InDepth

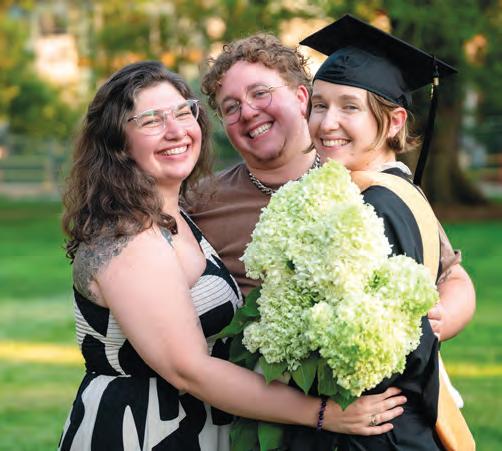

The annual opening ceremony is a joyous occasion as students return to campus and are reunited for a summer of deep learning and time in community. This year was no exception as this joyful embrace illustrates.

InDepth is published by the Smith College School for Social Work. Its goal is to connect our School community, celebrate recent accomplishments, and capture the research and scholarship at the School for Social Work.

EDITORIAL TEAM

Laura Noel Simone Stemper

DESIGN

Lilly Pereira

Maureen Scanlon

Murre Creative

CONTRIBUTORS

Kira Goldenberg

Katie Potocnik Medina

Faye S. Wolfe

Megan Rubiner Zinn

PRINCIPAL PHOTOGRAPHY

Shana Sureck

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR AND ALUMNI UPDATES CAN BE SENT TO:

InDepth Managing Editor Smith College School for Social Work Lilly Hall Northampton, MA 01063 413-585-7950 indepth@smith.edu ©2025

As part of the Juneteenth gathering organized by ARPG participants created quilt squares in honor of the day. The quilt was later stitched together by SSW Manager of Faculty Support and ARPG Member, Nieves Ayala and is on display in Lilly Hall.

smithcollegessw

instagram.com/ smithcollegessw

SMITH COLLEGE SCHOOL FOR SOCIAL WORK

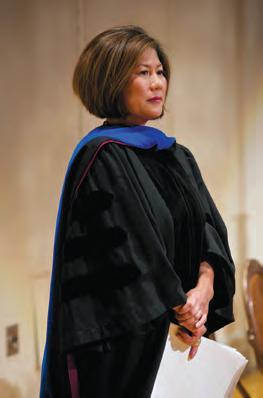

MARIANNE R.M. YOSHIOKA, M.S.W., MBA, PH.D., LCSW

My Fondest Adieu

I did not plan to step down during a time of such upheaval in the country. Higher education is facing complex and very real challenges: budget constraints, shifting enrollment patterns, and growing scrutiny about the value of what we do. And yet, I want to be clear, our School is in a good place. Yes, we face challenges, but we remain deeply committed to our core mission: delivering outstanding teaching and learning, and producing innovative scholarship and research that pushes the field forward.

This summer, I had the honor of delivering my final commencement address as dean of the Smith College School for Social Work. After eleven years in this role, it was a moment of profound transition, not only for our graduates stepping into the next chapter of their professional lives, but for me as well. On June 30, 2026, I will step down from this position and take on some new projects of my own in the community as I move into retirement.

When I first arrived in 2014, both the world and the field of clinical social work looked very different. Since then, we have lived through seismic shifts: the rise of transformative social movements like Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, a global pandemic that fundamentally altered how we work and connect, and the rapid emergence of artificial intelligence and other digital technologies. These forces have reshaped our society and they have profoundly impacted how we teach, learn, and practice clinical social work.

At Smith, we have met these changes with adaptability, creativity, and care. It has not been a straightforward linear journey and there have been many lessons along the way, but we pulled together, we faced our problems head on, and we grounded ourselves in community.

I’ve had the extraordinary privilege of witnessing this community up close. I’ve worked with faculty who care deeply about teaching and learning—not just teaching content but helping students to gain perspective,

to understand what it means to be a social worker, who care so deeply that their students not only leave here with knowledge, but with a sense of how to practice in the world with integrity. I’ve seen students arrive with bold voices and deep commitment, organizing and questioning while caring for each other in quiet, powerful ways. I’ve worked with staff who bring such skill, generosity, and collaboration to their work, creating the conditions that allow this School to thrive. And I’ve met alumni, so many of you, whose enduring devotion to Smith continues to inspire me. Your belief in the education you received and the relationships you built continues to sustain this community.

I did not plan to step down during a time of such upheaval in the country. Higher education is facing complex and very real challenges: budget constraints, shifting enrollment patterns, and growing scrutiny about the value of what we do. And yet, I want to be clear, our School is in a good place. Yes, we face challenges, but we remain deeply committed to our core mission: delivering outstanding teaching and learning, and producing innovative scholarship and research that pushes the field forward. Our work is guided by our Core Principles which will continue to shape how we teach, how we lead, and how we grow as a community. The shifts in the larger environment do not change these commitments.

We will continue to build a school that is both rigorous and responsive,

a teaching and learning environment where critical thinking, clinical excellence, and our profession’s values of social justice are deeply interwoven commitments. Our curriculum will continue to evolve to reflect the complexities of contemporary practice, while remaining firmly rooted in our psychodynamic foundations, foundations that enable students to work relationally and attend to the inner lives of those they serve. We will continue to expand our efforts to recruit and support a diverse student body and faculty, even as we navigate new legislation that shapes how this work can be done. We will continue to deepen our investment in practicum partnerships that prepare students for the shifting realities of clinical work. And we will remain steadfast in growing a beloved and accountable community, one that makes room for one another, asks for accountability and repair when missteps occur, and fosters connection through shared learning and meaningful relationships.

I am excited to see how the next leader will carry SSW into its next chapter, guided by our Core Principles and grounded in deep care for this extraordinary place.

Thank you for allowing me the privilege of serving as your dean. It has been a life-changing experience for which I am deeply grateful. I am a better person for having been welcomed here.

Once a Smithie, always a Smithie. ◆

Says Dean Yoshioka: “I like to start my day with reading, spending time with my partner, exercising, walking the dogs, eating breakfast, and doing a first round of emails. I find spending a little extra time doing this every morning sets my day up in the best way possible.”

SSWorks

News from Lilly Hall

Current student Gabrielle Samaripa displays her creation for the SSW Juneteenth quilt.

BY MEGAN RUBINER ZINN

The Changing Landscape

SSW’s practicum placements refocus to better meet current needs

The SSW practicum process has evolved to meet the changing needs of students and agencies. A particularly marked change is how students are matched to placements and how they are supported through the process.

These changes are not specific to SSW—Katya Cerar, M.S.W., Ph.D. ’13, senior director of practicum learning, knows from interactions with other social work schools that they’re all grappling with the same issues. “It’s the landscape we’re living in.”

Historically, SSW staff would place M.S.W. students at agencies—they did not interview for their positions and they had no control over where they worked. Ph.D. students, because they were licensed practitioners, would

usually do their practicums at the sites where they were already employed.

The M.S.W. positions were unpaid— in return for their work, students received supervision, mentorship, education, and access to clients.

Over time, placement sites and students increasingly requested interviews to confirm fit. Students also sought more choice in location, particularly because financial limitations and family responsibilities meant they couldn’t relocate.

What agencies can offer has changed as well. Some no longer have the resources and staff to provide the same level of one-on-one time to students. With significant turnover and high caseloads, “I think there’s more pressure to just do the work, versus let’s make space for your learning,” Cerar said.

Cerar observed that students also need more preparation and support. Many are entering the program with limited experience, some as career changers, and often they are younger and dealing with residual trauma from the pandemic. They need guidance in navigating the culture of the worksite and in developing a sustainable worklife balance. They also need more training to make up for a decrease in mentoring and supervision.

The unpaid internship model has also become unrealistic for many social work graduate students, and many have expressed concern about providing free labor for the agencies. Further, it has limited the number of students who could consider attending SSW, particularly impacting students from marginalized communities.

Longtime practicum advisers Laura Flanagan, M.S.W., and Shiva Jyoti, M.S.S.W., have experienced many of these shifts firsthand and have unique perspectives on them.

