75

AÑOS DE SU CREACIÓN YEARS OF ITS CREATION

HISTORIA DE LA CPA HISTORY OF THE CPA

AÑOS DE SU CREACIÓN YEARS OF ITS CREATION

COMISIÓN MÉXICO-ESTADOS UNIDOS PARA LA PREVENCIÓN DE LA FIEBRE AFTOSA Y OTRAS ENFERMEDADES EXÓTICAS DE LOS ANIMALES

MEXICO-UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PREVENTION OF FOOT-AND-MOUTH DISEASE AND OTHER EXOTIC ANIMAL DISEASES 1947-2022

AÑOS DE SU CREACIÓN YEARS OF ITS CREATION

Sader

Víctor Manuel Villalobos Arámbula

Secretario de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural

Secretary of Agriculture and Rural Development

Senasica

Francisco Javier Calderón Elizalde

Director en Jefe

Chief Director

DGSA

Juan Gay Gutiérrez

Director General de Salud Animal

General Director of Animal Health

CPA

Roberto Navarro López

Director de la CPA

Director of CPA

Roberto Navarro López

Dirección y gestión de proyecto

Direction and project management

Álvaro Martín Guillén Mosco

Edición y revisión de contenidos

Editing and proofreading of content

Susana Arellano Chávez

Colaboradora

Collaborator

Gustavo Medina Jaramillo

Ilustración de portada

Técnica: acrílico sobre papel, 27.5 X 40 cm estilo expresionista, 1995

Cover illustration

Technique: acrylic on paper, 27.5 X 40 cm expressionist style, 1995

Alejandro Katsumi Lemus

Ilustración página 56

Técnica mixta: carboncillo sobre papel y retoque digital, 2023

Illustration page 56

Mixed technique: charcoal on paper and digital retouching, 2023

Kely Rojas González

Diseño y formación

Design and formation of the text

Wendy González Montes de Oca

Formación libro-álbum: Brote de fiebre aftosa en México, 1946

Formation of the album-book text: Outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in Mexico, 1946

Karla Rojas González

Susana Vázquez García Corrección de estilo

Style correction

Evelyn Beatriz Flores Campos

Valeria Cristina Del Río Manjarrez

Valeria Fernanda Pacheco Sánchez

Ingrid Arely Vidal González

Asistentes

Assistants

Fotografía

Photography

Acervo de la CPA

Hemeroteca Nacional de México, UNAM Mediateca del INAH

Biblioteca Nacional de Agricultura, USDA Universidad de California

Primera edición, diciembre 2023

First edition, December 2023

Impreso en México

Printed in Mexico

CONTENIDO CONTENTS

7

Introducción

Introduction

9 Prólogo

Prologue

13 Antecedentes históricos

Historical background

27 La fiebre aftosa en América

Foot-and-mouth disease in America

33 Nace la Comisión Nacional de Lucha contra la Fiebre Aftosa-1947

The National Commission for the Fight against Foot-and-Mouth Disease is born-1947

51

Control y erradicación 1948-1954

Control and eradication 1948-1954

57 Brote de fiebre aftosa en México, 1946

Outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in Mexico, 1946

219 Creación de la actual CPA-1988

Creation of the current CPA-1988

223 Directores de la Comisión Commission Directors

281 Comentarios finales

Concluding remarks

283 Anexos Annexes

307 Evento conmemorativo del 75 Aniversario de la CPA

Commemorative event for the 75th Anniversary of the CPA

315 Corridos a la fiebre aftosa

Mexican songs to foot-and-mouth disease

INTRODUCCIÓN INTRODUCTION

Este libro fue realizado por la CPA para conmemorar el 75 aniversario de la creación del acuerdo bilateral entre México y Estados Unidos que permitió erradicar la fiebre aftosa en nuestro país. Es un homenaje a todas aquellas personas que intervinieron y brindaron su talento durante la erradicación de la enfermedad, para que posteriormente nuestra población pudiera acceder a alimentos de origen animal de alta calidad y los productores de ganado pudieran llegar al mercado internacional.

La publicación incluye diversos documentos de la época que forman parte del acervo histórico de la CPA: documentos científicos, relatos de actos heróicos que salvaron dinero de indemnizaciones y pago de rayas a sabiendas de una muerte inminente y actos de corrupción severamente castigados. En los primeros capítulos se describen las circunstancias nacionales que llevaron a la importación de ganado brasileño y el contexto geopolítico que marcaba al mundo en esos momentos, como el fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial y el comienzo de la Guerra Fría. Está incluido el libro-álbum Brote de fiebre aftosa en México, 1946, publicado en enero de 1952 por el Lic. Óscar Flores y por L. R. Noyes, directores de la entonces Comisión México Americana para la Erradicación de la Fiebre Aftosa, que se tradujo para este libro al idioma español, el cual nos proporciona una visión más amplia de las complejidades que vivieron los veterinarios y el personal en campo en seis años de lucha (1947-1952). Asimismo cuenta con entrevistas a algunos ex directores y ex codirectores de la Comisión, herederos de esta hazaña a partir de 1988, cuando se conformó la actual CPA.

Que este libro conmemorativo permita a los veterinarios y productores de ganado conocer los cimientos de la salud animal en México.

This book was produced by the CPA to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the creation of the bilateral agreement between Mexico and the United States that allowed the eradication of foot-and-mouth disease in our country. It is a tribute to all those people who participated and gave their talent during the eradication of the disease, so that our population could later access to high-quality animal-origin foods and livestock producers could reach the international market.

The publication includes various documents from the time that are part of the CPA’s historical collection: scientific documents, stories of heroic acts that saved money from compensation and payment of salaries despite the knowledge of an imminent death and acts of corruption severely punished. In the first chapters, the national circumstances that led to the importation of Brazilian livestock are described, as well as the geopolitical context that marked the world at that time, such as the end of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War. The album book Outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in Mexico, 1946, is included, published in January 1952 by Lic. Óscar Flores and L. R. Noyes, directors of the then MexicoAmerican Commission for the Eradication of Foot-andMouth Disease, which was translated for this book into Spanish, which provides us with a broader vision of the complexities that veterinarians and field staff experienced in six years of struggle (1947-1952). It also includes interviews with some former directors and co-directors of the Commission, heirs to this feat from 1988, when the current CPA was formed. May this commemorative book allow veterinarians and livestock producers to know the foundations of animal health in Mexico.

PRÓLOGO PROLOGUE

Peter Fernández

A lo largo de la historia se han documentado brotes de enfermedades animales a gran escala, a menudo con consecuencias devastadoras para los seres humanos y su salud, no solo como fuente de infección potencial, sino también por el impacto negativo en la seguridad alimentaria. Estas epizootias finalmente disminuyen, ya sea convirtiéndose en enzoóticas o desapareciendo, debido a factores limitantes de la enfermedad asociados con el agente o el huésped y su entorno, o mediante la intervención humana.

La vieja máxima de que “la enfermedad no conoce fronteras” sigue siendo válida hoy en día para la salud humana, animal y vegetal. Esta circunstancia llevó a la medicina veterinaria a prescindir de los términos “exótico” y “extranjero” por no abarcar lo que realmente significan para las naciones. Hoy en día el término más utilizado es el de “enfermedad animal transfronteriza” que se entiende como aquella enfermedad que tiene una importancia económica, comercial y de seguridad alimentaria significativa para un número considerable de países; que pueden propagarse fácilmente a otros y alcanzar proporciones epidémicas, donde el control/gestión, incluida la exclusión, requiere la cooperación de varias naciones.

Este libro no solo describe los efectos de diversas enfermedades transfronterizas en la evolución de México en el siglo XX, sino también, cómo a través de la cooperación con Estados Unidos se logró erradicar la fiebre aftosa y establecer un servicio veterinario sólido para controlar una gama más amplia de enfermedades. A menudo se olvida el logro que fue eliminar una enfermedad como esta, especialmente, considerando los obstáculos sociopolíticos y económicos, así como las limitaciones científicas que se enfrentaron a finales de los años cuarenta y principios de los cincuenta.

Animal disease outbreaks with great magnitude have been documented throughout history, and often they have devastating consequences for humans and their health, not only because they are a potential source of infection, but also because of their negative impact on food security. These epizootics eventually decrease, either because they disappear or become enzootic diseases, depending on disease-limiting factors associated with the agent or host and its environment, or through human intervention. The old statement that “disease knows no borders” is still valid today for human, animal and plant health. This characteristic of the diseases led veterinary medicine to not use the terms “exotic” and “foreign”, because it does not reflect what they really mean to nations. Currently, the most commonly used term is “transboundary animal disease”, which is understood as a disease that has significant economic, commercial, and food security importance for a considerable number of countries; that can easily spread to other individuals and reach epidemic proportions, where control/management, including exclusion, requires the cooperation of several nations.

