1 Stagnation Nation

Great Britain?

Names aren’t just convenient labels for people, places and things. They come with expectations. You learn this if you’re a Torsten who doesn’t speak a word of Swedish, and who regularly disappoints every Scandinavian he meets. Only the brave call their child ‘Adonis’.

Countries don’t normally have these pressures. But Great Britain? It’s quite a name to live up to. The Romans called us Britannia, and ‘great’ originally just meant that we were the biggest island in the north-west European archipelago or bigger than ‘lesser Britain’ (Brittany). The much later union of England and Scotland in 1707 brought the ‘great’ into our political label, creating the Kingdom of Great Britain. The additional challenge of living up to being a United Kingdom followed the union with Ireland a century later, posing deep constitutional questions that continue to this day.

Today, few people in the UK or anywhere else have any idea that the great in Great Britain referred originally to the size of the country’s main island. What began as a statement about our geography has become one about our quality – our significance rather than our landmass. The British government has embraced this reality in its marketing, spending millions on ‘the GREAT Campaign’ to persuade people at

airports, embassies and even the 2022 World Cup that this is a country that delivers on its billing.1

The British Empire and two world wars underpinned the domestic perception of greatness throughout the nineteenth century and most of the twentieth. All were long gone by the time I was coming of age in the 1990s, but I don’t think I had much doubt that Britain was still great. We had Britpop, and we had growth rates that were the envy of most of the advanced world. Britannia no longer ruled the waves, but it was cool and booming.

Living up to our national label feels harder today. Britain is a great country, but things have not been going great. And we know it: the polling company Ipsos conducted a survey for this book and found that three- quarters of us take that view. 2 This isn’t principally about our culture, nor our weather, but our economy. It’s about wages that stubbornly refuse to grow, and food- bank queues that too often do. About opportunities for the young and standards of care for the old which repeatedly fall short. About too many places being excluded from the shared national project, and too few workers treated with dignity and respect. And about the more than fifteen long years of economic stagnation that have not only held back our living standards, but also undermined our hope that tomorrow will be better than today.

Our nation’s name is not about to change, but we must do more to measure up to it. This book is grounded in years of research about the state of Great Britain – more fully, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. (I use ‘Britain’ and ‘UK ’ interchangeably throughout this book to mean the same thing. The shortened title is clearly not perfect, but we all use it every day so I hope you’ll allow it here.) If you share the widespread sense that the country is drifting

or declining and want to know why that is, and how we can set ourselves on a different course, read on.

In these pages you will find discussions of economic practice, not economic theory. A deep dive into the experience of a particular country, not another high-level sweep across all advanced economies. And a plausible project of national renewal for this time and this place. Britain today contains the raw materials to build a better Britain tomorrow. Forget the nostalgia; put aside the dreams of abstract utopias, and visions of a Singapore-on-Thames or an Anglophone Germany. It is through the hard yards of understanding our country that we can change our country. That is how we will give Britain its future back.

Too many questions

I should spell out why I have come to write this book. People, like countries, are path dependent. We might prefer to think we are entirely objective – and this is a book in which you will find no shortage of facts – but we are shaped by our experiences. So, in the interests of transparency, here are mine.

No one would have written a book like this in the mid 2000s, which is when I started my working life, walking into the Treasury one autumn day. What worried me back then wasn’t just the fact that my new manager didn’t turn up to meet me until an hour later (she was a wonderful woman, and I swiftly learned that she, like many of my new colleagues, preferred to work late into the evenings). It was also the seemingly ubiquitous belief that all the important economic policy questions had been answered.

