Marxist Journal of the Socialist Party

Issue 18 l Summer 2023

Marxist Journal of the Socialist Party

Issue 18 l Summer 2023

CONTACT

North: 07821058319

South: 0873141986

info@socialistparty.net

INTERNATIONAL

The Socialist Party is the Irish section of International Socialist Alternative (ISA), a socialist organisation with groups in over 30 countries.

In the previous issue of this journal we republished an article by Peter Hadden originally published in May 1998 entitled ‘Will the Agreement Bring Peace?’ Here, Ann Orr and Paudie McKee show how the analysis in that article has been borne out over the 25 years since it was written, as reflected sharply in the political and social crises that currently rack the North. The Good Friday Agreement was and remains incapable of overcoming sectarian division and bringing lasting peace. In fact, its inherent flaws mean that without a struggle by the working class to bring about genuine unity between Protestant and Catholic communities, the trajectory in the North is ultimately towards further division and a return to conflict.

25 years on – a different world War-weariness among ordinary people after nearly 30 years of the ‘Troubles’ brought about the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) in 1998. A consequence of this mood was dramatic developments within key political organisations, including the realisation by important sections of Sinn Féin's leadership that its military strategy could not succeed in defeating the British state, nor the opposition of one million Protestants to a united Ireland. Reflecting a global trend of social democracy and so-called national liberation movements moving away from socialist rhetoric, a political shift to the right also took place within Sinn Féin.

This international context was an important factor: the 1990s was a triumphant time for capitalism and the major capitalist powers – considered the unquestionable victors of the Cold War following the collapse of the USSR. This political and ideological momentum reflected itself in different peace agreements worldwide. For Britain, the US’s closest ally, there was a significant prestige element in wanting

to "resolve" the Troubles – during which over 3,700 people had been killed.

Twenty five years on, the differences locally and internationally are striking: far from triumphant, capitalism globally, and British capitalism in particular, is mired in profound crisis. Amplified by the Covid pandemic the world economy is still experiencing major shocks. Interimperialist tensions and military conflict are back on the agenda. The effects of climate change are increasingly severe, set to worsen drastically in the coming years as the world’s governments stand by and their policies compound the problem. There is a growing sense that the system cannot resolve these issues, nor the every-day oppression faced by so many. The result is political instability, including a rise of reactionary and far-right ideas in many countries, but also of struggle by working-class and young people.

The GFA was and still is held up by many establishment politicians as the only viable basis for a ‘prosperous’ Northern Ireland free from violence and sectarian division. In reality, young people face a scarred and deeply divided society, with a lack of opportunities and a declining standard of living. All of these provide the basis for sectarian division, racism, gender-based violence and the continuance of paramilitary violence. The recent femicide of Chloe Mitchell and the murder of Lyra McKee in 2019 by the New IRA are stark reminders of this.

The repetition of the process of raising expectations for change and a dashing of hopes has resulted in a new generation of working-class young people frustrated with the reality of Northern Ireland. To a degree, this is illustrated in the beginning of a change in attitudes regarding the GFA. According to a survey by NI Life and Times, support for the agreement is lowest in 18-24-year-olds, with only 12% believing it is the “best basis for governing NI” and 34% stating it is the “best basis but needs changes”, while 22% believe it is “no longer” or “has never been the best basis”.1

Some commentators brush off the growing questions young people have over the GFA as simply being because they did not live through the Troubles, and therefore take for granted the relative peace it has brought. For a minority this may be true, however in the main this is far off the mark. Young people overwhelmingly support the peace process and do not want to see a slide back into violence. Their doubts are based on the reality of the ‘peace process’ failing to deliver on its promises. After 25 years, housing in working-class areas is overwhelmingly segregated, with more peace walls in place now than in 1998. Even though the GFA also included recognition of the importance of facilitating integrated education, only 68 out of the 1,091 schools in the north are integrated,

with only 7% of secondary school pupils in integrated schools.

Combined with the segregation of community groups and sports, many young people grow up without knowing, never mind developing meaningful relationships with people from the other community until they join the workforce or attend university. This is not an accident, or a conscious choice by working-class people, but the product of the Stormont parties' reliance on sectarian division. Rather than tackle sectarianism, they have institutionalised and weaponised it to their benefit and the detriment of working-class and young people across the North. This is at its most vicious when used to stand over cuts, that the cuts increase the hardship of Protestant and Catholic working-class people equally, which has been a constant theme in the 25 years since the GFA.

Decades of neo-liberal policies carried out and sometimes celebrated by the Stormont parties at the behest of Tory and Blairite Labour governments has deepened the economic deprivation in working-class communities. While some multinational companies have set up shop in the North, for the vast majority of the working class and young people their living standards have not improved. Although unemployment is no longer stubbornly above the UK average, the quality of jobs has seen a marked downturn, with wellpaid manufacturing jobs being replaced with precarious hospitality and call centre jobs, stagnant wages and poor conditions, with many young people seeing no option but to emigrate.

“We were the Good Friday Agreement generation, destined to never witness the horrors of war but reap the spoils of peace. The spoils just never seemed to reach us.”

– Lyra McKeeViolent unrest breaking out is still an ever present danger in the North

It is in these conditions, in a divided society, that the naked sectarianism of Stormont politicians can gain an echo. In the most hard-pressed areas, it allows paramilitaries to thrive, recruiting the most alienated and desperate people. In the past 25 years, paramilitary violence has turned inwards for the most part, replacing the sectarian shootings and bombing with criminality and ‘policing’ of their respective communities. Often this takes the form of punishment-beatings and shootings. According to the Safeguarding Board for Northern Ireland 89 young people under the age of 18 have been subject to punishment shootings, with hundreds more being the victims of beatings since the GFA.2

The negative impact on the lives and mental health of the victims, their friends and families cannot be overstated. It is one of the many reasons for the mental health crisis in Northern Ireland, alongside the intergenerational trauma from the legacy of the Troubles, as well as poverty – and worsened by the continual cuts to the NHS and mental healthcare provision, resulting in over 16,000 people languishing on waiting lists for their first appointment. As such, suicide rates in the North are also the highest in the UK, with 14.3 suicides per 100,000 in 2021, which compares with a figure of 10.5 in England and Wales, and 8.2 in the South.3

At all times, British governments have represented their own interests – the interests of British capitalism and imperialism – not the interests of working-class people in the North, Protestant or Catholic. Their approach has modified as these interests also shifted. To solidify the partition of Ireland in the early 20th century, British imperialism whipped up sectarian tensions and divisions in what was coined by Lord Randolph Churchill as “playing the orange card”.4 For a period following the GFA the British government falsely portrayed itself as a neutral arbiter between two opposing sides.

In the 1990s and continuing into the 2000s the desire for greater stability in the North, and thus reduced need for a high and expensive security presence, was widespread among the representatives of British capitalism for reasons of reputation and prestige, as well as a desire to develop the private sector

of the economy. They would gladly have withdrawn from Northern Ireland while continuing to benefit economically from a single independent state – a state that would of course not threaten capitalist social structures. However, the conditions they had created over the previous decades meant that this was not possible due to the opposition from the Protestant population in the North – an opposition that has not diminished.

Today, the Tory government continues to defend the interests of British capitalism and the British state, as evidenced for example by their Troubles Legacy bill –designed to protect the state from allegations and prosecutions for killings committed during the Troubles. Tensions and struggles between the main imperialist blocks, Brexit and the pressures towards closer European cooperation in the context of the war in Ukraine are also factors that are impacting the attitude of the British government in relation to the North. In particular, it now fears the breakup of the union with Scotland, which would have significant economic implications and would constitute a massive blow to the prestige of a nation that was once a key imperialist power, but is now a two-bit player in the New Cold War and on the global stage generally.

