SOMETIMES THE LINE STARTS ELSEWHERE

Poems after Joseph Beuys

Poems after Joseph Beuys

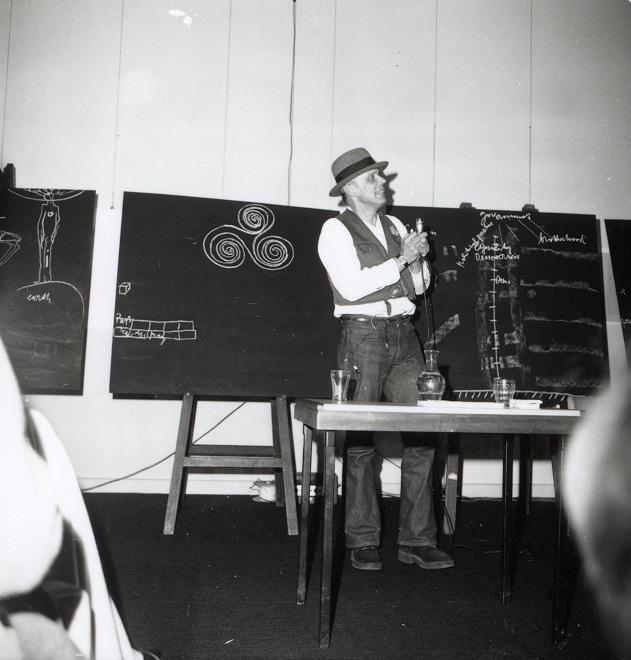

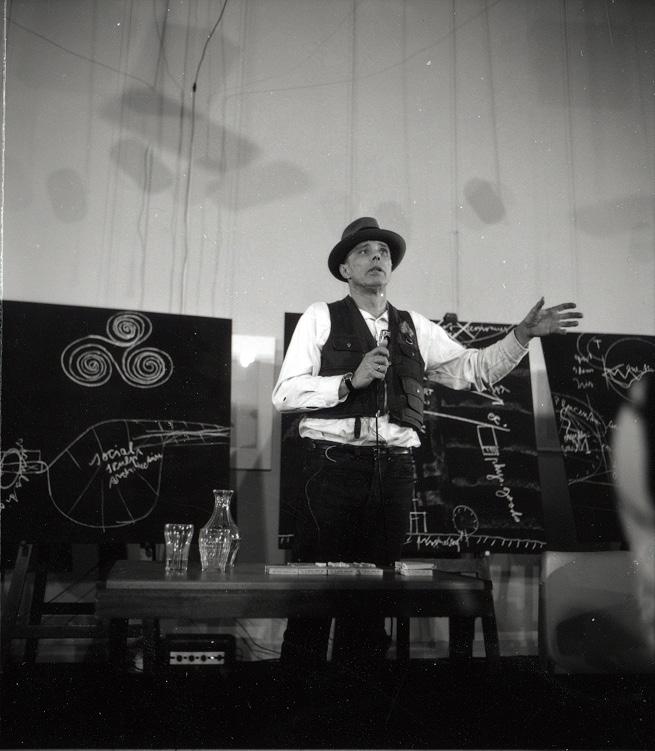

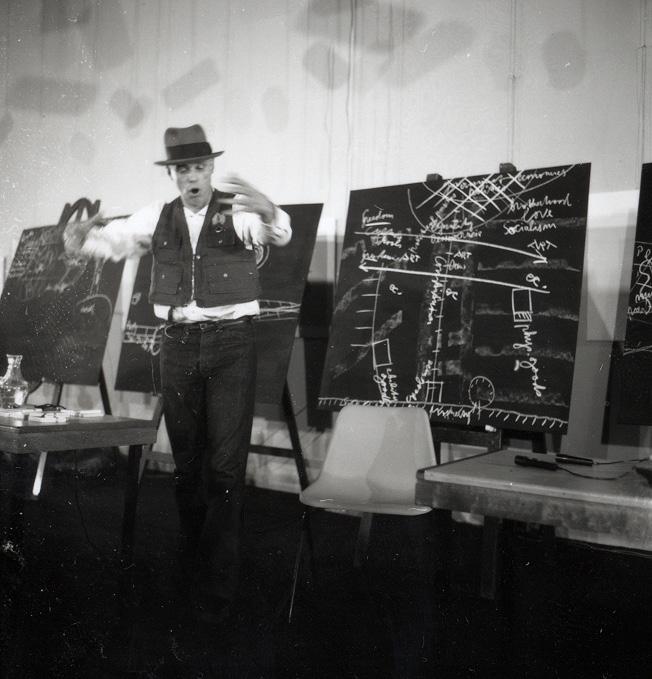

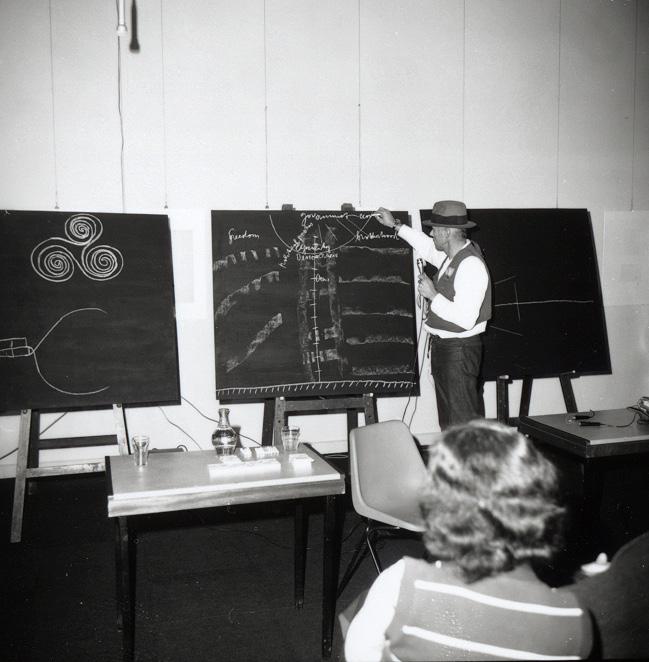

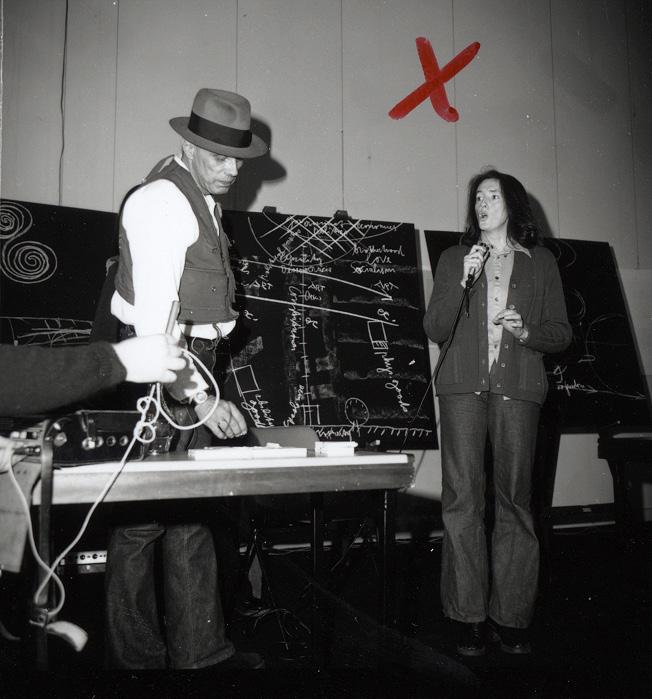

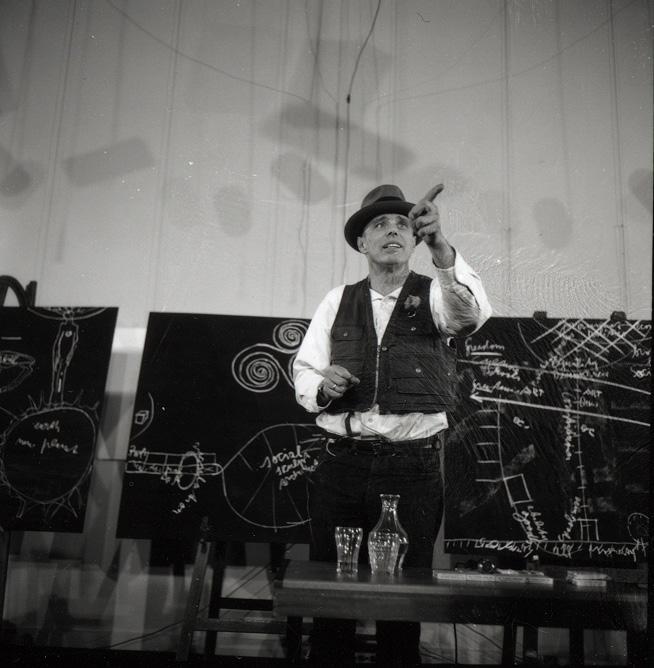

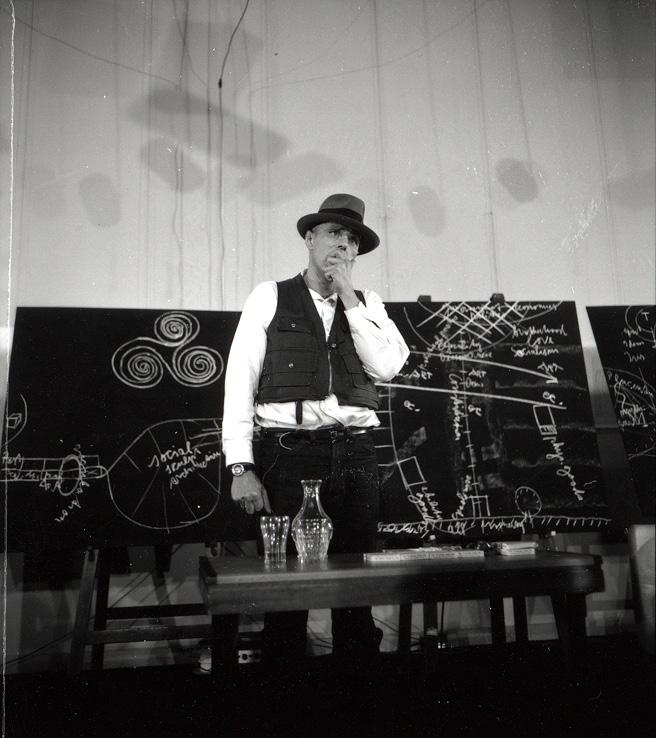

On the 18th November 1974, the German artist Joseph Beuys gave a performance lecture, or ‘Action’, in the Ulster Museum Fine Art Gallery. As was his practice, he illustrated the lecture on blackboards that have been in the museum’s collection since that day.

Beuys proposed the idea of art and creativity being at the centre of all aspects of society, presenting this as his concept of ‘social sculpture’ and inciting the potential for mass societal change through creative thinking.

