The common room

Written by: Elio

Baghdad,820AD.ThewarmflickersofoillampshelpingaPersianpolymathpenthefinishingtouchesofa treatisethatwilloutliveempires.Hedoesnotknowityet,buthispreciselinesofArabicplanttheseedsof mathematicalnightmaresthatwouldechothroughexamhallsforcenturies.

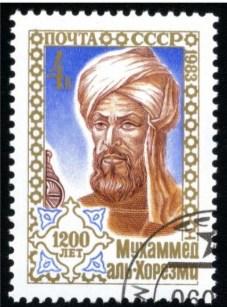

Often referred to as the Father of Algebra, Al-Khwarizmi was the most influential mathematician of the ninth century. His most popular work, alKitāb al-Mukhtasar fī Hisāb al-Jabr wal -Muqābalah or in more manageable terms, The Compendious Book on Calculation and Restoration—from which the term 'algebra' (al-Jabr) is directly derived. We often do not hear about Al-Khwarizmi in schools, but this man published the first set of systematic solutions of linear and quadratic equations- though his practical intent has since been buried under endless piles of exams. Unlike us, Al-Khwarizmi looked for the solutions to these equations to provide answers to people’s everyday problems such as splitting inheritance, paying labourers and dividing land. Algebra, in his eyes, was not abstract torture – it was useful.

The House of Wisdom, Bayt alHikmah, was the intellectual powerhouse of its time. Known also as the Grand Library of Baghdad, this major academy fostered what is now recognised as one of history’s most significant translation movements, seeing scholars render works from Greek, Persian, Indian and other languages into Arabic. Al-Khwarizmi, as one of the leading scholars, not only laid the foundations of algebra but also contributed to mapping the known world by tabulating coordinates of hundreds of cities while providing instructions for drawing a better map.

Perhaps the most underappreciated mathematical upgrade in history: a number system that finally made sense. The decimal number system we use today those familiar digits from zero to nine owes its Western debut once again to Al-Khwarizmi. Though the system had Indian roots, it was through his introduction to the Islamic world, and later via Latin translations in the twelfth century, that it quietly slipped into European mathematics (Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci). This shift unlocked new dimensions of calculation, liberating scholars from the burden of Roman numerals, and quietly laying the foundation for far more elaborate problems.

The Islamic Golden Age is the name given to this hidden, vibrant era where scholars like Al-Khwarizmi revolutionised mathematics and science through other numerous treaties not discussed. His al-Jabr did not simply solve equations but rather set minds alight from Baghdad all the way to medieval Europe. His name gave rise to the term algorithm (his Latin name was Algorismi), now a concept seen as the backbone to all computational innovation we interact with

daily. In his age of flickering oil lamps, he lit a spark greater than many of us can fathom.

Whether or not you are currently studying a mathematical science, this brief exploration into its Middle Eastern roots should offer a glimpse into the rich and diverse narratives waiting to be told in this subject. Too often, many cave to the idea of maths being a cold, ahistorical monolith. In reality, and perhaps fortunately, maths is anything but linear. A more fitting (and encouraging) observation is that mathematics is the melding of ideas across many cultures, languages and centuries of human curiosity.

Written by: Lucia

Lately, we’ve been hearing that AI, especially ChatGPT, won’t help us pass exams. But could it be doing something more concerning – taking our jobs in the future? Should we be worried at all ?

AI is rapidly transforming how we work, create, and interact. It learns from every interaction, mimicking speech, adjusting based on feedback, and evolving over time. To understand which jobs are at risk, we must ask: What can humans do that AI can’t – and vice versa?

When we think of automation, we often picture roles like assembly line workers or cashiers – and this shift is already happening. For instance, self-checkout machines at Tesco are replacing human cashiers. These jobs are typically lowincome and don’t require a degree, making workers vulnerable to automation. If this trend continues, it could increase income inequality. From a business standpoint, machines are cheaper – they don’t need benefits,

won’t ask for pay raises, and produce more consistent results.

This deepens the divide between those with higher education and stable jobs, and those without, undermining efforts to reduce inequality.

But AI isn’t just a threat to low-skill jobs. White-collar roles in finance, law, and healthcare are also at risk. AI processes data faster, reasons logically, and makes decisions with more precision than humans. Although these professions require years of education, AI can be deployed quickly to handle tasks like financial analysis, legal research, and diagnostics. This is unsettling for degree holders, who have long relied on higher education as protection from automation. However, many tasks in these fields are routine and data-driven – areas where AI excels. For example, AI is already predicting market trends and analysing legal precedents more efficiently than humans. If this

continues, it could lead to structural unemployment, as industries once reliant on human labour become automated.

However, AI can’t replicate everything. Humans still bring intuition, emotions, moral judgment, and adaptability. Jobs like those of musicians, artists, doctors, teachers, and skilled tradespeople rely on these uniquely human qualities. While AI can assist, a full takeover seems unlikely. For example, AI might help doctors analyse symptoms, but human judgment remains essential for complex or unique cases. In creative fields, while AI can generate art or music based on patterns, the true value lies in original creativity –fresh ideas and emotional depth that only humans provide. This will likely grow in importance in the future.

Given these changes, the question is: how can we, as students, adapt to an evolving job market? The answer is simple: we need to focus on what AI can’t do and play to our human strengths. Rather than viewing AI as a threat, we can use it as a tool to enhance our work. By combining ethics, empathy, emotional intelligence, and creativity with AI’s capabilities, we can shape a future where humans and machines collaborate, not compete.

This will, of course, impact the economy in several ways. On one hand, AI is a valuable tool that can boost productivity and increase Real GDP (the total value of goods and services produced in a country, adjusted for inflation), which is positive for economic growth. On the other hand, rapid automation could lead to structural unemployment. As workers

who specialized in certain tasks lose their jobs, they may struggle to find new employment without significant retraining. This could result in high unemployment and a concentration of AI’s benefits in the hands of those who own or control the technology. To address these challenges,

governments may need to intervene by investing in education and upskilling, offering support for displaced workers, and implementing fair taxation on companies that profit most from automation. This could help reduce inequality and ensure that the gains from AI are more widely shared, although this will also be a major challenge.

In conclusion, while AI presents both opportunities and challenges, its impact on the job market will largely depend on how we adapt. Automation may disrupt traditional roles, but it also opens doors for innovation and growth in areas that rely on uniquely human qualities like creativity, empathy, and moral judgment. As students, it's crucial for us to develop skills that complement AI, ensuring we remain competitive in a rapidly evolving world. By embracing AI as a tool, not a threat, we can shape a future where both humans and machines thrive together. Government intervention, such as investing in education and upskilling, will be essential to managing this transition and ensuring that the benefits of AI are shared more equitably. Ultimately, the future isn’t just about AI - it’s about how we, as individuals and as a society, choose to evolve alongside it.

Written by: Laurence

Modernism is an architectural style that emerged from the Industrial Revolution, best summed up by the phrase “Form ever follows function” – Louis Sullivan, (‘father of modernism and skyscrapers’). It was driven by a desire to break away from historical diversity and design purely for function. Though often criticised today, its impact has been immense. And so, architecture may never truly return to ornate styles like baroque or classical. Like it or not, modernism changed the fundamentals of how we design and use buildings.

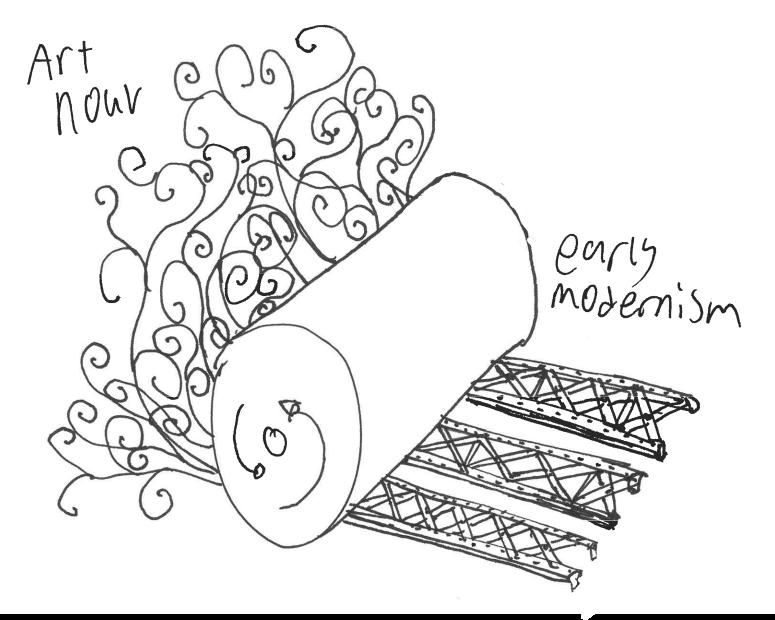

One of the most interesting aspects of modernism is its origins. Culturally, it was aligned with the broader Modernist movement in art and literature, which praised innovation and rejected tradition. Ironically, the Arts and Crafts Movement itself began as a reaction against industrial mass production, but inspired ideas that fed the ‘mass produced’ and modernist design philosophy. Architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner traced modern design’s roots back to William Morris, who advocated honesty of materials and craftsmanship, Pevsner believes Morris to be the true father of modern design. Pevsner believes that Morris ‘led the way to the Bauhaus’ and greatly inspired Walter Gropius in his school’s ethos. The Bauhaus school (founded 1919) was a school of modernist architecture, first focused on handcraft but later on mass production.

