Eine Frage Der Ehre

A Question of Honour

What Became of the TirpitzWreck?

An Ignominious End to the World’s Most Powerful Warship

The Missing Link

A Tantalising Clue into HMAS Creswell’s Aviation Past

Edition 73 - Sept 2023

The big news this month is the arrival of the longawaited book on the RAN’s A4 Skyhawk, crafted by coauthors David Prest and Peter Greenfield.

I was fortunate enough to receive an early copy of the publication, and, being that it is largely a collection of stories from maintainers and pilots, I’d expected a somewhat dis-jointed account - but not so. Its beautifully put together, with a well-written account of the history of the A4 and its years of service with the FAA holding together many fascinating personal accounts from those who fixed and flew the aircraft.

As I’ve said on page 14 of this magazine, if you only ever buy one copy of an aviation book, this is the one. And its not just for those that were directly involved with the Skyhawk: its pages drip nostalgia about the entire Fleet Air Arm of that era, and of course of life aboard HMAS Melbourne.

The book will officially launch on 01st September and we’ll bring you photos of that auspicious occasion in next month’s FlyBy - but it is available for immediate delivery and you can order a copy by clicking on the button on page 14. The two authors have signed away their royalties to the FAAMuseum, which is a fantastic cause. Last month I threw down a challenge to see if there was anyone who was prepared to put together a book on any of the other aircraft types that the FAA operated. Given that this magazine goes to over 1000 veterans and serving members, I’d hoped for a glimmer of interest but...NIL RETURN! Surely there’s someone out there who is interested in harnessing stories of the Wessex, Iroquois, Tracker or any of the other old birds that

THIS MONTH’S COVER PHOTO

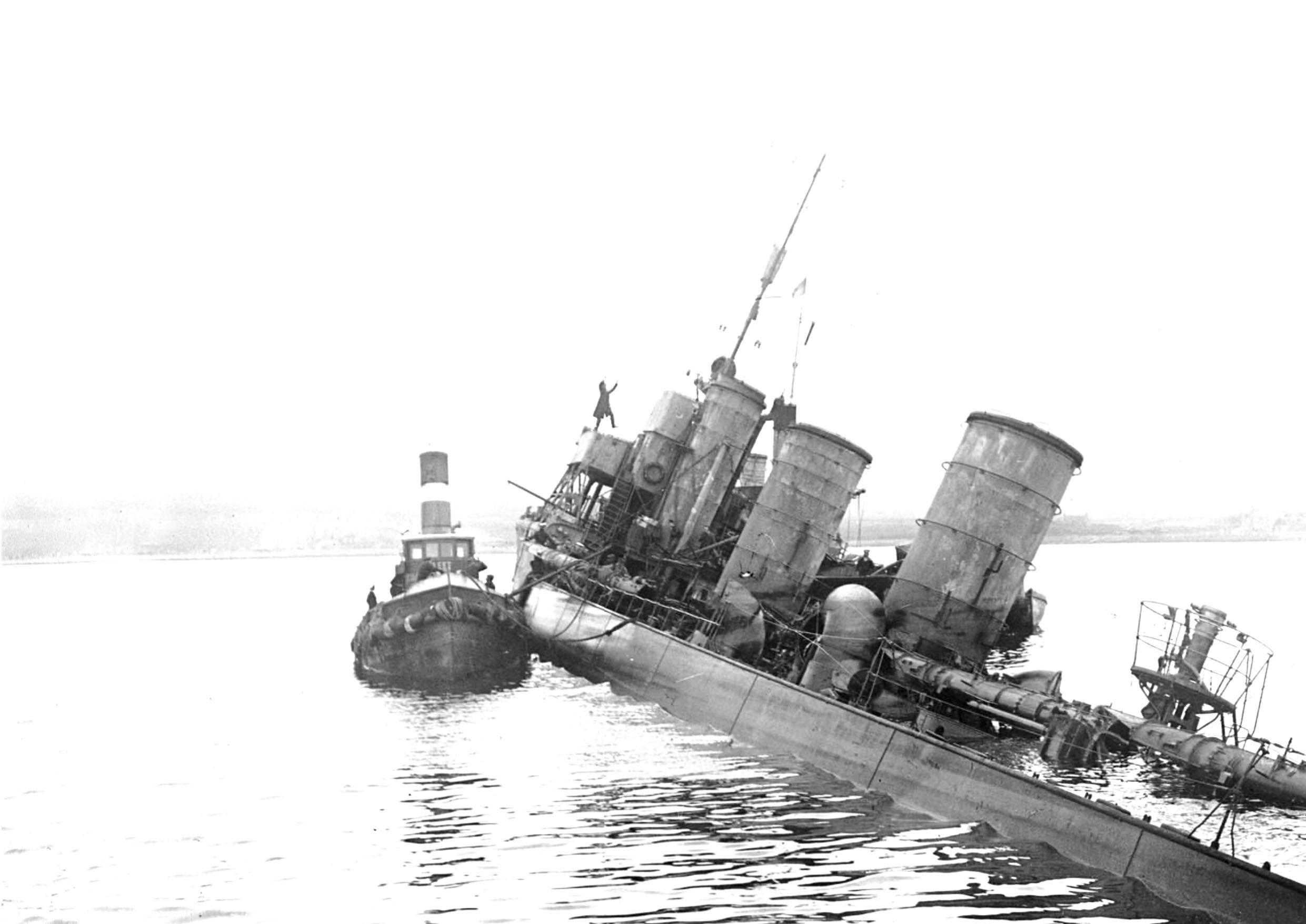

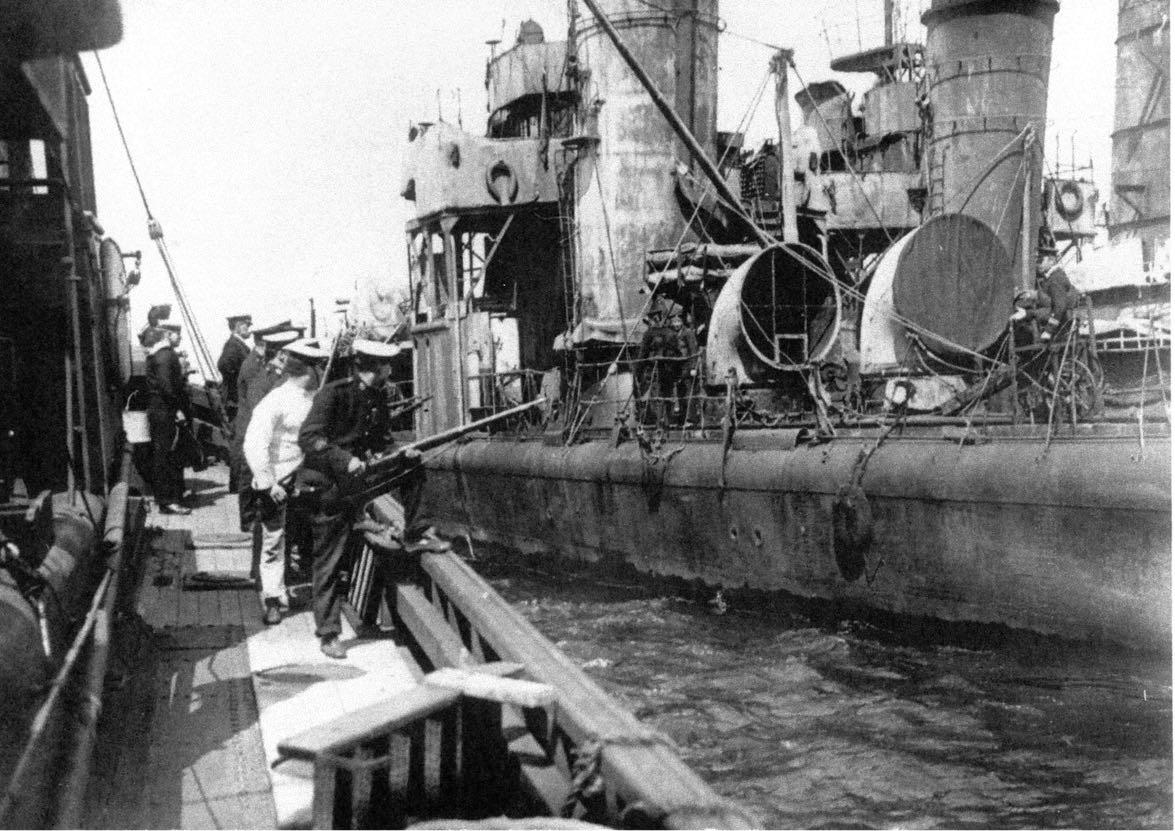

Elements of the German High Fleet and British escort vessels steam westwards towards the Firth of Forth on a grey day in November, 1918. The German High Fleet was to be interred as part of the Armistice ending the First World War.

THIS MONTH IN ‘FLYBY’

we flew or fixed? There would be lots of help and advice, so please don’t be shy. Simply contact me here Next month is the expected date of the Referendum, which will decide if Australians wish to see our Constitution amended to include provision for a “Voice” for Aboriginal people.

In keeping with the policy of this magazine to remain apolitical, I won’t try to suggest which way anyone should vote on the matter. That’s your privilege. But please don’t underestimate the importance of this event. The Constitution may appear to be a boring, dusty old tome but it is our “set of rules”. Simply put, it’s about the governance of this fine nation, the power of the Federal and State governments and how that power is distributed; the roles of executive government and the High Court, and some of the rights of Australian citizens. It is our blueprint for our way of life. And, as with any blueprint, uninformed tinkering carries grave risk. Once a change is made you have to live with the consequences, intended or not (Brexit comes to mind!). So, before you cast your vote, make sure you know exactly what the implications of the proposed change are.

There is a lot of material giving information about The Voice, so I urge you to read/listen widely and only then decide if you will support the motion or not. A good place to start is here, in which Professor Nicholas Aroney explains what the Voice is; and here, in which John Anderson (ex Deputy PM) spends ten minutes dismissing some of the myths surrounding it. I found the latter, in particular, well worth watching. ✈

REST IN PEACE

Since the last edition of FlyBy we have been advised that the following people have Crossed the Bar:

Bruce Lukey, John Mulhall

10 28 23 16

REGULARS

HERITAGE

02 Editorial

A few words and thoughts from the Editor of this magazine.

02 Rest In Peace

We remember those who are no longer with us.

04

Letters to the Editor

This month’s crop of correspondence from our Readers.

08

Jim Bush’s snippets on what you may be entitled to.

10

16

Mystery Photo

Last month’s Mystery answered, and a new one presented for your puzzlement (p21).

21

FAA Wall of Service Update

The status of orders for Wall of Service Plaques.

The Missing Link

An abandoned tunnel at HMAS Creswell gives a tantalising hint of a past Link.

28

Eine Frage Der Ehre

44

Bits and Pieces of Odd and Not-so-odd news and gossip.

