2021–2022 COHORT

JOURNAL

Southeast Asian Pasts and Futures (SEAPF | si•puf)

SEAPF is a cohort of undergraduates at the University of Washington with diverse class standings, cultural backgrounds, and personal experiences. As students, we strive to create an equitable, inclusive community and a brave space for all. We are mindful of our multiple, intersecting identities; we honor where we come from and want to make an impact. We care about minoritized stories and voices. We bring important perspectives as first-generation students and first- and second-generation immigrants to questions about culture and identity in diaspora and are listening to the perspectives of others. In choosing this space, we hold ourselves and each other accountable. We learn to heal and to grow. We recognize that access to elite spaces like the museum and the university is a form of privilege; we are committed to sharing our power.

SEAPF I School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences University of Washington Bothell Box 358530 18115 Campus Way NE Bothell, WA 98011-8246

Email: iasadv@uw.edu

Website: https://linktr.ee/uwb_seapf

SEAPF COHORT 2021–2022

Won Moon Cho Tu-Vy Chung Haari Durand

Wesley Huynh Molly Kappes

Ngoc-Vy Mai

Henry Nguyen

Trâm Nguyễn Vy Nguyen

Justin Totaan

Mindy Vu

FACILITATION & TEACHING

Raissa DeSmet Co-Director of SEAPF & Associate Teaching Professor

Nhi Phuong Tran Co-Director of SEAPF & Academic Advisor

Gabbie Mangaser Burke Museum Collections Liaison

CREATIVE DIRECTION

Crystal Ly Graphic Designer

Printed by Consolidated Press, 600 South Spokane Street, Seattle, WA 98134

Samantha Mafune

3 Table of Con T en Ts CONTINUITY 10 10 16 21 36 Won Moon Cho My Grandmother’s Blanket, Remembering Her Love Trâm Nguyễn The Wedding Áo Dài Wesley Huynh Woven with Love and Labor Henry Nguyen Chopsticks: More Than Just a Utensil INTRODUCTION 4 04 06 08 Land Acknowledgement What is SEAPF? Forward RUPTURE 40 HEALING 62 62 68 74 Tu-Vy Chung Embodiment Justin Totaan Flowers to Give to Your Parents Mindy Vu Embracing the Process 40 46 54 Haari Durand My Batiks, My Journey Molly Kappes What We Hold Onto Samantha Mafune The Shears A TALE OF TWO VYS 78 78 Ngoc-Vy Mai & Vy Nguyen CONCLUSION 88 88 Acknowledgements

l and aCknowledgemen T

As Asians, Asian Americans, and mixed-race people of Asian descent in the Puget Sound, we are settlers as well as immigrants. We live and work on the unceded lands of the Coast Salish peoples, whose ancestors have resided here since Time Immemorial. Many indigenous peoples thrive in this place–alive and strong.

4

5

whaT is sea P f ?

SEAPF is a cohort of undergraduates at the University of Washington with diverse class standings, cultural backgrounds, and personal experiences. As students, we strive to create an equitable, inclusive community and a brave space for all. We are mindful of our multiple, intersecting identities; we honor where we come from and want to make an impact. We care about minoritized stories and voices. We bring important perspectives as first-generation students and first- and second-generation immigrants to questions about culture and identity in diaspora and are listening to the perspectives of others. In choosing this space, we hold ourselves and each other accountable. We learn to heal and to grow. We recognize that access to elite spaces like the museum and the university is a form of privilege; we are committed to sharing our power.

6

7

Language has the effect of freezing a thing in motion, which makes Southeast Asian Pasts and Futures (SEAPF) hard to describe. It began as an idea, formed when Raissa visited the Burke Museum with her students and met Curator Holly Barker in 2015. “Would you like to see the collections?” Holly asked. Winding through the aisles of cultural belongings—cedar boxes, a spirit house, a row of finely carved paddles—she explained that some of the museum’s most important work happens not in the galleries, but behind the scenes, out of the public’s view. As colonial institutions, museums are haunted spaces. Pieces like those at the Burke were severed from their lived contexts by the forces of imperialism, militarism, and migration, making them not only powerful presences and forms of knowledge, but traumatic remainders. The Burke is part of a movement among museums to engage these violent histories and work towards redress. One way it does this is by inviting people whose ancestors made, used, and lived with these pieces into collections; recognizing their authority; and opening up

access to cultural belongings as bridges to the past and resources in the present.

A key site for decolonization at the Burke has been Research Family, a group formed by Pacific Islander undergraduates on the Seattle campus to activate Oceanic collections and create opportunities for students underrepresented in research. The program brings ties of kinship into academic space, and centers Pacific Islander ways of being and knowing. With support from Holly and Collections Manager Kathy Dougherty, students learn with and from collections to maintain relationships with their ancestors and support their communities. Projects flow from students’ own interests and commitments, and have ranged from advocating for COFA representation and access to health care in Washington State to collaborations with Pasifika elders. Hearing about this work made Raissa’s hair stand on end. “Could something like this exist for Southeast Asian students?” she asked. More than six years later, with transformative leadership

8

forward

from co-director Nhi and support from within and beyond UW, SEAPF is our answer to this question.

Formed in the wake of the Atlanta massacre and devastating losses in our own communities, SEAPF is an identity-centered, cohortbased program emphasizing anticolonial research methods and the ways material culture can support healing and resilience. We came together in the autumn of 2021: 11 amazing students from across the university, with diverse migration stories and relationships to Southeast Asia (as well as “Asian America”). Meeting each week for a full academic year, we engaged with cultural belongings, partner organizations, and each other. Sometimes we worked directly with pieces in the collections, like a Karen loom, once worn by its weaver, but we also turned towards our cultural belongings with new eyes. For one assignment, students produced a “biography” for a piece from their own homes and lives. Writing through their senses and memories, and their conversations with loved ones, they told tales of mothers, grandmothers, and aunties; bedtimes and mealtimes; longing and connection. When we shared these stories in our circle, we cried. Across these pages, we share them with all of you. With love from the students of SEAPF and from Raissa and Nhi.

9

My Grandmother’s Blanket, Remembering Her Love

My grandmother in Korea, who passed away last December at an age of 97, was a farmer, a mother, and a widow who lived alone for 50 years. Many of her words and actions didn’t really make sense to me when I was young. However, as I grew up, I began to understand more about her life.

WON MOON CHO (She/Her/Hers)

Junior, Majoring in Global Studies

I am a Korean Japanese American born in the States and raised in Korea. SEAPF allowed me to reflect deeply on my identity as an Asian American and explore diverse cultures through communities.

“Did you eat?” Coming back home from school, this was always the first thing she asked. Even though I constantly told her that I had lunch at school, she would always check on me to see if I had a proper meal. She cared so much about her grandchildren’s growth, so she wanted to know if she had to cook for us.

“I want to go home.” Whenever she visited our house and stayed for a few days, she would say that she has to go home everyday. She had crops that she needed to care for so that she can sustain her life by selling them.

10

11

12

I will never fully and truly understand her heart until I become a grandmother, but now, at least a little bit, I can feel that everything she did was based on love.

Even in her 80s, no matter how sunny or rainy it was, she went out to the field to help her onions, garlic, sweet potatoes, and lettuces grow. One thing I realized is that she raised vegetables because she didn’t want to be a burden on anyone; her work was all about her love.

After our family moved from the States to Korea, we used to drive an hour to a rural area to visit her. My father wanted my grandmother to live with us, so we brought several blankets, including one thick white blanket as a bottom layer right above the ground to lay on and one fuzzy magenta blanket with a flower pattern so that she could use it to sleep at our house.

13

Looking at the blanket reminds me of the precious time I shared with my family. Covered under the same blanket, my three younger siblings and I kicked, hugged, and entwined our legs, sleeping together through the night.

Recently, I learned that the blanket was made of hanbok, traditional clothing in Korea. Nowadays, the hanbok is worn only on formal occasions such as weddings; however, before, it used to be worn every day. The blanket has a pretty color of yellow and pink and a rougher texture than silk, which is closer to an everyday hanbok.

My father, Byung Seok Cho, told me that when someone got married in the family, even though hanboks are so expensive, my grandmother's children would give her beautiful hanboks as a gift with gratitude for raising them. Now this tradition doesn’t exist anymore, but I think all the good memories that our family made together are thanks to my grandmother.

(할머니 | /halmoni/ | grandmother), I wish I could have done more for you. Through this, I would like to say thank you again for all your love. With Love, Won Moon

14

할머니, 저는 벌써 스물네 살의 원문이가 되었습니다.

미국에서 이사 왔을 때의 어렸던 제가 벌써 어엿한 성인이 되었어요.

