Prologue

January Srinagar, Kashmir

It will have blood, they say; blood will have blood.

William Shakespeare

The Doctor

Saturday, 1 January. Night.

The knocking was soft. Insistent.

The doctor was lost in a deep, dreamless sleep when his wife shook him awake.

‘Wake up! There’s someone at the door,’ she whispered urgently. He lifted himself up on one side. Listened. Still. Senses on full alert. Heart hammering. The slats on the wooden bed dug into his elbow through the thin mattress. Hands on the bedside clock glowed 3.23 a.m.

Whoever it was didn’t want anyone in the vicinity to hear. Not that there were any neighbours left. Their properties had all been seized.

‘Do you think it’s . . . them?’ she asked. ‘Have they come for us?’

‘They would just break the door down. They are not this polite.’

‘What should we do?’ Her voice trembled in a way he had never heard in forty years of marriage.

‘I must answer. I might be needed.’

She grabbed his arm. ‘Ignore it. Maybe they will go away.’

He covered her hand with his own and gave it a squeeze. ‘I can’t, jaan. You know that.’

He got out from under the quilt. Shivered. The room was freezing. He groped for his woollen moccasins under the bed. Slipped them on.

‘Be careful,’ she said.

‘Don’t worry.’

Grabbing a shawl from the chair, he wrapped it around his shoulders and shuffled out of the room. This wasn’t the first time he’d been woken up for an emergency, but only someone foolish or desperate would come out on a curfewed night. He gripped the carved bannister to steady himself, gait heavy with dread. His footsteps echoed down the wooden staircase that led to the hall.

Switch the light on? No. Safer not to.

The knocking stopped. A voice whispered, ‘Doctor sahib?’

A surge of relief. Not the army.

‘Who is it?’

‘Please open.’

‘Who is this?’

‘Abdul Aziz.’

He hesitated. He had helped Aziz before. A hard man. Not someone to cross.

‘What do you want? It’s very late. There’s a curfew.’

‘I have urgent business. Let us in.’

Us?

He unbolted the door reluctantly, the rusty creak spinning around the hall like a vulture’s screech. A blast of raw air assaulted him. An icy full moon cast an eerie white glow over the frosty grass, making it seem illuminated from below.

Aziz stood silhouetted on the doorstep, dressed in a long pheran and thick coat. Propped up against him was a woman in a burqa. She was wheezing painfully, her face completely veiled except for the mesh in front of her eyes. The doctor looked beyond them to the perimeter wall of his compound, twenty metres away. No one watching. He pulled his shawl around him, trying to stop his teeth from chattering. He could make out the woman’s sturdy frame beneath her robe. No coat. She must be cold.

He stood aside as Aziz brought the woman in, holding her by

one arm. She seemed in pain and stumbled as she entered. The doctor grabbed her forearm to keep her from falling. Confused, he felt muscle.

He shut the front door and led them into the living room. Aziz walked to the window, drew the curtains closed, and switched on the light. The doctor blinked in the sudden brightness and tamped down his annoyance at Aziz’s temerity. He switched on the oil heater, sat the woman down on a sofa, and perched on a chair opposite.

Aziz’s face was dark and cracked from the harsh mountain sun. He bent and pulled off the woman’s burqa. The doctor gasped in recognition at the person under the veil. ‘Not you! You cannot be here. Leave! Immediately.’

He rose but Aziz pushed him back down and forced him to look into the agonised eyes of the man with the hawk nose and salt-and-pepper beard over a gaunt face; fists clenched, filthy nails digging into his palms.

‘Ghulam needs your assistance. They shot him. If you don’t operate and remove the bullet, he will die. You have done this for us many times. You made an oath to help, as did your mother and brothers.’

The doctor’s heart was beating like a jackhammer. ‘Against the army, yes. This man just blew up a busload of innocent Hindu pilgrims. Over fifty dead! This is not how we fight. Get out! I don’t want you or Ghulam Ahmed in my house.’

Ahmed’s eyes glittered. His hand shot up and grabbed the doctor by the throat, pulling him down. His grip was iron.

‘We need to speak the language they understand,’ he growled, his face an inch away from the doctor’s. ‘People like you are weak. You will not achieve freedom without getting your hands dirty.’

He let go. The doctor fell back, coughing. He looked helplessly at Aziz. ‘He is the most wanted man in Kashmir. If I am caught . . .’

Aziz’s tone was soft. Emollient. ‘Calm down. Nobody knows we are here. You just need to—’

‘What’s happening? Who is it?’

The doctor turned to see his wife peering into the room, blinking, her grey hair covered with a headscarf. He jumped up and tried to close the door on her face. ‘Nothing. Go back to bed. I am dealing with it.’

‘Who is this woman? Is she all right?’ She pushed past him, saw Ahmed, and went white.

‘Go to the bedroom! I have it under control,’ barked her husband.

Her eyes questioned Aziz.

‘He is hurt, madam. Doctor sahib must operate. You have helped us before. It is for the cause.’

A groan escaped Ahmed’s lips, and he pressed his hand to his side. She went over to him. ‘Let me see.’

Ahmed stood with some difficulty. Aziz lifted the burqa, revealing a shirt soaked red. Ahmed grimaced in pain as it came unstuck from the bullet hole. Blood was weeping from the wound.

‘I don’t have the equipment to operate,’ said the doctor. ‘He needs a hospital. The bullet may have penetrated a vital organ.’

