do not reduce in size Abbey Banner Winter 2022-23

Those who trust in God shall understand truth, and the faithful shall abide with God in love.

Wisdom 3:9 .

George Maurer

Abbey Banner Magazine of Saint John’s Abbey

Winter 2022–23 Volume 22 number 3

Published three times annually (spring, fall, winter) by the monks of Saint John’s Abbey.

Editor: Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

Design: Alan Reed, O.S.B.

Editorial assistants: Gloria Hardy; Patsy Jones, Obl.S.B.; Aaron Raverty, O.S.B.

Abbey archivist: David Klingeman, O.S.B.

University archivists: Peggy Roske, Elizabeth Knuth

Circulation: Ruth Athmann, Tanya Boettcher, Debra Bohlman, Chantel Braegelmann

Printed by Palmer Printing

Copyright © 2022 by Order of Saint Benedict

ISSN: 2330-6181 (print) ISSN: 2332-2489 (online)

Saint John’s Abbey 2900 Abbey Plaza Box 2015 Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-2015 saintjohnsabbey.org/abbey-banner

Change of address: Ruth Athmann P. O. Box 7222 Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7222 rathmann@csbsju.edu Phone: 800.635.7303

Subscription requests or questions: abbeybanner@csbsju.edu

Angels from the realms of glory, wing your flight o’er all the earth; ye who sang creation’s story now proclaim Messiah’s birth: Come and worship, come and worship, worship Christ, the newborn king.

James Montgomery

This issue examines the angelic choirs—those spiritual beings intermediate between God and humankind, God’s messengers of joy, the heralds of good news to the shepherds of Bethlehem, our personal guardians. Abbot John Klassen opens this issue with a reflection on faith and his own belief in angels. Brother Aaron Raverty outlines the role played by angels in the monotheistic traditions, including the interpretations of Saint Thomas Aquinas, “the Angelic Doctor.”

The archangel Gabriel delivered the good news to Mary that she would have a son and name him Jesus (Luke 1:26–38). Dr. Martin Connell presents Mary’s fiat—her assent to be the Mother of God—as interpreted by artist Corita Kent in her screen print Fiat. “When the song of the angels is stilled,” says poet and theologian Howard Thurman, “the work of Christmas begins: . . . to heal the broken, to feed the hungry, . . . to bring peace among people, to make music in the heart.” Father Nickolas Kleespie reflects on Dr. Thurman’s insights and the challenge to all who encounter the Word made flesh.

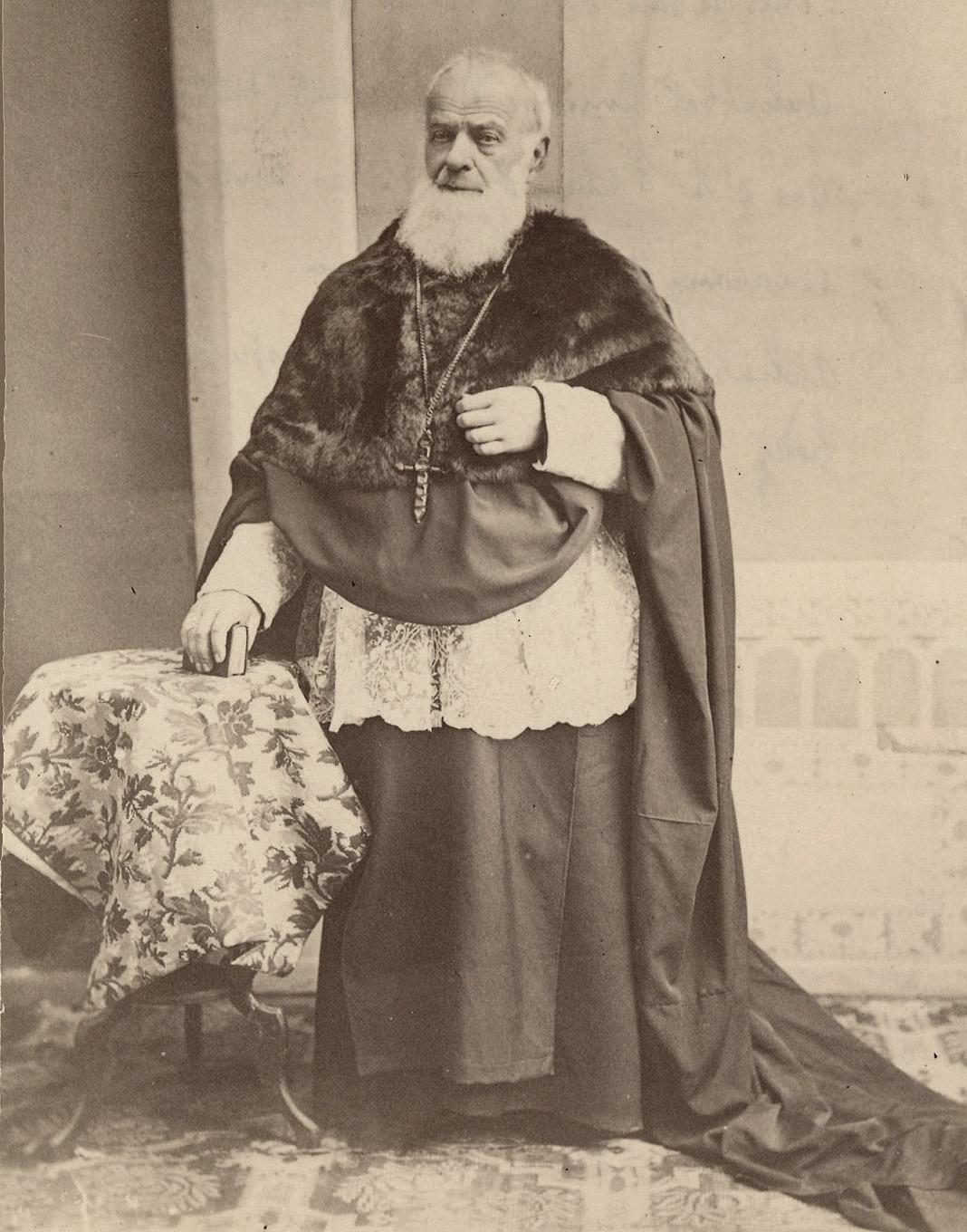

A priest, missionary, and monk, Boniface Wimmer came to the United States in 1846 from Metten Abbey in Bavaria to establish Benedictine monasteries that would serve and evangelize the German immigrants in the New World. Thirty years later, hundreds of Benedictine monks and sisters were working and praying in some sixty American monasteries—including Saint John’s Abbey. Brother Eric Pohlman introduces Abbot Boniface, a complex character regarded as one of the greatest Catholic missionaries of the nineteenth century and also reviled for his interference, redirection of funds, and high-handed treatment of Benedictine sisters.

Saint John’s University promotes its educational “brand” as: Inspired Learning. Inspiring Lives. Benedictine Volunteer and Saint John’s alumnus Mr. Matthew Gish inspires us with his heart-warming stories of heart-breaking situations in Nairobi, Kenya.

Faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen. Hebrews 11:1

Cover: Angel study (pencil on tracing paper, c. 1930) by Brother Clement Frischauf, O.S.B.

Photo: Alan Reed, O.S.B.

What do the critters in the woods do when no one’s watching? Mr. John Geissler shares the antics and adventures of wildlife in the Saint John’s Abbey Arboretum captured by motion-activated trail cameras. We also review award-winning publications of Liturgical Press, reflect on the law of love, listen to a Christmas pageant that ends with a twist, and more.

The staff of Abbey Banner joins Abbot John and the monastic community in offering prayers and best wishes for a joyous Christmas season and a healthy new year. Peace!

Brother Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

John Klassen, O.S.B.

John Klassen, O.S.B.

The scriptural accounts we hear during the Advent and Christmas seasons repeatedly describe human encounters with angels who shape the story of the incarnation. Angels are divine messengers of joyous power and magnificence. As a twenty-first century person, do you believe in angels?

The twentieth-century French philosopher Paul Ricoeur spoke of our religious faith, language, and ideas as young people as first naïveté. That is, we take things at face value, not questioning their truth content or historicity. But as we grow up, as we study, learn, experience, the questions come hard and fast, and we begin to develop a critical distance from many of these ideas. (At this point, angels are part of our childhood, perhaps diligent protectors.) We take the world as it is and trust the interpretations from science, history, philosophy, economics, and political theory. We are left with a profound distancing from any religious traditions. As adults we may become confident that religious traditions are part of the baggage that we can safely jettison.

Time passes. Things happen in our lives—things we could not have predicted and that we cannot explain. We discover the hard way that we may have an overconfidence in the fruitfulness and ability of scientific and technological adaptability to meet every new challenge. We may also become aware that we have an overconfidence in our own ability to navigate the modern world and to protect ourselves and those we love from harm, to recognize mortal, spiritual danger when it inevitably crosses our paths.

What Paul Ricoeur called the second naïveté flows from a deep inner experience of God, the ultimate source of life, redemption, and meaning. Within this landscape and horizon, we don’t doubt away what we learned in other spheres. Rather, we hold this knowledge and these beliefs with an awareness of our fragility and vulnerability—aware of all the paths/roads we have been on and that our lives could have turned out very differently, in many cases very badly. How did that happen? Where did that person—that angel—come from? Where did that impulse of grace, that insight originate?

In raising these questions and calling it the second naïveté, Dr. Ricoeur was being neither dismissive nor ironic in naming it so. Rather, he was trying to describe the faith of a seasoned person, someone who has been raised in the tradition and formed by religious language, and how that language and tradition are repositioned in relationship to contemporary experience.

At this point in my life, do I believe in angels? Absolutely!

Winter 2022-23 Abbey Banner 4 5

This Issue Do You Believe in Angels?

Abbot

Abbey archives

Nickolas Kleespie, O.S.B.

Every once in a while, within those big stacks of Christmas cards that so many of us receive, one card stands out because it includes a great image, a personal note, or a big family update. Rarely, however, does the inscription stand out. But that was not the case for me this past Christmas.

I received a card whose text was a poem by Dr. Howard Thurman (1899–1981), an American author, theologian, civil rights leader, and mentor to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. Thurman’s words capture the real meaning of Christmas as well as the challenge that the incarnation of Jesus presents to all men and women of good will. He writes:

When the song of the angels is stilled, when the star in the sky is gone, when the kings and princes are home, when the shepherds are back with their flocks, the work of Christmas begins: to find the lost, to heal the broken, to feed the hungry, to release the prisoner, to rebuild nations, to bring peace among people, to make music in the heart.

