REMEMBRANCE

REMEMBRANCE

November 2024-25

Volume 14

ISSN 2209-3826

The Shrine of Remembrance embraces the diversity of our community and acknowledge the Bunurong people of the Kulin Nation as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we honour Australian service and sacrifice. We pay our respects to Elders, past and present.

Remembrance is published by the Shrine of Remembrance

Editorial team

Sue Burgess, Sue Curwood, Ryan Johnston, Jessica Trigg and Laura Thomas

Art Director and Production Manager

Janine Dale and Christine Wallace, Paragon Art

Copy Editing

Paula Ruzek, Professional Word Services

Printing Gunn & Taylor

Special thanks Clare O’Connor

© All material appearing in Remembrance is copyright. Reproduction in whole or part, whether storied in an electronic retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, must be approved by the publisher. Contact programs@shrine.org.au for approval.

Every effort has been made to determine and contact holders of copyright for materials used in Remembrance.

The Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne welcomes advice concerning any omission.

KEY PARTNER

KEEP UP TO DATE WITH EVENTS, SERVICES AND EXHIBITIONS AT THE SHRINE SUBSCRIBE TO OUR E-NEWS AT SHRINE.ORG.AU

Stories of service and sacrifice may cause distress. If you or someone you know needs help, please make use of the following resources.

Open Arms: Free and confidential, 24/7 national counselling service for Australian veterans and their families, provided through the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA). Phone: 1800 011 046

Lifeline: Suicide and crisis support. Phone: 13 11 14

Kids Helpline: Australia’s only free (even from a mobile), confidential 24/7 online and phone counselling service for young people aged 5 to 25. Phone: 1800 551 800

Beyond Blue: Free, immediate, short-term counselling advice and referral via telephone, webchat or email 24/7. Phone: 1300 224 636

Suicide Call Back Service: 24-hour counselling service for suicide prevention and mental health. Available via telephone, online and by video for anyone affected by suicidal thoughts. Phone: 1300 659 467

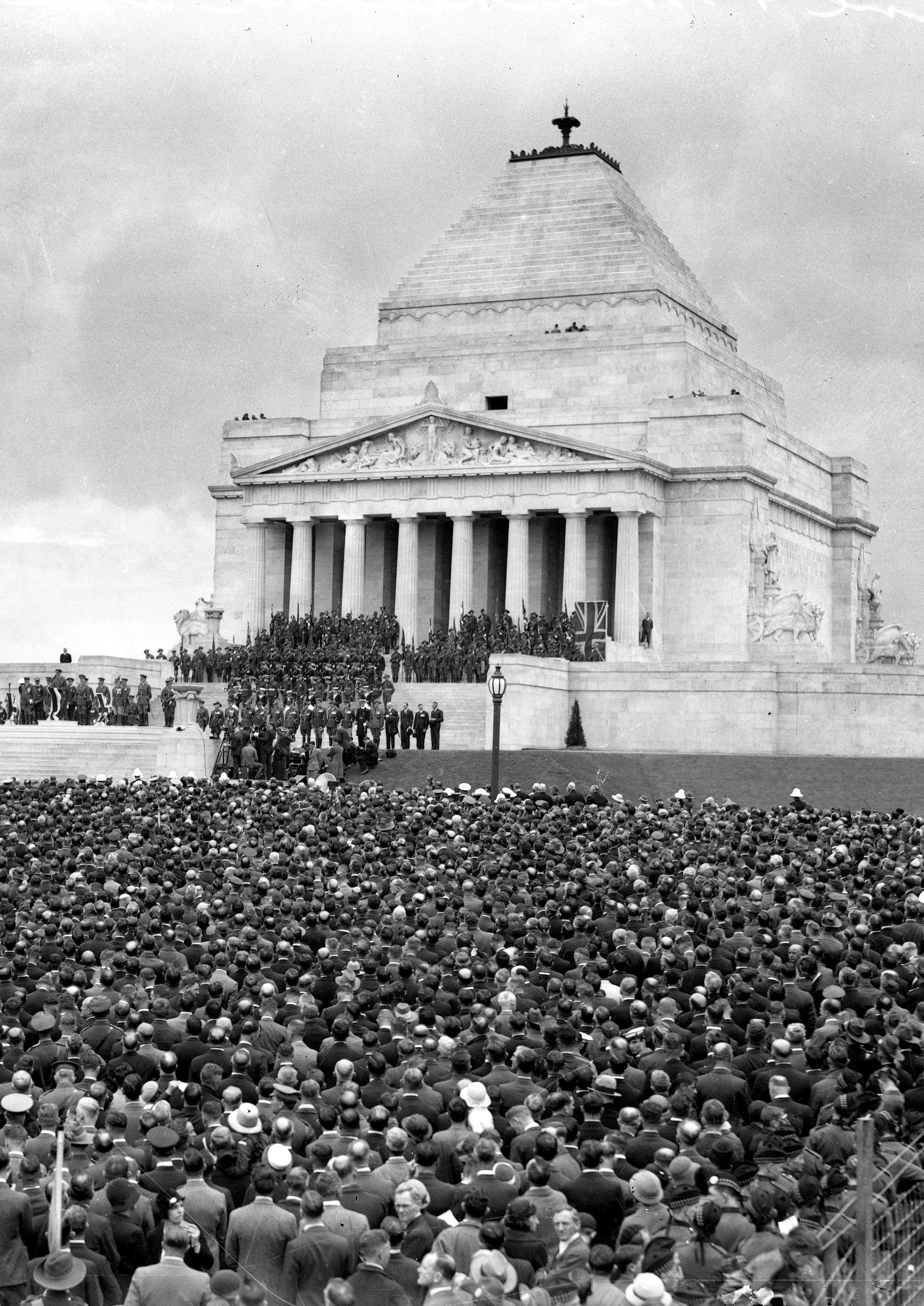

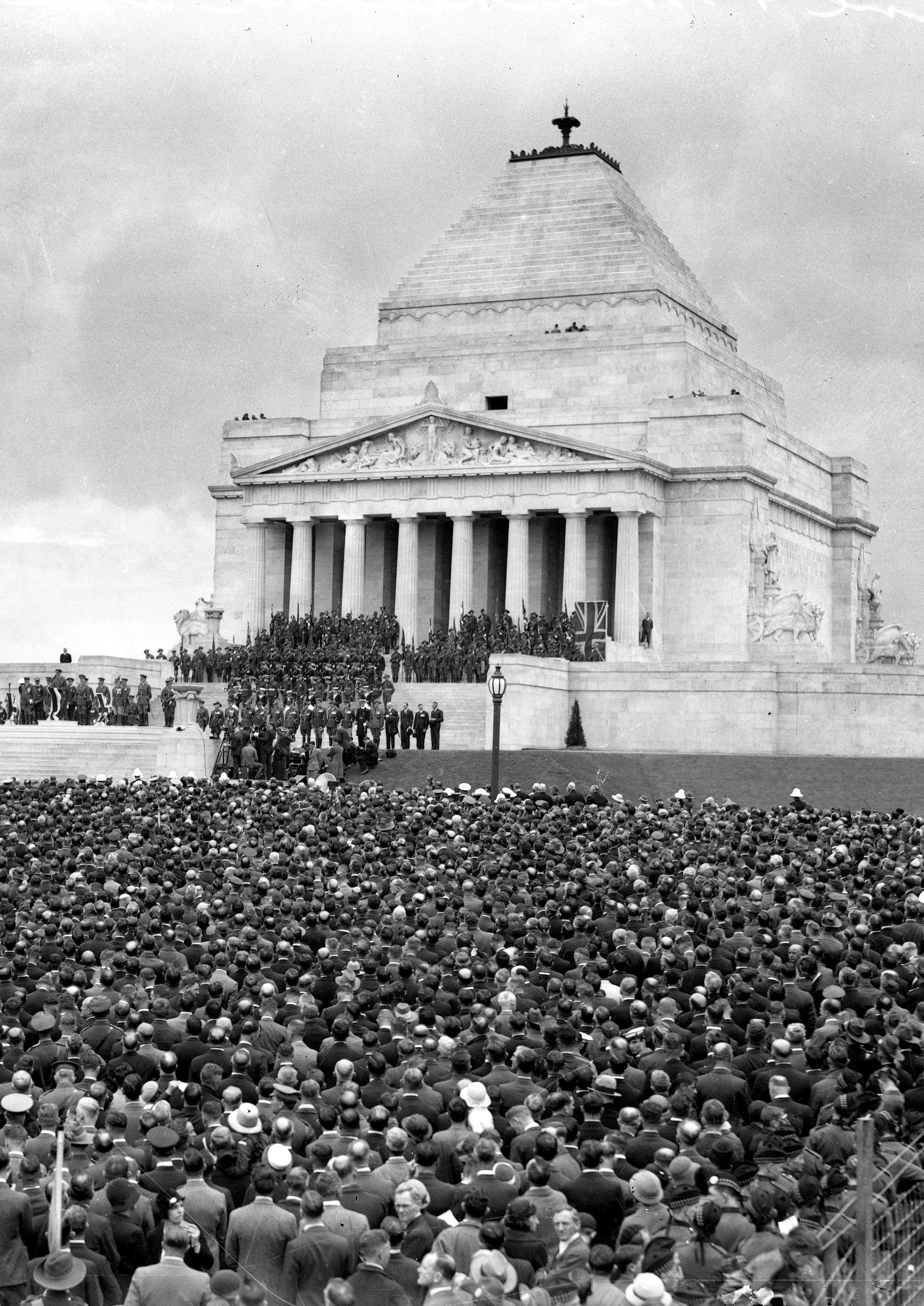

SUPPORTERS OF REMEMBRANCE MAGAZINE ON THE COVER: Dedication of the Shrine of Remembrance on 11 November, 1934