Viollet-le-Duc’s structural rationalism and Sullivan’s credo “form ever follows function” were guiding principles for 20thcentury designers. By the 1920s, movements like Constructivism, De Stijl, and Futurism were merging art, technology, and social utopianism, all feeding the modernist vocabulary.

Socially, modernist architecture carried a utopian dream of great living standards for all and post war reformation – it’s no wonder most of the modernist architects were socialists! After World War I Europe’s housing crisis gave Avant-garde architects an opportunity: They aimed for architecture to not only meet functional needs but “actively liberate and elevate” society. Creating affordable, hygienic housing for the masses, using modern insights in health (sunlight, ventilation) and efficiency. Although early ideas proved impractical (for instance the use of flat roofs and uninsulated walls) the ambition was bold.

Strangely, Modernism arose from a rejection of order. Art Nouveau, an organic and decorative style led by architects like Gaudí, influenced modernists through its expressive use of iron. Art Nouveau favoured iron for its flexibility and ease of manufacture. Their decorative use of iron helped inspire modernists, who saw its potential for larger structural applications, as seen in landmarks like the Eiffel Tower. This evolution led to innovations such as the first glass-walled building (the AEG Turbine Factory in Berlin), paving the way for grand modernist buildings like the Crystal Palace, and eventually modern skyscrapers.

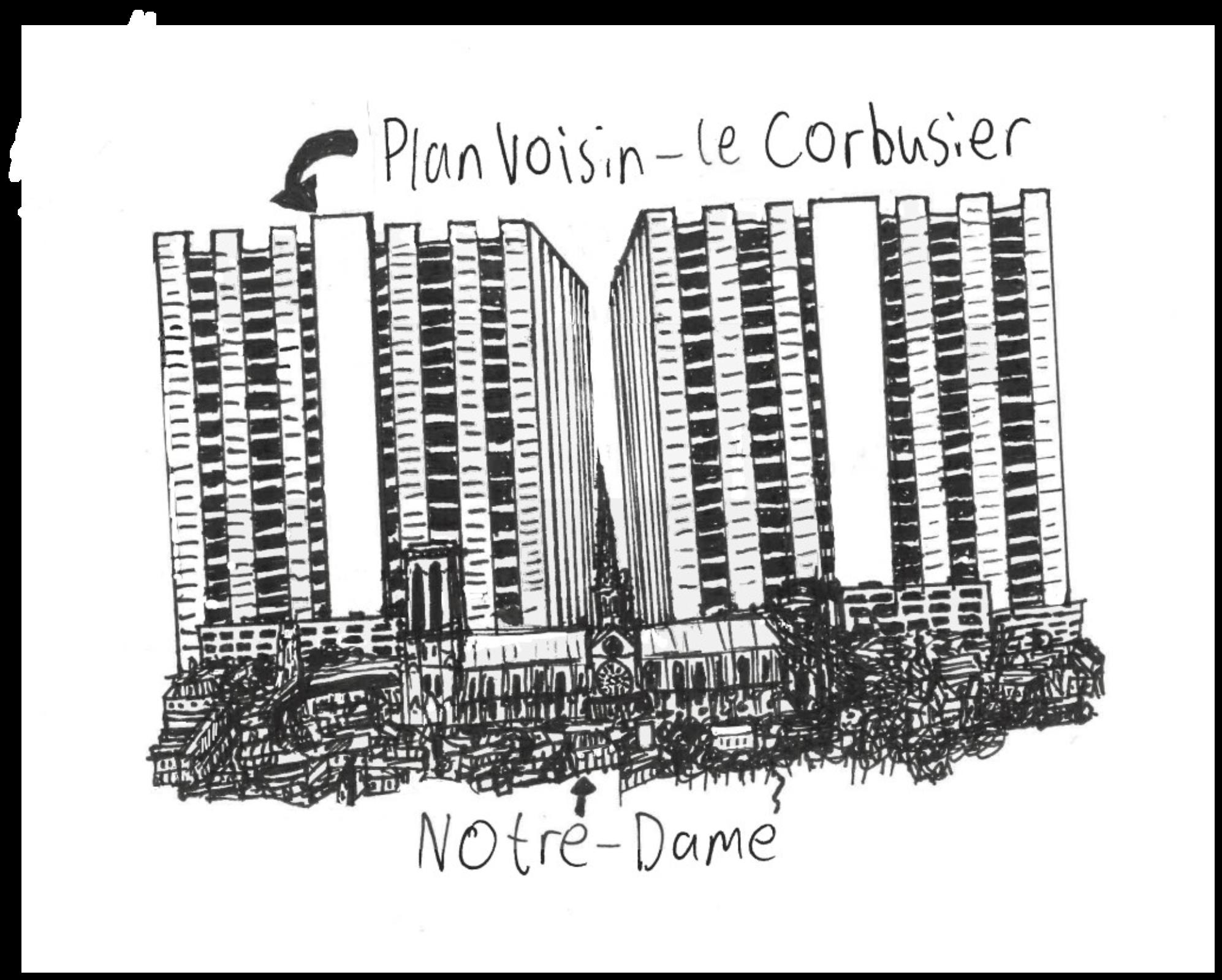

Modernism was widely accepted for its pragmatism and efficiency. Its use of steel frames, modular components, and curtain-wall construction allowed for faster, cost-effective construction. Le Corbusier’s unitised apartment slab, the Unité d’Habitation, offered a prototype for high-density living and inspired countless concrete housing blocks. Though admired by many, Le Corbusier was also seen as a bit too extreme, creating radical proposals like Plan Voisin, which suggested demolishing half of Paris to build a modernist utopia.

Governments and corporations were quick to embrace the International Style’s boxy, glassand-steel aesthetic as a symbol of progress and economic growth. By the 1950s Modernism projected an optimistic, forward-looking ethos that resonated with a public eager for change. It stood for a democratic, technological future, in contrast to classical styles tied to old regimes. Newly independent nations, especially those in the Middle East and Africa embraced the modernist style to signal a break from colonial rule and a step toward a new future. However, not everyone appreciated modernism. While many praised its simplicity and clean lines, others found it cold, impersonal, and lacking the warmth of traditional styles. By the 1960s, critics increasingly saw modernism as monotonous, dominated by uniform concrete towers and glass boxes. Opponents criticized the “loss of human warmth” exteriors of modern design.

The legacy of Modernism is arguably the largest of any architectural style. Many new movements grew upon or responded to modernism. My personal favourite branch of Modernism is Brutalism (starting in the 1950s). Brutalism embraced raw concrete and bold, sculptural forms. Named after Le Corbusier’s béton brut "raw concrete", it emphasized honesty in materials and a sort of monumental functionalism. Iconic examples in London are the national theatre and the barbican estate, an eco-brutalist icon and not a bad place to get lost in. Postmodern architecture emerged as a clear critique of modernism’s rigidity. Pioneers like Philip Johnson called for a return to ornament, historical reference, and playfulness. Postmodern buildings often mixed classical elements or bold colours with modern forms, breaking the modernist ‘rulebook’, with Robert Venturi’s famous jab, “Less is a bore,” directly parodying Mies van der Rohe’s “Less is more.”

