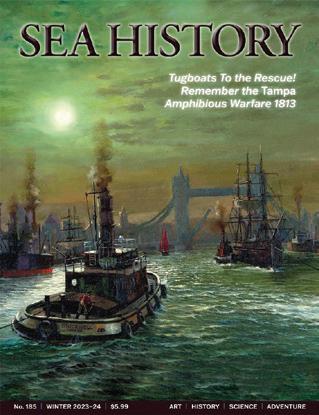

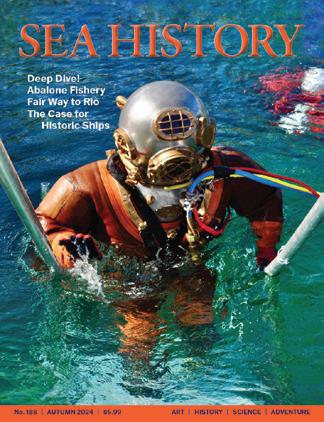

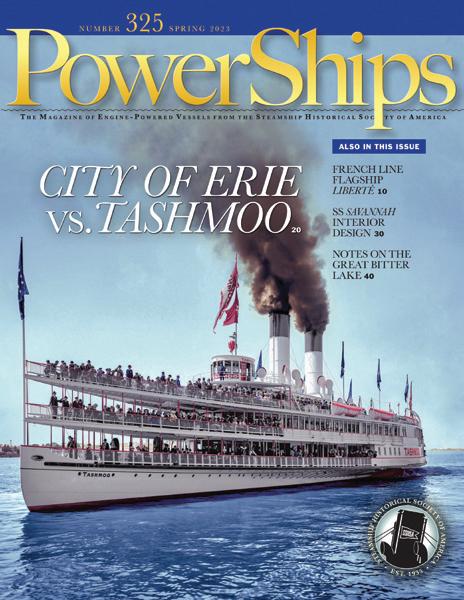

Ukraine Shipwreck Rescue

Lepanto and End of Galley Warfare

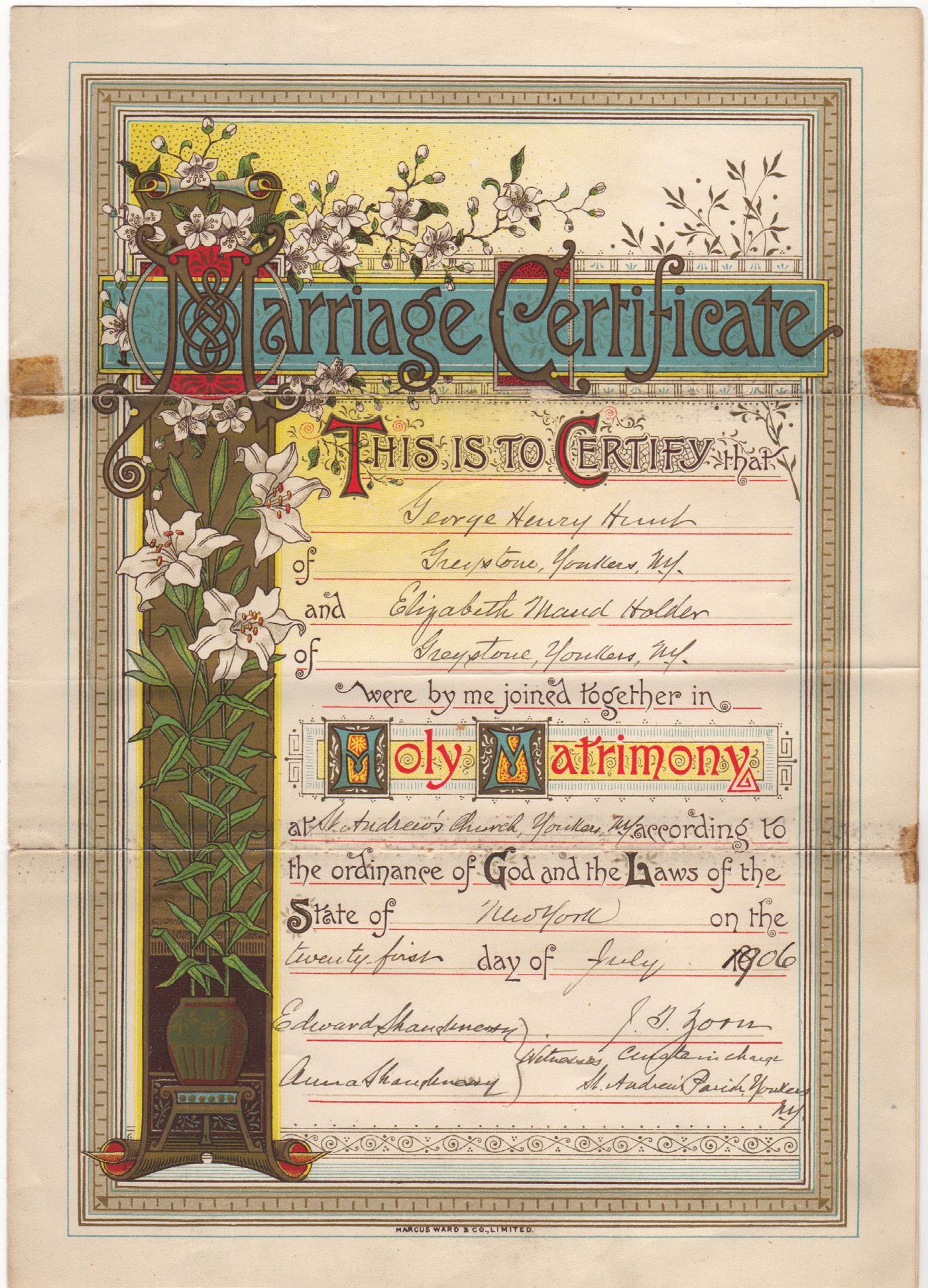

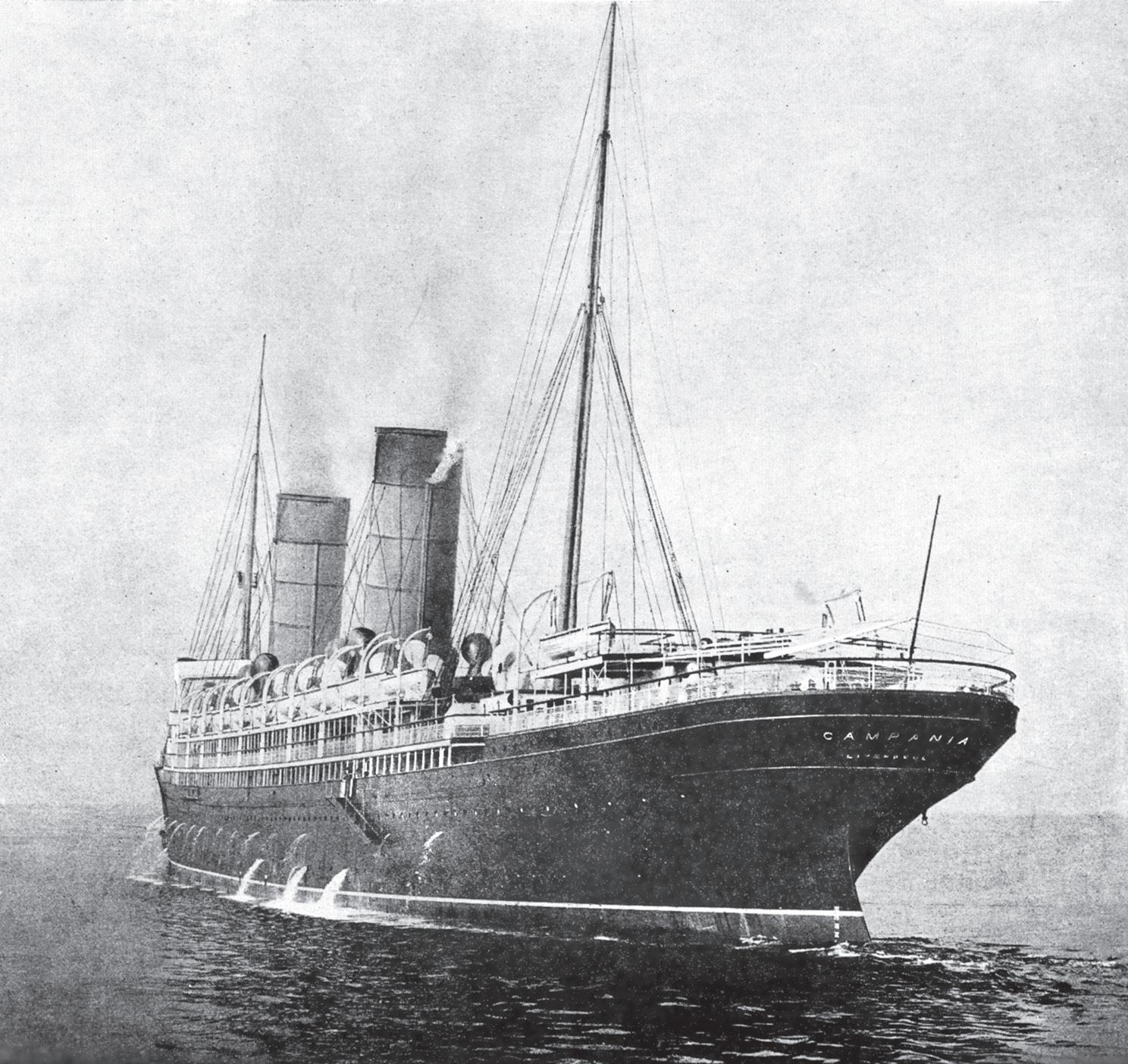

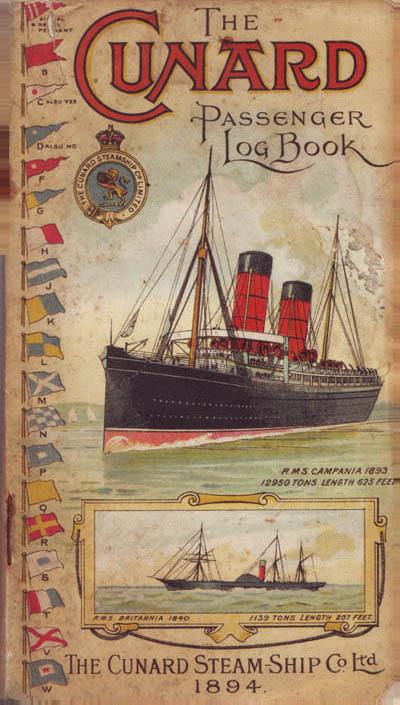

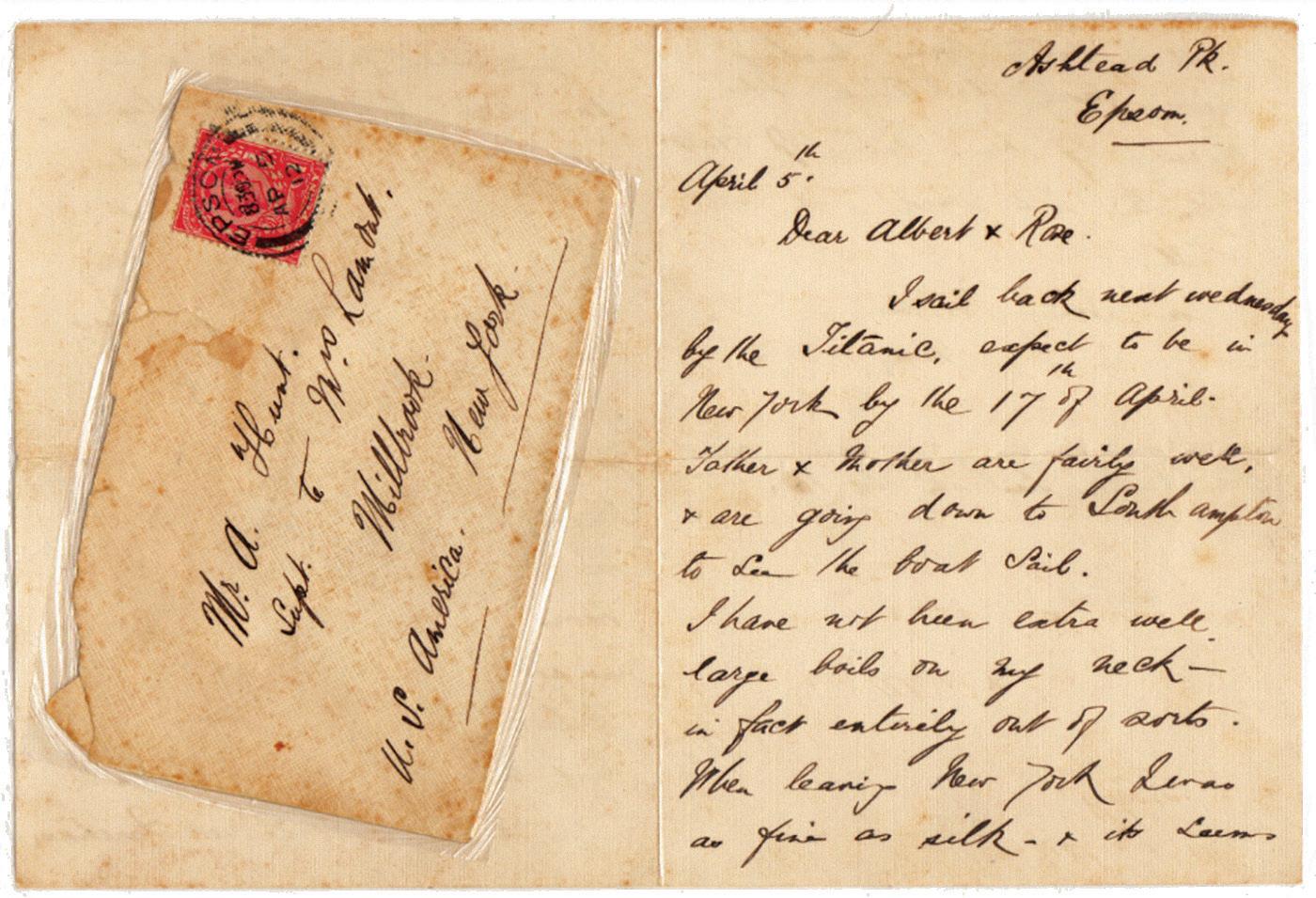

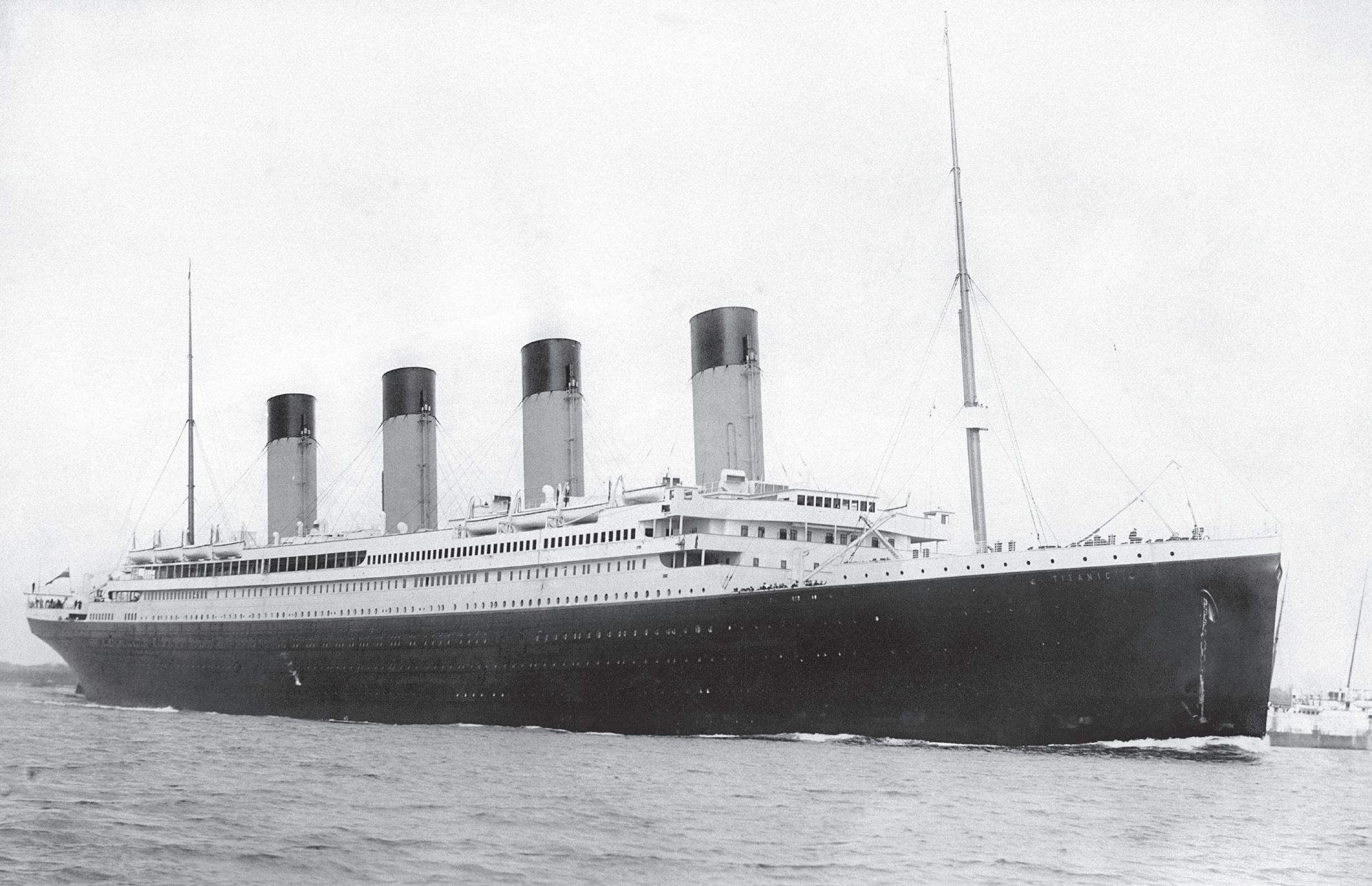

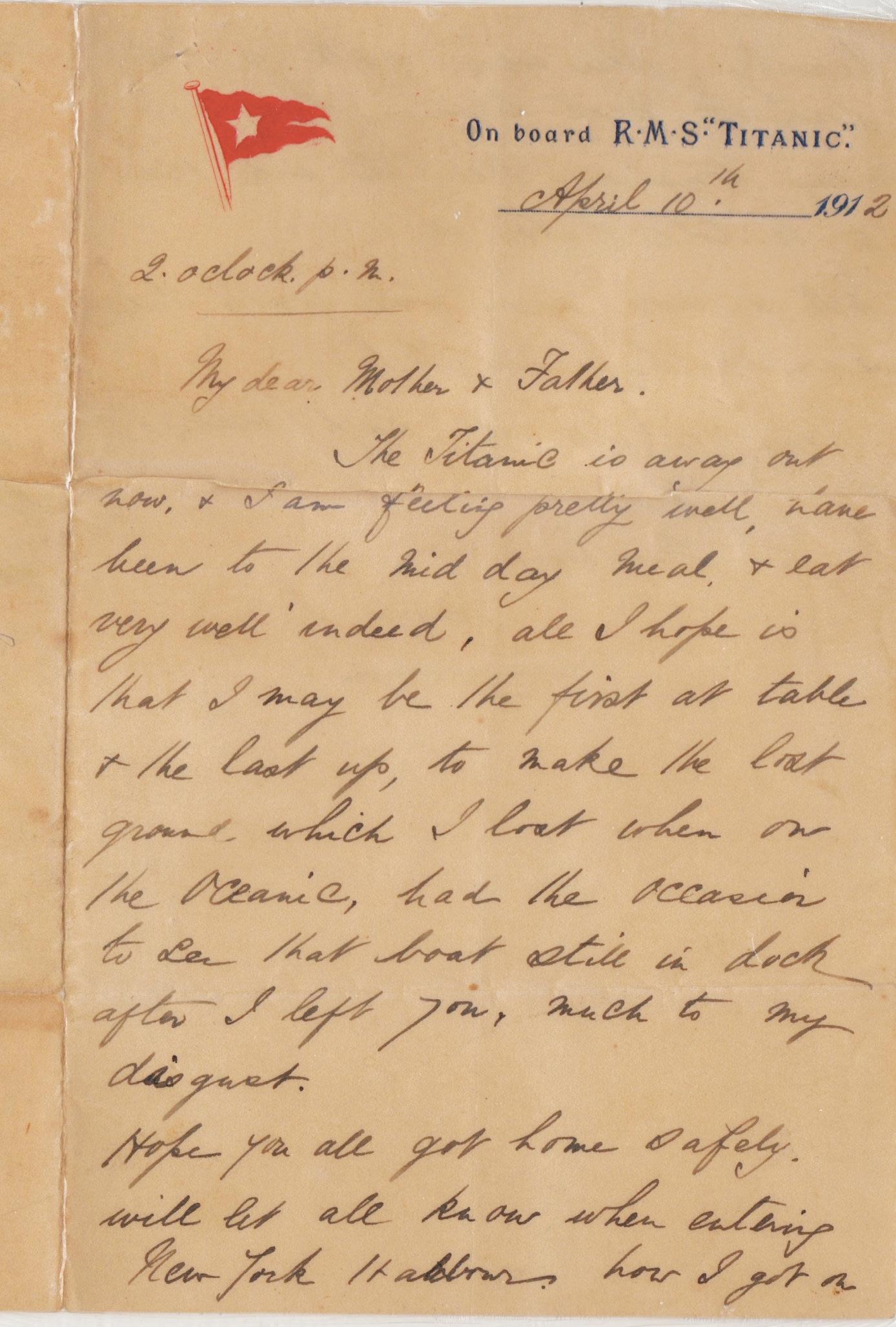

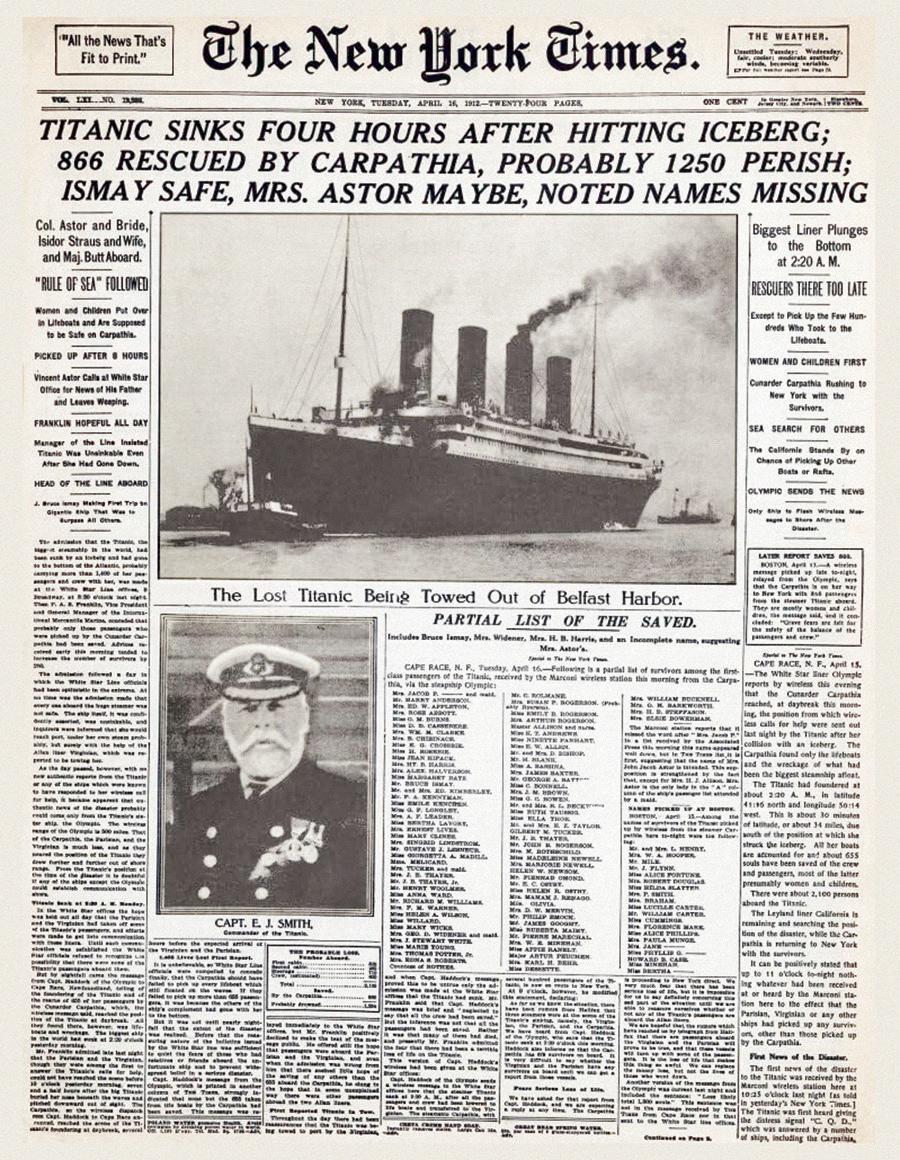

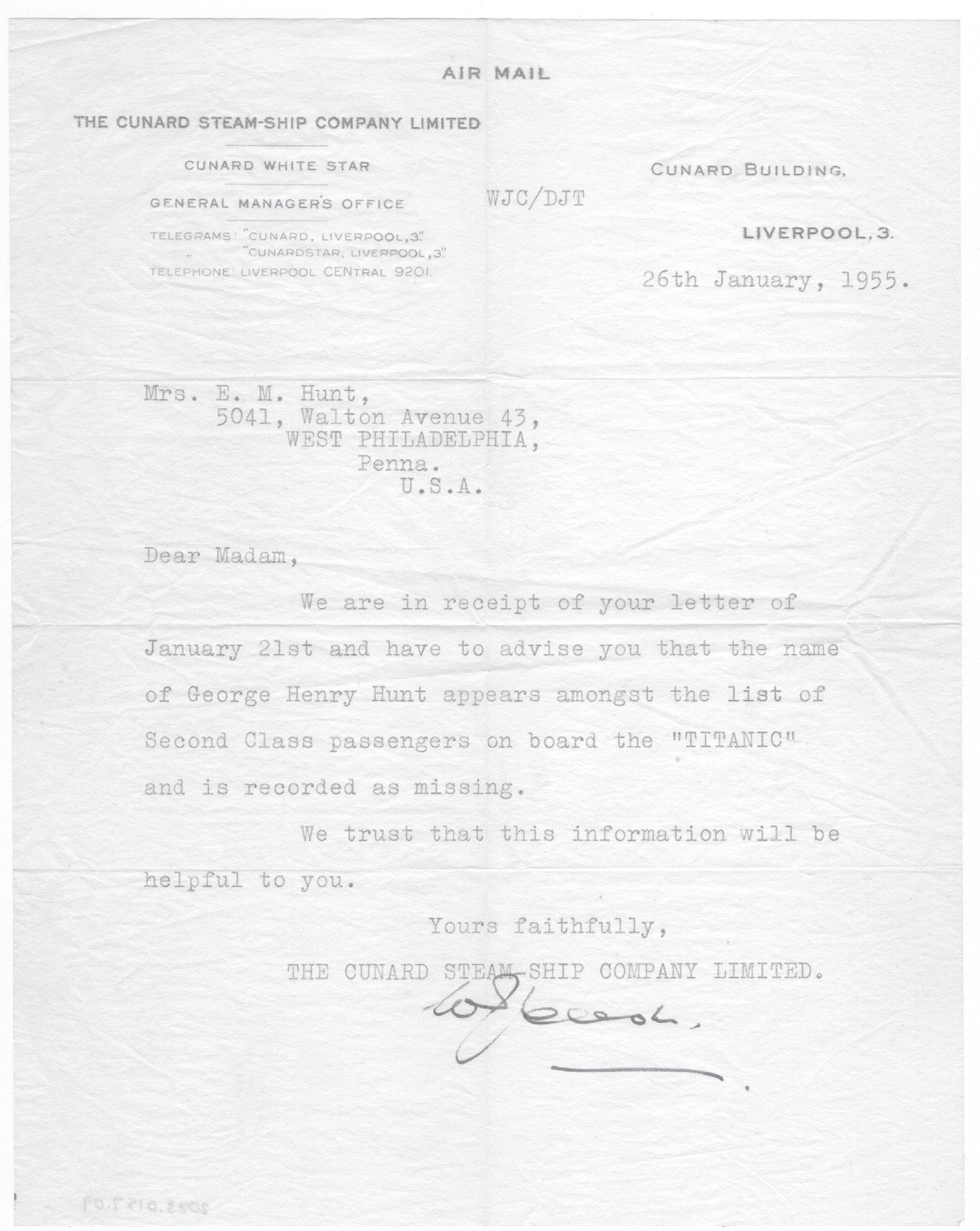

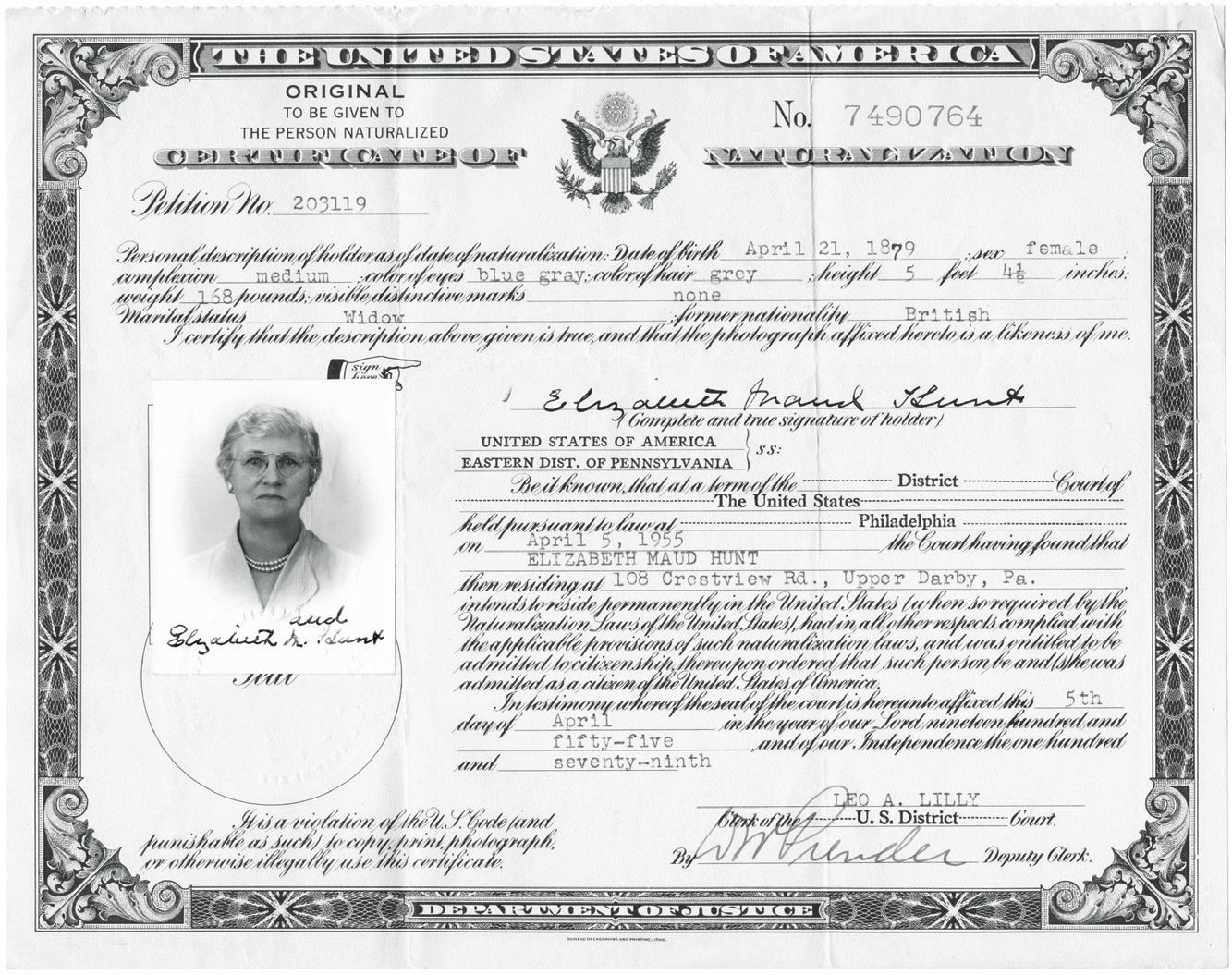

Titanic's Second-Class

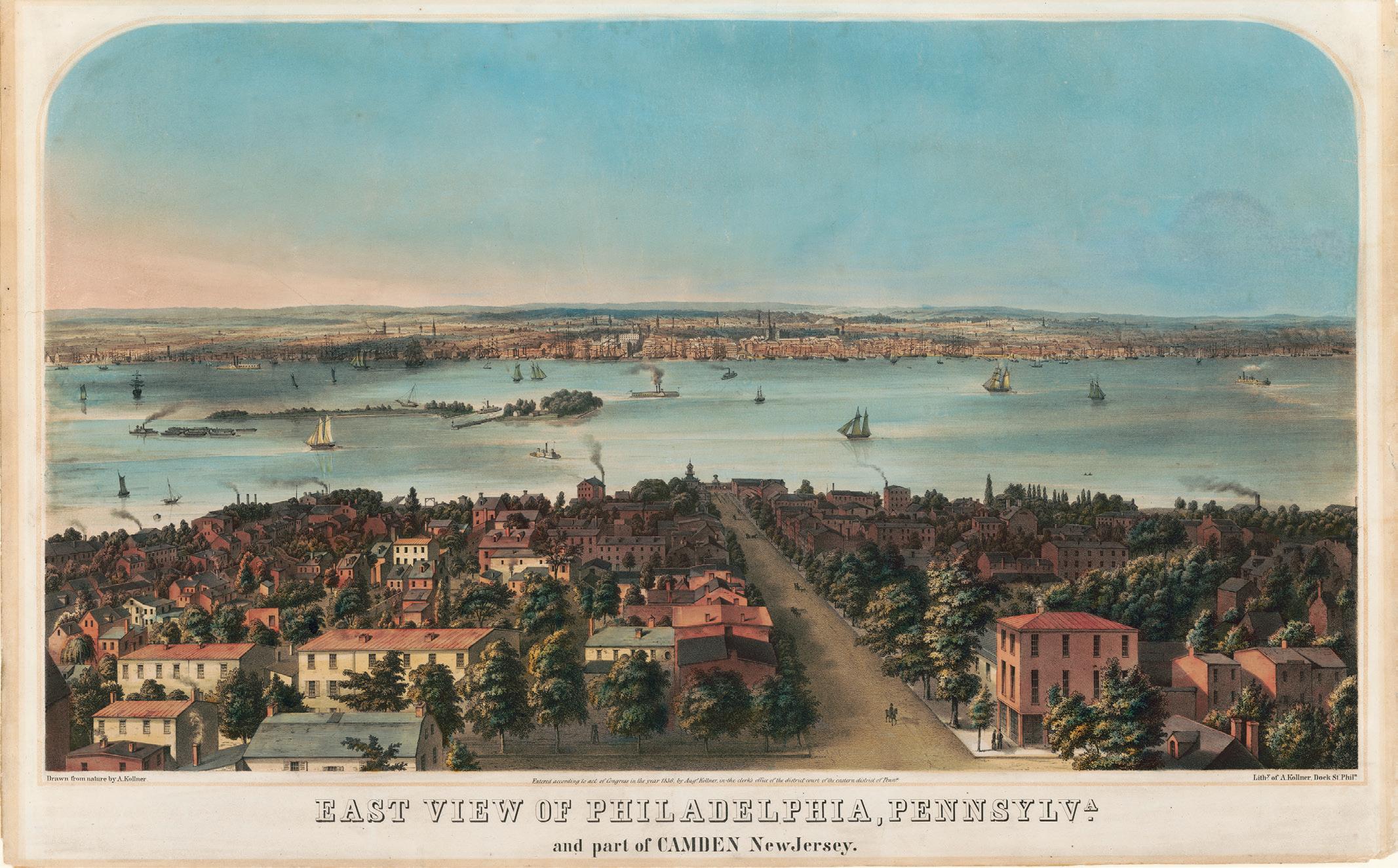

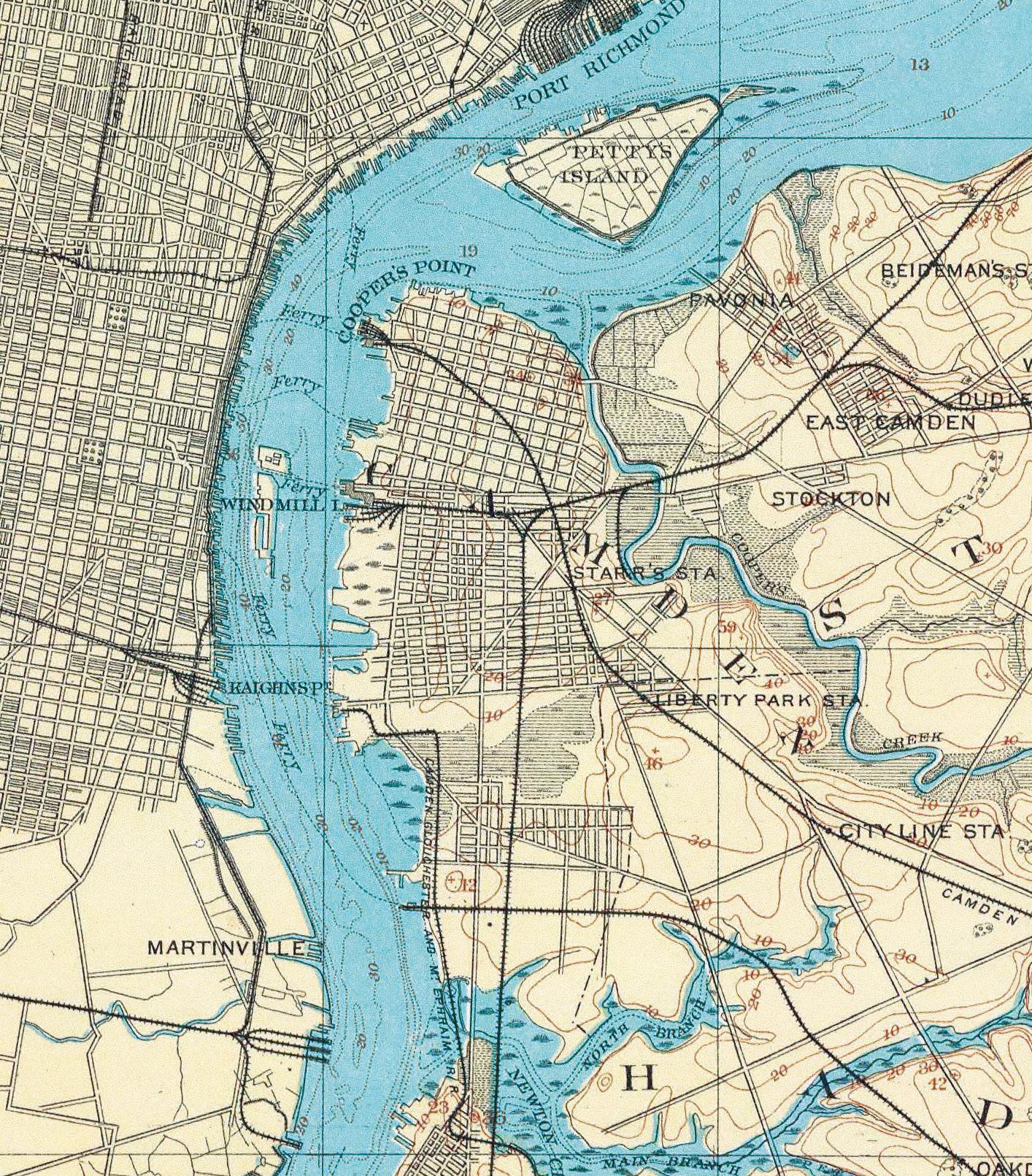

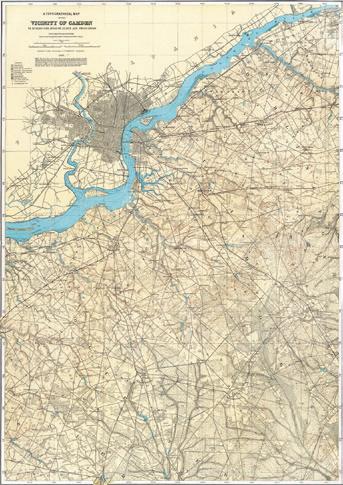

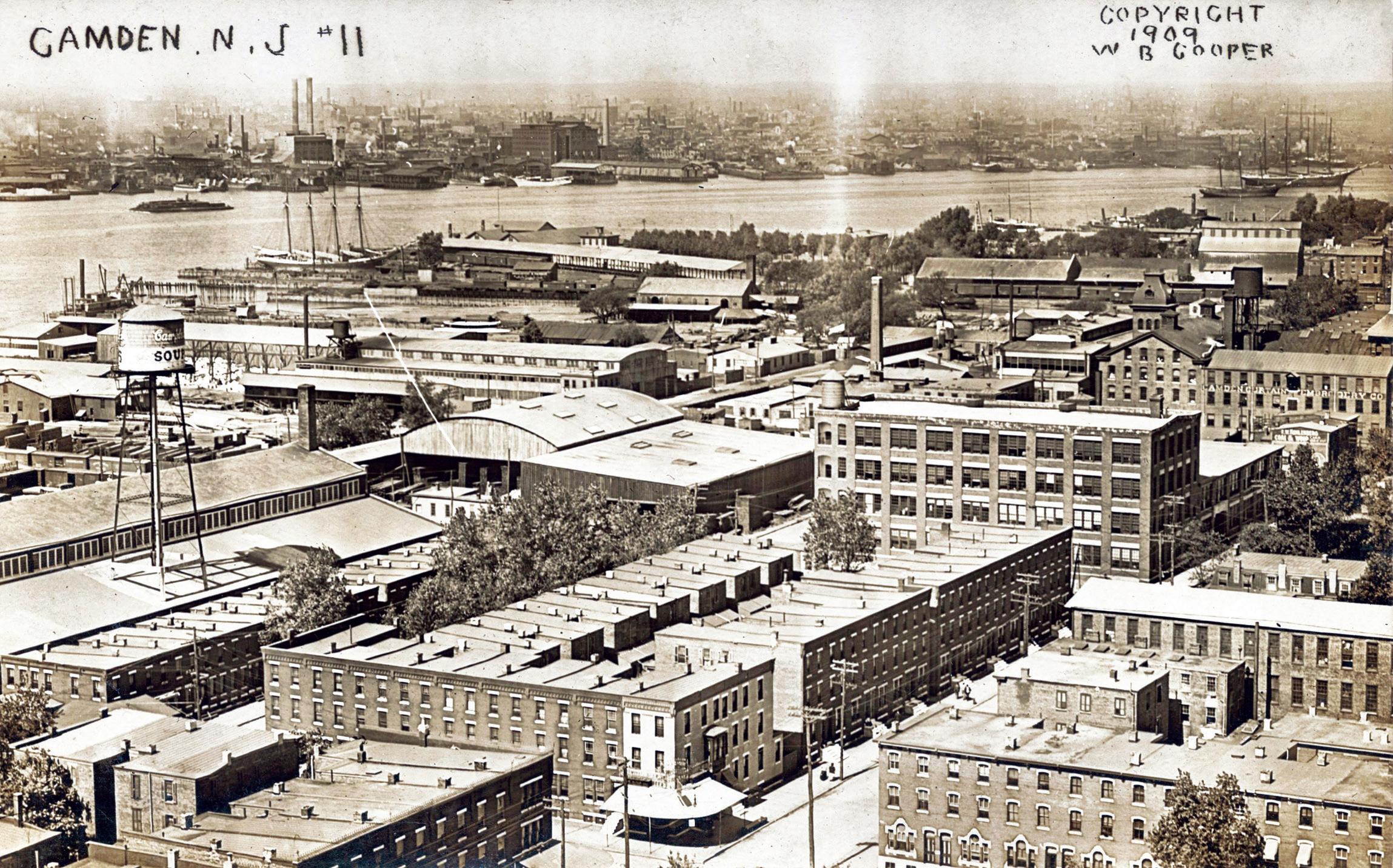

Camden Coming Back

Ukraine Shipwreck Rescue

Lepanto and End of Galley Warfare

Titanic's Second-Class

Camden Coming Back

fine paintings of maritime history

Commission a custom painting

Share your ideas with Patrick, and he’ll provide sketches for your approval before starting the fnal work.

Patrick is the President of The American Society of Marine Artists. Learn more about him, and how to commission a painting, at:

Southeast Sea Islands Cruise

9-day/8-night exploration

6 ports of call with guided excursion options at each

All onboard meals and our signature evening cocktail hour

Full enrichment package with guest speakers and nightly entertainment

All tips and gratuities

On this enchanting voyage from Charleston to Amelia Island, experience the charm and hospitality of the South. In the comfort of our modern fleet, travel to some of the most beautiful historic cities in America. The fascinating sites you visit, the warm people you meet, and the delectable cuisine you taste, come together for an unforgettable journey.

Haveyou ever truly felt a calling—to a service, a profession, or an opportunity? at call came loud and clear for me this past summer when I took part in a shipwreck archaeological expedition in Ukraine—yes, in Ukraine. It struck me on both a personal and professional level. Most importantly, it reminded me of what the National Maritime Historical Society is called to do in this time of change for all of us working in history, heritage, and preservation. As our nation approaches its 250th year, what is NMHS called to be?

We are sentinels, reminding the nation of the maritime stories and remarkable people who built this country over the past 250 years.

We are allies, standing shoulder to shoulder with museums, historic ships, and sailing programs across the nation that connect people to their maritime heritage, in particular young people who may not be aware of our nation’s—and their own—seafaring connections.

And increasingly, we are protectors, called upon to safeguard history itself. at calling has guided us throughout this past year. In September, NMHS brought together more than 300

people for the 12th Maritime Heritage Conference, carrying forward the legacy of the National Maritime Alliance. More than 130 presenters shared groundbreaking work, from innovative ship preservation techniques to new historical research and trailblazing approaches to interpretation. e Society’s 60-plus year e orts to bring diverse perspectives on historical events—written by an equally diverse range of authors in these pages—is another e ective way we continue to serve our community. Each issue of Sea History helps preserve not only the narrative of our maritime roots but also the ongoing story of our dependence on the maritime world today. e sailors, merchant mariners, and shipbuilders of the past, along with their families and communities, crafted the legacy we inherit. To overlook any part of that legacy is to lose opportunities for growth and understanding that re ection a ords.

Perhaps most concretely, NMHS partnered with the International Congress of Maritime Museums on an extraordinary expedition to Ukraine, where a team of maritime archaeologists met to document and excavate shipwrecks along the banks of the Dnipro River near the front lines of war (see pages 12–21). ese historic vessels were

The National Maritime Historical Society unites, connects, and advocates for us all. Please consider donating to support our work. If you love the sea, if you love history, make your gi today.

Seahistory.org/give Call 914-737-7878 ext. 0

Or please make checks payable to:

National Maritime Historical Society 1000 Division Street, Suite #4, Peekskill NY 10566

