RESEARCHING BEST PRACTICES

December 2022 Vol.1 | No. 2

13

Implementing Phonics Practice into the Classroom

Erica Hanowski

3

Handwriting That Sticks

Angela Prokop

A Kindergarten teacher explores the impact of daily instructional models on students’ handwriting.

A first grade teacher sought ways to increase the love and enjoyment of writing and reading through direct phonics instruction.

19

Active Play

McKinley Anderson

Incorporating active play with middle school special needs students found to have dramatic effects on students’ academics and participation.

25

Struggling Students and the Effects of Read Alouds

Jamie Copenace

This study examines the positive influence read alouds can play with struggling fourth grade readers.

32

Asking the Right Questions

Joan Foley

This high school biology teacher explores which type of questions had the biggest impact on retention of course content.

Action Research Articles – Launching a New Era at SMSU!

Over the course of the last few years, we have been contemplating what to do with our Action Research papers that have been written by our Masters of Education students. We felt we were not showcasing the amazing research being done in the field and after working on making the changes that best depict what our teacher leaders are doing in their classrooms and communities, we are excited to share this new format with you.

Our students now have an opportunity to publish their research in an article format. We feel we are expanding the knowledge base centered on current and best practices in education today by showcasing the work of our SMSU graduate students. We are using the latest version of APA Style Guide (7th Edition) to provide best practices in a formal style, while at the same time providing a platform for them to showcase their talents and expertise with others.

According to Emily Calhoun (2002), “Action research is continual disciplined inquiry conducted to inform and improve our practice as educators.” We embrace this concept wholeheartedly and welcome you as a reader of our talented educators.

Dr. Tanya Yerigan is a career-long educator with a background in education, business, and social work, with over 25 years in K-12 and higher education. She is currently a professor at SMSU in Marshall, MN and teaches in the graduate program.

Dr. Dennis

Lamb

is starting his 40th year in education. He began his career as an elementary teacher, served as an elementary principal, and currently is a member of the graduate faculty. He has been a facilitator in the Master of Science Education Learning Community program since 2007.

Considering a micro-credential?

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional Intelligence is a foundational component of effective teaching and leadership. In this course package, you will gain a better understanding of Emotional Intelligence and explore its professional and personal applications.

Self-Care Package

The Self-Care package focuses on the Six Tenets of Health and provides participants an opportunity to research and develop a self-care plan.

Culture of Poverty

The Culture of Poverty is everywhere. This package of courses promotes a proactive approach to finding solutions and resources to assist those children/ families needing attention at the local level.

Mental Health Coach & Toxic Stress

This package focuses on the physical, social, and psychological childhood stressors and seeking solutions to assist those in greatest need. Upon completion of this package, participants will receive certification in Adult MHFA and Youth MHFA.

Abstract

Handwriting is an essential skill, but is there one instructional model more conducive to a child’s development? A quantitative research design to compare the use of Zaner-Bloser and D’Nealian approaches of manuscript handwriting instructions was implemented in two separate groups of kindergarten students. Results dominantly favor one instructional model.

Definitions

Handwriting: A fine motor skill applied to form letters in a particular way with a writing utensil.

Manuscript: Handwriting form where letters are disconnected and are formed by a single continuous stroke or by two or more basic strokes (lines, circles, parts of circles, etc.).

D’Nealian: Instructional model using slightly oval and slanted strokes to form the letters.

Zaner-Bloser: Instructional model using more traditional ball and stick strokes to form the letters.

Please note: These terms were used in conjunction with the curriculum that was implemented throughout this study. Please use these working definitions throughout the paper.

Figure 1

Alphabet charts showing the differences between two handwriting instructional models

Introduction

Have you ever noticed how handwriting can look so different from person to person even though they are writing the same letters and numbers? Why is that? What things influence the development of a person’s handwriting? The researcher was curious to learn what kind of impact the instructional model used in direct instruction has on daily handwriting in kindergarten students.

Purpose

Handwriting is an essential skill. Current research provides evidence to support the need for and benefits of handwriting instruction in schools. There are several instructional approaches for teaching and learning handwriting. Teachers need to

make informed decisions when selecting the instructional approach they will teach. Research directly comparing instructional approaches for handwriting and its impact on everyday application by students is especially lacking. The purpose of this study is to determine how the instructional approach for handwriting impacts students’ application of instructed formation in their everyday handwriting.

Significance

The results of this study could benefit early childhood and primary elementary educators. It is in these classrooms where students receive their first formal handwriting instruction and the foundation is laid for their developing handwriting skills. Using research-backed information to aide in selecting the most appropriate instructional model would benefit both the educators teaching and the students learning. This study could also be helpful for parents wanting to learn more about the development of their child’s handwriting.

The Importance of Handwriting

Multiple studies provide evidence to support the critical need for handwriting instruction in schools yet today despite advancing technology (AlOtaiba & Puranik, 2011; Bara & Morin, 2013; Cup, de Groot, de Vries, Hendriks, Nijhuis-van der Sanden, & van Hartingsveldt, 2015). Laura Dinehart explains in more scientific terms: “We decode letters using the visual cortex, but actually writing them stimulates the brain’s prefrontal cortex, a region responsible for restraining bad behavior, sustaining attention and avoiding bad habits. These mental processes are essential for success in learning” (Dinehart, 2015, p. 85).

Especially in the early primary years, handwriting aides in literacy and emergent reading skills. Practicing the formation of letters leads to connecting the relationship between letters and sounds, and ultimately, that letters and sounds make up words (Bingham et al., 2012).

Marais, Oakley, and Staats (2019) refer to handwriting as a bridge between various writing tasks. They give the example: “Dictation is more difficult than copying, but composition is much more difficult than dictation; therefore, dictation can be considered a bridging task between copying and composition” (Marais et al. 2019, p. 551). Handwriting is a complex skill that provides beneficial support in school academics, but also lifelong benefits in other aspects of life including work, socializing, play, and leisure activities (Bialek et al., 2016).

Feder and Mainemer (2007) identify component skills that predict successful performance in handwriting including fine motor control, sustained attention, and visual-motor integration. A child must have the fine motor control to hold, grasp, and shift a writing utensil in hand.

Handwriting requires focus and sustained attention to practice and master formation. “Several studies have found visual-motor integration to be one of the most significant predictors of handwriting performance, with strong correlations documented between visual-motor integration and writing legibility” (Feder & Mainemer, 2007, p. 314).

Handwriting Instruction in Schools

Handwriting is often umbrellaed under general writing instruction. For students to

develop foundational skills, they need direct instruction in the classroom and be allowed adequate time to practice. Research shows that large segments of time do not need to be devoted to handwriting instruction and practice.

Rather, shorter amounts of time each day is more effective. Vander Hart et al. (2010) recommend 75-100 minutes of handwriting instruction per week, split into short periods of time daily, which makes it about 15-20 minutes per day.

In a study conducted by Coker et al (2016), “Most teachers (65%), reported that their instructional approach to handwriting, spelling, and composing was developed in house” ( p. 796). There are different instructional approaches for educators to use when teaching manuscript handwriting. These approaches vary in starting points, directionality, and strokes in letter formation.

Most approaches are quite similar in using traditional ball and stick letters. These include Zaner-Bloser, Handwriting Without Tears, and Sunform. “Often ball-and-stick is a favored approach because its font is thought to be similar to text young children read, although it has separate forms for manuscript and cursive” (Shaw, 2011, p. 126).