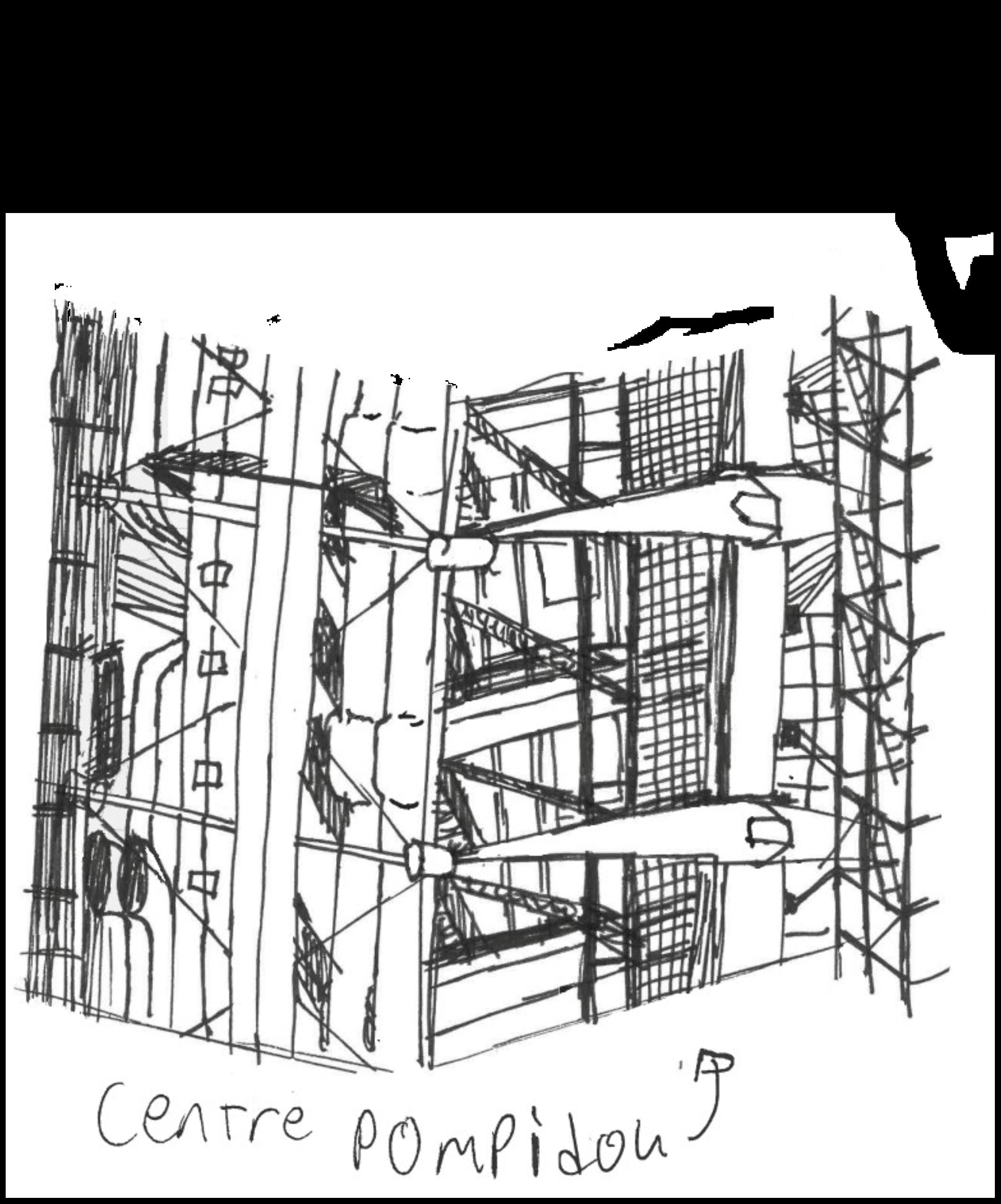

Following on from modernism came HighTech, (late modernism), and a personal favourite of mine. Lots of the greatest architects like Norman Foster and Renzo Piano and Richard rogers were late modernists. Piano and Richard Rogers took

modernism a step further with the Centre Pompidou – literally turned inside out, with all its structural and mechanical systems, pipes, ducts, and lifts not just exposed but colour-coded! Late modernism continues modernist ideals, but with a sleek, technological aesthetic: lightweight steel and glass, modular components, and a celebratory display of engineering.

In all its forms, modernist architecture reshaped the way we design and experience buildings. Born from innovation, idealism, and a desire for progress, it broke from tradition and embraced the future. Whether

Written by: Charlotte

In a world where significant strides have been made towards gender equality, it can be tempting to question whether feminist literature still holds the same weight it once did. Some argue that the genre’s key battles have already been won, expressing its relevance is fading in modern society. However, feminist literature persists not only as a record of historical struggle but as a dynamic force that continues to challenge, redefine, and expand conversations about gender, power, and identity. By tracing feminist literature from its early roots to contemporary works, its enduring necessity becomes undeniable.

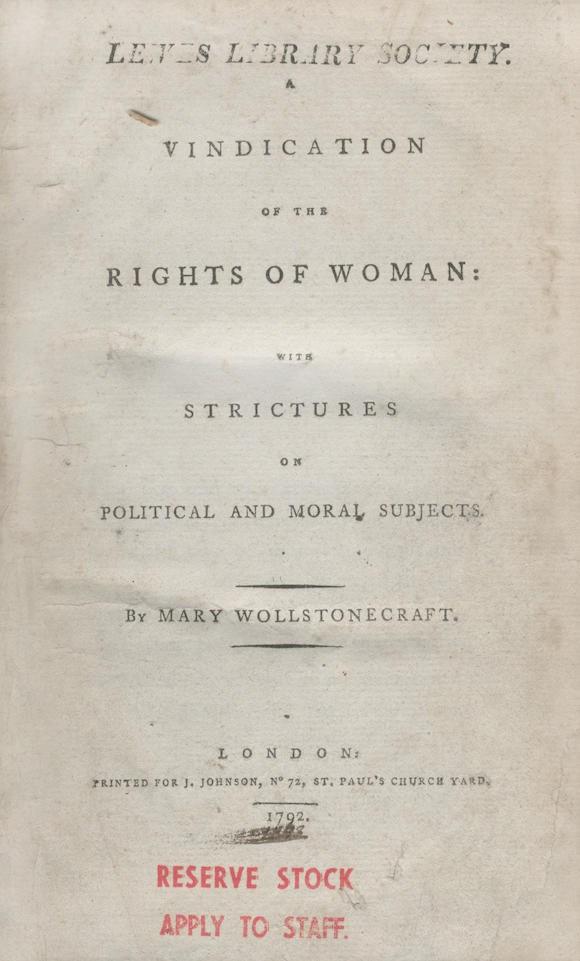

Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) stands as a foundational text in feminist literature, one that unapologetically demands education and intellectual freedom for women. Writing against the backdrop of Enlightenment rationality, Wollstonecraft's work challenges the notion of female inferiority embedded within social and literary structures of her time. Her argument (that women are not naturally inferior but only appear so because of their lack of access to education) remains essential when considering the global gender gap in education today. Critics like Cora Kaplan have noted that Wollstonecraft’s ideas established a lasting ‘feminist genealogy’ that subsequent writers would develop. Despite its age, the text’s call for equality in opportunity remains unfinished

business, particularly in societies where women’s rights continue to be restricted.

Later on, during the twentieth century, Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (1929) brought an introspective, literary dimension to feminist discourse. Woolf’s central claim, that women need financial independence and literal space to create, challenged not just societal norms but the maledominated literary canon itself. Her metaphorical “room” has since become symbolic of creative and intellectual freedom for women. Although some modern readers might argue that women now have this space, Woolf’s concern with systemic barriers to female authorship resonates in present discussions about intersectionality and suppression. Feminist Toril Moi has argued that Woolf’s work remains ‘uncannily relevant’ as it invites readers to question whose voices are still marginalised today, particularly women of colour and authors from marginalised groups who continue to face exclusion.

In the contemporary literary landscape, novels like Chimamanda Adichie’s We Should All Be Feminists (2014) illustrate how feminist literature has evolved into a global, intersectional movement. Adichie’s work reframes feminism in an accessible, conversational tone that speaks directly

to younger generations. Importantly, her writing confronts the idea that feminism is no longer needed; by exposing the subtle yet persistent inequalities women face across cultures. Adichie’s engagement with postcolonial and gender issues echoes the concerns of earlier feminist writers but adapts them to the complexities of the 21st century. She embodies the very argument that feminism must now account for race, class, and cultural specificity - a reminder that the fight for gender equality is far from over and will be an ongoing battle that the fight for gender equality is far from over and will be an

ongoing battle for the foreseeable future and beyond.

To suggest that feminist literature has become redundant is to overlook the nuanced battles that still shape women’s lives across the globe. Whilst the forms and focuses of feminist writing have evolved, its purpose endures: to question, to challenge, and to give voice to the silenced. Feminist literature still matters, not as a relic of the past, but as an ever-relevant guide for the present and future, to recognise and fight injustice and give hope to others who face discrimination.

Written by: Nicole

In December of 1989, Bret Easton Ellis amalgamated the excesses of 1980’s America in his novel ‘American Psycho’. The reader follows the double life of 27year-old Patrick Bateman. By day, he is a charismatic Harvard graduate working as a Wall Street investment banker. However, by night, he delves into a set indulgent lifestyle filled with extravagant and violent tendencies. Bateman does not have a personality outside of his materialism. Yet, this cannot be labelled as selfish or narcissism, as it was not his fault he was wired to embrace the revolting norms of the rising consumerist culture. He functions purely to feed into the system which

granted him status and power. Commodity fetishism, a term coined by Karl Marx, consistently recurs throughout the novel, exemplifying how intertwined tangible property is with the self-worth and emotional states of the characters. This is shown through Patrick’s disdain with not owning the best of the best, preventing him from being at a level of social dominance he wishes to be. For example, the ‘Pastels’ chapter, where Bateman and his friends compare business cards. Bateman not having the best, drives him into a panic attack, emphasising how his material belongings tie in to his self-worth.

In American Psycho, the bourgeoisie versus proletariat distinction is emphasised from the offset, as Bateman believes he is simply above those less affluent than him. As Cohen notes, ‘the proletariat lives a truly inhuman life, while the bourgeoisie lives a falsely human life. And this is why the proletariat desires to be truly human, and the bourgeoisie does not.’ This ties into how Bateman’s lifestyle essentially moulded his non-existent ego, deviant

superego and uncontrollable id. His superego is completely and utterly immoral, fantasising about every vile act a human can commit towards another. Of course, it is up to interpretation whether these events actually happened, yet he still thinks about them, and that is enough to define him as sadistic. His powerful superego and id work together against his ego, making him unstoppable.

