Abbey Banner Spring 2022

Everything growing on earth, bless the Lord; Praise and glorify God forever!

John Geissler

Daniel 3:76

John Geissler

John Geissler

Daniel 3:76

John Geissler

Abbey Banner Magazine of Saint John’s Abbey

Spring 2022 Volume 22, number 1

Published three times annually (spring, fall, winter) by the monks of Saint John’s Abbey.

Editor: Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

Design: Alan Reed, O.S.B.

Editorial assistants: Gloria Hardy; Patsy Jones, Obl.S.B. Aaron Raverty, O.S.B. Abbey archivist: David Klingeman, O.S.B. University archivists: Peggy Roske, Elizabeth Knuth

Circulation: Ruth Athmann, Tanya Boettcher, Chantel Braegelmann

Printed by Palmer Printing

Copyright © 2022 by Order of Saint Benedict

ISSN: 2330-6181 (print)

ISSN: 2332-2489 (online)

Saint John’s Abbey 2900 Abbey Plaza Box 2015 Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-2015 saintjohnsabbey.org/abbey-banner

Change of address: Ruth Athmann P. O. Box 7222 Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7222 rathmann@csbsju.edu Phone: 800.635.7303

Questions: abbeybanner@csbsju.edu

Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for through it some have unknowingly entertained angels.

Hebrews 13:2

This Issue of Abbey Banner explores the Gospel and Benedictine value of hospitality. Saint Benedict, mindful of Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 25:35, insists that all guests be “received like Christ” (Rule 53.1). Over the centuries, monasteries have become rest stops and sanctuaries for pilgrims, an oasis of peace and quiet for retreatants, and occasionally a “bed and breakfast” for tourists seeking less expensive accommodations. Whatever the guests’ motives, Benedictine hospitality requires that all be treated with honor and reverence. Father Nickolas Kleespie reflects on both the hospitality of the unnamed woman from Shunem, who welcomed the prophet Elisha, and on the hospitality of the Catholic Worker Movement, asserting: “Through hospitality, through the sharing of our abundant resources and love, God is revealed.” Father John Meoska revisits those icons of hospitality, Martha and Mary, the Good Samaritan, and Abraham and Sarah, as he reflects on the relationship between hospitality and mercy.

Abbot John Klassen opens our Easter issue with a reflection on our resurrection faith and its call for action. Dr. Martin Connell examines the parallels between the passion of Christ and the pain and suffering of humankind during the COVID-19 pandemic. Whatever the source of the pain and suffering, we are called “to suffer (-passio) together (com-): to compassion.”

What is the Benedictine Volunteers Corps? Mr. Joseph Pieschel reflects on what he’s learning, how he’s changed, and his deepening faith during his adventures and service as a Benedictine Volunteer.

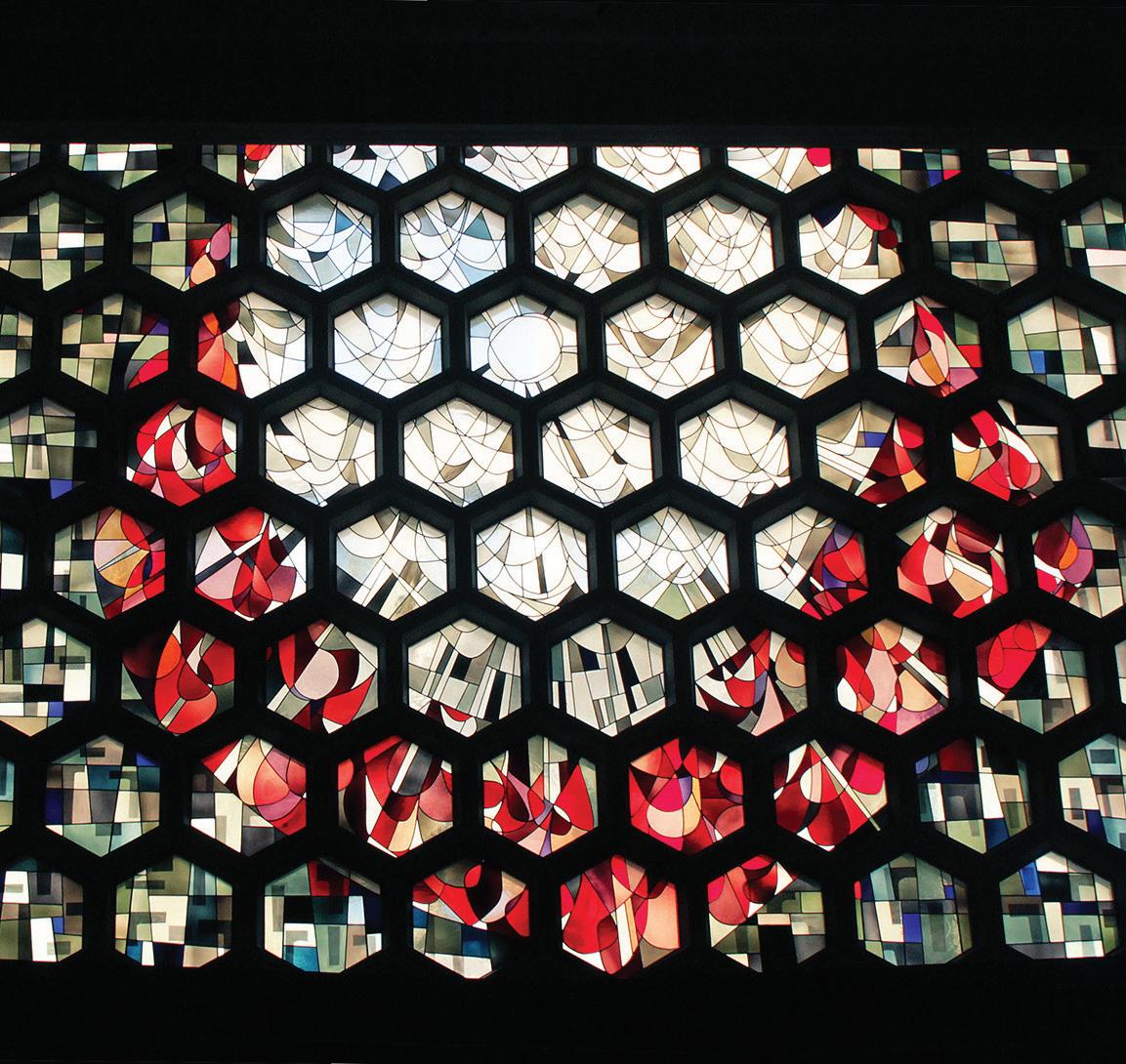

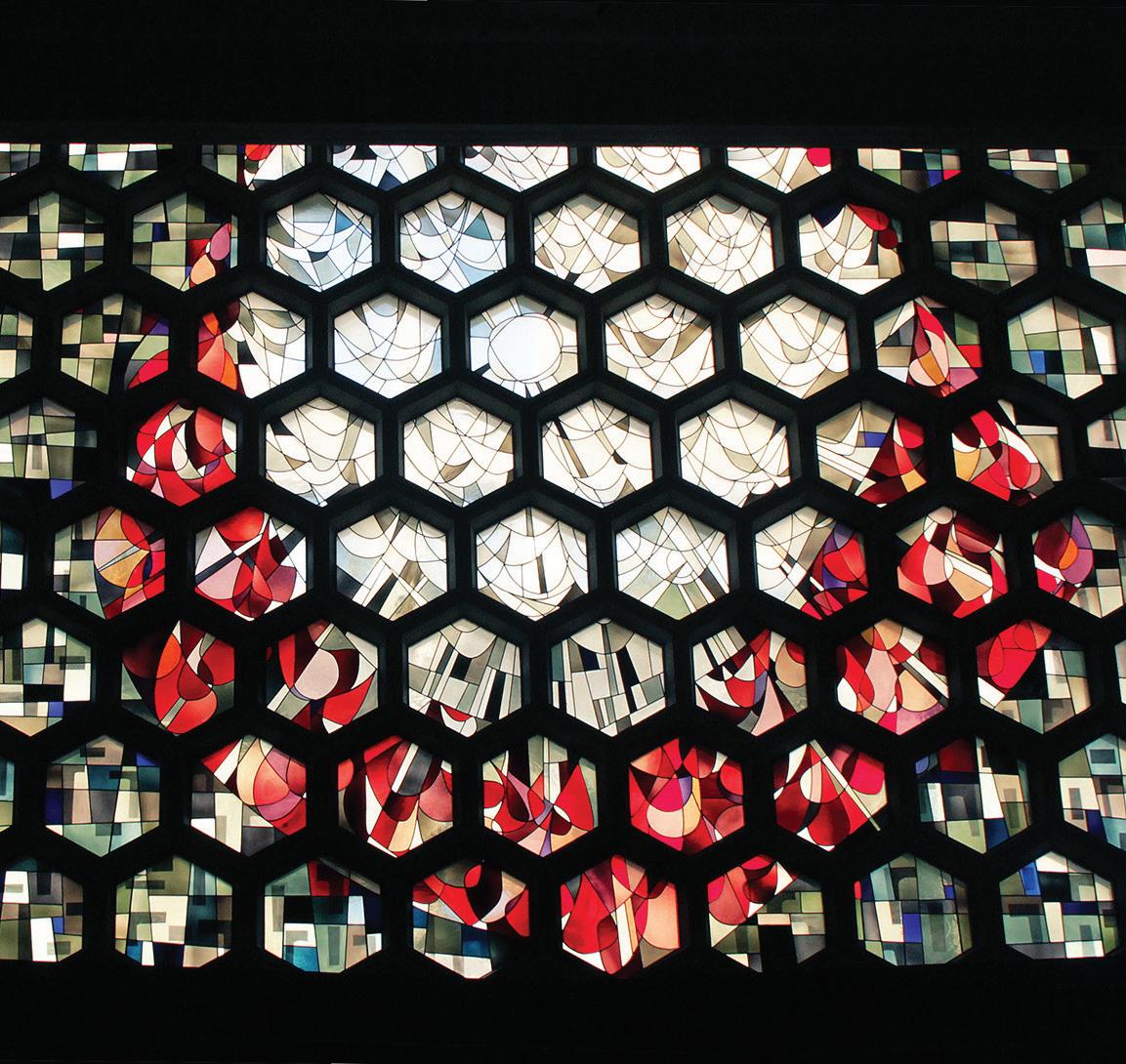

One of the most striking features of the Saint John’s Abbey and University Church is the north window—486 hexagonal panels of stained glass. We listen to Brother Andrew Goltz, the last living member of the team that worked with Mr. Bronisław Bąk to create Sursum Corda, “Lift up Your Hearts,” as he outlines the theme of worship and of the liturgical year, presented so dramatically in the window.

Resurrection faith calls us to respond with action.

Abbot John Klassen, O.S.B.

“Do not be afraid! I know that you are seeking Jesus the crucified. . . . He has been raised just as he said.”

Matthew 28:5–6

Human beings are afraid of many things. When we are little, we are afraid that we will be lost or that our parents will leave us stranded. Later we are afraid that we will not be liked, or that we won’t belong, or that we will look stupid. Still later, we are afraid that we will lose those we love.

Underlying all these fears is our awareness of our fundamental vulnerability as humans. We will never escape these fears—they are part of the human condition. But we have a risen Lord who walks with us, if we are willing to pray: “Into your hands, Lord, I commend my spirit, my life” (Luke 23:46). So often we are afraid because we are trying to control things beyond our control, thereby missing exactly those where we could make a difference.

When will we get back to normal? Whatever “normal” looks like, we know it will be different. Resurrection faith calls us to be confident, to trust that the risen Christ will walk with us and lavish the gifts of the Spirit on our families and communities. The Spirit will be the source of courage, wisdom, and resilience as we move into and create a new future.

Resurrection faith calls us to respond with action. First, resurrection faith calls us to conversion to the risen Christ. Our baptismal promises call us to resist sin that corrodes, undermines, and tears away at the fabric of our family, married life, or community. Saint Benedict urges us to avoid a false peace, to nourish kindness, to starve anger and resentment (Rule 4).

Cover: Sursum Corda, “Lift up Your Hearts,” central stained-glass panel in the abbey and university church, 1961

Designed by Bronisław M. Bąk

Photo: Alan Reed, O.S.B.