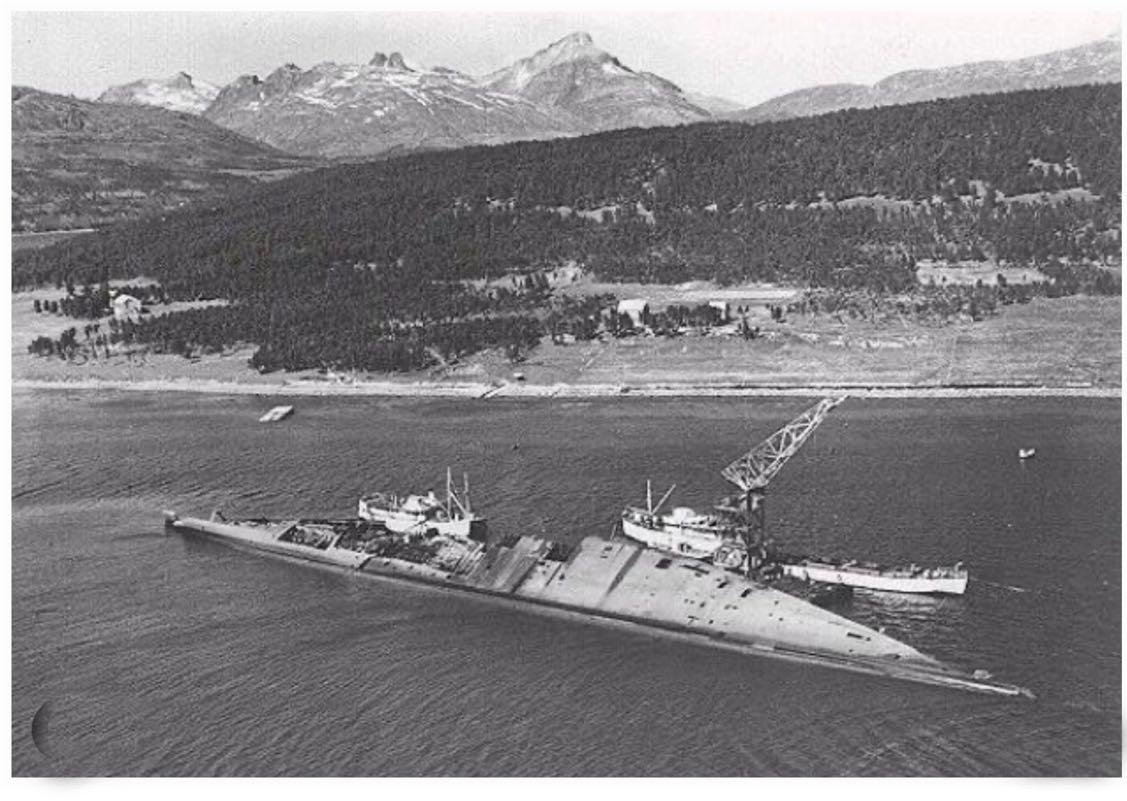

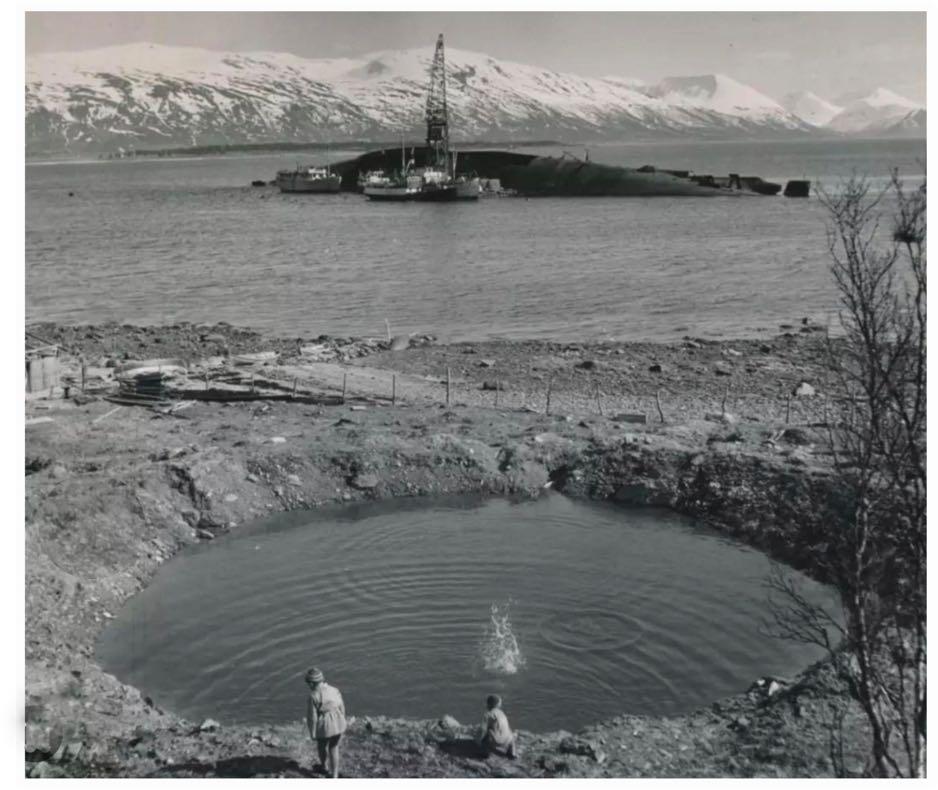

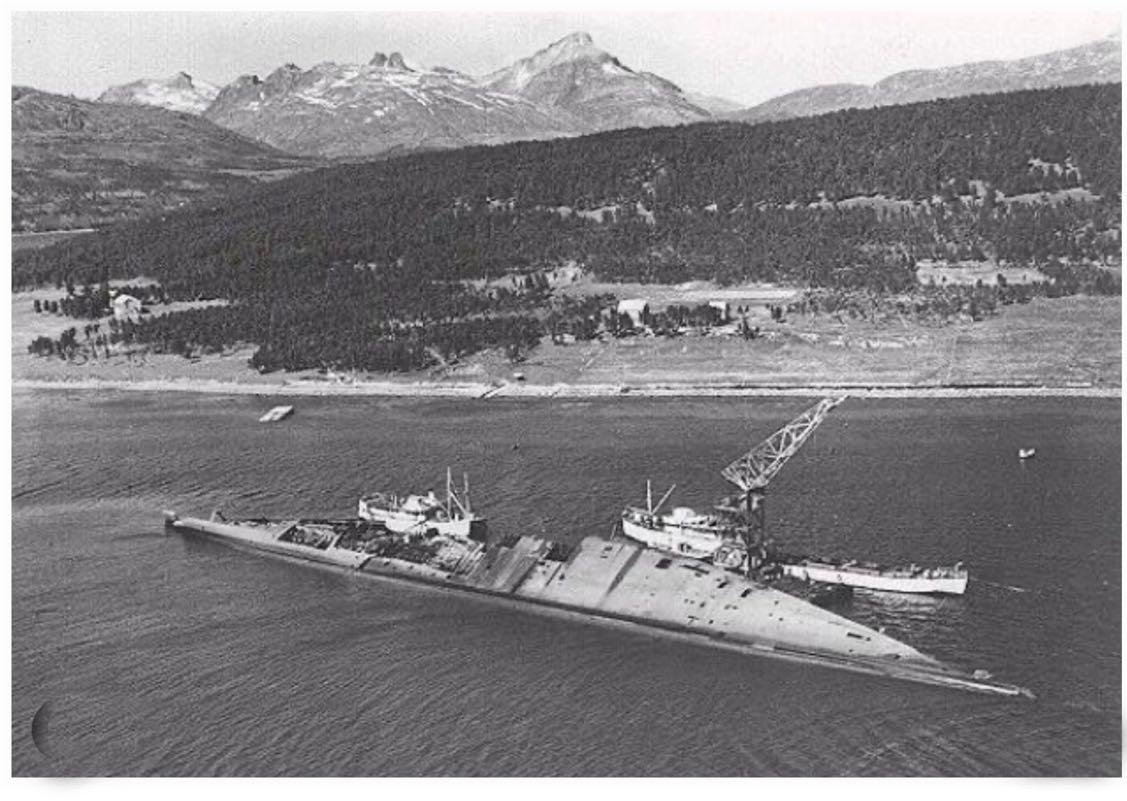

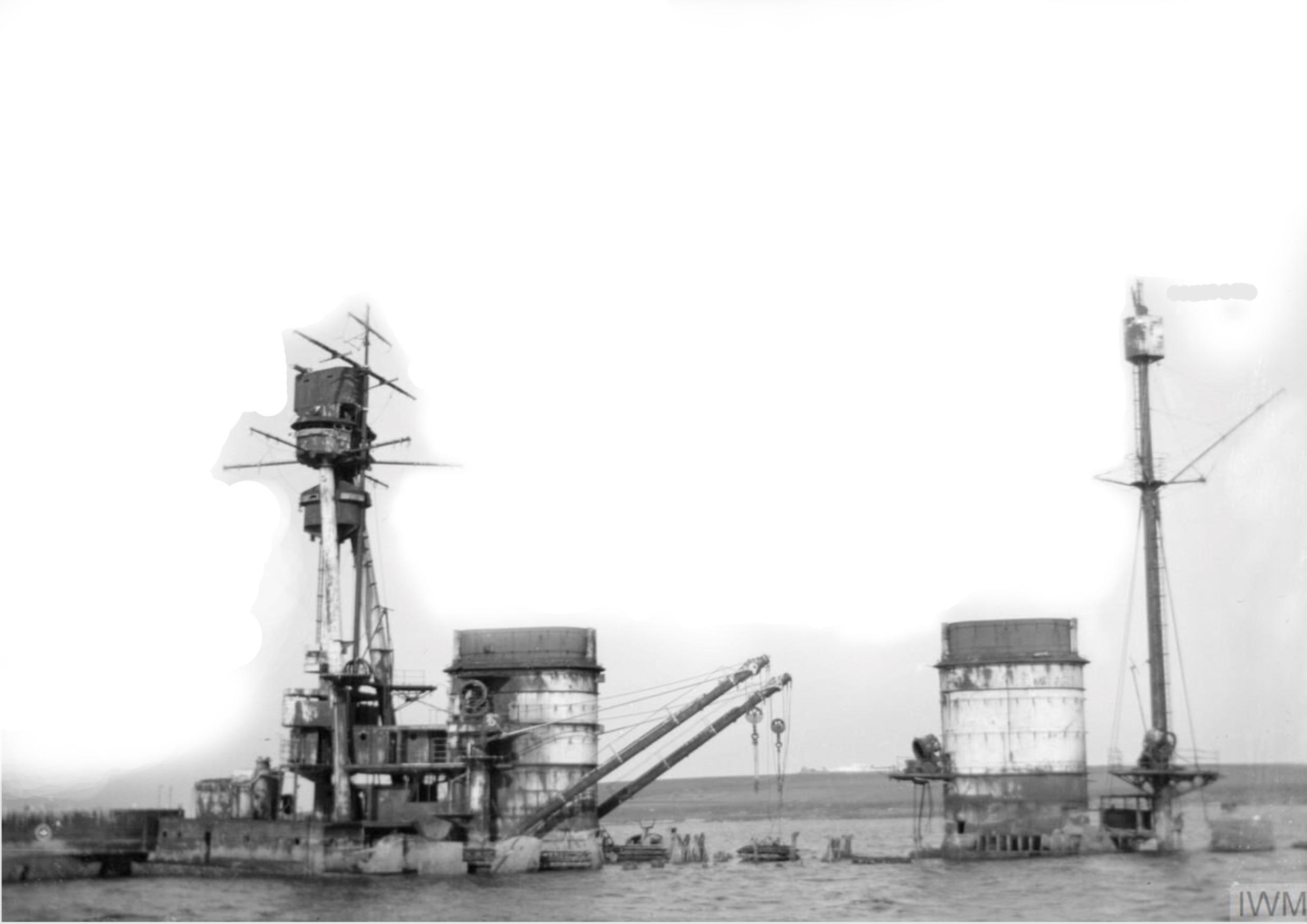

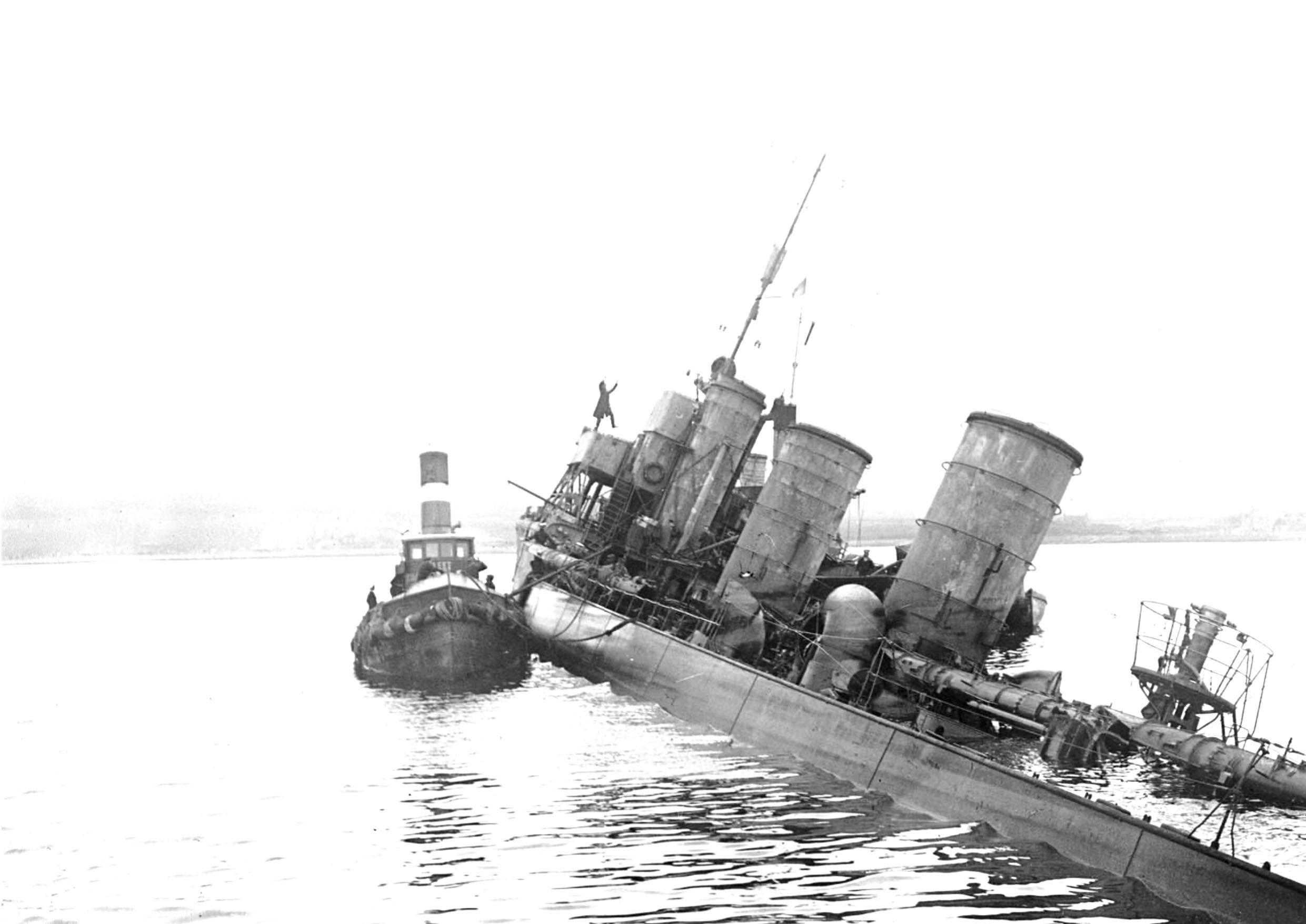

What Became of Tirpitz?

A final look at the fate of the great battleship.

48 Tracker Heritage

We remember the FAA’s S2 Tracker in this updated, re-digitised Heritage piece.

2 3 Editorial Content

Know Your Benefits

A Question of Honour. The extraordinary story of the German High Fleet. FEATURES REGULARS

22 Around The Traps

You can find further details by clicking on the image of the candle. ✈

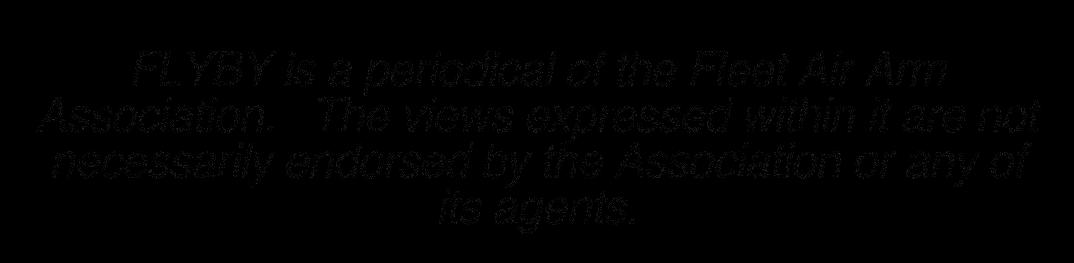

Dear Editor,

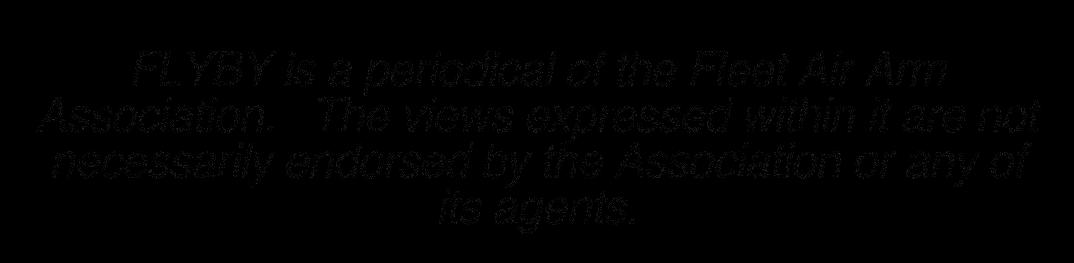

I attended Roger's funeral at Redcliffe yesterday & there was a good turnout of over fifty. Daggers, Gibbo, John Webb, Richard Scott, Bob Luxton & Steve Howlett were ones I knew. Scotto read a Naval eulogy. The service was 1½hrs long so I didn't attend the wake as I only knew five there & wanted to get back to Caloundra before the traffic built up.

I've attached some details of the service below. I'd known Roger for 43 years from when he relieved me in HMAS BARBETTE Oct '80. They stayed with us in Cairns when he first left pussers in ‘91 to work for Coastwatch & were looking for a place to live eventually settling on a lovely house at Stratford. At the risk of being called a pedant I've noticed that many matelots use the term "served on a ship" when the the correct terminology is "served ina ship" as per the Admiralty Manual of Seamanship

Vol 1 page 8 under "TERMS DEFINING POSITION AND DIRECTION IN A SHIP”

"Position in general. A landsman lives in a house, therefore a seaman speaks of living innot ona ship ...."

I'll never forget getting reamed out by the selection board when I got it wrong in answering a question on appearing before them in November 1967! Some time ago I mentioned that someone was looking for a contact for David Anderson amongst the SLEX 1/69 group. I had lunch with Boots Siebert 15 July & he has a contact, if anyone is still looking.

