Where do we go from here?

Also:

• Economist weighs in on China, crop insurance and cash rents

• Land market leveling out after ‘rocket fuel’ years

• Crop insurance faces opposition

North Central Illinois

AG Mag

MORE SUPPLY LESS DEMAND

PRSRT STD U.S. Postage PAID Permit No. 440 Sterling, IL 61081 CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED A PUBLICATION • WINTER 2024

ALAN DAVIS Crop Insurance Specialist Providing personal solutions to your unique operation! My clients get FAST & Accurate information regarding the best programs to use on Crop Insurance & also how that pairs with FSA Office programs to MAXIMIZE their total Farm Operation Protection Farm. Family. Food. Partnering to benefit Illinois Farmers CALL TODAY to schedule farm visit to make a plan for 2024 crop year Providing farmers excellent customer service with their Federal Crop Multi-Peril and Crop Hail policies PROUD TO SERVE YOU! Thank you for your continued business and making us your #1 Farm and Crop Insurance choice in Illinois Business Phone : (815)876-0577 204 N Main St. PO Box 365, Princeton, IL Email : alan.davis@countryfinancial.com Jessica Eickmeier • Assistant Jessica.eickmeier@countryfinancial.com 2 Winter 2024

Editor

Writers

Here for all your Ag Lending needs! 1693 N. Main St. Princeton, IL firststatebank.biz l 815.872.0002 Warm Up With a Cup of Hot Chocolate and a Holiday Pie Locally Owned & Operated by Paul and Mary Breznay SPRING VALLEY • MENDOTA • PRINCETON NOW HIRING Full/Part Time (EOE) SM-LA2137182 Ag Mag 3 Demand, supply top ‘24 list for farmers, markets ���������������������������������� 5 Economist weighs in on China, crop insurance and cash rents������������� 8 Land market leveling out after ‘rocket fuel’ years �������������������������������� 10 Crop insurance faces opposition 12 Farm bill outlook uncertain ������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 Corn Belt Ports docks in Peoria ������������������������������������������������������������ 18 Brazil’s share of global soybean market grows ������������������������������������ 22

Mag Bureau County Republican P O Box 340 Princeton, IL 61356-0340 815-220-6948

Ag

Advertising Director Jeanette Smith jmsmith@shawmedia�com

General Manager/

Jim

Henry

Designer Liz

Published by: est. 1851 Articles are the property of AgriNews No portion of the North Central Illinois Ag Mag may be reproduced without the written consent of the publisher Ad content is not the responsibility of the Bureau County Republican The information in this magazine is believed to be accurate; however, the Bureau County Republican cannot and does not guarantee its accuracy The Bureau County Republican cannot and will not be held liable for the quality or performance of goods and services provided by advertisers listed in any portion of this magazine CONTENTS

Martha Blum Tom C Doran Jeannine Otto Photographers Martha Blum Jeannine Otto

Klein

Truck Sales | Parts | Service Body Shop | Leasing | Finance CIT Trucks - Peru 2650 May Road Peru, IL 61354 800.331.1098 CIT Trucks - Mack 3030 May Road Peru, IL 61354 844.224.4747 SM-PR2135623 Together we do more® Save big on select compact and sub-compact tractors. Versatile, reliable and part of the #1 rated tractor brand for durability and owner experience in the U.S.* Stop in today for a demo.** 0% 84 APR MONTHS $300 SAVE UP TO UP TO PLUS VISIT US TODAY FOR THIS LIMITED-TIME OFFER Streator Farm Mart 1684 N 17th Rd Streator IL 61364 815-672-0007 www.streatorfarmmart.com KubotaUSA.com Award based on 2021 Progressive Farmer Reader Insights Tractor Study **Subject to availability. © Kubota Tractor Corporation, 2024. $0 Down, 0% A.P.R. financing for up to 84 months on purchases of new Kubota BX2680, L2501 and LX2610SU equipment from participating dealers’ in-stock inventory is available to qualified purchasers through Kubota Credit Corporation, U.S.A.; subject to credit approval. Example: 84 monthly payments of $11.90 per $1,000 financed. Customer instant rebates include Orange Plus Attachment Instant Rebate of $100 with purchase of the second qualifying new implement and $200 for the third new qualifying implement. There is no rebate on the first implement purchased. Offers expire 03/01/24. Terms subject to change. This material is for descriptive purposes only. Kubota disclaims all representations and warranties, express or implied, or any liability from the use of this material. For complete warranty, disclaimer, safety, incentive offer and product information, consult your Dealer or KubotaUSA.com. Streator Farm Mart 1684 N 17th Rd Streator IL 61364 815-672-0007 www.streatorfarmmart.com Once complete, click Finish button. DOWN 0% APR UP TO SAVE UP TO $300 PLUS 815-875-6600 140 N. 6th St., Princeton, IL 815-224-2200 3230 Becker Dr., Peru, IL www.libertyvillageofprinceton.com One Of Your Favorite Senior Facilities! Give us a call today to arrange a tour! SUPPORTIVE LIVING • 24 Hour Assistance • Elegant Dining • Health Monitoring • Laundry & Housekeeping Services • Medication Reminders • Spacious Living Area LIBERTY VILLAS • Spacious 2 Bedroom Floor Plans • Full-sized Kitchen • Attached Garage •Maintenance Free Exterior •Grounds Maintenance • Premier Post-Acute Provider • Medicare Certified • Caring & Dedicated Staff • State of the Art Therapy •Experienced Therapist •Personalized Recovery Plan Liberty Village RETIREMENT COMMUNITY NOT-FOR-PROFIT PROVIDER SM-PR2044764 • Stimulating Memory • Enhancing Socialization • Remain Active • Remain Engaged 4 Winter 2024

Demand, supply top ‘24 list for farmers, markets

By JEANNINE OTTO jotto@agrinews-pubs�com

ROCK FALLS, Ill. — More supply, less demand, where do we go from here?

Larger supplies of corn and soybeans and less demand will bring hard questions — and harder decisions — for farmers in 2024, according to a former Iowa State University Extension economist.

“I think maybe the bigger question mark for ‘24 is — are we going to have that demand out there?” said Steve Johnson, a retired specialist in farm management, at an outlook meeting sponsored by Whiteside County Farm Bureau.

“I think there are a lot of headwinds blowing against the grains for ‘24, just lots of uncertainty. We just harvested the biggest U.S. corn crop in history, 15.1 billion bushel crop. The supply is just way too large for the demand,” he said.

Two major markets, ethanol and biofuels and feed for livestock, continue to support the U.S. corn market, according to Johnson.

“Ethanol and feed is just carrying us right now. We need high crude oil prices so we can make ethanol. If you ever take ethanol, the Renewable Fuel Standard, away, you are going to have $2 or $3 in front of your corn,” he said.

“You ought to be fighting — whether it’s in Farm Bureau or a commodity group, you better be fighting.”

While livestock feed demand continues to be strong for corn and soybeans, demand from that sector may be slowing as 2024 moves forward.

“We have record ethanol demand, but now our livestock herds are getting thin. You have the smallest mother cow herd in 60 years. We just don’t have as many cows,” Johnson said.

“The hog industry does not look real profitable right now, thank you, California, and Proposition 12.”

Export demand has dropped. A higher U.S. dollar can shoulder some — but not all — of the blame.

