CREATING A VALUES-CENTERED APPROACH TO CIVICS IN YOUR SCHOOL: A PLAYBOOK

INTRODUCTION

In 2016, the contentious presidential election laid bare a concern many of us in education had been worrying about for some time: our limited ability as citizens to understand and connect with people who see the world differently than we do. As the rifts between Red and Blue have widened, we are losing a sense of the United States of America being a shared endeavor, and as we do we are also losing a sense of what even constitutes this nation of ours: as a 2018 study on civics education by the Center for American Progress notes, only 26 percent of American adults can name all three branches of government, and only 23 percent of eighth-graders performed at or above the proficient level on the National Assessment of Educational Progress Civics Exam.

At The Brandeis School of San Francisco, we asked ourselves as educators, “What can we do to better prepare our students to navigate and lead in civics and democracy?” We began by framing an aspiration in the Brandeis 2023 Strategic Plan: that “Brandeis graduates go on to be leaders in their communities and stewards of democracy.” That notion led us to undertake a variety of initiatives: creating an annual “Justice Brandeis Day” where we weave into our curriculum additional lessons on civics and democracy; partnering with Facing History to deepen our exploration of Jewish history in the United States; bringing in thought-leaders on matters of diversity and inclusion, to help us teach our students how to engage with those who are different from themselves. Ultimately, though, we saw a need for a comprehensive approach to teaching civics, democracy, and Jewish American history, which is why we sought the support of The Covenant Foundation. Because we believe a thriving democracy is critical to the long-range health of our American Jewish communities, we also believe a deep understanding of and engagement with civics and democracy should be central to the experience of a Jewish education in America. And so The Mifgash Project was born.

This playbook is intended to capture some of the learnings from the project, and to offer support to other schools who are interested in making an effort to bring valuescentered civics education into their curricula and programs.

THE שגפמ MIFGASH PROJECT

The

(Mifgash) Project (“mifgash” means “encounter” in Hebrew) is a comprehensive, multi-year curriculum development initiative aimed at integrating civic engagement with Jewish American history and ethics, specifically designed for K-8 students. The project follows four major strands, each contributing uniquely to the overall goal of fostering democratic habits, ethical thinking, and active citizenship in students.

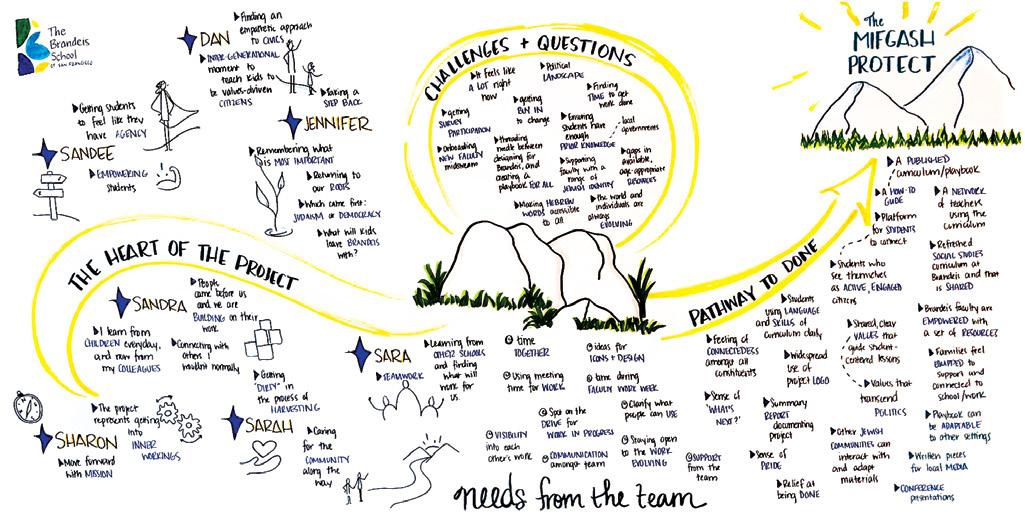

LEADERSHIP AND FACULTY DESIGN TEAMS

The project is spearheaded by Dr. Dan Glass, head of school at The Brandeis School of San Francisco, who serves as the project director. Dr. Glass works alongside a design team of eight teachers, each selected for their expertise in different grade levels and subject areas. This team plays a pivotal role in researching, developing, and piloting the curriculum (read more about that in Assemble a Team, page 6). Their work is collaborative, with regular monthly meetings, workshops, and design retreats where they share progress, reflect on challenges, and refine materials (you can read more about that in Process, page 4). The design team is divided into smaller units responsible for specific strands, with members contributing across grade levels and content areas. (You can read more about the team who worked on this project in the section titled Our Team, page 20.)

