SMALL STEPS FORWARD for the future of conservation

SMALL STEPS FORWARD for the future of conservation

Spring into our brand-new date ! Saturday May 3, 2025 7 : 30–10 p.m.attheWorld-Famous SanDiego Zoo

Good taste is now in full bloom. At this one-of-a-kind tasting event, Southern California’s best food, wine, and brews are mixed with wild entertainment and the world’s most fascinating wildlife. Join us for this can’t-miss, all-inclusive evening to savor and sip your way through dedicated party areas around the San Diego Zoo.

Raise a glass and take a bite out of conservation at the tastiest event—and put a spring in your step knowing you’re saving and protecting the future for wildlife and the planet we all share.

MANAGING EDITOR Peggy Scott

STAFF WRITERS

Eston Ellis

Mike Hausberg

Aubrey Lloyd

Ellie McMillan

Elyan Shor, Ph.D.

COPY EDITOR Sara Maher

DESIGNER Christine Yetman

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Ken Bohn

Tammy Spratt

DESIGN AND PRODUCTION

Kim Turner

Lisa Bissi

Jennifer MacEwen

PREPRESS AND PRINTING

Quad Graphics Let's Stay Connected

memories on social media.

The Zoological Society of San Diego was founded in October 1916 by Harry M. Wegeforth, M.D., as a private, nonprofit corporation, which does business as San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

The printed San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal (ISSN 2767-7680) (Vol. 5, No. 2) is published bimonthly, in January, March, May, July, September, and November. Publisher is San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, located at 2920 Zoo Drive, San Diego, CA 92101-1646. Periodicals postage paid at San Diego, California, USA, and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, PO Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112-0271.

Copyright © 2025 San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. All rights reserved. All column and program titles are trademarks of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

Wildlife care specialists at the San Diego Zoo are using meerkats’ natural behaviors to keep the colony running

The social structure of a meerkat mob ensures everyone has a purpose and someone to watch their back throughout the day.

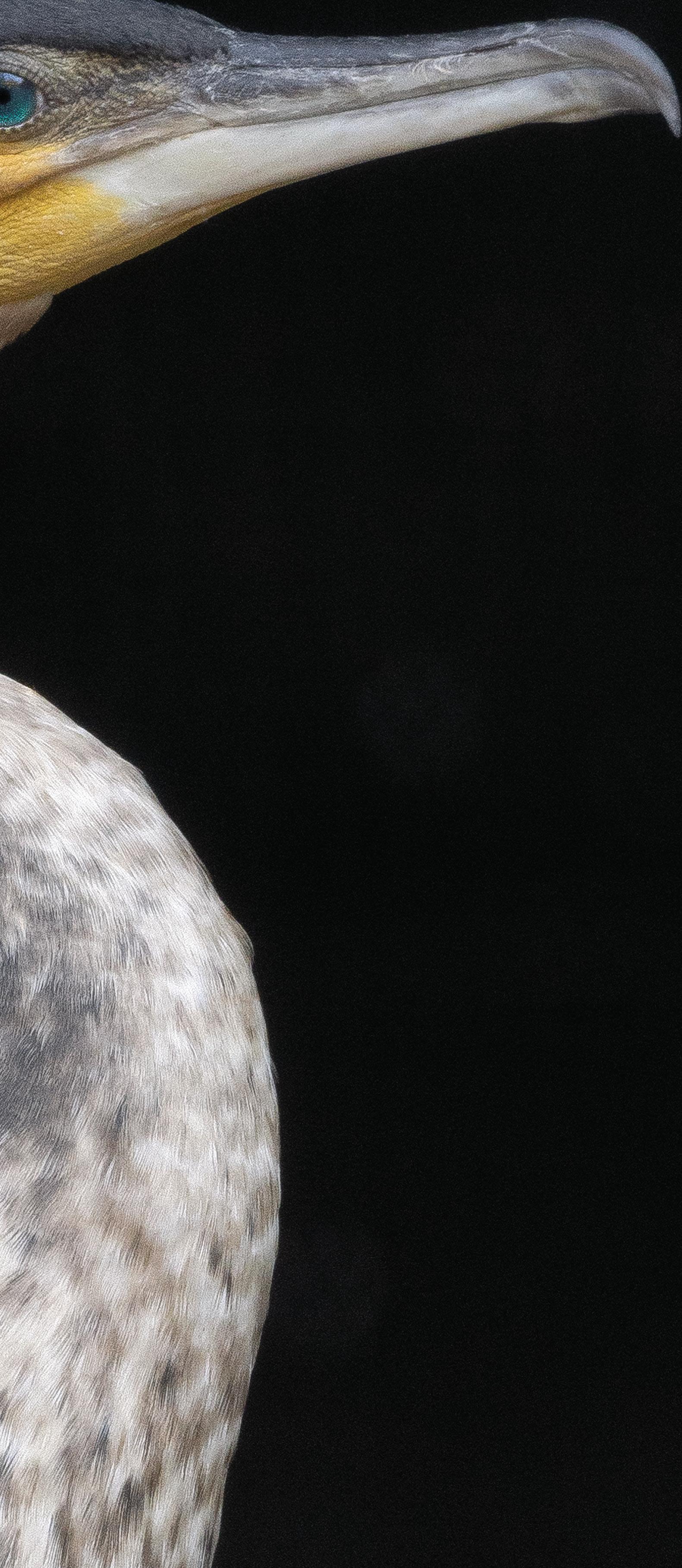

The white-breasted cormorant colony at the San Diego Zoo is a study in group dynamics—and nest-building skills.

Conservation wins mark milestones, but they’re not the finish line. As we celebrate successes, we also look ahead as we continue working to save, protect, and care for wildlife.

As part of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s commitment to conservation, This product is made of material from wellmanaged FSC ® -certified forests, recycled materials, and other controlled sources, chlorine free, and is Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC ®) (COC) certified. FSC ® is not responsible for any calculations on saving resources by choosing this paper.

If your mailing address has changed: Please contact the Membership Department by mail at PO Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112, or by phone at (619) 231-0251 or 1-877-3MEMBER

For information about becoming a member of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, please visit our website at ZooMember.org for a complete list of membership levels, offers, and benefits.

Paid subscriptions to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal are available. Contact the Membership Department for subscription information.

Impactful wildlife conservation is a collective effort, built on individual actions and collaborative partnerships. Our continued success relies on recognizing new opportunities to protect wildlife and ecosystems— whether those opportunities represent bold advances or incremental progress.

In this issue of the Journal, you’ll read about growing family groups at the San Diego Zoo. Each birth not only enriches our understanding of wildlife but also deepens our knowledge of their social structures and behaviors. From the intricate hierarchy of a meerkat colony to the unique dynamics of white-breasted cormorants, we see how even the smallest details can influence long-term harmony and well-being.