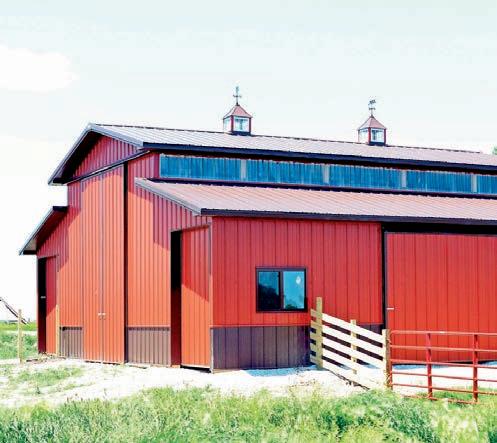

Even as he donned an orange Illini cap, Steve Johnson, retired from Iowa State University Extension, advised farmers attending a Whiteside County Farm Bureau-sponsored outlook meeting to adopt the “Hawkeye strategy” and “lower your expectations�” Large U�S� crops of corn and soybeans in 2023, along with reduced export demand, means that farmers will face headwinds in 2024 Johnson advised farmers that a lower-price environment for corn and soybeans may be the new normal as markets become more comfortable with lower ending stocks

“Where is the export market? People are finding someplace else to buy corn rather than from the U.S, primarily because of the high U.S. dollar,” the economist said.

Johnson said he is concerned that other factors may be impacting exports, indicated by the World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report published in November by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“What happened to our export market? Our exports were 2.4 billion in 2022. They are 2.05 billion bushels now. They were buying more of our corn when it was higher priced.

“Now that corn is lower priced, they are buying less corn? There is something going on in our export program that we are not seeing, in global demand for U.S. corn,” he said.

“That is a real concern that I don’t think we paid much attention to until we saw the November USDA WASDE report. There are some real issues. They increased demand for ethanol, increased demand for feed, but they left that export demand the same. What

happened to our exports, even at lower prices?”

So, what can farmers do?

“I think key for 2024 is the Hawkeye strategy. Lower your expectations,” the economist said.

Coming off of several years of record farm income and higher crop pr-ices, Johnson said farmers need to adjust their expectations.

“The reality is that we are going to likely trend into 2024 with lower prices for the ‘24 crop because we have such large ending stocks, especially on corn,” he said.

For corn growers, the answer is simple.

“Well, we have to stop growing so much corn — you go first!” said Johnson, to laughter from the audience.

If fall anhydrous application is any indication, it won’t be the “I” states that blink on corn planting for 2024.

“As I came across Iowa, I was more likely to hit a nurse tank than a deer. There was so much anhydrous going on across Iowa,” Johnson said.

Fall tillage also indicated that corn acres likely aren’t going down anytime soon.

He said he’s been seeing

big rippers being used to rip the cornstalks. “With this Bt technology, these stalks are extremely stiff and tight. You either have to mow them off, roll them up in bales or we bury the stalks. That was taking place everywhere,” Johnson said.

“Thirty-three percent of our rotation in Iowa is corn on corn. It tends to be one of the more profitable rotations. The reason we’ve seen so much corn on corn in Iowa is the demand for corn.

“With the livestock, we have to have so much corn and I think you are going to continue to see this deep ripping and incorporation of stalks.”

Barring a major weather catastrophe, technology will continue to push the production of large U.S. corn and soybean crops.

“The corn yields that we got on Nov. 9 were record yields in Indiana and Ohio. You have a lot of people who can grow a lot of corn. You did it this year with less than average rainfall. It probably says a lot about technology, whether it be seed or crop protection or tillage,” the economist said.

“You just don’t have to have a whole lot of moisture. Somehow, that corn finds that moisture and we don’t stress the crop like we did.”

Even as farmers may have to adjust their expectations away from recent high profit years, Johnson said they can still be alert to rallies and opportunities to sell at higher prices.

“You get a secondary chance. This doesn’t always happen. It happened in July. Funds came back in and bought, gave you another chance to sell, but around $5.60, $5.65,” he said.

“You say, ‘well, that’s not high enough, it has to go higher.’ It never went back. We’re not going back, folks. We’re not going back. Until we have some sort of shock, we should kind of get used to this.”

Setting a realistic price objective and keeping an eye out

See DEMAND page 6

Ag Mag 5

AGRINEWS PHOTO/JEANNINE OTTO

for rallies — and selling that rally — is one strategy.

“If I had to say, what is my price objective for this winter? The March. Five bucks. Not $6. Not $5.50. Five bucks. Sell the rally this winter, but sell it for the July,” Johnson said.

“Then, if you have the bushels and they are on your farm

and they are dry, great. Deliver them in May and June. That is when we probably see better basis.”

For soybeans, the picture is not quite as sober. Soybean prices may be reflecting a new normal when it comes to ending stocks.

“While we went to the moon last year, average cash prices over $14, now we are coming down. The world is becoming more comfortable with these tight ending stocks,” the econ-

omist said.

“Brazil is No. 1, then the U.S., then Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay. As long as every six months, we have a large crop, I think the market feels comfortable with these ending stocks of sub-300 million bushel.”

Johnson said farmers still holding soybeans should be keeping an eye on weather in South America.

“When we get problems in South America, sometimes we

see this late winter rally. That is probably one that I would want to take advantage of in pricing new-crop ‘24 beans. There is some concern and that is what is supporting the bean market,” he said.

“If we rally with that South American crop problem, I would be selling ‘24 beans. I think beans could be more profitable than corn. I think beans could be more profitable because the upside is still sitting there.”

A local Company, with local people, making local decisions, offering farm and home insurance. Hanford Insurance Agency Geneseo • 309-944-8670 CSB Insurance Kewanee - 309-932-2130 Mark Gillis Insurance Agency Rochelle • 815-561-2800 The Cornerstone Agency Tampico • 815-772-2793 Dykstra & Law Agency Fulton • 815-589-2200 Sauk Valley Insurance Services Dixon • 815-288-2541 Prophetstown Farmers Mutual Contact one of our Qualified Agents to see how they can help Founded by Farmers, for Farmers Meeting all of your Farm Insurance Needs SM-ST2135919 1609 1ST AVE., MENDOTA RIDLEYFEEDINGREDIENTS.COM SM-LA2137190 SM-PR2137619 Michael Michlig (815) 878-4430 Dane Robbins (815) 876-0445 SHEFFIELD, ILLINOIS Right Product. Right Acre. Right People. Pioneer brand products, service, Pioneer Premium Seed Treatment and PROBulk® System MJ Seed Agency 6 Winter 2024

FROM PAGE 5

Demand

Overlooking nothing. Ready for everything.

Farmers and ranchers, the world relies on you. And you deserve a bank that’s rooted in the details and dedicated to helping you do more.

/agribusiness

Ag Mag 7

FAST FIVE: STEVE JOHNSON

Economist weighs in on China, crop insurance and cash rents

By JEANNINE OTTO jotto@agrinews-pubs com

ROCK FALLS, Ill. — He’s now retired from Iowa State University Extension, but the economist from Cyclone Nation donned the orange and blue of the Fighting Illini to talk about the future — and the past — to a group of northern Illinois farmers.

Steve Johnson, retired farm management specialist, wasn’t talking about $8 corn or $16 soybeans.

In fact, Johnson outlined the list of headwinds aimed at U.S. farmers in 2024, from large stocks of corn and soybeans, to reduced demand, especially on the export side.