The school also collaborates with external partners such as Civic Spirit and Facing History, whose resources and expertise in civics and Jewish history enrich the project (there is a list of organizations we partnered with directly, or just admire in this space, in the Toolkit, page 18).

THE FOUR STRANDS OF THE MIFGASH PROJECT

Each strand of the project focuses on a key element of civic education and Jewish engagement:

1. ENCOUNTERING DEMOCRACY

This strand emphasizes direct civic engagement by bringing students into contact with local government officials and civic processes. For example, middle school students participated in a spring semester elective that involved studying the structure of local government and teaching third-grade students about civic participation. This hands-on approach included meetings with figures such as San Francisco city supervisors, enabling students to experience leadership and democracy in action.

2. JEWISH CONTRIBUTIONS TO AMERICAN DEMOCRACY, DEMOCRATIC CONTRIBUTIONS TO AMERICAN JEWRY

This strand connects the history of the Jewish American experience with the development of democratic institutions in the United States. The design team works on creating curricular units that highlight key Jewish figures and moments in history that contributed to American democracy. This strand ensures that Jewish American history is integrated into the broader civic education of the students

3. JEWISH ETHICS AND DEMOCRATIC HABITS OF MIND

In this strand, the curriculum focuses on embedding Jewish ethical principles into the practice of democratic citizenship. The team is developing classroom practices like democratic class meetings where students can exercise respectful dialogue, debate, and decision-making grounded in Jewish ethics. A key deliverable is an infographic poster on “Living Ethically, Acting Democratically (L.E.A.D.)” which outlines the core ethical practices students will be taught as part of their civic engagement

4. REFLECTIVE PRACTICES IN REAL TIME

This strand equips teachers with the tools to engage students in real-time discussions about current events. A guide has been developed to structure classroom dialogues in ways that integrate Jewish values and encourage critical reflection on contemporary issues. This allows students to connect their civic responsibilities with ongoing developments in their communities, such as local and national elections, social movements, and other major events

The Mifgash Project has been an excellent vehicle for our school to deepen its work in and commitment to valuescentered civics education. What follows are suggestions for other schools interested in pursuing something similar in their own educational settings, whether Jewish, faith-based, or otherwise.

PROCESS

We believe there is value in pursuing this work as a coherent project at the school level, rather than in the context of a single classroom or curriculum.

The basic structure of our project, which works well to maintain momentum on smaller elements as well as fidelity to the larger goals of our work, involves monthly meetings of a full design team. In between these monthly meetings, “strand teams” of two teachers meet to continue work on their particular subject areas. The project lead serves as chair of the design team meetings, circulating an agenda in advance, which typically consists of a check-in on the four strands, followed by shared work on a specific question or project.

In addition to our monthly meetings, we hold an annual retreat, during which we engage an outside facilitator to help the team broaden their perspective on the work (often through creative practices like painting or writing) and think ahead to our goals for the following year. These Design Team Retreats take place in June each year of the project.

Our project unfolds over three years, with distinct phases and activities in each year.

In Year One, to ensure the work reflects the community’s needs, faculty and staff survey the current curriculum. The survey results provide valuable insights that guide research priorities and inform the development of early pilot projects. By the end of the year, these efforts culminate in the creation of initial school-wide initiatives, designed to connect students to real-world experiences and lay the groundwork for deeper, systemic change.

Year One also includes our first pilot projects, undertaken in the classrooms of Design Team members.

In Year Two, the work continues with a summer Design Team Retreat, where the successes and lessons of Year One frame the next phase of work. Monthly meetings persist, fostering collaboration and ongoing progress. Partnerships grow stronger as research into thematic strands deepens, and the school community benefits from the perspectives of civic-minded speakers invited to share their expertise and experiences.

With these inputs, educators begin developing and testing new curricula and projects in their classrooms. To sustain and share resources, a communitywide resource library is created, serving as a hub for tools, ideas, and inspiration. School-wide initiatives expand, offering students even greater opportunities for real-world learning. Simultaneously, faculty and staff collaborate to link the school’s core values to democratic habits of mind, ensuring a clear connection between teaching practices and broader civic goals.

By Year Three, the initiative reaches a stage of reflection, refinement, and celebration. Another Summer Design Retreat sets the tone for the year, centering on evaluating impact and planning next steps. The team shares their story beyond the school walls, presenting their progress and successes at educational conferences to inspire and connect with other educators.

Over three years, this journey transforms the school, creating a vibrant and responsive learning environment where students are empowered to connect their education to the real world and the values of civic engagement. Each step—from the first retreat to the final reflections—lays a foundation for lasting impact, rooted in collaboration, innovation, and a shared vision for the future.

