2025

Communication + Place

Introduction

The Society for Experiential Graphic Design (SEGD) is a multidisciplinary community collectively shaping the future of experience design. We are designers of experiences connecting people to place.

We are a thought leader and an amplifier in the practice of experience design. Our work puts people at the center. We are motivated by our impact and our belief in the power of design to improve the human experience in the environments we create. We cultivate equity and inclusion because we value diversity in many forms, advocating for representation of all voices and equitable access to our profession. Learning is at the heart of our mission; we promote mentorship, knowledge-sharing, and continuing education. We build relationships, encourage strategic collaboration, and value a multidisciplinary, cooperative, and user centric-design process. We encourage sustainability, conservation, and preservation of resources to ensure a healthy future for our planet and its people. Our work is defined by professionalism, and we foster skill, judiciousness, and a code of ethics. Above all, we are propelled by the pursuit of excellence, challenging ourselves to make meaningful and inspiring work.

We live all of these values through the work of our committees, who support SEGD initiatives in education, inclusion, sustainability, and accessibility.

For over fifty years, SEGD has been the go-to resource for wayfinding, placemaking, and experience design. SEGD’s education conferences, events, and webinars span our practice areas including: branded environments, digital experiences, exhibition, placemaking, public installation, strategy / research / planning, and wayfinding. SEGD actively collaborates with and provides outreach to design programs at internationally recognized colleges and universities. Our signature academic education event is the annual SEGD Academic Summit, a two-day virtual event. Design educators and researchers from around the world are invited to submit papers for presentation at the SEGD Academic Summit and publication in SEGD’s blind peer-reviewed Communication + Place journal, which is published electronically on an annual basis. The Summit and e-publication are platforms for academic researchers to disseminate their creative work, models for innovation in curriculum, and best practices for research related to experiential design.

2025 Academic Task Force

Chair: Joell Angel-Chumbley | University of Cincinnati DAAP, City of Cincinnati

Aija Freimane | TU Dublin School of Creative Arts, Ireland

Angela Iarocci | Sheridan College

George Lim | University of Colorado School of Environmental Design

Christina Lyons | Fashion Institute of Technology

Tim McNeil | University of California Davis

Muhammad Rahman | University of Cincinnati DAAP

Debra Satterfield | California State University, Long Beach

Neeta Verma | Researcher, Designer, Educator

Michele Y. Washington | Designer, Design Researcher, Strategist

The annual SEGD Academic Summit … “creates an inclusive, global forum where diverse voices connect through dynamic panels and breakout sessions that open space for shared ideas and transformative learning.”

On behalf of SEGD — and the Academic Task Force (ATF), we celebrate the selected authors whose research will be featured in the 2025 Communication + Place academic journal. These contributions advance our collective mission to foster collaboration and community in practice, ensuring that design education is a space for knowledge, shared exploration, and co-creation. By highlighting the critical role of experience design in shaping communities, the research reinforces the importance of engaging with diverse perspectives and navigating the ethical responsibilities inherent in storytelling and public-facing design.

The SEGD Academic Task Force is a global, multidisciplinary collective of educators, researchers, and practitioners dedicated to cultivating inclusive and transformative approaches to design education, research, and professional development. At the heart of its work is the annual SEGD Academic Summit — a forum where authors, selected through a rigorous, anonymous peer-review process, present their research, share insights, and publish full papers.

More than a showcase of research, the Summit serves as a collaborative forum for dialogue and open exchange. Through dynamic panels and breakout sessions, participants examine design’s social impact, confront ethical challenges, and collectively envision the future of experiential learning and practice. Here, the politics and ethics of storytelling move beyond abstract debate, becoming lived, practiced, and shared experiences.

To learn more about the SEGD Academic Task Force or explore ways to engage, please contact:

Joell Angel-Chumbley, MFA Chair, SEGD Academic Task Force academic@segd.org

“The future of design lives where bold ideas meet thoughtful inquiry—led by minds unafraid to question, explore, and reimagine what’s possible.”

This year marks a powerful milestone for the Communication + Place Academic Journal and Summit. With our highest number of submissions to date—and of the strongest caliber yet—it’s clear that the academic arm of SEGD is not only growing, but flourishing. These contributions reflect a rising energy across our field, one fueled by curiosity, rigor, and a commitment to shaping more meaningful experiences through design.

At SEGD, we believe in creating space for dialogue between generations, disciplines, and perspectives. The SEGD Academic Task Force continues to play a vital role in amplifying brilliant minds and elevating critical discourse that shapes our future. From students and emerging professionals to tenured educators and seasoned practitioners, our community thrives on this dynamic exchange—one that nurtures growth, challenges norms, and pushes our collective understanding of design’s role in society.

In this edition of Communication + Place, we celebrate the convergence of research, experimentation, and purpose. The ideas presented here reveal not just where our field is headed, but how we might get there—with empathy, equity, creativity, and care.

To everyone who contributed their voice, we thank you. Your work helps illuminate the future of our profession and the value of academic inquiry within it.

With gratitude,

Cybelle Jones Chief Executive Officer, SEGD

Transforming Public Spaces Enhancing Community Engagement through Experiential Graphic Design in a Street Parking Garage

Huiwon Lim Assistant Professor of Graphic Design, Pennsylvania State University

Phil Choo Professor of Graphic Design, Pennsylvania State University

Abstract

This study explores the potential of experiential graphic design (EGD) to activate overlooked public infrastructure and enhance community engagement. Conducted within an undergraduate graphic design studio course, the project challenged students to reimagine a multi-story parking garage in downtown State College, Pennsylvania, as a space of cultural storytelling and inclusive public interaction.

Working in teams, students applied human-centered design methodologies—including site analysis, interviews, surveys, user journey mapping, and persona development—to understand the physical and emotional dynamics of the space. Their process was iterative and collaborative, informed by community feedback and local narratives. The project emphasized accessibility, identity, and sustainability, encouraging students to consider design as both visual communication and social infrastructure.

Each team developed a distinct concept and visual strategy that reflected shared community values. The final outcomes included high-fidelity mockups, 3D simulations, process books, and public presentations, all of which were showcased to local stakeholders and exhibited at a regional sustainability event. Community members responded positively to the designs, highlighting their cultural relevance and visual impact.

This project demonstrates how EGD can serve as a catalyst for reimagining civic space and contribute meaningfully to design pedagogy. It also offers a replicable model for integrating community engagement into design curricula, fostering critical thinking, interdisciplinary collaboration, and civic responsibility. Future plans include exploring pilot installations and continued partnerships with local organizations to bring select concepts to life.

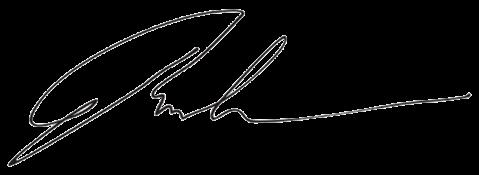

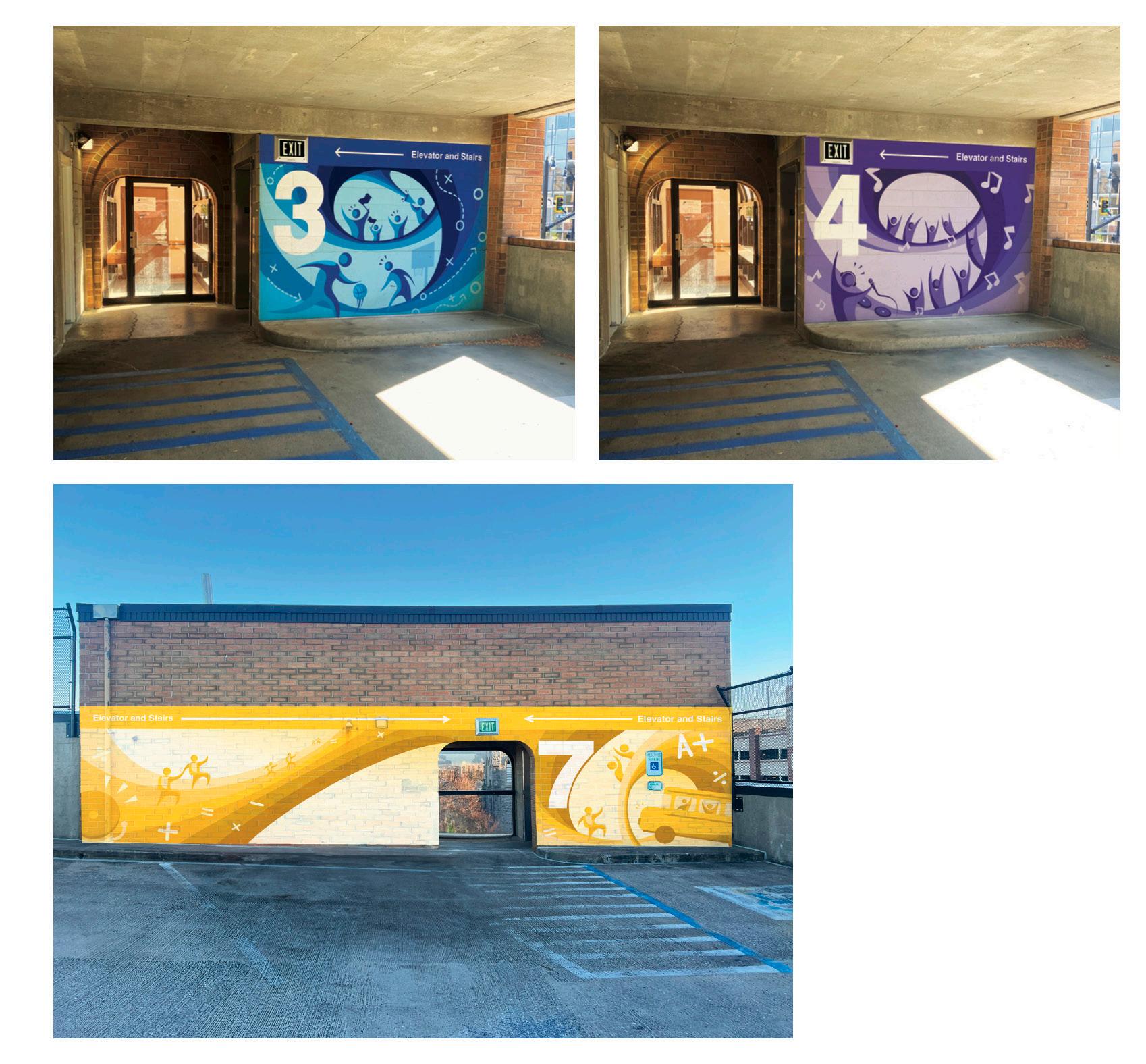

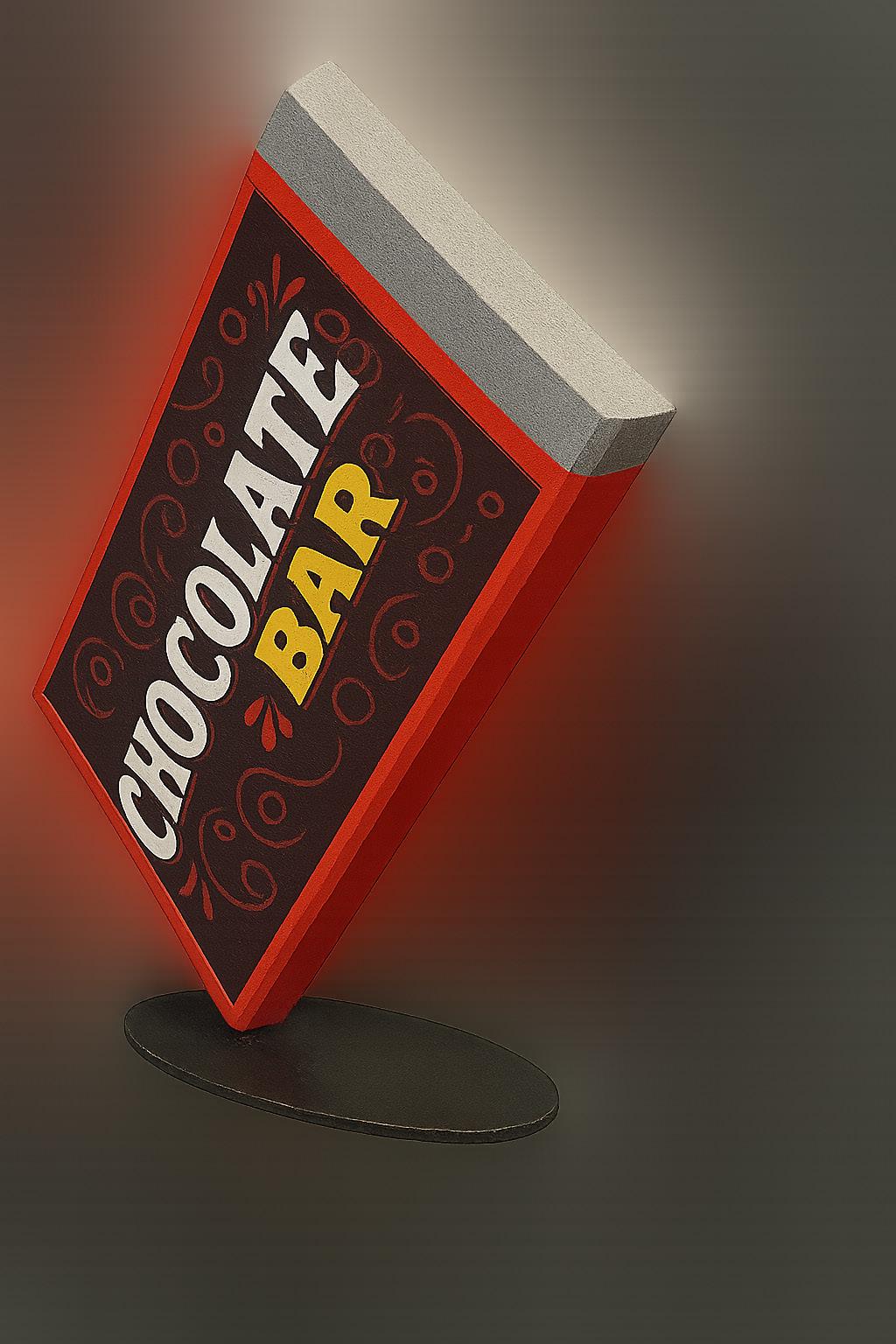

Figure 1. Fraser Street Parking Garage, site of the experiential graphic design project. (Photo by author)

Introduction

Public spaces play a vital role in shaping social interactions, cultural identity, and collective memory. However, many urban infrastructures—such as parking garages—are often overlooked in the discourse of place-making and remain underutilized in terms of community engagement and cultural activation. As cities seek to create more inclusive and responsive public environments, experiential graphic design (EGD) offers a compelling approach for transforming utilitarian spaces into meaningful community assets.

This paper presents a design initiative conducted within an undergraduate graphic design studio course that explored how EGD can activate a street parking garage as a site for community engagement, visual storytelling, and cultural expression. The project was situated in State College, Pennsylvania, and involved collaboration between graphic design students, local government officials, and community stakeholders. Through

methods grounded in human-centered design and cocreation, students developed context-sensitive design interventions that reflected the lived experiences and values of the surrounding community.

This project aims to address the following research question: How can experiential graphic design be used to reimagine public infrastructure as a platform for community engagement and cultural identity? By examining the design process, pedagogical structure, and outcomes of this initiative, this paper contributes to the discourse on EGD’s role in participatory urban transformation and design education.

Pedagogical Framework & Institutional Collaboration

This project was embedded within a second-year undergraduate studio course, Graphic Design Studio I (GD200), at Penn State University. The course emphasized experiential learning through the

Figure 2. Site visit photos of the Fraser Street Parking Garage taken during the initial research phase. (Photos by students)

application of human-centered design principles, aiming to equip students with the skills necessary to address real-world challenges with empathy, cultural sensitivity, and collaboration.

Students were introduced to and practiced a range of research methods rooted in human-centered design, including site analysis, user journey mapping, persona development, interviews, and surveys. These tools enabled students to gather both observational and selfreported data about how the space was used, who the users were, and what values and stories were embedded in the community. By combining direct engagement with users and contextual analysis, students developed nuanced insights into the physical and social dimensions of the site.

In addition to research and inquiry, the course incorporated systems thinking, visual storytelling, and the integration of physical and digital media as key components of the design process. These frameworks encouraged students to move beyond surface-level aesthetics and consider how design could foster interaction, inclusivity, and a stronger sense of place

The project was supported by a cross-sector collaboration involving the Department of Graphic Design, the Penn State Sustainability, and the State College Borough. This partnership enabled direct engagement with the site and community stakeholders, and provided platforms for public presentation and feedback. The collaborative structure also served as a model for integrating community engagement and social responsibility into the design curriculum.

Methodology

The project followed a structured, four-phase design process grounded in human-centered and co-design methodologies. Each phase built upon the previous, integrating community input and iterative development to ensure that the final design proposals were contextually relevant and culturally meaningful.

Phase 1: Research & Site Analysis

Students began by conducting site visits to observe the physical environment, patterns of use, and user behaviors within the parking garage. They developed user journey maps to visualize how different users

interact with the space and identified friction points or opportunities for engagement.

Through interviews with local residents, municipal staff, and nearby business owners, students gathered qualitative insights into community perceptions, cultural narratives, and values associated with the site.

Additionally, surveys were used to collect broader input from community members, including preferences, memories, and aspirations related to public space.

This combination of observational and participatory methods provided a comprehensive understanding of the site’s social and spatial dynamics.

Phase 2: Concept Development

Based on their research findings, students generated a range of design concepts that aimed to reflect the cultural identity and needs of the community. Each team synthesized their data into design directions that emphasized inclusivity, storytelling, and spatial awareness.

Initial ideas were visualized through sketches, mood boards, and design frameworks. Teams underwent critique sessions and later regrouped based on conceptual alignment, fostering shared authorship and collaboration.

Phase 3: Design Execution

Selected concepts were further developed into detailed proposals. Students produced both physical prototypes (such as scaled models and mockups) and digital renderings to simulate the integration of experiential graphics within the existing architecture of the parking garage.

Attention was given to materiality, accessibility, legibility, and interaction, ensuring that designs could be implemented in real-world public contexts.

