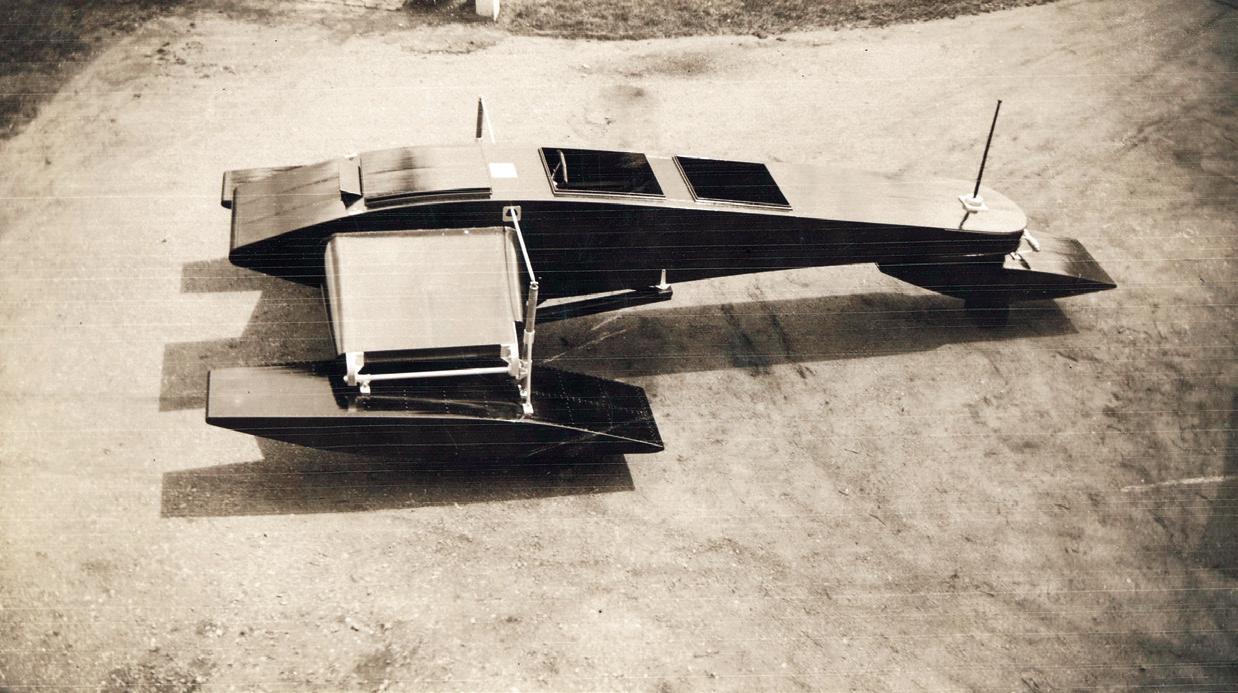

Artist/Captain Ants Lepson

SS Lexington Disaster

The Real McCoy

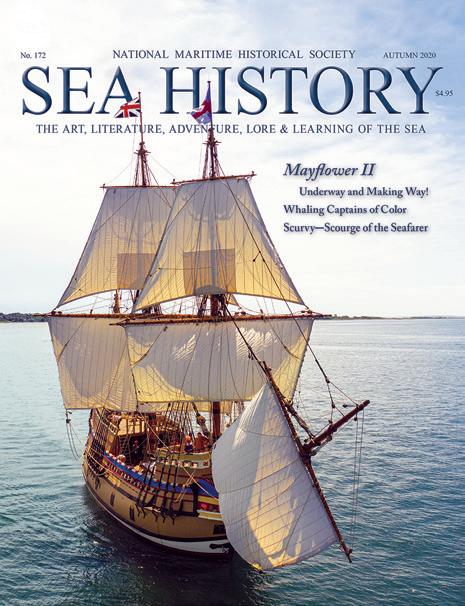

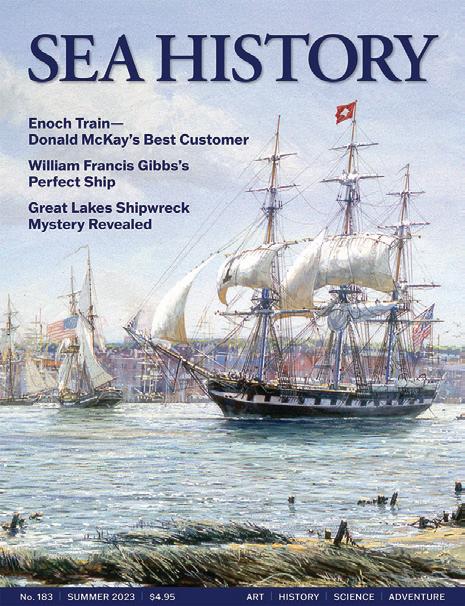

ART | HISTORY | SCIENCE | ADVENTURE N o . 184 | AUTUMN 2023 | $4 . 95

14k 18k

- Fish Float

n/a ------------- $2100.

Flemish

$1650.

$2100.

$2100.

$1100.

J

Strand Turk's

$4400.

$5900. K - Port & Starboard Hand Enameled Dangle Earrings ------------------------------------------------n/a ------------- $2250. • 18" Rope Pendant Chain $750. C A G B D J E H F K ® A.G.A. CORREA & SON JEWELRY DESIGN I PO Box 1 • 11 River Wind Lane, Edgecomb, Maine 04556 USA • 800.341.0788 customer.service@agacorrea.com • Please request our 52 page book of designs • M-F 10-5 ET • agacorrea.com Over 1000 more nautical jewelry designs at agacorrea.com ©All designs copyright A.G.A. Correa & Son 1969-2023 and handmade in the USA Jewelry shown actual size | Free shipping and insurance

A

Sphere with Aqua Chalcedony Pendant (U.S. Patent D678,110)

B -

Coil Pendant (matching earrings available) ----------------------------------------------

------------

C - Compass Rose with working compass Pendant -----------------------------------------------

------------ $2900. D - Correa/Chart Metalworks 3/4" Sailboat Pendant (additional designs available) -- $1850. ------------ $2500. E - Bowline Knot Earrings (please specify dangle or stud) ------------------------------------------

------------ $1500. F - Deck Prism Anchor Chain Dangle Earrings (matching pendant available) --------------n/a ------------- $2300. G - Monkey's Fist Stud Earrings (matching pendants available)--------------------------------- $1400. ------------ $1900. H - Original Working Shackle Earrings ------------------------------------------------------------------------ $950. ------------ $1300. I - Two Strand Turk's Head Ring with sleeve (additional designs available) ------------- $2300. ------------ $2900.

- Two

Head Bracelet --------------------------------------------------------------------------

------------

Portland Rockland Boothbay Harbor Bath Camden Bucksport Gloucester Bar Harbor Boston Atlantic Ocean Provincetown Newport Martha’s Vineyard MAINE NEW HAMPSHIRE MASSACHUSETTS RHODE ISLAND From the rich maritime heritage of whaling towns to quaint island villages and grand seaside mansions of the Gilded Age, our small, comfortable ships can take you to the heart of New England’s most treasured destinations. Be welcomed back to your home away from home, where you can delight in the warm camaraderie of fellow guests and crew. Small Ship Cruising Done Perfectly ® HARBOR HOPPING New England Cruises AmericanCruiseLines.com Call 866-229-3807 to request a FREE Cruise Guide

42 20 36 THE MARINERS’ MUSEUM AND PARK

US NAVY 2 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023 CONTENTS No. 184 | AUTUMN 2023

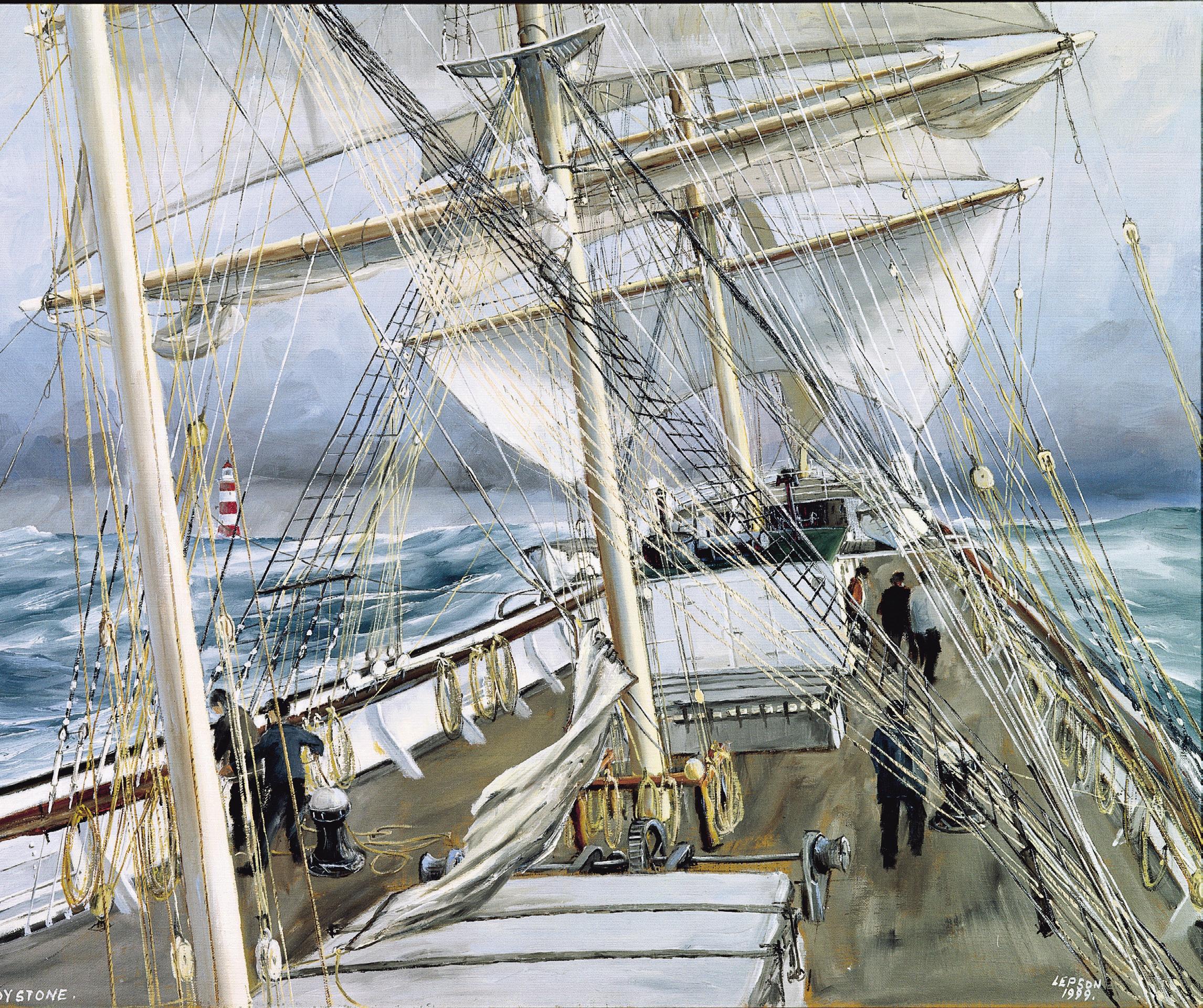

©ANTS LEPSON

28

14 NMHS 2023 Annual Awards Dinner

by Julia Church

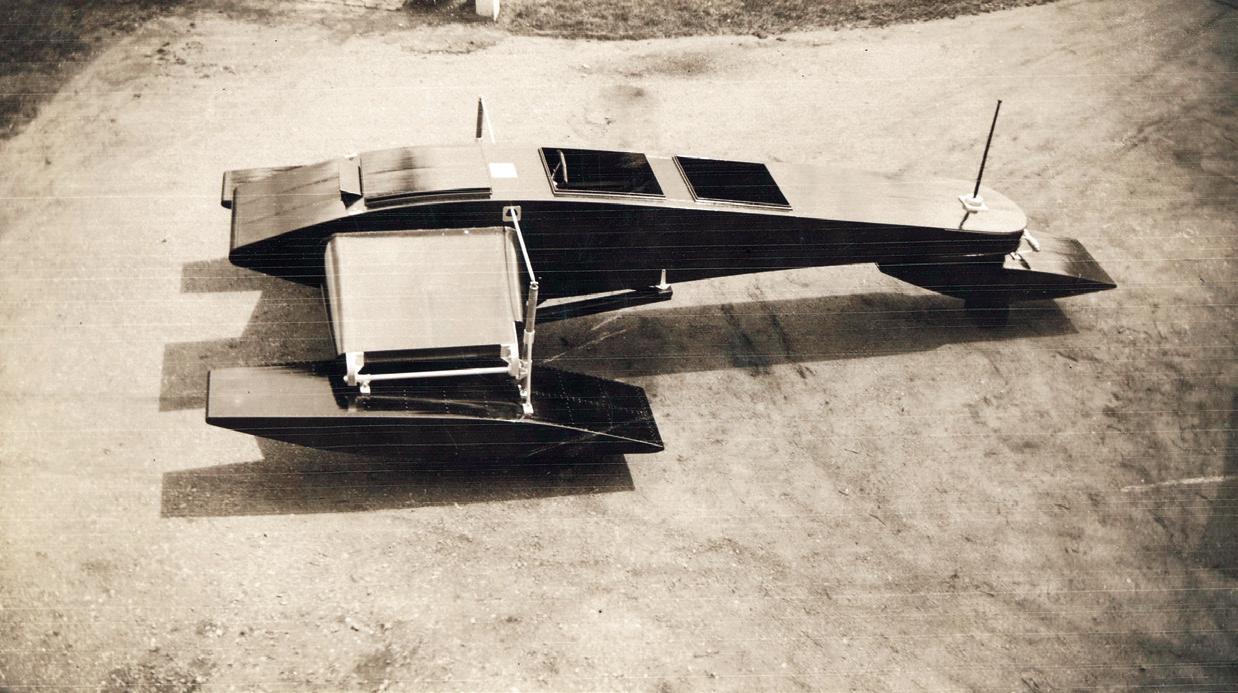

20 It’s the Real McCoy!

The Capture of Prohibition’s Most Notorious Rumrunner

by CAPT Daniel A. Laliberte, USCG (Ret.)

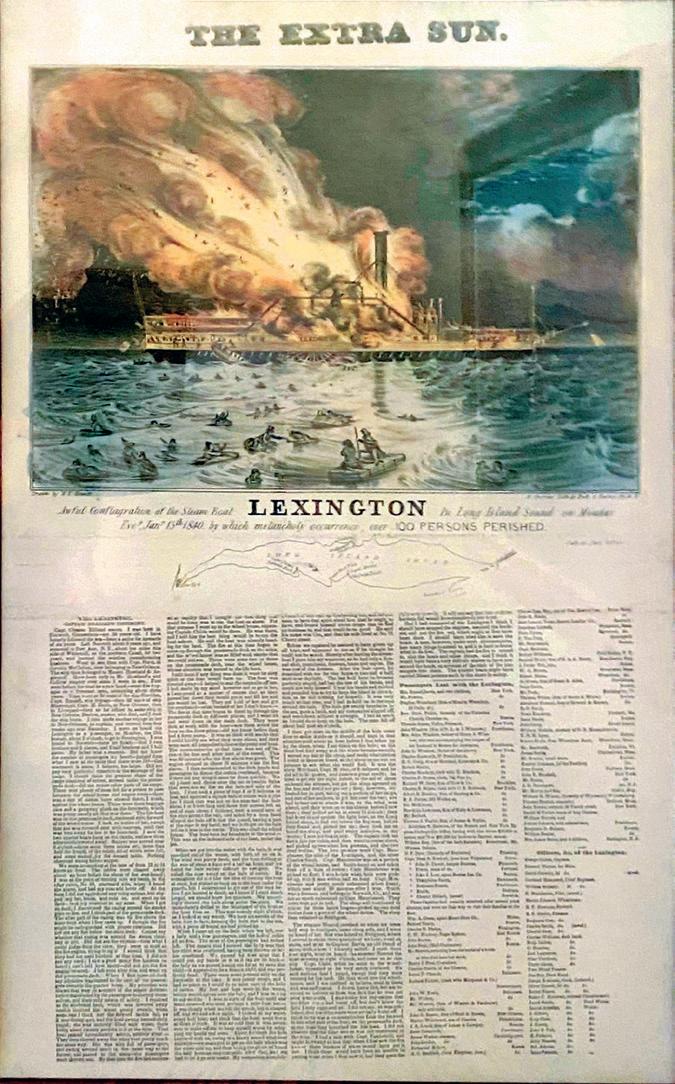

28 “Appalling Calamity”

