L.A. NOIR shadOws in pAradise

The Limey (1999)

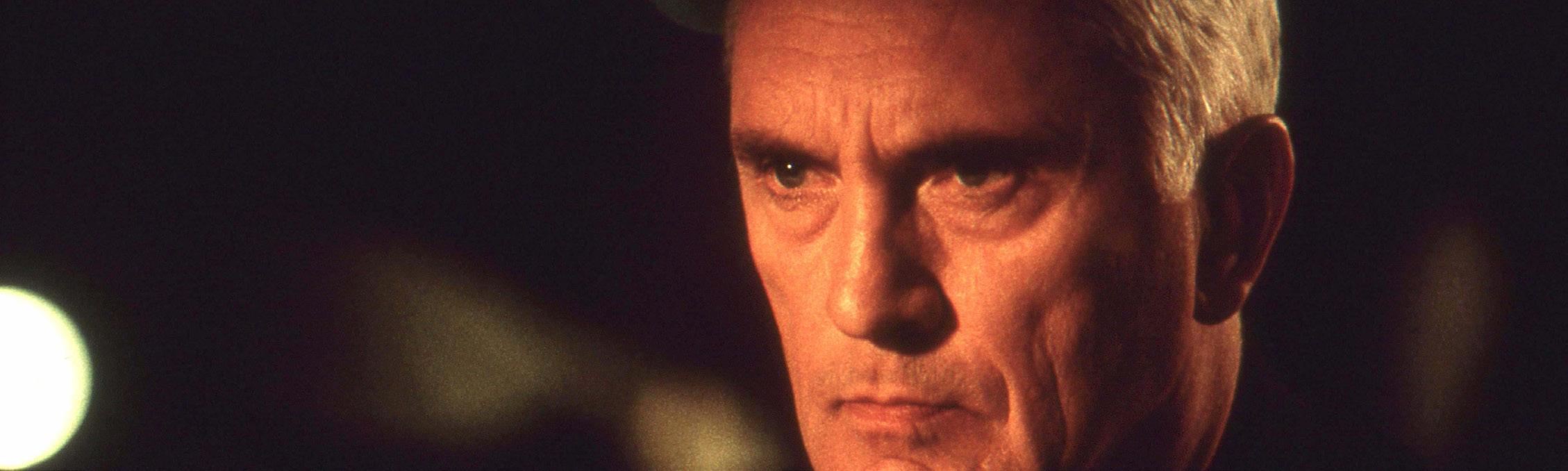

The late, great Terence Stamp (1938-2025) was part of the swinging 1960s London cultural scene. He and Michael Caine roomed together, and Stamp’s romance with It Girl actress Julie Christie inspired The Kink’s Ray Davies to write the immortal song “Waterloo Sunset.” Stamp recalled his first dinner date with Christie. “Her eyes were brilliant, almost turquoise and, although she glanced down at the tablecloth a lot of the time, whenever I caught her eyes on me they were defiant and glittered like a dragon’s. When she finally spoke her voice was low and husky. It wasn’t the easiest blind date I’d had. As we walked afterward I plucked up my courage and asked for her phone number. I didn’t have anything to write with. She said, ‘you won’t remember it.’ But I did.” Terence’s brother Chris managed The Who, so Pete Townshend’s song “The Seeker” perfectly opens The Limey. In 1967 Stamp starred in Ken Loach’s film Poor Cow, and flashes of that film provide backstory glimpses of Wilson’s life.

Terence Stamp:

When I told Steven, “Yes!! I’ll be in your film,” he sounded relieved. I said, “Was there ever any doubt I’d want to?” He replied, “Its not many leading men who relish being up there with their thirty years younger selves.” This was all over the phone. My only meeting with Steven before filming was in the garden of the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles. He told me that when you looked at most people, you could imagine cogs turning in their heads. What he wanted to feel from my character Wilson was the presence of a bigger cog behind the others, moving in increments, but powering their motion. Then he asked me what Wilson would wear. Both of these seeming flecks of direction created a reverberation in me. In fact, they were all the tips I needed.

Steven Soderbergh:

One of the things I like best about The Limey is how much of Peter Fonda (1940-2019) is in it. We’d be doing a scene, there’d be no marks for him to hit, I’d just let him go and have multiple cameras running. If he ended doing something off the cuff and great, I didn’t have to ask him to do it again. His spirit really comes across in the film. We were shooting him driving on the Pacific Coast Highway, and at the location I saw Peter and Terence greet each other for the first time since the 1960s. And the first thing out of Peter’s mouth was, “Do you remember where we were?” Terence replied, “The Taormina Film Festival in Sicily.” And Peter said, “That’s right; I wonder what happened to her.” Turns out they were both wooing the same woman, but she got away.

The film started out as a linear narrative, but we redrafted it as a memory piece, with contemplative interludes. The editor Sarah Flack and I had conversations about layering in those shots, how to establish certain story points. We were asking the audience to embrace a polyphonic structure, so balance was critical. It’s pretty aggressive in how non-linear it is, impressionistic, an internal experience.

Thanks to poet, film curator and teacher Tova Gannana for her film essay and her L.A. Cruising, Radio On pre-film playlist.