The shepherds in Luke’s Gospel (2:16–20) arrive in haste to find Mary and Joseph caring for the infant Jesus in the manger. Almost as quickly, the shepherds departed, glorifying and praising God. What does it mean to have encountered the incarnation—the Word made flesh— and then to leave glorifying and praising God? Dr. Thurman’s poem provides the answer, and it is precisely what we need to do throughout the Christmas season and every day of our lives: to find the lost, to heal the broken, to feed the hungry, to release the prisoner, to rebuild nations, to bring peace among people, to make music in the heart.

Mary shows us the beauty of receiving the Word of God into our lives and how to trust in our participation in the Word made flesh. Abiding

in such trust, Mary became the ultimate disciple, the essence of what it means to follow Jesus. She is the one who surrendered her ego and fears, opening her heart to the fullness of divine grace and peace. Her work was not complete in giving birth to Jesus nor even in the raising of her son. Mary is a witness and exemplar of the meaning of raising up the lowly and bringing about peace.

In his address for the 54th World Day of Peace (1 January 2021), Pope Francis described the encounter with the incarnation and its movement toward action as a “Culture of Care.” He wrote: “The culture of care thus calls for a common, supportive, and inclusive commitment to protecting and promoting the dignity and good of all, a willingness to show care and compassion, to work for reconciliation and healing, and to advance mutual respect and acceptance. As such, it represents a privileged path to peace. ‘In many parts of the world, there is a need for paths of peace to heal open wounds. There is also a need for peacemakers, men and women prepared to work boldly and creatively to initiate processes of healing and renewed encounter’” (§9).

The work of Christmas has indeed just begun. Throughout this Christmas season, may we be reminded of the actions of the shepherds and the example of Mary who guide us today in establishing a culture of care. Following their example, may we go forth in the days and years ahead to glorify and praise God as we bring peace among people and make music in the heart.

Father Nickolas Kleespie, O.S.B., is a faculty resident and chaplain at Saint John’s University.

The poem, “The Work of Christmas,” is excerpted from The Mood of Christmas and Other Celebrations by Howard Thurman and used with permission of Friends United Press [https://bookstore.friendsunitedmeeting. org]. All rights reserved.

All artwork: Franck Kacmarcik, Obl.S.B.

A Culture of Care as a Path to Peace

Every aspect of social, political, and economic life achieves its fullest end when placed at the service of the common good (§6). May we never yield to the temptation to disregard others, especially those in greatest need, and to look the other way; instead, may we strive daily, in concrete and practical ways, “to form a community composed of brothers and sisters who accept and care for one another” (§9).

Francis, Bishop of Rome

Winter 2022-23 Abbey Banner 6 7 The

Work of Christmas

Stories of Nairobi Matthew Gish

This past spring, I lifted an uneasy finger and then let it fall decisively onto my computer mouse. That nervewracking click delivered an email to the Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine confirming my deferral of matriculation in favor of a year of service in Kenya with the Benedictine Volunteer Corps (BVC). My decision to delay medical school for a year was difficult to make—and even more so to justify. As I struggled to provide explanations to my loved ones and to my own anxious mind, I found solace in the stories that I would surely bring back home.

A member of the monastic community once told me that many people spend their lives building their résumé, but the wiser ones spend their lives crafting their eulogy. A morbid thought? Perhaps. But in light of Saint Benedict’s exhortation to keep death daily before our eyes (RB 4.47), we would do well to ensure that our parting paragraph be rich with good stories. With this in mind, I joined the BVC in Kenya, hoping to return with a lifetime of experiences to share.

In only a few weeks, I have amassed a multitude of stories— some humorous, some humbling, some inspiring, and many embarrassing—thanks to the

abundant service opportunities in Nairobi. At a small hospital run by the Missionary Benedictine Sisters of Ruaraka, my BVC partner Griffin Scholl and I assist in the laboratory, the injection room, and the childwelfare clinic. We teach science and math to children at St. Benedict’s Primary School. We regularly walk deep into the Mathare slum to Saint Benedict’s Children Centre (affectionately known as Madodo, in honor of the signature lunch of cooked beans), where we prepare kids for entry into the Kenyan education system for which they currently lack the resources or support. We work with Alfajiri, a rehabilitation center that uses art, dance, karate, and other creative outlets to guide street children toward brighter futures. And because the BVC experience

is more than just work, we’ve had opportunities to explore the city, feed giraffes, eat street food, run in the forest, attend feasts with monastic communities, and hike many of the tallest peaks in the country. I even have a standing offer to travel to a rural village to slaughter a ram!

Each day in Nairobi brings experiences that I will treasure for the rest of my life. I’ve found that the most impactful stories come not from my mouth but from the people all around me. I’ve had to teach myself not to get caught up in my own journey in Kenya and thus fail to listen to the incredible people here. I have learned that simply sitting and listening provide more precious memories than days on Mount Kenya. I listened, for example, to a social worker

named Vincent from Madodo explain the challenges of getting kids from the slum into schools. He was frustrated with apathetic parents and a national education system that is too expensive for many kids to attend even primary school. Yet he perseveres in his work, pointing to eight pictures of young men and women, donned in caps and gowns—each is a college graduate who came to the center years ago. Like a proud parent boasting of the accomplishments of his children, he beams as he explains that the success of a few kids makes the struggle worthwhile.

I have also chatted with a teenager named Rafiki. He recalled how he fled from an abusive father and traveled many miles to the streets of Nairobi, where he soon became addicted to huffing the jet fuel that dulled the pain of his difficult life. He was blacklisted from rehabilitation centers due to his propensity for relapsing. Only after the Alfajiri program offered him the grace and patience required for his rehabilitation was he able to keep himself sober and excel in school. He spoke with a firm sense of peace and gratitude, never expressing anger about the hand that he had been dealt in his young life.

Perhaps the most powerful conversation I’ve had was expressed in just two words. While walking through Mlango Kubwa, a particularly unruly section of the

The joy that the slum cannot steal.

slum and home for many young street kids, I encountered a boy named Yosef. Tugging my arm, he pointed to a slab of concrete beneath a porous tin roof and whispered nalala hapo: that is where I sleep. He spoke no English, and my Swahili skills are a work in progress. But I observed what words could not express. The scars on his young face confirm his past difficulties, while his unwavering smile speaks of hope in a brighter future. Skipping and dancing through the littered dirt roads, he silently reveals: “I have a joy that the slum cannot steal.”

During my brief service in Kenya, I have gained a lifetime of experiences and insight. I have learned that the stories I love the most will never be my own. Listening to others has deepened my knowledge and wisdom more than any personal adventure. I’m grateful for my education here and for the Benedictine Volunteer Corps that has taught me to incline the ear of my heart (RB Prol.1) so that I may say: Vincent. Rafiki. Yosef. Mnasikika. You are heard.

Mr. Matthew Gish, a biochemistry major from Bemidji, Minnesota, is a 2022 graduate of Saint John’s University.

Winter 2022-23 9 Abbey Banner 8

Benedictine Volunteer Corps

Mathare slum, Nairobi

BVC archives BVC archives

Martin F. Connell

Not unlike the message of Advent and Christmas, Corita Kent’s screen print Fiat at first perplexes before sharing its promises of brightness to come.

Corita Kent (1918–1986) and her art became widely known in 1985 after the U.S. Postal Service issued a 20-cent Valentine’s LOVE stamp inspired by a brilliant rainbow mural she had painted on a 158-foot tall liquified-natural-gas storage tank in Boston. Decades before such notoriety, decades before she would be called “the Pop Art nun,” she had been exercising her creativity as an artist and a teacher of art at Immaculate Heart College, Los Angeles. She was a member of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart, 1936–1968.

The title Fiat is taken from the infancy narrative of the Gospel of Luke—formerly proclaimed in Latin. There, the angel Gabriel delivers to Mary the news that she would have a son and name him Jesus (1:31). Mary’s initial response was not one of eager acceptance but rather perplexity: Quomodo fiet istud—the virgin’s query in Luke 1:34—“How is this possible?” So too with Joseph whom the Gospel of Matthew describes as vir justus

[In Fiat] I have tried to show the unison of love, faith, and hope by a distribution of their three colors, red, blue, and green; shocking the entire combination with something of the excitement this moment of history carries with it. Corita Kent

(a fair man), and who, on hearing that his betrothed was pregnant, but not by him—vóluit occúlte dimíttere eam—“wanted to dismiss/divorce her quietly” (Matthew 1:19). Luke’s Mary and Matthew’s Joseph responded to the angels’ messages not with an immediate “thumbs-up” but rather with words of confusion and concern.

The Holy Family’s initial deflection of God’s gift—Mary’s “Why me?” and Joseph’s “Can’t we keep this secret?”— is confirmed in the mottle of

Corita Kent’s Fiat, the splay of colors complementing the expectant parents hearing of the arresting—and so far, not good—news of pregnancy by divine favor. The characters of the artwork are discernible by starting with faces and hands. At top center right, Mary’s face—under her crown as queen of heaven—comes forth. At top center left, the angel Gabriel’s face is visible. Both central figures have long noses, with Mary’s eyes open wide toward the viewers and Gabriel’s eyes fixed on

her. Between the two faces is Gabriel’s dark brown hand, with splotches of animating colors; below it, Mary’s light brown hand, similarly splotched. The Blessed Mother-to-be is in the traditional, if inventive blue, not the celestial blue so common in nineteenth- and early twentiethcentury devotional art. Gabriel, Mary’s celestial companion, is depicted in bold red, apt for the bearer of God’s light—the light bursting between the angel’s face and spindly digits.

Barely discernible are God the Holy Spirit, to the right of Mary, and God the Father, to the left of Gabriel. The Gospel of Luke uniquely attributes to the Holy Spirit God’s gift of the incarnation: “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you” (1:35). The

image of the Holy Spirit darts toward Mary’s head as birds in flight in the top right corner. God the Father appears along the left edge, a splash of colors through a figure with arms extended—the giver of the gift of Christ, with the guarantee of salvation by the incarnation of Jesus Christ in her womb.

Modestly scribed at the very bottom right is “Sister Mary Corita.” The baptized Frances Elizabeth Kent received the name Mary Corita when, at age 18, she entered religious life. She could hardly have imagined that her artwork would be pasted on American correspondence in years to come!

Before creating Fiat in 1953—as a Catholic school girl as well as during the decades of her religious life—she would have routinely heard the biblical readings proclaimed and prayed in Latin. She would have heard the eventual assent of the virgin, Fiat mihi secundum verbum tuum—“Let it be done with me according to your word” (Luke 1:38). Corita extracted the Latin fiat to capture the saving moment in the life of the world.