The Lexington Disaster on Long Island Sound

by Bill Bleyer

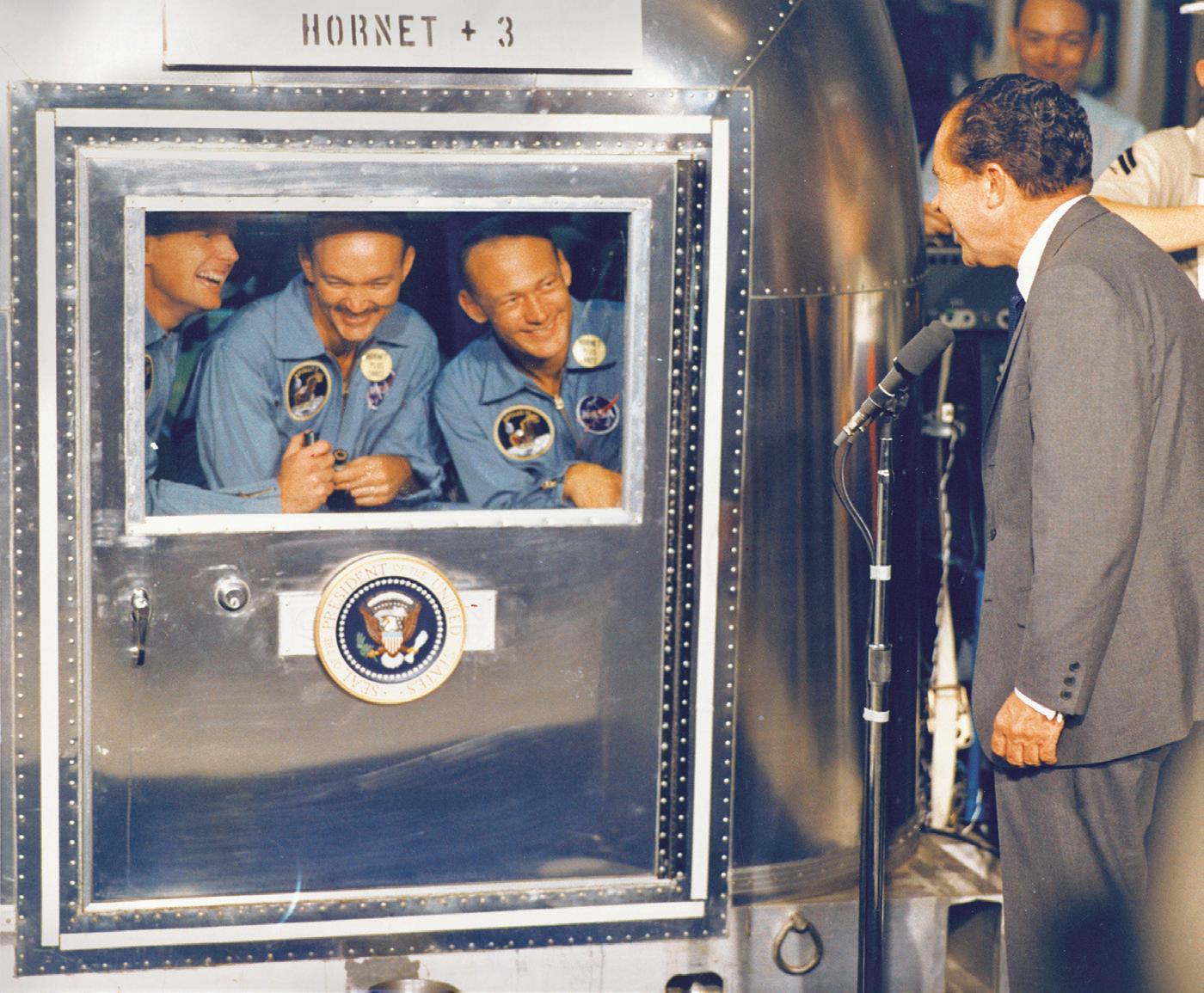

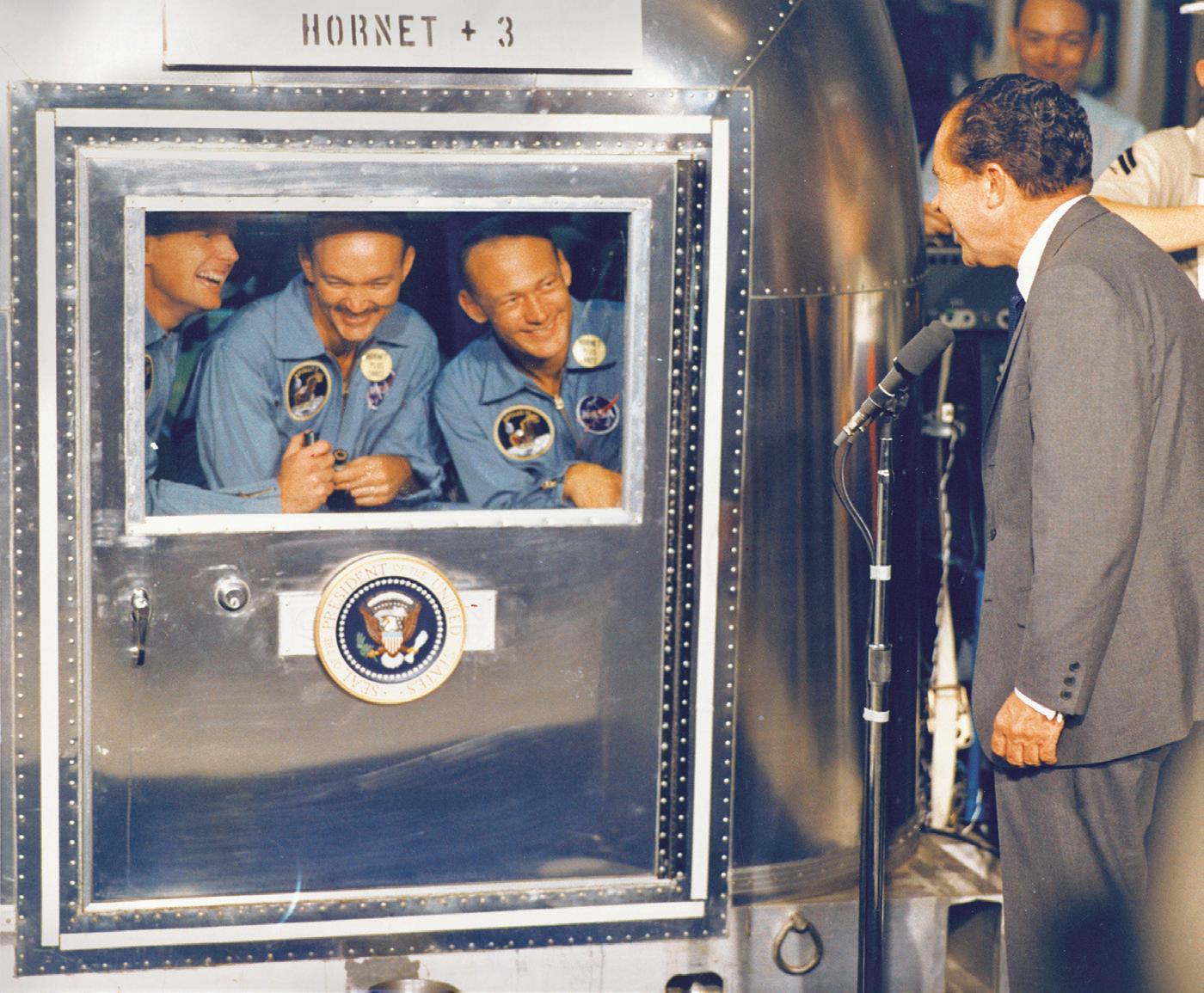

36 Happy Birthday USS Hornet!

by Chuck Myers

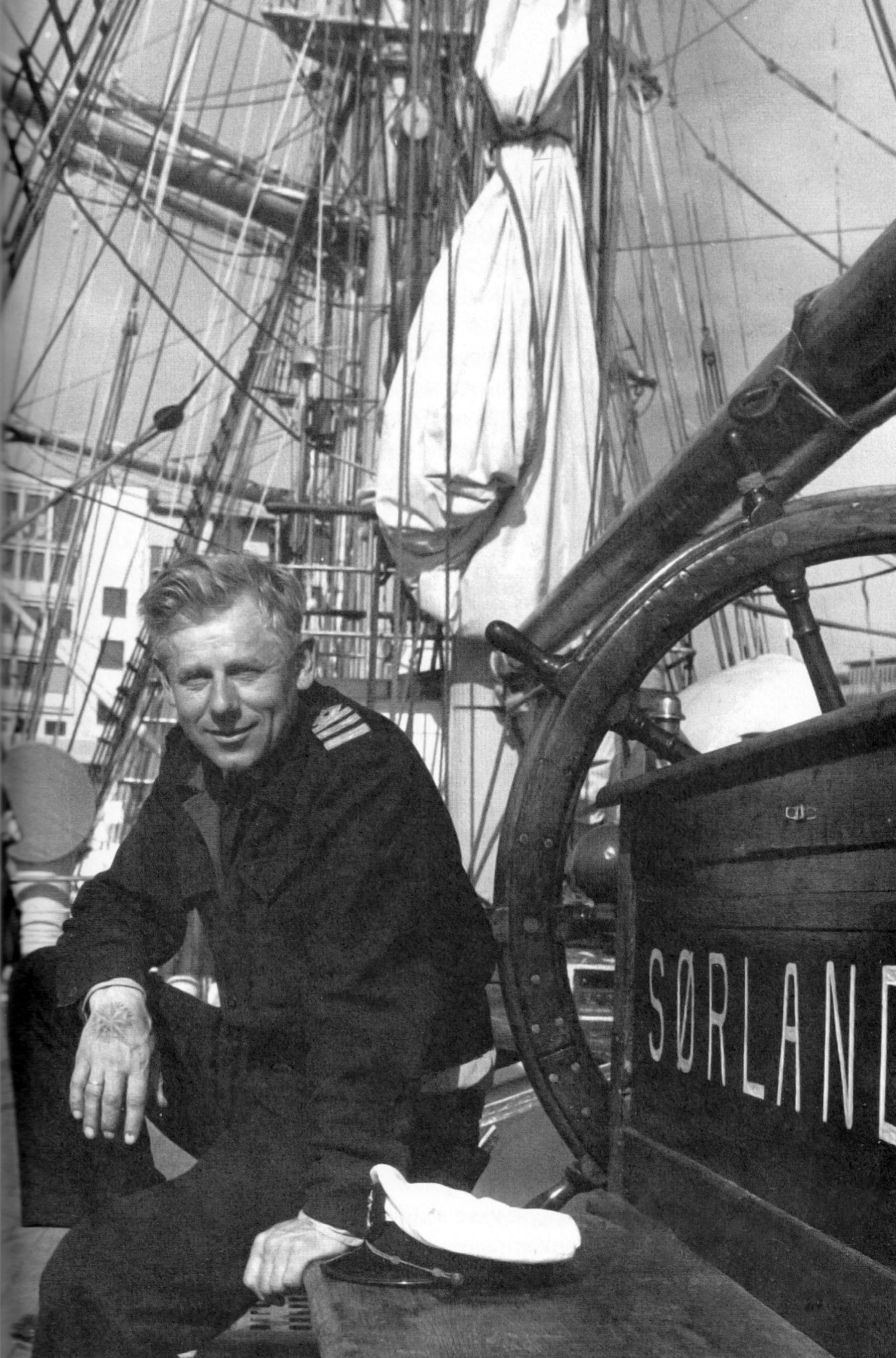

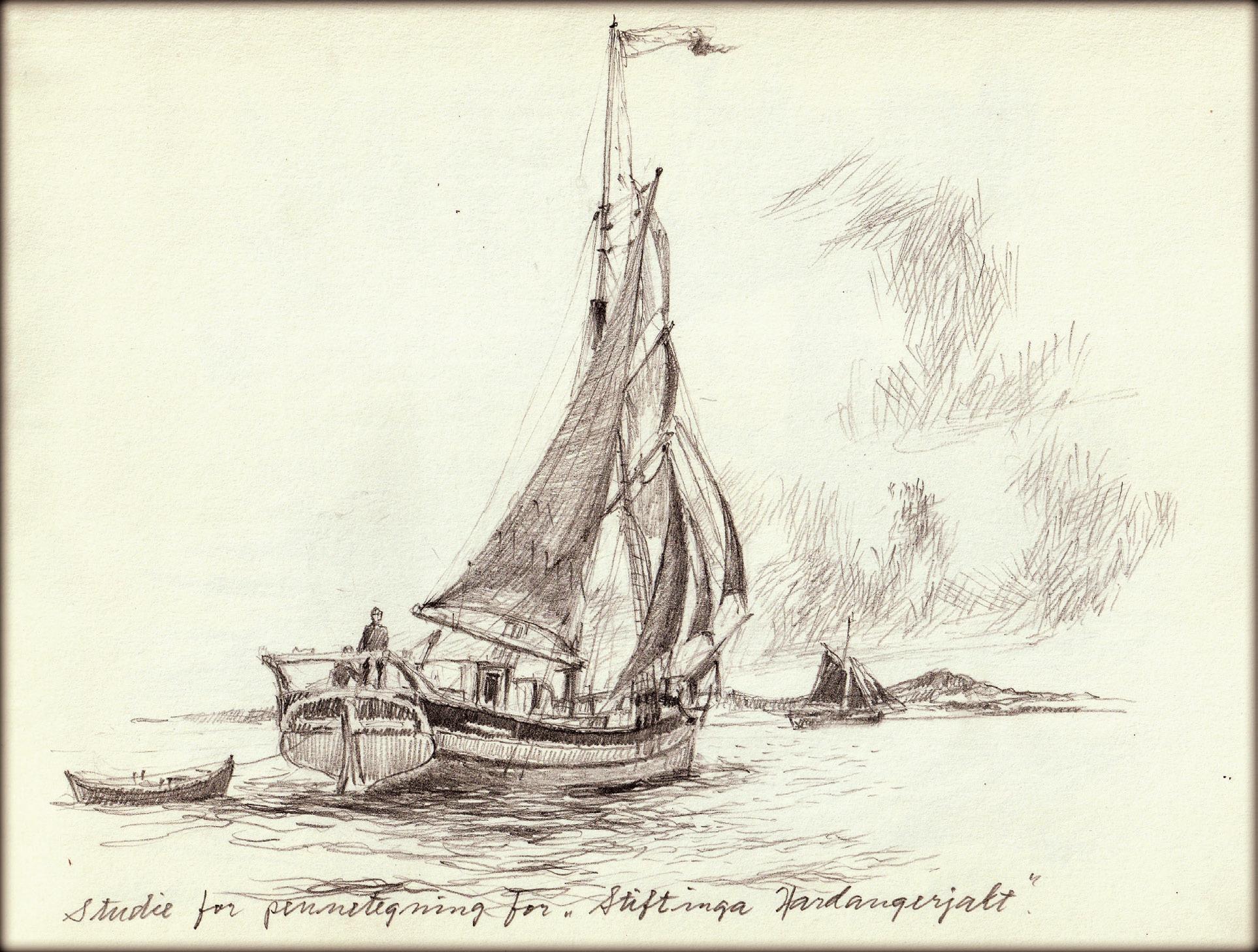

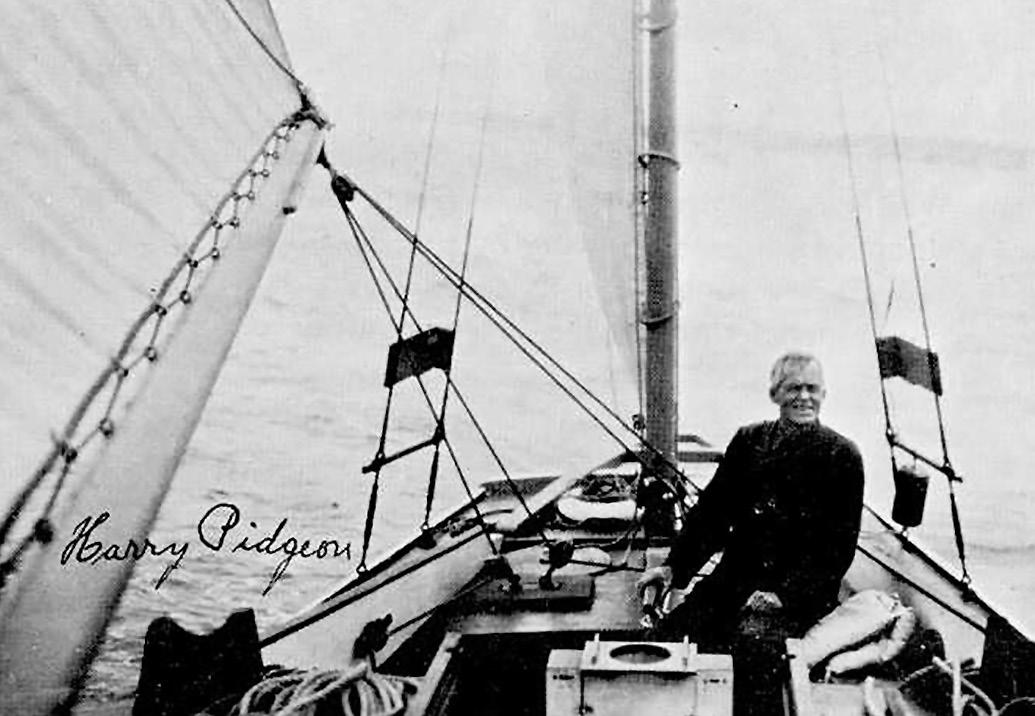

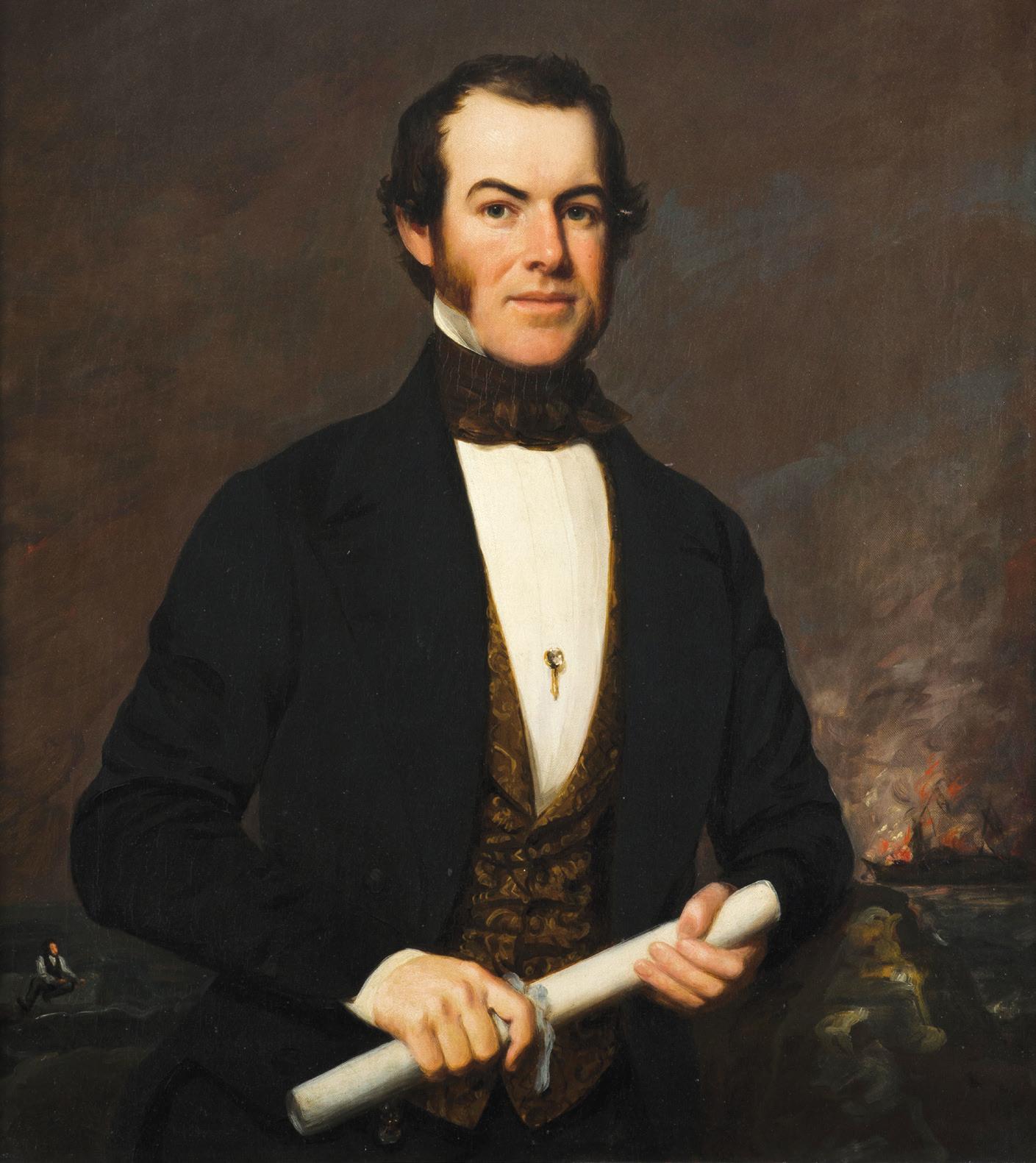

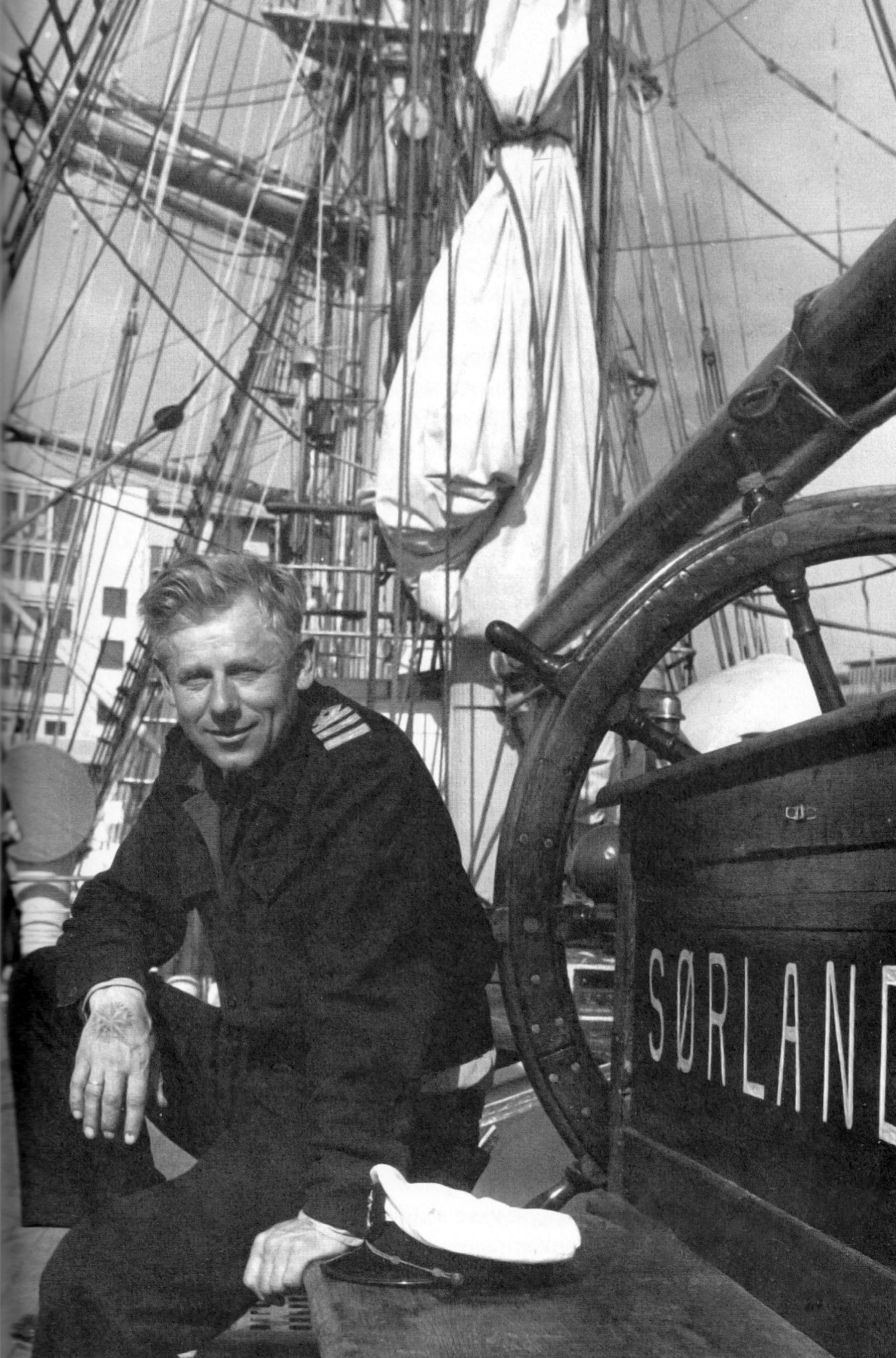

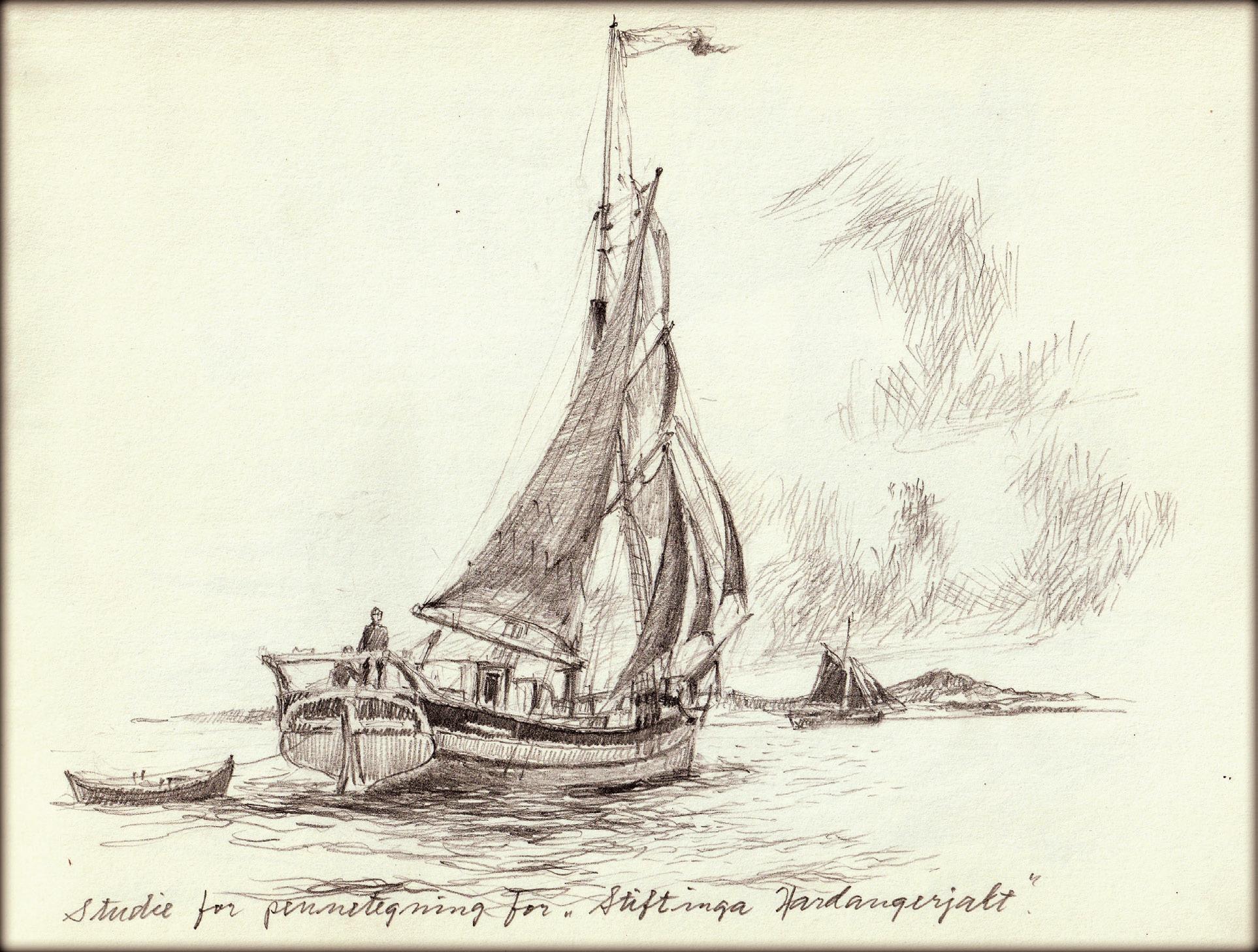

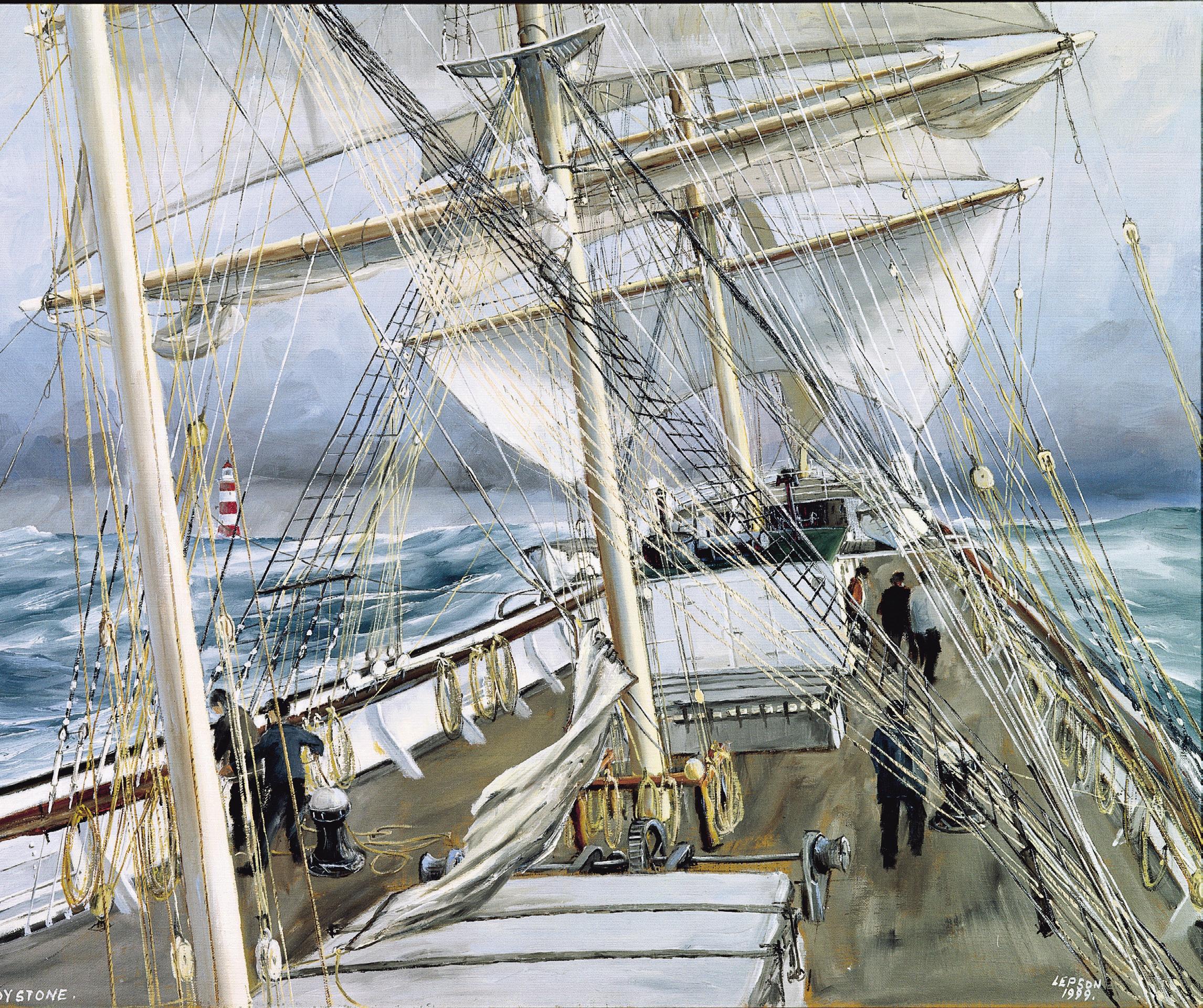

42 Master of Sail, Steam — and Oil!

Artist / Captain Ants Lepson

by Deirdre O’Regan

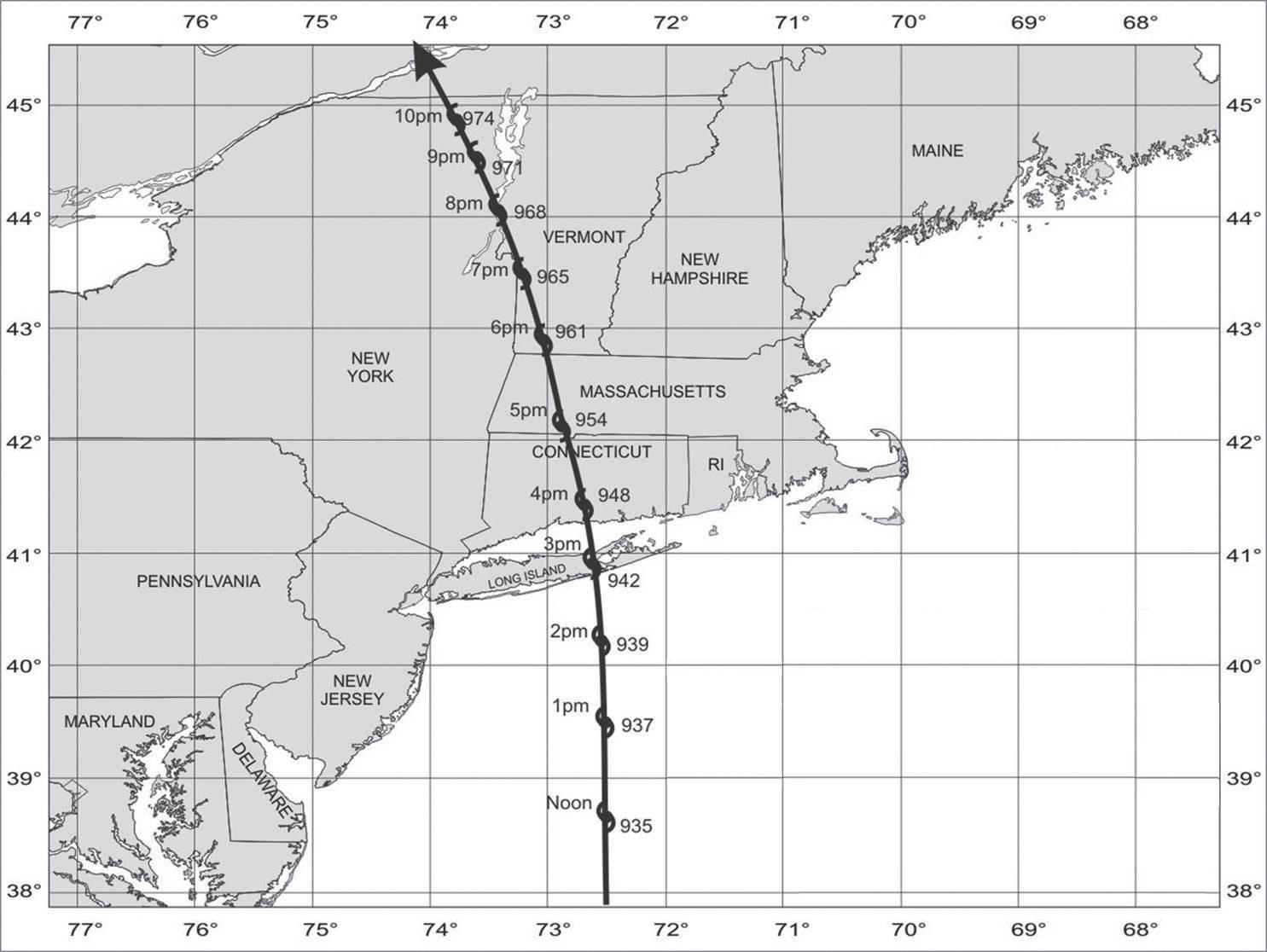

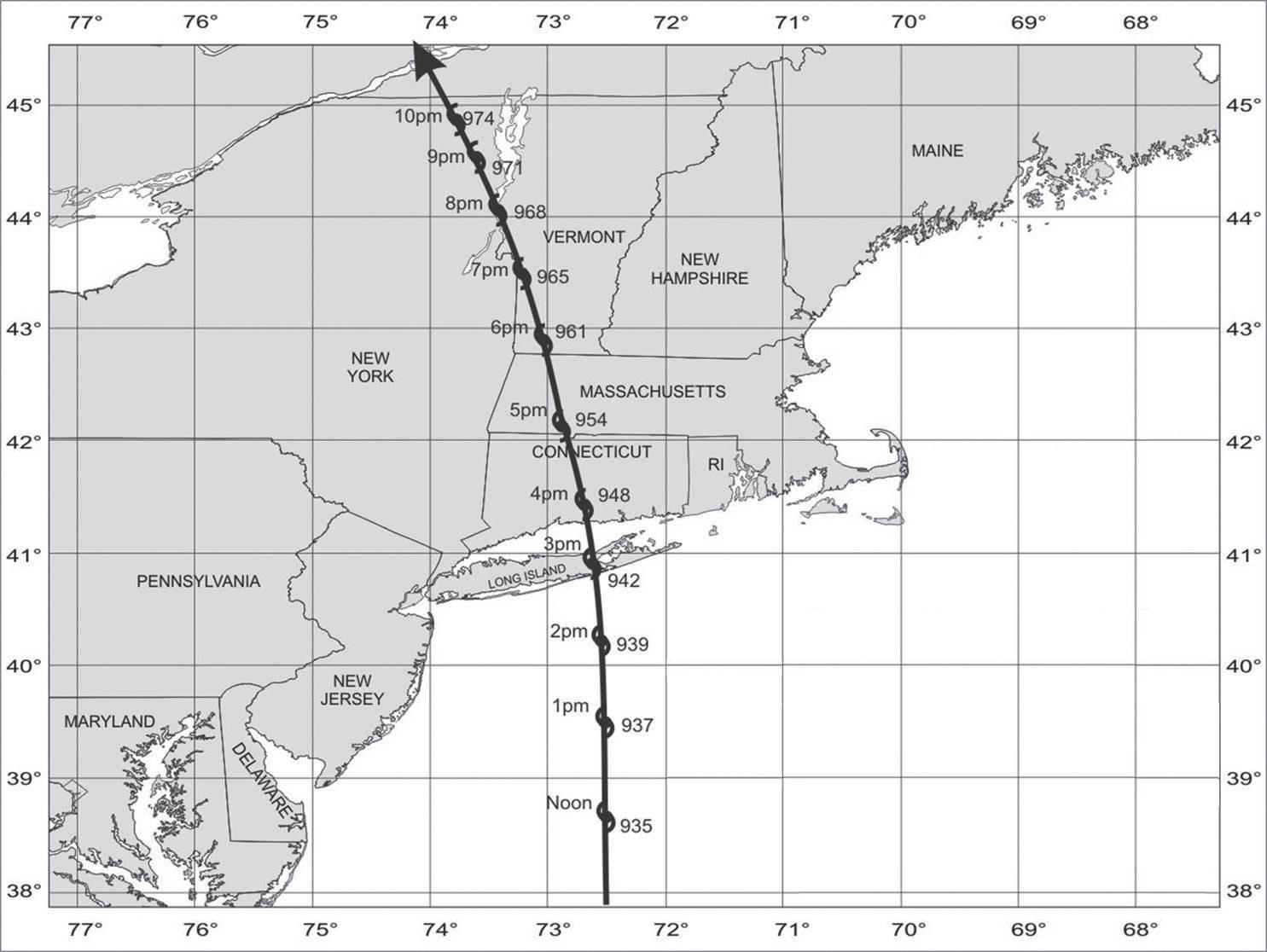

50 The 1938 Hurricane

The Coast Guard’s Last Ba le Before the War

by William H. Thiesen

4 Deck Log

6 Le ers

10 NMHS Cause in Motion

12 Fiddler’s Green

34 Curator’s Corner

56 Sea History for Kids

62 Ship Notes, Seaport & Museum News

71 Reviews

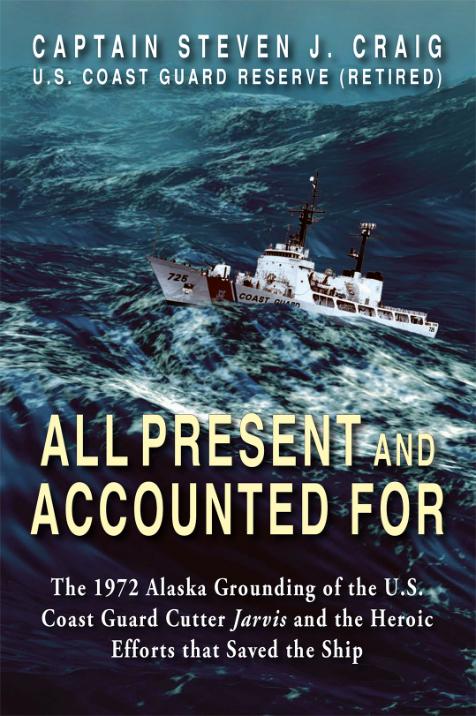

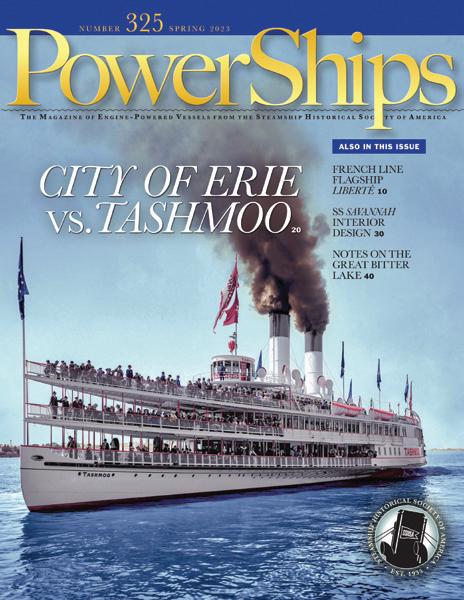

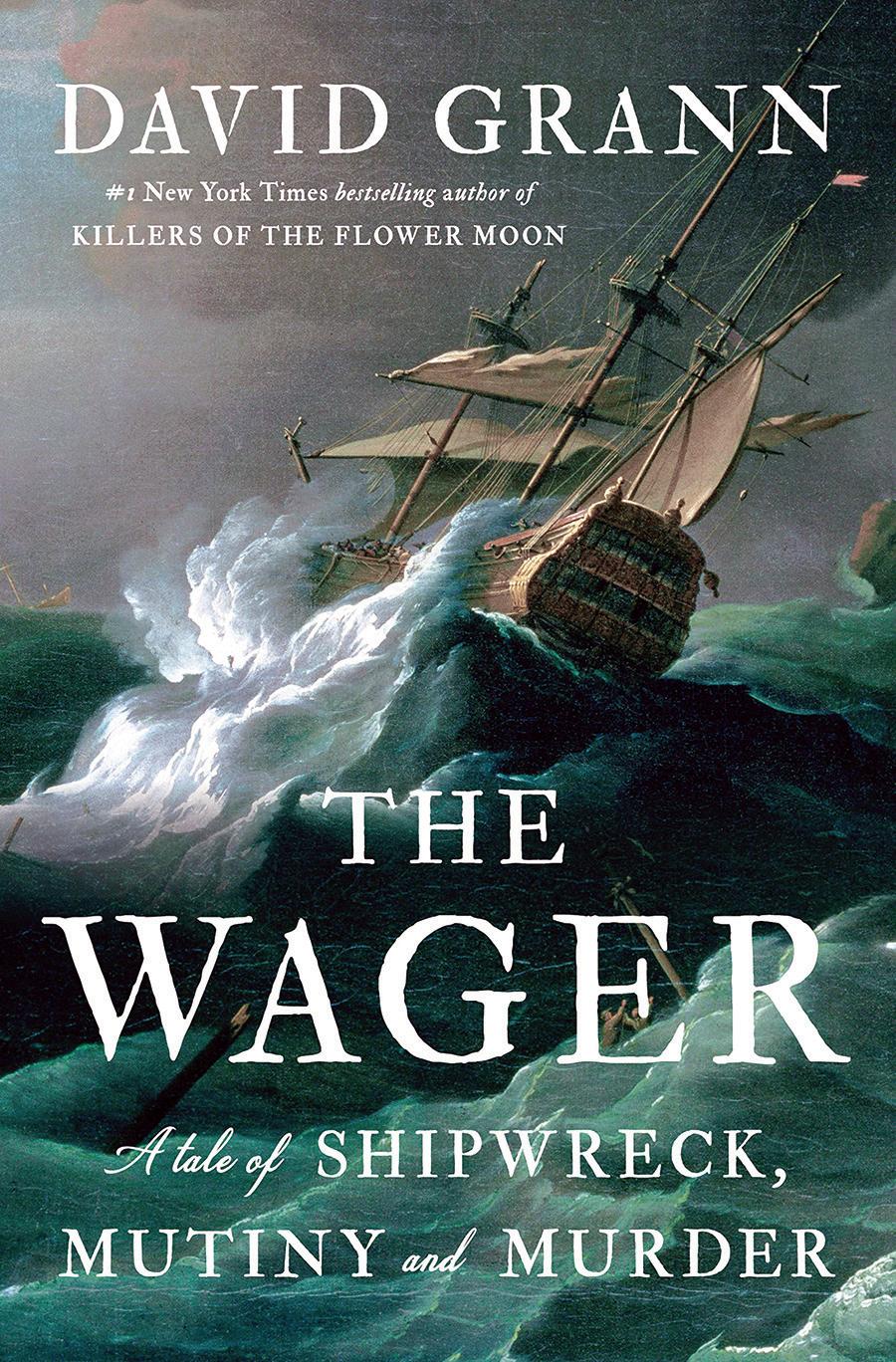

Cover: 40 South by Ants Lepson.

See article on pp. 42–48.

DEPARTMENTS

50 NEW YORK SUN, 1840

SeaHistory.org 3

ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS

Fill Our Sails!

NMHS 60th Anniversary Membership Campaign

e National Maritime Historical Society was founded 60 years ago as a membership organization, and because of the dedication of our members we have grown to be the voice of America’s maritime heritage, partnering with a myriad of other organizations along the way to preserve and promote our rich seafaring legacy. e Society has not only survived the ups and downs of the non-pro t world over the decades, but it has grown and ourished in what it seeks to accomplish and what it o ers to those who support our mission. While the reach of the organization has expanded, our membership numbers have not. We are asking you to help us grow our membership, and we are giving you an easy way to gift your friends a full membership at prices you won’t believe because, at this moment, growing our membership and getting our message and Sea History out to more people across the country is our most pressing concern. is 60th Anniversary Membership Campaign is underwritten by the NMHS Trustees.

Back in 1963 the price of membership was $10, and we are returning to this symbolic gure this year only for NEW members. BUT WAIT—there’s more! For that same $10, you can give a gift membership to up to 6 people (since we’re celebrating 6 decades of NMHS) … that’s just $10 total for all six! Our strength is in our numbers, and this campaign seeks to get our mission, Sea History, and our programming o ers out to as many people as we can. Over and over again, we nd that when people learn about NMHS and Sea History, they are excited about it and can’t believe they have never heard of us before. is is your chance to introduce NMHS membership to 6 friends, family members, neighbors, colleagues, fellow sailors, local businesses that have waiting rooms, o ces, libraries and boat clubs, colleagues, lovers of

history, the student down the street, the friends who go on cruise ships or the neighbors with a kayak on their car. is deal is for our 60th anniversary year only. At the stroke of midnight 31 December 2023, this campaign vanishes. e price is just $10, whether you send us 1, 2, 3, 4 ,5 or 6 new members, it’s a great opportunity.

Recently, we were poking around our archives and reread what NMHS President Emeritus Peter Stanford wrote in the second edition of Sea History, which was a yearly publication at the time.

Seaward! It’s said man is the only animal that laughs. There must be a kind of wisdom in that whether the observation is strictly true or not. But unmistakably, man is the only being around the planet who learns consciously from his past, and can extend his experience and his understanding across generations. He is a voyager in time. It is right that a nation born of endeavor by sea come back to its sea heritage for be er bearings. Let us come to the task with openness and laughter (that vanishing a ribute of man!) and with all the arts we’ve mastered in our voyaging through time. For this heritage lives only as it lives for us today, no other way.