One of the critical features of the project is the involvement of the entire school community in its development. Regular workshops should be held for the full faculty, which can include training sessions on how to incorporate civic education into their classrooms, regardless of the subject area. For instance, between Years One and Two, Dr. Glass led a session for 80 faculty and staff members on “Civic Imagination,” helping teachers see themselves as educators of democracy, not just in social studies but across disciplines.

ASSEMBLE A TEAM

It sounds like the start of a bad joke: what do you get when you combine lower school teachers, middle school teachers, general studies teachers, Judaic studies teachers, a humanities teacher, a STEM teacher, a learning specialist, a maker educator, and a head of school? For us, this unusual collection of educational professionals resulted in a team that helped one another to broaden our understanding of democracy, deepen our thinking, and find connections to democracy in surprising places.

A diverse community representation on a team helps to approach civics education from new and interesting perspectives. The goal becomes less about having a specific civics curriculum and more about finding opportunities to highlight democracy throughout the entire school. While having representation from those who traditionally teach civics is essential, we found our understanding of the nuances of democracy was deepened when we looked at how we could address it through non-traditional disciplines. A middle school Judaic Studies teacher saw a triumph of democracy in Judith Kaplan, the first American woman in modern history to celebrate a B’nai Mitzvah. A general studies teacher dove deep into how democratic processes enhance her classroom protocols and develop democratic habits of mind. A maker educator latched onto the active nature and democracy and married themes of civic action with mechanical engineering projects. Middle school humanities teachers were able to use the structure of the project to review the curriculum, and look for opportunities to tune it toward greater integration of civic education.

We landed on a team of eight faculty members, with a ninth project lead who was an administrator. This allowed the team to break off into pairs to work on four different project areas between our monthly meetings. To gather our group, we described the project to our full faculty at a start-ofschool pre-service meeting, and invited people to apply to be part of the design team. We looked for team members who had an authentic interest in the subject matter, and also those who would be able to design and pilot projects or units for their own classrooms or for the school as a whole.

Things to be aware of:

• The span of a project like this inevitably means that there will be natural attrition with members of the team changing—be aware that this enriches the project by infusing new blood. Those joining will need to come up to speed quickly to maintain momentum, so the team should consciously explain the process to ensure that new members can understand the broader objective of the project.

• The project lead should be very accessible to help brainstorm and provide feedback to all members.

• Frequent meetings as a group help incorporate new members. Make time in these meetings to share incremental successes and explore solutions for roadblocks individuals and small groups encounter.

• Valuing people’s time by offering stipends can help elevate the importance of this work.

EXAMINE YOUR VALUES

The goal of a project such as this is to deepen your practices around civics education, based upon your school’s values and mission, in such a way that it shows up in the lived experience of your students, your faculty and staff, and all of your stakeholders. Many schools already have explicitly stated shared values—core values, community values, even language in mission statements—which may contain some democratic elements, but have not been examined through this lens. In linking school values with democratic habits and ideas, schools can strengthen their commitment to creating civic-minded students who can then go out into the world as active and informed citizens.

We started by generating a list of democratic habits of mind (you can consult the organizations in the Toolkit section (page 18) for more ideas on democratic practices). We were aided in this particular part of the project by the presence on our team of Sara Goldrath, who was completing her Master’s Degree and writing a thesis on this topic. The democratic habits of mind we came up with, which you are welcome to use as a starting point, are:

• Making Shared Decisions

• Collaborative Problem Solving

• Taking Action and Standing Up for What’s Right

• Taking Care of Our Community

• Respecting Other Perspectives

• Engaging in Civil Discourse

This list was created with input from our full design team, as well as academic leadership in our school, and from our faculty as a whole. This list works for our purposes, aiming at language that is suitable in a K-8 context, but you may find that there are other aspects of democratic practices and processes that you want to highlight, or that better fit your school’s culture.

Next, we turned our attention to the question of our shared values. Again, the easiest place to start is with your school’s published statements of values. Consider your school’s mission statement, and core values. Where in those articulations of your shared commitments can you find connections to democratic habits of mind? Perhaps global citizenship leads you toward respecting other perspectives, or you find a connection between leadership and standing up for what is right. It might be helpful to make a T-chart, with the democratic habits of mind on the left and your school’s shared values on the right.

