Do you know which way dreams fly

As they ricochet off stars

And spiral into the dark?

Let wanderlust surround you

As madness absorbs control

And the moon sets once again.

Evasive of mankind’s touch

Slipping through the fingers of time

A fragile picture covered in glass

As the faded ink melts into dust.

A fleeting eternity of painful freedom

Like a bird cutting crisp into a silky blue sky

As the morning tide sweeps out to sea

The luminescent angel of fading youth.

Sweet remembrance of seasons lost

Dreaming of reckless abandon

It crashes like waves and pouring rain

Washing away a delicate bloom.

Sparking a scorching flame that dances

Wild across the water as girl becomes woman

Dimmed but never extinguished

The golden match glowing within the soul.

TEXTILE BY XOCHITL SUH

TEXTILE BY XOCHITL SUH

Very little light enters the upstairs hallway of Belrose Library. When the sun is at just the right angle, it can reach the rooms along the right-hand wall, but it can’t make it past the dustchoked transoms. The lamps lining the left wall haven’t been relit in ages: they probably don’t even work, and no one comes up here anymore. At least, no one who needs light to see.

So it is all the more surprising when a flashlight clicks on in the stairwell.

The beam sweeps about the ceiling and bounces down the hall, scattering shadows as it goes, and a boy peeks his head above the floor.

The spiders take stock of this new intruder—the spray of cinnamon-star freckles; the fluff of reddish hair; the graphite stains on the side of his hand; a band-aid on his knee.

They settle back into their webs.

The boy doesn’t notice the spiders as he climbs the rest of the stairs, but he does pull the collar of his t-shirt above his mouth and nose to block out the dust, so he must have some wisdom.

He creeps down the hallway, scanning the floor before turning his flashlight onto the walls. The spiders are briefly blinded, but he flicks the beam away from their webs as soon as he spots them. This, too, the spiders note.

He looks into each room, eventually choosing one to explore further—the third from the stair. He is only inside for a few minutes before the clerk from downstairs comes up to investigate.

The spiders know her, the clerk. She comes here often when she wants peace. She is not afraid of the spiders. Sometimes she tells them stories, never questioning whether or not they understand.

Like them, she is a spinner, but her webs are of a different sort.

The clerk notices that the third door is open and starts for it, intending to reprimand the boy, but instead, she holds back, leaning on the doorframe, and watches him search the room. It used to be a bedroom, but now it’s filled with books. Some are in boxes, others stacked, still more lie spilled across the floor. The boy takes care not to touch any of them, which the spiders remark upon, but the clerk withholds comment, waiting one more moment before she knocks the heel of her boot against the floor.

The boy jumps at the sound, turning around and starting again at the sight of the person who moved so silently and now stands

so casually in the doorway.

“You can’t check any of these out, I’m afraid,” she says. They’re nothing-words, to fill the silence and buy her time, and the clerk and the boy and the spiders know it. “They’re in storage. Out of circulation.”

“I—I know that. I was just…” he trails off, deeming ‘I just wanted to see what was up here’ an inadequate explanation.

The clerk guesses what he’s thinking. Leading him away, she tells him: “curiosity is a good thing, but you ought to know caution, too. Always know your way out.”

He stares at her—her heavy black boots and gray lace shawl, wisps of almost-white hair that hang in her dark, dark eyes, a pendant strung with a miniature glass sword that rests just below her collarbone. The badge swinging on her lanyard reads Thierry Day, but that name doesn’t fit her, somehow.

“Is it dangerous up here?” he asks.

“Yes.”

As they descend the stairs, the boy asks another question, the clerk gives another answer, but their voices have faded out of the spiders’ hearing.

Three Hat Men sat in the armory of Starriver Manor, talking in low voices as they cleaned and polished the assortment of weapons kept by the house’s guard. Their black coat-collars were turned up, and their black hat-brims were pulled down, so all anyone could see of their faces were their noses, as is the custom of Hat Men—or Hats, as they are more colloquially called.

Rule Number One: a Hat Man’s face is never seen.

The tallest, in a fedora, leaned against the sword cabinet, polishing one of the many displayed inside. The Hat Man of middling height was not a man at all. She wore a wide, mushroomstyle hat, and was the most experienced of the three. She kept up an animated but quiet conversation with the Hat in the fedora as she inspected polearms, taking note of scratches and scrubbing away rust. The shortest sat in a corner, with his boater hat pulled down low—low even by Hat standards—and re-strung crossbows that had gone slack. He kept to himself, listening to Mushroom and Fedora, but not adding in.

Rule Number Two: a Hat Man’s voice is not heard by non-Hat

Men unless necessary.

The armory was a thing of appearance more than anything. Hats don’t need pesky metal things to do their jobs, but even Captain Eta had to admit that it was useful to have something for her troops to cross as they hissed menacingly at would-be intruders, or to assign the job of cleaning them to fresh-out-oftraining Hats not yet ready for another job or as punishment for misbehavers.

