News

the

Must-see exhibitions

of

From top: Work by the woodcarver Per Norén aka Spångossen; a silver deer from Buccellati’s Furry collection; detail of an Isamu Noguchi sculpture at the Goodwood Art Foundation, England.

Patrick Seguin collects to celebrate triumphs of

By James Haldane

How does collecting differ from hoarding? By Orna Guralnik and Ruby Guralnik Dawes

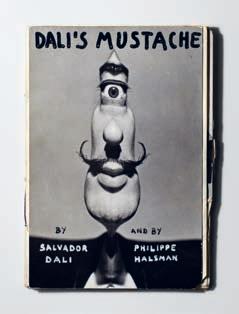

How Philippe Halsman and Salvador Dalí initiated one of the great collaborations of the 20th century. By Oliver Halsman Rosenberg, as told to Julie Coe

Photography by Henry Leutwyler

When art

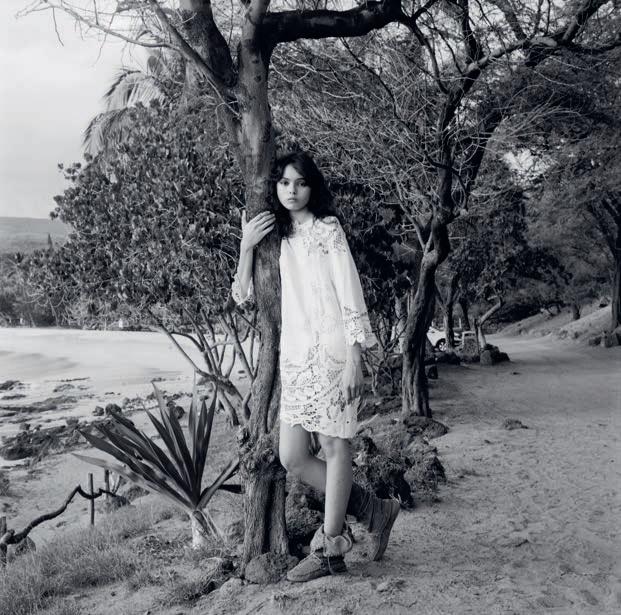

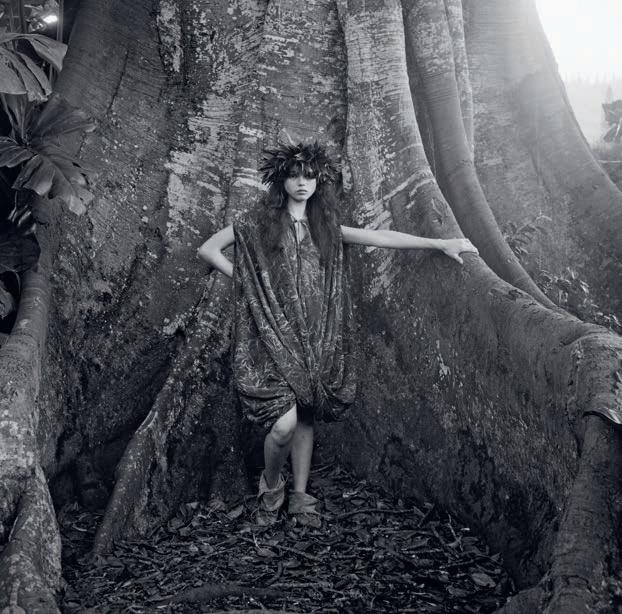

At Sensei Lanai, A Four Seasons Resort in the misty uplands of the Hawaiian island, a world-class tropical sculpture park provides the perfect frame for this season’s breeziest silhouettes.

Photography by Olivier Kervern

Styling by Tony Irvine

The fantastical aura of the director’s movies shines through in the shots he takes on set and elsewhere, on view in his first photography show this spring. By David Kamp

Photography by Angelo Pennetta

An Italian Design Story

The founders of interior design firm Casalta, Catherine and Nathan Bruckner, use their Fifth Avenue apartment and highly personal art collection, stretching from Botticelli to Basquiat, as a proving ground for ideas.

By Sarah Medford

Photography by Victoria Hely-Hutchinson

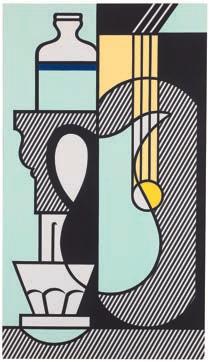

A preview of the new Goodwood Art Foundation, where Charles Gordon-Lennox, the 11th Duke of Richmond,is forging an ambitious program of contemporary art among the lush lands of a historic English estate.

By Vassi Chamberlain

Photography by Simon Watson

In an excerpt from “The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland,” writer Michelle Young recounts how Valland, a young Jeu de Paume employee, quietly kept score as the Nazis filled her beloved museum with looted art.

By Michelle Young

In the centenary year of the art deco movement, L’Oréal scion Jean-Victor Meyers is throwing an evening ball at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris to revive traditions of craftsmanship and patronage in fashion, art and design.

By James Haldane

Photography by David Sims

98 EXTRAORDINARY PROPERTIES

Partner content by Sotheby’s International Realty.

108 GOING, GOING, GONE

A royal passion for pugs.

By James Haldane on the cover

Yorgos Lanthimos standing in front of the Webber 939 gallery in Los Angeles, where the first exhibition of his still photography is on show, photographed by Angelo Pennetta.

follow @sothebys on all platforms

From top: (Left to right) Bayley Mizelle (Webber Gallery), Rosie Coleman Collier (MACK), Yorgos Lanthimos, Michael Mack (MACK); Jan Sanders van Hemessen, “Christ as Triumphant Redeemer,” circa 1546; a trio of letter openers from the collection of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, sold in 1997.

As the seasons continue to shift, there’s a feeling of new light and life continuing to reveal itself. The theme of unveilings resonates throughout the issue, with discoveries of new talents and Old Masters alike.

this month, sotheby’s will offer the Saunders Collection in New York, one of the greatest assemblies of Old Masters to come to auction in living memory. Fittingly, collectors Jordan and Thomas Saunders were advised by one of our chairmen and longest-tenured specialists, George Wachter, who first joined the Old Master Paintings department in London in 1973. He spent many years guiding the couple as they assembled the collection for their home, sourcing works around the world,focusingonqualityaboveallelse.

Wachter recollected to me the story of hunting down this painting by Jan DavidszoondeHeem,forwhichhetraveled to Rome. “We spent four days there, workingoutoftheofficewehadonthePiazzadi Spagna. A man arrived and trudged up the threeflightswithagarbagebag.Atthetop, he pulled out this masterpiece—a knock your socks off masterpiece—we almost fainted when we saw it.” The work’s virtuoso rendering of flowers and their rich palette of colors serves as the inspiration forourthreeeditorialactopeners.

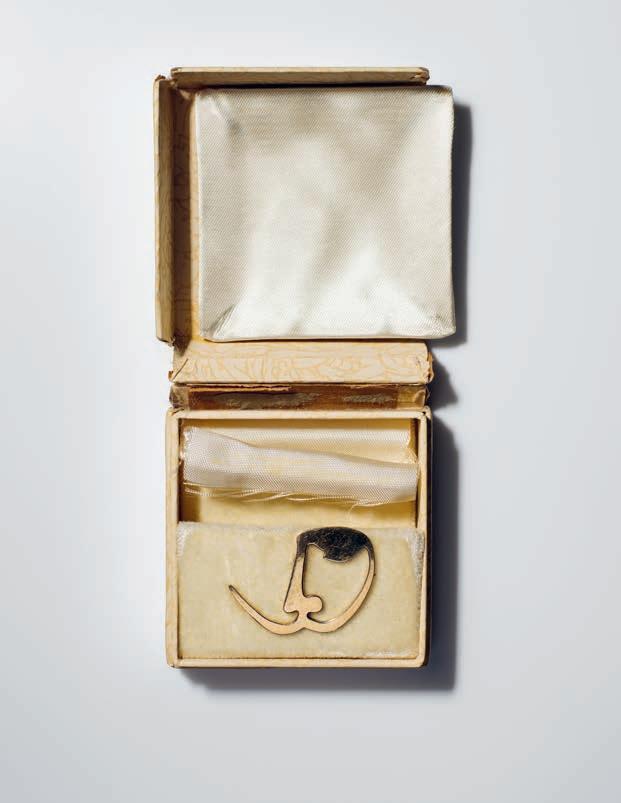

Thinking of new masters, our Collector’s Item story details the relationship between Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí and photographer Philippe Halsman. It’s illustrated with images of Halsman’s studio kit, taken by our regular contributor, Henry Leutwyler, who, in producing such anextensivebodyofworkonafellowpractitioner’s approach, pioneered a new form oflayeredstorytelling.

Our cover story reveals how star filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos is exhibiting his passion for still photography for the first time. In other features, we preview the Goodwood Art Foundation, where the Duke of Richmond is connecting contemporary art with nature, and stop in at the apartment of Nathan and Catherine

Jan Davidszoon de Heem, “Still Life of Roses, Tulips, a Sunflower, Lilies, an Iris, Poppies, Honeysuckle and Other Flowers in a Glass Vase with Two Birds, a Grasshopper, and a Snail.” $8,000,000-$12,000,000, “Elegance & Wonder: Masterpieces from the Collection of Jordan and Thomas A. Saunders III,” May 21, Sotheby’s New York.