The Tories have therefore adopted a more stringent opposition to a border poll and the growing calls for Scottish independence. The concern is never for the interests of working-class people, regardless of national identity and aspirations, but rather the issue of what suits the establishment at any given time, regardless of the consequences. The same applies to Rishi Sunak's deal with the EU, the Windsor Framework. Stabilising the situation in the North is part of the aim, but not out of concern for the living standards of working-class people here, but to ensure the basis is laid for further

agreements in the economic and political interests of Britain in the future.

At times the utter lack of understanding and shere disregard towards escalations of sectarianism is exposed. This was the case earlier this year when joint authority (over Northern Ireland by the governments in London and Dublin) was raised. Because the Northern Ireland Office did not immediately rule this out as an option, loyalist paramilitaries threatened to bomb a Southern governmental building – a clear indication of the volatility in the present situation. It is also the case that every action to "resolve" a phase of the conflict has laid the basis for future disagreement. In the same way as its use of sectarianism to fortify partition later meant the British government could not leave the North as it would have liked, it was its decision to institutionalise sectarianism with the GFA and sell it on the basis of conflicting and irreconcilable promises that is now a key reason for its inability to find a way out of this impasse.

For 35% of the last 25 years, the Stormont Executive has not sat because one of the two main parties refused to participate. This has been a consistent reminder of the shallowness of the agreement. The core of the issue lies in the conflicting national aspirations held by workingclass people here – a conflict that on the basis of capitalism cannot be resolved without resorting to some form of coercion. This means either coercing the Catholic population into a Northern Ireland state that has overseen a century of discrimination and repression, or coercion of a future Protestant minority into a united Ireland, which on a capitalist basis would make them an oppressed minority. Neither are resolutions to the issues faced by the working class and neither will overcome divisions. As we wrote in 2018:

"The real reasons for the difficulties in reaching agreement on Brexit [...] are fundamentally a consequence of the inability of capitalism to achieve a lasting solution to the national question in Ireland. In the 1980s, The Economist magazine wrote that the Troubles in Northern Ireland were “a problem without a solution”. This seemed a rational conclusion at the time, but then the 1998 Good Friday Agreement gave the appearance of falsifying this prognosis. In fact, the Good Friday Agreement did not represent a solution then or now."5

Today, 25 years after what was heralded as a groundbreaking peace agreement, the threat of a return to violence and irrevocable collapse of the institutions is more acute than ever. This is recognised by many, including even Brandon Lewis, former NI Secretary (2020 - 2022), who stated that the peace agreement was “fraying, if not outright broken”.6 The main political parties, as well as the British and Irish governments, are restricted to trying to find a way forward on the basis of the current system. The suggestions vary from a return to some form of power sharing, even if it involves renegotiation of the agreement to include mandatory coalition; to some form of direct rule from Westminster; to joint authority by London and Dublin; to a united Ireland as a result of a border poll. None of which would begin to address the conflicting national aspirations or working-class people. None is a solution to division and conflict.

Only

As alluded to above, the GFA and the political institutions it created were major prestige projects for the British and also the Irish governments. Tony Blair, the Labour Prime Minister at the time and his Irish counterpart, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, were held up as the men who brought about peace in Northern Ireland. They, alongside US president Bill Clinton, were part of the discussions that culminated in the GFA. How the GFA was reached has far more to do with other factors, however. The context was shaped by a growing realisation that a military defeat of the British army by the IRA was not possible on the one hand (and viceversa), and a growing understanding that the situation in Northern Ireland would remain volatile and contrary to the image the UK wanted to portray globally on the

other. What Reginald Maudling, the British Home Secretary in 1971, described as “an acceptable level of violence” was also not sustainable, as tensions regularly spiked.7

However, albeit connected to these points, the key factor that pushed for an end to the Troubles and for some political action remained the strong warweariness among working-class people reflected in the important strikes organised in response to sectarian violence, for example following the Teebane Massacre in 1992 or the 80,000 who protested after the Greysteel Massacre in 1993. These were illustrations of the crucial role of the united working class in challenging the poison of sectarian division and violence.

In the intervening years, while the working class has at different times demonstrated its capacity to come together, we have not yet seen the full potential power of the united working class. This power finds expression in different ways, but most clearly in workplaces and trade union organisations, where workers have won significant victories including on pay in recent months and in repeated defeats of water charges and other austerity measures. We have also seen this unity in joint active movements for abortion rights, LGBTQ rights and in the movements of young people on the climate crisis.

There is an urgent need also for this power to find expression and to be built on a political level. None of the main parties represents the interest of workingclass people. They rely on sectarian voting patterns, so none of them has any interest in overcoming sectarian division. To a lesser extent that also applies to Alliance. It is not a “green or orange” party, and presents itself as an alternative to sectarian voting. However, its approach and politics do nothing to overcome sectarian division. In fact, Alliance is the most openly neo-liberal party in Stormont – supporting water charges and “rationalising”, i.e. cuts to public services hitting working-class communities the hardest. Its approach cultivates the conditions in which sectarianism thrives. To challenge this, a new party that can bring together working-class people across the sectarian divide to fight for our common interests is essential.

Such a party would need to be steadfast in its defence of working-class interests, including in actively challenging sectarianism. It would need to adopt a strong stance against all forms of oppression, and support struggles such as the fight against genderbased violence, and for trans rights. Such a force, based on anti-sectarian and anti-capitalist politics could be hugely attractive to young people, giving a voice to their struggles and an arena for organising. It could cohere the resistance of working-class people to the coming onslaught on our public services, jobs and rights, as well as on issues like housing, climate and war.

Such a force needs to be urgently built. It must arise out of the struggles we see in workplaces and in numerous campaigns. The trade union movement, which already organises 250,000 workers from all

backgrounds across the North, clearly has a particularly crucial role to play, not only in popularising a call for a new working-class party but in actually bringing this about. It is precisely while engaged in struggles on such issues that the direct experience of fighting together, side by side and in our shared interests, that even deep-seated attitudes, including sectarianism, can be overcome.

The conflict of national aspirations in the North is irreconcilable on the basis of the capitalist status quo, which will ultimately always involve coercion of one community in some form. To actually resolve the national question means challenging capitalism, fighting for the socialist alternative to this brutal system, and deeply rooting this struggle at all times in building working-class unity across sectarian and all divides. Capitalism’s whole history on this island speaks to its brutal nature, including the violent and divisive role of British imperialism, the exploitation of Ireland for raw materials, food and later also cheap labour sources for manufacturing in Britain's industrial cities.

Furthermore, in any capitalist society, minorities are at risk of discrimination and oppression. This is also the case in the South, as evidenced by the experience of the Irish Traveller community and also of refugees, with the Fine Gael / Fianna Fail / Green Party coalition government for example deciding they will no longer house refugees from outside of Ukraine.

Removing exploitation and oppression at its root necessitates a struggle for a socialist transformation of society – taking society’s wealth and resources into democratic public ownership and planning their use to meet the needs of all. This can only be achieved through collective struggle of all the exploited and oppressed. Furthermore, unity among working-class people in struggle is precisely how mutual understanding and respect can be attained – providing the basis for a real resolution to the national question. This is what is contained in our call for a socialist Ireland free from all coercion and in which the working class collectively would guarantee the rights of all minorities. Working-class people of all nationalities have a common cause in opposing capitalist exploitation and likewise in building a socialist society based on equality and freedom. In this vein we furthermore call for a free and voluntary socialist federation of Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales as part of a socialist Europe, with the right to opt out of any arrangement.

