SHARMIN YEZDI BHAGWAGAR

SELECTED WORKS

Yale School of Architecture, M.Arch II

Academy of Architecture, B.Arch

2009-2019

p.7 Between Land, Dust and Skies | Marfa, Texas | Spring 2019

Lost Paradise | Playa Grande, Costa Rica | Fall 2018

Easy Office | Culver City, Los Angeles | Spring 2018

Monumental Waste | Fresh Kills, Staten Island | Fall 2017

Cinema Beyond Borders | Film City, Mumbai | Spring 2014

Nostalgia| Hughes Road, Mumbai | Summer 2014

The Potter’s Retreat | Vasai, Mumbai | Fall 2013

The Mount Bungalow | Little Gibbs Road, Mumbai | Summer 2014

Professional Work | 2014-2017

Words, Images, Objects and more

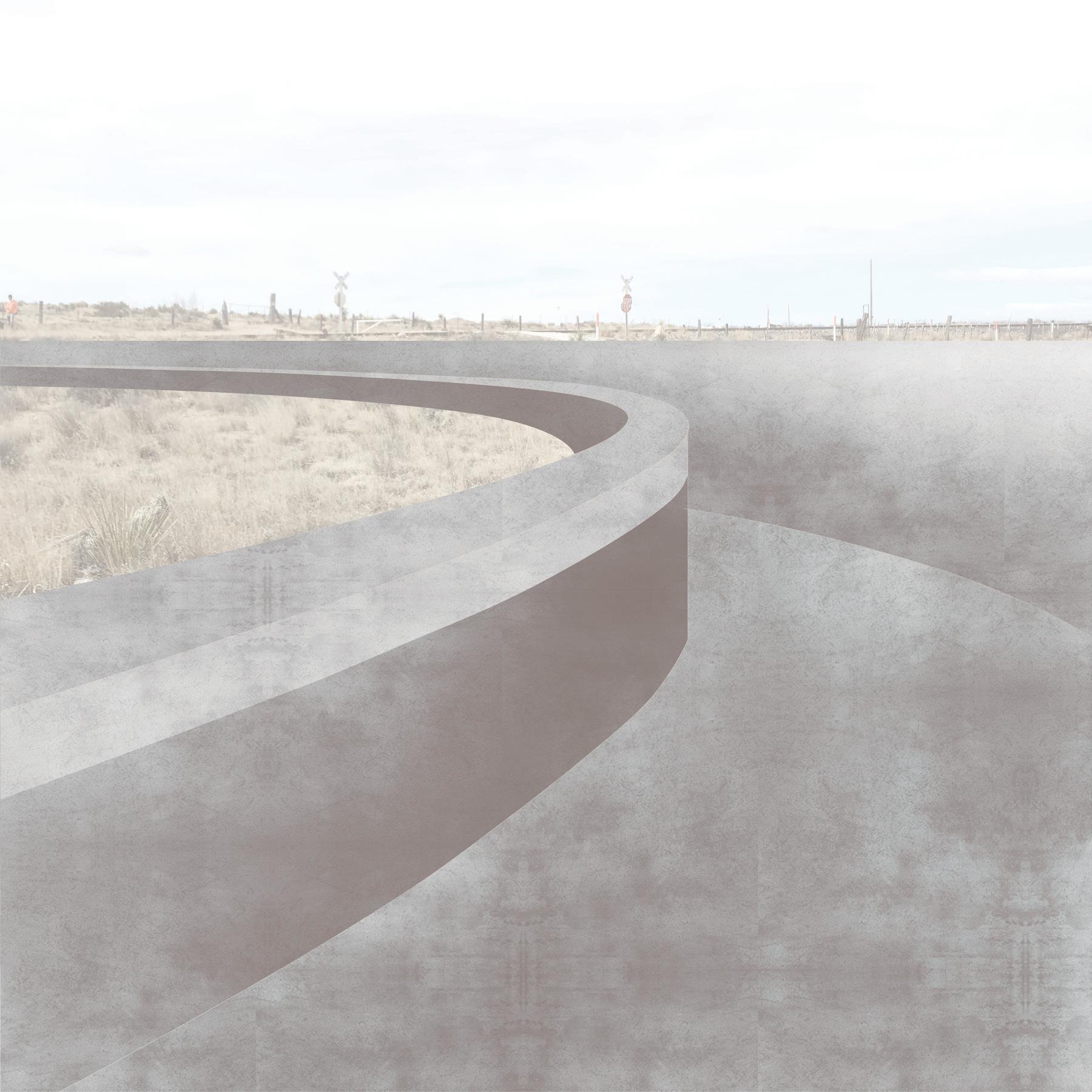

Between Land, Dust and Skies

Thomas Phifer with Kyle Dugdale

Yale School of Architecture

Spring 2019

The absence of descriptive or obvious stylistic embellishment creates an aesthetic so spare that it is, at times, almost aggressive.

Karen Stein, “The Plain Beauty of Well-Made Things”

In January 1972 the artist Donald Judd moved to the “utter isolation” of Marfa, Texas, to escape the growing commercialism of the New York City art scene. It was in Marfa, surrounded by the open desert landscape, that he sought to build a world for himself, for his family, and for his work; while simultaneously maintaining a property on Spring Street in SoHo, putting Marfa on the international art map. No longer a place where “only 10 visitors might drift in annually,” by 2016 the number of visitors had risen to 40,000, such that Marfa is now “popularly perceived as an outpost of Manhattan in Far West Texas” (Josh Franco).

The project aims to propose a more immersive experience of Marfa than is currently afforded. The two components: a point of arrival and individual sleeping accommodations are located in two different locations; the point of arrival being in the town and the residences in the desert. The governing intent is to permit an experience of Marfa that engages as directly as possible both with the nature of the place - landscape, material, light, climate, and history - and with the specific concerns of Judd’s work. By eschewing any preconceived notions about Marfa that come with the imagery of Marfa available to us today, the project addresses the elements of Marfa which create a true sense of place; its vast landscape, its walls and streets, its dust, and its skies.