in imminent danger of being lost forever. anks to international collaboration, they are now preserved and recorded for future generations.

Which brings me back to what it means to answer a call. Saving pieces of history—literally—is deeply important, and I am grateful NMHS was able to have a role in this e ort. But the lasting impact for me was personal, far outweighing any help we provided with trowels and tape measures. I am forever changed by the strength, determination, and hope I witnessed in my Ukrainian colleagues, who are struggling but determined to save the physical remains of their maritime heritage in the middle of a devastating war.

I hope our presence there, standing beside friends facing daily the consequences of war and threats to their culture, made clear that people around the world are standing with them. I hope that by sharing their story here, we a $ rm that message once more: history matters, heritage endures, and together we must continue to answer the call.

Cathy Green, President, NMHS

Sea History e-mail: seahistory@gmail.com

NMHS e-mail: nmhs@seahistory.org

Website: www.seahistory.org

Phone: 914 737-7878

Sea History is sent to all members of the National Maritime Historical Society. MEMBERSHIP IS WELCOME: Afterguard $10,000; Benefactor $5,000; Plankowner $2,500; Sponsor $1,000; Donor $500; Patron $250; Friend $100; Regular $45. Members outside the US, please add $20 for postage. Individual copies cost $5.99.

PETER ARON PUBLISHER’S CIRCLE: Guy E. C. Maitland, Ronald L. Oswald, William H. White

OFFICERS & TRUSTEES: Chairman , CAPT James A. Noone, USN (Ret.); Vice Chairman , Richardo R. Lopes; President: Catherine M. Green; Vice Presidents: Deirdre E. O’Regan, Wendy Paggiotta; Secretary, Capt. Je rey McAllister; Trustees: Charles B. Anderson; CAPT Patrick Burns, USN (Ret.); Samuel F. Byers; CAPT Sally McElwreath Callo, USN (Ret.); William S. Dudley; Karen Helmerson; VADM Al Konetzni, USN (Ret.); K. Denise Rucker Krepp; Guy E. C. Maitland; Elizabeth McCarthy; Peter McCracken; Salvatore Mercogliano; Brandon Phillips; Kamau Sadiki; Richard Scarano; David Winkler

CHAIRMEN EMERITI: Walter R. Brown, Alan G. Choate, Guy E. C. Maitland, Ronald L. Oswald; Howard Slotnick (1930–2020)

FOUNDER: Karl Kortum (1917–1996)

PRESIDENTS EMERITI: Burchenal Green, Peter Stanford (1927–2016)

OVERSEERS: Chairman, RADM David C. Brown, USMS (Ret.); RADM Joseph Callo, USN (Ret.); Christopher Culver; Richard du Moulin; David Fowler; Gary Jobson; Sir Robin Knox-Johnston; John Lehman; Capt. James J. McNamara; Philip J. Shapiro; H. C. Bowen Smith; Philip J. Webster; Roberta Weisbrod

NMHS ADVISORS: John Ewald, Nathaniel Howe, Steven Hyman, J. Russell Jinishian, Gunnar Lundeberg, Conrad Milster, William Muller, Nancy Richardson, Jamie White

SEA HISTORY EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Norman Brouwer, Robert Browning, William Dudley, Lisa Egeli, Daniel Finamore, Kevin Foster, John O. Jensen, Frederick Leiner, Joseph Meany, Salvatore Mercogliano, Carla Rahn Phillips, Walter Rybka, Quentin Snediker, William H. White

NMHS STAFF: President, Catherine M. Green; Deputy Director, Susan Sirota; Vice President of Operations, Wendy Paggiotta; Senior Sta Writer, Shelley Reid; Business Manager, Andrea Ryan; Manager of Educational Programs, Heather Purvis; Membership Coordinator, Marianne Pagliaro

SEA HISTORY: Editor, Deirdre E. O’Regan; Advertising Director, Wendy Paggiotta

Sea History is printed by e Lane Press, South Burlington, Vermont, USA.

Our Contributors Make It Happen I read the note “From the Editor” in the Autumn 2025 issue of Sea History, thanking the contributors who write articles and donate photographs, illustrations, and artwork for use in the magazine. I’m sure that I speak for many readers who also appreciate these contributions. e articles are interesting and well-written. e photographs are clear and sharp. e illustrations and artwork are amazing and depict a moving and dynamic environment in fascinating and unique ways. Together, they take the reader on a journey like no other. ey take us back in time. ey take us on deck and in the rig, and they take us to sea in good conditions and bad. is is what makes this magazine so unique and why many of us read it from cover to cover. ank you to all the contributors. Please know that we, the readers, value your work and how much it means to this community.