This was the peak of western economic smugness. Capitalism had triumphed over communism. Boom and bust had

been abolished, with independent central banks setting interest rates to steer us wisely through the economic cycle. If stability was delivered, the economy would grow, raising living standards and funding public services. The UK was even more confident than most countries, having outperformed its competitors during the late 1990s and early 2000s as part of a continuous economic expansion stretching over sixty-three consecutive quarters. The Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, travelled to Leicester in October 2003 to celebrate the preceding ten years, acclaiming them as a NICE decade.3 The acronym was easier to say than ‘noninflationary consistently expansionary’, but it also summed up the mood of the era. The books the Treasury published were manuals on how to do economic policy, which its staff were invited around the world to talk about.4

There was much that was right in those manuals, but no one today thinks we have all the answers, and we’re no longer invited to give those seminars. I was still in the Treasury when the complacency of British, and western, economic policymaking was shattered by the global financial crisis, including the UK ’s first bank run in over a hundred years. Despite a heavy rewriting of history after the fact, almost no one saw it coming. The Conservative opposition was arguing for looser financial regulation in the run-up to the crisis, while the Labour government and financial regulators should have been tightening it. When the crisis hit, my then boss, the Chancellor, Alistair Darling, was faced with many new questions demanding answers. How do you best nationalise failing banks? Answer: swiftly, and ideally over a weekend when markets are closed. What does the Bank of England do when it has already cut interest rates to near zero, the lowest since its founding at the end of the seventeenth century, but the economy is still tanking? Answer: quantitative

easing: buying financial assets to push down longer-term interest rates.

And nor did anyone anticipate the aftermath. Plans were made for tackling surging unemployment, home repossessions and business insolvencies, because that is what had happened in the recessions of the 1980s and 1990s. But history did not repeat itself. Repossessions got nowhere near the peaks of 1991, when lenders took back 75,500 homes; far fewer businesses went bust; unemployment rose, especially for younger workers and Black men, but to nowhere near the terrible 3 million seen in the aftermath of those earlier downturns.5

By the time we learned what the lasting impact of the financial crisis would really be, I was working as the Labour Party’s director of policy, which I did from 2010 to 2015. It isn’t a job I’d recommend to anyone who values low blood pressure or seeing their family. British politics spent those years rowing about public debt and deficits, especially the depth and pace of cuts to public spending as austerity was rolled out. Today, almost all economists agree the fiscal consolidation should have been slower, with tax rises reducing the unprecedented depth of spending cuts. Those cuts have proved politically unsustainable, economically damaging and socially disastrous. Austerity has left deep scars across the country.

This was also the dawn of Brexit. On 23 January 2013, David Cameron headed to Bloomberg’s London headquarters intending to settle the Tories’ internal divisions on Europe and hold off the challenge from UKIP by promising a referendum on the UK ’s membership of the EU after the next general election. Some in Labour argued that their party should do the same.

Amid austerity and the preamble to Brexit, the politics of

the early 2010s focused criminally little on an emerging problem: the gradual improvement in living standards that we used to take for granted was grinding to a halt. The most significant economic legacy of the crash, something not once discussed or anticipated in a single government meeting, was a monumental pay squeeze. Real earnings (after accounting for inflation) had fallen by almost 10 per cent by 2014. This wasn’t in anyone’s textbooks. Nor was it in enough news bulletins, even as the squeeze deepened. The unfolding eurozone crisis provided more media-friendly moments of drama, as the likes of Ireland and Greece required outside help from the EU or IMF to stay afloat.

The emergence of this entirely unexpected, and poorly diagnosed, squeeze was a big part of why I moved to my present job in 2015, as chief executive of the Resolution Foundation, an economics research institute, or think tank, explicitly focused on the living standards of households on low to middle incomes – that is, the poorer half of households in Britain, who are living on disposable incomes (income after tax) equivalent to £30,000 or less a year.6 Where better to wrestle with this huge question? But the move also made me nervous. Would a switch into economic thinking be too distant from doing anything?

Years of being surrounded by academics hasn’t made that anxiety entirely disappear. People usually study economics because they want to make the world a better place, but once they become academic economists, the incentive is to publish technical papers in a handful of top journals, which often leads them far away from the messy world of policy. And if anyone responds to incentives, economists certainly do.

