do not reduce in size (size or place between 100% and greater) use alternative logo for smaller size

Abbey Banner Fall 2023

The LORD is my shepherd; there is nothing I shall want. Near restful waters he leads me, to revive my drooping spirit.

Psalm 23:1, 3

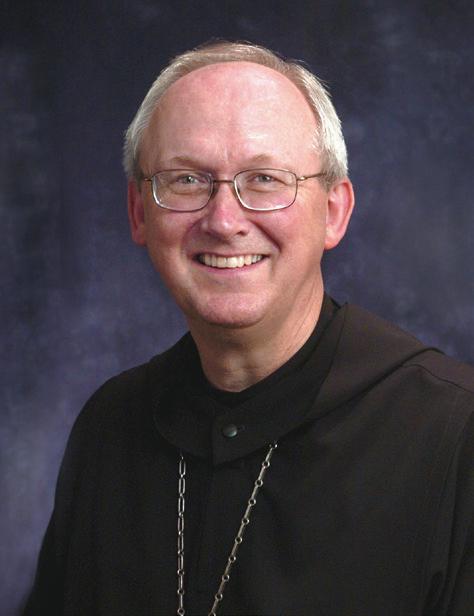

Michael Peterson, O.S.B.

Michael Peterson, O.S.B.

Abbey Banner

Magazine of Saint John’s Abbey

Fall 2023 Volume 23, Number 2

Published three times annually (spring, fall, winter) by the monks of Saint John’s Abbey.

Editor: Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

Design: Alan Reed, O.S.B.

Editorial assistants: Gloria Hardy; Patsy Jones, Obl.S.B.; Aaron Raverty, O.S.B. Abbey archivist: David Klingeman, O.S.B.

University archivists: Peggy Roske, Elizabeth Knuth

Circulation: Ruth Athmann, Tanya Boettcher, Debra Bohlman, Chantel Braegelmann

Printed by Palmer Printing

Copyright © 2023 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota.

ISSN: 2330-6181 (print)

ISSN: 2332-2489 (online)

Saint John’s Abbey 2900 Abbey Plaza Box 2015 Collegeville, Minnesota 56321–2015 saintjohnsabbey.org/abbey-banner

Change of address: Ruth Athmann P. O. Box 7222 Collegeville, Minnesota 56321–7222 rathmann@csbsju.edu Phone: 800.635.7303

Subscription requests or questions: abbeybanner@csbsju.edu

Behold, in his loving kindness the Lord shows us the way of life. . . . And so we are going to establish a school for the service of the Lord.

Rule of Benedict, Prol.20, 45

This issue celebrates the latest graduates of the Collegeville district’s school for the service of the Lord. The monastic community rejoiced this summer as Novice Augustine Oh and Brother David Allen professed their first and solemn vows, respectively, and seven confreres observed milestone anniversaries: Father Michael Peterson (25), Father Michael Kwatera (50), Brother Kelly Ryan and Father Mel Taylor (60), and Fathers James Reichert, Alberic Culhane, and Gordon Tavis (70). For their generous service, we give thanks.

Education is a key element of Benedictine monasticism. In Minnesota, the monks of Saint John’s Abbey and the sisters of Saint Benedict’s Monastery established schools to serve the early immigrant communities as well as Native Americans. In 1973 the sisters of Saint Benedict’s made the difficult decision to close their girls’ high school. The monks of Saint John’s promptly agreed to enroll girls at its formerly boys-only prep school. Ms. Peggy Roske shares the story of the first class of female Johnnies.

Saint Benedict cautions against being a respecter of persons—offering preferential treatment to others based on their social status. Rather, he insists that all persons be honored and respected (Rule 2.16–18; 4.8, 70–71; 63.10; 72.4). Nonetheless, the Church and society have struggled with modeling equal treatment. Racism often overpowers the divine command to love our neighbor. Brother Aaron Raverty introduces Saint Maur’s Priory, one of the first interracial religious communities in the U.S., established in response to racist segregation.

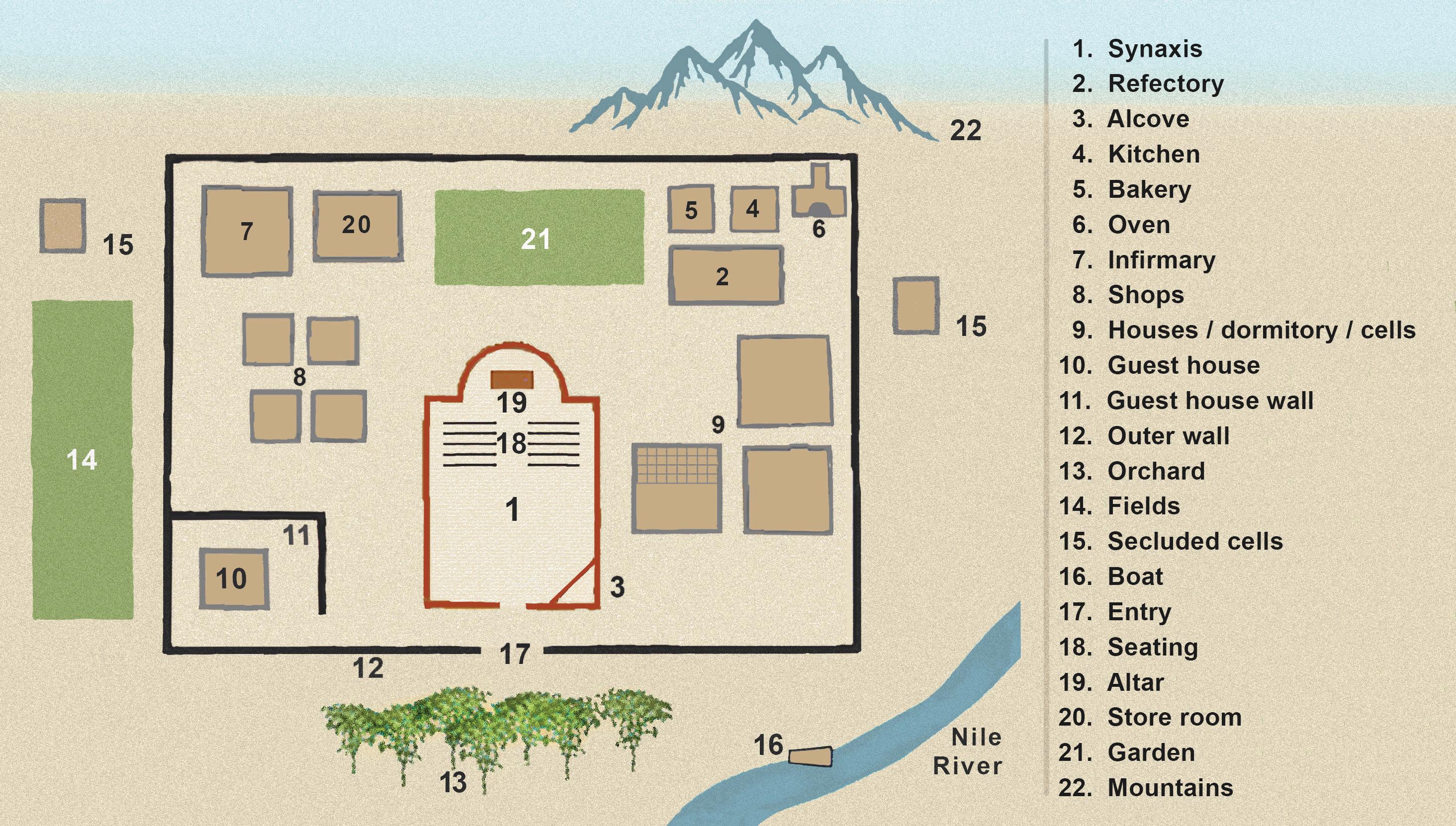

It’s about time! Before the advent of clocks or watches or even hourglasses, how did monks tell time? How did they know when to arise from sleep and go to prayer? Father Cyprian Weaver introduces Saint Pachomius, fourthcentury monk, and his rule (Regula Pachomii) to begin a series of articles investigating how, in the beginning, time was measured and how it regulated the activities in the daily life of monks.

The monks of Saint John’s Abbey have utilized local resources for their buildings and furniture throughout their history. Abbey woodworkers have crafted chairs and tables, doors and desks, coffins and urns—and even baseball bats! This Issue shares the story of Brother Hubert Schneider’s contribution to little leaguers during World War II. We also learn about a new nursery, explore the cluttered life of some confreres, meet a musician monk from Iowa, and more.

Cover: Following his profession of solemn vows, Brother David Allen greets his confreres and receives their blessings.

Photo: Félix Mencias Babian, O.S.B.

At the beginning of a new school year, the Abbey Banner staff, along with Abbot John Klassen and the monastic community, extends prayers and best wishes to all our readers for ever deepening knowledge, insight, and wisdom. Peace!

Brother Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

Abbot John Klassen, O.S.B.

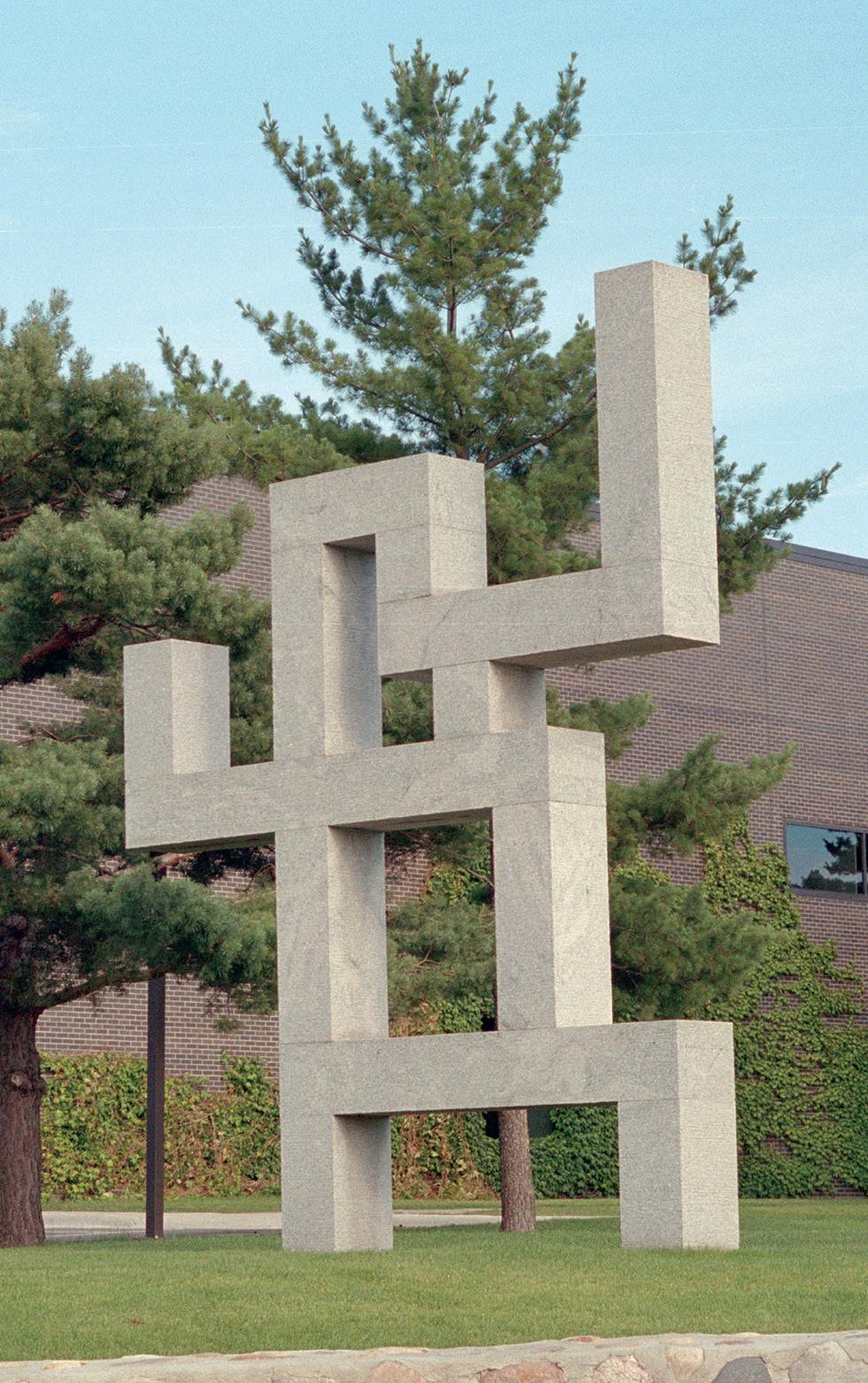

Iwell remember when I came into the monastery in July 1971 and had the opportunity to soak in the carefully chosen religious art in the cloister. It was present as a sacramental way to remind monks of the central mysteries of the Christian faith as well as significant monastic saints.

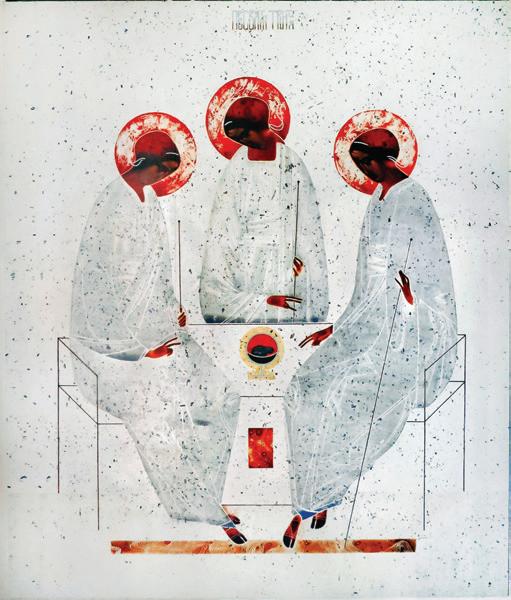

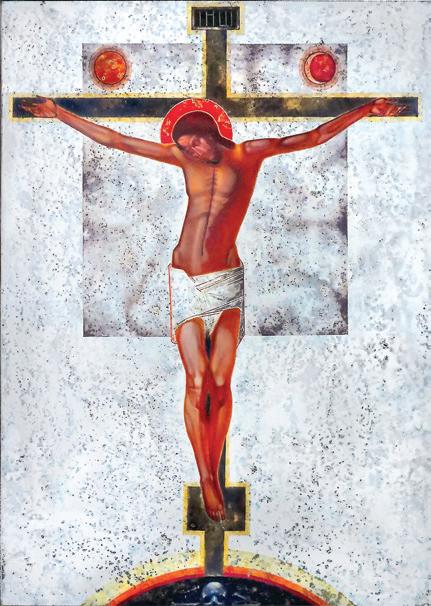

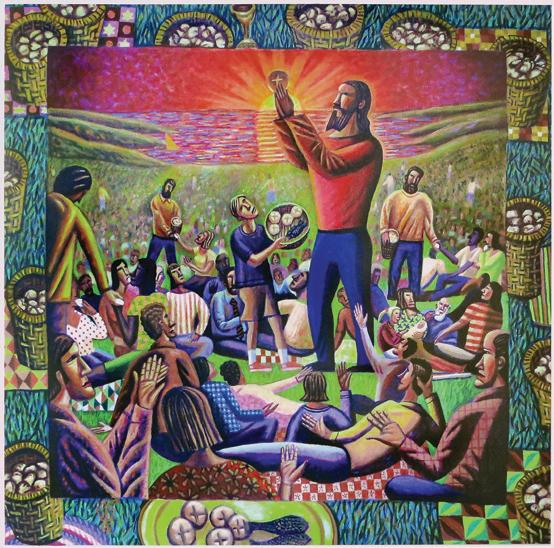

We had planned to install new murals at key locations when we completed the renovation of the Breuer monastery in 2021 but were unable to do so at that time. This summer, however, we made significant advances on this project with the installation of three large images.

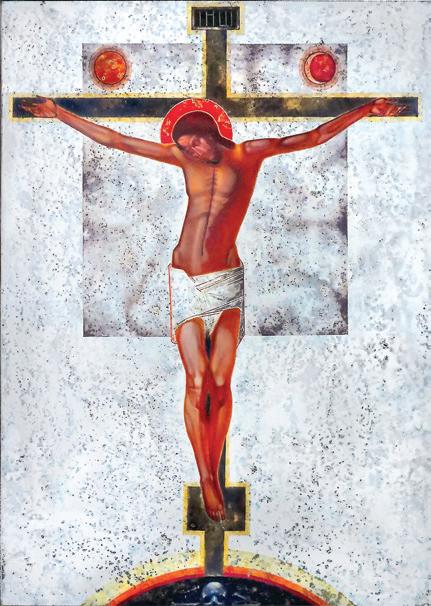

On the first floor is the Crucifixion by Ivanka Demchuk, a Ukrainian artist who specializes in colorful, classically designed iconographic presentations. The crucified Jesus is presented in warm red-orange, life-giving vibrancy, crushing death and evil at the foot of the cross. The textured background does not compete but supports the icon.