어린 원문이는, 꼬마일 때의 저는 할머니의 삶이 잘 이해가 되지 않았어요. 우리 집에 오시면 집에 가겠다는 할머니, 매번 저를 보면 대화의 첫 마디가 “밥 먹었냐?”고 물으시는 할머니, 틈만 나면 “느그 엄마 아빠는 어디 있냐?”고 물으시는 할머니, 우리 가족을 위해서 뭔가를 해주려고 하시는 할머니. 인제야 조금씩 이해가 됩니다. 어린 나이에 저에게 75세 차이가 나는 할머니가 사랑을 표현하는 방법이 이해하기 어려웠나 봅니다. 점차 어른이 되어가면서, 97세 평생 중 살아계셨던 50세 기간 동안 할아버지 없이 혼자서 얼마나 힘들었을까 생각도 해보고, 또 그만큼 자녀분들에게 부담이 되지 않고자 하는 마음에 열심히 농사일하셨겠다고 하는 생각도 들었어요. 햇볕이 강하게 내리쬐는 날에도 비가 억수로 많이 내리는 날에도 어김없이 80대이신 할머니는 밭에 나가서 매일 양파와 고구마, 그리고 다른 농작물들을 할머니의 자녀와 손자를 사랑하는 것처럼 돌보셨어요. 너무 대단하신 것 같아요. 존경합니다. 할머니. 아직 죽음이라는 게 어떤 것인지 가늠이 되지 않지만, 할머니께서 영계에서 편안히 지내시면 좋겠어요. 할머니 살아계실 때 더 잘하지 못해서 죄송합니다. 할머니께서 주신 사랑을 마음속에 더 잘 간직할게요. 할머니 사랑합니다. 원문 올림

15

The Wedding Áo Dài

TRÂM NGUYỄN

(She/Her/Hers)

Senior, Majoring in Media & Communication Studies and Society, Ethics & Human Behavior

I was born and raised in Vietnam, so you can call me an authentic Saigonese! SEAPF has granted me the best community that I could ask for!

Ever since I was a child, I have always been curious about the black garment bags folded and placed neatly on the top drawer of my mother’s closet. Even though we moved houses over the years, those bags always had a special place on the shelves, and in my mother’s heart. We were never close when I was growing up, as she always arrived home after I went to bed and left before I woke up. But my first serious conversation with her was about what was inside those bags. I could never forget how her eyes lit up when she showed me her wedding áo dàis and gown that she kept and cherished since 1997. Among my mother’s wedding attire archive, my favorite piece is the scarlet red embroidered brocade áo dài that she wore during the traditional Vietnamese ceremony on the morning of November 10th, 1997, in Saigon, Vietnam. There are photos of my parents’ traditional ceremony in our family album, and my mother, in her red áo dài is the most beautiful woman I have ever seen.

Áo dài, which literally means long shirt, is the traditional national costume of Vietnam. The long-tail gown is accompanied by a long pair of trousers and a round,

16

matching headpiece. Like its country of origin, áo dài has constantly undergone transformation throughout Vietnamese history, with traces of colonization reflected in its changes. The early áo dài was adapted from another type of traditional Vietnamese costume, áo tứ thân, and Chinese-style long tunics and pants. Modern touches were inspired by and added under French colonialism (Leshkowich). In the 1930s, an artist of the same name created a modernized, French-inspired version called Lemur. It was criticized for being “too French,” yet its nipped-in waist, tight sleeves, collar, and tailored flared

pants had become the essential features of today’s modern áo dài (Tran). Since then, new techniques and trends have been applied to the creation of áo dài, and in a way, it reflects Vietnam’s ever-changing identity and development. My mother’s áo dài was tailored for her in 1997 when the Raglan sewing technique was popular among the áo dài tailors. Sleeves were sewn into the upper body part, while the two flaps were attached by a row of buttons above the hip, and the pants became slightly longer past the heels. This

17

innovative, Western-inspired technique, created by Dung

Tailor in Saigon, gave the wearers more flexibility, comfort, and style (Duong and Bao). My grandmother took my mother to a tailor, and together they chose the fabric, patterns, and style. In Vietnamese culture, red symbolizes happiness, luck, and love, and the golden embroidered coin-shaped patterns signify prosperity. Born in a family of twelve children, my mother also did not get to spend a lot of time with my grandmother. So the wedding áo dài was a gift to her–a gift of time spent with her mother. My mother was showered with love on her wedding day–a traditional ceremony at her brother’s house in the morning, a lunch reception at a restaurant, and a Westernstyle evening celebration in a wedding hall of a five-star hotel. After the 1986 Đổi Mới (Reform), wedding rituals became a mix of traditional and modern, and my parents’ wedding celebration was common among adults in their 20s and 30s living in Saigon (Nguyen and Belk). Yet, her favorite part of the day was during the morning ceremony, in her red áo dài, when she got to thank her parents for raising her and wave at them goodbye before leaving the house with her newlywed

husband. Her eyes glistened ten years ago when I first asked her about the áo dài, and they still do when I talked to her before writing this. Dry-cleaned at least twice a year, the red áo dài is in pristine condition; however, it has shrunk over time, and the flaps are not the same length as they used to be. It is stored in our family home in Vietnam, still in that top spot in my mother’s closet. To the right, you will see a photo of my first time wearing it when I was seventeen. Since áo dàis are tailored, it did not fit me as well as it did my mother, but I could not forget the rush of emotions that I felt when I tried it on. I never felt as connected to my mother as when I saw that red and gold embroidered fabric embracing my reflection in the mirror. My mother shed a tear when she saw me in her áo dài as it reminded her of the youth that time made her forget. It was an object that held so much meaning for someone I love dearly, and how fortunate I was to be able somehow to relive her memories through my experience of that object.

18

19

Duong, Thi Kim Duc, and Mingxin Bao. “Aesthetic Sense of the Vietnamese through Three Renovations of the Women’s Ao dai in the 20th Century.” Asian Culture and History, vol. 4, no. 2, July 2012, pp. 99-108, doi:10.5539/ach.v4n2p99.

Leshkowich, Ann Marie. “The Ao Dai Goes Global: How International Influences and Female Entrepreneurs Have Shaped Vietnam’s ‘National Costume.’” Re-Orienting Fashion: The Globalization of Asian Dress, edited by Sandra Niessen, Ann Marie Leshkowich, and Carla Jones, Oxford and New York: Berg Publishers, 2003, pp. 79-115.

Nguyen, Thuc-Doan T., and Russell Belk. “Vietnamese Weddings: From Marx to Market.” Journal of Macromarketing, vol. 32, no. 1, Mar. 2012, pp. 109-120, doi:10.1177/0276146711427302.

Tran, Lan. “A Brief History Of The Áo Dài.” Saigoneer, 04 Sept. 2014, https://saigoneer.com saigon-culture/2633-a-brief-history-of-the-ao-dai. Accessed 26 Nov. 2021.

Works Cited

20

Woven with Labor & Love

Introduction

Detail is everything. Some things we take for granted are made with love and are part of our everyday lives. Embroidery is such a natural part of my life that it blends in like the rest of the things in my house. I must have seen hundreds of embroidered tapestries throughout my childhood, but I never stopped to appreciate the effort, energy, detail, labor, and time that goes into creating a piece.

WESLEY HUYNH

(He/Him/His)

Senior, Majoring in Law, Economics & Public Policy (Bothell), Mathematical Thinking, and Visualization

I am a Vietnamese American, born and raised in Washington and Portland, Oregon. SEAPF has changed how I approach my Asian heritage, my understanding of myself and my family, and what it means to be Asian American. I was able to experience a different learning style that showed me new ways of gaining and producing knowledge.

In spring quarter, I was struggling and unsure about the focus of my piece for the SEAPF Journal. I also found it difficult to connect to a cultural belonging. Then I thought back to an experience early in the year, when Dr. Holly Barker led our class into the area that housed textiles from Southeast Asia and showed us an embroidered tapestry she purchased while in Vietnam. Upon seeing the tapestry, I was super excited and giddy. I exclaimed to the class, “Oh this is what my family does, my aunt still embroiders!” This moment kickstarted my journey of wanting to learn more about embroidery and its connection to my family.