Sydney Voelbel, M.S.W. ’25, works with a client in their home during her second year placement.

Both agreed that students are coming in with less life experience and with less experience navigating a workplace—especially a social service agency. Perhaps because of this inexperience, they have noticed that students have become more demanding. “I would say what encapsulates them is—you’ve heard the phrase ‘Be the change’—they really take that to heart. They feel that they have a right to question. They want to make sense of things,” Jyoti said. “I think the students come in wanting more because there is more. They come in wanting the entire buffet, which is a very positive change for our profession.”

One of the changes pushed by students that Jyoti has been glad to see is paid practicums. “I think the conversation about whether internships should be paid or not—opening up that dialogue with the agencies—is a very valuable one to have.”

SSW has been responding to these evolving needs over a long period of time, with the initial changes put into place by the previous director of practicum learning, Katelin LewisKulin, M.S.W. ’00, and now further developed by Cerar and her team.

Throughout the process, the placement office’s priority has been to meet evolving needs while still centering education. (See more about how SSW is addressing these challenges in the sidebar.)

To begin, students have more choice in their placements and they all

SPOKEN WORD

SSW students are really being taught better how to include intersectionality, issues of oppression, into psychodynamic clinical work, and students are using it more easily and gracefully in their internship work.

—LAURA FLANAGAN M.S.W., PRACTICUM ADVISER

interview, unless their practicum is at a site where they already work. The practicum staff are able to facilitate connecting students to agencies that are a strong match for them and they have far more flexibility in placing students where they live. “We are much more attuned to these needs, given the economic landscape, the trauma landscape, the challenges that people are facing,” Cerar said.

In recent years, SSW has instituted more structures to ensure students are better prepared and more thoroughly supported through the process.

Notably, they’ve developed a required practicum prep course. In this remote class, instructors address the nuts and bolts of practicum work, what to expect, the relationship with supervisors and the faculty adviser, how to resolve conflicts, how to deal

with racism and microaggressions, and where to go for help.

Because students have often felt disconnected from SSW during placements, the School has also implemented a remote practicum seminar that meets monthly. The focus of this course is connecting summer coursework with practice. It also serves as a place for consultations, with students presenting cases and getting feedback from their instructor and peers.

“ You are part of a noble profession that is necessary to creating the change we need in the world. You know we can not separate the individual from the systemic. Our systems will not become healthy again if our individuals are not healthy. And you, you, you social workers each know how to do this.”

MIRIAM YEUNG, SSW 2025 COMMENCEMENT KEYNOTE SPEAKER

Another addition is simulation-based learning. Trained actors portray patients or clients, and students meet with them as if it’s the first time and then again as if they’ve been meeting for a number of weeks. Students then get feedback on the interactions from the instructor and their peers.

Finding ways for students to receive funding for their practicum work has been a particularly challenging but important change. Because students receive academic credit for their placements, SSW itself cannot pay them. Funding must come from agencies, but many do not have the resources to provide it.

SSW is addressing the issue in two key ways. One approach is working with agencies to develop more placements with stipends or, in some cases, to hire the students as employees.

The other is approving employment-based practicums. In these cases, students who already work with agencies can stay with those agencies as their practicum site, as long as they have a structure to offer mental health treatment. SSW has gone from allowing these on rare occasions to seeking them out whenever possible, even suggesting them to students if they see from their application materials that they’re working at an appropriate site.

Through all of the changes SSW has experienced, one thing hasn’t changed: With their combined academic and practicum training, SSW graduates are in great demand among employers.

“The majority of our students get offered work in their second-year internship, or the first-year internships will say, ‘When you graduate, get back in touch with us,’” Cerar said. “We get a lot of cold calls from agencies asking, ‘Can you post this job? I really want to hire a Smith student. There’s something different about your students.’”

Jyoti credits the SSW academic training for creating such a solid foundation. Expanding on that, Flanagan said, “I think even during internship, they stand out because their actual theoretical training is much deeper and richer and better.” Flanagan also noted that “SSW students are really being taught better how to include intersectionality, issues of oppression, into psychodynamic clinical work,” and that students “are using it more easily and gracefully in their internship work.”

“I’ve had some agencies say, ‘Your students are sometimes better than clinicians we’ve had for three or four years,’” Cerar added. “‘They are deep thinkers. They’re critical in their thinking. They seem to understand the clinical work in a way that my other clinicians don’t.’” ◆

EXAMINING OUTCOMES AND AFFORDABILITY

There is a significant and important change on the horizon for Smith SSW. Beginning in fall 2026 the School will reduce the weekly practicum requirement to 24 hours for both first- and second-year students. This change was carefully considered through the lens of the School’s five Core Principles, feedback from past students, shifts in the national economy, recent research about hour requirements, the goals of national Pay for Placement (P4P) movement, and in particular the 2024 Student Experience Survey Report administered by students in the Smith SSW chapter of P4P. Importantly, this change still exceeds the CSWE minimum required hours.

“We did not make this decision lightly,” said Katya Cerar, M.S.W., Ph.D. ’13, senior director of practicum learning. “Over the past two years, the Office of Practicum Learning has been deeply engaged in examining our required hours through the dual lenses of student learning and affordability. What we have observed is that more hours do not necessarily mean better learning outcomes, and in the current national and professional context, the burden of the current requirement may actually be impeding student learning.”

The reasons supporting this change are numerous and varied. For students, data shows that many graduate with significant debt, an added challenge as they enter a historically low-paying field. In addition, agencies across the country have found it more and more difficult to provide the required supervision due to staffing shortages and budget cuts. Finally, social work schools across the country have dropped their required hours to the CSWE minimum of 900 hours. SSW and its students have not been immune to these external factors and while the School has worked hard to mitigate them, maintaining the nearly full time requirement has posed challenges.

“It’s hard for the field placement to feel like a learning experience when you have such little time to reflect. Between doing 30 hours/week unpaid labor, 16 hours/week part-time job for pay, homework, process recordings, attending seminar, CBARE hours, it’s challenging to find time to integrate the experience, let alone find time to sleep/ cook/eat/spend time with family and friends.”

—Student feedback

“We have made significant progress securing funding for students during their placements through private gifts and federal and state grants,” said Dean Marianne Yoshioka. “However, these gains have been slow and are not guaranteed. Most students remain significantly under-resourced during their internships and many students report having to work a paying job while also parenting or caregiving. The 30 hour per week requirement does not allow for rest, for deep investment in academic work, or for personal wellbeing. In short, the current structure has become untenable.”

“A reduction in hours allows space for students to invest in academic and professional development, caregiving, parenting, rest, and overall wellness which is in deep alignment both with the NASW Code of Ethics and the School’s values,” said Yoshioka. “Our final Core Principle asks us to stay open to and actively engage with change. We know this change is in the best interest of student learning and wellbeing while still maintaining our commitment to excellence in teaching and learning.” —Laura Noel