One approach is set apart from the others, using slightly oval and slanted strokes to form the letters. The argument in using slanted strokes is to make the transition to cursive writing more smoothly because the slanted formation in manuscript letters sets up the connectivity used in cursive handwriting.

Not all agree with this reasoning. “D’Nealian letters are abstract and may challenge students to remember distinct motor plans, which may result in open, distorted and illegible letters” (Shaw, 2011, p. 125). Shaw conducted a study with kindergartners comparing the differences found in their handwriting. Some students had been taught with the D’Nealian approach and others a basic print manuscript approach.

Directionality and integration of letter formation were the two areas scored in the study. Results showed students who received the basic print manuscript approach scored significantly higher for both. “The D’Nealian students had considerably lower scores on missing or extra strokes, distortions and open letters” (Shaw, 2011, p.125).

In a study conducted with 600 students in grades 4-9, Berninger, Graham, and Weintraub (1998) concluded: “Slanted manuscript letters are no more successful than traditional manuscript letters in enhancing the transition to cursive writing or improving overall legibility of students’ manuscript writing” (p. 290). A third study comparing D’Nealian and Zaner-Bloser approaches from manuscript to cursive in first grade students had the same conclusion: “Instruction of cursive letters was not enhanced by employing D’Nealian manuscript instructional materials” (Cooper et al., 1984, p. 345).

Achieving fluency is the goal in handwriting in school. Being able to write letters and words with speed and legibility allows for handwriting to become more automatic. When the formation of letters is automatic, students can focus their attention on the content and ideas they are communicating in

their writing. Consistency with instruction and time practicing is key in helping students develop these skills.

The research reviewed demonstrates using a more basic print manuscript to be more favorable for young children as they begin learning handwriting skills. There is not enough research to declare with certainty and reliability that one is a more appropriate approach for handwriting instruction.

Sample

The subjects in the study were from a rural school district comprised of two local communities in southern Minnesota. The district houses students from preschool through 12th grade in one building. Enrollment for the district was approximately 670 students for the 20202021 school year.

The sample size was drawn from the kindergarten grade, which in the 2020-2021 school year contained 44 students total. Only a sample of students from two classrooms were participants in the study. Both classes had 15 students. Class A had 10 boys and five girls. Class B had nine boys and six girls. At the time of the study, students in this class ranged in age from five to six years old.

The participants from Class A included 10 boys and ten girls. Of the eight participants: one student was on an IEP, one student received OT services, one student received Title One services, one student received tutoring services through Reading Corp and two students were part of social skills groups with the school social worker. All students from Class A were Caucasian. The participants from Class B included four boys and four girls. Of the eight participants: one

student received Title One services and two students received EL services. In Class B, five students were Caucasian and three were Hispanic.

Methods

Over the course of this study, three data collection methods were used to analyze how the instructional approach used to teach handwriting affects the development and use in a daily writing by kindergarten students. Class A students were taught handwriting following the Zaner-Bloser instructional model. Class B students were taught handwriting following the D’Nealian instructional model. Data was collected over five months, from September to January.

Instrumentation #1: Sound Spelling Procedure Observations and Rubric An observation procedure was implemented to see if students apply the handwriting guidelines taught during direct instruction when writing outside of direct instruction. The sound spelling observations were conducted and recorded three times over the duration of the study, every six weeks. Allowing time between direct instruction and the observation gave students time to develop mastery of the letter formation.

The researcher conducted the sound spelling procedure and observation for both groups of students in the study. The procedures were conducted orally with individual students so a complete observation could be done. The sound spelling procedure itself was modeled after the sound spelling practice from the Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Saxon Phonics and Spelling kindergarten curriculum.

During the procedure, the researcher said a sound, which was then echoed by the

student. The researcher asked the student to name the letter that makes that sound. The student named the letter and then wrote it, both capital and lowercase, on the directed handwriting line.

For the purposes of this study, paper and pencil were used to write the letters. The researcher then assessed the students’ handwriting using a rubric. The rubric was created by the researcher and targeted the same three handwriting guidelines from the direct instruction rubric.

Instrumentation #2: Weekly Direct Instruction Handwriting Sample and Rubric

Student handwriting samples were collected weekly over the five months. Both groups of students completed the handwriting worksheets in a whole class setting during direct instruction from the teacher. Each sample collected included the capital and lowercase forms of only the letter of focus in the kindergarten literacy curriculum that week. The worksheet had the standard handwriting lines and starting points. The students were able to practice the strokes by tracing first and then writing the letter independently.

The researcher created a rubric to assess these handwriting work samples. Three handwriting guidelines were targeted on the rubric: starting point, formation, and line awareness. The educator scored yes or no to indicate if the student met each of the targets.

Instrumentation #3: Student Survey

Surveys were conducted at the beginning, middle, and end of the study. This assessment was given to students to view

their personal feelings on different aspects of handwriting. The survey consisted of six statements. The researcher met with students individually to give directions and read the statements for them.

Students answered each statement by circling a green, yellow, or red face that best showed their feelings. The faces were described to the students as follows: green=yes, definitely; yellow=sometimes or kind of; red=no, not really.

General Findings

When data collection was complete and had been analyzed, the findings clearly swayed in favor of one instructional model over the other. The discrepancy between Class A and Class B in applying the instructed handwriting strokes was significant across the board.

Direct Instruction Handwriting Samples

Out of the three handwriting guidelines targeted on the rubric, only two had noteworthy contrast between Class A and Class B. The first guideline, a student uses the starting point, showed very few students or occasions where this target was not met. Of direct instruction work samples for the 13 letters introduced over the course of the study, there were differences between Class A and Class B.

Class B, the D’Nealian group, had a more significant percentage of students meeting the target for line awareness for six of the work samples collected. Class A, the ZanerBloser group, had a greater percentage of students meeting the target in the other seven. As the breakdown in meeting the line awareness target among the students was fairly even in both groups, the instructional approach to handwriting does not seem to

directly impact a student’s awareness of space and lines.

In analyzing the results, variations were seen more due to the letter being instructed rather than the student’s formation to write it. Letters that had curved or round strokes proved to be more difficult for students despite the direct, guided instruction they had when completing these handwriting samples.

Specifically, letters with a starting point that did not sit on one of the handwriting lines were most challenging for students to fill the appropriate space. The third guideline on the rubric, formation of the letter applying the instructed strokes, had a greater discrepancy across the board between Class A and Class B.

As can be viewed in Figure 2, Class A, the Zaner-Bloser group, had greater percentages of students who applied the correct, instructed strokes when forming the letters in 10 out of 13 work samples. The three work samples that Class B, the D’Nealian group, had greater percentages of students using the instructed strokes, the variation was between 3% and 23%.

In the 10 work samples where Class A had the greater percentages, the variation was much greater, ranging from 12% to 75%.

With Class A having greater percentages and by a widened range, students taught with the Zaner-Bloser handwriting model are more successful in their application of the instructed strokes during direct instruction.

Figure 2

Application of Correct Formation of Letters on Direct Instruction Handwriting Samples

Independent Handwriting Observations

The most telling results came from the observations of students’ independent handwriting outside of direct instruction time. Three observations of handwriting were completed in the duration of the study. In the three observations, Class A, the Zaner-Bloser group, had higher percentages of students meeting the rubrics’ targets used to analyze these independent work samples.