Phase 4: Final Presentation

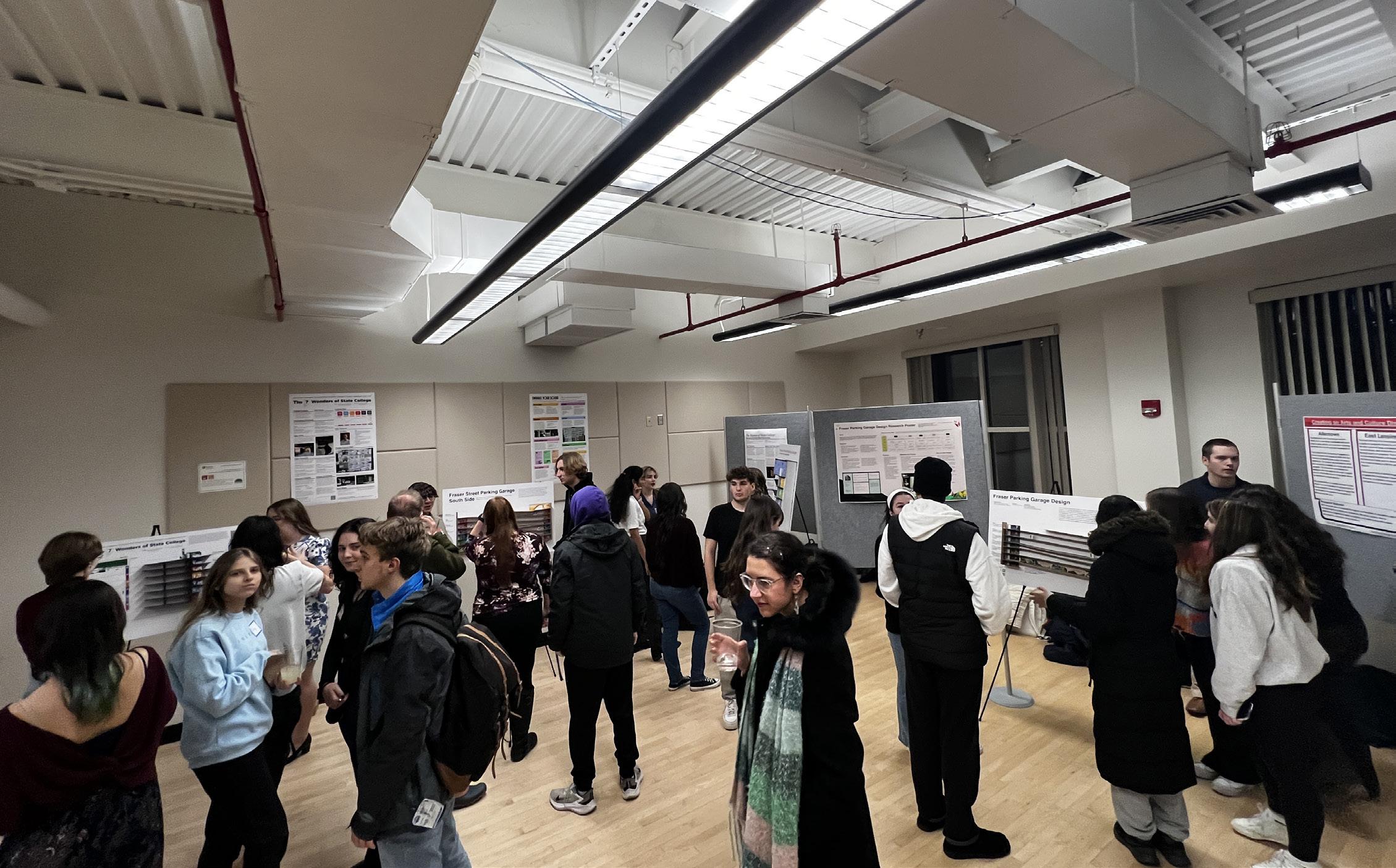

The project culminated in formal presentations to local government officials, community stakeholders, and the general public. Presentations were held both

on campus and at a regional sustainability event to gather diverse feedback.

Students communicated their design process, rationale, and intended impact, creating a platform for community dialogue and validation of their proposals.

Outcomes

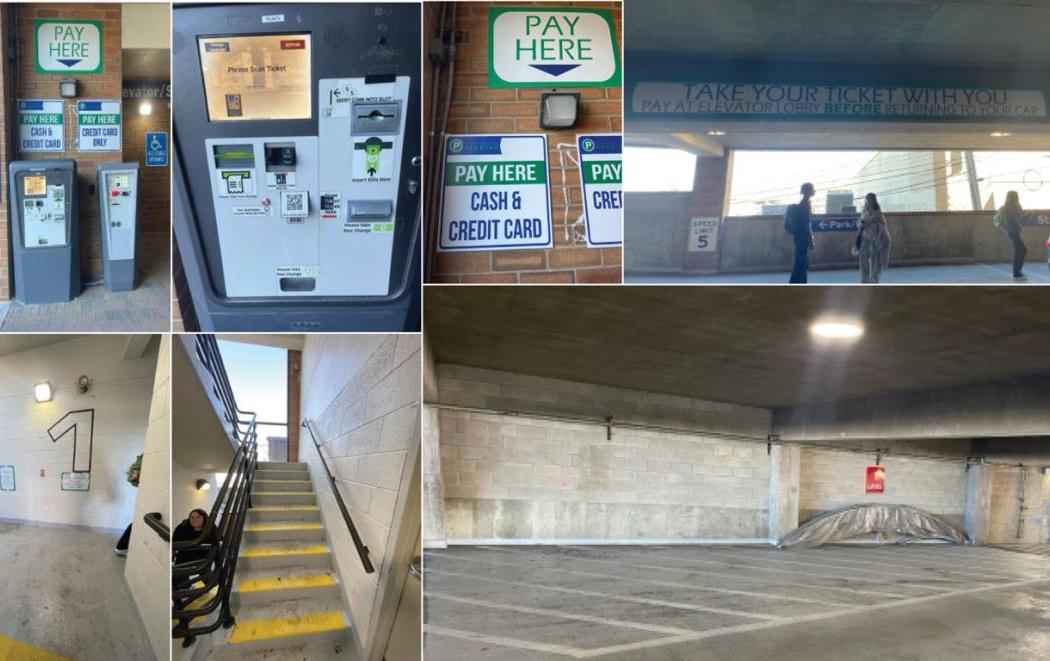

This project culminated in four distinct, researchdriven design proposals that reimagine the Fraser Street Parking Garage as a site for cultural connection, environmental awareness, and community storytelling. Each team demonstrated a unique conceptual direction informed by field research, community input, and human-centered design methodologies. Below, each team’s concept and contribution is described in detail.

Team-Based Design Concepts Team 7 Wonders

Members: Cori Chen, Ava Conner, Lillian Gerhart, Erin Gibbs, Charlie Papiernick, Emma Wassel and Harris Woodward

This team transformed each of the garage’s seven levels into a historical tribute to local landmarks, capturing the evolution of State College’s identity. Iconic locations— like Old Main, The Corner Room, and Mount Nittany— were featured through stylized visuals and educational signage. Color-coded wayfinding and inclusive graphic strategies were used to enhance navigation while promoting community pride and place-based storytelling.

Team The Voice

Members: Karalina Ptakowski, Abby Droege, Mia Lane and Kaitlyn Crenshaw

This team developed a concept rooted in musical metaphors, using sound as a symbol for unity and expression. Each garage level represented a unique “sound” or theme, such as ambition, pride, and celebration. Vibrant silhouettes of musicians and dynamic graphic rhythms conveyed emotional resonance, tying into the civic energy of the adjacent MLK Plaza.

Team Garage Goblins

Members: Shalini Prasath, Lillian North, Abigail Dougherty, Catherine Frank, Elias Kronberg, Kristin Muir and William Shin.

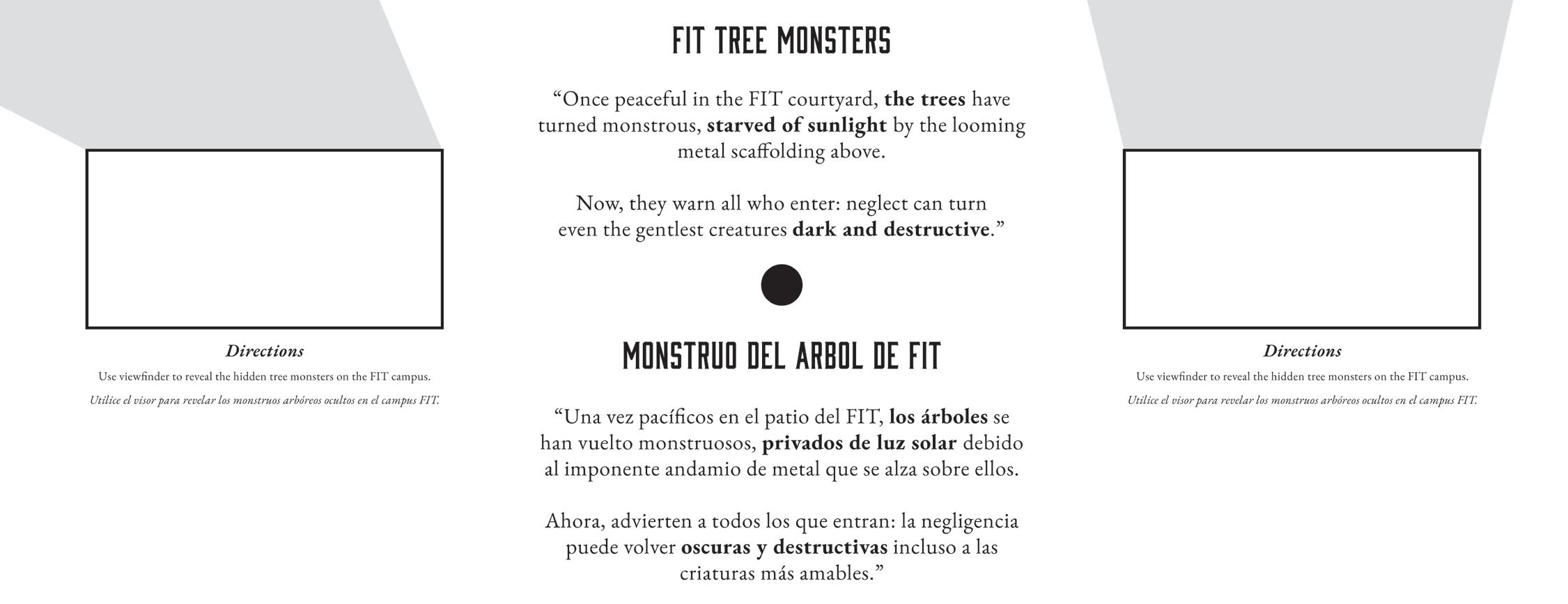

This team’s concept embraced “unexpected delight” and whimsy. Inspired by fantasy folklore and hidden narratives, they introduced playful goblin-like characters to engage users of all ages. The visual system turned mundane garage elements—like pipes, corners, and ramps—into imaginative scenes where “goblins” were discovered building, playing, or offering advice. This approach subverted expectations of public space aesthetics and encouraged re-enchantment through visual surprise.

Team TreeHugger

Members: Hannah Mattamana, Ella Hummel, Bianca Eckhardt, Jaime Franchino, Mazie Kemper,Cory Korsah, Juliana Lavinio and Dean Alcaro.

This team developed a layered environmental theme that used Mount Nittany as both a literal and symbolic structure. Each garage level represented a different layer of nature—from forest roots to sky and stars— symbolizing community growth and environmental stewardship. The visual language included handdrawn textures, flowing typography, and a narrative ascent toward a peak where a Nittany Lion planted a sustainability flag. The mural and graphic system emphasized local ecology, unity, and a collective future.

Visual Documentation

Each team submitted a comprehensive set of visual artifacts, which served both as design deliverables and reflective tools:

• Research Posters distilled user insights from interviews, surveys, and journey maps.

• 3D Mock-up Posters visualized the spatial integration of design proposals within the actual garage architecture.

• Design Proposals detailed each team’s visual systems, typographic strategies, placement plans, and thematic justifications.

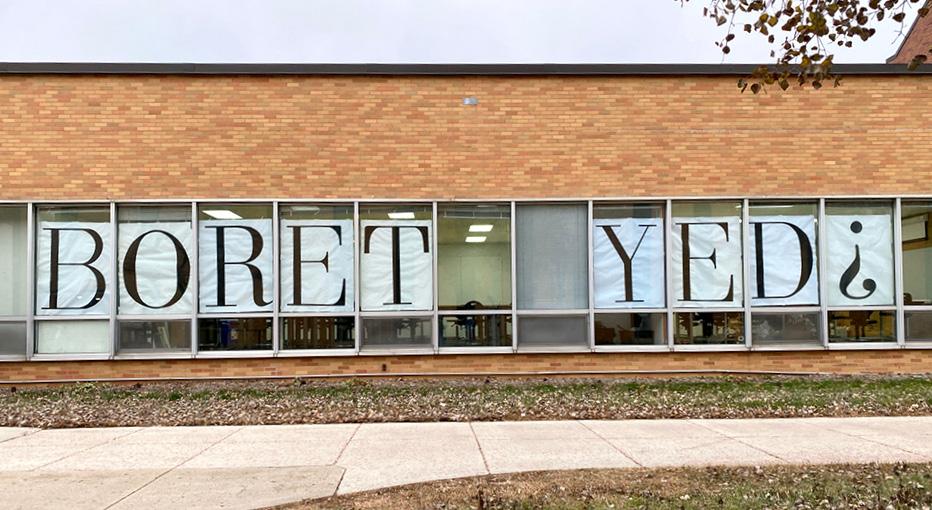

Figure 5. Progress wall used during group discussions to visualize design development and organize peer critique. (Photo by author)

Figure 4. Peer feedback and discussion during a concept development critique. (Photo by author)

Figure 3. Students presenting initial design explorations during a studio critique session. (Photo by author)

Figure 6. Final design proposal by Team Voice, featuring a seven-level wayfinding system using music-inspired themes and bold, colorful illustrations to convey shared community values. (Image courtesy of the designers)

“This project really helped us grow together, get closer, and learn more about each other and our strengths.”

- A student

Figure 7. Students presenting their design proposals at the Sustainability Expo held at the State College Borough Building.

(Photo by author)

• Presentation Boards were used in classroom critiques and public events to communicate the value and feasibility of the designs.

• Process Books chronicled each team’s full trajectory— from initial observation through synthesis and refinement—demonstrating a rigorous application of human-centered design methods.

These visual materials will be reproduced in the final publication to offer readers a rich, layered understanding of each proposal’s evolution, impact, and potential.

Educational Impact

This project served as a pedagogical model for integrating human-centered design, community engagement, and interdisciplinary collaboration into undergraduate graphic design education. Through a structured, research-driven process, students were challenged to navigate the complexities of public space design while considering the social, cultural, and emotional dimensions of visual communication.

Students gained direct experience in:

• Applying research methods including interviews, surveys, site analysis, and user journey mapping.

• Synthesizing qualitative data into visual narratives and experiential graphic systems.

• Collaborative authorship, adapting to team restructuring and shared conceptual development.

• Communicating with non-design stakeholders, including local government officials and community members, to justify design intent and receive constructive feedback.

The course design emphasized reflective practice through iterative critiques, in-class peer reviews, and process documentation. At the conclusion of the project, a peer evaluation survey was conducted to assess individual and team performance. Students evaluated dimensions such as role clarity, communication, accountability, and group dynamics. These results were anonymized and shared back with the class to facilitate reflection and guide future team-based work.

Importantly, the project underscored the role of design education in preparing students to become active participants in civic discourse and community

development. By positioning students not only as visual problem-solvers but also as social collaborators and cultural interpreters, the course expanded their understanding of what it means to design for—and with—the public.

Contribution to the Field

This project contributes to the evolving discourse of Experiential Graphic Design (EGD) by demonstrating how public infrastructure can be reframed as a site for community participation, cultural storytelling, and pedagogical experimentation. By engaging undergraduate students in real-world, place-based design challenges, the project serves as a replicable model for embedding public engagement into the design curriculum.

From a theoretical perspective, the project aligns with Christian Bason’s (2017) notion of public design leadership, which emphasizes empathy, collaboration, and user insight as drivers of innovation in civic systems. Likewise, it resonates with Gregor H. Mews’ (2022) advocacy for co-creation in public spaces, particularly through playful and narrative-based design interventions that activate emotional and cultural memory.

More specifically, the work extends EGD practice by:

• Shifting its application from branded environments and institutional signage to civic infrastructure and community-scale spaces.

• Incorporating participatory research methods such as interviews, journey maps, and persona development to deepen context-driven design.

• Highlighting the importance of co-authorship, not only between students but also between academic institutions, municipalities, and residents.

Educationally, the project supports the growing need to reframe design education beyond commercial problemsolving toward socially engaged, interdisciplinary learning. By anchoring the studio in real civic contexts, the initiative reflects how EGD can bridge aesthetic practice with public value, and how students can meaningfully contribute to conversations about identity, belonging, and sustainability in everyday urban environments.

Future Opportunities & Implementation

While this project was initiated as a pedagogical exercise, its outcomes have generated momentum for potential real-world implementation. In partnership with the Penn State Sustainability and the State College Borough, discussions are underway to explore the feasibility of a pilot installation based on one or more of the student design proposals.

Future steps include:

• Selection of pilot elements that are low-cost, high-impact, and logistically feasible—such as mural components, signage prototypes, or modular wayfinding systems.

• Collaboration with local artists to refine and adapt student designs for installation, ensuring alignment with community values and technical constraints.

• Grant funding applications, including proposals to the Hamer Center for Community Design and municipal sustainability initiatives, to support fabrication and maintenance.

Beyond physical implementation, the project has set the foundation for expanding community-based design studios as part of the graphic design curriculum. This model can be applied to other underutilized civic infrastructures such as transit stops, pedestrian walkways, or park facilities, allowing students to work across scales and mediums.

Importantly, the process has opened long-term possibilities for university–community partnerships, where design is framed not only as a product but as a process of ongoing dialogue, care, and co-creation. Through its emphasis on accessibility, identity, and public interaction, this initiative positions EGD as a vital contributor to the social and emotional fabric of urban life.

Conclusion

This project demonstrates the transformative potential of experiential graphic design when applied to overlooked public infrastructures such as parking garages. By engaging students in a process that combined research, co-creation, and contextual storytelling, the initiative redefined a utilitarian structure into a canvas for cultural expression and community engagement.

The four design proposals generated by students reflect diverse perspectives, interdisciplinary thinking, and a strong commitment to place-based design. Through themes such as local history, musical identity, environmental stewardship, and playful storytelling, each team articulated a vision of public space that is inclusive, participatory, and emotionally resonant.

Educationally, the project positioned students as active agents in civic dialogue, encouraging them to design not just for but with communities. Their work exemplifies how design education can extend beyond classroom boundaries to foster real-world impact, critical thinking, and collaborative authorship.

Looking ahead, the potential for physical implementation and continued university–community collaboration reaffirms the value of integrating public engagement into the design curriculum. This initiative not only enriches students’ educational experiences but also contributes meaningfully to the discourse on how EGD can cultivate belonging, visibility, and connection in the built environment.

Resources

Bason, Christian. Leading Public Design: Discovering Human-Centred Governance. Danish Design Centre, 2017.

Crawford, Margaret. Everyday Urbanism. Monacelli Press, 2008.

Mews, Gregor H. Transforming Public Space through Play: The Role of Play in the Design of Public Space. Routledge, 2022.

Rendell, Jane. Art and Architecture: A Place Between. I.B. Tauris, 2006.

Sanders, Elizabeth B.-N., and Pieter Jan Stappers. “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign, vol. 4, no. 1, 2008, pp. 5–18. Taylor & Francis, https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068.

Tunstall, Dori. Decolonizing Design: A Cultural Justice Guidebook. MIT Press, 2023.

