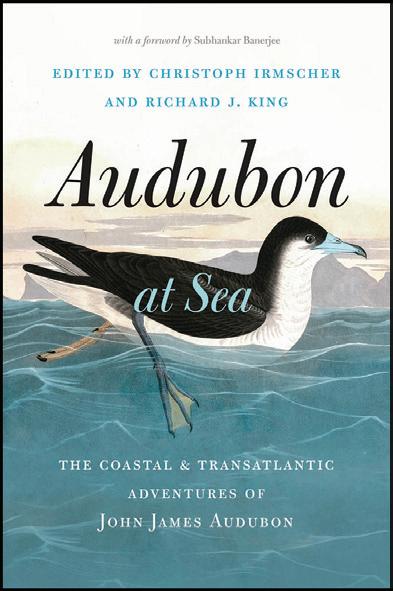

WINTER 2022 – 23 No. 181 THE ART, LITERATURE, ADVENTURE, LORE & LEARNING OF THE SEA $4.95 SEA HISTORY Blockade Runner Aground Spanish Plate Fleet Wrecks U-boats vs. Windjammers NATIONAL MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY

14k 18k A - Fish Float Sphere with Aqua Chalcedony Pendant (U.S. Patent D678,110) n/a ------------- $2100. B - Flemish Coil Pendant (matching earrings available) ---------------------------------------------- $1650. ------------ $2100. C - Compass Rose with working compass Pendant ----------------------------------------------- $2100. ------------ $2900. D - Correa/Chart Metalworks 3/4" Sailboat Pendant $1850. ------------ $2500. E - Reef Knot Bracelet -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- $5250. ------------ $6900. F - Monkey's Fist Stud Earrings (matching pendants available) --------------------------------- $1400. ------------ $1900. G - Deck Prism Anchor Chain Dangle Earrings (matching pendant available) -------------n/a ------------- $2300. H- Cleat Hitch Dangle Earrings (hand-tied and matching pendant available) ----------- $1900. ------------ $2750. I - Port & Starboard Hand Enameled Dangle Earrings -------------------------------------------------n/a ------------- $2250. J - Anchor with Rope Earrings (matching pendants available) ---------------------------------- $1400. ------------ $1850. K- Two Strand Turk's-head Ring with sleeve (additional designs available) -------------- $2300. ------------ $2900. • 18" Rope Pendant Chain $750. C A G PO Box 1 • 11 River Wind Lane, Edgecomb, Maine 04556 USA • M-F 10-5 ET customer.service@agacorrea.com • Please request our 52 page book of designs • 800.341.0788 • agacorrea.com B D J E H F K Over 1000 more nautical jewelry designs at agacorrea.com ® A.G.A. CORREA & SON JEWELRY DESIGN I ©All designs copyright A.G.A. Correa & Son 1969-2022 and handmade in the USA Jewelry shown actual size | Free shipping and insurance

Portland Rockland Boothbay Harbor Bath Camden Bucksport Gloucester Bar Harbor Boston Atlantic Ocean Provincetown Newport Martha’s Vineyard MAINE NEW HAMPSHIRE MASSACHUSETTS RHODE ISLAND Immerse yourself

the

Small Ship Cruising Done Perfectly ® Explore New England with the Leader in U.S. Cruising Call today 866-229-3807 to request a free Cruise Guide Your New England Explorer Cruise Includes: 11-days/10-nights on board the ship An exploration of 10 ports of call, with guided excursion options at each All onboard meals and breakfast room service Full enrichment package with guest speakers and nightly entertainment Our signature evening cocktail hour with hors d’oeuvres

in

sights, sounds, and tastes of New England. From the quaint island villages of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard, to the scenic beauty of coastal Maine, summer in New England is a delightful experience. Enjoy a local Lobsterbake, indulge in the area’s rich maritime history, and witness magnificent mansions of the Gilded Age.

Sail Aboard the Liberty Ship John W. B roW n Reservations: 410-558-0164, or www.ssjohnwbrown.org Last day to order tickets is 14 days before the cruise; conditions and penalties apply to cancellations. Check our Website for 2023 Cruise Dates On a cruise you can tour museum spaces, bridge, crew quarters, & much more. Visit the engine room to view the 140-ton triple-expansion steam engine as it powers the ship though the water. Project Liberty Ship is a

all volunteer, nonproft organization. SS

W.

is maintained in her

Visitors must be able to climb

Mystic Knotwork A New England Tradition For 60 Years 25 Cottrell St. • 2 Holmes St. Open 7 days a week - 860.889.3793 MysticKnotwork.com Traditional Knotwork made in Downtown Mystic CHESAPEAKE BAY MARITIME MUSEUM Your Chesapeake adventure begins here! 213 N. Talbot St., St. Michaels, MD | 410-745-2916 | cbmm.org

Baltimore-based,

JOHN

BROWN

WWII confguration.

steps to board.

CONTENTS

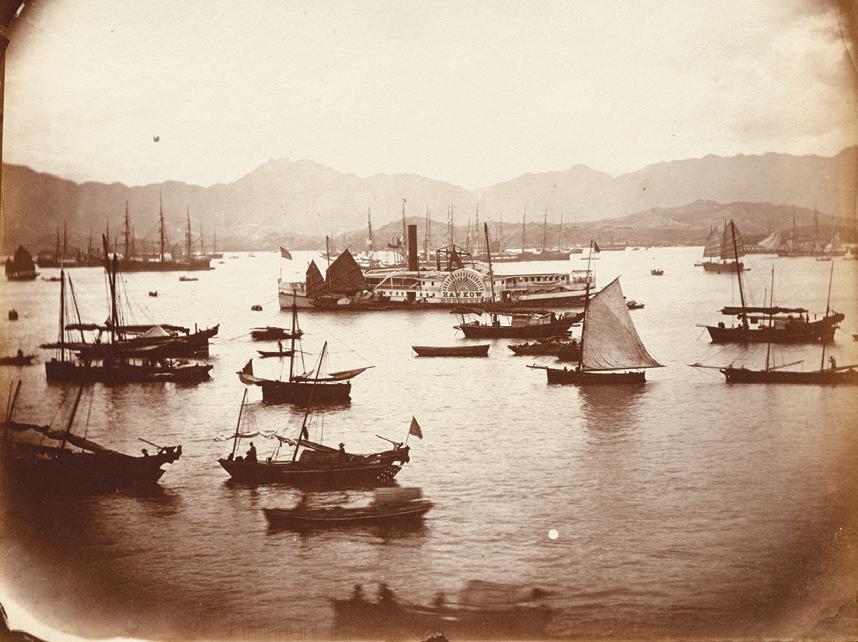

10 Submarine Warfare and the Decline of Sailing Fleets, 1914–1918 by Steven Woods

By the start of WWI, sailing vessels were still a popular choice for carrying cargo, but they were relatively easy prey for submarines. Steven Woods discusses how it was the U-boat, and not the steam competitor, that contributed most to the decline of the sailing ship.

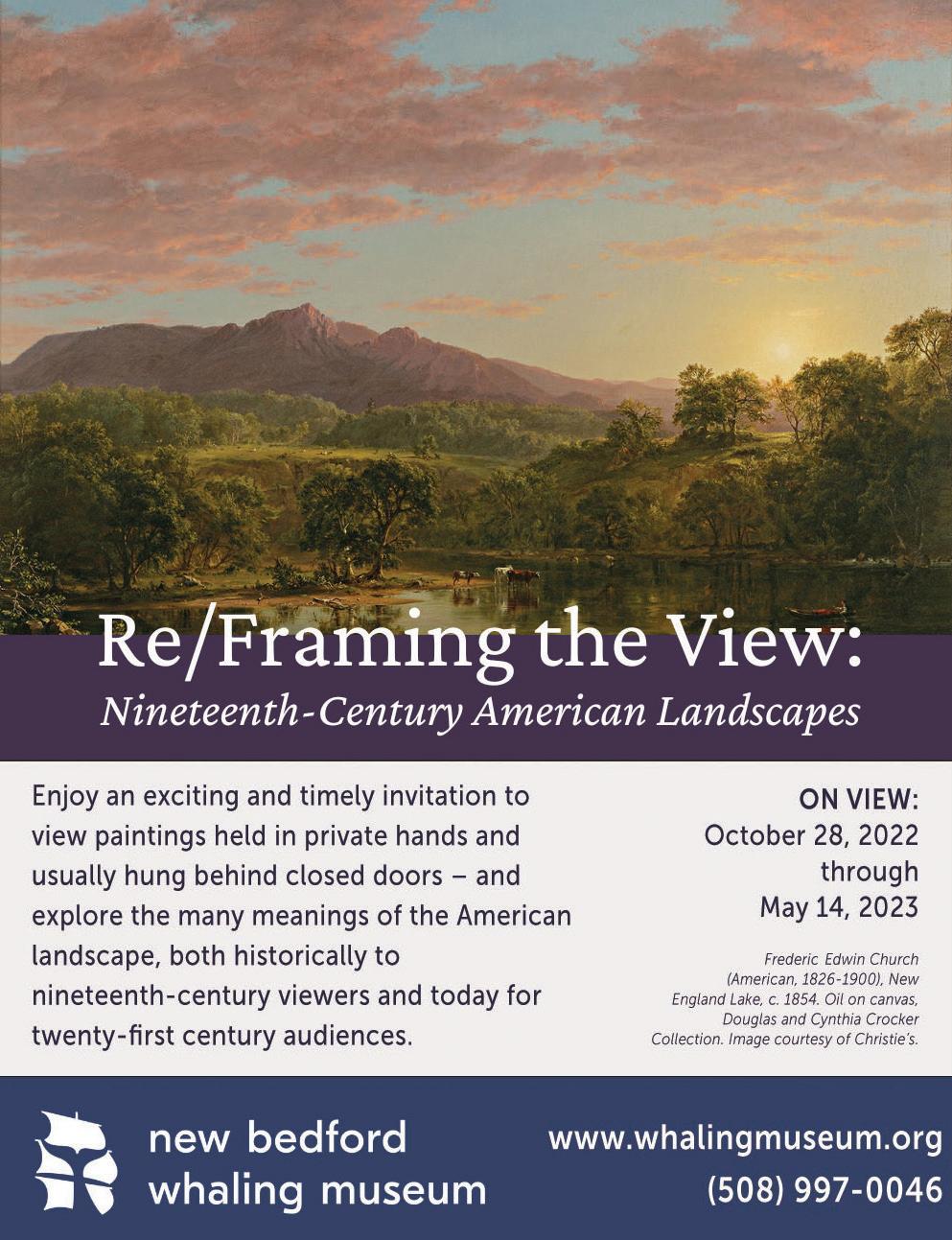

14 Marked for Disaster— e Tragic Loss and Inspiring Legacy of the 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet of Padre Island, Texas by Amy Borgens e 1964 discovery of a legendary 16th-century eet of treasure-laden ships o the coast of Texas, and the state’s legal struggle to establish control over the site, inspired the establishment of a legal framework for the protection of Texas’s underwater heritage assets.

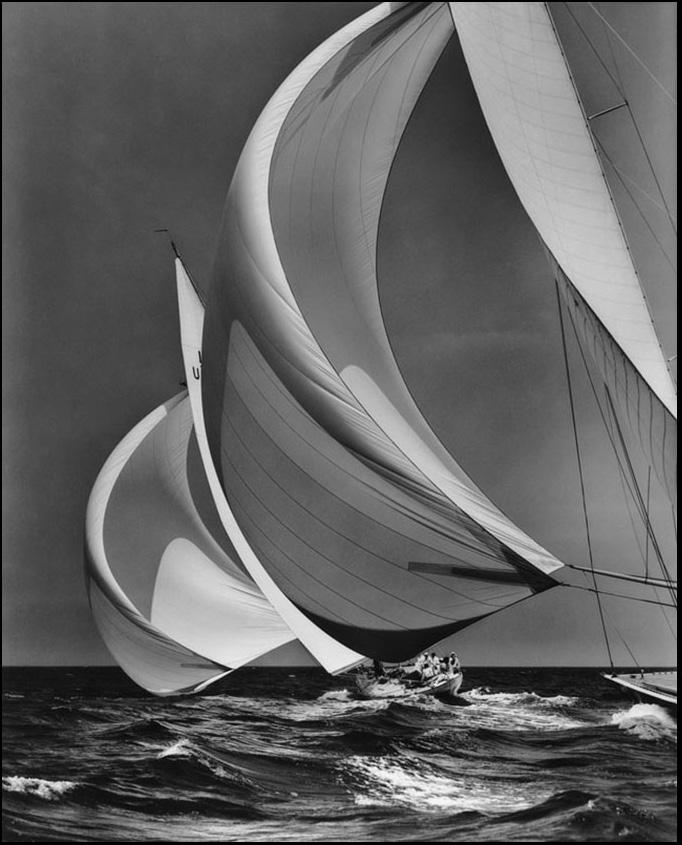

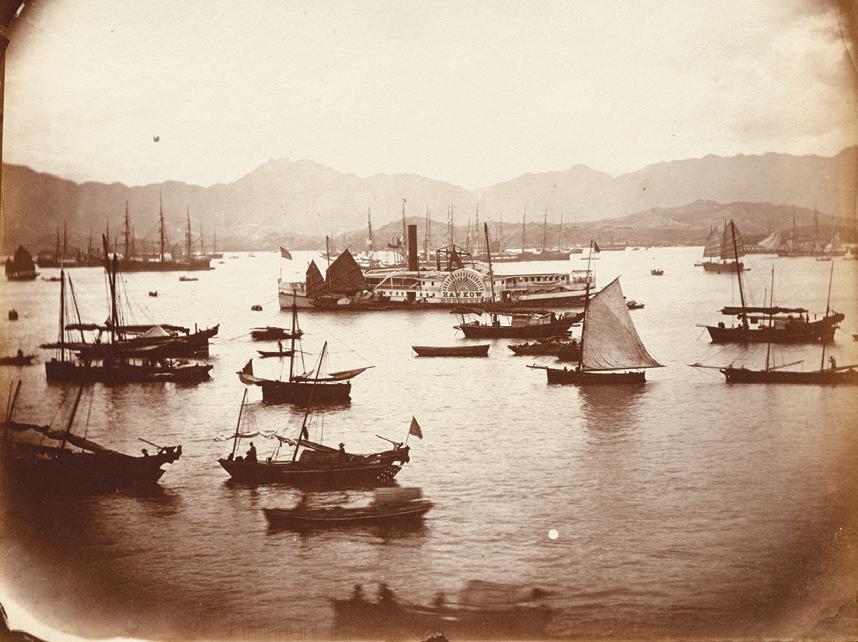

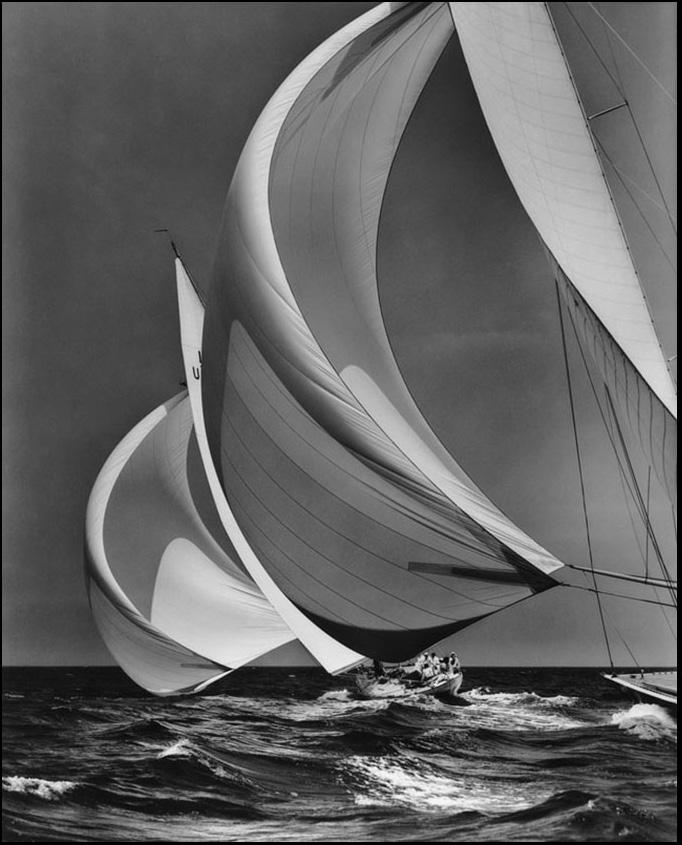

22 Curator’s Corner—Historic Photos from the Archives by Kevin Cullen

Wisconsin Maritime Museum curator Kevin Cullen combed the archives, and shares a charming 1890 photograph of a winter scene on Lake Michigan, shot by Captain Edward Carus, who faithfully documented much of the maritime heritage of his Great Lakes routes.

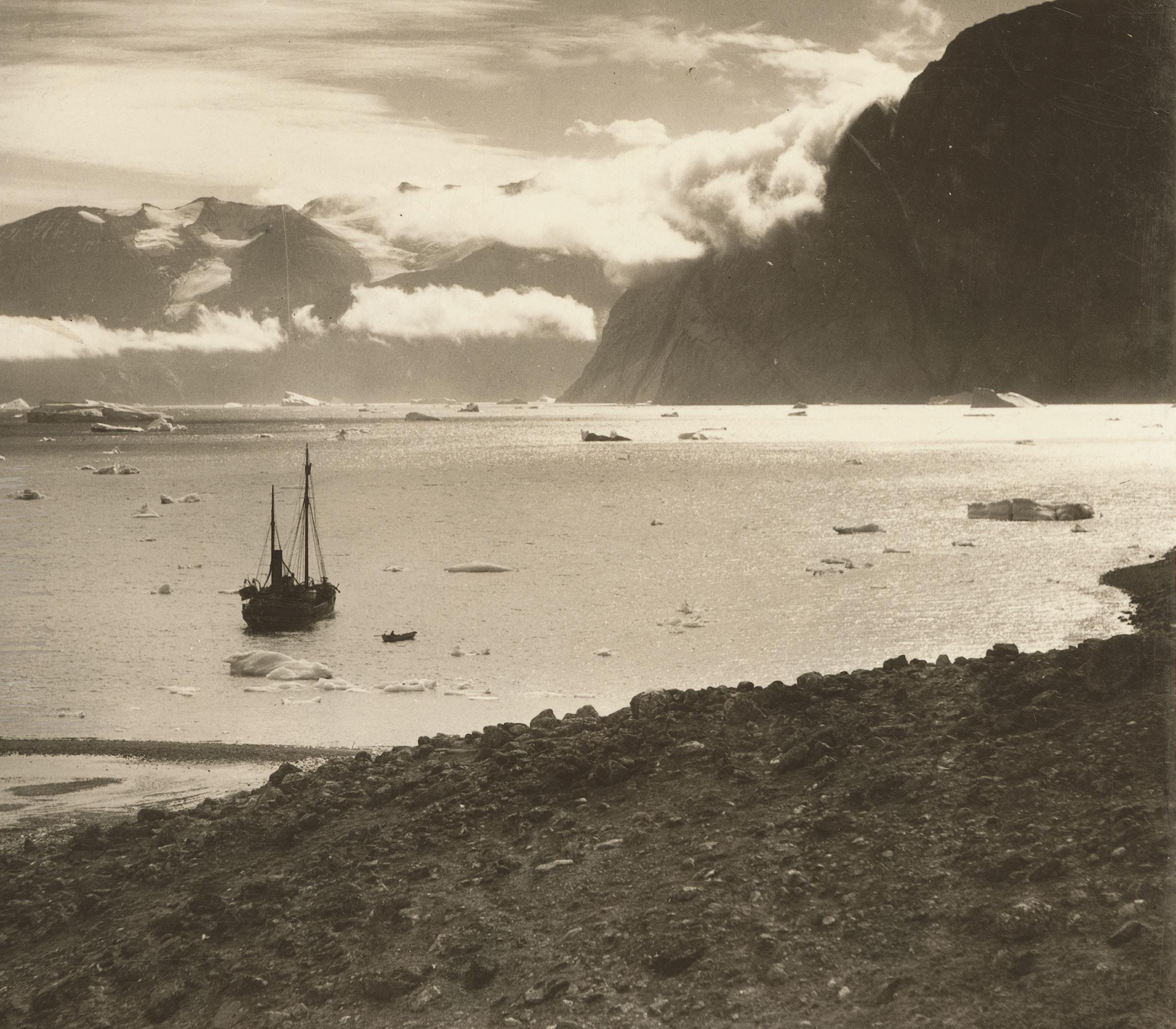

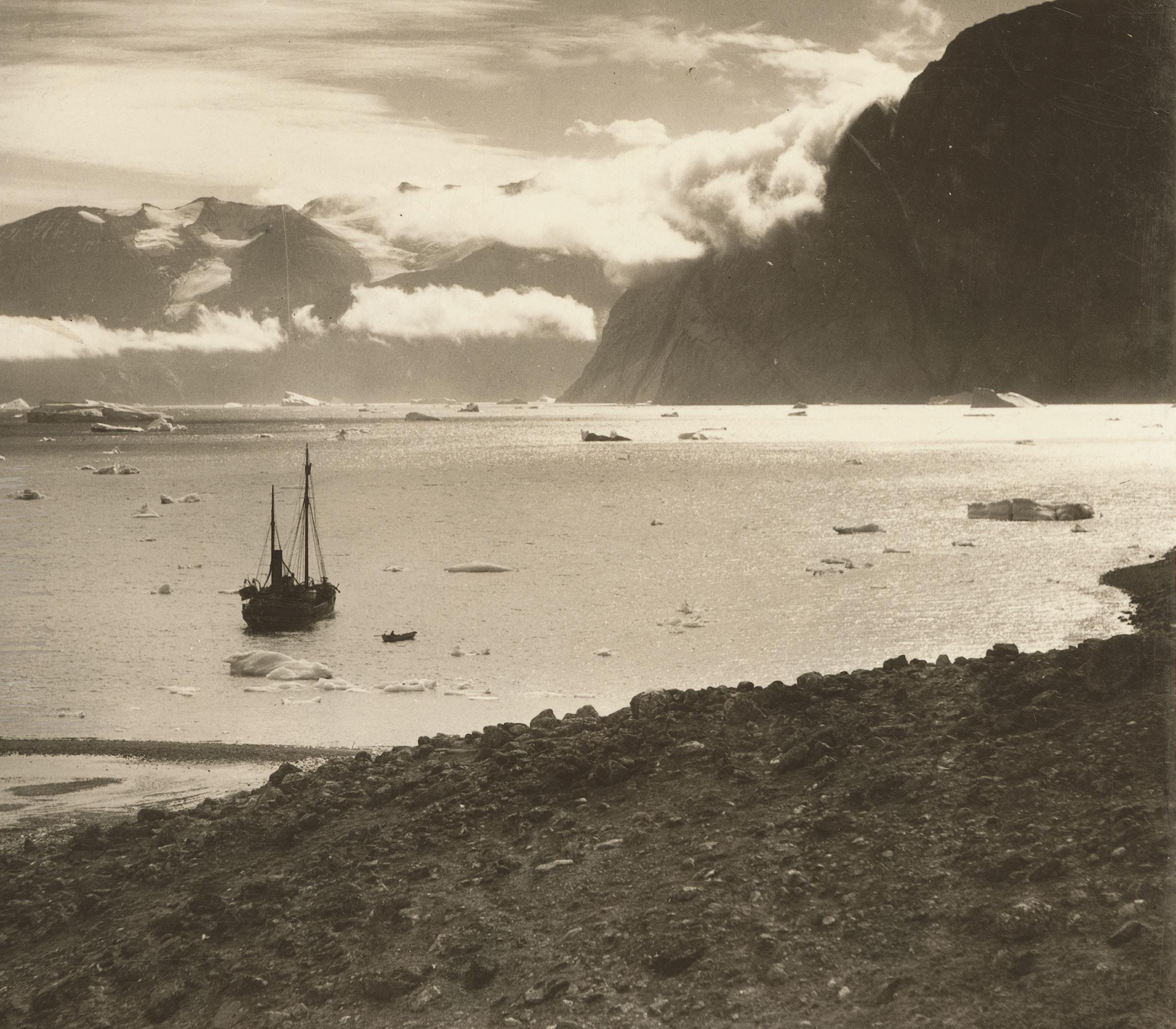

24 Greenland Beckons: Explorer Louise Arner Boyd aboard the Veslekari by Joanna Kafarowski

In the 1930s, high-society heiress, Arctic explorer, and dedicated geographic photographer Louise Arner Boyd organized, paid for, and led four expeditions to the Arctic. For each mission she chartered the Norwegian sealer Veslekari, sister ship of explorer Roald Amundsens’s Maud.