For Joseph’s part, we hear that he did as the angel of the Lord commanded him; he took Mary as his wife (Matthew 1:24).

Luke’s Gospel of the annunciation to Mary is heard twice each year: on 25 March, the Solemnity of the Annunciation; and on the Fourth Sunday of

Find the brightness of God’s glory not just in the past but in each new day.

Advent. For Christians, Mary’s fiat changed access to God’s life among us, for the Word became flesh (John 1:14) and lives among us. Mary’s assent—her fiat, her “let it be”—occasioned the incarnation, God’s gift in the past to Mary and still God’s gift continuing to the present, for the incarnation is revealed day by day. Mother Mary’s eyes spark us to see Sister Mary Corita’s brilliant reds, blacks, oranges, blues, pinks, whites, and yellows as she did.

This Advent, this Christmas, and throughout the new year, our Church and society need brightness. We can help realize God’s incarnate gift by greeting people who suffered during the pandemic, by chatting with neighbors whose political views differ from our own, or by asking those who worship in other churches what Bible passages were proclaimed or what their pastor preached about. Mary’s fiat and Corita’s depiction of Gabriel’s annunciation to Mary nudge us to find the brightness of God’s glory not just in the past but in each new day. Fiat. Let it be.

Dr. Martin F. Connell is professor of theology at Saint John’s University.

Winter 2022-23 Abbey Banner 10 11 Fiat: Let it Be

Fiat by Coria Kent, 1953. © 2022 Estate of Corita Kent/ Immaculate Heart Community/ Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Used with permission.

Hill Museum & Manuscript Library

Geissler

For the last few years the land management staff has deployed motion-activated trail cameras in hopes of capturing images of the more elusive and/or nocturnal critters that inhabit the Saint John’s Abbey Arboretum. The trail cameras are strapped to trees in strategic locations throughout the woods or wetlands. Then, after a few weeks and with great anticipation, we collect the cameras and download the wildlife images.

A few of the more rewarding highlights of this effort include pictures and sometimes closeup videos of black bear, great horned owls, flying squirrels, fisher, mink, ermine, and otters.

Sometimes there are curious twists to our recording efforts. For example, in one of our first attempts to obtain otter photos, we attached our camera to a tree near the pond shoreline where we knew the otters liked to frequent. Unfortunately, the next night a beaver visited this same site and decided to cut down the tree to which our trail camera was attached! Luckily the tree fell toward the land and not into the water. The comical sequence of photos captured by the camera included a picture of the beaver approaching the tree, followed by blurry images as the tree (with camera) fell, and finally an extremely close-up picture of the ground! Unfortunately, I have somehow lost

these photos. But this really happened!

We do, however, have photos to prove another story—a story that you really do have to see to believe. Many years ago, when I was working in northern Minnesota, I was helping a wildlife researcher set up and check several trail cameras. As I approached one of the cameras, I was surprised to see an old beer can lying directly under the trail camera—the can had not been there when I set up the camera

To

a week before. When we examined the photos, we found—to our great surprise—several images showing a wolf carrying the discarded can to the trail camera, dropping it there, and then looking closely at the camera as if to say, “Here you go. Please take this litter out of here!”

sion as it moves from place to place. The edges of wetlands are some of my favorite spots to explore for tracks in the winter—especially because I can’t easily explore these areas any other time of the year. In the winter, they are almost always loaded with tracks. Depending on the depth of the snow, I will explore the territory with snowshoes, backcountry skis, or just my boots on a quest to find and follow some of my favorite tracks. My most rewarding discoveries include finding the sliding tracks of a group of otters or the wing prints of a pouncing raptor.

edited by

https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=sYzvHTB7asE

Trail cameras are limited to detecting wildlife in a small radius of wherever they are set up. A fresh blanket of snow, however, allows the careful winter explorer to observe the evidence of every critter that walks, hops, bounds, or touches down anywhere on the local snowy landscape. After the first few snowfalls, I enjoy watching for the small bulldozer trails of the shrew or the common hopping track of the deer mouse that leaves a slight tail impres-

Whether we are checking trail cameras or reading the stories of tracks left in the snow, it is fun and enlightening to examine the areas utilized by the many animals that we don’t typically see. Though somedays it is difficult to leave a warm house and venture into the wintry world, the rewards of such explorations are many. A treasured mentor of mine repeatedly said: “There is a new story out there every day. We just have to get out there to discover it.” I encourage all our readers “to get out there” and regularly explore any nearby natural areas and see what stories can be discovered.

Mr. John Geissler is the land manager of Saint John’s Abbey and director of Saint John’s Outdoor University.

Winter 2022-23 Abbey Banner 12 13

Discovering New Wildlife Stories

John

view activity on a beaver lodge on Lake Sagatagan and other summer 2022 scenes, visit this video compilation

Mr. Kyle Rauch:

Photos: Shy doe by Kyle Rauch. Wolf series by Bryn Evans. Fisher by Kyle Rauch.

My introduction to Benedictine spirituality was through a Jesuit! Before moving from Massachusetts to Collegeville six years ago, I was steeped in the Ignatian world— and have been trying to understand what “Benedictine” means ever since. Learning of my upcoming move, this dear Jesuit brought me to the nearest monastery for Evening Prayer and gifted me my first copy of the Rule of Benedict, adding: “It’s a little intense on the discipline (very Jesuit), but this will help you understand the spirit.”

During my first year here, I asked members of the community for advice on assimilating. I longed for a quick fix, a Google Translate of Jesuit-to-Benedictine! I kept reading the Rule and attended Mass at Saint Benedict’s Monastery and Saint John’s Abbey. I’ll never forget how Father Don Talafous responded to my inquiry: “Come to prayer. Pray with us!” And so, I did.

I have come to understand “Benedictine” as a lived way of being. More than catchphrases dropped on websites, Benedictine values are now most evident to me through the lived expressions of the monks, sisters, and friends I’ve come to know and love. Between the dedication to some task (such as woodworking, pottery, business, theology) and the consistency of the “Work of

God” (prayer), the ora et labora rhythm animates all the other values.

This way of being is grounding for me. It brings me peace and stability, focus and assurance, amid a hectic life. While I often lament not being able to attend all the liturgical services with the monastic community, I am aware that my attention to my kids during these hours is my own prayer in between the work I love at campus ministry.

Have I converted? Tough to say. But remembering that first prayer experience in Massachusetts—that I found to be slow and tedious—I now find to be life-giving.

During a retreat, I confessed to the students that it peeves me when we boil down Benedictine values to a set of buzzwords. They are a whole life! The students agreed, recognizing that we can’t separate out one value from another. We arrive at “community” through “hospitality,” being the first to show care and respect to another (RB 72.4). “Care for creation” is also “respect for persons,” since climate change disproportionately hurts those who are already marginalized.

I was once the newcomer, but I now joyfully introduce this way of life to the newer arrivals. I invite them first to “pray with us.” After all, is not the final commitment of Benedictine life

to conversatio morum! It is a daily conversion, and I’m on the way.

Ms. Margaret Nuzzolese Conway is the director of campus ministry at Saint John’s University.

ule of Benedict

Our Core Business

Eric Hollas, O.S.B.

One can hardly fault Saint Benedict for his focus on the interior life. After all, personal and community dynamics were Benedict’s major preoccupations. But what about the world on the other side of the monastic gate? Was it of no concern to him at all?

Benedict did not ignore the outside world, nor was he oblivious to the existence of values very different from the ones he hoped to nurture in the monastery. He alluded to the purchase and sale of goods, for example. He anticipated that monks would go on journeys and that guests would always come calling. The quality of these exchanges needed constant attention and care.

In The Dialogues Pope Saint Gregory the Great noted Benedict’s efforts to evangelize the neighbors around Montecassino. He also described what had to be the tense negotiations between Benedict and the barbarian chief who had come to destroy the monastery. Benedict was successful, but the failure of one of his successors left the monastery in ruins. Such examples suggest that monks can benefit from training over and above the spiritual.

Clearly, life in Benedict’s monastery was more complicated than his Rule lets on. Then, as now, monasteries have always been integrated into the social, eco-

nomic, and political fabric of society; and interactions with the outside world have only intensified through the centuries. Long gone are the days when monasteries were self-contained agricultural units. In their stead stand religious communities that must tend to all sorts of things that Benedict could not have anticipated.

All of this hints at the expertise that a monastery, such as Saint John’s Abbey, must have at its disposal. Those skills often require advanced training or education, with the result that we come to depend on specific monks who have unique skills. Saint Benedict was cautious about that sort of thing (RB 57.1–3), but monks have for centuries learned

Prefer nothing whatever to Christ.

Rule 4.21; 72.11

to live with this risk. In fact, we would not have it any other way. To cite but one example: I have yet to meet the confrere who is eager to take over the management of our Medicare forms! We all remain grateful to the monk who can and does do it.

Is Benedict’s emphasis on the spiritual regimen hopelessly out of date? Not at all! The professional cares that tug at modern monks are very real, but the Rule provides the focus. It serves as a daily reminder that the core business of the community is the glory of God and the search for Christ in ourselves and in our neighbors.

Father Eric Hollas, O.S.B., is the prior of Saint John’s Abbey.

Winter 2022-23 Abbey Banner 14 15

A Way of Being

Margaret Nuzzolese Conway

Aidan Putnam

Alan Reed, O.S.B.

Aaron Raverty, O.S.B.

Attitudes toward angels are rarely neutral. Some find them intriguing—personal, invisible, and powerful forces to be reckoned with in our modern world—even displaying angel facsimiles as part of their bodily adornment. For others, they are simply products of an overactive imagination—fanciful beings, the trappings of children, not to be taken seriously.

Angels and their kin have been around for a long time. Nineteenth-century anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor considered a belief in spirit beings (animism) the earliest form of religion in the genus Homo, perhaps going back hundreds of thousands of years. Angels fit this category as incorporeal creatures—created by divine beings or force—with unique personal characteristics, some of whom are even named. They are generally coupled with theistic traditions. Their very definition, as heralds, derives from their association with a belief in God or gods who send and charge them. This narrows their niche in the universe of spirit beings. Their ability to act, most often as messengers, is always divinely directed.

Angels are associated with all the monotheistic Abrahamic traditions. According to “Angels in Islam: Creatures of Light” (IslamOnline), the Qur’an “speaks of angels as playing a crucial role in processes like

creation, prophecy, spiritual life, death, resurrection, and the workings of natural elements.” It was the archangel Gabriel (Jibrīl) who revealed the Qur’an to the Prophet Muhammad and acted as his guide during the journey from Mecca to Jerusalem to heaven on the Night of the Ascension, Al-Mi`raj. Adherents of the (non-Abrahamic) Zoroastrian faith name archangels (“beneficent immortals”), guardian angels, and a long list of angels (“adorable ones”) among those whom they honor and praise. Christianity inherited many of the angelic types

from Judaism, and angels also figure prominently in Jewish folklore.

