CHAPTER THE NOUGHTH

The Beginning of the Year 1764

It started with the discovery of a child in a museum – a place she had no business to be.

The child in question – a golden-guinea-eyed thing – was so young she was speechless. She was found wandering among the shelves of priceless vases and coins, shimmering branches of coral, and very-dead crocodiles with malicious grins. She had no name that anyone could guess, nor parents to be found.

But the Assistant Keeper’s assistant (who found her) sent word to the Assistant Keeper (who did not like children), who sent for the Keeper himself (who did). And the Keeper had sense enough to see that this child was special, and that

she deserved to be loved; therefore he (as was right) loved her instantly.

All this was uncommonly lucky.

And so the Keeper gave the wide-eyed, unspeaking girl a warm home – where he kept the truth of how she came to be his daughter for a later time, when she was old enough to want to know it.

CHAPTER THE FIRST

The Spring of the Year 1774

‘G

ood morning, my dear Tomato,’ said Sir Joshua, using his walking cane to drag an Ancient Greek vase across the table. He often called her Tomato; though sometimes it was:

‘Cucumber, dear, could you help me to find my spectacles?’

or, on occasion,

‘What do you think the inscription on this coin says, my little Cauliflower?’

Lettice would wander up to his desk on her way to her favourite window seat, pick up the coin and say something like, ‘Well, the gold is worn so it’s hard to say for sure, but I think that’s Emperor Hadrian, in one of his scruffier phases,’

and Sir Joshua would nod, smile over his spectacles, and say, ‘Clever Lettice. Thank you.’

And Letty would curtsy as a joke, and say, ‘You’re welcome, Pa,’ even though strictly speaking Sir Joshua Breech wasn’t her father (and there were some people who thought that she should call him ‘my lord’). But there were many odd things about Number 6, Lamb Place, and this was by no means the oddest of them.

It had been ten years since Sir Joshua brought young Lettice (as he’d named her) home to Number 6, having retired from the museum in which he’d found her, and established a personal one of his own (‘open to Scholars by Appointment only’). And what a lot she had learned since then. For instance:

Example the first: she now knew that she was not, despite Sir Joshua’s jokes, named after a salad vegetable, but that her name meant joy.

Example the second: at four she could natter away not only in English, but also in Latin.

Example the third: at six, under Sir Joshua’s patient teaching, she could write Ancient Greek as well as she could draw a pigeon’s skeleton, which is to say very well indeed.

Example the fourth: by the age of eight she had learned a smattering of languages – Persian, Assyrian and Ancient Hebrew, too.

And now that she was nearly twelve, Letty was as knowledgeable as any Eton-schooled gentleman from the Royal Society. And her eyes still shone like golden guinea-coins.

Using his Collection of historical objects and curiosities – which were displayed throughout the tall house in which they lived – Sir Joshua had taught Letty to spot the difference between Ionic, Doric and Corinthian columns (Corinthian, of course, being by far the best), and to distinguish Devon marble from Yorkshire; he had shown her how to tell her aquatints from her mezzotints;* and he had not neglected, in addition to this thorough grounding in the arts and sciences, to teach her how to be kind.

Despite Sir Joshua’s vast intelligence and the importance of his Collection, he recognized kindness as the greatest lesson of all.

But only once in recent memory had he talked to Letty about something other than fascinating ancient artefacts.

‘When I am gone,’ he had begun, and Letty had covered her ears with her hands.

Sir Joshua gently pulled them away.

* A subject upon which I will not elaborate here, being too busily engaged in telling Letty’s story; but you must be content with the fact that it has something to do with water . . . I think. Or is it the wood upon which the carving is made? Oh, dear me! I shall have to go and look it up in the library.

‘When I am gone,’ he continued quietly, ‘all this is yours, dear Letty. You will be Keeper of this Collection, my girl. It is yours, and my only request is that you open the house as a public museum, so that all people may see.’

What could Letty do but agree?