At the same time, we’re embracing innovation to improve how conservation work is done. As natural habitats continue to change at an unprecedented pace, technology is providing powerful solutions to meet today’s challenges. From monitoring remote polar bear dens in Norway to using drones to respond to the needs of wildlife in our care, technology is expanding the possibilities for conservation science.

When we work to protect or save a species, we make a promise for the future. We are proud to be at the forefront of these efforts, ensuring all wildlife thrives at the San Diego Zoo, San Diego Zoo Safari Park, and across the globe. Whether it is a birth at the Zoo or Safari Park or a population increase within one of our Conservation Hubs, each small milestone reflects the promise of a brighter tomorrow.

Thank you for being part of our ongoing journey of discovery and for standing with us as an ally for wildlife.

Onward, Paul A. Baribault President and Chief Executive Officer

Officers

Steven S. Simpson, Chair

Steven G. Tappan, Vice Chair

Rolf Benirschke, Vice Chair

Adam Day, Treasurer

Gary E. Knell, Secretary

Trustees

Tom Chapman

E. Jane Finley

Clifford W. Hague

Bryan B. Min

Kenji Price

Corinne Verdery

‘Aulani Wilhelm

Trustees Emeriti

Javade Chaudhri

Berit N. Durler

Thompson Fetter

Richard B. Gulley

Robert B. Horsman

John M. Thornton

Executive Team

Paul A. Baribault

President and Chief Executive Officer

Shawn Dixon

Chief Operating Officer

David Franco

Chief Financial Officer

Erika Kohler

Senior Vice President and Executive Director, San Diego Zoo

Lisa Peterson

Senior Vice President and Executive Director, San Diego Zoo Safari Park

Nadine Lamberski, DVM, DACZM, DECZM (ZHM)

Chief Conservation and Wildlife Health Officer

Wendy Bulger

General Counsel

David Gillig

Chief Philanthropy Officer

Aida Rosa

Chief Human Resources Officer

David Miller

Chief Marketing Officer

Technology is making a powerful difference in the world of conservation. At the San Diego Zoo, San Diego Zoo Safari Park, our Conservation Technology Lab, and conservation sites across the globe, our teams are at the forefront of cutting-edge science. They develop revolutionary tools to bridge gaps in knowledge and inform conservation decisions that save, protect, and care for wildlife.

40+

Through innovative conservation techniques, we’ve successfully reintroduced more than 40 endangered species into their native habitats.

500,000

Our Conservation Technology Lab is training and implementing AI algorithms to process approximately 500,000 images and videos per day.

1

Thanks to advances in conservation technology, we successfully conducted the first-ever C-section on a North American porcupine.

12

While only two northern white rhinos remain on Earth, we have 12 living cell lines carefully cryopreserved in our Frozen Zoo® .

100

Using samples from our Wildlife Biodiversity Bank, we’re collaborating to sequence whole genomes of nearly 100 koalas to create the world’s largest koala genomic database.

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) protects and restores nature in eight Conservation Hubs on five continents. Below are recent discoveries and progress reports from around the world.

Our team and partners from California and Baja California, Mexico, contributed to the official publication of Baja California’s native flora. The publication lists 2,352 native plant taxa, of which 520 (or about 22 percent) are categorized as protected. The publication also includes categories for rare and endemic plants. With these categories defined for species in Baja California for the first time, Baja California and California now have the same protection categories for plants found on both sides of the border. This is crucial for achieving protections for species throughout their binational ranges.

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s Disease Investigations team was awarded a Coin of Excellence by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Clark R. Bavin National Fish and Wildlife Forensic Laboratory. The coin recognizes our years of contributing high-quality samples (such as feathers and bones) the Forensic Laboratory can reference during investigations of wildlife trafficking and poaching. Our team has partnered with the Forensic Laboratory for more than 30 years, and we have sent them approximately 1,200 specimens since 2003. This is the first time the Coin of Excellence has been issued, and we are honored to be recipients of the inaugural award.

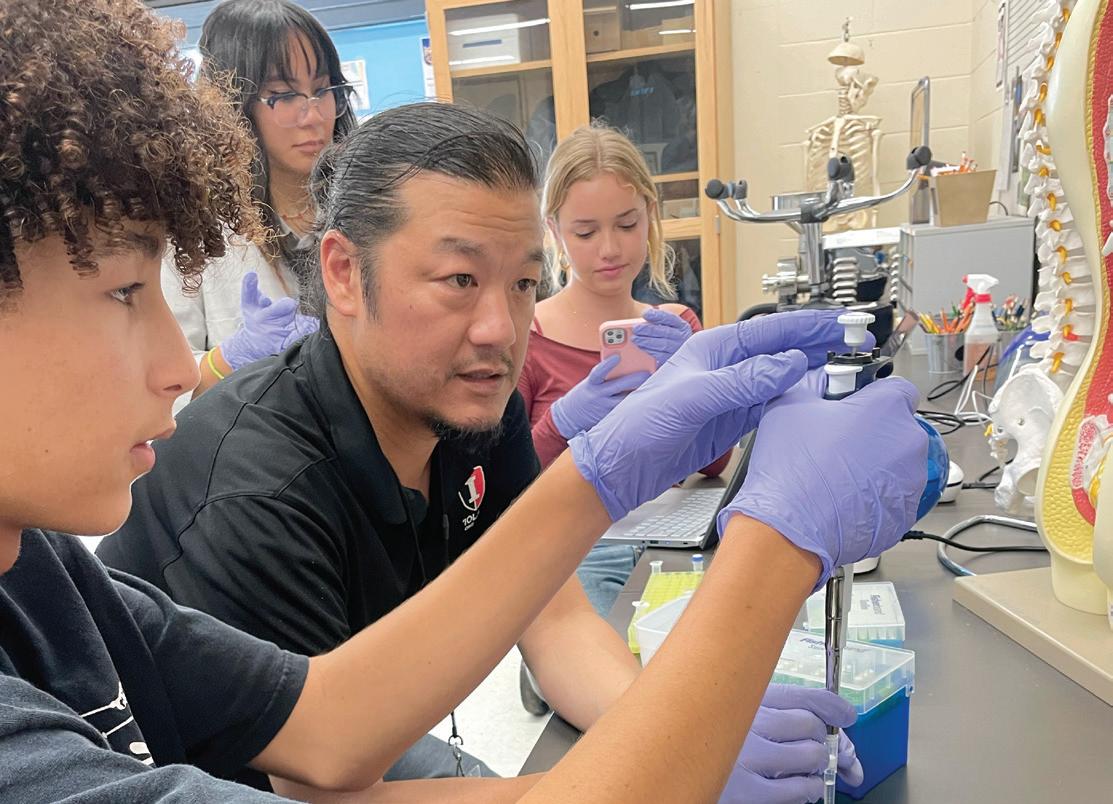

High school students in Hawai'i are leading the effort to sequence the genome of the palila, a critically endangered native Hawaiian bird. Utilizing palila cells that were banked in San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s Frozen Zoo, our team is working with six students from local high schools to prepare, sequence, and analyze palila DNA. This project will last at least one school year and include opportunities for the students to present their work and engage in other activities to connect with native birds, conservation, and science. Another significant component of the project is fostering discussion about Indigenous data sovereignty, including the question of who owns the data the students will generate; at the end of the program, the students will be the ones to determine whether to make their data public.