Best wishes & keep up the good work.

Mick Storrs. ✈

Dear Editor, Great Flyby as usual.

They extended the approach to 26 after the 60 Venom crash but it was not until the Venom crash in 63 that they extended the approach further east. There a was also a Caribou crash after the Venom - not sure if before the 2nd extension or after.

I attended Scovelli's funeral service yesterday and it was a very moving experience. There were many unknown tales of Rogers pre service and service life, that most never heard before. He was a young tearaway it seems.

Good turn out with many reunions of long lost mates. The hardest part was recognition...Oh how we have aged!!

Have a good holiday in Fiji. Cold Fiji Bitter is top notch.

Cheers Ball. ✈

Dear Editor, Page 16 of the August Flyby has an erroneous date for the accident Bob Ray witnessed It was 05/06/68 (not 1958), Huey 896 had just delivered Bob to theBeecroft Range when it crashed into the sea killing the crew of LEUT(P) P.C Ward RAN, POACMN D.J Sanderson & SAR diver NAMAE R.K Smith. Aircraft had hit a mound at the bottom of a torque turn and bounced over the cliff edge into the ocean. As an aside Peter was my first Nowra instructor. Had I not had my own car accident not long before it was highly likely that I might have been in the other seat.

Salute Bob, a wonderful individual.

No matter where you are you can't hide - a travellers tale.

Going through passport control with good lady and child at Gatwick airport for a flight to Charlotte, USA on a British Airways Boeing 767, the IRA had bombed Fleet Street that week and armed guards were thick on the ground patrolling the terminal, so it was no surprise the immigration chap was giving us a good seeing to.

On completion and handing passports etc back he asked "Do you know Keith Engelsman?" Well, what could one say, I was inclined to ask why he might think I possibly would, the detail they have on their computer screens makes you wonder.

Upon giving confirmation that indeed I did he said, "When you next see him tell Keith he's a @$#%", all said in a good natured jocular manner, with that he handed over his business card. Keith subsequently visited my place of work in his capacity as CASA test pilot and the verbal message and business card were duly passed. Memory doesn't recall the chaps name or how he knew Keith. Cheers, Brian Abraham. ✈

Dear Editor,

Thanks for the latest ‘FlyBy’ – and as ever full of interest.

Good to see the item about the 03 June 1942 USAA B26 crash at Nowra appearing in the ‘Letters’ page. This and the Captain Robert Ray obituary on page 16 with the link to the fatal Iroquois crash on Beecroft Peninsula, on 05 June 1968, reminded me that the question of wind shear was never raised at the subsequent inquest, despite Lt Cdr Whitton giving evidence that wind was Westerly at 25 knots gusting to 35 knots. No doubt the fact wind shear wasn’t raised is because it wasn’t closely investigated in aviation circles until the 1970s. Yet with wind gusts from 270 degrees the 90-meter cliffs at Beecroft would be an ideal setting for severe turbulence. It’s a bit late now but I’ve always suspected that wind shear at Beecroft was a contributing factor.

Cheers, KimDunstan. ✈

Dear Editor,

It is a pity that the one of the highways in Highway 1 is forever mis-written, by I'm sure, Victorians, as the Princess Highway.

As one who lives nearby to the Princes Highway, I'm sure you will cringe when you spot the error on Pg 32 of last month's FlyBy.

Regards, David Elliston

By Ed. Cringe-worthy indeed, David, and inflicted by a New South Welshman who knows better! Will try harder next time... ✈

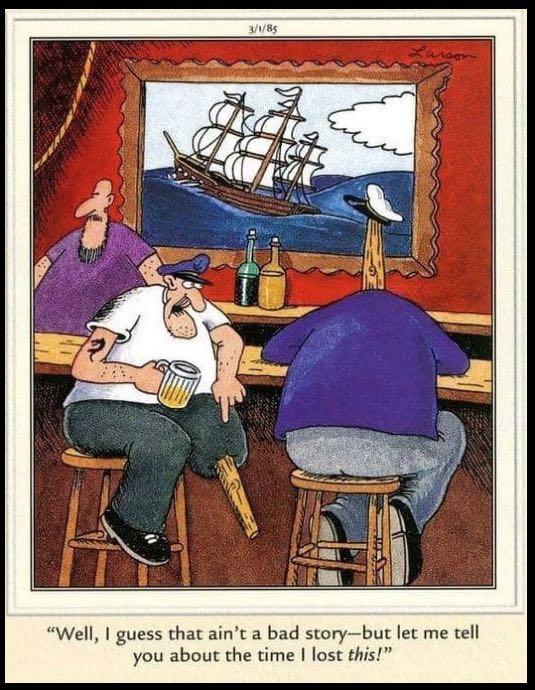

Dear Editor,

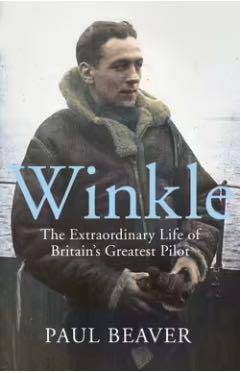

Please can you mention in next month’s FlyBy that there’s a new book out on Winkle Brown. It’s called “Winkle - The Extraordinary Life of Britain’s Greatest Pilot”, and is by Paul Beaver.

Cheers, Robin Spratt.

By Ed. Sure, Robin. See advert to the right. The book is available in all good bookshops, or here. ✈

[Publisher’s Blurb]

Eric 'Winkle' Brown was Britain's greatest pilot. His extraordinary flying career saw him fight in the Battle of Britain, narrowly escape death on a torpedoed aircraft carrier, achieve a litany of new records and firsts as a test pilot, and fly more kinds of aircraft than any other pilot in history.

With a life as remarkable as his flying, Brown faced imprisonment in Germany at the outbreak of WWII, and after theAllied victory his fluent German saw him interviewing senior Nazi officials and participating in the liberation of Belsen - an experience that haunted him for the rest of his life.

A rival to Chuck Yeager and hero to astronaut Neil Armstrong, by the time of his death in 2016 Winkle Brown had become a legend in his own lifetime and a national treasure.

Drawing on Brown's own papers and fascinating new research, Paul Beaver uncovers surprising new truths and incredible achievements in the definitive account of a pilot and man who was revered around the world.

4 5 Letters to the Editor Letters to the Editor

Dear Editor,

Thanks for and congratulations on a terrific newsletter – so much great info every month.

You asked for comment on the pics of three 816 squadron members carrying out rifle practice on the flight deck of the Sydney in 1954, one of whom is said to be me. Not so.

I never served in Sydney and in 1954 was otherwise engaged. Besides, the one said to be me has a better head of hair than I ever had. There was another Observer, Len Anderson, with whom I was often confused. Perhaps that’s him in the pics?

I do well remember Arthur ‘Wacker’ Payne, mentioned in the story – one of the Air Arm’s great characters.

Cheers, Les Anderson.

By Ed. Thanks Les. A case of mistaken identity, it would seem. There were names on the back of the photo but the handwriting was, well, dodgy, so it could well have been an ‘n’rather than ‘s’. Good to get the record straight.✈

Dear Editor,

I’m not a fan of getting tats (chicken!) but I enjoyed the book mentioned in the last edition of Flyby

They were very tame compared to some I had witnessed in my time, but censorship was to be expected.

The best and most elaborate tat I ever saw was of the 'Hunt' starting in the RN sailor’s forward regions, heading over his shoulder, down his back and ending with the fox tail disappearing where the sun don't shine. It was one of ‘Pinkys’, the famous HK tattooist.

One Sunday morning in Honkers a group of us, including a Midshipman (from an overseas Navy) in Vampire’s rugby team, started in the China Fleet Club and ended up in Pinkys.

The poor Mid, who still should remain nameless, was conned into getting a tat on his backside. He elected for a heart - which was embellished with an endorsement surreptitiously suggested by his mates - reading "I LOVE MAL" - Mal being a huge sailor and captain of the rugby team. Little did the Mid know about the addition until he was tabled at a wardroom mess dinner by ‘Mr Vice’ and asked to drop ‘em and please explain the endorsement.

The Mid eventually went on to become Chief of his country’s Navy.

Cheers, Ball

By Ed. Thanks mate. Yes, censorship and PC have taken charge in the tat industry too - but perhaps for the best, being that you’re pretty much stuck for life with what might have seemed funny the night before.

One such example was the first fresh tat I saw when I was a very green Duty Officer in HMS Eagle, back in ‘72. It was on a young sailor who tripped over to fall at my feet when he returned on board after a particularly savage run ashore in Honkers. Across his back was a beautifully rendered (and very large) image of Snoopy sitting on his kennel wearing his fighter pilot goggles, with the (uncensored) words “F*#K YOU RED BARON” in 200 point Helvetica Bold emblazoned above it.

This was before the age of punks, bikies, internet porn and explicit tee shirts, so it had taken an act of brazen courage (mostly from a beer glass) for him to choose that design. I often wonder what his Mum said when he got home. ✈

Dear Editor,

I saw the side bar by Cris George within the article on the torpedo history of NAS Nowra. I have a copy of "Wounded Eagle" by Dr. Peter Ewer and it contains a section on the Rabaul "debacle", so thought I might expand on the response from RAAF HQ. Early in January Squadron Leader Lerew had sent a strike against the Japanese advanced float plane base at Kapingamarangi Island, with poor results. The commander responsible for sending Lerew north (with dummy bullets!) -AVM Burnett - sent 24 Sqdn a message critical of the number of unexploded bombs and threatened to withdraw the unit unless there was an "improvement in the quality of work".

On the 20th January 1942, 24 Squadron (Wirraways) were carrying out routine patrols. IJN carriers Kaga, Akagi, Shokaku and Zuikaku

DO YOU GET PRINTED SLIPSTREAMS?

At the time of going to print, 374 of our members receive their quarterly Slipstream magazine in ‘hard’ copy - that is, printed on paper and sent through the post.

Over 80% of these members have valid email addresses, though, so could receive their magazine electronically. This would save work for our volunteer ‘packers’, reduce printing and postage costs and, of course, would spare a bunch of trees. So, would you consider switching to ‘soft’ copy distribution? It will get emailed to you in ‘flip page’ format, will still be available on the website if you want it, and you can change back to hard copy if you find its not for you. There will always be that option for as long as Slipstream keeps going.

Simply click on the button below to access a request chit, and we’ll do the rest. ✈

Did You Know?

In 2012 the then Chief of Navy, Vice Admiral Ray Griggs AO CSC RAN announced that each Division at the Recruit School at HMAS Cerberus would be named after sailors:

Leading Seaman Ronald “Buck” Taylor, who was killed in action on the 4th of March 1942 in HMAS Yarra.

Leading Seaman Francis Bassett “Dick” Emms, killed in action on the 19th of February 1942 in HMAS Kara Kara, a boom defence vessel in Darwin.

Chief Petty Officer Jonathan “Buck” Rogers, recipient of the George Cross, who perished in the HMAS Voyager disaster on the 10th of February 1964, and

Leading Aircrewman Noel Ervin Shipp, killed in action on 31st May 1969 whilst serving with the second contingent of the Royal Australian Navy Helicopter Flight, Vietnam.

You can read a little about each of these inspiring individuals by clicking on their name. ✈

launched 100+ aircraft on a raid to Rabaul, which included Mitsubishi "Zero" fighters. They arrived over the Australian base at just before noon. The Zeros proceeded to carve up the much inferior Wirraways, and in the space of 10 minutes eight Wirraways were shot down, with the loss of 11Australians killed, wounded or injured out of the 16 airmen that took off.

At the end of the raid, with most of his crews dead of incapacitated, Lerew demanded HQ supply his men with proper fighters. HQ replied that regrettably they had none to send, but sent further gratuitous orders to send "all available aircraft" to attack Japanese ships. Upon inspection Lerew found just one serviceable Hudson.

He then sent the immortal phrase Nos Morituri te Salutimus ("we who are about to die salute you").

For his temerity Lerew was relieved of his command and sent back to Port Moresby. Hope this is of interest.

John (Bomber) Brown ✈

Dear Editor,

Thank you so much for your information about the Board of Inquiry regarding the death of my father, LEUT Peter Arnold. I am more than happy to share some information about what happened to the family after his death.

Following the accident

my mother left Nowra and returned to Perth, where my father’s family lived. Mum moved in with my paternal grandparents, and my brother, Peter James Arnold (named after his father), was born on 15th July 1959. None of the reports mention that mum was pregnant at the time of my father’s death, and I cannot imagine how much harder this made the situation. Mum said that she had gone through the pregnancy and Peter’s birth in a haze. I was too young to remember any of this period.

6 7 Letters to the Editor Letters to the Editor

Peter Arnold’s fatal crash on 30 Jan 1959. You can read more about it here.

that took place on Australia Day, for instance. She was particularly devastated, as Peter had been her younger son. My grandmother was the glue that ensured relationships with my father’s family remained strong.

Tragically, my grandfather died of a heart attack in London in 1962, but still my grandmother came to visit us in England for the summer holidays every two years, and would take me on trips around Europe with her. She based herself at our family home for the period each time. When I had turned 18, in 1974, I made my first solo trip to Perth, the first of many visits.

By Ed. Shortly after the previous letter I received another, forwarded on from Peter Arnold’s sister, Helen. In part of it she said:

“I found the reply from the FAAAA so very compassionate and sympathetic. It is the first time that this awful tragedy and its effects on our family have been acknowledgedand validated to me by anyone from the Navy. I am so grateful for those kind words. They have had a very healing effect on me. Will you please pass my sentiments on to Marcus. with my sincere thanks.” ✈

RSL NSW President Apologises For Treatment of Vietnam Veterans.

We remained in Perth for a further 5 years. Mum worked as a radiographer at Royal Perth Hospital. Had it not been for the pregnancy, she would have returned to England immediately after the accident. During that period in Perth, mum received invitations to Naval events in WA. In early 1963, I believe – at a welcome party for HMS Tiger – she met a British Naval officer, Lt. Cmdr. Keith Bright, who was from Portsmouth, England. In September, 1964, my mother, brother and I left Fremantle and arrived in Southampton in October.

We settled in Plymouth, where my mother’s parents lived, (and where she and Peter had met in 1954) and stayed there until June of the following year. Mum and my stepfather were married in Plymouth on 17th April 1964. We moved to the Portsmouth area that summer. In 1977, when Queen Elizabeth celebrated her Silver Jubilee, my brother and I were invited on board HMAS Melbourne (a ship on which my father had served) for a tour of the ship and lunch in the Mess. We met one officer who had known our father in Nowra, and still have the memories and photos from that visit.

My stepfather, who treated both my brother and I as his own from the first, died in January 2007. My mother passed away on 31st December of the same year. She never really spoke about our father; the memories were just too painful, but she had kept all the photos of their wedding and family time together, along with every newspaper article and photos of his funeral, cards and messages, and shared these with my brother and me when we were in our early teens. I still have them all. Obviously, Peter’s death also had an enormous impact on his parents and siblings. My grandmother would never watch any of the navy fly-pasts

My husband and I married in 1984 and my grandmother was the guest of honour at our wedding in Southampton. Our son, born in 1989, bears James as his second name in memory of my father. Our younger daughter, bears my grandmother’s name, Alice, as her second name, in memory of my grandmother.