Overall, though, I was mistaken. I was wrong because the problem had changed – rather than there not being enough

questions to answer, there were now far more than could ever be wrestled with in politics or in government, where time to reflect on how your economy or indeed society is changing is just not available. The massive privilege of the last decade has been working alongside a brilliant team of researchers whose job is to do exactly that reflecting, and who get up every morning committed to understanding Britain and what it means for us all as workers, consumers, citizens and families. The need for that understanding has never been greater, and the work of those years is the core of this book, which aims to offer an alternative perspective, one that bridges economic doing and thinking.

Pandemic lessons

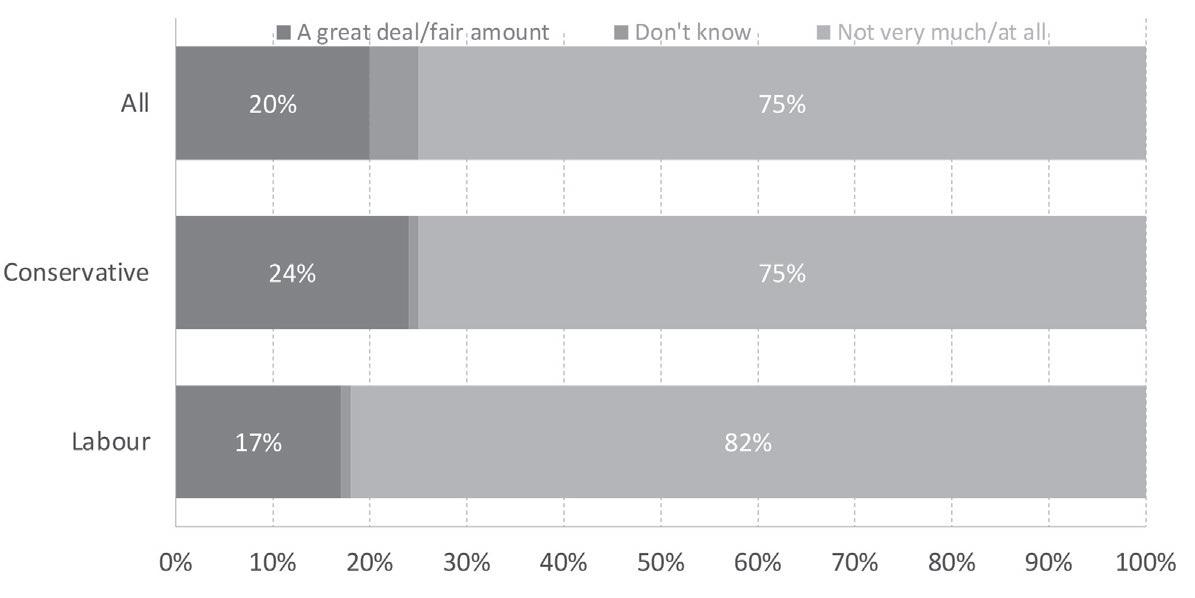

You don’t need two decades working on British economics to know that the country is in trouble. That Ipsos poll showed almost everyone now recognises we’re not in a good way. Rich and poor. Young and old. Whoever you vote for, and wherever you live.

To what extent would you describe Britain as doing ‘great’?

This sense has been building for some time. But it has been turbo-charged by the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis that have dominated the early years of the 2020s. Along with the financial crash, we have lived through three once-in-alifetime shocks in just fifteen years.

Policymakers will never be able to eliminate the risk of such crises happening, although reducing the likelihood of them should be on their to-do lists. When they do arrive, the immediate task is to respond, addressing the root cause, whether bust banks or a contagious virus against which we have no vaccine. But we also must learn from them, because these shocks have painful lessons to teach us about the state of our economy and our country.