In an attempt to maintain the horizontality of Marfa’s landscapes, the point of arrival carefully aligns with and orders itself around the rules created by the existing urban fabric whereas the residences slowly descend into the ground in the desert. This allows for a truly immersive experience where the visitor comes in touch with these raw elements which make Marfa the strange yet beautiful town it is known as today.

Between Land, Dust and Skies

Thomas Phifer with Kyle Dugdale

Yale School of Architecture

Spring 2019

The absence of descriptive or obvious stylistic embellishment creates an aesthetic so spare that it is, at times, almost aggressive.

Karen Stein, “The Plain Beauty of Well-Made Things”

In January 1972 the artist Donald Judd moved to the “utter isolation” of Marfa, Texas, to escape the growing commercialism of the New York City art scene. It was in Marfa, surrounded by the open desert landscape, that he sought to build a world for himself, for his family, and for his work; while simultaneously maintaining a property on Spring Street in SoHo, putting Marfa on the international art map. No longer a place where “only 10 visitors might drift in annually,” by 2016 the number of visitors had risen to 40,000, such that Marfa is now “popularly perceived as an outpost of Manhattan in Far West Texas” (Josh Franco).

The project aims to propose a more immersive experience of Marfa than is currently afforded. The two components: a point of arrival and individual sleeping accommodations are located in two different locations; the point of arrival being in the town and the residences in the desert. The governing intent is to permit an experience of Marfa that engages as directly as possible both with the nature of the place - landscape, material, light, climate, and history - and with the specific concerns of Judd’s work. By eschewing any preconceived notions about Marfa that come with the imagery of Marfa available to us today, the project addresses the elements of Marfa which create a true sense of place; its vast landscape, its walls and streets, its dust, and its skies.