Aziz snorted. ‘His life expectancy there will be measured in seconds. Do what you can here.’

The doctor glanced helplessly at his wife, who said, ‘Let’s take him into the dispensary. Help him up.’

As they took Ahmed’s arms, there was a banging on the door.

‘ARMY! OPEN UP.’

The four of them froze, looking at each other in confusion. Grimacing with pain, Ahmed reached behind into the waistband of his trousers and pulled out a gun.

‘What are you doing?’ hissed the doctor. ‘They will kill us all.’

Ahmed’s voice was guttural. ‘Then I will take them with me.’

The doctor was panicking. ‘Wait here. I’ll get rid of them.’

‘No tricks,’ whispered Aziz. ‘She stays with us.’ He grabbed the woman’s wrist and switched off the light.

The doctor picked up his shawl and walked into the hall. Took a deep breath to compose himself. Switched on the lamp and opened the door. In the shaft of yellow light that split the night, he saw an officer he knew from the club, flanked by three paramilitaries. Their white uniforms and matching balaclavas made them almost invisible against the snow. He forced a smile onto his face. ‘Major Dixit, what are you doing here? It is late.’

His eyes flitted to the soldiers’ drawn guns as he tried not to show concern.

‘Who is in the house?’ said Dixit. His bland, unlined face with the grey toothbrush moustache was impossible to read.

‘Only me and my wife. Why?’

Dixit’s eyes turned black and cold as the night sky. ‘You are harbouring a wanted terrorist. Get out of my way.’

‘No, no. There is nobody here. You have my word. I—’

‘I will deal with you later.’ He gave his men a brief nod. They pushed the doctor aside and rushed into the house. Took up positions by the closed living-room door.

He ran after them. Whispered, ‘Please, Major. They forced me. You know me, I would never . . .’

‘He is in there?’ murmured Dixit.

The doctor nodded dumbly.

‘GHULAM AHMED,’ the Major roared, making the doctor jump. ‘We know you are inside. Come out peacefully and you won’t be harmed.’

‘Please, my wife . . . she is with him.’ The doctor could barely speak. ‘Don’t put her in danger.’

Dixit gave him a dead stare. ‘Let the woman out, Ghulam. This will not end well.’

The door creaked open. A rush of warm air hit the doctor’s

face. He gasped as he saw his wife’s terrified expression. Ahmed was behind her, arm around her waist, gun to her head.

‘Let me go, Dixit, or I will kill her,’ he said.

Dixit saw the agony in Ahmed’s eyes. ‘Release her, Ghulam. It is over. My bullet is killing you. We will take you to the hospital and extricate it. We won’t harm you. You are worth more to us alive than dead.’

The jihadi gave a bitter laugh. ‘Your word is worth less than the cow dung on my boot. Move aside. I will release her when I am safe. Otherwise, she dies.’

Dixit sighed. ‘Let me save you the trouble.’ He raised his gun and shot the woman point blank in her head as Ahmed jumped away. The doctor’s ears rang with the explosion. Time fragmented. He didn’t hear the shriek that came out of his mouth. Two more explosions. Ahmed was on the ground, moaning. Abdul Aziz lay silenced in a crumpled heap on the colourful Kashmiri rug, now dyed with his blood.

Frozen with shock, the doctor could not comprehend what had just happened. His shawl slipped from his shoulders, but he was numb to the chill of the hall.

Dixit said to his men, ‘Take Ghulam Ahmed alive. I need him.’ Then he turned to the doctor. ‘You are done. I can shoot you now or take you in to be hanged. Which do you prefer?’

The doctor stared at the rag doll of his wife’s broken corpse. His mouth opened and closed, but no words emerged. He turned his pleading eyes to Dixit but saw only blankness. He looked around the house he had built for his family one last time. Then raised a limp hand and pointed at the Major’s gun.

The doctor’s final thought before he died was Allah, keep our son safe.

Anjoli

Sunday, 2 October. Night.

Anjoli sat at her usual spot on the side of the spotless anodised copper bar, nursing a glass of wine. The waiter at the next table recited, ‘Asparagus and morels with hen’s egg and cardamom wind,’ as he decanted dry ice into a bowl. She suppressed a smile. Chanson would have a fit. It was supposed to be cardamom air. She waited for the obligatory ‘oohs’ and Instagram clicks as the spice-infused smoke wafted towards her. She’d have to tell the server to modulate his tone. He sounded like he was announcing the 4.50 from Paddington.

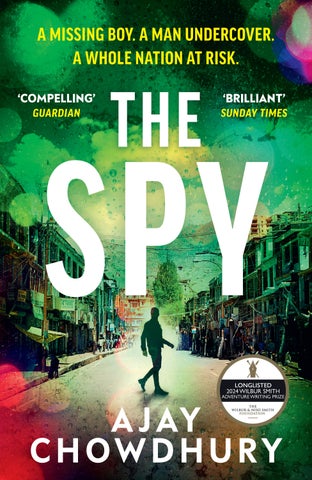

Sunday nights were normally quiet, but after the rave reviews in the Guardian, the Sunday Times and the Michelin Guide, availability in Tandoori Knights was rarer than a Birkin in Brick Lane. People were making the trek from as far afield as Manchester, Birmingham and Edinburgh to sample the menu that was ‘a masterpiece of originality and precision’.