The pandemic triggered the biggest slowdown since the Great Frost of 1709, as we shut down large parts of our economy to save lives. Every country in the world faced Covid-19, although the economic hit was bigger than most in the UK , as delayed lockdowns became deeper ones.7 The lack of resilience in British households was painfully clear. Almost half (45 per cent) of working-age families did not have even one month’s worth of income in savings in March 2020.8

You were more likely to face an income fall in the UK than elsewhere (30 per cent, as against 20 per cent in Germany). And those that did struggled: 17 per cent took on debt to cover living expenses, twice the share seen in France or Germany.9 More generally, we in Britain tend to be far more reliant on high-interest debt, from credit cards to ‘buy now, pay later’ schemes, which are not the stuff of stable household finances.

The fundamental weakness of our social security system was also reflected in the scale of support that had to be suddenly introduced. The government was forced to ramp up the basic level of benefits with a £20 per week increase (or 27 per cent for a single person over 25), without which,

shockingly, basic unemployment support would have been lower in real terms than at any point since the early 1990s.10 Largely following Resolution Foundation recommendations, an entirely new safety net was also created.11 The Coronavirus Job Retention (or furlough) Scheme paid the wages of 11 million workers between March 2020 and September 2021. This policy meant the pandemic saw the smallest unemployment rise of any recession in living memory, but it cost £54 billion and had to be rolled out at such pace that widespread fraud was inevitable.12

The pandemic also put up in lights many of the inequalities that shape twenty-first-century Britain. Richer households saved far more during it – being barred from restaurants or expensive holidays does have that effect. In contrast, many poorer households saw their costs rise. Having children at home is expensive, and many of the traditional ways in which you cope on a low income – from eating with extended family or neighbours, or travelling further to cheaper shops – were no longer available.

How different work is for high and low earners was also laid bare. The biggest impact on the former was the move to home working, something many have wanted to retain postpandemic. Meanwhile, lower earners were far more likely to lose their jobs, and tragically far too often their lives, as they continued delivering frontline work in care homes or supermarkets. This was briefly recognised as the country took to their doorsteps to clap for carers during the crisis, but that recognition has driven no lasting improvements to their jobs.

The housing that Brits so love to talk about, which leads to vastly unequal experiences of life – and indeed life chances – was also centre stage. Where you were locked down made a huge difference. A fifth of children in low-income households spent lockdowns in homes that were overcrowded.13 Many

people spent the first, ridiculously warm, lockdown month of April 2020 in the garden, but almost two in five ethnic minority children had no such option. Unsurprisingly, the already large well-being gap between those who rent and those who own their homes rose. Worse, variations in mortality rates showed the high price for living in places with densely populated, poor-quality housing.14

The pandemic posed tests for all of us, from enduring social isolation to home schooling our children (a test that I certainly failed). But it also did so for our country. This universally shared disaster revealed deep divides, spelling out who Britain does, and does not, work for.

A costly living

As the pandemic receded, our cost of living rose. The deepest recession for three hundred years was replaced by the highest inflation in four decades. Price rises, particularly for goods for which global supply chains had been disrupted by the pandemic, had already begun before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. They rocketed afterwards, not least the price of gas in Europe, where Russia had previously provided 40 per cent of the supply.

The cost-of-living crisis is best thought of as a cost-ofessentials crisis. First, energy prices surged. Even with government capping them, and paying a chunk of everyone’s bills, the typical household bill more than doubled, up by almost £1,400 by April 2023. Very little is more essential than heating – but food is. And, food prices shot up by almost a third between the autumns of 2021 and 2023. Inflation rates can sound abstract, but the impact of this was very palpable indeed: families’ annual food bills rose by £1,000 on average.15

A surge in the cost of essentials has always bitten those on the lowest incomes hardest – there is a reason why large increases in the price of bread or other basic foodstuffs have often fostered the conditions for revolutions. If most of what you spend goes on essentials – poorer households spend almost 40 per cent more of their disposable budgets on food, fuel, clothing and transport than the richest households – the pressure on the family budget can quickly become unmanageable when those prices rise.16

