THE FUTURE OF Survey

Insight and Foresight

The 2025 study confirms that the classic 1995 trust model — comprising ability, integrity, and benevolence — remains highly relevant for Gen Z, with ability emerging as the top factor for both building and losing trust in leaders. The research reveals that trust is built slowly (13 – 24 months) but lost quickly (within 12 months for most), and while skills and transparency drive trust-building, self-interest and ethical lapses are the primary causes of trust erosion. Critically, trust in leadership is significantly linked to greater job satisfaction, retention, and leadership development, underscoring its direct impact on organizational success.

The 2026 Survey will broaden the respondent base to explore how tenure influences perceptions of trust-building and loss. We aim to examine whether time in employment affects how quickly trust is formed or broken. Additionally, we will investigate the specific incidents that lead to trust erosion, offering deeper insight into the sub-components of ability, integrity and benevolence.

CONTACT: ruchin.kansal@shu.edu or karen.boroff@shu.edu

Ethics

BY MARY TUNNY WEICHERT

ASHISH GUPTA

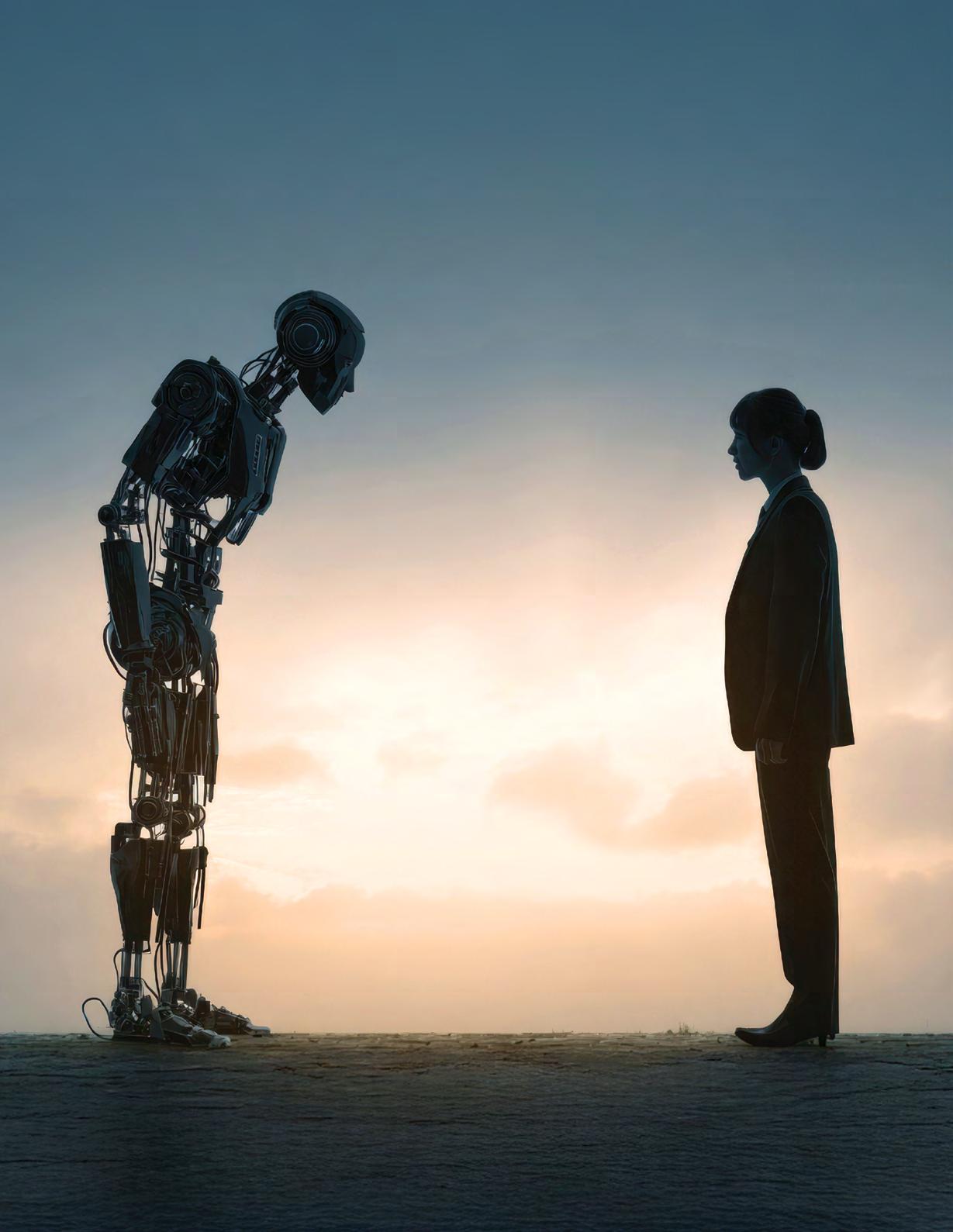

Trust is the linchpin of human-robot teaming in modern warfare.

BY ERICKA ROVIRA

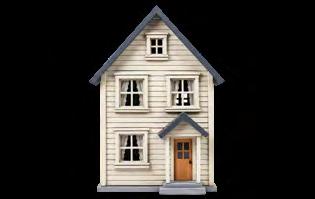

A discussion on how leadership and trust function in both traditional workplaces and the creator economy.

From crisis to growth: How involving employees helped a dealership thrive during industry-wide disruption.

DAVE GARRISON

Kaylyn Sanbower ’15, an economist at the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, shares her career journey and insights on building trust. She emphasizes that trust relieves you of the burdens that exist in its absence.

The trust imperative: Next generation evidence for leadership effectiveness.

Cultivating unbreakable trust from the battlefield to the boardroom.

BRYAN C. PRICE

Trust is a priceless commodity requiring a committed investment.

CINDY M C GOVERN

In Ros Taylor’s The Future of Trust, Alexander and Wood find trust is no longer optional and is essential for navigating business, technology and institutional uncertainty today.

Paula Becker Alexander, Ph.D., J.D.

is an associate professor and chair of the Department of Management at the Stillman School of Business at Seton Hall University. She developed the curriculum for Corporate Social Responsibility, a core course in the school’s M.B.A. program. Routledge published her business ethics textbook, Corporate Social Irresponsibility, in 2015. Her research focuses on firm financial performance, executive comp and socially responsible management.

Bryan C. Price, Ph.D.

is the founder of Top Mental Game, where he helps business leaders and athletes perform at their best when it matters the most. Price graduated from West Point and served as an Army officer for 20 years, with combat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. He is a certified executive coach and keynote speaker who works with Fortune 100 companies, military units and athletic teams. He earned his Ph.D. from Stanford University.

Karen Boroff, Ph.D.

is professor emeritus and dean emeritus at the Stillman School of Business at Seton Hall University. As interim provost, she led the creation of the University-wide Leadership Development Program. She earned her Ph.D. in Business from Columbia University, where she concentrated in Industrial Relations and Human Resources Management. She was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

Jess Rauchberg, Ph.D.

is an assistant professor at Seton Hall University. Her research and teaching investigate cultural production and labor inequalities in creative industries. She is a founding member of the Content Creator Scholars Research Network, and a global member of the TikTok Cultures Research Network. Her work appears in top academic media studies journals, and her expertise on influencer culture is quoted in over 40 press interviews. She received her Ph.D. from McMaster University.

Anthony W. Caputo, M.A.

is an organizational psychologist and COO/CPO at Remesh. He has driven growth of $16 million in revenue and more than 200 employees, transitioned to a four-day work week, launched new products, and enhanced market position. He frequently contributes to SIOP and HR Tech conferences. Caputo has held roles at Stanford, Columbia Business School, the UN, global consultancies and the EEOC. Caputo holds degrees from Columbia and Seton Hall.

Ericka Rovira, Ph.D. is a professor of engineering psychology in the department of behavioral sciences and leadership at United States Military Academy at West Point. Her research investigates human autonomy teaming in high-risk complex environments. Rovira’s interest lies in understanding how to improve trust and reliance in robots, including team cohesion and the role of individual differences in cognition. She holds a Ph.D. in Applied Experimental Psychology.