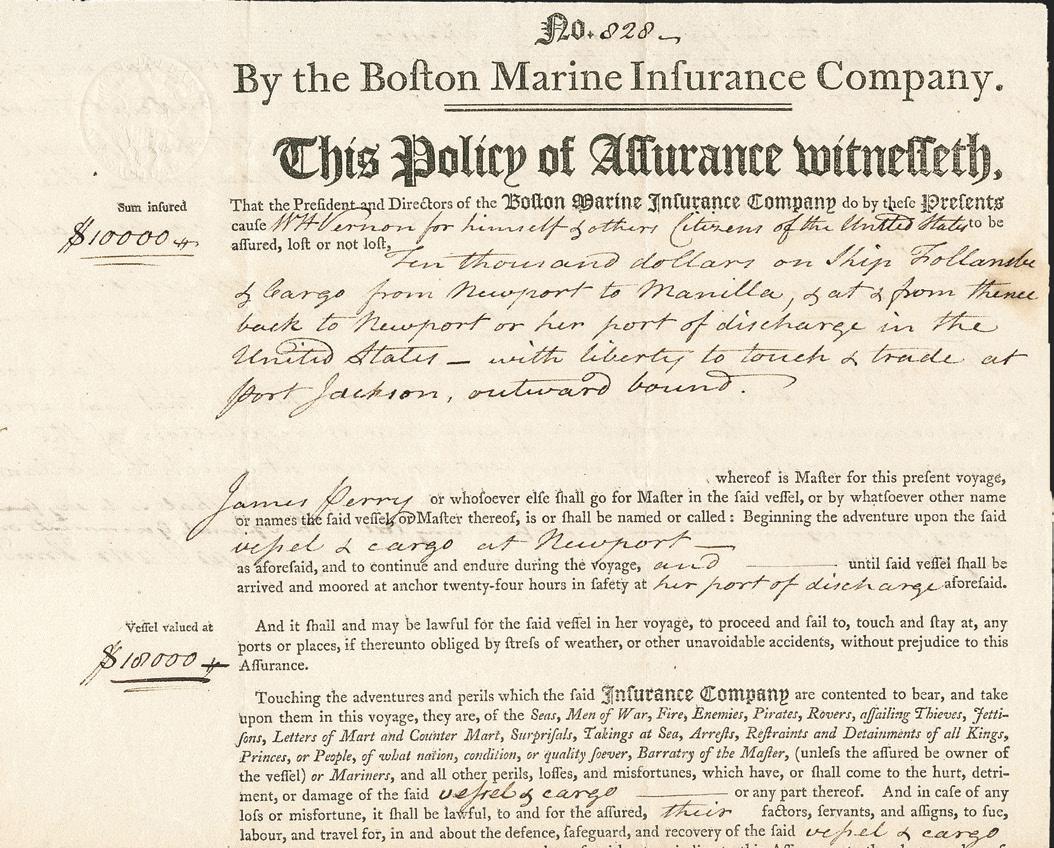

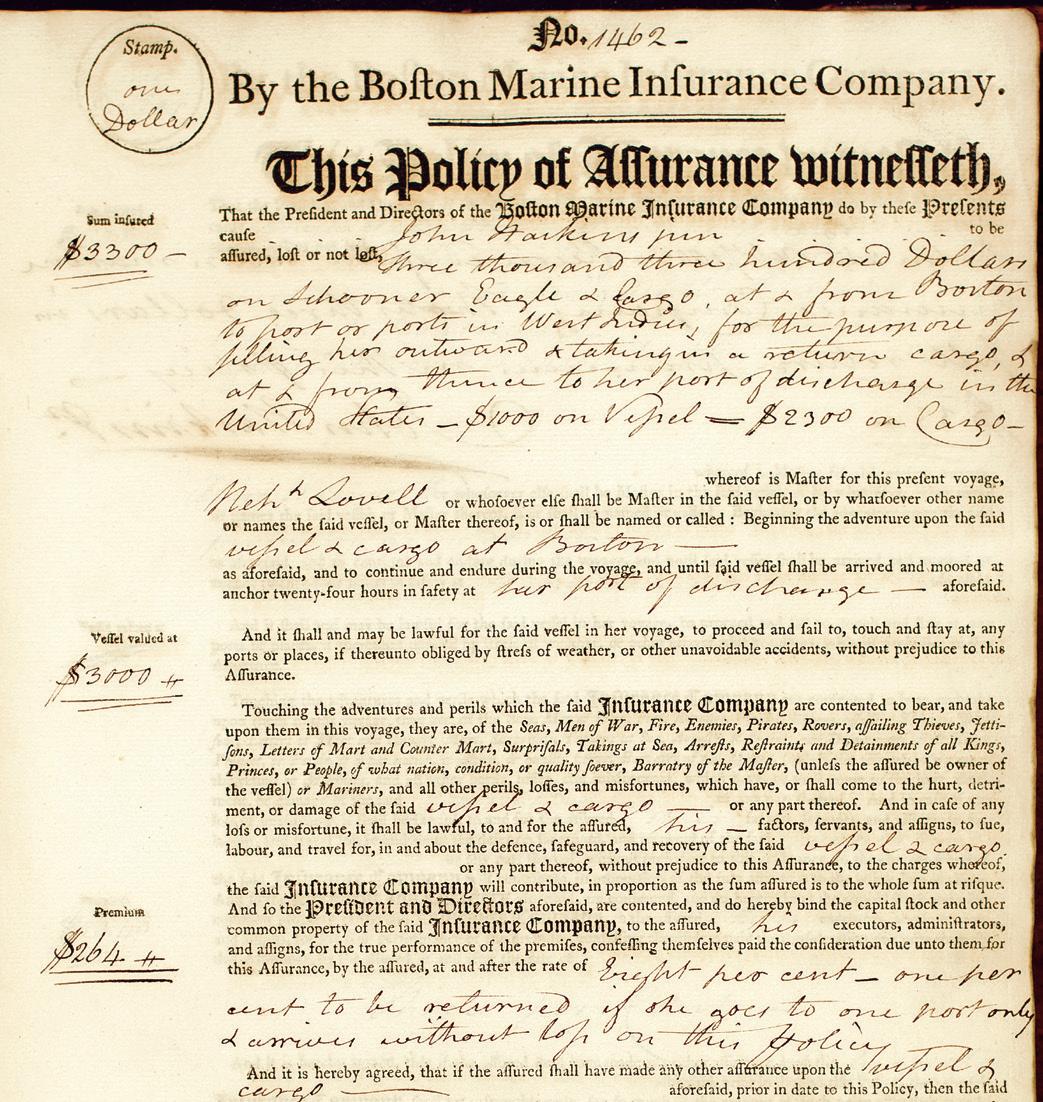

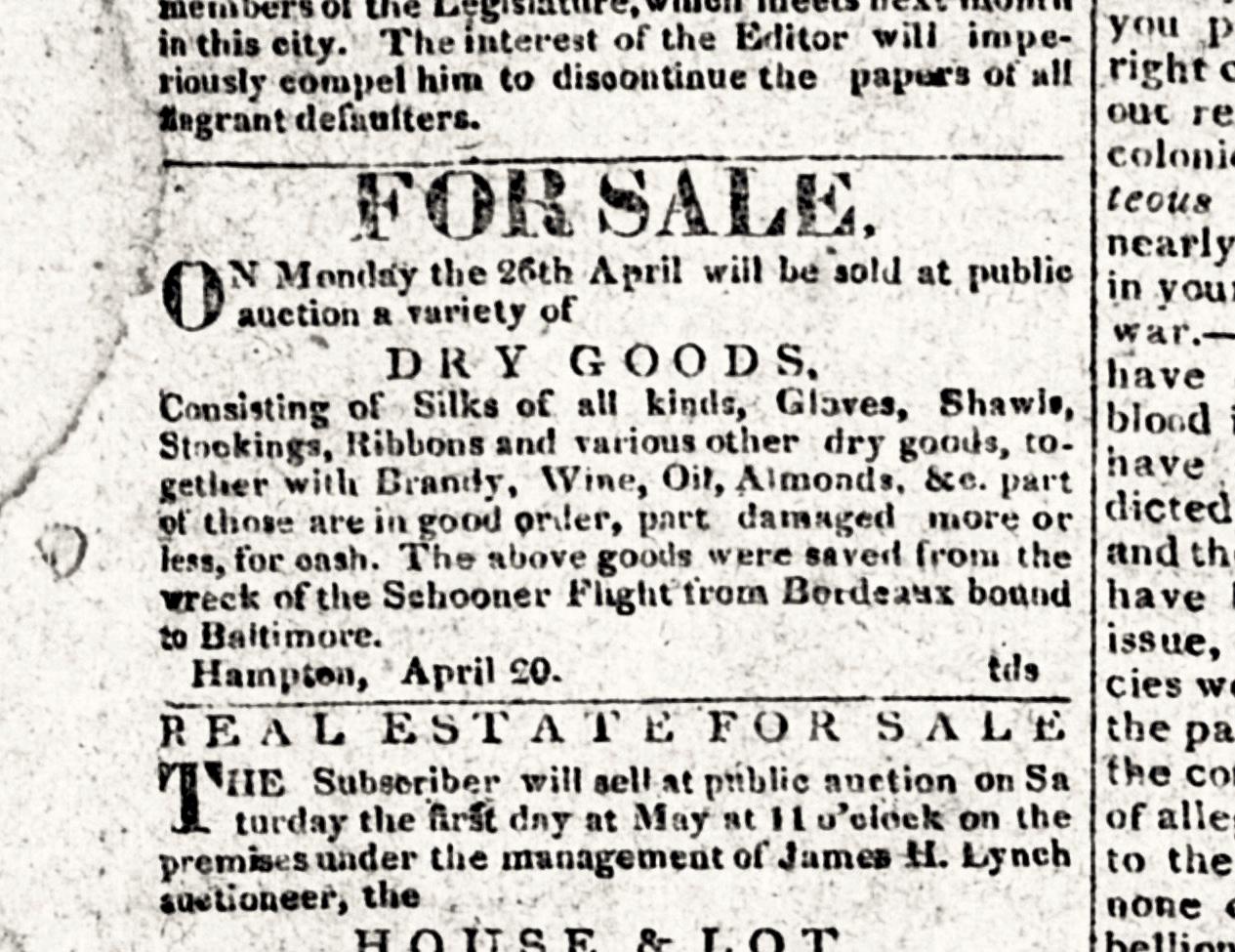

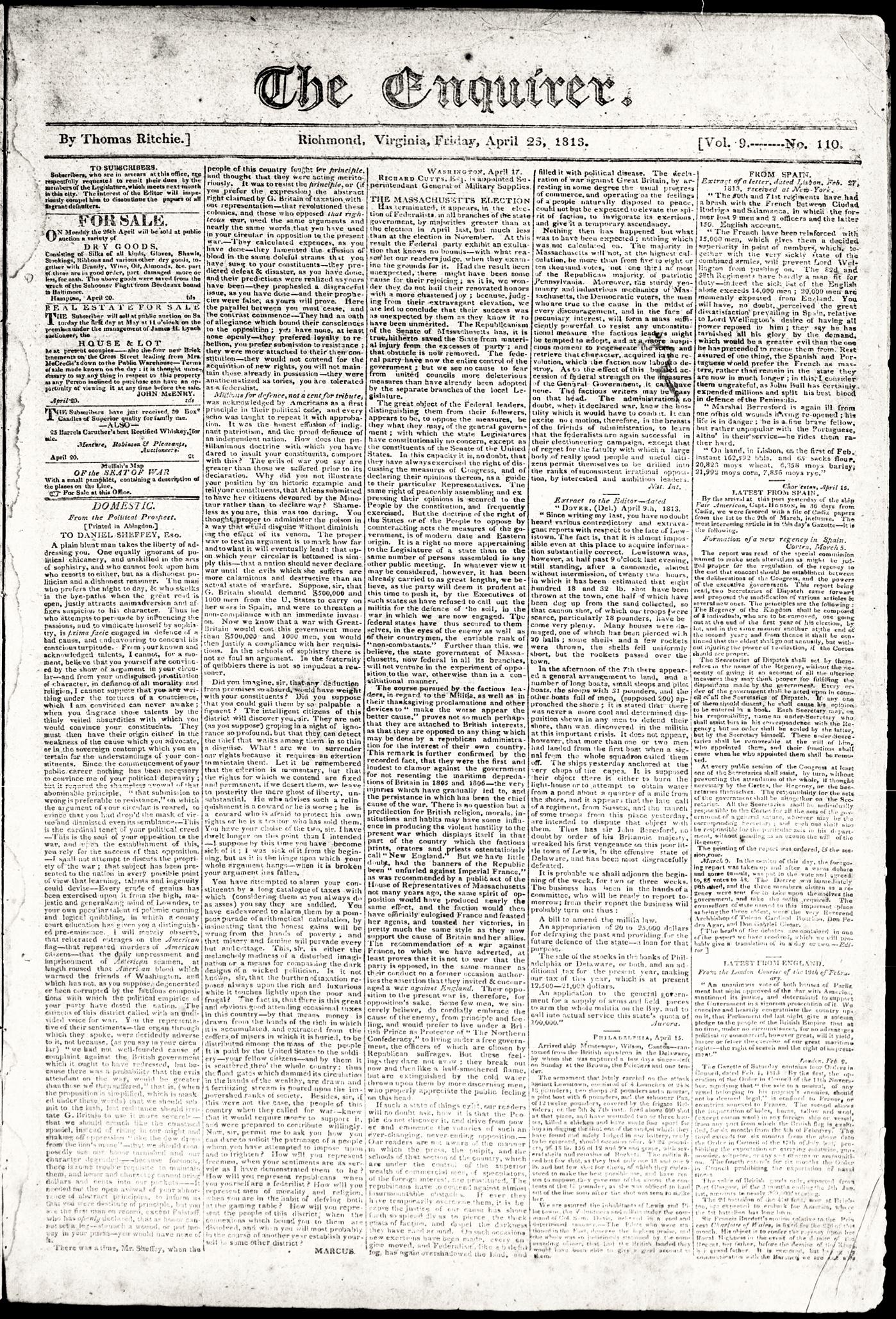

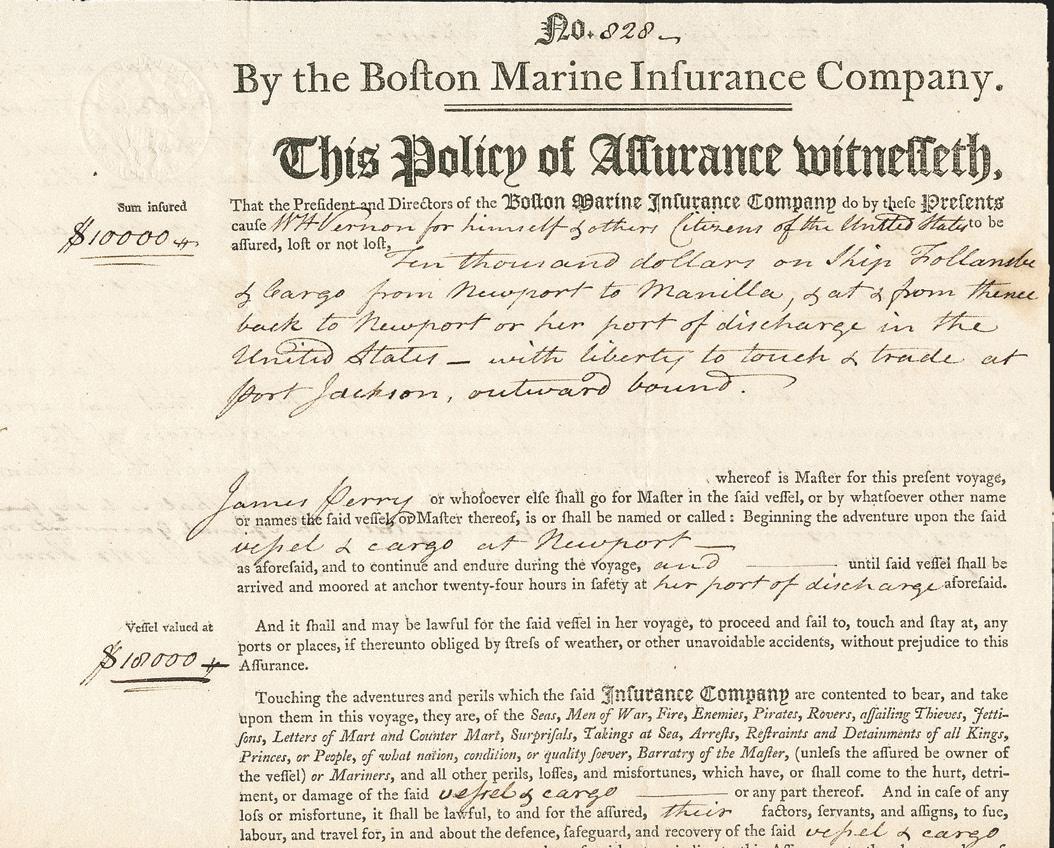

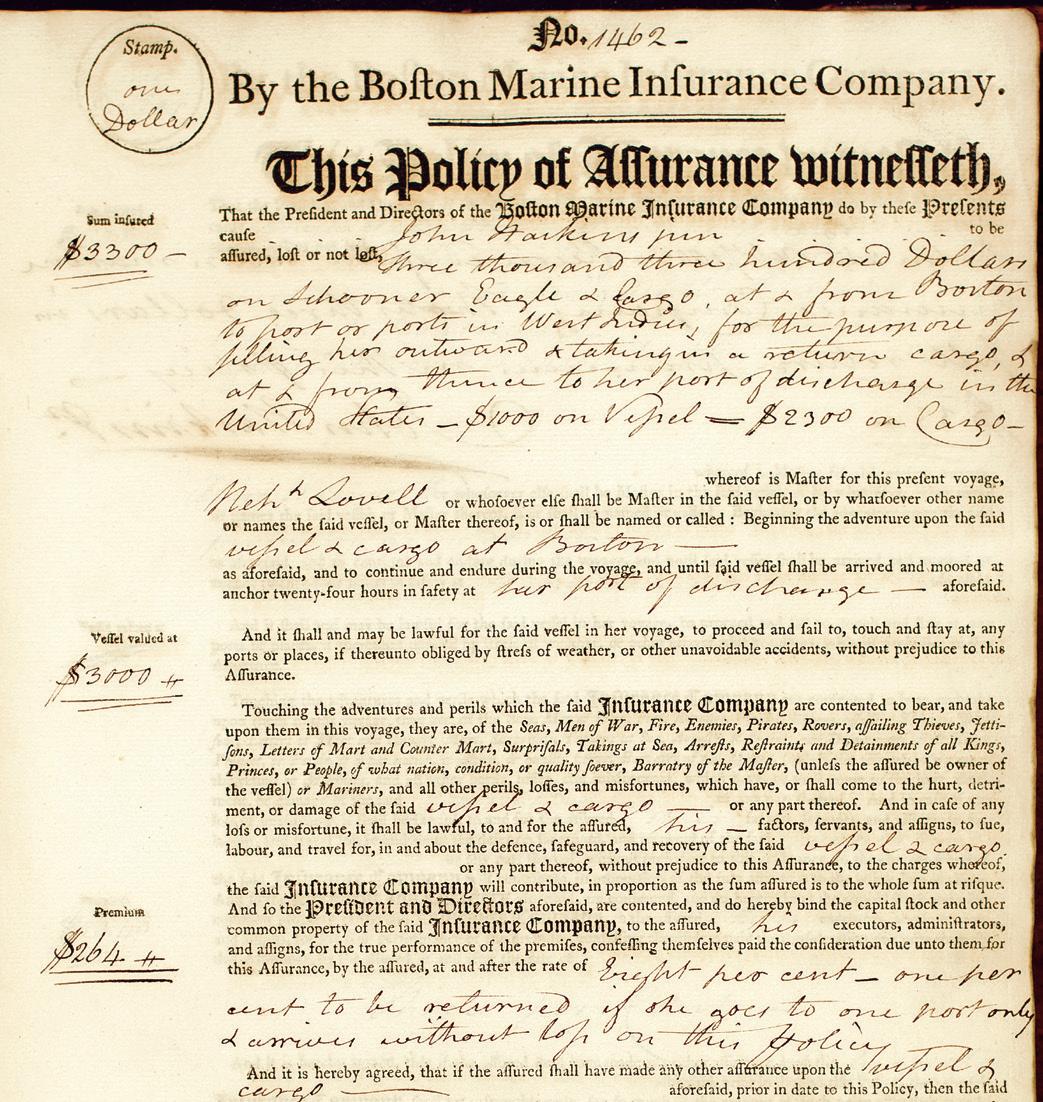

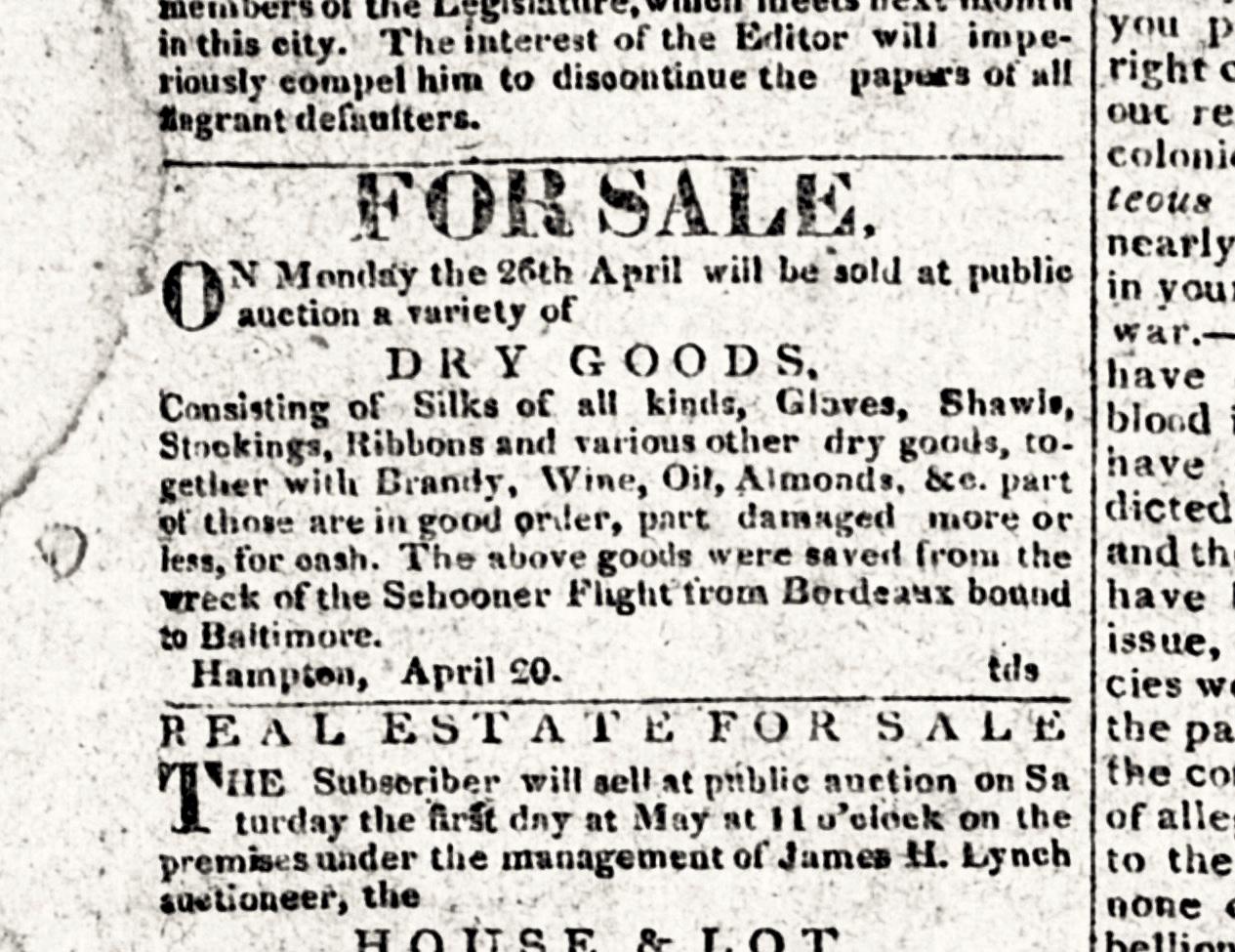

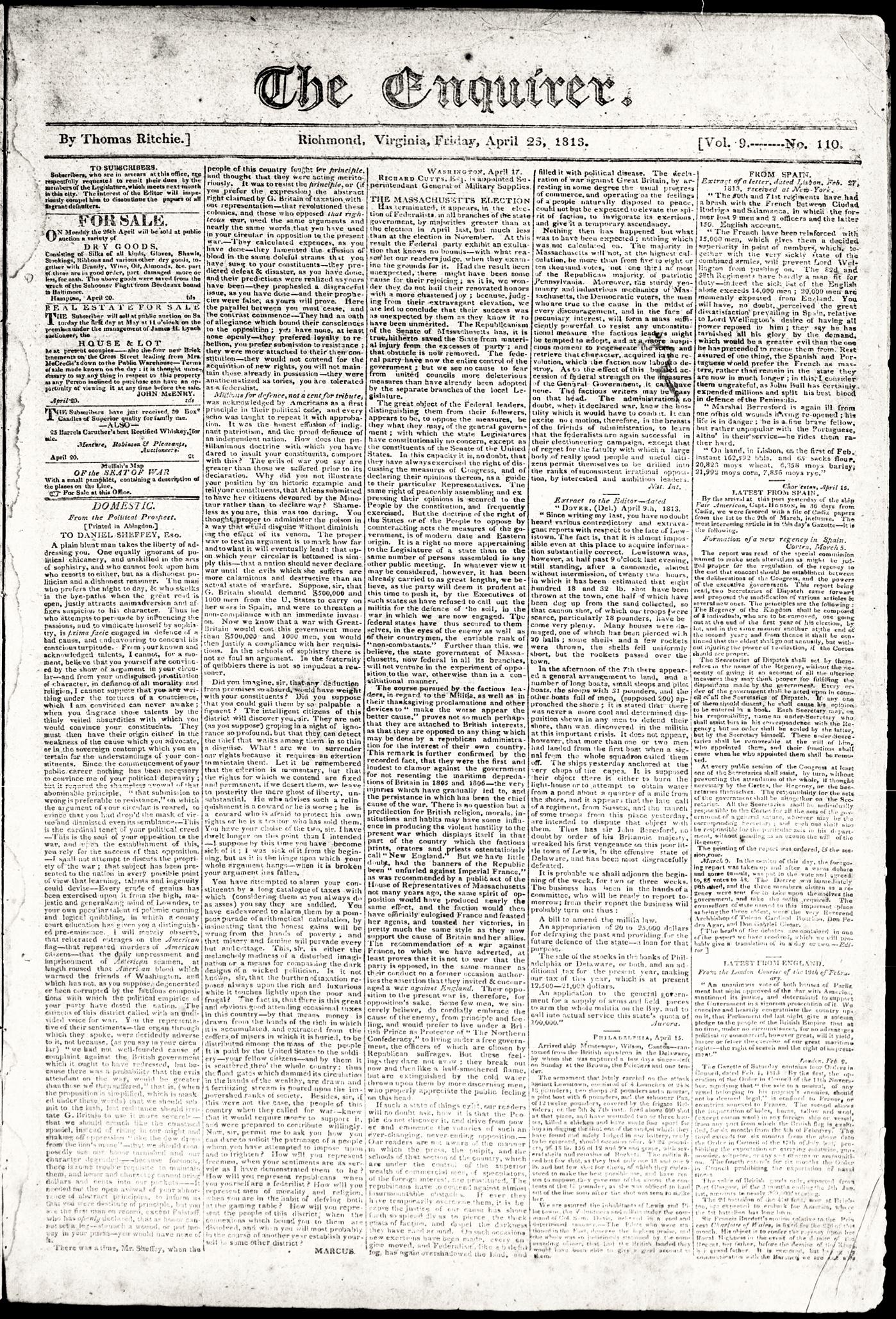

30 Navigating Risk: Early American Marine Insurance and the Growth of a Nation by Hannah Farber, PhD

