13 minute read

Arts & Culture

Portrayals of the American West

Much of what we know about life in the American West at the turn of the 19th century comes from the work of photographers who took up the developing art and recorded the lives of indigenous people, ranchers, pioneers and wildlife of the era.

Possibly for the first time, the works of five legendary photographers – Roland Reed, Edward Curtis, A.G. and Augusta Wallihan and L.A. Huffman – are being exhibited together this winter at the Steamboat Art Museum, aka SAM.

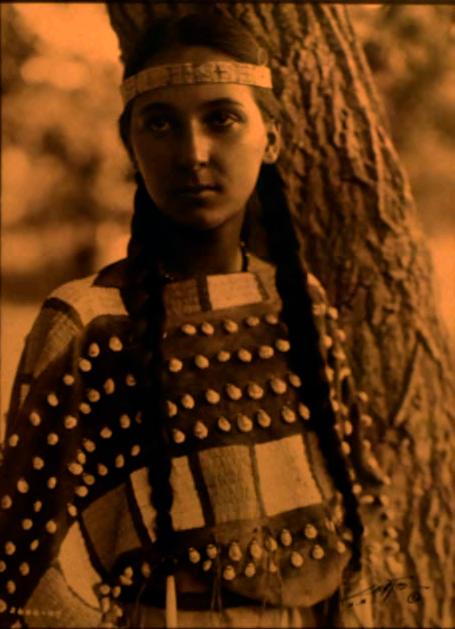

“Travois,” by Roland Reed

COURTESY JACE ROMICK GALLERY

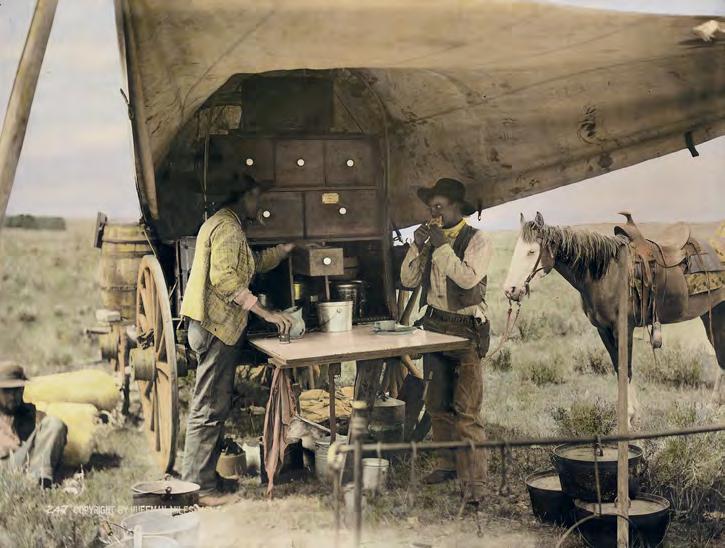

Each of these photographers has an amazing story. Roland Reed’s admiration for indigenous people began when he was child living near an Indian trail in Wisconsin. Throughout his life, he traveled from Alaska to Minnesota, from Montana to Colorado, and from California to Arizona as an explorer, artist and photographer. At one point, he went to live with the Ojibwe for two years to undertake his “long-deferred campaign in portraying the North American Indian,” as he later wrote. Augusta and A.G. Wallihan were filled with similar determination. Concerned that rampant, reckless hunting in the West would soon eradicate multiple species, they began photographing them for posterity. And that is how Lay, a sleepy little town 20 minutes west of Craig, became the birthplace of wildlife photography in America. Legend has it that Augusta, who had come to Northwest Colorado to live with her brother after a failed marriage, was snowbound in a cabin in Lay with her brother’s business partner, A.G., who was 20-plus years her junior. To avoid scandal, the two decided to marry, and thus began a lifelong adventure as pioneers, hunters and photographers. One image of Augusta, entitled “Grocery Shopping,” shows her with an ammo belt around the waist of her prairie dress, a bonnet on her head, a Remington rifle in one hand and a skinning knife in the other, standing over “Sioux Maiden,” a mule-deer buck. Augusta was a crack shot and expert by Edward Curtis hunter who once wrote that, over time, she had dropped 31 deer with her Remington, “only wounding three and losing none.” The buckskin gloves she wore in that image could have been the very ones she and A.G. traded to a passing missionary for a camera, which they then taught themselves to use. In those days, it wasn’t a matter of loading film into a camera, but of handcoating glass plates with light-sensitive material, delicately placing them into a light-blocking container and loading that into the back of a view camera. The couple’s photographic talent, along with Augusta’s hunting skills, brought them to the attention of Rough Rider Teddy Roosevelt, who invited them to the White House. He also paved the way for them to present their work at the 1900 Paris Exposition, where they received critical acclaim. Edward Curtis, who also worked around the turn of 19th century, is known internationally as the photographer whose imagery epitomizes the indigenous people of the Old West. Curtis left school in the sixth grade and built his own camera. When he was 27, he shot his first portrait of a Native American woman, and so began his lifetime endeavor to document Native American traditional life before it disappeared. Curtis worked with a number of photographic processes, ranging from rotogravures – an intaglio printing process using a rotary press – to goldtone, platinum and silver gelatin prints. During the same era, L.A. Huffman was chronicling life in the last two decades of the Montana frontier. Dubbed the “Charlie Russell of Western photography,” he shot Yellowstone’s geological marvels, ranchers, wild horses, herds of sheep, landscapes, Northern Plains Indians and the last of the buffalo in Montana territory. Watching the destruction of the herds may have also kindled his interest in wildlife conservation. The synergy that brought this display together is remarkable. “The thing I love about this exhibit is that it’s a regional collaboration,” says Betse Grassby, SAM’s executive director.

