Stuart Greenbaum

Symphony No.6 – Pulse of the Earth (2024)

Analysis by the composer

Background

This symphony in two movements was written for The University of Melbourne Orchestra, under the direction of my colleague, Richard Davis. It was conceived at the Akiyoshidai International Art Village (AIAV) in Japan, where I was Artist in Residence in 2019, and again in 2023.

The two movements are based on permanent works of sculpture created and installed in 1998 for the opening of AIAV. Created by Japanese artists, they are quite different but equally invite our contemplation of human presence in the natural world. For new visitors to the Art Village, they function as signposts leading to the facility designed by architect Arata Isozaki. AIAV is located far away from the noise of everyday city life and is surrounded by natural resources.

The premiere performance was given by The University of Melbourne Symphony Orchestra with Richard Davis (conductor) at Hamer Hall, Melbourne, on 11 May 2025.

Orchestral forces

The work was deliberately scored to almost identical forces to my 3rd symphony; that being triple winds (with doubling), standard 4331 brass section, timpani + 4 percussion, harp and keyboards, strings. Both works were written for the University of Melbourne Symphony Orchestra (some 7 or 8 years apart) and both afforded large forces.

Composition process

The work was initially developed on a short score of 5 staves:

• melody

• motive / ostinato

• harmony / chords

• bass

• rhythm

This 5-stave grid was rarely used in full. On average, most systems involved any 3 of those 5 staves at any one time. It typically looked like this example at letter C from the 1st movement:

This format provided a little more scope than a standard grand staff (2 staves) and indicated many (but certainly not all) aspects of likely instrumentation. When scoring this in full, some changes were made but the majority of planned solos and section colours were orchestrated as intended.

The second movement was written first. It was started in Moonee Ponds (Melbourne) in June 2023. I took a sketch of around 8 bars of material to Japan later that year and finished the movement in short score. Those 8 bars did not turn out to be the beginning of the movement. I constructed a gradually revelation of the material across the first 30 bars.

In November 2023, I still had a few days left in my residency in Japan, so I sketched out the beginning material of the first movement. And that was subsequently completed back in Melbourne. I also added 32 bars to the start of the first movement once it was almost complete, partly to create a more dramatic opening, but also for balance – given everything else that had unfolded. Over the Summer of 2023/2024, I orchestrated the full 20-minute symphony, arriving at a first draft by 25 February 2024. I created orchestral parts over the Summer of 2024/2025 and in the process made some fine adjustments to some of the individual instrumental writing. This was not so much compositional revision (the piece was nominally finished) – more making each part idiomatic to play. So, from conception to a finished full score and parts, the process probably took around 18 months.

Created by Yonekichi Tanaka, Untitled No.218 outlines a giant red steel rectangle. The gate of the Art Village is located in a narrow gap between the hills. You start from the very narrow space of the gate, then a path leads you along to the broader space. As you go farther beyond the gate, you can sense how spacious the land is, how deep the green colour of the mountains is and how high the sky is.

In responding to this sculpture (which I walked or cycled past each day), I had a handful of key words:

• grand

• imposing

• delightful

• ceremonial welcome

• attracting

• generating

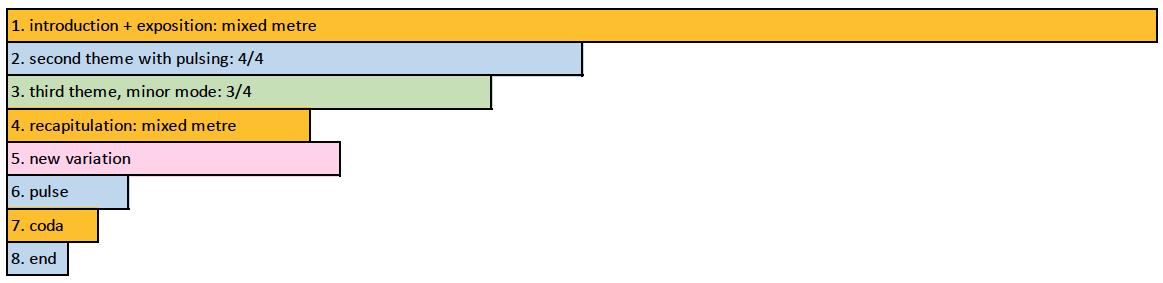

The structure of the first movement might be described as telescopic or reductive, in that the sections generally get shorter and shorter:

The slight exception is the new variation toward the end; but there is a clear overall pattern of sections getting shorter across the 10-minute duration of the first movement. This was not formally planned – it was arrived at intuitively, and only revealed upon analysis after the movement had been finished in short score.