When shipowners began buying shares in multiple vessels vs. owning fewer outright, it was in large part to share the risk if the ship and cargo were damaged or lost. Historian Hannah Farber deciphers a typical contract between American shipowners and early marine insurance underwriters.

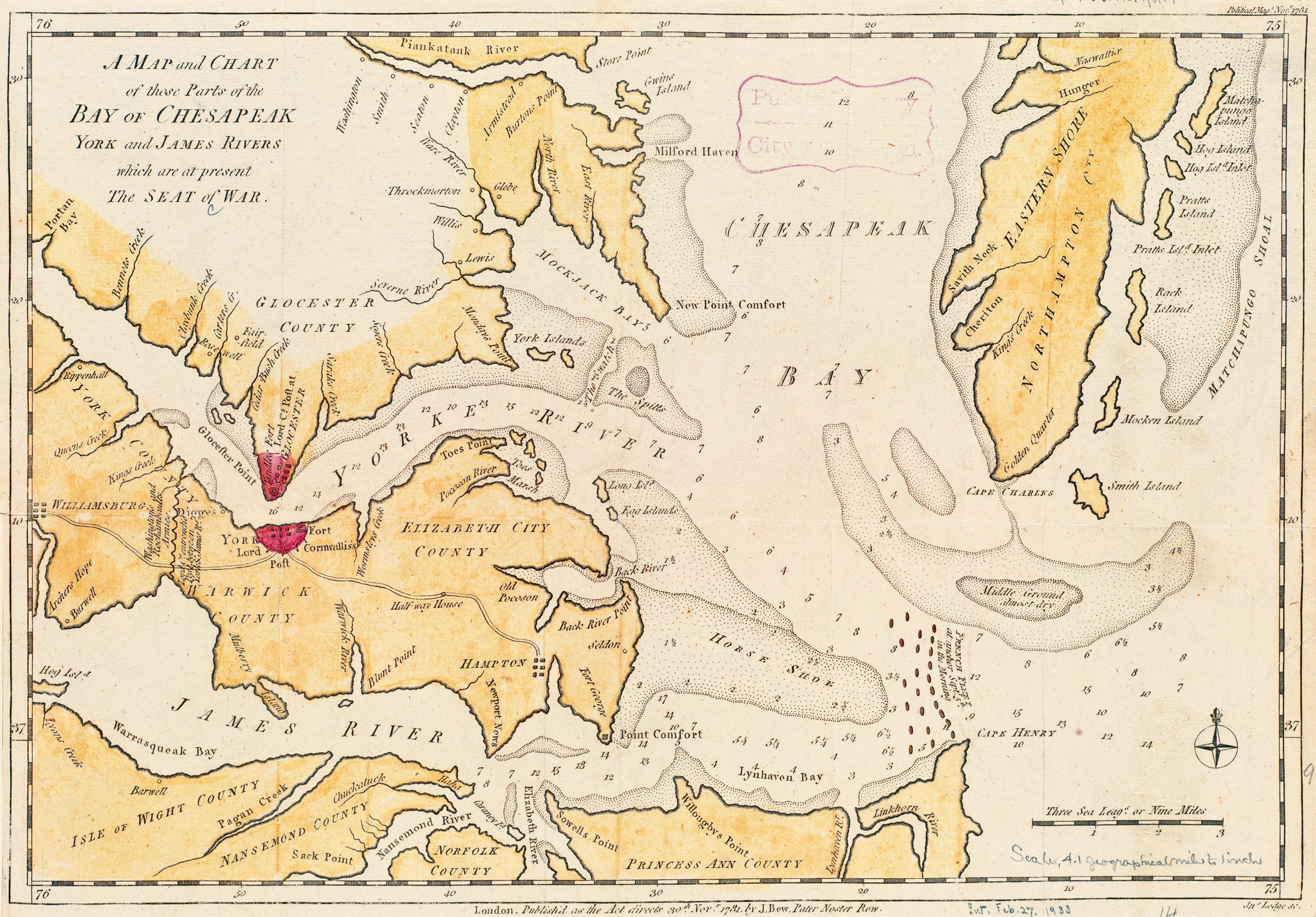

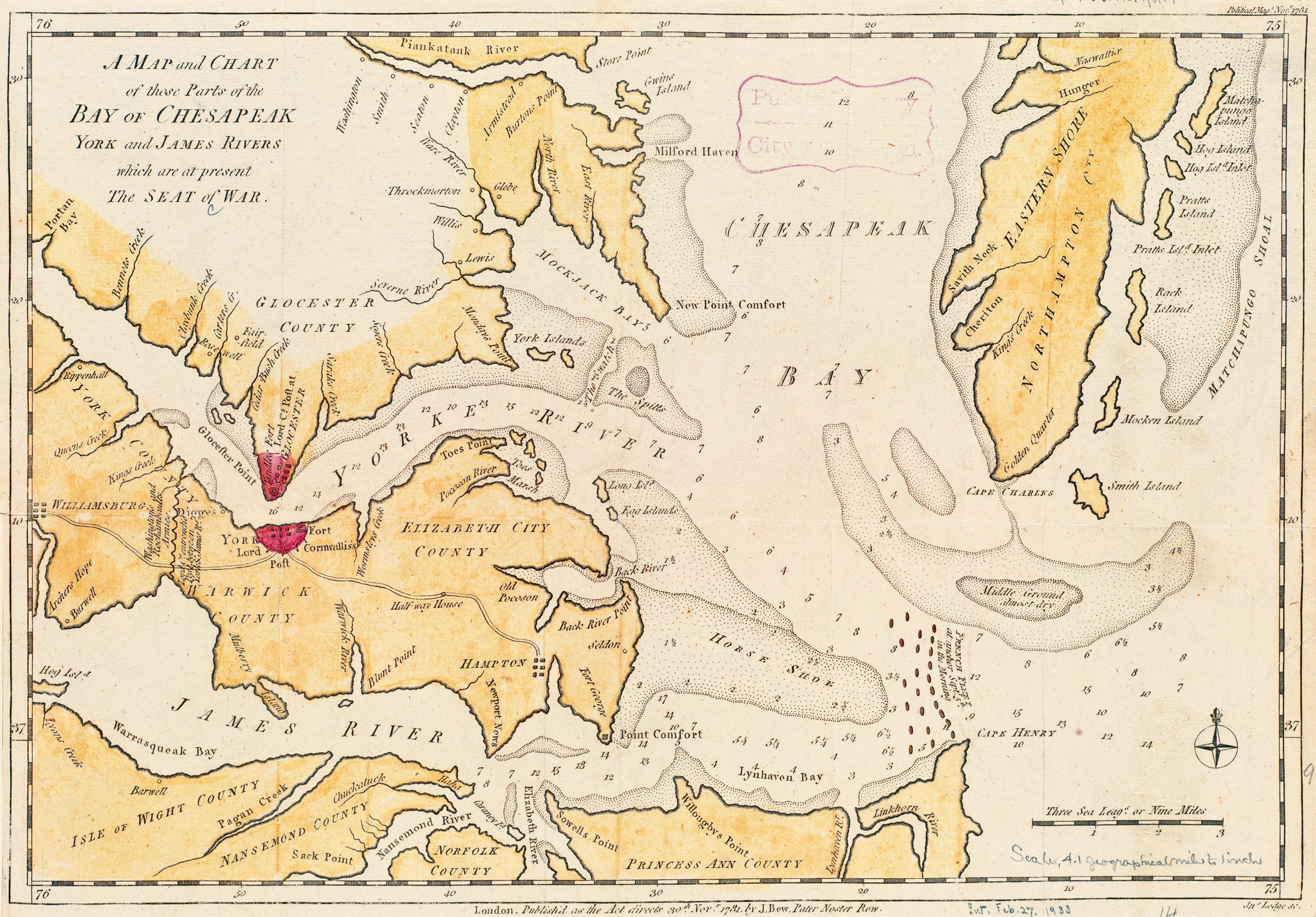

34 A Grounded Flight: e Harrowing Rescue of an American Blockade Runner in the Dark Days of War by CAPT Daniel A. Laliberte, USCG (Ret.)