The state did step in, and the public cost of assistance with energy bills ran to over £60 billion between March 2022 and April 2024.17 Despite this, the impact of the cost-of-essentials crisis has been a disaster for all to see, not just in the statistics but on our streets as well. Three times a week my children come out of their primary school, turn right and head into the hall next door for a boisterous after-school club. Younger children’s cries are heard there every Monday morning, when it hosts a parent and toddler group. But every Sunday now, that same hall provides something very different: the local food bank, providing food parcels of three days’ worth of emergency supplies for those in real deprivation. Demand for those parcels is higher than I would ever have thought possible in a relatively prosperous part of Britain. But this is far from unusual. Little over a mile further east, long queues form outside a church, not for Sunday services, but on Saturdays for another food bank. These scenes are more common – and more visible – in big cities, but the need they are addressing is now everywhere. In 2022/23, 3 million food parcels were handed out by the Trussell Trust, a 37 per cent increase on the previous year.18 Of those, 1.14 million were for children.

We’re sometimes told the growth in food banks is simply a result of people abusing worthy but misguided charitable

intentions. Some British newspapers used to revel in the idea that food banks, far from responding to growing hunger, were creating the demand for their services.19 Most of us have now woken up to the reality that even the huge proliferation of food banks has not been able to prevent many going hungry. In spring 2023 one in five Britons were skipping meals or eating less because of financial constraints.20 Meanwhile 11 per cent of teenagers say they are missing at least a meal a week, compared with 2.6 per cent in Portugal (a much poorer country than the UK ) and an average of 8 per cent across OECD advanced economies.21

This is not what we expected the 2020s to look like. The disgrace of what we are allowing to take place in our country stretches beyond food banks. The numbers experiencing destitution, the most extreme form of material hardship – meaning people lack the resources for the very basics: staying warm, dry, clean and fed – rose to 3.8 million people in 2022, up two and a half times compared with 2017.22 Those who are young, disabled or Black are in the firing line: the last are three times more likely to face destitution than the population as a whole. In fact, we have decided as a country that state support for young adults facing hardship should be so minimal as to make destitution almost inevitable.

Meanwhile, homelessness in England and Scotland is at record levels. 23 This takes various forms. There is the visible homelessness of people in tents or sleeping bags on the streets or in parks. Less visible, but far more prevalent, is the kind that leaves families applying to their local council for emergency accommodation. This is happening in every corner of the country. Evictions are easy to serve on private renters, but nothing is easy for the children growing up in B&Bs, placed there by a state that long ago ran out of suitable accommodation. And even these grim official statistics

ignore the hidden homelessness of people staying on mates’ sofas or in sheds.

Those on lower incomes or unlucky enough, as any of us can be, to lose their jobs or fall ill were most exposed to the challenges of the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis. But those challenges and the pressures they created extended far beyond the extremes of going without food or a roof over your head. The middle, not just the bottom, has been squeezed. Surging energy bills saw three-quarters of adults (35.4 million people) cutting back to cope in the autumn of 2022.24 Only richer and older households’ family finances were noticeably more resilient: those aged 35–44 were twice as likely to have cut back a lot compared with those aged over 65. As interest rates rose in response to high inflation, the increase in bills for a typical borrower remortgaging in 2023 was £2,444 a year. Even middle-class families have suffered, in part because the share of their budgets taken up by essentials had increased even before the cost-of-living crisis, rising by 5 percentage points between 2006 and 2019. That’s why it felt harder for everyone.

The state we’re in now

British households are poorer at the end of the 2019–24 Conservative government than they were at its start. This is the only time on record when that has happened between general elections. Of course, it isn’t a surprise that a pandemic and an inflation surge have been painful. But there is nothing inevitable about how vulnerable we have been to them. Ultimately, we have struggled so much with these acute emergencies because of deeper crises that have been troubling the country and steadily building for decades. This is

what lies behind the belief that Great Britain is not doing great at all – that the country is in fact heading in the wrong direction. Six in ten Brits now take that view, with far fewer, just 16 per cent, thinking we’re on the right track.25

That is not a healthy place for us to be. It is dangerous for our democracy as well as our economy. History warns that this mood, if unaddressed, can be exploited by demagogues at home or bad actors abroad. It is a recipe for division, as people protect what they have from each other rather than focusing on what they can build together. Britain did a better job of escaping these outcomes than many other European countries during the twentieth century, but simply assuming this will be the case in the future isn’t a gamble worth taking. Just because we cannot see a Trump or Le Pen in Britain today does not mean they will not emerge. And if they do, the risks are if anything higher in the UK . Our unwritten constitution and centralised state leave us more reliant than most countries on the character of our leaders.