21

History of Vietnamese Embroidery

All over Vietnam, people use embroidery as a form of personal and cultural expression. This ancient technique involves sewing on fabric by hand to produce decorative patterns and shapes. It was introduced into the northern provinces of Vietnam during the 17th century from China, where originally silk embroidery only used five thread colors—yellow, red, green, violet, and blue. According to one online source based in Vietnam, “the history of this traditional work is connected closely with the spiritual history of Vietnamese women in the past.”1 From a distance, Vietnamese silk embroidery is often mistaken for paintings due to the seamlessness of the image. However, up close, you see the intricate density of thousands of silk strands finely woven together to create picturesque landscapes and motifs of birds and flowers. Embroidered tapestries or silk paintings are unusually given as a gift to show appreciation, confidence, as well as to wish people prosperity. It is common to see multiple embroidered pieces framed and hung on the wall of Vietnamese households.2 Though there are conflicting accounts, it is believed that Dinh Xuan Nghenh and Dinh

22

Xuan Xoan, first introduced, the lace craft to the village of Van Lam in the early 20th century.3 Today, Van Lam is known as the embroidery village, with more than 75% of the population skilled in embroidery with lace due to teachings being passed down through generations. Outside of Van Lam, embroidery has developed into an art form for many communities. Hmong and Dao artisans use their own unique intricate embroidery and braiding styles to embellish their clothing. The Hmong create beautiful batik designs to decorate their clothing. For example, applique is used by the Hmong to indicate particular communities as well as for storytelling.4

Women are the ones that usually do traditional embroidery. Confucianism has four virtues that are vital to the very structures of life: labor, appearance, speech, and behavior. Almost all women know how to embroider, but hand embroidery, in particular, was prominent during the Hue Dynasty and again in the 1960s.5 Embroidery is a painstaking art. The individuals that work on these pieces are highly skilled and have the talent, a keen eye, and the ability to render the scene before them. Embroidery painting is especially difficult, requiring immense time and determination to complete. And yet this art has been practiced in Vietnam for centuries.6

1 “Viet nam hand embroidery,” ebroideryviet.com, Vietnamese Embroidery Painting, https://embroideryviet.com/vietnamese-embroidery-painting/

2 “Viet nam hand embroidery,” ebroideryviet.com.

3 Duyen,“Van Lam Embroidery Village,” originvietnam.com, originvietnam, 9/26/2022, https://www.originvietnam.com/destination/vietnam/ninh-binh/ van-lam-embroidery-village.html

4 Duyen,“Van Lam Embroidery Village,” originvietnam.com.

5 Duyen,“Van Lam Embroidery Village,” originvietnam.com.

6 “Viet nam hand embroidery,” ebroideryviet.com.

23

The Value of Women’s Work

It is a core tenet in Vietnamese culture to put “family before oneself.” Therefore, many women in my family had to give up their dreams and passions to work in order to take care of the family. In Vietnam, it was much easier to take part in art because there is more time for casual hobbies. My family is “traditional,” meaning there are specific gender roles that men and women must follow. Though workload is shared amongst the family, the man is usually the head of the household, making decisions on economics and social matters, while women take responsibility for housework and raising the children. Men in my family don’t do things that are considered feminine such as art. Therefore, knowledge and skills of embroidery were only passed down through women.

When Aunt Diep moved to the United States, she had to stop doing embroidery and get a job quickly to contribute to the household. Having a good relationship with all of our relatives and being loyal to the family is really important. Therefore, to demonstrate that “một giọt máu đào hơn ao nước lã” or “blood is thicker than water,” Aunt Diep wanted to show appreciation to Aunt 5 who sponsored her to come to the United States.

Aunt Diep felt it was her duty to not be a burden and help the family by contributing financially and overseeing household tasks (e.g. cooking, cleaning, and child-rearing).

24

Embroidery and My Family

this knowledge herself. At that time in Vietnam, there were dedicated stores that sold embroidery kits containing tools and general instructions, so my aunt took the advice from her friend and went to a store near her school to purchase one bag. She developed her skills through trial and error, with some help with threading techniques from her mother. Even with careful study and practice, embroidery takes time. It took Aunt Diep about eight hours a day, every day for two-three months to complete a 91 x 49 centimeters piece.

Over many generations, my family participated in embroidery work. Today, sadly, many of them refuse to talk about it because it is painful. Embroidery was one of the things they let go of, out of necessity to survive and move forward in the United States after leaving Vietnam. Though embroidery is part of my family’s history, it is part of the past and the past is often associated with difficulties. My family doesn’t like to speak about the past, they would rather focus on the future and move on with their lives. For example, my dad often tells me, “If you live in the past, you can’t advance in the future.” My family hopes for a future where we all have an education, a house, and live comfortably, which is our American Dream. Therefore, the only person that has continued to engage in the practice of embroidery is my Aunt Diep Van Nguyen during her spare time. Aunt Diep took the initiative to learn embroidery while in college, when she saw her friend doing it for the first time. She remembered that the women in the family used to embroider, but neither her mom nor aunts practice embroidery. While learning to do embroidery, she had to ask her friend a lot of questions because her mother was not able to pass on 25

Q1: How would you describe yourself as an artist/artisan?

A: Oh tôi không xem tôi như một nghệ nhân, tôi chỉ làm việc đó như một sở thích. nó chỉ là niềm vui và tôi thích làm điều đó.

I don’t consider myself an artist; I just do it as a hobby. It is just fun, and

I love to do it.

Q2: What is your style of embroidery and technique?

A: Phong cách thêu này không phải là cách thêu truyền thống.Trong bức tranh có rất nhiều ô vuông tôi sẽ thêu mũi thêu đầu tiên từ trái sang phải và mũi thêu thứ hai sẽ là từ phải sang trái. Mỗi ô vuông tôi sẽ thêu cùng 1 cách thêu như vậy. Với những người khác ô đầu tiên họ sẽ thêu mũi thứ nhất từ trái sang phải mũi thứ hai sẽ là từ phải sang trái nhưng ô kế tiếp họ sẽ thêu ngược lại. Cách thêu đó sẽ làm cho bức tranh ko được đẹp

This embroidery style that I do is not traditional embroidery. In the picture, there are many squares. I will embroider the first stitch from left to right and the second stitch will be from right to left. For others, the first square will be embroidered with the first stitch from left to right. The second stitch will be from right to left but on the next square, they will embroider in reverse. That embroidery will make the picture not beautiful because of the inconsistency of how the lines are stitched and it will show on the image.

Conversations with My Aunt, Diep Van Nguyen

26

SCAN TO WATCH My Aunt Embroidering

Q3: When, timewise, did you feel comfortable embroidering fluently or feel confident that you had gotten better?

A: Sau 1 tuần thì tôi đã có thể thêu thành thạo và nhanh chống. Tôi cảm thấy tôi có thể làm giỏi sau vài tuần.thời gian bạn đặt vào nó thay đổi bạn sẽ nhận được tốt như thế nào. After one week of study and practice, I could embroider fluently and quickly. After a few weeks, I felt like I had become really good at creating embroidery pieces. The time you put into it changes how good you will get.

Q4: How many pieces do you make in a year? Are you working on several pieces at a time? How much time does one piece take to make?

A: Trước khi tôi qua Mỹ tôi hoàn thành ba bức tranh trong một năm. Nhưng sau khi tôi đến mỹ tôi mất gần một năm để hoàn thành một bức tranh thôi. Tôi chỉ thêu một bức tranh cho đến khi hoàn thành rồi tôi mới bắt đầu thêu bức tranh tiếp theo. 96 inches cho bức tranh nhỏ nhất và tôi hoàn thành nó trong 2 tuần. Before, when I lived in Vietnam, I created about three embroidery pieces a year. But once I moved over to the United States, I could only spare time for one embroidery piece a year. I only work on one piece at a time because one embroidery piece takes a lot of time on its own. The smallest size that I have created is about 96 inches, which takes about two weeks; [I] consider this the average due to the amount of work and time available.

27

Q5: How do you find the time to do embroidery?

A: Hiện tại tôi không còn làm nó nữa vì khi tôi qua Mỹ tôi đã không còn thời gian cho việc đó. tôi dừng thêu tại vì tôi phải đi làm. Đi làm tốt hơn cho việc bán những bức tranh.Tôi dành thời gian vào cuối tuần để tôi làm.Tôi làm việc từ 2 giờ chiều đến 12 giờ sáng làm việc 5 ngày một tuần. Now, sadly, I don’t do it as much anymore because when I came to the US, my time was consumed with other priorities, thus causing me to stop doing it as often. Because duties like work are more sustainable and profitable than selling the embroideries. During the weekends, I find time as best I can to dedicate to embroidery work. I work from 2:00 pm to 12:00 am five days a week.

Q6: How do you know doing embroidery is worth the effort?

A: Khi tôi mang những bức tranh thêu mà tôi hoàn thành đến tặng cho người thân của tôi họ rất vui và hạnh phúc khi nhận được nó. Và tôi đã thấy họ treo chúng trên tường nhà khi tôi ghé thăm. Nó làm cho tôi rất vui khi tiếp tục.

