at home in Connecticut, highlight the most stylish new watches, meet an innovative generation of Japanese lacquer artists and get a fresh perspective on Vermeer. the Bauhaus visit Laurie

A century after its founding, the Bauhaus Dessau in Germany remains a beacon of modernity—an experiment in light, line and life. Conceived by Walter Gropius in 1925 as a living laboratory for design, it united art, craft and technology under one roof. Now home to the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, the UNESCO World Heritage site provides the backdrop for a story in classic tailoring—where timeless forms echo the school’s enduring principles of function and beauty.

TAILORED SOLITUDE

MATERIAL RHYTHM

Clockwise from top left: Chloé dress in a Bauhaus conference room; shadows stretch across the outdoor cafeteria; color-saturated interiors of the Meisterhäuser; paper-folding exercise from the permanent exhibition “Education Space Bauhaus” at the Bauhaus. Opposite: Zegna jacket, Wolford turtleneck and vintage Hermès trousers.

The

silhouettes

Opposite: Loewe dress and shoes and Wolford tights. Top left: A Prada bag rests on Walter Gropius’ F51 armchair reimagined by Katrin Greiling in the director’s office at the Bauhaus. Bottom left: Alaïa coat.

For artists Carroll Dunham and Laurie Simmons, work-life balance begins at home, which happens to be a country estate in Connecticut.

Packing the contents of your studio into a van and crawling across New York City to a new one is no picnic— just ask the painter Carroll Dunham, who did it 11 times in 30 years. Always chasing more square footage, cheaper rent, better light, a shorter commute, a less tragic deli or maybe just a slightly longer lease, he stored his paint in plastic squeeze bottles and hoarded nothing. “I enjoyed setting up studios and felt that my work would happen wherever I was,” Dunham says. For his wife, the photographer and filmmaker Laurie Simmons, whose practice often involves camera rigs, elaborate sets, props and costumes, moving was to be avoided at all costs.

In 2007, the couple bought a house in Cornwall, a town in the green northwest corner of Connecticut. They hadn’t lived and worked in the same place since sharing two floors of a forlorn SoHo loft building in the ’80s, and it suddenly seemed like a good idea. “I wanted to stop running,” Dunham says, recalling the pressures he was feeling at the time. He remembers telling himself, “We’re going to spend less money. We’re going to travel more. It’s going to be great.”

Over the past 18 years, they’ve settled into rural life with obvious pleasure, but they haven’t stopped moving. The Cornwall house, which the artists, both 75,

occasionally share with their children Lena, 39, and Cyrus, 33, is a comfortable home and an extravagant warren of studio spaces, a variable landscape that flourishes on their commitment to making and living with art.

On a Friday afternoon, Simmons and Dunham are unwrapping sandwiches from the local deli at a long table in their kitchen. Like the rest of the Georgian-style house, it’s generously proportioned, with high ceilings, intricate moldings and a fireplace. A supersized central island with a milk-glass top reflects a row of candycolored Murano glass lights, supplying a little ice cream parlor giddiness.

The week before, a joint exhibition of the artists’ work finished a six-month run at the Consortium Museum in Dijon, France. It was a first for them, and it broke a privately held taboo.

“Years ago it would’ve been an automatic no,” Simmons says of the invitation to show side by side. “We had a kind of unspoken rule about things like that.” But they liked the museum’s curator, Éric Troncy, and decided they might learn something from lying back and letting things happen. Troncy shaped the list of works without their input, and when the couple arrived in Dijon, posters featuring Simmons’ portrait of their collie, Penny, hung all over town.

The show was “nothing but delightful,” she says. “Everything informed everything else in a new way, and—I don’t want to speak for Carroll—but it made me look at things I’d done in the context of his work, which was really interesting.” The installation was playful and associative, a sign of how times have changed for a pair of provocateurs whose work has often been seen as mutually allergic.

Roberta Smith, the former co-chief art critic of The New York Times, met Simmons and Dunham in 1979, two years after they met one another. She told me that despite differences in media and technique, both artists carefully construct their images and “let you see the seams.”

For most of Simmons’ career, Smith says, “Laurie has arranged sets, dolls, images and props into barely put-together scenes. Even now she disrupts her relatively slick AI-generated images by adding things like fabric and jewelry to the surfaces. Carroll has an evolving repertoire of parts—figures, trees, wood-grain cabins or interiors, a dog or a horse, color and line, sculptures—that he builds and re-builds into different scenes with a different sense of dramatic tension.” Stylistically, she suggests, “both of them are closet formalists, despite their clear involvement with subject matter, narrative and politics.”