The starting point over the next two chapters is to explain why we are failing on the basics of what binds advanced economies and diverse societies like ours together. As traditional hierarchies of faith or class have weakened, the promise of rising and widely shared prosperity has become central to the social contract. But we are not delivering on those promises today. The social contract is fraying.

Britain, long a high-inequality country, has now also become a low-growth one. For the last fifteen years we have been falling further behind rather than catching up. This combination of low growth and high inequality has proved toxic for poorer and middle-class Britain. Both sections of society are now far poorer than their peers in countries that we normally compare ourselves to, from France, the Netherlands and Canada to Germany and Australia. That is why we

struggle when higher energy bills, or whatever challenge comes next, arrive. Richer Brits might be protected by their bigger slice of our smaller pie, but an unequal country in relative decline, growing more slowly than its peers, is not a happy place to be. It is a stagnation nation.

Underpinning our social contract is another contract – an intergenerational one. Different generations supporting each other as they move through life is how a society hangs together – just as most of us see our own families doing. We measure the success of our society by how we provide for older generations, and whether we enable each successive generation to have a better life than the one before. We are managing neither. The young are earning lower wages than their predecessors, in more insecure jobs, while renting smaller properties for longer, as their aspirations to homeownership sail out of view. Meanwhile, we are not providing the health and social care our ageing population requires. Instead of a strong intergenerational union, we risk being stuck in a generational conflict, as older voters stand in the way of economic growth – and pretty much anything getting built – while the millennials understandably resist bearing the brunt of tax rises needed to deal with record NHS waiting lists.

Where do we go from here?

So the task facing Britain, if we are to live up to the Great label, is to end our stagnation and to build a country that works for the poor and the young, not just the rich and the old. One that has narrowed the gaps between prosperous and deprived places, and has navigated the next phase of the net zero transition. The purpose of this book is not just to

recognise what has gone wrong, but to wrestle with what can be done about it. This is what Chapters 4–8 address, outlining the change we need – the approach to take, and the agenda to prioritise.

Standing in the way of progress are mistakes that are as much cultural as economic: the wrong kinds of patriotism or radicalism. Confusing nostalgia with patriotism leaves too many treating Britain’s past, rather than its present, as the guide to our future. This kind of nostalgic patriotism ironically often doesn’t much like the Britain it claims to be patriotic about, seeing the country as too woke, too multicultural, too educated. It wishes we were a manufacturing nation rather than celebrating that the UK is the second-biggest service exporter in the world. Far from keeping Britain as it is, this type of patriotism is taking us backwards. It hinders our ability to bind ourselves together and lacks a vision of the better country that people of all ages, classes and races can help build.

Just as dangerous is believing that everything about Britain is broken, ignoring our strengths and claiming that only ripping everything up and starting again can turn things around. This isn’t radical. It’s nihilistic, resulting in claims that big constitutional changes will magic away our economic problems. Brexit, whatever you think of it, hasn’t done that. This belief sees the left dreaming of turning us into Germany, rather than doing the hard work of turning us into a better Britain. And it leaves the right – most obviously Liz Truss – recklessly announcing huge tax cuts, without any engagement with why taxes have been rising under a Conservative government.