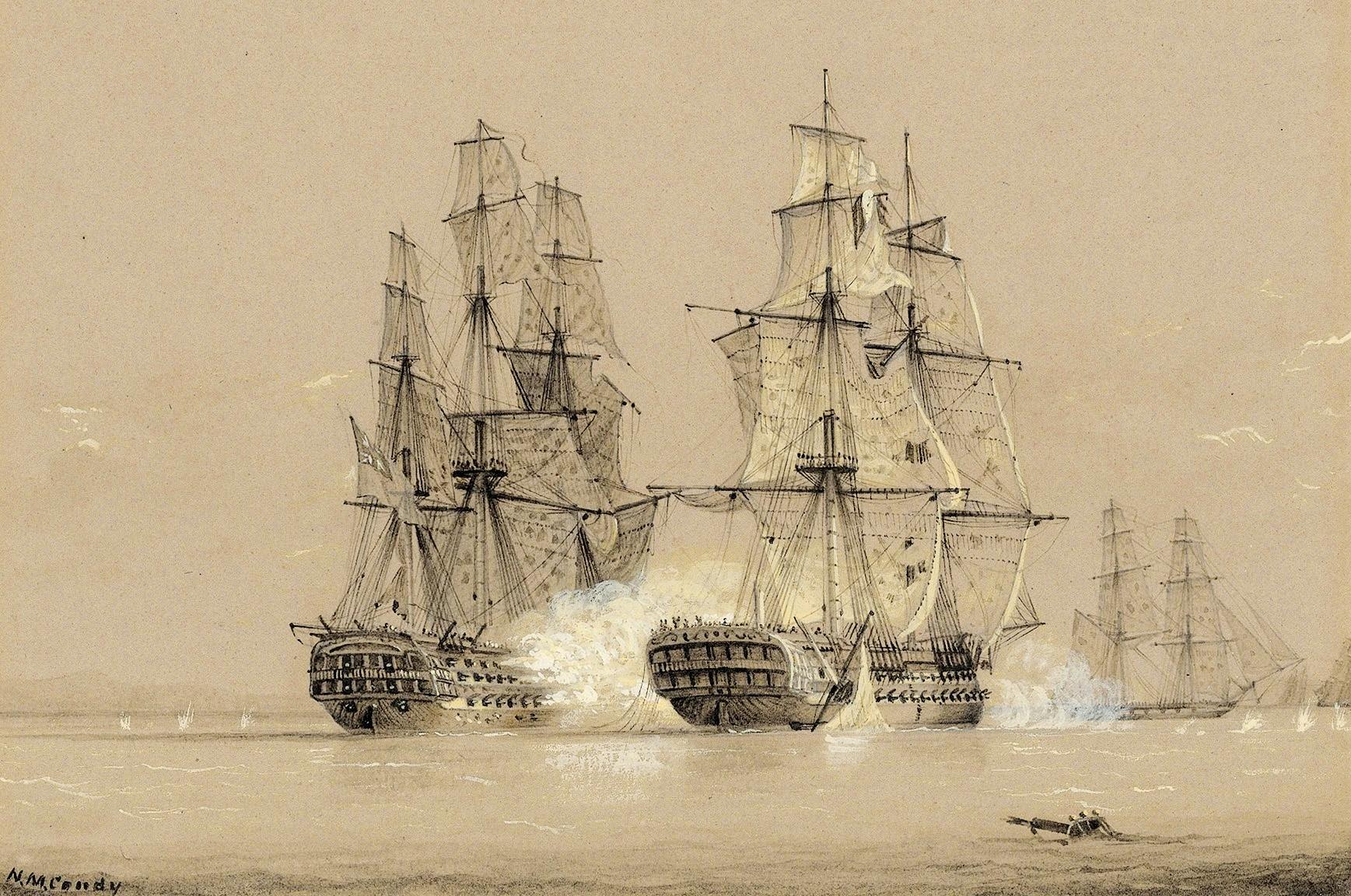

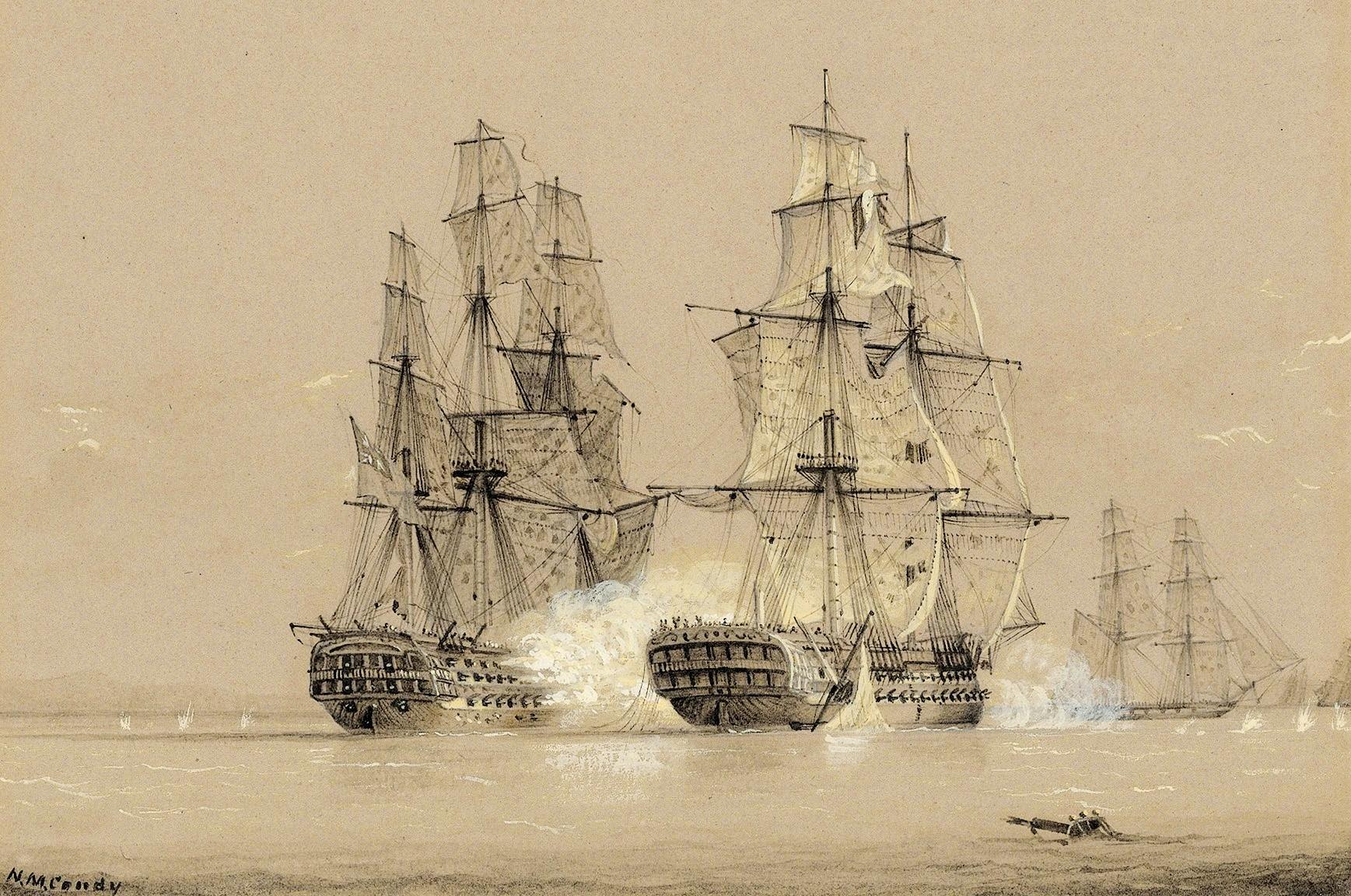

During the War of 1812, the treacherous shoals of the Chesapeake Bay and the vagaries of weather often contributed to the jeopardy of the cat-and-mouse pursuit of blockade runners and British ships.

Cover: US Revenue Cutter omas Je erson chasing down three Royal Navy boats on 11 April 1813. Painting by Patrick O’Brien, courtesy USCG Art Collection. See article on pp. 34–38.

Sea History and the National Maritime Historical Society

Sea History e-mail: seahistory@gmail.com • NMHS e-mail: nmhs@seahistory.org Website: www.seahistory.org • Ph: 914 737-7878; 800 221-NMHS

MEMBERSHIP is invited. Afterguard $10,000; Benefactor $5,000; Plankowner $2,500; Sponsor $1,000; Donor $500; Patron $250; Friend $100; Regular $45. All members outside the USA please add $20 for postage. Sea History is sent to all members. Individual copies cost $4.95.

norsk

SEA HISTORY (issn 0146-9312) is published quarterly by the National Maritime Historical Society, 1000 North Division St., #4, Peekskill NY 10566 USA. Periodicals postage paid at Peekskill NY 10566 and add’l mailing o ces.

COPYRIGHT © 2022 by the National Maritime Historical Society. Tel: 914 737-7878.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Sea History, 1000 North Division St., #4, Peekskill NY 10566.

HISTORY No. 181 WINTER 2022–23 4 Deck L og 5 L etters 8 NMHS: A C ause in Motion 40 M arine A rt News 42 Sea History for K ids 46 Ship Notes, Seaport & Museum News 56 R eviews 64 Patrons NATIONAL MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY

24

polarinstitutt DEPARTMENTS SEA

10 nhhc , us navy 14 art by peter rindlisbacher 30 boston public library

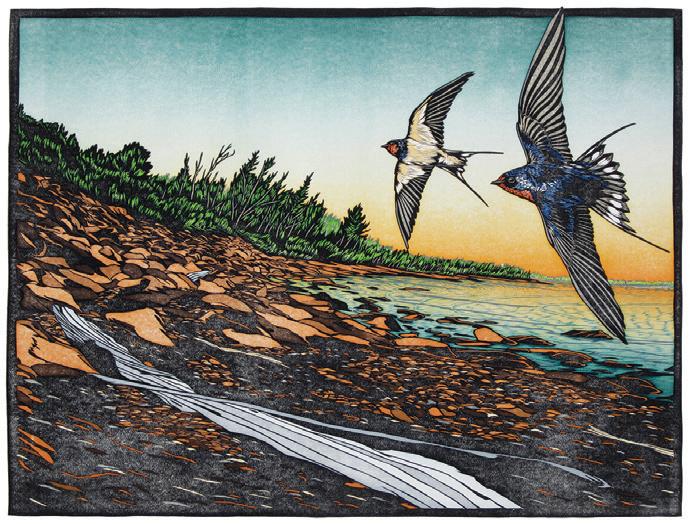

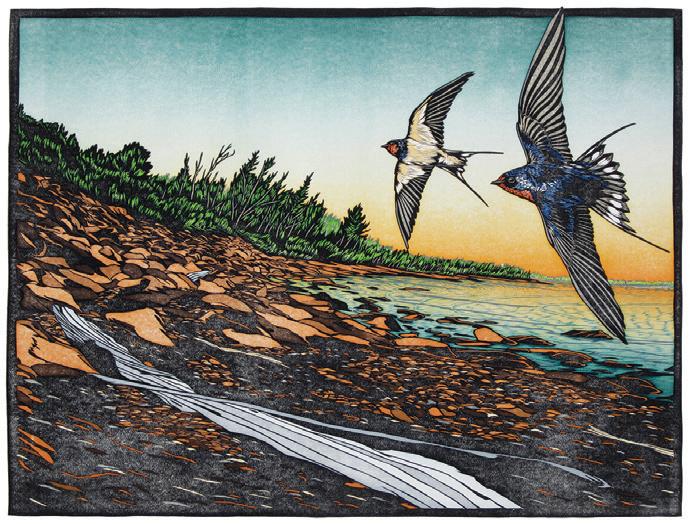

DECK LOG

A New Decade Invites Us to Set New Goals

In 2023, the National Maritime Historical Society will celebrate its 60th anniversary. As we look to the future, we’re also giving a lot of thought to what has been our mission since 1963, and what it means today to “preserve maritime history, promote the maritime heritage community, and invite all to share in the adventures of seafaring.” As we chart the course ahead, we’re asking ourselves how we can improve our programs, embrace new perspectives, and expand our impact.

NATIONAL MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY

PUBLISHER’S CIRCLE: Peter Aron, Guy E. C. Maitland, Ronald L. Oswald

OFFICERS & TRUSTEES: Chairman, James A. Noone; Vice Chairman, Richardo R. Lopes; Vice Presidents: Jessica MacFarlane; Deirdre E. O’Regan, Wendy Paggiotta; Treasurer, William H. White; Secretary, Capt. Je rey McAllister; Trustees: Charles B. Anderson; Walter R. Brown; CAPT Patrick Burns, USN (Ret.); CAPT Sally McElwreath Callo, USN (Ret.); William S. Dudley; David Fowler; Karen Helmerson; VADM Al Konetzni, USN (Ret.); K. Denise Rucker Krepp; Guy E. C. Maitland; Salvatore Mercogliano; Michael Morrow; Richard Patrick O’Leary; Ronald L. Oswald; Timothy J. Runyan; Richard Scarano; Capt. Cesare Sorio; Jean Wort

CHAIRMEN EMERITI: Walter R. Brown, Alan G. Choate, Guy E. C. Maitland, Ronald L. Oswald; Howard Slotnick (1930–2020) FOUNDER: Karl Kortum (1917–1996)

PRESIDENTS EMERITI: Burchenal Green, Peter Stanford (1927–2016)

OVERSEERS: Chairman, RADM David C. Brown, USMS (Ret.); RADM Joseph F. Callo, USN (Ret.); Christopher J. Culver; Richard du Moulin; Alan D. Hutchison; Gary Jobson; Sir Robin Knox-Johnston; John Lehman; Capt. James J. McNamara; Philip J. Shapiro; H. C. Bowen Smith; John Stobart; Philip J. Webster; Roberta Weisbrod

I am inspired by the conversations and exchanges that I’ve had with so many of our members over the last few months, and I look forward to continuing the dialogue in the year ahead. anks to the leadership of people like the late Peter Stanford, Burchenal Green, and our dedicated board of trustees, we’ve come a long way over the past six decades, broadening our horizons from an initial focus on historic ships and ship-saving to include the world of marine art, mariners and the blue economy, ocean conservation, maritime archaeology, and broader maritime history.

In addition to Sea History, published since 1972, we hope to launch a new educational publication aimed at school-aged children. Building on the success of Sea History for Kids, one of the magazine’s most popular regular features, our goal is to invite this youngest generation to a lifetime of interest in and awareness of our maritime world. To succeed in reaching out to new and diverse audiences in an increasingly digital world, we also plan to invest in our educational content and to expand our presence online.

We hope you’re as excited as we are. Please wish us a happy 60th and let us know how we’re doing! You can share your vision with me at nmhs@seahistory.org, or schedule a time to chat about all the work we’re doing. I look forward to hearing from you!

—Jessica MacFarlane, NMHS Executive Director

—Jessica MacFarlane, NMHS Executive Director

NMHS ADVISORS: John Ewald, Steven A. Hyman, J. Russell Jinishian, Gunnar Lundeberg, Conrad Milster, William G. Muller, Nancy H. Richardson

SEA HISTORY EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Chairman, Timothy Runyan; Norman Brouwer, Robert Browning, William Dudley, Lisa Egeli, Daniel Finamore, Kevin Foster, Cathy Green, John O. Jensen, Frederick Leiner, Joseph Meany, Salvatore Mercogliano, Carla Rahn Phillips, Walter Rybka, Quentin Snediker, William H. White

NMHS STAFF: Executive Director, Jessica MacFarlane; Vice President of Operations, Wendy Paggiotta; Director of Special Projects, Nicholas Raposo; Senior Sta Writer, Shelley Reid; Business Manager, Andrea Ryan; Manager of Educational Programs, Heather Purvis; Membership Coordinator, Marianne Pagliaro

SEA HISTORY: Editor, Deirdre E. O’Regan; Advertising Director, Wendy Paggiotta

Sea History is printed by e Lane Press, South Burlington, Vermont, USA.

4 SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23

in the wild productions

photo by chris hamilton ,

LETTERS

Fair Winds Burchie Green!

On 22 September, a group of women, known in the New York maritime industry as the Waterfront Wenches, gathered on board the historic Coast Guard buoy tender Lilac at Pier 25 in Manhattan to honor one of our longtime members on her retirement from the National Maritime Historical Society. Due to the pandemic, it had been a number of years since our last

We Welcome Your Feedback!

Please email correspondence to editorial@seahistory.org.

events and at informal get togethers; for your support in publishing my Harbor Voices book; for earning an a ectionate place in the hearts of so many people over so many years with your arduous work and your beautiful smile. Sea History magazine has ourished over the past two decades due to Burchie’s leadership, and Deirdre [O’Regan] carries on Sea History’ s mission smartly and engagingly. Burchie always

e Launch is Just the Beginning for Maine’s First Ship

Many thanks to Charley Seavey for his ne account of the launch of Maine’s First Ship, the pinnace Virginia, in the autumn issue of Sea History, an excellent account of a day

NMHS president emeritus Burchenal Green (center) is fêted by the Waterfront Wenches, Lauretta Bruno (left) and Lucy Ambrosino, aboard the historic buoy tender Lilac in NYC.

get together, but Burchie’s retirement was an event we could not let pass without a salute to her many years of devoted service to NMHS and Sea History and the maritime industry as a whole. A wonderful time was had by all, reconnecting with old friends, toasting the memory of one of our original founders, the late Linda O’Leary, and wishing the best to our friend and colleague—dear Burchie.

Janet H ellmann

Staten Island, New York

How tting to honor Burchie on a New York Harbor pier! I know that all present felt a ectionate and grateful for this power lady’s years of smart, capable, successful attention to all things maritime. She and Peter Stanford worked grandly together. I know that he believed in her deeply, as did other seasoned ship souls near and far. Burchie, thank you for the million ways in which you have helped maritime history stay alive and well in the hearts and minds of so many.

You have been my steadfast friend: for always greeting me so warmly at NMHS

made all of us welcome with her warm smile, incredible memory, attention to detail, and the greeting in her eyes.

Happy retirement to you, Burchie!

Terry Walton Cold Spring Harbor, New York

that turned out better than any of us had dared hope, even after more than a year of planning. It will surprise no reader of Sea History to learn that putting the ship in the water does not mean that construction is done. Far from it. And indeed, work has been ongoing since her launch in early June. I thought perhaps an update on Virginia’s progress and her future might be appropriate to share with your readers.

e most visible progress has been on the ship’s rigging, where a gang of about

Join Us for a Voyage into History

Our seafaring heritage comes alive in the pages of Sea History, from the ancient mariners of Greece to Portuguese navigators opening up the ocean world to the heroic efforts of sailors in modern-day conficts. Each issue brings new insights and discoveries. If you love the sea, rivers, lakes, and

bays—if you appreciate the legacy of those who sail in deep water and their workaday craft, then you belong with us.

Join Today ! Mail in the form below, phone 1 800 221-NMHS (6647), or visit us at: www.seahistory.org (e-mail: nmhs@seahistory.org)

SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23 5

Yes, I want to join the Society and receive Sea History quarterly. My contribution is enclosed. ($22.50 is for Sea History; any amount above that is tax deductible.) Sign me up as: $45 Regular Member $100 Friend $250 Patron $500 Donor Mr./Ms. ____________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ZIP_______________ Return to: National Maritime Historical Society, 1000 North Division St., #4, Peekskill, NY 10566 181

courtesy james nelson

courtesy

Maine’s First Ship, Virginia.

janet hellmann

seven volunteers (numbers vary) and I have been getting the shrouds set up and ratlines in place, and installing the hundreds of blocks, pennants, lizards, etc. that we have built in the loft over the past ve years. We stepped the mizzen mast in September. Shortly afterwards, we were contacted by a television production crew from the Midwest, who wanted to shoot a piece on sea chanteys based on the new book Songs of Ships and Sailors, by Maine’s First Ship volunteers Fred Gosbee and Julia Lane. Of course, if we were going to sing a hauling chantey for the cameras we needed something to haul, which was excellent

motivation to get the mizzen yard rigging and ready, which we did.

OWNER’S STATEMENT: Statement led 9/30/22 required by the Act of Aug. 12, 1970, Sec. 3685, Title 39, US Code: Sea History is published quarterly at 1000 N. Division Street Suite 4, Peekskill NY 10566; minimum subscription price is $27.50. Publisher and editor-in-chief: None; Editor is Deirdre E. O’Regan; owner is National Maritime Historical Society, a non-pro t corporation; all are located at 1000 N. Division Street, Suite 4, Peekskill NY 10566. During the 12 months preceding October 2022 the average number of (A) copies printed each issue was 10,875; (B) paid and/or requested circulation was: (1) outside county mail subscriptions 5,734; (2) in-county subscriptions 0; (3) sales through dealers, carriers, counter sales, other non-USPS paid distribution 3,503; (4) other classes mailed through USPS 526; (C) total paid and/or requested circulation was 9,763; (D) free distribution by mail, samples, complimentary and other 693; (E) free distribution outside the mails 248; (F) total free distribution was 941; (G) total distribution 10,704; (H) copies not distributed 171; (I) total [of 15G and H] 10,875; (J) Percentage paid and/or requested circulation 91%. e actual numbers for the single issue preceding October 2022 are: (A) total number printed 9,905; (B) paid and/ or requested circulation was: (1) outside-county mail subscriptions 5,610; (2) in-county subscriptions 0; (3) sales through dealers, carriers, counter sales, other non-USPS paid distribution 3,463; (4) other classes mailed through USPS 312; (C) total paid and/or requested circulation was 9,385; (D) free distribution by mail, samples, complimentary and other 0; (E) free distribution outside the mails 515; (F) total free distribution was 515; (G) total distribution 9,900; (H) copies not distributed 5; (I) total [of 15G and H] 9,905 (J) Percentage paid and/or requested circulation 95%. I certify that the above statements are correct and complete. (signed) Jessica MacFarlane, Executive Director, National Maritime Historical Society.

Below decks, work has also continued under the supervision of Rob Stevens, master shipwright of Virginia since before the keel was laid, and Jeremy Blaiklock, who oversees vessel construction. Watertight bulkheads have been installed and crew quarters in the forecastle are taking shape. Aft, the engine is slowly coming on line with fuel tanks, controls, venting, and all the myriad things an iron topsail requires. e ultimate goal, of course, is a Coast Guard Certi cate of Inspection (COI), which will allow us to sail with passengers, trainees, and school children. We still have a long passage ahead before we get there, but we hope to have the COI in hand by summer 2023.

Along with Virginia, Maine’s First Ship oversees the Bath Freight Shed (a wonderful historic building in its own right), on the banks of the Kennebec River, where the ship is tied up. Under the direction of Lori Benson, we maintain a visitors center and use the space for demonstrations, educational programs, lectures, rental space, and other events, including a farmer’s market in the winter months.

For all of the ongoing activity, Maine’s First Ship is without doubt in a period of transition. For more than a decade now, the organization has been essentially a loose-knit group of men and women dedicated to building a wooden ship, drawn to the project by the camaraderie, the chance to learn new skills, and the opportunity to be part of this greater thing. With

the ship in the water and the bulk of the construction completed, over the next year we’ll move from the task of building a ship to operating one, with all that entails, including sta ng, programming, scheduling, and more intensive fundraising. We are on the verge of becoming an entirely di erent kind of project.

e change began most clearly with the hiring of an executive director, Kirstie Truluck, MFS’s rst full-time employee. With eyes toward how the ship will be used in the future, we are beginning to do outreach programs in the local schools, Maine Maritime Museum (just down the road a piece, as we say in Maine), and the Bath community, looking for how to best utilize Virginia going forward. It’s a brave new world, but like the colonists who built the original Virginia, we’re eager to explore.

Readers can learn more about Virginia at www.MFShip.org, visit our Facebook page, or follow us on Instagram. e Kennebec River, Virginia’ s usual home, is not a great place to be in the winter, given the strong current and massive ice ows that come sweeping down. For that reason the ship will over-winter at the town dock in nearby Wiscasset. Come spring, she’ll be back on the waterfront in Bath, where she will once again welcome visitors who wish to see her up close. I would encourage all sailing ship enthusiasts to pay us a visit, learn about this unique vessel, and, the Good Lord and the Coast Guard willing, come with us for a sail.

Jim Nelson Harpswell, Maine

6 SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23

Virginia’s deck has been a hive of activity since her launch on 4 June 2022.

courtesy

james nelson

J.P.URANKERWOODCARVER WWW.JPUWOODCARVER.COM THETRADITION OFHANDCARVED EAGLES CONTINUES TODAY (508) 939-1447 ★ ★ ★ ★

NMHS Legacy Society

Help keep history alive!

Each one of us can make a difference. Together, we make change.

— Senator Barbara Mikulski, 2015 NMHS Distinguished Service Award recipient

Since our founding in 1963, the National Maritime Historical Society has striven to tell the stories, great and small, near and far, that make up the broad panorama of our maritime history. Over the last six decades, hundreds of thousands of readers have discovered in the pages of Sea History magazine a treasure-trove of stories that captivate, connect and enlighten us all about the vital role of our seas, rivers, lakes and bays.