This culinary performance of Chanson’s new Indicular gastronomy dishes would have horrified Baba. For him, a well-made chicken dhansak, served on a clean plate, had been perfectly sufficient. ‘What is this gastro-nomie phastro-nomie?’ she could imagine him saying. ‘Charging fifteen pounds for a dry mushroom with chilli butter? This is cheating, not eating.’

The familiar wrench in her heart returned as she thought of her father and how much she missed his smile and warmth.

Since he and Ma had passed, everything had changed – his restaurant, his clientele, and . . . his daughter. She was all grown up, no longer Saibal’s princess.

She handed a waiter the bill for table three and fired up her banking app. Another month in the black. Fourth in a row. Even though these fancy ingredients pushed expenses ever higher, money was definitely trickling in. She allowed herself a congratulatory sip of pinot. Got to celebrate the little wins. But no sooner had she done so, there was the return of that familiar imposter syndrome gnawing at her insides. She tried to rationalise. These are just unhelpful thoughts. I need to push them aside. But she felt like a fraud. Couldn’t stop the pattern of judgements that made her question her own achievements.

After all, wasn’t it purely luck she had met this weird dude in ripped jeans and a faded Metallica T-shirt at the British Curry Awards, looking totally out of place, yet tranquil, amongst the curry-house kings and queens in their tuxedos and ballgowns? He said his name was Chanson. He’d trained at Gaggan in Bangkok. Was ready to make his mark in the UK, doing something ‘down, dirty and dingy’ in East London.

Kamil hadn’t hidden his doubts when she’d hired him. ‘Come on, Anjoli, he doesn’t cook proper Indian food. How can anyone be satisfied after five tiny courses? And what’s with that shavenheaded, tattooed look? That thick neck? He looks like he’s auditioning to be a goonda in a Bollywood flick.’

But she had followed her gut, and the gamble had paid off. Whatever Kamil might believe, Chanson was a genius. It showed in their takings, reviews and the satisfied faces of her diners. Ah, there was the rub: the success of the restaurant wasn’t her doing. It was Chanson’s.

And it was lonely running the business on her own. Now that Kamil had gone, she still suffered the unsettled disquiet of his absence, both emotionally and physically. He had been her

best friend and housemate and . . . ? Well, they had never got that far.

Although she was loath to admit it, she needed a new adventure. The excitement and adrenaline rush of solving those murders with him would never be matched by a good night of earnings. Although it came close when Ed Sheeran pitched up with his entourage one evening. Life was a bloody seesaw. Business up, love-life down. The only things up simultaneously were her ennui and alcohol intake.

She drained her glass and poured another as a voice said, ‘Which planet are you on tonight, Anj?’

‘Tahir!’ She came out from behind the bar and stood on tiptoe to kiss him on both cheeks. He embraced her.

‘You look great, as usual. We were in the area and thought we’d try our luck for a drink. Do you have a free table? This is Anneka, by the way.’

She shook hands with the willowy young blonde in the red dress standing next to her friend.

‘Sorry, we’re full. I can get you two seats at the bar?’

‘Brill.’

They perched on the padded stools as she handed them the cocktail list.

‘I’ll have the Spicy Nicey,’ said Tahir. ‘Anneka?’

‘Ooh – tequila, black salt and chilli peppers. Sounds amazing! Same.’

As she mixed their drinks, Anjoli said, ‘So how’s life in the world of policing, Inspector Ismail? Working on anything exciting?’

‘Nah. Same old, same old.’

‘Are you a cop too, Anneka?’

Anneka laughed. ‘No way. Dental hygienist. Any time you want an oral check-up, I’m your girl. That’s a funny slogan.’

Anjoli glanced down at her T-shirt that said Just Vindaloo It. ‘Thanks, I make them myself. How did you guys meet?’

Anneka flipped through the menu. ‘Swiped right. He looked good.’

‘He is good.’ Anjoli cut slits in two chillies, popped them on top of the drinks and passed them over. ‘I’ve known him since we were teenagers. He was . . .’

‘And you can stop right there,’ said Tahir. ‘Childhood stories give me heartburn.’

She threw Anneka a grin, then turned to Tahir. ‘How’s Kamil? Settled back in at work?’

Tahir turned serious. ‘I really don’t know what you were thinking, Anjoli, kicking him out of house and home. You need to cut the guy a break. He misses you.’

‘I wasn’t thinking anything. He needs to get his head together. Some time on his own will be good for him. No way am I going to be anyone’s second choice.’

‘You’re not!’

‘I’ve seen how his eyes light up when he sees Maliha. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not blaming her. She got a good job in London and moved here. I actually like her. But the damn fool must decide. You’re his friend. Help him.’

‘I’ll try. But . . .’

‘No buts. This is all on him. Enjoy your drinks.’

Annoyed with herself for asking after Kamil, she left them to it. Chanson was yelling at the sous- chef in the kitchen. ‘No! You cannot use whisky instead of cognac with the scallops. I roasted the spices specifically to go with sour cream and Hennessy, not bloody Johnnie Walker. Get some from the bar.’ He turned to her. ‘Honestly. Sometimes I feel I have to explain every little thing. How can I work like this?’

‘Don’t worry,’ she soothed. ‘You’re the artiste. They’re just your acolytes. They’ll learn.’

He slung a muscular arm around her shoulders and gave them a brief squeeze, making her shiver involuntarily. She

hadn’t been touched in a long time. He smelt of sweat, smoke and spices. It wasn’t unpleasant.

