Carrier Evolution

How Carriers became the shape they are

GulfWar Operations

What it was like to use the little Squirrel in a War Zone.

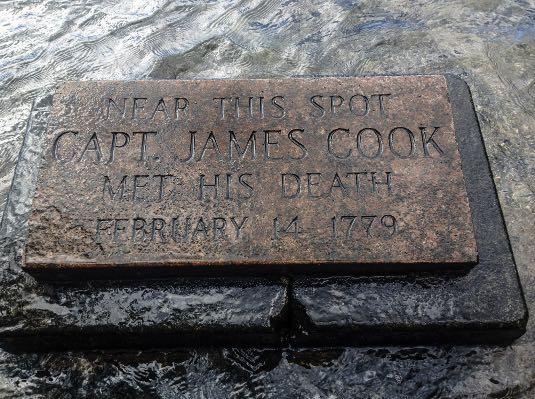

Death of an Explorer

The Brutal Death of James Cook

Edition

82 - June 2024

Earlier this year I received an email from a member who, having read the “Rest In Peace” column of this magazine and the linked obituaries, realised that many of the names therein were of people he joined the Navy with. He enclosed a short blurb about his life and asked us to store it for when his time came to sail over the bar.

Its good practice as one of the things we invariably have trouble with is finding information on those who have passed away. It is a source of regret to me that many of our obituaries are scant, and I’m sure that more than a few contain inaccuracies or omissions.

So, why not send us a few paragraphs about yourself and what you’ve done in your life? We’ll store it in the “Personal Info” tab on your database record and, when the time comes (hopefully in many years), you can rest in peace knowing that your Obit. Is right. Simply send it on an email to the Editor here

Speaking of emails, it was disappointing to see fewer “Letters to the Editor” this month. What people think about is always of interest to readers, so please - if you see something here (or anywhere else for that matter) which inspires memories, irritation, happiness, scorn or admiration, then pop it in an email to the address above.

The other good reason to contribute is to support this magazine. A good proportion of it each month is generated by the Editor and after six years his creative imagination is wearing thin...so please help him out with interaction, however slim.

Good news this month: Graeme Lunn’s new book on the life of VAT Smith is expected onshore soon. I’ve seen the draft and its an extraordinary work about a fascinating story. If you want to register your interest in buying a copy, click here to go to a little form on our website, which will ask the Publisher to give you a shout when its available. It does not obligate you to buy, but assures you of early advice and a good opportunity to do so.

On another matter, I’ve been slandered on social media! A comment by a Mr Peter Clark on the “Shoalhaven News” Facebook page mentioned me by name and said that I was suggesting the FAA Museum should elicit other (non FAA) artefacts and exhibits to make it more appealing. I don’t know Mr Clark but I wonder how he could have got it so wrong. My recent letter to CN argued exactly the opposite. I’ve posted a rebuttal on the offending FB page but once false information is out of the bottle its hard to put back.