Bruckner, founders of the interior design practice Casalta. Touching on new books, we carry an excerpt from “The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland” by writer Michelle Young, and ask design expert Patrick Seguin to answer our Collected WisdomQ&Aashereleasesanewtomeon hiscollectionofJeanProuvéobjects.

We also see fashion in new ways. In The Artist Portfolio, photographer Olivier Kervern transports us to the art-filled Sensei Lanai, A Four Seasons Resort, on the Hawaiian island, where

the season’s new looks harmonize with sculptural forms. Lastly, catch a first look at the capsule collection by FRAME in collaboration with Sotheby’s—31 pieces that marry our legacy with FRAME’s signature spin on modern classics. Available June 4 at frame-store.com. Get it before it’s going, going, gone.

David Kamp Writer

Michelle Young is an awardwinning journalist, author and professor whose works have been published in Hyperallergic, The Wall Street Journal and more. A Harvard and Columbia graduate, she founded Untapped New York. Her new book is “The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland” (HarperOne). The Curator Versus the Nazis, p90.

Editor in Chief – Kristina O’Neill

Creative Director – Magnus Berger

Editorial Director – Julie Coe

Director of Editorial Operations –Rachel Bres Mahar

Executive Editor – James Haldane

Visuals Director – Jennifer Pastore

Design Director – Henrik Zachrisson

Entertainment Director –Andrea Oliveri for Special Projects

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Akari Endo-Gaut, Frank Everett, Cary Leitzes, Sarah Medford, Lucas Oliver Mill

CULTURESHOCK

Chief Executive Officer – Phil Allison

Chief Operating Officer – Patrick Kelly

Head of Creative – Tess Savina

Production Editors – Rachel Potts, Antonia Wilson, Emma Nicklin

Art Editor – Gabriela Matuszyk

Designers – Ieva Misiukonytė, Michal Kuzmierkiewicz

Subeditors – Emily Hawkes, Mark Grassick, Sean McGeady, Kenneth R. Rosen

PARTNERSHIPS

Head of Global Partnerships –Eleonore Dethier

David Kamp is an author, journalist and lyricist. His most recent book is “Sunny Days: The Children’s Television Revolution That Changed America” (Simon & Schuster). His work has appeared in Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, Vogue, Air Mail, The New York Times and GQ.

Yorgos Lanthimos, Photographer, p70.

Vassi Chamberlain Writer

Vassi Chamberlain is a LebaneseGreek-British award-winning journalist who writes for The Times (London), Air Mail and British Vogue. Over the years, she has interviewed Robert De Niro, Julian Schnabel, Tom Ford and Donna Langley. She covered the Ghislaine Maxwell trial and has published two books with Assouline.

From the Foundation Up, p84.

Olivier Kervern Photographer

Based in Paris, Olivier Kervern has self-published three books; a fourth was published by Soft Copy. Last year his work was in a collective exhibition of contact prints entitled “Contacts” alongside that of Guido Guidi, Luc Chessex and Walker Evans. His photographs can also be found at the A Foundation in Belgium. The Artist Portfolio, p52.

PUBLISHING

US (New York, Northeast and Michigan) Fashion – Judi Sanders LGR Media Plus – judi@lgrplus.com

Jewelry & Watches – Jill Meltz jill.meltz.consultant@sothebys.com

US (Southeast and West Coast) Mark Cooper TL Cooper Media markcooper@tlcoopermedia.com

US Galleries and Museums - Ian Scott TL Cooper Media ian.scott.consultant@sothebys.com

UK and France

Charlotte Regan Cultureshock charlotte@cultureshockmedia.co.uk

Italy

Bernard Kedzierski and Paolo Cassano K. Media bernard.kedzierski@kmedianet.com paolo.cassano@kmedianet.com

Switzerland Neil Sartori Media Interlink neil.sartori@mediainterlink.com

France Guglielmo Bava Kapture Media gpb@kapture-media.com

India and GCC Region Marzban Patel Mediascope marzban.patel@mediascope.co.in

SOTHEBY’S

Chief Executive Officer – Charles F. Stewart

Chief Marketing Officer – Gareth Jones

Chief Communications and Partnerships Officer – Karina Sokolovsky

Global Head of Brand – Jacqueline King

Global Head of Content – Nick Marino

Global Head of Growth Marketing – Tracy Heller

Global Head of Social Media – Anne Johnson

Global Head of Video Production – Rachel Roderman

Head of Events and Preferred, Americas – Richard Drake

Head of Events, UK – Lydia Soundy

Head of Procurement – Eduardo Guerra

Production Manager – Stephen J. Stanger

GENERAL INQUIRIES sothebysmagazine@sothebys.com

Please note that all lots are offered for sale subject to Sotheby’s Conditions of Business for Buyers (which include our Authenticity Guarantee), which can be found on the relevant sale page on www.sothebys.com. Sotheby’s, Inc. License No. 1216058.© Sotheby’s, Inc. 2025. Information here within is correct at the time of printing.

David Zwirner

NEW YORK

JUNE 11-12

Creations by the 20th century’s greatest designers from the U.S. and beyond.

Paul Dupré-Lafon, “Mappemonde” low table. $150,000-$200,000, “Important Design.”

NEW YORK MAY 28 - JUNE 18

The finest jewelry, watches, extraordinary handbags and sneakers.

MILAN MAY 22

The automotive auction returns to Palazzo Serbelloni, an 18th-century jewel in the Porta Venezia neighborhood.

1974 Porsche 911 Carrera RS 3.0.

€1,100,000-€1,500,000, “RM Sotheby’s Milan.”

PARIS MAY 20

NEW YORK MAY 21-22

Comprising over 50 masterpieces from the collection of Jordan and Thomas A. Saunders III.

Adriaen Coorte, “Still Life of a Porcelain Bowl with Wild Strawberries,” 1704. $2,000,000$3,000,000, “Elegance & Wonder: Masterpieces from the Collection of Jordan and Thomas A. Saunders III.”

Remarkable creations by Les Lalanne and other greats of 20th-century design.

David Webb, pair of

and diamond

earclips. $40,000-$60,000, “High

Maria Pergay, dining table, 2007. €150,000-€200,000, “Important Design.”

For our full auction calendar, visit sothebys.com/calendar

LONDON MAY 23

A remarkable collection of folios by the Bard of Avon.

William Shakespeare, The Four Folios, 1623-1685. £3,500,000-£4,500,000, “The Four Folios of Shakespeare.”

COLOGNE JUNE 4-5

Bringing together works by celebrated artists of the 20th and 21st centuries.

LONDON JUNE 24-25

Trailblazing works from modern and contemporary masters and designers.

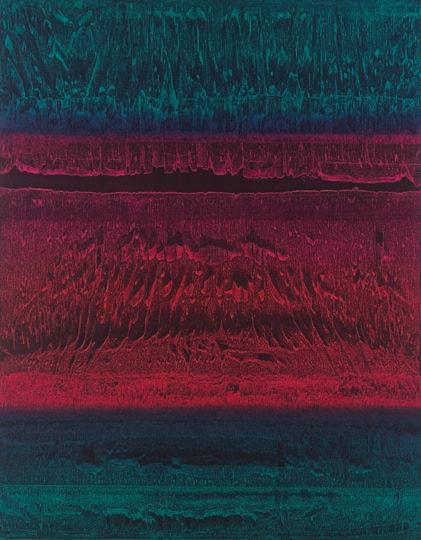

Roy Lichtenstein, “Purist Still Life with Pitcher,” 1975. Estimate upon request, “Modern & Contemporary Evening Auction.”

PARIS JUNE 12

Fine Asian art, from Buddhist sculpture to jades and furniture.

Gilded bronze Avalokiteshvara statuette, Dali Kingdom, Yunnan, 10th-12th century. €250,000-€350,000, “Asian Art.”

NEW YORK JUNE 24 - JULY 23

Dedicated to celebrating the rich history and cultural significance of sports through exceptional artifacts.

Kobe Bryant “Rookie Season” 19961997 game-worn sneakers. $300,000-$400,000, “Summer Classics.”

Lovis Corinth, “Walchensee (Gemüsegarten),” 1924. €350,000-€550,000, “Modern & Contemporary Discoveries.”

MILAN MAY 28

Bringing together works by celebrated artists of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Lucio Fontana, “Concetto Spaziale, Attese,” 1968. €1,600,000-€1,800,000, “Modern & Contemporary Art.”

The seal of Napoleon, seized after the Battle of Waterloo, carries history in its golden detail.

Unseen by the pUblic for decades, this seal represents an important and moving chapterofFrenchhistory.Fashionedfrom ebony and gold, and bearing a large imperial coat-of-arms, it is tied to one of the most consequential military campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte’s First French Empire. The fine materials and exacting quality of its engraving suggest that this seal could only have belonged to the emperor himself, a physical testament to the height of his ascendancy.

Following the Battle of Waterloo of June 18, 1815, at which Napoleon was decisively defeated by two armies of the Seventh Coalition, a force led by British and Prussian contingents, the French leader fled towards Paris in a convoy of 14 vehicles. As the roads became congested, he was forced to abandon his carriage, allowing Prussian infantry and cavalry troops to descend upon it.

Silverware crates were torn open, and other luxury items were carried away. Some of the looters were later compelled to offer their spoils to the King of Prussia, who gifted them to deserving officers and allies.

Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher (17421819), field marshal of the Prussian army, reportedly received the emperor’s hat and uniform, along with this gold seal. A note accompaniestheseal,recountingitsstory in German. This letter is signed, perhaps by August Wilhelm Antonius, Count Neidhardt von Gneisenau (1760-1831), a member of an important Prussian family, who fought alongside von Blücher.