COURTESY TREAD OF PIONEERS MUSEUM

COURTESY MUSEUM OF NORTHWEST COLORADO

Overlooking Steamboat, 1890, sepia tone print by A.G. Wallihan of Lay. He and his wife, Augusta, were recognized for their work by President Teddy Roosevelt and are commonly considered to be the first wildlife photographers in America.

T aylor Z ach

adventurous.

subscribe

steamboatmagazine.com/pages/subscribe

Jace Romick, owner of the Jace Romick Gallery on Eighth Street in Steamboat Springs, is a renowned Western photographer in his own right. His excitement for historic imagery led him to the work of Roland Reed, and ultimately to acquiring much of the collection of Reed’s glass plates and other relics – a significant acquisition.

“The Reed prints are of the highest quality. They will blow people away,” says Rod Hanna, president of SAM’s board of directors and curator of the exhibit.

The Museum of Northwest Colorado lent SAM works from its collection of more than 400 Wallihan glass plates, one of which is an early image of Steamboat.

The Tread of Pioneers Museum in Steamboat also made a noteworthy contribution to the exhibit. One of Routt County’s pioneer families, the Ferry Carpenter family, bequeathed a collection of Curtis photogravures to the museum. Some of them will be featured in the SAM exhibit, along with Curtis prints from other local collectors.

The late Doug Kenyon, who was a Steamboat resident, had acquired a collection of contact prints from the

“Roundup Cook and the Pie-Biter,” by L.A. Huffman

Huffman family collection, and his daughter Christine has arranged for SAM to display a select group of reproductions of them in this exhibit.

“Portrayals of the American West” opens Friday, Dec. 3, and runs through Saturday, April 2. For more information, visit SteamboatArtMuseum.org.

Creating unique architecture in harmony with the environment

WagnerDesignStudio.com 970-846-0905

A Giant Tale

| BY SUZI MITCHELL

When the Steamboat Springs School District got the green light from public voters in November 2019 to build its first school in 40 years, district officials wanted the design to impart a legacy. A commissioned art collection shares the story of the area on the west side of Steamboat Springs, where the Sleeping Giant School for pre-kindgergarten through eighth grade opened its doors to students on Tuesday, Aug. 24.

In agreement with the Sleeping Giant Art Committee, the district enlisted Denver-based NINE dot ARTS® to curate the artwork sourced through regional and local artists. The goal was to honor the area’s rich history through depictions of the indigenous Utes, along with the site’s wildlife and natural beauty.

Joe Norman, a Loveland-based sculptor, was drawn to the symmetry of the local sandhill crane population and nearby nesting sites for his threepiece installation. “I drew a parallel with the migratory pattern of birds and my own school-age daughter for inspiration,” he says. “The birds are gone in the winter but back for the summer, which is the opposite for students.”

