BROWN

From Here

for Ensemble and optional Chorus

Score

for Ensemble and optional Chorus

Score

L E I P ZI G · L ONDO N · NE W YOR K

Earle Brown

Commissioned by The Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, New York

First performance: October 11, 1963, Town Hall, New York

Conductors: Earle Brown (orchestra), Alvin Lucier (chorus)

Score (transposed)

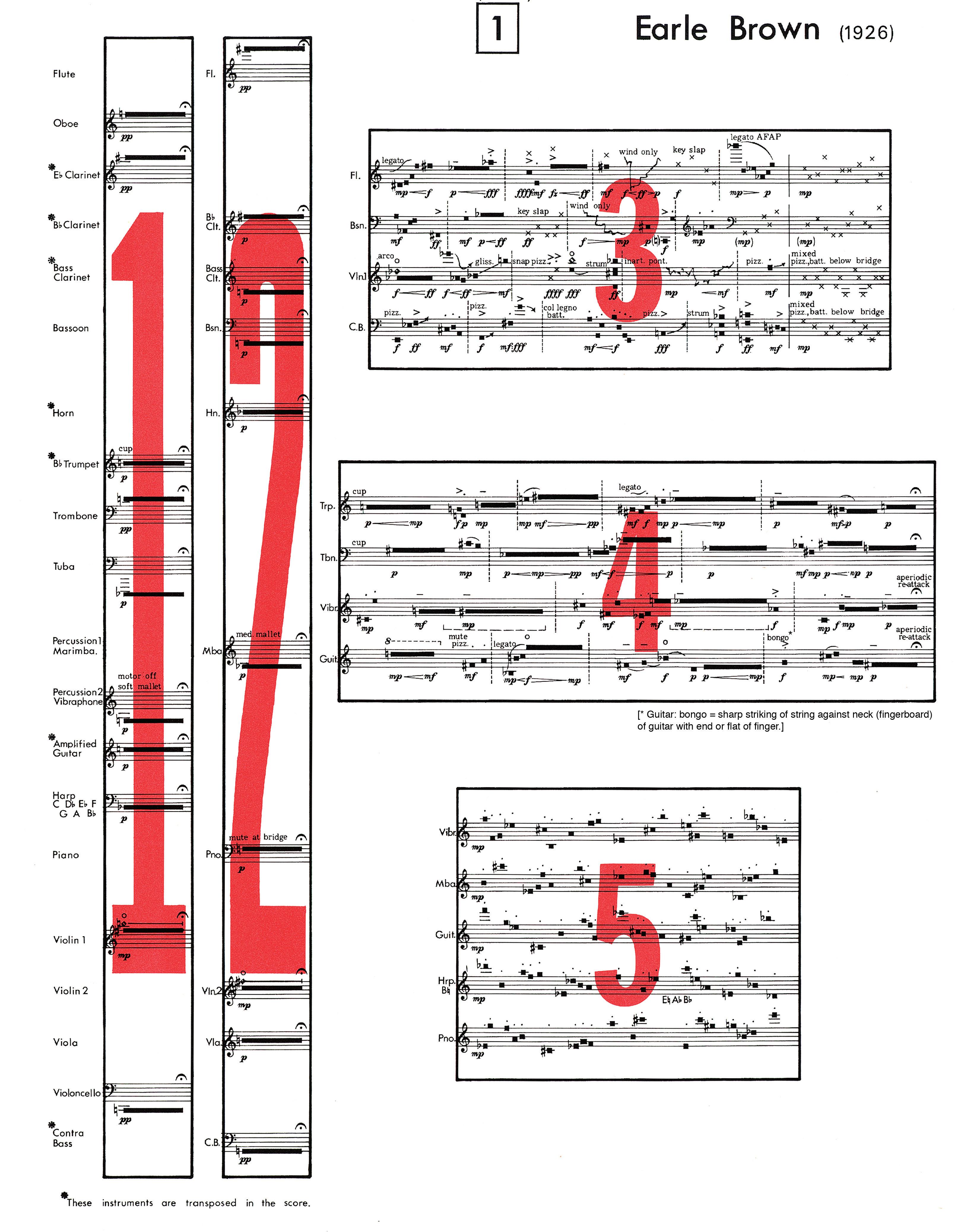

Instrumentation

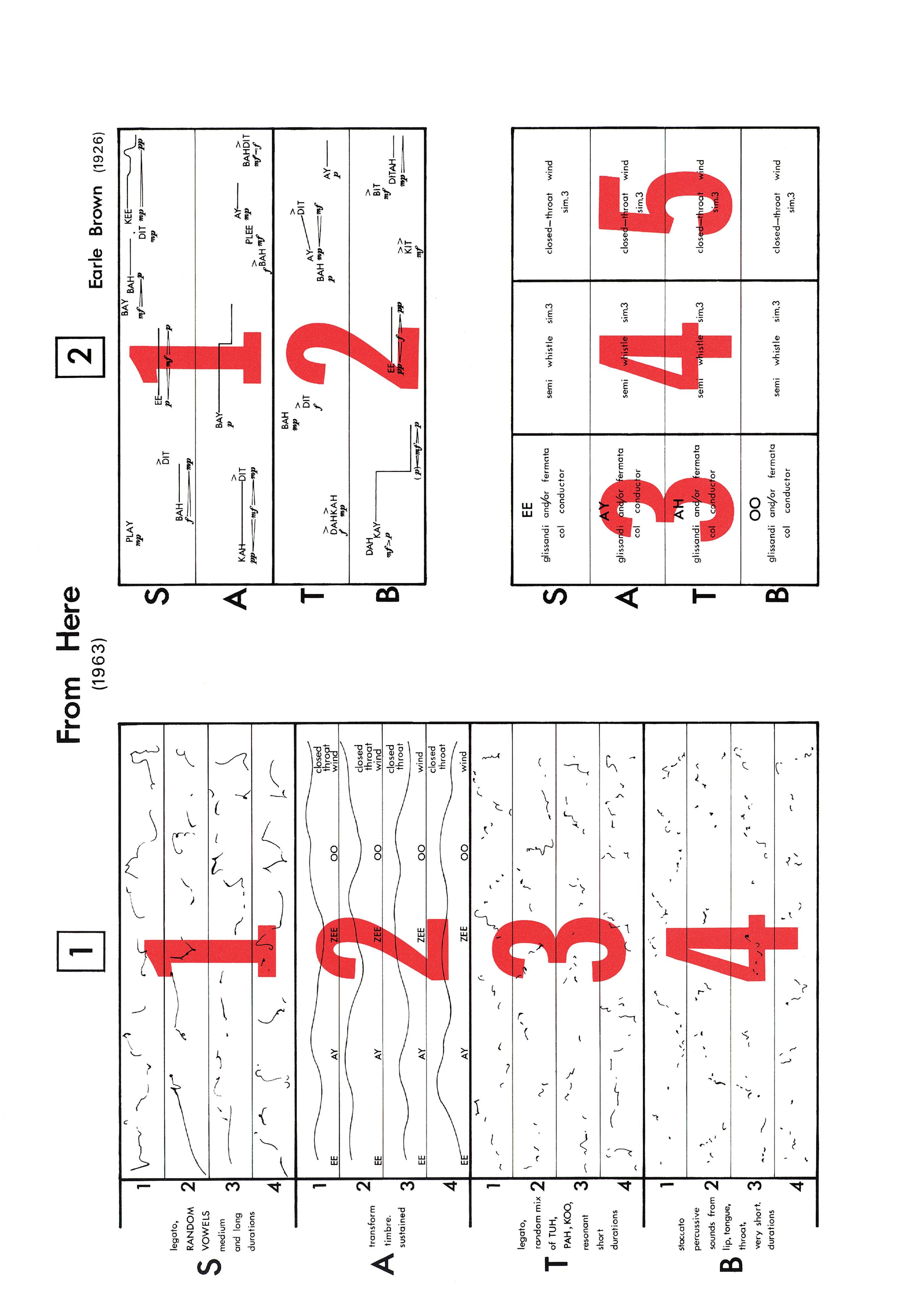

Chorus SATB (optional; requires an additional conductor)

Flute

Oboe

E Clarinet

B Clarinet

Bass Clarinet Bassoon

Horn

B Trumpet Trombone

Tuba

Piano Harp

Amplified Guitar (with volume pedal)

Percussion 1 Glockenspiel Marimba Tympani

Percussion 2 Xylophone Vibraphone Tympani

2 Violins

Viola

Violoncello Contrabass

Duration: 10 -20 minutes

The conductor needs an arrow indicator with numbers 1 - 3 (provided with score) to show the musicians which page to perform from.