The basis was not laid for the resolution of the conflict with the GFA agreement, but instead, as we argued at the time, a certain space was provided for working-class people to push things in a different direction. Since the GFA, workers have also repeatedly stood together in the face of paramilitary threats or violence. This was the case for example when probation workers or translink staff walked out following

paramilitary threats against colleagues. It was also evident when people joined vigils and protests in the aftermath of the killing of Lyra McKee in 2019, and most recently when 1,000 people attended a protest called by the Omagh Trade Union Council following the shooting by paramilitaries of an off-duty police officer in front of a busy sports complex. These are some of the powerful moments in which working-class people came together to halt any threat to go back to the dark days of open sectarian conflict.

To be able to build a basis on which the national question can be overcome, however, will require more than challenging incidents or examples of escalating tensions and paramilitary violence. Since the GFA there were several moments in which the potential for workers finding a different way forward was posed in outline form. This included 2011, when workers in the public sector stood side by side in their struggle against pension reforms; part of a movement linking with their colleagues across Britain, which at its height saw 2 million workers participate in a strike day in November that year. If the union leaders had not sold out the workers, the government could have been forced to scrap its draconian plans. This would have invigorated the trade union movement, but also shown in practice the power of workers united in struggle.

In fact such struggle can have a transformative effect in breaking down barriers and challenging division. When the Harland & Wolff shipyard workers occupied their yard in 2019 the mainstream press repeatedly commented on the significance of the main union organiser being from the South, given the history of the shipyards. For the workers themselves, it was without question that Susan Fitzgerald, who is a member of the

Socialist Party, was their most effective representative. Twenty years ago school students here participated in the global mass anti-war movement against the invasion of Iraq. This movement questioned the brutality of a system that leads to war and destruction, and brought young people – mostly educated separately – together in a common movement. The more recent climate strikes also reflected this, with thousands participating at the high point of 2019. Similarly, mobilisations for LGBTQ rights and against genderbased violence have shown the common experience and basis for struggle of working-class people, both Protestant and Catholic.

History has shown that the ruling elite will not hesitate to use sectarianism to cut across and disorientate any movement of the working-class and oppressed. Thus, it is also of vital importance that these struggles take conscious steps to challenge sectarianism and division. This must be a consistent, determined part of the urgent struggle for socialist change, in a movement that can unite all the exploited and oppressed against capitalism.n

1 NI Life & Times Survey, 2022, www.ark.ac.uk l 2 Dr Jacqui Montgomery-Devlin, Nov 2022, Briefing Paper No. 2, ‘The influence of paramilitarism in Northern Ireland on the recognition of child sexual exploitation in young males’ l 3 Allan Preston, 1 Dec 2022, Suicide figures for Northern Ireland reveal 237 deaths in 2021’, www.irishnews.com l 4 Quoted in ‘Lord Randolph Churchill and Home Rule’, published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 July 2016 l 5

Socialist Party Statement, 23 Nov 2018, ‘Brexit and the Irish Border: A Warning to the Workers’ Movement’, www.socialistpartyni.org l 6 Brandon Lewis, 22 Feb 2023, ‘The Good Friday Agreement must evolve to bring effective government’, www.brandonlewis.co l 7 Reginald Maudling, UK home secretary, on 15 December 1971, www.oxfordreference.com

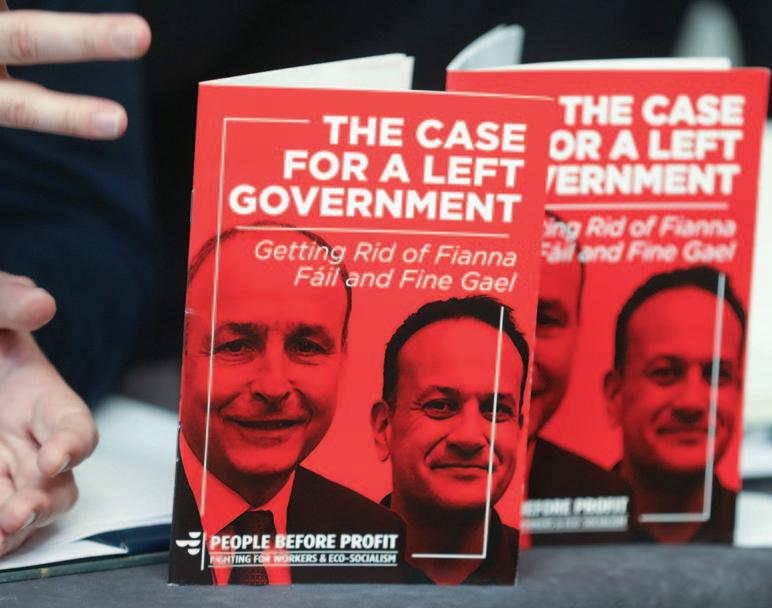

Sinn Féin continues to be the most popular party in the South in all opinion polls, but whether it will be able to lead a government after the next election remains far from certain. What such a government would look like, and who else it would involve, is also very uncertain. PBP has renewed its call for a ‘left government’ led by Sinn Féin with the publication of a new pamphlet on the topic. Here, EDDIE MCCABE critically reviews this document.

Sinn Féin became the largest party in the south for the first time in the general election of 2020, with 24.5% of the vote. In three opinion polls after the election but before the outbreak of the Covid pandemic it shot up to 35%. The instability of the pandemic allowed Fine Gael, the biggest government party, to regain ground and some stability in its support. But this began to dwindle in late 2020 with SF overtaking it again, and since July 2021 every poll has put Sinn Féin as the largest party, usually in the low- to mid-30s – with Fine Gael (FG) hovering around the low-20s, and Fianna Fail (FF) around the high teens.

This is a significant change in the political landscape in the south, and coupled with Sinn Féin’s rise to become the largest party in the north, means that the dynamic around Sinn Féin and where it goes will be a defining feature of Irish politics in the next few years.

Potential does now exist for a government without either FG or FF for the first time in the history of the state, which would be viewed as momentous. Naturally, this trend has generated ample commentary and analysis from all quarters, including in previous issues of this journal.1 In the last such article we detailed Sinn Féin’s further shift to the right, ingratiating itself with the business establishment in particular, and we critically analysed People Before Profit’s (PBP) view of Sinn Féin and the misguided tactical approach that flows from this, including the problem of sowing illusions in Sinn Féin.

Since then PBP has gone somewhat further in developing both its view of Sinn Féin and the potential for a ‘left government’ in Ireland, with the publication in February of its pamphlet: The Case For a Left Government – Getting Rid of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael 2 In some respects this pamphlet indicates a more clearsighted position on the question of a left government and the challenges it would face, but its overall analysis is not fully coherent, in large measure because of its contradictory but on the whole mistaken view of what Sinn Féin is and where it’s heading. This article will briefly explain where we think PBP gets it wrong, which will hopefully contribute to a better understanding of how the question of a Sinn Féin government should be approached by those on the left.

The PBP pamphlet tells us plainly that, “the privileged elite hate and despise Sinn Féin.” It asks us to:

“Imagine for a moment, the reaction in the Shelbourne Hotel bar or the Portmarnock Golf Club to the news that a left-wing party or Sinn Féin will form the next government. A mood of fear mixed with horror would overtake the gathering.”

This hatred and fear of Sinn Féin, we’re told, explains, “why there is a continual onslaught on the party from the mainstream media.” But is any of this a true reflection of how Sinn Féin is viewed by the capitalist establishment today?