Ensure our maritime history is not lost.

It is more important than ever to bring the lessons of our maritime heritage to young people tomorrow’s maritime leaders. Now you can create a legacy for the next generation of sea service men and women, underwater archaeologists and ocean conservationists, maritime librarians and museum curators, shipwrights and preservationists, marine artists and musicians, ocean racers and tugboat captains, history teachers and writers.

Making a legacy gift to the Society is a deeply personal and transformative way to support our lifelong work, helping us to prepare for the future while bolstering the work we do now for our maritime heritage.

Including the National Maritime Historical Society in your will or living trust is one of the most effective ways to provide for the Society’s future while retaining assets during your lifetime. No matter the size of your gift, you’ll be playing an important role in preserving our shared maritime heritage and inspiring future generations.

Please email plannedgiving@seahistory.org, or call us at (914) 737-7878 Ext. 0 for more information.

Have you already made a legacy gift?

We hope you will notify us when you have included us in your future planning so that we may thank you and welcome you as a new member of our NMHS Legacy Society.

SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23 7

NOAA divers explore the shipwreck of the Schurz. Photo: Tane Casserley/NOAA.

NMHS: A CAUSE IN MOTION

A Celebration of Our Maritime Heritage & the Contemporary Maritime Community— e 2022 National Maritime Historical Society Annual Awards Dinner

e National Maritime Historical Society is grateful for our esteemed honorees, presenters, dinner committee members, trustees, and guests for enriching this year’s Annual Awards Dinner with their incredible insight and experience, generous support, and for giving us moments of laughter, admiration, and re ection.

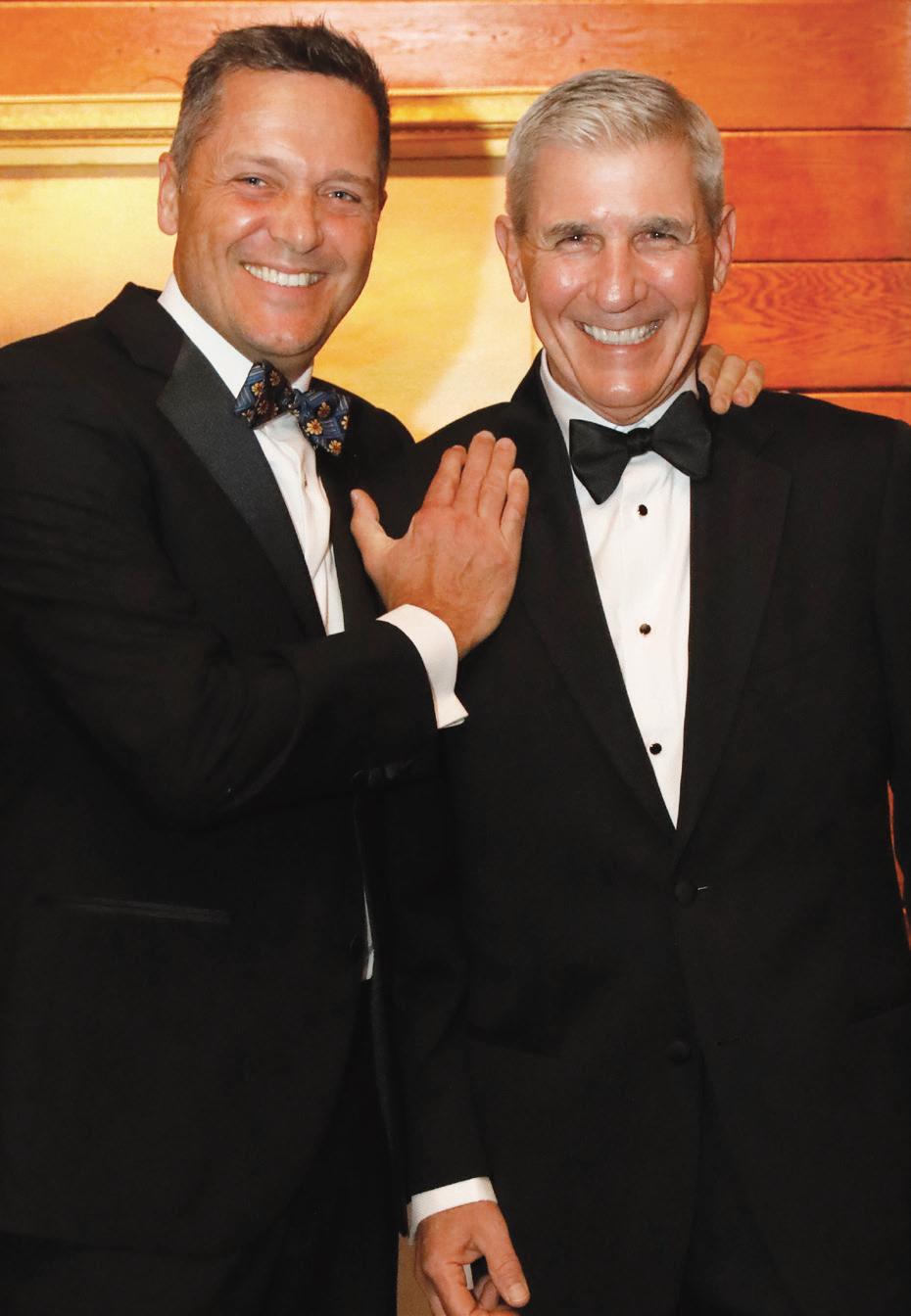

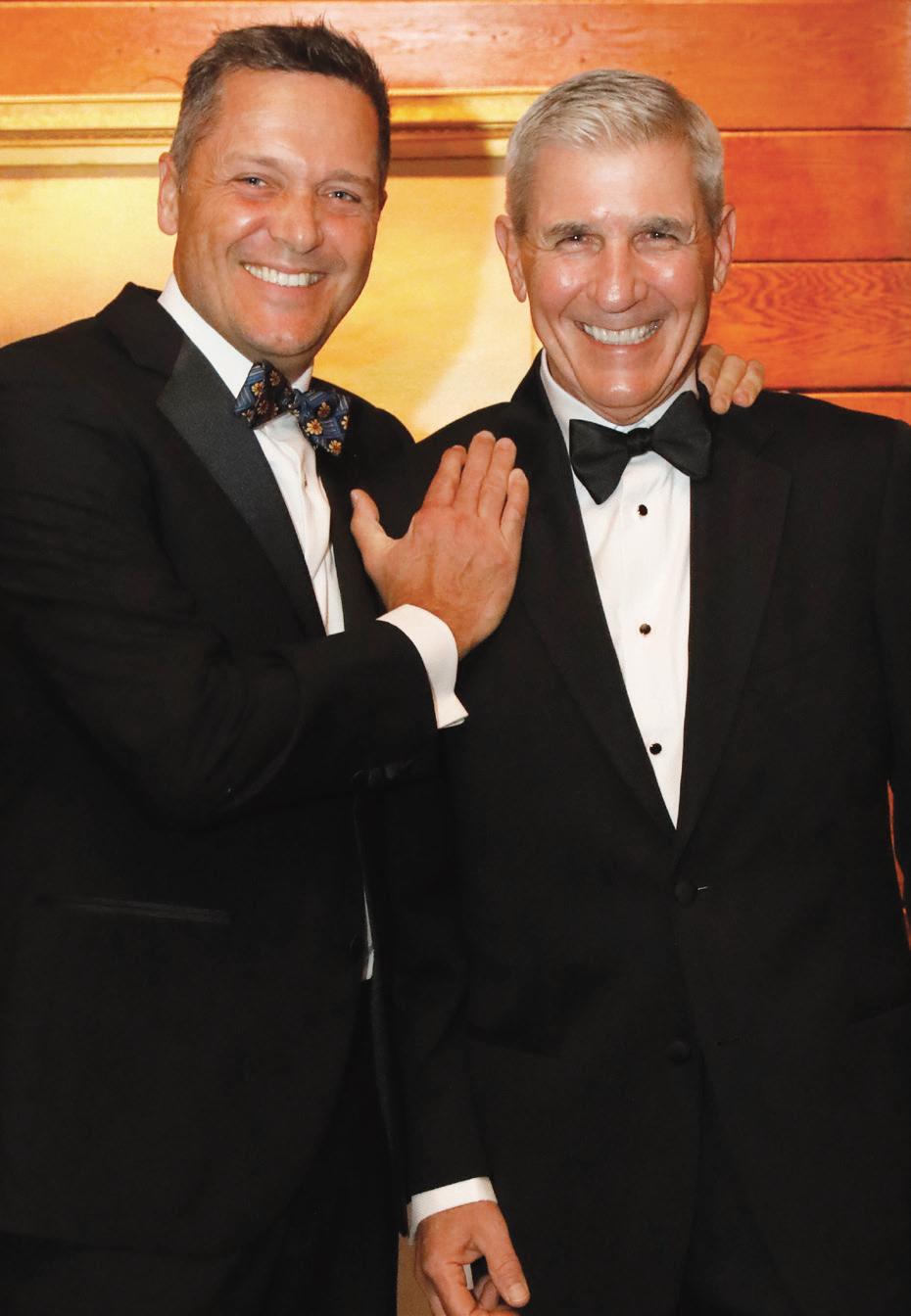

It was heartwarming to be able to meet in person again at the historic New York Yacht Club for the rst time since 2019, when we honored Matt Brooks and Pam Rorke Levy for their restoration of the 1929 Olin Stephens-designed Dorade and returning her to blue water racing. Our dinner chairs were joined by nearly 200 guests from diverse maritime elds—a wide-ranging group of dedicated leaders exemplifying the strength and vitality of the maritime heritage community today. We were gathered to honor the extraordinary accomplishments of RADM Joseph Callo, USN (Ret.), CAPT Sally McElwreath Callo, USN (Ret.), Steven P. Kalil, and omas A. Whidden.

As Pam Rorke Levy poignantly remarked from the podium, “Innovators today are the people who are making history, and the four people we’re honoring here tonight certainly demonstrate that not only are they a part of our history, but that even today they are still innovating and changing the way we all sail and appreciate and enjoy and bene t from our relationship with the seas.”

NMHS chairman CAPT James A. Noone, USN (Ret.) paid tribute to the remarkable work of our president emeritus Burchenal Green, “who has been the heart of the Society since joining it over a quarter century ago.”

Before taking to the podium to fête this year’s honorees, dinner chairs Pam Rorke Levy and Matt Brooks (center) pause for a photo with master of ceremonies Richard du Moulin (right), America’s ambassador of sailing Gary Jobson (left), and NMHS Distinguished Service Award recipient omas Whidden (second from right).

Our awardees were pro led in videos produced by NMHS vice chairman Richardo R. Lopes and his son Alessandro Lopes of Voyage Digital Media. Erik K. Olstein, former president of the Board of the American Friends of the National Museum of the Royal Navy and former NMHS trustee, presented RADM Joseph Callo, USN (Ret.) and CAPT Sally McElwreath Callo, USN (Ret.) with the NMHS David A. O’Neil Sheet Anchor Award in recognition of their important work as NMHS global ambassadors and on behalf of the naval and maritime heritage communities. Introducing the Callos, Olstein said “ ey are the epitome of excellence, grace and humility… and the personi cation of sel ess service.”

Erik Olstein (left) presents the David A. O’Neil Sheet Anchor Award to CAPT Sally McElwreath Callo and RADM Joseph Callo.

8 SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23

photos by allison lucas

In perhaps one of the most charming moments of the evening, RADM Callo focused his remarks on “my sailing companion, Sally. She’s not only my buddy, but she’s my true partner… there could not be a better partner in a boat.” CAPT McElwreath Callo added “that it is truly amazing to be rewarded for doing things that you really love to do, and it’s been a very interesting journey.”

Capt. Jonathan Boulware, president and CEO of South Street Seaport Museum, presented Steven P. Kalil with the NMHS Distinguished Service Award in recognition of his outstanding expertise, commitment, and vision that have helped steer Caddell Dry Dock to great success. “ e phrase ‘maritime heritage’ runs through the evening here,” he said. “I don’t know how many people have had the privilege of being at Caddell Dry Dock, but it is a place that typi es that exact thing. But we’re also in the company of contemporary maritime, which will be maritime heritage as it ages. It is a continuum.”

Ever modest and gracious, Steve Kalil shared his initial reluctance to accept the Society’s Distinguished Service Award, stating “I really don’t belong here”—we couldn’t have disagreed more. Under Kalil’s leadership, Caddell Dry Dock has continued the maritime traditions of an exceptional shipyard business founded in 1903, constructing and servicing thousands of vessels, and working on some of our most signi cant historic ships. “I really thought it was going to be a summer job,” he said, “but it wasn’t, and here I am, 47 ½ years later, and who knows when I’ll nish. I love this job.”

We saw a glimpse of the long-standing friendship between master of ceremonies and NMHS overseer Richard T. du Moulin and America’s ambassador of sailing Gary Jobson: “You might have noticed Gary trying to get up to the podium before me,” said du Moulin. “Gary, Tom Whidden, and I have been racing against each other and with each other for our whole sailing lives, and Gary, I’m supposed to go before you because I’m introducing you.”

Jobson then introduced omas A. Whidden, presenting him with the NMHS Distinguished Service Award in recognition of his outstanding contributions to yachting, for his unparalleled leadership in the design and manufacture of technologically advanced sails, and for encouraging younger generations to value and participate in the sport. Jobson said: “Tom was on winning boats and he’ll tell you he was on losing boats too. And sometimes I think you learn more when you lose than when you win. It’s a great testament to how when things go bad, don’t give up. Tom came back and went on to an even greater high.”

Tom Whidden told us: “It has always been amazing to me to be recognized for the only thing I really ever wanted to do with my life.” Of NMHS, he said “our missions are quite comparable. We both live to promote the maritime heritage community and to share in the sport of sailing and more generally enjoying the sea, whether it be racing, sailing or cruising, making a living on or o the water or around the sea, or just appreciating the deep history that the maritime community enjoys.” He added, “I did okay for a guy with a full-time summer job.”

—Jessica MacFarlane NMHS Executive Director

e vocal talents of the US Coast Guard Academy Cadet Chorale, directed by Director of Cadet Vocal Music Daniel McDavitt, are always a highlight of the NMHS Annual Awards Dinner.

SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23 9

Jonathan Boulware (left) had the honor of presenting Steven Kalil with the NMHS Distinguished Service Award.

Submarine Warfare and the Decline of Sailing Fleets, 1914–1918

by Steven Woods

Large sailing ships were still viable into the 1930s. is 1933 photo was shot by Alan Villiers from the deck of the Flying P Liner Parma and shows the barquentine Mozart (left) underway, with the barque Penang at anchor. e Penang was still sailing commercially until 8 December 1940, when she was torpedoed by U-140 northwest of Tory Island, o the west coast of Ireland. Penang capsized after the hit and sank.

Conventional wisdom holds that the early 20th century saw the end of working sail, what is now termed “sail freight,” on transoceanic routes because windjammers lost the technological race around this time. Under close examination, however, we discover this conclusion doesn’t hold up. Not until 1900 did the steam tonnage of the American eet exceed sailing tonnage, with Europe passing this mark only eleven years before.1 Sailing cargo vessels were still being built worldwide, employed extensively in the nitrates and collier trades, as well as lumber and grain.2 On some routes, sail freighters could out-perform steamers in both speed and cost, meaning the technoeconomical advantage was not entirely in favor of fossil-fueled vessels.3 Windjammers were still being ordered and built into the 1920s, both in Maine and Europe.4

Competition from the diesel-cycle marine engine was relatively minor until 1920–40, when it became more fuel and space-e cient than steam turbines. It was predicted in December of 1920 that advanced windjammer designs would remain pro table for many years to come.5 Longdistance routes were still economically viable for windjammers into the 1940s, with new motor-sailing vessels being built through the 1920s.6 With many sailing

ships having a service life of 25–50 years, and nearly 50% of global tonnage under sail in 1900, one would expect retirement by attrition to be a slow process lasting into the 1960s and 1970s. Instead, a rapid decline in the use of sail freighters for transAtlantic trade was seen in the rst quarter of the 20th century.

In 1914, the First World War broke out across Europe and its global empires and rapidly intensi ed into the rst truly mechanized war. is con ict was not limited to land, of course, as the submarine made its debut during this era. German U-boats became legendary for their devastating e ects on international shipping, especially during the periods of unrestricted submarine warfare. It was this outside force that was responsible for greatly reducing the transoceanic windjammer eet.

Sailing ships were especially vulnerable to submarine attack, as they were unable to make rapid course changes to avoid torpedoes, the recommended course of action when a torpedo launch was detected. Compared to submarines, which could make sixteen knots on the surface and eight submerged,7 windjammers were relatively slow and particularly at risk when winds did not favor a high cruising speed.

When armed, windjammers had a means to deter U-boats, and some sailing

vessels actually sank their attackers. One such incident was described in the Naval Institute Proceedings in 1918: “As the German [U-boat] came within range his re was answered, the sailing vessel ring 13 shots. e chief gunner was a former petty o cer in the British Navy and he scored eight bullseyes in a space of less than two minutes.”8 Most windjammers, however, sailed unarmed. A lack of armaments to issue to merchant vessels compounded the problem: “ ere are not enough small guns loose in the world to arm every merchantman. Few if any sailing ships are armed. At any rate a gun… compels in most cases a torpedo attack. at means expenditure of torpedoes.”9

e main method of defending merchant shipping, whether under sail or steam, was the convoy system. Although adopted relatively late in the war, this system placed a screen of anti-submarine vessels around the cargo-carrying ships. It was opined that of the measures taken to reduce losses to submarines by 1918, “the most important [is] the convoy system. All ships, including sailing ships and shing craft, are convoyed. e late sinkings have been chie y of slow or isolated steamers… e sinkings are now accidental. It is like walking past a building and being hit by a falling brick.”10

10 SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23

p d national maritime museum , uk

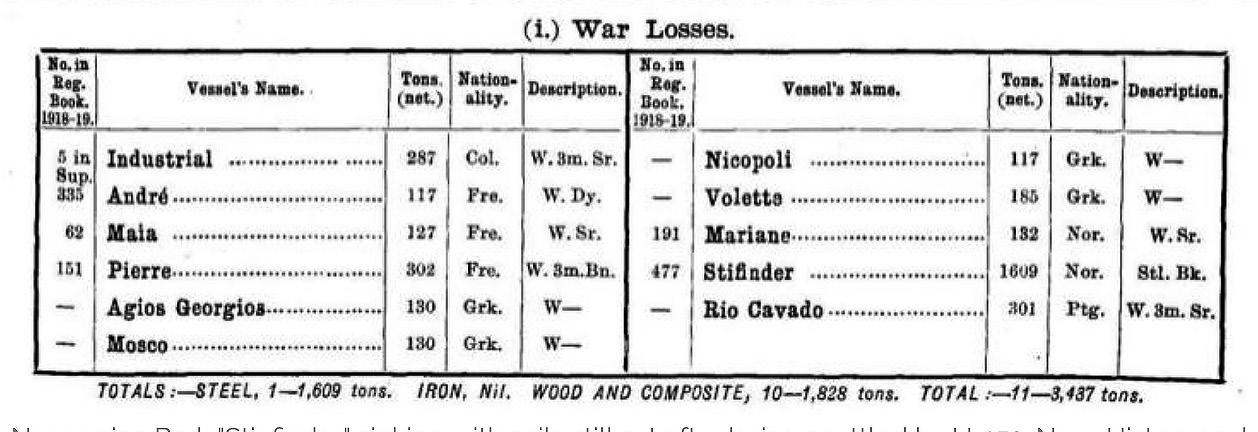

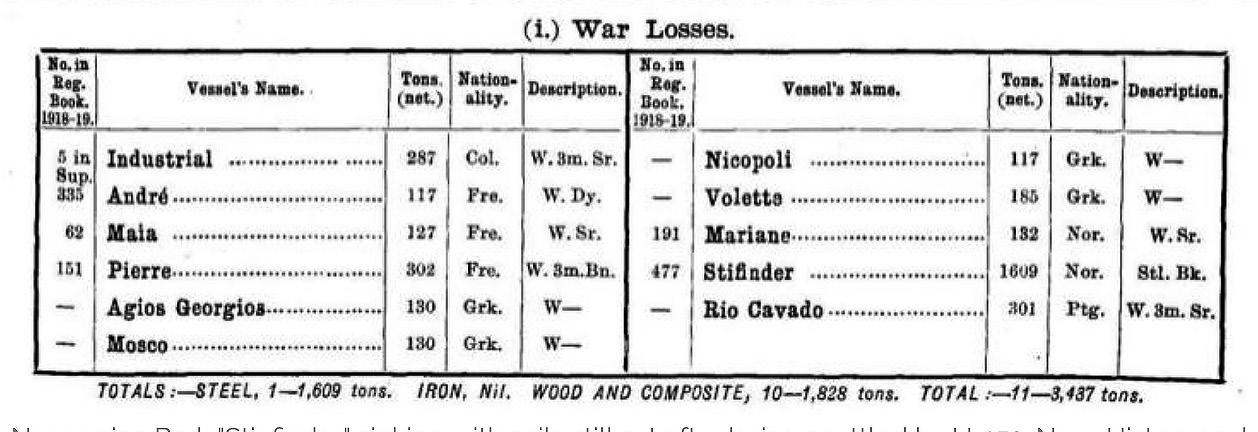

On 13 October 1918, the Norwegian barque Sti nder was en route between New York and Fremantle with a cargo of case oil when she was stopped at sea by U-152. e German crew ordered the crew to abandon ship in the barque’s two long boats and then sank the windjammer 1,000 miles from land. Ten of the crew made it to shore. e second boat, with the captain onboard, was lost at sea. (above left) Lloyd’s Register list of 1918–19 war losses. Sti nder is listed in the 2nd column.

ere were a number of other e orts undertaken to reduce ship casualties from U-boats. Aside from arming ships and convoys, dazzle camou age was developed by using disruptive patterns and bold colors to confuse U-boats,11 but it isn’t e ective on sailing vessels, as their sails and the wind action provide the data for torpedo targeting and course prediction. e recommendation of the O ce of Naval Intelligence was to steer an unpredictable course if sailing under 16 knots, or to rely primarily on speed if capable of exceeding this mark.12 It is very di cult for windjammers to reach 16 knots in most conditions, and even more di cult for them to alter course as frequently as was recommended, about once every 10 to 20 minutes.

e e ect of submarines on sailing vessels was bad enough that the United States banned their charter to the war zone, favoring the use of sailing vessels in the coastal and South American trades, which

was deemed considerably safer. ese policies likely preserved a signi cant amount of the American sailing eet, as had US neutrality earlier in the war. e following excerpt from the Second Annual Report of the US Shipping Board neatly summarizes the threats faced by sailing vessels crossing the Atlantic:

As early as May, 1917, the Shipping Board announced the policy of refusing charters to American sailing vessels to foreigners to go into the war zone because of the danger of destruction and because the owner would want to sell the vessel if it reached a foreign port safely rather than risk a return voyage, for which the freight rates were not so attractive.