Unlike the human creation accounts in Genesis 1–2, the creation of angels was in heaven, although it is otherwise shrouded in mystery. As purely spiritual creatures, angels lack gender; they are neither male nor female. They do not eat, enjoy sensory perception (according to Saint Thomas Aquinas), or reproduce. However, in artistic renderings of the Renaissance and Baroque, the cherubim especially were depicted as chubby infants with

wings (“cupids”). In the Jewish and Christian Scriptures, angels are most often anthropomorphically depicted as young men. This makes them easier for mere mortals to single out, recognize, and relate to. Remember the three angels disguised as men who came to visit Abraham in the desert (Genesis 18:2).

In the Judeo–Christian tradition, angels take on a set of even more specific attributes. As created by God (creatures) and thus separate from the Godhead, angels possess intelligence, will, and moral agency. Unlike mortal

human creatures, though, angels have been gifted with immortality and do not die. In his Homily 34, Benedictine Pope Saint Gregory the Great emphasized that angels are defined by their function and not by their nature. Most of them are God’s messengers and are recognized as such both in Jewish and Christian traditions.

In formal academic terms, angelology is a section of systematic theology. Angels in the Christian tradition, derived from Judaism, became uniquely interwoven into the scriptural account of salva-

tion history. Angels thus constitute an article of faith in the Catholic Church and, as such, are part of its doctrine. (See the Catechism of the Catholic Church, §328–336.) By the fourth and fifth centuries, nine ranks or choirs of angels—the angelic hierarchy— were recognized by the Fathers of the Church and elucidated by the mysterious Neoplatonic figure of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite in his Celestial Hierarchy. These ranks were derived from Scripture. Gregory the Great outlines them in his Homily 34, and they are also affirmed by Saint Augustine: seraphim, cherubim, thrones, dominions, powers, virtues, principalities, archangels, and angels.

As messengers, angels are God’s communicators; they fulfill God’s assignments. They derive their agency from God. Within the Christian tradition, only archangels, that is, those who figure prominently in Scripture as significant messengers with important missives, are given names.

Michael: “Who is like God” (Daniel 10:13, 21; 12:1; Jude 9; Revelation 12:7-9)

Gabriel: “Strength of God” (Daniel 8:16; 9:21; Luke 1:19, 26)

Raphael: “Medicine of God” (Book of Tobit)

One can uncover many activities of angels by searching the Scriptures. Although the specific scriptural references are too numerous to cite here, we learn that angels perform the following functions:

Winter 2022-23 Abbey Banner 16 17 Angels

Shakko/Wikimedia Commons

Archangel Michael, eleventh-century mosaic in Monastery of Hosios Lukas, Greece

Shakko/Wikimedia Commons

Archangel Gabriel, eleventh-century mosaic in Monastery of Hosios Lukas, Greece

adoration, proclamation/messaging, oversight/governance, judgment, protection (guardian angels), and intercession. As intercessors, angels are included in that “great cloud of witnesses” (Hebrews 12:1), the communion of saints. We do not worship angels (Revelation 22:9), but we can ask them to intercede for us in prayer. They, in turn, pray for us.

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the Angelic Doctor, stressed the unique individuality, the personal nature, of each angel. He also taught that angels possess a moral sense; they know the difference between good and evil. Since angels possess moral agency, they can choose to act in good or bad ways. This is

the basis for the great battle in heaven between the “good” angels (who remained loyal to God and later received the beatific vision) and the “bad” angels (who transferred their allegiance to Lucifer—originally a member of the cherubim—and were driven out of heaven by Michael the Archangel and his minions [Revelation 12:7-9]). Angels can be considered as personal, creaturely extensions of God’s salvific will in the world. According to Dr. Joseph Magee’s interpretation of Aquinas: “In all cases, the purpose of the appearances of angels is to inform humankind of divine realities, and so to lead people to God.”

The ever-inquisitive mind of Thomas Aquinas, as revealed in

the discussion of angels in his Summa Theologiae, wondered whether several angels could occupy the same space at the same time. This query later took the form of “How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?” and came to be an indictment of the impractical musings of medieval philosophy.

The Guardian Angels are the patrons of the American–Cassinese Congregation of Benedictine Monasteries. In one of his sermons, Saint Bernard declared: “To those beings so sublime, so blessed, because they stay so near [God] and are really members of [God’s] household, [God] has given command concerning you.” In his book Angels in the Bible, Father George M. Smiga provides us with scriptural support for our belief in guardian angels: Genesis 48:16; Exodus 14:19–20; 23:20–22; Numbers 20:16; Psalms 34:7; 91:11; 1 Kings 19:5, 7; Daniel 9:23; Tobit 3:17; 5:4, 22; Matthew 1:20–21; 2:13, 19–20; 4:6, 11; 18:10; 26:53; Mark 1:13; Luke 22:43; Acts 5:19; 12:7–10; 27:23. The early Church Fathers were quick to use this scriptural evidence to support the idea of personal guardian angels.

There are many allusions in formative Christian ascetic/monastic liter-

ature for the desire to acquire the “life of angels” (bios angelicos). Although this may initially have been a yearning to rid themselves of the encumbrances of the “corruptible flesh” to join the state of the angels as “pure spirits,” those who stuck more closely to the bodily resurrection vision of Saint Paul and other early Christian thinkers were hoping that human beings would eventually undergo an essential transformation. Perhaps what Paul was hinting at was that “our citizenship is in heaven” (Philippians 3:20) alongside the angels and saints in our glorified, resurrected state, adoring God face-to-face and singing God’s praises.

My ethnographic research on the New Age movement revealed a romanticized image of angels enlarged beyond the standard scriptural/theological functions

listed above. Author Rosa Huotari, for example, asserts, “in the New Age movement, unlike in Christianity, angels are encountered in novel ways and defined separately from biblical tradition. Instead of being just messengers of God . . . angels are interpreted as subjects themselves who support, advise, and help in difficult situations.”

Angels today have been belittled both in media (the Touched by an Angel television series) and marketing (various tattoos/ jewelry items). They are trivialized as marketing brands—the tissue roll labeled “Angel Soft” says it all!

As did some early Christian ascetics, we too might envy angels. They are so close to the Godhead and have been gifted with superior intellect, great power, and immortality, which mortals lack. However, let us

not forget the message of the Letter to the Hebrews: that God’s only begotten son, Jesus Christ, reigned over the angels. He did not aspire to an angelic state but became for a time lower even than the angels to incarnate—taking on our very humanity—for our salvation (2:5, 9, 14–17). Thomas

Aquinas asserts that the angels always stand in the presence of God, praising and adoring God. Let us, too, raise our voices in praising and adoring the Lamb of God, and rejoice with the angelic choirs as they welcome us, after the journey of this mortal life, to join them in the communion of saints.

Brother Aaron Raverty, O.S.B., a member of the Abbey Banner editorial staff, is the author of Refuge in Crestone: A Sanctuary for Interreligious Dialogue (Lexington Books, 2014).

Winter 2022-23 Abbey Banner 18 19

Wikimedia Commons

The Annunciation by Henry Ossawa Tanner, 1898 painting, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Cherubs, detail of Sistine Madonna painting by Raphael, c. 1513, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