The lecture became a key moment in the history of Belfast art. BEUYS 50 Years Later: Action, Society, Performance and Change takes the opportunity to look at the ideas discussed and their impact on the creative community of Belfast over the last 50 years.

In order to bring these ideas into the present the museum has worked with current practising Belfast-based artists. Taking the two primary focuses at the heart of Beuys work – performance and drawing.

The photographs from Joseph Beuys Performance 1974 are reproduced here courtesy of National Museums NI, Ulster Museum Collection

This year, the poets of the Seamus Heaney Centre have responded to BEUYS 50 Years Later: Action, Society, Performance and Change. Commemorating fifty years since Joseph Beuys gave his performance lectures at the Ulster Museum and Belfast School of Art, this exhibition prompts us to consider how we might capture and display the ephemeral. BEUYS breaks down the boundary between the remembered past and our living moment, inviting the viewer to step into the perspective of a student who might learn from Beuys but also, as some did in 1974, push back. Glazed blackboards from the original lecture, audio extracts and photographs appear as artefacts excavated from the cultural past. Just as Beuys was drawn to the symbology of Ireland’s neolithic history in his practice, the poets in this pamphlet take and remake these Beuysian artefacts for their own purposes. Alongside these materials, a film work by Amanda Coogan, ‘Gnawing on the bones - Reflections on Beuys’ (2022), and a series of curated drawings by Sally O’Dowd continue Belfast’s dialogue with Beuys into the 21st century. These responses to Beuys and his legacy offered our poets the opportunity to explore his place in Belfast art history, to expand their definitions of the gallery space, and to embrace the difficulty that this work involves.