Integrating Theories, Expanding Practice

New M.S.W. electives prepare students for diverse practice settings

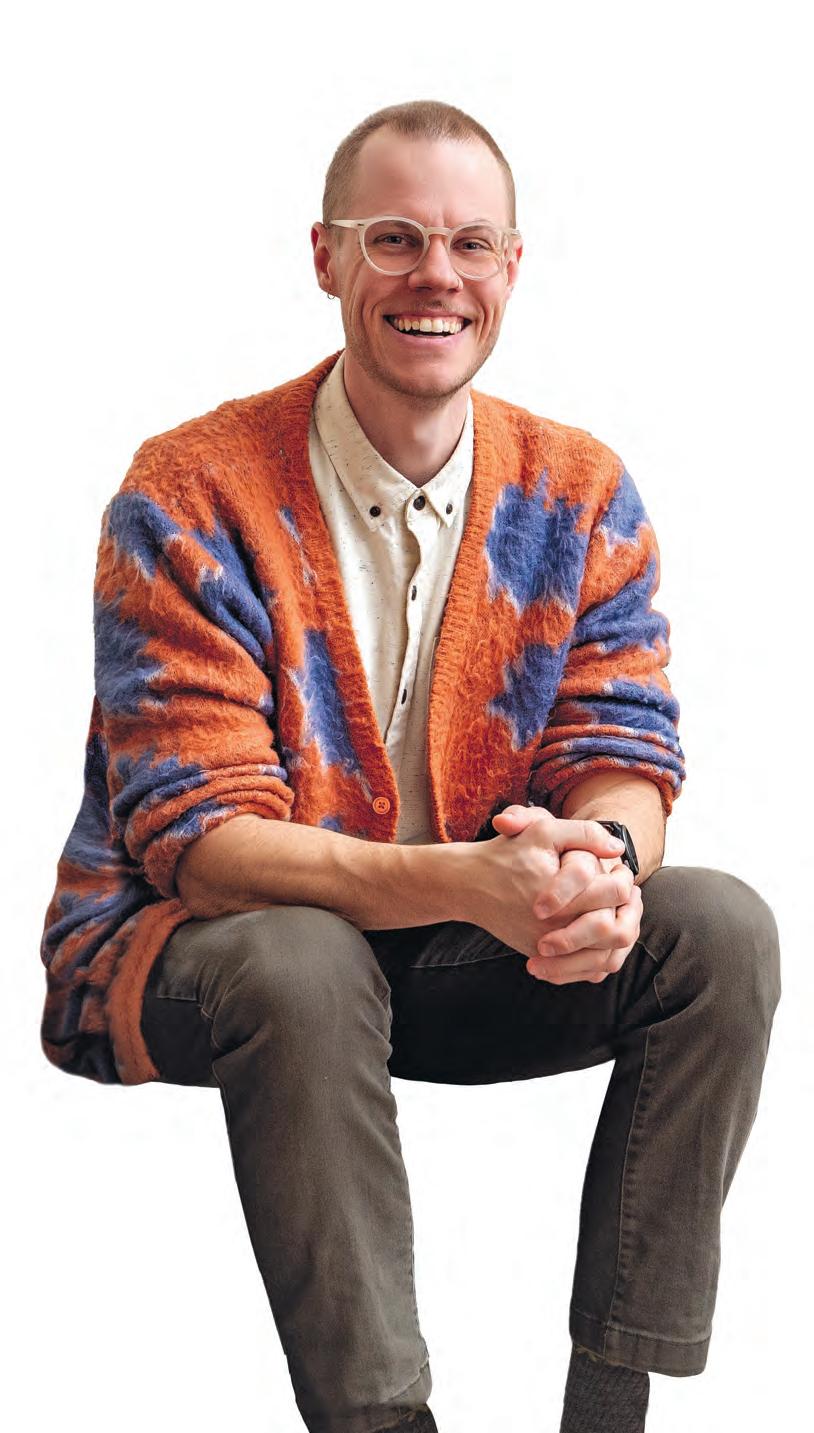

SSW is offering two new electives inspired by interdisciplinary social work practice. Professors Hugo Kamya, M.Div., M.S.W., Ph.D., and Shveta Kumaria, M.A., M. Phil., Ph.D., LICSW created the courses based on the impact of integrated approaches on clinical social work practice outcomes.

Kumaria’s course sits at the intersection of theory, practice and research, providing students with a strong and flexible theoretical base to effectively support a broader range of clients.

The course, Bridging Psychodynamic and CBT: An Introduction to Integrative Psychotherapy, came out of her experiences adapting her practice to different countries and cultures and weaving together theories to support the client in the way they need. Kumaria said she was excited to introduce the field of psychotherapy research, and share the proven success of the approach.

work. Designed by Kamya, the course teaches narrative therapy (NT) which seeks to build collaborative, respectful, and socially-just ways of understanding people and problems. NT stands against individualizing and pathologizing discourses of people’s suffering which helps students come to their practice from a place of empowering their clients.

me. I say it found me.

Research shows most therapists identify as eclectic or integrative, but Kumaria says it’s rarely discussed. “In practice, if we’re all doing this, let’s teach our students how to do it; let’s set them up for success.”

Kumaria explains that the course builds on what students have learned and integrates their own background and how they understand mental health, cures, and illness. There is “a focus on the self of the therapist in the course, and we also focus on the therapeutic relationship and how the student comes in with their own humanity and vulnerability. How do they understand that and use it in the service of the client?”

The second course, Narrative Approaches to Social Work Practice, also builds on students’ previous

Creating this course has been a lifelong process for Kamya. “People ask me if I found NT or if it found

Growing up, I was told stories about land, resources, climate, and in a way, I was operating in the land of stories.” Kamya says that his understanding of self came from the stories he heard starting in childhood, from his parents, family and community, and they all shape who he is today. “As I work with people, [the stories they share] speak about identity, speak about hope, speak about growth, development, understanding.”

In creating the course, Kamya wanted to address NT theories, interventions, and techniques because a story is not just a story, he says. “ I like to provide [this approach] to students as an advanced way of working with people. What inspired me was to provide students a place to combine perspectives and approaches with NT to broaden their understanding and to be building their practice as they grow.”

“[This] approach helps people broaden stories, expand those stories,

give audience to those stories in a way that allows for healing to happen, in a way that provides people even greater ways of understanding themselves and their communities. These stories come from a place of collective expertise.”

Kamya brings together social work, psychology, and theology in his work and explores the integration of spirituality in clinical practice. He’s been involved in NT for 25 years, and has utilized it in teaching and research. A culmination of this work is his forthcoming book, Narrative Practices for Resilience and Hope: Rewriting Stories of Trauma in Clinical Work.

In the classroom, Kamya creates an environment grounded in curiosity, openness, and respect. NT seeks not to replace other knowledge or theoretical perspectives, says Kamya, but instead to honor psychodynamic, relational, cognitive behavioral (CBT), and neurobiological perspectives. “I am excited about the opportunities that NT practices offer to expand people’s stories into more satisfying, thicker self descriptions.”

Said Kumaria, “Smith SSW is known in social work circles as producing some of the best clinicians that are out there.” These thoughtful and responsive new courses support that perception by helping students get a solid grounding before stepping into their professional practice.

Simone Stemper

Providing students with a strong and flexible theoretical base allows them to effectively support a broader range of clients.

Above from left, Hugo Kamya, Shveta Kumaria

More than 146 clinicians flocked to campus on August 1, 2025 for the annual Deepening Clinical Practice Conference. Following the conference, alumni gathered to network and connect with final summer students and each other.

laughter &

heart

DEAN YOSHIOKA’S

LE GACY AT SSW

STORY BY KIRA GOLDENBERG

PHOTOGRAPHY BY SHANA SURECK

Thenation was a vastly different place in 2014, the summer when Marianne Yoshioka first became dean of the Smith College School for Social Work. COVID-19 had not yet reshaped years of reality. George Floyd was alive in Minneapolis. Barack Obama was president.

Shortly after taking the helm, though, an avalanche of unprecedented events began, from pandemics to racial justice reckonings to rapidly shifting industry norms. And when it did, it inevitably impacted an institution full of attuned students training for a social justiceoriented helping profession.

“So much has happened,” said Yoshioka, who announced earlier this year that she is retiring from the role at the end of June 2026. “When I first came [to Smith], I don’t think I had any understanding of the situation I was walking into, which was that there were many great things about this School and this community but there was change poised to happen. This change would have happened regardless of who was the dean,” she said, but “there were things that I triggered in particular, maybe unwittingly, then there was the crash of time, of external events.”

As she, colleagues, and mentees survey her time leading SSW, one theme rises to the top: Yoshioka has spent her time in the role listening closely to guide collaborative change, shifting the School and its curricula toward a more equitable future. She has shepherded in a faculty sea change—they are now majority scholars of color—as well as an inclusive School culture, racial justice-focused guiding principles, and a larger research focus.

“We are still deep in this cultural transformation,” she said. “It felt, when I first got here, like we as an institution—as a group of people—that we had gotten a little stuck, unsure of how to respond to the evolving world and demands on us as a school for social work and our history. History is really important at Smith. The key was how to let loose just enough to let us move without unravelling and negating all that came before.”

Dean Yoshioka bikes through campus in 2014.