All three of our children (and I) are dual Australian, British citizens, and both my son and elder daughter attended university in Melbourne. My son is now living in Toronto, and my daughters in England. My husband and I spent many years in Dubai and retired to Portugal in 2017. I visited Perth for my aunt’s 80th birthday in 2018 and am still in regular contact with my cousins.

My brother, some years ago, visited the Fleet Air Arm museum and brought back photos of the roll of honour. I am hoping we will visit again next year. One interesting fact that I do not think was made public is that on the day of the accident, my father’s cousin by marriage, who worked for Qantas, was in the tower at Bankstown. He passed away several years ago and no one in the family felt comfortable asking him what he heard, but he most definitely did hear what was going on and we believe there was some direct communication with my father. It was said that he could have possibly parachuted from the plane, but chose to stay in the cockpit and fly towards the river, as it was Australia Day weekend and he was flying over a populated area.

We, therefore, have always seen him not only as a parent who died in a tragic (and unnecessary) accident, but a hero who deserves to be recognised for his selflessness.

I hope you find this of interest and thank you so much for taking the time and effort to reply and to send the documents to me. I have shared these with my brother and also my cousin in Perth. With kind regards, Lyn Soppelsa (nee Arnold).

Occupational Therapy

DVA may cover the cost for Occupational Therapy (OT) treatment services for eligible veterans and beneficiaries to provide more comfort in work and every day activities. Some methods an occupational therapist may use include home or workplace modifications, mental and/or mobility exercises or mental health treatment.

Holders of a Veteran Gold Card may receive OT treatment for an assessed clinical need. Holders of a Veteran White Card may receive treatment for an accepted condition covered by their card.

The OT services, eligibility requirements and procedures for access are set out in the DVA web page information sheet and may be read here ✈

Obituaries

Sometimes its hard to find information about our departed shipmates. If you read an Obituary on our website that you think needs more (or is missing altogether), please contact the Editor here ✈

The president of the New South Wales Returned and Services League (RSL), Mr Ray James, has made a formal apology to veterans who were ostracised by the organisation on returning from the Vietnam War.

Mr James,who is himself a Vietnam War veteran, said their sub-branch or club rejected many who fought in the conflict as the feeling was they didn't fight in "a real war".

Speaking ahead of Vietnam Veteran's Day on 11 August 2023, which marks 50 years since Australia withdrew from the war, Mr James says he wants to acknowledge the organisation’s past mistakes publicly.

"I didn't experience that personally … however, I know that a lot of my fellow Vietnam veterans were refused entry to join the RSL movement," he said.

"Over many years, that has hurt some of our veterans

"I've decided now, as the RSL NSW president, to say sorry to my fellow Vietnam veterans."

Mr James said not everyone who fought in the conflict was mistreated, but many of those who were have remained hurt by it today.

He says 4,800 Vietnam veterans have signed up to the RSL in NSW, but more than 8,000are still not members.

"We've got to move on and move forward from what happened," Mr James said.

There has been a somewhat mixed reaction to the apology from veterans, with some acknowledging that it was a genuine attempt to move on, whilst others regarded it as a ‘political stunt.’

One, who marched in Liverpool in the 1970s remembers how his troop was pelted with coins and beer. “The RSL didn’t support us then,” he said, “so what’s changed now?”. ✈

8 9 Letters to the Editor

(Photo: NSW RSL)© Provided by ABC News (AU)

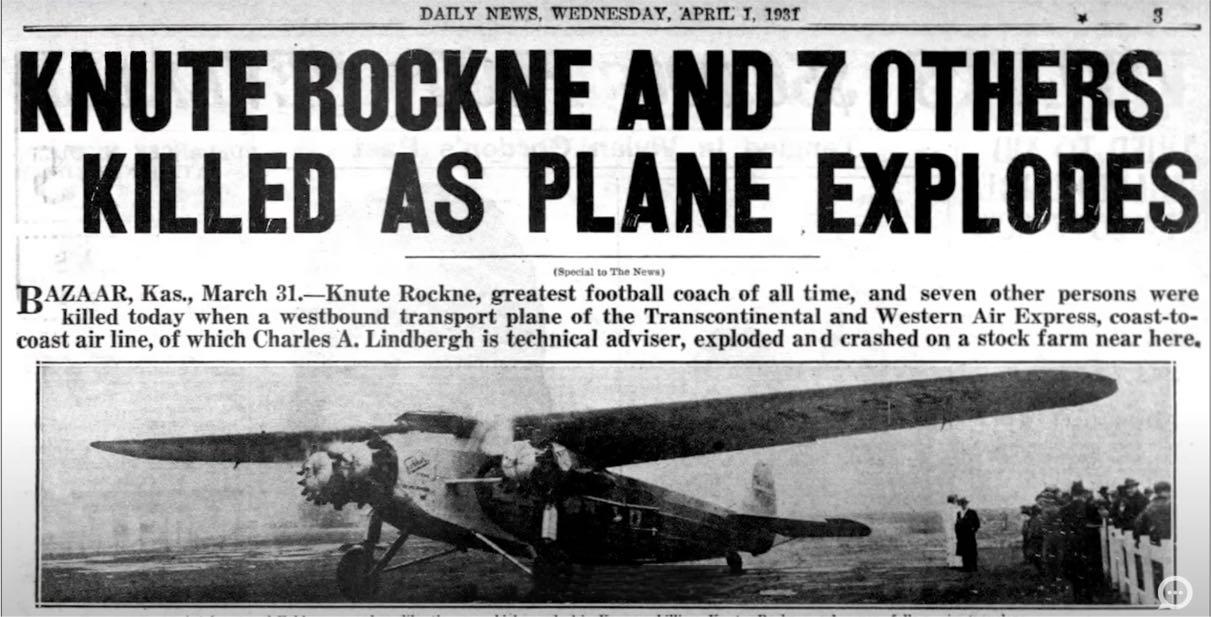

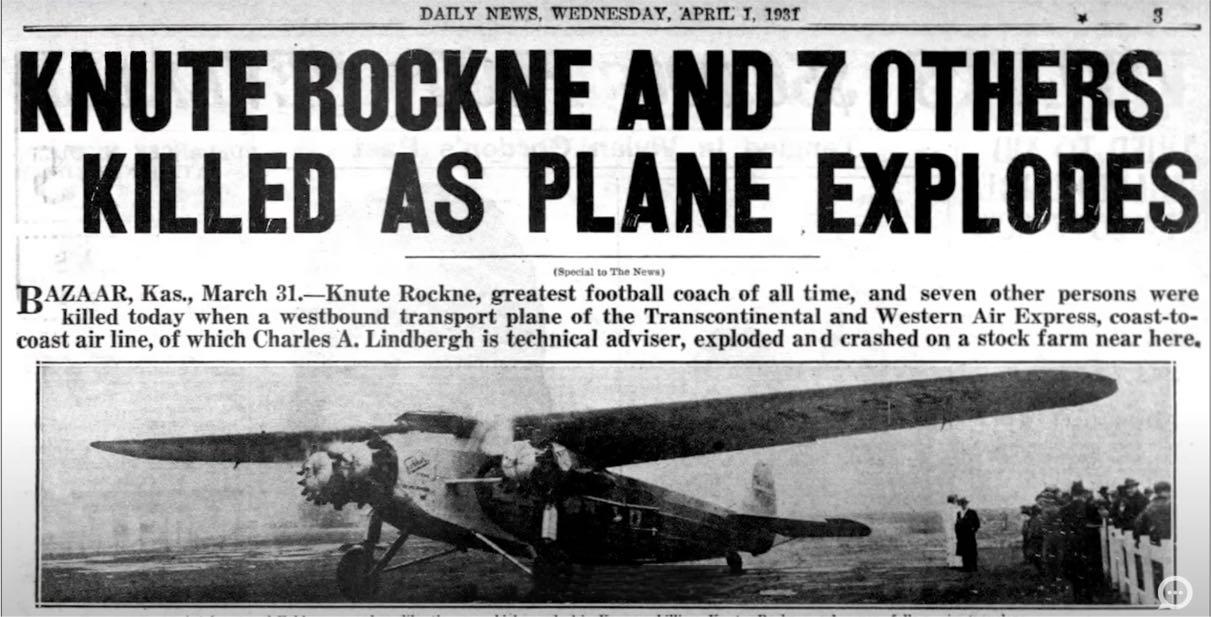

Last month we printed a photo of a Fokker F-10 which crashed in 1931 killing all eight people aboard. We asked what had caused the accident and how it was to lead to the introduction of an aviation legend.

ANSWER

TO LAST MONTH’S

MYSTERY PHOTO

craft design, manufacturing, operation, inspection, maintenance, regulation and crash investigation that was ultimately to transform airline travel from one of the most dangerous forms of transport to one of the safest.

An immediate outcome was the grounding of the Fokkers and the imposition of very stringent regulations on the use of wood as a structural material in aviation. In one stroke this rendered wooden aircraft obsolete, and drove an urgent requirement for more modern replacements.

TWA , with its fleet of Fokkers suddenly inoperative, turned initially to Boeing. The manufacturer had developed a new all-metal craft designated the 247 - a sleek design which could carry 12 passengers. This was two less than the Fokker, which was a disadvantage, but in all other respects the 247 was perfect for TWA.

❛

The outcry over the accident triggered sweeping changes to aircraft design, manufacturing, operation, inspection, maintenance, regulation and crash investigation that was ultimately to transform airline travel from one of the most dangerous forms of transport to one of the safest.

Air Travel in 1930

On 31 March 1931, a Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA) Fokker F-10 Tri Motor crashed in Dakota, killing the eight people aboard. It was determined that a possible cause of the crash was delamination of the main spar due to water ingress.

The crash was particularly noteworthy as one of the passengers was Knute Rockne, arguably the greatest US football coach of the time.

Rockne’s death triggered a national outpouring of grief. President Hoover called his death ‘a national loss’, and more than 100,000 people lined the route of his funeral procession. The outcry over the accident triggered sweeping changes to air-

But in those days Boeing was part of a consortium which included what was to become United Airways. The manufacturer told TWA that, should it wish to buy any of its 247s, it would have to wait until United’s order for 60 aircraft had been filled.

TWA was not inclined to do that. In 1932 it issued an invitation to a number of other manufacturers inviting them to bid for an order for a new commercial aircraft which, it said, should be of allmetal wings and structural members, have retractable landing gear and three engines so that it could remain in flight should one of them fail.

The Douglas Aircraft Company was interested in the tender, although it worried that there would be insufficient orders to meet the 100 aircraft breakeven figure. Further, the company didn’t have any experience making commercial aircraft, since its production was exclusively for the military.

Nevertheless, within a fortnight of receiving TWA’s letter, Douglas submitted a design for an all-metal, low wing, twin engine aircraft that would carry 12 passengers, two pilots and a flight attendant. The company gave the new design the moniker DC-1 - the ‘DC’ standing for “Douglas Commercial”.

Although improvements in aircraft design brought such innovations as a fully enclosed passenger cabin, air travel in the late 20s/ early 30s was far from safe.

In fact, 1929 was the most crash-ridden in aviation history, with 29 fatal accidents reported. The overall accident rate was about one per million miles flown, which would equate to about 7000 fatal accidents per year if converted to today’s figures.

Passengers would frequently make a will before travelling. They would then put up with uncomfortable, noisy and unreliable aircraft, fitted with few navigation aids. Aircraft were unpressurised, so flights were either through or around bad weather. Every accident like the TWA Fokker in ‘31 reinforced the perception that air travel was extremely dangerous. But better aircraft design and stringent governance rapidly improved the situation. By the late 30s the accident rate was about onetenth of its 28-29 level. Within another 20 years it was one-tenth of that. Since 1997 the rate has been at or below one in 2 billion miles flown.

❜

10

11

The Birth of a Legend

backwards. Once fixed (and the design changed to ensure the error could not be repeated) the engines performed normally.

Douglas accepted the aircraft with a few modifications, including more powerful engines and an increase to 14 passengers. This production aircraft was designated the DC-2.

TWA ordered twenty DC-2s, the first of 130 civilian orders over the life of type. No doubt it would have been more but for the insistence of American Airlines CEO, C.R. Smith, who demanded a sleeper aircraft based on the DC-2 design. The result was the DC-3, with a wider cabin, more powerful engines, longer range and 21 seats (or 14 sleeper berths).

The first and only DC-1 was rolled out in June 1933. It then performed more than 200 test and evaluation flights, to show that it exceeded TWA’s specification in every regard, even with only two engines. The flights demonstrated its superiority over the most common airliners of the time, and it set a trans-America record of 13 hours and 5 minutes.

It hadn’t been all roses, however. On its very first flight both engines lost power before spluttering back to life. The same problem occurred several times before Douglas engineers discovered the carburettors had been installed

The one-off prototype DC-1, having done its job, was sold to Lord Forbes in the UK in 1938, who operated it for a few months. It was then employed by two Spanish airlines before it crashed in Spain in December 1940, following an engine failure shortly after take off. The Captain elected to land straight-ahead, wheels up, and the aircraft sustained damage beyond repair.

The sleeping-berth option wasn’t a success but the DC-3 airframe was an immediate hit. Over 600 civilian hulls were built, some under licence overseas, and military variants brought that total to over 16,000.

The DC 3 popularised air travel not only in America, but across the world. For the first time passengers had the opportunity to enjoy a much safer, relatively quiet and comfortable journey which was affordable.

Following WW2 the world was awash with surplus C47s (the military designation for the DC3) and, with the global aviation industry booming, many airlines and start-up operators took advantage. The faithful “Dak’ could be found everywhere: from reputable airlines such as Qantas and BOAC, to somewhat less particular outfits doing nefarious business in countries like South America and Africa.

Today, the venerable DC3 is still flying, although its numbers have been much reduced by regulatory governance. None are operating scheduled passenger flights, but the old birds still perform charter and freight duties, or perhaps just take to the air for enthusiasts. In only another decade, they will have graced our skies for a hundred years. Isn’t that, truly, the definition of ‘legendary’? ✈

12 13 Mystery Photo Answer Mystery Photo Answer

❛

The only thing that can replace a DC-3 is another DC -3.❜

Old pilot’s saying.

The long-awaited book on the RAN’s Skyhawks has arrived and is available for immediate purchase. Filled with first-hand accounts on the fixing and flying of this iconic aircraft and its service aboard HMAS Melbourne, it is a must-read for anyone who served in the RAN during that period.

“The aircraft continued to descend downwind and then erupted into a huge fireball as it ploughed into the ground a few miles south of the field. I’d never witnessed an aircraft crash and all I could think was ‘How could I have saved that aircraft?’ I know, a stupid thought, but here was this beautiful TA-4 gracefully gliding to its inevitable demise right in front of my eyes...”

“...such was the enthusiasm of the people carrying the stretcher I was dropped a number of times before reaching the lift...”