‘What would I do without you to run my atelier, Anj?’ He lifted a heavy sauté pan and tossed a slab of meat effortlessly onto it, muscles flexing under the straining sleeves of his chef’s whites. ‘Listen, I was thinking.’ He poured some liquid into the skillet from a height and a huge flame rose briefly. Now she understood why his head was shaved. ‘I haven’t hit the London scene since I’ve been in this country and we’ve both been working like dead dogs. As they say, when the going gets tough, the tough go clubbing. Shall we?’

She tried not to let the surprise show on her face. ‘Oh. Maybe. Let’s see.’

‘Great.’ He turned to bark at a hovering waiter. ‘Don’t forget the jujube jelly for the masala chai.’

Later that night, as she lay in bed, drifting in the liminal space between wakefulness and sleep, she had a fugitive memory – or was it a dream? She was six or seven years old, dressed in a pink party dress, walking in the park with her mother. Clutched in her tiny hand was a shiny helium balloon.

‘Shall I tie it to your wrist, so it doesn’t fly away?’ said Ma. ‘You don’t want to lose it.’

Anjoli shook her head and held it even tighter while her mum walked on ahead. She suddenly wondered what it would be like to see it float off – up, up into the sky. Before she knew what she was doing, she unclenched her little fist, and it was gone.

She stared in fascination as the silver rose against the intense, cloudless blue. The balloon drifted higher and higher, the sun reflecting off it in iridescent colours until she couldn’t see it anymore, however much she squinted.

Anjoli reached instinctively across her bed but felt only emptiness.

Kamil

Sunday, 2 October. Night.

The traffic on Whitechapel Road is a disaster, and the bus gets me to my destination at 9.45 p.m. I jump off as a few worshippers board, chattering to each other after Isha prayers. The East London Mosque looms in front of me, the floodlit, redbrick edifice glowing against the night sky, the two floating minarets seeming to say: Enter, you are welcome.

I make my way to the imam’s office through the narrow corridors. He rises and embraces me, his long beard tickling my stubble as he kisses me thrice.

‘Thank you for coming, Kamil. Please take a seat. All is well?’

‘Yes, Sheikh.’

‘Tea?’

‘No thank you, I’ve just had dinner.’

‘Good. Good.’

I sit and wait, trying not to tap my foot. Why has he summoned me with such urgency? Knowing the imam, he’ll get to it in his own time. I look at the holy books stacked on the shelf behind him as I breathe in the familiar wood and leather smell of his room.

I prompt him into the preliminaries. ‘Building started again?’ The mosque is expanding. In the summer, we’d discovered four dead bodies on his site and construction juddered to a halt.

‘This week, Inshallah. It was amazing how you and Anjoli

found out what happened with those people. I hear you have returned to the police?’

‘Yes, Tahir got my suspension lifted.’

‘He is a decent man. Anjoli is well?’

I’m tired and ready for bed and don’t want to get into my personal or work life with him. He is my rock, but this isn’t the time.

‘Yes, Sheikh. We are all well. You wanted to talk to me?’

He sits back in his chair, fingering the prayer beads on his tasbih with his right hand, beard bobbing up and down in sync. But he still says nothing. Just stares past me at the poster of the Kaaba in Mecca on his wall. All I can do is wait.

‘Kamil.’ He stops and looks at me, lips moving as though he’s praying silently, brow furrowed with some disquiet. This is unusual. Imam Masroor is the most serene man I know. His calm normally radiates around him like a force field of peace and love. My tired irritation dissolves. He has been my guide and advisor ever since I arrived in London and is the closest I have to a father, given my distance – physical and emotional – from my real dad.

‘What is troubling you, Sheikh?’ I say softly.

‘Erm . . . Kamil. Perhaps I have called you out for no reason. I am sorry.’

His fingers resume counting the beads.

‘Please, Sheikh. I’m always here for you. Tell me how I can help.’

A pause. He takes a deep breath and slowly exhales. ‘Tell me, do you know the Jamia Masjid in Loxford?’

I shake my head, then stop. ‘Wait. Didn’t you mention it to me at the restaurant a couple of months ago? Yes, you said you were worried something was going on. I was supposed to call you, wasn’t I. I’m sorry, Sheikh, with everything that’s been happening, it totally slipped my mind.’ A stone settles in my gut and I disperse my self- critical thoughts so I can concentrate on what he is saying. Plenty of time to berate myself later.

‘That is not a problem, Kamil. You have a lot occurring in your life, I know. The Jamia Masjid is a small mosque in Loxford. Near Ilford.‘

He goes quiet again. I give him an encouraging look. He continues, ‘You may not be aware, but around ten years ago, there were allegations about extremists fomenting trouble in our masjid here. It was untrue, and we refuted those statements. You know me, Kamil, I would not accept anything like that. We are here to build harmony between faiths, not division.’

‘Of course, Sheikh. But what has this got to do with Loxford?’

‘I heard . . . something.’

Another silence.

‘What? You can tell me.’

‘Things are difficult for us. The government is becoming very aggressive with immigrants. Violence against Muslims has increased. We must be careful.’

His words peter out. He looks visibly disconcerted by what he’s trying to articulate, and I start to worry.

‘And?’ I prompt.

He looks at me as if wondering what to say. ‘I have heard that someone may be planning . . .’