C aptai( Da)id Cha,-.( Clearwater, Florida

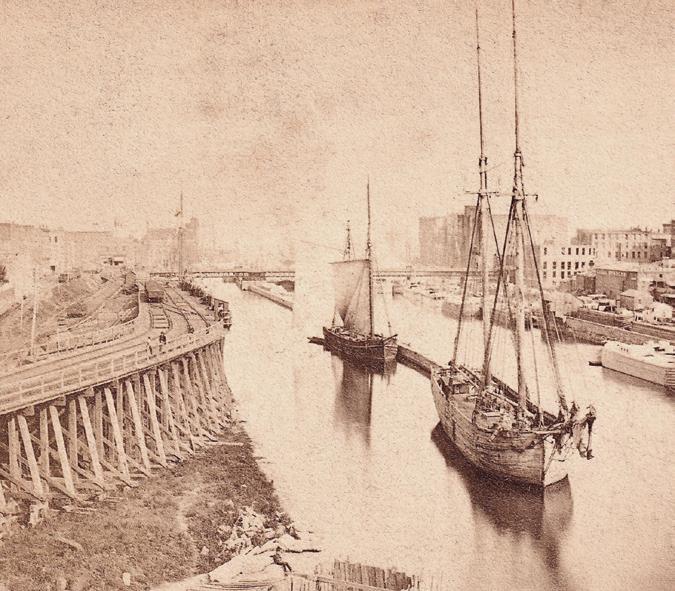

Following a Historic Voyage on the Erie Canal

I would like to thank the organizers of the 12th Maritime Heritage Conference that took place in Bu alo, New York, in September. Members of the National Maritime Historical Society and the Historic Naval Ships Association did an outstanding job keeping things running smoothly. From my experience, the four-day conference was a complete success. e World Canals Conference also took place that week. Both conferences were scheduled to coincide with the 200th anniversary of the opening of the Erie Canal, which in 2017 was designated a National Historic Landmark. To mark this special occasion, the Bu alo Maritime Center built a full-size replica of the Seneca Chief, the rst canal boat to travel from Lake Erie through the 363-mile-long canal to

New York City. Along the route, the boat had to maneuver through more than 80 locks, as Lake Erie is more than 560 feet higher in elevation than the Hudson River. Today, the canal follows a slightly altered route; it was upgraded and rerouted in places in the early 20th century.

e Seneca Chief replica departed Bu alo on 24 September 2025 and arrived at Pier 26 in New York City on 26 October, completing the nearly 500-plus-mile route in 33 days. Since the Seneca Chief has no propulsion of her own, the entire trip was made possible by the Bu alo Maritime Center’s wooden tugboat, CL Churchill, to move the canal boat through the waterway and maneuver through the extensive system of locks between Bu alo and the Hudson River. When the conference in Bu alo was over, I caught up with the Seneca Chief in Fairport, New York, on my way home and then followed her progress through the Buffalo Maritime Center’s website.

One of the more remarkable lock systems along the canal is the Waterford Flight, where a series of ve locks allows vessels to access the Mohawk River from the east and the Hudson River from the west. I decided to catch up with the Seneca Chief there, and having never seen a lock in action before, I felt

like a kid on Christmas morning as the Seneca Chief entered the westernmost lock of the Waterford Flight. I followed the boat as she worked her way through

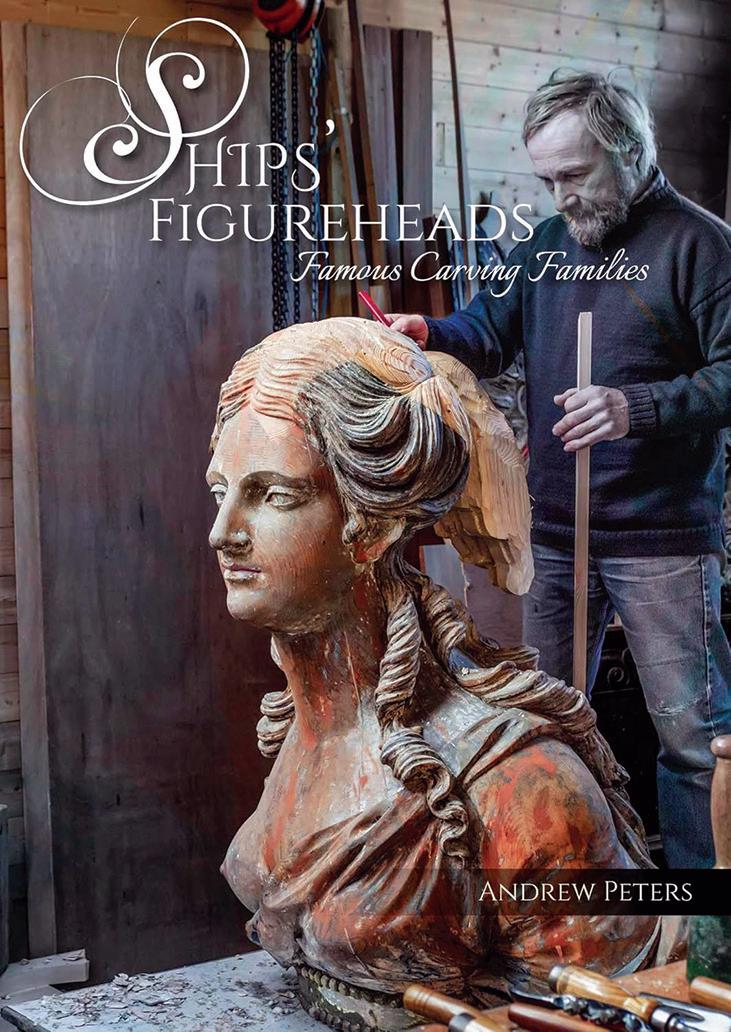

THETRADITION OFHANDCARVED EAGLES CONTINUES TODAY

(508) 939-1447

OWNER’S STATEMENT: Statement filed 9/22/25 required by the Act of Aug. 12, 1970, Sec. 3685, Title 39, US Code: Sea History is published quarterly at 1000 N. Division Street Suite 4, Peekskill NY 10566; minimum subscription price is $27.50. Publisher and editor-in-chief: None; Editor is Deirdre E. O’Regan; owner is National Maritime Historical Society, a non-profit corpo-ration; all are located at 1000 N. Division Street, Suite 4, Peekskill NY 10566. During the 12 months preceding October 2025 the average number of (A) copies printed each issue was 10,955; (B) paid and/or requested circulation was: (1) outside county mail subscriptions 5,193; (2) in-county subscriptions 0; (3) sales through dealers, carriers, counter sales, other non-USPS paid distribution 4,436; (4) other classes mailed through USPS 241; (C) total paid and/or re-quested circulation was 9,870; (D) free or nominal rate distribution was: (1) outside county 400; (2) in-county 0; (3) mailed at other classes through the USPS 200; (4) outside the mail 130; (E) total free distribution was 730; (F) total distribution 10,600; (G) copies not distributed 355; (I) total [of F and G] 10,955; (I) Percentage paid and/or requested circulation 93%. The actual numbers for the single issue preceding October 2025 are: (A) total number printed 10,547; (B) paid and/or requested circulation was: (1) outside-county mail subscriptions 4,726; (2) in-county subscriptions 0; (3) sales through dealers, carriers, counter sales, other non-USPS paid distribution 4,451; (4) other classes mailed through USPS 186; (C) total paid and/or requested circulation was 9,363; (D) free or nominal rate distribution was: (1) outside county 130; (2) in-county 0; (3) mailed at other classes through the USPS 200; (4) outside the mail 520; (E) total free distribution was 850; (F) total distribution 10,213; (G) copies not distributed 334; (I) total [of F and G] 10,547; (I) Percentage paid and/or requested circulation 92%. I certify that the above statements are correct and complete. (signed) Catherine Green, President, National Maritime Historical Society.

