Missions in Congo, Syria and Yemen

Henrik XMagnusson

Henrik XMagnusson

Mission Congo, Yemen, Syria

Automatiserad teknik vilken används för att analysera text och data idigital formi syfte att generera information, enligt 15a, 15b och 15c §§ upphovsrättslagen (text- och datautvinning), är förbjuden.

©2025 Henrik XMagnusson

Publisher: BoD· BooksonDemand,Östermalmstorg1, 114 42 Stockholm, Sweden,bod@bod.se

Print: LibriPlureos GmbH,Friedensallee273, 22763 Hamburg, Germany

ISBN: 978-91-8097-215-4

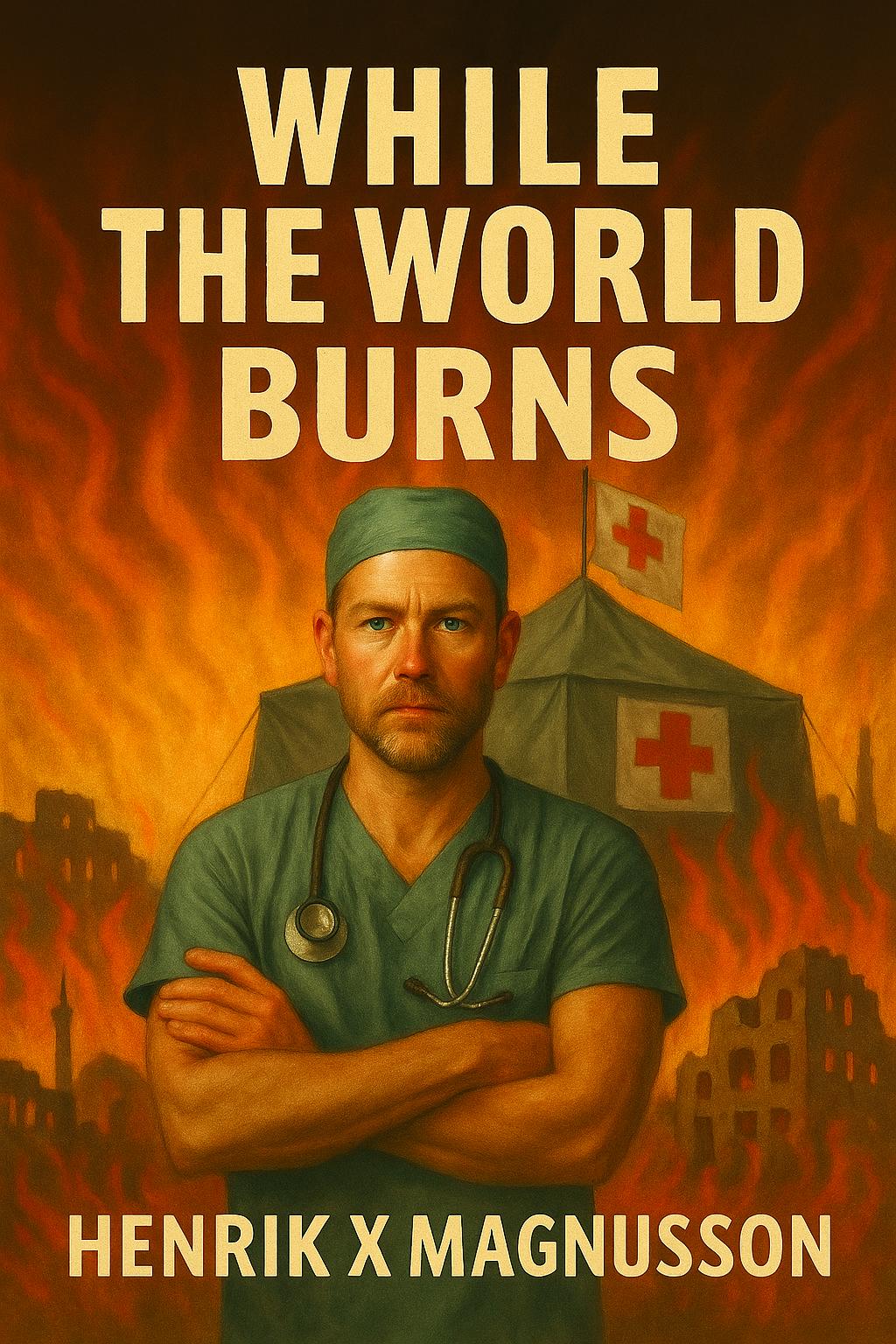

Viktor Seger is afield doctor in aworld where violence never stops. Together with his team fromMédecins Sans Frontières, he is forced to make impossible choices every day: Who should be saved when there are not enough resources for everyone? How do you retain your humanity when death becomes part of everyday life? And what is the cost of staying when everything tells you that you should flee?

In the shadows of war–from Yemen's shattered cities to Syria's refugee camps and Congo's jungle hospitals –Viktor Seger and his colleagues are forced to navigate between medical protocols and human needs, between safety and conscience. Here, it is not enough to be adoctor.You also havetobeanegotiator, abridge builder and ahuman being.

Agrippingtrilogy about courage, sacrifice and the invisible heroes who refusetogiveup–evenwhen the price is high.

The stories are fictional, but the reality they depict is frighteningly true. The wars are ongoing.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo) is bleeding, even though its soil is overflowing with riches. "Africa's World War" (1998-2003) claimed fivemillion lives and threw millions more into the hell of refugee camps. In eastern Congo, armed militia groups extract minerals from the earth's bowels –gold and coltan stained red with blood while Rwanda and Uganda lurk in the shadows.

The M23 rebelsbrutally occupied parts of eastern Congo. Humanitarian disasters darken the country: children with guns instead of toys and internally displaced persons wandering through the jungle in search of shelter. The UN peacekeeping forces (MONUSCO) are powerless in the face of an inferno of ethnic revenge and political corruption. Several organisations are trying to help the population, including Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, which is the French and international abbreviation).