Tonight, though, there were no newbies or troublemakers, so they’d drawn straws, and these three had the luck to get the chore.

Rule Number Three: a Hat Man always completes the mission.

“So, have you heard the rumors?” asked Mushroom.

Fedora groaned. “I hope you’re not talking about the lucid dreamer that’s supposedly wandering all around the Glasswood. That’s all anyone’s been talking about for the past week, and personally, I don’t believe a word of it.”

“Of course you don’t. But that’s not the one I mean.” Mushroom swung her arm, forgetting the reach of the halberd in her hand.

Fedora leaned out of its arc, grunting a “hey, careful!”

“Sorry,” she said, not sounding like she was.

A few seconds passed.

“What’s this other rumor, Mushroom?” asked Boater softly.

“He speaks!” exclaimed Fedora. “We’re not on-duty, y’know.”

“Technically, we are.”

“Okay, rule-book, carry on. But it’s only Hats allowed down here. Nobody’s gonna hear us.”

“Forget I asked, then,” Boater finished mildly, returning to his work.

“Hang on, I didn’t mean that. I’m curious, too. Mushroom, what’d you hear?”

Mushroom heaved an exaggerated sigh. If her eyes were visible, she would be rolling them. “Well, since you asked so nicely, it seems Cobweb’s been spotted back in the Glasswood.”

Boater choked. Fedora scoffed.

“Yeah, right.”

“I’m serious! You know how the mist is getting thicker. The forest is restless.”

“That could mean any number of things, not that Cobweb is back. I mean, didn’t Lady Eridani exile her to the waking world or something?”

“You think the White Widow can’t find a loophole?”

“That’s… ominous,” Boater remarked. Mushroom laughed, startling both of them.

“Look at you two, scared out of your brims! You shouldn’t

believe everything you hear, guys.”

Fedora chuckled. “You really got us, Mushroom.”

Boater hummed. Everyone had heard of Cobweb. She used to be one of Lady Eridani’s closest advisers, even a friend. They called her the White Widow, not because of any deceased spouse—in fact, she’d never taken a lover, much less been married—but because she was a shrewd tactician, letting her opponents believe they’d outsmarted her, only to find that she had them defeated by their second move. None crossed her. She had Lady Eridani’s total trust, until the day Eridani uncovered a plot to overthrow her, headed by Cobweb herself, and none in the Glasswood saw her again.

So it was said, anyway.

Some time later, Fedora stood up, stretching. “That’s the last of the swords. How’s everyone else doing?”

“I’m done,” Mushroom piped.

“Almost.” Boater finished putting all the bows away, and then the three Hats left the room—Mushroom locking the door behind them—and bid good-nights to each other as they split off to their respective quarters.

Boater walked in silence, eventually leaning against the door at the very end of the hall, swinging his way into his room. The chamber was just big enough for him, a bed, and a table. The bed was barely wide enough for him to roll over. The tabletop was mostly taken up by a basin and a water pitcher, but the table did have a drawer. A mirror hung on the wall above opposite a small collection of maps.

He took off his gloves, throwing both them and his coat onto the bed, and then he followed them, elbows weighing on his knees, head buried in his hands.

He took off his boater, the shadows falling from his face.

The man beneath the hat could only be called a man if the word young were attached to it, and even then it wouldn’t quite fit him. His face was still fresh. His brown eyes hadn’t lost their inquisitive shine despite having long ago given up focusing on things more than a foot away. His freckles—only a few shades off from his coppery hair—had faded in the time he’d been in Glasswood but stubbornly refused to vanish completely.

He was not a Hat called Boater.

He was a dreamer named Emil.

Eventually, Emil got up and splashed some of the water from the basin on his face, wiping it with his sleeve. Then, refreshed—or at least more awake—he fixed his glasses and pulled open the table drawer, digging through socks and gloves in various shades of charcoal to find a packet of chewing gum and a small analog

watch.

The watch’s face read 2:03, and he might have believed it if it hadn’t told him the same thing ever since he’d arrived in this forsaken dreamworld. The gum was cinnamon flavored.

He folded a stick of gum into his mouth, reining in his thoughts with spicy-sweet shock. Chewing, he hid the watch and the gum packet back underneath wool and leather. When he glanced up, he bit his tongue trying to stifle a yelp.

There, on the mirror, rested a large white spider.

He chewed his gum harder, resisting the urge to squash it. The spider regarded him as reproachfully as a spider can regard someone, so he decided it was best to leave it alone. It was just as much a pawn in all this as he was.

The spider waited while he put on his gloves and his coat and his hat, then dropped delicately to the floor, where it scuttled across the boards and under the door. Emil followed, hanging back a few paces but still making an effort to keep up with the spider’s surprising speed.