Six or so years ago, when Gerry Adams was still leader of Sinn Féin, such an assessment would have had more legitimacy, but that’s no longer the case. With the ascension of Mary Lou McDonald and particularly with its rise to become a realistic prospect to lead a government in the short-term, which has coincided with a further shift to the right by Sinn Féin itself, there has been a notable softening towards Sinn Féin by the mainstream media. It isn’t vilified in the way it once was – as merely the political wing of a paramilitary organisation, even one that’s no longer active. McDonald and most current Sinn Féin TDs were never part of the IRA. As such, it just doesn’t work. Moreover, as the main opposition party Sinn Féin is well represented in mainstream political discourse – where its policies are treated with increasing credibility by establishment commentators. Hence, we read in the Irish Independent, historically the newspaper most hostile to Sinn Féin, analysis such as this:

“On corporate tax, the tech titans have little to worry about. Sinn Féin now resembles Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil far more closely than Irish left-wing parties… On EU policy, Sinn Féin is unrecognisable from the party that regarded the EU as a neo-liberal, military plot and campaigned against every EU treaty up until relatively recently. There is no longer any fear that the party opposes EU-wide laws.”3

And in The Irish Times we read that:

“While Gerry Adams famously said in 1979… that the party was ‘opposed to big business, to multinationalism... to all forms and all manifestations of imperialism and capitalism’, it has more recently taken to courting enterprise – with its leader Mary Lou McDonald’s recently travelling to Silicon Valley, addresses to Ibec and senior party figures increasingly meeting business leaders.”

The same article tells us that:

“‘Sinn Féin in government won’t be anywhere near as radical as many might think…’ Sinn Féin has been moderating a number of policy positions in recent times, according to [Prof. David] Farrell of UCD, and is likely to compromise on others in any coalition discussions.”4

Articles like these are hardly uncommon. Arguably, they could be read as attempts by these media outlets to undermine Sinn Féin among those working-class and young people who would like to see Sinn Féin take a more radical stance; to move further left not further right. But Sinn Féin is in fact moving to the right, and this is the message Sinn Féin itself is trying to present. Thus, Pearse Doherty is quoted as insisting that: “Sinn Féin are pro-business,” and that, “nobody who wants to see a radical programme by Sinn Féin wants business to be punished.” He further states that Sinn Féin will “balance the books”, echoing the neoliberal tropes of his two main rivals.

Of course those rivals, FG and FF, are still the preferred options of the ‘privileged elite’, and certainly FG and FF politicians ‘hate and despise’ Sinn Féin; but this is less and less to do with Sinn Féin being seen as a threat to the interests of Ireland’s capitalist establishment, and more and more to do with Sinn Féin being seen as rivals to represent the interest of Ireland’s capitalist establishment – at the expense of FG and FF, and particularly their elected reps.

Now, it’s not as if PBP doesn’t recognise this shift to the right by Sinn Féin; it does – it just seems unwilling to accept the full import of what this means for the prospect of a genuinely left government. And this refusal is a by-product of PBP’s more fundamental illusion that Sinn Féin is more radical than it really is, which is linked to its mistaken belief that nationalism is more progressive than it really is.

This is evident in the overemphasis PBP puts on the issue of Sinn Féin being open to coalition with FG and FF. Absolutely this is significant, and should be highlighted to expose the reality of SF’s desire to, in reality, be part of the capitalist establishment rather than upend it. As such it is correct to demand that Sinn Féin should rule out such coalition deals, and to criticise its refusal to do so. However, the impression one could take from PBP’s analysis is that the danger of such deals is that they will stifle or obstruct Sinn Féin from implementing the radical change that it would implement if only given the chance. For example, PBP says:

“These right-wing parties represent the interests of the rich and privileged and so would only join a Sinn Fein led coalition to ‘house train’ the party into the practices of the Irish political establishment.

Unfortunately, recent experience in the North illustrates this. Sinn Féin has been in coalition with the DUP from 2007 to 2020. During that time, they implemented austerity policies and supported measures to reduce corporation taxes on the wealthy… There can be little doubt that the presence of Fianna Fail in a coalition with Sinn Féin would produce a similar conservative result.”

While this is partially true, it’s not actually the main issue. Sinn Féin’s openness to cooperate and compromise with these right-wing parties says something about Sinn Féin itself: that fundamentally its political programme and approach are closer to those of these capitalist parties (FF especially) than they are to those of anti-capitalist and socialist parties. The DUP didn’t force Sinn Féin to implement austerity policies, it did that willingly.

Anyone expecting radical change from Sinn Féin will be seriously disappointed. Indeed Sinn Féin has been careful in recent times to moderate its stances, which is part of a strategy to ensure it says and does just enough to do well in elections, but also that expectations of what it will deliver are not too high. Its housing policy, for instance, is for 100,000 public homes to be provided over five years.5 This would be an improvement on what’s gone before, but it’s still considerably short of the 250,00 that even Leo Varadkar has conceded is needed – and even this is reliant on private contractors to build them, which is far from a surety.6

Again it’s not as if PBP doesn’t see any of this in Sinn Féin. Its pamphlet notes that,“Sinn Féin’s policy is to leave intact the main pillars of tax haven Ireland” (not exactly a minor difference with a left or socialist policy). Yet PBP’s consistent refrain is to be surprised7 and aghast8 at every about-turn Sinn Féin makes as it prepares for power9 – the latest being Sinn Féin’s announcement that it will not withdraw Irish defence forces from EU and NATO military arrangments such as Pesco and Partnership for Peace.10

The seeming inconsistency in PBP’s analysis is partially explained by its view of “a contradiction at the heart of Sinn Féin”, which it says flows from Sinn Féin’s attempt to “straddle different constituencies and different classes, avoiding taking clear stances that will alienate some of its support base.”

There is of course a contradiction in Sinn Féin’s attempt to win support from those looking for radical change (workers and young people) and those looking for temperate change (some corporations, bosses and wealthy people), which can’t both be satisfied by the same policies. But PBP overstates this contradiction, which in any case is not unique to Sinn Féin. While it tries to play a balancing act between the interests of working-class people and the system that exploits them, there’s little doubt on which side Sinn Féin will come down in the end. Still, PBP holds out some hope, writing:

“However, even while making these moves to the centre, the party sometimes tacks left. It plays an active role in the Cost of Living Coalition (COLC) and has helped mobilise thousands of people on the streets…

All of this means that while Sinn Féin can be a vehicle for working-class aspirations, the

contradiction in its ranks means it will constantly try to moderate these. It will not promote people power from below and will urge waiting for governmental change. This, however, is a grave mistake for two reasons. The more working people remain passive, the more de-politicisation and right-wing cynicism grows. Moreover, if Sinn Féin is adopting a moderate left strategy now, the chances are that it will succumb to capitalist pressure when in government.”

This whole analysis is inaccurate, beginning with PBP giving credit to Sinn Féin for its role in ‘mobilising thousands on the streets.’ With its position as the main opposition party, the party with most TDs, probably the largest active membership, the most financial resources, and the party consistently leading in opinion polls for two years now, Sinn Féin would surely have enormous capacity to mobilise people into active struggle. What’s striking is what little inclination it has to use its resources and influence in this way. At most it has engaged in token mobilisations of its own members on certain issues like housing and cost of living, but little else – and it has been notably absent from efforts to actively resist the emerging far right.

Historically, Sinn Féin has never based itself on mass struggles of working-class and young people; indeed whenever such struggles have developed from below, as with the water charges and repeal movements in the South, Sinn Féin has been extremely flatfooted.

In that sense, PBP has it all wrong: Sinn Féin cannot be ‘a vehicle for working-class aspirations’, precisely because these aspirations can only be achieved through struggle. But then PBP does also acknowledge this (undermining its previous point about COLC), noting correctly that Sinn Féin will tend to steer people towards elections, not active struggle. PBP insists that this is a ‘grave mistake’ and a boon to those forces who would rather see working-class people unengaged and atomised. What PBP fails to see, however, is that Sinn Féin is one of those forces, and far from a mistake this is a calculated strategic decision on its part.

Similarly, PBP fails to see that the problem is not that there’s a good chance Sinn Féin will ‘succumb to capitalist pressure when in government’, of which its ‘moderate left strategy’ is a forewarning; it’s that its moderate left strategy is evidence of its already having succumbed to capitalist pressure. This is vital to understand, and should inform how the question of a left government is posed and approached.