A trio of three-foot sandhill cranes morph into the figure of a child as you move around each piece at the front of the school. To withstand the weather, Norman used stainless steel, which he painted on one side. The other side was left as brushed raw steel with clear coat varnish to give a reflective quality. “Humans have a complicated relationship with reflective surfaces. There is something emotional about seeing a picture of yourself in something,” he says. Norman said the metaphor of migration is a useful tool to understand the process of education as students come and go throughout the seasons and eventually leave the school for other adventures.

Inside the building, on a wall beneath a learning space encased in a treehouse, hang three standalone pieces by Windsor-based artist Ashley Stiles. Her mixed media work, “Original Influencers,” represents the past, present and future of the indigenous Utes through their contributions to art, medicine and nature. “Many of my friends are Ute. This is their story and I wanted to make sure I was accurate,” says Stiles, a member of the Chickasaw tribe. The middle piece shows a young boy engaged in a traditional bear dance. Bear was chosen as the school mascot. Three human silhouettes cut from mirrored material reflect the diverse roles of the modern Ute in society. “I hope people will see the pieces and want to learn more about the indigenous people,” she says.

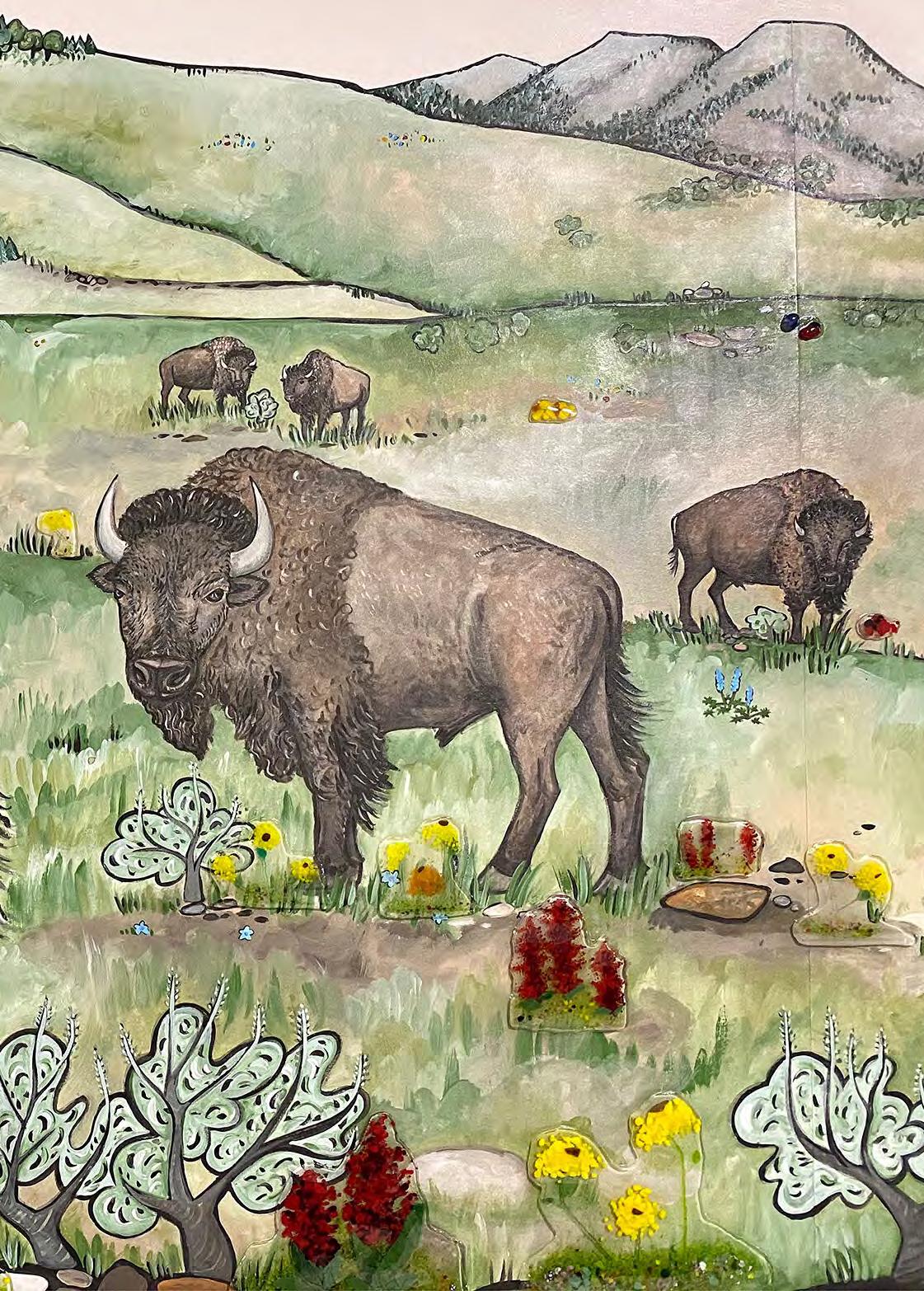

Three Steamboat based artists collaborated on the final installation, a 46-foot-long mural titled “The Sleeping Giant’s Past.” Jill Bergman, Jennifer Baker and Sandi Poltorak, partners at Pine Moon Fine Art, combined their talents to create a design that was initially sketched by Bergman, a printmaker and mural artist.

Bergman painted the foundation of the piece onto poltab. It includes the Sleeping Giant, native aspens and local wildlife along with a herd of bison in a nod to the indigenous communities of Colorado. Baker, a glass artist, created impressionist style wildflowers and bluebirds, which were epoxied onto the polytab to give a three-dimensional appearance while enabling Bergman’s paint to show through. Sandi Poltorak added four framed charcoal and colored pencil drawings of moose, an eagle, two sandhill cranes and tipis in another nod to the Ute.

The 46-foot mural, “The Sleeping Giant’s Past,” was created by Jill Bergman, Jennifer Baker and Sandi Poltorak.

COURTESY JOE NORMAN XX

Joe Norman’s sculptures of children transform into the figure of sandhill cranes when viewed from a different angle. Building green since 1980.

“We have three very distinct mediums, but I think they blended very well,” Baker says. The trio had two practice shots at laying out the final piece before Bergman and her husband, Matt Irvin, had the unenviable task of hanging the polytab. “There were definitely sleepless nights, but we did a lot of research, took some artistic license and supported each other through the process to bring it all together,” Bergman says.