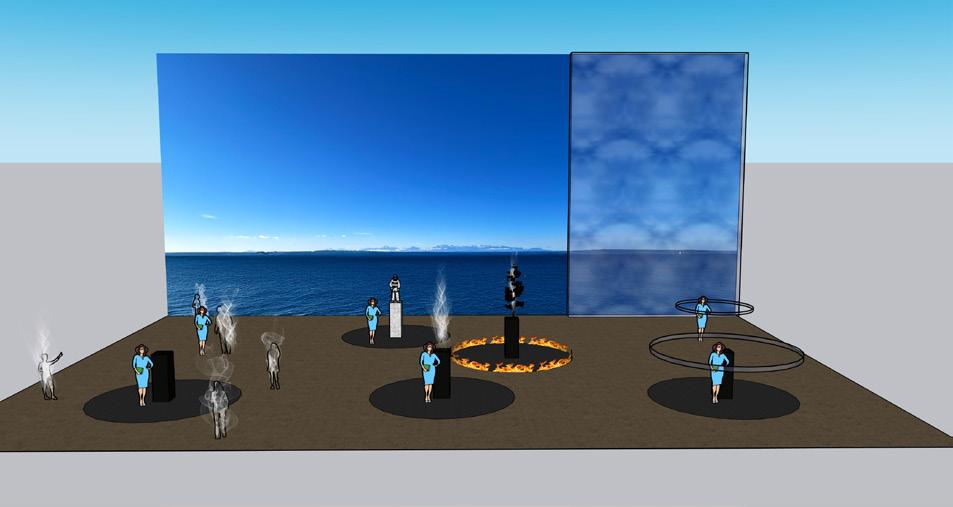

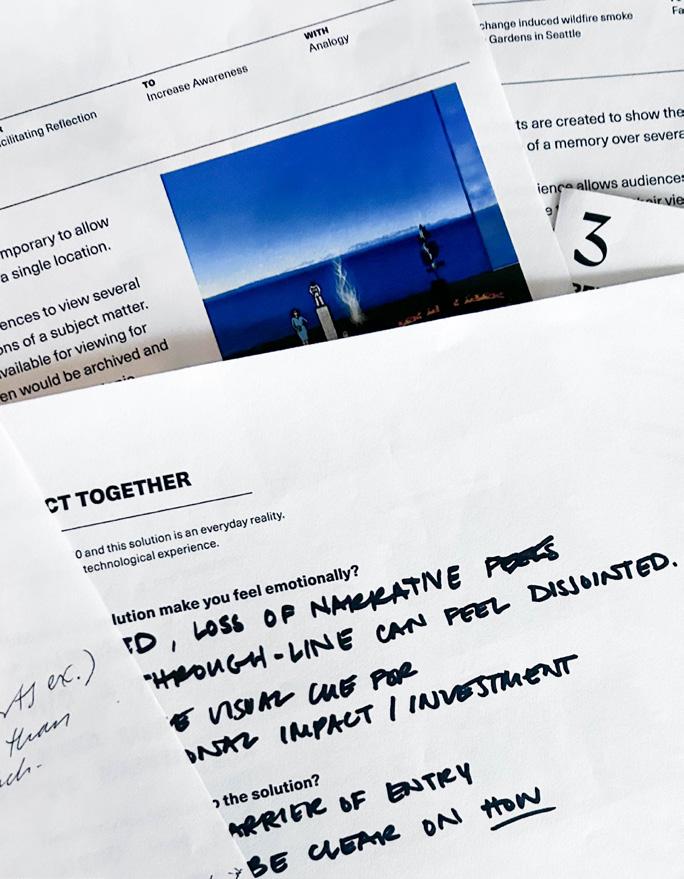

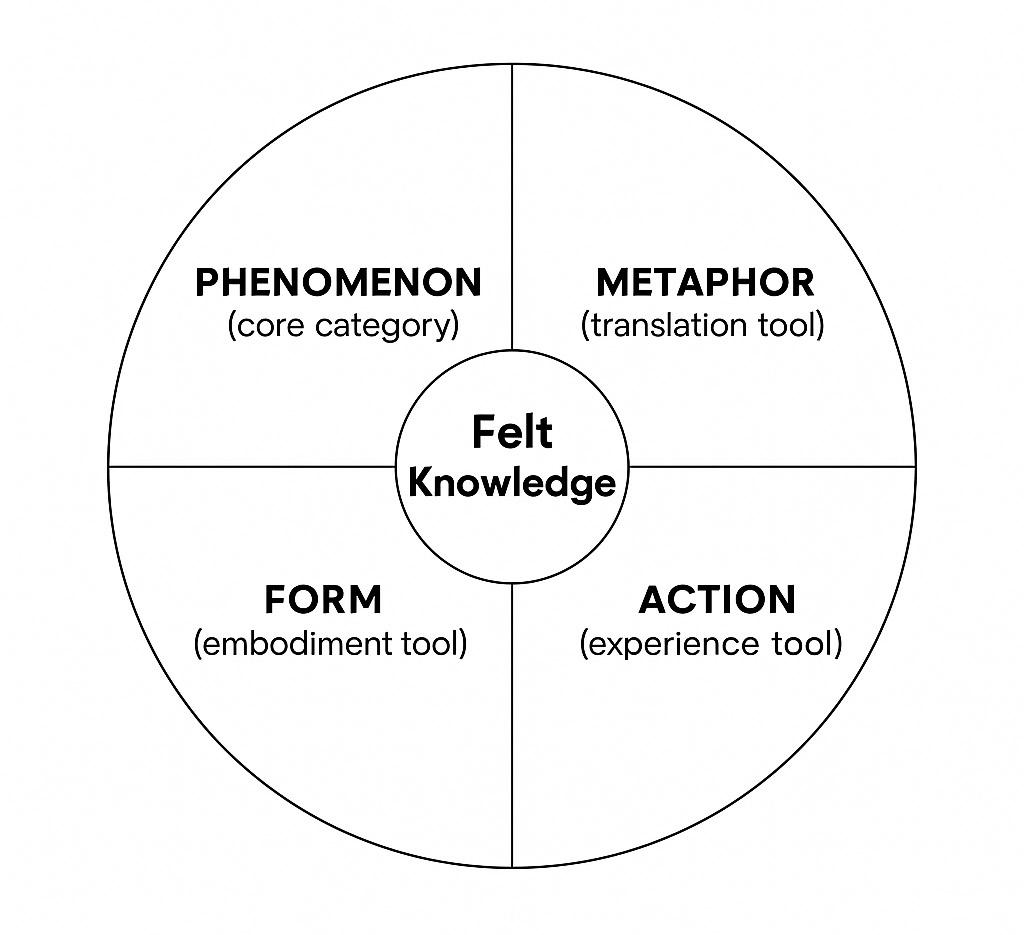

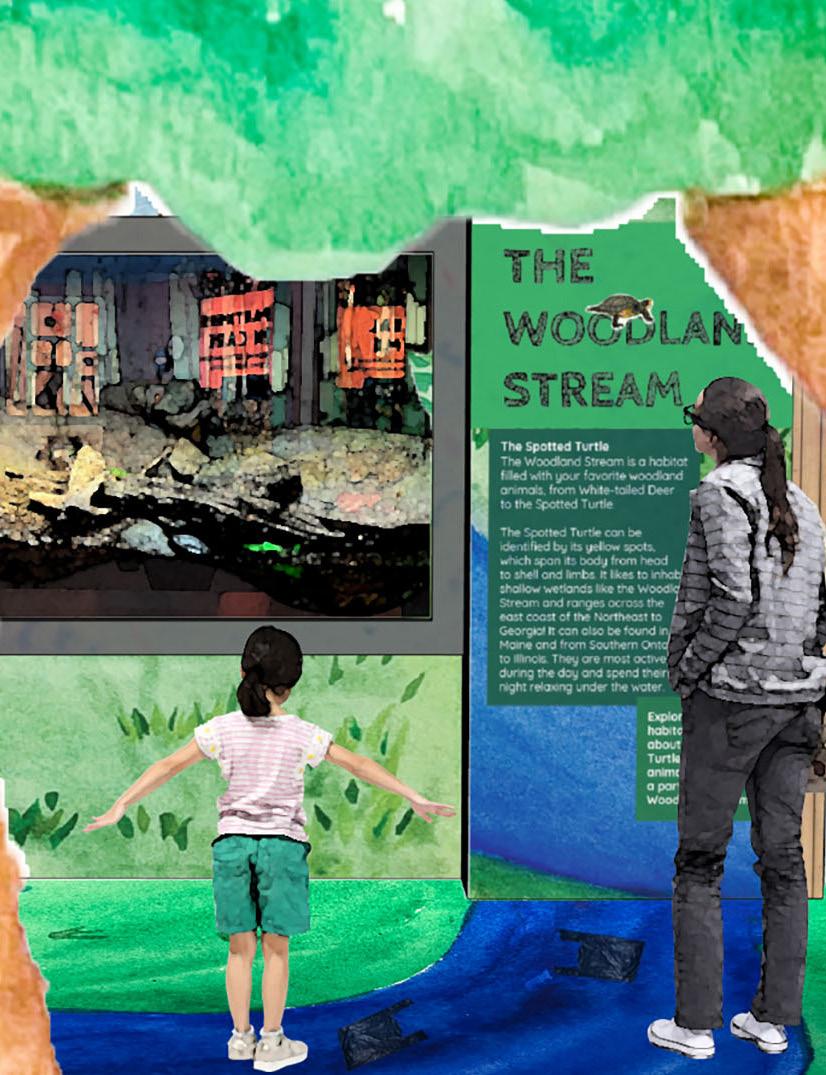

Perception of Space

Participant Activated, Experience Oriented Exhibition Design

Sofia J Ingegno Graduate Student, Human Experience

Design Interactions

California State University Long Beach

Abstract

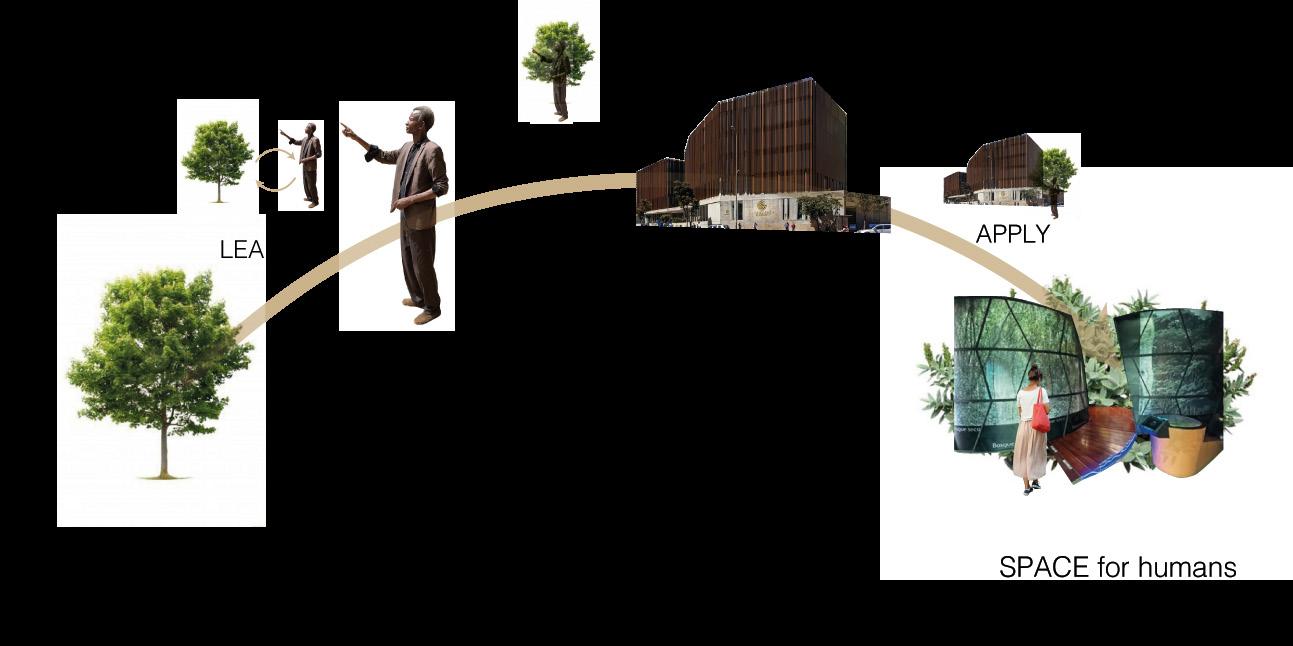

Exhibition spaces within educational and for-public institutions, such as Museums, traditionally strongholds of curatorial authority, are facing a growing need to engage audiences in a more active and meaningful way. This project proposal explores the limitations of the current “observer” model and proposes a framework for participatory exhibition design. Through a review of existing literature, case studies, and a proposed research plan, the project investigates how museums can shift their focus from static displays to collaborative environments, empowering visitors to become stakeholders in the cultural narrative. While the essence of Perception of Spaces’ structure can be analogized as a new twist on a familiar recipe, the project’s engagement is captured through the metaphor of a community potluck. Each participant brings a unique dish (their perspective), and the collective gathering forms a richer, more diverse cultural experience.

Project Themes

Exhibition, Active Participant, Passive Participants, Connection, Community, Public Space, Cultural Artifacts, Cultural Narratives, Co-Creator

Introduction

Public arts and education institutions, such as museums, act as vital community stakeholders in society, contributing significantly to the economy while fostering education, enjoyment, and cultural exchange. However, the traditional model of exhibition design, where visitors passively observe curated objects, is increasingly questioned. This project proposal argues that a shift towards participatory design is necessary to develop a more engaging and meaningful experience for the visitor.

Domain & Value

The project targets the domain of public exhibition spaces. According to the American Alliance of Museums, “museums contribute $50 billion to the U.S. economy each year”, annually receiving nearly “55 million visits” from student school groups. Addressing the desire for an engaging and educational exhibition experience, as valued by 97% of Americans, through transforming static exhibitions into collaborative environments fosters curiosity and empower communities to actively participate in cultural narratives. This ultimately strengthens the economic and social fabric, as valued by 89% of Americans, of the surrounding area.

The value of this project lies in enhancing engagement in exhibition spaces and transforming static displays into dynamic environments that foster curiosity and active participation. Interactive and immersive exhibits encourage visitors to become active participants, revitalizing the experience. This transformation empowers communities by incorporating their voices and perspectives into the cultural narrative, ensuring inclusive and authentic representation. Increased visitor engagement also strengthens the social and economic fabric of surrounding communities, attracting more visitors, generating revenue, and promoting cultural tourism. While this value is not directly tied to the project’s outcomes, its societal implications further legitimize the need for its inclusion. This approach demonstrates the powerful role exhibition spaces can play in education and societal development.

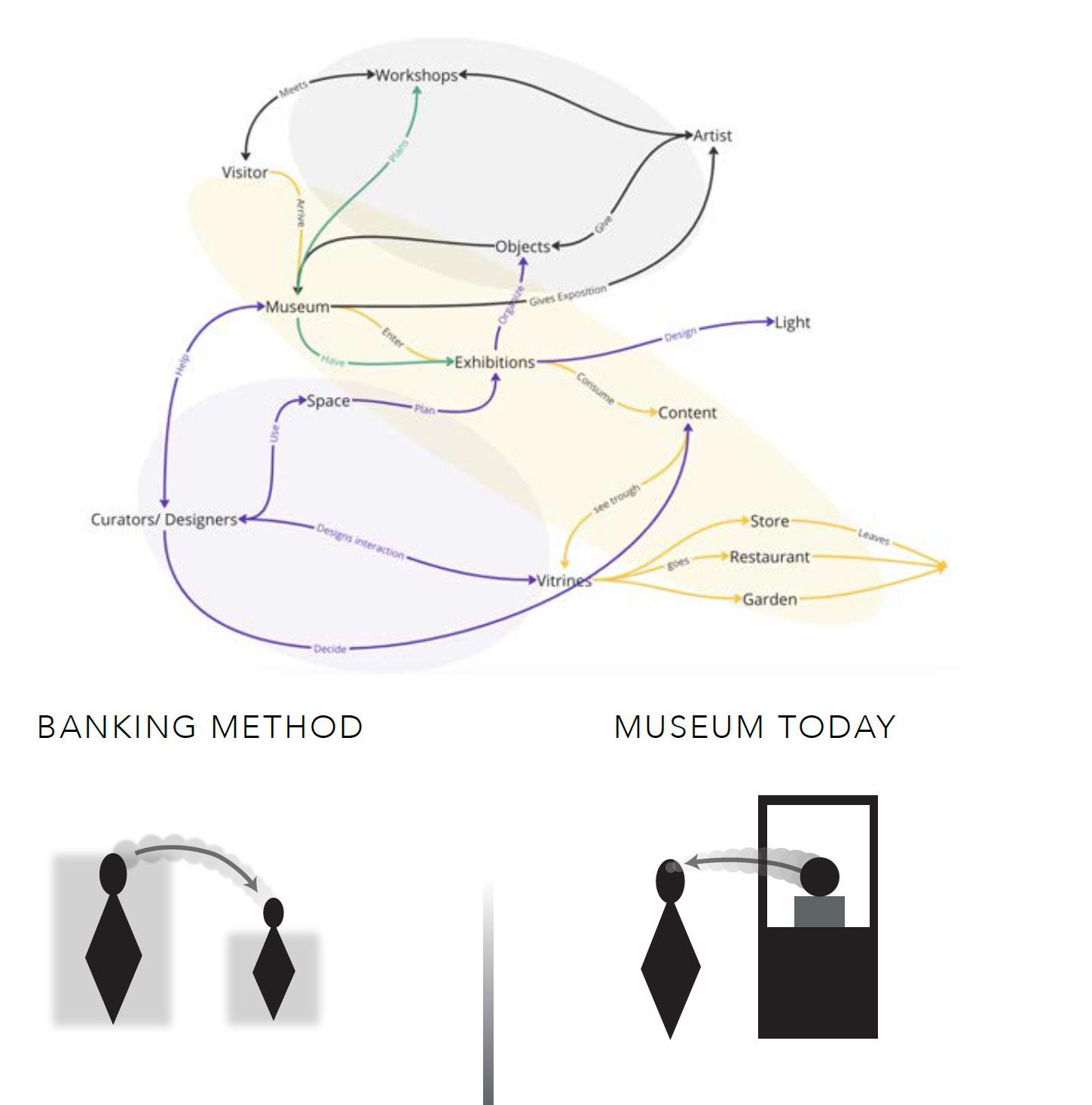

Research Questions

Published in the 2022 issue of the Journal of Applied Science and Engineering, Sun and Wang’s research on Digitalization Exhibition Design underscores significant shifts in exhibition formats. The study emphasizes a transition from object-oriented information delivery towards a people-oriented approach, facilitating greater participation and engagement among attendees. This evolution is exemplified by the progression from “Designer-led Design” to “Participatory Design,” highlighting a move towards collaborative and inclusive exhibition planning and execution. Moreover, the research introduces the concept of immersion as a bonding experience within exhibitions, suggesting that deep engagement and sensory involvement foster stronger connections between visitors and the displayed content. Through these themes, Sun and Wang’s work offers valuable insights into the evolving landscape of exhibition design, emphasizing the importance of interactivity, collaboration, and experiential engagement.

Furthermore, the work of authors Popoli and Derda, published in the 2021 issue of the Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship, reveals overlaps in several key themes pertinent to modern museum practices. The authors discuss the transition from an encyclopedic approach to a co-creator/co-producer model, wherein museums shift from being repositories of knowledge to fostering collaborative relationships with their audiences. This transformation also entails changing passive visitors into active participants, engaging visitors in co-creating and co-curating content within the museum space.

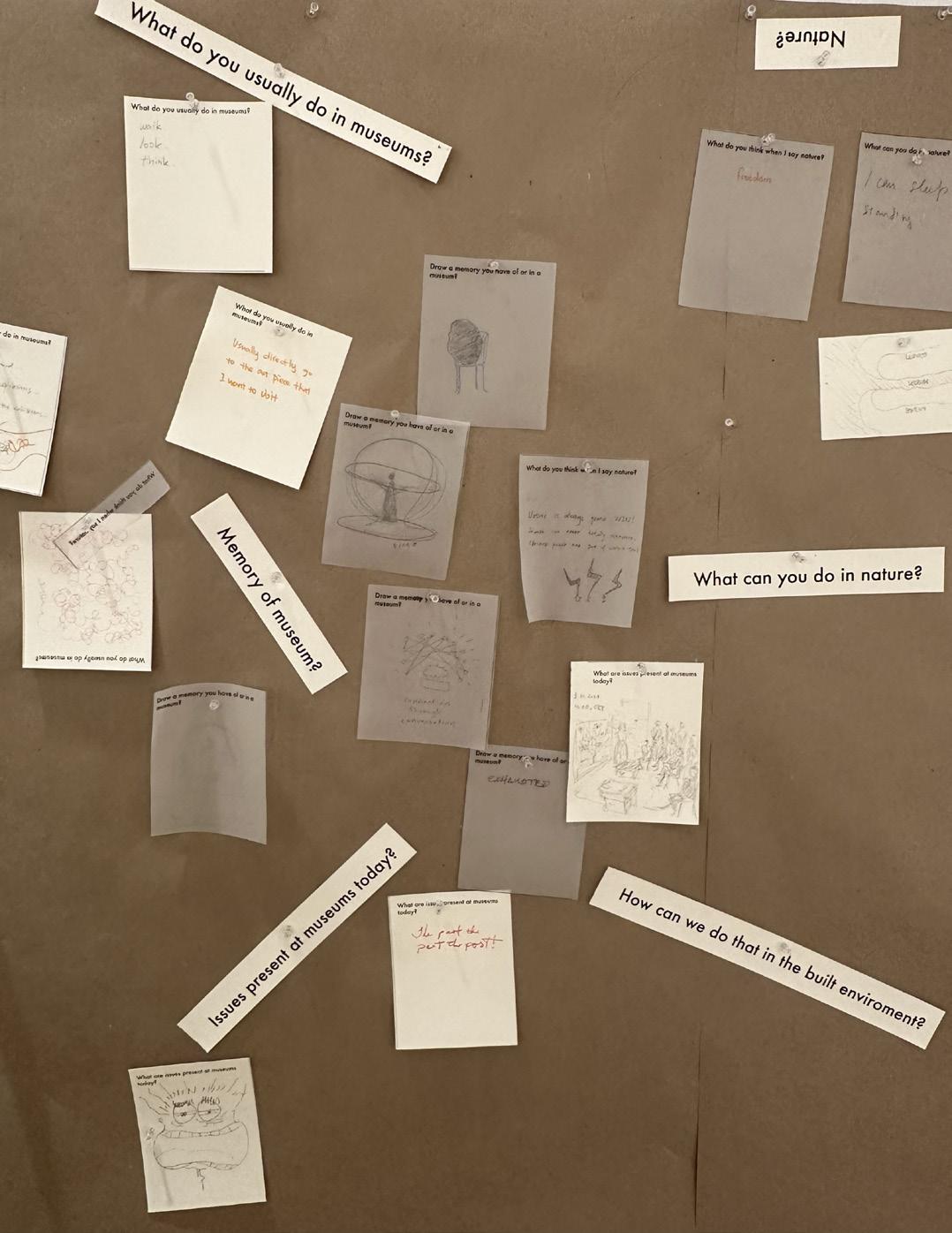

The existing curatorial models in exhibition spaces prioritize the curator’s narrative, fostering passive observation among visitors rather than encouraging active participation in cultural exploration. This direction prompted the formulation of two key research questions that framed the preliminary investigation for this project.

