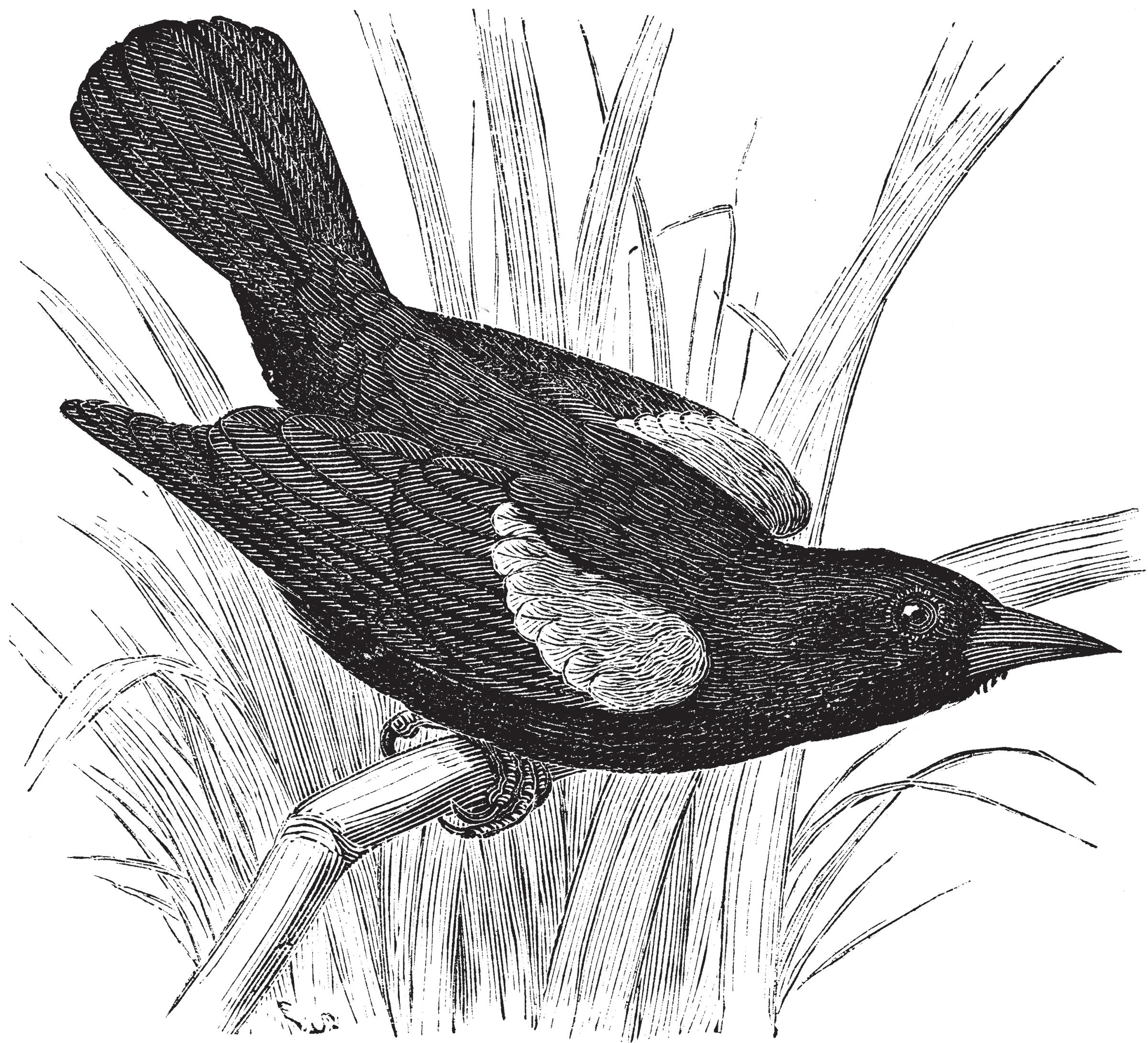

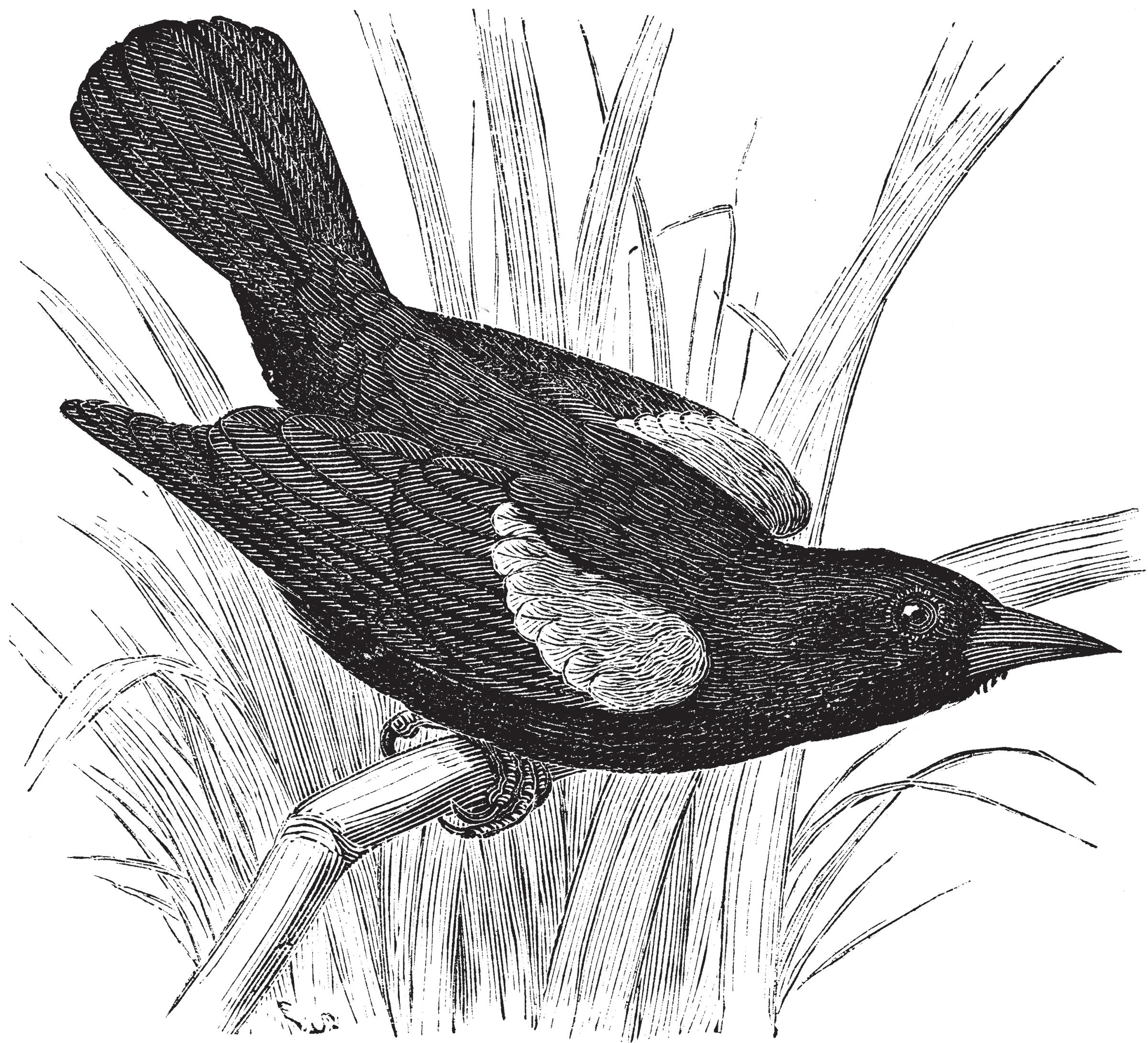

BLACK BIRD

An anthology of new poetry and fiction by graduates from the Seamus Heaney Centre at Queen’s, 2022 Guest edited by Wendy Erskine and Denise Riley

1

2

Wendy Erskine and Denise Riley are supported by the editorial team: Suzi Bloom, Dara McWade, Rose Winter, and Publishing Fellow 2022, Dr Hilary McCollum.

Dr Sam Thompson Lecturer in Creative Writing

In October 2003, walking to work on his first day as director of the newly-formed Seamus Heaney Centre, the writer Ciaran Carson saw a blackbird. As he later told the story, the bird was ‘scuffling around in the shrubbery’ on University Square, and it started a small cascade of inspirations: Carson, reminded of an Early Irish poem known as ‘The Blackbird of Belfast Lough’, which Heaney had once translated, was moved to make his own version, and in doing so he found a fitting symbol for the new enterprise he was to lead. ‘There are,’ he said, ‘to paraphrase Wallace Stevens, at least thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird; and the blackbird can be heard in many ways. Poetry resides in that ambiguity, and that is why the blackbird has been chosen as the emblem of the Seamus Heaney Centre.’

For two decades that bird has been a faithful spirit for the Centre, and the cascade that began with Carson’s glance into the shrubbery has not ended. The Seamus Heaney Centre has flourished as the home of poetry and creative writing in Queen’s University Belfast and as a hub for a wider creative community, where all forms of literary practice meet and converse: poetry, fiction, playwriting, screenwriting, memoir, translation, literary criticism, song.