Again, the rubric targeted three handwriting guidelines. Across the board for all three handwriting guidelines included on the rubric, Class A, the Zaner-Bloser group, had a higher percentage of students meeting each target (see Figure 3).

In the first observation, 68% of Class A students applied the instructed Zaner-Bloser strokes to form the letters. Class B had 11% of students that applied the instructed D’Nealian strokes to form the letters. This

was a 57-percentage point difference between the two groups.

In the second observation, 61% of Class A students applied the instructed Zaner-Bloser strokes to form the letters. Class B had 25% of students that applied the instructed D’Nealian strokes to form the letters. This was a slightly smaller discrepancy of 36 percentage points.

In the third observation, 67% of Class A students applied the instructed Zaner-Bloser strokes to form the letters. Class B had 31% of students that applied the instructed D’Nealian strokes to form the letters. As in the second observation, this was a smaller discrepancy of 36 percentage points. The other two handwriting guidelines targeted on the rubric, starting point and line awareness, had similar trends.

Figure 3

Application of Correct Formation on Independent Handwriting Samples

A similar study the researcher discovered looked at kindergarten handwriting focusing on the directionality of letters and the integration of the instructed formation for letters. The results in student independent handwriting samples would support findings of this study. In both studies, students who received the basic print manuscript approach, not D’Nealian, scored significantly higher (Shaw, 2011, p. 125).

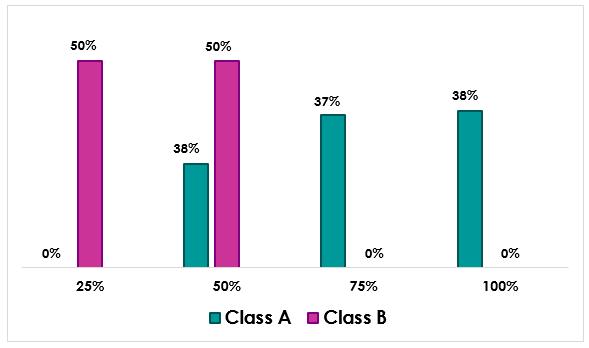

When looking at individual student growth and maintenance from the initial handwriting sample from direct instruction to the third observation and independent handwriting sample, Class A did considerably better than Class B. Using the Zaner-Bloser model, 25% of students in Class A achieved or maintained the correct formation for less than 50% of the letters. Class A had 37% of students who achieved or maintained correct formation 38% of students who achieved or maintained correct formation for between 75-100% of the letters.

Figure 4

Application of Correct Formation on Independent Handwriting

Samples

Comparing Boys and Girls

Using the D’Nealian model, 50% of Class B students achieved or maintained formation for less than 25% of the letters. The other 50% of Class B students achieved or maintained formation for between 25-50% of letters. As Figure 5 shows, Class A, using

the

Figure 5

Students Who Maintained/Achieved Correct Formation

The second survey, given at the midpoint of the study’s duration, showed more varying responses than the beginning and ending surveys. Even with a few more varying responses, the majority of students from both groups circled all green. With the pattern of all green responses and no visible pattern to the varied responses, students did not use the survey as a self-reflective piece. Rather, it was as if they thought the researcher wanted a specific response from them. After analyzing the data, the researcher did not feel it contributed any substantial findings to the study.

Limitations

Percentage of letters students achieved or maintained their application of the correct formation throughout the study.

Student Surveys

All students participating in the study were given a survey at the beginning, middle, and end of the research period. The goal in surveying the students was to see kindergarten students’ reflections and feelings about handwriting and if either D’Nealian or Zaner-Bloser was more positively reflected in the responses.

From the initial survey, the researcher noticed a pattern in student responses. In both Class A and Class B, the majority of students circled the green happy face for all six survey statements. Very few students paused to think about the statement; it was an automatic response to just circle the green.

A few limitations should be considered when analyzing this study. First, the greatest limitation to consider is that this study was implemented in the middle of a global pandemic. As a result, student attendance was greatly affected, due to frequently changing regulations regarding quarantining. This made collecting some of the work samples challenging.

Also, attendance related, one student in Class B moved out of state shortly into the study’s duration and then moved back into the district towards the end of the study. This student’s work sampling and observations were incomplete, leaving the study samples from each class imbalanced.

Next, the study included only a small sample size of students from each class. Results may vary with a larger sample size. Something else that could influence the results of this study is students’ prior exposure to handwriting practice.

With a smaller pool of students, it was not possible to ensure all student participants had the same preschool background,

exposure, and instruction coming into the study. Finally, the length of the study should be considered as a limitation as it lasted five months. Ideally, implementing the study from the beginning to the end of a school year and including all 26 letters of the alphabet would produce more thorough findings.

Recommendations

Over the course of the study, I have thought about and developed recommendations for educators and researchers to consider when implementing the practice or replicating the study.

1. Create and use a separate rubric for lowercase and capital letters. Some letters are similar in formation between both, but others vary drastically. Assessing each letter formation separately would give a more specific picture of students’ application of the different strokes in each.

2. Extend the duration of the study. Having the entire school year would be ideal as data and work sampling would include all 26 letters of the alphabet.

3. Complete observations of students’ independent handwriting samples more frequently. These observations were done individually and took a lot of time. Under the circumstances for my study, it was not manageable to conduct more frequent observations. The additional samples would provide more data points in looking at students’ consistent application of the strokes and growth from beginning to end.

4. Consider handedness of the student. Two students in my study were left handed. It

sparked some questions about that impact in the ability to apply the strokes to form the letters in D’Nealian and Zaner-Bloser models.

5. Use a larger sample size. The size of my district only allowed for a small sample size, which could have impacted the results. A larger sample size may provide future researchers with more trends and results.

Conclusions

The overarching conclusion from implementing this study is yes, the instructional approach to handwriting does impact kindergarten students in their daily handwriting. Kindergarten students who were instructed using the Zaner-Bloser model had quite notable success in applying the instructed formations compared to the students instructed with the D’Nealian model.

In Class A, the Zaner-Bloser group, a greater percentage of students were able to carry over what they learned in class and apply it in their independent work. Without prompting or redirection, these students used the strokes to form the letters the way they were taught.

As a kindergarten teacher of 11 years and having personal experience teaching handwriting with both of these instructional models, I am not surprised by these findings. The simplicity of circle and stick strokes seems more easily learned and used by these young learners.

Though research in this area is more limited, the data collected in this study reinforces past studies’ findings regarding the use of different instructional approaches to

handwriting. Based on the data I have gathered throughout this study, I would recommend using the Zaner-Bloser model for teaching handwriting to kindergarten students.

About the Author

Angela Prokop is an 11th year kindergarten teacher living in rural southwest Minnesota.

References

AlOtaiba, S., & Puranik, C. S. (2011). Examining the contribution of handwriting and spelling to written expression in kindergarten children. Reading & Writing, 25(7), 1523-1546.

Bara, F., & Morin, M. (2013). Does the handwriting style learned in first grade determine the style used in the fourth and fifth grades and influence handwriting speed and quality? A comparison between French and Quebec children. Psychology in the Schools, 50(6), 601-617.