Please take this opportunity to join us in strengthening NMHS—your organization—by getting the word out and building our membership. It will be the future support of new members that will keep our advocacy and resource and educational programs alive.

Let us join the NMHS Trustees on their 60th Anniversary Membership Campaign as a voyager back in time revisiting the prices of our rst year to build our membership. $10 for up to six gift memberships—seriously, it doesn’t get much better than that! (www.seahistory.org/anniversary.) As Peter Stanford stated, “It is right that a nation born of endeavor by sea come back to its sea heritage for better bearings,” and we ask your help as we do just this.

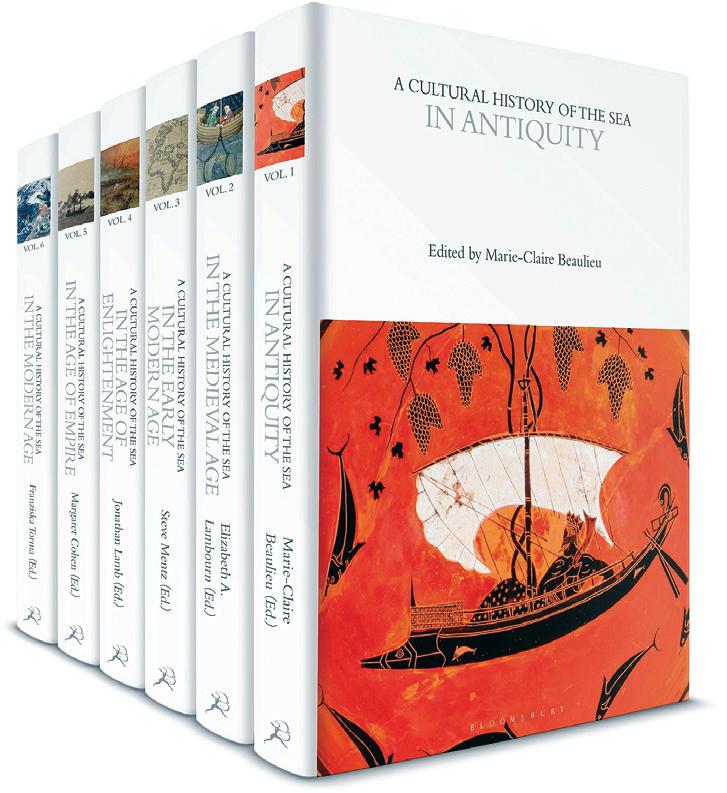

—Burchenal Green, NMHS President Emeritus

DECK LOG 4 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023

Love ships and the sea? We do too and we know there are lots more out there who would love to know about Sea History and the work the National Maritime Historical Society does to keep these stories coming. Strength is in numbers and we can’t do it alone, so please take this opportunity to share what we do with those in your lives who might like to join us!

6 Memberships for $10!

Get your membership online at www.seahistory.org/anniversary.

Thank you!

Sea History e-mail: seahistory@gmail.com

NMHS e-mail: nmhs@seahistory.org

Website: www.seahistory.org

Phone: 914 737-7878

Sea History is sent to all members of the National Maritime Historical Society. MEMBERSHIP IS WELCOME: Afterguard $10,000; Benefactor $5,000; Plankowner $2,500; Sponsor $1,000; Donor $500; Patron $250; Friend $100; Regular $45. Members outside the US, please add $20 for postage. Individual copies cost $4.95.

PETER ARON PUBLISHER’S CIRCLE: Guy E. C. Maitland, Ronald L. Oswald, William H. White

OFFICERS & TRUSTEES: Chairman , James A. Noone; Vice Chairman, Richardo R. Lopes; Vice Presidents: Deirdre E. O’Regan, Wendy Paggiotta; Treasurer, William H. White; Secretary, Capt. Je rey McAllister; Trustees: Charles B. Anderson; Walter R. Brown; CAPT Patrick Burns, USN (Ret.); CAPT Sally McElwreath Callo, USN (Ret.); William S. Dudley; David Fowler; Karen Helmerson; VADM Al Konetzni, USN (Ret.); K. Denise Rucker Krepp; Guy E. C. Maitland; Salvatore Mercogliano; Michael Morrow; Richard P. O’Leary; Ronald L. Oswald; Timothy J. Runyan; Richard Scarano; Jean Wort

CHAIRMEN EMERITI: Walter R. Brown, Alan G. Choate, Guy E. C. Maitland, Ronald L. Oswald; Howard Slotnick (1930–2020)

FOUNDER: Karl Kortum (1917–1996)

PRESIDENT EMERITUS: Burchenal Green, Peter Stanford (1927–2016)

OVERSEERS: Chairman, RADM David C. Brown, USMS (Ret.); RADM Joseph Callo, USN (Ret.); Christopher Culver; Richard du Moulin; Gary Jobson; Sir Robin Knox-Johnston; John Lehman; Capt. James J. McNamara; Philip J. Shapiro; H. C. Bowen Smith; Philip J. Webster; Roberta Weisbrod

NMHS ADVISORS: John Ewald, Steven Hyman, J. Russell Jinishian, Gunnar Lundeberg, Conrad Milster, William Muller, Nancy Richardson

SEA HISTORY EDITORIAL ADVISORY

BOARD: Chairman, Timothy Runyan; Norman Brouwer, Robert Browning, William Dudley, Lisa Egeli, Daniel Finamore, Kevin Foster, Cathy Green, John O. Jensen, Frederick Leiner, Joseph Meany, Salvatore Mercogliano, Carla Rahn Phillips, Walter Rybka, Quentin Snediker, William H. White

NMHS STAFF: Executive Director, Burchenal Green; Vice President of Operations, Wendy Paggiotta; Senior Sta Writer, Shelley Reid; Business Manager, Andrea Ryan; Manager of Educational Programs, Heather Purvis; Membership Coordinator, Marianne Pagliaro

SEA HISTORY: Editor, Deirdre E. O’Regan; Advertising Director, Wendy Paggiotta

Sea History is printed by e Lane Press, South Burlington, Vermont, USA.