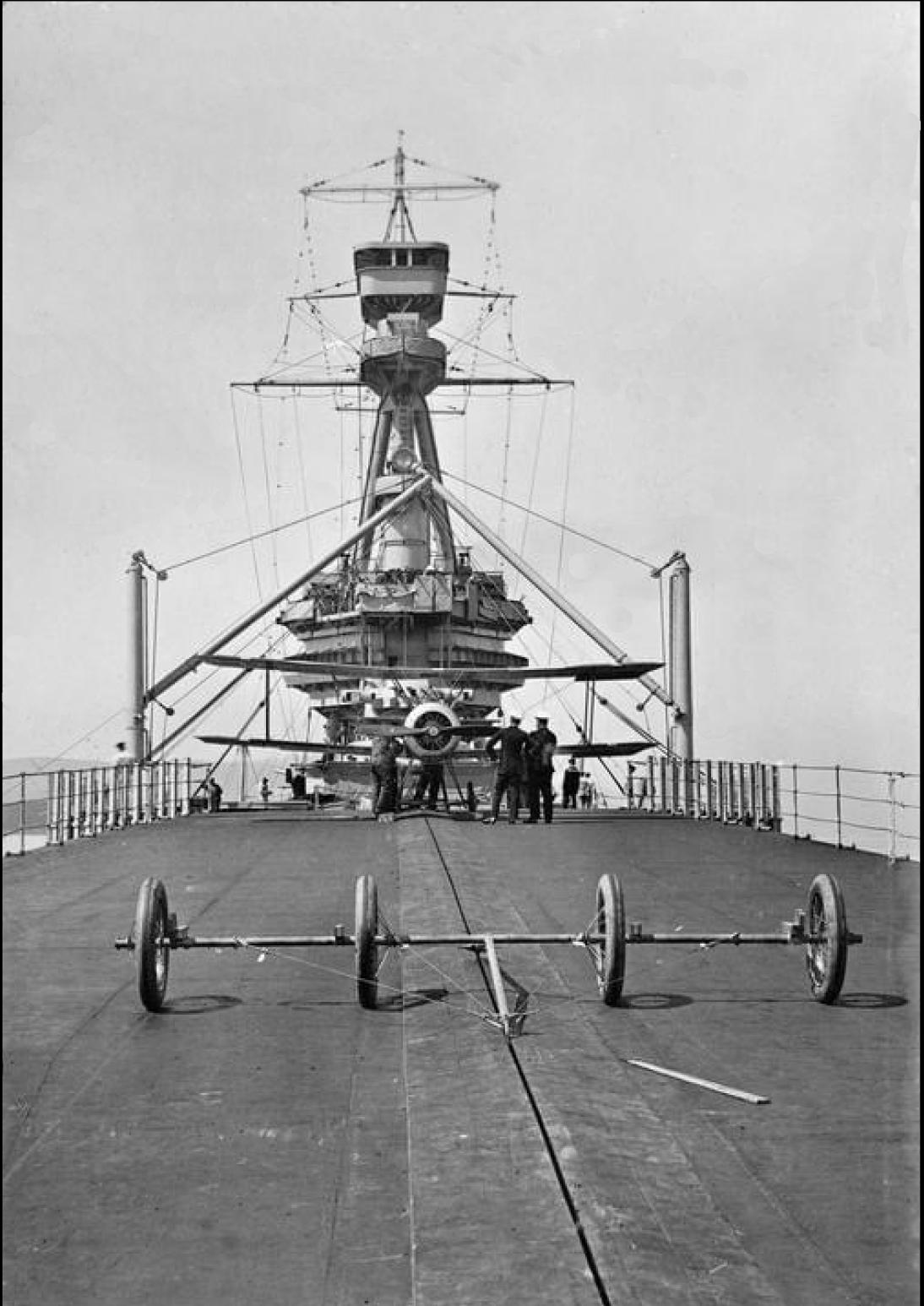

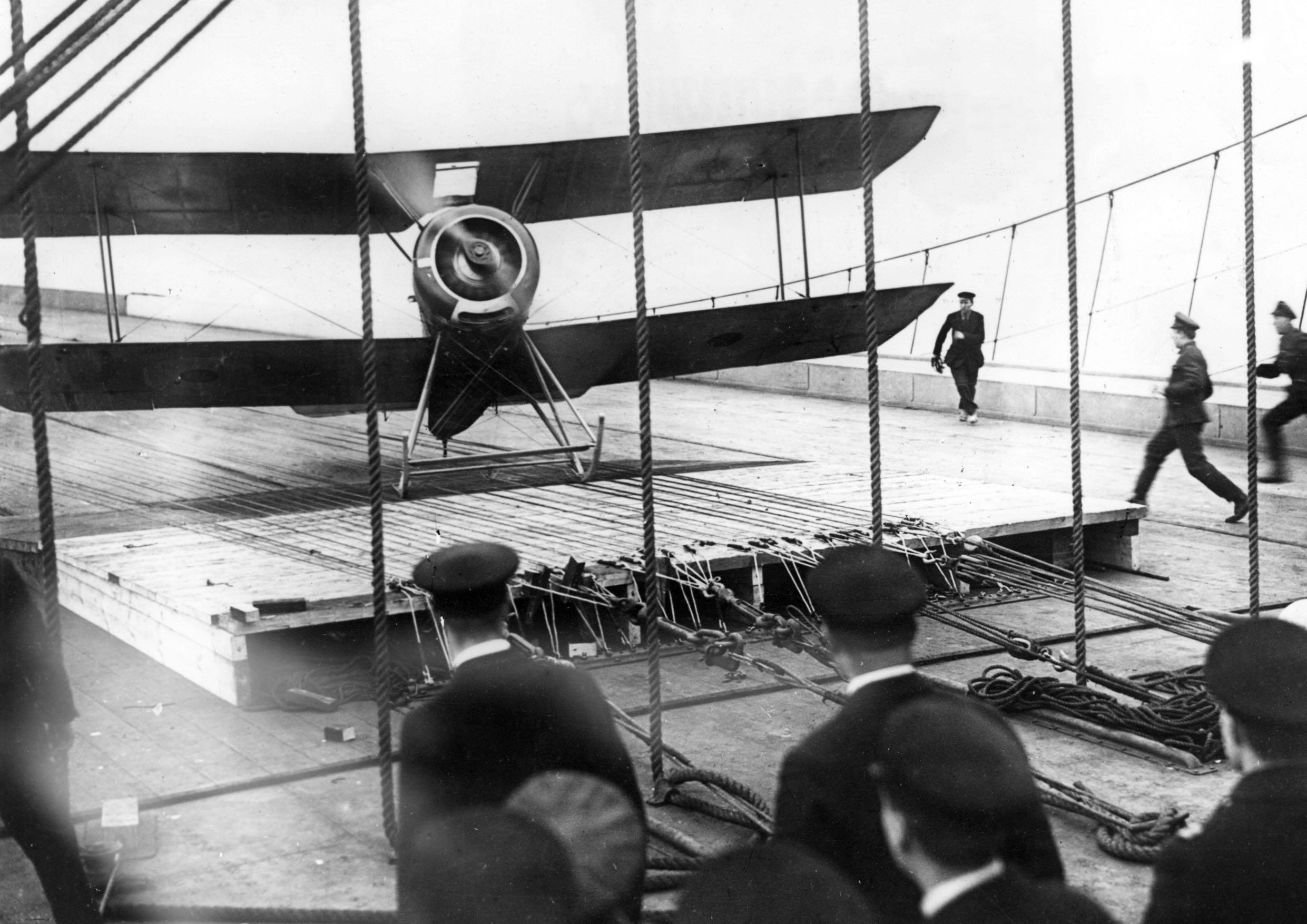

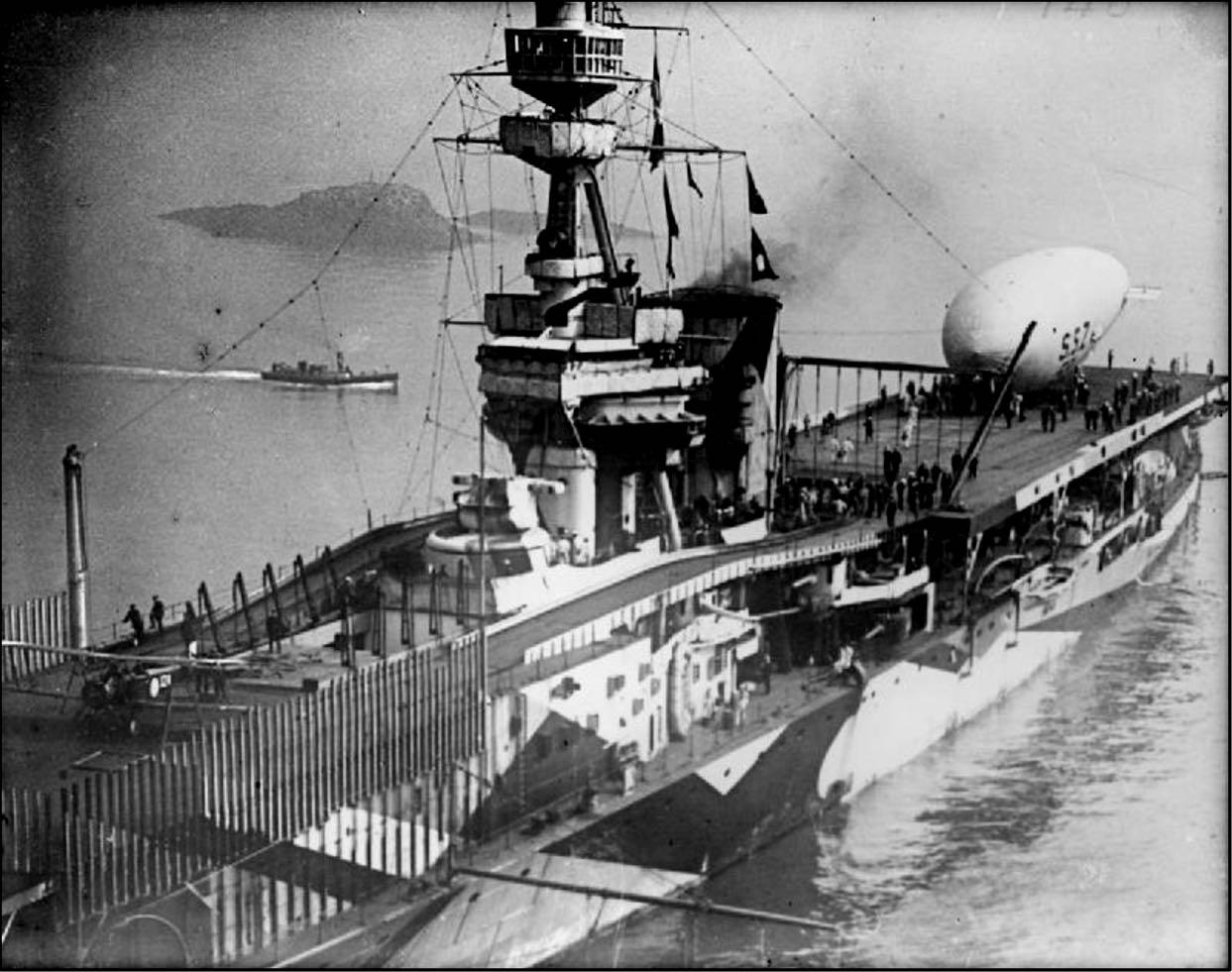

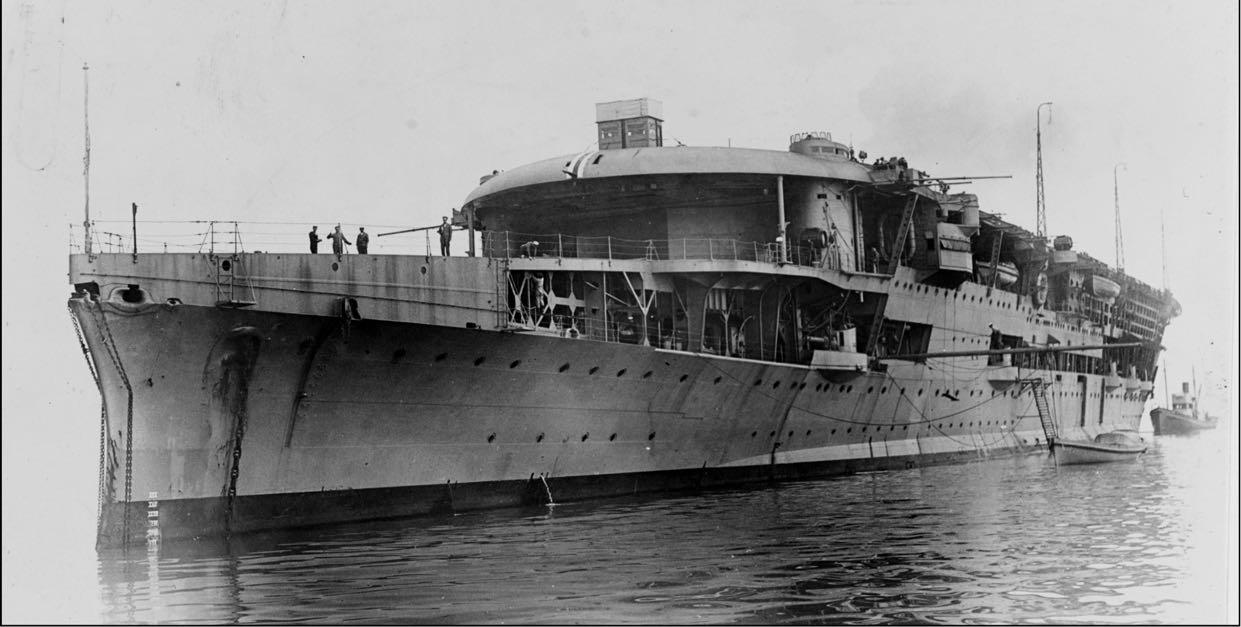

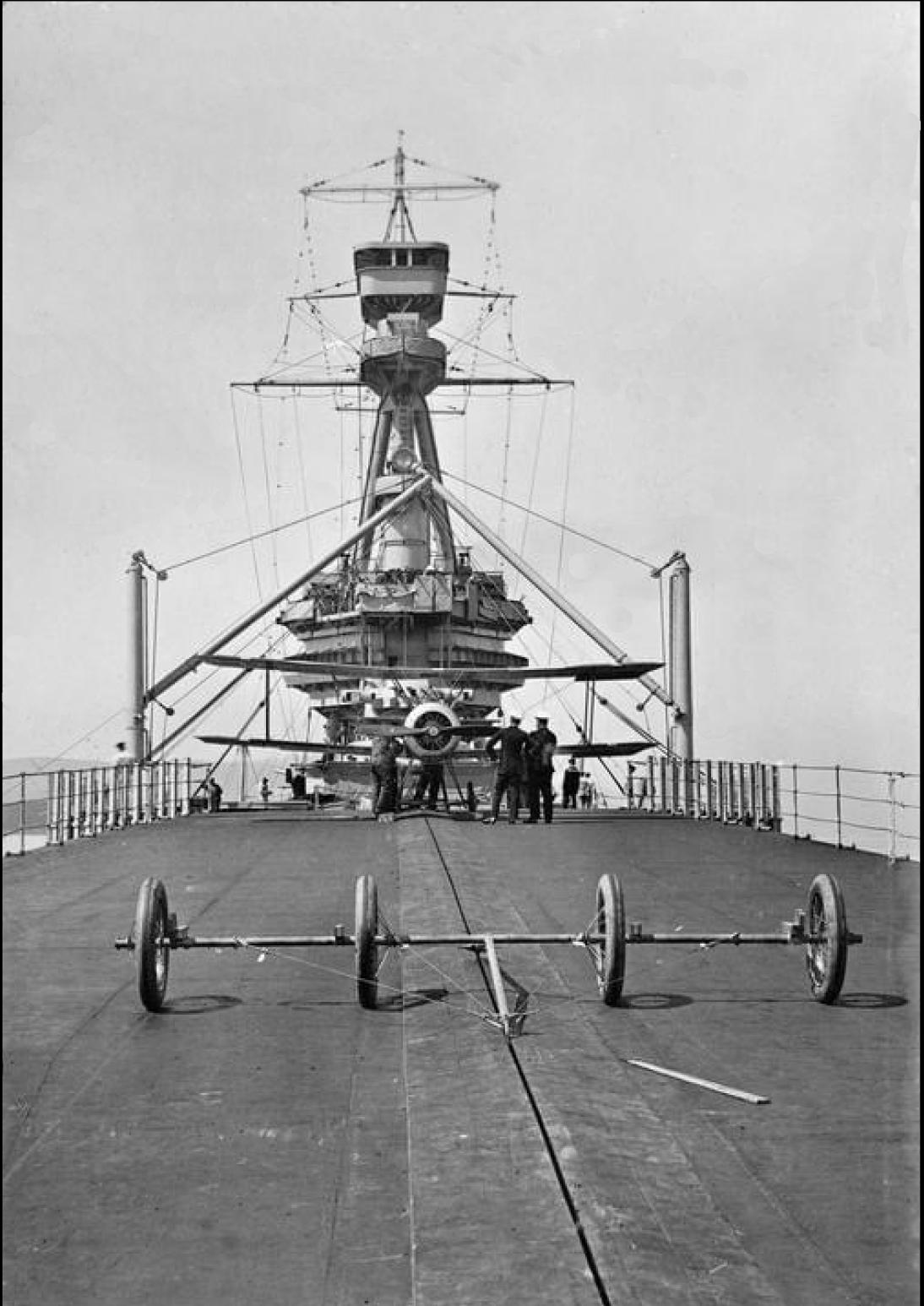

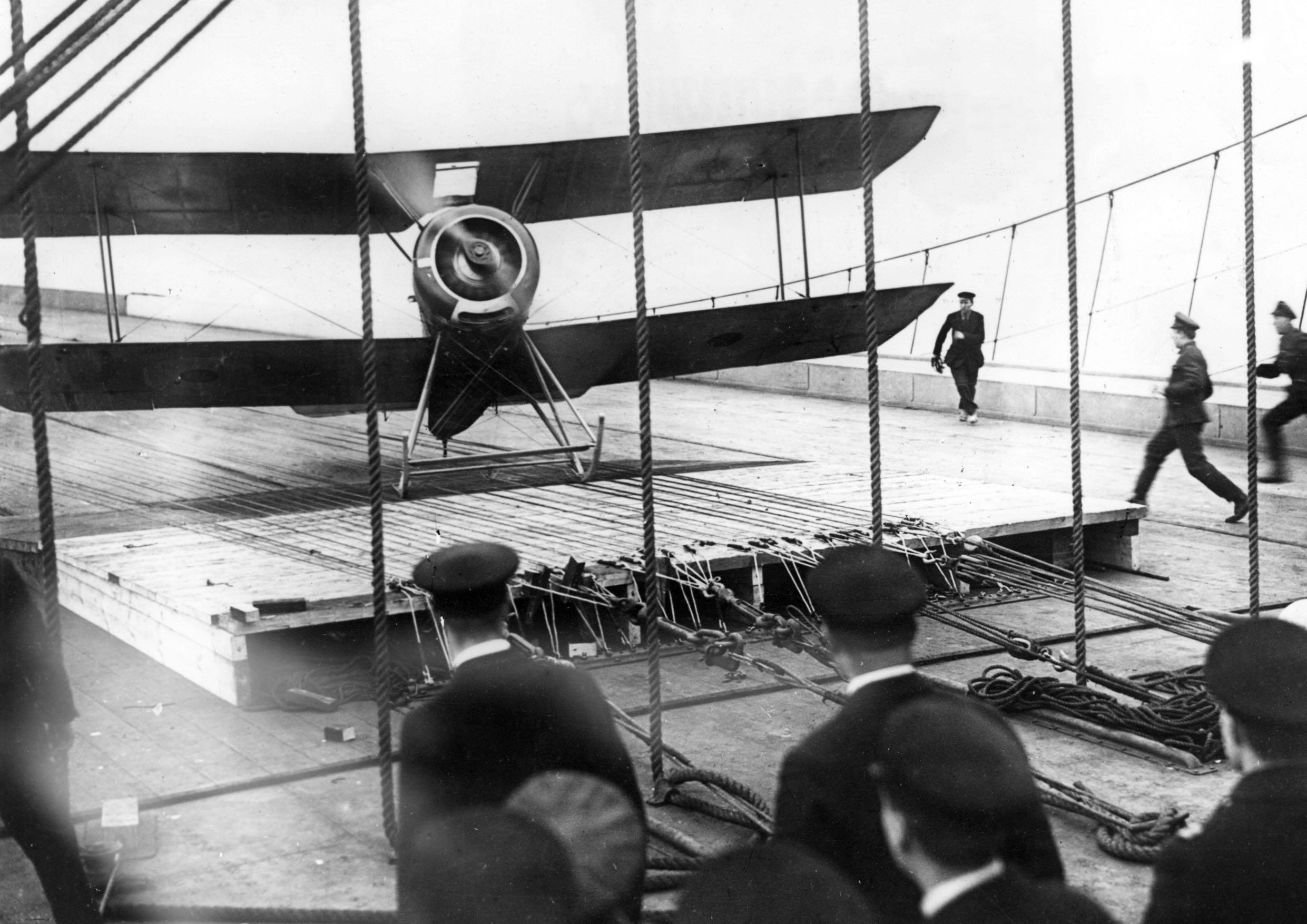

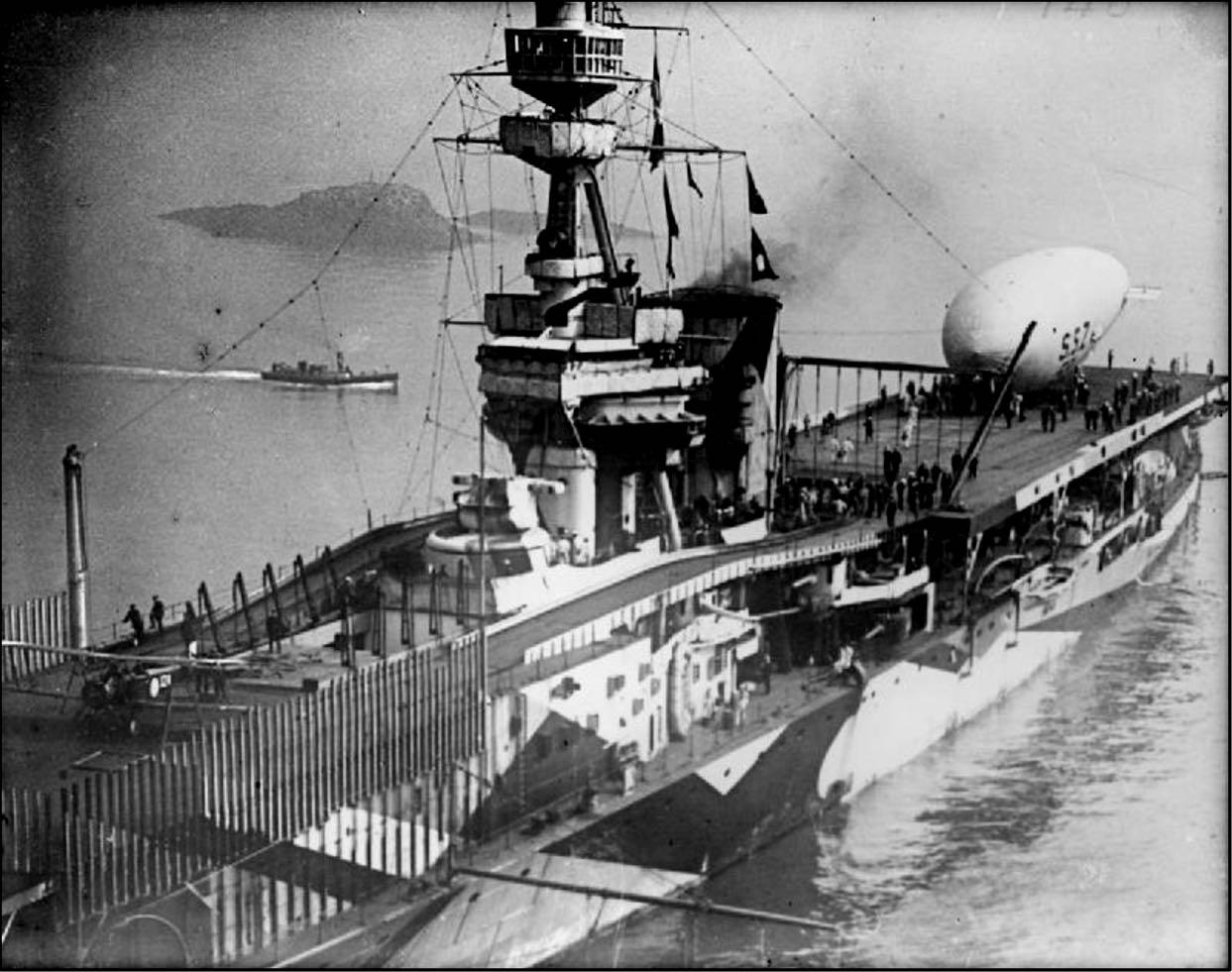

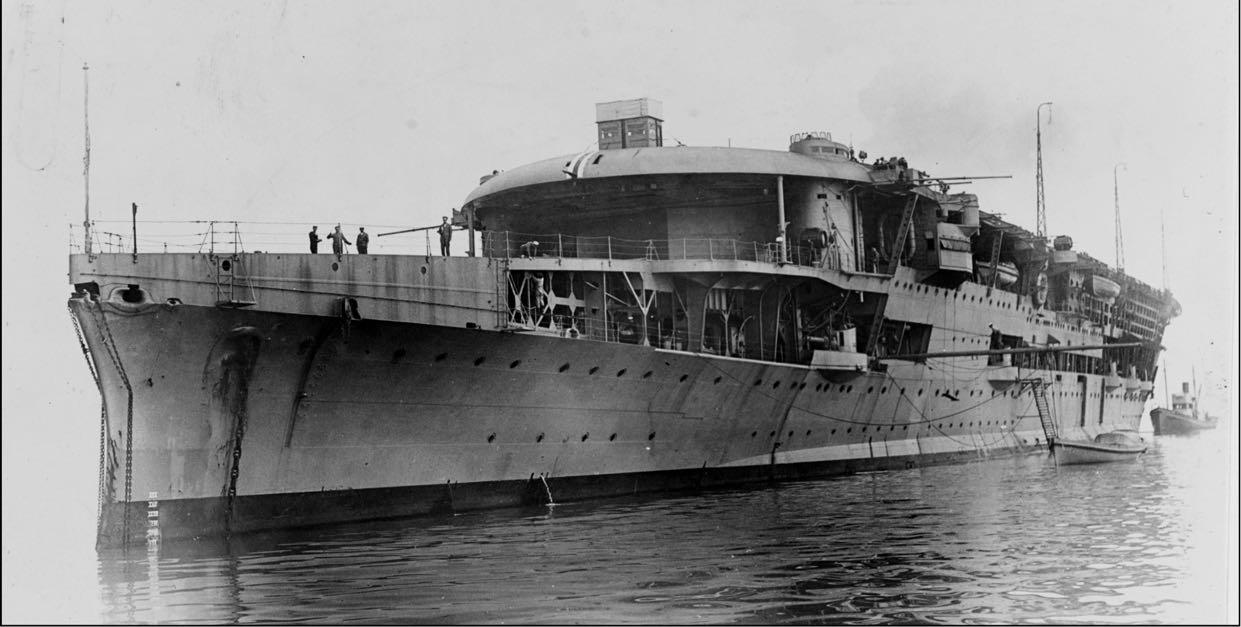

Finally, there’s a great article in this month’s edition (aren’t they all!?) about how aircraft carriers got to be the shape they are Here’s a teaser photo of H M S Argus, te s t i n g t h e func ti onali t y o f a s t a rboard island made out of wood Our thanks to Graeme for both the article and the photo ✈

REST IN PEACE

Since the last edition of FlyBy we have been advised that the following have Crossed the Bar: Greg Dawes, Phillip Robinson

REGULARS

02 Rest In Peace

Remembering those who are no longer with us.

02 Editorial

A few words from the Editor of this magazine.

05 Wall of Service Update

The status of orders for the Wall of Service, and a chance for you to order a plaque.

16 Around The Traps

Bits and Pieces of Odd and Notso-odd news and gossip, snippets and scraps.

11 Mystery Photo

Last month’s Mystery answered, and a new one presented for your puzzlement (p13).

20 Gulf War Ops

Taking the little Squirrel to War wasn’t what it was for, but we did it anyway.

30 The Death of Cook

How the great explorer met his death on a beach in Hawaii.

34 Carrier Evolution

Carriers didn’t come with their present shape - they had to learn to get that way.

You can find further details by clicking on the image of the candle. ✈ ✈

2 3 Editorial Content

THIS

MONTH

THIS MONTH’S COVER PHOTO

FEATURES

FEATURES

20

06 30 34

Dear Editor,

For some years I have, on occasion, idly wondered why, with so many retired Naval aviators in the Shoalhaven and adjacent areas, there aren’t more informal get togethers. I know the engineering fraternity have a long-standing lunch group and I had the fleeting thought more than once that “someone” should organise something similar for the flyers. After bumping into the engineers’ group at their culinary endeavours a couple of months ago, I finally thought “now’s the time!”

I went home and dug out my “someone” name tag, got busy and started the email search for Ps and Os in the local and near-local areas. Obviously, everyone was just waiting for “someone” to do something about it and get in touch with them, because the response has been terrific. The result is an informal monthly get together over lunch, scheduled for the first Thursday of each month. The first event was held on 02 May 2024 at the Worrigee Sports Club with 26 old’n’bolds attending, although there are 50 names of the list who want to be involved - some people just can’t let go of having a day job! I have attached a couple of photos you might be able to use.

To any P or O in the Shoalhaven and adjacent areas that I haven’t already contacted, if you are interested you can get in touch with me through the Editor.

Yours aye, Paul Folkes

By Ed. Thanks Paul. From the reports I’ve heard it was a cracking inaugural event, much enjoyed by all who attended. If anyone wishes to be put on the mailing list for future events, let me know here. ✈

The inaugural luncheon at the Worrigee Sports Club on 2nd May was a great success and a similar event will occur on the first Thursday of each month. Names of those in the photos are: [1] Dick Chartier, Dave Jones, Murray Lindsay, Al Byrne.

[2] Pete Laver, Peter “PJ” Croft (mostly obscured), Rick Sellers, Andy Sinclair, Tanzi Lea, Jock Caldwell (obscured, but with a nice shirt on!).

