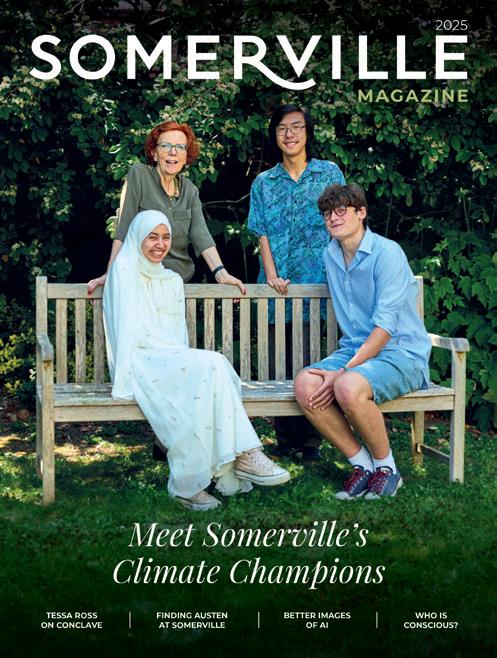

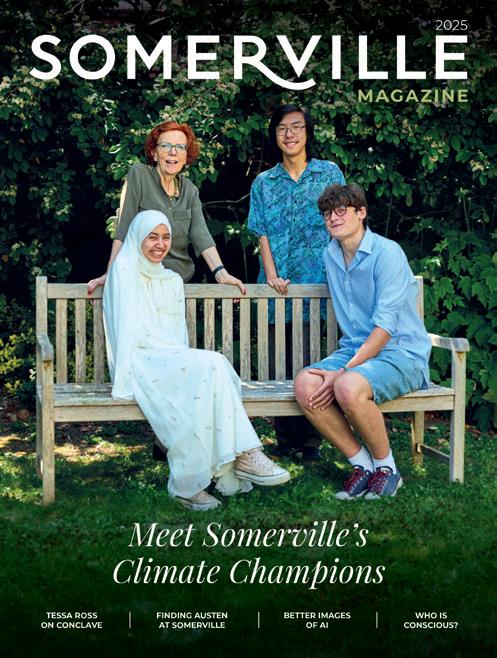

Cover: Principal Jan Royall with OxGreen founders Ben, Mariam and Harry (see p12) ©FisherStudios/C.Darvill

Editorial: Matt Phipps and Em Pritchard

Design: Laura Hart

Contact: communications@some.ox.ac.uk

Cover: Principal Jan Royall with OxGreen founders Ben, Mariam and Harry (see p12) ©FisherStudios/C.Darvill

Editorial: Matt Phipps and Em Pritchard

Design: Laura Hart

Contact: communications@some.ox.ac.uk

Eight

years ago,

I came to Oxford as a stranger, and a rather fearful one at that. I just couldn’t believe that Somerville College, the place where I was headed for a job interview, would ever welcome someone like me.

But the moment I walked into Somerville’s peaceful, beautiful quadrangles for the first time, and started meeting the bright, welcoming people who live and work here, my nerves melted away. To my delight, I knew right away that Somerville was a place where I might not only belong, but be of use.

Now, it is time to leave the place I have called home for the past eight years. As I prepare to hand over the reins to my excellent successor, Catherine Royle, a sense of reckoning inevitably creeps in. I ask myself, have I achieved anything? And the answer to that question is, quite simply, ‘not alone’.

Community has been the greatest gift of my time at Somerville. Whatever progress we have made in taking this proud, brilliant institution forward, we have made together.

It was together that we got through Covid-19 and made Somerville one of the most expansive providers of scholarships at the University. It was together that we developed the vision of a new, sustainable building to create much-needed teaching space, and together that we updated Somerville’s founding promise to include the excluded by becoming a College of Sanctuary.

These milestones remind us that Somerville is, and has always been, bigger than individuals. Bigger in heart and bigger in mind, the scale of what we can achieve is multiplied by Somerville’s ethos of collaboration and sharing of knowledge. It has been one of the great privileges of my life to support that process.

Of course, life at Somerville also happens in the spaces around these milestones – in the hundreds if not thousands of committees, lectures, dinners, choral contemplations and meetings with students that I have been proud to attend over the past eight years. I shall miss these cherished rhythms of the academic year at Somerville – and all of you who make it possible – more than I can say. Thankfully, I have been reliably informed that ‘Once a Somervillian, always a Somervillian’.

As to the future, I have no doubt that Somerville will continue to be exceptional, and continue to do the right thing. This year’s magazine gives me absolute proof of this. Devoted to the theme of ‘scholarship for others’, it shows that our College’s research brilliance, quietly radical philosophy and care for the world all burn as fiercely as ever.

Long may that continue.

Jan Royall, Principal

The Ratan Tata Building was announced as the flagship project of the College’s new RISE campaign, with plans to break ground in September 2025 (see p11).

The Oxford India Centre for Sustainable Development launched the Oxford Schmidt Africa-India AI in Science Faculty Fellowship, in collaboration with Africa Oxford Initiative (AfOx), and Somerville, Linacre, Mansfield, and Reuben colleges.

Somerville College Choir went on a US tour in March, performing at St Philip Presbyterian Church, Texas, and the Church of Our Saviour, Vassar College and Saint Thomas Church in New York.

Our Senior Research Fellows Professor Sir Marc Feldmann and Professor Tony Bell were honoured with Royal Society Awards for their outstanding contributions to science and medicine.

Our Senior Research Fellow Philip Poole was elected Fellow of the Royal Society for his work on bacterial genetics.

Oxford Semantic Technologies, cofounded by our Senior Research Fellow Professor Boris Motik, was acquired by Samsung Electronics.

Professor Aditi Lahiri MAE, FBA, CBE, our Senior Research Fellow, and Professor Elena Seiradake, our Fellow in Biochemistry, were both awarded ERC Synergy Grants.

Our Junior Research Fellow Dr Andy S. Anker was recognised as one of the world’s 30 most promising young scientists at the Inflection Award (see p12).

Our Fulford Junior Research Fellow Dr Tin Hang (Henry) Hung was appointed MoCC Scholar at the world’s first museum dedicated to climate change, based within The Chinese University of Hong Kong (see p12).

A colloquium, titled ‘Multivocality and Responsiveness: Medieval Literature in Dialogue’, was held in Freiburg in honour of our Fellow and Tutor in German, Professor Almut Suerbaum

In the Vice-Chancellor’s Awards, Somerville Research Fellow Jim Harris received both the Teaching and Learning and Research Culture awards. Somerville DPhil student Utsa Bose received the Research Culture award as a member of TORCH’s Medical Humanities Hub.

Our Junior Research Fellows Dr Andrea Kusec and Dr Giuseppe Gava received the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences’ Public Engagement Award for their work educating children about memory and the brain.

Professor Beate Dignas, Barbara Craig Fellow and Tutor in Ancient History, was appointed to an Einstein Visiting Fellowship in Berlin.

Aivin Gast (2018, Classical Archaeology and Ancient History) helped discover the biggest pair of black hole jets ever seen.

Susan Owens (1990, English) won Book of the Year in the 2024 Apollo Awards for The Story of Drawing

Our Honorary Fellow Professor Lorna Hutson (1976, English) won Research Book of the Year at the Saltire Society National Book Awards 2024, with England’s Insular Imagining

Our Honorary Fellow Tessa Ross (1980, Oriental Studies) produced Conclave (2024), which won four BAFTAs and Best Adapted Screenplay at the Oscars (see p9).

The 2023 memoir Wavewalker by Suzanne Heywood CBE (1987, Zoology) is being adapted into a TV show by Jack Thorne, writer of Adolescence

Meryem Arik (2016, Physics) and Dr Jamie Dborin (2014, Physics) secured

over £9m in funding for their AI startup Doubleword.

Julian Brave NoiseCat (2015, MSt History) won the US Documentary Directing Award at the Sundance Film Festival and was nominated for Best Documentary at the Oscars for codirecting Sugarcane (2024).

Juliette Perry (2015, PPE) won gold for Great Britain at the 2025 European Rowing Championships.

Dr Tess Little (2010, History) was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize.

Toyo Odetunde won Food Writer of the Year at the Fortnum & Mason Awards 2024 and the Guild of Food Writers Awards 2025.

Corinne Clark (2024, DPhil English) won the Lord Alfred Douglas Memorial Prize for their poem ‘1929-’.

