18 minute read

UPS & Standby Power

from DCR Q3 2022

Are we ready for change?

Could locked-in, longterm UPS maintenance contracts be beneficial for data centres? Louis McGarry, Sales & Marketing Director at Centiel UK, explores the pros and cons.

Advertisement

We seem to be living in a world of uncertainty. Locking-in to fixed-term contracts can offer a stable solution which works for both parties. Mortgages are a great example where guaranteed fixed-rates, avoid the uncertainty of tomorrow.

Locking-in to contracts has advantages. Data centres have the flexibility to offer services on a short-term basis, but long-term agreements mean they can offer commercial rewards as rates can be fixed from day one. Clients and the data centre can also plan and manage costs more effectively. Surely this creates a win-win situation for all?

Interestingly, although locking-in appears to be the new normal when it comes to mortgages and data centre contracts, it is generally not the case when purchasing and maintaining a UPS system. However, perhaps it could or should be? With ever-rising costs, now is the perfect time to discuss the benefits of fixed-rate agreements that ensure the integrity of UPS systems from start to finish to avoid unexpected costs.

OpEX An objection to locking-in to a UPS maintenance contract might be that, “We can’t commit our OpEX budget for 10 years, we only plan a few years ahead.” I’d counter that argument with: “A UPS is not a disposable item. The initial purchase already enters the data centre into a 10-15 year relationship with the equipment and manufacturer. This means data centres must be prepared to invest in the maintenance and remedials during that time anyway. As soon as the CapEx is committed, so is the OpEX.” Therefore, a formal long-term maintenance contract would actually be beneficial as it will reduce costs and ensure the system is always kept in optimal condition

No hidden costs The ideal scenario would be for a data centre to enter into an agreement with a UPS manufacturer to purchase a solution and maintain it over the next, say, 10 years. This long-term contract would include everything – remedials, caps replacements, preventative maintenance, all parts and labour etc., and the cost would be spread over the time period. This means a flat rate would be due regularly. The manufacturer would simply arrange any necessary replacements at the agreed time and there would be no unexpected costs for the data centre to worry about.

With the recent strain on the global supply chain, guaranteeing the price of parts and labour for several years to come could be a very wise move for data centres. Although the thought of a long-term commitment can put off some organisations, the assurance that all remedials are prepaid and completed when necessary should outweigh any concerns.

And regular remedial works are essential to guarantee the full working life of a UPS system. For example, a capacitor failure can be catastrophic, resulting in loss of load and damage to expensive equipment. It’s easy to see how costs would escalate following the replacement of a damaged UPS due to poor maintenance. A long-term contract would ensure caps are replaced at the appropriate time with no additional cost, for full peace of mind.

Short-termism Although it may be in the best interest for a data centre to lock-in to a long-term UPS maintenance contract, it won’t necessarily be suitable for a facilities management contractor, as they may only be responsible for the installation and short-term management of equipment. It is rare to see FMs still involved five or 10 years later.

On the one hand, conducting regular tenders for FM contracts can ensure charges remain competitive, but on the other, it can result in a change of FM every couple of years. Although costs are reduced in the short-term, this approach can have adverse effects on the effectiveness and overall cost of maintenance agreements, meaning data centres actually lose out on Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) savings. So, how can FMs and UPS providers work together to ensure that they are doing the right thing for the data centre?

A conversation upfront with the data centre who owns the equipment is important, to see how they’d prefer to work. One viable solution could be that the long-term UPS maintenance contracts are handed over and accepted by the new FM at the same price. This could become a Standard, much like the approach to transferring the FM workforce when they TUPE (Transfer of Undertakings Protection of Employment) across, and they agree to honour the terms of the contract.

To achieve this result requires some joined-up thinking. Why not invite manufacturers into the discussion earlier to pool knowledge resources, ideas and come up with workable options which will save client costs over the long term?

Working with manufacturers I also believe the scenario of locked-in UPS maintenance contracts will only be beneficial for all parties if clients work directly with trusted manufacturers. Manufacturers can guarantee to support and maintain a product at least 10 years after the last one rolls off the production line. Manufacturer trained and approved engineers will also have the relevant expertise, access to technical support and firmware updates, or spare parts, to prevent putting the load at risk. Resellers may not be able to guarantee these terms.

A refreshing approach What if there was a world where clients no longer had to rip out their systems and replace infrastructure when going through a product lifecycle refresh? What if manufacturers could guarantee a complete system refresh after, say, every seven years, when the first capacitor replacement is due?

