/ Shigeru

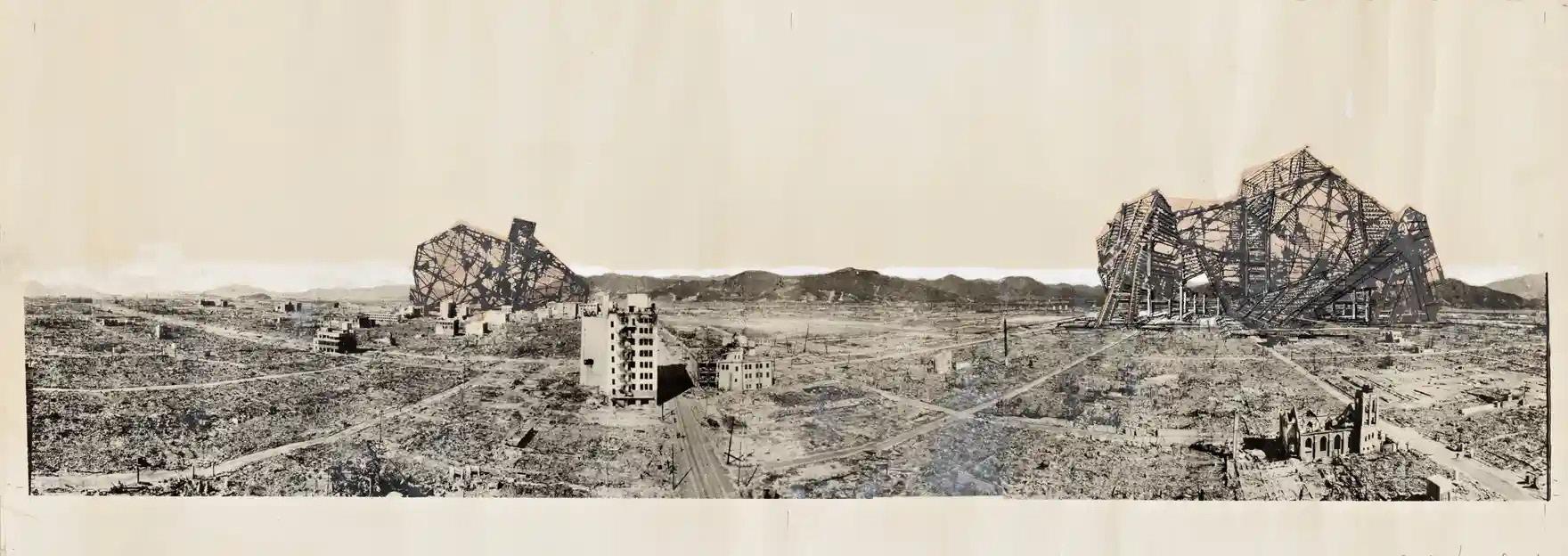

Ban, Paper and Disaster Relief Architecture

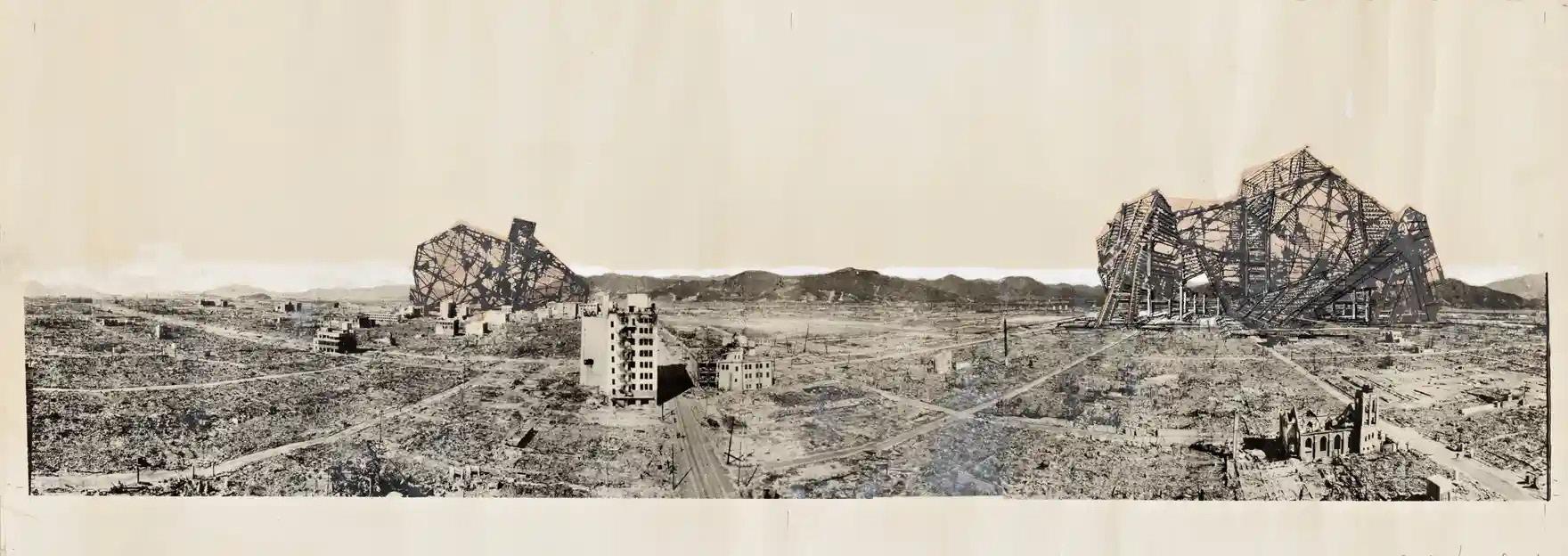

Two contorted silhouettes of metal, appearing like other-worldly rollercoasters, dominate the horizon of a devastated Hiroshima. The imprint of the former grid, to which a lonely church and apartment building cling, defines the desolate landscape over which the steel frames stand as ghostly reminders of what once was. The apocalyptic collage depicts a Japanese approach to architecture, developed through centuries of natural disasters and exacerbated by the atomic bombings of 1945: “Whenever you draw up a project plan with the intention of it being realised, you have to accept it will eventually be annihilated 1 ”. A second interpretation of the collage is conveyed by another Isozaki quote: “the fragments that remain after a disaster require the operation of the imagination if they are to be restored 2 ”. It is through these polar views – the persistence of disaster, and the resilience to rebuild – and within this typically Japanese “designing with and from disaster” mentality that the figure of Shigeru Ban begins to emerge.

01.1 Shigeru Ban / A Humanitarian

Shigeru Ban can be described as many things, above all, perhaps, he is a humanitarian. Though his disaster relief interventions formally begun in 1995 after the Great Hanshin earthquake, the propension towards the theme can be traced back to his cultural and geographic upbringing. The Japanese archipelago is situated along the ring of fire making it highly exposed to a variety of unpredictable environmental risks, from earthquakes to tsunamis and volcanic eruptions. This has led to the development of a pronounced social and multi-sector technical consideration towards the issue at a global level. Being exposed to the reality of destruction caused by extreme natural disasters has evolved a fraternal compassion towards those people afflicted by similar fates. The Japanese government has often offered financial aid to countries devastated by earthquakes in support and demonstration of unity in face of adversity. Simultaneously this cycle of destruction and reconstruction, physical and social, that the country endures has formed a resilient architectural and cultural tradition. Japanese architecture has devised simple technologies

“designed with disasters”. The very essence of the archipelago’s traditional architecture is enclosed in the employment of wood as main structural and joinery material: its flexibility allows it to absorb sudden applied loads. This founding construction principle is applied to Shigeru Ban’s disaster relief projects and adapted to the specific sensitivity that characterise his work.

At the root of his efforts, we find his recognition of a straightforward truth: “People are not killed by earthquakes, they’re killed by collapsing buildings.”3 This realisation reinforces his belief that architects should take full responsibility of the buildings that people use and live in, and, above all, are called to respond to whatever a given situation requires of them. Paper tubes, the building blocks of most of his interventions, are an end result rather than a formal starting point. Their local availability, standardisation and unconventionality in the building sector shapes them into the optimal low-cost tool, untouched by market price fluctuations following a disaster, to ensure a fast response to the immediate needs of the displaced.

Fig. 1, Arata Isozaki, Re-ruined Hiroshima, 1968

02

01.2 Shigeru Ban / A Student

So how and why did Ban begin using paper?

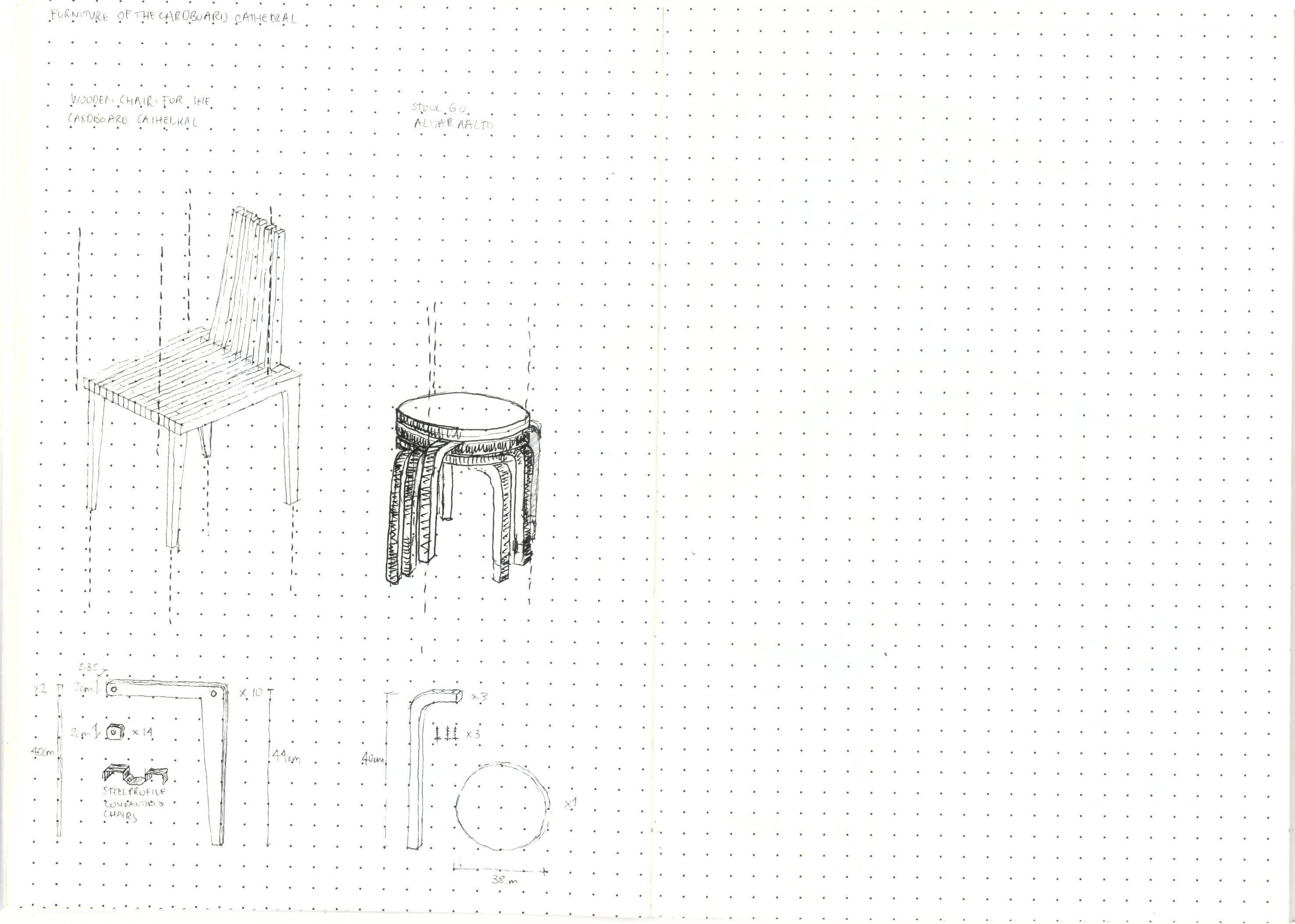

This material was already commonly associated to Japanese shoji screens, the movable ricepaper partitions giving flexibility to internal spaces. Ban, who effectively refuses any direct connection to nipponic tradition, discovered paper tubes by chance: finding them at the core of fabric rolls he had used for the Emilio Ambasz Exhibitions in 19854. A year later, he first employed them for the construction of a temporary furniture and glass exhibition of Alvar Aalto’s production at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The choice was motivated by budgetary constraints, as the desired wooden boards, required to effectively recreate an Aalto-like space, were too expensive; and desire to recycle the paper tubes of the textile industry. The material exploration which led to the design of the ceiling, undulating partitions and display stands marks the beginning of Ban’s “paper architecture”.

The global availability of paper tubes as well as their mass production – ensuring homogeneity in length, diameter, and thickness – proves precious in Ban’s research towards a “flexible standardisation”5. A concept explored by Aalto’s standardised housing units for war homeless in the 1940s, which holds the potential to enhance the innovation and effectiveness of responses to humanitarian needs in disaster afflicted areas. Ever since the first paper exhibition Shigeru Ban has worked to actively pursue perpetual innovation. Each new problem is approached with a tireless drive to solve it, whatever form this solution takes is then applied to the next project. This cumulative method can be sensed in the cohesiveness and gradual evolution of his projects throughout the years.

The 2007 exhibition “Alvar Aalto through the eyes of Shigeru Ban”, curated by Ban himself, expresses just how much the Japanese architect owes to the Nordic master in terms of aesthetics, materials, and ethics. Ban “is acknowledged as one of the post-war generation of architects who carry on Alvar Aalto’s legacy today”6 Most importantly they share what he calls “Aalto’s compassionate approach to architecture” placing human needs at the core of their production7. From the Nordic master Ban learns two crucial lessons that shape his work. The first lesson is that “the context is crucial”8. Ban’s design process is characterised by on-site.

exploration and research of the architectural, social, and cultural tradition of the disaster-stricken area. A necessary step to truly comprehend the needs and suffering of those he is designing for. His works seek to dialogue with the surrounding environment, a dialogue deemed essential for returning dignity and belonging to the displaced. The second lesson, an extension of the first, is the importance of using “local materials”9. In his interventions the Japanese architect combines local architectural and artisanal tradition to his paper tube structures. This provides a continuity between the temporary structures and the socio-cultural context.

Shigeru Ban’s humanitarian approach is also akin to Buckminster Fueller’s “doing more with less” design philosophy and their shared maxim of improving the standard of living for all humanity10. Fueller and Frei Otto represent important connections to the material experimentation and engineering features that fascinate Ban. He was attracted by the idea, exemplified by Otto and Fueller, of developing

Fig. 2, Temporary Alvar Aalto Exhibtion, New York MoMA, 1986

Fig. 3, Flexible standardisation explored in Aalto’s housing units for war homeless, 1940s

03

structural systems and textural approaches independent from the style of the time11. Finding in paper, or more precisely cardboard tubes, the base of his stylistic research. Inspired by Otto’s experimental method and self-formation principle; whilst the latter believed in the natural occurrence of form, Ban’s designs take shape according to the problem they seek to solve. Model-making and structural tests, stemming from the consciousness towards disaster-resilient architecture, hence acquires a central role in his design process.

Materiality or viewing the buildings as “things” in their physicality, determines the design philosophy adopted for his projects12. The preoccupation with structure and materials was inspired by a unique aspect of Cooper Union, his alma mater in California. Fifth year students attended poetry classes held by poet David Schapiro, it is here that Ban developed the parallel: design as if composing a poem, compose a poem as if designing. A poem is written starting from a structure, its main composing element, which is then enriched by “selecting and setting the minimum phrases, repeating certain phrases, allowing one phrase to have various meanings”13. The same is true in the architectural practice. The suitability of materials, their employment “in a way which makes sense14”, and their relationship with one another is central in defining the palettes which compose a project. This respect towards materials also translates into a greater attention paid to the joints between members, key constructive elements which are thoroughly discussed for each case study in the pages ahead.

His role as a socially conscious architect should not overlook his deep investment in aesthetics which serve to enhance his pro-bono projects. He is an architect that places his faith in geometry and the study of the great Renaissance masters: the paper tube colonnades which appear time and again in the projects explored in the thesis capture the essence of the great architectural works of the past15. The sense of aesthetics and proportions which has matured over the span of his career manifests itself in the scale and proportions of his buildings. The temporary structures are thus able to offer beautiful and spacious solutions on top of convenience: a revolutionary manifesto in a time where temporary emergency housing is built to satisfy low quality standards. He perceives his disaster relief

efforts as a way to provide common people a monument of their own16

Kenneth Frampton best summarises the conundrum represented by Shigeru Ban’s complex architectural persona.

“Underlying his work is an idea of a minimalism based on the notion of energy and ecological sustainability. He’s connected to the Japanese tradition, but also very influenced by America and a Yankee-tinker attitude, which was Buckminster Fuller’s approach. It’s a value-free technical performance, detached from anything you could call a critical cultural position.”

Kenneth Frampton on Shigeru Ban

01.3 Shigeru Ban / A Teacher

Acknowledging some intangible truths of the architectural world today: namely that less than 20% of the world population benefit from the great architectural and engineering opus, and that the humanitarian crises affecting well over 50% of the world population (war, natural disasters, national bankruptcy, etc.) are for the most part untouched by the risk management measures in action today17. Shigeru Ban strives to educate and form a more conscious generation of architects. His pursuit anchors itself in the on-site action of VAN and his lectures at Keio University.

His concerns for environmental and humanitarian issues are what first drove him to intervene in the planning and construction of paper shelters in Kobe in 1995. In the same year he founded the Voluntary Architects’ Network, a non-governmental foundation whose aim is to build aid facilities for the victims of natural or man-made disasters. This was essential for continuing his practice in refugee support as, in practice, refugee camps are organised and constructed by NGO’s appointed by the United Nations. The VAN Foundation’s activities focus on the research, design and erection of emergency buildings. Activities which are based at the Shigeru Ban Lab at Keio University. One specific intention is to provide specific solutions for minority victims which might sift below the radar of governmental and UN support systems18, a goal which was already visible since the first multi-layered intervention

04

for Vietnamese immigrants in Kobe. The volunteers engaged in the organisation are mostly students of Shigeru Ban’s, as well as students and architecture professionals who come from various parts of the world to participate in the humanitarian endeavours. Through the relief interventions, on top of fulfilling the immediate needs of the displaced, a double pedagogical purpose unravels. On one hand the involvement of the local population in the assembly procedure provides technical skill which is essential, in the long term, for the native community to gain independence from humanitarian aid. On the other the collaboration with student volunteers functions to mould a specific sensitivity within the younger generation of professionals, whilst offering valuable on-site experience and insight. In many geo-cultural areas where his work has been constructed Ban has also held numerous public seminars on buildings techniques, disaster response and disaster prevention. Creating a web of globally shared knowledge is part of his educational and architectural mission.19

“The work of architects is creating buildings, but I keenly believe that what is truly significant is fostering people.” 20

Shigeru Ban, 2014

Notes

1 - Isozaki A., Electric Labyrinth for the XIV Milan Triennale 1968 ; In May, Isozaki designed a large-scale installation with mobile screens, ambient sound, and projections on drawings and photographs titled Electric Labyrinth pivoting around the theme of “dead architecture” (landscapes and cities destroyed by violence).

2 - Isozaki A., Electric Labyrinth for the XIV Milan Triennale 1968

3 - Dogan R., Disaster Relief Architecture: Mitigating Environmental Hazards And Preparing For Disasters (2023) , Parametric Architecture Available at: https://parametric-architecture.com/disaster-relief-architecture-mitigating-environmental-hazards-and-preparing-for-disasters/ (Accessed Spring-Summer 2023)

4, 5, 7, 8, 9 - Kimmelman M., (2014) Shigeru Ban: Humanitarian architecture - essay “Shigeru Ban: in the service of society” p. 21-22

6 - Pallasmaa J. and Sato K., Alvar Aalto Through the Eyes of Shigeru Ban, Exhibition catalogue, Black Dog Publishing in association with Barbican Art Gallery, London, 2007, p. 62 9, 10, 11 - Kimmelman M., (2014) Shigeru Ban: Humanitarian architecture - essay “Shigeru Ban: in the service of society” p. 21-22

10 - Fuller’s Influence, Available at: https://www.bfi.org/ about-fuller/biography/fullers-influence/ (Accessed: SpringSummer 2023)

11 - Saval, N. (2019) Shigeru Ban is changing the priorities of Architecture, The New York Times. Available at: https://www. nytimes.com/interactive/2019/10/15/t-magazine/shigeru-ban.html (Accessed: Spring 2023).

12 - Miyake, R. and Makabe, T. (2017) Shigeru Ban: Material, structure and Space preface On Shigeru Ban, p. 9

13 and 14 -Miyake, R. and Makabe, T. (2017) Shigeru Ban: Material, structure and Space preface On Shigeru Ban, p. 15

15 - Miyake, R. and Makabe, T. (2017) Shigeru Ban: Material, structure and Space preface On Shigeru Ban, p. 11

16 - Goodyear D. , Paper Palaces The architect of the dispossessed meets the one per cent (2014) The New Yorker, Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/08/11/ paper-palaces (Accessed Spring-Summer 2023)

17 - Miyake, R. and Makabe, T. (2017) Shigeru Ban: Material, structure and Space preface On Shigeru Ban, p. 7

18 - Pollock N. (2014) Shigeru Ban: Humanitarian architecture - essay “The Architecture of Shigeru Ban: Blurred LInes and Ambiguous Boundaries”. p. 35

19 - Kitayama K. (2014) Shigeru Ban: Humanitarian architecture - essay “A conversation between Koh Kitayama and Shigeru Ban”. p. 44-46

05

02 Paper Case Studies / Shelter

Shigeru Ban began developing paper shelters in 1995 to help people displaced by the earthquake in Kobe. Paper shelters have mostly been kept as temporary solutions, with a range of construction complexity and lifespan determining at what post-disaster phase they are employed. These are then adapted to site, political situation, and material availability; allowing these systems to be integrated within the socio-cultural context. Shigeru Ban’s research and work in the field of emergency shelters revolves around some key questions:

“How could the consideration of intangible cultural heritage and the diversity of cultural expressions be incorporated into housing construction?

How could these housing constructions contribute to refugees’ sense of self and community identity, and promote greater social cohesion with host communities?

Similarly, how could we build houses that ensure an open dialogue with the people who are living in them, with nature, and with the surrounding environment?” (Montail P., 2017)

The following section will seek to provide some answers through the analysis of various case studies of paper shelters and their employment in different situations. These are categorised into 3 main typologies according to planned duration of use:

1. Emergency – paper emergency shelters,

2. Temporary – paper partition system,

3. Semi-permanent (or transitional) – paper log houses

02.1 / Paper Emergency Shelter

Tents are the first phase of intervention in many emergency situations. Their size, shape and lifespan depend on the context and conditions in which they are used; on the manufacturer, on the climatic conditions, and the occupants’ behaviour.