Frances England (2024, GE Medicine), Daniel Radford-Smith (2024, GE Medicine) and Caitlin Ashcroft (2025, GE Medicine) were elected Foulkes Foundation Scholars.

Grace Yu (2023, Maths and Statistics) won a Bending Spoons’ Women in Science Scholarship, one of the twenty top winners out of 1,600 applicants, and the only UK winner.

Following the W1 team securing blades at Torpids for the first time since 2019, Somerville College Boat Club’s three women’s teams won triple blades at Summer VIIIs (see p18).

Flora Prideaux (2022, History) and Sam Martin (2023, History) won two of the four available Geddes Student Journalism Prizes 2025 (see p12).

Somerville’s Commemoration Service this year was held on Saturday 14th June in the College Chapel.

This important event in our calendar underlines the enduring relationship between Somerville and its members, as we celebrate the lives of all College alumni who have died in the past year alongside the annual commemoration of our founders and major benefactors. The address was given this year by Dr Luke Pitcher, our Fellow and Tutor in Classics. The service can be watched again on the Somerville College YouTube channel.

All Somervillians are welcome to attend this annual Service, and we particularly invite close families and Somervillian friends of those who have died to join us. Next year’s Commemoration will take place on Saturday 13th June in the College Chapel.

If you know anyone whom you think should be included in next year’s memorial, please contact jacqueline.watson@some.ox.ac.uk

Barbara Maud Everett on 4 April 2025, aged 92. Senior Research Fellow in English.

Catherine Peters on 12 January 2025, aged 94. Lecturer in English.

Patricia Elizabeth Allison née Johnston (1958) on 27 February 2025, aged 84. History.

Shirley Mary Beck née Clayton (1950) on 19 December 2024, aged 92. Physics.

Chloe Marya Blackburn née Gunn (1950) on 26 June 2024, aged 93. History.

Sylvia Mary Blundell née Lee (1951) on 4 November 2024, aged 91. Mathematics.

Hannelore (Hanna) Broodbank née Altmann (1943) on 18 July 2024, aged 100. Modern Languages.

Mary Alison Caniato née Kershaw (1946) on 29 May 2024, aged 96. English.

Penelope (Penny) Jane Chapman (1970) on 16 October 2024, aged 64. History.

Marieke Cambridge Faber Clarke (1959) on 20 February 2025, aged 84. History.

Linda Joan Crawford née Robertshaw (1967) on 22 February 2025, aged 75. Physics.

Emma Rose (Rosie) De Falbe (1974) on 13 December 2024, aged 69. Modern Languages.

Victoria Jane Gibson (1976) on 1 December 2024, aged 67. English.

Ann Dunbar Glennerster née Craine on 18 December 2024, aged 90. PPE.

Janet Glover née Hebb (1954) on 10 March 2024, aged 88. Literae Humaniores.

Pauline May Harrison née Cowan (1944) on 28 May 2024, aged 99. Chemistry.

Sophy Ann Hoare née Haslam (1965) on 22 January 2024, aged 76. Modern Languages.

Jacqueline Briony Houlder née Hibbert (1971) on 12 April 2024, aged 71. Geography.

Jane Mary Hunt née Williams (1966) on 13 June 2024, aged 75. Jurisprudence.

Josephine Mary (Mary) Jones née Tyrer (1965) on 13 January 2025, aged 77. Mathematics.

Teresa Jane Kay née Dyer (1947) on 10 June 2024, aged 98. English.

Jane Khin Zaw (1956) on 10 July 2024, aged 87. PPE.

Virginia Kirwan Lindley née Dickinson (1970). English.

Helen Clare (Clare) Mackney née Humphreys (1975) on 4 July 2024, aged 67. Geography.

Christine Louise Maclean (1942) on 21 March 2024, aged 100. English.

Clare Mainprice (1974). English.

Margaret Wendy (Wendy) Marks née Frazer (1951) on 5 September 2024, aged 91. Geography.

Jose (Jo) Agnes Murphy née Cummins (1950) on 6 December 2024, aged 92. Chemistry.

Jennifer Mary Newman née Hugh-Jones (1950) on 7 February 2025, aged 93. Zoology.

Marianna Oliver née Egar (1943) on 27 January 2023, aged 98. Modern Languages.

Judith Burgoyne Rattenbury (1958) on 18 May 2024, aged 84. Physics.

Irene Ridge née Haydock (1961) on 5 February 2025, aged 82. Botany.

Lidia Dina Sciama (1970) on 31 May 2024, aged 92. Anthropology.

Diana Elizabeth Senior (1962) on 20 March 2024, aged 80. English.

Denise Melbourne Street née Fraser (1961) on 14 March 2024, aged 80. Biochemistry.

Marie Elizabeth Sturridge née Thomas (1950) on 28 December 2024, aged 93. Modern Languages.

Pamela Jean (Kim) Taplin née Stampfer (1962) on 29 March 2024, aged 80. English.

Virginia Tsouderos (1942) on 11 June 2018, aged 93. PPE.

Dorothy Turk née Armitage (1947) on 16 November 2024, aged 94. Geography.

Barbara Joyce Turpin née Edwards (1946) on 11 December 2024, aged 96. Physiology.

Janet Isabel Watts (1963) on 17 July 2024, aged 79. English.

Carolyn Margaret White (1970) on 8 March 2025, aged 81. Diploma in Social Administration.

Margaret Stella Willis née Andrews (1940) on 24 November 2024, aged 102. Modern Languages.

In 2014 the Royal Society described Professor Marian Stamp Dawkins FRS as ‘having done more than anyone’ to change the perception that animal ‘feelings’ cannot be measured. Ahead of her eightieth birthday celebrations in September, Somerville’s Emeritus Fellow in Biological Sciences kindly joined us to discuss her new book, Who is Conscious?, and explain why asking that question matters more than ever.

Ihave always been fascinated by what might be happening in the minds of animals. I was just ten years old and already keeping all manner of strange pets when I first read Konrad Lorenz’s extraordinary book about animal behaviour, King Solomon’s Ring. I can still remember the thrill of recognition I felt. Here was someone saying what I had always believed: of course animals have feelings and personalities. All we need is the means to understand them.

I followed this conviction to Oxford and Somerville, hoping to be taught by the great ethologist, Niko Tinbergen. I was lucky enough to become Niko’s doctoral research student and then to be able to pursue a lifetime of research on animal behaviour, including how animals communicate, how their vision works and their ability to make choices.

So why, towards the end of my career, have I decided it’s important to go back almost to first principles and ask who is conscious?

There are two reasons. The first is that asking ourselves who is conscious is rather a good way of reminding ourselves that we still don’t actually understand how consciousness arises in any of us.

If human consciousness remains a mystery, it becomes doubly difficult to know what is going on in the brains of other animals, particularly those such as octopuses with brains very different to our own. Factor in artificial intelligence, which might soon approximate consciousness without requiring an organic brain at all, and it’s clear why we may need to expand our ideas of who is conscious and who is not.

The second reason I wanted to write this book is because the question of who is conscious has urgent implications for the field of animal welfare in which I have worked for the past 50 years.

We live today in a world of multiple, overlapping claims about who is conscious. Almost all of us feel that mammals, birds and even reptiles are capable of conscious experiences. Many scientists argue that there is good

We still don’t understand how consciousness arises in any of us

evidence that fish, octopuses and other cephalopods also have the capacity for conscious experiences. Others argue that flies and crabs should be included. Then there are those who think that plants may be conscious, and yet others who think consciousness is a property possessed by all living things and the entire non-living world, an extreme view called Panpsychism.

This is not a good state to be in.

I have spent my career seeking to advance the scientific case for

consciousness in animals, hopefully with lasting benefit for the policy and practice of animal welfare. But I have become increasingly concerned at seeing so many claims about animal consciousness go unchallenged. In my lifetime, we have gone from a position where nobody was willing to say animals might be conscious to one in which no one wants to examine these claims lest we jeopardise the ethical gains we have achieved.

To lose the progress we’ve made in animal welfare would be tragic, but that is not the purpose of asking these questions. The fact is that we need to know where to draw the line between animals that have conscious experiences and those that do not precisely because it has such major implications for the way we treat them. The alternative is that we may one day be unable to discriminate between the ethical consideration given to the fleas on a dog and the dog itself, or between the mites on a chicken and the chicken itself.