So Letty grew plump and happy year on year, absorbing her lessons on constellations and artists and mathematics as easily as a lettuce draws water from the soil. And at the end of each day, the content of more books absorbed, and even more coins identified, Sir Joshua would unfurl his tired spine, rise from his desk, and climb slowly up the stairs (candlestick in hand), his white hair shining in the gloom.

And every night, after reading a bit more of her favourite story, the Odyssey, together (in its original Ancient Greek), he would say, ‘Goodnight, Lettice, my little fact-hunter. How lucky I am to have you for a daughter. There is no such gem as you throughout the whole of the ancient world.’

Letty would look up from beneath her fringe and say, ‘But Pa – I want to see these marvellous places! I want to walk among the ruins of the Forum at Rome! I wish to stand at the centre of a Roman theatre and contemplate the writings of Pliny and Horace! Can we go on Grand Tour soon?’

And Sir Joshua would chuckle, and say, ‘One day. But en’t our Collection here enough?’

‘With the world as wide as it is?’ Letty would reply. ‘With all those wonderful objects waiting to be found? Never!’

And she would retire to her room with its yellow flocked wallpaper, and jump on to her high four-poster bed, and draw its thick green curtains; and she would move the candlelight over her atlas, which catalogued the countries from which all the wondrous curiosities in their home had journeyed. And then she would dream of distant lands, and of objects waiting to be found, and things she didn’t yet know.*

* A brief note upon aquatints and mezzotints. I have now returned from the library, where I learned a great deal about the difference between these two printing methods; but my margin here is too narrow for the purpose of explaining very perfectly, so I will say no more upon the matter.

Well, truth be told, I have got into something of a muddle myself. I think that perhaps mezzotints are more difficult to do. Yes, that is probably it. Now, think no more upon the subject and skip neatly along to the next chapter, like a good reader. Thank you kindly.

Off you go. I shall watch to see that you close the door snugly on your way out. That’s right. Go on – stop letting the heat out, please. Be off, now! Shoo! Stop bothering me here in this cramped and untidy space. There is nothing for you here! Away with you!

CHAPTER THE SECOND

Letty was standing in the picture gallery when a magpie landed on her shoulder.

‘Diderot! What have you got there?’

She pulled something gently from his beak: it was a length of shiny red thread, thieved from Sir Joshua’s best waistcoat.

‘Oh, Deedee – that isn’t a worm! But what shall we do now? You know I couldn’t sew even a buttonhole. And I certainly can’t ask Mary to fix it. ’

Diderot looked at her with a bright eye, and she forgave him straight away. She’d raised him from a chick, and he always sought her out like a compass seeks north.

So she coiled the thread up and bunched it into her skirt pocket. Then she turned back to the image in front of her.

When she wanted to think very hard, she’d come here to the gallery, folding out the hinged wooden panels bearing paintings of ancient ruins and distant hills, searching for a particular map. It was the one which sang to her.