When I bring the embroidery work that I finished to give to my family members, they are very happy and are grateful to receive it. I’ve seen many of them hang the embroidery work on the wall and when I visit I see it hanging nicely in their house. It makes me happy to continue.

28

A: Tôi vẫn tiếp tục thêu tại vì tôi vẫn còn một vài bức tranh chưa hoàn thành và khi tôi sang Mỹ tôi quen thêm một vài bạn bè nên tôi vẫn tiếp tục để tặng họ khi tôi hoàn thành chúng. Vì tình cảm tôi dành cho gia đình tôi chính vì thế nó đã truyền cảm hứng cho tôi để tôi tiếp tục thêu những bức tranh đó.

I still continue because I still have some more embroidery pieces that I feel like I should complete. When I came to America, besides giving it to my family, I have made a few friends and would love to gift it to them when I am able to finish. Because of my love for my family, I continue to be inspired to work on these pieces.

A: Nguồn cảm hứng để tôi thực hiện tác phẩm này là do lần đầu tiên tôi được gặp gia đình mà tôi chưa bao giờ được gặp vì trước đó tôi sống ở Việt Nam. Lần đâu tiên tôi đến Mỹ và định cư tại Mỹ. Tôi muốn làm 1 cái gì đó thật sự ý nghĩa để tặng người thân của tôi nên tôi đã chọn cách thêu này bằng chính tay tôi. The inspiration to do this work came from meeting my family in the US for the first time. I wanted to make something really meaningful to give to my loved ones, so I chose this embroidery with my own hands.

Q7: Though you can’t dedicate 100% of your time to embroidery, what makes you want to continue even though time is limited?

Q8: Why is embroidery important to you and what does it mean to you when you give it to someone?

29

Q9: What would people within the family do with the piece of art when they receive it, and what is the purpose of having it in their possession?

A: Họ treo những bức tranh trong nhà để trang trí và nó quan trọng tại vì nó mang lại may mắn hoặc mang lại thành công cho họ. They would hang the embroideries in the house for decoration, and its importance is to provide good luck to the family or success and future prospects to the individuals.

Q10: Since you don’t view embroidery as work, how does embroidery represent your love for your family?

A: Tất cả các bức tranh tôi đã dùng chính đôi bàn tay của tôi để thêu việc đó đòi hỏi sự khéo léo, kiên trì, rất cực khổ và khó khăn như gia đình tôi. All the embroidered pieces I gifted were made with my own hands. Embroidery requires ingenuity, perseverance, very hard work, and courage in the face of difficulty, like in my family.

Q11: What piece are you most proud of and why did you choose to make it?

A: Bước tranh mà tôi tự hào nhất là bức tranh thêu về cành đào tôi mất gần 2 tháng để tôi có thể hoàn thành nó. Tôi chọn phong cách thêu này tại vì trong thời gian đó nó rất được ưa chuộng và nó thật sự dể thêu là rất thu hút tôi khi tôi thấy nó. Bức tranh đó tôi làm để gửi tặng đến dì 5 của tôi. Dì 5 là người đã giúp tôi để tôi có thể định cư được ở nước Mỹ. Tôi mất 5 tháng để hoàn thành bức tranh. The piece that I am most proud of is the embroidery of a peach blossom that took almost two months to complete.

I chose this specific style of embroidery because, during that time, it was a very popular option to create, and it was really easy to embroider, which attracted me when I saw it. The picture that I made and gifted to my Aunt 5. Aunt 5 is the person who helped me to settle down in the United States.

30

31

Q12: Do you think anyone can do embroidery?

A: Họ làm được, họ chỉ cần mua bộ tranh về và làm theo sự hướng dẫn.

Anyone can do it. The person that is interested in it would just need to purchase a kit that would provide everything that the individual would need to begin creation of the embroidery. Just some trial and error would be involved throughout the process of making it.

Q13: How long would you like to do embroidery?

Would you like to teach someone?

A: Có thể tôi làm việc này cho đến khi nào tôi không thể làm được nữa. Có thể tôi sẽ chỉ cho Wesley nếu anh ấy muốn.

I would like to do it until I can’t anymore. I would like to teach Wesley, if he would like to create his own.

SCAN TO WATCH Me Practicing Embroidery 32

Conclusion

For me, hand-stitched embroidery is art. I feel that embroidery made using machinery lacks feeling and value. Hand embroidery allows for a variety of stitches, thread, and fabrics. Every work is unique to the seamstress. On the other hand, machine embroidery is very uniform and identical, which feels impersonal. I recommend holding embroidery in your hands, feeling its weight, and seeing how the thousands of tiny handstitches blend together to form a beautiful silk painting. Though Aunt Diep does not consider herself an artist and only does embroidery as a hobby, to me, she is an artist. Working on this project not only gave me the opportunity to learn more about the history of Vietnamese embroidery, but also spend more time with family, specifically with Aunt Diep. Growing up, I have always been close to Aunt Diep, however, over the years we spent less time with one another. As a result of this project, I spent many hours and days with Aunt Diep interviewing, reconnecting, laughing, and sharing meals. Aunt Diep was very supportive of me and easy to talk to/with and I am glad to know that she is still my buddy. I decided to take up Aunt Diep on her offer to teach me embroidery as well as a specific style of hand stitching.

For example, she taught me the technique that helped make the work starting from the top right to the bottom left of the square and again from the top left to the bottom right of the square on each pixel of the picture. From the embroidery process as a whole, I would say learning the experience was difficult. Depending on the amount of time one person practices embroidery, they can get as good with a lot of time and dedication. With my limited experience in embroidering, I would say it was difficult because of the attention that needs to be taken to stitch each corner of each box. I was intimidated by the work, but not only that, I struggled to maintain the other side of the embroidery, where the embroiderer has to make sure the silk is straight and not tangled, and too far pulled out on the back. When this happens, it looks like a loop is stuck, clogging the embroidery and stalling the whole process. It's frustrating! I do have a whole new appreciation for my aunt because ten minutes of me working only resulted in five stitches.

33

Aunt Diep spent the majority of the time laughing about how hard it was and me while trying to instruct me in English. Besides trying to teach me how to embroider, I appreciated learning more about her journey to the United States and how she learned embroidery as a young girl to a full-blown adult still working on embroidery in her free time. The conversations I had with Aunt Diep and family were invaluable, for I was able to feel and understand both the joy and pain associated with embroidery and leaving Vietnam when talking to my family members about this project. This project also reinforced some of my family values, such as “every action and decision is for the love and well-being of the entire family.” For instance, Aunt Diep’s biggest motivation for continuing embroidery is gifting the art to family members as a sign of appreciation. Everyone in my family has sacrificed individual happiness and passions to not be burdensome and for betterment and survival of family. Though my family rarely says, “I love you” to each other, we show “love” through sacrifice, family meals, and spending time together.

34

Finally, I would like to thank Aunt Diep for the immense assistance she has provided me with this project. I owe both her and my family the world for what they have done for me. I acknowledge that my younger cousins and I can go to college and have more opportunities available due to the hard work and sacrifice of the previous generations.

Works Cited

1. The Best Van Lam Embroidery Village Travel Guide. (2020, November 28). Accessed 9/8/2022, from https://www.originvietnam.com/ destination/vietnam/ninh-binh/van-lam-embroideryvillage.html.

2. Cammann, S. (n.d.). Embroidery techniques in old China. JSTOR. Accessed 9/9/2022, from https://www. jstor.org/stable/20067040.

3. Hand-embrodiery-viet-nam. Emboideryviet. (2018, February 24). Accessed 9/8/2022, from https:// embroideryviet.com/vietnamese-embroidery-painting/

4. Vietnam Times. (2021, March 31). Vietnamese silk embroidery art impresses international media. Vietnam Times. Accessed 9/8/2022, https://vietnamtimes.org.vn/ vietnamese-silk-embroidery-art-impresses-internationalmedia-29986.html.

35

Chopsticks: More Than Just a Utensil

My grandma and I were never on good terms. Our relationship dynamic was filled with hopeless optimism. I spent my entire childhood being optimistic that we would figure it out at least one day. Unfortunately, we were just hopelessly running around in circles. No matter how hard I tried, it seemed like I would never live up to her expectations.

HENRY NGUYEN (He/Him/His)

Junior, Majoring in Media & Communications Studies and Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies. I was proudly born and raised in the South of Vietnam. Being a part of SEAPF encourages me to embrace my identity and use my privileges to uplift other BIPOC communities.