I believe modern modular UPS now offer this opportunity. Data centres are able to select flexible, scalable systems, with a reduced footprint that can be adapted to most, if not all, applications.

A further benefit of true modular UPS systems is that they have the facility for components to be removed and replaced seamlessly (zero downtime), which could form part of a service exchange programme. The ageing UPS modules would then be reconditioned ready for another service exchange opportunity. Clients would then be ‘good to go’ for a further seven years.

It leads me to ask the question: with UPS solutions reaching the maximum efficiency levels with really <3% left to improve on, why shouldn’t we try to extend the life of the current UPS system? Could manufacturers agree to a refresh programme, with all purchase, installation, replacement, and maintenance costs amortised over time to ensure there are no hidden surprises, no big bills and with everyone knowing the costs in advance?

The life of the UPS system could essentially be doubled with reconditioned modules being replaced at the appropriate times. There would be no need for a big system replacement in the future as newer modules replace old, all certified with the latest software and firmware.

This whole topic is certainly one for further discussion. I believe this industry is moving towards locked-in contracts for the benefit of clients and to think everything will remain ‘how it’s always been’ is a mistake. The question is, as an industry, are we ready for change?

Mitigating the risks

Alastair Morris, Chief Commercial Officer at Powerstar, considers the ‘energy trilemma’ and the necessity for a forward-thinking energy management strategy.

An uninterruptible power supply (UPS) is business-critical for data centres – a sector where even the slightest fluctuation in, or loss of, power can have serious operational, financial and reputational consequences. The issues are even more pressing in the current geopolitical climate, as we face the full impacts of an energy trilemma: balancing the competing demands of affordable, sustainable and secure power.

While the UK is in the top five, globally, on the World Energy Trilemma Index, the recent report flags up serious issues relating to the UK’s position for energy security and equity – reflecting concerns about the lack of energy storage capacity and the high cost of electricity. Clearly, this is a global problem, but there are obvious signs from the UK government that the trilemma is a pressing problem for the country. In late May, Business and Energy Secretary, Kwasi Kwarteng, wrote to the National Grid ESO, requesting that they explore options to boost energy security for this winter.

There is no easy solution to the current energy crisis. Cost and security of supply will be volatile for the foreseeable future. This is more complex than a quick switch to renewables, with a need for careful balancing – and the nature of the trilemma means there are competing agendas at play. Waiting for a stable and affordable energy supply from the Grid, one that meets the net zero demands of current legislation, is a risky option. Perhaps now, more than ever before, the climate demands that businesses – and data centres are a clear case in point – mitigate against geopolitical and financial risks by taking control of their energy supply.

New solutions As power disruption is one of the most significant risks to data centre operations, the sector has traditionally relied upon uninterruptible power supply (UPS) to protect critical equipment and prevent the loss of vital data in the event of disruption. These older UPS systems usually rely on lead-acid battery technology which, while covering the basic and critical requirement of preventing disruption to supply from affecting sensitive equipment, have significant drawbacks – impacting on affordability, sustainability, as well as being potentially insecure. In the context of the energy trilemma, a traditional UPS looks increasingly untenable as a long-term solution.

Modern UPS technology involves the combination of a control system and sophisticated battery energy storage (BESS). This offers ultra-fast switching to connect the battery to the site supply in less than 10ms, protecting all equipment on site in the case of any power disruption. Critically, and additionally, power management software offers the capability to forecast and manage multiple power loads, as well as any on-site power generation to help achieve the cheapest, most sustainable, and stable electrical supply.

With energy costs spiralling, the storage element inherent in a BESS solution can offer significant benefits when factored into data centre energy management infrastructure – helping to address the affordability arm of the energy trilemma. Energy can be purchased when prices are at their lowest and retained, to be used when needed. Renewable firming offers the built-in capacity to store energy generated on-site, which can then be stored and used when needed or sold back to the Grid. It is this opportunity for a new revenue stream that can be most compelling.

A BESS solution allows businesses to capitalise on the National Grid’s Demand Side Response (DSR) opportunities. Balancing services are used by the Grid to even out demand across the UK’s power supply and, as inflexible renewables are increasingly important within the country’s energy mix, balancing services show continued growth. Companies who have the storage capacity and the technology to engage in balancing services receive a guaranteed income if they can be flexible.

This is one of the greatest assets of a BESS, which can rapidly draw down electricity from the Grid or release it back again, to be available at times of peak demand, meaning that the company can fulfil their contractual obligations and introduce a new revenue stream – a far more positive option than the sunk costs of older UPS.