‘Planning what, Sheikh?’

‘Something . . . I don’t know. I have no details.’ His voice becomes firmer, and his fingers move faster across his tasbih. ‘I know the imam there. He is a little bit rigid, but I am sure he would never condone these things. I spoke to him about it, but he said it’s nothing, just people talking nonsense.’

‘Where did you hear this?’

‘From a worshipper who attends here sometimes. He is a good man. A chemical engineer. From India like you. But Kashmiri, not Bengali. He was approached in Loxford Jamia Masjid six months ago and . . .’ he shrugs.

‘Approached,’ I coax. This is like pulling teeth.

‘Yes. By an acquaintance from the Young Muslim Organisation.’

This is pulling teeth. ‘And what did this acquaintance want?’

‘This fellow asked him about his views on what was happening to our people in India. Of course, like everyone else, he is angry about the situation and said so. They met a few times for tea and his companion enquired if he wanted to help alleviate their plight. He agreed. But now . . . he is having second thoughts. He does not know how to stop.’

‘Second thoughts about what? Stop what?’ I hope my frustration isn’t becoming obvious.

The imam pauses again. ‘He didn’t give me any details, but it is not good. My friend was not very clear, but it sounded to me like he was asked to make some sort of . . . device. But look, Kamil, it’s possible I’ve misunderstood.’

Device? The word explodes in the room, and I catch my breath. My mind flies back to photographs of the bus with its roof blown off in London. And the wall-to-wall TV coverage of the smoke billowing above the Taj Hotel in the Mumbai terror attack. Has it already been over a decade? It seems like yesterday. Militant Islamism in the West has quietened down since then, but if a new plot is in progress . . .

I calm myself. ‘So, it’s more than a rumour. Did he tell you who this acquaintance was?’

The imam shakes his head. ‘He came to me ten weeks ago, when I mentioned it to you. Said something vague about antiBritish things happening in that mosque. Then I heard nothing, and I thought it had gone away. But he returned yesterday and told me what he has been doing for them. His wife is now with child, and he is ashamed of his involvement in . . . whatever it is. But he does not know how to get out of it.’

‘What’s his name?’

The imam hesitates. ‘I would need to ask his permission to tell you, Kamil. I don’t wish to get him in trouble.’

I lean forward. ‘This is serious. You must tell me, Sheikh. Why did he come to you?’

‘He wanted my advice.’

‘What did you say?’

‘I told him to go to the authorities. But he is worried they will arrest him. That is why I wanted to see you. Can he talk to the police without putting himself in danger?’

I consider this. ‘I suppose it depends on what he’s done. If he has involved himself in a terrorist plot, he will be arrested. They’ll take into account that he informed them, but . . .’

The imam’s shoulders droop, and he looks crestfallen. Suddenly, he seems old and worn out. He leans his elbows on his desk, takes his head in his hands for a moment, then looks up and entwines his fingers beneath his chin. ‘He is not a wicked man, Kamil. This fellow led him astray. He is trying to atone.’

‘I understand.’ I take a breath and exhale. ‘What would you like me to do about it? I can tell Tahir, but then your friend will almost certainly be brought in for questioning.’

‘I know. If something happens, la samah Allah, it will be terrible for all of us.’

I should feel burdened by this knowledge, but there is a selfish spark of hope igniting in a part of me that an hour ago felt utterly demoralised. This could be my way out of purgatory. ‘Sheikh, I have to report this.’

‘But what if I am wrong? What if this is all innocent? I know nothing for certain.’

‘We can’t take that risk. You know that, Sheikh.’

His eyes turn to the image of Mecca again. He sits up straighter.

‘He has a wife and a child on the way. She comes to this masjid as well, sometimes. I cannot leave them bereft. I must try to help him.’

‘Help him? How?’

He hesitates. ‘Maybe I can talk to this man who approached him? Persuade him to move away from this path?’

He sees me shaking my head and leans forward urgently. ‘Kamil, this may just be some angry young gang member who is fighting with a rival organisation. Nothing to do with Islam or terrorism. I must do this. I could not forgive myself if an innocent worshipper was sent to prison. Or can you advise anything else? You have more experience of things like this.’

He looks lost.

I’m not sure how to help. I’ve never been involved with terrorism, and, while I had some basic training in my course, there’s not much advice I can give. ‘If you can get this other guy’s details, I can see if he is in our system and pass it on to people who’ll know what to do. We may be able to leave out your friend’s name. Maybe he can call the police anonymously himself and tell them.’

He leans back. ‘I suggested that, but he is frightened. He thinks this acquaintance will know it was him. Then he is putting his family at risk.’ He nods his head decisively. ‘Here is what I will do. I will insist my friend take me to meet with this fellow. And if this fellow is a foolish man who has taken the wrong path, I will get him to stop this nonsense. My friend can go back to his family and we can forget all about it.’

‘How will you stop him?’

‘I will explain the consequences of his actions to him.’ His worried face transforms into a twinkling smile. ‘I can be quite persuasive, you know. If he listens to me, I will not need to give you their names and have them be put on watch lists or whatever. Once you get on these databases, it is very difficult. I have read about this.’

‘And what if he doesn’t listen?’

‘If I think he is a genuine threat, I will give you his details and

you do what you must. I have seen enough of these types of people to know the difference between a silly young man and a real . . . troublemaker. Just promise to try to keep my friend out of it.’