Field doctor Viktor Seger smelled Congo before he saw the country itself. The damp scent of tropical soil penetrated the aircraft's ventilation system and hit him almost physically. It wasamusty smell reminiscentofthe compost heap behind

his grandmother's cottage in Dalarna, but thicker, more intrusive–mixed with diesel, wood burning and something sweet and meaty that he would rather not identify.

Through the small, scratched window, he saw the landscape spread out like agreen carpet. Not the orderly greenery of Swedishforests with their straight spruce trees and tidy paths, but something wild and impenetrable. The jungle stretched as far as the eyecould see, broken only by winding rivers glisteninginthe late afternoon sun. Here and there, columns of smoke rose into the blue sky.

Field doctor Viktor Seger, who specialised in surgery, thought of his children back home in Stockholm –how Mira would havepressed her nose against the cold window and asked if there were lions down there, how Joel would have wanted to know if the trees were bigger than the Globe Arena. The thought of these small, playful children in their safeterraced house inÅrsta made hisheartache.

It wasonly six months since he had sat at the kitchen table at home reading about the situation in Congo, while the evening light fell through the window and the children playedinthe garden outside. Mums Hanna and Malin had placed acup of coffee in front of him without saying anything, but he had felt their gaze –that mixture of support and concern that he had learned to recognise. They already knew what he wasgoing to say, long before he himself had realised it. But he couldn't sit still while the world was burning.

"First time in Congo?"

Thevoice came from the woman next to him, andViktor jumped as if he had been awakened from adream. Doctor

Catherine Moreau had that wayofsitting that Viktor had come to recognise in experienced female field workers –her back straight but not tense, her eyes constantly scanning her surroundings, even here, confined to an aeroplane seat at an altitude of ten thousand metres. Her hands rested relaxed in her lap, but Viktor saw the scars that ran like white spider webs across the brown skin of her knuckles.

Catherine wasinher fifties, with grey, practical short hair and aface that bore the smallscarsthat came from years of working in deserts and jungles. It washer eyes that caught his attention –theywere warm and intelligent, but also contained somethinghard, something that spoke of things she had seen and could not forget.