This book not only describes the effects of various transboundary diseases on the evolution of Mexico during the 20th century, but also how the cooperation with the United States led to the eradication of foot-and-mouth disease, and also the development of a strong veterinary services to control a wider range of diseases. The achievement of eliminating such a disease is often forgotten, especially if we consider the socio-political and economic obstacles and scientific limitations faced in the late 1940 and early 1950.

The control and eradication of these diseases requires the cooperation of neighboring countries, not only because of the geopolitical variety, but also

El control y la erradicación de estas enfermedades requiere la cooperación de los países vecinos, no solo de la variedad geopolítica sino también de las disciplinas afines y sectores públicos y privados. México y los EUA pudieron forjar una asociación zoosanitaria sólida a través de experiencias interculturales y respeto profesional mutuo, lo que resultó en la comisión conjunta México-Estados Unidos (CPA) y sus numerosos éxitos documentados en el tiempo. En la conferencia de 2004 de la Comisión Hemisférica para la Erradicación de la Fiebre Aftosa del Centro Panamericano de Fiebre Aftosa (PANAFTOSA), celebrada en Houston, Texas, se documentó una revitalización del compromiso político para la erradicación de la aftosa en las Américas. Para promover y obtener apoyo para la cooperación bilateral y multilateral en estos esfuerzos, México presentó su experiencia histórica con la fiebre aftosa y el trabajo colaborativo con EUA en la que funcionarios veterinarios de América del Sur, el último vestigio para la enfermedad en el hemisferio, se acercaron a México, interesados en replicar este tipo de estrategia cooperativa, eventualmente se enviaron representantes de la CPA a varios países de esa región afectada. Hoy en día, la fiebre aftosa no se ha detectado en la gran mayoría de los países de América del Sur durante más de 10 años y PANAFTOSA estima que casi el 99 % del ganado está libre de la enfermedad. Este logro es un tributo a los esfuerzos dedicados de mujeres y hombres de los servicios veterinarios y sus partes interesadas en las Américas con la guía de agencias intergubernamentales como PANAFTOSA. Lo que era una aspiración para México a finales de la década de 1940, se está convirtiendo en una realidad para el hemisferio americano. Las experiencias zoosanitarias de México captadas en este libro son parte de esa realidad.

of the different related disciplines and the public and private sectors. Mexico and the USA were able to establish a strong relationship through cross-cultural experiences and mutual professional respect, which resulted in the United States-Mexico joint commission (CPA) and its numerous documented successes over time.

A renewed political commitment to eradicate foot-and-mouth disease in the Americas was documented at the 2004 Conference of the Hemispheric Foot-and-Mouth Disease Eradication Commission of the Pan American Foot-and-Mouth Disease Center (PANAFTOSA) held in Houston, Texas. In order to promote and obtain support for bilateral and multilateral cooperation on these efforts, Mexico presented its historical experience with foot-andmouth disease and the collaborative work with the USA, in which veterinary officials from South America (the last vestige of the disease in the hemisphere) approached Mexico, interested in replicating this type of cooperative strategy. Afterwards, representatives of the CPA were sent to several countries in the affected region.

Nowadays, foot-and-mouth disease has not been detected in the vast majority of South American countries for more than 10 years. PANAFTOSA estimates that almost 99 % of cattle are free of the disease. This achievement is a tribute to the efforts of the women and men of the veterinary services, as well as the stakeholders in the Americas, with the guidance of intergovernmental agencies such as PANAFTOSA. What was an aspiration for Mexico in the late 1940, is becoming a reality for the American hemisphere. The Mexican animal health experiences captured in this book are part of that reality.

Las áreas afectadas por la fiebre aftosa son el hocico, las patas y los pezones. Todos los veterinarios están obligados a usar overoles de hule completos mientras realizan la inspección de cualquier animal sospechoso.

The areas affected by foot-and-mouth disease are the mouth, feet and teats. All veterinarians are obligated to wear complete rubber apparel while making inspection of any suspicious animals.

ANTECEDENTES HISTÓRICOS

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

CONTEXTO POLÍTICO SOCIAL EN MÉXICO

La fiebre aftosa (FA) representa un problema sanitario que afecta a la ganadería de todo el mundo, es un problema de bienestar animal, producción, comercio nacional e internacional de animales, sus productos y subproductos. Llegó a México a finales de 1946, en ese tiempo uno de los pocos países libres de la enfermedad.

Para entender lo que significó esta epizootia en México, es necesario remitirse a los factores sociales que marcaron a nuestro país, a través de las referencias escritas como las del profesor en historia de la Universidad de Montana, Manuel A. Machado, en el libro Aftosa: A Historical Survey of Foot-and-Mouth Disease and Inter-American Relations (1969), en donde se puede encontrar un artículo titulado “La revolución mexicana y la destrucción de la industria ganadera mexicana”, en el que nos explica a detalle el cómo esta gesta social dejó a nuestro país económicamente devastado y afectó de manera importante la producción ganadera del norte del país. Dentro de los problemas posrevolucionarios que afectaron la ganadería y que causaron inseguridad en el norte de México, se consideran tres de relevancia:

1. Las fuerzas federales que se dedicaron a sofocar la actividad rebelde y a su vez se apoderaban del ganado para sustento militar.

2. La actividad de los bandidos o cuatreros que llegaron a matar a productores mexicanos o estadounidenses para robar su ganado.

3. La inestabilidad política que provocó la venta de animales para la adquisición de artillería militar.

En 1910 México poseía poco más de 5 millones de cabezas de ganado, de las cuales alrededor de un

SOCIAL POLITICAL CONTEXT IN MEXICO

Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) is a health problem that affects livestock all over the world; it is a problem of animal welfare, production, national and international trade of animals, their products and subproducts. It arrived in Mexico at the end of 1946, which at that time was one of the few countries free of the disease. To understand the importance of this epizootic in Mexico, it is necessary to refer to the social factors that marked our country, through written references such as those of the professor of history at the University of Montana, Manuel A. Machado, in the book Aftosa: A Historical Survey of Foot-and-Mouth Disease and Inter-American Relations (1969), where there is an article entitled “The Mexican Revolution and the destruction of the Mexican Livestock Industry”, In which he explains in detail how this social movement left our country economically devastated and significantly affected the livestock production in the north of the country.

Among the post-revolutionary problems that affected cattle raising and caused insecurity in northern Mexico, three are considered important:

1. The Federal Army that were dedicated to suffocating rebel activity and at the same time seized cattle for military sustenance.

2. The activity of rustlers or bandits that killed Mexican or American producers to steal their cattle.

3. The political instability that provoked the sale of animals for the acquisition of military artillery.

In 1910 Mexico had just over 5 million of cattle, of which about one million were in Chihuahua, representing 20 % of the national inventory. Due to the revolutionary movement, by 1928, that is, 11 years after the end of the revolution, this figure decreased

millón estaban en Chihuahua, lo que representaba el 20 % del inventario nacional. Debido al movimiento revolucionario, para 1928, es decir, a 11 años de haber terminado la revolución, esta cifra disminuyó un 67 %. El despoblamiento obligó a que se exportarán en 1922, 34 096 cabezas de ganado.

En aquellos años, incluso actualmente, el ganado del norte de México ha representado un papel importante en el comercio con los Estados Unidos, país en el que se gestaron, a raíz de la revolución industrial, la mecanización del campo y la investigación agrícola como ejes de desarrollo, que capitalizaron con rapidez y cambiaron al mundo, progresos que nuestro país no pudo lograr en ese momento. Para complicar más la situación, muchos ganaderos perdieron sus tierras con el reparto agrario debido a que el gobierno revolucionario prometió la destrucción de los latifundios, esto entre 1920 y 1930.

La persistencia del abigeato en el norte presionó al gobierno a pedir ayuda a los Estados Unidos para detener la venta de ganado robado, al considerar que estaban siendo afectados ganaderos estadounidenses en México, por lo que el país vecino dio instrucciones a los inspectores de la Oficina de la Industria Animal (Bureau of Animal Industry, BAI, por sus siglas en inglés, actual Agencia de Protección de Plantas y Animales, APHIS), para intentar frenar el movimiento de ganado robado hacia su territorio a través de medidas zoosanitarias.1

En 1924 dos brotes de fiebre aftosa ocurrieron en los Estados Unidos, uno en California y el otro en Texas. Dos años después, en Tabasco, México, surge otro brote, detectado por veterinarios nacionales y del BAI, que fue erradicado con la matanza de 1 200 animales con el apoyo de Tomás Garrido Canabal, personaje revolucionario y político, gobernador de Tabasco. Al cabo de un año del brote, el país fue declarado libre de fiebre aftosa.