[3] Back L-R: Mark Ogden, Greg Tindall, Mike “Irish” MacNeill. Front: Darryn Jose, Tim Leonard, Vince Di Pietro. Images by Paul Folkes. ✈

Have you thought about getting your name put on the FAA Wall of Service?

It’s a unique way to preserve the record of your Fleet Air Arm time in perpetuity, by means of a bronze plaque mounted on a custombuilt wall just outside the FAA museum. The plaque has your name and brief details on it (see background of photo above).

There are over 1000 names on the Wall to date and, as far as we know, it is a unique facility unmatched anywhere else in the world. It is a really great way to have your service in the Fleet Air Arm recorded.

It is easy to apply for a plaque and the cost is far less than the retail price of a similar plaque elsewhere. And, although it is not a Memorial Wall, you can also do it for a loved one to remember both them and their time in the Navy.

Simply click here for all details, and for the application form. If you have any questions you want to ask about it before committing, email the Editor here ✈

The following plaques from Order No. 53 are being manufactured at the Foundry and are expected to be finished soon.

• R.J. Cluley LSATA S 113325 Jul 72-Jul 81.

• D.R. Hooper WOATA S 133260 Apr 82-Apr 06.

• M.A. Sandberg ABATWL S 125208 May 78-May 88.

• E.D. Sandberg LCDR(O) O 1024 Apr 50-Sep 90.

• A. Clark CAF (A) R35828 Mar 48-Mar 63.

• A. Gillam CPO ATWO/ETW S 118699 Jan 76-Jan 96

• B. Thompson LSATC S 128255 Mar 80-Jan 93

• J.W. Lyall WOSN R 65884 Nov 66-Nov 86

• I. Sausverdis CPOATWL R 62399 Jul 63-Jul 92

• M.A. Dagg CPOATV S 129644 May 80-May 00

• L. Stevens CPOATV 8209580 Feb 02-Feb 24

• A.W. Healey LSATWL S 130197 Jan 81-Jan 90

• J.A. Konemann LCDR (P) O 120636 Jul 76-Aug 01

• A.B. Sinclair LCDR (P) O 108473 Mar 71-Apr 84

• D. Mowat L.R.E.M. (A) R 50764 Feb 55-Apr 61

• P. Halley PTE 6708577 2RAR HFV 67-68

Order No.54. is open with one name on the list so far:

R.B. Sellers CMDR(P) O 126762 May 79- Jul 10. ✈

4 5 Letters to the Editor Wall of Service Update

1 2 3

Next Lunch Thursday 6th June. Click here to go on list.

Letter from the IslandsAdmiralty

Dear Editor,

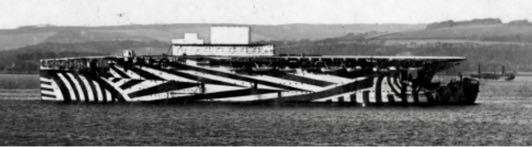

I’m currently lucky enough to be touring through Micronesia and Melanesia and thought readers might be interested in learning a little of the wartime history of two places visited - Ponam Island and Truk Lagoon.

During the war the Royal Navy formed Mobile Naval Air Bases to support disembarked squadrons in distant operational areas. Each unit contained between 500 and 1,000 men with all the capabilities of a permanent air station - every facil-

ity from radio technicians to air traffic controllers and medics. The first to arrive in the Pacific was loaned RAAF Base Nowra, which commissioned as Nabbington/Royal Naval Air Station Nowra on 2 January 1945. By agreement the RAAF loaned further airfields, Bankstown and Schofields becoming Naval Air Stations Nabberley and Nabthorpe respectively, while the airstrip at Jervis Bay became Nabswick.

The fourth unit, however, was diverted north to establish a forward station on Ponam in the Admiralty Islands. There they could support the British Pacific Fleet, now Task Force 57 of the US Fifth Fleet based two degrees south of the equator at Manus, largest of the Admiralty Islands. Fully wrested from Japanese control by April 1944, Manus’s protected Seeadler Harbour and shoreline had become one of the largest United States Navy bases in the Pacific. The main hospital could accommodate 1,000 patients and the floating drydocks, towed out from the United States, could even accommodate battleships. The new air stations advance party arrived aboard the maintenance carrier Unicorn on 7 March 1945.

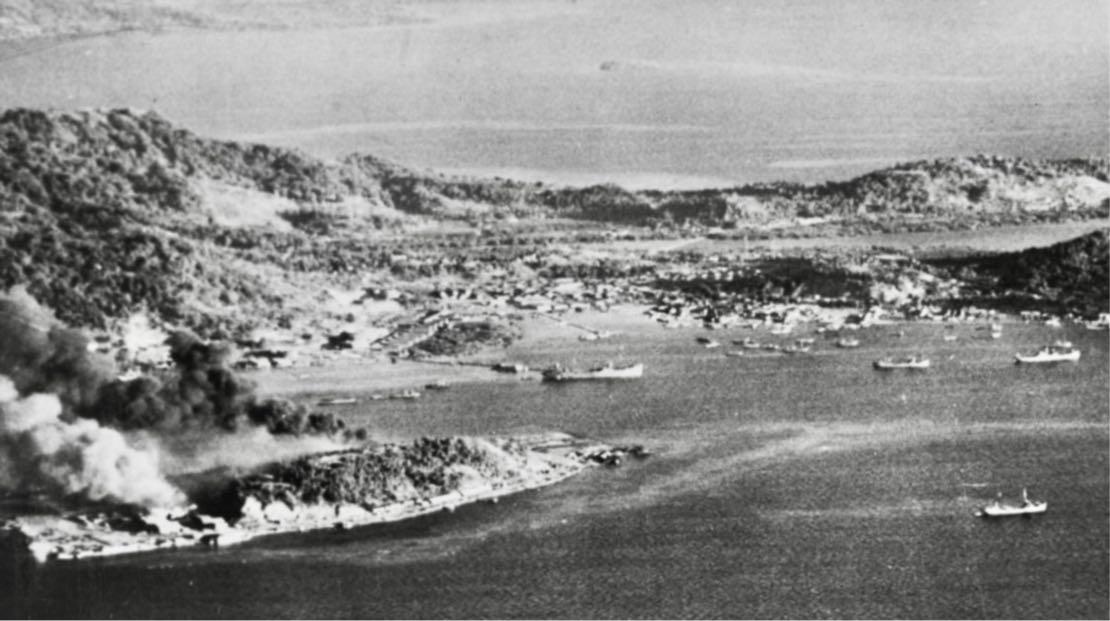

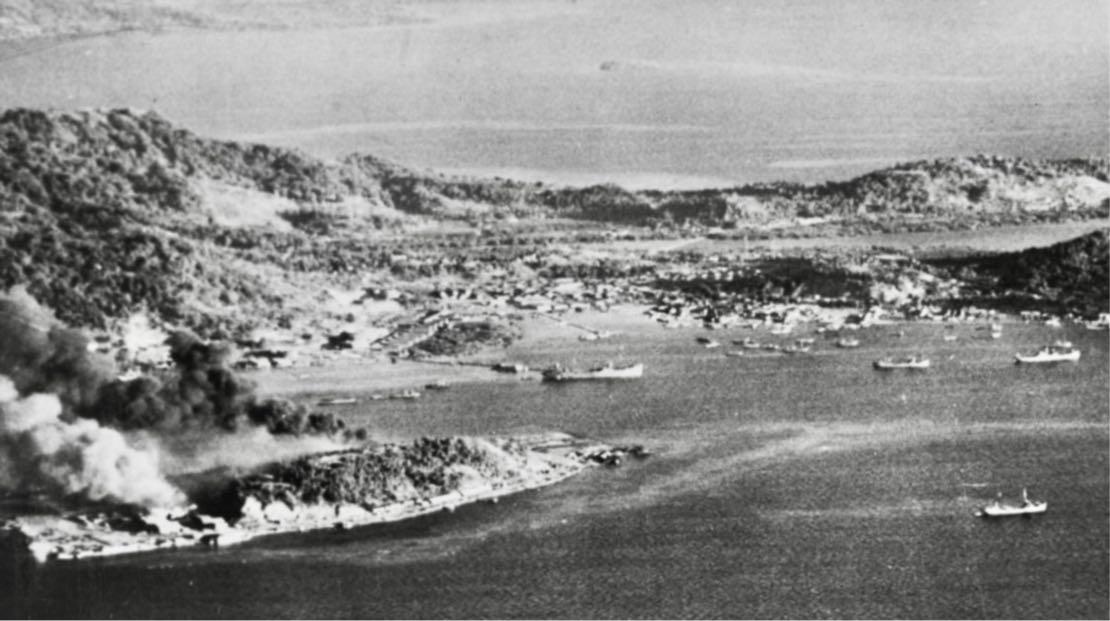

[1] The author (L) and Peter Jones on what was once the apron area of an air station on Ponam Island, b but is now the primary school. [2] The Admiralty Islands comprise about 160 small islands, the principal ones of which are Manus and Los Negros, located about 160nm north east of mainland PNG. Australian mandated territory in 1942 they were occupied by the Japanese and had to be recaptured in a series of costly battles. Once in allied hands, the Americans built airfields on some of them, the one on Ponam Island becoming British in 1945. [3] Airfield on Eten Island burning at left, as seen from a USS INTREPID (CV-11) aircraft on the first day of strikes, 17 February 1944. Dublon Island and town is in the middle background, with several merchant ships offshore, and one large tanker alongside the fuel pier in left centre. See next page for what it looks like now. ✈

7 Letters to the Editor

1 2 3 4

Ponam Island is 22 miles to the west of Seeadler Harbour, the major fleet anchorage of Manus. Commissioned as Nabaron/Naval Air Station Ponam on 2 April they made ready to support the British carriers on return from conducting their first strikes against the Imperial Japanese Navy. By August those carriers would number 21, with 750 Avengers, Barracudas, Corsairs, Fireflies, Hellcats and Seafires.

Of course many FAAAA members will have stopped to refuel at Manus’s HMAS Tarangau base as they deployed north to South-East Asia during their service careers. Being on the shores of Seeadler Harbour this base originally commissioned as HMAS Seeadler on 1 January 1950, the naming committee having forgotten that the protected anchorage was itself named after SMS Seeadler (Sea Eagle), a German Imperial cruiser of that belligerent nation’s New Guinea South Seas Station. Three months later an embarrassed Navy Office in Melbourne directed the base be recommissioned as Tarangau. From 1949-1953 it was also the site of a War Criminals Compound with 150 Japanese guarded by native police under RAN officers. In 1974 the base, along with five Attack class patrol boats, was handed over to the PNG Defence Force.

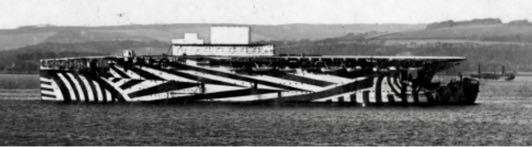

Knowing the place RN Mobile Naval Air Bases have in our own FAA heritage it was with anticipation that my naval college classmate Peter Jones and myself went ashore - with our patient wivesfrom Seabourn Pursuit to a colourful dancing welcome from the locals. Jungle, gardens and housing

cover the old air station and as you walk down a green path following the main runway you are occasionally aware of broken concrete underfoot and the foundations of station buildings, many now serving as the solid base for family homes. Peter, despite his gunnery background, when in charge of the tri-service Capability Development Group, was responsible for purchasing the flight-deck fitted strategic sealift vessel Choules and additional C17A Globemasters for the Air Force. We found it fascinating to see the remains of a Royal Navy air station and the occasional British symbols in this remote Pacific island group eighty years after the end of WW2.

Taking passage further north you could only ponder how battleship binoculars came to be hanging from a palm tree for use by the five residents of remote Oroluk Lagoon in Micronesia. A Zodiac ashore to Eten Island in Chuuk Lagoon (Truk) proved even more fascinating. A major Imperial Japanese Navy Fleet base almost 1,000 miles north of New Guinea it had been attacked in Operation HAILSTONE in February 1944. The 560 aircraft from nine carriers and six battleships under Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher, one of the earliest USN aviators in 1916, soon turned the lagoon into the Pacific’s premier wreck diving destination sinking six warships and 26 merchant ships. They also bombed the IJN 4th Fleet Headquarters and destroyed 270 aircraft over five airfields.

The raids on Truk and the Marianas showed both the striking and defensive power of a fast carrier task force, inflicting heavy losses on the Japanese

First Air Fleet. Even with the forewarning of US reconnaissance flights the Japanese could not prevent the attacks, demonstrating that carriers, concentrated in sufficient numbers and boldly handled, could operate against shore-based aircraft even when lacking the element of surprise. After supporting landings at Aitape and Hollandia in New Guinea the fast carriers struck Truk again at the end of April, effectively destroying it. Never invaded, in accordance with the ‘island hopping’ strategy, occasional bombardments by aircraft including B-29s prevented any operational recovery as a base by the thousands of trapped Japanese.

In June 1945 Operation INMATE was mounted to ensure the 80 aircraft and crew of the newly arrived fleet carrier Implacable were fully worked up before being committed to operations against the Japanese home islands. Using the escort carrier Ruler as a spare deck Truk was attacked in bad weather on 14/15 June losing seven aircraft and two aircrew. These strikes included the first night attacks by a British carrier in the Pacific and her aircraft provided gunnery spotting for the accompanying cruisers and destroyers. Implacable then joined Formidable and Victorious, with the US Third Fleet,

2 3

[1] The author standing in the heavily bombed ruins of the Japanese 4th Fleet HQ on Eten Island,, Chuuk Lagoon. [2] An external shot of part of the HQ. Jungle is rapidly reclaiming the fortified ruins. [3] A large pair of salvaged warship binoculars on the beach of Oroluk Lagoon, for use of the five permanent residents there. ✈

for air operations in the Tokyo-Yokohama area beginning on 17 July. Their screen in Task Force 37 included four RAN destroyers - Quiberon, Quickmatch, Quality and Quadrant.

As we walked though gardens and plantations the occasional concrete underfoot indicated we were again walking over runway remains. Coming upon the fortified Fleet Headquarters buildings and blockhouses, overgrown by jungle vines and trees, felt like finding a lost Inca city. The explosive devastation of the strikes was starkly evident from the twisted blast doors and shattered steel reinforced concrete.

Next stop Guam!

Yours aye, Graeme Lunn. ✈

8 9 Letters to the Editor

Above. Eten Island, Truk, photographed from a USS Yorktown aircraft 17 February 1944. Note the large number of Japanese planes on the airfield and numerous bomb craters. Dublon island is in the background. The red dotted line is the track that the author took during his recent visit, although the island is now totally overgrown as shown by the coloured inset, top left. ✈

1

Offer of Counselling or Spiritual Guidance

Dear Editor,

I left the Navy in 1973 (Safety Equipment) and after several years I studied at Bible College with the Australian Christian Churches. Eventually I was ordained a Pastor and finally Emeritus Pastor in 2018.

I held various ministry positions including Senior Minister as well as providing counselling with folks with life problems. During that period I also provided assistance to the NSW Police Service and medical practitioners for MPD etc.

The purpose of my contacting the FAAA is to offer to our members a contact for those who might wish to seek spiritual advice or simply encouragement for life difficulties.

I would be delighted to be available to any member who might wish to have a chat 24/7. Obviously there is no cost whatsoever.

Kind Regards, Pastor Jon Dorhauer.