"Yes," replied Viktor, noticing how thin his voice sounded against the constant hum of the aeroplane engines.

"And you?"

"Seventh time."

She said it as others might say "seventh cup of coffee today" –an everydayness that made something turn in Viktor's stomach. Seventh time. That meant years of this, years of travelling to places where life hung by athread.

"Dr.Catherine Moreau, WHO." She held out her hand, and Viktor felt her handshake, which wasfirm even though they were greeting each other as you do when sitting close together on an aeroplane.

"Viktor Seger. Surgeon. Médecins Sans Frontières."

Catherine nodded, as if she recognised the type.

"First assignment?"

"In Congo, yes. I'vebeen to Mali and Afghanistan," Viktor hesitated, then added, "But nothing like this."

"No!" said Catherine, and her gaze softened slightly. "Congo is... special. It's not just acountry at war. It's acountry that has forgotten what peacemeans."

Shestudied hisface with the kind of attention he recognised from his own examinations of patients —aprofessional assessmentthat wasboth human and clinical.

"May Iask why you camehere? Really?"

Thequestion hit Viktor like an unexpected punch. He had expected the practical orientation, the advice on safety and logistics. Not this.

"I...Iwanted to make adifference," he said, and the words sounded hollow even to his own ears.

Catherine smiled, but it wasnot acynical smile.

"Everyone says that. But it's not enough here. The desire to makeadifference is abundant —what's missing is the ability to livewith the fact that the difference you make may not be enough."

Viktor felt seen through. Catherine continued in avoice that wasbothgentle and merciless:

"Advicefrom aveteran:the first month will test everything you thinkyou know about medicine. Forget textbook theory. Here, it's about urgent prioritisation amid chaos, surgery without electricity, and accepting that you can't save

everyone. The hardest part won't be the medical work –it willbelearning to livewith the choices you are forced to make."

Viktor thought about the evening when he made thedecision to applytogotoCongo. He had sat alone in his flat in Södermalmand readreports about overcrowded hospitals and flooded refugee camps, about children dying from diseases that had been eradicated in Sweden for fifty years. The feeling of meaninglessness that filled him every morning when he went to his secure job at Karolinska hadbecome unbearable. But there wasmore than idealism behind his decision, and Catherine seemed to see that.

"You havechildren," she said. It wasn't aquestion.

"Two. Mira and Joel. They're... complicated," said Viktor, looking out the aeroplane window.

"Complicated?" she repeated questioningly.

"They live with their two mothers. Iam... Iwas their donor at first, but then Ibecame more. Much more." Viktor fell silent, unsure why he wastelling this to astranger. "Now, when they need me most, I'm here instead of at home."

Catherine studied him silently. "Guilt?"

"What do you mean?" Viktor asked.

"You're running away from something. Guilt, responsibility, lovethat became toocomplicated. It's more common than you think. Many of us who work here do it," Catherine said.

Viktor felt exposed under her gaze. She wasright, of course. Guilt waspart of the picture —guilt over not being agood

enough parent, guilt over wanting more than the limited role he had played in hischildren's lives, guilt over the incident in Mali that still wokehim up at night.

"What about you?" he asked, changing the subject. "Why are youcoming back for the seventh time?"

Catherine wassilent for so long that Viktor wondered if he had asked something too personal. When she finally answered, it waswithavoice that carried theweight of years:

"Because I'm better at saving other people's families than building my own," he replied.

The plane hit the runway with abang that made Viktor grab the seat in front of him. His heart pounded against his ribs as theplane bounced and shook over the uneven asphalt. Through the window, he saw alow building made of yellowish concrete with broken windows and aflag hanging limply in the heat. Several UN vehicles were parked in the shade of largetrees,their white colour stained yellowbydust and time.

"Welcome to the heart of darkness," Catherine muttered as they got up to get off.

Theheathit Viktor as he stepped onto the steps. It wasn't just hot—it waslike throwing himself into an oven filled with humid air that madeevery breath an effort. Sweat began to run down hiswhite cotton shirt before he had taken three steps.