Continued on page 8

So how should we proceed? Until recently, our best options were to look for the behavioural correlates of consciousness, or the neural ones. As the name suggests, behavioural correlates are when we observe sensory, motor or cognitive responses that might suggest aversion or inclination. However, this method is limited by the same problem Niko used to warn me about during my doctorate – namely, that it is almost impossible to confirm a behavioural hypothesis in animals that do not possess language. A jumping spider might wipe its eyes, for example, but we cannot ultimately prove whether this was a conscious response or an automatic process.

Our second option is to look for the neural correlates of consciousness, an

area that has made great strides thanks to developments in neural imaging. This works well in humans, where we can see different parts of the brain light up in association with memory, affection, fear and so forth. But we cannot readily transfer these studies of the ‘hardware’ of consciousness across to non-verbal species with very different brains to our own, and even less so to the abstract world of AI.

For me, our best option is to look beyond the hardware of consciousness to the software, to the processes themselves. Some of the most exciting research happening at the moment is exploring the logic of how consciousness works, such as how memory works computationally. It is entirely possible that these logical-computational processes could delineate a unifying theory of consciousness.

Wherever we end up on these questions, I hope people will understand the deeper point of asking them. Asking questions is what scientists do, and I believe we’re most likely to reach a valid conclusion on an important topic like this one if the evidence we use has survived questioning and scrutiny. Ultimately, we owe it to animals to make sure that the case for their welfare is based on the best possible evidence about their sentience.

We owe it to animals to make sure that the case for their welfare is based on the best possible evidence

Who is Conscious? is published by Oxford University Press and free to download from September 2025. Friends and former students of Professor Stamp Dawkins are warmly invited to join us for her 80th birthday celebrations at Somerville on 20th September 2025.

Tessa Ross CBE (1980, Oriental Studies) is the producer behind some of the biggest independent films of the 21st Century, including Billy Elliot (2000), Slumdog Millionaire (2008), 12 Years a Slave (2013) and The Zone of Interest (2023). She received the 2013 BAFTA Award for Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema and her most recent film Conclave (2024) won the BAFTA for Best Film. Tessa joined Somerville Magazine to discuss her love of storytelling and championing the creative process.

Did Oxford prepare you for a career in film?

From 12 Years A Slave to Zone of Interest, you seem to go for depth above surface. Is that a characterisation you recognise and, if so, does it make your life as a commercial filmmaker harder?

You mean am I fighting against my own taste all the time? I don’t think so, because I think you’re only as good as your taste, and we’re all pretty useless at being part of something we don’t care about.

The truth is you have to love every project and, when it’s great, it’s all of it, from the deepest currents to the surface details. Big studios have the money to take a maximalist approach, shooting everything and then approximating taste through test screenings and market research. But I don’t tend to enjoy those films, and I don’t really understand the process. I’ve always had to follow my own taste, looking for stories that have that idiosyncrasy which holds me. Then you just have to hope other people feel the same way.

Did Conclave have any effect on your view of organised religion?

None whatsoever, I’m afraid! The papal conclave is a tremendously ornate and compelling world, and I loved filming on location in Rome. However, the thing that always struck me about Conclave is that we are essentially watching a conversation between men about power – and there are few more mundane experiences for a woman than that!

I’ve always had to follow my own taste, looking for stories that have that idiosyncrasy which holds me

In practical terms, not remotely! But in as much as being curious and excited by clever people is part of life as a student, then absolutely yes. You might even say my career has evolved out of the work I began as President of OUDS, when I spent all my time running around trying to find the cleverest people with the best ideas to make plays happen.

The same basic impulse took me from working in theatre to becoming a literary agent, then a script editor, a drama commissioner, TV producer, Head of Film 4 and now my current role as a film producer. Through it all, the one constant has been my love of working with clever, creative people, and going on that journey of getting the writing, the work and the ideas in the right place, at the right time.

Where Conclave departs from convention is that it introduces something new into this patriarchal conversation, something which asks these very powerful men whether they can accept change in the world they’re holding onto so tightly. If they can accept that change, then their world might survive –that’s what Conclave is ultimately about, I think.

Can you say more about the spiritual journey of Cardinal Lawrence (Ralph Fiennes)?

I think part of Cardinal Lawrence’s struggle comes from realising that he, too, wants power – which is something of a shock to him. But the more important aspect of his struggle is the loss of his ability to pray, essentially his loss of God, somewhere in the process of becoming this powerful bureaucrat, which he then rediscovers through the arrival of Benitez.

Why do you think the character of Benitez is so important to the film?

Well, I think Robert (Harris, who wrote the novel) added Benitez partly as a plot device to disrupt the conclave. But Benitez’s intersex identity, and his acceptance of that identity as God’s will, is also a powerful way of making Ralph’s character decide whether he will embrace a new understanding of the world.

For me, the most moving part about Benitez is that, in a world where we’re constantly asked to make binary choices, Benitez lives in the spaces in between. He presents us with the possibility that we can be anything and everything, without splitting ourselves. If you wanted an ideal future, that would be it, wouldn’t it? That we’re all of it. In what is otherwise a very mainstream film, that welcoming of otherness is the thing I find most beautiful. It says, we’re better for change and we’re better for difference.

Can you tell us about any forthcoming projects?

I’m very excited to be working with a couple of phenomenal women directors next year.

The one I can talk about is the new TV series by Charlotte Regan, whose debut film Scrapper (2023) introduced a really exciting new voice, comedic yet earthy, realist yet magical. The series is called Mint, and it’s a very funny, very dark tale about what it’s like growing up as the daughter of a crime family. After Conclave, which only had one female voice (though it was the incredible Isabella Rossellini), it’s the great perk of my job that I now get to move into an entirely new fictional universe such as this one.

Benitez presents us with the possibility that we can be anything and everything

Conclave is streaming now. Mint will air on BBC One in 2026.

In 2024-25, Somerville College finalised its largest-ever gift agreement with Indian philanthropist Mr Ratan Tata (19372024) and the Tata Group. The transformative donation will finance the construction of the Ratan Tata Building, a flagship for sustainability and academic excellence at the heart of the University’s new Radcliffe Observatory Quarter. Principal Jan Royall commented, “This stunning new building places Somerville’s commitment to exceptional Indian scholarship, to sustainability, and to delivering unparalleled academic opportunity squarely at the heart of all our future plans.”

This year, the results of the largest ever public survey on climate change showed that 80 percent of the world’s population want stronger action to tackle the climate crisis. At times, it is hard to believe that so many of us want change. But look a little closer at a community like Somerville, and you will see climate action happening at every level and in every way. Here we focus on the new generation of students and early-career academics driving climate solutions.

AMRIT

ROOPRAI –

An Entente Cordiale for Climate Transparency Second-year medic Amrit

Rooprai (2023) and two friends this year pitched a sustainability concept that took them to the final of the Entente Cordiale Challenge, a new academic competition between Britain and France’s top universities. Amrit and her team’s submission proposed the use of block-chain technology, a database mechanism that promotes data transparency through linked cryptographic hashes, to prevent corporate greenwashing. The finalists attended receptions with politicians and business figures at the House of Commons, and will attend a reciprocal ceremony at the Élysée Palace next year.

“As a medic and person of KenyanSikh heritage, I see it as vital that anyone who can advocate for biodiversity, climate solutions and developing nations does so in whatever way they can.”

Historian Flora Prideaux (2022) is a climate activist and winner of

the inaugural Paddy Coulter Prize for Opinion Journalism. The author of climate features for Cherwell and Oxford Diplomatic Dispatch, Flora founded the environment section of The Oxford Blue and served as Co-President of the Oxford Climate Society. In 2024, Flora attended COP29 as a member of the Oxford Delegation, and in November 2025 she will use her Coulter prize money to attend COP30 in Brazil, where she hopes her reporting will create greater transparency in climate negotiations.

“The most important thing we forget about climate change is that it’s an intersectional issue. Climate activists can and do stand against other systemic inequalities such as poverty and political repression, and we must keep pushing back against the fallacy that it’s one or the other.”

DR HENRY HUNG –Conserving Future Forests

In 2025, Somerville’s Fulford Junior Research Fellow

Dr Tin Hang (Henry) Hung was appointed MoCC Scholar at the world’s first museum dedicated to climate change, based at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Henry’s appointment recognises his work to conserve the rosewood tree, the world’s most trafficked species. The rosewood conservation project, based at the University of Oxford, tackles climate change by using genomic predictions to enable foresters and farmers to choose the optimal seed sources for fifty years’ time, when climate change’s impacts will be felt.

