Critical Thinking 2023/24 Does Crime Always

Inspire

Deserve Punishment?

WORKSHOP 4: WHAT IS PUNISHMENT?

2 Contents WELCOME TO INSPIRE CRITICAL THINKING? 06 What is the purpose of punishment? Antonia Sundrup and Alison Hills (Law) 11 How has punishment changed? Ross McKibbin (History) 14 Unusual punishments through time Alfie Dry (History) 17 Punishment within the animal kingdom: is it natural? Azeez Shekoni (Biology) 19 Critical Thinking Video: Ima Lyer campaigns for party leader Alfie Dry 20 Critical Thinking Skills: Appeals Lily Middleton-Mansell 23 How does prison affect the brain? Tom Kemp (Psychology) 26 The Tap Social Movement: the rehabilitation of prisoners through employment Eleanor Bowen, Jack Southall and Patrick Ashmore (Criminology) 28 Beheadings in Art History (EXTENSION ARTICLE) Lily Middleton-Mansell (History of Art) – and Summary Video - Carys Owen 32 How do prisons use science and technology to improve security? Ben Mesure (Technology) 35 St John’s Summer Schools 37 University Spotlight: Paintings of Punishment in the Ashmolean Museum Lily Middleton-Mansell 42 University Spotlight: Oxford Journalism Lily Middleton-Mansell 44 Workshop 3 Super Challenge Winners WORKSHOP FOUR: What is punishment? inspire@sjc.ox.ac.uk sjcinspire.com Crime and Punishment

WELCOME TO INSPIRE CRITICAL THINKING 2024

Dr Tom Kemp: editor, Emeritus Fellow in Biology, St John’s College; Lily Middleton Mansell: student editor, English graduate, St John’s College

This is the fifth year St John’s College has produced its Critical Thinking online programme, and we have grown very proud of it and the 1500 or more annual participants! It is aimed primarily at Years 9 to 11 and is designed for students of all abilities and interests. We are glad to say there is no charge for full participation, neither online nor for coming to our associated Oxford Summer School at St John’s College.

Each programme centres around a broad area of human interest, with contributions from many of our colleagues, who are leading, and often internationally renowned academics, and who bring to the topic a wealth of different scholarly viewpoints from the arts, the humanities and the sciences alike. We all share a passionate commitment to education at every level, encouraging students to broaden their understanding of the world and develop their critical thinking skills. We are bombarded nowadays with information from so many sources, some truthful and reliable, others sadly unreliable and maliciously prejudiced. If your generation is going to try and make the world a better place, then it is essential that you learn

how to critically assess rather than unthinkingly accept what you hear and read.

The broad area we have chosen for this year is “Crime and Punishment”. Few aspects of human behaviour have been so pervasive throughout society. Ideas of what even is criminal have changed throughout the course of history and amongst different communities. Philosophers have agonised over what are appropriate punishments, and social scientists over the causes of crime. Several branches of science look at improving ways of apprehending criminals, and medicine is interested in discovering treatments for a tendency towards violence and aggression. Think how much crime enters literature, from the great classics to all those detective novels, into film and drama. How many wonderful medieval and renaissance paintings depict cruel punishments?

DOES CRIME ALWAYS DESERVE PUNISHMENT?

The programme is divided into four successive workshops:

What is a crime?

Are some crimes excusable?

How effective is crime detection and the justice system?

What is punishment?

3

HOW DO I USE THE WORKSHOPS?

Submit your super challenge piece by the 26th April 2024 for a chance to win.

Throughout this workshop you will find several interactive tasks:

Think pieces

Have your say

Vote now Super challenges

These are all optional and give you the ability to choose how much you’d like to be involved. There are also resources to help you independently explore the topic in more detail.

The 4 super challenges require a little more thinking but offer you the opportunity to complete a task and a chance to win a prize! You may submit a response to one super challenge per workshop. This can be in any format you wish. Submit your super challenge response to inspire@sjc.ox.ac.uk for the chance to win up to £20 Amazon voucher. With your submission please let us know:

■ Your name

■ Your School

■ Your year group

■ Whether you are happy for us to share your work on social media.

4

X

WHAT IS PUNISHMENT?