1) How can an exhibition become a collective experience? A space that is actively changing and grounded by the audience rather than the institution and curators?

2) What makes an exhibition space become a participatory environment where visitors and patrons activate their atmosphere?

The Challenge

The prevailing “curatorial authority” paradigm positions visitors as passive observers, limiting the potential for self-discovery and active engagement. Research by Popoli & Derda (2021) highlights the need to move beyond the “encyclopedic approach” towards a model where visitors become “co-creators” and “story translators” rather than storytellers. Similarly the findings of Sun & Wang (2022) emphasize the importance of a “people-oriented” approach, fostering emotional connection and immersive interaction.

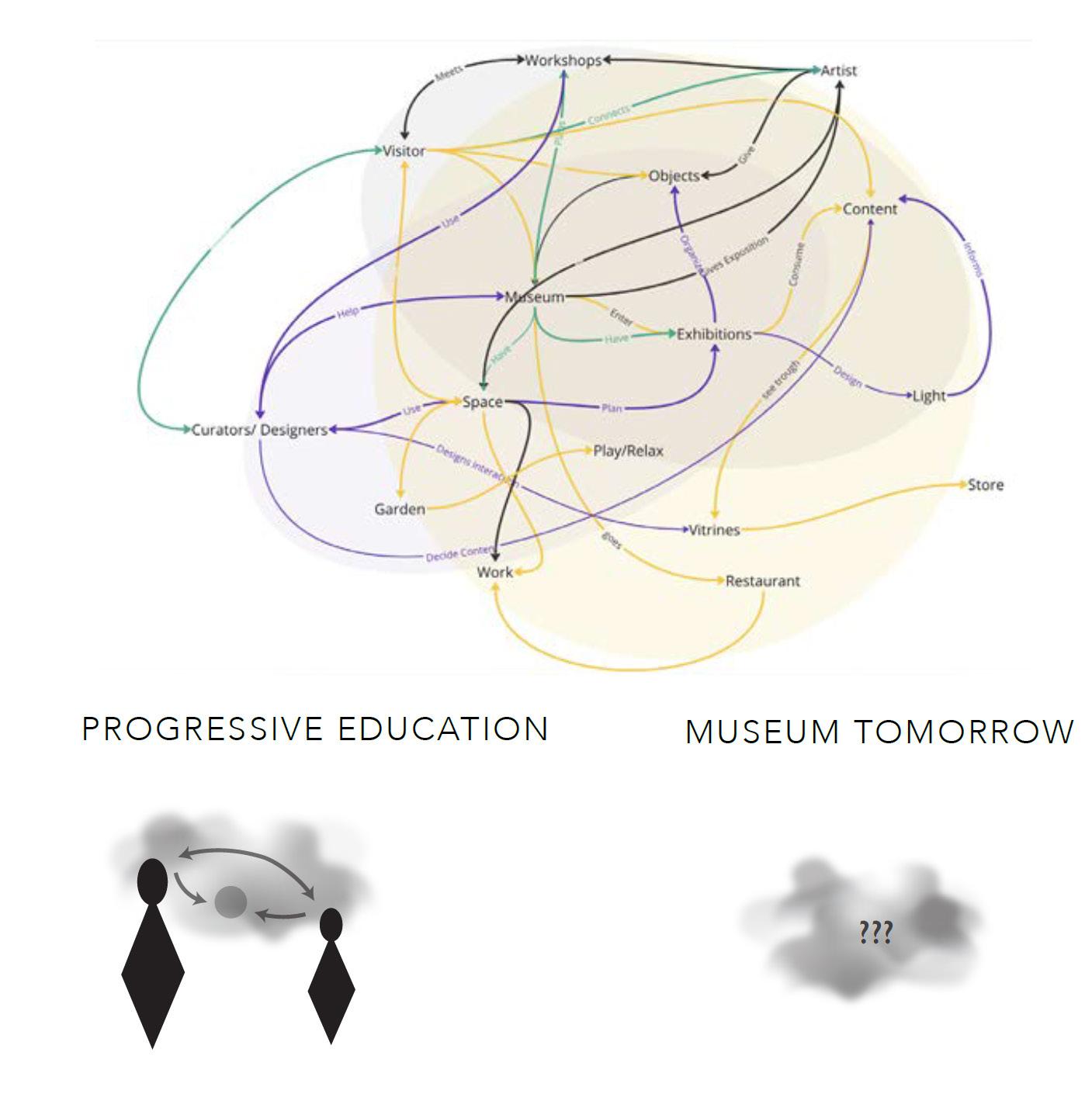

Project Statement

Perception of Space, redefines exhibition engagement by elevating the collective experience over the presentation of artifacts within artistic spaces Through a flexible layout, hands on engagement, and human dialogue, participants become stakeholders in a dynamic public environment, empowering active collaboration and curiosity with cultural narratives

Perception of Space’s approach to exhibition design, centered on active engagement and collaboration. The framework emphasizes three key components to enhance the visitor experience and promote community involvement. Firstly, a flexible layout enables the exhibition space to be modular and adaptable, facilitating dynamic reconfiguration. This feature not only accommodates various exhibition formats but also encourages community participation in shaping the exhibition’s narrative and layout. Secondly, the incorporation of hands-on engagement through interactive elements promotes active exploration and interaction with the cultural content. These interactive features enrich the visitor experience by allowing them to engage with the exhibits in a tangible and meaningful way. Lastly, the project underscores the importance of human dialogue by facilitating interactions between visitors. This approach fosters a sense of community and shared ownership of the exhibition, creating a more inclusive and engaging experience for all involved.

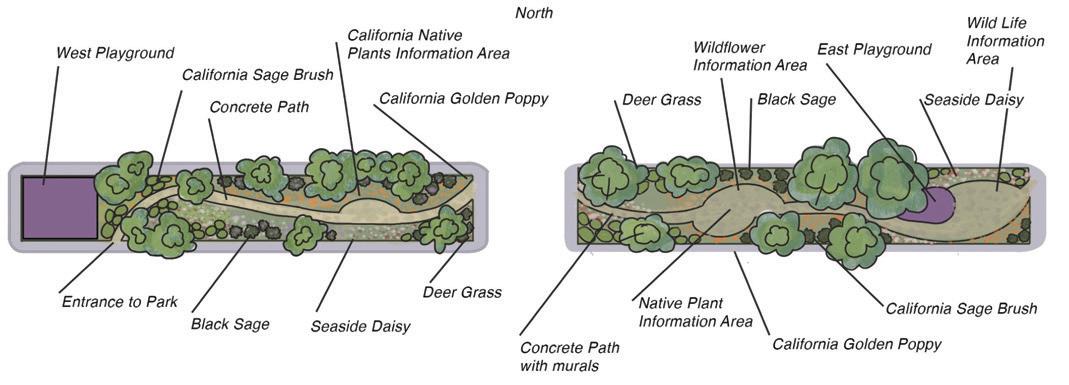

CSULB Art Park

With a deep rooting history of public art display dating back to the mid - twentieth century the CSULB campus has a vast range of public sculptures, murals and even a mosaic on the public outdoor grounds, however the context and content behind the works seen is difficult to locate. Presently the histories of each work that is included in the self guided tour map of the Art Park is only accesible by request through the website of the Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld Contemporary Art Museum.

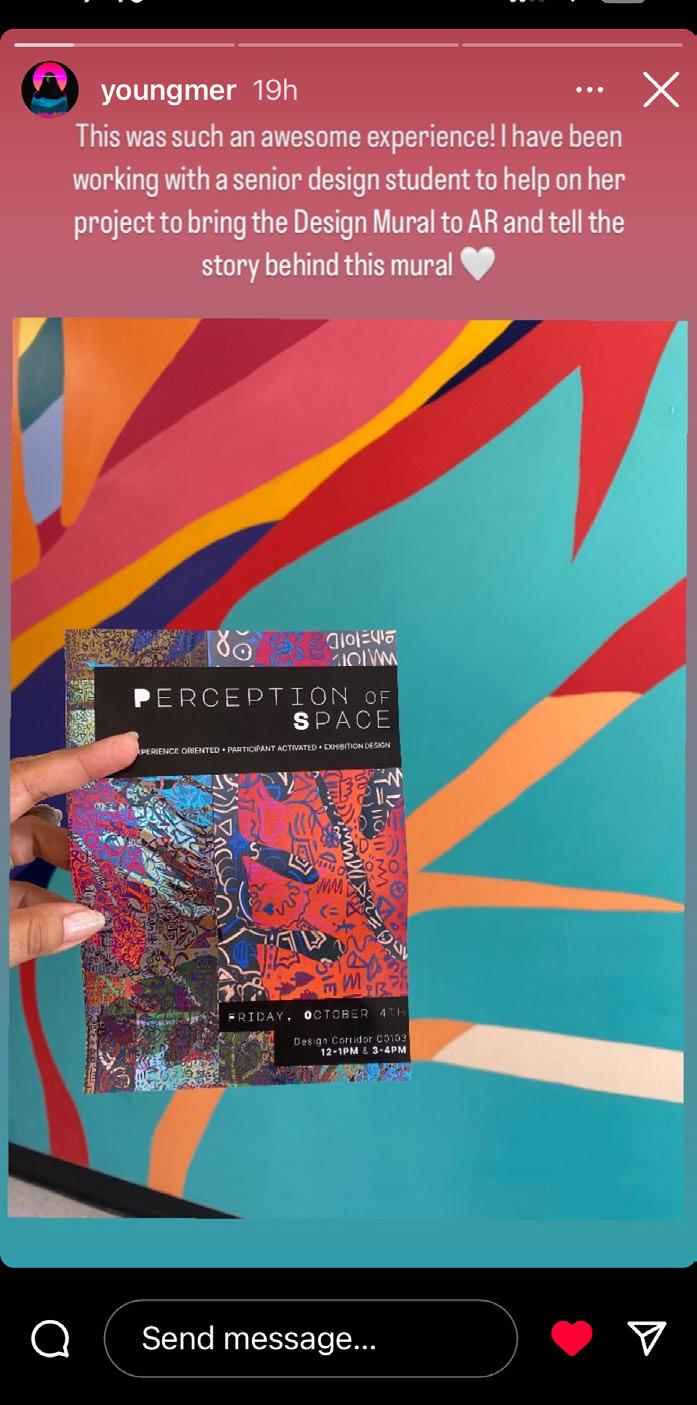

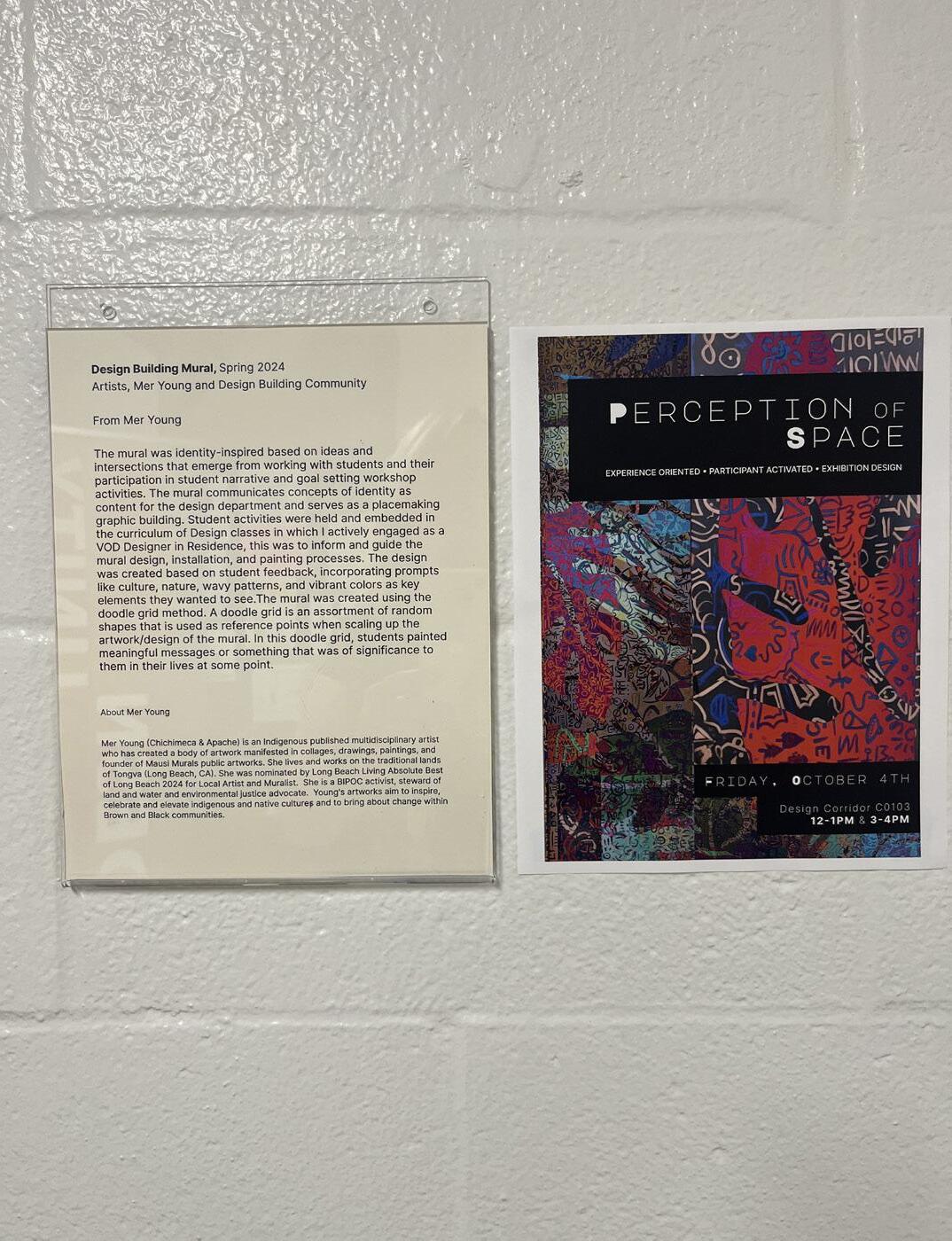

In spring of 2024 the design student community came together to design, collaborate and paint a mural with local indigenous artist Mer Young. It used a doodle grid to scale the final design, allowing for a unique, flexible, and expressive format in the process of making. It is located in located in design corridoor 112 A.

User Research and Data

A total of 50 indivuduals were surveyed with 8 indepth interviews conducted.

Survey Results:

• 65% exhibition spaces could improve on display and overall description

• 36% people felt the doodle grid represented “people” and “experiencing new things”

• 42% felt the mural represented “unity”

• 66% were unaware of the murals location

Development

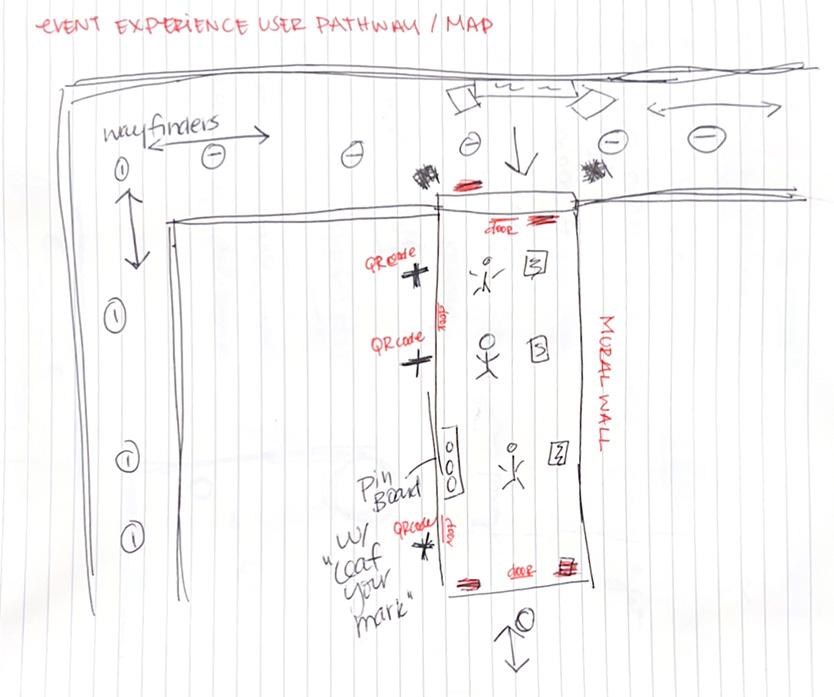

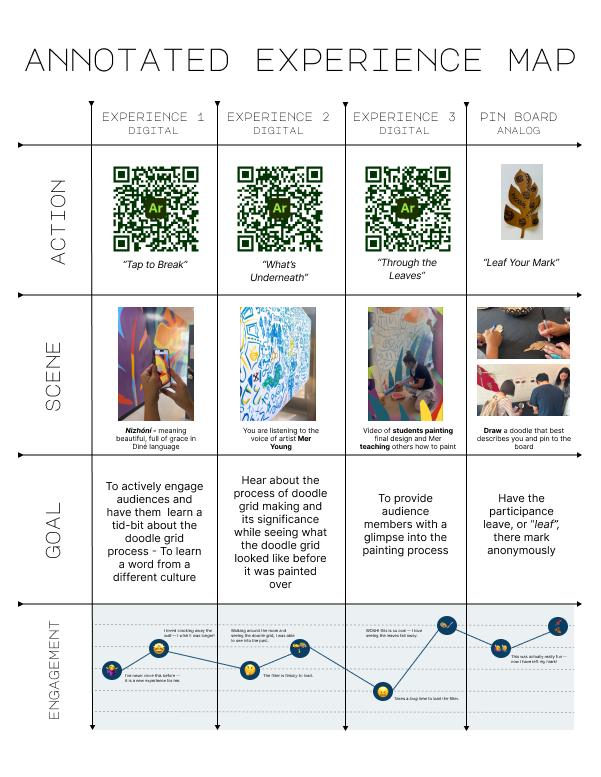

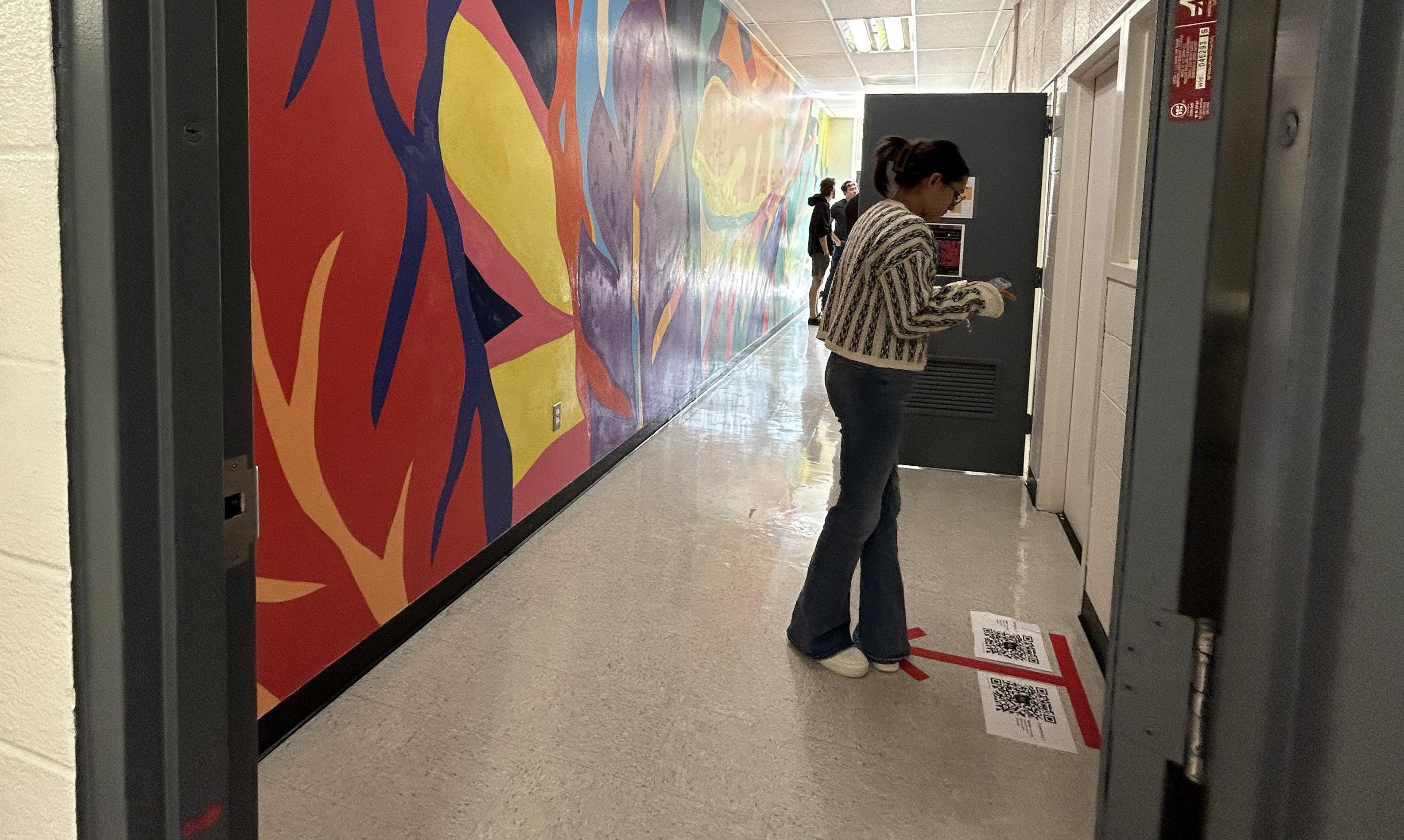

Over the course of 2 months the project was developed and launched with the final event hosted on October 4th, 2024. To balance digital and analog elements, Perception of Space consisted of three main groups with in these realms.