At the sunlit dining table, memories of their early typecasting still manage to tick them off. “We were operating in the same world, and sometimes even in the same galleries, but we were perceived as being from different aisles in the grocery store,” Dunham says.

“I was embarrassed to be dating him at first because he was a painter,” Simmons admits. “I mean, painting was dead. And I was like, I’m going out with one.”

“She liked me more than she liked my work,” he jokes.

“That’s not true,” she says.

“It is true.”

“You always say that. I don’t.”

“I liked your work more than I liked you,” Dunham jabs playfully. “But honestly, I think we were fortunate. We could take what the other was doing seriously, but we didn’t get in each other’s way.”

On buying the Cornwall property, Dunham found himself so out of the

way—out of New York, out of his element, out of touch with his wife, who’d stayed in the city until their younger child was out of high school—that he started graffitiing the walls of his studio bathroom. The three-story house, built by a local farming family in the early 19th century, had seen worse. Partly destroyed by fire in 1911, it was reconstructed a year later in brick with a fireproof lining, which Dunham discovered when he tried adding a dormer window and found himself mano a mano with a concrete wall.

In 1956, the building was acquired by a boy’s academy called Marvelwood School. When the school relocated in 1995, a developer swooped in, restored it to a private home and sold it to Simmons and Dunham, who also picked up the adjacent barn. The developer turned out to be “a real craftsman,” says New York architect David Bers, a friend of the couple who consulted on some additional work. “He actually made it smaller than it originally

was—I’d say he knocked down a quarter of the house to make it reasonable for someone to think about buying.” Weirdly, he stopped short of adding a kitchen or bathrooms (there was only one). What the couple bought, Bers says, “was more like a model of a house.”

This was catnip for Simmons, whose work often uses domestic settings as raw material to break down, send up and otherwise poke at subjects like consumerism and the constructed feminine self. The house starred in her 2018 feature film “My Art,” and it regularly slides into other projects, including her influential series of “Love Doll” photographs.

Left: Simmons’ “Some New: Lena (Pink)” from 2018. Below: On the wall hang, from left, “Deep Photos (White House Green Lawn/Swimming Pool)” from 2024, “Deep Photos (Deluxe Redding House/Dream Kitchen)” from 2023, and an unfinished “Deep Photos” work; leaning against the wall are, from left, “White House/Green Lawn” from 1998 and “Instant Decorator, Red and White Kitchen” from 2001. Opposite: In a bedroom sit a series of Simmons’ “Girl Dummies” from the 2021 work “First Week of School.”

“Laurie’s work is about imagining yourself in scenarios and situations,” says Bers. “She sees space as narrative.” In preparation for guests or for no reason at all, Simmons will enlist whoever is around to help her recast the dining room as a drawing room or the music room as a ballroom. Her design choices are equally ad hoc: the Farrow & Ball wallpaper in the living room, with its vermicelli squiggles, was chosen because it reminded her of Dunham’s loop-the-loop pencil drawings, and the persimmon-colored Togo sofas and chairs in the TV room were traded for art with a friend who was redecorating. (“I love orange,” Simmons explains.) Mid-century lamps with bombshell curves and kooky shades are Dunham’s contribution. And where the walls are densely hung with art—by friends, family and artists the couple admires—he has had a free hand. “He over hangs,” Simmons says with exasperation. “Honestly.”

By midafternoon, one end of the milk glass counter has disappeared beneath Dunham’s carton of black cherry seltzer, Simmons’ mug of Earl Grey tea and stacks of candy boxes belonging to Lena, who just celebrated a birthday. Now married and based in London, she’s back home in Cornwall for a few months to work on film projects for Netflix and Apple/A24, and living in a snug house she built with Bers at the rear of the property. For company she’s adopted a pair of 12-week-old piglets, which may or may not be appearing onscreen soon.

Simmons is taking it all in stride. “My daughter will have overflow guests and ask, ‘Can’t they just stay with you?’ And we’ll say, ‘We have no room.’” She pauses to open a box of chocolates. “Carroll and I have what a lot of artists have—we have space dysmorphia. It’s just never enough space. I mean, there are reasons Picasso filled up houses and shut the door and then got other houses. That would be a total fantasy.”