All I remember from childhood was being yelled at because of the way I used chopsticks. My grandma always closely scrutinized the movement of my chopsticks, waited for me to drop something, and criticized my table manners. Even though I managed to pick up the food without dropping anything or even making a noise, she still criticized me for having the pinky finger extended while holding the chopsticks. Sometimes, when tracing my childhood memories, I realize that my first time experiencing imposter syndrome was probably at the dinner table with my grandma. I remember vividly how my grandma praised my cousin for using utensils the right way. I remember how she appreciated my other cousin using chopsticks to pick up the right amount of noodles, gently placing the food on the spoon, and elegantly covering her mouth while chewing. I also remember the way she looked

36

at me with anger and disappointment, as if I was a complete failure. I will never forget how my heart broke into pieces whenever I became the target of my grandma. Dinner was so memorable since my bowl of rice was always seasoned with tears and anxiety.

*** Moving half the globe away from home–where people eat fried rice with a fork, where you have to ask for a pair of chopsticks even though you order noodles, where chopsticks are not a part of those recycled utensils kits–sometimes those dinner memories flashed back when I find myself in an Asian restaurant. I saw people doing little dances with their chopsticks. I saw people dropping their chopsticks multiple times. I saw people pointing chopsticks at each other. I saw people clumsily holding their chopsticks with more than two fingers pointing out. It drives me crazy seeing how people disrespectfully handle

37

their chopsticks. It was not fair when I am the only one who got punished for using chopsticks “incorrectly.” I was jealous of strangers for their freedom. In those moments, I wonder how my grandma would react if she happened to witness these wrongdoings. She would roll her eyes and sigh heavily. She would probably gossip about the strangers across the table. She would go on and on about how great my cousin’s table manner were. And it is totally okay. (I am working on knowing it’s okay). In between those eyerolls and grumbles, I just hope she changed her mind. I hope she realized I got better at using chopsticks. I hope she realized I spent my entire childhood learning how to use chopsticks just to seek for a sense of acceptance. I hope she realized I am not a failure nor a disappointment.

38

39

My Batiks, My Journey

Start by scanning the QR Code and listening to me speak about my journey and how it parallels the journey of batiks.

HAARI DURAND

(He/Him/His)

Senior, Majoring in Global Studies, Minor in Human Rights

I was born in Indonesia and raised in the French/German speaking part of Switzerland. Being a part of SEAPF allowed me to take a deeper look at my own roots and develop lasting relationships with other Asians/Asian Americans in an academic setting.

I was born in Indonesia, adopted when I was very young, and grew up in Switzerland. My brother and I were the only racial minorities in a town of 400 people, and not really in touch with our identities. We were raised as two “white” children, both playing an instrument and participating in scouts and sport like other Swiss youth. My first clear encounter with racism and xenophobia was during my time in the military, when I had to find inner resources to cope with overt and covert discrimination from other recruits. There is no BIPOC representation of any kind in the Swiss government, although roughly two million people are immigrants in a country of just nine million.

Cultural isolation has been a recurrent experience, even a “theme” in my life. Having traveled all over the world, and lived in places as far flung

40

as Russia and France, I didn’t feel a real sense of belonging until my wife and I moved to Kenmore here in Washington. For the first time in my life, I experienced an unguarded joy doing simple things like going to the store or the gas station. Then came Covid-19 and our moved to Sequim. The Olympic Peninsula is beautiful, but it is overwhelmingly white; my wife is the only Black female physician in her medical practice and experiences racism in her daily life. We take the ferry every other weekend to Seattle, just to be in contact with communities of color. Another way we stay rooted in our identities is through our work in West Africa. My wife and I make biannual medical trips to bring free, high-quality medical services and supplies directly to patients in The Gambia, and hope to those who often feel abandoned and forgotten. The trips last for two to three weeks, and connect a team of volunteer physicians and nurses from the United States with professionals on the ground. These partners include

41

doctors and nurses who speak local languages, understand local systems, and provide culturally sensitive care.

SEAPF has taught me that research can also be a form of care. Inspired by our work with cultural belongings at the Burke, including a wayang from Java (like me!), I turned towards my own Indonesian pieces, enquiring into them with the same form of careful attention. Batik cloth has been in my family home as long as I remember; I wore it at times, but never really thought about it. Being in SEAPF allowed me to dwell on the ways my own journey mirrors the global history of batik, how it traveled from Indonesia all the way to the Gulf of Guinea. I learned that… • Evidence of batik has been found in East Asia, the Middle East, Central Asia, and India dating back more than 2000 years. It is possible that the technique developed in these areas independently, without the influence of trade or cultural exchange. However, it is more likely that the craft spread from the islands of the Malay Archipelago and then overland to the Middle East along caravan trading routes.

42

•

Batik is produced through an artisanal wax resist dyeing technique developed in Java, whereby wax is applied before the fabric is dipped into dyes of various colors. The process was industrialized in the 19th century by Dutch merchants, but when Indonesians failed to buy the machined cloth, they were forced to sell the variant in their African colonies. Particularly in the Gulf of Guinea, batik is enormously popular and has spread over time and across the continent to become the very symbol of African culture and the African continent.

• We can think about the way material culture moves along migratory flows and how the circulation of goods shapes practices (techniques, tools, uses), iconographies (pattern, motif, symbol), and cultural identities. Rather than being bound to a certain place, textiles like batik are produced in the currents between Asia, Africa, and Europe. I am interested in how forms like these make meaning in “traditional” contexts, and how they are reworked by artists and designers, and by the people who wear them.

43

Connecting the dots has always been a priority for me as an adopted kid. In this program, I have found new brothers and sisters. I feel connected to the Southeast Asian community of the Puget Sound and have been able to explore my own Asian-ness. I am more at home in my identity and, for the first time, I am confident in my ability to become the change I want to see in the world. I highly recommend SEAPF to any Southeast Asian/BIPOC student willing to tackle the hard questions surrounding identity and exclusion in the USA and beyond.

44

45

What We Hold Onto

MOLLY KAPPES

(She/Her/Hers)

Senior, Majoring in Computer Science & Software Engineer

Being half-Khmer and raised in a mixed household, I’ve always tried to reconcile both halves of my identity. SEAPF has helped connect me to my roots and create a sense of community which I haven’t found outside of family.

Some of my earliest memories are of my mom cooking something for us in the kitchen. Each meal was made from the heart, and the amount of love she put in always hid the labor and skill required by traditional Khmer cooking. We had to eat everything on our plates, no exceptions—“Every bite is hard-won,” she would say. Throughout my childhood, I saw her meticulously smash, grind, and pound various ingredients in this mortar, and it became synonymous in my mind with family dinners and full bellies. Everything about this object was positive to me. Its worn appearance could tell anyone it was well-used, and, to me, it radiated love.

I didn’t know until I was older what significance this mortar and pestle held for my mom and our family history.

On April 17th, 1975, the Khmer Rouge won the Cambodian Civil War and took control of Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital. Led by Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge began to commit countless atrocities that over approximately three years, led to the loss of over a quarter of the country’s population (Chan, 2015). For my mom’s family, it started with the disappearance of her Chinese grandpa. My grandpa tried using his government connections to get his father back, but children were beginning to be taken and families sent to labor camps. It became increasingly clear that it was dangerous to stay. When my grandma was held at

46

47

48

gunpoint under suspicion of being Vietnamese, only being released once the village vouched for her Cambodian roots, they knew it was time to leave. They left their hometown of Battambang and headed north for the Thai-Cambodian border, beginning a three year journey of uncertainty and insecurity. Besides what few personal items each sibling could carry, her family took only their gold and jewelry, some woven mats, a silver spoon, and a mortar and pestle. This mortar and pestle saw the hardship of war. It holds memory of betrayal, theft, and murder. It bears the struggle of survival, the insistence of hunger, thirst, and sickness. It remembers the heartbreak of separation, not knowing when or if you will see each other again, and the unimaginable loss of family.

By the time they landed in Ohio as refugees, this was the only object that remained with my mom’s family. When I asked her why they carried such

49

a heavy and awkward object with them, even in times when they had nothing to smash, she responded simply: “You need it to cook.”

Despite the violence this object has seen, it isn’t a war relic to be merely observed. It’s a tool to be used, still capable of creating joy and fond memories. Learning about the mortar and pestle’s history didn’t taint the positivity I had formed around it—it extended it. To us, it’s a reminder of a family- and food-centered cultural resilience that is able to extend past tragedy. It’s an unshakeable symbol of spirit, where when nothing else is certain, you can still be grateful for the present and hope for the future.

Works Cited

Chan, S. (2015). Cambodians in the United States: Refugees, Immigrants, American Ethnic Minority. Oxford University Press.

50

51

52

Try my mom's family recipe for Khmer noodles.

I would consider this a Cambodian staple!

'Bouk' is the action of pounding in the pestle and mortar!