Dave Garrison, M.B.A.

is the author of the bestselling book The Buy-In Advantage: Why Employees Stop Caring and How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Give Their All. He is also CEO of GarrisonGrowth, dedicated to unlocking potential through human strategy. As a speaker and workshop leader, he has led hundreds of sessions for both for-profit and nonprofit organizations. Garrison has also been a guest lecturer at leading business schools. He holds an M.B.A. from Harvard Business School.

Kaylyn Sanbower, Ph.D.

is an economist at the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, where she investigates economic questions across various industries, including health care and airlines. She also supervises the division’s research analysts. Sanbower earned a Ph.D. in Economics from Emory University, where her research focused on healthcare markets. She holds a B.S. in Economics and Mathematical Finance from Seton Hall.

Ashish Gupta

is a respected leader in the manufacturing and logistics industry with a passion for unifying diverse perspectives in the workplace and beyond. With nearly three decades of experience, he is an advocate for cultural progression through thoughtful leadership and empathy.

A graduate of IIT Roorkee (1993) in Electrical Engineering, Gupta has been in leadership roles in Tata and Vedanta groups in India, and he has managed large work forces and multiple geographies.

Mary Tunny Weichert is an award-winning real estate professional and has been a leading broker in northern New Jersey for almost 25 years. Ranked among the top 0.5 percent of Weichert Realtors, she is known for her concierge-level service. A lifelong Chatham resident, Weichert is a devoted community advocate and philanthropist, supporting causes that aid children and the underserved. She is also a daily communicant at Mass, reflecting the faith that guides her.

Cindy McGovern, Ph.D.

is known as the “First Lady of Sales,” and the author of The Wall Street Journal bestseller Sell Yourself and Every Job Is a Sales Job. She is also the founder of Orange Leaf Consulting, where she helps organizations and individuals grow through intentional communication, personal branding and leadership development. McGovern seeks to help people see that every interaction is a sales opportunity, and trust is the foundation of every successful relationship.

Stephen Wood, M.S. consults and writes on policy topics after 43 years on Wall Street and in governmental finance. He specializes in infrastructure and project finance, public-private partnerships, federal and state grant and finance programs. He is also an expert in financial modeling for large, complex capital programs. A speaker at numerous industry conferences, he teaches about corporate social responsibility at Seton Hall.

Trust Drives Leadership

WELCOME TO THE 10TH EDITION!

Like everything meaningful, In the Lead began with a simple idea — to share the wisdom of today’s leaders with those who will shape tomorrow. The central idea for the magazine is rooted in the belief that leadership is learned through experience, shaped by perspective, and enriched through diverse voices.

Our goal then — and now — is to democratize leadership: to improve access to insights that inspire action, growth and accountability.

Over the years, we’ve explored themes that mirror the evolving dialogue of our times: a leader’s journey, leading through disruption, leading innovation, building high-performing teams, the future of work, navigating artificial intelligence, and the emergence of Gen Z in the workforce. We’ve shared real challenges and relevant solutions — grounded, adaptable and implementable.

Each year we have included findings from our Future of Leadership Survey — a longitudinal, Institutional Review Board approved study we launched in 2020. Drawing from a global pool of future leaders ages 18–30, the study continues to surface one unmistakable truth: Trust is the single most critical driver of leadership effectiveness.

And so, we’ve dedicated this 10th edition to what brings together diverse perspectives on how leaders earn — or erode — trust. At its core, trust is built on competence (I can do what I’m here to do), integrity (I’ll do what’s right) and empathy (I care about people). Trust is what future leaders expect. And that gives me hope — for a future where leaders internalize one essential truth: You are only a leader if someone chooses to follow you.

I began this publishing journey alongside two imaginative partners — Bryan C. Price, Ph.D., and Steve Lorenzet, Ph.D. — who both have pursued the call to leadership beyond Seton Hall. I felt it only right to invite them back to contribute to this milestone edition.

Ruchin Kansal, M.B.A.

is a professor of practice at Seton Hall University and the founding editor of In the Lead. Prior, he led the Business Leadership Center at the Stillman School of Business, and held senior leadership roles at Capgemini, Deloitte, Boehringer Ingelheim & Siemens Healthineers with a distinguished record in strategy and innovation, digital health, strategic partnerships and business launches. He received his M.B.A. from NYU-Stern.

They say, “it takes a village to raise a child.” So, too, to develop and produce a thought-provoking publication. In the Lead has been shaped by a remarkable village: Pegeen Hopkins, head of Strategic Communications and Brand; Melissa Cerciello from Public Relations and Marketing; and Eric Marquard, our university designer. Their passion and commitment have brought this vision to life issue after issue.

Thank you for your continued readership and support.

For now, I leave you with one simple, powerful question: Are you trusted as a leader?

– Ruchin Kansal

In 2025, Seton Hall University proudly celebrates a remarkable milestone — the 30th anniversary of the Buccino Leadership Institute — three decades of nationally recognized commitment to cultivating values-based, visionary leadership.

Celebrating a Legacy

For 30 years, the Institute has shaped leaders of character — empowering students to lead with integrity, inspire innovation, and serve with purpose. Graduates have gone on to influence industries, transform communities and make a difference around the world.

Buy-In Boom

From crisis to growth: How involving employees helped a dealership thrive during industry-wide disruption.

BY DAVE GARRISON

WHEN LOOKING out his window, Chris Hemmersmeier was accustomed to seeing parking lots filled with gleaming rows of new Buicks, Cadillacs and Chevrolets in every color and model imaginable. He is the largest shareholder and CEO of Jerry Seiner Dealerships, a multistate automotive retailer. The 40-year-old chain, headquartered in Salt Lake City, seemed like it was on a continual growth trajectory. That all changed in 2020, as the chain

endured three successive blows. First, General Motors, Jerry Seiner’s top brand partner, reduced shipments by 80 percent because of computer chip shortages. Trade-ins, a major source of used inventory, dropped by 80 percent, as customers realized it would be next to impossible to buy the new cars they wanted. And with the COVID-19 pandemic in full swing and few cars to sell, key employees — worried about both their health and their livelihood — were quitting.

Hemmersmeier, who’d been with the company for 30 years, knew he and his leadership team had to act quickly. To make the most of the little inventory they could still obtain, they began taking preorders for new cars weeks before the vehicles arrived. They also went into overdrive, promoting the fact that they had plenty of used cars to sell. At the same time, they stepped up the company’s service business, bringing in muchneeded revenue.

Their high-stakes “rewiring of the plane” at 20,000 feet paid off, and by early 2022, Hemmersmeier reported the company had its best year ever. That rapid growth has continued. Today, the company, which grew during the pandemic, has 13 franchises in Arizona, Nevada, California and Utah and 500 employees — and is once again primarily selling new cars.

So how did Jerry Seiner grow at a time when dealerships across the country saw their sales of new cars plummet? The crucial step to achieving extraordinary results was learning techniques to engage every employee at the dealerships in solving problems and to tap each team member’s unique abilities — so they not only took part in finding solutions but also supported them with enthusiasm.

But Jerry Seiner didn’t take these steps in isolation. The leadership team worked actively to shift the company’s culture in subtle ways that allowed them to truly connect employees to the company’s purpose and values. That led to more energetic efforts to do what the company was there for: to sell cars to people who needed them.

BUILDING A CULTURE OF BUY-IN

Many leaders believe that if only they could achieve more engagement among their teams, they’d be able to solve the pressing problems at hand and accelerate growth. What they really need to do is

solve the buy-in crisis: When their teams don’t support the strategies they’ve introduced because no one asked them for their ideas, or if those ideas were offered, they disappeared into the the proverbial black hole.

To tap the incredible potential of people and teams who are aligned, energized and empowered, companies must actively seek the buy-in of all their team members on how to achieve game-changing results within a company — and put a process in place to act on them. When they do, they build trust and can benefit from what we call the “buy-in advantage.”

To achieve this, companies must embrace a structured approach to culture building that conveys that changes to the workplace are being done with every team member, not to them. It is an intentional approach to problem-solving based on the premise that all of us are smarter than any one of us. And it isn’t the result of occasional town hall meetings or all-staff emails; it has to be baked into everyday moments and the culture at large.