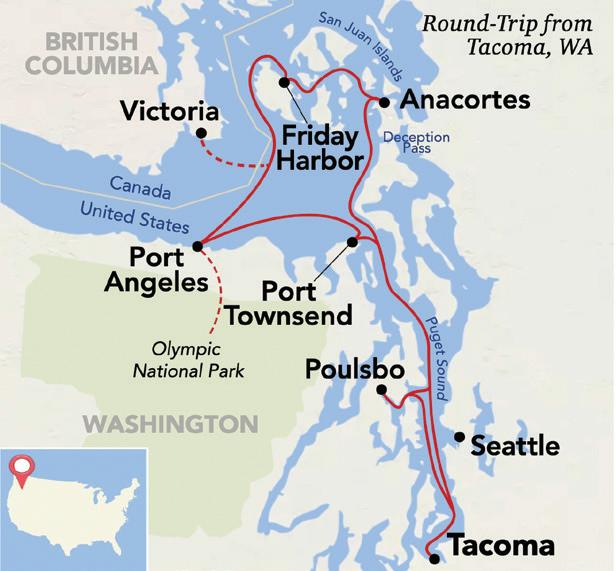

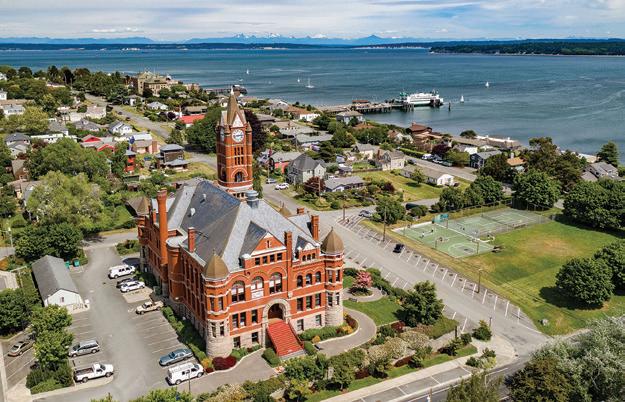

Join NMHS leadership and members on an unforge able cruise aboard the luxurious American Constitution, round-trip from Tacoma. www.seahistory.org/cruise2025

Embark on a voyage through time as we set sail on a tailor-made journey through the heart of Puget Sound. This exclusive itinerary—crafted especially for maritime heritage aficionados—offers NMHS members unparalleled access to historic ships, vibrant waterfront museums, and immersive cultural experiences.

Each day, gather for captivating lectures by renowned maritime historian Robert Steelquist and special guests, bringing the region’s rich nautical legacy to life. Go behind the scenes with unique tours of museums, artisan workshops, and off-the-trail adventures.

Included Pre-Cruise Night Hotel (27 March) at the Hotel Murano, Tacoma

From the storied shores of Tacoma to the Nordic charm of Poulsbo, this voyage is more than a cruise—it’s a celebration of our shared maritime past, curated with care and passion for those who cherish the sea and its stories. Be among the first to experience this unique offering, designed to inspire, educate, and connect.

To secure your place on this remarkable journey, contact Izzy Pearson, Group Manager, at izzy.pearson@americancruiselines.com or call 888-458-6027.

When making your reservations please use the code NMHS A portion of the proceeds will benefit the Society.

the remaining four locks, then I waited for them to arrive on the Waterford waterfront. A few days later, I picked up Seneca Chief’ s trail in Dutchess County and followed her down to Ossining, where the crew docked the boat at one of the marinas and invited the public to tour the boat. I stayed with it as she continued her route, and when she was scheduled to arrive in New York City, I drove down to Pier 26 and took a lot of photographs, as I had been doing throughout the canal boat chase. It was an absolute thrill to follow this beautiful replica, built by the hands of more than 200 volunteers over four years, under the guidance of several shipwrights. After a short stay in the city, Seneca Chief headed back up the Hudson to Waterford, where she will stay until the spring of 2026 before heading back to Bu alo.

Da)id R.cc.

Yorktown Heights, New York

Farewell Falls of Clyde

e Autumn issue of Sea History was of particular interest to me, featuring the stories about the demise of the historic ships Falls of Clyde and Tusitala For nearly eight years, I toiled happily as a rigger aboard Falls of Clyde in Hawaii. I have never hurt so much and been so tired at the end of the day, smelling like a forest re from slopping Stockholm tar on every piece of rigging, and looking forward to doing it again the next day. Working with ve other riggers alongside master rigger Jack Dickerho , we made shrouds and stays, backstays, and many more hundreds of lesser pieces of rigging. Hanging in a bosun’s chair at the end of a gantline, we set them in place or wrestled with heavy, massive steel yards, all while getting fried in the hot tropical sun with sweat pouring into our eyes—and loving it. By the time that the Winter issue of Sea History goes to print, she will have been scuttled in deep water o Oahu. I wonder if the two resident

Indrek Lepson making the first tuck of a massive wire splice for Falls of Clyde “Between the shrouds and backstays, there were 80 such splices, plus a zillion more on small stu like footropes and stirrups—12 per yard. I can a est that one does not learn to splice wire cable merely by watching a master rigger.”

ghosts, a man and a woman (for real!) who kept me company when I lived in a passenger cabin on the ship, moved elsewhere or if they went down with the ship, embraced in a spectral romance.

e loss of this important piece of not just American maritime history, but, as an oceangoing ship that sailed across the globe, world history, should be classi ed as one of the greatest mancaused American maritime disasters. After all, it was preventable. Unknown millions of dollars were expended over the years, all for naught. She came back to Honolulu in 1963 as an unrigged, grimy hulk with just the lower masts standing. And she went out 62 years later the same way, a battered hulk with just the lower masts standing—but a lot cleaner.

From the video I saw online, she went down stern rst, her bowsprit pointing skyward as if waving a last goodbye, a lasting legacy to the Bishop Museum and, perhaps, a classic case of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. She was once so close to complete restoration, until they decided to

abandon her and leave her to rot. I don’t know what took place in the boardroom to come to that decision. While I served aboard her, I was under the impression that she generated enough income for her upkeep. Maybe not, but clearly grants were awarded and squandered elsewhere.

Nobody loved her more or was sadder to see her go than I. Farewell, Falls of Clyde, I knew you well.

I(d012 L 1p-.( Louisburg, North Carolina

From the Editor: e 146-year-old Falls of Clyde, once the pride of the Hawaii Maritime Center and a xture on the Honolulu waterfront, was towed out to sea and scuttled in deep water on 15 October. e ship was the only surviving four-masted, iron-hulled, full-rigged ship in the world. You can read more about it on page 64 in this issue’s Ship Notes, Seaport, and Museum News. e video of her sinking—if you can stomach it—can be viewed online at the Hawaii News Now website (www. hawaiinewsnow.com; search for “Falls of Clyde.”)

Traditional Knotwork Downtown Mystic CT

25 Cottrell St. 2 Holmes St. MysticKnotwork.com

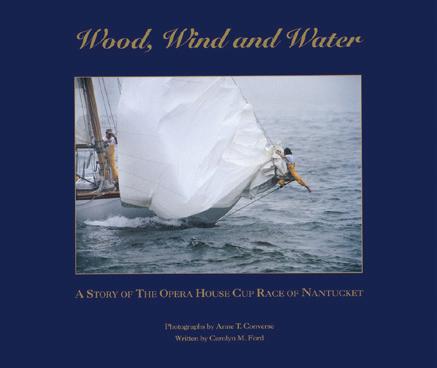

Anne T. Converse Photography

Neith, 1996, Cover photograph Wood, Wind and Water

A Story of the Opera House Cup Race of Nantucket

Photographs by Anne T. Converse Text by Carolyn M. Ford

Live vicariously through the pictures and tales of classic wooden yacht owners who lovingly restore and race these gems of the sea.

“An outstanding presentation deserves ongoing recommendation for both art and nautical collections.”

10”x12” Hardbound book; 132 pages, 85 full page color photographs; Price $45.00

For more information contact: Anne T. Converse Phone: 508-728-6210 anne@annetconverse.com www.annetconverse.com

The National Maritime Historical Society’s new wall calendar celebrates the American and international fleet of tall ships that will visit seaports from New Orleans to Boston for spectacular parades of sail and tours in 2026. Enjoy these stunning images of participating ships and make sure to plan to visit them next summer!

12-month calendar is wall hanging, saddle-stitched, and printed on quality heavyweight paper. 18”H x 12”W (open)

$14, plus $6 s/h (media mail) within the USA. NYS residents add sales tax. Please call for multiple or international shipping charges.

TO ORDER, call 914 737-7878 ext. 0, or online at www.seahistory.org/calendar2026.

e National Maritime Historical Society’s 2025 Annual Awards Dinner was an inspiring evening that brought together leaders and friends from across the maritime community to celebrate excellence, honor achievement, and support the Society’s educational mission. Held on 23 October at the New York Yacht Club, the gala gathered 200 guests for an evening that was as meaningful as it was memorable.

is year, NMHS proudly honored American President Lines, Leslie Kohler, and Captain Jonathan Bacon Smith for their extraordinary contributions to preserving and promoting our maritime heritage with Distinguished Service Awards. Each recipient’s story re ected a deep commitment to the values that de ne the maritime world— leadership, innovation, and service.

American President Lines was recognized for its enduring legacy as a pioneer in American shipping and as a steadfast supporter of maritime education and workforce development. Leslie Kohler, a long-time advocate for sailing education, was honored for her visionary leadership in providing barrier-free

“...An’ I don’t care if it’s North or South, the Trades or the China Sea, Shortened down or everything set — close-hauled or runnin’ free—

You paint me a ship as is like a ship . ...an’ that’ll do for me!’’

Known for his expansive inventory of seafaring poetry, from which he readily draws to share with his students and crew at sea, Captain JB Smith recited “Pictures” by Cicely Fox Smith as part of his acceptance remarks. His ability to charm and command an audience, whether on the deck of a schooner or at the New York Yacht Club, became clear to all.

access to sailing programs. Captain Smith received his well-deserved award for his exemplary career at sea in traditional sailing vessels and his dedication to education and mentoring the next generation of sailing ship mariners.

e evening’s program featured engaging presentations, heartfelt tributes, and beautifully produced video segments that brought each honoree’s story to life. e US Coast Guard Cadet Chorale, led by Dr. Daniel McDavitt, added a stirring musical dimension to the night’s celebration, reminding us all of the time-honored traditions that unite the maritime community. Emcee Richard du Moulin guided the event with warmth and a ability, while presenters shared re ections that were both personal and inspiring. e atmosphere was one of camaraderie and shared purpose—guests gathered not only to celebrate outstanding achievements but also to rea rm their commitment to preserving maritime history for future generations.

A highlight of the evening was the Education Paddle Raise, which invited guests to support the Society’s Sea History for Kids feature in Sea History magazine. anks to the generous contributions of attendees and advanced pledges from members of the NMHS board of trustees and supporters, the Society can continue to bring the stories from our maritime history to young readers across the nation.

As guests departed, many expressed their appreciation for an evening that both celebrated the past and looked forward to the future of maritime heritage. e success of the 2025 Awards Dinner was made possible by the dedication of the dinner committee, dinner chair Tom Whidden, award presenters, and sta members, whose e orts ensured a seamless and memorable occasion.

With gratitude to all who participated and supported this year’s event, the Society looks ahead to its next Annual Awards Dinner on 22 October 2026 and continuing a tradition that honors the best in maritime achievement while advancing the mission of the National Maritime Historical Society.

— Cathy Green, NMHS President

Monthly, all year: First Thursdays Seminar Series—Online presentations highlighting the art, history, science, and adventure of the sea.

27 March–4 April: Puget Sound & San Juan Islands Cruise— Sail with NMHS through the scenic Pacific Northwest.

27–29 May: NMHS Annual Meeting (joint meeting with NASOH) New Haven, CT. Presentations, tours, and networking.

June: Art of the Sea Online Exhibition—Juried maritime art show featuring works for sale.

Summer: Sail 250—Tall ship celebrations marking America’s 250th anniversary and its maritime heritage.

22 October: Annual Awards Dinner—Celebrate maritime excellence and leadership at our signature gala at the New York Yacht Club.

by Fred Hocker

The MiG-29 screamed over the river, barely a hundred meters above our heads and using the Naumova Rock outcrop to mask its radar signature. It banked left, the sun glinting on its canopy and showing o the bright blue and yellow tailplanes, and was gone, the roar of the twin Klimov engines echoing from the rocks. Bombed up and booking it, the ghter jet was heading east to deliver presents to the orcs.1

It was a powerful reminder of the violent history of this war-torn country, a battleground for millennia between empires crashing against each other. We were there to excavate the remains of just one of those con icts, from the

18th century, but we had to rst dig through the site of a 1943 battle while the current war played out in the sky above us.

In 1735 the Russian and Ottoman empires collided in one of their many wars over control of the Crimean Peninsula. For four years, Russian, Turkish, and eventually Austrian armies fought along the lower Dnipro River and into Crimea. Russian forces typically would invade Crimea in the spring and then retreat in the fall. Army commanders chose to use the island of Khortytsia, in the great bend of the Dnipro, as a winter camp. It lay just below the rapids at Zaporizhzhia, the e ective head of navigation in the lower river and within

1 Fans of J. R. R. Tolkien will recognize the word orc, which refers to humanoid creatures that served as the Dark Lord’s foot soldiers. In Ukraine, it has been adopted as a derogatory term to refer to Russian soldiers.

the area controlled by the Zaporizhzhian Cossacks, who were allied with Russia. e army had built a eet of transports, originally numbering about 400 vessels, to move men, horses, guns, and supplies down the river and back. ese vessels were built on a tributary of the upper Dnipro, north of Kyiv, and oated down to the lower river over the rapids, losing some boats in the process. By the winter of 1738–1739, the Dnipro otilla numbered about 300 boats, organized into three squadrons. When the army was in winter quarters, the boats were drawn up on shore or moored in the river along the west side of the island and the right bank of the river.

In 1738 the encampment was struck by the plague, forcing the troops to withdraw upstream. e boats were abandoned at their moorings, after being stripped of useful equipment, and in some cases after being partly dismantled to prevent their use by the Turks. Over the years, the river washed some of them away and buried others in sand. Mennonite settlers who came to the island after 1785 reported seeing the skeletons of boats along the shoreline.

e new Soviet Union, as part of its e ort to modernize the economy and develop the infrastructure within Ukraine, built a series of dams, locks, and hydroelectric plants along the Dnipro River between 1920 and 1960. is allowed navigation all the way to Kyiv and provided electricity and water reservoirs for new industrial cities, such as Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhzhia. Dams at Kakhovka and Zaporizhzhia created a lake more than 300 km long,