“...and then something caught my attention. I heard the hydraulic power rig start and thought “No, they wouldn’t do that, they know I’m in here.’ Soon after I heard the distinctive noise of the rig valves being operated to supply pressure to the aircraft. I yelled out, ‘NO, HEY, I’m in here!’ as I frantically tried to wrestle and wriggle myself out of the rear fuselage. Too late, the open hoses started spurting hydraulic oil all over me....”

“...he then said ‘follow me’ and led us down to the round-down. There he indicated two deep, newly painted gouges in the flight deck. These, he told us, were made by the wheels of a Skyhawk that had a ramp strike two nights ago. ‘Gentlemen,’ he said, ‘you do not want to be pilots!’ I kept my mouth shut, but I really wanted to be one now...”

“...Tom had flown A-4s in Vietnam and he showed me a photo he took over North Vietnam. He heard an audio warning that a surface-to-air missile radar had locked onto him, so he grabbed his camera, took a photo of the missile coming straight up at him, then carried out out a missile break. I was very impressed by his unflappable nature....”

“To move the engine, approximately 1,300 kg including the weight of its trolley, to the aircraft was a significant task and not for the faint of heart. There was just not sufficient space to simply push the trolley from C hangar, so a circuitous path had to be taken ...from C hangar, up the aft lift, forward along the pitching and rolling deck and then down the forward lift....”

“If you only ever buy one book on the Fleet Air Arm, this is it. It’s a smorgasbord of memories, stories and historical fact”

14 15 Advertisement

The Missing Link

Hidden away in a building at HMAS Creswell is a fascinating hint of something from its aviation past.

Cris George looks at the story.

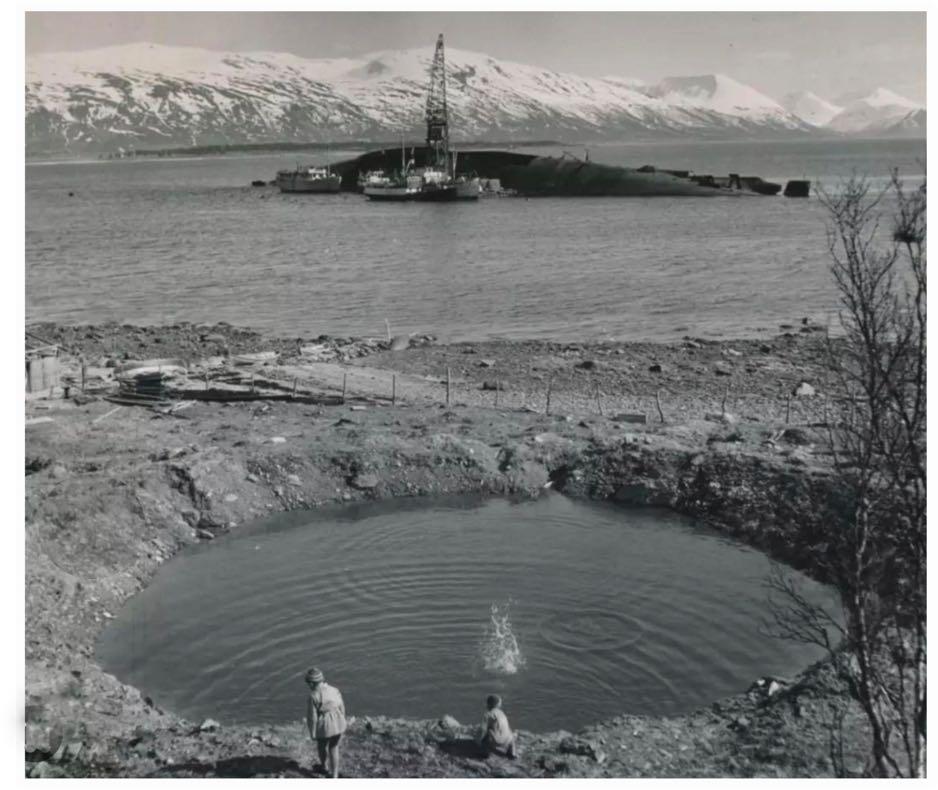

LCDR David Jones, HMAS Creswell’s Museum Officer, had long been puzzled by the circular markings and what looked like the entry and exit of a short filled-in tunnel in the concrete slab of the building known as the “Link Trainer site”, located on the right side of the road about 50 metres in from the Gangway at Creswell.

There is little mystery about a Link Trainer being situated at Creswell which was part of RAAF Nowra during WW2 before it was partially handed over to the Royal Navy’s British Pacific Fleet in late 1944 and given back to Defence in 1947.

During WW2 RAAF’s 6 Operational Training Unit (OTU) operated from both RAAF Nowra’s (now Albatross) and Jervis Bay Airfield. 6 OTU trained crews flying the Beaufort in the antishipping torpedo role with the USN’s Mark 13 and British Mk XII torpedoes.

The Link Trainer was named after its inventor and developer Edwin Link of US Link Organ and Piano Company and it was the standard instrument flying trainer present at most RAF and many Commonwealth air bases during WW2 and much later to provide for realistic training without the expense and risk of using real aircraft.

The generic Link Trainer of WW2 was often called the “Blue Box” (it was often painted blue) and was fitted with a standard set of flight instruments which were operated either mechanically or by vacuum. Able to rotate through 360º, a magnetic compass was installed to provide heading reference.

The simulated course flown was recorded and traced by an external course plotter (called the "crab") across paper, or a map on the instructor's desk who also had an instrument panel synchronised with the panel in the Trainer's cockpit.

The trainer, which had the appearance of a small stub-winged aircraft was suspended on a universal joint and free to rotate through 360º in azimuth and to pitch and roll plus and minus 30º. Its movement was initiated by the student pilot whose control column movements were translated into the inflation and deflation of air bellows which then moved the trainer to provide the selected attitude and the "feel" of flying. Turbulent flying conditions could be set by the instructor. And the trainer could apparently simulate stalls and spins when recorded airspeed and attitude moved outside pre-set values. In the 1930s the first Link Trainers

were delivered to the RAF and shortly after the RAAF. The Link Company claims to have assisted with the training of some 500,000 pilots during WW2.

An Office of Air Force History paper titled “Flight Simulators in the RAAF” records the following anecdote provided by a contemporary client of a Link Trainer.

“They were the major pilot training machine, certainly at Wagga and Temora and places like that. All had Link Trainers and you did not get in an aeroplane until you passed your Link training course. And anyway they were very important for pilot training but they were certainly the first simulator and they did a very good job too...The students were just too keen to line up to go flying. Anyway the Link Trainers were undoubtedly used as an aptitude testing tool for selecting candidates for pilot training as well.”

The authoritative website ADF-Serials has a section on Link Trainers which records that a Link Trainer was allocated to 6 OTU at Jervis Bay on the 7th October 1943 and then returned to storage on 13th March 1944, presumably as torpedo training at Jervis Bay reduced and 6 OTU disbanded.

The Serials website also records the allocation of Link Trainers to Navy at Jervis Bay on 21st January 1945 and 12th July 1945. Either this identification of the receiving unit as “RAN” is a misprint or the RAN was acting on behalf of the RN who by this time occupied the Nowra and Jervis Bay airfields (HMS Nabbington and Nabswick respectively-although the latter did not Commission until April of 1945). The RN’s Link Trainers were disposed of in June 1947, about a year after departure of the RN.

No mention of Link Trainer use at Nowra and/or Jervis has been found in relevant RN and RAAF archives but that is unsurprising as Link Trainer time flown for flying practice, rather than as part of a formal flying training syllabus, is not known to have been logged. They were, however, considered a valuable training aid although perhaps not always appealing to the younger aircrew set.

Research by Dave Jones found that a 1958 electrical plan of Creswell named the Link Trainer site as the “Kraille Trainer” but this was a misspelling of “Crail”. Further investigation found the trainer’s name was taken from a Royal Navy airfield (HMS Jackdaw) in Scotland, where on the instruction of RN, a visual Torpedo Attack Trainer (TAT) had been developed by the movie and theatrical lighting industry to train RN torpedo bomber crews. Crail trainers were built later at other locations to provide training for aircrew but also submarine and Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) crews in torpedo attack.

The Link Trainer

Ed Link was an innovator with a passion for flying. Born in Indiana (USA) in 1904, he took his first flying lesson at 16. Seven years later he took delivery of the first Cessna ever produced, which he used to eke out a living as a Barnstorming pilot.

He used apparatus from his father’s automatic piano factory to control sequential lights on the lower wing surfaces to spell out messages advertising shoes and other produce. To attract more attention he also added a small but loud set of organ pipes. These early inventions were the genesis of his later work to produce the world’s first simulator.

The expense of flying prompted him to channel his inventive streak into a flight simulation. His first model, the “Pilot Maker” was first manufactured in 1929. It was a fuselage shaped device that produced the motions and sensation of flying.

Easier said than done. Underneath the trainer was a vacuum pump which, through complicated sets of bellows, caused the fuselage to move in roll, pitch and yaw. A full set of Flight Instruments also relied on the vacuum pump, together with a Telegon oscillator to provide an electrical reference signal, and a wind drift analog computer. Outside the device was the instructor’s desk which contained a duplicate set of flight instruments and a motorised ink marker recorder, also known as ‘The Crab’, to plot the pilot’s track. Link was granted a patent in 1930 but his company struggled though the Depression. His big break came in 1934 when the Army Air Corps expressed interest in buying the trainer to the instrument flying skills of its pilots. Link, in a demonstration far more eloquent than words, flew into the meeting in fog so thick that the Air Corps evaluation team considered it unflyable. He sold six units in June of that year for $3,500 each, followed by more sales. The Link company claimed to have contributed to the training of 500,000 pilots during WW2 (including those of both sides).

After gaining the Air Corps contract his business expanded rapidly and tens of thousands of units were sold during WW2. His company is now a part of CAE Inc, which is engaged in the multi-billion dollar simulation industry. ✈

16 17 Historical Interest

Link Trainer at the Western Canada Aviation Museum

The Crail Torpedo Attack Trainer

Following the success of the Link as a procedural trainer, it didn’t take long for more specialised simulators to be devised where there was a particular need.

The Crail Trainer was specifically to teach pilots how to launch aerial torpedoes, both to improve their accuracy and safety whilst operating low over the water.