In an attempt to maintain the horizontality of Marfa’s landscapes, the point of arrival carefully aligns with and orders itself around the rules created by the existing urban fabric whereas the residences slowly descend into the ground in the desert. This allows for a truly immersive experience where the visitor comes in touch with these raw elements which make Marfa the strange yet beautiful town it is known as today.

Between Land, Dust and Skies

Introverted courtyards and play in ground level segregate the public spaces

Yale School of Architecture

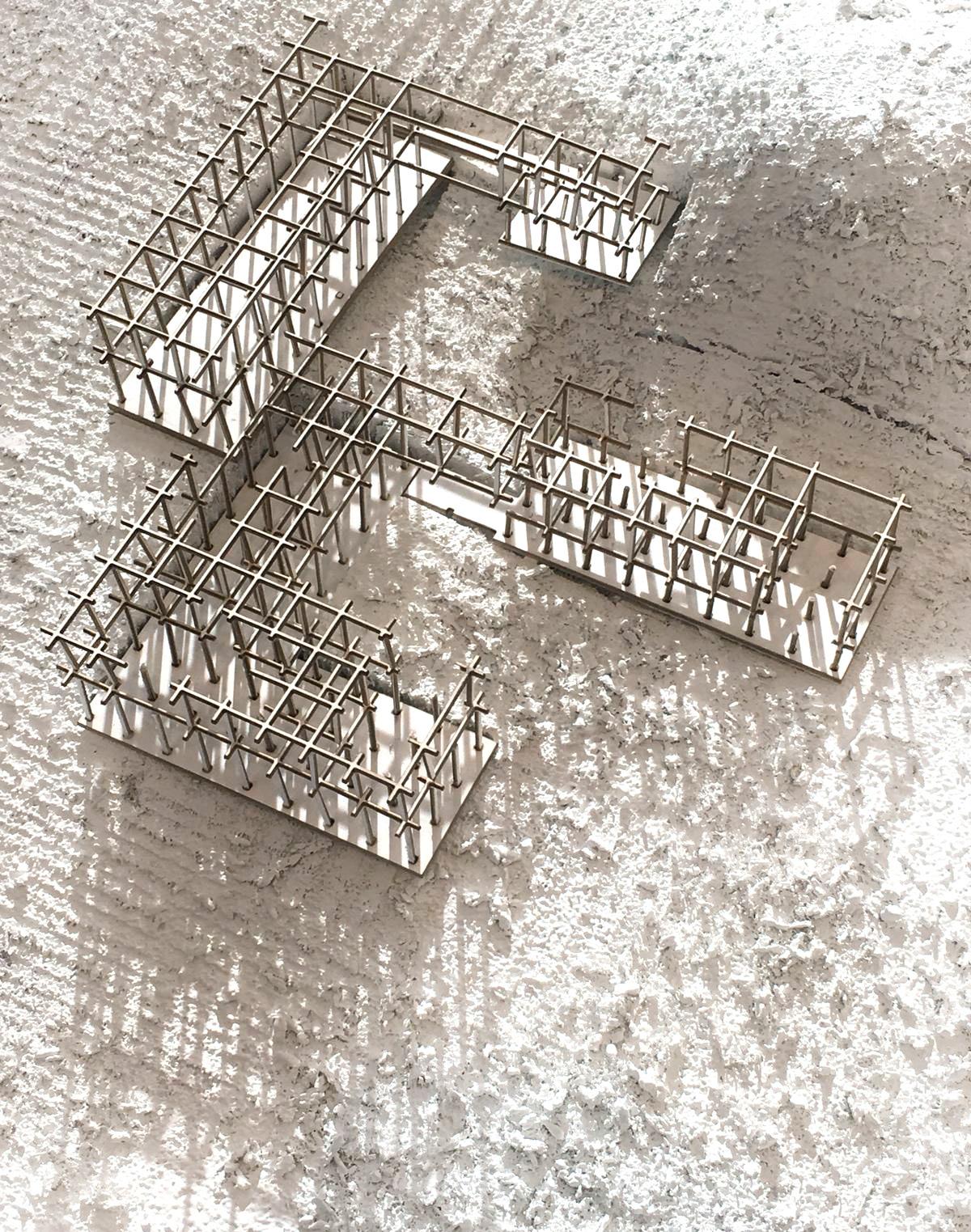

Between Land, Dust and Skies Site Plan - Residences

Yale School of Architecture

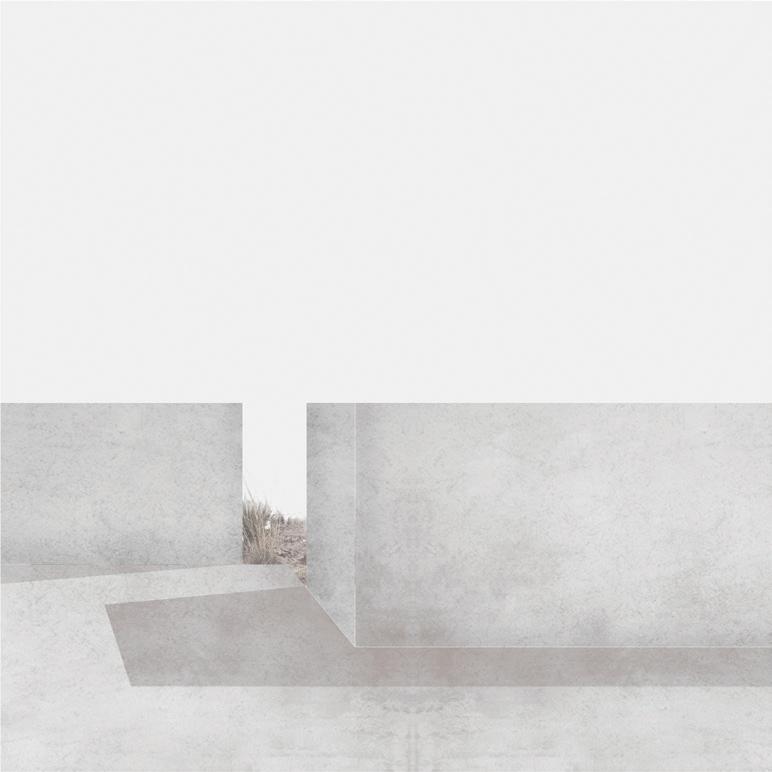

Between Land, Dust and Skies

Section through residences in the desert

Yale School of Architecture

Between Land, Dust and Skies

Yale School of Architecture

Sequence of experiences from landscape to living room

Between Land, Dust and Skies

through individual residential unit

Lost Paradise

Julie Snow with Surry Schlabs

Yale School of Architecture

Fall 2018

Nominated for H.I.Feldman Award, 2019 | Published in Retrospecta 42

At present, site is frequently seen as a synchronic phenomenon, irrevocably divorced from other times. The history of a setting is acknowledged only insofar as the forces acting upon it have affected its present visible form.

Carol Burns, “On Site”