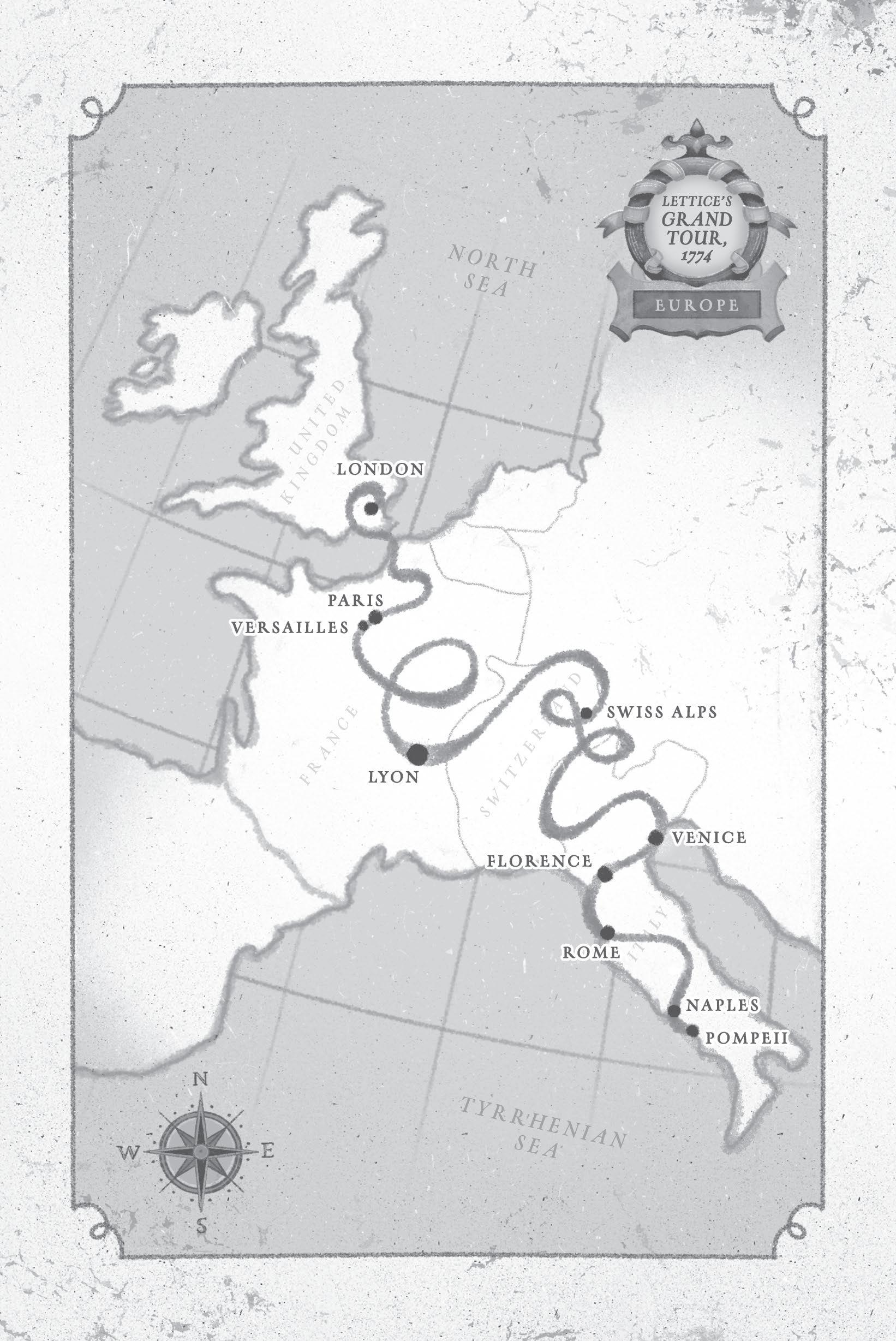

It was a map of western Europe, and upon it, picked out in gold, was a route. It was the way Sir Joshua Breech had taken on his own Grand Tour, fifty years before.

From London, the gold line set off boldly for Dover. Then Pa must have climbed aboard a ship, because the route went smoothly across the blank canvas of the Channel before alighting in Calais. From there it stitched itself, like a bright thread in a fine embroidered suit, to Paris; onwards (gathering speed) down through France; hopscotching across the Alps; zigzagging into Italy.

This was where the names of the cities made Letty’s breath catch the most: the thread took in all the best ones (Venice, City of Light; Florence, City of Art; Rome, the Eternal City) towards ancient Pompeii and Herculaneum (neither of which Letty had been born able to pronounce, but which she quickly learned were said ‘Pom-PAY ’ and ‘Her-cue-LANE -ee-um’) – cities which many centuries ago had been destroyed by a volcano.

Letty could lose herself for hours in this map, imagining taking the journey herself. She held her thoughts gently, as though they were a string of beads which became lighter as she went along the route, and her knowledge became more

patchy. London was all right, of course – she could imagine well enough the mud-coloured River Thames bursting free into the Channel. She could picture the ship to France, a breeze stirring her hair and skirts (though this took a little more dreaming, since Letty had never been aboard a ship).

Calais she thought of as a sort of English market town by the sea (except everyone was speaking French, of course). She’d read much about Paris – though her imaginings were of a distinctly papery appearance, since they were built on maps and sketches and books, and not experience . . . but –

Could she force her mind into Italy?