By Editor. Thank you for your kind offer. If anyone wishes to speak to Pastor Jon, his email address is chaplaincynsw@gmail. com

LAST MONTH’S

MYSTERY

P

HOTO

Answer

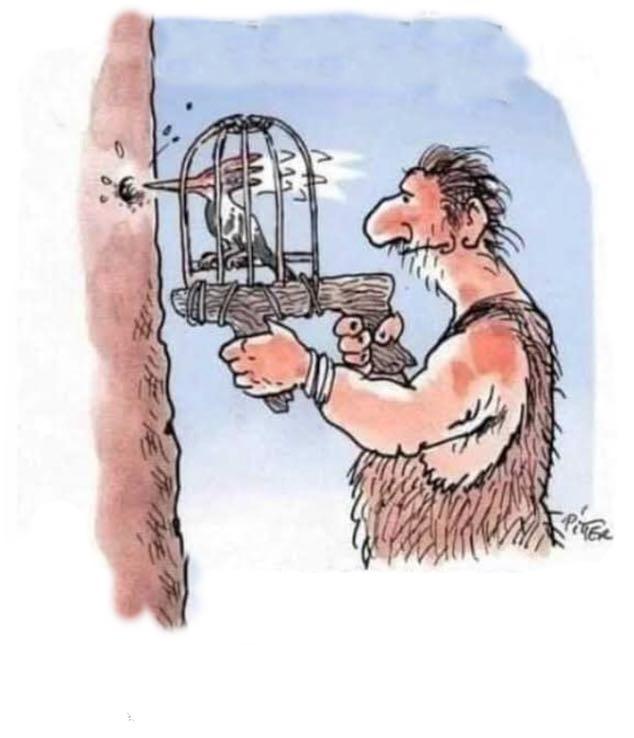

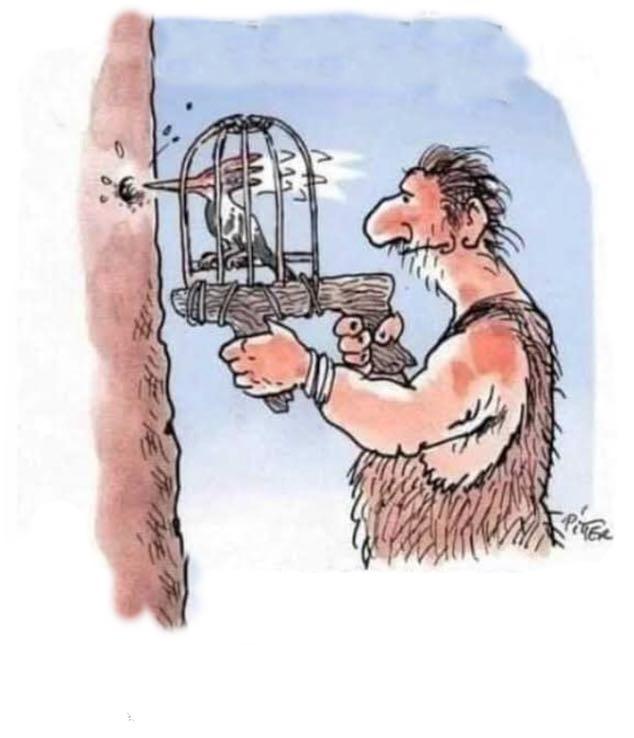

The very first cordless power drill

VETERANS Reunion

The annual Old Bar Veteran’s Reunion is on again, thanks to the hard work of John Macartney.

Full details and a booking form can be found here brief outline is as follows:

When: 16-18th August 2024

Where: Old Bar, NSW.

Activities: Range of activities depending on which days you wish to attend. Includes a Veterans’ Day Parade and Service as well as social events with your mates.

Cost dependent on which events you choose. See link above for full details.

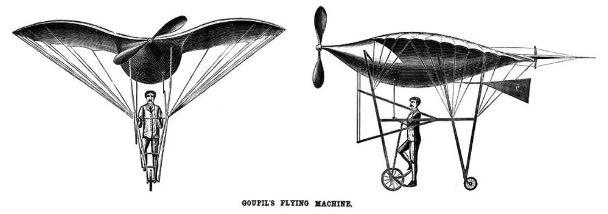

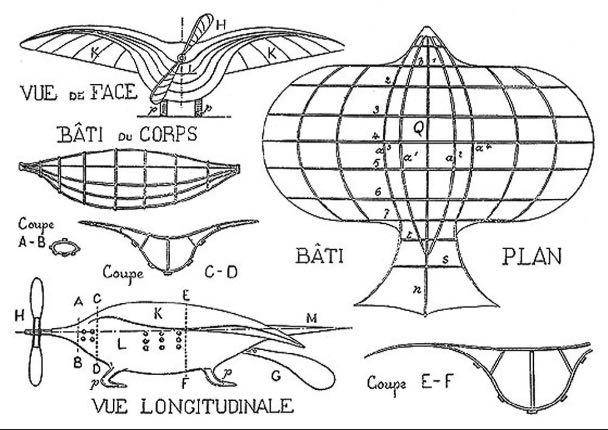

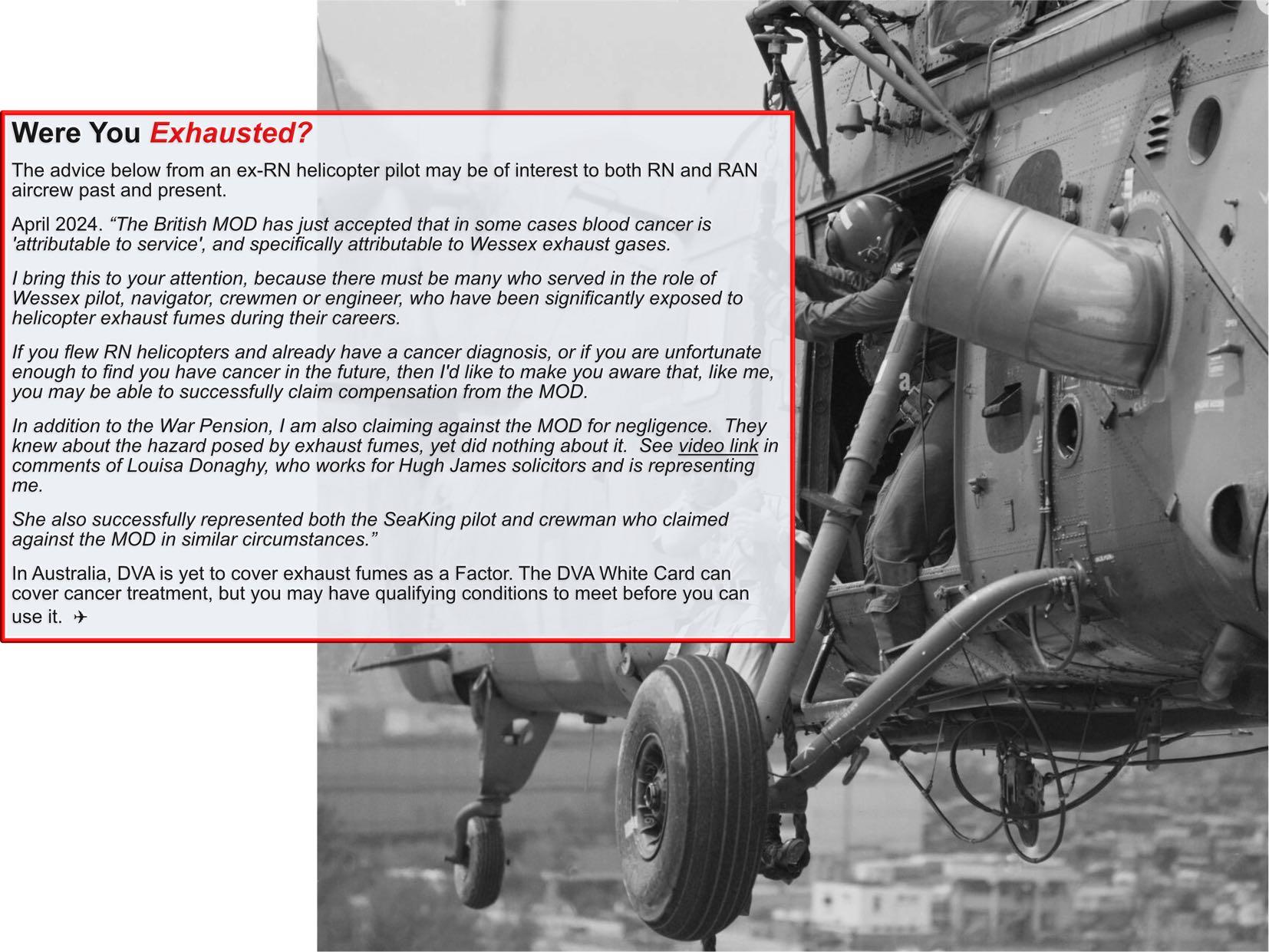

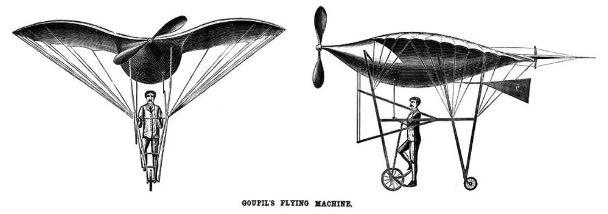

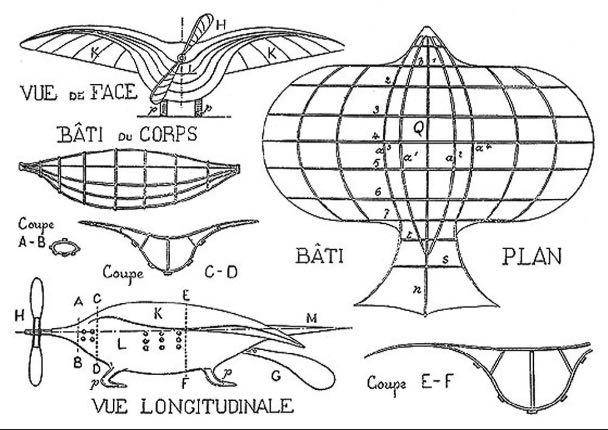

The dream of building a flying machine has captured the imagination of men ever since they first started walking upright. As time went by, some put their ideas to paper: perhaps most notably, Leonardo da Vinci, who was fascinated by the possibility of human mechanical flight. During his life in the16th century he produced over 500 sketches for several flying machines including a helicopter and hang glider.

So too did Alexandre Goupil, a frenchman, who in 1883 produced a drawing (see right, middle) of what he christened “The Duck”. He later built a smaller, man-powered model achieved successful unpowered test flights. One, into a slight headwind, generated enough lift to elevate the machine and two pilots into the air.

Goupil imagined a more sophisticated version (right lower) bearing a steam engine driving a single propeller at the front, but the technology of the time (a 1000lb engine producing just 15 hp) was not practicable - so, like many of the early concepts, his idea was therefore set aside.

Fast forward to 1917 when Glenn Curtis, an influential American entrepreneur and aircraft designer, was locked in a long-standing legal battle with the Wright Brothers for patent infringement. They maintained he had stolen their concept of lateral control.

Curtis looked around for evidence that lateral control methodologies had existed before the Wright brothers took to the skies, and his eyes fell on Goupil’s design. He recognised too the aircraft’s potential especially now there were

engines of much greater power to weight ratio.

Using Goupil’s original design derived from patent drawings, he constructed a Duck at his Buffalo plant in NY state. To power the aircraft he used is own OXX-6 engine, selected due to it’s 60% weight reduction over Goupil’s steam engine, whilst providing a 400% increase in power.

The Curtiss-Goupil Duck took to the air on 19 January 1917, first maintaining a straight path

10 11 Letters to the Editor Mystery Photo

and then successfully completing a circular flight. Although Curtiss had implemented several important changes to the original concept such as the engine, control linkages and longer wings, the core design remained unchanged.

The flights demonstrated that lateral control had existed prior to the Wright brothers’ patent, substantiating Curtiss’ claim. In the event, however, the lawsuit was settled through arbitration and Curtiss’ ‘Duck evidence’ was not used. The US Government also persuaded Orville Wright to release the Patent, citing the urgent need for combat aircraft for WW1. ✈

Top. Glenn Curtiss in his airplane workshop in Buffalo, NY. Middle. Another version of the CurtissGoupil Duck, this time on floats. It evidently wasn’t ideal as Curtiss went back to wheels. Lower. It looks like the wings should flap, but in fact they were fixed. Note the smaller lower winglets which were the means by which ‘lateral balance’ was achieved. This was the subject of Curtiss’ interest in resurrecting Goupil’s otherwise odd design, in order to prove that lateral control mechanisms had existed well before the Wright Brothers took to the sky in 1903. ✈

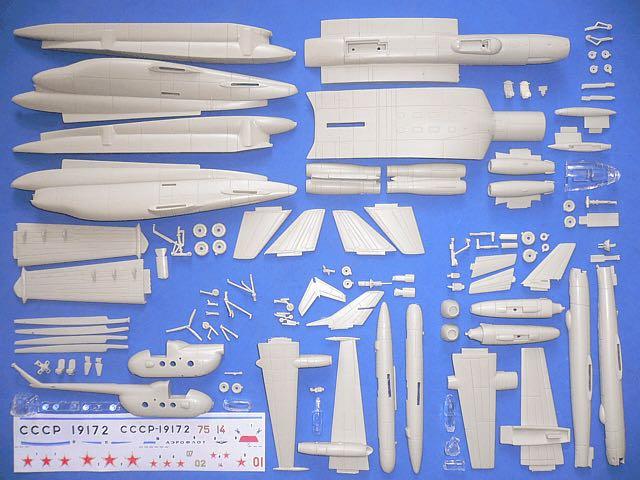

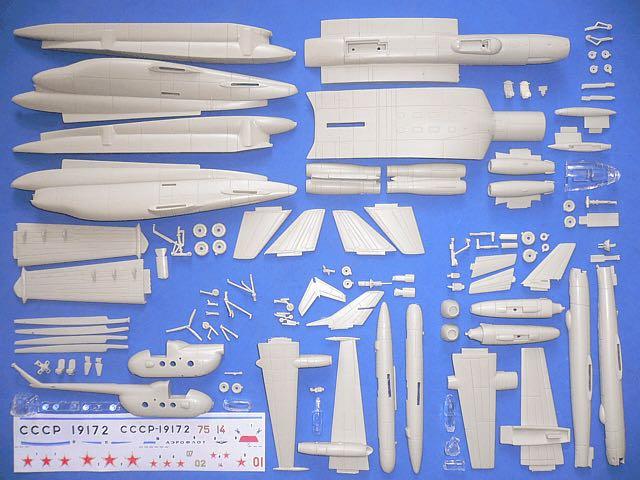

THIS MONTH’S MYSTERY PHOTO QUESTION

There’s one FlyBy reader who gets every single Mystery Photo right, and I’ve said on a number of occasions that I’ll finally find one that he can’t guess. So... cop this, Ted!

And just to muddle things further, it looks like some bits from two other kits are mixed in here too.

I can tell you that this aircraft was of soviet era, was produced quickly to counter a specific threat, and was a failure. And no, it wasn’t a helicopter.

Ok, ok, I know that’s unreasonable, so just to help things along, here’s a little picture of its cockpit.

Send your answer to the Editor here. ✈

BIG SUB!

How’s this for a big Unmanned Underwater Vehicle (UUV). Dubbed “Manta Ray” for obvious reasons, it looks like a cross between a B-21 bomber and something from a Sci-Fi movie. Not surprisingly, the US isn’t telling us too much about what it can do. We know it can be transported in five containers and assembled in situ; is one of a class of new long range and long duration UUVs, and is built by NorthrupGrumman. It has the ability to anchor itself to the sea bed and go into ‘hibernation mode’ to perform a number of missions. See here for more.✈

12 13

New Patron Appointed

The Fleet Air Arm Association of Australia is delighted to announce that Rear Admiral Anthony (Tony) Dalton AC CSM has agreed to become our new Patron.

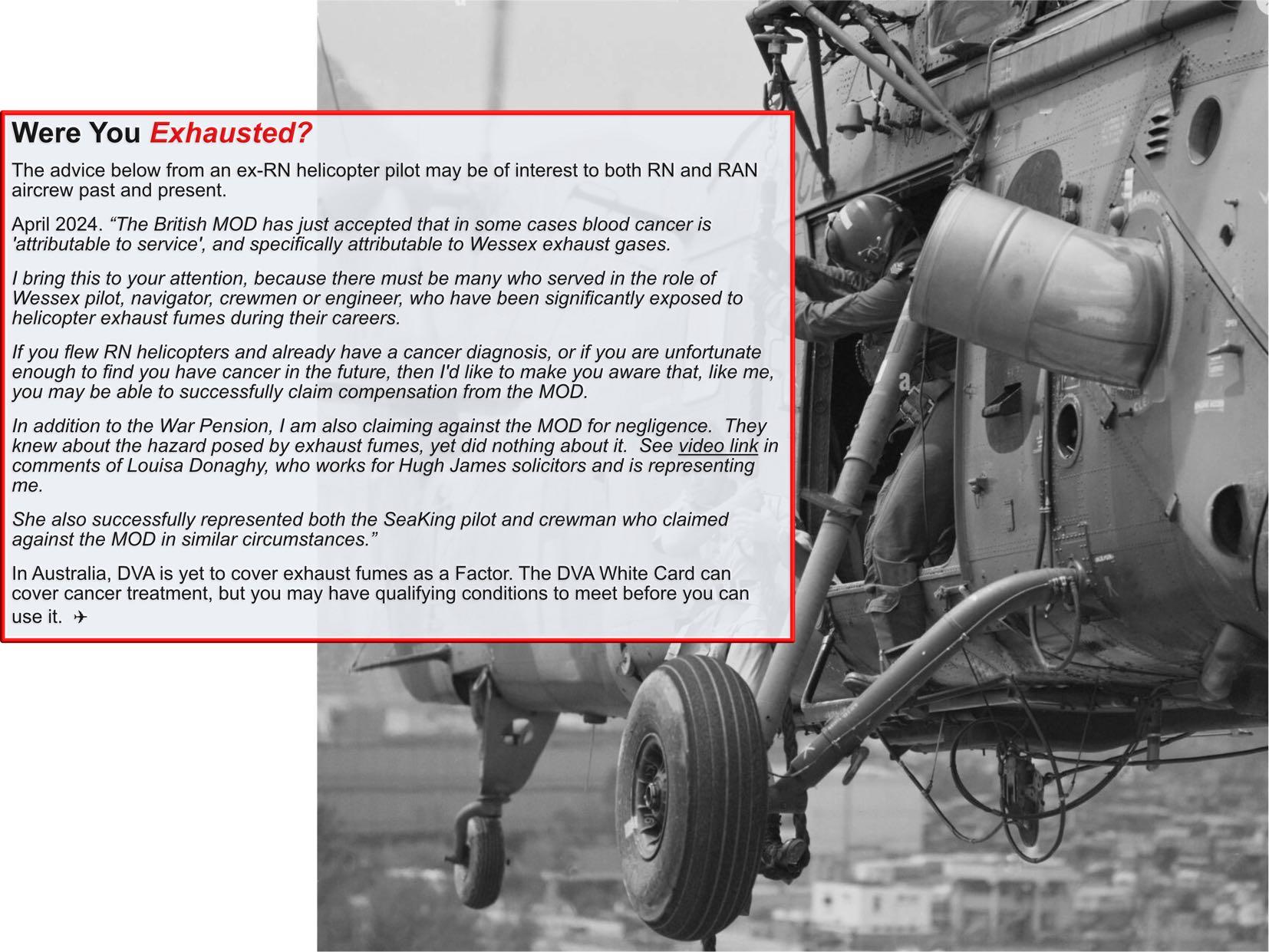

He replaces RADM Neil Ralph, who stepped down from the position after many years of stirling Service.