Viewed through this dual lens, Bateman becomes both the epitome of late capitalist fetishism and the embodiment of inner collapse. Externally, he is polished to the point of perfection. Every detail is carefully curated to signal wealth, status and impeccable taste. Yet beneath that façade lies a shattered psyche: a superego that revels in horror, an ego that has no moral anchor, and an id that revels in violence. In Bateman, the polished veneer of consumerist success masks a terrifying void. We must ask ourselves: in a world where identity is built upon possession and image, how many ‘perfect suits’ are really placeholders for souls hollowed out, and how close might any of us come to the depths he descends?

Written by: Laura

With the overturning of Roe v Wade and other rulings in favour of religion and religious organisations to what extent does the US Supreme Court remain areligious?

In the eyes of many, the Catholic Church is synonymous with conservatism due to their strong stance on traditionally conservative social issues, such as abortion. Therefore, the fact that 6 out of the 9 Supreme Court Justices are Catholic (including the Chief Justice, John Roberts) should not be surprising. Especially considering that the current US Supreme Court has been called the most right-leaning in modern US history. A claim that is substantiated by the six conservative leaning Justices appointed by Republican Presidents. Of which all but one are Catholic.

The significant Catholic majority of the Supreme Court is interesting for multiple reasons including statistical ones, especially since only around 20% of the US population identify as Catholic compared to over 40% who identify as Protestant. This raises the question: why is Catholicism so overly represented in the highest court?

Firstly, in the US there is a history of traditionally Catholic stances on particular social issues being adopted by the right. The most notable of which is the issue of abortion. Indeed, the Catholic Church is vehemently opposed to such a practice with the late Pope Francis likening it to hiring a hit man. Such a strong stance is entrenched in theological understanding of when life begins, as the Catholic Church teaches

that all life starts at conception thus, “Human life must be respected and protected absolutely from conception”.

Therefore, it should not be surprising that, under the current heavily Catholic Supreme Court, Roe v Wade (which established a women's constitutional right to an abortion) was overturned in a historic ruling. Despite the principle laid out in the First Amendment, that the government should not offer preferential treatment to any religion, it is undeniable that Catholic dogma has infiltrated the public sphere, including the Supreme Court.

However, the Reversing of Roe v Wade is not the only success for religion that has been achieved by the current Supreme Court. More recently, in the 2025 case Catholic Charities Beaure v Wisconsin Labour and Industry Review Commission, the Wisconsin Supreme Court made a ruling that Beaure was not exempt from paying unemployment tax. However, when the Beaure appealed the case in the US Supreme Court and the court ruled in favour of the Beaure on the grounds that such a ruling violated the First Amendment.

It is important to note that the nature of this ruling is not an isolated incident as in a study conducted by Lee Epstein – a professor at Washington University – found that the supreme court (under Robinson) had ruled in favour of religious organisations over 83%

of the time. Suggesting that religious freedom and liberty is being upheld in a way that “isn’t yet on par with freedom of speech but is getting a lot closer.” (Eric Rassbach, lawyer at Becket Fund for Religious Liberty).

But is this necessarily a bad thing? Presumably, for the religiously inclined (especially Catholics) this is something to celebrate. And even for those more opposed to religion can sorely understand the upholding of one's constitutional rights is a good thing. However, it is important that this protection of religion and religious organisations by the Supreme Court is not abused in a way so that it infringes on other right.

Indeed, some may argue that this has already been happening as the overturning of Roe v Wade place the matter of abortion in the hands of individual states, arguably limiting women's reproductive rights. However, the argument that the Supreme Court is a Catholic theocracy is still a weak one as their rulings ultimately align with the US constitution.

Written by: Leonor

The contrast in recognition between male and female athletes highlights the persistent issue of gender inequality in sports. For example, when Ronaldo scores, social media erupts with millions of interactions within minutes. In comparison, equally skilled female athletes like Millie Bright receive significantly less attention. Despite women’s incredible skills and achievements, they face broader issues such as unequal pay, limited media coverage, and fewer opportunities into and within sport.

Historically, women were prohibited from participating in certain events, such as the 800m Olympic races, under the assumption that it was too strenuous. Although progress has been made, these outdated beliefs have left a lasting impact. Many young girls today still feel pressured to choose traditionally "feminine" sports like gymnastics or ballet, while boys are encouraged into more competitive or "masculine" sports. This reinforces harmful stereotypes and limits aspirations. Statistical data further highlights this imbalance. According to Sport England, 40.6% of men play sports at least once a week compared to just 30.7% of women - a big difference. Moreover, women in sports are often only recognized when they break records or achieve extraordinary accomplishments, unlike their male equivalents who receive consistent attention and praise.

The inequality extends into financial issues. Prize money and salaries reveal significant gaps. During transfer windows, men are often sold for significantly higher fees for example: £70 million for Kai Havertz and £100 million for Mason Mount while top female players, like Lauren James, attract far less. This is an example of the money difference between men and women for the same sport being done as a full-time job. Additionally, the investment into a women's sport is a significant 62% less than the money being funded into men’s sports. Even the cost to attend events reflects this imbalance. Tickets for the women’s FA Cup Final are around £15, while the men's equivalent can cost over £80. These economic differences highlight how undervalued women’s sports remain in society. Lower funding results directly into lower salaries for female athletes, affecting their ability to support themselves and their families.

Some argue that women are fortunate to even have the current opportunities they are receiving. An example is how women’s teams are often unable to use major stadiums or facilities. For instance, Chelsea women’s team, struggled to access a stadium even a fifth the size of Stamford Bridge. This reliance on the infrastructure and finances of men’s teams highlights the barriers women

continue to face. Furthermore, media representation further contributes to the issue as coverage of women’s events is sparse. During the women’s World Cup qualifiers, minimal advertisements were aired, despite significant public interest online. There has been some progress, such as the inclusion of female referees in men’s games, but these changes remain rare. Businessmen continue to dominate sports leadership, and women are still seen as less capable in

managing or coaching high-level teams and commentators are predominately male. This results in a lack of female voices at the highest levels of sport.

The gender inequality that persists in sports reflects wider societal attitudes. Women face not only lower pay and recognition, but also constant underrepresentation and reduced opportunities. Encouraging investment in women-led teams, increasing media coverage and promoting participation of girls from an early age are crucial steps toward achieving equality.

Written by: Ruby

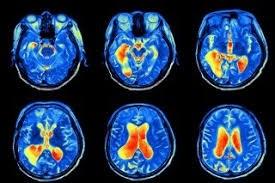

The nature of free will remains one of humanities most debated questions and is central to both philosophy and psychology. Emerging psychological evidence can both support and oppose the notion of conscious choice and agency. On one hand it can be argued that a sense of agency is merely a byproduct of neural processes, and on the other, the functions of brain regions can be used to provide evidence for autonomous decision making.

more like a narrator, not a driver. Wegner argues that our experiences of consciously initiating an action does not mean that we caused it. Instead, this feeling of agency is a psychological construction, our mind can make inferences about our behaviour and decision making after this action but is not responsible for the causation of it. The theory can be partially supported by split-brain research, for example Gazzaniga’s work, which demonstrates how our brains formulate explanations for our actions after our experience.

Psychologists such as Wegner have theorised that our conscious functions

In addition, fMRI scans provide opposing evidence to the existence of free will. In 2008, Soon et al used fMRI scans to analyse brain activity whilst participants engaged in a task of freely deciding to press a button with their left hand or right hand. The study found that brain activity in the prefrontal cortex and parietal cortex (which function to aid decision making and processing) could predict the participant’s decision 7-10 seconds before the reported being consciously aware of their choice. This posits the question, if we are not conscious of our decisions until neural processes have already initiated them, is the notion of deliberate and free choice undermined?

However, brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex can alternatively be used to support the existence of free will. Overall, the prefrontal cortex functions to make decisions. Within this, specific areas allow us to suppress emotional responses or impulses. This inhibition of particular actions links closely to the idea of choice, if we can resist a reflexive or automatic action and choose an alternative we demonstrate a degree of volitional control. MRI studies such as Aron et al, 2004, show increased prefrontal cortex activity during tasks that require levels of self-control. In addition to this the prefrontal cortex allows for future planning, and evidence for our ability to delay gratification and consider future consequences support the existence of free will.

The debate persists not because of limited evidence, but because free will may be less a matter of proof and more a matter of interpretation.

Written by: William

A democracy is a country where the power is held by elected representatives. In face value, Türkiye seems to fulfil this basic definition, with a function multiparty system with 6 different types of elections for all aspects of government that have seemingly worked since the 1950s. However, in Türkiye there seems to be a lack of checks on the power of the president, a clampdown on free speech and the press, and a politically controlled judiciary. This seems to directly contradict with the values of a ‘true democracy’, suggesting that Türkiye’s democratic nature is disappearing.