Monica Friend, a senior wildlife care specialist on the San Diego Zoo Safari Park’s Overnight team, takes a look at one high-flying technological tool that aids observation capabilities.

One exciting aspect of wildlife conservation has been the introduction of cutting-edge technology. Here at the Safari Park, we have begun using drones to elevate the care we provide for the wildlife entrusted to us. Safari Park Aerial Reconnaissance Conservation (SPARC) is a new and developing program that can be utilized in a variety of ways.

The drone we currently use the most is the DJI Matrice 30T (M30T). Some of the cool features include its three cameras—a 48-megapixel wide camera, a 12-megapixel telezoom camera, and a thermal camera. It has a 7,000-meter service ceiling, a flight time up to 41 minutes, maximum speed of 51 mph, and an ability to handle adverse weather with temperatures ranging from -4 to 122 degrees Fahrenheit. Add in the drone’s

laser rangefinder of 3 to 1,200 meters, and we have a device that allows us to document various wildlife care situations, navigate our unique landscape, and maximize nighttime surveillance.

Using drones, we are able to maintain a hands-off, nonintrusive approach to wildlife observation, while still being able to respond, if needed, in real time. With a giraffe in the field about to give birth, the drone can deploy 172 feet in the air, then zoom in and monitor how the birth is progressing. Wildlife care staff on the ground are a radio call away from assisting should the need arise. Once the calf is born, the drone can continue to monitor when it first stands and nurses, as well as monitor the behavior of other animals in the field. The bird’s-eye view offers a different perspective of wildlife space use and helps wildlife care specialists make the best decisions possible for

the well-being of the wildlife in our care.

There is another part of the Safari Park most guests do not get to see—the 1,000-acre Biodiversity Reserve. The reserve is one of the largest remaining expanses of coastal sage scrub and chaparral habitat and is located at the intersection of two critical wildlife corridors. Drones help us with monitoring and mapping this vital wilderness, which is part of our Southwest Conservation Hub. We can program the drone to map out and record sections of the reserve and, over time, use that information to better understand how to coexist with local wildlife and protect this threatened flora and fauna.

With the M30T’s thermal camera, we are even able to use the drone at night! With no lights in our savanna habitats or the Biodiversity Reserve, the thermal camera is a game changer. If there is a concern, we are

What a View (Facing page) Drones provide an unobtrusive way to keep an eye on the Safari Park. (Top)

James Sheppard, Ph.D., a scientist with the Recovery Ecology team, uses drones in his work in our Oceans Conservation Hub. (Bottom) Author Monica Friend uses a drone’s thermal camera over one of the Safari Park’s field habitats.

able to deploy the drone and monitor the area and animals discreetly and without disturbing them. Local wildlife is more active at night, and the drone helps navigate the landscape, making it easier to track the animals to better understand their patterns and help us coexist. We also use the drones to assess our perimeter fence lines, record situations to use as teaching tools, and for emergency and disaster response.

Drones are also a key component of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s conservation projects throughout the world, allowing scientists to identify, observe, and monitor wildlife and their ranges and, in certain instances, gather diagnostic materials. The drone program is a game changer, and it is exciting to think of all the possible new ways we can help wildlife here and around the world.