I consider this. I trust the imam, but what if he gets it wrong? ‘Now that you’ve told me, Sheikh, I can’t ignore it. I’ll be in trouble if I don’t report it.’

‘Give me one more day. Please. Till Tuesday,’ he pleads.

I don’t like it but find it very difficult to refuse him. My friend, normally dignified, now desperate, has never asked me for anything. ‘All right. Till Tuesday. Then I will alert the authorities. Do you think you will be able to meet this chap?’

‘I must try.’

‘Be careful, Sheikh. This could be very dangerous.’

‘I am invariably careful, Kamil. Thank you. My judgement was clouded, and you have given me clarity. It is late. I should let you go.’

I nod. He’s right. My friend is an excellent judge of character and will do what’s best for our community. There’s no point blowing things out of proportion.

We stand and he puts his hands on my shoulders, looks deep into my eyes. As always, he has a way of looking not at me, but into me. ‘You are an exceptional person, Kamil, but I understand you are disturbed. Is it the two women again? I think so. Come and see me and we will talk about what is on your mind.’

I feel bathed in his peace. He often has this effect on me and for a second, I believe he really can ease the anger, pain and agitation that’s afflicted me these past weeks. ‘I will. I promise.’

At the very least, it’ll be cheaper than therapy. Maybe Allah will reveal His plan for me.

I just hope the imam knows what he is doing.

Anjoli

Monday, 3 October. Morning.

Anjoli steered her trolley through the spice aisle of Hameed’s

Cash and Carry, which was busy for a Monday morning. Chanson was buying his meats, vegetables and unexpected herbs from artisanal producers, organic suppliers and urban hydroponic farms, so the provisions she had to purchase from the C & C had dwindled. But staples were staples. She checked the list on her phone and bags of cumin, coriander, turmeric, chilli powder and garam masala joined the onions, ginger, methi leaves and garlic in the trolley. Next, rice. Chanson insisted on Pakistani basmati rice because Indian long-grain rice wasn’t good enough for him. Did Hameed even sell the Pakistani variety?

Oh lord, this was dull . . . Her mind went back to his suggestion of a night out. Was it a good idea? She was thirty-two and could see her life slipping away in an endless stream of cloves, cardamoms and peppercorns. Why shouldn’t she go? She owned the bloody restaurant and could send others to shop for tomato paste and ghee. She deserved some fun. Okay, he was four years younger than her, but so what? She would take him to Trapeze and . . .

‘Damn,’ she said aloud as the trolley veered to the left. ‘Trust me to find the one with wonky wheels.’ With a clang, she crashed into someone approaching from the opposite direction. ‘I’m so sorry. This thing has a mind of its own and . . .’

‘It’s okay, Anjoli.’

She looked up and saw Sushmita Roy, an old friend of her mother’s. She almost didn’t recognise her. It had been some time since they’d last met, but she seemed far older than her fifty something years – face drawn, dark circles around her eyes with deep worry lines on her forehead.

‘Oh, hello, Sushmita Aunty. How are you?’

Sushmita didn’t meet her gaze and spoke mechanically, looking down at her empty trolley, as if wondering what it was doing there. ‘I’m fine, Anjoli. How are you?’

‘Are you okay, Aunty?’ Anjoli moved to the same side as her friend to let others pass. Sushmita raised her head. Anjoli noticed her eyes widen as though she was trying not to frown, and her strained smile.

‘I am fine. How are you?’ she repeated.

‘Really good, actually. The restaurant is doing well, and I’m just reassessing life and my priorities and . . .’ Sushmita appeared not to be listening, so she said, ‘Well, anyway. Nice to see you. Say hello to Anil Uncle and Rahul for me.’

There was no response, and she smiled and moved on. As she got to the end of the aisle, she turned and looked back. Sushmita was still standing there, looking blankly at a row of shelves.

Anjoli watched her for a moment, then abandoned her trolley and returned. ‘Tell you what, Aunty, why don’t we go for a nice cup of tea? We haven’t had a chat for ages.’

Sushmita’s knuckles were white on the trolley handle as Anjoli put a hand to her elbow. ‘Come on. I’m sorry I’ve not been to visit for a while. How old is Rahul now? Fifteen?’

Her friend’s face twisted, and she released the tears she had been holding back. She pulled a crumpled tissue out of her pocket and blew her nose. Anjoli led her out of the store into the adjoining café, where she ordered tea and two chocolate croissants. Sushmita sat mute, staring emptily, the damp tissue lifeless in

her hand. Anjoli had never seen her like this before. Something was very wrong. She hoped it wasn’t some terrible illness.

‘Tell me what the matter is, Aunty. Can I help?’

Sushmita produced a deep sigh. ‘Nothing is the matter, beti. What have you been doing? How is the restaurant?’

This would not be easy. Extracting information from an Indian aunty who didn’t want to share was like squeezing lemon juice from a rock.

‘TK is going well, thank you. You must all come some time. We have a new menu.’

Sushmita nodded. Then her face changed. She looked at Anjoli, frowning. ‘Tell me. Are you still living with that young Muslim waiter? The one who used to be in the police? Someone told me he moved out.’

Anjoli sighed. The Indian gossip factory travelled faster than the speed of light. ‘Yes, that’s correct, Aunty. He doesn’t work at the restaurant anymore. In fact, he’s joined the Met.’

‘He is a policeman again?’

‘Yes.’