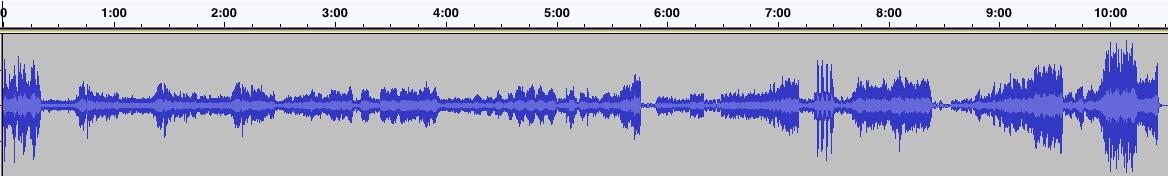

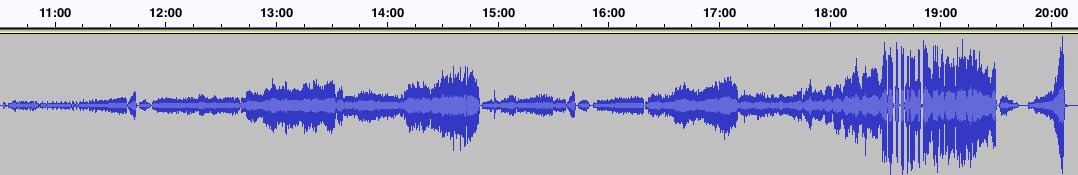

Viewed as an amplitude graph (generated by exporting the notation file to audio and opened in Audacity), highlights that telescopic shape, mapped against the bar graph laid out in a single line:

There are more intense, tutti bursts in the final third of the movement.

The idea of alternating 4/4 and 3/4 metre was conceived at the outset. Having two 4/4 bars in a row at the end of each 8-bar phrase was a subsequent adjustment to help keep the 8-bar loop fresh. This was influenced by the metrical phrasing of Philip Glass’s The Canyon (1988) which utilises this cell structure of quavers:

3+3+2+2

3+3+2+2

3+3+2+2

3+3+3+3

It’s a 10-beat phrase which lengthens to 12 beats on the 4th repeat. It adds up to 42 beats.

In the first movement of my Symphony No.6, the cell patterns (in crotchets) look like this:

2+2+3 (= 4/4 + 3/4)

2+2+3

2+2+3

2+2+2+2 (= 4/4 + 4/4)

As with the Glass example, the 4th phrase is not only a variation and a lengthening of the phrase. It also creates a longer string of 2-crotchet cells which loop back into a couple of 2-crotchet cells at the start of the sequence. It’s incidentally an inversion of the cell structure from The Canyon and adds up to 29 beats. The motives and metre are different to the work by Glass; but the concept of mixed metre, looping and a lengthening of the final phrase is a borrowed technique.

In refining the score, I found that every second loop flowed better with a further lengthening, making a combined 59-beat loop (29+30):