A balancing act The issue of affordability is intertwined with that of sustainability, where traditional UPS solutions are concerned. By its very nature, a typical UPS consumes significant amounts of energy, as it constantly switches between AC and DC, remaining powered up on standby,

with losses of between 10 and 15%. This compares to a BESS and smart microgrid solution which has typical losses of around 1%. For a 1MW UPS system, that means wasted consumption of about £200,000 of electricity each year.

Compared to a BESS, which will consume approximately 95% less power, the cost savings are reflected in the reduction in carbon emissions. The reputational impact is evident, worldwide, as highlighted by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal Strategy, which identifies net zero data centres as a cornerstone of clean energy infrastructure.

Customers and the supply chain are ever more aware of the need to act on legally binding targets for net zero and are making business decisions based on sustainability. Where data centres’ key client bases are increasingly focused on their own net zero strategies – with the NHS, public sector bodies, the financial sector and large corporates as obvious examples – being able to demonstrate clear steps towards decarbonisation in your own company will be reputationally critical.

Maintaining supply The third arm of the energy trilemma – security of supply – is most pressing and critical for data centres. As with the reputational issues highlighted above, any loss of data due to power disruption carries with it significant reputational and financial risk.

A study by the British Chamber of Commerce found that 93% of businesses suffering data loss for more than 10 days file for bankruptcy within 12 months, while another recent report found that data loss costs UK companies an average of £71 for each individual record lost.

While a traditional UPS generally offers sufficient protection for individual pieces of equipment, there is no way to monitor the state of charge of a battery, meaning that without proper maintenance – an additional cost – there will always be some risk of failure. Factoring this issue of security of supply into data centre energy management makes the case for embracing new technology ever more compelling.

Future-proofing is critical, to provide the resilience the data centre sector needs, as the world becomes increasingly digitalised, and as the energy trilemma becomes more pressing. Fortunately, for forward-thinking companies, there is technology to help address each of the issues. Modern UPS and smart microgrid solutions can offer site-wide protection, can help investment in on-site power generation to achieve a better return, and can even provide new revenue streams.

Investment in behind-the-meter generation and energy storage helps reduce the impact of Grid fluctuations, making companies less vulnerable while bolstering brand reputation, demonstrating a clear commitment to working towards net zero.

Evolving sustainable gensets

Pierre-Adrien Bel, Product Manager at Kohler, looks at the different options available to help reduce genset emissions.

Despite increases in efficiency, the power consumption of data centres is continuing its ever-upward path – and is estimated to be responsible for around 1% of worldwide electricity demand, both for powering servers and to cool them. In particular, the surge in demand for cloud services is driving the growth of large, ‘hyperscale’ data centres.

Regardless of their size, all data centres need to ensure a continuous electrical supply, to avoid data losses and outages in service. The diesel generator, or genset, has been the primary equipment used to fill any short-term emergency gaps in grid power – but there is increasing pressure to reduce genset emissions, or switch to alternative technologies.

The landscape for data centres Legislation to tackle climate change is making a big impact on data centres, and the industry is responding with self-regulation initiatives. For example, the Climate Neutral Data Centre Pact, where a group of cloud providers and data centre operators has submitted a proposal to the European Union to make data centres in Europe climate neutral by 2030. As well as greenhouse gases (GHG), there is also a drive to reduce other emissions that can be detrimental to health, such as nitrogen dioxide.

Hyperscale data centres need to deliver on the sustainability commitments made by their owners, and the companies that use them. Between them, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Apple use more than 45 TWh of electricity per year. These big five firms, known informally as GAFAM, have made strong public commitments on reducing their emissions, and need to hit these targets to avoid reputational damage and problems with legislators. At the same time, they are not willing to compromise on cost, performance, security or reliability in the drive towards net zero.

For example, Microsoft has committed to being ‘carbon negative’ by 2030, removing more carbon dioxide from the air than it emits. Similarly, Google has promised to power its data centres with carbon-free electricity by the same year. Amazon, Facebook and Apple all have broadly similar climate goals.

These trends mean that more action on sustainability is needed from genset manufacturers. The role of diesel gensets Diesel generators are a proven solution for data centres, with low operating costs, high energy density, and long-term reliability. They are easy to deploy and operate, and provide a highly available source of power.

However, diesel gensets have one major disadvantage: their environmental performance. While gensets are only used infrequently, the data centre industry expects them to move towards cleaner operation and lower emissions.