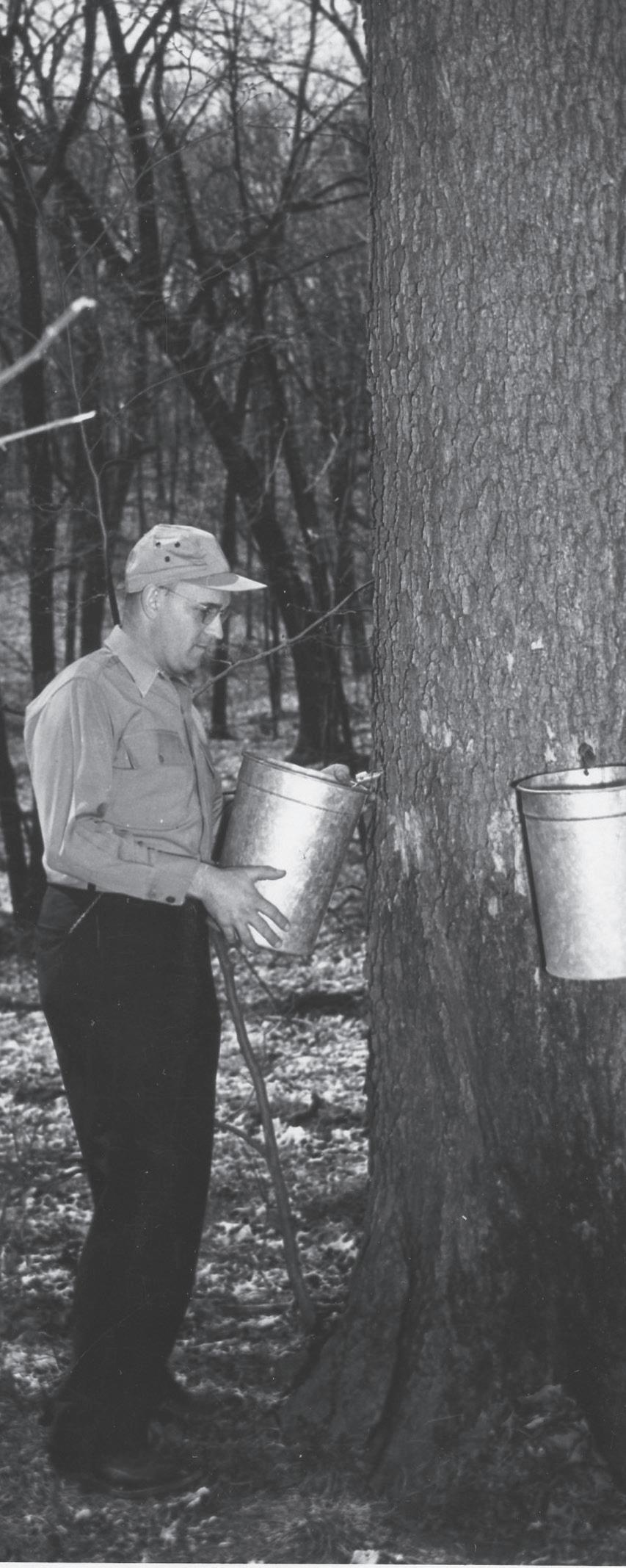

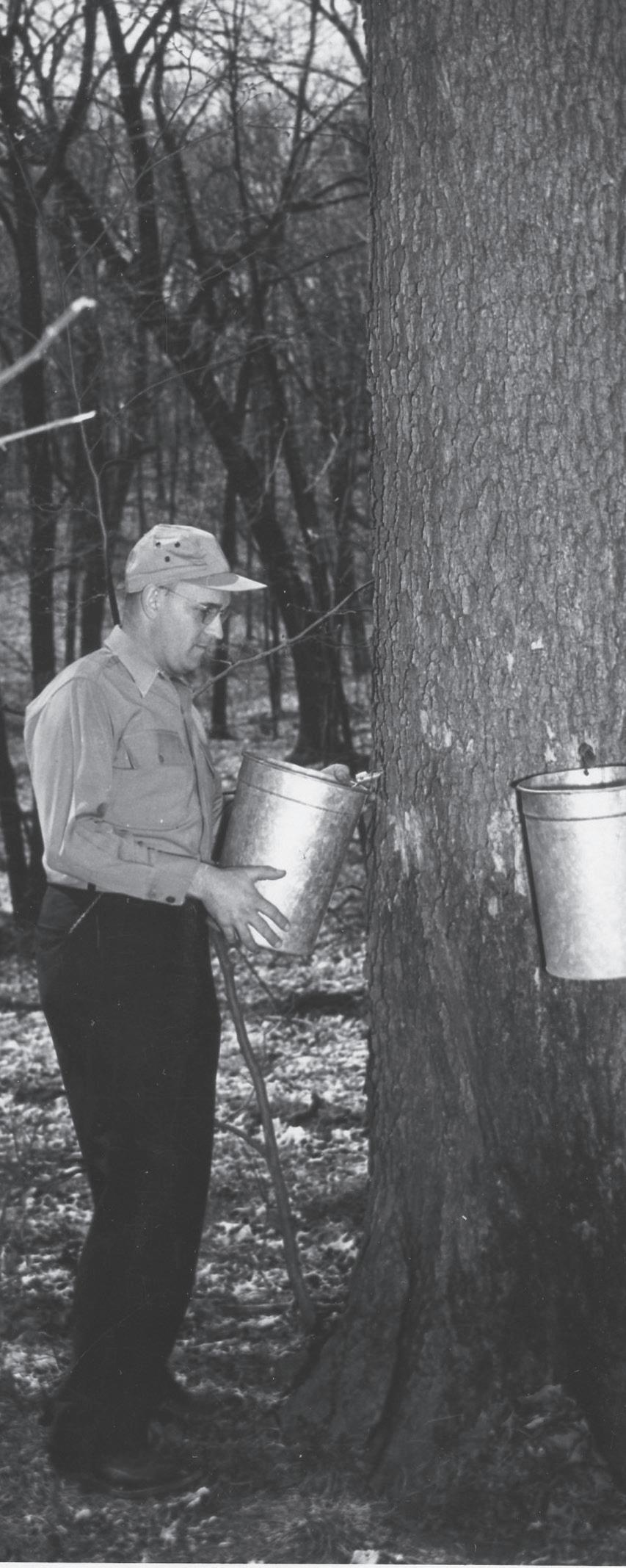

The fiftieth anniversary is golden; the sixtieth anniversary, diamond; and the eightieth is recognized as “oak.” At Saint John’s, however, maple may be more accurate. Brother Walter Kieffer shares the sweet details of our community’s maple syrup production during its eightieth anniversary.

Brother Aaron Raverty introduces us to a trio of monks, the Ortmann Benedictines. We also learn of the latest discoveries at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library; meet a monk from Currie; celebrate the gifts of the forest; illustrate the Year of the Tiger, and more.

The Abbey Banner staff joins Abbot John and the monastic community in offering prayers and best wishes to our readers for a blessed Easter season and a healthy spring. Peace!

Brother Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

Second, resurrection faith calls us to discern carefully the traditions, the rituals, the practices, the values that are core to who we are as families, businesses, and communities. We need to reflect carefully on what is nonnegotiable. If we have thrown something out that is important, we need to retrieve it as a necessary resource as we reinvent the future.

Third, resurrection faith calls us to help out. There are still many people who do not have the resources they need to get back on their feet. If we have resources as families or communities, we are called to be generous to help vulnerable people to make it through a very challenging time.

Easter promises a new Pentecost, a showering of gifts and blessings; a positive, creative response to our present situation. Through all of it, the risen Christ remains one with us.

Spring 2022 4 Abbey Banner 5

This Issue

Resurrection Faith

Abbey archives

Martin F. Connell

Still in the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Christian Church lifts up those who keep vigil with the worried and the symptomatic, with those who recovered, and with the countless who have died. Like Christ, the Church feels the world’s afflictions and sorrows and seeks divine intervention.

Now, as when Saint Benedict wrote 1,500 years ago, we know that “before all things and above all things, care must be taken of the sick, so that they will be served as if they were Christ in person” (Rule 36).

Christians might be consoled to learn that the Gospels’ Greek word for Easter is Πάσχα (Páscha), from πάθειν (pathein), “to suffer.”

Today, as in Christianity’s earliest centuries, Easter is not only a remembrance of Jesus’ resurrection but also of his passion and death. Easter during a pandemic takes us back to the cry of Jesus on the cross, “My God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46; Mark 15:34).

Christ’s suffering and Christian pain are illuminated in the stained-glass circle above the main entrance to the Great Hall at Saint John’s (the first abbey church) with the instruments used in the torture of Jesus. From left to right are a pincer, used to crush bones of criminals (John 19:36); a sponge, which the soldiers used to bring bitter wine to Jesus’ mouth (Matthew 27:34); a ladder, used

intersection of the crossbeams; Jesus’ robe, draped over the crossbeam; a pillar, to which he was bound, and reeds to whip him (Matthew 27; Mark 15; Luke 18:31–34; 23; John 19).

to lift and nail Jesus to the cross (John 20:25); a spear, with which Jesus’ side was pierced (John 19:34); and a mallet, to nail Jesus’ extremities to the cross. The neat, static arrangement does not match the dark, messy agony of Jesus’ death—or the agony of today’s sick and dying.

A Book of Hours in the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, written five-hundred years before the installation of the window, shows still more tools of pain. Here the torture devices surround Jesus in the Eucharist. Jesus stands on an altar, steadied by two angels, and around them are the tools: between the left angel and Jesus is the pincer; between Jesus and the right angel are the three nails that fixed Jesus’ hands and feet to the wood of the cross; under the right angel are three dice, recalling the soldiers who “cast lots” for Jesus’ seamless garment; in the upper right corner are the sponge and spear at the end of poles; the cross itself, here with the crown of thorns over the

These depictions are apt reminders of the passion and death of Jesus for us as we go to Mass to receive the Body of Christ and pray in adoration before it. Though redeemed by the death of Jesus of Nazareth, human suffering today weds us to the tortured body of the Palestinian Savior. Neither baptism into the Body of Christ nor eating and drinking of the Body and Blood exempt us from the inevitable suffering and death that visit all human life. Two years into a global pandemic, we are consoled that Jesus was “like us in all things but sin” (Hebrews 4:15). Among “all things” are suffering and death.

While the pandemic has brought immeasurable physical, emotional, and social pain, its agony also suspended attendance at the sacraments—our consoling remembrance of Jesus and his followers when his death was imminent. Like Saint Augustine just before his conversion, we confess: “I felt trapped and cast up my pitiful words, ‘How long, how long? Tomorrow and tomorrow?’” (Confessions, Book VIII, Chapter 12).

The details in the two works of art remind us that human suffering is never generic but tangible and concrete in its visitations. Whether pain comes from those who pierced the body of Jesus or from a pandemic transmitted without distinguishing sinful from righteous, we are called— by God’s Word, by the Eucharist, and by the Rule of Benedict—to suffer (-passio) together (com-): to compassion.

We see the processions lined up to receive the Body and Blood of Christ and remember the tools that wounded the body of Jesus. We also see gaps from the prepandemic procession to the sacrament, spouses turned widows and widowers, children turned parentless. We see blood flowing from the pierced side of Christ into the chalice, the cup we receive. We see the angels holding the body of Christ and pray for those who comfort the afflicted. With faith, we, the Body of Christ, don’t turn away from suffering. We keep processing forward to receive Christ’s body.

As the Church recovers and assembles as Christ’s body, our paschal sorrow is tempered with hope for brighter, better days ahead. We witness new life in the Easter baptisms the Church celebrates and hear what Easter has proclaimed for centuries: He is risen!

Title of Article Spring 2022 6 Abbey Banner 7 The Body of Christ in Pain

Dr. Martin F. Connell is professor of theology at Saint John’s University.

Alan Reed, O.S.B.

Mass of Saint Gregory from the Kacmarcik Book of Hours (Kacmarcik MS. 2; AARB 00002), Rouen, France, 16th century. © The Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, Arca Artium collection, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota. Used with permission.

Benedictine Volunteer Corps

Italy, Israel, and In-between Joseph Pieschel

With tears of awe in his eyes, a stranger opened his heart to me in a brief window of peace and rest during my first Friday of work. Standing in the rain and surrounded by a lush green landscape of palm, orange, and olive trees that is the backyard of my home in the village of Tabgha, Israel, he shook his head and looked to the sky, telling me what a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity this is for me: “The freedom! To stand in a new life and breathe the air and feel the culture around and within you, to go to the mosques and churches, to connect with people you know you will never see again, but it doesn’t matter because they are so important to you in this moment. To live and experience what it feels like to be alive on this earth! What a miracle! To know how fast life goes by and then death, and you know it’s right there. It’s amazing: to be your age and young and free! I have my wife and my child, and it just . . . I don’t know where that time has gone. It’s gone! Just like that!”

I was frozen by the gravity of the moment when, with a warm smile he said, “I envy you.” Chills ran through me, and I felt an overwhelming sensation of gratitude as I began to reflect more deeply on the question that began this whole encounter:

What is the Benedictine Volunteer Corps (BVC)?

My BVC journey began the day after I graduated from Saint John’s University. Under the guidance of BVC director Brother Paul Richards, I along with twenty other partied-out, freshly diplomaed Johnnies discovered the first Benedictine element to living a balanced life: prayer, work (ora, labora). Without phones, finals, friends, or family as distractions, we quickly formed a bonding brotherhood, living in community and learning each day (said Brother Paul) “more than you have in the last four years!” After two days, I called my parents to tell them I would not be returning home for the summer. Instead, I would begin my year of service early, waking up each day to participate in morning and then midday prayer, with the opportunity to take part in meaningful, diverse work in-between: collaborating with my college film mentor Brother SimonHòa, moving paintings with Father Jerome, working in the woodshop with Father Lew or in the abbey arboretum with

Brother Jeremy, and bottling maple syrup with Brother Walter. Connecting with monks within their specialties broadened my horizons and has grown my appreciation for the inner workings of Saint John’s, a place that for the rest of my life, I will call home.

Six days after learning of a temporary site opening, I found myself on an airplane to Rome and Sant’Anselmo, the international Benedictine house of studies. Soon I was busy washing dishes, mowing cloister lawns, cleaning the church, singing prayer in Latin, and enjoying multicourse lunches with a hundred monks of diverse origins. I was joining the life-or-death flow of Roman traffic on my way to learn Italian at Scuola Leonardo da Vinci. I was exploring museums, theater hopping the Rome Film Fest, and truffle hunting in the Bracciano countryside.

The Benedictine Volunteer Corps is a mosaic —something beyond its individual parts.

In an unexpected moment inbetween serving in Italy and Israel, I had my most meaningful experience in the Benedictine Volunteer Corps and one of the most powerful spiritual encounters of my life. While volunteering in Saint Raphael Hall, the abbey’s healthcare and retirement center, I was encouraged to introduce myself to Father Gordon Tavis, who had just found out that a dear friend was dying. I walked into his room, and he was crying, holding a book of prayers for the sick. All I could say at this delicate time

was: “I heard about your friend. I’m really sorry, and I want you to know that I’m here for you.” A moment later, Father Gordon learned that his friend was being placed on hospice care, likely with only a few more days to live. Less than an hour later, Father Gordon and I were with her. Gordon placed his hands on her, preparing to say goodbye to a friend of over sixty years, and explained: “I’m going to perform the Anointing of the Sick. Is that okay?” She mouthed, “Yes.” Together we prayed the Lord’s Prayer, and she mouthed every word.

The Benedictine Volunteer Corps is a mosaic—something beyond its individual parts. Like the honeycomb of our own abbey church, the world travel, the Benedictine life structure of prayer and work, serving others, the total immersion of self into another culture and way of life, each of these elements is beautiful on its own. But it is God who acts as the cement, connecting and breathing life into each element to form the whole. The day that I met Father Gordon, my life was missing the cement. I was unable to see past the parts. But as I watched him

breathe life into his friend with his words, and as we prayed the Lord’s Prayer, I could feel— deep in my heart—the Lord’s presence. God was revealed to me.

To all of those who make the Benedictine Volunteer Corps possible: grazie; toda raba; thank you.

Mr. Joseph Pieschel, from Springfield, Minnesota, is a 2021 graduate of Saint John’s University.

Spring 2022 8 Abbey Banner 9

BVC archives

Joseph Pieschel on the shores of the Sea of Galilee

One day Elisha came to Shunem, where there was a woman of influence, who pressed him to dine with her. Afterward, whenever he passed by, he would stop there to dine. So she said to her husband, “I know that he is a holy man of God. Since he visits us often, let us arrange a little room on the roof and furnish it for him with a bed, table, chair, and lamp, so that when he comes to us he can stay there.”

2 Kings 4:8–10

Nickolas Kleespie, O.S.B.

There is something profound about the actions of the unnamed woman of influence from Shunem. She sensed the prophet Elisha’s holiness, and she not only invited him in for a bite to eat and something to drink, but she also went beyond the norm and arranged a guest suite for him on the roof! If we hear, with Benedictine ears, her story and interaction with Elisha, we cannot help but think of her hospitality. She reminds us of Saint Benedict’s call to offer warmth, acceptance, and joy in welcoming others.

In chapter 53 of the Rule (On the Reception of Guests), Benedict challenges us to “Let all guests who arrive be received like Christ, for he is going to say, ‘I came as a guest, and you received me’” (53.1). Yes, this can be an overused catch phrase to describe a cliché Benedictine value, “Let all be received as Christ.” However, the Shunammite woman extended hospitality not out of a sense of duty or responsibility but as a very part of who she was. Hospitality became the

at times to assess what is at the center of our lives, to recommit to the mission, and to put Jesus and living the Gospel front and center in our lives. Hospitality is just one way we are called to take seriously what it means to live in newness of life.

identifying character of this unnamed woman—just as today monks extend hospitality, not out of an obligation to our observance of a Benedictine value but as an expression of our very identity. Benedictine hospitality means seeking Christ together, seeing Christ in the other and welcoming him or her into our midst.

A key element of how our community extends hospitality is through the ministry of the Saint John’s Abbey Guesthouse. The guesthouse mission states that “the Benedictine monks of Saint John’s Abbey welcome guests of all faiths to experience the abiding presence of God with a praying community.” Extending hospitality, however, is not merely the responsibility of those who minister at the guesthouse, nor the responsibility only of Benedictines. Rather, it is central to Christian identity. Indeed, all of us are called to a life of generous hospitality. All are called to welcome Christ in each person we meet.

It can be easy to take for granted why we do the things we do or even lose sight of our Christian mission. So, it is good for us

Jesus’ mission discourse (Matthew 10:40–42) elaborates on the theme of hospitality and its rewards. Jesus assures his disciples that mission in his name will involve them in the adventure of hospitality and will abundantly bless those who receive them. He makes hospitality central to the identity of a person who is to follow him. As in the case of the Shunammite woman and Elisha, Jesus promises, “whoever receives a prophet because he is a prophet, receives a prophet’s reward” (Matthew 10:41). An even larger context is revealed in the words “whoever receives you receives me, and whoever receives me receives the one who sent me” (10:40). In other words, Christian mission and hospitality are nothing less than living out a relationship with God.

Benedictine hospitality means seeking Christ together, seeing Christ in the other and welcoming him or her into our midst.