What Britain needs instead is a new patriotism, rooted in an understanding of our present and an ambition for our future, not just pride in our past. This approach is genuinely

patriotic: it does not ignore the real problems the country faces, but is confident that a better version of Britain, not an imaginary one, is desirable and achievable. Its method is one of radical incrementalism – radical to reflect how far the status quo is failing us, and incremental because lasting change is achieved by improving reality as we find it, not by wishful thinking.

In a time when people’s trust in a better future is dimmed, we need a political and economic project that offers hardheaded – believable – hope. At the core of this book is the bread and butter of economics as families experience it, and concrete steps that can be taken to restore faith in the possibility of progress. It is an argument for Britain to start investing in its future rather than living off its past, while fairly sharing the sacrifices that building a brighter future requires as well as the rewards it offers.

The Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf worries that ‘the UK has become accustomed to managing stagnation’ and ‘this frog is being boiled too slowly’ for politicians to do what is required.26 I am more optimistic, precisely because so many of us now recognise the hole Britain is in. It’s a damning indictment of where we are, but also the basis for a coalition for change. It doesn’t guarantee one will be built – but means one can be. It’s time to get started.

The Toxic Combination

All countries face challenges and choices. Britain has faced more difficult ones than normal in the early 2020s, with the first pandemic for a century and the biggest inflation shock for a generation.

I want to persuade you that we can’t just shrug our shoulders at a few rough years, praying that better luck, and better times, lie ahead. (Though I hope they do.) Instead, we should ask ourselves, why have we found these challenges so hard, why have their consequences proved so dangerous, and why do the choices we now face feel so constraining? To answer we need to lift our eyes from recent traumas and look at the structural forces shaping our country. Today’s Britain is defined by the coming together of two significant economic developments: the inequality of the 1980s and the stagnation of the 2010s. Each deeply damaged the nation. And when high inequality and low growth meet, they form a toxic combination, particularly for poor or even middle- class households.

Inequality

Let’s start with our inequality problem, because it started first. Inequality comes in many different forms, from social status to wealth, but income inequality matters profoundly,

not least because it intersects and is intertwined with many other inequalities, especially that of health. It is now widely recognised that poor health can be both a cause and a consequence of being poor: life expectancy for male managers, doctors and lawyers is over five years more than for men doing more routine work, behind the wheel of a lorry or the bar of your local pub.1

We must also be careful not to lose sight of the lived experience of these inequalities, their flavour and taste, and their varieties across genders, ethnicities and places. Statistics, indispensable as they are in painting a portrait of Britain from more than simply anecdote, inevitably miss much that matters. They measure inequality but cannot explain how it feels. Data can tell us what it means for our consumption but can’t fully capture what it means for our society. So, as we report low income levels, we should keep in mind the reality of living on them – the daily budgeting, the anxiety, the permanent pressure to shop around for cheaper deals, and the inevitable decisions about what necessity will be foregone. In Chapter 6, when we turn to the world of work, we focus as much on the way different workers are treated as on the size of their pay packets.

Inequalities are always relative, telling us as much about those on high incomes as on low. As R. H. Tawney noted back in 1913, ‘what thoughtful rich people call the problem of poverty, thoughtful poor people call with equal justice a problem of riches’.2 The dual role of the rich as perpetuators, but also on occasion victims, of inequality is at the heart of recent debates on meritocracy. Daniel Markovits, a professor at Yale, has highlighted how meritocracy, in valuing credentialled (principally academic) achievement, has created a society that favours liberal, professional elites.3 Those elites secure huge rewards for themselves today and make a mockery of social

mobility by investing heavily in the human capital of their offspring to ensure they secure those same rewards tomorrow. But Markovits emphasises that everyone loses. This pattern is bad for those who can’t break into a world that only rewards formal education. But it is a ‘meritocracy trap’ for the top too, who spend their youth cramming for exams only to qualify for the pleasure of working long hours as corporate lawyers.4

The 1980s

You are probably used to being told that inequality in Britain is constantly increasing. It is not. In fact, overall income inequality has hardly moved for decades. Getting this story straight is important. The notion that we are becoming ever more unequal is a recipe for fatalism – implying it’s an inherent feature of Britain, capitalism or globalisation, rather than something that can be shaped by politics. The problem instead is that inequality in Britain is simply far too high. Ours is the most unequal large economy in Europe.5