SeaHistory.org 5

PHOTO BY BURCHENAL GREEN NATIONAL MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Liberty Ships: Merchant Vessels Serving the Military

I’ve been a member of NMHS for a number of years and enjoy Sea History immensely. I’m a retired Coast Guard o cer and I’ve had over 36 years of service in a number of assignments; one in particular was Captain of the Port (COTP), Boston. While reading the summer issue of the magazine, I encountered an oddity in the identi cation of a photograph in the article “Naval Architect William Francis Gibbs: A Dream Deferred Never Died.” On page 17, the photograph of the launch of the WWII Liberty Ship Zebulon B. Vance is identi ed with the designation “USS,” which was reserved for US Navy ships, not a merchant vessel. If memory serves me correctly, the Vance should have been identi ed as “SS” not “USS.” I may be wrong, but to my knowledge Liberty ships were not combatants or US Navy vessels. ank you for your consideration.

Neal M. Doherty, USCG (R et.) Green Harbor, Massachusetts

From the editor: How right you are! anks for the keen eye and alerting me to this error, which I assure you is a misidenti cation all my own and not from the author of the article.

Titan, Titanic, and Deep-Sea Ocean Travel

e implosion of the submersible Titan and the loss of its ve occupants dominated the news last June and captivated the world. In the days after Titan went missing, still not knowing its fate, a massive surface and underwater search took place to nd the missing craft. While many suspected that the unconventional submersible and its owner may have met their end, there was hope that the craft may have lost power and was stranded on the bottom. e arrival of the Odysseus 6K, Pelagic Research Services’ remotely operated vehicle (ROV), con rmed the disaster, and questions were immediately asked of all those concerned: how could this have happened?

e irony of this event is that Titan was diving on one of the most famous shipwrecks in history, RMS Titanic. It was the loss of Titanic in 1912 that led to the passage of the Safety of Life at Sea Convention (SOLAS) that led to many of the safety measures that exist today in modern shipping. Today, all

(le )

ships, regardless of their country of registry, must meet certain international standards in not just safety, but also pollution, ship construction, and management. All nations, through port state authority, can inspect ships and ensure that they meet these standards, or hold vessels in port and require them to correct any discrepancy.

Titan was built in the United States to a much di erent design than any previous deep-sea submersible. In lieu of a single steel or titanium sphere pressure vessel, it had titanium caps with a carbon ber tubular hull to accommodate up to ve personnel. Most vessels built in the United States would have to obtain a Certi cate of Inspection (COI) from the US Coast Guard to carry passengers, but it does not appear that Titan ever received one. While it had made successful dives to Titanic in 2021 and 2022, its rst dive of 2023 met with disaster.

Titan fell into a loophole in that it was not a traditional vessel that sailed from port to port; instead, it was a submersible that was carried out to a dive

LETTERS We Welcome Your Feedback! Email correspondence to seahistory@gmail.com. 6 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023

The 10,000-ton SS Zebulon B. Vance was built at the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company and was launched on 6 December 1941, the first of 90 sister ships to be built for the Maritime Commission. Liberty ships were manned by civilian merchant mariners.

US OFFICE OF EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT PHOTOGRAPH, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.

OceanGate’s deep-sea submersible, Titan

OCEANGATE

site aboard a mother ship and apparently did not fall under that standard. Making matters more confusing, OceanGate, the company created by Stockton Rush, had its headquarters based in Everett, Washington, but OceanGate Expeditions, which ran the Titan expeditions to the Titanic wreck site, was registered in the Bahamas. Titan itself was not registered as a vessel with the United States nor with any other country. As part of traditional ship operations, vessels beyond their registry would have a ship society, such as the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS), Lloyds, or DNV, classify a vessel to provide third-party oversight, particularly for purposes of insurance.

OceanGate had one submersible classi ed with ABS, but Stockton Rush believed it would take the organizations too long to develop the needed procedures and standards for his new design. So, Titan was taken out of St. John’s, Newfoundland, aboard a Canadianagged support vessel, bound for international waters to visit the Titanic wreck site, more than two miles below the surface. It appears that no nation or authority had jurisdictional oversight over Titan as it made its descent that fateful day.

e US National Transportation Board and similar organizations from Canada, Great Britain, and France all initiated investigations into the loss of the submersible. e massive search, coordinated by the US Coast Guard in conjunction with the Canadian Coast Guard, along with military and private assets, was mobilized because OceanGate failed to have a backup plan, should something go wrong with Titan.

e question remains: since it operated outside the territorial waters of any nation, did any of these nations or organizations have oversight over Titan?

Some have prophesied the end of underwater dives on Titanic. In 1960, the bathyscaphe Trieste dived to the

bottom of Challenger Deep in the Marianas Trench with Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard and US Navy lieutenant Don Walsh on board. e loss of Titan and the ve people aboard is tragic, but it is the rst loss of a submersible at depth and resulted in the rst fatalities in sixty-three years of deep-sea manned exploration.1 When Titanic went to the bottom of the At-

lantic early on 15 April 1912, it did not mark the end of transAtlantic crossings. It is unlikely that Titan will end deepsea submergence diving; however, there need to be changes in how submersibles are regulated and operated when embarking passengers. Perhaps Titanic is not yet done in uencing shipping.

Salvatore R. M ercogliano, P hD Fuquay-Varina, North Carolina

Tired of nautical reproductions?

Martifacts has only authentic marine collectibles rescued from scrapped ships: navigation lamps, sextants, clocks, bells, barometers, charts, flags, binnacles, telegraphs, portholes, US Navy dinnerware and flatware, and more.

MARTIFACTS, INC.

P. O. Box 350190

Jacksonville , FL 32235-0190

Phone/Fax: (904) 645-0150

www martifacts com email: martifacts@aol.com

www.modelshipsbyrayguinta.com

e-mail: raymondguinta@aol.com

SeaHistory.org 7 J.P.URANKERWOODCARVER WWW.JPUWOODCARVER.COM THETRADITION OFHANDCARVED EAGLES CONTINUES TODAY (508) 939-1447 ★ ★ ★ ★ Model Ships by Ray Guinta Experienced ship model maker who has been commissioned by the National Maritime Historical Society and the USS Intrepid Museum in NYC. P.O. Box 74

Leonia, NJ 07605 201-461-5729

USS KIDD Open daily on the Mississippi River in Downtown Baton Rouge www.usskidd.com • 225 342 1942 • info@usskidd.com

1 With the exception of an accident that occurred in 1969, when aquanaut Berry Cannon died of asphyxiation, while making a repair to the exterior of SeaLab III at a depth of 610 feet.

Ballad of the Old Black Pearl Nicolas Hardisty’s excellent article about Barclay Warburton’s brigantine Black Pearl reminded me of a song about the ship. In 1970s Newport, Jim McGrath and the Reprobates often sang the “ e Ballad of the Old Black Pearl ” at the congenial bar One Pelham East on Newport’s waterfront. It remains a great song of the sea, and it’s available to hear on YouTube at www.youtube. com/watch?v=shdI_wTEMac (or search YouTube for “Ballad of the Old Black Pearl Jim McGrath”).

Bill G alvani Bainbridge Island, Washington

Gazela in Philadelphia

e photo on page 11 of the summer issue of Sea History shows Peter Stanford and John Stobart sitting in front of barquentine Gazela (1883), but the location as indicated in the caption is incorrect.

e photo was taken at Penns Landing in Philadelphia, with the Ben Franklin Bridge, visible in the background, to con rm this as the location.

L isa Kolibabek

East Haddam, Connecticut

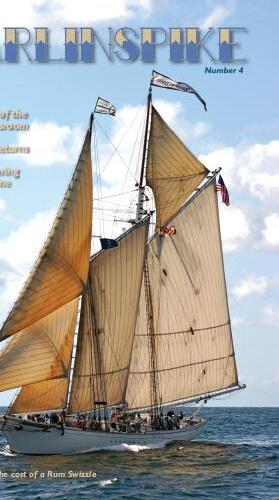

8 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023 The quarterly magazine devoted to traditional sailing vessels, sailors, and sail training! One year $29 * Two years $53 To subscribe, visit our website, call (978) 594-6510, or send a check to MARLINSPIKE 98 Washington Square #1, Salem MA 01970

A New England Tradition For 60 Years Open 7 days a week - 860.889.3793 25 Cottrell St. • 2 Holmes St. MysticKnotwork.com Traditional Knotwork Made in Downtown Mystic CT Nautical Ornaments MAINE WINDJAMMER CRUISES ® SELECT YOUR A DVENTURE ! Choose from 4 Traditional Sailing Vessels SWIFT Luxury Windjammer Sailing M ay – October Weekend 7-Day Cruises $755 and up Free 16-page Brochure 1-800-736-7981 NEW! OCEANGATE EXPEDITIONS THE FIREBOAT MCKEAN PRESERVATION PROJECT FIREBOATMCKEAN.ORG STONY POINT - NEW YORK

Mystic Knotwork

NMHS FILE PHOTO

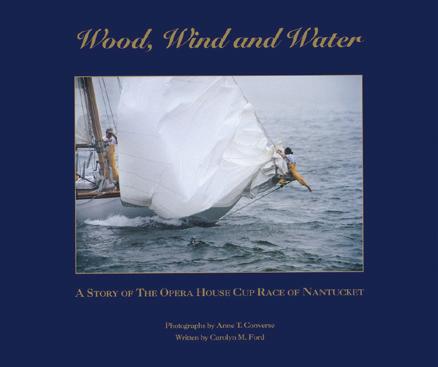

Neith, 1996, Cover photograph Wood, Wind and Water

A Story of the Opera House Cup Race of Nantucket

Photographs by Anne T. Converse

Text by Carolyn M. Ford

Live vicariously through the pictures and tales of classic wooden yacht owners who lovingly restore and race these gems of the sea.

“An outstanding presentation deserves ongoing recommendation for both art and nautical collections.”

10”x12” Hardbound book; 132 pages, 85 full page color photographs; Price $45.00

For more information contact: Anne T. Converse Phone: 508-728-6210 anne@annetconverse.com www.annetconverse.com

SeaHistory.org 9

Anne T. Converse Photography

The National Maritime Historical Society—Underway and Making Way!

e National Maritime Historical Society has been working to preserve and promote our maritime heritage for 60 years. We do that in myriad ways, where the need is great and when other maritime organizations are looking for support for their good works. is summer we were delighted to sponsor a fabulous concert for the Navy Memorial, and were honored to receive the National Lighthouse Museum’s National Maritime History Preservation Award. is fall we will host naval history scholars from around the world, and next spring we’ll dedicate our impressive maritime library. We are only able to do our work with the support of our membership. We invite you to join us, remembering that your membership starts with me and ends with ship

The United States Navy Memorial

e United States Navy Memorial is a magni cent tribute to the men and women who served in the US Navy. Its mission is to “honor, recognize, and celebrate the men and women of the Sea Services…and to inform the public about their service.” e organization is active throughout the year with events, concerts, and programs for visitors and Navy personnel. Check the Memorial website (www.navymemorial.org ) for scheduled events during your next trip to Washington, or just stop in to view the interesting exhibits. NMHS was honored to sponsor an evening concert at the memorial this June, hosted by four-star Admiral James Frank Caldwell Jr., Director, Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program, and to meet so many of the Navy personnel who work to keep our submarine and nuclear forces ready.

President and CEO of the Navy Memorial RADM Frank Thorp IV, USN (Ret.) (le ), thanks the Society for sponsoring the concert. Shown here (–r) Thorp; NMHS trustee CAPT Patrick Burns, USN (Ret.); Burchenal Green; CAPT Todd Creekman, USN (Ret.); trustee K. Denise Rucker Krepp; and NMHS chair CAPT Jim Noone, USN, (Ret.).

The National Lighthouse Museum

e National Lighthouse Museum (NLM) honored NMHS on Friday, 4 August, with its National Maritime History Preservation Award. e award was presented to NMHS chairman Jim Noone by Captain Joseph Ahlstrom, NLM chair, to honor the Society’s 60 years of work in historic preservation, education, and advocacy. e Society has worked closely with the museum and the many dedicated lighthouse preservation projects across the country, particularly in organizing sessions during the National Maritime Alliance’s Maritime Heritage conferences.

McMullen Naval History Symposium

NMHS will sponsor a luncheon on 22 September 2023 during the biennial McMullen Naval History Symposium. Dr. David Winkler and CAPT Jim Noone, USN (Ret.), will welcome our guests and host the event. is year’s symposium will be held in Annapolis, Maryland, on 21–22 September 2023; it has been described as the “largest regular meeting of naval historians in the world” and as the US Navy’s “single most important interaction with an academic historical audience.” We are grateful to Benjamin “BJ” Armstrong, Commander, USN, and 2023 Chair of the Symposium.

Ronald L. Oswald Maritime Library

Libraries have been the collective repository of the culture of every civilization. NMHS has been collecting maritime books for decades from members and outside donors from around the country. In 2018 we were awarded a $50,000 National Maritime Heritage Grant to digitize our library catalog, archives, and collections, and make them accessible to the public online, at our headquarters, and through the Westchester Library System and Hendrick Hudson Free Library. e 5,000-volume library catalog can be viewed at www.seahistory.org/education/library e library is named for our

NMHS CAUSE IN MOTION 10 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023

PHOTO BY A. E. LANDES

National Lighthouse Museum Executive Director Linda Dianto and Chairman Captain Joseph Ahlstrom present the National History Preservation Award to NMHS chairman Jim Noone and trustees Karen Helmerson and Rick Scarano.

PHOTO BY BURCHENAL GREEN

chairman emeritus Ronald L. Oswald, for his long and dedicated service. Ron is a voracious reader and amateur historian: “My life has been shaped by reading, by the worlds and knowledge introduced to me by books. Even my adventure with NMHS started from reading Sea History in a library. I know how important libraries are, and I cannot think of a more meaningful honor to me to have this in my name,” he remarked.

Please join us for a reception in spring 2024 (date TBD) for the o cial dedication of the Ronald L. Oswald Maritime Library at our headquarters at 1000 N. Division St., #4, Peekskill, NY.

Sail 250 New York

A spectacular celebration of America’s 250th birthday will take place in New York Harbor on 4 July 2026, continuing the extraordinary maritime tradition of gathering the world’s eet of tall ships. Sail 250 New York will host an armada of international naval and sail training vessels for a grand parade of ships in New York Harbor. e New York City port call is the centerpiece of a ve-port celebration on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. NMHS is working with Sail 250 New York to include an educational component for the event. We welcome your support and ideas at nmhs@ seahistory.org.

—Burchenal Green NMHS President Emeritus

NMHS 60th Anniversary Calendar 2024

Enjoy 12 months of stunning marine paintings from America's most celebrated artists, including John Barber, Peter Egeli, Kathleen Hudson, Russ Kramer, William Muller, John Stobart, & Len Tantillo.

This wall-hanging calendar is saddle-stitched and printed on quality heavyweight paper.

18" H x 12" W (open)

$13.60, plus $5.50 s/h (media mail) within the USA. NYS residents add sales tax. Please call for multiple or international shipping charges.

TO ORDER, call 914-737-7878 ext. 0, or online at www.seahistory.org/calendar2024.

SeaHistory.org 11

Russ Kramer, F/ASMA, The Corinthians, oil, 24" x 36"

PHOTO BY WILLIAM G. ARMSTRONG JR.

Peter Arthur Aron (1946–2023)

Peter Arthur Aron was the quintessential Renaissance man, really a modern-day prince. He grew up with a passion for all things maritime, as a child reading sea adventures by ashlight under the covers. He was quick to credit his interest and a good deal of his knowledge about history and the sea to his late father, Jack R. Aron, who was a founder of South Street Seaport. Peter and his father were instrumental in saving the 1911 four-masted barque Peking from the shipbreakers in England in 1974 and bringing her to the South Street Seaport in the challenge to keep alive the vibrant heritage of the Port of New York, which built the city, which built the country. Peter and Jack Aron were recipients of the NMHS Ship Trust Award in 1990 for their work saving the Peking. anks to them, the ship was saved and is now fully restored and homeported in Hamburg, Germany.

Peter Aron’s major involvements with maritime history included his service for over thirty years as a trustee of the South Street Seaport Museum, serving the last ten years of his tenure as its chairman, and then chairman emeritus. He and his family signed on at the very beginning, when Peter Stanford and Jakob Isbrandtsen made the rounds of all the maritime-related companies in lower Manhattan seeking help for the then-new waterfront museum. e Arons, then major importers of co ee, cocoa and sugar, along with the Aron Charitable Foundation, Inc., soon became supporters of South Street Seaport Museum. ey were among the early “Plankowners” for the 1885 full-rigged ship Wavertree when she was found by Karl Kortum in Buenos Aires and towed to New York for restoration. She has been fully restored and is an important and impressive historic reminder of the port.

Over the years, Peter Aron and his family have helped with the preservation of a number of vessels, including Ernestina/Morrissey, Matilda, and Lettie G. Howard. He served for a time on the Advisory Council of the museum at the United States Merchant Marine Academy, which is only about a mile down the road from his home in Kings Point, NY. He served as a trustee and corporate member of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Following a family tradition of service to his country, Peter served two years in Vietnam as a 1st lieutenant in the US Army. He was awarded the Bronze Star and Department of Defense Joint Service Commendation Medal for meritorious Vietnam service, among other decorations.

For many decades, Peter has been a strong supporter of Sea History magazine, founding the Publisher’s Circle to encourage supporters. “It is the best written, the most honestly researched, and just plain attractive of all the publications about history and the sea. Each issue gives everyone who loves ships and things-nautical a great ‘ x,’” he said. Mr. Aron was a leader in promoting the written voice of the heritage, the magazines and books that record the seafaring story. In 2005, Peter spearheaded a family gift in honor of his father to the Library of America’s Guardians of American Letters Fund to ensure that Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast and other Voyages would be kept in print. In 2008 he was the recipient of the NMHS David A. O’Neil Sheet Anchor Award, given to recognize extraordinary leadership in building the strength and outreach of the Society.

With a lifetime of active dedication to education and the arts, and as a highly successful and astute businessman and investor, he was a generous philanthropist, supporting his schools and numerous art programs, and was the recipient of numerous awards and recognitions. He was a collector of Asian and maritime art; he become a licensed helicopter pilot, a certi ed open water scuba diver, and an accomplished sailor and photographer. He enjoyed the opera and symphony. His great passion was for his family—his beloved wife of 51 years, Erika Kostron Aron, and their daughters Heather and Holly, and their families. He was known to say that one should live life with simple acts of love and kindness, that you should ask “if you are doing things right, or doing the right thing,” and that with a twinkle in his blue eyes, he would say, “that is all I have to say about that.”

Fair winds, dear friend and shipmate.

—Burchenal Green, NMHS President Emeritus

12 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023

FIDDLER’S GREEN

COURTESY THE ARON FAMILY

We were saddened to learn of the death earlier this year of our founding president and long-time NMHS Overseer, Alan D. Hutchison. A graduate of George Washington University School of Law, Hutchison was a lawyer in Washington, DC, in the early 1960s. His law rm was representing the Washington Waterfront Development Company, which hoped to revitalize the waterfront in the nation’s capital with a plan that included featuring a historic sailing ship that could connect visitors with America’s maritime origins. Hutchison sought the advice of noted maritime historian Karl Kortum, who advised him that the barque Kaiulani, the last American-built ship to sail around Cape Horn with cargo, would be the ideal vessel for this purpose. e Committee for the Preservation of the Kaiulani was soon formed to lead e orts to bring Kaiulani back from the Philippines, where she was being used as a lumber barge. As the project grew in scope, the National Maritime Historical Society was incorporated, with Mr. Hutchison as its founding president.

In 1964, Philippine president Diosdado Macapagal presented Kaiulani to the people of the United States in a formal White House ceremony.

e National Maritime Historical Society was appointed steward for the ship and continued to raise awareness and funds to bring her to the US. Despite the organization’s successes in raising money and securing a federally guaranteed loan, the ship proved to have deteriorated beyond what was reasonable to restore, and she was broken up.

Emerging business commitments spurred Mr. Hutchison to turn over the mantle of NMHS president to Peter Stanford. Mr. Hutchison wrote the full story of this adventure in Sea History 94 (Autumn 2000), and it can be accessed online at www.seahistory.org. In 2000 he provided the funds to purchase a Kaiulani model that had been lost, but later found in Florida.

e model needed extensive restoration, which was recently completed by Ray Guinta; the model is on display here at our NMHS headquarters. It serves as a constant reminder of Alan Hutchinson’s unrelenting e orts to save this ship—and later its model—and is a constant inspiration.

Mr. Hutchison joined InterAmerican Finance Corp. as General Counsel and Managing Director; in 1986 he was appointed to the National Advisory Committee on Oceans and Atmosphere.

Rest in peace, Alan Hutchison, and many thanks from a grateful organization.

Burchenal Green, NMHS President Emeritus

Sail Aboard the Liberty Ship John W. B roW n

2023 Cruise on the Chesapeake Bay September 17th

On a cruise you can tour museum spaces, bridge, crew quarters, & much more. Visit the engine room to view the 140-ton triple-expansion steam engine as it powers the ship though the water.

Reservations: 410-558-0164, or www.ssjohnwbrown.org

Last day to order tickets is 14 days before the cruise; conditions and penalties apply to cancellations.

SeaHistory.org 13

FILE

NMHS

PHOTO

Alan D. Hutchison (right) accepting the title to the Kaiulani from President Diosdado Macapagal of the Philippines, 23 November 1964.

Alan D. Hutchison (1931–2023)

Project Liberty Ship is a Baltimore-based, all volunteer, nonproft organization. SS JOHN W. BROWN is maintained in her WWII confguration. Visitors must be able to climb steps to board.

National Maritime Historical Society

2023 Annual Awards Dinner

26 October • New York Yacht Club • New York City

by Julia Church

Pam Rorke Levy and Ma Brooks, co-chairs of the 2023 Annual Awards Dinner, invite you to join us for good cheer and camaraderie at the New York Yacht Club on Thursday, 26 October 2023, as the National Maritime Historical Society once again hosts its annual gala.

The 2023 Awardees

e Barkers of Interlake Steamship Company will receive the NMHS Distinguished Service Award in recognition of their leadership in the maritime industry and service to the United States maritime community, as their vessels are American built, American owned, and American operated, and for their unwavering support to preserve the maritime heritage of the United States. We especially honor their commitment to restoring the historic ferry SS Badger, the last coal- red passenger vessel operating on the Great Lakes, a National Historic Landmark, and an icon on Lake Michigan since 1953.

James Rex Barker is a legend in Great Lakes shipping. As chair of the Interlake Steamship Company, he leads the largest privately held US- agged eet on the Great Lakes. A recognized expert and industry leader in marine transportation, Barker serves as vice chair of Moran Towing Corp. and Mormac Marine Group, Inc., and as chairman of SeaStreak, LLC. He is also chair of the National Maritime Council and is a director of the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS).