Wikimedia Commons

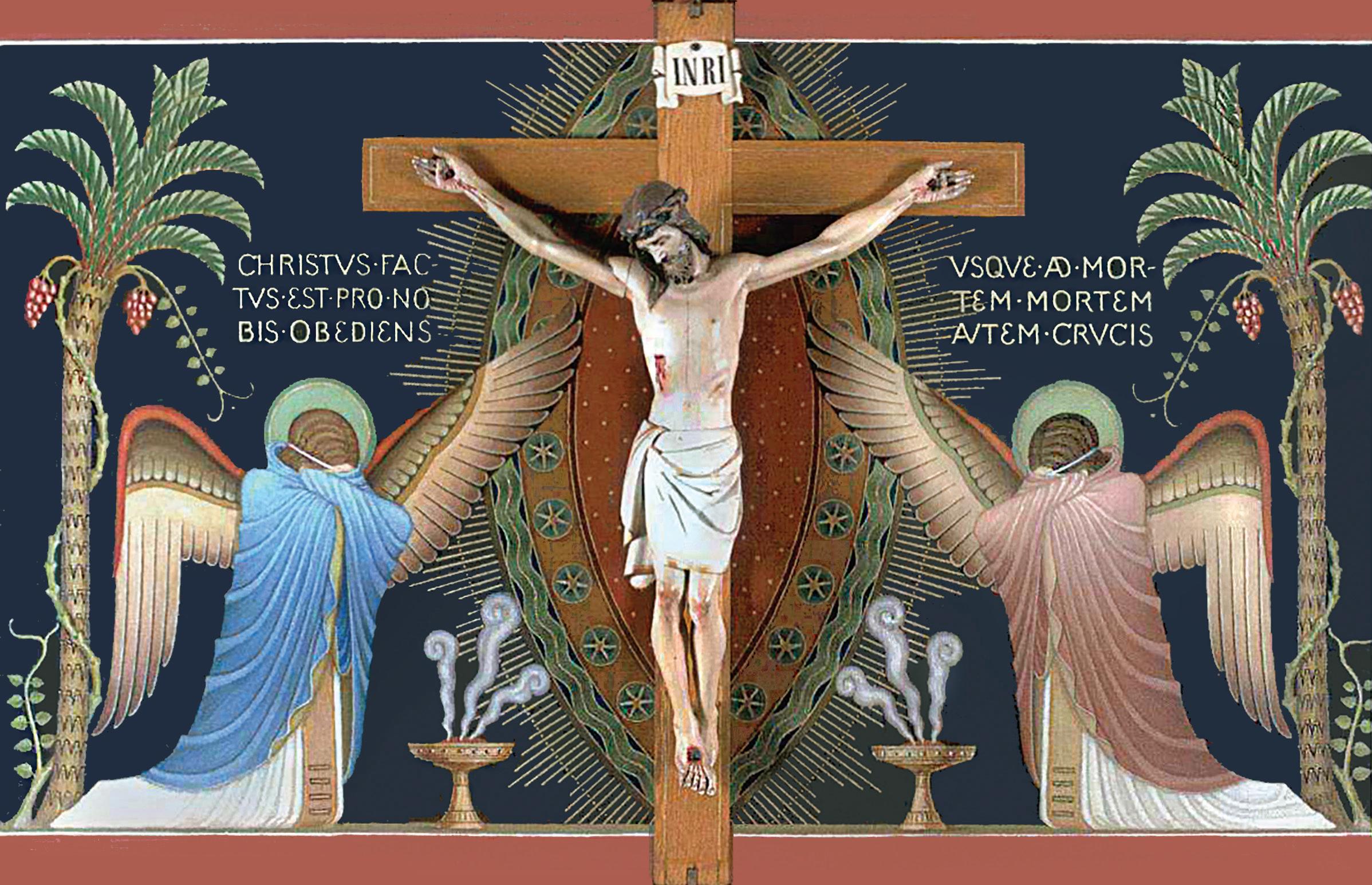

Abbey Angels

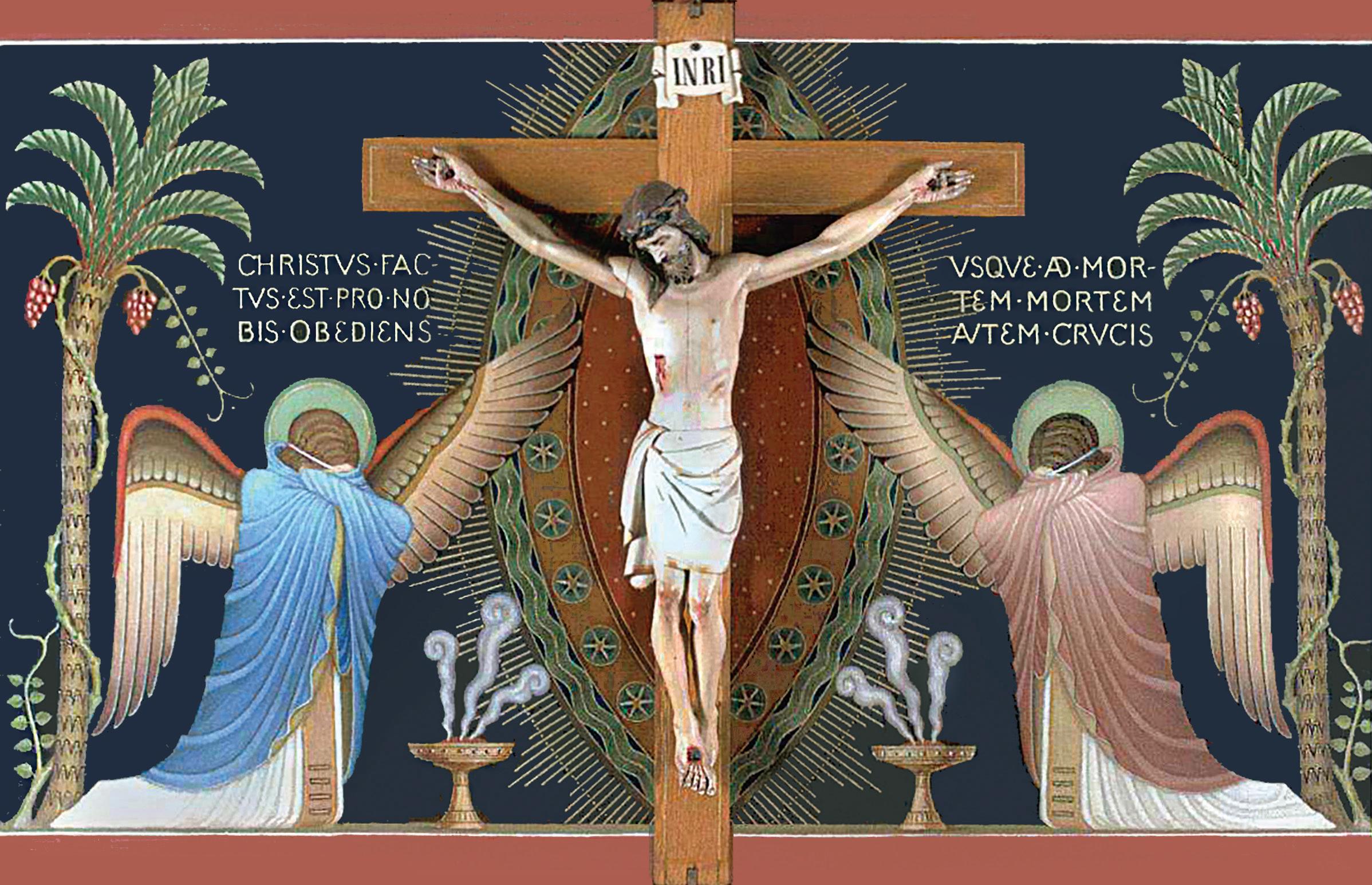

Saint John’s Abbey is filled with angels, especially those depicted in the stylized art of Beuron by Brother Clement Frischauf (1869–1944). Mr. Joseph O’Connell (1927–1995), a local artist, also contributed to the abbey’s angelic choirs.

Images (clockwise, beginning at upper left): Brother Clement’s angel acolyte study, angels adoring the crucified Christ, angel acolyte study, angels and monks praising God (1930s). Saint Michael the Archangel (metal sculpture, 1964) by Joe O’Connell. Study of an angel by Brother Clement.

Photos: Abbey archives

Photos: Abbey archives

Liturgical Press: Winter Reads

Tara Durheim

As we settle into the winter season, the long hours of cold and darkness (at least that’s the case in Minnesota!) are an ideal time for deeper reflection in the company of award-winning monastic and spirituality writers. Those craving contemplative, prayerful reading (in any season), need look no further than this list of recent publications from Liturgical Press.

Our journey of recommended reads begins somewhat off the beaten path with the spiritual writings of a seventhcentury saint—a sage little known to those outside the Eastern Church. In Diving for Pearls: Exploring the Depths of Prayer with Isaac the Syrian which received the first-place award in mysticism from the Catholic Media Association— author Andrew D. Mayes introduces us to Saint Isaac’s wisdom and insights. Isaac’s writings will inspire teachers and spiritual directors as it provides material ideal for quiet retreat days. Rev. Mayes also shares reflection questions and prayer exercises, so readers can be ready to celebrate God’s all-encompassing love and delve more deeply into prayer with Isaac the Syrian.

Going further back in time but continuing to engage the riches of the Eastern Church, readers

will also delight in learning about Saint Mary of Egypt in Bonnie B. Thurston’s new book, Saint Mary of Egypt: A Modern Verse Life and Interpretation. Professor Thurston’s lively poetry about “the third Mary” shares her story, one of redemption, as it shows the power of God’s mercy and love for all of us. This “verse life” is accompanied by the author’s scholarly prose that helps readers further explore Saint Mary’s life and its theological and spiritual implications.

Those troubled by the issues of the day will not want to miss Desire, Darkness, and Hope: Theology in a Time of Impasse and the work of Carmelite theologian Constance FitzGerald. The contributors to this book apply several of Sister Constance’s articles to issues such as systemic racism and the COVID-19 pandemic, as editors M. Shawn

Copeland and Laurie Cassidy aim to introduce Sister Constance to a wider audience of people who seek to strengthen themselves on their spiritual journey. This book is both thought-provoking and hopeful.

In a review, Paul Lakeland, professor at Fairfield University, asserts: “[this book] reveals how prayerful theology needs to be if it is to help lead us beyond the many impasses of our times.”

Gerhard Lohfink is a German author who has built quite a following in the United States.

In The Forty Parables of Jesus (honored with the first-place award in Scripture, academic studies, by the Catholic Media Association), the author takes a closer look at each of the parables, identifying the context around the original messages and situations, and then reflecting on what these stories tell us about

the mystery of Jesus himself. The parables have been told and retold, but this exploration from Professor Lohfink helps us to look at them as a whole, uncovering their deeper meaning.

For fans of Thomas Merton, the latest book from Gregory K. Hillis would be an ideal choice for the winter reading list. Some have questioned Thomas Merton’s Catholic identity because of his strong commitment to ecumenical and interreligious dialogue.

In Man of Dialogue: Thomas Merton’s Catholic Vision, Dr. Hillis explores Merton’s life and thought and shows how he was both formed and informed by his deep Catholic faith. In addition to being a substantial introduction to Thomas Merton’s life, this book confirms why his writings on topics such as Eucharist, prayer, and peace are still so influential today.

For those who are eager to spend more time reflecting on the Sunday readings—whether on their own or as part of group— but are not sure where to start, consider Ponder: Contemplative Bible Study for Year A by Mahri Leonard-Fleckman. The author provides readers with everything needed for an enriching experience of lectio divina and biblical exploration, including the text of the Sunday readings, commentary, reflection points, and guided instruction—all of which make this an especially rewarding

book for those new to lectio divina or praying with the Bible.

Finally, those lacking the time to dig deep—but who need to hear that God’s grace can be found in the ordinary and notso-ordinary struggles of daily life—will want to spend some time with award-winning storyteller Valerie Schultz. In her new book, A Hill of Beans: The Grace of Everyday Troubles, Ms. Schultz addresses hard questions with humor and humility—

using deeply personal accounts of family, career, addiction, alienation, romance, aging, and loss—to show readers how to find grace and God’s loving presence in the everyday.

May your winter reading warm your soul and bring light to your spiritual journey!

Ms. Tara Durheim is marketing director at Liturgical Press.

Liturgical Press Books

Diving for Pearls: Exploring the Depths of Prayer with Isaac the Syrian by Andrew D. Mayes. Pages, 184. Cistercian Publications 2021.

Saint Mary of Egypt: A Modern Verse Life and Interpretation by Bonnie B. Thurston. Pages, 136. Cistercian Publications 2021.

Desire, Darkness, and Hope: Theology in a Time of Impasse edited by Laurie Cassidy and M. Shawn Copeland. Pages, 480. Liturgical Press 2021.

The Forty Parables of Jesus by Gerhard Lohfink, translated by Linda M. Maloney. Pages, 272. Liturgical Press 2021.

Man of Dialogue: Thomas Merton’s Catholic Vision by Gregory K. Hillis. Pages, 320. Liturgical Press 2021.

Ponder: Contemplative Bible Study for Year A by Mahri LeonardFleckman. Pages, 336. Little Rock Scripture Study 2022.

A Hill of Beans: The Grace of Everyday Troubles by Valerie Schultz. Pages, 152. Give Us This Day 2022.

To learn more or to order any of these books, visit litpress.org; or call 1.800.858.5450.

Winter 2022-23 Abbey Banner 22 23

Abbey archives

Boniface Wimmer: Missionary Abbot

Eric Pohlman, O.S.B.