WHY I BECAME OBSESSED WITH BUY-IN

I began working with leaders on achieving buy-in after two decades as a CEO of rapidly growing companies, followed by another decade of coaching, advising and delivering workshops to thousands of leaders around the world. In the 8 million miles I’ve logged on airplanes in that time, I’ve seen firsthand the problems faced by small- and medium-sized organizations. In fact, I’ve either experienced the most imaginable problems myself as CEO, coached others through them or discussed them as a board member for companies such as Ameritrade.

Some of my clients run multibilliondollar companies, many lead startups, and some lead divisions within bigger companies. Regardless of industry or title, most face the same day-to-day challenges

of juggling their “must do now” list while identifying and implementing new ideas that will hopefully drive long-term growth. And they all spend a lot of energy trying to figure out how to motivate their people and align everyone’s priorities to make “great” happen. While some individuals may have a passion for their own parts of the business, or the people they work with, there may be a lack of collective passion, clarity of direction and intensity. They don’t have an agreement on how to create game-changing results.

Over the years, I’ve heard the same concerns over and over from these clients: How do I get my people to stay focused on the most important stuff and not get bogged down with side issues? How do I get them to reach across silos and cooperate to achieve our key priorities? How do we balance the need for shortterm results while not losing track of initiatives that will drive significant improvements in the long run? How do we create time to grow people — and what does growing our people even look like?

Right after sharing such frustrations, they are usually quick to point out all the things that are working well. In reflecting on their wins and successes, it’s easy for such leaders to dismiss their frustrations as fleeting and conclude that things are probably as good as they could ever get. However, working with thousands of leaders has proved to me the gap between potential and actual performance can be significantly narrowed.

What’s missing for many is the “how?” Here are five takeaways on what we’ve seen working for many companies to gain buy-in:

1. Achieving buy-in starts with leaders asking team members for their input. Seek their ideas about a problem or challenge before offering your own. Employees may not feel comfortable speaking up if they know the boss has a different point of view.

2. Holding meetings specifically focused on seeking employee input is essential. Slowing down to create the space for this allows for great ideas from the people most familiar with the work. One great solution from an employee could save a company days, weeks or months of wasted effort, or greatly improve profitability.

3. Seek out ideas for new and existing issues. Asking about what’s not working often leads to new processes and procedures that greatly improve efficiency. An employee engagement survey can spark ideas for discussion if it includes a question on what they might have been thinking about when they responded to that question in that way.

4. Keeping these discovery sessions small. Teams ideally will include three to seven team members, facilitated by a team leader, manager or supervisor. That way everyone has a chance to speak.

5. Create a space and utilize tools that allow all ideas to be heard. Gather to collect the ideas team members come up with. See if any can be combined or need further clarification. Prioritize the ideas using voting and, once you’ve decided on the one that will move the needle most toward the company’s biggest goals, ask team members for the criteria for a solution (for instance, “Implementation costs less than $1 million annually”). With those criteria in mind, ask the team to brainstorm solutions. Involving employees in creating solutions builds buy-in that supports implementation and results.

Ultimately, when employees know that their ideas count and the company is willing to act on them, it is easier for companies to achieve the buy-in they need for innovation and growth. The buy-in, in turn, leads to the Holy Grail for many companies: engagement. That’s a hard thing to achieve these days, but it’s not impossible if you have buy-in. L

Kaylyn Sanbower

Class of 2015

HOMETOWN

South Central, Pennsylvania

MAJOR

Mathematical Finance and Economics

CURRENT POSITION

Economist at the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice

IN THE LEAD Thank you for joining In the Lead, Kaylyn. Can you tell us about your journey?

KAYLYN SANBOWER I am an economist at the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). Prior to joining the division, I earned my Ph.D. in Economics from Emory University (Spring 2022). My dissertation research focused on health care, and in my work at the division, I continue to investigate economic questions in health care along with a variety of other industries. Before starting graduate school, I received a B.S. in Economics and Mathematical Finance from Seton Hall University in May 2015. In the following two years, I worked for the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency as an assistant national bank examiner before beginning my graduate studies.

ITL We are proud to see you as an economist at the DOJ. Could you share your journey with us?

SANBOWER Absolutely. Seton Hall is really the starting point of the career path that I’ve forged, so I’m excited to share what my career has looked like since my time there. At Seton Hall, I studied mathematical finance and economics, but I didn’t have a specific career path in

mind. As I got closer to graduation, I started thinking about the types of roles that interested me, and I was curious but uncertain about research and public policy jobs. I remember speaking with professors John Shannon and Kurt Rotthoff, who suggested that I consider Ph.D. programs if that was the route that I wanted to take. I had never considered a Ph.D. and wasn’t yet sold on the commitment that is a doctoral program, so I kept this option in mind and looked for a job instead.

I started my career at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. It was an excellent first job. I had the opportunity to

work on bank examinations with countless smart, dedicated colleagues, and I had a range of experiences and responsibilities that go beyond what one might expect from an entry-level position. After about a year in the position, though, I knew I wanted to pivot, and any role that spoke to me had limited growth unless I went to graduate school. I knew that if I were going to pursue a Ph.D., it was now or never.

I decided to go to Emory University, where I focused on applied microeconomics and developed a particular interest in health care. When it was time to enter the job market, I sought jobs that would allow me to work

on interesting issues and would have a tangible impact. That’s how I ended up at DOJ, which has been a great fit. Since I’ve been here, I’ve had the chance to work on a lot of interesting cases, predominantly in the airline and healthcare industries. I also supervise our research analyst (RA) program, which allows me to spend more of my time mentoring and supporting our research analysts, and it requires me to explore ways to continually improve the program in support of the RAs and the division’s mission.

ITL This issue of In The Lead focuses on exploring how leaders build trust. How do you personally define trust, and has that definition evolved over the course of your career?

SANBOWER I think of trust as the comfort and ease that comes with knowing you can have confidence in something. Trust is so powerful because it relieves you of the burdens that exist in its absence. I think that my definition of trust has always taken this shape, but the situations and relationships in which trust has been most readily showcased have varied over time.

Thinking back, my doctoral studies were essentially a multiyear adventure in building trust in myself. From the start, the demands of the program were onerous, and there were plenty of times that I struggled. But I consistently put in the work, and I started to understand concepts that had originally confused me. In turn, I became more confident in my ability to tackle new problems and concepts as they arose. While there were, of course, highs and lows during that time of my life, there wasn’t a single moment where I suddenly had trust in myself. Rather, it was the culmination of so many seemingly small moments where I proved something to myself. Effectively navigating the countless challenges that cropped up along my career path thus far has lent me the confidence to continue tackling new

challenges in my current role.

Another commonality through each step in my career has been the importance of my mentors and colleagues. At Seton Hall, I put a lot of stock in the guidance of my professors and mentors at the Stillman School of Business. I sought the perspective of professionals that I was connected with via the Leadership Program.

The same is true for each of the subsequent chapters of my career: I have been fortunate to make connections with generous, knowledgeable mentors who took the time to invest in our relationship.

and responsibilities, we ultimately have a shared responsibility to develop a holistic understanding of the case. For instance, the economists are responsible for diving into the data and uncovering and assessing empirical evidence. The attorneys do not need to understand the ins and outs of that analysis, but they do need to understand its implications. Communicating our work to the attorneys and other stakeholders requires open, clear, professional communication that is rooted in trust.

I could go on about copious other

I think of trust as the comfort and ease that comes with knowing you can have confidence in something. Trust is so powerful because it relieves you of the burdens that exist in its absence.

Across the board, I came to trust each of my mentors for the candor with which they spoke about their own personal and professional journeys and the honesty with which they delivered advice and feedback. There’s a level of vulnerability that comes with soliciting and providing mentorship, both of which are rooted in the trust you build together.

ITL In your current work, how important is trust — whether between team members, agency collaborators, or other stakeholders? How do you evaluate or build it?

SANBOWER The work that I do now is interdisciplinary, and our investigations at the division necessarily rely on a range of skills not held by a single person. I think the clearest example of this is the collaboration between attorneys and economists. We each have fundamentally different training, which means we each bring a different way of thinking to the case. We would not be able to do the important antitrust enforcement that we do without each other’s skills and knowledge.