Spontaneous decisions in the performance of a work and the possibility of the composed elements being “mobile” have been of primary interest to me for some time; the former to an extreme degree in FOLIO ( 1952 ), and the latter, most explicitly, in TWENTY FIVE PAGES ( 1953 ). For me, the concept of the elements being mobile was inspired by the mobiles of Alexander Calder, in which, similar to this work, there are basic units subject to innumerable different relationships or forms. The concept of the work being conducted and formed spontaneously in performance was originally inspired by the “action-painting” techniques and works of Jackson Pollock in the late 1940 s, in which the immediacy and directness of “contact” with the material is of great importance and produces such an intensity in the working and in the result. The performance conditions of these works are similar to a painter working spontaneously with a given palette.

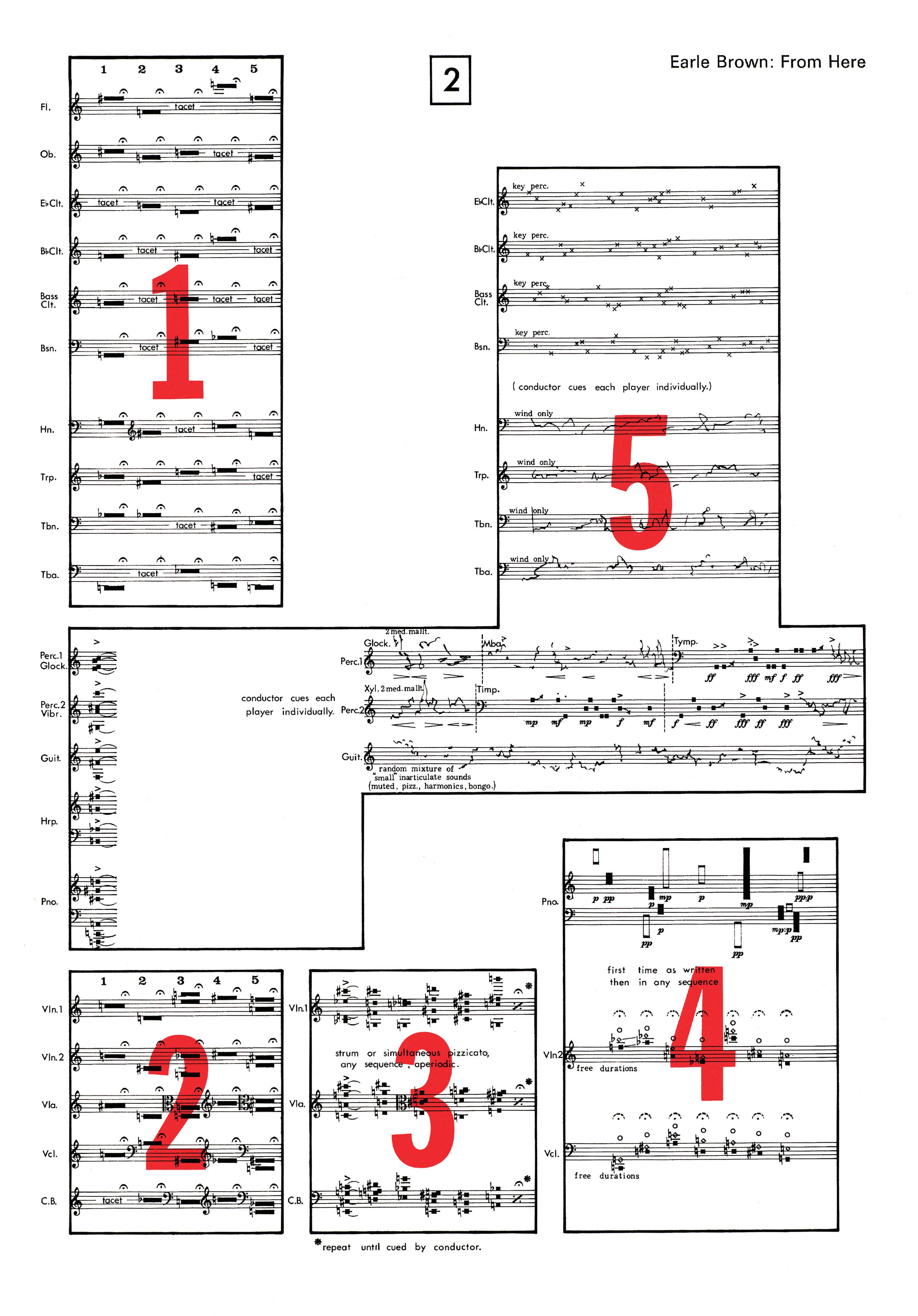

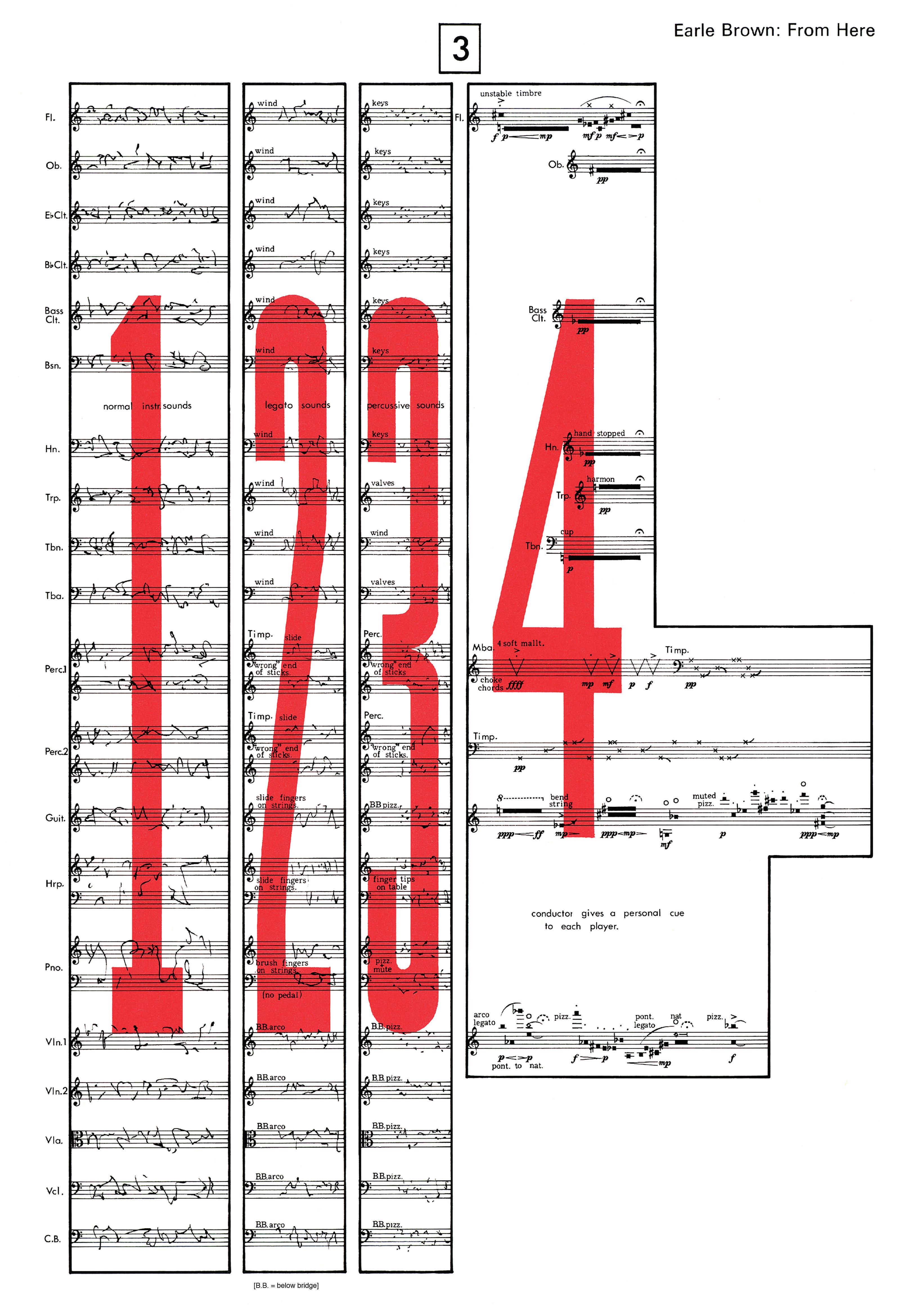

In FROM HERE , the instrumental sound materials are fully composed for the most part. Of the 14 sound-events, 4 are primarily “graphic” (rhythm, trajectory, color and density indicated only by drawings of the activity), the other 10 sound-events being very specifically notated in regard to the above qualities but in the rather flexible “timenotation” that I have used since 1952. The chorus materials are phonetic sounds and the vocal action is indicated graphically but organized in sonic and texturally controlled “events.” The orchestral material may be performed apart from the chorus but the chorus material is not basically intended to be performed independent of the orchestra.