The adventure of hospitality is central to the mission of Catholic Worker houses across the country—an expression of their relationship with God. Through hospitality, through the sharing of our abundant resources and love, God is revealed. By feeding others, welcoming the homeless or those with criminal backgrounds, and advocating for peace and justice, the members of the Catholic Worker Movement demonstrate their commitment to the Gospel call to receive Christ and to offer a simple cup of cool water, the simple gift of love and hospitality. Dorothy Day writes, “When you love people, you see all the good in them, all the Christ in them. God sees Christ, His Son, in us and loves

us. And so we should see Christ in others, and nothing else, and love them. There can never be enough of it. There can never be enough thinking about it” (The Catholic Worker, April 1948).

Our Christian identity matters. It changes us. It calls us to rethink our value system, to review what truly counts, to

Christian mission and hospitality are nothing less than living out a relationship with God.

recommit ourselves to what will last against all odds. Jesus asks us today and every day to reimagine our commitment to hospitality, to be a community of people dedicated to witnessing to the world what life could be like if we were willing to be transformed and changed. In the Eucharist, Christ offers us his body and blood—like a cup of cool water shared with a guest, the sacrifice of total self-giving. This is a strong reminder of the abiding commitment God has to sharing eternal hospitality with each of us.

Father Nick Kleespie, O.S.B., is the chaplain at Saint John’s University where he also serves as a faculty resident.

Title of Article Spring 2022 10 Abbey Banner 11 Mission of Hospitality

The Christ of the Breadlines, woodcut by Fritz Eichenberg, 1951

Hospitality and Mercy

John Meoska, O.S.B.

The hospitality of mercy. The mercy of hospitality.

The Gospel story of our Lord’s visit with Martha and Mary (Luke 10:38–42) is often the springboard for reflections on the priority of contemplation over action. Our reflections may be more fruitful, however, if we substitute receptivity for contemplation.

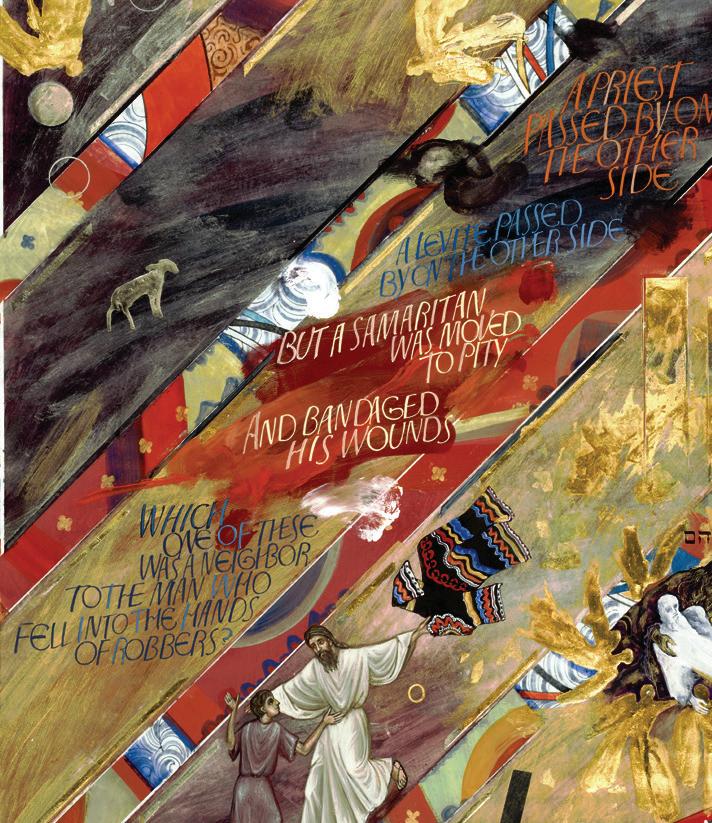

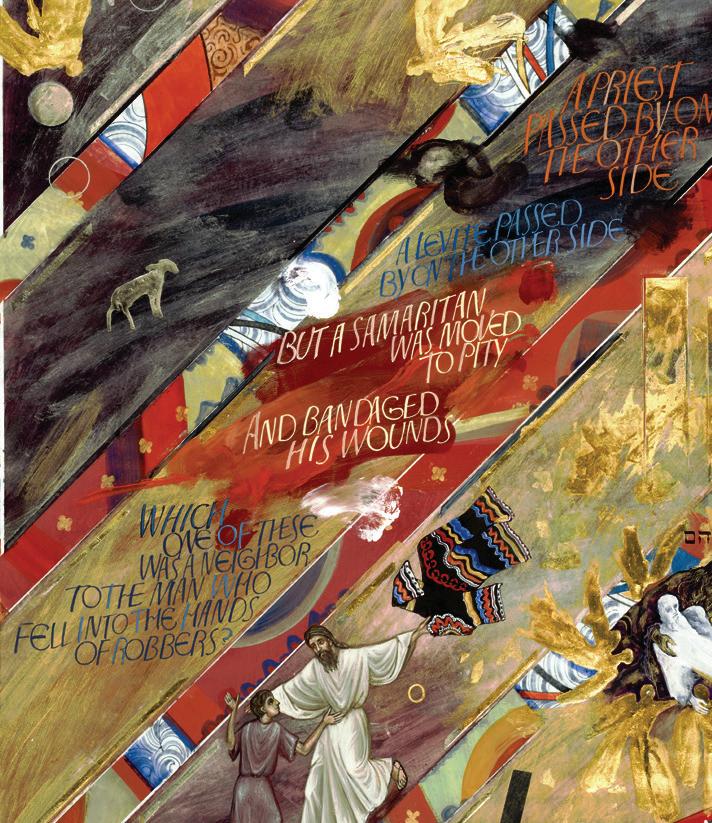

To understand the story of Martha and Mary, we need to consider the larger context of Luke’s Gospel. The overarching theme of Luke 10 is hospitality. Immediately before Luke introduces Martha and Mary, he tells the story of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37). It was the Good Samaritan who extended the hospitality of mercy to the man who was beaten and left for dead alongside the road. That parable of Jesus was prompted by a question posed by a scholar of the Mosaic Law: “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” (10:25). The question and Jesus’ answer were followed by an important, but often overlooked, statement: “but because he wished to justify himself, the scholar said to Jesus, ‘And who is my neighbor?’” (10:29). The scholar was seeking to justify himself; and Jesus responds with the parable about the hospitality or action of mercy. “Go, and do likewise,” says Jesus (10:37).

In the story of Martha and Mary, there is an almost imperceptible shift—in fact, a reversal of sorts.

Martha does something alright, but she takes it on the chin for her action! Mary seems to do nothing and is rewarded for her seeming inactivity! A case could be made, however, that Mary exemplifies the receptivity and presence that initiates hospitality, in contrast to the activity of hospitality exemplified by Martha. Many have firsthand experience of these two expressions of hospitality—such as

when we have delighted in a fine meal at a friend’s home but left hungry because the hosts spent the whole night fussing over the meal instead of being present to the guests. It is not merely food for which we hunger!

The scholar of the law asked Jesus: “What must I do to inherit life?” We could reframe the question as: How must I work out my salvation? Attending

to the corporal and spiritual works of mercy—the hospitality of mercy—is part of the story. Pope Francis focused on this often during the Year of Mercy (2015–16). The message of the Good Samaritan story and the exhortation of Pope Francis are the same: we must receive all God’s people and serve them with mercy. But before that, we must first receive the gift and author of our salvation, Jesus Christ. Jesus is the visible manifestation of God’s hospitality to humankind. In Jesus, God first welcomes us. Thus, Mary models for us our primary task: to receive the salvation that comes from God—the mercy of hospitality. And Martha models for us the salvific mercy we must extend to others—the hospitality of mercy.

In both the Old and New Testaments, hospitality is held in high regard. More than just a nice idea or option, it is a duty. And it is also a multifaceted virtue. The story of Abraham and Sarah (Genesis 18), for example, teaches us that the facets of hospitality are initiative, eagerness, generosity, courtesy, and humility. Abraham ran out and begged the passing strangers to be their guests. He did not wait to see if, by chance, the strangers would pass by without imposing on them. Abraham, Sarah, and their servants then baked bread, killed the fatted calf, brought fresh water, bowed down in reverence before the strangers, and served a generous meal.

Hospitality means primarily the creation of free space where the stranger can enter and become a friend instead of an enemy. Hospitality is not to change people, but to offer them space where change can take place. It is not to bring others over to our side, but to offer freedom not disturbed by dividing lines.

Hospitality is not a subtle invitation to adore the lifestyle of the host, but the gift of a chance for the guest to find his or her own.

Henri J. M. Nouwen

The story of Martha and Mary gives us something else to consider. Martha was in the kitchen, out of sight, preparing the food. That was the place assigned to her by the culture of the day. Some of Martha’s anxiety might well have been her reaction to Mary’s audacity to sit at the feet of a male guest and teacher—something unheard of in first-century Palestine. True and genuine hospitality, reflecting divine hospitality, tears down the boundaries of gender, race, creed, color, nationality and, especially, of merit.

No one deserves the hospitality of God’s mercy. And yet, God, in Jesus, offers the mercy of salvation to everyone without prejudice. It is incumbent upon us who have received this gift to extend generous hospitality and mercy to all others. Rather than closing our borders or our doors or our hearts to strangers, aliens, and exiles, we must follow the example of Abraham and Sarah, Martha and Mary, Jesus and the Father,

and open the doors of welcome. Indeed, at the end of the day, are we not all strangers and guests, sojourners and exiles in a strange land?

In the biblical stories, those who extend hospitality typically end up receiving disproportionately more than they give. The widow of Zarephath who welcomes the prophet Elijah (1 Kings 17) and, in faith, feeds him her last morsel of bread, is promised that her jug of oil and jar of flour will never be empty. For their generosity, Abraham and Sarah become the parents of a baby, and the father and mother of many nations. And we, sojourners on this earth, receive a heavenly homeland and welcome.

The hospitality of mercy. The mercy of hospitality.

Father John Meoska, O.S.B., is a woodworker at the abbey woodworking shop and a faculty resident at Saint John’s University.

Spring 2022 12 Abbey Banner 13

Reaching Out: The Three Movements of the Spiritual Life, 1975

Luke Anthology (detail), Donald Jackson with contributions from Aidan Hart. ©2002 The Saint John’s Bible, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota, U.S.A. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

The Ortmann Benedictines

Aaron Raverty, O.S.B.

German immigrant families who settled in central Minnesota in the nineteenth century were steeped in their Catholic heritage. One of the reasons German-speaking monks came to this area was to serve the families’ sacramental and educational needs. Perhaps the strongest evidence of such devotion came from the Margaret and Luke Gertken family, eleven of whose members became Benedictines! Another source of religious vocations was the Ortmann family that contributed three Benedictine priests to serve the faithful.

In 1880 Bernard and Bernadina Ortmann and their four children left their home in Holdorf, Lower Saxony, Germany, and immigrated to America. The family traveled directly to Meire Grove, Stearns County, Minnesota.

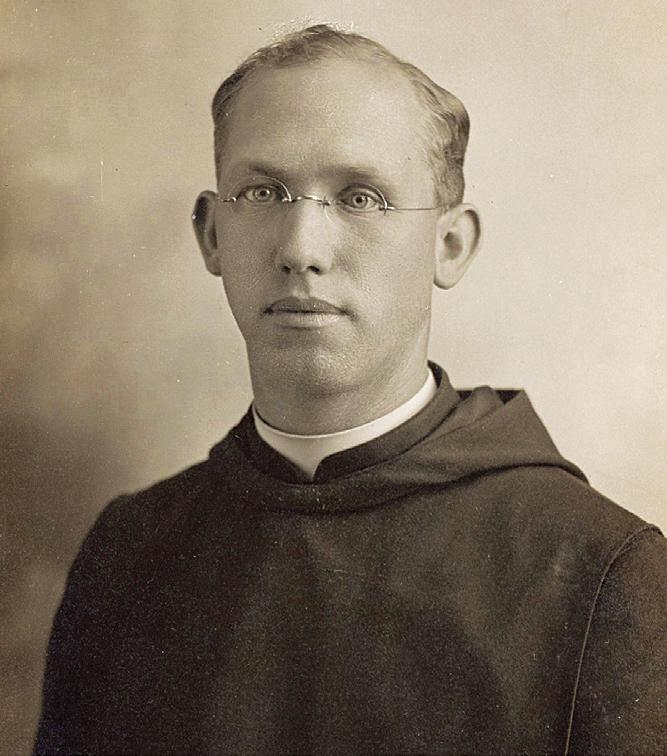

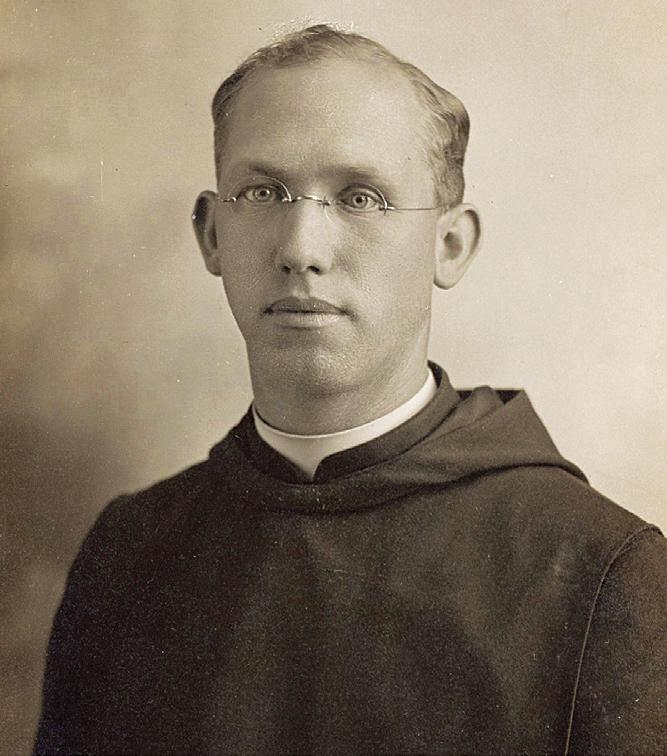

Anselm (John) Ortmann, O.S.B. (1872–1953)

John Ortmann was born on 3 February 1872 in Damme, Lower Saxony, Germany, the third child of Bernard and Bernadina (Kruse) Ortmann. He traveled to the U.S. with his parents when he was eight years old, settling in Meire Grove where he received his First Communion in 1884. Three years later, he came to Collegeville as a student at Saint John’s Preparatory School. He continued his studies here until his entrance into the novi-

tiate of Saint John’s Abbey (taking the name Anselm) in July 1892. He received his bachelor’s degree (majoring in philosophy) from Saint John’s, with his diploma (dated 1895) signed by the future Saint John’s abbot, Peter Engel. In this same year, he received a master of accounts diploma. In 1893 Anselm professed his first vows as a Benedictine monk; three years later, on 8 September 1896,

Abbot Peter Engel received his solemn profession. Between 1894 and 1897

Brother Anselm pursued seminary studies.

In the years following his simple profession, Anselm taught Latin, Greek, French, and

mathematics in the prep school at Collegeville. The year following his ordination he was assigned to study science and mathematics. In Saint John’s centennial history, Worship and Work, Father Colman Barry notes: in 1898 Abbot Peter Engel sent Father Anselm “to take graduate courses in physics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Father Anselm was the first member of St. John’s to do graduate work at a recognized secular university, and when he returned did much for the improvement of the physics department, laying particular stress on experimental work” (228).

Upon his return to Collegeville, Father Anselm began teaching math, physics, physical geography, and astronomy. For the

next thirteen years he continued his work in math and science, adding at various times to his schedule the teaching of trigonometry, calculus, analytics, geometry, and geology. From 1907 to 1909 he was also a student chaplain at Saint John’s.