“Receiving this recognition from my alma mater while continuing my research in Oxford reminds us that nature has no borders, and I look forward to many future collaborations between my two homes in this capacity.”

OXGREEN – Closing the Intention-Action Gap

The biggest obstacle to young people adopting sustainable behaviours, research suggests, is the gap between positive intentions and having the means to implement them. OxGreen is a mobile app developed by Somervillians Ben Chung (2022), Harry Stewart Dilley (2023), Mariam Mehrez (2024), and Brandon Tay (Jesus) that seeks to close the “intention-action gap”. The app combines habit formation and gamification to incentivise long-term change, and was one of three projects invited to the Vice-Chancellor’s Colloquium on Climate Change, where it won seed funding from the University.

“We believe that meaningful change starts with individuals who feel capable, informed, and supported – and that small, routine actions, when amplified across a community, can shift cultures.”

Meaningful change starts with individuals who feel capable, informed, and supported

DR ANDY ANKER –Creating AI Labs to Supercharge Sustainability

Dr Andy Anker was recently recognised as one of the world’s 30 most promising young scientists working on solutions to climate change. The recognition comes for his work to develop ‘self-driving laboratories’ that will accelerate climate technologies such as nanocatalysts. Nanocatalysts enable the production of chemical fuels like methanol from CO2, water and surplus renewable electricity, and you can read more about Andy’s research on p28.

“At a time when climate crisis research cannot happen fast enough, these self-driving laboratories are a huge accelerator, doing research in days that would otherwise take years.”

Tabina Manzoor (2024) is an OICSD Amansa Scholar from Kashmir reading for an MSc in Water Science, Policy and Management. In June 2025, Tabina delivered the opening address at the Right Here, Right Now Global Climate Summit in Oxford, the world’s largest colloquium advancing the conversation around climate change and human rights. Tabina used her experiences of trying to raise awareness of water security in Kashmir, a region defined by its volatility, to highlight the global plight of communities caught between human-made crises and the slow violence of climate change.

“Climate change knows no borders, respects no treaties, and recognises no economies. It demands a radical rethinking of how we talk about justice, survival, and peace. To speak of climate without speaking of conflict, of human rights, of survival, is to speak in half-truths.”

The early science of IR was more marital and domestic than patrilineal

Professor Patricia Owens is Somerville’s Fellow & Tutor in International Relations. Here she tells us the story behind her latest book Erased, in which a field built on the intellectual labour of women sought to erase them.

At the origin of twentieth-century histories of international thought we find a gendered intellectual appropriation. Florence Melian Stawell’s proposal for a popular history of the League of Nations was first seen, then poached, by Gilbert Murray, Oxford’s Regius Professor of Greek. In its place, Murray suggested Stawell write a history of international thought. Stawell duly produced the first history in this field. Murray’s book on the League, meanwhile, was never completed.

And so it was that, entirely by chance, a sixtyyear-old woman who shared her life with another woman, and who left academia due

to ill-health, inaugurated a genre from which she and all other women, people of colour, and those living non-heteronormative lives would in due course be erased.

My new book Erased is a feminist intellectual history set in twentieth century Britain that reclaims from erasure women like Stawell, who were the early scholars of what was then the new and magnificent subject of International Relations (IR). The book follows a cohort of eighteen women, almost all of whom were engaged with International Relations as it was forming in the academy, and all of whom thought deeply about the relations between peoples, empires, and states.

Some, like Stawell, traced international thought back to ancient Greece. Others envisaged international relations as a new science of contemporary history. Many of them wrote on how to govern – or dismantle – the British Empire, on anti-colonial movements, and the rise of non-Western powers. At a time when imperial frontiers were closing, they sought new perspectives on a changing world order.

Yet Erased is not only a history of these women and their thought, but also how they were later purged from intellectual histories of IR. The erasure of women is an old story, of course, one that feminist historians have exposed many times in philosophy, law, the sciences, and the arts. But IR’s is a more paradoxical story of gendered power, knowledge, and erasure.

IR has long presented its history as a dialogue among elite white men—a patrilineal narrative of “fathers” and “seminal” thinkers. And yet IR was a highly feminised field from its inception. Its emergence coincided not only with the closing of imperial frontiers, but also the rise of the international suffrage movement and the entrance of women into higher education. It was a practical and intellectual field in which women could get ahead.

Patricia Owens

Often these women were associated with Oxbridge women’s colleges. These include Somervillian Agnes HeadlamMorley, who in 1948 became Oxford’s first woman to hold a professorial chair, yet whose research suffered under the heavy teaching burdens then imposed on women academics. Across the road at St Anne’s, Merze Tate became Oxford’s first African American graduate student. At Cambridge, meanwhile, the University’s first IR course was taught for nearly two decades by Glwadys Jones.

And yet, to understand IR fully, we must also look beyond the women’s colleges. In Erased, I show how the early cross-disciplinary science of IR was more marital and domestic than patrilineal, emerging from a complex, interdependent network of intimate and domestic spaces. It is within this catalogue of homes, hotel rooms, summer schools and salons that we find an alternative genealogy of spouses, lovers, siblings, and friends—including same-sex relationships – pursuing a common intellectual cause. It is a world of feminised labour that necessarily includes the effects of unfinished work, illness, overwork, and marginalisation.

It was in this world, rather than the universities, where IR’s institutional consolidation happened. Margaret Cleeve was formative at Chatham House, overseeing its information services from 1921 to 1955. Margery Perham was the Establishment’s most authoritative voice on empire and

To understand IR’s past, as well as imagine its future, we must take seriously the personal, the contingent, and the erased

decolonization from the 1940s to the 1970s – a very “respectable radical”. Claudia Jones, a British subject from Trinidad, founded The West Indian Gazette and became the most influential radical Black Atlantic voice in 1950s and 60s Britain. Susan Strange, a mother of six, rose to become the most influential British IR scholar of her time, despite being bullied out of her first academic post for having too many children.

These women, and the few men who worked alongside them, were united not by ideology but by their historical imagination. To understand IR’s past, then, as well as imagine its future, we must look beyond the canonical texts and formal institutions. We must take seriously the personal, the contingent, and the erased.

Erased is published by Princeton University Press, and is available now.

250 years after Jane Austen’s birth, acclaimed Austen scholar and Professor Emerita of St Anne’s College, Oxford, Professor Kathryn Sutherland (1972, DPhil English), returns to trace the formative impact of Somervillian writers and academics on Austen studies and feminist literary thought.

In 1923 one of the few official monuments to female literary genius was R. W. Chapman’s edition of the novels of Jane Austen. In its pages Chapman elevated Austen to canonical status, ‘part of the soil of England’, whose novels of village manners and politics were rooted in a wider system of aesthetic and environmental connection that together connoted the best of civilisation—the very thing that his generation went to war to defend. In various reissued formats, Chapman’s Austen text has saturated the market ever since.

Female genius Austen may have been, but Chapman located her within an elaborate network of male talent and male scholarship. His annotations linked her to Shakespeare, Milton, Johnson, Cowper, and to an Augustan and classically derived tradition. In his preface to the 1923 edition, Chapman acknowledged the male scholars whose textual work underpinned his own: A. W. Verrall, Henry Jackson, George Saintsbury, A. C. Bradley.

But where were the female literary models and the women scholars in all of this?

One answer is that they were at Somerville College, Oxford. The academic community of Somerville was from the early years of the twentieth century to the outbreak of the Second World War a fertile ground for developments in feminist politics, Georgian history, and Austen studies, the latter inaugurated by Katharine Metcalfe, Assistant Tutor in English (1912-13). Metcalfe’s pioneering 1912 edition of Pride and Prejudice was bookended in 1939 by Mary Lascelles’s landmark critical study Jane Austen and Her Art. Lascelles, Tutor in English (193167), paid tribute in her opening pages to Metcalfe’s description of Austen’s ‘rare combination’ as a writer of ‘a sense of disillusionment and gaiety of temperament.’

Where Chapman scrutinised the Austen text inside a scholarly template, suggesting comparison with Aeschylus and Euripides, Metcalfe’s 1912 edition of Pride and Prejudice, Austen’s most celebrated novel, immersed the reader in a simulated Regency experience. Many features of Metcalfe’s edition now routinely inform the apparatus of every modern packaging of a classic novel. In 1912, however, the approach was fresh, throwing a bridge between the Regency world and the early twentieth century, with appendices on Jane Austen and her times: ‘Travelling and Post’, ‘Deportment, Accomplishments, and Manners’, ‘Social Customs’, ‘Games’, ‘Dancing’, and ‘Language’.

Nothing is read in a vacuum; the repackaging inaugurated in 1912 was made more urgent after the historical events of 1914-18. Metcalfe’s sociohistorical refit supplemented Austen’s thrifty text with detail that enlarged its emotional structure, a contribution best seen in the context of its historical moment. Gender imbalance interacts complexly with genre: a matter of political and educational opportunities

as well as hierarchies of writers and readers. Chapman dignified (and perhaps patronised) the female novelist by submitting her to the rigours of male classical textual criticism. But in the early decades of the twentieth century, women graduates found intellectual space and a voice in sociological readings of literature and history. They found themselves in history by finding women from the past inside history.

Foremost among Austen’s interlocutors at this time were Margaret Kennedy, who went up to read History in 1915, and her second-generation suffragist contemporaries Hilda Stewart Reid and Winifred Holtby. Kennedy was both historian (her first book, A Century of Revolution (1922), was a study of the years 1789 to 1920) and historical

novelist; she would publish a biography of Austen in 1950 and a general study of fiction, The Outlaws on Parnassus, in 1958. She also found time to lecture on Austen, with the perfectly turned opening sentence from one of her lectures reproduced below.

Holtby wrote regional novels whose strong modern heroines champion social change. She edited the influential feminist review Time and Tide (founded by another Somervillian, Lady Rhondda), and produced a feminist historical survey Women (1934), which included a section on ‘The Importance of Mary Wollstonecraft’. Reid’s historical novel, Two Soldiers and a Lady (1932), set during the English Civil War, was praised in the New York Times for its ‘abnegation’ of conventional history.

100 years ago these women were themselves looking back 100 years. Education and the social cataclysm of war propelled them, and others like them, into history. They saw that fiction might offer a space for mapping alternative histories and supplementing the official record. Jane Austen was a point of orientation. For Holtby, writing the first critical study in English of Virginia Woolf (1932), it meant answering the question ‘Why Woolf is not Jane Austen’ and determining why Woolf’s heroines could no longer be content to ‘sit behind a tea-tray’.

Professor Kathryn Sutherland will present the full version of this lecture at a day-long Austen Celebration held at Somerville on 8th November 2025, alongside Professor Fiona Stafford and others.

2024-25 has been a historic year for Somerville College Boat Club. At Torpids, our W1 team became the first Somerville crew to take blades since 2019. Then, in Trinity, all three women’s teams won blades at Summer Eights in what Cherwell called a “remarkably impressive” achievement – and an unprecedented one for Somerville!

SCBC alumna and Senior Associate of Somerville Caroline Lytton (1999, Physics), who coxed the WI boat at Torpids, commented that, “Rowing was a formative part of my time at Somerville. It was an absolute honour to come back and race with both the men’s and women’s crews in Torpids this year, and the icing on the cake to see so many women achieve blades this summer.” If you would like to support the Boat Club’s continued rise, please contact Ian Pickett, Chair of the 1921 Club: chair@the1921club.com

Rukhsar Balkhi is an MSc student in Modern South Asian Studies at Somerville and an EAA Qatar Sanctuary Scholar. She is also pursuing a master’s in International Affairs at Columbia, and has held roles with the US Embassy in Kabul, Afghans for Progressive Thinking, and the UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs.

When I first stepped onto the cobbled paths of Oxford in late 2024, it felt less like an arrival and more like a return – an affirmation of a long and winding journey shaped by history, perseverance, and purpose. The centuries-old stone walls spoke to me not only of tradition, but of transformation. I knew then that this chapter would mark a profound continuation of a story I had long been writing.

Born in Afghanistan, I navigated years of upheaval before finding refuge in the US, where education became my anchor. That journey – shaped by displacement, resilience, and aspiration – ultimately led me to Oxford. Each step, from Kabul to New York to Oxford, has deepened my commitment to justice, belonging, and global engagement.

I came to Oxford to pursue an MSc in Modern South Asian Studies. I wanted not only to deepen my understanding of a region I hold close to my heart, having spent the early years of my life close to South Asia, but to critically engage with the forces that have shaped its contemporary realities. My research delves into South Asia’s postcolonial histories, its shifting foreign policy architectures, and, most significantly, the evolving role of US diplomacy in the region.

In a world where strategic alliances and regional tensions continue to redefine global politics, I examine how international engagement has influenced democratic institutions, security frameworks, and development trajectories across South Asia.

We do not dilute academic excellence; we expand its horizon

At the heart of this inquiry lies the question: what does the future hold for us, the young leaders and thinkers of this region, who must navigate both inherited legacies and urgent futures?

But my journey to Oxford was never just academic. It was a personal leap across continents, cultures, and educational systems – a transition shaped not only by ambition, but also a deeper search for belonging. That sense of belonging came to life through Somerville College.

Somerville is a College of Sanctuary – a recognition that holds immense personal meaning for me. Sanctuary, in our college, is not merely symbolic. It is structural, ethical, and lived. As someone whose own path has been shaped by displacement and re-rooting,

to be welcomed into a college that foregrounds inclusion was profoundly affirming. From the very first day, Somerville felt like a community that had been waiting for me.

The support that I received at Oxford – through the Scholarship and the quiet, unwavering kindness of my faculty, professors, and fellow students – was not just institutional; it was personal. It helped me to engage in the type of reflection that moulds not just academic work but also individual purpose. Somerville, in particular, provided academic freedom and emotional safety – a unique combination in which I could challenge boldly, think broadly, and speak from both scholarly foundation and experienced reality.

These deeply educational experiences expanded my capacity to think across disciplines, cultures, and ideologies. Oxford didn’t just challenge me; it refined me. It taught me to be both precise and patient, ambitious and grounded. It reminded me that education is not simply the

accumulation of knowledge, but the pursuit of insight, integrity, and empathy.

Now, as I look ahead, I carry with me more than a degree. It is a sharpened sense of the responsibility that we all have. I believe that institutions like Oxford – and communities like Somerville – have a vital role to play in shaping a more just and inclusive global future. By creating platforms for students from all walks of life, we do not dilute academic excellence; we expand its horizon.

In the years to come, I intend to continue working at the intersection of policy, peacebuilding, and development – drawing from both my lived experiences and academic training to inform more equitable approaches to diplomacy and governance. I hope to contribute to international institutions that recognize the complexity of conflict and the urgency of youth inclusion in peace processes.

To current and future students of Somerville – especially those who arrive here feeling uncertain about

whether they belong – I want to say: you do belong. This college, this university, and this world need your questions, your insights, and your courage. And to the broader Somerville community, I thank you for being a place that proves sanctuary and scholarship are not opposing ideals, but rather, mutually reinforcing commitments.

At Somerville, the place I call my home in the UK, I didn’t just study history. I became part of a new story, one that continues to unfold with purpose and with hope.

Nemone Lethbridge was one of the UK’s first female barristers. She has lived a pioneering life, but when she talks about Somerville, one subject lights her up: the girls of the bottom table. The friends ate all their meals together at the bottom table in Hall, and in the seventy years since she left Somerville, they have stayed close to her heart.

We visited Nemone in the home she has lived in for over half a century, inspired by her recent appearance on Desert Island Discs. At 93, she is bright eyed, beautiful, and sharp as ever. She is very much someone you would want on your side in court – and many did, including the infamous Kray twins. Nemone represented the twins for years, and was so valued by them that she had to refuse their offer of money (and a crocodile handbag!), firmly reminding them she was paid by legal aid.

Today, however, Nemone tells us about the girls of the bottom table. There were her two closest friends, the outrageously brilliant classicist Xanthe Wakefield, and the ‘lovely’ Liverpudlian Audrey Briscoe, who studied Law with Nemone. There was Anjali Chanda from India, who left to get married, but stayed friends with the group, and a Spanish girl called Montserrat Trueta whose father ultimately withdrew her from Somerville because he thought it was too frivolous. There was the ‘very clever’ Jenifer Western, who wore couture clothes, Wendy Marks, who later became a model, and Betty Robertson from Lancashire, who changed her name to Liz, to avoid being seen as working class.