Reproduced courtesy City of Melbourne Libraries/McKenzie Collection

UNFORGETTABLE HOUR by Peter Luby

SHRINE OF REMEMBRANCE AT 90 by Dean Lee 04 14 20 22 26 30 34 40 42 44 46 50

DESIGNING REMEMBRANCE by Neil Sharkey

FROM THE COLLECTION by Toby Miller

BEYOND THE BLUEPRINT by Dr Katti Williams

CONVERGENCES by Garry Fabian

TALES OF THE SHRINE’S TREES by Mary Ward

GUARDING THE SHRINE by Katrina Nicolson

BECOMING A YOUNG AMBASSADOR by Benjamin Bezzina

FROM THE COLLECTION by Tessa Occhino

KIPLING’S ODE TO THE SHRINE by Carolyn Argent

REMEMBER FOR THE FUTURE by Bai Yang Pogos-Hill

Reflections in our 90th Year

DEAN LEE

Chief Executive Officer

Ifirst visited the Shrine in the mid1990s and remember being roundly reprimanded by a uniformed person for the ‘crime’ of sitting on the steps. My father was a Royal Australian Air Force officer and, while I understood our military history and why the Shrine was built, at the time I had little appreciation of what it represented in the hearts and minds of Victorians.

I returned to the Shrine on 14 May 2015. I had just interviewed for the role of Chief Executive Officer. I’d spent the prior 18 months deeply immersed in the commemorative community preparing for Centenary of Anzac events and leading development of the National Anzac Centre in Western Australia. I now understood well what war memorials embodied.

I approached the Shrine from the city, awed by its resolute presence.

Autumn rains washed the monument and Reserve; the chill air was warmed by the vibrant reds and golds of the turning leaves. I lingered many hours and reflected deeply— very deeply. I had successfully led larger and more complex organisations, but the responsibility of stewarding this place would be incomparable.

I joined the Shrine as CEO in July 2015. The task assigned to me by the Trustees was to leverage the $45m State and Federal investment in the Galleries of Remembrance— to attract new audiences and consolidate the Shrine’s operational, governance and financial capacity to advance and secure its future.

Through the combined efforts of so many dedicated people we have made great progress, sensitively threading a path that safeguards the Shrine’s traditional values while

contemporising them in ways that are relatable and engaging in a fastchanging world.

I have served as the Shrine’s CEO for nine years in its 90-year history. There is not a day I approach this place without remembering that day in May 2015. I feel the privilege and the responsibility we shoulder as custodians of our nation’s wartime grief, bound within these walls.

I draw satisfaction knowing that, today, we welcome people from all walks of life and guide their engagement with this remarkable place less through the application of rules and more through education and learning. Yet some restrictions endure: Rocky impersonations running up and down the monument steps are a no go!

CAPTAIN STEPHEN BOWATER OAM RAN

Chair of the Shrine of Remembrance Trustees

Ninety years ago, amid echoes of history and whispers of sacrifice, Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance emerged as a beacon of reverence and resilience. Today, as we mark this significant milestone, we honour the unwavering spirit of those who have served and sacrificed for our nation. Their courage and selflessness are etched into the very stones of this hallowed monument, a testament to the eternal gratitude of a nation forever indebted.

As custodians of this sacred space, the Shrine Trustees, Governors, staff and volunteers are united in our commitment to preserve stories, honour the fallen and educate future generations. May the Shrine continue to stand as a symbol of peace, unity and everlasting gratitude, embodying the values of service and sacrifice that define our national identity.

All Victorians bear the solemn responsibility of preserving the Shrine’s legacy, ensuring that the memories of the fallen are etched into the collective consciousness of our nation. The Shrine is not merely a structure of stone and marble; it is a living testament to the sacrifices made in the name of freedom, democracy and peace.

In commemorating the Shrine’s 90th anniversary, we acknowledge that the world has undergone profound transformations over the decades. Yet, amid the ever-changing backdrop of history, one constant remains—the Shrine’s steadfast commitment to honour, remember and pay tribute to the sacrifices of our servicemen and women.

It remains a timeless symbol of gratitude and unity and serves as a poignant reminder of the enduring values that transcend generations—

values of courage, sacrifice and selflessness that resonate as powerfully today as they did nine decades ago.

Today, the Shrine’s role as a custodian of memory and a beacon of reverence remains as vital as ever. As we look to the future with hope and determination, let us take comfort in the constancy of the Shrine’s mission—to ensure that the sacrifices of the past are never forgotten and that the stories of heroism and valour endure.

On this momentous occasion, we reflect on the past with solemnity, look to the future with hope, and reaffirm our pledge to ensure that the flame of remembrance burns brightly for all eternity.

Lest we forget.

NOBODY WHO WITNESSED THE DEDICATION AND NOBODY WHO LISTENED IN ON THE WIRELESS WILL FORGET ARMISTICE DAY, 1934…

UNFORGETTABLE HOUR

BY PETER LUBY

The Dedication of the Shrine of Remembrance in November 1934 was one of the most impressive and moving spectacles ever seen in Melbourne. It took place during a State Centenary and a Royal Visit, but eclipsed them both. News reports, letters and Shrine records build a picture of a cathartic, overwhelming experience—a ceremony of intense precision and solemn grandeur—as the city held its breath for an unforgettable two minutes’ silence.

Eleventh hour, eleventh day, eleventh month, 1932: the Sanctuary of the National War Memorial of Victoria. For the first time, members of the public watch in silence as a slanting beam of light strikes the ‘Rock of Remembrance’. This was not a formal ceremony: no words were spoken, no bugles sounded. But the presence of this small group of men and women in the Shrine spoke of the magnetic hold the monument already had on the public imagination.

The building was unfinished, despite four years of construction and a decade of planning. Hopes that the formal dedication would take place in 1932 had evaporated in the grimmest year of the Great Depression, a casualty of the slow drip-feed of funds. State Premier Sir Stanley Argyle now proposed that Victoria should invite a Royal Visitor to dedicate the Shrine during the forthcoming State Centenary.

For two more years Victorians kept visiting the Shrine, climbing to the Balcony, watching politicians, veterans and sportsmen lay wreaths in the Sanctuary. But in January 1934

parts of the building were still not ready: the Crypt; bronze cases in the Ambulatory; Pool of Reflection; floodlight pylons; and sculptural groups for the tympana. One month out from the Dedication hundreds of unemployed men on sustenance payments were still landscaping the lawns and approaches.

Anticipation grew as November loomed. Although the Centenary would run until July 1935, the Dedication was being billed as its ‘climax’. Brigadier General Stewart was appointed Marshal of the ceremony and worked with the Shrine Trustees, Melbourne City Council, the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League (RSSILA), Police and the St John Ambulance Brigade to prepare for the largest public event in the state’s history.

On 18 October, a small fleet of Empire warships escorted HMS Sussex through the heads of Port Phillip Bay, 50 RAF and RAAF planes flying a protective screen overhead.

A flotilla of steamers, launches and yachts collected around the heavy cruiser as it docked at Port Melbourne. At 1.35pm, His Royal

Highness Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, third eldest son of King George V of England, disembarked to a 21-gun salute. Thousands of loyal Melburnians cheered his carriage up Beaconsfield Parade and down the length of St Kilda Road. As he passed the Shrine of Remembrance “he gravely saluted”. On the steps of State Parliament, the Duke read a message from the King. Centenary celebrations had begun.

That evening, the Centenary Illuminations were switched on and the city lit up in a festive blaze. For months, sightseers would flock to central Melbourne at dusk to gaze on the “fairy land” of buildings and monuments flood-lit red, green and tangerine along the axis of Swanston and Collins streets.

That first night of the Royal Visit, the city also endured the dubious spectacle of a mock air raid – an aeroplane trailing magnesium flares onto the Manchester Unity skyscraper and T&G Building, which “exploded” with fireworks, smoke and searchlight beams. Beyond the brilliantly lit pylons of Princes Bridge, the Shrine gleamed white under

IMAGE LEFT Newsreel, press cameras and a sea of upturned faces focus on the Shrine moments before the Dedication.

Photographer Hugh Jones Bull, the Age Reproduced courtesy City of Melbourne Libraries (MCK062)

“A blaze of red and amber glory”: Flinders Street transformed by the Centenary Illuminations. Reproduced courtesy of State Library Victoria (H2017.205/226)

Town Hall and Manchester Unity Building glowed red, green and amber for Centenary Celebrations. City streets were lit up by 600 “Venetian poles”.

Photographer for above three Walter McRae Russell Reproduced courtesy State Library of Victoria (H92.388/144)

Rain and grim weather dogged Melbourne in the weeks before the Dedication. Photographer Hugh Jones Bull, the Age

Reproduced courtesy City of Melbourne Libraries (MCK099)

floodlight in the Domain, safe from air attack. Its moment in the spotlight was a month away.

The weeks leading up to the Dedication were fraught. October was unseasonably wet, drenching Centenary events and the Royal Melbourne Show, and rain was feared on Armistice Day. A plague of grasshoppers descended on crops in the Mallee—millions of insects on a “front” from Mildura to Swan Hill. Newspapers reported on disarmament in Europe and war manoeuvres in Japan.