Beuys comes with challenges, and so too does this exhibition – from the interpretation of Beuys’s ideas and his esoteric blackboards, to what it means for art to be for ‘everyone’. All of these questions come dragging the weight of fascism in Beuys’s past and our present. These poems do not shy away from these challenges, these bones on which we continue to gnaw. We might read these poems as Belfast answering back to Beuys, but this formulation suggests that Beuys started the conversation. After all, sometimes the line starts elsewhere.

Thank you to Anna Liesching, Curator of Art at the Ulster Museum, for providing us with further insight into the exhibition and for encouraging our poets to take up the challenges that BEUYS presents us with.

after ‘How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare’ by Joseph Beuys

As soon as I asked you here and you accepted, this room was yours. As soon as you walked the perimeter, I knew it: this is a coyote room. These are coyote walls, coyote windows, the floor is wood from coyote trees, and I am a broken sink or washing machine, dumped from a van into your forest. I know my place and let you make me into a new shape. First, you move me into the corner with your eyes. I bow to you until I am a crouched blanket with a sword in my stomach. You roll around for a break (well earned), then pull at pieces of me until I am a wooden swan, thin and shivering, a wrinkled hand, flexed, a single finger, curled. With a final tug, you straighten me out until I am as tall as death himself, proud with cloak and scythe. I came here sick, now I am realised.

I DON’T KNOW HOW TO EXPLAIN IT, SAYS BEUYS, THE GENOCIDE? I SAY. NO,

how to explain pictures to a dead hare? Forgo gold leaf, honey. Don’t cradle the beast. Hold its lids open, make it stare

at the stillness of a living room, bare walls acned with IKEA prints. Got it? Not the least?

How to explain pictures to a dead hare –

to respect the game’s intellect, to be fair to its status as cognisant, imaginary and deceased –hold it, lids open, have it stare

at Arbus’ twins with the headbands. Abut Maier’s jaywalking horse to Newton’s saddled woman. Capisce? God. How to very explain pictures to a dead hare.

Carry it to a dog park, wave it, flaggy, in the air. Gather the mutts. Pull out the camera. Release. Hold it! Lids open. Make that stare

fierce, bunny. Focus. Shoot. Frame the snare of teeth. Snap. Be natural, loosen up. In pieces – a piece. How to explain pictures to the next dead hare? Hold its lids open, make it stare.

after ‘How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare’ by Joseph Beuys

Fernando sits on my bed licking his paws and I’m scribbling on my walls thinking about class. His tail twitches. The chalk squeaks and screams frantically like the brakes on my rusty childhood bike that I use during the summer sometimes. I think about being poor and how I feel stupid because I can’t pronounce oven or shower or mirror; I used to practice elongating the vowels but then I got bored. Fernando licks his bum because he feels safe around me.

I draw a large swirl to represent the class system –I put the working class in the belly; swallowed whole. Bones gnawed. Myself in the wet, warm centre. Fernando blinks slowly. I think about getting fired from my job; I have no money.

(I think I have no talent but that’s the part I can’t say out loud)

I draw a tree; I scrawl art on the tree. I draw a man; I scribble money on his left arm, his right arm is wrapped around the tree.

Fernando jumps off the bed which is a shame because I was just about to explain the class system to him. Never mind. He wouldn’t understand. He’s just a cat.

OLIVE FRANKLIN

BY MARINA ABRAMOVIC

I waited decades to meet you; you had a beautiful wire face, filled a birdcage with vegetables whenever I arrived home late. I never played with dolls; I only played with shadows. Your feet felt warm like water tipping up the sides of an old tin bath.