BY LACY-JEAN PEARSON

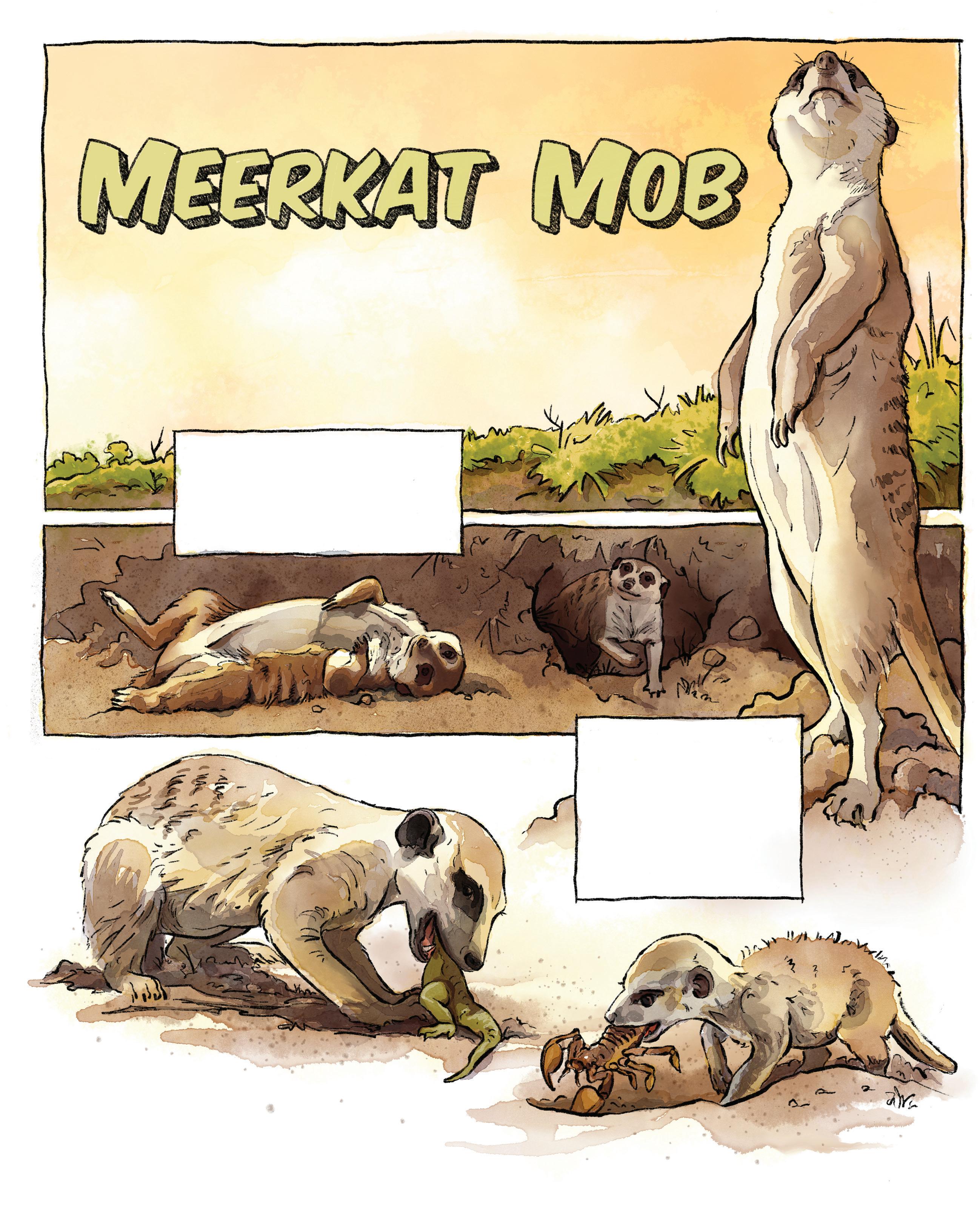

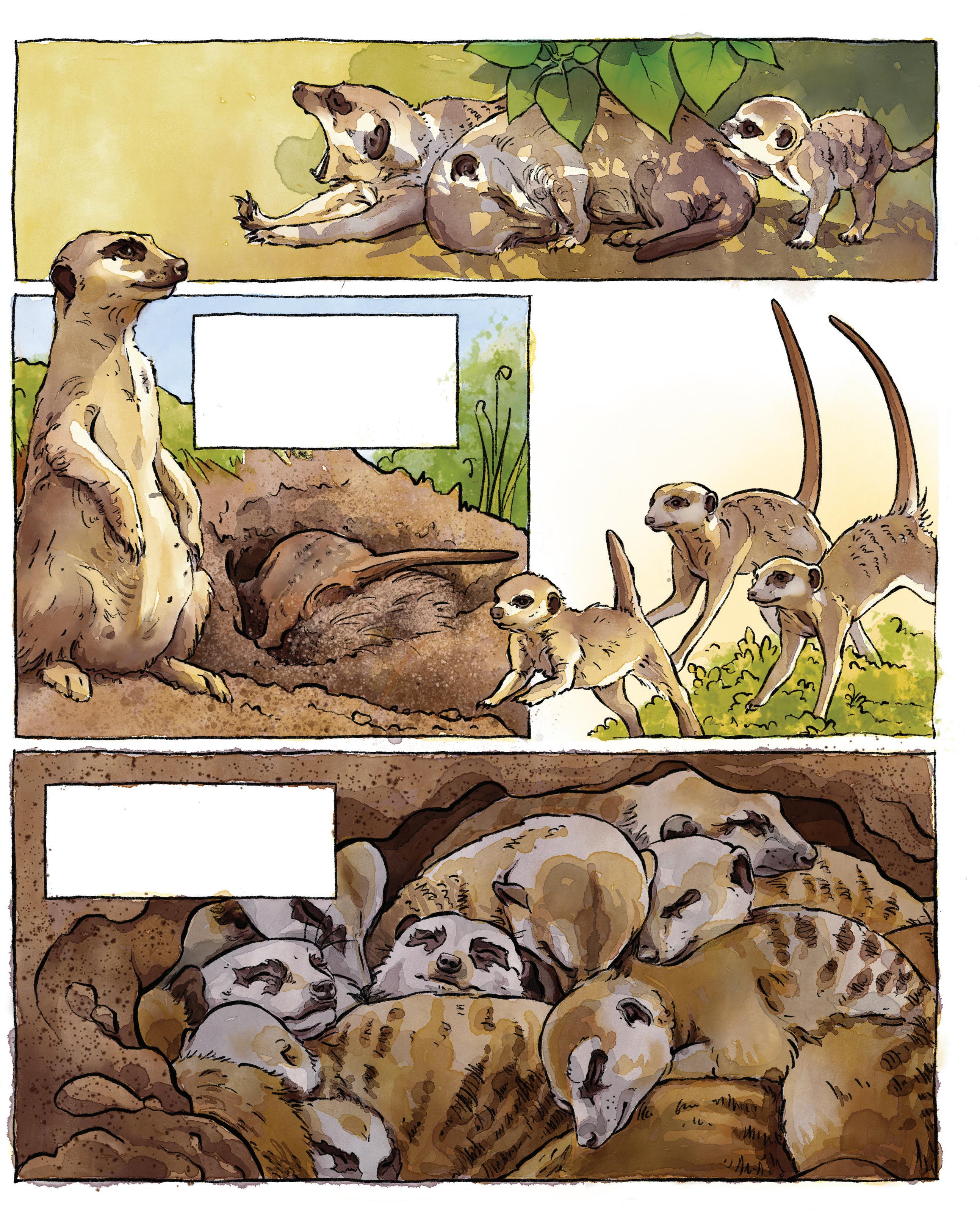

It’s quite the “mob scene”—the San Diego Zoo’s Conrad Prebys Africa Rocks desert habitat provides guests the opportunity to observe a mob of meerkats interacting with their environment, and each other, as they would in the Kalahari Desert of arid southwest Africa. This matriarchal society is constantly in flux as each member of the mob works to feed themselves while evading predation and maintaining their status or attempting to increase their status among their group.

These diurnal mammals spend most of their waking hours above ground sunning, foraging, grooming, and resting in the shade during the heat of the day. During such active times, at least one member of the mob can be seen watching the sky and surrounding area from a high vantage point for potential threats at all times. This individual will make a low, constant vocalization, which is known as “the watchman’s song,” while there are no imminent threats, and then alarm call when a threat is identified. The type of vocalization used is specific to the type of threat observed, allowing each member of the mob to react to the threat accordingly, oftentimes by dashing to the safety of their underground tunnels. The type of stress evoked by an alarm call is eustress, or a moderate type of short-lived stress that has a positive result. Eustress is experienced by humans during exercise, at which time the mind and body endure moderate levels of stress to lead to a boost in mood and better long-term health. Similarly, meerkats experience alarm call-induced eustress multiple times a day as a means of survival.

BY:

Meerkat burrows have an average of 15 entrance and exit holes and tunnels and chambers at several levels, some as deep as 6.5 feet (2 meters).

Each meerkat colony is made up of several family groups, but one dominant pair produces most of the offspring.

Some meerkat colonies (or “mobs”) can include up to 50 individual members.

As obligate cooperative breeders, meerkats benefit from living in mobs of up to 50 individuals. Larger mobs allow individual meerkats to allocate less time to watching for threats and instead spend more time on self-maintenance, foraging, resting, and breeding behaviors. In fact, breeding success in meerkats has been shown to significantly increase as meerkat mobs grow. The matriarch of a mob changes, on average, every three years. Usually the largest and oldest female secures a place as the matriarch and can give birth up to four times a year if resources are sufficient. The mob works together to help raise these pups, and this behavior, though it seems altruistic, may in fact be self-serving. Most female members of the mob are related, and females hoping to become the matriarch may bide their time helping raise other young that are distantly related before assuming the matriarchy to have their own young. While the mob sounds like a cooperative utopia on paper, in action, it can be anything but peaceful.