The seal’s design presents an iconography of power, anchored by an eagle clutching a thunderbolt below a visored helm and an imperial crown. Also featured is a draped mantle decorated with bees—Napoleon’s own emblem—overlaid with the chain and pendant of the Légion d’Honneur, crossed behind by the scepters of justice and mercy.

Von Blücher played a pivotal role at Waterloo. Leading a corps of 34,000 soldiers, he arrived at the battlefield late in the afternoon, bolstering the forces led

BY LOUIS-XAVIER JOSEPH Senior Director, Head of Department, European Furniture and Decorative Arts

by Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1769–1852), to crush the French.

Offering the Prussian commander, whose interventionmaywellhavetippedthebattle’s outcome, such a personal item from the fallen emperor would make fitting a war trophy. Without von Blücher’s aid at Waterloo, the coalition troops might have faltered.

The seal’s next owner may have been Wellington—Napoleon’s greatest foe. A towering figure in British military history, he first defeated Napoleonic forces in Portugal in 1808, and then again in a series of further engagements during the Peninsular War. It is thus conceivable that von Blücher presented Wellington with this seal to mark their shared triumph.

Beyond their rivalry, it is known that the duke admired Napoleon’s strategic genius. At his London home, Apsley House, purchased from his elder brother in 1817 and visitable today, Wellington amassed an impressive collection of paintings and Napoleonic relics tied to Waterloo. Among them stands Canova’s colossal marble statue, “Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker.” A gift from King George IV, who knew of Wellington’s fondness for the sculptor’s work, it stands about 12 feet tall, looming in the entrance hall as a striking tribute to his historic adversary.

With its links to three titans of 19th-century military history, the seal represents a unique highlight in a remarkable collection assembled over more than 40 years in tribute to an eternal figure.

A gold and ebony personal seal of Napoleon, featuring the Great Imperial Coat of Arms, and its case, taken from his carriage on the evening of the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815. Estimate upon request, “Napoléon: Une Collection Historique,” June 25, Sotheby’s Paris.

A rare Lalanne ostrich bar hides a secret beneath its biscuit porcelain wings.

In 2017, as sotheby’s prepared to offer an example of Bar aux Autruches from the collection of interior designer Jacques Grange, we reached out to ClaudeLalanne,thewifeofitslatemaker, François-Xavier Lalanne, for cataloging information.Sheenthusiasticallyinvited us to the home they had shared in Ury, a house and workshop with Île-deFrance village charm. Upon our arrival, she suggested we enjoy lunch first. Claude was an excellent cook, and the wineswerealwaysexceptional.Thatlate summer day, she welcomed us with fine food and a view of the garden where she nurtured flowers and plants to become worksofart.

After the meal, she led us upstairs to François-Xavier’s untouched bedroom, tucked under the eaves on the first floor, whereIdiscoveredanotherostrichbar— the ostrich bar. Claude told me it had been her husband’s favorite sculpture. In the 1970s, it had stood in the home’s entrance, but François-Xavier, weary of collectors and dealers constantly trying

to buy it, had moved it to his bedroom wherenoonecouldaskforit.

In 2019, following Claude Lalanne’s passing, Sotheby’s was asked to inventory her home and studio. Once again, I found myself before this extraordinary work in François-Xavier’s bedroom. Only six examples of the ostrich bar were ever produced, between 1966 and the early 1970s. Two remain in French national collections—one at the Manufacture Nationale de Sèvres and another at the Élysée Palace, placed there under President Georges Pompidou. As part of France’s inalienable state collections, these will never be sold. Of the remaining bars, only three have ever been offered for sale—François-Xavier keptoneforhimself.

Withimmensejoyanddeeprespect,we now present François-Xavier Lalanne’s personal edition. This masterpiece embodies his artistic vision—functional, humorous, poetic and universal. The living specimens of these birds are imposing in stature—unable to fly, yet incredibly fast—creating a striking contrastbetweenlightnessandstrength.

Lalanne plays on this paradox, sculpting two life-sized ostriches in porcelain, their articulated wings revealing hidden bar compartments. In the center, an egg

BY FLORENT JEANNIARD Chairman, Co-Worldwide Head of 20th Century Design

becomes an ice bucket, adding a touch of humor. With a surrealist spirit, Lalanne transforms the animal into a hybrid creation—half sculpture, half functional object. This playful reinterpretation recalls René Magritte and Salvador Dalí, where the unexpected sparkswonder.

Rooted in the grand tradition of decorative arts, the ostrich bar echoes precious 18th-century furniture once adorned with Sèvres porcelain. By reviving this savoir-faire, Lalanne bridges past and present, crafting a timeless and modern work. The piece also evokes Renaissance-periodcabinetsofcuriosity and ceremonial furniture, when exoticism and rarity symbolized ultimate luxury. Here, the ostrich transcends nature, becoming a sculptural tribute to thebeautyoftheanimalworld.

Lalanne’s collaboration with the Manufacture de Sèvres gives the work a singular aura. The fusion of metal and porcelain showcases masterful craftsmanship, blending technical precisionwithpoeticimagination.Byinfusing furniture with a dreamlike quality, Lalanne redefines design, proving that function and beauty can coexist. His art transforms the ordinary into the extraordinary, inviting us to see the worlddifferently.

This work embodies one of his core beliefs: art should not be merely contemplative but should inhabit everyday life—tosurprise,delightandstiremotion. With the ostrich bar, François-Xavier Lalanne reminds us that imagination and humor are essential to beauty and that art, above all, is an invitation todream.

François-Xavier Lalanne, Bar aux Autruches, 1967-1968. €3,000,000-€4,000,000, “Important Design,” May 20, Sotheby’s Paris.

Act One: The Opening Bid, in which we present news from the worlds of art, books, culture, design, fashion, food, philanthropy and travel. Plus, The Global Agenda, which highlights not-to-be-missed exhibitions opening in May and June.

Edited by Julie Coe

this spring and summer, 200-plus subtropical plants will manifest their own ecosystem inside a building in Venice. The Belgian Pavilion at the Biennale Architettura 2025 is hosting this experiment in artificial, natural and collective intelligence, titled “Building Biospheres,” which grew out of a decade-long conversation between Belgian landscape architect Bas Smets and Italian neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso. Meters and weather stations monitoring the plants’ inner workings supply information to an AI system that controls light, water and air. If photosynthesis stops, the artificial sunlight turns on; if evapotranspiration stops, the water switches on; if evapotranspiration stops, but thesoilisstilldamp,theventilationstartsuptolower the humidity. “The plants don’t speak. They don’t push buttons. But they are doing it,” explains Smets. “A plant is very good at understanding its environment.Sothere’sthisideathattheplantsatsomepoint will know how to activate a light. Is it true or not? We’ll test it.” In Smets’ view, architecture is fundamentallyaboutsurvival,aboutbuildingaroofagainst the elements, and with climate change, we may need to extend this protection to plants, bringing them indoors for our mutual benefit. Smets, whose Brussels-based firm has envisioned innovative landscaping for the Luma Foundation in Arles, France and Notre Dame cathedral in Paris, hopes for a future where nature and architecture are no longer in opposition, but become something more hybrid.

“We’re opening doors for a new understanding of architecture,” Smets says, “not as an inside cut off from an outside, but as a continuum of biospheres andatmospheres.”

Dominique Crenn roSe To FAme in San Francisco, where her restaurant Atelier Crenn received three Michelin stars–making her the first woman chef in the U.S. to achieve that distinction. After decades in California, though, she’s still inspired by the food of her native France, especially Brittany, where she spent many childhood summers. This year, in collaboration with Les Bateaux Belmond, she has created a series of menus for Belmond’s fleet of 4- to 12-passenger boats that navigate French waterways. Each route offers a different gourmet itinerary, such as a tasting tour of Bordeaux châteaux or a pilgrimage to five of Burgundy’s Michelin-starred restaurants, but they all share the opportunity to relish Crenn’s onboard fare. Voyages through southern regions will emphasize Mediterranean cuisine–vegetable-heavy soupe au pistou, Comté-filled ravioles du Dauphiné and roasted sea bream–while northern journeys will go back to the land, highlighting spring peas, morels, green peppercorns and braised leeks.

On Milan's Via Manzoni stands a former private mansion that Molteni&C has converted into a striking new flagship, with interiors by Belgian designer Vincent van Duysen, the brand’s creative director. First built in the 19th century, the structure was given a Liberty style makeover in 1922. More recently, two new aerie-like stories were added to the top of the building, where Molteni will host events like designer talks and book readings.

At this yeAr’s sAlone del Mobile in Milan,Loewedebutedaseriesof25unique teapots, each envisioned by a different artist or creative type, such as painter Rose Wylie, designer Patricia Urquiola and architect David Chipperfield. Shown here is the vessel by Walter Price, the 36-yearold painter from Macon, Ga., whose practice sits somewhere between abstraction andrepresentation.

Walter Price teapot, price upon request; loewe.com

Assouline’s new Library Collection is for book lovers who want a chic backgammon set or plinthshaped walnut bookends to go with their artfully produced volumes. The offering also includes candles with scents like paper, cigar and wood to conjure up historic Parisian reading rooms.