www.fox-construction.com

970-879-7529

Ralph Oberg | “Old Kani near Phurbe, Tsum Valley, Nepal” | 11 x 14

Ekphrasis 2021

The Greek word “ekphrasis” refers to a literary description of, or commentary on, a visual work of art. In summer 2021, Steamboat Magazine partnered with Steamboat Art Museum and Off the Beaten Path Bookstore to host the fourth annual Ekphrasis writing competition, inspired by the pieces in Steamboat Art Museum’s “Four Directions, Common Paths: Oberg, Smith, Whitcomb, Young” plein air painting exhibit. Entrants wrote stories or poems based on their painting of choice, and in late July, celebrity readers, including Lisa Popovich, Ulrich Salzgeber and Sarah Jones, read selected entries at the Steamboat Art Museum event. The winning entry was an homage to climber George Mallory.

An Homage to Mallory

| BY MANDY MILLER

Pasang’s voice was no longer muffled by the wind which had howled since we left Everest base camp days before. “Georgie, we must go. Our last chance.”

I nodded. Climbing season was over, every other team gone along with their dreams of the Summit. Not one soul had made it in 2020, at least not there and back. Usually someone does, often a high net worth dilettante, albeit tethered to a Sherpa’s back, the mountaineering equivalent of a sedan chair. Grandfather would have been appalled at what he wrought.

Pasang unzipped the tent and held the flap back, letting in the glow of the full moon, a golden gong punched out of the midnight sky.

“Look, he said,” pointing to the pyramid, the top of the world. “All is calm.”

I staggered out, body and mind sluggish at 27,390 feet.

He held out a gas canister attached to a mask, the type Grandfather surely used in the Great War. “Maybe you should.”

I waved him off, heart tom-toming in my chest.

I pulled on hobnail boots as Grandfather had done exactly ninety-six years before, then rearranged myself in the prickly layers of wool I had worn overnight to ward off the cold. Just as he had. And then the canvas overcoat. Just like his.

I grabbed the binoculars from Pasang and turned them down the Khumbu glacier high above which Grandfather’s body lay, frozen in time and place. I brought the stupa, a mere cairn now, into focus. More of an arch than a holy place, but then what should a holy place look like? A lama had blessed Grandfather there with a puja, burning juniper and smearing tsampa flour on his and Irvine’s faces for protection. Mother said her father

was “driven by action, not superstition.” Still, I imagined the old war horse saying, “Better safe than sorry,” his stiff British upper lip curling into a sly smile. Not that any of it had mattered in the end.