2+2+3

2+2+3

2+2+3

2+2+2+2

2+2+3

2+2+3

2+2+2+2

2+2+2+2

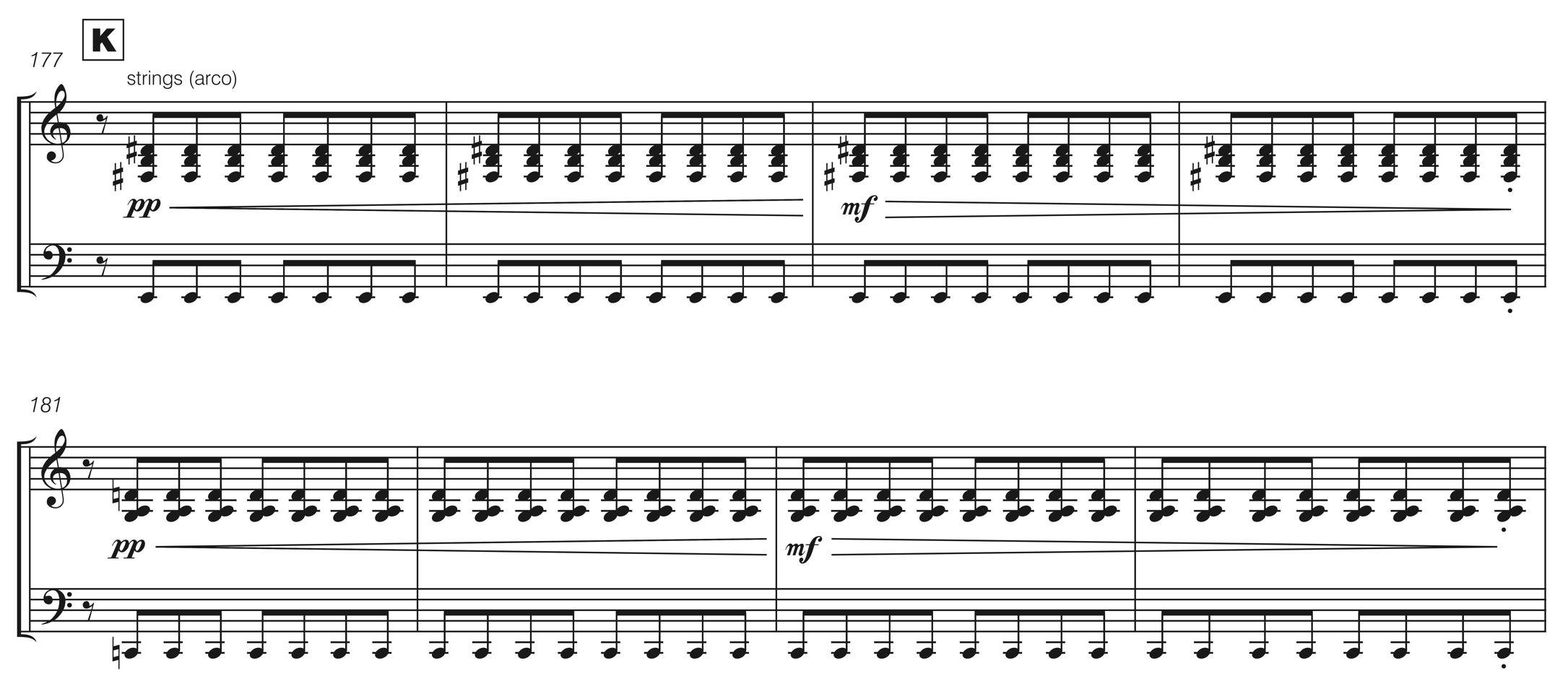

Noting that ‘2+2’ represents a 4/4 bar and that ‘3’ represents a 3/4 bar, the above pattern is therefore a 16–bar cycle. And before that cycle appears as a fully scored and harmonised ostinato at bar 33, there are two 16–bar sections. The first (bars 1–16) is an orchestral fanfare to represent the ‘grand ceremonial welcome’. This presents motivic fragments of what is to come with the full orchestra tutti in a glittering, swirling, call and answer texture, that establishes a fast tempo of crotchet = 168. The second (letter A, bars 17–32) immediately drops back to a soft dynamic. It introduces one part of the quaver ostinato against falling harmonic tones. This sets up the arrival proper of the fully formed ostinato texture at letter B, that is foregrounded in the violins:

The double quaver arpeggio pattern is designed to highlight the vibrancy of the gateway/passage into the village, mountains and blue sky. Consequently, the entire movement pulses, with the only pause or breath being at b.400 (just after letter Y).

The alternation of 4/4 and 3/4 bars is broken up by two consecutive 4/4 bars at the end of the second system and then with four consecutive 4/4 bars in the fourth system.

The double-bowed pattern could technically be compared to the violin scoring just after the opening of Schubert’s Symphony No.8 – Unfinished (1822). More by texture than motivic material.

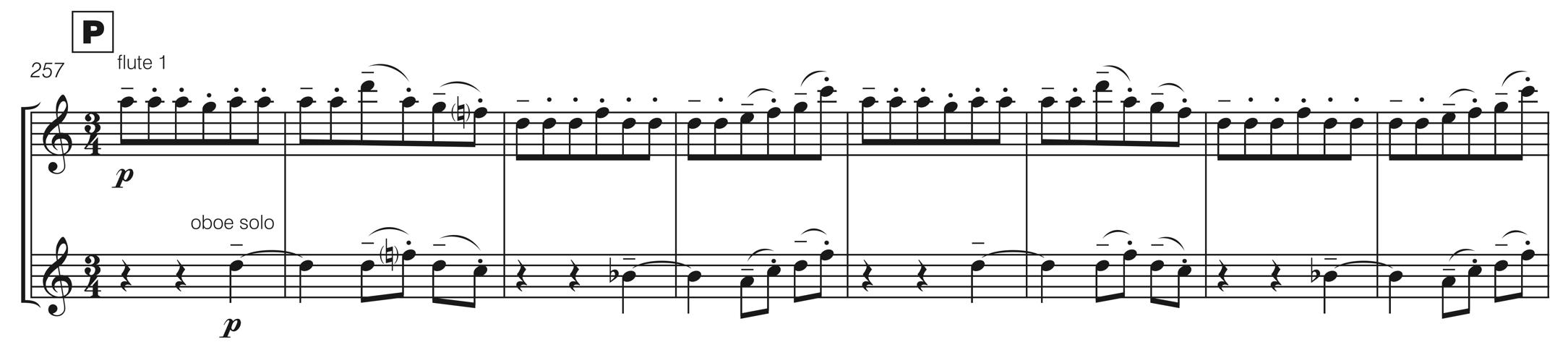

At letter C, a flute solo is overlaid against this pulsing harmonic texture:

This is the central melody of the movement. Bars 51 and 55 lock into the D∆7 harmony of the pulsing texture. The surrounding melodic shape features mostly conjunct motion. It’s repeated at letter E, harmonised in 3rds with a second flute; and it returns in the recapitulation (letters W + X) doubled with clarinets and then additional winds and violins.

The history of music is of course filled with harmonisations in 3rds. There are many examples; but the one that was perhaps most influential (even if subconsciously) at the time of writing is The Gathering Sky, cowritten by Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays on their 2002 album, Speaking of Now. This 4th track on the album opens with the melody doubled in octaves between the upright bass and piano, then in unison between electric guitar (clean) and piano. And then later harmonised in 3rds between guitar and synth. This is a particularly sweet example and hearing it on car trips (and such) was not only an outright joy, but a reminder that in the right context, simple techniques can be powerful and redolent. So that track certainly influenced me in laying down a melody over the double quaver arpeggio and then repeating it harmonised in diatonically in 3rds. Then, in the recapitulation, it returns straight up in 3rds and then harmonised fully triadically (3rds and 4ths).