Twist bookend, $375; assouline.com

the swedish woodcArver Per Norén, who also goes by Spångossen, thinks of his work in musical terms. “I tune the different aspects of the shape,” he explains. “It’s bass notes in someareas,andthemostdelicate parts shimmer in the upper part of the frequency.” Norén, who lives in the Hälsingland region, takes inspiration from the area’s folkmusic, folkdräkt clothingand UNESCO-recognizedfarmhouses, as well as sloyd woodworking traditions. He works mostly on commission, often fielding inquiries via Spångossen’s Instagram account. Later this year he’ll have his first solo show at the Hälsinglands Museum, featuring “maximized” versions of his exquisitely etched spoons andcontainers.

instagram.com/spangossen; halsinglandsmuseum.se

The V&A’s new museum, the V&A East Storehouse,

after a wildly successful collaboration with the Ritz Paris, it’s Sotheby’s turn to get a fresh look from fashion brand FRAME. LaunchinginJune,the31-piecelimited-edition collection leans into the preppy-chic aesthetic of Sotheby’s Upper East Side

location. There are argyle sweater vests and wool double-breasted jackets, not to mention classic tees and totes emblazoned with the word “collector.” The pajamas, boxer shorts and bathrobe are the perfect attire for logging in to bid from home.

Karl Fournier and olivier Marty, partners in the Paris-based architecture firm Studio KO, like to ask themselves more questions than they can answer, a habit they picked up as students at the École des Beaux-Arts in the ’90s. Certainty is outside the mindset of Studio KO, which prides itself on sensitivity to context and a perpetual attitude of discovery. The firm, which celebrates its 25th birthday this year, is probably best known for the Chiltern Firehouse hotel in London, a Victorian fantasia that opened in 2013 (and recently endured a tragic fire—it is now being restored). But the project that put it on the architectural map is the Yves Saint Laurent Museum in Marrakech, a tour de force of sunbaked brick completed in 2017.

Studio KO’s love for the handmade took root in Morocco, and a new project there with Beni Rugs has alreadybecome a touchstone in the firm’s anniversary year.WorkingwithBeni’sweaversoutsideMarrakech, it has designed 10 carpets that take the techniques of flatweave, intricate knotting and embroidery to new levels of refinement. The collection launched in April, ahead of another exercise in culturally attuned reinvention: the Fashion & Costume Museum in Arles, where three centuries of Provençal artisanship will play out against Studio KO’s transformation of a Baroque-era hôtel particulier.

In Tashkent, Uzbekistan, Studio KO’s design for the Center for Contemporary Arts will open in the fall, recontextualizing a series of existing buildings for use as exhibition and teaching spaces and an artists’ residency. And finally, an anniversary project close to home: the Bus Palladium, a much-loved Parisian nightclub, is also set to reopen this fall as a concert venue topped with a luxury hotel.

Aquartercenturyon,whatsurprisesFournierand Marty most about their continued success? “Creating your own work is somewhat like giving birth to a living organism,” Fournier says wryly. “It quickly escapes your control and follows its own growth.” —Sarah Medford

Top: Zsa‑zsa Korda’s daughter Liesl, played by Mia Threapleton, with Tilman Riemenschneider’s “Lamentation of Christ” to the left and Juriaen Jacobsz’s 1678 “Dogs in Combat” to the right.

Above, from left: Bjorn, played by Michael Cera, with Julius Von Ehren’s “The Barbara‑ Altar (Four Copies After Master Francke),” from 1925; Floris Gerritsz van Schooten’s “Still Life of Breakfast With Roast Ox” sits between Zsa‑zsa Korda (Benicio Del Toro) and one of his sons (Gunes Taner); Liesl with Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s “Enfant Assis en Robe Bleue (Portrait d’Edmond Renoir Jr.),” 1889.

The films of Wes Anderson offer a multilayered viewing experience, thanks not only to their extensive and memorable casts of characters but also to their expertly executed, instantly recognizable visual style. Highly detailed sets featuring spot-on interiors help build an entire world around each narrative.

Anderson’s latest, “The Phoenician Scheme,” adds blue-chip artwork, borrowed from museums and private collections, to this approach.

“The Phoenician Scheme” stars Benicio del Toro as international businessman Zsa-zsa Korda, one of Europe’s richest men. Korda is “a ruthless, uncompromising dealmaker, a man of exquisite taste and a pathological collector of people, places and precious objects,” says Jasper Sharp, a curator who worked on the film. “It was imperative that he have

an impressive art collection.” Tasked with assembling this trove, Sharp brought together several Old Master works, including German altarpieces and Dutch still lifes and hunting scenes, as well as two later portraits: Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s 1889 painting of his young nephew and what Sharp calls an “enigmatic, brooding” canvas painted by René Magritte in 1942, only a few years before the film’s midcentury setting. Together these works, Sharp says, “provide an elegant foil to the madness that often ensues around them.”

Sharp’s curation serves as a magnifying glass for Korda’s character, with each artwork representing, he notes, “a strand of Zsa-zsa’s complex personality, a resultofhisdealmakingandatangiblerepresentation of the fortune that he puts on the line.”—Sarah Massey

In France, new ideas are growing among the vines. This year marks the 10th anniversary of UNESCO recognizing the climats of Burgundy— 1,247 small vineyards that make up the Côte de Nuits and Côte de Beaune ON LOCATION

wine regions—as a World Heritage Site. GuillaumeKoch,directoroftheHospices Civils de Beaune—the organization that today hosts the world’s oldest charity wine auction, held annually since 1859— wanted to use the occasion to celebrate the area’s cultural history in a fresh way. He has invited Mode 2, a Mauritianborn graffiti artist who honed his skills in London and Paris, to devise a program with La Karrière, a nearby arts space based in a former stone

quarry. Mode 2 has commissioned three fellow street artists—Jace, Eron and Delta—to create a series of artworks on show through until late in the year at the Hôtel-Dieu, Beaune’s original 15th-century hospital building. “I always look for people who are curious about humankind in general, passionate about what they do and open to art history,” explains Mode 2. —James Haldane

Creating exquisite flora and fauna has been part of Buccellati’s DNA since its early years. In the 1960s, the Furry collection introduced novel silversmithing techniques that captured the details of feathers and pelts. The jewelry house’s Naturalia exhibition, celebrating this silver menagerie, went on view in Milan in April and travels to the US later this year.

Armani Casa’s Vivace chair mixes the elegance of its sloping curves and embroidered-silk upholstery with the playfulness of its bamboo-textured metal frame.

Vivace chair, price upon request; armani.com

on amsterdam’s prinsengracht canal, the 17th-century edifice that served as the city’s Palace of Justice for nearly 200 years reopens June 1 as the new Rosewood Amsterdam. The building’s formerjailcellsandcourtroomshavebeen handsomely reimagined as 134 rooms

and seven suites by Dutch design firm Studio Piet Boon, and the new courtyard garden features the artistry of landscape designer Piet Oudolf. For interested guests, the hotel offers tours of the newmedia showcase Nxt Museum and the gallery scene in Amsterdam North.

Paul Poiret: Fashion is a Feast opens at the

Rick Owens: Temple of Love opens at the Palais Galliera in Paris. Canton Modern: Art and Visual Culture, 1900s–1970s opens at M+ in Hong Kong.

Act Two: In which we delve into the minds of creators and collectors, discussing the long-sought works that got away, tracking the place art has on our walls, learning from artists’ fruitful collaborations and parsing the psychology behind it all.

The French dealer, an authority on 20th-century design, together with his wife, Laurence, has assembled the leading collection of objects by the self-taught architect Jean Prouvé, as revealed in their new book.

BY JAMES HALDANE

Describeyourcollectioninthreewords?

Art, design and architecture.

What was your very first collection, maybe as a child or a teenager? I grew up in a simple environment. Art came into my life later, when I was about 20.

Does art play a role in your romantic relationship? My wife, Laurence, and I founded Galerie Patrick Seguin together in 1989. We share the same passion, which we’ve turned into our profession.

How would you change the art world?

There is too big a distortion in personal collections between art and decorative arts. What I mean is that there are so many collections among the houses we visit where the collection of modern or contemporary art is incredible, but the furniture is ordinary, far from matching the quality of the art. Yet the dialogue between the two is so strong.

Who is the most unjustly overlooked artist? Mike Kelley and Bruce Nauman.

Favorite art fair and why? Art Basel has long been the best international fair, but I have to admit that Art Basel Paris has become very active recently.

What “tools of the trade” do you use to keep building your collection? One of the advantages of being a gallerist is collecting for yourself. I specialize in historic French mid-century furniture, so I know this field intimately. I have my own trusted networks for sourcing the best pieces. For

art, it’s a different story. I have connections with many international galleries and have built close friendships with certain artists. This network was notably strengthened through the “Carte Blanche” exhibitions I organized at the gallery. Starting in 2002, I invited contemporary art galleries to curate shows in my Parisian space during FIAC/Art Basel Paris, giving them complete creative freedom. The first gallery I hosted was Jablonka Galerie, followed by others like Gagosian, Presenhuber, Paula Cooper, Luhring Augustine, Massimo De Carlo, Sadie Coles, Hauser & Wirth and Karma.

Favorite curator and why? Bob Nickas, withwhomwehaveorganizedtwofantastic exhibitions. I also loved the late Germano Celant, especially his remarkable reconstructionatthePradaFoundationinVenice of the Harald Szeemann exhibition “Live In Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form” from 1969. It was extraordinary.

What non-art object do you find most beautiful? I love everyday objects from Japan. For example, I have an old rice measuring box that I find magnificent.

Who is your collecting wingman?

Guillaume Houzé (an entrepreneur, art collector and director of image andcommunicationattheGaleriesLafayette Group).