Berninger, V. W., Graham, S., & Weintraub, N. (1998). The relationship between handwriting style and speed and legibility. The Journal of Educational Research, 91(5), 290-297.

Bialek, K., Clarke, M. L., Jansson, J. L., & Shah, L. J. (2016). Study of prehandwriting factors necessary for successful handwriting in children.

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Educational and Pedagogical Sciences, 10(3), 707-714.

Bingham, G. E., Gerde, H. K., & Wasik, B. A. (2012) Writing in early childhood classrooms: Guidance for best practices. Early Childhood Education Journal, 40(6), 351-359.

Coker, D. J., Farley-Ripple, E., Jackson, A. F., Wen, H., MacArthur, C. A., & Jennings, A. S. (2016). Writing instruction in first grade: An observational study. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 29(5), 793-832.

Cooper, J. O., Hill, D. S., Lanunziata, L. J., Swisher, K., & Trap-Porter, J. (1984). D'Nealian and Zaner-Bloser manuscript alphabets and initial transition to cursive handwriting. The Journal of Educational Research, 77(6), 343-345.

Cortesa, C., Fitzpatrick, P., & Vander Hart, N. (2009). An in-depth analysis of handwriting curriculum and instruction in four kindergarten classrooms. Reading & Writing, 23(6), 673-699.

Dinehart, L. (2015). Teaching handwriting in early childhood: Brain science shows why we should rescue this fading skill. District Administration, 51(6), 85.

Feder, K. P., Mainemer, A. (2017) Handwriting development, competency, and intervention. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology; London, 49(4), 312-317.

Implementing Phonics Practice into the Classroom

Erica HanowskiAbstract

Many students in first grade lack phonics skills and the ability to recognize blends and digraphs in reading and writing. Due to this, students' love and enjoyment of writing is limited. Students were selected to participatein a phonics study, while being introduced to three new blends/digraphs a week during the six week study. Teaching specific first grade phonics improved the love for writing in students.

Key Words: Phonics, Blends and Digraphs, Writing Phonics

Phonics is a method of teaching people to read by correlating sounds with letters or groups of letters in an alphabetic writing system. Phonics is needed to be learned at the beginning stages of reading, in order to sound out words.

Importance of Phonics

Fountas and Pinnell stated the following: Dochildren need instruction in phonics? Why isthere an argument? The answer is “yes.” Even children who “crack the code” early and appear to have noticed lettersound relationships and figured out how to use them will benefit from systematizing their knowledge and developing effective,

efficient ways to use their knowledge not only of letters and sounds, but also of patterns involving larger chunks of words.

At the bottom line, the more rapidly and efficiently children can decode words, the more accurate and fluent their reading will be, making it possible to give greater attention to comprehension and deeper thinking.

Research by Fountas and Pinnell found that Children need numerous opportunities to hear written language, read aloud, to read and talk about books with others, to choose and read books independently, and to write daily in a variety of genres. They also need the experience of isolating the building blocks of language letters and sounds studying them, making connectionsbetween them, seeking patterns and using them, and becoming so familiar with this content that, eventually, they can use it easily, rapidly, and automatically.

According to Tankersley (2003), When reading becomes hard, it becomes a burden. Students will not be confident,

nor eager to want to try to read. With the encouragement and different programs one sets up in their classroom, they are able to implement more phonics strategies and lessons to help. Phonics should be a strong component of all kindergarten and 1st grade instruction so that students build strong word attack skills as foundation for all of their reading skills. (p.63)

It is important when students who leave first grade, leave at a top tier level. Without the continued practice of phonics in the everyday classroom routines, it will be hard for the students to move up and meet the reading level by the end of the year.

“Adding a sprinkle of phonics here and there is just not enough”- Redford

Phonics Chart

The phonics chart above is an important tool for students in primary grades to use to

practice their vowels, digraphs, and blends. The chart was incorporated into a first grade classroom and used every morning during morning meeting. The students were expected to use the chart as a song with a visual. It would be instilled in their memory and the song with body language would be pulled from their working memory, when needed during their writing or reading. Students found this chart very helpful and very fun!

How to Incorporate Phonics

According to Fountas and Pinnell, in order to become a more confidentand fluent reader, phonics need to be incorporated in a teacher’s daily phonics lesson. It is expected teacher’s will find out where students are phonemically. Then, the teacher movesforward with grouping students with similar needs. Teachers teach whole group lessons and individualize groups based on similar needs. “Grouping is a nice addition where the teacher can divide students into groups so they can work together to fill those holes.

“Phonics is an oral language that is communicated through sound we put together to form words, phrases, and sentences that have special meaning for other speakers. Children learn oral language easily and interactively” (Pinnell & Fountas, 2003, p. 13). Phonics is introduced with age appropriate sounds in Kindergarten. When kindergarten students come to first grade, they should be introduced to a variety of new age appropriate sounds.

International Literacy Association (2018) found the following: There are many ways toteach phonics, and there are similarities underlying the various methods used to teach letter sound relationships and word patterns. Successful programs or methods use explicit phonics instruction that is systematic. They also provide clear examples for students to build on as they develop their awareness of the written code of how words are spelled.

Students store information better when they can hear something, see something, and try it themselves. - Literacy Leaderships

Research has been done and proven that reading comprehension is greatly enhanced when the students are phonics instructed students. Those who are not are spending time sounding out the word instead of reading for meaning (Fountas & Pinnell, 2003).

Phonics in First Grade

Literacy Leadership (2018) states: Phonological awareness is a particularly important language skill to acquire before phonics instruction begins. Phonological awareness includes the ability to separate oral language into syllables and individual phonemes, the distinctive sound for the language the student is learning to read (English has 44). It is learned through singing, tapping syllables, rhyming, and dividing words into individual sounds.

“Phonics lessons should be well ordered andsequential. They should be fast-paced, multimodal, fun, and very focused. A good phonics program will contain instruction on phonemes, individual letters as well as blends, sound combinations, and other linguistic structures” (Tankersley, 2003, p.80). A teacher who can apply all of those things into a phonics lesson will benefit the students in more than one way.

Phonics Research in First Grade

This study used three students in the first grade for the practice of phonics. Students were taught phonics in the classroom daily, using research-based phonics techniques. Data was collected throughout the study

formally and informally to measure the impact of daily phonics. The study was designed to investigate how the students were affected by the teaching of daily phonics and the increase in their reading and writing ability as well as their love for writing. The data was collected in a classroom setting for 10 weeks. After reviewing the data collected informally and formally, it was clear that the correlation between teaching phonics increased their ability in performance and love for writing.

The correlation between the two appeared to go hand-in-hand with the variety of activitiesthat the students were able to understand, remember, and carry out into the classroom for daily activities. However, at the beginning of the study, we had the ability to assess and practice “in person instruction'', but this was interpreted due to transitioning to distance learning. The instruction and data continued online. However, these results are inconclusive, due to the small test group and various outside influences on individual students.

Students Selected

The participants of this research project were three first grade students who were in the same first grade classroom in a central Minnesota school with low poverty. All three white, participants received the same tools, techniques, and opportunities to practice their phonics. The three students were chosen as participants because of their similar gaps that needed to be filled after viewing the first spelling inventory assessment.

Student A was a six year old male in the first grade at Nisswa Elementary in Minnesota, who was being tested for special education services. When tested, Student A was one of

the students with the most “holes” in phonics.