Screenplay

Cinematography by: Ed

Music by: Cliff Martinez

Edited by: Sarah Flack

THE PLAYERS: Terence Stamp as Wilson

Peter Fonda as Terry Valentine

Lesley Ann Warren as Elaine

Luis Guzman as Eduardo

Barry Newman as Avery

Joe Dellesandro as “Uncle John”

Nicky Katt as Stacy

Amelia Heine as Adhara

Melissa George as Jenny Wilson

Michaela Gallo as Young Jenny Wilson

William Lucking as Warehouse Foreman

Steve Heinze as Valentine’s Bodyguard

Nancy Lenehan as Lady on Plane

TOVA GANNANA

In The Limey (1999), Wilson (Terence Stamp) travels light. He has come to LA for his daughter Jenny (Melissa George), not to visit— she’s dead—but to avenge her death. What weighs him down are his memories of being her father: In a happy memory, young Jenny is at the beach, a straw hat hanging off her shoulders, cord around her neck, smiling. She looks to Wilson for reassurance, offering him a rock. In a sad memory, Jenny looks at him from a doorway, the door half open. She knows what she’s seeing is something she’s seen before. She knows what will come after. She knows her father—a thief—will be caught and sent away.

The Limey plays with audio over a repetition of images; like a seance, the film conjures meaning through memories, the first line spoken over a black screen: “Tell me, tell me what happened to Jenny.” The way The Limey is told, Wilson is in flight for much of the film, 35,000 feet above sea level. Because the film flickers between moments, Wilson is in a constant state of arrival and departure. The sound of an airplane taking off and the sound of waves hitting the beach reverberate like markers on a highway, telling the miles gone and the miles left to go. Wilson is performing the last rites for his daughter.

When Jenny arrives in LA, she goes to the beach. “She was 21 when she came to me. Straight from leaving you,” Elaine (Lesley Ann Warren), Jenny’s best friend and voice coach tells Wilson, as they sit facing each other in a red vinyl booth. They banter sharply about Jenny, “Security like that can’t be bought. It must be more comforting than having a daughter to greet you,” Elaine tells him before walking away, though later she’ll let him come into her apartment, then walk with him by the water; Wilson grows on her. Through Wilson, Elaine is close to Jenny again.

Wilson is in LA not to explore or expand, or make love. He has come for one reason. He’s a seeker: He wants to know what happened. He knows it was bad, because that’s the kind of relationship he and Jenny had. In a suit and tie, Wilson smokes, knows how to read and work a room; his dimples—once a youthful mark—now mix with his wrinkles and charm. Jenny was a powerful being. She touched other people with her strength. She wasn’t afraid. The worst had happened to her in childhood: abandonment, loneliness, shame. For her stability didn’t mean money, but rather living an honest life.

While dead Jenny shows up in the film only as a memory and in a photograph, she’s the reason for the story: It’s her hand directing her father and her boyfriend Terry Valentine (Peter Fonda); like marionettes, she conducts their movements. When they come face to face—both draw blood—it’s Jenny who’s between them. “Tell me, tell me about Jenny,” Wilson demands breathlessly of Terry.

The Limey is filled with quiet, introspective moments, characters looking at one another, not needing to speak because their expressions do the telling. “He’s King Midas in Reverse” by the Hollies plays as a montage introduces us to Valentine: gazing in the mirror checking his teeth, sucking at a drink, smoking on a porch, laughing carefree in a car with the top down, all that California wind and sun making it look like he’s always making his money

good. Valentine has money, whereas Wilson never did. But Valentine hires muscle for his deals, whereas Wilson is his own barracuda.

“Who done it then? Snuffed her?” Wilson asks Eduardo at a picnic table in his backyard. “Look. There was an investigation, OK? The car was totalled. Jenny was... her neck was broken, they said... on impact. Those streets up them hills, man you got to be careful, you got to keep your eye on the ball. Two o’clock in the morning, it’s dark, your minds a little agitated, driving a little too fast, those curves don’t kid around. It could’ve happened to anybody. I didn’t know Jenny to be reckless, but you know,” Eduardo tells Wilson, his two fists on the table. “No. Not my girl. Self control she had. It was a point of pride,” Wilson replies. An invisible cord runs between Jenny and her father, all feeling and memory; she’s the fine sand forever on his fingertips.

“A couple of weeks before Jenny died, she asked me to drive her downtown. She said she wanted to talk to her boyfriend, Valentine. I think she was looking for him,” Eduardo tells Wilson. “Trying to catch him with another bird?” Wilson asks. First stop: Get a gun. Eduardo facilitates. Wilson isn’t a trans-Atlantic traveler, but rather a time traveler, stuck on lather, rinse, repeat.

In LA, Jenny wasn’t alone. She found people to become close with, a makeshift family. Eduardo she’s met in an acting class. He looked out for her like an older brother; Elaine, like a big sister; Terry, whom she loved and had high hopes for the two of them, which is why when he let her down, she got so mad. Valentine said that Jenny had never spoken of her father to him, so Wilson came to LA to speak up for Jenny. Wilson kills most of the men involved in Jenny’s murder coverup, but he doesn’t kill Valentine, who’s responsible for her death. Wilson leaves Valentine alone, crumpled and defeated on the beach. It’s now Valentine who will be awash with memories of Jenny.

The end of the film has a memory without Jenny; just a young Wilson and his wife. He sings to her sweetly, he’s smiling. It’s as if in leaving LA, he found in his memory bank an old new beginning.