After his presentation, AgriNews sat down with Johnson to get his thoughts on five hot topics.

ON CROP INSURANCE

IN THE 2024 FARM BILL

“The best-case scenario for crop insurance in 2024 is the same level of spending. If we did away with crop insurance and crop insurance subsidies, we would have the farm crisis of the 21st century. It would probably be even worse than what we saw in the 1980s. So many people are dependent upon that subsidized crop insurance to manage the financial risk associated with production. I think that if there is something to eliminate in the next farm bill, eliminate ARC/PLC. What difference does that make? We don’t need an ARC/PLC program — we need a strong

crop insurance program.”

ON CORN ACRES

“We just need to rotate 10 million acres to soybeans, then we’ll trash the soybean market, but we’ll capture that corn market for a year. Farmers don’t think like that. They think of their own operation and they think, ‘why doesn’t Iowa not grow 10 million acres of corn?’ I think there is a concern that we should have seen, that we should have chased those corn acres out of those peripheral states that have fragile soils and don’t have water-holding capacity. But it didn’t happen this year. When you look at the last six months, where did all those extra corn acres come from? Then we have the corn yield, then we lose export share and now we’ve got corn exports down to 2.05 billion bushels. There are a lot of headwinds blowing against the corn market that aren’t going to turn anytime soon, in my opinion.”

ON CORN EXPORTS

“I think there’s a real concern. I don’t think it’s just politics. I think it’s the U.S. dollar. I think it’s the fact that we have competing entities in the world, especially with Brazil and the corn they have available. We have got to rethink our corn export market or we are going to have to expand domestic use or we are not coming out of this.”

ON CASH RENTS

“We had record net farm incomes in 2021, 2022, and the fact is cash rents will be slow. (University of Illinois agricultural economist) Gary Schnitkey says they are sticky. They just don’t flow with the net value of the crop. Some of the work going

on, Iowa State was using 30%, of the value of the crop is reflected in fair cash rent, 40% of the value of soybeans. I think we probably have got to go back and start reflecting cash rents as a percent value of that crop and not some ‘what is the perceived market value.’ We are going to have a lot of operators who are going to have trouble in 2024 with these lower crop prices. We haven’t dropped costs far enough and I would say we are going to have lower net farm income in 2024.”

ON TRUMP AND TRADE

“Trump negotiated a threestage purchase of ag products that they were going to purchase annually. They met the required purchases the first year, but it was a threeyear process, 2019, 2020 and 2021. As soon as Trump was not reelected, China said we negotiated with the Trump administration, so we are not going to honor it. So, they left. The whole idea of holding China’s feet to the fire went away. There was COVID and other issues. But China never came back into that market and never purchased as many agricultural goods as they agreed to in the agreement. We negotiated with China and China agreed that they were going to buy all these agricultural products over this period of time. They did that for one year. Why didn’t they buy any more? Because Trump wasn’t in power anymore. It’s a whole different administration. Why didn’t China purchase what they said they were going to purchase? Part of that was COVID and the world economy slowed down, but China just walked away from the trade deal, they just walked away.”

8 Winter 2024

Johnson

SM-ST2136038 WWW.FARMERSNATIONALBANK.BANK GREAT DEALS GREAT SERVICE SINCE 1926 HIGHWAY 52, SUBLETTE, IL 61367 1-800-227-5203 • 1-815-849-5232 VAESSENBROTHERS.COM YOUR CHEVROLET TRUCK HEADQUARTERS SM-LA2137187 Ladd, IL • 815-894-2386 Hennepin, IL • 815-925-7373 www.northcentralbank.com Member FDIC Deb Schultz dschultz@northcentralbank.com • Operating lines of Credit • Land Purchases • Equipment Purchases • 100% mobile, we come to YOU! Banking for the Busy Farmer Ag Mag 9

Land market leveling out after ‘rocket

By JEANNINE OTTO jotto@agrinews-pubs com

NEVADA, Iowa — The market for Midwest farmland remains strong, but sales show signs that the market is reaching a plateau, after several years of upward momentum.

“We are still seeing really strong sales for the best quality farms. But for the first time in three or four years, we have also started to see a few no sales, here and there. We are in a different market than we were 12 months ago,” said Doug Hensley, president of real estate services at Hertz Farm Management.

Sales and values appear to have leveled out after consecutive years of strong farm income that propelled farmland sales.

“In 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2020 and 2021, in particular, this market was just on

rocket fuel. 2023 overall was a period where things didn’t necessarily come back to Earth, but the market has transitioned into more of a plateaued situation,” Hensley said.

While the demand for top-quality farms remains strong, he said that buyers, from farmers to investors, have pulled back on the amount of risk they are willing to take.

“When things are really, really good, people are willing to take more risk than they are when things are a little tighter. Not that we are in an unprofitable time, because 2023 was a profitable year, it just wasn’t as profitable as recent years. So, people are just protecting their liquidity in a way that they did not a year or two ago,” he said.

The big change has been in the number of people interested in lower-quality farms.

“In the fall of 2022, we would have seen upwards of six or eight active bidders at every auction, regardless of the quality. In 2023, there were two or three fewer bidders at all the sales, including best-quality farms. When it comes to the B and C quality, the market is much thinner than a year ago,” Hensley said.

Farmers still are lining up to buy those “once-in-a-lifetime” farms.

“If you are in a neighborhood where a really high quality farm is coming on the market, you only get one shot to buy a farm. You buy it when it’s available, not when it’s convenient,” Hensley said.

“But it seems like the threshold for taking those risks got a little higher in 2023 because margins are tighter. The lesser-quality farms are less worthy of somebody sticking their neck out. That is what we are

years

seeing, there are fewer people really willing to compete and participate for those B and C quality farms.”

Hensley said he will be keeping an eye on several factors that impact farmland sales and value.

“No. 1 is commodity prices. That establishes a baseline level of profitability and interest from farmers and non-farmers alike for making a living and creating a return on a farm. I am paying attention to input prices, as well, because that impacts profitability and margins at the farm level and that goes along with commodity prices,” he said.

While interest rates affect value and sales, the impact from higher rates has yet to be felt heavily in the farmland market.

“I think we have seen very little impact thus far from the higher interest rate environment as it relates spe -

Check Us Out Online! 250 Marquette St. LaSalle, IL 61301 1300 13th Ave. Mendota, IL 61342 101 N. Columbia Ave. Oglesby, IL 61348 2959 Peoria St. Peru, IL 61354 105 West 1st South St. Wenona, IL 61377 Your Source for Ag Financing *Loans and Lines of Credit are subject to credit approval. Agricultural Real Estate Loans Equipment & Machinery Loans Operating Loans & Lines of Credit Livestock Financing Joe Brizgis Brad Cook Contact the experts at Eureka Savings Bank today! NMLS# 447018 ELMORE ELECTRIC 815-643-2354 ELMORE HVAC 815-643-2631 205 North Street - Dover, Princeton, IL 61356 www.elmoreelectric.com Like us on Facebook Free Estimates Available SM-PR2137623 504 S. McCoy St., Granville 815-339-2511 alcioniford.com MAKE SURE YOU HAVE THE RIGHT EQUIPMENT BEFORE GOING OUT TO THE FIELD! Come see your trustworthy President Award winning Ford Dealer! 10 Winter 2024

fuel’

cifically to farmland. Most farmland buyers still are not borrowing a lot of money to make purchases. Most of the purchases are being powered by liquidity and strong earnings from the last several years,” Hensley said.