One week out from Armistice Day, rain and gloomy skies continued to dog Melbourne. On Tuesday, a horse named Peter Pan ran on a very heavy track at Flemington to win the Melbourne Cup for the second time (the Duke of Gloucester presented the Cup). Attorney-General Robert Menzies banned a Czech anti-war activist from entering Australia to prevent him speaking at the AllAustralian Congress Against War. Egon Kisch—a communist—was kept “prisoner” on a ship off Station Pier

until after the Dedication. He had been a prisoner of the Nazi regime and had come to Melbourne to warn about the threat of Hitler.

Saturday 10 November was cloudy with occasional showers and the Melbourne daily newspapers made a last-minute appeal for 30 cars to transport wounded veterans and “cot-cases” from Caulfield Military Hospital to the Shrine tomorrow “so that none of the incapacitated returned men shall be disappointed”. The Duke’s schedule that day was exhausting. He watched the Duke of Gloucester Cup at Flemington, a Grand Military Gymkhana at the Showgrounds, then drove through a traffic jam of well-wishers to the RAAF Air Pageant at Laverton to present a Gold Cup to the winners of the Centenary Air Race.

On Saturday night, he entered the Melbourne Town Hall through lines of 600 cheering ex-servicemen to speak at a RSSILA dinner. Although he’d been too young to serve in the First World War, he was a soldier and to these men he represented

the monarch and cause they had served in that war. All stood in silence to remember departed comrades. The Duke anticipated the next day’s sentiments: It is most fitting that we should have paid our silent tribute to our comrades, but while Armistice Day brings back these solemn thoughts, it is also an occasion for rejoicing for the return of peace. The atmosphere was highly charged. The old Diggers sang Tipperary and There’s a Long, Long Trail, and the Duke joined in, enjoying “the fire of chaff and banter” as he moved between the tables.

Late that night, members of the Victorian Homing Association collected 75 wicker panniers from their metropolitan clubrooms and drove to the Shrine. In darkness they hauled baskets full of 10,000 fluttering pigeons up two flights of stairs to the Upper Balcony, ready for tomorrow’s ceremony. When rain fell in the early hours the pigeon fanciers threw tarpaulins over the panniers to protect their birds.

The Duke of Gloucester and State Governor Lord Huntingfield (centre, front) pictured at Government House a few days before the Dedication ceremony.

Photographer Spencer Shier

Reproduced courtesy State Library of Victoria (H81.281/16)

BUT FROM OUT THE ETHER COMING

I COULD HEAR A VAST CROWD’S HUMMING

HEAR THE SINGING, THEN –THE SILENCE. AND I KNEW THE HOUR HAD COME…

– C.J. Dennis

The sky at dawn was sullen and grim, but when Police contingents arrived at the Shrine at 5am to take up position people were already gathering. The St John Ambulance Brigade had stations and tents set up by 8am. Detachments came from Geelong to bolster total officers and nurses up to 354. The public were advised to be in the city by 9am to allow time to get through the crowds and take up vantage points, but by 8.30am thousands had already found spots on the grassy slopes.

Predictions that half a million would descend on the Shrine had prompted anxiety over transport arrangements. Victorian Railways came to the rescue with a schedule of special trains leaving the farthest edges of the state at 4am to bring country travellers to Melbourne. Return fares were capped at the price of a single fare. The Tramways Board had trams rolling out of depots at 6.30am to reach Flinders Street Station and the Shrine by 7.15am. Every inspector was on duty, extra crews were on standby, and conductors with extra bags of change were stationed on St Kilda Road.

To cope with demand, suburban electric trains were running every 10 minutes. Between 7am and 10am, trains rattled into Flinders Street Station at a rate of one every 53 seconds. Travellers poured through the ticket gates as the half-muffled bells of St Paul’s Cathedral rang out. The solemn chimes followed the “seething mass of people” moving towards the Shrine on foot, in crowded trams, by car. By 9am, the monument appeared to be a great magnet drawing “almost a whole city toward its base”.

The east slope of the southern lawn promised the best view of the Duke, but couldn’t be entered after 9.30am. Holders of colour-coded

tickets were advised to take their places early. Red, Blue and White areas (for the choir, musicians and Shrine guests) were to the west and centre. The Green area for disabled soldiers and “cot-cases” was nearest the steps with a view of the dais, Yellow (widows and bereaved mothers) and Brown (for fathers of the fallen) to the east. On the lawn further east, a field gun stood ready to fire.

A large area in front of the south steps was reserved for the returned men of the AIF. This great “mufti” army had orders to assemble in their divisions in the side streets around Melbourne Grammar by 8.30am. Navy, Air Force and Light Horse veterans, and Imperial troops from Canada, New Zealand and South Africa, formed up nearby. Bands played as columns of men moved off just after 9am in a carefully orchestrated pincer movement, swinging east off St Kilda Road or west along Domain Road then wheeling north toward the Shrine in strictly prescribed order, 120 men abreast.

“The Deathless Army” – 27,500 men led by their officers in dress uniform – moved up the slope in wave after wave, thousands of medals clinking, and swallowed up two acres of green at the base of the Shrine. Twenty Artillery trumpeters and 18 Army buglers marched from the western terrace to the tap of Naval Reserve drums, drawing up in lines on the steps and turning to face the crowd.

The public kept streaming up from the city, up and around the hill, until “the lawns were black with people”. Some climbed trees or threw simple rope swings over branches to get a slightly elevated view. Small boys pushed through the throng hawking unauthorised souvenirs and trays of ice-creams, to the disapproval of many. Cine-cameras from the newsreel companies and press photographers from across Australia stood high up on scaffold platforms, clustered near the dais, or captured the majestic scene from the Balcony.

From a microphone on the steps, Professor George S. Browne was broadcasting a live, descriptive commentary for radio station 3LO.

Shrine Trustees printed 20,000 pasteboard tickets for the colour-coded Reserved enclosures at the Dedication. The Red enclosure was filled by 5,000 choir members and 30 brass bands.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria (SH 990739)

Henry, Duke of Gloucester.

Photographer Raphael Tuck and Sons Ltd. (London) Reproduced courtesy State Library of Victoria (H26147)

The Shrine’s floodlight pylons were converted into giant speaker stands for some of the 32 loudspeakers that broadcast the ceremony to the crowd.

The Melbourne Herald, November 10, 1934

A “splitter panel” on the Balcony fed “distortion-free” sound through eight 20-watt amplifiers and underground cable to 32 Amalgamated Wireless loudspeakers banked on the floodlight pylons or grouped across the hill. Browne, an educator and decorated veteran, asked the crowd to refrain from cheering when the Duke arrived.

His words went out across the Commonwealth, into churches holding morning service, to the radios the RSSILA had set up at country town cenotaphs. In the lull before the Duke’s arrival, the commentary “filled in”, describing the scene at the Shrine for listeners and citing Will Longstaff’s painting Menin Gate at Midnight. In 1927, this famous image of a ghostly army gathering on a field around a great monument had struck a nerve with grieving postwar Australians.

The craze for Spiritualism that blossomed in the wake of the Great War was very much alive in Melbourne in 1934—dozens of churches still advertised seances or promised “overhead messages”

to those yearning for contact with the souls of the Fallen. On the morning of the Dedication, many gazing up at the sculptural group of the south tympanum (‘The Homecoming’) must have felt that perhaps the spirits of the war dead were gathering there, to be laid to rest—symbolically at least—on home soil and “sacred ground”.

10.25am

Thirty military and municipal brass bands began to play Handel’s stately Largo, setting the tone for the ceremony ahead. The smokehaze hanging over the hill from thousands of pipes and cigarettes slowly thinned and disappeared out of respect. The last notes of the Largo faded, the bands played the first line of Lead Kindly Light, and the massed choir of 5,000 led the crowd singing Cardinal Newman’s beautiful prayer for guidance and hope in darkness.

The night is dark, and I am far from home, Lead Thou me on…

“Always a favourite hymn with the soldiers, it was sung wonderfully well,

everyone endeavouring to put feeling into it,” one “Digger” wrote. Voices of widows and grieving parents blended softly with the swell from the great choir.

And with the morn, those angel faces smile, Which I have loved long since, and lost awhile!

The Age reported “there could have been nothing more appropriate”. Nearer My God to Thee followed and “again the multitude burst into song”. Voices “became like the roar of sea surf… volumes of sound rolled on until they broke against one another…”

10.45am

A troop of the 13th Light Horse cantered off St Kilda Road onto Domain Road ahead of the Royal Humber. The Duke stepped from the gleaming car wearing the khaki service uniform of his regiment, the 10th Royal Hussars. State Governor Lord Huntingfield greeted him and they joined the official cortège: Brigadier General Stewart, Chairman of the Shrine Trustees General Sir Harry Chauvel, Premier

Souvenir postcard of the Dedication viewed from the air. The Sun reported that the unpleasant noise of aeroplanes during the ceremony “were like blowflies in a church”.

Argyle, Melbourne’s Lord Mayor George Wales, Victorian President of the RSSILA, Brigadier-Generals, naval and air force Commanders, Sir Alexander Godley who led the New Zealanders at Gallipoli, and Miss Grace Wilson, Senior Matron of the Australian Army Nursing Service and Shrine Trustee.

There were 500 former Army nursing sisters dotted across the crowd in their red-and-white.