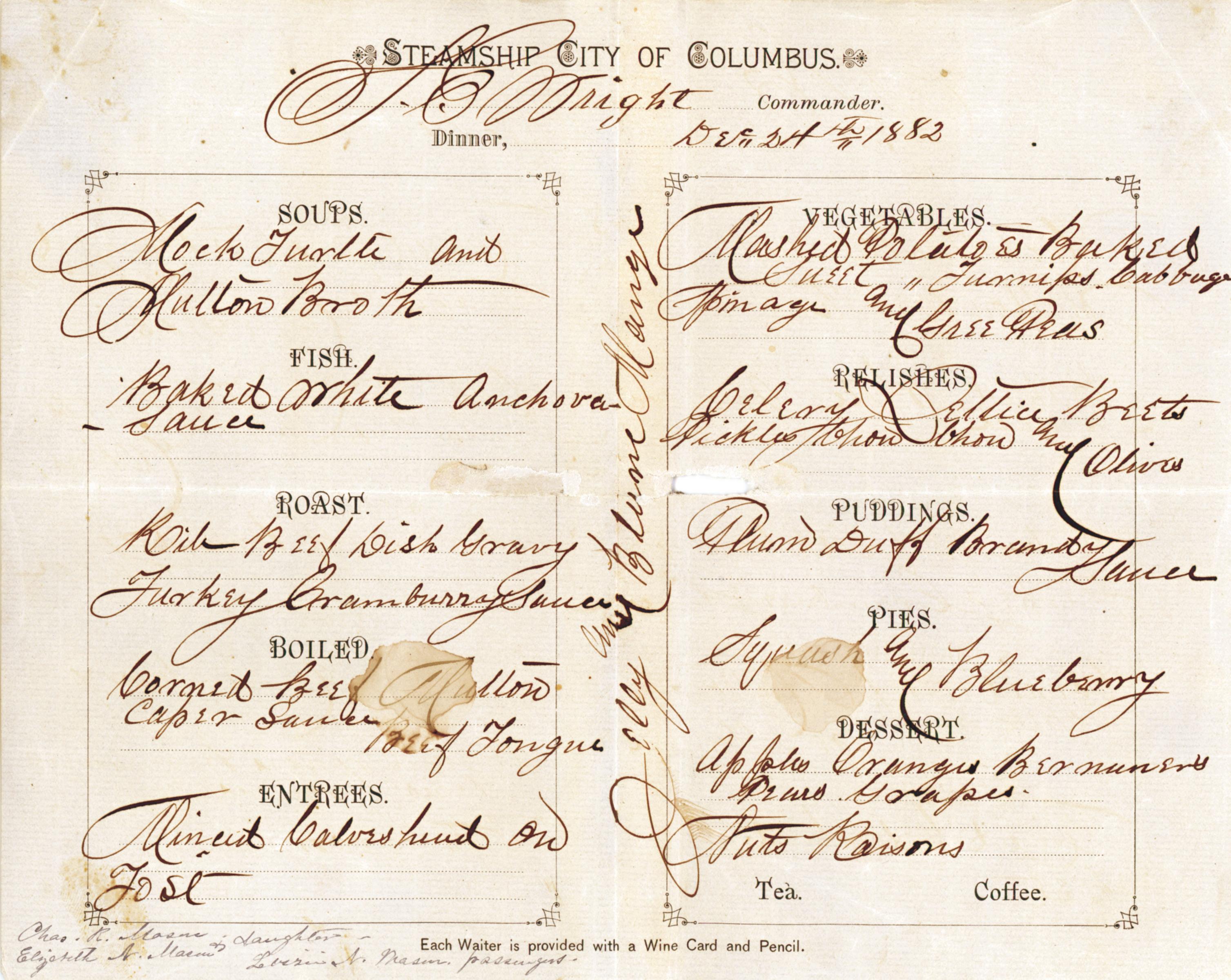

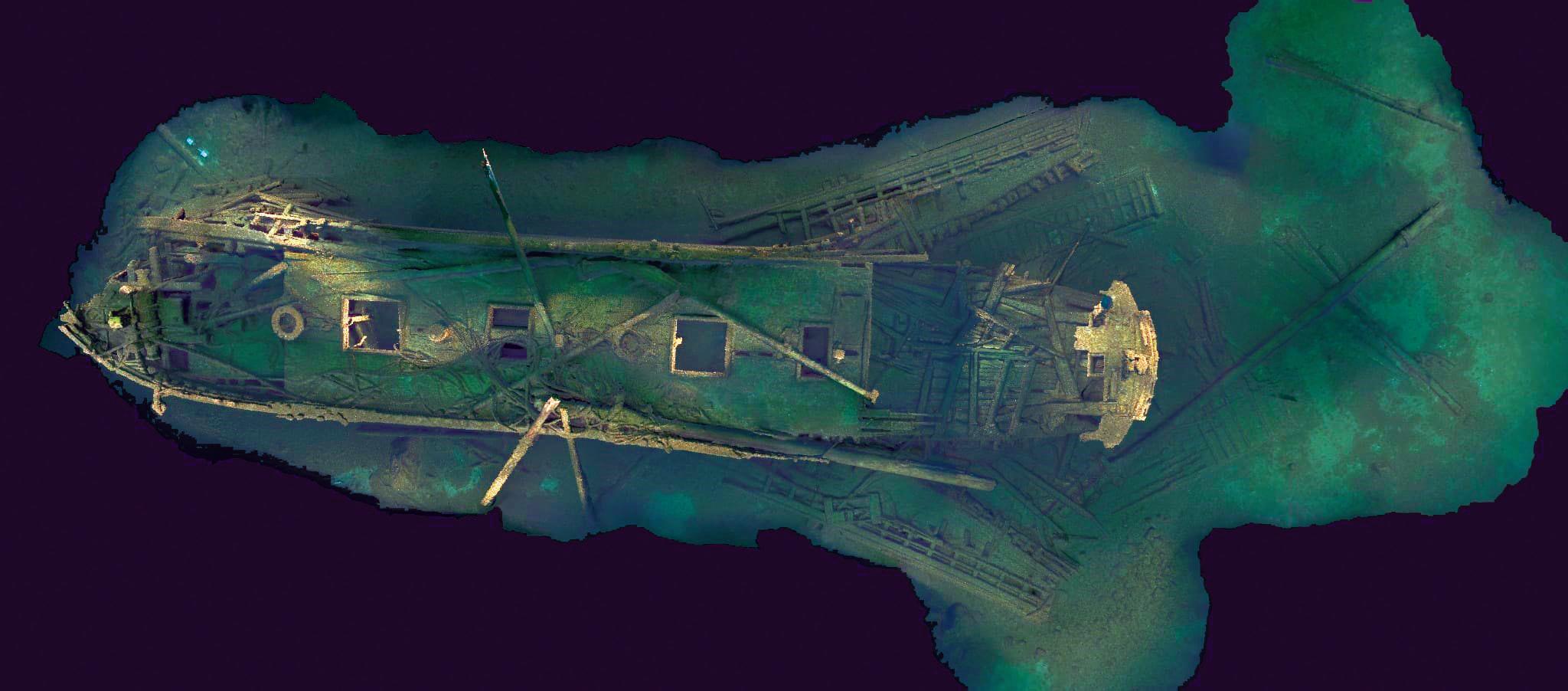

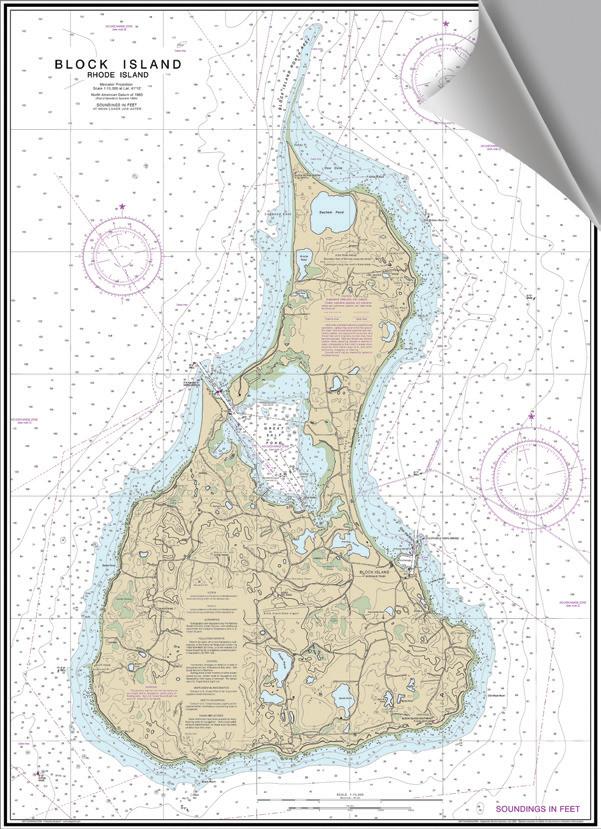

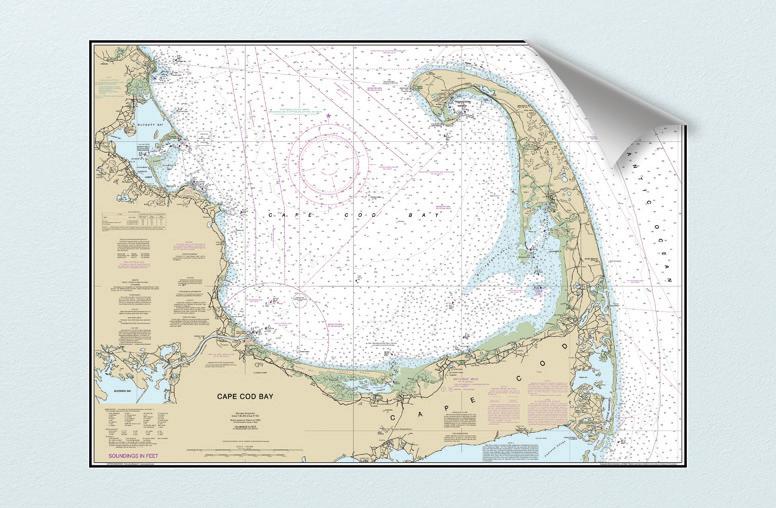

The shipwreck site near Zaporizhzhia lies just north of Russian-held territory.

ooding over 2,000 square kilometers of what is called the Great Meadow, the low-lying land downstream of Zaporizhzhia. e rising water covered medieval settlements, ancient Scythian grave elds, and what was left of the 1738 eet.

In the 1970s, divers led by Ivan Shapovalov began exploring the wrecks in the lake and discovered several remains from the 1738 eet. By the 1980s, the island had become a national park, the Khortytsia National Reserve (KNR), which combined a nature reserve with a museum of local archaeology and Cossack culture. When spring oods in 1998 eroded away parts of the riverbed around the island, more wrecks were exposed, and the underwater archaeological team based at the KNR began to investigate them. Over the course of the next twenty years, they recovered one largely complete horse transport, most of a heavy sailing vessel, and fragments of three large, open troop transports. ese have been conserved by polyethylene glycol (PEG) impregnation and are on display at the southern end of the island in a repurposed storage hangar.

Russian forces destroyed the Kakhovka dam in June 2023 to head o a Ukrainian anking attack, which

(above right) In June 2023, Russian forces destroyed the Kakhovka Dam downstream from Zaporizhzhia, causing water levels to drop 6–12 meters and se ing o widespread humanitarian, cultural, and ecological impacts.

(right) Several vessels from the 1738 fleet had been previously excavated and conserved. Unable to be moved to safety when the invasion began, they remain in their display hanger on Khortytsia Island. In the past 12 months, the building has been hit by Russian drone strikes, but so far the vessels inside have not been damaged.

drained the lake between Kakhovka and Zaporizhzhia. is lowered the water level by 6 to 12 meters and exposed the original shoreline. e ow of the river, once more in its smaller original channel, accelerated, causing erosion of its new (old) banks.

e archaeological and conservation sta of the KNR are responsible for documenting and preserving the cultural heritage of the island and the northern part of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, most of which is currently occupied by Russian forces. ey have been busy since the full-scale invasion began in 2022 trying to evacuate, stabilize, or

protect the artifacts and monuments in their care. When the lake was drained, they also became responsible for surveying the newly exposed shoreline and stabilizing archaeological sites—all taking place in an active war zone.

ey noted the appearance of several boats along the northwestern shore of the island, in the same area where the KNR had recovered the other 1738 vessels. Two of the exposed wrecks appeared to be substantially preserved troop transports, which had previously only been seen in badly broken up examples. Both were in the same stretch of beach, at the ends of a shallow

BY

embayment between the ends of a crescent-shaped cli , Naumova Rock.

e one at the north end (Object 1) was entirely submerged except during periods of low water during the summer months. Most of the vessel remains were buried under the sand, except for a couple of meters at the bow. e other (Object 2) was at the southern end of the beach, lying parallel to the waterline and just clear of the water in the summer. It was the detached bow of a nearly identical vessel, broken into two pieces and lying on its port side. Just to the north was what looked like the end of a hull plank, lying loose in the sand.

e KNR sta stabilized the remains as much as possible with geotextile and sandbags, but when the water rose the following spring it was clear that Object 2 would eventually be undermined and washed downstream. It needed to be excavated and moved to a safer location, but the Reserve was short on sta , with many of its male employees ghting on the front lines and nancial resources limited.

In autumn 2024, the head of the archaeology department, Dmitry (Dima)

Kobaliia, contacted me about a possible collaboration. He had just been discharged from the military after more than two years of deployment with a mortar battery in Donbas and was eager to get back to the project. My employer, the Swedish National Maritime and Transport Museums, had worked with the KNR in 2023 on a project documenting and stabilizing the previously conserved wrecks, now in the hangar. We invited some of their curatorial and conservation sta to Stockholm in March of that year to share their experiences and discuss how we could help them. Two of us had spent a week in the hangar in May, so we already had a good working relationship.

Dima and I discussed a possible rescue excavation while we were both attending the biannual meeting of the International Congress of Maritime Museums (ICMM) in Rotterdam and Amsterdam in September 2024 and presented a proposal to the meeting: ICMM would create an international cooperative project to assist the KNR in saving the wrecks during the following summer. e executive council of ICMM approved the project, several

member museums stepped forward to o er support, and individuals began to o er their services as eld sta e rst person to volunteer was Cathy Green, the president of the National Maritime Historical Society.

Over the winter we made all the normal preparations for a eld project: raising money, recruiting sta , developing plans and equipment lists. We also had to consider the security situation. e site lies only 30 kilometers from the front line, within artillery range, and the city of Zaporizhzhia is regularly attacked with missiles, drones, and glide bombs. We had to decide how much risk we could accept—both as individuals and as a team—and began monitoring the situation in Zaporizhzhia. In spring 2025, things were relatively calm—at least calmer than they had been in 2023—and I was able to make a brief trip to Khortytsia in April to see the site for myself and make concrete plans with the Reserve sta

We decided that Object 1 was not seriously threatened and could be protected by building a partial co erdam around the exposed bow to divert water ow and trap sediment. I had constructed a nearly identical structure to protect a wreck in similar circumstances in the Savannah River in 1992, and that co erdam is still doing its job. e conservation sta , under the leadership of Valery Nefyodov, would handle this task, while Dima and I would manage the excavation of Object 2 with a larger team of KNR sta , plus Ukrainian and international volunteers. Once it had been excavated and documented, Valery’s team would be able to move its

Russian drone and missile a acks are a daily reality for most of the country. This 28 August snapshot from a widely circulated air-alert app illustrates the hundreds of airborne threats within a 24-hour period.

components upstream a few hundred meters to a conservation facility.

I recruited two more colleagues to the international team, who eventually came to be known as the Zaporizhzhia Zouaves, a reference to the colorfully dressed exotic troops used in the Crimean and American Civil Wars. Larry Babits, a retired director of the maritime archaeology program at East Carolina University and a leading con ict archaeologist, has excavated everything from Revolutionary War battle elds to World War II prison camps. He was also part of the Savannah River project I directed in 1992. Jon Faucher has been working in maritime archaeology for three decades, although he is currently employed as a paramedic and rapid-response logistician for FEMA; he has helped hurricane, wild re, and

earthquake victims in remote places and survived a helicopter crash high in the Andes. e risk of working in Ukraine probably seemed dull by comparison. e team from KNR was made up of the core sta of the park’s heritage

departments, including three of the colleagues who had visited Sweden in 2023 (head of collections Alina “Alya” Budnikova, archaeologist Tetyana “Tanya” Shelemetyeva, and conservator Polina “Polya” Petrashnya) and Dima’s father,

The site on the western side of Khortytsia Island. Object 1 is just outside the frame at the far le . The camp is in view in the upper le corner. (le of center) Archaeologists finish restoring portions of the beach that hide a treasure trove of ship timbers. (center right) Object 2: The team excavating between frames in preparation to move the vessel. (lower right corner) As timbers were removed, they were placed in a holding pen in the river to keep them hydrated before transport to the conservation lab. Note: special government permission was obtained to fly a drone to document the site. Drones in Ukraine are not usually friendly or tolerated.

Ruslan Kobaliia, known as “Bagratich” or sometimes just “Pa.” Anatoly “Tolek” Volkov was responsible for photogrammetry, while the museum’s photographer visited regularly to document the project. Dima had also recruited some of his colleagues from other museums as volunteers, and Tetyana’s husband, Andrej, served as our main cook. For most of the project, we had a core sta of about a dozen, plus guests who would come to dig for a few days, including the now-retired Ivan Shapovalov and the former director of KNR, Maxym Ostapenko. e excavation is the subject of a documentary being produced by NOVA/Blink Films, so we had a resident cameraman/host/producer, Ben Holgate, on site for most of the time. ese days, you cannot just hop on a plane to Ukraine. We ew into Krakow and took a car across the border to Lviv, where we were met by Dima’s wife, Kseniya. She is a translator by profession, but also a crack photographer and an undisputed wizard of logistics.

She managed to sort out all our land travel, on the long-haul overnight trains between Lviv and Zaporizhzhia, and accommodation in hotels. Once we were in Krakow, we put ourselves in her hands, and she made miracles happen. e eld campaign ran for four weeks, beginning 10 August with the construction of a eld camp and infrastructure. Because the local weather that time of year is hot and very dry—a steppe climate—one challenge throughout the project was keeping exposed timbers from drying out and cracking. To keep the site (and the diggers) in the shade, we erected a canopy over the wreck. A few people would have to overnight at the site to guard equipment, so a camp was set up on a sand ledge above the beach against the base of the cli , with tents, a eld kitchen, and a tarp erected over a long dining table and benches. Bagratich, our resident eld engineer, also built a staircase of rocks down the face of the ledge to make access to the camp easier.

e archaeological site is a sandy beach between spurs of the Naumova Rock, which with a matching outcrop on the opposite (west) bank constricts the river to only a few hundred meters wide. Access is by boat, by clambering over the fallen boulders at either end of the beach, or by climbing down the cli face. We usually arrived over the boulders at the southern (downstream) end of the beach. I took the cli route in April; I do not recommend it. e wreck lay in the sand, hard against the boulder pile at the southern spur parallel to the water, with its bow towards the north (facing the current) and the keel about ve meters above the water’s edge and up the slope. e boat had leaned over onto its port bilge, and the upper half of the port side had pulled away from the stem and broken along the turn of the bilge to lie at on the lower slope. e upper part of the starboard side had been partly dismantled and deliberately burnt at some point in the past, and the after two thirds of the wreck was missing. e boat lay with its bow deeply buried in the sand but rising towards the stern, so the after part of the hull had probably been resting on the boulders. Some of the wreckage found in earlier years in the water just downstream may be the missing parts of the rest of this boat. e rst stage of the excavation required uncovering the wreck, removing the textile and sandbags used to protect it since 2023. is revealed that the uppermost parts of the wreck had dried out to some degree, but the structure was still intact, in two main pieces. It was immediately clear that most of the bow survived up to the railing on the

Boat timbers lay beneath the sand between Objects 1 and 2. This section of the site was documented and reburied, requiring more than 20 tons of sand to be removed and then put back.

port side, with a prominent mounting block for a windlass and a large bitt for a swivel gun bolted into the heavy railing structure. e upper part of the stem was missing, but most of the rest of the backbone was present, including a heavy keelson or maststep timber.

We divided our crew into two teams. e larger group began the process of removing the remaining sand from the wreck, while the smaller group investigated the loose plank to the north. Digging soon became a competition between Larry and Bagratich. Both retired and veterans from opposite sides of the Cold War, they are double tough and neither was going to be outworked by an “old man.” e sand ew faster and faster until it became obvious there would be no winner, but they had become friends in the process.

As we shovelled more than 25 tons of sand into mounds along the water’s edge, we discovered that there was much more to this site than had rst appeared. A ground-penetrating radar survey commissioned after my visit in April suggested that there might be another wreck about midway between Objects 1 and 2, and there were wrecks known from the beach to the south, as well as vessel remains in the water below the beach. We had planned to test a few of the buried features revealed by the radar, but what lay north of the wreck was a surprise. e plank turned out to be over 6 meters long and led to a

(above right) Object 2: The starboard bow emerges from the beach. As each shovelful of sand was removed, more of the vessel’s construction details were revealed, as well as the stratigraphy of the riverbed embankment.

(right) The final stages of excavation included undercu ing the wreck to insert supports so it could be moved into the river and floated to the conservation facility a short distance upstream.

large heap of boat timbers, mostly loose planking and frames, but also a swivel gun mount, carelessly piled like a giant game of pickup sticks. e excavation eventually expanded to an area about 20 meters long and 6 meters wide before the pile ended. e timbers tended to lie deeper towards the north, so the excavation reached a maximum depth of more than 1.5 meters, and even then it was clear that we had not reached the bottom of the pile.

It was while we were excavating this pile that we came upon evidence

of a battle fought between Axis and Soviet troops in 1943. In World War II, Hungarian troops attached to the German army occupied the island, and as the Soviet Army began to push Hitler’s army back out of Ukraine, re was exchanged on the beach. We found red Soviet bullets and un red rounds of Hungarian ammunition. Jon Faucher even excavated a fully loaded magazine for a Solothurn 7.92mm machine gun, as well as fragments of grenades. is was not one of the risks we had anticipated in our project planning, but our

colleagues from the Reserve reported that they had boxes full of this sort of thing from previous excavations all over the island; they had not thought it unusual enough to mention, just part of the background noise of local archaeology in a region that has been heavily contested for centuries.

e loose timbers lay deep enough in the sand that they were still wet and not threatened by the river, so we elected to record them and rebury them, but they suggest that there is much more to be discovered along this little stretch of beach. ere are probably wrecks from one end to the other.

Object 2 revealed new features with each passing day of shoveling. Although it had been mostly stripped of useful equipment, there was still some material just thrown out onto the beach or left in the bottom of the boat. Rigging tackle, including a deadeye and a block, as well as military equipment, were the most common nds. ese included musket parts (two intlocks, gun ints, a brass ramrod pipe) and

even a complete musket with bayonet (model 1715, one of the main weapons of the Russian army) under the keel. ere was a fair amount of rope, much of it small cable running along beside the keel, a sheet-iron bucket, a few uniform buttons, and even a curved sailmaker’s needle. Some ammunition in the form of 3-pounder and 1-pounder shot lay in front of the bow, and one 24-pound shot was found at the north end of the beach, near Object 1.

