A COLLABORATION OF ADVENTIST ACTIVISTS

AUGUST 2025

ISSUE 17

CHRISTIANITY SHOULD RADICALIZE YOU

THE LEAST WE CAN DO

APF CALLS TO LAMENT SUFFERING AND MILITARISM

REVIEW: NO OTHER LAND

LIVING AHEAD

AUGUST 2025

ISSUE 17

THE LEAST WE CAN DO

APF CALLS TO LAMENT SUFFERING AND MILITARISM

REVIEW: NO OTHER LAND

LIVING AHEAD

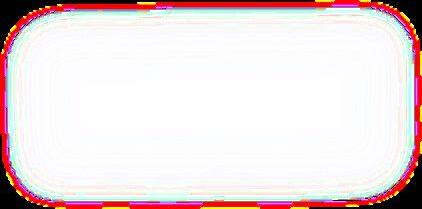

One of the most moving moments at the General Conference Session was a Spectrum event featuring Kevin Burton, PhD, director of the Center for Adventist Research at Andrews University. Before a distinguished audience in the Spectrum lounge, he spoke about his forthcoming book, Apocalyptic Abolitionism: How Immediate Millennialists Helped Abolish Slavery and Reform America, which explores how early Adventists specifically millennialists fought for the abolition of slavery. These were socially engaged, justice-oriented believers of fierce conviction unafraid to take bold stances. By today’s standards, they would be called “woke.”

Activism is not an accessory to Adventism; it is deeply embedded in its foundation The early church was formed by people who believed in equal rights and were willing to take clear political and social positions That spirit of involvement is central to who we are as a denomination. Yet modern Adventism often leans toward neutrality, offering carefully worded, politically correct responses in moments that call for moral clarity.

Burton spoke with the kind of conviction and depth that comes only from years of research, and I found it compelling that this facet of

Adventist history had never received this thorough of a scholarly exploration His research feels both urgent and restorative, giving Adventists the chance to reconnect with the values that once helped the church grow. His presentation resonated with me in a deeply personal way, especially because he began this research in 2020 during the pandemic the same period when my own relationship with the church began to shift I watched as people who looked like me were murdered by police brutality without cause, waiting for support, for action from Adventist leaders But the silence felt deafening. I began to wonder why I was giving so much to a church that did not seem to see me. Something in me broke, and I feared it might never mend

But hearing Burton speak offered a glimmer of hope

His words have the power to bring healing, not just to me, but to many who feel silenced or overlooked by Adventism His presentation offers something meaningful to young adults who are leaving Adventism at record rates, not because they have lost faith in God, but because they are disillusioned by the church’s lack of engagement with issues of justice. His forthcoming book has the potential to shift the landscape of Adventism, helping us become a denomination that is safer, more honest, and more inclusive for those on the margins.

York University Press I do not know all the reasons behind this, but to me, it says a great deal. It feels like, once again, we are missing the opportunity to tell a most powerful story––a story that could help guide us forward

Kevin Burton is doing work that could help us remember who we once were. My hope is that his research inspires us to reclaim the spirit of our beginnings, because a church that forgets its justice roots is a church that forfeits its future.

A church that forgets its justice roots is a church that forfeits its future.

And yet, one detail is impossible to ignore. Burton’s book is not being published by an Adventist press It is being published by New

Ezrica Bennett is a writer, public speaker, and coach, passionate about working with young adults to help them navigate life and faith, and a youth elder at the Loma Linda University Church

Excerpted from “Five Way Adventism Fumbles the Bag at GC Sessions” published by Spectrum on July 31, 2025: bit ly/PulseSpectrumAAR

Political engagement certainly comes with moral risks and temptations, but these are diminished if we think of politics as a baseline or bare minimum understanding for our public and community engagement, and the work of justice that we are called to do. In this sense, politics is literally the least we can do It is important, but often quite weak a response to the world around us in comparison to our calling to the faithful work of justice

As a demonstration of this, consider some “political” impulses that have been dismissed from time to time as “political correctness” or “wokeness” or using similarly disparaging terms

Often, it is not that these values are unreasonable or overwhelming, but that they are really weaker goals than what faithfulness calls us to

Tolerance is sometimes criticised as a kind of weakness, perhaps a form of political noncommitment to whatever goes and whatever anyone chooses to be or do. It might have a “live and let live” or “you do you” feel to it, but some degree of tolerance is necessary for any kind of life and relationship with others. When tolerance is practised and celebrated, it tends to speak of respecting the differences between us and holding space for the different lives, cultures and aspirations we have among us.

By contrast, love is the higher command for followers of Jesus As we have seen, love is not

mere tolerance Rather, love actively seeks the good of the other person, even an enemy.

Tolerance is something we can do politically and this can be a worthwhile project As Dr King put it, “It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me, but it can stop him from lynching me, and I think that’s pretty important ” While tolerance is the necessary least we can do, love is our higher calling.

Similarly, basic justice is something that we might work towards politically, seeking to enact just laws, ensure a functioning criminal justice system, and work towards greater social and economic justice in our communities and nations However, this does not necessarily lead us to the larger understanding that includes the restoration of our broken human relationships Neither does it, in the strictest sense, make space for mercy

One of the Bible’s most quoted verses in justice conversations is Micah 6:8: “He has shown you, O mortal, what is good And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God” (NIV). As much as this is a justice-doing text, its call is to love mercy. Mercy is not merely treating people as they deserve, insisting on their basic rights and needs as important as that is for those whose rights are not respected or protected but treating people better than we deserve or merit This kind of mercy is a higher priority and perhaps more apt to restoring

relationships than a “least we can do” kind of justice As Jesus taught His followers, “God blesses those who are merciful, for they will be shown mercy” (Matthew 5:7)

While we continue to advocate for equality and equity for all people, one of the ways in which we do this is by seeking to serve and sacrifice for the good of others.

Another buzzword that is almost equally applauded and derided in contemporary political debate is equality Sometimes also talked about as equity is this basic assumption that all people should have equal opportunities, equal access to the basic goods and choices in society, and some kind of equal voice in decision-making processes. Of course, this is not close to a reality in most societies in history or in our world today This is a key element of the work of justice and something we should continue to champion, particularly speaking with and on behalf of those who continue to be excluded and unheard Again, ancient Hebrew wisdom prompts us towards this work: “Speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves; ensure justice for those being crushed. Yes, speak up for the poor and helpless, and see that they get justice” (Proverbs 31:8, 9).