“Gangway please! There are some returned nurses with blind soldiers late – wanting to reach their front positions allotted to them, and what a track was made for them. The Prince did not have a more uninterrupted pathway to the Shrine than those nurses and blind men had, passing through hundreds of soldiers.” – A “Digger” from Ouyen

A member of the Father’s Association of Victoria from Shepparton was moved by the “cot-cases”:

“… brought thither in vans kindly furnished for the purpose by city business firms, unable to move, these sorely stricken soldiers were tenderly lifted into positions where they could see and hear something of what was going on. Looking at them, something approaching realisation of what an accursed thing war is came home to the mind, and made one ready to join with heart and soul in the prayer Give Peace in Our Time O Lord.”

The Duke progressed up towards the Shrine through ranks of silent veterans, his path flanked by the fixed bayonets of the Navy and Militia. Armed colour parties of 22 Victorian Infantry Battalions and Light Horse regiments paced behind. Women in the crowd took compact mirrors from their purses, turned, and held the mirrors up to catch a reverse glimpse of the Duke over the heads of the crowd. Several fixed these makeshift periscopes to the ribs of umbrellas and held those aloft to get an advantage.

Secretary of the Shrine Trustees

Jack Barnes and members of the Centenary Committee met the cortège at the south steps. The bands struck up the national anthem—God Save the King—and the Duke stood to attention, saluting. Brigadier General Stewart had timed to the minute how long it would now take for the cortège to proceed via the western terrace, ascend the steps on the north side, and walk through the Sanctuary doors at exactly two minutes before 11am.

Banks of blue-black cloud still blocked the sun. The colour parties spread out across the steps and faced the Shrine. The far-off muffled bells of St Paul’s had stopped. Trumpets sounded two long warning notes of ‘G’. Half a minute to 11.

In the amber glow of the ‘Inner Shrine’, the Duke looked down at the Rock of Remembrance. The official cortège stood behind, heads bowed. Beside the Duke was Captain

Cornetist Roy McFadyen (front row, third from right) pictured in the West Preston School Band. His bandmaster picked him to “echo” the Last Post from the Shrine’s Balcony. Reproduced courtesy of Ian McFadyen

William Dunstan VC, of Ballarat, representing the AIF. Dunstan was awarded the Victoria Cross for “exceptional courage” at Lone Pine. Today he held a wreath of poppies and bay laurel, the tribute of King George V, brought from England. Dunstan handed the wreath to the King’s son.

The Silence

The dark clouds finally shredded and sunshine broke from blue sky. Road traffic around the Shrine slowed, pulled over, stopped mid-street. Tram drivers pushed their control handles to ‘off’ and trams ground to a halt. Electrical current to the entire city tram network was now cut off.

East of the Shrine, the field gun boomed to signal the 11th hour. The echo of the shot drifted across bowed heads and “the great concourse fell into an awed silence, terrifying, profound, sacred”. The wind was at rest. Faintly, the clang of the South Melbourne Town Hall clock marked out 11. After that, only the sound of weeping, “the sibilance of the whispered prayer of a woman standing near,” and the distant drone of aeroplanes high above. For two minutes a city of almost one million was still.

Within the Shrine, a beam of sunlight was falling “like a glittering sword through the semi-obscurity of the upper spaces of the dome”. It “flooded the tablet and softly lit up the Sanctuary”. One account records the Duke was so entranced by the

light moving imperceptibly over the inscription ‘Greater Love Hath No Man’ that Jack Barnes had to prompt him: “Lay the wreath, Sir”. Jogged from reverie, the Duke lowered the wreath to rest on the memorial stone.

At the end of the two minutes there was a mighty, soft sigh from the crowd. Sunlight flashed on bugles rising up to sound “that silver evocation,” the Last Post. Shrill, clear, melancholy, “last bugle call of the soldier’s day, the requiem of the dead”.

High up on the “parapet” of the Shrine was fifteen-year-old cornetist Roy McFadyen, one of four boys recruited from suburban brass bands to “echo” the Last Post from the corners of the Balcony - pushing the sound out over the city and suburbs. He later recalled how his band master “insisted that on this special day I get it right”. As the notes drifted down from the northeast corner, “young as I was I could detect the sadness of the crowd…”

A pause, then the trumpets rang out Reveille, rousing and hopeful and fading again to silence. The south doors of the Sanctuary opened and the Duke emerged. Buglers and colour parties divided to let the cortège through to the dais.

11.06am

Bands played the Old Hundredth and the multitude took up the great hymn, led by the choir. Senior Chaplain A. P. Bladen read the

prayer: “Eternal Father, before whom stand the spirits of the living and the dead… bring us, in this day of remembrance and dedication of this Shrine, into fellowship with those Thy servants who laid down their lives in the time of war…”

11.13am

Sir Harry Chauvel stepped to the lectern to introduce Premier Argyle, who made a short speech of thanks for the Royal presence and then declaimed the words of the Ode written by Rudyard Kipling expressly for this moment. He then asked the Duke of Gloucester to dedicate the Shrine. The Duke moved to the microphone. His voice shook slightly, “for he shared the emotion that stirred the huge assemblage”.

“This noble Shrine, which I am invited to dedicate, has been erected as a token of our gratitude to those who fought for us… they fought to secure to the world the blessings of peace. It is for us to seek to repay their devotion by striving to preserve that peace, and by caring for those who have been left bereaved or afflicted by the war.

To the Glory of God and in grateful memory of the men and women of this State who served in the Great War, and especially of those who fell, I dedicate this Shrine.”

A roll of drums and a fanfare from the trumpets was cue for the Duke to press a button on the lectern, sending

The crowd listens as HRH Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, dedicates the Shrine. Note the women in the foreground using their mirrors as periscopes.

Photographer Hugh Jones Bull, the Age Reproduced courtesy City of Melbourne Libraries (MCK092)

an electric charge to the Union Jack draping the stone pier beneath the portico. The flag that had once hung on the Cenotaph in London jerked aside to reveal the Dedication stone.

Bands struck up Kipling’s Imperialist hymn Recessional and “the vast crowd sang with vigour”, the timeless phrase of remembrance, “Lest We Forget”. Sombre clouds framed the Shrine again. The bands played Chopin’s chilling Marche Funèbre, as if the mood of grief at large on the hill needed any further expression.

Dr Head, Anglican Archbishop of Melbourne, pronounced a Benediction and God Save the King was sung again. The Duke’s entourage promenaded around the eastern terrace to the north side where architect Philip Hudson presented the Prince with “a gold key” to unlock the great bronze door. Thus the Duke became the first person to enter the Shrine after the Dedication, and Hudson conducted him on an inspection of the interior.

Around this time, plainclothes policemen pushed through the crowd at the Pool of Reflection and arrested a man wearing a red antiwar ribbon. Harold Fletcher threw a handful of pamphlets to the ground, kicked them about, yelling “I protest! Down with the warmongers! Release Kisch!” Struggling to break free, he was bundled down to St Kilda Road and into a car, shouting “scurrilous statements”.

Fletcher was later jailed for 23 days for ‘delivering handbills in public places’. He told the court he was at the service out of respect for his comrades who gave their lives in the war. The magistrate said it was lucky he didn’t cause a riot. A local printer was prosecuted under the Shrine of Remembrance Site Act for using “a substantial likeness of the Shrine” (without approval) in the offending pamphlets, which asserted that returned soldiers “built their own monument for 12 shillings a week”.

11.43am

The reappearance of the Duke from the south doors triggered the release of the 10,000 pigeons quivering in panniers on the Upper Balcony. They rose “like a huge puff of smoke”, hovered as they got their bearings, then circled over the Shrine and wheeled away across Victoria to their lofts.

The sight of the pigeons, the meaning attributed to them, captivated the press: to some they were the outbreak of peace 16 years before; to others “the homeward movement that commenced on the day the Armistice was signed”. British Poet Laureate John Masefield watched them circle round the

Shrine against a black cloud lit by the sun. He thought them “the climax of beauty and inspiration of a deeply noble ceremony”.

The press built up the number of birds from 10,000 to 15,000 to 20,000 and the further the newspaper from Victoria, the more fanciful the reports. Perth’s Daily News had promised the spectacle of 20,000 Diggers “acting as one man” throwing 20,000 champion homing pigeons high in the air as the choir sang “a hymn of triumph”. Brisbane’s Sunday Mail claimed the Duke himself would “make an inspection of the Shrine and release 20,000 pigeons from the Upper Gallery”.

As the Duke of Gloucester moved off the eastern terrace to rejoin his car, the crowd broke out with a roar of cheering, especially from the wounded returned men. Cheers followed his car as it headed for Government House, with the Light Horse escort at the trot. The Dedication was over. It had lasted just a few minutes over one hour. Magically, the fog of cigarette and pipe-smoke returned to the Shrine and shrouded the heads of the crowd like a sigh of relief.

Wreaths were now laid in the Sanctuary by Empire dominions and foreign dignitaries. Canada laid a wreath of maple leaves, Scotland a cross of wildflowers and heather. At the special direction of the Japanese Government, Consul-General Mr Murai had come by train from Sydney. Sailors and marines from HMS Sussex carried in a giant wreath in the shape of an anchor. Masefield left a wreath on behalf of the Poets of England; visiting British golfers brought a cross of white flowers and lavender.