While we have some distinct roles

examples, but ultimately, the takeaway is that we do important, complicated work that often requires teams of people, with each person taking ownership over distinct responsibilities. As a team, we trust that each of our teammates will execute on their responsibilities and thoughtfully communicate to support the team’s understanding of the evidence.

ITL Can you share a moment when trust played a pivotal role in your decision making as a leader?

SANBOWER Last year I took on the additional responsibility of supervising our research analyst program. Our RAs provide data wrangling, management and visualization prowess, and their skills are in high demand across our cases. To drive the program’s success and growth, I knew I needed to earn each of their trust. I took the time to get to know each of them individually, learning about the types of projects that excite them, the areas in which they’d like to improve, and ultimately, the careers that they hope to build. I sought their perspective on how

the program supports their growth and professional development, and I’ve used that knowledge to advocate for them within the organization of the program. I think that this approach — informed by the relationships that I’ve had with prior mentors and advisers — has fostered a level of mutual respect that might not exist if I hadn’t prioritized earning their trust.

ITL In an era of remote work and digital communication, how has your approach to building and maintaining trust evolved?

SANBOWER Trust is such an interpersonal, emotive thing, so I think it requires a concerted effort to build trust in the absence of in-person interactions. While I certainly don’t need to become

personal friends with my colleagues to build trust, I do think that gaining insight into other dimensions of my colleagues’ lives lends a human element to our professional relationship that helps accelerate our trust in one another. I find that impromptu conversations in the office or stepping out to grab coffee is the most natural way to facilitate this. It simply isn’t as organic over video calls.

That said, I work with plenty of colleagues who aren’t in the same office as me, so I do as much as I can over video calls instead of email. When I have an idea that I want to flesh out, I jump on a call. If we’re preparing talking points for a briefing, I jump on a call to work through that together. Intentionally creating times

to talk to one another opens the door to conversations that wouldn’t naturally arise in email. You get a lot more mileage out of a quick “How’s everything going?” on a call than you do with the dreaded “I hope this email finds you well.”

Overall, the better I’m able to know my colleagues for the range of interest, abilities and stories that comprise them rather than simply for the role that they fill at a given moment in time, the better we are about to foster trust.

ITL Was there a particular moment or activity at Seton Hall that marked a turning point in your leadership development?

SANBOWER I have so much gratitude for the leadership program and the range of opportunities it afforded me. Possibly one of the most influential features of the program, though, is the consistency with which it forces you to meet and interact with successful, high-powered professionals. That type of interaction can be intimidating — whether it’s a networking event or an important meeting — but having the confidence and poise to hold one’s own in those moments is invaluable.

ITL What advice would you give to your younger self, knowing what you know now?

SANBOWER Ask questions. I have yet to encounter a role or responsibility where I was expected to know everything. The expectation has instead been that I would be industrious enough to figure it out. Being curious and willing to learn has paid dividends for me, and as I’ve gotten better at quelling my fears of looking dumb or out of place, and leaned into the vulnerability that comes with asking questions, I think I have earned the trust of my colleagues and ultimately built my confidence in myself. L

The views presented here are not purported to represent those of the Department of Justice.

STEM - Designated Graduate Business Programs

By 2028, it is estimated that there will be more than a million jobs in the science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields. In preparation, these STEM-designated programs offered by the Stillman School of Business at Seton Hall will equip you to utilize technology, data and business analytics to make effective business decisions and solve complex business problems.

• NEW M.S. in Professional Accounting and Analytics

Students with a bachelor’s degree in accounting learn about data analytics, business intelligence, database management and enterprise systems.

• NEW M.S. in Financial Technology and Analytics

Students receive an interdisciplinary education to prepare them for careers in the emerging and rapidly growing area of financial technology and analytics.

• M.B.A. in Business Analytics

Students receive an experiential learning experience by analyzing actual data used to determine findings essential for decision making in management.

• M.B.A. in Information Technology Management

Students develop technology management skills critical for protecting confidential data for high-profile organizations.

• M.B.A. in Supply Chain Management

Students receive high-level training to apply analytical and technical methods required for enhancing supply chain operations.

• M.S. in Business Analytics

Students receive an experiential learning experience by analyzing actual data used to determine findings essential for decision making in management.

An Ethi cal Foun dat ion

Ethics and fiduciary duty are the foundation of trust in real estate.

By MARY TUNNY WEICHERT

IN MY VIEW, ethical behavior is the key to building trust. After nearly 25 years in the real estate business, I’ve seen how ethics have evolved, and why they matter now more than ever.

Sadly, real estate agents are often ranked among the least trusted professionals, a perception the industry has tried to counter by mandating ethics training every two years. Ethics in the industry cover everything from avoiding presumptive bias to resisting the subtle pull of commission-based incentives. And while that might seem excessive, I understand why. When your income depends on persuasion, the temptation to act in self-interest is real.

However, real estate isn’t governed solely by rules, but by interpretation, precedent and a commitment to fairness. It’s not courtroom litigation, it’s about mediation, responsibility and, often, doing what’s right, even when no one is watching. That’s exactly why I’ve always grounded my practice in one simple principle: serve as a true fiduciary — someone held in trust or confidence.

Our fiduciary duty isn’t just legal; it’s foundational. It means putting clients’ interests ahead of our own, acting with care, loyalty, good faith and full disclosure. To me, that’s not just a professional code, it’s a life philosophy.

UNDERSTANDING FIDUCIARY DUTY: REAL-LIFE APPLICATIONS

■ Duty of Loyalty: This means acting solely in the client’s best interest. When I sign a listing agreement with a seller, I’m upfront that I likely won’t produce a buyer myself. Instead, I commit to promoting the sale of their home to the thousands of hardworking agents who might. While this initially surprises some sellers, they eventually appreciate that opening the listing up to the entire market, not just my client pool, is the best way to secure the strongest terms. That’s loyalty: representing their interest, not my own.

■ Duty of Obedience: This requires that agents follow all lawful instructions. The key word here is “lawful.” If a seller asks me to do something discriminatory, I have the right and obligation not to comply. The New Jersey Real Estate Commission provides clear guidelines on this. For instance, if a seller instructs me to omit known water issues on a disclosure form, I’m required to correct that. Misrepresentation isn’t just unethical; it’s a violation of both obedience and loyalty.

■ Duty of Confidentiality: This means safeguarding personal information that could influence negotiations. For example, revealing that the sellers are getting a divorce could tip buyers to push for faster, lower offers. That’s a breach. However,

confidentiality does not cover material issues with a property — those must be disclosed to protect all parties involved.

■ Duty of Accounting: This requires agents to handle funds with complete transparency. Escrow deposits, for instance, must be documented through formal escrow letters. No commingling of accounts is allowed, and each transaction must have a distinct paper trail. While terms often change during attorney review, all agreements must be in writing and acknowledged by all parties.

My path into real estate wasn’t traditional. I studied English and education at Douglass College, then spent 10 years in banking. When Jim Weichert, my late husband’s Uncle and co-president and founder of Weichert Realtors, suggested I join the firm, I said no. Twice. I didn’t feel “cut out” for the role. I was juggling three jobs and couldn’t afford to take a risk on commission-based work.

But Jim persisted. “You are honest with a strong work ethic, and people buy people before they buy homes.” Eventually, I said yes, with hesitation.

My first year, I made $7,000. I kept my other jobs. But slowly, I found my footing. Year Two was better. And now, 25 years in, real estate has changed my life and my family’s future.

I share this story not to highlight my journey, but to emphasize that ethics are the foundation of everything we do. In a business built on trust, clients deserve professionals who lead with honesty, loyalty and a deep sense of responsibility.

Ethics aren’t a requirement to be checked off. It’s a commitment to doing right by every person we serve. When done right, real estate isn’t about selling houses. It’s about serving people. L

Trust : The Invisible

Glue

Cultivating authentic connections and consistent leadership.

By ASHISH GUPTA

WHEN WE THINK of great leadership, we often imagine visionaries, strategists or powerful communicators. But if you strip away the charisma, the credentials and even the accomplishments, one core attribute shines through: trust.