The couple’s spatial preoccupations have clearly been contagious. Cyrus, a writer and activist living between New York and L.A., remembers the repeated scenario of coming home from school to a new living room: “Sometimes it bothered me, but I definitely caught the bug. Whenever I’m in a low mood or need some inspiration, I do the same thing.”

Clockwise from top left: The house, which was once part of a boys’ school; a desktop vignette with, clockwise from top center, Madame Yevonde’s 1935 image “Mrs Edward Mayer as Medusa,” a detail from a Simmons painting and a Dunham drawing; Murano lamps hang over the table.

Lena sees the behavior less like an illness and more like a cure. “I have come to believe it’s part of what keeps my parents together, this constant shifting vision of what an ideal space is and how to use it,” she says. “My friends often comment on how youthful they seem and how vital they are, and I think this sustained interest in the world—nothing is fixed— is a big part of that. They both came from homes that were a bit stuck in time: the couch went someplace and it stayed there, and that was a stand-in for rigid thinking. In a way, I’m at home on a film set because my life has been a film set.”

Simmons suggests a walk, and we head out past a vegetable garden and over to the barn with Penny in tow. We pass a handful of Dunham’s sheet-metal sculptures in the tall grass.

“This was Carroll’s studio, but he gave me a little chunk as a present,” she says as we enter the barn, which once held school classrooms and several faculty apartments. “I needed another viewing area.” Hanging on the white walls of her not-so-small space are four unfinished works from a new series of photographs generated from text-to-image AI programs, their surfaces clotted with hand-stitched

Gaetano Pesce’s “Nobody’s Perfect” chair stands near Albert Oehlen’s “Untitled” painting from 2015.

embroidery. Down a hallway, a cedarpaneled, color-coordinated apartment Simmons uses as a set displays the bodypaint portraits she first exhibited in 2018. Dunham’s unfolding series of rooms is on the other side of the wall.

“I’ve never seen anyone feather their physical nest to make art quite like Carroll Dunham,” says Bers. “Before he does a painting, he’ll lay clean canvas across the floor. He’ll put a beautiful pine ledge on the wall. He stages environments to make the paintings. And it’s always in flux.”

Back in the main house, Dunham’s former workspace has been replaced by a tidy gym and a guestroom painted a refulgent lilac. Next door, an assistant is assembling a photo archive of Dunham’s works on paper; his first drawing retrospective will open in January at the Art Institute of Chicago, “mostly curated from my flat files,” the artist says.

Though he rarely exhibits them, drawings have played a critical role in his practice for decades. “There are always people who understand how interesting and beautiful and important drawing is,” he says. “Although I feel like that’s not top of mind now, with how much people are focused on spectacle and on market results and stuff like that. Drawing doesn’t give you the kind of wow that hundred-million-dollar paintings do.”

The night before, one of Dunham’s paintings had set a new auction record for his work in a Sotheby’s New York sale from the collection of Barbara Gladstone, his longtime dealer. His market has shown a steady, career-long rise, especially when compared with the highs and lows of some of his peers. After leaving Gladstone last winter, he joined Matthew Brown Gallery in New York and continues to exhibit with a handful of other dealers in London and Europe. Simmons has a solo show up at Almine Rech’s gallery in Paris through December 20, and her recent AI series is currently on view at Miami’s Andrew Reed Gallery.

Fiercely independent as artists, they have always been united as a couple. “Carroll and Laurie have forged an amazing partnership that has sustained them through thick and thin, two kids and numerous changes of address,” Roberta Smith says. “Jerry and I haven’t faced some of the pressures they have”—Jerry Saltz, Smith’s husband, is the art critic of New York Magazine—“but it’s clear to each of us that we all do work that can be very isolating and that it is amazing to share it with a partner who understands exactly what you’re going through.”

Up in Cornwall, work gets done, and the scene keeps shifting. A few years ago, Dunham cut a hole in the barn’s second-floor ceiling to access the attic and discovered a two-bedroom apart-

ment, complete with a child’s wallpapered bedroom. “It was so freaky!” Simmons says. “It looked like a set from one of my photographs.” They decided to gut the attic space and build “the New York loft we could never afford,” she jokes, ever the disaffected New Yorker. The result, as conceived by Dunham, is a loft in the empyrean sense—more CGI than IRL, with a pair of Danish black leather sofas and a cast iron soaking tub among a handful of furnishings allowed on the satin-finished oak floors.