Working with the Leatherback Trust Organization to design a marine biology station Playa Grande, Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica, the project explores new opportunities for architectural performance within social, cultural, political and environmental context. A gift of a 14 hectare site in Playa Grande to The Leatherback Trust offers an opportunity to move the existing station from protected public land at the beach. The new site has been previously grazed, resulting in an eroded grassland condition that is partially in an estuarial watershed. Guanacaste province is a dry tropical forest making water a precious resource and a principal deterrent to occupation of the site.

Since the 1950s, approximately 60% of Costa Rica’s forests have been cleared to make room for cattle ranching and other agricultural practices. In the 1990s the country’s commendable efforts to shift the economy from agriculture to eco-tourism has led to a vast decline in deforestation. Nevertheless eco-tourism is viewed as a rather unstable primary source of income. Murren Reserve is a site of deforestation and has been undergoing natural regeneration for the past 10 years. The project aims to combine an agroforestry research centre with residential units for researchers. The built volumes enclosing private spaces such as labs and residences are held in place by a permanent wood scaffolding. The scaffolding allows for flexible arrangements of agroforestry test plots also serving as containers for public spaces. The integration of agriculture and forestry allows Murren Reserve to be used as a protoype and site for the investigation of a sustainable source of income for the locals at Playa Grande.