But, as followers of Jesus, equality is not our highest goal In our exploration of Jesus and His work, we reference the early Christian hymn that explained the descent and self-sacrifice of Jesus in terms that are both poetic and profoundly theological: “Though he was God, he did not think of equality with God as something to cling to. Instead, he gave up his divine privileges; he took the humble position of a slave and was born as a human being” (Philippians 2:6, 7).

Introducing his quotation of this hymn, the writer and early church leader Paul moved beyond grand ideas and made it remarkably practical He did not cite this hymn to make a theological argument, but to urge people who follow in the way of Jesus that this is how they should live and serve: “Don’t be selfish; don’t try to impress others Be humble, thinking of others as better than yourselves Don’t look out only for your own interests, but take an interest in others, too You must have the same attitude that Christ Jesus had” (Philippians 2:3–5) While we continue to advocate for equality and equity for all people, one of the ways in which we do this is by seeking to serve and sacrifice for the good of others and for the restoration of all our relationships.

In the work of justice, engaging in politics is the least we can do But bringing the best of our love, mercy and service to others in our public lives means a better kind of political engagement and a deeper, more faithful kind of justice-doing. These attitudes and practices also reach far beyond the merely political realm. They are a way of relating to others that will work to restore relationships in all areas of our lives and in all the work we do to create and contribute to greater justice, truth and beauty in our communities and our world

The verse that radicalized me is a familiar one. It can be found in Matthew 25: “The King will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.’”

“Radicalization” is a popular topic. When I say I have been radicalized, I don’t mean that I’ve been shaped by a rigid set of beliefs that draws hard lines between who’s in and who’s out. I mean that I’ve been transformed by the teachings of Jesus, which challenge me to practice a radical form of love for others.

A question has been trending across TikTok: “What radicalized you?” Users’ answers expose the irony of conservative critics’ attempts to rebrand Christian teachings as “woke” or “sinful” by conservative critics Throughout scripture, Christians are commanded to love their neighbors as themselves, to welcome the stranger, and to care for “the least of these.” Yet President Donald Trump, who has promised to restore our nation to some former Christian glory, has spent the entirety of his political career working with lawmakers to create policies that hurt the most vulnerable

In Trump’s latest string of cruelty, masked Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents have kidnapped and dragged immigrants out of

workplaces These immigrants have been ripped from their families and their communities, deported, and imprisoned abroad without due process To add insult to injury, some conservative Christians are celebrating these inhumane policies.

Having grown up charismatic and conservative, I’m grateful for the radicalization (that is, the process of learning) that saved me from the trap of idol-worship and nationalism. The way I see it, my radicalization happened at three different stages: In the classroom, through studying scripture, and learning from my community

During my freshman year of college, a film professor assigned the documentary Which Way Home. Watching that film was the first time my beliefs about immigration were challenged. The documentary follows the story of several unaccompanied minors as they make their way from Central America to the US–Mexico border. For these children, the decision to migrate was one of desperation; the journey was dangerous, and the chances of a successful entry were slim. I couldn’t get their faces out of my head, so I made immigration the focus of a research paper

for my sociology class That’s when I learned that nearly every story I’d grown up hearing about undocumented people was fictitious. As it turned out, immigrants paid billions in taxes, committed fewer crimes than citizens, and didn’t so much “steal” jobs as much as they filled the ones Americans refused to take.

Through my research, I also learned the uncomfortable truth about the United States’ role in destabilizing countries like Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador In the name of stopping Communism or monopolizing agricultural industries, we funded coups, trained soldiers in scorched earth tactics, and drove native farmers off their land all while creating the conditions that force people to migrate in the first place. Though it might be inaccurate to say the US is completely responsible for the border crisis (other countries played a part as well), it’s irresponsible and dishonest to pretend our hands are clean.

Perhaps the most significant myth that was busted for me during my time in college was this: That there was a “right way” to immigrate to the United States

I’d heard that phrase my whole life My family came to the United States “the right way” so that my siblings and cousins could inherit the blessings of my parents’ conscientious choices

But when I studied further, I discovered a backlogged immigration system that hadn’t been updated since 1990 I learned that some groups were welcomed to the US through politically motivated decisions, while others were not I found that our immigration system is not only broken but comically difficult to navigate One legal pathway to citizenship allows a Mexican-American US citizen to sponsor their adult sibling But the estimated wait time for that family-sponsored visa is about 224 years under our current immigration system, according to data from US State Department and US Citizenship and Immigration Services

immigrants and criminal, undocumented immigrants The tension was between the fortunate and the unfortunate, between those who came from the right place at the right time and those who did not

My radicalization continued when I joined a college campus ministry that taught me how to contextually read the Bible. Despite growing up in the church, I gained a deeper understanding of Jesus for the first time and learned that the circumstances surrounding his birth, life, and death ought to inform the way his followers view and treat others today

Jesus was born in a stable to a mother fleeing an oppressive government; he aligned himself with tax collectors, sex workers, fishermen, lepers, and ethnic enemies; he was executed by the state, and he identified most closely with those on the margins. He disrupted systems of power as he reserved his harshest criticism for the wealthy and religious elite. To many in his time, he was considered a “radical” because everything he did challenged the status quo Jesus’ upside-down kingdom was scandalous, beautiful, and to this day, extremely g to anyone who hoards power and ion

My black-and-white narratives about who came to the US “the right way” crumbled It became clear that the tension about accepting immigrants into the US wasn’t really rooted in distinctions between patriotic, law-abiding

With this fuller understanding of Christ, it became impossible to see him in the dangerous rhetoric of politicians who cloak their agendas in Christian language I realized that religious justification for inhumane polices was often rooted in isolationism and nationalism concepts not supported by the teachings of Jesus Through studying the historical context of scripture, I learned about a different version of Jesus than the one I had been taught to accept growing up Jesus was not a cowboy-gunslinger riding a horse, shooting the bad guys, and justifying violence in God’s name. Jesus was riding a donkey, bringing a message of peace and hope to the poor and powerless He was a striking departure from the militaristic conqueror so many expected.