1) AR Filters (digital) and Wall Didactics (analog)

2) Wayfinding Floor Decals (analog)

3) “Leaf Your Mark” Pin Board (analog)

The AR filter prototypes consisted of experiementing with Location Anchors, in which the augmented reality

filter is anchored by the location of the outdoor class room and interior mural hallway and Image Anchors where the augmented reality filter is anchored by a sectional image of the mural. The prgram used was AdobeAero due to its user ease and stability in development.

When prototyping the floor decals, usability testing found that 50% of people noticed the decals when walking in the halls. Further more people who noticed them, proceeded to look into the mural hallway.

Delivery and Results

Hosted on October 4th, 2024, the pilot event for Perception of Space was held. Fliers were posted througout the student body on campus, emails send and posts made through social media platforms. When individuals entered the Design Building, they were directed by the wayfinding floor decals to the design corridoor and prompted to scan the QR codes with their mobile device and visualize or particiapte in each interaction. There were a total of 4 interactions, three were digital and one was analog. The first “Tap to Break” had prompted participants to tap the screen and break the wall revealing the a doodle underneath the section of painted mural, the second “Whats Underneath” revealed the doodle grid as it was in full scale accompanied by an audio voice over of the murals meaning intentions and development along side the students at CSULB, the third and final filter “Through The Leaves” revealed a video of artist Mer Young teaching students how to paint a mural. The fourth and final engagement was the “Leaf Your Mark” pin board in which participants were encouraged to draw a doodle or write a message on small lazer cut leaves from recycled paper bags and then pin it to the larger leaf styled pin board. It acted as not only a balance of digital and analog activities but as a play on the sentiment behind the development of the Design Building Mural the semester before.

Event Results:

• 46 total participants

• 82% of people experienced all AR filters

• 70% felt inspired by cultural narratives

• 73% left their mark on the “leaf your mark” pin board

Testing and feedback showed that some filters took a long time to load, sound was not made to be a clear part of the experience, additionally Android phones were unable to load the filters due camera recognition because of the hallway depth. Many explained that the user flow of the space and location of the QR codes should be improved upon. This feed back was vital as having feed back enables the project to meaningfully improve and grow.

The next steps in this project are to refine the user flow in the design corridor, refine the AR filters for the space and resolve the technical issues that arose during testing. On a larger scale, this project can expand experiences across the entire CSULB campus, contextualizing cultural narratives of the public art included in the Art Park.

Thank you to the HXDI X5 Cohort, my comittee members: Debra Satterfield, Judit Samper-Albero, Mer Young and Michael LaForte as well as the SEGD community.

Povuu’ngna

Tongva leaf created by Mer Young

“A museum is a collaborative institution with storytellers and community stakeholders.”

Katie Naber · Exhibition Designer · The Walters Art Museum

Setting up for the Perception of Space event on October 4th, 2024. Temporary wayfinding decals were installed as well as fliers being handed out.

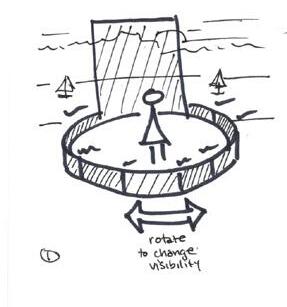

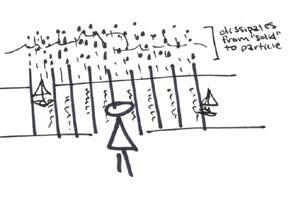

A preliminary sketch of the user experience throughout the space with in the CSULB Design building.

“How might we develop an exhibition design space where visitors actively collaborate with cultural narratives, sparking curiosity?”

Perception of Space · Challenge Statement

A final annoted experience map developed based upon survey results and observations from users the day of the event.

Caption text

A doodle leaf for the “leaf your mark pin board.

for the event

“There are over 21 public art installations or spaces on display across the CSULB campus, dating from 1965 to present and yet there is only context provided for one of the installations.”

Perception of Space · Statement of Need

The first iteration of the way finding decals used

Caption text

Caption text

Caption text

Social Media Post for the event

Wall didactics and event fliers

A student user scaning the filter QR codes

The doodle grid used as the guide to paint and scale the final mural design.

The final mural design

This is a representation of what the images look like atop of one another, to demonstrate how the doodle grid was used to scale the final design that was super imposed aboved the doodle grid

Resources

American Alliance of Museums. “Museum Facts & Data.” American Alliance of Museums, www.aam-us.org/ programs/about-museums/museum-facts-data/#_edn28 . Accessed 25 April 2024.

American Alliance of Museums. “Learning from the Double Diamond: How Divergent and Convergent Thinking Can Improve Collaboration and ProblemSolving in Museums.” American Alliance of Museums, 5 Apr. 2024, www.aam-us.org/2024/04/05/learningfrom-the-double-diamond-how-divergent-andconvergent-thinking-can-improve-collaboration-andproblem-solving-in-museums/. Accessed 25 April 2024.

Derda, Izabela, and Zoi Popoli. “Developing Experiences: Creative Process behind the Design and Production of Immersive Exhibitions.” Museum Management and Curatorship, vol. 36, no. 4, 2021, pp. 384-402.

Design Council. “The Double Diamond.” Design Council, www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-doublediamond/. Accessed 1 May 2024.

Madsen, Kristina Maria, and Mia Falch Yates. “Mapping and Understanding the Potentials of Co-Creative Efforts in Museum Experience Design Processes.” Academic AAU, Akademisk Kvarter; Quarter Research from the Humanities, vol. 23, 2021, pp. 123-139.

“Street Art Factory.” Accessed 1 March 2024, https://www.streetartfactory.eu/en/maua/.

Sun, Hongxia, and Xiong Wang. “Research On Digitalization Of Museum Exhibition Design Based On Image Emotional Semantics.” Journal of Applied Science and Engineering, vol. 26, no. 5, 2022, pp. 739-746.

“The Punk Rock Museum.” Accessed 28 February 2024, https://www.thepunkrockmuseum.com/.

American Alliance of Museums. “Museum Facts & Data.” American Alliance of Museums, www.aam-us. org/programs/about-museums/museum-facts-data/#_ edn28.

American Alliance of Museums. “Learning from the Double Diamond: How Divergent and Convergent Thinking Can Improve Collaboration and ProblemSolving in Museums.” American Alliance of Museums, 5 Apr. 2024, www.aam-us.org/2024/04/05/learningfrom-the-double-diamond-how-divergent-andconvergent-thinking-can-improve-collaboration-andproblem-solving-in-museums/ .

Beale, Gareth, et al. “Digital Creativity and the Regional Museum: Experimental Collaboration at the Convergence of Immersive Media and Exhibition Design.” ACM Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, vol. 15, no. 4, 2022, article 78, pp. 78:1-78:23.

Beisiegel, Katharina, editor. New Museums: Intentions, Expectations, Challenges. Translated by Robert McInnes and Russell Stockman, Hirmer Verlag, 2017.

Derda, Izabela, and Zoi Popoli. “Developing Experiences: Creative Process behind the Design and Production of Immersive Exhibitions.” Museum Management and Curatorship, vol. 36, no. 4, 2021, pp. 384-402.

Design Council. “The Double Diamond.” Design Council, www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-doublediamond/.

Dewey, John. Art as Experience. Capricorn Books, 1958.

Diaz, Abigail, and Sunewan Paneto. “The Human Condition: Health, Wellness, & Emotional Connection in Museums.” Curator: The Museum Journal, vol. 63, no. 4, 2020, pp. 579-83.

Janes, Robert R. “Why I Don’t Like Museums: A Reply to the Commentary ‘Personal, Academic and Institutional Perspectives on Museums and First Nations’.” The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, 1994, pp. 147-56.

Kim, Dubeom, Byung K. Kim, and Sung D. Hong. “Digital Twin for Immersive Exhibition Space Design.” Webology, vol. 19, no. 1, 2022, pp. 4736-4744.

Lanir, Joel, et al. “Visualizing Museum Visitors’ Behavior: Where Do They Go and What Do They Do There?” Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, Nov. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-016-0994-9.

Lee, Jihye Park, et al. “Do Immersive Displays Influence Exhibition Attendees’ Satisfaction?: A StimulusOrganism-Response Approach.” Sustainability, vol. 14, 2022, pp. 1-20.

MacLeod, Suzanne. Museums and Design for Creative Lives. Routledge, 2021.

Madsen, Kristina Maria, and Mia Falch Yates. “Mapping and Understanding the Potentials of Co-Creative Efforts in Museum Experience Design Processes.” Academic AAU, Akademisk Kvarter; Quarter Research from the Humanities, vol. 23, 2021, pp. 123-139.

Simon, Nina. The Participatory Museum. Museum 2.0, 2010.

Sun, Hongxia, and Xiong Wang. “Research On Digitalization Of Museum Exhibition Design Based On Image Emotional Semantics.” Journal of Applied Science and Engineering, vol. 26, no. 5, 2022, pp. 739-746.

Creating with Community Imagining

Collaborative,

Justice-Oriented

Spaces

Kellyn Nettles Worker-Owner + Designer, Àrokò Cooperative

Abstract

This paper explores some of the necessary parameters, including concepts, physical structures, and strategy, for exhibition designers to consider as part of the cocreation process in local communities, with the goal of sustaining movements for broader social change. Through research and applied design practice, I aim to unpack how the principles of co-design and co-collaboration can be utilized in the exhibition design field to increase community engagement and education with important issues, thus creating change to the lived experiences of Black communities experiencing the impacts of repeated systemic failure under capitalist infrastructure.