She could not.

That was how her map-dreams always ended.

So next she wondered what Pa would discuss at his lecture tonight, to which many notable historians and the London press had been invited.

And thirdly, and most frequently, she thought about her birthday later this month, and what it would feel like to be twelve.

Her pleasant musings were interrupted by the approaching sound of singing. It was a nice sound, but it heralded the arrival of trouble: and as soon as the singer rounded the corner, the song stopped abruptly, mid-phrase. The person who had been singing so sweetly was Mary, the maid, carrying a mop and bucket back down to the scullery, and now frowning the special frown she reserved only for Letty.

‘Daydreaming again ?’ Mary put such disdain into the words that she might as well have said ‘Picking your nose?’ or ‘Belching?’ She curled her lip. Letty turned away, frowning harder at the map in front of her.

Mary was hired to help Letty – but when she brushed Letty’s hair, she pulled; she ‘forgot’ to light Letty’s bedroom fire on cold December mornings; and sometimes she ‘accidentally’ left a thistle in Letty’s soft bed. ‘You’re useless,’ Mary would hiss. ‘All your learning, yet you don’t know how to wash a smock, or scrub a floor, or how to boil so much as a potato.’

This was perfectly true. Letty’s mind was already filled up with the dates of ancient kings and the precise nature of the poison of an asp, and she didn’t think there was extra room for potatoes or laundry.

What stung more were Mary’s jabs about Letty’s adoption. ‘Lettice Nobody,’ she’d slip in, or ‘Lettice Cuckoo’s Egg’ – as if Letty, like the cuckoo bird, had hatched in a nest not her own. It was ’specially sad because Letty wished sometimes for a sister – someone close to her own age, who would share in her joy of discoveries – but Mary, when it came to companionship, was worse than nothing.

‘By all means,’ Letty said, stepping aside, ‘examine the map yourself.’

Mary’s frown deepened into a hard scowl, which had a particularly curious effect when coupled with the gently

faded felted-wool heart she had pinned to her apron. Letty couldn’t work out its meaning; surely thunder-brow Mary couldn’t have a sweetheart, even with that glorious singing voice?

‘What do I want to look at your stinking old map for?’ said Mary. ‘It’s just a big bragging list of where all this –’ she gestured to the room at large – ‘stuff comes from.’

‘Stuff?’ Letty inhaled. ‘This is one of the finest Collections of historical objects in the whole of –’

‘Still stuff,’ Mary interrupted. ‘Pinched stuff, most likely.’

Letty bristled. What did Mary know? ‘Pa bought all this, or dug it out of the soil himself! He’s never stolen anything in his life.’

‘Stuff! Pinched from people all over the world, if you ask me.’

‘I wasn’t asking you.’

Mary sniffed and brandished her mop in a final sort of way. ‘I don’t have time for you and your debates. Some of us have to work for a living. And when the master has unannounced guests arriving at all hours, Cook expects me to work twice as hard.’ She flounced away.

‘Unannounced guests?’ said Letty to Mary’s back and her coiled, annoyingly splendid red hair. Guests at Lamb Place were always exciting.

Letty hurried along the panelled corridor towards the library, and softly opened the door. Pa was there, standing

beside the fire, his back to her; facing him, talking urgently, was a man with a rosy face and an enormous, curled wig: Letty recognized him immediately. It was Isaiah Sackville, who had once been a great Professor of the History of the Study of the Book. He must have caught a very early coach down from Oxford.

Letty was about to greet her friend, put out that Pa hadn’t already told her he was here – for Isaiah Sackville, as well as being one of the very cleverest of the clever people she and Pa knew, was sparklingly funny. Letty remembered laughing so hard at a quip he’d made once that she’d spurted hot chocolate through her nose. But now his face had not the slightest hint of joke in it. He was leaning forward towards Pa, talking, talking, talking, and he was still in his travelling cloak and gloves.

‘I tell you, Breech, there’s no need to worry about Professor Roche.’