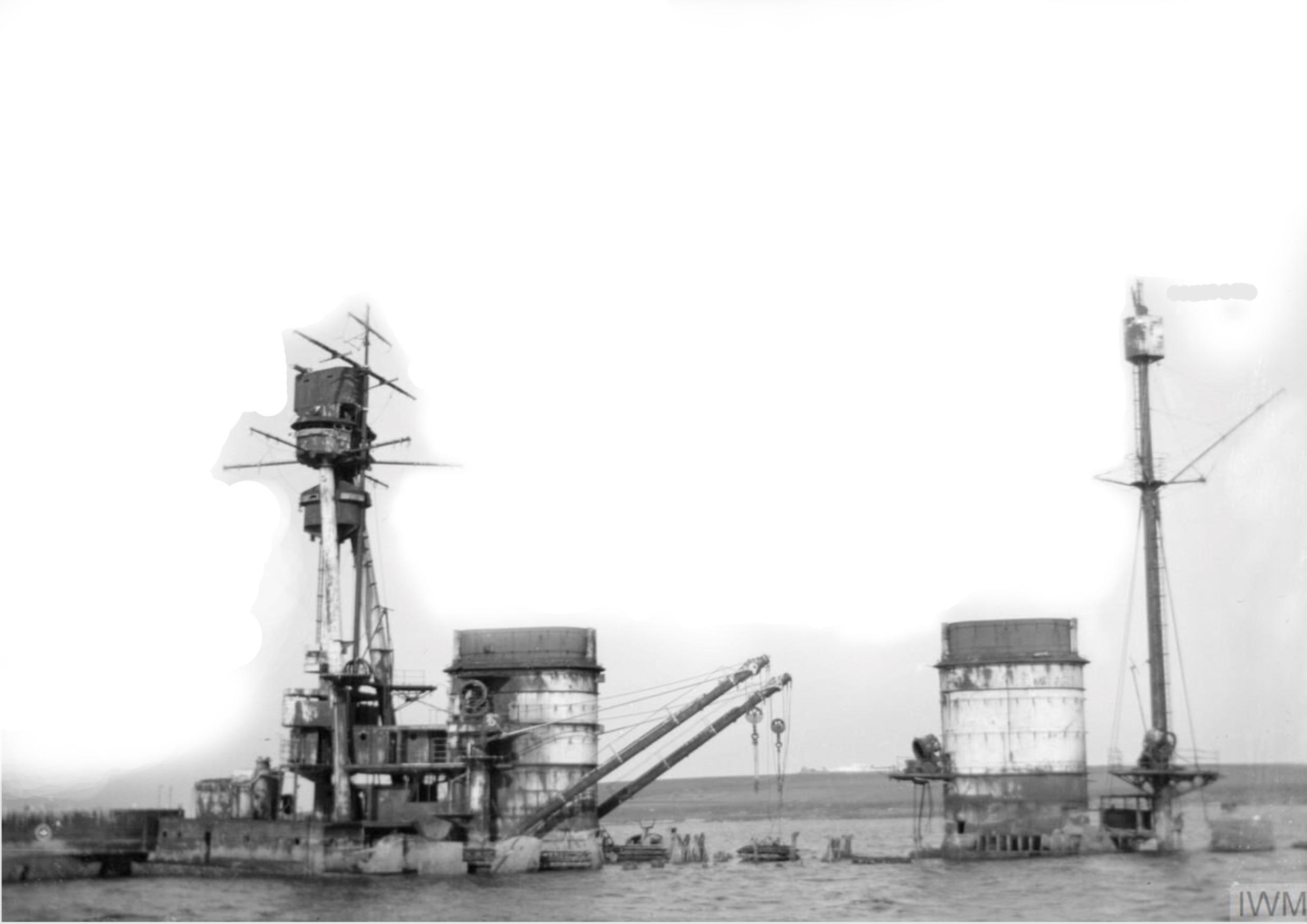

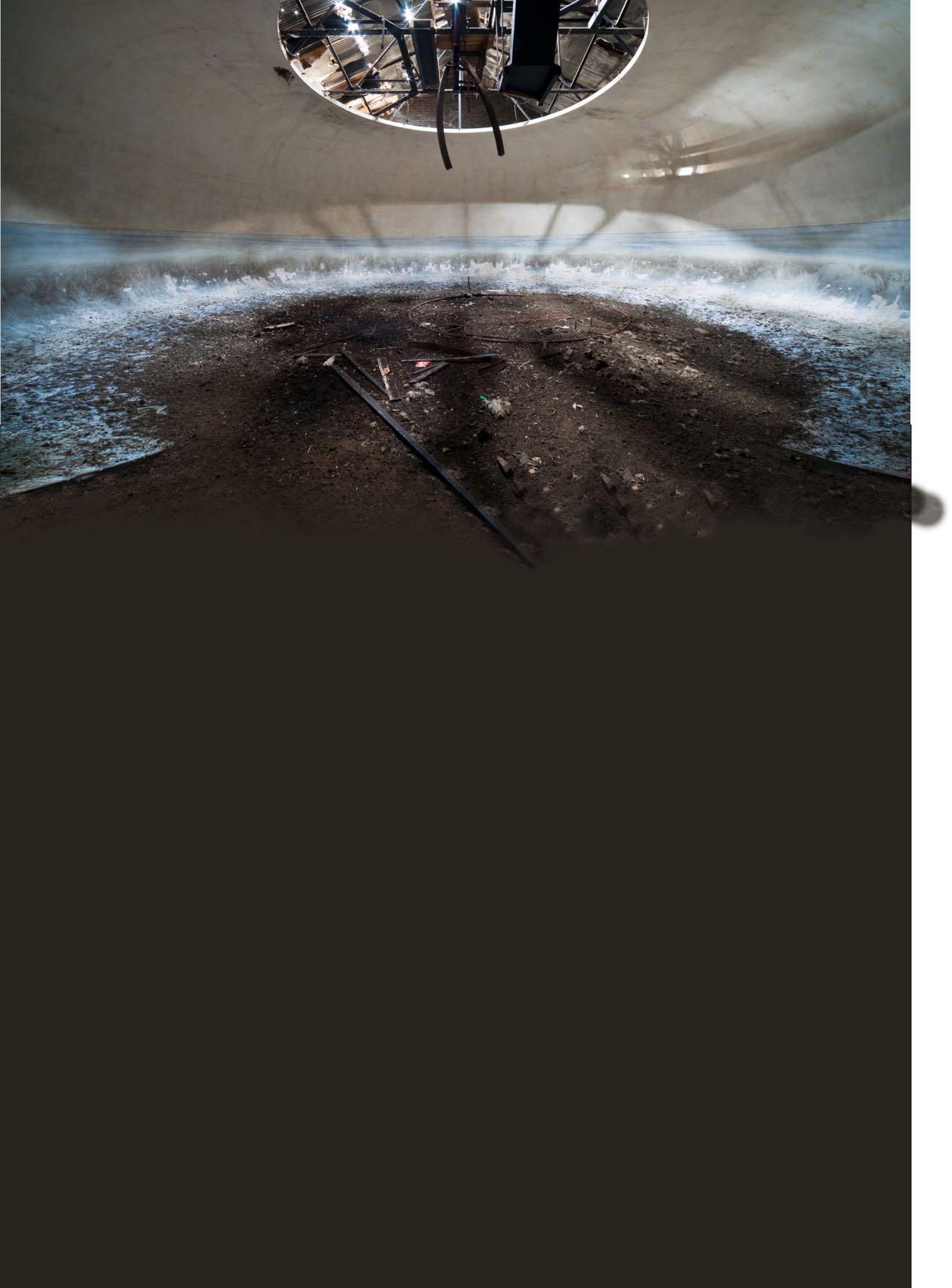

The central component of the system was a modified Link trainer with controls similar to the type of aircraft being flown. It was mounted on a gimbal on the floor of a large, circular dome shaped structure known as a ‘cyclorama’.

The 360˚ walls of the dome were painted with a sky, a horizon and a seascape. The area immediately below the trainer, which was the floor of the dome, was unadorned as the pilot could not see this part of the structure.

Projectors above the trainer added moving images of weather conditions such as waves, fog etc, and moving targets which could be varied by the instructor from a battleship to a tugboat.

Sitting in the trainer the student would see the panorama before him, including the target which would grow larger as he ‘approached’ it. He would need to estimate his attack angle, speed and release point, and would perform all the checks and actions necessary to actually drop his weapon.

After release the torpedo's track would be shown as a white line superimposed on the seascape, revealing if the trainee's aim and releasehad been accurate. The student would then be required to make his escape run, including evasive tactics against theoretical enemy fire. He would subsequently be debriefed by the instructor on his performance and profile.

The cyclorama was realistic as the images projected on the dome walls were films taken from aircraft executing the same manoeuvres. ✈

Australian National Archives records reveals the two Crail Trainers were allocated to RAAF by MOD (UK) in March of 1942 (which was before RAAF Nowra became a manned base) and set to work at the end of 1943, just as the RAAF’s interest in developing a useful operational capability with air launched torpedoes was coming to an end.

This was not solely due to the poor performance of the allocated Mark 13 USN torpedo which had yet to be improved. Other more successful techniques for attacking shipping had been developed particularly Skip-bombing which was used with great success by USAAF and RAAF at the Battle of the Bismarck Sea in March of 1943. And targets were becoming fewer. The RN had also reduced torpedo training activity at that time.

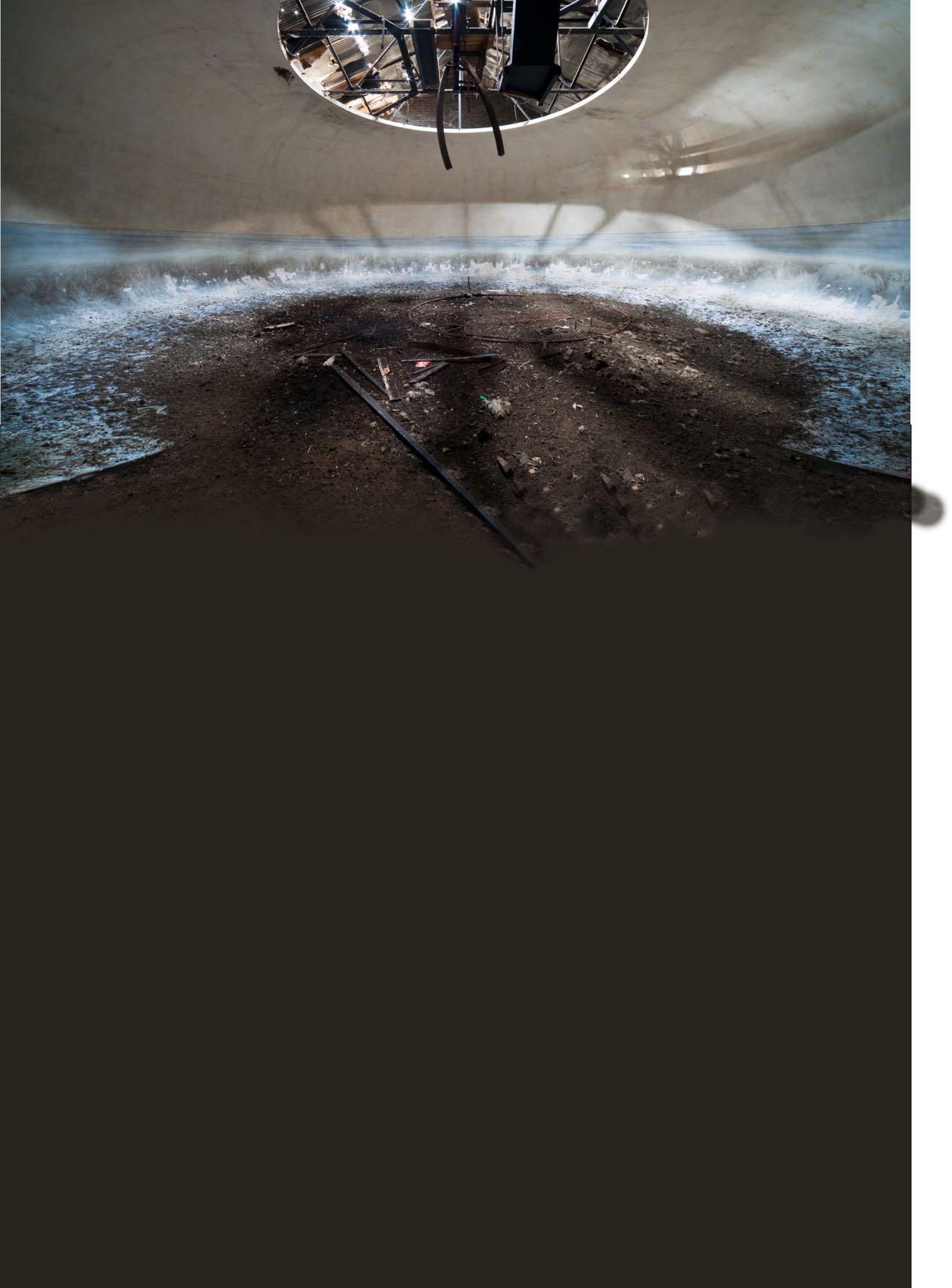

Above. A photograph of the inside of a Crail trainer in disrepair. The hole in the ceiling of the dome can be clearly seen, with the suspension arms from which the projector would have been suspended. The ceiling of the dome is painted a light cream, ready for projection of images. Around the circumference a painted blue horizon can be seen, with a sea scape artistically fashioned below it. The brown area in the lower part of the image is the floor of the cyclorama, cluttered with the detritus of the ruined building. In the original structure this area would not have been painted as it was out of the pilot’s field of view.

Below. This IWM image shows a trainer in the cyclorama. The flat plate above it hid the projector from the pilot’s view. You can see some faint images projected/pained on the walls around the trainer. The main photo on the previous page also gives a good idea of the workings. ✈

More detail on the Crail TAT is provided on the page to the left. In summary, it was a simulator which used a number of film projectors to provide a realistic sea-scape (filmed by actual aircraft) with options of different weathers, lighting and target shipping on a circular semi-spherical screen 44 feet in diameter and 23 feet height. The visual projection system was linked to a modified Link Trainer (in which the trainee pilot sat) and a projector which provided the torpedo track after it was launched by the attacking aircraft. Post attack analysis of results was also provided.

In 1941/42 when the Crail TAT was being developed in UK radar was not yet routinely fitted to torpedo bombers and the determination of the correct torpedo release range and lay-off to allow for target motion while flying at very low altitude and airspeed directly into the target’s gunfire was a difficult art. The Crail Trainer was estimated by the flight simulation industry to be about two decades ahead of its time. It was very advanced but is not remembered, perhaps because it provided limited in-service use to the RAAF.

Other archival files covering RAAF Nowra and Jervis Bay Airfield reveal that there were both a Crail and Link Trainer buildings at Creswell (then RAAF Nowra). The tunnel, which is still evident, was to provide access beneath the 360° circular screen of the Crail. Not all Crail Trainers including the developmental system had a 360° screen and these were fitted with an access door at ground level.

The presence of the Link Trainer and Crail Torpedo Attack Trainer and other facilities at (now) HMAS Creswell indicates one of the considerable logistic challenges presented by the location of the main RAAF Nowra airfield, with its torpedo maintenance and storage facility (BTU) over 20 miles distant from Jervis Bay.

Much of the logistic overhead of RAAF Nowra torpedo training operations was involved with transporting maintenance and aircrew personnel along with their torpedoes from base to base and back. The Beaufort aircraft could be armed and fuelled at either Jervis Bay or Nowra airfields but there was still an enormous effort involved with recovering the torpedoes after they had been dropped into Jervis Bay and then returned across the Marine Section at Creswell to be trucked for servicing in preparation for next day’s flight at BTU on today’s BTU Road. Maintenance other than flight line servicing of aircraft was still required to be done at the Nowra airfield.

The problem of distance was understood early in the life of RAAF Nowra when RAAF authorities, having experienced engineering problems while developing RAAF Nowra airfield, declared the site unsuitable in December 1941. The official history does not indicate if planned torpedo training influenced this decision but an alternate site was identified by RAAF at Jervis Bay where the Jervis Bay Range Facility (JBRF) airfield remains.

The record advises that Nowra Council intervened at the political level, (the town had given up its airfield to enable RAAF Nowra to be built). As a consequence of losing the political case, RAAF’s decision was overturned and work resumed on the original RAAF Nowra site and BTU. JBRF was not completed until sometime after RAAF Nowra airfield. The distance problem remained.

In June of 1943 6 OTU was formed at RAAF Nowra airfield to consolidate and coordinate all torpedo activity. In early September of that year, to reduce travel time, the move of 6 OTU with 23 Beauforts, 3 Wackets, and 2 Oxford aircraft to JBRF and some facilities within Creswell occurred. Facilities for torpedo servicing and aircrew training (including location of the Crail Trainer) at Jervis Bay were begun to be established. The move to Jervis Bay was evidently undertaken with energy, and an attitude which appears to have recognised the move was essential and must succeed. However experience proved that neither aircraft nor torpedo maintenance was fully practicable at Jervis Bay. Additionally RAAF authority appeared to have decided at the end of 1943 that torpedo attack was no longer a high priority role. 6 OTU moved back to RAAF Nowra during March of 1944 and disbanded shortly afterward.

In March of that year Number 2 Medical Rehabilitation Unit moved into formerly RAAF Nowra facilities at (Creswell) Jervis Bay and remained there for just over two years, providing care for returning POW. RAAF Nowra ceased to function as a base

Ben Cooper. Torpedo Trainer. Flickr.

18 19

in September 1944. The RN Fleet Air Arm component of the British Pacific Fleet began arriving to occupy former RAAF Nowra and Jervis Bay in a month later, remaining until March 1946.

During WW2 accommodation at Jervis Bay was provided by civilian hotels and public accommodation. And this was utilised by RN squadron when they were disembarked at JBRF. There is not much made of RAAF Nowra’s activity during WW2, and it is little remembered - but the pace of operations during the life of RAAF Nowra and later the RN FAA was evidently often frenetic.

The Australian built DAP Beaufort was a brand new aircraft just entering service. The USN torpedo was not suited to carriage by the Beaufort and was ineffective as a weapon. Overlaid on those challenges was the aircrew training task in a role which RAAF had no experience with. Despite that, the records demonstrate that the RAAF worked tirelessly both here and in the Operational Area to achieve a useful role performance. It didn’t quite work out.

In the category of “lessons learned” the reader is invited to study the following link here. ✈

Completed plaques for the following names have now been received back from the Foundry and will be affixed to the Wall in the next couple of weeks: M.Cowley; J.O’Regan; A.R.Milsom; B.J.White; D.M.Prest; K.J.Skomba; K.Yates; P.B.Cosgrove; D.J.Spratling; J.R.Buchanan.

Order No. 53 is now open for anyone who wishes to apply for a plaque. This order will be submitted to the Foundry once we have a sufficient number of

applications to make the manufacturing process viable. Current applications are:

R.J. Cluley LS ATA S113325 Jul 72 - Jul 81.

D.R. Hooper WO ATA S133260 Apr 82 - Apr 06.

M.A. Sandberg ABATWL S125208 May78-May88.

E.D. Sandberg LCDR(O) O1024 Apr50-Sep90.

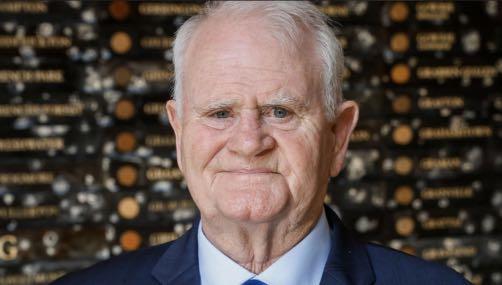

For those who don’t know, the Wall of Service is a way to preserve the record of your Fleet Air Arm service in perpetuity, by means of a bronze plaque mounted on a custom-built wall just outside the FAA museum. The plaque has your name and brief details on it (see background of photo to left). There are over 1000 names on the Wall to date and, as far as we know, it is a unique facility unmatched anywhere else in the world. It is a really great way to have your service to Australia recorded.