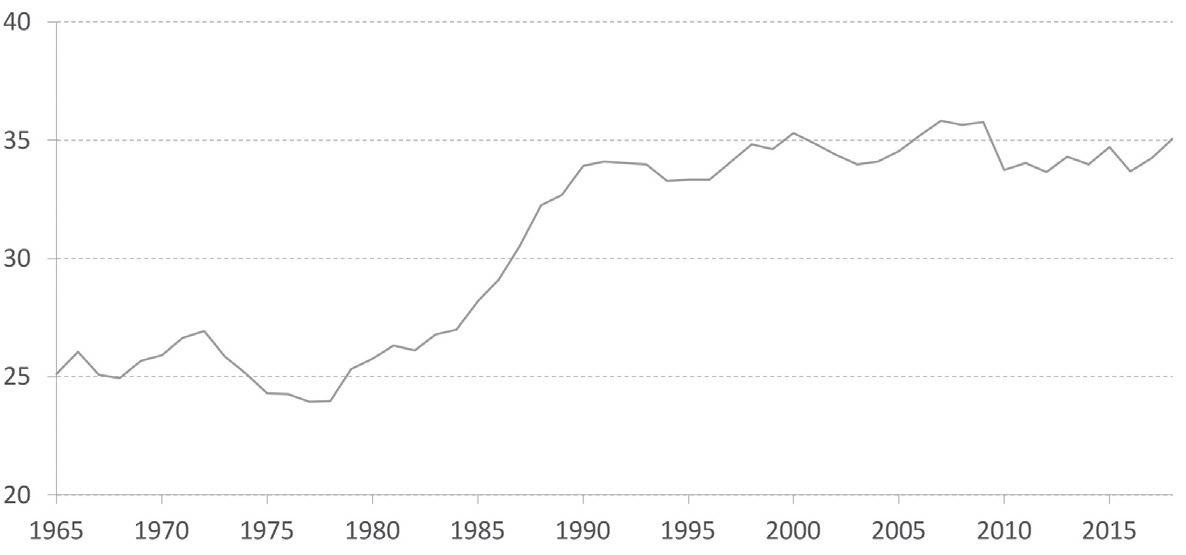

British inequality is like our worst music: it’s all about the 1980s. Synthesisers as well as Margaret Thatcher have a lot to answer for. The 1980s was the decade in which a gulf opened between rich and poor. It’s one that has remained ever since. Social scientists normally talk about inequality in terms of the Gini coefficient (a measure that goes from 0, if everyone has exactly the same, to 100, where one person has everything). On that measure, income inequality rose by 8 points between 1980 and 1990. That sounds abstract, but it represents a seismic change to the economy, and British society.

At the dawn of the 1980s we were an unremarkable economy inequality-wise – about as equal then as Scandinavia is

today. We’d largely been that way since the Second World War, in part because major conflicts tend to push down inequality by directly destroying wealth and pushing up taxes for the richest (once the state has required many on lower incomes to sacrifice their lives, it tends to ask the better-off to sacrifice some of their cash).6

Incomes for rich and poor grew at similar rates throughout the 1960s and 1970s. But that dramatically changed in the decade that followed.7 This was an era of economic rupture. New service industries grew as other industries dwindled. Manufacturing employment fell by 39 per cent between 1979 and 1993, while pits closed despite the bitter miners’ strike of 1984 and 1985.8 The change was so rapid and so destructive because it happened at the confluence of structural economic changes – with technological progress meaning fewer workers were required to produce the same goods – and an ideological programme. The former would always have meant far-reaching disruption, with winners and losers. But the pace of change plus the scale of losses and rewards reflected political choices too, including smashing the power of organised labour and reducing taxes for higher earners.

UK income inequality measured by the Gini coefficient