After graduating from college, I felt as though my education had been completed. But through relationships, I realized I still had so much more to learn

In 2017, I spent a summer volunteering at a local church with a large Congolese refugee congregation During that time, I witnessed a faith community truly live out its calling as the body of Christ as they welcomed the stranger and cared for families fleeing violence Later that same year, I started working for an organization that supported migrant farmworkers and asylum seekers. On one occasion, an immigrant mother welcomed me into her home and fed me She spoke proudly of her love for her children, and even more proudly of her love for Jesus. By the end of our conversation, she was in tears It was 2018, and the Trump administration’s inhumane immigration policies were just beginning to take shape.

I don’t recount these experiences to boast, but to reflect on a humbling and illuminating time in my life. Without meaningfully engaging with those impacted by injustice, our commitment to justice can grow anemic, and we risk forgetting what “radicalized” us in the first place

There’s a real human cost, for example, to Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill, which Congress passed

on July 4 It will pump billions of dollars into disturbing immigration policies that criminalize desperation and stoke xenophobia. The more merciful and fiscally responsible choice, according to a study by the Christian humanitarian aid organization World Relief, would be to assist immigrant families with “legal services, resettlement and holistic care ”

Instead of retreating into echo chambers that defend political leaders unconditionally, we should avoid authoritarianism, practice principled dissent, and remember that our ultimate loyalty is to Christ alone.

When I say I believe more Christians should embrace a radical faith, I envision something entirely different from the radicalization we’re seeing on the far right Instead of retreating into echo chambers that defend political leaders unconditionally, we should avoid authoritarianism, practice principled dissent, and remember that our ultimate loyalty is to Christ alone. And instead of allowing media outlets to misinform us and profit from our outrage, we should step away from the noise and seek real connections with immigrants, with refugees, and with anyone who we’re told isn’t worthy of our time and care

The radicalization I long for is not a return to hierarchies or some nostalgic ideal of America, but a return to the resurrection power of Christ, which sets us free and awakens our imagination for an infinitely better world.

Emily Baez is a reporter in the Fall 2024 Sojourners Journalism Cohort This article was first published by Sojourners on July 24, 2025: bit ly/PulseSojoFeature

When you ’ re going through hell, keep going.

Winston Churchill

Ignorance gives one a large range of probabilities.

George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans)

If a man take no thought of what is distant, he will find sorrow near at hand Confucius THE LONG VIEW

Erasmus (1466-1536) PRIORITIES

If the only prayer you said in your whole life was “Thank You,” that would suffice. Cicero ONE PRAYER

When I get a little money I buy books; and if any is left I buy food and clothes.

Celebrity is the religion of our time

Maureen Dowd

Percentage of Americans who said that the Bible was “true” in 2016: 36

Who say so now: 48 August 2025

Work is love made visible Kahlil Gibran EMPLOYMENT

Practising Justice

Nathan Brown

Signs Publishing, 2025

Being a Geriatric Millenial or a young Gen Xer I’m right on the line, friends I don’t host many dinner parties But when I do, I go all out And by go all out, I mean I get the fancy paper plates from Costco. Chinet all the way, baby. It’s a haystack party

The lime-infused rice is done I’ve made a double batch of my best haystack beans, and I even experimented with making homemade veggie meat since the stuff from the ABC is clearly for someone in a different tax bracket. We’re ready. Everybody is here!

We layer our haystack plates in our correctto-us order and thoroughly enjoy our meal. After dessert, the deeper conversations rise. Employment frustrations Healthcare in America Injustice in the immigration system George Floyd. Racism in the workplace. We go deep. The white people in the room shut up and listen. We are keenly aware that we can’t fix everything, but empathy and solidarity are here at the table. Can we expect justice in this world?

Nathan Brown’s new release, Practising Justice, begins in this very place where we were sitting after the haystack. Injustice is not inevitable In fact, it can and will go on for so long that is feels like a fact of life And yet, there is a disconnect between our churches today and modern movements for social justice.

Citing the epic tale of Israel’s deliverance from Egypt, Brown points out that even when it feels like God is far away, He is aware of human suffering, is on the side of the oppressed, and has the power to act in His time. God brought justice to His people

Jumping forward to the time of Jesus, readers are reminded that in His pursuit of justice feeding the hungry, healing the sick, giving hope to the hopeless Jesus was a nonviolent disruptor of the political and religious status quo. Because of that, He was violently lynched His Resurrection defies the injustice of His death and gives us Salvation.

If we are called to be like Christ Jesus, we are, logically, called to practice justice even when it hurts

We

can’t fix every single injustice in our world right away, but we are clearly called to work toward justice and to practice justice every day.

Part two of Brown’s book serves as an instruction manual for following the Ten

Commitments, followed by Dr Martin Luther King, Jr, and those who were trained to help lead the Civil Rights movement. They are:

Meditate daily on the teachings and life of Jesus

Remember always that the nonviolent movement seeks justice and reconciliationnot victory

Walk and talk in the manner of love, for God is love.

Pray daily to be used by God in order that all men might be free

Sacrifice personal wishes in order that all men might be free.

Observe with both friend and foe for the ordinary rules of courtesy.

Seek to perform regular service for others and for the world

Refrain from the violence of fist, tongue, or heart.

Strive to be in good spiritual and bodily health

We can’t fix every single injustice in our world right away, but we are clearly called to work toward justice and to practice justice every day, however God calls us individually You may be called to public service, spiritual shepherding, or something in between haystack host? but the justice of Jesus means that we’re not chasing a win for dominance or revenge; we’re chasing reconciliation and mutual understanding.