In our case, we wanted to use this process as an opportunity to expand beyond our three community values. In a Jewish school, we have the opportunity to teach from a rich history of values, as will all faith-based schools. Whether you expand beyond your school’s published values or not, gathering information is a key component of understanding democracy’s roles in your school. You can gather in various ways: surveys, informal and formal discussions, asking individual teachers to examine their curriculum, engagement by grade level and or the whole department (subject and/or elementary, middle school, high school). We examined our own curricula and other resources on Jewish values, then made an initial list which we brought to our teachers in a faculty meeting. After getting their feedback in person, we then created a survey to better understand which values were regularly showing up in our teaching practices.

Ultimately, you want to generate a list that is user-friendly for teachers and students in your school, to increase the likelihood that it will get integrated widely.

LIVING ETHICALLY ACTING DEMOCRATICALLY

Be a L.E.A.Der at Brandeis!

DEMOCRATIC HABITS OF MIND

JEWISH

VALUES & ETHICS

Kehilah (הליהק) Community

Simchah (החמש) Joy and Celebration

Shalom Bayit (

) Peace In The Home

Derech Eretz (

) Respectful Behavior

Kol Yisrael Arevim Zeh Bazeh (

) Community Responsibility

Kavod (

) Respect

INTERNAL RESEARCH

In order to know a way forward around creating engagement in civic education, it is important to first look backward and survey where civic engagement currently exists in your school’s curriculum or organization’s mission. The Mifgash Design Team used a variety of tools to help gain that knowledge and also to discover where stakeholders would like to see a civics curriculum live. In gathering this information, the team was able to then look forward in terms of who might be responsible for teaching civics, how that teaching might occur and what tools would best support that process.

It is important to have a detailed understanding of the existing landscape of the curriculum across the grades, how the lower school interfaces with the middle school in both building on skills and knowledge. This data was collected in the following ways:

Anavah (

) Humility

Hakarat Hatov (

) Recognizing the Good/Gratitude

Tzedek Tzedek Tirdof (

) Pursuing Justice

Hachnasat Orchim (

) Welcoming Others

T’shuvah (

) Becoming Our Best Selves

Lomed Mikol Adam

FACULTY SURVEYS

Faculty were asked about what they currently teach about government, democracy, values, and elections. Additionally they were asked what resources would be most beneficial to support their work in these areas or to help them develop lessons in these areas.

FACULTY DISCUSSION AT STAFF MEETINGS

Several of our faculty meetings during the course of the year were dedicated to discussions around teaching civics, brainstorming on the role this teaching plays in preparing students for the future. We also beta-tested several parts of our project with staff at these meetings and their feedback was valuable to improving each part of the final project.

EXTERNAL ACADEMIC TEACHING RESOURCES

DEPARTMENTAL MEETINGS

Frequently in meetings, teachers and administrators were able to reflect on and plan for lessons, field trips, speakers, and books that were being used and could be used to further civics education.

FUTURE THINKING

The less direct method of data gathering was through the school’s leadership team envisioning the future of the school as part of larger strategic planning processes. These efforts, while peripheral in some ways, provided useful information. This was not simply through data, but by informing the initiative of the evolving values and, therefore, goals of the school. Do not underestimate the ‘soft data’ in helping to provide and refine the broader objectives. Understanding the changing values of the school helps harness the cooperation of the faculty, as it is seen as a common purpose. Making Shared Decisions Collaborative Problem Solving Taking Action and Standing Up for What's Right Taking Care of Our Community Respecting Other Perspectives Engaging in Civil Discourse

) Learning from Everyone

Surveys of resources like Facing History and Teaching Tolerance enabled the Mifgash Design Team to get a sense of what kinds of materials, lessons, and procedures were already available in the educational community. Understanding the landscape of materials that are available for educators made it easier for us to help teachers curate information to guide their individual teaching.

SNAPSHOT:

ELEMENTARY

SCHOOL DEMOCRATIC CLASS MEETINGS

Values-centered civics education lies at the intersection of cultivating democratic habits and instilling ethical frameworks in students. At The Brandeis School of San Francisco, we have developed a transformative approach to this challenge by embedding Jewish ethics into democratic classroom practices. By blending the wisdom of Jewish thought and values we have the tangible practices of citizenship, we aim to nurture students who are thoughtful, collaborative, and proactive members of their communities.

A cornerstone of this initiative is our Democratic Class Meeting. These meetings, a structured yet flexible classroom practice, empower students to voice their concerns, collaborate on solutions, and experience the deliberative process of democracy firsthand. They are designed to bridge theoretical civics education with lived experience, offering students a platform to grapple with the complexities of communal life.

Class meetings are conducted weekly, typically lasting 30 minutes. During these sessions, students discuss real-life challenges they face in the classroom or school environment. Examples of such issues might include disagreements over group projects or the equitable use of shared resources. In these meetings, students take the lead, proposing solutions, engaging in debate, and ultimately voting on a course of action to implement.