Como resultado de estas epizootias en ambas naciones, se generaron una serie de medidas

by 67 %. Because of this depopulation, Mexico exported only 34 096 head of cattle in 1922.

In those years, and even today, cattle from northern Mexico played a particularly important role in trade with the United States, a developed country where, as a result of the industrial revolution, mechanization of the countryside and agricultural research were conceived as axes of development, which quickly capitalized and changed the world in many ways, progress that our country lagged behind. To further complicate the situation, many cattle owners lost their land with the agrarian distribution because the revolutionary government promised the destruction of the latifundios, this between 1920 and 1930.

The persistence of cattle rustling in the northern states forced the Mexican government to ask the United States for help to stop the sale of stolen cattle, considering that American ranchers in Mexico were being affected, for which the neighboring country gave instructions to the inspectors of the Bureau of Animal Industry (BAI,) now Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), to try to stop the movement of stolen cattle into its territory.1

In 1924, two outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease occurred in the United States, one in California and the other in Texas. Two years later, another outbreak was detected in Tabasco, Mexico, by Mex can and BAI veterinarians. This outbreak was eradicated with the slaughter of 1 200 animals with the support of Tomas Garrido Canabal, a revolutionary and political figure, also Governor of Tabasco. A year after the outbreak, the country was declared free of foot-andmouth disease.

Because the epizootics in both nations, USA took a series of quarantine measures in the in order to prevent the entry of animal diseases. It was necessary to establish a bilateral agreement to reduce the chances of FMD becoming a permanent problem on both sides of the border. In addition, several Latin American governments made pressure to export livestock.

1 El BAI se conformó a finales del siglo XIX. Desde 1890 sabían cómo se transmitía y controlaba la fiebre de Texas o babesiosis, habían conseguido erradicar de los Estados Unidos la perineumonía contagiosa bovina, aún sin saber cuál era el agente causal, en 1903 iniciaron los trabajos de control del cólera porcino, en 1910 desarrollaron un proyecto para mejorar la producción láctea de las vacas, formando el “Dairy Herd Improvement Associatons”, con lo que aumentaron en cinco veces la producción de leche, para 1917 iniciaron su lucha contra la tuberculosis bovina y en los años 20 sus servicios veterinarios ya se habían enfrentado a la fiebre aftosa.

1 The BAI was formed at the end of the 19th century. Since 1890 they knew how Texas fever or babesiosis was transmitted and controlled, they had managed to eradicate contagious bovine pleuropneumonia from the United States, even without knowing what the causal agent was, in 1903 they began work to control hog cholera, in 1910 they developed a project to improve the milk production of the cows, forming the “ Dairy Herd improvement Associations”, with which they increased milk production fivefold, by 1917 they began their fight against bovine tuberculosis and in the 1920 their veterinary services had already faced foot-and-mouth disease.

cuarentenarias en la Unión Americana para evitar el ingreso de enfermedades animales, fue necesario establecer un acuerdo bilateral para reducir las posibilidades de que la fiebre aftosa se convirtiera en un problema permanente en ambos lados de la frontera, además de que existían presiones de diversos gobiernos latinoamericanos exportadores de ganado.

Entre 1924-1928 México y Estados Unidos intentaron llegar a un acuerdo sobre el control de las entradas de ganado, que consideraba la necesidad de los mexicanos de importar animales reproductores a precios razonables, para reconstruir su devastada industria. Para 1928 firmaron un convenio que solicitaba a cada signatario no introducir ganado de áreas donde existiera la fiebre aftosa endémica, en este acuerdo se menciona que, en caso de un brote de aftosa en alguno de los dos países, automáticamente se pondría en cuarentena todo el ganado durante 60 días hasta que fuera evidente que no existía la enfermedad; además, se proporcionaría asistencia mutua para erradicarla.

En este contexto, en 1928 funcionarios del BAI endurecieron su política zoosanitaria, al percatarse de que una serie de enfermedades en el ganado mexicano se propagaba rápidamente, entre ellas la tuberculosis bovina, el ántrax, las infestaciones por garrapatas, la sarna y las diarreas. Solamente por los brotes de diarrea en terneros se estima que se perdieron más de 87 mil cabezas, un duro golpe para nuestra nación y su reconstrucción ganadera. Otro gran problema se originó por la presencia de la fiebre por garrapatas (babesiosis), que impidió el libre flujo de ganado a los Estados Unidos, por lo que, tanto propietarios mexicanos como estadounidenses radicados en México, se vieron obligados a cumplir con las estrictas reglamentaciones para la protección de los rebaños de nuestro vecino del norte. Debido a que persistía la necesidad de exportación de ganado mexicano, los ganaderos y las empresas estadounidenses presionaron continuamente al BAI para que eximiera las reglas zoosanitarias a fin de poder exportar y así evitar las amenazas de incautación por parte de tropas mexicanas, bandidos o una combinación de ambos. Sin embargo, estos funcionarios fueron inflexibles y se exigió exportar animales sanos y sumergirlos en soluciones desparasitantes antes de ingresar a los EUA.

Ante estos hechos, la geopolítica zoosanitaria percibió un alto riesgo de reintroducir la aftosa considerando los siguientes fenómenos: a) la pérdida de los inventarios ganaderos causados por la revolución y la posrevolución, b) la disyuntiva causada

Between 1924–1928 Mexico and the United States tried to reach an agreement that would take into account Mexico’s need to import breeding cattle at reasonable prices in order to rebuilt its devastated industry. By 1928 they signed an agreement requesting each signatory not to import livestock from areas where endemic foot-and-mouth disease existed. In this agreement, it was mentioned that, in case of an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in either country, all livestock would automatically be quarantined for 60 days until it was evident that the disease did not exist; furthermore, mutual assistance would be provided to eradicate the disease.

In this context, in 1928, BAI officials strengthened their animal health policy when they realized that a series of diseases in Mexican cattle were spreading rapidly, including bovine tuberculosis, anthrax, tick infestations, scabies and diarrhea. It is estimated that more than 87 000 cattle were lost due to outbreaks of diarrhea in calves alone, a hard blow to our nation and its livestock reconstruction. Another major problem was caused by the presence of tick fever (Babesiosis), which stopped the free flow of cattle to the United States, forcing both Mexican and USA owners in Mexico, to fulfill the strict regulations for the protection of the herds of the northern neighbor.

Because the need for Mexican cattle exports persisted, USA ranchers and companies continually lobbied the BAI to waive animal health rules in order to export and thus avoid threats of seizure by Mexican troops, bandits, or a combination of both. However, BAI officials were adamant and all exporters were required to export healthy animals and dip them in deworming solutions before entering the USA.

In view of these facts, the animal health geopolitics perceived a high risk of reintroducing footand-mouth disease considering the following phenomena: a) the loss of livestock inventories caused by the revolution and post-revolution b) the dilemma caused by the need for foreign currency represented by the export of livestock and supplying the Mexican domestic meat market c) the presence of foot-and-mouth disease in most of the countries that could sell cattle to Mexico, among them, Argentina and Brazil who hoped to find a market for their cattle in Mexico.

By the 1930, with an agreement signed between both nations, the revolutionary fervor that inhibited the reconstruction of the cattle industry was being maintained, where the most important cattle ranchers disagreed with the destruction of the large properties in which large ranches had been destroyed or distributed by the victorious revolutionary forces.

por la necesidad de divisas que representaba la exportación de ganado y el abastecer el mercado mexicano interno, c) la presencia de fiebre aftosa en la mayor parte de los países que podían vender semovientes a México, entre ellos, Argentina y Brasil, que esperaban encontrar un mercado para su ganado en México.

En 1930 ya con un acuerdo firmado entre ambas naciones, aún se mantenía firme el fervor revolucionario que inhibía la reconstrucción de la industria ganadera, en donde los ganaderos más importantes estaban en desacuerdo con la destrucción de los latifundios en el que grandes ranchos habían sido destruidos o repartidos por las fuerzas revolucionarias vencedoras.

A finales de esta misma década, los pastizales de Chihuahua albergaban ya a 800 000 cabezas de ganado. Se estimaba que este estado podía solo manejar aproximadamente 2.5 millones de cabezas de inventario bien administrado anualmente. Los funcionarios del gobierno mexicano mantenían vigente la idea de reconstruir la industria ganadera del norte del país, no sólo para la exportación, sino también para satisfacer el mercado interno, pero esto último representó un problema al encarecerse al doble el costo del transporte hacia el centro del país.