Marcia Nordmeyer

The timeless Commitments remain applicable, and each one is explained in context with plenty of room for you to make a little note in the margin when necessary (provided you purchase a copy Do not write in a library book )

What do you do when the silence is deafening? As news reports filled media outlets in the US announcing the upcoming celebration of the United States Army’s 250th anniversary, I was arrested by the silence of Seventh-day Adventist churches. No sermons. No podcast segments No statements No-one spoke out against the sanctioned militarized violence we have been watching and soon celebrate. The celebration, scheduled for July 4, was reported to feature a parade of 7000 soldiers along Constitution Avenue, accompanied by tanks, an array of military vehicles, and aircraft. Such a display of military might has never been seen on US soil, and to know that while also watching videos and graphics shared on the official White House Instagram page showing persons being handcuffed, detained, and deported without due process, I found myself angry with the actions of the American government and disappointed at the silence of the Adventist Church I then saw a thread of emails in my inbox from the volunteer team at Adventist Peace Fellowship Each team member expressed feelings similar to mine There was a common sentiment that something needed to be said, and even more importantly, something needed to be done After meeting together, we agreed to release a public statement declaring our stance against militarism and to invite people to join us for a virtual peace summit on Friday, July 25

Releasing our public statement and the flyer for the summit on Friday, July 4, we declared

that “Adventist Peace Fellowship remains committed to peace, justice, and reconciliation. We reject any government system that seeks to dominate people and nations through violence and war. Following Paul’s exhortation in Romans 12:18, we encourage our leaders to ‘do all that you can to live in peace with everyone’ (NLT) ” But it was not enough for us to simply articulate a stance for peace, but to also articulate a firm objection to the use of violence as a means of resolving conflict “We believe that war and violence merely intensify suffering and do not pave the way for enduring peace. Jesus taught in Matthew 5:9, ‘Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.’

Furthermore, Ellen White noted, ‘War is a terrible evil It is the result of sin, and it does not resolve the problems of humanity ’ The escalation of military actions against immigrants, US citizens, and others threatens lives and undermines the potential for peaceful resolutions ”

This statement was posted with a flyer inviting others to join us in a discussion on militarism The suffering we have observed in Gaza, Sudan, Ukraine, and on US soil led the Adventist Peace Fellowship to a deeper understanding of the importance of lament as a spiritual practice Lament is a prayer expressing deep sorrow, pain, grief, and even confusion to God. In fact, Jeremiah was known as the “weeping prophet” due to his profound sorrow and lamentations over the impending destruction of Jerusalem and the sins of his people. We felt it necessary to create space for lament and to demonstrate this spiritual practice as part of our virtual peace summit.

Pastor Xisto did not simply pray for our engagement in the solution, but also lamented the sufferings around the world that we have all grieved over the years He declared, “We lament the bombs still falling in Ukraine We lament the slaughter of 1200 people in Israel on October 7, mostly civilians. We lament the ongoing genocide in Gaza, where 61,000 Palestinians have been killed, the majority being women and children. We lament that our attention span is so short that we’ve already moved on from these active tragedies We lament that some of us claim to follow Jesus and yet cheer as this spirit of violence and dominance tears families apart

“We lament the silence of faith leaders in the face of all these atrocities. We lament the witness we’ve lost as the church our courage to speak truth to power ” Remembering and calling out our Adventist legacy, Pastor Xisto repented for the church’s prioritization of silence, complacency, and comfort in exchange for the bold, prophetic voice we have been called to use to cry aloud and spare not.

“We lament the silence of faith leaders in the face of all these atrocities. We lament the witness we’ve lost as the church —our courage to speak truth to power.”

Pastor Daniel Xisto led our time of reflection, lament, and prayer. He spoke of “the spirit of militarism” and how it is showing up in the exploitative practices of the powerful, the privileged, and the rich.” Pastor Xisto prayed that we be “peacemakers in a militarized world, a world drunk on violence” asking that God give us the courage and the compassion to combat this spirit and emulate the character of Jesus. The most powerful moment of this lament was when

These words grounded the program, giving voice to our sorrow, holding us accountable for our sin, and issuing a call to action. Featuring clips of speeches and sermons from Dr Martin Luther King Jr, the summit then transitioned to a discussion on militarism, exploring the spiritual, theological, and practical implications for opposing powers that misinterpret Scripture to justify violence against the innocent Pastor Manuel Arteaga, Senior Pastor of the White Memorial SDA Church in Los Angeles, California, Dr Kevin Burton, Director of the Center for Adventist Research in Berrien Springs, MI, Dr Olive Hemmings, Chair of the Religion

Department at Washington Adventist University, and Dr Jason O’Rourke, Senior Pastor of the Emmanuel SDA Church in Chicago Heights, IL, served as panelists guiding our discussion for the evening

Upon the conclusion of the virtual program, many felt as though they were given the space to feel, process, and understand the violence that they have witnessed, experienced, and are actively combating as they advocate for the lives of others The thought I believe Adventist Peace Fellowship desires for everyone to remember is to take time in personal and corporate prayer to lament the suffering of our world We cannot continue to host spiritual worship services that ignore the illegal detaining and deportation of our brothers and sisters We cannot continue to preach sermons with no mention of the systematic starving and bombing of Palestinians. We cannot continue to enter into the House of the Lord with worship and praise on our lips, and no acknowledgment of the pain of the people around us.

May we cry for our nations Lament for our churches And advocate for the innocent For what is our religion if we do not heed the call of the prophet Isaiah to “learn to do good; seek

justice, correct oppression; bring justice to the fatherless, plead the widow’s cause ”

For what is our religion if we do not heed the call of the prophet Isaiah to “learn to do good; seek justice, correct oppression; bring justice to the fatherless, plead the widow’s cause.”

May we make peace where there is war, establish freedom where there is bondage, bring food where there is hunger, supply water where there is thirst, and protect the vulnerable where there is violence May we be the hands and feet of Jesus in Earth

To watch the virtual program: bit ly/PulseVirtualProgram

Link to Daniel’s lament: bit ly/PulseDanielsLament

Pulse is the monthly digital magazine of JustLove Collective

This month’s issue is sponsored by Adela and Arpad Soo (Thank you )

Designed by Jeffers Media

Unless indicated otherwise all Bible references are from the New Revised Standard Version.

serves as the Executive Director of Adventist Peace Fellowship and holds degrees from Andrews University and Georgetown University

Is professor emeritus at Union Adventist University where he taught English and communication courses, including Conflict and Peacemaking along with Critiquing Film He has also served as editor of Insight magazine, author of many books and articles, and pastor of two small churches.