“We’ve had so many lofts and lived in so many places, but this one is pristine,” Simmons says dreamily. “Because no one lives in it. If the kids ever take over the house, we would live here. And just go downstairs to work.”•

An early pair of pictures painted by Vermeer for the house on the Oude Delft can be identified from the Amsterdam auctioneer’s catalogue of 1696. The first vanished without trace after going under the hammer and is now presumed lost.

In an excerpt from his new book, “Vermeer: A Life Lost and Found,” Andrew Graham-Dixon brings fresh archival detective work to the Dutch master—tracing his elusive patrons, unraveling the quiet power of their faith and rediscovering the exact Delft doorway captured in a beloved masterpiece.

The second is in the collection of the Rijksmusem and has long been known as “The Little Street.” It was probably painted in about 1660.

Numerous failed attempts have been made to locate the scene depicted in the painting, which has been variously identified as a view from a rear window of the Mechelen Inn, a depiction of step-gabled houses on the Voldersgracht, a topographical record of buildings on the Nieuwe Langendijk, and (in laborious detail) a portrayal of the house on Vlamingstraat once owned by a great aunt of Vermeer’s named Ariaentgen Claes van der Minne, a tripe butcher who cleaned and prepared pig’s intestines on those same premises.

The chasing of such wild geese is unnecessary. Vermeer was not a topographical artist, a painter of random buildings represented for the sake of picturesque effect or as family mementos. His pictures for Pieter and Maria van Ruijven, his principal patrons, spoke to their religious convictions. So if he were to create a picture of a particular place to hang on the wall of their house, that place would have to be infused with religious significance for them. In all of Delft there was only one location that Vermeer could have thought, or been asked, to paint for his patrons. “The Little Street” depicts the hidden Remonstrant church on the Oude Delft, together with the houses adjacent to it, including that of Pieter and Maria themselves. Comparison of the picture with the present and past topography of the town bears this out.

A great deal has changed in Delft since Vermeer’s lifetime, but the corner occupied by the Remonstrant church is still

much as it was when he painted it. The canalside houses that he depicted have been remodeled but they are still in situ and the church itself is still there, albeit deconsecrated. Although it was rebuilt in the 19th century it occupies the same footprint as the building where Vermeer and his patrons probably worshipped, and is similar in appearance to it, being a modest two-story structure large enough for a congregation of about 400 people. It remains hidden, even more so now than in Vermeer’s time, because the gap between the houses in front of it has been built over. Having originally been converted from a malting house set behind the main street frontage, possibly with funds provided by the Van Ruijven family’s brewing business, it exists in the same relationship to the façades of the houses along the canal as it has for centuries. To get to it you have to pass through a door set into the street front, which leads to an alleyway of about 20 yards in extent. At the end of that alley is a second door, which lets you into the church.

Nearly all of this is visible in Vermeer’s painting and what is not can be inferred. On the left of his composition at street level we see a weathered black door set into a rounded arch. Behind it is the alleyway, blocked from sight but architecturally implicit, that still leads to the church today. The church itself is the foremost of the buildings in the left middle distance of the picture, behind the street façade. Its roof slopes at the same angle and has the same square-topped gable as that of the church that has replaced it. In Vermeer’s painting, the diagonal formed by the eaves of the church bisects the section of brick wall above the square-topped archway belonging to the house next door. The concealed alley leading

to the hidden schuilkerk is mirrored by an open passage running alongside the neighboring house. The entrance to that passage is a square-topped archway with no door, through which we can see a woman with a broom.

The same arrangement of buildings, on the exact spot of the Remonstrant church, is recorded in a map of Delft published by the cartographer Joan Bleau in 1649, about 11 years before Vermeer painted his picture. When mapping the houses on the northeast side of the Oude Delft between Butter Bridge and Pepper Street, a substantial block, Bleau registered a single alleyway piercing the street façade and giving pedestrian access to the buildings behind. As his map shows, that alley’s function was to act as a conduit to the hidden church. Despite working on a tiny scale, the cartographer even managed to indicate that the canalside entrance to the passage was guarded by a door set into a round-topped arch: the same black door that Vermeer painted. Behind the large house to the right of the church, Bleau placed a patch of green. Dead center of Vermeer’s painting a few sprays of foliage creep out from behind the left edge of that same house, at tree height, hinting at the presence of a concealed garden in the place indicated by the mapmaker.