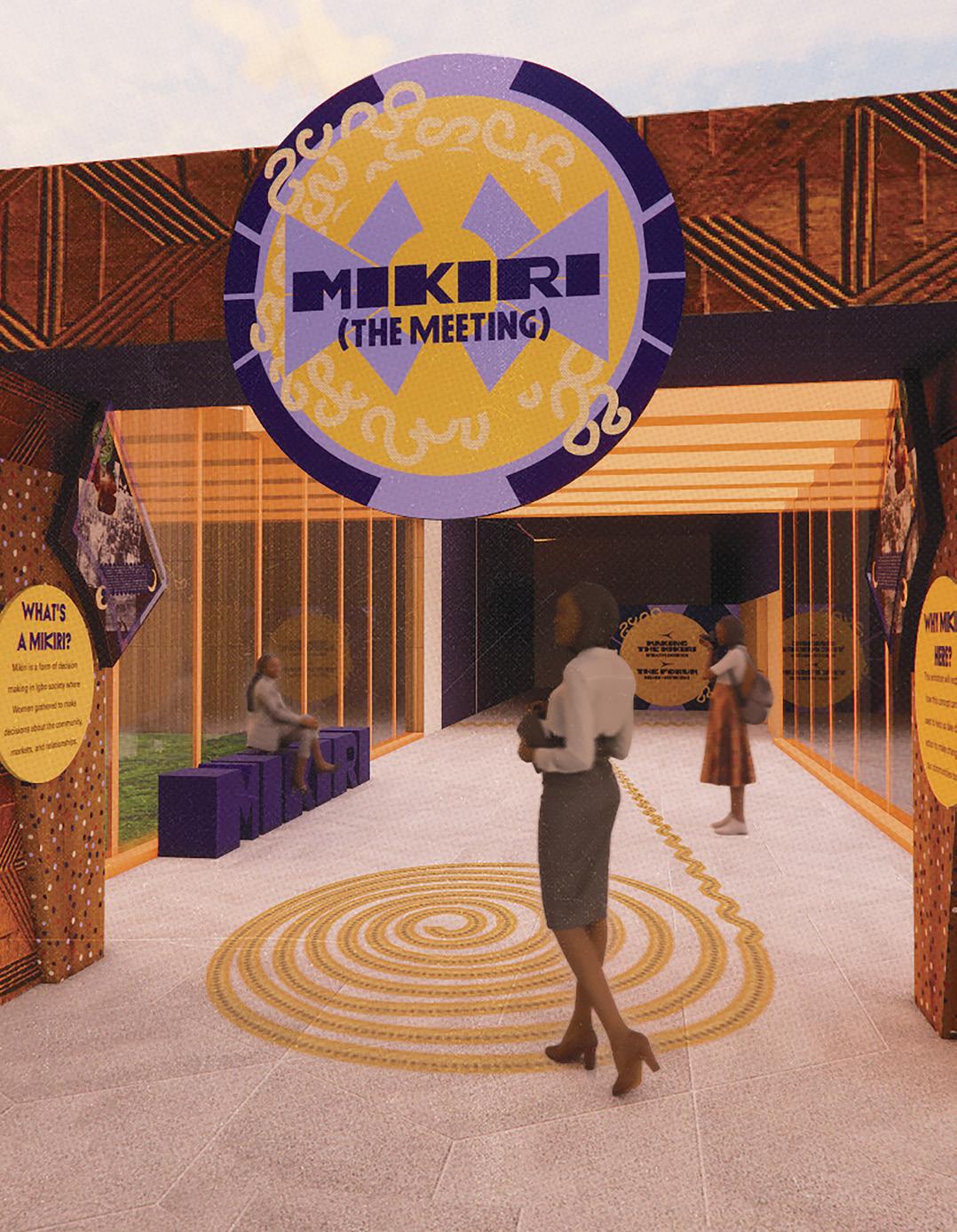

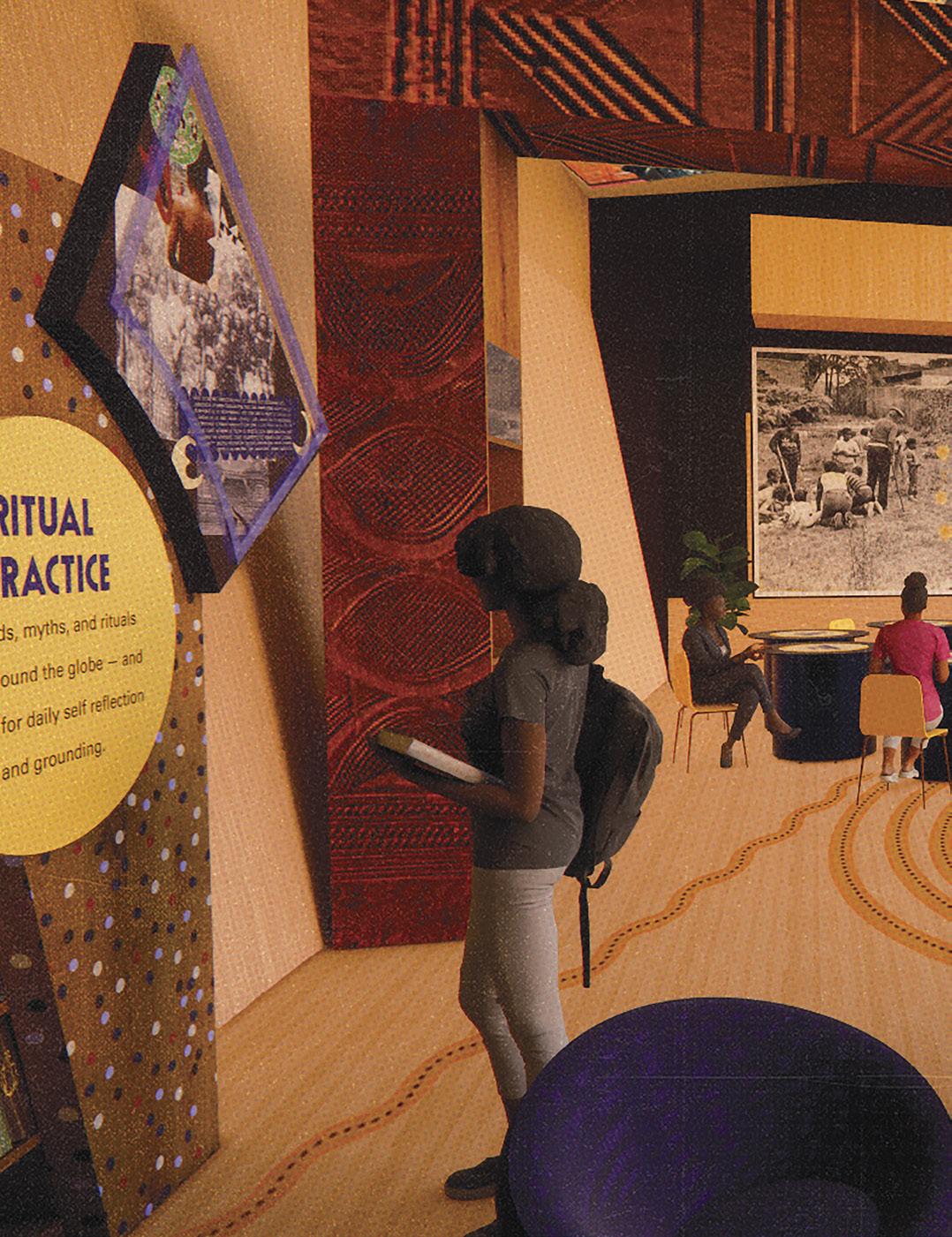

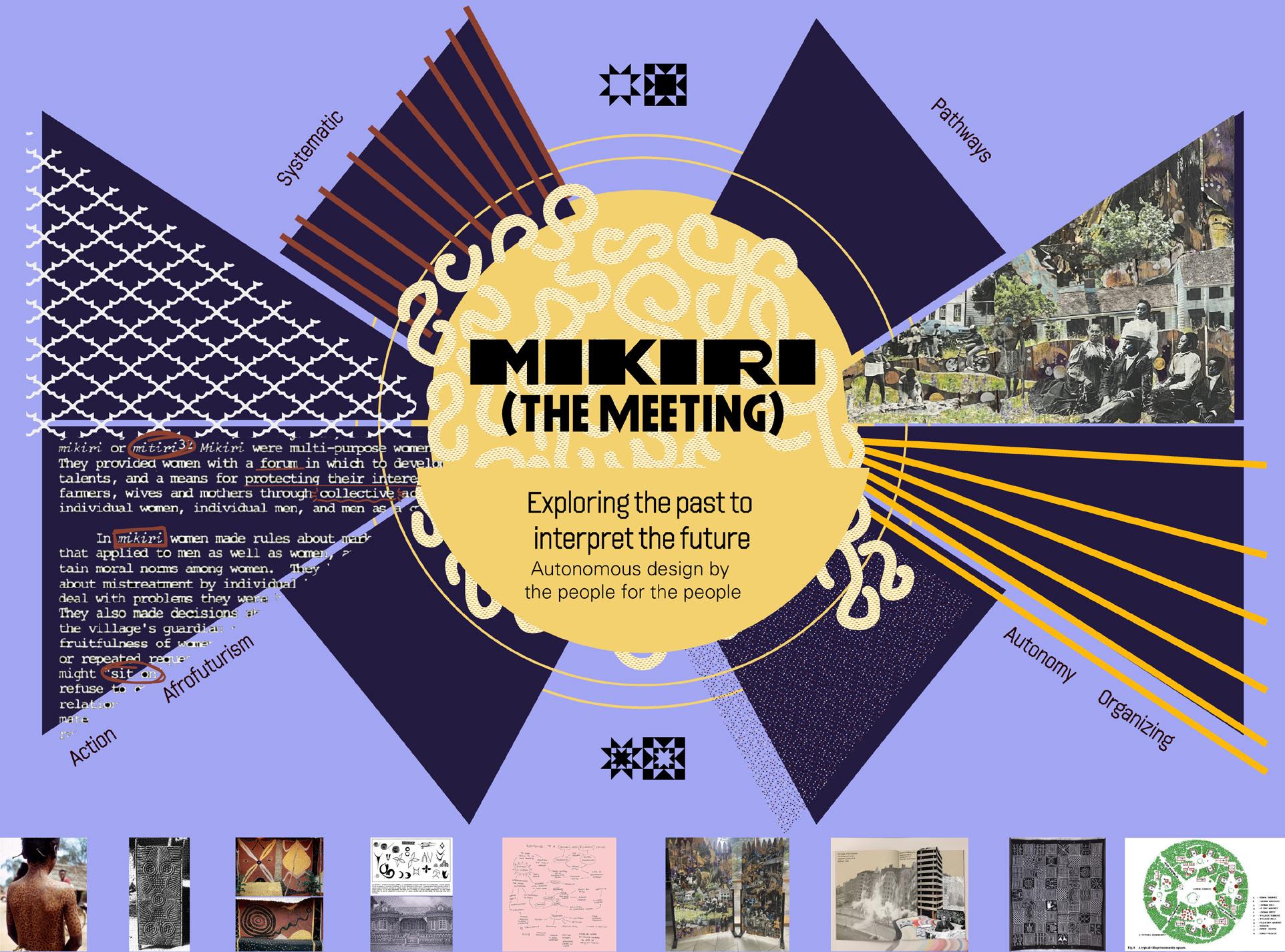

My goal is to create an incubation space that showcases strategies for utilizing historical and educational venues for liberatory practices and encourages Black community members to collaborate on creating change and strengthen a sense of mutual belonging in their neighborhoods. The proposed solution is based around the precolonial Igbo mikiri, a style of meeting where women could exercise their power. This collective meeting style could often lead to protests, and can be seen as the initial fire behind the Aba Women’s War in 1929, when thousands of Igbo women gathered to protest British colonial chiefs that restricted their access to these gatherings. The “Mikiri” exhibition project explores the Igbo concept of mikiri as a way of bringing power back to the people of Kingsborough Houses, a New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) property in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. The exhibition contains two central features: an interactive experience and a research hub for work, study, live programming, and events. I envision local organizations utilizing these assets to encourage education around social issues, giving Kingsborough Houses residents the space and resources to collaborate on how they will affect change in their community.

Overall, this project reflects that, by utilizing the design strategies of facilitation and planning to help communities engage with liberatory work in imaginative and speculative ways, exhibition designers can be integral to the cocreation process for grassroots liberation organizations.

Key principles of this research were outlined by members of Àrokò Cooperative in the Design to Divest manifesto.

Introduction

Historically, community-led collective action creates change. Current political systems in the United States exist because of documents produced at Constitutional Conventions—what can also be seen as a handful of community collaborations. Although the systems and policies that developed from these documents were exclusive to the white landowning men of the country, today many social justice-oriented designers have begun to focus on how collective imagining can help us rewrite these rules and create futures that are ecologically, economically, and socially prosperous and equitable.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel writes: “This [collective imagining] process is useful because it gives oppressed people space to dream where they might otherwise not have been able to … it gives people the space to be critical of their circumstances and to start thinking about a better way. This opens everyone up to move to action through design” (Noel 70). What Dr. Noel discusses here is also described by Dr. Arturo Escobar as autonomous design: “a design praxis with communities that has the goal of contributing to their realization as the kinds of entities they are” (Escobar 184). Autonomous design features five key elements:

“Every community practices the design of itself; every design activity begins with recognition that people are practitioners of their own knowledge; what the community designs is an inquiry or learning system about itself; every design process involves a statement of problems and possibilities, and the exercise may take the form of building a model of the system that generates the problem of communal concern” (Wizinsky).

The strategic collaborative focus on Black liberation in groups like The Combahee River Collective (a Black feminist collective formed in 1974) and The Black Panther Party for Self Defense (a militant Black power organization formed in 1966) showcases prime historical examples of autonomous design in action in the U.S., including specific details about what Indigenous, African, and ancestral African-American groups have done pre-colonialism to not only work together but to support each other. Today, there is a strong need and desire for good educational starting points, funding, and even sometimes common understanding on issues amongst community members. Interpretive exhibitions created by collaborative activist group visions can help

provide these solutions—in fact, there is already a small but emerging sector of physical activist spaces where experience and exhibition design around movement work can flourish: small archives, bookstores, and locallyfunded event spaces that center the values, voices, and identities of vulnerable members of Black communities. These places are passionate about preserving history and building environments that recognize the importance of our interconnectivity as living beings. They have a deep interest in educating the public on issues directly affecting them, and often become venues for community meetings and town halls. They also serve as incubators for cross-collaboration among liberation groups: they provide resources unique to each group and bring people together from diverse backgrounds to help build towards social change.

One prime example is Mayday, a community center in Bushwick, Brooklyn that serves as an organizing hub for activist groups (Mayday). Oftentimes spaces like Mayday encounter a few common obstacles when creating exhibitions: limited space for large crowds, poor sound control, and lack of sustained funding to name a few. Mayday space is currently experiencing grant funding delays, staff turnovers, and increasing access limitations from Bushwick Abbey, the church that owns the space the center runs out of (Mayday). These issues have forced them to put most of their organizing efforts towards fundraising just to keep the doors open. These obstacles can have a big impact on visitor experience and engagement with the space and the subject matter. They create barriers to entry, disability accessibility issues, and generally deter long-term engagement with the space—regardless of its intentions. Weaving exhibition and experience design strategy into these spaces, in a cross-cultural and co-created way, would provide better foundations for activist spaces to firmly address the needs of Black communities and leave room for larger dialogue amongst diverse communities. I believe that weaving exhibition design strategy into the creation of exhibitions in activist spaces will enable the educational, fundraising, and community support efforts of grassroots liberation organizations to be more effective in providing outlets for Black communities to grow and learn together for the purpose of autonomy and liberation.

I believe that experience and exhibition design in activist and/or community-centered spaces can define a new mode of existence for exhibitions beyond museums and brand environments—spaces that are created in, by,

with, and for Black communities, that feature engaging activations, and that encourage education. Autonomous design can help distinguish this space further, creating a push towards alternative modes of conceptualizing the future from the past.

Background Research

Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds by Dr. Arturo Escobar

In this book, Dr. Arturo Escobar puts forth ideologies for designing for pluriverses, or the concept of designing beyond the idea of one universe or plane of existence. With contextual examples from Afro-descendant Latin Americans and activist organizations like Las Zapatistas, Dr. Escobar explores how autonomous design allows communities harshly impacted by the detriments of capitalism and Western ideology to change circumstances for themselves, as opposed to waiting for said change from oppressive government structures. Dr. Escobar describes the outcomes of autonomous design as ontological approaches that provide “paths towards imagining design practices that contribute to people’s defense of their territories and cultures” (Escobar, 76). He investigates how this working approach differs from other scholarly perspectives, and he explores the multitude of ways formally trained designers can begin to contribute to this work. Ideas like decentering modernity, “degrowth,” and transition design are key pathways towards autonomous design featured throughout Dr. Escobar’s research. A big component of Dr. Escobar’s work is decentering both the designer and the human in the design process. I find this research to be highly compelling both to the future of design and to determining the potential outcomes of our future.

The positionality of this book suggests that design can be reflected in our systems, infrastructure, and everyday modes of living. Dr. Escobar encourages Western thinkers and designers to look to organizers and Indigenous groups in Latin America for real-life examples of people utilizing collective, transitionary imagination. For example, the post-development concept of Buen Vivir, or “Good Living”, that came out of Ecuador and Bolivia, “reject[s] the linear idea of progress, displace[s] the centrality of Western knowledge by privileging the diversity of knowledges, recognize[s] the intrinsic value of nonhumans (biocentrism), and adopt[s] a relational

conception of all life” (Escobar, 148). Dr. Escobar identifies practices of Buen Vivir as ways to build towards autonomous design, and reckons with what it would look like to incorporate these practices in the West, or other more urban populations.

Towards the end of the book, Dr. Escobar provides potential examples of what designing for pluriverses might look like in the Cauca River Valley, a place where capitalist development and demand for sugarcane devastated the thriving ecology of the region. Dr. Escobar proposed a number of ideas for autonomous transition design in the region, all of which involve the inclusion of a co-design team comprised of social movement organizations, marginalized communities of women and children, activists, intellectuals, non-governmental organizations, and academics. I found this example to be very poignant in my considerations of key stakeholders in the exhibition design process, and where I will be situated as the trained designer on the project. This book, overall, sets up ideological frameworks that helped guide the process of building out the exhibition design concept for this thesis research, and I strive to create an exhibition design that follows the transition design principles—one that “seeks to imbue design with a nondualist imagination” (Escobar, 157). I also appreciate Dr. Escobar’s exploration of transition design and autonomous design ideas as a new way to consider sustainability in design—not just considering sustainable materials, but considering the ways in which the natural environment designs human worlds and workflows.

Interview with Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, Ph.D.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel is the Dean of Design at Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD). Her design work takes emancipatory, critical, and anti-hegemonic approaches, focusing on equity, social justice, and the experiences of people often excluded from design research. Her research interests are community-led and involve design-based learning and thinking. She is co-chair of the Pluriversal Design Special Interest Group of the Design Research Society. In 2018 she received a Ph.D. in Design from North Carolina State University, where her focus was on agency and empowerment through design and education.

I was fortunate enough to be able to speak with Dr. Noel about her journey into co-design and co-creation after completing my case study on her book Design Social

Change. We discussed how her work began to take focus in co-design after her experience working on export product development. She expressed her discontent with the process of creating a product, and then sending it off to artisans to do the design work: “I just felt that the top down way that I had been trained to think as a designer didn’t make sense [for this work], and I felt that there were other ways to get people involved in the process” (Noel). Dr. Noel would later discover that getting other people involved in the design process would allow her level of participation in the process to shift, as began to take on the role of a facilitator as opposed to an expert designer.

The shift between designer and facilitator became a highlight of our conversation. As she elaborated on her transition from top-down design work into co-designed projects, we discussed the differences between the two work styles: In co-designed projects, control over individual design visions is relinquished in favor of the visions of the collective. This not only democratizes the design process, but allows the broader co-design community to grasp the level of personal impact they have on any design project. While the results might not always be readily tangible, Dr. Noel shares an example of the long-term effects co-designing can have on community members, as also illustrated in Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation:

“There’s some work that I did with people in New Orleans, and I don’t recall specifically a specific project, but I do remember us doing several kind of collaborative projects with them, and I don’t know if I can point to the exact outcome in the one project, but I know I met [a woman from the project] maybe some years later, and she was doing a lot more organizing in her community. She says it’s because she gained some power from the co-design work so that she then felt she could organize other things and do other things” (Noel).

This story highlights the very distinct impacts grassroots liberation organizations can have in local communities when it comes to engaging with ideas of agency and self-determination. These impacts can be built on the foundations of place-keeping—making sure that Black and Indigenous communities feel a sense of ownership to their homes—but Dr. Noel also reflected on concepts of place-building: the idea that the foundations of our communities serve as fertile ground for imagining new

realities beyond what is currently being preserved.

Dr. Noel provided additional insights into how facilitation of the co-design process still serves as an integral design element that makes co-creation and co-design successful:

“Sometimes I have to remind myself to be patient with the people who don’t want to dream, but over the years, I’ve been able to use a lot of techniques from design, from design studio, to get people to think about creating many solutions. Sometimes it is about me explaining the work that we do as designers, and letting people know we don’t just come up with one solution…so if people ask “why is this design?” that’s (emphasis added) why it’s design, to me. The fact that we’re brainstorming, and coming up with new ideas, and evaluating the ideas—all that makes it design” (Noel).

Co-design not only enables community engagement with design practices, but also expands the impact of the traditional designer: beyond the final design, the impact of the traditional designer is most felt in the sharing of strategies, and the guidance through different creative strategies with clarity and efficiency. This discussion allowed me to think more thoroughly about how to develop an exhibition design framework that provides ample room for community design and participation. This discussion also touched on useful tools from the exhibition design process that could help prepare communities for creative development in museum-like settings. The strategy behind determining materiality, narrative, and spatial integration of designed elements, once shared, can create a high level of impact in the design process, and allow for exhibitions about important issues to exist within communities and be approachable.

We closed our conversation by discussing the timing of the co-design process. In order to produce the most effective work, and achieve peak levels of community engagement, Dr. Noel emphasized the importance of lengthening the timeline of any co-design project. She detailed challenges she experiences in her current role as Dean of Design at OCAD, where at times the codesign process doesn’t seem accessible due to a sense of urgency around decision making: “It’s something to keep in mind—that it really slows down the process. Not every project has that budget to be able to do so much,

or to go on for so long” (Noel). Allotting time for fluidity in decision making is essential to the process—this will alleviate stress, and allow for more fruitful possibilities to be generated from the group.

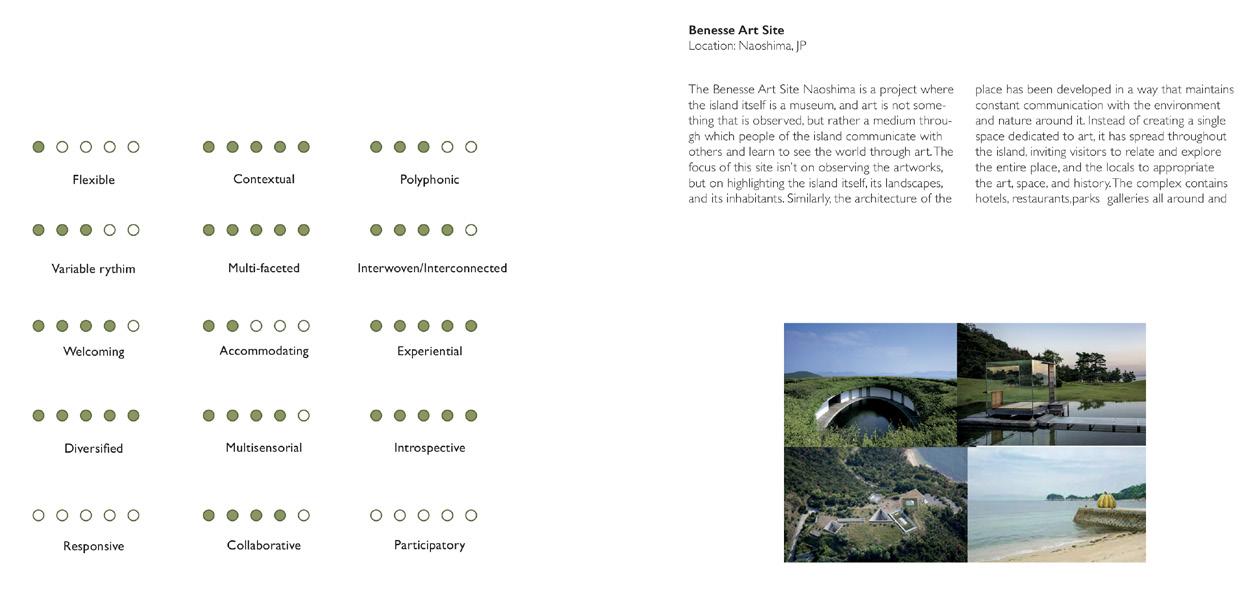

Applied Practice

The Mikiri exhibition speculates on the co-design process—showcasing an exhibition experience and design opportunity for visitors to engage with decision making styles of the Western Nigerian Igbo women, formally known as mikiri. This focus stems from the autonomous nature of precolonial Igbo society: communities weren’t set up in the same political sense that we observe today: groups were formed based on shared values, principles, and spiritualities, and decisions were made in conversational environments. Mikiri gatherings were where women of the community were able to exercise their collective power:

“Mikiri were held whenever there was a need. In mikiri the same processes of discussion and consultation were used as in the village assembly. There were no official leaders; as in the village, women of wealth and generosity who could speak well took leading roles. Decisions appear often to have been announced informally by wives telling their husbands. If the need arose, spokeswomen to contact the men, or women in other villages - were chosen through general discussion. If the announcement of decisions and persuasion were not sufficient for their implementation, women could take direct action to enforce their decisions and protect their interests” (Allen, 169).

While relationships with men were common topics at mikiri gatherings, women would also discuss matters of trading and farming, setting the norms to be set in these spaces. If any of the norms set in mikiri weren’t aboded by, the women would “sit on” or “make war on” a man:

“‘Sitting on a man’ or a woman, boycotts and strikes were the women’s main weapons. To ‘sit on’ or ‘make war on’ a man involved gathering at his compound, sometimes late at night, dancing, singing scurrilous songs which detailed the women’s grievances against him and often called his manhood into question, banging on his hut with the pestles women used for pounding yams, and perhaps demolishing his hut or plastering it with mud and roughing him up a bit. A

man might be sanctioned in this way for mistreating his wife, for violating the women’s market rules, or for letting his cows eat the women’s crops. The women would stay at his hut throughout the day, and late into the night, if necessary, until he repented and promised to mend his ways. Although this could hardly have been a pleasant experience for the offending man, it was considered legitimate and no man would consider intervening” (Allen, 169).