The primary daily focus of wildlife care specialists is to create opportunities for our wildlife that encourage both mental and physical fitness. Measurable outcomes of

good welfare can vary between species, but an increase in behavioral diversity in any species is perceived as an increase in welfare. Specialists work to provide opportunities for our wildlife to thrive based on their natural history and in a way that allows them choice and control over how they interact with their environment. Complicated, ever-changing group dynamics— like that of the meerkat mob—make this task more challenging.

It is not uncommon for meerkats to be run out of their mob over hierarchy changes in the arid, sandy savannas of Africa. In a zoological setting, however, such disputes require specialist intervention and can lead to a separation of mob members into two smaller mobs to reduce aggression. In fall 2023, the San Diego Zoo found itself in such a situation, with four female meerkats living in two separate mobs. While separation is a widely accepted and ethical practice, San Diego Zoo meerkat specialists set out to reimagine a management style that would encourage the mob to reduce aggression on their own terms and stay cohesive. Specialists identified that success of this management style could be measured by a decrease in tumultuous interactions between individuals, an increase in individual behavioral diversity, and, eventually, greater breeding success.

Using outcome-based care, wildlife care specialists worked backward from the desired behaviors of a cohesive meerkat mob to identify the inputs necessary to achieve such success. Specialists hypothesized that breeding success and increased time for self-maintenance are most likely secondary motivations for cohesion in a mob. The primary motivation for this obligate cohesive lifestyle was hypothesized to be the safety provided by increased mob size. Meerkat specialists suspect the reason cohesive mobs thrive in native habitats is in part due to the regular threats they face from extreme weather, predators, and lack of resources.

Meerkats in our San Diego mob experience six to eight foraging opportunities a day, very few predators, and near-perfect temperatures year-round. By redirecting the type of eustress being experienced in the mob, specialists hoped to strengthen the bond of the mob members.

Wildlife care specialists identified there were a number of inputs available on Zoo grounds that could be offered to the meerkat mob during times of elevated aggression to redirect the current eustress from internal factors (other meerkats) to external factors (potential threats). Meerkat specialists first worked to rotate the two mobs past each other on an increasingly

DID YOU KNOW?

Meerkats are not related to cats; they are a member of the mongoose family.

regular schedule to cue both mobs that there was another mob inhabiting the same area. During this time, an increase in explorative and scent marking behaviors was observed, indicating the meerkats were aware of each other’s presence. Next we coordinated with wildlife care specialists around the Zoo to acquire various novel scents that could be added to the meerkat habitat to mimic the presence of large or destructive wildlife in the area.

On the day the two mobs were to be reintroduced, all meerkats were brought into an indoor space adjacent to the large habitat and kept separate from each other while specialists placed feces from large and destructive herbivores (elephant, giraffe, and babirusa) throughout the habitat. Specialists observed the reintroduction, ready to intervene if needed, and the two mobs were released at the same time. Immediately all four female meerkats, with tails raised, began independently inspecting each pile of feces while vocalizing using a similar call. After 10 minutes of investigation, all four meerkats had retreated independently down the same tunnel. Nearly two hours after they disappeared, a cohesive mob of four female meerkats ventured back aboveground to forage. Over the next two weeks, specialists observed the individuals of the mob spending more time on self-maintenance behaviors than they had when they were in two separate mobs. A few months later, the same management technique was used to successfully introduce a young male to the mob.

Thrilled with the repeated success, specialists shared this management technique with the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ Small Carnivore Taxon Advisory Group and enlisted other facilities to attempt this technique and share their results. To date, at least two other zoos have successfully introduced meerkats using the same method and, as a result of our mob’s reunification, the San Diego Zoo had our first successful litter of meerkat pups born since 2018.

Aggression is a natural part of life in a meerkat mob, but using the implication of danger by adding scent cues (wolf urine, elephant feces) or visual and auditory cues (eagle kite, playing recorded hawk calls) during moments of heightened internal eustress can help redirect the mob to prioritize safety and reduce injuries, leading to increased welfare for each individual and an increase in breeding success for the mob.

BY:

BY SANDY MCCANN | ILLUSTRATED BY AMY BLANDFORD

Welcome to the world of meerkats, small but mighty mammals that live in the harsh deserts of southern Africa. Living in close-knit family groups, this social species works together to thrive. Follow along as we take you through a typical day in the life of meerkats, exploring their routines, behaviors, and remarkable teamwork from sunrise to sunset.

Morning As the sun rises, meerkats emerge from their burrows eager to warm up. They sunbathe with their bellies exposed to soak in heat, while one or two take on sentry duty as the group prepares for the busy day ahead.

Mid-morning

Meerkats dig for breakfast, hunting for insects, small reptiles, and plants. They work as a team, with one meerkat standing guard while the rest hunt and gather.

Protectors of the Pack Sentry roles are typically taken on by the most vigilant members. These sentinels stand watch for predators, using their keen eyesight, sharp instincts, and special alarm calls to keep the group safe while others forage or care for young.

Midday

During the hottest part of the day, meerkats retreat to shaded spots or burrows to rest. They strengthen their social bonds by playing with pups or grooming each other.

Adult meerkats teach pups how to dig burrows and catch prey. While they search for snacks, another meerkat takes over sentry duty to keep watch for danger.

Evening

As the sun sets, meerkats head back to their burrows. They may dig new tunnels or repair old ones before settling in with the mob for the night.

Safely underground, meerkats sleep in groups, huddling together for warmth and protection from nighttime predators like owls and jackals.

Stay fueled up by enjoying a delicious treat at one of our specialty snack stands on your next visit. The San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park thank our partners for their continued support!

M.F.A.

Population Sustainability Scientist San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

As a population sustainability scientist and the leader of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s Conservation Technology Lab, Ian and his team of engineers develop software, machine learning systems, and field sensor systems that leverage technology to solve conservation challenges.