The most obvious recent impact of higher interest rates was that investors started to move away from the farmland market.

“Two years ago, farmland at 3% return was really good and you had an investor crowd that was paying attention to farmland as an asset class because it was competing really strong versus other investment alternatives,” Hensley said.

As interest rates and the price of farmland rose, investors have found alternative places to store their money.

“I think the investor crowd has been drawn away from the farmland market, more so in the past year with higher interest rates simply because you can go to any

local bank or community bank and get a 5% almost risk-free return on a shortterm or medium-term CD. Compared to farmland, that looks pretty good, especially with farmland having had this strong run-up in prices in the last couple of years,” Hensley said.

While the percentages of farmers versus non-farmers buying farmland may bobble, farmers remain the biggest buyers of farmland.

“It kind of depends on the economic environment, but farmers are, by and large, the vast majority of the buying public and then the balance of farms are bought by local and non-local investors,” Hensley said.

Another trend that Hensley watches, to gauge value and interest in buying, is sale volume on a local level.

“You can have a market that, marketwide, may not be strong. If you go into a neighborhood with a really nice farm where nothing has sold in recent months,

you can have some local, pent-up, demand,” he said.

“On the flip side, if you have a neighborhood where half a dozen farms have sold in recent years or recent months, the seventh or eighth farm comes to the market, you have some localized weakness, just because there is not as much dry powder, so to speak, from those local buyers to participate.

“Every one of these townships is a micro market. If you go 15 miles in any direction from where you are sitting, you are in a little different market. As we look at sale volume overall, it does play a role in how strong or weak the market would be in a localized situation.”

The type of sale can also impact value and interest.

“It is part art and part science, being able to judge whether a farm is best offered through public auction or whether it should be offered through private brokerage, the sale method

that should be used,” Hensley said.

“At an auction, you need at least two buyers who will compete through the end for an auction to go through. For a brokerage, you only need one.”

One factor that hasn’t yet made an impact is the arrival of solar farms on farmland.

“I haven’t seen a significant impact of any sort from those renewable projects. The solar is newer and it’s changing the underlying use of the property, so that is probably the biggest thing that is different from the wind energy projects,” Hensley said.

“The reality is that solar has impacted so few acres that I don’t know that it has any meaningful impact, other than for those people who are transitioning those acres out of production. They are enjoying the substantial payments they are receiving for doing so. It hasn’t changed our farmland market.”

Get the financial solutions you need to achieve the success you deserve.

PeoPles NatioNal BaNk of kewaNee Kewanee • Annawan • Bradford • Dwight Manlius • Reynolds • Seneca • Sheffield • Tampico “The Bank for All the People”

NMLS # 462098 Ag Mag 11

Crop insurance faces opposition

Conservative groups seek spending limits

By JEANNINE OTTO jotto@agrinews-pubs com

WASHINGTON — With the 2018 farm bill extended until the end of 2024, and the timeline on a new measure uncertain, one factor that will be front and center is the cost of the new legislation.

Prior to the one-year extension of the 2018 farm bill, the new legislation’s total cost was estimated by the Congressional Research Service at $1.5 trillion.

While the nutrition titles of the farm bill, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women and Children, commonly known as WIC, and the national school lunch program, make up some 84% of that spending, spending on the commodity titles, including crop insurance, is also likely to be under scrutiny when negotiations get underway on a new farm bill.

Conservative groups and think tanks have expressed their opposition to and desire for reform of the commodity titles of the farm bill, including the federal crop insurance program.

“Congress should eliminate federal revenue-based crop insurance policies,” stated the Heritage Foundation, an influential, conservative think tank, in its “Budget Blueprint for FY 2023.”

“The federal government should not be in the business of insuring price or revenue; agricultural producers, like other businesses, should not be insulated from market forces or guaranteed financial success at the expense of taxpayers,” the Heritage Foundation said.

“Revenue-based crop insurance is unnecessarily generous and should be eliminated. Taxpayer-subsidized crop insurance should

be limited to yield insurance as it was in the past.”

More recently, the Heritage Foundation expressed opposition to raising reference prices in the yet-to-be-negotiated 2024 farm bill.

Raising statutory reference prices, currently $3.70 for corn and $8.40 for soybeans, is a farm bill proposal supported by farm membership and commodity groups.

“Increasing reference prices would be the latest instance of federal micromanagement of the agricultural sector at taxpayer expense,” wrote at the Heritage Foundation’s David Ditch, a senior policy analyst, and Rachel Greszler, a senior research fellow, in an Oct. 12 report, “The End of Business as Usual: On Supplemental Package, Farm Bill, and More, Congress Must Stop New Deficit Spending Immediately.”

“This is unhealthy both because of its baleful effect on the national debt and because of its interference with the market, the results of which are rampant political favoritism, inefficiency, and dependence on corporate welfare.

“In the case of reference prices, increasing PLC guarantees would make farmers less responsive to price signals that would otherwise cause shifts in how and what they choose to produce.”

The Heritage Foundation isn’t the only conservative group opposed to continuing the federal crop insurance program and the premium subsidy.

The Club for Growth, a conservative organization focused on economic policy and tax cuts, lists as one of its free trade policy recommendations: “Eliminate all agricultural subsidies like direct payments, crop insurance, and quotas.”

The Cato Institute, which brands itself as a libertarian think tank, headquartered in Washington, also opposes farm subsidies.

“Large farm subsidies ensure that farmer incomes are higher than the incomes of most other Americans,”

Not just a farmer safety net

By JEANNINE OTTO jotto@agrinews-pubs com

NEVADA, Iowa — Federal crop insurance isn’t just a safety net for farmers. It also serves as a backstop for rural communities and rural residents.

“I don’t think people put enough weight behind the importance of crop insurance and what crop insurance has meant to our farmland, our stability and not just our farmland, but really, our rural economies,” said Doug Hensley, the president of real estate services for Hertz Farm Management.

Of all the farm bill programs that impact production agriculture, Hensley said that crop insurance is the program that farmers and landowners and prospective buyers need to be watching.

“The most important thing that I think is going to come out of this farm bill, as it relates to production agriculture, is what is going to happen with crop insurance,” he said.

Federal crop insurance has been around since 1938, when Congress passed the Federal Crop Insurance Act.

In 1980, Congress revised the program to subsidize crop insurance premiums and to bring private insurance companies into the program. Today, the federal government

wrote Chris Edwards, director of tax policy studies at the Cato Institute, in the 2022 Cato Handbook for Policymakers.

“Farm programs are welfare for the well-to-do. They also induce overproduction, inflate land prices, and harm the environment. They should be ended, and American farmers should stand on their own two feet in the marketplace.”

subsidizes just over 60% of the premiums for crop insurance.

For the 2021 crop year, 444 million acres of U.S. cropland was covered by federal crop insurance. In 2021, row crops made up the majority, at 70%, of insured liability.

“Crop insurance has undergirded this safety net that has benefited local banks that are lending on operating loans,” he said.

“It has been a safety net that has allowed people to make payments on tractors and combines, which impacts implement dealers,” Hensley said.

He said that the impacts spread wider in rural communities.

“It’s not just the farmer it backstops. It backstops them very directly, but because they are backstopped, all the people who do business with the farmer also are backstopped,” he said.