‘Your weakness has always been certainty where there is no proof,’ snapped Sir Joshua, and Letty winced: the two great friends seemed to be arguing! ‘Isaiah, if Roche has contacted me, then he needs my help! There’s something amiss with his piece of the statue.’ Letty’s eyebrows met at the word statue, and she listened the harder to what Pa was saying. ‘I know it. We both know that he wouldn’t lie – and his mind is pin-sharp. Therefore, I will go to Paris –’

‘Piffle!’

‘No, sir – Paris.’ Letty had to suppress a snort of mirth as Pa continued. ‘He said that his piece had been moved – that someone moved it. It could’ve been stolen, replaced even. This is serious, Sackville. ’

‘But supposing – just entertain the idea, Breech – that you’re wrong, that Roche is wrong, that his memory is failing, that no one has touched his piece of the statue, and that he has simply . . . lost his marble?’

Pa replied quickly, ‘Have you lost yours ?’

Sackville looked at him, and then burst out in laughter. Pa chuckled too. Letty raised a puzzled eyebrow – were they arguing, or weren’t they?

Sackville drew in a deep breath, swallowing the last of his laugh, and fiddled with his gloves. ‘Jokes aside, my dear fellow, I truly believe there’s nothing to worry about. If we go troubling him about the statue it will only upset him further.’

His darting eyes suddenly caught Letty’s. Professor Sackville pinged upright like a jack-in-a-box, making a peculiar sort of spluttering noise as if he’d just swallowed hot chocolate the wrong way. Pa spun on his heel.

‘Ah, Letty, dear,’ he said, not quite meeting her gaze. ‘Would you be a good child and ask William to bring in some coffee?’

She looked at them both, expectant and confused. ‘Who is Roche? Is he a Keeper like you, Pa?’

‘Now, dearest?’

‘Oh! Yes, of course, Pa.’ Isaiah gave her an encouraging smile as she turned into the corridor, closing the door behind her, her brows making waves on her small forehead. Misplaced marbles? Pa and Sackville arguing?

Lettice Breech was a very good, and very obedient, daughter . . . almost all of the time. But she was also very, very curious. It was her curiosity which won now. She knelt down on the floorboards and pressed her eye to the keyhole.

If you have ever tried to glean much information through a keyhole, you will know that it is quite a frustrating business. Your vision is shrunk to the size of the average fingernail, with only a tiny portion of the scene on the other side of the door presented to you in useless little pieces.

Letty turned her ear to the hole instead, and that was a little better: it allowed some of the words to squeeze through. And the words that Letty heard were: the vow ; and to protect, to honour and to mystify ; and here was a word Letty couldn’t quite catch but sounded like ‘ak-ee-ans’ – oh! She knew this name from her favourite story, the Odyssey. But what had Odysseus’ sailors, the Achaeans, got to do with anything? And then she heard her pa’s footsteps walking towards the door, and the cuckoo clock in the hall, competing with the grandfather clock on the landing –

BONG! (CUCKOO!)

– and she jumped away from the keyhole, as if she’d been scorched.

CHAPTER THE THIRD

Sir Joshua Breech and Professor Sackville never got their coffee. Letty did go towards the kitchen, but by the time she’d reached the door she’d forgotten why she’d come, and turned round again empty-handed.

She went over in her mind what she’d heard through the keyhole. The vow . . . ? To protect . . . to – what was it? – to mystify ? Who were they mystifying, aside from her? Had Isaiah really said something about Achaeans? The words, beside each other, made no sense. And then there was the very fact of Pa and Sackville arguing –

‘Oops-a-daisy!’ She looked up into the talking obstacle she’d just walked into. It was Fortnum, their butler, who was setting out chairs in the drawing room. ‘Miss Lettice.’ This was a joke: Fortnum called her ‘Letty’ just as her father

did. ‘You can help me, if you like,’ he said. ‘Mary’s absented herself again.’

‘Mary . . .’ said Letty, her mind snagging on the word like a fish in a net. ‘Fortnum, why does Mary hate me?’ She set a chair with four gilt legs precisely on the floor rug.

The old butler considered the question for a moment, and then replied carefully, ‘Do you like Mary?’