Para los años 40 Estados Unidos estaba fortalecido con altas producciones y servicios veterinarios que habían erradicado con éxito diversas enfermedades, incluyendo episodios de fiebre aftosa mediante el rifle sanitario, motivo por el cual, la posible presencia de esta en México le representaba una amenaza para su desarrollo, ya que se perfilaba para ser una potencia mundial, no sólo por su capacidad militar, sino también por su capacidad económica, productiva y tecnológica.

Al inicio de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, ya contaban con un enorme potencial productivo gracias a la mecanización del campo e investigación científica que habían logrado con fuertes inversiones, que llevaron a acrecentar su producción agropecuaria y de otros sectores a niveles nunca vistos, de hecho, lograron duplicar su PIB de 1939 en sólo cinco años.

La mecanización del campo en los Estados Unidos generó excedentes forrajeros que aunado a su investigación científica permitieron, entre otras muchas cosas, una sobreproducción de leche de vaca que se industrializaba y se vendía a México evaporada, o almacenada en forma de polvo que requería un mercado. En paralelo, iba aumentando la necesidad de mano de obra en el campo, debido a que los ciudadanos norteamericanos eran reclutados por su ejército, situación que causó el éxodo de mexicanos

At the end of this decade, the grasslands of Chihuahua already housed 800 000 head of cattle. Estimates indicated that Chihuahua could handle approximately 2.5 million head of well-managed inventory annually. Mexican government officials kept alive the idea of rebuilding the cattle industry in the north of the country, not only for export, but also to satisfy the domestic market, but the latter represented a problem because it doubled the cost of transportation to the center of the country.

By the 40’s, United States was strengthened with its high production and veterinary services that had successfully eradicated various diseases, including episodes of foot-and-mouth disease through sanitary rifle, reason for which, a possible presence of this disease in Mexico, it represented a serious threat for its development, since it was shaping up to be world power, not only because of its military capacity, but also because of its economic, productive and technological capabilities.

At the beginning of the Second World War, they already had an enormous productive potential thanks to the mechanization of the countryside and scientific research, which they had achieved with strong investments that led to increasing their agricultural production and that of other sectors to levels never seen before, in fact, managed to practically double its 1939 GDP in just five years.

The mechanization of the countryside in the United States generated forage surpluses, which, together with its scientific research, allowed, among many other things, an overproduction of cow’s milk that was industrialized and sold to Mexico evaporated or was stored in powder form which required a market. At the same time, the need for labor in the countryside was increasing, due to the fact that North American citizens were recruited by their army, a situation that caused the exodus of Mexicans called braceros to that country in search of employment, especially in the year 1942.

Under the above context, the situation of Mexico in those years, in which the events that led to the foot-and-mouth disease epizootic took place, are explained. This information shows the importance of this disease in the agrifood development of our country and the world.

Lázaro Cárdenas acompañado por campesinos y funcionarios públicos.

Lázaro Cárdenas with farmers and state employees.

denominados braceros a ese país en busca de empleo, sobre todo en el año 1942. Bajo el contexto anterior, se explica la situación de México en esos años, y los hechos que propiciaron la epizootia de fiebre aftosa. Información que muestra la importancia de esta enfermedad en el desarrollo agroalimentario de nuestro país y el mundo.

General Lázaro Cárdenas del Río (1934-1940)

El periodo posrevolucionario hasta finales de los años 30 se caracterizó por el reparto agrario, este se convirtió en el principal programa de acción política para resarcir las condiciones de inequidad en el campo y las demandas históricas, étnicas y comunitarias, las cuales habían llevado al campesinado a involucrarse en la gesta revolucionaria. Las tierras entregadas principalmente bajo la forma de dotación o restitución fueron más de 20 millones de hectáreas, beneficiando a 771 640 personas.

En su política agropecuaria, Cárdenas abarcaba la organización de los productores de los sectores más pobres de la sociedad, constituyendo la Confederación Nacional Campesina (CNC) y la Confederación Nacional Ganadera (CNG), además fomentó la asistencia técnica, la capacitación, la investigación, la educación agrícola y el crédito agropecuario.

The post-revolutionary period up to the end of the 1930s was characterized by agrarian distribution, which became the main political action program to compensate for the conditions of inequity in the countryside and the historical, ethnic and community demands that had led the peasantry to become involved in the revolutionary movement. More than 20 million hectares of land were distributed, mainly in the form of endowment or restitution, benefiting 771 640 people.

In his agricultural policy, General Cárdenas included the organization of producers from the poorest sectors of society, establishing the National Peasant Confederation (CNC) and the National Livestock Confederation (CNG), he also promoted technical assistance, training, research, agricultural education and agricultural credit.

General Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940-1946)

President Manuel Ávila Camacho faced the consequences of the Second World War that began in 1939, a period in which there were shortages of goods and food for common use due to situations derived from the war economy.

During his mandate, he reoriented the agrarian reform towards the support of small property as the axis of the agricultural economy At the same time,

El presidente Manuel Ávila Camacho enfrentó las consecuencias de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, que dio inicio en 1939, periodo en el que había escasez de enseres y alimentos de uso común por situaciones derivadas de la misma.

Durante su mandato reorientó la reforma agraria hacia el apoyo a la pequeña propiedad, como eje de la economía agrícola, a su vez, impulsó la ganadería, en donde decidió pasar por alto el tratado entre México y EUA de 1928, que prohibía la importación de animales de pezuña hendida en donde hubiese o se conociera la existencia de fiebre aftosa, por lo que importó ganado cebuino en 1945 y 1946 procedente de Brasil con la finalidad de repoblar el hato ganadero, con semovientes resistentes a enfermedades y condiciones climáticas adversas, para hacer producir las extensas zonas tropicales y subtropicales de las costas del Pacífico y del Golfo de México, lo que provocó serias protestas norteamericanas. Por desgracia, este hecho trajo como consecuencia la llegada de la fiebre aftosa a México.

Existen diversos argumentos sobre cómo llegó el virus de la aftosa a nuestro país, que refieren desde un simple accidente, hasta complots y conspiraciones internacionales que incluían bloquear la exportación de carne brasileña, o el favorecer el sacrificio de animales para la alimentación de los soldados norteamericanos en Europa.

Una de estas noticias fue publicada en marzo de 1947 en el periódico Excélsior, refiriéndose a un complot, en donde se afirma que el ex cónsul de

he promoted livestock production, but he decided to ignore the 1928 agreement between Mexico and the United States, which banned the importation of cloven-hoofed animals where there was or was known to be foot-and-mouth disease. He imported zebu cattle in 1945 and 1946 from Brazil with the purpose of repopulating the cattle herd, with cattle resistant to diseases and adverse weather conditions, so the extensive tropical and subtropical zones of the Pacific and Gulf of Mexico coasts would be productive, which provoked serious North American protests. Unfortunately, this resulted in the arrival of foot-and-mouth disease in Mexico.

There are several arguments about how the foot-and-mouth disease virus arrived in our country, ranging from a simple accident to international conspiracies and plots that included blocking the export of Brazilian meat, or promoting the slaughter of animals to feed USA soldiers in Europe.

One of these news items was published in March 1947 in the Excelsior newspaper, referring to a plot, where it is stated that the former Mexican consul in Rio de Janeiro, Rubén C. Navarro, who negotiated with the Secretary of Foreign Relations Francisco Castillo Nájera the importation of the 327 zebu to Mexico, entering into controversy with the Secretary of Agriculture and Development, the Agricultural Engineer, Marte R. Gómez, who in turn assured that it was President Manuel Ávila Camacho himself, who gave the instruction through the Secretary Castillo Nájera to receive the cattle. His book: The truth about the zebus: conjectures about foot-and mouth-disease, 1948, he wrote he following:

México en Río de Janeiro, Rubén C. Navarro, gestionó con el secretario de Relaciones Exteriores, Francisco Castillo Nájera, la importación de los 327 cebúes a México, lo que causó controversia con el secretario de Agricultura y Fomento, el ingeniero agrónomo, Marte R. Gómez, que aseguró que el propio presidente Ávila Camacho dio la instrucción a través del secretario Castillo Nájera de recibir el ganado. En su libro La verdad sobre los cebús: conjeturas sobre la aftosa, 1948, escribió lo siguiente: […] el señor doctor Francisco Castillo Nájera, secretario de Relaciones Exteriores, me llamó por teléfono para comunicarme [que]: ‘El señor Presidente de la República no deseaba que tuviéramos con el gobierno brasileño el gesto poco amistoso de devolverle su ganado; que sin perjuicio de la Secretaría de Agricultura y Fomento tomara toda clase de precauciones para evitar cualquier peligro de introducción de la fiebre aftosa y a petición del señor Embajador de Brasil que lo había visitado, autorizara que los 327 toros brasileños fueran desembarcados y cuarentenados en la Isla de Sacrificios, con el mismo rigor con que habían sido tratados los 120 cebúes desembarcados en 1945.