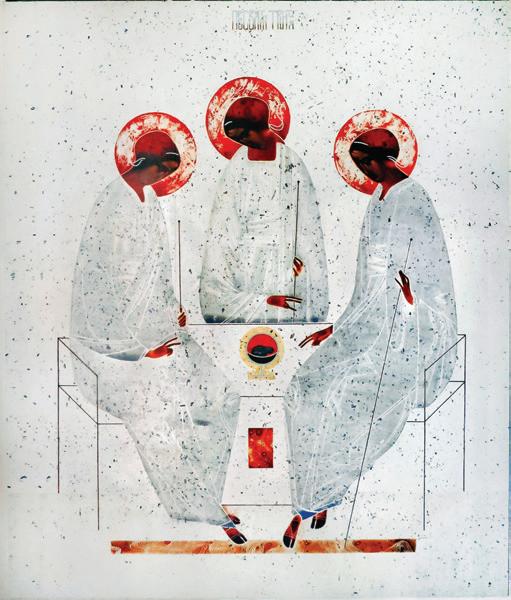

Ivanka Demchuk also created the image of the Trinity that dignifies the top of a stairwell. This presentation (13' x 11') takes its inspiration from Rublev’s famous work. Ms. Demchuk carefully presents the Trinity in figures and colors that are not overpowering: three Persons in almost outline form, light coloration; only faces, hands, and feet are a reddish color.

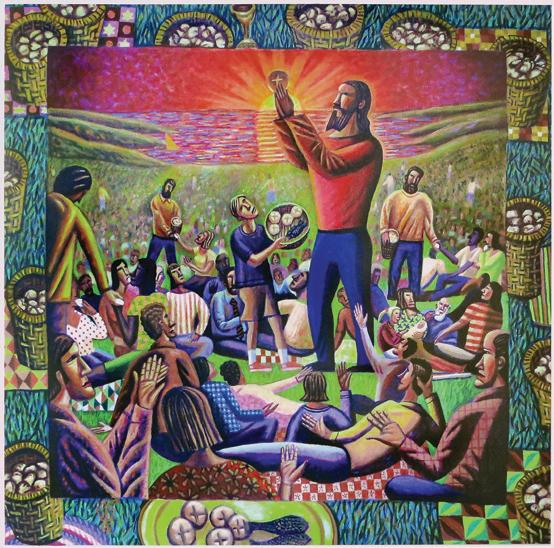

In our basement recreation room, artist James Janknegt gave us a brightly colored, evocative presentation of the Feeding the 5000, a scene that is repeatedly mentioned in the Gospels. Surely Mark 6:34–44 is the inspiration, with Jesus as a robust peasant and the crowd sitting on the grass in small groups. An abundance of bread and fish is vividly presented. How fitting for a room that brings us together for rejoicing!

The installation of these murals was complicated. It required skilled workers from our physical plant to prepare perfectly smooth wall surfaces to receive the printed images. Before that, the artists had to transmit high-resolution digital images to a local firm for printing.

We await a newly commissioned icon, Baptism of Christ, also by Ivanka Demchuk. Since we commissioned these works, there has been a war in her country, and she and her husband have welcomed their second child. Truly, we know it is worth the wait!

Banner This Issue Surrounded by Beauty

Abbey

4 5 Fall 2023

Alan Reed, O.S.B.

Abbey archives

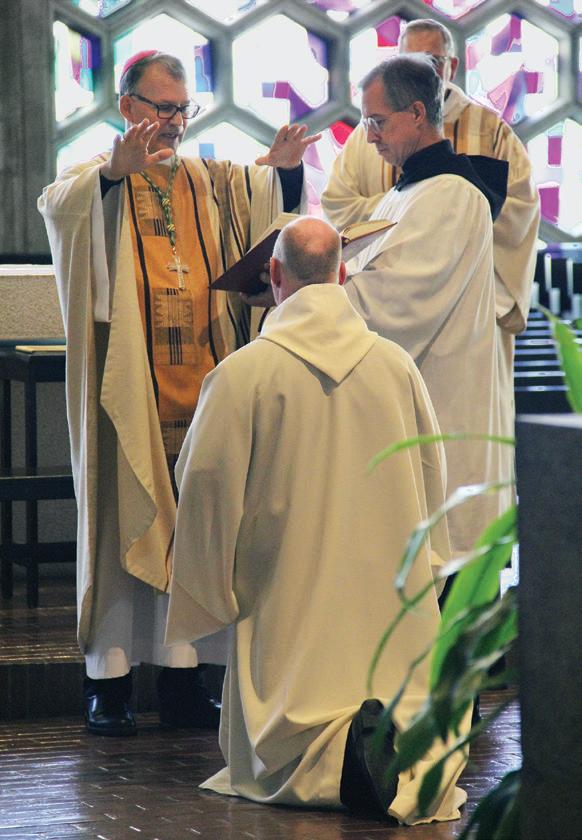

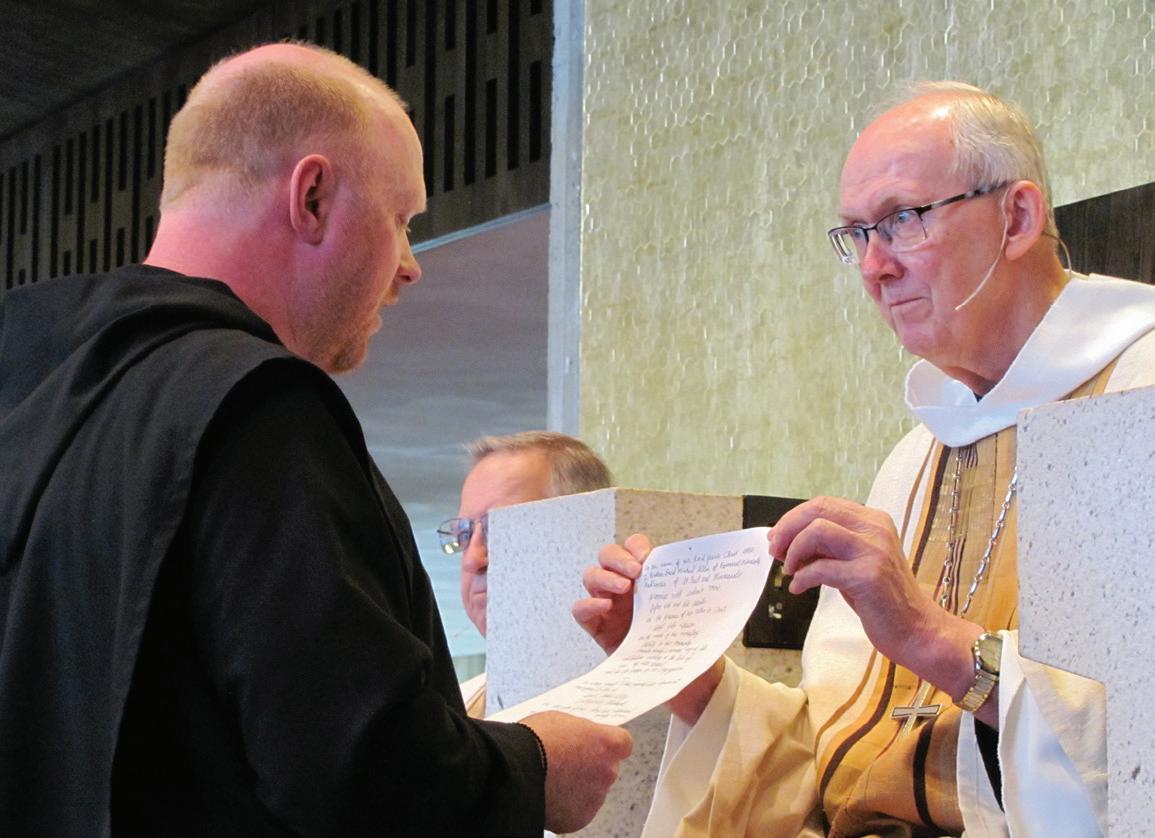

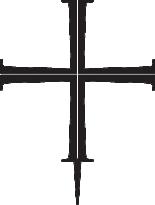

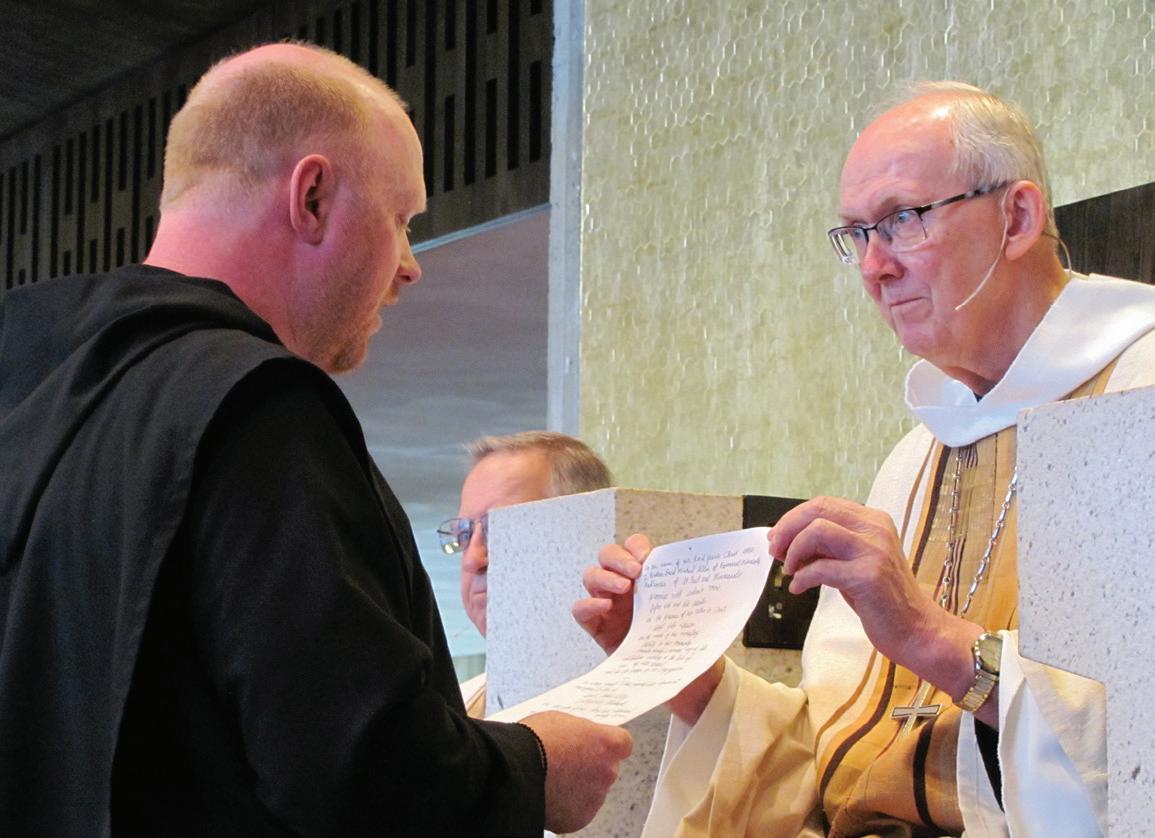

During a festive Eucharist on the feast of Saint Benedict, 11 July, Abbot John Klassen, O.S.B., and the monks of Saint John’s Abbey, along with many friends and family, witnessed Brother David Allen, O.S.B., profess solemn (lifetime) vows as a Benedictine monk and honored seven others celebrating their silver, golden, diamond, or platinum jubilees of profession.

Solemn Profession

Brother David Allen (36) is a survivor: of premature birth (the first five months of his life were spent in a neonatal intensive care unit); of an earthquake (while serving in the Benedictine Volunteer Corps in Chile); and of nine years of monastic formation. He professed his first vows in 2012 but three years later discerned that the time was not right for solemn vows. “Leaving the monastery in 2015,” Brother David recalls, “was a decision I did not make

lightly but needed in order to be shaped into the monk I am today. Returning to the community in 2019 was an ongoing decision for me, challenging and humbling. Saint John’s Abbey has always felt like home; I feel deeply connected to our prayer, the amazing and talented men whom I share this life with, and the wonderful roots monastic life gives me in pastoral ministry.”

A former member (drumline) of the acclaimed Rosemont High School Marching Band and an alumnus of Saint John’s University, David is an EXTROVERT. “I love to connect with others and listen to their stories,” he says. “I do well with deep, ongoing relationships and people of all ages.” In addition to assisting his retired and infirm confreres, he is pursuing seminary studies. “I am attracted to parish ministry because it provides opportunities for witness, outreach, and care for the local

Church,” he reflects. “I believe monastic life at Saint John’s is the best way for me to become a person of prayer, to deepen selfunderstanding and love. I am called by the vow of conversatio [monastic manner of life] to live with the tension between boldness and tradition, community and self-interest, trust and discovery in God.” Following ordination to the diaconate in August, Brother David is serving at the Harvest of Hope Area Catholic Community in central Minnesota, sharing his energetic spirit.

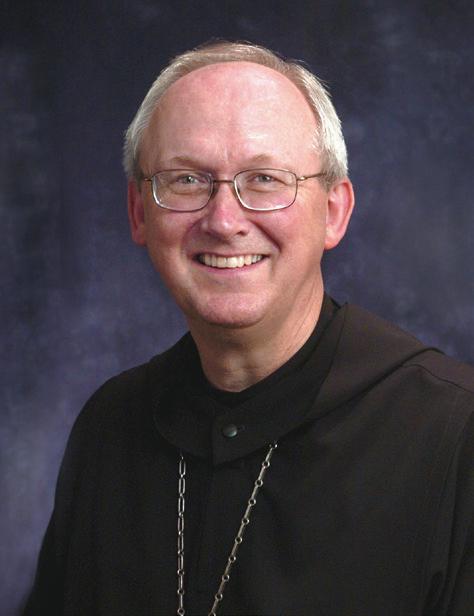

Silver Jubilarian

Silver jubilarian Father Michael Peterson, O.S.B., is well acquainted with the “hard and rugged ways” that define the journey to God (Rule 58.8). A convert to Catholicism from his lifetime as a Lutheran and an Evangelical, he professed his first vows as a Benedictine monk at Blue Cloud Abbey in South Dakota in 1998. He loved his prairie home and its way of life and was grieved when Blue Cloud closed in 2012. Shortly thereafter, Michael found himself back in his native Minnesota at Saint John’s, a place where he had once studied theology. He formally transferred his vow of stability to our community in 2014 and transferred his love for the Dakota prairie to a love of the blue waters of Lake Sagatagan. No stranger to work, Father Michael has served as organist for the Liturgy of the Hours, as sacramental minister to the students of the College of Saint Benedict, as assistant

director and then director of oblates since 2013, and as the abbey’s vocation coordinator for the past four years. He has enlivened the life of the community by sharing his mastery of Native American flutes, including playing his own compositions inspired by Lake Sagatgan. A self-described “builder of bridges,” Michael is pleased to promote the relationship of the Catholic Church with the local Muslim community.

Golden Jubilarian

Fifty years after professing his first vows, Father Michael Kwatera, O.S.B., accepted a cere-

monial wooden cane along with the thanks of Abbot John and the community for his decades of dedicated service. Worship is Father Michael’s work! Throughout his monastic life, he has shared the insights of his training in liturgical studies (master’s and doctoral degrees from Notre Dame) with his confreres and the local Church as a pastor of central Minnesota parishes and as a teacher of theology at Saint John’s. Since 2006 he has served as the abbey’s liturgy director—his third time in the position. Michael has assisted the Saint Cloud diocesan Office of Worship and led work-

shops for liturgical ministers. He authored two books on liturgical theology and many articles for popular liturgical journals. A man of prayer, Father Michael is also a composer of prayers, hymn texts, and blessings—he especially enjoys preparing texts for the blessing of athletic facilities where his creativity and mastery of metaphor come into play. For most of the past two decades he has shared his pastoral skills as a faculty resident for university sophomores and as chaplain for the Franciscan Sisters of Little Falls.

Fall 2023 Abbey Banner 6 7 Monastic Profession and Jubilees

Robin Pierzina, O.S.B. Brother David Allen professes his solemn vows.

Félix Mencias Babian, O.S.B.

The newly professed and jubilarians receive the well wishes of their confreres and guests. L to R, first row: Fathers Alberic Culhane, James Reichert, and Gordon Tavis; standing: Father Mel Taylor, Brother Kelly Ryan, Father Michael Kwatera, Abbot John Klassen, Father Michael Peterson, and Brother David Allen

Diamond Jubilarians

In 1963 Brother Kelly Ryan, O.S.B., and Father Mel Taylor, O.S.B., began their monastic journey as they professed their first vows as Benedictines. Sixty years later, Abbot John invited the monastic community and congregation to pray with him for God’s blessings on Brother Kelly and Father Mel as they continue on the road that leads to eternal life.

Brother Kelly Ryan’s journey to Saint John’s began in Hutchinson, Kansas. He found the climate here conducive to the growth of African violets and has nurtured hundreds of them over the years. He also nurtured

the growth of hundreds of Saint John’s Preparatory School students as a teacher of Spanish and English as a second language. He served the community as subprior and vocation director and developed the highly successful Monastic Experience Program at Saint John’s—a monthlong, livein experience for those discerning a vocation. Before retiring, Kelly spent twenty-one years assisting three abbots as their secretary.

Father Mel Taylor traveled to Collegeville from County Sligo, Ireland, by way of the Bronx, New York. He served in pastoral ministry throughout his life, ministering at Saint Anselm

and Saint Benedict’s parishes in New York and at Saint Bernard (Saint Paul) and Saint Boniface (Cold Spring) in Minnesota. For thirteen years he was the prior of Saint Augustine’s Monastery in The Bahamas (founded by Saint John’s Abbey) and assisted in a number of parishes on the out islands and in Nassau. Mel continues to share his pastoral presence with our retired and infirm confreres in Saint Raphael Hall.