Student B was a six year old male who was in a first grade classroom at Nisswa Elementary in Minnesota. He is diagnosed as EBD. He received special education services.

Student C was a six year old male who was in the first grade classroom at Nisswa Elementary in Minnesota. He received special education services at the time of this study.

Student A

Baseline data indicated that Student A was able to increase his awareness of phonics and carry it through onto his assessments. When the first assessment was given in September, Student A identified one initial consonant sound, one final consonant sound,and one short vowel.

When Student A was tested in November, he knew four consonant sounds, five final consonant sounds, one short vowel sound, and one blend. Student A was able to increase his ability to use the initial consonant, final consonant, short vowel, and blend awareness.

Over the course of the study, student A was seen using the phonics chart chant to figure out sounds in words and in books. He gained a skill that helped identify sounds and connectthem to pictures and chants.

Student B

Baseline data indicated that student B was able to increase his awesomeness of phonics and carry it through onto his

assessments.

When the first assessment was given in September, Student B identified three initial consonant sounds, three final consonant sounds, and one short vowel. When Student B was tested in November, he knew six consonant sounds, seven final consonant sounds, two short vowel sounds, four blends, and seven digraphs. Student B was able to increase his ability to use the initial consonant, final consonant, short vowel, and blend awareness.

Student C

Baseline data indicated that student C was able to increase his awesomeness of phonics and carry it through onto his assessments.

When the first assessment was given in September, Student C identified six initial consonant sounds, four final consonant sounds, and three short vowels. When Student C was tested in November, he knew seven consonant sounds, seven final consonant sounds, and five short vowel sounds. Student C was able to increase his ability to use the initial consonant, final consonant, short vowel, and blend awareness.

Data collection

In September of First grade, the students were given a “spelling inventory,” that our district uses to collect the data of the current phonics that my class has in place. We look at the results and find the holes and begin to look into what the students need to have all the phonics skills in place when they leave for the summer in May.

Three students were selected to research

during this implementation time and see how the purposeful teaching applied to them, how they were able to use it in reading and writing, and follow up on how they would use it on the test again in November.

Figure 1

Student A Test Results

Figure 2

Student B Test Results

Figure 3 Student C Test Results

Figure 4

Students A, B. and C Composite Scores

References

International Literacy Foundation. (2018). Explaining phonics instruction: An educator’s guide.

Pinnell, G.S. & Fountas, I.C. (2020). Twelve compelling principles from the research on effective phonics instruction. Heinemann.

The students were all about ‘the grow’ and presented those skills taught on the spelling inventory given to them. It was fun to see such growth with such different students!

Recommendations

I recommend using daily phonics songs/charts, incorporating it into your morning meeting and literacy stations, as data proved that my students were able to grow.

The Chart provided the students a way to remember the sounds by singing the song and doing the movements. This was extremely helpful in sounding out words and writing words down. They could hear the sound, see it, and record it on paper.

About the Author

Erica Hanowski is a 1st Grade teacher at Nisswa Elementary in Brainerd, MN ISD181 School District.

Pinnell, G. S. & Fountas, I.C. (2003). Phonics lessons: Letters, words and how they work. FirstHand/Heinemann

Redford, K. (2019, March 19). Explicit phonics instruction: It's not just for students with dyslexia. Education Week.

Tankersley, K. (2003). The threads of reading: Strategies for literacy development. ASCD.

Active Play in a Special Education Classroom

McKinley Anderson

Abstract

Many middle school special education students in today's schools are given less time for active play and have higher expectations by their teacher on academics. In my research, students were selected to participate in active play to improve academic scores. My goal was to implement active play before math lessons to increase class participation and academic scores.

Definition

Active play includes any activity that involves moderate to vigorous bursts of high energy. Put simply, if it raises an individual's heart rate and makes them "huff and puff", it’s active play. Children should enjoy active play every single day. It's this kind of routine that will help kids form lifelong habits of daily physical activityACT Government.

Purpose

The purpose of this action research was to see if using active play at the beginning of class each day would increase class participation and increase test scores with special education students within the math classroom.

Active Play: Further Examined

Oftentimes, low test scores are correlated to students being overwhelmed with material and not having proper preparation for a test. Students are sitting through 60 minute classes expected to retain everything that their teacher says or shows. The amount of

time a student can stay focused on a specific task is about the same as their age in minutes. Knowing this, educators need to be implementing active play breaks into their class schedules. According to the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), physical activity has an impact on cognitive skills, such as concentration and attention, and it also enhances classroom attitudes and behaviors, all of which are important components of improved academic performance.

Researchers have found that just one session of moderate physical activity instantly boosts kids’ brain function, cognition, and academic performance. An overlooked idea by many educators is how to implement active play into an academic lesson. Active play can be any physical activity to get students' heart rates to increase and can be implemented at the beginning of school or class, or even as a mid-class break. According to Barile (n.d.), The Naperville, Illinois district implemented an early morning exercise program called Zero Hour, which sought to determine whether working out before school gives students a boost in their academic ability. Since introducing this program, the district has seen remarkable results in both wellness and academic performance. (para 3)

Active play can be as simple as standing exercises, stretching, yoga, and resistance training. “In October 2014, researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology found that resistance training can enhance episodic memory, also known as long-term memory

in healthy young adults” (Bergland, 2014, para. 19).

Active play is so beneficial in student academic success, that Dr. John J. Ratey (n.d.) at Harvard Medical School wrote a book about the importance of active play in learning. Dr. Ratey stated, First, it optimizes your mind-set to improve alertness, attention, and motivation; second, it prepares and encourages nerve cells to bind to one another, which is the cellular basis for logging in new information; and third, it spurs the development of new nerve cells from stem cells in the hippocampus. (para. 4)

Having as little as 5 minutes of an active heart rate can increase many things in the brain, such as oxygen levels, the number of neurotransmitters (assists ability to focus, learn, and handle stress) and the number of neurotrophins (responsible for learning, memory and higher thinking) (Ratey, n.d.)

Recent advances in neuroimaging techniques have rapidly advanced the understanding of the role physical activity and aerobic fitness may have in brain structure. “In children a growing body of correlational research suggests differential brain structure related to aerobic fitness showed a relationship among aerobic fitness, brain volume, and aspects of cognition and memory” (Chaddock 2010, para. 48).

Chaddock and his colleagues observed larger bilateral hippocampal volume in higher-fit children using MRI, as well as better performance on a task of relational memory.

Brain processes such as directing one’s attention, switching attention between tasks,

and moving information from short- to longterm memory are necessary actions for learning. Recently, scientists have been examining the underlying brain functions that may explain some of the immediate and more gradual academic benefits of physical activity.

Figure 1

Brain Image

Physically fit children demonstrate memory and efficiency of the brain by allocating more working memory to complete a given task through two learning strategies. “The first strategy is relational memory, which involves remembering objects by using cues, such as turn left after you pass the school and the second strategy is working memory, which involves moving information from the short- to long-term memory” (Kamijo, 2011, p.3).

This is important because children use relationships, such as understanding that “three groups of three” and “three times three” are both math facts with the same answer, to remember and recall information. “Physically fit children have larger hippocampal volume and basal ganglia” (Chaddock, 2012, para. 49). Both of these

brain structures have been associated with learning in children.