In my own journey as a leader — across functions, geographies and diverse teams — one lesson has emerged time and again: Without trust, leadership is hollow. With it, even the most ambitious goals become possible. ► ► ► ► ►

TRUST ISN’T JUST A VALUE. IT’S A VIRTUE. It sees you through crises, builds belief during transitions and fosters loyalty through uncertainty.

TRUST IS AN INVISIBLE GLUE. You can’t quantify it on a balance sheet. But you can feel it in every team meeting, every brainstorming session and every tough conversation. It’s what allows a junior team member to speak up with a risky idea. It’s what keeps people from second-guessing your motives. It’s what creates true alignment, not just on key performance indicators, but on purpose.

Many leaders talk about “earning trust” as if it’s a moment in time. But trust is not earned in a day. It’s built brick by brick, word by word, action by action. And like a building, it can collapse quickly if its foundation is weak.

TRUST BEGETS TRUST. It isn’t just about being transparent — it’s about making people feel seen, respected and safe, even when the news isn’t good.

And let’s be clear: Trust isn’t about being nice or liked. It’s about being consistent, honest, fair and courageous. It’s about showing up even when it’s hard and doing what you said you would do. Even when no one is watching.

So how do leaders earn trust. Or lose it? Much the same way organizations do. People evaluate a leader’s trustworthiness based on competence, motives, means and impact. They want to know: Can you make good decisions? Do you care about something beyond your own success? Do you act with integrity? Are people better because of your leadership?

And there’s one more dimension that’s unique to leadership: legitimacy. People need to believe that you’ve earned your seat at the table, that you’re not just occupying a position, but embodying its purpose.

PEOPLE TRUST WHAT THEY CAN PREDICT. That means showing up the same way, especially when things get tough. Whether you’re celebrating a win or navigating a crisis, consistency gives your team the psychological safety to focus on solutions rather than second-guessing your intentions.

Too often, leaders believe they need all the answers to maintain trust. But the truth is, authenticity trumps certainty. What your team really wants is clarity on what you know, what you don’t and what you’re doing to find out. Vulnerability doesn’t erode trust — it strengthens it. When paired with honesty and direction, it becomes a bridge between leaders and teams.

Trust isn’t only built through major decisions. It’s built when you follow up after a difficult conversation. When you remember someone’s birthday. When you acknowledge effort even when outcomes haven’t landed. These micro-moments signal something deeper: I see you. You matter. When people see that

their leader pays attention to the small things, they trust them with the big ones.

Sometimes, we confuse trust with leniency. But trust doesn’t mean letting things slide. The most trusted leaders are those who create a culture of fairness and accountability. That includes giving tough feedback, making hard calls and holding yourself to the same standards as everyone else. If you want people to trust you with their best work, they need to know you’ll hold the line. Not just for them, but for everyone.

As leaders, we often focus on how to get people to trust us. But real leadership begins when we start trusting others, especially our teams. Micromanagement isn’t a sign of high standards. It’s a symptom of low trust. When you trust your team’s judgment, give them ownership, and back them even when they fail, you’re not

Trust isn’t just a value. It’s a virtue. It sees you through crises, builds belief during transitions and fosters loyalty through uncertainty. You can’t quantify it on a balance sheet. But you can feel it in every meeting.

just developing capability. You’re saying: “I believe in you, even when the stakes are high.” That’s when people begin to surprise you, and often, themselves.

There’s no faster way to build — or break — trust than in the way that you listen. Listening isn’t just a “soft skill.” It’s a strategic advantage. I’ve found that when people feel truly heard, they become more receptive to feedback, more engaged in their work and more committed to the outcome. Great leaders don’t just listen to reply. They listen to understand. To create space. To build trust.

You don’t really know how strong your leadership is until you go through a crisis. Layoffs. Market downturns. Pandemics. Scandals. These moments don’t build character — they reveal it. And they test the depth of the trust you’ve built. In times like these, teams don’t need perfection. They need clarity. They need their leaders to communicate transparently, act with empathy, make decisions decisively and take responsibility for outcomes.

The leaders who navigate crises well aren’t the ones with all the right answers. They’re the ones who show up as humans, communicate with courage and make decisions with integrity. That’s the kind of leadership that doesn’t just survive tough times, it grows stronger through them.

WHEN TRUST IS HIGH, EVERYTHING MOVES FASTER. Teams collaborate more easily. Decisions take less time. Innovation flows more freely. People go above and beyond. This is what Stephen Covey called the “trust dividend.” It’s the compound interest of great leadership. Like any good investment, it starts with putting in more than you take out.

Even if trust has been broken — or never fully built — it’s never too late to start. One of the most effective first steps is to conduct a trust audit. Ask your team:

• Do you feel heard?

• Do you believe I’ll back you when it matters?

• Do you think I hold myself to the same standards I ask of you?

The answers may be uncomfortable. But discomfort is often the first sign of real growth.

The next step is simple, but not always easy. Say what you mean and do what you say. Consistency between words and actions is one of the most powerful ways to rebuild credibility. And finally, lead as a human first. Share your own challenges. Show empathy. Create room for vulnerability. When leaders walk into the room as people, not just titles, they create a culture where trust can truly thrive.

Trust, in its truest form, is relational. It cannot exist in isolation. While systems, policies and even branding may reflect a trustworthy organization, it is the quality of interpersonal relationships that truly determines how trust is felt and sustained. And that responsibility often sits squarely with the leader.

Building positive relationships isn’t just about being friendly or available — it’s about creating a deep sense of connection where people feel valued, understood and respected. At the heart of every high-performing team is a culture where individuals know they are not just seen for what they produce, but for who they are.

Positive relationships flourish in environments where empathy is practiced consistently. Leaders who take the time to ask how someone is doing without a transaction will plant seeds of goodwill that grow into trust. It’s in remembering small details, offering help without being asked, or simply creating space for others to speak candidly that relationships are strengthened. These aren’t grand gestures. But over time, they create an emotional bank account of trust that teams draw on in moments of pressure.

Covey famously said, “Trust is the glue of life. It’s the most essential ingredient in effective communication. It’s the foundational principle that holds all relationships.” That glue is only as strong as a leader’s ability to demonstrate good judgment, especially when it matters most.

Judgment is where values, experience and discernment meet. It shows up when a leader must balance competing priorities, make decisions with limited information, or address conflict

without bias. People won’t always agree with your choices, but if they believe your decisions are guided by sound reasoning and a principled approach, they’ll respect them.

Inconsistent or erratic leadership, on the other hand, erodes trust quickly. When team members can’t predict how a leader will react, whether with support or criticism, they begin to self-censor. Innovation stalls. Engagement declines. Relationships grow strained under the weight of uncertainty.

That’s why consistency is such a powerful form of leadership currency. Being consistent doesn’t mean being rigid. It means being reliable. It means your words, your mood and your expectations don’t fluctuate wildly based on stress, personal biases or external pressures. It means that your team can trust the emotional climate you bring into the room.

Consistency also applies to how leaders show up across different relationships. Favoritism — whether perceived or real — can quickly erode the sense of fairness and safety within a team. Leaders must hold themselves accountable to treating everyone with respect, applying the same standards to all, and ensuring feedback and opportunities are distributed equitably.

In practical terms, this looks like giving credit where it’s due, calling out unacceptable behavior regardless of hierarchy, and offering feedback that’s direct but delivered with care. It also means not changing the goalpost after someone has done the work or withholding praise because it didn’t match your personal style. Over time, these seemingly small moments either build or break trust.

Leaders who are intentional about these dynamics often go one step further: They name and nurture trust-building behaviors within their teams. They create rituals around recognition, establish norms for open communication, and model what it looks like to navigate disagreement with grace. In doing so, they empower others not only to trust them but to trust each other.

There’s a reason why organizations with high-trust cultures report stronger performance, better employee retention and higher levels of innovation. People want to work where they feel safe, where their voice matters, and where they can depend on their leaders to act with integrity, empathy and sound judgment.