Is book editor at Signs Publishing, based near Melbourne, Australia. He is author of 22 books, including Practising Justice, Thinking Faith and Do Not Be Afraid (the devotional book for 2025, published by Pacific Press in North America.

Is a circulation/reference associate at Union Adventist University's library in Lincoln, Nebraska. She is happily married to Jeremy. Their two children are encouraged to read banned books

From the beginning, the mission was a message. Then a kind of social activism, responsive to the Bible’s vision of justice, came into play. But in later Adventism Adventism after Ellen White it was substantially lost. Still later, social activism came into play again, but only in the background The church’s white, male leadership, not least at the height of the American Civil Rights Movement, persisted in reducing the mission to merely a message

Following the Great Disappointment of 1844, the pioneers of Adventism coalesced around a proclamation of Second Coming imminence that gave new meaning to William Miller’s apocalyptic vision and new urgency to the experience of Sabbath-keeping At first, mere speech the end-time theory the pioneers were sharing was all that mattered. Energetic engagement of social and political challenges seemed irrelevant. In countenancing slavery and thus ignoring, said Ellen White in 1858, “the cries of the oppressed” America had forsaken its own principles But there was no real hope for improvement: the earliest reading of the prophecies made Adventists so pessimistic that most of them thought slavery would last until the Second Coming

But Adventists eventually softened their sense of American intransigence. By the 1870s and 80s, they were seeing more potential for at least delaying the beast-like American behavior they expected to worsen before Christ’s return. It made sense to vote and lobby on behalf

of religious liberty and temperance. In 1883, Ellen White even suggested to Battle Creek College students that they could aim to sit in the nation’s “deliberative and legislative councils.”

The early Adventist story on race Soon after the Great Disappointment, the community that in 1863 would organize into the Seventh-day Adventist Church had begun to identify with the biblical motif of the “remnant,” those who remain in faithful solidarity with Christ even through times of crisis. Two signature passages Revelation 12:17 and 14:12 sharpened their sense that authentic faith is faithfully aligned with Jesus. That in mind, with support from pioneer leaders, some members engaged in civil disobedience of America’s 1850 Fugitive Slave Act.

By the 1890s, with the church now applying itself to at least some of society’s ills, a crisis in race relations was sweeping through the United States. Legislation in the South and Supreme Court decisions in Washington were undermining rights American blacks had gained following the Civil War. White Northerners were increasingly xenophobic, and many had begun to empathize with Southerners who were dealing with a “foreign” presence in their midst. At the same time, social Darwinism was gaining a foothold, and the sense of white superiority over darker-skinned peoples was increasing Acts of terror against African Americans were also on the rise: in the 1890s alone, nearly

1700 blacks died from lynching 1

In 1894, while the country was in the midst of this crisis, James and Ellen White’s second son, Edson, launched an effort to address the plight of blacks in Mississippi He put together a team and oversaw construction of a paddlewheel steamer. In August, the boat, christened The Morning Star, left Chicago, threading its way by canal and river through Illinois to the Mississippi and down that grand waterway to Vicksburg.

The team was soon attracting black students, who assembled at night to learn about the Bible and also how to read with the aid of a book Edson had written under the title Gospel Primer. Vicksburg had (overcrowded) schools for black children, but provided no education for black adults and the team’s initiative flourished. Prospects seemed so bright that the church’s General Conference, prodded by Eds mother, took steps to establish a sch black youth in Huntsville, Alabama, an now thriving as Oakwood University

By late 1897, Edson White had ex operation by taking The Morning Sta Yazoo River to Yazoo City Further ex came with construction of a chapel a schoolhouse in Calmar, about halfwa Vicksburg and Yazoo City Here gues included E A Sutherland and Percy T down from Battle Creek College, and students were benefitting from instr better agricultural techniques All this alarmed local whites. Blacks outnumber region of the Mississippi Delta, Adventist-facilitated spread o among the former slaves, the s whites at the top, blacks at the suddenly at risk.

Cumberland River, hoping to expand work among blacks in a place where prejudice would be less violent.2

The deepening rancor was by now affecting Adventism itself By the early 1900s, General Conference leaders were asking for congregational segregation. In Washington, DC, in 1902, an integrated church split, at least officially, into two, one black and one white But about half the white membership remained with the mother church in defiance of the General Conference plan, and Ellen White came for an affirming address 17, noting His follow

An incident of white-on-bla including a public flogging and wounding, soon took place at t In Yazoo City, white youths beg principal of the Adventist scho local newspapers accused Adv fomenting religious discord and advocating “social equality ” In spite of all this, the Adventist presence in the area remained, although Edson soon took The Morning Star to Nashville, on the

In the end, however, the severe racial discord led Ellen White to advise restraint She came the point herself of suggesting, as temporary measures, separate worship places for blacks and whites, and even suspension of agitation for racial equality. The context, it must be emphasized, was the still-spreading acrimony that continued after the1890s crisis of violence And Ellen White insisted (writing in 1908) that her advice was to hold only “until the Lord shows us a better way ”3

From the beginning, key Adventist leaders had lived ahead of the majority on the question of race in America Many had repudiated slavery and borne public witness against American society and government for what was going on. Some had put themselves at substantial risk in the service of former slaves still living, in the 1890s and thereafter, under conditions of crushing injustice When societal pressures kindled compromise in the early 1900s, Ellen White kept alive the vision of “a better way.”

When societal pressures kindled compromise in the early 1900s, Ellen White kept alive the vision of “a better way.”

She knew the God-bestowed worth of every person, the Bible’s rejection of in-group/outgroup justifications for abuse of others, the divine requirement to care for the neighbor as we would care for ourselves. She had cited Micah 6:8 to make the point that every human being has the “the right to receive and to impart the fruit of his own labor.” She had quoted repeatedly from Isaiah 58:6–11, where the prophet identifies true faithfulness with loosing “the bonds of injustice,” letting “the oppressed go free,” satisfying the “needs of afflicted,” and had said once that Isaiah here describes “the work that God will . . . bless His people in doing.”