Physical activity can have both immediate and long-term benefits on academic performance. Almost immediately after engaging in physical activity, children are better able to concentrate on classroom tasks, which can enhance learning. According to Castelli (2014), Over time, as children engage in developmentally appropriate physical activity, their improved physical fitness can have additional positive effects on academic performance in mathematics, reading, and writing. Recent evidence shows how physical activity’s effects on the brain may create these positive outcomes. (p.2)

Methods

This study was conducted at an alternative education center in Central Minnesota within a 6th-8th grade middle level alternative program. MLAP has 17 students in grades 6-8. There are 6 students in 6th grade, 3 students in 7th grade, and 8 students in 8th grade. The socio-economic status of the school is 100% free and reduced lunch. The participants for this study were five special education students in my math class. There were four 6th grade students, three males, one female, and one 7th grade male student.

All five participants received free/reduced lunch, one was from a two-parent home, four were from a one parent/one step-parent home, and all five were Caucasian. Each student was on an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) for various Learning Disabilities (LD), Autism (ASD), Emotional/Behavioral Disorders (EBD) and Other Health Disabilities (OHD).

The design of this research was to be completed in school. The first six weeks of research was in class and the last four weeks was completed through distance learning. The research began in September of the 2020-2021 school year. Data was collected from the school-wide student information system called Skyward, as well as a daily data collection format on Google. This was completed prior to implementation of resistance band training for four weeks of the school year.

This information examined class participation in the classroom, as well as math test scores. Students took part in this study as a class together; they were not separated or placed into groups.

Before implementation of resistance band training in the classroom, I collected data and reviewed all student class participation and test scores during the current school year. I also noted outside factors prior to implementing resistance training in the classroom and noted concerns and specific areas to focus on during data collection. The study was conducted on all five students within the classroom and focused on the following: class participation and math test scores.

Every day at the start of the math period, the students would take out their heart rate sheets and write down their pre-active play heart rate. The students then would grab their appropriate weighted workout band for the resistance training. Each student would have enough room between themselves and others to complete all movements. The routine would start with continuous shoulder presses, for 20 seconds and then rest for 10 seconds. After the rest period, we would move onto tricep extensions, bicep curls, squats, and lunges.

After every movement, there was a 10 second rest period before the next movement. After the students completed each movement twice, the students then took their own heart rate and wrote it on their heart rate sheet. The goal for the student heart rates, was to be between 2 and 3 times their resting heart rate.

Active Play Results

Figure 2 shows the pre-active play test scores. Students were performing at a very low academic level prior to implementation. Two students received the letter grade D and three students received the letter grade F. At this time students had high test anxiety, poor study habits, and short attention spans.

It is reasonable to recommend increased physical activity at school as an evidencebased strategy to improve academic performance. – Johnson Foundation (2015)

Figure 2

Pre-test Scores

As shown in Figure 3, students were showing immediate benefit from active play performing at a higher academic level. Three students received the letter grade B and two students received the letter grade D. After the implementation of resistance band

training into the classroom, students were retaining more information, having increased attention time, and lower anxiety in class.

Figure 3 Post-test Scores

Figure 4 shows students’ academic scores on their daily homework. At this point in time, students were very selective on when they wanted to work and when they didn’t. One student received the letter grade A, one student received the letter grade D, and three students received the letter grade F. During this time, students were struggling to stay focused and give maximum effort and participation in class.

Figure 4

Pre-homework Scores

As displayed in Figure 5, students increased their homework scores immensely. The increase in student effort and participation during class allowed for more academic retention. Students were also showing an increased attention span. Two students received the letter grade A and three received the letter grade B.

Figure 5

Post-homework Scores

Figure 7 shows the daily participation by students after active play was implemented. The results from active play in the classroom made students engaged and wanting to take ownership of their learning. Lecture times increased by an average of almost ten minutes because of continuous student participation. The student participation average increased to 4.1 times per day.

“Physical activity has been shown to improve convergent and divergent thinking which leads to creative problem solving ability” (ParticipACTION, n.d., para. 7).

Figure 7

Post-Participation Averages

Shown in Figure 6 is the daily participation average of students before active play. During this time, students would sit through class with very minimal questions. I would have to call on students to have them engaged in the lesson. Student participation was at an average of 1.4 times per day.

Figure 6

Pre-participation Averages

Conclusion

Throughout the course of the research study, I found that implementing active play into the classroom was beneficial. Looking at the figures above, student test scores, homework scores, and class participation averages were all increased with active play.

An outside factor I did not think about while creating this research topic was increased self-confidence. Three of the five students showed and verbalized increased selfconfidence throughout implementation.

Another interesting finding from this research was that distance learning had a negative effect on special education students. Every single one of my students were affected greatly by distance learning in more than just academics.

References

Barile, N. (n.d.). Exercise and the brain: How fitness impacts learning.

https://www.wgu.edu/heyteach/article/ex ercise-and-brain-how-fitness-impactslearning1801.html

Bergland, C. (2014, October 2). 8 ways exercise can help your child do better in school.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/bl og/the-athletes-way/201410/8-waysexercise-can-help-your-child-do-betterin-school

Bitonte, K. (2012, March 26). Strength training beneficial to bodies and brains, experts say. https://www.usatoday.com/story/college/ 2012/03/26/strength-training-beneficialto-bodies-and-brains-expertssay/37390221/

Chaddock & Colleagues, Kamijo, Kohl (2013, October 30). Physical activity, fitness, and physical education: Effects on academic performance. Educating the Student Body: Taking Physical Activity and Physical Education to School., U.S. National Library of Medicine, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2015 01/

Crothers, L., & Demetriou, A. (2014). Physical exercise influences academic performance and well-being in children and adolescents.

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Da nilo_Garcia4/publication/259975972_E

DITORIAL_Physical_Exercise_Influenc es_Academic_Performance_and_Wellbeing_in_Children_and_Adolescents/lin ks/0f31752ed2964b7b7b000000/EDITO

RIAL-Physical-Exercise-InfluencesAcademic-Performance-and-Well-beingin-Children-and-Adolescents.pdf

Literacy Planet Legends (2017). How physical activity affects school performance.

https://www.literacyplanet.com/au/legen ds/content/how-physical-activity-affects school-performance/

Marques, A., Hillman, C., & Sardinha, L. (2017, December 20). Physical activity, aerobic fitness and academic achievement.

https://www.intechopen.com/books/healt h-and-academic-achievement/physicalactivity-aerobic-fitness-and-academicachievement

ParticipACTION, readersdigest.ca. (n.d.). 7 science-backed ways exercise improves students' grades.

https://www.readersdigest.ca/health/fitne ss/students-exercise-grades/

School Specialty (2017, July 20). How does physical activity affect academic performance?

https://blog.schoolspecialty.com/physica l-activity-affect-academic-performance/

Wood Johnson Foundation, R. (2015, January). Active education: Growing evidence on physical activity and academic performance.

https://activelivingresearch.org/sites/acti velivingresearch.org/files/ALR_Brief_A ctiveEducation_Jan2015.pdf

About the Author

McKinley Anderson is currently a special education teacher at the Middle Level Alternative Program (MLAP) in the Brainerd School District at the Brainerd Learning Center.

McKinley enjoys being outdoors, especially hunting and fishing. He is a coach for the Brainerd Warriors football and basketball teams. He also enjoys spending time with his girlfriend Faith and dog Chloe.