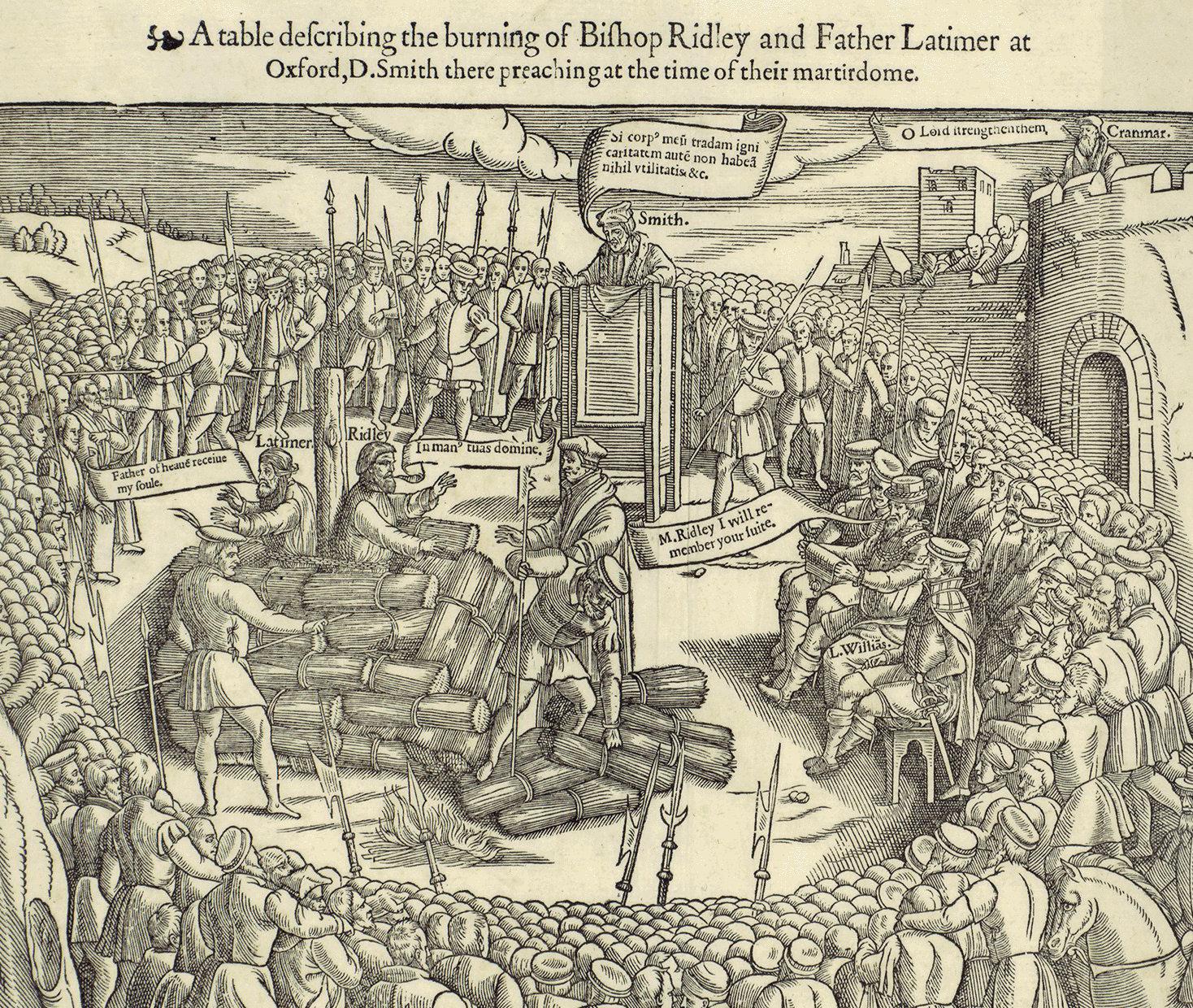

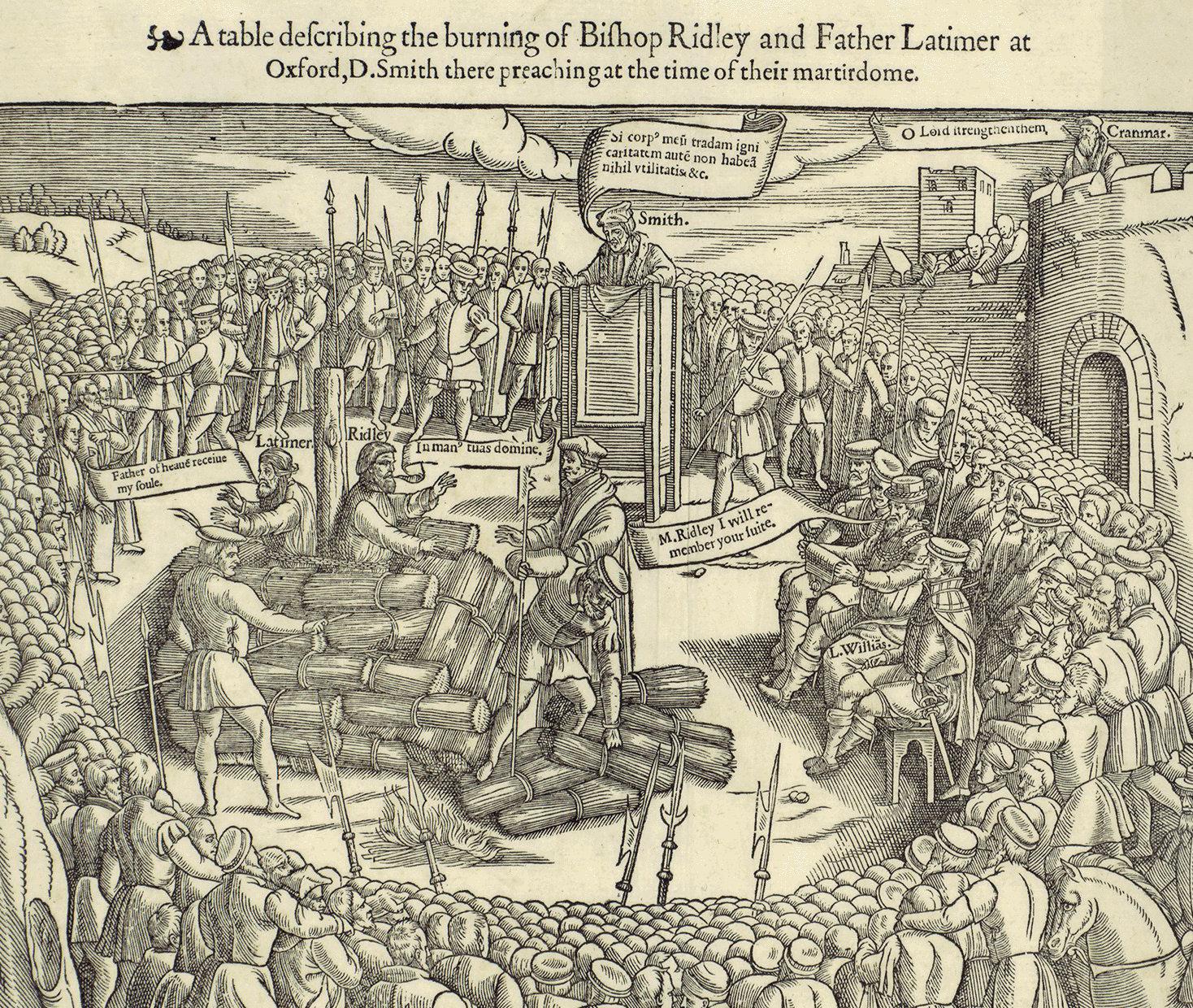

Welcome to the fourth Workshop, where we turn from a focus on crime to a focus on punishment. Meting out punishment to individuals who transgress the rules of society is as old as recorded human history, and no doubt a good deal older. Over the centuries though, two aspects of punishment have drastically changed. The first is that it has become generally less severe, and you may wonder why this is so. For example, in pre-Confucius China almost every crime judged to have been deliberate, no matter how relatively minor to modern eyes, could result in execution. In Britain until well into the 19th century a culprit could be hanged for sheep-stealing, poaching, forgery, cutting down trees and some 200 other offences. The list of capital offences was whittled away until only murder, treason and piracy remained, and the death penalty for these was finally abolished in the 1960’s. Other forms of punishment such as flogging and burning at the stake, as well as public humiliation in the stocks have also long since disappeared.

The second big change is a more nuanced perception of the purpose of punishment. By and large most societies today have adopted a more humane view of the rights and dignity of all individuals, even those who have committed serious criminal offences. At least four competing theories are put forward by criminologists about why criminals should be punished, if indeed they should be at all. As you read the articles you will be able to think for yourself how best to balance these competing views.

The more extreme forms of punishment have figured extensively in art, especially Medieval and Renaissance painting. Images of the punishment of Christ by crucifixion and of the torture and killing of saints are legion. You might wonder why this obsession with such violent acts had such a hold.

The final article on critical thinking is about how advertising and political campaigning use appeals to the emotions rather than facts and reasoning as a way of persuading people to accept a message. In its various forms, appeal is a device that can have a powerful enough psychological effect to quite overshadow our critical facilities if we are not alert to it.

Dr Tom Kemp, editor Lily Middleton-Mansell, student editor

INTRODUCTION TO WORKSHOP 4

5

6

What is the Purpose of Punishment? LAW

Authors: Antonia Sundrup, 3rd Year Law student, and Professor Alison Hills, Tutorial Fellow in Philosophy, St John’s College

Inthe UK, most of the time criminal punishments consist of fines, prison sentences, and occasionally community service. But let’s suppose we had an alternative; a device called the Pulverizer. This device can be used to dematerialize murderers –meaning they just disappear, never to be seen again, without suffering any pain. Everyone thinks that they just disappear into nothing, but in reality, they are catapulted to Candy Mountain, a paradise where they are living much better lives than ever before. This would have many advantages: the murderers could no longer be a threat to anyone, the state would not have to spend money on prisons and those close to the victims would feel like the murderers received a fair punishment – since they do not know about the Candy Mountain. No one is worse off, but the murderer is better off. Do you think that this is a fair punishment? Whether you do will depend on what you think the purpose of punishment is.

Let’s suppose that Jill has murdered Jack. The reason for punishing her might be very simple: Jill has done something wrong and

deserves to be punished. The purpose of the punishment would therefore be what some academics call retribution – punishment because someone has committed a wrong. For high-profile crimes this will often be a central discussion in the media, but many criminologists think that retribution is outdated and focus more on the effect of punishment in real life. When looking beyond retribution there are many other reasons to punish people when they commit a crime.

One is the hope that the prospect of punishment will stop people from committing crimes, which is referred to as deterrence among academics. It has two aspects: firstly, in our example, Jill herself might be less likely to commit another crime when she gets out of prison, because she has been in prison before and wants to avoid returning. Secondly, everyone who hears about Jill’s case may be less likely to commit a crime as they want to avoid punishment. This is obviously a desirable result, but there is some doubt as to whether punishment does deter people from committing crimes. This is partly because it can only have an effect if criminals think they will get caught.

Some research shows that deterrence through punishment often has a bigger effect for minor infractions, such as illegal parking, and is much less effective in reducing major crimes.

There are also indications that social control, meaning the influence of family, friends and community, may be more effective in deterring crime than punishment.

Even if punishment does not have a significant deterring effect, a prison sentence may at least stop someone from committing crimes for as long as they are in prison. A person may therefore be imprisoned for the purpose of incapacitation. In the UK, if Jill had completed the prison sentence she was convicted to, but was considered a ‘habitual criminal’, she might receive an additional sentence for this reason – because it is considered unsafe for others to release her. Incapacitation can only justify some punishments: it does not apply to punishments such as fines or very short prison sentences, of which there are a lot. Some crimes

7

can also still be committed in prison – for example against other prisoners or staff.

During much of the 20th century, there was a focus on rehabilitation as the main purpose for punishment.

This approach focuses on the idea that criminals are not necessarily bad people, but rather are badly integrated in our social order and bad at following rules. However, the goal of punishment is to help them become productive members of society again. Those in favour of this goal often call for changes in the criminal justice system, emphasising that many offenders who are released from prison are in a bad place to reintegrate into society and find employment. There is research to support that prisons often do a bad job at rehabilitation: an Australian study found that for crimes such as non-aggravated assault, imprisonment increased the likelihood of future offending. If you believe that rehabilitation should be the goal of punishment, then you might favour changes such as job training in prison. The purpose of punishment matters a lot when deciding who to punish and how. If you subscribe mainly to the incapacitation argument, you might advocate for stronger sentences for those offenders who are statistically more likely to commit further crimes, which is, for example, true for young people. If you think the point of punishment is deterrence, then you might want to make sure that life in prison is hard and unpleasant –but if you believe in rehabilitation your view will be different.

8

Prisoners from the Coyote Ridge Corrections Center participating in a conservation project

You’ve read an Oxford Law student’s perspective on why people punish, now here is an Oxford Philosophy Professor’s account. This article will help you answer the challenge question about planning an ideal method of punishment.

In England between 1352 until 1870, any man found guilty of high treason was hanged until he was nearly dead, cut down and disembowelled, beheaded, and his body chopped into four pieces. Women found guilty were merely burnt at the stake.

These days, legal punishments are much less dramatic and less bloody. If you are convicted of a crime in the UK, you might be fined or sent to prison for a number of months or years. These

punishments are less serious than the death penalty. But that doesn’t mean that they are not serious at all. Under normal circumstances, it is wrong to take away someone’s money without their consent, and it is very wrong to lock them in a room and refuse to let them leave. We normally have a right to our property and a right to freedom. So how can it be legitimate for a state to impose fines or imprisonment as a punishment?

The obvious answer is: punishment is a response to crime, and it is legitimate to punish criminals. This is clearly on the right track, but the exact link between punishment and crime is surprisingly hard to pin down. Philosophers have tried to defend legal punishment in different ways, by proposing different theories of punishment. We will discuss three here: deterrence, retribution, reform, and finally we will consider abolitionists who do not think punishment is justified.

DETERRENCE

If there were no police, no law courts and no prisons, anyone thinking of committing a crime would know that afterwards, they would have a great chance of getting away with it. They could steal, cheat, even kill someone and nothing would happen to them. So surely without punishment, many more people would commit crimes. We would all be worse off. So the reason we have to punish people, and the reason punishment is legitimate, is to deter people from committing crimes in the future.

RETRIBUTION

Anyone who commits a crime harms other people. A burglar violates rights to property. Murderers violate the right to life. Perhaps by violating other people’s rights, criminals forfeit their own rights and so punishing them is

9

permissible. Perhaps we have reason to punish them because they are bad people who have acted wrongly who deserve to be punished.

REFORM

Anyone who commits a crime has made a bad choice. Perhaps they are a bad person, or perhaps they were in a difficult situation with limited options. Either way, it would be better if they understood the impact of what they have done. Perhaps the purpose of punishment is not to inflict hardship on criminals but to help them to find a better path in the future.

ABOLITIONISM

Abolitionists believe that punishments are not justified. Sometimes they target a specific kind of punishment, for example, arguing against the death penalty, or against prison. Abolitionists sometimes argue that the actual punishments imposed in real life are wrong because they do not work: for instance, that prison makes criminals more likely to reoffend, not less likely. Sometimes they argue that in principle punishments are wrong: for instance, that the harm a criminal does to their victim cannot be erased or made better by imposing another harm, on

the criminal themselves. It is hard to imagine a large, modern society working without the police, criminal courts and prisons. But abolitionists have powerful arguments. Punishments deter criminals only if they expect to be caught, and many do not expect to be caught.

Punishments are deserved only if criminals are fully responsible for what they do. But are they? Many criminals are addicted to drugs, are they responsible for what they do to get hold of their drugs? Do they not deserve help rather than punishment?

But if we think of punishment as a way of educating, helping and so reforming criminals, surely the criminal justice system as it exists does not work as it should. So are abolitionists right that we should get rid of it all and start again, designing a whole new system for a wholly new purpose?

Have your say

What would you say is the best justification for the following punishments?

• Incapacitation

• Deterrence

• Retribution

• Rehabilitation

Want to find out more?

LINK > LINK >

● Why Should We Punish? Theories of Punishment

● Attitudes in the 16th and 17th centuries - Attitudes to punishment

– WJEC - GCSE History RevisionWJEC - BBC Bitesize

LINK >

● Drawn and Quartered – Worst Punishments in History of Mankind

10

11

Sock theft =? Fraud Assault Murder

How has Punishment Changed?