Yale School of Architecture

The project is experienced as a series of follies in the landscape connected by trails and outdoor furniture

Yale School of Architecture

The residential zone is split into two levels and follows the natural topography

The agroforestry test plots serve as a central spine and penetrate through public spaces such as the community kitchen

Yale School of Architecture

Section through the residential units

Section through the community kitchen, labs and other amenities

Yale School of Architecture

Yale School of Architecture

Detail Model; Scale 1:50

Detail Model; Scale 1:50

Yale School of Architecture

Detail Model; Scale 1:50

Model; Scale 1:50

Yale School of Architecture

Community Kitchen with the wooden scaffolding as armature for storage and circulation of plant and human life

Yale School of Architecture

Sterile wet laboratories and other private spaces remain raised from the ground where agroforestry may be practiced

Easy Office

Florencia Pita, Jackilin Bloom with Miroslava Brooks Yale School of Architecture

Spring 2018

“What is so remarkable is the near total disengagement from signification of any kind. Such a condition is immensely difficult to achieve; mere abstraction does not begin to approach it.”

Robin Evans, 1984.

In the documentary Brillo Box (3¢ Off), when Andy Warhol is asked why he turned a common Brillo box into sculpture, he casually responded, “because it’s easy to do.” He may have been referring to the ease in the ability to quickly make many screen printed boxes, but it’s safe to assume that Warhol was referring to how an everyday consumer item is replicated, compositionally stacked and is easily appropriated as art. Appropriation yields irony which is easily interpreted, but is paradoxically difficult to attain without an alignment of particular social, economic and cultural forces at play. Architecture today struggles to produce easiness. While on the one hand it is operatively easy to make new architectural forms, complex geometries, and provocative representations, producing visual immediacy that simultaneously allows for unexpected readings and interpretations is difficult to realize. As a broader disciplinary discussion, the project aims to engage the topic of “easy” and “difficult.”

“Easy Office” is the design of an office space in Culver City, an area of Los Angeles that has transformed from a light industrial zone to one that is populated with creative office spaces. The studio intends to explore the formal agenda of building instances of interior office conditions. After researching the history of the office space from the pre-technological to the hyper technological office; the studio engaged in understanding spatial and programmatic organization through figural geometries and unexpected material articulation. Programmatically the office space is viewed as an open landscape of follies/individual clusters, each having its own unique identity, yet retaining certain memories of the original warehouse. As the organization begins to expand the boundary porosity increases and eventually the boundary ceases to exist and the only memory of the original warehouse remains in the materiality of these clusters. The project culminated into an abstract model expressing these diverse spatial conditions in a state of transition, frozen in time.

Yale School of Architecture

Yale School of Architecture

Yale School of Architecture

Yale School of Architecture

Unfolded Elevation and plan indicating the gradual disintegration of the warehouse

Drawing indicating the gradual disintegration of the warehouse

Monumental Waste

Joel Sanders, Leslie Gill and Mike Jacobs with Minakshi Mohanta

Yale School of Architecture

Fall 2017

Published in Retrospecta 41

“The church is no more religion than the masonry of the aqueduct is the water that flows through it.”

Henry Ward Beecher

Fresh Kills was once the largest landfill in the world until its closure in 2001. Since then, the landscape has been engineered with layers of soil and infrastructure, and the area has become a place for wildlife, recreation, science, education, and art. In keeping with the historical context of Freshkills the project aims to combine a Material Recovery Facility and Art Hub with the proposed ferry terminal connecting Staten Island to New York City.

The Ferry Terminal and Art/ Research Facilities are integrated with the Material Recovery Facility as a spectacle for arriving visitors. The linear form connects Freshkills Creek to the level of the road and the programmatic requirements of the recovery facility are carefully woven into the built volume creating moments of pause and reflection as one traverses from the terminal to the road.