Letty thought. ‘I don’t hate her. She’s just . . . unfriendly. And I haven’t given her any reason to hate me.’

‘Have you given her any reason not to hate you? Think about it as though you were Mary. You were both foundlings. And yet: your lovely room, your education from your father, the love you receive every day, regular as square meals, Letty – have you wondered how that might seem to her?’

Letty, like the rational girl she was, gave this question due consideration. ‘But I always remember to thank her, and I offered to teach her the Greek alphabet when I was six.’

Fortnum smiled a small smile. He was like a rather dignified old beagle: stiff-legged and sensible. ‘You perhaps might wish to give her a real reason to change her mind.’

‘I shall try to think of something,’ said Letty, through a sigh. Mary was like an angry black cloud spiriting around the house, sparking little bolts of lightning. Letty wondered briefly about harnessing Mary’s ire to a lightning rod, and doing something useful with the electricity.

Fortnum, meanwhile, had laid out ten chairs to Letty’s

one. ‘One hundred and ninety-nine . . . two hundred. What on earth is my master lecturing on tonight, to warrant such a crowd?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Letty, and the sting of this came afresh. Normally Sir Joshua would ask for her opinion on his lecture notes, making sure they would be clear to not only the experts in the audience, but also to the newspapermen – some of whom could mangle the instructions for peeling an orange. That was as mysterious as his conversation with Sackville. ‘He didn’t tell me.’

‘Well, you can explain it to me tomorrow morning, I dare say,’ said Fortnum. To amuse herself, Letty started arranging the wine glasses on the side tables in strict diamond formation: the logical way she liked.

Now the doorbell was jangling, and William, the footman, was hurrying to his position to receive the guests. Fortnum brisked efficiently into the echoing hallway, his shoes sparkling. Letty thought it best to make herself scarce, and went to see if Sir Joshua was ready.

She tried the library first, but the fire in the grate there blazed only for itself. Instead, she found him in the Monk’s Crypt. This was the name they gave a funny little room stuffed full of marble carvings: coffin-like sarcophagi from Egypt; grave-marking stele from Ancient Greece; headstones from second-century Rome, displaying portraits of long-ago senators and their hard-haired wives.

Isaiah Sackville was nowhere to be seen, but Sir Joshua was sitting in a high-backed chair beside the fire, smoking his pipe and flicking through his notes. Letty, leaning over his shoulder, glimpsed something that seemed to be in a strange kind of language: but it wasn’t one she immediately recognized. And there was an expression on his face that she didn’t recognize either. He actually jumped when Letty spoke.

‘The audience is arriving, Pa.’

‘Ah! Are they, Lettice?’ He fumbled his notes out of sight. His voice, normally so assured, was . . . squeaky.

Nerves, realized Letty, amazed. That was it. The great Sir Joshua Breech was nervous.

‘Can I assist you, Pa? With the lecture?’

Sir Joshua merely smiled a little, seemed to gather himself, and kissed the top of her head. ‘Dear Lettice. Kind, clever Lettice. You are my joy. But, no – I need to deliver this one by myself. And then, Sackville’s visit has decided me. I must visit some old friends . . .’

Letty’s mind was burning with questions, but she knew better than to push him. ‘What can I do, Pa?’ she asked, in the most practical voice she could muster.

‘You can carry this.’

From under his chair he brought out a small leather case, and placed it in her hands.

CHAPTER THE FOURTH

Letty settled into her usual lecture seat – a discreet recess piled with cushions, to the side of the podium from which Pa would be speaking. She adored this spot. Cosy and hidden, she could listen to his talks while casting an interested eye on the audience. And what an audience it was. Isaiah Sackville, from his front-row seat, caught her eye and gave her a little wink. Around Sackville, Letty recognized many a Fellow of the Royal Society – men with intent expressions, their buckled shoes gleaming, leaning over their seats to greet each other. Learned ladies perched on chairs with extra space either side to allow for their fashionably broad-hipped dresses, and discussed the latest findings from Pompeii. Next there were the dealers in antiquities, with their shrewd faces, who knew the worth of each of the treasures in this