HISTORY

Author: Ross McKibbin, Emeritus Research Fellow in History, St John’s College

Throughout our history human beings have been punishing other human beings: the point of the punishing being to cause pain. Why have we done that? In many respects, the most common and long-lasting reason lies in the belief that some people deserve punishment, and nearly all societies think that. We all have a sense that some crimes are such that people should receive their ‘just deserts’. We feel that it would be unfair if they were not, and there is a class of acts that most societies think should be punished: murder, assault, robbery and theft, fraud and embezzlement, and similar offences. Essentially the punishments we inflict on those who commit these acts are retributive: we think these offenders deserve what they get. Thus, the murderer should be executed. For much of British history, the only punishment for murder was execution, almost regardless of circumstances. (Though in the nineteenth century, it was agreed that some people might commit murder while of unsound mind. They were not executed.)

We also punish because, it is argued, punishment, particularly severe punishment, acts as a deterrent. This is an argument

frequently deployed since it is thought to be common sense. People don’t like punishment and will avoid it, so it is said, by not breaking the law. This was the argument always used to defend capital and corporal punishment. In fact, there is little evidence to suggest that punishment acts as a deterrent and even some to suggest that the people likely to be deterred are unlikely to commit crime in the first place. There is some evidence, however, that adolescent would-be delinquents are deterred by the prospect of being caught and a fear of the consequences; though it is unlikely that being flogged had that effect. Given, however, that the great majority of adolescent offenders are not caught, and they know it, we should not be too confident that this is true.

The punitive character of punishment, we should note, is often modified by a notion of fairness, a notion embodied in the old adage that the punishment should fit the crime. Therefore, someone who steals a pair of socks should be punished (if at all) much less severely than someone who assaults and robs a person. This is something most people in modern Britain

would accept. That, nonetheless, has not always been so.

For much of its history, Britain was known for the harshness of its criminal laws and the huge number of offences for which the prescribed punishment was death.

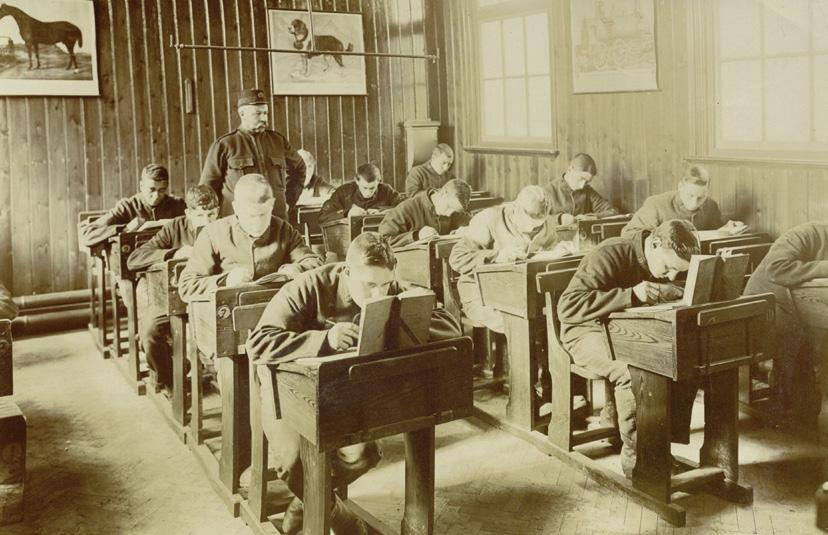

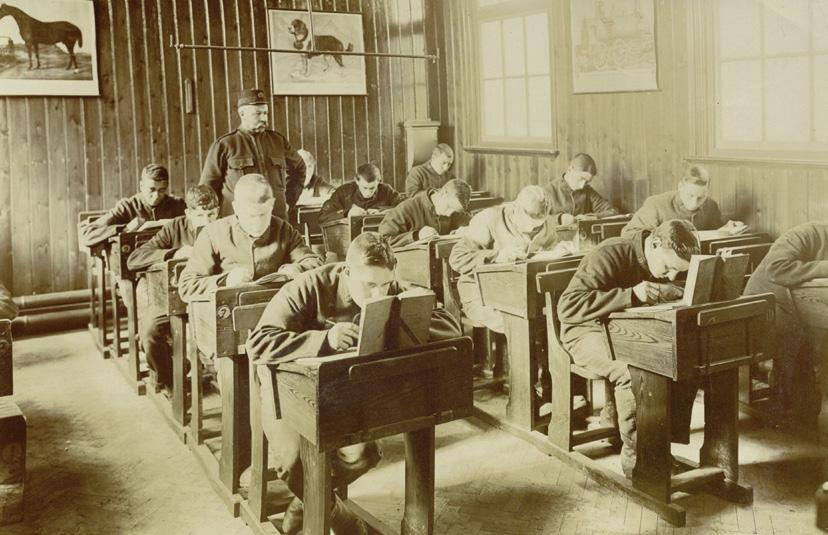

In the nineteenth century, while many of the death penalties were repealed, many exceptionally grim fortresslike prisons were built in the belief that they were not only a deterrent to crime but encouraged criminals, in their imposed isolation, to reflect on their sins, and so to become better people. The idea that punishment could be designed not merely as retribution but as a way offenders could be taught to live successfully in modern society became an important element in British attitudes to the law. Increasingly, therefore, the aim was to keep younger people out of these grim fortresses, though not necessarily out of institutions like Borstal; and the adult prisons themselves became less severe and a little more like educational institutions. There was a semi-recognition that those being punished were as much victims of

12

society as its enemies.

In the last quarter of the twentieth century, however, the cycle has turned again, as it always does when crime is an issue. Prison sentences have become longer, there is constant pressure to make prisons less like ‘hotels’, a view held by much of the tabloid press, and to send more people to them. Popular attitudes have become more punitive, often influenced by American examples.

There are now 80,000 people in Britain’s very overcrowded prisons – 2 million in America’s – and what social purpose they had has largely disappeared.

It would be wrong to say a prison sentence is always futile since there are clearly people who are a danger to society and to themselves, and prison is often the only way to protect both. The idea, however, that punishment can or might make people better has largely disappeared. If people emerge from prison today more socially aware and helpful, as many do, this has rarely been the result of imprisonment. As sentencing policy becomes harsher the less is it thought that people can become better or that

making them better should be an aim of imprisonment.

Are there any lessons we can learn? From the history of British crime and its punishment there are certainly two. One: It is a mistake to base the criminal law on people and pressure groups, or institutions like the press, whose views are strongly held, but often mistaken and frequently driven by political considerations. Two: it is a mistake to believe that the prison system and the types of punishment it represents, always have the effects that we would like. Sometimes they do; but as often they do not.

Want to find out more?

● Timeline of prisons in England

- BBC NEWS | UK | Timeline: Prisons in England

● Jeremy Bentham came up with a design for the “perfect” prison called the Panopticon: The Panopticon | Bentham ProjectUCL – University College London

● How corporal punishment ended in schools: BBC News report

Do you think the prison system in the UK is effective? Do you think early release for ‘good behaviour’ is fair?

13

Borstal

>

>

> X

LINK

LINK

LINK

Vote Now

14

Punishment by ... the goat’s tongue?

What Unusual Punishments have been used throughout History

HISTORY

Author: Alfie Dry, Human Sciences graduate, St John’s College

Here are eight strange punishments that have existed throughout history. Do you think they fit the crime?

GET YOUR GOAT

In medieval France, goat torture was used to extract confessions from a prisoner. In this seemingly mild torture method, the victim’s feet were trapped by stocks and covered in salt water. A goat would then be brought in to lick the person’s feet. Goats have particularly abrasive tongues, and would not stop licking while they had a supply of salt. This would start off as feeling ticklish, but quickly become unbearably painful as the goat’s tongue stripped the flesh from the prisoner’s feet.

A BARREL OF LAUGHS

Originating in 16th century England and surviving into American societies up until the 19th century, the drunkard’s cloak refers to a punishment enforced on those who indulged themselves too heavily in alcohol. With a hole cut out for the head, and one for the feet, drunkards were made to wear a barrel around their body and parade the streets to demonstrate the foolishness of alcohol.

WHO TURNED OUT THE LIGHTS?

In 1998, a landlord in New York was convicted of failing to take the proper measures in keeping her tenants safe, namely ensuring adequate heating and lighting. On refusing to pay the appropriate amount necessary to restore the building to adequate living standards, the landlord was sentenced to spend a minimum of four nights a week in her own building which had grown unbearably cold and dark until she had the building fixed.

LEST WE FORGET

Translating to ‘damnation of memory’, Damnatio Memoriae refers to a Roman punishment inflicted on those considered excessive tyrants, traitors, and enemies of the state. In an effort to remove this person from existence, any record of their existence would be destroyed, including removing their faces from artwork, scrubbing their name from registers, and re-writings of events in which they played a role. Interestingly this punishment was given to Caligula and Nero, which is ironic considering they are now two of the most well-known emperors!

15

TAKE A HIKE

In August 2015, an 18-year-old in Ohio refused to pay a cab driver for the thirty-mile journey he had just taken her on. Judge Michael Cicconetti, who is known for giving unusual punishments to first-time offenders, gave the woman a choice between spending thirty days in jail or going on a thirty-mile hike. She paid the cab driver the amount due and then went on the thirty-mile hike, which only took her two days to complete.

TAKE THE RAP

In 2008, a man was fined $150 for blasting loud rap music from his car. The judge offered to cut the fine to $35 if the defendant agreed to listen to twenty hours of classical music. The punishment was issued to demonstrate the annoyance of having to listen to music you do not enjoy. Fifteen minutes into the first hour of listening to classical music, the defendant gave up and paid the full fine.

FLYING PIGS

In fifteenth-century France, a sow (a female pig) was found guilty of murdering and devouring a child. Her piglets, although found at the scene of the crime, were deemed innocent due to their youth and the ‘misleading influence’ of their mother. Dressed up in human clothing and made to parade through the market, the sow was then hanged for her crime.

THIS ONE’S IN THE BAG

In Roman society, those found guilty of patricide (killing your father) would be beaten with rods before being sewn into a sack alongside a monkey, a dog, a rooster, and a snake. The writhing sack would then be thrown into the sea leaving both accused and animals alike to drown together.

Have your say

Do you think any of these punishments fit the crimes?

Vote Now

Should punishments always fit the crime?