It is easy to apply for a plaque and the cost is reasonable, and far less than the retail price of a similar plaque. Simply click here for all details, and for the application form. ✈

Another view of the cyclorama in which the Crail Torpedo Attack Trainer was situated. The size and scale of the building can be better seen here, as can the roof structure that supported the projecting mechanism. The wall at the far end would have been behind the pilot’s field of view as he sat in the trainer, which would have been mounted close to the middle of the foreground. ✈

Last month’s Mystery Photo proved to be a bit esoteric, so we’ve wound the ‘make it easier’ knob up a few notches. Can you tell us what the above aircraft is, and, for a bonus point, which carrier it is on? Click here to submit your answer. ✈

20 21

THIS MONTH’S MYSTERY PHOTO

Historical Interest

HMAS Albatross gets $124m airfield upgrade.

Work on a $124 million airfield upgrade at HMAS Albatross is scheduled to begin this month, to support the expansion of the Fleet Air Arm’s Seahawk Romeo fleet of helicopters from 23 to 36. It is expected to be complete early in 2025.

The work will include the resurfacing of runways, taxiways and aprons, some reconstruction of concrete pathways, and airfield stormwater and lighting upgrades. At its height it will employ 120 workers, and will source 90% of its materials from the local area.

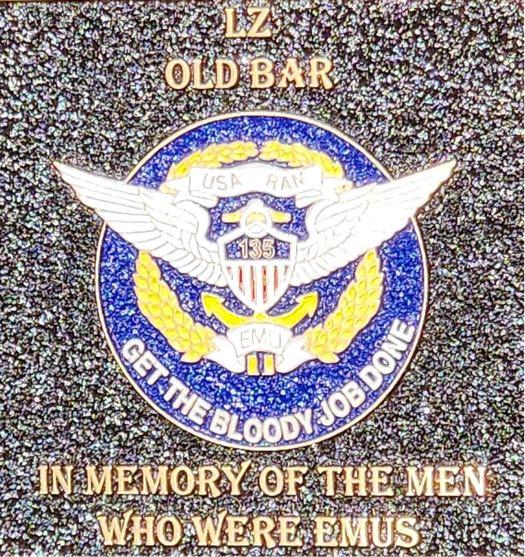

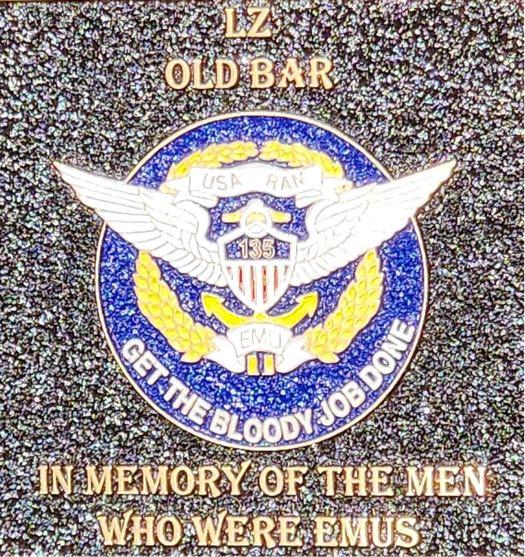

Old Bar Vietnam Veterans’ Day

The Royal Australian Navy Helicopter Flight Vietnam (RANHFV) had it’s yearly gathering in Old Bar and this year was joined by some members of the Fleet Air Arm Association of Australia as well as some members of the Old Bar community.

Unfortunately no helicopter this year, but we did have Master Chief Jeff Maki from the US Embassy in Canberra as a guest. He partnered with Old Bar Public School Principal Deb Scanes to unveil a monument dedicated to the members of the RANHFV and the US Army personnel who served on the US Army’s 135th Assault Helicopter Company in Vietnam.

The Old Bar Public School successfully applied to the Department of Veterans’ Affairs for a grant to have a permanent monument at the school which was supplied and installed by Nowra Memorials.

This year marked the 50th Anniversary of Australia’s withdrawal from Vietnam and also the 56th Anniversary of the formation of the RANHFV. Words and Pictures by John Macartney. (John has also provided a link to a library of more photographs of the event, here.)

Australian Artist Has The Goods!

Drew (isn’t that a great name for an artist?) Harrison is a local artist who specialises in paintings of military subjects.

He recently contacted the FAAAA and was kind enough to send us a couple of examples of his fine work. He commented: “While I paint many different genres, aviation has always been a passion. I also enjoy researching Australian aviators as a hobby interest and have collected information and several logbooks particularly of WWII fighter pilots. Along the way my interest has extended to naval flying. [The late] Bob Geale kindly provided a wealth of information about Australian FAA aircrew from the 1920s to WWII. Since then, I have managed to identify a few others with Australian connection and continue to research this often-neglected area of aviation.”

Drew is keen to establish links with the FAA/FAAAA and is always available for commissions. His contact details are: Drew Harrison. Mobile 0431 055 406. Email: artist@drewharrison-art.com His excellent website is here.

22 23 News, Views and Items of Interest

Left to Right: Reunion Organiser John Macartney, Master Chief Jeff Maki, Principal Deb Scanes and Member for Lyne Dr David Gillespie at the unveiling on a very windy afternoon.

Huey 898 of the HARS Navy Heritage Flight flew into Figtree last month as part of a visit to honour the four Vietnam Veterans buried in the nearby Memorial Gardens. The aircraft was one of 723 Squadron’s Iroquois used to train Navy personnel destined for service in the 135th Assault Helicopter Company from ‘67 to ‘71. Shown here are the veterans who attended the day, including Vic Battese and Michael Hough from HARS, both of whom also served in that theatre. A HARS Caribou also flew over the Memorial as part of the ceremony. Image: Howard Mitchell, HARS. ✈

CAUSE OF CRASH STILL NOT KNOWN

At the time of going to press the cause of the MRH90 helicopter crash that took the lives of four Army Aviation personnel on 28 July has still not been released by Defence.

Here is what we know so far:

• The accident occurred during Exercise Talisman Sabre, near Lindeman Island in the Whitsunday group.

• The helicopter was part of a ‘group of four’ flying at the time, although not necessarily in company. A second MRH90 raised the alarm.

• It was reportedly flying low over the water at night and no distress call was received.

• Parts of the helicopter and a ‘debris field’ has been located in about 40m of water.

• Parts of the wreckage recovered so far suggest catastrophic high speed impact with the water.

• The Voice and Flight Data Recorder (VFDR) was recovered ten days after the accident.

• The recovery of the remains of the four aircrew is a continued priority for Defence.

• The remaining Australian MRH90s are grounded, pending an understanding of what caused the accident. The Kiwis, who operate eight helicopters of this type, have ‘ungrounded’ theirs however, citing “no identification of new hazards or elevated risks.”

There has been much speculation in the Press that the ‘troubled history’ history of the MRH90 may have caused, or contributed to, the accident. Examination of the life of type suggests, however, that the ‘troubled history’ was more about logistics, serviceability and availability than safety concerns. ✈

Think B4 u fly!

So you’re going on your dream holiday, right, and you need to get to the Victoria Falls. Your friendly travel agent does her thing and, in due course, you get your tickets.

You notice that sector is flown by PlummetAirlines and, for the first time, a little warning bell sounds in your head. So you change the booking to Air Zimbabwe, and feel a bit safer. But should you?

In this case the name of the first airline was a trigger, but in reality that’s never the case (the only airline we know which does have a really dodgy name is SCATAirlines, in Kazakhstan). So how can you tell if an airline is safe - or at least adheres to reasonable safety standards? A good start is to type ‘banned airlines’ into your search engine and have a look. In the results you’ll find a list of those companies who are black-listed from entering US/EU airspace due to safety non-compliance. In most cases the list is unsurprising, but there are a few you might not have known about - and yes,Air Zimbabwe is up there with them.

It’s not foolproof, of course, but its a good start as an indicator. If the EU won’t let them into its airspace for safety reasons, then you might question whether its safe to get into one of their seats anywhere in the world. ✈

Can You Patch Us In?

Anyone remember this? 817 Squadron took over responsibility for Operation Bursa in ‘86, and the Squadron seemed to have a more-than-usual liking for patches. The top one is obviously a take on the famous SAS badge “Who Dares Wins”, but we’re not sure what the centre design replicated on the second badge meant. Any takers?

The patches pictured here weren’t the only ones to bring a lighter moment to Bursa. During the operation the SASR suggested that the display of aircrew names on uniforms and flying suits could be a security risk, and offered to pay for fake name patches to be produced for use during exercises. 817 Squadron aircrew jumped at the opportunity and following a rowdy crewroom meeting came up with many new aliases such as ‘Perry Scope’, ‘Pete O’Tube’, ‘Hertz Van Rental’, ‘Ben Dover’ and ‘Neil Down’ to name but a few. Unfortunately, we don’t have any modelling shots for those. ✈

Concorde back in the skies?

Well, not quite, but this picture of what appears to be the famous delta wing airliner flying under a bridge does suggest that. In fact it was just being moved by barge a couple of weeks ago whilst its museum home is being refurbished. ✈

24 25 News, Views and Items of Interest News, Views and Items of Interest

Vietnam Fallen Honoured

August marked the 50th Anniversary since the involvement of Australia in the Vietnam war, and vigils were held by the graves of those who gave their lives for their country in that conflict.

The full story will be in the forthcoming (September) edition of “Slipstream” magazine, due out in a couple of weeks. ✈

Most Expensive Fire Lighters?

In keeping with my theme of bashing Electric Vehicles (EV), which I regard as one of the greatest cons on the planet, here’s an advert which appeared on Facebook recently for a well known brand of EV. Thanks again to supersleuth Ron Marsh

Whilst on the subject, you might like to check out this extraordinary video here, one frame of which appears below. Draw your own conclusions about the country featured, and its predilection to squander everything on Earth. Ed.

Aussie Stringbags!

19 August 1944 Swordfish

MkI V4692 landed onboard HMS Hunter, missed the cable and went into the crash barrier. The aircraft caught fire and burnt-out. Lt Cdr R.G. How RN escaped uninjured. (It is not known if anyone else was onboard)

V4692 had an interesting story. She was one of six Swordfish shipped in crates to Australia. Arriving unexpectedly at Fremantle docks, the crates were transported to RAAF Pearce. When the contents were discovered the CO ordered they be assembled. No one there had any first-hand knowledge of the type, but they seemed to go together OK… and the CO flew the first test-flight.

They were used by No.14 & 25 Sqn for ASW patrols, off Rottnest Island and the approaches to Fremantle; and communication flights with outlying stations. Eventually RAAF Headquarters got wind of this, and ordered the aircraft disassembled and forwarded to the intended recipients in Nairobi, where it was allocated to 810 NAS. ✈

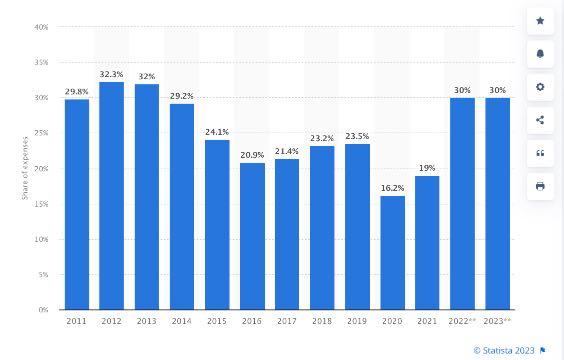

The New Shape of Wings?

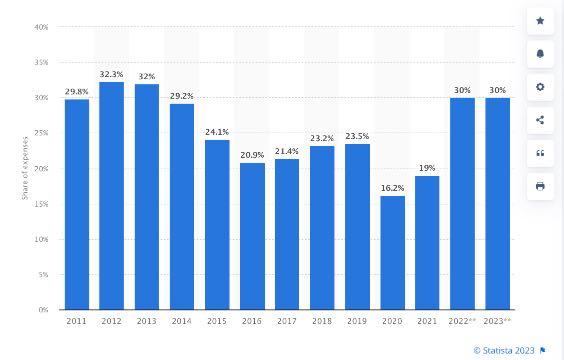

The price of fuel is a significant factor in airlines’ operating costs. As shown in the graph to the right, it accounts for about 30% of their expenditure in the year 2023 to date, which is approaching the highs of a decade ago - and, if forecasts are to be believed, it will only go up. Little wonder then that aircraft and engine manufactures are constantly looking for ways to make their products more efficient.

Most changes over the last two decades have been evolutionary: higher bypass ratios in turbofan engines have typically delivered efficiencies in the order of 10%, and airframe designs somewhat less.

But even modest efficiency gains add up. Swiss Airlines used a drag-reducing film on its Boeing 777s to deliver a 1% gain - and with just 12 aircraft, anticipated saving 4,800 tonnes of fuel per annum. A similar efficiency gain for a company like American Airlines, with its 1000+ aircraft fleet, would have harvested savings in the order of US$0.5 bn per annum.

And now a new wing development promises an even bigger revolution in fuel efficiency - the Boeing Transonic Truss-Braced Wing (TTBW).

So what’s the thinking behind the concept?

Its all about the Aspect Ratio (AR) of the wing. AR is the ratio of the wing’s span (distance from wingtip to wingtip), to its chord (mean distance from leading to trailing edge). Long, thin wings, such as found on gliders, are known as ‘high aspect wings’ whilst those which are short and stubby are low aspect.

By way of example, the AR for an Airbus A350 is 9.5, compared to a high-performance glider which may have an AR of around 33. In contrast, a small highly manoeuvrable fighter such as the FA-18 may have an AR of 3.5. Concorde, with its close-set delta wing, was half of that.

Fuel costs as a % of an airline’s operating costs. In 2023 to date it stands at about 30%, not far below the 2017 high of 32.3%

High AR wings produce less overall drag and are therefore more fuel efficient, but there are compromises. Long thin wings may require bracing, have less internal volume to accommodate fuel, and may be too long for airport facilities. All of these disadvantages can be overcome, but require compromises and clever engineering.

Enter the TTBW, which has been in development for about four years and is now reaching the point where a full scale demonstrator is in the works. There is hope that TTBW aircraft could be in service in the first half of the next decade.

"When combined with expected advancements in propulsion systems, materials and systems architecture," reads a Boeing press release, "a singleaisle airplane with a TTBW configuration could reduce fuel consumption and emissions [of] up to 30% relative to today's most efficient single-aisle airplanes, depending on the mission." ✈

26 27 News, Views and Items of Interest

✈

27

News, Views and Items of Interest

Eine Frage der Ehre

(A Question of Honour)

The story of the German High Fleet

November 1918 - June 1919

by Marcus Peake

by Marcus Peake

28 29 General Interest Article

General Interest

Prelude to Surrender

By 11th November 1918 the German Navy was in a state of disarray. Two weeks earlier Admiral Von Scheer, the Chief of the German Navy, had ordered the whole of his High Fleet to sea to engage the Royal Navy in one great, possibly final, battle.