Just to be safe, I had said a silent prayer there too. For Pasang. I didn’t believe in incantations. But Pasang did, and he was the one with no reason to climb this mountain, yet again. But, like Grandfather, Pasang would, because it was there. Chomolungma, Goddess Mother of the World to the Sherpa, the people of the East, was once the holiest of sites, but is now a desecrated monument to ego masquerading as the Sherpa way of life.

I pulled the gold watch from my pocket much as Conrad Anker had pulled it from Grandfather’s when he found him still tied to a line in 1999. The crystal is gone, the hands too, but their rusty stencil on the still white face is frozen at 12:50. Whether Grandfather was on his way down from the Summit cannot be known. Hillary has the glory of that first.

“We must turn by that hour,” Pasang said.

Together, we climbed, our bodies dying cell by cell. Having failed on the first attempt, Irvine persuaded Grandfather to use “English gas,” the Sherpa name for bottled oxygen. I, however, had persuaded Pasang to go without, to accomplish what Grandfather had set out to do when he returned. The Somme had left him with the need to suffer for those who had perished.

At the Second Step, we paused, scanning the precarious perch as one might for a lost pet, but Grandfather’s body was gone. A propitious wind had revealed it to the worthy Anker who returned with only the watch and his word as proof. I like to think they shared toast before Anker moved on to live. And Grandfather, into the abyss.

I shifted my gaze to the ribbon of snow trailing off the summit, borne on the jet stream. Where would those flakes come to rest? Upon whose body?

“We have time,” he said. “The light is with us.”

Soon, we stood on the earth’s highest balcony for but a moment. There was no question of a photograph. Photographs are for those for whom the Summit is the destination.

Pasang faced down Chomolungma and bowed to where the stupa would have been but for the shroud of clouds. He pointed at his watch, a rubber affair with a digital display. It read 12:50.

I kneeled and hollowed out a cranny in the snow with my ice axe. I set the watch with no hands into the frigid grave where, I pray, it will remain. Timeless. For Eternity. Like Chomolungma.

YOU BUILD IT... WE PROTECT IT. Specializing in high value properties

405 South Lincoln Ave. Steamboat Springs

(970) 879-1363

www.steamboatselectins.com

SERVING ALL YOUR INSURANCE NEEDS HOME & AUTO • COMMERCIAL LINES • HEALTH BENEFITS

We Build: FOR COLORADO

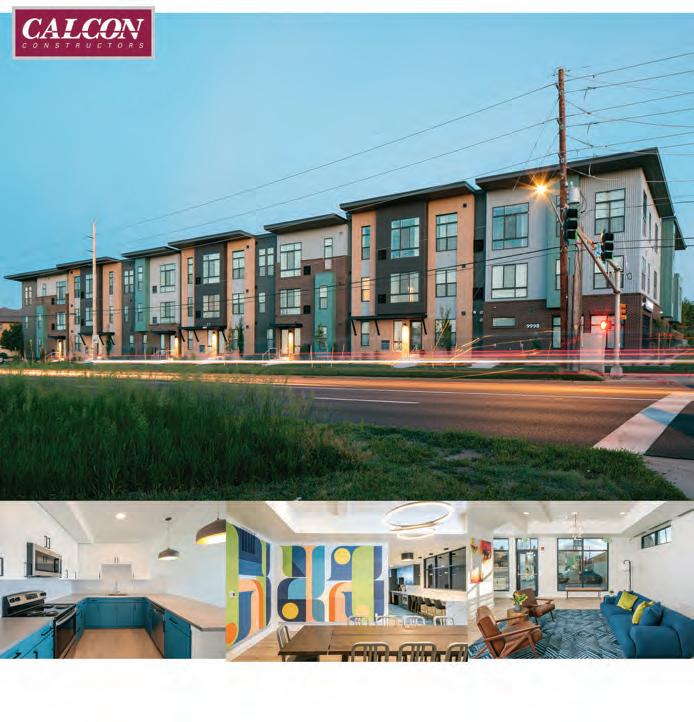

SAGE CORNER APARTMENTS

Lakewood, CO