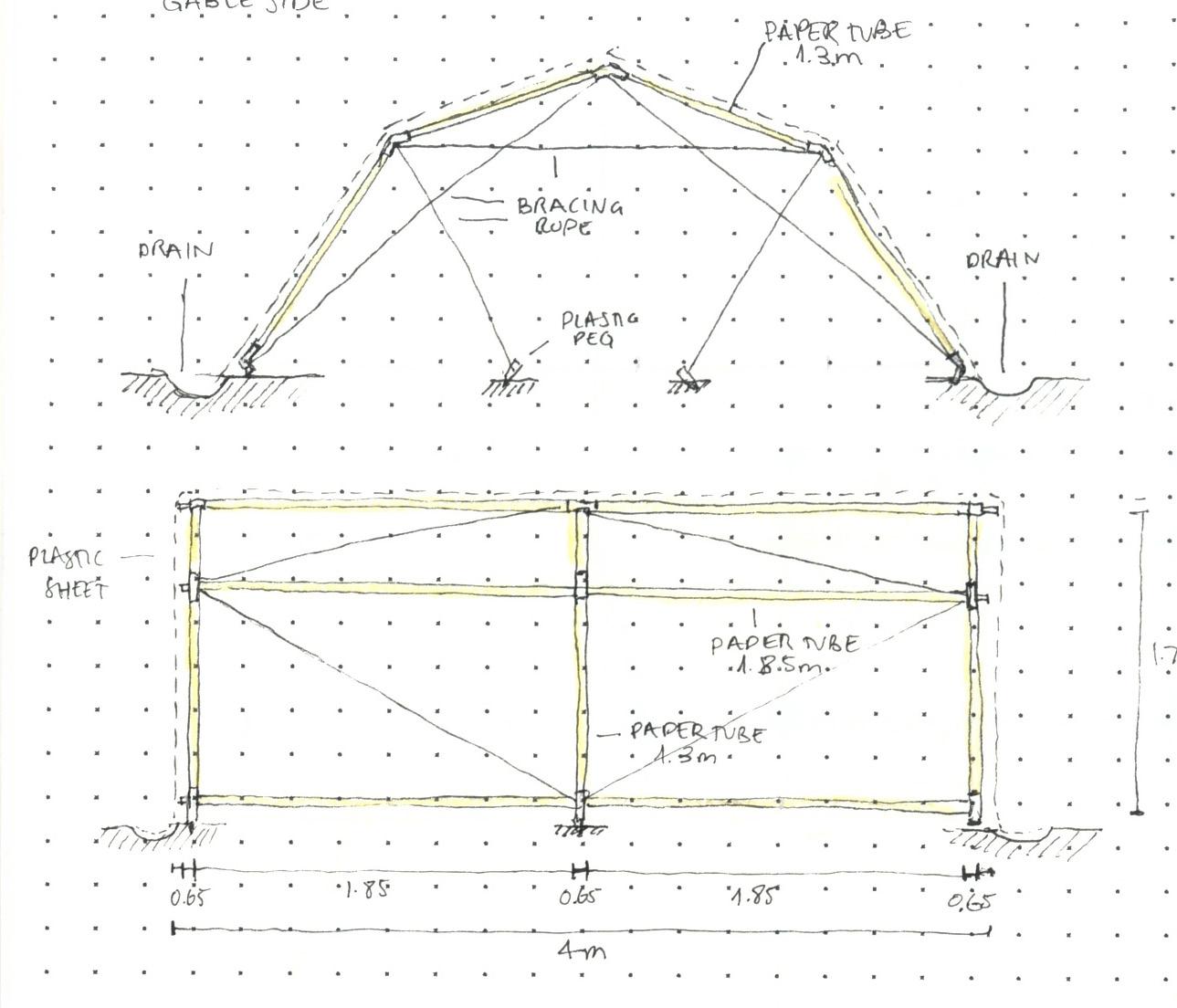

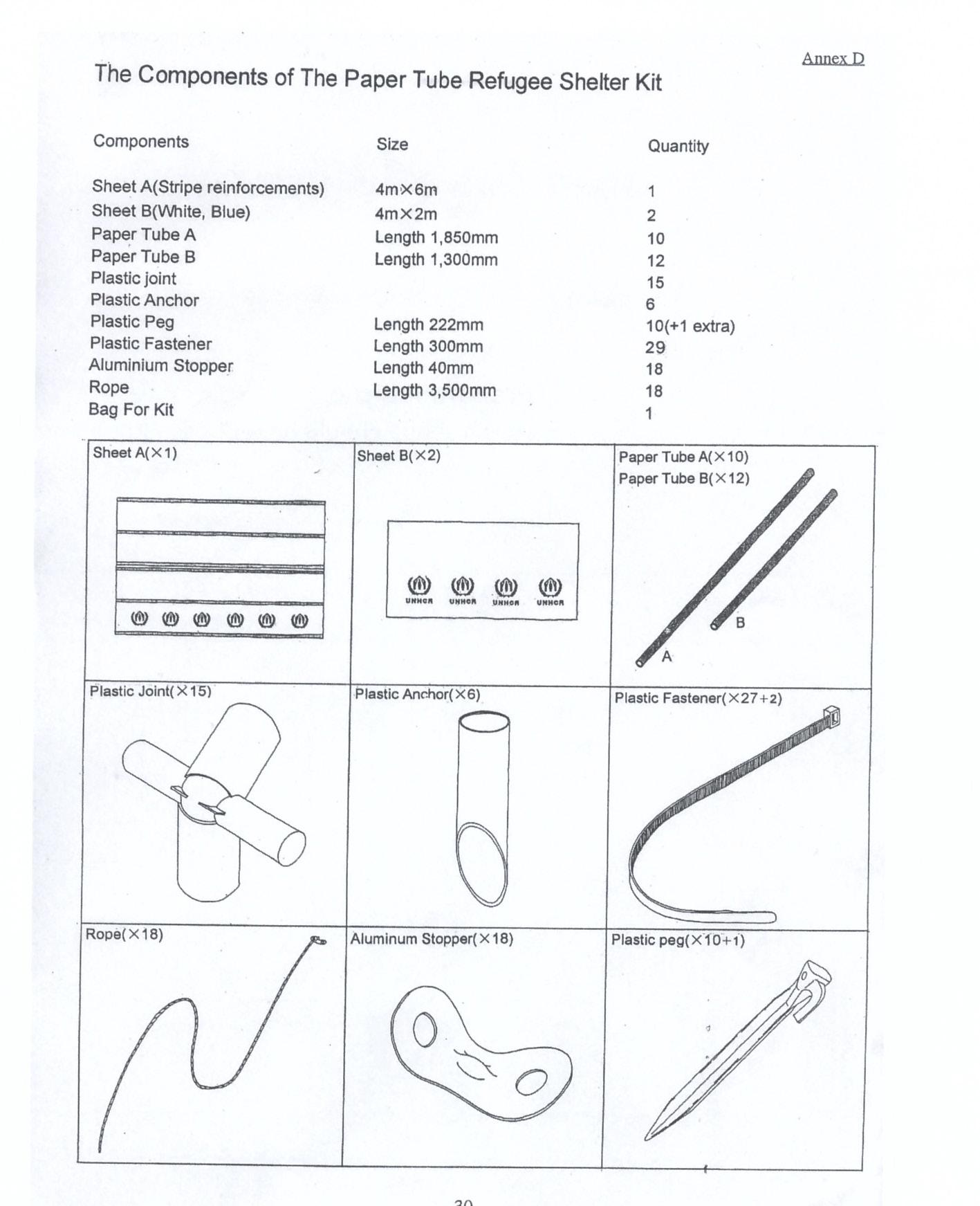

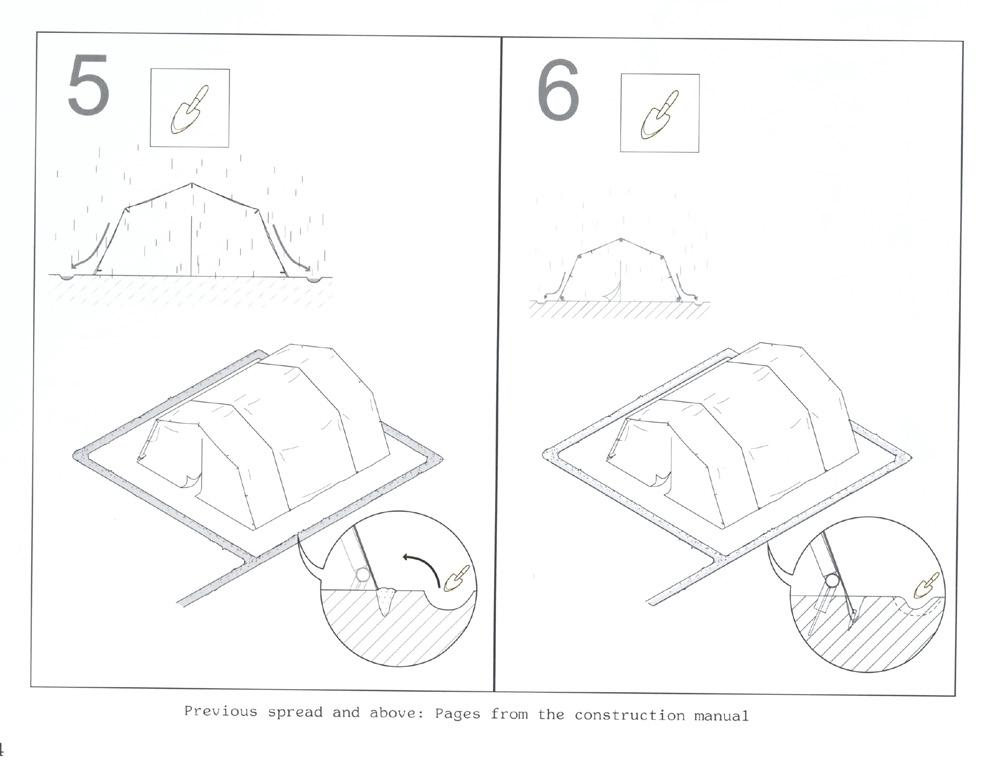

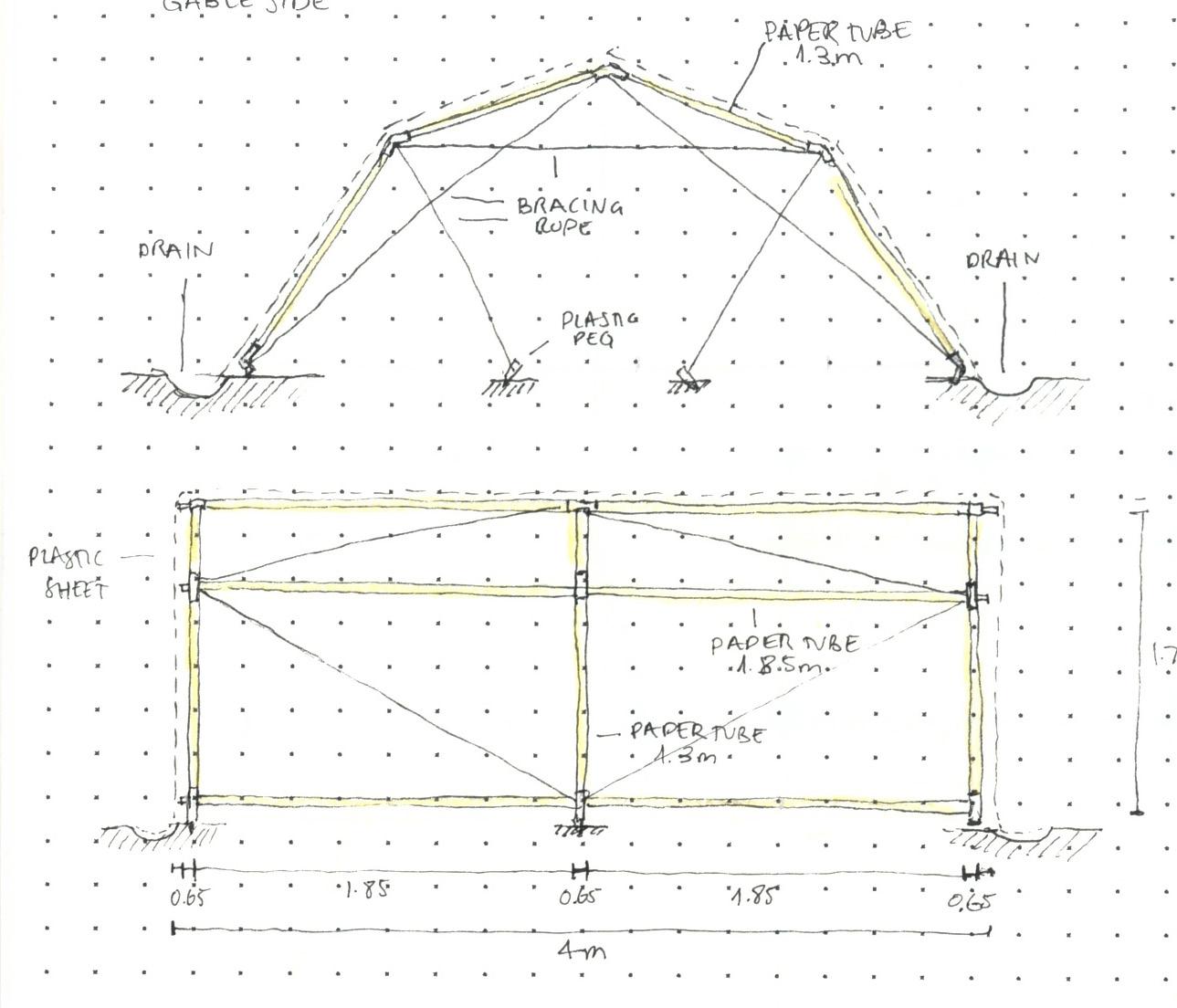

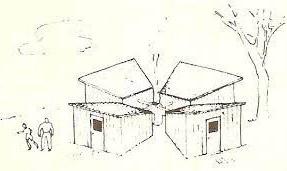

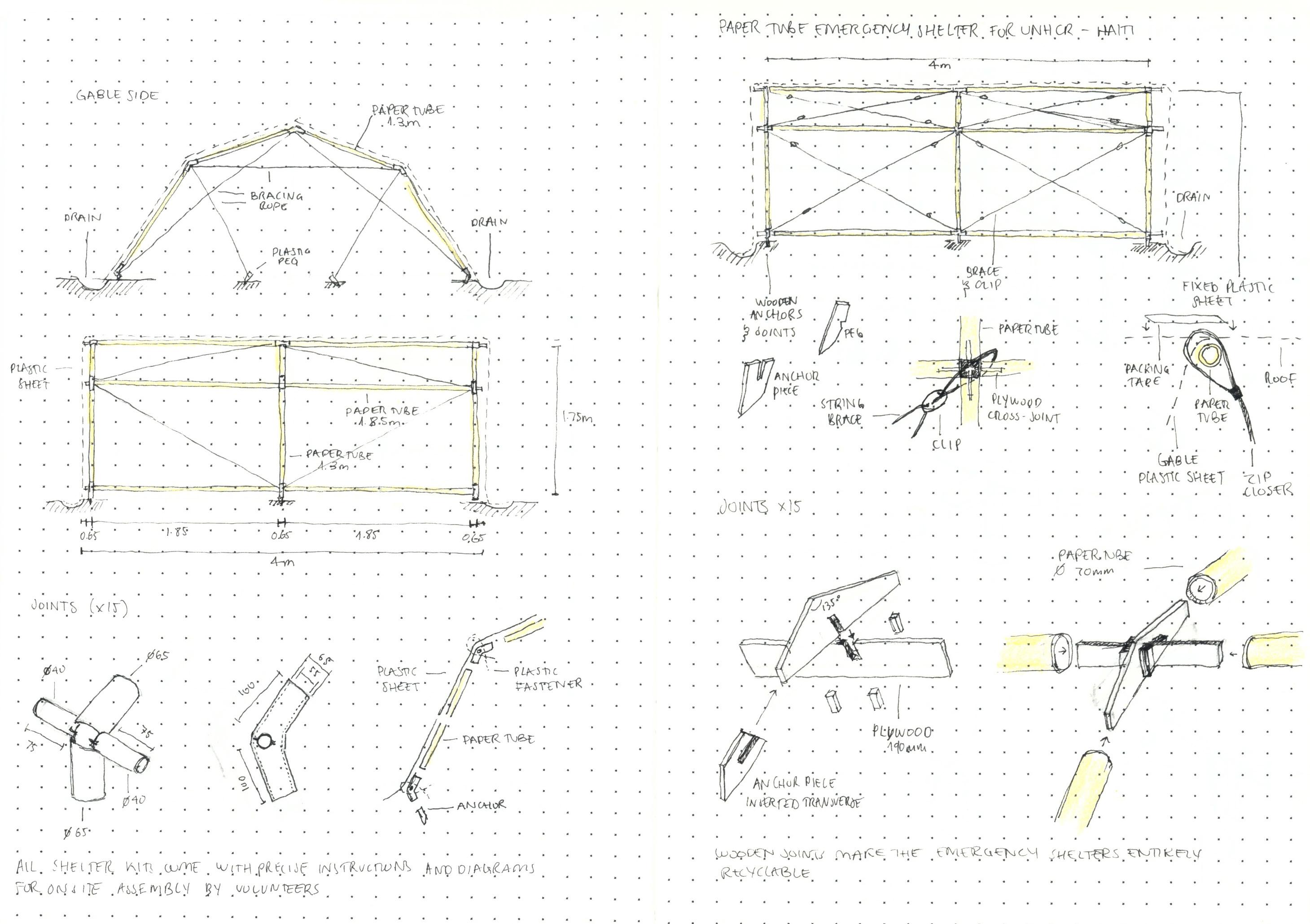

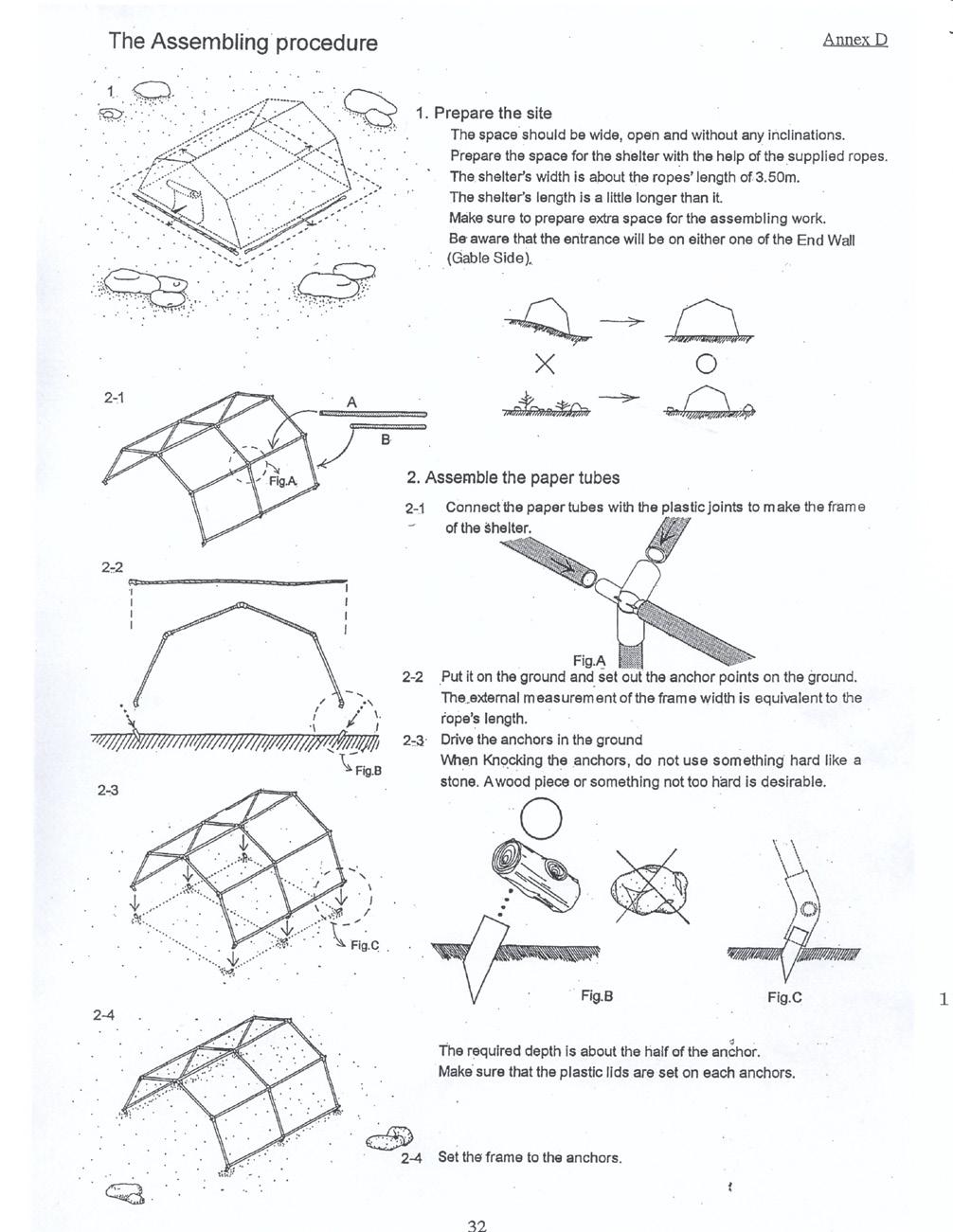

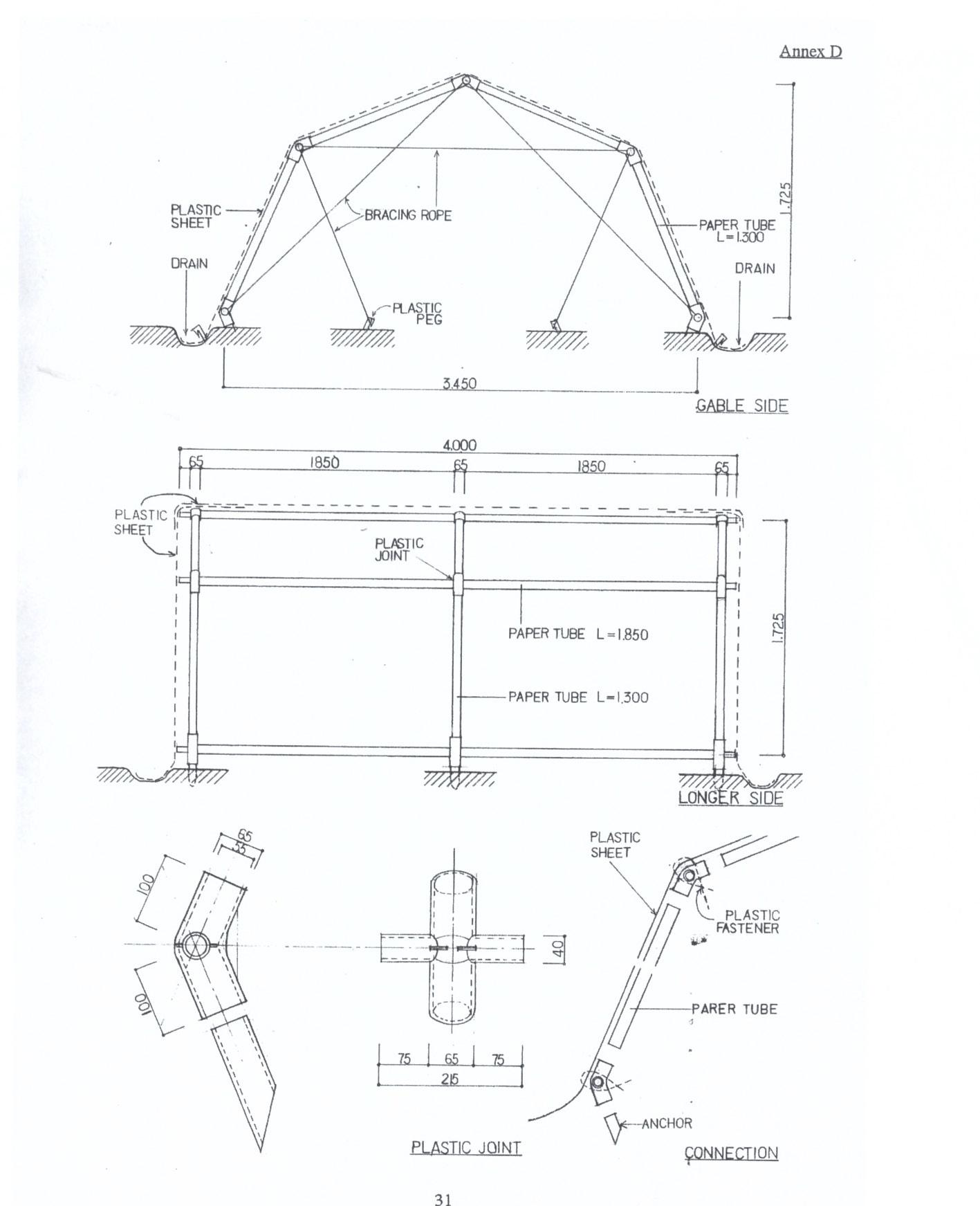

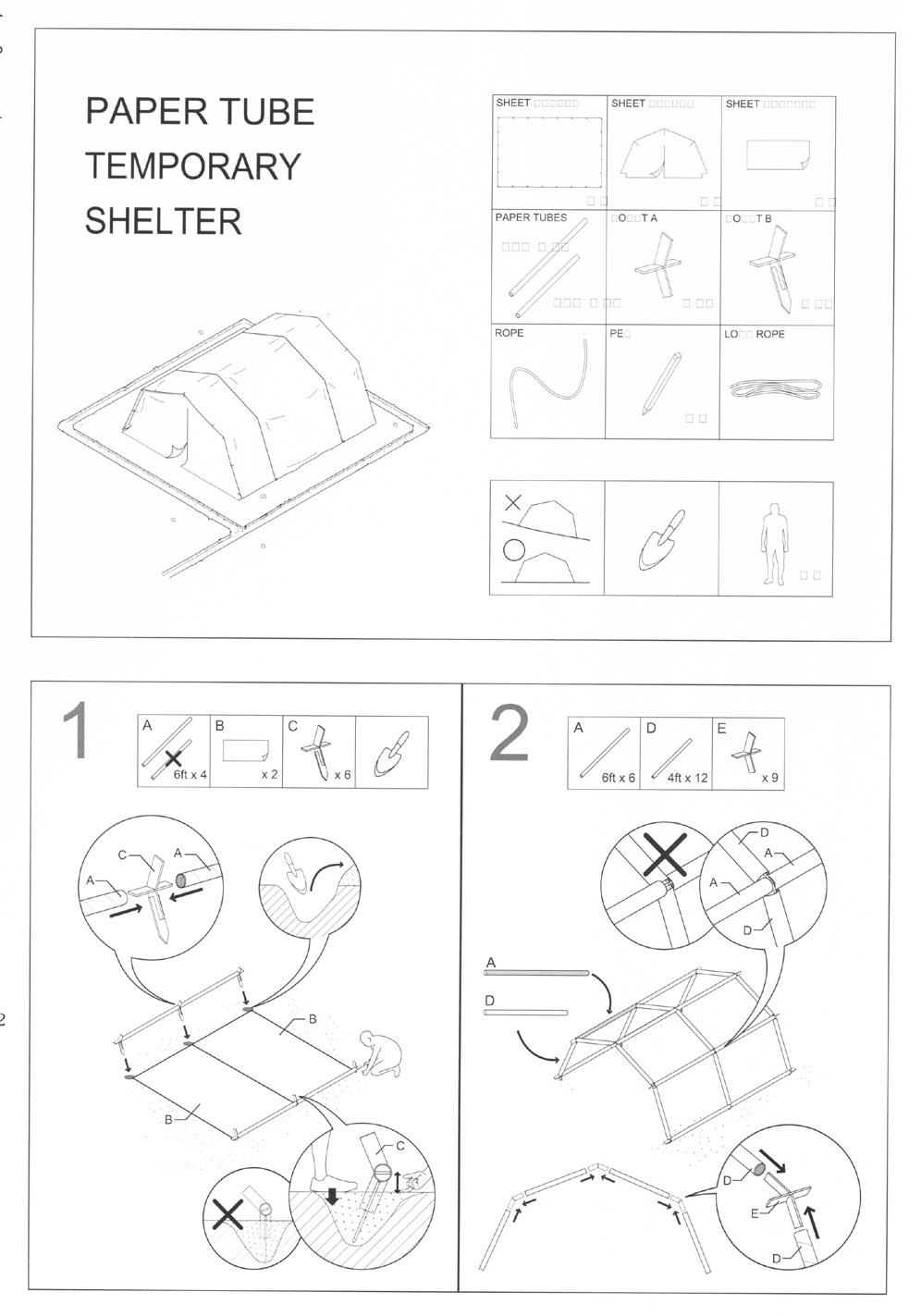

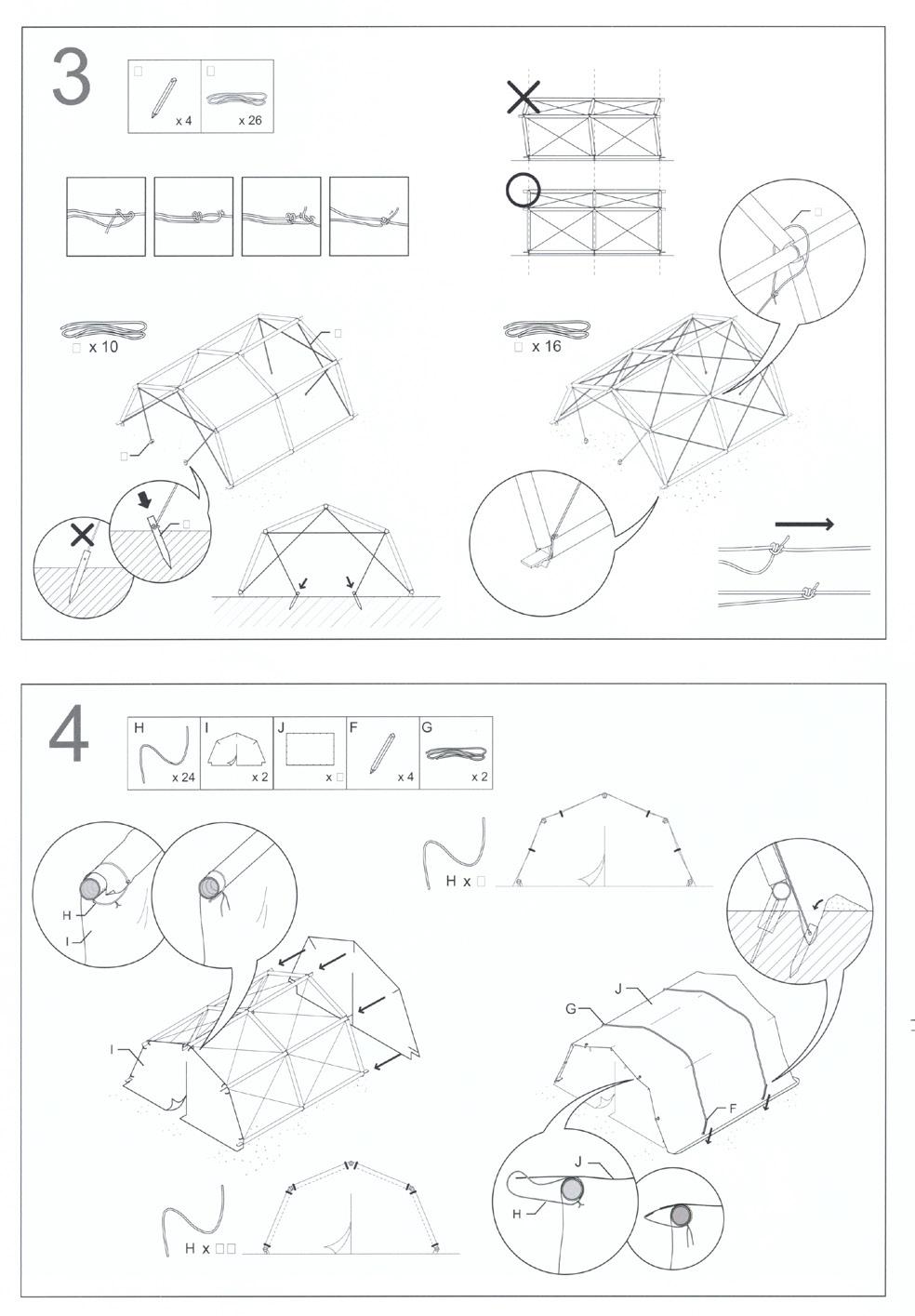

The most common tents consist of two layers: a waterproof external layer and an inner tent with a 12cm continuous insulation gap between the two. However, most tents do not provide the sufficient thermal comfort and in situations in which their use is prolonged can add great unpleasantness to the refugees. Shigeru Ban developed a modular paper tube system following the same structural logic as the traditional aluminium skeleton.

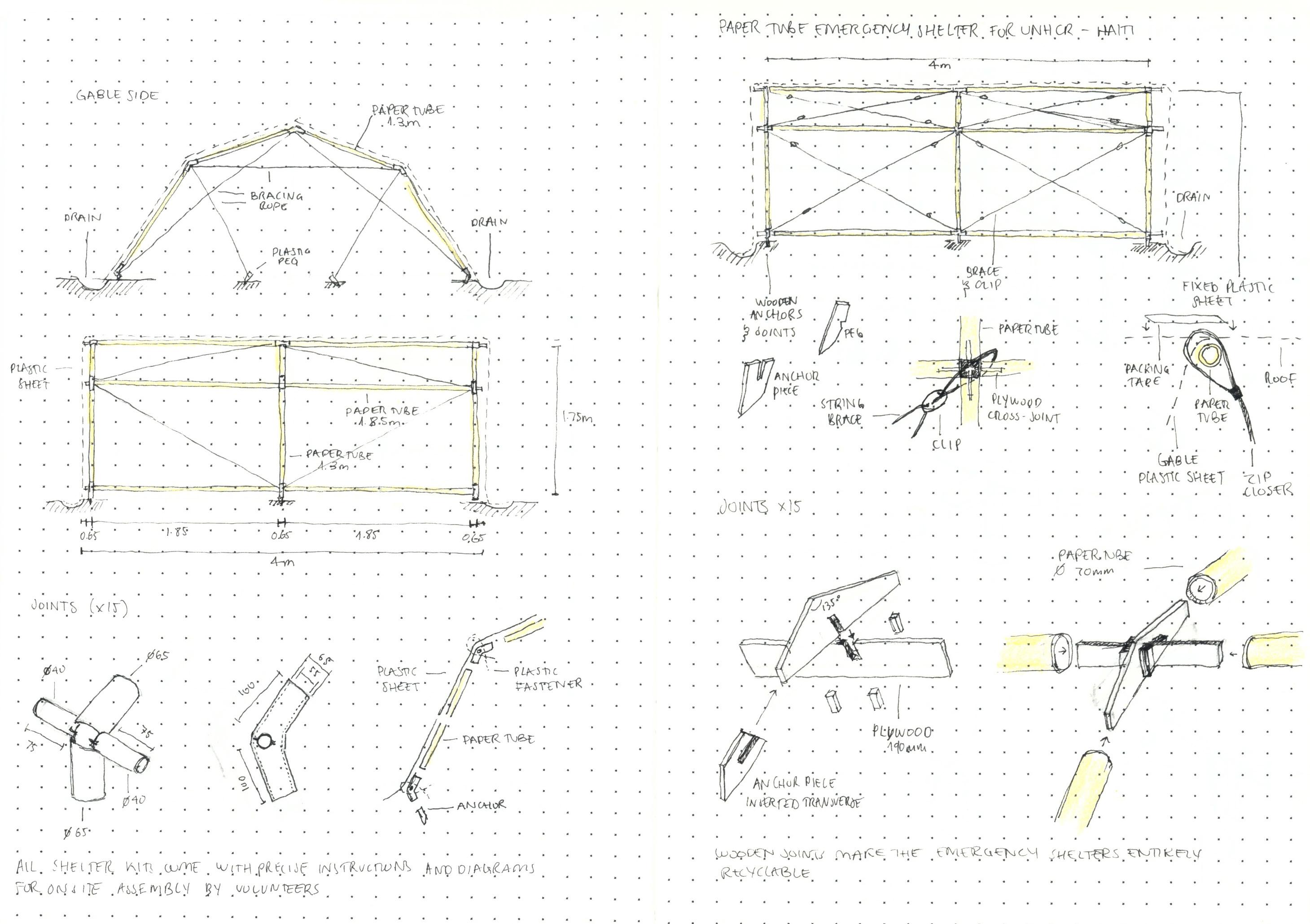

Curved plastic tube joints connect the frame elements and tensioned strings function as lateral braces. An evolution of the initial solution - introduced in Rwanda in 1994 - was applied in recovery attempts after the 2008 earthquake in Sri Lanka, with the substitution of the plastic joints with wooden elements. This jointing method was perfected with the paper emergency shelters sent to Haiti following the 2010 earthquake. Advantages of using wood instead of plastic include a complete recyclability of the tents once no longer in

use. However, considering the time factor of fabrication of such wooden joints, in its latest application in Nepal, tape was used to connect the paper tubes. A structure as simple as an emergency tent has underwent, through the guidance and continued exploration of Shigeru Ban and his team, numerous changes. Demonstrating a degree of adaptability which is crucial in architectural soltions for disaster relief.

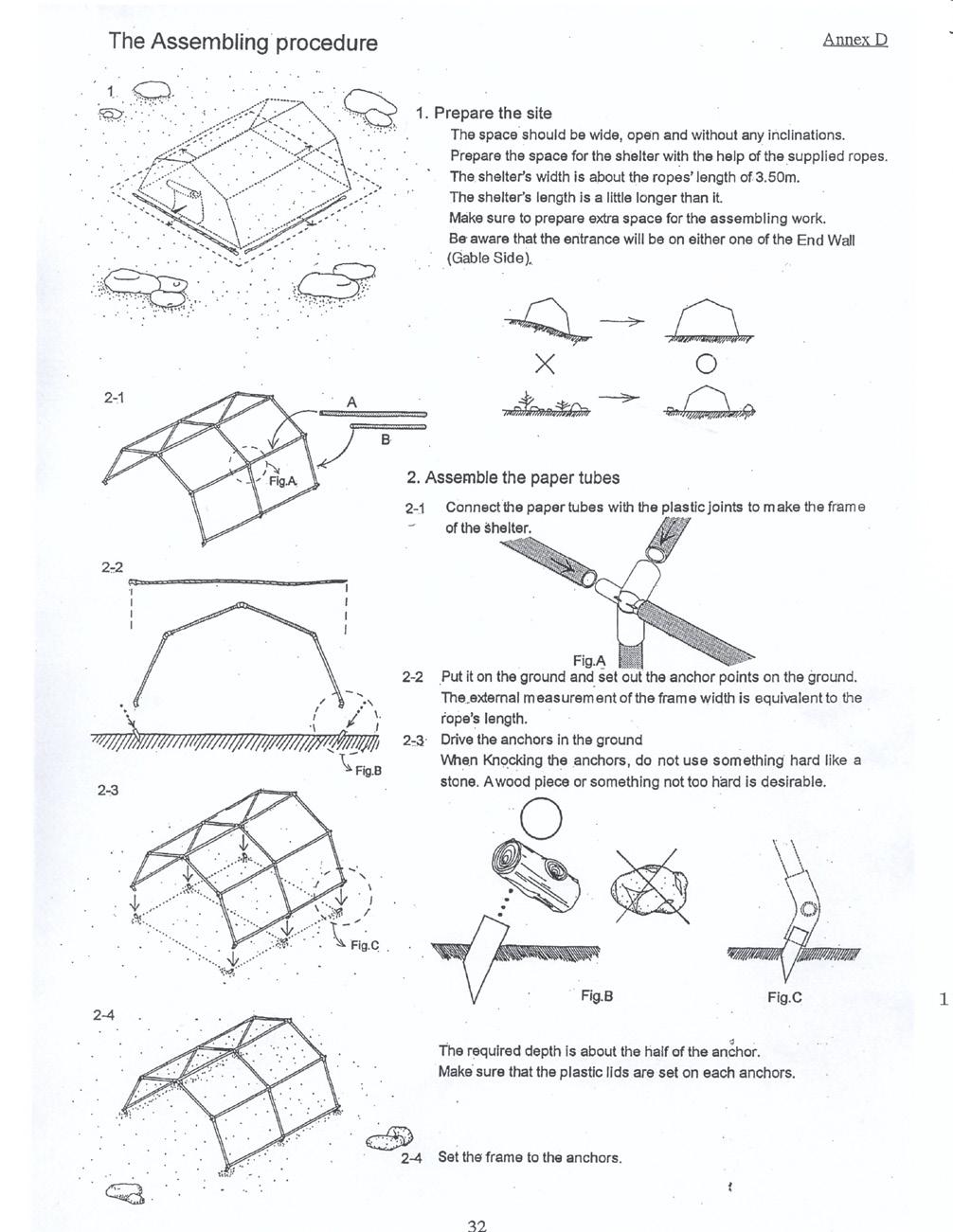

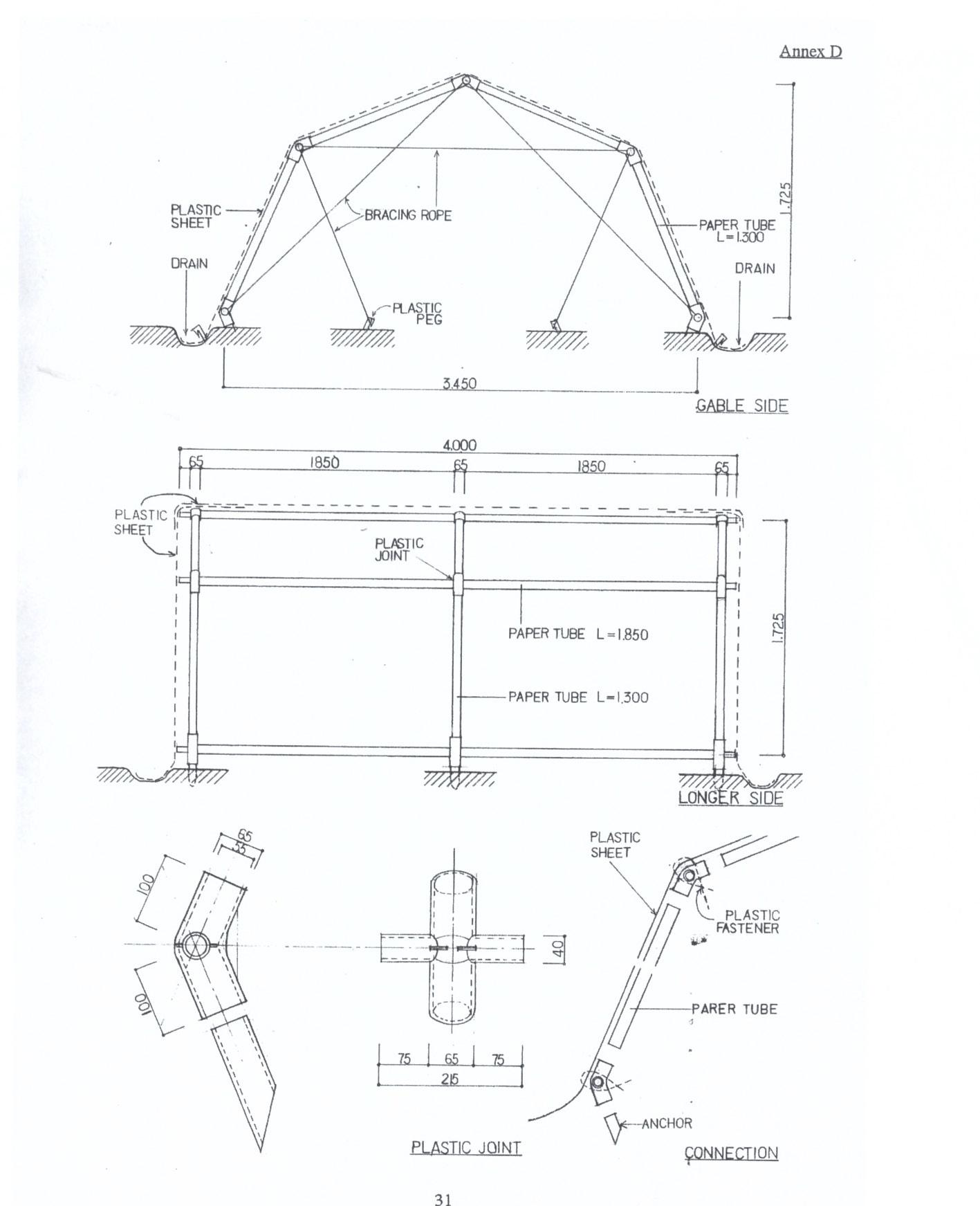

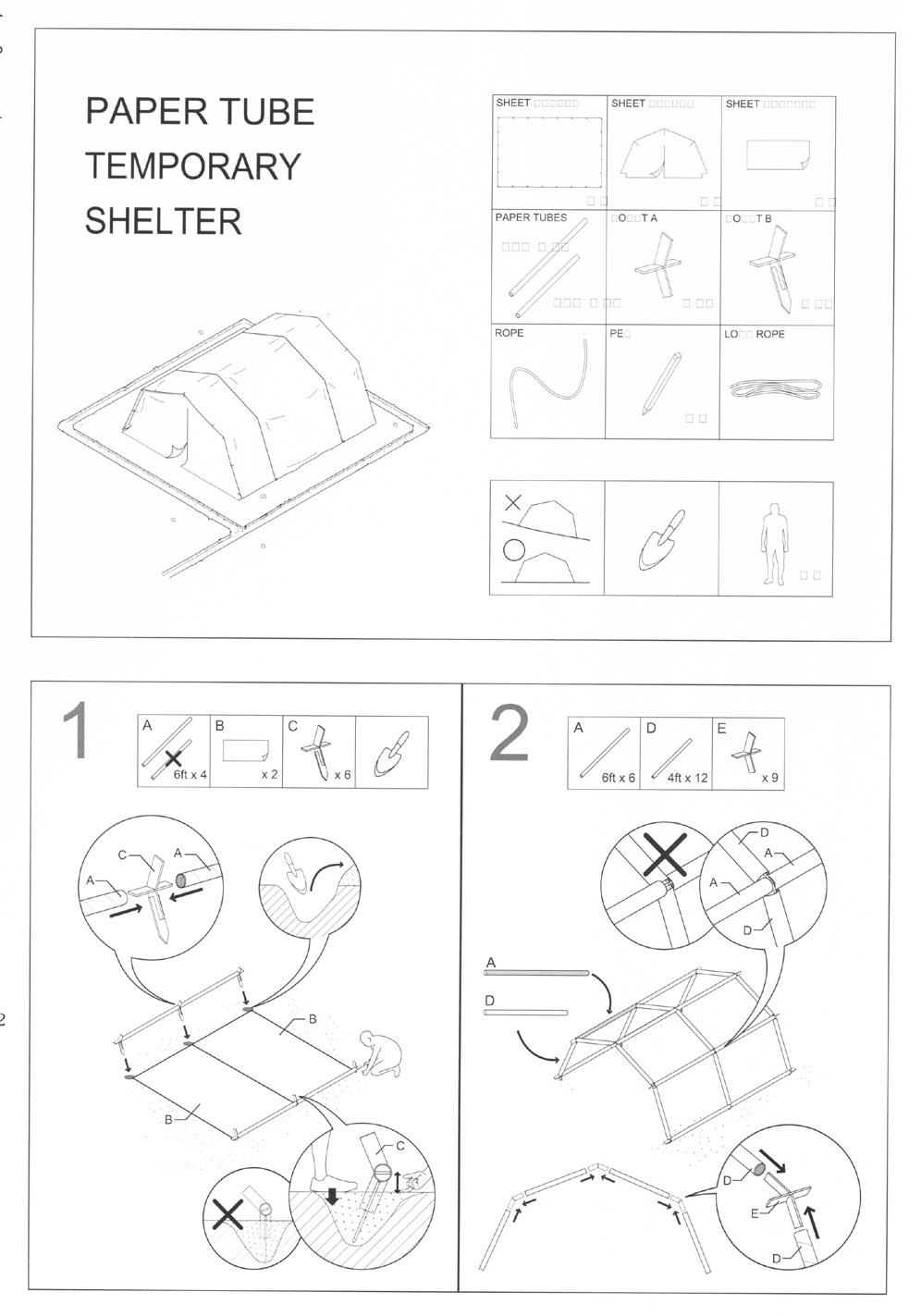

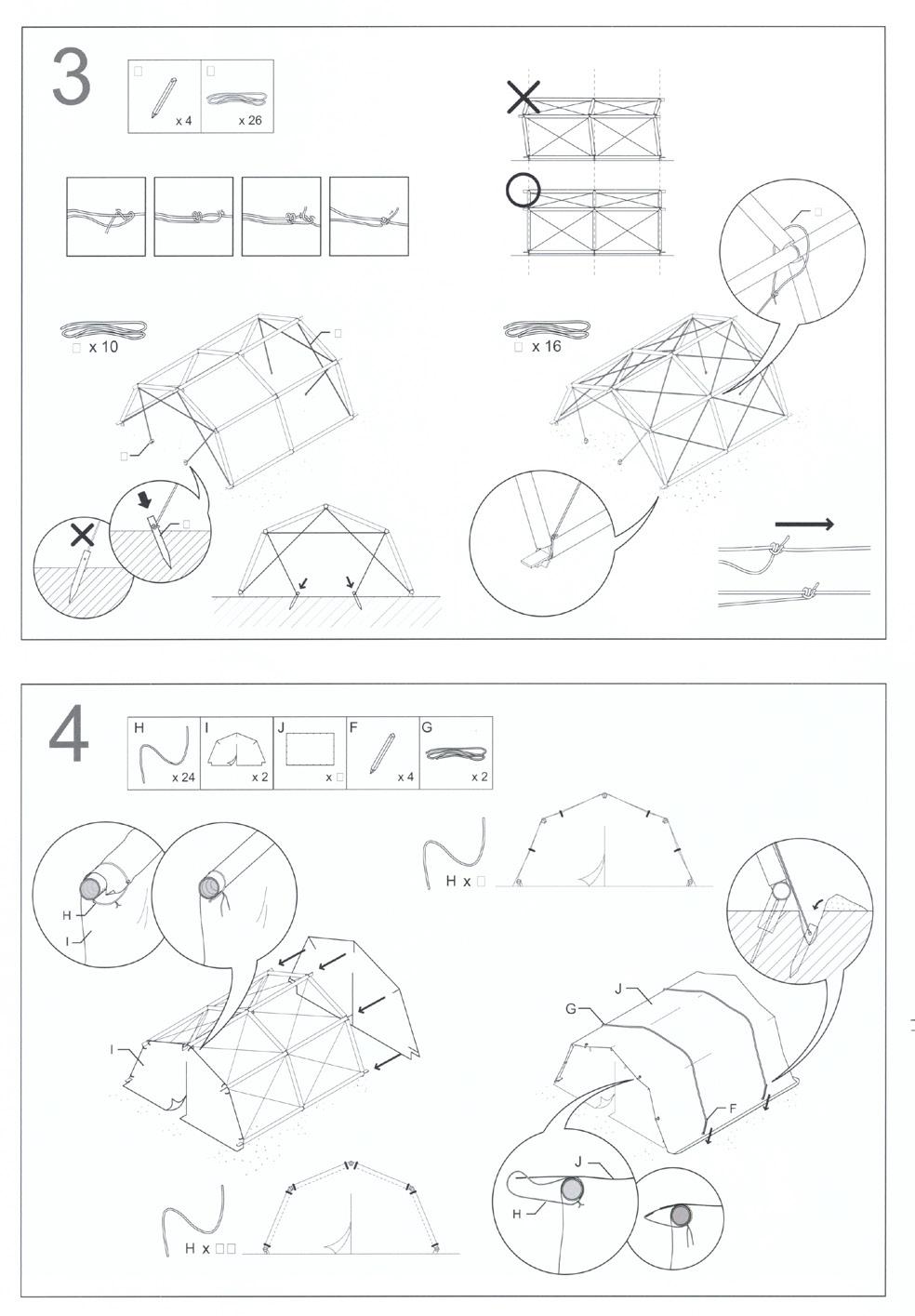

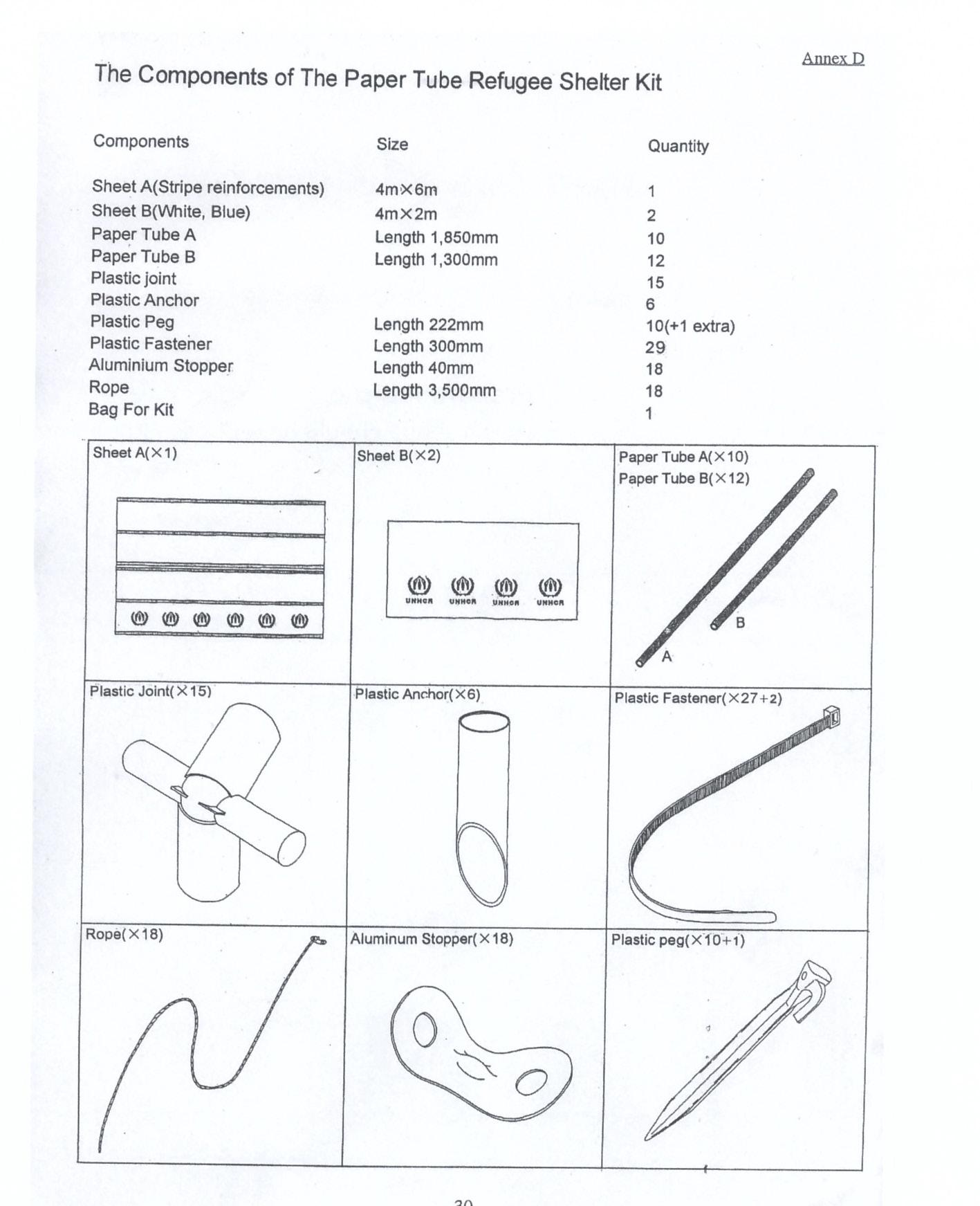

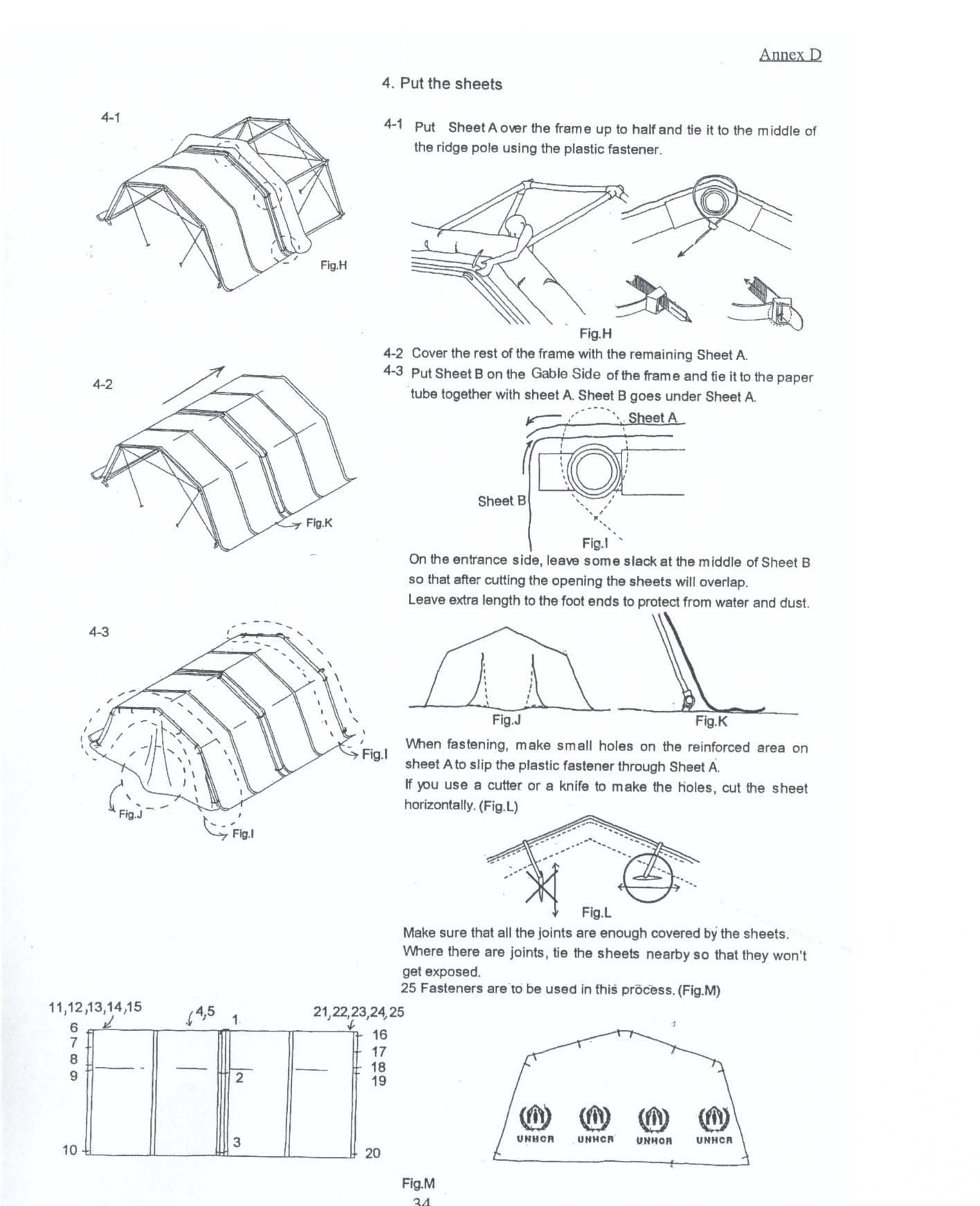

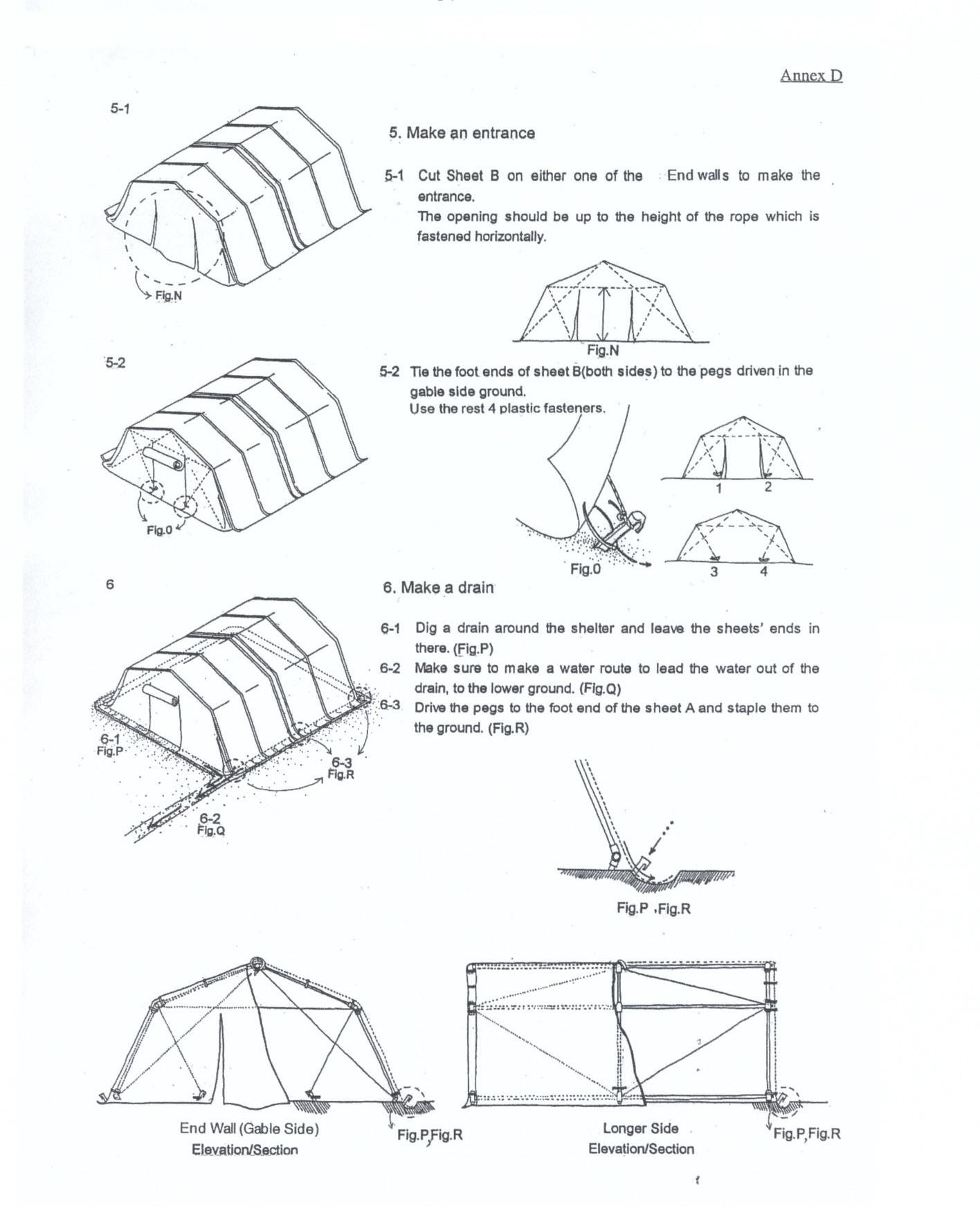

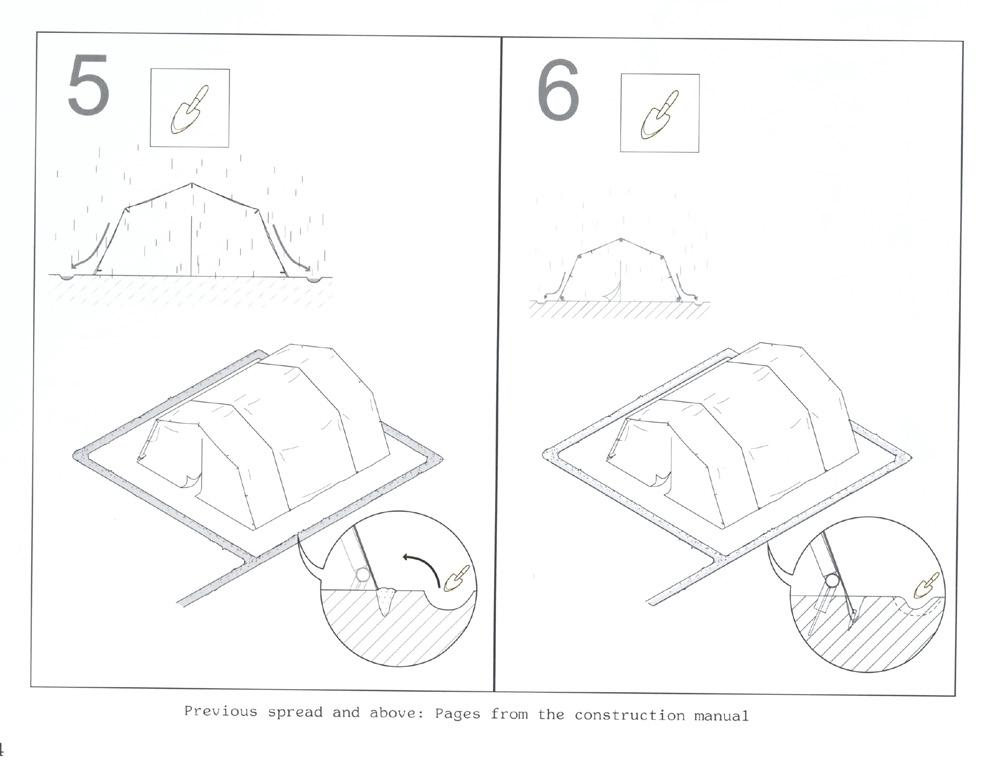

As typical in temporary emergency shelters the tents developed by Ban were sent in easy construction kits with illustrated guides for erection (see Appendix 01 and 02). The main steps are summarised below:

1. Prepare the site, a flat ground (3.5x4m)

2. Assemble the paper tubes and plastic joints

3. Drive the anchors into the ground using a piece of wood for approximately half their length at distance equal to one of the ropes provided