He rounded a corner and collided with a young woman in a Hat’s clothes, but with a black visor instead of the hat.

“O-oh!” he stammered. “My apologies, Captain. Are you alright?”

“I’m fine,” Captain Eta told him, straightening her coat. Her visor took an eerie violet sheen in the dim hallway. She tilted her head quizzically.

“I was…going to the toilet.” He didn’t have time for a better excuse. The spider was getting away. “Ha-have a good night!”

With that, he dashed off.

Luckily, he didn’t run into anyone else, and the spider took him outside. He passed by beds of flowers and carefully pruned hedges, making his way to the border of the dense forest that surrounded Starriver.

The Glasswood.

Mist curled around the long thorns that gave the forest its name. The moon was barely a sliver, but they gleamed in its light anyway. Emil hadn’t gotten close enough to see whether they were actual glass or not—it was a haunted place, and one of its ghosts was standing in the shadows just outside the trees.

She looked the same as when he’d first met her in the library. Maybe her shoes were a little more scuffed, her lace a little more frayed, the shadows under her eyes darker, but she wore the same impossible-to-read expression.

“I warned you long ago, Emil,” said Cobweb. “Don’t get into something you don’t know how to get out of.”

“It’s a little late for that, don’t you think?”

The words had more bite to them than he’d intended, but she didn’t offer him a reaction.

He continued. “I’m done with this, Cobweb.”

“What do you mean?”

She sounded as though she already knew what he meant, which frustrated him more.

“I mean that I’m tired of skulking around pretending to be a Hat.”

She sighed. “Would you rather I pull what little influence I still have to convince a noble to let you pose as one of their entourage? Being a Hat puts you in the best position to find your way back to the waking world while avoiding being questioned about your ‘skulking around’.”

She was dodging again. Emil shook his head. “That’s not it! I don’t understand why I have to go through any of this just to get back. You were banished, the way to Glasswood was shut to you, but here you are! Why can’t you send me to the waking world the same way?”

Cobweb laughed bitterly. She reached up, unclasping the tiny sword from her neck, and held it out to him.

He watched it swing on its chain. It was even more intricate up close—the silver hilt and the glass blade. It looked like there was something trapped inside: a wisp of smoke or a swirl of dust. The pommel and crossguard had hair-thin patterns etched into them, maybe words, but too small to read. He reached for it, but just before he touched it, the mist reared up. The sword rattled and the thorns clattered against each other in sympathy, vibrating with rage. A whistle filled his ears, growing and growing until all his senses were consumed by an ancient, angry shriek.

He snatched his hand away, gasping. Cobweb took the pendant back, calmly refastening it.

“I was banished. As you said, the way was shut to me, but I have ways of getting past locks. You are trapped, which is much harder. The way is wide open, but whoever brought you here took something from you, to keep you here. The only way to leave is to get it back.”

“But how do I find a thing that I don’t know I lost?”

She shrugged. “That’s up to you.”

“So…” he turned his gum over in his mouth. “If it’s lost, there’s got to be a place where it’s supposed to go. If I find that empty space, I can get an idea of what I’m looking for.”

She nodded. “That’s a way to do it.”

“I’m guessing you can’t help?”

“Only indirectly.”

“Mmm. You ought to know, there’s a rumor that you’re back.”

This time, her laugh was genuine. “Good. And you should know, Hats have noses like hounds. Make sure they don’t trace that cinnamon smell back to you.”

He laughed with her. “I’ll be careful.”

“If you’re in trouble, the spiders will know.” She turned back to the forest. The mist was already reaching for her. “Good luck.”

And then she was gone.

Emil stood at the edge of the garden for a few more moments, and then he turned around and walked back to Starriver.

He wouldn’t check his watch until the following morning, but as he stepped away, the minute hand ticked to 2:04.