‘Oh.’ Sushmita lapsed into silence once more.

‘Do you need to talk to the police?’ Anjoli probed.

‘No!’ said Sushmita with surprising vehemence, looking around her as though checking if anyone was listening.

Anjoli leaned forward and whispered, ‘Rahul and Uncle are not . . . in any trouble, are they?’

Sushmita bit her lip and her eyes glistened. She dabbed them with her tissue and mumbled, ‘No, no, nothing like that.’

Their teas arrived. Anjoli stirred in a spoonful of sugar and took a sip. ‘You can talk to me, Aunty. You always said I’m like your daughter.’

‘I know, beti.’ She appeared to decide. ‘Maybe you will be able to help. You and that boy assisted Neha, didn’t you? Few years ago? Your mother told me.’

Neha had been arrested on a murder charge. What kind of trouble was Sushmita in ?

‘Yes, we did, Aunty.’

Sushmita was finding it difficult to form words. ‘You see . . . Rahul . . . Rahul has been . . . taken.’

Anjoli looked confused. ‘What do you mean, taken?’

The dam broke. Sushmita spoke in an urgent whisper. ‘Rahul disappeared three days ago. He went to a friend’s house to play video games and didn’t return. Anil and I were out for the evening. We got back late, and like a fool, I did not check on him. I thought he must be asleep in his room. I was so stupid.’

‘Oh my God, I am so sorry! When did you realise he hadn’t come home? And why do you think someone took him?’

‘I realised the next morning. Saturday. I went to get him up for his tennis lesson at seven-thirty. And he wasn’t in his bed.’

‘Did you call his friend to see when he left the previous night?’

‘Of course. Half-past nine, he said.’

‘And you tried ringing him?’

‘Yes, there was no answer on his mobile. It’s switched off. He never switches it off.’

‘Has anything like this ever happened before?’

‘Never.’

‘Did you have an argument?’

Sushmita shook her head.

Anjoli considered this. ‘But why do you say he’s been taken? Young boys can be silly sometimes. Maybe he just went off with another friend. What did the police say?’

Sushmita paused. ‘Before we could call them, a man phoned Anil. He . . . he said Rahul was safe, but if we told the police or anyone at all, our son would be . . .’ Her voice fell to a broken whisper. ‘Killed. I . . . I . . . we . . .’

Time stopped, and it was as though the entire café went silent

as Anjoli tried to take this in. She stared at Sushmita in confusion. ‘Someone’s kidnapped him?’

Sushmita gave a small nod. The tears flowed now, and she dabbed at her cheeks as the people at the neighbouring tables looked away. She wiped her nose, looked around, then took a bite of her croissant, followed by a sip of tea.

Anjoli was finding this hard to take in. Rahul’s father owned a successful catering business, and Sushmita was a teacher. They were unlikely targets for a large ransom demand. And that sweet, sweet boy . . . All she remembered of him was that he was obsessed with his Xbox and Harry Potter. Of course, it was some years since she’d last seen him and cute little boys often grew into difficult teenagers, but still. ‘Have they asked for money?’ she whispered.

Sushmita appeared to have gained some composure after her tea. ‘No, that is the thing we can’t understand. They have not demanded anything. He said they are watching us.’

Anjoli looked around involuntarily but saw nothing strange – just the handful of people in the café on their phones and iPads. She moved her head closer to Sushmita’s and whispered, ‘Did they let you speak to Rahul?’

‘Not directly. But Anil said, how do we know you really have him? Then they sent us a video. He was . . . hurt. My poor boy.’ She broke into tears again.

‘Oh no! Hurt how? Can I see?’

Sushmita shook her head. ‘Not here. I can’t bear it. Please don’t tell anyone about this. What do you think we should do?’

Anjoli’s heart went out to her friend. Rahul was their only child, and they’d had him late in life. She had seen the pride they took in him, posting every one of his minor achievements on Facebook. No wonder Sushmita looked broken. What did these kidnappers want? She had to do something. She reached across the table and held Sushmita’s hand. ‘I’m so, so sorry. You

and Anil Uncle must be terribly worried. I am too. You really should tell the police. They’ll know exactly what to do. They deal with these types of things all the time.’

Her friend shook her head emphatically.

‘No, no, we can’t. The kidnapper said they will hurt Rahul even more if we do. Anil says the police won’t care, anyway. We are small people. And Asian. You know what they are like with us. They’ll just say he has run away because of family pressure or something. I thought maybe your friend could advise, but if he has joined the police, we cannot confide in him.’

‘Then let me help.’

A look of bewilderment came across Sushmita’s face.

‘You? What can you do to help?’

Anjoli felt a pinprick of irritation. ‘I helped Kamil with Neha. And on two more murder cases after that. I’ve got a lot of investigative skills myself.’

Scepticism painted over the surprise. ‘Really?’

‘Yes. Really.’ She took Sushmita’s arm and stood her up. ‘Let’s go to your flat and you can tell me everything that happened. Don’t worry, Rahul will be back before you know it.’

Kamil

Monday, 3 October. Morning.

The alarm wakes me at seven. Monday bloody Monday. A leap out of bed with a spring in my step and a gleam in my eye at the thought of starting a productive new week? Not a chance. It’s a bash at the snooze button, a long stare at my dampstained ceiling, then a pillow over my head as I listen to the rain sputter outside my window. Is Anjoli listening to the same rainfall? There had been so many nights when I’d wanted to slip into her room and slide into her bed. But I’d never been able to psych myself up enough to cross those few metres. Now I never would.