In the calendar, each day of June is greased with red paint. Even when I work hard the gull still lurks in the foyer. Everything is coming for me. My own body weight in potatoes holds down the body that looks out to sea.

Boarding a civilian plane to Liverpool I’m leaving Belfast as Joseph Beuys says to me—Come now, stay You have a Germanic soul, and your mother she has in her an Irishness and, yes, your body. Your body, and, yes!

But Belfast wasn’t the same after Easter Tuesday. One-hundred and eighty Luftwaffe flew over the Lagan and killed nine-hundred people. And Beuys was keen for us to remember that the performance of death was more important than the death itself.

It was so easy for him to take a life. He downed our flight over the Isle of Mann on his way to talk at the Ulster Museum, to chalk himself over Belfast. His Messerschmitt sparked and scritched along our spitfire-wing. Seems like nonsense to me, he said.

Soon though Beuys was out of fuel, and landed on Black Mountain, his plane’s swastika a target to shoot out of the chalk board sky. Clouds reiterating their whiteness were lit up against a black painted night by AA guns. Landing on Hatchet Field he wrote a letter to Werner Georg Haverbeck, an SS officer and head of training for the Hitler Youth,

asking for money. It read, Our world’s world will be on the island of Ireland. I could see the dust settling over the chalkboard city. Years later, I would lie about the plane crash:

I landed like Thomas Mann on magic mountain! Beuys would have loved it, the ephemeral overcast, the paleness: I could hear him shouting across the snare drum sea—Yes, like a chalk board! Like how I imagine and how I love a chalk board to be. Just like me. Like chalk on a board.

When Jospeh Beuys shot me down over the Irish Sea, he asked me quietly: you belong to where exactly, with that body?

sometimes the line starts elsewhere, off of the page, inking its way onto white cardstock & demanding attention

an infinite black string connects haphazard bodies: bodies of water / bodies of words / bodies of bodies

strung together by association / circumstance / the inability to lift your hand & stop this permanent decree

start:

a knitting together of lives in an unnamed city

start:

a series of eggs watching with yolk eyes

start:

i made you a drawing / i turned you into a drawing / i took your edges and pulled them onto my page / you expand, boundless / you there, you reading this / see that? i just made you mine / i just made you a drawing i just made you a sandcastle i just made you purple i just made you i just made i just i

Lift a box of chalk and hear their excitement to grate, their chatter. Draw a piece: a bone, so slim and balanced, cool and spinnable, pressed between the fingers. Makes itself familiar with the fingerprints and lines. And here are four full hours of chalk painted onto greenblack. One slim bone expending into barrow, flower globe and deer. Hours of dusty mouth, of speech that scatters particles. Of muscles straining for the top of wood and wrists that imperfect the lower scrawl. Eyes, hands, mouth respond to this theatre, this scratching classroom. To the side-rubbed lines, their slow dramatics and the hard knocks that pile on matter. Lessons about goods and freedom, deer and suffer, Art and Art and Art are blooming heads.

Strange, for chalk to stay for fifty years. Strange, for glass to press against all wither, sleeves and all erasing bumps because this hand made this happen. Strange to hold your breath, though there is no need.

I am interested not only in the woman or the goldleaf but also the honey shining cruelly on her face,

and not in water but water’s evaporation transforming nectar into honey, not in home/ place but in the fragile space

between the body’s start and end. I have seen white chalk on black chalkboards creating a trinity of spirals—

I know that from father and son proceeds ghost—I imagine ghost as a sweet substance passed between them, as the forager bees pass nectar to the hive bees and they in turn to the honeycomb cell, mouth to mouth

to the mouth of the cell, and how in winter the male drones with their appetites are killed off

and the new queen bee in her closed throne of lemon and sugar listens to the worker bees slowly taking

into themselves the sweet food of her prison. In my mind the woman who has covered herself in honey,

opening and closing her mouth, eats through the goldleaf, not a queen but the golden statue of a queen.