A functional democracy requires 3 basic organs, which must all act independently and have fairly equal powers. These are the executive, legislative and judiciary. In Türkiye, the executive, President Tayyip Erdogan has far more power with very limited checks and balances. This is due to a referendum in 2017, which hugely increased the

President’s power, and was described as an opposition MP as ‘entrenching dictatorship’. This referendum was after a coup attempt in 2016 by part of the

military to ‘protect democracy from President Erdogan’. The coup failed due to a lack of support and led to over 6000 people being arrested, including senior military figures and judges. This was one of four military coups since 1960, showing the instability of the democracy in Türkiye, and the extent that the military has a large influence over the politics. The referendum in 2017 meant that the President became the head of the executive as well as the head of state, and also being able to dismiss Parliament and declare a state of emergency. Furthermore, it meant the President was able to appoint ministers and judges. This led to the politicalisation of the Judiciary, which should be an independent branch of government in a democracy. Furthermore, the legislative has been made incredibly weak, meaning that the executive, and so President Erdogan, has far more control due to the dominance of the executive over the other two organs of state.

This has been shown in several ways over the last few years. One of these is the lack of free press in Türkiye, a core part of democracy through its use to educate the population and prevent corruption. This is shown through Türkiye arresting 231 journalists since 2016, as well as 90% of the media in Türkiye being state owned. This shows

that Erdogan is repressing free speech and criticism throughout Türkiye. This is further shown by the clampdown on protests throughout Türkiye. The largest protests in Türkiye in the last decades were prompted due to the arrest of Erdogan’s main political rival, the hugely popular mayor of Istanbul, Imamoglu, who had announced his running for presidency. These protests have led to over 1000 protestors being arrested as well as Türkiye being denounced world-wide due to the excessive use of force to shut down largely peaceful protests such as the use of water cannons or batons by the police. Furthermore, the arrest of Imamoglu as well as the stripping of his degree, which is required to run for president, could be seen as the Erdogan, who has been president since 2002, getting rid of a key political rival.

Overall, it seems clear that Turkey, despite its many flaws, should still be considered a democracy. However, it could be perceived as slipping away from key democratic principles due to the imprisonment of rivals, a hugely powerful president with few limitations and an allegedly corrupt judiciary, as well as the compromise of free speech. However, a key signpost to whether Türkiye can still be considered a democracy will be the 2028 presidential elections, as Erdogan is constitutionally term-limited, and so cannot run, ending his then 26 years run as president. Therefore, if Erdogan leaves office peacefully in 2028, as the constitution dictates, Türkiye can still be considered a democracy, just a very flawed one.

Written by: Michael and Hugues

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky is often regarded as his magnum opus, a monument of Russian literature. Einstein considered it the ‘supreme summit of all literature’. We are very much inclined to agree. As is the case with all great classics, The Brothers Karamazov is not just a story: it is a snapshot into human existence, providing insights into our nature and the human condition. A good novel will provide a means of enjoyment and escapism. A classic will shake your ideas and certitudes, make you question what you believe in and ultimately, may even shape your way of life.

The story is set in a small Russian town, where a wicked man – a merchant named Fyodor Karamazov – resides. Though he leads a solitary life of decadence, caring for only himself, he is wily, and amounts a small fortune. He marries a young girl, who gives birth to a boy named Dimitri. However, being both a dreadful husband and a father, he quickly neglects and forgets his son; his wife passes away and the boy is abandoned, until he is taken under the wing of his maternal uncle. From this point, he grows up and joins the army as an officer. After a second marriage with a meek and innocent girl, Fyodor Karamazov has two sons, first Ivan and then Alexei.

But they too are quickly neglected, and after the death of their mother, they fall into the care of a benefactor. Ivan, the brightest and most intellectual of the brothers, goes on to Moscow to pursue his studies, whilst the youngest brother Alexei, enters the monastic life.

However, our story truly begins when, by a turn of fate, all three brothers find themselves drawn to their native town. The family could not be more dysfunctional: the immoral father, the honourable but brash and sensual officer, the cynic scholar and finally, the innocent and pious saint. The internal conflict in the family, centred around the rivalry between Fyodor Karamazov and his son Dimitri over the love of the beguiling woman Grushenka, contains a much deeper undercurrent which poses questions about morality and the human condition. The story takes a dramatic turn after a murder, leading to a gripping mystery and investigation that culminates in a courtroom drama –exposing the labyrinth one must navigate to find the meaning of life.

Each of the three Karamazov brothers represent different facets of the human condition.

Dimitri is the man who believes and indeed loves God, but is not able to resist temptation, and thus, is unable to escape his immoral life. Dimitri is very much conscious of the choice between right and wrong but always tends towards the latter and hates himself for it. He is emblematic of the weakness of the human souls: the desire to change, but the inability to actualise it. Therefore, Dimitri stands out as the most relatable; he showed us that we are not alone in our shortcomings, but it is these very shortcomings that makes us human. All one can do is recognises their vices so that we can strive to correct them and become a better version of ourselves.

Ivan, the middle brother, has perhaps the most complex outlook on human existence and God. His scepticism, and pessimistic view of the world means that he simply is unable to accept God; he cannot accept the idea of the gift of eternal life. That being said, Ivan is deeply insecure in his beliefs and wants to have in God. This paradoxical philosophy leads him to be tormented by his own intellect; as a result, Ivan does not what he believes in and thus, does not know who he truly is.

Alexei, though his faith in God’s justice and benevolence momentarily falters, he ultimately finds solace in the idea of an all-encompassing love and the possibility of redemption through it. Alexei is symbolic of the good that exists in us all; our capability to love selflessly and ‘accept everyone else’s sins as our own’.

For centuries, the question of the existence of God has tormented man, and continues to. Being in a Catholic school, we have some sort of religious background and have been exposed to the idea of God. The fact is though, faith is very personal. While there are a select few who may have a pious conviction in the existence of God and eternal life, the great majority of people have their doubts, and there are some who simply do not and cannot believe. The thought of death is a terrifying one; we spend most of our time ignoring death, pushing it out of our minds. When, through the loss of our loved ones, we are forced to face it, this can be extremely upsetting. Thus, one can only prepare oneself as best as one can to face death head on. We believe that the Brother’s Karamazov not only prepares us, but can bring contemplation, comfort and peace to the soul.

Overall, The Brothers Karamazov is not your average read; its unorthodox and complex style of writing may be a challenge. However, it was undoubtably rewarding, and looking back, we can happily agree it is the greatest novel we have

· ‘Without God, everything is permitted.’

· ‘What is hell? I believe that it is the suffering of being unable to love.’

· ‘Nowadays, almost all capable people are terribly afraid of being ridiculous and are miserable because of it.’

· ‘It’s not that I don’t accept God. Only that I must respectfully return him the entrance ticket.’

· ‘The more I love mankind in general, the less I love people in particular.’

· ‘Accept everyone’s sins as your own’

· ‘I suffer, but still, I don’t live. I am X in an indeterminate equation. I am a sort of phantom in life who has lost all beginning and end, and who has even forgot his own name.’

· I think that if the devil does not exist, and man has therefore created him, he has created him in his own image and likeness.’

· ‘No animal could ever be so cruel as a man, so artfully, so artistically cruel.’

Written by: Evie

Throughout the twentieth century, fascism cast a long shadow over Europe, culminating in catastrophic wars and the collapse of liberal democracies. While Italy and Germany succumbed dramatically to authoritarian regimes, Britain is often portrayed as the stable bastion of parliamentary democracy, unshaken by the ideological extremism sweeping the continent. Yet beneath this reassuring narrative lies a more complex reality. Was Britain ever in real danger of going fascist? The answer is not a straightforward yes or no. Rather, it requires a careful examination of political, social, and cultural currents during the interwar period and beyond. Though Britain never came close to fullscale fascist revolution, the nation was far from immune to fascist sympathies, and certain moments suggest that under different conditions, the threat could have been far more serious.

successful policies in the mid 1930s, ultimately, fascism was unable to actually become a leading and dominating political stance in Britain due to problems both within the movement, and external factors.

Firstly, Mosely was a weak leader who was not good at ensuring organisation and unity within his party. He heavily neglected working class issues, with his upper class background failing to secure him support from the elite as well. The movement failed to develop a coherent economic policy or a mass base that could rival the established political parties, particularly the Labour Party, which effectively channelled working-class discontent. Additionally, the BUF’s overt antisemitism, violent tactics, and admiration for foreign dictators repelled much of the British public, who remained committed to democratic values and suspicious of continentalstyle authoritarianism. These internal flaws, combined with effective state restrictions and widespread public opposition, ensured that British fascism remained a marginal and ultimately selfdefeating force.

Many of the British right admired Mussolini’s fascist dictatorship in the 1920s - European fascism was characterised by a hatred of Jews although its tendency towards violence, intolerance and reliance on a blind obedience towards leaders found little favour in Britain. Still, the British union of fascists (BUF) was formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley who soon became known for his fascist and extreme right wing ideologies, which he managed to gain a support system for. Although fascism had recently seen a surge of support after 1932, and after Mussolini’s

Externally, there were also significant issues which meant that fascism could never take over in Britain. The government took clear policy against incidents that would provoke public order within the public order act of 1936. Additionally, the growing support for the Nazis in Germany as well as the threat of war acted against support for fascism as it seemed to go against British national interests and instead align with those of the enemy. Thus, the strength and stability of Britain’s parliamentary system, along with a

deeply rooted political culture that valued liberal democracy and civil liberties, left little space for authoritarian alternatives. The mainstream political parties, particularly Labour, effectively addressed economic and social grievances that fascist movements elsewhere had exploited. Britain also avoided the extreme post-war instability and humiliation that had fuelled fascism in Germany and Italy. Public reaction to fascist violence, particularly after events like the Battle of Cable Street, further marginalized the movement, while the press and civil society groups actively criticized and monitored fascist activities. Legal restrictions, such as the Public Order Act of 1936, curbed the BUF’s ability to operate publicly and reduced its visibility. Finally, the outbreak of World War II and the association of fascism with enemy regimes discredited the ideology, reinforcing national unity around democratic values and leaving British fascists politically isolated and socially unacceptable.