This process is not just about problem-solving—it is a deliberate exercise in practicing democracy. Students learn to listen actively, present their viewpoints persuasively, and collaborate toward consensus. Teachers facilitate the meetings, ensuring a respectful and productive environment, while the onus of leadership and decision-making lies squarely with the students.

The goals of these meetings are multifaceted. First and foremost, they aim to instill cooperation, collaboration, and problem-solving skills. Students are not merely participants in the classroom community; they become

stewards of it, accountable to their peers and their shared values.

Additionally, these meetings help students develop essential leadership skills. By leading discussions and holding one another accountable, students practice key aspects of civic engagement. They are encouraged to reflect on their experiences, asking how their meetings could be improved, and share their insights with the larger school community.

The significance of Democratic Class Meetings extends far beyond the classroom. They meet two fundamental needs: students’ desire to be heard and teachers’ need to build a cohesive, inclusive community. In an era where polarization often dominates public discourse, these meetings serve as a microcosm of functional democracy, demonstrating that deliberation and compromise are not only possible but essential.

Moreover, these meetings underscore a critical lesson: democracy takes practice. Engaging in democratic processes from a young age equips students with the habits of mind necessary for active and informed citizenship. Through these meetings, students internalize the understanding that their voices matter and that their actions can effect change.

Reflection is a key component of Democratic Class Meetings. Both students and teachers are encouraged to consider what they notice, wonder about, and appreciate during these sessions. This reflective practice ensures continuous improvement, fostering an environment of growth and accountability.

As educators, we are reminded that our role extends beyond imparting knowledge; we are also cultivators of character and community. Democratic Class Meetings exemplify how values-centered civics education can transform classrooms into spaces where students not only learn about democracy but live it.

SNAPSHOT: JUSTICE BRANDEIS DAY

One way that we have brought civics and our school-wide community values into closer conversation with each other is through our annual celebration of Justice Brandeis Day. We take time each November to remember our school’s namesake, by learning about and exploring his legacy, and how it connects to our values today. We started this tradition when we discovered that our graduates did not know who Justice Brandeis was! In 2017, we created a committee to help engage our entire school community in a day of learning.

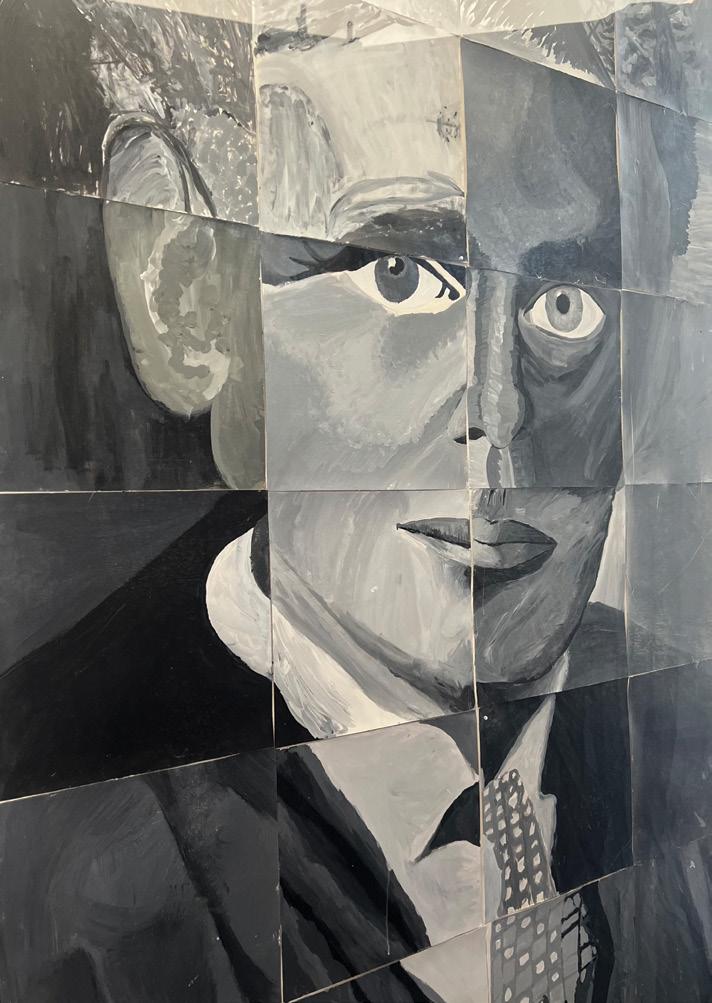

Over the years, Justice Brandeis Day has served to teach our students and community about who he was, what he stood for, and what he has contributed to Jewish and American history. There is typically a biographical component, so future graduates know who he was, and a creative project that brings together older and younger students, using a quote or idea of his to connect to our community values. We often hold school-wide assemblies as part of the day, and we also bring in speakers to teach about aspects of his legacy. Our lobby now has multiple art projects that have

been created by students as part of Justice Brandeis Day, including the beautiful group portrait you see above.