Reflecting on the church’s ministry in the South, she had quoted Jesus’ inaugural sermon at Nazareth, with its prophetic summons to attend to the poor and brokenhearted, the captive and the bruised; and she had there remarked that God loves “all His creatures” and “makes no difference between white and black, except that He has a special, tender pity for those who are called to bear a greater burden than others. ”4

All this reflects the spirit of Hebrew prophecy, with its passion for justice, for the kind of restorative other-focused relationships that flower forth into peace, or the shared, delightful well-being of all This was a spirit embodied, too, in Jesus. And just to the degree that it infused the pioneers, and they were living ahead of the majority around them, their witness, though certainly imperfect, did, indeed, reflect the “remnant” ideal. As New Testament scholar G H C Macgregor put it, the “remnant” is precisely “a minority ready to think and act ahead of the community as a whole, and so keep alive the vision of God’s redemptive way.”5

But all this changed and, by the time of the American Civil Rights Movement, the change was dramatic Now a movement was afoot that had its roots in biblical faith, including the nonviolence of Christ, and that, although controversial, was receiving substantial support from America’s cultural leaders, white as well as black. The hope was to affect the nation’s public policy and overall ethos so as to loosen the bonds of injustice and bring freedom to a stilloppressed racial minority. But the editors of Review and Herald the church’s official magazine considered the movement to be a distraction for anyone (certainly clergymen) whose focus was the Adventist mission

In 1963, associate editor Raymond Cottrell wrote in an editorial that ministers who participated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom had, by declaring that their convictions about justice could be reflected in the law, drifted “far beyond the example of commission” of Christ and thus abdicated the

church’s “Heaven appointed task.” In 1965, expanding on the point about church witness and law, he said that “political questions not directly involving religion or matters of conscience are strictly out of bounds for churches and church agencies ” A farm labor issue gave rise to this remark, but the cultural context was the Civil Rights Movement, and witness intended to affect public policy was, he said, “omitted from the gospel commission ”

Three months earlier, in late April of 1965, the head editor of Review and Herald, F D Nichol, had said that church efforts to “reform the social order” were manifestations of a distortion he named “the social gospel.” Although he expressed sympathy for the ideal of racial equality, he urged a “more quiet and distinctively Adventist” approach than that represented by the Freedom Marches. That approach would center on words “Preaching the ‘everlasting gospel’ is our great assignment from Heaven,” he said.6

Meanwhile, however, some black Seventhday Adventists were acting on convictions that had germinated even earlier within the church’s black membership. As African Americans, these Adventists were directly familiar with the pain of injustice; they interacted, moreover, with leading black Christians outside as well as inside of their own denomination Experiences of this kind helped open their eyes to what Adventist historian Samuel G London calls a “liberationist” reading of Scripture. They took action against prejudice inside the church They joined the Freedom Marches.

There was no sign that attempts to bring the spirit of the Hebrew prophets back into Adventism were having substantial effect on the church’s white, male establishment.

Central Conference medical van all the way to “resurrection City” on the Washington Mall in support of the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign The storied evangelist and General Conference leader E Earl Cleveland wrote in a book published in 1969 that Adventist “passivism regarding social justice was “a type of selfrighteous inertia” incompatible with a true service to God. In 1970, in the newly founded Insight magazine, Charles D Brooks, another storied evangelist, descried the church’s moral blandness” regarding racial injustice and called for a recovery of early Adventism’s moral passion That same year, a black layperson and activist educator Frank Hale made the case, in Spectrum magazine, for taking up “the unfinished task of liberating black people” from their oppression.

Some white writers were chiming in as well, both in Insight and in Spectrum, and a vocal minority of Adventists would continue to build a specifically Adventist perspective on the prophetic vision of justice and peace. But a story about ferment in Adventism appeared in Newsweek magazine, and two things the editor of the Review and Herald said in response shed disturbing light Addressing reported desire, by some Adventists, for a return to the vigorous debates of the pioneer period, Kenneth Wood scoffed Our doctrines are now “well established,” he said, and our time is best spent “taking sharp issue” with the doctrinal mistakes of others. As for the reported desire that leaders and church members recognize the Second Coming’s power to motivate action for change in the here and now, he said that we should emphasize “telling others” what is ahead “How misguided” it would be, he went on, to focus on “restructuring the social and political order.”7

One minister, Charles Dudley, incurred the white bureaucracy’s wrath by sending the South

There was no sign that attempts to bring the spirit of the Hebrew prophets back into Adventism were having substantial effect on the church’s white, male establishment Several scholars offered interpretations of the “remnant” motif that incorporated insights from Hebrew prophecy, one of them the by-nowelder-statesman of Adventist theology,

Jack Provonsha 8

But few of the church’s most visible leaders since that time, nor the scholars they embraced, haven taken the trouble to refute or even to acknowledge these efforts

Shortly after the death of Ellen White in effect, the end of the pioneer period Adventist administrators, editors and teachers of religion and history convened for the 1919 Bible Conference in Takoma Park, Maryland The nature of Ellen White’s own authority was among the points at issue; so, at least indirectly, was the nature of scriptural authority

By now the American fundamentalist movement was gaining strength, and it was, as historians widely agree, an understandable, yet deeply defensive reaction to modernity Modern ideas put faith at risk and, in face of this, the most conservative Christians seized upon the Bible as their solid ground They affirmed scriptural inerrancy (as Ellen White had not done) and made their settled beliefs the litmus test for Christian orthodoxy

The gospel commission drive Adventist mission, and it mak justice as well as evangelism into core responsibilities.

called “the social gospel” with “modernist” theologians, they dismissed its legitimacy

In his biography of then-General Conference president A G Daniels, Ben McArthur tells how fundamentalism affected conversation at the 1919 Bible Conference. George Knight, in his study of the development of Adventist doctrine, argues that from the 1920s through the 1950s the fundamentalist notions of inerrancy and verbal inspiration came to have greater and greater influence in Adventism Richard Rice shows how inerrancy, the fundamentalist “rallying cry,” continues, at least through its “logic and language,” to appear in many Adventist discussions regarding the interpretation of the Bible. This is so, he contends, even though inerrancy is difficult to square with the centrality of Christ and impossible in any case to maintain consistently

Theological study was not so much a challenge to the church’s own false securities as an effort to shore up boundaries against secular or rival Christian points of view. Now the focus of Bible study could be key texts, understood as relevant and illuminating in themselves, without particular attention to context. The sense of the Book’s own story, and of its development toward the grand ideal embodied in Christ, slipped out of mind. Readers approached the Bible selectively, overconfidently, with little attention to long passages, whole books, the complete story. And because fundamentalists associated prophetic social passion what they

All this constitutes a lens for closer inspection of Civil-Rights-era editorials that, in effect, disavowed the relevance of the Hebrew prophets for Adventist mission The writers could appeal to the gospel commission against engagement of justice issues because Adventism had by then become captive to a fundamentalist at least a fundamentalistleaning ethos Key elements of fundamentalism, including aversion to “the social gospel,” appear in those editorials, which testifies to a telling fact about later Adventism: it fell under the sway of a perspective not its own. The editorials are deeply inconsistent with both the spirit of the Bible and the most arresting stories of the pioneers.