16

X

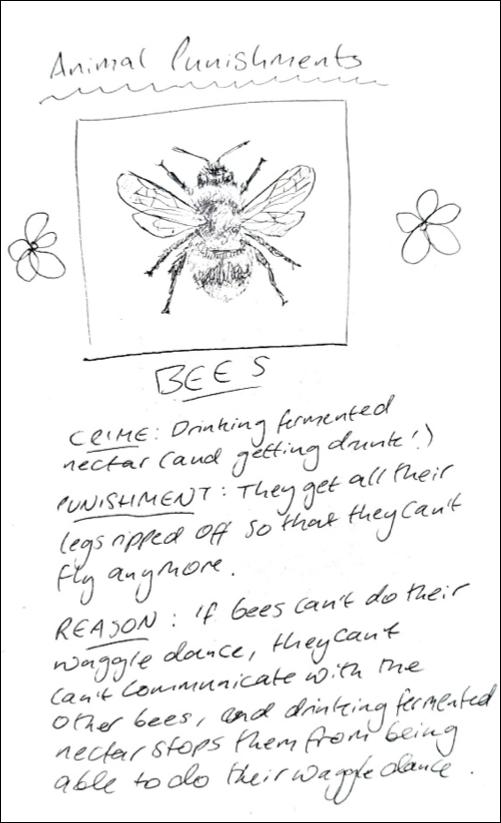

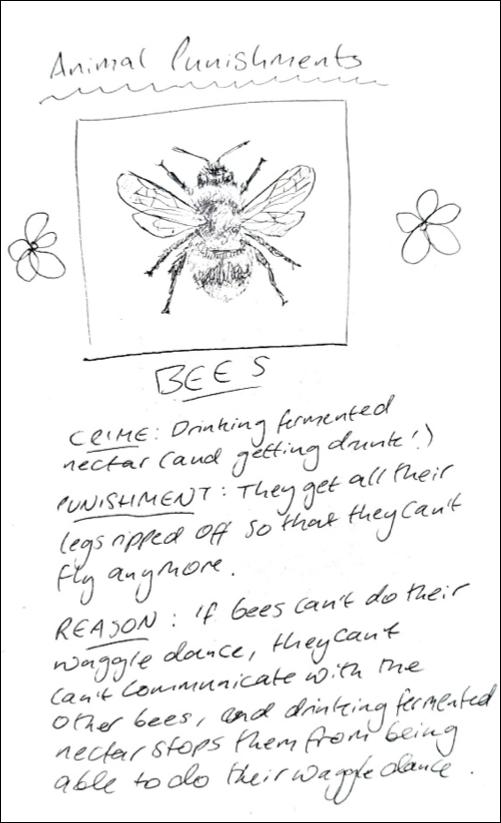

Punishment in the Animal Kingdom: Is it Natural?

BIOLOGY

Author: Azeez Shekoni, 2nd Year Medicine student, St John’s College

Want to find out more?

● Unlike humans, chimpanzees only punish when they’ve been personally wronged (nationalgeographic.com) LINK

● Do Animals Know Right from Wrong? New Clues Point to ‘Yes’ | Live Science

17

LINK >

> LINK >

Super Challenge

Do some research into another kind of animal that carries out punishments (you can use the further resources to help you). Make a profile card about that animal and the punishments that it carries out. Make sure to include the crime, the punishment and the reason behind it.

18

Critical Thinking Video: Ima Lyer

Ima Lyer is campaigning to run for leader of the political party. Obviously, she needs to be as persuasive as possible so her party members will vote for her. Will she succeed or will the appeals in her argument be flawed?

Watch the following video to find out! Then, familiarise yourself with the different types of appeals on the following page so you can try the super challenge task.

19

LINK >

Critical Thinking Skills: Appeals

Author: Lily Middleton-Mansell, English graduate, St John’s College

An appeal is a rhetorical device (a technique for persuading people) that aims to sway an audience through emotional persuasion rather than rational argument. Often used in advertising and political campaigns, appeals emphasise values that have a lot of weight in society, but often don’t have much foundation in reason: authority, tradition, history, popularity and emotion. While appeals can be extremely persuasive, being able to think critically about the (often inaccurate) assumptions on which their effectiveness rests will help you look beyond the emotion underlying an argument, and instead consider its application in reality.

APPEAL TO AUTHORITY

This is an appeal to a figure of authority when making a particular claim - it could be a doctor, a politician, an academic, etc. Think of the classic toothpaste advert: “9 out of 10 dentists recommend our toothpaste!” While an appeal to authority may well be truthful, especially if the person or group being appealed to has relevant expertise, it also contains an underlying assumption that, just because a particular person says something is the case, it must be true.

APPEAL TO TRADITION

An appeal to tradition suggests that something is correct because it has always been that way. For example, the tagline “Over a Hundred Years of Coca Cola” would be an appeal to tradition, because it implies that Coca Cola is valuable because it has existed for a long time. A large part of the impact of this appeal relies on nostalgia, the emotional connection that people feel to the past. However, it is important to think critically about such appeals: there can be reasons for something to last a long time beyond the fact that it works well. Sometimes it’s better to take the approach of “out with the old, and in with the new!”.

APPEAL TO HISTORY

This is where evidence of past performance is used to predict future performance. Imagine that an American President is running an election campaign for their second term. They might put an advert out exclaiming, ‘Four great years, another four to go”. This suggests that, because the President has performed well in their first term, they will also perform well in their second. This seems like good logic, but while past performance may be able to predict

the likeliness of future success (or failure) to a certain extent, it is no guarantee. The President may not be up to the job anymore; or perhaps this time around there are candidates running who would be a much better fit.

APPEAL TO POPULARITY

Appeal to popularity, also known as the Bandwagon Effect, is where the weight of numbers is used to support a conclusion. Think about your favourite TikTok accounts: some might do a challenge or a giveaway when they reach 10,000 followers. This isn’t only a celebration of their success; it is also a form of advertising. The suggestion is: “So many people have followed me, you should do it too.” Most people want to be part of what’s popular, but it’s important to remember that popularity is not always a sign of quality and, as today’s fast fashion trends show, it often doesn’t take long for something to drop out of public favour.

20

8 out of 10 clinicians recommend Thonk!

APPEAL TO EMOTION

This is where rational argument is replaced by overtly emotional factors. Opening scene: A skinny puppy sits trembling in a dark alleyway; cut to a ragged cat sheltering in a dustbin; cut to both animals being cuddled by a happy family in a warm, inviting home; end screen: Whiskers Cats and Dogs Home: We Don’t Throw Our Love Away. This kind of advert uses both negative and positive imagery to appeal to the emotions of its audience. It relies on instinctual response, rather than logical persuasion. This is a very effective form of advertising, but it also discourages people from questioning what lies behind the emotions. While such appeals are often used in favour of a good cause, they can also work to prevent people from thinking critically about the ideas that they are buying into.

Thonk!, popular for over 10 years

Thonk!, celebrating 10 glorious years, many more to come!

500 users can’t be wrong

Thonk!, for our cherished loved ones

21

THONK!

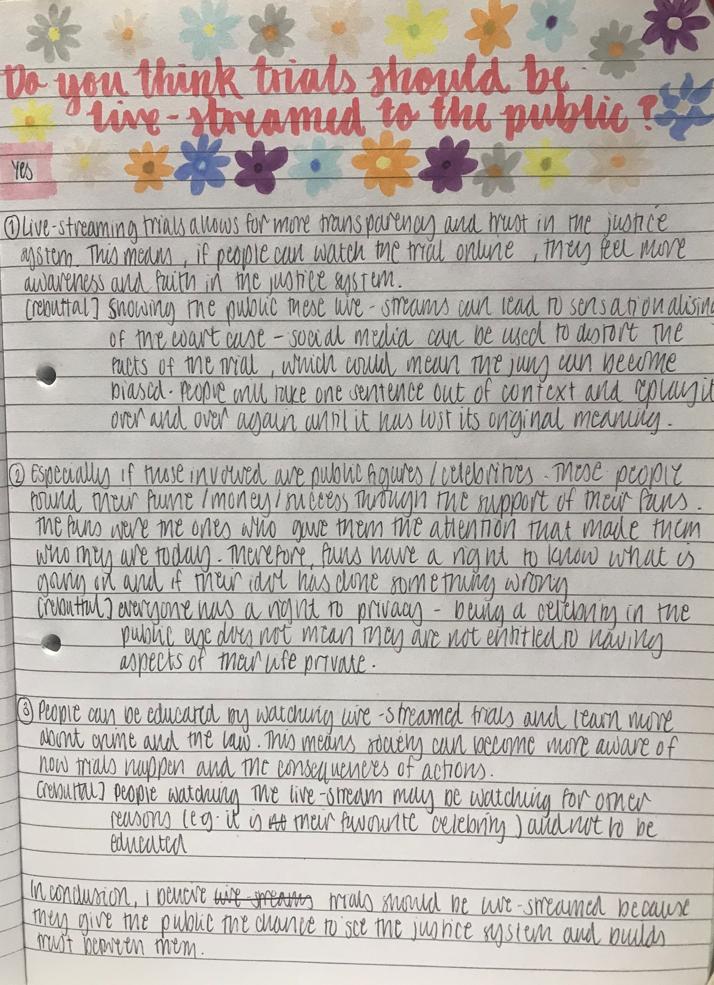

Super Challenge - test your critical thinking skills

Click on this link to read Barack Obama’s victory speech after he won a second term as US President in 2012.

See how many different appeals you can identify in his speech. In no more than 300 words, write a paragraph explaining the impact of those appeals, as well as critiquing their flaws.

22

LINK >

23

Prison Brain?

How Does Imprisonment Affect the Brain?

PSYCHOLOGY

Author: Dr Tom Kemp, Emeritus Fellow, St John’s College

The main kinds of punishment available to a justice system include execution, corporal punishment, imprisonment and fines, plus more minor forms like community service, probation, admonishment and social shaming. In theory, all forms of punishment depend on being disliked by the convicted person and therefore, be it a matter of pain, loss of freedom, financial cost or loss of esteem, it is preferably avoided. Neurophysiologists have studied the affect on the brain of animals such as laboratory rats. If the animal is treated experimentally with an unpleasant experience such as application of a painful stimulus, being under or overfed, or deprived of a drug it has become addicted to, it responds by showing signs of distress and actively trying to avoid the situation. This is described as aversive behaviour. During the experiment the pattern of activity in different parts of the brain, and the levels of particular brain molecules can be measured, and correlations between these measurements and the specific behaviour give insight into the underlying brain mechanisms producing aversion.