“You can just go down the list of all the vendors and input suppliers that play into this agricultural economy across the Midwest. Crop insurance has been super, super important to creating a stable market that we have today.”

Taxpayers for Common Sense is a budget watchdog group, based in Washington. The group describes itself as “an independent, nonpartisan voice for taxpayers working to ensure that taxpayer dollars are spent responsibly and that government operates within its means.”

In a Nov. 28 fact sheet

See INSURANCE page 14

12 Winter 2024

Hensley

Customer satisfaction is our goal! Quality Work - 20 yrs. experience - Dedication SM-PR2140761 Let us help your farm reach its potential! GPS Integrated - Plow & Trencher Tile Installation - Maintenance Customer satisfaction is our goal! Quality Work - 15 yrs. experience - Dedication Colton (309) 238-8627Aaron (309) 238-8626 C&A FARM DRAINAGE GPS Integrated - Plow & Trencher - Tile Installation Maintenance - Discounted Pattern Tiling Prices Excavating * Bulldozing Colton Poignant: (309) 238-8627 Aaron Poignant: (309) 238-8626 Let us help your farm reach its potential! Ag Mag 13

INSURANCE

FROM PAGE 12

about the federal crop insurance program, “Cashing In On Federal Crop Insurance Subsidies,” TCS stated: “An insurance program in which payouts routinely exceed premiums cannot accurately be labeled as insurance, especially one that is highly subsidized by taxpayers.

“Farmer-paid premiums fall far short of covering indemnity payouts every year in the federal crop insurance program. For producers of particular crops and in particular regions, where payments exceed premiums every year, the program acts more like a federal income entitlement than actual insurance.

“We must make crop insurance more like insurance and less like an income guarantee for farm businesses year after year. Lawmakers should reform the complicated web of subsidies in the federal crop insurance program to make it a tool to manage risk rather than maximize payments for select businesses.”

The R Street Institute is a center-right think tank, describing itself as “engaged in policy research in support of free markets and limited, effective government.”

While the R Street Institute does not oppose the federal crop insurance program, it has called for reforms of the program.

“Because the subsidies predominantly go to Americans who would engage in the economic activity even without the subsidy (farming is profitable even without the FCIP), the program functions as a wealth transfer from taxed Americans to subsidized corporations and farmers. And as the subsidies grow, their negative economic impact worsens,” wrote Phillip Rossetti, senior fellow for energy and the environment at R Street Institute, in his Nov. 23 analysis “Federally Subsidized Crop Insurance Lacks Economic or Environmental Justification.”

In the analysis, Rossetti suggests several ways to reform crop insurance.

“Simple reforms could be adopted to eliminate the wasteful aspects of the FCIP. The subsidy component of the premiums could be reduced or eliminated to make the program function more like a conventional insurer that would need enough premiums to cover losses,” Rossetti said.

“Means testing could be incorporated into the FCIP to ensure that the subsidies protect only those farmers for whom the insurance makes or breaks their farm viability.

“And small reforms to the program could be implemented, such as eliminating the ‘harvest price option,’ which causes the program to pay out much larger subsidies than what is needed to cover expected losses to a farmer if the price of a failed crop increases after planting.”

The Environmental Working Group, an environmental activist and advocacy group that publishes the recipients of federal farm program benefits, excluding federal crop insurance premium subsidies, suggested several possible reforms to the program.

“The federal crop insurance program needs to be modernized to better serve farmers, cut costs for taxpayers and strengthen American agriculture against the extreme weather linked to climate change. Many of these reforms have had bipartisan support in the past,” wrote Anne Schechinger, of EWG, in her Sept. 7 analysis, “Crop insurance costs soar over time, reaching a record high in 2022.”

“Congress could pass multiple reforms to help: reduce subsidies to crop insurance agents; decrease underwriting gains paid to crop insurance companies; lower premium subsidies on highrisk land to reflect the risks that farmers are taking; improve transparency of crop insurance subsidies, in alignment with more-transparent farm subsidy programs; require a means test to qualify for crop insurance premium subsidies, like farm subsidy programs have; create a cap on how much money in premium subsidies farmers can receive.”

FARMLAND?

Brokerage Land Auctions

Management

Land Pro LLC

brokerage marketing system attracts serious, qualified buyers to

sale,

auction

exclusive listing. Our specialized expertise ultimately maximizes your property’s sale price. Visit landprollc.us to find out if your property is suited for an auction or a traditional exclusive listing! Chip Johnston licensed IL Real Estate Managing Broker 815.866.6161 farms1@comcast.net based in Princeton, Illinois Land Pro LLC Ray L. Brownfield ALC AFM Designated Managing Broker 2681 US Hwy 34 Oswego, IL 60543 www.landprollc.us concentrating in West and North Central Illinois a full service Land Real Estate Brokerage Company 14 Winter 2024

Thinking of Selling

Land

Farm

Land Consulting The

land

every

regardless of whether it is an

or traditional

Over 140 years of farming innovation 1501 1st Avenue • Mendota 815-539-9371 HCCINC.COM Frank McConville McConville Insurance Agency Mendota & Tonica, IL 815-539-9714 815-866-9715 Linda Dose Dose Agency Oglesby, IL 815-883-8616 Neal Hodges Hartauer Insurance Agency LaSalle, IL 815-223-1795 Carly Gonet Hartauer Insurance Agency Granville, IL 815-339-2411 Visit us online at www.perumutual.com Call an agent today! PERU WALTHAM SERVING YOUR HOME & FARM INSURANCE NEEDS SINCE 1878 SM-PR2137625 (888) 426- 6733 | COMPEER .COM COMMITTED TO YOU.

AdamKing NateEdlefson

•AgriculturalFinancing • CropInsurance •Appraisals SM-PR2131469 SM-PR2137634 Cultivate Success with river Valley Cooperative WWW.RIVERVALLEYCOOP.COM | 1-866-962-7820 Ag Mag 15

Dan Legner MyronRumbold

Farm bill outlook uncertain

ARC, PLC, EQIP programs benefit from extension

By MARTHA BLUM mblum@shawmedia com

DEKALB, Ill. — Since the U.S. Congress extended the 2018 farm bill for 2024, farmers will have the option to enroll their base acres in either the Agriculture Risk Coverage or Price Loss Coverage programs for the upcoming growing season.

“ARC is a revenue program, with a five-year look-back and it uses the Olympic moving average of prices and yields,” said Jonathan Coppess, associate professor and director of the Gardner Agriculture Policy Program in the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences at the University of Illinois.

“It drops the high and low, so it moves up slowly and adjusts downward slowly to smooth out some of the volatility to get to the revenue benchmark,” said Coppess during a presentation at the Illinois Farm Economic Summit, hosted by farmdoc and U of I Extension.

“Your guarantee is 86% of that, so if actual revenue in the crop year is below 86%, that triggers a payment on the difference,” he said.

“The revenue has been really high the last couple of years, so that should pull it up some and carry through for a few years.”

PLC is a fixed-price program.

“It is going on 50 years in operation in one form or another,” Coppess said. “It’s built around the statutory reference price, which is $3.70 for corn, $8.40 for soybeans and $5.50 for wheat.” In the 2018 farm bill, the

U of I associate professor said, Congress added a provision that affects the reference price.