Archival snippets hint at some of Father Anselm’s other talents and accomplishments. A catalog of insects for the Saint John’s University collection was assembled between 1892 and 1894. Records from Saint John’s entomological department indicate that Anselm may have assisted other confreres with collecting insects at West Union and Collegeville and classifying them. A flyleaf (dated 10 June 1904) of a textbook on civil government for the Commercial

College includes Father Anselm Ortmann’s name. From April 1895 until September 1897, he served as weathermonk at Saint John’s. According to Father Colman, “Father Anselm Ortmann edited a Catechism of Astronomy (Baltimore, 1905) when he succeeded Abbot Peter in astronomy” (Worship and Work, 235). He was also a member of a musical band at Saint John’s.

In 1910 Father Anselm left Collegeville to undertake additional pastoral service, becoming chaplain at the Villa Sancta Scholastica in Duluth (the motherhouse and academy of the Benedictine sisters) where he also taught chemistry. After a threeyear stint as assistant pastor at Richmond, Minnesota, beginning

in 1916, he spent the next eleven years as pastor of the Benedictine parish at Albany, Minnesota. He left Albany in September 1930 to become pastor of Saint Joseph’s Church, Minneapolis. After guiding this parish through the stress of the Depression years, he was appointed pastor of Callaway, Minnesota, in 1937. Ten years later he retired to Saint John’s. Father Anselm died on 13 March 1953 and is buried in the abbey cemetery.

Odilo (Henry) Ortmann, O.S.B. (1888–1931)

Father Odilo Ortmann (Father Anselm’s brother) was born in Meire Grove, Minnesota,

Spring 2022 14 Abbey Banner 15

Anselm Ortmann

Father Anselm (left), students, and Abbot Peter Engel, 1909

Anselm Ortmann (back row, far right) with Singing Choir, 1880s

University

Abbey archives

archives

University archives

Abbey archives

Odilo Ortmann

3 January 1888, the youngest of the ten children of Bernard and Bernadina Ortmann. Despite the loss of sight in one eye as a youth, his life was marked with vigor and energy. Following his studies at Saint John’s, he moved to Mount Angel, Oregon, in 1913. After a year of seminary studies, he entered the novitiate of Mount Angel Abbey, professing his vows on 8 December 1915. In 1918 he was ordained a priest and afterward taught mathematics at Mount Angel College except during his pursuit of a master’s degree at Oregon University. Following the awarding of the degree, he returned to Mount Angel and served as the college’s prefect of discipline for five years, 1920–1925. From 1926 until his untimely death in 1931—at age 43 due to a streptococcic infection that settled about his heart—he worked as registrar and director of studies as well as rector of the seminary. His obituary noted: “The halls no longer rang with his merry laughter,” and friends and callers at the abbey no longer were met “with his congenial spirit and Benedictine hospitality.”

Cyril (Bernard) Ortmann, O.S.B. (1898–1962)

Bernard Ortmann (nephew of Fathers Anselm and Odilo) was born in Lastrup, Minnesota, on 5 January 1898, the son of schoolteacher and farmer Theodore and his wife Katherine Ortmann. Following elementary school in Lastrup, Bernard

central Minnesota when appointed pastor at Saint Martin in 1940. Two years later he became pastor at Beaulieu, Minnesota. For several years, beginning in 1944, he was pastor of Saint John the Baptist Parish at Collegeville. Returning to Saint Martin in 1947, he took up beekeeping, serving as pastor and head apiarist until his death on 5 May 1962.

Sursum Corda: Lift up Your Hearts

Andrew Goltz, O.S.B.

tled or surprised. And he would do the same at this point!)

enrolled at Saint John’s Preparatory School in 1917. He attended Saint John’s University and was invested as a novice (taking the name Cyril) by Abbot Alcuin Deutsch in June 1923 and professed his first vows as a Benedictine monk on 11 July 1924. Cyril graduated from Saint John’s University in 1926 and subsequently attended Saint John’s Seminary. He professed his solemn vows in 1927 and was ordained in June 1929 in the abbey church by Bishop Joseph F. Busch.

Father Cyril’s first assignment was as socius (work boss) to the novices from 1928 until 1930. In 1930 he was assigned to the Church of Saint Bernard in Saint Paul as assistant pastor; from 1935 until 1940 he served as assistant pastor at Saint Boniface in Minneapolis. He returned to

The abbey archives has a letter from Father Cyril to Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy dated 22 February 1961, in which Father Cyril urged that federal aid to education be applied to secondary as well as elementary education, and to public and private schools alike, issuing “warrants” (not cash) to parents.

Three Benedictine priests— Fathers Anselm, Odilo, and Cyril—were members of the immigrant Ortmann families who originally settled in central Minnesota. Two nieces of Fathers Anselm and Odilo joined the Franciscan sisters of Little Falls, Minnesota. Along with their many relatives who attended Saint John’s schools, they remain great examples of the German Catholic faith that radiated throughout nineteenthcentury Minnesota and beyond.

Brother Aaron Raverty, O.S.B., a member of the Abbey Banner editorial staff, is the author of Refuge in Crestone: A Sanctuary for Interreligious Dialogue (Lexington Books, 2014).

When the north window of our church was made, the language of the Church was Latin—hence the title of this presentation: Sursum Corda or “Lift up Your Hearts,” from the preface to the Eucharistic Prayer of the Mass. It is intended to be descriptive of the whole theme of the window —the theme of worship: the who, the why, the how, and the what of worship. There are lots of misconceptions about the window. We’re going to tear them apart and look at the plan as Bronisław, a.k.a. Bruno, Bąk intended it to be known.

The middle section of the window is built around the theme of worship; the rest of the background refers to the different seasons of the liturgical year, reading from left to right. The most unique hexagon is the center, the circular window. Bruno Bąk thought of it as a modern rendition of the medieval symbol of the Eye of God—the all-seeing Eye of God, the all-knowing, the eternal, the Creator. The white area around it, he said, was heaven; and the floating shapes are the inhabitants of heaven, the angels and saints surrounding the throne of God. This section of the window is quiet, serene, peaceful. (When Mr. Bąk himself explained the details of the window, he would interrupt his dialogue by saying the angels were always going, “Ahhh!”—a sudden intake of breath, as if star-

The red part is creation, specifically the creation of humankind. The rays coming out from the center are divine grace, the power of God, the sustaining grace of God. (Mr. Bąk repeatedly said, “The divine grace of God comes into human hearts, and they are enkindled with the fire of divine love; they return their worship to the throne.”)

For Christians, the New Testament rests upon the Old Testament—and that’s what the green on each side represents. This is the Old Testament: the foundation of our faith. The tree of life, also known as a tree of good fruit, is represented in the green column on the left. (There are even a few little red fruits on it.) The symbolism comes from the Book of Genesis. On the left is the tree of knowledge of good and evil (which we got tangled up with); and on the right is another symbolic tree from the Old Testament, the Tree of Jesse—the genealogy of Christ descending from the patriarchs, prophets, kings, the house of David.

On this foundation of the Old Testament, we come to the New Testament. We enter the Church through the waters of baptism. We become members of the Mystical Body, the people of God; and the focus of our worship of God is the Mass. The liturgical year is presented: from the left, Advent; then Christmas, and so on.

Advent. The color is much more yellow than many realize—it’s actually a bright golden column. Bruno Bąk talked about this heaviness in downward pressing lines. Advent is a time of waiting. The promise is made; the Messiah will come. It’s a time of Isaiah—all the readings of Advent are filled with hope, anticipation. “Incompleteness” was one of the terms Mr. Bąk often used for this part of the window.

Christmas. But Christmas comes! The Christmas panel depicts the Incarnation, which Mr. Bąk said, “bursts upon crea-

Spring 2022 16 Abbey Banner 17

Cyril Ortmann Abbey archives

Alan Reed, O.S.B. Advent

tion like exploding stars.” So he made a panel full of exploding stars! They go all the way to the ceiling of the church. Christmas is a joyous time, a festive time.

Lent. Next we come to Lent —the purple column. It’s not intended to be tied to the liturgical colors because there are no liturgical colors in this window. Advent is not gold. But the purple column is the time of Lent. Christ’s mission on earth didn’t end all that well; people didn’t receive our Lord very well. He was hung on a tree and crucified. So the season of Lent ends with crucifixion. Mr. Bąk used to talk about this column as

Q & A

Where does the glass come from? Most of the blues come from France. Most of the other colors come from Germany. The purples are from England, and there is a small amount of American glass. In the area depicting water, there is some knobby glass—that is American glass. It’s not blown glass; it’s rolled glass.

Were monks involved in designing the window? No. This was Bruno Bąk’s idea, Bąk’s design and his interpretation.

Outline the planning of the window. We worked on the window for about two years. [We had originally hired a union glass cutter.] We were not a union shop, but he thought we ought to follow union rules. We didn’t, and so he quit. Then the abbot told me that I was going to become the glass cutter because I had cut glass for a picture frame or two! So, I walked into the glass studio one day, picked up the glass cutter (held it wrong—like a pencil) and was immediately told: No, that’s wrong. This is how you hold a glass cutter, so that you can follow the curve. So I became a glass cutter!

We made our cartoons and patterns and had a special scissors to cut the cardboard for making the patterns. In the master drawing, all the windows were numbered—across the room and in the alphabet going down (such as A-2, M-5, etc.). We made the windows and the patterns for each hexagon and stacked them in the barn. I’ve forgotten the exact number [486] of windows.

heavy, dark purple, draped cloth, hanging from the tree. Jesus was crucified.

Easter. After the crucifixion comes the Resurrection. This is Easter time, shown as a coiling line. This reminds us that Christ was in the tomb and arose from the tomb—there is a spiraling line that goes up to heaven in the Ascension. It is not Pentecost per se; it is the Easter season from the Resurrection to the Ascension. This column presents bursts of glory (the little circular things), Bronisław Bąk’s bursts of glory!

Pentecost. Ascension is followed by Pentecost—the gold column on the far right of the window. We see the descent of the Holy Spirit, in the era in which we live, the current time, a time of the Church on earth.

One of my favorite views of the window—although I’m pretty intimately connected with each and every piece of it!—is when I’m walking from the choir stalls, down the east side of the church. From this vantage point, I can say that, yes, my heart is filled with the Holy Spirit. And yes, I can join the angels. I can “lift up my heart” to God in worship and praise. Hallelujah!

Brother Andrew Goltz, O.S.B. (1933–2021) assisted Bronisław Bąk in the creation of the stained-glass window, 1959–1961

We used the connecting link between the two wings of Tommy Hall to display the cartoons of the full-sized hexagons. The side pieces were placed on the gym floor. Bruno Bąk, observing from scaffolding in the gym, directed the guys: Go to this hexagon and draw a sweeping arc there. No, that’s too curved, flatten that out—and so on!

From the paper cartoons came patterns, and a special scissors was used to take out the thickness of the leading that had to go between the pieces of glass. (The glass cutter takes the cardboard, puts it on the piece of glass, cuts it out and snaps it out.)

The text of this article is excerpted from a transcription by Father John Meoska of the audiovisual presentation, “Sursum Corda: The Breuer Stained-Glass Window for Saint John’s Abbey Church,” by Brother Andrew Goltz, 30 September 2014.

The enameled glass went into the glass kiln, where it was fired—each window got its own treatment. After it came out of the kiln and cooled, it went to the leading table. That was Mr. Dick Haeg’s job. Then the glass had to be puttied. We made our own putty. Brother Placid Stuckenschnieder helped with the putty and with the reinforcing rods in each hexagon.

Is there anything you want to tweak? Yes, I want to remove the balcony!

Spring 2022 18 Abbey Banner 19

Lent Easter Pentecost

Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

Alan Reed, O.S.B.

Christmas

Bronisław M. Bąk

A native of Poland, Bronisław Marian Bąk (1922–1981) was 17 and a member of an irregular unit of the Polish army when Germany invaded Poland in 1939. Following his capture, he was a prisoner-of-war laborer for three years before being incarcerated in a Nazi concentration camp in 1943. After the war, he chose to live in Germany rather than in Soviet-dominated Poland. In Germany Mr. Bąk studied art and particularly the art of stained glass at the Mannheim Freie Akademie. After emigrating to the United States, he joined the faculty of the Saint John’s University art department in 1958 and shortly thereafter was commissioned to design the north window of the church.

Sursum Corda

The middle section of the window is built around the theme of worship; the rest of the background refers to the different seasons of the liturgical year, reading from left to right. There are no liturgical colors, but the window is organized against a background of blue French glass. On one side is the column of Advent, and on the other side, Pentecost—the gold colors balancing each other. Christmas balances Easter with their bursts of glory and exploding stars. Lent is the purple column. Green is a complement of red; green (each side of the red) balances the red center: Sursum Corda: “Lift up Your Hearts.” The window includes 486 hexagons.

20 21

Alan Reed, O.S.B.

Joseph Rogers

Begun in 1964 as a project to photograph Benedictine manuscripts in Europe, the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (HMML) has evolved into a global cultural heritage organization whose mission is to preserve and share the world’s handwritten history. Preservation involves working with communities all over the world whose precious manuscripts are at risk of destruction—due to war, political instability, or the ravages of time. In partnership with these communities, HMML photographs every page of their manuscripts so that digital versions will be available forever.

Trust is essential when working with communities of various faiths and traditions. Personal relationships, forged over a long period, are required for success.

Before COVID-19, Father Columba Stewart, O.S.B., HMML’s executive director, would travel to preservation sites and potential sites to nurture such relationships. The pandemic has curtailed this part of HMML’s work.

Mali and New Communities

Despite the challenges posed by the pandemic, the Hill Museum’s preservation work continues across the globe. Teams in Croatia, Egypt, India, Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Malta, Nepal, Pakistan, and Ukraine continue their work to digitize collections.

Twice in 2021 Father Columba traveled to Mali, the site of HMML’s most ambitious project to date. The work there began with digitizing the manuscripts evacuated from the fabled city of Timbuktu, in partnership with the SAVAMA-DCI (Sauver et Valoriser les Manuscrits, un devoir), the Malian organization that brought the manuscripts to

safety. Digitization work with SAVAMA-DCI will be completed in 2022, but this will not be the end of our work in Mali.

One new project is in Djenné, an historic center second only to Timbuktu in importance for Malian culture. Others are planned for Gao and Ségou. Gao is especially significant as the third historic city of Mali along with Timbuktu and Djenné. It is located in a region that has experienced a good deal of conflict. Political instability, a rise in violence, and the deterioration of Mali’s relations with its neighbors and with its former colonial overlord, France, have

made communication and coordination difficult. Though not easy to work under these conditions, these challenges underscore the importance of HMML —the threat to cultural heritage is real.

While work in Mali continues, the Hill Museum is always seeking new communities to work with. We have begun discussions with the Embassy of Uzbekistan in Washington. There are opportunities awaiting us in India, Nepal, and Pakistan. There are multiple new projects in Italy, set to begin this year. The Balkans also represent a rich source of potential opportunities, thanks to HMML’s close relationship with Dr. István Perzcel of the Central European University and Bishop Jovan Ćulibrk of the Serbian Orthodox Church. While many of the collections preserved in the Balkans so far have been Serbian Orthodox in origin, Bishop Jovan is helping HMML open doors with Catholic communities in the region as well. We expect to work with more collections from this fascinating region in the years to come.

Recent Discoveries

Our efforts to catalog and make accessible cultural heritage through HMML’s online platforms Reading Room (for manuscripts) and Museum (for art objects) has been going at an unprecedented pace. With help from a National Endowment for the Humanities grant, HMML has assembled the largest and

most impressive team of catalogers and curators in its history. Over the past several months, tens of thousands of new records describing manuscripts, printed books, and art objects have been added to our Reading Room and Museum—available to anyone, anywhere, with internet access.

HMML catalogers and curators must first read each manuscript and describe it in a systematic way. This ensures that someone looking for a specific text or author will be able to find it online. Through this process, we frequently make surprising and exciting discoveries. For example, while cataloging a manuscript from the Syriac Orthodox Church of Saint George in Aleppo, Dr. David

Calabro (curator of Eastern Christian manuscripts) came upon a special text. Most of the manuscript was Christian in nature, but one text written in Arabic Garshuni (Arabic written in Syriac script) began with the following passage: “We begin by the help of God, may he be exalted, and the goodness of his blessing, to write the story of Sindbad the Sailor and what happened to him on his seven voyages, a thing that will amaze those who hear.”