The harmonic progression of the 1st movement was not planned – more developed and adjusted as the movement expanded. The starting point was the modal alternation (D∆9 / D–7) from letter A:

This reduction accounts for most of the first movement. From letter A to letter K, the reduction shows the oscillation of two chords: D∆9 and D–7 (add11). It’s a form of modal alternation. Steve Reich noted his fascination with John Coltrane, who could evidently solo over just one or two chords for extended periods:

“If you’ve got melodic changes, rhythmic complexity, and temporal variety, then you can stay put on it!” 1

1 Grossman, David Meir, Arts & Letters, April 2014

And I, in turn, was influenced by a number of Reich’s works that do that harmonically. There are many examples but a memorable one is probably Music for Mallet Instruments, Voices and Organ (1973).

Playing the 2 chords above from letter A at a piano ten times over is not interesting. But with changes in orchestration, colour, texture and motivic material, there are other parameters keeping the music moving forward. Two-chord oscillations also feature at letters K, V and Y. Sometimes the bass note is the same, other times a major third lower; but in both cases the harmonic distance is separated by 2 or 3 sharps.

Modal alternation features in a number of my works from around 2000 onward with the solo piano work, Equator Loops – but perhaps overtly from around 2008 with the second movement of my Chamber Concerto, which in turn was influenced by the pop song, War of the Hearts, released by Sade (Helen Folasade Adu) on her 1985 album, Promise. In the first movement of Symphony No.6, this modal alternation constitutes the majority of the duration of the movement.

There’s an intriguing comment from French composer, Gérard Grisey, who said: “Everybody can have an idea. Everybody. The problem is to have a second one. This is a greater problem. And the major problem is to know where and when to bring in this second idea.” 2

I decided early on in the planning stage to have some contrasting sections only in 4/4 or only in 3/4 to complement the mixed metre. This also is a technique I learned from Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays – this time from their 1984 work, The First Circle. What I didn’t yet know was how long those sections might be. In the case of the first movement, something new was needed – a second idea – and by letter K, the shift to regular 4/4 with pulsing repeated quavers in strings felt right:

This texture obviously references the music of Steve Reich. And in addition to pulsing strings, there are longer crescendo waves in the low brass that layer and contrast against that:

2 Bundler, David; interview with Gérard Grisey, 20th Century Music, March 1996.

Greenbaum, Symphony No.6 analysis, pg. 7

Reich once responded to a query about whether he was only writing fast music:

“What I’m trying to do is present a slow movement and a fast movement simultaneously in such a way tha t they make music together.” 3 The idea of fast music and slow music coexisting is a constant possibility in my own music.

I had been listening to Reich’s Variations for Winds, Strings and Keyboards (1979) in regard to brass crescendos and pulsing loops in mixed metre. I had been incorporating some of those textural ideas using my own material against that. But I later took a look at the score, just to see exactly what Reich was doing and found a few surprises. One was that the long brass section crescendos were doubled with arco double basses. I hadn’t initially picked that up just from listening and I decided to incorporate that subtle orchestrational doubling into my own score.