And when trust becomes embedded not just in the leader but in the very relationships that define a workplace, something remarkable happens: People begin to take risks, stretch beyond their roles, and support each other through failure and success alike. That’s the kind of culture where performance becomes sustainable — and leadership leaves a lasting mark.

In the end, leadership isn’t measured only in profits or promotions. It’s measured in trust. In the loyalty you inspire, the culture you create, and the people who choose to follow even when they don’t have to. Leadership without trust is just a title. But leadership with trust? That’s a legacy. L

Bey0 nd the Code

Trust is the linchpin of human-robot teaming in modern warfare.

By ERICKA ROVIRA

SOLDIERS MOVE into formation, and their attention shifts to a four-legged robot engineered for rugged terrain and high-risk environments. It falls in with them, navigating obstacles as it advances toward the objective: a dilapidated two-story warehouse.

The team halts at a tree line a few hundred meters out. On cue, the robot detaches and slips through a breach in the fence, hugging the ground. Its thermal imaging and 3D mapping activate as it navigates inside the building’s debris-strewn halls and climbs stairs. Microphones catch muffled voices. Heat signatures confirm three armed people on the ground floor near a stack of wooden crates and two patrolling a catwalk above.

In a corner, behind a concealed panel, the robot flags a weapons cache containing small arms, ammunition, and likely shoulder-fired munitions. Nearly a half mile away, the command tablet in the team leader’s hand lights up with the live data stream. Wireframe overlays display interior layouts, enemy positions and points of interest.

The robot has done its job: The team knows what awaits them. With targets marked and entry points identified, the lead operator gives a nod.

As emerging technologies reshape combat, soldiers adapt to teaming with robots, unmanned vehicles and decision-support tools driven by artificial intelligence. The military has long used robots for reconnaissance and explosives disposal, but modern systems increasingly operate autonomously. These machines can learn and adapt to their environments, recognizing patterns and making decisions faster than humans can.

It remains unclear how much soldiers will trust and use robotic teammates. Drones and ground robots are increasingly deployed for reconnaissance, logistics and threat detection,

promising extended capabilities and reduced risks to personnel. But success depends not only on technical performance, but on human trust and engagement. Building and maintaining trust is crucial; without it, even advanced robots may be sidelined. This article examines how trust and leadership shape effective human-robot teams, drawing insights from military operations.

WHAT IS TRUST? IDENTIFYING SOME PERFORMANCE CONSEQUENCES OF OVERTRUST AND UNDERTRUST IN AUTOMATED SYSTEMS.

■ Trust is one of the most common variables measured in human-robot interaction literature (O’Neill, McNeese, Barron, & Schelble, 2022). Lee & See (2004) define trust as an attitude toward an agent (robot) that will help achieve an individual’s goals in situations characterized by uncertainty and vulnerability. Further, like Mayer et al. (1995), we hold that there are three established bases of trust:

• Capability: Can the robot reliably perform its intended tasks?

• Integrity: Is the robot’s behavior predictable and aligned with mission goals?

• Benevolence: Does it act to support human safety and success?

In human-autonomy teams, trust is essential for effective coordination, morale and team performance. When trust develops over time, it enhances collaboration and enables human and machine agents to operate cohesively. However, when trust is misaligned, either too high or too low, it degrades performance. And “overtrust” often leads to complacency, where operators disengage from active monitoring. Parasuraman, Molloy and Singh (1993) examined automation-induced complacency, showing that when operators relied too much on automation,

they were less vigilant and slower to detect failures. This is especially dangerous in high-consequence environments where rare but critical system errors require timely human intervention.

A related issue is the out-of-the-loop unfamiliarity performance problem (Wickens, 1992). When operators monitor automated systems, they may lose situational awareness and become poorly equipped to take control when needed, particularly during abrupt or unanticipated events.

The other extreme is disuse or under reliance, where users either ignore automation or turn it off, even when it may enhance performance. According to Parasuraman and Riley (1997), disuse arises from a lack of trust in the system’s capability or transparency. When operators reject automation, they may take on tasks they are less suited for, increase their cognitive load, or compromise mission success.

THE DYNAMICS OF TRUST DEVELOPMENT IN HUMAN-ROBOT TEAMS

■ Historically, trust in automation has been described as a matter of calibration, aligning trust with system capability. While this may apply to static automated systems, it falls short of capturing the dynamic behavior of modern autonomous agents. In these

performance standards than human teammates.

Indeed, Phillips, Ososky, Grove and Jentsch (2011) pointed out that as robots move from tools to teammates, appropriate mental models of robot capabilities and behaviors are critical in maintaining trust.

Failures in systems reduce human-autonomous performance (Hillesheim & Rusnock, 2016), lower trust (Hafizoğlu & Sen, 2018a, 2018b) and increase workload (Chen et al., 2011). Failures create uncertainty, making trust repair essential. Without it, operators may reduce reliance, increase their own workload, or assume tasks they are not well equipped to perform. Several researchers have examined trust violations and repair strategies such as apologies and explanations (e.g., Baker et al., 2018; de Visser et al., 2018). More recently, Esterwood and Robert (2022) highlight two persistent issues: inconsistent findings across studies and a lack of strong theoretical frameworks to account for these varied outcomes.

To address this, Pak and Rovira (2024) apply the Elaboration Likelihood Model (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), framing trust repair as persuasion, so that the autonomous system is attempting to change an individual’s trust toward it following a trust violation. According to their model, trust repair depends on

In short, leaders are the decisive factor in closing the gap between technological potential and practical, trustworthy integration.

systems, trust must be understood as a continually evolving process shaped by real-time performance, transparency and shared decision making. Understanding how trust forms, breaks down, and recovers over time is critical to building resilient, effective human-autonomous teams.

As individuals encounter new information or experiences, their trust shifts, sometimes consciously, but often not. Trust is essential to coordination, morale and performance.

While human-to-human trust often stems from empathy, communication, and reciprocity, trust in autonomous systems depends more on perceived reliability, predictability and transparency. Malle and Ullman (2021) argue that trust in less autonomous systems centers on reliability and capability, however as robots become more socially expressive, trust may increasingly involve moral dimensions such as benevolence, integrity and authenticity.

Trust in machines can be shaped by distinct design choices, and trust embedded within robotic systems. Moreover, humans often anthropomorphize machines, projecting human-like traits onto them, especially when systems are socially expressive or embodied. This can lead users to form emotional attachments or unrealistic expectations, even while holding machines to stricter

whether it occurs through the central or peripheral route, which is determined by the information presented in the repair strategy and the way the recipient interprets and engages with that information. They argue that outcomes hinge on cognitive engagement, workload, attentional capacity, motivation and timing of the repair strategy.

Transparent operation, timely feedback and adaptive responses to errors increase the likelihood of regaining user trust. Robots that communicate the nature and resolution of failures are more likely to be trusted. How trust repair and other trust affordances are made part of the design of autonomous tools remains a critical area for research and development.

MILITARY APPLICATIONS: WHERE TRUST IS TESTED

■ Trust must be earned through repeated, reliable and mission-relevant performance. Hoff and Bashir (2015) identify dispositional trust (a user’s baseline tendency to trust), situational trust (based on the immediate context) and learned trust (built through experience). In military operations, all three intersect, especially when robots are introduced into mission-critical scenarios. If operators have no prior exposure to the system, or the system’s behavior is unclear or unpredictable, situational trust

breaks down quickly, regardless of its technical potential.

Trust is especially fragile in military applications. Initial exposure matters: When soldiers are not trained with robotic systems, they may hesitate to use them under pressure, leading to underutilization or rejection. Even high-performing systems can suffer from trust erosion due to delays, erratic behavior or confusing interfaces. These issues signal unreliability and disrupt the fluid coordination needed in time sensitive operations.

Robots must do more than function; they must communicate effectively. Clear, intuitive feedback and the ability to signal both success and failure in understandable ways are essential. Realtime interaction and user centered interfaces directly influence whether a system is seen as a helpful partner or a burden.

The “tool vs. teammate” distinction is often put to the test in field conditions; soldiers may initially treat robots as tools, but perceptions shift when the system proves it can reliably execute

tasks, respond to commands and support goals. Conversely, it may be discarded when it looks more sophisticated than its performance bears out. In military environments, where performance during uncertainty is the norm, trust is a central requirement for adoption and sustained use.