Ships began to gather off the mouth of the river Elbe, but their crews were discontented. Why, they reasoned, would they go to sea to die when peace was so close to hand? By the end of October they had mutinied, and every vessel flew a red flag from its masthead, signifying it was under the command of a ‘Council’ of the Soviet of Workers, Soldiers and Sailors. All officers were removed from their ships and Soviet delegates were installed instead. It was a mutiny of epic proportion.

Under the terms of the subsequent Armistice, however, senior officers of the German Navy were obliged to meet with the allies to discuss exactly how the interment of their fleet was to occur.

The Armistice

Just after 5am on 11th November 1918, a group of grim-faced and weary men put their names to document that would, after four years of slaughter, finally silence the last of the guns in the Great War.

Previous agreements had already been signed by Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire and AustriaHungary. Now it was Germany’s turn. Exhausted by war, its population hungry and dispirited and its military might exhausted, the German Government had finally sued for peace.

Two clauses in the document specified that Germany surrender 160 submarines and all their armament, and that German surface warships designated by the Allies be disarmed and interred, with only caretaker crews aboard.

The list contained the names of six battle cruisers, ten battleships, eight light cruisers and fifty of the most modern destroyers - a total of 74 vessels. All other warships were to be disarmed and placed under the supervision of the allies in situ. ✈

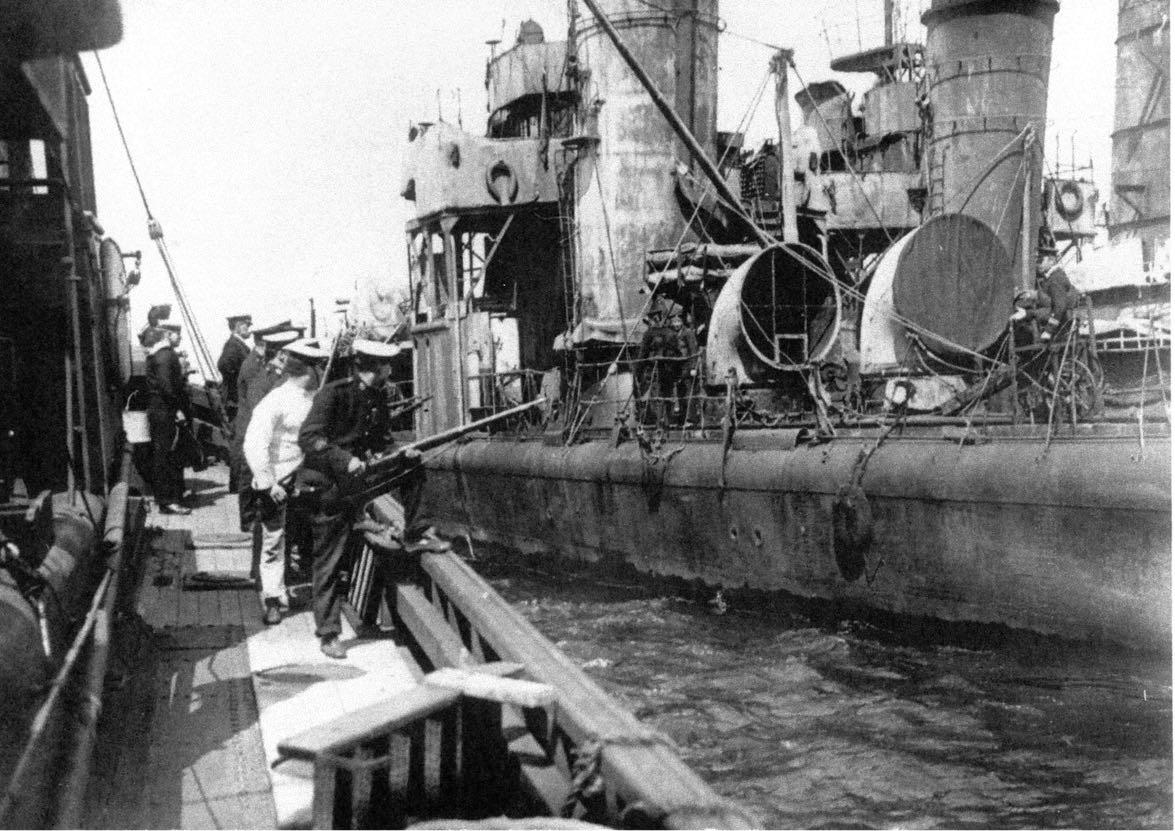

The Commander in Chief, although no longer in command, asked Soviet Council for a vessel to be sent to British waters to make arrangements to execute the terms of the Armistice. Unable to deal with this request, the Council agreed that selected officers could embark on the SMS Konigsberg for passage to Rosyth.

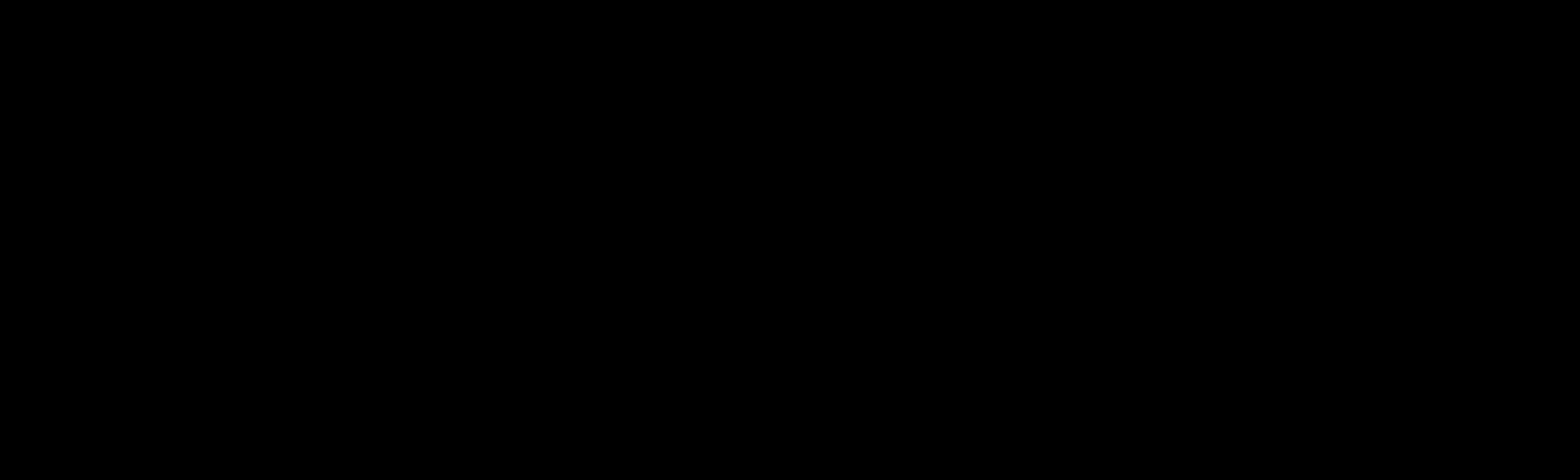

On the afternoon of 15 November the German cruiser was sighted by a waiting British Squadron and was escorted to the Firth of Forth. The accompanying British cruisers and destroyers anchored around her, guns loaded and ready, and small boats patrolled nearby to prevent any Germans from escaping. Admiral von Meurer, who had been appointed to the task, was taken aboard HMS Queen Elizabeth where, flanked by Royal Marines with fixed bayonets, he was escorted to the cabin of the Commander in Chief of the Grand Fleet, Admiral David Beatty.

It is difficult to imagine the disbelief the British delegation must have felt as Admiral von Meurer explained that he was only ‘a technical adviser’ and that representatives of the Sailors and

Workers Soviet of the North Sea Command were the actual plenipotentiaries with whom the British must deal, through him. One can only feel sympathy for him: a proud officer reduced not only by the act of surrender, but by a mutiny that had robbed his country of any vestiges of professional pride.

Nevertheless, the details of the interment were worked out.There were many: exactly which ships were to be handed over, what crews and stores they would carry, where they were to meet the Grand Fleet and where they would then be taken, and how. It was a long, protracted business for neither side spoke the other’s language and many of the fine points had to be checked with Admiral Hipper, waiting in Germany. In two days it was done, however, and Von Meurer was taken back to the Konigsberg which sailed at once for Germany.

Planning

The German surface ships were to come initially

to Rosyth, escorted by a powerful force of British, American, French, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand warships. The rendezvous for the two great fleets was at a position 56° 11' N., longitude 10° 20' W and was to be at precisely 0900 on the 21st of November, 1918.

Back in Germany, the Soviet Workers Council called upon the new Government to resist the ‘uncalled for presumption” of the Allies. It soon became clear to them, however, that resistance would be in breach of the terms of the Armistice with potentially devastating consequences, and so they agreed.

At first, the Council insisted that every ship would fly the Red Flag as its pennant, but it was pointed out they might be regarded as pirates and fired upon, so the German Imperial Ensign was hoisted instead.

Admiral Hipper had decided that Admiral Ludwig von Reuter would accompany the Sailors Soviet Union as another ‘technical adviser’. Other senior officers were to go with him: Commodore Taegart aboard the battle cruiser Seydlitz, and Commodore Harder aboard the light cruiser Karlsrhue. Altogether, nine battleships, five battle cruisers, eight light cruisers and fifty destroyers were prepared for the voyage - two ships short of the list specified in the original Agreement. They slipped moorings on the clear and sunny morning of 19th November 1918. Slowly steaming in formation they passed Heligolland, reminiscent of the great battle of Jutland over two years earlier, and then into the North Sea. One destroyer struck a mine and sank, and the cruiser Coln reported she could not maintain speed due to a condenser leak. Nevertheless, the column of great, grey ships made progress towards the appointed rendezvous.

Surrender

At 0200 on the morning of the 21st of November, 370 ships of the Royal Navy, the United States, Canada, France, Australia and New Zealand, slipped their moorings and shaped course to the east. The capital ships formed up into two great lines 15 miles in length, with seven cruisers and eight flotillas of destroyers between and ahead of

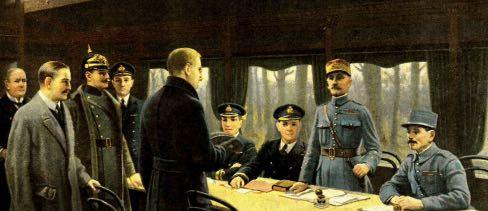

The interior of the fore-cabin of HMS Queen Elizabeth with senior Royal Navy and German Navy officers sitting either side of a long table. Admiral Sir David Beatty sits fourth from the left holding a roll of paper in his left hand and reading out the terms of the surrender to the German officers, who sit opposite him. The table is covered in rolls of paper and there are two Royal Navy officers with swords sitting on chairs separate from the table on the right. (Image and caption: IWM). ✈

30 31

them. About one hundred miles separated them from the German fleet, which was steaming west at a leisurely 11 knots in a single line with the destroyers clustered behind them.

The dawn came slowly, the dark of night gradually slipping away to reveal a grey, misty morning, but by 0800 the sun began to penetrate the fog. Closed to Action Stations and with all guns loaded, lookouts on the British ships strained their eyes to see the enemy they had sought to hunt down for the past four years. There was a single question on everyone’s lips: would the German ships submit, or would there be a final, brutal battle? It seemed inconceivable that the second most powerful fleet on the planet would succumb without firing a shot.

At last last the lead vessels of the High Fleet were sighted - perhaps from one of the balloons or airships above - and the lines of British ships turned sixteen points either way to envelop them. Slicing through the icy grey water, the allied vessels then wheeled in unison to sandwich the German line, and the C-class cruiser HMS Cardiff took her place at their head to lead the enormous armada back to British waters.

For the Soviet supporters aboard the German ships, it must have been a crushing experience. Rumour was that British crews had also turned against their officers, and there would be sympathetic eyes there - but they saw that none flew the Red Flag.

And the breathtaking scope of the world’s greatest navy was now laid out before them: aircraft carriers, battle cruisers and battleships, light and heavy cruisers and a myriad of destroyers. All worked together in crisp, efficient unity, their sombre grey lines glinting in the early morning sun - whilst overhead two airships kept a watching eye on the activity. It was a stunning display of force that could not have failed to emphasise the hopelessness of their position. A German perspective on the event was given by Friedrich Ruge, the CO of one of the Torpedo Boat Divisions, who described what it was like as the

German Fleet was met off the Firth of Forth: “They came in the poor light of a grey November morning and surrounded us from all sidessquadron upon squadron and flotilla upon flotilla. In addition to the 40 British capital ships, there were almost as many cruisers, 160 destroyers, an American squadron, a French ship and also aircraft and small non-rigid airships. Everywhere the crews stood by the guns ready for action equipped with gas masks and flame-proof asbestos helmets. If the situation was depressing for us, the deployment of such over-whelming strength looked like a grudging recognition of the former power of the High Seas Fleet.”

A Times correspondent watching from the deck of the British flagship HMS Queen Elizabeth waxed a little more lyrically:

The light cruiser, HMS 'Cardiff' (1917), flagship of the 6th Light Cruiser Squadron, leading the main body of the German High Seas Fleet to the Firth of Forth, prior to their formal surrender to Admiral Beatty, commanding the Grand Fleet there, and subsequent internment at Scapa Flow. Bernard F. Gribble. 1918 National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. ✈

The light cruiser, HMS 'Cardiff' (1917), flagship of the 6th Light Cruiser Squadron, leading the main body of the German High Seas Fleet to the Firth of Forth, prior to their formal surrender to Admiral Beatty, commanding the Grand Fleet there, and subsequent internment at Scapa Flow. Bernard F. Gribble. 1918 National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. ✈

❛ I wish I had not been born a German. This despicable act will remain a blot on Germany’s good name forever... Although our army is still much respected by foreigners, the actions of our High Seas Fleet will live on with shame in history. ❜

Seaman Richard Stumph, diary entry 24 Nov 18.

General Interest

“The annals of naval warfare hold no parallel to the memorable event which it has been my privilege to witness today. It was the passing of a whole fleet, and it marked the final and ignoble abandonment of a vainglorious challenge to the naval supremacy of Britain.”

Admiral Chatfield, also aboard HMS Queen Elizabeth, summed up the feelings of professional British fighting sailors when he wrote:

“The surrender of the German Fleet was to many of us a highly painful if dramatic event. To see the great battleships coming into sight, their guns trained fore and aft; the battle cruisers, which we had met under such very different circumstances, creeping towards us as if it were with their tails between their legs, gave one a real feeling of disgust.Surely the spirit of all past seamen must be writhing in dismay over their tragedy, this disgrace to all maritime nations.”

But not a shot was fired, and by noon of that day the German ships were anchored in six lines in the Firth of Forth. The British command ordered that the German Imperial ensign flying above each ship be lowered. Little did it know that within the year every one of them would be raised again for the last time, if only for a few brief minutes.

Captivity

Once anchored, each German vessel was assigned to the custody of a British ship, which sent aboard a party to inspect it for hidden explosives and to instruct the captain. The 74 ships were then escorted to Scapa Flow, the vast natural harbour in

Friedrich Ruge, CO of German Torpedo Boat