The conductor of the orchestra is primarily the one responsible for the “forming” of the work in performance. He may begin the performance with any one or more of the 14 sound-events in the orchestral score or he may give a cue to the chorus conductor to begin with a vocal event, the chorus being one of the elements that he may call for within the process-evolution of the piece. After cueing the chorus conductor, the conductor of the orchestra cannot be exactly certain of which chorus event will be forthcoming.

He then responds with orchestral sound-events which seem complementary and appropriate.

In this manner of collaborative feedback the piece begins its growth and process-development to become the poetic and formal expression of itself which is unique to that particular performance. If the chorus is not used in a performance the feedback still exists between the conductor, the musicians and the various potentials inherent in the sound-events themselves.

The conductor(s) may conduct the events in any sequence or juxtaposition, in changing tempi, loudness, and in general mold and form the piece. The inherent flexibility of the materials allows the work to constantly transform itself and re-express its potential, while the sound materials and characteristics which I have composed contain the essential “identity” which makes this work different from any other.

I have felt that the conditions of spontaneity and mobility of elements which I have been working with create a more urgent and intense “communication” throughout the entire process, from composing to the final realization of a work. I prefer that each “final form,” which each performance necessarily produces, be a collaborative adventure, and that the work and its conditions of human involvement remain a “living” potential of engagement.

Either conductor may begin a performance with any event on any page and may proceed from any page to any other page at any time, with or without repetitions or omissions of pages or events, remaining on any page or event as long as he wishes. Both conductors conduct simultaneously but independently. This “independence” is of course conditioned by the coexistence of the other group and, ultimately, is a collaborative and dependent process. It must be understood that this is one composition for essentially one group, a performance of which is the product of sympathetic musical collaboration between the two conductors in relation to the composed material and its formal potential.

The numbers of the score pages to be played from are indicated to the musicians by a movable arrow on a placard displaying the page numbers 1 to 3 — the number and arrow being clearly visible to all members of the group, and the arrow comfortably within reach of the conductor.

It is suggested that the podium be wide enough (or that enough music stands be used as a podium) for all score pages to fit next to one another so as to be visible to the conductor at all times during the performance. (In the parts, all of the events on all of the pages are visible to the musicians without the necessity of page turns.)

There is a built-in factor of flexibility in the notation and scoring of this piece because the availability of forms is based on letting go of the idea of metric accuracy. This is achieved through the notational system used in this work. This system, which I have called a “time-notation,” is a development of the work in FOLIO (1952 and 1953) and most clearly represents sound-relationships in the score as I wish them to exist in performance, independent of a strict pulse or metric system.

It is a “time-notation” (now generally called “proportional notation”) in that the performer’s relationship to the score, and the actual sound in performance, is realized in terms of the performer’s time-sense perception of the relationships defined by the score and not in terms of a rational metric system of additive units. The durations are extended visibly through their complete space-time of sounding and are precise relative to the space-time of the score. It is expected that the performers will observe as closely as possible the “apparent” relationships of sound and silence but act without hesitation on the basis of their perceptions.

It must be understood that the performance is not expected to be a precise translation of the spatial relationships but a relative and more spontaneous realization through the involvement of the performers’ subtly changing perceptions of the spatial relationships. The resulting flexibility and

natural deviations from the precise indications in the score are acceptable and in fact integral to the nature of the work. The result is the accurate expression of the actions of people when accuracy is not demanded but “conditioned” as a function within a human process.

The graphic notations as in events 1 , 2 and 3 on page 3 are a generalized way of indicating instrumental activity and non-characteristic sounds. Observe very carefully the character and rhythm of the graphics, the verbal indication of technique of articulations, and the approximate frequencies covered by the rise and fall of the graphic line. All sounds are basically delicate, rambling and microtonal.

The conducting technique is basically one of cueing ; the notation precludes the necessity and function of “beat” in the usual sense (although the conductor does indicate the relative tempo). The page which contains the event to be played is indicated by the arrow, as previously explained. The number of the event to be performed is indicated by the left hand of the conductor — one to five fingers. A conventional (right-hand) down-beat initiates the activity. The relative speed and dynamic intensity with which an event is to be performed is implied by the speed and largeness of the down-beat as given with the right hand. Nearly all of the events in the score have been assigned dynamic values. These are acoustically accurate in terms of instrumental and ensemble sonority and balance and must be respected as written, although the conductor may “over-ride” the indicated dynamic values and raise or lower the over-all loudness.