On October 10, 1917, the Shipping Board advised… sailing

vessels bound on voyages from ports of the United States or its possessions to European or Mediterranean ports were subject to excessive war risk… allowing no sailing vessel to clear for any… European or Mediterranean port.

Sailing vessels are obviously unsuited for war zone trade, particularly as they furnish a ready source from which submarines may obtain fresh supplies. ey are, however, valuable for replacing vessels taken from the coastwise and South American trade.13

Lloyd’s casualty registers for the First World War show the tremendous loss of tonnage from both normal attrition and war-related sinkings. In 1914, the major European and US eets (Great Lakes exclusive) amounted to some 5,787 vessels

SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23 11

stifinder photos and lloyd ’ s list courtesy naval history and heritage command (nhhc)

of 3,368,984 net tons. By 1920, when summaries were again published, the eet had declined to 4,220 vessels of 2,987,719 net tons, a 27% loss in vessels and 11% loss in tonnage. e di erence between these two numbers is 1,567, however between 1914 and 1918 some 2,049 sail freighters were lost, 977 directly attributed to war losses.14 e discrepancy is explained by the fact that at least 482 new sailing vessels of over 100 net tons were built or purchased into these major eets during the war.

By 1919 Russia’s windjammer eet was at 17.6% of its pre-war strength, while neutral Norway was at 33.8%. e only eets to have made a gain were those of Spain, which started out with 58 ships and ended the war with 148 (255% of pre-war strength), and the British colonies, which replaced Atlantic windjammers with steamers from elsewhere.

More than 1.3 million net tons of windjammer capacity were lost during the war, 3.4 times the di erence between the

pre- and post-war listed tonnages for the major powers. Tonnage losses listed in Lloyd’s Register of Shipping were 51.4% “war related,” with 47.7% of vessels lost— meaning above-average sized ships were being sunk. From 1909 to 1914, the sailing eet declined some 26.5%, while during the war it declined by 27.1% in vessels. It should be noted that the above 482 new vessels brought into these eets are not included here: a corrected vessel decline rate is 35.4%, nearly 9% more than the pre-war era. Wartime attrition was 134% of the peacetime rate.

ese numbers only consider vessels over 100 tons, but many smaller vessels were also targeted. Small coasters, trawlers and other commercial vessels were frequently subjected to U-boat deck guns. As they carried little more than small arms, their crews o ered no real resistance to this new type of warship. Small vessel losses would not appear in the Lloyd’s Register, but news reached the New England coast.

Four men landed in a dory at Cape Porpoise today reporting that their shing schooner the Robert and Richard of Gloucester had been sunk by a German submarine on Cashe Bank… e submarine, the men stated, came out of the water a few hundred yards distant and sent a shell across their bow. The crew promptly swung the schooner up into the wind and took to their boats. en the raider sent a boat aboard the schooner, apparently took only her papers, placed a bomb and left her. A few minutes later an explosion sent the trim little knockabout to the bottom.15

e Robert and Richard appears in the List of Merchant Vessels of e United States in 1917 at 89 net tons, below the Lloyd’s Register threshold. She was built at Essex, Massachusetts, in 1915,16 and was torpedoed with no loss of life on 22 July 1918.17

ere are three pages listing sailing vessels lost that year, six listed as “submarined,” with only one fatality. Twenty-nine of the vessels lost were under the threshold for inclusion in Lloyd’s Register at 100 net tons.18 In the 1918 volume of the same publication, 158 sailing vessels are reported lost, with a total tonnage of 106,566, and 173 lives lost; 34 are attributed to “war loss.”19

Estimating casualties from this period is di cult, as Lloyd’s casualty returns do not list fatalities. On the high seas, most crews from targeted vessels could not be put ashore and were unlikely to be rescued; coastal sailors were frequently put in their small boats su ciently close to shore to survive. is case o the Canadian coast in 1918 is typical: “

e Hollett after being robbed was sunk… e schooner was built in 1917... Search was continued by government vessels today for the German submarine which since Friday has destroyed six sailing ships and the Standard Oil tanker Luc Blanca… [Except for two of the tanker’s crew] all hands reached shore safely.20

12 SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23

popular mechanics , vol . 3 0 , iss . 4 . ( oct . 1 9 1 8 )

A 1918 Popular Mechanics article featured these photos of the damage a windjammer su ered from an attack from a German U-boat in the Atlantic.

Mariners attacked in the English Channel were generally let go. is was a prudent move on the part of U-boat captains, as it allowed them to both save ammunition and resupply from the ships they stopped and boarded.21

In some cases, crews were taken onboard the submarine until they could be sent ashore, which seems to have been the norm during raids along the US Eastern Seaboard in 1917–18. Many of the vessels sunk in these operations, such as the schooner Edna, are not listed as “submarined” or even “lost” in the list of US merchant vessels, meaning any registry-based research on this topic will result in an undercounting of the real toll of submarine warfare.22

As the world once again considers moving freight under sail as a viable option to move cargo in a carbon-constrained future, research on the practicalities and efciencies of sail freight are paired with historical research on its decline. 23 e e ects of the First World War and submarine warfare in accelerating the decline of sail freight have not been well researched, despite their clear and lasting impact. Sail was already in a slow decline, but the increase of attrition and the predominance of steam and diesel propulsion in newly built ships for higher survivability meant little was left of the transoceanic windjammer eet after the war. is non-econom-

NOTES

1 Marine Review Publishing Co., Blue Book of American Shipping, 5th ed. (Cleveland: Marine Review, 1900). 4.

2 Ralph Linwood Snow and Capt. Douglas K Lee, A Shipyard in Maine: Percy and Small and the Great Schooners (Bath: Maine Maritime Museum, 1999).

3 Felix Riesenberg, Standard Seamanship for e Merchant Service 2nd ed. (New York: D. Van Norstrand, 1936).

4 Snow and Lee, A Shipyard in Maine

5 C. O. Liljegren, “Coal Oil or Wind?” Transactions of the Institution of Engineers And Shipbuilders In Scotland, Vol 64, 1920. 242–309.

6 Riesenberg, Standard Seamanship for e Merchant Service.

7 O ce of Naval Intelligence, Analysis of the Advantage of Speed and Changes of Course in Avoiding Attack by Submarine, ONI Publication No. 30. (Washington, DC: Government Printing O ce, 1918).

8 US Naval Institute Proceedings 44. (Annapolis:

Receipt given to the master of the American schooner Hauppauge by Korvettenkapitän Nostitz, 25 May 1918. e German commander brought the schooner’s crew onboard the U-boat so that their presence o the East Coast would not be detected. e crew was kept onboard for 8 days before being put into the schooner’s lifeboats (which were being towed by the U-boat), from which they were later rescued by an American steamship. e attempt to scuttle the Hauppauge failed and the schooner was later salvaged.

ic pressure needs to be understood when looking at the decline of sail freight in the Atlantic World.

It should also be noted that sail freight, while diminished, never completely stopped. Coastal sailing eets survived in Ireland and Australia into the 1960s and 1970s, while sail freight has endured in many small island states of the South Paci c.24 ose interested in learning more about sail freight should visit the Hudson River Maritime Museum’s exhibition,

US Naval Institute, 1918, 1144).

9 Henry Reuterdahl, “War Invisible” Saturday Evening Post, 189:48. (Philadelphia: Curtis Publishing Co., 1917. 67).

10 US Naval Institute Proceedings 44. 2183.

11 Waldemar Kaemp ert, “Fighting the U-boat With Paint” Popular Science Monthly 94:4 April 1919.

12 ONI, Analysis of the Advantage of Speed and Changes of Course in Avoiding Attack by Submarine

13 US Shipping Board, Second Annual Report of the United States Shipping Board ( Washington, DC: Government Printing O ce, 1918).

14 Lloyd’s Register of Shipping: Returns of Shipping Totally Lost, Condemned, etc. (London: Lloyd’s, 1914–1920).

15 US Naval Institute Proceedings 44. 2198.

16 US Bureau of Navigation, List of Merchant Vessels of the United States 49th ed. (Washington, DC: Government Printing O ce, 1917. 59).

17 US Bureau of Navigation, List of Merchant

A New Age Of Sail: e History And Future Of Sail Freight On e Hudson River on view at the museum and online through 2024. (www.hrmm.org)

Steven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He earned his master’s degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, where he wrote his thesis on the revival of sail freight for supplying the New York metro area’s food needs.

Vessels of the United States 51st ed. (Washington, DC: Government Printing O ce, 1920. 448).

18 US Bureau of Navigation, List of Merchant Vessels of the United States 49th ed. 59.

19 US Bureau of Navigation, List of Merchant Vessels of the United States 50th ed. (Washington, DC: Government Printing O ce, 1918).

20 US Naval Institute Proceedings, 44. 2203.

21 US Naval Institute Proceedings, 44. 2202.

22 O ce of Naval Records and Library, German submarine activities on the Atlantic Coast of the United States and Canada (Washington: Government Printing O ce, 1920).

23 Steven Woods and Sam Merrett, “Operation of a sail freighter on the Hudson River: Schooner Apollonia in 2021,” Journal of Merchant Ship Wind Energy, 2 Mar 2021.

24 Richard J. Scott, e Galway Hookers: Working Sailboats of Galway Bay (Boyle: Ward River Press, 1996). Rick Bullers, “Annie Watt: e Career of a Coastal Trading Ketch,” e Great Circle 36, no. 1 (2014), 8-32.

SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER

13

2022–23

naval history and heritage command ( nhhc )

Marked for Disaster

The Tragic Loss and Inspiring Legacy of the 1554

by Amy Borgens

Cramped in close quarters, the deafening sound of the heavy wind and waves only heightened the anxiety of the passengers and crew as the four ships moved perilously close to shore. e decision to sail closer to the mainland had been risky, perhaps intending to capitalize on the faster coastal currents to make up time lost at sea. e ships— San Esteban, Espíritu Santo, Santa María de Yciar, and San Andres —were already twenty days into a voyage that often just took twelve. ey had departed San Juan de Ulúa, o Veracruz (present-day Mexico), on 9 April, bound for Spain by way of Havana, Cuba. Unable to prevail in their e orts against an unexpected storm, three of the ships ran aground at Padre Island, present-day Texas, on 29

April 1554, with a precious cargo in silver, cochineal, and other goods intended for Spain. e loss of life was stunning—an estimated 300 individuals perished, and news of the tragedy e ected an immediate response from Spanish o cials in Mexico City to search for survivors and salvage the cargo.

For more than 400 years this story would be lost to history, save for the occasional silver coins that wash ashore, particularly after storms, fueling the local lore of treasure lost at sea. e accidental discovery of this forgotten eet in 1964, and its later salvage in 1967, would culminate in a landmark lawsuit, the passage of Texas’ antiquities law, and the state-funded and state-led excavation of San Esteban e archaeological investigation under-

taken by the Texas Antiquities Committee (TAC)—predecessor to the Texas Historical Commission (THC)—beginning in 1972 is believed to be the rst scienti c excavation of a shipwreck in the United States. During the second year of eldwork in 1973, the TAC partnered with the University of Texas (UT) to conduct an archaeology eld school, possibly the rst program of its type in US waters. With the 50th anniversary of the investigations in 2022, the importance of the 1554 eet cannot be understated for its contribution to the emerging eld of underwater archaeology. In the years that have passed since its discovery in 1964, these shipwrecks remain the oldest excavated wreck sites in the United States and the Gulf of Mexico.

14 SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23

(top) Shipwreck: San Esteban Survivors Land on the Texas Coast by Peter Rindlisbacher, 2022. Mural for the Texas Maritime Museum.

Spanish Plate Fleet of Padre Island, Texas

Under the protection of a six-ship armada, the ill-fated San Esteban, Espíritu Santo, and Santa María de Yciar departed Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Spain, in November 1552, as part of a 54-ship otilla led by Captain-General Bartolomé Carreño. ese vessels comprised the regularly scheduled commercial eets that carried goods between Spain and its American colonies, including invaluable raw materials from New Spain—in particular, silver and cochineal. After experiencing severe losses in men and ships during their Atlantic crossing, the surviving 29 vessels diverged once they entered the Caribbean Sea. Sixteen sailed for San Juan de Ulúa, o Veracruz (New Spain), and the remaining ships set a course for Cartegena, in accordance

Plate Ships in the Rising Wind

by Peter Rindlisbacher, 2022

by Peter Rindlisbacher, 2022

SEA HISTORY 181,

15

WINTER 2022–23

art by peter rindlisbacher

art

by peter rindlisbacher

with their original plan. e ships heading to Veracruz arrived in February and March 1553. At that time, the region was still recovering from an autumn 1552 hurricane, which delayed the unloading of the larger ships. ese challenges caused the vessels to miss the scheduled rendezvous with Carreño in Havana, and they remained in port to await the next convoy.

Finally, a rendezvous was arranged with an incoming eet commanded by Captain-General Cosme Rodríguez Farfán. After more than a year’s wait, they would accompany Farfán’s eet to Havana and then onwards to Spain. Sentiments changed, however, and it was decided they would depart alone to take advantage of favorable weather and sailing conditions.

e four-vessel otilla departed on 9 April, three weeks before any vessels of Farfán’s eet arrived at San Juan de Ulúa on 1 May. is change in plans would, of course, prove to be their undoing. e ships were still underway in the Gulf of Mexico heading for Havana, when a violent storm

ultimately drove them ashore along the barrier island. Only San Andres made it to Havana, but in too-damaged a condition to continue its voyage.

Conditions for the survivors at Padre Island were stark and unrelenting. A small group, led by Francisco del Huerto, master of San Esteban, rigged a small boat and sailed south to Veracruz to get help, arriving in May. A second group of approximately thirty survivors ultimately decided to march overland to Pánuco, near Mexico City, believing it to be a two- or three-day journey; it was, in fact, more than 500 miles. ey built a raft to cross the Rio Grande River and proceeded southwards, all the while being attacked by local indigenous tribes. Believing the attackers’ interest was solely aimed at material goods, such as their clothing, the survivors hesitantly surrendered them. With few possessions and nearly naked, they continued walking, but all were ultimately killed, except Fray Marcos Mena and the soldier Francisco Vásquez, who had earlier abandoned the

trek and returned to Padre Island. Mena’s survival was miraculous, as he had been wounded and partially buried, assumed by his comrades to be near death after being struck by arrows. With rest he was able dig himself out and continued on alone, wandering aimlessly in a dire condition. He was discovered by Indians at the Pánuco River, who helped him to Tampico. From there he traveled to Pánuco, where he recuperated from his injuries before continuing onward to Mexico City. News of the loss of the ships had already reached Spanish o cials, and a salvage expedition had been dispatched. It is Mena’s story, recounted to Fray Agustín Dávila Padilla thirty years later and published in 1596, that survives as the only rst-hand account of the tragedy.

Spanish o cials at Mexico City arranged for salvage of the vessels, valued then at more than 1.5 million pesos (worth more than 50 million USD today), rst sending troops overland in June to reconnoiter the coast and search for survivors.

In this detail of an early 18th-century Herman Moll map, the cartographer included the route that Spanish ships typically followed when sailing from Veracruz to Spain (with a stop at Havana) across the Gulf of Mexico. “ e Tract of ye only Passage of ye Flota from Vera Cruz to ye Havana occasioned by the Trade winds.” It is believed that the 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet ships were sailing closer to shore, far west of the traditional route, when the weather turned foul.

16 SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23

map of the west indies , mexico or new spain , publ by bowles , london , 1736 david rumsey map collection

e commander of the land expedition, Ángel de Villafañe, arrived at Pánuco and organized a small-scale salvage e ort of San Esteban using a diver he retained from Veracruz. e recovered objects were then shipped overland from Pánuco to Mexico City, arriving safely at their destination on 30 July, by which time the salvage expedition of the ships and cargo, commanded by Captain García de Escalante Alvarado, had already commenced. Alvarado’s squadron of six vessels anchored o Padre Island on 22 July and set up camp onshore. e wreckage of Santa María de Yciar and Espíritu Santo was no longer visible from the surface. As a means to rediscover the shipwrecks, the salvage crews rigged a cable slung between two shallops as a dragline Divers worked to recover materials from the wrecks, which were carefully weighed and inventoried—a process that was completed on 12 September. In total, Spain salvaged less than half the collective cargo from the three shipwrecks, and a rather extensive political dispute ensued regarding the nal disposition of this wealth. In the years since, this tragedy was largely forgotten, albeit piquing interest on occasion when coins would emerge on the beach, adding to the already extensive mythos of mysterious shoreline treasures that abound in the region.

For Vida Lee Connor, the August of 1964 may have begun typically for that time of year, without any premonition of

how the end of summer would unfold. Connor was part of a voluntary exploration group working with noted oceanographer Harold Geis to help map o shore reefs. She discovered several reefs o Mans eld Cut, now believed to comprise portions of Sebree, Steamer, and Seven and One-Half Fathoms Reefs. An outdoors enthusiast and adventurer, known locally as a trophy

sher and avid sailor, Connor often entertained guests aboard a 42-foot power yacht named for her—Vida Lee III. She also had access to a private plane. During an aerial visual reconnaissance for reefs in 1964, Connor observed a “dark patch” in the water and later dived it. She observed sixteen underwater features, which at the time she misunderstood to represent sixteen unique shipwrecks. ese were, in fact, the disarticulated, concreted remains of the 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet.

In the spring of 1965, Connor cosponsored a student on a research trip to visit Spanish archives, during which the Padilla account was successfully located. In 1966 Connor announced her discovery to regional newspapers, including the location of the shipwrecks, their identity, and that she had marked the sites with buoys. She hoped to encourage other divers and specialists to validate her discovery, but on a subsequent return to the sites, she encountered a professional salvage expedition “draglining” one of the shipwrecks and removing artifacts. is unexpected event

SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23 17 author

s collection

Plate Ships Driven by the Gale by Peter Rindlisbacher, 2022.

art by peter rindlisbacher

Vida Lee Connor and Harold Geis, press photo, Houston Chronicle , 2 October 1966.

brought Connor’s investigations of the shipwrecks to a close but opened the next complicated chapter in this story—one that exposed inadequacies in the state’s ability to protect its archaeological heritage on state property.

In the 1960s underwater archaeology was a new discipline pioneered by the graduate work of George Bass at the Late Bronze Age Cape Gelidonya shipwreck in Turkey, while a student at the University of Pennsylvania. At the time of the Texas discovery and salvage in the mid-1960s, the protection of submerged cultural resources was not directly addressed by existing Texas and federal laws. In Texas, for example, one needed to seek approval from a landowner or county commissioner for permission to search for an archaeological

Archaeologists recover a huge anchor from the wreck site, 1973.

site on private property or public land, respectively, but ownership, management authority, archaeological permitting, curation, reporting, and other now commonplace processes were not directly de ned or described.

In 1967, the Texas General Land O ce (GLO)—the state land manager— led an injunction against Platoro Limited, Inc., halting salvage by citing the Indiana-based company’s failure to obtain a permit to work within Texas, a requirement for out-of-state entities. us began a contentious lawsuit between the state and the salvors that would last 17 years. In 1984, Texas was awarded ownership of the collection. A bill was introduced in 1967 to create a state antiquities law. It was not enacted by the close of the legislative session and was reintroduced in the 41st Legislative Session of 1969, passing during a special session. e Antiquities Code of Texas (ACT; Natural Resource Code Title 9, Chapter 191) established protections for historic buildings, structures, archaeology (including shipwrecks), and other cultural heritage on state public lands, and introduced processes for protecting cultural resources in advance

State Marine Archeologist and Project Director Carl Clausen (right) and Assistant Project Director J. Barto Arnold (left) during excavations of San Esteban in 1973.

18 SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23

texas historical commission

texas historical commission

of construction projects and the designation of state antiquities landmarks. e TAC, since merged with the THC, was created as the management authority for state cultural heritage on public lands with regulatory responsibilities for conducting project reviews on behalf of federal and state laws to ensure protection of cultural resources in advance of development activities. As part of these duties, the THC requests archaeological surveys, issues antiquities permits, and reviews technical reports summarizing investigative ndings.