4. Attach the frame to the anchors

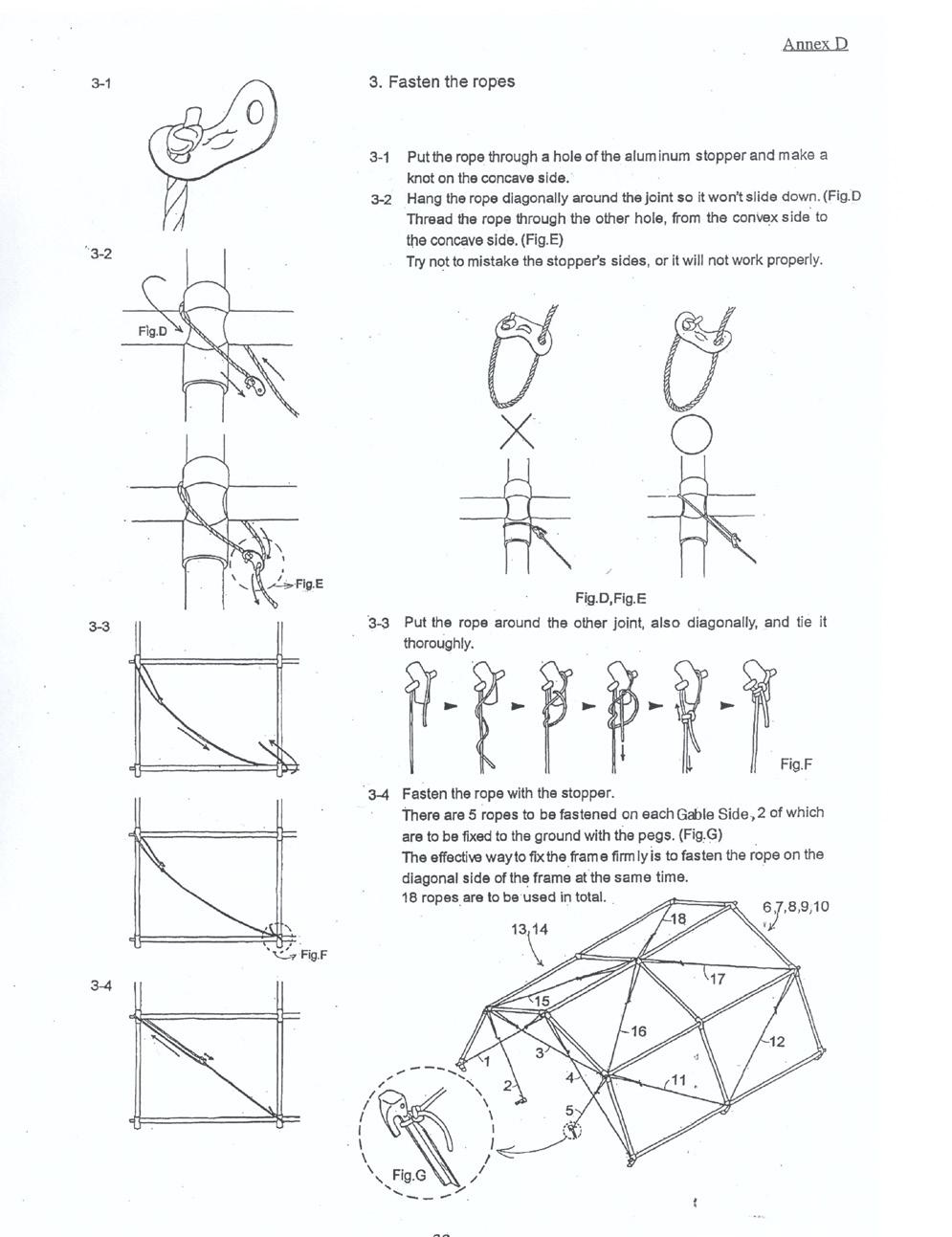

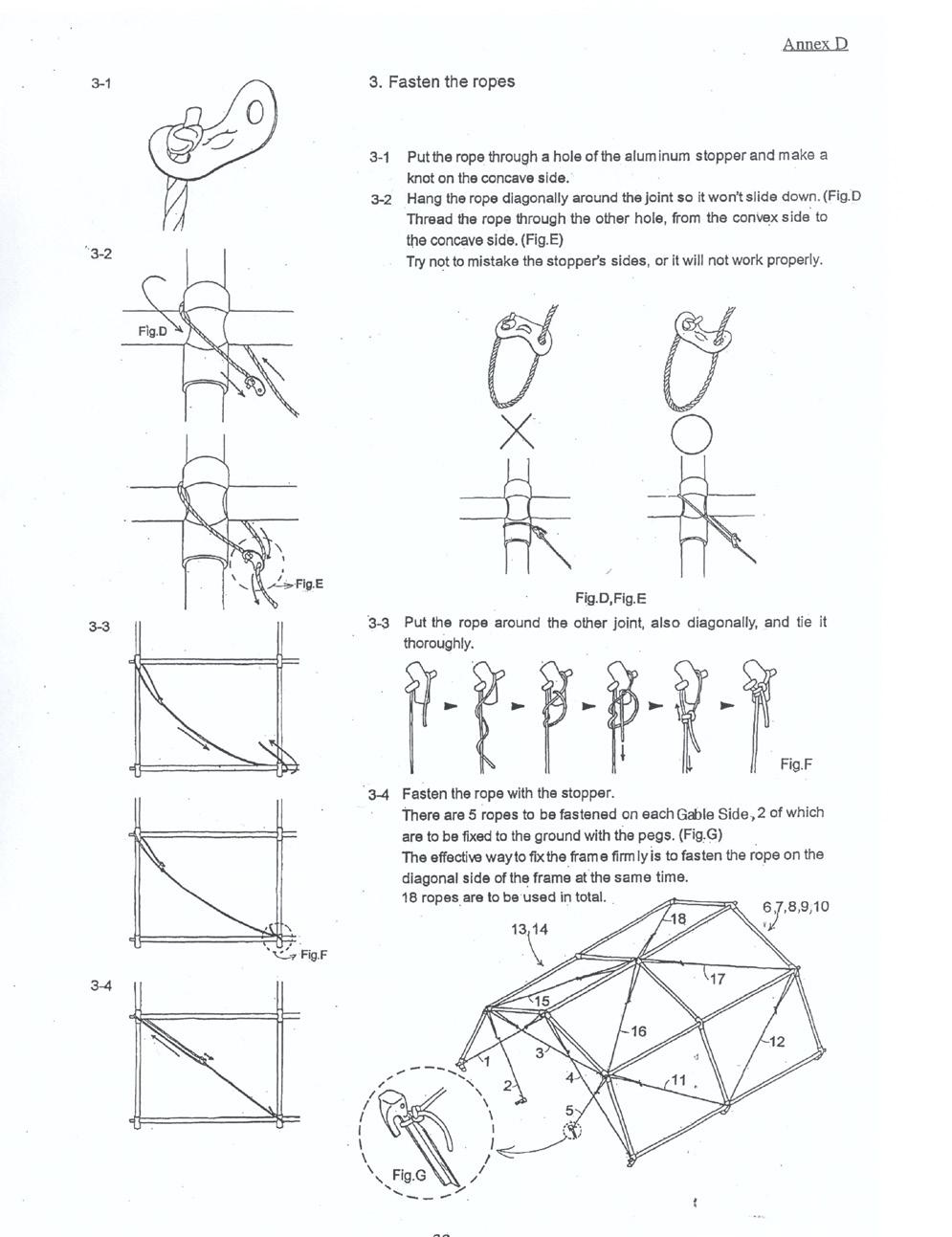

5. Fasten the ropes. Hang it diagonally over the plastic joints and fix with the aluminium stopper

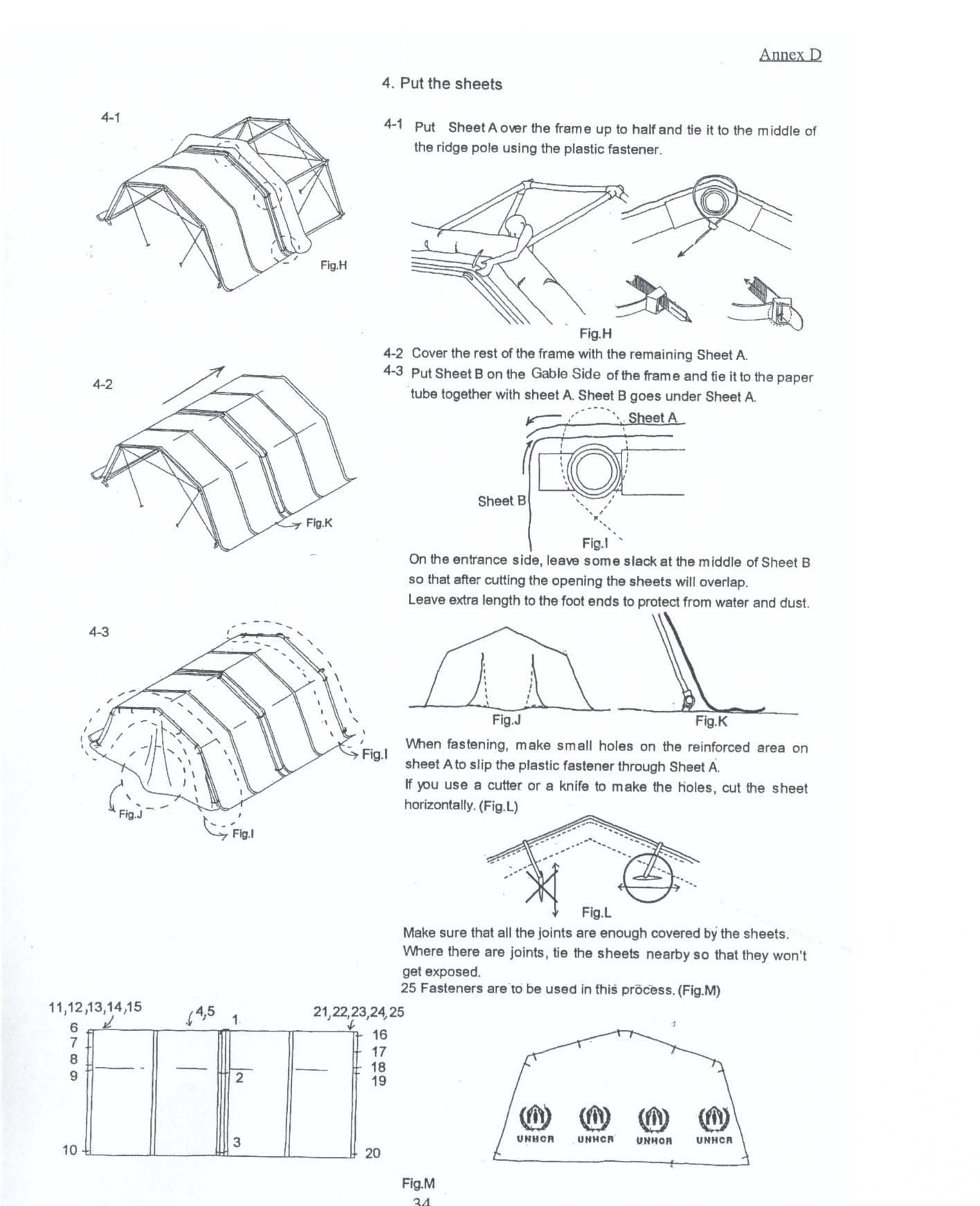

6. Fix the sheets onto the frame using the plastic fastener (sheet B below sheet A)

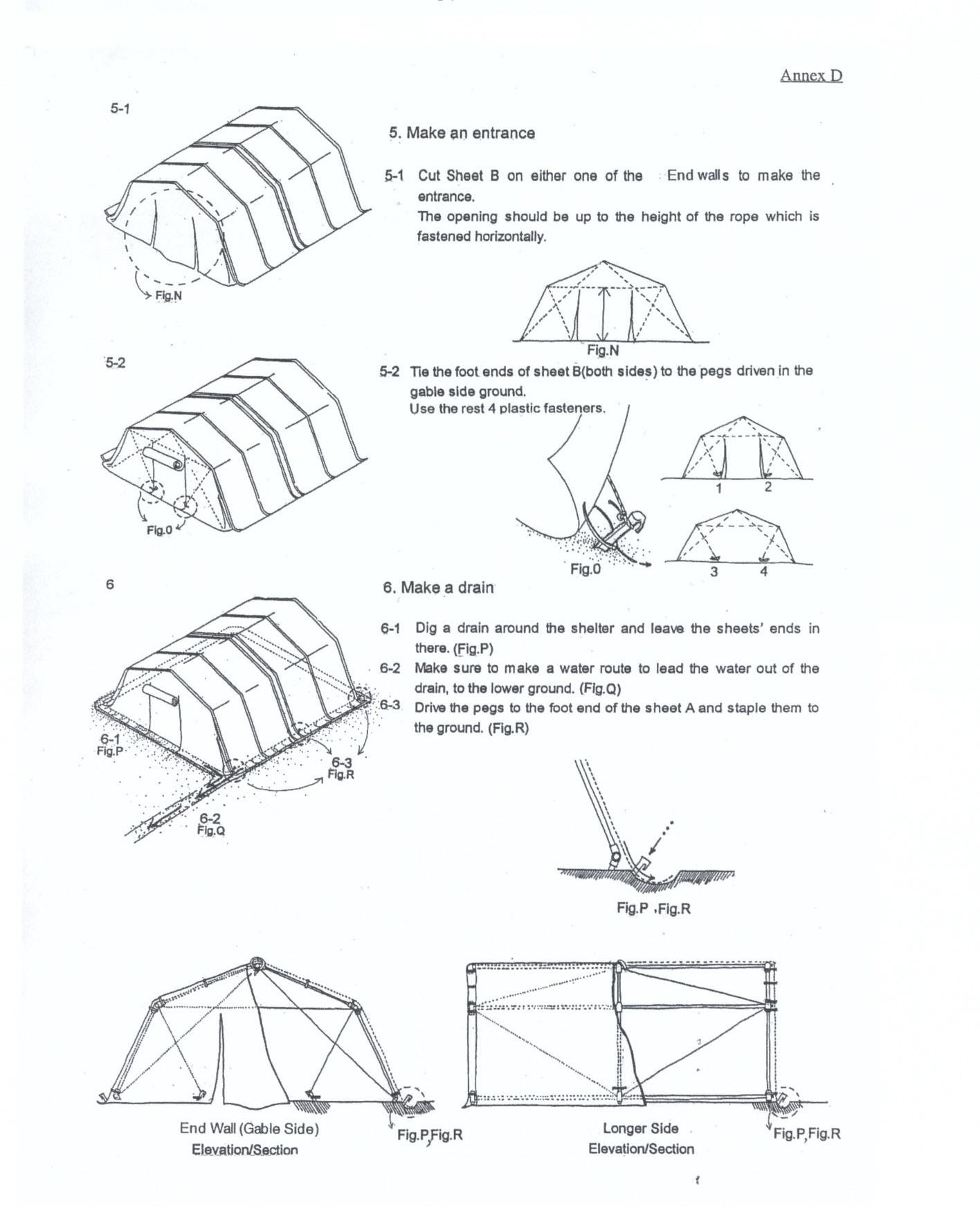

7. On the entrance side cut an opening

8. Dig a drain around the shelter

06

02.1.1 / Case Study / Rwanda and Zaire / 1994-99

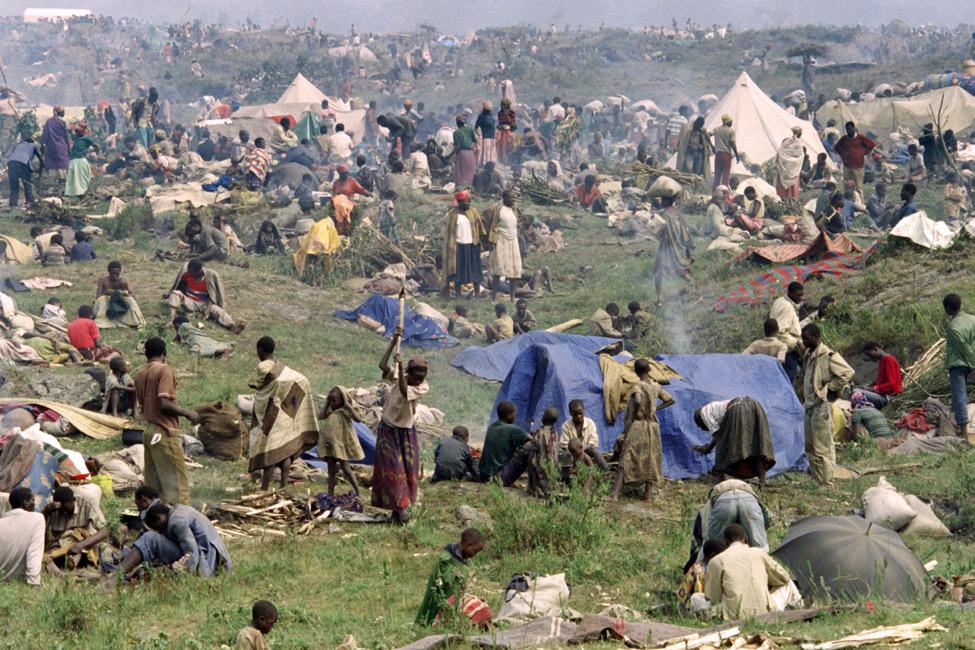

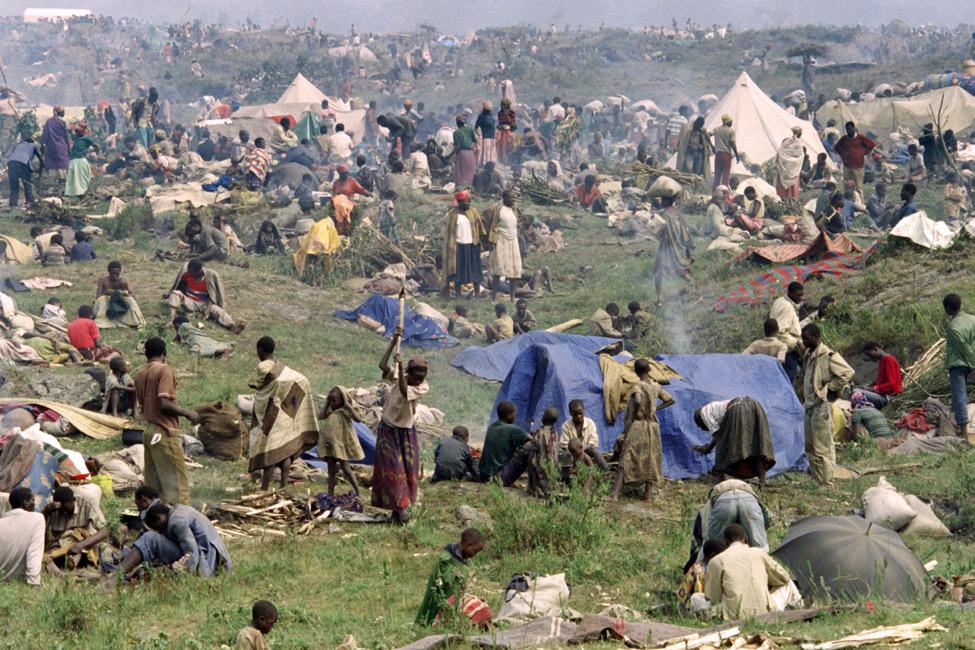

Ethnic conflict was at the root of the civil war which broke out in Rwanda in 1994. Nearly one million people lost their lives, and more than three million people were displaced . Many fled to neighbouring countries where they were given asylum and placed in refugee camps. By 1996 Rwanda was experiencing an inverse flow of people – either returning to reconstruct the country or fleeing from violence – that needed to be reintegrated and accommodated. More camps were quickly set up, housing primarily women, children, and elderly.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) office supplied plastic sheets and aluminium poles to construct temporary shelters. However, refugees would often cut down trees to use as supports for the plastic sheets and sell the aluminium poles. While this entrepreneurialism provided a rare opportunity to accumulate capital, it also led to deforestation around the camps. Ban, who was appointed as counsellor for refugee shelters by the UNHCR in 1995, criticised the organization and quality of these temporary settlements: “They were so messy. The shelters were just not good enough; people were freezing-cold during the rainy season” (Ban S. ,1995) In response to these issues

he suggested paper tubes, which refugees could not sell, as a low-cost alternative to the aluminium poles. Since paper tubes can be manufactured cheaply and by small and simple machinery, the potential to produce the materials on-site would reduce transportation costs whilst adding to the economic growth of the area. Three prototype shelters were designed and tested for durability, assessed for cost, and termite-resistance. In 1998, the selected emergency shelters were erected at the congolean Gihembe Refugee Camp rising at the border between Rwanda and Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo). Plots were excavated and tents were orderly placed along the hilly terrain. Though still temporary, the chaos which characterized the previous settlement had been resolved.

The humanitarian emergency that Ban’s tents responded to in Rwanda – the lack of accommodation for refugees at Gihembe – is linked to a second emergency: the normalised long-term emergency in which stateless refugees indefinitely occupy camps and depend on

Fig. 1; Evolution of the Paper Emergency Shelter. Final form with ross section made of 4 paper tubes at 135° angles Plastic joints used in Rwanda (left) and wooden joints and bracing system used in Haiti (right)

07

humanitarian assistance Though local authorities and international humanitarian organisations continued supporting the camp, the involvement of skilled architects was interrupted briefly after Ban’s intervention leaving much of the communal development up to residents. In the more durable wood frame and mud-plaster housing which quickly replaced Ban’s short-term emergency shelters, large families were cramped in the 12sqm homes lacking proper fenestration and lighting. The wood harvesting that Ban had proposed a solution to, through his temporary paper tents, nonetheless continued as the need to yield building material for these semi-permanent structures rose. The only part which could be repurposed of the tents was the plastic sheet, inherited from the UNHCR’s emergency shelters, which residents who couldn’t afford corrugated metal used as roofing.

The images of Ban’s emergency shelters should be viewed in relation to the protracted temporary condition in which Gihembe’s refugee residents still reside. Truthfully, they continued to live in an emergency, no longer crowded into tents but rather crowded into windowless houses, for twenty years. It would be unfair to assume that, since no image of the situation of the Gihembe camp has gotten the attention of Ban’s intervention, the emergency tents solved the shelter problem. Viewing humanitarian efforts within a time continuum, it becomes increasingly precious to understand their short-term and long-term influences on the affected communities – socially, economically, and culturally. Architectural humanitarian interventions must thus respect this chronological necessity protracting any effort through time, in different structural phases if necessary. Such short and long term analysis of the case studies is kept, when sufficient data was available to the author, throughout the following pages.

For over two decades, the refugee residents of Gihembe were unable to return to the Democratic Republic of Congo, where they are considered Rwandan; at the same time, they were unable to return to Rwanda, where they are considered Congolese. They appeared to be indefinitely blocked at a permanently temporary threshold space with just the bare minimal conditions for life4

Fig. 2; Refugee Camp in Goma, Zaire, 1994

Fig. 3; Assembly of one of the fifty Paper Emergency Tents in Gihembe Refugee Camp, 1998

Fig. 4; Gihembe Refugee Camp, 1999

Fig. 5; Gihembe Refugee Camp after substitution of emergency shelters with temporary housing, 2000s

Fig. 2; Refugee Camp in Goma, Zaire, 1994

Fig. 3; Assembly of one of the fifty Paper Emergency Tents in Gihembe Refugee Camp, 1998

Fig. 4; Gihembe Refugee Camp, 1999

Fig. 5; Gihembe Refugee Camp after substitution of emergency shelters with temporary housing, 2000s

08

Discontent in lack of educational facilities and

communal facilities was openly expressed by residents, yet these requests were never adequately responded to.

The belief the settlement was temporary, though ultimately it became a permanent aggregation of provisional infrastructure, deterred any significant intervention. For over two decades the living conditions of refugees at Gihembe remained precarious, with a single secondary school rising within the boundary of the camp, unreliable electricity and overcrowding becoming the permanent conditions for the more than 12000 people who have lived in the camp throughout the years. No true solution was found for the settlement: no efforts towards the liberation of these people from their temporary state as refugees were successfully made. In 2021 its inhabitants were relocated to the Mahama Camp or registered as urban refugees, protracting their milieu.

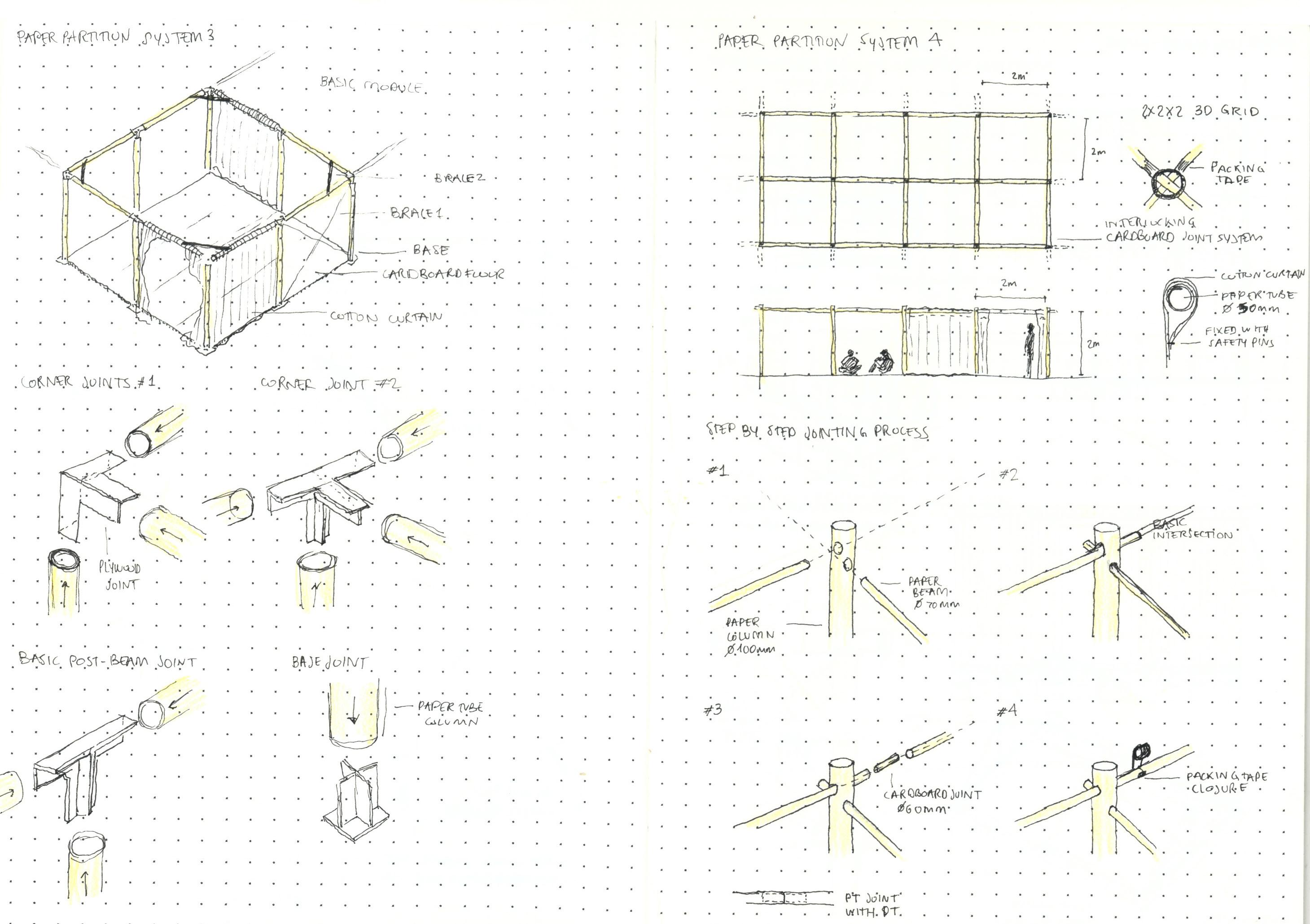

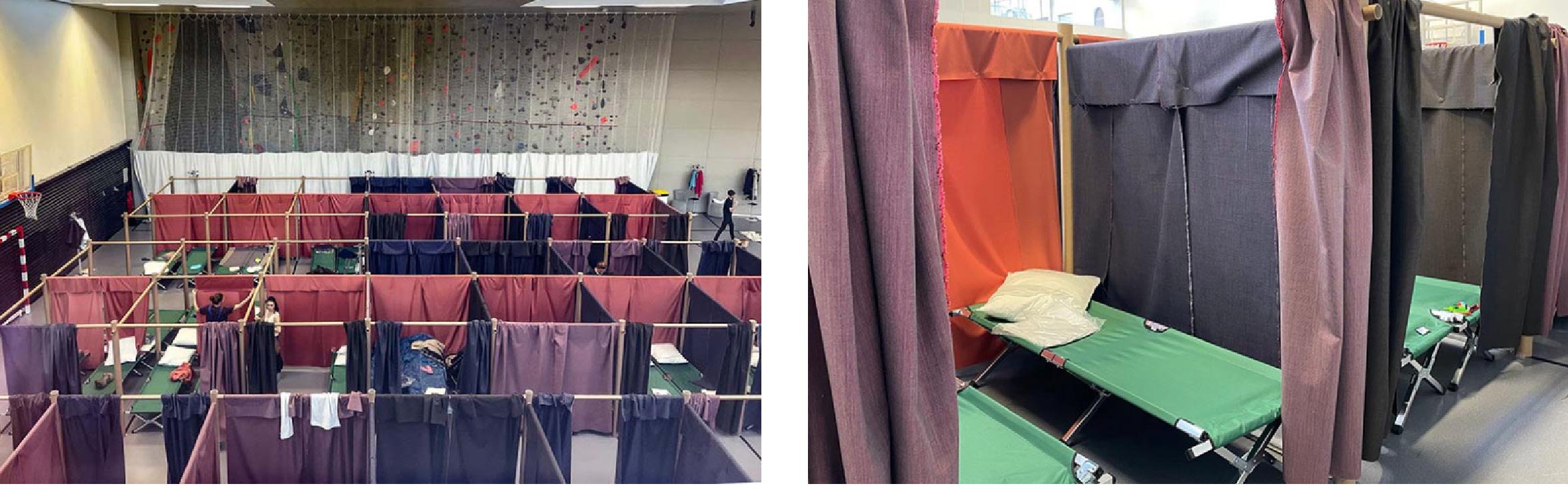

02.2 / Paper Partition Systems

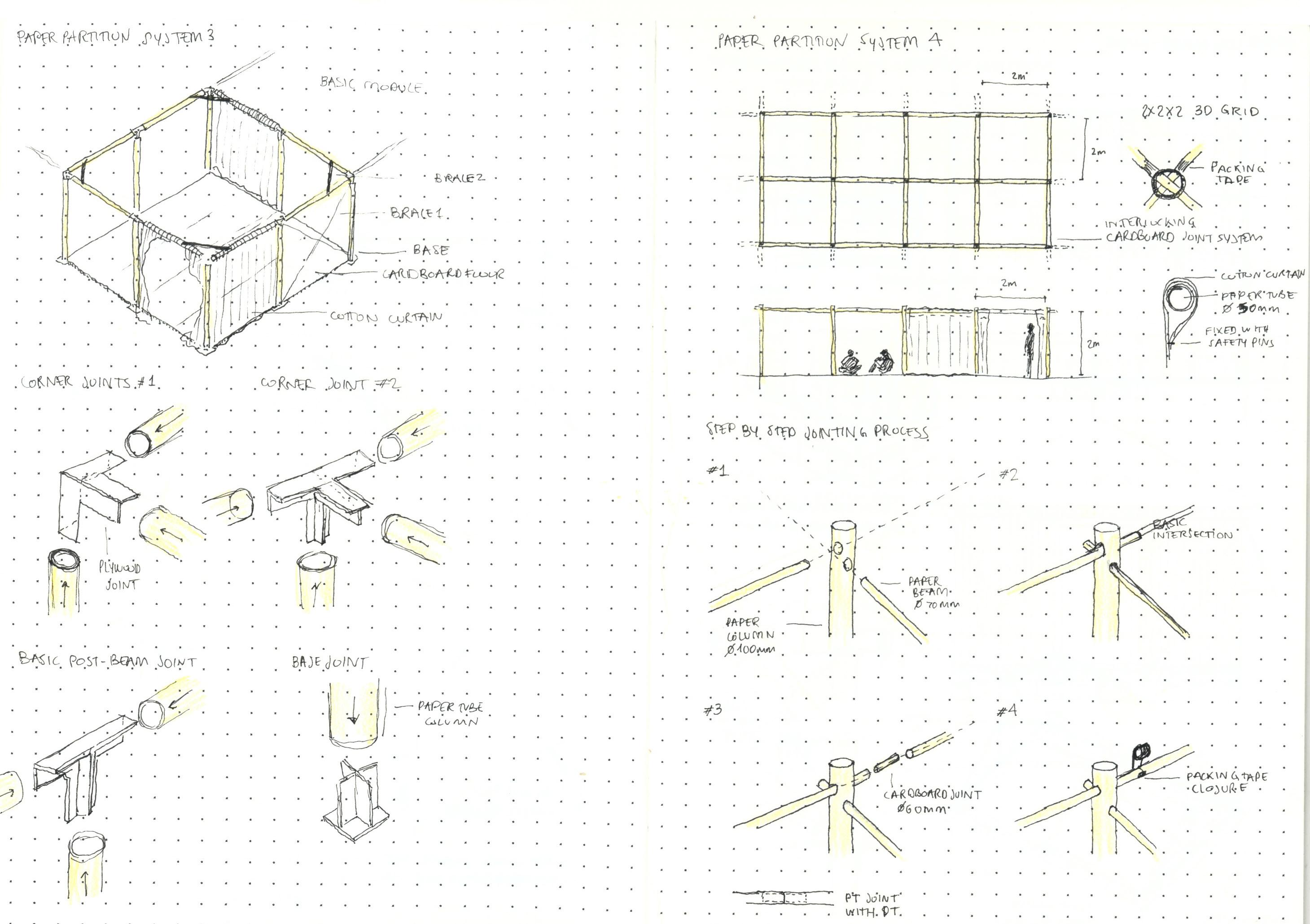

One of the main issues in the first phase at evacuation sites is the high density of refugees. Immediately following natural disasters and complex humanitarian emergencies, until temporary housing is built, the displaced population take shelter in public buildings and large facilities like auditoriums or sports centres (when available). Within these spaces overcrowding and the lack of privacy emerge as primary factors bringing discomfort to the residents. The Paper Partition System (PPS) aims to address these issues through standard units which divide the halls: white curtain partitions supported by paper-tube frames. The modular organization allows adaptation of the size of the living spaces according to family size through curtain partitions which can be opened or closed, reminiscent of traditional shoji paper screens.

02.2.1 / Evolution of the System

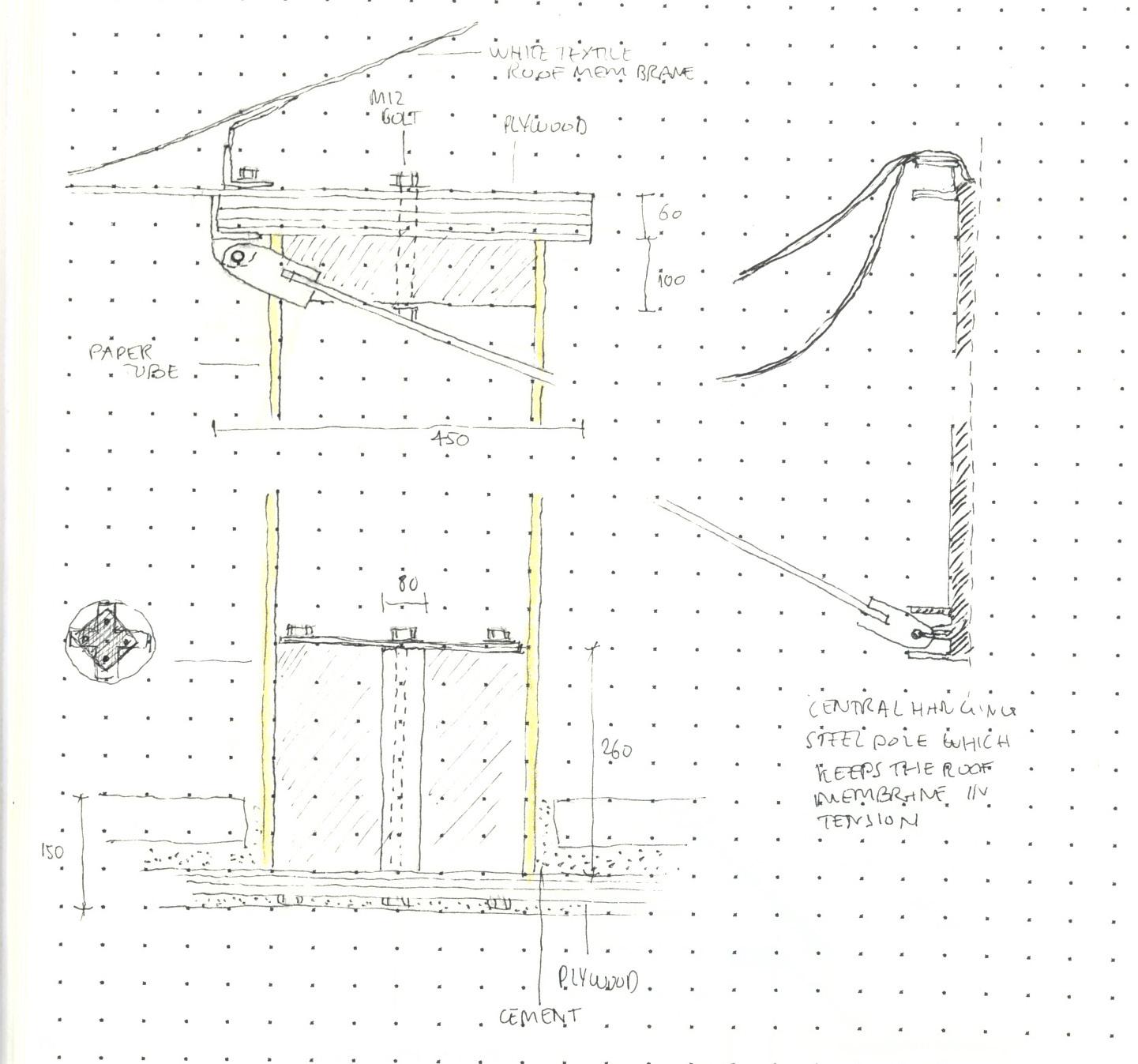

Following the 2004 Niigata earthquake, people were forced to evacuate to gyms and large building with high ceilings where Shigeru Ban first observed the aforementioned problems linked to this typology of disaster relief. The Paper Partition System #1 was developed as a single prototype by Ban and his students from Keio University, to be erected inside an evacuation site to provide some privacy. Cardboard was used for flooring and walls which were covered by a wooden square roof structure covered by a white textile. The

construction was quite simple: vertical cardboard panels are kept in place through longitudinal top joints and angled vertical joints. Upon this wall system a pre-assembled roof composed of a cardboard frame and a tensioned white textile closes the space. The small size of the unit made it easily transportable, and the simplicity of the jointing system required for the minimal structure meant refugees could quickly construct it without specialist knowledge. Though PPS1 was designed for family use, it was ultimately adopted by the evacuated community as a play pen for children and a temporary clinic for the elderly.

The PPS underwent constant revision every time an emergency situation in Japan required the application of temporary partitioning in large public halls, aiming to fit the needs of evacuation sites. For administration it is impossible to forecast the exact needs for partitions, so speed of assembly and modularity became crucial elements in further developments. Paper Partition System #2 was introduced one year later after the Fukuoka earthquake. The honeycomb cardboard panels, approximately one meter high, were used as flooring and to create borders between families. The same jointing

Fig. 6; Assembly of the PPS1 Walls in Niigata, 2004

Fig. 7; Assembled PPS1 in the gymasium in Niigata, 2004

09

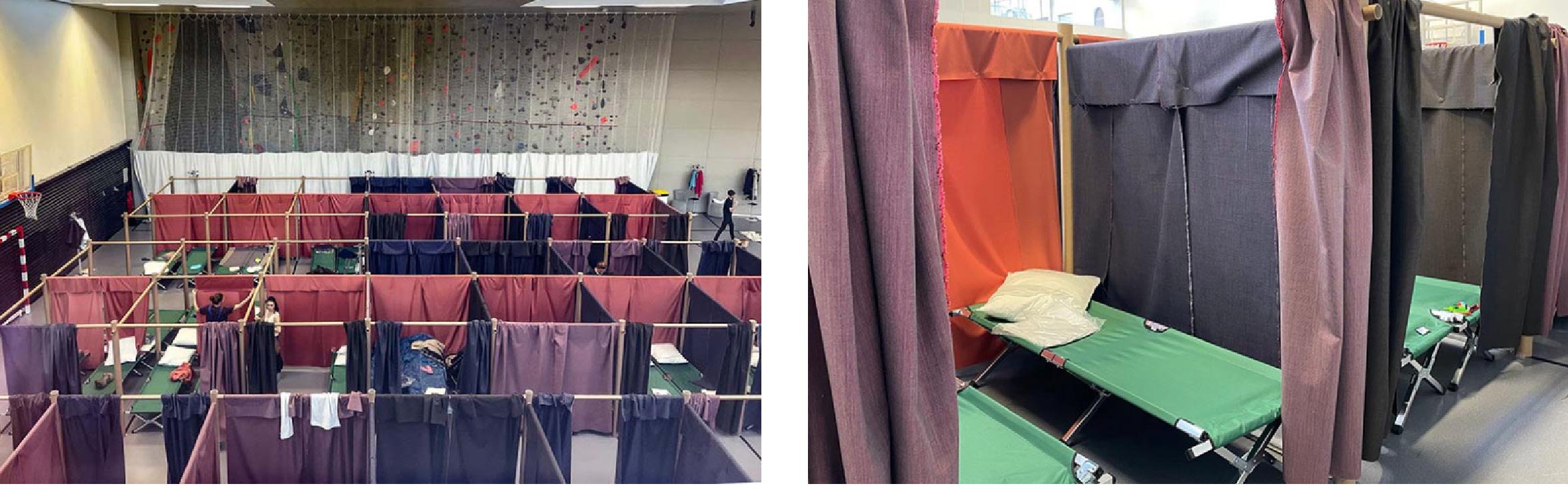

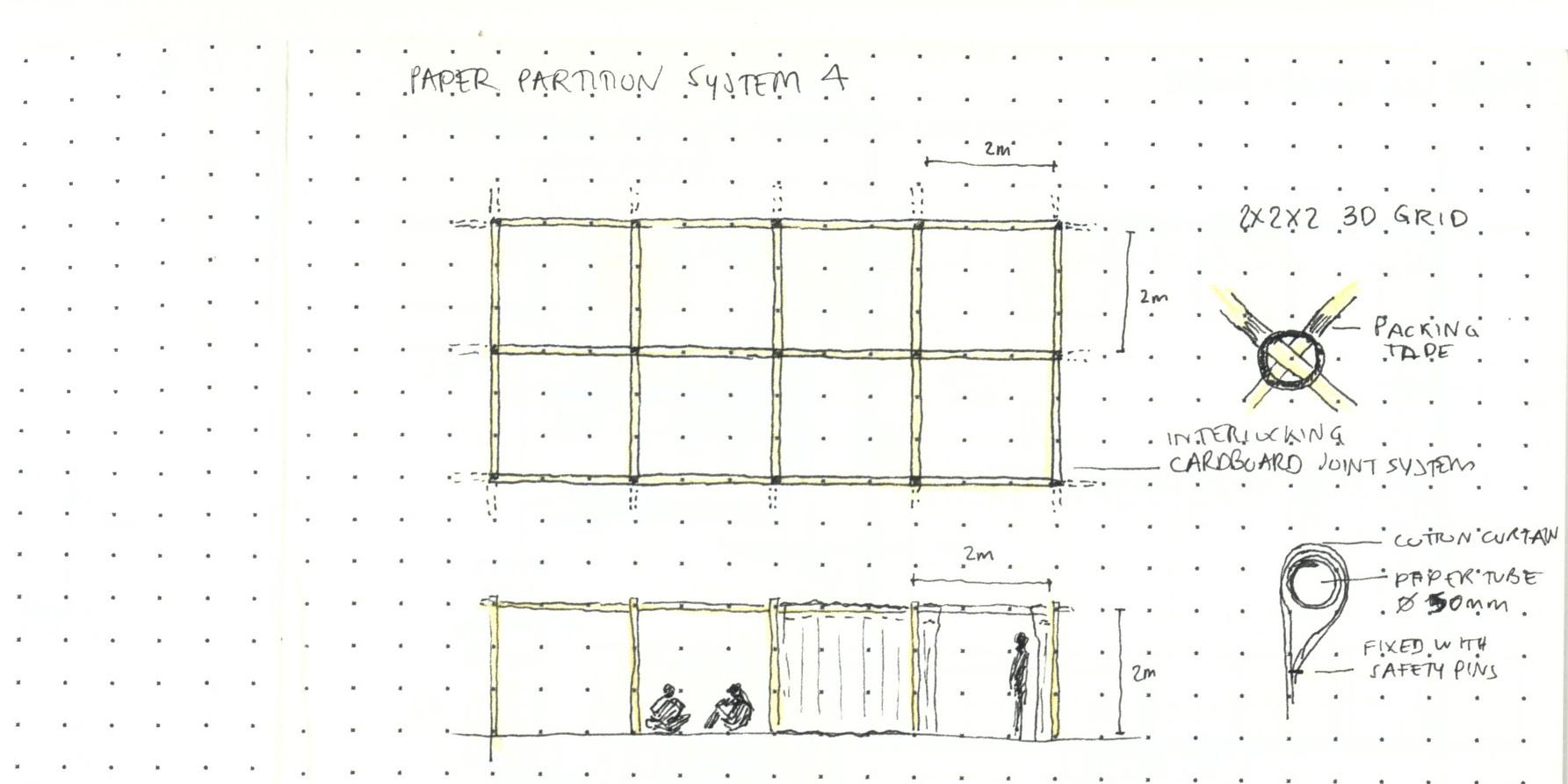

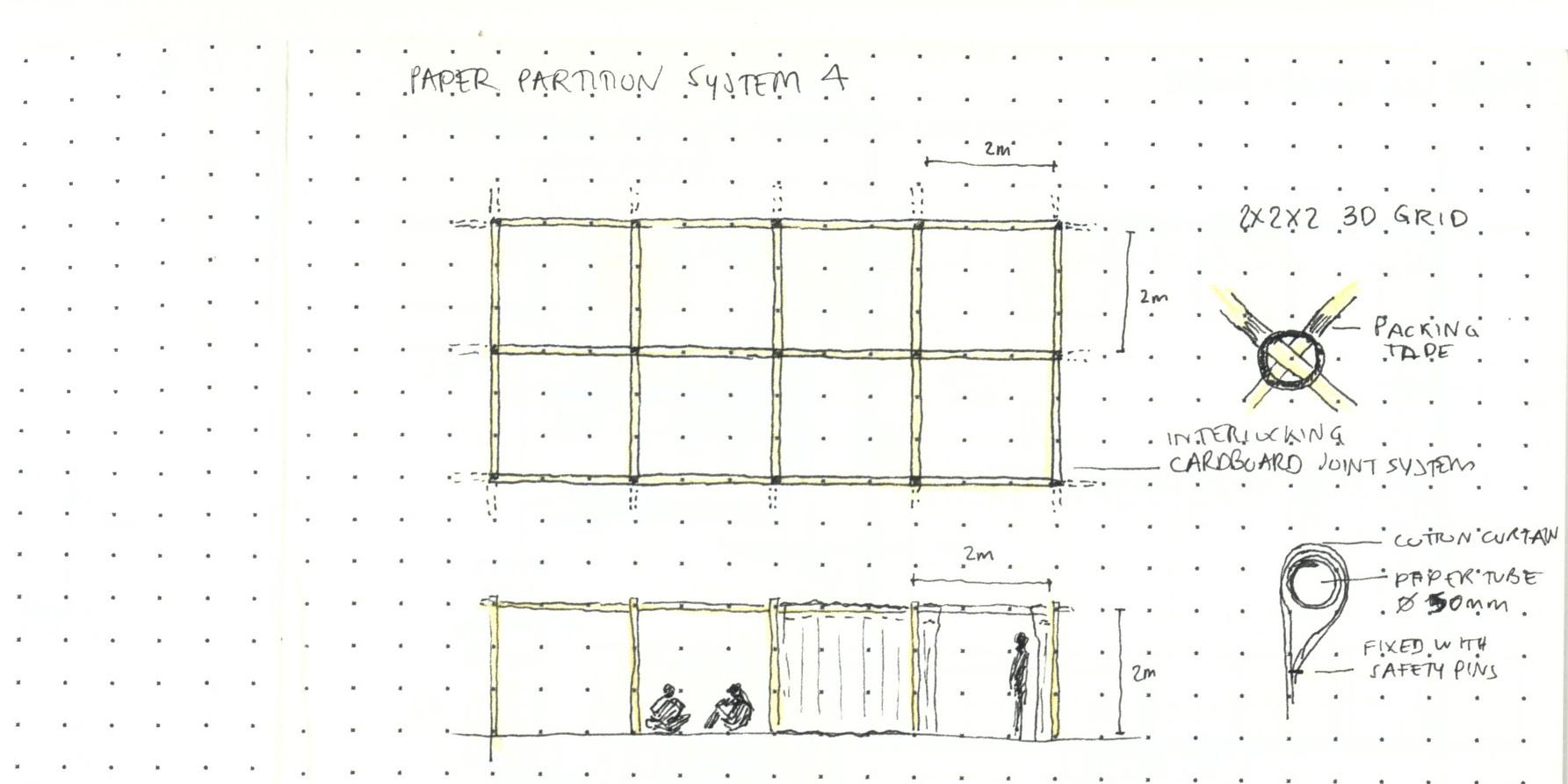

was used for PPS2, with rigid cardboard connection giving structural stability to the vertical panels. The lower borders gave more control and overview of the crowded spaces compared to PPS1. The latter, with its reduced visibility, though granting greater privacy, created the potential for violence. An efficient merging of the privacy of PPS1 and the safety of PPS2 was found in the Paper Partition System #3, where the solid walls were replaced by white cloth supported by a post-beam paper tube structure. The plywood joints and rope bracings used in PPS3 were ultimately substituted by the insertion system of PPS4, resulting in even faster construction and lower costs. The last developed Paper Partition System #4 was first used (1788 units constructed in 49 locations) in the Tōhoku Region of Japan after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. PPS4 has been applied, with minor alterations, ever since.