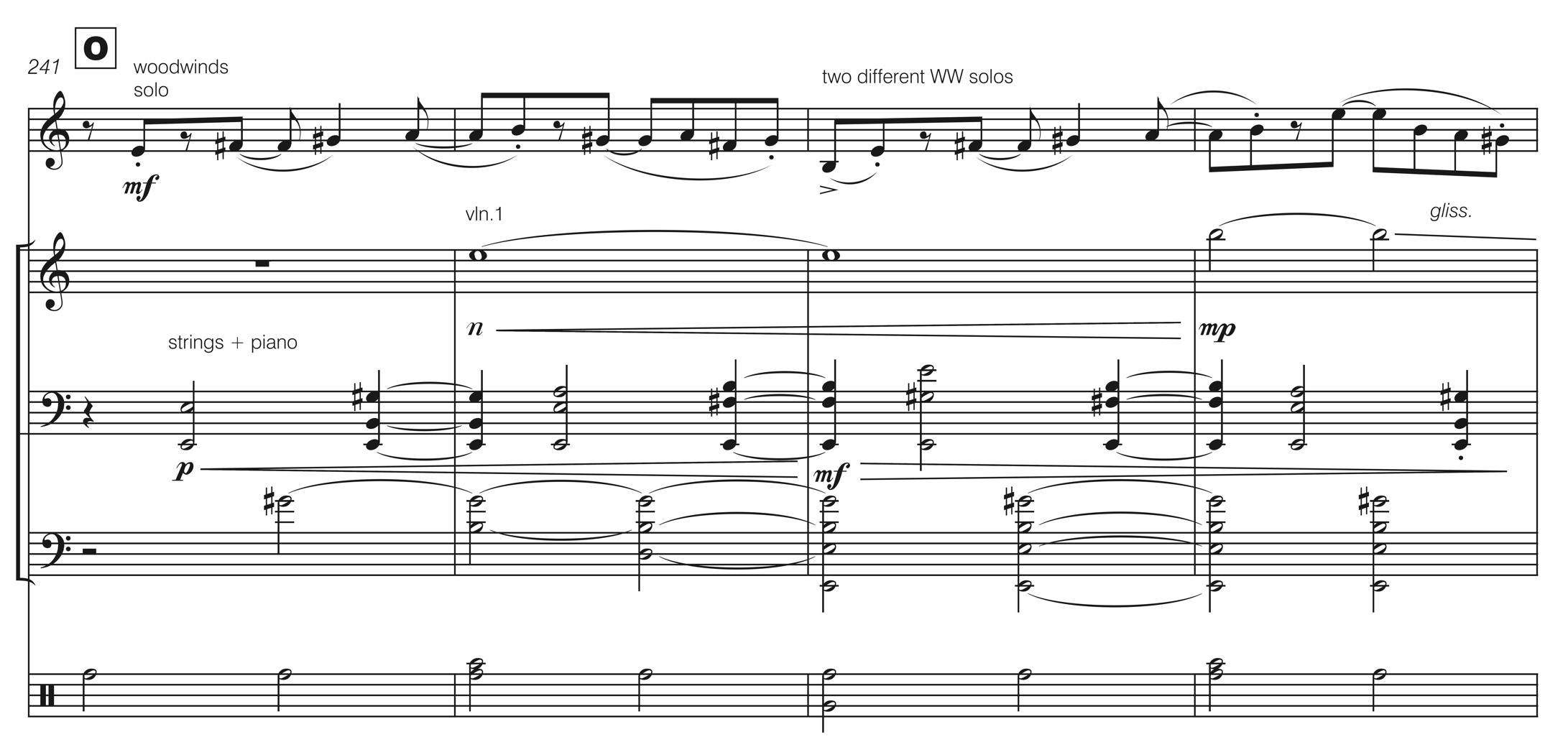

This second theme area was making use of backbeats (2+4) in the rhythmic structure. And I gradually diminished and augmented the durations of those backbeats to create a new rhythmic fabric. This can be seen at letter O:

From top staff down to bottom, the backbeats are:

• offbeat quavers

• offbeat semibreves

• offbeat crotchets

• offbeat minims

• minim pulse with offbeat semibreves (bars 2+4) and offbeat breve (bar 3)

They are all backbeats by rhythmic diminution or augmentation – even the notes that look like they are on strong beats (1+3).

3 Steve Reich in Conversation with Jonathan Cott, liner notes, The Desert Music, Nonesuch Digital 979 101-2, 1985

At letter P, there’s a third theme area in the minor mode (D Aeolian) and all in 3/4. There are some bass note variations – but the mode is stable for longer This new material also features repeated quavers, but the motivic shape is different:

It starts out just with a flute and oboe and gradually builds to feature the full orchestra. The music of Arvo Pärt has been a strong influence on my music in general for some time. When writing and developing the material at letter P, I didn’t have a particular work of Pärt’s in mind, but I was mindful of referencing his tintinnabuli technique (arpeggio against mode or scale) and augmentation of rhythmic values. This also relates to Reich’s vision of slow and fast music at the same time (layered) but plays out a little differently in style.

At letter P, the oboe solo is effectively an augmentation – revealing a 3/2 grouping spread across two bars of 3/4. This could be viewed as fast and slow music simultaneously, and also as a form of rhythmic suspension or dissonance (hemiola).

Letter V (from bar 345) represents an overt recapitulation of the opening by motive and mixed metre; though the scoring is altered for dramatic impact.

Further, from bar 393 (letter Y) the metric changes are customised, deliberately breaking patterns to create a more unpredictable flow and lift the tension and forward direction of the music. Up to this point, there has been metrical variety – but exclusively in 8–bar phrases. The phrase lengths (number of bars) from letter Y however are:

This is not the only adjustment, however, as the ordering of 4/4, 3/4 and 2/4 bars is also less patterned across these 5 phrases:

4334 4444

4334 43334

4334 43332

4334 44434

44434

It’s a subtle difference as it uses only a few motivic shapes, but it eludes prediction. The same metrical sequence could also be laid out by alternation:

That breaks up the phrase structure but shows the expansion and contraction of duple and triple metrical units.

At letter AA, there is more notable chromatic activity – especially in the falling, chromatic bass line:

It’s not only the most chromatic passage, it’s also the fastest rate of harmonic change and metrical variation – all building tension and momentum to arrive at letter BB:

The arrival at letter BB leads to a more stable D major (over a dominant pedal of A). It’s not a resolved state – more like hovering on a dominant chord waiting for resolution. But it’s stable in as far as being less chromatic and pausing the relatively fast rate of harmonic change. To the ear it feels like harmonic arrival. And it actually doesn’t resolve to the tonic anyway – it initially shifts to the subdominant (G∆9). And that underlines that the work uses tonal elements (chords, scales, voicing leading) but is not technically common practice tonality. If anything, the modality of the middle section at letter P is a more likely indicator of harmonic function: modality more than tonality.

The five chords shown at letter DD again present modal alternation. But here, almost at the very end of the movement the 3/4 metre also alternates its rhythm, deliberately grouping every 3rd and 4th bar in a 6/8 grouping (still in 3/4 metre) to create a compressed hemiola effect:

This grouping is most clear in the lower grand staff. The upper melodic line creates some rhythmic ambiguity against that. It’s all designed to increase intensity and excitement before the end of the movement, that comes to a pulsing close on D major – but with added tones (add 9+11) – again connecting to Ionian modality.

