Designer

- GILL

Prod Controller

- CAT

Pub Month

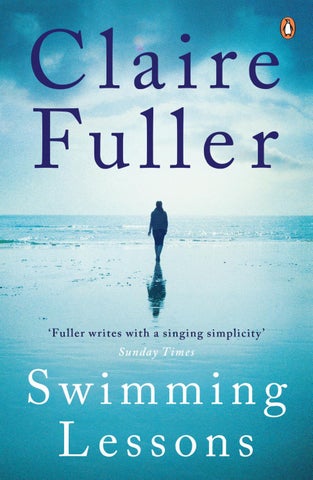

Twelve years ago Flora’s mother Ingrid disappeared, vanishing from a Dorset beach. Everyone – especially Flora’s sister and father Gil – believes Ingrid is long dead. Everyone, that is, except Flora. So when she hears that her father has had an accident, and is insisting that he saw his wife, Flora rushes home. But the answers Flora seeks are nowhere to be found – only further questions: What are the mysterious letters Gil keeps referring to? Why is the house filled with towering piles of books? And who was it her father actually saw?

‘Bewitching and page-turning. An extraordinarily smart and satisfying read’ Paula McLain, author of The Paris Wife ‘Hauntingly sad. An eloquent tale of squandered love and seething secrets’ Sunday Express ‘Assured, multi-layered, well-crafted, compelling, excellent’ Mail on Sunday ‘A beautifully told story of motherhood, marriage and infidelity’ Good Housekeeping I S B N 978-0-241-97637-1

9

780241 976371

90000

PENGUIN Fiction

129 X 198 MM

Print Size

129 X 198 MM

Finish

18.5 MM - MATT LAM

Special Colours

NONE

Foil Ref

NONE

Spot Varnish

YES

Emboss

YES

Other

NO

Inside cov printing

NO

Endpapers

-

Case Stock

-

Case Foil

-

SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS TO REPRO

X

COVER SIGN OFF DIGI EDITOR

WETPROOF ED2

NOT FOR EXTERNAL USE

IMAGES

PRODUCTION

£00.00 Cover image © Mark Owen / Arcangel Images

FINAL PRINT SIGN OFF EDITOR

9780241976371_SwimmingLessons_COV.indd All Pages

B PB

Trim Page Size

Spine Width

S wimming L essons

As Flora assembles the pieces of this puzzle the true and troubling portrait of her parents’ extraordinary marriage is slowly revealed . . .

Format

C l a i re Fu l l e r

‘Thrilling, captivating, sophisticated suspense. More than matches the power of Fuller’s debut’ Sunday Times

- 02 / 18

24/11/2017 09:57 NOT FOR EXTERNAL USE

ED2