The PPS4 is easily constructed on site through a collaboration of the Voluntary Architects’ Network and the evacuated families themselves, each unit taking about 5 minutes to build with the help of three people. Two-meter horizontal tubes are inserted within perforated vertical supports and connected to one another through a transition cylinder and adhesive tape, finally textiles are hung as curtains on the horizontal beams

t Additional partitions can be made by placing cardboard tubes on the 2x2m frame and fixing them with adhesive tape, a solution adopted by families which may require a greater separation of spaces.

In 2011, after years of resistance on behalf of the Japanese government, VAN managed to obtain a disaster prevention agreement with some of Japan’s largest prefectures. This document states that the administration will bear the material costs of the installation of PPS4. Accelerating the bureaucratic steps translates into a more efficient assembly of required partitions especially relevant in such time sensitive situations.

Fig. 8; PPS2 in Fukuoka, 2005

Fig. 9; Step by Step Assembly of PPS3 (left) and PPS4 (right)

Fig. 8; PPS2 in Fukuoka, 2005

Fig. 9; Step by Step Assembly of PPS3 (left) and PPS4 (right)

10

11

Fig. 10 and 11; Tōhuku Gymnasium Before and After Application of the Paper Partition System 4, 2011

02.2.2 / Case Study / Ukraine / 2022 – in progress

Since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Shigeru Ban and his NGO have been supplying Paper Partition Systems to Ukrainian refugees throughout Europe. Whereas evacuees of natural disasters might find it easier to imagine a return to their lives, the mindset of war refugees is completely different as there is, to this day, no end in sight. Even more so structures provided by architects can help ease the sudden change in lifestyle, with private spaces becoming crucial to metabolise the situation. Media floods us with numbers and data, yet in the midst of this we have very real people facing very real everyday problems. “Privacy is a basic human right. I [Ban] saw my solution of paper partitions which I developed for the earthquake and tsunami in Japan, as appropriate.9” Intimate spaces and mental health are undoubtedly linked to one another, especially in an emergency: “the entire aim of this design is to create an ersatz room where you can process your emotions in at least a little bit of seclusion” (Pekalski D., 2022) . Though the impression of privacy created is fleeting, it is sufficient to provide a sense of safety in the refugees.

The intervention began in March 2022, with the New European Bauhaus providing strategical help, at proximity to the Ukrainian border to then spread through Europe parallel to the diaspora of refugees.

A former supermarket in the Polish city of Chelm, the first stop of trains traveling from eastern Europe, was supplied with 319 paper partitions, the system was adapted to the space with single units now measuring 2.3m x 2m and housing up to 6 people. The construction time was limited to a single day, with the help of students coordinated by Weronika Abramczyk professor at the Wroclaw University of Science and Technology11. Inhabitants were “delighted” (Ban, 2022). The structural and construction methods have remained the same, with slight alterations in cloth partitioning depending on availability and sponsors. Supply of material has depended on local industries and private donations. Corex, a Belgium company, with branches all over Europe has stopped their own production to provide VAN the required paper tubes free of charge. The Paper Partition System has the intrinsic ability of transforming any building into a flexible liveable space, be it a supermarket, the gymnasiums in Paris, or the Tegel Airport in Berlin. Perhaps, photographs better than words can express the efficiency of the PPS4 in dealing with Ukrainian Evacuees around Europe.

Fig. 12; Map showing cities where PPS4 has been installed following the start of the RUsso- Ukranian conflict

Fig. 12; Map showing cities where PPS4 has been installed following the start of the RUsso- Ukranian conflict

12

Fig. 13-16; Chelm Supermarket / 319 PPS; prepping of paper tubes, planning of interventions and final installation

Fig. 13-16; Chelm Supermarket / 319 PPS; prepping of paper tubes, planning of interventions and final installation

13

Fig. 17 and 18; Wroclaw Rail Depot / 60 PPS

“We’ve only been here eight hours, but the kids finally calmed down. Before that, they were afraid of even a knock on the door, scared as if it was an explosion. There were tears of joy when we came here”

Natasha, 36-year-old from eastern Ukraine temporarily in Chelm

Fig. 19 and 20; Warsaw Biennale Warszawa Gallery / PPS

Fig. 21 and 22; Paris Marie Paradis Gymnasium / 48 PPS

Fig. 23 and 24; Paris Victor Young Perez Gymnasium / 28 PPS

14

These makeshift rooms have granted, alongside the much-needed privacy, a sense of belonging which would have otherwise been lost. For many, the cubicles, especially those set up closest to the borders, are transit points intended for just a few days. Yet, the thoughtful design, also makes them the first place they can truly rest and figure out their next steps. Reception centres, modelled after the first one in Chelm, are provided with separate play areas for kids, a medical station, a dining room with meals provided by the World Central Kitchen, a laundry area and a free store with clothing and toiletries. Shigeru Ban’s efforts in the emergency are a mere portion of the forces in action to deal with the substantial number of displaced evacuees, what is significant is the network of connections working alongside the Japanese architect: from local manufacturers to the New European Bauhaus. It is only through this collaborative effort that the situation can be dealt with in the most efficient and appropriate manner.

The timeframe issue related to Ukranian evacuees is that many express a desire to return home once the emergency will subside, at the same time, the uncertainty of the situation makes it difficult to imagine an extended permanence in the temporary paper partition systems. It is complex to understand how the refugees could be welcomed in proper structures were the conflict to continue, hence designing solutions poses itself as an even greater challenge. A second phase of intervention is being considered and analysed. Voluntary Architects’ Network (VAN) and Shigeru Ban are exploring the possibility of producing a Styrofoam Housing System (SHS) in Europe and within Ukrainian borders as part of the reconstruction efforts, moving away from the use of paper for a more long-term housing solution. The SHS is a panel-type housing which can be easily assembled locally by a non-skilled work force using lightweight fibre reinforced plastic (FRP) panels wrapped around a Styrofoam insulation. The construction is a simple cube, with fenestration for ventilation and lighting of the interior open space, the functionality is minimal yet complete with a kitchen, a living area, a bed and a bathroom. Currently mockup versions are being constructed in Wroclaw and structural tests are being done to ensure the safety of the houses.

The protracted involvement of Shigeru Ban and other actors in these relief efforts speaks to the learning curve over the past 30 years. Whilst in Rwanda the collaboration of skilled individuals was interrupted quickly after the first phase of intervention, perhaps also due to political constraints, the response to the current crisis demonstrates the improvement of the humanitarian networks and protocols in action today.

Fig. 25 and 26; Styrofoam Housing System (SHS) Mock-up Exterior (top) and Interiors (bottom)

15

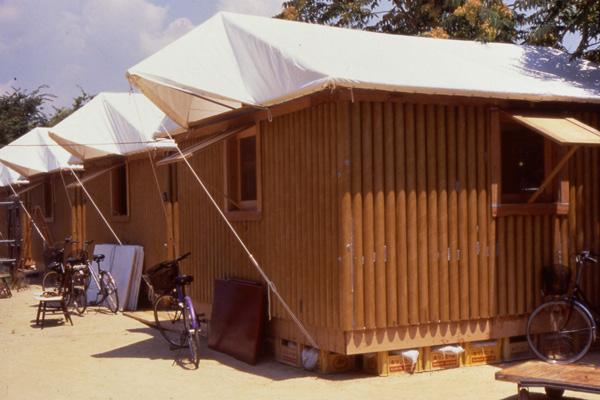

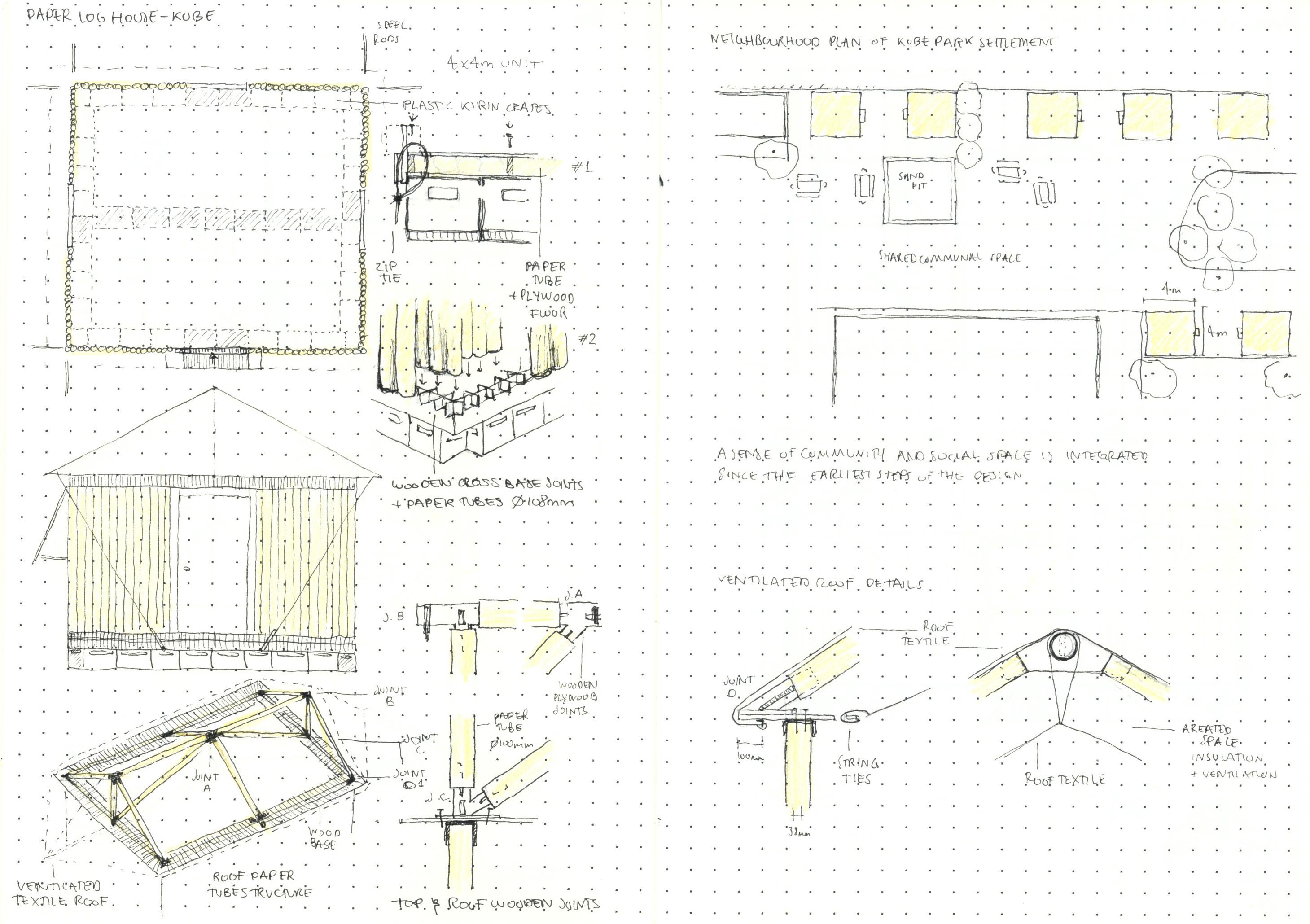

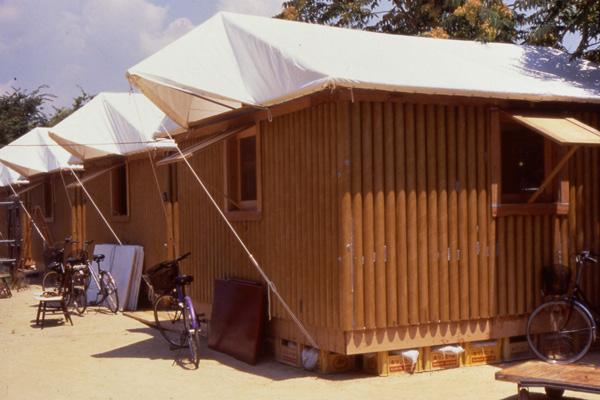

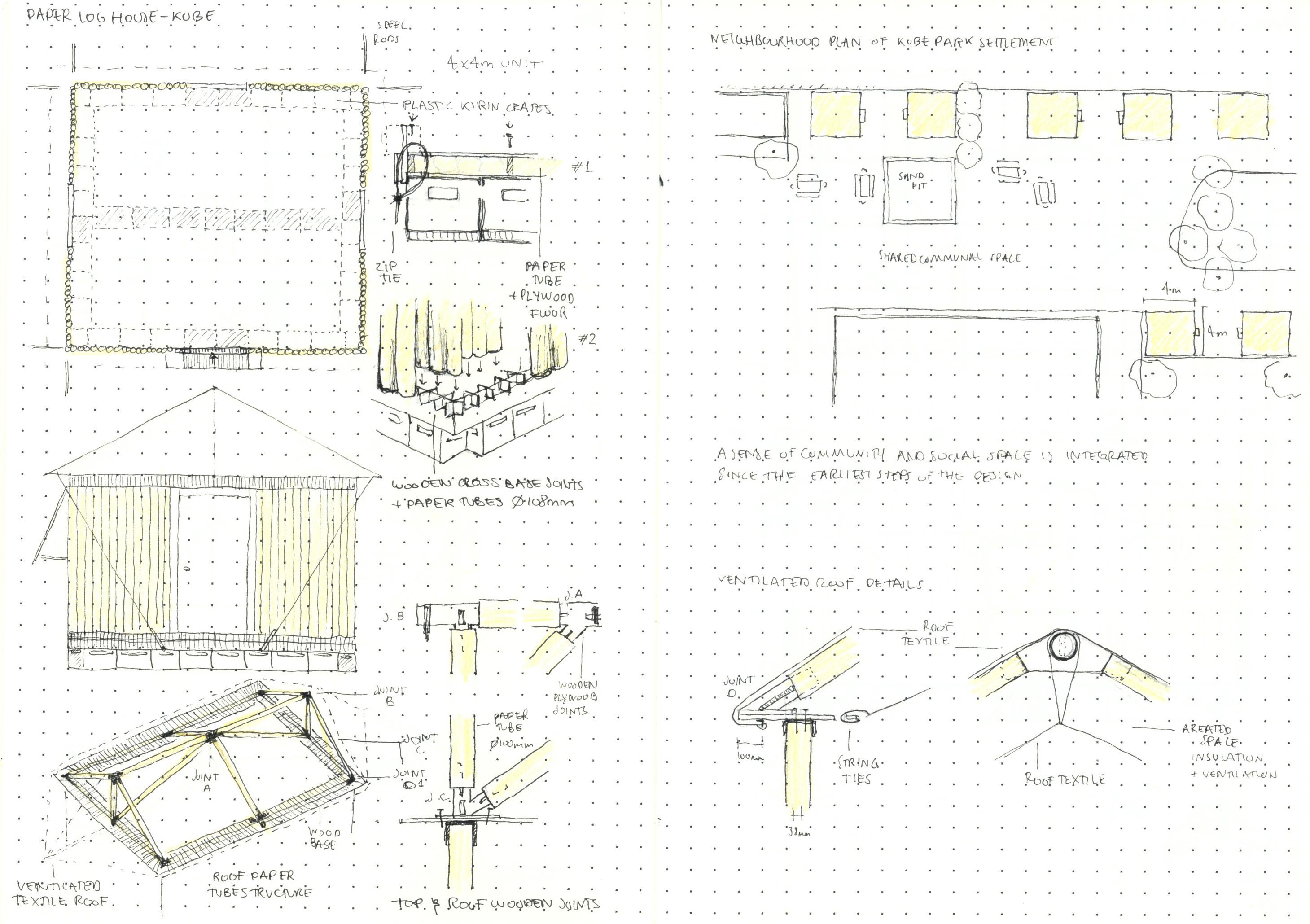

02.3 / Paper Log Houses

The 1st of January 1995 at 5:46am the coast of Japan was hit by the 7.3 magnitude Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake with epicentre just 20km off the city of Kobe. The catastrophe resulted in 300,000 displaced residents with 240,000 damaged homes and infrastructures. The urgent need for temporary relief shelter prompted the design of the Kobe Paper Log House, which launched Ban into the humanitarian architecture realm. As seen in the more temporary PPS and emergency shelters, speed of construction, reduced material costs and ease of application are central in the development of the emergency housing solutions.

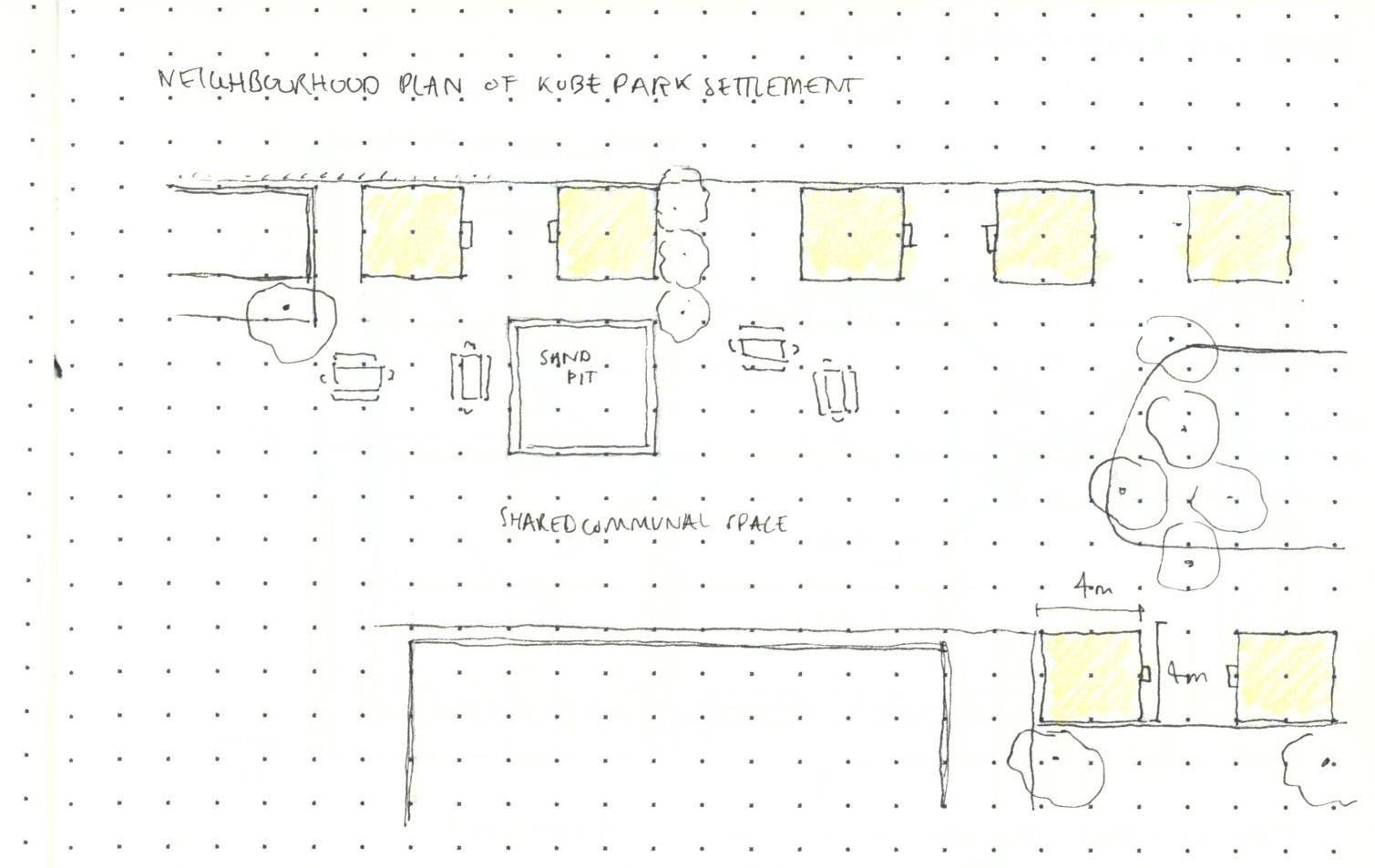

His initial proposal for housing and a paper church (see 03.1.1) were received with scepticism, but the situation direly required an intervention so Ban built the first temporary house to his expense. The 28 units which were then constructed served to give refugee to Vietnamese workers that had set up a shantytown in a park in Kobe as moving to the government housing outside the city would have meant losing their jobs in the local leather industry. Particular attention was dedicated to this community, for whom the Paper Church was also designed, as “its always the minorities who suffer more after a disaster since government agencies tend to cater to the majority”.

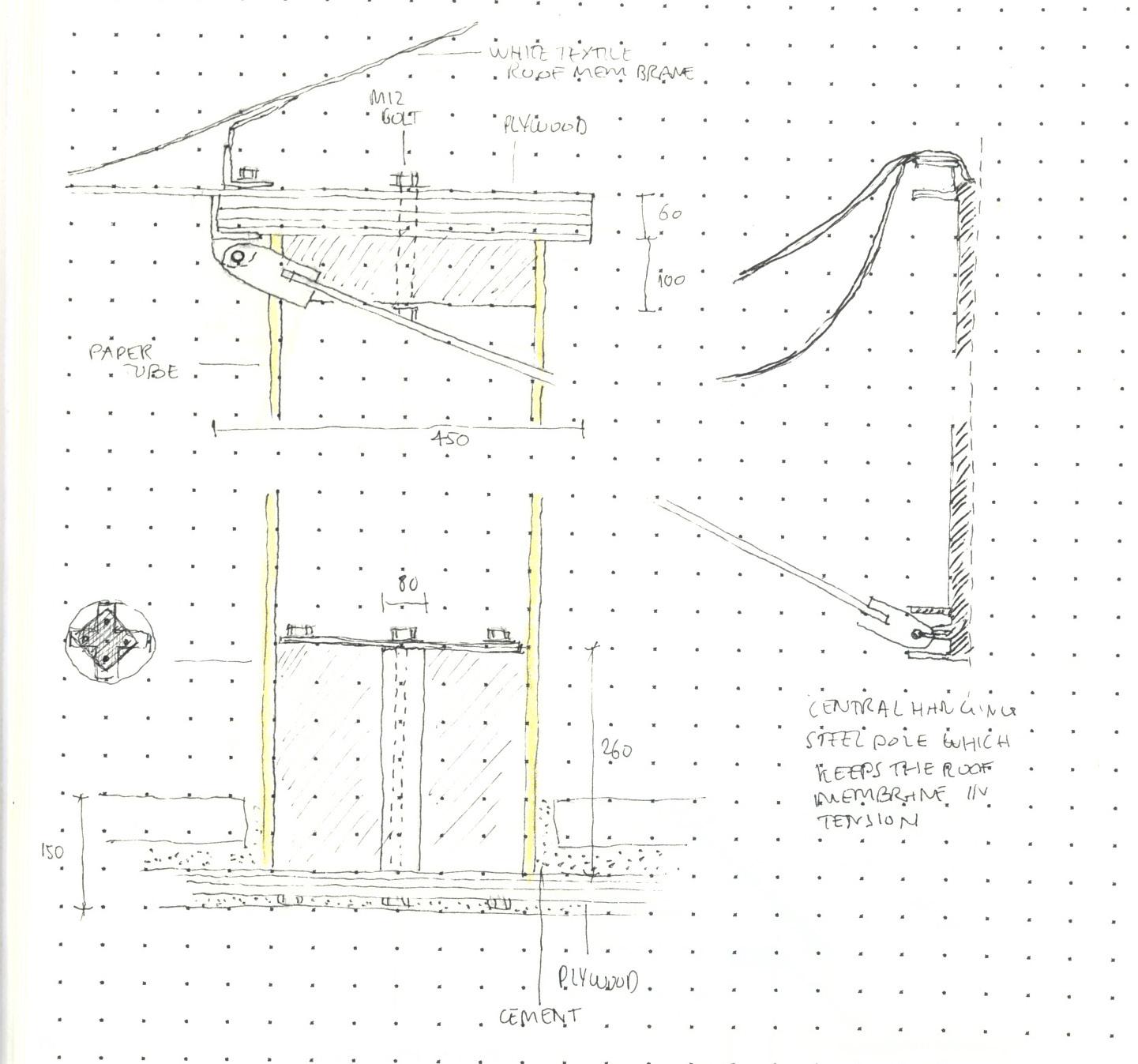

Donated Kirin beer crates loaded with sandbags are used as foundation, with pegs fixing the two plywood panels and hollow carboard tubes sandwich floor. The walls rise out of 106mm diameter, 4mm thick paper tubes, insulated through a waterproof sponge tape sandwiched between the single vertical elements and horizontal steel rods provide additional support. The use of these additional stiffening elements is reminiscent of the tie beams used in traditional japanese framing (nuki). The tubes are fitted into plywood bottom peg joints. Fenestration is created with a simple wooden frame and panel shading, allowing proper ventilation and lighting whilst still ensuring privacy of the inhabitants. The tented roof is supported through cardboard tube trusses connected with wooden joints. Intended as a separate element, the roof membrane can be opened or closed for proper ventilation in the summer and trapping warm air in the winter. Homes are placed 1.8m from one another, with this space becoming a shared area, introducing that aspect of community rebuilding which is essential in the wake of a disaster.

The cost for materials of a 4x4m unit is below 200$, it is easily assembled - under 6 hours for a single house - dismantled and disposed or recycled fulfilling all requirements of a low impact relief shelter, minimising

Fig. 27; Kobe Paper Log House

Fig. 27; Kobe Paper Log House

16

the waste left over after usage. Paper Log Houses were designed for a longer intended use compared to the other typologies, seen as “transitional” rather than “temporary” and becoming permanent settlements in the rebuilding period which can last many years. Though the interior space created is minimal it has proven effective in providing a private space from which inhabitants can begin to reconstruct their lives, the proper insulation from weather conditions and the thermal comfort given by the openable roof are all details which have contributed to the success of this design solution.

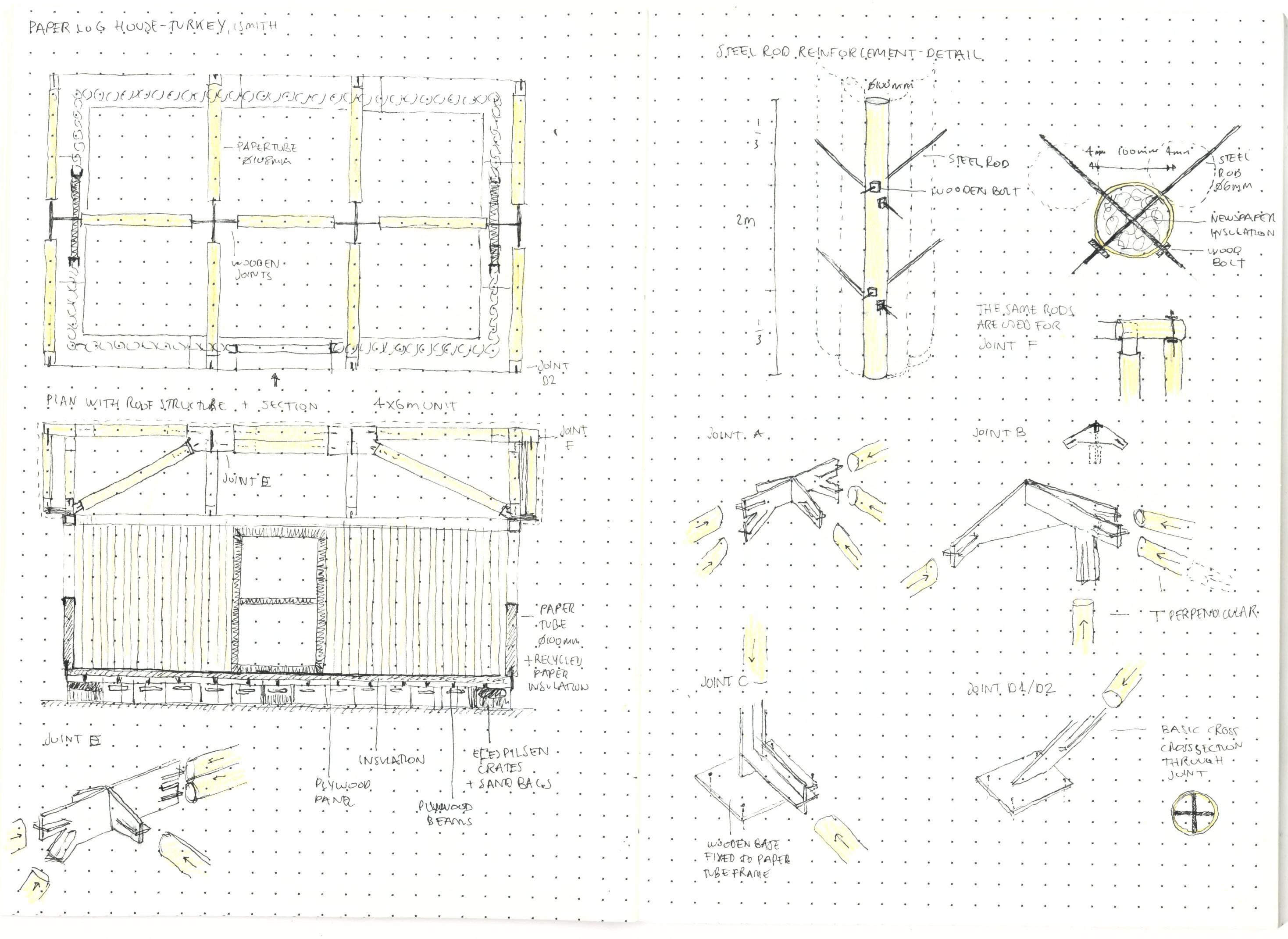

02.3.1 / Applications and Adaptability

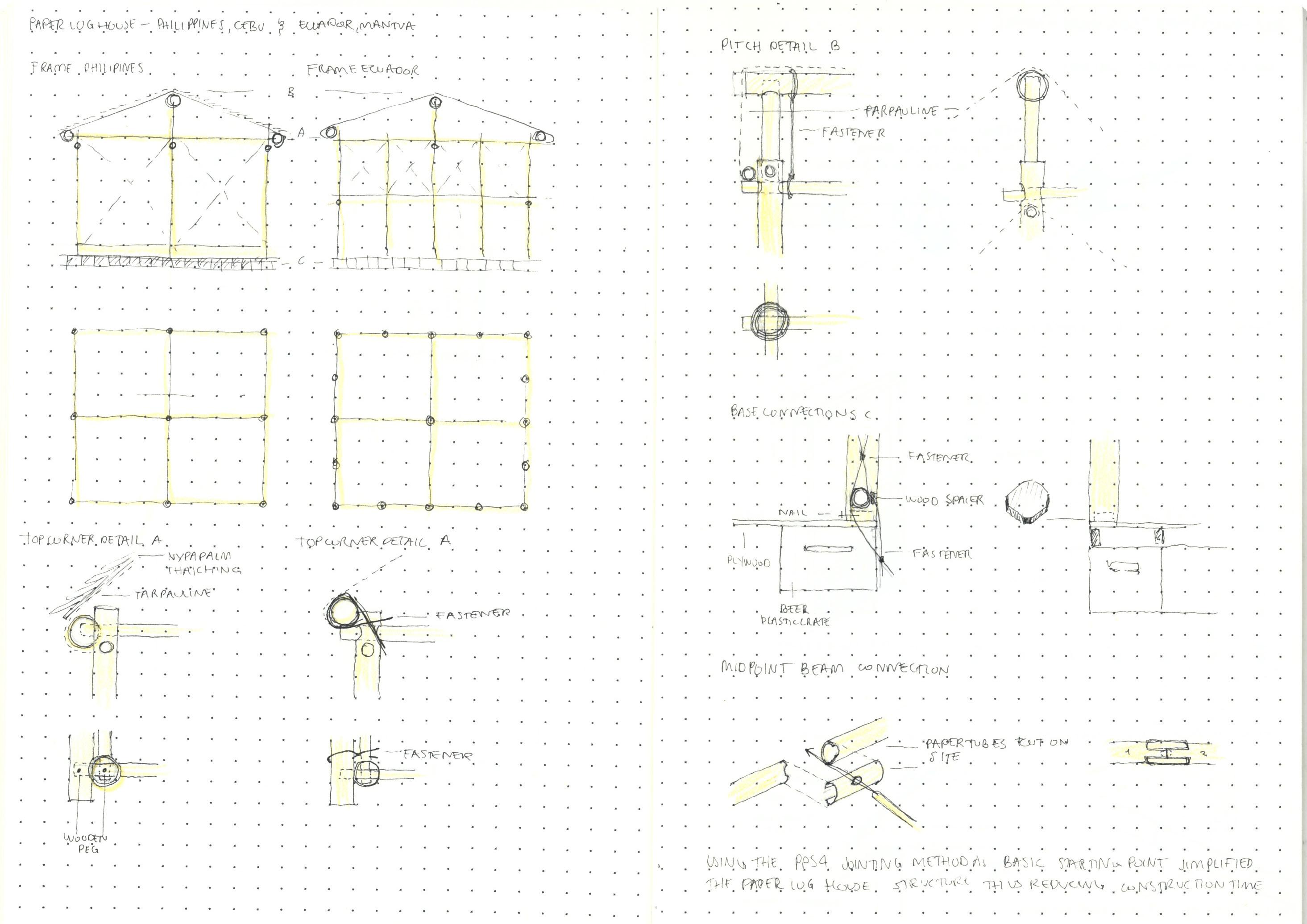

The Paper Log House unit presents itself as a highly adaptable system, with its crucial characteristic elements being relatively fluid in application and form. In the following section four case studies are analysed through comparison with one another, demonstrating the versatility of the initial Kobe model. Though cost constraints and efficiency dominate the development of the Paper Log House typology, each version has its own style and visual harmony.

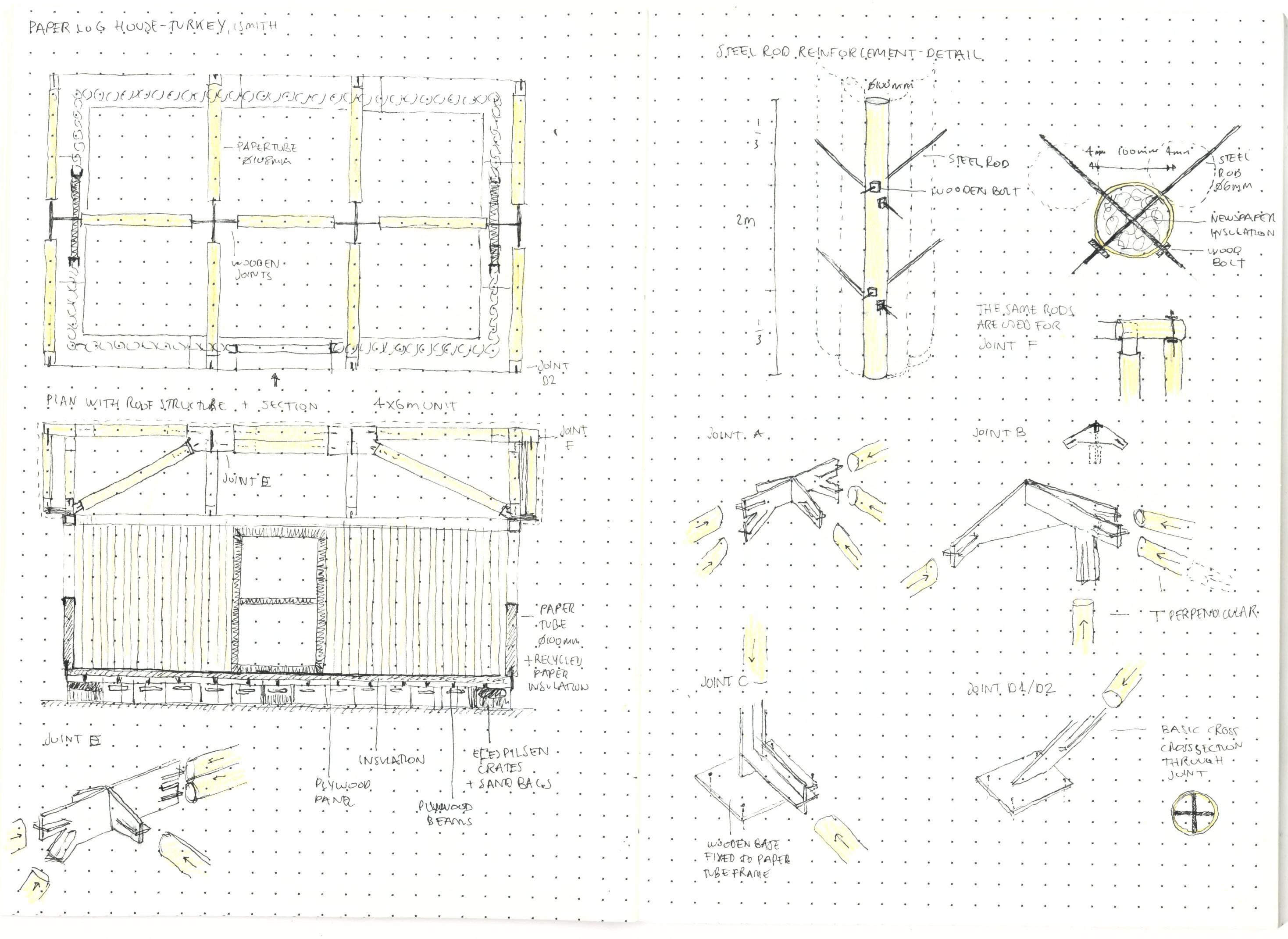

paper log house. was applied with improvements made to better fit the cultural and environmental context, a lesson learned from Alvar Aalto. Giving the positive international feedback received with the Kobe Log Houses, Ban convinced a Japanese corporation to donate plastic sheeting with the company logo on it obtaining crucial building material in exchange for a good publicity stunt. Local blue plastic beer crates were adopted as foundation, distinguishing itself from the typically yellow crate used in Kobe five years prior, harmonising on the same colour palette of the blue printed roof tarps. The size of the single unit was slightly increased due to the standard size of plywood in Turkey but also the country’s larger average family size. Moreover, the colder climate was tackled by an increase of insulation with additional shredded wastepaper inserted inside the tubes, and fiberglass in the ceiling. The general response to the paper houses, though culturally Turkish people are accustomed to masonry structures, was described by Ban himself as a fascinating insight into the psychological relationship which develops between earthquake refugees and architecture. People said they felt more comfortable

Following the 1999 Ismith earthquake in Turkey, the 17

Fig. 28; Paper Log House / Plans, Sections and Construction details

in the paper houses as it had been the concrete and brick houses which had collapsed and killed people during the earthquake: the paper log homes wouldn’t fall on them in the middle of the night.

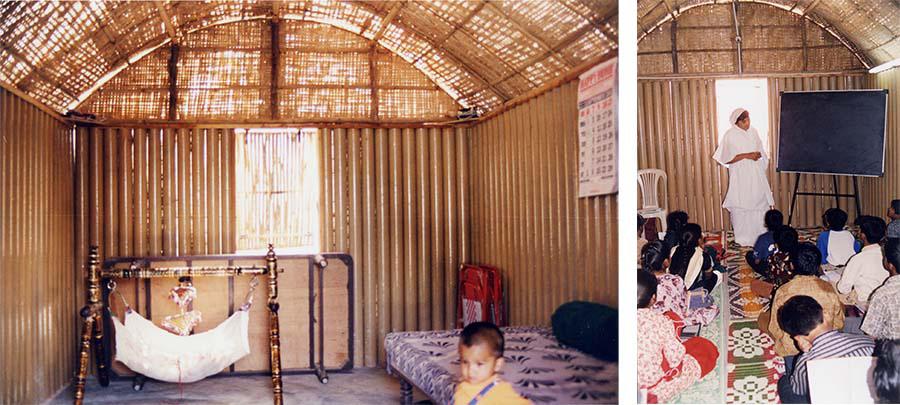

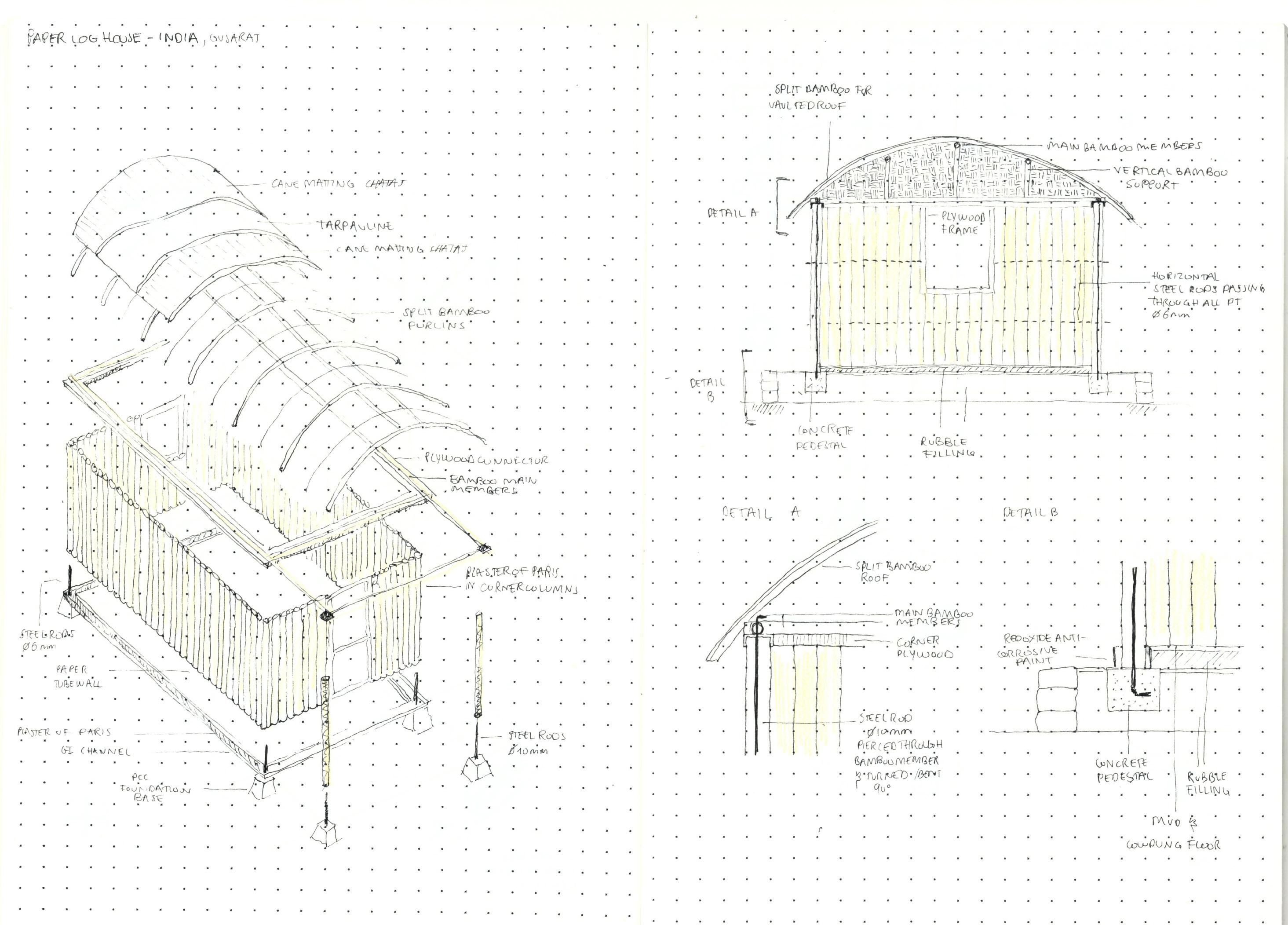

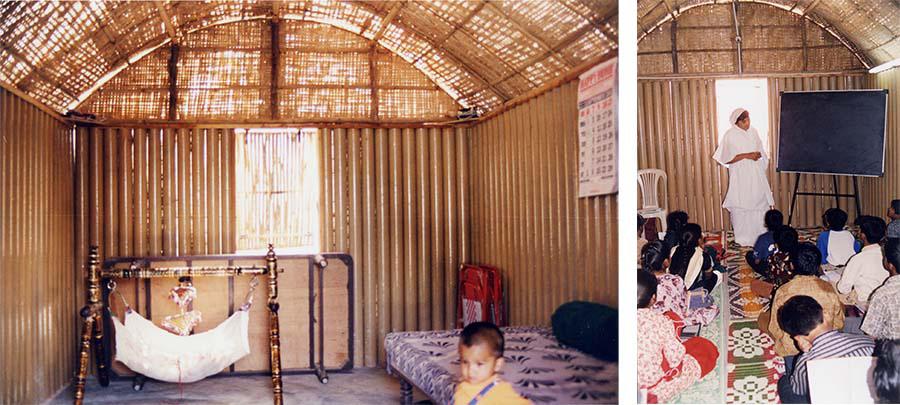

The system was further developed in India, Philippines and Ecuador where climate conditions and construction tradition greatly influenced the design. India’s log house was designed after the 2001 Gujarat Earthquake differing significantly from the Kobe version. Paper tubes, once again, were adopted as main construction material for their local availability and low cost: the primary local industry involved textile production, textiles which are wrapped around paper tubes. Beer crates were not locally available - alcohol consumption being prohibited in the area - so rubble from destroyed buildings was used as foundation and topped with the traditional mud floor. The Gujarat region is situated in the northeastern part of India where employment of local tribes primarily involves the traditional bamboo craft industry. House roofing, chhaj, is typically a mix of indigenous tiles and woven bamboo able to ventilate the household. The log house adapts this local tradition into a split bamboo rib vaulted roof which extends outwards creating a portico providing exterior shade. Whole bamboo ridge beams are covered by locally woven bamboo mats sandwiching a waterproof layer of plastic tarp which protects from the heavy rains and winds of the monsoon season. The structures were used as homes, classrooms and other public functions as the impacted areas were undergoing reconstruction: a multifunctionality made possible by the simplicity yet effectiveness of the spaces constructed.