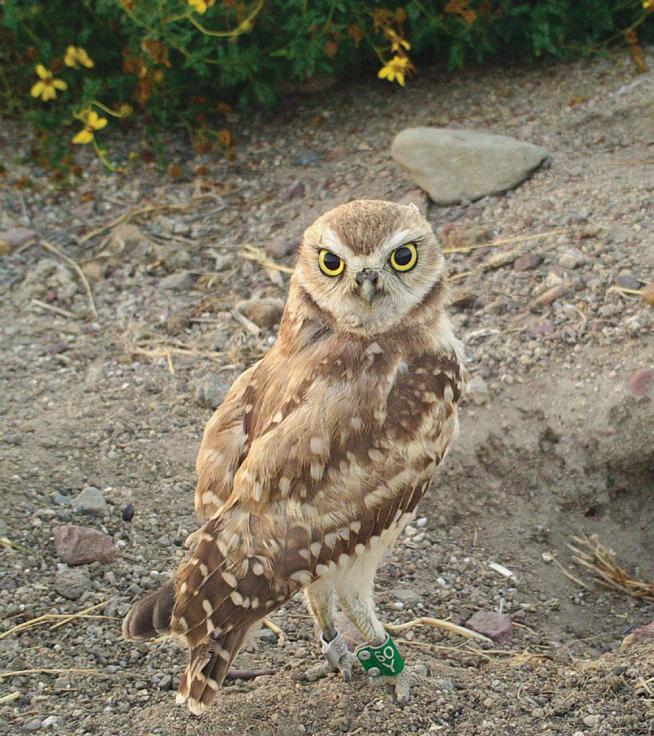

We use technology in so many different aspects of our conservation work! For example, we use machine learning algorithms to automatically identify species in images and videos taken by off-the-shelf trail cameras. We also develop custom camera systems that meet the needs of specific projects, such as the DenCam systems we built in collaboration with Polar Bears International to monitor polar bear maternal dens in the Arctic. In tandem with the image-based systems, we use acoustic recorders in places like the Peruvian Amazon and burrowing owl habitat here in Southern California to collect sound recordings, which can be “listened to” by machine learning algorithms that have been trained to identify species by their vocalizations. Ultimately, tools like these accelerate and amplify our ability to collect and preprocess data; this helps us better understand wildlife and the actions we need to take to protect them.

Conservation challenges can be complex, so when approaching a new challenge, what is involved in the process to get from challenge to idea to solution?

It’s mostly about breaking problems apart into smaller pieces and then

trying to determine if each of the pieces is individually solvable. But in the case of technology, there is often a missing piece, and without this missing piece—also called an enabling technology—a problem could be too difficult to tackle at that point in time. However, with technology advancing at such a fast pace, that missing piece might be just a couple of years away from existing. So part of what one does is keep a register of what’s missing for a particular solution and keep an eye out for when the enabling technology clicks into place. The deep learning revolution of 2012 is a prime example of enabling technology: the resultant groundbreaking advances in computational sensing allow computers to “perceive” the imagery and sounds from our conservation projects much faster than humans can, helping solve the problem of rapidly processing enormous amounts of data.

I traveled to Svalbard, Norway, to help deploy our DenCams in that epic, rugged, ice-crusted landscape. Flown by helicopter to be dropped off a few kilometers from a polar bear den, we then skied the last few kilometers to within a few hundred meters of where a mother polar bear and her cubs lay hidden beneath the snow, ensconced in their secret sanctum. I think it was about -13 degrees Fahrenheit out there—very cool.

It is going to be young people who have trained as engineers and who choose to devote their careers to conservation and to the efforts to save species, habitats, and biodiversity.

Sleek, athletic, and equally adept at sea, on land, or in the sky, the cormorant is the triathlete of the bird world. These champion divers descend up to 150 feet beneath the water’s surface in search of fish and other aquatic prey. Sharp talons and powerful legs allow them to perch in trees as comfortably as they climb steep seaside cliffs or walk along the beach. With a wingspan that equals their body length (35 inches), these avian wonders soar, flying up to 200 miles in a single day. It’s no wonder cormorants are a winning design, with 42 living species spread around the world.

The white-breasted cormorant, the largest cormorant in its range, is native to South Africa and Namibia, like the African penguin. You might think two such superficially similar birds would compete for resources, but they fill different niches in the same habitat and ecosystem. Penguins are pelagic hunters—chasing prey out in the open ocean—while cormorants are coastal or demersal hunters, catching prey near the shore or bottom of a body of water. African penguins nest in burrows on the ground, while white-breasted cormorants nest in trees near water or on inaccessible rocks overlooking the sea. Like many seabirds, cormorants are colonial breeders. This means each nest is maintained independently by one socially monogamous pair, but all pairs nest in close proximity. There are downsides to having so many neighbors—squabbles over space and resources are common—but together the colony deters predators that would make short work of a single pair.

DID YOU KNOW?

The white-breasted cormorant is the largest of five cormorant species found in South Africa.

Even though cormorants are remarkable athletes and fill a role in their ecosystem, cultural attitudes toward them can vary significantly. In parts of China and Japan, cormorants were historically trained by fishermen—similar to how falconers use birds of prey—but in most of the world, they are often regarded as pests. Cormorants are culled by the thousands to protect commercial and sport fish populations, despite little evidence for the efficacy of this management strategy. Fish with economic value make up only a small percentage of the average cormorant’s diet. Undoing human damage to aquatic ecosystems is a more proven way to increase fish populations.

Cormorants also garner a negative reputation for their pungent guano (droppings). They favor nest sites overlooking the water, the same types of locations humans value for recreation and development. This leads to conflict in which cormorant nests are deliberately cut down or vandalized, leaving chicks to die. The same guano that makes

such a stink has great benefits for the natural environment. It reduces seaside erosion, transfers nutrients from marine to terrestrial ecosystems, and fertilizes the phytoplankton and aquatic plants that make up the base of the food chain. And while their nesting habits and spatial needs can make their care complicated, the San Diego Zoo is home to a colony of white-breasted cormorants, which can be found in the African Marsh habitat below Eagle Trail.

Though cormorants at the Zoo may look identical, each individual has a unique personality. Three-year-old Brown, for example, is always eager to explore, while her older girlfriend seems most content as a homebody, sticking close to the nest. Pink collects sticks and feathers (long, pink flamingo feathers in particular), so she contributes most of the construction materials and nest defense in her relationship. Her mate, Yellow, spends more of his time carefully arranging the materials and sitting on eggs. The oldest male in the colony, Gold Daddy, earned his nickname for

his gold color band and extreme enthusiasm for parenting. He allows his mate to do most of the incubation, but as soon as eggs hatch, he always takes over 90 percent of the chick rearing. Gold Daddy’s adult son, Red, models the same enthusiasm for feeding and brooding babies. Such attentive parenting pays off: this year, Gold Daddy became the colony’s first grandfather through Red’s production of offspring. And sometimes, perpetuating a species does take a village (or colony); while one of our cormorant pairs has never produced a fertile egg together, they have incubated and raised five foster eggs to adulthood.

Some cormorants mate for life, while others form temporary partnerships lasting a single season or a few years at a time. Regardless of how long they have been together, bonded cormorants constantly reaffirm their devotion to each other with entwined necks, stick-waggling, wing-waving, and gargling calls. Males and females are alike in appearance, and both initiate courtship, build the nest, and take care of chicks.

Because white-breasted cormorants are

“A” IS FOR ALTRICIAL Altricial species like cormorants (and humans) have young that are unable to walk or feed themselves at hatch (or birth). Male and female cormorants care for their young until they fledge at 6 to 8 weeks of age.