Barker grew up in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan, where his uncle and grandfather worked on supply boats that serviced the Great Lakes eet. During World War II, he and his cousins got an eyeful with 300 vessels passing by between Lake Superior and Lake Huron. “We knew them all,” Barker shared.

A US Coast Guard veteran, Barker served from 1957–61, after his graduation from Columbia College, and was assigned to the US Coast Guard base in Sault Sainte Marie as the executive o cer. In 2022, the United States Navy Memorial honored him with its Lone Sailor Award, given to sea service veterans who have excelled with distinction in their respective careers during or after their service. “I am most proud of this honor,” Barker says.

He studied transportation and nance at Harvard Business School, graduating with distinction in 1963. ere, Barker met Paul Tregurtha and the two formed a lasting partnership that continues today. He returned to Cleveland

to join the Pickands Mather Marine Department, which then operated Interlake. In 1971 Jim Barker was elected chairman, president, and CEO of Moore McCormack Steamship Company. An innovator in the eld, he pioneered the use of 1,000-foot freighters and containerization in Great Lakes shipping. Tregurtha joined him and together they grew Moore McCormack into a resources and water transportation company. In 1987 Barker purchased Interlake, and seven years later he and Tregurtha acquired Moran Towing Company, the oldest and largest tugboat company on the East and Gulf Coasts.

Barker served on the Services Policy Advisory Committee of the US Trade Representative during the Reagan Administration, the Business Advisory Committee of the Transportation Center at Northwestern University, and the Board of Visitors of Columbia College. Le Sault de Sainte Marie Historical Sites honored Jim Barker as Man of the Year in 1976 and inducted him into the Great Lakes Hall of Fame. In 1995, the United Seamen’s Service presented him with the Admiral of the Ocean Sea Award.

His namesake ship, MV James R. Barker, with its distinctive horn known as the “Barker Bark,” was built by the American Ship Building Company at Lorain, Ohio, and was the rst 1,000-foot-class vessel constructed entirely on the Great Lakes.

“I’m proud of the role the American maritime industry plays in the health of the American economy. Our industry

14 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023

James R. Barker and Mark W. Barker

is nearly invisible, yet its role is incalculable. On the Great Lakes, the main commodity that we move is iron ore, the raw material for making steel—the backbone of American industry. e American maritime industry is the invisible grease that keeps our economy moving.”

Mark W. Barker has been at the helm of Interlake since 2007 as its president. “Great Lakes Shipping has played an incredible role for our nation,” he said. “ e only way to get through or around America was by boat. e iron ore found in the North Range started the building of America from the industrial age. Our company found its roots in the need to move iron ore from Minnesota and Michigan down through the Great Lakes.”

Interlake Steamship Company carries more than 20 million tons of cargo each year. e company operates and manages a versatile eet of nine self-unloading vessels that range in carrying capacity from 24,800 to 68,000 gross tons and have a total trip capacity of 390,300 gross tons. e company’s new 639- foot Mark W. Barker, launched in spring 2022, is the rst US- agged Great Lakes freighter built in almost 40 years. She was named 2023 Ship of the Year by Professional Mariner. e self-unloading bulk carrier is the lead ship in Interlake’s River class and is the rst ship to operate on the Great Lakes with EPA Tier 4 engines. Designed to ensure a low environmental impact, the steel ship was built by Fincantieri Bay Shipbuilding. She will carry all types of cargo throughout the freshwater lakes and river systems but was speci cally designed to navigate the tight bends of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River. “We are moving the building blocks of America; we are moving the raw materials to create steel,” said Barker. “ e Great Lakes are an important aspect of our economy and an incredible resource for this country. Shipping is the invisible industry. We literally glide into port and deliver, and no one even knows we are there.”

Mark Barker’s maritime career was launched at SUNY Maritime College, where he studied marine engineering.

Prior to joining Interlake, he sailed aboard numerous vessels in the Great Lakes, Gulf of Mexico, and transAtlantic trades. He has an MBA from Case Western Reserve University’s Weatherhead School of Management and holds an Unlimited ird Assistant Engineer License.

“I grew up around the maritime industry and learned to love it, much as my father did as a child. My dad shared his passion for the ships and his deep passion for the history of the boats. I grew up learning that from him and experienced it as a young child when I got to go onboard the ships myself.”

Barker is chair of the National Museum of the Great Lakes and a past chair of the Lake Carriers’ Association. He serves on the board of Moran Towing Corporation and is an active member of the Council of the American Bureau of Shipping. “Without US shipbuilding capability, we not only can’t build merchant ships, [but] we can’t build Navy ships. It’s an important thing we need to keep alive and on the forefront.”

Richard du Moulin will present this award to NMHS’s rst father-and-son recipients. Jim Barker shared with us that he gave Rich his rst job in the eld, which makes the award that much more meaningful.

SeaHistory.org 15

James R. and Mark W. Barker

COURTESY JAMES AND MARK BARKER

Bolero O Antigua

by Russ Kramer

Bolero, the historic 73-foot wooden yawl, was designed by Sparkman & Stephens and launched in 1949. She is considered to be near the apex of the Top 10 of the great designs of Olin Stephens II. Bolero had a fine racing career in Sweden and San Francisco, across the Atlantic, and along the US East Coast. With 2,980 square feet of sail, she won the 1956 Bermuda Race, a record that stood until 1982.

Russ Kramer, a past president of the American Society of Marine Artists, is widely regarded to be among America’s leading marine artists, specializing in historic yachting scenes.

Paper/image size 30” x 20” paper/trim size 36” x 27”

Signed & numbered limited edition of 500 $450

Signed & numbered remarqued edition of 50 $700

Double-remarqued artist proof edition of 5 $900

—add $30 S/H within the US

Canvas/image size 36” x 24”

Signed and numbered limited edition of 175 $900

Artist proof edition of 5+ original 8” x 10” sketch $1,350

—add $75 S/H within the US

To order call 914 737-7878, ext. 0 or visit our website at www.seahistory.org.

NYS residents add applicable sales tax. For international orders, please email advertising@seahistory.org.

You can own this spectacular print by acclaimed artist Russ Kramer and support NMHS at the same time.

Edward W. Kane

Ed Kane will receive the 2023 NMHS Distinguished Service Award for the restoration of Bolero, the historic 74-foot wooden yawl designed by Sparkman & Stephens and launched from the Henry B. Nevins Yacht Yard in 1949.

Originally built for John Nicholas Brown, then Under Secretary of the Navy and vice commodore of the New York Yacht Club, Bolero arrived on the yachting scene with the reputation of being both luxurious and fast, rst to cross the nish line in the Newport-Bermuda Race in 1950, 1954, and in 1956, setting a course record that stood until 1982. “Restoring Bolero was important for four reasons,” Kane said. “She was commissioned by Commodore Brown of the New York Yacht Club; she was designed by the late Olin Stephens, one of the greatest yacht designers in the world; she was built at Henry B. Nevins shipyard in New York; and Bolero has an unbreakable connection to the New York Yacht Club—I have always been very involved with it. ese considerations were important to me.”

In 1989 Gunter Sunkler found Bolero abandoned and rotting away in a Florida canal; he rescued the vessel and set to work restoring the topsides and interior. Kane bought Bolero in 1999 and proceeded to make major repairs to the hull, adding a new stem and replacing the mahogany planking under the waterline. Bolero’s iconic sail was designed by his wife, Marty Wallace, with a motif depicting a Spanish Bolero dancer. “ e Browns [Bolero’ s original owners] named their yachts after Spanish dancers. We wanted to create a motif that would continue that legacy.”

His restoration projects date back to when he and Marty Wallace funded Musketaquid , a replica of the ski that Henry David oreau and his brother rowed from Concord, Massachusetts, to Concord, New Hampshire; oreau later wrote about it in A Week on the Concord and Merrimack

Kane learned to sail in Marblehead during his graduate school years at Harvard. Buying his rst sailboat in 1979, he sailed it in Maine with only a compass and a chart to guide him. With his racing days mostly behind him, the

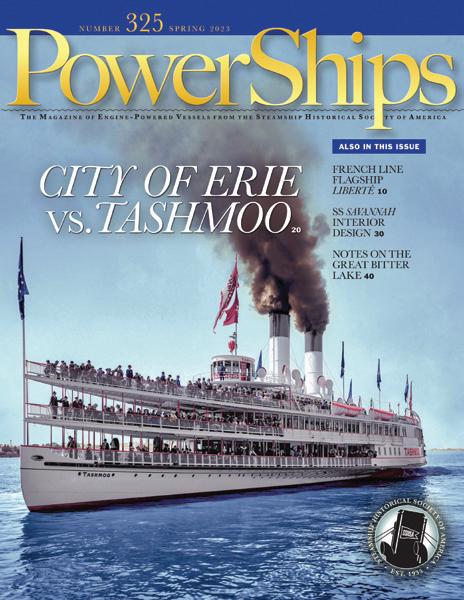

Rick Scarano

Vice President of Scarano Boat Building and NMHS Trustee Rick Scarano will receive the 2023 David A. O’Neil Sheet Anchor Award in recognition of his extraordinary leadership in building the strength of the Society. His exceptional work as co-chair of the NMHS Membership Committee has effectively expanded the Society’s reach through promotion and marketing. e National Maritime Historical Society has bene tted from his leadership, enthusiasm, and par-

Kanes use Bolero primarily for cruising now: “Racing is a young person’s sport. It has become much more competitive, and people don’t do family racing anymore.”

Kane is a trustee emeritus and supporter of the International Yacht Restoration School (IYRS). He has funded projects such as IYRS’s replica of Olin Stephens’s 1930 6-meter Cherokee and the restoration of the 1926 Nathanael Herresho -designed Marilee. His generosity also helped establish the school’s Edward W. Kane and James Gubelmann Library with its unique collection celebrating the maritime heritage of Rhode Island. Kane is a partner with HarbourVest Partners, a venture capital rm that he cofounded in 1982. He earned a BA from the University of Pennsylvania and an MBA from Harvard Business School. Kane was a US Army paratrooper and a major in US Army Intelligence; he graduated from the US Army Command and General Sta College.

NMHS Annual Awards Dinner co-chair Pam Rorke Levy will present the award .

ticipation in countless events and initiatives and has been the recipient of signi cant in-kind support from him and Classic Harbor Line.

As vice president of Scarano Boat Building, Rick is responsible for business development and management, systems installations, quality control, and production. Scarano Boat Building has a special niche in the production of replica sailing vessels and certi ed passenger vessels, and has

SeaHistory.org 17

Ed Kane at the helm of Bolero during Antigua Race Week. COURTESY EDWARD W. KANE

designed and built private and commercial vessels ranging from steel crane barges and upscale yachts to commercial USCG-certi ed power and sailing vessels. Scarano also operates Adirondack Sailing Excursions, which operates Classic Harbor Line, with a eet of nine passenger vessels designed by Scarano Boat Building.

With more than 200,000 people sailing with them annually, Classic Harbor Line operates out of Boston, Massachusetts; New York, New York; Newport, Rhode Island; and Key West, Florida. eir agship, America 2.0, a stunning 105-foot sailing yacht, is a tribute to the 1851 schooner America —winner of the rst America’s Cup.

e Scarano brothers took to the water at an early age, learning to sail in upstate New York on a small lake in “the tub”—an 8-foot vessel made out of a World War II bomber fuel tank that was split in half and converted into a lug-rigged sailboat. “We grew up spending our summers playing in boats—canoes, kayaks, sailboats that were barely considered sailboats, and little speed boats. We had eight boats at one time, almost the size of the current Harbor Line eet! My brother John was the one who was inspired to design, build, and operate boats for a living, and he has designed every vessel that we have ever built.”

Scarano boats are rooted in the past—yet wed to the present. According to Rick, “I think to a large degree, sailing is traveling back in time. We do our best to integrate performance with the old-time aesthetic, and we love when the boat, under wind power, takes o and really performs. e wonderful thing for us is to introduce people to sailing, which is a multi-sensory thrill.”

A trustee for the National Maritime Historical Society since 2008, Rick is an active member of the American Sail Training Association, Friends of Hudson River Park Trust, the Waterfront Alliance, and the Passenger Vessel Association. Rick is an in uential, respected, and generous leader in the East Coast maritime world.

You’re Invited!

We are excited to gather again with old friends and shipmates and welcome new friends to our yearly gala. Our co-chairs Pam Rorke Levy and Matt Brooks, recipients of the 2019 Distinguished Service Award for the restoration of the classic yacht Dorade, welcome you!

Richard du Moulin will return from hiking the mountains in northern Canada to serve as our Master of Ceremonies. NMHS Vice Chair Rick Lopes took time away from lming the NMHS documentary, Sails Over Ice & Seas, about the 1894 schooner Ernestina-Morrissey to produce the tribute videos for the event. ese biographical mini-documentaries are always a highlight of the evening and a great way to acknowledge our award

recipients. e US Coast Guard Cadet Chorale, directed by Daniel McDavitt, DMA, will perform a traditional seafaring and patriotic set for the evening’s entertainment.

We gratefully acknowledge our event Marquee Sponsors Matt Brooks and Pam Rorke Levy—and our Commodore Sponsors Caddell Dry Dock & Repair Company, Inc., Interlake Steamship Company, Moran Towing Company, and William H. White.

To register, or to congratulate our recipients with an ad in the dinner journal, please visit www.seahistory. org/aad2023, or contact Wendy Paggiotta at vicepresident@seahistory.org or 914-737-7878, ext 557. Seating is limited, so make your reservation today!

18 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023

Rick Scarano at the helm.

COURTESY RICK SCARANO

Rik Van Hemmen will make the presentation.

Share Sea History for $10

60 TH ANNIVERSARY MEMBERSHIP CAMPAIGN

Back in 1963 the price of membership was $10 and we are returning to this symbolic figure this year only and for new members only.

For that same $10, you can give up to 6 people (that’s 6 for the 6 decades) a gi membership…that’s $10 for all six, or for 1!

Our strength is our numbers and this campaign seeks to get our mission, Sea History, and our programming o ers out to as many people as we can.

Please take this opportunity to join us in strengthening NMHS your organization by ge ing the word out and building our membership. You will help us, and we o er up to 6 gi s you can give for the price of $10.

This special o er to members is for your US friends only and starts with the winter issue. Go to www.seahistory.org/anniversary, or mail us your list with a check.

SeaHistory.org 19

It’s the Real McCoy! The Capture of Prohibition’s

Most Notorious Rumrunner

William “Bill” McCoy watched with a mixture of amusement and consternation as a whaleboat from Coast Guard Cutter Seneca pulled through the rough seas in the wake of his 90-foot schooner

by CAPT Daniel A. Laliberte, USCG (Ret.)

by CAPT Daniel A. Laliberte, USCG (Ret.)

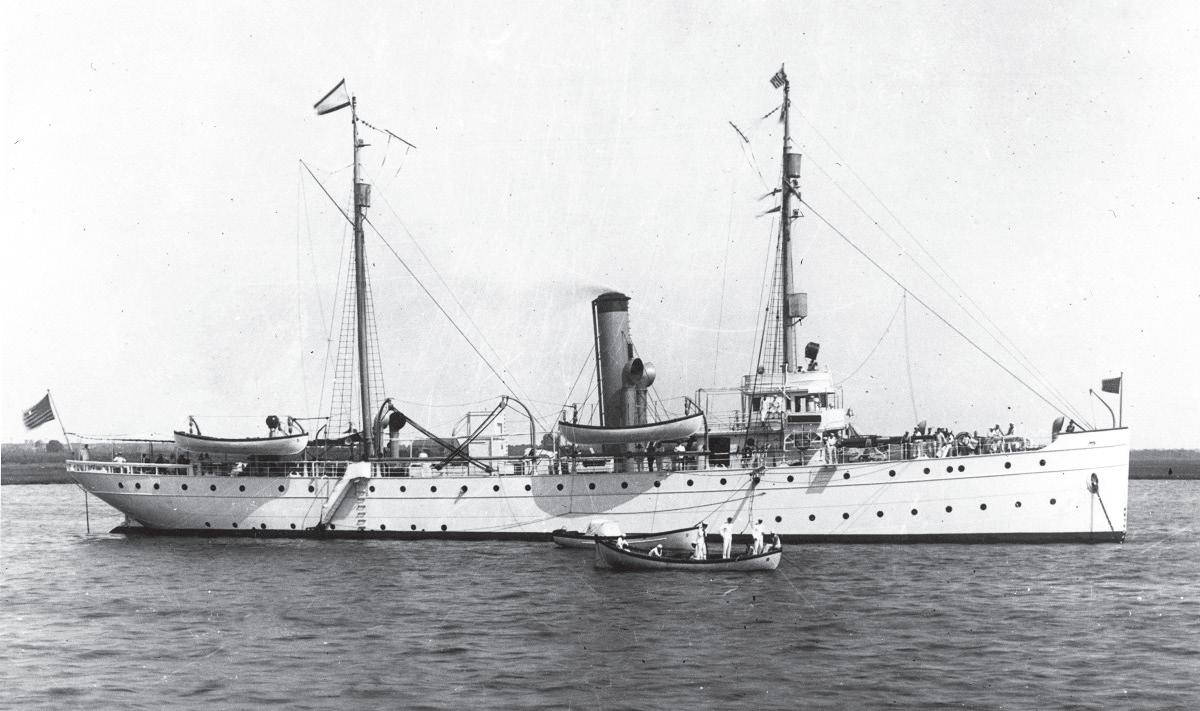

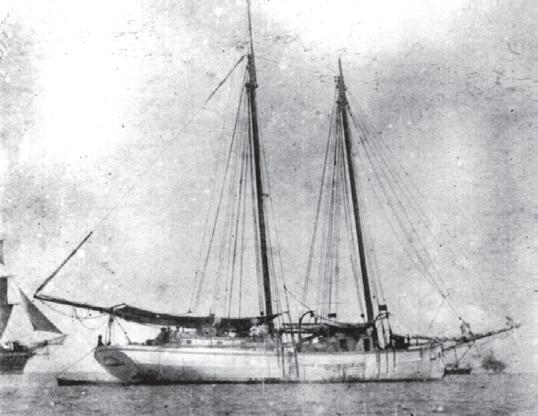

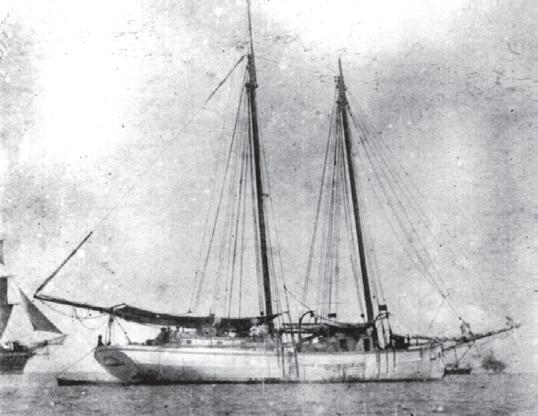

Tomoka (ex-Arethusa of Gloucester, Massachusetts). He had been toying with the Coast Guardsmen for the better part of an hour—since 1030 that morning, 24 November 1923, when the Seneca had rst ordered him to “heave

to for boarding.” While he had initially slowed his vessel to appear he was complying, as soon as the cutter’s boat was launched, he proceeded to adjust his speed to stay just beyond the reach of the struggling boat.

When the commanding o cer of the Seneca , Lieutenant Commander Philip F. Roach, nally reached the limit of his patience, he “called [his] guns’ crews to quarters, cast loose No. 1 gun, stood over to Tomoka, and directed the master to heave-to and permit his crew to board him.”

Staring into the muzzle of the cutter’s forward 3-inch/50-caliber deck gun, McCoy nally relented and steered his schooner’s head into the wind. McCoy felt uneasy as he waited for the eight-person boarding party to scramble over his gunnel, as he had 150 cases of Bacardi Rum—the tiny remnant of a load of more than 4,500 cases of whiskey he had delivered over the last four days—stored in his hold. Normally that would be enough justi cation for the Coast Guard to arrest him and seize his vessel for smuggling alcohol, but by his reckoning, he was about 6½ miles o the coast of New Jersey, well beyond the three-mile limit of US territorial waters. Since he had changed Arethusa’s registry to British to avoid US jurisdiction on the high seas, the Coast Guard would need proof that he had been in contact with a boat from shore to take law enforcement action under the National Prohibition Act.

20 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023

COURTESY THE MARINERS’ MUSEUM AND PARK

The 1907 schooner Arethusa (later renamed Tomoka) underway. Bill McCoy purchased the fishing schooner to use her for rum-running during Prohibition.

When Prohibition went into e ect on 17 January 1920, McCoy was quick to see the opportunity it presented, knowing that demand for liquor would not evaporate just because the government had banned it. Concealed stockpiles, diversion of medicinal and industrial alcohol, and “moonshining” soon proved inadequate to satisfy the continued demand. Smuggling across the land borders with Canada and Mexico quickly took o ; however, getting the booze to the largest concentration of customers in coastal New York, New Jersey, and the southern New England states required additional risky and complex land transportation. Smugglers turned to the sea.

e Coast Guard’s East Coast Florida Patrol—a handful of former Navy submarine chasers—and a few outdated cutters on the Paci c coast began seizing rumrunners barely four months after the enactment of Prohibition. Seizures of numerous small vessels, carrying from a few dozen to around 400 cases of alcohol, quickly became so frequent that the Commandant of the US Coast Guard felt compelled to caution the commander of the Florida Patrol against neglecting his other missions to the exclusion of alcohol enforcement, while the Customs Service began encountering di culty nding spaces to hold the many vessels awaiting forfeiture hearings.

McCoy, a Florida-based boatbuilder by trade, found a safer and more lucrative solution. He purchased the shing schooner Henry L. Marshall for $15,000, modi ed her internal conguration to maximize storage of dry cargo rather than sh, and sailed her to Nassau. ere he re- agged his vessel under the Union Jack, purchased 1,500 cases of whiskey, and returned to the US East Coast to sell his rst load. In that single run, he cleared enough to recover the entire purchase price of his vessel. By the summer of 1920, McCoy was making regular runs from Nassau to points o the coast of New Jersey and New York and was making a lot of money doing it.