RADM Dalton, a Victorian by birth, joined the Royal Australian Navy in 1980 as a direct entry aviator, completing his pilot training the following year. He flew most of our helicopter types during his service on four Naval Air Squadrons, including with the Royal Navy’s 705 Squadron. He Commanded 805 Squadron and served as Commander Fleet Air Arm, before heading to Canberra to hold various staff appointments, including as Head of the Defence Material Office Helicopter Systems Division and Head of the Joint Systems Division.

After leaving the Navy he held high-ranking positions in the APS in the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group before his eventual retirement not long ago. He lives in Berry, NSW.

A Patron is not an executive position. Rather, it is a person of high standing who is prepared to lend his name to the organisation to add to its credibility and integrity, and to provide his experience to guide and influence ideas and purpose. RADM Dalton is extraordinarily well qualified to meet the position, and we welcome him. ✈

PLEASE HELP CUT OUR SLIPSTREAM COSTS

Our long-standing printer of “SlipStream” magazine is closing shop and we will have to find a new one. Estimates indicate that even the cheapest quote will be substantially more than we have been paying before.

Over 80% of our members who get “Slipstream” in hard copy have an email address, so could easily read it in ‘soft copy’ instead. If you choose this option you get a link (similar to this magazine) which would let you read Slipstream in “Flip Page” format, or via a fully scalable PDF file - which you can also download and/or print should you wish to do so.

If nothing changes then it is inevitable that the cost of Slipstream will go up to cover our costs, and nobody wants that. The best way to save money is for people to read it on line as it not only means less printing, paper and trees, but also less postage costs.

So, please, if you currently receive Slipstream through the mail, consider switching to soft copy. You can do it quickly and simply here. ✈

FLY NAVY STICKERS

We still have stock of FLY NAVY stickers. If you are interested in buying a few just point your phone at the QR code and it will generate an email for you to send, asking for details. ✈

Tracker Reunion

Bruce Saville is organising a Tracker Reunion over two days (14th and 15th October 2024) and wishes to advise that tickets are now available for purchase. You can attend for just the first day on the 14th, or buy a ticket for both days if you prefer.

Full details are available on the Friends of the RAN Grumman Tracker Website

A minimum of 60 attendees is required to make the event viable, so please get your name down. A link to buy the tickets is given on the above website, together with a programme of expected events. ✈

Question: Aside from being made by Supermarine, what do the two aircraft shown here have in common? Answer next edition. ✈

?

14 15 General Notices General Notices

No More FOD

An Israeli company is taking a novel approach to FOD risks at airports, with remote sensors and AI scanning paved surfaces for adrift objects that represent a hazard to aircraft operations. According to recent industry estimates, FOD related damage at US airports alone cost around $25m per year, with global direct and indirect costs estimated at $23bn.

The sensors continuously scan the surface and distinguish between FOD and wildlife, and provide live video coverage of runway activities in all weathers, day and night. Each sensor scans its predetermined sector between aircraft movements within 60 seconds.

The FAA requires any FOD detection system to identify objects as small as 25mm, but the manufacturer of this one revealed that it detects objects much smaller, although he did not elaborate. You can see a video on the system here. ✈

Fairey Gannet in Flight?

We hear a lot about photos generated by Artificial Intelligence, where you ask a program such as Chat GPT to draw you an image and it does so using its vast database of subjects and learned knowledge.

Richard Kenderdine decided he’d test the concept and requested images of “[an] Australian Navy Fairey Gannet in Flight”and voila! the four images to the left were produced.

Hmmm. Not so intelligent after all, it seems.

Just for a bit of fun I thought I’d ask it to create an image of my own choosing. Guess what the subject was... ✈

Anzac Day Victoria

Like many of us, the Victorian Division of the Association was out and about on Anzac Day.

Pictured are (L-R) Alice Butler, Rob Gagnon, Paul Thitchener— partially hidden, Chris Fealy, John Scott, Mal Smith, Greg Williams and Jeremy Butler. Photo courtesy of Mal. ✈

Aircraft Hydrographics Catching On

The way of decorating or finishing surfaces in your BizJet or any other aircraft is changing, with Hydrographics taking off (if you’ll excuse the pun) in a big way.

Hydrographics, also known as hydro-dipping or water transfer printing, is a process of applying a lightweight film onto an aircraft surface.

For a bulkhead, for example, the surface is removed, cleaned, stripped of any previous finish and then primed. Customers (continued next page)

17

16

can choose a solid base colour that shows though the patterned film to create a unique appearance.

A pattern is then printed onto a specially treated film and is applied to the surface before being immersed into a tank of water, which causes the film to become pliable and to adhere to the cabinetry. The item is then rinsed, dried and sprayed with a protective coat.

If the cabinetry is too large or difficult to remove then sheet metal pieces can be dipped and applied to the component.

The range of designs is almost limitless, allowing the owner of the aircraft to customise in a truly unique way. Generally, the cost is 10-20% less than traditional veneer finishes.

We wait to see if Navy takes it up for our fleet of aircraft. ✈

That the many articles, stories and notices in “FlyBy” magazines over the years can be found by using the dedicated on-line index? Simply type “FlyBy Index” into our website search box, or click here

New Book Coming Soon! Book your copy here.

VAT

18 Around The Traps

The Story of

Smith

Did You Know?

19

Drew Harrison

AS350B Flying OPS during Gulf War I

LCDR Denes “Ralph” Illyes RAN

The lead up for my involvement in Gulf War 1 was extremely hectic. Having completed No. 26 Observers course mid-1990, Flight Observer Training (FOT) on the Squirrel began in July and consisted a handful of utility refreshers and straight into a utility check (thanks to recent previous history on the aircraft as an Aircrewman).

This was followed by Navigation and Tactical phases and, in what was probably record time due to the need to fill a Flight Observer position, my conversion on type was completed in September with embarkation in FFG HMAS Sydney IV in October 1990.

Weekly running, conducting workups, and the ship itself being fitted with all manner of new technology, was happening at a frightening pace. Before I could stop to really take stock of the past few months’ activities, I found myself one evening in the middle of

the Indian Ocean in transit to Diego Garcia (Sydney was in company with HMAS Brisbane) en route to the Gulf, night flying a long way from Mother with a brand new set of Night Vision Goggles (NVGs).

A makeshift cardboard dashboard extension cut out the glare from internal lights; I was looking into the dark void for distant light sources and sneaking up on and identifying merchant vessels with our landing light. The Squirrel had a single light source generating light for instruments through fibre optics, so a non NVG compatible light system required the dash lights to be switched off and the use of our aircrew torches with red filters and only the Observer wearing NVG. This allowed the Pilot to stay on the clocks with rudimentary lighting.

Other than the hum of the ever-reliable Arriel-1B gas turbine above and some radio chatter about the surface picture with the Ops Room, it was a tranquil and relatively

calm evening, there was next to no moon light and a handful of visual idents to conduct. I felt strangely comfortable, satisfied that the intense build up and kitting out was almost appropriate; but this really was just the calm before the ‘Desert Storm’.

I really had no idea what to expect in theatre and we completed our INCHOP and handover from HM Ships Adelaide and Darwin in Muscat Oman on 3 December 1990. Adelaide and Darwin subsequently returned to Australia whilst Sydney, Brisbane and Success continued into the Gulf of Oman for patrols.

We eventually transited through the Straits of Hormuz into the Northern Arabian Gulf (NAG) and things became very busy. Our flying consisted of constant daily surface picture compilations and identifying and tracking the vast plethora of merchant vessels within our range, as well as transporting COMFLOT to several USN capital ships.

These included US Ships Midway, Theodore Roosevelt, Blueridge, Lascalle, Missouri and the sister hospital ships Comfort and Mercy. Several frigates and AEGIS Cruisers were also visited such as Princeton, Bunker Hill and Oldendorf, to mention a few, as well as many auxiliary and supply ships.

As tensions escalated and conflict became imminent, the deadline for withdrawal of Iraqi forces from Kuwait was set at midnight of 16 Jan 1991 local time. Our job in the Squirrel became to warn off supertankers and merchant ships from heading to their intended gulf ports as they would likely be standing into grave danger.

Using Channel 16 to initially contact vessels, then chopping to discrete maritime frequencies and reading the UN Sanction 661 script, we in our fearsome battle budgie coerced many a ships master to turn for safer waters.

20 21 Historical Interest Reproduced

with the kind permission of Fleet Air Arm Safety Cell “Touchdown 2023”

SH70B Seahawk 873 (Tiger 73) and AS350B Squirrel 860 (Taipan 860) on the flight deck of HMAS Sydney, alongside in Freemantle - the last Australian Port of call before sailing for the Gulf in mid November 1990. ✈

Sometimes this required brandishing a loaded Mag-58 (Machine Gun) near bridge windows to convince them to wisely wheel over. One morning during our Surface Picture tasking, we flew with stealth in close to the Iranian coast to view the remnants of the ‘Surf City’, a US registered tanker holed by an Exocet missile fired from an Iraqi Mirage F1, the result of a previous conflict involving Iran. On our approach to the tanker, we were challenged by the Iranians on guard frequency via a Mode Charlie interrogation for apparently encroaching on their 12 nautical mile territorial limit. We made a hasty retreat without getting any more useful intel pics.

The stroke of midnight and 17 Jan 1991 saw a rain of Tomahawk cruise missiles leaving the silos of several USN ships in salvos and the tactical displays in the Ops room aboard Sydney were lit up like Christmas trees. The four Carriers operating in the NAG sent waves of an assortment of aircraft including FA-18s and F14 Tomcats deep into Iraqi territory on continual raids.

The USN promulgated communications plan (COMPLAN) for coalition aviation assets read in part words to the effect ‘Squawk and talk and don’t become a smoker, or share your cockpit with SM1’, a stark warning of the no nonsense approach to dealing with unidentified inbound airborne contacts. Knowing the no radio track-

ing procedures verbatim for identification was therefore high on the agenda. The merchant ship traffic had all but stopped and our role became one of own ship defence.

Predominantly flying in three-hour dawn and dusk patrols ahead of the ship, we conducted creeping line ahead pattern mine searches, as Iraqi forces had released hundreds of free-floating mines into the NAG.

We also trialled, and to some degree optimised, the laying of chaff cloud barriers around the ship with the hand launched ‘chaff hotel’ packets, to seduce any inbound missile that had potential to penetrate our ships defence systems. This activity required us to sometimes sit on deck at alert five.

Other water vessels created problems too.

Small, multi engine and extremely fast gunboats, known as ‘Boghammers’, posed a potential threat to warships and often fishing dhows would venture too close, requiring us to conduct hovering interrogations and force fishermen to uncover loads at gunpoint to ensure their cargo was indeed fishing equipment. Circular crayfish pots looked suspiciously like mines when under a canvas cover and needed to be identified. These encounters were potentially risky yet necessary part of daily business gaining our callsign ‘Taipan six zero’ the nickname ‘terror of the dhows’.

Above. AS350B airborne with GPMG mounted in the rear cabin.✈

Saddam Hussein’s troops had also lit up hundreds of Kuwaiti oil rigs, making visibility extremely poor with SMOID (Smog, Oil and Dust). The sunsets were spectacular but early mornings, in the heavy air, our visibility was sometimes down to just a few hundred metres and a sharp clear horizon was a rarity. This brought about risks of mid-air collisions for the low flyers. There were coalition force helicopters flying at level from several countries’ warships. There were numerous occasions of close encounters and crossing paths with USN Sea Knights, Sea Stallions and Sea Sprites or RN Jungly Sea Kings and Lynxs, and even an encounter with a Russian Helix. The Russians were interestingly flying with the doors off and in shorts and thongs.

Most encounters were dealt with rapidly using standard break procedures by all parties. Sometimes aircraft would slide into formation on each other to say G’day. The use of UHF ‘Winchester’ (303.0) frequency on UHF was a godsend as a means of inter helo chat and to aid self-separation, as the guard frequency became overused much of the time. The need for heads up flying, rapid and accurate navigation decisions and eyes out with good scanning technique was paramount to Situational Awareness (SA).

Whilst we kept our wits with air contacts, we were also often challenged by coalition warships for encroaching their individual five-mile radius limits, imposed to allow Close In Weapons Systems (CIWS) such as Goalkeeper and Phalanx to actively track and if need be, engage any hostile inbound traffic. Poor visibility and lack of radar allowed us to often, but never deliberately, encroach these limits. It was like flying in a pinball machine and there was never a straight-line track for any of our missions. We would periodically need to broadcast on guard frequency and turn away safely ensuring we were squawking ident.

There were however two occasions that made me almost pull on my brown corduroy trousers. One morning in the usual pea-soup visibility, we flew directly across the bow of the battleship USS Iowa, appearing suddenly in a low mist of SMOID and looking terrifyingly menacing. Flag Bravos, indicating live firing, were hauled closeup on her masts and we made a ‘check’ call on guard, albeit we were outside their broadside firing trace. Nonetheless it was a sobering experience considering the turrets of her 16-inch guns were poised downrange to unleash a herd of Volkswagen weight shells across the horizon into Iraq.

The other was a brief altercation with a USN F/ A-18A Hornet that pulled up abeam us in loose

23

formation less than 50 metres to our starboard side, clearly packing heat on its wingtips, sitting in high alpha (AOB) to maintain our relatively slow airspeed and very keen to identify our nationality. We managed to somehow convince the curious ‘knuck’ with some rudimentary sign language that the roundel on our side was a kangaroo and that we were indeed friendly and did not wish to share our cockpit with his AIM.9 He seemed satisfied enough and left us in a vapour trail of after-burner and with our hearts pounding.

This certainly wasn’t the last of these such interceptions and we agreed to carry a six pack of Fosters, which was a readily identifiable and universal symbol of our solidarity with our USN counterparts on all of our subsequent encounters. After all, there were only two RAN Squirrels operating in the entire theatre and no-one knew too much about us.

The routine of getting up at 0400 every morning was not difficult to adjust to as our days ran into each other in a metronomic fashion. Our daily three-hour morning sortie included a mid-flight hot refuel on deck followed by a post lunch three-hour sortie into dusk. The six hour flying days didn’t relent for seven weeks straight whilst at sea. The Sydney was part of a ‘ring of

steel’ of picket ships operating with one or more of the Carrier groups operating in geographically assigned boxes in the NAG.

The aircraft performed extremely well with the tender loving care of our four dedicated and enormously talented maintenance staff. They looked after our aptly named ‘Stealth One’ (as we were hard to see visually or on radar), with meticulous detail and we were rewarded with consecutive months of 100% serviceability and availability. Our extremely proud achievement of cracking one hundred flying hours by Australia Day for the month of Jan 1991, saw us fly over 116 hours for that month and a total of well over 200 hours for the two months of Jan/Feb 1991, with hostilities ending on 28 Feb 1991.

Whilst we were operating within our crew duty limits at the time, these have changed significantly over the years and the insidious nature of chronic fatigue had set in. All the signs where there but we didn’t realise or acknowledge them. Whether by good fortune or otherwise we were dealt a hand of aces and maintained a solid safety record for the deployment. The levels of stress and fatigue may have fluctuated day to day at sea, but without doubt, and with the benefit of hindsight, there were longer term effects manifest that become more obvious well after our return home.