The project aims to challenge preconceived notions about infrastructure as that which is outside the realm of architecture, or as that which “serves” architecture. Using the material recovery facility as not only a spectacle to be displayed but also as a guide for programmatic organization and circulation pathways, the project critiques the fact that waste recovery facilities are usually considered urban externalities. Carefully integrating art exhibition spaces and education centers between networks of conveyor belts and storage containers allows a more intimate experience of these vital facilities that enable life in the city.

Yale School of Architecture

Celebrating Fresh Kills history as a landfill

Use and Reuse of materials recovered from the facility

Telescopic columns allowing flexibility due to the flood risk

Connecting Staten Island to the Fresh Kills Ferry terminal

Establishing the stratum for connectivity

Volume of the Material Recovery Facility

Extension of the existing topography of Fresh Kills Park

Introduction of the Material Recovery services

Part erosion of the built form as public landscape

Exploded isometric drawing indicating the flow of material and people between the terminal and the city

Visitors are encouraged to engage with the processes of material extraction along the journey

Yale School of Architecture

Fenestration in the exhibition spaces oriented towards the infrastructure

Cinema Beyond Borders

Shashank Ninawe Academy of Architecture

Spring 2014

Nominated for the Charles Correa Gold Medal + Economic Times Design Summit

“The Festival is an apolitical no-man’s land, a microcosm showing what the world could be if people would communicate directly with one another and speak the same language.”

Jean Cocteau

The cathartic property of celluloid, which allows spectators to explore the uncharted territories of human imagination, occasionally untrammeled by convention and custom, as well as address realistic issues that society tackles or has done so in the past, is what makes cinema so prestigious.

The project aims to explore the relationship between filmic sequencing of events and architectural spaces. Inspired by Tschumi’s Screenplays, 1976, the project follows a sequence of events which create the architectural spatial configurations and uses transformational devices to affect the following sequences. Linear circulation pathways are conflicted with alternate parallel narratives connecting existing buildings and use light and material to inform spatial hierarchy. The existing stream and museum create the “site” of these events and the project is purely a circulation pathway connecting these various sites and engaging with the existing context in playful ways.

Programmatically, the proposal is a center for film festivals, dedicated to preserving Indian film culture, promoting young film makers, and allowing Indians to imbibe world cinema. A film archive, a cine-plex, as well as a performance hall is envisaged as a part of the center. Parking is partially converted into a Drive-In cinema in order to revive the Drive - In culture, once prominent in Mumbai.

Site topography Academy of Architecture

Existing hydrological networks

Existing circulation networks

Existing buildings in Film City

Plan indicating conflicting circulation pathways and programmatic sequencing Academy of Architecture

Section along the transverse axis connecting the museum to the auditoria complex

Proposal

2014

“I think that architecture is gone. It’s a very interesting question whether it is gone forever or whether under certain circumstances we can imagine that it will come back. In any case, it is gone for now.”

Rem Koolhaas, 2009, Paul S.Byard Memorial Lecture

Historically, each new preservation law has moved the date for considering preservationworthy architecture closer to the present (Source: Preservation is Overtaking Us, OMA). For Mumbai city, preservation has been a harsh battle with a few survivors. The project intends to explore the meaning of preservation in a city where there is no space for affordable housing, education centres or medical facilities. Mumbai has been victim to development control regulations which are monolithic laws governing the building industry, slowly ruining its urban fabric.

Quietly nestled in the bustling heart of Mumbai, lies a sprawling 4500 square meter complex, belonging to the British Colonial era of Mumbai. The Framjee Dinshaw Petit Parsi Sanitorium lay silently, barren and dormant, immune to the rapid growth and chaos around it. Like an oasis, unaffected by its surroundings, it remains to be one of the last few remnants of virgin heritage architecture in Cumballa Hill which we must struggle to preserve. The proposal involved refurbishing the existing building in order to use it as an exhibition and design center. The extension wing would comprise of an Auditorium and a restaurant intended to compliment the Exhibition Centre. The challenge was to accommodate an inward looking space in the courtyard, half of which has been subject to litigation for over a decade. By allowing for a change in the ground level, the basement becomes the inward looking space, and is directed towards the existing building as a backdrop. Maintaining the symmetry of the existing building and keeping the intervention as simple yet effective as possible was the key to the success of this proposal.