(Left) White-breasted cormorant eggs are pale blue with a chalky calcium deposit when first laid. The blue fades over the course of incubation until the egg is white. This may allow females to detect and discard eggs laid later in her nest by another female. (Right) Cormorants use a variety of materials to build strong nests; this nest contains sticks, papyrus, rosemary, and flamingo, pelican, and even other cormorant feathers, all cemented together on the outer rim by the birds’ own guano.

sensitive to nest disturbances and may abandon eggs or chicks—sometimes for a prolonged period—when stressed, wildlife care specialists at the Zoo have conditioned the colony to accept human proximity by offering high-value nest material by hand. Their favorite, sticks of freshly cut lavender, naturally repel mosquitos and other harmful insects. Now several of the cormorants will remain on the nest in exchange for a big bushel of lavender while specialists carefully reach under them to briefly exchange real eggs for dummy eggs. This allows us to candle eggs to check for fertility. Chick mortality is lower when they have fewer siblings to compete against, so if we candle a clutch and find that all the eggs in one nest are fertile, while a neighbor’s eggs are consistently nonviable, we can foster one or two of those fertile eggs under the infertile pair. When we are done candling, the cormorants get another big handful of lavender, and the specialist swaps the dummies back out for the real eggs.

The San Diego Zoo’s reproduction program has been quite successful. The colony has grown from 4 birds in 2016 to 35 individuals in 2024. Five adult cormorants from the San Diego Zoo Safari Park joined the Zoo colony in 2022, but the rest hatched on view to the public in the African Marsh habitat. Zoo visitors can

watch the entire process, from nest building to hatching to young fledglings learning to swim, socialize, and navigate the wider habitat on their own. But of course, a lot of hard work and consideration went into creating this outcome.

The main factors contributing to a consistent increase in the Zoo’s white-breasted cormorant population are the changes in the way we manage birds. We no longer pinion cormorants, which has led to more successful nest building and foraging. We used insights from a trip to the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds (SANCCOB) to modify the way our colony’s nest structure was set up and how we presented nesting material to stimulate breeding behavior. We enclosed the exhibit, which prevents wild herons and egrets from predating cormorant chicks. And we combined birds from two smaller colonies into one super colony.

Though the white-breasted cormorant population is relatively stable, there are several cormorant species at risk of extinction, including the bank cormorant and Cape cormorant of South Africa. Seabirds as a whole—a group that includes iconic birds like albatrosses, puffins, and penguins, in addition to less-revered birds like cormorants—have dropped 70 percent in number since 1950.

Climate change, overfishing, ocean plastics, entanglement in fishing gear, oil spills, invasive species, disease, and human encroachment on coastal breeding habitat are all contributing to seabird decline. These are big, complex challenges that require global collaboration to resolve.

It may seem dire, but there are things you can do as an individual to help. You can avoid single-use plastics and dispose of trash properly, which decreases the amount of litter washing down storm drains and eventually out to sea. You can eat only sustainably harvested seafood. At the beach, be mindful not to disturb wildlife in their home. Local San Diego birds like the least tern, snowy plover, and Brandt’s cormorant nest on the coast and are adversely affected when people and pets cross barriers protecting breeding sites. Just learning about the great diversity of bird life in your own community and sharing that knowledge can encourage others to be mindful of how their actions impact birds, too.

Next time you are at the Zoo, or the beach, or a lake, stop and watch the cormorants for a moment. These underappreciated birds may surprise you!

Caitlin Morrow is a senior wildlife care specialist at the San Diego Zoo.

BY ELLIE MCMILLAN

Swooping overhead, scurrying underfoot, and rustling through treetops and grasses, wildlife all around us are thriving because of conservation successes that allies like you help make possible. Across the globe, we collaborate with partners on innovative, multidisciplinary efforts to help ensure that wildlife—and the ecosystems we all share—can thrive.

Conservation wins mark monumental milestones, but they’re not the finish line. As we celebrate these successes, we also look ahead as we continue working to save, protect, and care for wildlife. Here are a few examples of wins you’ve been part of and the hope you bring to endangered species here in San Diego and across the globe.

For the first time in nearly 50 years, eastern black rhinos are roaming their native rangelands across Loisaba Conservancy in northern Kenya. Once abundant in this area, they disappeared due to poaching. Together with our partners, we helped translocate 21 black rhinos to a new protected sanctuary, marking a triumphant return for this critically endangered species. In the reserve, the growing population will have the space, resources, and protection they need to thrive and create a sustainable population of black rhinos in this area of Kenya once again.

Blending into the dark volcanic rock of their native Australian islands, these unusual so-called “tree lobsters” were once thought to be extinct. But in 2001, a resilient population of Lord Howe Island stick insects was rediscovered, launching international recovery efforts to secure their future. For more than a decade, the San Diego Zoo has been home to a conservation breeding program for the critically endangered insect—one of the only programs like it outside of Australia. This collaborative effort will eventually lead to the next phase, which is to reestablish populations in their native ecosystems. You can connect with this fascinating nocturnal species at the Zoo’s Wildlife Explorers Basecamp.

This spring we were overjoyed to welcome Emaay, the 250th California condor chick to hatch at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. This is a landmark moment for the local species, which once came within a breath of extinction. Emaay’s father, Xol-Xol (pronounced “HOLE-hole”), made this arrival even more special. In 1982, Xol-Xol was one of only 22 California condors remaining on Earth. Over the last 40 years, we’ve developed cutting-edge solutions to help restore sustainable California condor populations across the region. Through a long-term collaborative conservation breeding program, we incubate, hatch, and raise condors at the Safari Park for reintroduction into native ecosystems. Xol-Xol went from being one of the last of his kind on Earth to helping his species make a remarkable comeback. He’s fathered over 40 chicks and today, with help in part from Xol-Xol himself, there are nearly 600 California condors soaring over the deserts and coastlines of the American Southwest.

Przewalski’s horses are known as the last wild horses. Yet by the 1960s, they had disappeared from their native habitat. Their situation was dire, and we knew we needed to act. Together with partners worldwide, we’ve collaborated on groundbreaking conservation breeding programs to boost populations and reestablish herds across their native grasslands. Although we’ve made strides in recovering populations, the work to save this endangered species isn’t over yet.

helping bring genetic diversity back. His living cell lines were preserved in our Wildlife Biodiversity Bank’s Frozen Zoo®, and he’s now been cloned not once, but twice. In fact, Kurt and Ollie mark the first time that an endangered species has been cloned more than once. These young horses represent the essential next step in saving this species and are a beacon of hope for wildlife worldwide.