New legislation, more taxes and tougher regulation are likely to make diesel steadily less attractive; for example the UK has recently prohibited the use of low tax ‘red diesel’ in data centre generators. Singapore has gone even further, imposing a moratorium on new data centres in 2019 partly due to environmental concerns, which has only recently been lifted.

Microsoft estimates that diesel contributes less than 1% of its overall emissions, but it is still pushing to end its use of diesel gensets for emergency power by 2030. It is exploring options including biogas, natural gas, and hydrogen, but it’s not yet clear if it has any solutions that can scale sufficiently to replace diesel. Another option, followed by Facebook and other large players, is to locate data centres where the local power grid is proven to be robust, so there will be fewer outages to cover.

Optimising gensets Diesel technology is constantly evolving. Genset vendors have invested massively in reducing emissions, and made substantial improvements. They are also working towards digitalisation, using the Internet of Things (IoT) and remote monitoring for improved diagnostics.

In-cylinder technologies reduce the pollutants emitted by the diesel engine. For example, shifting from mechanical fuel systems to electronic fuel injection can significantly reduce the creation of pollutants. Computer-aided engineering tools and computational fluid dynamics have also enabled the modelling of engine behaviour to become more sophisticated. Together, these and other in-cylinder developments, such as exhaust gas recirculation, have allowed optimisation of the system to improve fuel consumption and reduce emissions.

Another major area of improvement has been the reduction in ‘wet stacking’. This is when unburned fuel builds up in the engine’s exhaust

system, leading to excessive wear and damage. This is usually addressed by burning off unused fuel every month by running generators at 30% of their rated capacity for at least 30 minutes – but this is an expensive waste of diesel and results in higher emissions, particularly for large data centres with multiple generators.

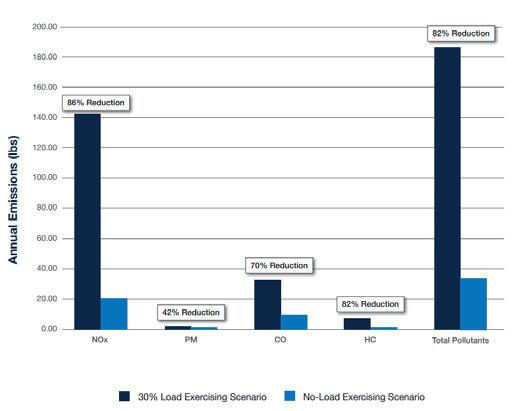

Kohler has addressed wet stacking with highly optimised engine design, enabling operators to run their monthly generator tests with no load, only running a load test annually. This has a big impact, and can reduce overall generator emissions by up to 85% (see Figure 1).

As well as the engine itself, after-treatment systems are used to reduce emissions. These systems include diesel oxidation catalysts, diesel particle filters and selective catalytic reduction, to capture the different gases and particulates present in the engine’s output. New after-treatment technologies are continually improving the performance of these systems. The evolution of future technologies Looking beyond diesel, biofuels can provide another way to reduce GHG emissions, by using renewable fuels where carbon has been captured from the atmosphere by plants, rather than fossil fuels.

An attractive option is Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO), also known as renewable diesel. This is produced from waste and residual fat from the food industry, as well as from non-food grade vegetable oils. HVO overcomes some of the problems typically associated with biofuels, such as instability and ageing when stored over long periods of time.

HVO can be used as a direct replacement for regular diesel without engine modifications, reducing carbon emissions by up to 90%, and can also be mixed with diesel in any proportion.

Looking further ahead, lithium-ion batteries and fuel cells are two new technologies that are being widely considered for data centres, with many operators running trials. Fuel cells run on hydrogen, with water as the only waste product. If the hydrogen is made using renewable power, so-called ‘green hydrogen’, then they provide a zero-emission emergency power solution.

However, compared to diesel generators, batteries and fuel cells have disadvantages in terms of scalability and cost. For example, batteries that are big enough to use for back-up power are very expensive, and can have a significant environmental impact in their production and disposal.

Fuel cells would require substantial investment in infrastructure to transport and store enough hydrogen; for instance, 100 tons of hydrogen would be required to power 30MW of IT equipment for 48 hours.

In the long-term these technologies hold great promise, but widespread deployment is likely to be at least 10 years in the future.

With the climate crisis becoming a major challenge for us all, genset manufacturers have a responsibility to improve environmental performance. This includes optimising their existing diesel technology, and developing new solutions that can bridge the gap to fully renewable power. Diesel gensets are going to be around for many years, and there is a lot we can do in that time to reduce their environmental impact.