Existing condition of the building and proposed minimal interventions

“We are living in an incredibly exciting and slightly absurd moment, namely that preservation is overtaking us. Maybe we can be the first to actually experience the moment that preservation is no longer a retroactive activity but becomes a prospective activity.”

- Rem Koolhaas, 2009

Plan indicating areas requiring structural and programmatic interventions

Lowering the level of the courtyard level to avoid interference with the neighbouring property

The Potter’s Retreat

Prateek Bannerji

Academy of Architecture Fall 2013

“I look at a tree and the tree doesn’t tell me anything. The tree does not have a message; The tree does not want to sell me something. The tree won’t say to me - ‘look at me, I am so beautiful, I am more beautiful than the other trees.’ It’s just a tree - and it’s beautiful. Nothing special - incredibly powerful.”

Peter Zumthor, 2013, Presence in Architecture - Seven Personal Observations

The project began with an exploration of materiality and its relationship to site. Local stone and bamboo were chosen as materials and the form slowly evolved from a dialogue between the two materials. A careful understanding of the local weather conditions led to a simple square courtyard layout. A porous bamboo exterior wraps itself around the heavy stone interior providing shade and a lower interior temperature. The natural waterbody is enclosed in the building and is used as a central feature in the design. Light, trees and water are the primary focus of this immersive experience.

The goal of the project was to design a program for the local artisans of Vasai-Virar , a historical suburban town located 40km North of Mumbai city. Originally, a very important trading center, Vasai-Virar had a predominantly agrarian society. Vasai Virar has been changing rapidly due to a large influx of people in the early 80s leading to affordable housing complexes, schools and hospitals.

Traditional handicrafts from agricultural waste is a dwindling practice among the local farmers of Virar today. Rice, betel, sugar cane are few among the crops grown here. The goal of the program was to encourage indigenous art forms practiced by farmers’ wives and to generate additional income for the locals by allowing foreign artists to visit and stay in the Artist’s Village.

Conceptual diagrams indicating enclosure of the vernal pool and boundary porosity

Artist studios are located on the lower level and exhibition spaces overlook them

The Mount Bungalow

Independent Proposal

Summer 2014

“What we seek, at the deepest level, is inwardly to resemble rather than physically to possess, the objects and places that touch us through their beauty.”

Alain de Botton, The Architecture of Happiness

The city of Mumbai has undergone rapid changes in the past few decades. From simple low lying buildings to high rises attracting the city’s affluent, Mumbai’s residential architecture today strives for more amenities, more gated communities and more program. South Mumbai particularly suffers from this epidemic. Being the financial hub of the city, living in this location is considered a sign of wealth and social status.

Nestled in the heart of South Bombay, this narrow plot is situated on Little Gibbs Road, surrounded by the only surviving forest of South Bombay. The bungalow is meant to house two related families. The clients expressed a desire to design two separate but interconnected units for each of the families. Contrary to developing it into a high rise with more amenities the clients sought to build a smaller footprint than usual, with multipurpose spaces for flexibility.

Since the site is on a Hilly Region a double height living room overlooking the hills and the forest is envisaged. A garden has been provided on the upper levels over looking the hills to filter the harsh South Light and to enjoy proximity to nature. The site constraints allowed for only a certain amount of horizontality. A smaller footprint, but taller structure also allowed for the individual units to function as separate homes; with connecting common spaces and gardens overlooking each other. The double height spaces include the living rooms and the garden terraces and the single height spaces include the bedrooms and the libraries. The clients wished that this little oasis be as compact in layout and simple in its appearance.