This anthology showcases some of that creativity. The poetry and fiction that follows is the work of students on two taught postgraduate programmes, the MA in Poetry: Creativity and Criticism and the MA in Creative Writing. The MA courses are vital to the life of the Centre, being populated by dedicated, eager writers who, while they may only study formally in the Centre for a year, will always afterwards belong to its community. The anthology owes its existence first to these writers, but also to Denise Riley and Wendy Erskine, Seamus Heaney Centre Fellows for 2021-22, who took on the difficult task of selecting the pieces you can read here, and to the staff and students who produced the book. As is the way of the Centre, all did their parts to carry writing from the solitary place where it begins into the shared enterprise through which it can be heard.

3

Editor’s note — Wendy Erskine

Editor’s note — Denise Riley

Clare Watson School Days

Akshay Anilal Sreeja A Solicitation in Writing, To Be Burned Afterwards

Morgan Ventura Leathem Demi-Requiem in Violet

Sorcha Ní Cheallaigh A Christmas Scene and Meet the Wives

Joseph Scott Wrath

Alanna Offield I Bring Nothing to the Table

Fiona Anderson Buyer Beware

John James Reid Serpentine

Matthew McGlinchey The Helicopter and Clementine

Jamie Anderson Catholic Guilt

Eimear Lugh Devlin Shepherd

Viviana Fiorentino A New Language

Helen I. Brower Daytime Coyote (extract)

Conall McGuigan Blanket and Transparency

Megan McGarrity Yellow Pig

Gianna Sannipoli Lovers On Different Tracks and The Right Reasons

Maggie Doyle Bridges of India and Heartbeat on Palestine

Michael Hall Judgement

Eoghan Totten Transatlantic and AI Paints Cityscape at Night

Fionnbharr Rodgers Fleamarket Symphony

Eoin Kelly Pup

Chris Wright Invisible Ink

Charlie McIlwain Swerve

5 Contents

Artist Biographies Page 6 7 9 13 14 15 17 21 22 26 27 30 35 36 37 43 45 48 50 52 55 58 59 60 62 63

Wendy Erskine Seamus Heaney Centre Fellow 2022

These stories are significantly different in terms of focus and tone. We encounter derelict streets and drug-dealers; children playing spygames; phantasmagoric bar scenes; houses for sale; anger; memory; regret; humour; angst; fun. Illuminating and vivid, they are, whatever the subject, full of emotional enquiry. All of them allow the reader to enter worlds which are carefully realised and often unexpected. I hope reading this selection proves to be a satisfying experience.

6

Denise Riley Seamus Heaney Centre Fellow 2022

The editors-in-chief of the Blackbird Anthology will be heartsick of this obvious Wallace Stevens joke; my only excuse for trotting it out is that, for a while, exactly thirteen MA students had sent in work. When I’d selected one or two poems by each of our final fifteen writers, I wondered what if anything there might be by way of linked sensibilities, or traces of any common ancestry of reading? Studying the passages from each contributor that had most struck me, I made them into a composite document, then [respectfully!] massacred some to fit my allotted word count. But yes, I’m left wondering how to answer my own questions. Meanwhile I’m finding great pleasure and interest in trying – for which I’m so grateful to these student writers.

‘Fifteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird Anthology’

1

Words too big for the room.

2

He’s not here, she’d lie, moments later, taking us children for stupid. He’ll never come back, she’d say, as yellow headlights retreat further into suburban darkness, fractured, pixelated by snow.

3

O come and behold the unstirring child undisturbed by cattle or human form. There will always be room in the manger where there is never enough food to feed.

4

We speak of the nothing your mother served for special occasions, a favourite of your father’s. Through him, you developed a taste for nothing.

5

It abuts its clay neighbour, grounded in layered silence, while its fancy friend poses for serious attention. The bold creation invites a popular photograph; its translucent womb covered in cappuccino cream.

6

We talk about the future drinking mint tea on the kitchen floor, when to get married, what jobs we want, how to not feel sorry for leaving friends behind in a flash.

7

7

I’m no stranger to the dead. I was born and bred to jump on rusty gates and play in muddy fields where my dad’s sheepdogs are buried. I was raised to shake my arms and shout at birds if I see them skulking around the lambs who wandered too far from their mothers.

8

One late March morning, we shed our skin under the sun and a flight of an oystercatcher, a stagger of a wing made us look at the grey blue sea

9

Moonlight makes a different gas alive out of animals who respond musically to the failing light.

10

Wrong and violent is the man who looks into pleading eyes and sees nothing but his own reflection.

11

A grand entrance with a red fanlight door, a black bike in the hall going nowhere

12

We look for the hint of mauve in Hopper’s Night Windows from our lovers, just visible, encased in lemon chiffon.

13

Now on an idle Sunday, Cynthia Keening, 80 years young, picks up the thing, and really likes the look; asks ‘how much?’ but talks and talks a while, before anything goes down in the book.

14

Look how the foxes patrol along the flat of the wall, then disappear through the gap in the viburnum. And how the pup follows, almost exactly.

15

It is near enough to knowing

there are others. Love them.

8

SCHOOL DAYS

What could I do to stop it happening tomorrow? What did everyone else do? Bring a note in? A letter explaining. No, I saw how that went. She would hate that child even more. Snide looks and cutting jibes all day. Breathe. Perhaps I could distract her, somehow. Her favourites did that. Breathe. Telling her stories, bringing things from home to show her, but it was different for me. Breathe. She liked them. They were clever, lived in big houses, wore fancy clothes and had flash cars.

My hands prickled. I was so confused. What could I bring into school? If I could think of something, she’d at least have to feign interest in it. There had to be something. Flowers? Photographs? My jaw began to release its grip. Maybe. Photos of what? Shoulders gradually descend. I’ll grab something from the album in the morning. Anything. It would force her to say nice things. To be kind to me, even for only a split second.

Breathe out. Releasing, relaxing, softening shoulders, loosening jaw. There’s a growing feeling of relaxation, a mellowness taking over. A soft, limp feeling in my body. A slowing down, disengaging, calmness. Candy clouds in a bright blue sky. Green pastures filled with grazing sheep. I am the master of my imaginings. My mind is finally quiet.

We had moved house 6 times in as many years. Each time it was a great adventure. But each time it meant leaving the streets I’d become so accustomed to and the new friends I’d made. Crying in the makeshift tent, a sheet flung over the washing line, I told Pamela we’d keep in touch, maybe even write to each other. It was unlikely we’d see each other as we went to different schools and the new house was 21.4 miles away, according to Dad. My parents made sure I remained at the same school; that way the upheaval wouldn’t be so unsettling. Even if it meant a longer journey back and forth, I’d still have continuity of school friends and comfort of familiarity. I concluded that a lengthy journey was preferable. It prolonged the dreaded arrival. It also meant more time in the car to revise everything we’d worked on since getting home from school the previous afternoon.

We were a team, me and Da. He sat night after night, finding new ways to help me memorise huge quantities of homework freshly distributed. He wiped away my tears of frustration, distracting me by humanising the monster in my head.

‘She’s no better than any of the rest of us,’ referring to the teacher. She’ll have the rollers in and the teeth out. Don’t think about it anymore,’ he’d say ‘You’re just putting yourself through it twice. She may even forget to ask you. It mightn’t play out the way you think.’’ I’d eventually traipse to bed, where my brain would begin again, imagining the worst anyway.

Getting out of the car at the school gates, screamed for extreme pluck. The moment I knew I’d be on my own, no longer wrapped in the protective layers he warded me with. The heavy imprisoning doors looming ahead, would seal my fate for the next six hours. It never got any easier. I’d take a deep breath, grimace, and soldier on.

9 CLARE WATSON

* * *

‘Atta girl. You can do this,’ he encouraged. ‘Remember she’s normal, like you and me. She’s probably already spilt the cereal and forgot the ham for lunches this morning. What time is your English class?”

“After break.”

“Ah, she’ll have forgotten by then. You’ll be worrying for nothing; she won’t even ask you.”

‘But what if she does?’ I whimpered. He said he’d wait in the carpark, and we could go over it again together at break time. A wave of relief flooded over me. Not on my own just yet.

From the classroom window I spied the pea-green Fiat, comforting from a distance, my protection. I was brave with Da nearby. Pulling the old photograph from my school bag I watched for my moment; after prayers but before work began. There would be others ploying too. I needed to get to her before them, because she would often draw close to the line of waiting children and begin the day’s work. I saw my moment and took it. Only one girl in front of me. I hoped the story wouldn’t take long. She was equipped with a pile of leaves, collected for the nature table. They were well received and spread out for others to view. My turn, I held up the photograph. It didn’t seem interesting anymore, but it was my only chance.

“It was my cousin’s wedding,” I meekly mumbled. ‘I was the flower girl.’ It trembled in my hand. I tried to steady it. She leant in to look, not touching. Strangers standing on the steps of St Joseph’s Chapel. Me, positioned to the side, a basket full of petals over my wrist and donning the pink satin dress my aunt had made. I was sure her head nodded slightly, as she said ‘lovely.’ She swivelled, headed straight to her desk and work began. I was happier knowing I’d been responsible for putting her in better humour. Everything would be fine now.