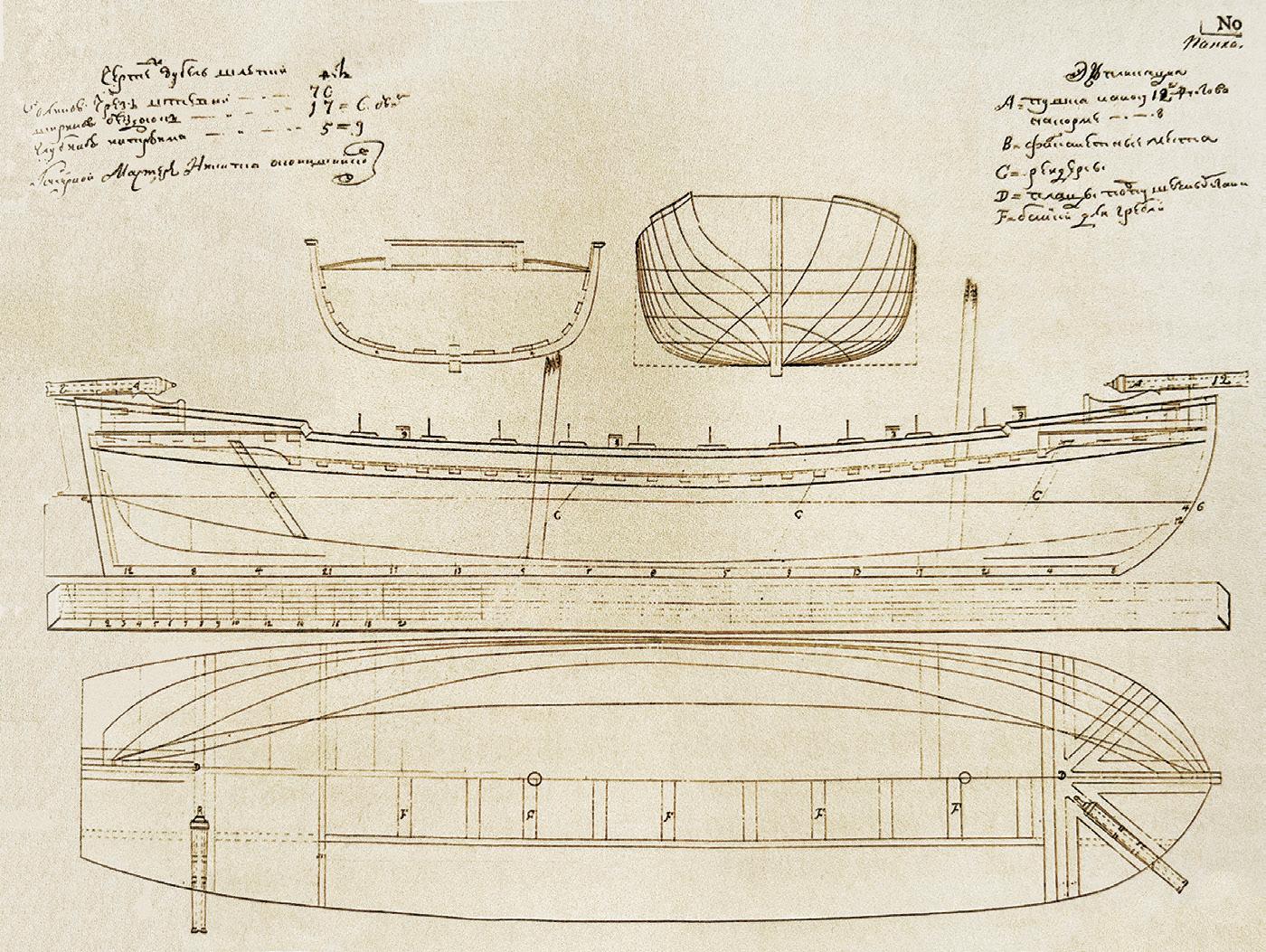

e boat itself proved to be one of the large troop transports known as double chaloupes. ese were open boats, 16 or 18 meters long with a simple schooner rig and 16 to 20 oars. ey could transport about half a company of soldiers and were armed for defense with three small swivels on each side (at the bow, stern, and amidships). Chaloupes were relatively lightly built and not very durable; many broke apart in the rapids while being delivered to the theater of war. e hull shape is surprisingly graceful, with a hollow entrance and easy bilges, and the standard of

construction is good, with tightly tting joints and fair plank runs. ere are some unusual features, such as an odd arrangement of oor timbers and futtocks, as well as the mix of wood species and how they were used. e backbone timbers are all oak, but the framing and planking are a mixture of oak and pine. e rst, second, fth, and sixth strakes of nine total are oak— the rest are pine. e frames in the bow have pine oor timbers, which are little more than thick planks, with oak futtocks, while the frames in the middle of the ship are oak oor timbers and pine futtocks of equal size. ere is some indication of haste in their construction, with standardized dimensions and parts and the use of nails for fastening nearly everything together. e visible part of Object 1 at the north end of the beach is another vessel of the same type, with its bow still intact. ese troop transports were the most common type of vessel in the eet, and several fragments had been found previously, although none this complete or well preserved.

Once it was fully exposed, we could see that it would not be possible to lift the wreck as a single piece. e lower hull, up to about the fth strake and the turn of the bilge, was still relatively solid, except for a long plank extending more than two meters farther aft than the last frame. e upper part of the port side had separated from the lower hull and, except for the railing structure, was not held together by much more than the rusty nails between the planks and frames. e ceiling on the inside of the frames was also quite fragile, so we decided to dismantle much of the upper section. Once this began, we could see that the nails were no longer holding; the ceiling could be lifted easily o the frames and some of the futtocks could be removed. Loosened timbers were stored temporarily in a holding

pen built in the river. e two coherent sections of the hull were slid over skids into the water, where they could be buoyed for the short tow upstream to the conservation facility.

e visiting archaeologists—our team—began making our way back home on 29 August, leaving on the last train out of Zaporizhzhia that evening. e calm that had descended on the city since the previous winter had broken, as Russian forces began stepping up their nighttime attacks on civilian targets all across Ukraine; while we were in the city, they destroyed the bus station, a hospital, a supermarket, and several apartment buildings. In fact, three of the most extensive air raids of the entire war to that point occurred in August, and we were not spared on the ride home. Drones and missiles rained down on Ukraine during the night, and on two occasions hit train stations fewer than ten minutes after we passed through them.

One may ask if a 290-year-old boat of unremarkable construction is worth risking your life for, and those of us who travelled to Zaporizhzhia in August 2025 have been asked variations of that question many times. Each person must make their own choice for their own reasons. In my case, I am helping my Ukrainian colleagues, letting them know that they are not forgotten. We shared their world for a few weeks, but they have been living with the constant threat of destruction for more than three years. By organizing this project, we could help give them a chance to do the jobs they love in a way they have not been able to since 2022, and to allow them to think of how the world might look after the war.2

It is also a chance for me to contribute my specialized skills to something

that is not just a luxury. ose of us who work in history and archaeology like to talk about the importance of learning and preserving history as an essential component of the knowledge base needed for planning a better future, but in reality, what we mostly do is provide interesting stories to entertain. We do not feed the hungry or heal the sick, but in this case, we can reach closer to that higher purpose. An important goal of the Russian assault is to extinguish and erase any

memory or thought that Ukraine ever existed as a separate culture or state, and to that end, Russian forces have been plundering and destroying cultural heritage sites across the country.

e cultural heritage of Ukraine is a vital component of its identity, and its future independence requires the physical remains of its past. I am too old and lack the right training to carry a gun in the defense of my friends, but I can use a shovel to make sure that their identity survives.

Fred Hocker is the director of research at the Vasa Museum and the Swedish National Maritime and Transport Museums. He holds a PhD in anthropology from Texas A & M and was a former professor of maritime archaeology there. He has participated and directed numerous maritime archaeological excavations in the United States, Northern Europe, and the Mediterranean. He serves as a trustee with the Kalmar Nyckel Foundation and on the board of governors for the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Learn more about this expedition by viewing the NMHS First Thursday Seminar Series from 4 December 2025, online at www.seahistory.org/latest-news/seminars.

2 The regional government hopes to establish an international center for river archaeology and cultural heritage when the war is over. Right now, the remains at the Khortytsia site that have been identified are all relatively protected, but the KNR would like to continue the excavation, with international participation, when it is practical to do so.

by CAPT Daniel A. Laliberte, USCG (Ret.)

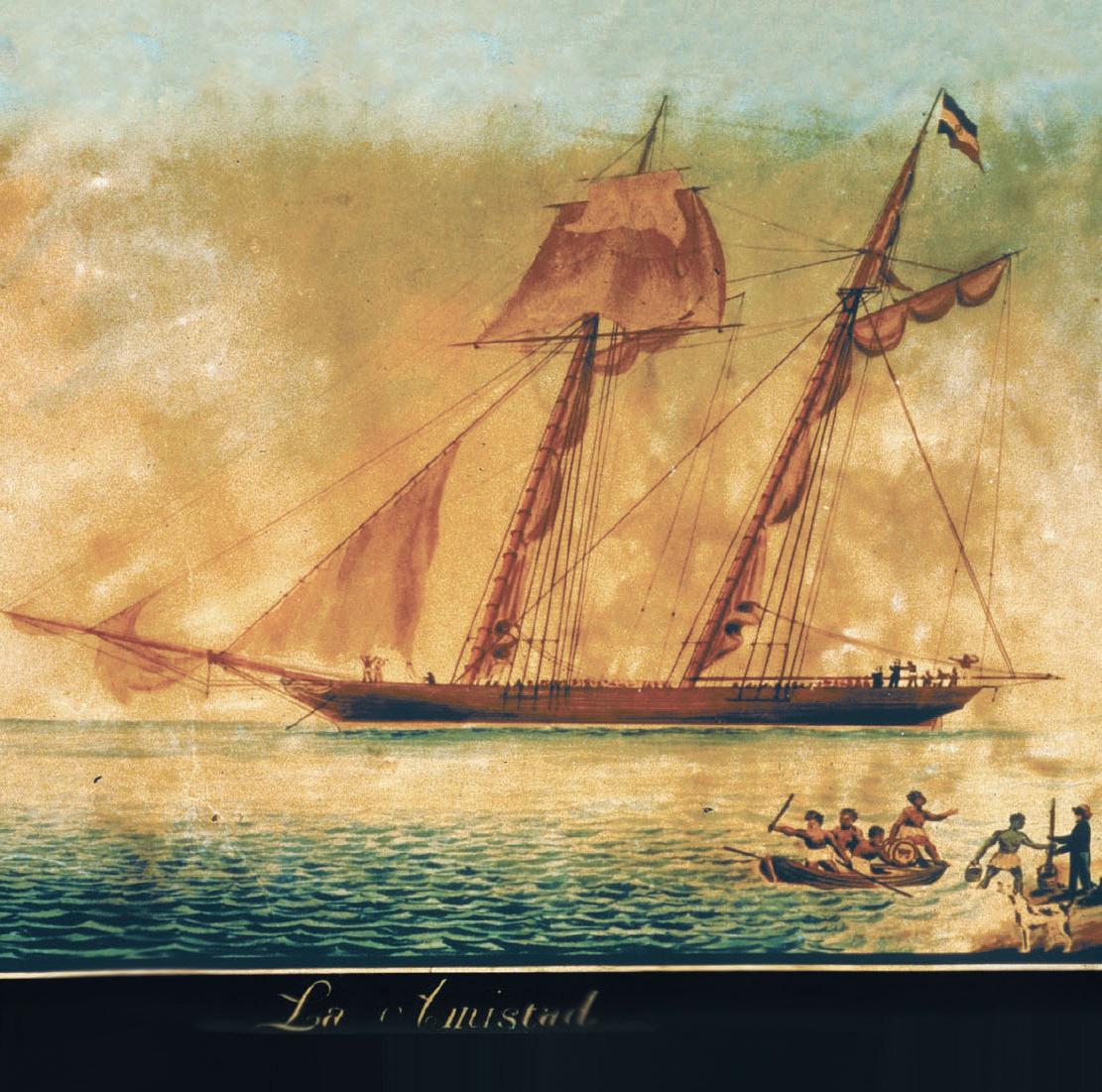

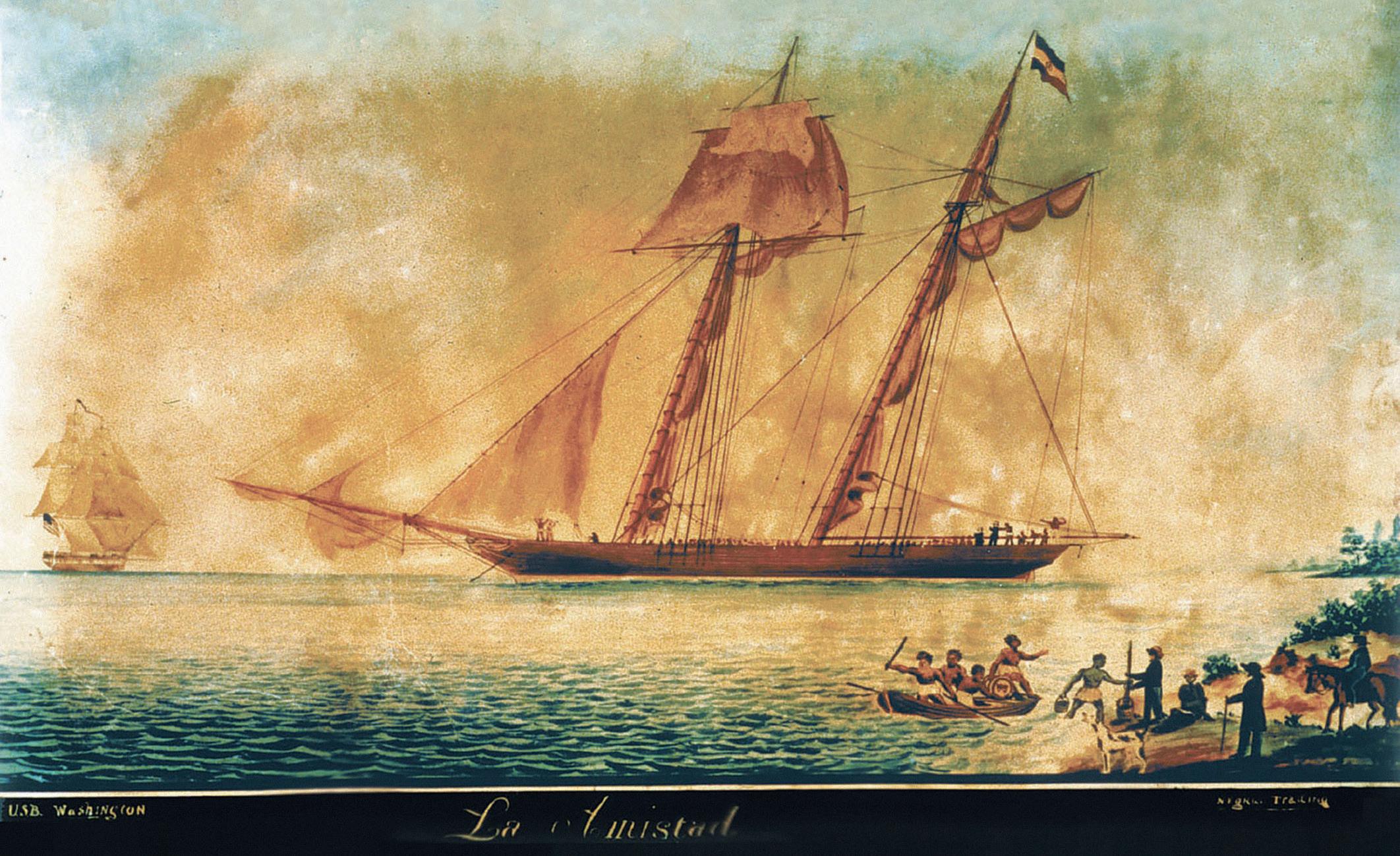

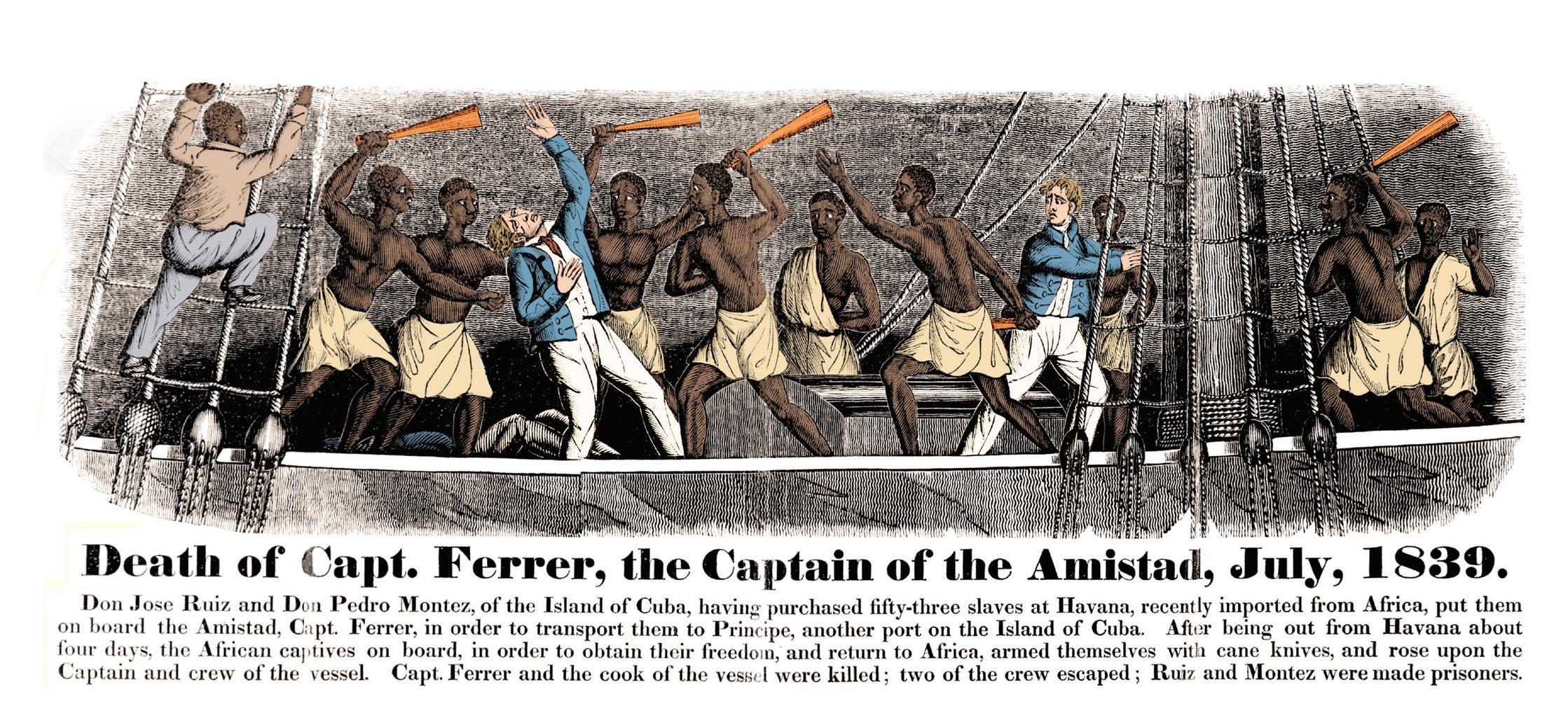

On the morning of 28 June 1839, the Spanish merchant schooner Amistad cleared the port of Havana, bound for Guanaja, under the command of Captain Raymon Ferrer. e 300-mile route eastward along the coast was a regular route but posed signi cant challenges for vessels in that era. e initial relatively open passage through the Straits of Florida would soon begin to narrow at the San Nicholas Channel and could be quite restricted through the subsequent Old Bahama Channel. Adverse winds and a variable current out of the east could lengthen the four-day voyage to two weeks, or worse, drive a vessel onto the Grand Bahama Bank or the reefs all around the Cuban coastline. Amistad ’s tiny crew of two seamen, a cook, and a cabin boy placed their trust in Ferrer’s seamanship and the schooner’s manageable 5½-foot draft, which enabled them to pass safely over some of the hazards lurking beneath the waves along the way.

