Designer Prod Controller Pub Month

ASSUME NOTHING . . .

Format

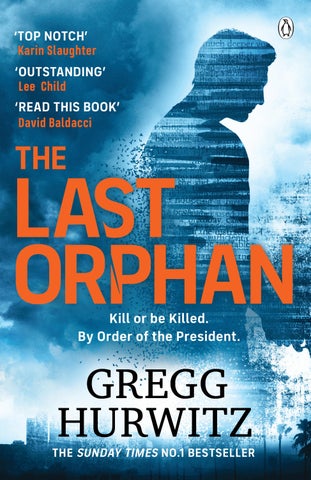

Trained as an off-the-books government assassin code-named Orphan X, Evan Smoak left that life behind to protect the helpless. Saving lives beats taking them. Until a trap sprung by the President pulls him back into his old world.

Jon Percie / Alice Aug 2023 B PB

Trim Page Size

129 X 198 MM

Print Size

129 X 198 MM

Spine Width Finish Special Colours Inside Cov Printing

27.5 MM MATT LAM PANTONE 021 C YES

FINISHES

Her instruction is clear: kill a man who she believes is a clear and present danger to the country. Or face execution himself. But the President should know better. Because forcing Orphan X into a corner has only ever made him more dangerous. Especially if he suspects that his target may not be the real threat to national security . . .

‘PULSE-POUNDING, HEART-STOPPING AND THOUGHT-PROVOKING’ Meg Gardiner ‘CRAFT, ACTION AND SUSPENSE, HURWITZ’S ABILITIES ARE AS FINE-TUNED AS EVER’ Express

Kill or be Killed. By Order of the President.

Kill or be Killed. By Order of the President.

COVER SIGN OFF

‘IMMENSELY ENTERTAINING’ The Times

WETPROOF

DIGI

FINAL

EDITOR

I S B N 978-1-405-94273-7

9

781405 942737

90000

ED2

PENGUIN Fiction

IMAGES

U.K. £0.00 Cover images © CollaborationJS / Trevillion Images and © Shutterstock

SIGN AND RETURN BY

/ 9781405942737_TheLastOrphan_COV.indd All Pages

24/07/2023 15:46

/