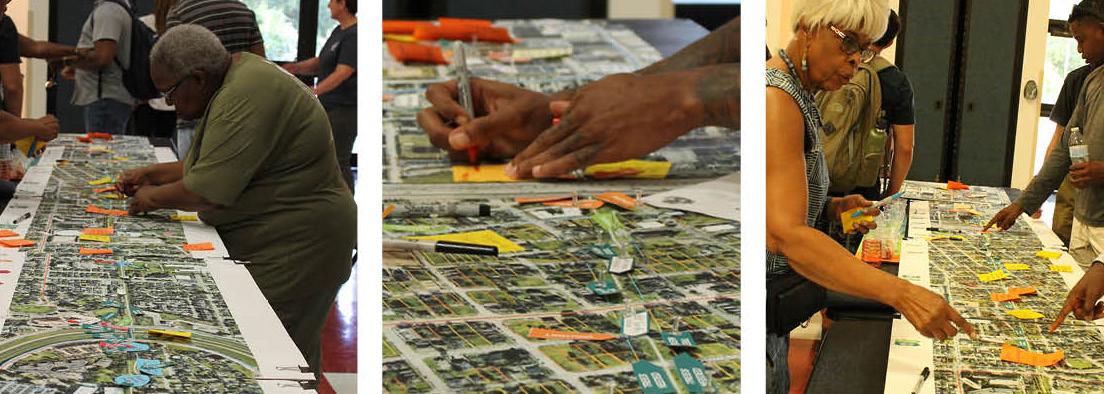

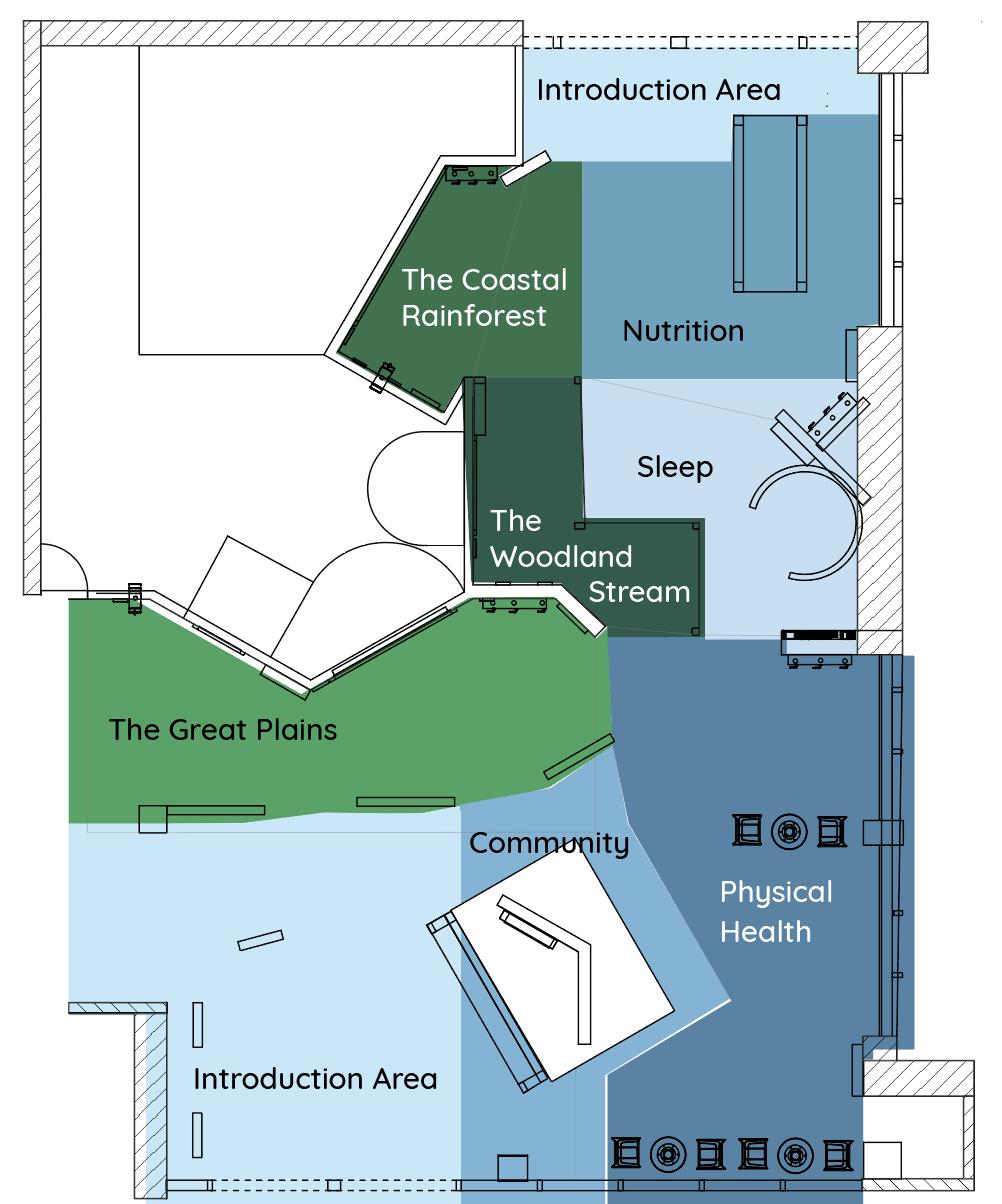

The exhibition design interpretation of this research takes the form of a design incubator and interactive experience that explores the concept of mikiri at Weeksville Heritage Center, a historic site located across the street from Kingsborough Houses (in Crown Heights, Brooklyn) that preserves the legacy of one of the largest free Black communities in pre-Civil War America (Weeksville). In 1968, community members gathered and created the Weeksville society to take a stand and stop the destruction of the Hunterfly Houses, the only existing remnants of 19th century Weeksville (Zenz). This is the same kind of collective action that would take place in a traditional mikiri, and allows the exhibition to deepen visitors’ understanding of the center and their continued commitment to the community.

This experience utilizes interactive elements to explore visitor’s relationships to community initiatives and projects, giving them the opportunity to get involved with local working groups or the inspiration to start their own. There are two interactive activities that offer visitors the opportunity to engage with the history of a mikiri. The first interactive is a digital “portal” that guides visitors through a world-building experience on individual-yetconnected tablet screens. They will learn about The Social Change Ecosystem, a framework that can help individuals, networks, and organizations align with social change values, individual roles, and the broader ecosystem, and have the opportunity to decide which of the framework’s outlined movement roles align with how they envision themselves showing up in community work. Based on the selected role, visitors can then determine a new norm for the group, reflect on their decision with other interactive participants, and receive information about an upcoming event or social action they can participate in within the Brownsville, Crown Heights, and Bedford-Stuyvesant area. These events would be regularly reviewed and developed by members of the codesign team—forming a continuation of the exhibition’s design opportunities for the community and additional

conduct independent

opportunities for connection to additional grassroots liberation organizations.

The second interactive gives visitors an opportunity to explore protest-like actions within the setting of a museum, engaging with the concept of “sitting on” or “making war” on a man. To incorporate this action into the exhibition environment, visitors will have the opportunity to “slam” their provided stickers onto an aluminum wall structure—simulating the feeling of noise making actions. This experience will allow visitors to feel a moment of energy release, while also being able to assess the roles of others, and experience being a part of something bigger than the exhibition.

To supplement this content, a research hub will be available next door to the interactive space. This research hub, called “The Forum,” utilizes an open floor plan design to allow for natural conversation amongst visitors and provide space for research and engagement with ancestral and indigenous practices that ground

this collective action work. To make this engagement feel approachable, this space is modeled after a living room—a place where, in Black American households, conversations and decisions are often made. The space will also feature digital workstations that allow for online research and connection to the digital Mikiri exhibition community. This space will also be open to live programming and events—hosted by community members, grassroots liberation organizations, or members of the co-design team.

In the outdoors portion of the exhibition, visitors will learn about Mmuo Mmiri, or “Mamy Wata”—an Igbo Water spirit said to be the bringer of change. A spiral pathway will lead visitors to a fountain, while snakelike stanchions guide visitors through the folktale Mamy Wata and the Monster, which tells a tale of Mmuo Mmiri’s generosity and openness and showcases ways we can show love and care for our neighbors.

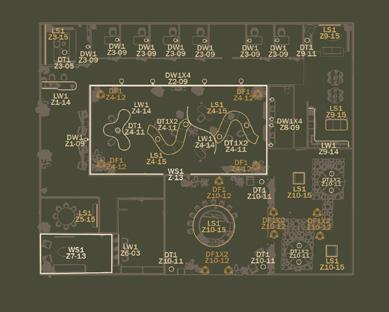

Fig. 1. Area Floor Plan diagram. Visitors of the Mikiri experience can engage with an interactive exhibition,

research, and enjoy a meditative walk outdoors.

Fig. 4. “Making the Mikiri” digital interactive. A docent will be present at this interactive to facilitate any questions from participants.

Fig. 2. Exhibition entryway rendering and description.

Fig. 3. “Making the Mikiri” exhibition space overview rendering.

Fig. 5. Digital interactive. Visitors can select from provided options and will be prompted to provide a reasoning for their selection.

Fig. 6. “Making the Mikiri” sticker interactive. Visitors can choose a sticker that outlines their role, and slam it onto the aluminum wall.

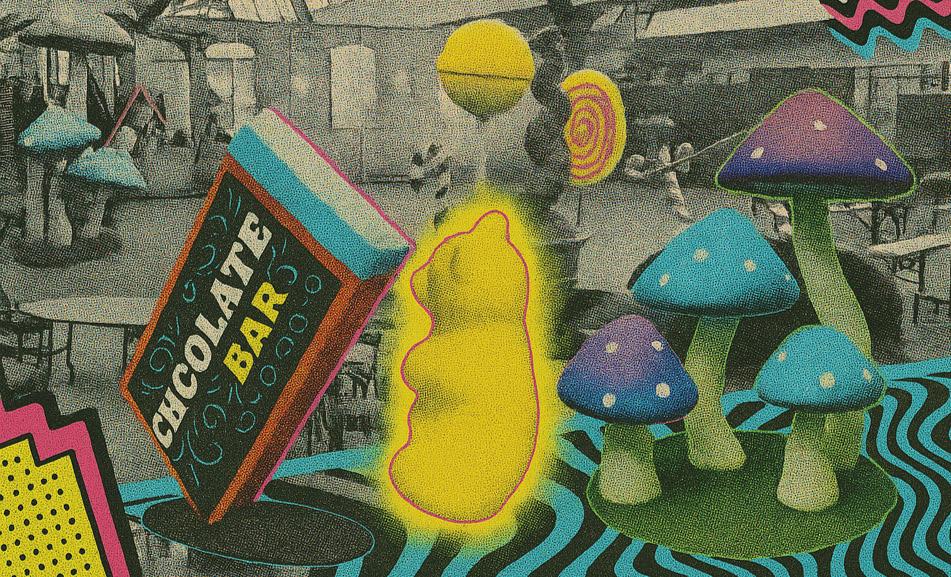

The graphic design of this exhibition is heavily inspired by traditional Igbo community design and uses Afrofuturist themes in collage to speak to the connection of the past to the present and future. Colors are pulled from the natural items used to make paint in Igbo murals, with pattern decals and motifs that also show up frequently in the architecture and mural paintings of the community. Font selections utilize Black type designers and reference moments in history where people took actions into their own hands to make a change: Vocal Type’s “Eva” font is pulled from signage from the Buenos Aires women’s suffrage demonstration in 1947, and Univers was the font commonly used in the Black Panther Party Newspaper. Stickers serve as the main source of collateral for this exhibition because of their sharability— allowing visitors to expand the reach of the exhibition to their interpersonal communities. Visitors should feel encouraged to take action in their neighborhoods, and feel proud to take home some of these items as a token of the work that they’ve done to make their communities a place they enjoy.

7 & 8.

Forum” renderings. This area is for independent research and can feature live programming from local organizations.

Fig. 9. “Follow the Path of the Steam” rendering. This outdoor walking path gives visitors an opportunity for reflection and relaxation.

Fig.

“The

10. Exhibition graphic system. References to Igbo architecture and collage serve as a tie between the past, present, and future. The typography of the exhibition includes typefaces from Black designers, and references to revolutionary media and actions.

Caption text

Fig.

Conclusion

This project outlined how exhibition designers can be integral to the co-creation process for grassroots liberation organizations: by utilizing facilitation and planning strategies to help communities engage with liberatory work in imaginative ways, exhibition designers can help develop community-centered approaches to expanding movement work. I showcased an exhibition with multiple levels of visitor interaction, and how it succeeded in expanding on visitor knowledge and engagement with topics set forth by the chosen grassroots clients. The exhibition experience provides audiences with the opportunity to establish their own meetings to determine the actions necessary to have autonomy in our own neighborhoods. It asks visitors to meaningfully show up and participate in the best way they can, and aims to reflect back onto visitors how they can continue this participation in their local community. Utilizing Weeksville Heritage Center as an incubator for future change activates a close-proximity audience, and engages them with the same movement building work that led to the creation of the Weeksville Society. Not only will visitors gain an understanding of the foundations of the Weeksville Heritage Center, but they will additionally gain new resources for taking action and creating change for themselves beyond government support. While it may not fully restructure

the way Brooklyn thinks of public housing, this exhibition gives visitors a strong place to start, providing a variety of ways to show up for one another in the neighborhood, opening the imagination to new decision making strategies, and providing a space for gatherings around issues that impact the community on micro, meso, and macro-social levels.

Fig. 11. Exhibition poster promotion rendering.

Resources

Allen, Judith van. “‘Sitting on a Man’: Colonialism and the Lost Political Institutions of Igbo Women.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines 6, no. 2 (1972): 165–81. https://doi. org/10.2307/484197.

Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds Duke University Press, 2018.

Mayday. “About Mayday.” Mayday, 2020. https:// maydayspace.org/about/.

Mayday. “What’s Been Going on at Mayday?” Instagram, September 17, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/ DABrJIHPgMw/?img_index=3.

Noel, Lesley-Ann. Design social change: Take action, work toward equity, and challenge the status quo Emeryville, CA: Ten Speed Press, 2023.

Noel, Lesley-Ann. Interviewed by author. Zoom, December 2, 2024.

“Weeksville Heritage Center | About Us.” Weeksville Heritage Center, January 2, 2024. https://www. weeksvillesociety.org/about-us/.

Wizinsky, Matthew. “Autonomous Design.” Design after Capitalism, 2022. https://designaftercapitalism.org/ autonomous-design.

Zenz, Cassandra. “Weeksville, New York (1838- ).” BlackPast, October 14, 2010. https://www.blackpast. org/african-american-history/weeksville-newyork-1838/#:~:text=Weeksville%20residents%20 established%20churches%2C%20schools,country’s%20 first%20African%2DAmerican%20newspapers.

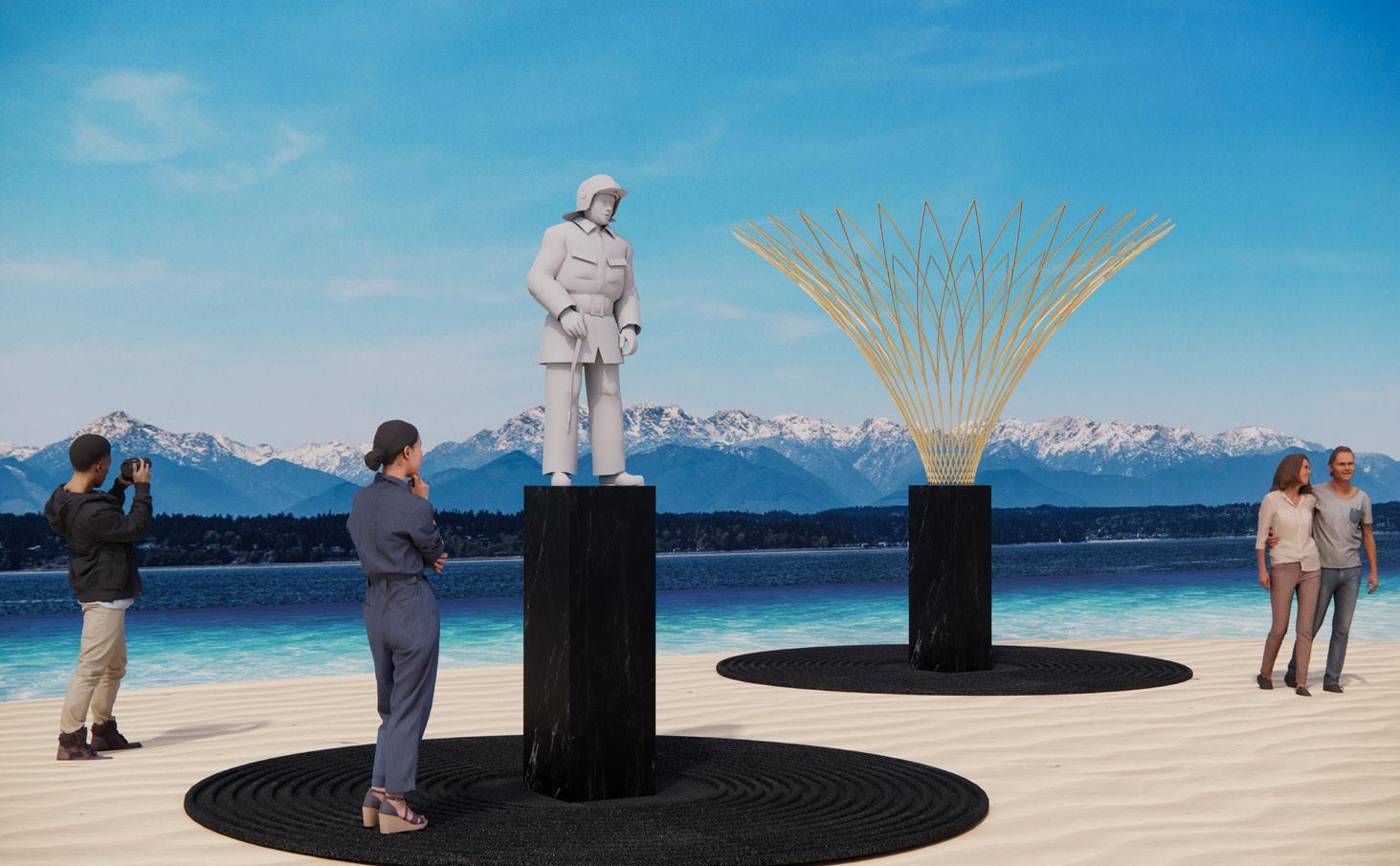

Shaping EGD Education Case Studies in Industry Collaboration and Urban Design

Julie Hurley Department of Design, California

State University Long Beach

Abstract

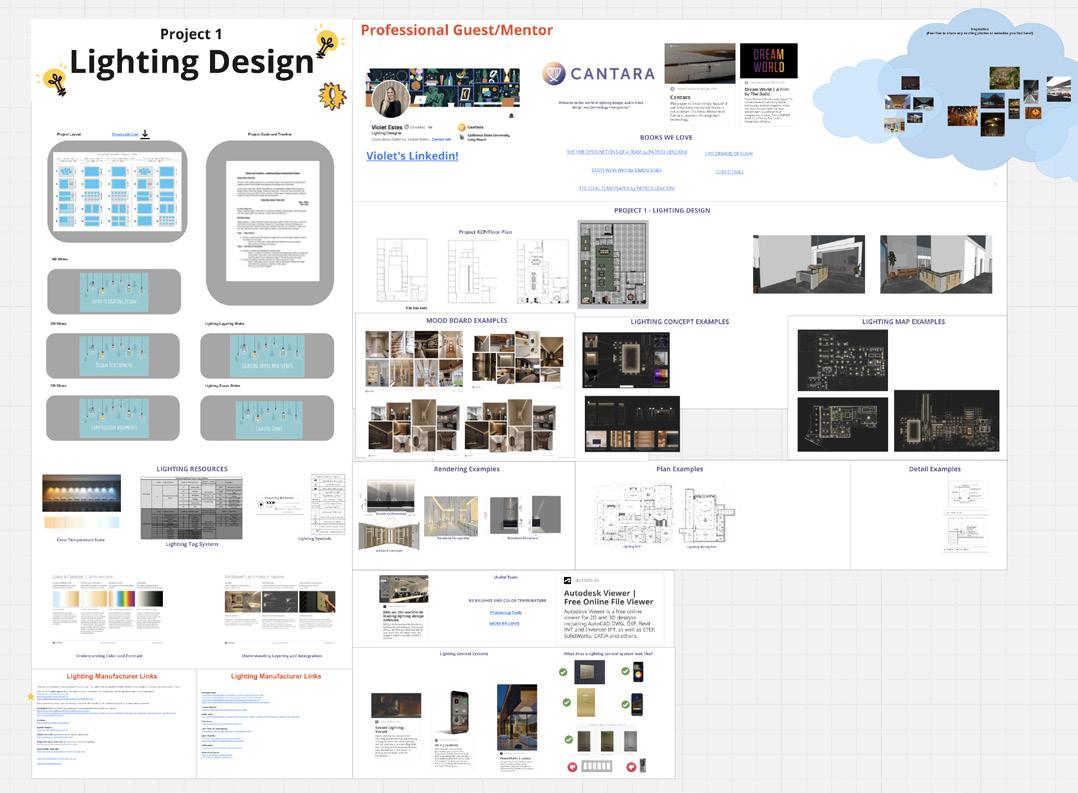

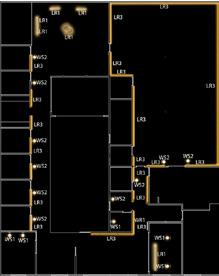

This paper outlines the design and delivery of an upperdivision studio course in Experiential Graphic Design (EGD) focused on public spaces, narrative environments, and industry collaborations. The course has two key objectives: (1) to develop students’ applied design competencies, and (2) to provide exposure to professional practices through high-impact, project-based experiences. Throughout the semester, students participated in three major projects, each developed in collaboration with a professional. These various collaborations emphasized signage, wayfinding, lighting design, spatial storytelling, and civic engagement. Through these experiences, students encountered the realities of practice, developed critical thinking, and built confidence in navigating complex design challenges. The course provides a scalable model for integrating experiential learning, virtual internships, and civic partnerships within EGD curricula.