Therefore, in conclusion, it can be said that although fascism undeniably gained support in Britain during high tensions and desperation of the era there were heavy barriers to fascism's gain in support which proved to be set in stone. Thus, arguably Britain was never at risk of going fascist due to barriers to it gaining support.

Written by: Rufus

Manchester United’s flotation on the New York Stock Exchange made headlines and millions, but for many fans, it symbolised the moment football stopped being a passion and became a business. Football clubs are no longer locally run sports institutions but are now massive global brands with revenue streams all around the world. Football clubs today act like businesses but maybe they shouldn't.

At the elite level, clubs like Real Madrid and Manchester City operate like global corporations. According to Deloitte’s 2024 Football Money League, both earned over €700 million last season through a multitude of key streams, including broadcasting, sponsorship, merchandise, and leveraging their

global fan base to create sales worldwide. Brands pay millions to have their names on the shirts of star players, stadiums, and even training facilities. Examples include Qatar Airways' huge 6-year commercial deal with PSG for 70 million Euros yearly and Real Madrid generating millions from its Adidas kit deal.

These corporate interests often collide with fans who may think that owners prioritise profit over football culture and community. The introduction of club ownership by private equity firms introduced a shift from passionate local owners to international investor groups, which often prioritise profit over fan interests. Private equity firms are institutions that buy companies, grow their value, and sell for profit often using leveraged debt, which can be detrimental

leveraged debt, which can be detrimental to a club's running. The famous example of the American Glazer family who purchased Manchester United and have often come under scrutiny from fans with slogans such as “Glazers out” becoming a

common sight at old Trafford, due to the billion pounds of debt the club has accrued, as well as perceived lack of investment into the club by the Glazers. Other examples include the Italian-based club AC Milan, which was sold to RedBird Capital for 1.2 billion euros in 2022. These new owners often have no historic or emotional ties to the club or community, leading to a disconnect between fans and ownership groups purely prioritising return on investment.

Bury FC is a heartbreaking illustration of this disconnect. The English Football League dismissed the 1885-founded team in 2019 when businessman Steve Dale took control of it. He failed to manage the

club's £8 million debt and acknowledged he had no football knowledge. This ultimately led to Burys' collapse, and a local asset, many cared about and lived for, was ultimately destroyed. This not only affects fans but also snowballed into many other areas, such as local businesses, like cafes and pubs who lost matchday income. Examples such as

that of Bury demonstrate that private equity firms are more than just different kinds of owners; they radically alter the purpose of a

football team. They are operated for financial gain rather than for fans. In a business sense, this isn't necessarily incorrect, but football is a special kind of business where the "customers" are also the product's essence. Ignoring them causes the system to collapse

The answer to this problem may well be fan-owned ownership models, which have been proven to work across the world. Fan-owned clubs function more like co-operatives or social enterprises, meaning they have long-term financial stability, voting rights for fans as well as the added community benefit of being able to run schemes such as youth football or fund charitable causes for locals. Tens of thousands of members, known as socios, own clubs like FC Barcelona and Real Madrid and have a say in important issues like budgets and presidents, showing that even with giant international clubs they are still able to inject community or fan involvement in its running not by rejecting financial aspects of the club but by putting purpose alongside profit.

Without a doubt, football teams have grown into massive corporations, managed by billionaires, impacted by private equity, and moulded by financial priorities. However, these clubs carry generations of history, identity, and local pride with them, unlike regular businesses.

Although investor ownership can lead to expansion and a worldwide presence, it frequently runs the risk of eroding the bonds that bind clubs to the communities that founded them. Although fan-owned models aren't flawless or always financially competitive, they demonstrate that football can be managed with both vision and morals.

Written by: Ruby

In recent years, mental health has become an increasingly prevalent theme in Young Adult Literature. From bestsellers like Normal People by Sally Rooney to The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky, there has been a notable increase of representation for mental health sufferers. The rising frequency of portrayals of depression, anxiety, PTSD and OCD presents the questionare authors becoming increasingly representative of society or are they exploiting young adults’ trauma?

opportunity to escape from harsh realities and establishes a normality among victims, creating a sense of community and belonging. The authenticity of these characters offer validation to a young adult reader and their own experience while simultaneously reducing the stigma around mental illness. It is this same stigma that behaves as the most insurmountable barrier to seeking support. By reaching for that book on the shelf, this stigma is gradually eroding. Authors are no longer shying away from the panic attacks, crying fits and therapy as Young Adult Literature becomes a platform to influence discussions on mental health issues and serves as an inferior, but nevertheless vital mechanism for support.

The ubiquity of mental health and its corresponding illnesses is often adopted by authors as a mechanism to confront the current mental health crisis. In 2023, 1 in 5 young people aged 8 to 25 years in England faced mental health challenges, while it has been revealed that approximately 25% of modern Young Adult novels now feature characters with mental or psychological disorders. To accompany the growth in mental health struggles, the exploration of mental health in Young Adult Literature has gained significant traction. One factor for the surge in sufferers is the COVID-19 pandemic. It has had a significant impact on young people’s mental health, with NHS referrals for anxiety skyrocketing among young children from just under 4,000 in 2016-2017 to over 204,000 in 2023-2024, and the pandemic identified as a catalyst.

Young Adult Literature provides an

Understandably, a misrepresentation of mental illness in an attempt to be “relatable” can be damaging. For some readers, the decision to oversimplify, overcomplicate or romanticise mental health struggles can minimise real pain and distort reality.

While authors exploring themes of mental health catalyses the erosion of harmful stigmas - its prevalence among Young Adult Literature may paradoxically induce feelings of depression or anxiety in an entirely unrelated audience. Moreover, authors oftentimes fundamentally lack the expertise and finesse that a topic mandates, and thus its emergence in mainstream literature could be harmful to vulnerable audiences if unregulated.

“There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” Maya Angelou

Written by: Innes

It is widely known that engineering is a ‘concrete’career choice, we are constantly told that the world needs engineers and will continue to need them. But for what do they need them? To build more iPhones with five cameras? Or send a rocket with celebrities into space? Is the application of engineering being used for good in enough cases? Although it's a respected career, if I were to ask you to compare an engineer to a doctor, you may say that a doctor can do better for people or have a greater impact on a community. Yet an engineer's job can be just as political as a doctor and have a wider impact therefore why isn't the importance of ethics being stressed enough in engineering. Engineers have the responsibility to play a key role in helping society achieve sustainable human development now and in the future.

Personally, I think there are fantastic applications of engineering, being used to create actual positive change in our everexpanding world. Such as ‘Aqua for all’ based in the Netherlands they work to create innovative, sustainable water and sanitation solutions in East Africa and SouthAsia or how a student from Stanford has created a paper centrifuge and microscope that costs only 68 cents and is being used to diagnose malaria, making medical equipment more accessible in the poorest of nations (I highly recommend watching ‘How to save 51 billion lives for 68 cents with simple Engineering’on Mark Robers YouTube, it is what inspired me to do engineering from a young age). These are only two of what I hope you can imagine is a large community of engineers who want to do good.

However, I believe the prospects of creating the next flashy car only available to the top few percent obscure an engineer's goals to create a more equal world.

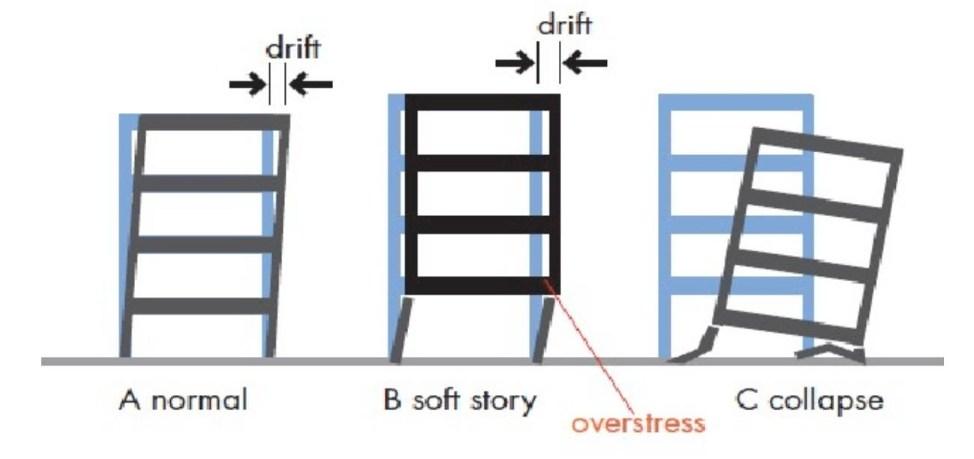

On February 6th of 2023, on the border of Syria and Turkey, Turkey was hit by a 7.8 and 7.5 earthquake with several aftershocks. This was due to the geographical location of Turkey. It is surrounded by 4 tectonic plates on all sides and a build-up of pressure over time, causing catastrophic damage on February 6th. The 2023 Turkey–Syria earthquakes exposed deep vulnerabilities in regional infrastructure. These earthquakes took the lives of 46 thousand people, towns wiped out and families destroyed, it was the worst earthquake disaster in Turkey’s history by almost every measurable standard. Some may think that when it comes to natural disasters there is nothing an engineer can do but with Turkey's history of earthquakes, 3 since 1970 of magnitude 6 and greater, it was never a question of if turkey was going to have another earthquake but when? So why wasn't more done to prevent the devastation.