Platinum Jubilarians

Abbot John and the community also offered their blessings to Fathers James Reichert, O.S.B., Alberic Culhane, O.S.B., and Gordon Tavis, O.S.B., who have sought the mercy of God and

fellowship in this community for the past seven decades.

Father Jim Reichert, a skilled teacher of Latin at Saint John’s Prep School, also served as an English and math teacher at Abadía de San Antonio Abad, Puerto Rico (founded by Saint John’s). After working in the business office of the monastery, he spent twenty-three years in pastoral service in parishes in Saint Paul, Albany, New Munich, and Avon, Minnesota; and nine more years as chaplain at Saint Therese in New Hope, Minnesota. In retirement, Father Jim continues to exercise his expert card-playing abilities.

First Profession

To the oft-asked question, “Can anything good come from Mitchell, South Dakota?” Father Alberic Culhane is the answer. Early in his monastic life he fell in love with Scripture and with archaeological research at biblical sites. He directed the Saint John’s Scripture Institute for ten years, taught undergraduate biblical theology, and participated in many archaeological digs in Jordan and Israel. A veteran of thirty-seven years as a university faculty resident, Alberic also planted hundreds of trees, helping to create the welcoming campus of Saint John’s.

Father Gordon Tavis served in the Navy Air Corps before joining the monastery. After directing the Mental Health Institute, he began a long career in the Saint John’s business office, including service as physical plant director, director of planning, university vice president of finance, abbey treasurer, and financial/demographic consultant to the American-Cassinese Congregation. At an age when most would settle into retirement, he brought his trademark enthusiasm and positive energy to the task of headmaster of Saint John’s Prep School for eight years, guiding the school to a new level of excellence.

On 15 August 2023, Novice Hang Geum Augustine Oh (47) professed his first vows as a Benedictine monk. A native of Seoul, South Korea, Augustine grew up in a Confucian and Buddhist society. At the age of 7, he was received into the Catholic Church, along with his entire family.

In 2004, while serving as a volunteer at the Athens Olympic Games as an interpreter of Korean-English, he observed that South Korea did not have expert lawyers in the field of sports arbitration—and he decided to do something about that. He pursued a bachelor’s degree in law (Seoul National University), a master’s in international arbitration (University of Miami School of Law), and juris doctor degree (Chung-Ang University, Seoul). More recently he ran his own business as a consultant for a Korean battery company for all-electric vehicles.

While enrolled in a liturgical music program at Saint John’s School of Theology, Augustine felt that God was calling him to monastic life. “I am interested in monastic life,” he says, “because I feel that God created me to give glory to God. Whenever I have asked what the ultimate way to seek God is, the answers have included the monastic life.” Seeking the mercy of God, he feels, is a means of solving “various issues of life and to get answers from various questions of life.” He is especially drawn to the ecumenical spirit of Saint John’s: “I have observed that the abbey practices it by welcoming and integrating others of various religious backgrounds into our liturgy as brothers under Jesus Christ.” Brother Augustine continues his discernment while serving as assistant abbey refectorian and Spiritual Life Program coordinator.

Fall 2023 Abbey Banner 8 9

The monastic community and congregation pray for God’s blessings on the jubilarians.

Alan Reed, O.S.B.

Brother Augustine Oh Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

Benedictine Volunteer Corps

Jersey Lessons

Thomas Skindingsrud

During my senior year at Saint John’s University, I had considered joining the Benedictine Volunteer Corps (BVC). However, the pressure of “you need to get a good, highpaying job” was constantly on my mind. Following my graduation in 2021, I joined the workforce as an accounting and finance recruiter for a large corporation in the Twin Cities. I enjoyed many aspects of this sales-driven job, but I had this lingering question in my mind, “Is this what you want to do for the rest of your life?” After six months, I knew this was not the path I was destined to go down. I quit my job, started looking at other career paths, and began questioning myself, “What am I passionate about?” Luckily, three of my six roommates from my senior year were Benedictine Volunteers, and I learned about their incredible journeys. Speaking with them about their experiences allowed me to reach out to the BVC. The director informed me that there was one opening left, and it was in Newark, New Jersey. After a week of further reflection with family and friends, I said “yes.”

A year after graduating, I found myself back at Saint John’s, and I knew immediately that I had found what I was looking for. Being back on campus, being surrounded by its beauty and

amazing people—from the monks to the employees who take care of this remarkable place—was pure bliss. I remember being upset that I didn’t go directly into the Benedictine Volunteer Corps after graduation, but sometimes we learn the hard way about what the right steps are. After spending a few days helping in the abbey woodworking shop, I packed up my car and began my twenty-hour journey to the East Coast. My first impressions of Newark were, “Wow! These are the most confusing road systems,

jam-packed with people from left to right.” I was no longer in the Midwest, and the culture shock was setting in.

Upon my arrival, I was greeted by the dean in the boys division at St. Benedict’s Preparatory School, and he gave me the lowdown on what to expect, not only at the school but also in Newark. I met the house parents and a student named Logi, who stands 6 feet 9 inches tall! Logi is from Mali in West Africa and is one of the most amazing human beings I’ve ever had the privilege of getting to know. He has a strong work ethic, was the captain of the basketball team, house leader, and overall role model at St. Benedict’s Prep. I lived in the dorm that housed many international students— from Mongolia, Brazil, Sweden,

Ghana, Bolivia, Nigeria, Denmark, and more. This house was remarkable as students of all faiths and backgrounds could learn from one another. The love in that house was palpable.

At St. Benedict’s Prep I was a teacher, substitute teacher, faculty resident, and garden club moderator—all of which provided a bounty of work, but work that I found incredibly meaningful. Without any previous teaching experience, I had become a full-time teacher faced with a huge learning curve. The sudden shift from being a stu-

dent to teaching and leading a class was truly challenging but also a time to learn and grow. I taught a class that encompassed current events, geopolitics, political theory, philosophy, and history—all subjects that I’m passionate about. Being able to share that passion with others was another blessing.

There were difficulties along the way, but I recognize that to learn and grow, we must face adversity. St. Benedict’s tested me in so many ways and exposed my weaknesses, which allowed me to confront them. The school

environment was very unfamiliar, so it took me about a full semester to figure out how to fit in and let my voice be heard. Getting to know the students at school and in the house allowed for relationships to form and flourish. (I grew up with one sister, and I always longed for brothers, which I now have in abundance!)

I came to admire the culture on the East Coast. People there are direct and say what is on their minds, which I find to be authentic and refreshing. Coming home to Minnesota was another culture shock as people are often hesitant to say what is really on their minds. I often find myself saying “well, in Jersey”—until my mom cuts me off, saying “we’re not in Jersey, Thomas.” St. Benedict’s and Newark are both tough places, but they help create strong leaders who are resilient and have thick skin, another discovery that I find refreshing.

I will be forever grateful for the BVC experience. There isn’t enough space, even in a book, for me to revisit all I’ve experienced and learned. But I want to say a special thanks to Michelle Tuorto (associate headmaster) and Father Asiel Rodriguez who guided me along the way, providing exceptional support throughout my time in Jersey.

Fall 2023 Abbey Banner 10 11

There were difficulties along the way, but I recognize that to learn and grow, we must face adversity.

BVC

BVC archives

Mr. Thomas Skindingsrud is a member of the residential life staff at Saint John’s Preparatory School.

archives

The core pillars of St. Benedict’s Prep: community, student leadership, counseling, and experiential education

John Geissler

As we continue our efforts to regenerate and restore the native plant communities at Saint John’s Abbey Arboretum, I have enjoyed learning more about the science and art of collecting, storing, and planting seeds. Not only is it fun to grow native wildflowers, grasses, shrubs, and trees from seed, but it is also very cost effective!

Fall is a prime time for the abbey land stewardship team to collect many types of seeds. When we take a closer look at these “tiny plants in a package,” we notice that they come in all sorts of shapes, sizes, and textures—with different strategies for getting started in new places. Some of them fly; others hitch a ride; still others explode, float, or attract critters to eat and spread them, and more. Whenever possible we let seeds disperse naturally, but when we are restoring a disturbed habitat, we assist in the process. In a treasure hunt to collect some seeds from as many species as possible, our outstanding and dedicated Abbey Conservation Corps volunteers and staff fan out across the abbey arboretum

with paper bags and five-gallon buckets to collect native seeds from a variety of habitats. The seeds we collect will be utilized in many ways to aid our stewardship efforts.

One of the easiest methods to aid restoration is to collect native wildflower or grass seeds from the established prairie or oak savanna and then immediately distribute them in disturbed areas that match their growing requirements—sunlight, soils, moisture levels, etc. At the next level, we save some of the seed, prepare it by simulating winter conditions, and then in March

plant them in starting trays in the greenhouse. By June we have beautiful plugs ready for planting wherever we need them. Over the last two years, we have grown over 4,500 individual native wildflower and grass plugs that have increased biodiversity in a growing number of inner campus pollinator gardens and targeted new prairie/oak savanna restoration efforts in the greater abbey arboretum.

Our most exciting new initiative is a longer-term, seed-starting endeavor charged with growing strong oak tree seedlings from our own acorns. Driven by a

desire to increase the survivability and long-term health of our oak plantings, we reviewed the literature. Most everything we read was backed up by the advice and proven results of an experienced local tree-growing expert, Mr. Larry Huls. (I am so appreciative of Larry and all the other dedicated Abbey Conservation Corps volunteers—you know who you are—who regularly advance our stewardship mission in so many ways!) The successful results of several pilot tests over the years with Larry’s tree seedlings inspired us to begin this effort in earnest.

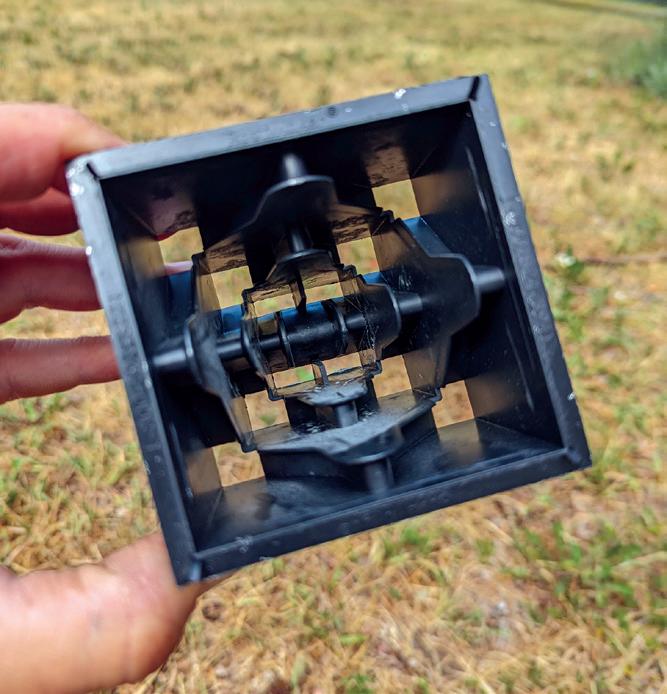

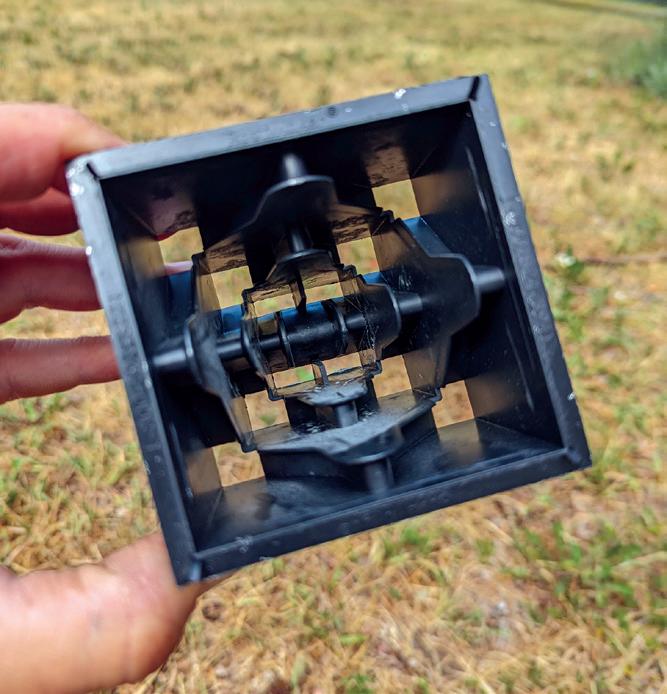

The process began with the purchase of specially designed “air pruning” four-inch pots to start our acorns in the greenhouse. In a normal pot, the typical single taproot that comes from an acorn endlessly circles around the bottom of the pot and quickly develops a terrible circular root structure that will actually slow and eventually thwart the tree’s growth. On the other hand, in an air-pruning pot, the tip of the taproot is quickly guided out of the pot where the air naturally dries the end of the root. This spurs significant lateral branching of the living portion of the root inside

the pot. Eventually all these lateral branches also grow out the bottom or side of the pot and are also air pruned, stimulating even more root branching.

Fall 2023 Abbey Banner 12 13 Abbey Forest Nursery

One of the easiest methods to aid restoration is to collect native wildflower or grass seeds from the established prairie or oak savanna.

Acorns are collected from the abbey arboretum and placed in storage until March. In March acorns are planted into individual pruning pots in the greenhouse. The holes and ridges in the pruning pot (below) guide the roots out the bottom of the pot.

This strong, branched-root structure is established after about two months. We then plant approximately one-foot-tall seedlings outside in the ground in the new Saint John’s Abbey Forest Nursery—located just north of the abbey vegetable gardens. Imagine a garden full of rows of trees! Here the trees will be pampered with the best possible growing conditions: full sunlight, toughened in the wind, with regular watering. For two growing seasons they will grow big and strong in these perfect conditions before they are at the optimal size for transplanting. At that point their trunk at the base will be about the size of an adult’s thumb, about three feet in height, and have an outstanding root structure. This large root mass with many branches is capable of gathering more water and nutrients than a single taproot and allows the plant to handle the shock of transplanting more readily. Less shock and better water/nutrient gathering capability means less watering by bucket out in the forest, increased survival, and faster growth to get above deerbrowse height. All of which make our team smile.

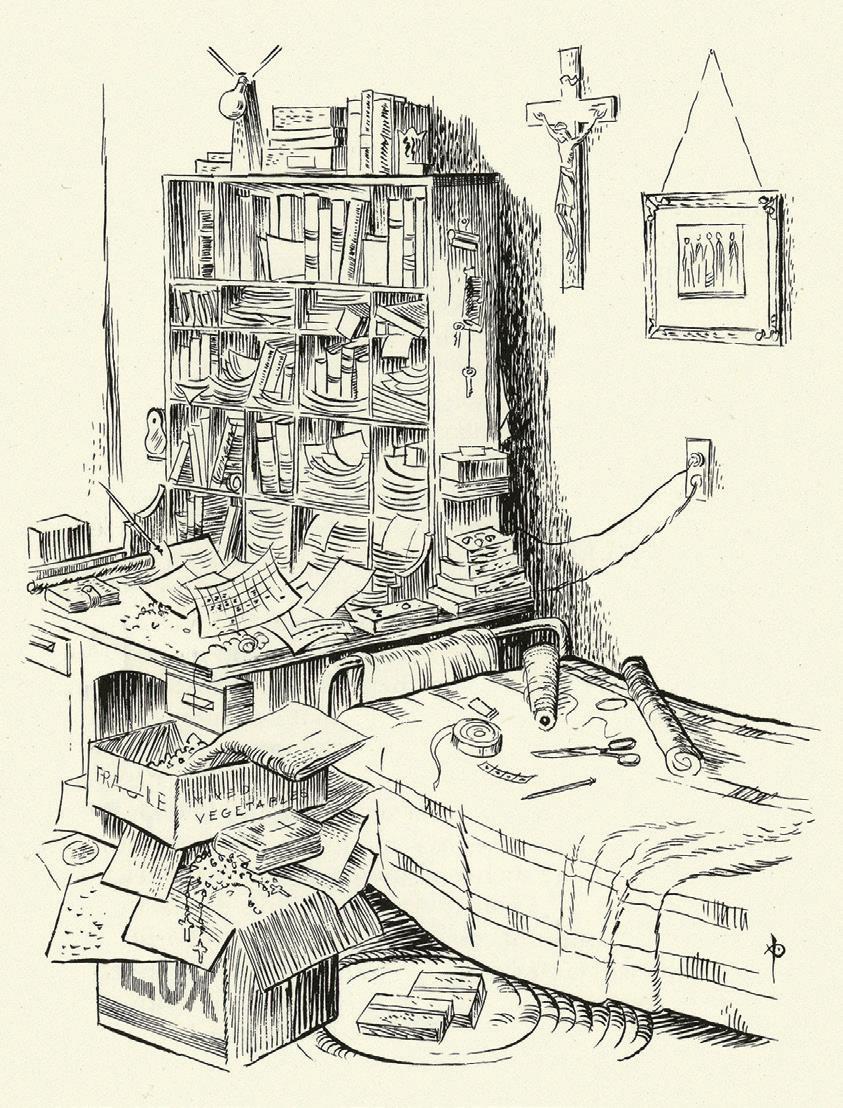

An Uncluttered Life Eric

Hollas, O.S.B.