One of the key discoveries has been that the aversion system is closely related to what is called the reward system, which is broadly the opposite of aversion. Several of the same molecules and the same parts of the brain are involved. Neurotransmitters are molecules that transmit impulses from nerve to nerve, and the brain contains many of these acting between its neurons. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter whose presence in some parts of the brain is associated with reward stimuli but in other parts with averse behaviour. Acetyl choline is another, which modulates the effect of dopamine. Also involved are receptor molecules, which are found on neuron membranes and are activated by neurotransmitters. At least three different opiate receptors occur, which are stimulated by opiate molecules. Mu-opiate receptors are generally associated with euphoria (feeling good) and reward behaviour while kappa-opiate receptors with dysphoria (feeling bad) and evasion behaviour. At the moment the picture of how these different molecules interact to produce their effects is very far from clear, and, little is yet known about how far the discoveries in rat brains indicate what happens in humans.

Other investigations on animals have shown the effect of an impoverished, sedentary environment on the brain. In rats, there is a negative effect on the prefrontal cortex, which is a region of the brain that is essential for executive functions, such as decision making and problem solving.

It is difficult to know how far the results of animal experiments can apply to humans, on whom it is impossible to do the same sorts of experiments, but they can be suggestive.

For example, humans have the same suite of brain molecules acting on comparable regions of the brain, so it is safe to assume that the aversion to punishment that prisoners experience is a response to alterations in their reward/evasion system is even less clear. Similarly, it is likely that the impoverished environment that prison entails has a possibly permanent effect on the brain. Psychologists know a good deal more than neuroscientists about the effects of imprisonment.

24

Tests on prisoners show an impairment of executive functions, those functions associated with making decisions. Attention declines, as does working memory needed to remain focussed on a specific end. Cognitive skills and problem-solving ability are reduced, as is self-control. Some psychologists have even suggested that there is a condition they call PIS (postincarceration syndrome) which is similar in some respects to the well know PTSD.

Symptoms include recurrent nightmares, an institutionalised personality unable to cope well with free life, socio-sensory disorientation leading to easily getting lost and finding social interaction difficult, and a sense of alienation frog fellow humans. There are also various other kinds of mental health issues.

Of course, to some extent these psychological conditions may have been more common in people who find themselves imprisoned in the first place, rather than caused by prison. But studies do show a

deterioration over time in young prisoners tested at intervals while in prison. If one of the main aims of prison is to deter individuals from re-offending after their release, then it is clearly very important to understand the neuroscientific and the psychological causes of the negative impact prison conditions can have, and to consider ways to alleviate them.

If prison affects your brain permanently, is that enough of a punishment?

25

your

Have

say

The Tap Social Movement: the Rehabilitation of Prisoners Through Employment

CRIMINOLOGY

Authors: Eleanor Bowen, 1st Year Classics, and Patrick Ashmore, 1st Year Geography, St John’s College

Tap Social was founded in 2016 with the aim of creating a craft brewery and hostility social enterprise that works with service and recently released prisoners.

THE SHIFT TO OPEN PRISONS AND REFORM

Before the dawn of the open prison, the primary form of incarceration was focused on punishment rather than rehabilitation. Traditional prisons, also known as closed prisons or maximumsecurity facilities, were the norm. These prisons had strict security measures, high walls, and limited freedom of movement for inmates. This was a more punitive approach, with emphasis on isolation and control. However, over

Eleanor and Patrick met with Tess Taylor, Tap Social’s Communications and Marketing Director, to find out more. Watch the interview here.

time there was a shift in thinking about the purpose of imprisonment. Recognising the importance of reducing reoffending and promoting successful integration, the concept of open prisons emerged.

In the UK, open prisons, also known as “open conditions,” have been part of the penal system since 1933. They focus on rehabilitation and preparing inmates for eventual release. These prisons allow more freedom of movement within the facility, and even “day release” allowing prisoners to work outside of prison grounds during the day. There are a few examples of open prisons in the UK. One well-known prison is HMP Ford, located in West Sussex. It has been operating as an open prison since the 1960’s. HMP Ford ran the UK’s first day release program, serving as a way to gradually reintegrate individuals into the community before their full release. During day release, inmates are allowed to leave the prison during the day to engage in activities such as work, education, or community service. In the words of Sir Alex Paterson: “You cannot train a man for freedom under conditions of captivity”.

In the USA, open prisons, often referred to as “honor farms” or “minimum security facilities” serve a similar purpose. They provide a less restrictive environment for inmates who have demonstrated good behaviour and have a low risk of escape. These prisons typically have less security

26

LINK > S P OTLIGHT O N OXFORD

measures and inmates often have more privileges and opportunities for work, education, and vocational training.

Open prisons represent a shift in correctional philosophy, moving away from purely punitive punishments to a more reintegrative approach. As such, open prisons are often linked to rehabilitation programs, providing inmates with opportunities for personal growth and skill development. Open prisons offer a range of educational programs, including adult literacy courses, vocational training and higher education courses. Inmates may also have the chance to work both within the prison and in the community. Open prisons often also provide access to counselling and therapy services to support inmates in addressing personal challenges, such as addiction, mental health issues, or anger management.

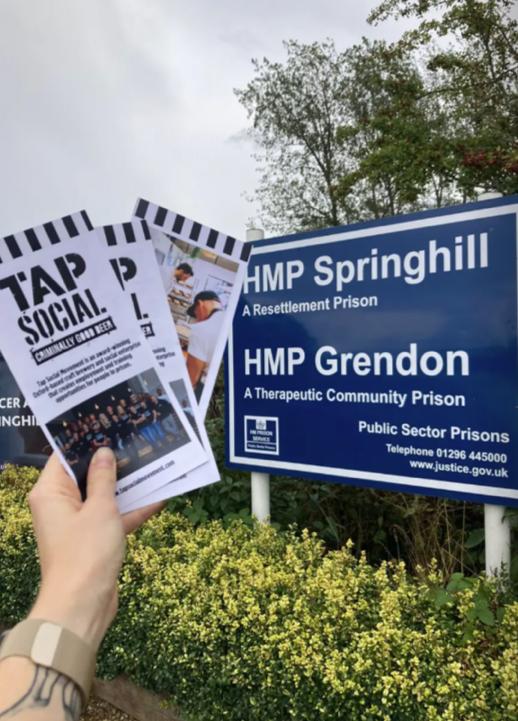

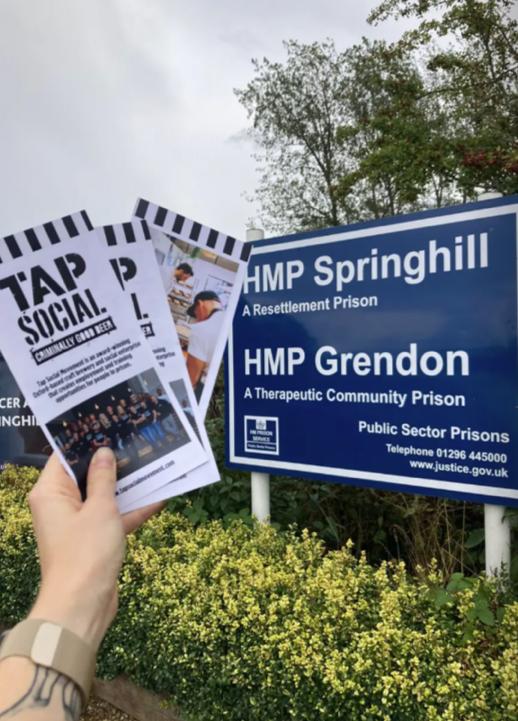

An example of this rehabilitation program is the Tap Social Movement, a social enterprise based in Oxford.

They combine craft beer brewing, hospitality and baking with a mission to provide training and employment opportunities for those who are or have been incarcerated. Their first site employed dayrelease prisoners from HMP Spring Hill, an open prison. They have since expanded to 6 sites, with over 40 employees from prisons.

This model has produced wildly successful results, with a 6% reoffence rate compared to a 50% national average. The central aim of Tap Social and its various enterprises is to ensure employment for prisoners after they are released, reducing reoffending rates and increasing national productivity through this untapped labour market. In their annual “impact” progress report, the company founders outlined their mission statement: To “demonstrate that employing prisoners and prison leavers is a good business decision through our first-class products”, “raising public awareness of the problems and solutions (in the prison system) and working hard to make it as easy as possible for companies to employ prisoners through national and local policy reform”.

Rory, a prison leaver and employee of the tap social movement summarised his experience as an open category prisoner, securing employment in a Tap Social bakery. Rory describes a dignified work environment where

“I don’t feel judged or looked down upon for coming from a prison, I’m treated with respect and dignity”.

He describes learning “hard skills like baking”, as well as “soft skills, I have learned to improve my communication, diligence and tolerance”. Through Tap Social and the open prison system, Rory has developed the necessary skills and confidence to successfully reintegrate into society. He has secured accommodation, future employment and has even founded a clothing company.

Like any criminal system, open prisons pose limitations and drawbacks. Not all inmates in the UK are eligible for open prisons, the selection process is quite rigorous. This is compounded by limited capacity in open prisons across the UK, resulting in long waiting lists of eligible candidates. Moreover, public perception of open prisons is mixed. Some people have concerns about the concept of an open prison, fearing that inmates may take advantage of the system or pose a risk to public safety.

There are around 20 prisons in the UK, and, this number is growing. There is growing recognition of the benefits in terms of rehabilitation and reintegration. This is symptomatic of a broader focus in the criminal justice system on providing more flexible and effective approaches to offenders’ transition back into society.

Super challenge

Are there any businesses near you that help to support former prisoners and prisoners on day release?

27

28 Caravaggio’s Medusa

Reframing Beheadings: Caravaggio’s Medusa and Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

HISTORY OF ART

Author: Lily Middleton-Mansell, English graduate, St John’s College

This article was written to be a little more challenging, either in content, theme or style – give it a go if you want to push yourself even further!

By examining visual art, you can witness for yourself the punishments of the distant past. Representations of punishment are a key part of the history of art, both demonstrating historical responses to crime and exploring the social conflicts that they represent. Italian Art in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is known for its particularly bloody depictions of violent punishment, using special artistic techniques to create dramatic effect. This article explores the role of punishment in art through two near- contemporary Baroque paintings of beheadings: Caravaggio’s Medusa and Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes.