HERE ARE SOME SUGGESTIONS FOR HOW YOU CAN DO SOMETHING SIMILAR IN YOUR SCHOOL COMMUNITY

1. CHOOSE A COMMUNITY HERO (OR

HEROES).

When choosing your community hero it is important to keep in mind a few elements: your hero should have a substantial and diverse body of work, so that you have options to choose from, as well as opportunities to iterate in the future. They do not necessarily need to be the person your school is named for, but they should be someone that your community will be excited to learn more about, and someone whose values align with those of your school.

2. CREATE A COMMITTEE.

The goal here is to bring your whole community together, so try and get a committee that is broadly representative of different subjects and grades. It is important that school leadership is involved, as well.

3. CHOOSE A DATE. The date should be one that can be expected to regularly work on your school calendar, and have a connection to your hero. We chose a November date because that is the birthday of Justice Brandeis, and it is also when we typically hold our elections. Over the years, we moved from a specific calendar date to a Friday around that date, as we saw that Fridays were easier for special schedules.

4. WHAT IS YOUR CONTAINER? When making a school-wide program, it is important to find a container for it to exist in. Maybe this is something your school already has. Perhaps you need to create it. In our school Justice Brandeis Day “lives” in our Chaverim Program. In our Chaverim Program, different grades are paired together, with an older student being paired with a younger student for the year. The activities that the students participate in are planned by a student board which meets on a weekly basis to develop monthly activities for the chaverim This structure has worked well for Justice Brandeis Day over the years, and is typically where the creative activity part of the day happens.

Justice Brandeis Day has brought memorable moments to our school, such as an antitrust lawyer teaching our middle schoolers about the ongoing cases against some of the major technology companies, and how they rest on legal theories developed by Justice Brandeis, and most importantly, instilled pride in our students.

SNAPSHOT: TEACHING LOCAL CIVICS

We chose the title Mifgash or “Encounter” because we wanted our students to come into direct contact with civic leaders, to truly understand how democracy unfolds in a day-to-day way in their communities. That said, there was a point in our work on this project when we became aware of a disconnect: elected officials kept encouraging us to teach our students to learn about local government, but there were very limited curricular resources available for K-8 students on the topic. Even as we built out a school library on civics and democracy, we could find vanishingly few books on how local government works. While this is doubtless partially due to the fact that there are many different models of local government here in the United States, and because our collective attention tends to be drawn to national politics, it remains a challenge in teaching young students about civic engagement.

In the spring semester in 2023, we implemented a pilot elective curriculum for seventh and eighth grade students focused on the guiding question: How might we teach third grade students about our local government in a way that engages and excites them to see themselves as active citizens and agents of change in their local community?

The elective had three main components: developing lessons and activities to teach our third graders about our local government, developing and implementing a project to improve our local community, and examining local issues and interviewing community leaders.

Transforming our seventh and eighth graders into teachers of local civics was a heartwarming success. First we asked them to do a deep dive into the structures and functions of our local government. Once they developed a good understanding of how our local government works, we gave them a crash course in how to develop engaging lesson plans for their third grade students. They took this work very seriously and made sure to create lessons and activities that were informative and interactive. Some groups created games, like Pin the Responsibility on the Mayor, or developed engaging hands-on activities such as urban

planning manipulatives. The day they taught these lessons was really delightful and a great example of democracy in action as they worked to inform and engage younger citizens.

We found ourselves in a bit of a time crunch as we approached the second phase of the elective as it coincided with many end-of-year traditions. However, our students were able to identify issues in our immediate school and neighborhood that they felt empowered to address. These ranged from coming up with recess activities for our younger students who do not enjoy sports-like play to sidewalk clean-ups and efforts to attract more, diverse birdlife to our street and campus. Among the most impactful parts of the elective was inviting our city supervisors to our campus to meet with our students. Having had an opportunity already to think about issues in their immediate communities, and also to teach about local government to their younger peers, our middle schoolers were ready to talk to their elected officials. We prepared them to write thoughtful questions, and then spent an entire class period meeting with two city supervisors: the one whose district our school sits in, and another who happens to be an alumnus of our school. There was a particularly profound moment when our middle schoolers asked about a recent spate of teen violence at a local mall, and were able to hear from their district supervisor about their City’s efforts to address the matter with local schools, law enforcement, and shop owners.