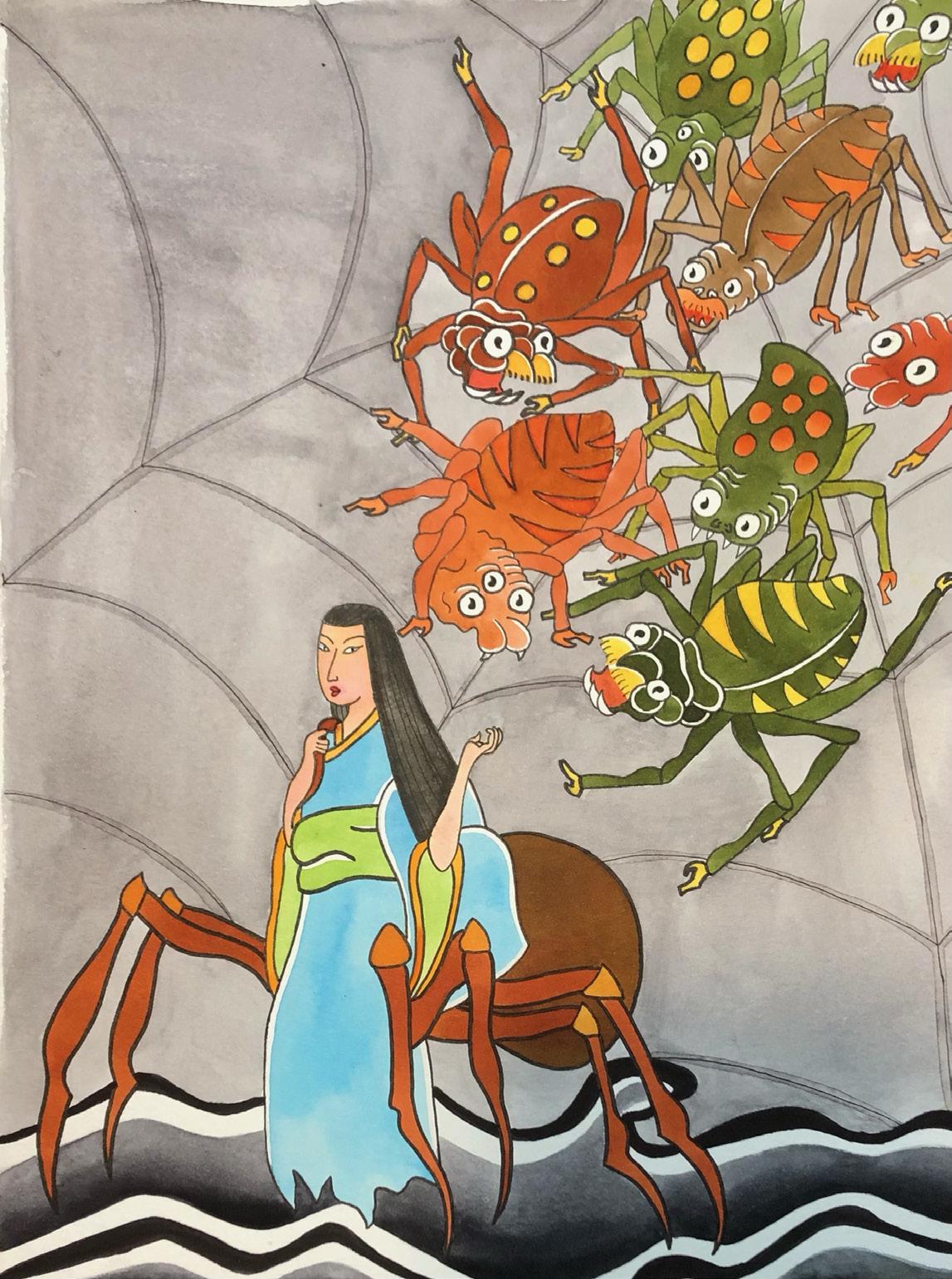

PAINTING BY CHARLIE KEEFE

PAINTING BY CHARLIE KEEFE

POETRY BY NICKO FRIEDMAN

Fold me up like a paper star

And write a secret message along my back

Your nightmares in black ink across my pages

Hide me in the darkest corners

Of your secret hallways and passageways

Just a toy for the cats to play with

I am an ocean and i am a sky above it

And the waves look like stars far below me

Or above me, fathoms or light years

Drop me like a rock into the water,

A stone to wash up on the beach

And be buried in sand

Burn your symbols into my bones

Searing metal and blistering skin,

Keys all across my collar

The blades and the delicate ends all there in the scars

A swirl that shows a secret

A map hidden in bone that only you can follow

Whisper your secrets into my wings

And throw me into the night sky

A smudge of black against black against black

Watch me fly away

And know that i will return again

When you are long gone below the ground.

MIXED MEDIA BY AUDREY MOREHEAD

hunger

mouth

“plastic jesus”

morphine

dead dove: do not eat

the hours in between

suicide jokes

contact sports

faith (or belief or truth)

hi, my name is

When we met the skies would turn, So many things she made me learn. It was love at first sight So each night

I’d lay in the light.

Dreaming up ways I could ignore this warning.

I pass her every morning. She sends a smile my way, I stutter, she made my day.

Every moment with her is a sparkling shell in a vast unknown,

so every second I see her she shows me what could never be shown.

Perfection is the only description

For her glistening, glittering, lovely little brain.

And an intonation in the way she breathes, is a million damnations on the way I see.

So I’ll play this game, but I know I can’t win. I’ll pop tiny pills, and let them seep in.

Crumpled up papers, stained with bright love poems, Inked-out feelings of putting her on podiums.

I draw this target with my glare… Bang.

Her arrow hits me, it’s not fair. She has this passion, and I know it’s not rational, But she’s just TOO. GOD. DAMN. PRETTY.