All of this leads to a peculiar disconnect between PBP’s outline of what a left government should or would do and its focus on the prospect of a Sinn Féin-led ‘left government’.

For example, some of what PBP describes as what a left government would mean is noteworthy: a raft of pro-worker policies, including taxes on wealth and profits, massive investment in public services, and some nationalisations; an inevitable confrontation with

the capitalist state, financial institutions, and the EU; and the need to consistently mobilise ‘people power’ enmasse, including potentially forming ‘people’s assemblies’ – the embryo of a radically democratic alternative to the capitalist state. Much of this is laudable, and indeed a progression on PBP’s own position, which has rarely if ever been articulated in this way before.

So good in and of itself, but all of which also makes its focus on Sinn Féin all the more incongruous. Not only has Sinn Féin given no indication that it favours such a radical programme, it has explicitly and repeatedly explained that it is opposed to anything resembling such a radical programme. Yet PBP continues to speak of and argue for a left government led by Sinn Féin as if this wasn’t the case.

Again this relates to PBP’s inconsistency, which manifests in it more often presenting a potential left government as something far less radical than the above. The impression is often given, including in parts of this same pamphlet, that a left government would be any government that doesn’t include FG and FF – and implements some reforms. No doubt Sinn Féin offers the most likely route to such a government, but as well as Sinn Fein’s own moderate programme being dominant, that government would most likely also include some combination of the Labour Party, Social Democrats and the Green Party.11 In which case, while it would technically be a leftward shift from what FG and FF represent, it would not be a left government that would in any way challenge capitalism, or fundamentally improve the lives of workers and young people.

Referring to this prospect as the ‘left government’, which PBP has a tendency to do, is therefore hugely problematic.

After outlining its perspective on Sinn Féin and the potential for a left government, PBP sums up its position as follows:

“However, while openly arguing that Sinn Féin cannot be trusted to carry through a consistent left programme, People Before Profit recognises that

many working people currently see it as a vehicle for their aspirations. This is why we commit in advance of an election to vote for Mary Lou McDonald as Taoiseach if she is willing to lead a government that does not include Fianna Fail or Fine Gael…”

This position is similar to the one we advocated in our last article. If votes are needed to allow an alternative government, without FG or FF, to come to power, socialist TDs could facilitate that without supporting that government – from the inside or outside. In this way a Sinn Féin-led government can be tested in practice while a genuine left alternative is built in opposition: both inside the Dáil – where socialist TDs will vote for policies that are in the interests of workingclass people, and against those that are not; and outside the Dáil – where struggle is organised in workplaces, communities, colleges and schools. Make no mistake, even if a Sinn Féin-led government implements some improvements in some areas in the short term, the logic of the capitalist system it’s determined to work within means that its reverting to attacks on working-class people is only a matter of time.

But PBP goes further, writing:

“We go further and state openly that we want to participate in a left government that transforms people’s lives for the better and represents real change from the old Fianna Fail-Fine Gael status quo… We will participate fully in that project, but such a government must be willing to break the rules of capitalism and challenge the obstruction of the rich and encourage the struggles of workers against the for-profit system.

In the event of TDs being elected, we shall enter discussions with Sinn Féin to form a left government without the two right-wing parties. We know that many of their own base support this and Sinn Féin should come under pressure to keep their word.”

Here PBP is in danger of making the mistake we warned about in our last article: of making commitments – for tactical reasons – that it can’t fulfil, which can both undermine its position in advance of an election,12 and backfire on it after it. The problem again goes back to PBP conflating the discrete ideas of a Sinn Féin-led government without FG and FF, which is a possibility, and a Sinn Féin-led government that challenges capitalism, which is not a possibility.13 Sowing illusions in Sinn Féin and what a Sinn Féin-led government can achieve is to mislead the working class, which is obviously not in the interests of the working class, and certainly not in the interests of socialists. It’s a recipe for mass demoralisation, which will benefit not only the right-wing establishment, but the nefarious forces of the far right.

Housing will be key for SF at the next election, but its policy is insufficient to tackle the crisis, and contrary to what PBP claims SF has engaged in little more than token protests on the issue

achieved, as well as its limitations and what’s really needed. But a skillful engagement with those workers and young people looking towards Sinn Fein, with a view to shifting them further left, beyond Sinn Fein, can be carried out effectively without the elaborate, ultimately misleading and counterproductive, tactical ploys PBP seems wedded to.n

After the next election PBP wants to negotiate with Sinn Féin about forming a ‘left government’, indeed it wants to discuss this with Sinn Féin in advance of an election. But what exactly it will be negotiating it doesn’t tell us, which is strange given that this pamphlet was billed as a development of its position. Yet PBP is even more cagey about the possible demands and ‘red lines’ it would insist on in order to participate in a government with Sinn Féin – things it has alluded to in the past, and things people will want to know.

No matter what PBP comes up with, however, Sinn Fein could make some concessions that can make PBP look unreasonable as a result, and responsible for any failure to agree a programme for government, and the dashing of hopes PBP itself has raised; by promoting the prospect of a left government that doesn’t really exist. Is PBP prepared to resist the pressure it would come under from all sides – from Sinn Fein and other parties, from the media, and even from its own supporters and voters? Or is it prepared to compromise? Of course it shouldn’t, as nothing good for the left can come from participation in what would be a capitalist government. But if it isn’t then why bother engaging in this charade at all?

There is unquestionably a real desire among working-class and young people to get rid of FG and FF. This is positive, and socialists have to be able to positively engage with this – explaining how it can be

1 Kevin McLoughlin, ‘Sinn Féin preparing for power in the South: Can it deliver real change?’, Socialist Alternative #14, & Kevin McLoughlin, ‘Socialists and a Sinn Féin Government’, Socialist Alternative #16 l 2 PBP, Feb 2023, The Case For a Left Government – Getting Rid of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. All quotes are from this pamphlet, unless otherwise indicated l 3 Adrian Weckler, 11 Sept 22, ‘Mary Lou hitches up Sinn Féin party-mobile for Silicon Valley drive-by’, www.independent.ie l

4 Joe Brennan, 14 April 23, ‘Sinn Féin’s high-wire act: courting big business and those ‘left behind’, www.irishtimes.com l 5 Mairead Maguire, 8 Sept 22, ‘Sinn Fein promises 100k homes if elected’, www.newstalk.com l 6 P. Hosford & E. Loughlin, 8 Mar 23, ‘Leo Varadkar: Ireland has a shortfall of 250,000 homes’, www.irishexaminer.com l 7 PBP statement, 16 May 23, ‘Defend neutrality – but where does Sinn Fein stand?’, www.pbp.ie l 8 PBP statement, 28 Feb 23, ‘NATO & Ukraine: Where does Sinn Fein stand?’, www.pbp.ie l

9 Other recent examples include Sinn Fein attending the coronation of King Charles, or its effusive welcome of President Joe Biden to Ireland. l 10 Pat Leahy, 13 May 23, ‘Sinn Féin drops pledges to withdraw from EU and Nato defence arrangements’, www.irishtimes.com

l 11 PBP wrote to Sinn Féin, Social Democrats and ‘left independents’ in March about discussing the formation of a left government after the next election. It has elsewhere ruled out including Labour and the Greens as part of such a coalition, even though their numbers are likely to be needed to form a government ‘without FG and FF’. l

12 If Sinn Fein is promoted by PBP as key to a ‘left government’, many people will just vote for Sinn Fein over PBP – as the larger of two supposedly left parties. l 13 Note also that PBP’s formulation, “break the rules of capitalism and challenge the obstruction of the rich”, is sufficiently vague that it can mean something far less radical than an actual challenge to the rule of the capitalist system, which is what a real left government would be. But in fact this is also in line with PBP’s own politics: its programme in all its key policy documents, its budget statements and even the books by its leading members is an explicitly reformist one – much more radical than SF’s, but not one that breaks with the capitalist system.