Caravaggio’s Medusa depicts the moment in Classical Greek mythology when Perseus slays the gorgon Medusa. Medusa was once a human, but the goddess Athena turned her into a monster as a punishment after the god Poseidon had sex with her in Athena’s temple: Medusa’s hair was transformed into snakes and anybody who looked at her would be turned

into stone. Perseus, the demigod son of Zeus, eventually succeeded in decapitating Medusa using various gifts from the gods, including a mirrored shield from Athena. Instead of looking directly at Medusa (and being turned to stone), Perseus looked only at her reflection, thus managing to escape Athena’s curse. Caravaggio takes the figure of the shield and turns it into a canvas for his picture of the just-beheaded Medusa, painting the decapitated head, with the image cut off at her still-spurting bloody neck, on an actual commemorative shield.

The period in which Caravaggio painted Medusa was marked by several run-ins with the law: he witnessed a crime and was arrested multiple times after being accused of various offences. Caravaggio’s painting emphasises the complex networks of punishment that underline the Greek myth. Medusa’s initial punishment from Athena (being turned into a Gorgon) does not close the matter of her apparent crime against the goddess, but rather becomes the cause for a second punishment: Perseus then slays her due to her ability to turn people into stone, which was caused by this transformation into a Gorgon. Caravaggio’s decision to use

a shield as his canvas captures this complicated nature of punishment as something that can extend the violence of a crime rather than resolving it. Not only is Medusa immortalised, in a painful irony, in the very reflective surface that aided her own demise (Perseus’ shield). But her apparent crime (turning people into stone) is also extended regardless of her punishment. After Perseus beheaded Medusa, he took her head, which still turned onlookers to stone, as his own weapon, before eventually giving it to Athena to place on her shield. The use of her decapitated head as an object of war means that her death did not stop her from turning people into stone, but rather facilitated it further through its role on the battlefield.

This interpretation can be used to make a wider comment on the nature of crime and punishment in Caravaggio’s own society.

Caravaggio’s painting is not just a picture of punishment in action, it also demonstrates the fact that punishment does not necessarily put an end to violent crime.

29

Rather, it simply draws it into more socially-acceptable systems such as the justice system or the military. Consider why is it a punishable crime for Medusa to turn people into stone when her head is attached to her body, but when it is decapitated and wielded by Perseus the same head becomes a weapon for justice, used to fight a war and displayed on the shield of the very goddess who initially condemned her. These complex networks of punishment, emphasised by Caravaggio’s use of a shield as the canvas for Medusa’s beheading, demonstrate that punishable crime is often not a question of judging the action itself, but rather the status of the person responsible. Why is punishment, which is often also a form of violence (emphasised by the blood Caravaggio paints dripping

from Medusa’s neck), considered distinct from the crime it echoes? Does the relationship between crime and punishment function to excuse as well as prevent forms of violence, when exercised by figures of authority?

The most striking aspect of Caravaggio’s depiction of Medusa is the fact that, despite her decapitated state, her intense expression makes her still appear alive. Caravaggio was known for his talent in chiaroscuro, a painting technique developed during the Renaissance period, characterised by the contrast of light and dark to heighten realism and dramatic effect. Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro in Medusa results in a strikingly human embodiment of Medusa’s death. Many feminist scholars have read Caravaggio’s painting as a vivid display of the misogyny that pervades

both Classical and Caravaggio’s society. More modern readings of the Medusa myth interpret her encounter with Poseidon in Athena’s temple as an instance of sexual assault, for which she, instead of Poseidon, is punished by Athena - an injustice typical of patriarchal society. In this sense, therefore, Caravaggio’s violent depiction of the monstrous Medusa’s punishment can be taken as reflecting misogynistic perspectives of crime and punishment in his period, in which female victims are presented and punished as perpetrators.

However, this interpretation is complicated by the fact that Caravaggio uses his own face as the model for Medusa’s head. This, alongside the liveliness of Caravaggio’s painting style, undermines readings of his depiction as dehumanising. While Caravaggio often used his own face in his paintings, his decision to do it for a female subject makes this particular instance stand out. It suggests a personal identification with Medusa that undermines conceptions of her as a perpetrator and a monster. This nuance to Caravaggio’s depiction of Medusa does not completely eliminate the misogyny that underlies it, but it does complicate the gendered power structures of the painting. As demonstrated at the start of this article, Caravaggio’s use of the shield as a canvas highlights how punishment often perpetuates violence as well as preventing it, and his projection of his own face onto Medusa’s encourages a more empathetic view of an apparent perpetrator, making room for a critique of the systems of punishment in his

30

SUMMARY VIDEO > LINK >

Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes

Have your say

What interpretation do you have of the two paintings?

society. This demonstrates that, while systems of crime and punishment in Caravaggio’s (and Classical) society were inherently misogynistic, art represents a means of expressing critiques and complications of such misogyny within the same society. The study of art helps to locate ideas and opinions throughout history that have more nuance than the political consensus of the period.

If you want to explore this complex position of art within the political atmosphere of a society through the work of a female painter, it is worth considering another depiction of beheading: Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes.

The painting depicts an episode from the Old Testament, in which Israelite heroine Judith, helped by her maidservant Abra, beheads the Assyrian general Holofernes after he has fallen asleep in a drunken stupor. Caravaggio painted the same scene some years earlier, but Artemisia, while likely influenced by Caravaggio’s depiction, focuses more on the female perspective of the story. The painting has been linked to the Renaissance “Power of Woman” theme, the practice of using figures from the Bible, ancient history or romance to emphasise female-centric themes: female power, the importance of love, the trials of marriage. Gentileschi’s painting reverses the typical power positions of women in seventeenth century

Should graphic content, like punishments, be depicted in paintings or the media? Vote now!

society, presenting them as holding the authority to enact punishments, rather than as the victims or perpetrators (as women were usually framed). Some critics interpret the violence of the painting as a form of artistic revenge following the rape of Gentileschi by Agostino Tassi in 1611. For women, who had little to no legal or political power in seventeenth century society, art could act as an outlet for their desire to punish their male oppressors. Gentileschi was heavily influenced by the work of Caravaggio, also using chiaroscuro, and the blood spraying from the head of Holofernes echoes the jets from Medusa’s neck. However, by including the murderers themselves in the frame (Judith and Abra) - rather than, like Caravaggio, cutting the painting off at the neckGentileschi cuts through the ambiguity of Caravaggio’s presentation of the relationship between crime, gender and punishment in his painting of Medusa and instead presents a striking display of female action and, most notably, strength. The giant fist of Holofernes at Abra’s neck does little to prevent their vengeance, undermining the usual assumption of male physical power over women. Both beheadings demonstrate how art can bring nuance to the legalities of crime and punishment, in particular providing space to question the gendered power structures underlying them. They demonstrate how, when approaching visual art, a reading that compares the paintings’ sources, their society and the implications of their execution can bring forth a complexity which may not be immediately apparent on first sight.

Want to find out more?

LINK >

● Watch this video by Mary Beard about the silencing of female expression and adaptations of Caravaggio’s Medusa over time: (180) Mary beard - women & power - YouTube

If you’re also interested in conversations about how race was understood in Classical times, read these articles about the debate over a BBC video about Roman Britain:

LINK >

● If Mary Beard is right, what’s happened to the DNA of Africans from Roman Britain? | Roman Britain | The Guardian

LINK >

● A Kerfuffle About Diversity in the Roman Empire - The Atlantic

Super Challenge

Find another painting that links to punishment. Design a poster that includes this painting and your analysis of it. Consider what you can see and what this suggests about punishment at the time it was created, about the society/individual, or the crime that was supposedly committed.

31

Prison break?

32

How do Prisons use Science and Technology to Improve Security?

TECHNOLOGY

Author: Ben Mesure, Worcester College graduate

Greek philosophers, such as Plato, first explored the notion of using punishment as a means to reform offenders. Imprisonment in the desmoterion (“place of chains”) was most often reserved for Athenians who were unable to pay fines. The Romans later developed the concept of prisons, adapting existing structures into detention centres, often featuring metal cages. The Mamertine prison, established in 640B.C., consisted of a large network of dungeons within a sewer system beneath Rome.

Whilst the premise and purpose of prisons established by the Romans have remained strikingly similar into the present day, the science and technology which inform how prisons function have evolved significantly.

PRISON SECURITY SYSTEMS

Security technology has developed exponentially over the past century. Between 1610 and 1776, England adopted a practice of punishment by exile: convicted criminals were imprisoned aboard prison ships destined for penal colonies, such as those in America. At a time when cross-Atlantic sailing was the pinnacle of progress, technology, and Empire,

what could be more secure than isolating your convicted criminals aboard a ship destined for the New World? Today, prison ships feel a far cry from advanced technology. Maximum security facilities in the 21st Century hold the convicted under lock and key on home soils, where technological advances enable secure detainment.

ARCHITECTURE

18th Century philosopher, Jeremy Bentham, devised architectural plans for a new type of prison: The Panopticon.

Bentham envisaged it as a circular building with the prisoners’ cells arranged around the outer wall, and an inspector occupying the centre. From this tower, the prison’s inspector could look into the cells at any time, though the prisoners would be unable to see the inspector. The prisoners would therefore have to assume that they were being watched at all times and behave in order to avoid punishment if they breached the Panopticon’s rules. Many countries replicated this design with Cuba having the largest, until it closed in 1967.

You can see how the Panopticon worked in this video.

The first line of defence in prison security is to utilise architecture to ensure security. Many will be located to use surrounding geographical features – think of old castles using moats or Alcatraz prison being on its own island north of San Francisco. Prisons have historically utilised features like fencing and high walls to minimise the chance of escape. As technology has developed, these have been advanced, such as through the invention of barbed wire, invented originally within agriculture but weaponised during World War 1. Perimeter security has developed further with technological advances. For example, electric fences improve the security of standard fences. Modern prisons are also often built with guard towers – structures which improve the perimeter view for guards and, in some circumstances, provide a space from which snipers can aim.

33

LINK >

This also exemplifies another aspect of the ways in which prisons improve security: by adapting technological advances in other industries to be repurposed within a security and punishment role. From prison ships, to barbed wire, to the use of weaponry: these advances all were conceived within different contexts, yet have all served a role within prison security.

An interesting example of prisons adapting scientific advances to inform prison architecture has been in the use of Baker-Miller pink. In the 1960s Alexander Schauss studied the psychological and physiological response the body can have to different colours. During his studies, he observed that a particular shade of pink, which he named BakerMiller pink, had a calming effect on observers, with a lowering of heart rate, pulse and respiration, and, as an effect, levels of aggression. The concept has been controversial, and many more recent and more robust studies have somewhat discredited the concept. Nevertheless, many experiments have been conducted within prisons in which cells have been painted BakerMiller pink to psychologically influence aggressive behaviour from inmates. It is not only technological inventions that have informed prison architecture and security; other scientific research, such as in psychology, is also regularly adopted in the hope of influencing behaviour.