In the gospel commission, Jesus said, “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you.” The shortest version of what He commanded was “Follow me,” and He Himself, according to the gospel testimony, was the embodiment of justice and also of peace, its ideal fruition. Nor was His a merely senti mental spirituality His passion for the vulnerable alarmed both religious and political authorities (see, for example, Matthew 12:17–20, Luke 1:70 and Luke 4:16–20)

The gospel commission drives Adventist mission, and it makes justice as well as evangelism into core responsibilities. Despite resistance in later Adventism, the point is that

simple It may, for the insufficient attention it receives, seem unfamiliar, but the old, old story, taken whole, will make the point familiar to anyone who reads mindfully It could become familiar enough, indeed, to fuel the remnant vision and thus sustain, by God’s grace, a people ready to think and act ahead of the world around it

6

3

4

2

See Samuel G London, Jr (2009), Seventh-day Adventists and the Civil Rights Movement, University Press of Mississippi, pages 39–44

1 ibid, pages 45–59

Ellen White, Testimonies for the Church, Vol 9, page 207

See Ellen White, Testimonies for the Church, Vol 7, page 180; Testimonies for the Church Vol 4 page 60; The Southern Work pages 9–14

G H C Macgregor (1936), The New Testament Basis of Pacifism, The Fellowship of Reconciliation pages 82–3

5 R F Cottrell, “Render to Caesar What Belongs to God,” Review and Herald, 17 October 1963 page 12; R F Cottrell “Church Meddling in Politics” 29 July 1965 page 12; F D Nichol, “Unity in the Faith,” 29 April, 1965, page 12

7

K H Wood, “The Newsweek Story,” Review and Herald, 1 July 1971, page 2

8 Adventist Forums, pages 98–107

See Jack Provonsha, “The Church as Prophetic Minority” in Roy Branson (editor, 1986), Pilgrimage of Hope, Association of

The Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA) premiered a documentary on the plight of the world’s refugees on Thursday, July 10, in the Ferrara Theatre at the General Conference (GC) Session in St Louis, Missouri, United States.

Called Strangers Among You, the story follows refugees, migrants and displaced people as they fight to feed their families, find employment, stay safe and make new starts The documentary was filmed in Colombia, Lebanon, Canada, Poland, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Thailand

Director of the film, Arjay Arellano, said he started shooting the film in 2022 and was editing the 75-minute documentary right up until an hour before the first screening

“[Strangers Among You] is a documentary film born out of countless miles travelled, countless stories heard and countless moments of humanity captured on camera, because storytelling has power it can tear down walls, soften hardened hearts and spark action. It reminds us that behind every statistic, every news headline, there is a face and a dream,” he said.

Mr Arellano believes the film’s human stories are relatable. A mother from Ukraine cannot find work in Canada, a father from Syria struggles to make enough money to feed his family, an ADRA worker in Colombia thinks about her unborn child as she feeds and interviews families of caminantes (walkers) walking across borders to provide a better life for their children.

The name of the documentary is based on Leviticus 19:34

“As Christians we’re called to look after the least of these, to welcome the stranger, to love our neighbours near and far,” said Mr Arellano “My hope tonight is that this film opens our eyes, moves our hearts and reminds us that in God’s kingdom there are no strangers.”

The film draws attention to some of ADRA’s projects, including those that have struggled to maintain funding and are at risk of shutting down, such as a school for refugees in Lebanon

Israa, from Syria, whose family is featured in the documentary, shares her dreams of getting an education. Her little brother wants to become an engineer or a doctor

“I think I can speak on behalf of all of us when I say if that movie right there didn’t

move you, there’s something not quite right on the inside,” said Korey Dowling, ADRA International’s vice president for people and excellence “Because it just can’t help moving you to action, to do something ”

For Mr Arellano it is important to tell the stories in a way that retains the dignity and humanity of the subjects

“I feel as though the documentary helps to explain what ADRA does, but I want [viewers] to think about the people in the film,” said Mr

Arellano “These are families and communities they have dreams, and because of what’s happening around the world, all these opportunities are being taken away from them ” ADRA hopes to distribute the film on Adventist campuses and in ADRA offices around the world.

For updates on the film, visit https://adra.org/strangersamongyou.

Jarrod Stacklerith is editor of Adventist Record, based in Sydney, Australia. This story was first published on July 16, 2025 by Adventist Record

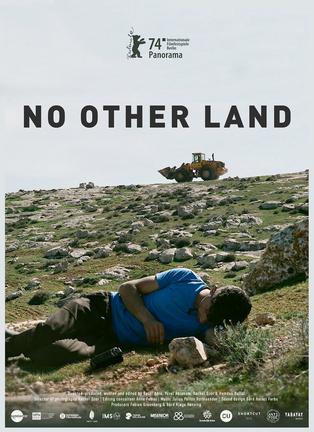

I suspect that I am not alone in this, but my primary awareness of No Other Land was the prominence and controversy that came with the documentary’s Oscar for Best Documentary presented earlier this year. I felt like I should watch it, but its limited release and availability offered a ready excuse Anyway, I thought I knew the story of the inexorable and systematic dispossession of the Palestinian people I have read the tragic headlines and a handful of books that explore the history of the Israel-Palestine “question.” I have even visited Hebron, the largest city in the West Bank of the Palestinian Territories and the region in which the documentary was filmed, where our tour group experienced a small example of the abuses of the Palestinian people in that occupied city So I thought I knew this story at least in general terms and I could choose not to spend 92 minutes immersed in it