Reefs and submerged hazards would certainly have concerned Ferrer, but he was likely more worried about the

risk that the 55 passengers posed to the safety of the ship and the $40,000 worth of foodstu $ s, clothing, dry goods, agricultural supplies, tools, and gold coins sitting in his hold. ey had crowded aboard after nightfall the previous evening; all but two of the 55, however, were there against their will.

Transporting slaves was not something Ferrer did regularly. His vessel was con gured to move goods—not people—in the coastal trade. Amistad lacked the “slave deck” characteristic of a true “slaver.” Without a slave deck, which typically sported only 3–4 feet of clearance and was built to restrain prisoners securely within, the risk of a successful uprising dramatically increased. is risk was compounded by the small size of Ferrer’s crew.

Nevertheless, Captain Ferrer was not averse to transporting “docile” slaves in short hops between Cuban ports. Two wealthy Dons—Jose Ruiz and Pedro Montes—had booked passage for themselves and 53 slaves intended to work their sugar cane plantations near Puerto Principe. In

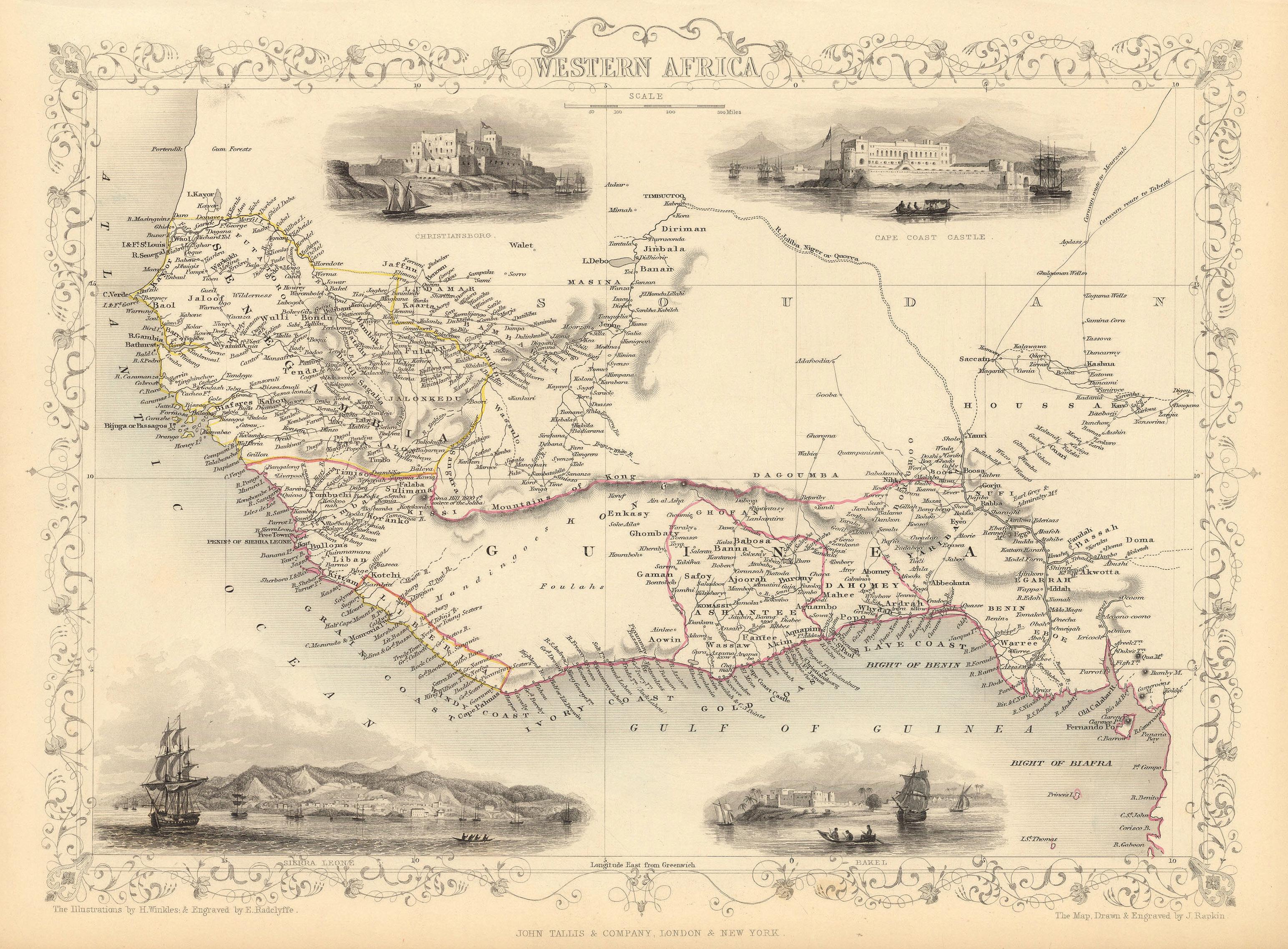

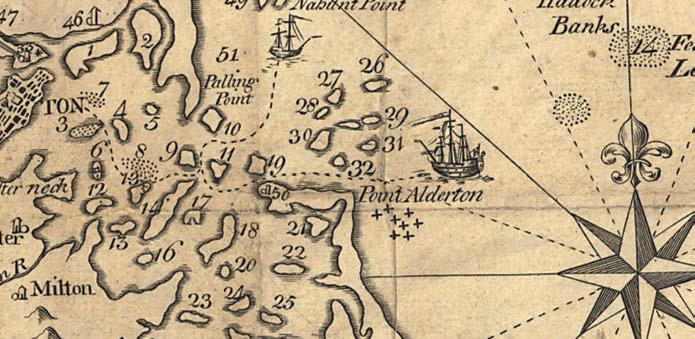

1851 map of West Africa. The Africans aboard the schooner Amistad came from what is now Sierra Leone and were held and sold at Lomboko, a major slave “factory” at the mouth of the Gallinas River. By 1839, when the Amistad captives passed through Lomboko, the transAtlantic slave trade had been abolished by the United States, Great Britain, Portugal, and Spain, yet the Gallinas coast remained a major hub for illicit tra icking. An estimated 1,500–2,000 Africans a year were still brought to Lomboko and shipped into slavery. A decade later, in 1849, the British West Africa Squadron a acked and destroyed the slave factory, freeing the people held there and ending its operations.

this case, he probably assumed, or at least hoped, that the slaves purchased by Ruiz and Montes had accepted their fate and posed minimal risk of rebellion. He would further mitigate the risk by securing in the hold the few troublemakers he had suspicions about. e rest would be allowed topside during the day, as long as they behaved.

e Africans onboard were originally from Mende-land, a region that lay in what is now southeastern Sierra Leone. Some had been prisoners captured in the constant wars that wracked the area, some had been sentenced to slavery after committing crimes, others had been sold to settle debts, and some were simply travelers, caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

At some point after having been seized, they were taken by their African captors to be sold or bartered to the Spaniard Pedro Blanco at the infamous “slave factory” at

Lomboko. Lomboko’s fortress, barracoons (rough slave quarters), open pens, market areas, and administrative buildings sat astride a tight group of islands just o$ the Gallinas Coast. It was here that the 53 Mende who would later be resold to Ruiz and Montes were initially sorted, bought, and processed.

In mid-April 1839 they were forced, along with hundreds of others, aboard the Portuguese brig Teçora. A purposebuilt slave ship, Teçora could carry up to 500 persons shackled in its slave deck for the Middle Passage across the Atlantic to Cuba. During the crossing, about a third of the prisoners died from disease or dehydration. ose who survived the voyage were landed at a small village outside of Havana in early June, where they were met by Ruiz and Montes, who accompanied the Africans as they were smuggled into Havana. e landing and subsequent

movement of ship’s human cargo was done in secret, necessary because every aspect of this undertaking had been in direct violation of both Spanish and international law.

Nineteen years earlier, Spain had joined an already decades-old agreement between Great Britain and the United States to ban participation by their ships and citizens in the international slave trade; Portugal had also signed, although only three years earlier. e agreement banned new enslavement, but allowed the domestic sale of those who were already slaves and the continued enslavement of their descendants.

e Martinez and Co. slave house in Cuba used by Ruiz and Montes was part of an illegal infrastructure designed to skirt that agreement. e company was infamous for forging the documents to establish “Bozales” (the Spanish term for Africans who had been only recently brought from Africa) as “Ladinos” (those who had been enslaved prior to Spain’s ban). Using those documents, Ruiz and Montes were able to obtain the appropriate licenses and customs clearance permits required to ship their newly purchased “slaves” to Guanaja, the seaport nearest the location of their respective sugar cane plantations.

e rst three days out of Havana had gone smoothly, with Amistad making it approximately two-thirds of the way to her destination. e fourth day, however, brought constantly shifting winds and frequent downpours. By nightfall, progress had been slow, and although the rain had let up, a heavy cover of clouds obscured most of the light the moon would otherwise have provided.

By midnight, with the crew exhausted and the weather having calmed down, Captain Ferrer caught some sleep

on a mattress on deck back aft, while a single crewmember manned the helm. e rest of the crew was sent below to get some sleep. e passengers on board were asleep in various locations about the ship…except for the few captives restrained in the cargo hold. ese men were locked up with a padlocked chain passed through a loop on their iron slave collars, which was then bolted to the hull. ese “troublemakers” did not think of themselves as slaves, but rather as free people who had been kidnapped and transported against their will, thousands of miles from home. Rather than sleeping, they were plotting their escape.

One of them found a nail among the building supplies stored nearby. He passed the nail to Sengbe Pieh, who used it to break the padlock securing the chain that bound them together. After pulling the chain through the links on each their collars, a more thorough search through the cargo turned up cane-cutting knifes—similar to modern machetes—and blunt instruments that could be used as clubs. us armed, the group ascended to the main deck and stalked aft. Others quickly joined the revolt; some set o$ in search of the ship’s cook, Selestino. Although he was, himself, a slave, Selestino had become a trusted long-time companion to Ferrer and had used his position to mercilessly taunt the prisoners over the last three days. When the captives found him asleep, they fell upon him with clubs and knives. He never woke up.

Back aft, Ferrer awakened to chaos and confusion about the deck. Many of his erstwhile prisoners had scattered seemingly randomly about the ship, ransacking living quarters, breaking open containers, and strewing their contents about the deck. He shouted for his cabin boy, Antonio, to

toss bread among them, hoping to distract their attention; however, the rioters were undeterred.

Eventually, Sengbe and three others engaged Ferrer on the fantail. e captain fought desperately with either a sword or a long knife, by some accounts killing two of the freedom seekers before being brought down himself. Miraculously, the two deckhands, Manuel Pagilla and another known only as Jacinto, somehow managed to avoid notice as they launched a boat and escaped into the darkness. Although the Mende now controlled the schooner, the problem of getting back to Africa remained. None of them knew how to sail or navigate.

is lack of knowledge saved the lives of Ruiz and Montes. e 52-year-old Montes had been a ship’s master before becoming a plantation owner. He made this known

through the interpretive services of Antonio, the cabin boy, who spoke a smattering of the Mende language. e Mende reluctantly agreed to the proposal to spare the Spaniards in return for their services.

Montes and Ruiz convinced them that a larger store of water and provisions would be needed for the lengthy trip east. Nassau, on New Providence Island, which lay more than 200 miles to the north, was chosen as the most likely port to allow them entrance, since it was under British rather than Spanish control. Amistad, however, would rst need to cross the treacherous Grand Bahama Bank.

Amistad altered course for her new destination, but it was a struggle to get down the Old Bahama Channel towards the Ragged Islands, where a passage north could be found. Due to constantly “boxing” winds—an archaic term

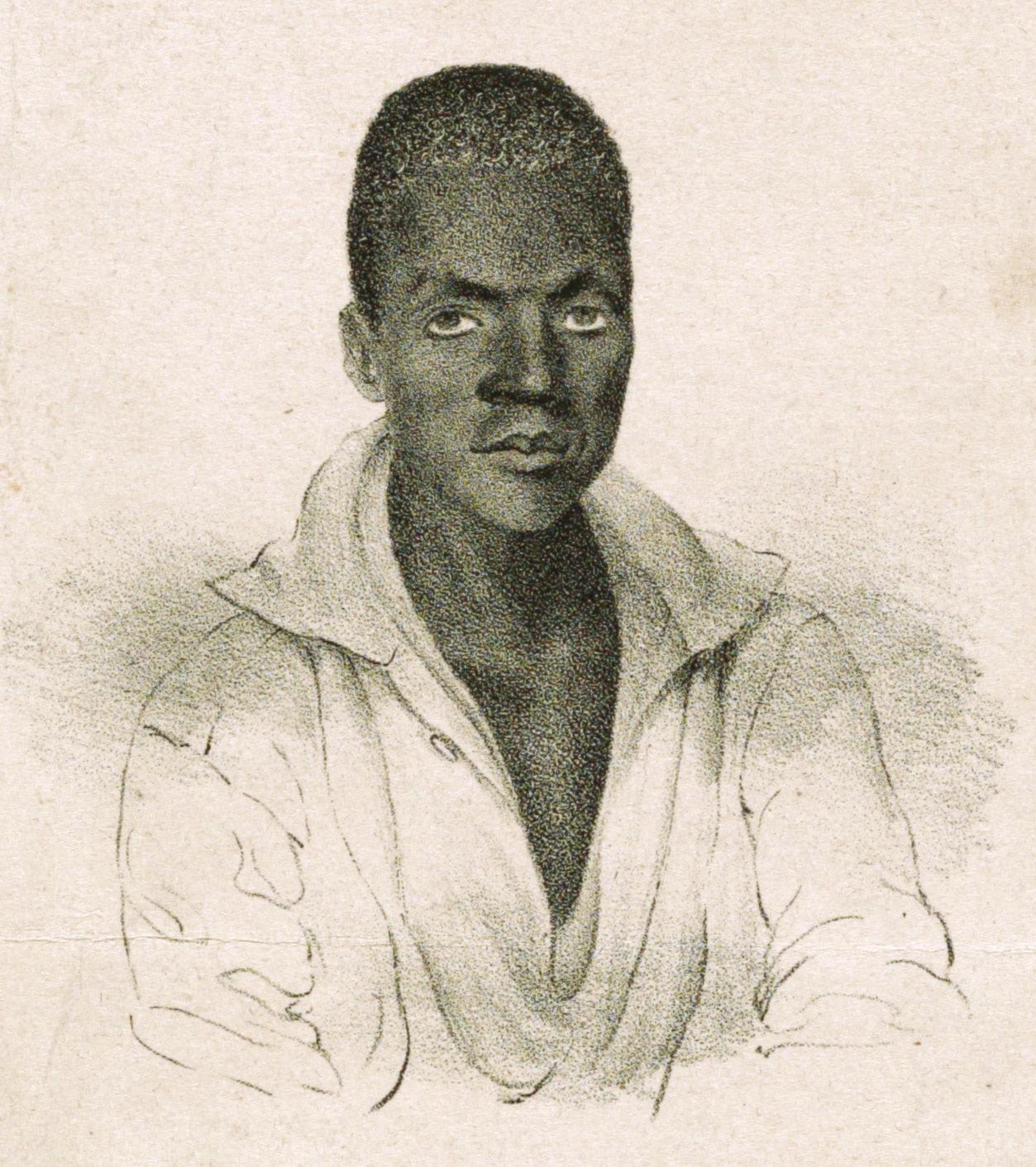

Sengbe Pieh (also referred to as Joseph Cinqué) was a rice farmer in West Africa with a wife and three young children when he was abducted. In 1841 Sengbe Pieh and the surviving Amistad captives finally made it back to Mende-land. Not much is known of his life a er his return home, but it was reported that he never found his family, that they likely had perished in ongoing local conflicts.

describing winds that seemed to shift among all points of the compass—the schooner took several days to reach its rst stop, Saint Andrew’s Island. is was probably the island more commonly known today as Little Ragged Island—although locals still recall its older moniker.

Sitting at the southern tip of the Ragged Island chain, not far from the eastern terminus of the Old Bahama Channel, Saint Andrews provided a sheltered anchorage and fresh water. It was also not far from the southern end of what is now called the Blossom, or Old Mailboat Channel, running roughly NNW from the Ragged Island Chain to the Tongue of the Ocean, which then provides easy access to New Providence. Modern sailors cruising the Bahamian archipelago can make the entire 170 or so miles from the Ragged Island Chain to New Providence in a matter of days; Amistad took several weeks, anchoring thirty times along the way.

Although several vessels were encountered during this passage, the Mende always con ned Ruiz and Mendes

below deck during any interaction—wisely suspecting that they would attempt to betray them. e next stop along their route was at Green Key, not far from the exit of Blossom Channel into the Tongue of the Ocean. ere, the schooner once again took on drinking water before getting underway for what was believed would be the nal jumpingo$ point for the long oceanic voyage.

Upon arriving at New Providence Island, Amistad was denied permission to enter the port. e schooner gave every appearance of being a pirate, and authorities ocially wanted nothing to do with it. Many private merchants shared no such reservations, however, and were more than happy to barter or sell supplies at a nearby anchorage.

When Amistad nally exited the Bahamas via the Northeast Providence Channel, the schooner initially headed east. Although unskilled in seamanship, the Mende had learned enough to keep the vessel moving during the day, but they still relied on Montes and Ruiz to navigate through the night. Montes exploited the opportunity to steer northward and westward rather than towards Africa, hoping to reach New England or encounter a vessel that might free them.

On 18 August, Amistad met a schooner out of Kingston, from which the new masters of the Amistad bought some water and supplies. Although Ruiz and Montes had again been con ned below during the exchange, reports of a suspicious “long, low, Baltimore-built schooner” of about 120 tons, “with a black hull, green bottom and two gilt stars on its stern,” began to circulate among the maritime community.

Two days later, having sailed, unknowingly, to within 25 miles of New York, they were hailed by the New York pilot boat No. 3. Montes and Ruiz were con ned below while Amistad declined assistance and sailed on. A short while later, Pilot Boat No. 4 approached and hailed. is time, the Mende refused more forcefully, brandishing weapons to warn o$ the pilot.

By now, Ruiz and Montes believed that their subterfuge had been realized and feared they might be killed at any time. With the Amistad needing to reprovision before striking out across the Atlantic for Africa, the Mende tried to approach the shore near Montauk, at the eastern end of Long Island. On 24 August, Amistad came to anchor in 3½ fathoms of water, about a half mile o$ Culloden Point. A shore party was dispatched via the ship’s boat and promptly encountered Henry Green, a ship’s captain who lived nearby, who was happy to facilitate the purchase of supplies.

Fate can be ckle, and shortly thereafter a US Coast Survey vessel, the brig Washington, happened upon the scene. e Washington had been transferred for the summer

from the US Revenue Marine to assist with charting the coast. As part of its new duties, the brig “was sounding this day between Gardner’s and Montauk Points” and sighted the suspicious schooner “lying inshore o$ Culloden Point [with] a number of people on the beach with carts & horses and a boat passing to and fro.”

Everything about the scene gave the appearance of a pirate surreptitiously “unloading” ill-gotten gains to enthusiastic residents. Washington’ s captain, USN Lieutenant Richard Gedney, dispatched an armed boarding party that seized the Amistad, rounded up those who had gone ashore, and freed Montes and Ruiz—who immediately spun a tale of mutiny and murder. With the Mende unable to communicate their side of the story, Gedney decided to escort the Amistad —under control of his crew—and all the persons aboard across Block Island Sound to Fort Trumbull at New London, Connecticut, where he sought judicial guidance.