Licenciado Miguel Alemán Valdés (1946-1952)

A la llegada del presidente Miguel Alemán Valdés, primer presidente posrevolucionario no militar, daba inicio la Guerra Fría, en un ambiente de propaganda anticomunista. Su gabinete lo conformó con personas de clase media y alta, civiles de extracción universitaria, salvo en las Secretarías de la Defensa y Marina que siguieron ocupando militares. En su discurso de toma de posesión señaló la necesidad de aumentar la producción agrícola mediante las obras de riego, por lo que anunció la creación de la Secretaría de Recursos Hidráulicos. Prácticamente a su arribo a la presidencia tuvo que enfrentar la epizootia de fiebre aftosa, creando para ello la Comisión Nacional de Lucha contra la Fiebre Aftosa para controlarla y erradicarla, evento zoosanitario que generó grandes pérdidas al país por el cierre de fronteras y matanza de animales. Durante este sexenio se implementaron políticas públicas, para frenar las revolucionarias radicales tomadas por sus antecesores, con estas se detuvieron las actividades de la reforma agraria, se introdujo el juicio de amparo y la inafectabilidad para propiedades agrícolas o ganaderas en el Artículo 27 constitucional, así se proteg a la propiedad privada

[…] Dr. Francisco Castillo Nájera, Secretary of Foreign Affairs, called me by phone to inform me [that]: ‘The President of the Republic did not want us to have the unfriendly gesture of returning his cattle to the Brazilian government; that without prejudice to the Ministry of Agriculture and Development, take all kinds of precautions to avoid any danger of foot-and-mouth disease introduction and, at the request of the Ambassador of Brazil who had visited him, authorize the 327 Brazilian bulls to be landed and quarantined on the Island of Sacrifices, with the same rigor with which the 120 zebus landed in 1945 had been treated.

Mr. Miguel Alemán Valdés (1946-1952)

Upon the arrival of President Miguel Alemán Valdés, the first non-military post-revolutionary president, the Cold War also began in an atmosphere of anticommunist advertising. His cabinet was created up of people from the middle and upper classes, civilians with university degrees, except in the Secretaries of Defense and the Navy, positions that continued to be held by militaries.

In his inaugural speech, he pointed out the need to increase agricultural production through irrigation works, for which he announced the creation of the Secretariat of Hydraulic Resources. Practically when he was taking office, he had to face foot-and-mouth disease, creating the National Commission to Fight Foot-and-Mouth Disease, to control and eradicate it,

de cualquier amenaza de expropiación con la finalidad de atraer capital para implantar una agricultura de alto rendimiento, esto a pesar de la oposición de la corriente cardenista representada por Natalio Vázquez Pallares.

La posguerra

La Segunda Guerra Mundial causó un profundo trauma para el conjunto del continente europeo, en donde murieron alrededor de 60 millones de personas, la mayor parte fueron civiles. Igualmente fueron destruidos importantes núcleos de poblaciones e infraestructura, se dieron profundos cambios territoriales a nivel global. Había escasez de comida por la falta de cultivos, saqueo y destrucción de los pocos que quedaban, así como de los medios de irrigación; los sistemas de transporte y de distribución se encontraban paralizados; se rompieron los medios de producción y comercialización, así como, los bienes de subsistencia de las personas que comenzaron a emigrar.

La guerra generó escasez de casi todo y provocó hambrunas, la de Holanda, al término de la guerra es un claro ejemplo, al igual que la que sufrieron los alemanes cuando fueron derrotados. El alcance del daño total es desconocido, pero como ejemplo, se sabe que en Polonia se perdió el 70 % del ganado, el 25 % de los bosques y el 15 % de las construcciones agrícolas.

La devastación de la guerra en Europa fue de tal magnitud, que hizo que los líderes de ese continente comprendieran que su futuro debía centrarse en la cooperación e integración entre ellos. Estas fueron las consecuencias más importantes del mayor conflicto bélico de la historia.

En 1946, cuando apareció la FA en México, daba inicio a lo que ahora conocemos como la Guerra Fría, que se considera el enfrentamiento político, ideológico, económico y cultural que tuvo lugar al término de la Segunda Guerra Mundial entre dos bloques de países liderados por los Estados Unidos y la Unión de Repúblicas Socialistas Soviéticas (URSS).

En el periodo 1947-1948 la producción mundial de alimentos estaba un 7 % por debajo del nivel que tenía antes de la guerra. El problema en Europa no sólo era de privación de activos, a pesar de la severa destrucción, sino de una grave escasez de suministros esenciales, una población debilitada y subalimentada. Se necesitaba con urgencia la llegada de alimento, maquinaria y combustibles para iniciar una recuperación en la producción, pero no se disponía de los medios para pagarlas.

generating millionaire losses to the country due to the closure of borders and the slaughter of animals. During this six-year term, public policies were implemented to stop the most radical revolutionary policies taken by his predecessors, stopping the activities of the agrarian reform, introducing the amparo lawsuit and the un-affectability of agricultural or livestock properties in Article 27 of the Constitution, protecting private property of any threat of expropriation in order to attract capital to implement high-yield agriculture, this despite the opposition of the Cardenista current represented by Natalio Vázquez Pallares.

The post war

The Second World War caused a profound trauma for the whole of the European continent, where around 60 million people died, most of them civilians. Likewise, important population centers and infrastructures were destroyed and profound territorial changes occurred at a global level. There were food shortages due to the lack of crops, looting and destruction of the few that remained, as well as the resources for irrigation; transportation and distribution systems were paralyzed; the sources of production and commercialization were broken, as well as the subsistence goods of the people who began to emigrate.

The war generated shortages of almost everything and caused famines, the one in Netherlands at the end of the war is a clear example, as is the one suffered by the Germans when they were defeated. The extent of the total damage is unknown, but as an example it is known that in Poland 70 % of livestock, 25 % of forests and 15 % of agricultural buildings were lost.

In Europe, the devastation caused by the war was of such magnitude that it made the leaders of that continent understand that their future should focus on cooperation and integration between them. These were the most important consequences of the greatest war conflict in history.

In 1946, when FMD appeared in Mexico, it began what we now know as the “Cold War”, which is considered the political, ideological, economic and cultural confrontation that took place at the end of the Second World War between two blocs of countries led by the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

In the period 1947-1948 world food production was 7 % below its pre-war level. The problem in Europe was not only a shortage of assets, despite

La situación se agravó por muchos otros factores, incluyendo grandes deudas públicas, olas de inflación, pérdida de mercados y relación de intercambio desfavorable, trastornos sociales y políticos. Pronto se hizo evidente que Europa no podría llevar a cabo la tarea de reconstrucción sin ayuda. Ante este escenario, el presidente de los Estados Unidos Harry Truman (1945-1953), lanzó la llamada Doctrina Truman, que consistía en apoyar a sus aliados de Europa occidental y evitar la expansión soviética por el continente, ante el temor de que las ideas socialistas y comunistas se extendieran. La expansión económica de esta doctrina se conoce como el Plan Marshall de 1947, que apoyó la reconstrucción de Europa occidental, ofreciendo asistencia técnica y administrativa a los países, así como 13 mil millones de dólares para reactivar sus economías. En un inicio, esta ayuda consistió en el envío de alimentos, combustible y maquinaria, más tarde en inversiones en industria y préstamos a bajo interés.

México en esos años se consideraba un país agrario o rural, en donde el cine mexicano exaltaba la comedia ranchera con artistas como Pedro Infante y Jorge Negrete, entre muchos otros, que llegaba a la población migrante del campo a la ciudad en busca de mejores oportunidades como sigue siendo en la actualidad.