The sound hit him almost as hard as the heat—a constant hissing and buzzingfrom insects, mixed with distant shouts in languages he didn't understand and the constant hum of 13

generators. The air vibrated with life in away that made him think of alarge, panting organism.

Asmallgroup of people with MSF signs were waiting at the airfield. Viktor identified them immediately by the waythey stood –the same controlled exhaustion he had seen in colleagues returning from other missions. They had the special posture of people who had learned to conserve energy, never wasting strength on unnecessary movements. Their clotheswere practical and worn, their faces sunburnt but alert.

Awoman in her thirties with light blonde hair tied back in a ponytail walked straight towards him with purposeful steps. Shewas slim andtanned, with scars on her forearms that Viktor immediately recognised as surgical wounds. Her eyes were light blue in the bright sunlight, but they held a hardness that made him think of frost.

There wassomething in her movements that spoke of years of efficiency. She held her shoulders alittle too high, herhead a little too straight—the body language of someone who had learned never to showweakness. But Viktor also saw how her gaze flickered over his shoulder toward the aeroplane, how her fingers unconsciously touched asmall pocket knife in her belt.

"Dr. Seger? I'm ElinHammar, senior consultant in intensive care and medical director of the Ituri team."

Her voice waslow and controlled, but Viktor could hear the underlying tension. They shook hands, and her grip wasfirm and cold despitethe heat.

"Welcome to hell," she added, and Viktor understood that it wasn't drama—it wasapractical warning.

"Hell?" Viktor asked, trying to lighten the mood with asmile thatfelt stiff.

"You'll understand in aweek," Elin replied and turned away. Elin pointed to aToyota Landcruiser that looked like it had survived both warand natural disasters. The paint wasworn away to bare metal in several places, and Viktor could see patches along the sides that spoke of damage from shrapnel or bullets.

"Hop in. We haveafour-hour driveahead of us to base camp, and we don't want to driveafter dark," she said.

There wasanabsolute quality in her voice that said this was not arecommendation —itwas arule of survival learned through bitter experience.

As Viktor loaded his heavy rucksack into the car, he discreetly studied thewoman who would be his colleague for the coming months.Elin Hammar had abeautiful face. Her skin wastanned to adeep golden brown, but Viktor noticed the smallscars on her temples—probably from broken glass—and the place where one of her eyebrows was interrupted by athin, white line. It washer hands that told the most. They were slim and strong, with short, practical nails,but Viktor saw the small marks from surgical thread thathad gone wrong, the almost imperceptible tremor that came when adrenaline had stopped pumping through the system too many times.

"How long haveyou been here?" Viktor asked as they drove out of the airport through Goma's busy streets.

"Thirteen months. Ioriginally came for six months, but..."

Elin shrugged, agesture that Viktor suspected concealed more than it revealed.

"You'll understand why many of us stay longer than planned," she added, and Viktor heard anoteoflost innocence in her voice.

As they drovethrough the outskirts of Goma, Elin told him about her past, her voice growing quieter with each sentence.

"I'm originally from Umeå. Istudied medicine there, but wanted to try something new, so Isigned up with Doctors Without Borders and went to Sudan, and it changed me completely," Elin said.

Viktor understood. He thought of his own first gunshot wound patient in Mali.

"When Icame home," Elin continued, "I couldn't explain to my boyfriend what had happened. How Ihad changed. How everything at home–his worries about gym times, our friends'discussions about buying aflat –just felt... irrelevant."

"So you came back?" asked Viktor.

"I came back. The second time waseasier. The third time was natural. Now Idon't even know what Iwould do at home anymore," she replied.

Wardestroys cities. It tears families apart. It crushes

Field doctor Viktor Seger has made it his mission to fight back, not with weapons, but with compassion. In the ruins of bombed-out hospitalsand shattered streets, he and his medical team risk everything to

From the frozen frontlines of Ukraine to the deserts of Sudan and the chaos of Haiti, Viktor faces not only disease and danger, but the darker forces that use war

He hates war.Yet in itsfire, he finds what it truly

Agripping and deeplyhuman novelabout courage, the innocent first.

save lives where humanity seems lost. for power and profit. means to be human. morality,and hope, when everything is burning.