21ST CENTURY TECHNOLOGY

Security systems go beyond just the architectural design of prisons. Prisons are also equipped with cutting-edge devices and infrastructure which improve security.

Surveillance Technology: cameras are commonplace in cities to deter and monitor crime. CCTV is an essential

part of the security infrastructure within prisons, enabling guards to observe the entire complex remotely. Surveillance technologies are moving beyond just traditional cameras: prisons are increasingly using LiDAR technology. LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) is a form of remote sensing that uses light pulses to create 3D images with fine detail. LiDAR and other monitoring technologies, such as motion and heat sensors, enable superior surveillance compared to traditional cameras.

Aerial Security: an increasing issue in prison security has been the use of drones to smuggle in contraband items. Creating an aerial perimeter using virtual tripwires to alert security teams to drones entering prison air space is possible. Additionally, prisons may utilise drones themselves as an additional aid in patrolling the perimeter.

Scanners: a common mental image associated with visiting prisons is that of security searches to ensure visitors do not smuggle in contraband items. The use of body scanners, metal detectors, and X-ray machines can be used effectively to conduct body searches in a non-invasive way. Such technologies are also better at finding items smuggled in unconventional places.

Biometric Technology: biometrics measures and analyses people’s physical and behavioural characteristics. Characteristics measured by biometrics may include fingerprints, facial recognition, and voice analytics. The technology is mostly used for identity verification – such as unlocking a smartphone using your fingerprint – so can be used within prisons to control access to certain spaces for both inmates and staff. It can also be used to identify perpetrators of crime: by analysing

fingerprints, facial footage, or even footage of how someone walks, we can potentially identify who committed a crime.

Personal Protective Equipment: prison technology is not just about keeping inmates from escape, but also about keeping everyone safe. Prison guards will often wear personal protective equipment (PPE) whilst on duty. This can include personal radios, body-worn cameras, and man-down sensors. Using these technologies, a central team can monitor staff to track their position and condition at all times, ensuring they are kept safe.

Technology as Reward: some prisons prioritise rewarding good behaviour rather than adopting more of a punishment-based approach to incarceration. Technology can be an effective incentive for good behaviour, such as accessing a TV in your cell, gaming consoles, and internet access.

Super Challenge

Prisons have always used the most up to date science and technology to inform their design and operation, ensuring they are as safe and secure as possible.

Using the ideas discussed here, which technologies would you adopt in order to design a high security prison? Draw and design your plan to include labels explaining why you have chosen those technologies. Your plan should fit on an A4 page and can be done by hand or electronically. Can you figure out a way in which you could escape your high-security prison?

34

INSPIRE CRITICAL THINKING SUMMER SCHOOL FOR YEAR 11

Are you looking for something fun and CV-boosting to do this summer? Then why not apply to our Inspire Critical Thinking (Year 11) Summer School!

Our Inspire Summer Schools offer you the opportunity to experience life as an Oxford student by staying in St John’s Halls of Residence, taking part in exciting academic sessions, and getting involved in fun extra-curricular activities! The Year 11 Inspire Summer School programme includes:

•Exciting academic sessions in a range of subjects

•A lecture from Dame Professor Sue Black

•A Garden BBQ and Formal Dinner in our beautiful Hall

•Theatre performances, punting, museum trips and more!

The Inspire Critical Thinking (Year 11) Summer School will take place Monday 29th of July – Thursday 1st August, and is entirely free of charge.

Applications will open later in the Critical Thinking cycle and we will consider your engagement with the Critical Thinking workshops (submitting super challenges) as well as contextual information as part of your application.

35

APPLY HERE! LINK >

St John’s College Virtual Summer School

12th - 16th August 2024

Open to anyone on Inspire Critical Thinking! You will receive an email invitation in the summer.

What’s included?

• A range of academic talks

• Featured career talks

• An essay competition with prizes

• Study and revision guidance

• Information on our other outreach programmes

37 S P OTLIGHT O N OXFORD

University Spotlight: Paintings of Punishment in the Ashmolean Museum

ART HISTORY

Author: Lily Middleton-Mansell, English graduate, St John’s College

The Crucifixion of Christ may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about crime, but a visit to the Ashmolean Museum, the main art museum in Oxford, highlights the complex role that it plays in early depictions of punishment. In the Bible, Jesus was arrested (after being accused of blasphemy) and tried by the Sanhedrin and then Pontius Pilate, who sentenced him to flagellation two followed by crucifixion. Jesus was then entombed (and eventually resurrected). The Crucifixion, therefore, is a depiction of punishment: the fact that Jesus is hung on the cross between thieves emphasises the event’s place as part of a Roman justice system that was made for ordinary citizens. Part of the function of this is to emphasise Christ’s humanity. Under Christian doctrine , Christ was born a man, and died like one too. His place among criminals demonstrates that he died like an ordinary sinner. The religious reason for the Crucifixion was to redeem humanity of the Original Sin, while also encouraging people to repent for their own personal sins. Christ represents all of humanity, but at the same time transcends humanity through this universal representation, as his punishment pays for all sins

rather than just his own. In this sense, the justice of the Crucifixion in fact lies in its absolution of crime – that of the Original Sin. Artistic depictions of the Crucifixion emphasise this possibility of punishment as a symbol of forgiveness, a goodness attached to the violence of crime. Explore this virtual tour of the Ashmolean’s Crucifixion paintings in order to consider their implications for conceptions of crime and punishment.

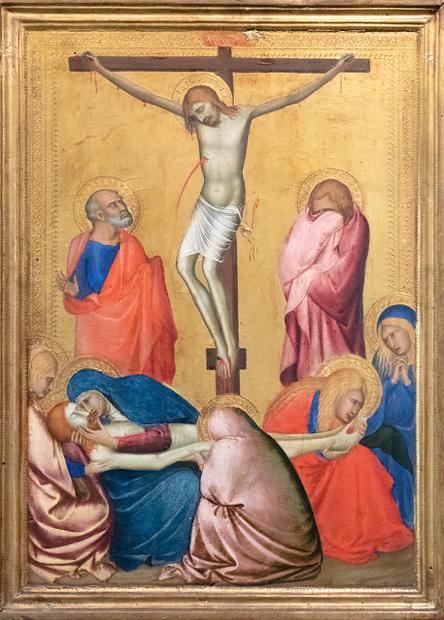

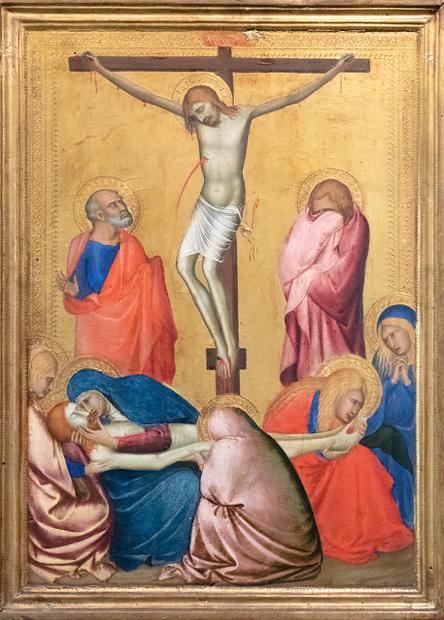

The Crucifixion and Lamentation (Tempera and gilding on panel, integral frame, around 1317-56) by the Circle of Simone Martini, possibly Lippo Memmi: Christ on the cross is flanked by Saint Peter and Saint John the Evangelist. The body of Christ is mourned by the Virgin Mary at his head, and Mary Magdalen at his feet, with three other women. The combination of the Crucifixion and Lamentation is very unusual and creates a highly emotional narrative. This expressive image was once the right-hand part of a pair of panels hinged together, forming a diptych. They were portable works that could be used for private devotion.

CRITICAL THOUGHT

● This painting brings two bodies of Christ into one image: Christ dying (in the Crucifixion) and Christ dead (in the Lamentation). In doing so, the artist transforms a scene of punishment into a scene of mourning. The emphasis is less on Christ’s punishment than its wider consequences - the human, emotional response to Christ’s death.

● The vivid red blood dripping from Christ’s hands, side and feet echoes the brightness of the Saints’ clothing,

38

S P OTLIGHT O N OXFORD

bursts of colour that contrast with Christ’s otherwise pallid form. In 14th century art, fine, colourful clothes were often used to represent high social standing. The parallel between Christ’s red blood and the Saints’ red cloth therefore suggests that his wounds are a symbol of status, rather than the public shame that punishments such as crucifixion are meant to represent.

● The fact that the painting used to be part of a diptych, made to be portable, highlights the continuous nature of private devotion. Viewing a painting in a Museum gallery usually only involves seeing it relatively briefly, perhaps once or twice if you decide to return. But this piece was originally made to be contemplated regularly and for long periods by the same person. Punishment is often seen as something that closes the conversation - it represents the end point of a crime. However, depictions of punishment in paintings such as this instead use it to start a conversation or a line of thought. Paintings of the crucifixion were intended to shape the daily actions of their perceivers, to remind them of the belief that Christ died so that they could live a life free of sin.

Think piece

1. Do you think that a crime has taken place in this painting? If so, why? What crime has been committed?

2. How does the use of colour in this painting impact our perceptions of the punishment it depicts?

3. Why do you think the artist decided to depict both the Crucifixion and the Lamentation in the same frame?

Saint Francis (tempera and gilding on panel, around 1480) by Nicola di Maestro Antonio d’Ancona: Saint Francis of Assisi opens his habit to reveal one of the wounds of Christ on his body, a sign of his holiness. With its companion, this shaped panel formed part of a large altar-piece once in San Francesco delle Scale, Ancona. It was painted about 1480. The expressive figures are painted on gold. This technique was becoming less common by the late 1400s.