Dr. Calabro was reading a rare early version of the famous tale of the “Seven Voyages of Sindbad”! The story of Sindbad would eventually be included in the collection known the world over as the Arabian Nights.

Spring 2022 22 Abbey Banner 23 Hill Museum & Manuscript Library

Meeting with manuscript communities in Gomitogo, Mali, near Djenné

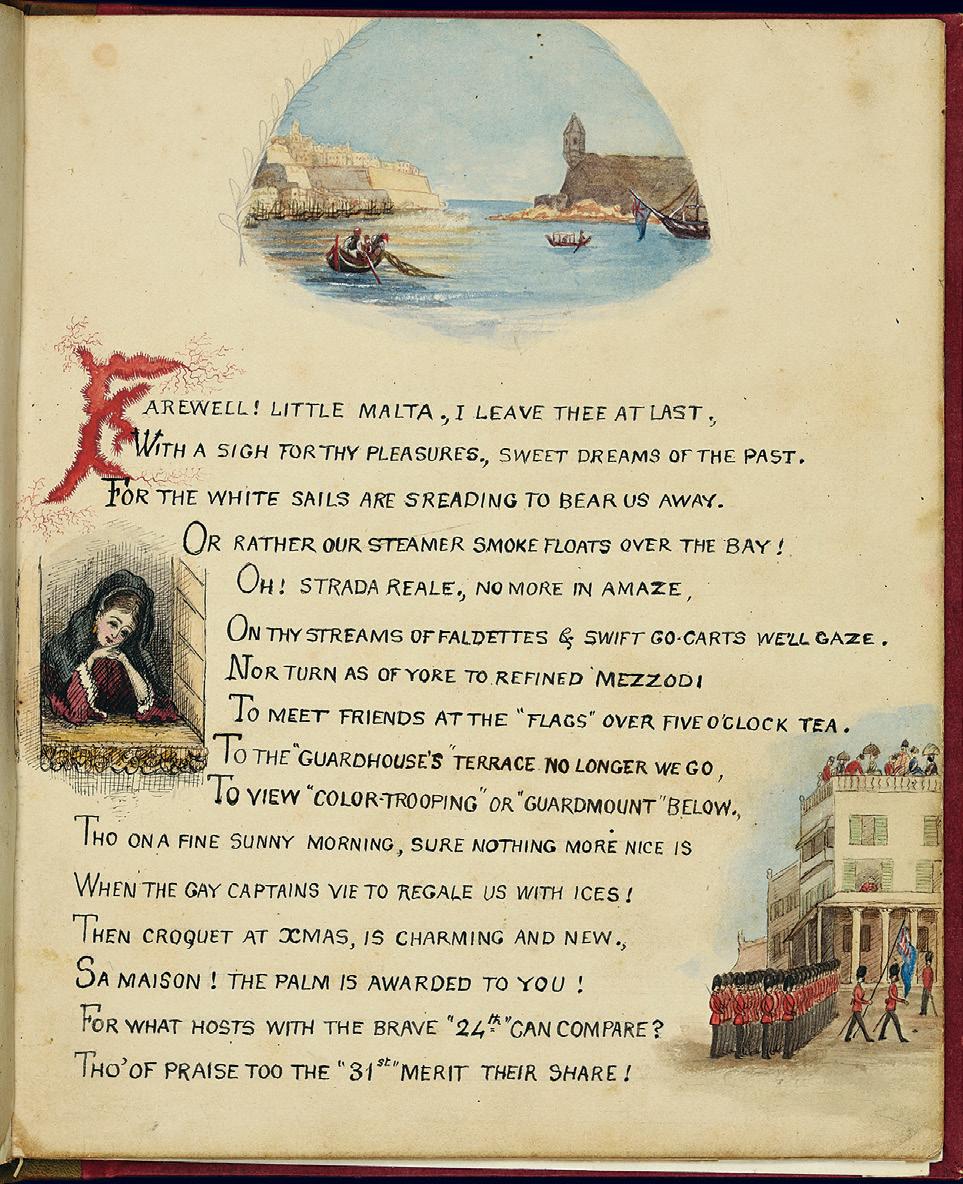

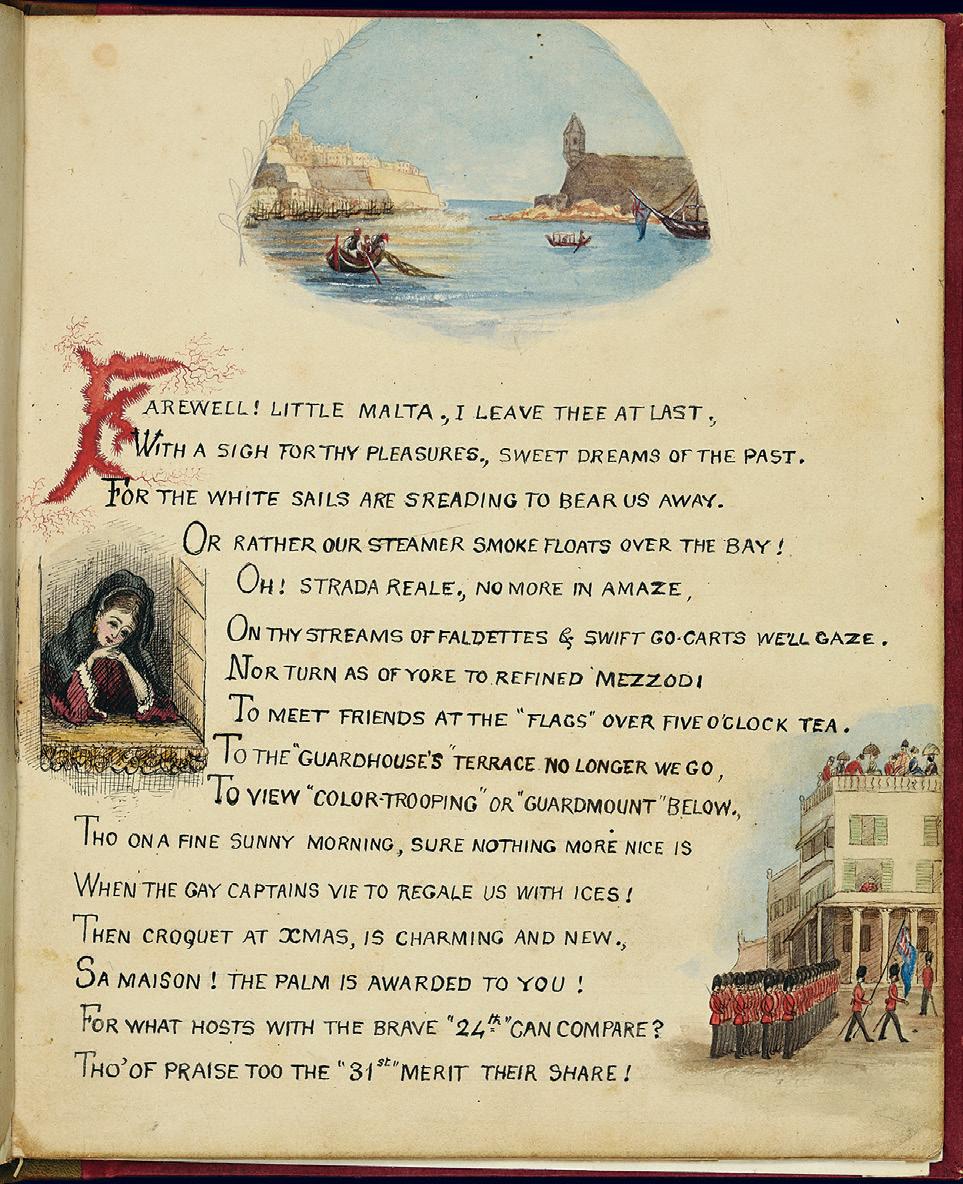

The beginning of a Malta memory book by Fanny and Louisa Bunbury, 1872

Hill Museum & Manuscript Library

Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (HMAR 00025)

Eastern Christian transmitters played a vital role in bringing some of the tales that we now associate with the Arabian Nights to a Western audience in the eighteenth century. Dr. Calabro says that scholars still have much to learn about how these popular stories circulated among communities and across cultural and religious traditions. Religious and chronological indicators within the Arabian Nights suggest that some stories crossed back and forth between religious communities, gathering details from one or the other with each pass. In that way, the stories are not unlike Sindbad himself, traveling from one place to another, gathering treasures of all kinds along the way.

Another interesting example is provided by Dr. Daniel Gullo (Joseph S. Micallef director of the Malta Study Center) who found a small manuscript in the collection from the Malta Maritime Museum. The manuscript, entitled “Three Months in Malta,” was created by Fanny and Louisa Bunbury during their visit in 1872, a time when Malta was a British colony. The two young women were sisters from Australia enroute to England, likely in search of suitable marriages. They were accompanied by their mother

who had spent her early years in Malta. The manuscript contains both text and illustrations and is a sort of memory book for their experiences during their visit. In just a few pages, this manuscript contains a veritable goldmine of insight into colonial life in Malta during the Victorian era. Unlike most of HMML’s manuscripts, it is written in English, so mastery

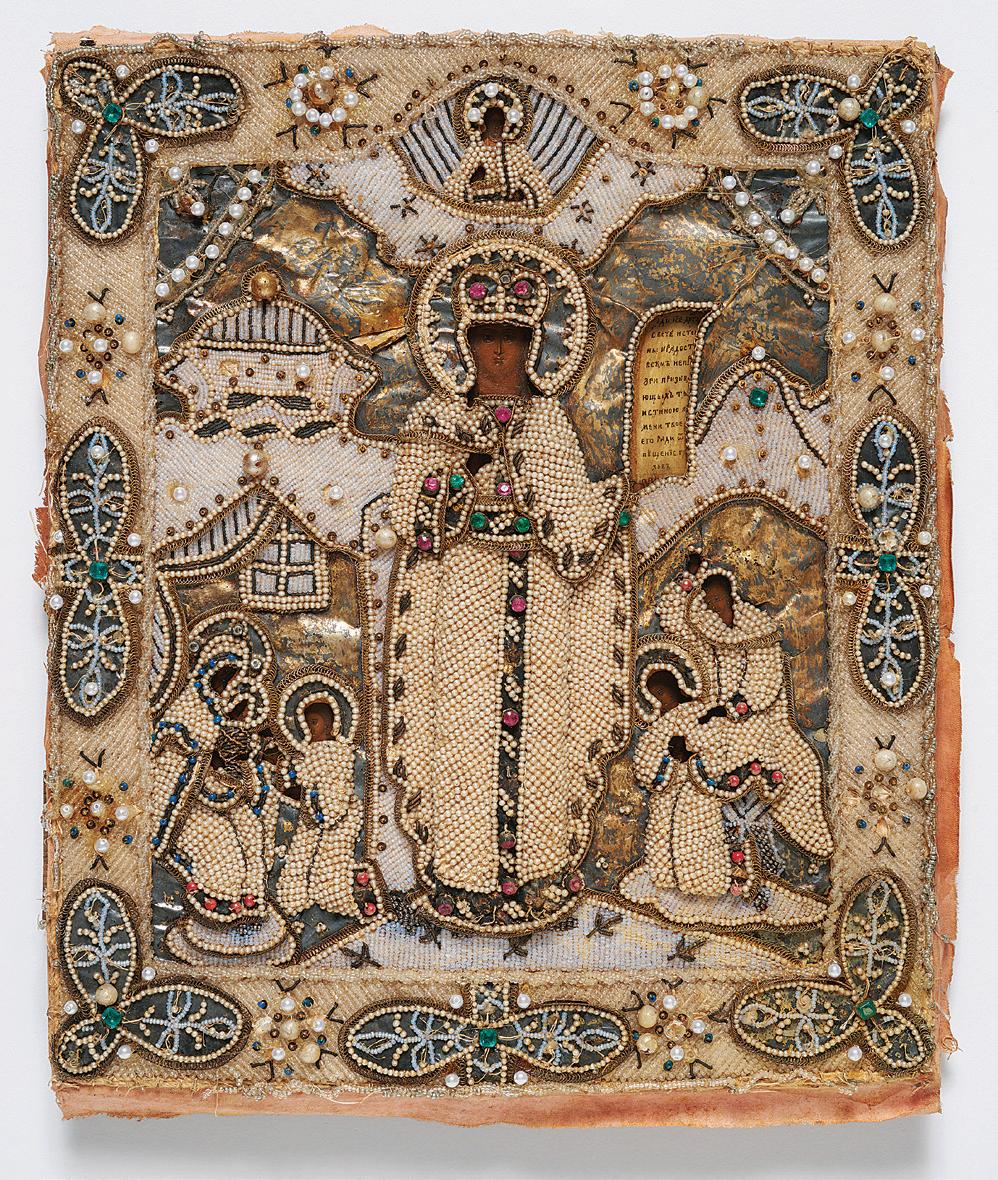

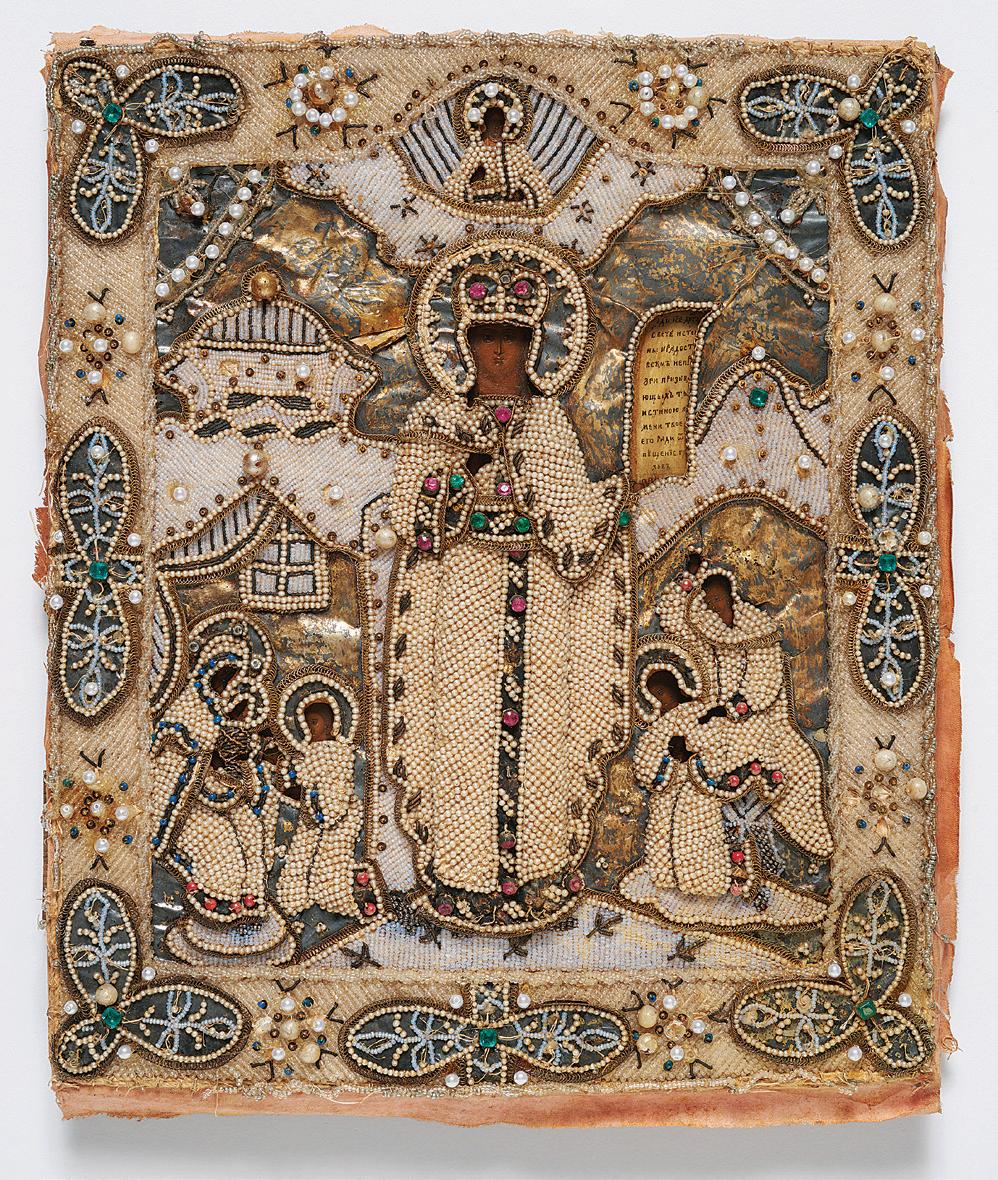

Cataloging the new collection was completed by Ms. Katherine Goertz (curator and registrar of the art collections). Many of the icons include a riza, a cover that hides most of the icon from view, usually showing only the hands and face of the portrayed figures. Often the covers are metal, with the most elaborate ones made of silver and gold. Professional metalsmiths in Russia sometimes had hallmarks, so, with the help of specialized mark dictionaries, Ms. Goertz traced where several of the icons have been and who made their rizas.

of Latin, Syriac, or Arabic is not required to read the text.