Dean Yoshioka walks with Juanita Dalton Robinson, M.S.W. ’51, and her daughter, Rachel Robinson, M.S.W. ’94 during the School’s Centennial celebration in 2018.

“She has the ability to see what needs to be done, to move things in that direction, and to hold the complexity of situations. I find her to be a very inspirational leader, very real, personable, and kind.”

SARAH YANG MUMMA, PH.D. ’2 3

She did all this, according to Professor Emeritus Josh Miller, M.S.W., Ph.D., with a quiet-but-strong leadership style.

“She was really very fair and evenhanded,” said Miller, who was associate dean at the start of Yoshioka’s tenure.

Sarah Yang Mumma, Ph.D. ’23, who has taught at SSW and, before that, was Yoshioka’s dissertation advisee, agreed.

“She has the ability to see what needs to be done, to move things in that direction, and to hold the complexity of situations. I find her to be a very inspirational leader, very real, personable, and kind,” she said.

Yoshioka was recruited to the SSW after eight years as academic dean at Columbia University’s School of Social Work, following a decade on the faculty where her work focused on studying domestic violence among Asian Americans. Before that, she earned her doctorate in social work at Florida State University, where she worked with women at risk of contracting HIV. Yoshioka earned her M.S.W. from the University of Michigan.

“I was looking for a change,” she said. “To be in academia for the long haul, you need to reinvent your circumstances periodically to stay fresh—you have to keep growing and learning.”

When Miller and former Associate Dean Irene Rodríguez-M, Ed.D., invited her for coffee during the Council on Social Work Education conference in 2013, she was not initially sure about transitioning from a large urban school to a small one in the wilds of Western Massachusetts. But the more she mulled it over, the better the idea seemed.

“What really seemed to stick with her more than anything was the School’s anti-racism commitment, and she has often said since then that had a lot to do with her applying for the job,” Miller said.

detail-oriented, with a wide portfolio of responsibilities. Her purview there prepared her better than she anticipated to become the kind of leader she wished to be at Smith.

“It’s critical,” she said, “to lead with integrity: to stay grounded in your values, to be transparent about what is possible and what isn’t, and to hold space for both truth-telling and relationship-building.”

“It got me excited for the challenge of it,” Yoshioka added. “I struggled with imposter syndrome—worries of ‘Could I?’ but I decided I would go for it.”

ANTI-RACISM AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Her academic deanship at Columbia required her to be procedurally- and

The largest overarching shift Yoshioka oversaw while leading SSW was the creation and rollout of the School’s five Core Principles. Unveiled in 2020 after a multi-year, multi-constituent planning process, the Core Principles were created in response to consistent feedback that the School’s original anti-racism commitment, dating back to 1995, was inadequate for the present moment. The updated Principles emphasize intentional action, accountability, repair, and centering community members from historically marginalized populations.

“The work of getting to there was shaped by these broader principles of collective endeavor, authenticity, space for people to be their full selves and to retreat if necessary,” said Smith

At right: Dean Yoshioka poses with the class of 2016 after Baccalaureate. Inset round photo: Dean Yoshioka introduces a speaker during the 2018 Public Lecture Series.

College English Professor Michael Thurston. As College provost from 2019 to 2024, Thurston and Yoshioka met regularly, giving him a frontrow perspective on her leadership and thought processes. She aimed to ensure, he said, that the School created a deep culture change, not just “a topdown, technocratic fix.”

Accordingly, under Yoshioka’s guidance, an acronym-rich collection of committees labored, collectively, to align the School’s actions and offerings with the Principles, arranging offerings from anti-racism learning opportunities run by outside consultants to rolling out a set of commu nity agreements, which guide how to handle relational ruptures.

It’s “an evolving document that calls on each member of our campus to take responsibility for their actions and words, to make room for others, and to center care in our relationships,” Yoshioka said. “It asks us not to cancel one another in moments of disagreement, but to stay in conversation and hold space for accountability and connection.”

In the years since the debut of the five Core Principles and Community Agreement, Yoshioka has noticed an increasingly inclusive campus community. “[A] culture change is taking hold based on the tenets of our Community Agreement, which encourages listening, learning, and developing accountability for our words, actions, policies, and procedures,” she wrote in an update in late 2024. “The empathy and self-reflection required by the Community Agreement is helping people who spend time on campus feel more ease and generosity with one another.”

FACULTY OVERHAUL AND CURRICULUM REFORM

Yoshioka’s commitment to anti-racism and inclusivity has extended to reforms in areas formerly considered sacrosanct: faculty and curricula.

She has overseen a shift from a majority-white to a majority-BIPOC

faculty by prioritizing diversity in hiring and helping create policies aiming to repair historical inequities. These include adjusting faculty workload requirements to recognize the disproportionate mentoring load often shouldered by BIPOC professors and doing away with the residency requirement that required faculty to live locally.

“She completely rebuilt the faculty in a way that included the faculty,” Miller said, calling it an “enduring commitment to values that she just

would not compromise on.” The shifts have meant that students are able to seek mentorship from faculty whose lived experience—in terms of both race and geography—better reflect their own.

“Marianne happens to be the second dean of color in a row,” said Yvette Colón M.S.W. ’90, Ph.D., a member of

Top: Dean Yoshioka and 2024 Alumni Award Winner Adama Sallu, M.S.W. ’93. Inset round photo: Dean Yoshioka chats with 2025 graduates Iain Cooley and Isabel Snodgrass. Bottom: Dean Yoshioka smiles with 2019 graduates Brian Mai and Alexandra Sobieraj.

the Alumni Leadership Council who won the School’s Day-Garrett Award in 2024 for her leadership in oncology and palliative social work. “I think that was really meaningful for the School, because we had two people who really understood the importance of psychodynamic theory but from lived experience, from work experience, and were much more grounded in how we can all use psychodynamic theory to challenge colonialized mental health.”

This valuable lived experience was also reflected in the type of work Yoshioka has championed. She helped Yang Mumma hone and sharpen her dissertation on how multiracial therapists navigate identity within the context of their clinical work.

“It was so powerful for me to have her see the value of that research. She spoke about how there’s so many mixed students who would really benefit from having this area of research explored,” Yang Mumma said.

In addition to a positionality that sought to incorporate anti-racist principles into both faculty workloads and scholarly work, Yoshioka’s leadership also allowed for movement on the formerly intractable issue of incorporating more research into the School’s curriculum. Psychodynamic

theory has always been SSW’s grounding clinical lens, a practice traceable back to the discipline’s foundational Freudian theories. There are deep disagreements in the profession over the efficacy of psychodynamic theory both inherently—it was forged from a white, male, 20th century worldview— and in opposition to more mechanistic modalities.

But generations of students have attended Smith for its psychodynamic emphasis, creating generations of alumni who want to make sure that the School does not back away from its commitment to psychodynamic clinical practice.

“The themes of the conversation have been a fear of letting go of the curriculum that really is unique and meaningful in this world, coupled with the challenge to train students to work in contemporary practice,” Colón said.

Yoshioka has been clear about the School’s commitment to its roots—she has proposed a D.S.W. that would prepare graduates for leadership in psychodynamic-oriented clinical practice, supervision, and education— while also pushing to position students as competitively as possible in the contemporary social work milieu. To that end, the School has honed its

LEADING THROUGH COVID

As Yoshioka worked toward her largerpicture goals for the School, COVID-19 descended.

“The School had to move extremely quickly,” Miller said, both transitioning academic and internship placements from in-person to digital and juggling the less glamorous aspects of the moment, like interfacing with tech employees and accreditation officials. “I think she did a great job, and she supported the creativity of other people…. She always kept the College informed and she kept faculty informed about what the College wanted and what the College was doing.”

Then, after two remote summers, Yoshioka oversaw the transition back to in-person learning. There were masking and testing rules, an emphasis on outdoor activities, and a need to orient a cohort of students who had never set foot on campus into a shifting community culture.

“These moments often brought heightened anxiety and, at times, feelings of chaos,” Yoshioka reflected. “What I’ve learned, and tried to model in my leadership, is the importance of always coming back to community.”