But when No Other Land appeared prominently among the “entertainment” options for a cross-country flight a few weeks ago, I could not so easily swipe past this story in favour of something more frivolous. And while I was correct in assuming that I was familiar with many of the bold strokes of the story, I was not prepared for how it felt. To some degree, No Other Land offers an insight into the sense of frustration and futility, despair and anger that is the lived experience of the oppressed in the Palestinian Territories and too many other places in our world

The documentary is filmed by its central characters and records the experience of Basel Adra, whose family home is part of a small village in an area designated by the Israeli government as a military zone. To give effect to this designation, villagers’ homes and schools are being systematically demolished, often with only enough warning for the residents to grab a few positions and escape as the bulldozers advance Any protest or resistance is crushed as effectively as the buildings are levelled. We become witnesses of the cruelty and futility of this destruction, even as villagers begin to rebuild, often under the cover of darkness The occasional flashes of violence are rendered less shocking by how routine it all seems and that the entire inexorable process is violence

Filmed over a period of four years (2019–2023), No Other Land is both a small story a few family members and friends in one little village south of Hebron and a much larger picture. Adra is joined by an Israeli friend Yuval Abraham in recording these grinding outrages and sharing their hopes for some kind of sustainable future. However, Abraham is able to travel back to the comparative freedom of his home each night, highlighting the very different circumstances in which they live, even as they choose to work together.

As such, No Other Land was not the most entertaining way to use my time on that flight, but it was compelling and offered me a new empathy for the people behind the headlines

Wherever we might be on some of the “political” questions, we must be closer together on the people questions and this documentary invites us closer to the people themselves The relentless, grinding destruction of people, families and communities is wrong and something that must be resisted and protested, as the film both documents and enacts

However, the narrators of No Other Land also ask questions about the value of what they are doing in making this documentary: Does “raising awareness” work to change anything? What response were they hoping for from those who would watch some or all of their footage?

Possibly proving their point, Awdah Hathaleen a young Palestinian activist who was part of the team that created the film was shot and killed by an Israeli settler on July 28 Perhaps No Other Land now becomes something of a memorial to Hathaleen, at the same time as it is a demonstration of the futility of even an Oscarwinning documentary As one of his fellow activists put it, "His killing was really a shock for me but to be honest it was not a surprise.”1

Like Abraham, we might have the privilege of being able to turn away But for the sake of those like Adra and Hathaleen who do not have that choice, we can choose to sit with them at least for that 92 minutes Watching a documentary will not change the world, but it can change us. It can make us feel and understand in new ways And that might compel us to speak and to act in the ways that we are able.

Nathan Brown

Eric Tlozek, “Palestinian Awdah Hathaleen who helped make Oscar-winning documentary No Other Land killed in West Bank,” ABC News, July 30, 2025: ab co/40QJdop

A House on Fire: This Adventist Peace Fellowship podcast series is based on the excellent book on race and racism

Adventist Voices: Weekly podcast and companion to Spectrum designed to fost community through conversation

The Social Jesus Podcast talks about the intersection of Jesus, faith, and social justice today

Red Letter Christian Podcast: Christian commentary on the way of Jesus in the world today

Adventist Pilgrimage: A lively monthly podcast focusing on the academic side of Adventist history

Just Liberty: A fresh, balanced take on religious liberty where justice and liberty meet

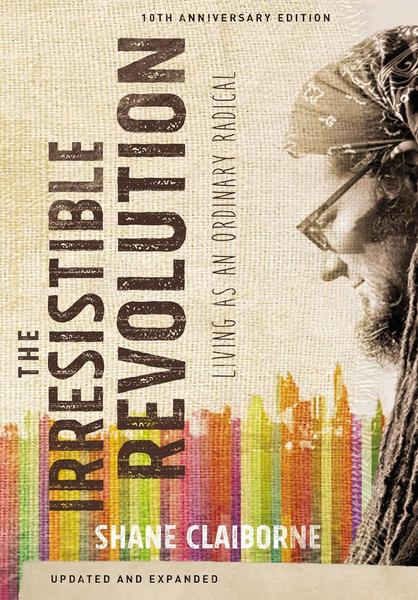

Our next Book Circle is on Saturday, September 20 We will discuss the seminal book The Irresistible Revolution by Shane Claiborne (tenth anniversary edition) Shane is a powerful, fresh voice for biblical justice, a friend of JustLove Collective, and the co-creator of Red Letter Christians.

Please purchase a copy of The Irresistible Revolution for your library and join the discussion on September 20 (We will provide a link for you ) All are welcome! Each session invites us to reimagine faith as a force for social transformation.

Discover JustLove Notes a twice-monthly Substack offering illuminating the vibrant intersection of faith, justice, and love. Each issue features curated book recommendations, evocative music, and thought-provoking articles designed to inspire your spirit and empower meaningful change. Join us on this journey of discovery and transformation.

We are particularly grateful for every contribution to JustLove Collective Donations are tax-deductible Though we are a global movement of volunteers, we do need to pay for expenses related to this magazine and to the Summit. For more information, please see our website at justlovecollective.org

Norma and Richard Osborn

Something Else Sabbath

School

Adventist Peace Fellowship

Rebekah Wang Cheng and Charles Scriven

Anonymous

Yolanda and Chris Blake

Jill and Greg Hoenes

Julie and Ty McSorley

Elizabeth Rodacker & Ed Borgens

SDA Kinship International

Adela and Arpad Soo

Gillian and Lawrence Geraty

Alta Jean & Richard Paul

Karah & Tre Thompson

Linda & Larry Smith

Marit & Steve Case

Jackie and Brian Starr

Harry Banks

Eileen and Dave Gemmel Heart, Soul & Mind Discipleship Class

AdventInnovate is an experimental platform from Adventist Today (AToday.org) dedicated to inspiring and supporting the Adventist community in new approaches to faith. Hosted by Rebecca Barceló, the platform celebrates innovation and entrepreneurship. It champions creative ideas, fresh perspectives, pioneering efforts, and inventive ministries that reimagine faith in today's world.