“It uses the five-year moving average, drop the high and low, and if 85% of that is above the statutory reference price, we can increase the statutory reference price automatically,” Coppess said.

“Now that we’ve had a couple of years of high prices, we’re pulling it up and in 2024 it should be $4.01 for corn, $9.26 for soybeans and wheat will still be $5.50,” he said.

For the conservation programs in the farm bill, Congress authorizes fixed amounts of funding.

“It is about $2 billion for the Environmental Quality Incentives Program and $1 billion for the Conservation Stewardship Program,” Coppess said.

“We’re seeing more demand for these programs than funding available,” he said. “In Illinois, about 40% of projects approved are not able to be funded for EQIP.”

For the Conservation Reserve Program, farmers receive annual rental payments to take acres out of production.

“The program is limited on acres so only 27 million acres can be enrolled,” the associate professor said.

Coppess provided information about the net farmer benefit of crop insurance, which equals the total indemnities paid out minus what farmers pay in.

“Farmers in Iowa, Illinois and Indiana pay more into the crop insurance program than they typically receive in indemnities,” the associate professor said.

“This plays into the policy discussion because if you make changes to the program that alters this, we can get into challenges around how it operates and what the premium cost is,” he said. “The Midwestern states have very low loss ratios in the last five years which is a measure of the performance

of the program.”

Coppess said it is unclear what to expect in a farm bill debate this year.

“My outlook is exceptionally cloudy,” he said. “It doesn’t look good in 2024 because there are three fundamental problems in the way of getting a farm bill completed in this Congress.”

The first problem is the reference prices for corn and soybeans.

“They are already going to automatically increase for 2024 and for wheat will likely increase next year,” Coppess said.

“One of the major hurdles of getting a farm bill done has been a demand that Congress increase the statutory reference price,” he said.

However, under budget law, Congress can’t increase the statutory reference price.

“Any change to the statute has to be scored by the Congressional Budget Office against the existing projection for spending, otherwise known as the baseline,” Coppess said. “That cost projection is over 10 years into the unknown future.”

Depending on how much the reference prices are increased, the associate professor said, that could cost from $20 billion to $50 billion over 10 years.

“The problem is that has to be offset so under budget rules you have to cut something else to cover that cost,” Coppess said.

“There are really three places you can take it — crop insurance, which is pretty much off the table,” he said. “Some are reporting that the House is looking at cutting the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or conservation spending.”

The second problem involves money for conservation and the Inflation Reduction Act.

“In 2022, Congress passed this act which is a massive piece of legislation that includes roughly $18 billion for conservation,” Coppess said. “Cutting this comes

with consequences and using it as an offset is challenging at best.

“One thing it would mean is that funding which is available for farmers now to do conservation would go away and be gambled on whether it would increase prices,” he said. “The act was passed by Democrats in Congress without a single Republican vote, so the biggest defenders are Democrats.”

“Problem No. 3 is the 118th Congress has not been the most productive and one of the reasons is it is a divided Congress,” the associate professor said. “The Republicans control the House, the Democrats control the Senate, there’s not a lot of agreement and the majorities are narrow.”

If the House Agricultural Committee cuts SNAP and conservation funding, Coppess said, it is unlikely to have any Democratic support for that bill.

“Also, that bill has no chance in the Senate, so cutting these programs to increase subsidy payments is not a strategy for success,” he said.

Coppess is not optimistic for a 2024 farm bill.

“If there is a path, the key time frame for the House Agricultural Committee is March and April in terms of getting a bill produced,” he said. “But to our public knowledge, there is no progress on getting this done.”

The CBO will reforecast all of its spending and projections sometime in April, Coppess said.

“And the Senate Agriculture Committee could get something done in May to June,” he said.

But since the election is in November, Coppess said, it is likely nothing will happen with a new farm bill from July to November.

“We’re unlikely to see progress,” he said. “The last window of opportunity is the lame-duck (session) after the election, but it’s incredibly hard to see the farm bill getting done this year.”

16 Winter 2024

Coppess

To Find an Agent NEAR YOU Log on to www.bradfordmutual.com or Call 815-456-2334 Member Owned and Operated Since 1869 “154 Years of Neighbors Helping Neighbors” HELPING FIND SOLUTIONS FOR YOUR FARM INSURANCE NEEDS 245 Backbone Road East Princeton, IL 61356 815.875.4404 1701 4th St., Suite 200 Peru, IL 61354 815.223.7923 Find out more at: DIMONDBROS.COM ������� F��� ��������� F�� ���� F��� ��������� ����� CALEB DICKENS 815.875.4404 Ext. 1613 caleb.dickens@dimondbros.com PETE MANGOLD 815.875.4404 Ext. 1808 pete.mangold@dimondbros.com | DIMONDBROS.COM Find out more at: ������� F��� ��������� F�� ���� F��� ��������� ����� CALEB DICKENS 815.875.4404 Ext. 1613 caleb.dickens@dimondbros.com PETE MANGOLD 815.875.4404 Ext. 1808 pete.mangold@dimondbros.com | DIMONDBROS.COM Find out more at: ������� F��� F�� ���� F��� CALEB DICKENS 815.875.4404 Ext. 1613 caleb.dickens@dimondbros.com | 245 Backbone Road East | Princeton, IL 61356 | 815.875.4404 1701 4th St., Suite 200 | Peru, IL 61354 | 815.223.7923 SM-PR2137645 Hartman Statewide Buildings, Inc. Ryan Hartman13062 IL HWY 26, Princeton, IL HartmanStatewide@gmail.com HartmanStatewide.com 815.830.1975 ENDURING STRENGTH. UNCOMPROMISING VALUE. Ag Mag 17

Corn Belt Ports docks in Peoria

New office to transform use of Illinois River

By MARTHA BLUM mblum@shawmedia com

PEORIA, Ill. — Corn Belt Ports, the Heart of Illinois Regional Port District and the Illinois Waterway Ports Commission have a new office in Peoria.

“I commend all of those that brought this into fruition,” said Rita Ali, mayor of Peoria. “Ribbon cuttings make it look really easy, but there’s a lot of things that happen behind the scenes that led up to today.”

Ten counties have come together voluntarily to create a port and be federally recognized as a port, said Bob Sinkler, Corn Belt Ports executive coordinating director.

“It started at the county level and snowballed,” Sinkler said.

“This new office will transform the utilization of the

Illinois River while providing opportunities for additional resources,” Ali continued. “The purpose of the Illinois Waterway Ports Commission is to attract additional federal, state, business and nonprofit investment into our multi-modal transportation and natural infrastructure.”

Since the Corn Belt Ports initiative was established in 2019, Ali said, the Illinois Waterway has received nearly $1 billion in additional federal and state multi-modal transportation and natural infrastructure investment.

“The Corn Belt Ports handles nearly 100 million tons of freight every year and that is expected to increase year after year,” she said. “The 2022 recognition of the Illinois Waterway Ports as a Top 50 Power Port in the U.S. signifies the importance of the Corn Belt Ports to move massive freight and thereby attract additional investment.”

Community members in Peoria have recognized the

Illinois River as a valuable asset, the mayor said. “The maintenance and expansion of the waterway contributes to the economic growth from employment to transportation to recreation and it is essential our waterways are protected and we are stewards of the environment,” she said.