The devastation of this earthquake could have been prevented, the reason for so many deaths was dues to most the buildings, most affected by earthquakes were “soft-story structures”, these buildings were constantly rebuilt post disaster to solve the problem of overcrowding, the bottom floor of a multistory building is significantly weaker or more flexible than the floors above it meaning during an earthquake it easily collapse and then the rest of the building follows. Historically these “soft story” buildings did not withstand earthquakes well, in India Nepal and Haiti the collapse caused many people to become trapped under large pieces of structural material that cannot be removed by hand. historical patterns signalled the potential for a severe impact and yet people were still being housed without consideration for their wellbeing or their future.

Changes should have been made after the first ever earthquake in Turkey, but instead cheap and deadly buildings were constructed, despite building codes with emphasis on earthquake safety being introduced, they were not enforced during construction due to corruption amongst engineers and politicians. Engineers should treat safe housing as a human right! Changes could still be made: columns supporting these “softstory structures” could be reinforced with steel (which allows them to bend instead of collapsing), and walls could be bolted and braces added to add stability to the buildings.

So, you see, in part engineers are responsible for not protecting the lives of fifty thousand people that died on February 6th. Engineers are trained to solve problems, build systems, and improve efficiency. But when society

prioritizes profit over people and ignores ethical implications it creates conditions where engineering serves narrow interests, not the public good. Engineers need a stronger voice in policy and corporate decisions to prevent this. Now you know that engineers can help or not help as many people if not more than doctors therefore Engineering education must include ethics, climate, and social justice just as much as doctors learn. Lastly, Turkey should do more, as it's actually in Istanbul where the largest seismically isolated structure is built to date. designed by ARUP with 300 isolators which absorb energy from the earthquakes. The Sabiha Gokcen Terminal serves as proof that change can happen and initiative ideas can be designed by engineers to serve the interest of the public good.

Written by: Daisy

The inclusion of transgender athletes in competitive sports has sparked widespread debate across the world. Supporters argue it’s a matter of inclusivity and equality, while critics raise concerns about fairness and physical advantages. As this issue grows more visible the sporting community seeks for a balanced solution. This article presents arguments for both sides of this difficult debate, aiming to provide a clear understanding of a sensitive topic.

To begin with, many would argue that the inclusion of transgender people in sports is unfair and unethical. Biological differences and advantages are a major topic in this debate. In an interview Dr. Bradley Anawalt (an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at the University of Washington) he had argued that even after testosterone suppression trans women may retain physical advantages such as greater muscle mass

and bone density, which can impact fairness in competitive sports. He suggests that these lingering differences raise legitimate concerns about safety and equality especially in contact and elite level sports. Many athletes have publicly expressed concerns or opposition against transgender inclusion in sports, particularly focusing on transgender women competing in women’s categories, such as Sharron Davies a former Olympic swimmer who has been a vocal critic of transgender women competing in women’s sports due to concerns of fairness and equality.

However, others would argue that transgender athletes should be included in sports due to human rights concerns about discrimination. A survey done in the UK by YouGov and Equality survey showed that there is a clear age gap in support of this cause with only 16% of 16

–24-year-olds being opposed to trans women in women’s sports versus 61% of older adults. Although divided, there is still a lot of support amongst younger generations. Transgender people are estimated to be around 0.6-3% of our population despite being the highest suicide rate compared to the global population. Globally, studies show attempted suicide rates amounts trans individuals typically range from 32-50%. These horrific numbers highlight the mental health and belonging issues that’s transgender people face and discrimination from sports would worsen theses issues.

Overall, the debate is a very serious but difficult topic and with many different opinions a compromise that makes everyone happy is possibly unlikely. So therefore, this topic remains ambiguous and up for debate

Written by: The Youth in Asia.

Professions in the world of medicine are closely involved with the most vulnerable and emotionally tumultuous events of human nature, from the stages before and during birth, to the stages of treatment towards death and it's no surprise there is a plethora of moral debates surrounding the conduct of various medical procedures across history. It has been apparent that in order to prevent chaos in the functioning world of medicine, there is a need for both medical law and medical ethics.

Given how both concepts govern the ways in how medicine should be practised it is easy to assume that the

two concepts are intrinsically linked, but it must be noted that Medical law is enforceable while medical ethics is not and instead more so advised. Medical law refers to the legal rules and regulations governing the practice of medicine, while medical ethics refers to the principles and values that guide healthcare professionals in their interactions with patients. Reading this, it may be clear to simply follow all orders in medical law, yet the controversial case of Dr Nigel Cox in 1992, perhaps may give an instance of which this isn’t as straightforward as it may sound.

In his case, Cox was convicted of attempted murder of his patient Lillian Boyes who had been suffering from Rheumatoid Arthritis to a degree of which she had been reported to have ‘howled and screamed like a dog’, whenever she had been touched.

Being unable to absorb prescribed pain relief, Boyes had pleaded with several members of staff in the hospital to take her life, but was repeatedly met with refusal. Cox had developed a friendly rapport with Dr Cox, and by the 16th of August 1991, Cox administered 100mg of diamorphine to Boyes in attempts to relieve her pain, and when this was not achieved, he injected potassium chloride - a substance that can induce death - and Boyes passed on shortly after.

Despite receiving gratitude from Boyes’ sons for his actions, Cox would go on to be reported by a nurse who had noticed that under Boyes’ hospital records, Cox had logged that he had administered twice the amount of potassium chloride required for death. This would lead to Cox receiving a suspended sentence for 12 months under the conviction of attempted murder. This was as Boyes’ body had been cremated prior to being investigated for the direct cause of her death, and this could no longer be determined.

It is not difficult to support Cox’s actions, as the Boyes’ family did. They had supported Cox throughout the court case, despite how Euthanasia and the ethics of the role of a doctor and end of life care have been debated about for centuries, even going as far back as the Roman times. While the Cox case sparked various debates and a demand for a change in the British law surrounding the illegality of euthanasia (from figures such as the late Ludovic Kennedy, vice president of the Voluntary Euthanasia society), it had been concluded that Dr Cox’s actions were

due to an ‘error of judgement’ as it went beyond the ‘legal constraints’ of his job which was said by Sir Raymond Hoffenberg - who was one of the three rheumatologist consultants that presented evidence to the GMC, which prompted them to cease further charging Cox.

Hoffenberg’s words relay back to how the influence of medical law governs the practice of doctors more than medical ethics. Following his comment he went on to say that he would have sedated Boyes into virtual anaesthesia if he had been in his position (taking the route of passive euthanasia opposed to active euthanasia as Dr Cox had done), but being aware of the rapport between Cox and Boyes, the group of consultants couldn’t deny that Cox had ‘acted in good faith in what he thought to be the best interests of his dying patient’ and was also sympathised for the decision he made given the complexity of the situation he was in.

The criminal court said that they had ‘tempered justice with mercy’ when handling the Cox case which is emphasised with the fact that had Boyes’ body been investigated and discovered that Cox’s injection of potassium chloride had directly killed Boyes, he would have faced a murder charge along with a mandatory life sentence.

It must also be noted that Dr Nigel Cox is one of the few doctors to have been convicted of attempted murder, let alone of this manner, and despite multiple members of staff refusing Boyes’ request in death, Cox went out of his own way to administer the potassium chloride to Boyes, which was considered to have been made out of sympathetic ties developed towards her over time. All types of Euthanasia are still illegal in the UK today and while this situation had been a highly complex and ethically difficult one to navigate through, Cox

never should have made such a grave decision alone. Had he spoken with other hospital staff involved with Boyes’ treatment plan they could have come up with a legal solution that ties sufficiently with moral ethics.

As harsh as it may seem, the legislations issued by medical law are present in order to ensure that the roles of the doctor, within public institutions like the NHS for example, are necessary to ensure that there is a general consensus of medical ethics that are obeyed by all doctors, especially as the complex world of medical ethics is one that is full of diverging opinions and evolves along with the changes of human society. On top of that, all workers of healthcare, like Dr Nigel Cox, are capable of having a personal ethical outlook on the way they should provide medical service, but chaos may arise if these ethical views are acted on sporadically, emotionally and impulsively, particularly in the stressful environment of a hospital ward where quick decision making is often prioritised

but the deep and philosophical approach to decisions surrounding medical ethics can be easily get compromised.