En los años 40, nuestro país aún no se recuperaba de la crisis producida por la revolución y la Guerra Cristera. De acuerdo a los datos oficiales, en esa época, alrededor del 60 % de los mexicanos vivía en zonas rurales, de los cuales con un porcentaje similar padecía de desnutrición. Los mayores retos estaban íntimamente relacionados con la nutrición, el analfabetismo, las bajas tasas de escolaridad y paupérrima tecnificación, que no podía darse sin los profesionales de la ingeniería o la medicina, que eran muy pocos. Para resolver este problema de falta de profesionistas, el 31 de diciembre de 1945 durante el mandato de Manuel Ávila Camacho, se aprobó la Ley sobre Fundación y Construcción de la Ciudad Universitaria, para el siguiente año el presidente Miguel Alemán recaudó los recursos para dar inicio al proyecto de construcción.

En lo que se refiere a la producción de alimentos, y de acuerdo a un informe del Banco de México, la producción agrícola de 1947 fue ligeramente mejor, pues casi todos los cultivos registraron un apreciable aumento con relación al año precedente, a pesar de que hubo sequías, principalmente en la zona central del país, en donde se desarrolló la epizootia de fiebre aftosa.

severe destruction, but also a serious shortage of essential supplies such as food, generating a weakened and undernourished population. It was urgently needed the arrival of food, machinery and fuel to start a recovery in the production, although the resources to buy them were not available.

The situation in Europe was worse by many other factors, including large public debts, waves of inflation, loss of markets and unfavorable terms of trade, as well as social and political upheavals. It soon became clear that Europe could not carry out the task. reconstruction without help.

Faced with this scenario, the president of the United States, Harry Truman (1945-1953), launched the so-called “Truman Doctrine”, which consisted of supporting his allies in Western Europe and avoiding Soviet expansion, fearing that socialist ideas and communists spread on that continent. The economic extension of this doctrine is known as the “Marshall Plan of 1947”, which supported the reconstruction of Western Europe, offering technical and administrative assistance to European countries, as well as 13 000 million dollars to reactivate their economies. Initially, this aid consisted of sending food, fuel, and machinery, and later investments in industry and low-interest loans.

In those years, Mexico was considered an agrarian or rural country, where Mexican cinema extolled the “ranch comedy” with artists such as Pedro Infante or Jorge Negrete among many others, who reached this migrant population from the countryside to the city looking for better opportunities as it is now.

By the 1940, our country had not yet recovered from the crisis produced by the revolution and a cristero war in the center-west of the country. According to official data, at that time about 60 % of Mexicans lived in rural areas, of which a similar percentage suffered from malnutrition. The greatest challenges were closely related to nutrition, illiteracy, low schooling rates and extremely poor technology, which could not occur without engineering or medical professionals, who were very few. In fact, to solve this problem of lack of professionals, on December 31, 1945, during the mandate of Manuel Ávila Camacho, the Law regarding the Foundation and Construction of the University City was approved, and it was President Miguel Alemán, in 1946, who obtained the resources to begin the construction project.

In terms of food production, according to the Bank of Mexico report, the agricultural production of 1947 was slightly better than that of 1946, since

Los datos de 1947 señalan un incremento del 13 % en el área cultivada con maíz, respecto a la de 1946, y un ascenso del 7 % en la producción de este alimento básico. En cuanto al trigo, era insuficiente para las necesidades de consumo, si bien en 1947 se registró una sensible mejoría con aumentos del 14 % en la extensión cultivada y de 10 % en los rendimientos, se esperaba reducir más el déficit con el fomento del cultivo por parte del gobierno. Contrario a lo sucedido en 1946, la cosecha de frijol fue 30 % superior, según apreciaciones oficiales, con lo que el abastecimiento interno estaba asegurado; por otra parte, la producción de arroz excedió a la del periodo anterior, pues tanto el área cultivada como la producción fueron superiores en 17 y 8 % respectivamente. La producción de azúcar, insuficiente en años anteriores, llegó a registrar un excedente, que empezó a exportarse a fines de 1947. Tanto la producción de algodón, como la de oleaginosas fueron un poco mejor que la de 1946, al igual que la de café, tomate, plátano y garbanzo.

El mismo informe del Banco de México señala que la propagación de la fiebre aftosa afectó seriamente a la, ya de por si golpeada, actividad ganadera, al decretarse un cierre de fronteras a la exportación de ganado, situación que motivó a la construcción de los establecimientos Tipo Inspección Federal (TIF) para garantizar la calidad higiénico-sanitaria de los productos cárnicos y de esta manera ingresar a los mercados internacionales.

En este sentido, los primeros establecimientos construidos con una estructura definida fue La Empacadora Juárez Meat Products Co., cuya construcción se inició en 1943 bajo el gobierno del General Manuel Ávila Camacho, la cual operaba en un principio con carne de caballo y posteriormente con carne de bovino. Le siguió la Empacadora de Tampico, conocida como Empacadora Lucio Blanco, que inició operaciones el 8 de mayo de 1947 con ganado bovino huasteco, esta fue la primera empacadora autorizada para operar bajo los lineamientos Tipo Inspección Federal.

Sus productos enlatados comenzaron a exportarse a Europa de acuerdo al Plan Marshall, con destinó al ejército norteamericano estacionado en Europa y Asia. De esta manera se produjeron millones de latas de carne con caldillo y productos de carne que se vendían a la Commodity Credit Corporation.

Los alimentos de origen animal eran escasos y costosos, pero la gente de las ciudades los buscaba al considerar que eran de países desarrollados y tenerlos era un símbolo de mejor estatus social.

almost all the crops registered an appreciable increase in relation to the previous year, despite the fact that there was dry weather mainly in the central zone of the country where the foot-and-mouth disease epizootic developed.

Data from 1947 show a 13 % increase in the area cultivated with corn, compared to 1946, and a 7 % increase in the production of this basic food. As for wheat production, it was insufficient for consumption needs, although in 1947 a significant improvement was recorded with increases of 14 % in the cultivated area and 10 % in yields, hoping to further reduce the deficiency with the promotion of its cultivation by the Government.

Contrary to what happened in 1946, the bean harvest was 30 % higher, according to official estimates, estimating that the internal supply was assured; on the other hand, rice production exceeded that of the previous period, since both the cultivated area and production were higher by 17 and 8 %, respectively. Sugar production, insufficient in previous years, reached a surplus, which began to be exported at the end of 1947. Both cotton and oilseed production were slightly better than in 1946, as was coffee, tomato, banana and chickpea.

The same Bank of Mexico report indicates that the spread of foot-and-mouth disease seriously affected the already hard-hit livestock activity, by decreeing a closure of borders to the export of livestock, a situation that led to the construction of the Federal Inspection Type establishments (TIF), to guarantee the hygienic-sanitary quality of meat products and thus compete for international markets.

In this sense, the first two establishments built with a structure defined by architectural plans were Empacadora Juárez Meat Products Co., whose construction began in 1943 under the government of General Manuel Ávila Camacho, initially operating with horsemeat, later changing to beef. This was followed by the Empacadora de Tampico, later known as Empacadora Lucio Blanco, which began operations in May 8th. 1947 processing Huasteco cattle, this was the first authorized plant to operate under the Federal Inspection Type guidelines.

According to the Marshall Plan, canned products began to be exported to Europe, to be consumed for the North American army posted in Europe and Asia. In this way, millions of cans of “meat with caldillo” and meat products were produced, which were sold to Commodity Credit Corporation.

The animal foods were scarce and expensive, even so, the people from the cities, looked for them because they considering that they were foods from

La realidad era que los animales como los bovinos servían para las yuntas y los animales de producción como las gallinas, los guajolotes y los cerdos se criaban principalmente en traspatios para alguna festividad.

Las autoridades de salud erróneamente consideraron que la dieta de los mexicanos era una de las principales causas de su pobreza y atraso. La producción de alimentos estaba centrada en los campesinos, sector más empobrecido de la población que producían básicamente maíz, frijol y chile para autoconsumo en pequeña escala.2

Se estima que en los años 40 la porcicultura desempeñó un papel importante en el campo mexicano como una fuente de auto abasto alimenticio, bajo un tipo de explotación de traspatio o rústico. Posterior a la aftosa, la porcicultura se convirtió en la segunda fuente de abastecimiento de carne en México aportando cerca de 20 % del total producido.

La producción avícola en esta época era muy precaria, se había limitado a pequeñas explotaciones donde solo se producía huevo, ya que las explotaciones de pollo en engorda aún no se conocían. Fue hasta la llegada de la fiebre aftosa que se impulsó su desarrollo y el de otros sectores pecuarios, para satisfacer la demanda de productos ricos en proteína.3

El eterno problema de la leche

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial hubo escasez de leche en México, por las interrupciones en los sistemas de producción y distribución de este alimento, situación que se agravó por la epizootia de FA.