He ploughed the fields and scattered the good seed on the land.

Three years ago, I joined a confrere on his family visit to Texas. Our touring included the marvelous missions in San Antonio. At Mission San José, our jaws dropped when the guide shared that red-brick repairs in several of the stone arches dated to the Civil War era, “when the mission was in the care of Benedictine monks from Pennsylvania.” That would be the same group of monks who founded Saint John’s! We had traveled 1,142 miles from our cloister in the North Star State to the Lone Star State, and still we could not escape the legacy of Boniface Wimmer! Saint John’s and the entire American–Cassinese Congregation owe their existence to the determination of this formidable nineteenth-century prelate. (What follows, including all quotations, was gleaned from An American Abbot by Jerome Oetgen [Washington: The Catholic University of America Press, 1997].)

Sebastian Wimmer was born in 1809 in Thalmässing, Bavaria, on a European continent recovering from Napoleonic wars and the concurrent secularization of many religious institutions. After success in Latin school and a year of seminary at Regensburg, he enrolled at the University of Munich to study theology.

The city widened his options, and young Wimmer was tempted to study law instead, and then almost abandoned his studies altogether to join the Greek army! But after twice failing to meet up with the recruiters, a timely scholarship notification kept him on his original trajectory.

He was ordained a priest in 1831 and a year later joined the refounded Benedictine abbey at Metten, making his solemn profession immediately after his novitiate year in 1833. His monastic name, “Boniface,” though simply in honor of a diocesan priest, became most fitting as Saint Boniface had been a monk-missionary to the Germanic peoples a millennium earlier. For a dozen years Father Boniface was caught up in regional issues but then learned of the plight of German-speaking Catholics in America. A pivotal meeting with Father Peter Henry Lemke, successor in western Pennsylvania to the legendary

missionary priest Prince Demetrius Gallitzin, gave Father Boniface vocational clarity: he would lead a mission to America.

be at Saint Joseph’s Church at “Hart’s Sleeping Place,” a log structure erected by pioneers in 1830. It lay just a few miles from the newly-platted settlement of Carrolltown, Pennsylvania—named for the first American bishop, John Carroll of Baltimore. It was a disappointment to Father Lemke that Boniface found the site wanting and instead accepted Pittsburgh Bishop Michael O’Connor’s offer of the “Sportsman’s Hall” parish near Latrobe, already with a decadeold brick church named for Saint Vincent de Paul.

(Germany) and Solesmes (France). Some looked to the Cistercians of the Primitive Observance, and Boniface allowed them to try out this austere form of monasticism at Gethsemani, Kentucky. Not infrequently the “Trappist cure” worked, and the monks in question returned to Saint Vincent, chastened and cooperative.

Forward, always forward, everywhere forward! We must not be held back by debts, bad years, or by difficulties of the times.

Man’s adversity is God’s opportunity.

Convincing his superiors took some time. He also needed to win the support of King Ludwig, whose mission society would finance the endeavor. He even resorted to anonymously publishing a manifesto, his “Charter of American Benedictines,” to drum up support. Such was his determination that he once declared that if he could not go as a Benedictine, “I will go in another habit.” That was not necessary as permission was granted in February 1846.

Father Boniface left in July, not with other seasoned monks, but with eighteen untried candidates. The long ocean crossing at least gave him time to school them in the basics of the Benedictine charism and customs.

Father Lemke planned for Father Boniface’s new monastery to

It is an understatement to say that not everyone shared Father Boniface’s clarity of vision of establishing centers of German culture and seminary education to supply German-speaking priests. He clashed with Bishop O’Connor when the latter wished him to accept Englishspeaking diocesan seminarians and when the bishop, a proponent of temperance, objected to his investing in a brewery. His tragic disagreements with the Benedictine sisters, particularly Mother Benedicta Riepp (founder of the Sisters of the Order of Saint Benedict in the U.S.), are referenced to this day. Finally, segments of his own community often worked against him, the would-be reformers advocating for less missionary activity and more attention to ascetic, liturgical, and spiritual practices, after the example of the Benedictines of Beuron

Boniface Wimmer’s insistence on mission flowed from his understanding of the historical moment: “America is the turning point in the history of the world,” he asserted. “[T]o create an attachment to religion is more necessary here than anywhere else because we have absolute liberty as regards religion itself, its practice and the persons who take part in such devotions.” Yet, “Because I am an American, I can do as I please without waiting for the permission of a royal minister, or the president. I am sure of success, if I undertake something good and use common sense.”

Five times he was obliged to return to Europe to advocate for his enterprise. The second journey, in 1855, included his first trip to Rome and an audi-

ence with Pope Pius IX. The Saint Vincent community was given abbey status, the first independent house in the new American–Cassinese Congregation. Boniface was appointed abbot of the former and president of the latter. In lieu of the customary abbatial blessing from a bishop, he received a pectoral cross and ring personally from the pontiff. He returned to Latrobe, now with a mandate for expansion.

Wasting no time, Abbot Boniface wrote to several bishops interested in receiving his missionaries. The community decided to commit to the first reply. Despite his letter having to come

Winter 2022-23 Abbey Banner 24 25

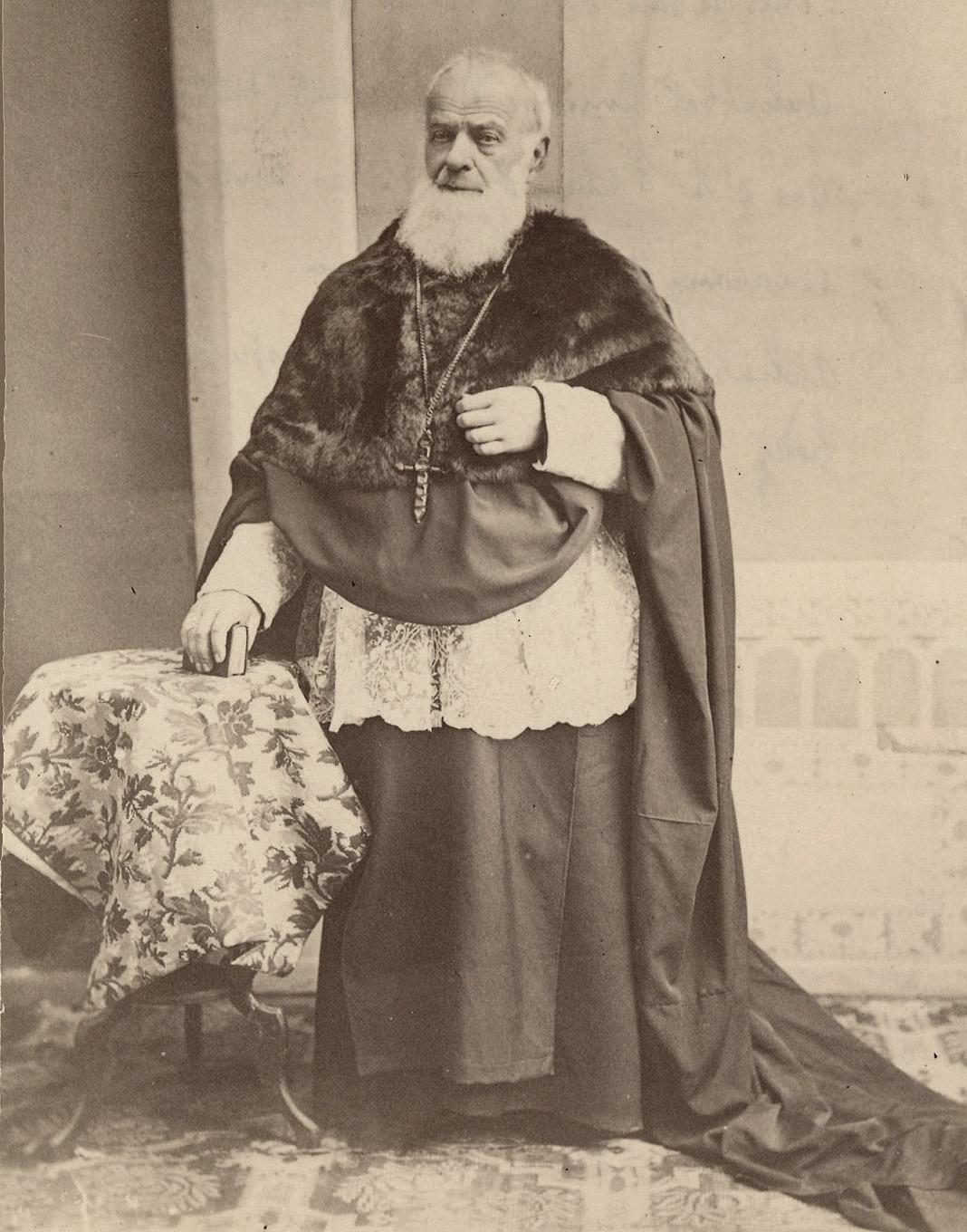

Boniface Wimmer, O.S.B.

Wikimedia Commons

Ludwig I, King of Bavaria

Abbey archives Boniface Wimmer, undated

the farthest, the honor went to Bishop Joseph Crétin of Saint Paul in the Minnesota Territory. A five-member founding party settled in what is now Saint Cloud in May 1856. From this seed would grow Saint John’s Abbey.

Meanwhile, Father Lemke, who had joined the Saint Vincent community in 1851, bristled at his junior status where he once pastored absolutely at the Carrolltown priory. (Abbot Boniface considered most every parish his monks staffed a “priory” or potential abbey.)

Without permission, Father Lemke fled for Kansas! Yet with hindsight, this too would be seen

as providential. Recognizing the needs of German settlers there, Abbot Boniface begrudgingly agreed to send monks, the foundation of what would become, after many missteps, Saint Benedict’s Abbey, Atchison.

More foundations would follow. Some, like the Texas priory, would fold. But eight current American–Cassinese abbeys trace their origins to the Wimmer era. After the Civil War, the South was a focus area; Abbot Boniface was determined to minister especially to the freed slaves. Complaints of a young monk assigned to this work in Georgia reached the abbot’s ears, whose reply was swift: “[The Negroes] are also people and God’s children, and Christ has also died for them. There fore, under pain of mortal sin, you must love them as you love yourself. That means to pray for them and work for their conversion as much as you can; otherwise you yourself have a black heart, although your face is white, and you are no child of God.”