My mom always made this a lot for me, but I never realized how labor intensive it was until I grew up. It's made with lots of love for sure, and I hope you all like it!

53

The Shears

The Japanese shears

stories

SAMANTHA MAFUNE (She/They)

Senior, Majoring in Community Psychology and Gender, Women, & Sexuality Studies

I am a mixed-race American with Japanese and European ancestry who has resided in Washington for the entirety of my life. SEAPF introduced me to a community where I was comfortable and proud to explore the part of my identity that is 25% Japanese when I’ve passed as a Caucasian individual my entire life.

When I joined Southeast Asian Pasts and Futures (SEAPF) in the Autumn of 2021, I had primarily joined because I knew the two instructors that were teaching it. It also satisfied my major and minor requirements, so I thought why not. What I did not know was that it would impact my identity more than any other course I’ve taken here at UWB.

On the first day of class, I felt a bit out of place when everyone was introducing themselves with both their American name and their family or cultural name.

All I had was one name—Samantha. I believe this discomfort was good for me to experience because I can only imagine how uncomfortable it may have been to change one’s given name to a name more easily pronounced by English speakers. After the introductions and a few class gatherings, the cohort really started to shine, and a community was formed amongst us all. We represented different cultures and backgrounds and felt comfortable sharing with one another.

I miss your deep history Forgotten

54

55

56

The main assignment or “final” for the Winter quarter was to find a cultural belonging from our own family and write a few pages meditating on the history and meaning of the object, drawing on an interview or conversation with a family member. To say I struggled with this final assignment is an understatement. I know part of this had to do with the fact that I was in a course that focused on Southeast Asian Pasts and Futures, and I felt very American growing up. As someone who is part Japanese, but passes as Caucasian, it was hard for me to embrace an identity I felt so disconnected and distant from.

these stockings, so I figured why not examine them as my cultural belonging. As I began researching and speaking with my mother, I found that the majority of Christmas stockings had very little association or history in relation to Japanese culture. There I was again: Allowing myself to be detached from my Japanese roots and culture. As the Spring quarter came around and the weather got a bit brighter, I started to tend more to my indoor plants. Realizing that the shears I used to prune, propagate, and cut leaves were the same exact type of shears that had been passed down from generation to generation on my Japanese side of the family. The shears were my great-great-great-grandmother’s and she specialized in Ikebana arrangements, which is a special form of floral arranging originating in Japan. Her love of flowers was passed down to my great-great-aunts who ran a floral shop down in the University District for over thirty years. Maybe my admiration for flowers and plants comes from my Japanese ancestors, at least that is what I would like to believe.

As I pondered what I had around my home I thought why not do this assignment on the Maneki-Neko, also known as a Japanese lucky cat! I have a few of those as decorations in my home… but as I started the assignment, I felt very little connection to this little glass cat even though I had seen it almost every day. It was close to Christmas and as I decorated my home, I had a collection of stockings that were handmade by my grandmother on my mom’s side of the family. I grew up with 57

Through my research, I discovered that gardening was an important form of agency for Japanese Americans in the time of Executive Order 9066. A study was done by Anna Tamura in 2004 titled “Gardens Below the Watchtower: Gardens and Meaning in World War II Japanese American Incarceration Camps” analyzes the ways in which Japanese Americans showed levels of resistance to the War Relocation Authority (WRA), and how the gardens served as cultural resources showcasing “evocative of human agency within landscapes of persecution and racism.” There were two kinds of gardens that were constructed during the time of interment. Agricultural projects provided food and were known as "victory gardens," and ornamental gardens included ponds, waterfalls, flowers, and bonsai trees. It's unfortunate that most of these gardens no longer exist, but the ones that remain are healing spaces that hold many emotions for Japanese Americans.

SCAN TO WATCH Video of Ikebana Arrangment

58

Self-love is some of the best love you can have. Cheers to that, Samantha Ryoko Mafune Works Cited

59

Works Cited

Tamura, Anna Hosticka. “Gardens Below the Watchtower: Gardens and Meaning in World War II Japanese American Incarceration Camps.” Landscape Journal, vol. 23, no. 1, 2004, pp. 1–21., https://doi org/10.3368/lj.23.1.1.

Tamura, Anna Hosticka. “Gardens below the Watchtower Gardens and Meaning in WW II Japanese American Concentration Camps.” YouTube, YouTube, 9 Nov. 2021, https://www.youtube.com watch?v=Zsic1KXdoEw.

SCAN TO WATCH

Video in Works Cited

60

61

62

Embodiment

TU-VY CHUNG

(She/Her/Hers)

Senior, Majoring in Global Studies

I am a Vietnamese-American, born and raised in West/South Seattle. SEAPF helped me explore what my place was in my communities, what it means to be part of diaspora, and how to properly tell the stories of those in my diasporic community.

I love the small collection of áo dài that I have in my closet. Each occupies its own hanger, each with its own color and design. Some are protected from the elements, from aging, and from other garments; the rest hang with their shoulders held high. I have a few different colors displayed: a warm yellow, a cool baby blue, a soft peach, and a vibrant ombre of pink and purple. However, one is hung towards the front of the opening of my closet: a red áo dài, decorated with stems, leaves, and red flowers all along the entirety, and matching red silk pants to complete the look. The neckline is tight and stiff so that the rest of the áo dài flows down softly. There are two layers of fabric to the main body: a red tulle that the flowers lay on, and an opaque red underneath that keeps it modest. The sleeves go down to my wrists, which is also made of the tulle that runs down the length of the áo dài. Many other details were put into play, such as the bust and waist area carved to create a feminine silhouette. The measurements of my body proportions were noted all around, from the length of my arms, to the height of my body, to even the

63

diameter where my arms would go through the sleeves. All were taken note by my mom, who sent the measurements to my aunt, a seamstress living in Bao Loc, in order for her to create the áo dài that is designed for me only. This is the áo dài I wore to my senior prom and posed in in pictures with my friends, the Seattle skyline in the background. I stood out because the garment was from another country and culture. At 18 years old, I wanted to stand out just like every other girl on their prom night. But what did it mean specifically for me to come forward to this big event dressed in my áo dài? Why did I go through measuring my body to a T, sending ideas back and forth to my aunt an entire ocean away, and anxiously wait for my garment to arrive on the week of prom?

It was years later, that I began to realize the impact of wearing cultural attire. For me, wearing my áo dài meant that I had to sit a certain way, that I had to stand tall; that the way I acted in jeans and a sweater did not “fit” to this other self, covered in the tunic and pants. When I initially wore the áo dài, it meant

64

65

that I was representing my Vietnamese heritage openly.

While I would typically dress in order to express who I was as an individual, that night, I was dressed to proudly center my ethnicity. This was emphasized by the fact that I attended a school in a relatively diverse school district, so visibility was something that many cultural groups and students of different ethnicities were advocating for.

When I was wearing my áo dài, it became obvious that I was under the public gaze. At that moment, I was not only a representation of my heritage, but my family. I wore what my mom and aunt helped create. My mom and family looked a me wearing the áo dài with pride. I too felt proud and special that night because I was different. Prom is a dance that many teens anticipate to be their night to stand out, and my choice to wear my áo dài embodied that.

66

67

Flowers to Give to Your Parents

I am the offspring of the forest and the sun

My parents call me their sonflower.

My parents are Filipino, foreign.

They hoped by planting me in the soil here,

JUSTIN TOTAAN

(He/Him/His)

(He/Him/His)

Senior, Majoring in Media & Communication Studies and Gender, Women, & Sexuality Studies

I am a first-gen Filipino-American. Before SEAPF, I experienced in the ebb and flows of identity. Being around individuals in SEAPF helped me find community and direction.

That it would help me grow better than they did.

On the first day of school, I am teased for the fullness of my stump,

For the distinctiveness in my appearance. I then throw dirt on my roots,

68

Dig them into the ground, Where they are nowhere to be seen, Nowhere to be found.

I begin to sleep on tear soaked pillows

As if my soil was an overflowing sink. I ask myself do they love or hate me?

As I pick my own petals. I took the time necessary to fit into their standards, Snipping my petals, covering my roots.

Growing in a way that doesn’t make them uncomfortable.

As I bud into adulthood, my head may be held high but my chest remains hollow.

69

There, an unhealed child continues to grow, Making decisions on behalf of my adulthood.

What seems to be an evergreen spirit, Withers and wilts as seasons cycle through changes.

What am I? Who am I?

I am in a tide of a constant Ebb and flow between the identities I carry, Thus, severing the relation from my parents and I As if we snipped thorned stems from a rose.

What am I? Who am I?

A flower who doesn’t know home, disconnected from its roots. Considered foreign in both soils I call home.