Each spring, the off-campus Graduate Learning Communities host an Action Research Conference held on the SMSU campus in Marshall, MN. Graduate students from around the region share their research with fellow educators and their topics are linked with the standards established by the Minnesota Board of Education’s requirements for re-licensure. You can earn CEU’s by attending the sessions.

Struggling Students and the Effects of Read Alouds

Jamie Copenace

About the Author Abstract

Children love being read to and the importance of reading to children for literary success is highly stressed in the field of education. What can be done for the struggling student? How can implementing read alouds in the classroom affect comprehension and motivation in struggling students?

Purpose

The practice of storytelling dates back to ancient civilizations with many stories including teachings for those who listened.

With the development of the written word, publication, and distribution of text; the modern-day world finds importance on the skills needed to attain literacy for academic success. This article will explore the arena of the classroom and ways educators can foster skills to aid in comprehension and motivation in struggling students.

Students who are most at-risk for reading difficulties in the classroom have not been consistently read to in their earlier years and therefore, have not had the exposure to spoken language patterns. Reading a story aloud to children prepares the brain to connect reading with pleasure Hazzard (2016). It also provides a reading role model, creates background knowledge, and helps build vocabulary.

The method of implementing a read aloud in the classroom seems feasible, considering

the reading to children aspect. Morrison and Wlodarczyk (2009) state, “Read-aloud is an instructional practice where teachers, parents, and caregivers read texts aloud to children. The reader incorporates variations in pitch, tone, pace, volume, pauses, eye contact, questions, and comments to produce a fluent and enjoyable delivery” (p.110).

Read alouds provide opportunities for students to become active participants by keeping them engaged, as the teacher models fluent reading. Reading aloud with expression and intonation provides students with a model for how fluency should sound. This builds student comprehension and they become better readers.

During a read aloud, the objective is for students to actively listen, in order to gain an understanding. As educators, it is vital to keep the central focus on meaning because if there are multiple teaching goals, then the meaning of the text may be lost for students (Wright, 2018).

Careful planning is key to implementing read alouds. Educators should preview the text and also conduct an initial read through to choose vocabulary to focus on and consider stopping points to ask open-ended questions. Open-ended questions are ones that do not have one right answer and requires students to think about the topic. Asking open-ended questions allows students to use their potential for higher order thinking to understand a concept and not simply restate it.

Students need coaxing to elaborate their answers. Educators can do this by asking questions that are designed to make students explain their thoughts in more detail. Accordingly, educators should focus on using questioning strategies based on Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a hierarchical classification system used to decide which objectives and activities engross students in higher level thinking. Therefore, educators should use Bloom’s Taxonomy to create activities for students that use higher level thinking. Implementing read alouds in the classroom can provide struggling students the opportunity to engage levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy as they must first attain mastery of the lower-level skills, such as remembering and understanding before moving onto the more complex categories.

Teaching students to make inferences is another strategy that will assist in reaching higher order thinking. In reading, inferences are when students fill in information about the story that has not yet been revealed. Making predictions about what may happen next in a story can generate inferences from students.

Giving students the time for discussion during a read aloud is beneficial because it allows them to engage in conversation with their peers and express their favorite parts, any questions they may be wondering, or perhaps even debate about the characters or plot.

According to Gainsley (2020), discussion before, during, and after a read aloud is significant to students’ overall literacy development because it draws on their abilities to ask and answer questions, make predictions, and make connections to their own personal experiences, thereby engaging in analytical thinking.

There are three types of connections students can make to enhance their comprehension. A text-to-self connection is when they can make a connection to their own life from something they are reading in a text. A text-to-text connection is when they can make a connection to something they have read in another text from something they are currently reading.

reasons. They may come from a home where English is a second language or a home where adults have low reading skills or levels and may also have hearing or speech impairments that would affect their ability to acquire the skills needed for comprehension.

The need for educators to serve as mediators is crucial to provide clarity on challenging words by explaining the meaning of words before, during, or after a read aloud. Keeping the focus on one to three words will ensure the student stays engaged and they will be less likely to become overwhelmed. Offering one or two sentences of childfriendly explanations will aid in retention of new words. Applying understanding of the vocabulary can be practiced through discussion of antonyms and synonyms related to the words or using the new word in a sentence (Wright, 2018).

A text-to-world connection is when they can make a connection to something happening in their community, country, or world from something they are currently reading (Morrison & Wlodarczyk, 2009).

Struggling Readers

Struggling readers may enter the classroom with a limited vocabulary for a variety of

Allowing students a chance to collaborate and talk with their peers about open-ended questions will enhance comprehension. Hibbard (2009) adds that having students work in pairs is helpful for learning new words and they are able to engage in discussion of the word and possible

meanings. Working in pairs provides students with the comfort and confidence needed to correctly identify word meanings.

When working with struggling readers, a strategy to teach is using context clues to find meaning. Context clues are words surrounding a new or unfamiliar word that can give the reader a clue about the meaning. This strategy teaches students to problem solve when they come across unknown words. Zorfass and Gray (2014) suggest that educators model a selfquestioning strategy that focuses attention on the unknown word with possible clues to its meaning.

Starting with small sentences to find the meaning of unfamiliar words is more manageable for students and less overwhelming. Students are able to selfmonitor and focus better with a smaller amount of text. Once students are well practiced with small sentences, they can move on to larger amounts of text to find the meaning of unfamiliar words (Hibbard, 2009).

Choosing the right text for read alouds can help students build knowledge when the texts are from a variety of genres. A fictional story can help students understand the text structure of a narrative by focusing on plot elements. Nonfiction informational texts can be integrated in science and social studies as sets of related texts on topics that address the standards of each subject with the goal of building knowledge over time. Students will acquire the stamina to

comprehend more and more challenging texts.

Educators should also consider texts that align with the cultural knowledge and background of students to support reading comprehension. Struggling students need characters and situations that are similar to their experiences so they can relate and make connections. When they become more involved, they are more interested. This is especially beneficial to minority students and those who come from lower socioeconomic classes. When students bring more related knowledge to a text, the better they are at comprehension (Wright, 2018).

It is equally essential when students have the choice in what books they can read because it can also increase their motivation. Offering students choices about their learning empowers them to become deeply engaged, display more on-task behavior, participate in creating a more collaborative learning environment, and it helps increase their social and emotional learning (Anderson, 2016).

Struggling students tend to credit their difficulties with reading to other things such as task difficulty, distractions, or unfair teachers and do not recognize that their lack of skill is the cause. They may give up trying and be viewed as defiant or unmotivated (Tankersley, 2005).

Building positive relationships with struggling students in the classroom is crucial. Low achieving students need to

connect with their teachers before they will initiate the necessary effort for academic success (Cambria & Guthrie, 2010). Offering effective praise based on high expectations when appropriate and honoring the effort of students will foster independence. Kaufman (2021) states:

Positive relationships are built on positive interactions. Each of these interactions has a powerful effect on the brain. When you authentically praise a student or have a positive interaction, the student’s brain releases dopamine. This creates a cycle. You provide positive feedback. The student’s brain releases dopamine. The student feels good and is motivated to feel that way again. With this increased motivation, students spend more time and attention working on a skill. They build those skills. You give more praise--sparking the release of dopamine. And the cycle starts all over again. (para. 4-5)

inspiration that comes from outside of the student, such as a reward. It is the goal of the educator to instill intrinsic motivation in all students and the reason behind many learning strategies.