A LEADER’S ROLE IN SHAPING HUMAN-ROBOT

TEAMING INTEGRATION AND TRUST

■ Traditionally, military leaders have played an important, but somewhat indirect, role in technological acquisition and deployment. While high-level decisions are often made by defense agencies, acquisition organizations and government bodies, military leaders are typically involved in setting operational requirements, providing feedback and shaping doctrine that guides technology use.

Today, their involvement is becoming more direct and critical, as leaders set the culture for who and what is trusted and valued. Trust is not only technical, it is cultural. Leaders create the conditions under which soldiers are willing to rely on nonhuman teammates. Lack of leadership engagement often leads to robots being seen as distractions or burdens.

It is essential to cultivate leaders who possess the vision, adaptability and technical expertise to integrate emerging technologies, thereby maximizing lethality and operational advantage on the modern battlefield. Today’s leaders must actively shape how human-robot teams function under stress and uncertainty. That means supporting the development of robotic platforms that communicate clearly and respond intuitively, enabling soldiers to understand not only what a system is doing, but why.

It means planning for failure, not just success: Trust repair must be part of design and doctrine. Soldiers will only reengage with autonomous systems if they can understand and recover from errors.

Leaders must create environments that allow trust to form: low-risk training, repeated exposure and consistent messaging that robots are part of the team, not just tools to be discarded when inconvenient. They enable soldiers to be creative and adaptable in integrating emerging technologies. The “tool vs. teammate” distinction isn’t settled in code; it is shaped by experience and command emphasis.

In short, effective leaders are the decisive factor in closing the gap between technological potential and practical, trustworthy integration.

CONCLUSION

■ Leaders must recognize that successful human-robot integration is not just fielding advanced systems, but also building conditions where trust can form, break and be repaired. Leadership sets expectations, shapes training environments, and reinforces the view of robots as mission-critical teammates.

Trust is central to this integration, and it demands consistent reliability, intuitive design and command support.

Human roles will evolve, not disappear. Robots are not replacing people; they are redefining roles and reshaping responsibilities. Leaders must ensure teams are trained to work with robots, not merely operate or supervise them. This requires deliberate attention to team dynamics, adaptability and shared mental models between humans and machines.

As technology evolves, success depends not only on the sophistication of intelligent systems, but on how effectively people and machines collaborate under pressure. The future of military advantage lies not in autonomy alone, but in leadership that ensures these systems are understood, tested and trusted, turning technical potential into operational performance. L

In the lead with...

Jess Rauchberg

In the Lead With is a conversation with industry leaders on key trends and leadership challenges. In this issue, we spoke with Jess Rauchberg, assistant professor and digital media scholar, who discusses how leadership and trust function in both traditional workplaces and the creator economy.

Ruchin Kansal (RK) Jess, thank you so much for joining us for the 10th edition of In the Lead. We’re focusing this issue on trust and leadership — two themes that consistently emerge in our research on the future of work. You bring such a unique perspective to this space through your work in digital media and labor. Let’s start there — can you tell us a bit about what you do and what drives your interest in this area?

Jess Rauchberg (JR) Thank you, Ruchin, and congratulations on the 10th edition — how exciting! I’m honored to be part of it. I’m an assistant professor in the Department of Communication, Media and the Arts at Seton Hall in the College of Human Development, Culture, and Media. My research focuses on digital media and the cultural implications of these technologies — how they shape our work and how they reflect or reproduce inequalities from our offline world.

A significant part of my work involves examining the creator economy — a vast, global, multiplatform labor market comprising individuals who utilize content creation platforms to promote, publish and monetize their work. I study how traditional inequalities around labor, like race, gender and disability, often get reproduced in these digital spaces. I’m particularly interested in three key aspects: authenticity, credibility and power. How do audiences perceive influencers as “real”? Why do we turn to them for not just product recommendations but also politics and ideas about how to live?

I came to this work as both a scholar and a former content creator. I spent about two years creating educational content on Instagram that addressed disability and media representation. I was what you’d call a nano-influencer — I had a couple of

thousand followers, not huge — but I learned a lot about how people perceive credibility and influence. That experience helped me realize I had a unique vantage point. I was doing this work while finishing my Ph.D. in media studies, and I thought, “What happens if I bring an academic lens to this lived experience?”

I’m interested in how leadership and trust are turned into commodities that can be bought, sold or profited from, whether by platform companies like Meta or ByteDance or by individual creators themselves.

RK Leadership and trust can be sold as “commodities.” That is intriguing. Can you say more about that?

JR Yes. When I say that leadership and trust are objects, I mean they can be packaged, sold and profited from. In the creator economy, being seen as a leader means having visibility and shaping people’s ideas, consumer habits and even their politics. And trust — especially credibility — is part of that brand.

As my colleague Mariah Wellman puts it, credibility becomes “the branding of trustworthiness.” You’re essentially selling the idea that “I’m someone you can trust.” That has real value, and that value is monetizable — whether it benefits a creator or the platform company behind them.

RK Trust is monetizable. I think our readers will enjoy reflecting on that! Before we dive deeper into the creator economy, I want to go back to the traditional workplace. So many organizations are still hiring humans, but they’re also increasingly digital and saturated with social media. What can leaders in traditional organizations learn from your work?

with... Jess Rauchberg

JR I think a lot about this when teaching undergraduates, many of whom want careers in professional industries but who are also deeply immersed in digital culture. Some want to be content creators themselves, especially as AI accelerates that possibility.

One of the ways I prepare students for this hybrid workplace is by building classes around real-world skill sets. For example, when I first joined Seton Hall in 2023, I came across a white paper from the World Economic Forum listing the top 10 skills employers will be looking for by 2027. It included things like familiarity with generative AI tools, but also soft skills: flexibility, resilience, selfstarting and communication. So, I reverse-engineered my courses to build those into the curriculum.

And I emphasize understanding how industries work. It’s not enough to know how to make a podcast or video; you need to

understand the structures behind them. Who profits? What’s the platform’s business model? That kind of media literacy is key for students to become leaders in these spaces.

RK Would you say the same skills — resilience, flexibility, people skills — are essential in the creator economy?

JR Absolutely. The creator economy is valued at around $250 billion globally. It really began in the mid-2000s with video platforms like YouTube, and it took off after the 2008 recession.

A lot of young people who couldn’t find internships in industries like fashion or beauty journalism started blogging and vlogging — and advertisers noticed. They realized these creators had direct access to audiences. It was a workaround that didn’t have the same journalistic ethics constraints.

Over time, the industry professionalized, but regulation still lags. The FTC didn’t release guidelines about disclosure until 2019, and even now enforcement is minimal. So, creators have to navigate a really unstable environment. Platforms come and go. Vine is a great example; people built careers there, and when it folded, some couldn’t transition to other platforms.

So yes — resilience, adaptability and creativity are essential. You have to constantly reinvent yourself, and that’s a lot of work. Being a creator sounds fun, but it’s laborintensive and precarious. There’s no union (yet), no benefits and limited protections.

RK So, despite the differences, trust in both traditional and digital industries still come down to the same foundations?

JR Yes. They may look different, but those soft skills — resilience, adaptability and communication — are what allow people to build trust and succeed. Whether you’re a creator or a corporate employee, it’s hard to thrive.

RK What are three things anyone, whether in a traditional workplace or creative one, should do to build trust?

JR First, be transparent. Whether you’re sharing where your information comes from or explaining how you arrived at a decision, people value clarity. A lot of successful creators show their process, behind-the-scenes content and context for their choices. It helps build that connection. In the

Be honest. That’s the key. You don’t have to share everything, but don’t mislead. In such an oversaturated market, honesty is what makes you stand out, and helps you lead in whatever space you’re in.

Second, diversify your skill set. Don’t stick to one niche. That’s especially true in the creator economy, where you can’t rely on just one platform. In traditional work, this might mean learning additional programming languages or understanding how digital tools intersect with your industry.

Third, be real. We are in an oversaturated market, whether it’s suntan lotion or lifestyle content, and people gravitate toward what feels consistent and relatable. That doesn’t mean you have to share everything, but the creators and professionals who succeed are the ones who feel human and genuine.