Stress was sometimes raw. Lengthy separation over a Christmas period are times with family and loved ones that we can never recover and a great frustration was receiving news from home weeks later via normal ‘snail’ mail. We did not have the luxury of today’s mobile phones and internet technology and could only ring home during rare and brief port visits or by INMARSAT phone for dire emergencies. We all had our race faces on during the deployment, but the fear in peoples eyes the first time the general alarm was sounded, signalling Action Stations in the early hours after the war had begun, was apparent; and the tension in the air was palpable.

The Iraqi Air Force was large and formidable and waves of Mirage F1s and MIGs made several feints into the NAG but it was eventually nullified by coalition air superiority. Scud missiles however, were a fire and forget ballistic weapon that could splash down anywhere and with a

variety of potentially dirty payloads. A large explosion nearby one evening woke many onboard yet remained unexplained. The danger of hitting a mine, particularly at night kept sailors on watch on the bow day and night and those on the bridge scanning on the EOS; the ship was making only enough headway at night to maintain steerage to minimise risk of a contact. The rest of us went to our bunks at night with one eye open. We didn’t fly at night in theatre, albeit we had NVG and TI available but that risk was indeed too great, nor was it warranted for our range of tasking.

Early in the deployment I inadvertently outran my furthest on circle of navigation whilst in the thick of reporting merchant vessels about 80 Miles out and we needed Mother (Sydney) to shine Father (TACAN) whilst we proceeded at buster with Sydney closing us at speed. To make matters worse we needed to make

On deck USS Missouri, conducting a transfer on 18 February 1991, on the gunline off the coast of Iraq. ✈

24 25 Historical Interest

some CIWS encountered doglegs to dodge being locked onto. We landed on with 8% of fuel (published minimum land on fuel for embarked ops was 15%). It was an error I only ever made once and a serious situational awareness awakening for becoming too task focussed. Albeit, any one of our coalition vessels enroute could have happily accommodated a refuel.

Environmentally, the NAG was a cess pit. Flotsam and jetsam littered the waters; it included items lost or perhaps deliberately tossed overboard from merchant vessels (such as fridges and the like), the remnants of sunken Iraqi ships and blown-up oil rigs, dead whales, with their carcasses ripped open and schools of sharks darting in and out in feeding frenzies. Birds covered in oil were flopping on to our decks, exhausted; dolphins were seen trapped in clean water patches within oil slicks trailing in the shamal winds stretching for hundreds of metres. The garbage, such as wooden cable reels and rafts of floating debris provided good targets to hone my skills with the GPMG and I sunk my fair share of garbage with plenty of good practice, burning through about 15,000 rounds of 7.62 ball and trace.

Of the hundreds of free-floating mines, the very day after the conflict had ceased, two were struck almost simultaneously and only 10 miles apart by the USS Princeton, a Ticonderoga class AEGIS cruiser that needed to be towed into Dubai with serious injuries to personnel as well as superstructure and transmission damage; our Seahawk was actioned to provide assistance. The other vessel Tripoli, an Iwo Jima class amphibious assault ship, fared somewhat better with its battleship design hull structure.

The crew flooded the damaged forward compartments, ballasted, and continued on with business as usual.

We ate well onboard, probably too well, and the lack of ability to conduct quality routine cardio exercise took its toll, although our resident club swinger did a fantastic job in helping us keep in some kind of shape, with his trademark PTI issued wit and humour.

Other than the pre deployment jabs, the entire crew were also required to take daily (NAPS)

tablets as a prophylactic for a potential chemical exposure to nerve agents. We just weren’t sure what the Iraqi’s might throw at us. The side effects were many and various and my usually cast-iron gut was no longer so. Many suffered flatulence and the ship was like a methane factory so flying or being out on the uppers was precious.

For the more junior officers, accommodation was scarce and we bunked in the stokers mess full of watchkeepers, sharing a small enclave with some Electronic Warfare (EW) Gollies that had posted on to bolster the intel crew. The usual 180 ship’s company (by design) had swelled to 225 and, consequently, sleep hygiene was not optimal for fatigue management.

The Gulf War was a steep learning curve for all involved. Our rush to reach operational preparedness was a rude awakening to the fact that we hadn’t seen any active conflict since Vietnam and we needed to get it together quickly. A lot of effort was thrown at shoe-horning a bunch of new equipment both aboard ship and on the aircraft at very short notice.

If I were to dissect the modules of current NTS doctrine against what we were doing at the time, there were flaws everywhere in ergonomics, automation, workload, human ma-

chine interface, stress, fatigue management, SA, communication, error management, human performance limitations and the list goes on.

That’s not to say that we didn’t act entirely professionally and with best intentions and good judgement to achieve our objectives; after all, we all came home safely to our families; but we were also probably lucky.

The improvements I have seen over the years in Airworthiness, risk management, safety management systems development, NTS training, tactics, policy and procedures, even attitudes, are a quantum leap from our business of flying 30 plus years ago, but it’s not an excuse to become complacent. Flying in a contested environment is a dangerous business but it does have its benefits.

We find out what we’re really made of; whether our training passes the litmus test for preparedness. We gain enormously important experiences from which to further learn and develop our tactics; we tend to see much needed injections of capability and upgrades and we develop and hone our training and doctrine to keep the tip of the spear sharp.

The humble AS350B Squirrel might not have been a purpose-built military aircraft, yet we

26 27 Historical

Interest

HMAS Stuart ploughing into heavy swell during predeployment work off the coast of Newcastle. The image was taken from the Flight Deck of HMAS Sydney by the author.✈

squeezed every ounce of potential out of it and it now resides proudly on the Australian War Memorial inventory as part of the Fleet Air Arm’s colourful history and yet another RAN aircraft type that has seen active service.

During my years as a safety investigator, I recall conducting my first accident investigation of an Army Blackhawk; in the training documentation for the activity subject of the accident I read a line that still resonates with me on the importance of applying every piece of skill, knowledge and attitude to the art of flying in a hostile environment:

‘Don’t crash and do the enemy’s job for them’. ✈

Upper Left. On deck of USS Midway for passenger transfer 6 March 1991. Middle:

Flight and Deck crew in front of their Squirrel on Australia Day 1991, with a sign marking their 100th flying hour for the month. Below:

The author (foreground) sitting with pilot LEUT Simon Thorn. Opposite page: the author with the Mag 58 General Purpose Machine Gun about to go on a live firing practice. ✈

COULD YOU DO IT TODAY?

Flying in an operational or war zone is an extremely dynamic environment. All the scripts of training and exercising go out of the window, and the fog sets in: or, in this case, the SMOID (Smog Oil and Dust) of the Northern Arabian Gulf.

The AS350 was a civil (non MILSPEC) designed single-engine, skidded aircraft. It had no redundancy in its electrical system with a single generator and alternator, a single hydraulics system and no shielding of its electrical systems. It carried no sensors, weapons or countermeasures and it had a basic suite of terrestrial navigation aids and a Lightweight Doppler Navigation System (LDNS) that was prone to drift.

Simply put, the AS350B Squirrel was not designed for any operational military purpose. The RAN had procured them in the 80s for a training role at the ADF Helicopter School and HC723 Squadron. The task of Navy’s Squirrels was expanded later to include a tactical role, and they were eventually embarked with crews in Adelaide Class FFGs for several years, proving to be a highly reliable and useful platform.

These roles, and the involvement in a hostile operational environment would likely have been considered untenable by today’s airworthiness standards and risk management processes.

This stretching of the aircrafts’ employment rubber band came in the years prior to the robust Defence Airworthiness regulatory

System we work within today; it was also prior to formal risk management processes and Non-Technical Skills (NTS) training being embedded into our day-to-day business; as well as mature safety management systems. Take a moment to consider whether a Statement of Operating Intent would see the AS350 helicopter conducting similar operations today. Would the platform be fit for purpose or meet the rigours for military certification?

Some of that changed almost overnight when Iraq invaded Kuwait and the aircraft was sent to war embarked in RAN FFG’s and HMAS Success. The aircraft was fitted with an APX-72 transponder allowing the ability to Squawk on military Modes 2 and 4, making it possible to be identified by allied interrogations in theatre; a JLR 4200 GPS, designed for maritime use, was also fitted on the dashboard.

The GPS had its flaws keeping up with the dynamics of the aircraft velocity as well as antenna blind spots and, at the time, in an incomplete constellation of satellites in semi-synchronous orbits, meant very small windows of opportunity to gain accurate position fixing. A pintle mount was designed by the Aircraft Support Unit to carry the MAG-58 General Purpose Machine Gun (GPMG) in the rear cabin as well as a large and cumbersome Thermal Imaging (TI) camera for night ops.

Aircrew were issued with ballistic vests, 9mm sidearms, gas masks for NBC conditions, Helicopter Emergency Egress Devices’ (HEED), ANVIS 2 Night Vision Goggles (NVG) a hand-held radar warning receiver and skillets of Chaff Hotel (broad frequency hand launched countermeasures) stuffed into nav bags. To top off the ensemble, the usually unobtrusive white and blue visage of the Squirrel was given a face lift with a more menacing dark grey non reflective coat of paint and low vis roundels.

Overnight the Squirrel had become affectionally known as the ‘battle budgie’. In latter years the aircraft was upgraded to the BA model with wider chord blades and 150Kg increase in its maximum all up weight. ✈

28 29 Historical Interest

The Brutal Death of James Cook

Regarded by many as one of the greatest explorers of the 18th century, James Cook was nothing if not courageous.

But a series of disastrous decisions brought his life to an end three days after his 51st birthday, on a remotebeachinthePacific.

David Prest tells the story.

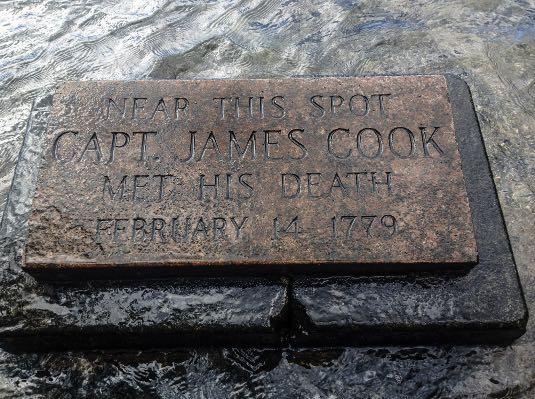

We all knew that James Cook was killed on Hawaii on 14 February 1779. He attempted to kidnapKalaniʻõpuʻu, theruling King/Chief of the island, to take back to his ship after the natives had stolen a longboat and other items from Cook's expedition. This resulted in Cook being confronted by a crowd of Hawaiians atKealakekua Bay seeking to rescue their hostage. The ensuing battle killed Cook and several Royal Marines, as well as a number of Hawaiians. King Kalaniʻõpuʻu survived the exchange.

Cook’s death was on his third voyage into the Pacific (to discover the North-West passage to link the Atlantic and the pacific oceans). He was the first European to “discover” Hawaii.

He is also reputed to have been unwell following his second voyage with his normal calm demeanour replaced by stern discipline and increasingly indecisive/confused decision making as the voyage progressed.

Additionally, his preparation for the voyage was not up to his usual standard of preparation for the voyage and supervision of repairs to his ship, carried out by the corrupt London Deptford shipyard. The result was his crew having to make numerous repairs throughout the voyage. The condition of his ship, known as “The Deptford Disease” was a factor in his death.

James Cook arrived in Kealakekua Bay in “Owhyhee”, as the natives called the island, on 16 January 1779.

The Hawaiians had a tradition that Orono Makua, the god of Hawaii’s season of abundance, would one day appear in a great canoe to be greeted by the islanders with white banners. Orono would then coast the island from north to east, to south and to west, at the season of greatest abundance, and his appearance would be marked by ceremonies of a religious nature when he arrived in the Kealakekua Bay.

30 31 General Interest

Nathaniel Dance-Holland c.1775.

‘Death of Captain Cook’ by John Cleveley the Younger.

Cook’s ship HMS Resolution and her sister ship, Discovery had arrived at Hawaii exactly at the right time, had proceeded round the island as legend had predicted, and had been received with white banners, to which Orono had replied by breaking out his flag. Moreover, Orono had come to Kealakekua, “the path of the gods” and halted before the morai (a temple) as predicted. The extraordinary coincidence was almost beyond belief, but was true.

In the following days, Cook was treated as a god as the Resolution was Oronos morai with telescopes and navigating equipment, etc exhibited as his sacred symbols. Wherever he went he was subject to a god-like respect with feasts occurring as he explored the island. Cook seemed to play along with this pretence.

With time, both the natives and Cook thought it was time to move on, as the thieving from the natives and the retaliatory action from Cook was starting to wear out the welcome. Additionally, the food reserves of the island were being expended and were getting short.

Cook sailed from Kealakekua Bay on 4 February, intending to continue the surveys of the islands. However, on 8 February a ferocious gust split the foremast during a storm: another of the “Deptford Disease” problems to affect the ship.

Repairs were estimated at two weeks, and to fix the leaking hull required a safe anchorage. Two options were considered: either to find another Bay to anchor in, or to return to Kealakekua - which might not be acceptable to the natives there. Option two was adopted.

His return to Kealakekua was subdued, as he arrived from the wrong direction with the bay now filled with Hawaiians in a restless mood and with the King displeased with the reappearance of his unwelcome visitors. The “outrageous and blatant” thefts of equipment from Resolution resumed, resulting in one thief being given forty lashes and others being shot at.

The thieving escalated, with a serious loss of valuable blacksmiths tools, and on 14 February, a ship’s boat. Cook went ashore to retrieve both it and the stolen tools, but his efforts were unsuccessful. Crew excursions ashore were generally met with hostility and a shower of stones.

In desperation Cook decided to bring the King aboard to apply leverage to have the stolen items returned. A confrontation occurred on the beach with a large group of Hawaiians armed with spears, clubs and daggers. Cook’s prediction that the indigenous people would never stand up to musket fire had been proven incorrect.

The ships’marines, knowing that it took up to 20 seconds to reload, fled in panic as others in the party were stabbed and killed. As onlookers on the ships watched, Cook - seemingly oblivious to the threatening crowd - walked calmly away from the natives until one hit him on the back of his head with a club. Cook staggered, dropped to one knee and at the same time, dropped his musket. He attempted to rise but was stabbed and fell into knee-deep water.

As Cook struggled to keep his head above the surface, another native “gave him a shattering blow on his head with a club” and he went down for the last time as warrior after warrior knifed his corpse.

William Bligh (yes, that Bligh), later claimed to have been watching with a spyglass from Resolution as Cook’s body was dragged up the hill by local inhabitants and torn to pieces. As part of a ritual of respect his heart was eaten by the four most powerful Chiefs. Resolution then reportedly bombarded the nearby village as an act of revenge.

At some point, natives rowed out to Resolution and gave parts of Cook’s body to the captain. More remains were obtained and on 22 February 1779, they were buried at sea.

The following day both Resolution and Discovery raised their anchors for England with Bligh navigating.

There is a monument to James Cook situated at the exact spot where he was killed at Kealakekua Bay.

Reference: Captain James Cook, a biography, Richard Hough, 1994, Hodder & Stoughton.

Images: Wikipedia. ✈

32 33 General Interest

George Carter, 1783, Bernice P. Bishop Museum.

Carriers weren’t always the shape they are today. They went through many iterations, each one the result of lessons hard learned.

Graeme Lunn looks at the story.

34 35 Historical Interest

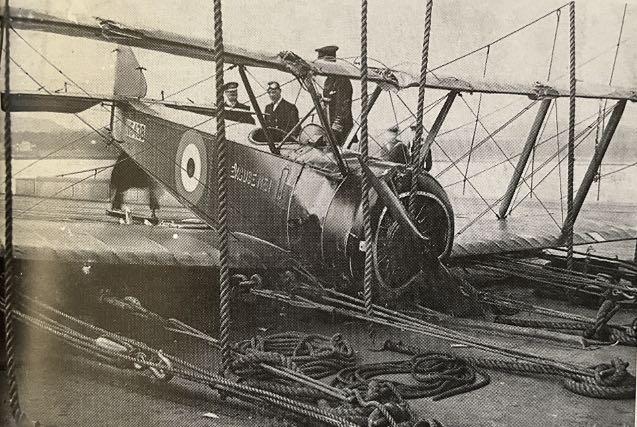

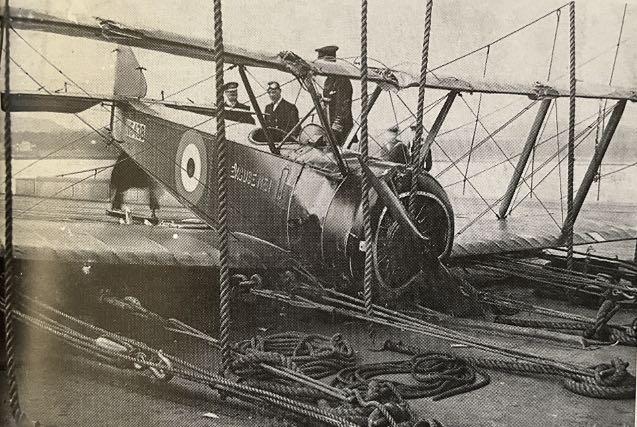

Australian ‘Harry’ Busteed landing his Sopwith Pup on HMS Furious in March 1918 and about to enter the barrier. The ‘goofers’ behind it obviously have great faith in its stopping ability. ✈

The Birth of Air Power Awareness

Prior to WW1 there had arisen the concept of ‘battle cruiser’ ships to protect trade routes against enemy cruisers. With the firepower of a battleship but trading weighty armoured plate for speed they were criticised by battleship adherents as being innately vulnerable in fleet actions.