The work of the Corn Belt Ports brings much needed attention to the underutilized regional transportation asset of the Mississippi and Illinois rivers, said Doug House, who spoke on behalf of U.S. Rep. Eric Sorensen, the Democrat representing Illinois’ 17th Congressional District.

“This is important work and the work they have completed will have far-reaching and generational impacts both economically and environmentally,” House said.

Additional new resources will help construct the reliable river transportation system that farmers and businesses need with larger locks that are properly sized and maintained for the channels,

the congressional staff member said.

“Additionally, good-paying jobs will be created by the initial construction and improvements of the lock and dam system, as well as the operation of the ports,” House said.

“What makes Congressman Sorensen so confident in this organization’s success is no other effort in the Midwest lends itself to such a strong bipartisanship as the Corn Belt Ports initiative,” he said. “He lends his full support in their efforts to grow our economy, rehabilitate habitat and improve water quality.”

“Congressman LaHood wants to congratulate everyone who has been involved in this long process to bring this to fruition,” said Katherine Coyle, downstate director for U.S. Rep. Darin LaHood, the Republican representing Illinois’ 16th Congressional District. “What you have been able to accomplish is quite amazing.”

And, the congressional staffer noted, it is really just

18 Winter 2024

AGRINEWS PHOTO/MARTHA BLUM

The opening of the new Peoria office for Corn Belt Ports is celebrated with a ribbon cutting that included elected officials, Illinois waterway stakeholders and members of the community Along with Rita Ali, mayor of Peoria, and John Kahl, mayor of East Peoria, the ribbon was cut by Bob Sinkler (holding scissors on left), executive coordinating director of Corn Belt Ports, and Dan Silverthorn (holding scissors on right), chair of the Heart of Illinois Regional Port District Board

Sinkler

See PORTS page 20

Count on it. Lawn Care... www.exmark.com Smith SaleS & Service 1604 Peoria Street • Peru • 815-223-0132 Snow plows and parts ....get it done the easy way! SM-LA2139881 Home: 815-379-9317 • Cell: 815-303-9321 Answering Machine: 815-379-2350 Email: haroldrollo@yahoo.com www.rolloconstruction.com AGRICULTURAL • RESIDENTIAL EQUESTRIAN • COMMERCIAL Custom Buildings for All Your Storage Needs Call Now for a Free Quote SM-PR2137629 LICENSED AND BONDED FOR BROKERAGE SERVICE Serving The Ag Community Since 1983 Schoff Farm Service, Inc. Walnut, Illinois SM-PR2137640 BU IL D IT ON CE BU IL D IT RI GHT FIREPL ACES BATHROOMS EXTERIOR DOORS CABINETRY& COUNTERTOPS WINDOWS STONE, SIDING& ROOFING KITCHENS DECKING& FLOORING INTERIOR DOORS ma ze lu mber .c om Wa te r St re et , Pe ru | 81 5- 22 3- 17 42 PL AC ROOMS EX TERIOR DOORS CABI NDOWS STONE, SIDING& ROOFING ma ze lu mber .c om Wa te r St re et , Pe ru | 81 5- 22 3- 17 42 R DOORS CABINETRY& COUNTERTOPS G& KITCHENS FLOORING INTERIOR DOORS om ru | 17 42 Ag Mag 19

PORTS

FROM PAGE 18

the beginning.

“The financial resources that could potentially pour into our region to support industry and economic competitiveness is incredibly exciting,” Coyle said.

“We know how important it is to the constituents of the 16th District, especially

farmers and manufacturers that rely on our waterways to get their goods to market,” she said. “It is essential for economic competitiveness here and around the world.”

“The inland marine transportation system is a critical component in our nation’s ability to remain competitive in the global economy and inland ports play a vital role in this mission and help keep connections strong between the Midwest and the rest of

the world,” said Maj. Matthew Fletcher, deputy district commander at the Rock Island District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

“The Corps’ ability to provide safe, reliable, efficient and environmentally sustainable water transportation systems for the movement of commercial goods, national security needs and recreation would not be possible without our ports,” Fletcher said.

“We appreciate the time

and effort that has gone into the development of this new facility and we’re glad to see partnerships strengthen even more between the corps, the navigation industry, the coast guard, the corn growers and the soybean association,” he said.

“We look forward to working with everyone as we continue to improve the efficiency, reliability and safety of our waterborne transportation.”

Gripp Custom Farming Corp Forging The Path To Agronomic Excellence We are committed to supporting all your agricultural needs with exceptional service. • Crop Protection & Nutrition • Fertilizers • Ground Spraying • Sweetwater Technologies • Drone Service • Fungicides • Plant Growth Regulators • Biologicals • Soil Testing www.grippcustomfarmingcorp.com www.sweetwatertechnologies.com Wyanet West 401 West Main St Wyanet IL 61379 815-454-9600 Wyanet East 121 East Main St Wyanet IL 61379 815-454-9600 Sheffield 3981 1945 North Ave Sheffield IL 61361 815-454-9600 Manlius 815-445-6951 Walnut 815-379-9295 We are dedicated to helping our customers achieve maximum success. When you meet and work with a member of the Nutrien Ag Solutions Team, we are confident you will see our strengths first-hand and “Profit from our experience.” SM-PR2138126 20 Winter 2024

that’s about the stories of your life, Imagine a bank and not just about transactions. We’re here to help you achieve the story of your life. We bring neighbors and local businesses together to help you thrive. Bank wisely to live confidently. From crop yields to bank yield, count on Heartland Bank to help cultivate your family’s legacy. Ag Lending Farmland Sales/Auctions Farm Management Farmland Appraisals 012024-C www.capitalag.com LICENSED REAL ESTATE BROKERS Farmland Auctions Real Estate Brokerage & Farm Management Call me on how I can assist with your agricultural needs Timothy A. Harris, AFM Designated Managing Broker, IL Lic. Auctioneer #441.001976, Princeton, IL 815-875-7418 timothy.a.harris@pgim.com Skid Loader, Backhoe, Wheel Loader, Dozer & Excavator Work Black Dirt and White Rock Custom Ag Applications • Concrete Recycling Phone: 309-364-3672 Fax: 309-364-2666 312 Jefferson • Henry, IL • edhartwigtrucking@frontier.com • Basements • Water Lines • Septic Systems Fully Licensed and Insured • Sewer Lines • Footings • Driveways • Roll-Off Containers • Building Demolition • Free Estimates SM-PR2137626 Ag Mag 21

Brazil’s share of global soybean market grows

Competition impacts U.S. trade exports

By TOM C. DORAN tdoran@shawmedia com

WASHINGTON — Brazil’s record high soybean production, depreciating currency and an expected boost in exporting capabilities through expanding transportation infrastructure will have important implications for U.S. international agricultural markets.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service issued a report last month on soybean production, marketing costs and export competitiveness in Brazil and the United States.

The United States was the world’s largest soybean exporter until the 2012-2013

marketing year when Brazil exported more soybeans than the United States. Since then, Brazil’s share of the global soybean trade has increased.

“Projections indicate that the Brazilian share of global soybean trade could increase from 51.6% to 60.6% between marketing years 2021-2022 and 2032-2033. Soybeans are Brazil’s main agricultural commodity export by volume, and the country exports more than 60% of the soybeans it grows,” the report stated.

“The international market is of great importance to the U.S. agricultural economy, with soybean exports accounting for 48% of total production.