Best art gift, given or received? Richard Prince, who is a long-time friend and who is one of the best living artists in my opinion, gave me a very special gift. It’s a beggar’s cup, which he very ironically cast in gold. He gave it to me to cheer me up at a time when I underwent a minor surgical procedure. It is an unusual object with a particular history.

Favoriteworkofarchitectureandwhy?

In the late 1930s, Jean Prouvé developed a constructive principle for demountable houses, which he later patented. It’s so clever and simple that it’s still relevant today.

Which piece doesn’t ‘fit’ in your collection but still works? “The City” by Michael Heizer.

What’sthepiecethatgotaway? A painting by Christopher Wool. I always wanted to own one, and I will.

Which collectors do you admire? Mitchell Rales, for creating the Glenstone museum in Potomac, Maryland.

What place is most inspiring to you? When I need to recharge my batteries, we go to the South of France, where we have a house designed by my lifelong friend Jean Nouvel. It’s an extraordinary place, open, sun-drenched and surrounded by nature.

Opposite: Patrick and Laurence Seguin in their Paris apartment. Clockwise from left: Jean Prouvé’s long-lost Maxéville Design Office; “Jean Prouvé: From Furniture to Architecture, The Laurence and Patrick Seguin Collection”; gold beggar’s cup by artist Richard Prince.

What tips do you have for collectors juststartingout? Bewell-informed,read, see as many shows as possible and trust your own intuition.

What artwork or object have you restored back to life? Jean Prouvé’s Maxéville Design Office, built in 1948. For years, it served as a swingers club called Le Bounty in an industrial suburb of Nancy, its architectural significance hidden under layers of club decor. I discovered that much of the building was intact, protected by its aluminum cladding. I acquired it, relocated it to a warehouse, and fully restored it to its original beauty.

What’s the best compliment someone has paid to your collection? Once we hadRichardandRuthieRogerstolunchat home, and it went on all afternoon. A few days later, I received a very moving letter from Richard. •

In an ongoing column, a psychologist and a curator delve into the various meanings behind the act of collecting, exploring its significance both for individuals and society as a whole.

BY ORNA GURALNIK AND RUBY GURALNIK DAWES

TradiTional psychoanalyTic practices are all about narrative, translating psychological distress into the realm of storytelling.Narrationwithintheanalytic space allows patients to transform inchoate emotional experiences into coherent form, a sequence that creates meaning. Language adds weight to memory otherwise bound to the prelinguistic realm of dreams or memories. In other words, formulation into verbal narrative facilitates psychic integration.

In “Psychoanalysis as Therapy and Storytelling,” Antonino Ferro suggests that psychoanalysis is a form of literature. The narratives constructed between analyst and patient are a medium to access deeper truths, which is healing. Owning and organizing possessions can be seen as a rare opportunity to have total control over those narratives.

While hoarding and collecting may look like cousins—each involving the accumulation of objects—the psychoanalytic stories they tell are fundamentally different. Hoarders often feel uncomfortable about revealing the degree of their compulsion and the state of their homes. On the other hand, collecting is an ego-syntonic activity: the collector feels at one with their act of collecting.

Artist, co-founder of the iconic Paper magazine and self-proclaimed “cultural anthropologist,” Kim Hastreiter reigns over an eclectic collection, ranging from ceramic babies to Tauba Auerbach paintings. Her recent memoir, “Stuff,” paints an audacious narrative of her life through the objects she keeps in her Manhattan apartment. She talked us through what it’s like to live with every object she has collected—instead of arranging and rearranging them in a public space, museum or storage. Her desire to collect stems from a place quite different from that of

a museum curator or an investor with a personal art advisor. The things she buys are reanimated by their relationship to her home, not necessarily to each other. The destination, therefore, becomes the organizing principle of selection.

“My collection tells the history of my life,” she says. From a young age, Hastreiter’s life has been all about collecting—both art and people. She invests emotion, memory and at times her entire essence into her objects, breathing meaning, import and context. She anoints the things she collects with the status of “just right.” While her approach to collecting could be thought of as unsystematic, without any particular order —she eschews seriality or repetition and detests anything that comes in a complete set, which categorically devalues an art object—she says she would “never put an artist up that [I] thought would hate the artist next to it.”

We paused to wonder with Hastreiter whethershesawhercollectingasahoarder’scompulsion.“Therearecertainthings I didn’t buy, and I obsess for years,” she told us. For both collector and hoarder, holding onto objects that recall memories or sensations ensures that these memories or sensations never fade. One could say that while hoarders cannot be selective about the things they keep, collectors have to be excellent editors. A good narrative, after all, needs a good editor. When Hastreiter falls for an object, she must have it. Yet, she can also conclude that an acquisition was “wrong.” She speaks frequently and eloquently about her capacity for editing, including knowing how to get rid of things. “Put me in a room with a thousand photographs, I’ll find the best one in five minutes,” she says. “Editing is one of my skills. I never even went to school for it, but over the

years I realized I have certain skills that I’m really good at, and certain things I’m really bad at. I can go to the biggest thrift store on earth and I’ll find the Hermès scarf in, like, 10 seconds. I know what’s mediocre and what’s fabulous.”

On the other hand, hoarding is defined as a chronic inability to discard possessions. Typically, hoarders struggle with a compulsive urge to save items from being thrown away, passed on or sold. For the hoarder, as for the collector, a deep psychological worry can develop at the thought of letting objects go. Each item bears its own psychological weight and functions as an emotional stand-in, an objectified nostalgia. For the hoarder, homes become labyrinths of clutter. The clutter becomes a fortress against psychic emptiness, tangible proof that their inner worldwon’tdisintegrate.Freudassociated hoarding with the anal stage of development, suggesting a symbolic attachment to control, order and retention.

Collectors invest meaning in their chosen objects that help construct identity, narrative and even legacy. Think of Freud himself, who surrounded his consulting room with a curated array of Etruscan artifacts and Greek figurines—arguably a personalmuseumthatreflectedandstabilized his intellectual and cultural identity. Collecting, in this view, is a symbolic and often future-oriented act. The collector is not just acquiring but organizing, narrating, mastering. It is an expression of desire, not compulsion; agency, not anxiety. Hoarding, by contrast, is marked by disorganization, distress and a collapsing of symbolic meaning. In hoarding, objects ceasetobesymbolicrepresentations;they become defensive shields against loss, abandonment and psychic fragmentation. Where collecting externalizes meaning, hoarding internalizes fear. •

Oliver Halsman Rosenberg, the photographer’s grandson, is working on a documentary about his grandfather’s life. His family retains the majority of Halsman’s archive, including projects the Latvian-born photographer and Spanish artist collaborated on together. As Rosenberg recounts, Halsman reached his creative and technical heights alongside Dalí, his co-conspirator for 37 years.

PHOTOGRAPHY

BY

HENRY LEUTWYLER

PhiliPPe halsman started his career in Paris during the 1930s. When he came to the U.S. as an immigrant at the end of 1940, he had 12 prints, the camera he invented and a young family to support. While he was known in France as an emerging portrait photographer, he was unknown in America, and he needed to hit the pavement and look for work. He ended up finding a job with the Black Star photo agency.

In 1941, Black Star sent Philippe on assignment to the Julien Levy Gallery to photograph the installation of Dalí’s show there. Later that year, the two joined forces on a picture of a Ballet Russe dancer in a chicken costume Dalí designed, and it ended upbeingLife’sphotooftheweek.Andthatwasabigdealbecause Philippe had never had anything published in Life before.

Because they both spoke French, there was an instant camaraderie. The next time they met, Philippe went to Dalí’s suite at the St. Regis Hotel, where Dalí would often stay for an extended period of time, and said, “Dalí, I read that you remember your prenatallife.Iwanttotakeapictureofyouasifyou’reanembryo in an egg.” And Dalí said, “That’s a fantastic idea. Do I have to be naked?” And Philippe said yes, and Dalí said, “OK, come back next week.” So, Philippe came back and took a picture of Dalí in an egg. (My mom likes to say that before there was Photoshop, there was Philippe.) And that opened the door for this 37-year collaborative relationship. Every time Dalí came to New York, he would meet with Philippe, and they would dream up new concepts.

Philippe was interested in photographing ideas and concepts. He wasn’t just a straight photojournalist. He had this kind of creative streak.

The inspiration for “Dalí Atomicus” [the famous 1948 photo of Dalí jumping, cats hurtling through the air, easels and chairs flying and water splashing] came from a Dalí painting of Dalí’s wife, Gala, floating on a throne above the water. But the water itself wasn’t touching the beach. Everything was in levitation. Dalí was really interested in research on atoms and nuclei and protons and neutrons, how everything in the universe vibrates and nothing actually touches. He took that concept and applied it to his idiosyncratic, surrealist, Renaissance-inspired portraiture, with Gala as the muse. It was called “Leda Atomica.” So Philippe said, “I want to do a ‘Dalí Atomicus,’ a photograph of you levitating.”

I think there were 28 attempts. Sometimes the composition would be perfect, but the chair was in front of Dalí’s face or the water wasn’t good. These days we can take a picture and we can see it instantly. But at that time, Philippe had to run upstairs, develop it, make a contact print of it and then say, “Oh, we have to do it again.” In a way, it gave everyone time to collect themselves between the breaks. My mom, who was a kid at the time, was running after the cats and drying them off.

Now people would just do a composite in Photoshop, but the magical part of this photograph is that unique moment in time, which will never exist again.