CRITICAL THOUGHT

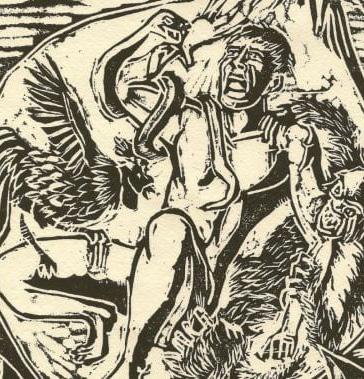

● Saint Francis gained the wounds of Christ (or ‘stigmata’) after having a vision on the mountain of Verna. Brother Leo, who had been with Francis at the time, said: ‘Suddenly he saw a vision of a seraph, a six-winged angel on a cross. This angel gave him the gift of the five wounds of Christ.’ Suffering from these wounds and other illness, he was brought to a

hut and spent his last days dictating his spiritual testament, until he died while singing Psalm 141, ‘Voce mea ad Dominum.’

● The sight of Saint Francis’ fingers in his wound is a visceral reminder of the violence suffered by Christ. It also emphasises both Christ’s (recalled by the model Francis holds of him on the cross) and Saint Francis’ embodiment: the viewer is reminded of the physicality at the core of the Crucifixion. This painting reverses the value associated with punishment. Rather than Christ’s wounds being depicted as a negative thing, an affliction, they are represented as a blessing. Francis’ expression is not horrified at his injury, but rather peaceful and contemplative.

● This portrait, like the first painting, is painted on gold. This kind of gilding was often used in the late medieval period to emphasise the importance of a work of art and the high status of what it represents. While most depictions of crime and punishment are likely to go for a much more sombre background, the gold detailing on paintings such as this mark its difference from more ordinary pictures of violence.

Think piece

1. Are the wounds of Saint Francis a punishment or a reward? Why?

2. How does this painting use a different perspective of violence than that associated with crime?

3. What impact does the material of a painting (such as gold gilding) have on its interpretation?

39

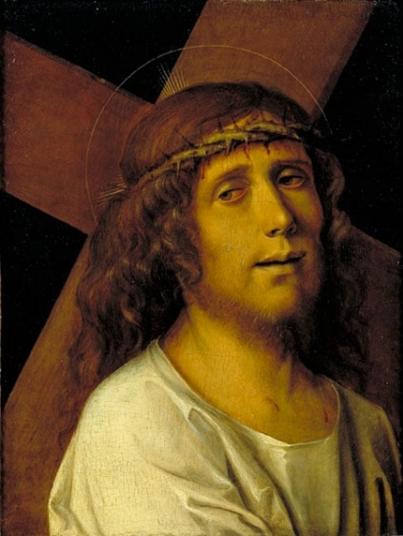

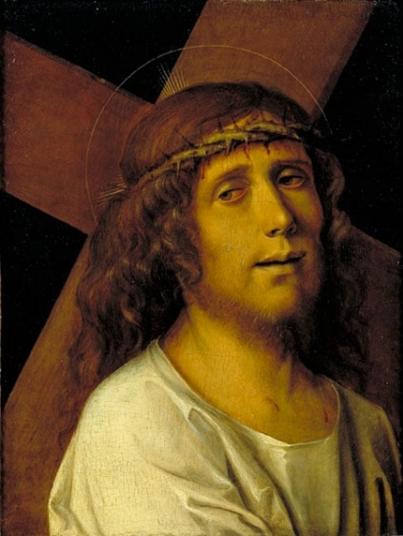

Christ carrying the Cross (oil and tempera on panel, around 1450-1523) by Bartolomeo Montagna: A close-up view, this was intended as a graphic reminder of the agony of Christ during the Passion. This kind of private devotional image became popular in the early 1500s in Venice, especially in the circle of Giovanni Bellini and Titian.

CRITICAL THOUGHT

● This painting focuses less on the physical violence of the crucifixion than on Christ’s emotional response to his punishment. Through his realistic facial expression, the viewer is encouraged to identify with Christ as a person.

● Nevertheless, the blood dripping from Christ’s crown of thorns, highlighted by the redness encircling his eyes, reminds the viewer of the story behind his pain. The crown of thorns was placed upon Christ’s head by the Roman soldiers in order to mock his claim of authority as the son of God - it was part of his

punishment. However, in artistic depictions of the crucifixion, the thorns have come to represent the very authority and status that they were made to ridicule, as they function as a symbol of Christ that allows viewers to identify his elevation above other sufferers.

● The close-up framing of this painting gives it a sense of intimacy. The viewer is made to confront Christ directly, rather than perceiving the Crucifixion as part of a wider scene (as in the first painting in the tour).

Think piece

1. How does the intimacy of this painting impact perceptions of Christ’s punishment?

2. What elements of the painting differentiate Christ from other victims of punishment?

3. What kind of expression does Christ have in this painting? How should it make the viewer feel?

Barrett Browning’s translation of Aeschylus: ‘Night shall come up with garniture of stars to comfort thee with shadow.’

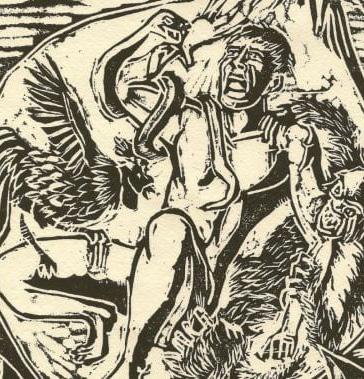

CRITICAL THOUGHT

Prometheus (oil on canvas, 1889) by Briton Riviere: Riviere studied at St Mary Hall, Oxford, and with his father, a drawing master, and later became well known for his paintings of animals and subjects from mythology and history. In Greek mythology, Zeus banished Prometheus for several acts of defiance, by ordering him to be tied to Mount Caucasus, where every day an eagle devoured his liver, which was restored during the night. This depiction of the fall of night, and the coming of relief, was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1889 with a quotation from Elizabeth

● While this is not a painting of the Crucifixion, both the imagery and the story behind it hold similarities with that of Christ. The Y-shaped position of Prometheus on the rock, with his arms apart and his legs tied together, recalls the pose of Christ on the cross. Prometheus, like Christ, is presented as a martyr for humanity. The painting depicts his punishment for stealing fire from Olympus and giving it to humans. This piece can therefore be understood as representing a secular (in the 19th century) version of a similar sacrifice and punishment to that of Christ. In Western Classical tradition, Prometheus has come to represent human striving, especially for scientific knowledge, and the tragic

40

consequences that can come from it.

● The dull lighting and sombre colours of the painting create a general atmosphere of despair. However, the faint stars in the distant sky represent a symbol of hope, of relief beyond Prometheus’ punishment. While traditional motifs of light and dark tend to present the day as a good omen, while the night brings foreboding, in the story of Prometheus this pattern is reversed as his liver, eaten by an eagle during the day, is restored overnight. The painting therefore suggests that hope can be found in darkness, just as the story of both Prometheus and Christ imply that punishment can be a symbol of good rather than criminality, when it is understood as a sacrifice.

● The dramatic position of Prometheuschained to a cliff-face rather than nailed to a cross - emphasises the powers at work behind this punishment. This is not a misplaced punishment enacted by humans (as in the story of Christ), but rather a fate decreed by the Ancient Greek gods.

Want to find out more?

1. Is a secular understanding of religious stories useful for thinking about crime and punishment? In what way?

2. Is it okay for certain crimes to be committed in order to serve a greater good?

3. How important is the authority of someone who enacts a punishment? What kind of different authorities are there in relation to crime and punishment?

Are you interested in finding out more about the pieces in the Ashmolean collection? Watch the videos below to learn about objects from a range of different places and periods.

● ANCIENT OLYMPICS | Ashmolean Museum

● ANCIENT EGYPT | Ashmolean Museum

● ANGLO SAXONS | Ashmolean Museum

41

LINK > LINK > LINK > S P OTLIGHT O N OXFORD Have your say

Introducing ... Oxford Journalism

OXFORD SPOTLIGHT

Author: Lily Middleton-Mansell, English graduate, St John’s College

Oxford University is known for its thriving range of newspapers and magazines, which are perfect for students interested in a career in journalism, or those just looking for an outlet beyond their academic work. Involvement in student journalism isn’t limited to people who are good at writing - publications also have positions in social media, events, editing, design and more. The newspapers and magazines often function as societies as well as publications, providing new social circles to those on the team and running events for the whole university. While there are too many different Oxford newspapers and magazines to include in one article, the four that follow demonstrate the diversity of student journalism at Oxford University.

CHERWELL

Founded in 1920 and named after a local river, the Cherwell is known as Oxford’s oldest student newspaper. The paper prides itself on its independence from the University of Oxford, being run almost entirely by students. Its first editorial declares its intention ‘to exclude all outside influence and interference from our University. Oxford for the Oxonians.’ However, over time it did become much more of a university-focused newspaper. Notable past contributors include Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, John Betjeman, L. P. Hartley, Cecil Day-Lewis

and W. H. Auden. Available both online and in print, the Cherwell keeps students updated on news across the university and Oxford as a whole, as well as running literary and comment pieces. It is also renowned for its long-running ‘John Evelyn’ gossip column, created in 1964, through which an anonymous member of the Oxford Union (the private society and debating club) keeps readers updated on all its drama.

Papers such as the Cherwell often see part of their role as holding Oxford University to account, as their articles highlight any controversies or issues students might have with the university. However, its main function is to keep students in the know about all aspects of Oxford University life.

ISIS

The term ‘Isis’ has a negative weight among the general public due to its political connotations, but in Oxford it refers to an arts magazine named after yet another river - the Isis in Oxford. Founded in 1892, the Isis spent some time as a rival to the Cherwell newspaper, but this antagonism was dissolved in the late 1990s when the magazine was acquired by the Cherwell’s publishing house, Oxford Student Publications Limited. The

magazine’s founder, Mostyn Turtle Piggott, intended the Isis to be an apolitical magazine, declaring that ‘We have no politics and fewer principles.’ However, this neutrality didn’t last too long. Today, the magazine’s website proudly declares that

‘We have been banned in Germany, threatened by blackmail, and mocked by Punch Magazine. Along the way our reporters have been prosecuted under the Official Secrets Act, hosted by Wikileaks, and forced to walk out over threats of editorial censorship during The Isis’s radical left-wing heyday.’

Every term, the Isis releases a theme to inspire submissions. The theme for October 2023 is ‘A Few Words for the Firing Squad’, asking students to ‘remove whatever silencers, muzzles, or mutes you may be using to make your voice more palatable. In a world where the arts are continuously asked to justify themselves, where temperatures are rising and democracies are flailing, we want to know what stories you tell yourself when your back is against the wall, what do you have to say for yourself?’ The magazine may not declare any specific political alliances, but it encourages a general philosophy of free speech and social criticism.

42

S P OTLIGHT O N OXFORD