Terrace Level Plan

Apartment 2 : 2nd Level Plan

Apartment 2 : 1st Level Plan

Apartment 1 : 2nd Level Plan

Apartment 1 : 1st Level Plan

Stilt Level Plan

Basement Level Plan

Individual Floor Level Plans

“Architecture, even at its most accomplished, will only ever constitute a small, and imperfect (expensive, prone to destruction, and morally unreliable), protest against the state of things. More awkwardly still, architecture asks us to imagine that happiness might often have an unostentatious, unheroic character to it, that it might be found in a run of old floorboards or in a wash of morning light over a plaster wall—in undramatic, frangible scenes of beauty that move us because we are aware of the darker backdrop against which they are set.”

- Alain de Botton, The Architecture of Happiness

Professional Work

Single Level Family Residences

Basement Level 01 - Under Construction

Level 16 - Under Construction

Basement - Swimming Pool + Compound Wall - as constructed

Threshold between indoor and outdoor space - as constructed

between indoor and outdoor space - Plan

Drawings and Details

Drawings and Details

Words,

Images, Objects and More

Anarchitecture

Edited with Tayyaba Anwar

Yale Paprika! 4; Issue 02

Published on September 20, 2018

Anarchy: a state of disorder due to absence or non-recognition of authority or other controlling systems.

(Oxford.)

Following similar concepts, the notion of “Anarchitecture,” introduced by Gordon Matta-Clark, is one that remains politically, socially, and theoretically challenging. In the times of global political flux, it seems obvious that one would hope to indulge in ideas that explore tensions and conflicts that are an integral part of the current built environment. With that in mind, we invited our contributors to articulate their perspective on the contemporary spaces of “Anarchitecture.”

While provocative questions and celebration of expression lay within the very framework of Anarchy, it has become increasingly crucial to investigate architecture in terms of its relationship to the Anarchic forces that revel within it. “Is Anarchy inherent to anarchitecture?”

Amir Karimpour with Lara Al Khouli

Yale School of Architecture

Fall 2017

Traditionally the Roshan (window bay) was designed to control the flow of air into the house. Comprised of a base, screens and a crown, traditional Roshans were originally made from wood. The project aims to recontextualize a Roshan in contemporary Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

The Roshan was fabricated without any screws or nails and all wooden joints were designed to allow ease of assembly, the key idea being that these Roshans may be deconstructed as and when required.

The base was CNC milled as a fixed element, while the screens and louvers were fabricated in panels no larger than 12” x 12”. Each panel was carefully designed parametricizing traditional patterns which vary based on their orientation with respect to the sun. The louvers and screens were laser cut and raster engraved and assembled onto the supports with pivots. The crown was laser cut to resemble the original crowns as present in the Roshan.

Yale School of Architecture

Computation and Fabrication

Fabric Casting

Yale

Kevin Rotheroe

School of Architecture

Fall 2018

In this experiment, the fabric casting of concrete involved the pouring of cement into a textile mould held in place by a wooden formwork. The fabric can be manipulated, tightened or loosened, for a few minutes before hardening; allowing any adjustment if required. The formwork is also available for reuse since the wood is not damaged during the process of curing. The dialogue between what appears to be a fluid, loosely structured fabric and a heavy concrete panel inspired many possibilities for architectural deployment in Rudolph Hall due to the tactile qualities inherent in its existing structural and non-structural systems.

Yale School of Architecture

These sculptures were created with found fabrics whose back-story is embedded in the material. The process of inlaying used fabric into concrete panels creates a tension between the two characteristically opposing materials. The panels were hand sanded and certain marks were accentuated or blurred, dissoving and embedding certain moments, while revealing new qualities in the concrete panel.

Yale School of Architecture

A series of 12” x 12” thermo-formed panels were created in an attempt to maximize the potential of thermo-forming. Yet again, found objects were collected, collaged and composed on a plate. These were then thermo-formed and released leaving their impressions on the plastic. The drape and natural fillet along the seams were in some cases exaggerated creating new silhouettes around these found objects.