“These were high-stakes moments,” she continued, “the kind that test not just leadership but the integrity of an entire institution. And while we didn’t always come together right away, we ultimately did—and we emerged stronger for it.”

research graduation requirements and restructured the Ph.D.

“What sets us apart is that we’ve stayed steady in our convictions,” Yoshioka said. “Amid rapid changes, we’ve continued to prepare students exceptionally well, balancing rigorous clinical training with deep attention to social justice, ethical practice, and the relational foundations of our work.” ◆

Recognizing Leadership & Innovation

STORY BY FAYE S. WOLFE

If you spend time talking with social workers the idea of “being seen” will likely come up. They know the need for—and the inestimable value of— seeing deeply and truly who people are, where they come from, where they are, and where they want to be. From this way of seeing comes the power to nurture positive change and growth. With these profiles, we offer you the opportunity to see four outstanding alums as we highlight and celebrate the many ways they educate, build knowledge, elevate their profession, fight for justice, and heal.

CATHLEEN MOREY

Leadership Ethics in Practice

The Social Work Leadership Award honors a mid-career alum who has demonstrated exceptional leadership in the social work profession.

It’s not surprising that her fellow alums chose Cathleen Morey, M.S.W. ’00, Ph.D. ’19, to be this year’s recipient of the Social Work Leadership Award. She has amply met the award’s requirement of having “demonstrated exceptional leadership in the social work profession.”

And in a time when certain prominent leaders are, to quote Shakespeare, “full of sound and fury, signifying

nothing,” Morey’s leadership style is exceptional for being, as she described it, “quiet.” After a moment, she elaborated: “My way of promoting the profession, it’s about doing the work, working on the ground, focusing on infrastructure, effecting change over the long run.”

She knows something about the long run: She was awarded her Ph.D. at age 59 and has worked at the renowned Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Massachusetts for 21 years.

“I thought I’d go to Riggs for a couple of years,” she remembered, but the center proved to be just too good a fit. In 2013, she became its director of clinical social work. Among the things she values about Riggs are its deep commitment to education, its emphasis on intersectionality, its sociocultural values, and its systems-based and psychodynamic orientation.

The psychiatric residential facility approaches treatment in a “deep, nuanced way,” she said. For example, “The patient family-history assessment gathers information on three generations, toward understanding the context of a person’s struggles.” This approach speaks to Morey’s own interest in intergenerational family dynamics, one of several subjects she has published papers about.

As her list of publications reveals, an ongoing area of investigation has been how clinical systems work—or don’t. Her research has shown that when a patient with multiple comorbidities and a complicated history isn’t getting better, the treatment team may say the patient is the problem. But the team may be part of the problem, their own histories unconsciously influencing their behavior and the patient’s. Institutional stresses—staff shortages, financial pressures—may come into play. The result of this perfect storm is a system enactment. Morey’s goal in studying that phenomenon is not just to describe it but also to delineate solid, evidence-based means—skills, knowledge, steps—to repair and restore broken-down systems.

“In a system, we all contribute. The scientist in me wants to approach problems with clarity and propose usable solutions. I want to show how

social work leadership AWARD

to apply new, positive approaches, to create a supportive framework for both patients and staff, a therapeutic culture.”

More recently, Morey has delved into how the ethics of social work are taught.

“I began by looking at the scholarship,” she said. “Much traditional ethics training and education seemed focused on procedure and compliance. It didn’t take into account how power dynamics, privilege, oppression, and racism affect contemporary multicultural practice, and it didn’t address ethical issues clinicians I was teaching were grappling with.

“What I find exciting,” added Morey, “and what people respond to, is reconceptualizing ethical practice, moving beyond a regulatory focus, developing a deeper knowledge, and encouraging aspirational ethics, that is, being accountable to the values of our profession: justice, dignity, integrity, commitment to anti-oppression.”

Her research has led to her giving ethics-related seminars through SSW’s Advanced Clinical Supervision program and Austen Riggs’s Erikson Institute for Education, Research, and Advocacy. Last fall, she was an invited guest speaker at a day-long ethics training for school social

workers in Portland, Maine. In April, as an invited guest speaker, she presented “Ethical Dilemmas in Clinical Social Work Supervision” at the American Board of Clinical Social Work’s annual conference.

Morey sees herself as part of an “intergenerational legacy.” Mentored at Smith by leaders in the profession such as Kathryn Basham and Joanne Corbin, she seeks to do the same in her role as an SSW adjunct assistant professor and professional education instructor. And several years ago, she was instrumental in establishing internships at Austen Riggs for students from Smith and other social work programs.

With her Austen Riggs position, her teaching, presenting, and publishing, Morey might be excused for thinking she was doing enough to “elevate social work practice,” a lifetime goal. Not so. Since 2020, she has volunteered with the nonprofit International Social Work Solutions, developing and consulting on programs for NGOs operating in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda. Last year, she designed and co-led a trauma-training conference in Ghana for young women who had been subject to ritual servitude and sex trafficking.

In describing that intense experience, Morey praised her co-leader’s contribution at length. About her own, her quiet leadership style showed itself as she said simply, humbly: “I was honored that the participants let me into their lives.” ◆

Change Agent AWARD

Pushing Boundaries, Building Change

Lisa Lynelle Moore, M.S.W. ’98 is this year’s recipient of the Change Agent Award, which honors a School for Social Work alum “who embodies the spirit of transformation in the profession, driving positive change through groundbreaking approaches.”

Asked why she thought her fellow alums might see her as a change agent—put on the spot, in other words— Moore pointed to her teaching. Having previously taught at Boston University and St. Olaf College, she is now a senior lecturer and the director of the master’s program in Social Work, Social Policy, and Social Service Administration at The Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice at the University of Chicago, where she also serves as a faculty resident head. She has previously served as assistant dean for multicultural affairs at Reed College, assistant director for the Women’s Community Center at Stanford University and as director of the Mary McLeod Bethune Multicultural Center at Clark University. In these administrative positions, each one new to the institutions, she was responsible for building infrastructures for supporting students, staff, and junior faculty from historically underrepresented populations.

“I’ve been in higher education for 26 years, as a student, an administrator, adjunct faculty, tenured professor,” Moore noted, adding almost shyly, “I think I’m a pretty good teacher.” Then her face lit up as she talked about how exciting teaching, working with, and mentoring students has been and still is to her. She spoke enthusiastically about the “creative, amazing things” former students are doing and about the career of a “brilliant” former student she was about to visit in Massachusetts.

As evidence of her change agent status, Moore might also have cited her impressive, innovative research. Having studied political science as an undergrad and social and cultural anthropology for her doctorate, she brings an interdisciplinary perspective to investigating where the personal and the institutional converge and how concepts drawn from psychology, Black feminism, and philosophy can be combined to create a broader, more relevant understanding of how trauma affects individuals, families, and generations of

The Change Agent Award celebrates an alum who embodies the spirit of transformation in the profession.

LISA MOORE

families. “Taking psychodynamic theory beyond the individual, uncovering the relationships between the individual and systems and institutions— which is what social work is about—is really important to me,” she noted.

In conversation, Moore reveals her wide-ranging intellect, referring to the poetry of Smith College professor Yona Harvey and the teachings of Buddhist nun and author Pema Chödrön. She names Jean Baker Miller, originator of relational theory, as a key influence and, has been, in her words, “obsessed” recently, by the work of British social worker Foluke Taylor, whose work takes a self-reflexive look at the genealogy of psychodynamic/ psychoanalytic therapeutic practices through a Black feminist lens.

She has built some of her recent talks around the work of Franz Fanon, the revolutionary French Martinican anti-colonial philosopher and psychiatrist. His concept of phobogenesis (fear of the Black body) captures the processes of dehumanization of Black bodies and offers language for identifying and addressing it in psychoanalytic theory and practice.

While Moore is obviously drawn to thinkers who push conceptual boundaries, she is modest about her own status as someone who does just that. “I like being in the background, not being the center of attention,” she said.