We followed the usual routine. Roll call first. Surnames only. We were addressed as ‘you’ or ‘girl’ the rest of the time. My da always joked she’d be no good at the homework as she can’t even remember our names. At the same time every morning, the caretaker would enter and set a cup of strong tea and a biscuit on her desk. It was calm then. We worked from textbooks as she looked down on us, China cup stained with red lipstick. The scratch of pencils and the smell of lead. The permeating tick of the clock. Beady eyes nervously stealing glances to the second hand. Waiting. willing, watching. And there it was, the break bell. Doors were flung open. Screeches and hollers of ‘Who’s on it?’ and ‘Dip, dip, dip…’ as a tangled mass of girls flooded into the yard. They synchronised to form a circle, shoving scuffed shoes together in a bid to decide who would be ‘It.’ The squeals faded as I made my way in the opposite direction. Much as I wanted to join them, I made my way to rehearsals again in the Fiat.

With arms folded she awaited our return. Meekly we scurried past and resumed positions. Frozen stillness followed, in anticipation. It was the same every day. No one wanted to be asked. No one dared move. We stared, steely, like children caught in the headlights, not wanting to look, not wanting to look away. Exuding calm on the surface, burrowing frantically below. On the inside, each of us was fervently praying to God that she would ask anyone else.

The only movement was the shaking limb of the child to my right. Thumping loudly with back foot on the floor, warning the others ‘there is danger.’ I willed her to sit still, she was too revealing. An age passed as the hunter stalked the room. Heads down, eyes fixed, not wanting to see, or be seen.

10

Click, click, silence, click, click, silence. Pursuing. Subsequently, her voice, “You!” shooting through the still. Relief for a split second dashed by the nudge of an elbow. My gaze raised on the glowering predator. In a room full, why me?

I prodded my chest, querying incredulously “Me?”

“ Does it look like I’m asking anyone else?”

Wincing as the metal chair legs scraped across the tiles, I stood. The voice within rallys ‘you can do this.’ But the voice outside betrays me with a squeak. A false start. Heat travelling from my neck to face. I could feel it, red.

“Is there anybody there?” she sneered, prompting me with the first line of the poem I had been trying to memorise. A deep breath and I began rattling. My second start.

“‘Is there anybody there?’ said the traveller, knocking on the moonlit door, as his horse in the silence, champed the grasses of the forest’s ferny floor. A bird flew up out of the turret…” The words tumbled out all on their own. Imprinted in my brain even though I had no understanding of what they meant.

“...But no one descended to the traveller; no head from the leaf-fringed sill leaned over and looked into his grey eyes, where he stood perplexed and still…” I was going well. Feeling more assured. He was right. I could do this.

“And he felt in his heart their strangeness, their stillness answering his cry. While his horse champed the grasses of the forest’s ferny floor. A bird flew up out...”

“Stop!” Shot in mid flow. Bang, the ruler against the desk. I started.

“Haven’t you already said that?” over-enunciated. Petrified, my stony brain couldn’t understand. Confusion taking over. What had I said? trying to recall my last words. Had I written it down wrong? Had I learnt the wrong lines, or had I said the wrong thing?

“Well?” Did she want me to answer her? Should I say something? I could feel myself shaking. I glanced round the room for answers in the other’s eyes. Empty. What was I supposed to do?

“Bring up your book.” Her voice was quiet and calm. Oh God! Breath suspended. Clambering out from behind my desk, I weaved through rows of burning eyes, book in hand. Rancorous red nails snatched it from me with disdain. Studying the words on the page, she transitioned before our very eyes. Smudged mouth upturning, furrows set, eyes squinted and threatening. Wide flaring nostrils distorting her whole face. A ruddied fury awaking and travelling through her. And here she was, the monster I had imagined. Hoisting the book high in the air and with fervent force, she flung it straight for me. An instant sting as it whacked against my arm and thudded on the floor next to her desk. The throbbing began.

“Pick. It. Up!” she hollered. The room flinched, resonating ears. There was a whimper from somewhere within. My tears intensified but I fought to hold them back, to show no weakness. I bent to lift it from the floor. Before I knew what was happening, she was close, my ponytail bound around one fist and the book in the other. With scalp burning, and a blur of tiles flashing past, I was dragged across the room towards her desk. Bent over, shuffling to keep up, gaze fixed on the ground, evading my humiliation reflected in all eyes.

Broken strands of hair fell to her desk as she let go. I retreated, aching, finished. But she wasn’t done with me yet. She opened the book on the splintered wooden surface and signalled me to come closer.

“Look at it!” Edging in, I felt a sudden force from behind and heard the thud. My forehead had been shoved into the desk. The pulsations began, battering from the inside,

11

aching to get out. The familiar burning as she jerked me back up using my hair as leverage. Bang! Down went my head again. I screamed, unable to keep the fragment of wood slicing into the middle of my forehead, to myself. As she pulled me up by the hair, I glimpsed the gawping faces through a haze. What were they thinking, seeing me like this? The girl who was dumb, not smart enough. Relieved it wasn’t them? Horrified faces. A gasp, was it from me? A warm trickle travelled and dropped from the tip of my nose, dripping red on the white page. Dead. She’d surely kill me now. Blood on my pristine exercise book. I hunched my shoulders and ducked my head waiting for the next blow to power over me. Expectant. But there was nothingness. I read the eyes of the children in front of me. Could they see what I couldn’t? A breath from behind. Cold chill on the back of my neck. She was too close. I staggered forward in a dazed attempt to escape. She lifted the bloodied book from the desk. Puce now, rage bubbling. Hurled it. It smacked against the painted wall in the far corner of the room, behind the door.

“Stand there until you know it!” She said, screeching with veins surging. “Turn around! I don’t want to look at your worthless face.”

Between the stench of the bin and the peeling walls my empty body, with weighted head, sapped. Finally permitting the eruption of warm salty tears from my inflamed eyes. Soundlessly sobbing, silently shaking. My scalp tender and stinging. My forehead jagged and stabbing. Constant banging inside my head. Brown drying blood wiped on the back of my hand. The overwhelming, mortifying sense of a room full of eyes boring into my back.

“Right, who’s next?” Click, click, silence.

I was quiet on the car journey home that day. He’d asked me how it went the moment I got in. But I think he knew.

“Forget about now. It’s done with. Tomorrow will be better.”

At the end of every school day, I emerged with her warning, “Woe betide anyone who puts a foot over my threshold tomorrow not knowing this!” etched in my bones; traumatised, because I knew she meant it.

And so, it began. All evening, learning a new list of words, prayers, or poems. Agonising at night with compressed, compacted limbs and a clacking, clenching jaw. Nausea rising from the pit of my stomach. I could never sleep…

12

A SOLICITATION IN WRITING, TO BE BURNED AFTERWARDS

Rain, inquiring fingers, the traffic lights are all red. A wave crashes into shore, your lips drain away from mine.

A long breath, a mighty heave, a hand adrift in plain air, a love story in four words Stay for a while.

You tilt your head back,

a world

slows down. Thunder, it’s storming, there is laughter, so soft it’s a secret.

It’s a little brown book of revelations of our own.

The click of a lighter, a promise You will watch me burn the cigarette, truncating, a long word abbreviating with every drag.

Words too big for the room. There are four walls. It might seem like a prison. It’s not, it’s a city, walled in.

Together we shall listen to silence tell stories of green carnations that went up in flames

You will travel there and wish to have started the fire. I will hand you the flames and wish to be the city that burned.

13 AKSHAY ANILAL SREEJA

DEMI-REQUIEM IN VIOLET

In the evening light it all shivers purple, bruised porcelain. My father outside in the snow, calling, and my mother answering him, shrill voice drowned out by Christmas tunes

He’s not here, she’d lie, moments later, taking us children for stupid. He’ll never come back, she’d say, as yellow headlights retreat further into suburban darkness, fractured, pixelated by snow.

The utter whiteness unsettles me, pallor grasping for something to hold on to but emerging a starved corpse.

The flowers on the table wilted that evening as my brother poisoned himself with my bottle of glue.

I named the flowers Violet and Violet because they were violets.

What golden abandonment, what technique of memory, engraves grief into violets!

Every Christmas I relive it all, hide my art supplies, and kill my floral arrangements.

This is generosity, I think, opening my blinds, as my grandmother’s ghost lingers in the background.

The lights in the distance transmute yellow to purple. They are too close to comfort.

14 MORGAN VENTURA LEATHEM

SORCHA NÍ CHEALLAIGH

A CHRISTMAS SCENE

after Wendy Cope

A figure cut from ice remains planted asleep in the crib. A distinctly grown babe, five foot five and a half with shuttered eyes sculpted never to say “see?”

Maintained figures were once found to attend the scene in droves, but year by year declined the invitation. The babe must be birthed alone. Immaculate without a host.

O come and behold the unstirring child undisturbed by cattle or human form. There will always be room in the manger where there is never enough food to feed.

15

SORCHA NÍ CHEALLAIGH

MEET THE WIVES

A housewife is an acquired taste –part-volatile, part-delusional, and equal parts unhinged – devised to embrace discomfort with a mouth formed in silent screams:

I don’t want to get old. Rooted in holy matrimony, a decree to marry the bank secures rapid affairs in the south of France, assured that no husband could ever leave.

It’s just money, she announces to the bankruptcy court following a divorce proceeding documented by John John Kennedy and Madonna.

Lost, she finds Jesus and takes him to Target. He is disorientated by the range of hand creams specifically for stigmatists (with SPF).

She will skin herself through the needle’s eye, despite each currency licking the ear of a willing host. It’s just money, despite all intents to the contrary.