Successes and disappointments continued. The

American–Cassinese general chapter of 1881 included a surprise celebration marking the abbot’s fifty years of priestly ordination. Two years later came his golden jubilee of monastic profession. When he learned of plans to fête him again, he tried to have the event cancelled. A protégé, Abbot Innocent Wolf of Kansas, pushed back: “We must celebrate this jubilee, and you must not be a kill-joy. . . . We owe you and your work such an honor.” Accolades from Rome followed: the title “archabbot” and the privilege to wear the cappa magna. His reaction was mixed: “All this is very nice and wellmeant. But it does not help me get to heaven, and I could easily get a few years in purgatory for it. I did not know whether to laugh or to weep, so I did neither. I just let them do with me what they wanted to do. Now I want to start all over again trying to be a good monk.”

A kidney ailment slowly took his health and then his life. Boniface Wimmer died at Saint Vincent on 8 December 1887, age 78. At Saint John’s he is memorialized with Wimmer Hall, attached to the quadrangle, and Wimmer Pond, beside the restored prairie.

Name That Monastery

Klingeman, O.S.B.

In Worship and Work, the centenary history of Saint John’s Abbey, Father Colman Barry, O.S.B., notes that the chapel of the monastery established on the banks of the Mississippi River near Saint Cloud was finished and dedicated on the feast of Saint John the Baptist, 24 June 1856. Aware that Saint Benedict had dedicated his first chapel at Montecassino to John the Baptist, “the monks decided to name their little house of prayer after Saint John, patron of the missions.” The monastery never completely lost this name, even though the foundation received several titles as it changed locations.

According to Father Alexius Hoffmann, O.S.B. (History of Saint John’s Abbey, 1931), Abbot Boniface Wimmer wished to call the new foundation “St. Louis,” but the monks preferred St. John’s. “It is known as the ‘Convent of the Order of St. Benedict, St. Claud’ in the Catholic Almanac for 1858; as the ‘Priorate of St. Cloud’ in that for 1859; as ‘St. Cloud’s Independent Priory’ in that for

1864 and 1865, and simply as ‘Independent Priory’ until the monastery became an abbey in 1866.”

On 17 March 1867, the Holy See changed the name of the establishment from “Priory of St. Cloud” to that of “Abbey of St. Louis”—in gratitude for the patronage of former King Louis of Bavaria—and authorized the addition of the words “on the Lake” because it is near a lake. Henceforth, says Father Alexius, “the official name of the institution was to be the ‘Abbey of St. Louis on the Lake, near St. Cloud.’” (The name for the college, “St. John’s,” was retained since it had been chartered under that name by the Minnesota Territorial Legislature, 6 March 1857.)

Brother Eric Pohlman, O.S.B., serves as the abbot’s secretary at Saint John’s Abbey.

The acts of the chapter held at Saint Vincent Abbey in Pennsylvania in September 1858 mention “St. Louis” as titular saint for the monastery in Minnesota. But, asserts Father Alexius, “St. John the Baptist was the preference of the Fathers in the West, and they clung to the name. As late as November 1861 the acts of the local chapter are drawn up at ‘Saint John’s near Saint Cloud.’”

Abbot Alexius Edelbrock was upset “that he presided over an institution bearing two names— St. John’s College and Abbey of St. Louis on the Lake.” In 1880, on a trip to Rome, Abbot Alexius and Father Peter Engel secured authorization to change the name from “St. Louis on the Lake”to ‘St. John the Baptist.’” The 1881 Catholic Directory states: “St. John’s Abbey (formerly ‘Abbey of St. Louis on the Lake’),” ending twenty-five years of name changes.

Brother David Klingeman, O.S.B., is the abbey archivist.

Winter 2022-23 26 27 Abbey Banner

David

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose By any other word would smell as sweet.

William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

Saint Vincent Archabbey

Painting of Boniface Wimmer, c. 1890, artist unknown

Gloria Hardy

Saint John’s Abbey coat of arms in the crypt ceiling of Montecassino, Italy

John Meoska, O.S.B.

Jesus, speaking to his disciples, says that he has come, not to abolish the Law or the Prophets, but to fulfill them. He then sets about to tease out the deeper implications of the Mosaic Law, using the now familiar teachings: “You have heard that it was said to your ancestors, . . . . But I say to you, . . . .” (Matthew 5:21-22). Using this pedagogical technique, Jesus teaches that God’s ways are different than the ways of the world.

It probably came as a surprise to many of Jesus’ audience that the familiar, divine command, “You shall not kill,” would now include such socially normal and common behaviors as anger toward a brother or sister, or calling another person a fool or empty-headed—which is the translation of the word, Raqa. Jesus puts his listeners and us on notice: what was once normal is no longer acceptable. Further, Jesus attaches the same levels of liability to the seemingly lesser sins of anger and name-calling that he does to the obviously greater sin of killing. Each transgression leaves the offender liable to judgment and the fires of Gehenna.

But Jesus also presents us with an opening. “Therefore,” he says, “if you bring your gift to the altar, and there recall that your brother or sister has anything against you, leave your

gift at the altar, go first and be reconciled, and then come and offer your gift” (Matthew 5:2324). The integrity of our offering and worship is directly related to the integrity of our relationship with others.

How does Jesus’ message relate to us today? There seems to be

a pervasive and steady decline in civility, decency, and charity occurring across our society and around the world. A few years ago, for example, a college student in England was asked by an unemployed, homeless man on the street if he could please spare some change. The student removed a 20-pound

sterling banknote from his pocket and gave it to the man. The homeless man was filled with gratitude. But then the student took it back, lit it on fire with his cigarette lighter, and said: “How’s that for change? I changed it into flames.” That student did not kill anybody, nor for that matter, do anything illegal. But his action was an assault on human dignity.

You have heard that it was said, . . . . But I say to you, . . . .

Hatred paralyzes life; love releases it.

Hatred confuses life; love harmonizes it.

Hatred darkens life; love illuminates it.

Martin Luther King Jr. Strength to Love

as kids, or because their parents did not have a summer home on the lake. We get that way because anger, fear, resentment, or indifference have taken root in our hearts.

If Jesus were teaching us today, I can imagine him saying to us: You have heard the American laws and constitution. Everyone is guaranteed the right to free speech. But I say to you: Do not misuse free speech by neglecting the attendant demands of charity and responsibility. Do not shout racial, ethnic, or sexist slurs and epithets at others, or you will be liable to judgment. Do not intimidate or frighten others by the graffiti you write on the walls of synagogues or mosques, by the slogans you chant on buses, or by the flags you wave in ethnic neighborhoods, or you will be liable to judgment. Do not demean others by the memes, comments, and cartoons you post on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, or you will be liable to judgment.

The author and theologian Father Henri Nouwen once said that nobody is shot with a bullet who is not first shot with a

word; and nobody is shot with a word who is not first shot with a thought. The deliberate taking of another person’s life is wrong, of course; and we would never do so. We would never shoot someone with a bullet. But do we take the same moral high ground when it comes to what we say and do? We Americans like to claim that we are a Christian country, and we like to claim that we are Christian in our welcome and outreach to others. Is that true? Or do our words, actions, and attitudes tell another story?

You have heard that it was said, . . . . But I say to you, . . . .

Nobody is shot with a word who is not first shot with a thought. Father Nouwen’s observation invites us to reflect on the inner thoughts and attitudes from which spring our words and actions. Those who say or write something that is hurtful and hateful do not get that way because they drank Grade B milk

The ancient monastics taught the importance of nepsis—the constant examination of our thoughts—because thoughts become attitudes, and attitudes become words and actions. Thoughts matter. To paraphrase Saint Paul: If we are thinking like God, we will never again crucify the Lord of glory in the person of a brother or sister (1 Corinthians 2:7-8). If we want to change the world, change the tenor of our political discourse, and return civility and charity to our public life, we must begin by asking the right question. And the right question is not: When are you (or they) going to change? The right question is: When am I going to change—first my thoughts, then my words, then my ways of acting?

Civil laws provide some guidance, and so do the laws of the Church. Laws and the rule of law are important; they never go far enough, however. The law of love compels us to go further and demands more!

You have heard that it was said, . . . . But I say to you, . . . .

Father John Meoska, O.S.B., is a woodworker and a faculty resident at Saint John’s University.

29 The Law of Love Winter 2022-23 28 Abbey Banner

Alan Reed, O.S.B.

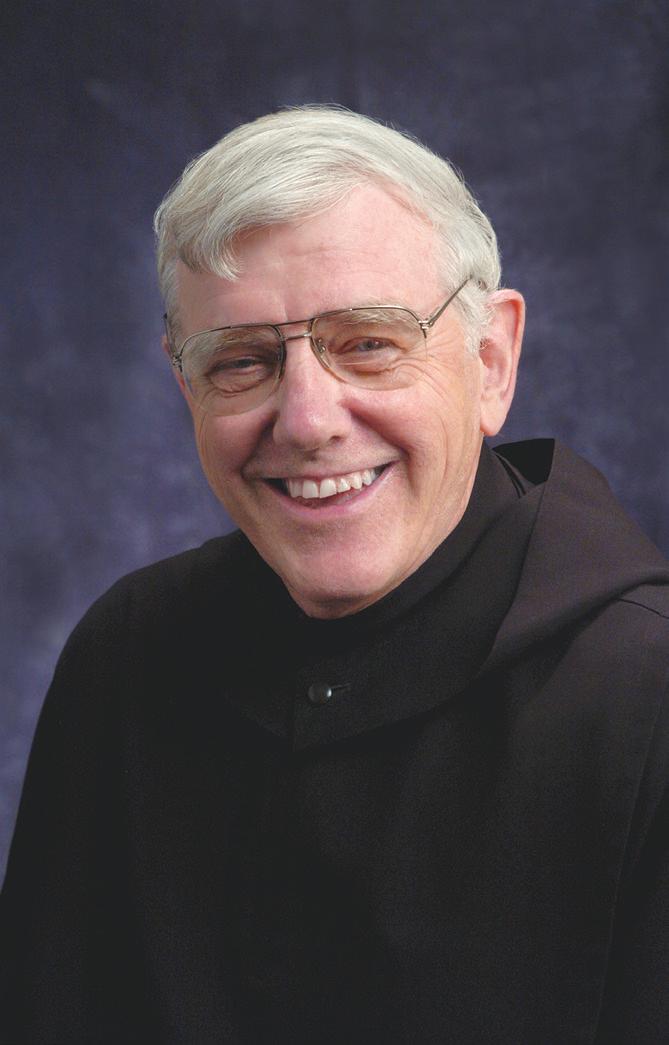

The first of two children of Alvin and Marian (Diegel) Ness, Father Bernardine (Alvin John) Ness, O.S.B., was born on 16 February 1938 in Minneapolis. He grew up in Wayzata, Minnesota, before enrolling at Saint John’s Preparatory School. He developed his lifelong interest in radio at the prep school, where he was president of the radio club and earned his ham radio license under the tutelage of our confrere Father Fintan Bromenschenkel before graduating in 1956.