“With amazing order”, the crowd outside dispersed or began the march back to the city: “an army of men and women moving on a front hundreds of yards wide, to the conquest of Melbourne”. Thousands surged up into the Shrine, waited silently to inspect the King’s wreath resting on the Rock, or filed down stairwells into the Crypt. When evening floodlights came on, hundreds still lingered around the Pool of Reflection, not wanting to let the day go.

Brigadier Stewart estimated the crowd at the ceremony was 317,500, “probably the largest gathering that has ever assembled in Australia”.

The St John Ambulance Brigade treated 478 cases of fainting and collapse. Civil ambulances attended 70 cases of “emotional prostration” and took eight people to hospital. For many, the Dedication had been the long-delayed or denied ritual of mourning—the funeral service for a loved one, a laying to rest.

Private grief wasn’t resolved or ended by the formal Dedication, but with the building complete Victorians felt they now had a place where their emotions could find public expression and acceptance. A day after the Dedication, the Melbourne Herald published a poem by its resident bard C.J. Dennis. Come Ye Home captured in a dream-like vision the sentiments of that vast crowd before the Shrine on Armistice Day, 1934.

I could see the kneeling thousands by the Shrine’s approaches there. Then, above those heads lowbending,

Like an orison ascending, Saw a multitude’s great yearning rise into the quivering air… There, I saw from out high Heaven spread above the great Shrine’s dome,

From the wide skies overarching, I beheld battalions marchingMates of mine! My comrades, singing: Coming home! Coming home!

Peter Luby is an Education Officer at the Shrine of Remembrance.

AHS R ETHIS ARTIC L E

The “silver grey mass” of the flood-lit Shrine. Thousands lingered after the Dedication, not wanting to let the day go.

Photographer Walter McRae Russell Reproduced courtesy of State Library Victoria (H2017.205/213)

Field Artillery trumpeter Sergeant Holt led the Reveille in the Dedication ceremony. Sun News-Pictorial, November 12, 1934

A vision for Melbourne:

Hope and resilience after the First World War

The shared history between Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation and the Shrine of Remembrance shaped and changed the trajectory of Melbourne to help it become the beautiful and vibrant international city it is today.

In the early 1920s, Melbourne was recovering from the influenza pandemic and the First World War. As soldiers returned home over months and years, they brought with them many health problems and traumas of war. With the public’s charity diverted to the war effort and healthcare costs rising due to inflation and demand, Melbourne’s overcrowded, under-funded public hospitals were struggling.

In the years between 1918 to 1925, maintenance costs for hospitals increased by 50 per cent, and funding was never certain as government funding for hospitals was limited.

Melburnians were generous donors, but fundraising collections could be haphazard. In 1922, the city took a major step forward. The Lord Mayor of Melbourne, Sir John Swanson, assembled a committee of councillors, philanthropists, business owners and hospital staff to address hospital fundraising.

Sir John Swanson was a visionary businessman who could see the need for improved public access to

hospital care after the war, and the need to publicly honour returned service men and women. He established the Lord Mayor’s Fund for Metropolitan Hospitals and Charities in 1923, whilst also serving as Chairman of the National War Memorial Committee. This committee was responsible for selecting the design entry that would ultimately become the Shrine of Remembrance.

These two important projects provided Melbourne with the hope it needed to recover from the First World War. They provided the people of Melbourne a trusted place to make donations for hospitals and a special place to honour and commemorate Australians in service.

Community efforts after the First World War paved the way to also address the devastation of the influenza pandemic.

Today, Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation continues to support the health and wellbeing of Greater Melbourne through grant making and donor services, and the Shrine of Remembrance is one of Australia’s most important memorials, honouring the service and sacrifice of Australians in war and peacekeeping.

Learn more about Melbourne’s incredible history at shrine.org.au and Imcf.org.au

The Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation is a supporter of Remembrance magazine

Above: A view of Melbourne’s CBD from the Shrine of Remembrance. Image reproduced courtesy Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation Archives

Left: Melbourne’s Lord Mayor Sir John Swanson established the Lord Mayor’s Fund for Metropolitan Hospitals and Charities in 1923. Today, Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation continues to have a significant positive impact on the health and wellbeing of Greater Melbourne. Image reproduced courtesy Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation Archives

Right: The Lord Mayor’s Fund for Metropolitan Hospitals and Charities received special permission from the State Government to continue fundraising for Melbourne’s hospitals and charities during the Second World War. Image reproduced courtesy Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation Archives

Designing

REMEMBRANCE

BY NEIL SHARKEY

The Shrine of Remembrance’s special exhibition, Designing Remembrance: Alternative Visions for Victoria’s War Memorial, tells the story of the fateful 1920s architecture design competition that determined the form of the National War Memorial for Victoria. Designing Remembrance reveals the competing visions for the state’s war memorial, in particular the six shortlisted designs, and for the first time in a century presents alternatives to the Shrine of Remembrance—the competition’s winner.

It was on 4 August 1921, at a public meeting at the Melbourne Town Hall, that the Minister for Public Works, Frank Clarke, first moved a motion for a national war memorial for Victoria. Clarke proposed a nonutilitarian monument that would commemorate ‘the services of those who enlisted and fought in the Great War’. An architectural competition would determine the memorial’s form.

The conditions, devised in consultation with the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects, were circulated just under a year later in July 1922, together with a survey map of the preferred site—an elevated section of Crown Land at the corner of Domain and St Kilda roads known as ‘The Grange’. The site had been associated with the earliest phase of

European settlement and was, as it remains, important to the peoples of the Kulin nation.

The competition was open to ‘Australasians and British Subjects resident in Australia’ and the Lord Mayor’s office had received 83 preliminary designs by the competition’s closing date on 30 June 1923.

General Sir John Monash, wartime commander of the Australian Corps, was appointed competition judge together with George Godsell and Kingsley Henderson—presidents of the Federal Council of the Australian Institute of Architects and Royal Victorian Institute of Architects, respectively. These men selected a shortlist of six designs in July 1923.

Revealing the winners

Only Sir John Swanson, the Executive Committee’s Chairman, knew the identities of the architects of the six shortlisted entries when the competition judges passed final judgement on 9 December 1923. The winner, Philip Hudson and James Wardrop’s ‘A Shrine of Remembrance’, was publicly announced four days later.

More than a month passed before ordinary Victorians got to see the competition entries for themselves at an exhibition held at the Melbourne Town Hall between January and February 1924. A large plaster model and 15 drawings of ‘A Shrine’ were the highpoint among the ‘piles of costly plans and drawings’ arrayed around the hall.

The Shrine’s Doric porticoes echoed those of the Parthenon, while its stepped pyramidal roof referenced then-contemporary artistic reconstructions of the long-destroyed Mausoleum at Halicarnassus—one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. By employing the famous tomb as their starting inspiration, Hudson and Wardrop were acknowledging the Shrine’s solemn, funereal purpose.

Shrine pilgrims would arrive at a column-lined inner sanctum, enriched with carefully placed sculptures and friezes. A ‘quiet soft light’ would stream through a glassed opening in the steeply tapering ceiling, illuminating a ‘Rock of Remembrance’. This stone, sunk beneath floor level, forced pilgrims to look down—as if into an open grave—to contemplate the absent war dead.

General Sir John Monash enthused that one could walk into and through the Shrine, which would facilitate marches, pilgrimages and commemorative events. The Shrine provided ‘a soul … an interior (as well as an exterior) where an atmosphere of solemnity and reverence would be established’.

An original set of reproductions of the Hudson and Wardrop winning design and an actual 1923 watercolour by Philip Hudson, depicting the original concept for the Shrine of Remembrance’s Sanctuary, occupy pride of place in the new exhibition, just as they did in the Melbourne Town Hall exhibition a century ago.

Unfortunately, few visual records of the other 83 entries submitted to the design competition are so well represented by original material, not even the most important—the other five shortlisted designs.

All unplaced submissions were returned to their creators soon after the selection of the shortlist. No final list of names—not of the architects or their designs—was ever kept. The drawings and models for all six shortlisted entries became the property of the selection committee. The winning plans went into a Melbourne City Council strong room. The other five designs are recorded in a Shrine Committee minutes book

as being placed in a storeroom off the Town Hall. This storeroom was destroyed by fire in 1925.

Designing Remembrance may not have been possible at all if images of all six shortlisted entries had not been published in a 1924 Art in Australia journal article titled ‘The designs for the Victorian War Memorial’, by Australian artist Blamire Young. Copies of each of the shortlisted architects’ ‘statements of intent’, meanwhile, have survived in the private papers of General Sir John Monash.

Young’s article remains our only visual record for most of the designs featured in the exhibition. The team behind Designing Remembrance hope that the new exhibition will help uncover other competition entries, plans and images that may lay hidden in forgotten archives and family collections.

The roads not taken

Designing Remembrance features several interesting unplaced competition designs that showcase important early 20th architectural movements. The American ‘Prairie School’ designers of Canberra, Walter Burley Griffin and his wife Marion Mahony, entered the competition with a young Australian protégé Eric Nicholls. The trio envisioned a glittering modernist edifice comprised of rows and columns of five-foot modules that could be ‘increased or decreased at will by adding to, or subtracting from, the five feet’. Arts and Crafts champion Louis Williams, meanwhile, created a grand medieval tower of flying buttresses and Gothic arches.

However, all of the entries that were eventually shortlisted, including the Shrine of Remembrance, employed Classicism in formal or abstracted form. Consciously derived from the architecture of ancient Greece, Classicism stresses symmetry and proportion. It dominated Western architecture, particularly monumental architecture, from the Renaissance to the Second World War and the style appears to have resonated strongly with the competition judges.