That was just one of many creative ideas they explored. It was likeDalígavePhilippepermissiontogocrazyandbeexperimental. Dalí was his muse in a way.—As told to Julie Coe

For more of Halsman’s archive, see Henry Leutwyler’s “Philippe Halsman: A Photographer’s Life” (Steidl).

“This is a one-of-a-kind object that shows the collection of failures in the attempt to achieve the iconic image.”

“Philippe’s brother-in-law, René, was a jeweler, and Philippe tried to support him by buying his jewelry. René made this tie pin based on a photo of a mustache-shaped mobile in ‘Dalí’s Mustache’ (far top right). The question is ‘Have you evolved a definitive style?’ And on the next page, alongside the photo, it reads ‘No, I am completely mobile.’”

“It was like Dalí gave Philippe permission to go crazy and be experimental.”

—Oliver Halsman Rosenberg

Right: “‘Dalí’s Mustache’ (1954) was a question-andanswer book. For instance, on one page it says, ‘Why do you paint?’ On the next page, it reads, ‘Because I love art.’ But in the adjoining photo, Dalí’s mustache forms a dollar sign. I see a lot of meme-like energy in what Philippe was doing here, especially the idea of text and images going together incongruously.”

Below: “This photo really shows their relationship. They’re just having fun. Philippe is holding the camera he invented, the Halsman Fairchild, and Dalí is sitting on a cube. They both liked to use cubes in their work.”

How collectors have found innovative ways to hang Lucio Fontana’s epic 1965 copper diptych.

BY LUCAS OLIVER MILL

When Argentine-itAliAn Artist Lucio Fontana arrived in New York in November 1961, the city’s harsh winter air was not the first thing he noticed. He glanced up to see buildings like he had never seen before: columns of glass and steel that pierced through the clouds, the sun ricocheting off their mirrored facades. At night, the skyscrapers would come alive, city lights dancing across their surfaces.

Fontana had seen modernity before, but not at this scale. It was here, amid the glimmering labyrinth of skyscrapers, that he conceived his legendary “Metalli” series: a group of artworks that saw him abandon the canvas in favor of the metallic surface. He punctured, ruptured and slashed sheets of metal as he had done before with his knife and the canvas, but now with

heightened aggression and intensity. He would use hand tools such as awls, punches and chisels to pierce and gouge the metal. These were not neat, machined holes—he intentionally allowed the material to resist him, creating jagged, irregular perforations. The violence of the gesture was key. “Sometimes scratching them vertically to convey the idea of skyscrapers, sometimes puncturing them with a metal punch, sometimes flexing them to suggest dramatic skies,” Fontana would later recount.

Four years later, in 1965, astronaut Alexei Leonov became the first human to perform a spacewalk. That same year, grainy images captured by NASA revealing the surface of Mars were beamed back to Earth. It was a transformative year for human exploration and scientific discovery. Now, back in his Milan atelier, Fontana followed these developments closely. Deeply inspired by the ongoing space race and the chase for discovery and the unknown, Fontana eagerly pushed his own creations to grow in size and ambition. Among the works he created in 1965 was “Concetto Spaziale,” a monumental diptych forged from copper. The glowing hues of orange emanating from the copper plates echoed those first images of the Mars surface, the holes he broke through the plates like craters from an otherworldly terrain.

Just after completion of the diptych, the work was acquired by Fontana’s friend, collaborator and supporter, Mario Bardini, who had been closely following Fontana’s trip to New York, as revealed in personal letters between the two. “New York is more beautiful than Venice! The skyscrapers of glass look like great cascades of water that fall from the sky!” Fontana wrote to him.

A photograph from Bardini’s villa in Varigotti, in northern Italy, reveals the work in a particularly unusual setting: mounted above his fireplace. Bardini, an architect by trade, had first met Fontana in the 1950s and collaborated with him on a series of site-specific projects —such as slicing through the walls and ceilings of hotels and residential buildings— that combined Fontana’s artistic practice with Bardini’s architecture. Bardini’s decision to mount the “Concetto Spaziale” to look like an architectural element may have been an homage to their collaboration, transforming his own fireplace into a grand artwork. The Fontana remained in Bardini’s collection until 2004, a year before his death.

In 2004, film producer Ronnie Sassoon was sitting in her London living room, sifting through a Sotheby’s auction catalogue. “I saw a photograph of the Fontana and simply had to acquire it,” she tells me. At the time, she had been on the hunt for one of the artist’s “Natura” sculptures, but the luminous, industrial presence of the “Metalli” caught her attention. Already a collector of Fontana’s work—including a canvas with seven tagli (Italian for “cuts”) and a “La fine di Dio” (one of a rare group of egg-shaped

canvases)—this was her first Fontana that wasn’t white. Sassoon has a decisive eye. Her collection always falls within a chromatic group: black, white, brown and the occasional hint of metal.

After successfully outbidding a number of important dealers, Sassoon brought the Fontana to New York—the original site of its conception—and hung it in her Soho loft. Like Bardini, Sassoon had an unusual idea for the hang. She positioned the work between two 19th-century fire escape windows so that it appeared to float in the space. “Fontana once said thathe was more interested in what was beyond the canvas rather than just the mere surface, so I thought he might approve,” she notes.

During the pandemic, Sassoon left the city and sought refuge in her hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio. There, the Fontana found a new home in the Weston House—a two-story modernist structure perched high on a hillside, designed by Carl Strauss and Ray Roush. Mounted on the central wall in the living room, the Fontana hung right below a slim horizontal window. Rays of light streamed into the room, reflecting off the copper canvas. Fontana’s cuts, once deemed radical, feel just as electrifying today. In a time defined by rupture—technological, political, environmental—they remind us of the importance of seeing beyond the surface of things, for chasing a new future rather than retreating into the past. Sassoon, like many Fontana aficionados, once considered Fontana’s “Metalli” to be secondary to his works on canvas. However, after living with the copper piece for 20 years, she views it as “one of the most important works I’ve ever owned.” •

How you need to fly private isn’t the same as anybody else. While our competitors think you should fit into one of their offerings, we believe your plan should be crafted to fit you.

Let’s craft your perfect approach.

Earn your certification in Art Business with a flexible, self-paced online program.

Sotheby’s Institute of Art’s Online Certificate in Art Business offers an in-depth exploration of the art world and advanced insights into art market trends, auction practices, and cultural management.

sothebysinstitute.com/certificate

Act Three: In which we escape to the artfilled wilds of Hawaii’s Four Seasons Sensei Lanai, take in “Poor Things” director Yorgos

Lanthimos’s cinematic photography, learn about a French curator who tracked art collections looted by the Nazis, meet the collector establishing an annual Parisian art ball and more. we escape to artin “Poor Yorgos cinematic Nazis, meet

At Sensei Lanai, a Four Seasons Resort in the misty uplands of the Hawaiian island, nature and art are in quiet conversation. Site-specific works by world-class artists dot the grounds like a tropical sculpture park. Against this inspired backdrop, this season’s breeziest silhouettes find their perfect frame.

BY DAVID KAMP PHOTOGRAPHY BY ANGELO PENNETTA

An avid camera collector, the Athens-based filmmaker has become so enamored with photography that he recently installed a darkroom in his house. The fantastical aura of his movies shines through in the shots he takes on set and elsewhere, on view in his first photography show this spring in Los Angeles.

If you’ve seen the films of Yorgos Lanthimos—perhaps “Poor Things” (2023), for which Emma Stone won the Oscar for best actress, or “The Favourite” (2018), for which Olivia Colman did the same—you are familiar with his rich visual vocabulary. The fish-eye-lens shots that signal mental dislocation. The super-wide establishing shots that help the director do his loopy world-building. The soberly framed silly dancing. The textured interior walls that seem to be alive, as damp and undulatory as the inside of a teapot. The suturing, figurative and literal, of things that don’t really go together: flying trams in a Victorian sky; a chicken with the head of a pig.

For all this, says Lanthimos, who is 51 yearsoldandhastenfeaturestohisname, “I am a young photographer.” What he means is that, though he has been directing since the 1990s, when he established himself in his native Greece shooting musicvideosandTVcommercials,hehad not until recently had the gumption to show his still photography to the public.

Not that Lanthimos wasn’t already snapping away. He owns well over 100 cameras, most of them of the old-fashioned film variety. “I’m a hoarder. I think I’ve bought every kind of medium-format camera that exists,” he says, speaking from his home base in Athens. “I usually get them from eBay or find people who knowpeoplethatsellthem.I’llreadabout a camera, think, ‘Oh, I’d like to have this one,’ search for it, and get it. And then use it for a week and probably go back to the other camera I was using.”

“Yorgos Lanthimos: Photographs,” the firstexhibitionofthefilmmaker’sstillwork, isnowonviewuntilJune21(extendedfrom April) at Webber 939 in downtown Los Angeles. The show features photos taken duringthemakingofLanthimos’twomost recently released movies, “Poor Things” and last year’s “Kinds of Kindness.” (His next feature, “Bugonia”—his fourth starringStone—willbeoutlaterthisyear.)

It was the quasi-Victorian world of “Poor Things”—in which Willem Dafoe’s Frankenstein-like mad scientist reanimates the dead body of Stone’s suicidal socialite by implanting in her head the brain of her unborn child—that prompted Lanthimos to break out his camera collection and put it to serious use. “Because it was a period piece, I thought it would be nice if I took some black-and-white portraits in 4 by 5,” he says. For these, he used a large-format Chamonix camera. While shooting the film’s even more fanciful color sequences, in which Stone’s character leaves her native London for adventures in Lisbon, Alexandria, Marseille and Paris, Lanthimos used a medium-format Plaubel Makina, shooting in 6 by 7.