The abbot should provide all the necessary articles: cowl, tunic, sandals, shoes, belt, knife, stylus, needle, handkerchief, and writing tablets.

Rule 55.18–19

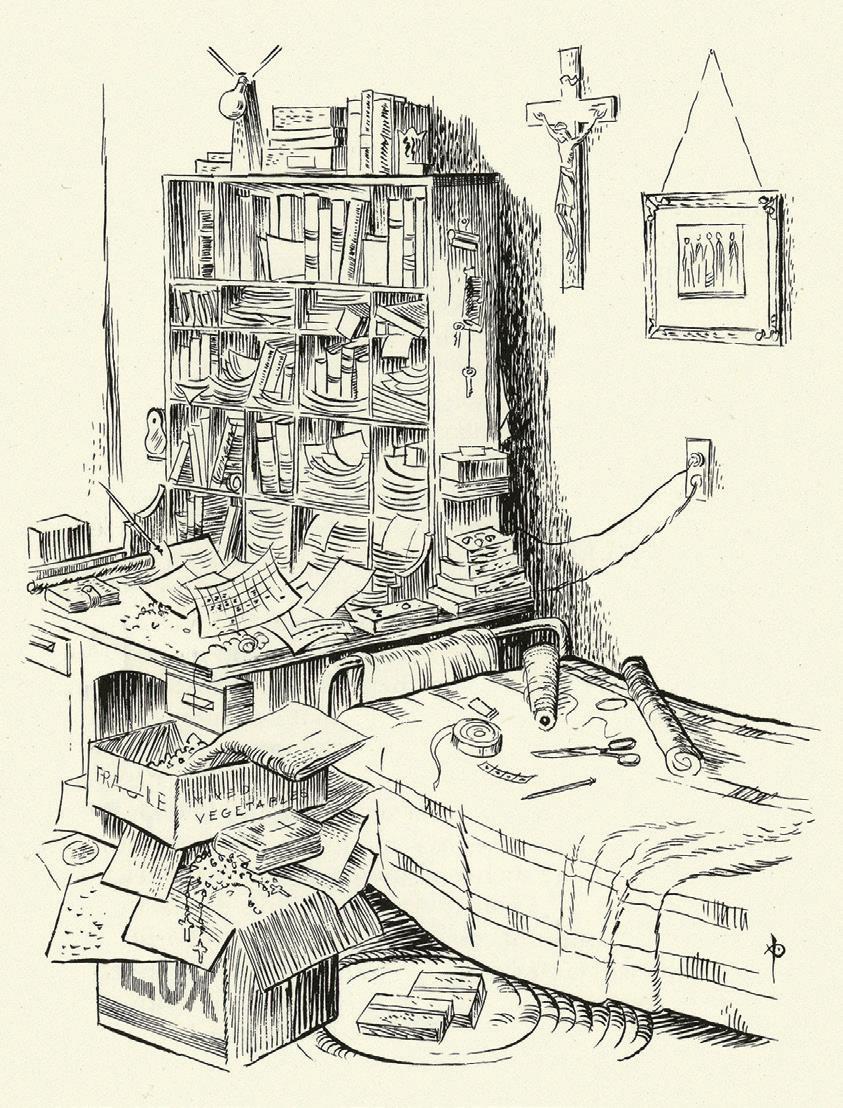

Chapter 55 of the Rule of Saint Benedict can be a real eye-opener. Was this spare life what Benedict expected of all his disciples? If so, why did subsequent generations feel free to push the envelope when it came to personal possessions? After all, few Benedictines live that simply today, and they haven’t done so for centuries.

Much has changed since Benedict wrote. In his monastery, the habit served both utilitarian and sacred purposes. A monk lived, worked, and prayed in it. Most people at that time had only one or two changes of clothing. Books were few and far between —and expensive. Through the early Middle Ages many monasteries had fewer than a hundred books. In the eleventh century, rare was the abbey that had a thousand manuscripts on its shelves. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that private collections in the cloister were unheard of.

Change came slowly and yet inevitably. The common dormitory gave way to individual cells, and these gave monks a place to store private property.

Still later, inexpensive books and increased professionalism made book ownership more feasible and even necessary. Collections of a thousand or more books were no longer rare in monasteries. Finally, the advent of mechanical devices led to practical clothing that distinguished the habit as a primarily sacred garment. The habit was illsuited for work with modernday farm machinery, nor was it made to tangle with either cars or the wheels of a desk chair.

What has been the cumulative impact of these changes? Monks now share with many others the challenge of life in a consumer society. Stuff piles up in the cells of monks just as it does in ordinary homes. Papers and cell phones and computers obscure

Like everyone else, monks wonder whether their possessions own them, or vice versa.

desktops. Like everyone else, monks wonder whether their possessions own them, or vice versa.

Perhaps we can better appreciate what Saint Benedict wrote in chapter 55. He never intended that his monks be relics of the sixth century, nor did he mean chapter 55 to be the final draft of what monks should or should not own. Rather, he was emphasizing the importance of simplicity. The job description of a monk has not changed. The monk comes to the monastery to seek God. That is best accomplished by living an uncluttered life.

Father Eric Hollas, O.S.B., is the prior of Saint John’s Abbey

Fall 2023 Abbey Banner 14 15 ule of Benedict

Placid Stuckenschneider, O.S.B.

Mr. John Geissler is the land manager of Saint John’s Abbey and director of Saint John’s Outdoor University.

By June the seedlings are close to one foot in height. They will spend two growing years in the abbey nursery before finding a permanent home. Photos: John Geissler

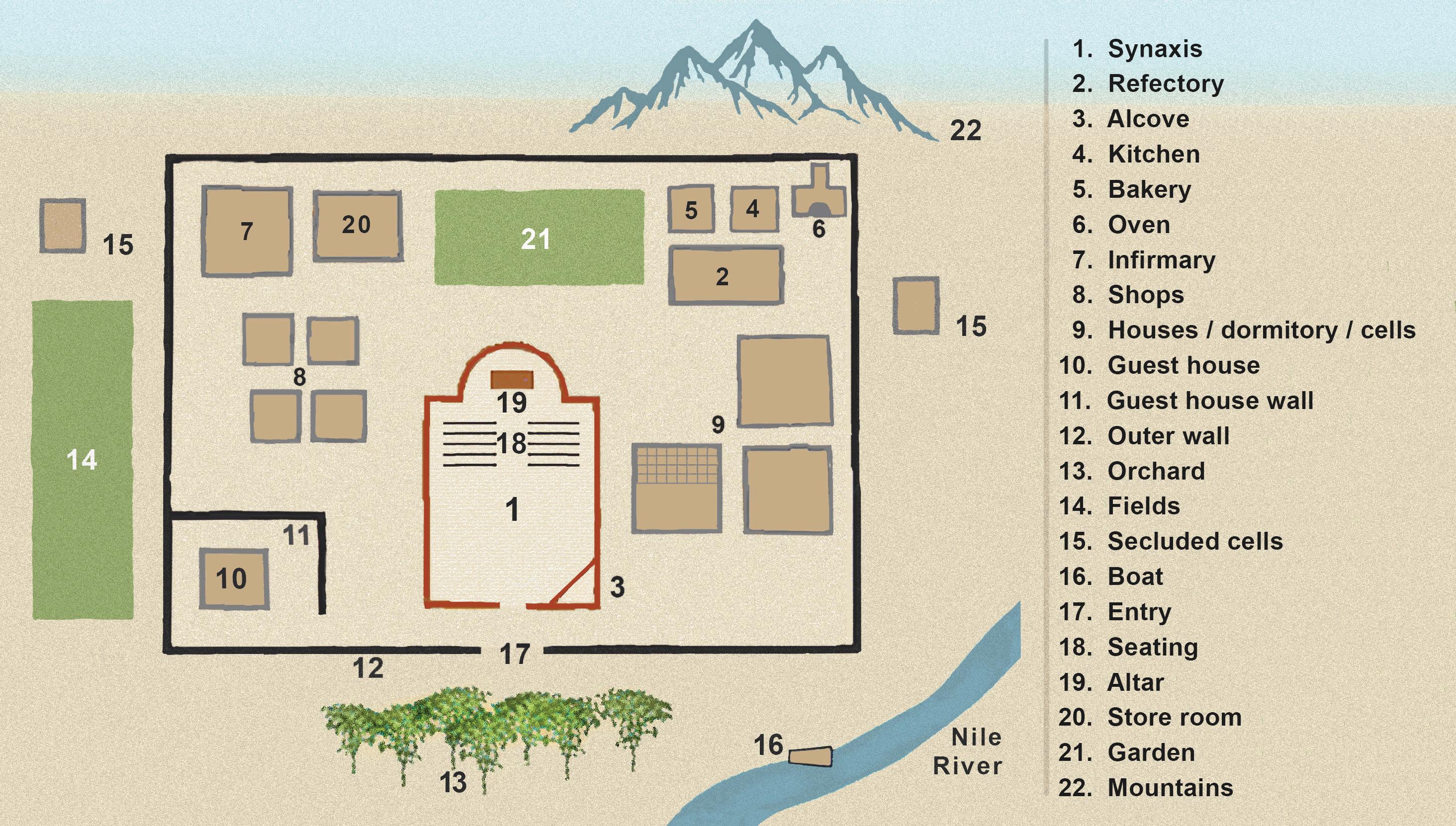

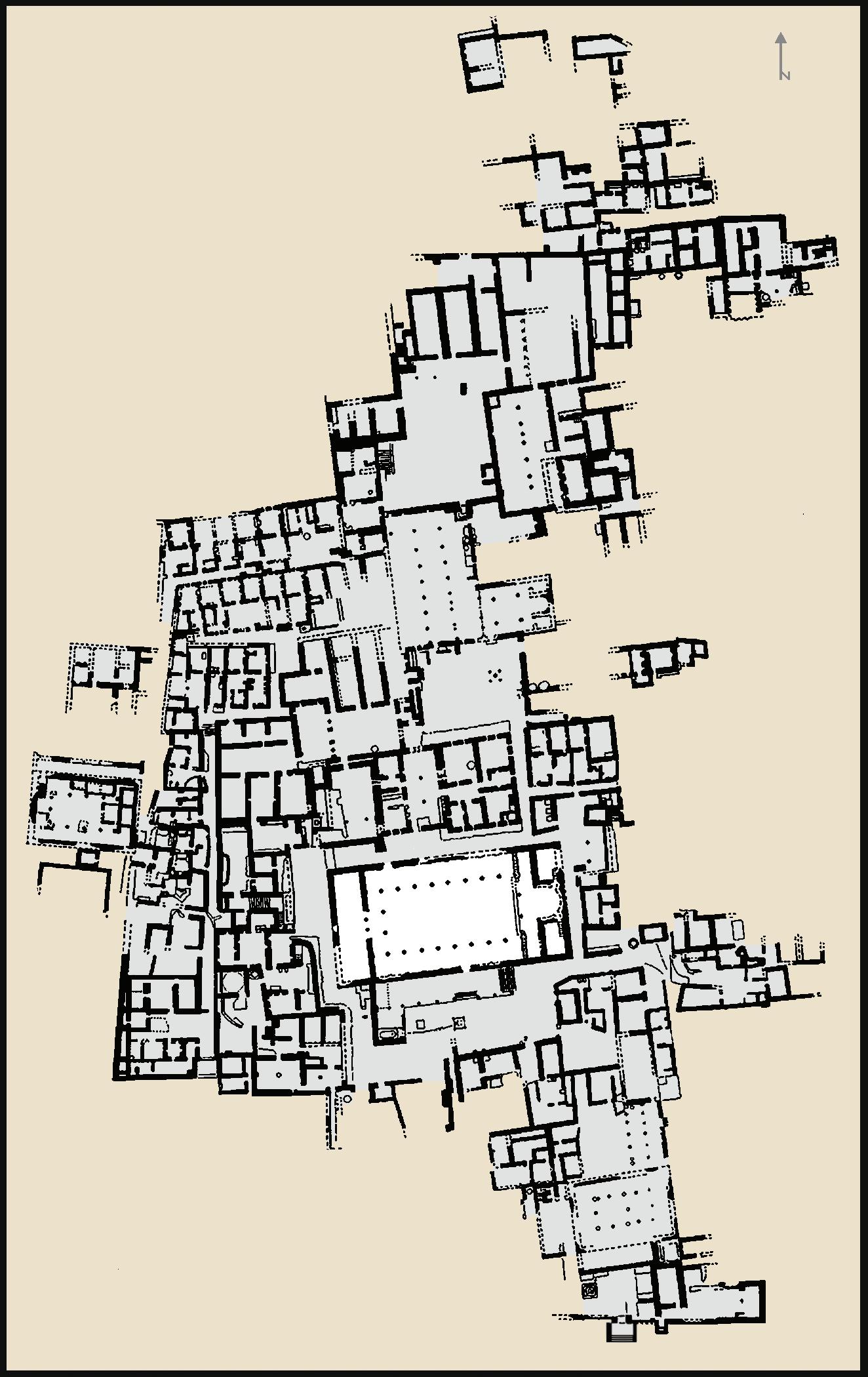

Saint Pachomius

Cyprian Weaver, O.S.B.

Peter the Venerable (c. 1092–1156) relates the story of one of his Cluniac monks, Brother Alger, who thought he heard the signal bell for Nocturns. Arising from his bed and imagining the other beds in the dorm vacated, he quickly dressed and rushed to church. The bell no longer sounding in the cloister meant he was late, and the closed church doors indicated still further that prayers had begun. He placed his ear to the door, but instead of chanting voices, he heard nothing but dead silence. Returning to the dormitory he discovered his brothers sound asleep and he, a victim of a dream—a phantasmagoria of the devil contrived to rouse him at the wrong hour so as to make him too tired to hear the true bell of Nocturns.

While Peter may have elaborated somewhat upon retelling the story of Brother Alger, he knew well the crucial factor of the timing of prayer life since Cluny was well known for its elaborate horarium (daily schedule) of canonical recitation. But who would have rung the signal bell that Brother Alger thought he heard? No one had a horologium or other timepiece—mechanical clocks would not appear until the thirteen century; and quartz watches, not until the twentieth century. How did monks awaken to pray before the bell existed? What was the relationship between the monastic cloister’s need for regulating canonical prayer and the development of the measurement of time? How did the monastic horarium come to temporally organize much of the secular life and world outside the cloister? This article is the first in a series that will explore the origins and early growth of timekeeping within monasticism.

The word “monk” (Greek: μοναχός, monachós; Latin: monachus) derives from the Greek root mónos, meaning one, single, alone. It became the moniker of those ascetics of the late third and early fourth century who sought out the solitary life

in the desert in their observance of the spiritual life. Leaving behind family, a perhaps contentious Christian community, and a decadent secular society as well as the throes of persecution, they fled to the western desert areas of Lower Egypt (such as Nitria, Kellia, or Scetis; south of presentday Alexandria) to live out radically the Gospel— total abandonment of self through poverty and an ascetical regimen of contemplation and prayer. Another form of monastic life also arose in the same context in the southern Thebaid region of the Upper Egyptian desert that found expression in a cenobitic (κοινοβιάτες) lifestyle. Cenobites were monks who lived together under an abbot and a rule in a communal pursuit of spiritual ideals, those whom Saint Benedict would later call “the strongest kind of monks” (Rule 1.13).

When Benedict of Aniane (c. 747–821) created a code of regulations (Codex regularum) at the Aachen Assemblies of 816–17 to reinstate the rigorous observances of monastic life that had become less stringent over the course of recent centuries, he collected thirty monastic rules—twenty-four rules for monks and six rules for nuns from the fifth to seventh centuries. Later, in his commentary Concordia regularum, he collated each chapter of Saint Benedict’s Rule with corresponding chapters from these monastic texts and thereby promoted the adoption of one rule and one custom (una regula, una consuetudo) in all abbeys of the Frankish realm. Within these rules, the details of daily life as they relate specifically to the management of time and timetables are difficult to establish. The texts are often imprecise, with some providing excessive details on certain points while leaving others with few particulars or with labyrinthian treks.

To begin our investigation of how time was measured and how it regulated the activities in the daily life of monks, this article will consider the monastic rule of Pachomius (Regula Pachomii). Though none of Pachomius’ manuscripts has survived, details of his life were preserved by the fifth-century historian Palladius (Galatian monk, bishop, and

chronicler) in his Lausiac History. The Pachomian rule was translated into Latin by Saint Jerome.

Saint Pachomius the Great (c. 290–346) was the leading exponent of cenobitic monastic life and later acknowledged as its father. His rule became

tion, and Scripture, with time for manual labor as well as individual spiritual reading. It includes a number of time-dependent events in the daily life of a monastery (italics added):

RP3. As soon as he hears the sound of the trumpet calling the [brothers] to the synaxis [word for both prayer and church], he shall leave his cell, reciting something from the Scriptures until he reaches the door of the synaxis.

RP5. But at night when the signal is given, you shall not stand at the fire usually lighted to warm bodies and drive off the cold, nor shall you sit idle in the synaxis.

RP6. When the one who stands first on the step, reciting by heart something from the Scripture, claps with his hand for the prayer to be concluded, no one should delay in rising, but all shall get up together.