Her hair is like snow, and her eyes have this glow. My heart is her palace, She sips blood from my chalice.

I think I’m going delirious from this beautiful experience The pages keep turning So my mind keeps yearning

But I stop. And I think. So I remember

I can never shape her. I can never change her. I can never erase our history, And I can never rewrite the way she thinks and feels Because she will never—

Just one oversight. like a pair of cups I’ll overflow, Falling into this trap of give-and-go

I’m turning every shade of indigo While I tutter and tatter

And pitter and patter

My brain starts to shatter and As my heart sinks and the flutter fails to flap its wings— “I love you!” she screams. But she’ll never love me.

DIGITAL ART BY ROSLYN CARLE

DIGITAL ART BY ROSLYN CARLE

sometimes i am dancing, holy and free, and the whole world feels infinite, and i am the whole world, and i am dancing, dancing, dancing, and i am the spitting image of god,

and sometimes i am the influenza. a leech swallowing whole, devouring, and not even god dares go near me,

and sometimes getting out of bed feels like giving up, but then so does showering, and packing myself lunch, and calling my mother.

i haven’t danced in so long, but then neither has god.

DRAWING BY ISABELLE CARTER

PHOTOGRAPHY SERIES BY TOMMY MARX

The fog isn’t really fog. It hangs in the air just at eye level, swirling like food coloring dropped into water, turning over itself and shifting hues with each moment. It’s a psychedelic cloud that Evien struggles through, chasing after the golden doe.

It smells like incense. Evien is reminded of the last time she was at Xechiech, when the scord rended her in nearly two and Triairi did his best to smoke the injury out of her. It smells the same as that. Like honey and cloves and burning hair and burning wood. Evien doesn’t mind. It’s a sickly sweet scent, and it reminds her of her mother’s old perfume.

Behind the food coloring smoke, the ground is made out of sandy yellow stairs. No matter how high she climbs, Evien can’t seem to escape the incense-scented fog. She can barely see the stairs beneath her—just feel them under her socked feet.

She can see her socks, and her attention catches on them for a moment. Where are her shoes? She finds that she can’t remember. She finds that she doesn’t care.

There is a stick in her hands. She doesn’t know when she picked it up, but now she swings it through the liquid fog, listening to the swishswishswish of it against the air and the splooshsplooshsploosh of it entering the swirling clouds. She swings it like she is a child playing pretend, imagining that she is a knight. Evien is not a knight. You have to be a good person to be a knight, and Evien can’t view herself objectively and say that every action she has committed follows the rules of knighthood, or chivalry, or whatever.

if you die who would miss you if you die would they care if you cannot save them how can you save yourself whats even the point why not just stay here and listen to that swishswishswishsplooshsplooshsploosh stay here and never leave because if you leave you will only be unhappy so staystaystay

Evien’s imaginary sword cuts through the air before her. She climbs ever-lower. The golden doe flits off into the

nothingness beyond and Evien continues down, and then up again, and it strikes her that that…shouldn’t happen if she is just walking in a square. She remembers Jasper, talking about the penrose staircase. She continues along it for what feels like minutes, what feels like hours.

Time always works differently when she’s high. And that’s what this is, isn’t it? Evien Juno Rowsell is high.

Up. Up. Down. Down. Impossible turns. Non-euclidean geometry.

She’s clearly not high enough if she can remember shit about geometry, so real-world Evien fumbles around with the pill container that’s labeled with the impossible-topronounce name of her antidepressants but has for months now contained the little purple-pink-yellow pills that bring her here, and show her that golden doe. She dry swallows and real-world Evien fades out.

Hazy Evien feels much more solid, and the world shifts on its axis. There’s that golden doe, flitting back down-then-up the stairway past Evien, and the fog swirls greenbluepurplepinkredorangeyellow. Evien follows the deer because the deer knows the way to go.

Save me from this madness, Evien says, but not really, and the doe speaks back in Cass’s voice.

You will be your own undoing, she says, and Evien laughs, ahahahaha, and sets off into a run. Her feet hit the playground-sand-yellow stairs and sink in, the stone reaching up and grasping with dirty hands at her calves.

Mum’s going to be upset that my leggings are dirty, she says, but the stone continues climbing her legs, completely covering her feet until she can’t move, grabbing her thighs and then her stomach and then her chest, until she is entirely swallowed by the stairs.

She falls, then. Down, down, down, no up, just downdowndowndowndown. She sinks through the stone that gives way to water until she is sinkingsinkingsinking through the ocean, bubbles escaping her mouth blubblubblub until there is no more air in her lungs and they

are burning like ice and fire, all together.

She gasps in a breath, and the water fills her lungs, cold and salty. It is drowning and being reborn. Reborn, born again, againagainagain, and the smoke fills her lungs and she breathes in and her blackened lungs expand. She is aware of every rib in her body, every vertebra in her spine, every purple-yellow-black-blue bruise across her wrists or her throat or her heart.