It’s just skin and loathing –despite the deposition. A sanguine face like a pizza pie peers through the monitor, lost betting against someone else’s muse.

Exfoliated raw in preparation for the next reality-star-in-waiting: if you don’t like me acquire some taste.

16

WRATH

He lives in the backstreets about fifteen minutes away from me. The terraced houses all look the same. Derelict. Windows and doors are covered by an ugly brown metal with a red number painted on them. The metal windows are decorated in white writing that reads, PSNI OUT, TOUTS OUT, DECKY NLR, the usual rubbish.

His house looks like one of the few that actually has a person in it. The once orange bricks are turning black, the plastic gutter pipe has snapped off at the bottom, and a little river of rainwater drips onto the street. His white door is black at the bottom, and his blinds are only open halfway, like he is trying to block out the sun from this rainy overcast day.

I sit in my car and watch. The radio has weatherman Frank on. He’s telling me how Stormont is still empty, and how this June weather is unusually cold for this time of year. I turn on the heat in my car. The condensation fogs my view, so I roll down the window. Still nothing. He’s not leaving. I check my phone to see twelve missed calls from Paul.

My eyes meet the little Jesus crucifix that dangles over my rear-view mirror. My thoughts go straight to him, and something inside me takes control. I open my car door. The squeak of it is the only sound the street makes. The rain beats me across the face as I walk up to his window. Someone is in there, but it’s hard to tell. The windows haven’t been cleaned in God knows how long.

I walk to the door and wrap on the letterbox.

No answer.

I place my hard on the letterbox again, worrying that if I wrap it any louder it will fall off. The thing seems to be just about hanging on.

The door opens.

He stands there, white T-shirt, grey joggers, a face like a brick.

‘You alright love?’

Love. It seems like once you’re over 40 everyman thinks he can call you that.

‘Aye,’ I say.

‘Your name?’

‘Deirdre.’

‘How’d ye hear about me?

‘Steven.’

‘Wee Steven?’

‘Aye. Wee Steven.’

He steps aside. This must be his way of inviting me in.

The weed hits me straight away, up the nose and to the back of the throat. His hallway has black marks all over the floor, like no one uses the door mat to clean their feet, but I do. He smiles at me while I do so. In front of me is his staircase, coated in a dark green carpet that looks like if you walked on it, it would make a soggy sound. He opens the living room door and holds it open for me.

17 JOSEPH SCOTT

The living room is nice, you can tell this is where he puts his money. An L-shaped sofa, a flat screen TV, far bigger than anything I’ve got.

‘Drink?’ he says.

‘I’m ok.’

My eyes look up to the celling as I hear the creaking.

‘Someone else here?’ I say.

He returns from the kitchen holding a can of Coke Zero. ‘Aye, my son.’

The thumbing of feet running down the stairs, gets louder and louder, until the living room door busts open.

The son stops in his tracks when he gets a look at me. He’s a young lad, maybe sixteen, my eyes go straight to his feet. Bright blue football shoes.

‘Right?’ he says.

‘Hi.’

He walks over to the cubbyhole and starts looking for something.

The man stares at me sipping his Coke Zero as if he can see straight through me.

‘So how do we do---’

‘Wait till he leaves,’ the man says, his voice firm, controlling the room. His son pops his head out of the cubbyhole to look at his da. His da nods back at him, and his son goes back searching for whatever it is he’s looking for.

He comes out with a football.

‘Later,’ the son says.

‘Later.’

I walk to the living room door and hold it open for the son. As he walks past me it’s like he slowed down just to stare at me. He has the same brown eyes as Steven, and for a moment I thought it was him. It took everything in me not to reach for his hand. To pull him towards me in order to double check.

The idea of this man having a son makes me sick, I think about if my little hands could wrap round his neck. Could I squeeze tight, watch as he fights for air.

‘Yo!’

I snap out of it, he’s looking at me like I have two heads, me standing by the open living room door staring out into space, his son, now long gone.

‘Take a seat,’ he says.

I do so.

‘How much ye got?’

I open up my handbag and take out my wee coin purse that Paul got me last Christmas.

He snatches it off me and starts looking through it. He takes out two twentypound notes. Then hands me back my purse.

‘Wait here.’

He leaves the room, and I can hear him walking upstairs. I can hear the creeks and cracks along the floorboards as I sit and look at the TV that’s casting its black reflection.

I can’t help but wonder if this is where Steven had sat, how many times has he been here? Is this where he did it? Or did he go somewhere else? I don’t even know how it got a hold of him. One day when he was about seventeen, Paul was smacking him about. I screamed for him to stop, asked what he was doing, he told me he caught Steven sniffing

18

lighter fluid. As the years went on it just got worse between him and Paul. The arguments started getting violent, even football wasn’t bringing them together anymore. The day before his birthday I found Steven about to head out the door, he claimed he has had enough. I begged him to stay but he told me he would be ok. He promised.

If I was lucky, I saw him maybe once or twice a year. His hair would be long, his eyes would struggle to stay open, he would say little, but I was glad he was home, I was glad he was safe. He was a handsome fella, all the girls liked him, he was a wee wiz at I.T. When he was younger, he said he was going to go to university and get a degree. I told my sister about that every chance I got. First one in the family to get a degree I would say, she would nod, while sipping on her cuppa.

My next-door neighbour came to me one night and said that her and her husband had seen Steven sitting on the street. I could feel my chest getting heavy and the tears were begging to come out of me right there and then. When Paul came home from work, we drove around all night looking for him. Eventually found him outside a Paddy Powers with some girl. They were sitting outside, a blue sleeping bag between him, cardboard on the floor, with his black hat laid out in front of them with about three quid inside it. I begged, I screamed, Paul at one point had to take me off him, because no matter what I did, he wouldn’t come with me. Said he was fine.

I searched for help, everyone telling me its not my fault or they will get him off the streets, but it’s not just getting him of the streets, it’s the dealers. Get the dealers off the streets I would tell them. They would sit behind their desks and nod. Paul would try his best to comfort me at nights, his work shirts would be soaked with my tears. He’s just not at the stage where he wants to get help, he would say.

Sometimes throughout the year when walking through town I would see him. Sometimes he looked nice, sometimes he had a black eye. He would never tell who or why, but the thought of someone hurting my wee man. It broke me. The girl he was with always told me she would look out for him, but no harm to her, but she could barely walk when I would see her.

I myself got help. Help is all I wanted for my wee man. Some help, but they seem to like to separate the mentally ill and the addicts.

The last time I saw him he was sitting outside McDonalds with that girl of his. I just left Primark and I offered to buy them some new clothes, they said no, of course. I didn’t want to leave them, so I offered them some McDonalds, with that they both looked at one another.

I ordered three big Macs, and we sat near the window. I told them, they could stop by for dinner tomorrow, I was making a Sunday roast. He said he would stop by and that he loves me and his da.

They never showed up for dinner and two months later he was found dead outside the Grand Opera House. I couldn’t listen to the details, but Paul knows all. The whole family came to the funeral, the girl who he was with came too, and soon she would be gone. Paul started drinking more, and one day we had a fight too big to come back from.

I’m still getting used to living by myself. I’ve got tons of time to search the web. It’s becoming my escape, whether that’s a good or bad thing is yet to be discovered.

Everyone is on Facebook, I recently just got on it, got myself eighty friends on my first day. My sister has over two thousand. She always has to be number one. She shared something with me. This man named Frankie was getting blasted for selling drugs in our community. Had to move house and all because people were throwing bricks at his windows,

19

and writing DRUG DEALERS OUT on his door. That didn’t stop people from finding his new address. That was shared on Facebook too, for all to see.

The living room door opens again, the man is standing there with a little seethrough bag of heroin. He places it on the table in front of me.

‘You can do it here if ye like or go somewhere else.’

The truth is I don’t know what I’m doing here, I don’t know if I’m looking for someone to blame. But I do wonder if I have the strength to smack him across the mouth, if I could knock out his little yellow stained teeth, if I could stand over him and watch as the teeth fly across the room. I wonder if I could grab his brick head and smash it against this coffee table, I wonder if I could do it all. Then simply leave.

20

I BRING NOTHING TO THE TABLE.

I set the plates and cutlery just so. I polish fingerprints from a glass. I fluff the flower arrangement for no reason. An alarm rings, and I bustle to the oven. The nothing is ready and best served hot. With mitts on, I take the bubbling nothing to the table to rest. I carve the appendages first; then, I crack the sternum so the nothing lays flat. I plate and garnish. Serve and smile. You mumble your thanks and say the nothing smells wonderful. I say a blessing, thanking God for what we are about to receive. I watch you take a bite of nothing. I see you politely dab crumbs of nothing from your chin and dribble nothing on your shirt. We are having a lovely time. You wash the nothing down with one glass of water, then another. We speak of the nothing your mother served for special occasions, a favorite of your fathers. Through him, you developed a taste for nothing. I smile and say wow, that is so interesting. I offer you a second serving, a third. I fill you up with nothing until it all comes back up. Hot, partially digested nothing fills your throat and mouth. It fights your body like a salmon travelling upstream. It takes everything with it and makes a home in your trachea. And the autopsy will read death by asphyxiation. I will float around the mortuary, the graveyard, and the church reception hall. I will dab my tears with black lace and tell your loved ones how happy you were in those final candlelit moments, how you turned to me, in fact, and said I should bring nothing to the table more often. That you smiled and said I should bring nothing to the table every night.