Subsequent to this elective, we have looked for opportunities to bring other local civic leaders in to meet with our students—both those in government positions as well as community organizers. You do not have to hold office to have an impact in your community!

In our experience, local elected officials and civic leaders are excited to talk with students. If you are thinking about undertaking something similar at your school, we recommend that you consider following the same three-part process we did:

1. Invite students to identify an issue of interest in their neighborhood or community.

2. Empower students to learn about how local government interacts with the issue they are exploring, and then teach other students about what they have learned about how their local government works.

3. Bring local elected officials in to meet with your students, setting aside time beforehand to discuss the questions they have of their elected leaders.

SNAPSHOT: LOWER SCHOOL ELECTIONS

We have also found that making time for our older students to visit centers of local government— court houses and city hall, for example—can offer powerful reinforcement to the lesson that local government is a meaningful part of our everyday lives as citizens.

One way to engage elementary school students with civics is to hold mock elections parallel to local or federal elections. In this way students learn about how the American electoral system works, what constitutes a good political candidate and what is the process by which a candidate campaigns for office. Students become active participants in the election process when they meet candidates from different ‘parties’, vote in a primary, engage in the production of a party platform (older elementary students), attend a party convention, hear campaign speeches, and vote in a final election. Students even gain an understanding of the electoral college as the vote is tallied and each classroom’s results are shared based on the electoral college votes. A mock election works particularly well when the candidates are not specific students but are symbols of the school (animals chosen to represent the school’s values); this brings issues to the forefront rather than the ‘popularity’ of an individual. Jenny Rinn, lower school director, designed and implemented mock elections for grades K-4.

STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE TO CONDUCTING MOCK ELECTIONS IN AN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

PRIMARY

ELECTION - ABOUT 2 WEEKS

1. CREATE FICTIONAL PARTIES AND CANDIDATES

Choose three fictional political parties, each with three candidates. Consider using your school’s values as inspiration. At Brandeis, we chose:

• Kindness: Koala, Kangaroo, Komodo Dragon

• Integrity: Ibex, Ibis, Iguana

• Service: Sloth, Spotted Hyena, Seal

2. STUDENTS CHOOSE A PARTY AND CANDIDATE

Students receive a mock Registration Card with their name, grade, and chosen party.

3. PARTY REPRESENTATIVES VISIT CLASSROOMS

The eldest students from the Lower School act as representatives for each party. These representatives will visit each classroom to give short speeches, or platform statements about their party, using the following lesson plan, which is directed at fourth and fifth graders):

ONE-SENTENCE PLATFORM STATEMENTS

Objectives:

• Students choose candidates to support.

• Students write one-sentence platform statements based on the value of the candidate’s party (kindness, integrity, service) and positive attributes of the candidate (animal).

Introduction:

• Define a platform statement:

VOTE

• Students create a print campaign ad featuring a candidate’s platform statement, headshot, and party affiliation.

A political platform statement is a big list of ideas and promises that a person or group running for office compiles to show what they believe in and what they want to do if they are chosen. Their statement explains what they think about important things such as:

• Schools: What they will do to make schools better for students and teachers?

• Nature: How they will protect the earth, like cleaning the air and water?

• Fairness: How they will treat people equally, no matter who they are?

Each part of the statement addresses one important thing, and helps people know what the person or group plans to do if they win.

• Using a capybara as an example, the teacher walks students through the process of finding common points between the definition of the value (community) and the positive attributes of a capybara.

Independent Activity:

• Students determine which of the candidates they want to support.

• Working in groups, students will:

• Read one of the candidates that corresponds with their candidate of choice.

• Identify common points between the candidate’s party and their positive attributes. Students may highlight commonalities.

• Write a one-sentence platform statement using the candidate’s party/value and the positive traits of that animal. “When I am president, I will….”

• Using a 11x13 inch sheet of paper, the headshot of their candidate, and the platform statement, students will create a print ad.

4. CLASSROOM PRIMARY ELECTIONS

After hearing from the party representatives, students vote for one candidate in their classroom using a paper ballot.

Each student receives an “I Voted” sticker after voting.

5. LOWER SCHOOL CONVENTION

Hold a Lower School Convention where each class ballots is based and throws their support for one candidate from each party. Students also learn what electoral college votes they will receive in each class.

Electoral College Explanation:

• Classes with fewer than 20 students receive 1 electoral vote.

• Classes with 20 or more students receive 2 electoral votes. Teach the students about the Electoral College System and how it works in a mock election.