Their envisioned role, however, was flagship of a fleet unit in far-off stations attended by cruisers, destroyers and submarines. It was this strategy that led the new Royal Australian Navy to be based around the 18,800-ton Indefatigable-class 25 knot battlecruiser HMAS Australia, and the construction of her sister ship HMS New Zealand which was paid for by that dominion.

At the Battle of Jutland in mid-1916 Admiral Sir John Jellicoe sortied the Grand Fleet without his seaplane carrier Campania, while further south Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty’s battlecruiser squadrons only accompanying seaplane carrier was the 2,550-ton Engadine. Also missing from Beatty’s line of battle was Australia, undergoing repairs after a collision with New Zealand

Engadine had launched a reconnaissance sortie from her vanguard position ahead of the force. Lieutenant Frederick Rutland, in his Short Type 184 with Assistant Paymaster George Irwin as observer, spotted German cruisers and destroyers, earning a DSC and the lasting nickname ‘Rutland of Jutland’.

With the forces moving at speed during the battle’s opening phases the 21 knot Engadine, needing to stop to recover floatplanes, then trailed the main forces and played no further active part in the battle. Among numerous Admiralty committees considering the disappointing outcome of Jutland the inability of the Royal Naval Air Service to contribute significantly was addressed when Beatty formed the Grand Fleet Committee on Air Requirements in January 1917.

In the forefront of these considerations were two Australians. Sydney born Wing Commander Arthur Longmore RN, whose ‘A’ turret barbette in the battlecruiser Tiger had been hit by a shell from Moltke at Jutland, was appointed Assistant Superintendent for Design in the Air Department and was a member of the Committee on Deck Landing. At the same time Squadron Commander Henry ‘Harry’ Busteed RNAS from Melbourne, who had survived the torpedoing of the seaplane carrier Hermes in October 1914, was in command of the Experimental Construction Depot.

In 1911 Longmore and Busteed had been among the first 100 to receive a Royal Aero Club pilot’s certificate, No.72 and No.94 respectively. Busteed had refused the offer in 1912 to be a founding member of military aviation in Australia. Remaining with the British and Colonial Aero Company as Chief Pilot he joined the Royal Naval Reserve as a Sub-Lieutenant in October 1913. ✈

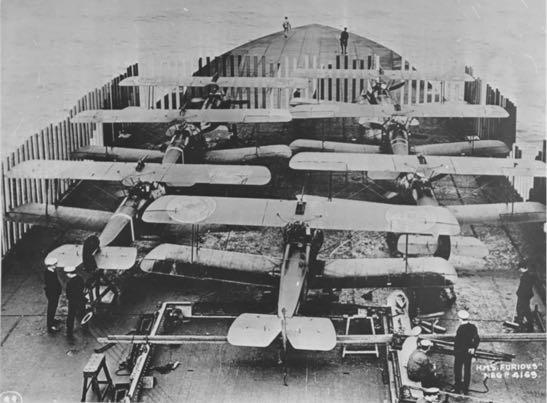

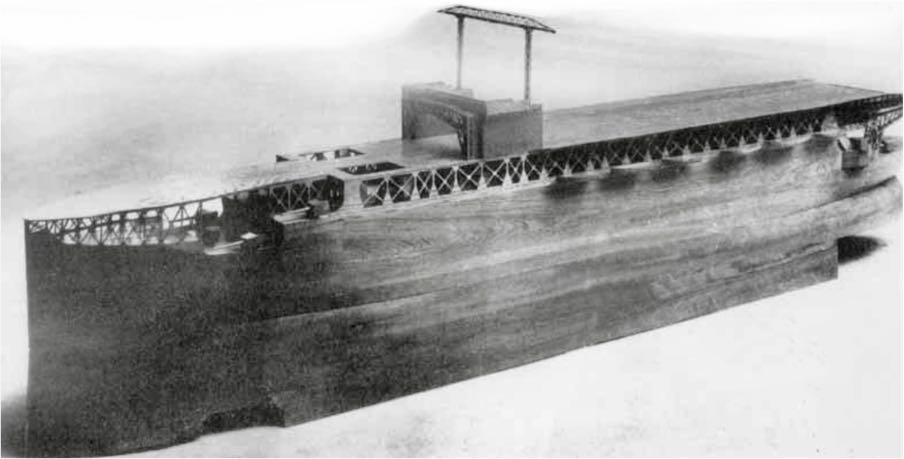

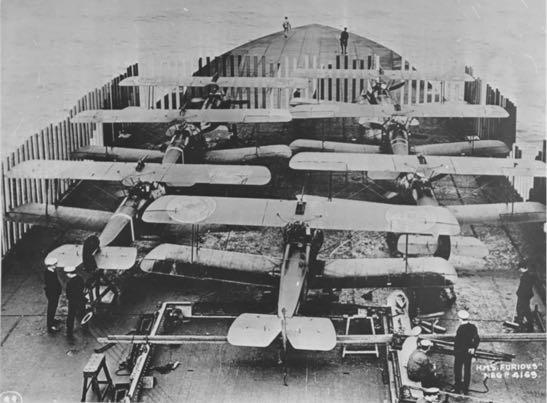

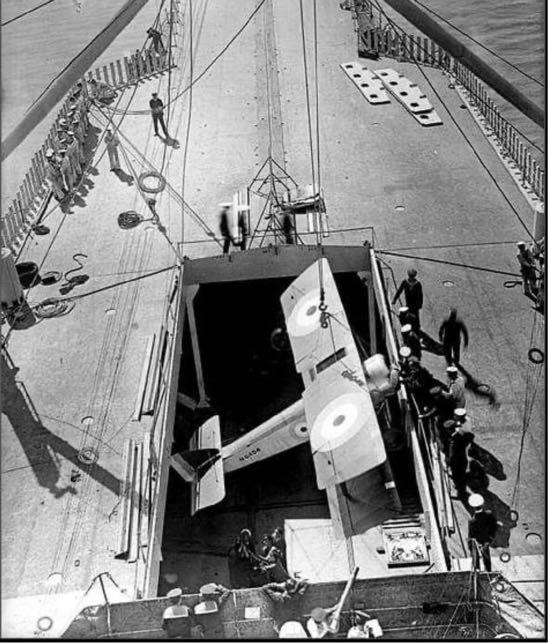

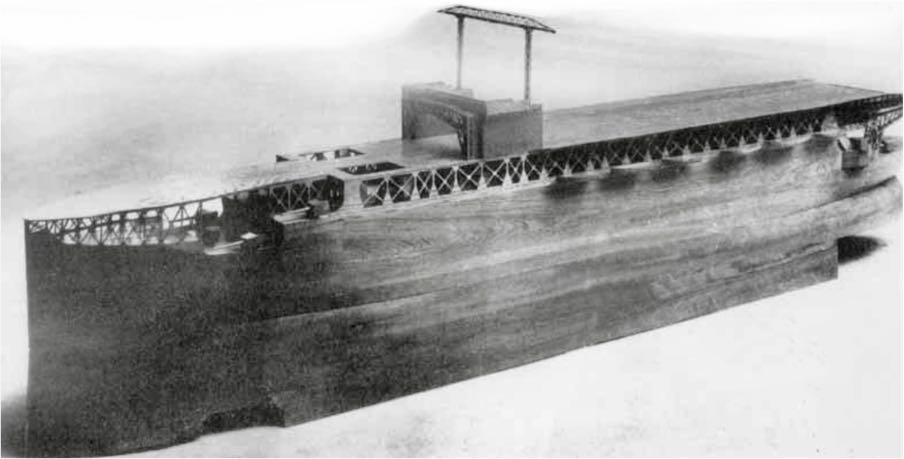

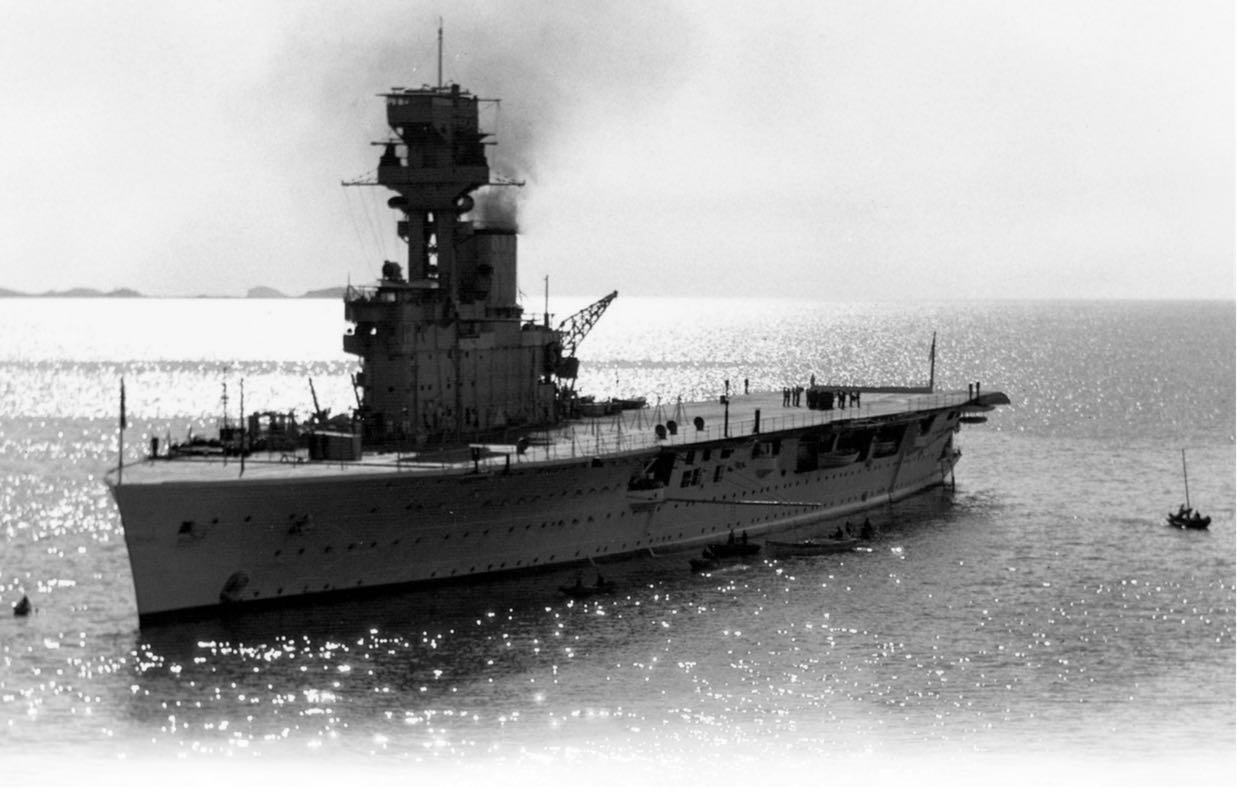

When VAT Smith, Senior Observer of 807 (Fulmar) Squadron embarked on the 27,165-ton carrier Furious after Operation Specimen in March 1941, he landed on a ship that had been a major test bed for carrier design since conversion from a 19,100ton battlecruiser in 1917. More than any other vessel Furious’s four stage evolution from that 18” battlecruiser to her 1941 configuration of starboard side island, transverse arrester wires, hydraulic lifts and accelerator (catapult) had helped establish the basic configuration of all RN and USN aircraft carriers.

played their part in early naval aviation.

In 1917 the need for aviation assets to operate from warships underway at sea was clear. On 28 June 1917 the newly promoted Squadron Commander Rutland flew a Sopwith Pup off the light cruiser Yarmouth after a five metre run with 26 knots of wind over the deck. Cruisers and capital ships were fitted to launch wheeled fighters on one-way sorties from fixed, and later rotating, turret platforms, while observation balloons were deployed on vessels of all sizes. The deficiencies of the existing small and slow seaplane carriers, such as Engadine with her four aircraft, needed to be addressed if greater numbers of aircraft were to operate with the Grand Fleet.

Courageous, lead ship of a new battlecruiser class, the first capital ships fitted with geared steam turbines capable of 30+ knots, had commissioned in November 1916 with her sister ship Glorious commissioning two months later, both then joining the Grand Fleet. The third sister, Furious, was still fitting out on the Tyne in the first half of 1917 when the committee recommendation, endorsed by Beatty, was made to modify the incomplete battlecruiser to allow flight operations as a seaplane carrier with six reconnaissance and four ‘anti-Zeppelin’ aircraft embarked. All three ships, nicknamed Outrageous, Laborious and Spurious, eventually

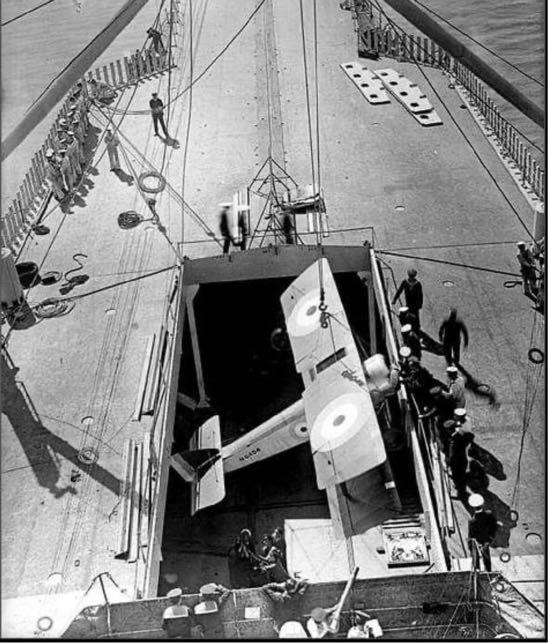

Removing Furious’s forward 18” turret a hangar was constructed with a sloping flight deck above. Aircraft were lifted by electric derricks through a hatch onto the flight deck for a free take-off by wheeled aircraft, or sitting on a reusable trolley along a fixed track if a floatplane. The tactical concept was for the the oilfired steam turbine powered Furious to remain with the main battle fleet launching her wheeled Sopwith Pups and Short 184 floatplanes for reconnaissance, antiZeppelin patrols and gunnery spotting. The obvious catch was those aircraft could not land back on but would be recovered by a slower following seaplane carrier such as Nairana, or ditch (if a Pup) near a destroyer.

While Furious was being fitted out for her new role the 32 year old Australian Test Pilot Squadron Commander “Harry” Busteed was conducting both flight deck and catapult trials at the Royal Naval Air Station Isle of Grain, as well as sitting on a sub-committee working on the design for flight deck arresting gear.

Ahectic flying schedule under wartime pressure saw him testing such things as detachable floats, deck landing hooks and skids, rocket armament and emergency sea landings. Busteed oversaw the 210 foot/64 metre circular wooden deck constructed at the station (the original ‘dummy deck’) and Squadron Commander Edwin Dunning, standing by Furious as her Senior Flying Officer, practiced there with his aircrew in their Sopwith Pups.

Commissioning in June 1917 take-offs from

Top: Furious post June 1917 - her first iteration, with the aft turret intact but a flying-off deck replacing everything forward of the superstructure. Middle: August 1917. Edwin Dunning makes the first ever deck landing aboard Furious by side-slipping his aircraft to align it with the flying-off deck. His arrester mechanism consisted of companions from the Wardroom grabbing parts of the airframe.. Dunning was killed a few days later (Lower) on another landing attempt, when he plunged over the side and was drowned. A ship’s report suggested recovering to the forward deck could be done, but the life expectancy of each pilot would be ten landings. ✈

37

HMS Iron Duke: Jellicoe’s Flagship

Furious were quickly routine but landing attempts on the forward deck by sideslipping around the bridge and funnel with its associated turbulence proved deadly, with only three successful attempts recorded. The famous first landing on a carrier underway was by Dunning in his Sopwith Pup N6452 on 2 August 1917 with the ship making 26 knots into a 21 knot headwind. There was no arresting gear but a deck party of ship’s officers reached up and grabbed the toggles fitted to wingtip and tail, hauling it down to the deck. Replicating the feat five days later in Pup N6453 Dunning was killed having ditched overboard after an engine failure on touching down. Busteed then embarked and made the third landing in a repaired Pup N6453 on 27 August.