The Cox case is a case turned cautionary tale, that urges doctors to remain aware of the guidelines issued out by medical councils such as the GMC; acknowledge and respect the decisions made by members of the multidisciplinary team they have to rely on and to prohibit the interference of personal ethics or the sometimes blinded nature of human kindness into their work. Yet, it is intriguing how some individuals like Ludovic Kennedy may instead view the Cox case as a cautionary tale instead for the British medical law and its current status on illegal euthanasia. As more people go onto protest for voluntary euthanasia, the Cox case acts as a warning urging figures such as those of the GMC, to make changes to medical law so no more doctors are put in the same ethically and morally complex situation Cox was in September of 1991.

Written by: Vittoria

The English legal system, also known as the common law system, is one where the judiciary plays a crucial role in shaping the law through judicial decisions. It’s characterised by a combination of statutory and common law. In law, fairness signifies treating all parties impartially and reasonably, ensuring no bias in cases.

The English legal system, particularly its judiciary, is often applauded for its independence and impartiality, widely recognised and globally popular. It's often chosen as the primary governing law for international contracts due to its neutrality, established reputation and its success in solving disputes. Nonetheless, public perception in the

UK shows a significant lack of trust and concerns about accessibility and fairness.

The UK has always had a strong and principled judiciary, structurally and practically independent from both the legislature and the executive. This independence guarantees a fair and predictable dispute in court that is not driven by bias. This is demonstrated by the judiciary’s impartiality, meaning the judgment and final verdict of the case is solely based on the evidence presented to them in court by the prosecution and defence. Furthermore, during an ongoing trial, jurors are forbidden from looking for information online about the case or

the people involved, and they must not discuss cases with anyone who is not on the jury, including family and friends. This ensures that a final verdict is not influenced by external factors. Hence, parties can be confident that their disputes will not be concluded based on any references to politics or preference.

The English legal system promises a presumption of innocence, something that has been part of legislation for centuries, with elements of it being traced back to the Magna Carta: “No free man shall be... punished... except by the lawful judgment of his peers.”. This principle denotes that if there is “reasonable doubt”, an accused person must be given the benefit of the doubt and thus acquitted because “proof” has not yet been presented. This is predominantly used in the criminal system, where everyone charged with a criminal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to the law. The fairness of this principle is also reinforced by the independence of the English courts; therefore, the judges are free from political interference, meaning it can be rigorously upheld in court decisions.

One of the greatest strengths of the English legal system is its transparency in court proceedings. It strives on this transparency through various measures such as open court hearings and publication of judgments. The general rule in civil procedures is that a person who is not a party to proceedings may still obtain a controlled amount of court records, such as a statement of the case. This transparency has even been extended to minor areas of the law, with its introduction in all family courts throughout the UK from January 2025. Under these provisions, accredited journalists and legal bloggers are now allowed to report on proceedings they witness, provided transparency is granted. This alludes to fairness

because it ensures accountability within the court, allowing those involved to understand the rationale behind the verdict, building confidence and trust in the English legal system.

However, the English legal system is far from perfect.

In 2015, a survey led by Hodge and Jones announced that only a quarter of the population believed the UK’s legal system to be “fair and transparent”. Patrick Allen (leading solicitor at this firm) responded to this by stating that “if millions of people across the country felt intimidated by the prospect of seeking justice in 21st Century Britain, then we should consider our legal system to have failed in its fundamental duty to provide justice for all.” This verdict arises from the concern that the best legal representation seems to only be available to those who are very wealthy. Legal support can be overly expensive; therefore, it makes it difficult for individuals to access support to help protect their rights. This was also made a concern in the survey, where two-thirds of individuals felt that wealth had become a more important factor in gaining justice than it used to be.

Additionally, a lack of understanding of the legal system creates barriers to accessing justice. Furthermore, the complexity of legal procedures and terminology used in courts can be completely overwhelming for the complainant, making the court proceedings difficult to understand. Most importantly, there are deep-rooted concerns about racism and sexism in court proceedings.

However, since then, the English system has done an increasing amount to

enhance fairness. A more recent survey (2022) run by the Sentencing Council, exploring the confidence in the effectiveness and fairness of the criminal justice system, found that around 53% said they had seen an improvement in fairness. Asian (minority) adults were more likely than other groups to have confidence in the system.

As of 2025, England has done a lot to enhance the fairness of the justice system.

In April, the English government addressed sentencing inconsistencies. The Sentencing Guidelines bill was introduced, preventing guidelines from referring to personal characteristics such as race, religion or belief and cultural background in their guidance. This emphasises fairness because it removes the possibility of discriminatory sentencing practices, with the bill seeking to ensure that everyone is equal before the law.

Furthermore, the Crime and policing bill (2025) aims to support the government’s “safer streets” mission, including reducing knife crime and violence, particularly against women and girls. Also, the bill implemented new police

powers, hoping to tackle the epidemic of violence against women that is ever present in society. Additionally, it has increased accountability of officers, preventing further wrongful convictions based on stereotypes. This demonstrates fairness in the legal system because it promises better safeguarding of minority groups, making them feel better protected by the law.

Moreover, there is a strive to help increase legal education for the public. For example, organisations such as the law society are actively involved in legal education, which aims to improve public understanding of their rights, the legal system and everyday legal issues. This promotes fairness because it means that individuals, when involved in a case, a more aware of what is happening and can be more actively involved.

Overall, this demonstrates that the English system is a fair one, particularly due to independence and transparency. It continues to try and advocate for more fairness to ensure all individuals are equal before the law. Despite its strong foundations, the legal system is far from perfect, and must keep striving to achieve true fairness

Written by: Alissandra

The firmly established stereotype, “pink is for girls and blue is for boys” is apparent in society today. However, this is only relatively new. While there exists the notion of gendered colours today, there was no such thing before the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Gender neutral clothing was the norm before the 20th century with infants and young children usually dressed in white as it was

easier to clean using bleach. Later once they reached six or seven, is when gender specific items of clothing and coloured clothing started to be used. That being said, it would only be light, pastel colours that were used as it was associated with youth and innocence.

Indeed, the concept of gendered colours is mostly imposed onto children, yet for aristocratic families in the earlier centuries, this was not yet a norm.

Both wealthy men and women wore most colours, and European aristocrats would wear ‘powdery’colours to symbolise class and luxury.

For example, Madame de Pompadour, the chief mistress of Louis XV, was so in love with a powdery shade of pink, that the porcelain manufacturer Sèvres created a charming shade of it and named it Rose Pompadour. Regardless of this, pink was a very much a unisex colour.

Even though decades later the individual colours of pink and blue started to be linked to gender, at this point it was the other way round. Pink came from red and white being mixed together with ‘Red’ connoting aggression, blood, passion and strengthstereotypically masculine traits. Therefore, it was considered more suitable for boys to wear pink since it was a sub-colour of red and had associations to the military.

Pink was rendered more powerful than blue, which was attributed to calmness, innocence and most importantly, divinity. Mary, the mother of God, is usually depicted in art wearing blue to symbolise these traits. This rendered blue as the colour of virtue, and it was

clear therefore that aristocratic women chose to wear blue.

It was only until just before WWI that colours were gendered. In June 1918, the trade publication Earnshaw’s Infants’ Department made reference to colours as gender claims: “The generally accepted rule is pink for the boys and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger colour, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and daintier, is prettier for the girl.” Henceforth, though there was no unanimity, department stored began marketing gender-specific colour of pink being for boys and blue for girls or other stores marketing the reverse.

However, the more recent association of pink with women and femininity started around the early to the mid-20th century. According to Valerie Steele, director at the Museum at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, “men in the western world increasingly wore dark, sober colours,” so the pastel and brighter colours were left to women. “The feminisation of pink really began around there,” she said. “Pink became an expression of delicacy, as well as froth.”

Amidst the fact pink had earned its place in high fashion, and due to branding and marketing postwar, western societies adopted it as a symbol of femininity, establishing the “pink for girls, blue for boys” stereotype that is known by today's society.

The marketing postwar which Steele refers to, started during WWII where the German army changed colour conventions and gender colours that would dictate gender

identity. Just as Jewish people were forced to wear a yellow star to identify themselves, homosexuals were forced to wear an inverted pink triangle . Since this gruesome moment in history, pink changed to being thought of as a nonmasculine colour reserved for girls since it was used to ridicule gay men by labelling them as feminine.

Thus, this unusual reversal occurred, and nowadays in western countries pink is a sweet and maternal colour associated with innocence and delicacy, but also with frivolity and immaturity, while blue became masculine and “for boys” instead. Now, toys, clothing and any consumer product is marketed without a second thought in these (new) gendered colours

Written by: Charlie

The portrayal of women in literature has long been an issue, particularly when it comes to authenticity and depth. Whilst many male writers have attempted to create compelling female characters, these efforts often fall short, resulting in portrayals that feel one-dimensional, over-romanticized, or detached from authentic female experiences. This leads me to question why are male authors not pulling their weight in presenting women correctly in literature, opting instead to present women as something ‘less’?