GENERAL ELECTION - ABOUT 1 MONTH AFTER THE PRIMARY ELECTION (ONE DAY)

1. CAMPAIGNING AND ELECTION PREPARATION

• The eldest students from the Lower School will create posters to hang around the school, informing students about the candidates and the results of the Primary Election.

• Each party will now have one candidate remaining, based on the primary results.

2.

ELECTION DAY

• On Election Day, set up a “polling place” somewhere on campus.

• Students present their Voter Registration Card, which shows their political party, to vote.

• Each student votes for one candidate from the remaining options based on the Primary Election results.

• After voting, each student receives an “I Voted” sticker.

KEY LEARNING POINTS:

• Understanding the Electoral College System.

• Participating in a democratic process with voting.

3. ANNOUNCE ELECTION RESULTS

• After all votes are counted, share the results of the General Election with the entire Lower School.

• Show both the popular vote results and the Electoral College results.

4. VISIT BY THE WINNING CANDIDATE

• The winning candidate will visit each classroom in the Lower School, spending one week in each classroom.

• The students share their issues and concerns with the newly elected leader.

• Learning about campaigning, political platforms, and how elections work.

TOOLKIT

Following is a list of organizations that we partnered with on this project, each of which offers significant resources in considering civics education, as well as a list of books that our team developed for teaching about values-centered civic engagement.

ORGANIZATIONS

A More Perfect Union:

The Jewish Partnership for Democracy

Focus: Jewish-centered civics education programs for schools and communities.

Website: https://www.jewishpartnership.us/

The American Democracy Project (ADP)

Focus: Supports higher education initiatives to prepare students for democratic engagement.

Website: https://www.aascu.org/programs/ADP/

Center for Civic Education

Focus: Provides materials and training for educators to teach civics effectively.

Website: https://www.civiced.org/

Citizen University

Focus: Building a strong civic culture by empowering individuals to take responsibility and actively engage in democracy.

Website: https://citizenuniversity.us/

Civic Language Perception Project

Focus: Examines the ways people understand and engage with civic language to foster effective communication and inclusive civic participation.

Website: https://pace.citizendata.com/

Civic Spirit

Focus: Civic education with a focus on faith-based schools, including Jewish and Catholic schools.

Website: https://www.civicspirit.org/

The Civics Center

Focus: Voter registration and civic engagement among young people.

Website: https://thecivicscenter.org/

The Covenant Foundation

Focus: Committed to recognizing and supporting those with creativity and passion to innovate in Jewish education.

Website: https://covenantfn.org/

Facing History and Ourselves

Focus: Integrates history and ethics in classrooms, exploring issues like racism, anti-Semitism, and prejudice.

Website: https://www.facinghistory.org/

Generation Citizen

Focus: Action civics curriculum to empower students to engage with local issues.

Website: https://generationcitizen.org/

iCivics

Focus: Interactive civics education tools for middle and high school students.

Website: https://www.icivics.org/

The Jewish Studio Project

Focus: Cultivates creativity as a Jewish practice for spiritual connection and social transformation.

Website: https://www.jewishstudioproject.org/

Newsela

Focus: Provides current event articles and lessons tailored to various reading levels, with a focus on civics and government.

Website: https://newsela.com/

Repair the World

Focus: Social justice and civic engagement through Jewish service-learning programs.

Website: https://werepair.org/

The Shalom Hartman Institute

Focus: Jewish ethics, pluralism, and democracy education.

Website: https://www.hartman.org.il/

Time Magazine for Kids

Focus: Delivers age-appropriate news articles, activities, and resources to help students build literacy and critical thinking skills while learning about current events.

Website: https://www.timeforkids.com/

We the People: The Citizen and the Constitution

Focus: Promotes understanding of the U.S. Constitution and democratic principles.

Website: https://www.civiced.org/programs/wtp

CIVIC ENGAGEMENT PICTURE BOOKS

NOVELS

OUR TEAM

As noted in the Assemble a Team section, given the duration of this project, we had a number of team members who joined for a time and then left due to things like parental leave. Maddie Adler, Nicole Dixon, and Mark Fritzel all made important contributions to this work. We were lucky to also have a core group that was part of the work all three years. This is our team that assembled this playbook, with asterisks denoting those who were on the project from beginning to end.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to The Covenant Foundation for making this vital work possible. Our deepest thanks also go to the Mifgash design team, Brandeis faculty, and the incredible organizations we partnered with for your dedication and commitment to advancing the shared values of civics and democracy.

We invite you to stay in touch and share how this work is taking shape in your schools—we look forward to learning from your experiences and continuing to grow together in this important endeavor!

Contact us at mifgash@sfbrandeis.org.

CREATED BY THE DESIGN TEAM OF: AT WITH THE SUPPORT OF: