EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

Jason Fettig, President

Matt Temple, President-Elect

Elva Kaye Lance, Vice-President

Randall Coleman, Immediate Past President

Scott Tobias, Executive Secretary-Treasurer

Jason Fettig, President

Matt Temple, President-Elect

Elva Kaye Lance, Vice-President

Randall Coleman, Immediate Past President

Scott Tobias, Executive Secretary-Treasurer

Al & Gladys Wright Distinguished Legacy Award, Rebecca Phillips

Alfred Young Band Composition Contest, Audrey Murphy Kunka

AWAPA Commission, David Gregory

Citations & Awards, Heath Nails

Constitution & By-Laws, Jason Fettig

Corporate Relations, Gary Smith

Foster Project NBA Representative, Wolson Gustama

Hall of Fame of Distinguished Band Conductors Board of Electors, Thomas Fraschillo

Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, & Awareness, Ingrid Larragoity & Elizabeth Peterson

Marching Band Committee, Adam Dalton & Bobby Lambert

Merrill Jones Composition Contest, Matt Smith

National Programs of Excellence, Myra Rhoden

NBA Foundation, Susan Creasap

Nominating Committee, Rebecca Phillips

Research Grants, Brian Silvey

Selective Music List – Concert, Arris Golden

Selective Music List - Jazz, Steve Shanley

Selective Music List – Marches, Col. Don Schofield

William D. Revelli Composition Contest, Matthew McCutchen

Young Composer Jazz Composition Contest, Richard Stichler

Young Composer Mentor Project, Frank Ticheli

Young Conductor Mentor Project, Linda R. Moorhouse

To promote and empower band performances throughout the world.

To encourage and promote the commissioning and performance of new wind band music.

To provide inclusive and authentic professional development opportunities and resources for everyone.

To acknowledge and celebrate the diversity of bands, educators, performers, and band support organizations.

To promote pride, commitment, and enthusiasm among band directors and performers.

To encourage lifelong involvement in music and to support interested students in pursuing musical careers.

To promote an inclusive community among directors, performers, the music industry, and all other band support organizations.

NBA Journal Editor, Matthew D. Talbert

NBA Journal Layout & Design, Nash P. McCutchen

Articles presented in the NBA Journal represent views, opinions, ideas and research by the authors and are selected for their general interest to the NBA members. Authors’ views do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Band Association, nor does their publication constitute an endorsement by the National Band Association.

New year, new me! They say that most New Year’s resolutions end on the second Friday of January. That sounds about right, but I am determined to make some of mine last this time around. I am still in my “new” phase in my current job and learning tons about myself, my strengths and weaknesses, and most importantly, how our processes evolve as the scenery around us changes. In a sense, we probably take it too far too often; forming resolutions for something “new” doesn’t need to be completely new. Perhaps a better way is to take a look at the things that are already ingrained in us and help them evolve just one step at a time. Not only does that validate the good stuff in who we already are and how we operate, but it also feels a whole lot more sustainable than trying to start something over-over and over again.

I’ve been trying to apply this approach in my own growth as a teacher and to encourage my students to do the same. It is very much aligned with the pedagogical aim to “scaffold” new ideas and fundamentals so that they can grow into something substantive. But the key to scaffolding is to arrange it and care for it so that it doesn’t come tumbling down! What sticks is what we see works, which is what then builds confidence, which is

then what motivates us to keep at it. But if we move too fast or try to change too much before each element has a chance to take root, we can easily slip back into status quo.

As a teacher, I have discovered that this is pretty difficult to navigate, because you are not only charged with curating this process in your individual students from where they are, but we must also model it ourselves so that it has a meaningful impact on our own growth at the same time. So, in the spirit of “taking care of yourself so you can take care of others,” I’d like to offer a few areas I’ve been working on, and a few tips to try out this year:

At the heart of the work for those of us who conduct and teach band is the music we choose, and how we choose to present it—to our students, our colleagues, and our audiences. The ever-challenging process of programming is both easier and harder in 2025 than it ever has been. Easier because there is more music than ever to choose from, and harder because there is more music than ever to choose from. Challenge yourself to pick at least one piece for each program that is markedly different in style or construction than anything you’ve done

... Perhaps a better way is to take a look at the things that are already ingrained in us and help them evolve just one step at a time.

President’s Message, Jason K. Fettig, cont.

before and find a creative way to elegantly weave it in to a concert. Bonus points if that piece is by a composer you had previously never heard of.

As a conductor like many of you, I am at the mercy of those who regularly play in the ensemble— every “signature” gesture, catch phrase, pet peeve, and idiosyncrasy of any kind is noticed and likely referenced (lovingly, I’m sure) when I am out of the room. I have also recently been made aware that I wear quarter zip sweaters to almost every rehearsal. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: we are at our best as musical leaders when we mix it up and keep the energy in the room a bit unpredictable. That takes some effort on our part, and seems to get harder the older we get, so start with just one change that will definitely get noticed in the room. That change—whether it’s a new warm-up routine, a wildly new gesture, different vocabulary, or an uncharacteristic emotional share—could end up being the new norm. For the record, though, there’s nothing wrong with my quarter zips.

One of the important lessons I learned in the Marine Corps is that everyone wants/needs to be heard and validated, including those who

are in charge. But the process of listening and making empathetic resolutions is especially important when you are the one in charge. Opening that door can be scary and sometimes frustrating, but once you have felt validated about the work you do, it becomes easier to hear about the parts that could be better. I invite us all to lean into the listening, and then change just one thing about how we regularly relate to each person in our lives. It doesn’t really matter what it is but make it a point for that change to be deliberate and generous.

Before we know it, it will be time for those resolutions once again. But this time, they won’t be the same, because we won’t be the same.

Thank you for being a part of the National Band Association. I look forward to partnering with each of you in this new year to continue to keep this organization a relevant, evolving, and empowering community. As I said to our present members at Midwest in December, this is the place where everyone is in, and no one is out.

That is what band is all about.

Warmest wishes,

Professor Jason K.

Fettig

President National Band Association

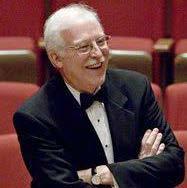

Welcome to 2025! Even though the New Year happens right in the middle of our “school” year for most of us, it is nonetheless exciting to think about turning the page from an old calendar year to a new one. Fresh starts, new beginnings and opportunities for positive change all make the “new” year in the middle of the “school” year a time for both reflection and projection ... all in hopes of making 2025 the best year yet for us all.

From my perspective as a veteran teacher, I keep returning to one trait of a successful, top-tier program that seems to be missing in so many good programs. This trait has nothing to do with how well the students play their instrument, how well the ensemble plays in tune, or what commission consortium the program has joined. It deals with something altogether different. I tell my students all the time that there are three groups that we are responsible for “educating” … the students, the administration and the parents or community. Of course, the job of educating our students is the most time consuming and involved of the three groups … but the other two are extremely important as well. A large part of establishing a quality program is working to help our

community, our administrators, colleagues and parents … most of whom are not musicians … understand what we do and why it is important. It is about creating a positive and educational culture for our program.

Culture is defined as “a system of shared beliefs, values, practices, and behaviors that define a group of people”. As you reflect on your own program, do all three groups … your students, your administrators, and your parents/ community … share and display your beliefs, values, practices and behaviors that you would like? Many times, when we perceive that a program doesn’t get the support it should from the administration or parents, it may have a lot to do with a lack of understanding rather than a lack of support. For our students, building a positive culture is one of the key aspects of a well-rounded and healthy program. As the director, we have access to a multitude of books and resources on building culture in our organization…but I have found one of the most effective tools for instilling a strong and healthy culture in your program is for YOU as the director to demonstrate those qualities that we want our program to reflect. Professionalism, dedication, honesty, commitment, and a positive attitude from the director each day will soon “catch on”. As

Continued on next page

Randall Coleman

... Many times, when we perceive that a program doesn’t get the support it should from the administration or parents, it may have alot to do with a lack of understanding rather than a lack of support ...

Immediate Past President’s Message, Randall Coleman cont.

one of my wonderful mentors always reminds me “the program is a direct reflection of the person on the podium”. Your administrators, parents and most importantly your students, look to you for “the norm” …what to do; how to act; what to say; what NOT to say…. your actions, as the leader of your program, matter. I encourage you to focus on the tremendous responsibilities of our profession that might not have anything to do with music…but have everything to do with helping our students be successful in life. We all know that only a small percentage of our students will move on to a career in music, so providing those educational experiences that transcend the boundaries of subject matter will be the lessons that our students will always remember, no matter what their chosen profession might be. Perhaps this quote sums it up best:

“What a teacher is, is more important than what they teach.” - Karl Menninger

I hope you enjoy a healthy and successful “new” year! Please do not hesitate to reach out if I can be of assistance to you or your program.

Randall Coleman Immediate Past-President

The National Band

Association

BY

The mission for directors of school bands is understood inherently by those who think of themselves more often as instrumental music teachers rather than simply as band directors. The basic objective of instrumental music education is that students will learn performance skills in order to understand musical language and to experience the joys of recreating music in the expressive medium of their choice. Music education should prepare students also for a fuller understanding and appreciation of the music they will be hearing the rest of their lives regardless of its style or venue. Efforts to address the National Standards for Music Education in band class by including music theory, music history, improvisation, and composition will help the students be better listeners in adulthood and will make better musicians of those who wish to pursue musical careers or practice music as an avocation in adult life.

The National Band Association would like school administrators, teachers, and parents to recognize that students elect to study instrumental music for a variety of reasons, including: as an outlet for creativity, a source of social interaction with like-minded peers, a possible career choice, gratification that comes from recognition by responsive audiences, discipline through study and practice, and service to school and community. The evaluation of instrumental music programs should be grounded in a review of the educationally and aesthetically justifiable objectives that are explicit in this mission statement.

The long-respected model for learning to play a musical instrument based on the role of artist-teacher with a studio of private students applies as well to school bands. Band class must provide these same foundations: a correct concept of characteristic tone quality, development of technique based on a graded course of study, a formal system for counting rhythms, practice in developing good intonation, and the sure goal of playing expressively.

An instrumental music program should offer a broad range of musical experiences: an extensive solo and chamber music repertory that provides subtle opportunities for nuance and other systems of expression; a school jazz ensemble that stresses rhythmic precision, understanding of harmonic progression, and creative improvisation; a concert band, the core of the program, where our musical heritage is transmitted through inspirational compositions by the most creative composers.

Service activities such as marching band are often important to the school and community, and students who participate gain social, educational, and musical values. Because evaluative competition can raise standards and motivate progress, NBA strongly recommends that all bands participate in festivals or contests sponsored by district and state music education associations, especially when a rating rather than a ranking is the goal. However, the integrity of the instructional program can be threatened by a disproportionate emphasis on competitions and servicerelated performances. Marching band activities that require extra rehearsals and travel time should be scheduled with concern for the many responsibilities that students have in addition to their musical studies, and must never be the focus of the instrumental music program. Excessive demands on students, parents, and community––financial and otherwise––bring about consequences harmful to the essence of the instrumental music program.

History demonstrates that those who cultivate a special intelligence in an area of personal interest make great contributions to the way we live. Efforts by legislators or educators to emphasize one area of study alone stifle the pluralism that has been one of this country's strengths. Rather, schools should provide a broad base of knowledge for students and also encourage development of the special abilities of those who demonstrate the capacity to excel. Instrumental music studies provide a laboratory of artistic and social opportunities for individual development that contributes to the collective good.

The arts provide unique forms of knowledge, present a basic means of communication, and produce lasting works that are the hallmarks of a civilization. President Abraham Lincoln reminded us that education is not for the purpose of learning to earn a living, but for learning what to do with a living after it has been earned. Whether in the arts or other areas of interest, students who are encouraged to develop their talents and interests participate in the continuous regeneration of our democratic ideals.

The National Band Association was founded on September 11, 1960. This new organization was the dream and brain child of Traugott Rohner, the editor and founder of The Instrumentalist magazine. Rohner set up a meeting with two of the most capable leaders among America’s band directors, Dr. Al G. Wright, who was at that time Director of Bands at Purdue University, and John Paynter, Director of Bands at Northwestern University, and these two very able leaders established a new, inclusive band organization which grew into the largest band organization in the world.

Al Wright was the NBA’s first president, and he soon became aware of a need to establish a special, high level award program to recognize excellence and exceptional service to bands. The result of this was the establishment of The Academy of Wind and Percussion Arts (AWAPA). This award was established for the purpose of recognizing those individuals who have made truly significant and outstanding contributions to furthering the excellence of bands and of band music, and it was not to be limited to band directors, but to anyone who’s contributions were determined to be so outstanding that they deserved and warranted honor and recognition.

The nine-inch silver AWAPA figure is designed to be the “Oscar” of the band world. Elections to the academy are made from time to time by the Board of Directors acting upon nominations from the AWAPA Commission. Presentations of AWAPA awards are made at band performances or meetings of national significance. The new recipients of the award are announced at the annual National Band Association Membership Meeting at the Midwest Clinic in Chicago each December, and the honorees from the previous year are invited to attend that meeting for a formal presentation of the award.

If the recipient is not able to be present at that meeting, the award is presented at another prestigious band event where the recipient is properly honored and recognized. The award consists of a silver statuette, a silver medallion, and an engraved certificate. The Academy of Wind and Percussion Arts represents the highest honor which the National Band Association can confer on any individual.

The NBA represents the best there is in a great, proud profession. When we honor our very best, we bring honor on our organization and on our profession. A list of the past recipients of the AWAPA Award is literally a “Who’s Who” list of some of the greatest leaders involved in the band movement during the past six decades. The list includes an international cross section of important individuals representing all aspects of the band world, who have rendered remarkable service to bands.

William D. Revelli

November 25, 1961

Karl L. King November 10, 1962

Harold D. Bachman January 9, 1965

Glenn Cliffe Bainum February 21, 1965

Al G. Wright March 7, 1969

Harry Guggenheim August 18, 1969

Paul V. Yoder December 18, 1969

Toshio Akiyama December 13, 1970

Richard Franko Goldman July 23, 1971

John Paynter March 5, 1972

Roger A. Nixon July 12, 1972

Traugott Rohner

February 11, 1973

Sir Vivian Dunn March 2, 1973

Jan Molenaar July 11, 1974

Frederick Fennell August 3, 1975

Harry Mortimer August 3, 1975

George S. Howard December 16, 1976

Mark Hindsley March 2, 1978

Howard Hanson December 13, 1978

James Neilson December 13, 1978

Vaclav Nelhybel December 13, 1978

Leonard Falcone December 12, 1979

Alfred Reed December 12, 1979

Arnald Gabriel December 16, 1980

Nilo Hovey December 16, 1980

Trevor Ford December 16, 1981

Vincent Persichetti December 16, 1981

Clare Grundman December 15, 1982

Morton Gould December 15, 1982

Karel Husa December 15, 1982

Harry Begian December 14, 1983

Francis McBeth December 12, 1984

Normal Dello Joio December 12, 1984

J. Clifton Williams December 18, 1984

Frank W. Erickson December 17, 1986

Neil A. Kjos December 17, 1986

Merle Evans

December 20, 1986

Hugh E. McMillen

December 17, 1986

Claude T. Smith December 16, 1987

Warren Benson December 14, 1988

John Bourgeois December 14, 1988

Donald Hunsberger December 19, 1990

Edgar Gangware December 19, 1991

W J Julian December 16, 1992

Geoffrey Brand

December 20, 1995

Harvey Phillips December 21, 1995

Richard Strange

December 20, 1995

L. Howard Nicar, Jr. October 16, 1996

Kenneth Bloomquist December 18, 1996

H. Robert Reynolds December 18, 1996

Elizabeth Ludwig Fennell December 17, 1997

Arthur Gurwitz December 17, 1997

Russell Hammond December 14, 1999

William F. Ludwig December 14, 1999

John M. Long December 20, 2001

Raoul Camus December 19, 2002

Paul Bierley June 14, 2003

William J. Moody

December 18, 2003

Earl Dunn

December 16, 2004

Victor Zajec

December 16, 2004

James T. Rohner

December 15, 2005

Frank Battisti

December 21, 2006

David Whitwell December 20, 2007

Frank B. Wickes

December 18, 2008

Ray Cramer December 17, 2009

James Croft

April 16, 2011

Paula Crider

December 15, 2011

Mark Kelly

December 15, 2011

Bobby Adams

December 19, 2013

Richard Floyd

December 18, 2014

Edward Lisk

December 17, 2015

Linda R. Moorhouse

December 15, 2016

Thomas V. Fraschillo

December 21, 2017

John Whitwell

December 20, 2018

Richard Crain

December 19, 2019

Loras John Schissel

December 15, 2020

Bruce Leek

December 16, 2021

Julie Giroux

December 20, 2022

Frank Ticheli

December 20, 2022

Gerald Guilbeaux

December 21, 2023

John Stoner

December 21, 2023

Tim Lautzenheiser

December 19, 2024

Research relevant to the field that you would like to share?

Professional advice or tips that might help other band directors?

Something to say?

The National Band Association welcomes and encourages members to submit articles for possible inclusion* in future editions of the NBA Journal. Peer-reviewed** and non-peer reviewed articles are accepted. The NBA Journal is published quarterly and deadlines/ instructions for submission are as follows:

Winter Edition (published in February)

Spring Edition (published in May)

Summer Edition (published in August)

Fall Edition (published in November)

*Articles are published at the discretion of the editor and may appear in a later journal edition or not at all.

**For guidance on how to submit a peer-reviewed article, please see page 56.

Please submit your article in Word document format to NBA Journal Editor Matthew Talbert: talbertm@ohio.edu.

Al G. Wright

1960 - 1962

Honorary Life President

John Paynter 1962 - 1966

Honorary Life President

James Croft 1986 - 1988

Frank B. Wickes 1988 - 1990

Edward W. Volz 1966 - 1968

William J. Moody 1968 - 1970

Edward S. Lisk 1990 - 1992

George S. Howard 1970 - 1974

F. Earl Dunn 1974 - 1976

William D. Revelli 1976 - 1978

W J Julian 1978 - 1980

Kenneth Bloomquist 1980 - 1982

James Neilson 1982 - 1984

James K. Copenhaver 1984 - 1986

Robert E. Foster 1992 - 1994

John R. Bourgeois 1994 - 1996

James Keene 1996 - 1998

Thomas Fraschillo 1998 - 2000

Paula Crider 2000 - 2002

David Gregory 2002- 2004

Linda Moorhouse 2004- 2006

Bobby Adams 2006- 2008

Finley Hamilton 2008- 2009

John Culvahouse 2009- 2012

John M. Long 2010 Honorary President

Roy Holder 2012 - 2014

Richard Good 2014 - 2016

Scott Casagrande 2016 - 2018

Scott Tobias 2018 - 2020

Rebecca Phillips 2020 - 2022

Randall Coleman 2022 - 2024

BY MATTHEW MCCUTCHEN

It gives me great pleasure to announce that the NBA’s William D. Revelli competition is going strong. We received 62 entries this year, including several by international composers, and the most diverse group of composers since I have been involved with the committee. Following an exhaustive screening process the selection committee, consisting of accomplished directors from throughout the United States, determined through a thorough discussion that David Biedenbender’s “Enigma” is the 2024 winner.

Dr. Biedenbender teaches composition in the College of Music at Michigan State University. His pieces often explore the expressive power of combining strange and unusual elements— often timbres and textures—with things that are more familiar— like harmony and melody. He often embeds the resonance of

imagined spaces into the music itself, using acoustic instruments to emulate electronic processes. He composes for practically all mediums, but the wind band world likes to claim him as one of our own. His wind ensemble works are widely performed and have been programmed by the world’s preeminent wind bands.

Biedenbender writes:

I am a composer because of my experiences in band. Playing in my high school concert band, jazz band, marching band, pep band, pit orchestra, and several related chamber ensembles pulled me into arranging music, which, in my senior year, led me to write my first piece: a thirteen and half minute fantasy for band containing every musical idea I’d ever had, strung together with transitions… :-) – and I got to the conduct the premiere. I was hooked. I also got lucky: "the composer just down the street” was David Gillingham –

himself the 1981 winner of this award – and he became my first composition teacher. I went on to study with him at Central Michigan University.

In the summer of 2022, my other composition teacher from CMU, José Luis-Maurtua, passed away far too young after battling pancreatic cancer. José was into details. I remember one lesson spent on one bar of music –considering every possibility of orchestration, every nuance, and then notating it all with absolute clarity. When we were done, he said “now apply this level of care and attention to every bar in the piece.” It’s a lesson that stuck with me. He also taught me the importance of deeply knowing music that you love. We spent many hours dissecting and analyzing pieces in order to understand how they worked – "this forms the foundation of your compositional

Continued on next page

Continued on next page

David Biedenbener's Enigma ..., Matthew McCutchen, cont.

toolbox,” he said. Now, I often ask my students, “What do you love and how does it work? Start there.” This ethos has become the starting point for every piece I write.

J.S. Bach’s “Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor” has long been one of my desert island pieces, and I had been mulling over the possibility of writing some sort of homage to it, perhaps built on the same passacaglia theme, for years. After José passed, I decided that it was time. In “Enigma” I wanted to hide Bach's theme at first, revealing it gradually over the course of the entire piece. There is a long tradition of building a piece on someone else’s materials – in fact, this is how composition was taught for a long time, through counterpoint exercises. But I also think of this as an opportunity to converse with the past – to sort of write a love letter to music and a musician that I greatly admire. For me, there’s a paradox in this – that in building on something old we often discover something new. That was my hope with “Enigma”, and perhaps, in some small way, to commune with and remember José, thanking him for teaching me so much.

Enigma is scored for standard wind band instrumentation with the additions of soprano

saxophone, and optional piccolo trumpet and organ. It does not call for an extensive percussion section – just marimba, vibraphone, glockenspiel, crotales, chimes, tam-tam, suspended cymbal, bass drum, and timpani, but conductors should know that the mallet parts are crucial to the success of the work and that strong players are require on marimba, vibraphone, and piano. Five players are required to cover the parts. The work is 12 minutes long and employs several modern techniques that balance the familiarity of Bach Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor. The piece begins by utilizing delayed echo techniques that seem to mimic a reversed tape effect. While this isn’t an overriding feature of the piece, it is a compositional technique the returns several times, and is at times used to obfuscate the emergence of the familiar. Also interesting is his frequent use of a variety of Baroque-inspired grace notes, embellishments and ornamentations that are a clear nod to Bach, but used in manners that feels fresh and new. These appear most often, but not exclusively in solo passages and conductors will want to make sure the players know how to approach them.

Matthew McCutchen is the Director of Bands at the University of South Florida. He is also the founder and conductor of the Bay Area Youth (BAY) Winds and the Artistic Director and Conductor of the Florida Wind Band. He is the chair of the National Band Association’s William D. Revelli Band Composition Contest, is on the John Philip Sousa Foundation Legion of Honor Selection Committee and is a member of the American Bandmasters Association.

With each piece he releases Biendenbender’s mastery of color becomes more apparent. One

of the most brilliant aspects of Enigma is that once the Passacaglia begins, the listeners’ ears are drawn to the familiar theme, while different choirs of instruments dance around it. This is not a piece that is tremendously rythmically difficult, but Biendenbender’s frequent use of hemiolic passages create a consistent sense of motion through resistance so players must be rhythmically independent in order for the piece to work.

Continued on next page

In addition to paying clear homage to Bach, there are also echoes of Holst’s Hammersmith. Once the passacaglia is introduced roughly a third of the way into the piece (although it was hinted at long before), the theme is not consistently present, but is never far away. While both composers dance, dart, and distract from the themes, their respect for the familiar is at the core of the pieces. In both works the passacaglia provides a steady grounding, and each of them ends with one final, soft, solemn statement that bring the pieces to deeply satisfying conclusions.

The piece requires strong, but not virtuostic, players, which will make it accessible to a more ensembles that other pieces of its artistic equivalent. Once the parts are under the fingers the key to a successful performance lies in executing the dynamic contrasts. This is not a piece that thrives in the mezzo world, and the frequent substantial changes are magical when accomplished. Conductors should consider the dynmaic markings more about energy than volume.

Enigma was originally composed for brass choir and organ for the dedication of the Red Cedar Organ in the Michigan State University Alumni Chapel. The version for wind ensemble was commissioned by Henry Dorn, the conductor

of the St. Olaf Band, who studied conducting and composition at Michigan State. Dorn premiered this version of “Enigma” with the St. Olaf Band in January, 2024.

Enigma is available for purchase from davidbiedenbender.com, where you can also view a perusal score and see the video of the St. Olaf performance. It is worthy of mentioning that Dr. Biedenbender has been a finalist in this contest for the past two years and is also the recipient of this year ABA/ Ostwald Prize for his trumpet concerto “River of Time”. If you don’t know his work, now is a great time to start listening to his music.

The contest’s mission statement includes:

“It is the desire of the National Band Association that the winning compositions from this contest reflect its mission in helping further the cause of quality literature for bands in America. The winning works should be those of not only of significant structural, analytical, and technical quality, but also of such nature that will allow bands to program them as part of their standard repertoire.”

The members of the committee feel strongly that “Enigma” fits these criteria and is a piece that bridges the gap between audiences and performers. This

is a work that is worthy of joining our wonderful canon.

The remaining finalists for the 2024 contest are listed below. Each of these are interesting and compelling pieces well-deserving of performance and academic study.

A Hokusai Triptych – Ben Barker Boom Goes the Dynamite – Paul Dooley Forged by the Sea – Stacy Garrop Sunflower Studies – Nicole Piunno Declaration – James Stephenson Butterfly Cluster – Oliver Waespi

A note of thanks to all who served on the screening and selection committees and to JW Pepper for sponsoring the $5,000 prize. The caliber of entries this year was outstanding, and it is clear that wind band music continues to experiment, grow, and thrive.

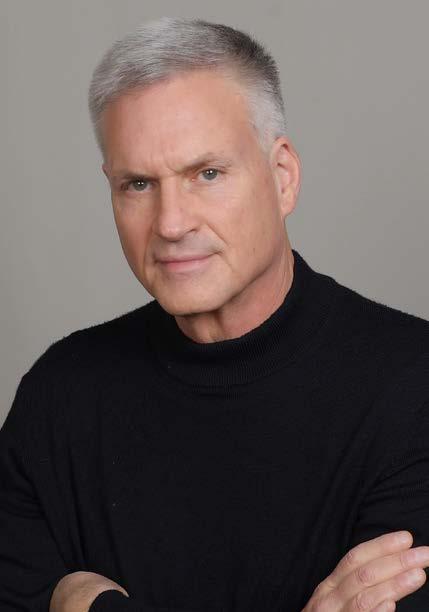

DR. TIM LAUTZENHEISER

has been named the newest recipient of the National Band Association Academy of Wind and Percussion Arts award and will be formally recognized at the NBA General Membership meeting during the 2025 Midwest Band and Orchestra Clinic. The Academy of Wind and Percussion Arts (AWAPA) award was established

for the purpose of recognizing those individuals who have truly made significant and outstanding contributions to furthering the excellence of bands and of band music.

Tim Lautzenheiser serves as Senior Vice President of Education for Conn Selmer, Inc. His career spans ten years of college band directing at Northern Michigan University, the University of Missouri, and New Mexico State University. After serving as Executive Director of Bands of America, he created Attitude Concepts, Inc. to accommodate the many requests for student leadership workshops, convention speaking and professional development presentations for educators. Tim's books, produced

by G.I.A. Publications, are bestsellers in the music profession. He is also co-author of Hal Leonard's popular band method, Essential Elements.

Tim is a graduate of Ball State University and the University of Alabama. He was awarded an Honorary Doctorate Degree from VanderCook College of Music. Additional awards include the distinguished Sudler Order of Merit from the John Philip Sousa Foundation, Mr. Holland’s Opus Award, and the Music Industry Award from the Midwest Clinic Board of Directors.

Congratulations, Dr. Tim, on being the newest recipient of the AWAPA award!

JOHN A. THOMSON

received his Bachelors and Masters degrees in trombone performance and music education from Carnegie Mellon University, where he studied with Richard Strange and Philip Catelinet. While completing course work towards a PhD in Music Education at Northwestern University, he served for two years as a Teaching Assistant in both the Departments of Conducting and Performing Organizations and Music Education, where he studied with John Paynter and Bennett Reimer.

Mr. Thomson was the Director of Bands at East Allegheny High School near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania from 1967 to

1981. Under his direction, East Allegheny bands presented feature performances at the 1976 Mid-West International Band and Orchestra Clinic, the 1975 Music Educators National Conference Eastern Regional Meeting, two Mid-East Instrumental Music Conferences in 1973 and 1977, and three Pennsylvania Music Educators Association Conferences in 1970, 1975 and 1980.

From 1982 to 2007, Mr. Thomson was Director of Bands at New Trier High School in Winnetka, Illinois. During these years, his ensembles regularly performed with established guest conductors, accompanied well-known solo artists, and collaborated with various contemporary composers leading to sixteen world premiere performances. In 1984, the wind ensemble completed a successful concert tour of Switzerland, Germany, and Holland. He conducted a New Trier Honor Band on a concert tour of Hawaii and Australia in 1998. Under his direction, New Trier wind ensembles performed at the l985 and l990 Mid-West International

Band and Orchestra Clinics, the 1994 Music Educators National Biennial In-Service Conference, the l989, l993, 1998 and 2007 Illinois Music Educators Association All-State Conferences, the l990 Western Illinois University Band “Showcase”, the 1996 Atlanta International Band and Orchestra Conference, the 1999, 2000 and 2001 Superstate Festivals at the University of Illinois and the 2003 Chicagoland “Invitational” Concert Band Festival. The wind ensemble received the Downbeat Magazine Award for best classical instrumental ensemble (band) in 1999, 2001, 2002 and 2004.

For twenty-three summers, Mr. Thomson conducted student and staff bands at the Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp in Twin Lake, Michigan, and conducted the camp’s 1992 International Band on their four week performance tour in Europe.

In addition, Mr. Thomson was a Contributing Editor and New Music Reviewer for THE INSTRUMENTALIST Magazine Continued on next page

2024 NBA Al & Gladys Wright Distinguished Legacy Award, cont.

and was active as a clinician, guest conductor and adjudicator. Following his New Trier retirement, he served for 10 years as an adjunct professor in music education at Roosevelt University in Chicago and has observed student teachers in the field for Northwestern University and the University of Illinois.

Personal awards include several National Band Association Citations of Excellence, the American School Band Directors Association Stanbury Award, the Mr. Holland’s Opus Award (sponsored by Bob Rogers Travel), the Chicagoland Outstanding Music Educator Award (sponsored by Quinlin & Fabish Music Company), the Phi Beta Mu Outstanding Illinois Bandmaster Award and the Phi Beta Mu Illinois Band Directors Hall of Fame at Northwestern University. Additionally, Mr. Thomson was inducted into the Pennsylvania Music Educators Association Hall of Fame.

Mr. Thomson was an elected member of the American Bandmasters Association and serves as that organization’s Goldman Memorial Citation Committee Chair. Additional professional affiliations included the National Band Association (Revelli Composition Award Committee), American School Band Directors Association (Past Illinois

State Chair), National Association for Music Education, Illinois Music Educators Association (Past District VII Band Chair and All-State Selection Committee), Phi Beta Mu and Phi Mu Alpha.

Mr. Thomson passed away in 2024 and is lovingly survived by his wife Susan, and two sons, Brian and Will.

johnathomson.com

is an internationally recognized clinician, conductor, and author. He is a graduate of Syracuse University School of Music with graduate studies at Ithaca School of Music, Eastman School of Music, Syracuse University, and Oswego State University. Mr. Lisk served with distinction for many years as the band director at Oswego High School (NY). His many contributions to music education include authoring The Creative Director series published by Meredith Music Publications, and coauthoring the highly

acclaimed 11-volume publication by GIA, Teaching Music Through Performance in Band. He is also the editor for the Edwin Franko Goldman March Series for Carl Fischer Music Publications, which include, On The Mall March, The ABA March, Bugles and Drums March, Onward-Upward March and On Parade March.

Mr. Lisk’s service to the profession includes having served as Vice President (Emeritus) of the Midwest Clinic Board of Directors and as a Past President and CEO of the John Philip Sousa Foundation. He is also a past- president of the National Band Association and served NBA as Executive Secretary Treasurer from 19972002. Additionally, Mr. Lisk was one of the original founders of the New York State Band Directors Association. Mr. Lisk is an inducted member of the prestigious American Bandmasters Association and in the year 2000, served as the 63rd President of this distinguished organization founded by Edwin Franko Goldman.

Called a “unique leader in the profession” and “a dynamic force in music education,” Edward S. Lisk has been invited to speak and conduct throughout the United States and abroad. His active guest-conducting schedule includes all-state bands, honor Continued on next page

bands, university, and professional bands. Since 1985, Mr. Lisk has served as an adjunct professor, appeared as a clinician/lecturer, adjudicator, and guest conductor throughout 85 universities in 46 states, five Canadian Provinces and Australia. He has served as guest conductor for the U.S. Air Force Band, Australian Wind Symphony, U.S. Interservice Band, U.S. Army Field Band and the U.S. Army Band “Pershing’s Own.”

Mr. Lisk’s many honors include the 2009 Midwest Medal of Honor, the 2012 Phi Beta Mu International Outstanding Contributor to Bands Award, the Sudler Order of Merit from the John Philip Sousa Foundation, the New York State Band Directors Association “Outstanding Band Director Award”, the “Key to the City of Oswego”, the Oswego School District “Administrator of the Year”, the Phi Delta Kappa “Area Educator of Year”, the Oswego Classroom “Teacher of the Year”, the A. R McAllister “Distinguished Bandmaster of America”, the Greater Oswego Chamber of Commerce “Civic Award”, the 2009 Syracuse Symphony Outstanding Music Educator Award, the 2015 NBA Academy of Winds and Percussion Award (AWAPA), and distinguished member of the National Band Association Hall of Fame for Distinguished Conductors.

2024 NBA Al & Gladys Wright Distinguished Legacy Award, cont.

(b. 2001) is an Oregon-born composer of wind ensemble, orchestral, and chamber music. His works fuse styles of the 18th, 19th, and 20th Century with modern techniques and contemporary instrumentation. Ryan currently pursues composition and wind conducting at the University of North Texas (UNT), where he has studied

with Dr. Sungji Hong, Dr. Kirsten Soriano, and film composer Bruce Broughton.

Ryan has earned several awards and accolades, showcasing his increasing popularity as an emerging composer. In 2024, he was named the winner of the Pennsylvania Symphonic Winds 2023 Composition Contest. Also in 2023, Ryan was recognized as the winner of the Austin Symphonic Band 2023 Young Composers’ Contest. He was a finalist in the ASCAP 2022 Morton Gould Young Composer Awards, and also earned second-place of the Florida Bandmasters Association 2021 Young Composers Competition. Ryan has received performances from several ensembles including the Royal Australian Air Force Band, the Pennsylvania Symphonic

Winds, and ensembles at UNT including the Wind Orchestra, the Wind Ensemble, the Concert Band, and the Symphony Orchestra. Ryan also frequently collaborates with student and faculty chamber ensembles at UNT to produce exciting and dynamic new chamber works.

Ryan’s passion and dedication as a composer has garnered recognition from many, who call him “one of the most promising young composers of his generation”, and one “[whose] fresh voice will undoubtedly craft a wonderful new addition to the wind band repertoire.” (Austin Symphonic Band)

ryanfillinger.com/about

(b. 1999) is a Korean-American composer who has been recognized by ASCAP and National Federation of Music Clubs and has been on the rise composing meaningful and exciting music meant for a variety of audiences in the Concert Hall. He also has been an enthusiastic supporter for bringing diversity into the Concert Hall. Minoo grew up in Suwanee, Georgia, where he was a passionate member of the music community, which eventually led him to develop his aspirations for becoming a composer.

Throughout his years of composing, he has been awarded the Donald Martino Award for Excellence in Composition,

Senior Composition Competition

Winner by MTNA, two NEC Honors Ensemble Composition Competitions, and a Finalist of the ASCAP Foundation Morton Gould Young Composers Awards Competition. Minoo’s pieces also have been performed at locations such as Carnegie Hall, Busan Cultural Center, Jordan Hall, and the Midwest Clinic.

Minoo earned his Bachelor of Music in Composition from New England Conservatory, where he studied under the tutelage of Michael Gandolfi. He is currently earning his Master in Music in composition at University of Texas at Austin’s Butler School of Music where he is under the tutelage of Omar Thomas.

minoodixon.com/about

ARBOR CREEK MIDDLE SCHOOL (CARROLLTON, TX)

Kimberly Beene, Sarah Ayoub, and Ben Koch, Directors

KILLIAN MIDDLE SCHOOL (LEWISVILLE, TX)

Trevor Ousey and Jenna Lenhard, Directors

LIGON MAGNET MIDDLE SCHOOL (RALEIGH, NC)

Renee Todd, Director

CUTHBERTSON HIGH SCHOOL (WAXHAW, NC)

Todd Ebert, Samantha Liddle, and Katie Ebert, Directors

SICKLES HIGH SCHOOL (TAMPA, FL)

Keith Griffis and Heather Lundahl, Directors

All winners of the following awards are listed at NationalBandAssociation.org/Awards-Recognition

Academy of Wind and Percussion Arts (AWAPA) Award

Al & Gladys Wright Distinguished Legacy Award

NBA Hall of Fame of Distinguished Conductors

Programs of Excellence Blue Ribbon Award

The NBA/Alfred Music Young Band Composition Contest

The NBA/Merrill Jones Memorial Band Composition Contest

The NBA/William D. Revelli Memorial Band Composition Contest

The NBA Young Composers Jazz Composition Contest

Mentor Award

Citation of Excellence

Outstanding Jazz Educator

Citation of Merit for Marching Excellence

Outstanding Musician Award

Outstanding Jazz Musician Award

Music Camper Award

Band Booster Award

It’s my pleasure to report that community bands in 2024 continued to rebound from the pandemic, and their audiences continued to increase as well. Players are returning to community bands as pandemic restrictions have been reduced or eliminated, and the fear of illness has abated. Likewise, concert venues have reopened to pre-pandemic levels.

The Association of Concert Bands (ACB) is the largest organization dedicated to supporting community bands, with members throughout the United States, in Canada, Germany, Ireland, Spain, Australia and the United Kingdom.

ACB supports community bands throughout the year on social media, including ACB Connects, a regular podcast focusing on issues all community bands face. The colorful ACB Journal is published three times a year, with

information and updates of interest to all community band members.

In a departure from past years, ACB held three events titled Regional Connections, which were two well-attended days of collaboration and discussion, education, and performance. Each event featured roundtable discussions of issues facing community bands, and an opportunity to exchange ideas and do regional networking. In addition, educational sessions included a new music reading session, guidance on grant-writing, information on jazz performance, concert band instrument history, and software for online collaboration. Concerts by ACB member bands as well as university ensembles were a highlight. The events were held in: Omaha, Nebraska (April 26-27) Richardson, Texas (June 14-15) and Carrollton, Georgia (September 20-21).

In 2025 the association will return to its single annual

Michael Burch-Pesses, the President-Elect of the Association of Concert Bands, is Distinguished Professor of Music and Director of Bands at Pacific University in Forest Grove, Oregon, where he conducts the Wind Ensemble and Jazz Band, and teaches courses in conducting and music education. He enjoyed a distinguished career as a bandmaster in the United States Navy before arriving at Pacific University. During his Navy career he served as Leader of the Naval Academy Band in Annapolis, Maryland; Assistant Leader of the Navy Band in Washington, DC; and Director of the Commodores, the Navy's official jazz ensemble. Dr. Burch-Pesses also is the Conductor of the award-winning Oregon Symphonic Band, Oregon's premier community band. In 2006 the band performed at the Midwest Clinic, and in 2007 the John Philip Sousa Foundation awarded the band the Sudler Silver Scroll, recognizing them as one of the outstanding community bands in the nation. He is the author of “Canadian Band Music: A Qualitative Guide to Canadian Composers and Their Works for Band,” and is a regular contributor to the “Teaching Music Through Performance in Band” series. He also is a Conn-Selmer Educational Clinician

convention format. This will take place at Fort Smith, Arkansas, June 4-8.

Continued on next page

2024 Community Bands Report, Michael Burch-Pesses, cont.

Last year at this time the ACB had 645 member bands, and that number has grown to 679. Individual memberships number 448, fewer than previous years, and the Association is working to increase individual memberships further in 2025.

ACB Corporate memberships, including music publishers, number 22, an increase over last year. Although this number is smaller than before COVID, the Association is working to increase these memberships now that bands are more active and are ordering even more music and other equipment.

I’m delighted to announce the winner of this year’s ACB Young Composers Composition Contest is Trenton Rhodes with his work, "Symphonic Mountain Fantasy." For the first time in the contest’s history, the judges came to a unanimous decision that this was the clear winner among the submissions. That should give you an indication of just how good it is! The winning composition will premiere at the 2025 ACB Convention in Fort Smith, AR.

THE NEW HORIZONS INTERNATIONAL MUSIC ASSOCIATION

The New Horizons International Music Association (NHIMA) provides music-making opportunities for adults, including those with no musical experience, and those who were active in school music programs but have been inactive for a long period.

Founded in 1991 by Roy Ernst, a professor at the Eastman School of Music, NHIMA represents more than 163 New Horizons bands, orchestras, choral groups and planning groups throughout the USA, Canada, Ireland and Australia. It has 11 business members.

In 2024, NHIMA hosted two camps in Cincinnati Metro and Lakeside Chautauqua, Ohio. Next year the Association will host three camps, in Rochester, NY; Cincinnati Metro, OH and Mt. Tremblant, Quebec.

NHIMA held 19 virtual classes in 2024, many of which were 4-6 weeks in length, including ukulele instruction, separate classes on the music of the Beatles and Louis Armstrong, a percussion class, and how to use MusicCloud.

The Association’s informative newsletter, New Horizons News,

combines with Music Forever, a bi-weekly podcast in which players and conductors from New Horizons bands and orchestras share their musical journeys and their passion and love of playing in New Horizons ensembles. Music Forever can also be found on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

There are many other community bands that are not members of ACB or NHIMA, and anyone wishing to join a local band can find an abundance of information on the web or by contacting ACB or NHIMA.

We offer our congratulations to numerous community band members who have been recognized by the American Prize this year. As of this writing: Conducting

Community Band Division

• Ken Bagley, Avon CTPlainville Wind EnsembleThe American Prize winner

• Christopher Ward, WestBloomfield, MI – Five Lakes Silver Band – 2nd Place

• Nicolas Propes, LeClaire, IA

- Big River Brass Band - 3rd Place

Composition

Band/Wind Ensemble

• Lee Hartman, Kansas City, MO - "Emerald" - 3rd Place

2024 Community Bands Report, Michael Burch-Pesses, cont.

Major Choral Works

• Augusta Cecconi-Bates, Cape Vincent, NY - "We Have a Dream"

Band/Wind Ensemble Performance Community Division

• South Jersey Area Wind Ensemble, Egg Harbor Township, NJ; Keith W. Hodgson, conductor - The American Prize winner

• The Allentown Band, Allentown, PA; Ronald Demkee, conductor - 2nd Place (tie)

• Cleveland Winds, Lakewood, OH; Birch Browning, conductor – 2nd Place (tie)

• East Texas Chamber Winds, Miami, FL; Roy Mclerran, conductor- 2nd Place (tie)

• Big River Brass Band, LeClaire, IA; Nicholas Propes, conductor – 3rd place (tie)

• Arizona Winds, Surprise, AZ; Rich Shelton, conductor - 3rd Place (tie)

Congratulations to the three community bands selected to perform at the 2024 Midwest Clinic:

• Cedar Park Winds from Leander, TX, Jeremy Spicer, conductor

• Naulu Winds of the University of Hawaii West Oahu, from Pearl City, HI, Chadwick Kamei, conductor

• Springboro Wind Symphony from Centerville, OH, Josh Baker, conductor.

2024 NBA Membership Report (one day snapshot – as of 12-15-24)

The horn’s reputation for being a difficult instrument is firmly set in the legends of band lore. With a “home base” setting that is higher up on the overtone series than the middle register of other brass instruments, the horn presents unique challenges for accuracy fairly early on in the hornist’s journey. Horn players also face other challenges of tone production, range development, pitch awareness, dynamic control, and the need to learn different marching band instruments. Although hornists have to navigate these slippery challenges more often than other brass students might have to, the technical passages they face are often not as numerous as those their trumpet, trombone, and euphonium-playing colleagues have to deal with.

Nevertheless, the large ensemble, solo, chamber music, and state-wide band and orchestra contest music hornists play in high school demands some advanced technical skill, even if these

abilities are less often called for than in other brass parts. In fact, the lack of technical passages for horn students at younger levels is partly why they might struggle with technique when more challenging repertoire is set before them in high school. However, without having to invest a lot of time into method books and extensive practice regimens, I believe a student and/or horn section could improve their technique to be ready for high school repertoire, or to catch up if they are a little behind, by practicing two basic exercises in the band class and/ or at home. I call these exercises the Rhythmic Accelerando and the Five Note Scale Exercise. They have helped my own beginner through collegiate-aged students immensely in the development of their technical abilities.

In isolating technical issues, we essentially have two main challenges to overcome: tonguing speed and coordinating the air, tongue and fingers. There are also occasional challenges of flexibility, but these challenges are more

Continued on next page

Matthew Haislip is Assistant Professor of Horn at Mississippi State University. He also teaches at Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp and is a member of Quintasonic Brass, Missouri Symphony Orchestra, Starkville Symphony, North Mississippi Symphony, and Meridian Symphony. He was previously a member of the Midland-Odessa Symphony (TX) and Kentucky Symphony and has performed with such ensembles as the Cincinnati Opera, Opera Naples (FL), Omaha Symphony, and the Billings Symphony (MT). He has published articles with the International Horn Society, British Horn Society, and Bandworld Magazine. Haislip’s book and music are published by book Mountain Peak Music, WaveFront Music, BrownWood Publishing, and the International Horn Society’s Online Music Sales. He led the composition consortium for Anthony Plog’s Horn Sonata and performed the world premiere in 2023. He holds degrees from the University of Missouri-Kansas City, University of Cincinnati, CCM, and Texas A&M University-Commerce. Matthew is a Yamaha Performing Artist.

Technique Tips for the Student Hornist ..., Matthew Haislip, cont.

rarely seen in high school music. (Flexibility can be addressed by working on exercises associated with range development of the air speed along the overtone series. Slurring and then tonguing arpeggios across the range of the horn can aid in developing sufficient flexibility for young hornists. Tension and rigidity are the enemy of flexible brass playing. The approach should be air-driven; not muscled.) With a coordinated approach to tonguing speed and finger dexterity, they will be ready for so much of what comes their way in the high school band experience.

SKILLTONGUING SPEED

Tonguing speed can and should be addressed sooner rather than later in the school band brass class. If it’s only in high school when students start to work on this skill, they will be left behind in faster passages. It takes months to develop incremental improvements in one’s tonguing speed, as the physical muscle of the tongue needs to get conditioned “up to speed” over time.

• a focused sense of subdivision is necessary to be productive in developing tonguing speed

• if the air stops, the forward momentum stops, so blowing a long tone and interrupting

it only with the tongue is the way forward

• a lighter tongue is a faster tongue

• a heavier tongue is a slower tongue

• lighter articulation involves more of a “doo” articulation than a hard “too”

• faster twitch muscle allows some people to tongue faster than others, but players with faster twitch muscle actually often have trouble tonguing slower, so students with an easy fast single tongue should also work on tonguing at much slower tempos

Continued on next page

TONGUING SPEED EXERCISERHYTHMIC ACCELERANDO

*play in two or three different keys each practice session

The Rhythmic Accelerando exercise asks the student to play just one pitch while articulating the rhythmic division of each beat one unit smaller (faster) each measure from quarter notes to eighth notes, triplet eighth notes, and sixteenth notes. Similar exercises have been used by countless teachers to instill good subdivision. It requires focused concentration to switch between the simple and compound division of the beat, which can be quite challenging for younger students. The growth benefits in personal musicianship and tonguing speed make this a time saving exercise for junior high school and high school-aged hornists. Students would benefit from working on both of the exercises in this article by working with a metronome, including placing the beat of the metronome on the upbeat so that the student is providing the downbeat with their internal pulse. I recommend adding a crescendo to the end of the line to keep the air consistently blowing forward even as we start to run out of air.

A good starting tempo for this

Technique Tips for the Student Hornist ..., Matthew Haislip, cont.

exercise would be quarter note=72 or slower, if necessary, working up to quarter note=120, if possible. Tonguing speed is limited by the muscle twitch speed capabilities of each person, so some students will not be able to single tongue at even quarter note=110, while other students may be able to single tongue as quickly as quarter note=176 or faster! After a well-grounded footing in single tonguing has been gained, it will be time to slowly introduce double tonguing. This could start as early as the second year of playing for students with solid fundamentals. The same principles apply for fluidity in double tonguing (lighter tongue, air-driven approach, etc.).

Experimenting with a “koo” or “kah” or “goo” or “gah” syllable will help each student find what works best for them. The ability to work on coordinating the tongue and air on just one pitch without having to involve the valve changes as well will keep the student from information overload and frustration with the process. The ideal sound produced for both single and double tonguing will be a beautiful immediate tone with a clear but light front moving rapidly and not changing tone color as the front and back of the tongue are

employed. This will be challenging to execute, so practice involving isolating the “kah” or “gah”, etc. in simple eighth notes will help train the back of the tongue.

This exercise does not take very much time out of a band rehearsal but packs quite a pedagogical punch. It could be useful for the entire band, including the percussion section. I appreciate that my own high school band director in northeast Texas worked daily with the band on single, double, and triple tonguing exercises and modeled them for us beautifully on his own trumpet. It paid off immensely in the level of repertoire the band could play.

After working on the tongue’s overall fluidity and speed, now comes the challenge of coordinating the air, tongue, and fingers with some speed as well. Students often struggle with producing a complete system of timing within their musical “engine”. They can grapple with flams and blips on notes if one or more aspects of this engine

are not lining up with the others. Coordination is the key to solving these technical problems.

A few tips:

• as with tonguing speed, a focused sense of subdivision is necessary for synchronous air, tongue, and finger coordination

• working slowly and gradually increasing the tempo helps ensure command of all aspects at an easier pace instead of attempting to put everything together at an uncomfortable quick tempo

• isolating two of the three

aspects at a time can help with coordination - for example, slurring through the passage first to coordinate air and fingers and then adding the tongue when the passage is slurred smoothly - or just using air sounds with the valves to line up the air and fingers before actually playing the instrument

• getting the air right at the front of the note, not separate from the tongue, is the key to a beautiful nuanced front to each note

• curving the fingers over the valves allows for a more

efficient range of motion instead of flattening the fingers out across the levers

• learning and memorizing all standard fingerings across the range of the horn is a must for execution of technical passages (and helps when marching instruments and new fingerings are introduced)

• mastering all twelve of the major scales from memory across two or more octaves with a good all-around sound and clear articulation is a helpful goal to build solid technique

Continued on next page

FIVE NOTE SCALE EXERCISE

*play in every key - perhaps around the circle of fourths through different octaves

The Five Note Scale Exercise tasks the student with tonguing the first five notes of a major scale up and back down with another rhythmic accelerando through quarter notes, eighth notes, and sixteenth notes. As this exercise consists of the first five notes of a major scale, students of a wide variety of ability levels can approach it and benefit from it. If it is played with clear articulation and a characteristic sound by employing a coordinated system of air, tongue, and fingers, the student can develop a greater connection to their instrument and a technical fluidity that all great players demonstrate. A crescendo to the end of the line is helpful to keep the air in motion to the end. If students cannot make it through the exercise in one breath, they can breathe at the end of measure two, changing the final quarter note to an eighth note. It is helpful to slur through the line with a great sound and a smooth connection between the notes first before adding articulation.

I recommend similar tempo guidelines (quarter note=72 to 120) in this exercise as in the rhythmic accelerando exercise, but it may need to be taken a bit slower for younger players. Students can and should take these tempo markings faster than 120 if they can play it cleanly at 120. This exercise, too, can serve as an approachable opportunity for working on double tonguing. An advantage of this exercise is that if students play it in every key, they will encounter some challenging cross fingerings (Concert A or Concert B, for instance) that can develop their overall fluency on the instrument. This exercise can be a good stepping stone to playing full one, two, or three octave scales at quick tempos if the student keeps the clarity and connection they learned with this exercise. This is an exercise I often practice myself in my own daily fundamental practice routines.

*note: a full packet of these two exercises is available on my personal website: matthaislip.com/teacher

Ideally, we want our concert band horn students to produce a beautiful heroic sound for the lyrical “Hollywood” horn moments, have a good sense of time for Sousa marches, and be able to call up a bit of flash for the technical passages that good writing for the horn employs. The Rhythmic Accelerando and Five Note Scale Exercise would be beneficial for the entire brass section and possibly the entire band. By working on their tonguing speed in isolation and then coordinating their air, tongue, and fingers, students will be more than comfortable to face whatever technical acrobatics come their way. From there, they can be freed from the burden of limitations to have FUN playing the exciting moments wind band students enjoy.

Ibelieve in mentorship. Mentorship has created and still creates the most impactful musical scenarios in music. Whether a person is in your rehearsal room or you were inspired by their book or recording, you learned from that person; mentorship is fluid and takes many forms. Anytime we hear a less than stellar performance, especially at an adjudicated event, we hear, “Did they ask anyone if they should have played that? Did they have anyone listen to the group before the festival?” Those questions are saying that someone, a mentor or maybe just a good friend, might have helped.

Has mentorship taken an odd turn? When I began teaching in 1977, we heard new music on sound sheets (“place nickel here”, if you remember), then we moved to cassette recordings which offered excerpts of pieces. It was a challenge to find a complete recording. Word of

mouth, recommending pieces, was crucial. Sometimes I played a piece at contest that I had never heard. We actually studied scores! Next came the cd which opened a whole new world of resources. All of the publishers began producing high quality recordings; no more excuses, we now had terrific models of almost any piece. You know what came next: The Internet! I have always been a literature hound. Some of us are relentless when it comes to searching out new music. The Internet brings everything to our fingertips. All we need is a Smartphone.

With all these tools at our fingertips, I am frustrated by the lack of initiative that many directors take to creatively program for their students. Unlike English teachers, we are given free reign over the literature we bring to our students. Most states use an extensive list of prescribed or suggested music and we have the luxury of choosing our music, yet the number of social media

Gary Barton retired from the La Porte, Texas Independent School District after thirty-seven years of teaching in five states. He received the Bachelor of Music Education from the University of LouisianaMonroe and the Master of Science in Education from Indiana University. A Past President of the Arkansas School Band and Orchestra Association and Past 2nd VicePresident of the National Band Association, he has written for numerous publications and has done clinics and presentations in sixteen states. He may be reached at bartonglp@gmail.com.

posts asking, “Please tell me what to play” are growing at, in my opinion, and alarming rate. “Here’s my instrumentation, tell me what to play” is not an unusual post. In many geographical areas, this has created a small number of “go to” pieces that are passed around and I see a piece played up to six times on a given day at an event. Some states publish data each year as to what pieces are played most

Continued on next page

We Don't All Like the Same Music ..., Gary Barton, cont.

frequently and which pieces tend to get a superior rating. While I believe there are no “first division pieces” this strategy does at times produce results, but is the growth of the director sacrificed?

The best practice I have seen comes from a young man in Texas. The Texas PML (Prescribed Music List) is a treasure chest of music at all grade levels and it is constantly growing and evolving; many states use the PML. He normally plays from the Grade 3 and 4 lists. He has scoured those two sections and made a list of the pieces he would like to use at some point. His list is also constantly changing. It’s a simple process. Go through the lists, go to the websites and listen. Often the score is displayed as well. It’s research, self-development, and it’s demanding of time. After all this effort, he decides what he would like to play and then asks opinions from colleagues. “Do I have the woodwinds for this?”

“Will it fit with this other piece?” “Is the program going to be too long for our endurance?’ This is when the mentorship begins. Yes, this takes a long time and you must invest. When you go to a doctor or dentist or lawyer, if they are using the latest techniques, they have researched, studied, and trained. Do you really want to go to a middle-aged doctor who hasn’t studied past his medical school graduation?

I have a few observations that usually tell me if directors are playing what they were told to play or if they chose the obligatory “you can make a 1 with this” piece. The performance is clean, in tune, first division, but there is little conviction, passion in the performance. A conductor’s passion for the music will be apparent. A lack of passion will also be apparent. Another “tell” can be embarrassing:

“Congratulations on your first division performance! What did you play?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Who wrote it?”

“I don’t remember.”

This is absurd, but if you try asking these questions you may find it more troubling than you expect.

We do not all enjoy the same music any more than we enjoy the same food. I live on the Gulf Coast and there are seventeen Tex-Mex restaurants on my street but I don’t eat seafood or avocados. It is also acceptable that you may not identify with every piece by your favorite composer. We are very fortunate to have the opportunity to present music to our students that we can be passionate about in every rehearsal. I substitute

Continued on next page

We Don't All Like the Same Music ..., Gary Barton, cont.

teach and I can attest to the fact that English teachers do not have our autonomy. They will teach that novel and their opinion may not be a concern. Or maybe they are forbidden to teach a particular novel. We are charged with producing technically and intelligently competent musicians, but I think musically excited student musicians must be the ultimate trophy. I have dozens of biographies of great conductors and I can promise you that they have surprising opinions about the validity of some of our greatest masterpieces. You will find it difficult to present a musically “on

fire” performance of a piece that does not speak to you. Do your own research, the rewards will last your whole career.

"If You Like Everything I Write, I’m Not Doing a Good Job." – Robert W. Smith

"Only the Mediocre are Always at Their Best." – Oscar Wilde

"Give a Man a Fish and You Feed Him for a Day. Teach Him How to Fish and You Feed Him for a Lifetime." – Lao Tzu

RECOMMENDED READING

Pierre Monteux, Maitre by John Canarina (Amadeus Press, 2003)

The Composer’s Advocate by Erich Leinsdorf (Yale University Press, 1981)

Erich Leinsdorf on Music by Erich Leinsdorf (Amadeus Press, 1997)

Boulez – Composer, Conductor, Enigma by Joan Peyser (Schirmer Books, 1976

When I consider what makes ensembles exceptional, I think not of the lofty goals we set but of the systems we use to reach them. A quote from James Clear’s Atomic Habits resonates deeply with me: “You don’t rise to your goals. You fall to your systems.” Success in music education—and life—depends less on the grand destinations we aspire to and more on the daily habits and systems that pave the way.

Building a successful ensemble requires navigating both the PROs and CONs of development— embracing systems that enhance performance while addressing challenges that arise in the process. Below, I explore the foundational principles (the PROs) of ensemble success, the obstacles (the CONs) that educators and students must address to achieve meaningful growth, and simple systems that

can be installed to help move us forward.

Exceptional ensembles don’t focus solely on the final performance product. Instead, they prioritize the processes that lead to consistent progress. To shift from what is possible to what is probable, rehearsals should follow a structured approach:

I. READ ("What?"): Begin with the basics—notes and rhythms.

a. Members are presented with material for the first time, or it is the first time the ensemble is working on the material with all members present.

b. Ensemble focuses on developing an understanding of the fundamental blueprint of the material.

c. Members should leave the rehearsal with answers to all “WHAT” questions

Dr. Adam J. Gumble is the Director of Athletic Bands at West Chester University. Dr. Gumble’s primary responsibilities include directing the “INCOMPARABLE” Golden Rams Marching Band, “Sixth Man” Basketball Band, Concert Band, and undergraduate conducting courses. Since arriving at West Chester University, the “RamBand” has performed in featured exhibitions at the Bands of America Grand National Championships, was named the recipient of the prestigious Sudler Trophy (the “Heisman Trophy” for collegiate marching bands), and has performed halftime shows at National Football League Playoff games. Most recently, the RamBand was honored to perform in the 2024 Rose Parade® in Pasadena, California.

Dr. Gumble is an active guest conductor, clinician, producer, adjudicator, and presenter across the United States. He serves as the Director of Educational Programming for Vivace Productions, Incorporated. Before his appointment at West Chester University, Dr. Gumble taught for 13 years in Pennsylvania public schools.

in the chunk/segment and be equipped with the tools to perform the notes and rhythms involved in the chunk/segment at the ensuing rehearsal.

d. Key Questions:

i. What is the key/tonal center?

ii. What technical demands are presented?

iii. What is the marked tempo?

iv. If the material is beyond my current ability, what “check patterns” or “target notes” exist that will allow me to participate in ensemble without developing bad habits?

v. What STRATEGIES can I employ to ensure that I’m eventually able to perform the material?

II. ROUGH-IN ("How?"): Shape dynamics, articulations, and tempo.

a. Members are expected to attend rehearsal prepared to perform notes and rhythms at a tempo approaching the performance requirement.

b. Ensemble focus is on building group awareness of role (see: Layering Balance) and shape (notes, phrases, and dynamics).

c. Members should leave the rehearsal with answers to all “HOW” questions present in the chunk segment and equipped with the tools to perform the Articulations and Dynamics (in addition to Notes and Rhythms) involved in the chunk segment at the ensuing rehearsal.

d. Sample Questions

i. What role(s) do I play during this segment? (See LAYERING)

ii. Who is the listening point for note length? What syllables are we using?

iii. Who is the listening point for dynamic growth? Are there any dynamic adjustments I need to make based on context? (Geography/Texture Register/Personnel)

iv. How does performance practice dictate my approach?

III. REFINE ("Why?"): Connect with the musical intent and artistry.

a. Students are expected to attend rehearsal able to perform all WHAT and HOW elements approaching performance tempo.

b. Ensemble focus is on fine tuning elements and realizing the emotional intent of the material.

c. Members should leave the rehearsal with answers to all “WHY” questions in the chunk\

segment and equipped with tools to connect with the material emotionally.

d. Key Questions:

i. What is the composer saying?

ii. How does my role evolve throughout this piece?

iii. Where is the emotional climax?

iv. Why is this music important?

v. What does this music mean to me?

This system ensures that every rehearsal builds toward a shared vision. Educators can implement this by mapping rehearsals, blocking time, chunking material, and creating a roadmap to keep progress intentional.

A goal without a plan is just a dream. While setting goals is vital for any ensemble, achieving them requires well-structured systems to turn aspirations into reality. Too often, we focus on the end result—whether it’s mastering a challenging piece or delivering a polished performance—without establishing the necessary steps to get there. This lack of planning can leave rehearsals feeling rudderless and students unclear about how to reach the goal.

Example in Context: A band

director sets a goal to perform a technically demanding piece but skips the foundational work of breaking it into manageable sections or teaching the musical concepts needed to interpret the composer’s intent. Students become overwhelmed, and the result is a performance that feels strained and unfinished.

The key to success lies in teaching students not only to set goals but also to develop action plans that connect their daily work to those goals. These plans should break big objectives into smaller, achievable steps, empowering students to take ownership of their progress.

1. Define the Goal Clearly: Encourage students to articulate their goals with precision, whether it’s mastering a specific phrase, improving tone quality, or aligning rhythms with the ensemble. A vague goal like "play better" doesn’t provide direction, but a focused goal like "play the sixteenth-note run in measure 32 at tempo without tension" sets a clear target.

2. Break the Goal Into Steps: Teach students to deconstruct their goals into actionable tasks. For instance, mastering