It was still unusual for women to be studying Law at Oxford in the early 50s – Nemone and Audrey were the only Law students at Somerville. For their main teaching, the two were sent to Keble, where their tutor told them, ‘Neither of you is clever, but it doesn’t

matter because you’ll commit matrimony anyway.’ Despite the misogyny the girls experienced and the intensity of their degree, Nemone describes Oxford as ‘full of interesting people and strange people’.

The friendship of the girls from the bottom table continued beyond Oxford, when Nemone moved into a house in Bayswater with Xanthe, Audrey, and other Somervillians. Nemone passed the bar exams in 1956, and began working as a junior barrister, despite the profession’s prejudice against women. Many chambers did not accept female lawyers at all, and for the first several years, her male colleagues refused to share bathrooms with her. Living with her Somerville friends must have been a comfort and source of necessary fun during this time, whilst Nemone made a name for herself representing the Krays.

The group’s friendship was tested, however, when Nemone married Jimmy O’Connor in 1959. Jimmy had been convicted of murder in 1942 on what Nemone and her family argue was very

doubtful evidence, and served 11 years of a life sentence. Whilst Nemone has always maintained Jimmy’s innocence, perceptions of him and their marriage had a devastating impact both on her career and her friendships. The head of her chambers refused to accept her rent and took her name off his door, claiming she was bringing the chamber into disrepute. Nemone found it impossible to find work elsewhere – whether because of Jimmy’s conviction, or because of the era’s prevailing misogyny.

Equally difficult was the reaction of ‘people I thought were my friends’. Whilst Xanthe and Audrey remained steadfast, other girls from the bottom table cut Nemone off, with one friend writing to her, ‘between you and me, there has to be a wide gulf fixed’. The pain this caused Nemone is still apparent today.

What hit even harder were the deaths of both Xanthe and Audrey, far too young, when the girls from the bottom table were not yet thirty. This intense loss of her two closest friends understandably

made returning to Somerville unthinkable. Nemone recalls how the three had planned to return to take their degrees together, but without them she ‘hadn’t the heart’. Reconnecting with Somerville all these years later for this interview will hopefully go some way towards healing that loss.

I loved the girls at the bottom table, and I remember them very well.

Despite the difficulties she experienced, Nemone has remained positive and energetic. She returned to the bar in 1981, after several years in Greece, where she began her writing career. She founded Our Lady of Good Counsel Law Centre in 1995, and even in her nineties, still works for them pro bono on ‘all sorts of weird and wonderful cases’, from personal injury to human trafficking. Nemone is also fighting to clear Jimmy’s name, and has good news on this front. The transcript of his trial, which for decades Nemone had been told did not exist, has finally been released, and she is convinced this will provide evidence of the misjustice Jimmy suffered. The case has been referred to a Queen’s Counsel who specialises in miscarriages of justice, and Radio 4 will be releasing a programme about it soon. Clearing Jimmy’s name, Nemone says, would ‘mean everything’ for Jimmy – and go some way to make up for the broken friendships amongst the girls of the bottom table.

The Oxford India Centre for Sustainable Development (OICSD) at Somerville College has always believed in pushing boundaries – of knowledge, of inclusion, and of global impact. This year, two remarkable scholars exemplify how the Centre is accessing new frontiers in sustainable development.

Dr Gladson Vaghela, the 2024 Savitribai Phule Scholar, and Adithya Variath, the 2024 Elizabeth Moir Scholar, are both tackling urgent but often overlooked challenges in India: mental health in marginalised communities and the legal vacuum surrounding outer space.

Gladson Vaghela’s journey into the world of public health began with volunteering. In 2019, while studying medicine in Gujarat, he tutored children at government shelter homes through the NGO Make a Difference. When the pandemic struck, he moved the classes online – but the transition laid bare how vulnerable these children were. One of his mentees, a young boy he had grown close to, died by suicide. It was a moment that changed everything.

“That loss triggered a deep reckoning,” Gladson says. “I realised how invisible the mental health needs of institutionalised children really are.”

Since then, he has focused his career on understanding mental health through an epidemiological lens. A grant from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research allowed him to evaluate suicide helpline services across 105 countries. He later represented India at the tenth Commonwealth Youth Ministers’ Meeting in London, amplifying youth voices in health governance.

Now at Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Population Health, Gladson is part of the Indian Study of Healthy Ageing – a collaboration between NDPH and the Tata Memorial Centre in Mumbai. His research explores risk factors for common mental disorders among older adults in Barshi, Maharashtra.

“I chose Oxford because of the methodological rigour,” he explains.

“The programme gives me hands-on training in areas like clinical trials, metaanalysis, and nutritional epidemiology. This isn’t just theoretical – it’s practical, applied, and deeply interdisciplinary.”

Crucially, Gladson sees mental health as more than a clinical issue;

it is a social and structural challenge.

“Mental health is part of sustainable development – but only if we treat it as a systemic issue, not a side note,” he says. His work aims to inform public health policy in ways that are inclusive, evidence-based, and sensitive to the lived realities of marginalised groups.

Gladson is also the second Savitribai Phule Scholar at the OICSD, a landmark scholarship aimed at the historically marginalised sections of Indian society. His appointment reaffirms the Centre’s commitment to representation and equity, not only in who gets access to Oxford, but in what knowledge is legitimised and prioritised.

The founding document in space law, the UN Outer Space Treaty, was co-written by a Somervillian, Joyce Gutteridge (1925).

Sixty years later, its utopian principles are being reimagined by OICSD scholar

Adithya Variath, who is determined, like Gutteridge, to preserve equality in outer space despite today’s increasing economic and geopolitical complexities.

A trained lawyer, Adithya founded the Centre for Research in Air and Space Law in Mumbai with early funding support from the Indian Space Research Organisation. His academic base in Mumbai, close to IIT Bombay’s Aerospace Engineering department, helped turn that vision into a hub of interdisciplinary research.

“In 2023, India opened its space sector to private players for the first time,” he says. “Today, there are over 800 space start-

ups. But we still don’t have a national space law.”

This rapid liberalisation has transformed India into a rising space power, but also exposed major legal gaps. Private companies now play a central role in satellite launches, research, and even resource mining. But without adequate regulation, there is a real risk of commercial overreach.

Adithya’s research at Oxford focuses on global governance frameworks for space resource mining and weapons in orbit –issues that lie at the intersection of law, diplomacy, and ethics.

“Space law isn’t just a legal subject,” he explains. “It’s about technology, geopolitics, and innovation. That’s why Oxford’s MSc in Global Governance and Diplomacy felt like the right fit. It allowed me to think beyond the law.”

He is already co-editing a volume with Oxford University Press and has two forthcoming books with Springer. But for Adithya, the ultimate goal is public engagement. His ambition is to return to India, teach, and work alongside the private sector and policymakers to shape a more inclusive and legallysound space industry.

“I want to take this research beyond the classroom,” he says. “India needs smart, equitable regulations that protect national interest while enabling innovation.”

India needs a smart, equitable space law

It’s been a wonderful year at Somerville, and, as ever, we can’t cover everything in the magazine. Instead, here’s a whistlestop tour through the highlights of the past year.

18 OCTOBER

In this year’s Mary Somerville lecture, our very own Jan Royall reflected on Somerville’s history, before having the honour of announcing the new Ratan Tata Building.

We were delighted to thank our generous supporters with a brilliant research showcase from our Junior Research Fellows, followed by lunch and a performance from the Choir.

Alumni who matriculated in 1984 returned to Somerville, marking 40 years since they first arrived in College. There was plenty of time to reminisce during a tour and dinner in Hall.

23 NOVEMBER

In this day-long literary extravaganza, Somervillian writers from across the generations gathered to share inspiration and ideas. We hope this will be the first of many such occasions!

Despite Heathrow’s closure, the Choir made it to the US and pulled off a packed performance schedule – as well as enjoying the jazz clubs and museums of Houston and New York!

Alumni and friends gathered at the House of Lords to celebrate Jan’s contribution over the past eight years –as Lord Patten put it, Jan has been ‘good for Oxford, and fantastic for Somerville’.

10 DECEMBER

Alumni filled the magnificent High Gothic church of All Saints, Margaret Street, to listen to the Choir’s beautiful voices – and eat mince pies! Always a highlight of the festive season.

15 MARCH

At the Somerville Association AGM, we heard from Honorary Fellow Shriti Vadera (1981, PPE) in conversation with Jan Royall on the response of the creative industries to a changing world.

24 MAY

On this special afternoon, we welcomed members of the Penrose Society for lunch, a Concert in Chapel, and a tour of the newly completed and beautifully blooming Somerville Remembrance Garden.

Erin Townsend is a Music finalist at Somerville. She co-leads the RETUNE Project, an Oxford-based initiative seeking to diversify the programming of concert music, and is an Artistic Director for its yearly festival.

When I tell people I read Music at Oxford, I often glimpse scepticism in their eyes. Classical music strikes people with the feeling that they won’t get it, that it’s not for them. I understand this feeling only too well – which is why I have worked so hard to break those barriers down during my time here.

When I first came to Oxford, the level of privilege in the classical music scene felt incredibly alienating to me. Many of my peers already knew each other from the National Youth Orchestra, and had benefited from private tuition from an early age. As a lower-class student, who had to work to afford instruments and lessons, this felt like an impossible scene to break into.

In contrast to the isolation I felt within the University music world, Somerville felt like an oasis. Before applying, I discovered Somerville Music Society’s Alternative Canon project online. The Alternative Canon aims to diversify the music performed in College and beyond, introducing audiences to lesser-known composers such as Ethel Smyth, Caroline Shaw, and Avril Coleridge-Taylor. This discovery was further confirmation that this was the college for me, and I got involved from my very first term at Somerville.

Which music is or is not performed is a political choice

In my second year, we launched RETUNE festival, which champions the commitment, courage and creativity of underrepresented music-makers. What began as blue sky thinking quickly became a reality. We met with the Music Faculty, and agreed to collaborate on their International Women’s Day event. Within a few whirlwind weeks, we had built a festival shaped by our passions.

This year we expanded RETUNE, collaborating with the University and the wider Oxford community. Our 27 events ranged from ‘A Night of Opera and Ballet’ to ‘Raga Explorations on the Organ’. My favourite event was where we had four different musicians interpreting Indian classical, some of it folk-inflected, and some traditional Hindustani and Carnatic music. Given that there are few Indian classical concerts in Oxford, this event felt really special.

There is a perception that classical music can stand apart from issues such as race and class. My degree has taught me that all music is affected by social forces when you start to examine it. Which music is or is not performed is a political choice. At Somerville, my friends and I have started making those choices ourselves by seeking to bring as much diversity into the music scene as possible. As someone who once felt like an outsider, I want to keep working to make everyone feel seen – and heard – in the music we make.

Dr Andy S. Anker is a Novo Nordisk Foundation postdoctoral fellow at the Technical University of Denmark and the University of Oxford, and a Junior Research Fellow at Somerville. He was recently named as one of the world’s 30 most promising young scientists working on climate change.

What if a robot could function not just as a tool, but as a collaborator in scientific research? My current project is the creation of ‘self-driving laboratories’, or ‘AI scientists’. At a time when climate crisis research cannot happen fast enough, these self-driving laboratories are a huge accelerator, doing research in days that would otherwise take years.

Robots have been used in chemistry laboratories for about a decade, and some already incorporate AI. However, its use has mainly been limited to simple tasks, for example to control colour. My work takes the use of AI robots to the next level – these AI scientists are

making complex decisions themselves based on the data they measure.

Like self-driving cars, you don’t need to tell these laboratories how to do the science, but rather your objective in doing it. The AI then decides which experiments to do, and continues these choices based on the resulting data. Using AI scientists produces more consistent results at a far higher frequency.

The ultimate goal of my research is to enable on-demand production of renewable energy materials. I collaborate with leading experts in sustainable materials and Power-to-X technologies

(processes that convert surplus renewable electricity into chemical fuels). One example is the synthesis of methanol from wind energy, water, and captured carbon dioxide. This liquid fuel can be used to power cargo ships or to store energy. Currently this process uses a lot of energy and money, meaning there’s not enough incentive for companies to use it.

To make these processes more energyefficient, we are experimenting with using ‘nano catalysts’ which reduce the energy required to make the chemical fuels. Being so small, nanoparticles have more surface area for catalytic reactions to take place. These nanoparticles are the size of 1000th of the width of a human hair, making them difficult to work with. Using AI scientists, we can equip the green experts with immediate access to high-quality nano catalysts. This will speed up investigating which materials are best to use for this process.

This work is hugely interdisciplinary, bringing in all sorts of different types of science. The advantage of being someone who gets bored quickly is that I have become a ‘jack of all trades’. I know enough about robots, quantum, nanomaterials, X-rays and AI to be able to communicate with experts in each field, and find ways to work together across various scientific languages.

The next piece in the puzzle is the ethics. My team and I will need to think about how to run self-driving laboratories in a responsible way – avoiding the possibility of others weaponising the AI scientists. That and the next round of grant applications should keep us busy on this exciting journey!

Zoya Yasmine is a Somerville DPhil student exploring the intersections between law, medical AI, and ethics. She volunteers at Better Images of AI, a non-profit collaboration which hosts an alternative gallery of more realistic, transparent and inclusive images of AI.

What images come to mind when you think of artificial intelligence (AI)? White humanoid robots? Glowing brains? Computer code cascading through a digital blue void? Or perhaps white men in suits orchestrating holographic interfaces?

These images are not only clichéd, but often unhelpful and even harmful. Abstract, futuristic and science-fiction inspired images often misstate the real capabilities of AI, masking the very real societal and environmental impacts of these technologies.

Images of pensive white robots solving equations, for example, suggest that AI is sentient. But this sets unrealistic expectations, reinforcing fears about AI achieving human-like intelligence. By suggesting that AI’s development is beyond human control, these visuals create an illusion of inevitability, thereby limiting space for public choices about technology through law, policy, and design.

Better Images of AI is a free alternative gallery of humanmade depictions of AI, led by myself and other researchers and passionate individuals. We have partnered with BBC R&D, the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, and the Alan Turing Institute, among others. The library has been viewed over two million times and its images spotted in places such as The Washington Post, TIME, LSE, and Business Insider. These images focus on the realistic applications and capabilities of AI, and better visualise its impacts on society now – not in some unspecified sci-fi future.

Images included in our collection feature microchips, rare metals, Finnish lakes, hair sculptures, and error messages, and range from archival collages, to works inspired by Persian Negargari. ‘Ceci n’est pas une banane’ by Max Gruber focuses

on a specific kind of AI called computer vision. Computer vision algorithms are used to identify and classify objects. In the image, there is a physical banana and a photo of a banana on a screen – and the algorithm doesn’t differentiate between the two.

I like this image because it does not oversimplify or overstate the capabilities of AI: these tools can be helpful, but can also make mistakes. Gruber introduces us to a limitation of AI and prompts us to think about the implications of the false identification of objects – especially in high-stakes contexts like medicine, self-driving cars, and surveillance technology.

As a researcher exploring the intersection of law and AI, I see how regulation is far more effective when grounded in a realistic understanding of what AI is and how it works. By volunteering with Better Images, I want to help change the way we visualise AI, and encourage meaningful conversations about its realities. This way, people can advocate for the ways that they do or do not want AI incorporated into their lives, and lawmakers can better regulate AI.

/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ l

Alexander Starritt (2004, History and Modern Languages) is the award-winning author of The Beast and We Germans. He joins us to explain how Larkin’s poem about Oxford inspired his new novel Drayton and Mackenzie

Ihadn’t even been to university when I first read ‘Dockery and Son’, Larkin’s poem about visiting his old college in early middle age. But it struck me deep.

In the poem, Larkin comes back for the funeral of someone he was at college with, Dockery. He’s shocked to hear that Dockery’s son is there now. So much of life has gone already. And why is it that Dockery’s life went one direction – he must have had this son at 19 or 20 – while Larkin ended up childless, miserable, and stranded in Hull?

Larkin’s answer is typically devastating. He says the innate assumptions that determine our lives don’t come from what we think truest.

“They’re more a style

Our lives bring with them: habit for a while, Suddenly they harden into all we’ve got”

I’m now about the age Larkin was when he came back for Dockery’s funeral. You’re definitely not young any more. The fizz of possibilities has resolved into something relatively fixed. You get the feeling that, barring disaster or running away with the circus, you can pretty much see the course you’ll roll down from here to the end.

I’ve written a new novel, Drayton and Mackenzie, to try and answer Larkin’s question: how did we get from the roiling amorphous potential we had at university to where we are now? It follows two friends from when they leave college, through the upheavals of the early 21st century, until they’re undeniably adults.