The Hill Museum & Manuscript Library’s collections also contain works of art, including prints, photographs, and sculpture. In 2021 HMML received a donation of Russian icons from the collection of Edmund Gronkiewicz.

Since many of the icons are composed of two parts—icon and riza—Ms. Goertz attempted to remove the rizas before the icons were photographed. One of the most exciting to remove was the elaborately beaded and very fragile riza of Saint Catherine of Alexandria. As the metal foil and pink silk riza was removed, a beautiful nineteenth-century icon in excellent condition was revealed. The Gronkiewicz icon collection is now fully cataloged and accessible online in the HMML Museum.

Fire. Flood. Political instability. War. The need for and the work of HMML continues.

Mr. Joseph Rogers is director of external relations for the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library.

Eric Hollas, O.S.B.

Eric Hollas, O.S.B.

Saint Benedict was attentive to detail—when he wanted to be. His treatment of the distribution of the psalms for prayer is a case in point, as are his comments on the degrees of humility and his expectations of the administrators of the monastery. On all counts he likely had more to say because each touched on his fundamental bias toward the spiritual life and the good order of the community.

On other matters, Benedict is vague or silent. For example, in his Rule, he references the oratory, the refectory, a dormitory, a guesthouse, and workshops. He even presumes that there would be an entrance where a senior monk, not prone to wander off (RB 66.1), would be stationed. Each of these spaces was necessary for the life of the commu-

nity. Yet, despite their importance, Benedict devotes not a single word as to how they might be fitted together to create a unified whole.

The cloister that we identify today as distinctly “monastic” likely had its roots in the Roman villa. In that home the protective walls kept out strangers and created a courtyard that became the center of life for the household. In time this quadrangular format would serve as the ideal physical embodiment of Benedict’s spiritual program. In the monastery, those walls carved out the sacred within from the secular without. There, within the cloister, the monk could meet Christ at every turn.

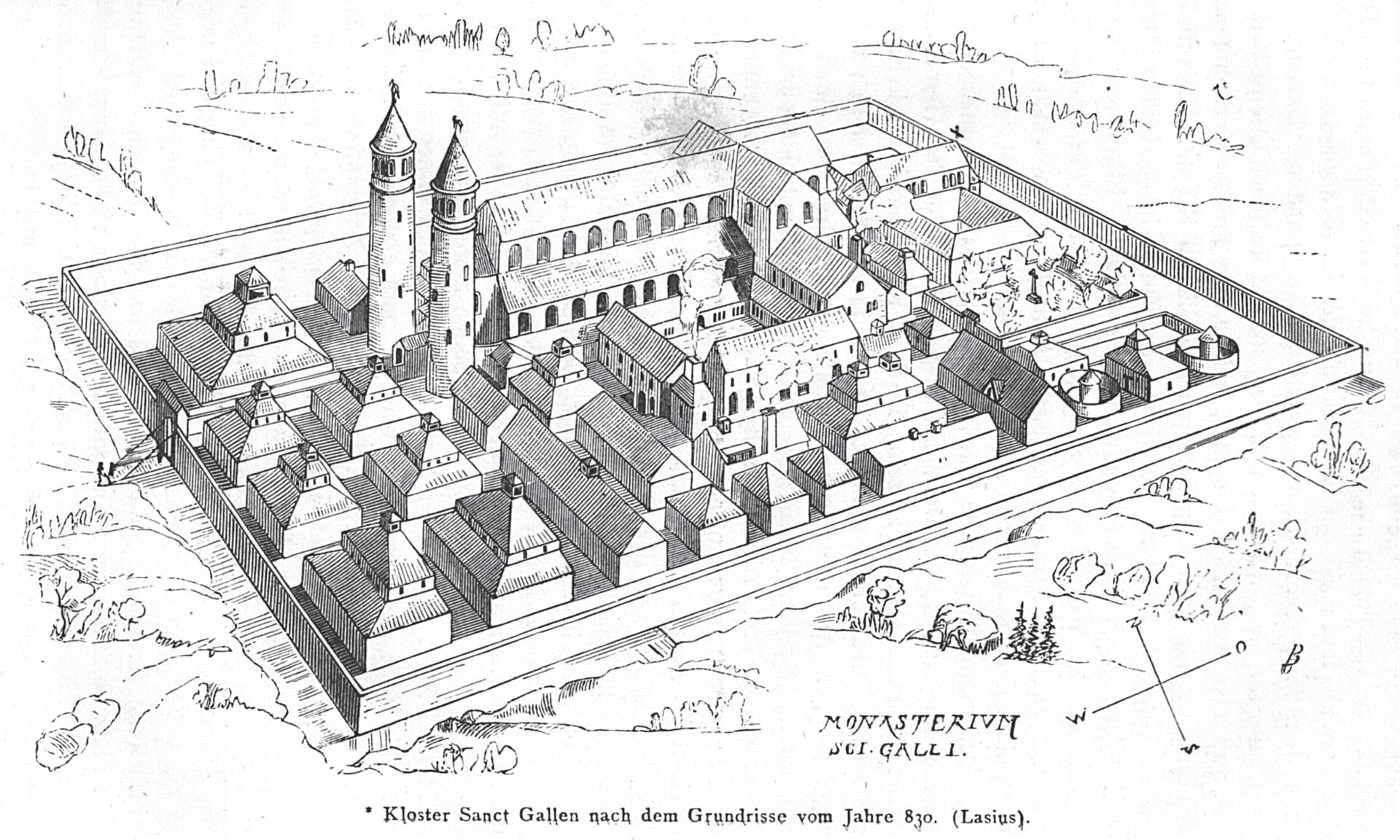

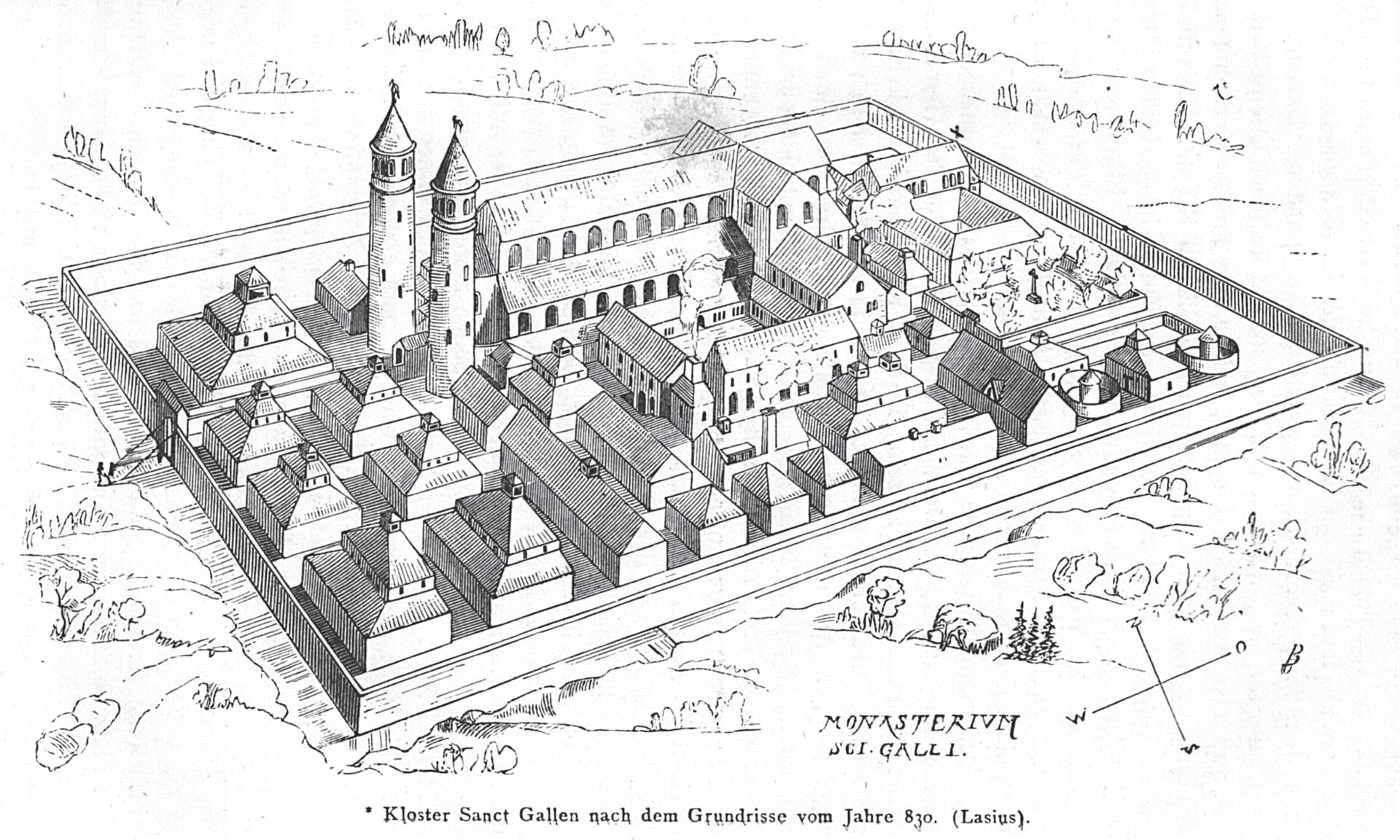

Why didn’t Benedict describe such a cloister? He likely had little experience of such a structure. The steep hillsides of Subiaco, where Benedict lived as a hermit, had no perch for such a

complex. Nor were large level sites readily available to monks in Benedict’s day. The royal patronage of the early Middle Ages changed all that, however. Someone drew up the Plan of Saint Gall (c. 820), whose cloisters conjure up popular images of Benedictine life today. That blueprint [above] became standard issue for monasteries in the Carolingian Empire, and it is reflected even in the quadrangle at Saint John’s.

The cloister walk and the quadrangular complexes of the Middle Ages are equated with the monastic life. We associate them with Benedict’s way of life, yet we have no way of knowing whether this is what he had in mind. Benedict might very well be astonished to see them today!

Father Eric Hollas, O.S.B., is deputy to the president for advancement at Saint John’s University.

Spring 2022 24 Abbey Banner 25

ule of Benedict

Cloister Walk and Quadrangle

Icon of Saint Catherine of Alexandria with a riza made of glass beads and pearls

Johann Rudolf Rahn/Wikimedia Commons

Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (AAJ1005)

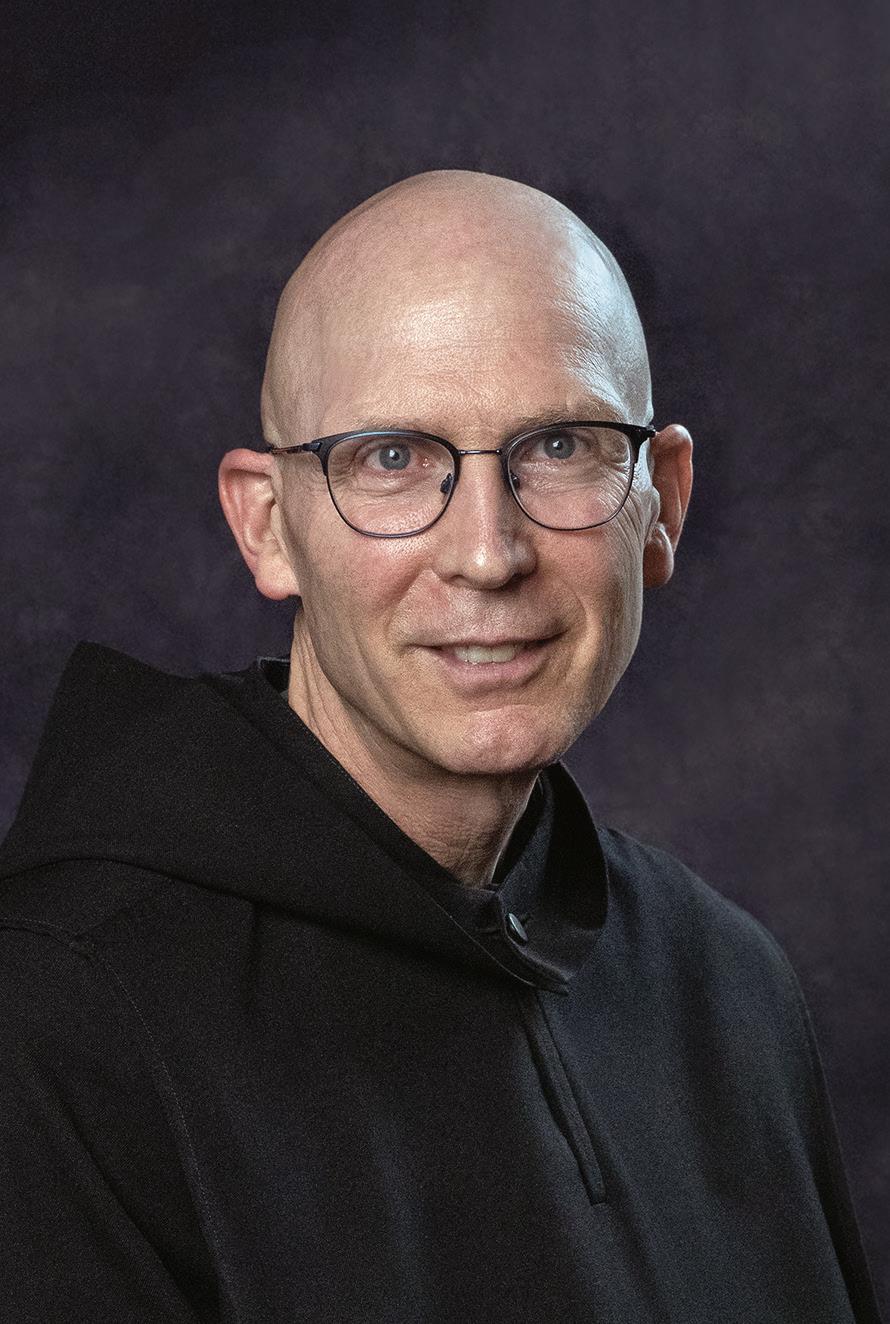

Timothy Backous, O.S.B.

In pre-COVID days, Saint John’s had a summer schedule that seemed to rival the school year. It was not unusual to have as many students at summer camps as there were during the academic year. One such group was Boys State—sponsored by the American Legion— that introduced those entering their senior year in high school to the workings of government. And so it was in 1976 that Tony Gorman first set eyes on Collegeville—which, in the fullness of time, was to become his home as a Benedictine monk.