70

I’m soiled. Tainted. Too American, Too foreign.

Two identities, not enough space.

Pick between the two, like the fruit on the trees That I bear from my ancestors’ labor. Is this where they wanted me?

To be, questioning, internally fighting, identity finally igniting Like the sun on my flag

Ancestors send me signs, through the embodiment of a Sag. Badge, regalia, this Barong

Tagalog, mother tongue, I shouldn’t be ashamed of Used to heal me with lullabies of love

71

And a razor to cut those who speak down to us.

What I thought to be the sheers that held me back

Was the photosynthesis I needed. I was displaced in the limbo of stagnancy Without knowing myself internally. Those who were doing the work to photosynthesize, shed light on my culture Giving me the necessary glucose

To comprehend the importance of my culture. Like the arms of a tree, we may oftentimes branch out different directions But everything is traced back to our roots.

72

We must water and sustain our roots, Healing our past, our future, and present.

As I grow in this foreign soil, I now know that I can bleach my hair but I can never escape my roots.

To my parents, From your son/sunflower, I’m proud to be y’orchid/your kid. Thank you.

73

74

Embracing the Process

MINDY VU

(She/Her/Hers)

Senior, Majoring in Health Studies and Educational Studies

I am a first generation Vietnamese American who was born and raised in Seattle, Washington. Being part of SEAPF has changed my world view, but more importantly, it has given me a community that I call family.

Being Vietnamese American comes at a cost. The cost is not like an item that comes with a price tag from the store. The cost of being Vietnamese American is to be constantly stripped of who you think you are. It’s only by having faith in your own embracing will you be able to put yourself back together and accept your existence in its entirety. To navigate the contradictions, the message to stay quiet and speak loudly. To discern whether to walk forward into assimilating or to back track deep into the roots of where you are from. To be resilient enough to find where you belong but also to be brave enough to say no where you don’t.

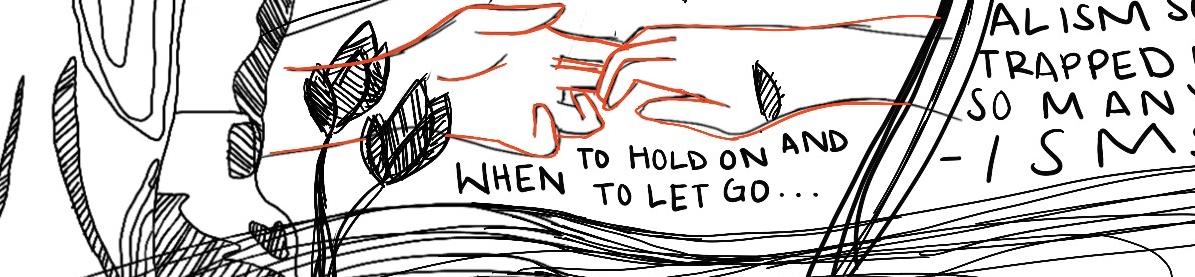

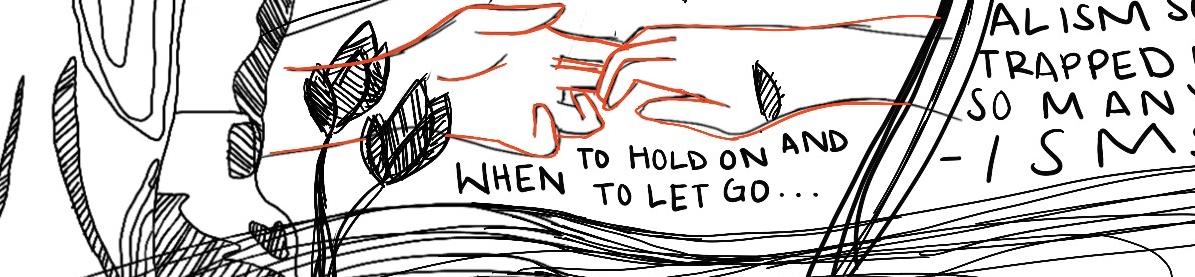

The piece that I made is a projection of raw experiences and emotions that dance and fight to find the right answer to “Who am I?” It is the letters and the lines that are obituary and disconnected, but letters and lines that I have spent my entire life piecing together. In this part of my identity, embracing 'Vietnamese American' means that much of what I know about myself is unfinished, unpolishing, uncolored. It gives me anxiety that it is not perfect,

75

that the piece is not done right here and now. It gives me anxiety because my parents raised me with the expectations that I would be strong enough, smart enough, self-sacrificing enough, old enough to know by now. It’s feels cold and empty, but I don’t know and I have to wholeheartedly accept that it’s okay not to know. It’s okay. It will be okay.

I know that being and becoming are a way of living. A way of living that love and labor define, specifically from the love and labor of those who came before you. But you have to determine for yourself whether to follow or not. You have to know when to hold on and when to let go.

But in wholeheartedly accepting what I don’t know, I wholehearted accept what I do know.

I know that love exists. It connects our hearts like a river that flows, pushes and pulls from one ocean to the next. Some people say that it’s God within our souls, others say it’s the energy in the universe, you can’t see it, you can’t hold it, but whatever it is, I say it’s real and it’s worth living for.

These are the things that I don’t know and the things that I know, and in the midst of the noise, I hope that lotus flowers, learning how the sunlight hits the surface of the earth, will continue to grow.

To the right, you will see three additional pieces related to the colored parts of my drawing. Please scan the QR codes to fully experience the meaning behind each color.

Love & Labor

I know that labor is a form of love. Labor is a way of love. It is not the only way, but it is the way that love flows from hearts, to hands, to making, and to the earth and materials that we cherish. You can hold labor. You can feel labor.

When to Hold On and When to Let Go Who Are You?

76

77

A Tale of Two Vys

NGOC-VY MAI

(She/Her/Hers)

Senior, Science, Technology & Society and Health Studies Majors and Global Health and Health Education & Promotion Minors

I am a Vietnamese and African American immigrant who came to America at 5 years old. SEAPF helped me embrace my culture and deepened my sense of belonging!

VY NGUYEN

(She/Her/Hers)

Freshman, Pre-Public Health

I am a Vietnamese American who has grown up mostly in Washington State. SEAPF helped me find a community of students with similar backgrounds and helped me experience my own culture in a deeper way!

SCAN TO LISTEN

A Tale of Two Vys Audio Clips

Why Did You Join SEAPF?

Ngoc-Vy: For me, this was a class that I was always looking for in my college journey because, growing up as an immigrant, I was embarrassed of my culture, and so I tried to hide my culture and kind of be more Americanized. I always had American friends—white friends. I didn't really have any Vietnamese friends besides when I was younger and I went to temple or when I went to school in Renton, but I didn’t keep in touch with them when I transferred to Bellevue. So when I saw Nhi [Tran’s] email about SEAPF I was like

[It was perfect] in my senior year because I wanted to leave a legacy as the first cohort [and] build something that people who are like me can look at and be empowered.

“Oh my God, this is the class for me!”

78

Vy: I agree with a lot of things that you said–just finding a community that embraces Southeast Asian and Vietnamese culture rather than pushing it aside and not talking about it. I feel like I haven’t done a great job at learning more about my culture, which is unfortunate, because there is so much to learn and it was my job and in my interest to find a community that [helped me] explore those things.

I think because I was just starting my college experience at a bigger university [the Seattle campus], I wanted to find a group of people who

I could relate to more than my peers who aren’t of the same ethnic background because it’s easier to find commonalities and connect to people, which is important, especially if you’re at a bigger university.

It’s easy to feel lonely or feel like you don’t have a place, so that was what I was searching for:

1) to learn more about my culture and 2) to find a smaller community within a larger pool of people.

79

Our Experience Together in SEAPF

Ngoc-Vy: I feel like—and the feeling doesn’t have to be mutual—but I feel like you are one of my best friends and we have grown up together and done a lot together but I had a really fun time being in a class together because we probably not going to get that experience again so getting to be in this class together and experience this together was fun for me. I got to learn more about you as a student and see your personality within the classroom instead of outside just like when we are chilling.

Vy: When you are a student, you are a different version of yourself than when you are a friend or when you are a girlfriend or a mom or whatever. There are different versions of yourself, so being able to see a different version of you, and you seeing a different version of me was beneficial. The more you know about a person, the better you understand how they interact with people in different situations and what they value in different situations and stuff like that. So if anyone or any family can take this class together they might be able to see those different sides of each other.

Vy: Yes. I agree.

You are my best best friend, so it’s really a cool experience to experience the classroom environment together.