RP9. When by day the trumpet blast has called [the brothers] to the synaxis, anyone who comes after the first prayer shall be punished.

foremost in guiding the formation and running of monasteries throughout Egypt. Pachomius was born into a pagan family near Luxor in the Thebaid region of Upper Egypt. After his conversion to Christianity, he sought out the ascetic ideal of the desert and observed an eremitical life under the guidance of the hermit Palaemon for seven years. Following this tutelage Pachomius set out to establish a monastery; between 318 and 323 he founded his first monastery at Tabennisi (north of Thebes) in Egypt. Others could join him and adopt a rule that envisioned his ideals of monastic observance.

The Rule of Pachomius (RP), like any rule, was organized around the liturgy of prayer, medita-

RP22. When the signal is given to assemble and hear the precepts of the superiors, no one shall remain behind.

RP23. And without [the superior’s] order, he shall not be able to give the signal for [the brothers] to gather whether for the midday or evening synaxis of the Six Prayers.

RP26. If in the morning he notices that still more rushes are needed, he shall dip them and bring them around to each house, until the signal is given for the meal.

RP36. The one who strikes the signal to assemble the brothers for meals shall recite while striking.

Fall 2023 Abbey Banner 16 17

Monastic Timekeeping

RP68. They shall not go to do laundry unless one signal has sounded for all.

RP90. Nor should one go in to eat at noon before the signal is given. Nor shall they walk around in the village before the signal is given.

RP103. No one shall leave his mantle in the sun until the signal is given at noon for the meal.

The mention of a trumpet (tubae) as a signal for synaxis (RP 3, 9) has been judged by most scholars to be an error on Jerome’s part from his

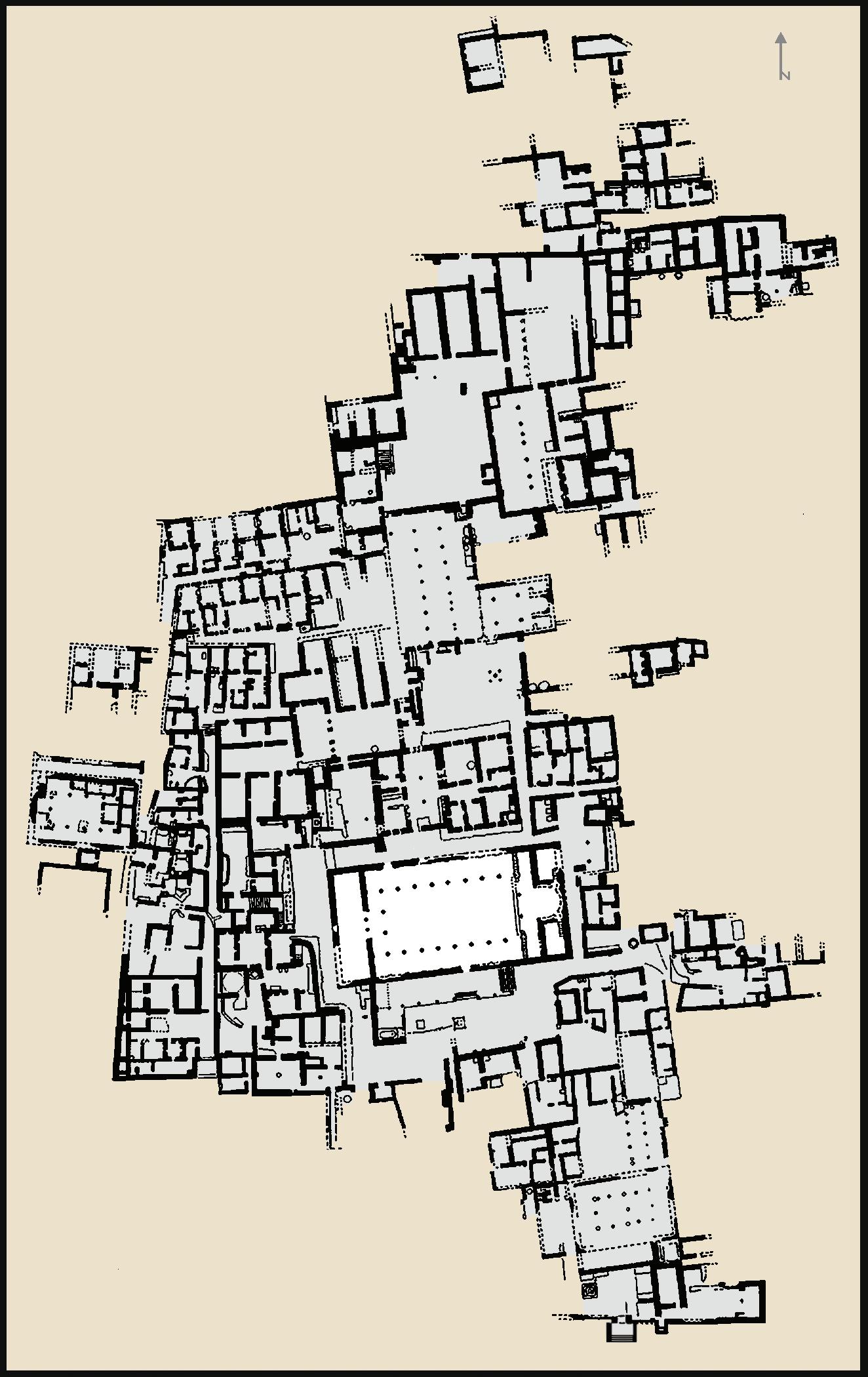

translation of the Pachomian Rule into Latin in 404. However, the Roman tubae, often known as the trumpet, was an ancient signal instrument utilized by the Roman military as well as in religious ceremonies. A trumpet call (Latin: gallicinium, which means “cockcrowing” or break of day in English) told the Roman units that it was time to change the guard for each shift. At the end of the 3 A.M. and 6 A.M. shifts, the guard change was announced by a Roman “cockcrowing” or by blowing a horn. In the other passages of the Regula Pachomii, Jerome simply speaks of a “signal,” perhaps aware of the dual nature of the instrument. From these instances one can appreciate the value that signals would play in organizing the collective life of early desert monastics, given Pachomius’ arrangement of the monastic enclosure—a spacious courtyard with individual “houses” where twenty to forty monks resided in cells along with various other structures, including the synaxis. Some signaling represented events occurring within the immediate vicinity, whereby signals are given by hand or mouth (RP 5, 6), but the majority may be interpreted as signals created by some instrument capable of alerting those at a distance (RP 3, 9, 22, 23, 26, 36, 68, 90, 103).

How was the timing for signaling a given event (synaxis, meals, laundry, or other communal tasks where time management was of the essence) determined? It is likely that more than one member was assigned the responsibility of recognizing and coordinating the timing required to sound the signals that alerted the others of communal functions. By the time he died, Pachomius had founded eleven monasteries, numbering more than 7,000 monks and nuns! This implies that each monastery, on average, may have had over 600 monastics in residence. The sheer number of monastics as well as the actual floorplan of monastic cells and common areas [left} would have made synchronous timing truly challenging. It would appear to be a logistical nightmare in the making!

Pachomian prayer life also implicates the role of time management, but like the primitive office of Tabennisi, they were relatively simple. Two daily offices embodied the spiritual domain of their cenobitic lifestyle. One came with the dawn and the sounding of the signal (noted earlier in RP 3), which beckoned the monks of each house to gather for morning synaxis. While some monastic commentators (such as Armand Veilleux, O.C.S.O.) have held that this was not an especially early office as in Lower Egypt, this would seem unlikely since most scholars agree the Egyptian day began at dawn, before the rising of the sun, rather than sunrise.

Unlike the morning liturgy, the evening office was recited together by the monks residing in each house before retiring and consisted of the so-called “Six Prayers,” the specific nature of which remains unclear, but is thought to resemble the pattern of the morning synaxis. The monks returned to their cells after the Six Prayers for further Night

Prayer or Vigils that ran continuously through the night from evening synaxis until dawn of the next morning. This was an exercise carried out individually as a private devotion rather than a communal practice—except at Easter or during the funerial waking of a monk. Nevertheless, the practice was common enough to evoke the praise of ancient observers for the Pachomian monks and their unusual habit of not sleeping conventionally but remaining awake on a “reclining seat” (kathisma) that might serve comfortably for a light nap but not a full night’s sleep. (The custom probably dated back to Pachomius’ early, austere years under the mentorship of Palaemon.) Needless to say, the assigned nocturnal sentry would have opted for the kathisma to remain vigilant for his duty of rousing the community at dawn.

Father Cyprian Weaver, O.S.B., a research scholar in the role of neuroendocrinology in regenerative and genomic medicine, is a retired associate professor of medicine, cardiology, at the University of Minnesota.

Title of Article Fall 2023 Abbey Banner 18 19 Title of Article

Upward Bound

Throughout his monastic life, Brother Benedict Leuthner has assisted the community’s land stewardship efforts by planting acorns, pruning trees, and clearing prickly ash and ironwood. Since 1986, when he began the candidacy program at Saint John’s Abbey, he has planted some 1,200 seedlings in the monastic gardens and in the abbey arboretum. Brother Benedict has not, however, been able to match the growth of his white oaks.

Mighty oaks from little acorns grow.

21 20

August 2017

July 2018

July 2019

August 2021

June 2023

Photos: John Geissler

Saint Maur’s Priory

Aaron Raverty, O.S.B.

When we visualize the membership of a monastery, the interracial composition is usually not in the foreground. Still, race is an issue in any but the simplest and most marginal of human communities. As attested by anthropologists, race is not a biological category, yet the differences it spawns inevitably create a response, and, as a social construct, race powerfully motivates human behavior.

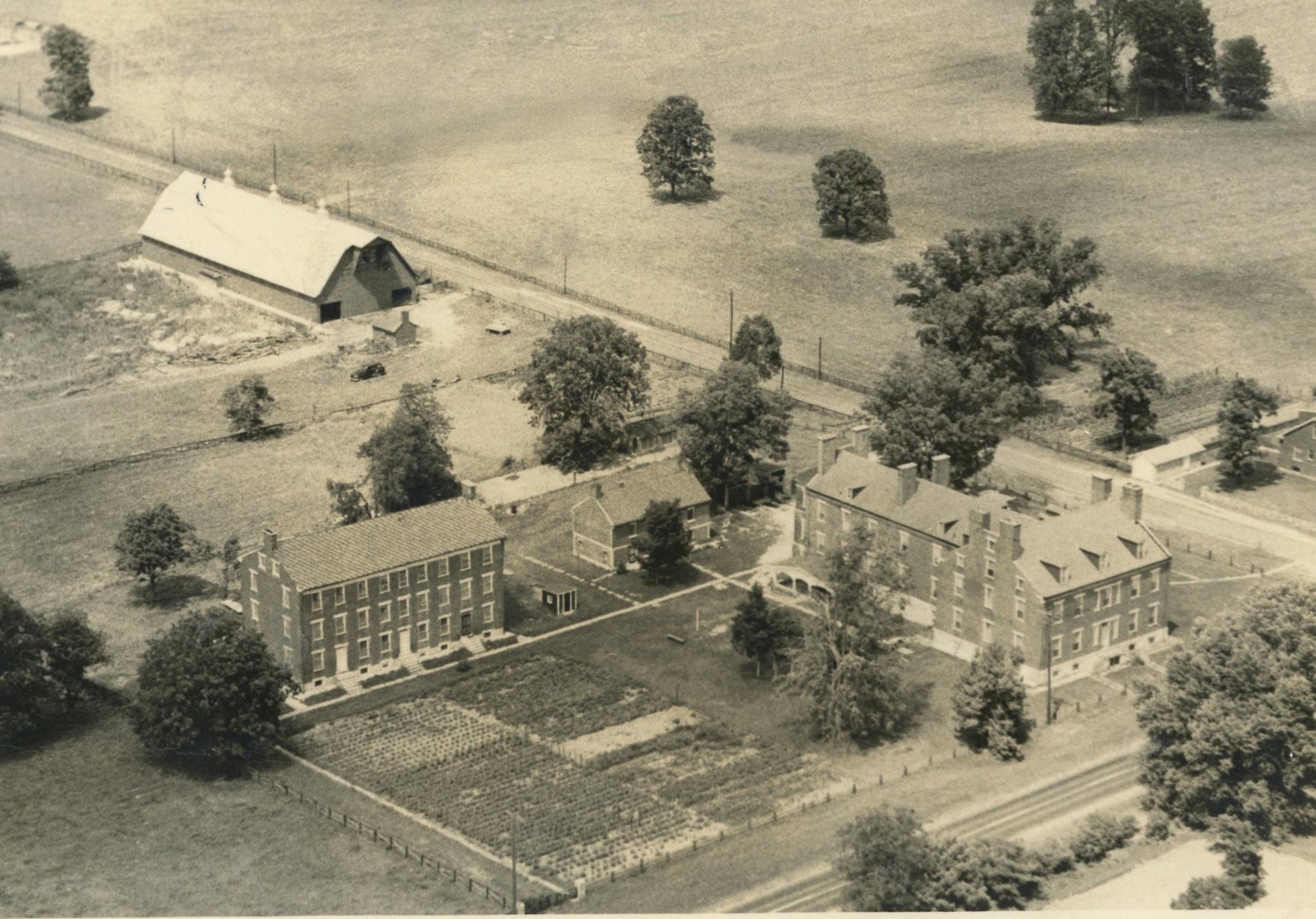

The founding of Saint Maur’s Priory in 1949 was marked by an interracial goal and an interreligious infrastructure. The fifth abbot of Saint John’s Abbey, Alcuin Deutsch, O.S.B. (1877–1951), was intent on establishing a monastic community that promulgated members’ racial diversity. Abbot Alcuin’s missionary zeal in the service of social justice was a bold move at this time in the United States. He was not the first Benedictine leader interested in service to people of color, however.

According to Father Gilbert Wolters, O.S.B., writing in The American Benedictine Review in 1951, already in 1877 Abbot Boniface Wimmer, O.S.B., had worked to support a French Benedictine foundation in Savannah, Georgia, that aimed to evangelize “the American Negro.” Saint Benedict’s Industrial School near Savannah opened a year later, Father Gilbert reports, “but never

developed, owning principally to the presence of malaria.” From 1929 to 1948, monks of Saint Vincent Archabbey (Latrobe, Pennsylvania) oversaw St. Emma’s Industrial and Agricultural Institute, “a Negro school,” in Rock Castle, Virginia.

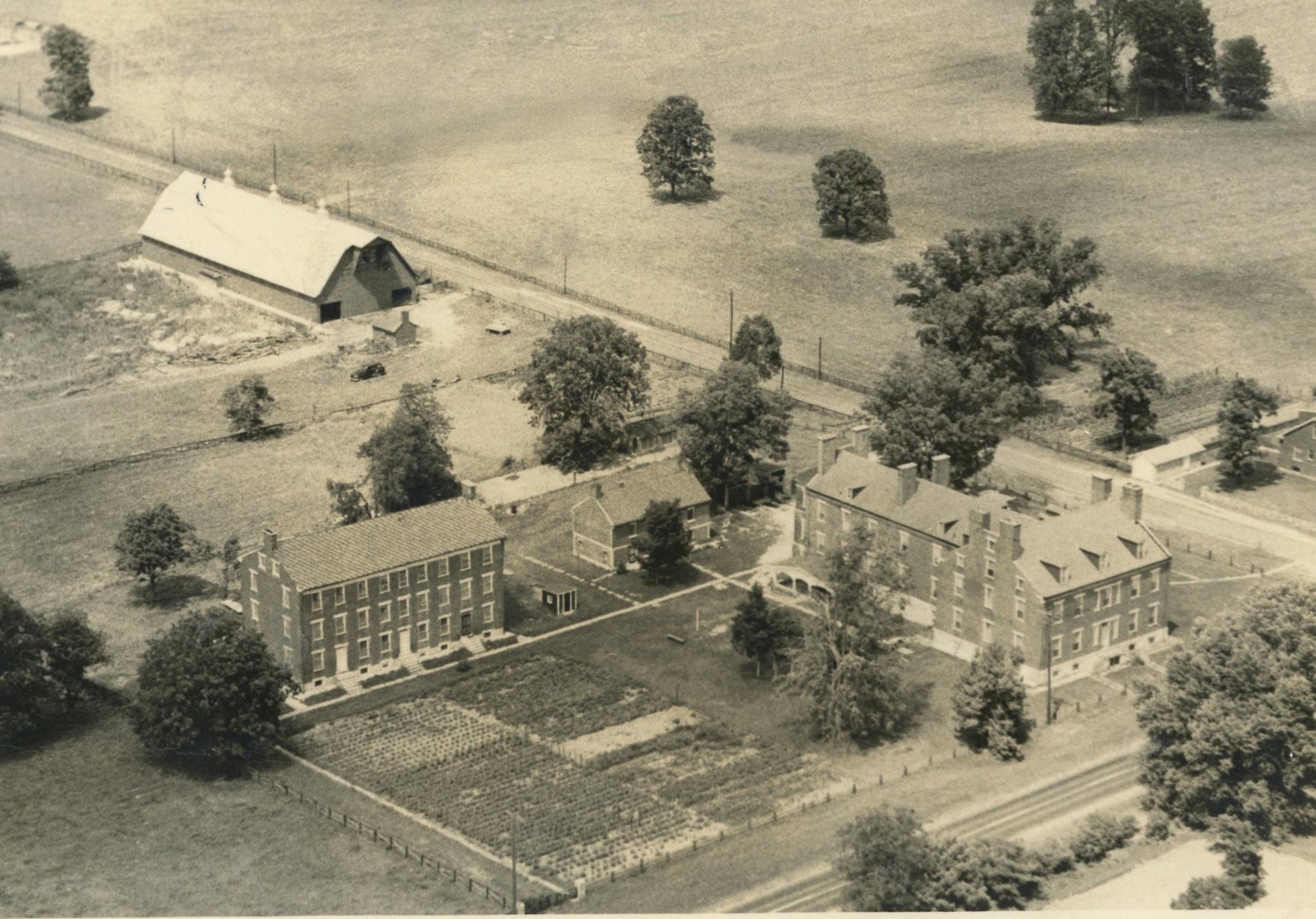

In 1948 Abbot Alcuin asked our confrere Father Alexander Korte to visit Fancy Farm, Kentucky, in the hope of establishing an interracial monastery in the area. Kentucky was deliberately chosen because it was a “borderline” Southern state, deemed a good location for such an enterprise. Bishop Francis Cotton of the Diocese of Owensboro wanted a monastic foundation in his diocese, although he was less concerned than Abbot Alcuin about the interracial aspect. He designated Saint Denis, a country mission with a two-story frame school building and a church, as the site for the community. A year later, with the bishop’s blessing, Father Alexander and the initial scouting group moved from Saint Denis to South Union, Kentucky, to the former settlement of Shakertown that had supported a thriving Shaker community in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Shakers, a non-Catholic Christian sect, could have had no inkling that their land and buildings would eventually be supplanted by another religious community. The Shakers, nonetheless, shared several features with monastic life: chaste

celibacy, asceticism, a life in common (but with sexual segregation), a communal work ethic and practice, and an ecstatic liturgical life. So impressed was Father Alexander and his associates with the amazingly intact building complex of Shakertown that they made this place—including fifty acres of land purchased by Saint John’s Abbey—the future site of Saint Maur’s Priory.