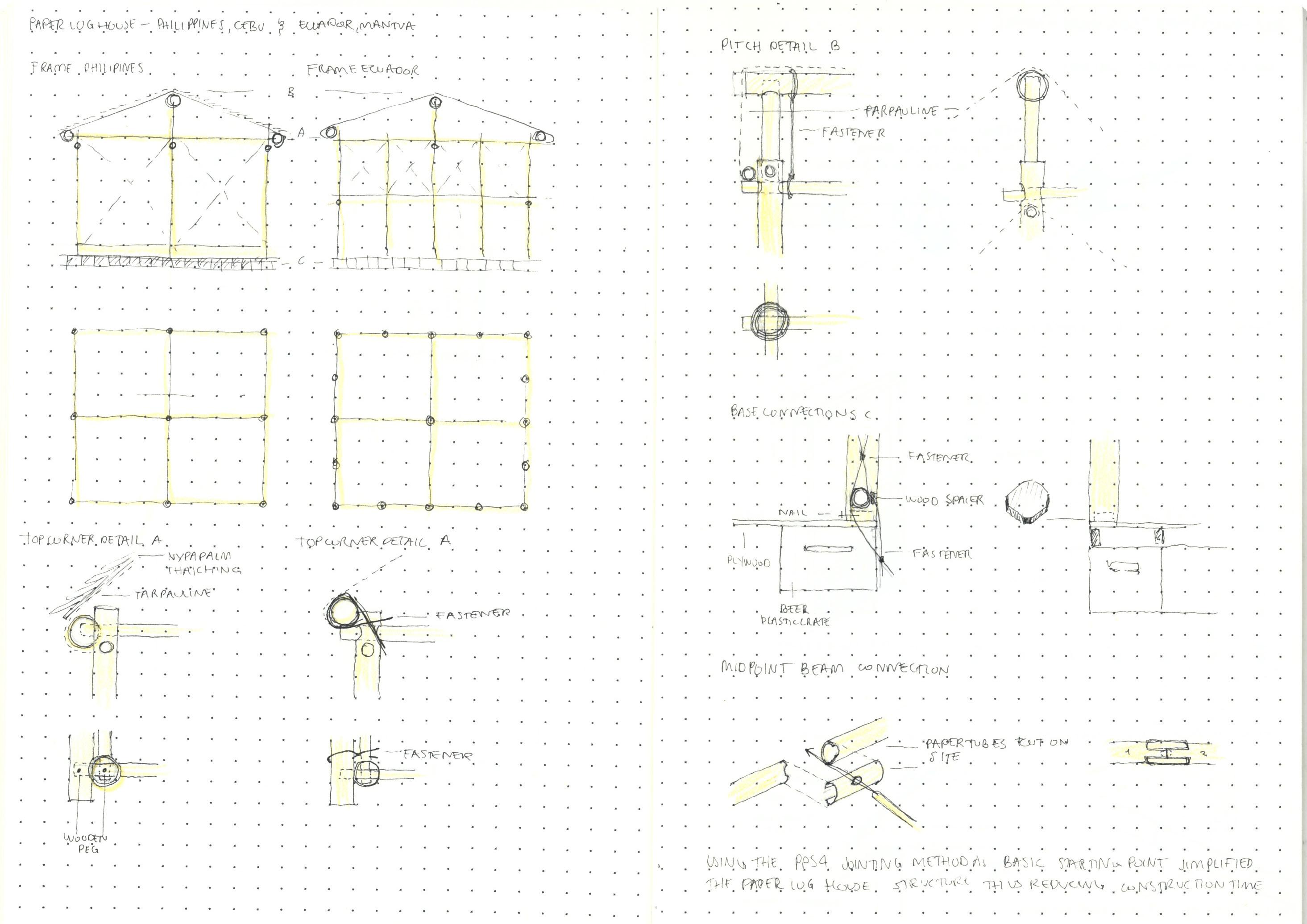

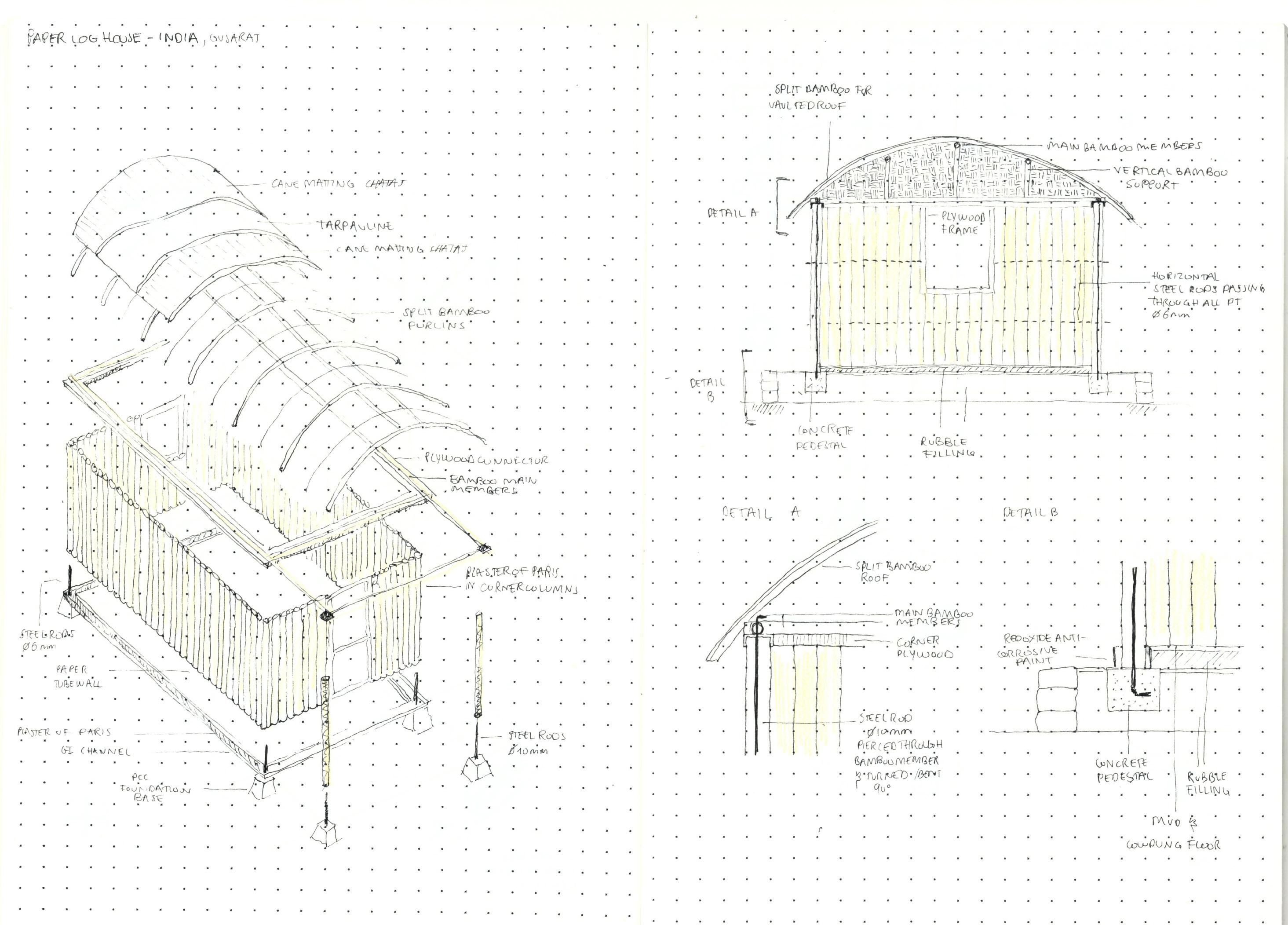

The Yolanda Typhoon hit the coasts of the Philippines in November 2013, the intervention was proposed in Cebu, the most hard hit city of the region. Three years later a 7.8 magnitude earthquake displaced 28,000 people on the Guadua coasts of Ecuador, with the heart of the city of Manta selected as the project site. The tropical coastal climates at both locations were tackled with similar temporary housing models.

Fig. 29-34; (top) Indian Paper Log House and (bottom) Philippines and Ecuador Paper Log House incorporated with PPS4 frame / Plans, Sections and Construction Details

Fig. 29-34; (top) Indian Paper Log House and (bottom) Philippines and Ecuador Paper Log House incorporated with PPS4 frame / Plans, Sections and Construction Details

18

Fig. 35 and 36; (top) Turkish Paper Log House and (bottom)

Fig. 35 and 36; (top) Turkish Paper Log House and (bottom)

19

Indian Paper Log House / Plans, Sections and Details

The connection system of the PPS4, with additional steel rod bracing, was incorporated with the Log House typology to simplify and shorten the construction period, which had become an issue in previous interventions when dealing with high volumes. Woven bamboo panels are applied to the post and beam paper tube frame, with an amakan weave and diagonal split bamboo weave (esterillas) used in the Philippines and in Ecuador respectively. Bamboo construction tradition is present in both the Philippino coasts and the Guadua cultural region in Ecuador for its local availability, ventilation qualities and structural bracing. The roof of the Cebu model consists of thatching of Nypa palms laid over plastic sheets, whilst a plastic sheet sandwiched between bamboo panels is used for roofing in the Manta version.

Given their greater complexity, Ban’s Paper Log Houses are exemplar in combining temporary structures with the ability to reunite communities through the implementation of basic construction methods. The success of the log housing is intrinsic with its employment of the local work force, architectural knowledge, and material availability. The adaptability in application of this typology of relief shelter reflects the necessity

Fig. 37; Paper Log House and PPS4 frame structure hybrid developed for the Philippines and Ecuador

to recover “a contextualised architecture, an urbanism that is related to the sites” (Ban S., 2016).

02.3.2 / Case Study / Self-Build House in Nepal / 2015

The flexibility demonstrated by the paper log house typology is perhaps best expressed in the project developed for Kathmandu in 2015, following the 7.8 earthquake and subsequent magnitude 7.3 aftershock that caused widespread devastation. The greatest issue of pre-existing architecture of the area lied in the lack of seismic resistance of brick buildings which brought many of the affected inhabitants to refuse to live in structures which weren’t regulated under this crucial aspect. Similar to what happened in Turkey, the traditional building method and typology was linked to the traumatic psychological impact of the event. At the same time, one of the most pressing tasks affecting the region was dealing with the huge volume of bricks from the collapsed structures. In this situation, Shigeru Ban saw the opportunity of adapting his paper log system to the specific socio-economic situation of the Nepalese context.

20

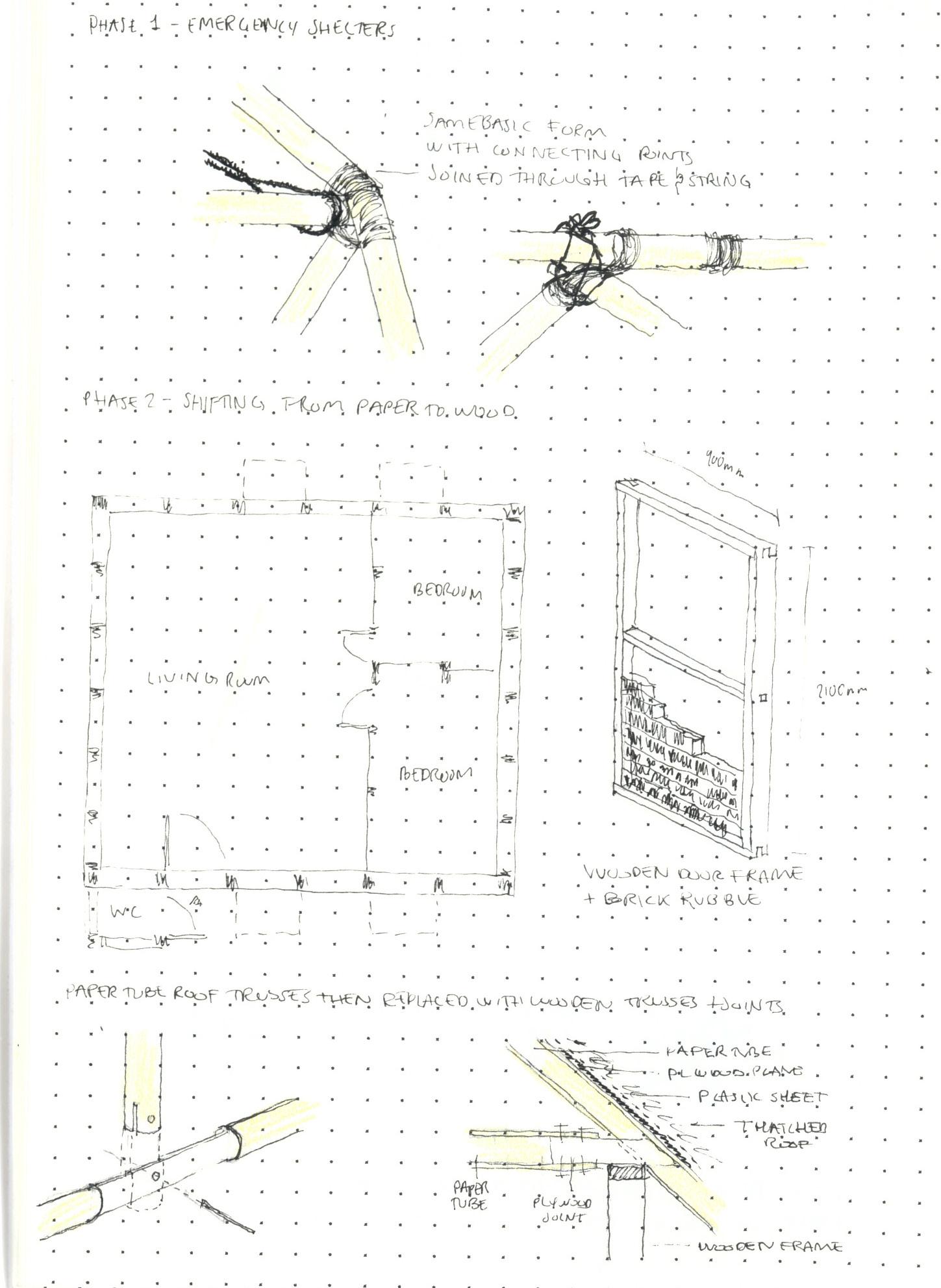

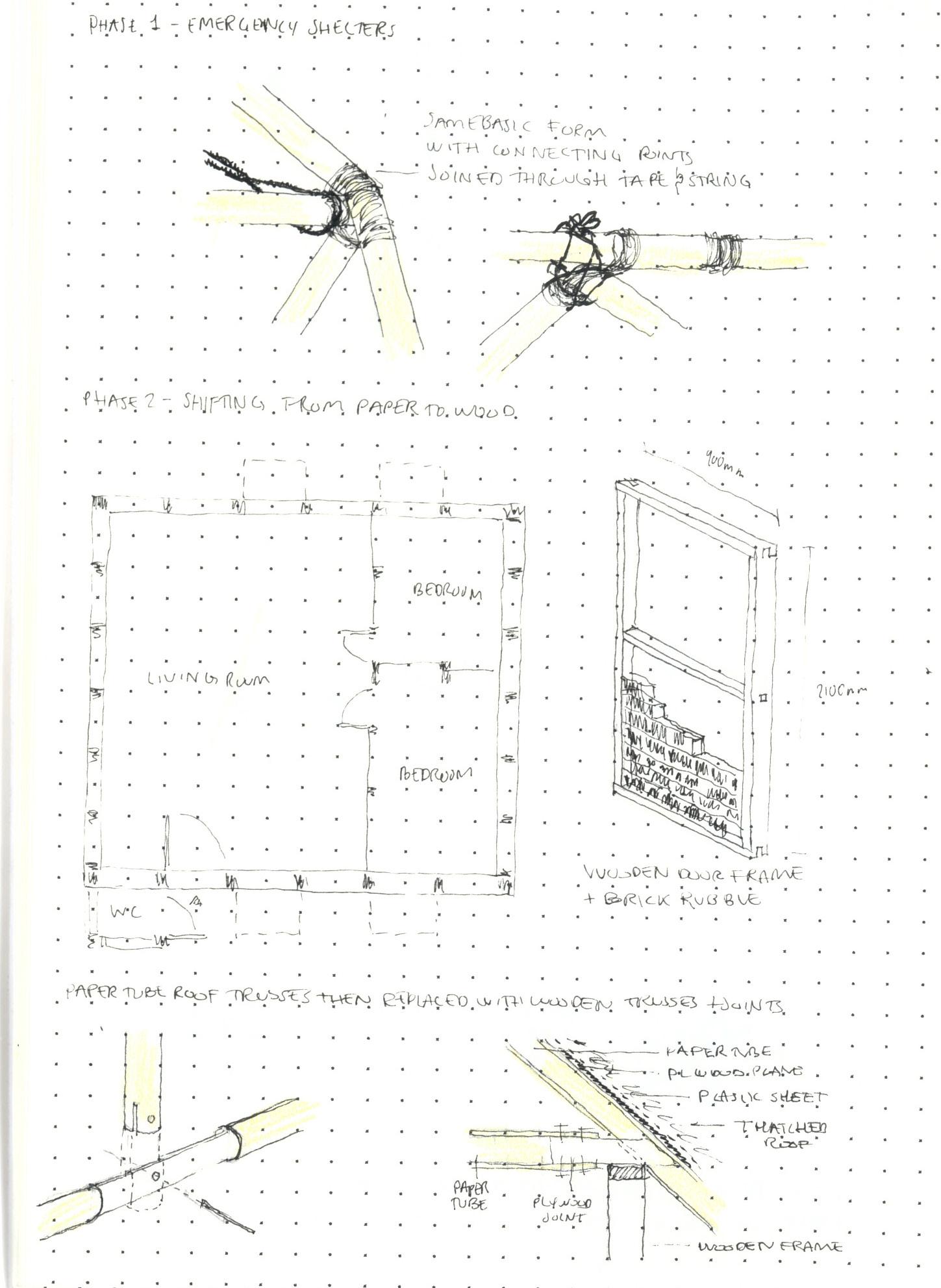

A first phase of intervention was dealt with through the paper emergency shelters seen in 02.1 As both plastic and plywood joints require a fabrication time, for the Nepalese version Ban experimented with gum tape connections and string bracing. This greatly reduced the already minimal erection time. The frame is fixed to a plastic crate base through the diagonal strings that serves as insulation from the dampness of the ground. A lesson learned from the paper log houses.

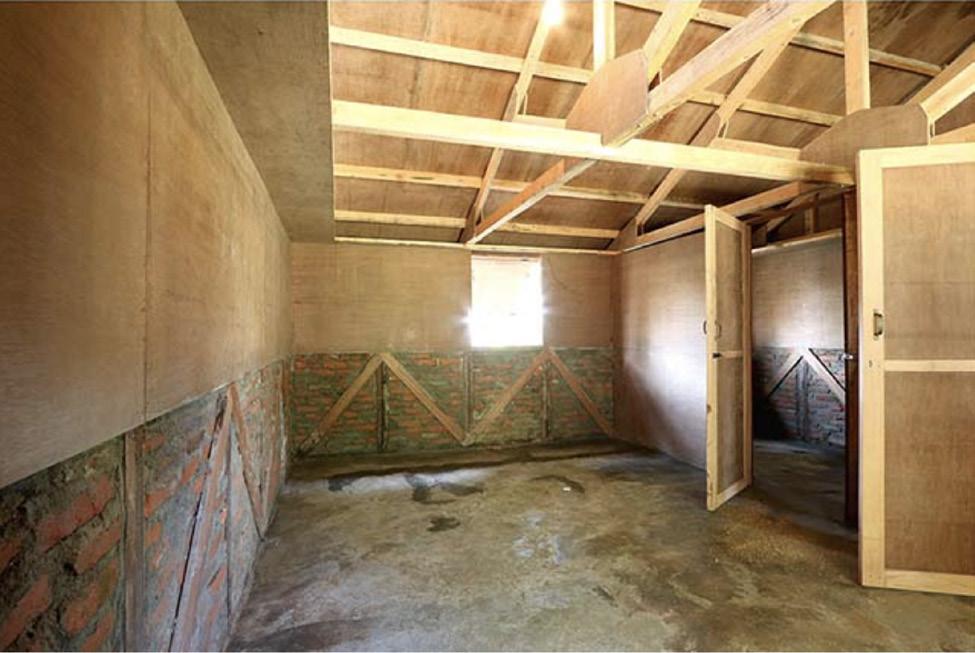

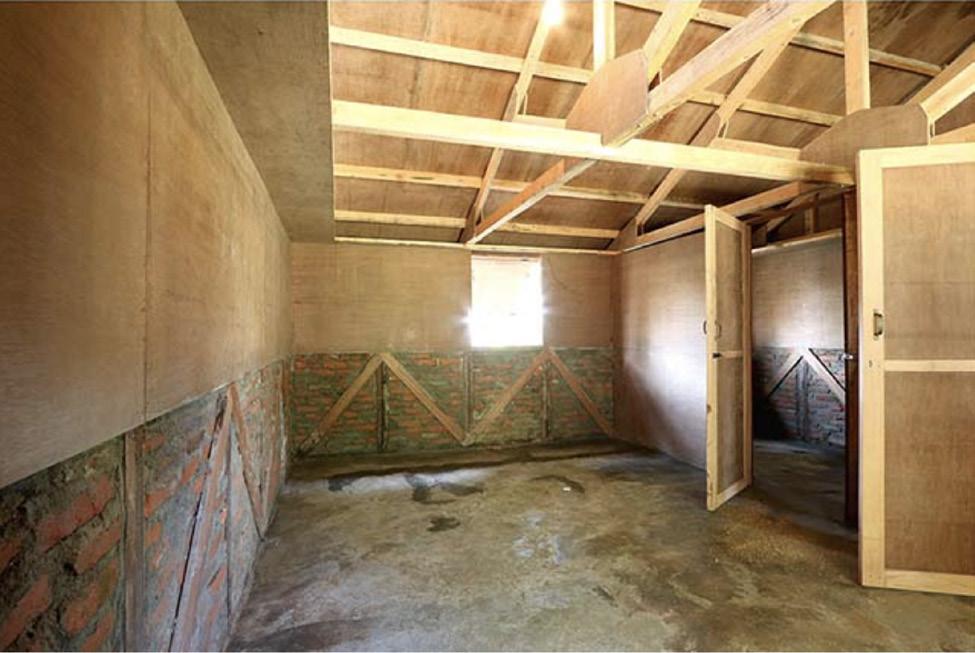

The second phase involved finding a creative solution to the main problems identified: the fear of brick construction and the quantity of brick rubble. Locally produced standard size 0.9x2.1m wooden door frames produced in local sawmills became the key to the project. The structural framework was designed around these standard size elements which recalled the beautifully carved wooden fixtures of the few traditional architectures that had survived the earthquake. These prefabricated frames were connected through steel bolts to make up the main 6x6m paper log houses. Plywood sheets were attached to the interior to ensure surface and structural rigidity whilst also providing support for the external cladding of bricks. A single panel unit was subjected to a fracture test at the Polytech Center Chiba to ensure it met Japanese seismic standards. The rubble, due to low availability of appropriate plastic crates, was also used for the foundations as already seen in the Gujarat Paper Log House. The prefabricated frames diminished the waiting time of future residents as “within these frames, even an amateur could easily lay the bricks” (Ban, 2021). The idea was that people could conclude the assembly of the external envelope whilst already being inhabiting the transitional homes. This modular construction allowed further interior partitioning offering a certain degree of customisability and opened the possibility of having multi-family row houses.

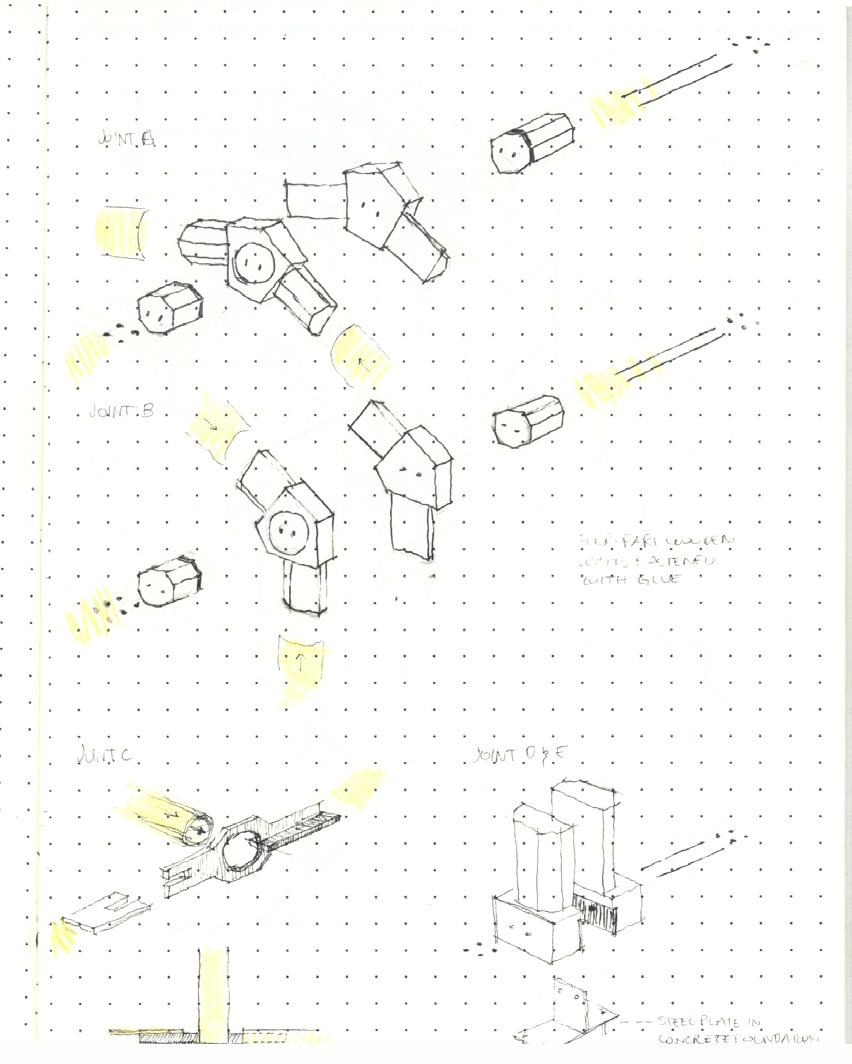

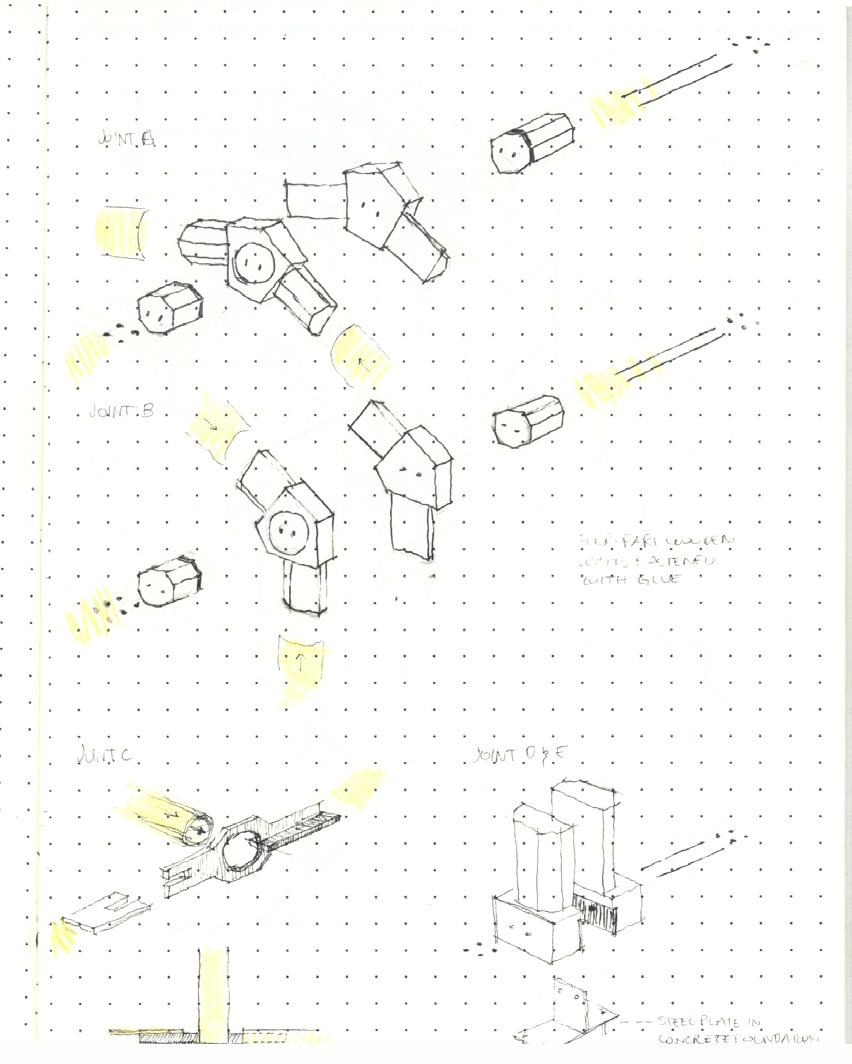

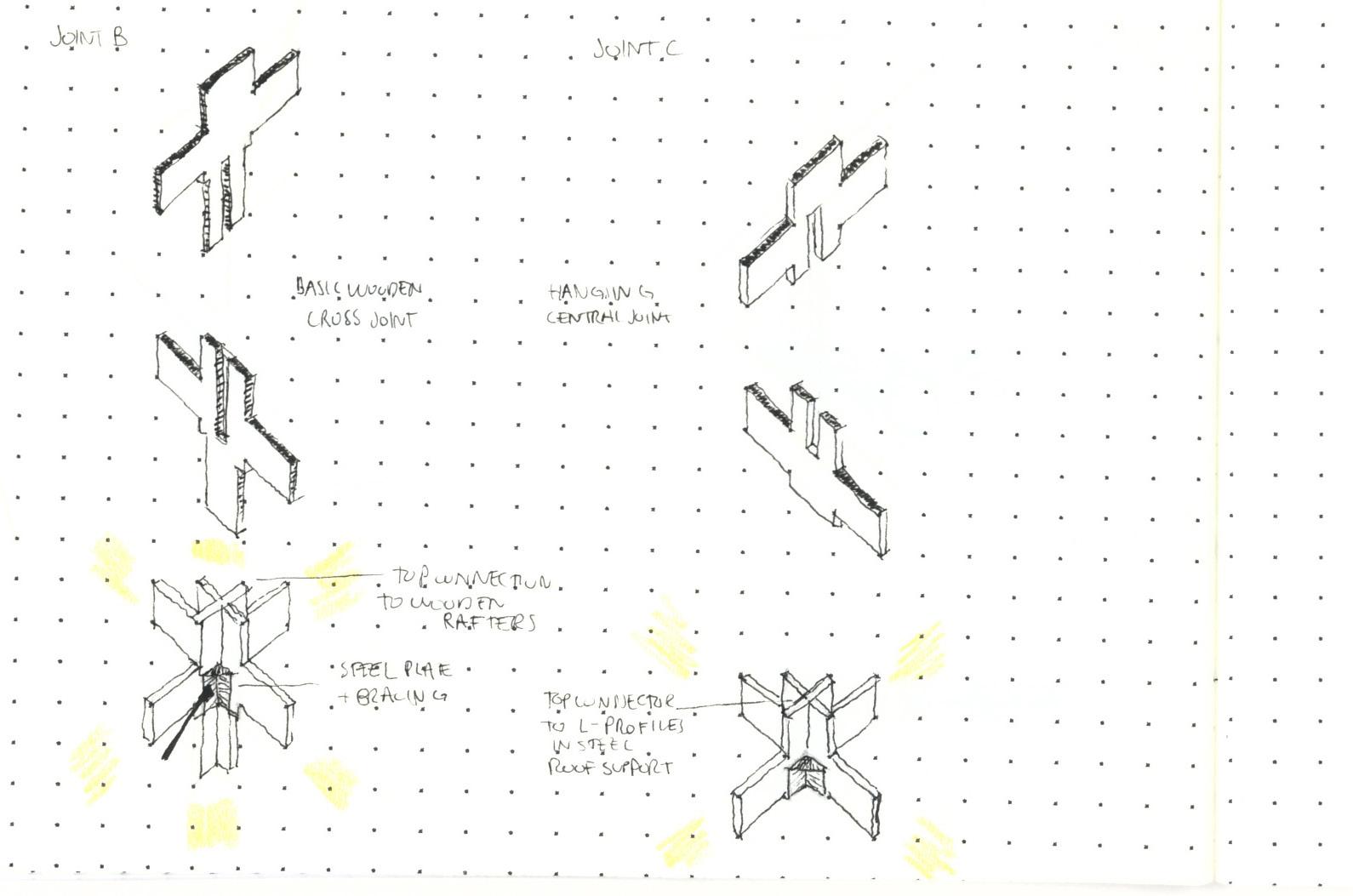

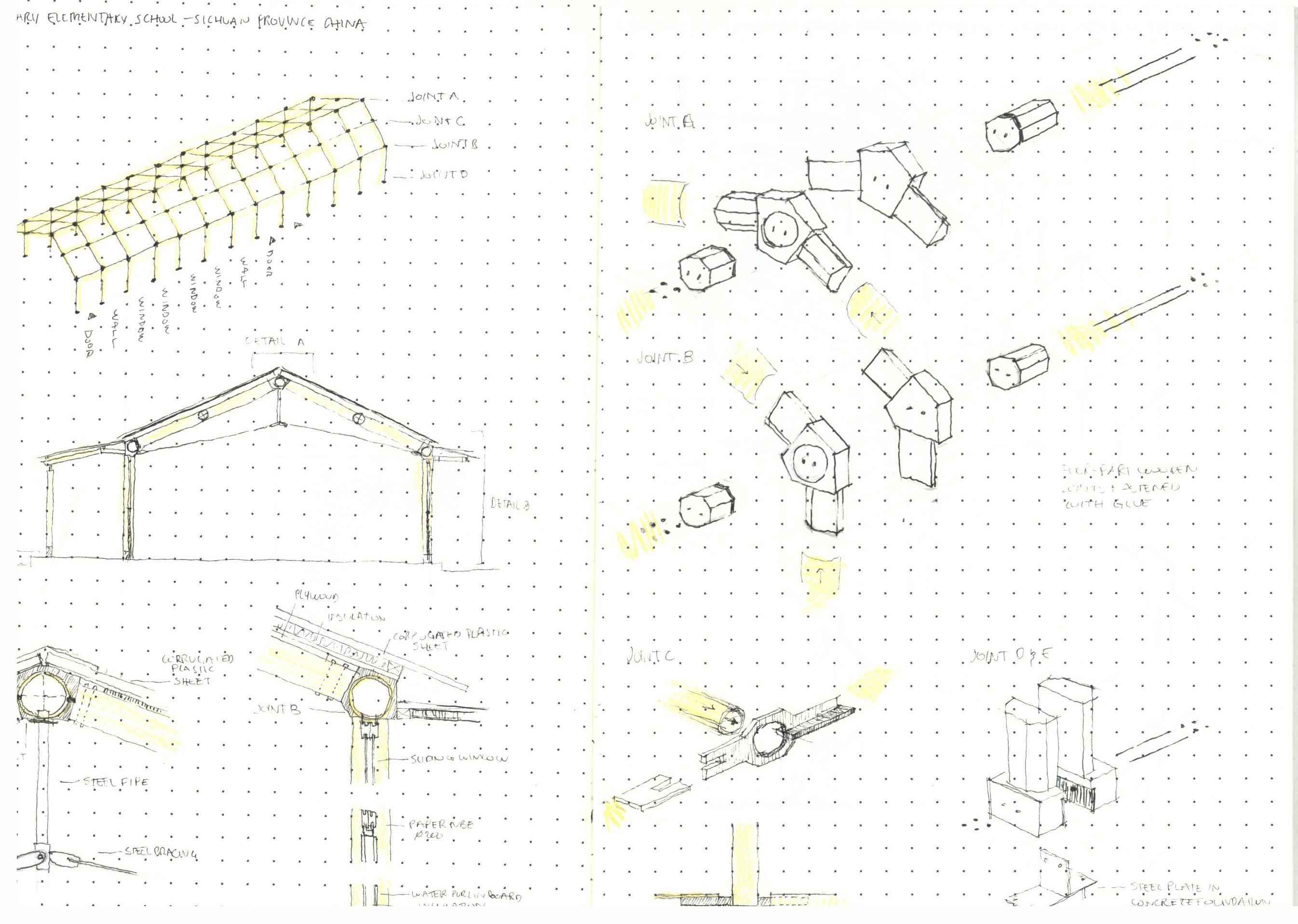

Paper tubes were envisioned to be used for the king post trusses with wooden joints. 4 types of connections were developed: Joint A and B deal with the diagonal connections at the pitch and along the rafters, Joint C is found at the pitching point where the truss is fixed to the door frames, and Joint D connects the post and the bottom chords. Joint A and B are cross joints, the only difference between them being the inclination of Joint A with its main arm with

Fig. 38; streets of Kathmandu following the earthquake

Fig. 39; Phase 1: Emergency paper shelters to provide short term solutions as the self-build homes were being planned

Fig. 40; Phase 1 and 2 details

Fig. 38; streets of Kathmandu following the earthquake

Fig. 39; Phase 1: Emergency paper shelters to provide short term solutions as the self-build homes were being planned

Fig. 40; Phase 1 and 2 details

21

a central angle of approximately 130°. Joint C is a longitudinal plywood element that extends into the diagonal rafter creating a 25° angle, fixed to the structural frame through steel welding. The king post and beam connection is particularly interesting as it involved the tailoring of the vertical element with a slit and two aligned holes allowing it to fit onto the plywood joint connecting the two paper tube beams. A wooden pin fixes these three elements. The roof was waterproofed with thick plastic sheeting clad with a thin layer of thatching for insulation and to harmonise with the surrounding architectural environment. Due to restrictions on oil imports from India, local paper tube factories were shut down so Ban had to reimagine the roofing with a more traditional wooden queen post fan truss system. 30 units were constructed in Phatakshila in the Sindhupalchok district in central Nepal.

Though the identifying material is absent in the final construction, the essence of the paper log home remains intact. The humanitarian efforts go beyond specific materiality and design specifics. Interventions are moved by a desire to construct safe spaces that the local population can benefit from in the shortest time span possible: paper tubes are a mean to obtain such a goal. The ability to react to political, social, and cultural

conditions speaks to the plasticity of Shigeru Ban and his designs. This characteristic is crucial to be able to respond and swiftly adapt to the ever-changing socio-political and economic situations of many of the countries in which the architect has intervened.

The same structural system was adopted in the reconstruction of Khumjung Secondary School (2017) at the foothills of the Himalayas, also destroyed by the 2015 earthquake. Since the village (altitude of 3800m) had no bricks, stone rubble was used as filling for the wooden frames which were assembled to form a single rectangular volume with three classrooms joined by an external corridor covered by the protruding corrugated roof. A similar design was previously used in his interventions in the Chinese Sichuan province, further explained in section 03.2.

Fig. 41-44; (top) Renders and (Bottom) Final Construction of the Nepal Paper Log House, adaptation of the truss systemw ith wood instead of the planned paper tubes

22

02.3.3 / Case Study / Kalobeyei Settlement Kenya / 2017 – in progress

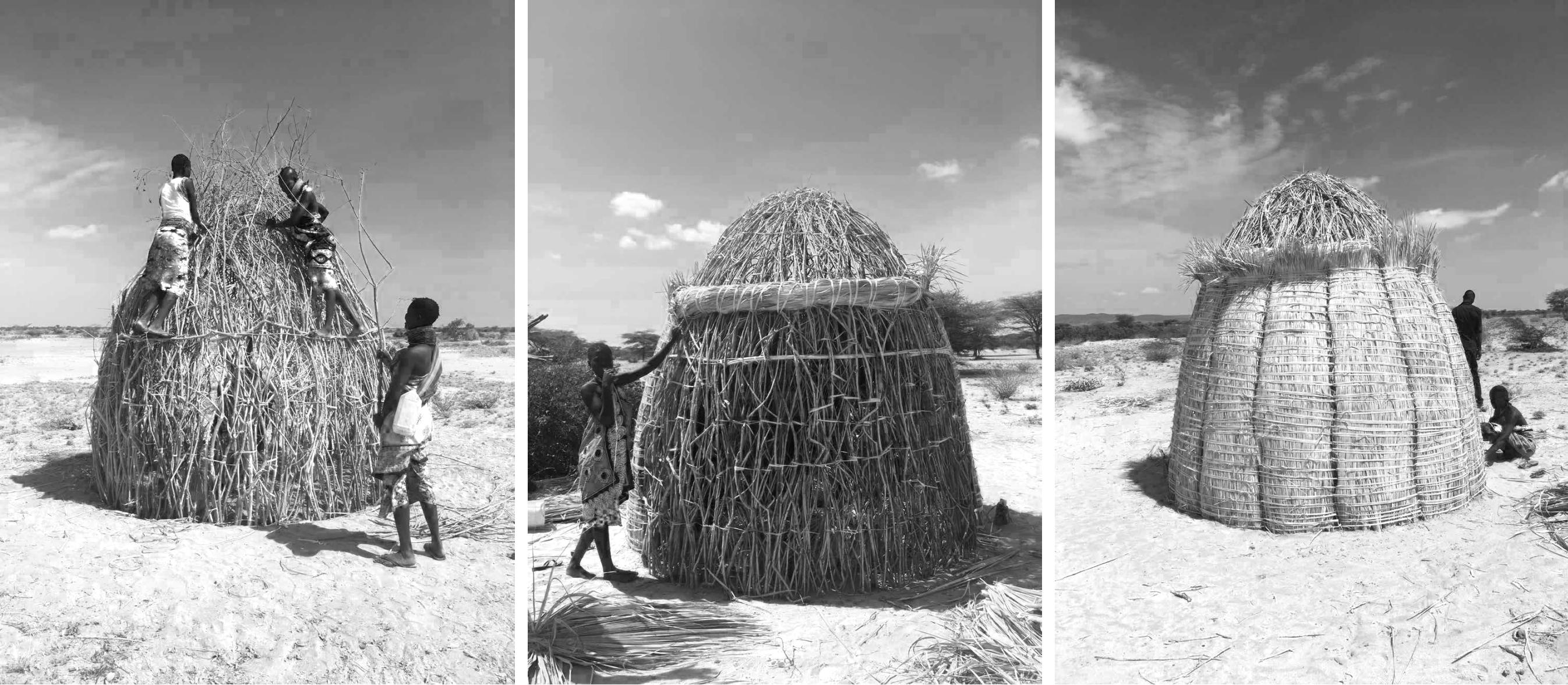

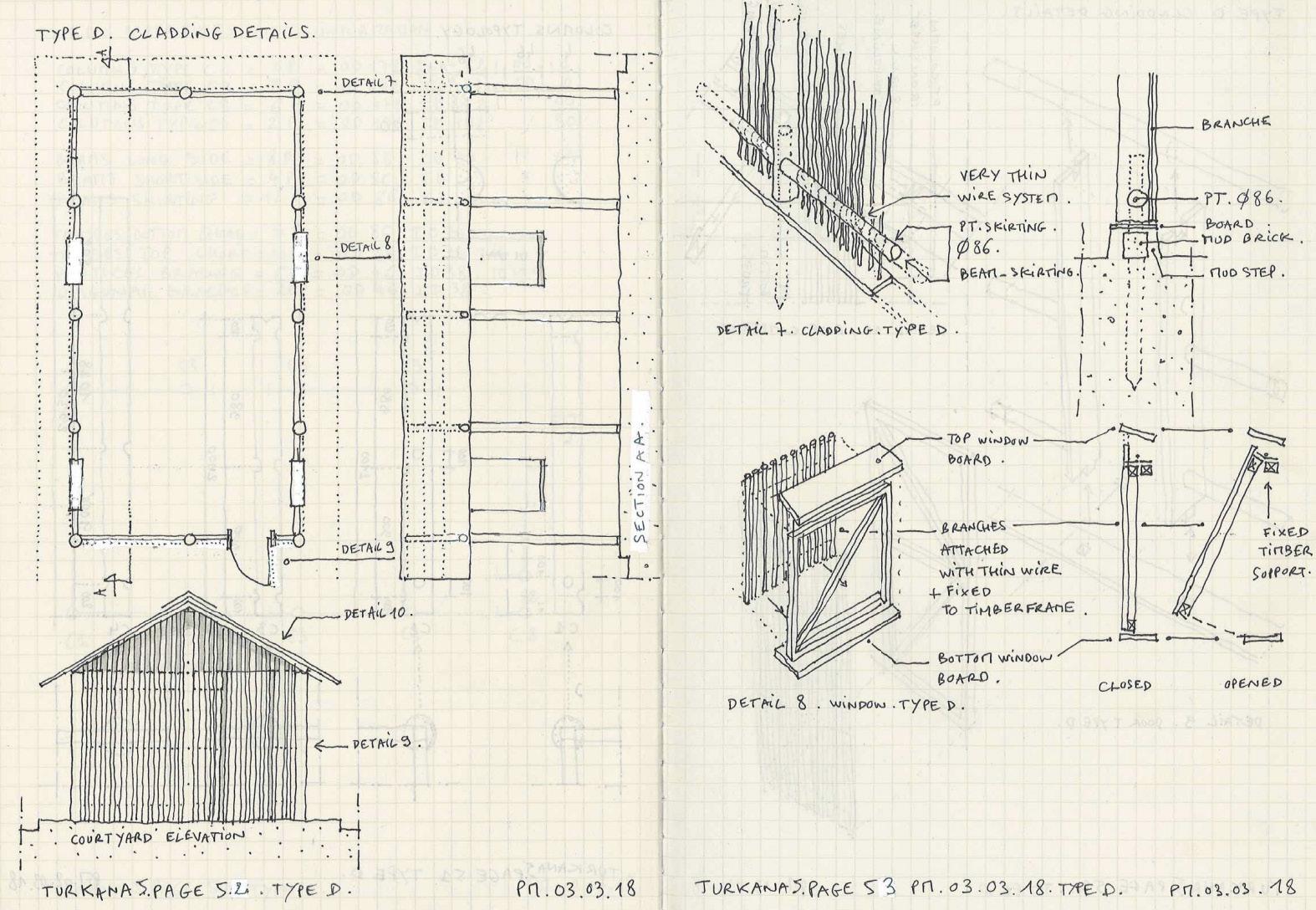

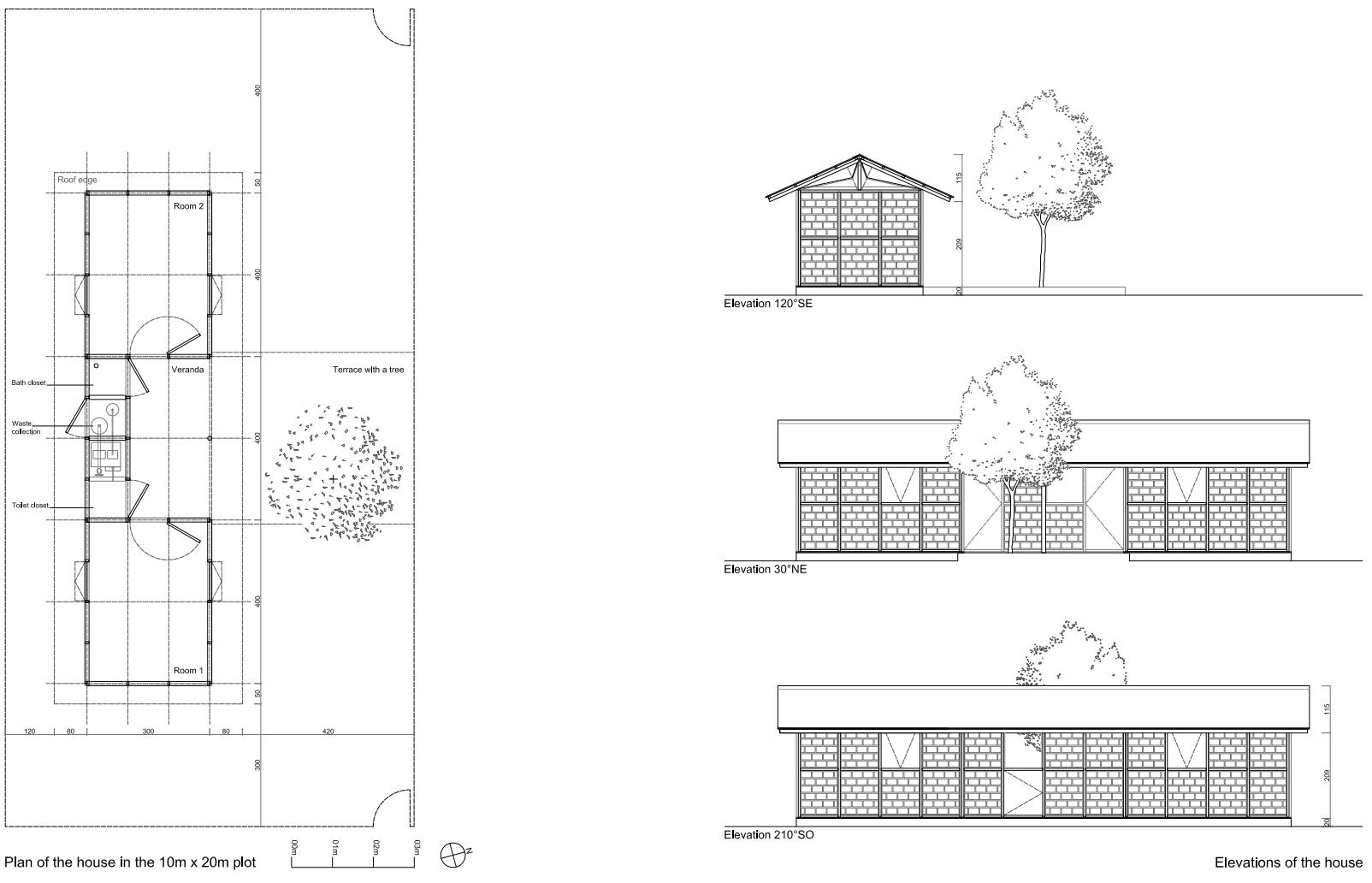

The Kalobeyei Settlement project embodies all previous experiences to date, demonstrating a valuable thought and design process for humanitarian action. Already in the project report for the Ecuador case study some valuable insight on the design process was provided. Interviews - to local authorities and the displaced population - and site visits have a significant role in understanding the needs of the affected community. 20 families had built their own shelters and community shelters, but the living conditions were poor with risks of it becoming a slum. The first phase involved transferring these families into better homes, the adapted paper log houses, to then develop an urban plan for the construction of a hundred of these same units. This methodology was matured through the decades of humanitarian work. However, the modus operandi is perhaps best expressed in the “Turkana Houses” project report by Philippe Montail on Ban’s ongoing development of the Kalobeyei Settlement in Kenya.