Bust of Phillip Hudson – one of two architects of the winning design by Paul Montford (1868 - 1938).

Reproduced courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria

Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin 27 July 1930.

Castlecrag, New South Wales. Photographer Jorma Pohjanpalo (1905–91)

Reproduced courtesy of the National Archives

The competition runner-up, William Lucas, an Imperial patriot, employed an abstracted classical style common throughout the British Empire in his design, ‘Place of Remembrance’. The vast open-air Greco-Roman-style theatre sought to accommodate rituals of mourning and cultural rejuvenation.

The circular plaza faced what is now the intersection of Domain and St Kilda roads and its northern edge terminated in large sculptural groups and broad stone steps. Behind these, and oriented towards the city, a large stone monolith pierced by an archway. A stone ‘Seat of Remembrance’ beneath served as a semi-private place for the contemplation of the ‘Tomb of an Unknown Warrior’, lying at the plaza’s centre.

The third-place winner, Donald Turner, was, at the time of the competition, serving with the Graves Detachment at Gallipoli. His ‘Pylon’ incorporated a tapering vertical form, anchored to the ground by gently curved colonnades. Its sweeping curvature echoed the contour of St Kilda Road to the west and directed the pilgrim’s path. Turner’s design brought Gallipoli’s cemeteries home to Melbourne,

evoking the state’s war dead ‘lying in foreign fields’.

Roy Lippincott and Edward Billson’s fourth-placed ‘Sanctuary of Peace’ comprised a towering campanile with a forward-projecting colonnade. Its forms were informed by Classical Greece, the Prairie School, but also Australia’s unique botany—indeed it was the only shortlisted design to explicitly reference the nation to whose dead it was dedicated.

‘Sanctuary of Peace’ is the only shortlisted design, other than the Shrine of Remembrance, for which Designing Remembrance’s curators have uncovered original visual records. There is a photographic reproduction of a competition drawing and a pencil tracing, donated to the State Library by the Billson family, which likely dates to the drafting phase.

The partnership of Arthur Stephenson and Percy Meldrum submitted the two entries ranked fifth and sixth—‘Cenotaph’ and ‘Victory Arch’ respectively. A collaborator on the latter design, Harold DesbroweAnnear, appears to have been the main creative force of that design.

Among Designing Remembrance’s outstanding exhibits is William Beckwith McInnes’s dark, tonal portrait of Harold DesbroweAnnear—the first-ever winner of the Archibald Prize in 1921.

Fifth-placed ‘Cenotaph’ comprised a shrine surrounded by colonnade on three sides, which Stephenson and Meldrum described as holding out ‘welcoming, all-embracing arms to pilgrims to the holy of holies’. The ‘arms’ cupped a central mass rising 175 feet above sea level. This ‘sublimated burial mound’ containing an inner chamber housing a ‘Stone of Remembrance’—the ultimate focal point of pilgrimage.

‘Victory Arch’ was, as its name suggests, a memorial in keeping with the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. Placed at the intersection point of The Grange site, the arch would not have permitted cars but been accessible to a steady stream of pedestrians. These pilgrims would have approached from multiple directions and moved unimpeded through and around the landmark’s pathways. Symbolically, it implied a second procession—an army of the dead—marching victorious through the arch’s massive portals.

Second place – ‘A Place of Remembrance’ 1923 by William Lucas. Reproduced from: William Blamire Young, ‘The designs for the Victorian War Memorial’, Art in Australia: A Quarterly Magazine (Series III, Number 7, 1924)

A difference of opinion

The Shrine was, by all accounts, a popular winner of the competition, certainly among visitors to the 1924 exhibition—but not universally beloved. The month-long information vacuum between the announcement of the winner and the Town Hall exhibition had upset many influential stakeholders.

The war memorial committee judges had always intended to release authorised photographs of the winning design to newspapers at the launch of the exhibition—so that ‘the public…might be able to estimate correctly the great beauty and artistry of the winning entry’. The Age broke the photograph embargo, however, putting chief editor of The Herald, Sir Keith Murdoch, in a retributive mood.

Murdoch initiated a public vote on the design in February 1924, encouraging dissatisfied readers to publicly vent their disapproval with the winning design—and disapprove they did. Construction of the Shrine of Remembrance was held up for years. The Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia pushed to build a war memorial at a proposed ‘Anzac Square’ near Parliament House and in September 1924, the Prendergast Labor state government indicated it might not honour the previous government’s funding pledge of £50,000.

It wasn’t until the influential head of Legacy, Colonel Sir Alfred Kemsley, and Lieutenant-Colonel Donovan Joynt VC, persuaded General Sir John Monash to publicly support the Shrine at an RSL reception for the Duke of York on 24 April 1927 that the Shrine project gained the necessary

traction. The Governor of Victoria laid the foundation stone for the Shrine of Remembrance on Armistice Day the same year.

There was one stand-out critic of the Shrine, however, whose opposition to the winning design demonstrated just how contested the competition had become. Second place-getter William Lucas absolutely refused to accept the worth of the Hudson and Wardrop winning design and almost immediately resolved to bring others around to his viewpoint.

Lucas authored a document evaluating each of the exhibition entries in turn, which he deposited in the Melbourne Public Library (now State Library Victoria). He heaped scorn on Hudson and Wardrop, accusing them of architectural plagiarism. The allegations, and Hudson’s responses, were sensationally reported in the press.

Third place – ‘A Pylon’ 1923 by Donald Turner.

Reproduced from: William Blamire Young, ‘The designs for the Victorian War Memorial’, Art in Australia: A Quarterly Magazine (Series III, Number 7, 1924)

Fourth place – ‘A Sanctuary of Peace’ 1923 by Roy Lippincott and Edward Billson.

Reproduced from: William Blamire Young, ‘The designs for the Victorian War Memorial’, Art in Australia: A Quarterly Magazine (Series III, Number 7, 1924)

Ultimately, Lucas’s efforts to convince his peers were poorly received. He was removed as editor of the Journal of the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects, convicted of professional misconduct and expelled from the association. Records of Lucas’s sensational hearing are featured in Designing Remembrance, as is his competition precis. These documents demonstrate the passion and competitive spirit that accompanied the design competition for the National War Memorial for Victoria.

Visitors to Designing Remembrance have the opportunity to reflect on the Shrine of Remembrance they love and imagine the alternatives that Melbourne might have had in its place.

Unplaced entry – ‘Anzac Memorial’ 1923 by Eric Nicholls, Walter Burley

and Marion

Reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Australia

DESIGNING REMEMBRANCE IS ON DISPLAY AT THE SHRINE UNTIL AUGUST 2025.

CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO THE DESIGNING REMEMBRANCE PODCAST SERIES, WHERE WE DELVE INTO THE DESIGNS THAT COULD HAVE BEEN, AND THE ARCHITECTS BEHIND THEM. LISTEN

Neil Sharkey is a curator at the Shrine of Remembrance.

Fifth place – ‘A Cenotaph’ 1923 by Arthur Stephenson and Percy Meldrum. Reproduced from: William Blamire Young, ‘The designs for the Victorian War Memorial’, Art in Australia: A Quarterly Magazine (Series III, Number 7, 1924)

Griffin

Mahony.

William Lucas, 1893. Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. photographer unknown Reproduced courtesy of The Baptist Union of Victoria Archives

From the Collection

BY TOBY MILLER

Alexander Colquhoun’s painting of the Shrine of Remembrance under construction was purchased for the collection in 2022. Read on to explore Colquhoun’s personal connection to the Shrine.

Alexander Colquhoun (1862–1941), Building the Shrine c.1932, Oil on canvas on board, 36.0 x 31.4 cm. Shrine of Remembrance Collection

Portrait of Private Quentin Colquhoun, 23rd Battalion c.1915. Reproduced courtesy the Australian War Memorial (H06535)

Sometime around the middle of 1932, Scottish-born Australian painter and art critic Alexander Colquhoun made a painting of the Shrine under construction. It is not surprising that Colquhoun, a ‘well known as a painter of Melbourne streets and buildings’, should choose the nascent monument for a subject. The rising mass of brick and stone in the middle of the Domain was in the process of altering the ‘landscape’ of Melbourne.

Colquhoun’s small sketch-like painting, acquired by the Shrine in 2022, reveals this transformation in progress. A scotch derrick, used for slewing stone and other materials to the upper level, is located where the North Tympanum now stands. A thin scaffold extends vertically through the middle of the painting, indicating where the Shrine’s now-iconic ziggurat roof will reach.

In the background, rendered by a stroke of paint, is the main tower crane. Horizontal lines across the middle of the painting depict what remains of the scaffolding around the colonnade. The Shrine’s external façade would be completed by year’s end and the first formal ceremony, featuring the Shrine’s iconic ray of light, would take place on Armistice Day the following year.

The painting may be Colquhoun’s Building the Shrine, which was exhibited at Grosvenor Gallery in December 1932 alongside 33 other modestly sized urban scenes. Blamire Young, himself a skilled watercolourist who, like Colquhoun, wrote art criticism for The Herald, commented: …it is possible that the Shrine was more paintable when broken with the elaborate scaffolding that surrounded it during the earlier stages of its construction than it appears today when the scaffolding has been removed. At any rate, Alexander Colquhoun has seized upon a satisfactory subject in Building the Shrine. His management of the greys and the contrast of the heavy shadows makes a pleasant picture. Like many of Colquhoun’s late works his painting lends the Shrine a restive quality while still capturing its monumental presence as it rises out from the Domain.