SeaHistory.org 21

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

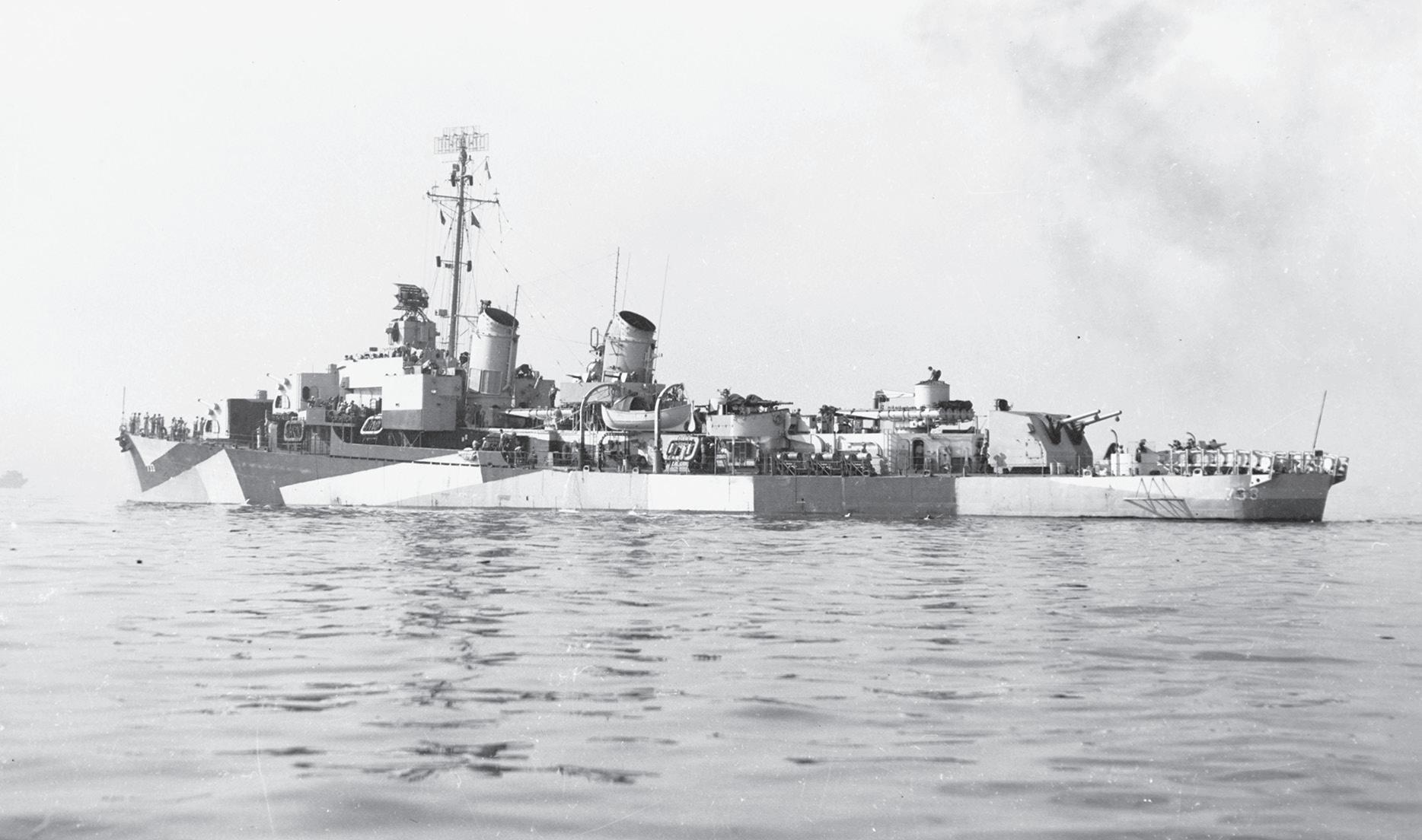

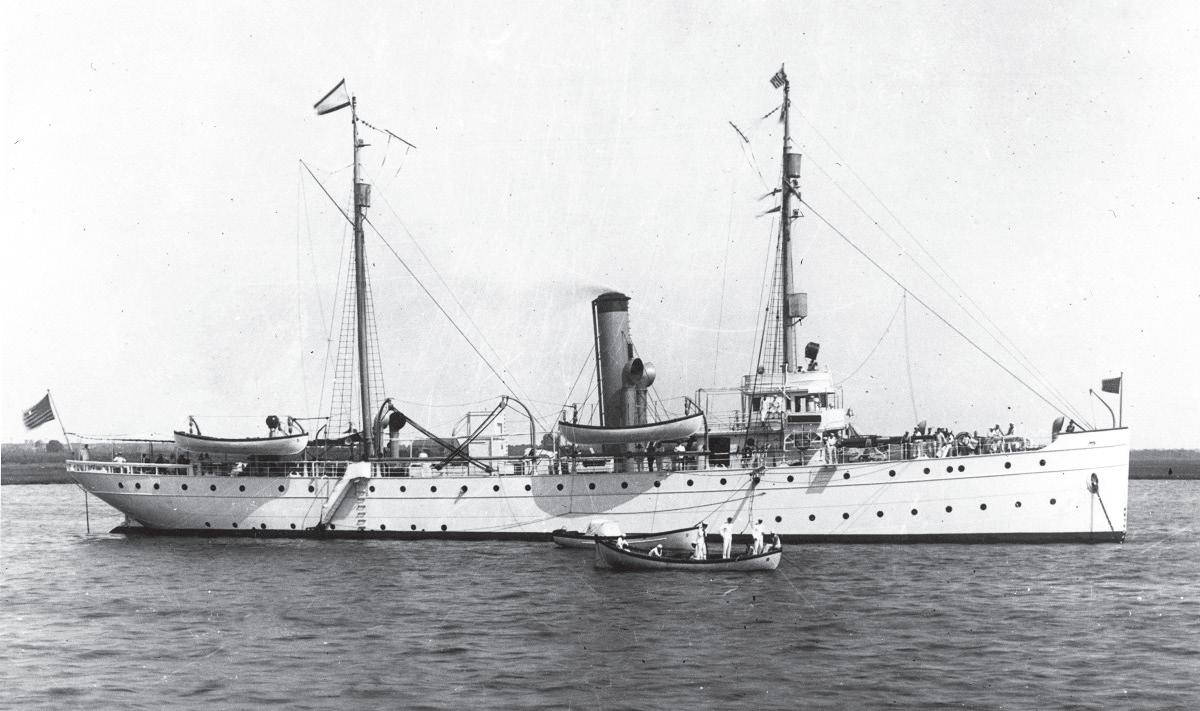

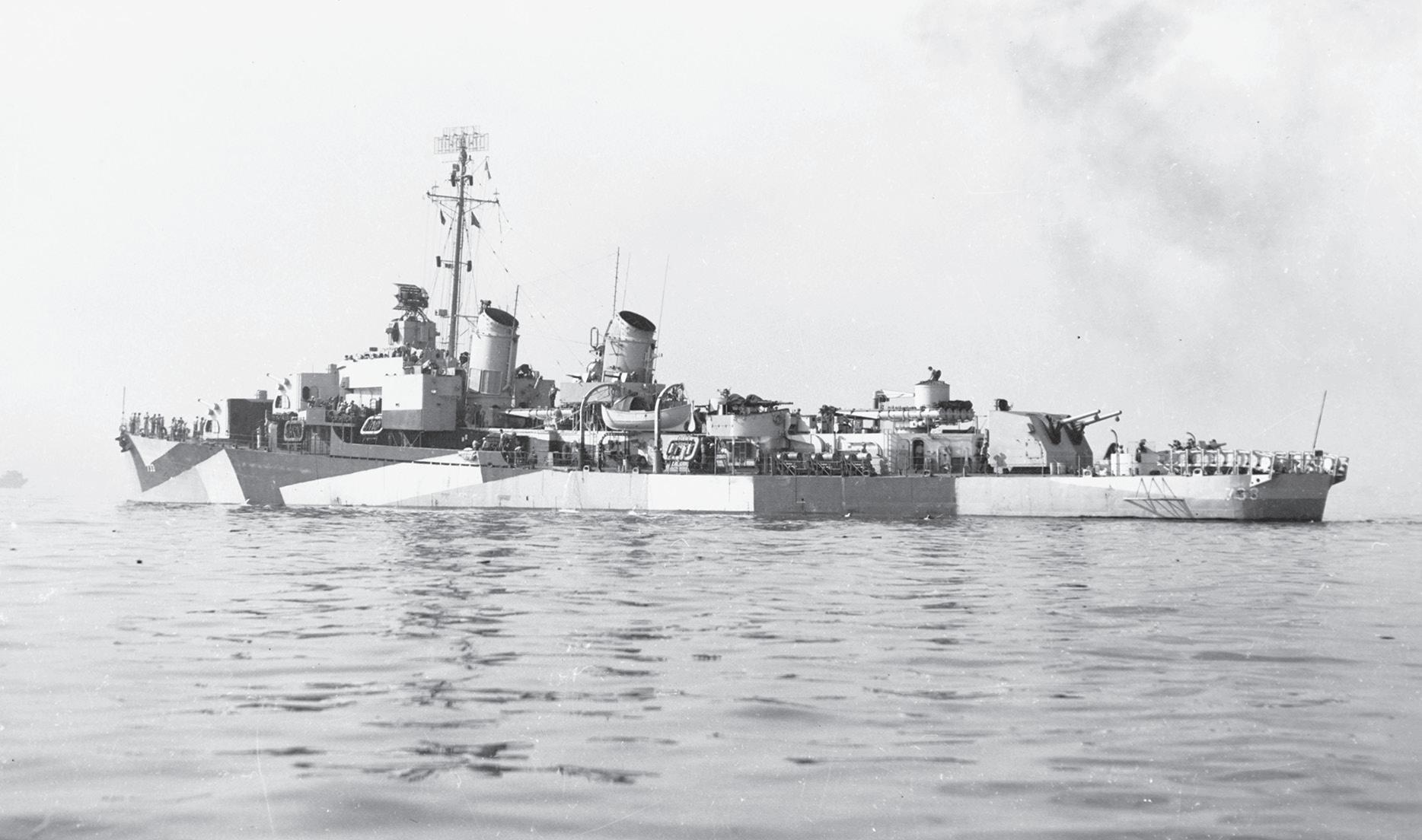

US COAST GUARD

US Coast Guard Cu er Seneca’s outdated 6-lb. rapid-fire deck guns were replaced with modern 3-inch/50-caliber gun mounts during an overhaul at the Washington Navy Yard in 1922. Despite having been designed and launched in 1908 for the destruction or recovery of floating derelicts, and for search-and-rescue under extreme sea conditions, Seneca proved to be an e ective law enforcement cu er during Prohibition. Inset photo circa 1908.

Even though he kept his activities quiet, other entrepreneurs caught on and copied his method. In the summer of 1921, newspapers began to report the presence of mysterious, unlit vessels hovering o the East Coast. ese sightings, of course, heralded the formation of “Rum Row.”

Far from the common misconception of a continuous line of vessels stretching the entire length of the Eastern Seaboard, Rum Row was actually several clusters of vessels anchored o of population centers such as New York, Boston, and Atlantic City. ere, the foreign- agged “motherships” would wait in safety for contact boats from shore to run out and purchase several hundred cases at a time. It was easy money for the motherships, with all of the risk assumed by the smaller boats making the nal sprint into the United States.

Rum Row would ourish for almost three years. Over that time, McCoy expanded his smuggling eet to

22 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023

COURTESY THE MARINERS’ MUSEUM AND PARK COURTESY

PARK

THE MARINERS’ MUSEUM AND

(above) McCoy mostly hauled Rye, Irish, and Canadian whiskey, with smaller amounts of other liquor and wine. To save space in the hold, o entimes bo les were removed from their cases, wrapped in burlap, and stored as “hams,” as is seen in this photo of Tomoka’s forward hold.

(below) Booze being loaded aboard Tomoka in the Bahamas, 1923.

ve schooners—all British agged to avoid US jurisdiction. It was during a routine run that McCoy rst came to the government’s attention. Until August 1921, his schooners had stayed under the radar by following four basic rules: “Stay true to your contract; stay clear of the government’s notice; stay well o shore; and stay vigilant to avoid the Coast Guard.” On this particular trip, Carl Anderson—who had eeted up from rst mate to captain of the Henry L. Marshall after McCoy added the Arethusa to his otilla—sailed to a position o of Atlantic City with 1,500 cases of whiskey. en he promptly proceeded to break every one of McCoy’s prescriptions.

On 27 July, local newspapers began running articles announcing the Marshall ’s arrival o shore—with whiskey for sale. When a journalist came out by boat to verify the rumors, Anderson brazenly granted an interview in which he gave a comprehensive overview of maritime smuggling operations and

even detailed the speci c modus operandi and history of McCoy’s operations.

Despite the publicity, Anderson might still have gotten away with this run if he had stayed true to the terms of his contract and quickly o oaded his cargo. Instead, when new buyers o ered $60 a case instead of the previously negotiated $40, Anderson sti ed the original buyers and waited to work out delivery details with the new purchasers. is gave time for intelligence to reach the Coast Guard leadership in New York, which promptly dispatched the Seneca to investigate.

e hot, windless afternoon of 1 August 1921 found the Seneca steaming at its full speed of 11 knots towards a 90-foot, two-masted schooner anchored about three miles due north of its position. As the 204-foot, coal-burning cutter closed on the schooner, Commander Aaron L. Gamble—who would be relieved as captain by Roach the next year—noted that the schooner t the

description of the subject of the intelligence he had been investigating for the last two days. Although a British ag dangled listlessly from the vessel’s mainmast, canvas covers draped over the vessel’s name and homeport gave Gamble the justi cation he needed to send over a boarding party to establish her identity.

Once aboard, Gamble’s lieutenant discovered the schooner’s entire crew to be, in seaman’s terms, “three sheets to the wind.” e only member of the ship’s company able to speak coherently, the supercargo (the owner’s representative responsible for the management, buying and selling of cargo) reported that the master and mate had departed earlier aboard a boat from nearby Atlantic City. He insisted that the British ag immunized them from Coast Guard scrutiny, since they were outside the US territorial sea. Gamble, however, continued the boarding under an old 1799 law, “An Act to Regulate the Collection of Duties on Imports

SeaHistory.org 23

COURTESY THE MARINERS’ MUSEUM AND PARK

Bill McCoy aboard his schooner. McCoy became somewhat of a folk hero during Prohibition.

and Tonnage,” which allowed Coast Guard o cers to “go onboard ships or vessels…within four leagues of the coast to examine manifests and cargoes to prevent smuggling.”

e search turned up several incriminating documents: ownership papers revealing the vessel to be the Henry L. Marshall, formerly of Gloucester, Massachusetts, and currently of Nassau, British West Indies, and multiple, con icting clearance papers for the same voyage—one for transporting 1,500 cases of whiskey to Halifax, and another for transiting in ballast to Gloucester. Notably, no cargo manifest was located—which was itself grounds for seizure. Along with 1,250 cases of scotch found in the Marshall ’s hold, Gamble had overwhelming evidence to seize the vessel and arrest her crew for suspicion of smuggling alcohol.

Within three days, further investigation by agents of the Prohibition Bureau resulted in the additional arrests ashore of the Marshall ’s master and

mate, and the owner of a local saloon in Atlantic City, where 250 cases of illegal whiskey matching that aboard the Marshall had been found.

While this event was groundbreaking for the Coast Guard—the rst seizure for alcohol smuggling of a foreign vessel outside the US territorial sea—for McCoy it was even more consequential. Additional papers found aboard the Marshall revealed that the transfer of his vessel’s ag from US to Great Britain was a sham designed to evade US jurisdiction. Even more damning was a set of written instructions for the smuggling venture from him to Captain Anderson.

A warrant was issued for McCoy’s arrest, but over the next two years his fame only grew as he played cat-andmouse with the cutters Manhattan, Seminole, and Seneca. McCoy became a folk hero—referred to in the press by monikers such as “Rummie Bill” and “King of the Rumrunners.” e origin of the well-known expression, “It’s the

real McCoy,” is still debated. It became a popular nickname for Bill McCoy’s product because he was scrupulous in his purchasing and only dealt in name brands with original labels—not watered-down concoctions that were rebottled and relabeled. Buyers could count on his product being the genuine article, as labeled.

McCoy was becoming an embarrassment to the US government in its e orts to keep liquor out of the country. Despite being the most well-known and hotly pursued rumrunner and despite the capture of several of his vessels, McCoy somehow seemed to stay just beyond law enforcement’s grasp. But, as the sun was setting on 20 November 1923 and the Tomoka was just starting to o oad cases of whiskey to a contact boat from nearby New Jersey, a sharpeyed lookout aboard the schooner shouted warning of the Seneca hull down on the horizon. McCoy immediately broke o operations. e contact boat raced o in one direction, while

24 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023

COURTESY THE MARINERS’ MUSEUM AND PARK

The schooner crew transferring cases of whiskey from Tomoka to a seaplane.

McCoy ran south. Despite the inauspicious start, his luck seemed to hold. Seneca faded into the gathering darkness, and over the next four days McCoy would successfully sell all 4,500 cases of whiskey—worth nearly $300,000 (more than $5 million in today’s dollars). Although the whiskey was already gone by the fourth night, he still had 150 cases of rum in the hold. A buyer interested in the rum requested that McCoy delay his departure until morning when he would return in a ski for the remaining booze. Despite feeling that he might be pressing his luck, McCoy deemed the risk low, especially since the Seneca had made no further appearances over the previous days.

As luck would have it, morning brought the approach not of the ski , but of the Seneca. By the time the cutter’s eight-man boarding party, led by Lieutenant Louis W. Perkins, nally scrambled aboard the Tomoka, tempers were already hot due to McCoy’s antics in stringing out the boarding process. Di ering expectations about what would happen during the boarding would raise them to boiling.

McCoy expected a few perfunctory questions and examination of his ship’s papers, perhaps followed by some good-natured taunting of Lieutenant Perkins as he departed after establishing his vessel’s identity. After all, Tomoka as she appeared on the rolls in Nassau,

was foreign- agged and outside of the three-mile limit, and, despite the rum in her hold, no contact boat was nearby. What McCoy did not realize was that the Department of Justice had directed the Coast Guard to “seize the Tomoka and her cargo of liquors anywhere within the 12-mile limit and arrest the crew. Be sure that Wm. F. McCoy does not get away.”

Accordingly, after establishing the identities of the notorious McCoy and his vessel, Perkins informed Seneca that everything was all right and that he would follow the cutter aboard Tomoka to the Ambrose Channel lightship at the entrance to New York Harbor. As Seneca departed and headed north,

SeaHistory.org 25

OF

Prohibition agents amid cases of whiskey in the hold of a ship that was caught by USCGC Seneca in 1924.

LIBRARY

CONGRESS

Perkins then informed McCoy that he was taking control of the vessel and bringing her to New York for further investigation.

McCoy sco ed and informed Perkins that he and his boarding party were instead coming for a ride to Nassau. Rather than heading north, Tomoka proceeded to the east. In response, the Coast Guardsmen drew their sidearms, but McCoy’s six-man crew in turn brandished an assortment of pistols and ri es and trained a mounted World War I-surplus .30 caliber machine gun on them. Tense negotiations followed, after which Perkins and his party were allowed to depart aboard their whaleboat.

While Seneca’ s Captain Roach paused to recover Perkins, McCoy red up his auxiliary engine and bent on more sail. A gale was approaching, and McCoy gambled that if he could increase his half-mile lead just a bit further, he just might be able to lose the Seneca in the approaching rain. McCoy did his best to foul the Seneca’ s eld of re as he ran, keeping himself in range of other vessels passing in the distance, but the deteriorating sea state favored the Coast Guard vessel. Although the Seneca had a top speed of only around 11 knots, it had been designed and launched in 1908 to conduct searchand-rescue operations under extreme sea conditions and to recover or destroy the many oating derelicts that infested the East Coast’s shipping lanes in this era. Within an hour, Seneca had overhauled McCoy and enjoyed a clear eld of re for her deck gun.

After receiving a warning shot across his bow, shots both ahead and astern of him, and a fourth round that landed only about ten feet o the Tomoka’ s beam—splashing water on his deck—McCoy nally surrendered. It had taken more than two years, but the Coast Guard had nally nabbed McCoy and the elusive schooner.

e case against McCoy would drag through the courts for nearly two years, but it eventually resulted in a conviction. After serving a minimal sentence of only nine months, upon his release McCoy found a drastically changed smuggling environment. A dramatically expanded Coast Guard had dispersed Rum Row. Faced with an expanded and integrated force of major cutters, patrol boats, and aircraft, smugglers had been forced to change tactics. Individual motherships—rather than clusters of vessels— had been pushed more than 50 miles o shore, where they met contact boats speci cally built for increased range, speed, and stealth. Additionally, freighters using false identities were increasingly used to sneak cargoes of spirits directly into port. Perhaps most importantly to McCoy, organized crime had mostly taken over smuggling, and individual entrepreneurs

like himself had been forced out or forced to work for the mob.

Faced with these changes, and after having smuggled hundreds of thousands of cases of liquor to East Coast buyers, McCoy declined to return to the game. While Prohibition would continue until repeal in 1933, no smuggler would ever match McCoy’s exploits or assume his title of “King of the Rumrunners.”

CAPT Daniel Laliberte, USCG (Ret.), served for more than thirty years in the US Coast Guard, during which time he participated in or provided intelligence support to the interdiction and repatriation of hundreds of undocumented Haitian migrants, and the seizure of numerous drug smuggling vessels and the arrest of their crews. He writes on historical topics involving the Revenue Marine Service and Coast Guard.

ShipIndex.org Research Tip:

To narrow a Google search, use the “AROUND(x)” operator, with ‘x’ representing the number of words. For example: “constellation AROUND(5) sloop-of-war”. For more research ideas, visit: https://shipindex.org/research help

Over 150,000 citations are completely free to search

Use Coupon Code “NMHS” for a special discount to access the full database.

With ShipIndex.org you can find vessel images, ship histories, passenger and crew lists, vessel data, and much more. Search over 1000 sources including books, magazines, databases, and websites, all at once.

26 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023

S h i p i n d e x . o r g p u t s o v e r 3 . 2 m i l l i o n c i t a t i o n s f r o m o v e r 1 0 0 0 r e s o u r c e s a t y o u r f i n g e r t i p s

Celebrate our maritime heritage this holiday season with NMHS greeting cards.

"Lulu W. Eppes at Ellsworth, Maine" by Victor Mays, F/ASMA Watercolor, 11 5/8" x 19 1/2"

Greeting reads: "May Your Days Be Merry and Bright - Warm Wishes this Holiday Season and Smooth Sailing in the New Year!"

Set of ten 5" x 7" cards: $14.95. Add $5.50 s/h for one set, and $2.50 for each additional set. NYS residents add sales tax. Please indicate your choice of holiday or blank note cards. Call for priority or international shipping charges.

TO ORDER, CALL 1-800-221-NMHS (6647), ext. 0, or online at seahistory.org/product-category/gifts/.

Handmade in the U.S.A. by Third Generation Master Craftsman Bob Fuller.

SOUTH SHORE BOATWORKS

CARVER, M A • 781-248-6446

WWW.SOUTHSHOREBOATWORKS.COM

SOUTH SHORE BOATWORKS X, www.southshoreboatworks.com

2.25”x 2” South Shore Boatworks #SH149 Revised

Beaufort Naval Armorers

Beaufort Naval Armorers

Beaufort Naval Armorers

CANNONS

CANNONS

CANNONS

Finely Crafted Marine Grade Working Replicas

Sit in the wardroom of a mighty battleship, touch a powerful torpedo on a submarine, or walk the deck of an aircraft carrier and stand where naval aviators have flown off into history. It’s all waiting for you when you visit one of the 175 ships of the Historic Naval Ships Association fleet.

Finely Crafted Marine Grade Working Replicas

Finely Crafted Marine Grade Working Replicas

Morehead City, NC USA 252-726-5470

Morehead City, NC USA 252-726-5470

Morehead City, NC USA 252-726-5470

www.bircherinc.com

www.bircherinc.com

www.bircherinc.com

For information on all our ships and museums, see the HNSA website or visit us on Facebook.