What I remember from university days is the sheer lightness with which you’d commit yourself to something, believing it wouldn’t be for long. A Somervillian friend studied Japanology, having never learnt Japanese or been to Japan, just because she liked the fabrics. And then before you know it, path dependence kicks in. Your only unusual skill is speaking Japanese, and the only people offering you a job are Japanese companies. With a hop, skip and a jump, you’re forty years old and living in Kyoto.

But now, looking back, I also notice that, of my closest college friends, one is a banker like his dad, another is a lawyer like his dad; a third even did her mum’s old job at World of Interiors. The counter-current to youthful whimsy is the deep continuity of doing what you know.

Curiosity and determinism, contingency and inheritance. These are the two forces propelling us through the years.

Drayton and Mackenzie (“an ode to the enduring power of male friendship” - The TImes) is out now. Alex will discuss the book with Rebecca Jones at Somerville’s Recent Alumni event on Tuesday 23rd September 2025.

Michèle

Roberts

Part food memoir, part recipe book, this unique offering by Michèle Roberts (1967, English) is a nourishing read for both body and mind. Michèle Roberts’ love of food has always shone through in her fiction, but here it takes centre stage, in the form of over 160 simple yet decadent recipes.

Julia

Nicholson

This fascinating book celebrates early women anthropologists, many of them Somervillian, and the people they lived among, including Barbara Freire-Marreco and the Pueblo people, Maria Czaplicka and the Siberian reindeer herders, and Beatrice Blackwood in rural Papua New Guinea.

Sarah

Bilston

In 1818 a single orchid cutting arrived in England, tucked in a packing case, just as orchid mania was sweeping across Europe. Sarah Bilston (1996, MSt. and D.Phil English) chronicles the search to rediscover this orchid in its natural habitat, seeing it as part of a pivotal moment in globalisation.

It’s been a bumper year for Somervillian book releases in academia and literature. Here we celebrate just some of the books published this year, which we have a feeling you might enjoy. To let us know about your forthcoming book, please contact communications@some.ox.ac.uk

Francesca

Kay

This intimate historical novel by Francesca Kay (1975, English) is set in Tudor England, where a young noblewoman lives quietly with her dying husband, as the world outside their house seeks explosive change. Hushed, personal, and precisely observed, this is writing to savour and enjoy.

Daniel

Yon

In this ‘lively read’ (The Guardian), neuroscientist Dr Daniel Yon (2010, Experimental Psychology) explores how the brain is like a scientist, building theories that construct the reality you live in. With transformative applications, A Trick of The Mind will revolutionise the way you think.

Kat Gordon

The spellbinding third novel from Kat Gordon (2004, English) blends historical fiction with Icelandic mythology. Moving between the early 20th century and the 1970s, it explores the progression of women’s rights in Iceland. When a body is discovered preserved in ice, a mystery begins to unravel…

By Jane Robinson, author and Senior Associate of

Somerville has a distinguished war record. And, despite what you might think, it is not all to be found in Vera Britain’s haunting Testament of Youth, or the sepia images of injured officers convalescing on the library loggia. The College’s contribution to both World Wars was as wide-ranging as it was valuable.

Perhaps the best known of our 19391945 heroines is our former Principal Dame Janet Vaughan (1920), who developed ground-breaking techniques to store and transfuse blood for casualties, pragmatically requisitioning ice-cream vans to deliver it in wartime emergencies. She was also one of the first civilians to enter Belsen, where her brilliance and deep humanity saved many lives. Her legacy continues to do so.

While we acknowledge famous women like Dame Janet with gratitude, there is a long roll-call of Somervillians who made vital contributions during the Second World War, yet whose stories are little known. Having unveiled Somerville’s new Remembrance Garden earlier this year (see over), now seems a good moment to tell some of those less-familiar stories of Somervillian service.

Evelyn Irons (1918) was appointed to The Daily Mail’s beauty pages after graduation. Soon sacked (with some relief) for ‘looking unfashionable’ – she never wore make-up – she then joined The Evening Standard, becoming one of Britain’s first female war correspondents. Evelyn was embedded with De Gaulle’s troops, sending some of the first dispatches from newly-liberated Paris and Hitler’s beloved Berchtesgaden mountain retreat, where she cheerfully appropriated a bottle of the late Führer’s ‘excellent Rhine wine’. She is best remembered now as the lover of Vita

Sackville-West, but should be celebrated for her pioneering journalism both during and after the war. Her resourcefulness in reaching Guatemala to report on the coup in 1954 was legendary. She reached the action on an ass, causing the editor of a rival paper to send his less enterprising correspondent a terse telegram: ‘Offget arse, onget donkey’.

The Jamaican-born nutritionist and paediatrician Cicely Williams (1917) also worked overseas, but in very different circumstances. When war broke out, she was in charge of some 300,000 patients in Malaya, where she was taken prisoner by the Japanese and moved to the notorious Changi camp. Despite being tortured and starved, she continued caring for over 6,000 souls incarcerated with her. Her paediatric care against a backdrop of chronic

malnutrition was legendary. She later recalled “Twenty babies were born, 20 breast-fed and 20 survived – you can’t do better than that.” The College still possesses some of the homemade birthday cards sent to Cicely by her fellow prisoners (see below): most feature fantasy feasts; all are full of love.

Twenty babies were born, 20 breast-fed and 20 survived –you can’t do better than that

Another much-loved alumna was our Principal from 1980-9, Daphne Park (1940). The extent of her career as ‘the Queen of Spies’ in the Cold War has only lately become apparent, but she also had a fascinating “hot war”. Having turned down jobs in the Treasury and Foreign Office, Park in 1943 talked herself into an interview with the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, a vital feeder group for the newly formed Special Operations Executive. There she gave such a detailed response to a question about ciphers that she failed the exam, but drew the attention of the head of coding, who put her on his staff.

Park was soon training the famous Jedburghs, a mixed force of commandos trained in sabotage and guerrilla tactics for deployment behind enemy lines. Further roles with SOE followed until the end of war, when Park went to Vienna. There the experience of seeing many Polish and Czech scientists whom she had trained being kidnapped by the Soviets set her on the path to join MI6. By the time of her retirement, Park had reached the

Park gave such a detailed response to a question about ciphers that she failed the exam, but drew the attention of the head of coding

highest operational rank possible, as ‘Controller of the Western Hemisphere’. Though her MI6 career was not without controversy, particularly in relation to the death of Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, the scale of her achievement is extraordinary – especially from someone once described as looking more like Miss Marple than Mata Hari.

Farmer Marion Wilberforce (1922) was another woman whose unassuming manner belied a dashing life story. As one of the eight founding females of the Air Transport Auxiliary, Wilberforce took on the dangerous job of flying brand new aircraft from factories to frontline squadrons around the country. Eventually qualified to fly every model of wartime aircraft, including the four-engine Lancaster, Wilberforce proved herself indomitable both in and out of the skies. On one occasion, she arrived at a factory to discover that the employees were on strike and the aircraft she had been sent to collect could not be released. She jumped on a table in the canteen and gave

a resounding speech about the war effort, thereby securing the release of her plane.

After the war, Wilberforce continued her uncompromising ways. Disliking its noise, she refused to carry a radio and would instead circle the airfield waggling her wings to communicate her desire to land. She was also famous for embarking on undeclared trips to Europe when bored, skirting the ground at two hundred feet to avoid radar. On one such outing, she strayed into Russian airspace, only to find herself being shot at before she turned tail and returned to neutral skies.

As Somervillians, we shouldn’t be surprised that we have a Commander of the Western Hemisphere in our ranks, to say nothing of a flying-ace farmer, a prisoner-of-war heroine, a crack war-correspondent, a founder of our national blood transfusion service, and crowds of dimly-lit individuals we sadly don’t have the room to name here, working behind the scenes at Bletchley and other secret establishments to defeat injustice. After all, if you want to change the world, you come to Somerville, and always have done.

Yet nor should we take these courageous women for granted. We owe every one of them a debt of thanks.

Read more in the Somervillians in Wartime booklet

The Somerville Remembrance Garden was created in 2025 as a tribute to the many Somervillians who fought for the sanctity of peace, life, and liberty in the two world wars. We wish to thank those members of the Somerville College community whose generous support enabled this project.

“To rescue mankind from that domination by the irrational which leads to war could surely be a more exultant fight than war itself.”

Vera Brittain