Harold Herbert, another fellow painter turned critic, noted in The Australasian that Colquhoun’s ‘appreciation of greys is well exemplified in a sketch of the Shrine of Remembrance’.

Such early painterly interest anticipates the transformative effect the Shrine would have on Melbourne’s physical and psychological geography. C.J. Dennis, writing under his pen name The Roustabout, suggested the Shrine finally furnished Melbourne with a European-style boulevard, comparing the new building’s prominent location on the Domain, facing Swanston Street, to the view from the Rue Soufflot towards the Panthéon in Paris. Dennis even suggested that the Panthéon’s revolutionary inscription – Aux grands hommes la patrie reconnaisante –which Dennis translated somewhat freely as ‘The grateful motherland pays homage to her illustrious dead’, would be fitting for the Shrine.

However, Melbourne in the 1930s was a far cry from revolutionary Paris. The collective suffering caused by the First World War was deeply felt, dispelling any notion that the Shrine might be dedicated to an illustrious few. Instead, General Sir John Monash’s words, inscribed on the east wall, succinctly captured the community’s sentiment:

THIS MONUMENT WAS ERECTED BY A GRATEFUL PEOPLE TO THE HONOURED MEMORY OF THE MEN AND WOMEN OF VICTORIA WHO SERVED THE EMPIRE IN THE GREAT WAR OF 1914-1918

As skilled with a pen as much as a brush, in December 1914 Colquhoun penned the following reflections about the early course of the war.

…the world is caught in the black war cloud, so dense, all-pervading, it cannot be lifted or pushed aside from home or hearth. A mother puts a wee babe in my arms, and the thought comes “And the child has come into the world at this dark time”…Nations fight nations, statistics lately given show that a third of the inhabitants of the globe belong to belligerent countries, battle lines extend over snow, ice and slush for hundreds of miles –the old world has changed from summer to winter since the sound of the first war trump, changed also in our hearts, which are trenched even as the miles of land.

Towns lie in blackened ruins, death-dealing machines are dragged over God’s fair earth, so many acres now have become cemeteries to cover the bodies of fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons; thousands of men have been

disabled for life. Men kill as fast as their machines will work, motorbuses have left their well known routes and are whirling along strange lanes carrying armed men and equipment. One reads in the paper “The lines were quiet yesterday, only shelling continued”! A rare day for these times. Unless an isolated and striking event occurs, such as a warship being sunk or a whole army corps annihilated, the sensibilities are too blunted to react, and one reads in a stupefied way of so many thousand being killed, men fighting behind the piled-up bodies of comrades, rivers choked with dead.

Less than two years later, Colquhoun would learn that his own son, Private Quentin Colquhoun, had died on the Western Front. As they did for many Victorians, details of his son’s death arrived slowly, facilitated largely through correspondence with the Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Bureau. ‘Queenie’, one eyewitness report stated, ‘was not in my platoon but he had come up to see his friends. He was standing in the trench, when a shell exploded between him and another man killing both outright’. Buried where he fell, his personal belongings, consisting of a can opener, shaving brush and tin, were all that was returned to his parents. In a letter to the Victorian Barracks in July 1917, Colquhoun reported that they would be grateful if someone could try and recover his son’s diary, carefully written and up to date.

It is doubtful the Colquhoun’s received any such final moment of intimacy. But it is another question whether any of this finds expression in Colquhoun’s painting. Stylistically, the painting owes much to Colquhoun’s friendship with fellow Scot and renowned pacifist Max Meldrum. Colquhoun’s simple sketch-like construction employs Meldrum’s much-vaunted use of tone to create mass and perspective without resorting to academic design. The result is a scene imbued with quiet dignity; given what is now known about Colquhoun’s personal experience during the First World War, it is perhaps more than just a ‘pleasant picture’.

Toby Miller is the Collections Coordinator at the Shrine of Remembrance.

THE

BEYOND BLUEPRINT

UNCOVERING THE STORIES OF THE SHRINE’S ARCHITECTS

BY DR KATTI WILLIAMS

View of the Shrine interior, by Philip Hudson, 1923. Reproduced courtesy of Cathy Rowland and Nick Wardrop

Dr

Katti Williams reflects on meeting the descendants of the Shrine’s architects, Philip Hudson and James Wardrop, and discovering the family treasures that are featured in Designing Remembrance: Alternate visions for Victoria’s war memorial.

It’s definitely a memorable way to spend Anzac Day. I’m kneeling on the carpet, next to Cathy. Our grandfathers were both young signallers who served in the cloying, nightmarish mud of France and Flanders in the latter half of the First World War. But while mine was a bank clerk, hers was an architect. An architect named James Wardrop.

Carefully placed on the floor in front of us is an original competition drawing of the Shrine, lovingly and carefully framed. In the corner of the work is a postdated attribution: ‘Philip B. Hudson, 1923’.

Gazing at its rich sepia toning, exquisite detailing and evocative perspective, I’m momentarily lost for words. The original competition drawings, meticulously prepared by the Shrine’s architects Philip Burgoyne Hudson and James Hastie Wardrop, haven’t properly seen the light of day outside of Cathy’s family for decades, possibly nearly a century. Kneeling in front of this object—an architectural holy grail of sorts—seems peculiarly appropriate.

For the past year, Shrine curator Neil Sharkey, with assistance from the Shrine’s Education and Volunteer Manager Dr Laura Carroll and myself have been working on an exhibition that delves into the forgotten designs for Victoria’s War Memorial. We share a love for the architecture of the Shrine and a passion for deep and sustained historical research. It has been an ever-broadening and at times frustrating hunt for documentation and objects through which to tell the story. As the months tick by, we’ve raided what feels like half the archival repositories on the eastern seaboard. We’ve painstakingly chased down tangents and often drawn blanks; other times, we’ve uncovered previously unseen material: a letter here, a report there. We start to weave these challengingly varied strands of knowledge and evidence into a cohesive and interesting visual narrative. But we’ve done this without original competition drawings for any of the six placed entries—a situation we became resigned to.

Until first one email, then a second, arrives from the United Kingdom, via a genealogy website. The kindness of strangers (who are, admittedly, fellow history obsessives, sharing family trees online) yields names and contact details. Thankfully, family members of both Hudson and Wardrop are happy to speak to us, aware of the great significance of their grandfathers’ achievements and rightly proud of their legacy. Family lore tells of both architects and, later, teams of draughtsmen (they were mostly men in those days), tirelessly preparing the drawings before and during construction.

Thus, I find myself in Cathy’s living room, frantically texting Laura and Neil, who respond with excitement. Cathy gets her brother Nick (who is based on the other side of the country) on speakerphone. We talk eagerly, seated in Cathy’s studio, opposite Wardrop’s own plan drawer, with his drawing board and T-squares still sitting on top.

Philip Hudson (far right) and James Wardrop (next to Hudson) beside the model of the Shrine of Remembrance at the exhibition of designs. The Herald, 21 January 1924

As Wardrop died in 1975, both Cathy and Nick have strong memories of him: a man with an exceptional eye and an enquiring mind, honed through pre-war travel and study in America and England and a long career in his home town of Melbourne. While he was nicknamed ‘The Duke’ for his height and somewhat imperious manner, he also had a wonderful and wicked sense of humour.

This is clearly expressed in one of the items Cathy shares: a sketchbook Wardrop carried throughout his time on the Western Front. Beautifully preserved, this rare treasure is one of the most evocative objects ‘on display’ - the exhibition is now open, featuring sharply satirical cartoons alongside sketches of everyday life in the trenches amid war-shattered surroundings. As a signaller, Wardrop was thrown into the task of repairing communication lines under horrific conditions, witnessing the chaos and carnage of the battlefields first-hand. After one particularly arduous incident on 10 August 1918 at Harbonnières (for which he was awarded the Military Medal), he was hospitalised in England suffering ‘debility’ or ‘effort syndrome’. A photograph from this time shows Wardrop partaking of a meal in bed in a British military hospital. While visibly exhausted, he still has a characteristic twinkle in his eye. He returned home in early 1919 to his love and future wife Lucia Hankinson, as well as to his profession.

A few days later, I spend several hours with Philip Burgoyne Hudson’s grandson, Tim, and fly interstate to meet with Tim’s brother, Andrew. Hudson collapsed and died while playing his beloved golf in December 1951, so neither Andrew nor Tim have first-hand memories of him. Hudson was a member of the Australian Club, a personal friend of John Monash, and a fixture in the social and sporting pages. Photographs from the time show a stocky, determined figure standing with the much taller Wardrop next to the model of the Shrine of Remembrance, or walking around the site. A bronze bust by Shrine sculptor Paul Montford, meanwhile, depicts an intense gaze.

What Andrew and Tim—like Cathy and Nick—do remember are the stories of their grandfathers’ unceasing devotion to the project, from design to completion. ‘I spent 11 years on the Shrine; it was my whole life,’ Hudson stated in 1947.

For Hudson, the project was acutely personal. He had served in France, first as a driver with the supply column, then with the 4th Pioneer Battalion. In 1918, with his wife seriously unwell, Hudson was torn between his duty as an enlisted man and his duty to his family, making repeated requests to return home on compassionate grounds. Yet when these were finally granted, his ordeal continued. En route to Australia, he caught the Spanish flu and was hospitalised in South Africa, then further delayed by an epidemic embargo. Six months after he left England, he finally arrived home.