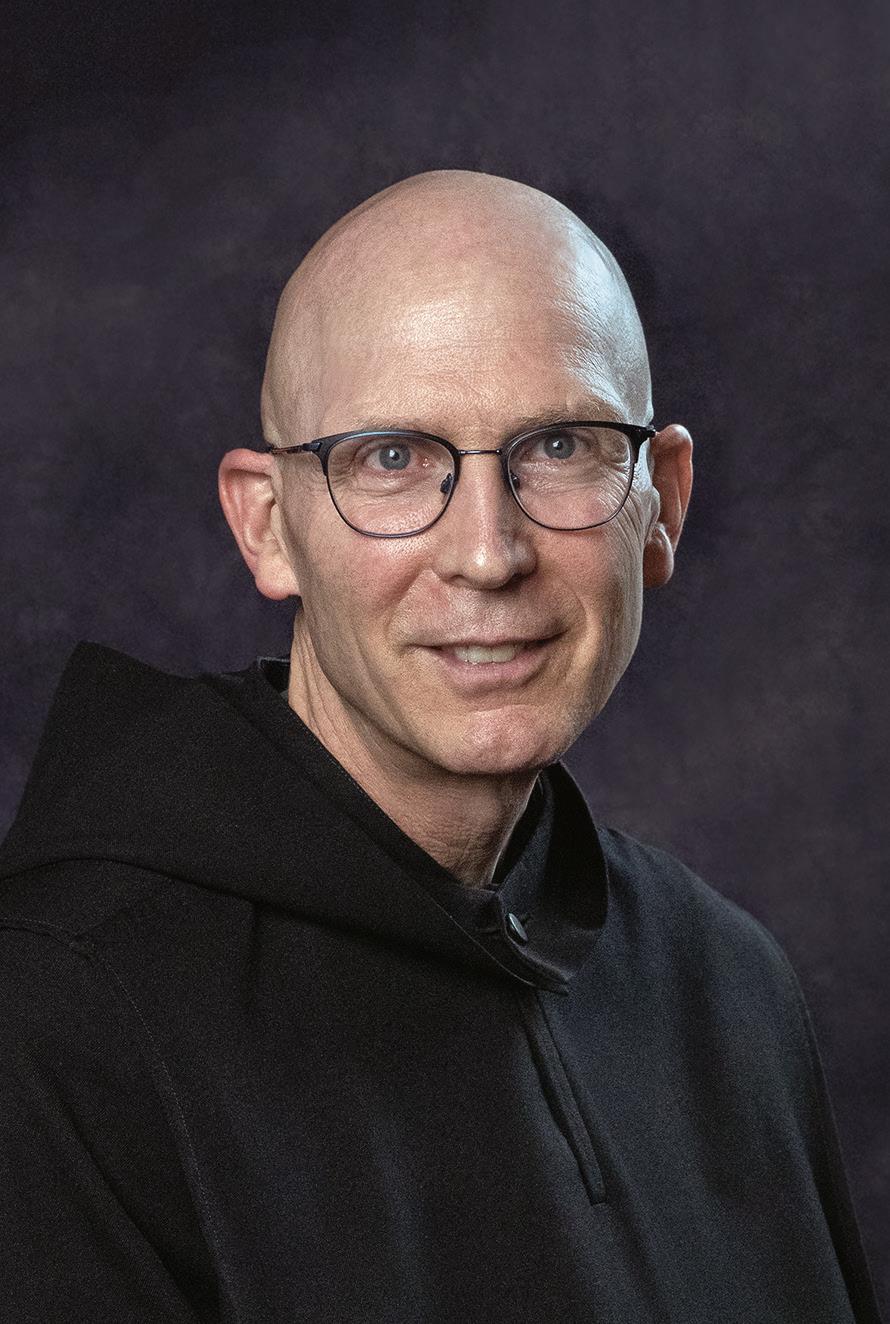

Father Cyril (Anthony) Gorman, O.S.B., was born in Worthington, Minnesota, but grew up in nearby Currie—which, he notes, is the birthplace of our late confrere Father Vernon Miller

and of Emmett Gorman, his father. His mother, Louise Kriz Gorman, was born in and grew up in Nebraska. Father Cyril is the middle of three children born to Emmett and Louise: Robert is his older brother; and Mary, his sister.

“Following graduation from high school (1977, Tracy, Minnesota),” reflects Father Cyril, “I struggled with health and what my vocation would be.” He enrolled at Worthington Community College (now Minnesota West Community & Technical College) but heeded his father’s suggestion to go to Saint John’s University because his brother was there and his sister attended the College of Saint Benedict. “Maybe they will cut us a deal,” his father said. “Ironically,” Cyril recalls, “after I came to Saint John’s with sophomore status in 1979, I worked in the financial aid office as a student worker. Maybe that was the deal dad was talking about!”

During his college years, friends influenced Cyril’s vocation. He

joined a group of students in a program called Ministry Preparation that involved shared meals, Evening Prayer with the monks, and a monthly speaker. Fellow students thought he might have a vocation to religious life. His roommate shared some of his own musings about vocations and recommended Searching for God by Basil Cardinal Hume, O.S.B. a book that Cyril uses to this day for retreats and conferences.

Father Cyril credits two Benedictine confreres with helping him bridge his early life and what would become his life’s calling in the monastery. One was Father Benno Watrin, who used to go on walks with him three or four times a week after Evening Prayer. The other was Father Alexander Andrews whose rough, drill-sergeant exterior did not deter the meeker Cyril from asking him to be his spiritual director. He still remembers Father Alexander’s advice about choosing a vocation: “If you want to be a monk of Saint John’s, I don’t see a problem.”

Cyril offers a third reason for taking the leap into monastic life: Sunday night Evening Prayer set to the music of Benedictine Fathers Jerome Coller and Henry Bryan Hays. The majesty of that music and the intensity of the monks as they sang it convinced him that he had found his home in Collegeville. He would enter the abbey’s novitiate in 1983, profess his first vows as a monk on 11 July 1984 and, following seminary studies, was ordained a priest in 1990.

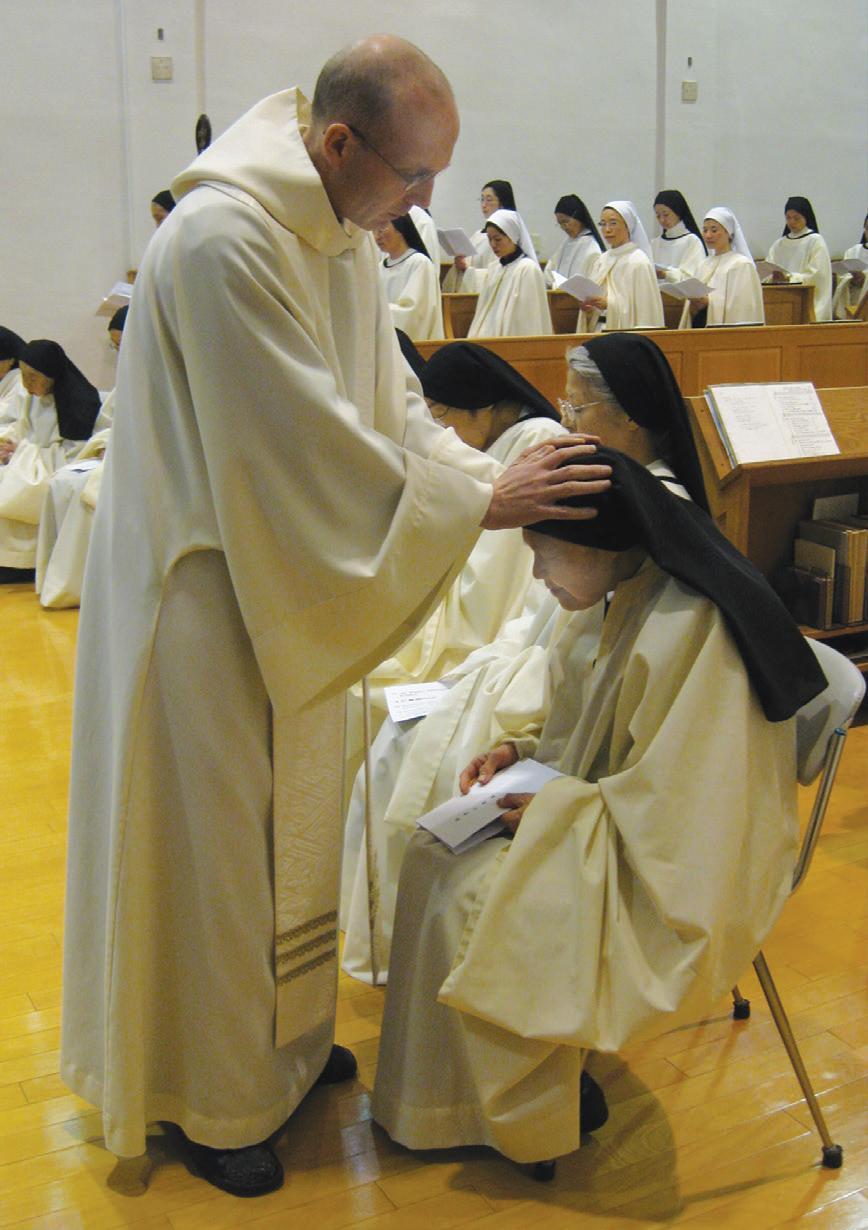

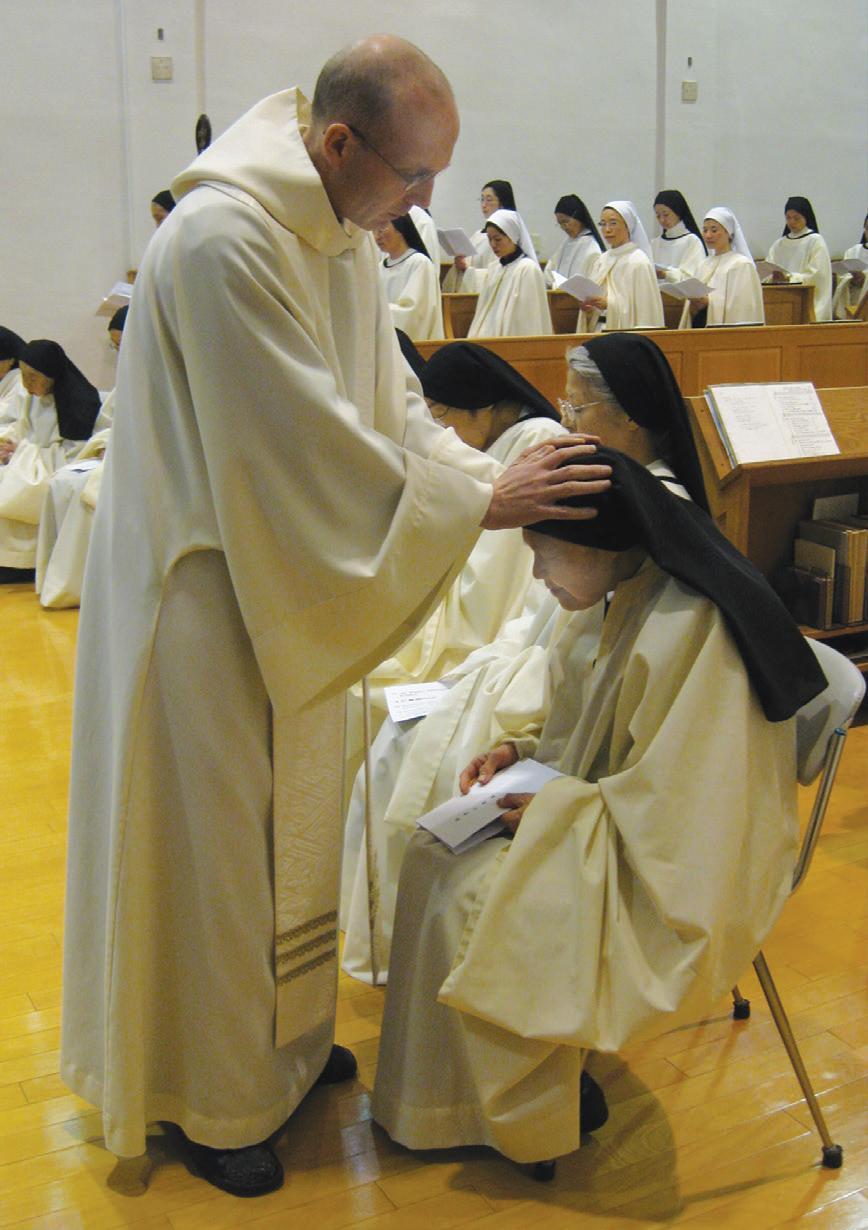

Father Cyril has served his monastic community in numerous ways—from firefighter, to socius (work boss) of novices, to university librarian. But it was the ten years he spent in the community’s foundation in Japan that offered the biggest challenges and grandest rewards. He recalls: “A big transition occurred in 2011. I was asked to

way he welcomes and carefully guides the guests—to those who accuse Cyril of being too bossy in his interactions with guests, he asserts that’s he’s just being “helpfully directive.”

become the chaplain for the sisters of Nasu Trappist Monastery. I arrived on 5 March. Six days later we were struck by a major earthquake. The sisters’ buildings were damaged, but there was no loss of life. It was a scary time at first. We were without power and did not know of the great loss of life elsewhere in Japan until the next morning. I stayed at Nasu most of the time until December 2017.”

Upon returning to Collegeville in 2018, Cyril was assigned to serve in the abbey guesthouse. He also began a certificate program in spiritual direction and now is a steady, calm presence for guests and retreatants. His enthusiasm for that work is evident in the

What is the best thing about monastic life to Father Cyril? “Many years ago,” he recalls, “I was speaking to a group at the Episcopal House of Prayer and was asked the hardest thing about monastic life. I immediately responded, ‘Other monks!’ I surprised myself with that answer! But I quickly added that other monks are also the best part of monastic life. A confrere recently explained to me that a fundamental human challenge is reconciling the desire to be alone and the desire to be with others. I am still learning one of Cardinal Hume’s insights: when others bother you, you likely bother others to the same degree. That is humbling but helpful.”

The vocational pathway of Cyril Gorman is neither dramatic nor unusual. The steady pull of monastic life that started in high school, strengthened in college, and culminated in the abbey church is something for which his confreres give thanks. And Cyril does as well.

