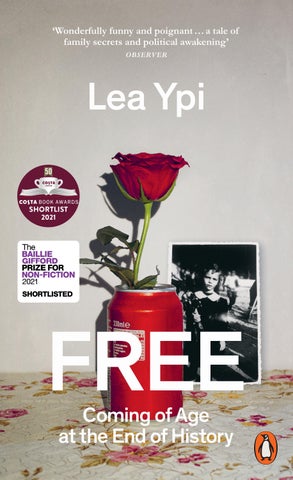

PENG UIN PRES S F REE

‘An astonishing and deeply resonant memoir about growing up in the last days of communist Albania … more fundamentally about humanity, and about the confusions and wonders of childhood. Ypi weaves magic in this book: I was entranced from beginning to end’

‘Wonderfully funny and poignant … a tale of family secrets and political awakening’

Date: 12/04/2022 Designer: Olga Prod. Controller: Katy Pub. Date: 26/05/2021 ISBN: 9780141995106

OBSERVER

Lea Ypi

S PINE W IDTH: 20

Estimated • Confi • rmed

Cover design: Olga Kominek Author photograph © Florian Thoß

L A U R A H A C K E T T , S U N D AY T I M E S

MM

F O RMAT

FREDERICK STUDEMAN, FINANCIAL TIMES, BOOKS OF THE YE AR

‘Utterly engrossing … brilliantly observed, politically nuanced and – best of all – funny. An essential book’ S TUA RT J E FFRI ES, GUARDIAN

‘Enthralling, a classic in the making’ DAV I D A B U L A F I A , T L S, B O O KS O F T H E Y E A R

‘If you read one memoir this year, let it be this’ S U N D AY T I M E S , B O O K S O F T H E Y E A R I S B N 978-0-141-99510-6

90000 AN

9

780141 995106

9780141995106_Free_COV.indd 1,3

U.K.

£9.99

ALLEN LANE BOOK

PENGUIN

LEA YPI FREE

‘A strange world and its legacy is now stunningly brought to life … a moving and compelling memoir as well as a frank questioning of what it really means to be free’

Cover 198x121mm Tip In 198x129mm PRINT

•••• CMYK F INIS HES

Regular Coated Matte varnish to seal

FREE

PRO O F ING METHO D

proofs • Wet only • Digital No further proof required •

COV OUT

Coming of Age at the End of History

Memoir

12/04/2022 16:02