His sister Pamela and his wife’s sister Marjorie were army nurses in India and France. Most significantly, his two younger brothers both fought in France—and died.

John, a medical student serving with the Australian Field Ambulance, survived a serious wounding in the Dardanelles. After a lengthy recovery, he was granted a commission in the Yorkshire Regiment, only to die in action on the Somme on 25 October 1916. His body was never found. Two months later, Roy—a gunner with the AIF’s 2nd Field Artillery Brigade— was gravely wounded by a shell while walking along a duckboard near Delville Wood. He was taken to the 36th Casualty Clearing Station at Heilly but died the following day, and was hastily buried at an adjoining cemetery.

Laura, Neil and I have long discussed the probable effect of these deaths on Hudson, serving so close nearby, but Andrew is finally able to provide definitive answers. He places a folder containing some of Hudson’s own war letters on the dining room table. It includes a powerfully emotional missive to his wife Elsie (née Yuille), written in Hudson’s small, precise hand, in which he describes being informed of his brother Roy’s death.

It was heartrending to me as I think that I was not more than a mile off from where he was killed. I think it was at Flers for I know that he was in that district at the time.

The ‘Victory Draft’, Hitchin, UK, March 1917, showing signallers James Wardrop (standing) and Roy Williams (author’s grandfather, seated). Reproduced courtesy of Katti Williams, with the kind assistance of Brian Rowland

… Roy was one of our most gallant heroes. – A true soldier & one of nature’s gentlemen. He hated the life – loathed it all, but I am proud to say always jealously guarded ‘Duty’ as his watchword. When we last met he was longing for our victory, which must & will come, and a happy & peaceful return to dear old Australia. However I know that in spite of all the hardships that he suffered that he was proud to have done his duty. His death has been a terrible blow to me (following so shortly after our dear old John’s death) but it had to be. We must face it all bravely. Better by far to do one’s duty than be a shirker. His lot was a hard one – a very hard one. But now his work is over & he is at rest. I thank God that he has done his duty. Dearest I know that you will tell the children some day what brave & gallant uncles that they once had. – Men who went out to fight for right & the freedom which is going to benefit humanity in the future.

Andrew and I pause and ponder these heartfelt words, in which grief is interwoven with a sense of duty. These are concepts which underpin the design of the Shrine: the expression of sacrifice alongside pride, and furthermore, the impulse to create a soulful, evocative physical structure in the absence of the bodies of the dead.

This absence—of John and of Roy, among the 19,000 Victorian First World War dead the Shrine commemorates—is alluded to in another family treasure, which Tim

brings along to our meeting. It’s an artist’s impression of the Shrine, etched by a young architect, Arthur Baldwinson, in 1929, when only the foundations and lower portions of the building had been constructed. The Shrine emerges from the shadows as if at dawn. In the foreground is a ghostly army, wearing tin helmets and carrying heavy packs and weapons.

Reflecting on the design process, Hudson famously wrote that he believed that the Shrine ‘must embody a soul, and this I realised could only be accomplished by designing a memorial with an interior (as well as an exterior) where an atmosphere of solemnity and reverence would be established’. His conception of an architectural ‘soul’ is a perceptive response to the nature of Australian grief, of which he had tragic firsthand knowledge. The Shrine, Baldwinson’s etching seems to state, carries the souls, the memories, of the dead with it. We don’t yet know whether Baldwinson’s etching was a commission, a gift, or a happy purchase, but Hudson clearly treasured it—as Tim does today.

The items of family history that Tim, Andrew, Cathy and Nick have carefully kept have tremendous personal meaning for their families—but they also have real historical importance for the Shrine of Remembrance. They provide wonderful insights into both Hudson and Wardrop and their profound experiences of the reality and tragedy of war, serving to illustrate

the story of the competition in a more vivid manner than Laura, Neil and I had hoped was possible.

A week after meeting Cathy, rereading Wardrop’s service record, a date and place jumps off the page: Hitchin, March 1917. I go through my own grandfather’s records, then his war photographs, until I find it: a shot of the signallers taken just before leaving the signal training school for attachment to different units across the Western Front. Seated on the ground is my grandfather, the soles of his hobnailed boots pointing towards the camera. Standing just behind him is a tall, lanky figure with a distinctive face and stance—the ‘Duke’, James Wardrop.

I quickly text a snapshot to Cathy and Nick. This time, it’s their turn to be lost for words.

With great thanks to Cathy, Nick, Tim and Andrew for so generously sharing their family treasures, and for many hours of enjoyable and illuminating conversation.

Dr Katti Williams is a research fellow in Australian architectural history in the Australian Centre for Architectural History, Urban and Cultural Heritage in the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at The University of Melbourne.

James Wardrop (at right) in Barry Road Hospital, Northampton, 1918.

Reproduced courtesy of Cathy Rowland and Nick Wardrop

Right: The National War Memorial of Victoria: an etching by Arthur Baldwinson, 1929.

Reproduced courtesy of Tim Brown

CONVERGENCES

BY GARRY FABIAN

Garry Fabian was born in 1934 in Stuttgart, Germany. Sharing his 90th birthday year with the Shrine, Garry reflects on his journey through conflict and the importance of sharing his story with younger generations.

Convergences – The Cambridge Dictionary defines it as: The fact that two or more things, ideas, etc become similar or come together.

This year–2024–the Shrine of Remembrance is 90 years old. This year, I also celebrated my 90th birthday. While the beginning of our journeys through time are quite different, they do eventually converge.

At the centre of almost every Victorian city and town stands a war memorial, obelisk and arch, broken pillar or a stern upright soldier, gateway, hall or avenue of honour. Most were raised in the 1920s and 1930s to commemorate the sacrifices made by Victorians in the First World War. The Shrine was a bit of a latecomer, opening on 11 November 1934.

My life journey travelled a different path. My Jewish family history traces back to the 13th century in Germany on both my maternal and paternal lines. I was born in January 1934 in Stuttgart, BadenWürttemberg, when the dark clouds of Nazi Germany started rolling in with rising anti-Semitism and associated restrictions. These

conditions worsened in 1935 when the Nuremberg laws imposed negative rules, including the loss of German citizenship on Jews.

These developments convinced my parents that there was no future for us in Germany and our wellbeing was in danger. We emigrated to the Czech Republic and settled in Sudetenland, a German enclave, in 1936. However, this proved to be a short-term solution; after the infamous Munich conference in September 1938, this area was ceded to Nazi Germany.

We packed up and fled four hours before the German Army occupied the area and headed to Prague, the Czech capital. Being stateless, we lived a very unstable existence as the local authorities were not accommodating to the swelling number of refugees. Often action was carried out to expel them from the country. When Nazi Germany invaded the Czech Republic on 15 March 1939, Jews became subject to extensive persecution and harsh rule, curtailing their daily lives. In 1941, deportations to

the concentration and later extermination camps started.

Our turn arrived in November 1942 when we were transported to a concentration camp, Theresienstadt, some 50 kilometres from Prague. This was basically a transit camp for transports to extermination camps in Eastern Europe.

In normal times, Theresienstadt had a population of some 3,500. But operating as a concentration camp, some 30,000 people occupied the town at any time, creating overcrowded and unsanitary conditions. This left us with an acute loss of privacy and lack of food, as well as constant uncertainty of what the next day or week would bring.

We were among the small minority who survived in the camp until liberation by the Red Army on 5 May 1945. During the four years from 1941 to 1945, some 140,000 people went through the camp. Of the 15,000 children under 14, between 120 and 150 survived. The odds for my survival were very long indeed.

But then another question arose: would we be able to return to normal life?

The Fabian family in 1947.

Returning to Germany, the home of our family for 700 years, would be impossible after what had happened. We instead returned to the town in the Czech Republic where we settled in 1936 as a

temporary measure, but the dark shadows of those years made it imperative to move as far as possible from Europe. At that point in time, I felt no affiliation to Germany, but over many decades I have drawn

closer, trying to establish bridges with today’s generation.

That’s how we came to Australia— the other end of the globe. Two of my uncles had settled here just before the Second World War in 1939. Both had served in the Australian Army, one in the Employment Brigade, the other as a doctor in the Army Reserve. That was an early connection—a convergence— between cultures.

We arrived on the 20 September 1947 with almost no knowledge of Australia and certainly not of its history, either civil or military. My late father served in the German Army as a loyal citizen in the First World War on the Western Front. He told me that he faced Australian Diggers in the trenches opposite, and they were regarded with some respect, but that was the extent of my knowledge of Australian involvement in that war. We landed to encounter a strange language and culture, but soon adapted and welcomed the opportunity to start a new life.

Up to this point, aged 14, I had only been to school for three years, and so I enrolled in Year 7 at Preston

Top Left: Garry in 1937. Bottom Left: The crew at HMAS Cerberus. Garry is on the far left of the front row.

Top Right: Garry and his wife Evelyn on their wedding day, 24 December 1959.

All images reproduced courtesy Garry Fabian

Technical School. My first lesson in Australian military history was in April 1948 when Anzac Day was commemorated, which prompted me to obtain more knowledge. During that year I also visited the Shrine on a school excursion. While it only gave me a very superficial impression, the various exhibits provided some harsh and lasting lessons of what transpired on the battlefield. This set me further on a path to learn more. The following year I attended Caulfield Technical School, obtaining a Junior Technical Certificate.