In reality, the entire movie was shot on soundstages in Budapest, its cityscapes the elaborate confections of Lanthimos, the cinematographer Robbie Ryan and the production designers Shona Heath and James Price. “We built our own darkroom in the bathroom,” Lanthimos says. “After every shoot day, I would go back to it. Emma [Stone] helped me process a lot of the negatives. We learned to do bothblack-and-whiteandcolorthere,and scanning as well.”

The results proved wondrous. The large-format photos—Stone in profile, a single braid snaking down her left shoulder; the actress Suzy Bemba seated in a wrought iron chair, her hair in tight cornrows, her sleeves enormously pouffed;MargaretQualley,herexpression stricken, mysterious smudges (blood? greasepaint?) on her face; a pig solemnly milling about a bedroom, not yet CGI’d into a chicken-pig—have the haunted quality of 19th-century daguerreotypes.

The color prints are more playful. In one, taken by a Budapest lake, one of the few real locations used in “Poor Things,” Stone sits pensively in full costume, looking like Shakespeare’s Ophelia on the cusp of her plunge into the drink. The

spell is broken by the object Stone is sitting on: an electric vehicle used for dolly shots, topped by a grimly utilitarian mover’s blanket, a takeout coffee cup and, in a clamshell container, Stone’s boxed lunch. “That could have been a simple portrait of Emma against the lake,” Lanthimos says. “I just love making the pictures a little dirtier. I love messing with the prettiness of that idyllic kind of space.” In another photo in a similar vein, the actor Jerrod Carmichael leans against the railing of the movie’s gorgeously steampunk steamship in a dandy’s spectator shoes and linens, but above and behind him are the industrial fans and lighting rigs that conspired to make him lookcoolandwindsweptinthecompleted film,aswellasthecurvedLEDscreenthat served as the ship’s “sea” backdrop.

Ryan, who has worked as Lanthimos’ director of photography on his last four films, observes that the sense of play the filmmaker brings to his still photography has helped him in his day job. “I think for Yorgos it’s a remedy for dealing with the pressures of day-to-day filmmaking,” he says. “He is very calm and relaxed and effortlessly mixes the two worlds.”

“Kinds of Kindness” marked a departure from “Poor Things” and “The Favourite,” in that it was filmed in the United States—New Orleans, specifically—and used real locations. Much of the photography from this period in the Webber 939 show is nonetheless recognizably Lanthimos-esque. There’s a night shot of Jesse Plemons in a walking boot, taken from behind (backs of heads being yet another Lanthimos motif) and a graphic close-up of a squishy leather couch cushion, taken with a Mamiya 7, that evokes the viscera that ooze so freely through “Poor Things.”

With open air, natural light and real city blocks available to him in New Orleans, Lanthimos began taking photos unrelated to “Kinds of Kindness,” such as a banana tree rapidly outgrowing

“I think I’ve bought every kind of medium-format camera that exists,” says Lanthimos.

its fenced-in lot and the city’s majestic Hibernia Bank Building as seen through a filmy, translucent curtain. “Hopefully,” he says, “I’m building a body of work that I’ll be able to put together at some point that is totally irrelevant to my filmmaking.”

Lanthimos is wary of citing the photographers who most inspire him, as he has spent the better part of his filmmaking career struggling to answer the question, What directors have influenced you the most? “I tried to settle on three who are so different from each other: John Cassavetes, Luis Buñuel and Robert Bresson,” he says. “I do admire them greatly, but at the same time, there are so many others. It’s the same with photography. I’m still learning and discovering, so I’m hooked on different things at different times.”

Michael Mack, whose MACK imprint recently published “i shall sing these songs beautifully,” a collection of the “Kinds of Kindness”-era photos, told Lanthimos his work evokes the spooked,

empty industrial parks and office spaces of the American photographer Lewis Baltz. “I didn’t know who Lewis Baltz was,” Lanthimos says, “but now I’ve bought all of his books.” Pressed, he offers a list of other American greats— Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Rosalind Fox Solomon, Mitch Epstein, Sage Sohier and Robert Adams—as current favorites.

Lanthimos finds himself more devoted than ever to still photography. “The exhibition has given me more strength and excitement to go out and focus more on it,” he says. “I’ve made three films back to back with no break, so I’d love to take some time off and just concentrate on making pictures.” To that end, he has installed a professional-grade darkroom in his home.

The move back to Athens happened only recently, after he and his family had lived in London for a decade. The time away has allowed Lanthimos to regard his native city with fresh eyes, through his 100-plus cameras. “When I was

really young,” he says, “I was like, ‘Why is everything so ugly? Why are there no beautiful buildings?’ Everything just got abandoned and demolished, which is still a problem today, unfortunately. But nowItrytoseethebeautyinthischaos— all these different elements that make the city what it is. I’m trying to capture it, share it and let everyone figure it out.”

He is too shy, he says, to stop people on the street and ask them if he can take theirpicture.Hishumansubjects,fornow, shall remain the people he works with on his films. Lanthimos has, however, been testing out his instant cameras, aMiNTandaPolaroid,onaliving,breathing subject.

“I take a lot of pictures of my dog,” he says. “His name is Vyronas. He’s a rescue, a beautiful mix of a Greek Shepherd with something we don’t know. He’s a big dog, very calm and quiet and traumatized, but very sweet.” Dog photos: It’s comforting to know that even the most transgressive of auteurs cannot resist them. •

Clockwise from top left: “Untitled 157,” 2021 (hand-printed silver gelatin); “Untitled 02,” 2021 (hand-printed C-type); “Nola 5,” 2022 (hand-printed C-type); “Untitled 206,” 2021 (hand-printed silver gelatin); “Nola 18,” 2022 (hand-printed silver gelatin); “Nola 16,” 2022 (hand-printed silver gelatin).

BY SARAH MEDFORD

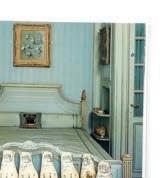

The founders of interior design firm Casalta, Catherine and Nathan Bruckner, use their Fifth Avenue apartment and highly personal art collection, stretching from Botticelli to Basquiat, as a proving ground for ideas.

The Bruckners’ living room, featuring Axel Vervoordt’s “Coffee Table Ghyka Square” and a custom bookcase with a sliding panel, upon which hangs an early painting, “Untitled,” by Jean-Michel Basquiat. A gray pottery horse from the Chinese Han dynasty sits atop a 1930s Italian rationalist side table, next to an 18th-century os de mouton fauteuil and a Móveis Cimo laminated wooden chair from the 1940s. Opposite: Nathan and Catherine Bruckner of Casalta in their dining room, with a stone bust of Harmodius, from the second century A.D.

It was an odd painting, no question about it. Jan Sanders van Hemessen’s “Christ as Triumphant Redeemer,” dating from the mid-1540s, had unusual looks and a twisted backstory, both intriguing to Catherine and Nathan Bruckner when they spotted the work in the winter of 2019 at a Sotheby’s Old Master preview in NewYork.Thepainting,whichhadturned up two years earlier at auction in Munich, had been triumphantly redeemed by a Dutch dealer, who’d guessed that the heavily overpainted panel might be hiding something. After buying it and funding its restoration, he was proved right.

TotheBruckners,somethingabout Christ’s newly revealed pose—shoulder defiantly back, elbow out, wrist flexed, hand on ribcage—and the almost kitschy, rainbow-colored backdrop struck them as very John Travolta in “Saturday Night Fever.” They nicknamed the painting “Disco Jesus.” And on the night of January 30, they placed a winning bid on it. Where to hang it was to be the next question.

The couple, who are partners in the Manhattan-based interior design firmCasalta,hadjustspenttwoyears transforming a loft downtown into a home for themselves, with three bedrooms, an old-world kitchen and a central enfilade of public rooms facing west along Fifth Avenue. Despite a slightly chaotic arrival, the Disco Jesus soon settled in among their vintage photographs by Berenice Abbott andHarryCallahanandasecond-century A.D. Roman bust. Some furniture slowly entered the picture, including a bentwood armchair with petal-shaped arms, by the Brazilian company Móveis Cimo, and a Baroque-era bench with the flat profile and scrolling edges of a party invitation. (More inviting for the eye than the body, perhaps—it’sshunnedbythecouple’stwo young children.)

appreciation for the angsty, attenuated lines of Egon Schiele, which trailed her through her studies at Central Saint Martins college in London. She and Nathan met in the city through a post-graduate decorative arts program. He’d grown up in Brussels, where his father, entrepreneur Yaron “Ronny” Bruckner, amassed a fortune in consumer products and real estate,investingsomeofitinawide-ranging art collection. The family homes in Brussels and on the Italian Riviera were designed by Axel Vervoordt, the

2025. But there was a very different game being played in 1986. He was one of those Renaissance guys who was just excited by art that depicts a culture, a moment, an emotion.” Nathan, Billault adds, seems to have absorbed these instincts.

From the day they moved in, the young Bruckners have made their apartment a proving ground for their ideas about living well with art and objects. They’ve edited and reedited its contents in search of a balance between the classical European references they grew up with and their current surroundings, on a retail-clogged stretch of lower Fifth Avenue. “We have to treat the past as an advantage but not feel trapped by it somehow,” says Catherine, running her hand along the edge of a polished stone coffee table in the living room. “For me, it really comes down to using pieces from different periods of time, so a room gains depth. I would addthatalmosthalfthethingswegot for the apartment were eventually edited out. Same with the art.”