The establishment of Saint Maur’s was an experiment in gauging whether a monastery in such a geographic setting could successfully attract candidates with different racial backgrounds. An early pamphlet describing its work states: “It has been the monastery’s policy not to deny qualified candidates entrance because of race or color.

We believe we are all one in Christ.” Could such an interracial

foundation not only survive but even thrive in this new homeland?

In the 1940s and 1950s segregation was rampant in the United States. Blacks did not enjoy most of the freedoms that their white counterparts took for granted. A sign protesting integrated neighborhoods in Detroit, Michigan (1942), reads, “We want white tenants in our white community.” The situation was particularly acute for people of color living in Southern states as attested by Jim Crow laws. Violence in many forms, including lynchings, was only too common.

Roughly the first half of the twentieth century witnessed the Great Migration of millions of Black Americans from the South to other locations (especially

cities) throughout the United States. Many Black Catholics were drawn to the lure of superior education offered by parochial schools over the public school system. But such exposure to Catholicism was not reflected in the numbers of Black candidates applying to religious orders or seminaries. Even here, white attitudes toward admitting people of color were equivocal at best.

Amid such an atmosphere, Saint Maur’s offered a breath of fresh air. “One might venture to say that the very existence of St. Maur’s is a living condemnation of race prejudice, segregation, and discrimination,” asserted Father Gilbert. During the community’s first years, its income was derived from its farm, including a dairy herd, as well as from assistance of neighboring

parishes, and Mass stipends. Three priests served the community, including Father Harvey Shepherd, “the Negro priest of the group,” whom Father Gilbert recognized as “ideal for the interracial project in that he understands and makes very broad allowance for white prejudice.” Two white professed brothers, five brother candidates —including four Blacks—a Black novice, and seven college or high school students—two white and five Black—rounded out the home community. Six additional candidates for the priesthood, “equally divided as to color,” were studying at Saint John’s Abbey.

Initially, claimed Father Gilbert, the interracial community encountered “no resentment at the idea of whites and Negroes living the common life, after it was apparent that no attempt would be made to force the idea upon their neighbors. The fact that they are Catholics caused rather more comment and suspicion at first.” Yet, Father Harvey Shepherd did “meet with some hostility in one parish,” and he “carefully avoids the race question in his sermons.”

A seminary was established at Saint Maur’s in 1954 with the addition of a prep school in 1957. Saint Maur’s achieved conventual priory status in 1963. Shortly thereafter, however, the priory was unable to self-sustain. Internal divisions that surfaced within the founding community

Fall 2023 Abbey Banner 22 23

Abbey archives

Abbey archives

Saint Maur’s interracial community

Saint Maur’s Priory, c. 1955

Baseball Bat Factory

contributed to its breakup, and it experienced difficulty attracting enough quality seminarians. Its out-of-the-way location amid agricultural fields proved to be a drawback. The original monastic community split in 1968.

Saint Maur’s moved to Indianapolis (along with the original seminary), and those who remained at South Union were renamed St. Mark’s, a dependent priory of Saint Maur’s. In 1971 Saint Mark’s became a dependent priory of the AmericanCassinese Congregation; and, in 1984, a dependent priory of Newark Abbey in New Jersey. Both Saint Maur’s and Saint Mark’s have since been dissolved.

A 1988 article claimed that “the social problems of the 60s and the national growth of interracial activities dented the plans of the founders.” Yet the roughly equal numbers of Black and white monks who populated Saint Maur’s Priory spelled success in modeling Father Gilbert’s hope that “a monastic example of complete disregard of race prejudice would . . . show up the sinfulness of race discrimination and segregation.”

Brother Aaron Raverty, O.S.B., a member of the Abbey Banner editorial staff, is the author of Refuge in Crestone: A Sanctuary for Interreligious Dialogue (Lexington Books, 2014).

The Dream

The deliberate policy would be to build up and maintain a mixed monastic community and a mixed school. The numbers of whites and Negroes would be fairly equal, and the two races would live under conditions of perfect equality both in the monastery and in the school.

The Church herself needs such an example so that Negroes will be accepted into every religious order, every parish, and every parish organization. Such an elite group would be powerfully influential in leavening society [and], in the spirit of Saint Benedict, there would be no “respect of persons” [Rule 2.16–18; 4.8].

“Interracial Monastery in Kentucky” in The American Benedictine Review, Winter 1951 (Volume II, Number 4), by Gilbert Wolters, O.S.B.

Last Surviving Member

The last surviving member of the former St. Maur’s Priory—one of the first interracial religious communities in the U.S.—died in Indiana on 19 February 2023, age 87. Born in 1935 in Faunsdale, Alabama, Brother Howard Studivant, O.S.B., entered religious life as a member of St. Maur’s. The community had been established by Benedictine monks from Saint John’s Abbey with the aim of challenging segregation by accepting men of all races. During the ban on Black Catholic seminarians in the United States, upheld to varying effect from the nation’s founding until the mid-20th century, the seminary attached to Saint John’s had been one of the first to accept Black men into stateside formation, beginning in 1939. One of the graduates, Father Bernadine Patterson, O.S.B., would become the first Black Catholic prior in U.S. history when he was elected to head Saint Maur’s.

After the community moved to Indianapolis, Brother Howard worked for eleven years at Saint Rita Catholic Church, the oldest Black parish in Indiana. Among other duties, he drove school buses for both St. Rita and Holy Angels Catholic Church. He also served for a time as the coordinator of Black ministry for the Archdiocese of Indianapolis and was active with the Black National Congress.

Nate Tinnner-Williams, Black Catholic Messenger, 1 March 2023

Baseball bats this spring have come to be regarded as prized possessions—at least in the Northwest—because [throughout the war years] the big leagues and the armed forces have first call on the entire output of such famous bat factories as the one at Louisville, where the “sluggers” are made. Many high school and amateur teams in this area are struggling along with just a few bats, and at one time at least one school considered cancelling its baseball program because of a lack of this equipment.

But out at [the Saint John’s Abbey Woodworking Shop] there is no shortage of bats because Brother Hubert [Schneider, O.S.B. (1902–1995)], cabinet maker of the institution, knows how to make them and has the material. He learned how to do it this spring—although he has had plenty of experience with other forms of woodworking and has manufactured a lot of beautiful hardwood furniture.

For baseball purposes, Brother Hubert selects white ash, grown at Saint John’s, being careful to choose pieces without knots and with the grain just as straight as it can be found. Saint John’s has a quantity of hardwood seasoning at all times for use in making school and church furniture and farm machinery. And the wood going into the baseball bats is at least six years old. The only difference, says Brother Hubert, between the

wood in his bats and that in the professional models is that his wood is seasoned in the open air while the “big time” factories use a dry-kiln process.

It takes him about two hours to find a piece of wood, rip it to size, turn it down, dress it with oil, get the Saint John’s trademark burned in by Brother Stephen [Thell, O.S.B. (1909–1996)] in the blacksmith shop, and give it to the team

to start counting the built-in base knocks. And when the Johnnie fans yell, “Get a wagon tongue!” at their batsmen, they aren’t kidding—much—because some of those bats they use were originally intended to become part of the poles of Saint John’s farm wagons.

This article is an edited version of “Look! A Baseball Bat Factory!” from the Saint Cloud Daily Times, 18 May 1945.

Fall 2023 Abbey Banner 24 25

Saint Cloud Daily Times/University archives

After crafting a piece of white ash into a regulation-size baseball bat, Brother Hubert presents it to members of the Saint John’s Prep baseball team. Home runs to follow.

W. Ray Scott/Abbey archives

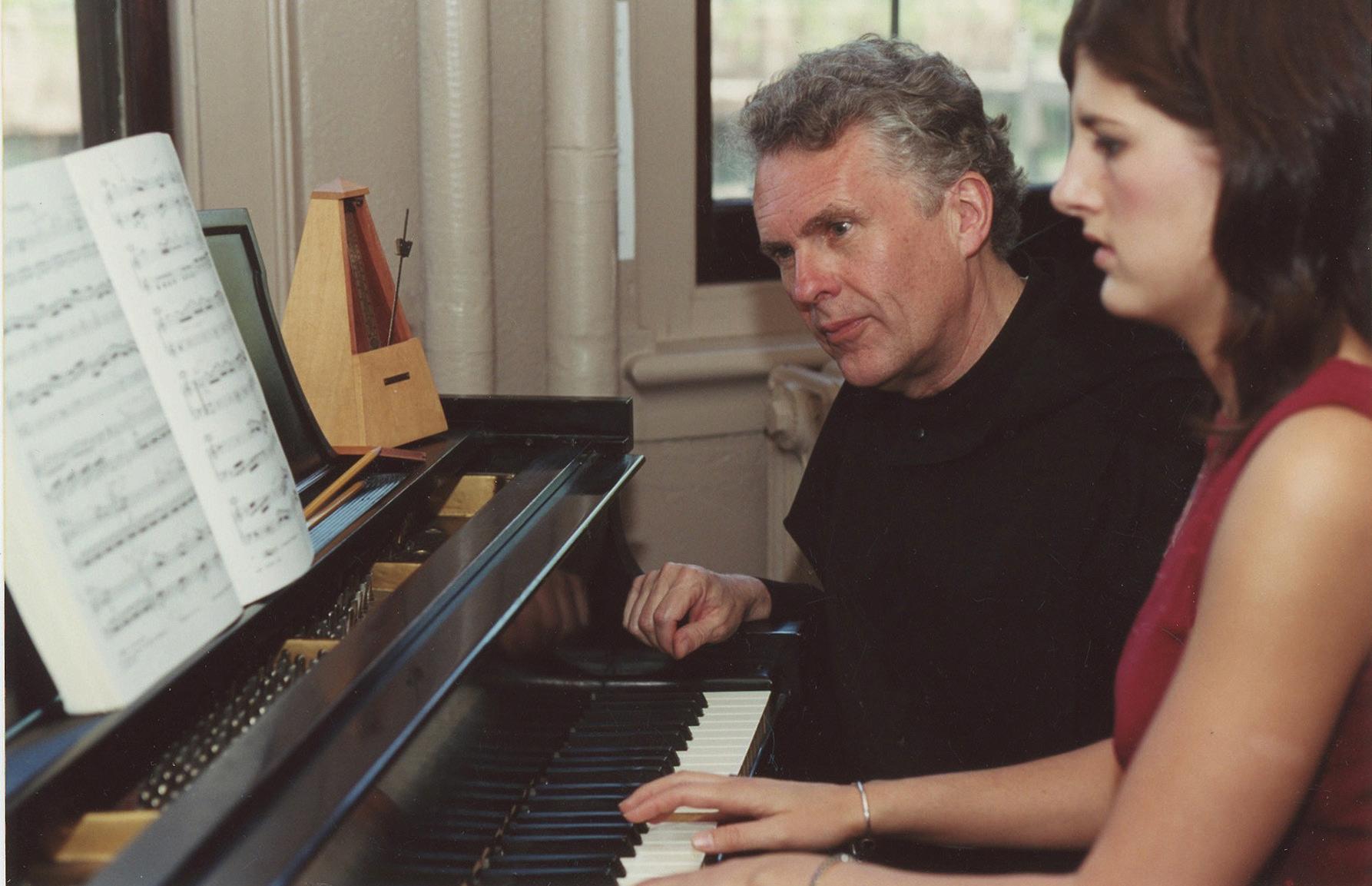

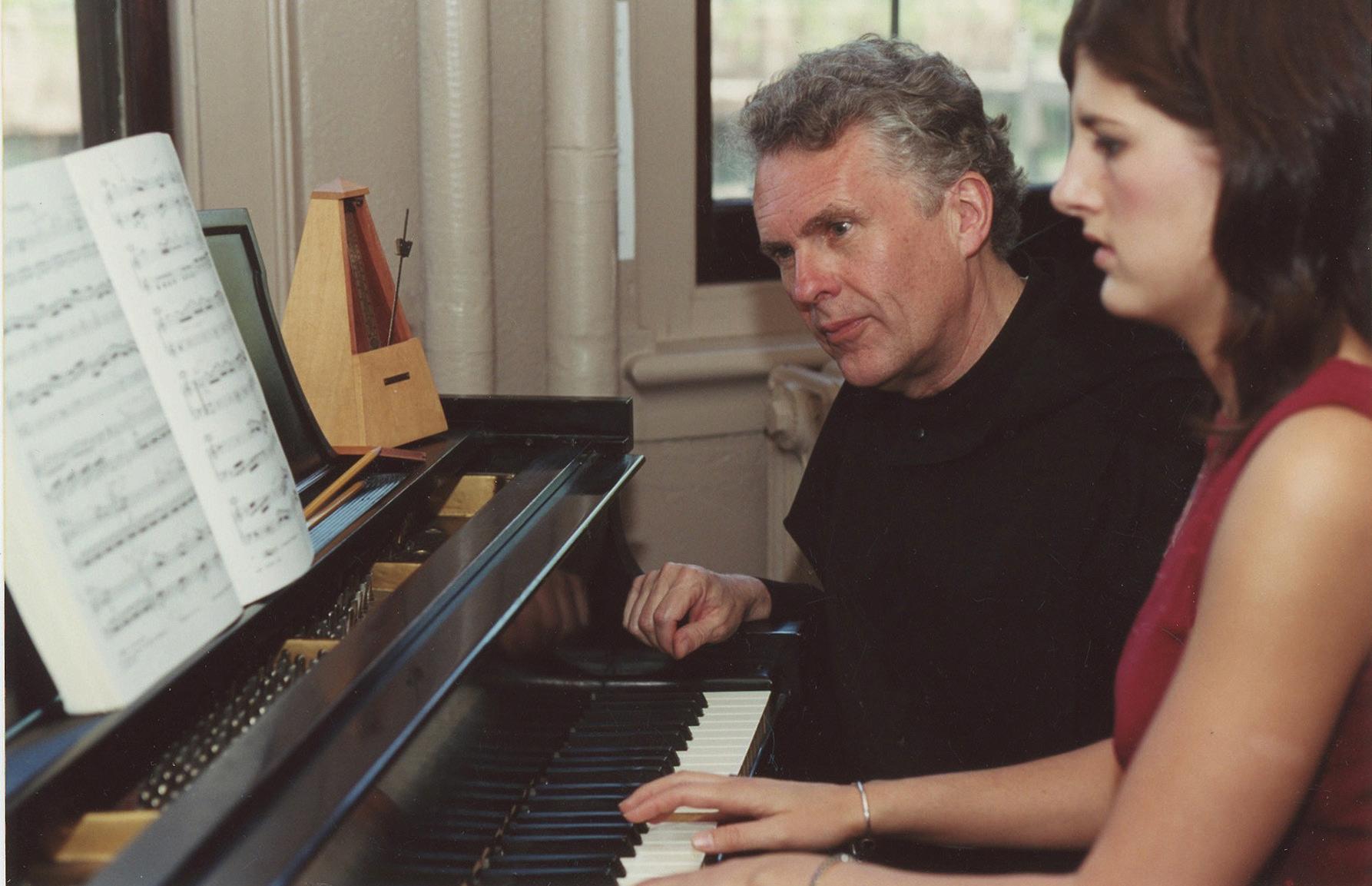

Meet a Monk: Robert Koopmann

Timothy Backous, O.S.B.