She sinks through the water, unsure which way is up and which way is down, only knowing that she is moving faster than she has ever moved before. And she sinks or she rises until her feet rest on the sand, and she walks through the water, her hair streaming out behind her like seaweed or smoke. The currents push her around like bullies on a playground, get out of the way, nerd, and she lets them, following where the water leads.

A school of fish swims by, and maybe she is upside down, or maybe they are, but gravity does not affect the fish the way it affects Evien, because they are stomach-up, flitting by swishswishswish and getting caught in her hair.

She stumbles and falls the sand below-above her and rollsrollsrolls head over heels over head over heels until she is no longer in the water. Her socked feet land on the floor of a wide, dark ballroom and she is wearing a dress made of roses and thorns that wrap around her arms, digging into her skin and the osiria roses are splattered with blood dripdripdripping that blends with the crimson undersides of their petals. She feels, in a phantom body, that she is not really here, that she is still in bed in Ibis’s massive sweater, but that thought flutters away as the music starts up.

Women and men made of stained glass fill the room, each wearing top hats and elegant suits and gowns. A saint with red skin and black wrought iron holds out a delicately blown hand and Evien takes it, letting herself be swept into a dance. The woman’s skirt drags across the ground like real fabric, but it sounds like shattering as cracks rush up her hollow body. The only part of her that is not glass is her black top hat, settled on crimsonblood hair.

They spinspinspin and the woman

crackscrackscracks until the song ends, the music fading out, and the saint shatters into a million pieces. Evien steps across the broken glass, the pieces cutting into the soft skin of her soles, and another saint offers his hand, this one the blue of the sky of ice of the delft pottery that Evien’s sister collects. Another song starts up and the stained glass man spins her in circles and spirals and her roses flow out behind her, dripping blood, and she leaves bloody footprints on the marble floor where her feet set down.

They waltz in a pattern that Evien cannot discern as the song plays. It plays on the pipe organ that makes up the walls and ceiling of the ballroom, louder than the thoughts in Evien’s head. She lets the stained glass saint spin her around until the organ quiets, the end of the song crescendoing and then coming to a sudden close. The saint shatters. Evien steps over his broken shards and leaves a trail of blood and scarletwhite petals behind her.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DELANEY MCDERMED

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DELANEY MCDERMED

The hand that is offered to her is the grey of wrought iron, silver skin covered in black tattoos. Evien sets her own grey palm in the offered one and looks up to see Key, dressed in an iridescent black suit and an emerald green cloak that shimersshimmersshimmers like a beetle’s wings. Their top hat is jade green.

May I have this dance, they ask.

I’d love nothing more, Evien says, and they spin her around, letting her blood drip down their arms and down their sleeves.

You look quite a mess, they say, what happened to you?

A lot, Evien admits. But I feel fine.

That’s a lie. Evien feels the opposite of solid, like smoke and clouds. She feels hazy and giddy and bloody, and she feels euphoric.

What about you? You look different.

That’s a lie, too. Key’s buzzed hair is every color it has ever been, and their tattoos shift in an undulating hue, but their skin is the same color, the color of graphite, and it feels dusty against her own pallid hands.

Oh, Vi, Key says. You know, one day you will be the king?

The king, the king, the king. King Evien. King Arthur. And Ibis will be the ibis, and Cass will be the Wild Queen, and James will end the storm. Vesper will rule the bees and

Evan will raise the dead. You will never die, Evien, King, Hanged Man, high priestess of the psychics. You will be eternity, and you will be nothing.

I am already nothing, says Evien. Nothingnothingnothing. How cruel of the world to create people who destroy themselves.

The song ends. Key shatters. They fall to the ground in pieces, pieces of bloodbloodblood and skinskinskin and bonebonebone, and a silk top hat sat atop the gore of Evien’s friend. She steps across the body, shards of bone joining the red and blue glass in her feet, and she takes the offered hand of an emerald saint.

I’d always imagined heaven looking a bit like Home Depot. Not all of it, of course—certain aspects of it are so poorly designed they could only be made by humanity’s worst—but the lamp aisle. My parents would wander down the uninteresting halls, and I, six years old, would wriggle my hand out of their grasp and slip away when their backs were turned. I knew where it was, every time. It was the brightest part of the entire store, and usually the quietest. There, I’d sit on the floor and just look.

It wasn’t difficult to imagine there was an angel up there, hiding somewhere between the spherical hanging lamp and the tall fixture. There could be anything up there—the lights seemed to stretch on forever, like a sky full of stars. Some of them reflected the light into sparkles that almost hurt my eyes, and some of them were regular lamps, emitting a warm glow. My favorite was a fixture that was bigger than I was, strung together by long metal bits, while tiny teardrop diamonds hung from the edges. I imagined it would make a little shiver if you moved it around, a high, tinkly sound like wind chimes.