“We must lead the struggle of the politically oppressed and unfree female sex into the broad course of proletarian liberation, just as we do that of oppressed peoples and nationalities. The demand for women to enjoy complete political equality before the law and in daily life will become a point of departure and a pillar of strength for the proletarian struggle to win political power… This demand [for women’s equality] signifies much more than sweeping away received prejudices, customs, and practices; much more than sweeping away male privilege. It becomes a struggle against bourgeois class rule and the bourgeois class state, and merges with the onward drive of the proletariat to win state power.”1

(our emphasis) – Clara ZetkinThis is a quote from trailblazing socialist feminist Clara Zetkin, a giant of the Marxist movement who played a vital role in Germany and internationally in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The 1921 language might be archaic but the prescient kernel contained in it is as current and urgent as can be. Let’s parse it in more contemporary terms.

Zetkin argues for socialists to strive to lead the feminist struggle that she attributes strategic importance to. Placing feminist demands seamlessly inside the working-class movement, Zetkin sees them flowing into “a struggle against bourgeois class rule” –a socialist struggle against class society, capitalism, and the capitalist ruling class. Moreover, this process adds value and impetus to the working-class revolutionary process itself. Taking this approach will prove to be a

“pillar of strength” for the working-class movement. Zetkin does not mince her words.

Marxism is often falsely purported as not reckoning with different forms of oppression; that it is innately ‘class reductionist’ – privileging class exploitation over other forms of oppression such as racism, sexism and LGBTQIAphobia, whose ravages it at least diminishes, if not ignores. This is a misconception as we will go on to show, irrespective of all the litany of mistakes of many left traditions on the question. In fact, this very organisation has written an analysis about deficiencies in our own tradition vis a vis fighting gender oppression, with a view to rectifying the same.2 While the most egregious and consistently poor approaches to oppression are located in left reformism, conservative trade union bureaucracies, and the Stalinist tradition –it’s not as if there aren’t still self-professed Trotskyist groups ranting and raving about ‘identity politics’ in a fashion that sounds like a right-wing talking point that continue to give Marxism a bad name.3 In this vulgar, spurious version of Marxism, ‘identity politics’ is the key tool of division used by the ruling class, rather than sexism, racism, transphobia etc.

Marxism is a philosophy that optimistically and humanistically advocates for a united, global, workingclass struggle against capitalism – a self-emancipatory vision and perspective for the exploited and oppressed themselves to rise up against capitalist class rule. It advocates for the urgency and necessity of building a determined struggle that can not only take society’s wealth, resources and industry out of private hands, but

“A PILLAR OF STRENGTH”

also goes up against the capitalist state that protects the status quo. Via this democratic movement of the masses from below, an alternative to the state has to be actively built. Such a revolutionary perspective for a rupture with capitalism – centring the unique power of a united working-class movement imbued with socialist politics – are at Marxism’s core.

This revolutionary process, and this united working-class socialist movement, are thoroughly and inextricably intertwined with the anti-oppression struggle. The revolutionary process unfolding without the latter is unthinkable – an impossibility. The radicalisation, the social ferment, the adding of value and impetus to the working-class movement – à la Zetkin above – that flow from struggles against oppression are part and parcel of the revolutionary process. Oppression is a tool of capitalist rule. Therefore it has to be challenged as part of any movement that is genuinely fighting capitalism. Moreover, the workingclass movement cannot be fought in the workplace alone if it’s to successfully challenge and defeat the capitalist class and system – and in order for it to be able challenge for power as a whole it must be able to take up all facets of social life.

A Marxist approach to fighting oppression is never about being any less feminist or less anti-racist in a deference to class oppression and exploitation. It’s about strengthening anti-oppression struggles in every way and simultaneously rooting them in a perspective that can win true, full, and lasting freedom. This piece will attempt, 1) to summarise some hallmarks of a Marxist approach to fighting oppression; 2) to illuminate in brief the problems with a liberal antioppression strategy; and 3) to rebut the idea that Marxism is class reductionist, relegating antioppression demands and struggles.

We will try to boil down a Marxist approach to fighting oppression to the following morsels: a) an analysis of where oppression is rooted; b) recognition of the interconnectedness of oppression and exploitation; c) self-emancipation; and d) always conscious, always combative.

A) Possessing an analysis of where oppression is and a laser focus on advancing the struggle against the same

In short, oppression in all its guises is rooted in and reproduced by capitalism: an innately patriarchal,

gender-binary promoting, racist, ecologicallydestructive and oppressive system. Gender- and sexuality-based oppression have their roots in the beginnings of the first class-divided societies. Racism has a much shorter life-span in history, with it being innately tied up with the development of capitalism and imperialism itself. While capitalism initially developed in Europe, endless expansion in search of new markets, resources and supplies of labour was in the nature of the system. This meant the colonisation of Africa and Asia, the ethnic cleansing of the indigenous peoples of the Americas and the horrors of the Atlantic slave trade. Such horrors were perpetrated in the interests of profit but also necessitated a categorisation and stratification of people based on the new criteria of race (a concept which of course has no biological basis).

Racism today remains a powerful ideological tool to divide and rule working class people and to justify the ongoing super-exploitation of the global south. Migrants and people of colour in Europe and North America are subjected to systemic state repression and are concentrated in the most exploitative sectors of the economy, all to the benefit of the system. These, and other forms of oppression have been deepened and reproduced by capitalism in an intricate web of ways.

A Marxist approach to fighting oppression at all times must retain a laser focus on oppression’s roots in capitalism, a system based on the systemic exploitation of workers and the poor – the vast majority of society –and the environment, in the pursuit of profits for a tiny elite. In this way, it means possessing a crystal clear view on the type of socialist struggle and change needed to end oppression; it means consciously imbuing this understanding into every act; it means understanding who are our enemies – the capitalist

class and its system, including the states that uphold its rule, and who are our potential allies – the exploited and oppressed of the world who have a common interest in uprooting the system that breeds oppression. In building our anti-oppression struggles, we may ‘march separately, but strike together’ –seeking to build the widest possible movement against any and all forms of injustice and oppression, but with a clear remit to cohere and win leadership for an approach and programme rooted in anti-capitalism, socialism, and working-class unity in struggle to achieve the same.

As Marx’s penetrating analysis of capitalism laid bare, worker exploitation is the central building block of capitalism. Profits are the unpaid labour of the working class. The capitalist compensates the worker just enough for their labour power to reproduce their labour power. The worker’s labour power, however, produces more value than it costs – a surplus value that the capitalist commandeers. In this way, the source of capitalist profits is the ability to compensate workers less than the full value of their labour, i.e. to exploit them. This exploitation is an innate contradiction of capitalism, underpinning the injustice and inequality at the core of the system. But it also means that workers are naturally infused with potential power. An organised movement of workers has special power to strike at the heart of the system that sustains class rule.

Behind and integrated into this central contradiction of capitalism is the gendered and patriarchal inequality of capitalism. The system requires the gender binary and backward gender roles, including because of the unpaid and underpaid reproductive labour that reproduces the labour force for capitalism, carried out mainly by working-class women. This work takes place often within the confines of capitalism’s patriarchal family structure, and also within the paid labour force –notably in health and education, female dominated sectors. Oxfam has estimated the value of the unpaid work of women and girls worldwide as $10.8 trillion per annum, over twice the size of the global tech industry.

Without the reproduction of the labour force there is no profit to be made. In this way, gender oppression and the imposition of a backward gender binary is not just floating about untethered in and around the system, it is inextricably tied into it – in this instance because of the workings of the interconnected spheres of production and reproduction.