RK That maps exactly to what trust literature says: Transparency reflects integrity, diversified skills show capability, and authenticity conveys benevolence. Now, let’s flip the lens. How do leaders, especially in creative or distributed environments, build trust with their teams?

JR In my research, I look at influencers who lead through consistency and niche. The leaders in this space are the ones who stick to a schedule, build audience expectations, and expand their brand over time.

Take Alix Earle, for example. She started with “Get Ready with Me” college vlogs and built a huge following. Now, she partners

with big brands like Dyson, has launched scholarships, and landed on Forbes’ “30 under 30” list. She didn’t stay stuck in one version of herself — she grew with her audience.

Or look at Nate the Hoof Guy, a bovine vet in Wisconsin. He has millions of followers just by posting videos about treating hooves. He’s consistent, informative and really niche. That’s leadership, too.

These creators aren’t just influencers, they’re entrepreneurs. They build trust by showing up and being themselves over and over again.

RK You’re reframing leadership as influence and trust as credibility. And once that’s established, can it be monetized?

JR Exactly. Once you’ve branded yourself as trustworthy, that becomes your value. Brands want creators who already have that audience’s trust. The more credible you are, the bigger your opportunities.

And it’s not just about products. Mormon women, for example, are huge in the lifestyle influencer space. Part of that is cultural — documenting family life is seen as part of their religious mission. But it’s also savvy. They’ve become trusted voices in fashion, home and parenting — and brands notice.

RK So your identity becomes your brand. The more authentic and credible it is, the more valuable it becomes.

JR Yes. But that also comes with responsibility. If you brand yourself as inclusive or body-positive and then do something that contradicts that, without transparency, it can break the trust. I recently wrote an op-ed about a plus-size fashion influencer who got weight loss surgery and didn’t disclose it to her followers for two years. The backlash wasn’t about the surgery — it was about the lack of honesty.

RK So, if there’s one takeaway for building trust and leading in today’s world, what would it be?

JR Be honest. That’s the key. You don’t have to share everything, but don’t mislead. In such an oversaturated market, honesty is what makes you stand out and helps you lead in whatever space you’re in.

RK Thank you, Jess. This was truly insightful. You’ve shown how, even in an evolving economy, the principles of leadership and trust remain deeply human.

JR Thank you, Ruchin. I’ve really enjoyed the conversation. L

The Trust Imperative: Next Generation Evidence for Leadership Effectiveness

Key findings of the 2025 Future of Leadership Survey

B y RUCHIN KANSAL, M.B.A., KAREN BOROFF, P h .D. and ANTHONY CAPUTO, M.A.

Does the generation now entering the workforce — commonly referred to as Gen Z — perceive organizational trust differently from previous cohorts, and do the dimensions developed over 30 years ago still matter? How much time elapses before employees feel they can trust a leader, or conversely, lose that trust? The 2025 edition of the Future of Leadership Survey focuses on answering these important questions.

Is trust the missing link in your leadership? In a time of unprecedented generational transition and organizational uncertainty, trust has emerged as a critical foundation of effective leadership. As Gen Z increasingly joins the workforce, early evidence suggests that their expectations of leaders differ from the past cohorts1. While leadership literature has evolved from an emphasis on traits and behaviors to contingency styles of leadership, recent discourse has shifted to a more urgent determinant of leadership impact measured by the presence or absence of trust.

BACKGROUND

■ The research of Meyer, Davis, and Schoorman (1995)2 first posited the three essential components to build trust in organizations:

1. Ability: The technical, human and conceptual skills to do the job as it is today and tomorrow.

2. Integrity: The adherence to a set of principles or values that employees find acceptable.

3. Benevolence: The belief that leaders in organizations will act consistently in employees’ best interests and are not self-serving; they act to serve others and not their self-interest.

Additionally, Colquitt, Scott, and LePine (2007) found that trust, trustworthiness and trust propensity each uniquely influence risk-taking and job performance, highlighting their distinct roles in workplace behavior.3

KEY FINDINGS 4

■ Based on the recently concluded stage of our fiveyear longitudinal study, we report that the 1995 tri-part model on trust is still compelling for Gen Z, affirming that older framework.

When we asked our respondents what instills trust

Dimension 1: Values and Character Traits of a Leader A LEADER

N =194 Responses

N=194 Responses

Numbers in bars represent percentage of respondents

Responses are sorted from most to least favorable

or leads to loss of trust in their immediate leader, the qualities of ability, integrity and benevolence still emerged as the dominant levers for both earning and losing trust, with ability being the No. 1 indicator in each case. We measured the dimensions of ability, integrity, and benevolence using a five-point scale, with five being most important. Here are the respective means, denoted as “M.”

For building trust, ability (M=4.56) is rated higher than integrity (M=4.39) and benevolence (M=4.25). For losing trust, ability (M=2.87) outranks integrity (M=2.53) and benevolence (M=2.38).

Furthermore, we learned that leaders have about one year to establish themselves as trustworthy or to be perceived as untrustworthy. Earning trust usually takes longer: The median time to build trust is 13–24 months. Losing trust is significantly faster: The median is within 12 months, with 44.1 percent reporting loss in ≤6 months and 69.6 percent in ≤12 months.

In this sample, trust is lost significantly faster than it’s earned. Statedly differently, subordinates seem to eye the overall actions of their superiors very carefully in year one or so, seeking cues and clues on their leaders’ ability to do the job, their integrity and their benevolence.

As subordinates process these cues and clues, we also saw a divergence of which of the three dimensions was most important. Across respondents, building trust is anchored in integrity and ability: Transparency and openness score high and align with integrity-based trust, but skills and competencies lead the pack;

attracting, developing and retaining talent also matters.

But, when trust is lost, benevolence and integrity become more important. Ratings on self-serving and violating principles are significantly worse than competence within the same people and track tightly with loss facets.

Essentially, leaders build trust through openness and capability (plus talent building) but lose it through self-interest and compromised principles.

Our research also unearthed the organizational benefits of building trust. The 2025 survey shows that trust is a statistically significant indicator of leadership effectiveness (r=.212). It also found trust to be correlated to job satisfaction (r=.274), retention (r=.140) and future leadership ability (r=.173). Employees reported high job satisfaction where they trust their leaders, and they are more likely to remain in the organization and believe that their own leadership development is more likely. Leaders who inspire trust bring tangible and positive organizational outcomes.

For the 2025 edition of the survey, we undertook a measured research strategy. This year’s 227 survey respondents were primarily Seton Hall University students (56 percent female; 71 percent white or Hispanic; mean age 23 years old). Even with this smaller survey size and population, several findings from our prior work matched findings from this year. For example, trust emerged as the most significant predictor of leadership effectiveness in our 2024 survey with 4,203 respondents. Further, looking at year over

Dimension 2: Competencies of a Leader THE LEADER

N =177 Responses

N=177 Responses

Numbers

Numbers in bars represent percentage of respondents Reponses are sorted from most to least favorable’

Responses

year, data results are consistent for value and character traits and competencies, giving us confidence in generalizability of our data, as depicted below.

Based on the similar findings over time, we believe that our work on trust, while preliminary, is robust enough to provide immediate courses of action for today’s organizations and executives:

• To build trust, today’s organizations have to be absolutely determined to hire for ability. Job responsibilities have to be clear, along with accompanying experiences that demonstrate job aptitude.

• Probing into the integrity of candidates will help ensure congruency between the candidate’s own integrity and those same sets of values in the organization.

• Candidates should be able to demonstrate how they have acted with benevolence in prior positions. Firms should consider obtaining reference checks from former subordinates or clients to try to determine a candidate’s propensity to be benevolent.

Aside from this screening when hiring, organizations should support new employees and established employees in new positions in their first year to prevent the risk of failure rooted in integrity and benevolence. Organizations should also undertake a trust inventory with existing managers. Is the organizational culture one that will nurture and support trust?

This also provides a compass for today’s executives and employees to develop their own career trajectories by embracing the three dimensions of trust in their self-development: ability, integrity and benevolence. These elements should be evaluated constantly, even if informally.

FUTURE RESEARCH