After the enactment of the ACT, archaeological work would recommence on the 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet, now under the auspices of the THC. It was a priority to excavate, record, and remove the rest of the ship remains and their artifacts so that they could be conserved for posterity and stored in a protective environment. Failure to do so risked continued unsanctioned activity on the shipwrecks and theft and damage to the sites. In 1969, state archaeologist Curtis Tunnell and Dr. George Fischer of the National Park Service (NPS) visually inspected the beach at Padre Island National Seashore seeking secondary artifact deposits (coins, for example) that might indicate the vessels’ o shore locations. is endeavor, however, did not detect any cultural material and the agency proceeded to coordinate with Southern Methodist University (SMU) to arrange for a remote-sensing survey to locate the wreck sites. SMU was part of a larger partnership of experts and specialists assisting the THC, including the NPS, UT, Texas A&M University (TAMU), Texas Tech

Astrolabes, coins, and other artifacts from the 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet shipwrecks.

University, and the GLO. An antiquities permit—the rst for an underwater archaeological investigation in Texas—was issued to the Institute of Underwater Research, helmed by SMU researchers. e eldwork in July 1970 detected numerous buried magnetic targets, but only one shipwreck, later identi ed as San Esteban, was uncovered and observed by divers.

To investigate the archaeological sites, the THC recruited Carl Clausen, the state underwater archaeologist for the Florida Division of Archives, History, and Records Management, to plan the eldwork. In 1972 he was hired as the rst state marine

archaeologist of Texas and as head of the Underwater Archeological Research Section (now known as the Marine Archeology Program). Fieldwork at San Esteban began on 15 July 1972, with UT conducting a eld school on the site in 1973. ese investigations focused on mapping and recovery of San Esteban, and in 1974 new remote-sensing surveys were conducted to relocate Espíritu Santa and Santa María de Yciar. Espíritu Santo was rediscovered, and eldwork in 1975 included recovery of additional artifacts from this wreck that had not previously been removed by Platoro, and a few objects from San Esteban.

SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER

19

2022–23

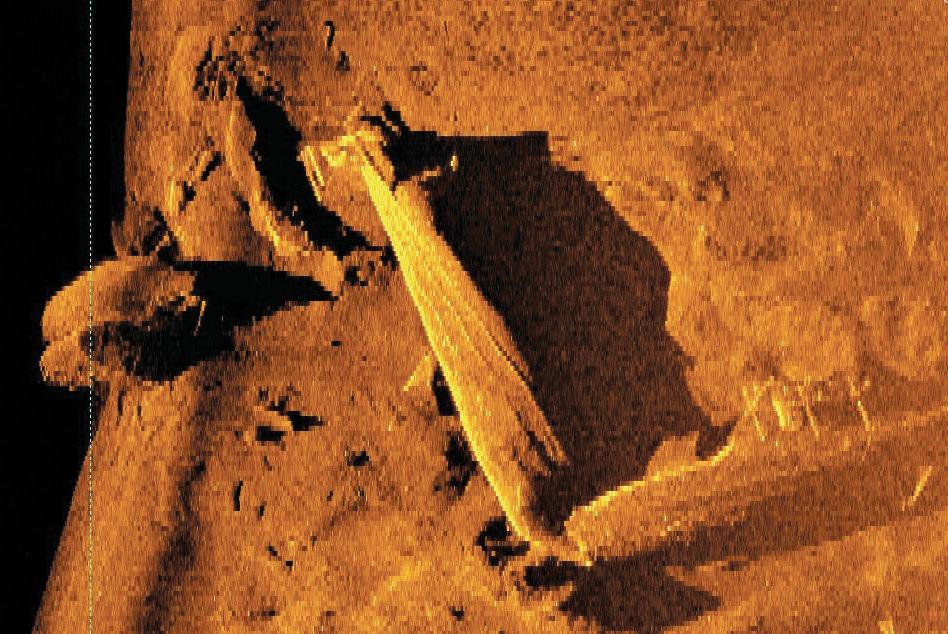

Drawing of San Esteban’s stern section.

texas historical commission texas historical commission

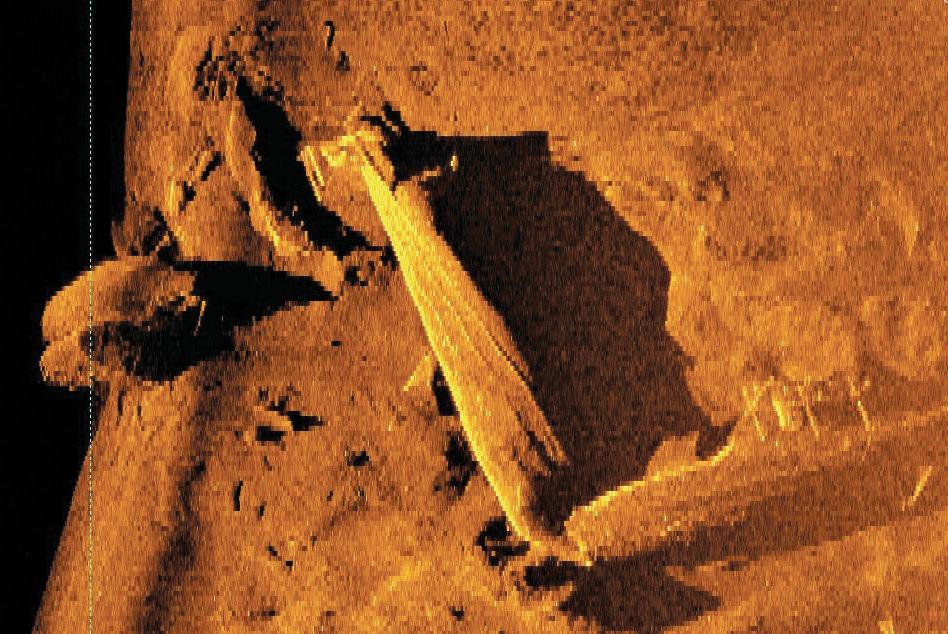

Very little of San Esteban’s hull remained, likely degraded over hundreds of years by teredo navalis mollusk consumption, common to the warm Gulf of Mexico waters. e archaeologists recovered an articulated section of the stern, measuring nearly sixteen feet in length. e remainder of the wreck site was characterized by an often non-contiguous assortment of artifacts and concretions. More than 5,800 artifacts were recovered from San Esteban, including artillery, munitions, anchors, silver coins and disks, potsherds, tools, spikes, and ballast. e collection from Espíritu Santo, totaling nearly 2,000 artifacts, also featured silver and gold artifacts, in addition to artillery, ballast, anchors, crossbows, and navigational tools. e artifacts from the 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet were conserved at the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory at UT, under the direction of Donny Hamilton (while a doctoral student) using new methodologies developed speci cally for fragile artifacts from a submerged saltwater environment. Hamilton’s dissertation on metal conservation would be published in 1976 as the TAC’s rst publication of its underwater archaeological series.

Under the direction of State Marine Archeologist J. Barto Arnold III, who had served as assistant project director under Carl Clausen, another investigation of Espíritu Santo occurred in 1977. e THC later partnered with the NPS in 1985–1986

to re-evaluate the sites as part of a broader e ort to examine all known archaeological sites at Padre Island National Seashore. Due to the discovery of a 16th-century anchor that had been snagged and pulled ashore at the jetties at Mans eld Cut, it has been presumed that dredging of the cut in the 1950s may have destroyed the wreck. ough numerous compliance surveys have been conducted in the area, none have discovered the elusive Santa María de Yciar, and new ongoing investigations, initiated in 2020 and led by the NPS in partnership with the THC, again seek to locate this lost vessel.

With this new work and continuing study of the artifact assemblage, the story of the loss of the 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet continues to be written. ese shipwrecks and their important cargoes are a material representation of the Spanish interest in the Americas, and the importance of the Spanish colonial enterprise that persisted for hundreds of years and nanced the power of the Spanish Empire. ey have left an undeniable legacy, not merely for the state of Texas, but for the discipline of underwater archaeology in general. is discovery and eld investigations in the 1960s and 1970s advanced the academic study of historic shipwrecks, provided a training ground for future maritime archaeological professionals, and increased awareness for this unique type of cultural resource inspiring the state’s protective

legislation to preserve this and all its cultural heritage.

You can view the artifacts and ship remains at the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History’s main exhibit, with smaller exhibits at Treasure of the Gulf Museum (Port Isabel), John E. Conner Museum at TAMU-Kingsville, and the Bullock Texas State History Museum. Researchers interested in the collection should reach out to the Marine Archeology Program (www.thc.texas.gov/preserve/projectsand-programs/marine-archeology).

Amy Borgens is the State Marine Archeologist of the Texas Historical Commission in Austin, Texas. She is coordinator of the Marine Archeology Program in the THC’s Archeology Division.

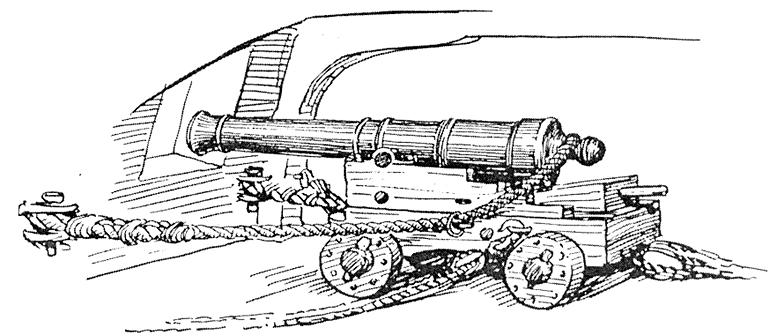

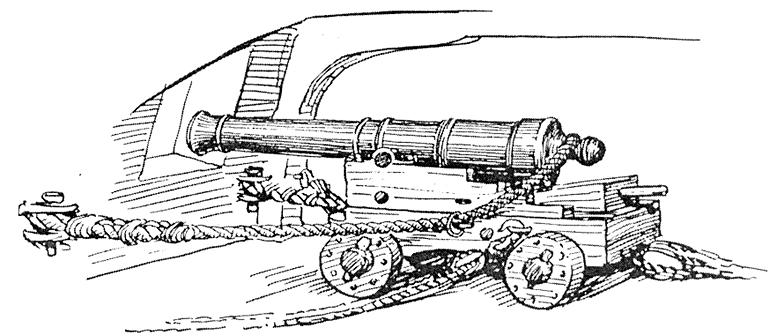

Artillery from San Esteban (above) and other artifacts are on exhibit at the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History.

A note on sources. e history, excavation, and conservation of the 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet are summarized in these TAC publications from the 1970s: Donny L. Hamilton, Conservation of Metal Objects from Underwater Sites: A Study in Methods (1976); Dorris L. Olds, Texas Legacy from the Gulf: A Report on the Sixteenth Century Shipwreck Materials Recovered from the Texas Tidelands (1976); John L. Davis, Treasure, People, Ships, and Dreams: A Spanish Shipwreck on the Texas Coast (1977); J. Barto Arnold III and Robert Weddle, e Nautical Archeology of Padre Island: e Spanish Shipwrecks of 1554 (1978); and David McDonald and J. Barto Arnold III, Documentary Sources for the Wreck of the New Spain Fleet of 1554 (1979). e TAC publications are hosted online: www.thc. texas.gov/preserve/archeology/1554-spanish-plate- eet. New information on the shipwrecks is featured in Amy A. Borgens, “Vida Lee Connor: Discoverer of the 1554 Spanish Plate Fleet o Padre Island,” (2022) Texas Historical Commission Blog at www. thc.texas.gov/blog/vida-lee-connor-discoverer-1554-spanish-plate- eet-padre-island and Amy A. Borgens, “ e Ill-Fated 1554 Spanish Plate of Padre Island, Texas, at the Semicentennial of the Archeological Investigations” in Plus Ultra: An Examination of Current Research in Spanish Colonial Underwater and Terrestrial Archeology in the Western Hemisphere, (pending) Springer Publishing, New York.

20 SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23

texas historical commission

SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23 21 e Promenade at Lighthouse Point, Staten Island, NY 10301 718-390-0040 • www.lighthousemuseum.org To preserve and educate on the maritime heritage of lighthouses, lightships and the stories of their keepers for generations to come... EVENTS INCLUDE: Lighthouse Boat Tours Museum Tours Presentations & Special Programs Lighthouse Recognition Weekend including the Annual Light Keeper’s Gala Lighthouse Point Fest featuring the Keeper’s Soup Contest K-12 Maritime Education Programs Home of the Great SI Lighthouse Hunt Contact the Museum to learn more about the

Campaign for Illuminating Future Generations.

C URATOR’S C ORNER : H ISTORIC P HOTOS FROM T H E A RCHIVES

During a tour of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum last spring, Chief Curator Pete Lesher showed us some compelling photos in the museum’s collections storage area. While available to researchers upon request, these photos don’t often see the light of day, so we decided to create a series in Sea History in which curators pick a particularly interesting, revealing, or representative photo from their archives and tell us about it. In this issue we are invited into the archives of the Wisconsin Maritime Museum. Enjoy!

Frozen in Time — Dozens of skaters glide past wooden steamships locked in the ice on this winter day in 1890 at Manitowoc, Wisconsin. e scene captures a moment of suspended animation: one can almost hear the scraping of metal blades on ice, while shouts of laughter punctuate the soundscape of a bustling Lake Michigan port town. Docked in the background are three wooden vessels of the Goodrich Transit Company eet. Depicted from left to right are the steamers Indiana, City of Racine, De Pere, and Menominee, wintering over at the company’s terminal on the north bank of the Manitowoc River. e newest of these vessels is the Indiana, built locally by Burger & Burger in Manitowoc. At 220 feet in length, she was launched on Saturday, 5 April 1890, to much fanfare as the “prettiest launch ever witnessed in the city.”1 While each vessel in this image has its own colorful history to tell, it is the photographer who deserves the spotlight.

Captain Edward Carus shot this photograph, one of nearly 3,000 in the Carus Collection at the Wisconsin Maritime Museum. Born in 1860 in Manitowoc, Carus began his career on the Great Lakes sailing aboard schooners and spent many years

1Manitowoc Pilot 10 April 1890, p. 2.

2 Manitowoc Herald-Times Manitowoc, Wisconsin 10 May 1961, p. 21.

as a captain for the Goodrich Line, where he was regarded as “sincere, outspoken, frank, jovial and cordial.”2 During his career, he also researched and recorded the maritime heritage of the areas where he sailed, particularly the western shore of Lake Michigan. By the 1930s, Captain Carus found himself in nancial distress, which motivated him to sell his collection to Henry Barkhausen, who in time donated it to the museum. Captain Carus died in August 1947, following a stroke he su ered while sitting outside his home at 1209 Franklin Street in Manitowoc. e Carus house was torn down in the 1950s to make way for a Chevrolet dealership parking lot. Today, that site and the property where the captain’s former home occupied are part of the museum’s o -site collections storage facility. is facility and associated grounds will undergo major renovations in 2023. Photographs taken by Captain Carus will be incorporated into a maritime mural on the exterior of the building. e mural and interpretive signage at the site will pay tribute to the legacy of the captain as an invaluable maritime chronicler during an era when Great Lakes transportation was rapidly modernizing.

—Kevin Cullen, Deputy Director and Chief Curator Wisconsin Maritime Museum (www.wisconsinmaritime.org)

22 SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23 wisconsin

maritime museum image id : p823700625b

THE FLEET IS IN.

Sit in the wardroom of a mighty battleship, touch a powerful torpedo on a submarine, or walk the deck of an aircraft carrier and stand where naval aviators have flown off into history. It’s all waiting for you when you visit one of the 175 ships of the Historic Naval Ships Association fleet.

For information on all our ships and museums, see the HNSA website or visit us on Facebook.

SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23 23 THE HISTORIC NAVAL SHIPS ASSOCIATION

www.HNSA.org

C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 2.25x4.5_HNSA_FleetCOL#1085.pdf 6/5/12 10:47:40 AM

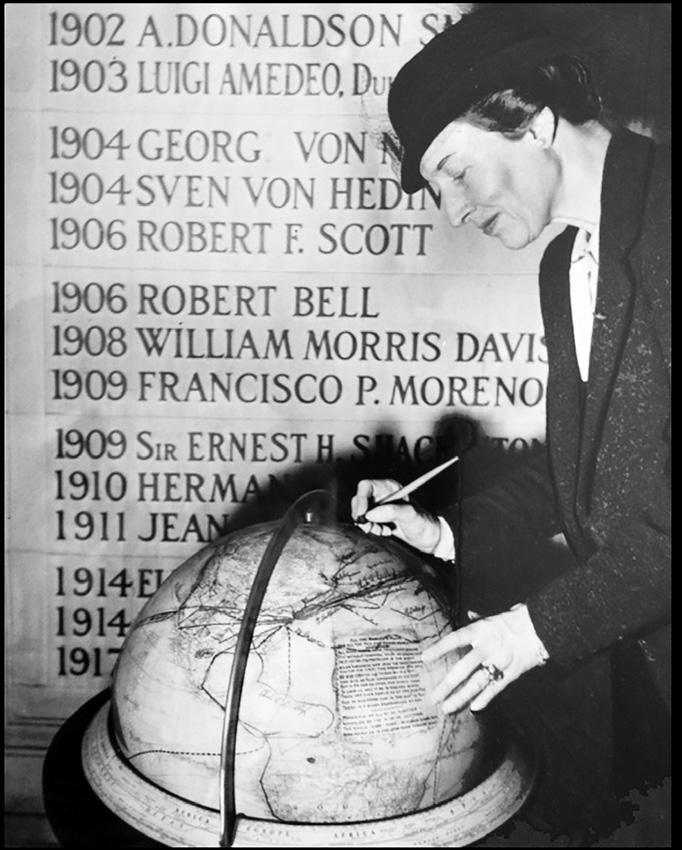

Greenland Beckons: Explorer Louise Arner Boyd aboard the Veslekari

by Joanna Kafarowski

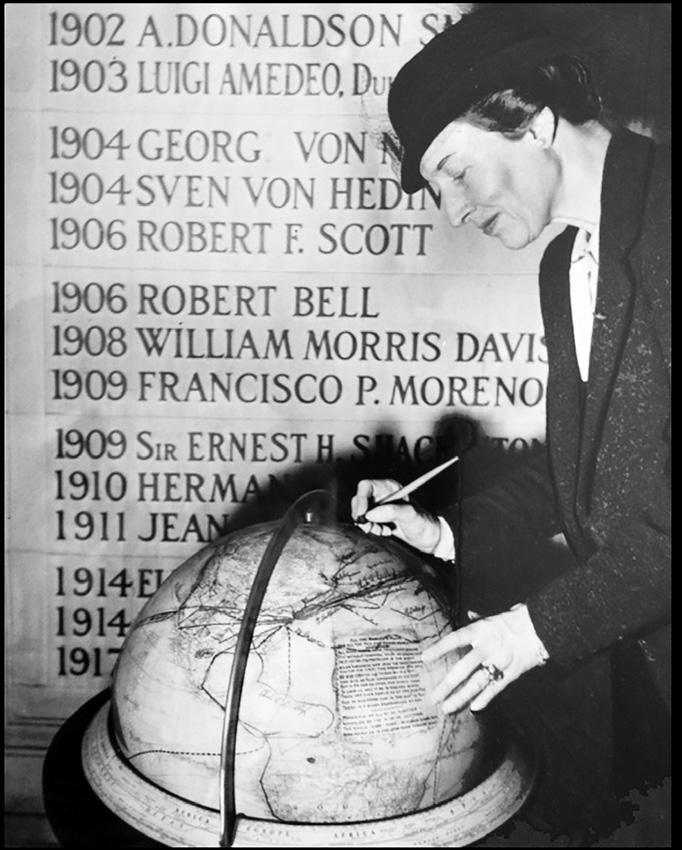

California native Louise Arner Boyd’s ambitious plan to sail to Greenland from northern Norway in 1928 was thwarted when she signed on to the international rescue mission to nd missing polar explorer Roald Amundsen, who had disappeared in June of that year.1 Tragically, Amundsen and his crew perished, but for Boyd the experience awakened a passion for exploring. Several years passed, and Boyd’s desire to launch