Rutland, in succession to Dunning, became Senior Flying Officer onboard and his report on the deck landing experiments reflected harsh wartime practicalities:

I beg to submit that, with training, any good pilot can land on the Furious flying off deck. But I estimate that the life of a pilot will be

Furious in her second iteration (post March 1918). Recovering aircraft to deck whilst under way was deemed tactically vital, and the loss of Edwin Dunning had proven the forward deck could not be used for landings. Accordingly, the dockyard removed the rear turret to accommodate a landing-on deck terminating in a barrier to avoid running into the superstructure. Narrow gangways either side of the central superstructure allowed folded aircraft to be pushed forward to the forward (taking off) deck. Parked aircraft were protected from the weather by wooden palisades.✈

approximately ten flights. I shall need tests under sea conditions to determine whether this average would be appreciably less.

The Sopwith Pup was powered by a 80 horsepower Le Rhone rotary engine. This 121 kilogram 9-cylinder air cooled-engine and propeller would revolve at 1,150 revolutions per minute around the stationary crankshaft. Such a rotating mass in an airframe that weighed at maximum 556 kilograms produced considerable torque, whose associated yaw made turns to the left easier than turning right. A secondary effect caused the nose to rise in a left-hand turn and drop in a right-hand turn, which was especially hazardous at low level.

Torque effect was even more pronounced when these engines were ‘blipped’, the high idle speed of 800 rpm precluding descent unless the ‘blip button’ on the control column was depressed to cut the ignition or alternatively the fuel supply was shut off. On releasing the button the rapidly accelerating engine produced a strong swing. Unremarked in the handling notes is that, physiologically, a righthanded aviator’s arm is strongest pushing the control column left across the body - adductingcompared to pulling right by moving the armabducting - away from the body.

Throughout these landing trials it had been observed that the aviators preferred to turn to port when recovering from an aborted landing. Without fully understanding the combination of torque, Pfactor, spiralling airstream and gyroscopic precession left-hand circuits, nevertheless, became the norm at sea.

It was considered tactically vital that the launched aircraft be able to land back on an underway vessel so Furious returned to dockyard hands in November 1917, where an aft hangar and flying-on deck with low sidewalls replaced the rear turret. Aircraft gangways, just wide enough for a folded aircraft to be pushed by the deck handlers, were constructed either side of the superstructure connecting the fore and aft flight decks.

Returning to service in March 1918 Furious was the first carrier with lifts, one hydraulic and one electric for comparison testing, for the sixteen aircraft carried. Aft was a large barrier between two gallows booms protecting the central superstructure and funnel. Furious was now flagship of the newly appointed Rear Admiral (Aircraft) with responsibility for all seaplane carriers and aircraft in the fleet.

Experiments with hooks, horns on the undercarriage and steel tipped skids to the 284 feet/87 metre upward sloping landing-on deck were more to prevent an aircraft lifting again with the wind across the deck or veering over the side. Stopping was not usually a problem given the slow approach speeds. The initial arrestor system was fore and aft longitudinal wires engaged by hooks on the aircraft’s undercarriage and transverse

Top Left: Furious also tested operations with a non-rigid Submarine Scout airship. Top Right The flight deck handling party hold on to the still inflated airship as the three-crew control gondola is lowered into the lift well. Middle Right. Sopwith Camels in July 1918 heading for the first strike in history launched from the deck of an aircraft carrier.Bottom Right. Before lifts were fitted a Pup is lowered through hatchway to the hangar below. ✈

39 Historical Interest

ropes weighted with sandbags. Wooden palisades were fitted to protect the fragile airframes from weather. Again the Furious aviators trained on the dummy deck at Grain under Busteed before landing trials at sea. In his diary entry for 20 March 1918 Flight Sub Lieutenant Jack McCleery recorded:

Rutland landed on deck…very bumpy indeed; machine practically out of control. Busteed…landed much too fast, deleted machine and cut his nose badly. Cheery start off.

Turbulence and funnel exhaust caused ten crashes from thirteen landing attempts by seven pilots. Rutland survived being blown over the side on 28 March and only three landings resulted in an uninjured pilot stepping down from a serviceable aircraft. The pilots concluded

Left Top: It wasn’t just ship design that was developing, but the SOPs of operating at sea. This image shows a network of ropes tensioned over the landing area to laterally guide and slow the aircraft, holding it to the deck once landed. Far Left. Busteed’s Pup, appropriately nicknamed ‘Excuse Me’. Despite the iterative improvements deck accidents remained common. Left. Another innovation: The wheeled trolley which facilitated float fitted aircraft taking off. Note the guide along the centre of the deck: not a catapult, as these were still under development,, but a means to keep on the centreline as the aircraft took off under its own power. Above Top Crashes and deaths made it vital to reduce the turbulence of a central superstructure design. Post war economies meant Furious did not emerge in her flush deck Iteration 3 until 1925 with bulk fuel tanks now replacing the two-gallon tins. From the lower flying-off deck forward the small fighters of the period could launch to speed up operations, since an aircraft landing on the main flight deck was struck below before the next could land. Both lifts were now the superior hydraulic design and the sloping forward edge of the flight deck and open structure aft were further attempts to reduce turbulence. Above Right: A raised barrier protects the Fairey Flycatcher from sea and wind before launch. The charthouse is retracted on the main flight deck above. ✈

that landing on Furious was ‘almost as hazardous as ditching’ but the official report blandly concluded that it was “apparent that the pilots might not be able to land on the deck” except under the most favourable conditions.

Furious returned to operations with the Grand Fleet Flying Squadron as a take-off only carrier for the remainder of the war. Embarking seven Sopwith Camels in July 1918 for the Tondern raid against the German airship base in Denmark it was the first attack in history by aircraft launching from the deck of an aircraft carrier.

After these trials a flush flight deck was considered

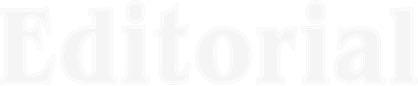

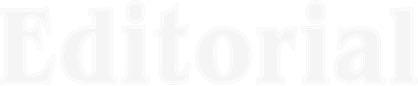

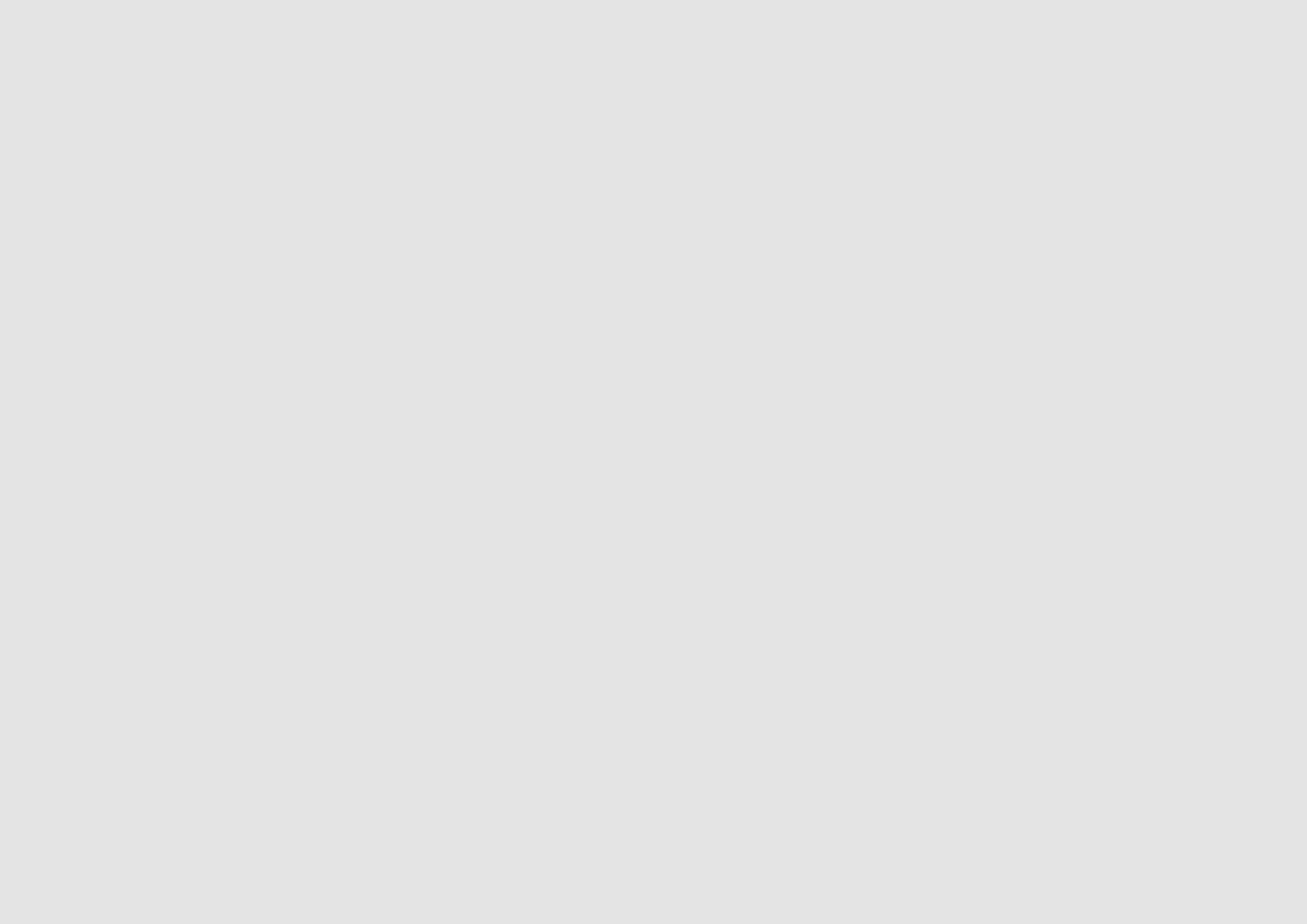

mandatory and the Advisory Committee for Aeronautics conducted further wind tunnel tests at the National Physics Laboratory. Under construction from a passenger liner hull was the 15,875-ton Argus, whose original design drawings showed take-off and landing decks separated by hangar and superstructure. The plans were then changed to show midships:

‘a large stop net between two erections, called islands, one on each side of the ship carrying a bridge structure across the top of them’.

This double island design gave a clearance below the spanning bridge deck to the flight deck of 20

41 Historical Interest

Above. The LH photo shows the original wooden model for wind tunnel experiments at the National Physics Laboratory. When the two-island idea was rejected, a ‘flat top’ design was adopted (above right), with Argus’s bridge tucked in under the flight deck - earning her the nickname ‘flat iron’ and a description ‘...of unsurpassed ugliness’. The copious wake funnel smoke visible in the image resulted in considerable turbulence on approach and spawned the concept of mounting a funnel above and to one side of the ship. This was first trialled on Hermes and led to the starboard-island convention that became universal to all western aircraft carriers from the mid 1920s onwards. ✈

feet (6.1 metres). After the Furious trials demonstrated turbulence was indeed the critical factor these side-by-side islands were not built.

Although Argus did not see operational service by war’s armistice, she commissioned in September 1918 as a flush-deck carrier with a full width bridge under the flight deck and retractable chart house forward. Initially no arrestor gear was fitted and aviation fuel was stowed in 4,000 two-gallon tins. Nicknamed the ‘Hat Box’ or ‘Flatiron’ she was described as ‘squat, box-like and of unsurpassed ugliness’. The United States Navy had been watching the evolving British carriers with interest and this general design was adopted by the first US carrier, the converted collier Jupiter, which recommissioned as the 14,000-ton Langley in 1922.

Routing the funnel trunking below the flight deck to exhaust under the flight deck aft reduced the available hangar space, caused hangar overheating and produced turbulence in the final stages of an aircraft’s approach. As landing trials commenced, led by Furious’s new SFO Lieutenant Colonel Richard Bell-Davies VC and Busteed flying Sopwith 1½ Strutters, a dummy island on the starboard side was constructed of canvas and wood with a smoke box to simulate funnel gases. Pilots reported favourably on the added vertical reference above the flight deck assisting their visual cues for landing (it was well before the era of Landing Signals Officers) which, coupled to their tendency to veer left after an aborted landing, saw starboard islands thenceforth adopted with only a few Japanese exceptions.

By the wars armistice there were more than 100 aircraft embarked on major warships and 247 ships were equipped with platforms and winches to operate kite balloons, although Argus did not see operational service. As active operations ceased there were three carriers under construction. The 12,600-ton Vindictive, based on a heavy cruiser hull, had the fore and aft configuration of Furious and commissioned in October 1918. After service in the Baltic against the Bolsheviks in 1919 she was placed in reserve and eventually converted back to a cruiser although she retained a hangar.

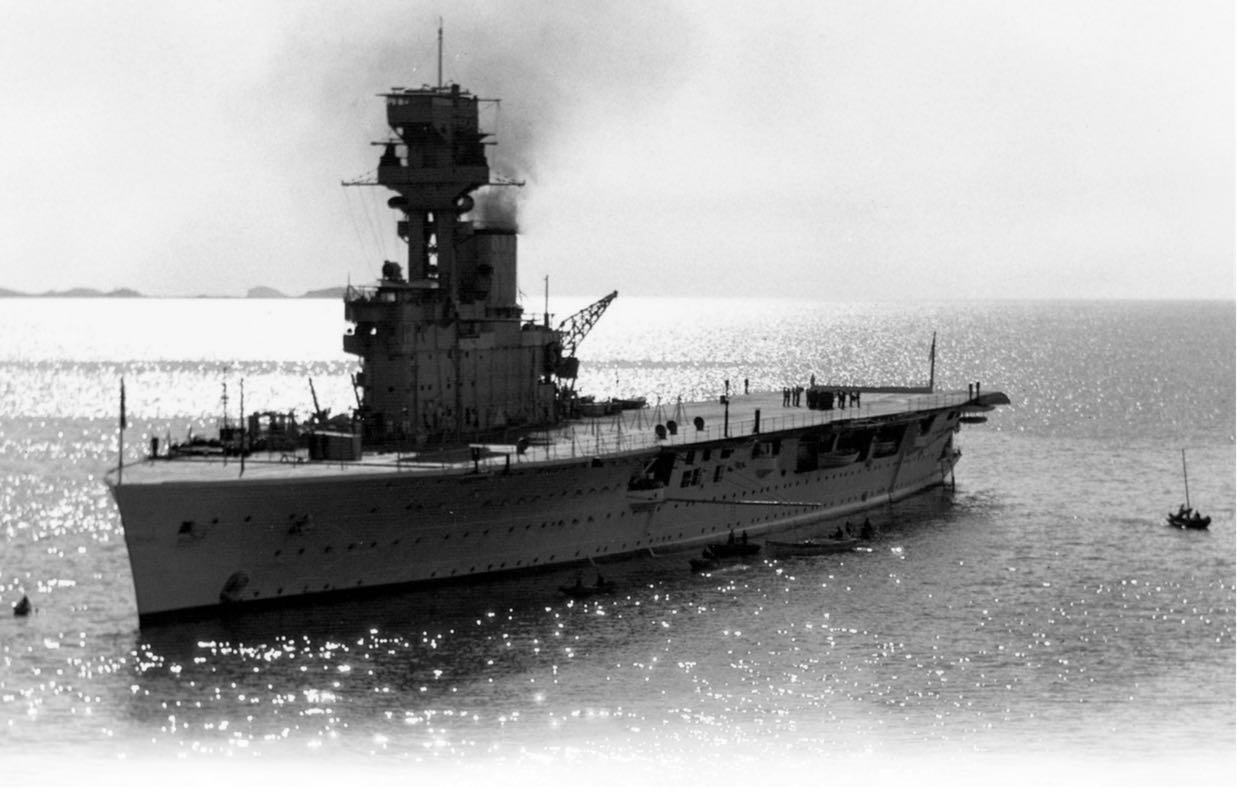

The first ship to be designed as an aircraft carrier from the keel up was the 13,900 ton Hermes launched in January 1918. Originally designed with a seaplane slipway astern it was then decided to fit a rotating catapult. As landing tests continued on Furious, then Argus, the Admiralty forbade further work above the hangar deck level until the single island configuration was adopted. Post war economies meant she did not commission until 1924 with a large island topped by an outsized tripod mast for gunnery control tops and director. Eagle, 22,200-tons and converted from a battleship hull also did not commission until 1924. Both Hermes and Eagle had been originally designed with funnels in port and starboard islands but emerged with a single starboard island containing bridge and funnel after the success of Argus’s canvas and wood mock-up.

Furious herself was placed in reserve until returning to the dockyard in 1921 for her third reconstruction. Her central superstructure was removed and the fore and aft flight decks joined,

giving a flush-deck with an uphill gradient forward of midships. A small flying-off deck was also fitted in the bows below the main flight deck. Recommissioning as a fleet carrier in September 1925 her Senior Air Force Officer, Wing Commander Busteed, joined that December to find that the fore and aft capture cable of the flight deck arresting gear was still being referred to as the ‘Busteed Trap’. This generally flawed system was removed in 1927 and for several years landing aircraft relied solely on their brakes until four transverse arrestor wires were fitted in 1933.