21 ALANNA OFFIELD

BUYER BEWARE

After the surge of nicotine, she heard the waking birds more sharply. She hated this time of morning, she should have waited. It reminded her of student days, coming home, coming down. Or lonely early feeds with the babies. Or the alarm sounding for the cheap Christmas flight to the folks’, that seasonal excitement, wrapped in caffeine fuelled dread.

When she felt the wave of nausea wriggle then rush to her throat, she darted inside. All the blood, puke and shite she had mopped up raising the kids never left her queasy like a 5am bursting with cheery birdsong; the chaffinches were the worst. On the living room rug, by the redundant fireplace, she fought the vomit, and in a star shape, she fell asleep.

A knocking woke her at nine thirty. Peering from the front window, she remembered the estate agent sign. With little luck, the sign guy attempted to bang the post into the stony driveway. She thought she might offer to help, tell him where it had been secured before, warn him about the flimsy fence but it was too late. He nailed it to the crumbling panels and when it appeared to stand straight, he hopped back into his van. Within seconds of him racing onto the Grove, the breeze had blown it sideways and the thick, red lettered – ‘For Sale’ - was looking straight at her.

From the window she squared up to it, but she knew she couldn’t drive back the kettle of au-pair-sharing-vultures on their way; couples ready to ‘knock through’ and ‘extend out’, probing about good schools, researching cycle repair shops and sustainable sourdough deliveries, deal breakers apparently.

They had been ‘open plan’ assholes too, once navigating the thirty- something selfimportant fog of baby slinged, Swedish furniture outings to find the perfect kitchen island and the perfect corner sofa that pointed at the perfect surround sound media unit. This prompted the nausea to wriggle again. She took a long breath, steaming up the centre of the filthy bay window as she exhaled; with her little finger

GoAway

she carefully wrote ‘Go Away ’ on the condensation.

She doubted the asking price was achievable given the state of the place. There were boxes stacked high in every corner and the children’s bedrooms needed a lick of paint to cover the Tiramisu of adolescent grime and self expressive decorating. The heavily debated Year 10 mural of Kurt Cobain looked like Bjorn Borg in a hostage situation and they never got to the bottom of why the ceiling in the girls’ ‘floor-drobe’ was still sticky after ten years.

In the kitchen she scoffed at the skirtings along the back wall running up to the patio door. They were scuffed, with tufts of cat hair and pieces of breakfast cereal welded to the

22 FIONA ANDERSON

paintwork. The Saturday afternoons joyfully spent tackling them with bleach and a cotton bud were no longer, and it was clear established house proud routines had been abandoned, like the decaying bagel squatting behind the toaster, if only she could get at it.

When at last the morning traffic had drowned out her chirpy foes outside, she enjoyed the reassuring chug of the trains heading to the coast past the bottom of the garden. Ciggie in hand, she paced the mossy path down and round and up and down and round until she had smoked it to the butt. She was delighted she could still enjoy a puff.

She could see the edges of the flower beds had been darkened by the frost and gathered mulch and she tried to recall what might grow come the better weather; the rising brambles meant it was tricky to see what was stifled. She thought she spied the dead heads of her lilac hydrangea, perhaps a wilted Lady’s Mantel, she’d forgotten what bloomed. The winter had been vicious and for a second, she felt guilty for ignoring the sound of branches splintering and falling in the storms.

She stepped back onto the patchy lawn, sorry for her jilted garden. She wished she could reappear with her wheelbarrow and secateurs and lovingly tend it, like it deserved. Apologising to the flowerbeds, she flicked her ciggie butt towards the base of the suffocating honeysuckle, where a hundred other butts lay, pretending to decompose.

Linda from the estate agency arrived the next morning with the first viewers, a matching fleeced couple from Edinburgh with twin girls and a Dachshund called Mervyn. By the end of the half hour tour, she and Linda were well informed about the family fertility journey including Mervyn’s; apparently, he only had one ball but fathered a litter last Spring. They hadn’t opened a cupboard or looked for a sign of damp and there wasn’t a mention of the garden. Mervyn barked at her for longer than the fleecy pair could fathom. Everyone knew they wouldn’t be back.

The afternoon duo brought their own expertise; thoughtfully walking backwards, head bobbing and sideways inspecting empty rooms. The tall one had a measuring tape, the small one took the end of it each time they debated whether a piece of their vintage midcentury furniture would ‘fit into this tricky space.’ While Linda took a call on the doorstep, she followed these two into the garden. Smoking on the rotting sun lounger, she watched them plan an assault of her beloved beds; ideas about Indian sandstone paving and ‘simple grasses’ dotted around artificial lawn. She blew smoke in their faces more than once and they marched back through the patio doors demanding Linda explain the foul smell at the rear of the property. Linda assured them there had been no odour problem flagged at survey, explaining, ‘it must be wafting from the road.’ Everyone knew they wouldn’t be back.

Within a fortnight Linda’s head was spinning. She had opened the house to 16 couples, 5 landlords, two polyamorous relationships, a Baptist minister planning a new church and a film location coordinator looking for a ‘an empty classic Edwardian’ for a new drama streaming in the autumn. ‘Obvs we don’t wanna buy the gaff, we’d just need it for a month, tops. The cornicing is a-maze-ing! But it does smell a bit weird.’ Not one offer could be squeezed from any of them.

23

Lying on the cushion-less sofa she watched Linda, head in hand, make the call. ‘Hi yes, great. Well, nothing yet. No nibbles sadly. Feedback? Yeah, feedback has been, I mean, everyone loves the location and all the classic features, what’s not to love? Em, … yes there’s still plenty of interest but unfortunately, we’ve had a few comments about noises and smells at the property. Yes, I know, very odd. What kind? Em…well, snuffling and snoring near the fireplace in the living room and at various spots in the house and garden there have been complaints about a strong, stale, nicotine odour. Yes, I know there was never any smoking in the house and I have tried my very best to reassure any potential buyers but to be honest, after almost thirty viewings it’s becoming more difficult. No, I’m sure you don’t want to drop the price. Perhaps you can come and see, I mean, hear, and smell for yourself. Okay, yes, that suits well. Many thanks. See you soon.’

From the front door she watched Linda almost stagger with exhaustion down the driveway, straightening the wonky ‘For Sale’ sign as she turned onto the Grove. She felt guilty for not feeling guilty. Linda had no radar for vultures or the horticulture-less. When clocks jumped in March, the dog walkers and marathon masochists were more visible from the porch, her evening spot. Occasionally she saw them stop at the gate, check what street they were on and scroll for the property info on their phones. Vulture like, they would throw themselves into loft conversion fantasies, pointing at the attic space guessing what value it might add but none stepped into the driveway for a closer look. She remained undisturbed.

On Easter Sunday the Grove was quiet. With the weather unusually hot, the locals had escaped to the beach. The garden was dry and crippled, struggling to flower. She longed for her watering can. Her Azalea was ready to take centre stage in the bed opposite the greenhouse, its crimson blossom straining to be seen amongst the tangle of bushy chickweed and ivy. Curled amongst the dandelion she lay in the decimated veg patch and let a tear drop onto the drooping yellow stem of a veteran scallion.

As the light faded, she had her bedtime puff. She could hear neighbours return from their day trips. There was laughter but grumbling as parents shouted requests for help with the bags and for the picnic things to be stacked in the dishwasher. It reminded her of the sunburnt family chaos of bank holidays on the coast; the kids filled with sugar and memories.

A giggle seemed to grow nearer and without warning a head popped over the side gate into the garden. ‘I can see it! It’s so beautiful, a little neglected but someone has loved it in the past, I can tell by the planting. I wonder if they’ve had any offers, the price is good. Oh look, a ruby red Azeala.’

Flinging her ciggie butt at the honeysuckle ashtray, she ran through the house and into the driveway. The owner of the head was wriggling on a pair of shoulders struggling to hold her up. ‘That compost heap looks great. Inheriting natural fertilizer like that could be a deal maker.’

She laughed above his shaking head.

24

‘Only you could get excited about compost.’

She thought about the years of clippings and grass cuttings and all the times she had drunkenly peed on that heap to keep it perfect for the soil, for her beloved plants. She was always excited about compost. The shoulders slipped, and the head came tumbling down on top of him. They rolled and giggled until they steadied themselves against the wall, sitting crossed legged on the stony driveway. The head lifted her phone from her pocket, soil visibly thick under her fingernails.

‘Let’s take our first ever selfie at our new house.’

‘Don’t get carried away green fingers, we don’t know if we can afford it.’

‘Of course we can, we must. That garden needs me.’

With the phone at his arm’s length, they stood tall and grinning below the bay window as he snapped. It was only then she could see their t-shirts, hers Bjorn Borg, his Kurt Cobain.

25

JOHN JAMES REID

SERPENTINE

After Chuc’s Café by Zaha Hadid

The old brick Armoury and Gunpowder Store, built in 1805 in Kensington Gardens, never imagined being silenced into the Serpentine Gallery, or extended into its side garden in the shape of a white explosion; a dominant new partner standing against history.

The convolving shape, like a sea creature, swoons over sinuous walls of glass rippling with reflections. It abuts its clay neighbour, grounded in layered silence, while its fancy friend poses for serious attention. The bold creation invites a popular photograph; its translucent womb covered in cappuccino cream. I wonder about the partnership of old and new.