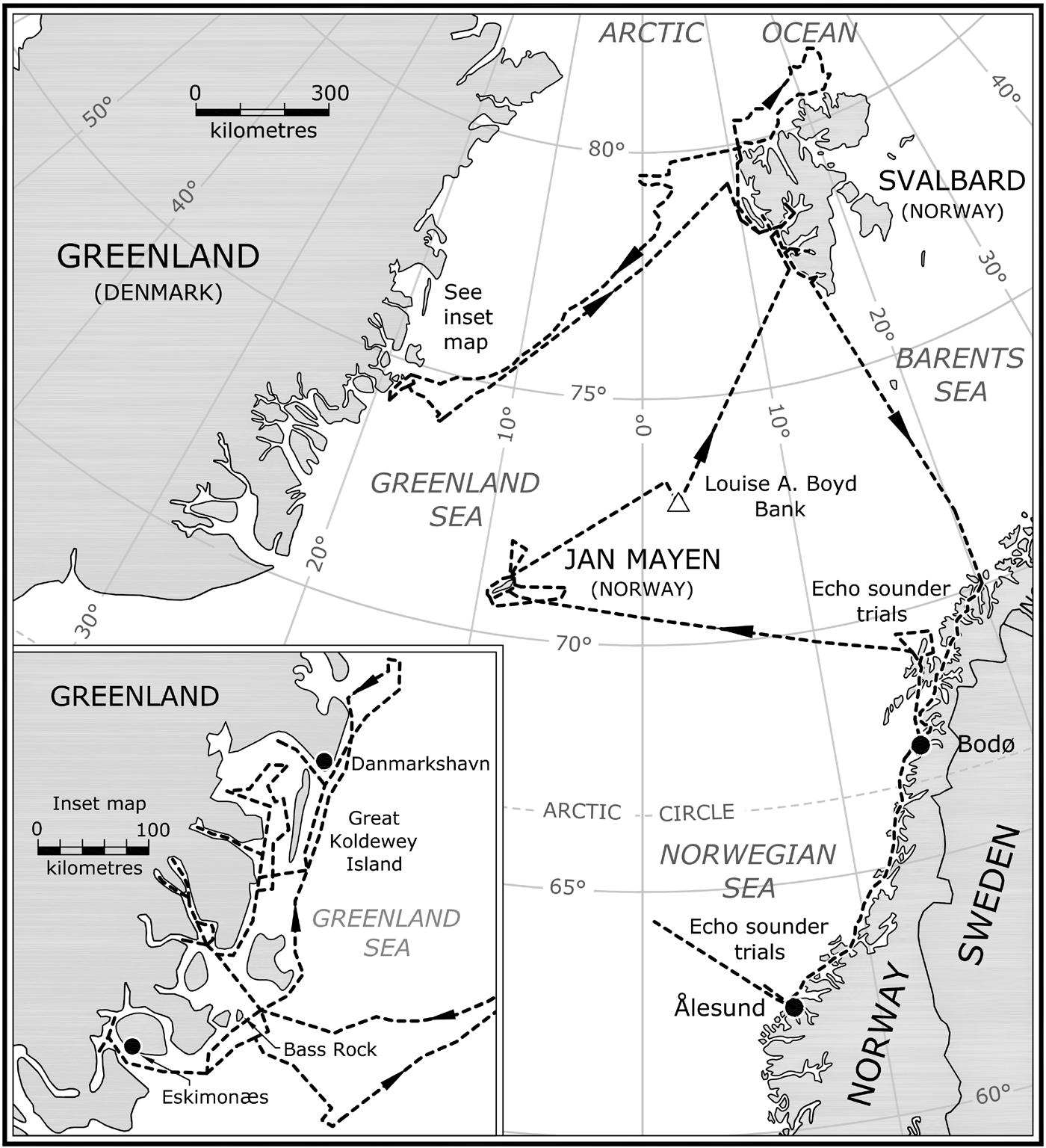

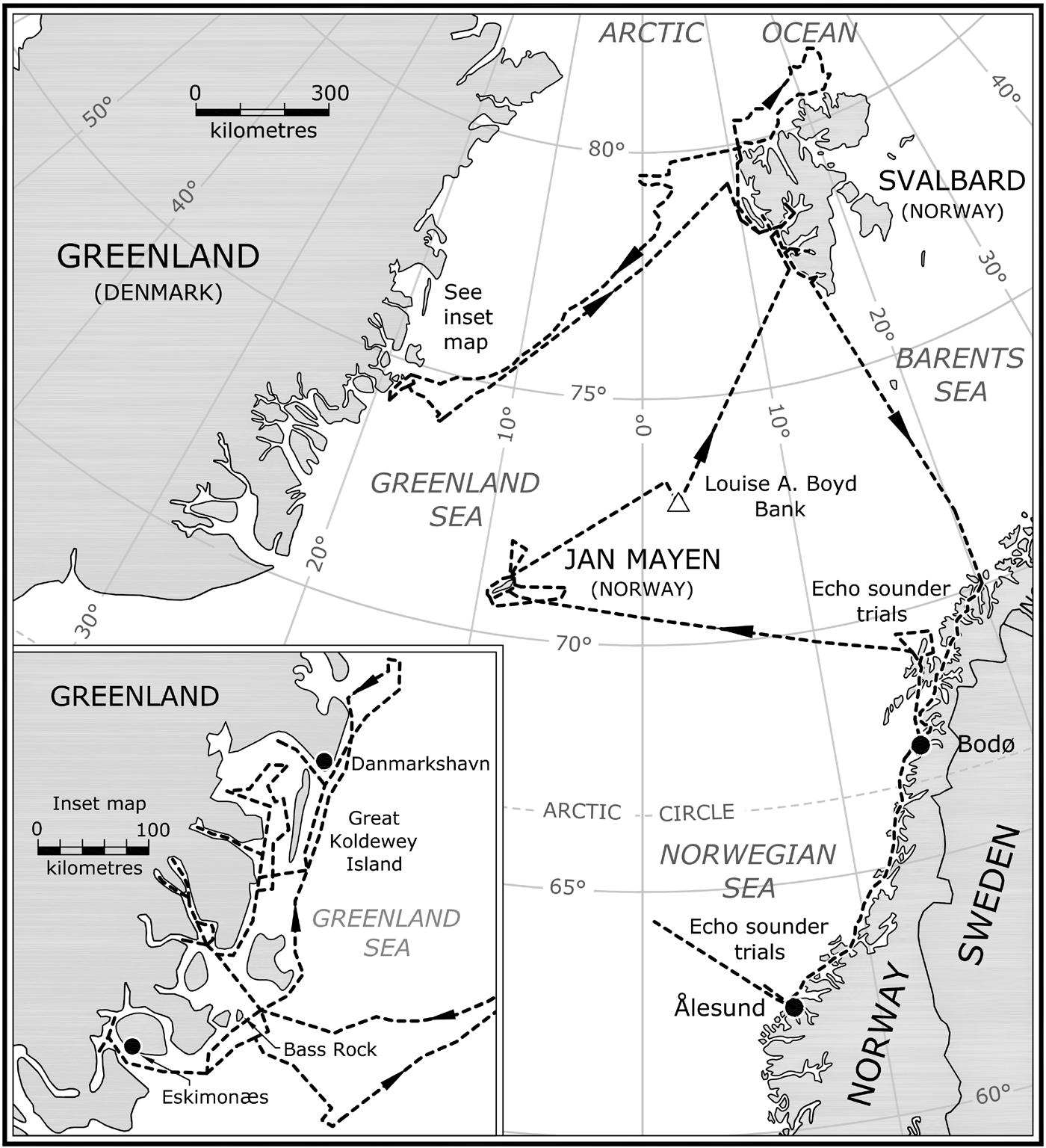

an expedition to East Greenland wasnally materializing. Her previous ship, the wooden steamship Hobby, was not available for hire. Instead, this would be the rst time she would sail in the sealer and expedition ship Veslekari, another respected Norwegian vessel. She and Veslekari (“little Kari” in Norwegian) would sail together on four successive voyages to East Greenland, Jan Mayen Land, and Svalbard, in 1931, 1933, 1937 and 1938.

roughout her long and illustrious career going to sea, Boyd developed a deep sense of connection with each of the three ships she sailed in, but Veslekari would be her favorite. ere were several available ships she could have chartered, but Veslekari’s connection to her hero Amundsen made it an easy decision. Veslekari was the sister ship of Maud —used by Amundsen during his 1918–25 transit through the Northeast Passage. ese vessels were constructed of oak, pine, and greenheart and built in Christian Jensen’s shipyard in Vollen in Asker near Kristiania (now Oslo). She had a gross tonnage of 285 and was approximately 134 feet in length and 27 feet on the beam. e vessel was ketchrigged with a maximum speed of 10 knots. Veslekari had also participated in the Amundsen rescue mission, so this new relationship boded well.

Exuberant crowds shouting “God Reise!” were on hand as Veslekari departed her home port of Ålesund, Norway, on 1 July 1931. While Captain Paul Lillenes and the rest of the local crew were familiar faces to the onlookers, few amongst the well-wishers were accustomed to seeing a woman expedition leader, and an American woman at that. Along with the sailing crew, Boyd had also invited Swedish geographer Carl-Julius Anrick and American botanist Robert Menzies. Both men brought their wives with them, although this proved to be one of the last times Boyd allowed other women aboard on her expeditions. Open con ict between Boyd and the geologist’s wife during the 1933 expedition con rmed her decision. From that point forward, Boyd was the only woman to participate in her expeditions.

Louise Boyd on the deck of her rst expedition ship, Hobby. “People openly told me the Arctic was a place only for men — that for me to go where I did was not to be taken seriously. Determination and persistence brought me to the position I achieved.”

—Louise A. Boyd

24 SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23

marin history museum

1 Read about this chapter in Louise Boyd’s life in Sea History 177, “Searching for Amundsen: Louise Arner Boyd aboard the Hobby.

”

e ship set a northwesterly course through the turbulent Norwegian Sea to Jan Mayen Land, located halfway between Greenland and Norway. e sea state during this passage was less than favorable, and one by one the expedition scientists disappeared below deck, leaving Boyd alone on deck with the sailing crew. It was a point of pride with her that she never succumbed to seasickness. e ship lived up to her lively reputation, and a crewmember reported: “Veslekari! God help us all! First she rolls like an ordinary boat, then she rolls some more, and then you think that she will go all the way around.” Louise Arner Boyd was steady throughout and carried on with her work—checking the ship’s progress or con rming the course plotted with the captain.

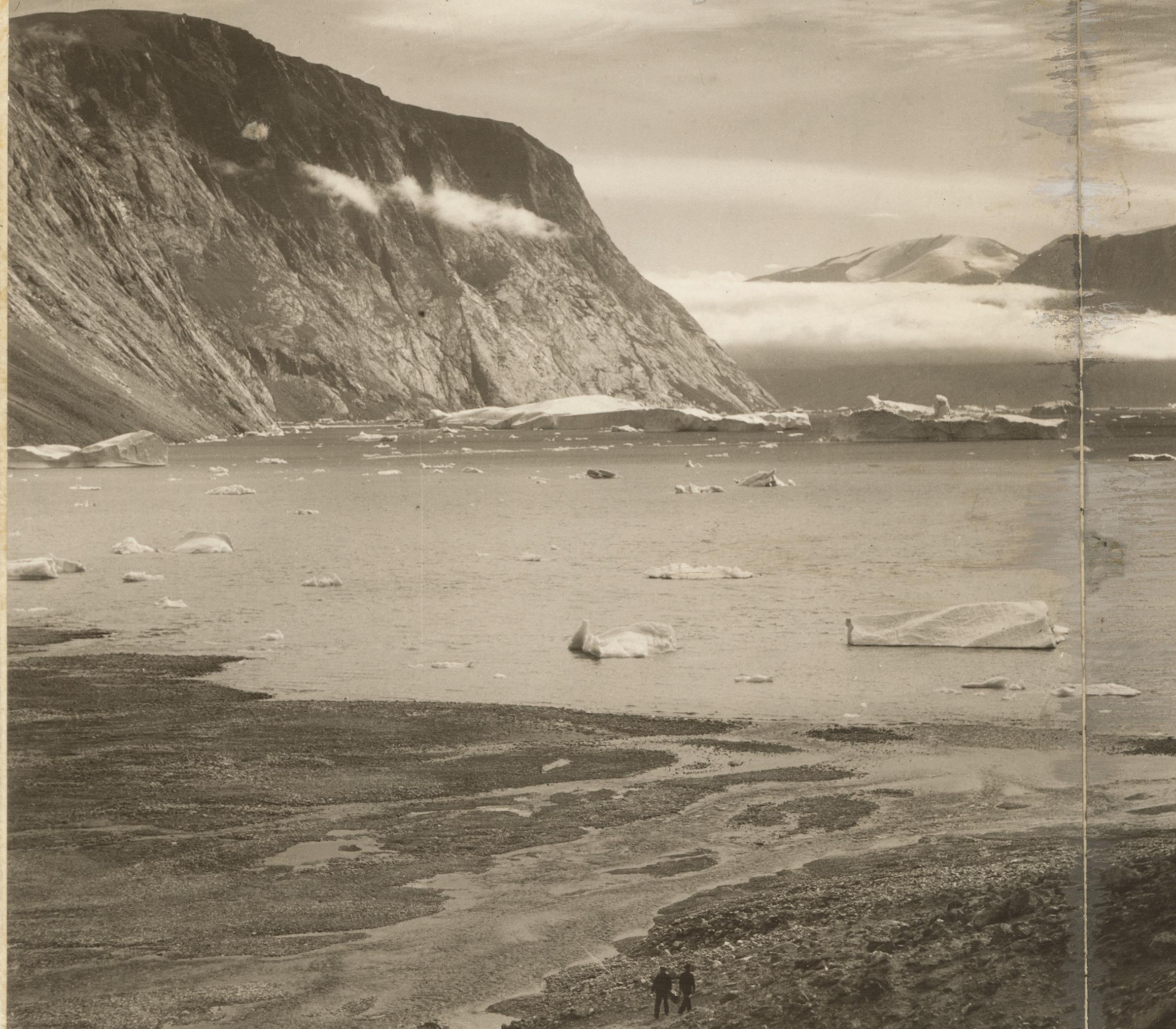

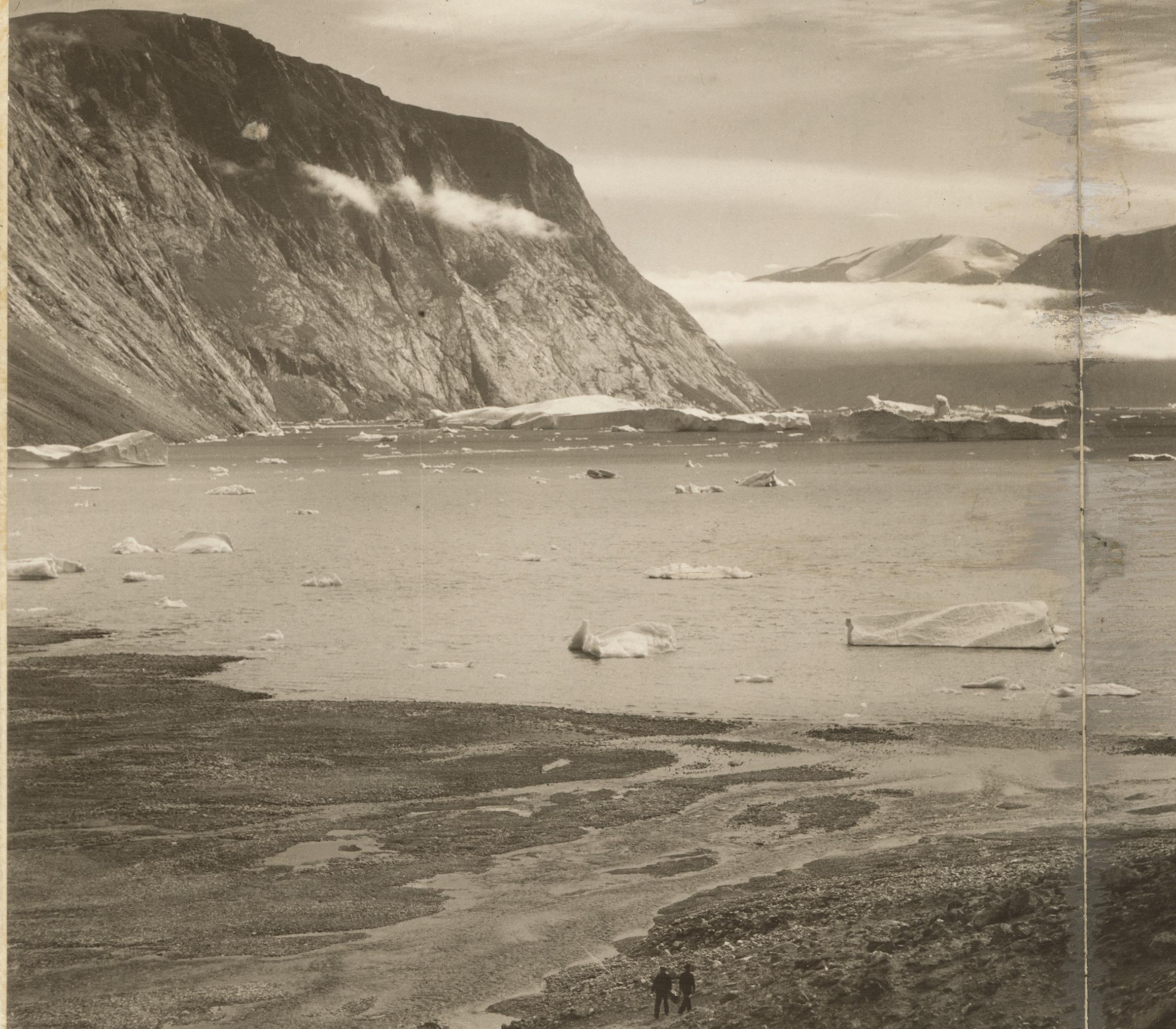

After spending time on Jan Mayen Land, the ship carried on to East Greenland, where the team conducted research in the Kjerulf and Kong Franz Josef Fjords. It was a remote area in a challenging part of the world. Veslekari was the rst ship to reach the region that summer, and Boyd was thrilled with a New York Times headline trumpeting: “ ree Greenland Groups Held by Ice Barrier: Bartlett 2 Caught but Miss Boyd Gets rough.” Despite her inexperience, Boyd’s decision-making and Captain Lillenes’s years at sea proved to be a potent combination. Boyd was not only the expedition leader, but the chief photographer as well. She enthusiastically lmed and took hundreds of images documenting the geographic features of the coast. ese images and the scienti c data

Veslekari in Ålesund, Norway. Veslekari was launched in 1918 from the same shipyard near Kristiania, Norway, that built Roald Amundsen’s expedition ship Maud. Built for sealing, she was well-suited for polar exploration. Louise Boyd chartered the ship for four expeditions to Greenland and the Arctic in the 1930s. Veslekari saw war-time service in World War II under the name HMS Branseld . She returned to sealing after the war and was actively working until 1961, when she was wrecked o Newfoundland.

collected by the team were later used to create new maps of the region.

Two months later, the ship returned to Ålesund and Boyd ew back to the United States. Her rst expedition to Greenland had been an outstanding success, including extensive photographic

documentation of the coastal regions of East Greenland, the discovery of a glacier located next to the Jaette Glacier, as well as several botanical species previously unknown to science and new data about musk oxen herds in Greenland and on Jan Mayen Land.

2 Capt. Bob Bartlett was an internationally famous Arctic explorer,

pedition leaders for Robert Peary’s quest to reach the North Pole, as

schooner E e M. Morrissey (now Ernestina-Morrissey).

SEA HISTORY 181, WINTER 2022–23 25

photo by finn bronner , courtesy of the author

having served as both master of SS Roosevelt and one of the ex-

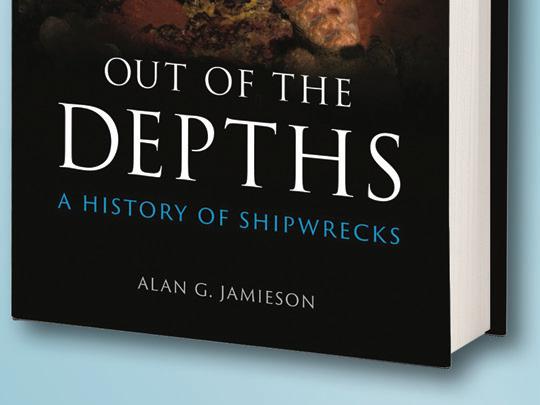

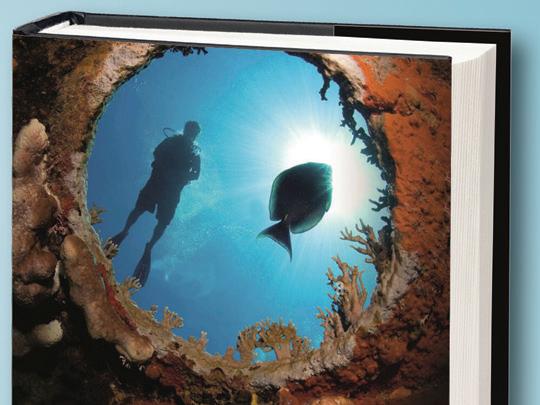

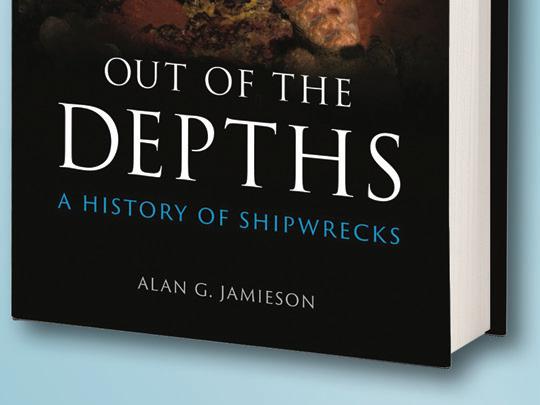

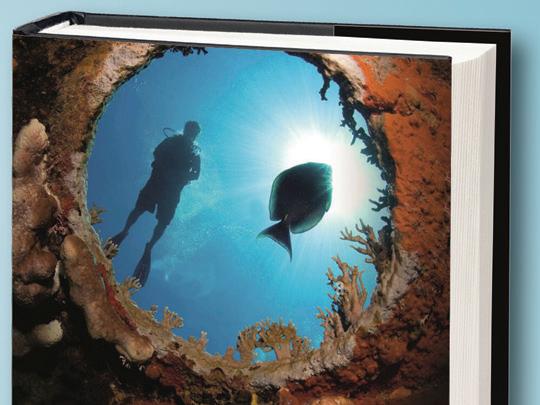

captain of the ill-fated Karluk expedition, and nally aboard his