Because san G

uine is a purple butterfly because he winged a fedora o N to his forehead like a heeling yacht because his chalk sque A ked like a church mouse because he cast po W erful spells because he was a d I va a rock star because he couldn’t help it he da N ced when he spoke and was like The Lorelei sin G ing because he fashioned swirling hooks and hung words like l O ve on branches in their minds and words like creativity and commu N ity in large block letters on large square blackboards because T hey listened in large box classrooms in large institutions because they H ad céad míle fáilte in their hearts because th E y let him speak over what they were already doing B ecause he was too too yes really he really was a l O t because only later did they know some details or they already k N ew some details but pretended and wrote an agreeable E nd to (t)his S tory— they fell at his feet like blue eggs spilled from a starlings nest cracked and oozing over ancestral stones yolks the colour of honey and gold-leaf

Back home, the good people of Ontario are resolved to not name anymore schools after P.M. J.A. McDonald. Elsewhere, statues of PM MacKenzie King lose their heads. Wild miles of boreal forest can’t silence small bones that insist on whispering, so we chisel names from stones.

No-one argues with pictures—Kelowna, BC, 1942— Get Out! Japs Not Wanted! When Pearl Harbour hits the headlines homes and citizens are seized. Twenty-five thousand Japanese -Canadians are relocated to farms, road, and labour camps. MacKenzie King writes The 100 Mile Rule—Japanese fisherman hang up their nets.

History is a flywheel spinning yarns and we try to untie what gets tangled in telling. We listen, close read our words, rescript our minds. Oh, friend, those swirls chalked on blackboards in Belfast—Look, don’t be afraid to improvise.

Enter stage right, the understudy’s been called in for you tonight. I’m naked, holding a wilted daisy. I drape it over my left breast.

Lights out

Black boxes change fast under my weight, my hand’s weighty weight.

Try stand inside one, sit on top, look past the dance I have done, here, it spells out suffering. Or maybe, something which I cannot read.

MALACHY HARRIS

Every human being is an artist. Brotherhood, love, socialism.

Dear friends, I came to speak about art as a revolutionary power.

—Joseph Beuys (various)

okay but why did he draw it on the blackboard. why did he draw it on the blackboard. gnawing spiral – spiral flyby. headline today: EVERYONE IS AN ARTIST. dear friends i came to speak dear friends i came to EVERYONE IS AN speak about art about art ARTIST art speak about art as a revolutionary art as a revolutionary as a revolutionary power. EVERYONE IS dear friends AN ARTIST revolutionary came to BROTHERHOOD. LOVE. SOCIALISM. power. BROTHERHOOD. LOVE. SOCIALISM. this just in: the pretend communist ex-nazi who hangs out with other former nazis has become an occultist. shocker. this just in: the pretend communist ex-nazi who hangs out with other former nazis is having coffee with yeats. this just in: the pretend communist ex-nazi who hangs out with other former nazis is out drinking with o’duffy in temple bar / is marching in spain / is writing in the united irishman. read all about it. gold leaf. EVERYONE IS BROTHERHOOD revolutionary friends i came to art LOVE. why did he draw it on the blackboard. earth new planet (my planet). love heart. winky face. dotted eyes. SOCIALISM dear SOCIALISM. why did he draw it on the blackboard. friends i came to LOVE art. EVERYONE EVERYONE EVERYONE so why did he draw it on the blackboard. why did he draw it on the fucking end dash – tree of life – fedora – (my planet) – blackboard. power BROTHERHOOD. the pretend communist ex-nazi is meeting me in the middle he says. hanging out. let’s get coffee. a drink. there’s a new spanish restaurant in the centre of town. someone stop him. hands reaching out running against my back hairs. too close. too close. too close face pressed against stop / stop / stop / stop / stop / stop / go / reborn in fire EVERYONE IS AN ARTIST. glitter on my

cheeks. blood in my eyes. violence begets violence. repeat it: dear friends i came to speak about art as a revolutionary ARTIST LOVE SOCIALISM. BROTHERHOOD. LOVE. SOCIALISM. BROTHERHOOD. ARTIST BROTHERHOOD. SOCIALISM BROTHERHOOD. BROTHERHOOD. BROTHERHOOD. BROTHERHOOD. POWER.