La ganadería lechera era una actividad económica desde el porfiriato. Durante la época porfiriana,

Eva Sámano de López Mateos visitando una lechería. Eva Sámano, President López Mateos’ wife, visiting a dairy.

developed countries, and having them was a symbol of better social status. The reality was that animals such as cattle were used for the yoke, and production animals, such as pigs, turkeys and chickens, were raised mainly in backyards serving as piggy banks or for some festivity.

The health authorities considered that the diet of the Mexicans was one of the main causes of their poverty and backwardness. Food production was centered on peasants, the poorest sector of the population, who basically produced corn, beans and chili on a small scale for their own consumption.2

It is considered that in the 1940, pig farming played an important role in the Mexican countryside as a source of food self -sufficiency, under a backyard or rustic type of exploitation. After the foot-and-

2 Médicos y nutriólogos reprodujeron el discurso de superioridad de la leche, aun cuando estudios del INN mostraron que la dieta tradicional de campesinos e indígenas, basada en maíz, frijol y chile, contaba con un valor nutricional óptimo, particularmente cuando se complementaba con plantas y animales silvestres, así como, insectos en algunas regiones. Jamás se consideró promover dichas prácticas a nivel nacional y en muchos casos se les identificó con el atraso. Si México quería ser como los países “civilizados”, debía de adoptar su dieta, comenzando por el consumo de leche. Artículo titulado El alimento más completo: debates y prácticas sobre el consumo de leche en México, publicado por Sandra Aguilar Rodríguez en 2021.

2 Doctors and nutritionists reproduced the discourse of superiority of milk. Even when National Nutrition Institute (INN) studies showed that the traditional diet of peasants and indigenous people, based on corn, beans and chili peppers, had optimal nutritional value, particularly when supplemented with wild plants and animals, as well as insects in some regions, it was never considered promote these practices at the national level and in many cases they were identified with backwardness. If Mexico wanted to be like the “civilized” countries, it had to adopt their diet starting with the consumption of milk. Posted by Sandra Aguilar Rodríguez in The most complete food: debates and practices of milk consumption in Mexico 2021.

3 La epizootia de la enfermedad de Newcastle en 1950 y 1951 redujo en gran medida la población avícola del país, provocando una escasez de huevo en el mercado nacional, por lo cual fue necesario que se importaran grandes cantidades de huevo para satisfacer la demanda provocando que el país perdiera divisas.

3 The Newcastle disease epizootic in 1950 and 1951 greatly reduced the country’s poultry population, causing a shortage of eggs in the domestic market, so it was necessary to import large quantities to meet demand, causing the country to lose foreign exchange.

la leche la suministraban pequeños productores urbanos directamente al público en las calles, en las plazas o en pequeños establos urbanos. Los productores tenían, como máximo, una docena de vacas. Esta actividad fue incrementándose conforme las ciudades se hacían más grandes hasta constituir grandes establecimientos lecheros.

A mediados del siglo XX la leche no se consumía de forma masiva por lo que los gobiernos no insistían demasiado en su control sanitario: las condiciones de producción eran precarias, se presentaban enfermedades en el ganado de forma recurrente, la calidad de la leche era pobre, se vendía caliente, sin pasteurizar y se distribuía en condiciones poco higiénicas, por lo que las enfermedades ligadas a la falta de control sanitario causaron muertes entre la población.

Los establos mexicanos no podían abastecer a la ciudad debido a la falta de ganado de raza pura y a un suministro muy limitado de pastos y otros alimentos, además de que existían serias disputas entre productores, comercializadores y gobierno, ya que su producción no estaba regulada o no se hacía caso de su inocuidad, lo que generaba en diversos sectores de la población desconfianza, ya que era un riesgo para la salud más que un alimento.

Ante este conflicto, el gobierno de México pensó instalar una planta rehidratadora de leche por sugerencia de técnicos norteamericanos. El presidente Manuel Ávila Camacho, cuya política era no interferir en la producción industrial privada, ordenó al gobierno de la capital que tratara de convencer a algún inversor para que construyera una planta, ofreciendo exenciones fiscales como incentivos. Ante estos hechos, el gobierno mexicano negoció con el gobierno de los EUA, que aceptó subvencionar la importación de leche en polvo a México. Los principales beneficiarios del acuerdo fueron las empresas importadoras Kraft Foods y una planta de rehidratación y pasteurización de propiedad mexicana llamada Lechería Nacional.

Las organizaciones mexicanas productoras de leche reaccionaron inmediatamente, rechazando este plan de rehidratar la leche en polvo y venderla en la Ciudad de México. La Organización de Ganaderos del Estado de México, que representaba a todas las organizaciones regionales de productores de las zonas suburbanas de la Ciudad de México, así como, la Cámara de Productores de Leche del Distrito Federal y la Granja Unida del Distrito de Coapa, publicaron varias cartas abiertas al presidente en las que protestaban por la injerencia del Estado en el mercado de la leche.

mouth disease, pig farming became the second source of meat supply in Mexico, contributing about 20 % of the total produced.

Poultry production at this time was very precarious, it had been limited to small farms where only eggs were produced, since broiler farms were not yet known. It was when the foot-and-mouth-disease arrived that the promoting its development until the arrival of foot-and-mouth disease, since this epizootic greatly reduced the number of heads of cattle in the center of the country, for which it was necessary to promote other livestock sectors. to meet the demand for protein. One of them was poultry farming, which, until then.3

The eternal milk problem

During the Second World War, there was a shortage of milk in Mexico, with interruptions in the production and distribution systems of this food, a situation that was aggravated by the FMD epizootic.

Dairy farming was an important economic activity since the Porfirio Diaz Administration. During the Porfirian era, milk was supplied by small urban producers directly to the public on the streets, in city squares, or in small urban stables. The producers had, at most, a dozen cows. This activity was increasing as the cities became larger until they constituted large dairy establishments.

In the middle of the 20th century, the milk was not consumed on a massive scale, so the governments did not insist too much on its sanitary control: The production conditions were precarious, diseases recurred in the cattle, the quality of milk was poor, it was sold “hot”, unpasteurized and distributed in unhygienic conditions, so that diseases linked to the lack of sanitary control caused deaths among the population.

The Mexican stables could not supply the city due to the lack of purebred cattle and a very limited supply of pasture and other foods, in addition to the fact that there were serious disputes between producers, marketers and the government, because its production was not regulated or its safety was ignored, which generated distrust in various sectors of the population, since it was a health risk rather than a food.

Faced with this conflict, the Mexican government considered installing a milk rehydration plant at the suggestion of North American technicians. The president at the time, Manuel Ávila Camacho, whose policy was not to interfere in private industrial production, ordered the government of the capital to

Los productores alegaron que, a las autoridades de la Ciudad de México ya no les importaba el estado ruinoso del negocio de la leche local, porque el país, en general, recibía enormes cantidades de leche en polvo de los Estados Unidos y Canadá, lo que significaba para ellos una competencia desleal. Una vez presente la aftosa en México en 1947 y a la matanza de ganado lechero por esta causa, se produjo escasez de leche, por lo que el gobierno de Miguel Alemán promovió el consumo de leche en polvo importada del país del norte, a través de la empresa Lechería Nacional, que avivó el conflicto con los productores locales que mantenían sus protestas ante la importación de esa leche. Además, los lecheros mexicanos exigieron que el gobierno incrementara los impuestos a estos productos y pidieron la suspensión de los anuncios publicitarios de productos lácteos provenientes de EUA en los medios. En la voz popular se escucharon rumores de que la fiebre aftosa: era una conspiración para vender leche en polvo.

En 1946, se importaron 40 mil toneladas de leche entera en polvo, 60 mil toneladas en 1947 y 30 mil toneladas en 1948. Estas cifras no incluían la leche descremada que la Lechería Nacional compró a productores estadounidenses. El gobierno defendía las importaciones de leche descremada en polvo, porque en ese momento este tipo de leche no se podía producir en México y muchas industrias como las panaderías, la utilizaban en sus productos. La epizootia de FA no sólo consolidó la creciente intervención del gobierno en el mercado de la leche, sino que hizo que el negocio fuera viable solo para aquellos productores con suficiente capital para invertir.

A finales de 1940, los productores lecheros poseían de cincuenta a trescientas vacas y plantas privadas de pasteurización, considerándose a los únicos productores locales de peso todavía en existencia en el centro de México, pues un gran porcentaje de pequeños productores de leche había desaparecido debido a la epizootia de aftosa, quienes sufrieron las consecuencias económicas de las políticas sanitarias para controlar la enfermedad.

try to convince an investor to build a plant, offering tax exemptions as incentives. Given these facts, the Mexican government negotiated with the USA government, which agreed to subsidize the import of powdered milk to Mexico. The main beneficiaries of the agreement were the importing companies Kraft Foods and a Mexican-owned rehydration and pasteurization plant called National Dairy.