An upbeat song was playing, as stores always play, but this time it was one I recognized. When did your heart go missing? asked the song, and I made a promise that I would watch my heart very, very carefully.

The lights were overwhelming, so I looked down. The floor wasn’t anything special, just some white tile that needed to be cleaned. It was cold when I pressed my palms against it, and I ran my fingernails through the unhygienic cracks between the tiles. There, I noticed something lying on the ground.

A little brown moth. Its wings had speckles, and with those speckled wings, it had made its way inside the store

and flown all the way over here. I imagined it circled around the lamps for quite some time before it got tired, or like me, overwhelmed. Someone would surely step on it if I didn’t do something, so I picked it up. I held it in my hand, then I held my hand up right beside a lamp so it would have a good view. It didn’t fly away—it didn’t even try, so I leaned back against the aisle, kept holding it up, and we looked.

My parents arrived a few minutes later, and I was certain I would get in trouble, so I cupped my new friend in my hands and tried to look inconspicuous.

“Where on earth have you been?” my mother asked me. I thought the answer was pretty obvious.

“We were just buying a new sprinkler, and we’re planning to set it up tomorrow, and then we won’t have to water the grass anymore. It’s automatically timed, so we won’t even have to turn it on. But you shouldn’t run through it, okay? You’ll get your clothes all wet. Now, I also saw your teacher here, and here’s what he said—” and I stopped listening. I felt the moth, delicate and powdery in my hands, like it was made of flour.

When we left the store, I opened my hands a little to let the moth breathe, but it escaped, right then and there. I felt a little disappointed, but it was probably for the best. Neither a hardware store aisle nor a child’s hands were a proper place for an insect to grow up in.

I never saw that moth again, but maybe it had children who were also drawn to light. My parents’ sprinkler ended up breaking. I graduated from second grade six months later and promptly forgot everything I’d learned in that class. But Home Depot was still there, with all its lamps. I think it’ll stay that way forever. I hope so.

DIGITAL ART BY ELISE HARDING

DIGITAL ART BY HAN MELLENBRUCH

Our hearts met under the shadow of the Eiffel Tower. Not the Parisian version, but rather the soulless replica that loomed over Las Vegas. It towered above my booth like a gaudy-tiered wedding cake at the world’s most lackluster reception, lime green spotlights blinding passing birds. Over the years, I had grown accustomed to the lights, just as I had become accustomed to the excitable shrieks of children when their fathers arced the baseball with enough purposeful direction to knock over the milk bottles, winning them my companions. At the start of my extended stay at “Milk Bottle Madness - Win Big!”, the arrival of children sparked a flame of hope to the dumpster fire that was my existence, but I soon came to realize that I would never be the prize that they clamored for. The tacky inflatable swords, oversized plush lions, and neon pink stuffed giraffes would all be taken by the end of the night, but I would remain the solitary unclaimed treasure. The plastic water-bottle-sized stuffed penguin, my candy cane striped scarf drooping against my starched white stomach. The flightless bird, forever anchored. By the time she arrived, I had become convinced that I would live an eternity confined to this rickety stand. If only I had known.

It was half past seven in late July when my world bloomed. Tourists were flocking to “Milk Bottle Madness - Win Big!”, and the poor teenager forced to man it had already needed to go into our discarded prize box to appease the masses. The hook next to me was empty, clanking lightly against its neighbor in the summer breeze. Then there she was. She was...magnificent. Her ears were perched upon her magenta fur with the elegance of teacups placed in their saucers, the fur itself retaining the texture of a windblown buffalo, majestic against the prairie grass. Her golden beak was pursed in annoyance at the informality of her setting, and I longed to utter something witty enough to inspire a smile to emerge on her delicate features. Her eyes...by thunder, those eyes. As bright, nay, brighter than the lights of infinite slot machines, they captured my very essence with a single blink. I had locked eyes with many Furbies throughout my career, but none shone as brightly as her. Without her even acknowledging my presence, I was hers, body and soul.

Yet as I was becoming ensnared in her aura, the father next in line was weighing the baseball in his hands. With the snap of his wrist, the ball was careening like a comet towards the milk bottles, his two children screaming with glee as it flew. A split second before shattering the precarious tower, the ball lurched directly towards the two of us, red laces spreading across its white leather like cracks on a frozen lake. The ball struck the two of us, and we were plummeting off our hooks and onto the unforgiving pavement below. We tumbled together through the crowded street, dodging the tennis shoes of tourists and the stilettos of showgirls, before crashing into a kiosk hawking sunglasses.

“Oswald,” I stammered as she shook the dust of the street off her tufted fur. “What?” She turned towards me, and I found myself trapped in her headlights. “My name. It’s Oswald.”

“Penelope.” It suited her perfectly.