NOEL HOWLEY

(Five blackboards at The Ulster Museum)

Not whiteboards or flipcharts

Not PowerPoints or slates.

Maybe an exclamation point or mark.

To begin again. The nuns hold all the secrets, are content to let us have them one by one. Draw an A on the board, in chalk, that might be rock art 30,000 years old. Or am I exclaiming another world?

A Time Tunnel in black and white, or in rusted steel The Matter of Time. Richard Serra’s torqued spirals always falling over, always holding fast between Torus and Sphere.

On a sun filled day you can see Democracy if the art is clear enough. I cannot lie. The gallery filled up with pupils; their golden scarves held my eye.

Omphalos, ombelico, ombligo, umbilical, or just plain old belly button of the modular man. Some ideals need money to make them work.

Down the long stairs, concerned about the head height. Another one: a simulacrum of differences, a sacred object for display.

You know nothing of Beuys. The 8D bus isn’t due for 45 minutes, and a walk through the museum will keep you dry. You make yourself visit the museum every now and again to pass yourself with friends who take art seriously.

In Room 4 you look at mounted blackboards. You think back to your schooldays when blackboards were filled with ideas to wind your mind around. And how the duster flew across the classroom when a teacher lost the run of themselves.

You pause at a collection of black and white photographs. You steady yourself. You see yourself looking back at you. You raise your phone and take a picture of the photograph in the cabinet in case your eyes are making a liar out of you. There is a second photograph. A man with long hair and glasses, holds the ring finger of your left hand. Not the man who walked you down the aisle.

You think about the good sitting room in your parents’ house. In the glass display cabinet, sitting pride of place, is the same baby picture of you. And while your parents frequently recycle the story of the fire that destroyed the family home and the photographs therein, you’ve never stopped wondering why aunties, or grandparents, or even a far out relative or neighbour had no photographs to offer.

You take yourself to the café and sit beside the floor to ceiling windows as rain batters the glass. You imagine your parents faces as you show them the pictures on your phone of the photographs of you in the Ulster Museum taken on 18 November 1974. And you wonder what story they will tell to explain this away, to assure you that you really were born on 25 February 1975, as documented on your birth certificate.

You always believed your parents to be low in imagination, not inclined towards fiction or film. Now you wonder if they’re more creative than you dared imagine. You wonder what kind of artists they might be.

You walk out of the museum onto Stranmillis and stand in the rain.

Unsure how to get home.

after Sandra Johnston

Take butter, take sugar, take bell take rope, take newspaper; sift, spread, pull, grease the rope with newspaper and by hand, stand barefoot, stretch the rope tied to the clapper.

Pull—clang, pull—clang, pull—clang, pull—snap!

Rope breaks free then flatlines between Sandra and Ricky until cracked back to life it whips the floor with more lashes, more lashes, and one more.

Carefully they carry the sodden white sheet and lay it down, pressing, smoothing, pushing in the pale white thoughts of their making, taking me with them, in a way J.B. never could.

And when he said in ’74, “I sleep so well here…”

Even so, I like the sound of his chalk on the board more than his obscure white lines on black, find nothing lacking in the long shadow of the shaman-

showman-visiting-live-action-man who fifty years after the fact led me to Sandra making ‘art’: her watch on the coffee table, a magnet from her mother to ward off anxiety with the power to stop time, set down as she talked about Beuys.

I felt a catch in my throat, slipped back to my student days at the school of art as Sandra’s voice cracked too at the sweet retelling of her interview when the artists crouched over her work, kneeled for a closer look and she knew, she knew.

After Käthe Kollwitz (1867 – 1945), Die Freiwilligen (The Volunteers)

Solid in her hands – she smells the pear wood ripe for cutting.

No umber strokes of etching, no blurred and softened lines:

a mother’s body aching for steel knives. Scalpel gouges

prime timber as she scorps him from grain: toy drum

around his neck, eyes blank as spent shells, boy snagged

on trench wire of a war she did not mark. This, her shrift, scratching

him alive, fingers braille wood and ink seeps through a shroud.

An Ekphrasis Project by the Seamus Heaney Centre at Queen’s in collaboration with the Ulster Museum