Yet when she is the center of attention, she is illuminating. “Mourning Walk,” a Zoom presentation she gave in 2021 is thought-provoking and moving. (Hosted by the University

of Minnesota’s Center for Practice Transformation, it’s available online.) In it she talks about such heady subjects as relational cultural theory, autoethnography, and epigenetics— and her own family’s traumatic history, including her uncle’s murder by white supremacists in 1958. At one point, she conveys what it’s like to be a person of color in a racist environment with this vivid analogy: “Imagine traveling someplace where you don’t speak the language, you don’t look like the people there…and imagine living in that space and never being able to leave.”

It’s been somewhat surprising but gratifying, Moore said, that she has been invited to speak about her work expanding the dimensions of psychodynamic theory by such organizations as the Manhattan Institute of Psychoanalysis, the American Association of Psychoanalysis in Clinical Social Work, and the New England Center for Existential Therapy. Last August, she was the keynote speaker at SSW’s Deepening Clinical Practice Conference. Her topic: “Complementary Trauma: Exploring the Uncertainty of Relational Dynamics from the Interpersonal to the Institutional.”

Moore was surprised to be given the Change Agent Award, she said, but it’s pretty clear from her teaching, research, and presentations (and “Lisa Lynelle’s Newsletter” on Substack) that she is all about evolving, extending, and upending ideas, empowering people, and changing things for the better. ◆

LAURIE PETER

Evolving Social Work Journey

The professional evolution of Laurie J. Peter, M.S.W. ’91, one of this year’s Day-Garrett Award recipients, exemplifies the dynamic nature of social work. Spanning three distinct yet interconnected phases, her multifaceted career demonstrates the breadth of opportunities within the social work profession.

Peter’s career launched with direct clinical practice following her graduation. As a clinical social worker in Oregon and later Colorado, she was embedded within critical care medical environments. Her role as part of a Level I trauma center’s patient care team involved supporting families navigating surgical intensive care situations, often during their most vulnerable moments.

“The work was simultaneously fascinating and challenging,” Peter said. “The fast-paced environment demanded constant vigilance, and the team was supporting people through some of life’s most difficult experiences—including times when their loved ones weren’t going to survive.”

In 2001, Peter relocated to New Jersey and transitioned into nonprofit governance, her second career phase. Her board service spanned multiple organizations addressing diverse social issues: the National AIDS Fund (now AIDS United), Jersey Battered Women Services (now JBWS) and SAGE (sageusa.org), a national organization that provides advocacy and services to LGBTQ+ older adults. She served as board vice chair for DigDeep, an organization tackling water accessibility in underserved American communities, including the Navajo Nation and Appalachian regions.

daygarrett AWARD

She currently serves on JBWS’s Leadership Advisory Council and on the AMA Foundation’s (the philanthropic arm of the American Medical Association) Fellowship Commission on LGBTQ+ Health. Peter described this work as addressing fundamental equity issues rooted in structural racism and systemic marginalization.

“Through DigDeep, I witnessed transformative change in water equity,” she explained. “My involvement began early in the organization’s development, as I helped scale the organization through board development and extensive fundraising initiatives.”

Peter firmly rejects the notion that board service represents a departure from social work practice. Instead,

she views it as an alternative application of social work principles. She cited examples of developing strategic plans, identifying service gaps, and creating new departments—all of which resulted in improved client outcomes and systemic change.

“Board membership provides opportunities to influence policy and have systemic impact,” she noted. “You’re practicing social work through a different lens, but the core mission remains unchanged.”

Now in the third phase of her career, Peter has returned to clinical work through private practice, using virtual platforms to serve clients. This transition required additional certification in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT),

The Day-Garrett Award, established in 1978 and named for Florence Day and Annette Garrett, pays tribute to a distinguished alum whose lifelong dedication and accomplishments have left an indelible mark on the profession of social work.

dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), psychodynamic approaches and trauma-informed care.

Her current clinical approach integrates insights gained through decades on the front line of death and dying, as a leader steering social service nonprofits and from her private practice.

At 60-plus, Peter brings seasoned wisdom to the latter, focusing on building client resilience rather than attempting to “save the world,” as she put it, a perspective that she believes comes with professional maturity.

Through each phase of her career, Peter believes, her Smith SSW education has been foundational. Her path to Smith began in a public library, where, in the pre-Internet era, she researched clinical social work programs.

SSW’s program had several key strengths that shaped her career, she said, including clinical and academic excellence, a comprehensive social policy education, and a strong commitment to social justice. Peter also valued the student community and faculty relationships that created lasting professional networks and friendships.

“The connections I formed at SSW have endured through my career, and the experience was genuinely enjoyable,” she said.

The Day-Garrett Award recognizes Peter as “a source of inspiration for future generations.” She hopes her career trajectory encourages emerging social workers to embrace the profession’s flexibility and its capacity for adaptation and growth.

“There’s no prescribed path in social work,” Peter emphasized. “The profession is continuously evolving, offering multiple avenues for fulfillment, meaningful impact and expression of its core values and mission. You can transition between roles, combine different approaches, reinvent your practice, and discover new ways to create change throughout your entire career.” ◆

daygarrett AWARD

JD FULLER

A Lifelong Mission to Decolonize Social Work

JD Fuller, M.S.W. ’99 has been deeply dedicated to social work from an early age. A psychotherapist, mental health coach, and consultant in private practice for 33 years, she has also been a psychiatric social worker and an outpatient therapist for agencies contracting with the Los Angeles Department of Mental Health; an administrator in nonprofits serving children at risk, people with disabilities, dual-diagnosed veterans and the unhoused population; and worked as a clinician in private schools. At Antioch University Los Angeles, and the New Center of Psychoanalysis, she has taught graduate-level courses in areas such as LGBTQIA+ affirmative psychology, multicultural counseling, and decolonizing mental health. Helping children has been especially important to her throughout her career, “giving them something I didn’t get as a child.” Now she can add Day-Garrett Award recipient to her long list of accomplishments.

The Day-Garrett Award honors alums who “have made an indelible mark on the profession.” Fuller has made a special kind of indelible mark on social work via a very contemporary medium: the podcast. From 2021 to 2024, she hosted Changing the Narrative with JD Fuller, interviewing guests on such diverse topics as aging, depression, addiction, decolonization, racism, art and activism, hip-hop, and historical trauma. (The 144 episodes are available on YouTube and other digital services.)

“It was so important to me,” she said, “to have conversations, to raise questions, and to create an environment for people to tell their stories, tell their truth.”

In those virtual interviews, and in person, Fuller is fully engaged, bringing intellect, warmth, conviction, civility, and a great sense of humor to the conversation. Her ability to engage, so essential to social work, is all the more remarkable given her childhood. “I was the youngest of nine—the least of all. I never had one teacher, one person in my life who saw me. I saw a lot; I was not asked a lot. I was riddled with anxiety and acted out. But I have high emotional intelligence, and that carried me.”

Childhood trauma makes some turn inward. “It made me curious,” said Fuller. At age 20, her curiosity led her to take her first step toward becoming her “essential self,” finding “her truest voice”: “I looked in the yellow pages—remember them?—and found a therapist.”

At age 36, Fuller started at Smith SSW. “My experience there was really formative. I discovered my racial identity. I hadn’t known how important that was—my family was not Afrocentric.” That personal discovery led to her researching and writing her thesis

“The Racial Identity Development of the African American Female.”

She also became an activist. “In fact, when I learned about the award,” she said wryly, “I wondered, ‘Do they know I was one of the leaders of a walkout?’ More seriously, Fuller noted, “I have been fighting systems my whole life, but at Smith I realized how important intentionality and strategy are in fighting systems.”

“That is the first order of business,” Fuller believes. “It’s a fallacy that there is any place for marginalized people in this system. It was built by us but

The Day-Garrett Award, established in 1978 and named for Florence Day and Annette Garrett, pays tribute to a distinguished alum whose lifelong dedication and accomplishments have left an indelible mark on the profession of social work.

not intended for us. My work is about empowering people. In my classes, I teach people to approach social work practice through a decolonial lens.”