It’s very different from a family environment, a friend environment, or a professional environment. It's like we are both learning, we are both students....Being able to interact together and be just students…[is] very cool and [a] privilege[,] and I don’t think... [we'll ever have that experience] again.

Ngoc-Vy: A takeaway…was our different personalities because we do have some similarities and differences. I remember on the first day of class we sat together, but it was Tu-Vy or Molly that sat at our table. I am a shy and introverted person, but you introduced yourself right away and introduced me, too, and forced me to get out of my shell. Although it made me very uncomfortable, it was also really appreciated. It is something I am not used to and I didn’t really make a lot of friends before SEAPF and after my nursing cohort; [I[...just went to class and left. And during COVID, you don’t really get to connect with people over Zoom. So getting to make

80

connections and build relationships with people and expand our relationship was really cool as well. Now that you are interning for MAWS [Midwives’ Association of Washington State], I already have an idea of what your work habits are like…because I saw you as a classmate. Another thing about… SEAPF…is you are going to UW Seattle, and this [program] is at UW Bothell. What are the chances you are going to take another UW Bothell class?

Growing Up Together

Ngoc-Vy: We're cousins, we both emigrated here from Vietnam, our hometown [is] Hue, and we are both firstgeneration college students. So although we do have a lot of connections and a lot of ties and similarities to each other….

Growing up, my family moved around a lot, so I was never really, like, tied down to one place. My first school experience [was in Vietnam.] I had already gone to preschool or kindergarten. When I came here [the U.S.], I went to a predominantly white school district and I remember I had two Asian friends. They were twins, and they were the only Asian friends that I remember having as a child. When I moved to the Renton School District, I had a lot more [friends of color]. Besides the friends I made…[at] temple and my parents’ friends’ kids that I was forced to play with at parties, I was introduced to Vietnamese classmates for the first time and that was very interesting for me. It was so interesting and eye-opening to go to another Vietnamese person’s house as their friend and not as my parents’ kid. Next, I moved to Bellevue School District

81

our paths were very different and our experiences growing up BIPOC…were very different…

and I honestly can’t think of a single Vietnamese person that I was friends with. I mean, Bellevue is predominantly white and also very wealthy, so I felt very ostracized. I also didn’t want any Vietnamese friends because I didn’t want people to know how Vietnamese I was, but once I got to UWB, I was like, no, I need these connections, and I want to make friends with people that are like me. I only made one Vietnamese friend throughout my whole UWB journey until SEAPF, and now I have many!

Vy: The first school district that I was at had a good diverse population and the second school district

I was in had diversity in the sense that there were a lot of Asian people, but not enough [broader] diversity. Still, I didn’t make a lot of Vietnamese friends because I feel like I couldn’t connect with Vietnamese people, but it was also circumstantial because a lot of them were already friends with each other before school. So in college, I wanted to make more Vietnamese friends because of the connection of culture. So this is why I wanted to join SEAPF and I want to join VSA next year.

82

Ngoc-Vy: Oh, I have a lot of friends in VSA, and Mindy and Tram are in VSA at UWB!

Vy: It seems like a fun club, but I felt like I never fit in.

Ngoc-Vy: Why do you feel like that?

Vy: I think it’s my personality.

Ngoc-Vy: Do you think you’re Americanized?

from high school, but we didn’t connect because we were Vietnamese. But with VSA, I tried joining this year but it’s such a big group of people and I don’t think I gave it enough of a shot.

Vy: No, I don’t think it has to do with culture, but I think it’s just my personality. If it’s a big group of the same people, I don’t like it. It just feels like I should be that way, too.

Ngoc-Vy: Well earlier, you said that you couldn’t connect with a lot of Vietnamese people at your school. Is it because of your personality or why is that?

Ngoc-Vy: That is really interesting because I also tried joining VSA, but it’s such a big group. I have trouble connecting with people because part of me feels that I’m “too Asian” because of the food I eat or the way I act. But, on the other hand, when I meet a Vietnamese person, I feel that I’m not Vietnamese enough, even though I was born in Vietnam and am fluent. Some of my friends will speak Vietnamese with each other, but they don’t speak Vietnamese with me because part of it is me. I guess I feel more comfortable speaking English, but, at the same time, I want to speak Vietnamese with them and be [included]. I guess maybe because I tried to Americanize myself when I was younger, now it feels uncomfortable.

Vy: No, I think it’s mostly circumstantial that I didn’t know enough Vietnamese people. I have Vietnamese friends

Vy: I agree with what you’re saying—feeling too Americanized and not Vietnamese enough.

83

Experience at the Burke & Community-Engaged Work

Ngoc-Vy: So for me, I really enjoyed the experience and I talked about it with so many people. I have never been to the Burke and didn’t even know it existed before this class, to be honest. So getting to work with the Burke and learn more about the museum and understand how the Burke is trying to...[intervene in] the history of museums…misidentifying communities’ cultures, …and getting to work with pieces that resonated with us was really special. Whenever I go to museums, I just look at it [as a cultural belonging], read about it, but not really think more about it. So getting to touch it, learn the history, learn how it… [came into collections], how it is stored, [and] how it… is presented was really unique and really informative.

Vy: Yeah I agree. I didn’t get to join for Winter and Spring, so I don’t know what else happened in the program and can’t speak on that, but seeing the journey that specific artifacts took to where it is housed…It is very informative, unique, and…cool to learn about not only your history [and where you] come from, but other people’s histories, and how…[they] might have been disrupted by certain things like the collection process…[and otherwise] exploited [under and after colonial rule].

84

Biggest Takeaway from SEAPF

Vy: Similar to my first answer—being able to find that community and knowing there were people there to support me. Raissa and Nhi were strong figures and support systems that I could [rely on]. Professors are sometimes very unapproachable, not because they mean to be, but Raissa and Nhi were very approachable and thought about our needs a lot rather than making sure everything gets done and the program goals were met. It was more like “What do the students need and how can we [support] them?” Which is better for our learning in general. So the biggest way I benefited from SEAPF was learning how to…interact with professors in a way where… [the relationship is marked by]…mutual respect and knowing I could go to these people for support.

our health, mental well-being, and our identity first rather than focusing on what we can produce and trying to make us all the same standardized students in terms of “I want you to do this this way,” they really let us explore ourselves and explore our identities, not just within SEAPF, but also as Southeast Asian students, UW students. We’re both going into healthcare, so [we learned] how to interact with other people who may or may not be like us. I had a lot to take away from this program and am really appreciative for what this program gave me, and personally speaking, I don’t know how much I contributed to the program in terms of producing work, but I really gained a lot.

this was definitely not like a traditional class and not a traditional classroom,

Ngoc-Vy: I agree. Yeah, I think which I really appreciate because it was different from anything that I had experienced before. Similar to what you said— having faculty and a professor that put us first, and

Vy: Just to add, I like that they [Raissa and Nhi] embrace individuality and they liked that each student had their own thoughts and personalities, and people were encouraged to express who they are, how they feel and how they’re thinking. Whereas other classrooms might appreciate more unity in students’ thinking, how they act and what they say in their work.

85

Final Message to Future SEAPF Cohorts

Ngoc-Vy: So I will go first. Like I said before, I really enjoyed getting to know everyone in the cohort, including Raissa and Nhi, and getting to share an experience with you and everyone in the cohort as similar people. Obviously not everyone is Vietnamese and not everyone has the same experiences as us.

Even though we were all different, we shared the same passions

—wanting to do more community-oriented work and explore our cultures and identities, so I think that was really special. To the future cohorts, I highly recommend you enroll in the… program…even if it is just for one quarter because you will learn so much, not only about the subjects that are being taught, but also about yourself.

[to] be with others who want to do the same thing and highlight our cultural identities,…and have that comfortable environment to do so and share not only about your cultural self and [but] how you feel in general. So yeah, I think this program was a huge privilege because there are not a lot of programs like it, especially in a college setting. A lot of colleges [are] a very competitive environment, [a] very cutthroat environment…[always] stressing that you need to be perfect….This program allowed you to be more of yourself and allowed you to explore more within yourself, within your cultural background, and other people's backgrounds. So that is my message to current and future [cohorts].

Vy: My message is both for current and future.

I think it is an incredible privilege to be able to come together in a setting like this and to to be able to explore our cultural identities...

Ngoc-Vy: Yeah, you really don’t get an opportunity like this in a lot of classes. At least for me, this is a very unique class. I have never experienced anything like this before. I have taken a lot of Raissa’s classes. She is an amazing person. Not only do you get to explore yourself and do community oriented work, you also get to build a relationship with Raissa and Nhi who care so much about their students.

86

87

aC knowledgemen T s

Southeast Asian Pasts and Futures (SEAPF) exists within a network of allies, mentors, collaborators, and supporters.