Bernardine entered the novitiate at Blue Cloud Abbey in Marvin, South Dakota, in 1958, professed his first vows as a Benedictine monk on 15 August 1959, and was ordained in 1964.

In 1967, while working at Saint Michael Indian Mission in North Dakota, Father Bernardine put his creative, hands-on skills to good use, helping to construct a TV translator and 300-foot tower so that Indigenous peoples could have television. Four years later, “having learned,” he said, “to listen and let others help do what needs to be done,” he traveled to Guatemala to begin ministry at Blue Cloud’s foundation, Resurrection Priory in Cobán, Alta Verapaz. He did not know Spanish nor the native Q’eqchi’ language. Nonetheless he proceeded to build a shortwave radio station that broadcast news, music, and the Sunday celebration of the Word in their native language to dozens of villages that had no Sunday Eucharist.

Radio was not Bernardine’s only work. He helped establish a human development program at Resurrection Priory, from which a diocesan evangelization project was launched. A threeday initiation enabled people to celebrate the liturgy of the Word in their communities. He also visited patients in a local hospital dressed as a clown, bringing a smile and comfort to the sick.

In all, Father Bernardine would spend forty years in Guatemala, many of them lived in fear of summary execution by military forces who were hostile to the Church and its ministers. In 1991 he returned home after twenty years, and

for the next two years worked in the American Indian Culture Research Center at Blue Cloud Abbey. Upon his return to Guatemala, he resumed his efforts at evangelization with an even stronger focus on community building, adapting a video on the life of Christ for people who had never seen television. His essential service was to share his own charism— wisdom, good humor, and appreciation of other people’s talents and needs—the fruit of a lifetime of care and concern for others.

These same gifts were to make Bernardine warmly welcome at Saint John’s Abbey in 2013 when he joined our community following the closure of Blue Cloud Abbey. He continued his service to local Latinx communities and assisted in the development of the Messenger Program that sent humanitarian aid as well as dozens of computers, refurbished by Bernardine, to the missions of Guatemala. A gentle giant, a humble learner, a monk missionary, he just kept going, learning, trying things, raising money, developing projects, and evangelizing.

After years of struggling with Parkinson’s disease, Father Bernardine died on 26 August 2022. Following the Mass of Christian Burial, he was laid to rest in the abbey cemetery.

Father Rene McGraw, O.S.B., was born in Litchfield, Minnesota, on 19 June 1935, the second oldest of five children of Joseph and Lucile (Ryan) McGraw, and baptized Thomas William. He received his elementary schooling in Litchfield and Little Falls, Minnesota. He was influenced by Benedictines throughout his formative years: from the sisters of Saint Benedict’s Monastery (elementary school) and his future confreres (Saint John’s Preparatory School and Saint John’s University). He made his first monastic profession on 11 July 1956 and was ordained to the priesthood in 1962. Father Rene continued his education, earning a master’s degree in philosophy at Duquesne University, 1966, and a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Paris-Nanterre, 1972.

For more than fifty years, Rene was a revered teacher and faculty resident at the university. He punctuated his academic career with sabbaticals at the New School for Social Research in New York City, at the Program for Non-Violent Sanctions at Harvard University, and at Oxford University. It was during these leaves that he cultivated his unique philosophical approach to and justification for peace studies—a program he assisted in creating for the undergraduate colleges in 1987. Among students, he had the reputation for being excellent and demanding, earning two teaching awards, in 1986 and 2007. His contributions to the monastic community were equally noteworthy. He served as formation director, 1987–1993, was a confessor or spiritual director for many, and a ready volunteer for any community service or task.

Rene lived simply and frugally. He liked chocolate, swimming,

the Minnesota Twins, and Emily Dickinson. For him, the heavenly banquet need have only one item on the menu: potatoes (pronounced botatoes), drowning in butter. He was a man of integrity with a strong moral compass. He excelled at Irish Catholic guilt. His homilies were typically dark: every silver lining was surrounded by a cloud.

Like the prophets of the Old Testament, he annoyed his listeners as he vigorously promoted social justice, peace, and concern for the poor. He chose protest and civil disobedience over violence and war. He gave up bacon and pursued a vegetarian diet to support sustainability.

After a serious fall in June 2021, Father Rene spent the rest of his days in Saint Raphael Hall, the abbey healthcare and retirement center, where he died on 20 November 2022. Following the Mass of Christian Burial, he was laid to rest in the abbey cemetery.

With little money in the family treasury, we manufactured most of our entertainment at home. It kept us together and under the influence of our parents.

Family prayer was a part of our daily schedule, and the family rosary is among my earliest recollections.

My contacts with my teachers and prefects [at the prep school] exerted an incalculable force driving me to the Benedictines.

Rene McGraw, O.S.B.

An advisor, mentor, and spiritual director to generations of students, colleagues, and confreres, Rene leaves behind a long line of friends and admirers. As his health declined, he was cheered by the steady stream of visitors who acknowledged how much they appreciated his insights and wisdom, his care and attention, his willingness to listen. He inspired learning. He inspired lives.

31

Bernardine Ness Rene McGraw

Abbey Banner 31 Winter 2022-23 30

Abbey

Abbey

archives

archives

The daily routine within the cloister is enlivened by the antics of the “characters” of the community. Here are stories from the Monastic Mischief file.

Fraternal Support

Brother, you’re the most enjoyable difficult person I know.

Father or Brother

Before he became a Benedictine monk, Brother Kevin had been married. He and his late wife were very proud of the couple’s only daughter who had joined a religious community. At the monastery, whenever visitors encountered Brother Kevin and inquired whether he was a father or a brother, he had a ready response: I am a brother who is a father who has a daughter who is a sister.

Home Cooking

[Mother’s] cooking experiences were punctuated with billows of smoke and occasional small explosions. In our house, as a rule of thumb, you knew it was time to eat when the firemen departed. Strangely, all this suited my father, who had what might charitably be called rudimentary tastes in food. His palate really only responded to three flavors—salt, ketchup, and burnt.

Bill Bryson, I’m a Stranger Here Myself

How Cold Was It?

It was so cold yesterday that the fundraising staff had their hands in their own pockets!

LOST

Volume III of the History of Vatican II, Editors: Giuseppe Alberigo and Joseph Komonchak.

It belongs to Father Godfrey, who wrote on the inside cover that I was to receive the book after his death. Since Godfrey did not show any signs of going

to glory soon (or wherever Godfrey will go when he goes) I asked him if I could read the book. I promptly lost it. Kilian, osb

The Three Stages of Life Young Middle age “My, you’re looking well.”

Minnesota, Hail to Thee

I came. I thawed. I transferred . . . .

If you love Minnesota, raise your right ski.

Minnesota: where visitors turn blue with envy.

Save a Minnesotan—eat a mosquito.

One day it’s warm. The rest of the year it’s cold.

Minnesota: home of blonde hair and blue ears.

Minnesota: come fall in love with a loon.

Land of many cultures—mostly throat. Where the elite meet the sleet.

Land of two seasons: winter is coming, and winter is here.

Minnesota: glove it or leave it.

Minnesota: have you jump-started your kid today?

There are only three things you can grow in Minnesota: colder, older, fatter.

Many are cold, few are frozen.

Land of 10,000 Petersons.

Land of the ski and home of the crazed.

Christmas Pageant

Little Jimmy had been cast to play the innkeeper for the parish school’s Christmas pageant. During the last rehearsal, Jimmy was in tears, unable to bring himself to turn away Mary and Joseph. Jimmy’s mother rescued the show, talking him through the matter and offering words of consolation. She agreed that if Jimmy had been the innkeeper in Bethlehem, there might have been a different ending. “Everyone knows you would have found space for Mary and Joseph. But that’s the way the story is written, honey, so it’s o.k. for you to tell Mary and Joseph they can’t stay here.”

On Christmas Eve, when Joseph knocked on the door, Jimmy replied, without hesitation: “I’m sorry. There’s no room at the inn. But would you like to come in for a beer?”

Labor Day in Collegeville was cool, but not cool enough to stop the monks from enjoying their annual cookout in the monastic gardens. Summery temperatures and high dew points returned the next day and kept reappearing throughout September. A light snow covered the landscape on 14 October, and a mixture of rain and snow fell throughout the afternoon. Three days later, a morning temp of 24 ended the growing season. The Halloween trick or treaters were blessed with comfortable temps in the 60s as were those who gathered in the abbey cemetery to remember the faithful departed on the feast of All Souls. Strong, blustery winds (with gusts up to 50 m.p.h. in Minnesota) and temps in the 30s on 6 November signaled that winter had arrived. Four inches of snow produced a winter wonderland in midNovember. A taste of January arrived on 19 November with brisk winds, temps in the teens, and subzero windchills. Lake Sagatagan froze over on the eve of Thanksgiving, 23 November.

Cold days, long nights, penance services, holiday baking, and Isaiah’s hope-filled verses are heralds of Christmas. O come, O come, Emmanuel!

August 2022

• Novice Hang Geum Augustine (Joseph) Oh, age 46, was clothed in the monastic habit and began his yearlong discernment of monastic life on 16 August.

A native of Seoul, South Korea, Novice Augustine completed a master of arts in liturgical music degree at Saint John’s School of Theology and Seminary.

• A gigantic Norway spruce (126 years old) that had dominated the monastic gardens throughout its mature life was cut down in midAugust, another victim of climate change. The iconic Norway spruce were introduced to Saint John’s by pioneer monks. According to The Nature of Saint John’s: “Fr. Adrian Schmidt, O.S.B. (1864–1940), descendent of foresters from the Black Forest (Schwartzwald) in Baden, Germany, wrote to his forester

father and brothers. They sent him conifer seeds by sailing ship, and Adrian established a nursery of thousands of seedlings by Stumpf Lake. He also gathered white pine seed, probably from the Sartell or Little Falls areas. Starting in 1896, Father Adrian and his confreres planted seedlings of red pine, Scots pine, and Norway spruce across ten acres, near today’s prep school”—and throughout the monastic gardens and abbey cemetery. The community is now planting more white pine, which seem to be more resistant to the stress brought on by global warming.

Winter 2022-23 Abbey Banner 32 33

Cloister Light

Abbey Chronicle

Alan Reed, O.S.B.

Novice Augustine Oh Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

Beginning in October and lasting for approximately six weeks, the east façade of the Great Hall underwent its first comprehensive tuckpointng project since the former abbey church was constructed, 1879–1882.

September 2022