Made from an imposing single piece of polished granite, Pulse of the Earth (ancient resonance) by Takeshi Tanabe is placed in a natural state at the turnoff leading to the Art Village: “the percussionist’s pulse laps over the endless resonance of the rippling waves that never stop travelling from the past and present to the future – a pulse of the Earth that never diminishes.”

If the first movement ticks away in constant motion, the second movement ‘breathes’. It’s a slower tempo and has over a dozen pauses or breaths along the way. For this movement, there were 4 words that I used to guide the emotional feel of the music:

• solitude

• perseverance

• consolation

• weightlessness

A structural overview of the movement shows the proportion of sections:

It’s a different shape to that found in the first movement, and an amplitude graph mapped above a structural line graph creates a complimentary picture to that:

It starts quietly, builds, drops back, builds again (repeatedly). It’s working toward the biggest, final climax.

As previously noted, the second movement was written first. It was started in Moonee Ponds (Melbourne) in June 2023. This was the very first material:

It’s an adagio (crotchet = 60) in G minor, that makes chromatic use of both F# (raised leading note) and F natural (Aeolian variation). The alternation of 3/4 and 2/4 creates a larger 5-beat two-bar phrase which is repeated sequentially with a rhythmic prolongation at the end (4/4).

A reduction of those 8 bars at Letter E reveals the core harmonic progression:

While analysed here with jazz chord symbols, it doesn’t sound so much like jazz harmony. The defining features include:

• a G minor harmonic centre

• a falling chromatic bass line (G – F# - F natural)

• significant presence of added notes and chord inversions

It’s a dark harmonic palate but the mood is one of consolation. The bass line in particular is generally falling (chromatically or diatonically) and that has an effect on the atmosphere of the music.

Of course, I didn’t yet know that it would be the main theme of a second movement – nor that it would fully form after 40 bars. It the outset, it was just 8 bars of material worked out at the piano. I took that to Japan in October / November of 2023 and expanded it into a complete 10-minute movement (still in short score).

The metrical structure from bars 31–66 show the 3/4 + 2/4 alternation:

3232 32342

3232 32344

3232 3234

3232 323444

What changes is the final few bars of each line. The phrase extensions get longer, shorter, then even longer again. And these phrase extensions are generally solo instrumental bridges leading to the start of the next phrase. In short score, the endings of phrases 1, 2 and 4 (which lead into letters E, F and H) look like this:

It’s an additive process whose rhythmic durations expand to the final semiquavers, triplet quavers, quavers and crotchets by reverse engineering. Further, this example highlights a general tendency over the entire symphony to gradually, construct or deconstruct material. In the music of Steve Reich, this would be described as music as a gradual process. This symphony might be seen as a post-minimalist rendering of that ideal.

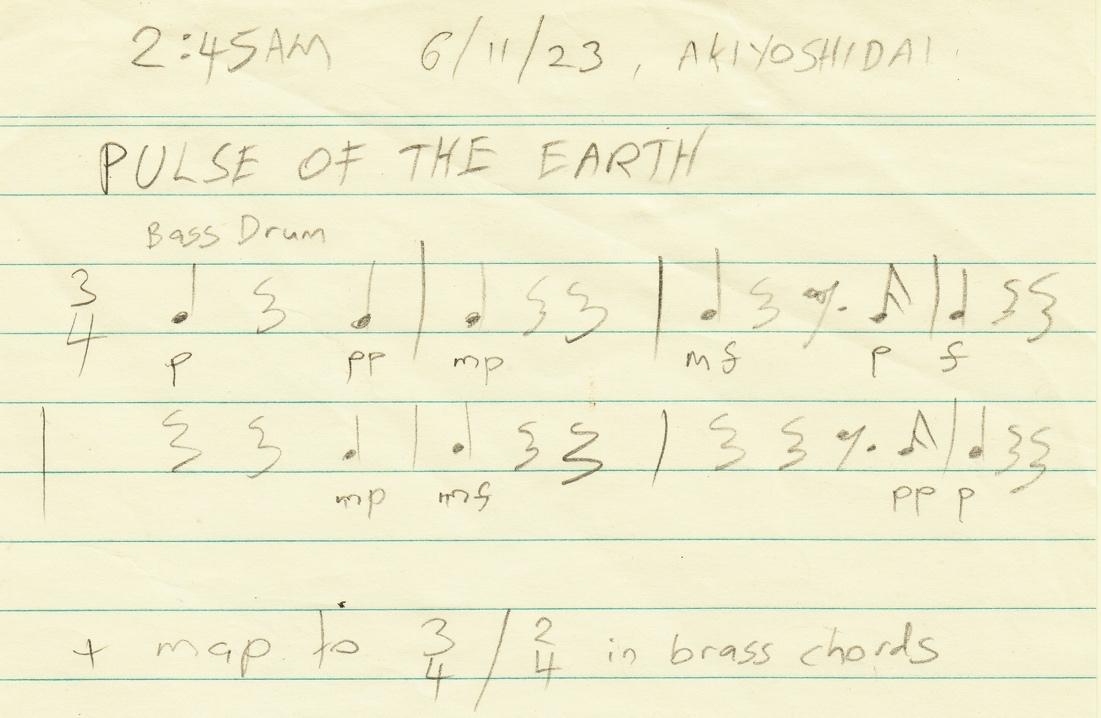

Two other notable things happened in Japan in November 2023. The first was that I woke in the middle of the night on 6 November at 2:45am and sketched out a motivic rhythm – Pulse of the Earth:

I had been thinking elliptically about this for a few days, having visited and photographed the granite sculpture of the same name. Trying to imagine what a ‘Pulse of the Earth’ might sound like. The idea of a deep pulse buried beneath the Earth – maybe like a distant, metrical earthquake – was playing on my mind. And the bass drum seemed a natural conduit for it. So, on waking, that became clear and didn’t take long to

pencil into a sketch book. I scored it in 3/4, knowing that it would also need to map to a 5-beat structure (3/4 + 2/4); but I was confident it could work in both regular 3/4 and in mixed metre.

The first 4 bars present a 2-bar motive in 3/4 with a long/short cadence. Bars 3+4 repeat that with the anacrusis beat shortened to a semiquaver. Bars 5–8 are an echo of that with two down beats removed and a dynamic shape that ebbs away (fade out) as opposed to opening 4 bars which crescendo. But while it gets louder then softer, it still emphasises the downbeat pulses.

The original harmonic motive seen at letter E was envisaged to be the basis of a monothematic work and perhaps the pulse of the Earth rhythm can be seen as another layer of that, as opposed to a completely separate idea.

But the other thing that happened to this movement as it was developing in Akiyoshidai was a growing sense that the middle of the movement might benefit from contrasting, new material. And that idea came to me while walking down the main path towards the village entrance. I hummed the theme in my head over and over until it was solid and then keyed it into a notation file when I got back to the studio. It’s first heard on a solo horn at letter H:

It initially outlines a C–7 arpeggio in the melody, but the mostly conjunct motion that follows that can be seen to relate quite clearly to the main motive from letter E. There are small differences, of course: the use of more regular 4/4 meter is sustained with the exception of a 2/4 phrase extension at the turnaround. And the harmony relates more to Eb major than the G minor that frames most of the movement.

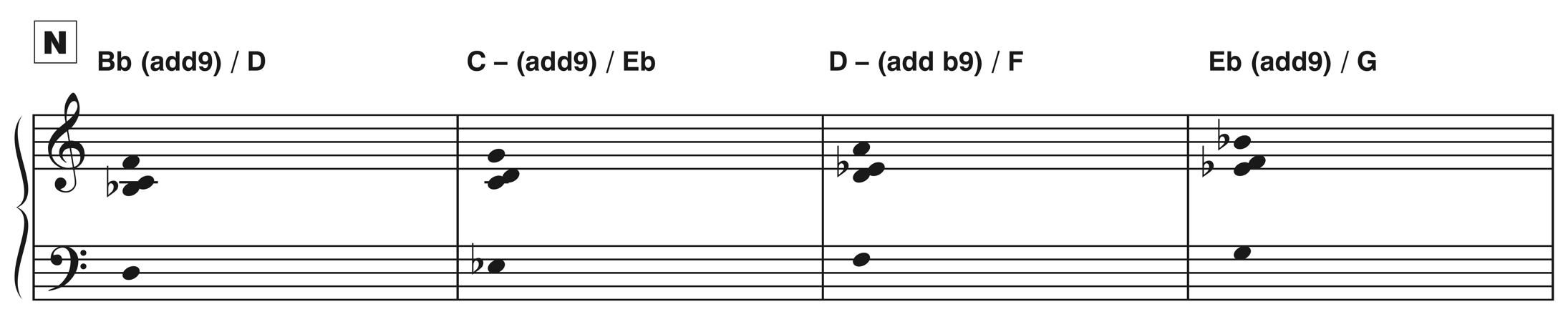

The secondary theme from letter H features a rising bass line and this is then cross-pollinated over to the return of the main theme in the major mode from letter N:

These chords are all in first inversion with added 9ths, rise sequentially and loop back over and over like a passacaglia or ground bass. The rising sequence coupled with the major mode tends to create a more uplifting feel.

It’s tempting to consider the music of Max Richter by comparison. Works like On the Nature of Daylight (2003) – partly for a similar mood of an adagio movement, but also for similar harmonic features as discussed above. I am a fan of Richter’s music and have heard much of it and been influenced by it. We were both born in the same year (1966) so we are contemporaries. But I was writing rising chord progressions like that shown at letter N back in the mid 1990’s – notably in my opera Nelson (Shadow of an Empty Cowl). That opera wasn’t fully completed until 2005 – but Shadow of an Empty Cowl dates from 1995 when I started writing the opera. And at that time, I didn’t know Richter’s music. But I did know Mozart’s Requiem (1791) – and a similar rising sequential progression of chords in first inversion can be found in the trombone solo of the Tuba Mirum. The example above is like Mozart with added 9ths.