The conception of the work is that the score presents specific material having different characteristics, and that this material is subject to many inherent modifications, such as modifications of combinations (event plus event), sequences, dynamics, and tempos, spontaneously created during the performance. All events are always prepared by a left-hand signal and initiated by a down-beat from the conductor; the size and rapidity of the down-beat implies

the loudness and speed with which the event is to be performed. The conductor must, as with any notation, insist on accurately articulated relationships from the rhythmic “shape” of phrase and pitch sequences in this work.

CONDUCTED FERMATA : the conductor may introduce a fermata at any time during the performance, in any single event or combination of events. Both hands cupped towards the orchestra and held stationary indicates that all musicians in that group should hold the sound or silence which they are at that moment performing, until the next sign from the conductor tells them either to cut off or to continue from the point of interruption. A cut-off is signaled with both hands and must be followed by another eventsignal from the left hand and a down-beat. To continue , the conductor moves both hands from the “hold” position back to the body and then outward towards the orchestra, palms up (as if giving the initiative back to the orchestra).

CONDUCTED STOP : the conductor may stop any event or combination of events at any time during the performance. The normal, two-hand cut-off signal will silence his entire group. Leaving the hands up will hold that silence until the signal to continue from the point of interruption is given. If the hands do not remain up in “hold” position, the musicians are to expect another event-signal from the left hand, and a down-beat.

MODIFICATION OF SINGLE EVENT : any two-hand cut-off signal affects the entire group. The conductor may wish, however, to modify only one event among two or more events being performed simultaneously. To do this he signals the number of the event to be modified with his left hand; then indicates the modification — a hold or cut-off — with only his right hand. (Events not indicated by the fingers of the conductor’s left hand continue to proceed normally.) It is absolutely essential that the orchestra members clearly understand this difference in signaling: a hold or cut-off by both hands affects an entire group; a hold or cut-off by only the right hand

affects only the event indicated by the fingers of the left hand. Players whose parts do not contain events signaled by the conductor’s left hand must remain unaffected by his subsequent right-hand indications.

As soon as the conductor initiates (by left-hand eventsignal and right-hand down-beat) a new event that appears on the player’s part, the preceding event is automatically cancelled. No specific stop-signal is required. The player simply discontinues the event he is playing and, without break between events, begins to play the new one.

With these procedures clearly understood by the conductor and the musicians it is possible to achieve smooth transitions and long lines of connected material of extreme complexity and frequent modification. The first impression derived from the score will be one of many sporadic fragments. This wealth of fragments shows the numerous formal possibilities inherent in the work, and it is this realization, not the fragmentations, that must become the dominant characteristic of performance.

DYNAMICS : all indications of dynamics are relative to the instrumental technique and register of the particular sound called for, i.e., a string sound to be played col legno tratto , sul ponticello , with a dynamic of ffff, must be played as loudly as possible regardless of the dynamic intensity produced by the same dynamic marking in an instrument of a different nature. Thus, a low C in the flute marked ffff is not expected to have the same volume as a middleregister tone marked ffff in a clarinet. This simply means that the flutist is to play his tones at the maximum volume available in that register of his instrument. The pppp indicates that the sound is to be as soft as possible. All dynamic indications are “balanced” in this way, relative to their acoustic functions within the event-structures and the characteristics of the instruments employed in them.

Earle Brown

Earle Brown was born in 1926 in Lunenburg, Massachusetts, and in spirit remained a New Englander throughout his life. A major force in contemporary music and a leading composer of the American avantgarde since the 1950s, he was associated with the experimental composers John Cage, Morton Feldman and Christian Wolff, who – together with Brown – came to be known as members of the New York School. Brown died in 2002 at his home in Rye, New York.

Earle Brown wurde 1926 in Lunenburg, Massachusetts, geboren und blieb im Geist ein Leben lang Neuengländer. Ab den 1950er Jahren war er eine treibende Kraft in der zeitgenössischen Musik und einer der führenden Komponisten der amerikanischen Avantgarde. Enge Verbindung unterhielt er zu den experimentellen Komponisten John Cage, Morton Feldman und Christian Wolff, mit denen gemeinsam er später der sogenannten New York School zugerechnet wurde. Brown starb 2002 in seinem Haus in Rye, New York.