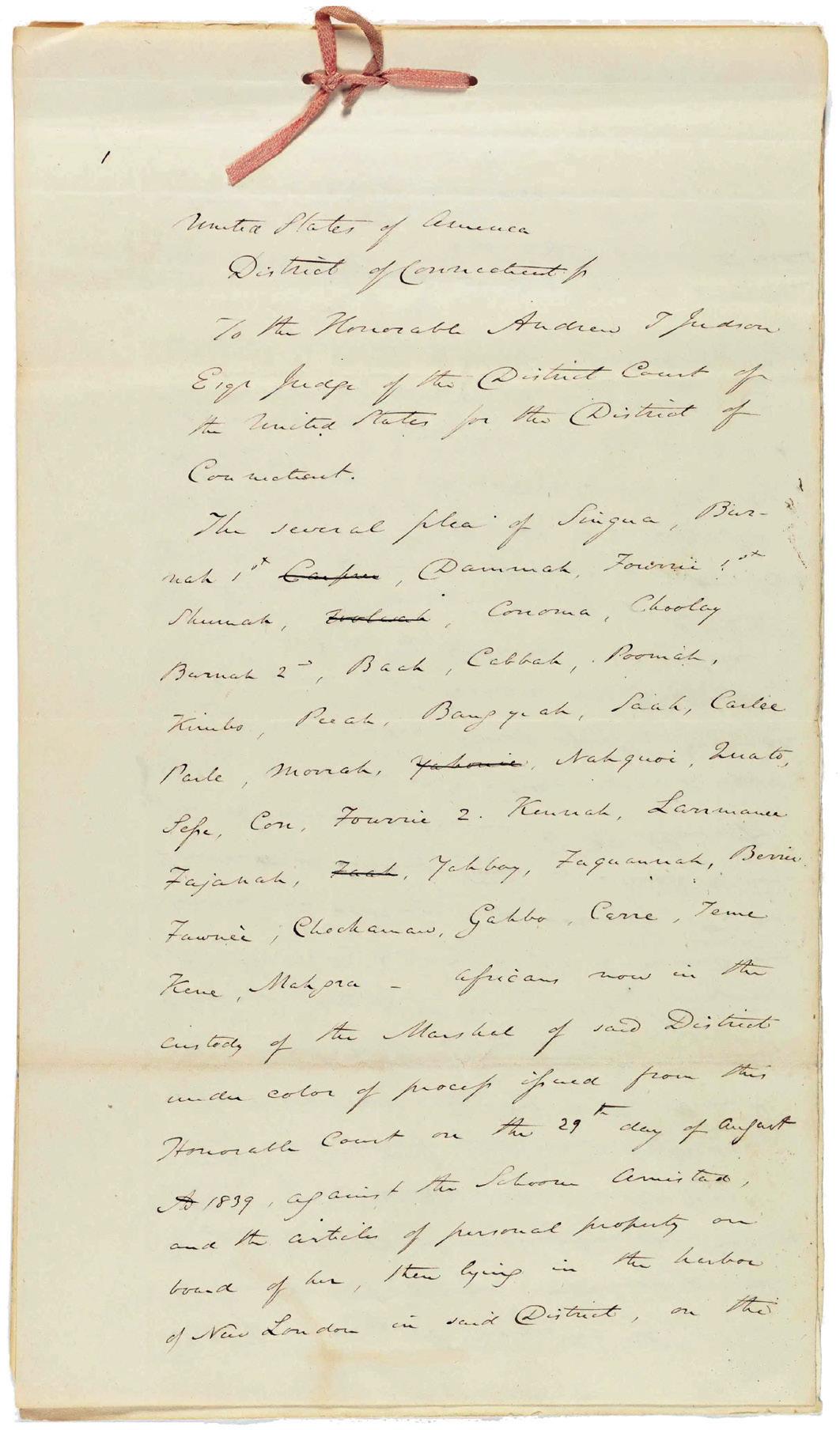

Justice A. T. Judson, Federal District Court judge, travelled from New Haven to hold an inquiry aboard the Washington on 29 August, after which he declined to grant the request of Montes and Ruiz to summarily return to them the vessel, its cargo, and those they claimed to be their rightfully owned slaves, but he also declined to decide that the Mende were “kidnapped Africans,” who had freed themselves from an illegal attempt to enslave them. Instead, the case venue was moved to the seat of the court in New Haven. ere, a more complete hearing was held, in which the Mende’s cause was aided by the translation services of James Covey, a seaman aboard the British brig Buzzard Covey had been born in Mende-Land, where he had been known as “Kaw We Li.” As a youth, he had been kidnapped and sold to slavers but had the good fortune to be rescued by a vessel from the British anti-slavery patrol. After receiving an education in a British-run school in Sierra Leone, Covey joined the Royal Navy. Serendipity placed the ship to which he was assigned in New Haven at the time of the trial.

Although Judson soon decided for the Mende, the Justice Department, at the direction of President Martin Van Buren, appealed his ruling. Van Buren did not want to roil relations with Spain, nor did he want to alienate voters from the southern slave states. After two long years of litigation, the Supreme Court nally a rmed Judson’s initial ruling and freed the long-su $ering litigants. With private donations supplementing government funding, a

vessel was chartered to repatriate them to Sierra Leone. is case settled the issue that all Africans arriving in the US after 1809 were presumed to be free; however, the pro ts involved would continue to drive the illegal trade until the Civil War and rati cation of the 13th Amendment on 6 December 1865 freed those still enslaved.

Daniel Laliberte served for more than thirty years in the US Coast Guard, during which time he participated in or provided intelligence support to the interdiction and repatriation of hundreds of undocumented Haitian migrants and the seizure of numerous drug smuggling vessels. He writes on topics involving the history of the US Revenue Marine and the US Coast Guard. A frequent contributor to Sea History, his work has also appeared in American History, Naval History, and the Nautical Research Journal.

In this court document, Sengbe Pieh stated that he and the others were “natives of Africa and were born free, ... and ought to be free, and not slaves...”

by John S. Sledge

By the spring of 1571, the Ottoman Empire had been jostling aggressively against the eastern borders of Christian Europe. With alarming speed, it had gobbled vast chunks of territory stretching from Anatolia through the Balkans into Hungary to the very gates of Vienna, and in the opposite direction through the Middle East and along the North African littoral all the way to Algiers.

!e fearsome agent of this stunning advance had been Sultan Suleiman the Magni cent, who died unexpectedly in 1566 while campaigning in Hungary. His son Selim II, derisively called “the sot,” preferred the pleasures of his harem to the rigors of the march. Nonetheless, he continued his father’s expansionist policies with the help of an experienced vizier and veteran military leaders. It was no secret that he coveted

Rome itself, “the Red Apple” as he called it, causing visions of a minaret rising over St. Peter’s Square to haunt Christian dreams. In the winter of 1570, Selim declared war on the Venetian Republic, whose holdings stretched far into the eastern Mediterranean Sea, and that summer landed his forces on the island of Cyprus.

!e Venetians, who preferred neutrality and trade, begged Pope Pius V for help. !ey were fortunate in their ponti . Ascetic to the point of conducting his o ces barefoot and in a coarse hair-shirt, Pius yearned to declare a new crusade. Venice’s plea meshed perfectly with this ambition. Energized, he hammered together a grand Christian alliance called the Holy League. !e signatories included the Papal States, Philip II’s Spain, the Republics of Venice and Genoa, the Knights of

Malta, and the duchies of Savoy, Parma, and Tuscany. Spain bore half the expense of raising a eet, Venice a third, and the Pope one-sixth. France declined to join due to antipathy towards Spain and an existing treaty with the Turks. Despite their confederation, the parties had di ering aims. Pope Pius coveted Jerusalem; Philip favored an attack on Tunis, whence erce corsairs continually harried Spanish shipping and coastal settlements; and the Venetian doge wanted Cyprus returned, and then peace. Neither the signatories nor knowledgeable observers placed much stock in the shaky alliance. Philip grumbled, “I do not believe it will do or achieve any good at all,” and the French ambassador to the Holy See quipped, “It will look very ne on paper, but ... we shall never see any results from it.”1 As for the Ottomans, they believed the Christians too quarrelsome to hold an alliance together for long.

Happily for the Holy League, Pius sagely selected Don John of Austria for its leader. Just 24 years old, he had already demonstrated signi cant diplomatic and military talents in southern Spain. He certainly looked the part of a hero. One contemporary described him as “handsome, alert, and courageous.” Born out of wedlock to Emperor Charles V and Barbara Blomberg, a burgher’s daughter and former singer, his father and his half-brother Philip did not hesitate to acknowledge him, though the latter instructed his courtiers to address the young noble as “Excellency” rather than “Highness.” !e pope minced no words when he addressed his favored captain: “Charles V gave you life. I will give you honor and greatness. Go and seek them out!”

!e League’s eet slowly assembled that summer at Messina, Sicily. Marcantonio Colonna, an Italian duke with Spanish service under his belt, led the

papal contingent; the hotheaded Sebastian Venier, 75, captained the Venetian complement, comprising half the eet’s ships, with the more eventempered Agostino Barbarigo as his second; Gian Andrea Doria, greatnephew of the famous Andrea Doria, led the Spanish vessels; and Álvaro de Bazán, a Spanish captain, the reserve. Due to ceremonial obligations along the way, Don John did not join them until 29 August. Locals thronged the shore when his agship Real nally hove into view. She made a marvelous show with her red-and-white striped sails, elaborately carved stern topped by three huge lanterns, and 24-foot-high blue banner depicting Christ on the cross. Surveying the united host, Colonna exclaimed, “ ! ank God we are all here, and that it will be seen what each of us is worth.”

If Pope Pius could have beheld the Christian eet, his heart doubtless

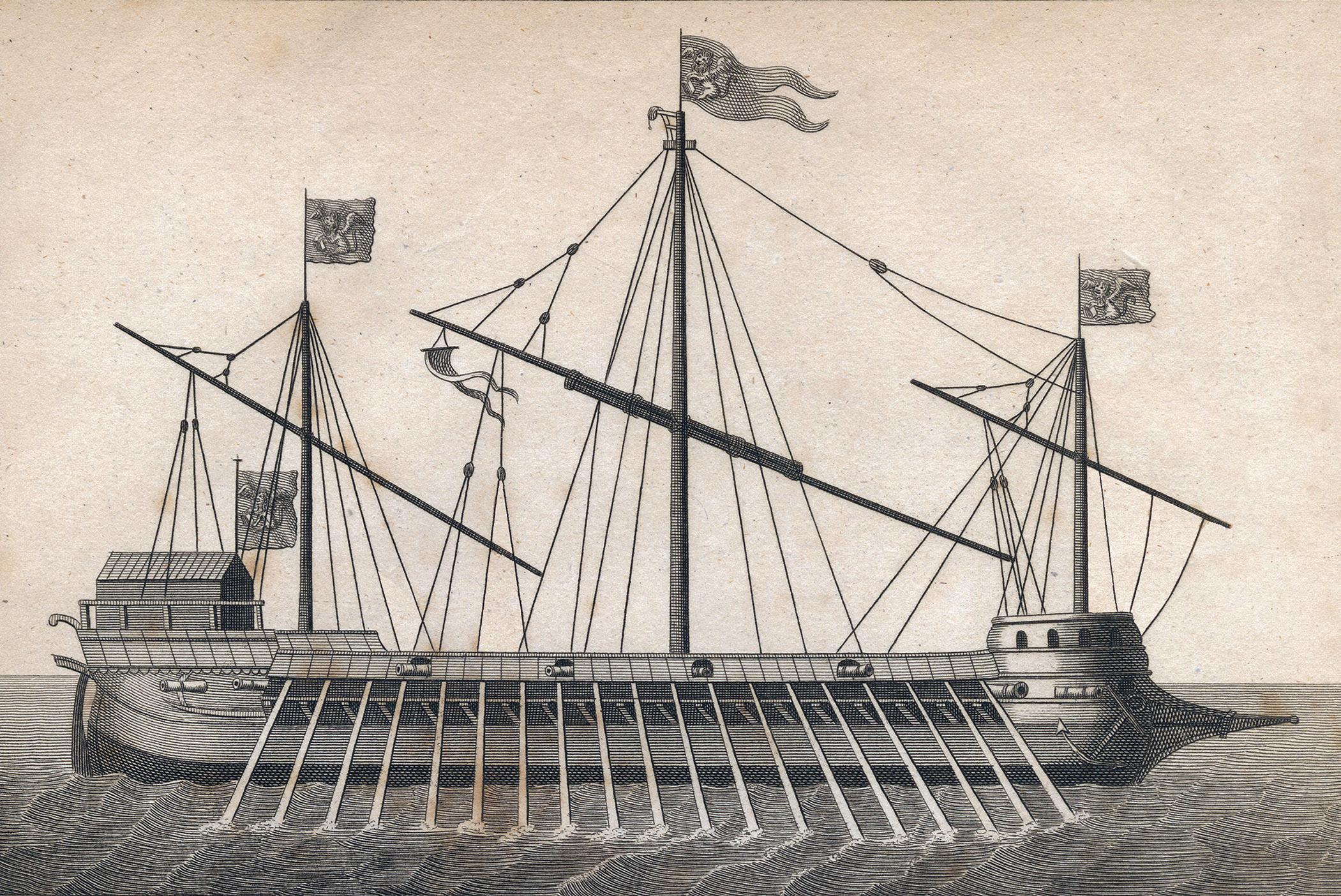

would have soared. Nearly 200 lowslung, oared galleys rode at anchor, along with six massive Venetian galleasses and dozens of smaller vessels.

!e typical 16th-century Mediterranean galley appeared little changed since antiquity. Powered by a combination of wind (three masts with lateen sails) and muscle (four men at each of the 24 oars per side) they displaced 200 tons and could do 12 knots with the

wind and four by the oar alone. Each ship featured a prominent ram and a ghting platform at the bow, where boarding parties could amass, a battery consisting of a powerful centerline bow gun capable of throwing a 60-pound shot, and a pair of smaller anking pieces. Swivel guns ranged along the sides. Nevertheless, it was the massive Venetian galleasses that provided the eet’s most devastating repower. Due to their bulk, smaller vessels had to tow them into ghting position. !ey carried 40 guns each—30- to 50-pounders, arranged within a forti ed roundhouse that allowed them to cover all directions.

Manning these ships were 1,500 Papal troops; 5,000 Venetians; 5,000 Germans; 8,000 Spaniards; 5,000 Italians; 4,000 gentlemen adventurers; and 40,000 sailors and rowers. Many of the latter were enslaved Muslims, but the Venetians took pride that their rowers were well-paid freemen. Given all these mouths to feed, the captains had to frequently dispatch shore parties to replenish food and water. Pius urged Don John to also mind the men’s spiritual nourishment and ensure that they “lived in virtuous Christian fashion in the galleys, not playing [gambling] or

swearing.” One of Don John’s lieutenants, more familiar with rough men, mumbled, “We will do what we can.”

!e Christian eet departed Messina on 16 September and arrived o Corfu 11 days later, but the soldiers appeared more likely to destroy each other than the Turks. When Don John sent Spanish troops to bolster the undermanned Venetian ships, brawls erupted and resulted in several deaths. Venier ew into a fury and hanged several Spaniards in retaliation. Whether the alliance could hold together long enough to even meet the foe looked doubtful.

Meanwhile, the Turks had not been idle. On 4 August, they captured the city of Famagusta on eastern Cyprus after a punishing siege. Enraged by their high casualties, they slaughtered the garrison and ayed its commander alive. To the west, their eet spent the summer raiding Greece and the Adriatic coast. On 8 August, after weeks of activity, the eet sheltered at Lepanto (modern Nafpaktos) where the Gulf of Patras narrows into the Gulf of Corinth, between the Peloponnese peninsula and the Greek mainland.

Securely anchored there, 49-yearold Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, Selim’s hand-picked Grand Admiral, pondered his next moves. Spies kept him apprised of the enemy’s activities. He knew he faced a severe test. He would have preferred to spend more time re tting, resting, and recruiting, but his orders were clear. “If the [Christian] eet appears,” the Sultan told him, “...confront the enemy and use all your courage and intelligence to overcome it.” Ali Pasha was certainly equal to the task. Of humble origins, he became a polished diplomat and skilled soldier,

Sketch of a typical Venetian galleass used at the Ba le of Lepanto. Note the round house on the bow, which held its heaviest guns.

fought at the Siege of Malta, and served as governor of Egypt. Everyone liked him; one admirer wrote that he was “brave and generous, of natural nobility, a lover of knowledge and the arts; he spoke well, he was a religious man and clean living.” Surprisingly humane for that brutal age, he considered the needs and feelings of everyone, no matter their station in life—including, to an extent, the galley slaves under his command.

Despite its hard usage, the Turkish eet still constituted a formidable force. !e Grand Admiral counted 208 galleys, 56 galliots (each with 16 pairs of oars, one mast, one gun) and a bevy of smaller vessels. His agship, Sultana, ew a bright-green swallowtail banner adorned with the name of Allah 28,900 times. His ships were lighter and faster than the enemy’s but woefully under gunned. Similarly, his troops, including 10,000 well-trained Janissaries, 5,000 Greeks, and contingents of Berbers, Syrians, and Egyptians, were lightly armed with scimitars and bows and wore insubstantial armor and turbans. Fifty thousand sailors and rowers kept the ships going, but many of the latter were enslaved Christians, apt to revolt at the earliest opportunity.

Like Don John, Ali Pasha relied on brave subordinates. Mehmet Sulik Pasha, an aggressive ghter nicknamed Sirocco after the powerful Mediterranean wind, was a former bey of Alexandria and a Malta veteran. Uluch Ali Pasha was an Italian captured by Barbary corsairs as a youth who had served as a galley slave until he converted to Islam and became a feared corsair himself. !e Grand Admiral knew he could expect complete candor from these men. When scouts reported the League’s eet at Corfu, he held a council of war. Uluch Ali cautioned: “ !e shortage of men is a reality. From this point of view, it’s best to remain in Lepanto harbor and ght only if the unbelievers

come to us.” Keenly aware of his eet’s weaknesses, Ali Pasha considered the matter, but mindful of the Sultan’s mandate, he decided to sail.

As Don John worked his way south along the Greek coast, he received two important pieces of news—the enemy was at Lepanto, and Famagusta had fallen. When details of the latter garrison’s slaughter and its commander’s ghastly torture raced through the eet, all rivalries vanished, replaced by a thirst for revenge. !e 7th of October was the fateful day. !e two eets sighted one

another that morning just o Scropha Point, within the narrow mouth of the Gulf of Patras. Nudged by a light breeze, the Ottoman ships glided west in a broad crescent formation that gradually straightened. Ali Pasha held the center with 87 galleys. On his right, close to the shore, Sirocco commanded 60 galleys, while Uluch Ali led 61 galleys and 32 galliots on the left.

!e Muslim eet presented an arresting spectacle. Bright banners and ags uttered from the masts, sunlight darted o polished weapons, and the

Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, the Turkish Grand Admiral depicted in all his finery before the ba le—and a erwards, his head on a pole. Though reluctant to give ba le, he confided to his trusted captains that he had no choice: “I continually receive threatening orders from Istanbul, I fear for my position and my life.”

sound of horns, cymbals, and drums rolled across the glittering water. !e Grand Admiral took up a recurve bow and addressed the enslaved rowers gazing up at him expectantly: “Friends, I expect you today to do your duty to me, in return for what I have done for you. If I win the battle, I promise you your liberty; if the day is yours, Allah has given it to you.”