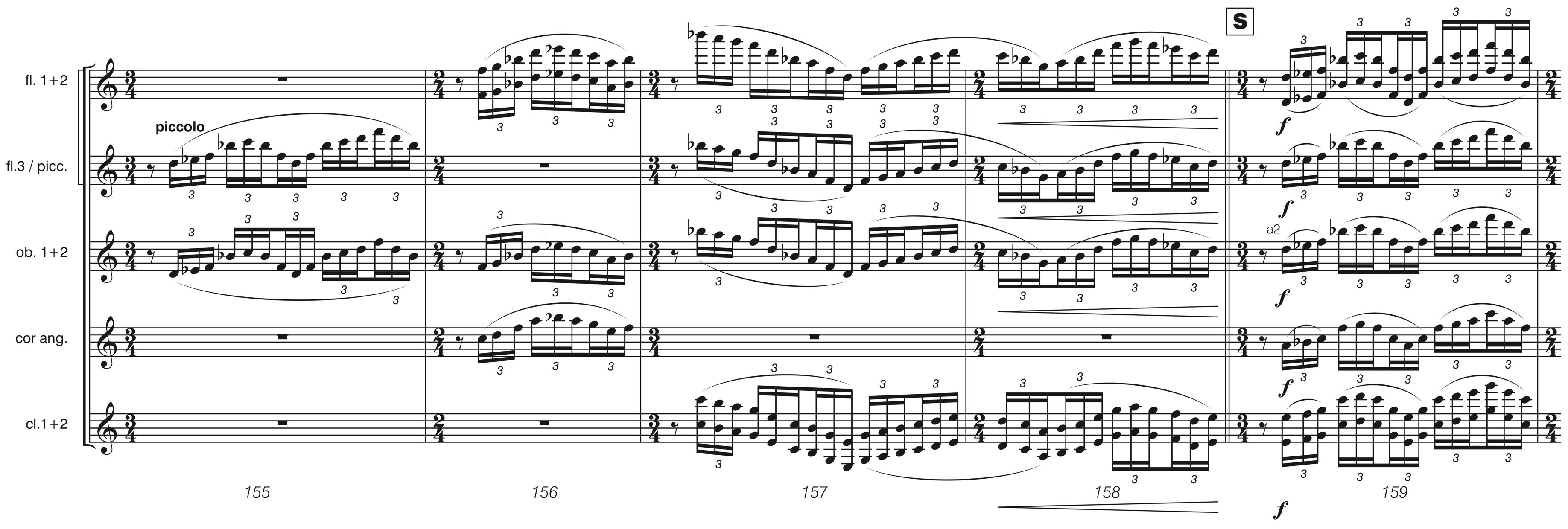

As this rising sequential 4-bar harmonic progression builds, upper woodwinds gradually add ornamental arpeggio figures in triplet semiquavers from letter P:

These woodwind solos thicken in doubling and grow in length so that by letter S it forms an almost unbroken arpeggio flow adding a swirling energy as the music heads toward the arrival climax:

The Pulse of the Earth rhythm mentioned earlier, is presented on solo bass drum at the opening of the second movement. It is subsequently woven through the subsequent musical discourse, notably at letters C, J, L, R and S. And as the movement builds, the Pulse of the Earth rhythmic motive is fused with the harmonic sequence of letter N to create the climax/arrival at letter T:

These monolithic chords are intended to echo out through the auditorium. The rests do not result in complete silence (due to acoustical reverb) but they create tension or expectation – as the audience waits for, anticipates the next chord in the rising sequential cycle that we have been listening to all along. The chords are familiar, the rhythm is familiar – but this final merger of the two intertwined ideas breaks the music down to its essential bare elements in dramatic fashion.

With the exception of the middle interlude (letter H), the second movement might be considered largely monothematic. It develops and grows toward the climax statement at letter T (shown above). That climax is pushed further upward in pitch and intensity until exhausted. A small chamber music variation leads to a final sustained crescendo in D major adding in strings, woodwinds and brass incrementally:

There are two ideas at play here. The first is that after hearing almost 10 minutes of sequential harmony with inversions, chromatic adjustments and modulation, the work comes to rest on a stable harmonic triad. The second though is that upon arrival at letter X, the woodwinds, brass and strings fall silent, revealing that same D major chord but with an added 9th and 11th and all in percussion. We don’t initially hear the percussion entry – that timbre and additional harmonic colour is revealed when the other instruments stop sounding. It’s a type of surprise egg – an epicurean analogy for a hidden centre to a dish. A final subtle surprise that rings and jangles.

Works for reference

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Requiem (1791)

Franz Schubert, Symphony No.8 (1822)

Steve Reich, Music for Mallet Instruments, Voices and Organ (1973)

Steve Reich, Variations for Winds, Strings and Keyboards (1979)

Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays, The First Circle (1984)

Sade (Helen Folasade Adu), War of the Hearts (1985)

Philip Glass, The Canyon (1988)

Stuart Greenbaum, Equator Loops (1999/2000)

Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays, The Gathering Sky (2002)

Max Richter, On the Nature of Daylight (2003)

Stuart Greenbaum, Nelson (2005)

Stuart Greenbaum, Chamber Concerto (2008)

Stuart Greenbaum, Symphony No.3 (2017)

article © Stuart Greenbaum, March 2025