Mexican milk producer organizations reacted immediately, rejecting this plan to rehydrate powdered milk and sell it in Mexico City. The Livestock farmer Organization of the State of Mexico, which represented all the regional organizations of producers in the suburban areas of Mexico City, as well as the Chamber of Milk Producers of the Federal District (Mexico City) and the United Farm of the District of Coapa, published several open letters to the president protesting state interference in the milk market. The producers argued that the authorities in Mexico City no longer cared about the dilapidated state of the local milk business, because the country as a whole received huge amounts of powdered milk from the USA and Canada, which meant for them unfair competition. Once foot-and-mouth disease was present in Mexico in 1947 and the slaughter of dairy cattle for this reason, there was a shortage of milk, for which the government of Miguel Alemán promoted the consumption of powdered milk imported from the United States through the company National Dairy, which intensified the conflict with local producers who maintained their protests against the importation of that milk.

In 1946, 40 000 tons of whole milk powder were imported, 60 000 tons in 1947, and 30 000 tons in 1948. These numbers did not include the skim milk that the “National Dairy” purchased from USA producers. The government defended imports of powdered skim milk, because at that time this type of milk could not be produced in Mexico, and many industries, such as bakeries, used it in their products. The foot-and-mouth disease epizootic not only consolidated the growing government intervention in the milk market, but also made the business viable only for those producers with enough capital to invest.

At the end of the 1940, dairy farmers owned fifty to three hundred cows and private pasteurization plants, considering themselves the only local weight producers still in existence in central Mexico, since a large percentage of small milk producers had disappeared due to the epizootic suffered most of the economic consequences of health policies to control the disease.

LA FIEBRE AFTOSA EN AMÉRICA

FOOT-AND-MOUTH DISEASE IN AMERICA

CONTEXTO HISTÓRICO-GEOGRÁFICO

Fiebre aftosa en Estados Unidos

En Norteamérica, específicamente en los Estados Unidos, la aftosa se presentó en nueve ocasiones: 1870, 1880, 1884, 1902, 1908, 1914, 1924 (dos veces) y por último en 1929, episodios que se atribuyeron a ganado importado y a productos pecuarios de países infectados. La epizootia más grave sufrida en EUA se extendió a 22 estados y al Distrito de Columbia, persistió desde octubre de 1914 hasta mayo de 1916. En Chicago murieron 175 mil animales, entre ellos, bovinos, ovinos y cerdos. Posteriormente, la enfermedad apareció en California en 1924 que afectó a los rebaños que pastaban en los bosques, obligando al sacrificio de más de 130 mil animales, incluyendo 22 214 venados. Mientras se realizaba esta campaña y sin relación aparente con la epizootia de California, surgió otro brote de fiebre aftosa en el estado de Texas, que impuso el sacrificio de más de 30 000 animales para controlarla. En 1929 la enfermedad invadió nuevamente el estado de California, aunque en esta ocasión fue descubierta antes de que pudiera extenderse.

Inicios del ganado cebú en México

De acuerdo a la información proporcionada por las organizaciones de ganado cebú en México, sabemos que este tipo de ganado ya se encontraba en nuestro país desde finales del siglo XIX. El ganado Brahman Americano ya se conocía en la década de los 30 por intercambio entre criadores americanos y mexicanos. En 1945 y 1946 ingresaron de Brasil ejemplares de la raza Indobrasil, Nelore y Gyr, que no fueron sacrificados por la epizootia y se consideran

HISTORICAL-GEOGRAPHICAL

CONTEXT

Foot-and-mouth disease in the United States

In North America, specifically in the United States, foot-and-mouth disease has occurred on nine occasions: 1870, 1880, 1884, 1902, 1908, 1914, 1924 (twice) and the last one in 1929, episodes that were attributed to cattle and their products imported from countries infected.

The most serious epizootic in the United States spread to 22 states and the District of Columbia and lasted from October 1914 to May 1916. In Chicago, 175 000 animals died, including cattle, sheep and pigs. Subsequently, the disease appeared in California in 1924, affecting herds that grazed in the forests, forcing the slaughter of more than 130 000 animals, including 22 214 deer. While this campaign was being carried out and with no apparent relation to the epizootic in California, another outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease arose in the state of Texas, which forced the slaughter of more than 30 000 animals to control it. In 1929 the disease invaded the state of California again, although this time it was discovered before it could spread.

Brief history of zebu cattle in Mexico

According to the information provided by the Zebu cattle organizations in Mexico, we know that this type of cattle was already in our country since the end of the 19th. The American Brahman cattle were already known in the 30’s. by exchange between American and Mexican breeders. In 1945 and 1946, specimens of the Indo-Brazilian, Nelore and Gyr, breed entered Brazil, which were not slaughtered due to the epizootic and are considered the last ones, in

Registros de fiebre aftosa en Sudamérica

Records of foot-and-mouth disease in South America

1953 Magdalena 1967 Choco

1961 Nariño 1953 Aruba 1950 Pto. Cabello

Carchi

1957 Leticia 1950 Arauca

1954 Roraima

1961 Rupununi

1953 Cayena

1870 Corrientes 1910 Cochabamba

1870 Mendoza

1871 Pemuco

1957 Aysen

1970 Livramento

1870 Livramento

1870 San José de Flores

1916 Pernambuco

los últimos, es decir, los de 1946, los portadores e introductores del virus de la aftosa a México, son a pesar de su culposa procedencia, la base del ganado cebú mexicano actual.

Fiebre aftosa en México

Ante las epizootias de aftosa en EUA en 1924 y en México en 1926, se firmaron acuerdos binacionales en 1928 para impedir a ambas naciones importar ganado de países en los que se sabía que la fiebre

other words, those ones of 1946, the carriers and introducers of the foot-and-mouth disease virus to Mexico, but which are, despite their guilty origin, the base of the current Mexican zebu cattle.

Foot-and-mouth disease in Mexico

Given the foot-and-mouth disease epizootics in the United States in 1924 and in Mexico in 1926, binational agreements were signed between Mexico and the United States in 1928 that prevented both

aftosa era endémica, que no se respetaron por ninguna de las partes, debido a la creciente necesidad de mejorar genéticamente los hatos ganaderos y explotar de forma más eficiente los campos.

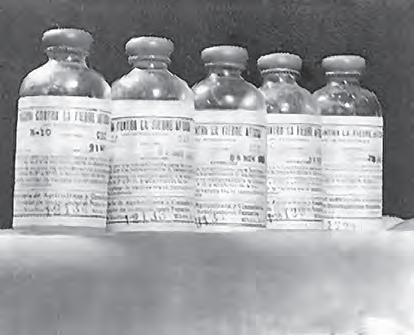

Se sabe de la importación de 120 toros brasileños en 1945 que no causó alarma, un año después, en mayo de 1946, nuestro país decide importar ganado brasileño, desembarcando 327 bovinos cebús procedentes de Uberaba, Brasil, en la Isla de Sacrificios, Veracruz, provocando que las alarmas internacionales se encendieran, por lo que nuestro vecino del norte cerró las puertas al ganado mexicano el día 5 de junio de 1946, lo que costó mucho dinero en divisas para México. Esta importación podría haber sido la que introdujo la aftosa a México, sin embargo, también se sabe de una importación de ganado de lidia desde España en 1946, incluso, de importaciones ilegales de animales desde Venezuela, como posible fuente de infección.

Para el mes de agosto de 1946 debido al revuelo de la importación brasileña, se realizó una reunión binacional de la Comisión de Agricultura México-Estados Unidos ante la presión de los ganaderos texanos para abrir las fronteras y permitir la exportación, por lo que se decidió muestrear el ganado importado para la realización conjunta de pruebas en la Isla de Sacrificios. Se comisionó a cuatro veterinarios, dos de cada país, del 1 de septiembre al 14 de octubre de 1946, para investigar si había casos sugestivos a FA, lo que resultó negativo.

El tribunal de Chicago sugirió una razón política para levantar la cuarentena el 18 de octubre. En la edición del 31 de diciembre de 1946 se incluyó la siguiente declaración: “El presidente Truman abrió las fronteras para la importación de ganado mexicano a mediados de octubre cuando los políticos demócratas lo instaron a poner fin a la escasez de carne antes de las elecciones de noviembre”.

Esta medida ocasionó conflictos políticos en ese país con acusaciones de que las prohibiciones de importación se levantaron bajo presión política.