Someone is satisfied and smiling in the famous park.

26

THE HELICOPTER

this noise, this thud-thud, this intimacy; this space, inside / outside, this room; this repetition, this architecture, this thing; this fly, this weight, this almost every other:

this night we are lulled into the darkness. My right hand was going numb when you turned to me and asked — with genuine curiosity — what do you think

it’s searching for? You looked almost too beautiful, the blue shimmer of tv light on your left cheek, the blue light in your eyes, your awkward tone of voice.

I’ve no idea. I thought of childhood and its moments of silence, marked by these endless undulations that alternated in pitch depending on how close it is –

Ardoyne, New Lodge, Antrim Road. We turned up the volume and readjusted our bodies, moved in closer to each other trying to decide which film to watch next.

But lower and louder and almost overhead, the helicopter descended as if oscillating directly above us, minutes or seconds from landing on the invisible H on our roof.

27 MATTHEW MCGLINCHEY

CLEMENTINE

Yes, we didn’t pick it straight from a tree in French Algeria and hold it to the light, remembering there’s nothing we don’t know! Look how far we’ve come! when the evening spills on the floor and all we have left to say to each other – forget the weather, forget the overdraft and the washing up – before laughing at the bulbous clementine in your hand is “I’m sorry.”

’Am sorry love, someone two doors up says. I’m sorry. We could sleep for two weeks at a mission in Albania, recovering from the joke. The joke that got us laughing, I remember, isn’t much of a joke but something we know about a guy called Declan, who one night in the pissing rain bet he could peel a clementine in his mouth lying on the ground.

It took him six goes. Out on the street. Lying on the ground. You can imagine the state we were in – no one saying sorry or trying to talk him out of it because of the rain, far from the Mediterranean shoreline and sunlight of Algiers. Thinking about it now and all the things we know about Declan, he’ll be eternally lying on a footpath laughing.

Outside our neighbour’s pleading to get in, crying and laughing, shouting to his girlfriend who’s throwing his things to the ground. Over and over he tells her what she already knows: “’Am sorry love, I was drunk…” – “you know ’am sorry…”

All of this somewhere else in an avenue or street in Alabama. Albuquerque. Atlanta. In Belfast it’s still raining.

We talk about the city beyond the window as a history of rain, rain in gutters, rain on a bonfire, rain on a couple laughing and kissing, rain filling a cracked plant pot on Atlantic Avenue. We talk about the future drinking tea on the kitchen floor: do we get married, what jobs do we want, how to not feel sorry for leaving friends behind in a flash? For all we know

28 MATTHEW MCGLINCHEY

all we care about is love. In your mid twenties you know everything but this clementine is useless. Tonight’s rain, tomorrow’s politics, how many times he says ‘am sorry? it was raining in the capital and all we think about is laughing, whether to have kids, Declan lying on the ground… Yes, we didn’t pick it straight from a tree in French Algeria.

But you know this clementine is never trying to be sorry, somewhere in Andalusia, being eaten on a bathroom floor beside a cat where it’s raining, and people next door are laughing.

29

CATHOLIC GUILT

Cathal Doyle became aware of his Catholic guilt the first time he masturbated. He was sixteen, a bit late to the game his mates had been playing for years. Puberty hit Cathal like a sliotar in the chest, but the urge to explore his body trailed several hundred yards behind his whiteheaded spots and emancipated balls. In the changing rooms at training, he shied away from the boys when they discussed what porn they had watched the night before, or what things they had got up to with their girlfriends. From the moment a couple of the lads had pointed at his snail trail and the hair forming around his nipples and laughed, he felt marked. He was conscious of growing at a faster rate than the rest of the boys, and conscious too that sex was of so little interest to him it would have exposed him to ridicule.

Before training, he always rehearsed a response were he cornered. If they asked which girls were fit in his opinion, he would say Ciara O’Neill because her tits had come on her like two melons and most days her tie could barely hide the strip where her buttons strained against their pressure. If they asked him what porn he liked he would laugh and say that anything got him off really.

He had googled porn categories one night when he was sure his grandparents were asleep. He lived with them because his Mam was an alcoholic and couldn’t be trusted in a house by herself. The list of hyperlinks, leading their way to different sites and a plethora of videos, was organised alphabetically. It went from Asian all the way through to Young and Old. He noted with some interest that there was no porn category for the letter Z, and then an ad protesting that he might like the Squirters Club burst onto his screen and he tried his best not to throw his phone across the room.

Sex never interested Cathal in those teenage days. When he got the talk in science, a class he usually loved, about the reproductive system, he didn’t raise his hand once. The labels for the different bits were repulsive, and the illustrations even more so. His only saving grace was that he went to the Catholic school in town and the school had not condoned the display of actual photographs of the reproductive organs. He didn’t know what he would do if he were shown a picture of the vagina surrounded by a class of his peers.

He made little time for sex. He knew the moment he crossed that line with his body would be the exact moment he had really grown up. As a child, he had always been witness to his mother’s sometimes violent alcoholism, so he felt he had grown up enough. The bottle was the only babysitter he had ever known, aside from his family who had swooped in to save him one evening when his mother was caught drink driving. Cathal felt he had done all the maturing he had to. He knew the world, and how it worked. He wanted to keep whatever semblance of childhood he could since so much of it had been denied to him.

And then one weekend when he was sixteen he decided he couldn’t play pretend for much longer. Most of his mates had girlfriends, the rest of the single crowd out every weekend at parties riding rings around each other. He would have to acclimatise or he would be left behind. He loaded up the same webpage he had fled from years before, and there, in a tiny box room in his grandparent’s house, he laid waste to his youth.

30 JAMIE ANDERSON

The Catholic guilt was almost immediate. Above his bed was a picture of Jesus with his crown of thorns, freshly crucified. He had never thought much of it before. It was grotesque, but much of his experiences with faith were. Catholicism was a strange religion, he thought, much of it unpleasant to look at. He had been wary of the picture when he first moved in with his grandparents, but was too full of faith - or too fearful of a slap - to remove it from the wall. After a while it became exactly what it was: a picture. When he got up after the act was said and done, however, and saw Jesus hanging there, staring through his half opened eyes, Cathal felt the guilt like a stone in his gut. Something thin and weak within him bent and snapped. What was once a picture was, in that moment, naked and having just shred the last of his childhood, a numen. Cathal felt burnt under the painted gaze. He was laid bare, having realised that the picture was witness to the whole thing. Jesus had watched him wank.

He didn’t even know if masturbation was a sin, but he was sure that doing it in front of Christ crucified was.

His mouth was dry and he could barely speak enough to tell the picture he was sorry.

He went to sleep that night with his back to Jesus Christ, whispering Hail Mary’s until he fell asleep. He wondered had he said enough, and considered even going to confession, but he couldn’t even imagine how he would tell Father Lynch what sin he had just committed. He attempted an Act of Contrition, but he couldn’t remember it, so he supplemented the Hail Mary’s with the occasional Lord’s Prayer, hoping that would be enough for Jesus.

When he woke the next morning to shower, eager to wash away the night before, he passed the font in the hallway and scrambled to bless himself, but the font was dry. He blessed himself anyway, but found himself more mortified than purified. When his granny came up the hall, asking why he was blessing himself, he couldn’t even find an answer for her so he turned and ran into the bathroom. He could practically hear Jesus laugh his arse off all the way from his bedroom.

From that moment onwards, Cathal Doyle felt Catholic guilt for a lot of things. It was weird the things you feel guilty for because you’re a Catholic. Anytime he touched himself. If he missed Mass. If he accidentally cut someone off at a roundabout. If he didn’t tip the waitress. He felt it especially the one and only time he had sex. He lost his virginity when he was seventeen, to Ciara O’Neill with the big tits of all people. It was in the back of his car. After he had dropped her home, he had felt so guilty he drove out to the chapel, but Father Lynch had locked up for the night. Some of the candles were still lit at the front of the chapel. Father Lynch was forgetful like that. The candles winked at him like eyes in the dark. When he got back to his car, he prayed and promised God he wouldn’t have sex outside of wedlock again. Then when he got home to the picture of Jesus above his bed, he said the same prayer and made the same promise.

He worked part time in Spar. He lived in a student house not too far away from the shop, so it was handy while he was in uni. He studied Computer Science at Jordanstown. He was thinking about his Catholic guilt for having missed Mass to cover a shift in work when Lucy Deans walked in. He was standing at the milk and just happened to look over his shoulder when she sailed through the automatic doors. She hadn’t spotted him. He sunk behind an offer end spilling over with Doritos and tea bags in an effort to stay hidden from her.

31

Cathal had not seen Lucy since results day in school. When he arrived at school that morning to collect his results, having already received his confirmation for his course at Jordanstown, she was coming out of the front doors. She smiled when she saw him, and pulled him in for a hug.

Mrs. Morris already told me you got Jordanstown, she said. Well done.

Cheers, he replied, trying his best not to blush. How’d you get on?

Two As and a B.

That’s class, he said.

I know, Lucy replied. I’m off to Liverpool for History.

Cathal didn’t know what to say so he smiled. He and Lucy had been in school together since they were four. All the way from P1. They used to be friends way back when you were friends with everyone in your class, and then they grew up and found their own different cliques. She hung about with the girls in the year above. Sometimes in school he had missed her. Things were easy around her. He didn’t need to pretend the way he had at training with the lads, or with the folk he passed himself with in school. With her, he felt like himself. He had always thought she was beautiful, and didn’t feel guilty about it, either.