Refugees in Kenya are hosted in cities or large settlements, they often live in close proximity to host communities leading to conflicts regarding resource allocation and distribution. As we have previously discussed, short-term strategies, such as UNHCR’s T-shelters, enable a fast emergency response though they are unable to create adequate long-term living conditions. In 2017, Shigeru Ban was called by UN-Habitat to design a permanent settlement in Kalobeyei with the construction of up to 20,000 units for the more than 37,000 south Sudanese refugees and local Turkana. The goal is to “develop sustainable and appropriate shelter options […] to give residents a sense of

dignity and a home for long periods of displacement” (Montail P., 2019). The key, as in all of Ban’s disaster relief shelters, is simplicity. The design process can be divided in 3 steps:

1. gain greater understanding of the South Sudanese and local Turkana Culture,

2. develop contemporary responses based on the research in the form of four pilot houses

3. build a team able to construct the pilot houses and subsequently oversee the development of the entire settlement.

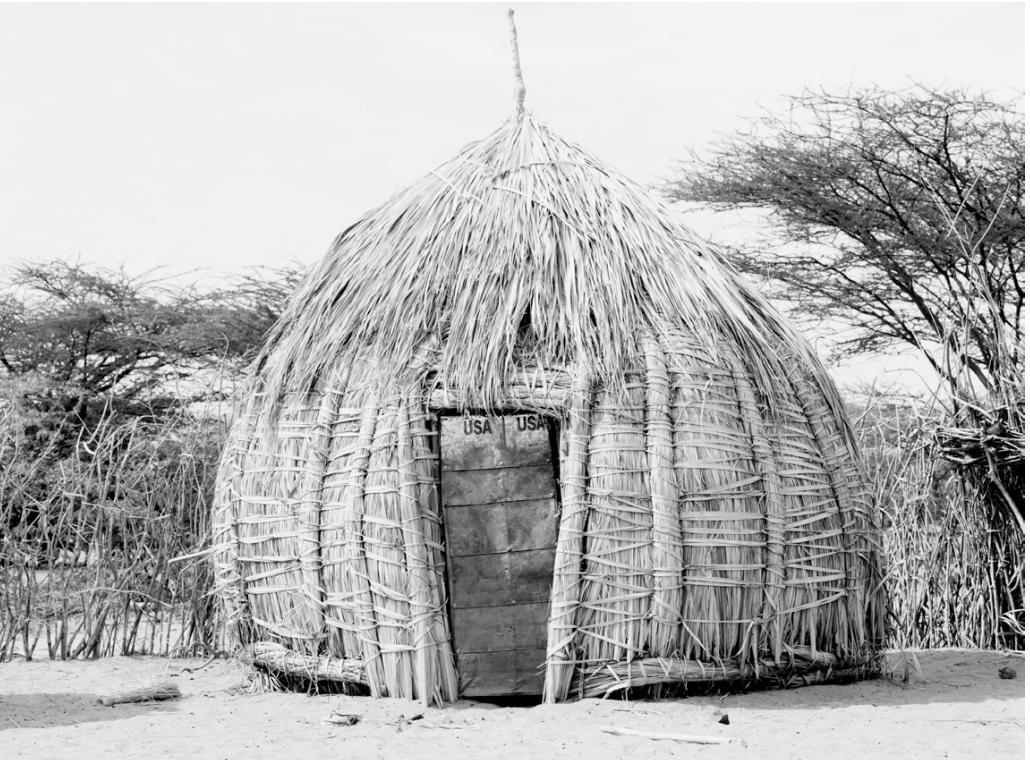

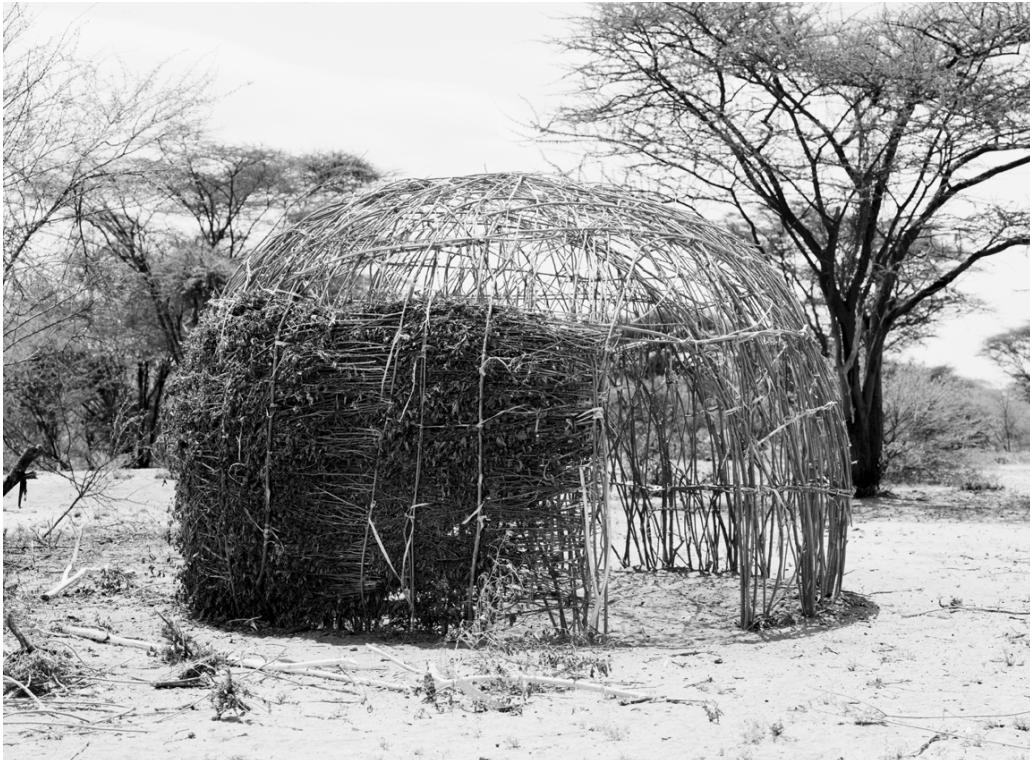

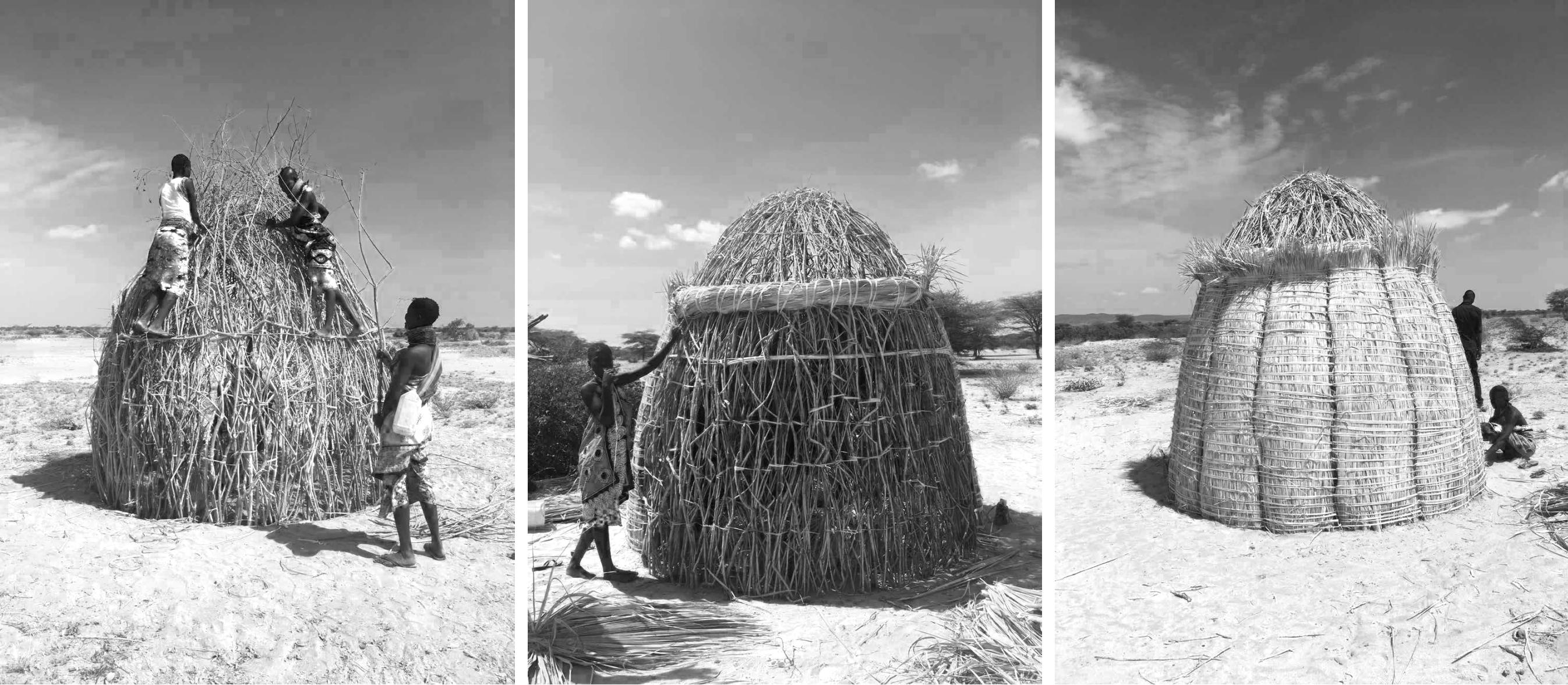

Climate, rather than political and cultural borders, defines the vernacular architecture of the region. The majority of South Sudanese live along the river Nile in tukuls: mudbrick clad huts with a thatched conical roof. The solid walls offer protection from predators and flooding. During the rainy season they reside in their permanent mudbrick settlements, whilst in the dry season everyone, except for the ill and elderly, migrates to the semi-permanent grassland settlements for cattle grazing. The tukuls reflect the way of living of the community, much more sedentary, though still nomadic, compared to the lifestyle of the Turkana people. In Turkana County, herders constantly face drought and are hence continuously on the move seeking for grazing pastures for their goats. Due to lack of water their shelters are simplified, with branch structures clad in whatever leaves and grasses they can find. The giant twig skeletons they leave behind slowly return to nature. Permanent settlements as Kakuma town, close to Kalobeyei, have a different organization. Single households are made up of various smaller huts, each for a specific function. In both cases, the branches are woven together with a typical construction technique developed by the Turkana women.

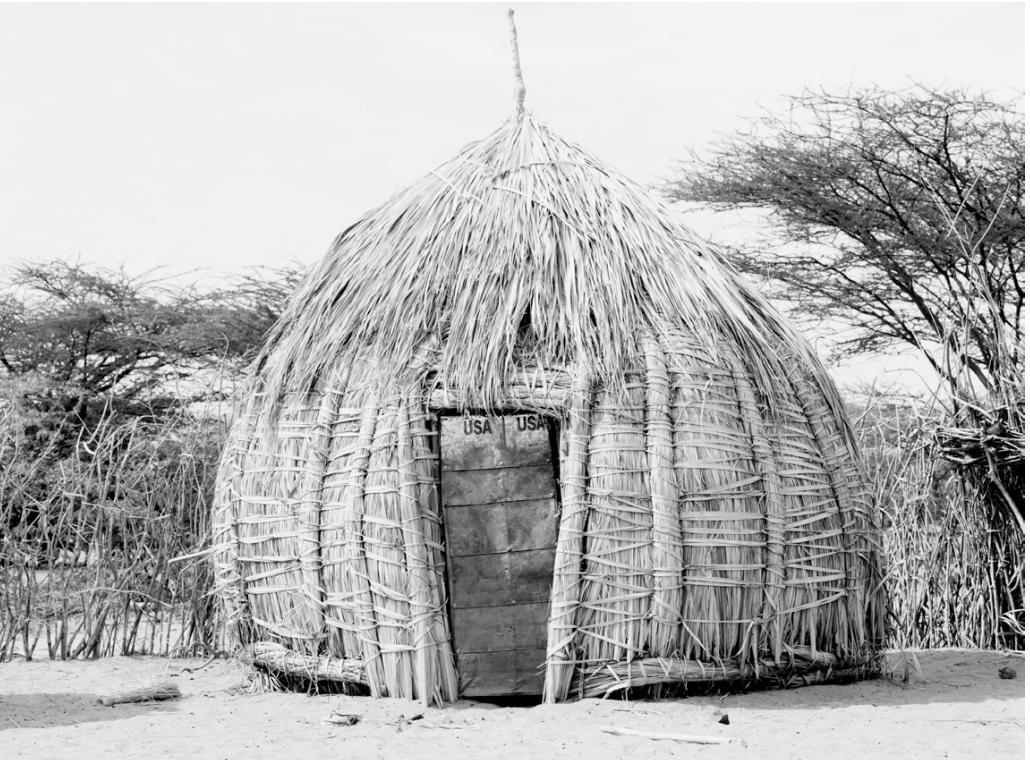

Fig. 45 and 46; South Sudanese Tukul / Permanent and Semi

Fig. 45 and 46; South Sudanese Tukul / Permanent and Semi

23

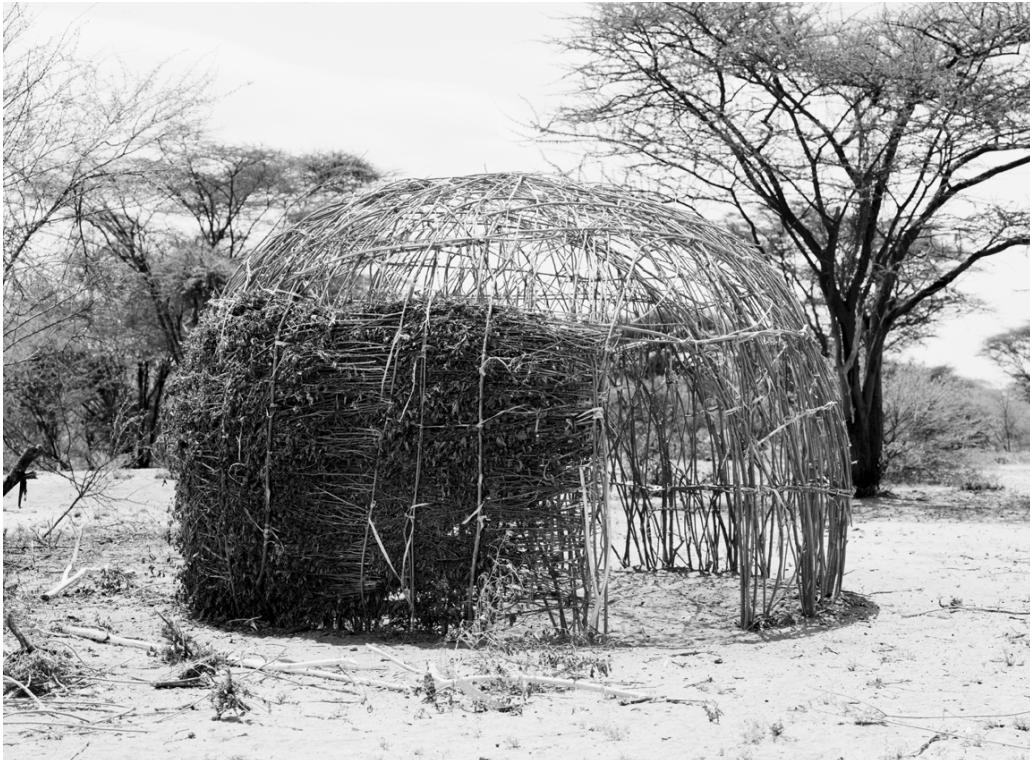

Fig. 47 and 48; Turkana Hut far from Lake Turkana

Fig. 49-51; Turkana Hut close to Lake Turkana

Fig. 47 and 48; Turkana Hut far from Lake Turkana

Fig. 49-51; Turkana Hut close to Lake Turkana

24

Fig. 52; Turkana Sleeping Hut in Kakuma Town, under the stars

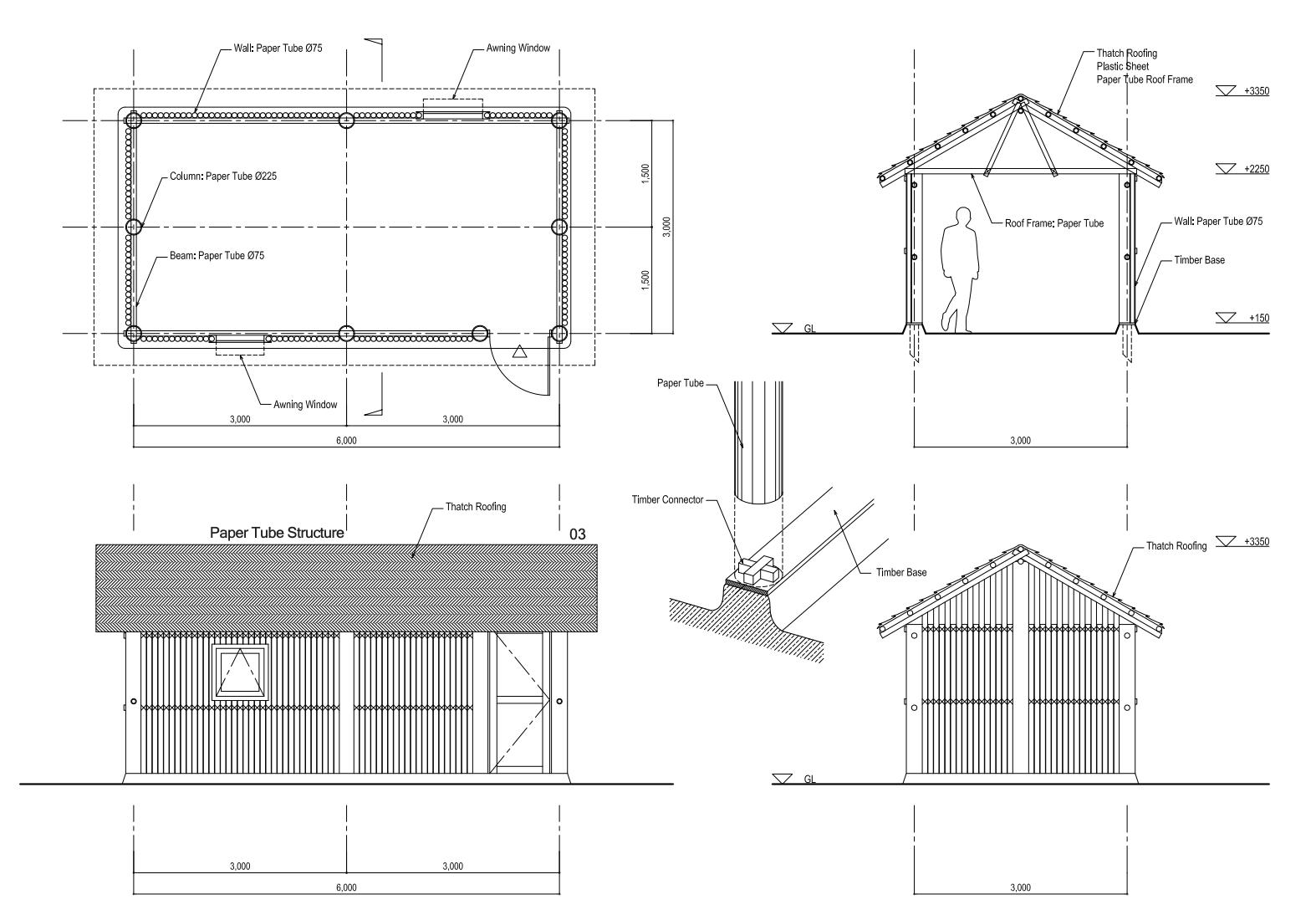

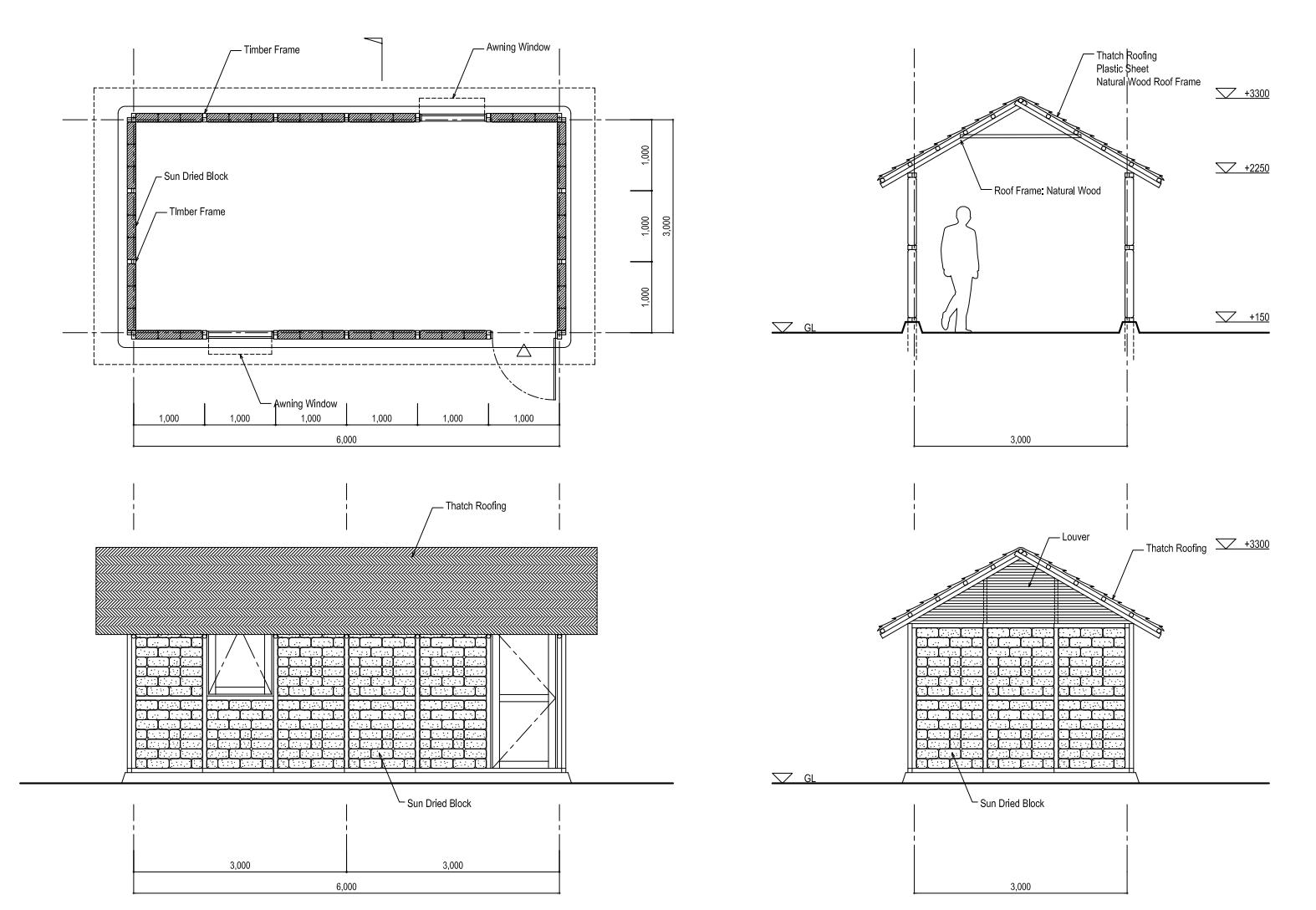

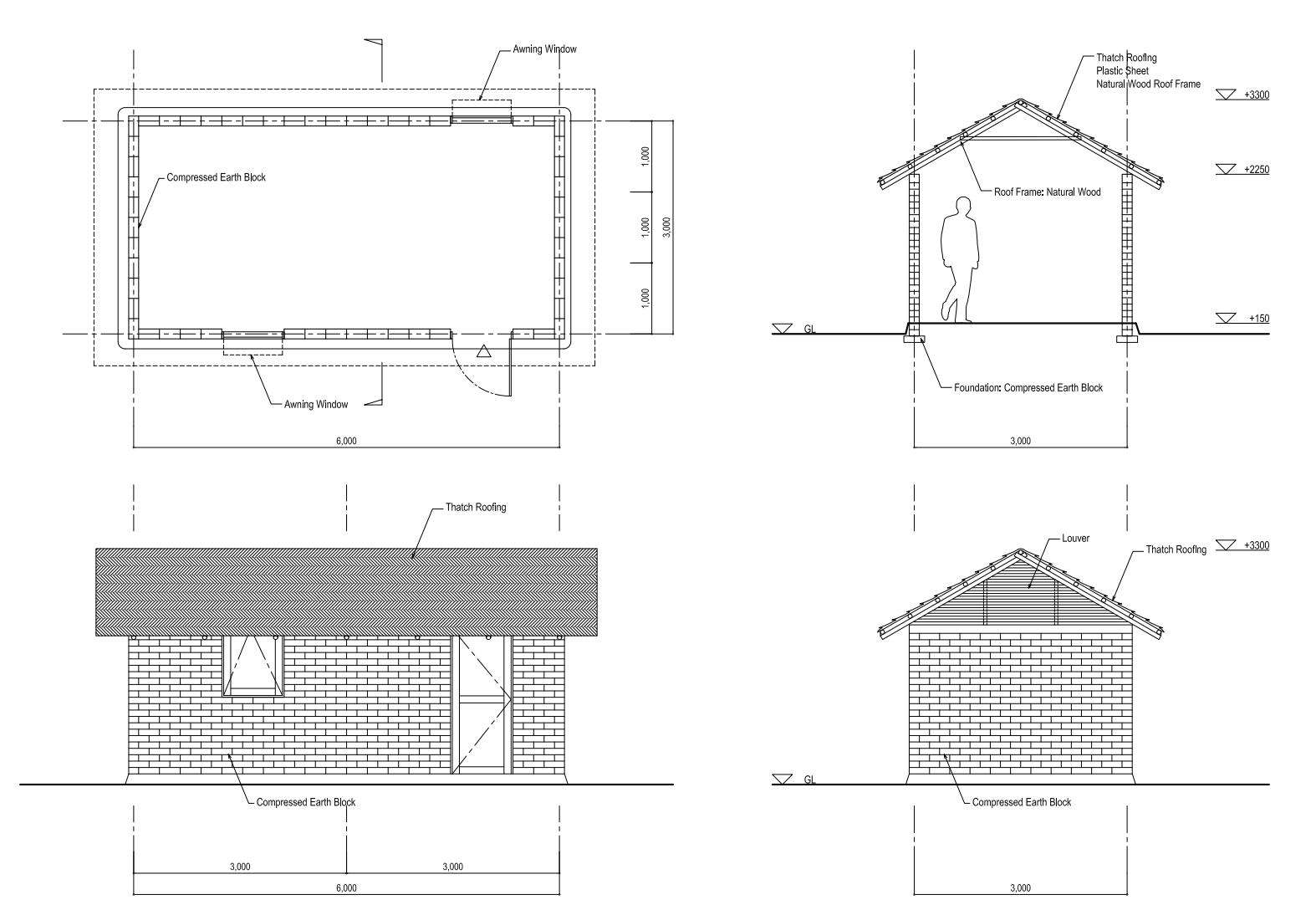

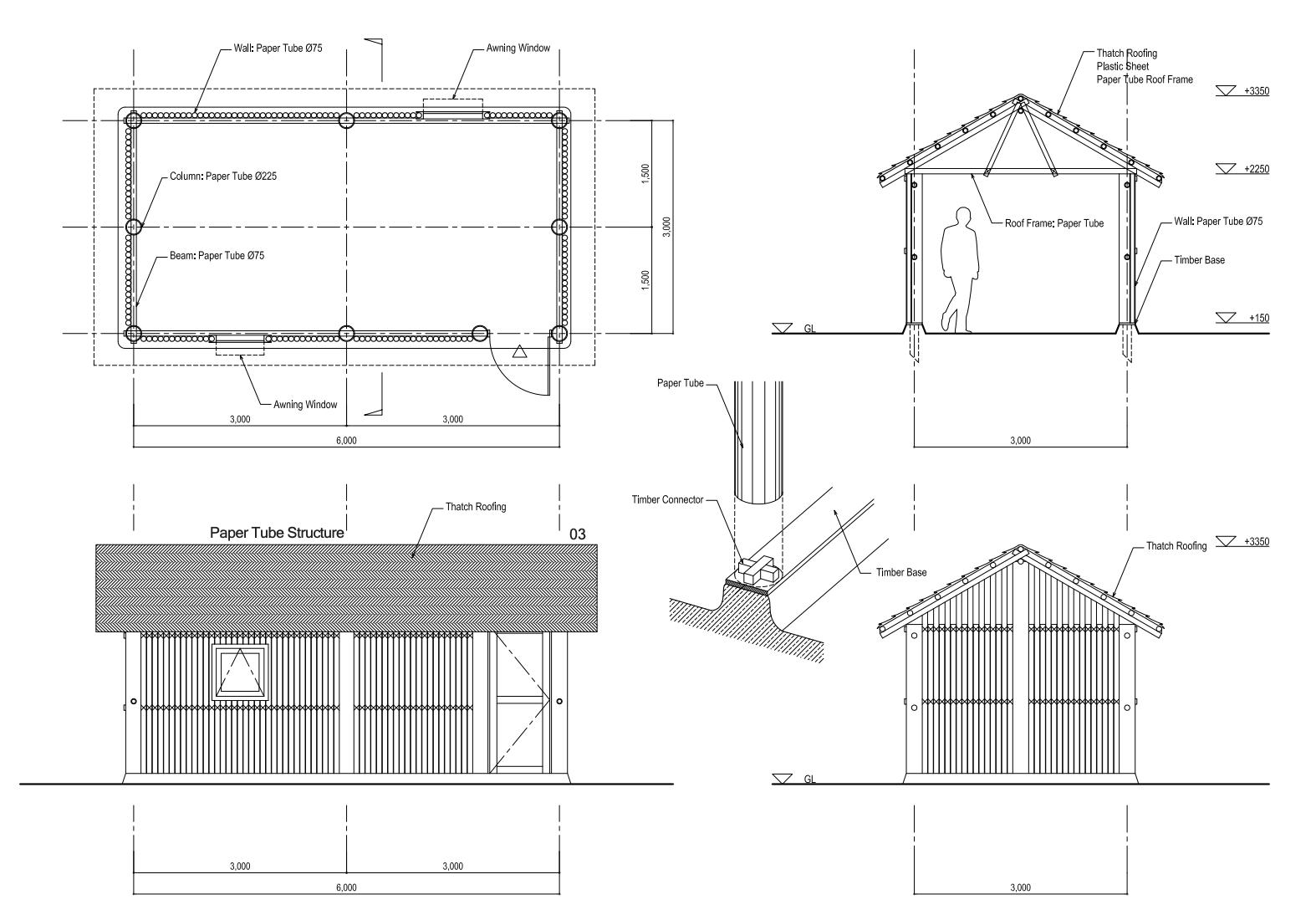

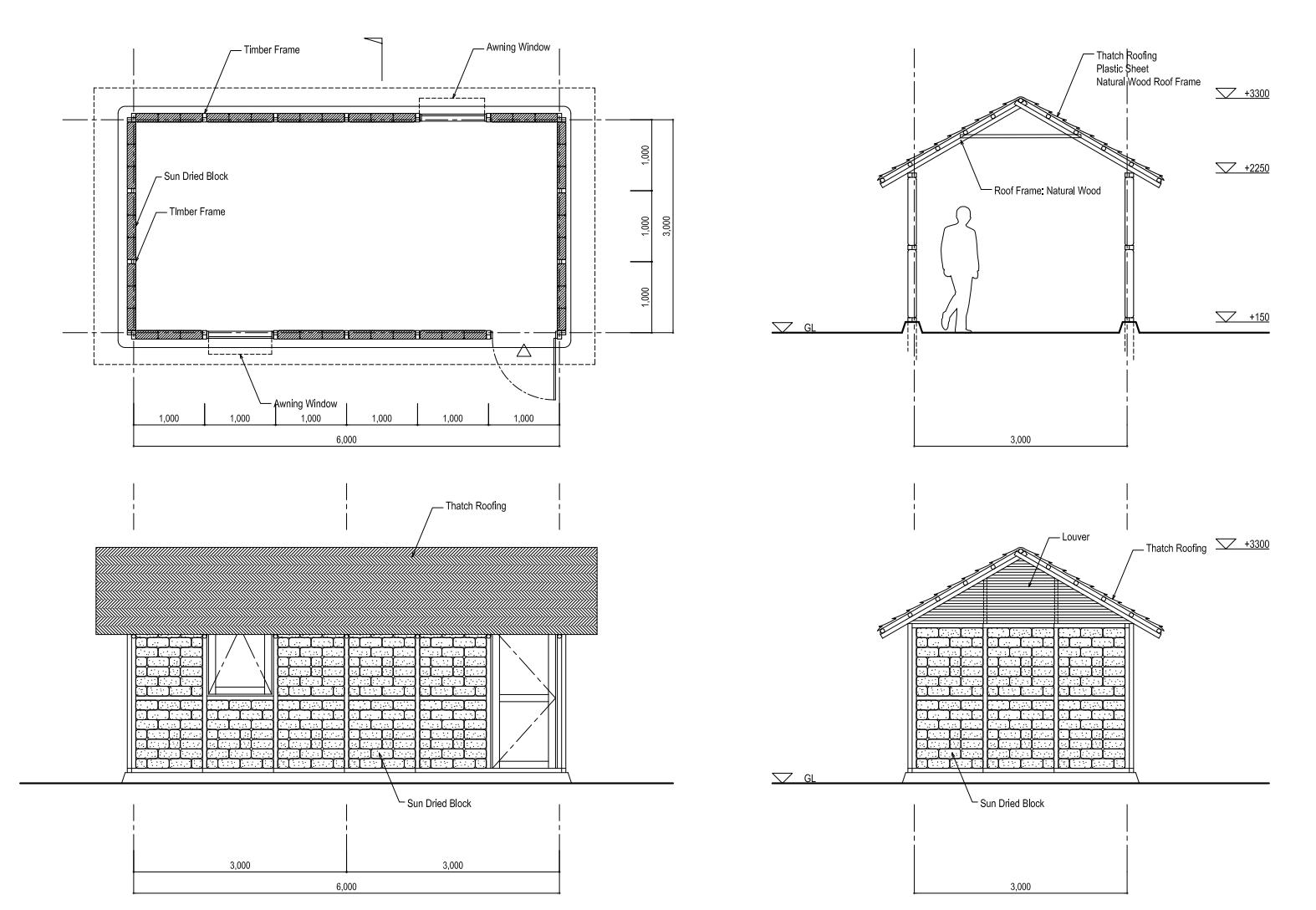

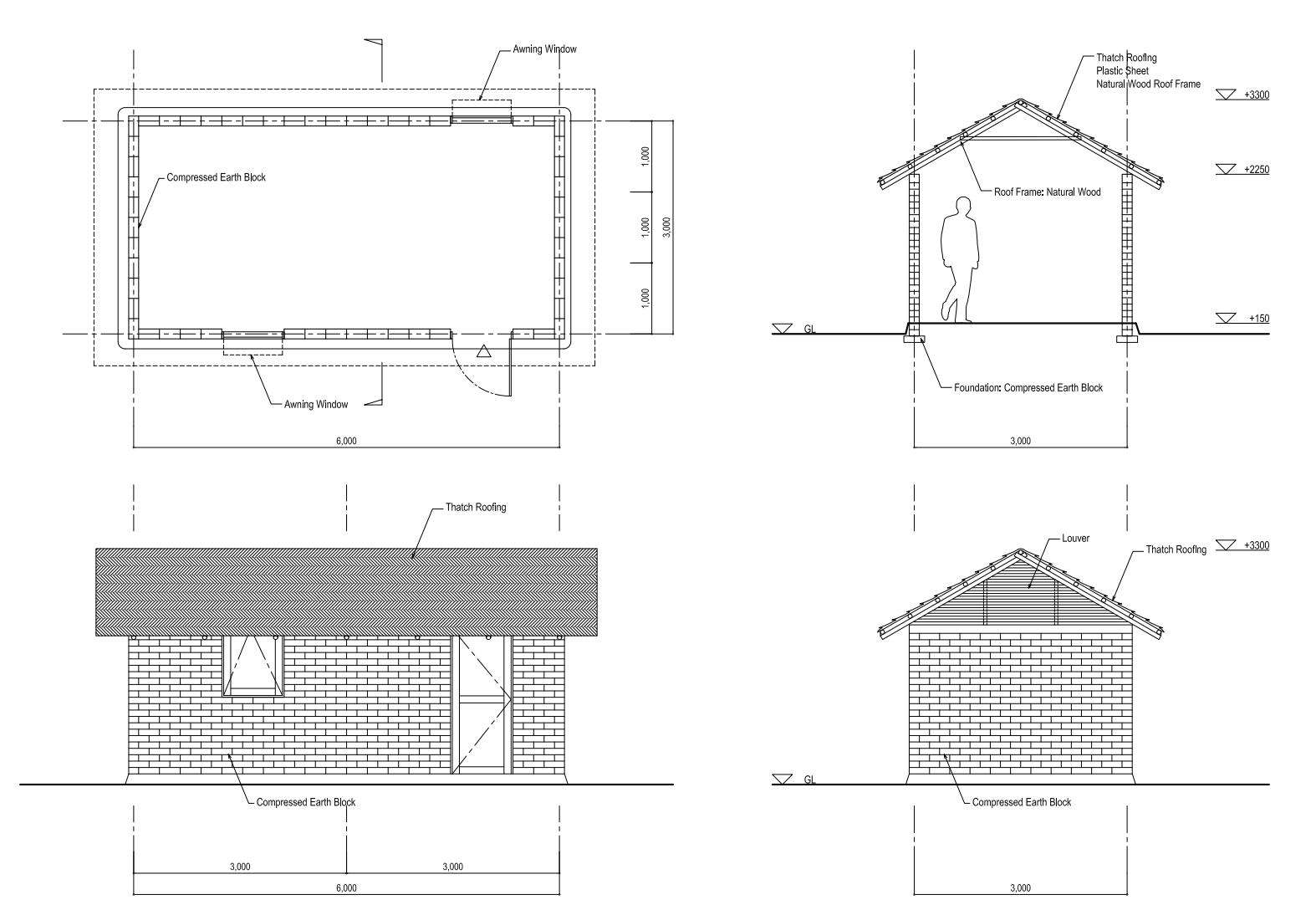

In light of the research done 4 pilot houses were constructed (Appendix 03 for technical drawings):

Type A. Paper tube structure covered with paper tubes. Similar to the 1995 Kobe Log Houses, except that the tubes are woven together with rope like the branches in the Turkana sculptural structures. The interaction between traditional vernacular architecture and contemporary architecture is clear.

Type B. Timber frame filled with burnt bricks.

Type C. House made of Compressed Earth Blocks (CEB), a common technique found throughout Africa.

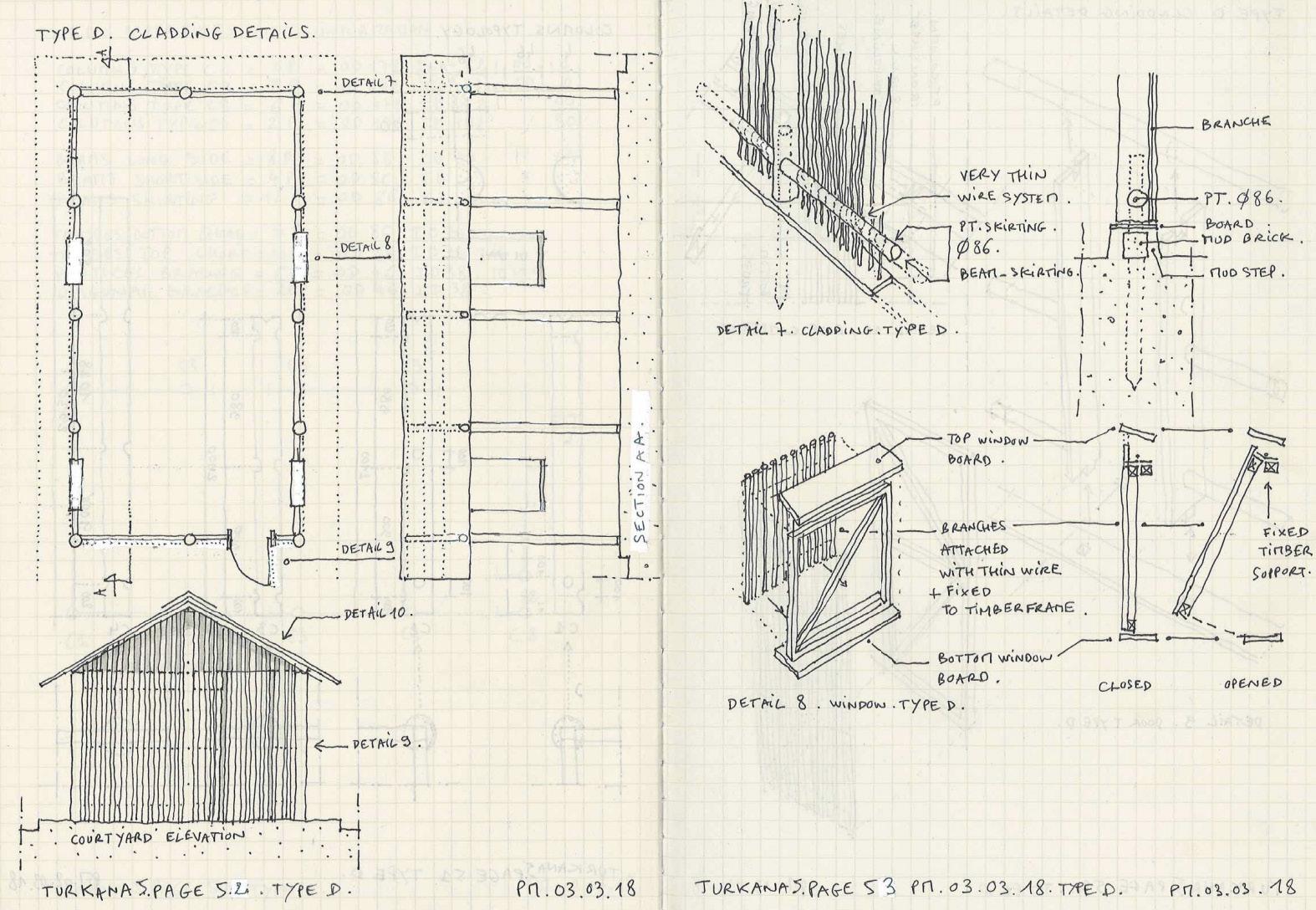

Type D. Paper tube structure covered by branches of local trees used for nomadic houses.