Spring 2022 26 Abbey Banner 27

Meet a Monk: Cyril Gorman

Abbey archives

Tracy track star, 1977

Robert (left) and Cyril

Ministering in Nasu, Japan

Gorman archives

Gorman archives

Fujimi archives

Gifts of the Forest

John Geissler

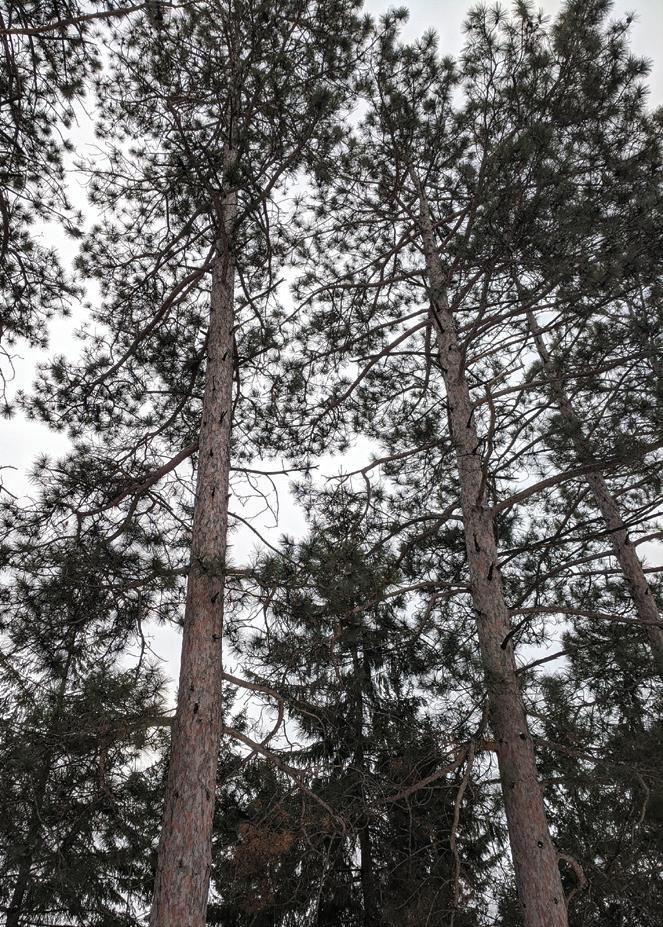

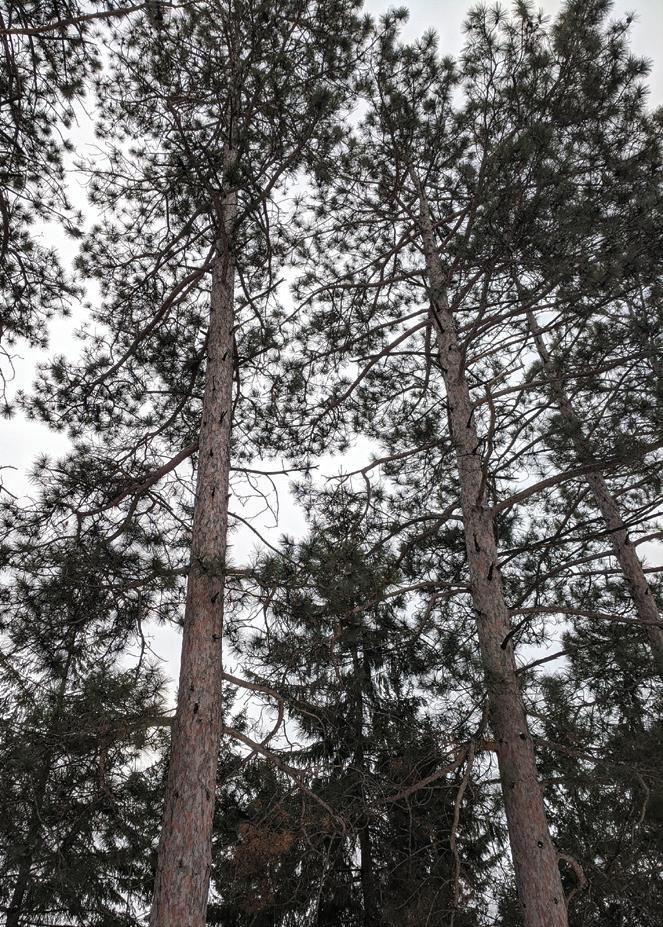

Spring in the Saint John’s Abbey Arboretum is a wonderful time to celebrate the gifts of the forest! Silent and dynamic, forests quietly make significant contributions to our quality of life. Forests provide syrup, oxygen, carbon storage, water quality, wood products, habitat, beauty, and spiritual renewal. These benefits are made possible by the Benedictine commitment to long-term forest stewardship that we model today and hope to pass on to future generations.

In the Saint John’s sugar bush, 1500 maples warm and donate 15,000 gallons of sap—one drip at a time. Amazingly, there are no other ingredients to make a gallon of real maple syrup—just forty gallons of sap, enough fuel to boil it, and a love of healthy physical labor to prepare firewood, collect the sap, and cook it down. Ready for action, the nearby woodshed is filled to the rafters with dry firewood. As the old saying goes, this firewood has already warmed its gatherers three times—once when they cut it, once when they split it, and once when they stacked it. At last, the prepared firewood enters the firebox and releases its stored solar energy to boil sap and produce the treasured “liquid gold” maple syrup—a sweet reward on top of a season spent enjoying the woods with community.

As the woodshed empties and the embers under the sap pan slowly fade, the tree buds burst open, officially ending the maplesyrup season. The new leaves emerging reveal the photosynthesis factories that provide two invisible forest benefits—oxygen for us to breathe and the capture of carbon. Although many take this gas exchange for granted, we cannot survive more than several minutes without oxygen. Please mentally thank a plant the next time you take a breath! The carbon that trees absorb is used in all parts of the tree from leaves to the roots. It is not difficult to visualize that the carbon trapped in the trunk of a longlived tree could be there for hundreds of years. Long-term carbon storage is important as large quantities of carbon dioxide formerly stored in ancient fossil fuels continue to be released. This increase in carbon dioxide

and other greenhouse gases is trapping additional energy in our atmosphere. One consequence, regionally, is intensifying and more frequent destructive weather events. Planting trees is a simple way to make a positive difference. This spring we are planting 1600 oak trees to create a new forest on eight acres. In the last three years the Abbey Conservation Corps volunteers and staff have planted and protected over 6000 seedlings. Planting a tree is an action of hope and always a step in the right direction.

In their first few years, young tree seedlings are vulnerable to drought and need moisture to get their root systems established. (The summer land stewardship team cheers every week it rains during the growing season as it saves us three full days of watering!) Another

difficult to detect but beneficial role that forests play is the ability to moderate the water cycle. Forests provide shade and limit drying winds to keep moisture in the soil between rains. During heavy rains, tree canopies and roots shield and hold the valuable topsoil in place. Stormwater runoff is one of the major reasons water bodies become impaired. The outstanding water quality of Lake Sagatagan is a direct result of the forests that make up the majority of its watershed area. In the reverse direction, trees act as huge humidifiers, moving excess water in the soil up to the leaves and back into the atmosphere through transpiration. This water vapor leads to cloud formation and the potential for more regular precipitation events. Moderated rains are

plan is to provide the healthiest forest that we can for the future. Our forests already support hundreds of species of plants, fungi, insects, mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, lichens— and we want to continue to improve the biodiversity found here.

good for tree seedlings, land stewardship teams, and the ecosystem as a whole.

Those who wander through the abbey arboretum will frequently pass old tree stumps and currently active logging sites. We don’t have to look any farther than the Saint John’s quadrangle or other campus buildings to see that the forests have provided lumber through the years that the abbey woodworking shop has skillfully transformed into integral and beautiful parts of the campus and monastery. The mature trees harvested today are part of a focused effort to increase forest age diversity and resilience within our woods. Extensive planning goes into our certified sustainable forestry operations. One of the top priorities in our forest stewardship

The symbiotic relationship between humans and forests is old and extraordinary. The variety of examples noted above illustrate how much we gain from forests, including supporting the core needs of our existence. I challenge each of our readers to take at least a fifteenminute hike through a nearby forest to see how it changes you. A growing body of studies is finding evidence that even limited time spent in forests has many health benefits, including reducing stress, improving mood, and increasing our ability to focus. Based on my experience, I wholeheartedly agree. It is my hope that more and more people will connect with and be inspired to care for our forests now and in the future. Our forests are definitely worth the effort.

Abbey Conservation Corps

Wednesday Workdays 1–3 P.M. Volunteers meet in Science Parking Lot #1

https://www.csbsju.edu/ outdooru/events/volunteer

Spring 2022 28 Abbey Banner 29

Mr. John Geissler is the Saint John’s Abbey land manager and director of Saint John’s Outdoor University.

John Geissler

Planting a tree is an action of hope.

Walter Kieffer, O.S.B.

Seed art by Stephen Saupe, 2022

The Sweet Beginnings

Walter Kieffer, O.S.B.

Brother Walter Kieffer, O.S.B., has assisted with the production of maple syrup at Saint John’s for the past sixty-one years. He shares tales of the early days that he learned as a young monk.

Saint John’s first maple syrup shack was built in 1942 in response to the national sugar shortage during World War II. Some of the brothers—who had worked with Native Americans and had knowledge of their spring ritual of maple syruping and the sugar it produced—decided to try making syrup here. Maple sap was collected and cooked down in an old steam kettle in the monastery’s candle shop. The monks were delighted with the outcome, but the syrup ran out too fast. The procurator proposed that a larger-scale operation be undertaken.

That first year provided enough syrup to last for two years, thus establishing a future pattern of tapping every other year—cooking one year, making wood the next.

The cooking process produced floods of steam. The first shack—maybe 16' wide and 20' deep—was built around the evaporator with little more than a walking space and a plank shelf on each side for storage of jugs and supplies. It was a steam bath inside with condensate dripping everywhere. I heard that the cookers wore raincoats in the early days! Eventually the steam was vented outside, making for a much nicer workspace.

When sap was being collected, we worked round the clock for days, getting a couple of hours of sleep each night, taking turns firing the cooker. Originally records were kept on wood shingles, recording the date and number of tankerloads hauled to the shack. Another board recorded the date and number of jugs in each batch, later adding the batch time and still later noting the size of the jugs (gallon or liter). These records were nailed around the shack but were lost in the fire of 1970, when the shack burned down.

Some speculated that students had entered the shack to have a party. It was cold, and they likely started a fire for warmth and maybe light. With the stove pipe removed and the hole to the chimney plugged, the sparks had nowhere to go and started the back wall on fire. We know the students were not there long because the keg was nearly full! So ended the life of the old maple shack.

Year of the Tiger

To celebrate the Asian (lunar) new year, Father Cyprian Weaver created an informal gallery of Asian art and artifacts in the monastery during the month of February. The display included statues, wood carvings, ceramics, scrolls, and seals accompanied by detailed descriptions of the significance of the artwork. Known as the king of beasts in China, the tiger is a symbol of strength, bravery, and power. Among those who were born in the Year of the Tiger are Queen Elizabeth II, Stevie Wonder, Lady Gaga, and Derek

Spring 2022 30 Abbey Banner 31

Photos: Brother John Anderl (top) collecting sap, 1949. Abbey archives photo. Brother Walter Kieffer stoking Big Burnie. Outdoor U archives photo.

Jeter.

Photos (clockwise, beginning at top of page): Lion (bronze, Shang Dynasty [1600 to 1046 B.C.], China); Zao Jun, Chinese household god (wood carving, Qing (Ch’ing) Dynasty [1644 to 1912], Taiwan); Vase featuring “Wu Fu Peng Shou” or Five Blessings design (porcelain, Qing Dynasty, Chengdu); Horse (polychrome glaze porcelain, Han Dynasty [206 B.C. to A.D. 220] reproduction, Palace Museum, Taipei); Bat, symbol of prosperity (wood carving, late Qing Dynasty, southern China).

31

Photos by Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

The daily routine within the cloister is enlivened by the antics of the “characters” of the community. Here are stories from the Monastic Mischief file.

Liturgical life

What time is complain?

Father Roman

Compline is at 8:30 P.M.

One can complain at any hour.

�� Father Anthony

The reason the ambulance was outside the music department today was because one of the choirboys ran into a tree while playing football during our recess. Good singer. Poor football player.

Rare books

Who borrowed my Presence, Power, Praise: Documents on the Charismatic Renewal (ed. Kilian McDonnell; Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1980)

3 volumes.

These are rare and expensive books. -Kilian, osb

Gloss: FOR SALE

500 copies of Presence, Power, Praise: Documents on the Charismatic Renewal.

$1.50/3 volume set. Call #1234

COVID-19

A confrere wondered why no one had commented on his unusual COVID-19 mask. Perhaps, Brother, because that mask is the least notable of your peculiarities.

Mixed monastic metaphors

If you don’t catch the bird, you miss the boat.

Just because it’s our baby doesn’t mean we get the first shot at it.

If we don’t nip this in the bud, it’ll snowball out of control, and bite us in the butt.

Don’t count your bridges until you’ve crossed them.

He’s a wolf in cheap clothing.

We’re burning the midnight oil from both ends.

Rather than wallowing in tears, let this compassionate community strike while the iron is hot.

You know you’re growing older when . . .

Everything hurts, and what doesn’t hurt, doesn’t work.

The gleam in your eyes is from the sun hitting your trifocals.

Your little black book contains only names ending in M.D.

You get winded playing dominoes.

You sit in a rocking chair and can’t get it going.

The best part of the day is over when the alarm clock sounds.

Your back goes out more than you do.

A fortuneteller offers to read your face.

You sink your teeth into a steak, and they stay there.

Your birthday candles trigger the smoke alarm.

Musical Notes

Angus Dei: To play with a divinely beefy tone

Dill piccolini: An exceedingly small wind instrument that plays only sour notes

Fiddler crabs: Grumpy string players

Flute flies: Those tiny insects that bother musicians at outdoor performances

Gregorian champ: The title bestowed upon the monk who can hold a note the longest

Tempo tantrum: What a school orchestra is having when it’s not following the conductor

Lost (or gained!) in translation

Black Forest notice

It is strictly forbidden on our Black Forest camping site that people of different sex, for instance, men and women, live

Lake Sagatagan froze over on 8 December, shortly after Collegeville recorded a temperature of -2 °F and windchill of -23. Lightning, thunder, and rain marked the Ides of December! The snow that began falling on Christmas Day continued until ten inches had accumulated three days later. Minnesota endured an old-fashioned winter—cold and snowy—throughout January and February. Below-zero temps and windchill readings of -20s were common; snowfall totaled twenty inches. The unseasonably cold temps continued until the Ides of March when more moderate weather spurred the flow of sap in the sugar bush and dreams of spring.

December 2021

Facemasks may have softened the volume of the abbey schola but could not limit the Christmas joy.

Bah humbug, COVID!

• The annual controlled archery deer hunt in the abbey arboretum, which had opened in mid-October, concluded on 31 December. The hunt is needed to reduce the deer population at Saint John’s to a level that allows natural regeneration of the forest ecosystem, essential to the longterm habitat of deer and other components of the ecosystem. Twenty-eight deer were taken.

together in one tent unless they are married with each other for that purpose.

Hong Kong dentist

Tooth extractions using the latest Methodists.

The word “omicron” entered our daily vocabulary the day after Thanksgiving. Less than four weeks later, the Omicron variant was identified in all fifty states and was causing more infections and spreading faster than the original SARS-CoV-2 strain of the virus. Early in the new year, a dozen monks—fully vaccinated and boostered—were infected; by the grace of God, none had to be hospitalized or taken to the cemetery. Confirmed COVID cases in Minnesota dropped dramatically in early March just as Johns Hopkins University announced that six million had died of the virus worldwide. We pray for a springtime of hope— hope for healthier days, hope in the rising Son. Alleluia!

• In 2008 Brother Paul-Vincent Niebauer and Saint John’s Abbey acquired a set of unique artifacts: the Amahl Puppets, twenty-three life-sized puppets commissioned by Queen Elizabeth II and created by the Little Angel Puppet Theatre of London. Following restoration work, the Amahl Puppets have returned to the stage for a dozen performances in five locations. Thanks to a generous sponsor, Amahl and the Night Visitors (a one-act opera by Gian Carlo Menotti) was to have been staged in Saint Joseph’s Catholic Church (Saint Joseph, Minnesota) in early December. Due to health concerns, however, the production was moved to the abbey and university church on 10 December.

• The monastic community welcomed friends and neighbors to celebrate the nativity of the Lord with festive liturgies.

February 2022

• Abbot John Klassen announced that Dr. Therese L. Ratliff will be the next director of Liturgical Press, the abbey’s publishing apostolate. She will succeed Mr. Peter Dwyer, who will be retiring in June after thirty-three years of service to the Press, twenty-one of them as director. Dr. Ratliff will be the second layperson and the first woman to lead Liturgical Press since its founding in 1926. She will bring a diverse and accomplished portfolio in Catholic book and periodical publishing to her new responsibilities. Previously she served as the publisher of books and devotionals for the U.S. divisions of Bayard, Inc.: TwentyThird Publications, Pflaum Publishing Group, and Creative Communications for the Parish. Before joining Bayard, she was employed at Pauline Books and Media. An alumna of Emerson College, Boston, Dr. Ratliff earned a master’s

Spring 2022 32 Abbey Banner 33

Abbey Chronicle Cloister Light

Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

degree in theology from Saint Michael’s College (Burlington, Vermont) and a doctorate in theology and education from Boston College.