He crept around the corner and down the dog food aisle and hoped to nip out to the storeroom to avoid her, but as he came to the end of the aisle, he bumped into her. She muttered some apologies before she noticed him. Oh my God, she said, smiling. She pulled him into another hug. Long time.

Sorry, Cathal said. I didn’t even see you.

You’re grand. How’re you keeping?

Aye, not too bad, he said. How’s Liverpool?

She laughed. That didn’t last long. Turns out Liverpool’s a bit shit.

Really? Why?

When they tell you it’s just like Ireland, they’re right. Everyone’s up their own holes.

So you came home to folk similarly up their own holes?

It’s cheaper to live with the arseholes at home than the arseholes across the water, she said. How’re you getting on at Jordanstown?

He felt a little giddy that she remembered where he went. It’s not bad, he said and didn’t elaborate.

I see, she said, reading his shrug. I’ll say no more then.

A buzz rang around the shop which told him he needed to serve at the tills. He looked back at the line. When he turned back to her, her eyes were on him. I’ll let you go, she said. It was nice seeing you.

You too, he said. He stood in front of her for a beat too long and then turned, embarrassed. He was just at the bottom of the aisle when she called out to him. Yeah?

Maybe we could catch up sometime, she said. She looked older than she had in school, despite the fact they had been barely out of it three years. She was as beautiful as ever; he felt as guiltless for thinking so as he always had.

Definitely, he said, and then the buzzer went again and they laughed in unison.

He picked her up outside her house in town. It was reading week, and he traded his student house for his own home with its grandparents and its picture of Jesus which now hung in the backroom. She was back living with her parents after dropping out of her course at Liverpool. When he pulled up outside, she was already at the door. She let out a long breath

32

when she got in the passenger seat which came out as a soft chuckle. You still have the same car, she said.

Yeah, he said. It’s never done having something wrong with it, but it gets me up and down the road.

Fair enough, she said. He pulled off and drove out of her estate slowly, too nervous to ask what she wanted to do. When they got onto the main road, she told him she booked bowling at the Ice Bowl for six o’clock.

How does that sound? She asked. She was looking at him.

Sounds great, Cathal replied, too afraid to look at her in case she saw the redness of his cheeks.

Bowling went well, at least in Lucy’s case. When they got back to the car, they laughed at all the times Cathal had thrown the ball and it had barely made it into the arrow zone before slipping off the lane. You should have seen yourself, she said, stamping her foot. It was the best thing I’ve ever seen. The couple who were in the lane next to them had joined in on Lucy’s laughter anytime he stepped up to the line. Usually this would have mortified him, but Cathal was too intoxicated by Lucy’s energy to even be bothered by it.

He turned the key in the ignition and pulled out of the car park. He took her to McDonalds and when he asked her what she wanted, she said an Oreo McFlurry. He got the same. He drove them to the hill overlooking town to eat them. She got out and sat on the bonnet of his car, and he followed her. The sun had already set, but the sky was still refusing to go to sleep. The red sky caught beautifully in her eyes, he noted. He looked at her several times, and looked away quickly before she noticed. They spoke very little, but the silence was comfortable. It felt like how it did when they were younger; nice and easy and honest. It was not until he looked out at the chapel on the edge of town that he realised he had not felt his usual Catholic guilt once that day. Not even when he cut someone off at the roundabout coming into Ards and the driver blared the horn at him, or when he passed a homeless man without a second thought of sparing change. It had been a guiltless evening with her.

When the crimson bled to black in the sky, he looked at Lucy again. The light was low but he could see that she was looking at him in return. She smiled, and he couldn’t help but smile back. Cathal hadn’t seen her in years and suddenly, in the space of a few hours, it was like they had never left each other. They said nothing for a moment, and then Lucy closed the space between them and placed her lips gently on his. He lifted a hand and rested it on the side of her face. The skin there on her cheek was soft. He used a thumb to trace a small, slow circle. A gentle, peaceful loop. When she opened her mouth to him, she tasted like vanilla ice cream. Her hands were on his chest, his own in her hair. Their tongues met, and distantly he could feel the night close around them, like it was watching them. When she pulled away from him, he could just about make out her smile in the dark.

Would you like to come back to mine? She asked. Yes, he said, without hesitation.

They spared little time, kissing intensely as they fell into her room and onto the bed. It was dark. She had missed the light switch when she swung out her arm, and they both cared too little to go in for a second attempt. She lay down on the bed, and he followed her lips until he was on top of her. They laughed when his erection rubbed against her jeans. Take them

33

off, she said. He did his best, while she removed her own. When they found each other again in the dark, he let out a long sigh as they clicked together. He pulled off his shirt. She rolled him over and got into his lap as she struggled with her bra. Fucking thing, she cursed. Hang on.

She leaned over to turn on her lamp and flooded the room with light. When she looked down at him she smiled, but his own face was caught in shock. His hands left the place they had taken on each of her exposed legs.

Are you okay? She said. Her lips were caught in the motion of a kiss.

He didn’t have an answer for her. He didn’t even have an answer for himself. His eyes were caught by the picture that hung behind her head on the wall. It was a picture much like the one that hung above his own bed as a child, but this time Christ’s eyes were open and staring right at him. He felt that familiar stone drop resolutely into his gut. He closed his eyes, once, then twice, but couldn’t get the picture to preclude its accusation.

He pushed her gently off him and stood to put on his jeans.

What’s wrong Cathal? Her voice was soft. She reached out to him but he avoided her touch.

I don’t know, he said, his own voice short and dismissive. He turned from her but it wasn’t her eyes that burrowed into the back of his head. It was the picture’s.

Was it something I did?

No, he said quickly, bending for his shirt.

Then what?

He didn’t answer. When he turned to her again, he found he couldn’t even look at her. Her eyes were as wide and as hurt as the picture that hung on the wall. He had crucified her. He had crucified himself.

I have to go, he said, and left her house without another word.

He thought about going home, but couldn’t stomach it, so he drove to the chapel instead. He was chanting Hail Mary’s under his breath when he went to the door, as he had the night he slept with Ciara O’Neill. The door was locked, as it was then. The gravestones in the cemetery stood witness to his excommunication. The stone in his gut turned to iron, and dragged through him, tearing him apart. His Catholic guilt was a sentient thing inside him, devouring him like a lion. There were no candles still lit inside the hall when he looked inside the stained glass window of the chapel.

They had been blown out. The world was in darkness.

34

EIMEAR LUGH DEVLIN

SHEPHERD

Walking along with no destination in mind, I saw a crow crushed under the tyre of a parked car; little claws crooked at angles reserved for corpses. My jaw dropped in a parody of its parted beak. Where does rubber end and feather begin? Why had it been so close to the road? Where are its eyes?

I didn’t move. I couldn’t. I was stuck and I stared and I stayed in my head thinking what a shame what a nasty way to go I might be sick. I barely made it to the alley at top of the street before I retched up the bile at the base of my throat.

I’m no stranger to the dead. I was born and bred to jump on rusty gates and play in muddy fields where my dad’s sheepdogs are buried. I was raised to shake my arms and shout at birds if I see them skulking around the lambs who wandered too far from their mothers. I watch and protect.

I’ve seen a crow pluck out the eye of a still-breathing rabbit. Better that than one of my flock my dad chuckled when I told him, tear tracks drying on my cheeks. When I crawled into bed that night I wondered if crows even like the taste of eyes.

In the alley, standing upright, I wiped the bile from my chin and collar. I looked back down the street to see the silver gleam of that car. I decide that the next bird I see so close to the road, I’ll shake my arms and shout at it.

35

A NEW LANGUAGE

One late March morning, we shed our skin under the sun and a flight of an oystercatcher, a stagger

of a wing made us look at the grey blue sea, suspended as if the world at the back faded,

eiders on the blue and a flock of lapwings in the distant mist soared into the air as if the vaults of the land collapsed.

Starry white wings on a cobalt blue, their movements nesting a new language.

Silently everything recoils, tears are gone, the breathing of the world is back to normal.

Sorrow and its wrapping are abandoned, every being has drowned for the other,

down to a Hades, a mute black eye disappearing in a gleam of a reflection.

36 VIVIANA FIORENTINO

DAYTIME COYOTE

Chapter One

Betsy is a piece of shit. Her passenger door whistles in the wind, threatening to pop open like a malicious jack-in-the-box. Her windscreen is cracked. The check engine light is our constant friend. In order to reach the pedal I wear big boots because the seat is immovably rusted to the length of my father’s frame. Returning from war, The Greatest Generation chipped their middle age away carving a flat line through the side of California’s Central Valley. All that remains of the line now is a neglected, pot-holed highway. Beaten down by semi-trucks hauling freight from Amazon and Walmart warehouses. Their bulky shapes interrupt the flow of the land. Hills buzz cut into parking lots. For all that pumping out product and printing money, they created some ugly, ass buildings. I slow to a curve and join the caravan of mismatched cars sweating behind a semi truck ladened with orange crates. Sunkist faded on each box. The cars ahead of me weave back and forth into the oncoming lane, hoping for a moment to pass the eighteen wheeler. I stay put. No matter my speed, my speedometer is stuck on 40. Betsy’s only flawless feature is her blinkers. I indicate right, the brakes squeal in compliance. ‘Easy,’ I pat the dusty console to calm her. I veer off the highway onto an unmarked dirt road which has one solar light, staked by foot, beside two worn out mailboxes. I roll past lowering the windows. Wheat grass grows along the yard lines and perfume the evening with dust. Betsy’s headlights peer up the winding road, like a near blind woman with the wrong prescription. The precious cargo in the bed of the truck heaves under the tarp. I am the only vehicle on this road. In the distance I see the highway lights wink out one by one. The hills swallow them from view.