Reflecting on psychiatry’s Eurocentric origins, she added, “I can respect the theories, but I resent so much of them being centered on whiteness, and I feel bound to challenge them. They’re not universal, not true across the racial and cultural spectrum, and it’s problematic not to see that.” In practice, she said, “It’s unethical to treat people if you don’t believe in the existence of structural racism and white supremacist ideology. I approach my own practice from a cross-cultural, multicultural perspective.”

Fuller is disappointed that social work associations haven’t responded to the current political climate. “Why aren’t we speaking out? We must be true to our profession. Silence equals collusion and in most cases, death. This is a moment when we should all be activists, ideally abolitionists, each in our own way.”

Her way these days is sharing information and supporting causes she believes in through social media. Like her podcasts, her posts convey her sense of urgency and draw from many sources, from The Humanity Archive to Sesame Street.

Last year, about to turn 65, Fuller decided to scale back professionally. “I was getting up at 5:15 a.m., working out, then teaching, working in private practice and on my podcast till 10 or 11 p.m. Now I’m concentrating on my private practice, teaching, and activism. Taking care of myself. It’s my own version of being an elder. I’ve also designated this ‘the Year of Yes’— whatever is being offered, I’m taking.”

And still giving her all to what she considers her most important labor: decolonizing social work and helping kids. She is using “her truest voice and using it unapologetically.” ◆

“I AM NO LONGER ACCEPTING THE THINGS I CANNOT CHANGE. I AM CHANGING THE THINGS I CANNOT ACCEPT.”

ANGELA DAVIS

STORY BY MEGAN RUBINER ZINN ILLUSTRATION BY BRIAN STAUFFER

“Every day I feel like I’m challenging something or convincing someone to think something different,” said Kelly Brown, M.S.W. ’03, a social worker at the James Baldwin School, a public transfer high school in New York City that

serves at-risk students with a restorative justice approach.

As a change agent, Brown is truly representative of Smith College School for Social Work alumni. Like the others profiled here, she has spent the last decade finding ways to creatively and relentlessly resist, challenge, and change systems of oppression, whether impacting individuals, communities, or populations around the world.

In the last five to ten years, Kelly Brown’s perspective on supporting students has evolved, especially in regard to discipline. “My lens has shifted in terms of how I’m thinking about the whole child before we make any decisions—really looking at how we respond to the needs of our students in a way that feels like we’re centering their humanity first,” she said. “We’re making sure that when we’re having conversations around students, student behavior, student need, that we’re really talking about that student. Are we figuring out their needs?” When there’s a conflict, her priority is to help students own what they brought to the conflict and the harm they’ve done and then move forward toward healing practices rather than punishment.

Brown also brings that spirit of challenging norms to her work with social work students. Teaching Foundations of Social Work Practice: Decolonizing Social Work at Columbia University and supervising M.S.W. interns, Brown encourages students to understand the field through a lens of power, race, oppression, and privilege. “I’m pushing them to do their best to really think about who they are, whether they’re walking in as a white person, and how that presents itself in the context of clinical supervision, clinical work, everything. How does who you are impact everything that’s in the room?” she said.

The past decade comprises most of the career of Man-Tso Wei, M.S.W. ’19, given that he started practicing in 2014. He earned his B.S.W. and practiced in Taiwan before attending SSW. A social worker at the Earth Circles Counseling Center in Oakland, California, Wei is committed to socially just relationship work,

Kelly Brown, M.S.W. ’03

examining how relational and societal processes impact individuals and their sense of belonging and well-being and how they can resist or transform these processes to facilitate healing and liberation. “It really starts with equity and justice,” he said.

Wei finds creative ways to challenge harmful cultural and societal norms with clients—“to make the invisible societal forces visible and address them.” With men, for instance, his goal is to help them see “the impact of gender socialization and how American society privileges the individual over the communal.” He recalls asking an Asian American teenage client to invite his friends and his mother to his final session, to frame it as a celebration and to de-emphasize masculine stereotypes of solitariness and invulnerability. “I was seeing these three teenage boys being vulnerable and talking about how they supported each other. That really gave me hope, to see we are resisting these gender scripts and resisting how society is really working against relationships.”

Wei has also been working to improve equity for community mental health practitioners. During the pandemic, working at a unionized agency, he and colleagues undertook a comparative salary analysis and found significant discrepancies between agencies. They successfully advocated for raises of 3% to 10% for all levels of mental health counselors in their division. Wei is next planning to advocate for equity for relationship work, after discovering that in his county, insurance and county medical systems pay less for family and couples therapy than they do for individual therapy.

Given the range of his professional roles, Cole Hooley, M.S.W. ’09, Ph.D. has opportunities to effect change on multiple levels. Hooley is a professor in

the Brigham Young University (BYU) School of Social Work, but is also a city councilor in his hometown of Lindon, Utah and maintains a small private practice.

Hooley broadly impacts mental health services by bringing his research to the public sphere as a consultant with government agencies such as the Office of Professional Licensing Review. In his research, he examines how to “change systems, structures, and policies to make them more responsive to the needs of individuals, particularly those who have been marginalized and made vulnerable by the systems.” As he explained, “I do research so that we can get what works to everyone who needs it rapidly, lastingly, and equitably.”

Providing access to a career in social work is a particular passion of Hooley’s. He is able to do this at BYU, training a new cohort each year. But this is also an important part of his outreach. He recently presented his research about licensing laws and the impact they have on access to the profession to regulators across the United States. Additionally, he is working with the United Navajo Health System, to help social workers navigate the state licensing system.

Hooley brings his attention to vulnerable populations in his community as a city councilor as well. “I think of all the different audiences that a city needs to tend to and try to make it a point to bring up those who will probably be hit the hardest by a decision. So if it’s an increase in a property tax or some regressive tax, I want to know who’s going to get hit hardest.”

Susan Munsey, M.S.W. ’93 , is the founder and director of programs of GenerateHope in San Diego, a residential program for women who have survived sex trafficking. In the program,

survivors participate in group and individual psychotherapy, complete their education, and build life skills.

Munsey founded GenerateHope in 2008 and has spent the last decade expanding their services and building partnerships. In that time, they have moved to a full-day program, added a second home in San Diego and one in Colorado and expanded what they offer survivors, including yoga, equine therapy, financial literacy, and career support. They’ve also built a network of providers who offer medical, dental, and psychiatric care, optometry, tattoo removal, and legal assistance.

With the program well established, Munsey has begun to focus on outreach and education to help prevent trafficking and to help women escape. Working on legislation has become an important part of GenerateHope’s work. Their emphasis is on decriminalization and penalizing buyers and sellers rather than the women. They’re currently advocating for California’s AB 379 bill, which will target the demand for commercial sex by focusing penalties on buyers. This would include a $1,000 fine that will go to programs like GenerateHope.

GenerateHope has also pivoted toward community education. “Every time I speak somewhere, there’s people that are flabbergasted that this is happening,” Munsey said. “I firmly believe that if people knew what was actually happening, they would want to do more to end it.” Munsey has been part of creating a human trafficking council in San Diego County, which she currently chairs. She also plans to do more work in educating legislators to ensure they understand the nuances of the issues.

Like Munsey, Caitlin Ryan, M.S.W. ’82, Ph.D., has spent the last decade continuing the work that has been

Man-Tso Wei, M.S.W. ’19

Cole Hooley, M.S.W. ’09, Ph.D.

Susan Munsey, M.S.W. ’93

at the center of her career. Since the 1970s, Ryan has concentrated on improving LGBTQ health and mental health. In 2002, she and Rafael Diaz launched the Family Acceptance Project (FAP) at San Francisco State University. FAP conducted the first research on LGBTQ youth and families and has developed the first evidence-based family support model to help ethnically, racially, and religiously diverse families learn to support their queer and gender-diverse children to prevent health risks and promote well-being.

In the FAP model, they treat families as partners and allies and take a distinctive approach in presenting information on supporting their children. “Because our work is grounded in the family’s values, including cultural and religious values, it’s not frightening, it’s very familiar. It’s a common language,” Ryan said.

FAP works with organizations, faith communities, families and providers to integrate their family-based support approach and has provided education and training for more than 130,000 families, providers, and religious leaders in every U.S. state and across the world.