Until recently, all living Przewalski’s horses were descended from just 12 individuals. As the population increases, this lack of genetic diversity is one of the greatest challenges for the species. Fortunately, there is hope. A stallion that lived more than 40 years ago is

Beyond the sprawling savannas of the Safari Park lies the Biodiversity Reserve, an undeveloped, 1,000-acre stretch of native coastal sage scrub and chaparral habitat. It’s one of the largest remaining expanses of this type of landscape and located at the intersection of two critically important wildlife corridors. San Diego County is the most biodiverse

county in the contiguous United States, and the Biodiversity Reserve reflects that. The reserve provides a home for over 179 bird, 24 mammal, 28 reptile, and 4 amphibian species. Conservationists study resident and migratory species here to better understand how they use the land and how we can protect it through our Southwest Conservation Hub. Recently, the Biodiversity Reserve was also designated as a protected space by 30×30 California, an initiative to protect 30 percent of all lands and waters by 2030.

Conservation wins like these represent something greater than each of us. Every success holds a hope and a promise for the future of the planet we all share. Across the globe, with the support of allies like you, populations of vulnerable wildlife are increasing and landscapes are being protected. Let these tales of triumph remind you that when we work together to save, protect, and care for wildlife, there’s no limit to what we can accomplish.

DID YOU KNOW?

San Diego County is the most biodiverse county in the contiguous United States, and the Biodiversity Reserve reflects that.

MARCH 29 THROUGH APRIL 20

Become immersed in the vibrant world of pollinators as you explore Butterfly Jungle (additional ticket required). Capture amazing photos while discovering the important role butterflies play in nature. This experience includes enrichment to offer the butterflies while you explore the habitat. For full details, visit sdzsafaripark.org. Spread your wings.

MARCH 15–APRIL 6

Extend your adventure! Enjoy even more time discovering amazing wildlife and exploring everything there is to see and do at the Zoo with expanded springtime hours from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. Albert’s Restaurant has special spring break hours, too—visit zoo.sandiegozoo.org/alberts for more information. (Z)

MARCH 21 AND APRIL 18

Plant Days

On these special days, guests can take a rare look inside the Zoo’s Orchid Greenhouse from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., learn about the Zoo’s botanical collection on the Botanical Bus Tour at 11 a.m. and noon, and check out the Carnivorous Plant Greenhouse from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. A variety of plants grown by Horticulture staff will be available at the Plant Sale, happening in front of the Orchid Greenhouse entrance from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. (Z)

APRIL 19–20

Wild Weekend: Amazonia

On these special days, guests can learn more about the Amazonia Conservation Hub and wildlife of the world’s largest tropical rainforest with special activities, wildlife care specialist talks, and more. (Z)

OFFERED DAILY

Wildlife Wonders

Wildlife care specialists will introduce you to wildlife ambassadors representing San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s conservation work around the world in Wildlife Wonders, presented daily at 2 p.m. at Wegeforth Bowl. Learn about amazing wildlife from the Amazon to right here in our own backyard in San Diego and find out what everyone can do to help conserve wildlife and the world we all share. Presentation runs 15 to 20 minutes. (Z)

MARCH 2 AND APRIL 6

Member Exclusive Early Hours Rise and shine with the sights and sounds of the San Diego Zoo. One Sunday each month, qualifying members* can enter the Zoo one hour before the general public. To join us, simply present your membership card at the main entrance beginning at 8 a.m. *Excludes memberships with blockout dates. (Z)

EVERY DAY

Wild PerksSM

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance members are eligible for Wild PerksSM. Show your membership card each time you make a purchase and save up to 20%, depending on your membership level. Some exclusions apply; for details, visit sdzwa.org /membership/wild-perks. (Z)

MARCH 29–APRIL 20

Become immersed in the vibrant world of pollinators as you explore Butterfly Jungle (additional ticket required). Capture amazing photos while discovering the important role butterflies play in nature. This experience includes enrichment to offer the butterflies while you explore the habitat. For full details, visit sdzsafaripark.org. (P)

OFFERED DAILY

Journey into the Wild

Join our wildlife care specialist team as they introduce you to wildlife ambassadors representing San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s conservation work in our Amazonia and Savanna Conservation Hubs and right here in our own backyard in the Southwest. This compelling conservation presentation begins at 2 p.m. daily at Benbough Amphitheater. (P)

OFFERED DAILY

Wildlife Safari

Travel into expansive savanna habitats in the back of an open-air safari truck with an expert guide. Book online at sdzsafaripark.org/safaris or call (619) 718-3000. (P)

March Hours*

San Diego Zoo

Most days

9 a.m.–5 p.m.

Extended Hours for Spring Break

San Diego Zoo

Safari Park

9 a.m.–5 p.m.

April Hours*

San Diego Zoo

Most days

9 a.m.–6 p.m.

Extended Hours for Spring Break

San Diego Zoo

Safari Park

9 a.m.–5 p.m.

MARCH 2 AND 20; APRIL 6 AND 17

Member Exclusive Early Hours

Rise and shine with the sights and sounds of the Safari Park. On select days each month, qualifying* members can enter the Safari Park one hour before the general public. To join us, simply present your membership card at the main entrance beginning at 8 a.m. (P)

*Excludes memberships with blockout dates.

EVERY DAY

Wild PerksSM

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance members are eligible for Wild PerksSM. Show your membership card each time you make a purchase and save up to 20%, depending on your membership level. Some exclusions apply; for details, visit sdzwa.org /membership/wild-perks. (P)

sdzwa.org

(619) 231-1515

*Programs and dates are subject to change—please check our website for the latest information.

(Z) = San Diego Zoo (P) = Safari Park

Visit the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Explorers website to find out about these and other animals, plus videos, crafts, stories, games, and more!

SDZWildlifeExplorers.org

Conservation researchers and scientists have a very useful tool for studying wildlife without disturbing them. Trail cameras can provide information on animal behavior, habits, and population numbers. That knowledge helps tell the story of the habitat. Can you write your own trail story? Ask a friend or family member to give you a word that fits the type written under each blank space, and write it in the blank. After you fill in all the blank spaces, read the whole story out loud and see what kind of wild tale you came up with! It was very in the forest. The scientist placed the camera in the . The camera would take a picture every time a went by. The next day, the scientist to the camera and reviewed the footage. She saw a jaguar . Then the jaguar found and ate . It was . Then a walked by, looked right at the camera, and . Finally, a mother and her babies walked by the camera on the way to their . Just as they got there, the mother turned and waved her at the camera. The scientist was to see the footage. If not for the trail camera, she would never believe her . Studying wildlife could be so .

ADJECTIVE

ADJECTIVE

One of the largest crocodilians in the world, gharials are native to North and East India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Their long, slender snout contains more than 100 interlocking, razor-sharp teeth. We partner with the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust and Centre for Herpetology in India to help protect this critically endangered species. Photographed by Ken Bohn, SDZWA Photographer.