Life is filled with decisions, most of which affect our lives in simple ways. But there are others that can completely change the trajectory of a life. Father Robert Koopmann, O.S.B., is no stranger to such moments. After graduating from Saint John’s University and fresh from completing a master’s degree, he signed a contract to teach piano at St. Norbert College, De Pere, Wisconsin, but something told him that a longheld interest in monastic life should be explored before he launched a career. And so he found himself back in Collegeville, responding to a call to stay longer at the place he had fallen in love with. It turned out to be a wise decision, one that changed his life and that of our community forever.

Born in Waterloo, Iowa, in 1946 to Cletus and Flora Koopmann, Bob was the first of two boys, his brother Steve being his only sibling. He grew up in a decidedly Catholic world living right up the street from the local church that he says played a large role in his family’s life. Having many relatives as priests and nuns added to his familiarity and comfort with religion and proved to be the seed of his own vocation.

At the tender age of 6, Bob began to explore the piano skills that would become a major element of his life and work. He recalls: “My mother and her

concert pianist both in the U.S. and abroad and has released a number of recordings since 1994.

sister played piano quite well, and my mother got me started playing when I was 6. I was playing ‘by ear’ at that time. I started formal lessons when I was 7. All the way through high school, I was taught by Dubuque Franciscan sisters, and they were good teachers who challenged me.” While a college student at Saint John’s, his teachers were primarily monks, many of whom befriended him. He would later pursue advanced degrees from the University of WisconsinMilwaukee (master of music), the University of Iowa (doctor of musical arts), and a master of divinity degree from Saint John’s School of Theology and Seminary. He did postdoctoral study with faculty of the Royal Academy of Music in London and The Juilliard School in New York. Bob is still active as a

Despite the initial bright promise of a musical career, Bob’s attraction to monastic life drew him back to Saint John’s. He was determined to answer the question about his vocation before submerging himself into a world of teaching and performance that he had already experienced in national and international programs. He professed his first vows as a Benedictine on 21 September 1971 and immediately put his musical talents at the service of the community—playing organ for liturgies and teaching piano in the university.

Bob’s natural gifts are not limited to the keyboard, however. He was chair of the music

department of the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University, 1977–83 and 1985–86. He served as a faculty resident, as a men’s spirituality group leader, and since 2000 has worked with the Saint John’s Benedictine Volunteer Corps. Father Bob also served as director of international studies programs in Salzburg and South Africa. “Teaching at Saint Ben’s and Saint John’s has been important to me from my early monastic life,” he says, “and I still love it. My piano students are teaching and performing around the country, in Europe, and Asia. I loved leading study abroad semesters as well as many trips for music teachers through the Minnesota Music Teachers Association.”

Bob also mastered the skills and delicacy of working in an academic institution, making him a person who was trusted, respected, and admired. It was no surprise when in 2009 the Saint John’s University Board of Regents chose him as the twelfth president of the university, a job that inspired and excited him. It gave him the opportunity of reconnecting with beloved alums and articulating the relationship between the university and the abbey. His leadership was instrumental in helping the university become even stronger in the arts and sciences. As president, he signed and sealed the newly created Saint John’s Bible on the altar of the abbey and university church. His sup-

port of the ensuing programs and presentations have drawn worldwide attention to our community and helped cement its reputation for spiritual leadership. He was also instrumental in bringing master organ-builder Martin Pasi to Saint John’s, first to expand the church organ and

most recently to establish an organ-building enterprise.

Despite health challenges, Father Bob continues doing what he loves most: practicing, performing, and engaging in the life of the schools. But his greatest love remains service to his monastic community.

“Making music for this community— playing the organ for Morning Prayer, Evening Prayer, and for Mass—brings me great joy,” he reflects. “If I can somehow inject life into our singing, then I’ve succeeded. I hope to keep making music as long as I live!”

His Benedictine brothers would heartily add: “So do we, Bob. So do we!”

Fall 2023 Abbey Banner 26 27

Bob: Age 3 Koopmann archives

Brother Bob: Monk Abbey archives

Abbey archives

Father Bob: Teacher

Maestro Bob: Artiste Koopmann archives

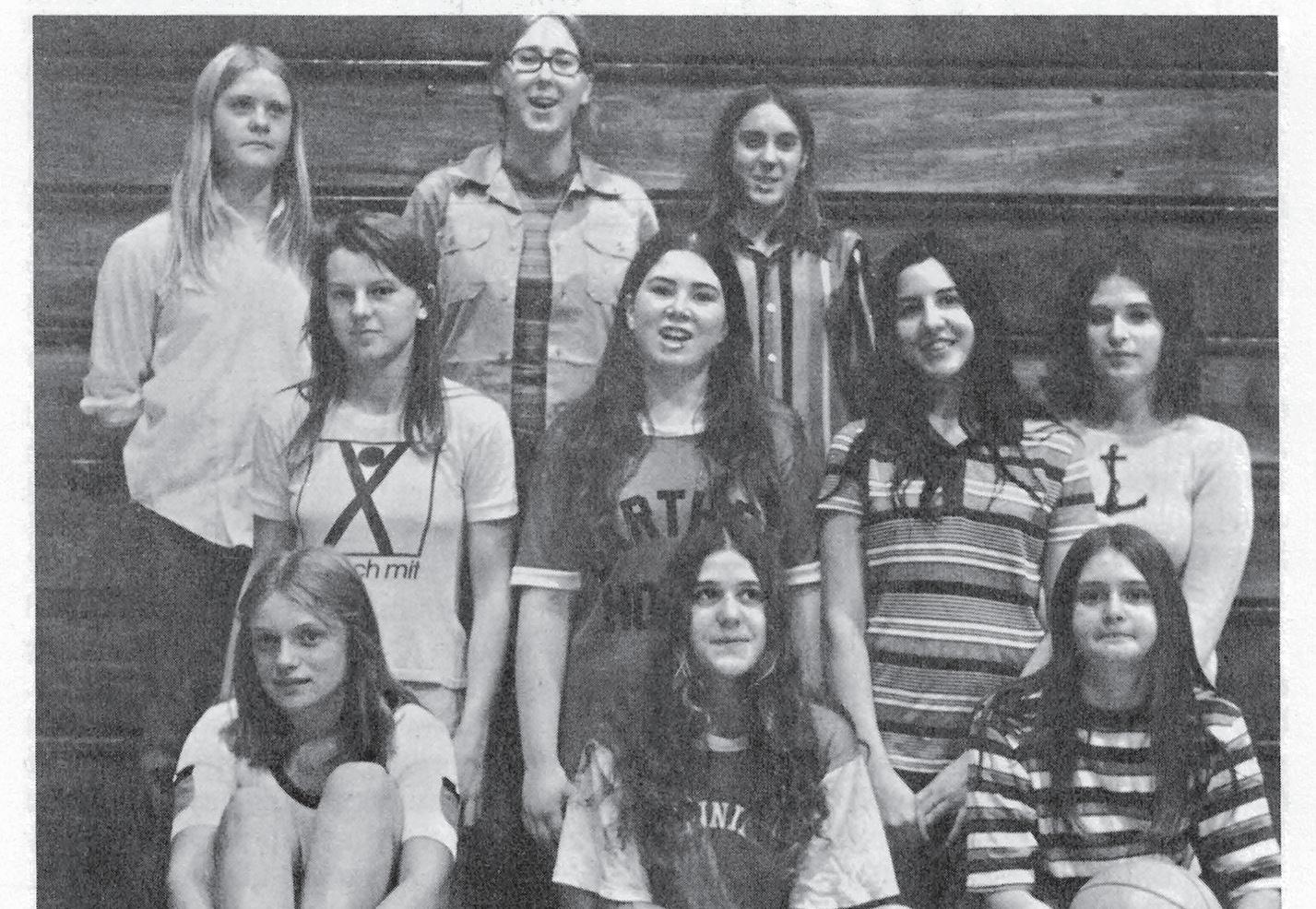

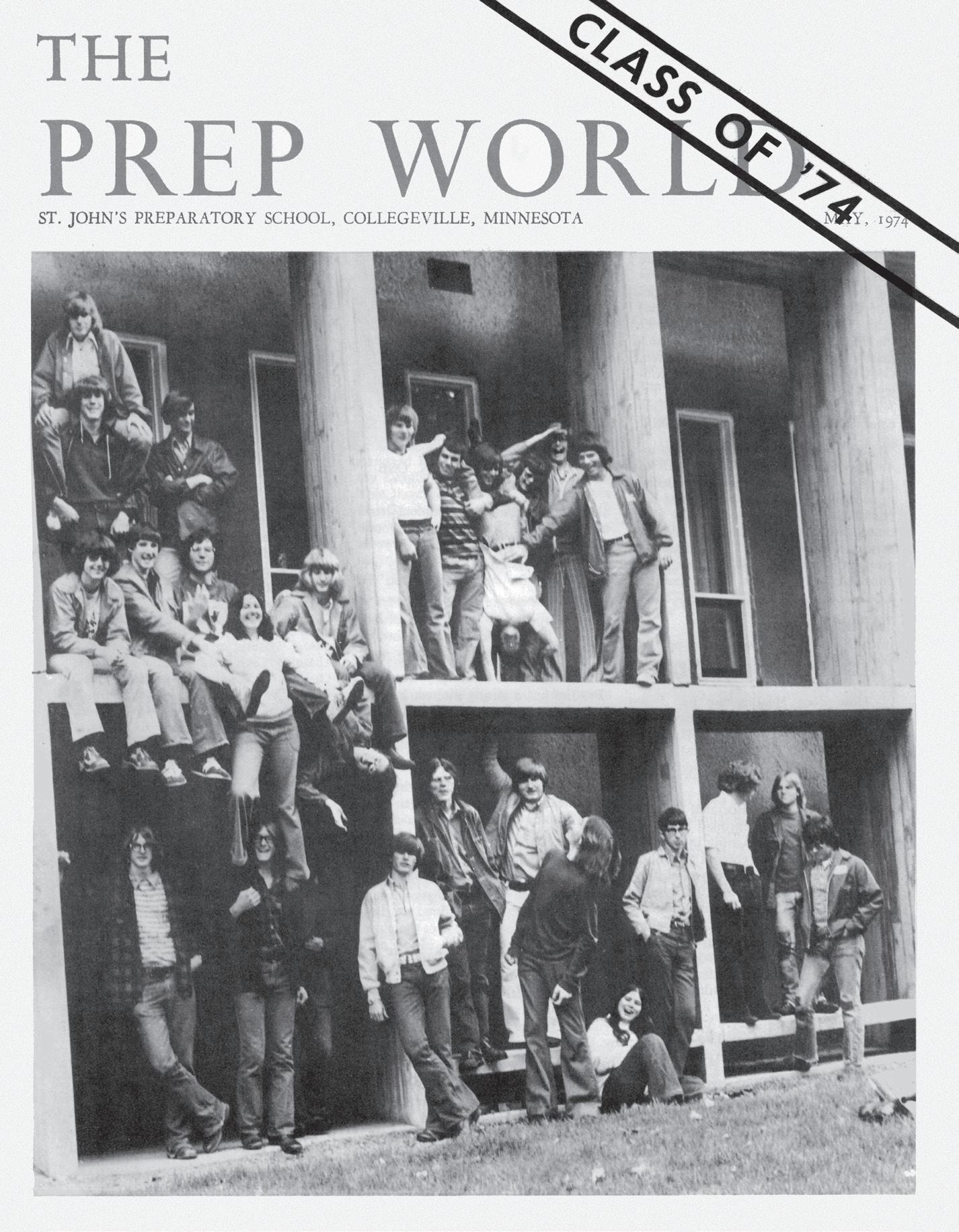

Coed Prep School

Peggy Roske

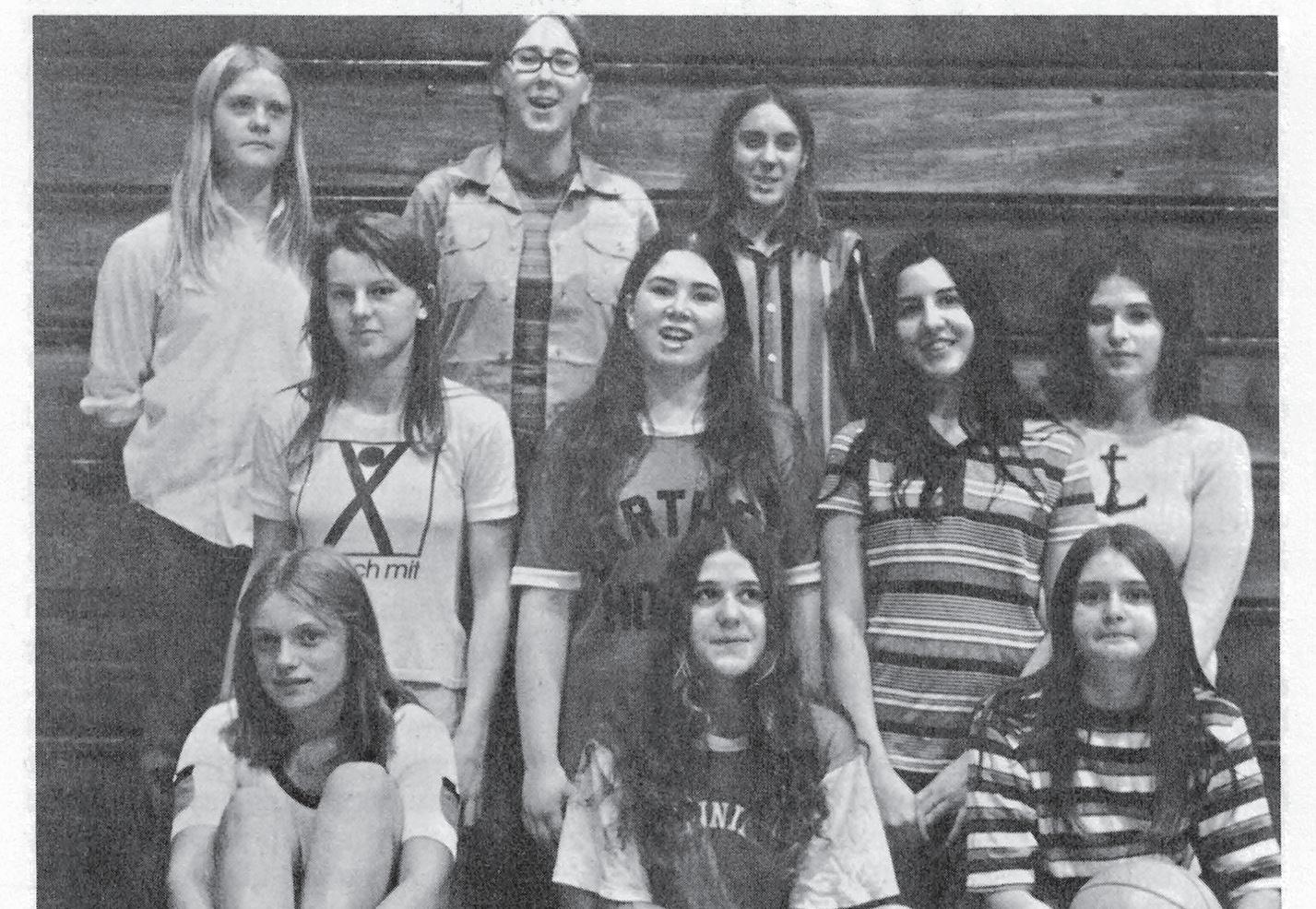

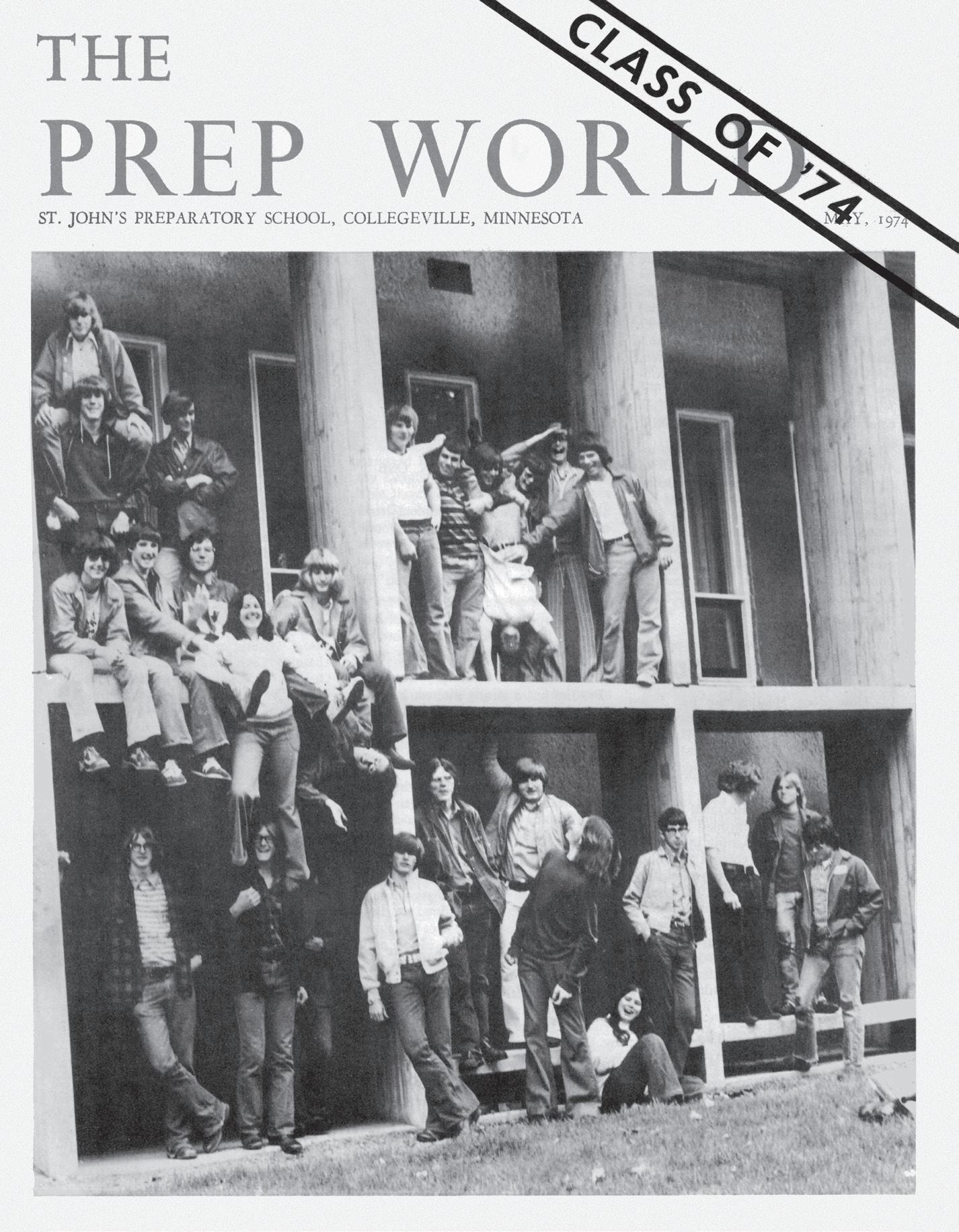

Fifty years ago, when the doors of Saint John’s Preparatory School opened for the fall 1973 semester, in walked the first twenty-one girls who could call themselves “Johnnies”! The prep school had officially begun accepting young women as students.