SeaHistory.org 27

O���� ��� ��� O������ D������� THE HISTORIC NAVAL SHIPS ASSOCIATION THE FLEET IS IN.

www.HNSA.org

CM MY CY CMY K 2.25x4.5_HNSA_FleetCOL#1085.pdf 6/5/12 10:47:40

WOODEN SHIP'S WHEELS

TRADITIONAL

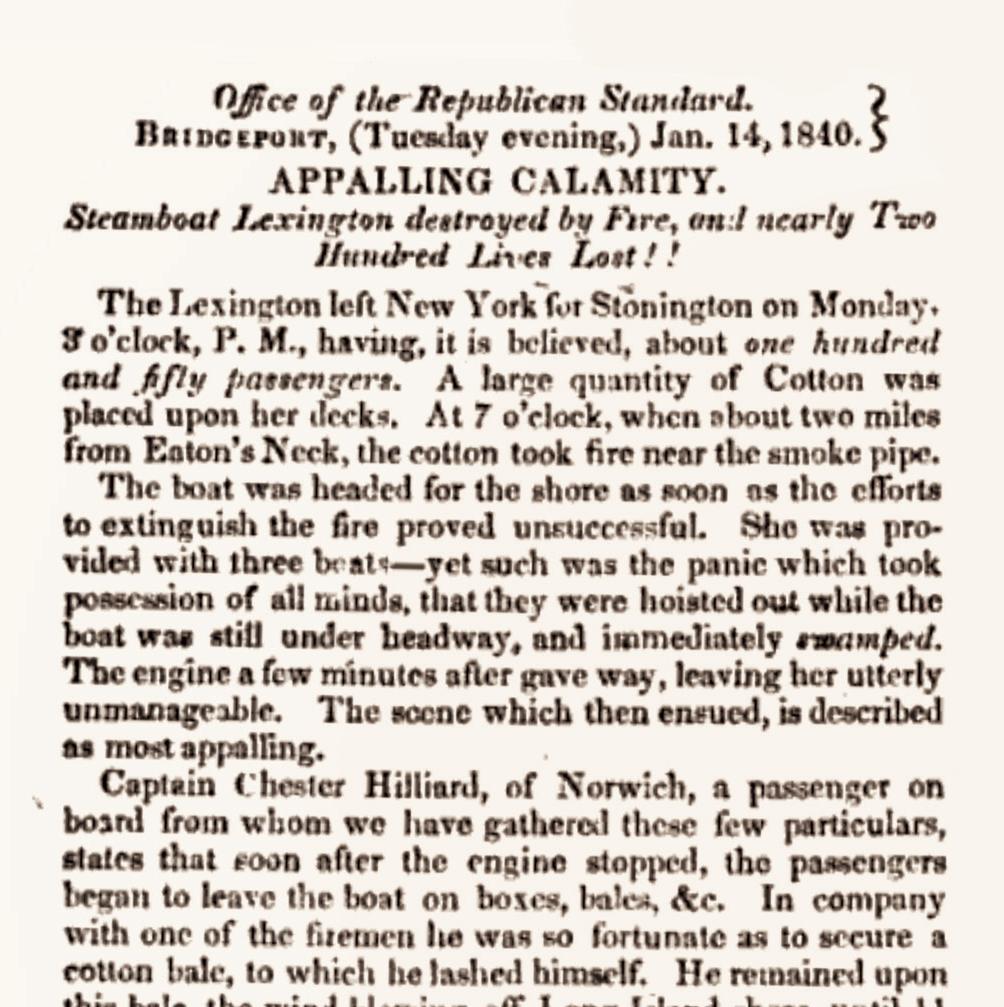

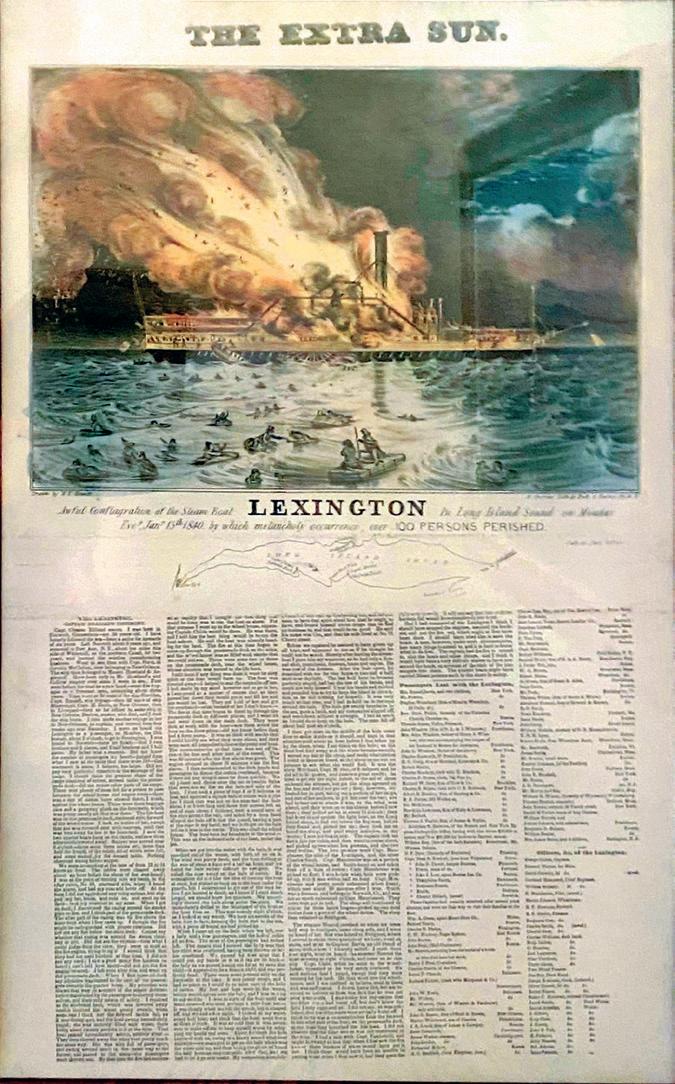

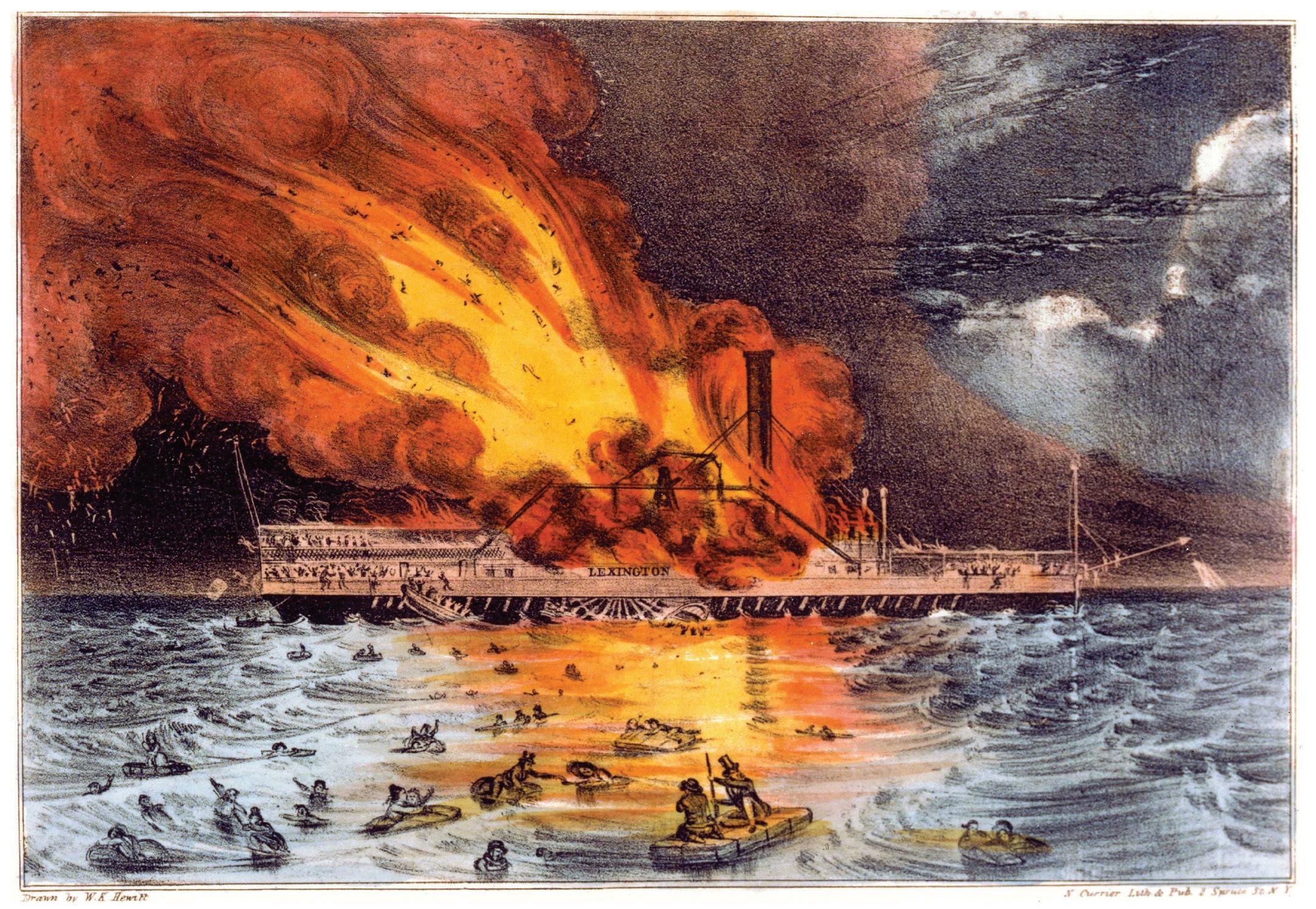

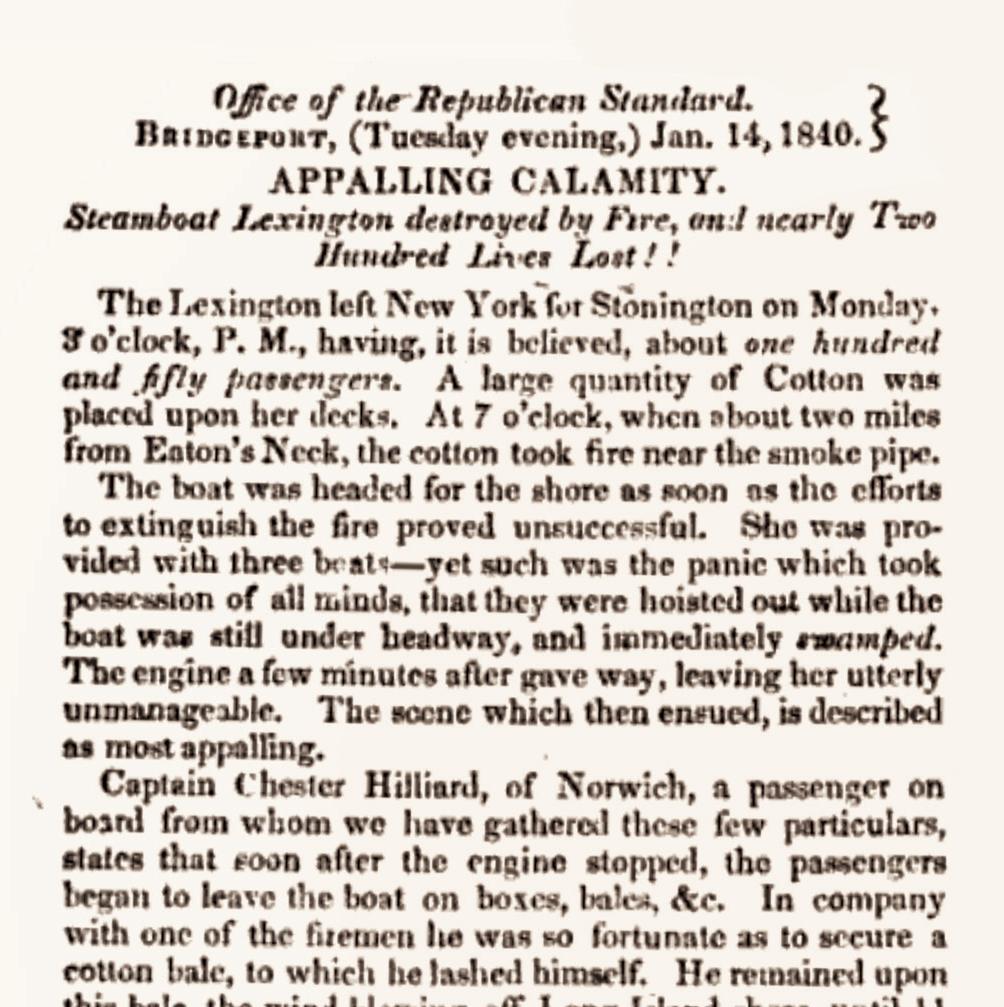

The Lexington Disaster on Long Island Sound

by Bill Bleyer

by Bill Bleyer

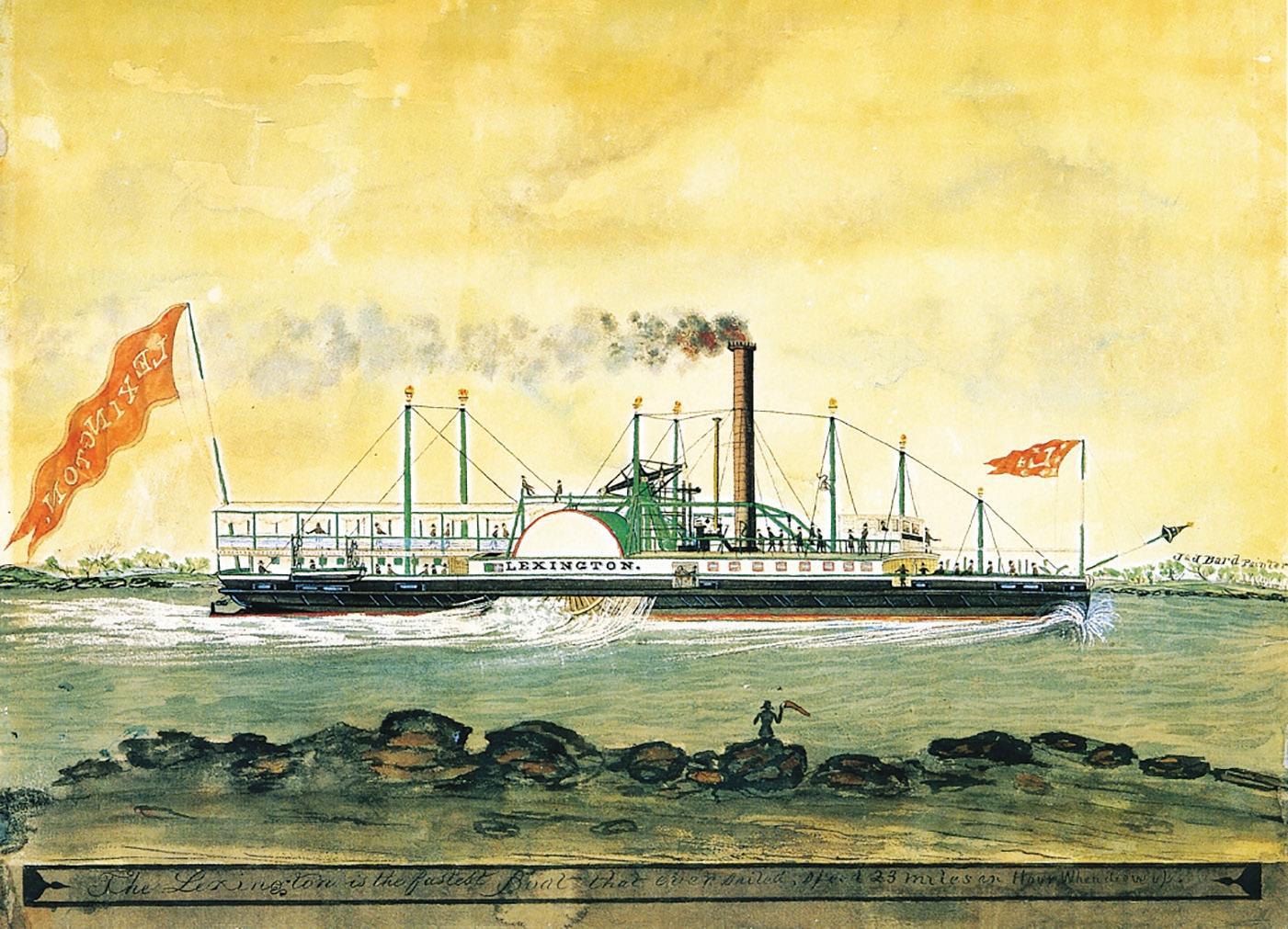

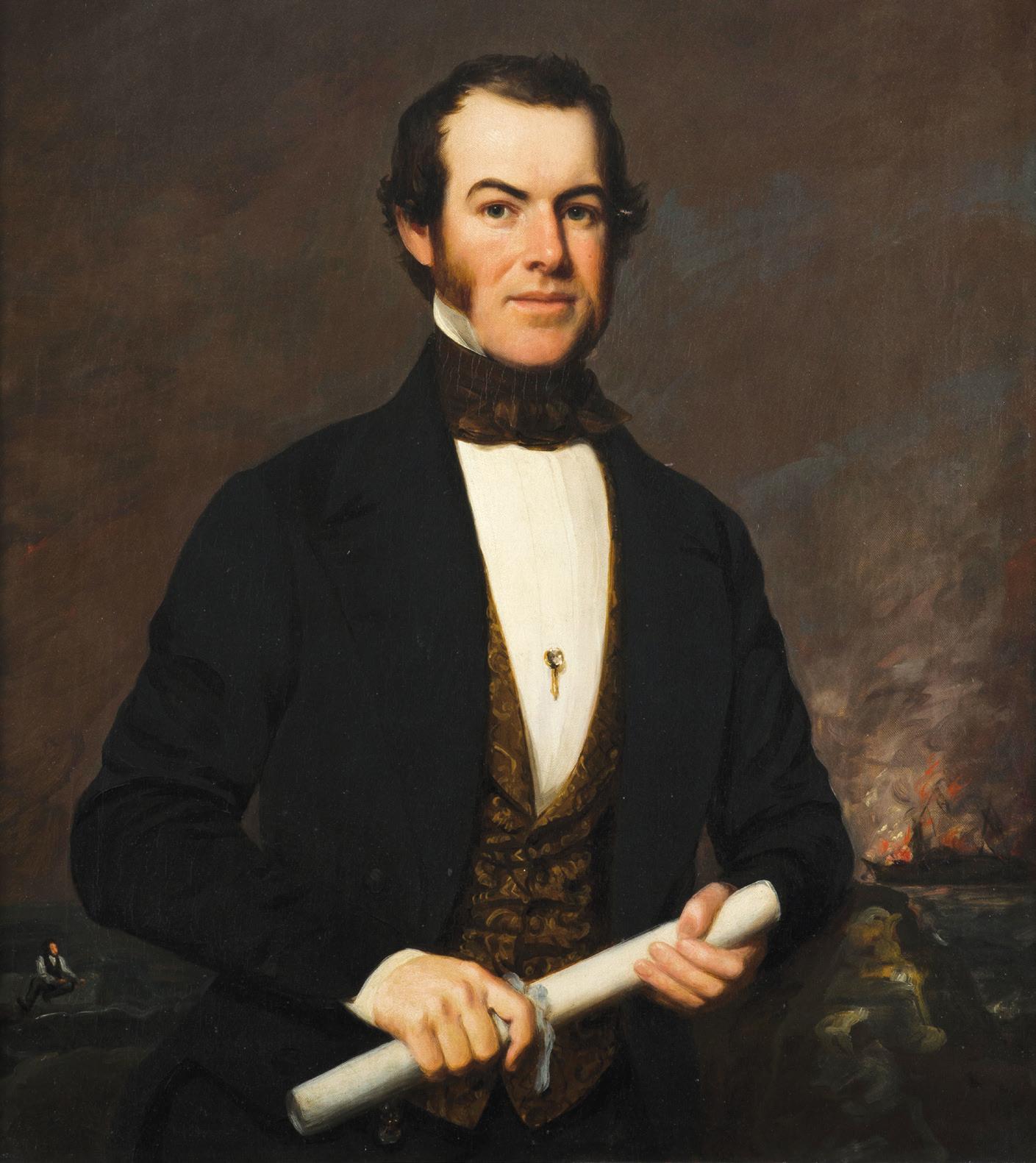

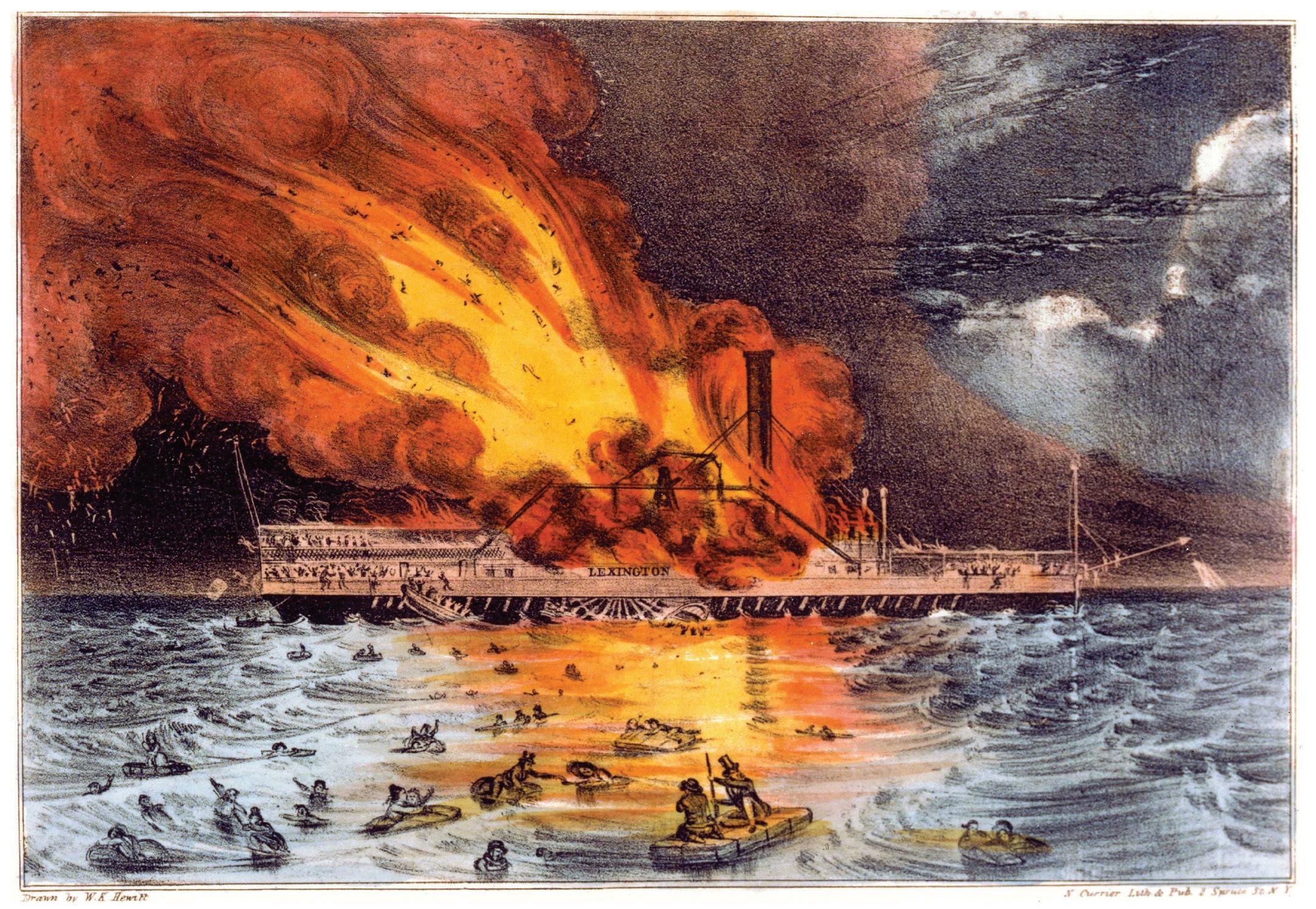

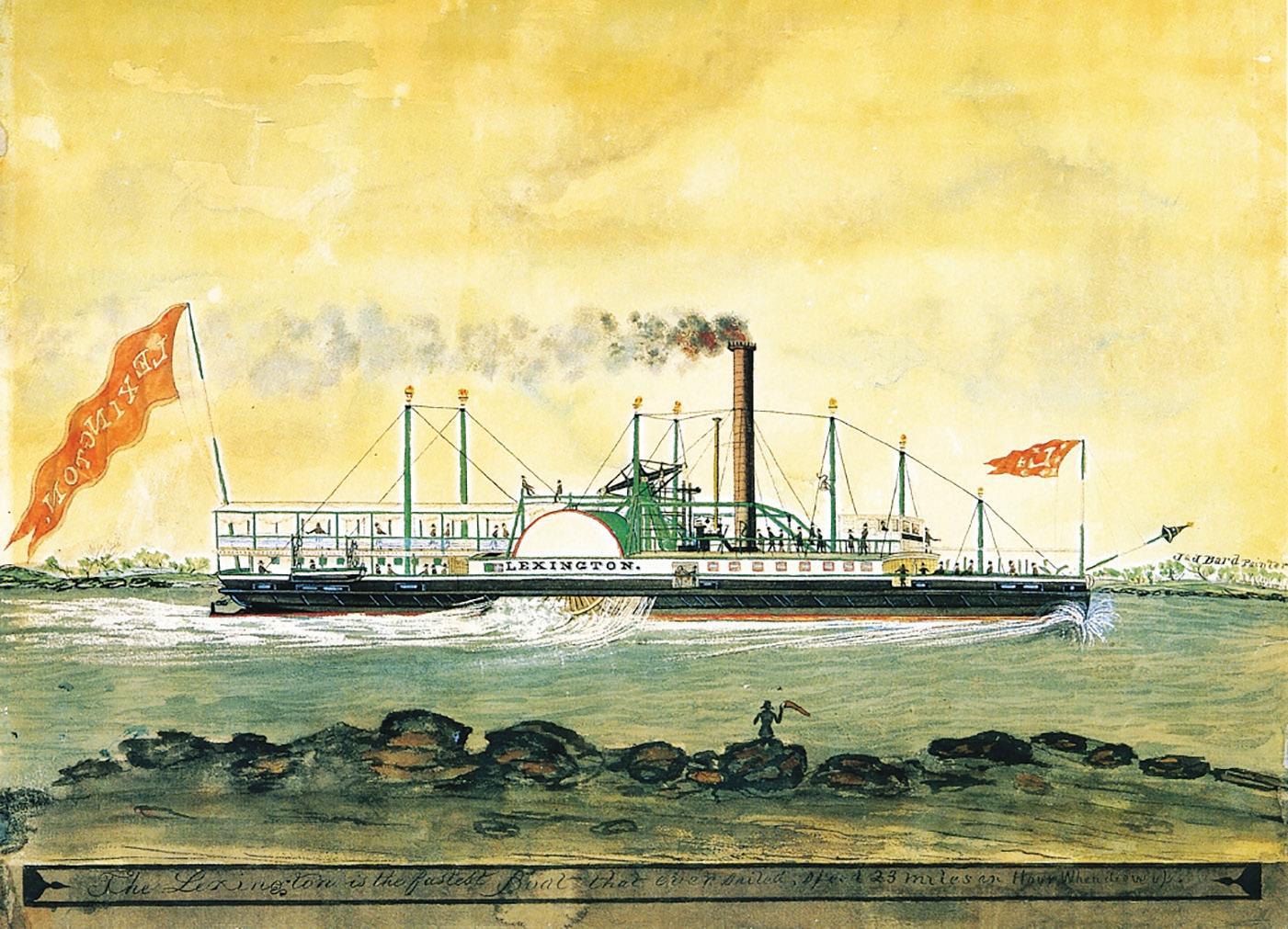

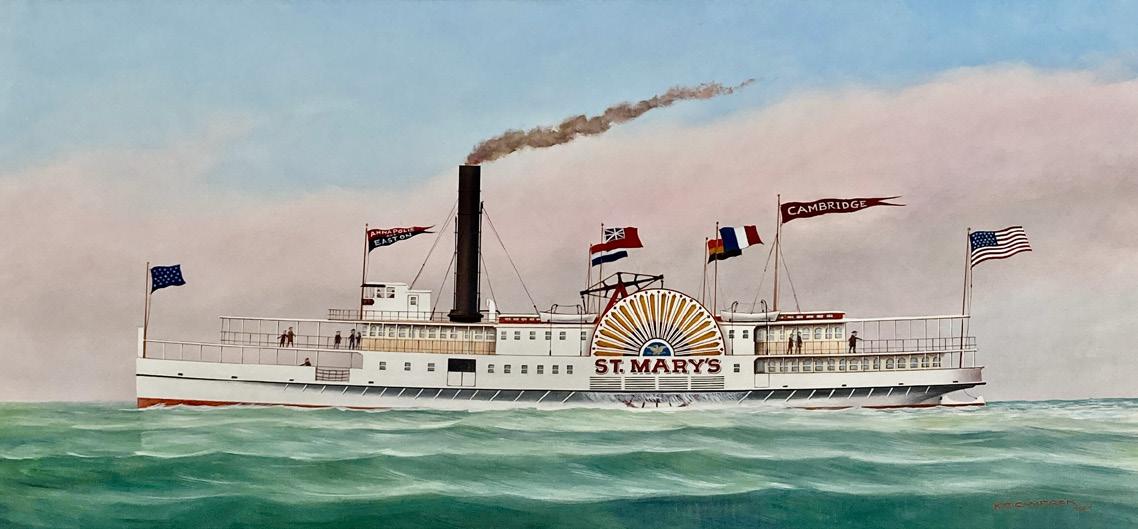

he steamboat Lexington left its Manhattan pier on the bitterly cold afternoon of 13 January 1840 bound for Stonington, Connecticut. It would never arrive. Before the night was over, all but four of the up to 150 people on board would be dead in the worst maritime disaster in the history of Long Island (as most people now think of it—Nassau and Su olk counties). Only a handful of maritime historians and scuba divers, as well as lithograph collectors, have ever heard of the re that consumed and sank the steamboat launched by Cornelius Vanderbilt in 1835, but at the time, the disaster was headline news that captivated and in amed the public.

Steamboat navigation on Long Island Sound began in 1815, and in 1829 35-year-old Cornelius Vanderbilt established his own steamboat company. After initially focusing operations in New York Harbor and on the Hudson River, in 1834 he shifted his attention to the growing market between ports on Long Island Sound.

Vanderbilt, who designed his own steamboats, began construction of a vessel with a unique boxlike latticeworktype hull design rather than the traditional plank on frame. He designed it with an angled deck that was higher amidships than at the bow and stern, based on similar plans he had seen for for a bridge ashore. It would be propelled by a single huge engine that could perform the work of two conventional engines. e interior was lavish and trimmed with teak railings, paneling, and stairways. Vanderbilt decided to name his revolutionary steamboat “Lexington,” after the place where a revolution of a di erent sort had begun.

In building the Lexington, Vanderbilt placed a high priority on safety, which provided a marketing advantage in an age when boiler explosions, res, and other steamboat mishaps were common. e smokestack was encased, as it ran up through multiple decks, and the vessel was equipped with a portable “ re engine” pump with hoses. Two lifeboats were placed near the stern, with a third on the promenade deck.

By the time Lexington was launched into the East River in April 1835, Vanderbilt had spent $75,000—the equivalent of about $2.5 million today—on its construction, but it proved to be an excellent investment.

e steamboat was placed into service on 1 June 1835, with a crew of about 35. On its rst trip, with streamers ying, the vessel covered the 210 miles between New York City and

Providence, Rhode Island, at an average record-setting speed of about 15 knots.

e twelve-hour trip awed travelers, who regularly spent eighteen hours or more on the route.

“FASTEST BOAT IN THE WORLD,” announced the Journal of Commerce

In 1838 Vanderbilt approached his major competitor, New Jersey Steam Navigation and Transportation Company, and threatened that if it did not buy the Lexington, which he now considered too small to operate pro tably, he would initiate a fare war. e company agreed to pay $60,000 for the ship and invested another $12,000 to refurbish it, convert its steam engine from burning wood for fuel to coal, and add blowers to force more air into the reboxes to increase its speed.

Before the ship got underway on 13 January 1840, the crew loaded al-

28 SEA HISTORY 184 | AUTUMN 2023

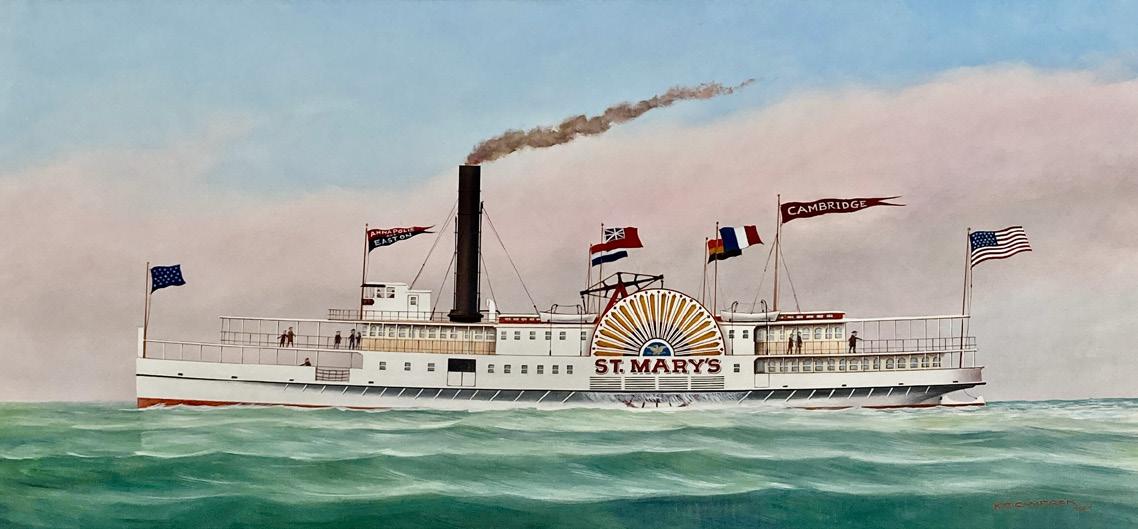