Similarly, the extraction from and exploitation of nature that is constant under capitalism – with its rapacious need for expansion of profits no matter the cost – is a current and active reproducer of a sort of neo-colonialism on a global level. The refugee crisis resulting from climate change is another active and present driver of capitalism’s racist inequalities.

Climate refugees could reach 1.2 billion by 2050 under current trends.

Oppression – a systemic subjugation – of course intersects and intertwines with exploitation. Nurses and care workers are underpaid and undervalued in a gendered fashion – in this instance because of the overall low value attached to what’s seen as “feminine” caring work under patriarchal capitalism. They are also exploited as workers, intensely so under pandemic conditions. Similarly, migrant workers regularly face more intensified exploitation as workers.

These examples are just a glimpse into the myriad intertwining of oppression and exploitation. Furthermore, the radicalising effect of oppression on those who face it, along with the class division that the majority of those with oppressed identities also face, creates an intensified radicalisation that can propel these sectors of the working class and poor to the forefront of struggle and politicisation. They can be among the first to draw more far-reaching, radical and revolutionary conclusions.

“The truth, not fully recognised even by those anxious to do good to woman, is that she, like the labour-classes, is in an oppressed condition; that her position, like theirs, is one of merciless degradation. Women are the creatures of an organised tyranny of men, as the workers are the creatures of an organised tyranny of idlers. Even where this much is grasped, we must never be weary of insisting on the non-understanding that for women, as for the labouring classes, no solution of the difficulties and problems that present themselves is really possible in the present condition of society. All that is done, heralded with no matter what flourish of trumpets, is palliative, not remedial. Both the oppressed classes, women and the immediate producers, must understand that their emancipation will come from themselves.”4 – Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling (our emphasis)

Eleanor Marx, daughter of Karl and trailblazing revolutionary socialist who, in fighting for her father’s politics with every fibre of her being, sought to weave feminist demands and struggles into the early workers’ and socialist movement. A beloved and legendary working-class leader in her own right – an organiser of dockworkers, gas workers, engineers and miners – who addressed the first ever May Day demonstration in London in 1890, Eleanor Marx’s radicalisation and political thinking were formed as a child and adolescent following, writing about and campaigning against the colonial oppression of the Irish people by the British ruling class. Writing here as early as 1886 alongside her life partner Edward Aveling (more on him later), she not only recognises the patriarchal nature of the capitalist mode of production, she also explicitly advocates for self-emancipation for women

themselves – and the same applies for any of those peoples facing a particular type of systemic subjugation.

Those who themselves suffer any particular form of oppression have a central role in fighting against the same. They understand what it means to be subjected to it more than anyone. Furthermore, getting active in any collective struggle is a radicalising and politicising experience: often transforming awareness about the systematic nature of oppression; dispelling illusions in the system; and illustrating in a living way the necessity for determined struggle and solidarity in order to enact any change. This can propel those people into a leading role in the working-class movement as a whole – à la the women and queer people on the frontline against the Iranian dictatorship in the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ social revolt sparked in September 2022.

Oppressed people getting active to fight their own oppression in struggle is innately a positive for the whole working class, including those that do not experience that form of oppression directly. Misogyny, racism, LGBTQphobia etc. are odious in themselves, have deleterious, sometimes deadly consequences for those affected by them. As well as being knitted into and reproduced in a myriad of ways by the capitalist system itself, they are also essential tools of the capitalist ruling class that needs division amongst the exploited and oppressed in order to maintain its rule.

As well as winning increased rights, collective antioppression movements fight divisions, prejudices, and backward ideas amongst the working class that damage solidarity. The Black Lives Matter explosion of multiracial mass protests onto the streets around the world after the murder of George Floyd in the US on 25 May 2020, that had iterations across the island of Ireland,

give an insight into this. It was the first time that widespread anti-racist protests here were led by Black people, especially Black young people. The depth of racism and its brutal toll were highlighted by those raising their voices. The reality of being ‘Black and Irish’, and the illustration of the deep hurt and alienation felt by those who are asked every day, ‘Where are you from? No, where are you really from?’, because of widespread racist prejudice, was brought into public discussion in a way that could never have happened without it being led primarily by those experiencing the oppression. It had a profound impact, and absolutely raised the consciousness of many working-class and young people from white backgrounds to strive to be more anti-racist. In the US, the June 2020 BLM revolt demonstrably delivered a leap forward in public attitudes – achieving a 17% nationwide increase in support for the movement in the two weeks of protests since George Floyd’s killing was publicised.5

In Poland during the pro-choice feminist Black Protests of 2016 – polls showed increased support for abortion in the context of this defiant struggle, in an upwards trend of support in the years since despite new devastating attacks from the right wing.6 An oppressed group rising up as agents in struggle, demanding their rights, often fighting tooth and nail against the same capitalist governments attacking working-class living standards and rights broadly, of course has a profound impact on all the exploited and oppressed, including those who don’t experience that oppression directly.

An oppressed group getting active in struggle can sometimes win increased rights even if it doesn’t spark a whole lot of wider solidarity. Usually, the active striking forward in struggle of one oppressed group

will evoke solidarity from other layers – evidenced in so many ways in the 2010s feminist and LGBTQ rights waves, from the movements in Ireland that won marriage equality and abortion in popular votes; to the abortion green wave in Argentina that provoked active support from the working class of all genders; to the movement against femicide that saw workers in a predominantly male car manufacturing workforce walking out against femicide in the Spanish state in 2021.7 Such solidarity deepens and strengthens the struggle.

Moreover, to take oppression up at the roots this solidarity is not only useful it is essential. “Both… women and the immediate producers, must understand that their emancipation will come from themselves”, says Eleanor Marx. The working class, united, politically conscious and organised as socialist, has special power to uproot the private ownership of wealth at the heart of capitalism – channelling this power and entwining it with every single revolt at the multiple fault lines of the system is the only way a serious, let alone successful, challenge to the system that perpetuates oppression can be mounted.

There’s no space for determinism or fatalism within a serious fighting Marxist approach. Its whole essence hinges around the exploited and oppressed taking their destiny into their own hands in a conscious struggle. This conscious struggle involves those organised as Marxists to always be seeking ways for any oppressed or exploited section to strike forward in struggle; to aid this struggle where possible to win victories; to deepen the active solidarity of other exploited and oppressed sections towards this struggle, enhancing its reach and simultaneously raising class consciousness; and to always seek to fill the burst of fresh air that any collective struggle creates for those active within it, with an increase in those who are conscious and organised as part of the revolutionary socialist movement.

The “always conscious, always combative” approach, not only pertains to the question of striking forward in struggle wherever possible; it also pertains to a conscious struggle within the broad working-class movement, and even within our own political organisations of the socialist left, to raise consciousness and challenge every vestige of prejudice, which is poisonous to solidarity. In fact, this is something we need to pay extra attention to at this historical juncture – when the feminist and LGBTQIA wave that soared from the 2010s into the 2020s is facing such a rightwing backlash. The attacks on the gains of MeToo; the vicious anti-trans offensive – all need to be met with a robust rebuttal, including within the trade union movement, and all left movements.