Antwerp-based master dealer who shared the elder Bruckner’s open-throttle approach to collecting.

Some fathers take their sons along on visits to their tailor or their personal trainer. Yaron Bruckner introduced his son to his art dealers and his auction specialists, with whom Nathan maintains relationshipstothisday.GrégoireBillault, Sotheby’s chairman of contemporary art, remembers meeting him as a quiet, thoughtful presence by his father’s side.

What remains tells a story not just of time but of material culture and personal taste, starting with the kitchen’s contemporary steel dining table and shelves lined with glass—18th-century American to 1930s Venetian—and walls tiled in amismatchedcollageofDelftwhites, suggesting artisanal production and everyday wear and tear. It’s highly particular, but still part of the current conversation, like the great aunt who shows up at the family picnic wearing Loewe shades.

As a teenager in her native Vienna, Catherine often spent weekend afternoons with friends at the Leopold Museum or the MAK, developing an

“Yaron was always interested in the full scope of collecting, from antiquities to Old Masters to Jean-Michel Basquiat,” Billault says. “It looks very obvious in

On the living room’s stone table, butter cookies are piled on a silver plate and an early Basquiat painting, a gift from Nathan’s father, hangs on a wall where the Disco Jesus has recently been. In the mid-1980s, Yaron Bruckner began buying Basquiat from dealers Enrico Navarra in Paris and Larry Gagosian in New York, amassing a large number of paintings and works on paper. Nathan remembers abirthdaysleepoverinBrusselswhenone of his friends was so scared of a painting that she couldn’t stand to be in the

Clockwise from top left: American and Venetian glassware line the kitchen shelves, near a pair of antique silver birds; Tsuyoshi Maekawa’s 1977 artwork “Untitled” in the foyer; Kaare Klint chairs with a custom mahogany dining table by Casalta; the Bruckners’ Danby marble bathroom, featuring a Pierre Chareau alabaster sconce and a custom mahogany pull-up bar above the door; one of the apartment’s three bedrooms, with a Marc du Plantier Egyptian chair, 1935, and a pre-Khmer torso of a male deity; a 17th-century Baroque Italian bench; the kitchen features a custom steel island and custom cabinetry inspired by Villa Necchi, with an antique Chinese hu jar above. Opposite: Sadaharu Horio’s 2018 artwork “Untitled” hangs above a 17th-century iron and walnut side table from Genoa, a custom daybed and antique Italian armchairs.

same room with it. “Our daughter, when she sees this, she’s scared too,” he admits sheepishly.

The couple’s collection, seeded by the Basquiat and a few other gifts—notably a compact, theatrical Botticelli portrait of a maiden—has grown to include some less than expected choices, from a 1966 Lucio Fontana metal piece to a puckered and stitched burlap painting in cyan blue by Tsuyoshi Maekawa. Even in this company, the Disco Jesus stands out. David Pollack, who handled its sale as head of Sotheby’s Old Master Paintings department in New York, sees a congruence between the painting and Basquiat’s treatment of the male body, foregrounding exaggerated gesture and the nude form.

“Obviously this is the Christ figure, which we see all the time in Old Masters,” Pollack says of the van Hemessen work. “But to have this electric light in the background,hisarminthisvery flamboyant pose—he’s muscular. He’s bloody. It’s weird. We’ve never seen anything like it.” Since the painting’s offering in 2019, Pollack observes, the market for Old Masters has continued to embrace tough, offbeat images—works that are patently old but appear new. “These narratives are playing out even further today, because you’re seeing more buyers of contemporary art dipping their toes into the Old Master market at the highest end,” Pollack says. “I think those folks would understand this picture better than most traditional Old Master buyers. Visually it’s a risky—and risqué—image, right? I think Nathan and Catherineweretakingachance,quitefrankly.”

at 17, he was already bidding by phone on Cycladic sculpture for his father, stretching the cord of a landline up to the top bunk of his New York University dorm room.

In the past few years, Casalta has learned to work in forward and reverse, finding a picture for a room or making a room for a picture. At Overstory, a bar the young firm designed for the 64th floor of 70 Pine Street, in downtown Manhattan, glowing alabaster sconces, a polished brass bar and puzzle-like herringbone

Casalta, a product of their respective creative backgrounds, already betrays influences of the couple’s passion for collecting. (The studio’s name comes from theavenueinBrusselswhereNathangrew up.) A distilled homewares collection that Catherine has taken the lead on was born out of her admiration for the goblets, forks and candlesticks that pop up in Netherlandish still life paintings. Nathan is a shrewd researcher and auction buyer:

floors lend the tiny room the potency of AdolfLoos’AmericanBarinViennawithout a shred of art in sight.

For Billault, Casalta’s work comes across “a bit like Vervoordt 2.0. You have that inspiration, but what’s interesting is what they do with it,” he says. “There is something humble and deeply elegant there. It’s not the idea to have the largest, the biggest, the most. It’s just to find balance between keeping space for those masterpieces, but at the same time offer-

ing a really new way of looking at them.” The couple’s drive to study their source material up close has led them around some pretty bizarre corners—like the afternoon they spent at a travel agency in Paris’s 16th arrondissement, pacing off the width of its door openings and snapping photos of its moldings and radiator covers. The space had been carved out of the lobby of a 1929 building designed by iconoclastic French architect Auguste Perret, a pioneer of concrete and mentor to Le Corbusier who had once lived in the building’s penthouse. Though the apartment had been preserved, the Bruckners’ repeated tries to gain access had failed; settling for the travel agency, they extrapolated its detailing and made an homage to Perret on Fifth Avenue.

As fate would have it, this past January Simon Porte Jacquemus held his Autumn/Winter 2025 runway show in the phantom Perret apartment. Suddenly, videos of the space began flooding Instagram.

“I recorded them all, because it’s like—oh, finally we see that wall!” Nathan jokes. “Whenever I see it online, it’s like, wow, we kind of nailed it.”

Lately they’ve been working on a project in the Hamptons with architects Olson Kundig and finishing upthehomewarescollection, whichlaunchesthissummer. A measured pace suits their highly personal approach, Nathan says. “We don’t yet have a big body of work, but in 10 years, I think what would be great is if, when looking back, it’s not all in a ‘Casalta formula.’”

As if to fend off that prospect, in the summer of 2024 the Bruckners bought an Upper East Side townhouse designed in 1941 by the Swiss-born architect William Lescaze, a frothy cocktail of built-ins, glass-block walls, sculpted plaster fireplaces and a floorplan that wouldn’t have been out of place on an ocean liner. How to respond to all this? Time will tell. •

BY VASSI CHAMBERLAIN PHOTOGRAPHY BY SIMON WATSON

A

preview of the new Goodwood Art Foundation, where Charles Gordon-Lennox, the 11th Duke of Richmond, is forging an ambitious program of contemporary art among the lush lands of a historic English estate.

charles gordon-lennox, the 11th Duke of Richmond, is an anomaly among his peer group; an innovator and original thinker who, since taking over the reins of Goodwood—his family’s 12,000-acre estateinSussex,England—fromhisfather in 1994, has catapulted its revenues from £1.9millionto£130milliontoday.Notbad for a man who dropped out of Eton at 16.

The tanned and youthful-looking 70-year-old, stylishly dressed in a dark blue double-breasted suit, black “Monk” shoes(theyhavetwobuckles),androundframed tortoiseshell glasses, greets me in the Large Library at Goodwood, where the decorative ceiling was painted by Charles Reuben Ryley in the late 18th century and over 3,000 mostly French dusty tomes line the shelves. Today, the piano is littered with silver-framed family portraits, a bar is stacked with booze and art magazines cover a large ottoman.

Gordon-Lennox, who has been married to his second wife, the Hon. Janet Astor, for 34 years, and with whom he has four children (he was previously married to Sally Clayton, the mother of his eldest child, Alexandra, 40), installs himself, a cup of Earl Grey in hand, on a damask armchair overlooking a portrait of his forebear, the fifth Duke of Richmond, while his smiling butler retreats quietly in the background. But that’s where the period drama cliche ends.

The iconoclastic aristocrat—an award-winning photographer, a vintage clothing aficionado and a devoted petrolhead who can’t help but think outside the box—has become known, not just for boosting revenues, but for spearheading slickly delivered annual events. The Goodwood Festival of Speed (one of the biggest motor racing competitions in the world) and the Goodwood Revival, which celebrates the period between 1948-1966 when his grandfather, the ninth Duke of Richmond, first opened a race track on the grounds and where attendees today parade in vintage cars, dressed in the fashion of the day, are both now staples on the British summer social calendar.

This month sees the launch of his most ambitious project yet—the not-for-profit Goodwood Art Foundation, a venture dedicated to creating a world-class contemporary art foundation in a 70-acre woodland. The lot will include a museum, a cafe and an amphitheater, and will open with works by globally renowned Turner Prize-winning artist, Rachel Whiteread, including her rarely seen photographs.

So far, so 21st-century stately home. Grand houses all over England—BlenheimPalace,Chatsworth,Waddesdonand Houghton Hall—have embraced artistic exhibitions on their land for decades.

But like his father before him, who set up an environmental educational

trust in the 1970s, which is still ongoing, Gordon-Lennox’s ambitions stretch beyond just high-class art. A program for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, who are increasingly being denied access to art lessons in the curriculum, will be run concurrently in the foundation’s bucolic woodland area.