Everyone assumes the countryside is silent. That’s why everyone with neighbors complains they can’t sleep out the farmland’s blankness. There is no sirens or honking. But it’s the other noises that keep them awake. The bugs, the wheat, the cows, coyotes. If you aren’t used to them, those noises will scrape the inside of your skull till sunrise. I like them. The way they soothe and build. Makes me feel like every small nook unworthy of mapping shares itself. Its size creeps up on the suburban world and buries it. Sound also travels faster here.

I hear Josie bark, her bouncy ears pop above the wheat. She’s a cross of something fuzzy and big and probably ugly. I never thought to ask around when she showed up on my back door step and that was fine. She keeps strangers from the road and friends from knocking and feral things from creeping out of the wheat. I unlock the door and Josie barrels past me through the living room to the man at the kitchen table. She slobbers on his hands. She is a sucker for a handsome face.

‘Good day?’ His voice is sweet and rough like sucking on a honey covered lemon.

‘It was average.’ I walk away to my sister’s small bedroom, that we once shared. This ranch house was old and practical with two bedrooms. I’m the only one left in the house now,

37 HELEN I BROWER

* * *

but I remain in that room. Changed the big one into an office. I only sit at that desk when I don’t want to speak to him. I’ve not invited him in that room.

‘Did you get the, uh?’ He can’t even say it, coward.

‘It’s in the truck.’ I strip my shirt not bothering with the door, he’s not one to notice. He strides up from the chair toward the front with Josie hot on his heels. Idiots, the pair of ‘em.

I sit in his spot in my pajamas, a free Case tractor t-shirt and pink polka dot flannels. He comes in smiling, a crooked, wonderful thing, till he sees me.

‘That’s my spot.’ He places calloused hands on the table top.

‘It’s my house.’

‘I already have my drink there.’

I slide his beer over to the next spot. He shrugs, sitting in the new seat, but his fingers tap on the beer glass. Josie has given up on us, claiming the couch in the living room. Her snores fill the house before our words do.

‘Did they think it was weird that you put it in the truck?’ He goes to the fridge. He pulls out eggs, cheese, mushroom, mayo.

‘People do it all the time. That doesn’t go in omelets.’ I say.

His hand pauses on the blue jar, ’But you used it last time?’

‘That was for egg salad. You’re not making egg salad, are you?’

He frowns. ‘Do you want coffee?’ He fumbles with a cutting board buried beneath the extensive amount of placemats my mother loved and I never got rid of.

‘Coffee keeps me awake.’ I stretch and undo my hair tie. His gaze follows the strands. He had a thing for hair. ‘It’s almost 11pm.’ I say.

’Yes, well, I’m assuming you didn’t have dinner?’ He focuses on chopping vegetables. ‘It’s okay to eat late if you don’t have anywhere to go in the morning.’ He slides all the vegetables into a pan. He swipes a butter pat with an overkill knife. It melts and the vegetables sizzle.

‘I’m too tired for this.’

He stares at me the way he did when we first met a month ago. I know he doesn’t see what he saw that night. He focuses on the meal. The only meal I know he knows how to cook.

I didn’t mean to find her. I never really mean to find anyone. Did she call me or I her? Guess it doesn’t matter. The day we met, we sat on the edge of the wheat field. It was green still. We stared at each other aware of what a few seconds on either side of this shared breath meant for the two of us. I slid my fingers up her slack arm. She allowed it, obviously lost in my eyes. I locked my hand around her wrist and broke our dream. She now saw me, not a vision, but a naked man. She raised her gun with my hand still clinging to her wrist and shot me.

I drag the curtains behind the couch closed. I can’t reach the end and he does not move for me. A reality show consumes his attention. I step behind him and my socked foot brushes his back. He wiggles away.

‘Are you ticklish, Smiley?’ I ask.

38

He shakes his head but clutches a pillow to his chest. I smirk and yank the curtains all the way trapping the night out.

‘You need to stop opening these at night and closing them in the morning, okay?’

Smiley nods. His eyes hop between the two sisters arguing on screen. He wears my old high school t-shirt and baggy pajama pants that were my dad’s.

‘Where do you go during the day?’ I walk back to my spot. We sit on opposite ends with an old blood stain between us.

He peels his eyes from the TV screen. ‘You need help?’

‘No, I’m just curious.’

A smile flits on his lips. ‘Hm, is that concern? That’s a first.’

‘I don’t know why I even try and start a conversation with you.’

‘Because you’re bored and I’m exciting.’ He twists and lays down on the couch. The blood stain peeks out from under his head. He stretches and his arms invade my personal space. He bops my nose. I stand.

‘Good night, Smiley.’

He catches my wrist. ‘I’ll stay tomorrow, if you want. To help.’

The TV sisters are best friends again, they wear white and the reflection glosses in his eyes.

‘See you in the morning.’ I say. He lets go and I walk to the room. Josie snores on my bed.

‘Good night Imka, kiss Josie for me.’

He calls. I click the door shut.

I stupidly forgot the entire bag of metal joints on the counter. I was too focused on loading the truck. Johnny called me. He left a rambling voicemail that cut off at three minutes. I’m sure he talked for three more before realizing the line was dead.

The bell dinged my entrance.

‘There she is! There, she is.’

‘Morning Johnny.’

Johnny leans on the blue counter of the hardware store with the cheesiest grin this side of the Grapevine. He is in his sixties and wears a faded baseball hat with a WD40 logo on it.

‘You forget something yesterday?’ He lifts the plastic bag. The joints jingle together like an untuned wind chime. I stride up.

‘Thanks.’ I reach for the bag. Johnny slides it back.

‘Hey now, you drive all this way, you gotta have a cup of coffee.’

‘Aw Johnny, I’ve got a busy day today.’

‘Now, now, every job’s gotta have room for shooting the bull.’

‘Johnny,’

’Now, think about it. If you were back in your fancy city. What would you be doing?’

‘Making more money.’

‘Going to walk down to your local fancy pantsy coffee shop on your break. I bet you don’t give yourself a break at all now, do you?

39

I stare at him. He smiles back. I snatch at the bag, he jerks it away. He was spry for sixty something.

‘Oh no, young lady. Not today! I’ll get you your cup of joe.’

‘Johnny! Seriously, I don’t even like coffee that much.’

‘Two sugars and cream?’ Johnny walks down the counter to where the coffee maker gurgles in angry puffs.

‘Make it three!’ I sit on the barstool. It has been duct taped to keep the fluff inside so it boasts only half of a Snap-On ad. I cross my arms and stare at the two rubbed down spots a foot apart from each other on the counter.

‘That’s where all the farmers and welders and workers and milkers rest their elbows, cause they can’t do it at home in front of their momma’s so they get it out of their system here.’ My dad planted his elbows in the spots. I tried copying. I was six, my hair braided long down my back. I scrambled to the top of the duct taped stool and my pink rubber boot plopped to the ground. My elbows did not reach.

They do now. I keep my arms crossed.

‘One steaming cup of Joe! Just how you like it.’ Johnny sets the styrofoam cup in front of me.

I tsk. ‘Johnny, thought we talked about styrofoam. The paper’s just the same price. Most people bring their own cup anyways.’

Johnny waves me off setting the bag back down. ‘I told you then, that I’ll get the lil’ paper ones when I ran out.’

‘That was three weeks ago.’

‘I buy in bulk.’ Johnny winks. My eye catches on a fluorescent pink flyer on the counter next to the business cards. I sip and half the sip is coffee grounds.

‘You think I can get one more pot outta that filter?’

I nod sliding the flyer closer. Bernett’s Farm Auctions.

Johnny sighs. ‘It’s the Miguel dairy this time,’ The bell dings and he jerks up smiling, ‘Morning!’

I creep my fingers to the plastic bag.

‘Morning Johnny, you got any coffee left?’ The man plants himself next to me, leaning his elbows on the counter. He smells of diesel.

‘I gotta fresh pot right now.’

‘Is it an actual fresh pot or you just put water in the back and use the same filter as yesterday?’ The man unscrews the lid from his metal travel mug handing it to Johnny.

‘That depends, you using me for my free coffee or buying something today?’ Johnny arches a brow walking to the machine.

‘I’m buying something I swear, my tow chain snapped yesterday. That worth a fresh pot?’

‘Fine, fine. Ray, you remember Imka don’t yah?’

Now we stare at each other. It is only 9am and Ray is covered in grease. I think mechanics and scrappers are fated to have oil stains on their hands.

‘Morning Imka, I wasn’t sure if it was you.’

We shake hands.

‘Morning Ray, how’s work?’

‘Yeah, yeah, work is work. Just keeps going, everyone always gotta junker they need taking care of.’

40

I swallow a mouthful of burning coffee.

‘You know, I, I hadn’t realized. That, the uh, well, cause we only spoke on the phone.’