This battle within the working-class movement was something Lenin spoke about in conversation with Clara Zetkin in 1920:

“Unfortunately, we may still say of many of our comrades, ‘Scratch the Communist and a Philistine appears.’ To be sure, you have to scratch the sensitive spots, such as their mentality regarding women…We must root out the old slave-owner’s point of view, both in the Party and among the masses. That is one of our political tasks, a task just as urgently necessary as the formation of a staff composed of comrades, men and women, with thorough theoretical and practical training for Party work among working women.”8

As far back as 1902, in the seminal What Is To Be Done?, Lenin made it clear what class consciousness, as distinct from ‘trade union consciousness’, really means. In raising class consciousness, Lenin advocates for socialist worker activists to be ‘tribunes of the people’ who speak up against all injustice meted out by the system – no matter what class is affected – in an effort to truly agitate against the system and build working-class agency, consciousness and power.9

The socialist project is no narrow one. So it follows that any narrow view of what constitutes working-class consciousness and struggle – for example a view that limits the same to either solely or primarily questions of wages and conditions on a workplace level, or any version of an economistic approach – cannot ever cut it. A social revolution is the ultimate act of human creativity, forged in struggle in an intense, kinetic moment in time, full of promise and potential and hope. Given this, how could a Marxist organisation worth its salt eschew questions of oppression, including by failing to seek to disabuse sections of the working class of the prejudices and oppressive practices that they have absorbed via the prevailing capitalist culture they’ve been conditioned by, if that organisation was truly basing itself on the type of revolutionary rupture with the system that’s objectively needed from the point of view of humanity and the planet?

Any mealy-mouthed approach on oppression would be blatantly incongruent with the type of change needed, with the type of change that is at Marxism’s core, and in fact would betray a lack of perspective for the same. Similarly, piecemeal offerings or zig-zagging in one’s commitment to the anti-oppression fight will not suffice. This is no abstract question. Observe the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ revolt in Iran: a revolutionary movement sparked by an act of patriarchal state violence in September 2022, infused in every way with the demand for women and queer people’s freedom, and gripping the whole working class and political and social life. It is a living, breathing, current example of the importance of questions of oppression in winning leadership for a programme for socialist change.

The “always conscious, always combative” approach was evident in the practice of women Marxists in the movement historically who embodied this struggle in every way, including establishing international

structures and conferences to organise and push a working-class feminism as a vital component of the wider working-class movement. The First International Conference of Socialist Women took place as early as 1907, alongside a conference of the Socialist International, founding an international movement of socialist women. Out of its 1910 conference came the proposal to establish International Women’s Day, now 8 March. This activity on behalf of Marxist women was often met with passivity, indifference and sometimes hostility by many of their conservative male comrades. A resolution passed at the 1907 Women’s Conference explicitly took this up, stating that:

“By and large, where the interests and rights of women were concerned, the [Second] International’s decisions were carried out only to the degree that organised socialist women were able to force the proletarian organisations in each country to do so.”10

Here we see how the self-liberatory element of a Marxist approach to fighting oppression is entwined with the “always conscious, always combative” aspect. It’s worth noting that many of the Marxist women who took on this struggle were also key advocates for maintaining a revolutionary, anti-imperialist stance, as the increasingly reformist trajectory of so many of the leading lights of the Second International saw them descend into brutal betrayal, including failure to oppose the imperialism of the First World War.

A liberal feminism or anti-racism is defined by an approach that works within the parameters of the capitalist system. Any approach to fighting oppression that is ultimately liberal is incapable of ending that oppression, and in the process often tends to accommodate and compromise with the oppressive status quo in a way that may subvert the demands and needs of oppressed groupings in struggle. It fails to see the significance of capitalism’s class divide – either from the point of view of the multifaceted impediments facing those from oppressed identities who are working class, or from the point of view of recognising the power of united working-class struggle in striking back against the capitalist class and system. A liberal commitment to personal freedom is often defined by an individualistic outlook, devoid of or countering a view of rooting oppression in capitalism and class society. A liberal approach also tends to eschew collective ‘struggle from below’, which is the way oppression is most effectively challenged.

Clara Zetkin, whose words comprised our opening salvo, excoriated the “bourgeois women’s rights” feminists – the elite class women who did not break in any significant way with the men of their class, and the system of class rule. She was particularly sharp when their demands or approach clashed with the interests of working-class and poor women, and the working class

and poor of all genders. In an example of where she clashed with the bourgeois feminists, and incidentally also with the increasingly conservative and reformist SPD leadership, Zetkin refused to co-sign a petition that meekly sought an increase in democratic rights to assemble for women, in a fashion that ignored the demands of the whole labour and socialist movement for wider change in this regard. She likened their tame appeal, dripping with pusillanimity, to the mindset of bourgeois feminists similarly conditioned by their elite bubble who had issued an odious petition a year earlier advocating for the criminalisation of sex workers.11

It’s patently obvious that there’s a class divide within feminist, anti-racist and other anti-oppression concerns. The most overtly class antagonistic approaches include a nakedly capitalist feminism, or capitalist anti-racism, anti-LGBTQphobia, etc. that hails (usually limited) increased diversity in the boardroom of giant corporations which perpetuate oppression, exploitation and ecological catastrophe in their operations; or representation in capitalist governments that attack working-class livelihoods, or use ‘feminist’ arguments to justify imperialism.

We can increasingly add a bourgeois transphobic ‘feminism’ to this list. The ‘Terf-ism’ of JK Rowling et al. – herself personally a super-rich, probably billionaire – is increasingly about reinforcing the backward gender binary, something very much needed by the capitalist system, as it aligns with further and further far-right forces that seek to crush the feminist and LGBTQ wave, and have migrants and people of colour in their crosshairs. All of these approaches are akin to attempts by shills for the status quo to co-opt the language of, or aspects of, issues raised by antioppression campaigns and movements. In this way, they are a class conscious attempt by ruling class interests to neuter or quell anti-oppression movements. However, within the active anti-oppression movements themselves, albeit with many contradictions, liberal approaches to fighting oppression inevitably abound, including amongst many activists and organisations who may also have positive attributes, who may even make anti-capitalist pronouncements from time to time. Here are some of these qualities in brief:

l A view that those who don’t experience the oppression themselves not only benefit from the oppression but have a vested interest in maintaining it. While it’s manifestly true that only those who experience a particular form of oppression can understand what it feels like, any implicit or explicit notion that takes the relative advantages that one section of the working class might possess vis a vis another section, and theorises that there is a vested interest on behalf of the latter to perpetuate that oppression is insidious. Of course there are benefits or advantages, some material, others relating to social status, self-perception that accrue to men, to white people, to cis people from oppression. However, they

do not alter the overarching interest for working-class people from these groups to challenge oppression because it ties them into a system which also exploits them. Moreover, any notion that there is a vested interest within parts of the working class in maintaining the status quo is laced with illusions in capitalism – a system in decay hurtling further and further into ecological catastrophe, incapable of providing for the needs of the vast majority of humanity. The truth is it’s urgently in the interests of the working class in the widest possible sense to unite to dismantle this system. Furthermore, any vestige of this liberal identity politics approach is damaging to the objective needs of any prospective anti-oppression movement that requires the building of the widest possible solidarity to sustain and empower it. Sometimes a reflection of this approach can be the idea that only those directly affected by any given oppression should talk about it. Of course those experiencing the ravages of the same should be the central voices in any movement vis a vis their issues, but in fact we urgently need to deepen the solidarity, widen the fightback – asking those within the working-class movement who are cis to speak up loudly in support of their trans siblings, or for cis-men to speak out against toxic masculinity. Yes, we absolutely need this and it should be encouraged in our struggles. One effect of this liberal identity politics approach in practice can be that working-class men do not actually have to concern themselves with women’s oppression and so forth – hiving off struggles against oppression, rather than making them central concerns for the whole working-class movement

l Connected to the above is a pessimism about the potential for class solidarity that tends to manifest itself in a limited scope for the change that is sought Sometimes that limited change will home in on a laudable quest to change backward and oppressive attitudes, but this quest is doomed to failure if it’s not infused with a dynamic attempt to build active struggles and movements that are consciously and primarily aimed at the system, and if it’s not dovetailed with a wholesale programme and perspective to attack the private ownership of wealth – the structural roots of oppression and exploitation. Other times, this approach can silo off different struggles of oppressed identities from each other, often then folding back into a very liberal and representation-based politics.