Ryan is currently implementing clinical trials on the family support model: one applying FAP online with families of color and one working with Lakota Two Spirit and LGBTQ youth and families to implement FAP on the Pine Ridge reservation. Additionally, she is working with a large hospital network to integrate the family-based care model into their systems.

Ryan has also embraced the opportunity to foster new generations of social workers. “One of the things that has been moving for me is to mentor younger practitioners to help them apply their work and continue to build

“We just keep going forward. One way or another, whatever the political system is, we will keep doing our work.” SUSAN MUNSEY, M.S.W. ’93

the field,” she said. “I’ve really learned how to hang in there, but also how to fight strategically, so I’m able to share that experience with others.”

The next decade is one that could be the most difficult of these social workers’ careers, as attempts to dismantle our social safety net and erase gains in equity for marginalized people occur. While realistic about the future, these Smith alumni are optimistic about the ways they see the field changing and the ability of social workers to meet the challenges.

Although GenerateHope may lose a small number of federal subcontracts, Munsey is more broadly concerned about how cuts in education, health care, and human services will impact vulnerable populations and put more girls at risk of trafficking. But she remains undaunted. “We just keep going forward,” she said. “One way or another, whatever the political system is, we will keep doing our work.”

Not surprising, given his advocacy to increase access to the field, Hooley hopes for a broadening of the parameters of social work: “I think there’s going to be some reckoning with how we maintain and expand in a way that feels like we can still look at ourselves in the mirror and say, ‘I like who I see’—that we’re still honest to who we are and we’re just making the table bigger.”

A theme these alumni raised consistently was the need to grapple with the positive and negative impacts of technology on social work, especially AI. “I still believe that mental health practitioners won’t be replaced by AI,

because we have this in-person presence, that connection, that warmth— that thing that cannot be replaced,” Wei said. But he sees opportunities in using AI to support clinical research—generating transcriptions and identifying themes— while recognizing the challenges in maintaining confidentiality and navigating ethical issues. “Hopefully we use it thoughtfully and wisely to really help us thrive.”

Brown is encouraged by the increased awareness and acceptance of mental health care, especially in BIPOC communities. “I’m excited to see what this world is going to be like even in the next year or two in regard to all of that.” At the same time, she is concerned about so many new social workers going into private practice. “I’m thinking about our practice and how it went from being on the ground and working with marginalized communities to now being a selective practice. And I’m worrying about people that won’t have access to that and what it’s going to look like.”

Ryan, on the other hand, hopes that the upheaval will spark a renaissance in community-based social work. She envisions social work schools pivoting to address gaps created and prepare a new generation of social workers—“a cadre of change agents” to rebuild the safety net. “I think this is a place where social work can become more visible and more prominent,” she affirmed. “It is an opportunity to assert our social work skills and expansiveness and the impact that we can have on society, but also an opportunity to create a plan for the future.” ◆

Caitlin Ryan, M.S.W. ’82, Ph.D.

Ph.D. speaker and 2025 graduate, Maria MaldonadoMorales, smiles with her grandmother, Berta Ines Morales, following the 2025 Commencement Ceremony.

Amid growing demands on our profession, social workers continue to show up. You do the invisible labor of healing, organizing, and caring. We see you. We thank you.

KATIE POTOCNIK MEDINA, M.S.W., LCSW Director of Alumni Engagement

Reflection, Clarity, Impact

Celebrating Dean Yoshioka’s legacy as we embrace the future

Again and again, our alumni have led with courage and clarity. Whether by creating more equitable access to mental health care, addressing racial injustice in clinical and community settings, shaping public policy, or advocating for systemic change, you have modeled what it means to be both clinically grounded and socially engaged.

You’ve shown up in therapy offices and classrooms, courtrooms and legislatures, hospital floors and city councils. You’ve held space for grief, anxiety, resistance, and joy. You’ve asked hard questions and built new practices. Through it all, your work has embodied what it means to challenge injustice and stay rooted in relational care.

This year, we had the honor of welcoming two powerful alumni voices back to campus for the Deepening Clinical Practice Conference. Lisa Moore, M.S.W. ’98, LICSW, Ph.D, delivered our keynote on relational trauma from the interpersonal to the institutional, reminding us of the complexity of healing and the need for systems that support real accountability. Representative Lydia Crafts, A.B. ’05, LCSW, shared insights during her plenary about her dual roles as legislator and clinician, highlighting how social work values are shaping behavioral health policy and workforce development in Maine. Both speakers reflect what so many of you continue to do every day: blend clinical depth with social change.

As we reflect on alumni impact, we also mark a major transition: Dean Marianne Yoshioka’s retirement at the end of term 1 next summer. Over the past decade, Dean Yoshioka has guided the School through

extraordinary challenge and change. Under her leadership, Smith SSW adopted the five Core Principles and integrated them into the School’s culture and operations. These principles were not aspirational words. They became our compass as we navigated a global pandemic, national uprisings for racial justice, and ongoing mental health crises.

Dean Yoshioka expanded our practicum partnerships, strengthened curricular innovation, increased diversity among faculty and staff, and elevated student voices. Her tenure has been defined by integrity, clinical excellence, and a deep commitment to community. We are profoundly grateful to her.

This issue includes reflections from alumni on what it has meant to do social work during times of uncertainty, change, and reckoning. These stories reflect challenge and growth, critique and care. They show how alumni have worked to resist, challenge, and change systems of oppression in impactful and creative ways, while continuing to draw on the rigor and relational foundation that makes Smith SSW distinct.

Amid growing demands on our profession, social workers continue to show up. You continue to work in systems that don’t always reflect your values, while also working to change them. You do the invisible labor of healing, organizing, and caring. You do the slow work of building trust, the hard work of repair, and the visionary work of imagining something better.

We see you. We thank you. And we remain inspired by you. ◆

’25

The 2025 Commencement Ceremony brought 97 M.S.W. graduates and four Ph.D. graduates together with their families to celebrate in John M. Greene Hall. The ceremony featured two student speakers: Wanja Kuria, M.S.W. ’25 and Maria MaldonadoMorales, Ph.D. ’25 as well as Miriam Yeung who delivered the keynote address. Iain Cooley, M.S.W. ’25, received the NASW Student of the Year Award.

IN MEMORIAM

This listing includes alumni who passed away between January 1 and December 31, 2024 and were confirmed deceased by the records department. To report the death of an alum, please email smithierecords@smith.edu.

Class of 1953

Gloria Lee Wong

Class of 1955

Fay Breuer

Class of 1956

Marilyn Voigt

Class of 1958

Gloria Rudman

Class of 1959

Natalie Woodman

Class of 1962

Margaret Smith

Class of 1963

Sybil Cohen Schreiber

Class of 1965

Nancy Bourne

Carolyn Otto

Gloria White Young

Class of 1970

Susan Colvin May

Nadine Matthaei

Nancy Smith

Rebecca Storey

Class of 1971

Sarah Wells Bowen

Class of 1974

Ann Curtin-Knight

Class of 1975

Deborah Farber Bittner

Class of 1981

Audrey Ringer

Class of 1982

Sydney Thorn

Class of 1985

Marilyn Collins

Class of 1986

Brian Hennigan

Class of 1993

Ann Daniels

Class of 2000

Adam Russo

Class of 2014

Carolyn Duncan

Class of 2018

Jacqueline Ortiz Miller

SSW: A LEADER IN CLINICAL SOCIAL WORK EDUCATION AND COFFEE LOVERS SINCE 1918

In 2016 as the School prepared to celebrate its Centennial anniversary, Dean Yoshioka collaborated to launch SSW’s first custom coffee blend. Bertha’s Blend coffee was as bold as its namesake! This rich, dark roast was fair trade and roasted in small batches. It promoted constructive dialogue in the interest of achieving social justice. We shared it with our alumni to enjoy and then go change the world!

Package design and art: Tom Pappalardo

Offering low-residency, 27-month M.S.W. and Ph.D.* programs with intensive clinical placements that will leave you better prepared than any other program. *For doctoral candidates a postresidency period follows. WE CAN

Lilly Hall

Northampton, MA 01063

ssw.smith.edu