Designer Prod Controller

‘Startling, packed with solid research and written by one of the foremost experts in a fascinating field’ Felicity Cloake, Literary Review

5/18

Format

B PB

Trim Page Size

129 X 198 MM

Print Size

129 X 198 MM

Finish

Serves up a mind-bending menu

of fascinating insights’ Observer

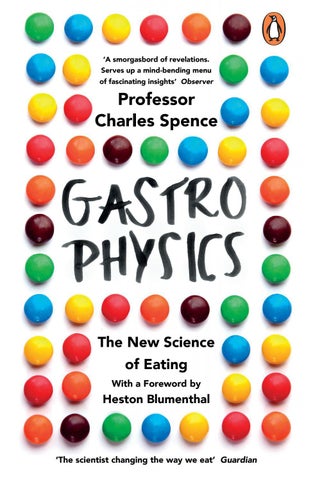

Professor Charles Spence

‘Gastrophysics is packed with tasty factual morsels that could be served up at dinner parties’ Daily Telegraph

CHARLOTTE

Pub Month

Spine Width

‘A smorgasbord of revelations.

CHRIS

20.5 MM MATT LAM

Special Colours

-

Inside Cov Printing

-

Endpapers

-

Case Stock

-

Case Foil

-

H&T Bands

-

‘Popular science at its best. Insightful, entertainingly written and peppered throughout with facts you can use in the kitchen, in the classroom, or in the pub’ Daniel Levitin, The New York Times bestselling author of The Organized Mind and This Is Your Brain on Music ‘Fascinating. His delight in weird food facts is infectious’ Sunday Times I S B N 978-0-241-97774-3

9

780241 977743

Professor Charles Spence

The New Science of Eating

With a Foreword by

Heston Blumenthal

‘The scientist changing the way we eat’ Guardian

COVER SIGN OFF

The New Science

DIGI

of Eating

WETPROOF

EDITOR

With a Foreword by

90000

ED2

NOT FOR EXTERNAL USE

Heston Blumenthal

PENGUIN Non-fiction £0.00

‘A smörgåsbord of revelations.

Serves up a mind-bending menu

of fascinating insights’ Observer

Professor Charles Spence

In Gastrophysics pioneering researcher Professor Charles Spence explores the extraordinary, mind-bending science of food. Whether it’s uncovering the importance of smell, sight, touch and sound to taste, or why cutlery, company and background noise change our experience of eating, he shows us how neuroscience, psychology and design are changing not only what we put on our plates but also how we experience it.

FINISHES

Why do we prefer to drink tomato juice on flights? Why do we eat less when food is served on red plates? Does the crunch really change the taste of crisps?

IMAGES

PRODUCTION

Cover photo by Neil Mockford

FINAL PRINT SIGN OFF

‘The scientist changing the way we eat’ Guardian

9780241977743_Gastrophysics_COV.indd All Pages

EDITOR

23/02/2018 16:57

ED2

NOT FOR EXTERNAL USE

SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS

X