Making connections with struggling students should be done early on in the school year to establish trust. I’ve found that offering a show and tell every Friday, even at the fourth-grade level gives good information about students’ interests and lives. This also aids in providing a positive learning environment that will support those who struggle.

Once student interests have been identified, then they can be used to select the first read aloud topics. Setting aside a specific time each day for a read aloud that is separate from a silent reading time where students read books independently helps establish a routine and procedure. As the year progresses and the students grow accustomed to the routine, they can start recommending books for read alouds. This is a great indicator of student engagement and motivation.

Qualitative data in the form of observations during the silent reading time can also offer insight to student engagement and motivation, as well as observation of input during discussion stopping points in the read aloud.

These practices will provide the students with confidence in their learning and lead to intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is inspiration that comes from within the student, whereas extrinsic motivation is an

I’ve found that the struggling students in my classroom are regular contributors to our discussions during our read aloud time and have made an effort to participate in the

silent reading time. A few students who struggle with decoding may benefit more from small group interventions during that time, which is something I will consider implementing in the future. These students are the ones who actively participate in discussions and show they comprehend what is happening in our read alouds, yet struggle when asked to write their answers on paper to answer pre-determined questions about the story.

Quantitative data in the form of online assessments can offer insight to comprehension and perhaps other aspects. The students’ performance on the Measure of Academic Progress for Reading was tracked in the fall and once again in the winter to measure growth. Only one of the three showed growth, while the other two had either made no growth or showed regression.

The student who didn’t show any growth struggled with decoding words and the student who showed regression had anxiety. There was also a low amount of Accelerated Reader tests taken, yet all had passed as they were the books our class had focused on for read alouds. The feature in the Accelerated Reader test that provides audio and read the question to the students was utilized and also a factor in their passing scores.

As a result of implementing read alouds in my classroom with the strategies mentioned in this article, I’ve learned that making connections with struggling students to build trust is important to establish early, in

addition to creating a positive classroom environment. Combined, they provide a solid foundation for struggling students to become comfortable and grow with confidence, once read alouds are introduced.

Although the data from the online assessments did not show much growth for the students, what stood out to me the most was the input during class discussions of the books we focused on in our read alouds. In this study, the qualitative data I observed was a more accurate display of student comprehension, engagement, and motivation. I credit that to the focus on active listening that read alouds provide and the opportunity for discussion to find meaning.

Some things I would do differently next time would be to offer small group interventions on decoding during silent reading time and complete running records to build fluency. I would also implement book conferences during silent reading, as a way for the students to talk about the books they’re reading independently; then track the number of books read and conferenced. Perhaps with these additional approaches, the online assessment data would improve.

Overall, this research proved to be effective because of the opportunity to apply certain strategies and assess how they impacted student comprehension and motivation.

References

Anderson, M. (2006, April). Learning to choose, choosing to learn. ASCD. http://www.ascd.org/publication s/books/116015/chapters/The-KeyBenefits-of-Choice.aspx

Cambria, J., & Guthrie, J. T. (2010). Motivating and engaging students in reading. The NERA Journal, 46(1), 1629.

Gainsley, S. (2020, September 1). How to build comprehension skills with readalouds. Highscope. https://highscope.org/buildingcomprehension-with-read-alouds/ Hazzard, K. (August, 2016). The effects of read alouds on student comprehension. https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/cgi/viewconten t.cgi?article=1360&context=education_ ETD_masters

Hibbard, R. (August, 2009). The effects of context clue instruction on finding an unknown word. http://reflectivepractitioner.pbworks.com /f/capstone3.pdf

Kaufman, T. (2021). Building positive relationships with students: What brain science says. Understood. https://www.understood.org/en/schoollearning/for-educators/empathy/brainscience-says-4-reasons-to-build-positiverelationships-with-students

Morrison, V., & Wlodarczyk, L. (2009, October). Revisiting read-aloud: Instructional strategies that encourage

students' engagement with texts. The Reading Teacher, 63(2), 110-118. https://www.readingrockets.org/article/re visiting-read-alouds-instructionalstrategies-encourage-studentsengagementtext#:~:text=Read%2Daloud %20is%20an%20instructional,a%20flue nt%20and%20enjoyable%20delivery

Tankersley, K. (2005, June). Literacy strategies for grades 4-12. ASCD. http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/ 104428/chapters/The-StrugglingReader.aspx

Wright, T. (2018). Reading to learn from the start: The power of interactive readalouds. American Educator. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ12002 26.pdf

Zorfass, J., & Gray, T. (2014). Using context clues to understand word meanings. Reading Rockets. https://www.readingrockets.org/article/u sing-context-clues-understand-wordmeanings#:~:text=When%20attempting %20to%20decipher%20the,as%20how% 20it%20is%20used

Question Format: Which is Better for Long-term Retention?

Joan FoleyAbstract

In this article, the author presents how question format impacts student retention in a high school science classroom. The study was conducted to determine whether multiple-choice or short answer question format is more effective in developing student retention of course content.

Introduction

With standardized testing and school report cards, it is essential to optimize student retention of course content. In Minnesota, math, reading, and science are tested in the spring with standardized tests. Many standardized tests have become more multiple-choice questions because of the ease of grading. An educator may question which format best serves students in the goals of retention and increasing scores on standardized tests

With this study, the researcher was seeking to determine if review question format impacts student retention. The researcher was primarily interested in the question formats of multiple-choice and short answer. The researcher was interested in improving standardized test scores and student retention within the district. There are research articles showing that multiplechoice and short answer formats may be comparable, but this depends on format. There is also research showing that multiplechoice review questions are better for preparing for a multiple-choice standardized

test. Other studies suggest that short answer questions are best for increasing student retention.

The participants in this study were from a public school located in rural, southwest Minnesota. In the 2020-2021 school year, the district enrollment was 670 students. The subjects were 10th grade biology students who are required to take a standardized test in the spring of the year.

Some factors need to be considered regarding the implementation of this study and the resulting data. The attendance of the students tested was not considered as part of the study. The district is primarily composed of Caucasian students. The class has been affected by mandatory quarantines imposed on students for direct contact with Covid-19 infected individuals. The school supplied staff with web cameras and microphones so that quarantined students may still attend classes and be part of class discussions

Literature Review

Research specific to student retention relating to the review question format used prior to tests was limited. Regarding retention in a study by Grundmeyer (2015), “The overall decline in student test scores 77 days after their original test score was 21%” (p. 6). This finding, in a profession based on standardized tests, highlights the need to improve student retention. In the book “Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning” (2014) by Brown et al., the authors stress the importance of retrieval in

the retention of content. Brown et al. (2014) state, “Practice at retrieving new knowledge or skill from memory is a potent tool for learning and durable retention” (p. 43). Brown et al. describe that “Effortful retrieval makes for stronger learning and retention” (p. 43).

Brown et al. (2014) added, “delaying subsequent retrieval practice is more potent for reinforcing retention than immediate practice, because delayed retrieval requires more effort” (p. 43). Brown et al. (2014) suggest, “Repeated retrieval not only makes memories more durable but produces knowledge that can be retrieved more readily, in more varied settings, and applied to a wider variety of problems” (p. 43). With repeated recollection of content in spaced retrievals, retention should increase.