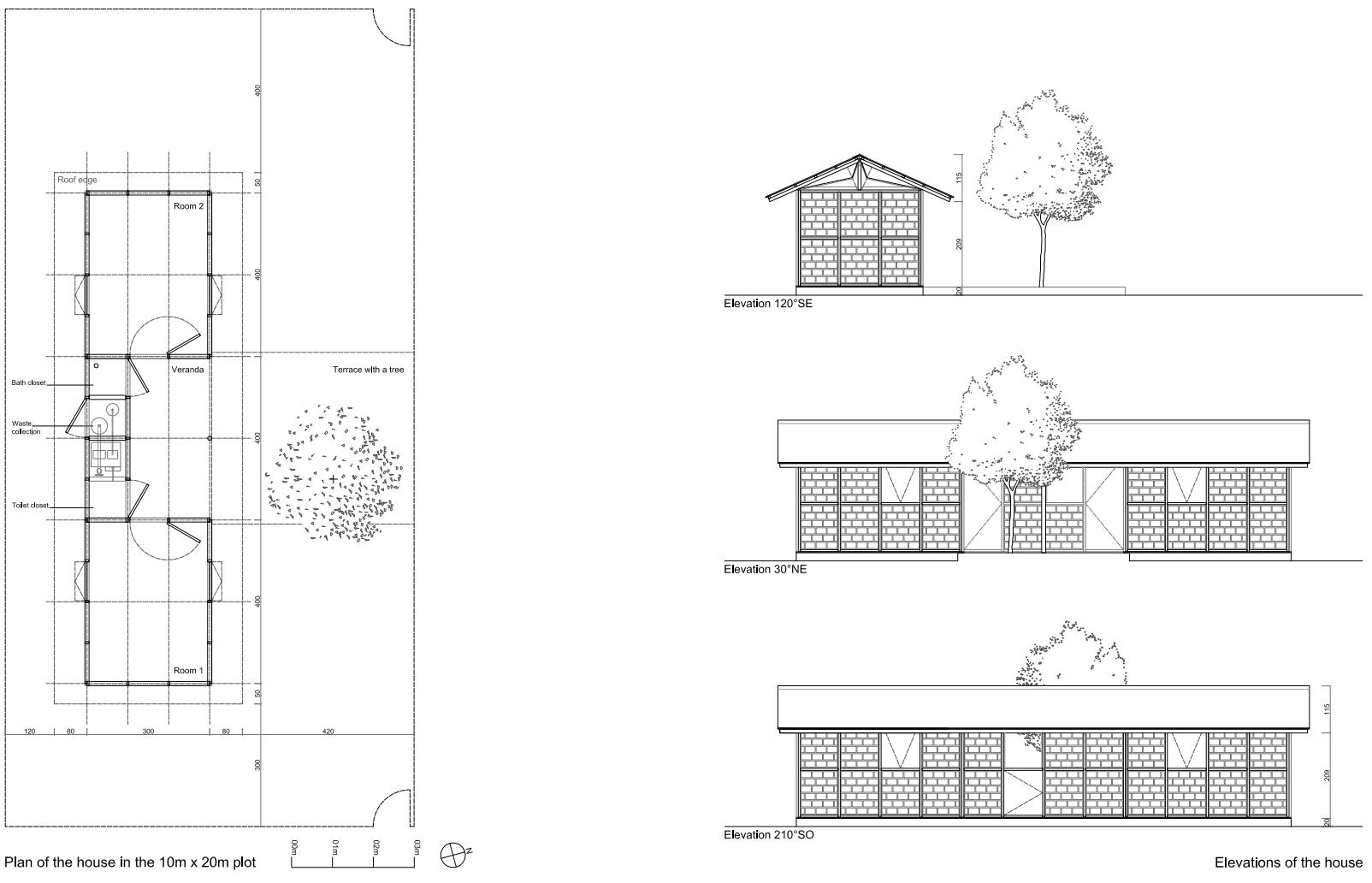

The pilots served as examples of aesthetics and as trials for construction details and durability in the Kenyan climate. Having a single 18sqm room made the pilots inadequate for entire families, it is only once the typology was selected and additional rooms – a terrace, a toilet unit, two bedrooms – incorporated that the Type B3 design was achieved. Architecture is a mean of artistic expression and support, as such it provides a way for each community to share their culture with others. The development of 4 models, rather than forcing a single typology on the residents, reflects this belief.

Site visits throughout the process were crucial in observing the local lifestyle and dwelling. Interviews before, during and after the construction of the 4 pilot houses allowed the selection of the most appropriate solution for the context and for its people. Ultimately both solutions employing paper tubes, Type A and Type D, were dismissed in favour of an evolution of the Type B. Paper, in the collective mind, granted little protection from the harsh environmental conditions of the area and its external sourcing brought less economic advantages to the local community than other models. Though the Type D House most closely mirrors the Turkana culture, one detail proved problematic for refugees: the reduced privacy due to the gaps in the branches of the cladding. This was less of an issue for Turkana people, perhaps because they recognised their cultural heritage in the Branch House or because refugees and locals have diverse needs for privacy. Turkana county is characterised by a nomadic

Fig. 53; Type A

Fig. 54; Type B

Fig. 55; Type C

Fig. 56; Type D

Fig. 53; Type A

Fig. 54; Type B

Fig. 55; Type C

Fig. 56; Type D

25

pastoralist nature of its people; the land, rather than their transient huts, is felt as their home. Refugees, as seen in previous case studies, may require greater privacy to satisfy their need for safety and belonging. Each context, with the culture and unique life experience of the single communities, requires a different solution. Ultimately, the final layout (Appendix 03 for technical drawings) is not a design research experiment as the 4 initial pilot homes, rather it is a design response to a specific cultural context with its inherent constraints acting as catalysts for imagination.

The question of employment is the most interesting and relevant theme in humanitarian projects today. The value of initiatives, such as this intense

collaboration between UN-Habitat and Shigeru Ban, lies in its ability to provide job opportunities to refugees and local people. It is seen, in confrontational contexts as the one observed in Kalobeyei, as an opportunity to “reduce existing tensions and encourage collaborative business activities” (UN-Habitat, 2019). The two-year process of constructing the pilot houses created business opportunities in terms of locally sourcing construction materials and workforce, ultimately bestowing valuable knowledge and skill to the locals. Reduced technical supervision needed for construction and use of local materials means that inhabitant can easily maintain their homes in the long term, gaining independence from humanitarian aid which is crucial for the rebirth of communities.

(see Appendix 03)

Fig. 57;; Type B3 - FInal House Type using a wooden frame and burnt bricks. A veranda separates the two main internal spaces creating an external, yet private, place for family life

26

03 Paper Case Studies / Community Centres

Shelter is a primary requirement but, to truly rebuild a community, public space is essential in its ability to reinforce a sense of belonging which may have otherwise been lost. In the following macro-section, five main projects are taken and analysed alongside their long-term effects on the local social and urban tissue. Given the multiplicity of uses of communal spaces, the interventions are selected related to the primary intended function: religion, education, and entertainment.

03.1 / Religion

Independently from geographic and cultural belonging, mankind has always looked for comfort in the intangible answers offered by religion. In a broader sense, celestial rituals have been opportunities for social gatherings throughout history; places of worship becoming centrepieces of the lives of entire generations of people. Though modernity has led to a somewhat decline of the role of religion, in face of disasters we still turn to these spiritual places for comfort and human interaction. The relevance of these spaces is proven by Shigeru Ban’s two religious projects dealt with in the following section: both were conceived as temporary structures yet their psychological role in the reconstruction process has transformed them into permanent monuments in their respective communities.

“It’s a question of love. If a building is loved, it becomes permanent […]”

Shigeru Ban

03.1.1 Kobe Paper Dome / 1995 and 2008

The 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in Kobe, that had also led to the design of the first paper log house (see 02.3), elicited the construction of a temporary public space for the local Vietnamese minority. The Takatori Catholic Church located in Nagata-Ku, Kobe, was constructed in 1927 serving as a gathering place for the local community with uses diversified from religious services. Already in the 1980s it became a makeshift classroom where the children of Vietnamese refugees who had arrived in the neighbourhood could be assisted by volunteer teachers from local schools and universities. Though the earthquake reduced it to rubble, on its former site, refugees would still congregate for the morning service around an open fire speaking to its role in the area. It is in this setting that Ban first imagined the potential of a temporary public building. His initial proposal of a temporary sanctuary was refused by the clergy. Only

after the construction of the 28 paper log houses which solved the more urgent housing crisis, did the friars consent to the project, provided it was the architect who would raise the money and find a volunteer work force. Through donations of materials and a student-based construction crew Ban managed to cap costs at 100,000$ and in five weeks the community centre was in full use.

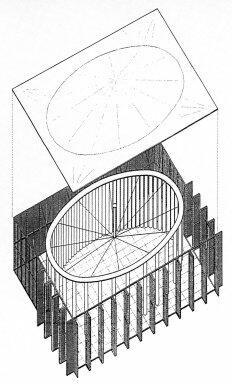

The connection between the internal congregation space and the exterior is perhaps the most crucial aspect of the design. The in-between space which develops within the rectangular perimeter and oval core, which expands the concept of the threshold in space and time.

Fig. 1 and 2; Kobe Paper Dome (top) Exteriors and (bottom) Interiors

Fig. 1 and 2; Kobe Paper Dome (top) Exteriors and (bottom) Interiors

27

When the fully glazed façade is completely opened, the main congregation eclipse is effectively transformed into an external space. Such functional desire is further emphasised by the later addition of an expansive overhanging roof. Perhaps reflection of the initial period after the disaster, Ban designed a space which could shield from the weather but, at the same time, provide that same spiritual connection with the surroundings. This theme is recurrent in his work, reflection of his cultural heritage.

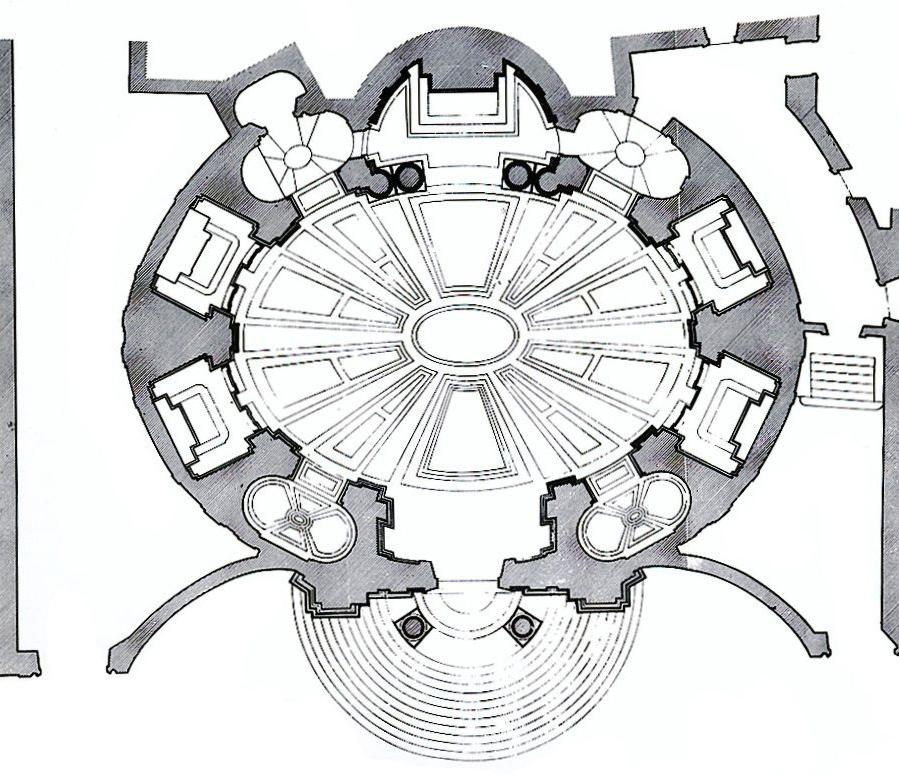

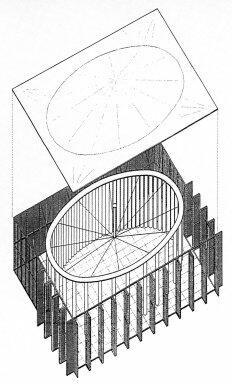

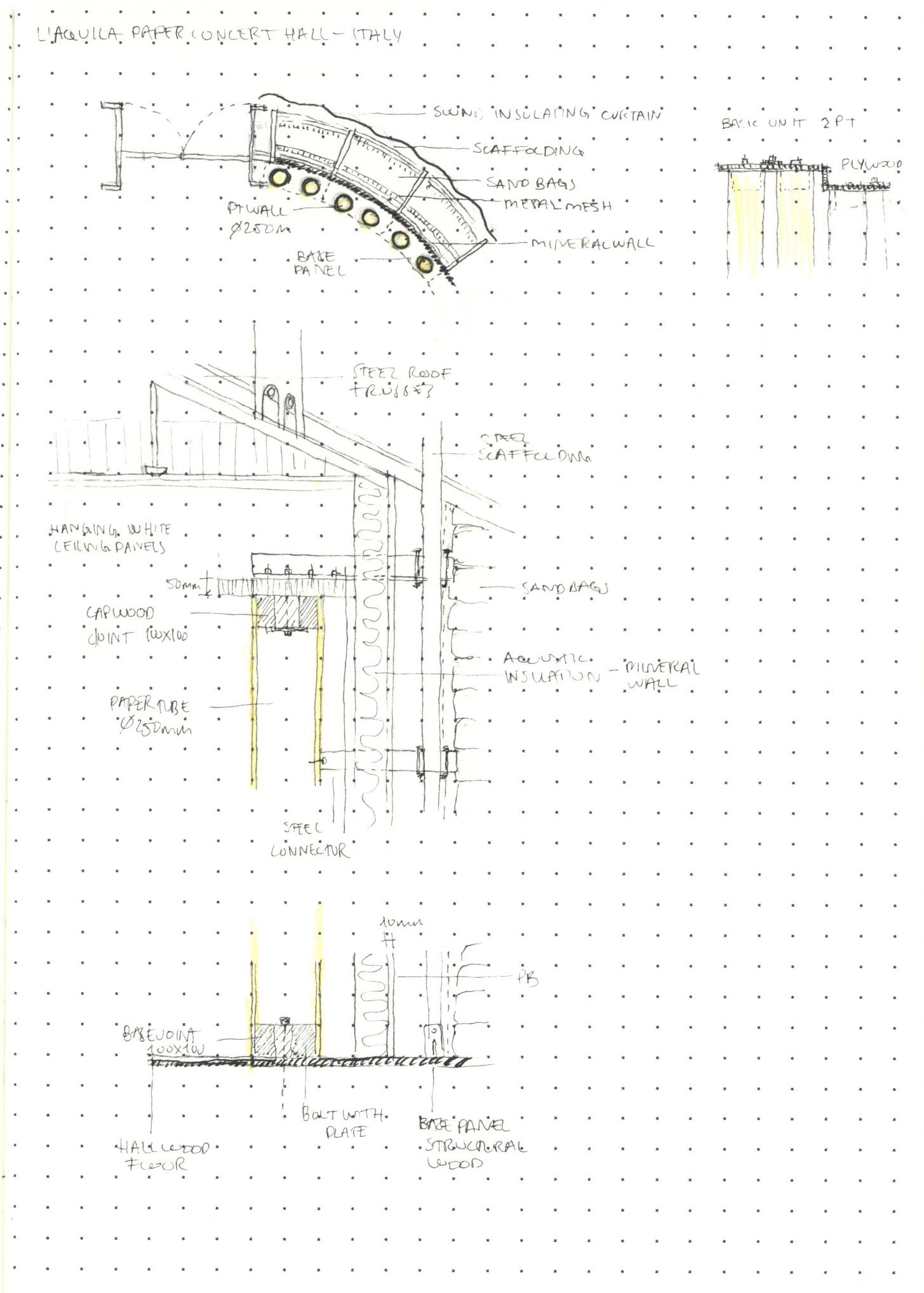

The beauty of the church lies in the modesty of its material and form. A rectangular volume, 10x15m in plan, enclosed within a skin of corrugated polycarbonate sheeting reveals an oval space of 58 paper tubes (each 5 meters high, 325mm in diameter, 14.8mm thick) covered by a tent-like white Teflon-coated fabric. The eclipse is inspired by Bernini’s designs, specifically the Colonnade of St. Peter’s Square and Sant’Andrea al Quirinale with which is shares the entrance along the short axis. This feature also determines the rhythm of the cardboard tubes: on the entrance side they are spaced at a wider distance to allow entry, the spacing diminishes up until the opposite end of the short axis. The gradual alteration in disposition naturally leads the eye to the core of the public space where a solid cardboard tube wall creates the backdrop to the altar. Though incredibly simplified, the paper columns recall those massive doric marble columns of St Peter’s Square and the rosy marble ionic columns that frame the altar in Sant’Andrea al Quirinale. Another element links the paper church to Bernini’s masterpiece: the white fabric elliptical roof diffuses light within the space much like the skylights in the latter. The space hence blends the dynamism intrinsic to the baroque oval plan with extreme structural and decorative minimalism typical of Japanese architecture and essential in emergency settings.

The Paper Dome was initially intended to last for three years, however its impact on the community was so powerful that it was used for over a decade as a religious centre and a place for mutual help and support. The structure saw an increase in the size of the religious community and in 2005, when it was deemed to have fulfilled its mission as the great number of congregates required a larger space, it was deconstructed.

Fig. 3; Exploded axonometry of the Kobe Paper Dome and the Oval Plan of the Baroque Church of Sant’ Andrea al Quirinale (1670)

Fig. 3; Exploded axonometry of the Kobe Paper Dome and the Oval Plan of the Baroque Church of Sant’ Andrea al Quirinale (1670)

28

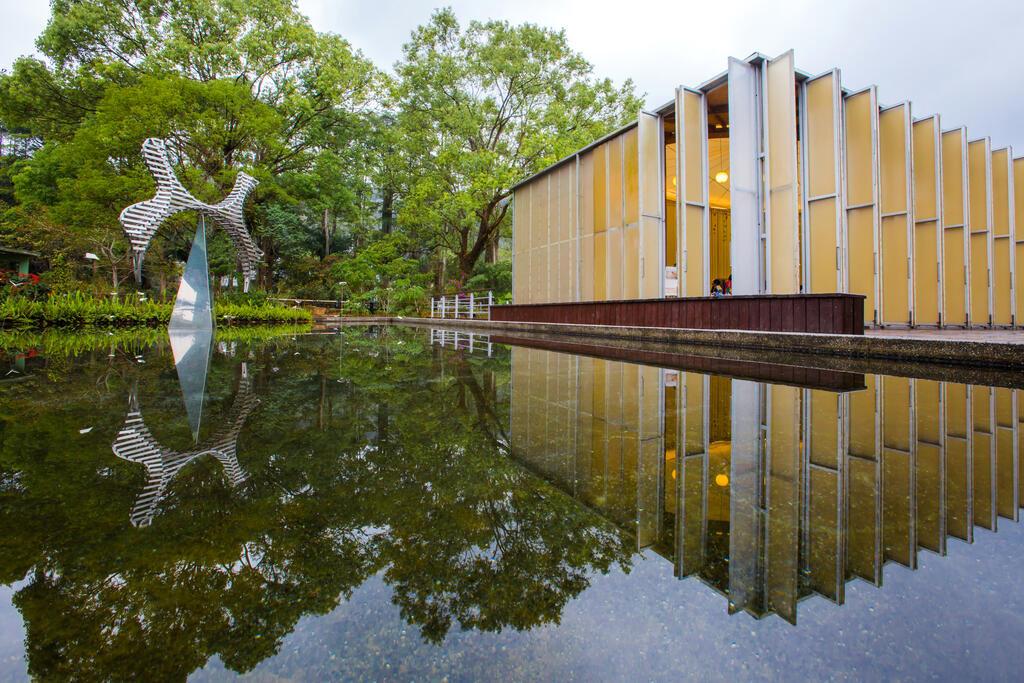

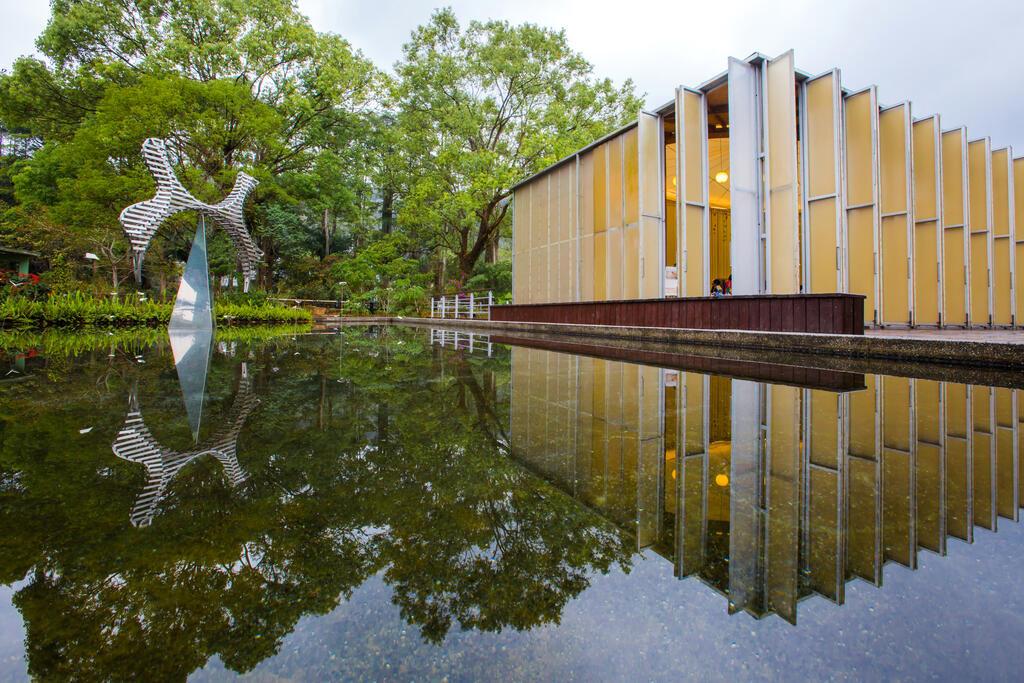

The top and bottom laminated timber joints holding the paper tubes in place meant the structure could be easily dismantled and transported elsewhere. It found its permanent site three years later, when it was reconstructed in Tao-mi Eco Village in Puli, hit by the 1999 earthquake in Taiwan. The Paper Dome connects two places and two communities, now rising on the edge of an artificial lake with additional cardboard benches designed by Ban himself. Its functions have

shifted, speaking to the fluidity of the space, now it has become a crucial learning platform and has played a significant role in post-disaster reconstruction and community building, allowing visitors to commemorate the event and the rebirth which followed.

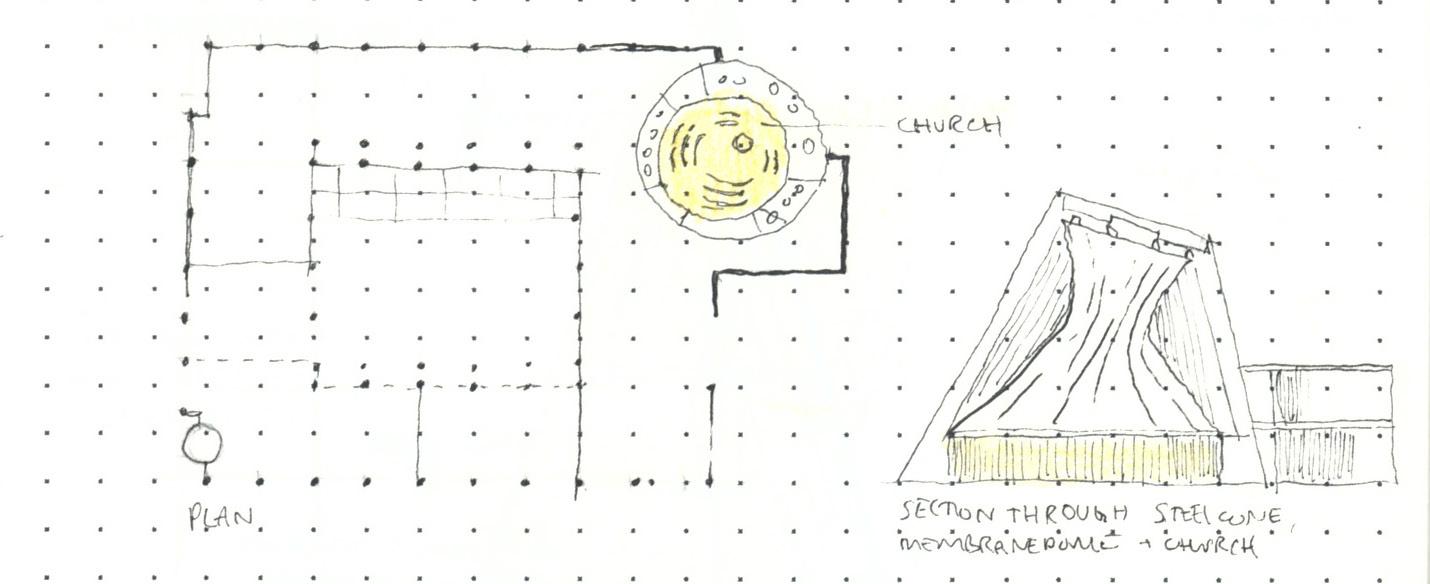

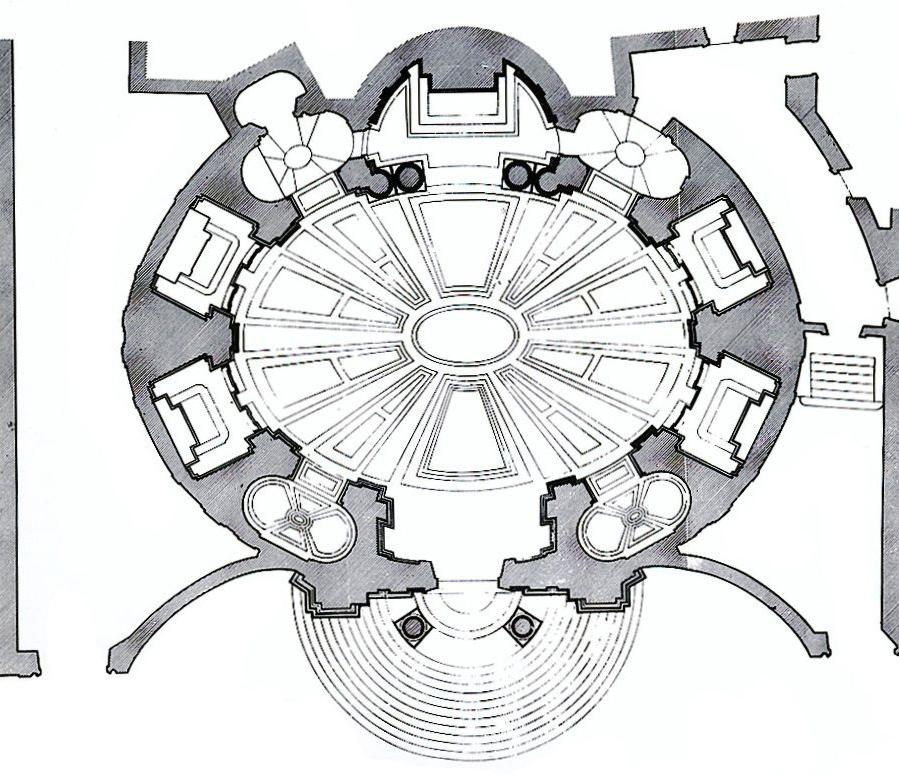

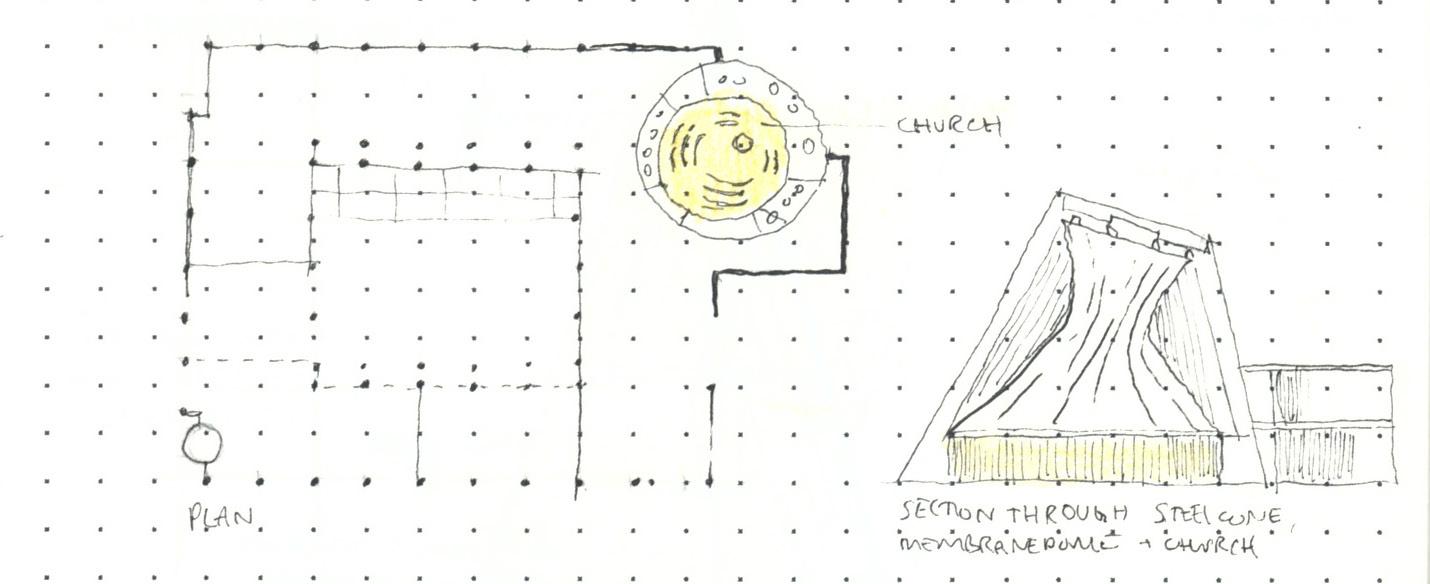

The continued needs of the Kobe community even after the removal of the Paper Dome were fullfilled by Ban through the construction of a permanent structure: the Takatori Catholic Church. This design concludes the disaster relief intervention process with a regeneration of the initial project into a multipurpose church facility. The new building is planned around a central courtyard with multifunctional spaces rising around its perimeter. A chapel shaped as an inverted cone and internally finished with a white membrane is used as the main congregation space. On the exterior, glass strips alternate the steel structure of the cone, giving the white textile a dynamic expression, which serves to visualise the passing of time through light. The harnessing of natural light through a medium of white membrane in tension recalls the former dome as does the employment of paper tubes, previously used as structural elements, in the interior finish for noise insulation (50mm diameter, instead of the 300mm diameter of the Paper Dome).

Fig. 6; Interiors of the Paper Dome with the custom paper tube benches and altar

Fig. 7; Plan and Section of the new permanent Takatori multifunctional center which replaced the Paper Dome

Fig. 8; The Domed Space of the Takatori Church recalls the original Paper Dome, slits of light convey the time passing

Fig. 5; the Paper Dome in its Permanent Site in Taiwan

Fig. 4; Details of the wooden joints connecting the paper tubes

Fig. 6; Interiors of the Paper Dome with the custom paper tube benches and altar

Fig. 7; Plan and Section of the new permanent Takatori multifunctional center which replaced the Paper Dome

Fig. 8; The Domed Space of the Takatori Church recalls the original Paper Dome, slits of light convey the time passing

Fig. 5; the Paper Dome in its Permanent Site in Taiwan

Fig. 4; Details of the wooden joints connecting the paper tubes

29

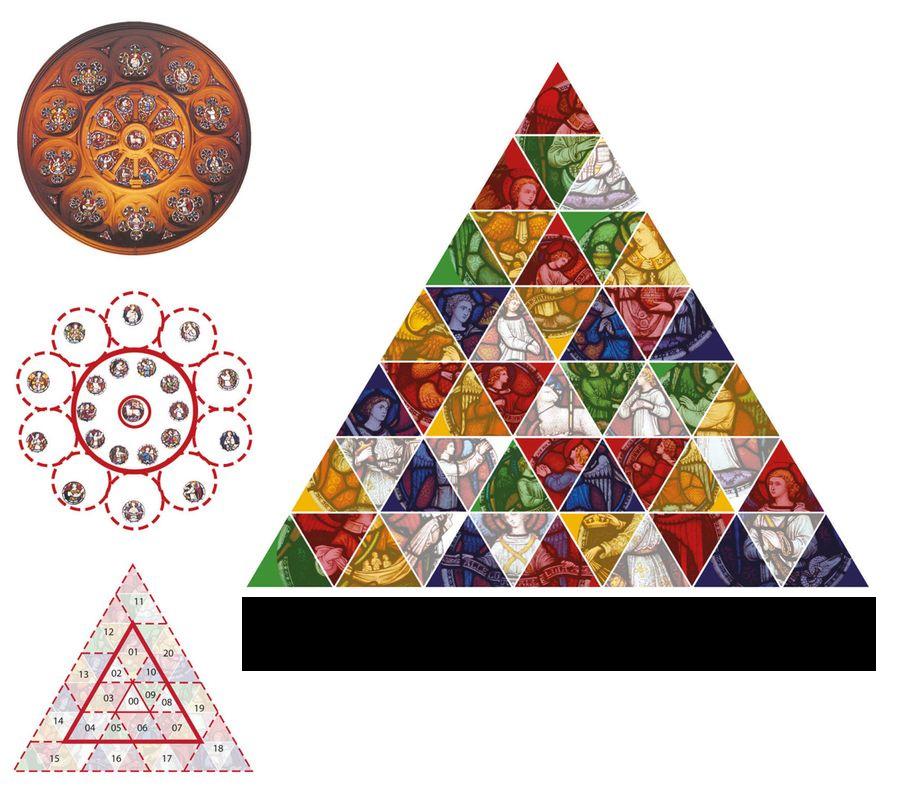

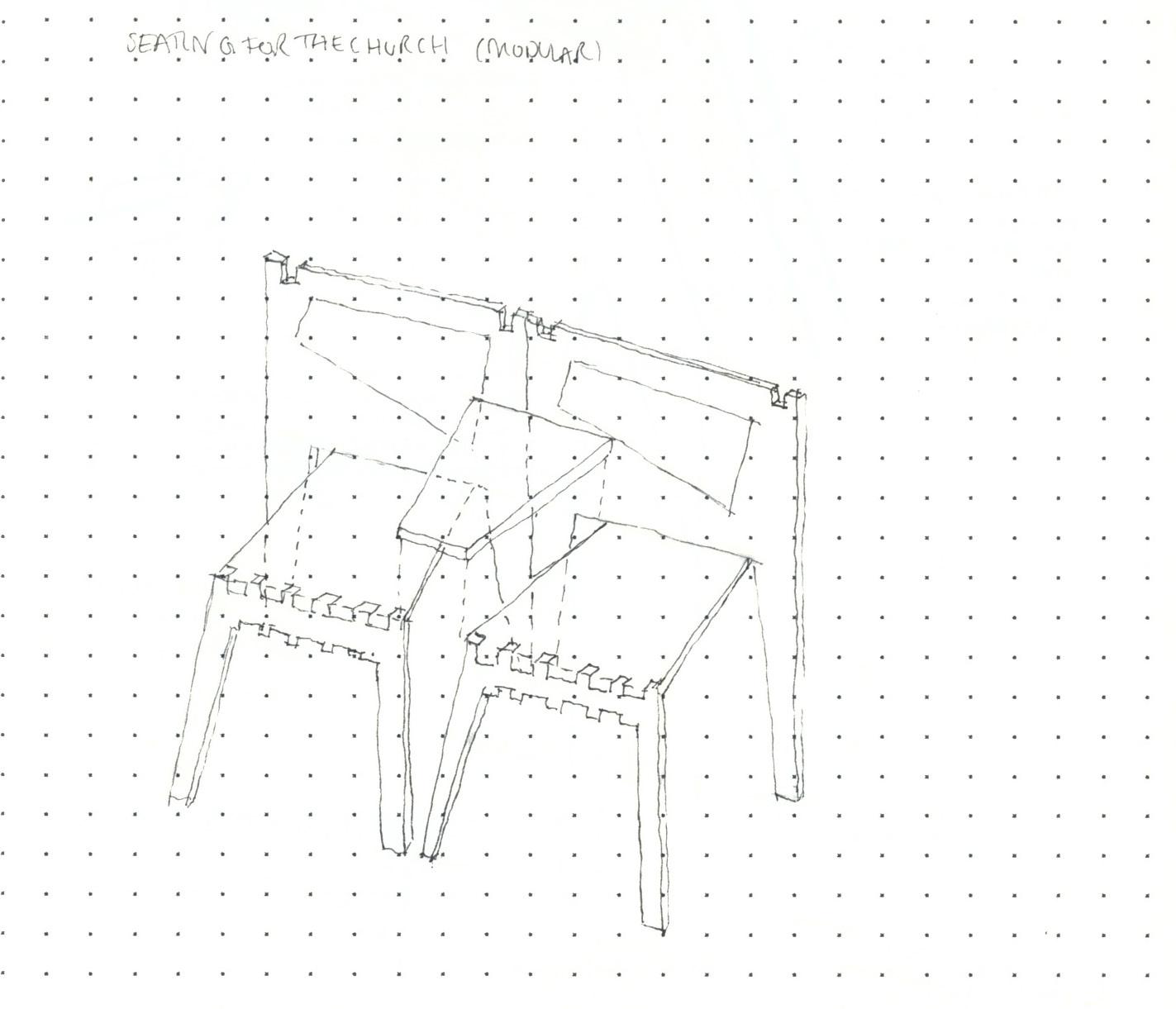

03.1.2 / Christchurch Cardboard Cathedral / 2007

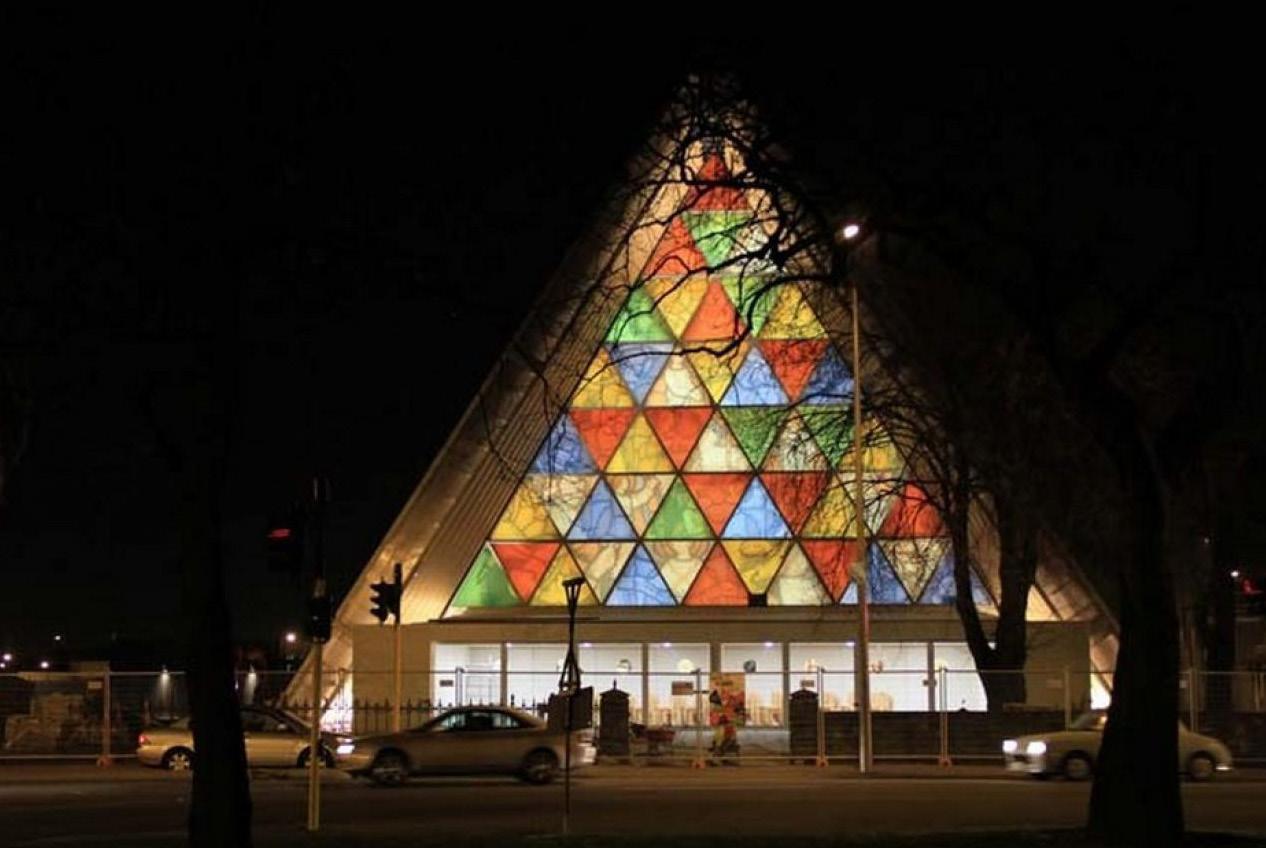

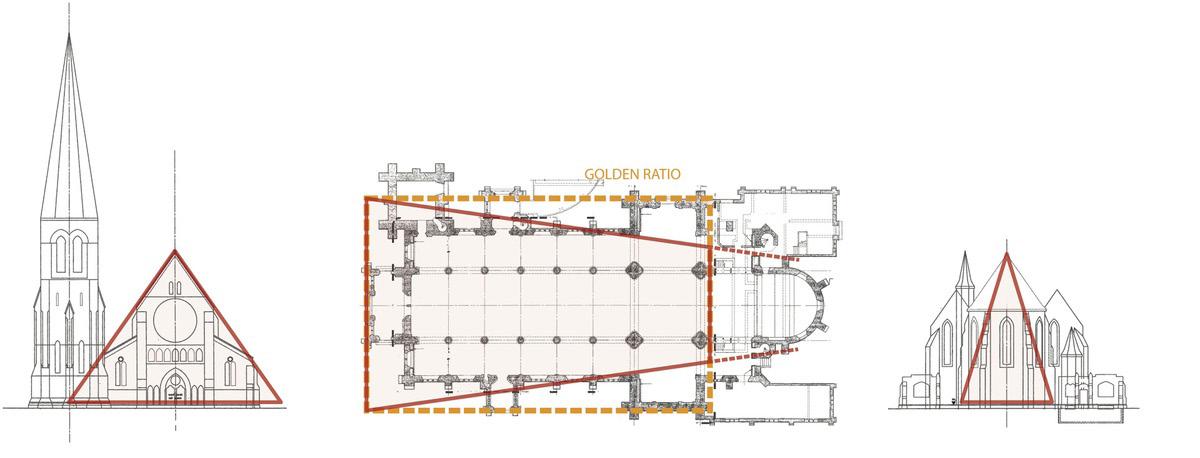

The Canterbury Earthquakes were a series of tremors that occurred throughout 2010-11 in the region of the city of Christchurch in New Zealand. The largest of these left the urban area in ruins, destroying many important landmarks such as the iconic Anglican Cathedral (1864). The Cathedral Church of Christ in Christchurch (or Christchurch Cathedral) is considered exemplar of the Victorian mid gothic style and important physical and symbolic landmark for the area. Constructed in 1864 in the new Christchurch settlement, it was deliberately placed in the center of the city-to-be on the eastern end of the cruciform Cathedral Square. Its functions broaden outside of spiritual significance with many important cultural events, since the European colonisation, taking place in the Cathedral. The building itself was a commemorative monument to the families of the diocese as many glass-stained windows, internal furnishings and bell towers exhibited plaques with names of donators and members of the community. Its architectural, social and historical value extended well beyond its religious functions thanks to the civic role it assumed throughout its lifespan. The distinctive spire and part of the tower were torn down and crippling damage to the structure was verified during the February 6.3 magnitude shock. Shigeru Ban’s desire was hence that of harnessing the multiplicity of purposes in a new temporary structure which would acquire a similar role in the collective society.