Introduction

As the boundaries between design disciplines continue to blur, Experiential Graphic Design (EGD) stands out as a field uniquely suited to addressing the complexities of contemporary public environments. Positioned at the intersection of graphic design, architecture, urban planning, and interaction design, EGD enables designers to shape how people perceive, navigate, and emotionally connect with space (Calori and Vanden-Eynden 3537). In response to the integration of multiple areas of design, the education structure must continue to evolve by incorporating the realities of professional practice into academic coursework, thereby better preparing students for the demands of the industry. By simulating the process of professional studios within the classroom, students gain experience navigating real-world constraints while addressing audiences, context, and outcomes. This pedagogical approach aims to close the gap between academia and practice (Davis). Students are not only developing technical skills but also assuming the roles of designers, collaborators, storytellers, and engaged citizens who shape the built environment.

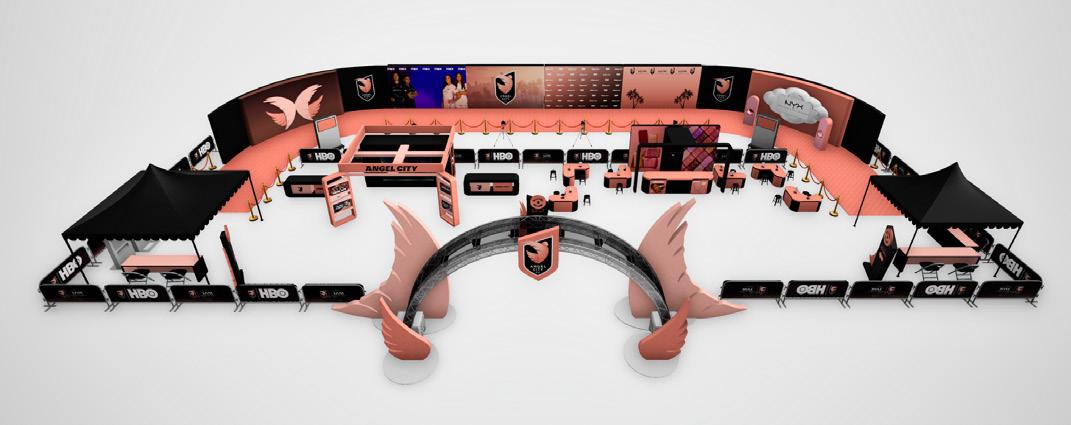

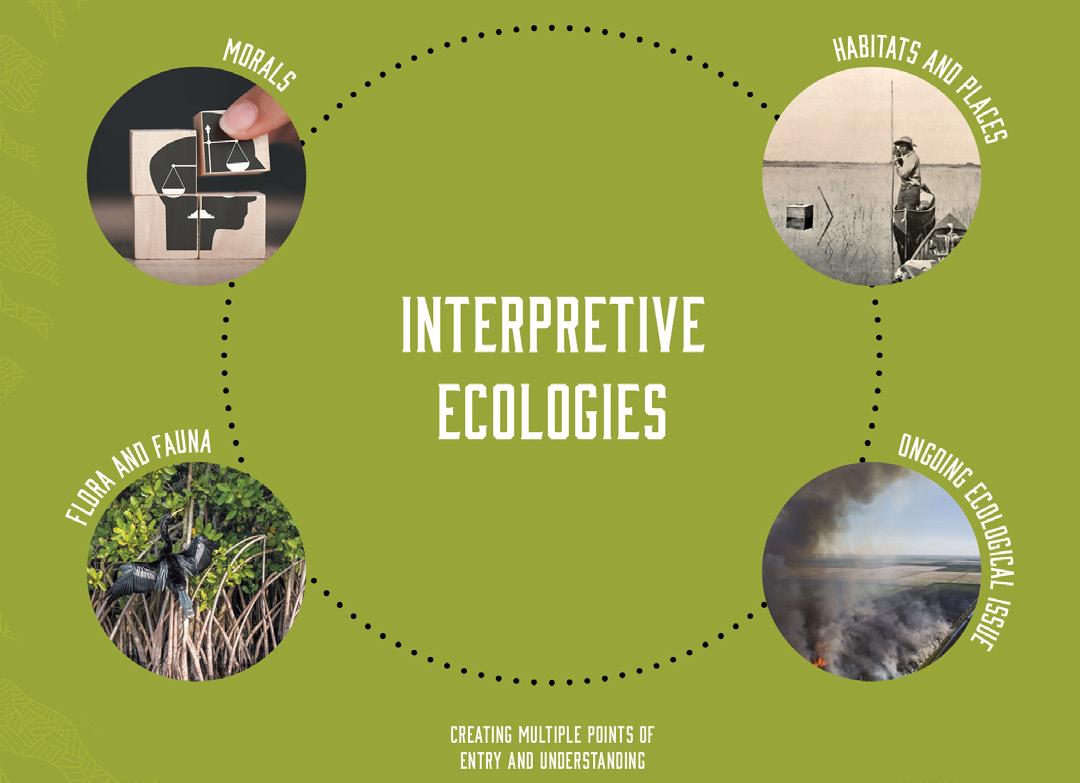

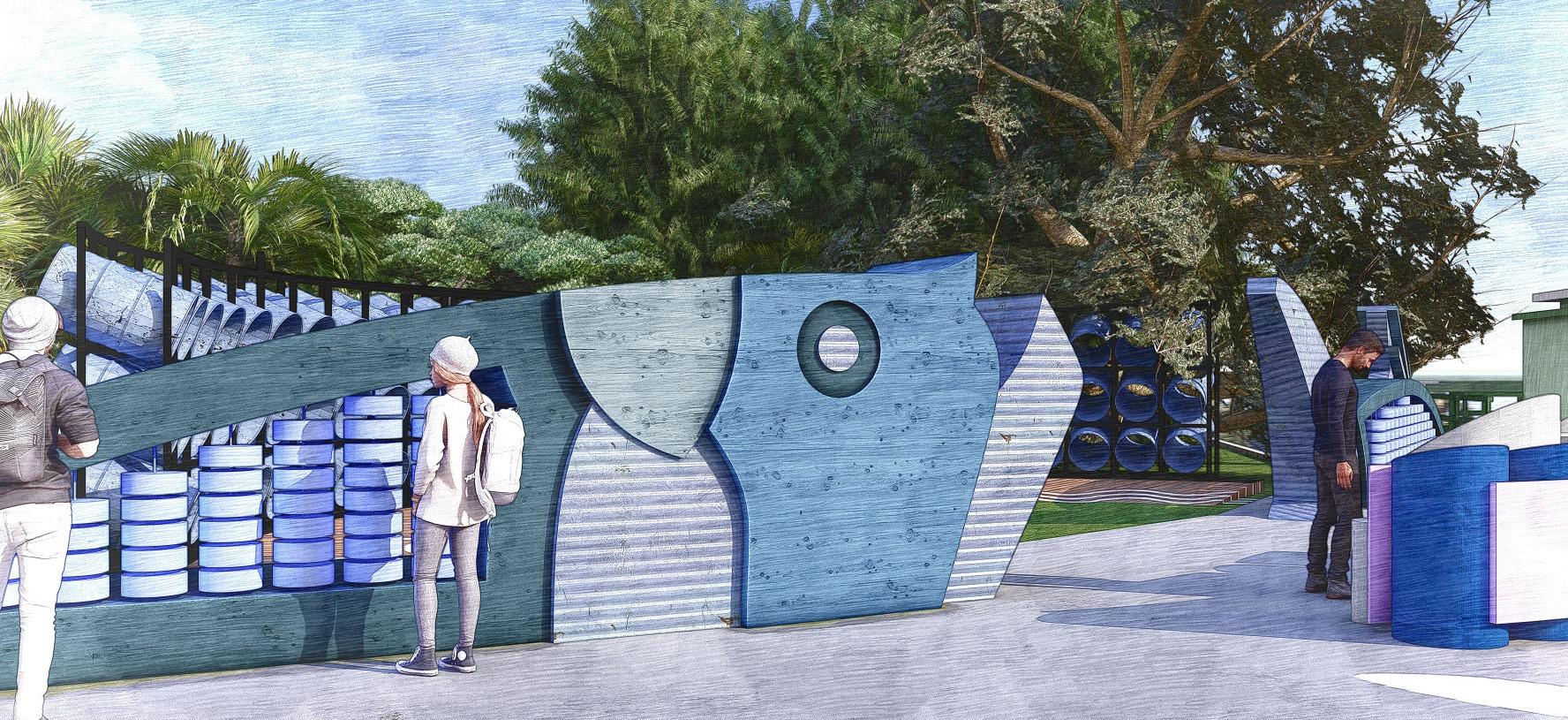

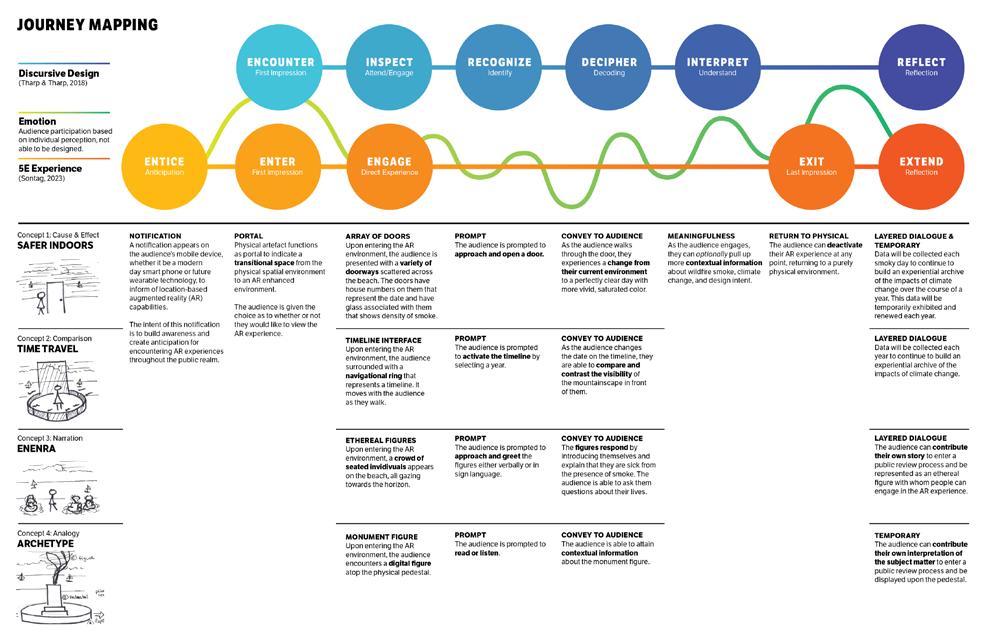

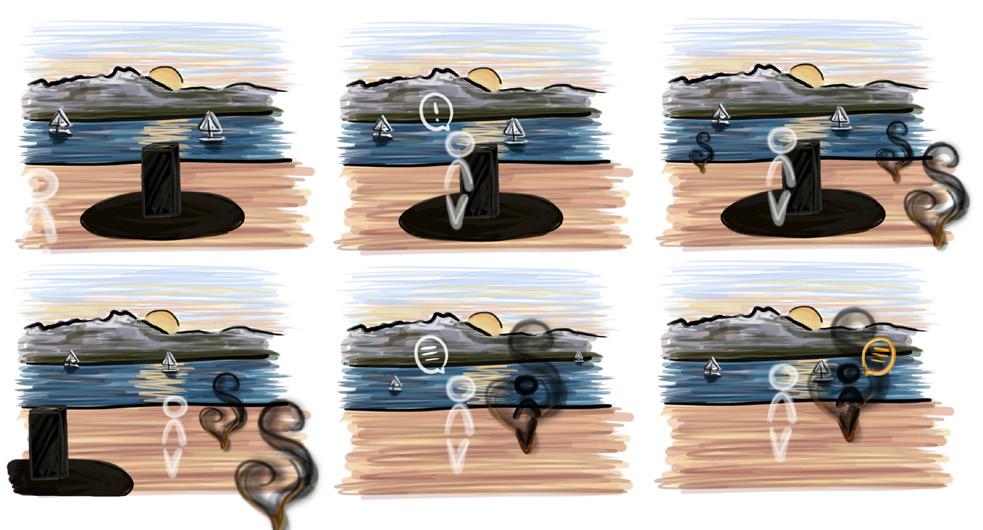

To operationalize this philosophy, we structured an upper-division EGD studio around three sequential projects, each developed in partnership with industry collaborators. Students worked in small teams, mirroring professional practice and encouraging peer-to-peer learning and collaborative problem-solving (Ambrose et al.; Hurley et al.). The curriculum centers on three thematic pillars: identity in urban space, storytelling through environmental experiences, and civic design via signage and branding systems. Projects progressed from speculative installations to immersive environments and systems-oriented interventions.

Each project incorporated high-impact educational practices, including site visits, iterative critique, formal client presentations, and sustained professional mentorship. These strategies grounded learning in authentic contexts, deepening engagement, and expanding student insight (Kuh; Provencher and Kassel).

Key industry partnerships—with organizations such as Cantara, Angel City Football Club, and RSM Design— brought external expectations and accountability into the classroom, fostering a collaborative environment that promoted learning and growth. Additionally, an ongoing relationship with the Society for Experiential Graphic

Design (SEGD) has provided students with access to a professional design community and opportunities for networking and critique (SEGD).

By the end of the course, students were completing assignments and working as emerging professionals. The students engaged in various design processes, managed collaborative tensions among teammates, and created solutions that were responsive to civil needs and compelling in their spatial storytelling. This experience reframed design education as a public practice rooted in empathy, purpose, and civic engagement.

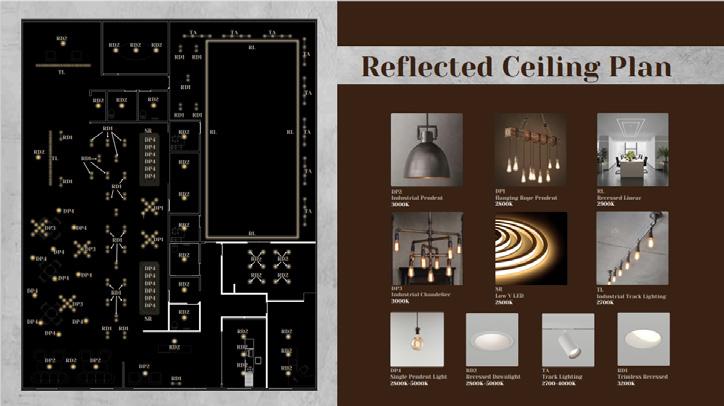

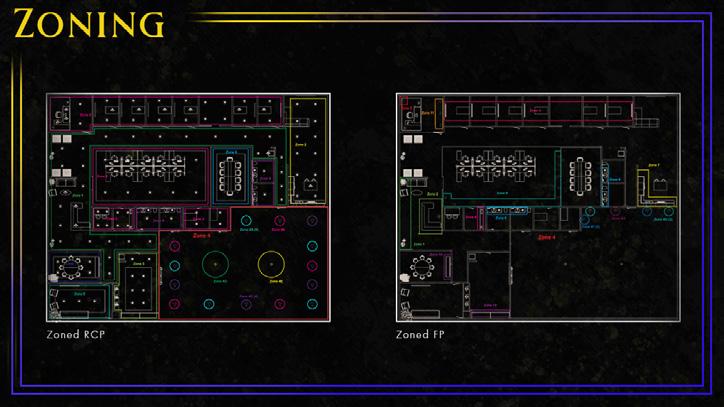

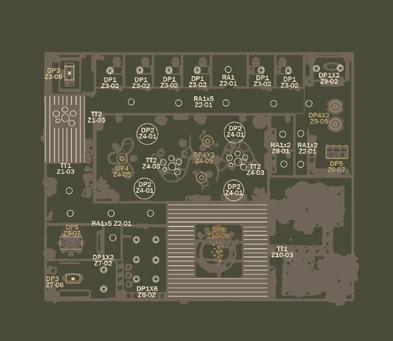

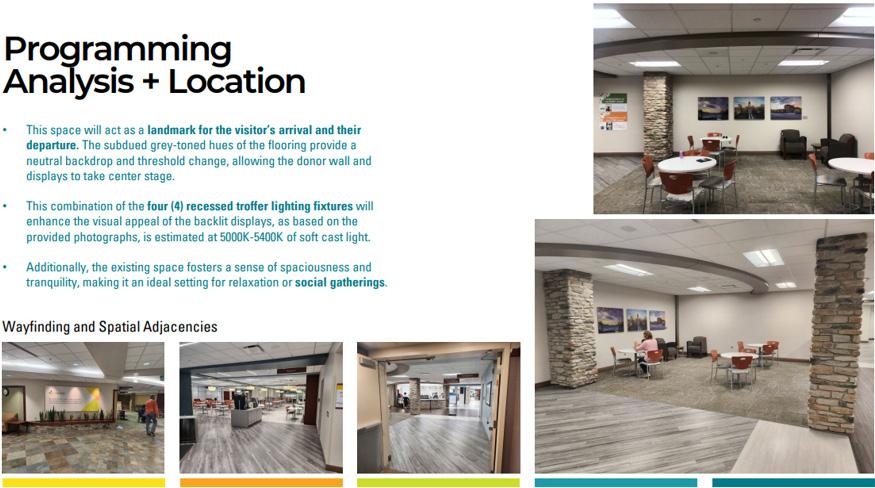

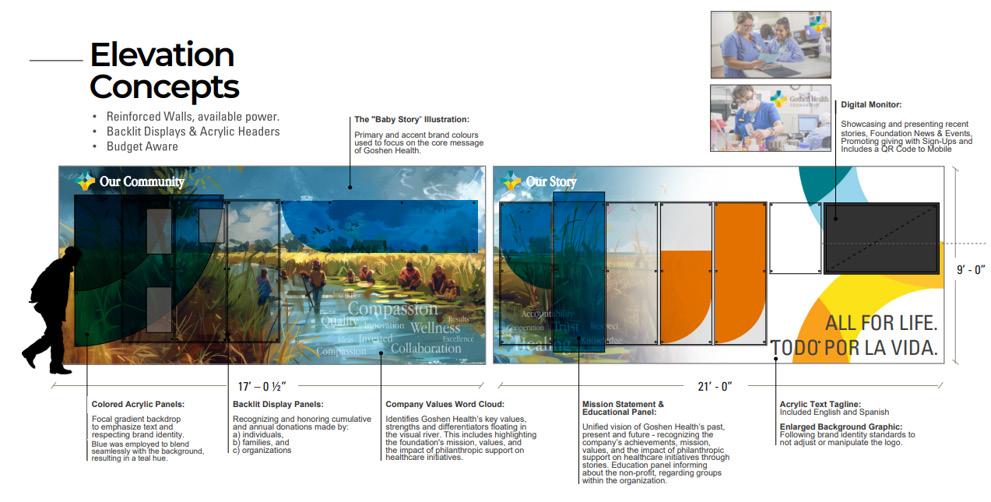

Methodology