“Brazil and the U.S. are major export competitors; thus, a comparison of their production costs will help infer how changes to factors underlying production, marketing costs and infrastructure affect their export competitiveness.”

Many aspects of the inter -

national trade dynamics of the soybean sector are rapidly changing. Some of these include changes in global demand, local currency fluctuations, transportation costs and input availability.

Brazil’s recent expansion of soybean shipments during September to December and recent disruptions to fertilizer imports that were exacerbated by Russia’s war against Ukraine also play a role.

Findings of the study describe many of the factors that affect production, marketing costs and export competitiveness of the world’s leading soybean exporters — the United States and Brazil.

The study compares the differences between farm-level production costs and returns for soybeans in the United States and Brazil from 20172018 through 2021-2022 for the most productive growing regions in each country.

With respect to production

AP PHOTO

Soybeans grow at the Passatempo farm in Sidrolandia, Mato Grosso do Sul state, Brazil

22 Winter 2024

costs, returns and competitiveness, the study finds:

• Costs of production differed between the United States and Brazil, partially reflecting Brazil’s greater reliance on custom services to provide equipment and labor for crop field operations as opposed to farm ownership of machinery in the United States. Land costs were also higher in the United States.

• Overall, allocated overhead costs — hired labor, opportunity cost of unpaid labor, capital recovery of machinery and equipment, opportunity cost of land, taxes and insurance, general farm overhead — were lower in Brazil at $155.12 per acre than in the United States at $337.72.

• Total costs per bushel of soybeans in the United States exceeded total costs per bushel of soybeans in Brazil in 2021-2022 by a $9.85 to $8.67 margin. The U.S. heartland average was $9.18 per bushel.

• Average national farmlevel production costs per acre for soybeans in Brazil at $425.97 were 19.9% below the United States at $531.67 in 2021-2022, largely because of lower land and capital costs. The United States had higher yields per acre than Brazil in the regions included in the study, particularly in the U.S. heartland region, which helped offset the higher per acre costs.

• Brazilian producers had higher national average returns per bushel over total costs than the United States in 2021-2022, $4.05 compared with $2.13.

• The U.S. heartland was the lowest-cost exporter of soy -

beans to Shanghai, China, at $463 per metric ton. Paraná in Brazil was the next lowest-cost exporter to China, at $469 per ton, primarily due to its location close to a port and low internal transport costs. The Brazilian state of Mato Grosso is competitive with the United States in the export of soybeans at $487 per metric ton to China from its traditional Santos port in the southern region despite higher inland transport costs due to lower soybean costs of production. Export costs to Shanghai via Brazil’s Santarém port from northern Mato Grosso is $462 per metric ton.

• Improvements in Brazil’s overland transportation infrastructure over the past decade resulted in cost savings per metric ton for exporting soybeans from the main producing state, Mato Grosso, through southern ports. Average inland transport costs in 2017-2018 through 2021-2022 decreased to $77 per metric ton, compared with $98 per metric ton in 2008-2009 to 2012-2013.

• Overland transportation improvements in central Brazil to provide access to the northern ports lowered truck rates, resulting in cost savings of $28 per metric ton, further improving Brazil’s Mato Grosso’s competitive position.

STUDY METHODOLOGY

To assess the relative competitiveness of Brazil and the United States in the global export market, this study compares farm-level production costs, as well as the cost of internal transportation and shipping costs, to a common

export destination, Shanghai in China. Soybean production costs are estimated on the costs per planted acre and the costs per bushel. The soybean cost accounts are divided into operating costs and allocated overhead costs.

Costs are compared at the national and regional levels for the most productive soybean growing region in each country: the U.S. heartland and Brazil’s Mato Grosso state, the largest soybean producer in Brazil since 2000.

For Brazil, the State of Paraná is also included to evaluate inland transportation costs for soybeans exported through southern ports.

To make the comparison less sensitive to annual price and yield variations, perbushel costs and returns are compared using five-year average prices and yields.

Brazil’s cost structures were converted to U.S. dollars using yearly changes of real, adjusted for inflation, exchange rates.

USDA ERS commodity costs and returns data was used for this study. Costs reflect those incurred through harvest and the prices are the harvest month price received for that marketing year.

The heartland region comprises parts or all of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio and South Dakota.

The five-year average cost per bushel is based on production costs for 2021-2022 and average yields and prices for 2017-2018 through 20212022.

Tonica - 815-442-8211 • Oglesby - 815-883-8400 • Lostant - 815-368-3333 illinistatebank.com Let us evaluate your current rates to see if we can help you save. Contact Dan or Alan at Illini State Bank today! Is Your Ag Line of Credit Costing YOU? Member FDIC SM-LA2136193 LandGuys, LLC of Illinois (481.013889) dba LandGuys 4331 Conestoga Dr., Springfield, IL 62711 LandGuys is licensed in IL, IA, WI & TN ©2024 LandGuys, LLC 4331 Conestoga Dr., Springfield, IL 62711 217.899.1240 LG00586 NATHAN CUMPTON Land Broker & Realtor® 815.878.6780 nathan@landguys.com FARMLAND | HUNTING | RURAL HOMES FERTILE OPPORTUNITIES CONNECTING BUYERS + SELLERS to Ag Mag 23

Steve

Craig Moritz, Dan Knight, & Diane Hamilton

With our industry knowledge, experience in the field, and years of working together as a team, our goal is to build alliances with new customers, as well as continue serving customers who have come to know our team over the past two decades. For all your crop protection needs, contact the team you can trust at R Alliance Ag Supply –located in Toluca, IL – right where we got our start in 2003.

serving the midwest by providing the best priced pesticides for you and your crop protection needs. We pride ourselves on family, service, and commitment to our customer base. As your allies in crop protection, we hope to build an alliance with you!

Steve Reichman

steve@rallianceag.com

Matthew Modro

matthew@rallianceag.com

P: 815-257-2011

Sydney Reichman

sydney@rallianceag.com P: 309-361-7888

Dan

Diane

Tyler Williams tyler@rallianceag.com

815-993-8260

SM-LA2137703

are back

TOP PRODUCTS VISIT US AT LOCATION! 650 State Route 117 Toluca, IL 61369 FOLLOW US ONLINE! www.rallianceag.com @rallianceag@rallianceag NEW NAME ~ SAME GOALS | WITH A TEAM YOU CAN TRUST COMING Phone: 815-800-0024 Contact Our Team: Customer Service Matthew Modro matthew@rallianceag.com P: 815-257-2011 Diane Hamilton diane@rallianceag.com P: 815-257-8789 Sales Team Steve Reichman steve@rallianceag.com P: 309-361-4050 Craig Moritz craig@rallianceag.com P: 309-303-1651 Dan Knight dan@rallianceag.com P: 309-830-4938 REQUEST A QUOTE! Go online at www.rallianceag.com or Scan this Code: GENERIC and BRAND NAME HERBICIDES, FUNGICIDES, INSECTICIDES & ADJUVANTS 650 State Route 117 | Toluca, IL | 815-800-0024 rallianceag.com

Reichman,

SALES TEAM

Moritz

P:

P: 309-361-4050 Craig

craig@rallianceag.com

309-303-1651

Knight

P:

Contact our Team: CUSTOMER SERVICE

dan@rallianceag.com

309-830-4938

Hamilton diane@rallianceag.com P: 815-257-8789

P:

@rallianceag @rallianceag 24 Winter 2024