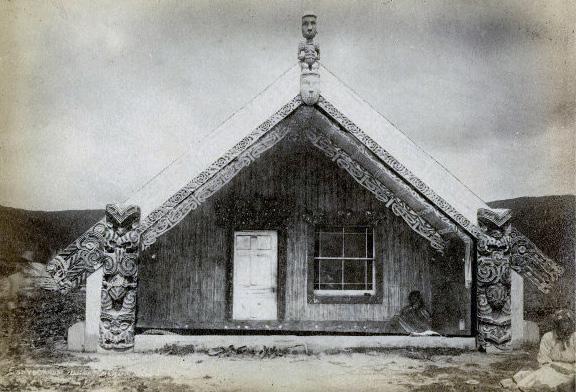

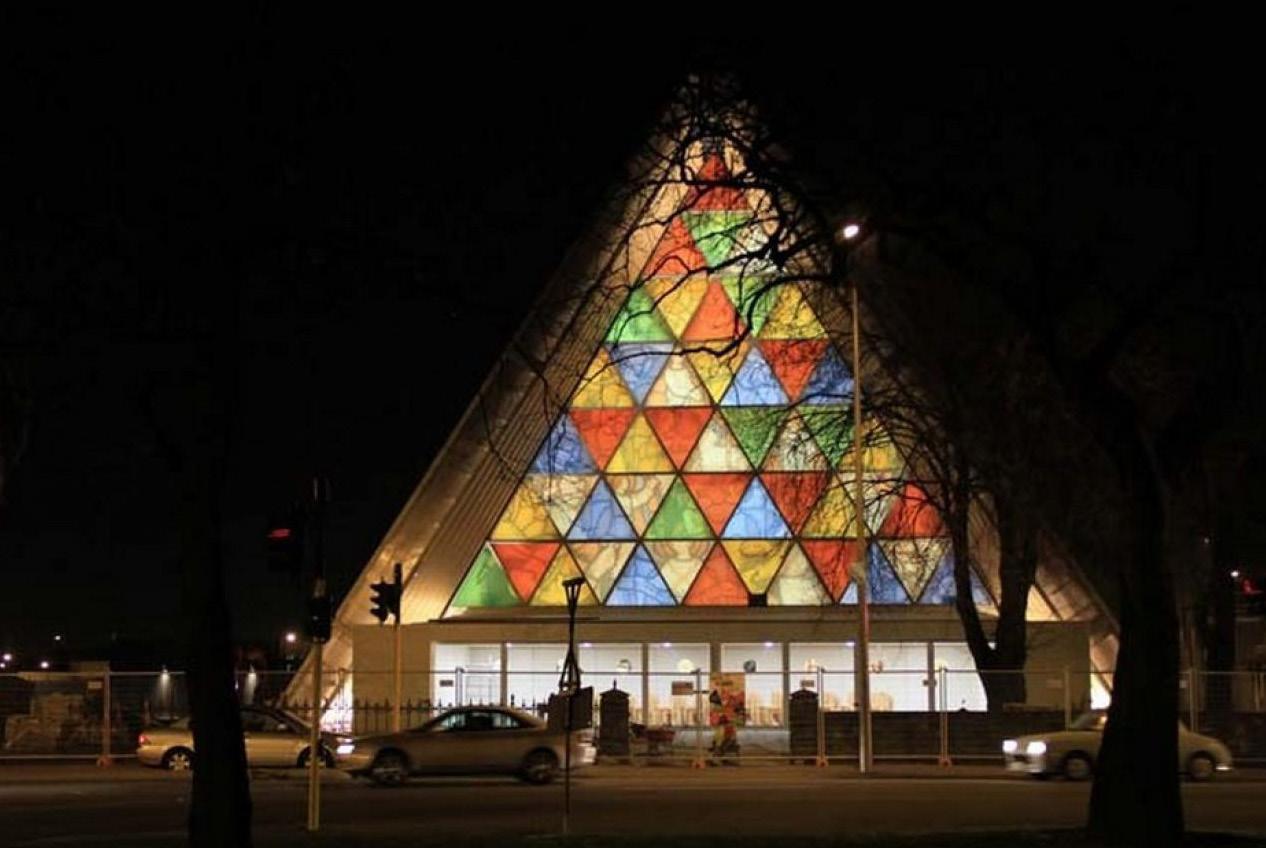

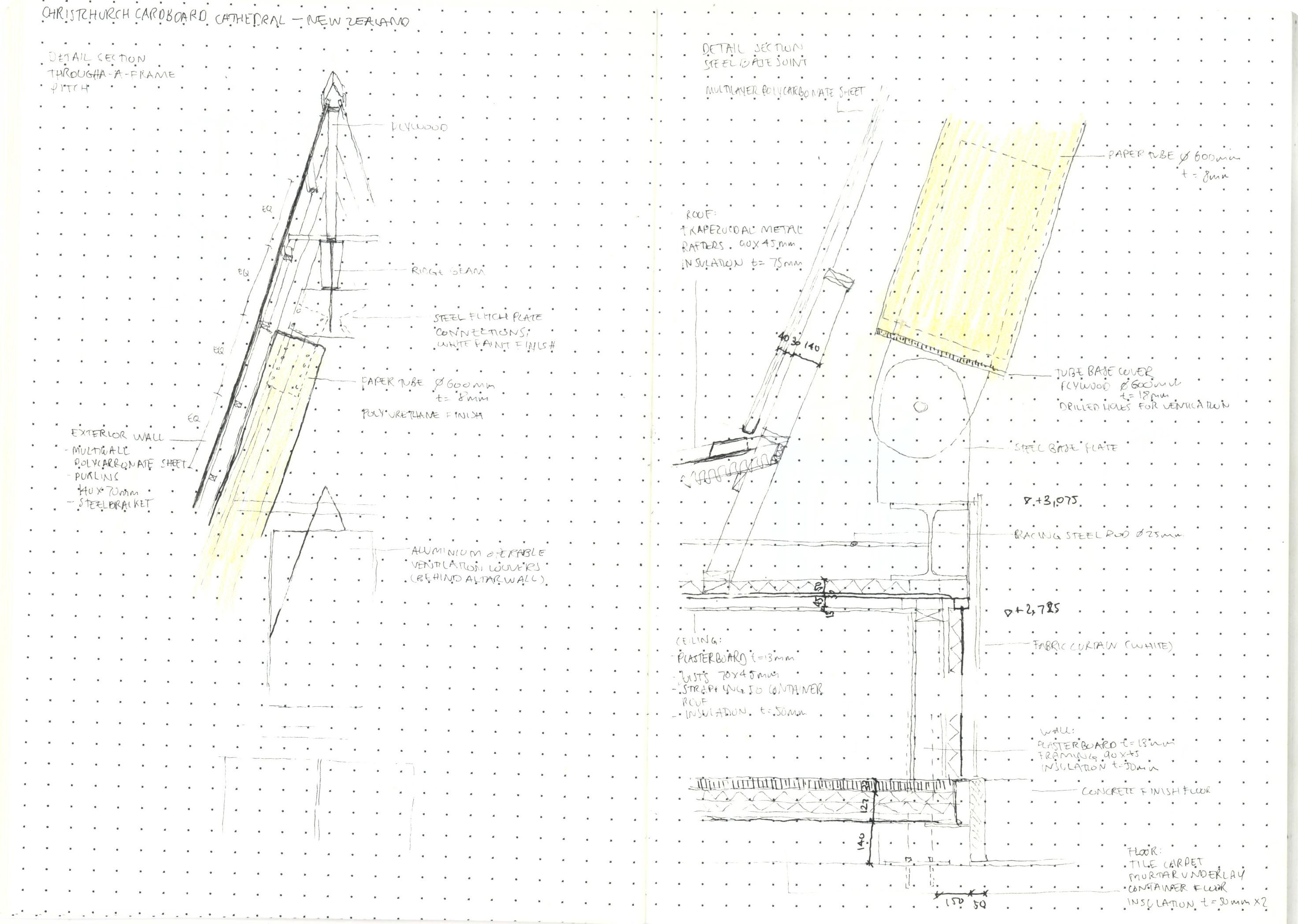

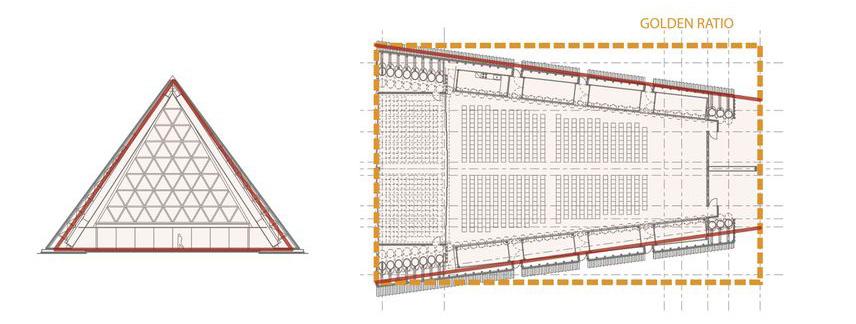

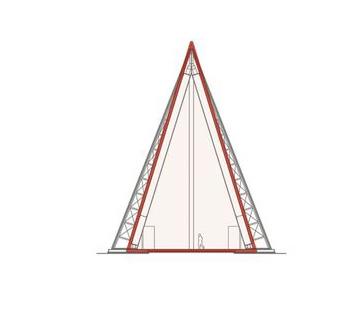

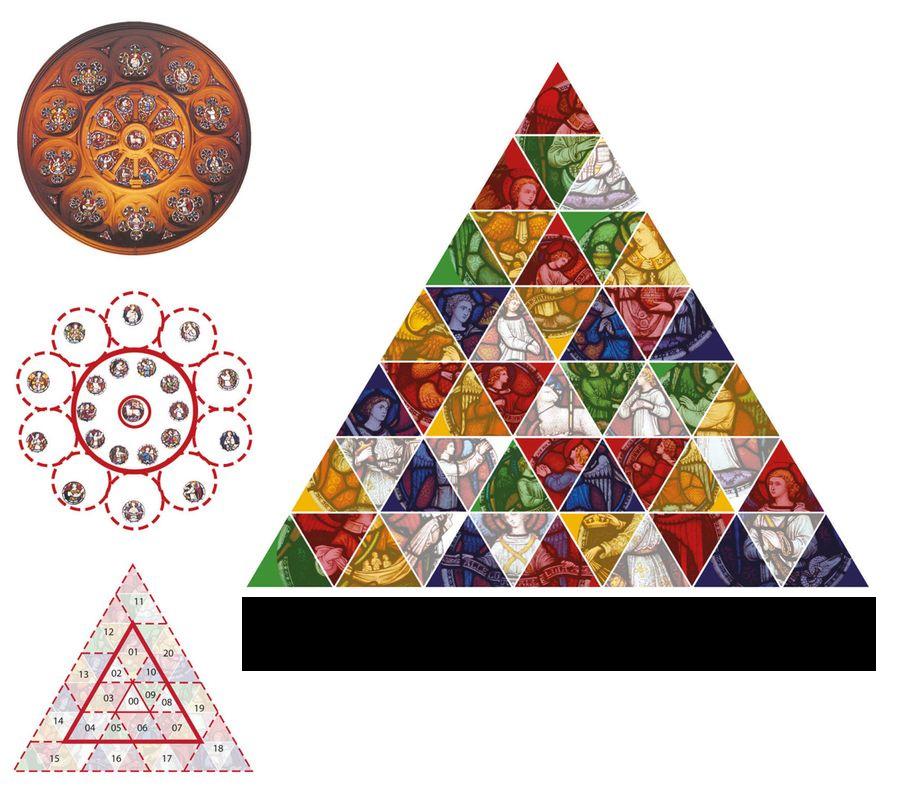

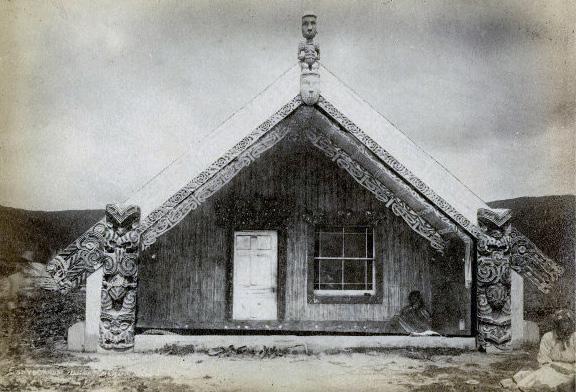

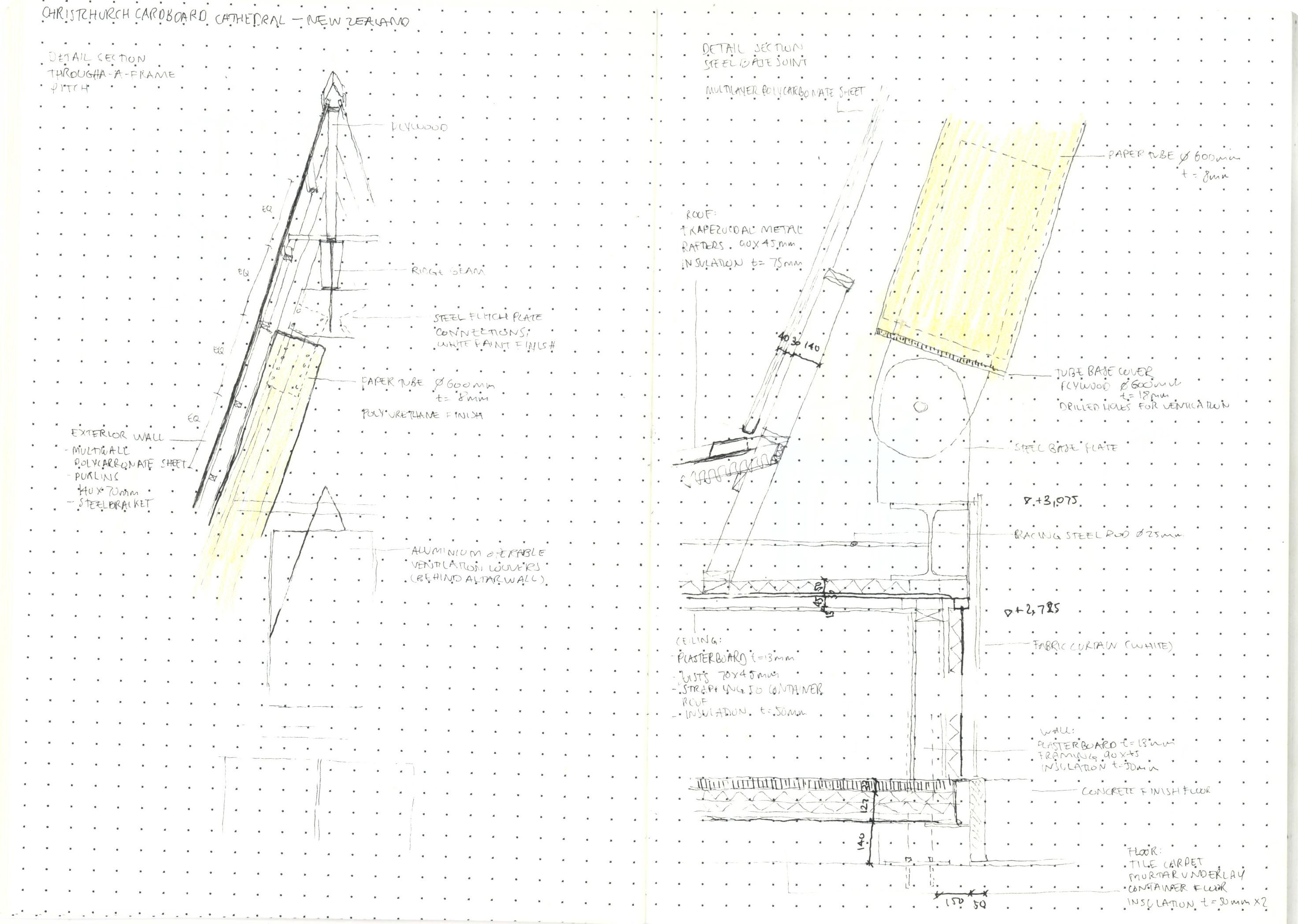

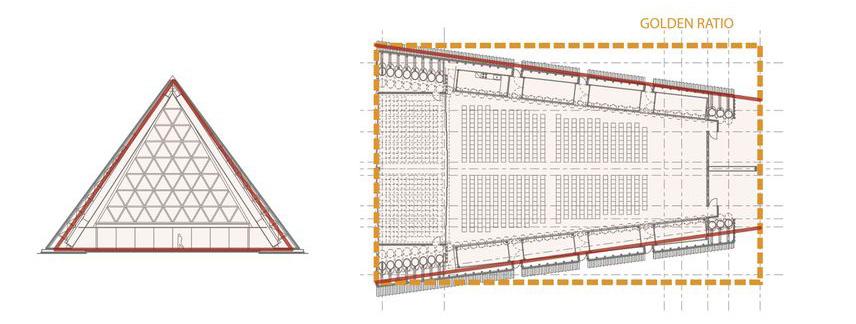

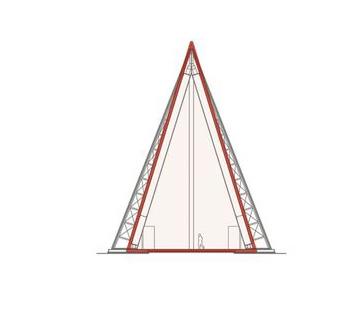

The Cardboard Cathedral is based on a simple A-frame structure, the fastest and cheapest to build in a short amount of time. “This is the most fundamental shape for shelter since the tubes form the walls and the roof at the same time” (Ban, 2013). A lightweight translucent roof encloses the structure allowing natural light to seep in through the gaps between the tubes during the daytime, as already seen in his Takatori Church in Kobe, and turning the building into an urban lighthouse in the darkness. Many locals linked the immediate perception of the form to traditional Maori meeting house structures, associating the A-frame to the typical overhanging steep pitched roofs of these gathering spaces.

The construction system makes up the peculiarity of the project. Rigidified by two huge steel tube frames

placed at both ends, the main structure is formed by 98 fire-resistant and water-repellent cardboard tubes (16m long) clad with polyurethane and containing a soul of laminated timber, which form a succession of portal frames 21 meters high. The structural compromise of inserting timber beams was motivated by the desire to use local materials: manufacturers would only provide 600mm diameter cardboard tubes instead of the structurally rigid 880mm diameter tubes.

Fig. 10 and 11; Daytime and Nighttime view of Christchurch Cardboard Cathedral: the polyurethane cladding allows the church to transform into a lighthouse in the darkness

Fig. 9; The sacred Maori Meeting Houses. The lintel (pare) above the portal signals the passage from the domain of the god of war (Tumatauenga), to the domain of the god of agriculture and peace (Rongo).

30

Eight steel shipping containers, secured to the concrete foundations, compensate the lateral pressures on the base of the A-frame. Prefabricated containers, much like paper tubes, are an easily accessible lowcost building ‘material’. They were previously used by the architect in the Nomadic Museum (2005) and in his Onagawa Temporary Shelter intervention (2011), both projects to which the Cardboard Cathedral is doubtlessly linked. The connections between the cardboard-wood tubes and the containers, and at the apex of the A-frame are done through steel pin joints which allow the gradual alteration of angles characteristic of the project.

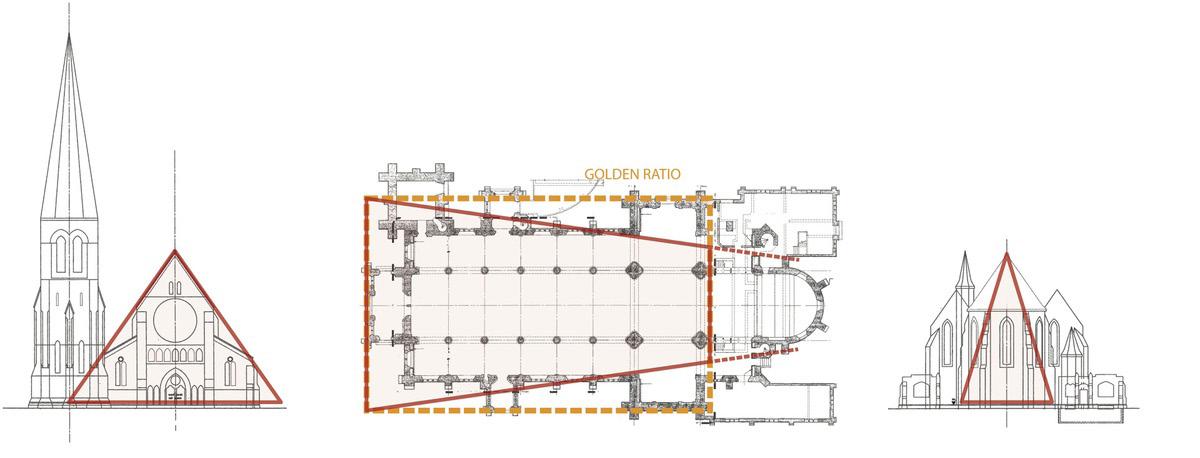

The geometry of the building was developed following plans and elevations of the original cathedral, giving continuity to the legacy represented by the destroyed cathedral in the city and community. Borrowing dimensions from the gothic façade and plan the crosssection gradually changes shape, as the angle of the pitch is reduced, from an equilateral triangle at the entrance to a 33° apex isosceles in correspondence to the altar resulting in a gradually taller elevation from 19.4m to 22.7m. The trapezoidal plan was also extracted from the geometrical analysis of the former

cathedral where lines extending from the entrance to the altar create a trapezoid inserted in a rectangle with golden-ratio dimensions. However, the most direct tribute to the original congregation space is the triangular stained-glass window which reimagines the gothic rose window. The 49 equilateral triangular coloured glass tiles (2.3m per side) create a “rose window of triangles”. Parts of the original rose such as recurring motifs and key colours were printed onto the glass creating a connection between visitor and architectural heritage. The feature piece lightens and gives life to the whole design both visually and spiritually. It is supported by plywood planks that further emphasises the geometry in the interior. Two side chapels, the chapel of memory and the children’s chapel, partially inserted within two containers mirror a feature of the original cathedral’s plan and creates a more private space for intimate ceremonies.

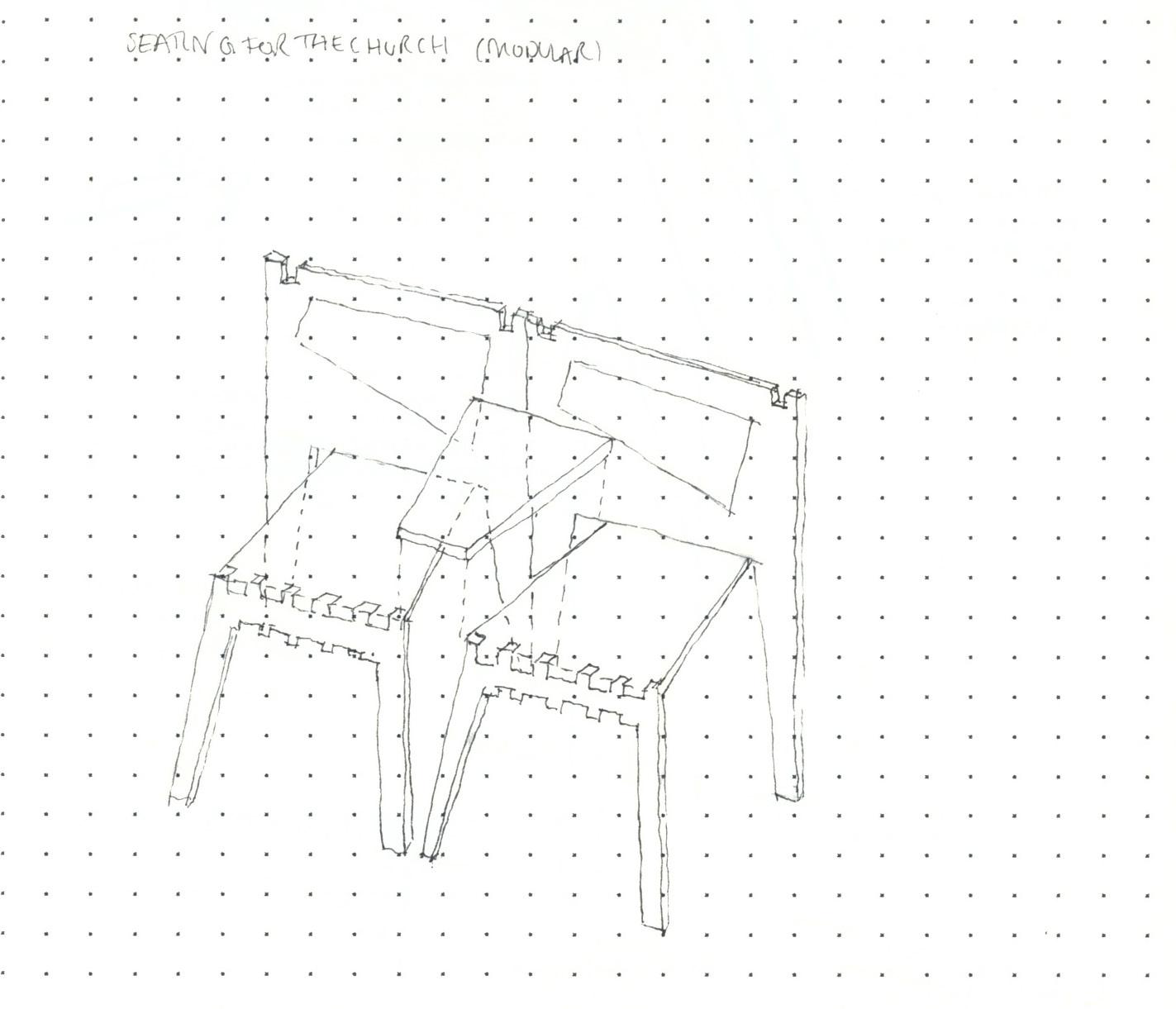

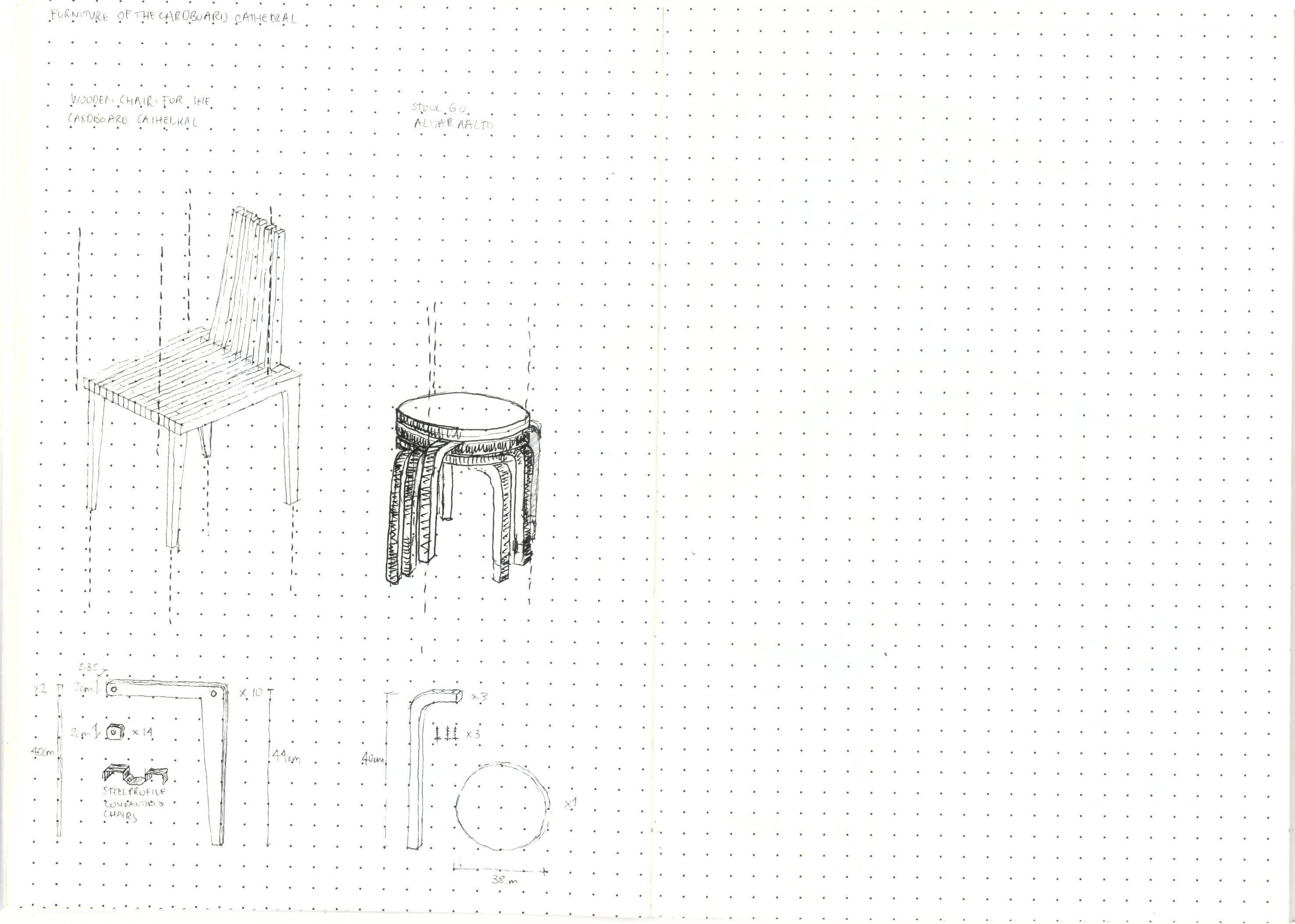

Much like the interiors for the Takatori Catholic Church, the internal furnishing was designed by Shigeru Ban, from the wooden seating to the cardboard collection boxes, candle holders and even the minimal cross

Fig. 12; Details of Steel Pin Joints at the base (left) and apex (right)

31

Fig. 13; comparison of the plans and sections of the Anglican Church of Christ and Ban’s Cardboard Cathedral

Fig. 13; comparison of the plans and sections of the Anglican Church of Christ and Ban’s Cardboard Cathedral

32

Fig. 14; The Trinity Window and its relationship with the rose window of the Anglican Church of Christ. The design translates the images and their geometric arrangement from the old building into the new

hung above the altar. It is especially in the stackable wooden chairs that we see the influence of Alvar Aalto and his stool 60 designed for the Viipuri Library. This observation leads to a completely new understanding of the internal space: the dual tone contrast between the cardboard and white curtains concealing the containers and the undulating rhythm of paper tubes become clear echoes of the multifunctional space of Aalto’s project. The furnishing system reflects the multiplicity of functions intended for the 700-seat auditorium designed to welcome religious celebrations, concerts and public gatherings of any kind. The Cardboard Cathedral was constructed with planned life span of 10 years. The 24-meter-tall cardboard A-frame building captured the collective imagination even before its completion, nationally viewed as a symbol to the city’s resilience. As such it has become a permanent monument in Christchurch. It reflects the legacy of the Anglican Church of Christ as well as adding a new layer to the urban heritage related to its rebuilding after the Canterbury earthquakes.

03.2 / Education

Issues related to education facilities, or lack thereof, also years after a disaster occurred, have already been noted in the Gihembe Refugee Camp case study (02.1.2). Especially in the long term, schools and community centres for younger generations become crucial in the continued growth of any community, even more so in areas affected by natural disasters or in settlements of war refugees. Corporations such as the NPO Soma Follower Team specifically aims to supports children affected by natural or man-made disasters. A paper tube and wooden structure was set up by Ban in 2013 for their activities. Organised in an oval plan around a central courtyard the Art Maison has a library, reading room, counselling room, training room, storytelling space and hanging vegetable planting system on the south façade.

Ban’s activity in the sector is extensive so the following section will deal with a double intervention in the Chinese province of Sichuan which was hit by two

Fig. 16; Interior view of the altar which corresponds to the highest pitch of the A-frame. A two-piece paper tube minimal cross overlooks the hall arranged with custom paper tube furniture and wooden seating

33

Fig. 15; Interior view of the Trinity Window. It is supported by a wooden beam. Plywood boards further emphasisize the triangular geometry. White curtains conceal the containers upon which the paper tubes are fixed.

Fig. 17;

dral,

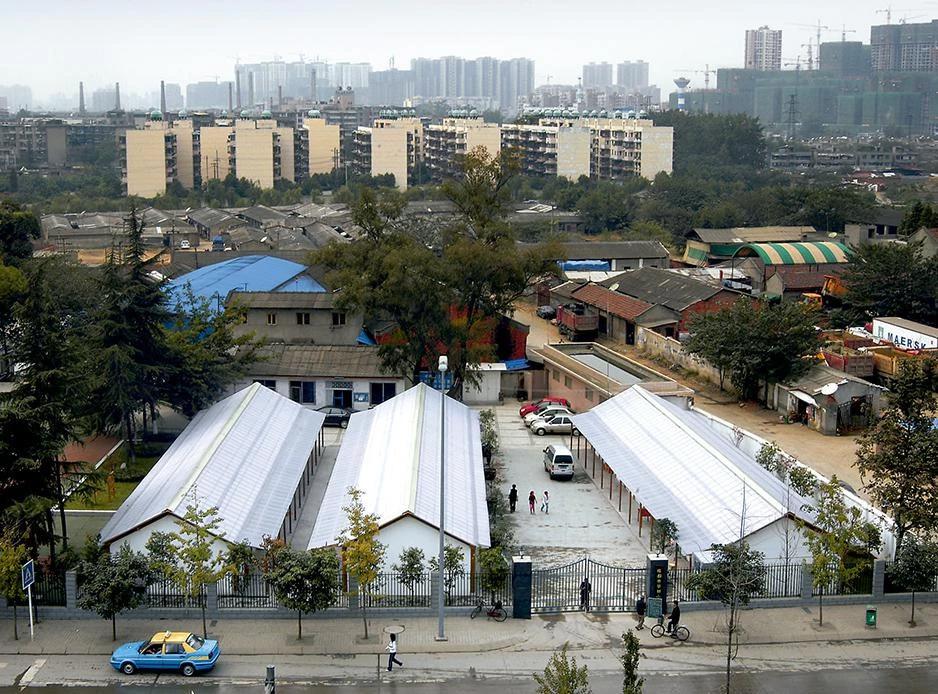

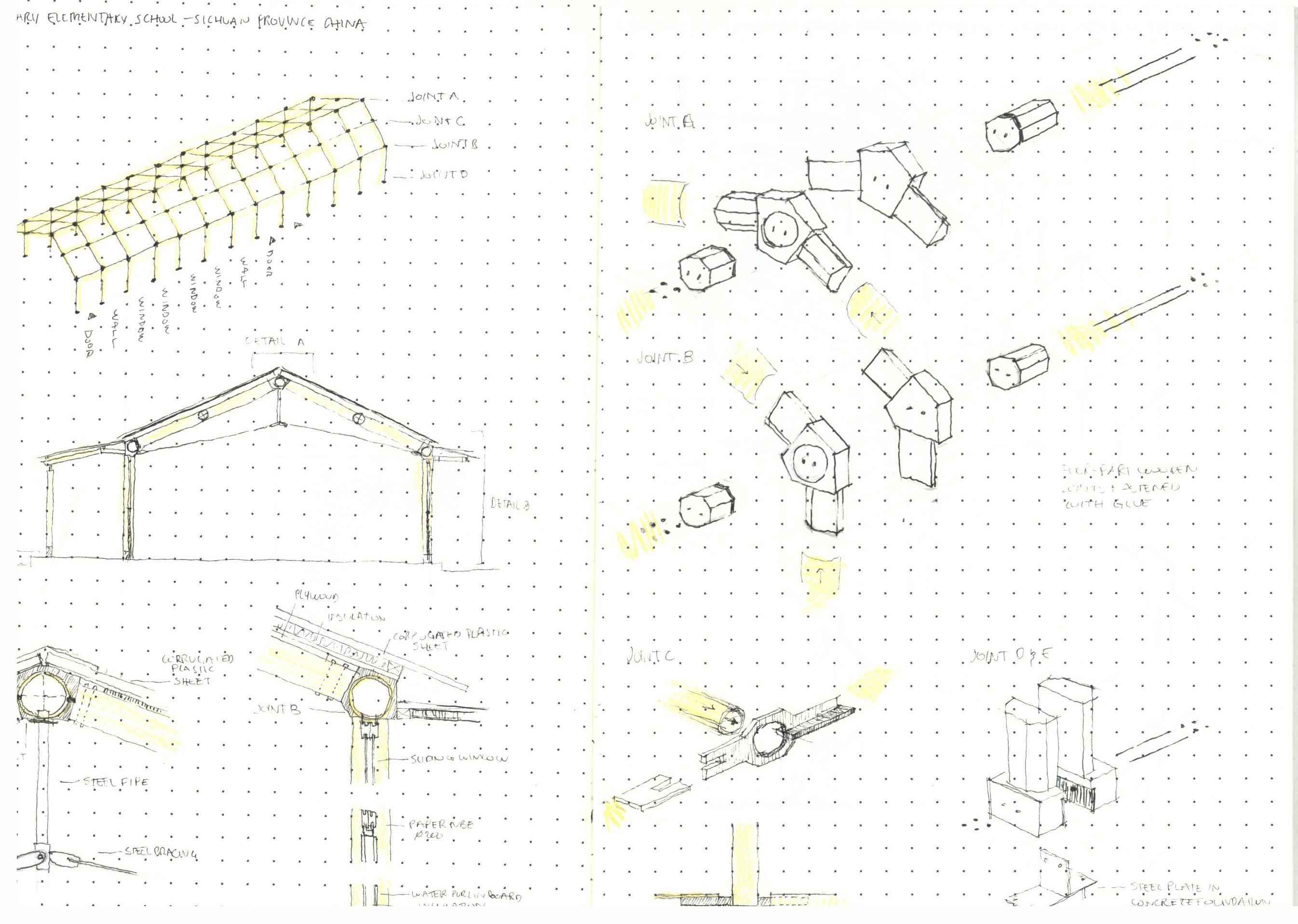

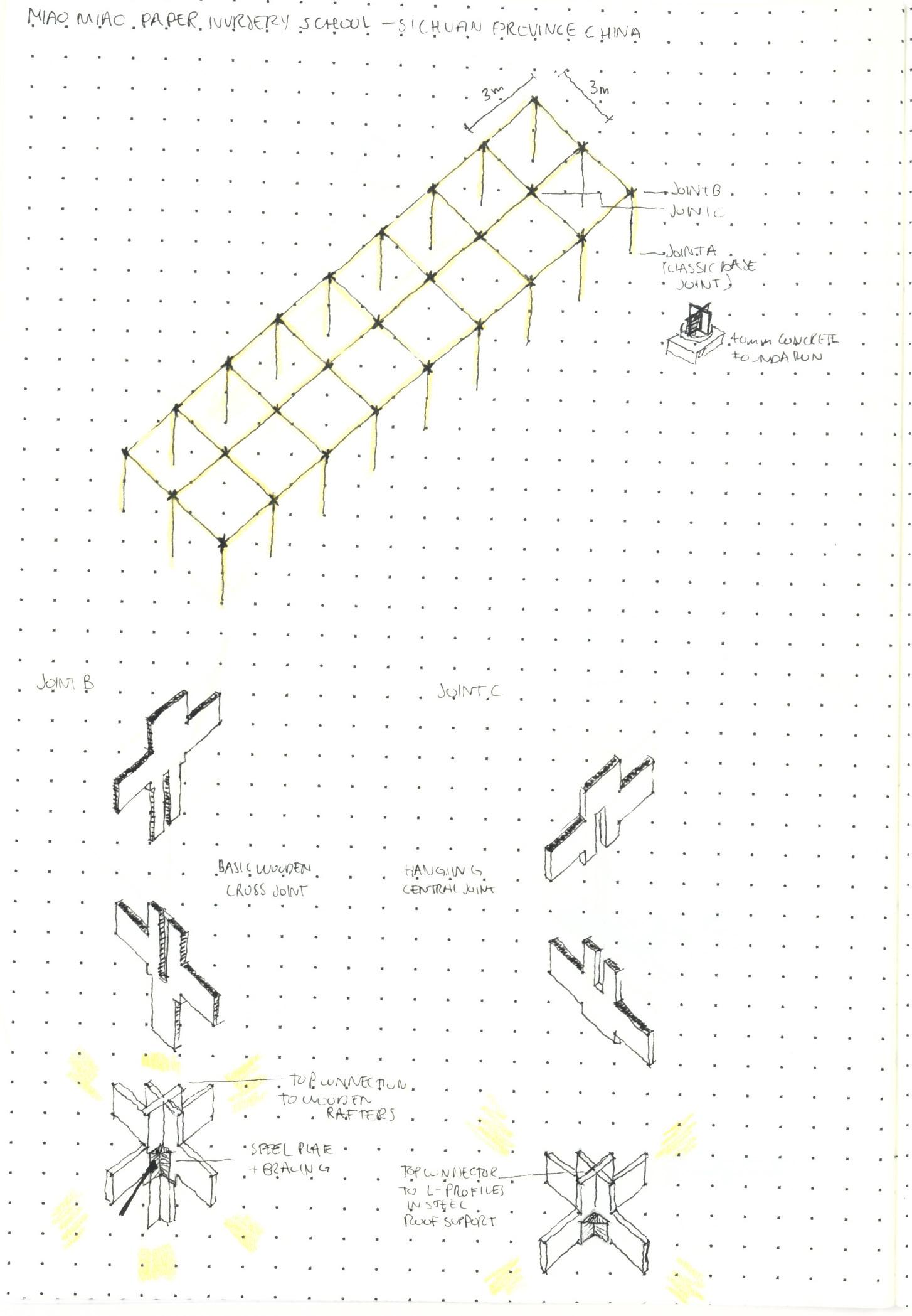

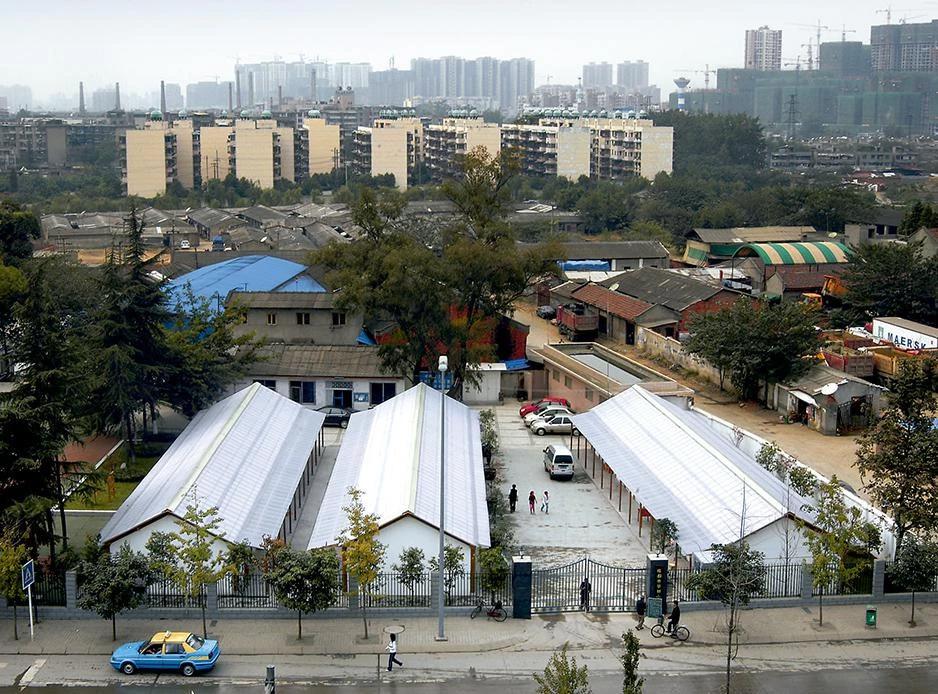

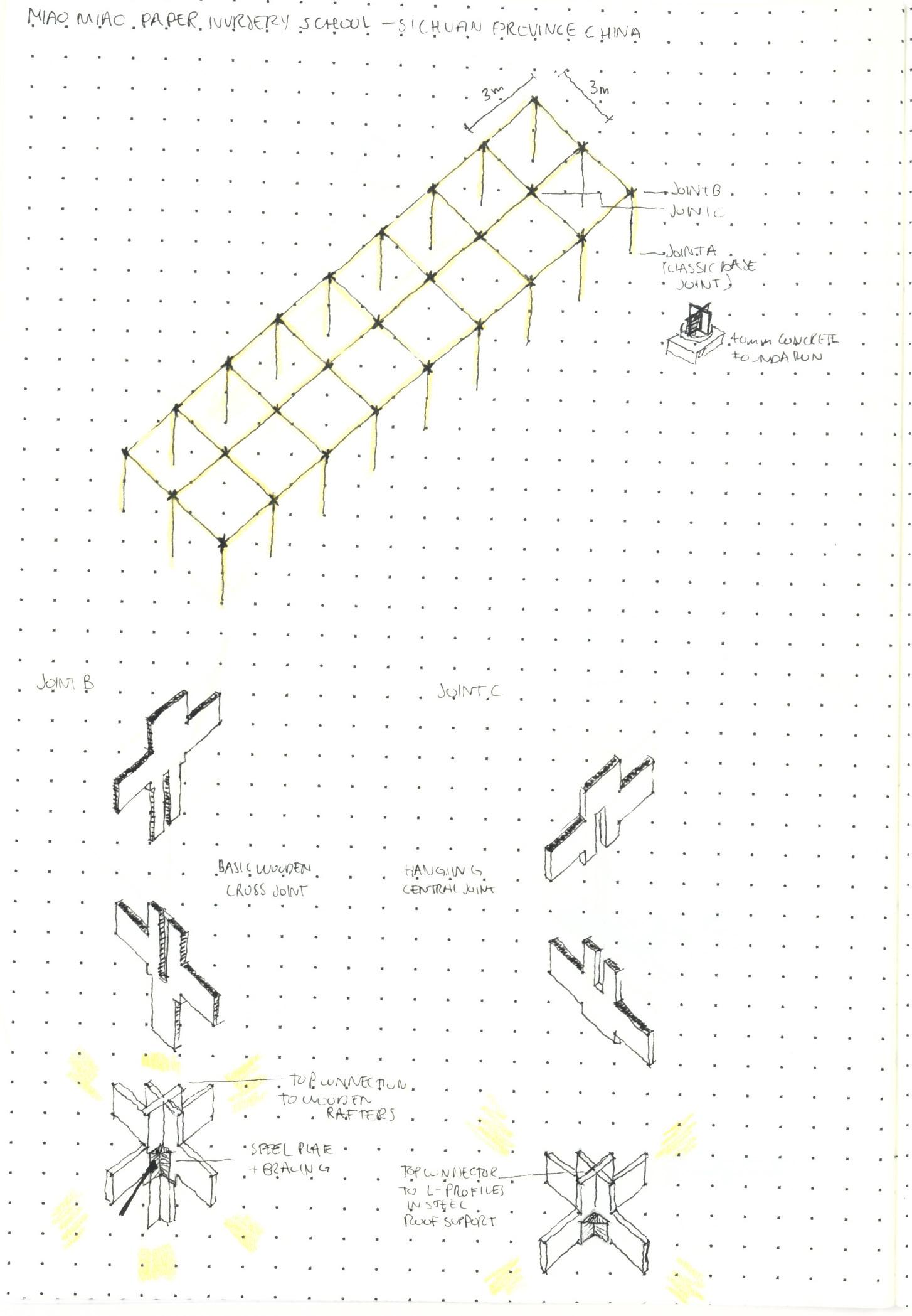

Alvar Aalto devastating earthquakes in 2008 and 2013. Shigeru Ban together with Voluntary Architects Network designed and built two temporary educational buildings: the Hualin Primary School and the Yaan Nursery School. 130 kilometres separate the two site which present themselves with similar functions, a paper tube base structure, and the same climate conditions. Differences in the structure and design approach are the results of the conditions associated with realities of the place, funds, cooperation with local companies and architectural offices as well as evolution of the design. The two projects are interesting as they allow us to sense more directly the continuous learning experience Shigeru Ban gains from his interventions and the continuous search for optimisation of construction and design processes.

03.2.1 / Hualin Temporary Elementary School / 2008

The 2008 earthquake hit Chengdu, the capital of the province. The Chinese government set up a competition to provide temporary housing to the victims of the