“So...what happens now?” The thought of life beyond “Milk Bottle Madness - Win Big!” had never even crossed my mind, and now it had been placed in my lap without struggle or effort. “Everything. We can go everywhere, see everything there is to see.” Her captivating features were reflected from the lenses of the sunglasses surrounding us, her pure joy apparent to all. “Everything seems like a good enough place to start.” Claw in fin, we set off into the night.

Together we sat, nearly an hour later, on the curb outside the cotton candy booth, spun sugar gritty on our tongues and staining our beaks a faded, smeared pink.

“Do you ever wonder what happens if you get chosen?”

I startled slightly at Penelope’s breakage of our comfortable silence.“Maybe from time to time. Do you?”

She sighed, slumping onto the concrete.“Constantly. I can’t decide...” Her words died out and she looked away from me, embarrassed.

“You can’t decide what?”

“If it’s like dying when you’re chosen, or...”

“Or?”

“Or if we’re not alive until we are.” I had nothing to say, no witty response, yet I desperately wanted to distract her, for her to focus

on me instead of on her sadness.

“I love this song.” Belinda Carlisle’s “Heaven is a Place on Earth” was statically playing through the tinny speakers that hung above us. I hoped that my attempt at a tonal shift would cause even a pleasant head nod, but when I looked at Penelope, I saw a solitary tear snake down her cheek. “Penelope, why are you crying?”

“This song. I...I used to dance to it. With my father. Before I was transferred to ‘Milk Bottle Madness - Win Big!’ I was a prize at ‘Dart Overload’. So was he.”

“You were?” My question fell on deaf ears as she gazed up into the Vegas night.

“This song was playing that night. It’s impaled into my memory like that dart was impaled through his heart.”

My stomach dropped.

“What?”

“A man came to the booth, staggering, his words flowing into each other like syrup. He had popped three balloons already, but on his fourth throw, he was distracted and turned his head towards his friends as he threw. Before I could even react, the dart was pierced through my father’s heart. And that man...that man and his friends...they laughed.” She was convulsing with sobs. I reached out and held her claw as she cried into my scarf.

“I’m so sorry, Penelope. But if his final company was you, then he died the best death a Furby could have.” She turned towards me, tears glistening like dewdrops streaked across her fur.

“Do you mean it?”

“I’ve never meant anything more.” She was so close.

“What happens when tomorrow comes? Will I see you again?”

“My only wish is to spend the rest of my days with you. But tonight...” It had always been her, and it had always been me. I took both her claws in my fins and dared to lean closer.“...tonight I’ll kiss you like there’s no tomorrow.” We crashed into each other. It was infinite. It was over torturously quickly.

We pulled apart, the taste of cotton candy still on my beak. She squeezed my fin with an intensity I’d never felt before.

“Oswald, I lov—”

I saw the girl before Penelope did. The pigtailed fiend, the freckle-faced demon that had crept from the lowest and most devilish pit of humanity to arrive here, now, on this street. Here, now, to take my Penelope. Her oafish hand descended upon us, wrapping around Penelope and hoisting her high, and once

again I prayed for flight, just for an instant, just for enough power to bring my beloved back down. But she was gone. And so was my nemesis, her pink tutu’s many layers of tulle mocking me for allowing myself to hope. My Penelope. A wave of loss crashed over me, but the tide quickly receded. I was left alone on the concrete curb, the love of my life stolen. Yet, I was numb. There was only one fragment of a thought left in my heartbroken soul, a familiar refrain even now. Why wasn’t I the prize that was wanted? Fin.

PAINTING BY CHARLIE KEEFE

First Movement

Which page?

Lying on the couch

Holding your hand. (a heart in)

All the folders of information in my brain, And I can’t close this one It lies open on my desk Staring at it.

“Quelle page?”

What ? (page) logan.

Tears like a typhoon through the heart

Who are you?

The voice of a devil perched upon my shoulder whispering insults in my ear?

Are you some god too great for my feeble mind to fathom? Perhaps a memory, Of a lullaby on Christmas Eve?

the notion of anticipation

Forgetting the break won’t put it back together.

Second Movement

You’re going to carry that weight

Upwards a thousand feet from the start to the finish (sprinting)

And yet the real weight isn’t in your backpack. A weight so heavy each step feels like a million pounds crushing with every step higher.

At the mountaintop you fall to the ground, feels like a thousand feet down The weight pushing you further.

I watched you climb that mountain from your side. My backpack was better packed.

Diminishing recourse. chords plucked at my heartStrings, vibrating with Life. “Different strokes”

- He said

Direct from the source: New goods trucked, preparing to depart! An unspoken myth. Life. “Music evokes” Now he’s dead

Lay down your head Death. “Breath chokes” “They’ll be forever with you, in your heart.”

A soul bucked

Off its course.

POETRY SERIES BY PAUL SERNINE