The mission of the Benedictine monks who came to central Minnesota in the mid-1800s, besides ministering to the spiritual needs of its German immigrants, was to educate its young men. A year after initiating a school for area children—boys and girls—in 1856, Father Cornelius Wittmann established the school for young men that evolved into today’s Saint John’s Preparatory School, Saint John’s University, and Saint John’s School of Theology and Seminary. After 116 years, that mission was suddenly enlarged to include enrolling young women at the prep school—a decision reached after only six intense weeks of deliberation.

This momentous change was precipitated by the closure of nearby Saint Benedict’s High School (SBHS) in Saint Joseph. With its enrollment declining to fewer than one hundred girls, staying open was unsustainable.

On 2 April 1973 the Saint Benedict’s Monastery Council agreed to discontinue the high school, and Prioress Mother Henrita Osendorf announced to the

students four days later that their school would close upon the graduation of its thirty seniors. Some juniors could qualify for college or trade school entrance by the fall; all the other students would have to transfer to other high schools.

While the decision stunned most of the students, the possibility

campus; a few students bused to the other campus; and some extracurricular activities were coordinated. The high schools’ faculty exchanges included Sister Terence Nehl teaching Latin at SJP and Brother Linus Ascheman teaching a psychology class at SBHS. (Brother Linus went on to become the school’s headmaster, 1980–88.) Sometimes it was the students who travelled to the other campus, such as Bennies taking physics (and driver’s training) from Mr. Peter Froehle at the prep school, or a group of preps joining Bennies to form a mixed chorus at Saint Ben’s.

of closing had deeply concerned the sisters for some time. Costsaving measures had been implemented, some of which involved cooperation with Saint John’s Preparatory School (SJP) in ways similar to the curricular cooperation between the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University in the 1960s: a few faculty travelled to the other

Beyond the classroom, Bennies were familiar with the prep school to varying degrees; for years, social events such as dances included the students from both schools, as did some extracurriculars such as theater and band. For a couple of years, a handful of Bennies had joined a few Johnnies as cheerleaders for prep athletic matches. Bennies regularly attended prep school basketball and football games, and they—along with girls from Saint Francis High School in Little Falls—were candidates for homecoming queen each fall.

Even before the closure was publicly announced, Prep School Headmaster Father James Tingerthal and the faculty had begun discussions about opening the prep school to the displaced Bennies and other area female students. On 8 April 1973, only

two days after Mother Henrita’s announcement, a letter from Father Jim went to the parents of the Bennies in grades 9–11. It said: “The St. John’s monastic community and the faculty and administration of St. John’s Preparatory School have given serious preliminary consideration to the proposal that the Preparatory School begin to admit girls as day students in the fall of 1973. In this preliminary discussion, both groups urged an immediate study of the feasibility and advisability of such a move, and a guarded optimism seems to be the mood in which the faculty undertakes this study.” The letter goes on to solicit interest: “In the light of this possibility, we would like to encourage all prospective St. Benedict’s students and their parents in the St. Cloud area to consider St. John’s seriously as

one of the options available as they make their choice for continuing their education for the coming year.”

A press release (16 May) confirmed that it would be a choice. The May 1973 The Prep World announced that “This year will go down in Prep annals as the ‘year of change,’” and went on to provide the backstory of how the change came about, detailing the work of six prep faculty committees formed to study the coed option and its implications regarding finances, personnel, the student body, and the curriculum.

A survey of the ’72–’73 prep students found “overwhelming support for co-education.” In just one week, the possibility of going coed had become a “definite probability.” English

Fall 2023 Abbey Banner 28 29

University archives

First coed graduating class of Saint John’s Prep, 1974 University archives

First girls’ basketball team of Saint John’s Prep

teacher Mr. Jerry Howard, the coeducation committee chair, said, “I have never seen the faculty work together so feverishly or so well.” Their proposals gained initial approval from the abbey’s senior council on 8 May; a week later, the monastic community gave its consent.

Fifteen of the Bennies came to the prep school, four of them as seniors. With the addition of a senior transfer from Saint Cloud, a few first-year girls, and two from Austria, twenty-one females joined about 200 male classmates. Also new to the prep school was the addition of its first full-time female teacher, Ms. Gayle Groebner, in art and physical education.

Despite all the goodwill and high anticipation, going from an allgirls school to integrating an all-boys school was a major adjustment for the Bennies. Being such a minority was also tough. Though initially they were stared at a lot, The Prep World that fall quotes Bennies as saying “everybody and everything seems to be pretty nice”; “the boys treat you right”; and it “has made the guys perk up some and clean the school a little, but otherwise they still dress and talk the same.” The girls’ hangout was an old bathroom converted into a girls’ locker room—“the one place where we could talk, laugh, and cry.” Retreat weekends for the girls at a home on Watab Lake

gave the girls a platform to voice issues. They recognized the advantages inherent in attending such a good school, but some encountered a “male chauvinistic attitude” among students and some of the male teachers. Being outnumbered ten to one meant that “everyone wanted a girl in their activity—the yearbook, the school play, their intramural team, or the homecoming court.” But they recognized that their contributions in presenting a woman’s point of view made a difference. They took pride in being trailblazers, leading the way for generations of female Johnnies to come.

Even today the Benedictine value of community prevails among

Quality Education

these students. Most of the forty members of the Saint John’s Preparatory Class of 1974 stay in touch with each other and turn out for reunion anniversaries. For most of the past fifty years, the four Bennies who integrated that class have gathered with their ’74 Saint Benedict’s High School classmates. The date for next summer’s reunion —for both classes, together—is already on the calendar, to take place in the old high school building at Saint Ben’s.

Ms. Peggy Landwehr Roske, archivist for the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University, was a member of the last graduating class (1973) of Saint Benedict’s High School.

I grew up in Saint Joseph, Minnesota, and attended Saint Ben’s High School for my freshman through junior years. I can’t really remember what happened on that first day [at Saint John’s Prep]. I remember being anxious and being stared at a lot. Lucy [Knapp] reminded me that she remembers us sitting in our living room in Saint Joe and saying to each other: “Did we make the right decision?”

I actually had the best of both worlds. I have my Saint Ben’s friends, who have always stayed in close contact, because we decided we never had any official closure to our high school careers. I also have the lasting friendships I made at Saint John’s Prep. In the end, the blending of those two experiences and those two communities has made me a better person.

The education that was instilled at the prep school and the important values I learned have framed my career in Wisconsin as the State Child Care Administrator. I advocate for children so that in their early years they have high quality experiences so that they are ready for school and can have productive lives. I learned early on from these Benedictine schools the importance of quality education.

Laura Lodermeier Saterfield, Saint John’s Prep,’74 Legacy Dinner comments, 7 November 2013

Father Allan (Richard Arthur) Bouley, O.S.B., was born on 22 April 1936 in Anoka, Minnesota, and died in the Saint Cloud Hospital in 2023 on his eighty-seventh birthday. He was the second oldest of six children of Richard and Agnes (Payette) Bouley. When Allan’s mother died in 1947, Aunt Emma Bouley left her job to help raise the family.

After attending Saint Stephen’s Grade School, Allan enrolled at Saint John’s Preparatory School, where his spiritual mentor and future confrere Father Eric Buermann would encourage him to consider the priesthood. Following graduation from the prep school (1954), he enrolled at Saint John’s University as a priesthood student. In 1956 he joined seventeen other young men in the novitiate of Saint John’s Abbey, professing his first

vows as a Benedictine monk on 11 July 1957. He completed his undergraduate studies in 1959, earning a bachelor’s degree in philosophy. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1962.

Father Allan pursued graduate studies in liturgy at Sant’ Anselmo, Rome, where he earned a licentiate in sacred theology (1966) and later a doctorate when he finished his dissertation, “From Freedom to Formula: The Evolution of the Eucharistic Prayer from Oral Improvisation to Written Texts.”

During the first years of his long career (1969–2008) of teaching liturgical studies at Saint John’s School of Theology, Allan assisted in the transitioning to the vernacular in the post–Vatican II Church. Those changes, he recalled, “caused a great deal of uproar in seminaries. I developed a course called Pastoral Liturgy to help seminarians become good presiders. That was a huge challenge because nothing I studied in Rome gave me any preparation for this.”

Despite the challenges, Allan became a skilled mentor for generations of seminarians in learning how to be prayerfully present as a presider—to be aware of pacing, the rhythm of sound and silence that makes liturgy powerful, prayerful, and reverent.

Father Allan also served as liturgy director for the abbey (1970–1976; 1978–1982) and

a member of the Liturgy of the Hours revision committee (1984–1987). He was an advisor to the U.S. Bishops’ Committee on Liturgy and a charter member of the North American Academy of Liturgy. He shared his considerable knowledge and insights as an exchange professor at Luther Seminary, Saint Paul, and taught a liturgy course at The Catholic University of America. For twenty-five years, he was an associate editor for Worship magazine.

Allan wrote many articles, presented lectures and workshops, and collaborated with coauthors on numerous liturgical topics. He compiled and edited Catholic Rites Today: Abridged Texts for Students (1992). The Saint John’s community and all those who have prayed with us for the past half-century are beneficiaries of Allan’s steady, lowkey leadership and sensibility that shaped the way our monastic prayer looks and feels with its attention to silence, to pacing, to the balance between recitation and singing.

The community celebrated the Mass of Christian Burial for Father Allan on 27 April 2023 followed by interment in the abbey cemetery.

In a time of rapid change, flux, ideas, and questions—about the liturgy, about the place of monastic life in the Church—Allan was a calm, thoughtful, and stable person.

Abbot John Klassen, O.S.B.

Title of Article Abbey Banner 30 Fall 2023 31

Allan Bouley

Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

The daily routine within the cloister is enlivened by the antics of the “characters” of the community. Here are stories from the Monastic Mischief file.

Self-knowledge

I was so smirky today, even I noticed it.

Father Cyril

Holier than thou

After completing a batch of candles, the candlemaker confrere declared proudly, “These candles were made by holy hands.”

“Oh, who made them?” replied a brother.

Artificial intelligence

If all your intelligent responses to the test questions were written down on a piece of paper, and if that piece of paper were rolled into a ball, and if that ball were shoved up a flea’s orifice, it would bounce around like a BB in a boxcar.

Father Alexander

Unfriend

Posted on a breaker panel in the pre-renovation of the monastery:

DO NOT USE SWITCHES

Behind this sheet PLEASE!!!

If you do, you may turn off computers, alarm clocks, answering machines, refrigerators, etc., and lose lots of friends.

For Whom the Bells Toll

During the planning for the construction of the abbey and university church, architect Marcel Breuer proposed to showcase the church’s five bells (the smallest of which weighs 1,600 pounds; the largest, more than four tons) in an opening in the concrete banner—thus allowing the bells to be both heard and seen. A few curmudgeon monks were skeptical, however. One confrere objected, fearing that “every time the wind blows, those bells will be ringing.” Mr. Breuer responded: “Father, if there is ever a wind strong enough to move those bells, they ought to be ringing!”

Divinity Saves

A postulant for a religious order of nuns recounted how fed up and frustrated she was on the first day of her assigned job of working in the sultry monastery laundry. She seethed with envy when she imagined how much fun her friends were having along the cool river back home. Mustering her courage, she confronted the postulant director. “I just can’t stand it here anymore! I want to leave now!”

Thereupon the superior took her leave, returning to the inflamed postulant in short order and offering her an open box of divinity candy. After sampling the tasty treats, the postulant ceased her protestations, but a few moments later repeated her threat to leave. After two more outbursts, soothed with two more wordlessly outstretched offers of divinity, the postulant finally abandoned her demands and returned to her assigned labors.

Decades later, when the young postulant—now a professed member of the community—visited her former superior in a home for elderly sisters, the once-upstart postulant asked her elder how she knew the offer of candy would do the trick. “Don’t you know, my dear,” replied the elderly sister, “that we’re always saved by the divinity?”

They say . . .

He can compress the most words into the smallest ideas better than any man I ever met.

Abraham Lincoln

Tact is the ability to tell someone to go to hell in such a way that they look forward to the trip.

Anonymous

Better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak out and remove all doubt.

Maurice Switzer

April is the cruellest month.

T. S. Eliot

March went out like a lion (polar bear?) with lightning and thunder, rain and snow, as a blizzard descended on central Minnesota. Another 5 inches of snow on the first day of the cruellest month brought the season’s total to 92 inches, with more to come. Lake Sagatagan opened on 25 April.

O the month of May, the merry month of May.

Thomas Dekker

Thomas Dekker

“Mayday!” more than “merry” marked the month of May. Smoke from Canadian fires fouled the air frequently throughout the summer. An orange, acrid haze covered Collegeville on 14 June, giving Minnesota the worst air quality in the country. June 2023 proved to be the second driest on record in Minnesota, and the third hottest. July was the hottest on record on Earth. Drought conditions prevailed in much of the state, shriveling corn and reducing crop yield.

In the face of climate change, the monastic community remains resolute in its commitment to moderation and responsible stewardship. We recognize the wisdom of Pope Benedict XVI’s observation that “technologically advanced societies must be prepared to encourage more sober lifestyles, while reducing their energy consumption and improving its efficiency.” We join Pope

Francis in prayerful supplication of the God of creation: “Teach us to discover the worth of each thing, / to be filled with awe and contemplation, / to recognize that we are profoundly united / with every creature / as we journey toward your infinite light” (Laudato Si’ §233).

April 2023

• During Evening Prayer on 16 April, Abbot John Klassen presided at a blessing ceremony for the Saint John’s Abbey Hymnal. The new hymnal draws heavily from The Collegeville Hymnal and The Hymnal 1982, the primary workhorses of Saint John’s liturgies for decades, and includes many recently composed hymns as well. A choir of monks (some of whom can even read music) assisted in the production of the hymnal, led by abbey music director Father Anthony Ruff and Brothers Jacob Berns, David Klingeman, and Paul Jasmer; Father Robert Koopmann; and Mr. Marc Cerisier. Brother Alan Reed designed the cover. Used copies of The Hymnal 1982 have since been shared with Holy

Trinity Episcopal Church in Elk River, Minnesota, and with Episcopal parishes in Liberia, West Africa.

May 2023

• In recent years, the abbey’s apiary has suffered from bear attacks as well as pathogens and pesticide exposure. In May Mr. Richard Koetter placed four hives (about 50,000 bees bred to withstand the bee mite) in the monastery vegetable garden. In addition to their value as pollinators and producers of honey, the “bees have provided me with the best of all places for contemplative prayer for several years,” said Mr. Koetter. “The bees are good prayer companions, never interrupting.”

• On 12 May members of the monastic community and the Saint John’s University Board of Trustees gathered for a prayer service, during which President Brian Bruess, Board Chair LeAnne Stewart, and Abbot John signed the Sustaining Agreement, pledging to nurture and promote “a lasting, effective, and genuine

Fall 2023 33 Abbey Chronicle

32 Abbey Banner Cloister Light

Alan Reed, O.S.B. Yellowwood (Cladrastis kentukea) in the east cloister garden

relationship in furtherance of the Catholic and Benedictine identity, mission, and character of the University.”

• Some sixty monks took part in a Defensive Driving Training session presented by Mr. Jerry LaGarde from Travelers Insurance. No one was cited for offensive driving, a more common infraction among male religious.

June 2023