I scrape myself out of my bed, drag myself to the station and snag a chocolate- chip muffin from the canteen. In the space of a couple of weeks of comfort eating, I’ve achieved definite dad bod and fear I will soon reach permanent paunch. I go to my desk to see what new depths of boredom I can sink to with the current accumulation of admin stacked in my in-tray.

I open a green folder and try to concentrate. My new boss, DS Protheroe, a man with fewer brain cells than a chicken jalfrezi, is investigating the case of some finance guy bludgeoned to death in Mile End and has had me:

• Poring over CCTV footage for hours to spot anyone suspicious.

• Doing door-to- doors.

• Putting up ‘did you see anything?’ signs; and

• Filling in countless bullet-pointed forms.

Protheroe’s idea of a joke is to mispronounce my name in as many creative ways as he can. ‘May I have the risk assessment, DC Rammin?’ ‘Where are you with the audit trail report, DC Ramen?’ ‘Please log the exhibits, Camel.’ I’m not saying he’s racist, but . . . actually I am saying he’s racist. Crazy racist. Forget institutional racism in the police force. This is mental institutional racism.

He has me indexing documents today – an admin job normally done by a desk jockey (‘Got to pay your dues. It’ll stand you in good stead in the long run. Trust me, lad.’). Lad! I’ve already paid a decade of dues. I should be running the damn club by now. To keep my mind from spiralling about the imam’s information, I get to work.

It’s clear Protheroe is making zero progress on the case I’m logging. Another notch on his ‘I don’t know what I’m doing, and I don’t give a fuck’ belt. My best hope is that at some point someone will realise how useless he is and promote him so he can be transferred to a different unit and be out of our hair. That’s how we did things in India – incompetent officers were shunted between districts with rave reviews to create minimum fuss, crawling up the ladder till they became a superintendent in Bangaon or Bardhaman, where they could subsist on bribes until retirement, not getting in anyone’s way and not doing anything harmful or useful.

After ten minutes, I realise I’ve been looking back and forth at the same piece of paper and the screen on my computer. I could be interrupting a terrorist plot right now if the imam had given me more information. Although, hopefully, he has the wrong end of the stick.

An image comes into my head of the Transport Police poster

I saw on the bus on the way in. See it. Say it. Sorted. Shit. What was I thinking, giving him a day? He saw it and said it. It’s my job to sort it. If his friend’s contact is a hardcore radical jihadi, he isn’t going to listen to some old imam, is he?

I call him. ‘Sheikh, I’ve been considering our conversation. I don’t think you should meet this man. Let me tell Tahir and—’

He interrupts. ‘Thank you for your concern, Kamil. But we must try to handle this within our own community. These security types always make things worse, and we are all tarnished. We had them involved in our own mosque some years ago, where they infiltrated us with their people. It caused a lot of bad blood and in the end, they found nothing. I have arranged to see my friend’s contact at a restaurant in Ilford tonight. I will find out what he is really thinking and remind him what the Quran says about right and wrong. Talk to him about the grave punishments that await evildoers in Jahannam. I will call you afterwards.’

‘Sheikh, I genuinely think—’

His voice is firm. ‘Kamil. You promised me a day. You must keep to your word.’

‘Why did he agree to see you?’

‘My friend organised the meeting. He has not told him I will be coming also.’

I look around. No one is paying any attention to me, as usual. Everyone is absorbed in their own conversation, but I lower my voice to a whisper. ‘Sheikh, please. This sounds risky. These people can be fanatical.’

‘You think I am not aware of that, Kamil? I have been fighting with them all my life. Don’t worry.’

‘Let me come with you.’

A pause. ‘No. He will not speak to me if you are there. Leave it to me. I know what to do.’

I don’t like this. I don’t like it at all. ‘All right. At least give me

the address and I will get a car and wait outside the restaurant for you. It’s the minimum I can do to keep you safe.’

He considers this. ‘Very well. We are meeting at nine p.m. Gobi Grill. Cranbrook Road.’

‘Okay, I’ll be there. Please be careful.’

He hangs up and I sit, a worm of anxiety nibbling away at my stomach. I pay a visit to the canteen and grab a snack. Back at my desk, I take a bite of my chocolate brownie, look around at the drab walls and then return to my folders of non-work. I can feel my neurons dying one by one.

The phone rings. 999 control room. A report of a break-in at Amnesty UK, could we attend? I’m about to explain that we’re detectives and they should send a PC when my pulse quickens. Amnesty is where Maliha works – maybe we’ll bump into each other. The chance of a fleeting sight of her is worth abandoning this crap I’m doing now. I scribble down the details and walk over to Paul Gooch, a DC I’d become friendly with on my previous case.

‘Hey, Goochy, just logged a code 30 at Amnesty. Want to check it out?’

‘Why us? Tell them to send a constable.’

‘Gets us out of here, no? On this lovely Monday morning.’ I wave my hand at the rain pouring down. ‘Better than sitting here and smelling Protheroe’s farts.’

‘Naah. Let uniform get it,’ says Gooch.

I come clean. ‘There’s someone I’d like to see there. I’ll owe you one.’

He pauses for a second, then nods. ‘Gotcha! Yeah, all right. Remember that when I want to swap a night shift.’

He gives me a friendly grin and we walk out.