The paddlewheel steamboat Lexington, launched in 1835, began regular service between New York and Providence and was considered the fastest and most luxurious steamer on that run.

WATERCOLOR ON PAPER BY JAMES AND JOHN BARD, P.D. VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

most 150 bales of cotton on the main deck, a cargo that would prove to be a godsend, but ultimately highly controversial. e air temperature was a mere four degrees, and sheets of ice were oating on the Sound.

A crew of 34 ran the boat and took care of passengers, who hailed from as far away as England and included two prominent comedy actors from Boston, Charles Eberle and Henry Finn; Charles Follen, a professor of German literature at Harvard College and a minister; new bride Mary Russell, who had gotten married the day before in New York and was returning to New England

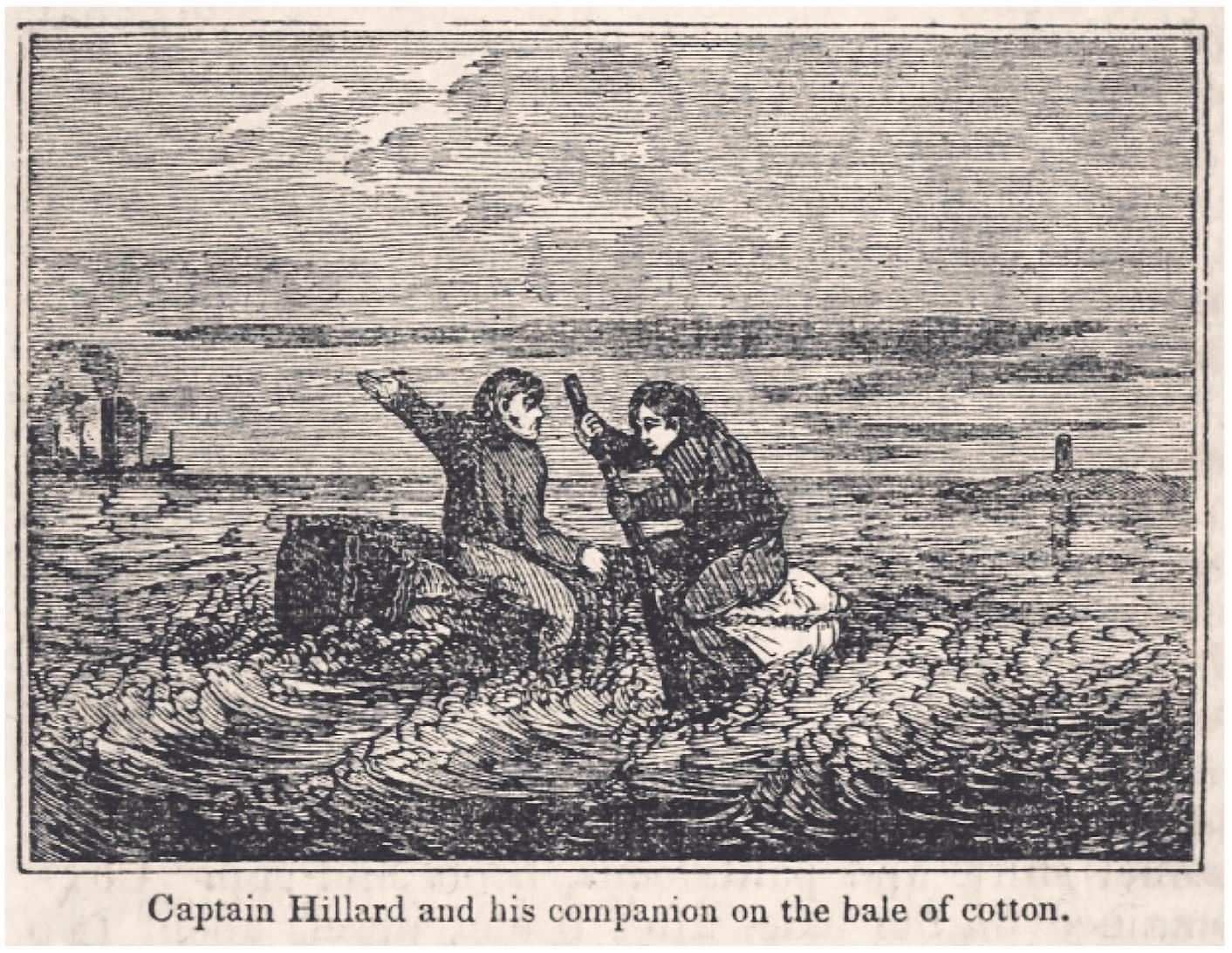

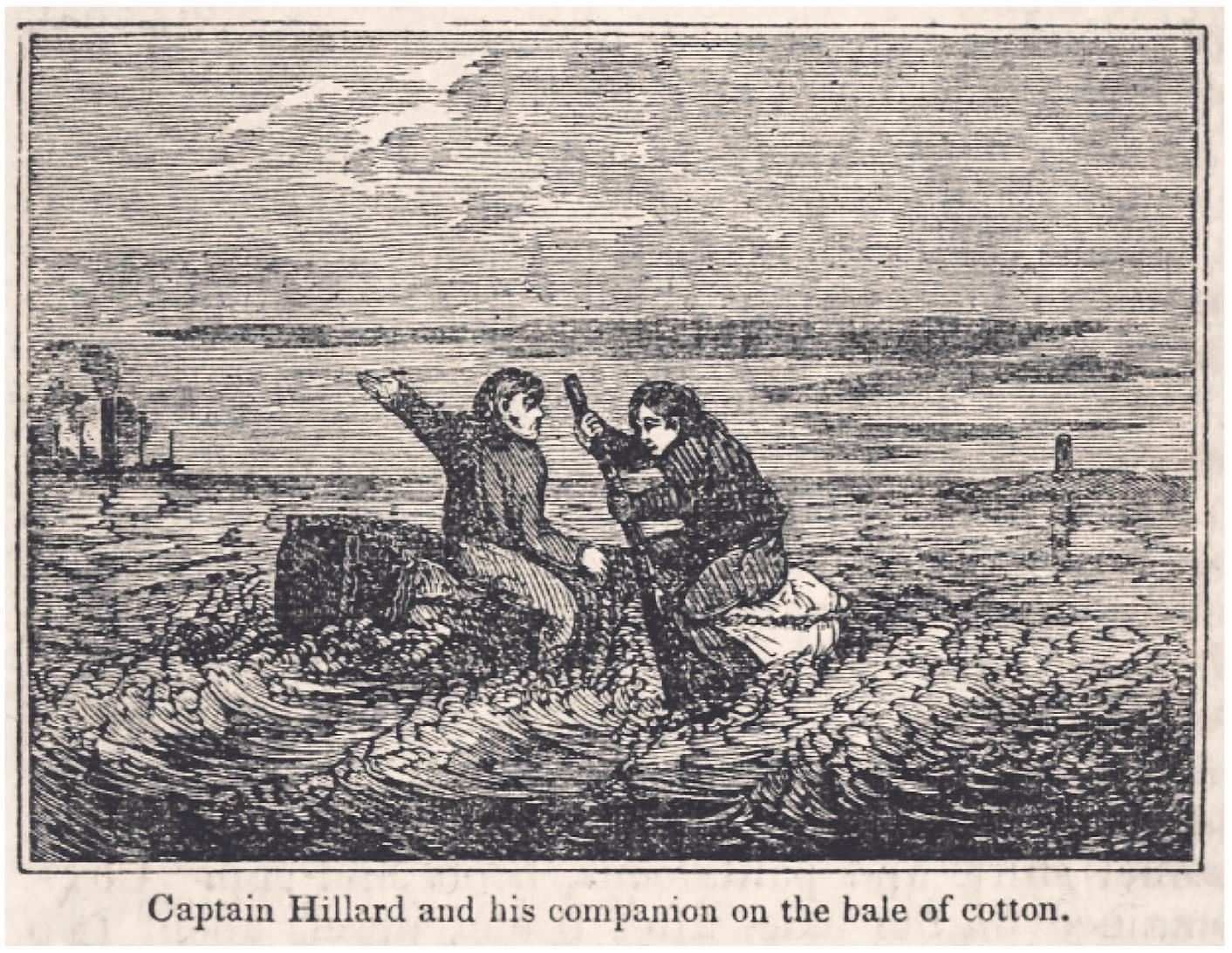

without her new spouse to break the news to her parents. ree members of the family of recently deceased Henry A. Winslow, including his widow, Alice, were accompanying his co n, which was stowed in the hold for burial in Providence. Many were traveling for business. Several ship captains were aboard traveling as passengers, including 24-year-old Chester Hillard, who would play a critical role in the events that followed.

Providence resident Stephen Manchester, the pilot, was navigating on the bridge when the re was discovered about 7:30 pm north of Huntington,

New York. One of three surviving crew members, Manchester testi ed at the inquest a week after the disaster: “Someone came to the wheelhouse door and told me the boat was on re. My rst movement was to step out of the wheelhouse and look aft; saw the upper deck burning all around the smoke pipe.”

Lexington’ s captain, George Child, made his way to the wheelhouse as the emergency was unfolding and joined Manchester, who was directing the helmsman to steer for the nearest point of land—Eatons Neck on Long Island, which he estimated was 20 minutes away at their cruising speed of 11 knots.

SeaHistory.org 29

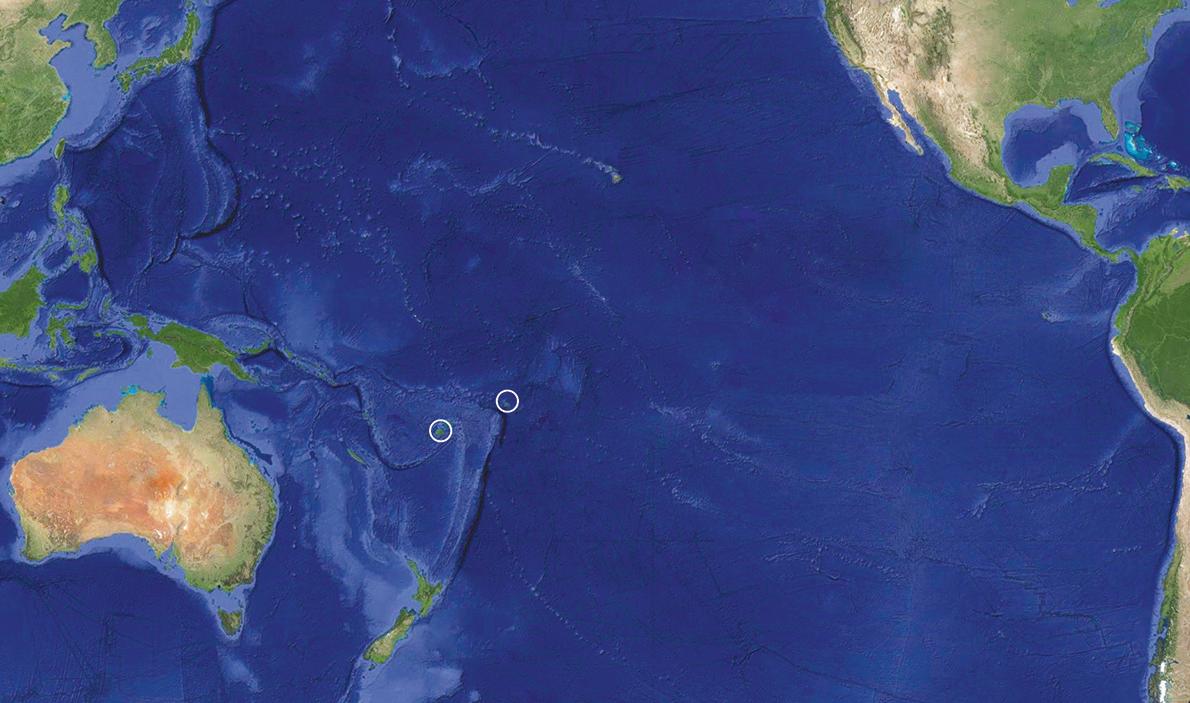

DAVID RUMSEY MAP COLLECTION

Stephen Manchester, serving as the pilot onboard Lexington when the fire broke out, a empted to steer for the closest point of land Eatons Neck on Long Island. With the flames visible from both shores, the captain of a sloop out of Southport, Connecticut, tried to get underway to assist but was, at first, blocked in by ice choking the harbor.

Eaton’s Neck

Southport

“We had not yet headed to the land, when something gave way, which I believe was the tiller rope,” he said. e Lexington had metal steering rods running under the top promenade deck, but the rods were connected on both ends by rawhide ropes, which apparently had burned and parted.

e crew tried to start the re pump, while others began using buckets to throw water on the blaze. One end of the rehose was in the re and unusable, and many of the buckets that were hung above the engine were out of reach because of the ames. To make matters worse, the engineering crew was forced away from the steam engine by the re and could not release the pressure, so the boat plowed ahead at cruising speed until the steam dissipated after about 15 minutes.

Even though the steamboat was still making way, Manchester, Captain Child, and the rest of the crew, assisted by passengers, tried to launch the three lifeboats. But all three boats were swamped and lost because of the forward motion. e passengers and crew who had been trying to launch the boats either drowned or died from exposure in the water.

e towering ames from the burning steamship were visible from the shorelines of Long Island and Connecticut. Men on both shores, including most importantly Captain Oliver Meeker of the sloop Merchant in Southport, Connecticut, tried to head out to assist, but were blocked by ice choking their harbors. Manchester, who was on the foredeck with about 30 passengers and crew, testi ed that they “took the ag-